Photograph by Stephen Gaillard

Portrait by Richard Banks

H.I.H. THE GRAND DUCHESS ANASTASIA NICHOLAEVNA OF RUSSIA

Title: Anastasia: The autobiography of H.I.H. the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nicholaevna of Russia

Author: Eugenia Smith

Dubious author: Emperor of Russia daughter of Nicholas II Grand Duchess Anastasiia Nikolaevna

Release date: July 28, 2022 [eBook #68616]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Robert Speller & Sons, 1963

Credits: Thomas Frost, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

$5.95

This is the only authentic autobiography of the Grand Duchess Anastasia Nicholaevna, fourth daughter of the late Emperor Nicholas II and the late Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia.

The Grand Duchess Anastasia furnishes authentic information and many previously unpublished details concerning the life of the Imperial Family and suite from the days of her childhood to the date of the murder of her parents and other members of her Family in Ekaterinburg on the night of July 16-17, 1918.

Her story is divided into six major parts: the youthful years, the period of the First World War, arrest and exile, life in Tobolsk, life in Ekaterinburg, and the period after the tragedy which includes her rescue and escape to Bukovina.

The life of a Grand Duchess of Russia was no downy bed of roses. Discipline was imposed by the Tsar and Tsarina, particularly the latter. Study was an essential duty which took many hours. During the war years there were responsibilities connected with the operation of hospitals for the wounded. Always over the Family hung the fear of the possible demise of the heir to the throne, the young Tsesarevich and Grand Duke Alexei Nicholaevich, who had inherited haemophilia through his Mother.

The Grand Duchess Anastasia rejects vigorously various accusations directed against each of her parents. She explains in her preface the reasons for her long submergence and for her present re-emergence forty-five years after her reported death.

Her style is brisk and invigorating. Her sense of humor repeatedly delights with accounts of lighter events and anecdotes.

This is an invaluable historical record.

ROBERT SPELLER & SONS, Publishers

33 West 42nd Street

New York, N.Y. 10036

[Pg ii]

Photograph by Stephen Gaillard

Portrait by Richard Banks

H.I.H. THE GRAND DUCHESS ANASTASIA NICHOLAEVNA OF RUSSIA

[Pg iii]

The Autobiography of H.I.H. The Grand Duchess

Anastasia Nicholaevna of Russia

Volume I

ROBERT SPELLER & SONS, PUBLISHERS

New York

[Pg iv]

© 1963 by Robert Speller & Sons, Publishers, Inc.

33 West 42nd Street

New York, New York 10036

Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 63-22672

First edition

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

[Pg v]

I dedicate this book

To My Family:

To My Father, His Imperial Majesty, the Emperor Nicholas II,

To My Mother, Her Imperial Majesty, the Empress Alexandra Feodorovna,

To My Brother, His Imperial Highness, the Tsesarevich Alexei Nicholaevich,

To My Sisters, Their Imperial Highnesses, the Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, and Marie;

To those dear and understanding friends who perished with My Family in Ekaterinburg;

Dr. Eugene Botkin, Mlle. Anna Demidova, Ivan Kharitonov, and Trup;

To those faithful friends and companions who, because of their loyalty to us, perished before or after the tragedy which befell My Family:

Countess Anastasia Hendrikova, Mlle. Ekaterina Schneider, Prince Vasily Dolgorukov, Count Ilia Tatishchev, Nagorny, Chemodurov, and Ivan Sidniev;

To My Brother’s youthful companion and helper, whose fate I never learned:

Leonid Sidniev;

To My Uncle, His Imperial Highness, the Grand Duke Michael Alexandrovich, and his secretary and friend, Nicholas Johnson, both of whom disappeared, apparently murdered by the Bolsheviks;

To My Aunt, Her Imperial Highness, the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna, and her faithful nun, Varvara, who were brutally murdered by the Bolsheviks;

To other members of the Imperial Family who were murdered by the Bolsheviks;

To all members of the Imperial Family who died during the First World War and the Civil War in Russia;

To all members of the Imperial Family, living and dead, who survived the Bolshevik revolution;

[Pg vi]

To those dear and helpful friends:

Count Apraxin and Captain Nilov;

To the two officers who came to pay their respects and salute My Father for the last time at the station at Tsarskoe Selo just before our departure for Siberia:

Kushelev and Artasalev (?);

To friends who voluntarily accompanied My Family into exile;

To my rescuer, Alexander;

To Nikolai; to the Serbian, the Croatian, and the former Austrian soldier; and to all others who befriended and aided me during the long journey from the vicinity of Ekaterinburg to a refuge in Bukovina;

To those millions of heroes of the Russian Empire, sung and unsung, who gave their lives in defense of their country against the Central Powers and against the Bolsheviks;

To all members of the Imperial Armed Forces who served their Emperor and their country faithfully and loyally at all times;

To the millions who died in Russia from execution, starvation and other causes deriving from Bolshevik cruelty, tyranny and misrule;

To the members of the Imperial Armed Forces who are now living outside their homeland and especially those among them who are maimed and destitute;

To all who have helped me in any way since I left Russia;

To all these—departed and living, known and unknown, relatives and friends—I am eternally grateful.

[Pg vii]

The present book could never have been completed without the encouragement, inspiration and help of friends who were interested in having the story of my family, as known to me, the youngest of the four daughters of the late Emperor Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra, and my own story made known to the world.

My indebtedness to these friends is deep and lasting. First of all must be mentioned the late Mrs. Helen Kohlsaat Wells, a close friend and confidante for many, many years. She worked with me closely during the years 1930 to 1934 during which we completed the first complete draft of the manuscript. Many years later we worked intermittently on revising the manuscript until Mrs. Wells’ untimely death. Also in a separate category is the late Mr. John Adams Chapman, whose friendship and counsel were so valuable at all times. Deserving of special gratitude are Mrs. Marjorie Wilder Emery, Miss Edith Kohlsaat, Mr. and Mrs. Norman Hanson, Mrs. John Adams Chapman, Mr. and Mrs. Louis Ellsworth Laflin, Jr., and Mr. and Mrs. Francis Beidler II.

[Pg ix]

