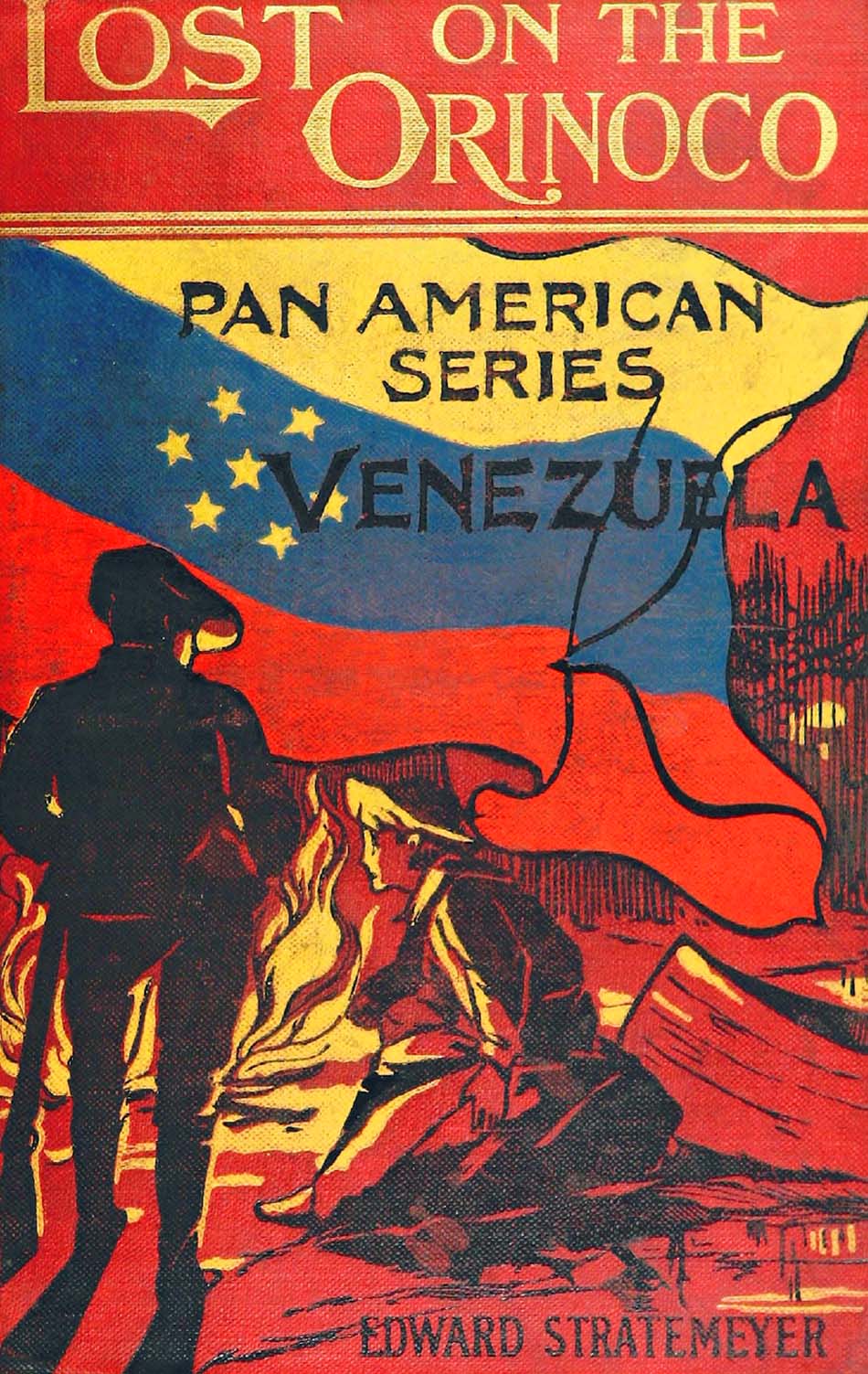

Title: Lost on the Orinoco; or, American boys in Venezuela

Author: Edward Stratemeyer

Illustrator: A. B. Shute

Release date: September 9, 2022 [eBook #68944]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Lee and Shepard, 1902

Credits: David Edwards, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

EDWARD STRATEMEYER’S BOOKS

Old Glory Series

Six Volumes. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

UNDER DEWEY AT MANILA.

A YOUNG VOLUNTEER IN CUBA.

FIGHTING IN CUBAN WATERS.

