Title: Samuel Reynolds House of Siam, pioneer medical missionary, 1847-1876

Author: George Haws Feltus

Release date: July 30, 2022 [eBook #68647]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Flemming H. Revell Company, 1924

Credits: Brian Wilson, hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

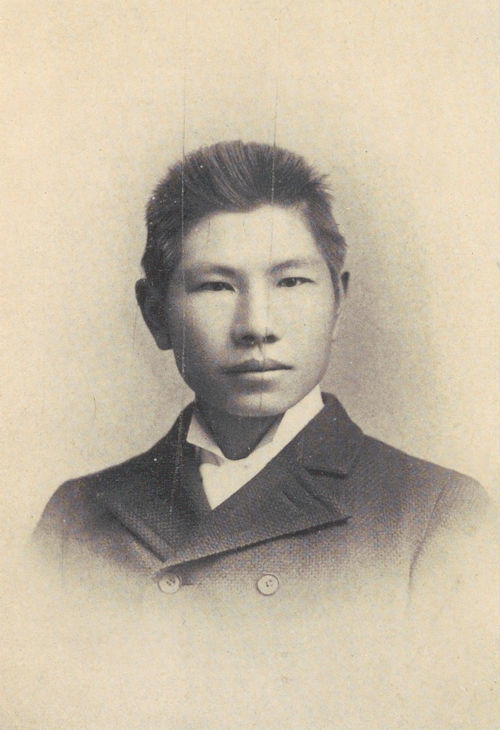

SAMUEL REYNOLDS HOUSE

“THE MAN WITH THE GENTLE HEART”

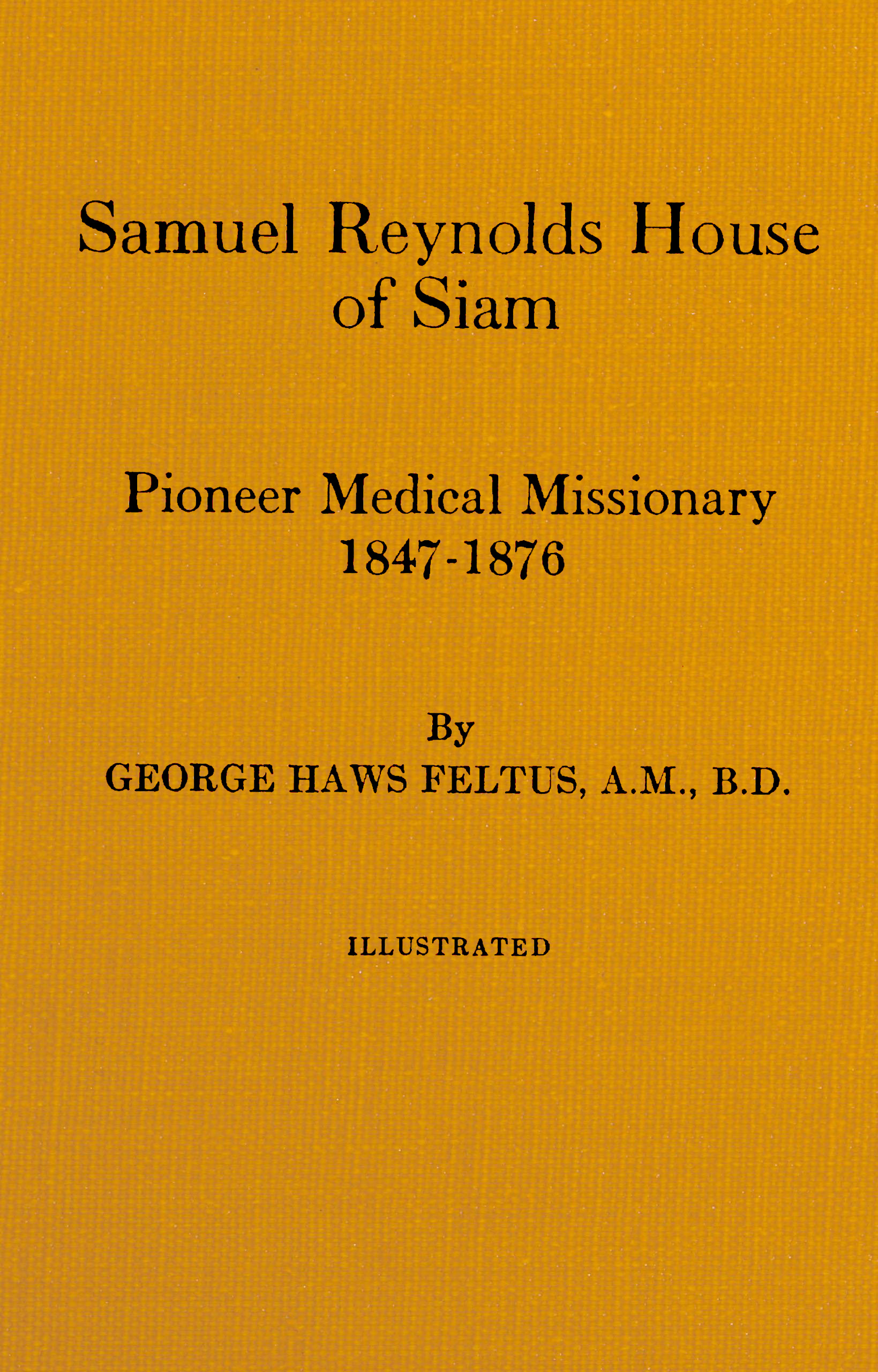

Rev. SAMUEL REYNOLDS HOUSE, M.D.

“The Man With the Gentle Heart”

Pioneer Medical Missionary

1847-1876

By

GEORGE HAWS FELTUS, A. M., B.D.

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, MCMXXIV, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

Printed in the United States of America

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 North Wabash Ave.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 75 Princes Street

Quaint, old-time title pages sought to present an epitome of the contents of the volume. While the name of Dr. House occupies the sole post of honour on this present title page, none would be more urgent than he to have that place shared by his wife, Harriet Pettit House, and her assistant, Arabella Anderson-Noyes, and by their godson, Boon Itt, whose achievements occupy a good share of the pages that follow.

The essential material in this book has been drawn from the letters and journal of Dr. House, now for the first time available for the purpose. This material has been supplemented by correspondence with various individuals connected with the principal persons mentioned. The facts thus ascertained have been interpreted and amplified by the careful reading of nearly every book in English on Siamese subjects. For this reason, the narrative may claim to be fairly complete and authentic.

Two reasons have prompted publication. One reason is to make accessible valuable historical materials. In the archives of the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions no records covering this period have been found other than the meagre references in the annual reports of the Board. The diary of Dr. House’s co-worker, Rev. Stephen Mattoon, was destroyed by fire; and, so far as is known, no other private records for those early years are in existence. The only primary source of information is the chapter, “History of[6] Missions in Siam,” from the pen of Dr. House, in the volume Siam and Laos, in which his modesty has obscured the importance of his own labours. So this book is offered as a contribution to the history of the Church in Siam.

The other reason is that the Church is entitled to the stimulus of the heroic examples of these godly people. Biographies, at best, do not appeal to a large circle of readers. Missionary biographies appeal to fewer still. However, a book that stimulates a few hundred workers in the vineyard of the Lord may effect more good in the long run than a book of great but passing popularity. I venture to believe that few will read the record of the life-work of Dr. and Mrs. House and the brief story of Boon Itt without being quickened by the example of their persistent faith, buoyant hopefulness, sublime trust and apostolic devotion.

Not the least worth while do I count it to be able to place this narrative in the hands of the young Church of Siam that she may transmit to the rising generation the story of “The Man With the Gentle Heart.”

I acknowledge with appreciation the hearty encouragement of friends to publish what my own inclination would have allowed to remain in private manuscript. Also, I gladly state that publication would not have been possible without the financial assistance of friends who feel that the Church of today should have the privilege of knowing these noble characters, but who themselves prefer to remain unnamed.

George Haws Feltus.

