Title: Travels in Western Africa in 1845 & 1846, Volume 1 (of 2)

Author: John Duncan

Release date: July 28, 2022 [eBook #68617]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Richard Bentley, 1847

Credits: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[Pg iii]

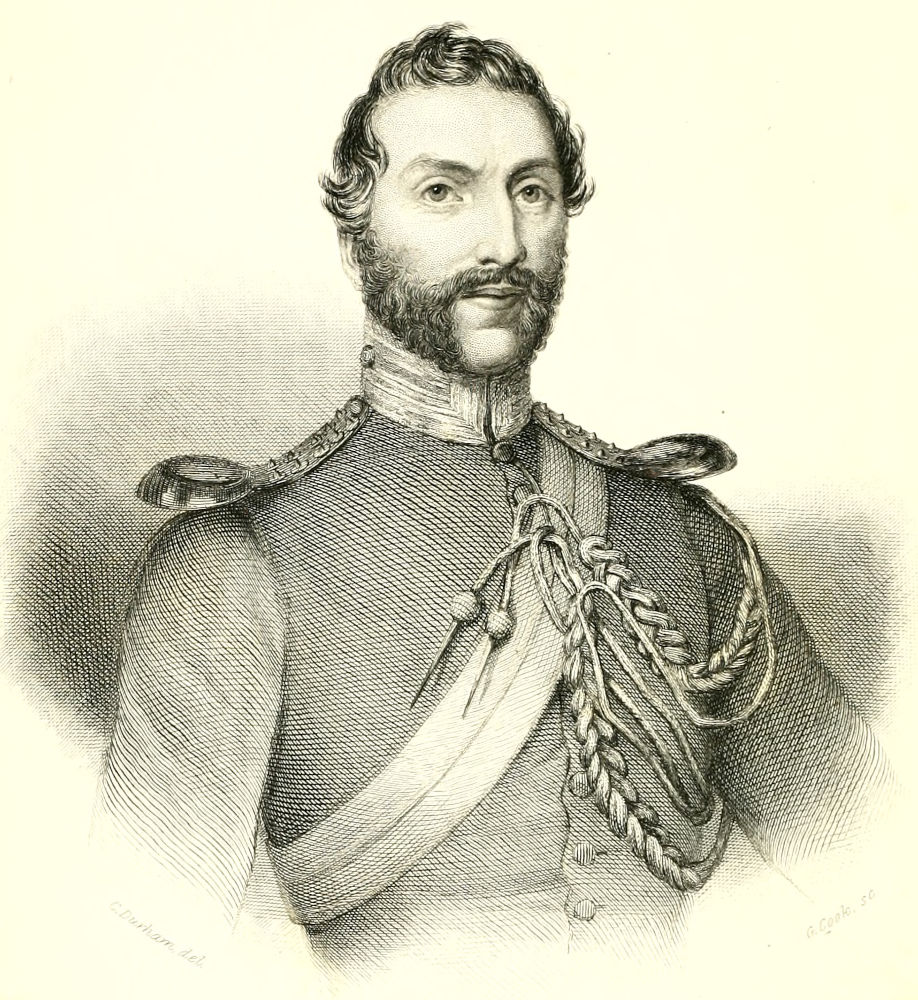

C. Durham, d.el. G. Cook, sc

Mᴿ. JOHN DUNCAN.

(Formerly of the 1ˢᵗ Life Guards.)

THE AFRICAN TRAVELLER.

London: Richard Bentley. 1847.

COMPRISING

A JOURNEY FROM WHYDAH,

THROUGH THE KINGDOM OF DAHOMEY,

TO ADOFOODIA,

IN THE INTERIOR.

BY JOHN DUNCAN,

LATE OF THE FIRST LIFE GUARDS, AND ONE OF THE

LATE NIGER EXPEDITION.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

RICHARD BENTLEY, NEW BURLINGTON STREET,

Publisher in Ordinary to her Majesty.

1847.

LONDON:

R. CLAY, PRINTER, BREAD STREET HILL.

In presenting the following Work to the public, it may be deemed proper that I should preface it by giving some account of my previous career, and of the reasons and circumstances which led to my Travels in Western Africa.

I was born in the year 1805, of humble parentage, on the farm of Culdoch, near Kirkcudbright, in North Britain. I had, at a very early period, a strong predilection for a military life, being of robust health and an athletic frame. In 1822 I therefore enlisted in the First Regiment of Life Guards, the discipline and appearance of which are, I may say, universally admired. During the hours not devoted[Pg iv] to military duties, I applied myself to the cultivation of the art of drawing and painting, in which I attained some proficiency, and acquired also considerable knowledge of mechanics, all of which I found of great service to me when I afterwards became a traveller.

After serving sixteen years in this distinguished regiment, I felt anxious for a field of greater enterprise, and therefore obtained my discharge, on the conditions of the late good conduct warrant, early in 1839. In consequence of meritorious service, I obtained the appointment of master-at-arms in the late expedition to the Niger. In this unfortunate enterprise, I narrowly escaped the melancholy fate of so many of my brave and talented countrymen. Of upwards of three hundred, not more than five escaped! When at Egga, on the Niger, I volunteered to proceed up that river, with a few natives only; but, on account of the increasing sickness of the Europeans, the project was abandoned. Before the Albert, indeed, had descended the[Pg v] Niger nearly all of them were either attacked by the fever or were dead! The season was declared by the natives themselves to be particularly fatal, even to them.

On my arrival at Fernando Po, I was myself attacked with fever, which so seriously affected a wound that I had previously received in my leg,[1] that gangrene commenced, and was only checked by the application of a powerful acid, which destroyed the part affected. At this time my sufferings were extreme; part of both bones of my leg was entirely denuded of flesh a little above the ankle-bone. I strongly desired to have the diseased limb amputated, but having already lost much blood, and the climate of Fernando Po being unfavourable to such operations, (in fact, it was considered that it might prove fatal,) my medical friends, Drs. M’William and Thompson,[Pg vi] promised to perform it when I should arrive at Ascension. The climate of that island is much superior to any other on the coast of Africa. Fortunately, by the unremitting attention of the medical officers, and the kindness of Commander Fishbourne, my wound and my general health much improved during my stay there. From its serious nature, however, I returned to England in an emaciated condition. Having naturally a very robust constitution, I rapidly recovered; but my limb never entirely regained its former strength.

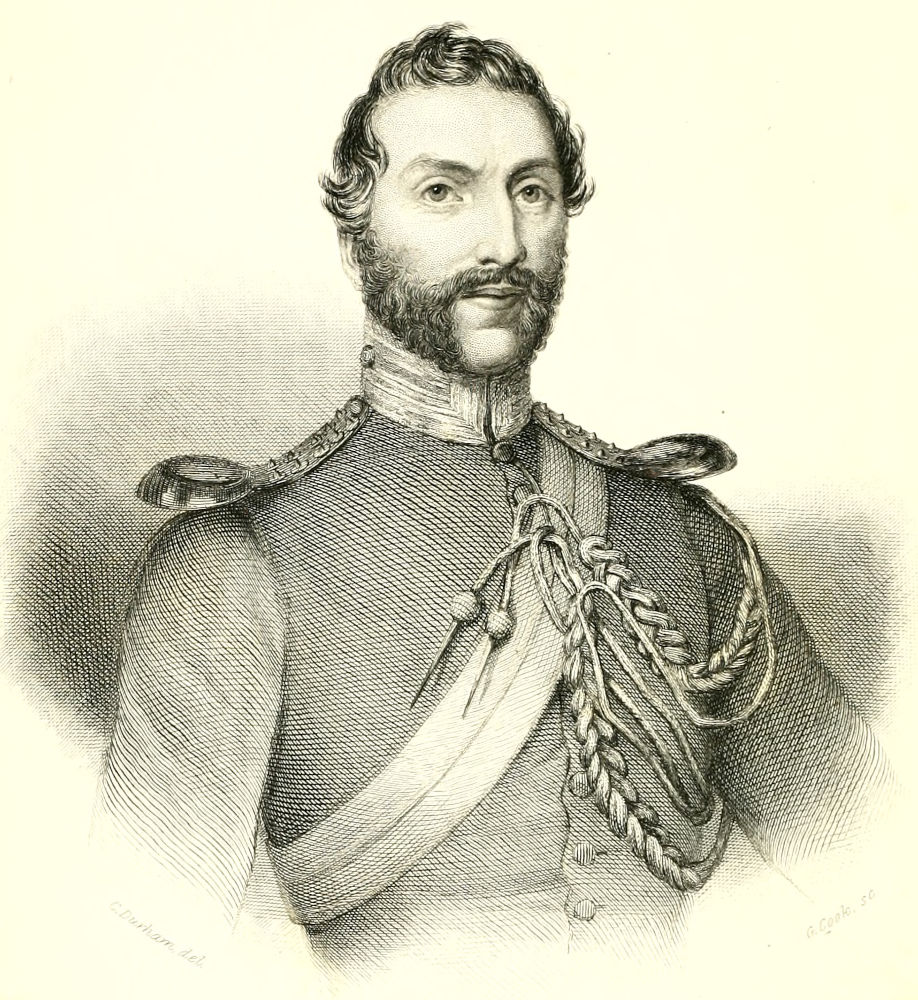

This, however, did not prevent me from offering my services to the Royal Geographical Society, to proceed to Africa and penetrate to the Kong Mountains from the West Coast, the narrative of which journey I now have the pleasure of submitting to the reader. I ought to add that the Society provided me with the necessary instruments and instructions; and that the Lords of the Admiralty directed that I should have a free passage to Cape Coast. The country I[Pg vii] traversed had been hitherto untrodden by any European traveller, and reached as far as 13° 6′ North latitude, and 1° 3′ East longitude.