UNDER OTIS IN THE PHILIPPINES.

THE CAMPAIGN OF THE JUNGLE.

UNDER MacARTHUR IN LUZON.

Bound to Succeed Series

Three Volumes. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00.

RICHARD DARE’S VENTURE. OLIVER BRIGHT’S SEARCH.

TO ALASKA FOR GOLD.

Ship and Shore Series

Three Volumes. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00.

THE LAST CRUISE OF THE SPITFIRE. TRUE TO HIMSELF.

REUBEN STONE’S DISCOVERY.

War and Adventure Stories

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

ON TO PEKIN. BETWEEN BOER AND BRITON.

Colonial Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

WITH WASHINGTON IN THE WEST; Or, A Soldier Boy’s Battles

in the Wilderness.

MARCHING ON NIAGARA; Or, The Soldier Boy of the Old Frontier.

American Boys’ Biographical Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.25.

AMERICAN BOYS’ LIFE OF WILLIAM McKINLEY.

Another volume in preparation.

Pan-American Series

Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume $1.00, net.

LOST ON THE ORINOCO.

Over it went, carrying the boys with it.

Pan-American Series

OR

AMERICAN BOYS IN VENEZUELA

BY

EDWARD STRATEMEYER

Author of “With Washington in the West,” “American Boys’ Life of

William McKinley,” “On to Pekin,” “Between Boer and Briton,”

“Old Glory Series,” “Ship and Shore Series,”

“Bound to Succeed Series,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY A. B. SHUTE

BOSTON

LEE AND SHEPARD

1902

Published in March, 1902

Copyright, 1902, by Lee and Shepard

All rights reserved

Lost on the Orinoco

Norwood Press

Berwick & Smith

Norwood, Mass.

U. S. A.

“Lost on the Orinoco” is a complete tale in itself, but forms the first volume of the “Pan-American Series,” a line of books intended to embrace sight seeing and adventures in different portions of the three Americas, especially such portions as lie outside of the United States.

The writing of this series has been in the author’s mind for several years, for it seemed to him that here were many fields but little known and yet well worthy the attention of young people, and especially young men who in business matters may have to look beyond our own States for their opportunities. The great Pan-American Exhibition at Buffalo, N. Y. did much to open the eyes of many regarding Central and South America, but this exposition, large as it was, did not tell a hundredth part of the story. As one gentleman having a Venezuelan exhibit there expressed it: “To show up Venezuela properly, we should have to bring half of the Republic[iv] here.” And what is true of Venezuela is true of all the other countries.

In this story are related the sight seeing and adventures of five wide-awake American lads who visit Venezuela in company with their academy professor, a teacher who had in former years been a great traveler and hunter. The party sail from New York to La Guayra, visit Caracas, the capital, Macuto, the fashionable seaside resort, and other points of interest near by; then journey westward to the Gulf of Maracaibo and the immense lake of the same name; and at last find themselves on the waters of the mighty Orinoco, the second largest stream in South America, a body of water which maintains a width of three miles at a distance of over 600 miles from the ocean. Coffee and cocoa plantations are visited, as well as the wonderful gold and silver mines and the great llanos, or prairies, and the boys find time hanging anything but heavy on their hands. Occasionally they get into a difficulty of more or less importance, but in the end all goes well.

In the preparation of the historical portions of this book the very latest American, British and Spanish authorities have been consulted. Concerning the coffee, mining and other industries most of the information[v] has come from those directly interested in these branches. This being so, it is hoped that the work will be found accurate and reliable as well as interesting.

Once more thanking the thousands who have read my previous books for the interest they have shown, I place this volume in their hands trusting it will fulfil their every expectation.

Edward Stratemeyer.

April 1, 1902.