The Manse, Waterford, N. Y.

| I. | A Sudden Plunge Into Work | 9 | |

| II. | “The Man with the Gentle Heart” | 23 | |

| III. | The Little Chisel Attacks the Big Mountain | 34 | |

| IV. | Relations with Royalty and Officials | 47 | |

| V. | Lengthening Cords and Strengthening Stakes | 63 | |

| VI. | Cholera Comes But the Doctor Carries On | 76 | |

| VII. | Providence Changes Peril Into Privilege | 101 | |

| VIII. | Siam Opens Her Doors—More Workers Enter | 131 | |

| IX. | First the Dawn, Then the Daylight | 156 | |

| X. | New King, New Customs, New Favours | 179 | |

| XI. | Harriet Pettit House | 195 | |

| XII. | Home Again, and “Home At Last” | 221 | |

| XIII. | Boon Tuan Boon Itt | 230 |

| FACING | |

| PAGE | |

| Rev. Samuel Reynolds House, M.D. | Title |

| Sketch Map of Siam | 34 |

| Harriet Pettit House | 196 |

| Rev. Boon Tuan Boon Itt | 230 |

Dr. Samuel R. House did not have time nor need to “hang out a shingle” upon reaching Bangkok. He had been there only a few days—not long enough to unpack his goods—when “a message came from some great man by three trusty servants that a servant whom he loved very much had got angry and had half cut his hand off with a sword.”

This wound was not accidental but self-inflicted. It was a perverted result of a Siamese custom. In those days slavery prevailed in the country. Besides the war-captives who were cast into slavery, custom made it possible for any of the common people to be sold into servitude. If a man failed to pay a debt there were two alternatives before him, to be confined in one of the horrible jails until he discharged his obligation, or to sell himself or his wife or children into slavery to remain in that state until the accumulated value of the services should cancel the debt.

Only too often these debts were the result of gambling, a vice that was universally prevalent under license of the government. If the debtor was fortunate enough, he might sell the chosen victim to some lord who was willing to accept the services in pledge for a loan with which to pay the actual creditor. Such an arrangement was not altogether without its[10] advantages, for many an improvident spendthrift had a comfortable living for himself and family assured by the better management of his lord. But once in servitude the victim was likely to be held in peonage indefinitely, because usury on the loan was liable to mount up faster than the value of services rendered.

It will readily be imagined that a man so improvident as to permit himself to fall into slavery would not be the most willing worker, and many would be the tricks of the lazy man to labour as little as possible. A rather common scheme to avoid an unpleasant duty or merely to spite the over-lord was to go to the extreme of inflicting upon self a wound that would incapacitate from work. Such was the nature of this first surgical case to which Dr. House was called.

The readiness with which this great man summoned a strange foreign doctor will be easily understood when it is known that for twelve years previous there had been an American physician in Bangkok. Since 1835 Rev. Daniel B. Bradley, M.D., representing the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (A B C F M), had been practising medicine and he had established a high reputation among all classes for western medicine and surgery. On account of the recent death of his wife, Dr. Bradley, with his young children, had sailed for home only a few weeks before the arrival of the new missionary.

When Dr. House set out for Siam he knew that Dr. Bradley was there and, having had no practical experience in his profession before leaving home, he looked forward to beginning his labours in association with one who not only was a skilled practitioner[11] but who also knew the pathological conditions of the Siamese. When, upon arrival, Dr. House discovered that Dr. Bradley had withdrawn he felt some alarm at the absence of professional counsel, for he had a constitutional lack of self-confidence that caused him to feel a painful burden of responsibility in prescribing for patients. At the end of the first six months he wrote:

“Whatever seemed once likely to be my fate it is pretty certain now that there is more danger of my wearing out than of rusting out in this land. Have been on the run or occupied with visitors all the day and evening ... and my poor brain has, like its fellow labourer the heart, been compelled to go through with a great deal. What sights of human misery I am compelled to see. And to feel that I have not the power of skill to alleviate,—the iron enters my soul.”

Whatever may have been the first effect of being compelled to enter upon his profession alone, it is doubtful whether Dr. House ever perceived that this constraint was probably one means by which he gained the confidence of the Siamese within a very short period. For instead of being regarded either as a competitor or as an assistant to Dr. Bradley, he was accepted at the outset upon the reputation which his predecessor had so firmly established. It was this repute of western medicine which caused the great man to send so promptly for an unknown physician to treat the self-mutilated servant.

Quickly it became known among the people of Bangkok that another physician had arrived. The calls for treatment came in such numbers and with[12] such importunity that in self-defense it was deemed wise to open the dispensary which had remained closed since the departure of Dr. Bradley, although there was only a limited supply of drugs on hand and the nearest base of supplies was London. The dispensary, or hospital as it was sometimes called, of which Dr. House thus suddenly found himself the proprietor and whole staff, was just one of the innumerable floating houses which lined the river banks of the Siamese capital. It is said that when this new capital was being established the common people were not allowed to build houses on land but permitted to live only in boats. At any rate, until modern times the larger portion of the population lived in floating houses.

These houses are simply constructed. A raft of bamboo forms the foundation, which is moored to the bank or to poles driven into the mud. Upon that foundation a one-story house of boards, thatched with palm leaves, is built. The house is, customarily, divided into three rooms. At either end, extending clear across the floor is a kitchen and a common bedroom. The space between is occupied by the common living-room and a porch. The living-room is fully open along the porch, from which it is separated by the rise of a step. Closely packed together in irregular rows, sometimes two or three deep, these houses are ranged along the banks of the river and of the many canals that form the Venetian highways of the city. The channel beneath the houses, kept from being stagnant by movement of the tide, served at once as the sewer and the family bath. Many of these houses are occupied as stores, with their merchandise[13] exposed to the full view of the customer who does his shopping in a boat.

It was such a house as this that served the missionary as a hospital. But “hospital” is scarcely the proper word to use judged from the equipment, which consisted of a chair or two, a table for operations and a few mats for the patients. But the place had one great advantage—the open side exposed the work of the foreign doctor to the gaze of the curious natives who stopped while passing in their boats, and then related to their friends the wonders they had seen.

Here in this rude native shelter, until he gave up his profession, Dr. House applied himself with deep devotion and self-abandon to relieving the physical sufferings of the people. He placed himself wholly at their service, and made no discrimination between rank of those he served. Frequently he would not reach the dinner table till the middle of the afternoon, detained by the importuning patients; and he even laments that the people would not summon him in the night time in case of serious need.

His record of patients, to one who is not familiar with a physician’s records, gives astonishment at the kind of cases which seemed to predominate. One class was the ulcers and running sores—many of them most aggravated. These usually were the result of long-neglected wounds. He writes of extracting bamboo splinters great and small that had become imbedded in the flesh and remained there to produce serious inflammation and infection. In such cases an ignorance too dense for intelligence to comprehend[14] was the contributory cause of untold suffering. A second class of cases frequently appearing was that of fresh wounds resulting from drunken brawls, street fights, treachery and revenge, or self-mutilation. Scarcely a week passed but a patient was brought in with head cut open, face gashed, back lashed, or some other gaping cut. But most loathsome of all were the diseases which the doctor characterised as the result of vices—diseases which found victims among all sorts and conditions of men who “working that which is unseemly” received “in themselves that recompense of their errors which was meet.”

A cursory review of one day’s succession of patients will be suggestive. Here returns a man with a tumor on his ear, having the previous day been advised to come for an operation:

“With good courage and I believe without a trembling hand, I sat down to this, my first operation not only in the Kingdom of Siam, but the first operation I think I ever undertook. It was a simple one, and oh, I cannot but catch such a glimpse of my Father’s loving-kindness in thus gently leading his poor ignorant by such simpler cases into the confidence in myself necessary to do the more serious cases which will doubtless fall to my lot.... Believing that without His blessing the simplest operation would fail and with it the most doubtful one might prosper, I lifted up my heart a moment to Him in whose name I had ventured to come among this people to try to do them good.”

While attending him, a boat came up with two women, one a loathsome object full of sores and scabs—face, hands and limbs—the scars of former ulcers. A Chinaman with a scrofulous neck—a lad[15] with gastric derangement—a boy whose leg was transfixed with a sharp piece of bamboo—so moves the procession. As he returns late for dinner he observes:

“This morning was fully occupied till dinner at 2 p. m., trying to do the works of mercy—how could I send any away empty! And oh, how happy I should have been in such Christ-like works had I but knowledge of the diseases, and judgment and skill. As it is now, the deciding what is to be done with each case is an act of the mind positively painful, because I am constantly fearing that I may not follow the best possible plan.”

On another day thus reads the entry:

“On going down to the floating house at 9 a. m., found several new patients. A Chinaman of fifty, with caries of the lower jaw, skin of cheek adhering, pus has discharged from a large cavity within the mouth. Another Chinaman with syphilitic destruction of the bones of the nose—a hole left in the flattened face where pus was discharging.... He seemed to be in great torment—eaten of worms literally. Now a mother brings a naked child of five, having large ulcers and a lump on the thigh, the sequel of the smallpox had two or three months ago. A Chinaman brings the child of a friend; poor lad, the smallpox had destroyed one eye and blinded the other—so no hope, no remedy.”

