Title: The Taylor-Trotwood Magazine, Vol. IV, No. 4, January 1907

Author: Various

Editor: John Trotwood Moore

Robt. L. Taylor

Release date: September 9, 2022 [eBook #68927]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Taylor-Trotwood Publishing Co, 1907

Credits: hekula03 and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

SUCCESSOR TO

BOB TAYLOR’S MAGAZINE and TROTWOOD’S MONTHLY

Published by THE TAYLOR-TROTWOOD PUBLISHING COMPANY, 11, 13, 16, 19 Vanderbilt

Law Building, Nashville, Tenn.

GOVERNOR BOB TAYLOR and JOHN TROTWOOD MOORE, Editors

| $1.00 A YEAR | MONTHLY | 10c. A COPY |

| Frontispiece —Portrait of General Lee on Traveler | ||

| Capability. (Sonnet) | John Trotwood Moore | 345 |

| Robert Edward Lee | Robert L. Taylor | 346 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Historic Highways of the South—Chapter XVI | John Trotwood Moore | 354 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| How Ole Wash Got Rid of His Mothers-in-Law | John Trotwood Moore | 364 |

| Some Beautiful Women of the South | 368 | |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Colonial Footprints | J. K. Collins | 373 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| History of the Hals—Chapter XVI | John Trotwood Moore | 379 |

| The Measure of a Man. (Serial Story) | John Trotwood Moore | 384 |

| Men of Affairs | 387 | |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Some Southern Writers | Kate Alma Orgain | 392 |

| Illustrated. | ||

| Twelfth Night Revels | Jane Feild Baskin | 395 |

| Uncle Abraham’s Sermon. (Story.) | John Marshall Kelly | 398 |

| The Story of the Year-Gifts | Robert Wilson Neal | 401 |

| The Shadow of the Attacoa. (Serial Story.) | Thornwell Jacobs | 403 |

| The Race Problem | James H. Branch | 415 |

| Remus. (Serial Narrative.) | Laps. D. McCord | 423 |

| Napoleon—Part V—Continued | Anna Erwin Woods | 427 |

| With Bob Taylor | 430 | |

| Sentiment and Story. | ||

| The Paradise of Fools. | ||

| With Trotwood | 439 | |

| The Last Drive. (Poem.) | ||

| The Problem of Life. | ||

| A Quail Hunt in an Automobile. | ||

| Books and Authors | Lillian Kendrick Byrn | 450 |

Copyright, 1907, by The Taylor-Trotwood Publishing Co. All rights reserved.

Entered at the Post Office at Nashville, Tenn., as Second-Class Mail Matter.

THE TAYLOR-TROTWOOD MAGAZINE ADVERTISEMENTS

In writing to advertisers please mention the Taylor-Trotwood Magazine

GENERAL LEE ON TRAVELER

“Robert Edward Lee,” page 346

Photographed from life. M. Miley, Lexington, Virginia

| VOL. IV | JANUARY, 1907 | NO. 4 |

BY JOHN TROTWOOD MOORE

God sends duties to those who show themselves capable of duty, and power to those who are worthy of power.—Wm. McKinley.

To write of Lee in the fulfilling of his manifold duties would be to fill volumes. Lee as an intrepid young officer in the United States army; as a practical military engineer; as a man among men; as a staunch patriot, a brilliant commander and a magnanimous foe; a hero whose strength was the might of gentleness and self-command; the chief of a vanquished army, setting an example of noble submission; in the sanctity of his home, consecrating his energies to the restoration of a prostrate and desolate country; as the head of a great institution for the upbuilding of character and scholarship; as parent, as husband, friend; and as a modest, God-fearing gentleman—in all of these critical relations which constitute the test of true greatness, the rich nature of Robert Edward Lee shone with unfailing steadfastness and brilliancy.

I cannot attempt, in the limits of a magazine article, to do justice to an inexhaustible subject. Why should I when the most eloquent tongues and pens of two continents have labored to present, with fitting eulogy, the character and career of our cavalier par excellence? It is the South’s patent of nobility that he is to-day regarded, the world over, not only as ranking with the greatest military geniuses history has known, but as having less of the selfish littleness of ordinary humanity than any of his compeers. I simply weave a wreath of memory to offer on his natal day.

That he was the son of Light Horse Harry Lee and Anne Carter, and was born at Stratford, the Carter ancestral home in Westmoreland, Virginia, the nineteenth of January, 1807, are well-known statistics. Miss Emily V. Mason, in her “Popular Life of General Lee,”[1] gives the following account of his early life:

When he was but four years of age, his father removed to Alexandria the better to educate his children, and there are many persons yet living in that old town who remember him at that early age. From these sources we are assured that his childhood was as remarkable as his manhood for the modesty and thoughtfulness of his character, and for the performance of every duty which devolved upon him.... At this period General Harry Lee was absent in the West Indies in pursuit of health, and he died when Robert was eleven years of age.... His mother was also an invalid, and Robert was her devoted cavalier, hurrying home from school to take her for her drive, and assuming all the household cares, learning at this time the self-control and economy in all financial concerns which ever characterized him....

General Lee used to say that he was fond of hunting when a boy—that he would sometimes follow the hounds on foot all day. This will account for his well-developed form, and for that wonderful strength which was never known to fail him in all the fatigues and privations of his after life.

It was natural that the son of Light Horse Harry should desire to enter the army, and he was doubtless also inspired to take this step by a desire to relieve his mother of the expense of his maintenance and education. “At West Point,” says General Fitzhugh Lee,[2] “he had four years of hard study, vigorous drill, and was absorbing strategy and tactics to be useful in after years. His excellent habits[347] and close attention to all duties did not desert him; his last year he held the post of honor in the aspirations of cadet life—the adjutant of the corps. He graduated second in a class of forty-six and was commissioned second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. It is interesting to note that his eldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, also entered the Military Academy twenty-one years after his father, was also the cadet adjutant, graduated first in his class and was assigned to the Engineer Corps.” Of still greater interest is the graduation, in 1902, of his greatnephew, Fitzhugh Lee, Jr., who, on his graduation, was appointed special aide to Mrs. Roosevelt.

Lee’s first assignment to duty was at Fortress Monroe, where he remained four years.

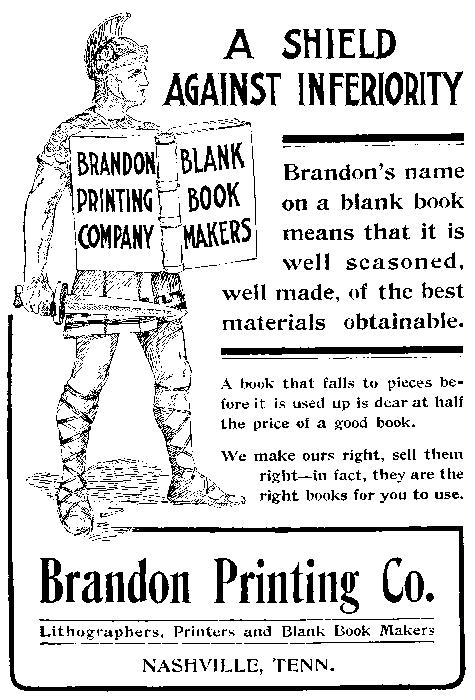

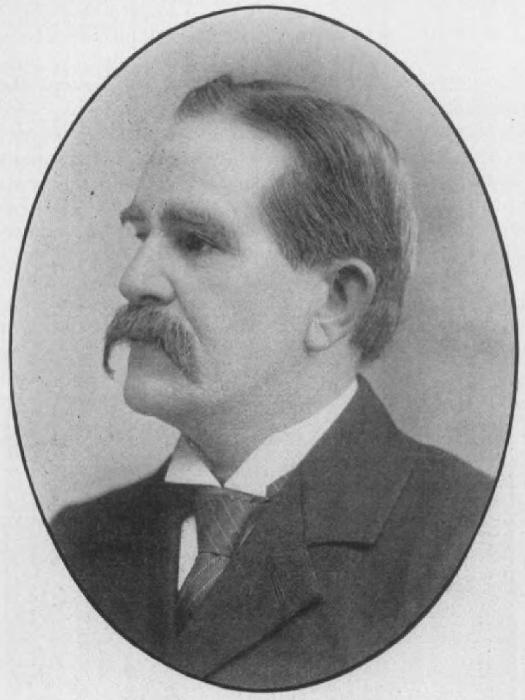

COLONEL R. E. LEE

About the time of the Mexican War

“He went much,” continues his nephew biographer, “in the society of ladies—always most congenial to him.... He was in love from boyhood. Fate brought him to the feet of one who, by birth, education, position and family tradition, was best suited to be his life companion. Mary, the daughter of George Washington Parke Custis, of Arlington, and R. E. Lee were married on the thirtieth of June, 1831.”

The modesty of the newly married couple was spared the modern newspaper accounts of the bride’s wedding[348] garments, her trousseau and trunks, the gifts and other intimate details now demanded by an insatiate public.

Mrs. Lee was possessed of a strong intellect, charming person and fascinating manners, being at the same time very domestic in her tastes, and “such a housekeeper as was to be found among the matrons of her day,” says her friend, Reverend J. W. Jones, who adds: “She was, from the beginning, a model wife and mother.”[3]

A short account of the children of this exemplary couple may not be amiss here. George Washington Custis Lee graduated, as has been said, first in his class, and at the time of the secession of Virginia was an officer in the Engineer Corps. He was appointed aide on President Davis’s staff, became brigadier and then major-general, and after the close of the war was made professor of engineering in the Virginia Military Institute and succeeded his father as president of Washington and Lee University. This position he held for twenty-six years, maintaining the high standards set by his father. Since his retirement, in 1897, he has resided at Burke, Virginia.