| List of Illustrations | xi | |

| Author’s Preface | xiii | |

| PART ONE | THE YOUTHFUL YEARS | 1 |

| Chapter I | Earliest Memories | 3 |

| Chapter II | School Days | 15 |

| Chapter III | Cruises | 25 |

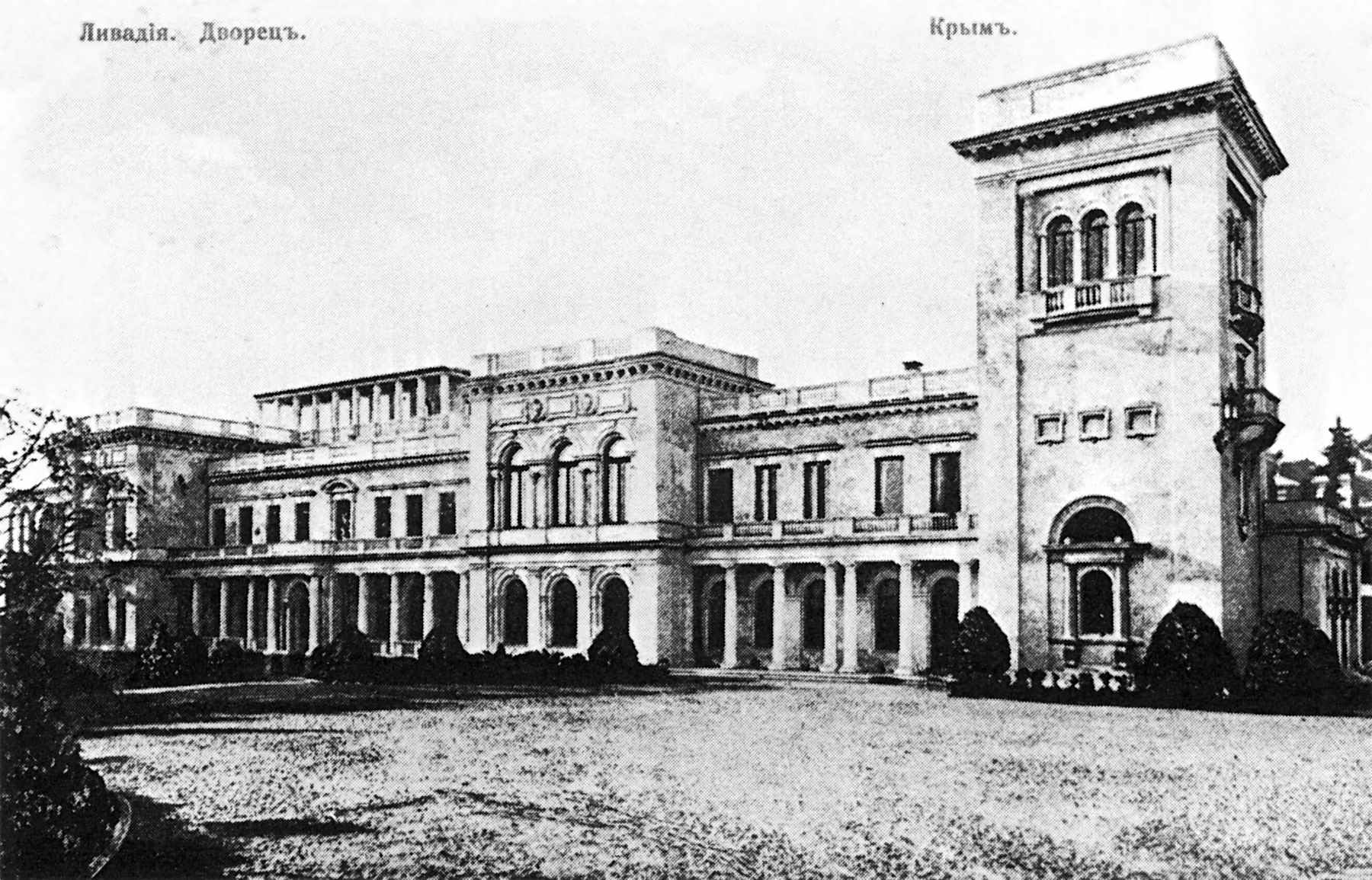

| Chapter IV | The Crimea | 40 |

| Chapter V | Spala: 1912 | 53 |

| Chapter VI | Jubilee: 1913 | 66 |

| PART TWO | THE FIRST WORLD WAR | 73 |

| Chapter VII | Eve of the War: 1914 | 75 |

| Chapter VIII | No Choice But War | 83 |

| Chapter IX | Family Heartaches | 95 |

| Chapter X | Mogilev | 113 |

| Chapter XI | Our Last Autumn in Tsarskoe Selo | 126 |

| Chapter XII | Revolution | 140 |

| Chapter XIII | Abdication | 152 |

| PART THREE | ARREST AND EXILE | 171 |

| Chapter XIV | Arrest | 173 |

| Chapter XV | Subjugation | 182 |

| Chapter XVI | Departure | 193 |

| Chapter XVII | Journey | 203 |

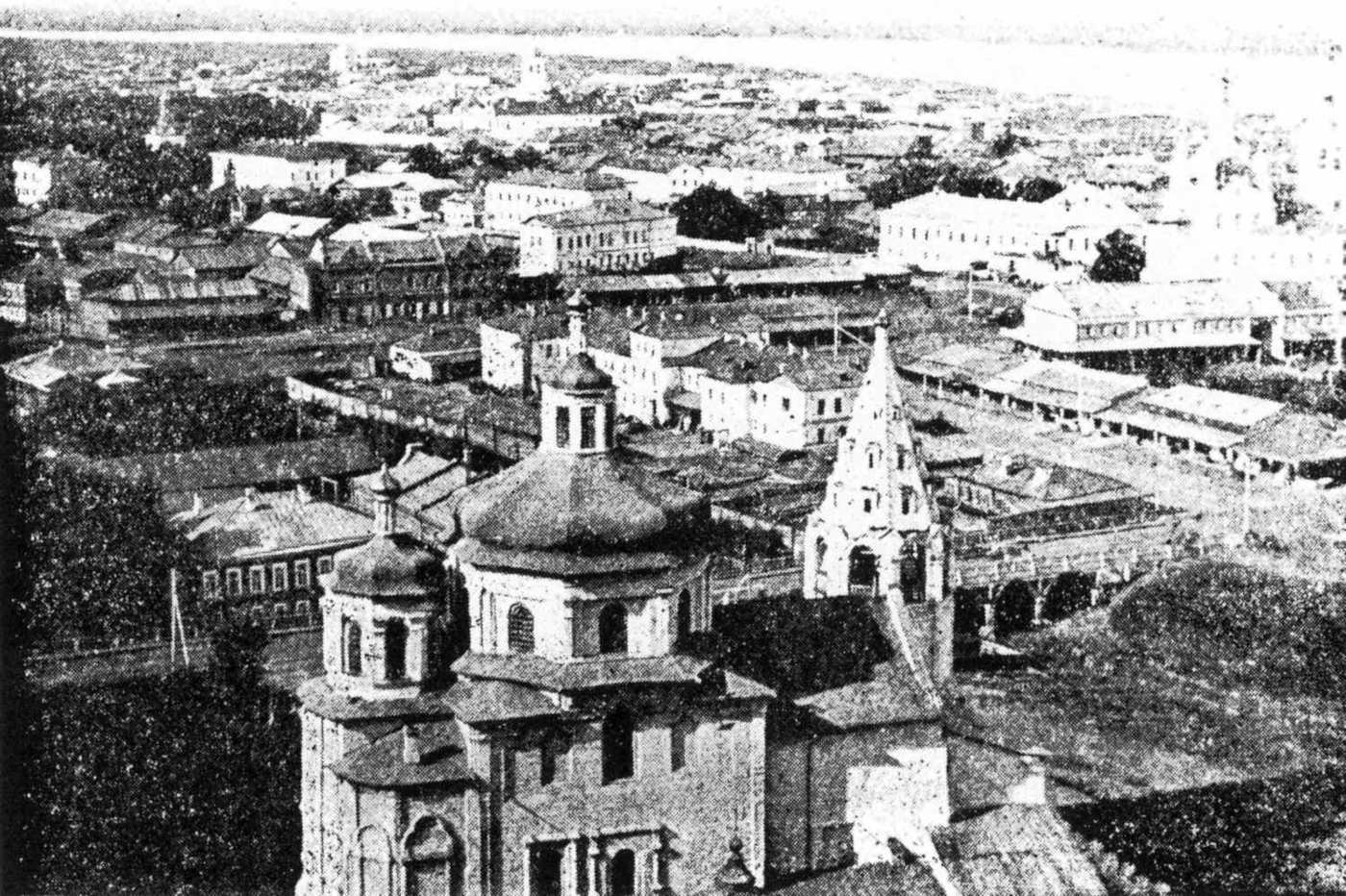

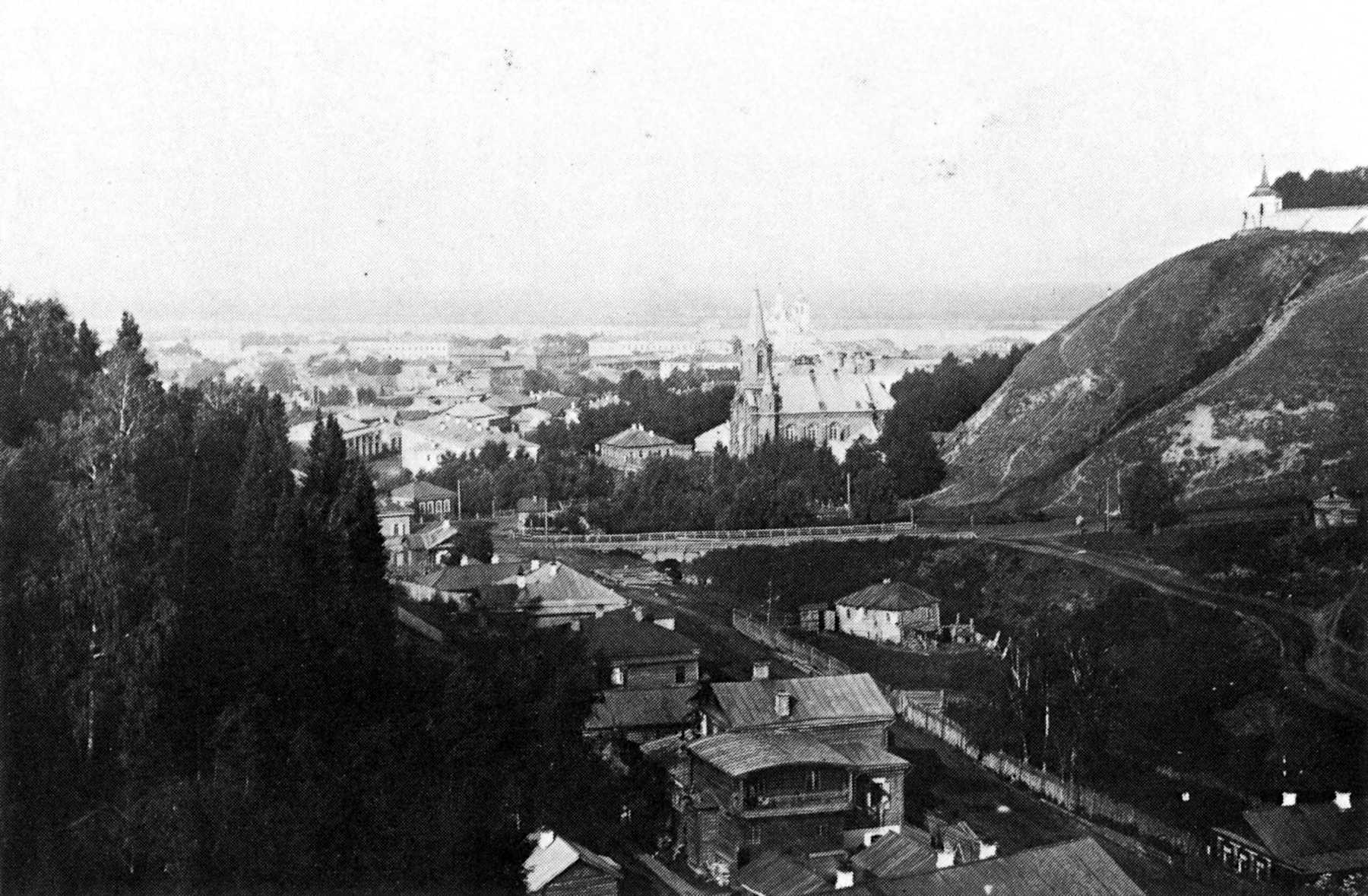

| PART FOUR | TOBOLSK | 209 |

| Chapter XVIII | Orientation | 211 |

| Chapter XIX | Winter | 226 |

| Chapter XX | Danger | 236 |

| Chapter XXI | Separation | 248[Pg x] |

| PART FIVE | EKATERINBURG | 263 |

| Chapter XXII | Reunion | 265 |

| Chapter XXIII | Deprivation and Courage | 278 |

| Chapter XXIV | The Nights Are Long | 286 |

| Chapter XXV | Accusation | 291 |

| Chapter XXVI | Fear and Dread | 297 |

| Chapter XXVII | Our Final Decision | 303 |

| Chapter XXVIII | Dawn Turns to Dusk | 314 |

| PART SIX | AFTER THE TRAGEDY | 321 |

| Chapter XXIX | Dugout | 323 |

| Chapter XXX | Recovery | 338 |

| Chapter XXXI | Westward Trek | 348 |

| Chapter XXXII | Alexander | 358 |

| Chapter XXXIII | Escape | 373 |

| Chapter XXXIV | Refuge | 378 |

| Index | 383 |

[Pg xi]