The hours at the hospital were daily from early morning, frequently from six or seven o’clock, till noon. During the latter part of the afternoon he answered calls in various parts of the city. By these calls he came into the homes of the people and became[16] better acquainted with them than he could have done under ordinary circumstances. He gives what he calls a fair specimen of the missionary physician’s life in Siam when his hands are full:

“When I awaked in the morning found two sets of servants waiting for me—one from Prince Chao Fah Noi, who had sent his boat for me to go up to his palace just as soon as I could finish my breakfast; another from Chao Arim, the King’s brother, wishing me to come over and see some one in his palace very sick. My first duty of course was to attend to little George, whom I found still living, though much the same. This occupied the time before breakfast. After a hasty meal, stepped into the sampan sent for me (the servants still waiting to take me across the river to Chao Arim’s)—having dismissed the Prince’s servants with a note requesting to be excused. On the other shore entered gates of the city wall.... While I was waiting for the Prince to be notified of my arrival, servants gathered around; examined my clothing, one wished me to take off my hat to see if my head was shaved, another admired my watch—the ticking pleased the children mightily. Some strong ammonia I had pleased them very much. A young man with a flaming long jacket of red silk (no shirt or vest above his waist cloth) came out; all servants squatted on the ground. This young Prince conducted me up a rude ladder to the bamboo dwelling of the sick man.

“Returning, invited to see the great man himself. The audience halls of these great men are after all rather well-adapted to the climate; immense rooms, lofty ceilings, furniture of matting, etc. Returning to my place, found a boatman from the Moorish Madras merchant’s awaiting me. Accompanied the Hindoo, who had been sent for me, in his open boat with umbrella over my head; the sun, however, very hot, though this is our cold season. Some distance down the river landed at the Nackodah’s commercial establishment, and found myself[17] in the midst of quite a number of intelligent looking and polite Mahommedan Hindoo merchants and clerks, with their picturesque costume; the turban of twisted shawl and robes of thin white muslin, and sandals. Was received very courteously, conducted to a bamboo house nearby. The patient, a fine looking man, swarthy, with aquiline nose and mustache, lay on a mat bed behind a screen.... And now the voice of Dit, a servant of Chao Fah Noi, was heard; he had followed on after me, not finding me at home—the Prince being very desirous of seeing me. So I stepped into the handsome boat he had sent, and was soon at the palace. Here received with a smile of welcome.... Wished me to shew him how to make chlorine gas. Succeeded well. Gave him a piece of fluorspar and directions for etching glass. Left several jars of chlorine. His boat in readiness to take me back.... In the evening a call from Prince Ammaruk, in his priestly yellow robes, several priests with him.”

All these interesting scenes and varieties of experience, however, did not lighten the burden of the heart. When a patient suffered pain and inflammation after an operation, he cries out:

“How can I go forward in a profession where I may inflict suffering. If it was only injury to property and not to life and health and senses! Alas, how hard a destiny, how could I choose this profession!”

On a Saturday night he sighs:

“And so ends another week during which mercies have been ever changing, ever new. It has been a week of labors for Christ ... and yet, though my poor head is ready to ache with the task of deciding, judging, prescribing,[18] I find a sweet kind of weariness that comes from serving Jesus Christ.”

Such a tender heart and sympathetic nature suffered most where it could help the least. The obstetrical customs of the country in particular caused the doctor both distress and irritation on account of the lamentable ignorance displayed and of the needless sufferings caused.

The experiences of his professional practise were not all depressing. Operations were successful in spite of his fears, and when least expected. Most cheering was the gratitude of the patients, many of whom acknowledged their lives reclaimed from death by his hands. The marks of appreciation on the part of some of these were most touching.

“Have been permitted by a gracious providence this week to have the happiness of saving the life of a fellow-creature, which the venom of a poisonous snake was appearing fast to be destroying. Poor fellow, he was thankful enough. The first symptom of returning consciousness before he regained his lost power of speech was his attempt to put his feeble hands together and raise them to his forehead in token of his gratitude to his doctor. When three days after, sound in health and limb, he came to see me. ‘Doctor, you are very, very good,’ was his very emphatic expression of what filled his heart. And then he grasped my hand—a liberty men of his condition in life seldom take—in both his and repeated, ‘You are very, very good.’”

Dr. House had adopted the policy of gratuitous[19] service. His motive was to exemplify the Christian spirit by rendering these inestimable benefits without charge. Perhaps at the time he did not know the philosophy of the Siamese in the matter of good deeds.

The theory of the Buddhist religion is that a good deed gains merit for the doer. As a sequence, to be the recipient of a favour is to assist the other person to earn merit; and since the merit is ample reward for the good deed it is not necessary to make any personal return for the favour received. When Dr. House later came to understand this philosophy he perceived why it was that “of ten healed only one returned to give thanks.” Yet there were not a few whose natural sense of gladness was not wholly suppressed by their religious theories. One day, three or four years after he had been in Siam, he went out along one of the canals into the country to a limekiln to get some lime for the new house under construction at the mission. An old woman came out to wait upon him, and to his surprise she refused to take pay; and explained that some time previously the doctor had healed her little girl.

The set policy not to accept fees was not so easily understood by the Chinese to whom he ministered. Frequently, to avoid offense, the Doctor found it necessary to compromise by accepting gifts in lieu of money; and then he would be the recipient of generous presents of fruit, quantities of rice, numerous cakes of sugar and small chests of fine tea—gifts in such abundance that he had to share them with his friends to dispose of all.

But not least of the rewards for professional service[20] did he esteem the acquaintance and friendships among the patients. These people came from many parts of the country and there were numerous representatives from other countries. Sailors from European ports sought him out for medical treatment, Chinese tradesmen and junk captains, Malays, Burmese, Peguans, Cambodians, Lao, and the foreign merchants from India. Then, too, Bangkok the capital of Siam was visited periodically by officials from the distant provinces, many of whom came for professional advice to the foreign physician. The contact established with these various peoples, and especially with the provincial governors, served to excellent advantage in after years when the doctor made tours into the far regions. In particular, the under-Governor of Petchaburi who came for professional advice, invited the doctor to visit his provincial capital, and in later years when he had been promoted in office and rank in Bangkok he remained the steadfast friend of Doctor House.

There were bits of humour now and then amidst the procession of human tragedies.

“While feeling the pulse of the patient and holding my watch to count its beat, another man sitting by begged me to feel his, and after I had counted it he gravely asked me ‘in just how many years after this he would die.’”

Some of the humour was grim humour indeed; for one day he was hastily summoned only to find that the supposed patient was a corpse. Humourous from[21] one point of view but quite perturbing for a physician was the innocent disregard for the directions left with medicines; indeed the doctor could never tell whether the failure of a prescription was due to the ineffectiveness of the drugs or to the failure of the patient to take the medicine as prescribed, for he found that the patient was liable to take the whole potion at once or just as liable to have another member of the family take the remedy vicariously.

Quite frequently, when the callers from a distance came to see him, they made the parting request for medicine to take home with them, and thought it altogether needless for the doctor to know what disease they expected to use it for. Pathetic was the case of the cholera patient consumed with fever who begged the doctor to give “medicine to cure the desire for drinking water.” Even more simple-minded was the old man who came to inquire if he could be healed if he “wyed” to Jesus,—that is to make the reverential bow of worship customarily accorded to the image of Buddha. Then there was the deaf man who came back to report that he had read “the Christian book of magic” and that it had failed to cure him.

Not the least perplexing of these absurd situations was the difficulty of securing necessary permission to administer the medicines even after the doctor had been especially summoned:

“The poor woman who lay on a mattress bolstered up was in great distress evidently—and I soon found that no time was to be lost. I shall never forget how piteously she turned her anxious eyes towards me as she faintly said, ‘Can you heal me?’ I recommend certain treatment. Nothing could be done, however, till the[22] matter had been submitted to the Praklang. So a messenger was despatched, His Excellency again aroused from his nap;—and what a message brought back: The application of hot cloths would be permitted, but the more effective treatment proposed was something new—he did not know—he could not consent to it. Thinking then of another mode of treating the case and not dreaming but that this I might venture to give—but no; this prescription must be reported to headquarters before it could be administered. Again a messenger was despatched. The answer came back: we must wait to see what a hot fomentation would do; if this did any good then the prescription might be tried.”

“This day thirteen years ago, while a just-arrived student at Dartmouth College, it pleased my sovereign Maker to manifest His everlasting love to me by inclining my heart to choose Him as my portion, and His service as my reward.”