In conclusion, I beg to state, that the Royal Geographical Society and several other gentlemen liberally contributed funds in aid of my enterprise, for which I cherish the warmest feelings of gratitude.

JOHN DUNCAN.

Feltham Hill,

August, 1847.

[Pg viii]

[Pg ix]

[1] I was wounded at the Cape de Verd Islands by the natives, while aiding my men, upon whom they were about to make a murderous attack. On retreating, one of them threw a poisoned arrow at me, which I parried from my face and body, but which struck my leg.

| CHAPTER I. |

| PAGE 1 |

| Departure—Arrival at Tangiers—Description of the Town—Market—Price of Provisions—Method of Storing Grain—Inhabitants—The Jews—A Jewish Dwelling—The Moors—Fruits and Flowers—Desolate State of the Town—Moorish Market-women—Gibraltar—Ascend to the Highest Point—A Pic-nic and an agreeable Reconnoitre—Cleanliness of the Inhabitants—Arrival at the Gambia—Bathurst—The Mandingos—Massacre of the Crew of the Margaret—Encounter of the Crew of the Courier with Pirates—Sierra Leone—Dr. Ferguson—Mr. Oldfield, his Hospitality—Give Chase to a supposed Slaver—Cape Coast—Governor Hill—Cape Coast Castle |

| CHAPTER II. |

| 22 |

| Attacked by Fever—Death of my Servant—Mr. Hutton—Buildings in Progress by him—Indolence of the Natives—Cheapness of Living—The Fantees—Their Superstition—Description of their Idol or Fetish—Their Customs or Holidays—Native Music—Rum, their favourite Liquor—Proceedings on occasion of a Death—Mode of Burial—The King’s Custom or Holiday—Character of the King—My Reception by his Majesty—Comparatively neglected by the British Government—Fetish Houses—Native Funerals—Want of Natural Affection—The Yam Custom—The Fantees, the worst of the African Tribes—Their Power of Imitation—Wild Animals—The Patakoo—Granite and Sandstone—The Dutch Settlement of Elmina—A fine Field for Botanists—State of Agriculture—Excessive Heat—Message to the King of Ashantee—Cattle—Artizans much wanted—Murder of an Ashantee Woman [Pg x] |

| CHAPTER III. |

| 39 |

| Annamaboe—State of the Fort—Indolence of the Natives, and Difficulty in procuring Labourers—Domestic Slavery—Missionary Schools—Want of Education in the Useful Arts—Hints on this Subject—Vegetables and Fruits—Town of Annamaboe—Soil—Natives—Reception of me by the King, and Conversation with him—Mr. Brewe—Mr. Parker—Excessive Heat—Little Cromantine, its impregnable Situation—The Fort—Cromantine—The Market-place—Extraordinary Tradition—Wonderful Dwarf—An Adventure—Accra—Wesleyan Missionaries—Natives—their Habitations—Wives and Slaves—Situation of the Town, and Soil |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| 58 |

| Strange Articles of Food—Native Cookery—The River Amissa—Reception by the Caboceer of Amissa—Soil, Fruits, &c.—An Adventure—Visit from a Hyena—The River Anaqua—Arsafah—Soil, Fruits, &c.—Beautiful Birds—Moors and Arabs here—Cattle—Return to Cape Coast—Hospitable Reception there—Invitation from the King of Ashantee—My Reply—Visit the Neighbourhood of Cape Coast—Coffee Plantations—Indolence of the Natives—The Town of Napoleon—Eyau Awkwano—Fruits Growing Spontaneously—Bad Roads—Singular Mode of Carrying Timber—Cotton Trees—The Dwarf Cotton Shrub—Scene of a Sanguinary Battle—Djewkwa—Native Houses—An Intoxicated Caboceer—The Caboceer’s Presents—Account of him—Return to Cape Coast—Sail for Whydah—Winnebah—Method of Curing Fish—Natives—Stock—Neighbouring Country—The Devil’s Hill—Soil—Yanwin (samphire)—The River Jensu—Beautiful Birds—The King-fisher |

| CHAPTER V. |

| 78 |

| Native Laws—Roguery of the Natives; White Men fair Game—Superstition—Fetish-houses—Colour, Habits, &c. of the Natives—Prevalence of Drunkenness—Disgusting Neglect—Fashion in Shaving—Tally System—Population—Accra—Mr. Bannerman and his Hospitality—Danish Accra, partly Demolished—Occasion of this—Attempt to assassinate the Governor—English Accra, its Trade much reduced by Competition with Americans—Currency—Merchants’ Houses—Fruits[Pg xi] and Flowers—The Coromantine Apple—Natives most expert Thieves—Population—Circumcision—Mode of Carrying Children—Sleep in the Open Air—Manufactures—Fish—Difficult Landing—Salt Lake—Soil—Gaming and Drinking—Population of English Accra—Stock—Cruel Treatment of Horses—Want of Natural Affection—Sail for Ahguay—Boarded by an English Brig—Mr. Hutton’s Factory at Ahguay—A Drunken Caboceer—His Dress and Attendants—A Principal Fetish-woman, her Dress—Dance performed by her—Natives of Ahguay—Slave-merchants—Cotton and Indigo—Markets—Treatment of Slaves—Characteristics of Africans—Fish—Method of Dressing the Crab—Alligators—Alligator-hunt—Plants and Fruits—The Velvet-Tamarind—Popoe—Mr. Lawson, a Native Merchant—Introduction to his Wives—Merchants, their Mode of Living—Slave-Trade—Population—Manufactures—Gaming and Drinking—Kankie—M. de Suza’s Slave Establishment—His House—His Domestic Slaves—Noisy Reception by the Caboceer—Treatment of Slaves |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| 105 |

| Gregapojee—Extensive Market at—Native Produce and European Manufactures—Popoe Beads, their Value; probable Origin of—Houses—Situation and Soil of Gregapojee—Fish—Alligators—Population—Return to Ahguay, and thence to Whydah—Toll-house—Fish-trap—Travelling Canoe—Beautiful Scenery of the Lagoon—Oysters growing to Trees—Old Ferryman—Gibbets of three Criminals—Murder committed by them—The English Fort at Whydah—Character of M. de Suza—Treatment of Slaves—Hints with reference to this odious Traffic—Price of Slaves—Slave Hunts—Necessity for Education—Cruelty in the Shipment of Slaves—Visit to Avoga—Account of him—Reception by him—Mode of Riding—Bad Road—Reason for not Repairing it—Market at Whydah—Native Manufactures, &c.—Duties imposed by the King of Dahomey—His Enormous Revenue—Head Money—System of Government—Severe Laws, and their Result—Paganism—Abject Superstition of the Natives—Dangerous to show Contempt for their Fetish—Anniversary Offerings for departed Friends—Usual Termination of such Festivals—Snake Worship—Houses built to contain them—The Snake-Lizard—The Field-Lizard—The House-Lizard—Vampire Bats [Pg xii] |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| 132 |

| Locusts—The Winged Ant—Its Destructive Nature—Horse attacked by them—Their Ingenuity in Building—Stock—Great Want of Mechanics—Portuguese Whydah—Emigrants from Sierra Leone—Their Deplorable Condition—English at the Fort of Whydah—Military Resources of Dahomey—Polygamy—Mode of Shipping Slaves—Brutality on these occasions—Porto Sogoora—Mr. Lawson’s Slaves—Greejee—Toll imposed there—Zahlivay—Yakasgo—Badaguay—The Cabbage Palm-tree—Wooded Scenery—The Palm-tree—Exploring Visit to the Haho—Misfortunes of Ithay Botho, Capt. Clapperton’s Servant—Adventures—Curiosity of the Natives—Podefo and its Market—Alligators—My Crew mutiny from fear—Hippopotami—Superstition of the Natives—A party of Fishermen, and their Fish-traps—Base Conduct of the Fishermen—My Punishment of them and my Crew |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| 164 |

| My lonely Situation—Akwoaay, its Population, &c.—Kind Reception by the Gadadoo—Native House of two Stories—Gigantic Cotton-tree—Etay, a Vegetable of the Yam tribe—Voracity of the Natives—Soil, Manufactures, &c. of Akwoaay—Natives of Porto Sogoora—Visit of the Caboceer—Mode of catching Crabs—Great Heat—Visit from Native Women—Mr. Lawson of Popoe—Character of the Natives—Attempt at Murder—Nocturnal Visit—Superstition—Vicinity of a Fetish-house—Flocks of Monkeys—The Monkey, an article of Food—Disagreeable Situation—Cravings of Hunger—Visit to the Greejee Market—An Alligator killed—Usual Notice to the Authorities on such occasions—The Alligator used as Food—Cruelty of the Natives to the Horse—Return to Whydah—Bad Conduct of my Canoemen—Adventures—Arrival at Whydah—Preparations for my Journey to Abomey—Country around Whydah—Farms—Emigrants from Sierra Leone Slave-dealers—Generosity of the King of Dahomey—Soil of Whydah—Corn-mill—Ferns, Vegetables, Fruits, &c. [Pg xiii] |

| CHAPTER IX. |

| 190 |

| Manufacture of Salt—Death of Dr. M’Hardy—Falling Stars—Manioc, the Food of the Slaves—Crops—Mode of storing Grain—Superstition—Hospitality of Don Francisco de Suza—A Tornado—Slave Auctions—Punishment for killing Fetish Snakes—Slaughter of Dogs, &c.—Dogs used as Food—An English Dog rescued—Thievish Propensities of the Natives—Falling Stars—Murder of two Wives—Adjito—A heavy Tornado—Robbed by my Servant—American Brig sold to Slave Merchants—Shipment of Slaves—Sharks—Death caused by one—Preparations for my Journey to the Kong Mountains—M. de Suza’s Liberality—His Opinion of Englishmen |