FRONTISPIECE

FIRST GROUP

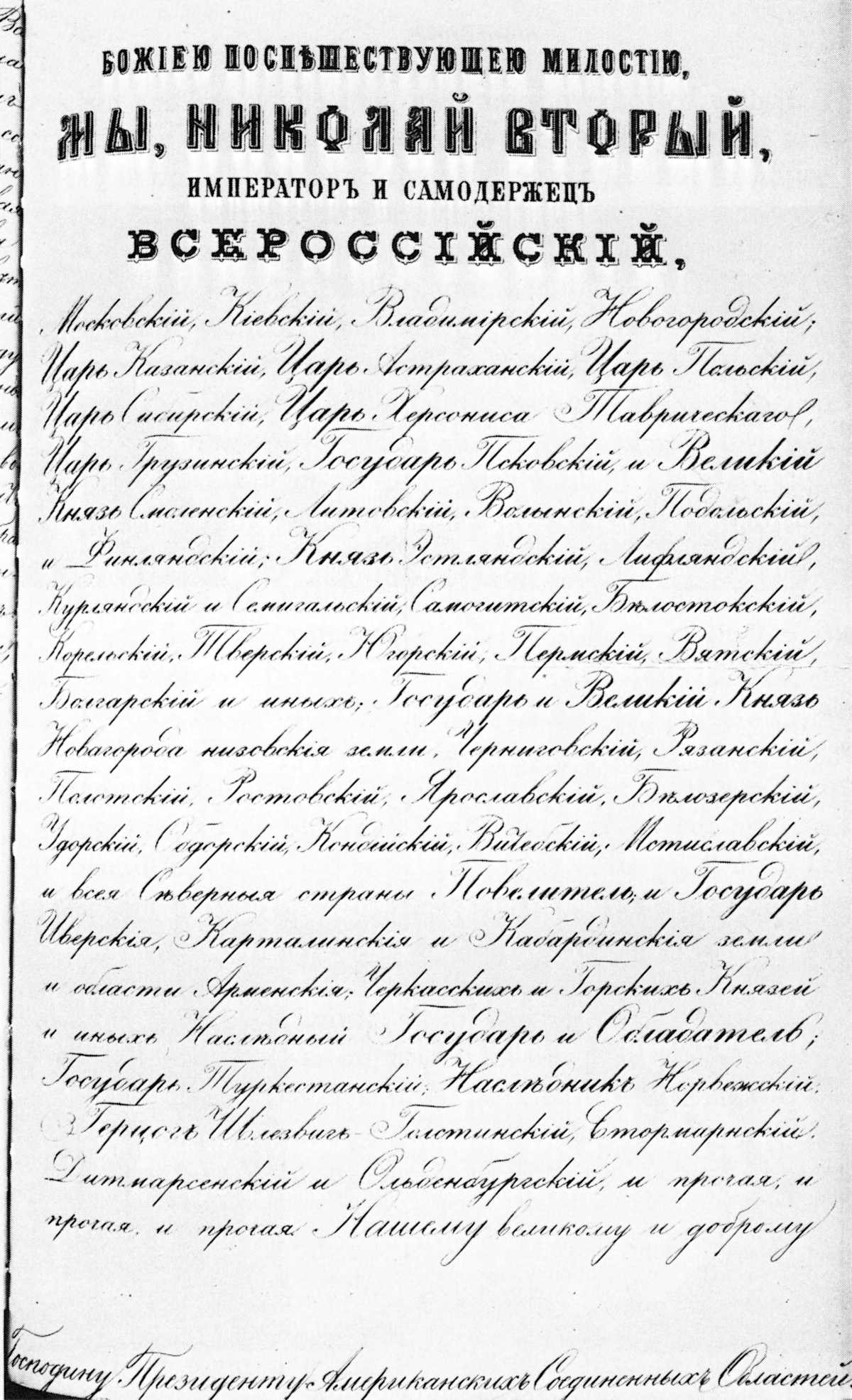

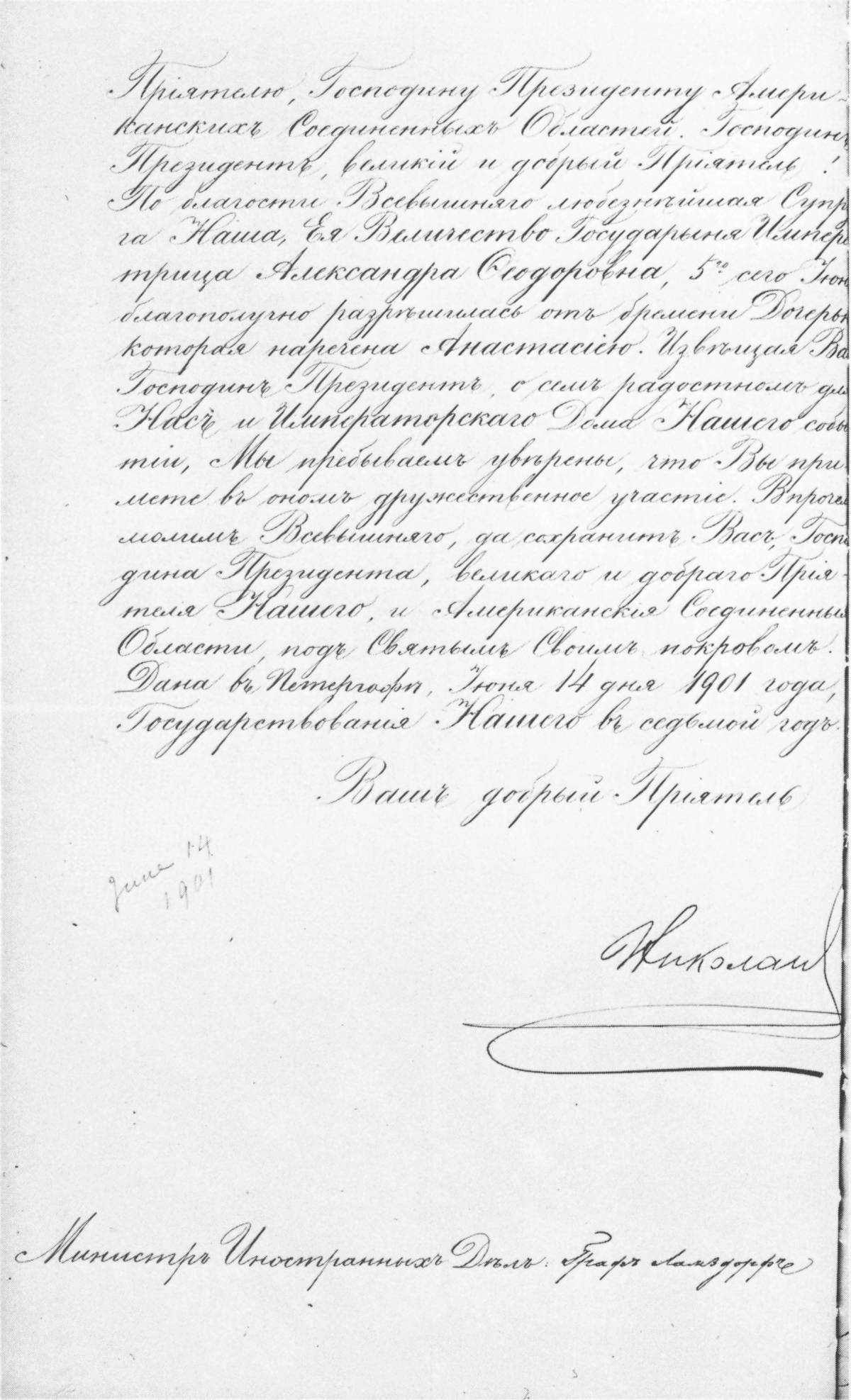

Announcement of Birth of the Grand Duchess Anastasia

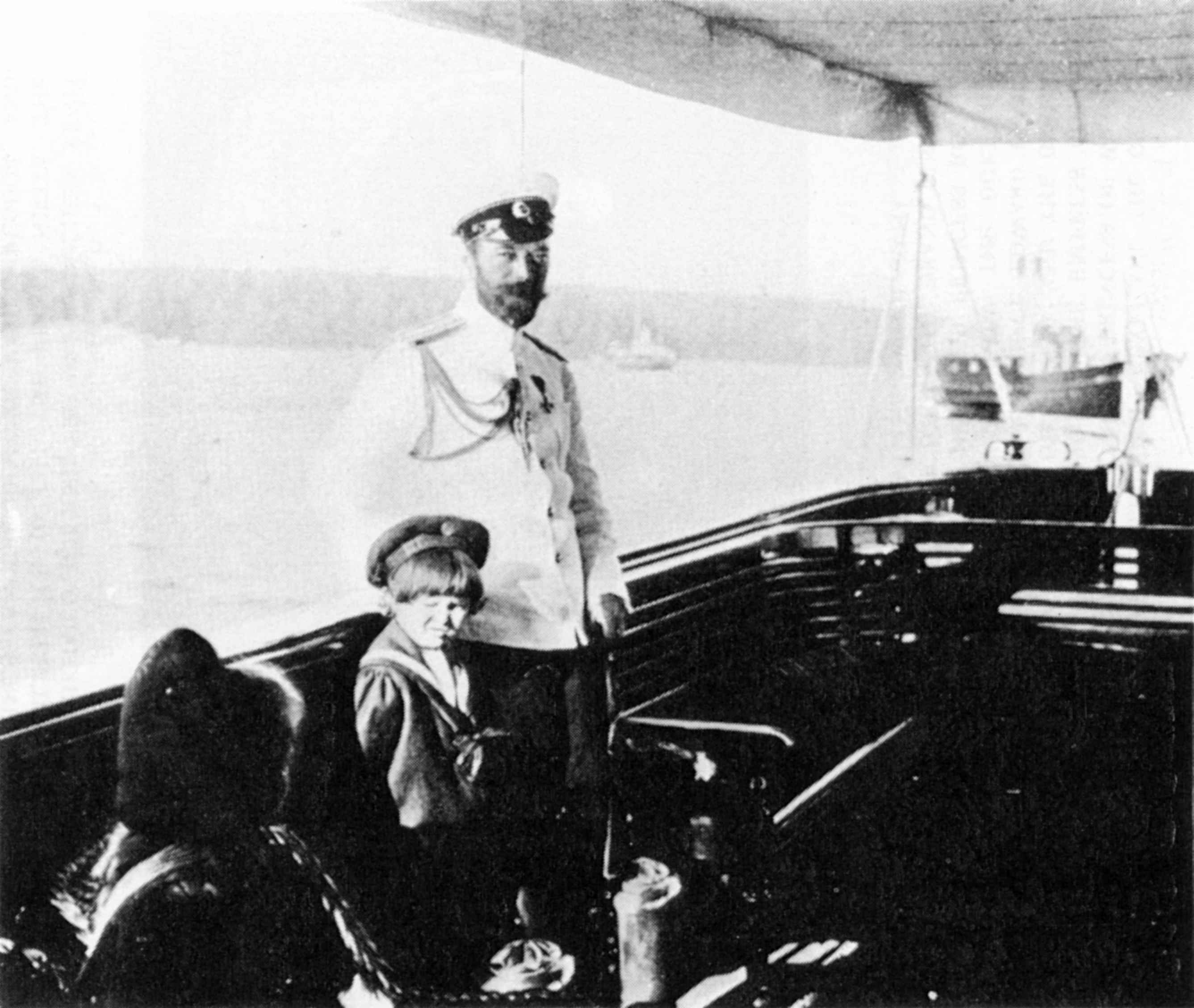

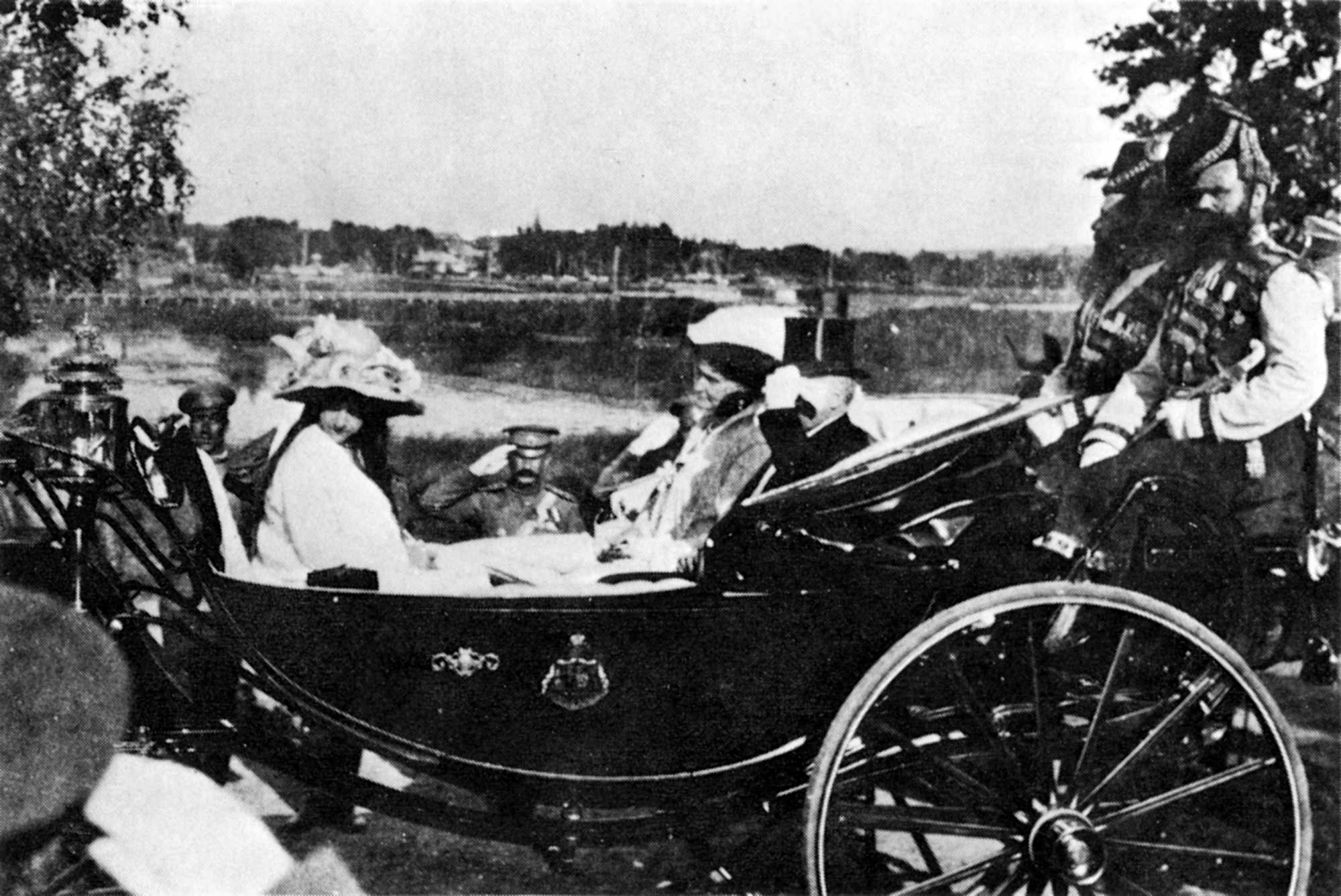

The Grand Duchess Anastasia, the Tsesarevich Alexei and the Emperor Nicholas II

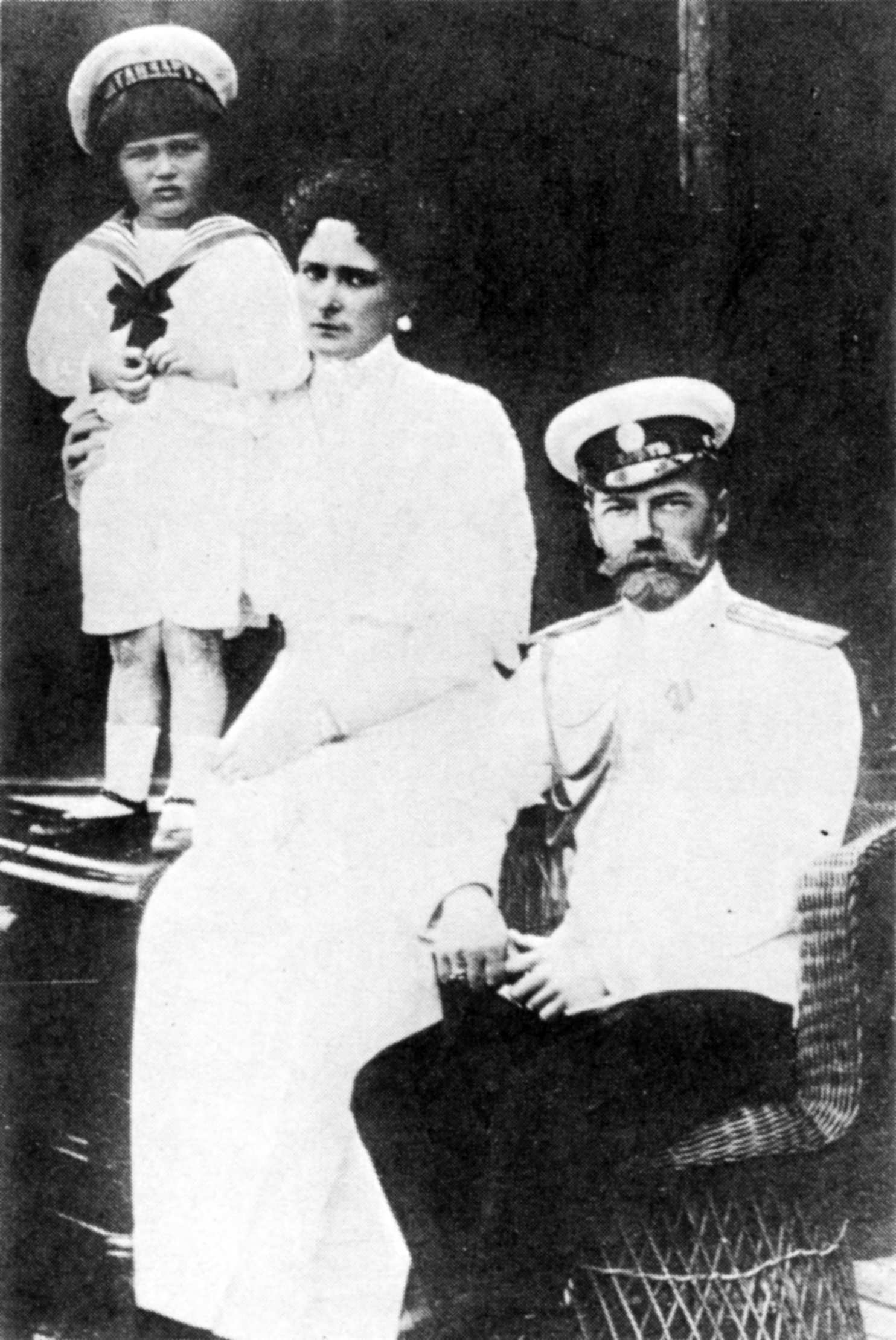

The Tsesarevich Alexei, the Empress Alexandra and the Emperor Nicholas II

The Russian Imperial Family on visit to the British Royal Family

The Grand Duke Alexander and the Grand Duchess Xenia and Their Children

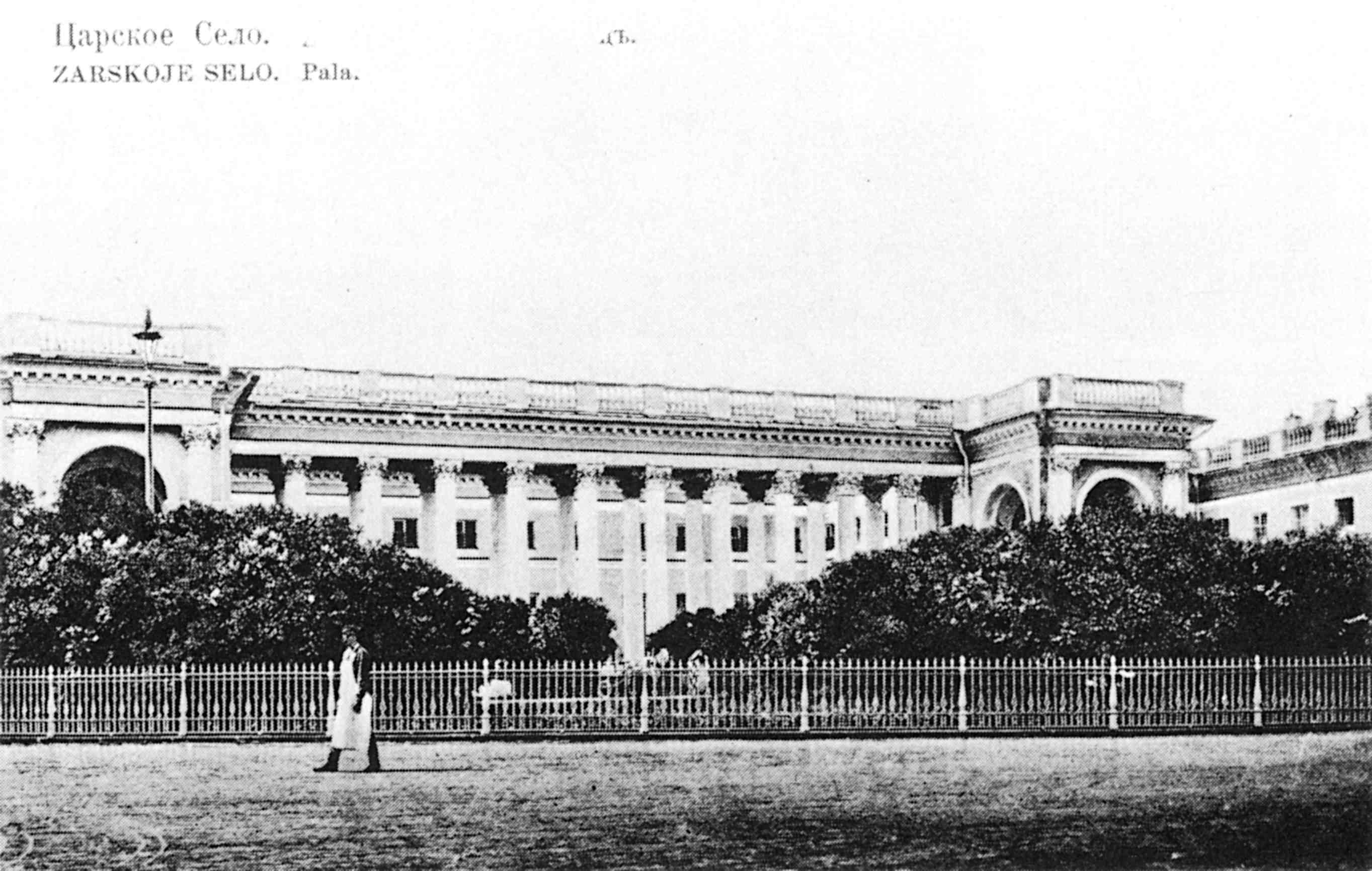

Alexander Palace, Tsarskoe Selo

Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra

The Grand Duchesses Marie, Tatiana, Anastasia and Olga

The Empress Alexandra with Her Daughters

Nicholas II and the Empress Alexandra and Their Children

The Grand Duchesses Olga and Tatiana

The Grand Duchesses Marie and Anastasia

The Grand Duchesses Anastasia, Olga, Tatiana and Marie

The Grand Duchess Anastasia, the Empress Alexandra and President Raymond Poincaré