Such is his salutatory in the service of God, as recorded by Samuel R. House, in his journal under date of Feb. 22, 1848. He had been in Siam less than a year; long enough however for the novelty of his situation to abate a little so that he had time to reflect. Reflecting, he sees how that youthful dedication was—so far as he was consciously concerned—the beginning of the lines of life that led him to Siam.

Four years later, on the anniversary of his arrival in Siam, contemplating the fruitlessness of those years and ready to incriminate himself for “a culpable ignorance of the language,” he again writes:

“How different doubtless am I regarded at home by over-esteeming friends. How false a biography would that be, some of them would write.... Let no one eulogise such a character, such a worthless, unworthy life as mine. If a Christian hope be the joy of my life, by the grace of God I am what I am; but my waywardness, my inefficiency is all my own.”

The cause of this despondency was not within himself.[24] It was the miasma arising from the spiritual decay around him. But as none liveth unto himself, so none dieth to himself. The example of such persistent faith belongs to the church; and it has too great a value for the living to allow the judgment of a passing despondency to prevail.

At length comes the valedictory. On the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of permanent work in Siam by the Presbyterian Church (U. S. A.) in 1897, Dr. House wrote to a friend:

“And now in my eightieth year, sole survivor of that little band, I feel it a privilege indeed to look back and see what God hath wrought since that day of small beginnings. Verily the little one has become a thousand—yes thousands. I am sure you, my friend, will congratulate me on being yet alive this blessed day of an abundant ingathering from that long barren mission field. How the loved ones that have entered into rest would rejoice if they could see how their patience of hope and labour and love have not been in vain in the Lord. There are many in heaven to raise the song of jubilee with them, even there.”

From that early dedication of self to God while in college, through the years “cast down but not destroyed,” to the golden jubilee—what a strain of human effort, what a magnificent persistence of faith, what a glory of hope realized!

The man who had this notable experience would not have been singled out, even by those who knew him intimately in early manhood, as the one most likely to achieve the results which we are to review.[25] The qualities casually observed by acquaintances were in his case those which men do not ordinarily associate with success. A study of his private journal and letters manifests traits which are corroborated by many who knew him personally. He was a man of deep piety. He was scrupulous regarding the outward appearance of religion, yet more so concerning his inner life. He was verily a man of God. His mental nature had a strong inclination to introspection, which led to self-depreciation and self-distrust. He recoiled from a new venture until he became convinced that it was the will of God; then, though still distrusting his own ability, he laid hold of the task with a simplicity of faith and a devotion to duty which made him invincible. It is an example of how the Holy Spirit, when fully occupying a man’s heart, enlarges and fortifies his native capacity until the one who is small in his own esteem becomes a giant.

That habit of introspection may have been due in part to the austere idea of religion which prevailed at the time; at any rate it gave him a somber demeanor. The solemn side of life seems mostly before him, although his associates found a playfulness and jocularity about him that offset his soberness. Only thirty years of age when he left home, yet from the first his letters to his father read more like the letters of a father to a son. But deeper and stronger than either of these traits was his tender sympathy. It was more than a sympathy of sentiment; it was a sympathy that caused him to share the sufferings of others. Concerning his medical work he said: “When I cannot relieve, I suffer.” This eagerness to relieve[26] pain led him to a forgetfulness of his own interests which his physique marvellously endured.

Then, too, he had a timidity which at times amounted to phobism and made it difficult for him to reach a decision and even caused him to appear fickle in purpose. But fortunately, along with that weakness he had a courage which nerved him to face any hostility or danger with a daring which compelled opposition to give way; and by that quality he carried through many a venture which for a time seemed doomed to failure. Humble to a point of self-abnegation, at times he was as lordly as a monarch in the exercise of the prerogatives of the liberty of the gospel; and beyond a doubt it was his refusal to imitate oriental truculence before provincial officials which inspired that class with respect for the rights of the foreigner. Among the Siamese who still remember him, he is spoken of as “the man with the gentle heart.”

Samuel Reynolds House was born in Waterford, New York, Oct. 16, 1817, being the second child of John and Abby Platt House. His parents both united with the Presbyterian Church of that village upon profession of faith, in 1810. At that time the Waterford congregation was in collegiate relation with the congregation of Lansingburgh, located eastward across the Hudson River, under the pastorate of Rev. Samuel Blatchford, D.D. In the next year John House was elected an elder in the collegiate church; and when the Waterford congregation became a separate organisation, in 1820, Mr. and Mrs. House became[27] charter members of the new organisation, and Mr. House was continued as an elder—an office which he held till his death, April 27, 1862.

The active interest of Mr. House in the spiritual work of the church is indicated by the fact that he conducted a Sunday school for coloured children in a room in a carpenter shop, and when the young church erected a house of worship, in 1826, this Sunday school was transferred to the gallery of the church. He is also recorded as having been the superintendent of the regular Sunday school of the church after it was established. His interest in the church continued active up to the close of his life. In his later years, when the congregation was considering the construction of a new “session house” for the use of the Sunday school and prayer meeting, John House sought the privilege of erecting the building at his own expense; and that fine building, erected in 1859, remains today as a memorial to his love and zeal for the church.

Abby House was one of the original members of the “Female Cent Society” of the Waterford church, organised in 1817. The object of this society was to “afford assistance to poor and pious young men pursuing their studies in the theological seminary at Princeton.” The quaint name of this society was double with meaning. Each member was pledged to contribute one cent a week to the fund, which was then placed in the hands of the moderator of Presbytery to dispense. Later the society co-operated with the American Education Society until the General Assembly forbade that organisation to operate within the denomination in competition with the new Board[28] of Ministerial Education. The word “female” suggests that the sex was about that period emerging into the self-consciousness of a separate work for religion and was not content to keep its labours hidden behind the mask of the male portion of the families.

If we were to seek for the motives that led young Samuel to dedicate himself to foreign missions we would not be surprised to find that the mother had some of the credit. He says that he was prompted to become a missionary because his mother dedicated him to God for foreign missions from his infancy. Out of that maternal inspiration came also the prayer of his youth:

The ambition thus early implanted was nurtured during the boyhood years by stories of missions. When in later years he visited the Hawaiian Islands on his way to Siam he recalls those stories:

“How little did I dream I was ever to see them, when that dear mother of mine used to tell me such interesting stories about the missionaries there and show me, out of her treasures kept in that always-locked drawer of her bureau, the precious bit she had of native cloth made of the bark of a tree. And when she took me to the ‘Monthly Concert,’ as she always did, how much I used to be interested in news from those far away isles.”

Closely associated with the motives to enter the[29] mission field are a man’s religious convictions. Those earlier missionaries were conspicuous for their lively sense of peril for impenitent souls. Dr. House had a spiritual sensitiveness which shared this feeling to the full. Frequent lamentation is to be found in his journal for the certain perdition of ones with whom he had been acquainted, and who died without an evidence of accepting the Christian faith. This was not merely a professional attitude towards the heathen. Upon news of the death of an old school mate he exclaims:

“Oh, did he die safely! What would I not give to be assured he did. But oh, I tremble. Procrastination thou art the thief of time, the murderer of souls. And conscience reproaches me with having too long postponed the sending to him that letter on the subject of the claims of personal religion, a draught of which has for years been lying in my portfolio. It might, under the blessing of the Holy One, have done him good—at any rate it was my duty, my privilege to invite him, to urge him to walk with me towards heaven. I have sinned. I have been unfaithful.”

When a Siamese lad who had been connected with the mission for a few months was suddenly carried off by the cholera, the anguish of the doctor brought him to tears of self-reproach, not because his skill had failed but because he had not been more insistent in urging the gospel upon the boy.

At this distance of time one can see that the failure of some of the Siamese to be persuaded was due to a want of concatenation in the heathen mind between the physical facts already familiar to them but not[30] comprehended, and the spiritual truths of this new religion. Behind the sublime faith of the missionary there was a rigidity of logic which failed to take these mental difficulties into account; as for instance when a young priest proposed this dilemma: “Who was the mother of Jesus? Mary. Who made Mary? God. Was Jesus Christ God? Yes. But if Jesus Christ was God, how could He make Mary his mother before He Himself was born?” Turning from the disputant, the doctor declined to discuss the problem because he thought the man was caviling.