| CHAPTER X. |

| 205 |

| Set out on my Journey for Abomey—Savay—Torree—My wretched Condition—Azoway—Parasitical Plants—Aladda—Cotton tree—Atoogo—Assewhee—Havee—A Butterfly-School—Whyboe—Construction of the Houses—Native Customs—Manufactures—African Character generally—Population of Whyboe—Akpway—An extensive Swamp—Ahgrimmah—Togbadoe—Scenery—Soil—Swarm of Locusts |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| 215 |

| Canamina, its Population—Adawie—Preparations for entering the Capital—Abomey—My hospitable Reception—Visit from Mayho, the Prime Minister—Message from the King—The Palace—The Market-place—Dead Bodies of Criminals hung up—My Reception by his Majesty—Ceremony on Introduction—Conversation with the King—Perform the Sword Exercise before him—His Approbation—Troops of Female Soldiers—The King’s Person—Ceremony of the Introduction of Military Officers—Dress of the Female Soldiers—Introduced to the King’s Chiefs—Visits—The King’s Staff—Review of Native Troops—Feigned Attack on a Town—The King’s Soldier-wives—Ashantee Prince—His Majesty’s Opinion of England and the English—The vain Boasting of the Ashantee Prince silenced by the King—Principal Officers—The Dahoman Women formidable Soldiers [Pg xiv] |

| CHAPTER XII. |

| 241 |

| Visit to the King at his Palace—Description of it—Reception by his Majesty—Gaudy Dress of the Attendants—Masks, Ornaments, &c.—Occasion of the War between the Mahees and Dahomans, and its Result—The King’s Walking-staffs—Dance performed by his Majesty—Another Review of Female Troops—Execution of Four Traitors—Horrible Occurrence—Disgusting office of the Blood-drinker—Ludicrous Scene—The King’s Mother and Grandmother—Dance performed by them—Costume of the King’s Favourite Wives—I perform on the Jew’s Harp—I dance with his Majesty—His Message to the Queen of England—Ridiculous Customs—Court of Appeal established at Abomey—Character of the King—Domestic Slavery—A Slave-hunt—Military Distinctions—Want of Natural Affection in the Natives—Roguery of my Servant—The King’s Commissions to me—An Interesting Incident—Murderous Attack on me by my Servant—Inquiry into the Occurrence—My Servant compelled to accompany me |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| 272 |

| Departure for the Kong Mountains—My Dahoman Guards and their several Duties—The King’s Wife—Neighbouring Krooms—Soil and Aspect of the Country—Varied Scenery—Cana—Bobay—Illness of my Servant—Immense Blocks of Granite—Custom-house—Duties imposed—Milder Laws established—Dtheno—Travelling Traders—The Azowah—Destruction of the Shea Butter-tree—Its Manufacture declared to be lawful—Description of this Tree—Immense Mountains—Ruins of Managlwa—Destruction of that Town by the Dahomans—Beautiful Scenery—Markets—Setta Dean—Reception by the Caboceer—Dance performed by him—Setta—Serenade—Supply of Provisions—Custom of Tasting—The Caboceer’s Speech—The Natives expert as Cooks—Variety of Food—Palm Oil—Occro—Presents from the Caboceer—The Widow’s Mite—Harmless Deception—Presents to the Natives—Dance performed by the Soldiers—Situation of Setta; its Soil, &c.—Its Population |

[Pg xv]

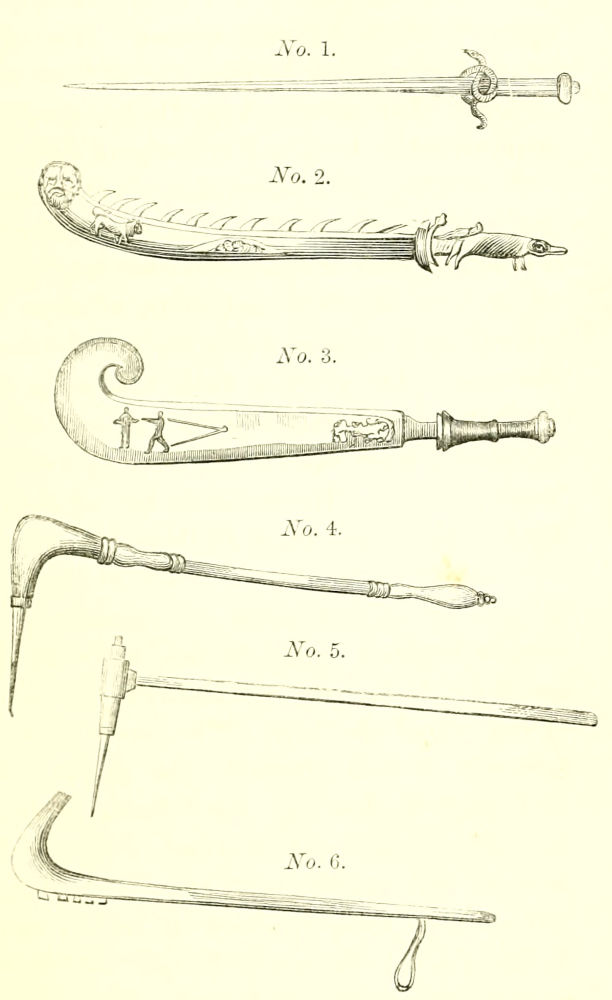

| Portrait of the Author | To face the Title. |

| Map of the Author’s Route | p. 1 |

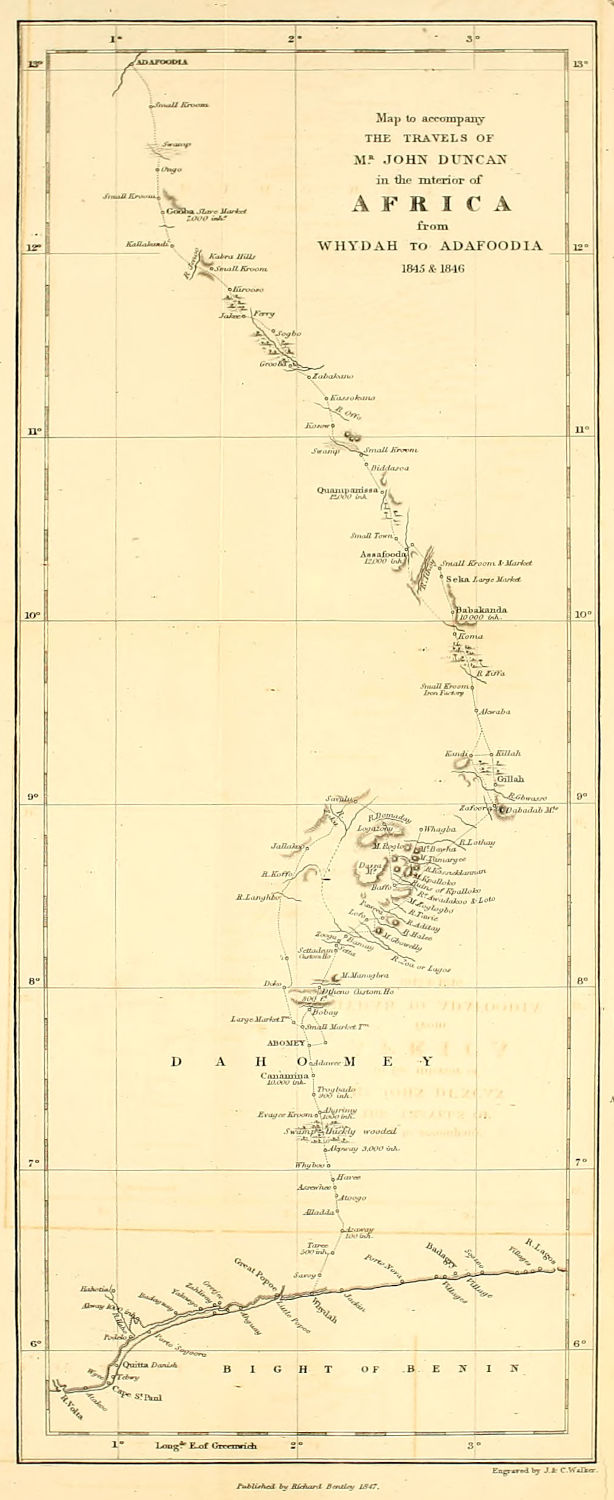

| Dahoman Weapons | 226 |

No. 1.—A long straight dagger, with snake on the hilt, to bite the Mahee people.

No. 2.—A large heavy knife, with imitation of tigers’ claws on the back, to hook the Mahee people when running away. This knife is about the substance of the English bill-hook.

No. 3.—A very broad, thin knife, with a Dahomey man in the act of shooting a Mahee man. This knife is made of silver, and is more for ornament than use.

Nos. 4 and 5 are King’s battle-sticks: the angle of the handle into which the blade is fixed is the natural growth of the wood.

No. 6 is a battle-stick, carried by all soldiers, male and female. This stick is used to beat people to death, when silence is necessary, as the report of a gun might give an alarm. By examining No. 6, five large knobs of iron are seen fixed to the under part of the head of the weapon.

Map to accompany

THE TRAVELS OF Mᴿ JOHN DUNCAN in the interior of AFRICA

from WHYDAH TO ADAFOODIA

1845 & 1846

Engraved by J. & C. Walker.

Published by Richard Bentley 1847.