[vi]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Boys Talk It Over | 1 |

| II. | Preparing for the Start | 11 |

| III. | On Board the Steamer | 21 |

| IV. | Venezuela, Past and Present | 33 |

| V. | Hockley Makes a Bosom Friend | 42 |

| VI. | A Plan that Failed | 54 |

| VII. | From Curaçao to La Guayra | 63 |

| VIII. | On a Cliff and Under | 73 |

| IX. | Hockley Shows His True Colors | 81 |

| X. | On Mule Back into Caracas | 90 |

| XI. | The Professor Meets an Old Friend | 100 |

| XII. | Markel Again to the Front | 109 |

| XIII. | A Plantation Home in Venezuela | 119 |

| XIV. | A Loss of Honor and Money | 131 |

| XV. | Something About Coffee Growing | 143 |

| XVI. | Darry’s Wild Ride | 151 |

| XVII. | A Talk about Beasts and Snakes | 159 |

| XVIII. | A Bitter Discovery | 168 |

| XIX. | Bathing at Macuto | 177 |

| XX. | A Short Voyage Westward | 186 |

| XXI. | The Squall on Lake Maracaibo | 196 |

| XXII. | Port of the Hair | 205 |

| XXIII. | A Stop at Trinidad | 214[viii] |

| XXIV. | Up the River to Bolivar | 224 |

| XXV. | Something About Cocoa and Chocolate | 234 |

| XXVI. | Camping on the Upper Orinoco | 242 |

| XXVII. | Bringing Down an Ocelot | 251 |

| XXVIII. | Monkeys and a Canoe | 261 |

| XXIX. | Lost on the Orinoco | 270 |

| XXX. | In the Depths of the Jungle | 279 |

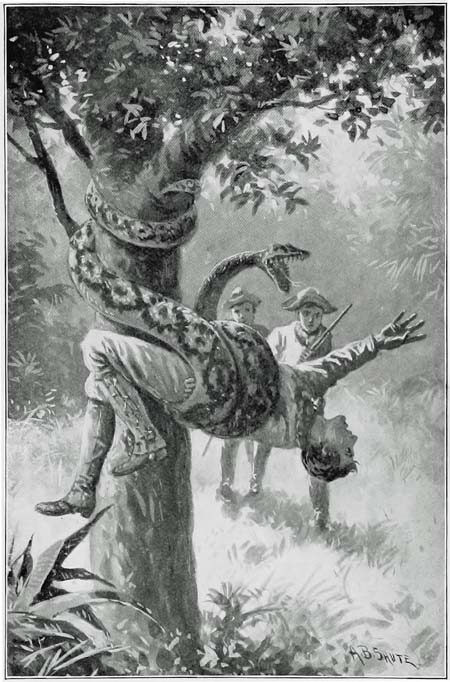

| XXXI. | Hockley and the Boa-Constrictor | 287 |

| XXXII. | A Peep at Gold and Silver Mines | 296 |

| XXXIII. | Together Again—Conclusion | 304 |

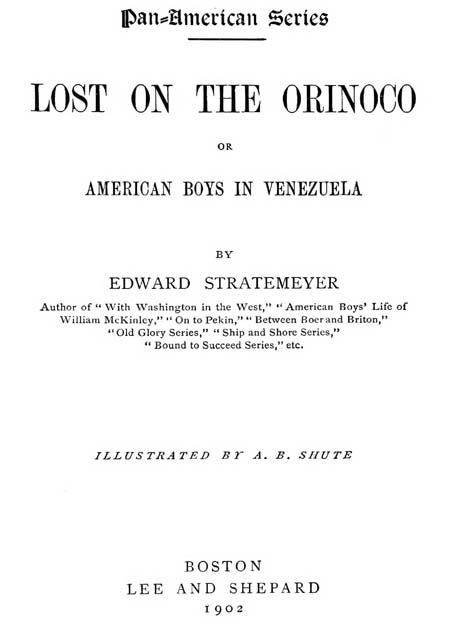

| “Over it went, carrying the boys with it” (p. 297) | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