At one period the doctor entertained a vivid expectation of the culmination of the Christian dispensation at an early date. He had enough of the mystical in his religious nature to look for signs. Thus he writes in view of the conditions of Europe in 1848:

“All Europe, every kingdom has felt the shock of the political earthquake in France. Kingdoms, principalities and powers tremble. These are signs that herald the near approach of the Coming One. The day of the world’s redemption surely draweth nigh.”

And again two years later he writes to Dr. D. B. McCartee at Ningpo:

“Surely the world must needs wait for but few of the signs, that are to herald His coming, to be fulfilled. ‘Wars and rumors of wars,’ earthquake and pestilence and famine, the ‘running to and fro,’ the gospel preached for a witness in every nation—what signs of the ‘ends drawing nigh’ is left unfulfilled in our day—unless it be that a few countries (central Africa, New Guinea, etc.) remain still unevangelised. The last of God’s elect, however,[31] may be born—nay, the messenger who is to call him, in Providence may have started on his errand; and who knows but that privilege is for you or me.”

But that type of speculation has its own antidote, viz., time. As his years drew out their number, the visions of youth gave way to the dreams of old men; and in reviewing what had been achieved and what remained to be accomplished the doctor displaced these speculations with the simple faith that the Lord would come again in His own time, but at a time unrevealed to men. It needs to be remembered that Dr. House had been trained in medicine, not in theology. Whatever may have been illogical in his tenets, there was in his heart the profound conviction not only that Jesus Christ was the only Saviour of the world, but that the Siamese would accept the Christian religion, if only they could be induced to examine fairly its claims.

Samuel received a careful and thorough education. After elementary work in the private academy of Waterford, at the early age of twelve he spent a year or more in the “Washington Academy” of Cambridge, New York, then under the principalship of Rev. Nathaniel Scudder Prime. In later years he recalled with pleasure some of his classmates: “We read Cæsar together; John K. Meyers, David Bullions (Latin grammarian), E. D. G. Prime (editor of the New York Observer), and I recited to Samuel Irenæus.” In 1833 he entered the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute at Troy, five miles from home.

In the winter term 1835 he entered Dartmouth College at Hanover, New Hampshire, but remained only till the close of that academic year. It was here that occurred the deeper spiritual experience which he recalls in the words that open this chapter; a conscious conversion during a revival which swept through the college that winter. It was following this experience that in the same year he united with the Waterford church upon profession of faith. Why he did not continue at Dartmouth does not appear; probably the difficulty of access would have been a chief factor. However, in the fall of that year he entered Union College, at Schenectady, a few miles from his home. His work at Rensselaer and Dartmouth qualified him to enter the junior class, so that he graduated in the year 1837. He received the degree A.B. in course and the honour of Φ.Β.Κ.; and following three years of post-graduate work in teaching, he received the degree M.A. from his alma mater. The three years immediately following graduation from Union were spent in teaching; one year in Virginia, a year as principal of Weston (Conn.) Academy and a year as principal of the private school “Erasmus Hall,” in Brooklyn. He now entered upon his medical course, spending the year 1841-2 in the University of Pennsylvania, and the next year in the Albany Medical College. With the lapse of a year not accounted for in the record,—probably teaching in Virginia, to which he refers in telling of some chemical experiments—he graduated from the College of Physicians and Surgeons of New York with the degree M.D. in 1845.

Upon completion of his medical course he offered[33] himself to the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions (Old School), and was commissioned in 1846. He was assigned to Siam together with his college-mate, Rev. Stephen Mattoon, of Sandy Hill, New York, (now Hudson Falls). Placing himself under the care of the Presbytery of Troy he was licensed to preach.

Siam was the first nation of the Far East to make a treaty voluntarily with Europe. Siam was the first Asiatic power with which the United States entered into diplomatic relations. Siam was the first Oriental people to adopt Western customs, upon accession of King Chulalongkorn, in 1868. Siam was the first non-Christian land to grant religious liberty to its subjects in relation to Christian missions, in 1870.

Siam was the first field entered by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions after its organisation. In Siam was organised the first Protestant church of Chinese Christians. In Siam the first zenana mission work was undertaken. Siam is the last independent state in which Buddhism is the established religion.

Yet Siam is little known to Western people. She is neither belligerent nor turbulent, therefore offers no military spectacle. She has no foreign ambitions, therefore arouses no diplomatic concern. Her trade is largely with China, therefore she makes no impress upon the commercial mind of the west. She lies off the beaten path of world traffic, therefore tourists seldom visit the land.

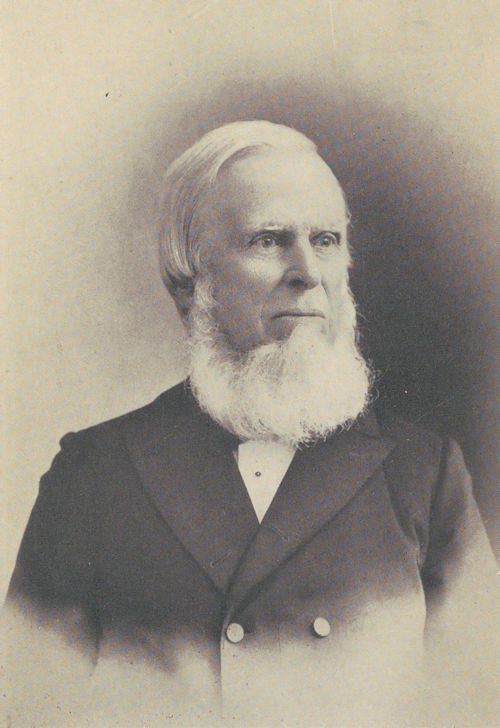

Sketch of

SIAM

as of 1847 et seq.

SKETCH MAP OF SIAM

Siam lies in what was formerly known as “Farther[35] India.” Shaped somewhat like a long mutton-chop, the northern portion is an irregular-oval, approximately six hundred by five hundred miles in reach, from which a long narrow leg extends some five hundred miles southward down the Malay peninsula. Within the fold of these two portions lies the Gulf of Siam. The main portion of the land lies between 12° and 20° 40′ north, and is confined on the east by French possessions and on the west by British Burmah.

Northern Siam occupies almost the entire drainage system of the Menam River, and a part of the western watershed of the Mekong River. The central part abounds with swamps, jungles and briny wastes, intersected by many branch streams and canals. The bulk of the population live along these watercourses. Bangkok is the largest city, and is both the commercial and political capital. Chiengmai is the principal city of the northern province, which was formerly known as Laos but is now a political part of the kingdom.

The relations of Siam with the nations of the west date back to the days of the Portuguese adventurers in the early part of the sixteenth century; relations which were not diplomatic but purely commercial. About the middle of the seventeenth century the king of Siam entered into relations with the English, French and Dutch, but only to the extent of an exchange of royal courtesies, which after a time became quiescent. Intercourse with the west was renewed by Siam when, upon her solicitation, a treaty was made with Great Britain in 1826. Doubtless fear was the motive which prompted King Phra Chao Pravat[36] Thong, who reigned from 1824 to 1851, to propose this treaty, for England had just compelled the neighbouring state of Burmah to open her doors to trade as the result of war.

The volitional act of the Siamese monarch was apparently a shrewd stroke of diplomacy, for having granted the right of trade admission and inland travel, the king adopted a policy of ignoring the few foreigners within his domains and thereby discouraging his people from having intercourse with them. At the same time he held a monopoly of Siamese shipping and levied heavy impost and expost so that what trade there was served to enrich his private treasury. In 1833, Honourable Edmund Roberts, who had been sent by President Andrew Jackson to explore the possibilities of trade with the native states of Farther India and Cochin China, succeeded in effecting a treaty only with Siam. The privileges granted under this treaty were not exercised to any great extent and were almost allowed to lapse because no consular representative was appointed. The early American missionaries relied chiefly upon the privileges kept alive by the “factories,” as the foreign trading establishments in Bangkok were called.

When one of the early missionaries explained to a nobleman that their purpose in coming to Siam was to supplant the native religion by Christianity, the nobleman replied: “Do you then with your little chisel expect to remove this big mountain?”—referring to Buddhism. How this mountain began to crumble during Dr. House’s twenty-nine years of service will[37] be best understood by giving a sketch of the work previous to his arrival.