[Pg 1]

TRAVELS

IN

WESTERN AFRICA.

Departure—Arrival at Tangiers—Description of the Town—Market—Price of Provisions—Method of Storing Grain—Inhabitants—The Jews—A Jewish Dwelling—The Moors—Fruits and Flowers—Desolate State of the Town—Moorish Market-women—Gibraltar—Ascend to the Highest Point—A Pic-nic and an agreeable Reconnoitre—Cleanliness of the Inhabitants—Arrival at the Gambia—Bathurst—The Mandingos—Massacre of the Crew of the Margaret—Encounter of the Crew of the Courier with Pirates—Sierra Leone—Dr. Ferguson—Mr. Oldfield, his Hospitality—Gave Chase to a supposed Slaver—Cape Coast—Governor Hill—Cape Coast Castle.

The Lords of the Admiralty having given orders that I should have a free passage to any port of the west coast of Africa, and Lord Stanley having also provided me with letters of introduction to the governors of the different settlements at the Gambia, Sierra Leone, and Cape Coast, with[Pg 2] orders to render me every assistance in their power, and being also furnished with letters by Mr. Bandinell, of the Foreign Office, to the different Commissariats on the coast, requesting them to render me assistance, I made preparations for my departure forthwith. The Geographical Society had kindly furnished me with the necessary instruments to make my geographical observations, and with the maps of Africa; and, in a generous and delicate manner which I shall never forget, presented me with a small sum of money. I now, therefore, merely waited for an official order to proceed by any vessel which might be directed to take me. This order soon arrived, and I went on board the Cygnet brig of war, Captain Layton.

I was received by the captain and the rest of the officers in the most cordial manner. After getting my luggage, however, on board, another order was forwarded from the Admiralty, transferring me to the Prometheus steamer, Captain Hay, then under orders for the Gambia with money. Accordingly, my luggage was put on board the last-named vessel, and on Sunday afternoon, the 16th of June, 1844, I and my servant, William Stevens, went on board at Spithead, where the several vessels, the St. Vincent, Prometheus, and Cygnet, were riding at anchor near each other. I was received in a very kind[Pg 3] manner by Captain Hay and Lieutenant M’Gregor, and the other officers of the Prometheus.

I must not forget to mention that Captain Johnston assisted me in obtaining a knowledge of the sextant, and Lieutenant Raper presented me with a copy of his valuable work on “Practical Navigation.” Captain Johnston, moreover, came on board the Prometheus at Portsmouth to request Captain Hay to make me as comfortable as possible, as well as my servant and my dog.

At four o’clock on Monday morning, June 17th, we weighed anchor (with steam up), taking the Cygnet in tow as far as Plymouth Sound. At a late hour on Sunday night Captain Hay unexpectedly received despatches ordering him to go to Tangiers and Gibraltar, at which I felt not a little disappointed, for I had fully expected to have an opportunity of visiting the island of Madeira, and of seeing my friend and countryman Mr. W. Gordon, whose kindness I had already experienced. However, my disappointment was fully compensated by being thus allowed to visit Tangiers, off which we anchored on the 23d. As Captain Hay had despatches for the Governor, I had an opportunity of going on shore for a few hours.

On landing I was stopped by several Jews as well as Moors offering their services to show me[Pg 4] the town and market, this day (Sunday) being their principal market-day. The town of Tangiers is strongly fortified towards the sea, but quite defenceless from the land. The houses are generally square, and nearly flat-roofed, and the whole town is built on a steep declivity towards the bay. There is no regularity in the streets. The main street is from the bay, or landing-place, close to which is the custom-house. It is about a quarter of a mile in length, narrow, crooked, and very badly paved, with shops on each side, similar to the butchers’ shops in England, but not so clean. This street leads through the centre of the town to the outer wall, immediately behind which the market is held. The market-place is in a hollow immediately behind the town, but not enclosed in any way. It appeared to be well supplied with cattle and meat.

In the market-place meat may be purchased at 1¹⁄₂d. per pound, but a duty is paid upon every article of consumption taken from the town to any other country, unless for the British navy. Vegetables are also very cheap, new potatoes (very fine at this season) are about one shilling per bushel; large oranges twelve a penny. The market is a miniature Smithfield with respect to cattle, owing to the great number of horses, camels, and asses, used in bringing goods to it, as[Pg 5] well as bullocks, sheep, and goats for sale. All goods are transported from one place to another on beasts of burden. I observed a great number of fowls at a dollar per dozen.

Their method of storing grain, in case of its not being sold or in case of rain, is very simple. At short distances from each other in the part of the market arranged or allotted for the sale of grain, holes are dug, about four or five feet square, and the same in depth, into which the corn is deposited until the next market-day. These pits are lined with wood, and when the grain or other goods are deposited, the cover is sealed by the market officer or sheriff, who regulates the price of every article of consumption exposed for sale.

The foreign inhabitants consist of various races, chiefly from France, Spain, Portugal, and England; the fewest in number are English, comprising only the English Consul’s establishment. With the exception of the native Moors, the French and Jews are the most numerous, and their character is the same as I have found it in all countries wherever I have met them. The moment you set your foot on shore you are assailed by a host of Jews and Moors, eager to direct you to their houses to trade with them. The Jews are generally most successful, being[Pg 6] more civilized than the Moors. They speak good English, as well as many other languages, and most of the Moors who can speak English or French, are employed by the Jews as “cads” to direct strangers to their employer’s house. If they find you at all impatient at their solicitations, they invariably invite you to go to their house and drink a glass of wine with them. If you deal with them, you are supplied with a glass, or even two, but are sure to pay for it in the price of the article purchased. If you should not purchase any thing, whatever wine or spirit happens to be your choice, they are sure to be in want of, or it is so bad that they cannot recommend it; yet upon the whole they are preferable to the Moors. If you have money they treat you with great civility.

Their houses are remarkably clean, and their dress is very simple and graceful. Both male and female Jews dress in the Moorish fashion. They seldom seat themselves otherwise than on a mat. Upon my entering a Jewish dwelling, in a hall on the left-hand side, the occupant’s daughter was seated busily engaged in sewing. She was certainly one of the most beautiful and graceful women I ever beheld, and readily offered to shake hands with me. On the opposite side of the entrance-hall lay a heap of wheat. The latter no[Pg 7] doubt for sale, and probably the former also to be disposed of in the matrimonial market. On entering an inner apartment, I was introduced to the rest of the family, five in number, all remarkably clean. In the corner of this apartment was a young man, about twenty years of age, apparently a Moor, who showed article after article for sale, as a hawker would in England. Amongst the articles exhibited were French and Spanish cottons, morocco slippers of various patterns, silk girdles beautifully embroidered, and ladies’ reticules of a very rich pattern, also beautifully embroidered with gold, on velvet of various colours, chiefly green or red.

I observed during my short stay only two different kinds of trade practised in Tangiers—shoe-making and gun-making. The gun-makers showed much ingenuity, considering the clumsiness of their tools: they even twist their barrels. In general, I cannot speak very favourably of the cleanliness of the Moors, as compared with the Jews. Their streets are very dirty,—sheep-skulls, horns, and other parts of different animals, being thrown into the streets; and on the outer skirts of the market-place may be seen a number of dead dogs and kittens, which have been carried there and left to perish, for they have not the humanity to put them to death by any other means.

[Pg 8]

I had an opportunity of visiting the Swiss Consul’s garden, which is laid out with considerable taste, and abounds with fruit, among which I observed very fine oranges and citrons, and remarkably fine figs. There is also a burial-ground, where Christians of all nations are interred, amongst which were pointed out by my Moorish guide the graves of an English family, consisting of a father, mother, and two children, who had been robbed and murdered by the Moors.

I was informed by several of the inhabitants that it is very dangerous for any stranger to proceed more than a mile or two from the town, unless attended by a mounted soldier, who is appointed by the Governor, and receives a dollar per day.

The cactus grows here wild, and of gigantic size; although in the immediate vicinity of the town little vegetation is apparent. Of the minor class, the orange, citron, and saffron shrub, with some large aloes, are the chief plants I observed. The place seems altogether poor; but from information I obtained, it would appear that trade was much better some time back, before many of the Jews left the place on account of the disturbed state of the country. In fact, the inhabitants are now in hourly expectation of the French blockading the town. There is at present a Spanish frigate at anchor abreast of the town; and since we dropped[Pg 9] anchor this morning, a French man-of-war steamer has arrived and anchored near the Prometheus.

The Jews here make a good trade by changing English money. They deduct three shillings in the sovereign for exchange, and at Gibraltar, two,—a serious disadvantage to English visitors.

Mules and asses seem of all animals most used as beasts of burden. The Moorish market-women have a very singular appearance, owing to their dress, which consists of a piece of thick woollen cloth, the same as a blanket, which envelopes the whole of their body, and entirely conceals their faces. From the slowness of their pace, and their figure, excepting the colours of their dress, one might imagine them part of a funeral procession. The men are generally tall and muscular, though not fleshy, and strict Mahomedans.

At six in the evening we weighed anchor, got steam up, and sailed for Gibraltar, where we anchored about nine o’clock. I was truly gratified at having an opportunity of visiting this place, which is, indeed, one of the wonders of the world. We carried despatches from the Consul at Tangiers to the Governor, Sir Robert Wilson. On the following morning, the 24th of June, I went on shore to see this impregnable rock, of which it would be presumption on my part to attempt a description, since it has been done by abler pens than[Pg 10] mine; but I will merely give an account of the treatment received by myself and two of the young gentlemen belonging to the Prometheus from some of the inhabitants when on shore, which I do principally to remove those prejudices against them which are sometimes entertained by the English. In fact, I had formed a very different opinion of the Spaniards from what I found them to deserve.