[Pg xii]

SECOND GROUP

The Grand Duchesses Anastasia, Marie and Tatiana

The Tsesarevich Alexei and the Grand Duchesses Olga, Anastasia and Tatiana

The Grand Duchesses Marie, Olga, Anastasia and Tatiana

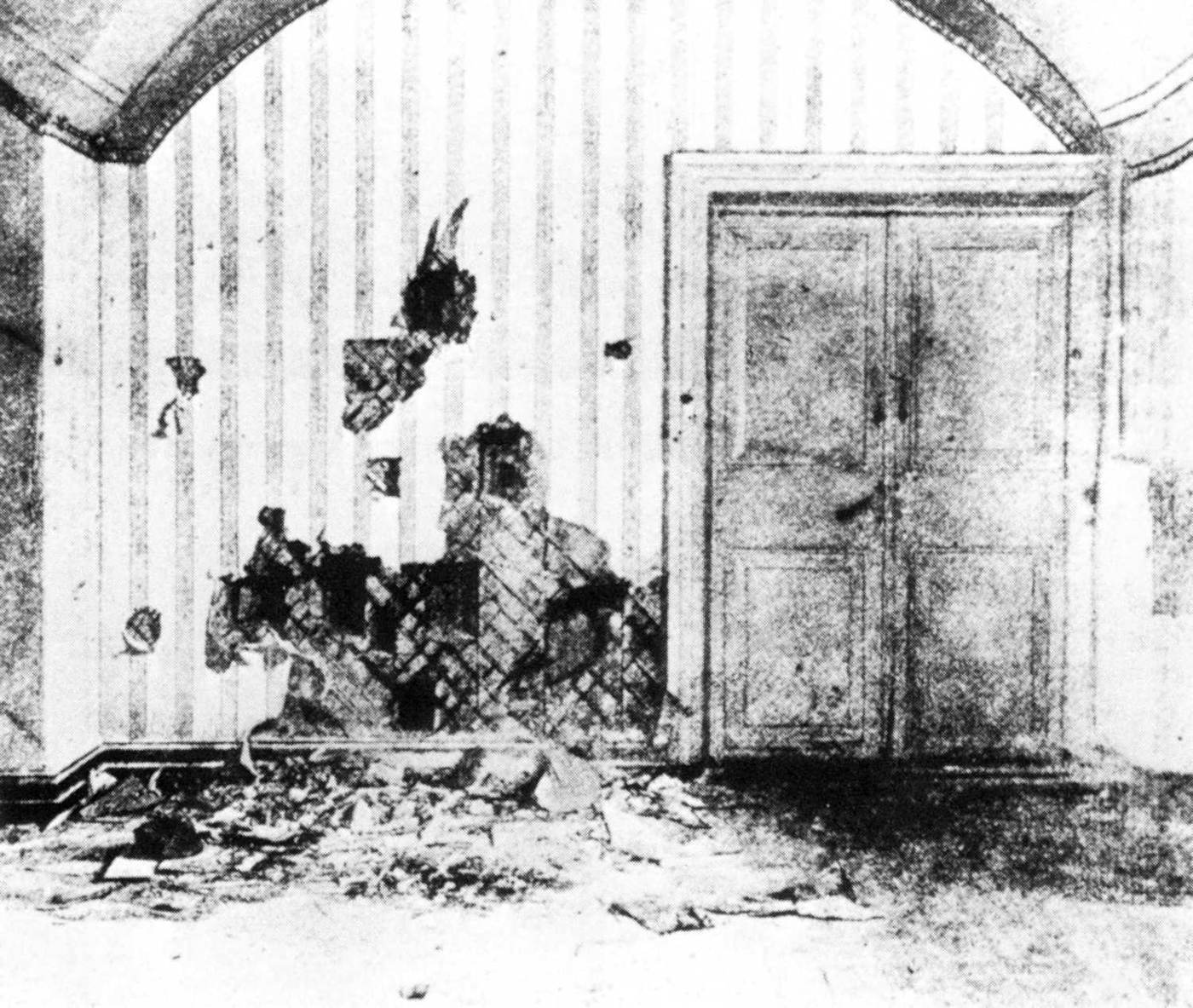

The Death Chamber, Ipatiev House, Ekaterinburg

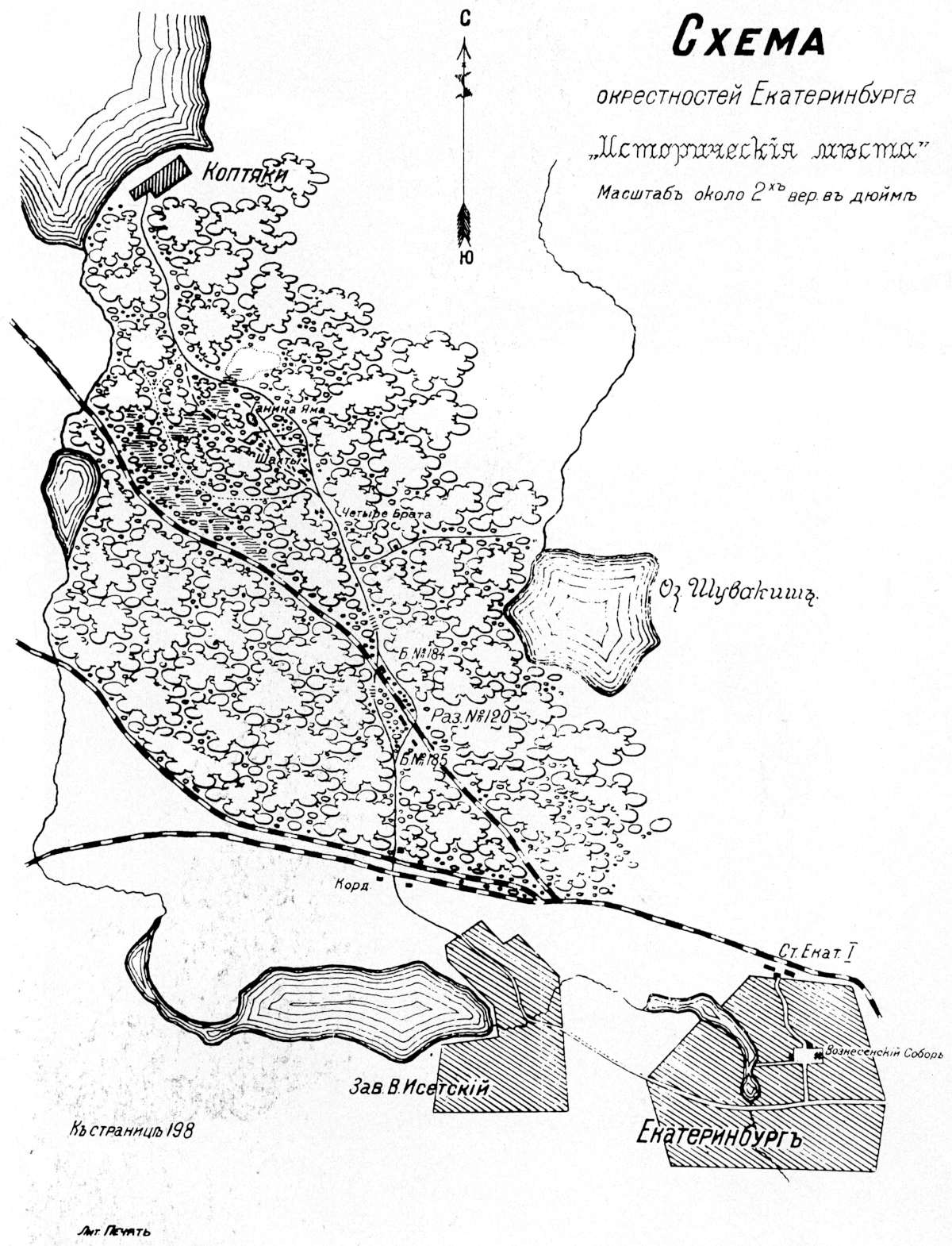

Map of Ekaterinburg and Vicinity

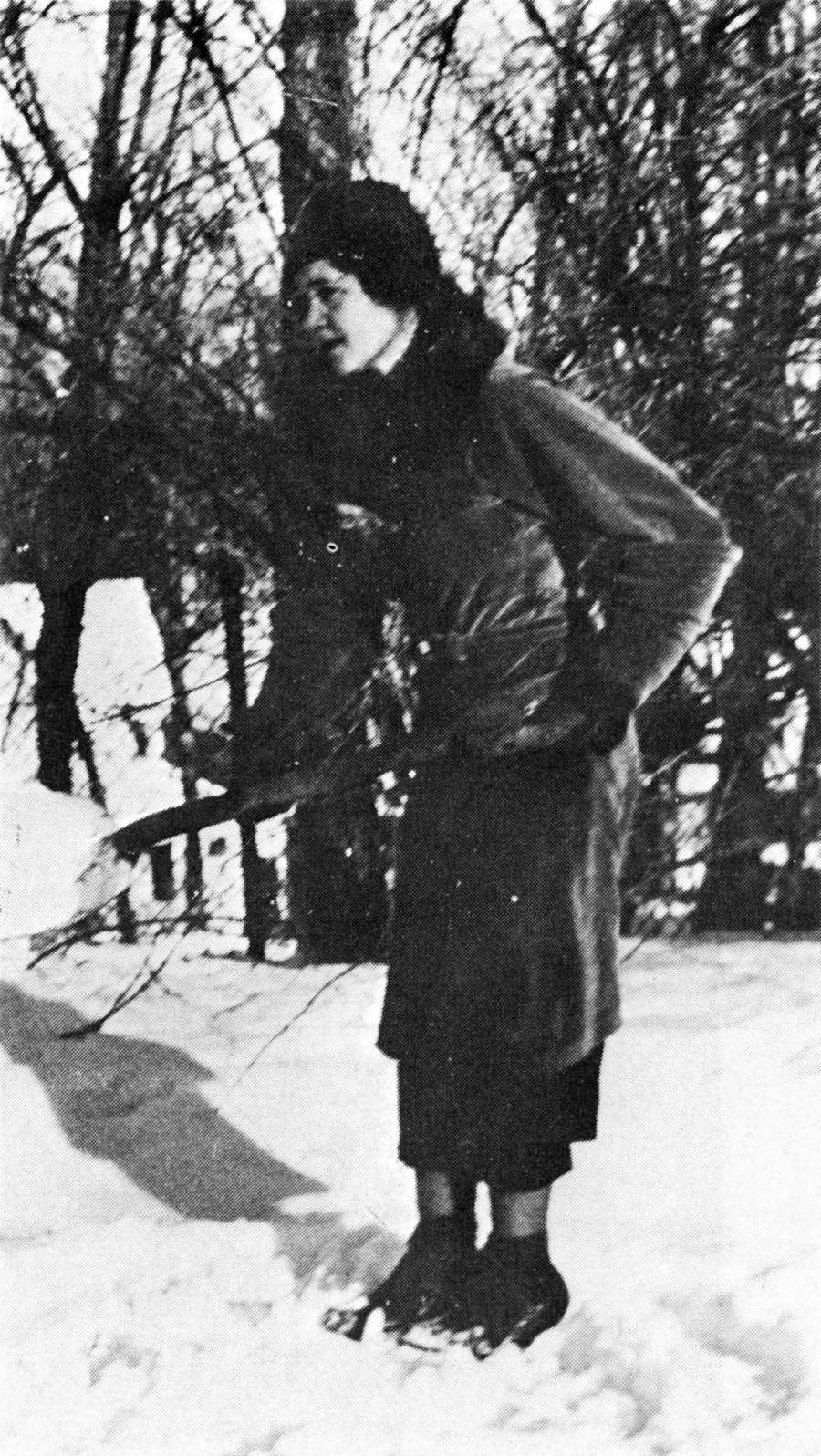

The Grand Duchesses Marie and Anastasia

Nicholas II with His Children and His Nephew, Prince Vasili

The Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Anastasia and Marie

THIRD GROUP

[Pg xiii]

A few weeks after my arrival in Bukovina—after I had had time to recover from the emotional and nervous shock and body wounds which I had suffered at the time of the tragedy on the night of July 16-17, 1918—I decided to write about my home life with my beloved family, about our arrest, about our exile in Tobolsk and Ekaterinburg, about the assassination of the family in Ekaterinburg, and about my rescue and subsequent escape across the frontier.

I made many, many notes, totaling over three hundred pages. I spent hours and hours in the writing, days and nights of introspective experiences, of grief and horror. I wrote in a peasant cottage in a lonely village dotted with thatched-roof houses. I wrote at night in the candlelight, agonizing over my story. At times the only relief I had from my misery was the howling or barking of a dog. I remembered my beloved Father’s words, “Dearest children, are you awake?” Tear after tear dropped as I labored.

I remembered also my Father’s desire that a history of Russia should be written by a member of our family. My Father had had in mind that such a history might be written by my two oldest sisters and, to that end, he gave them much valuable information. As it has turned out, it is the youngest sister, the one least prepared to do so, upon whom devolves the task of writing such a book, if it is to be written. That is something for the future.

In 1918, after my escape, I thought that the book I had decided to write about my family and myself might include historical data and interpretation which would be of interest[Pg xiv] to the world and would be of benefit to the Russian people and to their, and my, native land. I particularly wanted to let the world know the facts about the arrest, exile and murder of my parents, sisters and brother, and about the nature of the Bolshevik regime in my country. It was the notes for this book that I produced so painfully and painstakingly.