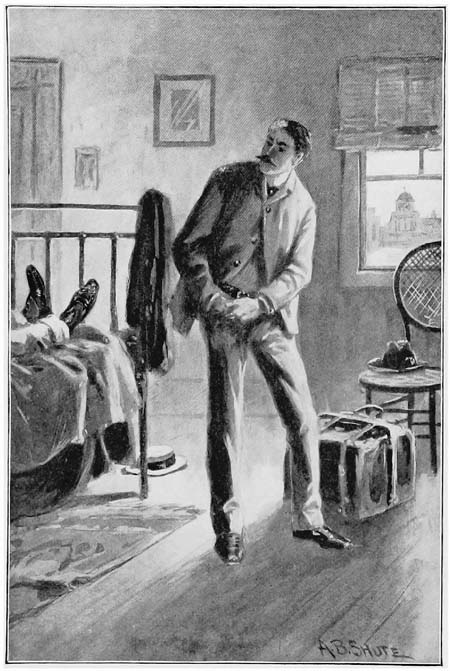

| “Stay where you are!” | 47 |

| A big mass of dirt came down | 80 |

| “I’ve got it,” he muttered | 142 |

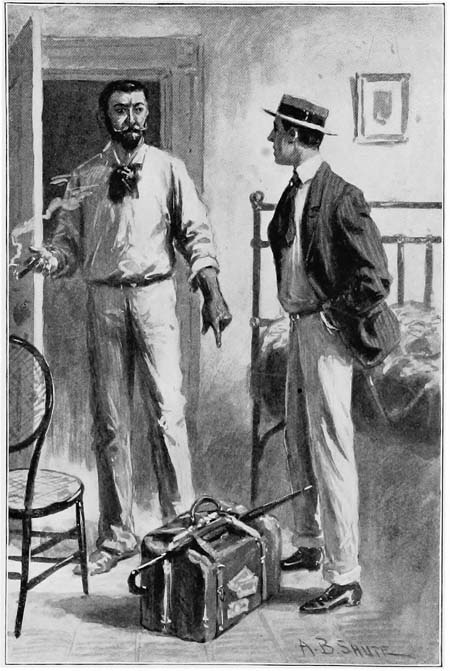

| “You have some baggage, that bag. I shall hold it.” | 173 |

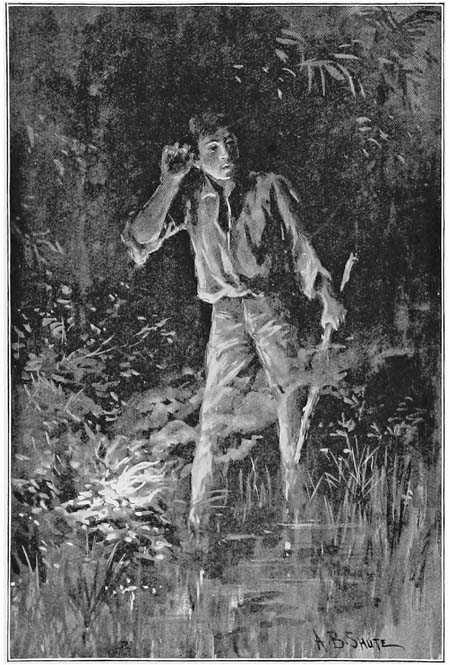

| “I heard something, what was it?” | 203 |

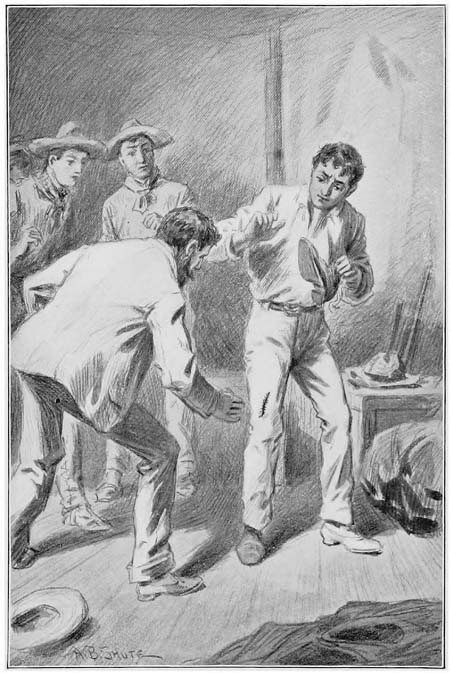

| “Take it off, do!” | 249 |

| “Help! Save me!” screamed the unfortunate youth | 291 |

LOST ON THE ORINOCO

“Hurrah, Mark, it’s settled at last.”

“What is settled, Frank?”

“We are to go to Venezuela and other places in South America. My father just got the word from Professor Strong. I brought the letter along for you to read.”

“That’s certainly immense news,” remarked Mark Robertson, as he took the letter which Frank Newton held out to him. “Does he say how soon he will be able to start?”

“Just as soon as he can settle up affairs at Lakeview Academy. I suppose he’s got quite something to do there yet. But we can hurry him along, can’t we?”

“I don’t think you’ll hurry the professor much,”[2] answered Mark, as he began to read the communication which had been passed to him. “He’s one of the kind that is slow but sure—not but that he can move quick enough, when you least expect it.”

“As for instance on the night we tried to hide all the schoolbooks in the old boathouse,” responded Frank, with a twinkle in his eye. “He caught us neatly, didn’t he?”