William Henry Fitzhugh, the second son, was a Harvard graduate and was appointed lieutenant in the army on the special application of General Scott, but had resigned and was living at home when the war came on, and he raised a cavalry company, of which he was made captain. He had command of two companies and was made major of the squadron. After the war he served in the Virginia Senate and in Congress until his death.

Robert E. Lee, junior, was a student in the University of Virginia when the war began, and promptly enlisted in the Confederate army. He served on the staff of his brother, General W. H. F. Lee, and rose to the rank of captain. Since the war he has been a successful planter, and in 1905 he completed the “Recollections of My Father,” truly a work of love.[4]

Miss Anne Carter Lee died during the war, and Miss Agnes shortly after the death of her devoted father. Miss Mildred Lee died in 1905, and Miss Mary Lee is still living, a prominent figure in all social and historical matters in her state and the national capital.

The oldest son was born at Fortress Monroe, but the other children were all born at Arlington, where Mrs. Lee passed much of her time when her husband was sent to distant stations.

Of Lee’s work as military engineer, Mr. Jones says:

The system of river improvements devised by Lee at St. Louis are still followed there, and to his next work, at Fort Hamilton, the city of New York owes its perfect defenses to-day.

His campaign under General Scott, in Mexico, was his first taste of actual service, and history has recorded his zeal, valor and undaunted energy in that memorable conflict. He now entered upon his real career. He was breveted major at Cerro Gordo, lieutenant-colonel at Churubusco, and colonel at Chapultepec. General Scott testified his appreciation in every report he made to the War Department, and Lee repaid the regard of his beloved general with an extraordinary admiration and devotion.

He brought his son, Robert, a mustang pony from Mexico. “He was,” writes Captain Lee, in his “Recollections,” “for his inches, about as good a horse as I ever met with. While he lived ... he and Grace Darling, my father’s favorite mare, were members of our family. Grace Darling was a chestnut mare of fine size and great power. He bought her in Texas from the Arkansas cavalry on his way to Mexico, her owner having died on the march out. She was with him during all of the war, and was shot seven times. As a little fellow I used to brag of the number of bullets in her, and would place my finger on the scar made by each one.”

In 1852 he was appointed Superintendent[349] of the United States Military Academy at West Point, where he remained for three years, when he was sent to Texas. His services on the frontier covered a period of five years, with one furlough home, during which he was sent, in October, 1859, to capture John Brown, at Harper’s Ferry. In February, 1861, he was recalled from Texas and ordered to report at Washington. He was not in favor of secession, for he loved the Union strongly, and he clung fondly to the hope that the breach might be closed, but he did not hesitate when he saw that his state would secede. A New York banker, an intimate friend of General Scott, asked him at this time, in the course of a conversation on the art of war: “General, whom do you regard as the greatest living soldier?” General Scott replied immediately: “Colonel Robert E. Lee is not only the greatest soldier in America, but the greatest now living in the world. This is my firm conviction from a full knowledge of his extraordinary abilities, and if the occasion ever arises, Lee will win this place in the estimation of the whole world.” Refusing the supreme command of the United States army, he cast in his lot with the Confederacy, and was placed in command of the troops of Virginia.

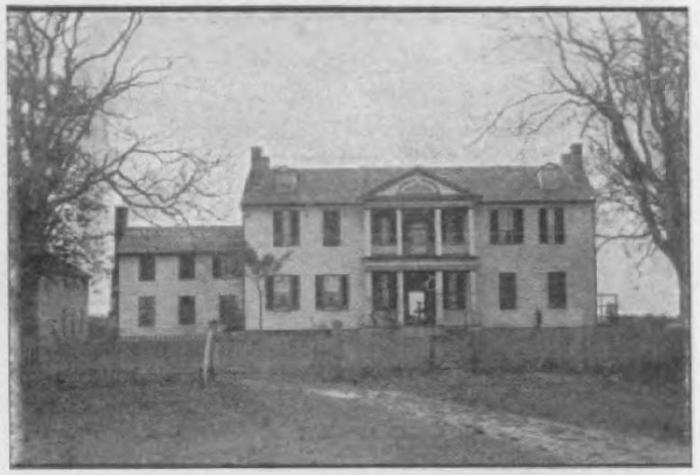

ARLINGTON, HOME OF THE LEES

Much discussion has been held concerning the occupation of Arlington by the Federal authorities, but it was claimed that this was a justifiable act, in view of the commanding position of the property. The White House and the department buildings near it were only two miles and a half from the highest point on the Arlington grounds; the Capitol only three and a half miles away, and Georgetown less than a mile. A battery established on the heights would have had the whole of Washington at its mercy. General Scott saw the importance of this position, and, reluctant as he was to turn Mrs. Lee from the lovely home where he had so often received her hospitality; deeply grieved as he must have been to humiliate by his first move one who had been his cherished friend and trusted aide, he sent General Mansfield to take it. “It is quite probable,” wrote the latter in his report,[350] “that our troops assembled at Arlington will create much excitement in Virginia; yet, at the same time, if the enemy were to occupy the ground there a greater excitement would take place on our side.”

Without going into particular details of the four years of fighting, I wish to quote Lord Wolseley’s beautiful tribute to Lee:[5]

It is my wish to describe him as I saw him in the autumn of 1862, when, at the head of proud and victorious troops, he smiled at the notion of defeat by any army that could be sent against him. I desire to make known to the reader not only the renowned soldier, whom I believe to have been the greatest of his age, but to give some insight into the character of one whom I have always considered the most perfect man I ever met....

Outsiders can best weigh and determine the merits of the chief actors on both sides.... On one side I can see, in the dogged determination of the North, persevered in to the end through years of recurring failure, the spirit for which the men of Britain have always been remarkable. It is a virtue to which the United States owed its birth in the last century.... On the other hand, I can recognize the chivalrous valor of those gallant men whom Lee led to victory, who fought not only for fatherland and in defense of home, but for those rights most prized by free men. Washington’s stalwart soldiers were styled rebels by our king and his ministers, and in like manner the men who wore the gray uniform were denounced as rebels from the banks of the Potomac to the headwaters of the St. Lawrence.... As a looker-on, I feel that both parties in the war have so much to be proud of that both can afford to hear what impartial Englishmen or foreigners have to say about it.

Describing Lee’s appointment to the command of the State Militia, he says:

General Lee’s presence commanded respect, even from strangers, by a calm, self-possessed dignity, the like of which I have never seen in other men. Naturally of strong passions, he kept them under perfect control by that iron and determined will of which his expression and his face gave evidence. As this tall, handsome soldier stood before his countrymen he was the picture of the ideal patriot, unconscious and self-possessed in his strength.... There was in his face and about his expression that placid resolve which bespoke great confidence in self, and which in his case, one knows not how, quickly communicated its magnetic influence to others.

Comparing Lee with the Duke of Marlborough, he says:

They were gifted with the same military instinct, the same genius for war. The power of fascinating those with whom they were associated, the spell which they cast over their soldiers, ... their contempt of danger, their daring courage, constitute a parallel that it is difficult to equal between any two other great men of modern times.

He repeats the following pleasantry overheard between two Confederates, after Pope’s dismissal:

Have you heard the news? Lee has resigned!

Good God! What for?

Because he says he cannot feed and supply his army any longer, now that his commissary, General Pope, has been removed.

A characteristic anecdote of Lincoln is also given. He was asked how many rebels were in arms and replied that he knew the number to be one million, “for,” said he, “whenever one of our generals engages a rebel army he reports that he has engaged a force of twice his strength; now I know we have half a million soldiers in the field, so I am bound to believe the rebels have twice that number.” General Wolseley justly criticises the lack of concerted action among our regiments.

No fair estimate of Lee as a general can be made by a simple comparison of what he achieved with that which Napoleon, Wellington or Von Moltke accomplished, unless due allowance is made for the difference in the nature of the American armies and of the armies commanded and encountered by those great leaders. They were at the head of perfectly organized, thoroughly trained and well disciplined troops, while Lee’s soldiers, though gallant and daring to a fault, lacked the military cohesion and efficiency, the trained company leaders ... which are only to be found in a regular army of long standing.

The Englishman concludes:

Where else in history is a great man to be found whose whole life was one such blameless record of duty nobly done? It was consistent in all its parts, complete in all its relations.

... The fierce light which beats upon the throne is as that of a rushlight in comparison with the electric glare which our newspapers now focus upon the public man in Lee’s position. His character has been subjected to that ordeal, and who can point[351] to any spot upon it? His clear, sound judgment, personal courage, untiring activity, genius for war, and absolute devotion to his state mark him as a public man, as a patriot to be forever remembered by all Americans.... I have met many of the great men of my time, but Lee alone impressed me with the feeling that I was in the presence of a man who was cast in a grander mould and made of finer metal than all other men. He is stamped upon my memory as a being apart and superior to all others in every way; a man with whom none I ever knew, a very few of whom I have read, are worthy to be classed.

This was one of the popular songs current after the close of the war:

Why Marse Robert? Major Stiles gives the reason[6]:

The passion of soldiers for nicknaming their favorite leaders, rechristening them according to their own unfettered fancy, is well known.... There is something grotesque about most of them, and in many seemingly rank disrespect.... However this may be, “Marse Robert” is far above the rest of soldier nicknames in pathos and in power.

In the first place, it is essentially military ... it rings true upon the elemental basis of military life—unquestioning and unlimited obedience.... There never could have been a second “Marse Robert,” and but for the unparalleled elevation and majesty of his character and bearing, there would never have been the first. He was of all men most attractive to us, yet by no means most approachable. We loved him much, but we revered him more. We never criticised, never doubted him; never attributed to him either moral error or mental weakness; no, not even in our secret hearts or most audacious thoughts. I really believe it would have strained and blurred our strongest and clearest conceptions of the distinction between right and wrong to have entertained, even for a moment, the thought that he had ever acted from any other than the purest and loftiest motive.... The proviso with which a ragged rebel accepted the doctrine of evolution, that “the rest of us may have descended or ascended from monkeys, but it took a God to make ‘Marse Robert,’” had more than mere humor in it.... We never compared him with other men, either friend or foe. He was in a superlative and absolute class by himself. Beyond a vague suggestion, after the death of Jackson, as to what might have been if he had lived, I cannot recall even an approach to a comparative estimate of Lee.