I had determined to reach the summit of that tremendous rock; and for that purpose I ascended by a zigzag path, passing several strong batteries, all commanding the town and bay. When we had gone half way to the top, we fell in with a large gipsying party (as it would have been termed in England), keeping holiday in memory of St. John, at the entrance of a large cave, in front of which a sort of platform had been formed, as it seemed, by the joint work of Nature and Art. As it completely commands the town and shipping, it was, doubtless, at some former period used as a battery. I was struck with the free, lively, and generous manner in which the whole party received us. Their number was about a hundred ladies and gentlemen, with several children. On our approach, we were cordially invited to join them, and partake of their refreshments, which they had in abundance. Their table was formed by a finely wrought grass mat, spread[Pg 11] in the entrance of the cave, which is about ten feet high in the centre, and about twenty feet wide. In the centre of its mouth is a basaltic column, resembling those in Fingal’s Cave. From this elevated spot, we commanded a view of the town of Gibraltar, its beautiful bay filled with shipping, among which we observed the Warspite with the Vesuvius and Prometheus steamers. The towns on the opposite shore of the bay were all perfectly visible; and the surrounding country, with its majestic mountains, formed a splendid scene.

The liveliness and hospitality of the party we met here gave me a very favourable notion of the inhabitants of Gibraltar. If other Spaniards are like these, I think they are among the gayest and happiest people in existence. After partaking of some wine and other refreshments, we were invited to join in a dance, and asked what dance we should like to see performed, English or Spanish. The ladies performed both with admirable grace, highly set off by their simple and graceful dress and fine figures, which give them a decided superiority over any other people I have seen. Their small feet, elasticity of action, and unaffected ease of manner, are certainly deserving of admiration. Their dark hair neatly plaited in two braids hanging down the back, with a small curl near the eye on each side, pressed close to the[Pg 12] temple, with their dark but bright expressive eyes, ivory teeth, and fine features, reminded me of Lord Byron’s descriptions. I was also struck with their remarkable abstemiousness: the women drink no wine, or any fermented liquor, except at meals, and even then seldom without water. The men are remarkably civil and obliging, and almost as abstemious as the women. Though it was a holiday I did not see one intoxicated. After several dances had been performed for our amusement, we proposed to go up to the top of the mountain, and the whole party immediately volunteered to accompany us. Everything was therefore got ready without delay; the asses were saddled, and a basket or cradle was attached to each, in which the youngest of the children were placed. As soon as all was ready, the word of command, “March!” was given by the captain of the party, the procession being headed by two men playing on guitars.

The path, though very rough and steep, was quickly ascended; and even along the brink of precipices the ladies and children passed without showing the least alarm. After a rather fatiguing journey we arrived at the summit of one of the two highest peaks, on which is a look-out house and a strong battery. On looking over the outer wall of this, the sight which presents itself is really[Pg 13] terrific, for the rock is here quite perpendicular from the base to its summit.

After resting for about a quarter of an hour, we re-ascended the rock for about half a mile, till we came to the path leading to the second peak, when we began our second ascent, and in about twenty minutes reached the signal-house, at the highest point of the rock. Among the artillerymen stationed there I met with one of my countrymen, M’Donald, a native of the Isle of Sky. He is a sergeant or sergeant-major of artillery, and is allowed to sell wines and other liquors. I was desirous to treat our party on arriving here: but none of the females would take anything but water, and the men could only be prevailed on to drink one glass of either porter or wine. When the younger ladies had performed a few favourite dances, we descended the rock as far as the mouth of the cave, where we again halted for about ten minutes. Dancing was here renewed; the cloth was again laid, and a very luxurious repast was set before us. The evening being now far advanced, we were obliged, with regret, to take our leave of this happy and most agreeable party.

On the following day, while we were getting in the requisite quantity of coal, I had an opportunity of visiting different parts of the town, which appears to be strictly governed. Every house is[Pg 14] visited by the police, before ten o’clock A.M., to see that it has been thoroughly cleaned,—a regulation which might be advantageously adopted in our own overgrown metropolis. Even the poorest of the inhabitants are remarkable for their cleanliness. Their linen is exceedingly clean.

On the 25th we hove our anchor, and I left Gibraltar with much regret. Nothing of importance occurred during our passage to the Gambia. The weather was fine, and I received such kind assistance from all the officers, particularly from Captain Hay, as I shall never forget as long as I live. Upon his learning that I had forgotten my telescope, he very kindly presented me with a very good pocket-glass.

On the 6th of July we arrived at the Gambia, and anchored abreast of the town of Bathurst, at twenty minutes past eight in the evening. On the following morning I saw with much regret the Wilberforce steamer lying partly dry, the tide ebbing and flowing into her. She formed a striking contrast to what she was when I left England in company with her in the ill-fated Niger expedition. About ten o’clock A.M. I went on shore, accompanied by our sailing-master and purser, and visited several European merchants and official gentlemen, as well as the Governor, for whom I had letters; all of whom treated me with[Pg 15] every mark of kindness, particularly Mr. Quin, who took great pains to show me everything of interest in Bathurst.

This settlement is not large; the houses are good, and well constructed for a warm climate. Behind the main town are a considerable number of conical huts, very close to each other. Upon the whole, Bathurst seems well adapted for trade, and capable of being greatly improved. As far as I could judge, it is in a thriving condition. It is much visited by Mandingos for the purpose of trade. These are a peculiar race, easily distinguished from any other, being tall and thin, very active, and very black. Their skin is apparently not so moist as that of some other African tribes; but their head is very singularly formed, tapering from the forehead upwards, to a narrow ridge along the crown. As this was the sowing season, fruits were not plentiful. Some bananas, cocoa-nuts, ground nuts, and other small fruits, were all that could be obtained.

We here received intelligence of the massacre of part of the crew of the Courier, William Vaughan, (which left London 29th April, 1844,) on the island of Arguin. On the 19th of May, it appeared, they got sight of land a little north of Cape Blanco, and on the 20th rounded the point or cape, and entered the bay of Arguin, when suddenly the ship got into[Pg 16] two fathoms water. Upon this the master instantly ordered the helm hard a-port, but before the ship could be got round she struck at three P.M. at high-water and spring-tide. Fifty tons of ballast were now thrown overboard, and at two on the following day, she being got off, the chief mate was sent to sound a-head, but was often obliged to anchor, owing to the incorrectness of the charts. He anchored with the long-boat under the island during the night, owing to the heavy sea running; but as he was rounding the point to return to the ship, he saw two natives and a white man coming towards the long-boat. The white man hailed the boat in English.

They again rounded the point to take in their countryman, upon which the two natives beat him unmercifully with bludgeons. One of the Englishmen then ran back to the boat and procured a musket, which he presented at the two natives, on which they immediately ran off. Upon reaching the poor Englishman, the mate and men belonging to the Courier ascertained that the barque Margaret, of London, had been plundered at the same place in the month of May previous, that almost all hands had either been murdered or taken prisoners, and that, besides himself, four more men belonging to the Margaret were still alive upon the island undergoing every hardship.

[Pg 17]

The commander of the Courier, upon being acquainted with this fact, made up his mind to ransom his countrymen, and for that purpose made proposals, which were agreed to; but after the natives got possession of what they asked, they made a second and a third demand, and ultimately compelled the boats’ crew, by firing upon them, to get into their boats, leaving their property behind. The Courier’s boat had got a small brass gun, which they fired on this occasion; but it recoiling to leeward, a man was shot and fell in the same direction, upsetting the boat with ten men, all of whom were either drowned or killed. The natives then got possession of the boat, and were actually coming alongside the Courier with her own boat to plunder the ship, when fortunately the boat came broadside on, and the master got a gun to bear and destroyed her. He then as soon as possible slipped his cable, and, with only four men, sailed for the Gambia, where I saw him.

I cannot help thinking that many masters of merchant-vessels run into great danger, and incur risk to their owners, without any chance of doing any good, merely to obtain a name for themselves. Had the master of the Courier sailed for the Gambia, and communicated with the authorities there, no doubt a man-of-war would have been despatched to Arguin, and the crew of the[Pg 18] Margaret recaptured. If Arguin should prove to be a profitable speculation in regard to the Guano trade, some permanent protection must be afforded by the Government.

It is generally believed that the Emperor of Morocco is cognisant of all the piracies committed; and if this be so, why not make him answerable, and take so much territory from him upon every outrage perpetrated by his people upon British property? If the French Government did the same, an end would soon be put to all such piracies.

On the 8th of July, at two P.M., we sailed from the Gambia for Sierra Leone, and anchored at Free Town on the 11th, in the evening. We anchored close to my old ship the Albert, of the late Niger expedition, now commanded by Lieut. Cockroft.

On the 12th, in the morning, I went on shore, and delivered my official letters, and met with a most cordial reception from every one. Dr. Ferguson was acting Governor at that time; he is a most excellent man. Here I was very agreeably surprised to find my old friend Dr. Oldfield comfortably settled. He was one of my most intimate friends many years before I left the First Life Guards. I found him still the same, and still possessing the same generous heart. Long may it beat tranquilly![Pg 19] I had many hospitable invitations; but accepted that of my friend Oldfield, who kindly opened his house for me during my stay here, and gave two large dinner-parties in respect to my presence. He also kept an excellent horse at my service during my stay. He keeps four of the best horses in the colony. I must be ungrateful, indeed, did I ever forget his kindness. I also experienced great kindness from the Rev. Mr. Dove, of the Wesleyan Missionary Church. The country is beautiful, and capable of great improvement; and I cannot help thinking that if it were cleared for some distance, it would be much healthier than it is.