“That’s what. Hullo! So Beans and Darry are going, too. I like that first rate. Beans is all right, even if he is from Boston, and Darry will furnish fun enough for a minstrel show.”

“To be sure. I wouldn’t want to go if they weren’t along, and you. But do you see what the professor says on the last page? He wants to take Jake the Glum along too.”

At this the face of Mark Robinson fell somewhat. “I wish he had left Glummy out,” he said. “He knows the fellow is sour to the last degree and a bully in the bargain.”

“I guess the professor wants to reform him, Mark.”

“He’ll have up-hill work doing it. Glummy has been at the academy two years and I know him pretty thoroughly.”

[3]“Well, he’ll be the richest boy in the crowd. Perhaps that had something to do with taking him along.”

“No, the professor doesn’t think so much of money as that. Each person in the crowd will have to pay his share of the expenses and his share of the professor’s salary, and that’s all, outside of the incidentals.”

“I wonder if the incidentals won’t be rather high.”

“I fancy we can make them as high as we please—buying souvenirs and things like that. You can be sure Glummy will try his best to cut a wide swath if he gets the chance.”

“Perhaps the professor will hold him in. But it’s great news, isn’t it?” And in his enthusiasm Frank began to dance an impromptu jig on the library floor.

Frank Newton was a New York city youth, sixteen years of age, tall, well-built and rather good looking. He was the only son of a Wall Street banker, and if his parent was not a millionaire he was exceedingly well to do. The lad resided in the fashionable part of Madison Avenue when at home, which was not often, for his family were fond of[4] going abroad, and either took the boy with them or sent him to boarding school.

Directly opposite the home of the Newtons lived the Robertson family, consisting of Mr. and Mrs. Robertson, Mark, and several smaller children. Mr. Robertson was a dry goods importer who owned an interest in several mills in England and Scotland, and he made trips across the Atlantic semi-yearly.

Although Mark Robertson was a year older than Frank Newton, the two lads were warm friends and had gone to school together for years. Their earlier education had been had in the city, but when Frank was eleven and Mark twelve both had been packed off to Lakeview Academy, a small but well conducted school nestling among the hills of New Hampshire.

Five years of life at the academy had made the place seem like a second home to the boys. The master, Professor Amos Strong, was a thorough gentleman and scholar, and under his guidance the boys progressed rapidly in all their studies. The professor had in his day been both a traveler and hunter, and the stories he was wont to relate during off hours were fascinating to the last degree.

As might be expected, the boys, while at school,[5] made many friends and also an enemy or two, although as regards the latter, the enmity was never very deep, for Professor Strong would not tolerate anything underhanded or sneakish.

Next to Mark, Frank’s dearest chum at the academy was Dartworth Crane, a slightly built boy of fifteen, who was as full of fun as a boy can well be. Dartworth, or “Darry” as he was always called for short, was the son of a rich Chicago cattle dealer, and the boy’s earlier days had been spent on a ranch in Montana. He loved to race on horseback and hunt and fish, and the master sometimes had all he could do to hold the sunny but impetuous lad within proper bounds.

As Frank had another chum, so did Mark, in the person of Samuel Winthrop, the son of a well-to-do widow who resided in the Back Bay district of Boston. Samuel was a tall, studious looking individual, with a high forehead and a thick mass of curly black hair. Because he came from Boston, he had been nick-named “Beans,” and although he did not relish the sobriquet it was likely to stick to him for years to come.

Among the lads to join those at the academy two years before had been Jacob Hockley, a thin, lank[6] youth of Mark’s age, with a white freckled face and hair strongly inclined to be red. Hockley was the only son and heir of a millionaire lumber dealer of Pennsylvania. His manner was peculiar, at times exceedingly “bossy” as the others declared, and then again morose and sour, the latter mood having won for him the nickname of “Glummy” or “Jake the Glum.” Hockley was given to spending his money, of which he had more than was good for him, freely, but even this had failed to make him any substantial friends.

The enmity between Hockley on one side, and Frank and Mark on the other, had arisen over the captaincy of the academy baseball team the summer previous. Jake wished to be the captain of the team, and had done his best to persuade or buy the boys over to vote for him. But Frank had advocated Mark for the captaincy, and Mark had won, much to the lank youth’s discomfiture.