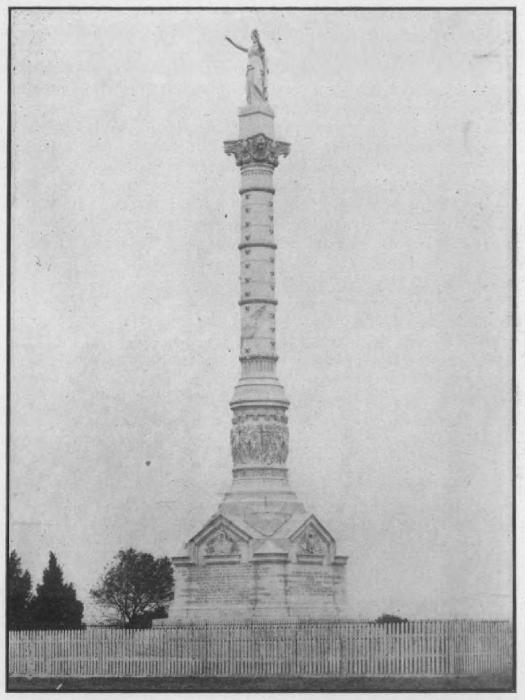

VALENTINE’S RECUMBENT LEE STATUE

At Washington and Lee University, Lexington, Virginia

Lee’s devotion to his soldiers and theirs to him are referred to by one of Pickett’s captains[7]:

Many of those who had been wounded in the battle of the first day went into the great charge on the third day with bandages on their heads or arms, at sight of which the imperturbable Lee shed tears.... Here was a devotion of which the Romans of old had never dreamed; here was a holocaust of sacrificial victims such as Greece had never known! The men who at Marathon and Leuctra bled were not greater heroes than those who fell at Gettysburg.

In a small volume of War Sketches, issued shortly after the war, I found the following anecdote contributed to a Washington paper by Miss Woolsey, a nurse sent to Gettysburg with the Sanitary Commission:

One of the Gettysburg farmers came creeping into our camp three weeks after the battle. He lived five miles only from the town and had “never seen a Rebel.” He heard we had some of them, and came down to see them. “Boys, here’s a man who never saw a Rebel in his life, and wants to look at you.” There he stood, with his mouth wide open, and there they lay in rows, laughing at him. “And why haven’t you seen a Rebel?” Mrs. ⸺ asked. “Why didn’t you take your gun and help to drive them out of your town?” “A feller might er got hit,” which reply was quite too much for the Rebels; they roared with laughter up and down the tents.

After the surrender at Appomattox General Lee joined his family at Richmond for a short period of rest before taking up the “burdens of life again.” “There was,” writes General Long,[8] “a continuous stream of callers at the residence ... upon every hand manifestations of respect were shown him.” General Long gives some touching incidents:

One morning an Irishman who had gone through the war in the Federal ranks appeared at the door with a basket well filled with provisions, and insisted upon seeing General Lee.... The general came from an adjoining room and was greeted with profuse terms of admiration. “Sure, sir, you’re a great soldier, and it’s I that know it. I’ve been fighting against you all these years, an’ many a hard knock we’ve had. But, general, I honor you for it; and now they tell me you’re poor an’ in want, an’ I’ve brought this basket an’ beg you to take it from a soldier.”

Two Confederate soldiers, in tattered garments and with bodies emaciated by prison confinement, called upon General Lee and told him they were delegated by sixty other fellows around the corner “too ragged to come themselves.” They tendered their beloved general a home in the mountains, promising him a comfortable house and a good farm.

“Great and star-like as was the warrior,” says Dr. Shepherd, “the man is greater.”[9]

It is said that General Lee was offered estates in England and in Ireland; also the post of commercial agent of the South at New York, and many other tenders of a home or livelihood. All of these he declined and accepted the presidency of Washington College, at Lexington.

Founded in 1789 under the name of “Augusta Academy,” the name was changed in 1782 to “Liberty Hall Academy,” from which was sent a company of students into the Revolution. Washington, who had accepted from the new State of Virginia 100 shares of the James River Company only on condition that he might give them to some school, chose this academy for beneficiary, and the name was changed in 1798 to “Washington College.” The buildings, library and apparatus had been sacked during the Federal occupancy, and the country was able to furnish only forty students at the opening of the term of ’65-’66. Nothing daunted, the new president gathered around him an able faculty, raised the standard of scholarship, renovated the old buildings and secured funds for new ones. He introduced the “honor system” and knew every student’s name, as well as his class and deportment record. Asked, at a faculty meeting, for a plan to induce students to attend the chapel, he advised: “The best way that I know of is to set them the example,” which[353] he invariably did. This gives the keynote to his remarkable influence.

The effect of his principles was all-powerful. It is doubtful if any other college in the world could show such a high average of morals and scholarship which obtained at Washington College during Lee’s presidency of five years.

I cannot resist relating an anecdote given by another of our soldier-authors, John Esten Cooke:[10]

Coming upon the chieftain conversing cordially with an humbly clad man, he supposed that it was, of course, an old Confederate, the more so as the general, looking after the retreating figure, said kindly:

“That is one of our old soldiers who is in necessitous circumstances.” Questioned, however, he admitted that the soldier had fought on “the other side, but we must not think of that,” was his verdict.

The death of General Lee, on October 12, 1870, brought forth more encomiums from the press, personages of exalted rank, and from the people generally than has ever been accorded any man who died in private life since Washington. “I do not exaggerate,” says Dr. Jones, “when I say that many volumes would not contain the eulogies that were pronounced, for I undertook to make a partial collection of them and have a trunk full now.” In the cemetery near him at Lexington bivouacs his great lieutenant, Stonewall Jackson. They were born in the same month, the one on the nineteenth and the other on the thirty-first of January. It is fitting that they should lie near together. “I know not,” further and most fittingly continues Mr. Jones, who was chaplain of the University, “how more appropriately the tomb of Lee could be placed. The blue mountains of his loved Virginia sentinel his grave. Young men from every section throng the classic shades of Washington and Lee University, and delight to keep ward and watch at his tomb.”

MERCIE’S MONUMENT, LEE CIRCLE, RICHMOND

[1] Popular Life of General Lee. By Emily V. Mason. Baltimore: John Murphy & Co.

[2] General Lee. By Fitzhugh Lee. New York: D. Appleton & Co. (Great Commanders Series.)

[3] Life and Letters of Robert Edward Lee. By Rev. J. William Jones, D.D. New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company.

[4] Recollections of My Father. By Captain Robert E. Lee. New York: Doubleday, Page & Co.

[5] General Lee. General Viscount Wolseley. Rochester, N. Y.: George P. Humphrey.

[6] Four Years under Marse Robert. By Major Robert Stiles. New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company.

[7] Gettysburg: A Battle Ode Descriptive of the Grand Charge of the Third Day, July 3, 1863. By R. W. Douthat. New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company.

[8] Memoirs of Robert E. Lee: His Military and Personal History. By General A. L. Long and General Marcus J. Wright. New York, Philadelphia and Washington: J. M. Stoddart & Co.

[9] Life of Robert Edward Lee. By Henry E. Shepherd, M.A., LL.D. New York and Washington: Neale Publishing Company.

[10] Robert E. Lee. By John Esten Cooke. New York: G. W. Dillingham & Co.

By John Trotwood Moore

By Lewis M. Hosea

[We give way in this issue to Judge Lewis M. Hosea, Judge of the Superior Court of Cincinnati and late Brevet Major U. S. Army, 16th U. S. Infantry, who gives us the viewpoint as seen by Buell’s army. In this paper by this distinguished gentleman, appears the best description of how it feels to be under fire and how the Confederate columns appeared that we have ever seen.

That particular description deserves to live as a classic and no one may read it without afterwards seeing “the surging line of butternut and gray moving rapidly across our front” and “the accompaniment of a leaden blast of hell sweeping into one’s face as though it were a sort of fierce and deadly wind impossible to stand against.”

It will also be observed that Judge Hosea takes decided issue as to certain facts published in the History of the Shiloh Battlefield Commission which we take pleasure in publishing and will accord the same privilege to any one who cares to reply, as it is by this kind of personal testimony that the truth of history is eventually established.

To the readers of Taylor-Trotwood we wish to state that these Historic Highways of the South have been running serially through Trotwood’s Monthly for fifteen months and include The Hermitage, The Creek War Highways, New Orleans, Battle of Franklin, Ft. Donelson, Shiloh and others.—The Editor.]

The two days’ battle at Pittsburg Landing on the Tennessee River, fought on Sunday and Monday, April 6th and 7th, 1862, viewed from the standpoint of forty years later, looms up as one of the most significant contests of the great Civil War. The entire battlefield was a wilderness of scrub oak and kindred growths, unbroken save by a few settlers’ clearings located at random upon a plain traversed only by irregular “woods-roads,” and by drainage ravines leading by winding courses into the two creeks bounding the field of operations on the north and south—these discharging into the Tennessee River behind the Union Army.

The troops were for the most part new and untried, and the conditions of the ground made the transmission of orders difficult and uncertain. It was impossible for commanders of large bodies to obtain a comprehensive view of the field so as to perceive and provide intelligently for the varying exigencies of the battle as it progressed. They could only guess the swaying movements of the fight by sounds of musketry and by the chance reports of messengers who could locate nothing by fixed monuments. Nor could the men in ranks, or even regimental officers, see beyond a limited distance; and the direction of enfilading or turning movements could be discovered only by the course of bullets among the trees or the tearing of the ground by solid shot or shell.