On the 17th we sailed for Cape Coast; and, on the 21st, at daybreak, a sail was reported on our starboard bow, which from her appearance was supposed to be a slaver. All hands were in anxious expectation of a prize; every glass or telescope in the ship was put in requisition to ascertain what craft she was. She changed her course two points, which occasioned still more suspicion. Consequently, steam was ordered on (we were before only under canvass) as quickly as possible, and the fires were backed up, so that we were in a few minutes in full chase of the supposed slaver. We gained upon her very fast, although she set every stitch of canvass, and in an hour and[Pg 20] a half we were alongside. All her guns were run out, and ready for action, and every man at his quarters. But, to our great disappointment, she turned out to be a French ten-gun brig, in so dirty a condition as quite to disguise her, so that we never suspected she could be a ship-of-war. The whole of her stern bulwarks were covered over with bamboos, and she altogether resembled a palm-oiler. She was named the Eglantine.

At ten A.M. on the same day we anchored off Cape Coast, and on the morning of the 22d I went on shore, and called at the fort to deliver my official papers from Lord Stanley to the Governor. I was, however, informed by his secretary, that his Excellency Governor Hill had not yet risen. I then waited upon Mr. T. Hutton, a merchant at Cape Coast, to whom I had letters of introduction. He received me with every mark of kindness, and allotted to myself and servant an elegantly furnished house, with servants to attend on us, assuring me that I was heartily welcome to any thing in his house. I afterwards called upon Governor Hill, and presented Lord Stanley’s letter, on which he wished me success in my arduous undertaking, but never once asked me where I intended to remain, or whether I had got my luggage ashore, or how I was accommodated. After visiting the fort, however, I felt very glad[Pg 21] that I had escaped such accommodation, or rather imprisonment. Governor Maclean, it appeared, upon his departure, took all his private furniture with him. Nothing consequently remained but the bare walls, and a few of the commonest Windsor chairs and plain tables, as the furniture of the Governor’s apartments. In fact, any part of the fort at Cape Coast far more resembles a prison than many of our prisons in England.

[Pg 22]

Attacked by Fever—Death of my Servant—Mr. Hutton—Buildings in Progress by him—Indolence of the Natives—Cheapness of Living—The Fantees—Their Superstition—Description of their Idol or Fetish—Their Customs or Holidays—Native Music—Rum, their favourite Liquor—Proceedings on occasion of a Death—Mode of Burial—The King’s Custom or Holiday—Character of the King—My Reception by his Majesty—Comparatively neglected by the British Government—Fetish Houses—Native Funerals—Want of Natural Affection—The Yam Custom—The Fantees, the worst of the African Tribes—Their Power of Imitation—Wild Animals—The Patakoo—Granite and Sandstone—The Dutch Settlement of Elmina—A fine Field for Botanists—State of Agriculture—Excessive Heat—Message to the King of Ashantee—Cattle—Artizans much wanted—Murder of an Ashantee Woman.

I had the good fortune to be lodged in the best quarters at Cape Coast, where I remained till the most favourable season for travelling had come on, and also till I had gone through my seasoning fever, with which I was attacked a few days after my arrival, as well as my servant, who, poor fellow! sank under it. Although the greatest attention and medical aid was afforded to him, he died on the 4th of August, 1844, at a time when[Pg 23] I was so ill myself that Mr. Hutton would not allow my attendants to make me acquainted with it till four days after it occurred. Of my own illness, though it was very severe, I can scarcely remember any thing, as I slept nearly the whole of the time. The late Governor, Mr. Maclean, who at the time had not left Cape Coast, was remarkably kind and attentive to me. His departure was very much regretted, as he had given great satisfaction to the merchants while he was Governor.

During my stay there, Mr. Hutton was building two very fine houses, one at Cape Coast, and the other in the wood-land tract about two miles to the north of it, on a spot commanding a beautiful prospect over a salt lake, about three quarters of a mile distant, with the sea, near Elmina, beyond it.

In this country, where manual labour is requisite, the greatest difficulty is experienced in getting the people to perform it as they ought. My attention to these undertakings for the space of two months gave me a very good opportunity of forming a fair estimate of the character and habits of the natives at Cape Coast.

Mr. Hutton had, at the time of my arrival, about one hundred hands employed, and I can conscientiously affirm that fifteen Englishmen would have done considerably more work in[Pg 24] any set time than these hundred Fantees. The men are, without exception, of all the Africans I have yet seen the laziest and dirtiest. They seem in every respect inferior, both in body and mind, to their neighbours, the Ashantees. They are remarkably dull of comprehension, and, unless constantly watched, will lie down and do nothing. Even if one of the party is appointed as foreman to the rest, he will be just as idle as the others. They seem to have no idea of anything like conscience.

Some time ago Mr. Hutton supplied his labourers with wheelbarrows to convey the stone from the quarry to the building they were working at; but instead of wheeling the barrowful of stones, they put it upon their heads, declaring it was harder work to wheel the barrow than to carry it. They will go the distance of a mile to the quarry, and come back, perhaps twenty in a gang, with one stone, not weighing more than nine pounds each, upon his head, so tedious is their manner of building, nor will they be put out of their own way on any account. As they can live almost for nothing, their only motive for working is to procure what they consider luxuries, such as rum, tobacco, and aatum, the name they give the cloth tied round their waist. They can live at the rate of a penny a-day upon yams or cassada[Pg 25] (manioc) and fish, which is remarkably cheap. This penny, and now and then a shilling, is earned by one of their wives, of whom they have sometimes several. The wife goes into the thickets with a child tied upon her back, and returns with a bundle of wood upon her head, which she sells in the town. All the drudgery, in fact, is done by the women, while their lazy husbands lie stretched outside of their huts smoking.

The Fantees are very superstitious, and one party or another is daily making Fetish[2] (performing a religious service) either for the advancement and success of some business in which they are interested, or invoking a curse upon some person who may have thwarted the effect of their fetish. For instance, if any person fall sick, the head fetish-man summons all his relations to meet on a certain day, at a certain time, to try by their fetish whether the sick man will recover; but if a surgeon attending him is successful in making a cure, they invoke a curse upon him for causing the fetish to lie. At Cape Coast their fetish sometimes consists of a bundle of rags bound together like a child’s doll; at other times a little image of clay, rudely fashioned, somewhat in the human shape, is placed in some public spot, frequently[Pg 26] by the roadside. These images, or fetishes, often remain in the same position and on the same spot undisturbed for a fortnight or three weeks.

The natives have a great many customs or holy days in the course of the year, during which it is unbearable to live in the town, such is the noise and uproar of the rabble. Their yells, roaring, and discord are indescribable. They have a sort of rude drum, about four feet in length, and one in diameter, called tenti or kin Kasi. This is carried on a man’s head in a horizontal position, and is beaten by another man walking behind him, who hammers away like a smith on his anvil, without any regard to time. This huge drum is accompanied by horns and long wooden pipes, the sound of which resembles the bellowing of oxen. The procession parades up and down the town nearly the whole day, and keeps up an irregular fire of musketry. On all these occasions an immense quantity of rum (which is only threepence per pint) is drunk. If any person of note dies, the relatives and neighbours assemble in front of his house, and continue drinking and smoking, yelling and firing off guns nearly the whole of the day; and one of the family invariably sacrifices a dog, to procure a safe passage to Heaven for the deceased. If none of the deceased’s relations happen[Pg 27] to have a dog in their possession, they sally out in a party and kill the first dog they meet.

They are very superstitious also respecting burial, and frequently bury the gold rings and trinkets worn by the deceased along with his body, so that the graves are frequently opened again for the sake of the property contained in them. An instance of this occurred while I was there. A Mrs. Brown, the widowed mother of a mulatto so named, who had been employed as interpreter on board the Albert steamer in the late Niger expedition, died in consequence of a blow from a younger son. The elder brother, having been much straitened in his circumstances through misconduct, ordered his mother to be interred in the same grave as one of her daughters, who had been buried with all her trinkets upon her. Brown, as an excuse, declared that it was customary to bury the parent below, and the sons and daughters above. Thus the sister was disinterred and stripped of her ornaments, which he put, as he no doubt thought, to a better use than leaving them for the worms.

The King’s custom, or solemnity in honour of the King of Cape Coast, is kept annually for fourteen days, in which interval none of his subjects are allowed to fire off a gun, or beat a kin kasi, (drum), nor are any dogs, sheep, or goats allowed[Pg 28] to be seen in the streets, or in any public place, on pain of death. This commemoration is tolerably observed, but though King Agray’s black flag is kept flying during the whole period, I am convinced that it is more for the gratification of his people, than from any wish of his own that such a ridiculous observance is continued; for he is a very intelligent venerable old man, highly civilized and polite in his manners, and very well disposed towards the English. His character is very much admired by all the merchants established there, as well as by his own subjects. From what I could learn, he is ever ready to patronize any effort on the part of the English to civilize and improve his people. In person he is a tall, thin, muscular, old man, though his years number upwards of threescore and ten.

A few days previously one of his messengers called upon me in great haste, to inform me that his Majesty was very anxious to see me in the dress of the First Life Guards that day. It happened that a short time before, the troops from Cape Coast having been ordered out for exercise, I was requested to accompany them in uniform, and in less than ten minutes the King was acquainted with the fact. Like the other kings in this country, he has spies to carry to him all news of however little importance.