The early treaty with Great Britain gave first entrance for Protestant missions. In 1828 Karl Gutzlaff, M.D., of the Netherlands Missionary Society, and Rev. Jacob Tomlin, of the London Missionary Society, went up to Bangkok to spy out the land. Before that date the Siamese had been the distant object of interest on the part of Ann Judson, of Burmah, who, as early as 1819, having met some Siamese at Rangoon, became interested enough to prepare in their language a catechism and the Gospel of Matthew—the first Christian books in the Siamese language. While Gutzlaff and Tomlin found the doors of Siam open and discovered that there was a considerable Chinese population there, they were not encouraged by their supporters to effect a permanent occupation. For this reason they issued an appeal to the American Church then newly awakened to missionary zeal, sending one copy of the appeal to the American Baptist mission in Burmah and another to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in the United States. This message was taken to America in 1829 by Capt. Coffin, of the American trading vessel which at the same time brought the famous Siamese Twins.

The A. B. C. F. M. was the first to respond. In 1831 they directed one of their men located at a Chinese treaty port, Rev. David Abeel, M.D., to proceed to Siam and make a survey. At Singapore he was joined by Mr. Tomlin, who had returned thither for recuperation, and the two reached Bangkok just a few days after Dr. Gutzlaff, disheartened by the death[38] of his young wife, had sailed away to China. Mr. Tomlin this time remained only some six months, but Dr. Abeel continued until November, 1832, when he was forced to leave on account of health. His survey of the field resulted in a report to the A. B. C. F. M. which induced them to attempt a permanent work. In the meantime, in 1833, the Baptist mission in Burmah responded to the appeal by sending two of their number, Rev. J. T. Jones and wife, to establish a mission. Two years later Rev. Wm. Dean was sent out from America by the Baptists as a co-labourer of Mr. Jones but to devote himself particularly to the Chinese.

In pursuance of Dr. Abeel’s report the A. B. C. F. M. sent out two men, Rev. Stephen Johnson and Rev. Charles Robinson, who reached Bangkok July, 1834, and these were joined the next year by David Bradley, M.D., and wife. Both the Baptists and the A. B. C. F. M. at this time regarded their work in Siam largely as a point of vantage for China proper on account of the large number of Chinese here accessible. The work among the Chinese was so fruitful that in two years’ time Mr. Dean was able to organise a church among them, the first church of Protestant Chinese Christians ever gathered in the Far East.

Siam was the first field to be taken up as a new enterprise by the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions after its establishment by the General Assembly. Until 1831 the Presbyterians in America had functioned chiefly through the A. B. C. F. M. in their foreign work. In that year a few presbyteries west of the Alleghanies organised the Western Foreign Missionary Society, to conduct their own foreign work. Beginning with missions to the Indians (then[39] regarded as “foreign”) they established work in India and Africa in 1833. The direction of its own foreign work by the church was one of the points involved in the division of the Presbyterian Church into the New School and the Old School in 1838. The Old School took over the Western Foreign Mission Society in that year as a nucleus for a new Board of Foreign Missions which their General Assembly established; and that Board has been in continuous operation ever since. In its first year the new Board directed Rev. R. W. Orr to proceed to Bangkok and report on the eligibility of Siam as a field for operation. Mr. Orr reported, recommending not only work among the Chinese but also advocating work for the natives. Accordingly the Presbyterian Board sent out Rev. Wm. Buell and wife, who reached Bangkok in August, 1840, the first missionaries to be sent out by the new organisation. These two remained for some three years, when on account of ill health of Mrs. Buell they were obliged to withdraw; and thereupon the mission was suspended for a time.

When, as a result of the opium war, the doors of China were opened, in 1846, both the A. B. C. F. M. and the Baptist society transferred their Chinese workers from Siam to China. The difficulty of getting response from the Siamese had caused their workers to devote their energies largely to the Chinese; and now when this Chinese work was terminated their missions in Siam were greatly weakened both in numbers and in effectiveness. The A. B. C. F. M. retained its Siamese workers until 1849, when it transferred its enterprise to the American Missionary Association, an organisation distinctly of the Congregational[40] Church; but this Association abandoned the field in 1874. In 1868 the Baptist Society gave up all except its work for the Chinese in Bangkok, leaving the Siamese wholly to the Presbyterian Mission. Thus Siam was freed from sectarian rivalry long before modern “comity” was brought into practise.

It was at the juncture of withdrawing the major portion of the force to China and leaving the Siamese missions undermanned that the Presbyterian Church undertook to establish anew its mission in Siam, having the native population as the primary objective. To that end it sent out Dr. House and Mr. Mattoon who, together with Mrs. Mattoon, may rightly be regarded as the founders of the permanent work of the Presbyterian Church in Siam.

In those days of foreign travel it was necessary to await a vessel that might by chance be sailing in the direction of the desired destination. Fortunately the ship Grafton, Captain Abbott, was found to be loading for a direct voyage to China, and passage was obtained for a party of missionaries en route for the Orient, including the trio for Siam. On July 27, 1846, the Grafton sailed from New York.

A journey to the Far East then was a matter of time and tedious delays, as well as of adventure. The course of the Grafton lay southward through the Atlantic, now near the coast of Africa, now near the coast of South America, with glimpses of Liberia and of Brazil; around the Cape of Good Hope and across the Indian Ocean, among the East Indies and[41] thence northward to China. The indirectness of the voyage by which Dr. House reached Siam is shown by this fact: one hundred days after leaving New York, the Grafton put in for water at Ampanan on the island of Lombok, one of the smaller of the East India chain. This port was within four weeks’ direct sail of the Siamese capital; whereas the Grafton was headed for the port of Canton, to reach which required fifty days more; thence by another vessel it was necessary to retrace the course to Singapore and transfer for Bangkok.

Could the missionary have taken passage direct from Ampanan to Bangkok he would have reached his destination in about two-thirds the actual time consumed. But even the most direct course to China could not then be taken because the season had arrived for the northeast monsoons on the China Sea, which are a peril to sailors. The Grafton was compelled to pass to the eastward among the Isles of Spice, past Pelew Island, out into the Pacific, east of the Philippines, within sight of Formosa and thence westward to Canton. The doctor writes home to the children of the Sunday school that “It was a dream of childhood come true to sail among these fabulous islands.” On the 28th day of December, one hundred and sixty days from New York, the Grafton arrived at Macao, the Portuguese port for Canton, which during the stormy days of early foreign relations with China was a place of safe entry, transfer and retreat for merchants and missionaries alike.

No vessel was to be found bound towards Siam, so the missionaries had to wait. The American merchants Olyphant & Co., of Canton, with hospitality[42] “as generous as it was elegant,” took the doctor into their home for the sojourn during the delay. Dr. House visited the mission school of Dr. Happer, located at the port, and also went up to Canton to visit the hospital conducted by Dr. Parker, who had been a lecturer in the University of Pennsylvania when he was a student there. On Feb. 7, the party for Siam took passage on the John Bagshaw, Captain Dare. After a call at Hong Kong they had a quiet passage southward through the China Sea, and on the 23rd reached Singapore, the maritime capital of the South China Sea.

Here they were fortunate in finding in the harbour the native-built trading vessel Lion, Captain Dupont, owned by the King of Siam. Although the ship was modeled after western vessels, it was of the rudest native workmanship, without conveniences for occidental travellers; and even the orientals who took passage had only deck space allotted to them. For these three Westerners one small cabin was made available and had to serve them day and night for the twenty-four day voyage, a sail cloth being suspended in the middle as a concession to foreign ideas of privacy. Provisions had to be secured at Singapore and the Chinese cook of the vessel paid to prepare them.

The passage from the South China Sea into the Gulf of Siam proved to be the climax of the whole trip. A violent and prolonged storm was encountered which not only added greatly to the misery of the ship’s company but imperiled their lives:

“For nearly three days,” writes Dr. House, “we have not had one cheering glimpse of the sun. Squall after squall of rain has burst in its fury upon us; indeed it has been almost one incessant rain, and the wind all the time from the most unfavourable quarter has at last increased to a gale, driving the ship from her course towards we know not what islands and rocks.... The waves are rolling wildly, scowling rain clouds begird the horizon and shut out the sky above us and the view before us. It is now three days since the captain has been able to get an observation, and the dead reckoning is in these seas little to be depended upon, owing to the strong currents. Our situation is no more safe than it is agreeable.... Every wave rolls us also to and fro, so that if one sits or stands he is obliged to be continually bracing himself, now this way, now that, to keep the center of gravity; and every now and then is pitched by some sudden lurch against the nearest object so that sides and arms and elbows fairly ache with the bruises.... And all this time there is in your ears the creaking of the rudder chains and the dismal splashing of the great waves as they surge up under the stern windows. But a greater annoyance yet remains to be spoken of. The deck over us (the roof of our cabin) leaks in a hundred different places upon us, not in drops but in streams. In my compartment there is but one dry place, and that is the mattress; and even that is not wholly dry, for now and then it drops down upon the pillow. The floor is as wet as if being mopped; wet trunks, wet books, wet baskets lie around. The chairs are too wet to sit upon, and so the bed is the only place for rest.”