These things made the battle a supreme test of the quality of the individual units of the army rather than of any directing skill of its higher commanders. The bulldog courage of individual groups of men who hung on and fought “to a finish,” or who, like Prentiss, sacrificed themselves where they stood because of no order[355] to withdraw, delayed the general advance of the enemy and thus saved the first day from overwhelming and complete disaster. It became a case of “night or Blücher;” and when, toward evening, the leading regiments of Buell’s army arrived upon the field and interposed a fresh line of resistance, the Union troops had been driven from the field and huddled as a mass of disorganized fragments in a semicircle of half a mile radius about the landing.

But the Confederates drew off flushed with the spirit of victory and ceased fighting only to prepare for an expected certain and triumphant finish in the morning. Knowing that they had the Union forces hemmed in the semicircle of their lines extending from river to river, every Confederate soldier fully believed that surrender or annihilation of the Union forces would be easy of accomplishment.

This was the spirit and purpose that animated the Confederate forces on Monday when they began to attack soon after daylight on that second day. To the forces of Buell, arriving during the night on transports from Savannah (on the river twenty miles below), and marching up the bank in the dim light of dawn to form a cordon around the fragments of Grant’s army, the scene was dismal and discouraging in the extreme. Making our way through the thousands of men huddled on the bank, hearing at every step the doleful prognostications of defeat, the wooded plain above presented to us visible proof of the disastrous conflict of the day before in the dead and wounded who lay unattended, and the broken and discarded arms and equipments that strewed the ground. These were the sights and sounds that greeted us as we marched to our place in line of battle on the second day; and they fully justified the compliment paid us by our brigade commander, General Lovell H. Rousseau, who says, in his official report of the battle in substance: “Seldom have men gone into battle under such discouraging circumstances, and never have they borne themselves more gallantly.”

In the personal reminiscences that follow I shall speak more particularly of the part taken by Rousseau’s brigade of McCook’s division.

I was personally present throughout the second day, as Adjutant of the First Battalion, Sixteenth U. S. Infantry—which, with similar battalions of the Fifteenth and Nineteenth Infantry, and the First Ohio, Fifth Indiana, and Sixth Kentucky Volunteers—constituted Rousseau’s brigade (4th) of McCook’s division (2d) of the Army of the Ohio commanded by General Buell.

My position as adjutant gave me a somewhat wider range of observation than that of a line officer on duty with a company, and I retain some very distinct recollections of the battle, which I will briefly state in so far as they bear upon the movements of Rousseau’s brigade; but I shall leave others to speak of the severity of the fighting, and leave to you to estimate the quality of the service the brigade rendered the Union cause.

Rousseau’s brigade reached Pittsburg Landing during the night of the 6th of April, 1862, by steamers from Savannah, and disembarked just before day. On the level just back of the landing, in the dim light of the coming dawn, we deposited knapsacks and advanced in a southwesterly direction through the woods, passing through camps (probably Hurlbut’s) where our dead lay unburied as they had fallen the day before. After a short halt we were advanced and deployed to the right and front at the hither edge of a broad and shallow depression, where a small brook coursed on to our right through a comparatively open forest without any visible clearing. Here we were halted, muskets loaded, and, in a short time, at a little after six o’clock, we heard firing toward our right rear, and almost immediately our own skirmishers were driven in and we were engaged with a battle line of the enemy. Then followed a steady and vigorous “stand-up”[356] musketry fight which lasted the greater part of an hour, when the enemy drew off, but soon renewed the attack with greater vigor, only to be again repulsed.

This position was probably on Tilghman’s Creek, shown on the map of the Shiloh Battlefield Commission to which I shall refer; but the hour stated on the map as eight o’clock is wrong and should be six o’clock. By eight o’clock we had been baptized with fire and blood. Here Captain Acker of the Sixteenth was killed, and a number of other officers and men were killed and wounded.

It is an old story, perhaps, to most of you—this first experience of actual battle; yet, even now, dimly remembered through the intervening years, it seems to me the most horrifying experience that can possibly fall to the lot of man.

First came the startling report of a musket fired by one of our own skirmishers out in our front; then a crackling of responses from the woods beyond, but we could see only a little blue smoke rising above the undergrowth—for it was early spring and the green leaves were just beginning to appear—and hear the skipping of stray bullets through the branches with a whirr of spent force. A stir went through the lines and faces grew pale, for we knew that the battle was sweeping toward us and that these shots were the first sprinkle of the coming storm. The quiet command of “Attention!” was obeyed ere it was uttered; but the climax of first impressions came with the order to “load.” That order, like the jarring touch upon the chemist’s glass, crystallized the wild turmoil of thoughts and focalized all upon the actual business of war. I can realize now how important a thing in war is the musket as a steadying factor for overwrought nerves; and how that first order to “load!” brought the panicky thoughts of men back with a sudden shock to the realization that they were there upon equal terms with the enemy to do and not alone to suffer. I remember the “thud” of the muskets as they came down upon the ground almost as one,—for our men had been well drilled,—and the confused rattle of drawing ramrods, and their ring in the gun barrels as they rebounded in ramming the charges home. Every movement and every sound was an encouragement; and in the reaction of feeling the interchange of boastful speech almost ripened into cheers. But, meantime, the fire of skirmishers increased to an almost continuous rattle and grew closer, until—for all this was a matter of minutes only—our skirmishers could be seen coming in, firing as they came, and half carrying two or three wounded men. This, of course, again deepened the tension of nervous expectation, and faces took on a look of grim determination, as eyes peered forward to catch the first glimpse of the approaching enemy. As our skirmishers came into the lines, there went a hoarse whisper down the ranks, “There they are!”—and looking out through the woods I saw the flutter of battle flags and beneath them a surging line of butternut and gray moving rapidly across our front just beyond the shallow ravine, perhaps fifty or seventy-five yards away. In a moment, as it seemed, there burst forth a rattle of musketry that almost drowned the command of our officers to “fire at will!”

The first shock of battle is appalling. The rattle deepens into a roar as men get down to the work of loading and firing rapidly; but it is not alone the noise of firing that appals, the vicious “whizz,” and “zip” past the ears; the heavy “thud” of bullets that strike the tree-trunks with the force of sledge-hammer blows,—all these make up a horrible din that has no parallel on earth. But with it all is the realization that this is but the accompaniment of a leaden blast of hell sweeping into one’s face as though it were a sort of fierce and deadly wind impossible to stand against; and the rain of leaves and twigs cut from the trees, and the occasional fall of larger branches, heightens this impression of a raging storm. After a little the smoke obscures everything[357] and the battle goes on in an ever-increasing acrid fog that would make breathing impossible were it not for the frenzy of battle that seizes upon every other faculty, physical and mental, and makes one oblivious to all other surroundings.

Here and there a man drops his musket, throws up his hands and falls backward dead; or another lunges heavily forward on hands and knees, mortally wounded; and no one who has seen it will ever forget that look of agony unspeakable on the faces of those stricken by sudden death in battle.

For what seemed an interminable time the angry buzz of bullets clipped by our ears and overhead; and I remember, that, as I passed up and down the line assisting the commanding officer of the battalion in encouraging the men to take time in loading carefully and aiming low, a bullet struck a musket in the hands of a young Irishman of my own company, just as he was about to bring it to his shoulder, and the force of the impact shattered the stock and turned him partly about and almost threw him down. I saw the blood spurt from his arm, for he had in the excitement rolled up his sleeves to handle his piece the better. I sprang forward to assist him; but with a cry of rage he stripped off his sleeve, and with the assistance of a comrade, bound up his wound, which proved to be not serious, and seized a dead comrade’s musket beside him and went on with the fight.

But after a time the whirr and hiss of the bullets slackened and finally ceased; finally, skirmishers were ordered out to reconnoiter, while disposition was made of the dead and wounded. Soon, however the skirmishers came hastily back and reported new and heavier lines advancing, and again we saw the battle-flags among the trees, nearer than before. This time, however, the fight opened with the thunder of field guns whose missiles went shrieking overhead with a horrible sound that made the blood run cold. Then came the order to hug the ground and fire at will; and the fight went on as before except that as we had advanced a few rods down the gentle declivity of the ravine, and the line of the enemy was at a relatively higher level, the majority of bullets and the cannon shots passed above us and but few came dangerously close.

But the success of our first experience seemed to tell upon the ranks, and the coolness and deliberation of both men and officers were noticeable thenceforward; and soon the artillery discharges ceased, and after a time we knew, as before, by the lessening of the whizz of bullets, that the enemy had again yielded the ground in our front.

As I look back upon it, it seems astonishing how soon all the natural feelings of apprehension and fear give way to what has been aptly termed the “battle rage” which lifts a man up to a plane where the things of the body are forgotten. Amid the roar and din of musketry and the horrible swish and shriek of shells, the intellect seemed to be disembodied, and, while conscious of the danger of being hurled headlong into eternity at any moment, the pressure upon the brain seemed to deaden the physical senses—fear among them. Fear came later when the fight was over, just as in the waiting moments before it began; but throughout the day while the battle was on I remember having a singular feeling of curiosity about personal experiences. I seemed to be looking down upon my bodily self with a sense of impersonality and wondering why I was not afraid in the midst of all this horrible uproar and danger. I suppose this was the common experience of soldiers, for if it were not so, battles could not be fought.