These early notes unfortunately vanished in 1919 when I was on my way by train from Rumania to Serbia—second homeland to us Russians—while in the vicinity of Turnu-Severin. I had accepted from another traveller—I thought he was an Italian—his kind offer of a slice of bread and a piece of ham. Three or four hours later I became ill and had to leave the compartment. When I returned some time later, the heartless traveller, who had no pity for a young woman travelling alone, had disappeared along with my suitcase and a blanket. The suitcase contained not only my precious notes, so laboriously produced, but also some personal belongings, some letters, and a list of about one hundred names of the men who had done most of the harm to Russia, and to my family. These names I had written down from memory, based upon information furnished by my rescuer, Alexander. Most of these names were already familiar to me.

In Yugoslavia, I resumed work on my book. I continued the task later in Rumania and, once more, in Yugoslavia. I again wrote many pages of notes, using a pencil stub and scraps of paper. Such of these notes as remained legible were used subsequently in the preparation of the first draft of the present book.

Later, in the early thirties, some years after my arrival in the United States, I began to revise my materials which were in a disorganized but generally readable condition, assisted by my good friends, the late Mrs. Helen Kohlsaat Wells, and her sister, Miss Edith Kohlsaat. During this phase of the undertaking I was determined to complete the book as soon as possible and to make provision for its publication only after my own demise.

For about twenty years, I was unable to work on the[Pg xv] manuscript, due to the necessity of making my own living. During this period I gave no attention whatever to the manuscript which I had confided for safekeeping to my lawyer, a friend who was aware of my real identity and who wished to help me ultimately to find a publisher.

Five or six years ago I decided to resume work on the book. A complete revision and reorganization of my materials were again required. Once more I had the benefit of Helen Wells’ assistance and counsel.

I had also the great and valued encouragement of my good friends the late John Adams Chapman and Mrs. Marjorie Wilder Emery.

Early in 1963 I mentioned to a friend in New York, who was unaware of my identity, that I had in my possession a manuscript on the Russian Revolution. He suggested I get in touch with a close friend, Dr. Jon P. Speller of Robert Speller & Sons, Publishers, Inc. This I did. The first member of the firm with whom I talked was Mr. Robert E. B. Speller, Jr., who surprised me with the depth of his knowledge of my family. I informed him that the Grand Duchess Anastasia had left the manuscript with me, a close friend, shortly before her death in 1919. I hoped—naively—to achieve early publication of the manuscript while keeping secret my true identity. Dr. Jon Speller then joined the conversation. He asked if I would be willing to take a polygraph examination to back up my statements. Upon my consenting to do so, they agreed to read the manuscript.

They, and their father, Mr. Robert E. B. Speller, Sr., President of the firm, after reading the manuscript became convinced for various reasons that the manuscript could have been written only by a member of the Imperial family. They questioned me at length and finally I confided to Dr. Jon Speller and then to Mr. Robert Speller, Jr. that their suspicions were correct, that I was Anastasia, but that, if possible, I would like to retain my anonymity.

Therefore the polygraph examination, given by the noted polygraph expert Mr. Cleve Backster, was begun by testing me[Pg xvi] on my statements that I was a friend of Anastasia. Mr. Backster quickly recognized that I was withholding pertinent information, even to the extent that I could be Anastasia; I finally admitted my real identity to him. In a series lasting more than thirty hours in all, Mr. Backster became convinced that I am really Anastasia. I signed a contract with Robert Speller & Sons and began editing my book with Mr. Earl L. Packer, senior editor of the firm, and Mr. Robert Speller, Jr.

My reasons for bringing the book before the world at the present time will, I hope, be readily understood. They are not complicated. First, I wished to come to the defense of my deceased parents, against whom many unfounded accusations and slanders were made. Second, I felt that various distortions of history which have been given wide circulation needed to be corrected. Third, I wished to expose the falsity of the claims of other persons to be the Grand Duchess Anastasia. Fourth, I desired to establish a foundation which would set up a museum, with a small chapel therein, to honor my family who loved Russia so faithfully; and also to assure, in so far as I might be able to do so, funds for its maintenance, hoping proceeds from the sale of the book might in large measure provide such funds. Fifth, I wished to establish a fund for the provision of financial assistance to destitute former Russian soldiers and officers; again I hoped that the proceeds of the sale of the book might help in this undertaking. Sixth, I planned that, in the event the proceeds of the sale of my book should provide sufficient funds to enable me to do so, I would assist financially a very small number of charitable and philanthropic organizations which, for the most part, I have already definitively selected.

Sometime earlier I had come to doubt that, if publication of the book were postponed until after my death, as I had earlier resolved, my projects would ever materialize. Also, I thought unlikely the possibility that anyone but myself could or would make knowledgeable and effective defense against whatever[Pg xvii] unfavorable criticism might be made of the book and myself upon its publication.

I have had the opportunity for a relatively quiet life in the United States, where I have had comparative freedom from all the attentions that might have surrounded an earlier reappearance in the world in my true identity. But my purposes, as enumerated above, could not be accomplished by remaining longer submerged. So I have resolved to balance the opportunities for good against the possible personal inconveniences, hoping still to be able, after publication of my book, to continue to live undisturbed a simple, private life devoted in large part to further writing.

A.N.R. 1963

[Pg 3]

It was June 5th, 1901, by the Russian calendar, June 18th by the new. Suspense and excitement abounded at Peterhof. The accouchement of the Tsarina was momentarily expected. The fourth child, surely this time it would be a boy. Russia bowed to the little Grand Duchess Olga, then to the baby Tatiana. But Marie, a third daughter in succession, had been entirely too many. However, all would be righted if this fourth child were the long-awaited Tsarevich.

At last, the guns: the baby had arrived; a three hundred gun salute would announce an Imperial Grand Duke and heir to the Russian throne. One hundred and one guns would announce a Grand Duchess. The guns saluted a second time. The people paused to count—three, four, five, on and on, came the rhythmical booms. The populace stood breathless. Twenty-three, on and on, one hundred, one hundred and one, the guns stopped. No, it could not be. It was not possible. Alas, yes. The fourth child of the Tsar and Tsarina of Russia was another daughter. Caught in an anticlimax, the man in the street went his way, but diplomatic Russia said “Bah” and resented the Tsarina who could not fulfill her function. The Tsar and the Tsarina accepted the inevitable and said, “It is God’s will.”

All the while I, the unconscious cause of this frustration, had lain peacefully in the same little crib which had cradled the three sisters before me. It was not long however before the unwelcomed wee one won the hearts of its parents and I[Pg 4] was christened Anastasia, but to the world outside I was number four, almost forgotten beyond the family circle.

As a child, my tomboy spirit predominated and I was permitted to indulge this urge until I became something of a novelty in a court reeking with formality. Nothing pleased me more than an audience, especially when they nodded and whispered “cute.”

My next older sister Marie and I were inseparable. At an early age my greatest delight was to arouse her curiosity. Often when we were at the height of some make-believe, I would suddenly dart away. Marie was as slow to action as I was quick, so I would slip out of sight into one of my hiding places. Then began the hunt I revelled in. The searchers went around, as I listened from my vantage point, purring with satisfaction when I heard the call, “Anastasia, where are you? Be a good girl and give us a hint.” These games began good-naturedly, but often when the hunt dragged on, I lost patience and felt compelled to reveal my whereabouts.

Secret hiding places became an obsession with me, especially tiny ones so snug I had to squeeze into them. There I often stayed gloating over the bewilderment and eventual rage of searchers. Once when I was quite young I slipped out of the nursery onto the balcony. It was late in the afternoon and the long shadows fascinated me, so that I must have remained there quietly for a long time. Suddenly I heard excited voices and I decided to keep perfectly quiet. At dusk, in the uncertain light, I flattened myself against the shadowed wall. The sentries were spreading over the park; the worry was growing. I was thrilled when I knew they were searching for me, but I was a little frightened of the gathering darkness. I ran quickly down the stairs and to the main floor. Mother was talking to one of the officers when her eyes suddenly fell on me.

“Anastasia,” she cried, “where have you been?”

“Right on the balcony and no one could find me,” I answered with all the glee in my voice I could muster.

[Pg 5]

Almost before I could finish, Father was beside me. He took me by the hand. One look at his face warned me that something was very wrong. Without a word he signaled to the distressed nurse. Her face was flushed. She marched me to my room and I never ventured one look of triumph as she undressed me. She did not say a word until I was in bed. Then she said, “You were a very naughty girl to worry your Mother so. She was very hurt.”

Mother always came to kiss me goodnight. I didn’t stir in my bed lest I should miss her footsteps. Finally I heard her approaching with my sisters; their voices sounded happy. She stopped at the door for only a moment, and Marie entered the room alone. When the nurse turned out the lights, I realized that Mother was not going to kiss me that night.

The next morning a penitent little girl asked herself: “Will Mother come to me now?” And: “Will she be cross with me?” I was full of contrition, but how could I express it if Mother were not in a receptive mood? My eyes fastened on the door, hoping to see Mother’s face. Suddenly she appeared. I ran to her and wrapped myself around her neck. I promised never to worry her again.

Mother’s daily round took her to the nursery the first thing every morning before breakfast to say a prayer with us children and to read one chapter to us from the Bible. She was usually attired in a beautiful dressing gown of white—occasionally in other soft colors—her hair braided and tied with silk ribbon to match the trimming of her gown, a habit acquired from her grandmother, Queen Victoria of England. These were precious moments to us children. She was a fairytale empress—stately and beautiful.

On July 30th, 1904, Russian calendar, August 12th by the new, my little brother was born on a Friday noon. Three hundred guns announced the birth of the heir from the Fortress of Sts. Peter and Paul, in St. Petersburg.

On the same day, it was learned that the Russian fleet at Port Arthur had been sunk on August 10th by the Japanese[Pg 6] navy. My Mother often said it was a day of sunshine and a day of darkness at the same time. It would have been customary to hold a large banquet to celebrate the birth of an heir to the throne but my Father would not hear of it. Instead, prayers were offered in the churches for the lost ones at sea and for the baby Tsarevich. All day long the bells rang out from all the churches of Russia. Thirteen years later Mother spoke of this day as being as gloomy as the day we arrived in Ekaterinburg. It was on Alexei’s thirteenth birthday, and about the same hour in 1917, that the family was informed they must leave their beloved home in Tsarskoe Selo.

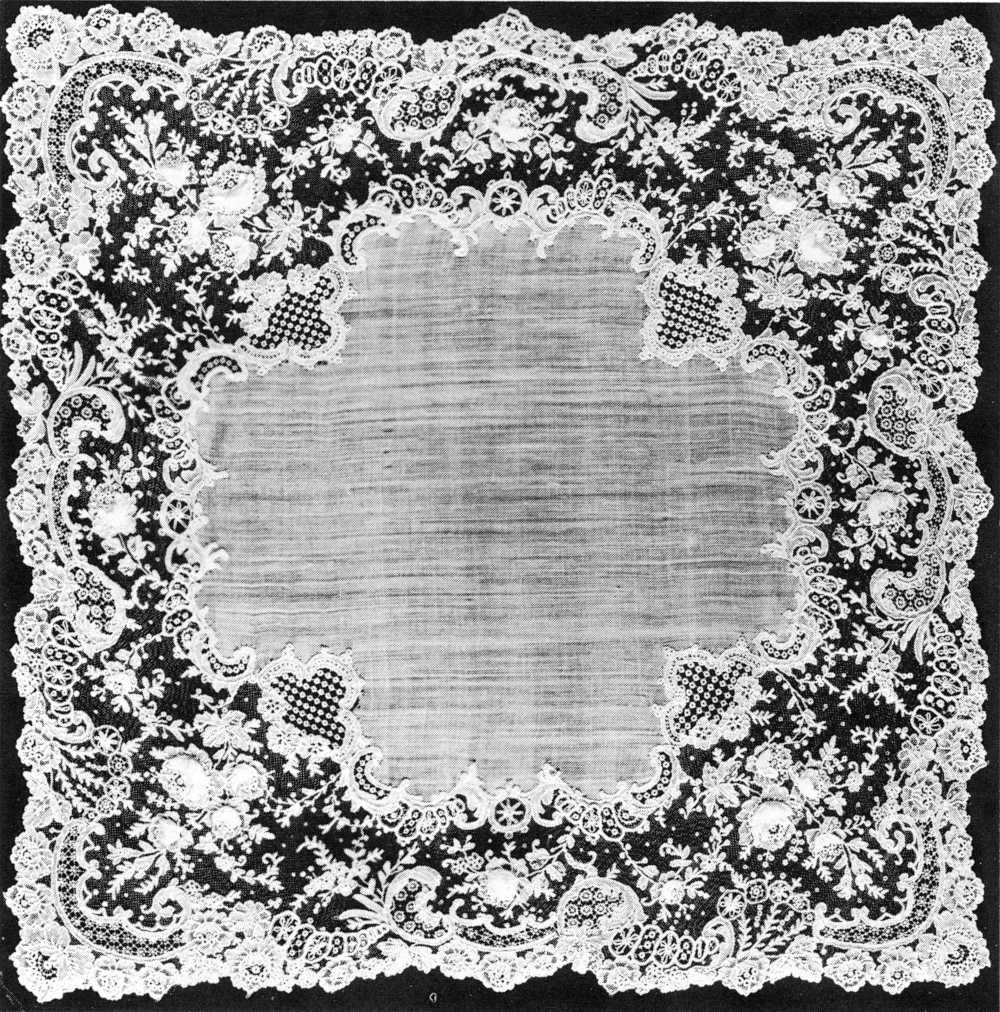

I do not remember Alexei’s christening since I was so small, but I have been told about it and have often seen his christening mantle and the cross which he wore on a chain around his neck. These were displayed in a glass case along with the christening dresses of us sisters. Olga’s was an exact copy of that of Marie Antoinette’s older daughter. It had been made in Lyons. Olga and Tatiana held a corner of the long mantle which was attached to the cushion because of its weight. Alexei’s godmothers were his grandmother, the Dowager Empress Marie Feodorovna; his sister, Olga Nicholaevna; his aunts, Mother’s sisters, the Princesses Irene of Prussia and Victoria of Battenberg (subsequently Marchioness of Milford Haven). The godfathers were his grand uncles, the Grand Duke Alexei Alexandrovich and King Edward VII of Great Britain; his cousin, Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany; his great-grandfather, King Christian IX of Denmark; his uncle, the Grand Duke Ernest Louis of Hesse, the Empress’ only brother; and his Aunt Irene’s husband, Prince Henry of Prussia. To commemorate his birth the cornerstone for the Feodorovsky Sobor (Church) was laid in Tsarskoe Selo.