Fortunately the voyage of twenty-four days was not all like this, and after the storm had abated there was much to make the days interesting. At length came the first sight of Siam:

“Friday, March 19. The first sight of Siam. Thy people, O Siam, shall be my people; but my God shall be their God. Here would I die and here would I be buried.... Henceforth I would live for Thee, my God. Thou art a kind Master; and oh, Thou hast bought me, every power and faculty; Thou hast bought me by Thy precious blood. Let me henceforth shrink from nothing—but sin and remissness in Thy blessed service. With the beginning of my missionary life I give myself anew, tremblingly but trustingly to do Thy will O God, my Creator, Guide and Redeemer.”

The following day, Saturday, March 20, 1847, Dr. House landed in Bangkok. The arrival of the new missionary party met with a most cordial welcome by the small group of fellow Americans already engaged in the work. At that time Siam was occupied by two American missions, besides French Catholic missions. The American Board was then represented by Rev. Jesse Caswell and Rev. Asa Hemmenway with their wives; while the Baptist Board was represented by the following men and their wives: Revs. J. T. Jones, Josiah Goddard, and E. N. Jenks, and Mr. J. H. Chandler, a lay missionary.

“Early on the morning of the 20th of March, just eight months to a day from the time of our leaving New York, we found ourselves at the bar which obstructs the entrance of the great river of Siam.... I was despatched with the captain in a swift, but alas open, boat that I might, if the ship was unable to get over the bar, make arrangements with friends to send down for Mr. and Mrs. Mattoon. After a rather broiling row of some twenty miles along a river far more beautiful than I had been led to suppose, arrived at the outskirts of this truly great city about sundown. We had still some three[45] miles or more before we reached the residence of the missionaries of the A. B. C. F. M., and it was then dark. Was most kindly welcomed by Mr. Caswell and Mr. Hemmenway, the only missionaries of that Board now left; and glad indeed they appeared to see me.”

On Monday the ship came up to the city and by that time plans had been made to house the newly arrived missionaries in two of the vacant houses in the mission compound where they had been welcomed.

The relations between the three sets of missionaries were most cordial. So far as economy of effort made it wise they co-operated in their undertakings. It was the dispensary of the A. B. C. F. M. that Dr. House re-opened. The tracts used by the three missions were printed by the press of the Baptist mission. Members of each of the missions took turns at the tract house maintained in the bazaar. Although the Presbyterians had previously been engaged in work in Bangkok they held no property there; and for the present it was neither advisable nor possible for the newcomers to obtain a location for themselves. It was arranged that they should live in the A. B. C. F. M. compound until there was time to obtain a desirable site.

The compound contained several houses built after the native style; set high upon posts, with an open space beneath, a verandah on all sides, no windows but openings for air. In one of these houses Dr. House lived for the first two years, having a servant to take care of the house but taking his meals with the Mattoon family. This arrangement entered upon temporarily continued by force of circumstances for three years until the return of Rev. D. B. Bradley,[46] M.D., with another physician, when a readjustment of housing was necessary. Thereupon Dr. House moved to one of the “floating houses” moored in front of the compound, and this continued to be his abode for more than a year until a permanent site was secured for the mission.

The members of the three missions held a common service of worship each Sunday morning and afternoon. At the morning service the sermon was in Chinese or Siamese, while the afternoon service was wholly in English. It is interesting to learn that an “original” sermon was unusual, the preacher of the day commonly reading a published sermon of some well-known divine. On Wednesdays there was an informal conference for all workers and servants. On Saturday evenings there was a prayer meeting for the missionaries only. Later a “monthly concert of prayer for missions” was established. When the number of Chinese increased a separate service was held for them, and likewise a Sunday school for the Siamese pupils of the day school.

Occasionally there would be in attendance on worship some officers from any English vessel in port and then in turn one of the missionaries would visit the vessel and conduct a preaching service for the crew. After the treaty of Great Britain, in 1855, the number of English families increased very rapidly, and while at first many of these attended the services at the mission, their number soon warranted the erection of a chapel for their own use.

Soon after their arrival Dr. House and Mr. Mattoon were taken by their fellow missionaries to call upon two princes who had manifested a friendly interest in the westerners. The acquaintance thus formed proved to be of large influence both to the mission and to the Siamese nation. One of these princes was entitled Chao Fah Yai, which signifies “The older brother of the king,” while his brother was entitled Chao Fah Noi, meaning “The younger brother of the king.” As Chao Fah Yai later became King of Siam and his brother the Vice-King at the same time and as this new king played a momentous part in the opening of Siam to intercourse with the western nations as well as showed much favour to the mission work, it is essential to give a sketch of that important personage.

When, in 1824, the throne was made vacant by the death of the royal father of these two men, the older son had expected to succeed to the throne. Apparently this had been the father’s intention, for he had given this son the name “Mongkut,” meaning “crown prince.” Through intrigue, however, the crown went to a half-brother who, under the title Phra Chao Pravat Thong, was the reigning king when Dr. House reached Siam. Chao Fah Yai, having[48] been thwarted in his aspirations towards the throne, entered the priesthood and retired to a watt, doubtless as the safest way to avoid the royal displeasure towards a rival,—a course which the custom of the country made possible for him.

The princely rank of this priest made him the leader of the Buddhist religion in Siam; and his great wealth enabled him to make his watt one of the most notable and influential in the country. He was a man of enlightened mind beyond his generation. In marked contrast to the king, he was interested in foreign affairs and amicably disposed towards the few foreigners living in Bangkok, especially towards the missionaries, because of their education and culture.

Having already learned Latin from the French priests, in 1845 (then about forty years of age), he invited Rev. Jesse Caswell, a missionary of the American Board, to become his tutor in English. To secure the services of Mr. Caswell he offered in return a reward which he perceived would be more prized than any fee of gold he could propose. He offered Mr. Caswell the privilege of using a room in one of the buildings connected with the watt for preaching the Christian religion and distributing tracts, and granted permission to the priests of the watt to attend if they wished. Mr. Caswell accepted the invitation and continued for three years, until his death, to teach English to the chief Priest of Buddhism in his own temple, and to preach Christianity to all who cared to listen. The esteem of the Prince for his tutor is evidenced by the fact that in 1855, when Dr. House was returning to America on furlough, he made the doctor the bearer of a gift of one thousand dollars to Mr.[49] Caswell’s widow in token of appreciation of her husband’s services, and again in 1866, by the same agent, he sent a gift of five hundred dollars. He also caused a monument to be erected, in memory of his tutor, at the grave of Mr. Caswell.

The more one contemplates the terms made by Chao Fah Yai with Mr. Caswell the more astonishing it appears. Here is the most influential priest in all Siam, the recognised head of the Buddhistic cult in Indo-China, inviting into his watt an uncompromising teacher of the Christian religion notwithstanding the known antipathy of the king to the westerners and their religion, and in return for instruction in the English language he grants him freedom to teach the moral and religious doctrines of Christianity within the precincts of consecrated ground and permits novitiates and priests under his authority to listen to that doctrine.

This broadmindedness of Chao Fah Yai is further shown by an incident which he related to one of the Protestant missionaries. Sometime previous to the engagement of Mr. Caswell a young priest of the watt became a Roman Catholic. The prince was urged to flog the young man for abandoning the religion of his country. To this suggestion the prince said he replied: “The individual has committed no crime; it is proper for every one to be left at liberty to choose his own religion.” On a later occasion the Governor of Petchaburi, having forbidden the distribution of books by the Roman Catholic priests in his province because he said they sought to shield their converts from the authorities when accused of crime, conferred with Chao Fah Yai as to whether he should place the same[50] ban on the books of the Protestants; but the Priest-Prince was able to explain to him the difference of policy between the Roman Catholics and the Protestants and to dissuade him from forbidding the distribution of Protestant literature.

From his intercourse with Mr. Caswell, Chao Fah Yai was quickened with an interest in Western learning, especially the sciences. By his association with these missionaries and the discussion of the evidences of Christianity he came to recognise that his own religion had accumulated a mass of unauthenticated teachings, the accretion of centuries of priestly fancy; and he perceived that this accretion must be sloughed off if his religion was to meet the pressure of foreign civilisation, which he foresaw could not be forever excluded. Accordingly he became the leader of a new party in Buddhism which rejected the uncanonical writings which had accrued to the extent of some eighty-four thousand volumes and held only to the authentic teachings of Buddha. As the leader of this new sect the Prince-Priest was doubtless responsible for the reinvigoration of the religion of Siam, enabling it better to meet the contest of time.