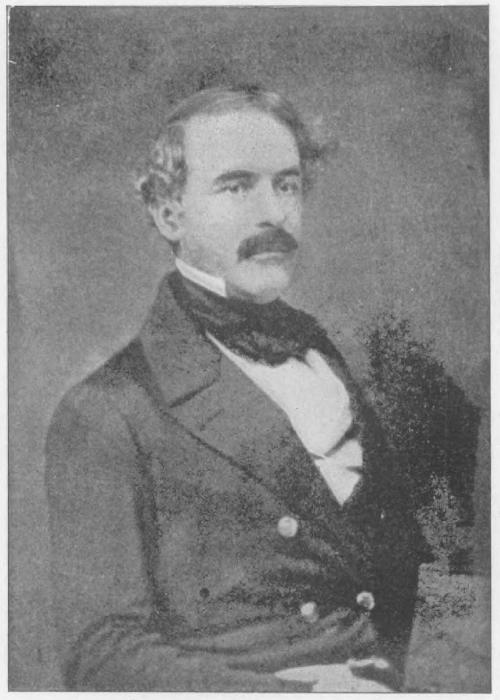

GENERAL FORREST AND HIS CAVALRY GOING OUT TO FORT DONELSON

From “Life of General Nathan Bedford Forrest.” Copyright, 1899, by Harper & Brothers.

After repulsing the second attack, at about eight o’clock, we moved forward slowly across the brook, with skirmishers advanced, fighting at intervals, for the enemy stubbornly contested the ground. On reaching a clearing (probably the Duncan field) in the line of our advance we were met by an opposing concentration of the enemy in great force at the far side of it, who attempted a desperate charge upon us. This was met by a steady fire and an unswerving line; and the fighting that ensued is described by Judge Force, in his account of the battle published in the “Campaigns of the Civil War” by the Scribners (p. 171), as a “desperate struggle”—and indeed it was! Guenther, with a section of Terrill’s battery, arrived upon the scene, coming in upon our right, which was unprotected, at the crisis of this fight, and, as the enemy gave way at our front and ran together in a mass to pass through a gate or break in a fence in the rear, he directed his rapid discharges of canister to the same point. The effect upon the enemy was appalling and horrible beyond all description. Among our killed were Lieutenant Mitchell, a most gallant officer of the Sixteenth, and it was here also that Wykoff, then a captain of the Fifteenth, lost his eye.

I recall one striking incident of a personal character connected with this part of the battle. A sergeant of C Company, which I had commanded, was wounded in the shoulder and disabled though not vitally hurt. A moment later, as the sergeant was making his way to the rear, I was knocked down by an exploding shell, whose fragments relieved me of one boot-leg and left one leg of my pants in shreds, but fortunately left the leg intact, except for a wrench and a few bruises of no serious consequence. It so happened that my sergeant saw me fall, and, as he was among the first of the wounded taken to Cincinnati, he reported me as killed, to the great distress of my family at home. My brother, who came down a few days later, found me very much alive, though very ragged, very dirty, and very thankful that the shell that took my boot-leg took no more. I was thankful even for the limp that made me the subject of good-natured derision for some days as I performed my duties as adjutant on one leg.

We immediately followed in pursuit, after this last fight, capturing two field-guns from the enemy, and continued the advance until we had repossessed General McClernand’s headquarters of Sunday, beyond which we again met a determined resistance, but eventually drove the enemy back through a large open field into what has been termed the “water oaks thicket.”

The enemy seemed to be massed in great force at and beyond this point to oppose our further progress, and a heavy line of battle occupied the woods beyond the clearing on the hither edge of which we were halted to replenish our exhausted ammunition.

Our advance, though slow, had been continuous and resulted in projecting a sort of wedge into the enemy’s lines, of which wedge we seemed to be the apex. It resulted, therefore, naturally and necessarily that the enemy concentrated more and more in our immediate front to break the force that was gradually splitting them in two and endangering their communications in rear. Firing still continued toward the rear on both flanks, for we had considerably outstripped the general advance. Our men fixed bayonets and lay down under orders to hold the position, if attacked, at all hazards. The firing against us grew quite heavy, but no reply was made, although some were killed, among them Lieutenant Keyes, a splendid officer of the Sixteenth, with whom I was standing arm in arm at the time his summons came,—for among the regulars it was not then considered “good form” for officers to take shelter.

I have before spoken of the impact of a minie bullet against a tree as like the blow of a sledge hammer. The Keyes incident gives a very realistic illustration. As I have mentioned in another place, Lieutenant Keyes and I were standing arm in arm—my right interlocked with his left,—in rear of his company. We were, as I recall, just exchanging sorrowful remarks over the death of a Sergeant Baker—a fine man—who received a bullet through the forehead just a moment before, while Keyes was exchanging[360] words with him. Just then the sledge hammer struck one of us—for a moment I did not know which—and hurled us both to the ground backwards. As I scrambled to a footing I saw Keyes’ blanched face and the torn garment showing the passage of the bullet through the left shoulder joint where a hasty examination showed that the bony structure of the vicinity had been shattered. He was taken to the rear and died the second day after.

Here, after a long wait, General Sherman came, and I saw him for the first time. I will let him tell you what next occurred. General Sherman is describing, in his official report of the battle, his own movements as he came up on our right; and is speaking of a battery that had reached him at the rear. He says:

“Under cover of their fire we advanced until we reached the point where the Corinth road crosses the line of McClernand camp, and here I saw for the first time the well ordered and compact columns of General Buell’s Kentucky forces whose soldierly movements at once gave confidence to our newer and less disciplined men. Here I saw Willich’s regiment advance upon a point of water oak and thicket, behind which I knew the enemy was in great strength, and enter it in beautiful style.”

(The thicket described by General Sherman, I may remark, was just beyond the field on the edge of which we were lying and through which it was necessary to pass. The Thirty-second Indiana was regarded as the crack German regiment of our western army.)

General Sherman continues:

“Then arose the severest musketry fire I ever heard, and lasted some twenty minutes when this splendid regiment had to fall back.”

(The Thirty-second, let me explain further, had passed around our left and formed in our front, in the open, in column of companies—“double column to the center,” as the formation is described by its commander in his report. The absurdity of this formation seemed to strike even the rank and file, for it drew a direct and enfilading fire from the extended line of the enemy in front that reached even the rear companies and gave rise to the claim on their part that they had been fired upon by the troops in their own rear. This claim was and is, of course, ridiculous. The regulars were at that moment engaged in replenishing their cartridge boxes in the rear of Kirke’s brigade which had been in reserve and had taken our position temporarily for this purpose. The claim was made as an excuse for a most unmilitary blunder in placing a column formation in the open in the face of a battle line, and, as it naturally resulted in a complete rout of the regiment, some excuse was sought as a salve for wounded pride).

General Sherman continues:

“This green point of timber is about five hundred yards east of Shiloh meeting house, and it was evident here was to be the struggle. The enemy could be seen also forming his lines to the south.... This was about 2 p.m. The enemy had one battery close by Shiloh and another near the Hamburg road, both pouring grape and canister upon any column of troops that advanced upon the green point of water oaks. Willich’s regiment had been repulsed, but a whole brigade of McCook’s division advanced beautifully, deployed, and entered this dreaded wood.... This I afterward found to be Rousseau’s brigade of McCook’s division.

“Rousseau’s brigade moved in splendid order steadily to the front sweeping everything before it; and at 4 p.m. we stood upon the ground of our original front line, and the enemy was in full retreat....

“I am ordered by General Grant to give personal credit where I think it is due, and censure where I think it merited. I concede that General McCook’s splendid division from Kentucky drove back the enemy along the Corinth road, which was the great center of the field of battle, where Beauregard commanded in person, supported[361] by Bragg’s, Polk’s and Breckinridge’s divisions.”

General Sherman lived many years in the belief that he had fully and truly stated the facts in this matter, but we now know from a veracious history to which I shall refer, “compiled from the official records upon the authority of the Shiloh Battlefield Commission,” that what Sherman supposed to be a concentration of the Confederate army under Beauregard, including many divisions under distinguished leaders, was only Colonel Looney, of the Shiloh Battlefield Commission, with his regiment “augmented by a few detachments” from others, “driving back the Union line to the Purdy road” and enabling the Confederate army to “leisurely” walk away unmolested without our even suspecting it!

At the time Sherman came to us, Willich, with his large regiment, was just going into the open field and our reserve brigade—Kirke’s—was taking our position while we retired to the road to get a supply of ammunition which had come forward meantime; so that Sherman saw the advance and repulse of Willich, and the re-forming, deploying and advance of Rousseau’s brigade that so favorably attracted his attention as to merit official praise.

Between three and four o’clock in the afternoon we had pushed the enemy, still fighting, back to the vicinity of Shiloh Church. This, as afterward appeared, was Beauregard’s headquarters which he vacated about two o’clock, from prudential motives, and, manifestly by an afterthought, sought to minimize the fact of his own defeat by making it appear that an order to withdraw his army had been given long before. As a matter of fact, we know now from the records that the only order given was an order to the extreme wings of his army to fall back to this very point as a concentration of his forces against the center of our army.

Rousseau’s brigade continued its slow but relentless advance until we reached and passed the church itself, when the forces immediately in our front in the vicinity of the road broke in disorder, leaving, however, a considerable body of the enemy on our right against whom the regular battalions right-wheeled and whom we pursued half way through the former camps of Sherman’s troops lying parallel with the Shiloh branch, completing the rout of all the enemy’s forces in sight. They fled in disorder across the branch, and we were ordered to rejoin the brigade. At the final rout of the enemy at 4 o’clock p.m., we were astraddle of the camps of McDowell’s brigade of Sherman’s division, and this is what General Sherman refers to when he says in his report:

“At 4 p.m. we stood upon the ground of our original first line and the enemy were in full retreat.”

In this final movement the troops of Sherman took no part, nor was the division of General Lew Wallace or that of McClernand in sight. And this is what General Sherman admits by his frank confession that:

“General McCook’s splendid division drove back the enemy along the Corinth road which was the great center of the field of battle.”

This crisis of the battle really lasted from about noon, when we faced the point of water oaks, until four o’clock, when the enemy were routed and fleeing in confusion across Shiloh branch. If there was any rallying force at all on the other side of this branch, it made no demonstration and certainly it was not a battle line of the enemy as represented on the map of the commission. The only rear-guard stand mentioned in the reports was at a point two miles further on and a final stand by Breckinridge’s division at Mickey’s still further toward Monterey.