Now that this handsome brother had arrived, the handicap of my life, that of being a girl, seemed somewhat lifted. Alexei was a beautiful little boy with a very light complexion and curly auburn hair which my Mother brushed lovingly into a curl in the middle, big blue eyes, long eyelashes and a[Pg 7] most alluring smile. He was the most fascinating thing in my existence, so whenever an opportunity presented itself, I ran into his nursery bringing various toys to him. Mother had many pet names for him, among them: “My precious Agoo” and “Kroshka” which means crumb. Olga and Tatiana were permitted to hold the baby; Marie and I could only hold his feet.

One of my most vivid childhood experiences, when I was nearly four years old, happened on a Sunday when we sisters as usual were dressed in white, ready to go to church. We heard excited voices and saw Mother running upstairs. This frightened us and we all ran after her to the nursery. There I saw a spot of blood on little Alexei’s shirt. While nurse was bathing him he sneezed, thereby causing a discharge of blood from his navel. Though I was very young, I could easily tell from the faces about me that something was wrong. At the time just what it was I could not understand. A few years later, when I was about seven, we three younger children were playing in the garden when our brother fell over his cart. Soon a large blue swelling developed around his ankle. When Mother came she fainted at the sight, knowing it was the dreaded haemophilia that might kill her son. As a result, the lives of Father and Mother were noticeably saddened. Father searched in every country for a specialist, but without success.

We were continually reminded that we must be careful of Alexei. He was so easily hurt. The toys I was in the habit of bringing to him were removed before they reached his hands. Once he fell on his head and his face swelled so terribly that his eyes were almost closed and his whole face became a purplish yellow, a dreadful sight. At one moment he would be perfectly well; an hour later, he would lie in bed seriously ill. We were instructed not to speak to anybody about it, but we innocently gave away the secret of his illness to some members of our staff who had led us into believing that they already knew all about it.

[Pg 8]

Mother was constantly at his side, never trusting any one else to care for him. Each time, when he recovered, Mother was entirely exhausted, so much so that she was unable to leave her room for days at a time.

When Alexei was well and his normal chubby self, it was hard to remember that we had to be careful when we played with him. I often felt belligerent when he teased me saying, “Go away, you’re playing just like a little girl; you don’t know this game.” I maintained my composure pretty well and occasionally retaliated by refusing to play with him, but he bitterly complained of such treatment. Suddenly he would be well again at which time it was difficult to restrain him from getting too bold or playing games that might end in disaster.

Alexei had several guards, Cossacks who were trustworthy and on duty day and night. Every morning they searched the palace grounds before any member of the family could walk about in them. Alexei also had two special attendants. One was Derevenko, nicknamed Dina, a huge strong sailor, a member of the crew of Father’s yacht, the “Standard.” He was no relation of Dr. Derevenko, Alexei’s physician. Dina applied hot compresses and light massages to Alexei, when they were needed. Dina also gave foam treatments, and always carried him around when he was not able to walk. Unfortunately Dina turned against his master during the revolution and was later arrested by the Soviets when they found some of Alexei’s belongings in his luggage.

The other attendant was Nagorny. He was the last to give Alexei his usual care. Nagorny took charge of him during the revolution, and was killed in Ekaterinburg because he defended the little boy’s property. These two, Dina and Nagorny, were constantly at Alexei’s side to see that he did not harm himself. They helped my brother to grow to normal boyhood by using the exercises prescribed by Dr. Derevenko and the suggestions of M. Pierre Gilliard, our French tutor. They helped to carry on in such a way that the little fellow never suspected that he was being shielded. For he was not told of[Pg 9] the serious nature of his illness but was to realize it for himself when he grew older.

At his birth Alexei received many titles: “Hetman of all the Cossacks,” “Knight of St. Andrew,” “Knight of the Seraphim of Sweden,” “Head of the Battalion of the Horse Infantry,” “Head of the Siberian Infantry,” “Head of the Cadet Corps” and others. Alexei loved everything military. I think he had a uniform for almost every military order in Russia. He was so proud to wear each one, and carried himself with true military bearing. From childhood he had worn a white sailor suit with ribbons around his collar. When we cruised in the Baltic, he wore a white sailor cap with the name “Standard” in white on a blue band. When cruising on the Black Sea he had a black band with yellow lettering.

One day in a snow storm I pulled Alexei on his sled. Then he insisted that it was his turn to pull me. Soon his hands became swollen but fortunately this did not result in one of his serious attacks. He was not permitted to take part freely in sports, though he was allowed to ride a tricycle and later a bicycle, when he was carefully followed by Dina. Finally he was allowed to drive a small motor car with his cousins or a friend.

Alexei had playmates other than myself. I remember a youngster who was driven up the driveway accompanied by a guard and well supplied with many toys. He had among other things a box of powdered chalk. Considering the boy an intruder and unable to hide my jealousy, while he was escorted by the runner, I snatched the box from his hand and scattered the contents all over the floor. It all happened so quickly that no one was able to stop me. Soon I was escorted to Mother. By the time I reached her I was all smiles—a bit strained to be sure. She sat silently and held my little hands, studying them and wondering how they could do such a thing. I peeked at her face, putting on my most winsome smile. Mother assured me that “Smiles will not help.” Just then Father came in and sent me to my room for the rest of the[Pg 10] day. Later he came to see me and said, “You must not fight with your younger friends. Always be a little lady.” “I don’t want to be a lady,” I said defiantly. Father answered, “Then you cannot live in this place.” “Where will I live then?” “In one of the guard houses,” said Father. My dear Father often apologized for Alexei and myself.

Gentle as Father was, I took those remarks seriously, because I knew he always meant what he said. So I applied myself to the idea of “being a lady.” It soon paid off. Some time later when I was roaming through the park I chanced upon two workmen who were fighting in the ravine. It looked serious and desperate. With all the ladyship I could muster I ordered them to stop. To my astonishment they did. The contrast between little me and those two, so huge and menacing, convinced me that there must be something in this ladylike business after all.

By nature I enjoyed the rough and tumble, while being a lady meant being dignified, sewing, practicing on the piano, in general following in the footsteps of Olga and Tatiana. I would much rather have played the kind of games that Alexei enjoyed. Marie did not like these games at all. She preferred dolls, which I thought were not half as much fun as shooting off pop guns. I often held the gun while Alexei slid down the toboggan slide held on the lap of his attendant Derevenko or his assistant Nagorny.

The park surrounding our home at Tsarskoe Selo lent itself to my eager desire for exploring the world around me, although even this could not satisfy my curiosity about that part of the world which lay beyond the fence. One afternoon I found an owl opposite the balcony in the garden. I had seen something flying which fell to the ground. When I ran to it I found an owl which did not move. I wanted to pick it up, but was told it was bad luck to do so. In spite of this advice, I picked up the bird and stroked and fed it. In a short time it became a real pet so it could even recognize my step. It always stayed nearby, hopping about in a small area, though[Pg 11] it didn’t seem to be hurt. Whenever it heard me, it would fly up and sit on the rail of the balcony. While the owl was perched there, it seemed to stare at me and I could not resist walking around, fascinated by its twisting neck and staring eyes which apparently followed my movements.

Most of the time I was content to wander through our fairyland park with my sisters and brother. Its beauty was overwhelming with fine vistas embracing gardens, ravines, lakes and even islands. We often sailed our toy boats on the lake or rowed Alexei in a boat Sometimes we sat on shore watching the varied reflections on the surface of the lake. These might be reflections of the Feodorovsky Sobor with its golden cupola, or again a glimpse of the luxuriant tree tops, or the rapidly changing cloud formations. On the lake the swans glided back and forth in graceful splendor, but, when they came near our shores, with one stroke they erased all the pictures before our eyes.

These swans were my special pets. I usually carried bread to throw to them. One day in a mischievous mood, I made them think I had come to feed them. When they swam toward me expectantly, I ran away. I was suddenly thrown to the ground, and the largest of the swans with his wings spread wide stood over me. He began to beat me with his wings. My screams brought help from one of the guards, who drove off the swan. When I stopped sobbing I had not lost my love for the swans, but I had learned I could not tease them.

Father found time to visit us at play every day, often only for a few minutes, but he made us happy with these visits. Sometimes he watched us as we went down the slide which had been installed in a large room on the ground floor. He whistled as each child took her turn and the rest of us jumped up and down expressing delight.

Several times, as a great treat, we children were permitted to take our bath in Father’s big, sunken tile tub, large enough for one to swim several strokes. After the bath we romped[Pg 12] over the huge couch in Father’s dressing room, watching the flames dance in the fireplace.

Mother called Father’s study “the forbidden land.” We children were not allowed to enter it, which made me rather curious about it. I often ran down the hall, hoping that I would find a way to get into the study, but there was always someone who would send me back. If I could have found out what Father did there, I would have been satisfied. One day I managed to slip through the narrow passage of his dressing room and opened the door leading into his study. I was breathless with excitement, but kept quiet. I was about to open the door for a tiny peek, to see if Father were there, when I heard footsteps. I decided to retreat quietly as if I had gotten there by mistake. But as I backed out I had moved too quickly and gone too far. I rolled down several steps right into the middle of Father’s sunken tub. Fortunately I was not hurt, but my feelings were. I extricated myself and retreated down the hall in the midst of laughter. I never did know my discoverer.

My curiosity was still not satisfied, and I was determined to keep trying. I used all sorts of excuses for going to his study with pressing messages or gifts. But Mother spoke with finality: “Father cannot be disturbed in his work.” In spite of Mother’s words, the opportunity finally presented itself. One day I stood quivering on the threshold. There was Father at his desk looking quite serious. I leaned forward on my toes to take in all that I could see, so far forward that I lost my balance and fell on my face into the room. I was terribly frightened, but Father rushed to me and with a smile picked me up saying: “What are you doing here, baby?” Then he sat me down at his desk and held me on his knees. I was speechless to think I was in the forbidden place. I glanced at piles of papers, then at Father’s face. With a hug and a kiss he deposited me in the hallway. “Now run along, my little Curiosity.” I skipped away elated and I could hardly wait to tell Marie I had actually been in “the forbidden land.”

[Pg 13]

I was often instrumental in getting my sister and my brother in trouble. When we drove to Pavlovsk, a short distance from Tsarskoe Selo, I watched for the moment when the nurse was occupied with my cousin’s attendant. I snapped my fingers—a signal to dash to the brook for the mud fight. Within seconds our faces and white clothes were beyond recognition. These mud fights made the nurse furious. Once when she rebuked me, she said it was a pity I had not been born a boy. This worried me so, I went to Mother with the question, “Do you love me, Mother?” “You know I do, little Shvibzchik,” was her reply, using her pet name for me. “But if I were a boy, would you love me more?” I questioned her tearfully. Mother understood; she shook her head a decided “No” and I was satisfied.

Sometimes after tea, I slipped into the servants’ quarters to partake of tea again, because I thought they had more interesting things to eat. I was quite wrapped up in my small world without realizing that there was any other. And yet being born into a royal family I still kept wondering whether I should have been someone else. I wondered if my grandmother, the Dowager Empress Marie, ever forgave me for not being a boy. That might explain her critical attitude toward me. I thought I sensed an unsympathetic bearing in her and I often retaliated by being irritable which in turn justified her criticism of me. On second thought this same Grandmother understood me perhaps better than anyone else. When all despaired of me, she would say, “Don’t worry, she’ll tame down after a while.” This may have been a comforting thought to my family, but not to me. I did not want to be like my Granny, not at all. She was small, dark-eyed, deep-voiced, always beautifully groomed. I wanted to be like Tatiana, tall, beautiful and graceful. Often after I was tucked in bed, I whispered a prayer that God might transform me overnight into a girl like Tatiana. Grandmother was Alexei’s favorite. He loved her more than we sisters did. She was Father’s mother and there was a strong bond between them.

[Pg 14]

I remember the satisfaction I felt when some Danish relatives were visiting us and my Grandmother said to one, “Anastasia is certainly small,” and the relative replied, “You are not very tall yourself.” This kind person must have sensed that I was touchy about my height and she attempted to defend me before Grandmother.

When Father’s work was done for the day, he would enter Mother’s apartment and whistle melodiously. This was the signal for a family get-together or for an exercise outdoors. Sometimes Father took me on a walk alone. He listened seriously to my talk and pretended to be concerned about my petty problems. I swelled with pride that he considered my little world was as important as his. He was a lover of nature, and this knowledge made our walks even more interesting.

Father had the reputation of being graceful and a good tennis player. He played with the best professionals in the Crimea and won most of the time. Olga and Tatiana often played with him and I looked forward to the day when I would be able to match him in a real game. But that day never came. Before the war I was too young, and during the war there was no opportunity. I did return the balls occasionally when Father was practicing.

[Pg 15]

With excitement I looked forward to my first day of school. I was anxious to make a good impression on my teachers. Dressed in a blue or white pinafore and with ribbon bows on my hair, holding my Mother’s hand, I felt quite grown up as I joined Marie in the school room on the second floor of the palace. I was proud to hear Mother say that I was good, quiet, and thoughtful as I sat at a fair-sized table opposite my tutor, answering the questions. But to Mother’s disappointment my good behavior did not last long. As the days passed, confinement began to irk me and I longed for the outdoors. School became a difficult chore for me, and no doubt I was difficult for my teachers. My mind turned to the other side of the classroom door. Only the threat of punishment could bring me to a school desk at all, and once there, instead of concentrating on my lessons, I planned my activities for the hours after school.

My mind dreamed about Vanka, the donkey, when she came as a present to Alexei. She was very bright and extremely stubborn. She was named for a character in a humorous Russian song of the time. Vanka was cunning. When Alexei hurt himself, she laid her head on his shoulder as if she were crying. She could shake hands, wobble as if dancing, and rolled her eyes flirtatiously. She understood every word we said, often shook her ears in joy. But when things were not in her favor, she stared straight at us. Her ears stood up into a half-cone. She had been a circus donkey, but she would only perform when she felt like it. Derevenko, the sailor, could make[Pg 16] her walk while I rode her, but she wanted a lump of sugar in payment for every step she took.

“Anastasia, put your mind on your work,” jarred my consciousness away from Vanka and back into the classroom. I did like arithmetic and drawing. I would often doodle until my pencil was taken away and the lessons resumed. In the spring it was more difficult to concentrate. The warm, sweet air and the chirping birds would not let me sit still.