[Pg 29]

His Majesty received me with all the politeness of an English courtier. After being seated, he asked me many important questions—when, at his request, I performed the cavalry sword-exercise in his presence, he noticed the differences arising from the late alterations in that exercise, supposing that I had made some mistakes.[3] He talked a good deal about the King of Ashantee, and reprobated much their horrid practice of sacrificing human beings. He seemed to have obtained a very correct idea of railroads, and to be strongly impressed with a sense of the advantages and disadvantages derived from them by the English nation. He can read and write well, and is, as I before observed, a clever, intelligent old man. The King’s house is furnished in the European style, plain though pretty good.

It is to be lamented that the English Government should have neglected so good a man as Agray, while much is lavished on such a villain as the King of Ashantee, who in fact is only led by it to suppose that the British Government fears him.

On my road yesterday for several miles through the wood, in search of birds and plants, of which there is abundance, I passed several fetish houses or temples, in the form of a long grotto, formed[Pg 30] by a vast number of running and creeping plants, at the farther extremity of which is sometimes found a large mass of stone or granite rock, which they say is related to some other fetish not far distant; and they even assert that, early in the mornings, this very stone may be seen in a human shape, going to visit his wife (a similar block of stone). They are also superstitious about our copper money; they call an Irish halfpenny a devil’s coin, on account of the harp upon it, which they call the devil; and they will not on any account take it in payment of anything.

Their funerals much resemble the Irish wake. As soon as the party is dead, the body is washed, and dressed in all its best clothes, which are very few. A party of the most intimate friends of the deceased is then invited. A goat, sheep, or dog is sacrificed, human sacrifices being now prohibited by the British authorities as well as by King Agray. After drinking a good deal of rum, the company begins to cry or howl hideously, and wishing a good journey and plenty of servants in the other world to the deceased (who is always seated in the circle as one of the party, being fixed in a rude sort of arm chair), the corpse is lowered into the grave, which is always under the floor in the centre of their dwelling. They also pretend to bury with him a quantity of rum as well as all his[Pg 31] trinkets. The rum, however, is generally well diluted with water.

Though they seem to have no parental or filial affection, they have a strong attachment to the house in which they were born, and can rarely be persuaded to leave it. Were they not prevented by our laws, parents would very readily sell you any of their children, or even husbands their wives. A woman, who is considered as very respectable, and keeps a stall in the market, was repeatedly offered to me for sale by her husband, and was herself very anxious for such a change, so as actually to take possession of my bed one night when I was absent. I ordered my servant to turn her out, and also sent her affectionate husband an intimation that if he hawked his wife to me any more, I should certainly punish him; this ended the affair.

The yam custom, or holiday, is another annual ceremony, kept up to prevent people from using yams before they are ripe, as they are then deemed unwholesome; and also to compel the people to use all the old ones, in order to guard against the consequences of failure in the yam crop of the following year. On this occasion all differences are settled and crimes punished; but no sacrifices are offered up here, as at Ashantee. The propensity for thieving is found in all the natives,[Pg 32] high and low; they are also, generally, void of all gratitude, and deem it part of their duty to rob white men whenever they can. In the market they invariably ask you four times as much as they will take. If your servant is unwilling to connive at their swindling tricks, they open a full battery of abuse upon him; but servants in this country seldom put them to that test.

Of all the African tribes I have met with, I consider the Fantees the worst. It is remarkable that one-eighth of the population is either actually crippled or suffering from a loathsome disease called craw-craw, which bears some resemblance to the mange in dogs or horses. In appearance and personal strength they are much inferior to most other Africans; probably from their great indolence and want of exercise. The wives are treated with great harshness by their husbands, in case they offend them.

They have no ingenuity, but a considerable power of imitation. Some of our British manufactured articles in wood or gold they can imitate very fairly, but when closely examined, their work will always be found to be defective. They seem never to improve by their own ingenuity, but always remain stationary in any art or trade which they have learnt. They seem to have no idea of a straight line, and cannot build a wall[Pg 33] straight, or make a hedge in a direct line; nor in the whole neighbourhood of Cape Coast is there a footpath in a straight line for the distance of twenty yards, although the ground is quite level. They certainly possess many strange ideas.

There are in the neighbourhood of Cape Coast some strange animals, among which is the Patakoo, a very large species of wolf. These are so ravenous as frequently to come down into the town and carry away pigs, sheep, and goats. They pay nightly visits to the beach, and seize on dead bodies which have been buried in the sand. As their slaves have no relations in the town or neighbourhood, as soon as they die their corpses are tied up in a coarse grass mat and thrown into a hole in the sand, without any ceremony; but on the same or following night, they are snatched up by the Patakoos, for whom they make a glorious feast. This beast has great strength, its size considered. When Governor Hill’s horse died, the officers of the First West India Regiment, stationed at Cape Coast, determined to leave part of its carcase on the beach, in order to attract the Patakoos, and it could not have lain there more than an hour before it was removed by a single Patakoo, though it was two men’s work to carry it.

There is plenty of excellent granite and sandstone at Cape Coast; yet nearly all the houses are built of[Pg 34] clay, as the people are too lazy to fetch the stone. Elmina, which is only eight miles distant, is a much superior settlement, and has likewise plenty of excellent sandstone, of which a great number of its houses are built. This place belongs to the Dutch, and carries on much trade, both with the interior and along the coast. It has a fine lake, connected with the sea by a narrow channel, which might with very little trouble be converted into a convenient harbour, which would be important, as the swell along the Gold Coast is always very heavy, and great difficulty is experienced in shipping and unshipping goods. I visited several of the most influential merchants at Elmina, and found them, as well as the governor, very hospitable. The abundance of new plants in this country would give plenty of employment to a botanist. A small shrub of the laurel tribe, bearing a white delicate flower, shaped like the blossom of the pea, grows here very plentifully, as also beautiful jasmines and honeysuckles, and several sorts of sensitive plants. Some very fine grasses, also in this neighbourhood struck me, but I did not observe many small annuals.

Agriculture has made little progress here, probably owing to the want of horses, which cannot live more than a few weeks, and from the indolence of the natives. Stock sufficient for[Pg 35] the consumption of the garrisons along the coast might be raised with a little care and exertion. The number of troops along the whole of the west coast is at present very small. Were their numbers doubled, there would not be too many, and they might be employed alternately in cultivating the farms and mounting guard in the forts. Yams, manioc, Indian corn, rice, and all sorts of vegetables, for the garrison and ships of war cruising on the coast, might in this way be easily obtained, and much expense avoided. This would also be useful as a pattern to the natives. The troops are paying at present one shilling per pound for meat, which could easily be raised at one-fourth, and the cattle might be employed on the farm instead of horses. An establishment of this sort would be very beneficial here, and I have no doubt would answer the purpose well. Unfortunately at present there seems to be no European at Cape Coast who either knows or interests himself in anything relating to agriculture. With the exception of Mr. Hutton, not a single English merchant at Cape Coast has even a garden, although the progress of vegetation is incredibly rapid. Some seeds of the vegetable marrow and water melon, given to me by Dr. Lindley of the Horticultural Society in London, which were sown on my arrival at Cape Coast, had grown to[Pg 36] the extent of twenty-four feet in two months, and the fruit of the water melon was as large as a man’s head.

The heat of the month of November is excessive. On the 8th, the quicksilver in the thermometer, in my bedroom, which is considered to be cool, stood at 88°; and in the sun it rose to 115°; yet, thank God! I was so well accustomed to it, that I felt very little inconvenience, though generally out the whole day, and exposed to the sun. I was then daily expecting a messenger from Ashantee, for one of the soldiers from the fort had been despatched by the governor, to ask whether the King would allow me to pass beyond his kingdom towards the Kong Mountains. During the interval I was engaged in laying out the ground for Mr. Hutton’s model farm.

The breed of cattle here is very handsome though small, but it might be greatly improved, and this would repay the expense very well, as the price of meat is so extremely high. Gold dust, unfortunately, seems to be the only thing thought of on the coast.

Schools of industry and agriculture are wanted on this coast more than any thing else. As land can be got for nothing anywhere on the coast,—land capable of growing any thing,—a few hundred pounds expended on a farm[Pg 37] of three hundred acres would be very profitably laid out. There are plenty of men who can read and write, begging for employment; and ten times their number, from the bush, such as might be deemed capable of learning, might be apprenticed to different kinds of trades for four or five years.

It is worthy of remark, that on the whole coast, from Cape Palmas to Accra, there is not a single shoemaker, although no trade seems to be so much wanted. Even the natives in the interior complain much of the want of shoes. Nor is there a tailor, a cabinet-maker, a wheelwright, or a blacksmith who can weld a piece of iron with any neatness in the whole settlement. Such articles, if manufactured on the coast, would draw trade from the interior, and excite the natives to industry; and thus British manufactures would be soon in great demand in the interior also. This would greatly reduce the Slave trade, as the minds of the people would be directed to agriculture and manufactures, particularly as it is well known that even in the Ashantee country the population is not on the increase. The Ashantees have indeed, for the last two months, been at war with the tribes to the north of them, bordering on the Kong Mountains, and have lost a great number of men, as their enemies, who have no fire-arms, no doubt did also.

[Pg 38]

The merchants of Cape Coast, Annamaboe, and Accra, experience great loss and inconvenience, in consequence of the trade being stopped between Ashantee and the coast. This was occasioned by the murder of an Ashantee woman by a Fantee, on her return from a trading journey to the coast. She had occasion to stop a little behind her companions, and was then robbed and murdered by this Fantee who overtook her. Her companions missing her, went back, and found her with her head nearly severed from her body. This took place in the Fantee country, between Cape Coast and Ashantee. The murderer, however, was seized and brought part of the way back to Cape Coast by a soldier from thence, on his way with the letter to the King of Ashantee, from Governor Hill, which I mentioned above.