A few of the Confederate authorities place their final “withdrawal” at two o’clock, and a few others at three, but the overwhelming consensus of testimony of the reports place the final and complete rout of the enemy beyond the Shiloh Church at and after four o’clock; and Sherman again in[362] his report particularizes 4 p.m. as the close of the engagement (p. 254).

After the fighting was over, General Sherman came over to us in his camps of the day before, and, speaking to Major Carpenter (of the Nineteenth), complimented most highly the work of the brigade and particularly of the regular battalions.

It was about this time also that General Thomas J. Woods arrived at the front, at the head of a brigade of his division, and, as Major Lowe reminds me, demanded in no “Sunday school language” to be allowed to go forward in pursuit of the enemy. But the darkness was approaching, and the impossibility of handling new troops in the dark in a wilderness of black jack was manifest, and the pursuit was given over for the night.

The map of the commission shows Wood’s entire division in line with us and taking part at 2 p.m. in the great and final crisis of the day, in which the musketry fire was, as described by General Force, “more severe than any that occurred on the field in either of the two days of the battle.” Wood’s division was not there. One brigade came upon the field just as the fighting was over, at about four o’clock, and the other did not leave the landing until dark. General Force’s statement, substantially to the same effect in his history of the battle (p. 177 in the Scribner’s Series) is:

“Wood’s division, arriving too late to take part in the battle, pushed to the front and engaged his skirmishers with the light troops covering the retreat.”

General Buell’s report states the fact as I give it from my recollection.

A TYPE OF TABLET SHOWING SHAPE ADOPTED FOR SECOND DAY’S BATTLE. THIS PARTICULAR ONE MARKS A POINT ON “HORNET’S NEST”

In the year 1901, I addressed a letter to the Shiloh Battlefield Commission, at the invitation of its chairman, stating the substance of the personal recollections herein given, with a view to the correction of some very serious errors in its official blue print maps. In this letter I referred to between thirty and forty official reports of field organizations engaged in the battle, all showing that the errors complained of existed; but from that day to this no notice whatever has been taken of the letter.

I had not then the slightest idea that the commission intended to constitute[363] itself the official historian of the Battle of Shiloh—for certainly the law of its appointment contemplates no such thing. But, during the year 1903, there appeared from the press of the Government Printing Office, Washington, an innocent looking work bearing on its title page the following:

“Shiloh National Park Commission. The Battle of Shiloh, and the Organizations Engaged. Compiled from the Official Records by Major D. W. Reed, Historian and Secretary, under the Authority of the Commission, 1902. Washington, Government Printing Office, 1903.”

There follows, on a subsequent page, a preface addressed by the Chairman of the Commission—

“To Shiloh Soldiers”—in which, referring to the intent of the statute establishing the Shiloh National Military Park to perpetuate the history of the battle on the ground where it was fought, he expresses the desire of the commission that “this history” (meaning this publication) “shall be complete, impartial, and correct,” etc. He then states, that, “to ensure this accuracy, all reports have been carefully studied and compared. The records at Washington have been thoroughly searched and many who participated in the battle have been interviewed.... It is, therefore, desired that the statements of the book be earnestly studied by every survivor of Shiloh and any errors or omissions be reported to the commission with a view to the publication of a revised edition of the report.”

This so-called official “history” of the battle contains in permanent form the same erroneous maps put forth as blue prints in 1901. The history proper devotes about sixteen pages to a description of the first day’s operations of the Army of the Tennessee, and one page to those of the second day covering the participation of the Army of the Ohio. Short as is the latter portion of the history, we learn that the weight of numbers really decided the issue before the fight began; and, while Beauregard made a show of resistance for a while, along about dinner time he sent Colonel Looney (of the Shiloh Battlefield Commission) with his regiment “augmented by detachments from other regiments,” who charged and “drove back the Union line,” and enabled Beauregard to safely cross Shiloh branch with his army and leisurely retire to Corinth thirty miles away! So skillfully was all this done, we are told, that the Confederate army “began to retreat at 2.30 p.m. without the least perception on the part of the enemy” (the Union forces) “that such a movement was going on”—and this is put forth as “history!”

When we look at the maps to which we are referred in connection with this account of the second day’s battle, the astonishing accuracy and completeness of this contribution to history begins to dawn upon us. There we find that the Union troops, after a late breakfast, came upon the field and did a little skirmishing with the enemy, who, as the odds were against them, could not be expected to stay in the game, and withdrew while the Union forces were at dinner, without letting us know anything about it. And we are told that this is real history, based upon an exhaustive search and comparison of all the records, compiled by a distinguished official body, assisted by a “historian,” and this is published by the Government of the United States!

Lest it be thought that I exaggerate, let me here quote the principal portion of this veracious history of the second day’s battle. Beginning with the statement that the battle of the second day was opened by Lew Wallace attacking Pond’s brigade, it continues:

“The 20,000 fresh troops in the Union army made the contest an unequal one, and though stubbornly contested for a time, at about two o’clock General Beauregard ordered the withdrawal of his army. To secure the withdrawal he placed Colonel Looney of the Thirty-eighth Tennessee, with his regiment, augmented by detachments from other regiments, at Shiloh Church, and directed him to charge[364] the Union center. In this charge Colonel Looney passed Sherman’s headquarters and pressed the Union line back to the Purdy road; at the same time General Beauregard sent batteries across the Shiloh branch and placed them in battery on the high ground beyond. With these arrangements Beauregard at four o’clock safely crossed Shiloh branch with his army and placed his rear guard under Breckinridge in line upon the ground occupied by his army on Saturday night. The Confederate army retired leisurely to Corinth, while the Union army returned to the camps that it had occupied before the battle.”

The final touch—“the Union army returned to the camps it had occupied before the battle”—shows how negligible a quality, in the mind of these able historians, was the contribution of Buell’s fresh troops who seem to have been spectators but nothing more.

By John Trotwood Moore

I was telling ole Wash the other night that I thought the President was a great man and that if he didn’t make any break from now on, as for instance about knocking out states’ rights and undue blowing about the devilish little Japs who are itching to scrap with us, he would rank among the great presidents.

The old man was thoughtful for awhile, looking into the fire.

“Wal, boss, he sho’ is got all the year-marks—a senserble, dermestic wife an’ no signs of a muther-in-law. Now, sah, befo’ eny man kin be great he must fus’ ax his wife an’ arter he gits her consent he mus’ ax his muther-in-law. Now, sah, no man kin be great, don’t keer how much ’bility he’s got, if his wife is in society an’ his muther-in-law is in de house. You can look all down de line, sah, an’ when you finds dat combinashun you’ll find a man whose growin’ gourd of greatness is liable to wilt eny day, like Job’s, at de fus’ good jolt it gits. Wid both of ’em in society an’ both in de’ house, why, Lord, boss, his gourd will nurver even sprout!

“Did I urver tell you ’bout my ’sperience in dat line an’ how nigh I cum to missin’ greatness, all on account of a few muther-in-laws? It wuz a close shave an’ if I hadn’t seed de way de ship wuz headed an’ steered out from dat combernashun, instead of bein’ de gent’man an’ floserpher whose ’pinions you so highly values,” he chuckled modestly, “you’d a had a ole nigger fit only fur de woodpile an’ de blackin’ bresh.

“Boss,” he laughed as he bit off a chew of Brazil Leaf Twist, bred in the hills of Maury, “did you kno’ the ole man am a Only? The only man dat ever lived dat had fo’ muther-in-laws at unct—driv’ a fo’-in-han’ of ’em, so to speak! Oh, I kno’ what you ’bout to say, sah,—but mine wuz legitermates, de actu’l product of de law an’ matremony.”

“Nonsense,” I said, “you couldn’t have been married to four women at once, as sly an old coon as you are. Though I did hear Marse Nick Akin say that he knew of his own knowledge that you once had three wives but gave two of them to the preacher if he would make you an elder in his church, which bargain was duly consummated. Oh, I knew you were driving a very long string of tandems, old man, but four abreast? Tell about it.”

He laughed so loud the pointer jumped up from his bed on the rug and barked.

“Did Marse Nick vi’late de conferdence[365] I composed in his veracity?” he laughed again. “Wal, I jis’ well tell it fur you’ll nurver guess how it wuz.

“Long in de fifties I spliced up wid a likely young widder dat wuz de sod-relic of Brer Simon Harris, a ’piscopal brudder up at Nashville. Befo’ dat she had been de relic of several gent’men of color. Fur a week or so I wuz so busy co’rtin’ her dat I wa’n’t very ’tickler jis’ whut her entitlements an’ habilerments wuz, nur jis’ whut mineral rights an’ easements went wid de property.

“I’ve allers noticed it’s dat a way in de co’rtin’ stage an’ hits a wise dispensashun of ole Marster to trap us all into matremony an’ make us blin’, like snakes in August; an’ eb’ry one of us, when he gits his seckin’ sight arter de entrapment, wakes up to fin’ dat in de deed to de state of matremony dar has been passed wid de free-hold a few hererditerments dat he didn’t cal’late went wid de lan’.

“Sum of us, of co’rse nurver gits dey seckin’ sight at all.

“But I ain’t talkin’ of dem. I’ve nurver writ a fool’s almernac yit!

“But I claims I am de only man dat urver got fo’ muther-in-laws, when I didn’t ’spec’ to git eny!

“Arter a breef but very pinted co’rtship, in which I done de usual close-settin’, low-layin’ an’ tall lyin’, I hitched up my team an’ driv’ up to Nashville an’ married Sally. Arter de circus I driv’ de team ’round to de door fur to carry her home an’ I went in fur to pack up her things. I got ’em all in one big box, fur Brer Simon hadn’t been very felicertus in passin’ round de hat, an’ when I tuck it out to de wag’n dar sot Sally an’ fo’ uther ladies all es cheerful an’ happy as fo’ ole tabby-cats in a hay loft.