“You’ll never win a game with Mark Robertson as captain and with Frank Newton on first-base,” had been Jake’s sour comment, but he was sadly mistaken. That summer the team played nine games with the teams from rival schools, and won seven of the contests. The winning made Jake Hockley[7] more down on Mark and Frank than ever, but as the others were popular he had often to conceal his real feelings.

On a windy night in June the cry of “fire!” had aroused every inmate of Lakeview Academy from his bed, and had caused all to leave the rambling building in a hurry. The conflagration had started in the laundry, and from this room quickly communicated to the kitchen, dining hall, and then the remainder of the stone and wood structure. In such a high wind, the fire department from the village, two miles away, could do little or nothing, and the efforts of the students, headed by the several teachers, were likewise of no avail. Inside of three hours everything was swept away and only a cellar full of blackened debris marked the spot where the picturesque academy had once stood.

Under such circumstances many a man would have been too stunned to act immediately, but ere the stones of the building were cold, Professor Strong was laying his plans with the insurance companies for the erection of a new and better structure. The students were cared for at some neighboring houses and then refitted with clothing and sent home.

During the fall there had been much talk of a[8] personally conducted tour to South America during the coming year, the tour to be under the guidance of Professor Strong, who had been South a number of times before. Letters had been sent to the parents of various students, but nothing definite had been done up to the time the fire occurred.

Mark and Frank had planned for the trip South, and could not bear to think of giving it up, and as soon as Professor Strong was in a position to give them his attention, Frank had gotten his father to write concerning it. Several letters passed, and at last Professor Strong decided to leave the building and the management of the new academy to his brother, who had just left the faculty of Harvard, and go with the boys.

While the trip was being talked of at the academy, previous to the fire, Jake Hockley had announced his determination to go, but since the boys had separated, nothing more had been heard from the lank youth, and Mark and Frank were hoping he had given the plan up. The announcement therefore, that he would make one of the party, put a damper on their enthusiasm.

“He’ll get us into some kind of trouble before we[9] get back, you see if he doesn’t,” was Frank’s comment.

“I’ll make him keep his distance,” was Mark’s reply. “If he attempts to go too far I’ll show him that I won’t stand any nonsense.”

The party of six were to leave for Venezuela by way of New York city, and a few days after the conversation just recorded Sam Winthrop came down on the train from Boston, to remain with Mark until the arrival of the professor.

“Beans, by all that’s delightful!” cried Mark, as he wrung his friend’s hand. “So glad you came a few days ahead.”

“I wanted a chance to look around New York,” answered Sam Winthrop. “I’ve never had a chance before, you know.”

“You shall look around, all you please, and Frank and I will go with you.”

“Is Darry here yet?”

“No, but Frank expects him to-morrow. Then we can all go around until Professor Strong arrives. But say, what do you think about Glummy going?” and Mark looked anxious.

“Can’t say that I am overjoyed, Mark.”

[10]“I wish it was anybody but Hockley—and Frank wishes the same.”

“Well, all arrangements have been made, so we’ll have to make the best of it. But I heard one thing that doesn’t please me,” went on Sam. “I got a letter from Dick Mason, and in it he said Glummy was talking of the trip to some of his chums, and said he was going just to show Frank and you a thing or two.”

“Did he? I wonder what he meant?”

“He didn’t mean anything very good, you can be sure of that, Mark.”

“You are right. We’ll certainly have to keep our eyes open and watch him,” concluded Mark, seriously.

On the following morning Darry Crane came in, on the Limited Express direct from Chicago. He sent a telegram ahead, to Frank, who went up to the Grand Central depot to meet his chum.

“Had a fine trip,” said Darry, “but, honest, I couldn’t get here fast enough, I’ve been that anxious to see you. Heard from Beans yet? I’ll wager he comes down with his grip loaded with beans, on account of the long trip, you know. What, didn’t bring any beans? Must be a mistake about that.”

“I guess he was afraid you’d forget the pork,” answered Frank, with a laugh. “But how have you been since you left school?”

“First-class. Went West, you know, with my father and nearly rode a pony to death on the Lone Star ranch. Oh, it was glorious to get over the ground. Beats a stuffy old city all to bits. Hold on, I’ve got to look after my trunk. Wouldn’t want[12] to lose that, for it’s got the whole outfit for the trip in it.”

“Our man will have the trunk brought to our house,” answered Frank. “You come with me, and I’ll take you down to Mark’s, where you’ll find Beans. By the way, heard anything of Glummy?”