Often after school, Mother would take me to my favorite farm where I felt complete freedom. Here were many soft creatures to cuddle: tiny pink piglets, toylike lambs, calves and colts, the cutest I ever saw. There were human babies, too, belonging to the farm workers, but Olga had a way of monopolizing them. Every place we went the children followed us and were anxious to show anything new that happened. They all spoke at once, excitedly. We pretended to be surprised, which encouraged them to tell each story over again.

One day one of the workers gave me a tiny chick, born late in the season. We put it in a basket with some straw in it. I covered it with my handkerchief and went ahead of Mother to hide it in the carriage, and waited there impatiently. I was afraid that the little thing would die before we reached home. Soon after Mother heard the chick cry, she said, “You have taken a baby from its mother. You must keep it well and happy.” This chick taught me my first lesson in responsibility. You never saw so much affection lavished on such a small thing. I fed it most tenderly and presented it with my precious pillow which until then had belonged to my doll. In spite of my devoted care the chick’s cries grew fainter and fainter and one morning I found it lying on its back. It was a shock.

I decided to give my chick a funeral. I dressed it regally with veil and gown and, as a great concession, I allowed Marie and Alexei to help lay the little form on a mattress of rose petals in a pretty box. A bouquet of white flowers was[Pg 17] placed on its breast. Then we invited everyone to the funeral. Besides, I wanted no one to miss seeing how beautifully I had prepared my pet. Alexei was the priest, Marie and I chanted mournfully. Derevenko, the sailor, prepared the grave. The box was opened for all to see. At last the box was closed and placed on top of a stretcher, which was hoisted up on the pallbearers’ shoulders. I, the chief mourner, led the procession with a black band on my arm. We buried the box amidst quantities of flowers, then marked the grave with the prettiest stones.

For a week I mourned at the grave every day, wondering how the chick looked after its journey to heaven. Finally, I dug up the box. I opened the cover expecting that the little angel had flown away, but instead I ran to Mother to tell her the worms were eating my pet. Mother explained that the box contained the shell of the chick, the soul was already flown away, now nature was destroying only the shell.

I was quite socially inclined, and made calls on anyone staying in the palace. I chatted with all on various subjects. “If Olga and Tatiana ever marry, will they leave us? Olga squeezed an orange peel yesterday and it squirted right into my eye. Do you know that Mashka (Marie) put on her underwear wrong side out and refused to change it, it is very bad luck. Did you hear that “baby” (Alexei) painted a droopy mustache on his face with a crayon? Olga says, he looks like the Cossack in Riepin’s painting. Do you know that painting? Why do you think Marie did not take her cold bath this morning? Olga says that mother kangaroos hide their babies in a sack on their bodies and the babies poke their heads out to see where they are going. Why doesn’t papa get cribs for the kangarooshkas?” These ideas or others like them were expressed to all in five to ten minutes of social visits. Sometimes I asked them to tell me stories like the Golden Apple and the Princess. I clapped my hands and thanked them for the most delicious story. If anyone was not well, I was ready[Pg 18] to play nurse. My one cure for the indisposed was always a wet towel on the forehead.

Some of my most pleasant early memories about Mother were the times when she told us stories. There was one favorite she was asked to repeat over and over. One day she changed the words slightly and I burst into tears, saying: “But, Mommy, I like the old story better.”

When I was older, Mother read to me an American book called Ramona. As much as I could understand, it was a fascinating story about an Indian girl. It made a big impression on me, and left me with the most tender feeling of affection for the Indian girl. Several years later, when I heard that an American gentleman was coming to see Mother, I begged to be allowed to meet him. I remember that I wore my best new dress, of white silk, a recent gift from Queen Alexandra of England. This frock had smocking at the waist. I was told it came from Liberty’s of London. I kept this dress until the war, at which time I gave it to an orphanage.

At the time of this American’s visit, the nurse was supposed to bring me downstairs when Mother rang the bell. But, when I heard the signal, I ran ahead, and flew down the spiral stairway as fast as my feet could carry me, and burst breathlessly into the room. A tall handsome gentleman arose and politely kissed my hand as we were introduced. Distressed, and almost in tears, I looked sideways up to him as I cried out in surprise: “Mother, this gentleman is not an American because he does not have his feather hat or his blanket.” The poor man, whoever he was, tried his best to explain, but to me, he still was not an American.

Mashka (Marie) had the most wonderful disposition, but I often got her into trouble. We used to practice on the piano in a room above Mother’s boudoir where she could hear us. When the instructor, Mr. Konrad, happened to step out for a minute, we began to roughhouse. Soon the telephone rang and we knew it was Mother to remind us to attend to our practice and not to fool around.

[Pg 19]

Mother realized that we missed having friends of our age, and she made up for it by forming a closer knit family of our own. Occasionally we saw the Tolstoy girls or the children of General Hesse, once Father’s aide-de-camp. We took some lessons, danced and played with them: two boys and a girl about the age of my sister Olga. But no intimacy whatever was allowed. We also enjoyed our cousins, Aunt Xenia’s children, when they were at home.

When Alexei was about seven years old, he had a nurse named Maria Vishniakova. She disturbed Olga and made her cry. Vishniakova told Mother that the muzhik Rasputin had been upstairs in our apartments and conducted himself improperly. According to the tradition of the Russian court, no men were allowed in the girls’ rooms except the two Negro doormen, Apty and Jim. Father became so upset by the report that he personally questioned Vishniakova. She was evasive, and gave one date, then another. When Father told her that Rasputin according to the report was nowhere near St. Petersburg during those dates, she admitted her whole story was a fabrication and that it was a malicious relative of the Imperial family who had had her say what she did. She then burst out crying and of course she was discharged. It was then that the attack on Rasputin began.

Another incident which caused a great deal of confusion some years before the war involved our governess, Mlle. Tutcheva, a native of Moscow. She spoke various languages, but no English. Aunt Ella (the Grand Duchess Elizabeth Feodorovna), Mother’s sister, had recommended her for this important position. Tutcheva was a cultured woman and came from a fine family, but at the same time was unpleasantly outspoken and domineering. She hated the English so that she would not allow the English language to be spoken in her presence, and often criticized the English, especially when we went through our albums of our trips. She even complained to us about our own Mother, that she was English and not a Russian, and constantly exchanged sharp words with Mlle.[Pg 20] Butsova, Mother’s favorite lady-in-waiting, addressing her in an abusive manner, but Mlle. Butsova spared no words for her either. All this made us children excited and nervous. Mlle. Tutcheva was also in continual conflict with others in the palace. To our dismay she also spoke unkindly of Princess Maria Bariatinsky. Later she told Aunt Ella that Rasputin visited our apartments although at no time had any of us sisters seen the man in the upper quarters.

Aunt Ella made a special trip to Tsarskoe Selo from Moscow to inform Mother of this gossip. This incident also came to Father’s notice and he came to our rooms to ask about it. We all said we had not seen the peasant in our apartments at any time. Then the police records showed that he was away on those days. Tutcheva finally admitted that the story was untrue and that she had never in her life seen Rasputin. She was dismissed.

Father loved everything about Russia: her people, her customs, her music and her national food, particularly he was fond of the dark bread. It was baked only in the military kitchens and was most delicious. He also enjoyed a glass of slivovitsa, a plum cordial. During the war he preferred non-alcoholic drinks and omitted strong drinks when prohibition was established, making no exception for himself. However, some wine and other drinks were served to high foreign military officers in Mogilev. Father disliked and often neglected taking medicine even though it was necessary for his weak stomach. He believed, as did his Romanov ancestors, that nature is the best medicine.

Father had the best possible education and training. One of his favorite teachers was the famous Konstantin Pobedonostsev. This man was an outstanding theologian and lawyer. He taught Father both law and religion, so that his faith remained strong to the very end. Another favorite was General Danilov who taught military tactics. He was carefully selected for this most important assignment. Father had a Swiss tutor who taught him the French language and literature,[Pg 21] and an English tutor, named Charles Heath, who acquainted him with the English language and literature.

Father had the most extraordinary memory. He was able to recite many Russian, French and English poems, including passages from Shakespeare. He was a fast reader and writer, his sentences being short and concise and always written in ink. He enjoyed the classics. His reading also included the works of Gogol; Gorbunov’s stories of Russia; and Feodor Dostoevsky, many of whose autographed novels were on the shelves of our library; likewise the works of Longfellow, Dickens, Wordsworth and many others. He was familiar with international law and often remarked that many diplomats complicated matters to such an extent that it took a great deal of time to unravel a simple problem.

On the “Standard,” the Imperial yacht, he had in his cabin the complete works of Shakespeare and other English contemporary authors, and books carefully selected by our tutors for us to read during our cruise.

The strict training demanded of my Father, the future Tsar, was due to the discipline of his austere father, Alexander III. Had Father not felt restrained by his oath of office, I feel sure he would have lifted some of the restrictions he had inherited from his predecessor. His love for his people and his gentle nature were often shown when he lessened the punishment of soldiers by their officers. He believed in a close family relationship and on one occasion, after receiving a request, he granted permission to a Jewish woman to see her sick son in their prison hospital as often as she pleased.

Father was very loyal to his friends, many of whom he had known from his childhood. He disliked the waste of time on petty talk.

Many requests were withheld from him, and occasionally actions were taken without his knowledge or approval.

In spite of previous attempts on his life, he had resumed the ancient custom of the “Blessing of the Waters” on the river Neva in St. Petersburg. When a little girl, I was told[Pg 22] that at one of these ceremonies an explosion occurred on the river, injuring several persons including my Father’s physician. Part of the canopy and the windows of the Winter Palace were shattered. Father, therefore, ordered the discontinuance of this tradition. When an epidemic broke out soon after, the peasants attributed it to the decree. So the order was rescinded and the Epiphany ceremony was resumed. Once I was present at this picturesque ceremony which was one of the great national and religious traditions of Russia.

At this ceremony the dignitaries of the Church and State gathered at the Winter Palace. The procession formed there and proceeded to the river, followed by the church dignitaries. Father took his position in front of a crimson and gold canopy. A hole had already been cut in the ice. At the end of the ceremony the priest handed Father the cross which he dipped in the water and then raised high and made the sign of the cross in the air. This was repeated three times. It was so cold that the drops of water froze as they fell on the ice. After the ceremony the procession returned to the Palace, where luncheon was served to hundreds of guests, who formed a brilliant array in their court regalia.

I remember how beautiful the ladies looked at the luncheon in the Palace following the ceremony. They wore long court dresses of various pastel colors and jeweled filets (kokoshniki) from which soft veils hung down. There were glittering diamonds, rubies, emeralds, sapphires and alexandrites, the latter a rare stone found in the Urals in 1833 and named after the future Alexander II, my great-grandfather.

Many officers wore the dress uniform of their regiment: the Horse Guards were in white and gold; the Cossacks in deep blue or crimson; and the Hussars in white and gold with scarlet dolmans over their shoulders. The “Blessing of the Waters” ceremony was conducted the last time in January 1916. It did not stir the same feelings as before. This time there were many dignitaries present and the foreign High Command, including[Pg 23] our friend, Sir John Hanbury-Williams, and, of course, Sir George Buchanan, the British Ambassador.

Grandeur surrounded us in the Winter Palace where I spent the first years of my life. But during the Russo-Japanese war in 1905 we moved to Tsarskoe Selo, when my childhood recollections began to take root.

The Alexander Palace at Tsarskoe Selo was our permanent home. Many members of the Imperial family had their residences in this suburb and nearby; it was only fourteen miles south of St. Petersburg. Our Palace stood in the middle of a vast park of about six hundred acres, in which were located stables, barracks, greenhouses and several churches, including the Feodorovsky Sobor (Church) and Our Lady of Znamenie which was my Mother’s favorite. There were islands nearby. On the “Children’s Island”, Alexei had a small house; the four rooms were left as they had been at the time of Alexander II. In a book case were some books by the poet Zhukovsky and there were also books by Byron, Schiller and other poets which he had translated into Russian. Zhukovsky who was the tutor to Alexander II spent a great deal of time with him before he came to the throne.

There were some tiny ports for landing, bridges, dog kennels and an elephant house, a concert hall and a Chinese village, a theatre and so on. In the palace grounds was also a white tower, a photographic building and an arsenal. The barracks for the regiments were located in the vicinity.

Before the war the cabinet ministers came to Tsarskoe Selo with their reports in the morning and were ushered into Father’s study by an aide-de-camp. Occasionally however, Father met various officials in St. Petersburg. In order to save time and money the private audiences once a week were held in the Winter Palace in the General Chamber. Because of several hundred audiences that were held during the day, Father could give only a few minutes to each of these audiences and they were held standing. The reports of the high officials were received from 10:00-10:30 after his walk.

[Pg 24]

Several hundred attendants took care of the grounds and buildings; many of them lived outside. The personnel included the Grand Marshals of the Court, Masters of the Hunt, Masters of Ceremonies, Equerries, Chamberlains, coachmen, valets, butlers, chauffeurs, gardeners, cooks, maids, etc.

In Tsarskoe Selo the Palace of Catherine the Great was surrounded by a tall fence featuring a finely wrought iron gate. This building was like a museum, with its matchless rooms of amber and malachite and its mosaic and gold decorations. Two rooms I especially recall: one an anteroom in which Catherine kept her famous collections of snuffboxes, and the other a drawing room with a ceiling of ivory silk satin, in the center of which a tremendous double eagle was embroidered. In a third room, the walls were of satin, with exquisitely embroidered golden wheat and pastel blue cornflowers. There was another room with a double eagle inlaid in its mosaic wooden floor.

The private chapel had a large balcony for the choir. This awesome Palace was in great contrast to Alexander Palace, which we thought had a homelike atmosphere.

While I was a little girl, during our absence the public had permission to go through the Palace, but it was reported that the men conducting the tours allowed their relatives to enter our private chambers. Mother resented this abuse and the tours were forbidden. Later even the park could not be visited and everyone had to have a special permit from the Household Minister to enter even the Tsarskoe Selo grounds; this rule applied also to those employed in our service.