Mr. Chapman, who had resided as missionary at Coomassie, the capital of Ashantee, for the last twelve months, arrived at Annamaboe on the 26th of November, 1844, with the intelligence that all the King required was that the murderer should be punished according to the English law. The King at that time expressed a great desire to see me in Ashantee, and promised me complete protection in his country; but said nothing about allowing me to go further.

[2] Fetish is corrupted from the Portuguese feitiço, witchcraft, conjuring.

[3] His Majesty had served several years on board a British man-of-war, previously to attaining his sovereignty.

[Pg 39]

Annamaboe—State of the Fort—Indolence of the Natives, and Difficulty in procuring Labourers—Domestic Slavery—Missionary Schools—Want of Education in the Useful Arts—Hints on this Subject—Vegetables and Fruits—Town of Annamaboe—Soil—Natives—Reception of me by the King, and Conversation with him—Mr. Brewe—Mr. Parker—Excessive Heat—Little Cromantine, its impregnable Situation—The Fort—Cromantine—The Market-place—Extraordinary Tradition—Wonderful Dwarf—An Adventure—Accra—Wesleyan Missionaries—Natives—their Habitations—Wives and Slaves—Situation of the Town, and Soil.

On Monday, 23d of November, 1844, Mr. T. Hutton and I started from Cape Coast for Annamaboe, a town of considerable trade on the coast, about thirteen miles from Cape Coast Castle, from which its magnetic bearing is about due east. It has also a very good fort, which, however, is gradually going to decay. Its ramparts are well supplied with artillery, and capable of making a good defence against an attack from the sea, if properly garrisoned, and it is quite impregnable by the natives from the land, or north side. It was at this place that the Ashantees made so determined an attack, and an attempt to blow up the gate of the fort. They, however, failed in all[Pg 40] their attempts during the late war of 1817. There are at present only two or three private soldiers and a sergeant of militia in charge of the garrison. Some of the apartments in the garrison are in a pretty good state of repair, and might be very profitably used in more ways than one, if from one hundred and fifty to two hundred militia-men were stationed here, and employed by turns in managing a farm in the immediate neighbourhood: the soil is capable of producing every thing necessary for the support of the garrison. In three or four years, on such a plan, this garrison would pay its own expenses.

The native kings or chiefs, and caboceers, are never to be depended upon; and even the humblest of the natives, when they imagine they have any power, although naturally great cowards, will bully and be very insolent. The natives are so lazy that at times the merchants cannot, without great difficulty, get men to load or unload their ships. This is a very serious grievance, and often exposes our merchants to great difficulties as well as loss. Were our merchants allowed to hold as many slaves as are requisite for the performance of domestic duties, and the carrying on of their business, it would act as a check to the exportation of slaves.

I have minutely observed and inquired into the[Pg 41] state and condition of domestic slavery amongst the native caboceers, and I solemnly declare that their condition is much superior to that of our English peasantry. One English labourer, on an average, does more work than any twelve Africans; and the provision of the latter being so cheap (one penny per day is sufficient for their support), they have always plenty to eat. I am writing from actual observation, having had for three months a number of hired men under my charge.

Another evil arising from the same cause, is, that if a man is urged to do anything like a tenth part of a day’s work, he will go away, and steal sufficient to maintain him for some time; consequently, the towns on the coast abound with thieves and vagabonds, who will not work. Had domestic slavery (or rather I may call it service) been tolerated, our merchants would have been encouraged to enter upon other speculations, such as agriculture, and even trades; since many of our merchants, who constantly employ five or six native and European carpenters, would put their slaves to learn a trade, whereas they have now no motive for doing so. Besides, the holders of domestic slaves would use all their influence in abolishing the removal of slaves into another country. In Elmina the Dutch settlers still hold their domestic slaves, and they are in a thriving[Pg 42] condition. In its immediate neighbourhood I was surprised to find several fine gardens and plantations, belonging to different merchants established there. Moreover, the surrounding country is well cleared of wood for a considerable distance, which renders that settlement much more healthy than Cape Coast, or any of our English stations. Although no man detests the Slave Trade more than myself, I cannot help feeling convinced that much evil to the natives as well as to the merchants has arisen from the abolition of domestic slavery in our African settlements.

Another evil I also believe to be this. In all our Missionary Schools, reading and writing, with a slight knowledge of arithmetic, is all that is taught. By this, undoubtedly, much good is done; but much more would be done, if these schools were also schools of industry. When a boy has left school in this country, you never see him reading a book, or even looking at a newspaper. All that these young men aspire to, is to get something in the fashion of European clothing, and to seek employment as clerks. I have already seen great numbers, who have been dismissed from school, and can write a little. They then consider themselves gentlemen, and their ideas are above anything under a clerk’s place. Now, it is well known, that among the few merchants established[Pg 43] on the coast, employment as clerks cannot be afforded to as many as are desirous of such a situation.

I will, therefore, endeavour to point out a remedy for this evil, which would, I think, not only benefit this class of individuals, but the country at large, as well as our manufacturers in England:—I mean, the establishment of schools of industry on a scale similar to that which I have recommended for the garrison at Annamaboe. Let a suitable piece of land be selected, which any one may have for nothing; build upon it dwelling-houses and offices, as well as workshops, which could soon be done in this country, if the people could be induced to work. Men willing to become apprentices to different trades should be selected, and bound to bricklayers, carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, weavers, wheelwrights, and cabinet-makers, for three or five years, as might be deemed most proper. These men might assist in building their dwellings and shops, before they began to learn their trades, which some of them would do by employment in this very work. Sufficient ground should also be enclosed for raising such food as is necessary for the support of these labourers.

Every article of subsistence is abundantly produced in this country, and many luxuries,[Pg 44] such as sugar and coffee. Vegetables, and great quantities of fruit, grow spontaneously. Civilization might thus be begun, but it could hardly be permanently advanced without a recourse to arms. The Kings of Apollonia and Ashantee possess too much arbitrary power to be withdrawn from their cruel and barbarous habits by any other means than the sword; and it is said, that very many other chiefs and kings are in the daily habit of making human sacrifices.

Although Annamaboe has been already often described, a few remarks upon it will not perhaps be unacceptable. Behind the fort, or on its north side, is a piece of ground about two hundred yards square, round which are built some very good houses, with their stores, belonging to English and native merchants. These houses and the mission-house are the only buildings worthy of notice, except the King’s house. This is new, and copied from those of the merchants; it is not, however, yet finished, and very probably never will be, in consequence of the extreme indolence of the people. The town may, perhaps, contain about three thousand inhabitants, and consists (with the exception of the houses already mentioned) of dwellings irregularly huddled together, generally built round a square of about seven yards each way, with only one outer entrance, each[Pg 45] house opening into the square, and forming its sides. Some of the principal houses of this description have benches running along the outside wall inside of the square. These benches are made of fine clay, in the form of sofas, and are handsomely coloured with clay of a different colour. It is here that they hold their palavers, all being seated around; the head man, or caboceer, is generally placed on a seat raised above the rest.

Although the soil in the neighbourhood of Annamaboe is excellent, yet it is very little cultivated; the natives chiefly depend upon the people in the woods for their corn and yams, vegetables and fruit, which are got in exchange for fish, a very plentiful article on the coast at certain seasons of the year.

The only thing in the neighbourhood of Annamaboe worth mentioning as a sign of either improvement or enterprise, is a good road for about ten or twelve miles into the interior, made for the purpose of conveying timber to the coast. This great undertaking was executed entirely at the expense of one person, a very intelligent and highly respectable native merchant, named Barns; but since the abolition of domestic slavery, he, unfortunately, cannot obtain labourers to carry on the timber-trade; though he has procured from England timber-carriages and every thing requisite—all[Pg 46] is sacrificed. In fact, a complete check is now put upon every effort of enterprise by the abolition of domestic slavery. These slaves were much better provided for than our labourers in England, for they had always plenty of food and clothing, and were never exposed in bad weather, nor was one quarter of the labour ever required from them that would be expected in England.

The natives of Annamaboe are in character much the same as those at Cape Coast, and many of them are thieves and vagabonds. During my short stay there my servant’s country cloth was stolen off him in the night. When inquiry was made for it every one denied all knowledge of the theft; however, on a closer search, the cloth was found rolled up tightly under the head of one of the servants of the house where I lodged. I had him well flogged; but nothing will cure these people of thieving, except a tread-mill for they fear nothing so much as labour.

During my stay at Annamaboe, the King sent me a pressing invitation to pay him a visit, and in order to appear before his Majesty in a suitable manner, I was advised by the merchants to send to Cape Coast for my regimentals. On the following day I paid him a visit in my uniform, with which he seemed much delighted. Having previously learnt that I belonged to Her Majesty’s Life[Pg 47] Guards, he asked me a great many questions respecting the Queen of England—how she was when I left England? and if Prince Albert was quite well? how many children she had? how long she had been married? and what were their titles? He laughed heartily when I informed him that Her Majesty had five children in so short a time, and asked me how I accounted for the English ladies being so prolific? Upon which I told him that the reason was, that in England one man had only one wife: he could not be persuaded, however, that one wife was sufficient for one man.

I experienced great kindness during my stay at Annamaboe from the merchants of that place, both English and native; and was indebted, during the whole of my visit there, to the hospitality of Mr. Brewe, a very respectable and enterprising merchant.

Among the native merchants I may justly point out Mr. Parker, who, though educated in Africa, would appear with advantage even in Europe. His memory is astonishing; he has read a great deal, and has a very good library of the best English writers. With regard to reading, indeed, he is an exception to the rest of his countrymen, owing, I believe, principally to their erroneous system of education.

[Pg 48]