The interest of Chao Fah Yai in the American missionaries was more on account of their intellectual culture than on account of their religion. On one occasion in conversation with Dr. House he frankly said that while he did not believe in Christianity he thought much of Western science, especially astronomy, geography and mathematics. His interest in these subjects was very keen and practical. From the study of navigation he was led into the subject of astronomy, and took interest in the calculation of[51] time, and was especially proud that his own calculation of an eclipse of the moon was almost identical with the Western almanac. His conversation showed considerable intelligence of the late developments in science. He was also a student of languages, and had a knowledge of several languages of eastern India, such as Singhalese and Peguan; he was familiar with Sanscrit, which had been a contributor to the Siamese language, and had studied Latin because he said he had been told that it was like the Sanscrit; besides these he was an expert student of the Pali, the sacred writing of Buddhism. The prince was also the first native prince of Farther India to procure a printing press, which he obtained from London, with fonts of English and Siamese type, and an alphabet of Pali of his own devising.

Apparently Chao Fah Yai approached the subject of Christianity as a vigourous mind approaches any ponderous subject that presents itself; he considered it philosophically. Every religion studied philosophically presents insuperable difficulties; a religion may be rightly judged only by its practical adaptation to life and its effects on the human heart. Had he attempted to study Christianity in a practical manner as he did the science of the West his conclusions would doubtless have been different. One evening the prince called at the home of Mr. Caswell just as the weekly prayer meeting was assembling and, upon invitation, remained to the meeting. His questions afterwards showed that he had given attention, for he inquired the meaning of such words as “redemption” and “Providence,” which he had heard used.

While it is a fact that on several occasions the[52] prince emphatically disclaimed belief in the Christian doctrines, nevertheless the arguments of the missionaries were not without effect upon his mind, for he felt himself called upon to do an entirely new thing—to publish an apologetic for Buddhism in the points where the Christian arguments were most aggressive. In another manner also he gave evidence that the Christian arguments were pressing upon his conscience. The Baptist mission for some years had printed an annual almanac filled with Christian truth and containing, besides other items of civil information, a list of officials of the government and of the watts. In 1848, for the first time, Chao Fah Yai took exception to the religious character of the almanac in which his name appeared as head priest of his watt. He wrote to the editor of the almanac, expressing a “wish to have added to the description of myself in the English almanac ‘and hates the Bible most of all’; we will not embrace Christianity, because we think it a foolish religion. Though you should baptise all in Siam I will never be baptised.... You think that we are near the Christian religion; you will find my disciples will abuse your God and Jesus.”

Concerning his attitude to Christianity a comment from Mrs. Leonowens’ book, An English Governess at the Siamese Court, casts a little light:

“He had been a familiar visitor at the houses of American missionaries, two of whom Dr. House and Mr. Mattoon, were throughout his reign and life gratefully revered by him for that pleasant and profitable conversation which helped to unlock for him the secrets of European vigor and advancement, and to make straight and easy the paths of knowledge he had started upon.[53] Not even his Siamese nature could prevent him from accepting cordially the happy influence these good and true men inspired. And doubtless he would have gone more than half way to meet them, but for the dazzle of the throne in the distance which arrested him midway between Christianity and Buddhism.”

This was the Priest-Prince upon whom the newcomers made their first call of respect. The acquaintance formed at this time ripened into a friendship that continued warm and true to the end. Dr. House, in his journal, carefully records the details of the call:

“His Royal Highness was somewhat unwell, but he would come down. A servant was sent to ask if we would not take some refreshments. Soon a plate of stone-fruit was presented, resembling in flavour our peach; also a plate of Chinese cakes, white and thin, with a bowl of dark Chinese jelly and sugar. Knife, three-pronged fork and teaspoon were brought and we made an excellent tiffin.

“I looked around the room; Bible from A. B. Society, and Webster dictionary stood side by side on a shelf of his secretary, also a Nautical Tables and Navigation. On the table a diagram of the forthcoming eclipse in pencil with calculations, and a copy of the printed chart of Mr. Chandler....

“This man, if his life is spared, is destined to exert an all-powerful influence upon the destinies of this people. He must possess a vigour of mind and much energy of purpose thus to commence the study of a new language at the age of forty. Indeed he seems Cato-like in other things....

“Soon the Prince-Priest appeared with two or three following, dressed in yellow silk robes worn as a Roman toga. His manners were rather awkward at introduction, and his appearance not prepossessing at first,[54] though we became more interested in him as we saw him more. He seated himself on a chair by the center table, and asked our names and ages and whether married. Wished to know if I could cure sick as Dr. Bradley did. Whether I could cure the dropsy, for there was a case in the watt. He understands English when he reads it, but cannot speak it well yet.

“We asked to see his printing room; several young priests and servants on bamboo settees folding books. One composing type, one correcting proof. They gave us a copy of a book published in the Prince’s new Pali alphabet—it was the Buddhist ten commandments and comments on them. Mr. Caswell had previously told him of the present of a keg of printing ink we had for him from our friend G. W. Eddy, of Waterford. He asked who it was from, and if ‘they had heard of him in America’; and was evidently well pleased to find that he was known. Upon taking leave, he promised to call in return upon his guests in a few days.”

This call of the new missionaries was returned by the priest, and on several occasions afterwards he visited the Doctor in his house. Occasionally he would send notes by his servants requesting various favours, medical attendance upon inmates of the watt, loan of books. On a second visit, when Dr. House went to engage the services of a young priest as instructor in Siamese, the prince proposed that the Doctor should come over to the watt and make use of the room which Mr. Caswell occupied for his class in English, and “there distribute medicines and teach the young men of the watt how to be doctors.” Among the papers of Dr. House was found an autograph letter in English written by Chao Fah Yai about this time inviting him and the other missionaries to attend a cremation ceremony at watt Thong Bangkoknoi;[55] and offering him the privilege of distributing religious books among the head priests assembled there from several watts and to preach to them on the new religion. On other visits he inquired about the new instrument that “would send intelligence quickly” (the telegraph), asked why American vessels so seldom came to Bangkok, and discussed the difference between the Latin and English Bibles.

In proper sequence of courtesy the new missionaries were taken to call upon the other prince, Chao Fah Noi. For some reason this prince had withdrawn from his former intercourse with foreigners, but he very courteously received the callers and was manifestly pleased with the attention. He, too, was interested in Western learning and especially inclined towards the physical sciences. On the palace grounds he had several shops, one for a forge, one for iron lathes, one for wood-working. Power for all this machinery was developed by slave-muscle. In one room was a working model of a steam engine, two and a half feet long, made entirely by the prince’s own hands. Being somewhat unwell he consulted Dr. House, but explained that he was under the King’s physician and to refuse to take his medicine would be an act of disrespect to His Majesty, and for that reason would not ask Dr. House to prescribe for him.

The acquaintance thus formed was used, at first, by the prince more as a means of securing personal instruction on physical sciences. Frequently servants were sent to Dr. House to borrow books or to ask for advice on chemistry, electricity, photography, lithography and kindred subjects; and on various occasions the doctor was summoned to the prince’s palace only[56] to find that his assistance or instruction was desired in some experiment. In after years, however, when Chao Fah Noi had become Vice-King upon the accession of Mongkut, his intercourse with Dr. House rested more upon the basis of friendship.

The acquaintance thus conventionally begun was quickened in mutual interest in an unexpected manner. When Dr. House reached Siam he found that the Baptist Mission press had for some time been publishing an annual almanac. He perceived that these almanacs were not only accepted by the ordinary people as they would accept Scripture tracts, but that they were eagerly sought after by a small number of nobles who were interested in Western science. These men were surprised to find that the eclipse for 1847 was much more accurately forecasted in this almanac than by their own astrologers, and they were eager to discuss the subject of astronomy.

This observation together with his own interest in science led him, in September of his first year, to institute a series of lectures for the benefit of the servants and employes of the mission compound “in hopes of waking up their dormant minds and accustom them to think, and so be a little benefitted by the preaching on the Sabbaths; as well as to impart useful information and to set before them the great proof of the existence and wisdom of the Creator, a fundamental truth all Buddhists deny.” The doctor was to furnish the outlines and perform the experiments while Mr. Caswell, experienced in the language, was to do the talking. There was a fair equipment at[57] hand: chemicals, a magnetic machine, a globe, a set of physiological and hygienic charts and a skeleton.