[Pg 25]

During the summer we vacationed on the yacht, but, since Tsarskoe Selo was inland, we went beforehand to Peterhof on the Gulf of Finland. There was a splendid feeling of anticipation of a trip ahead. The great palace of Peterhof was too formal with its many groups of fountains and Peter the Great grandeur. We preferred to stay in the little Alexandria Cottage, while we waited for Father to get away. It was exciting for us children. I remember how often I packed and unpacked my little suitcase, with scraps of papers, which I called my secret records. Among my prized possessions was an old bedroom slipper on which our dogs loved to chew. These things in the little suitcase were my precious childish treasures.

Alexandria Cottage stood to the east of Peterhof Palace; it consisted of two simple buildings joined to each other by an enclosed passageway. We had a glassed-in winter garden where palms and other tropical plants abounded and flowers flourished. Also, there were garden chairs and a doll house for us children to play in during the rainy days. Occasionally we had our luncheon here.

This estate had originally been purchased by my great-great-grandfather, Nicholas I, and he was the first to occupy it. There was a saying that Peterhof started with Nicholas and would end with Nicholas. The park was beautifully landscaped, with winding paths, ravines, and magnificent white birches against the green spruce trees. Its natural rustic beauty had been preserved since the time of Nicholas I.

[Pg 26]

The entrance to the grounds of Peterhof presented a breathtaking view. Tall, graceful trees on both sides arched the roadway, while between them were fountains, bronze statues representing various historical events and enormous urns filled with flowers. A short distance away was a pavilion, a tall tower which we often climbed to get a view of the activities on the Island of Kronstadt. We walked to worship at the nearby Alexander Nevsky Church, named after a national hero who defeated the enemies of Russia in the thirteenth century. From Peterhof we took a tender to Kronstadt, the naval base on the island bearing the same name. There we boarded the yacht, the “Standard”, which was too large to come in to the wharf of Peterhof. We youngsters were each assigned a sailor to watch over us. My poor sailor had his hands full since disappearing was almost an obsession with me. Once he caught me just in time as I climbed the ship’s rail and nearly fell overboard.

Our cabins were large and airy; they were upholstered in light chintzes and each had a washstand, cold and hot water, dresser and desk. Olga and Tatiana occupied one cabin; Marie and I, another. Dinners were held in the big dining salon on the upper deck. There was a chapel where services were held regularly by the ship’s chaplain. Mother as at home stood behind the screen. The “Standard” was painted black with gold decorations at the bow and the stern. It was a two-decker and had two smoke stacks.

I was often frightened on the “Standard” when at sunset a gun salute was fired from the deck. It hurt my ears. When it was time for the firing of guns I would run through the corridor down to the other side of the boat and hold my hands over my ears. The hoisting of the flag took place at 9:00 A.M. and the lowering at sunset.

Charles Dehn, captain of the “Standard,” was a person whose companionship Father enjoyed, and my brother was Captain Dehn’s shadow. Alexei never questioned anything “Pekin Dehn” said. Dehn’s wife, Lili, was a dear friend of[Pg 27] my Mother’s, as well as of us children. Mother was the godmother of their infant son, Titi, who occasionally came to visit us. When he was about seven years old, he could already speak several languages. We loved to see this handsome boy. At tea time he sat next to Mother. When she poured tea, he asked, “Sugar, Madame, and how many?”

Another officer of the yacht, Drenteln, was one of Father’s aides-de-camp and a devoted friend; he accompanied us on our trips. He knew Father from his young years and went with him to the Preobrazhensky regiment. Father found him interesting and they often talked all evening and well into the morning.

Father enjoyed all kinds of sports: tennis, boxing, swimming, diving; and he could stay under water some minutes. He was an expert rider and an excellent dancer, but was not especially fond of hunting. He was devoted to the Navy and when we were on our cruises he spent a great deal of time studying navigation. He was particularly proud of the “Standard” which was built at the Bay of Odense in Denmark at the time of his marriage. During one of our cruises we visited the yard where the boat was built. Each cruise brought fond memories to my parents of their honeymoon. Mother once said that the happiest years in her life were on board the “Standard”.

For us a cruise meant spending a part of each day on shore, tramping in the Finnish forests. On the yacht our attendants turned a rope for us girls to jump. Then there was the tug of war with an admiral or a captain and other officers joining in. Sometimes we roller-skated on the deck. Everyone participated in the fun, except Mother and Alexei. They could not enjoy activities, but they joined in the laughter.

Occasionally we received word that the Dowager Empress Marie, my Father’s mother, was cruising on the “Polar Star” in the neighborhood and would pay us a visit. On board was Admiral Prince Viazemsky. Immediately the holiday atmosphere changed to serious work. We children had to stay on[Pg 28] board, practicing our music, because Grandmother always liked to see our musical progress and a concert was invariably planned. Grandmother was a gifted musician herself and was brought up in a musical atmosphere with her whole family constituting an orchestra. I was told that on one occasion the public was invited to a concert in which her whole family took part, including her father (Apapa), who later became King Christian IX of Denmark, and her mother (Amama), subsequently Queen Louise.

When Grandmother Minnie arrived everyone became tense. I especially felt rebellious at the endless warnings to be on my good behavior. We three younger children had our own early supper, because we could not sit quietly through the dinner in her honor. Try as I might, I was bound to do the wrong thing and disappoint everyone when Grandmother was around. Fortunately her visits were not long and the minute she left we resumed our former manners.

When our yacht anchored in a sheltered cove, we went mushroom hunting. Mother and Alexei seldom joined us in this. But when Alexei came, together we darted this way and that way, dodging the tall trees, and trying to catch the scent of mushrooms. The ground was all springy with pine needles and moss so that we fairly hopped along. It was fun to hear the twigs crunch beneath our feet.

Father was a fast walker; to keep up with him, I had to run. On one of these walks we came to a little stream, partly covered with twigs and moss. Father jumped over it and stretched out his hand to me. “Jump,” he said. The ground was slippery and uneven and I failed to get a firm enough grip on Father’s hand so I fell into the middle of the brook, with its bed of yellow mud and clay. My face, hair and dress were plastered with mud and so were my canvas shoes. The long, wet walk sent me to bed for a while.

Before the war we used to take a trip every other year to Fredensborg Palace near Copenhagen. It was great fun for us children to visit the white villa at Hvidore, which stood[Pg 29] majestically amidst the flowering trees and bushes, with its terraces offering a magnificent view of the sea, each level rising smaller and smaller to the top.

From the terraces the sight of sailboats and yachts in the bay gave us a feeling of tranquility and relaxation. Beyond the marshes were the Danish farms with their charming thatched-roof houses, tall poplar trees, golden wheat fields and millions of scarlet poppies which added grandeur to this natural landscape. It was this that impressed my young mind during our first visit. This villa belonged to my little Grandmother and her sisters, Queen Alexandra of England and Thyra, Duchess of Cumberland. It was at this quiet place at Fredensborg where the happy family reunion took place during the summer months.

We were especially excited on one occasion when Queen Alexandra and Uncle Bertie (King Edward VII of England) joined us at Reval on their yacht, the “Victoria and Albert”. I recollect that King Edward came dressed in Scottish kilts. Grandmother Marie and Aunt Olga arrived on their yacht, the “Polar Star”. Later we were joined by Uncle George, who subsequently became King George V of England, with his wife May (Queen Mary) and their children, including the eldest son David, later Edward, Prince of Wales. In addition, there were many other boys and girls belonging to other relatives. We had a great family reunion and a full schedule of activities. Fishing, bathing, rowing, wading in the shallow waters in the bay and various games were the order of the day. We youngsters enjoyed the high swings which were put up especially for us. Alexei, though only four or five years of age, had been well versed in geography and could name all the various ports in the Baltic. The Russian Ambassador to London, Count Alexander Benckendorff, regarded Alexei as being an unusually bright child. Soon we were off again in the fiords for a glimpse of Norway. When we were in sight of Christiania (Oslo), so many yachts and other vessels surrounded[Pg 30] the “Standard” that we were forced to turn back. Apparently the news of our visit had preceded us.

On our return we brought with us a number of Royal Copenhagen pieces which were adorned with capricious scenes of winter or summer meadows, all interpreted so realistically, and also numerous figurines of animals and fowl, all executed in those soft blue and white colors, some with a touch of brown. Only the hands of Danish artisans could create those heavenly colors.

Once I remember Kaiser Wilhelm II was cruising on his yacht in our vicinity and our ship fired a salute to him. The salute was returned and when the Kaiser came on board our ship, he greeted Father with a kiss and exclaimed, “My most valued friend.” The German band played the Russian national anthem; then the Russian band played the German anthem. During the ensuing visits, the Kaiser took quite a liking to me, calling me “The Little Joker”. I also remember how he danced in a way that Mother thought was undignified and unbecoming to an Emperor. He was one cousin who drove us to despair.

Grandmother Marie joined us in Reval. She brought with her her sister-in-law, Queen Olga of Greece. Queen Olga was the consort of King George I, Grandmother’s brother who was later assassinated. This deed made a fearful impression on us. I remember when Granny cried, “Why do they want to kill an innocent man?” I remember King George as being quite bald, so much so that the Kaiser remarked one time that King George had his own exclusive moon. Extreme baldness seemed to be a feature of the Danish royal family. Kaiser Wilhelm referred to the Danish branch as the “deaf, bald-headed Danes”. King Gustavus V and Queen Victoria of Sweden also paid us a visit. They came on their yacht. We later returned their visit by going to Stockholm.

Quite often our trips were marred by unpleasant incidents, such as the time when, while cruising in Finnish waters, an English freighter persisted in coming too close to our yacht.[Pg 31] When our repeated warnings were ignored, we were forced to fire a shot which unfortunately wounded a member of the English freighter’s crew. On this trip we were invited to visit Prince Henry of Prussia (Mother’s brother-in-law) at a beautiful villa on the shore overlooking the sea at Jagernsfeld, so that the Kaiser could show us his fleet at Kiel. Unfortunately the weather prevented us from doing this and after a brief stop we proceeded to England.

A twenty-one gun salute greeted the “Standard” as we entered the English harbor of Cowes on the Isle of Wight. This was returned by the Russian warships and we passed through a cortege of yachts lined up on each side as we sailed down the middle. Soon the “Victoria and Albert” and the “Standard” were alongside each other. Cheers filled the air and salutes were exchanged. Not until the next morning did the real entertainment begin, when King Edward VII appeared on the bridge dressed in the uniform of a Russian admiral. Father stood next to him in the uniform of a British admiral. The Russian and the British flags were flying, as bands played both national anthems. Amidst the greetings and cheers we proceeded aboard the “Victoria and Albert” to the royal pier. We exchanged pleasant visits and many pictures were taken for our albums.

At luncheon on the yacht, we sat at a long table. King Edward sat in the middle, Mother, dressed in white, looking beautiful and radiant sitting beside him. Queen Alexandra was opposite the King with Father next to her. Alexei kept trying to get King Edward’s attention; until finally the King said: “All right, Alexei, what do you want?” Alexei replied gloomily, “It’s too late now, Uncle Bertie; you ate a caterpillar with your salad.” We were served from gold plates and the table decorations were in pink roses.

The other guests at dinner were the Crown Prince of Sweden, the Prince of Wales (later George V), Princess Beatrice, and Princess Irene, wife of Prince Henry of Prussia. Mother gave a dinner on the “Standard” for the ladies in[Pg 32] honor of Queen Alexandra. At the many dinners on our yacht, I remember there were many elegant and beautiful ladies, several hundred of them: friends, relatives, English, Swedish, German and Russian. On one occasion King Edward gave a talk thanking us for the visit and turning to my Mother called her his “dear niece”.

There were several excursions, and in the afternoon tea was served on the lawn of the Royal Yacht Club. Several hundred guests were present, mostly relatives and friends. Mother knew them all.

Alexei was accompanied by a playmate. One day we were all whisked to Osborne House, where Princess Henry, Mother’s sister, and Princess Beatrice played with us on the lawn. This included Marie, Alexei, his companion and myself. Alexei was all slicked up from head to toe in a white sailor suit. Both boys behaved disgracefully. In the afternoon before tea, this brother of mine crawled over a new car belonging to one of our relatives and by teatime his white sailor suit was completely wrinkled and disreputable. He refused to leave the car and added, “You girls can go to the tea; I am happy at what I am doing.” All of us were disgusted with our brother. Finally his sailor servant, Derevenko, took him off the car. At tea we frowned at him and motioned with our hands to keep at a distance from us, pretending that he did not belong to our family. Tearfully he added to our embarrassment by saying aloud; “What is the matter with you girls? I do not like your attitude. If I were not ashamed, I would cry.”

At another time Olga and Tatiana had quite an experience. Dressed in their gray suits they walked about the town of Cowes, unattended. They paused in their sightseeing before a window display and entered the shop to purchase postcards and photographs for our albums. As they came out of the shop a carriage bearing Count Benckendorff and a friend stopped on the other side of the street. The girls ran across to surprise them, and surprised they were—to find my sisters unescorted. My sisters became frightened when a large crowd,[Pg 33] having heard about our visit, recognized my sisters and gathered around them. Finally the girls made their escape through a store as a constable blocked the door against the pressing crowd. Two carriages were summoned, one for the constable, the other for the girls. At the suggestion of the constable, they finally avoided the crowd by taking refuge in a church. This was their first experience of an unescorted adventure, and their last. When they returned to us, we youngsters kept asking them about it a dozen times, especially when we saw the pictures of the incident in our albums. What a great and priceless triumph it was: that young girls of our position were allowed to show themselves unescorted in public.

Prince David, who was to become King Edward VIII, came by torpedo boat to Osborne House from Dartmouth where he was attending the Royal Naval College. And before we left, he took Father through his college. Father was so impressed with Dartmouth, he talked of sending Alexei there. This was the end of our visit. King Edward, Queen Alexandra, Prince George, then Prince of Wales, and Princess Mary with all their children came to bid us good-bye as we sailed away from Cowes after a most memorable visit.

As usual our party included Princess Obolensky, Mlle. Butsova, a lady-in-waiting, of whom Mother was very fond, as were we all; also Mlle. Tutcheva, our governess, with whom I was continually at swords’ points, because she could not hide her jealousy of Mlle. Butsova, and also because of her derogatory remarks about our English relatives. Present too, were Count Fredericks, Father’s chamberlain, Ambassador Izvolsky, Prince Beloselsky-Belozersky, Dr. Botkin, Dr. Derevenko, Captain Drenteln and many other Russians from our escort ships.