“’Dese am my muthers, Wash,’ sez Sally sweetly, ’an’ of co’rse dey am all gwine to lib wid us.’”

“‘Look heah, gal,’ sez I sorter faintly, ‘I ain’t nurver heerd of enybody havin’ mor’n one muther.”

“‘Dese other three am jes’ as dear,’ seys she, p’intin’ to de three ole ladies, ‘dat’s Simon’s muther, dat’s mine, an’ dem two ober dar—’

“Boss, I nearly had a fit! Do you kno’ dat gal had de muthers of ebry one of her fus’ husbands dar an’ claimin’ dey wuz mighty nigh to her?

“Dar wa’n’t nothin’ to do but to git a divorcement an’ as I wa’n’t quite ready fur dat yit, I made de bes’ of it an’ driv’ off; but I knowed if dar wuz ever a day when I needed sum brains now wuz de time. An’ de three sod muthers,—dat wuz de entitlement I gib to de three muthers of Sally’s dead husbands,—dey wuz jes’ plain ole grannies, wid de usual tongue an’ de perviserty fer huntin’ up trouble dat wuz natu’lly predistined fur sumbody else.

“But Sally’s muther she wuz a fine lookin’ ’oman, jes a shade heftier an’ handsumer than Sally so I teched her mighty tenderly an’ gin her to onderstan’ dat I fully intended to fulfill to de letter de scrip’tul injunshuns of filial affecshuns. She wuz a hefty ’oman, boss, but she wuz es bossy es she wuz hansum, es I found out. De day she landed at home, sah, I seed she’d sot in to own de place an’ in two weeks, sah, sides ownin’ Sally an’ de sod-muthers, she owned de mules, de cow, de pigs an’ de farm, me an’ my ’ligious convicshuns an’ perlitical preferment.

“But es I wuz sayin’, boss, she wuz a han’sum ’oman!

“Now I’m allers willin’ to be bossed fur a while by a handsum ’oman, but when it comes to dat batch of ole sod-muthers dat looked like busted bags of dried apples, dat wuz a nurr thing. But I’ve noticed dar is allers a kin’ of communercashun ’mong women folks es to de bossin’ of a man. It jis’ travels by grapevine, or dis here wireless business in de air, to de end dat when one ’oman kin boss a man all of ’em think dey can do it.

“An’ dey think right, only in dis case de thinkin’ hadn’t all ben dun yit. So dey all jes’ put me down as dead easy.

“I let ’em hab free han’ till de honeymoon wuz over. I didn’ think I orter mix eny vinegar wid dat; but by dat time de whole tribe of ’em wuz[366] needin’ sum of de salt dat Lot’s wife got, an’ mebbe sum of de fire an’ brimstone dat wuz de ’casion of her saltin’. Wal, sah, dey sot in fur infairs an’ didn’t do nuthin’ but eat fur two weeks. I had to give ’em three infairs myself an’ then they gin to nose aroun’ an’ git my naburs to have infairs. Fur two weeks mo’ dar wa’n’t nuffin but infairs fur de bride, an’ groom, fur my naburs wuz polite, all wucked up by dese sod-muthers, till dey wuzn’t a chicken or shote left in five miles of my home, an’ if dar had been a hard winter an’ de white folks’ chickens had-roosted high, we would a had a hard time of it.

“Wal, I stood dat, ’caze dar wuz a honeymoon an’ good eatin’ gwine on wid it, but ’long ’bout de thud week when de sod-mammies gin to tell me how I orter roach my hair an’ run my farm I gin to lay my plans fur acshun.

“Dey wuz all ’piscopaliuns, boss, es I wuz sayin’, an’ dey bleeved tarible in Good Friday; an’ ev’ry Friday wuz Good Friday wid dem when it come to eatin’. When I seed my chickens all gwine an’ de pigs an’ sich, I got so disgusted wid dese Good Fridays dat I wanted to be a jay-bird fur a while so I cud git off to hell ebry Friday myse’f! Frum dat dey begin to rub it in to me ’bout baptism an’ so forth an’ dat didn’t tend to make me change in de resolushuns I had fixed up. I went on fixin’ my plans an’ layin’ low, meek as Moses outwardly but inwardly full of wrath.

“By dis time dey gin to ax in all de bredderin of de chu’ch to he’p ’em eat an’ settin’ up by moonlight wid ’em a holdin’ han’s an’ prayin’. Now, boss, de hefty one nurver mixed up in dese small things—she wuz layin’ fur bigger game. She seed de sod-muthers wuz managin’ it all right an’ as she knowed she owned dem an’ Sally an’ dey all owned me, why she let it res’ at dat.

“Sides dat, as I sed, she wuz a han’sum ’oman!

“I let it run on till de time whut dey call Ash We’nesday come, when dey all had a feast an’ special prayers fur de souls of all who had died frum de beginnin’ of de worl’ till den,—or sumpin’ nurr like it. I had already spent all my money an’ dey had ordered lumber fur a new house, ’sides orgernizin’ a society to build de nigger preacher in town a rookery. Dey called it a pay supper—an’ I did all de payin’! It wuz all to cum off de night of Ash We’nesday.

“Now dat Ash biziness sot me to thinkin’. Here wuz my home turned into a karnival of noise an’ carousin’ an’ drinkin’ an’ hoodoo’in’, an’ me payin’ fur it.

“‘Wal,’ sez I to myse’f, ‘I’ll jes’ turn dis thing into a Ash We’nesday sho’ nuff, so I goes out an’ cuts down a ash tree an’ makes me a good, lithe stick dat would knock a bull down, an’ den bounce back into yo’ han’s. Dat wuz fur de bredderin. Den I broke up a good ash-bar’l an’ made de paddles handy fur de sisterin, an’ I sot ’em in de corner behin’ de cup’ard.

“De night cum, but by dat time dey didn’t keer enuff fur me to ax me into de feast. I wuz jes’ a common ole Baptis’ nigger. I waited till dey wuz all dar, de sod-muthers in white apruns, candles burnin’ an’ dude niggers an’ niggeresses frum town and ev’ry whar, all s’posin’ to be payin’ fur a thing dat finally cum outen my pocket. I walked in an’ sot down by de fire, but befo’ I got sot good, one of dem dude niggers put a insultment on me.

“Dat suit me all right. I didn’t want to start de fight in my own house—dat wa’n’t good manners—but soon es dat nigger put de insultment on me, I wuz reddy.

“‘Frien’s, sez I, ‘I am a plain ole Baptis’ nigger, but es I onderstan’ it, dis am Ash We’nesday.’

“‘You bet it am, ole Moses,’ sez one of de dudes, ‘an’ it ain’t a good place fur Baptists to eat—dey am liabul to hab de collect!’

“I didn’t see de p’int, but dey did, an’ all laf’d.

“‘Yes,’ sez I, ‘he mout, but he is mor’n apt to hab stumic enuff left to read de burial sarvices over a few dudes,’ an’ I lit in. I’d locked de do’[367] but fergot de winder; but I hearn tell arterwards dat only two niggers got out of dar wid a soun’ head, an’ dey didn’t stop runnin’ till Easter mo’nin’!

“I lit on de sod-muthers early in de game wid de staves of de ash bar’l till dey wuz meet fur repentunce, an’ de nex’ mo’nin’ I sent ’em back to town whar I foun’ dey all had husban’s livin’ dat dey had quit fur a easier job. Wal, dey had to take ’em back.

“Now, boss, I wuz keerful not to hurt Sally an’ her mammy—dey wuz both han’sum women, es I wuz sayin’.

“I wuz now rid of de sod-muthers, but how to git rid of Sally’s mammy wuz de nex p’int. I’d figured dat out too, case es I said, she wuz a han’sum ’oman. De tacticks I used, boss, is whut’ll s’prize you.

“Bout de thud night when I had her alone for a while on de little porch an’ we wuz waitin’ fur Sally to git supper, fur she had gone to wuck in earnest arter she seed how handy I wuz wid de ash bar’l, sez I:

“‘A good meny men hab muther-in-laws dat am homely. I’m mighty proud of mine,’ sez I, ‘she is so han’sum.’

“‘Why, Washin’tun!’ she sez, ‘does you really think so?’

“I seed it tickled her, an’ arter a while I slipped over closer an’ sed:

“‘An’ I nurver seed a muther-in-law wid sech b’utiful eyes as you is got,’ an’ I took her han’.

“Dat wuz mor’n she cu’d stan’ on a col’ collar an’ you orter seed her light out—light out an’ he’p git supper, too!

“I let it res’ at dat. I’ve noticed dat too many fo’ks plants dey truck too fas’ in de spring. An’ at de same time I’ve nurver let a late frost keep me frum believin’ it’ll be summer by an’ by.

“De nex’ night I sot out on de po’ch ag’in arter a hard day’s wuck an’ I tuck my stan’ whar I wuz de night befo’ fur I knowed de ole doe allers crosses de creek at de same place. Sho ’nuff, by an’ by heah she cum tipperty-tip—tipperty-tip.

“An’ all she wanted wuz to ax me if I thought de weather wuz gwine ter change! I sot up close ag’in an’ sed:

“‘Sum times a man makes a great mistake by marryin’ in too big a hurry.’

“‘How’s dat?’ she sed, tickled to death an’ nestlin’ up to me.

“‘Why,’ sez I, ‘he marries de gal an’ den he fin’s out dat whut ’ud suit him bes’ wuz de muther-in-law—shoots at de doe an’ kills de fawn,’ sez I, slippin’ my arm aroun’ her wais’.

“Up she jumps ag’in an’ goes up mad lak an’ big es a balloon.

“‘Ain’t you ’shamed of yo’se’f?’ sez she. ‘I’m gwine right in an’ tell Sally.’

“I knowed she wouldn’t an’ I set back an’ chuckled. It wuz all wuckin’ to suit me an’ I seed dar would soon be a complete separashun of de chu’ch an’ de state.

“Now, boss, you’ll wonder des why I’d play es hefty an’ han’sum a ’oman es she is sich a trick, but I ’cided dat one wife in de house am enuff in dat place.

“De thud night I had it fixed. I knowed she’d gone off mad, but I knowed a ’oman, arter one huggin’, is like a dog burryin’ a bone—he’ll leave it fur awhile, but he’s sho to cum back to it ag’in! I jes’ waited an’ let her cum back, fixin’ my plans. I tole Sally to set down in one corner of de po’ch in de dark an’ keep quiet—dat I had a s’prize fer her to sho’ how her virtuous husban’ wuz bein’ inticed by de Philistine.

“Dat wuz enuff—she sot.

“I waited till dark fore I cum an’ den I stomped aroun’, washed my face an’ han’s, an’ lit my pipe. An’ heah she cum tipperty-tip an’ all she wanted to kno’ wuz, if de moon had riz!

“Boss, I let her do de talkin’, fur she wuz ripe fur it, an’ ’bout de time she tole me dat she lubbed me frum de fus’ an’ dat I orter married her stead of Sally, I heerd a scufflin’ in de co’ner,—Sally riz up, dar wuz much excitement an’ scatterment of hair an’ when it wuz over dar wuz nobody on dat place but me an’ Sally, an’ I owned her.”

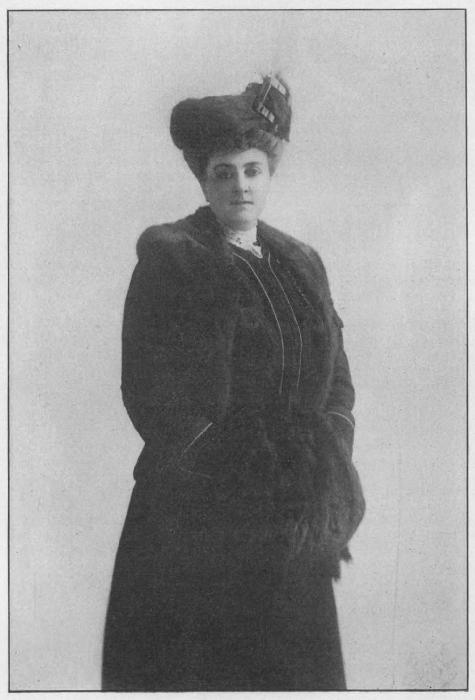

MRS. PAUL LANSING

Versailles, Kentucky

Buck, Washington

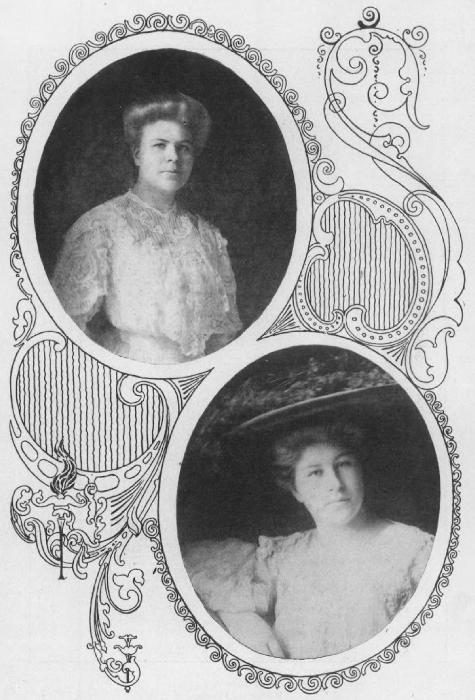

MISSES THEODORA AND MARGUERITE SHONTS

Twin daughters of Theodore P. Shonts, of Daphne, Alabama, Washington and Panama

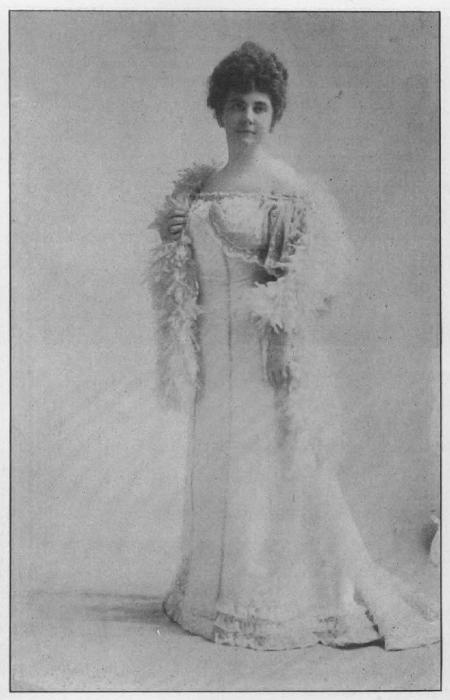

MRS. WILLIAM BAILEY LAMAR

Monticello, Florida

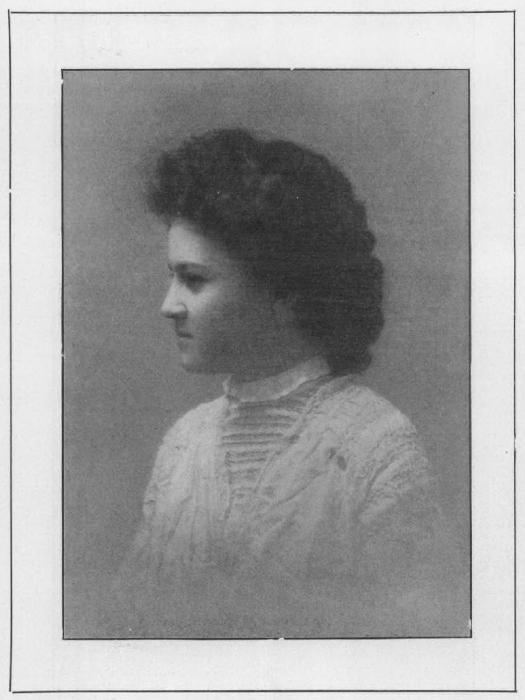

MISS OLIVE WIGGINS

Daughter of F. Lafayette Wiggins, Nashville

Turner, Nashville

MRS. SYDNEY JOHNSTON BOWIE

Anniston, Alabama

Buck, Washington

MARY WASHINGTON

Our forefathers were great fighters and excelled the world as makers of history, but unfortunately for us, they were not writers of it. When a duty was done or a great victory gained it seemed not to demand the attention from them that we of the present day think it deserved, but was set aside with perhaps a brief record. It had to make way for new duties demanded by the exigencies of the times.

While they carried the weight of the nation on their young shoulders, they have left us only “shreds and patches” from which to deduce anything like specific exactness of the manners and customs of those early days of our great country. It is, therefore, difficult to elaborate the conditions of the country and particularly the distinctive qualities which made up the social life of those who evolved and produced, to us, the best government in all the world.

The peculiar conditions of early times invest our greatest leaders with additional interest and make the fact of their greatness stand out all the more clearly. Schools were few and travel much restricted. Only about[374] thirty families had good libraries. To the women of that day has been ascribed the honor of training the great men of the nation. George Washington was only eleven years old when his father died. His mother daily taught him from a manual of maxims which he preserved and often consulted in after life. A French general, after a visit to Mary Washington, said, “No wonder America produces such great men when they have such mothers.”

Thomas Jefferson’s father died when he was fourteen. His mother was said to have been unusually refined and intellectual, evincing much literary taste in the art of letter-writing. This was the only field open to a woman with literary proclivities at that time. It was from her he inherited his intellect, and in the training of her boy all that was best and noblest in her was brought to bear upon the formation of his character. These two mothers of great men are not exceptions. History records the names of many noble women who have devoted their lives to their children, not only in Virginia, but elsewhere.

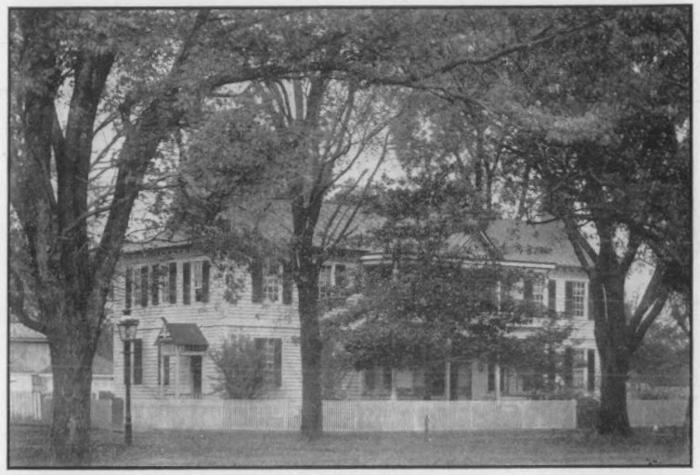

Virginians admired the king and the nobility but liked their own rights better. They loved the pride and pomp of aristocracy, but this was only a matter of taste. When it came to losing a freeman’s right they relegated their aristocratic tastes to the background. They loved the solemn ritual of the church. Governor Spottswood describes the Virginians of his time as “living in gentlemanly conformity with the Church of England,” and the famous old chapel, built in 1632, now familiarly called Old Bruton Church, is consecrated by many hallowed associations. Here worshiped the dauntless Spottswood, himself, as well as Lord de Botetourt, Lord Dunmore and many others in a pew elevated from the main floor and richly canopied. And here worshiped many men whose names are indissolubly bound up with the conception of this grand commonwealth. The churchyard is the place of sepulture of some of Virginia’s most distinguished men.

WILLIAM AND MARY COLLEGE