“Did I? Well, I just guess, Frank. What do you think? He actually paid me a visit—not very long, of course, but still he came to see me. Said he was passing through Chicago on a trip to St. Louis, and felt that he had to hunt up an old chum. I almost fainted when he said it. But he acted quite decent, I must admit, not a bit airish or sour either.”

“Did he say anything about this trip to South America?”

“Not much, excepting that he would like to go if it went through. I didn’t say much either, for I was thinking you and Mark wouldn’t like to have him along. You don’t, do you?”

“Not much, although I guess we can stand it if he lets us alone. We needn’t have much to do with him.”

Taking Darry’s valise from him, Frank led the way to the street and hailed a passing auto-cab, and both were speedily taken to the home on Madison[13] Avenue. A few minutes later they hurried across the way and joined Mark and Sam.

In anticipation of the good times ahead, all four of the lads were in a happy frame of mind, and the remainder of the day was spent by the New Yorkers in showing the visitors around Central Park and other points of interest. In the afternoon the four went downtown and crossed the Brooklyn Bridge. Then they came back to the Battery and took the little craft which plies hourly between that point and Bedloe’s Island, where is located the Statue of Liberty, standing as a gigantic sentinel to New York Bay.

“How big it looks when one is close to it,” remarked Sam, when they disembarked close to the base of the statue. “I thought climbing to the top would be easy, but I fancy it’s going to be as tedious as climbing to the top of Bunker Hill monument.”

And so it proved, as they went up the dark and narrow circular steps leading to the crown of the statue. They wished to go up into the torch, but the way was blocked owing to repairs.

Suddenly Mark, on looking around him, uttered an exclamation of surprise. “Glummy Hockley! How did you get here?”

[14]His words caused the others to forget their sight seeing for the moment, and they faced about, to find themselves confronted by the freckled-faced youth, who had been gazing in the opposite direction.

“I’ll thank you not to call me ‘Glummy,’” said Hockley, coolly, although he too was taken by surprise. Then he turned to Darry. “How do you do, Darry? When did you arrive?”

Mark bit his lip and looked at Frank, who gave him a knowing look in return. Clearly it had been an ill beginning to the conversation. Somehow Mark felt as if he had not done just right.

“Excuse me, Glum—I mean Hockley, I’ll try to remember your proper name after this,” he stammered.

“I don’t mind those things at school, but you must remember we are not at school now,” went on Hockley, with something of an air of importance. Then he smiled faintly at Sam. “How are you, Beans?”

“Excuse me, but we are not at school now, and my name’s not ‘Beans,’” was the dry response.

There was a second of silence, and then Darry burst into a roar of laughter, and Frank and Mark were compelled to follow, the whole thing seemed[15] so comical. Hockley grew red, but when Sam joined in the merriment he felt compelled to smile himself, although he looked more sour than ever directly afterward.

“All right, Sam, I’ll try to remember,” he said with an effort, and held out his hand.

The two shook hands and then the lank youth shook hands with Darry. After this there was nothing to do but for Frank and Mark to take Hockley’s hand also, and this they did, although stiffly.

But the ice was broken and soon all were talking as a crowd of boys usually do. Hockley had brought a field glass with him and insisted on all using it.

“Bought it down in Maiden Lane this morning,” he remarked. “Got the address of a first-class firm from a friend who knows all about such things. It cost me sixty-five dollars, but I reckon it’s worth it. Ain’t many better glasses around. I expect it will be just the thing in Venezuela.”

“No doubt,” said Darry, but felt somewhat disgusted over Hockley’s air of importance. Nevertheless, the glass was a fine one, and everybody enjoyed looking through it. Ships coming up the Lower Bay could be seen at a long distance, and[16] they could also see over Brooklyn and Long Island, and over Jersey City and Newark to the Orange Mountains.

“What are you fellows going to do to-night?” questioned Hockley, when they were going down the stairs again.

“We thought something of going to Manhattan Beach to see the fireworks——” began Frank, and broke off short.

“I was thinking of going to Coney Island,” went on the lank youth. “Supposing we all go there? I’ll foot the bill.”

“I shouldn’t care to go to Coney Island, and I don’t think Darry and Sam will care either,” said Mark.

“Let us all go to Manhattan,” broke in Sam. “I’ve often heard of the fireworks.” He had not the heart to give Hockley too much of a cold shoulder.

So it was arranged, on the way back to the Battery, and then there was nothing to do but ask the lank youth to dine with them.

“We are bound to have Glummy on us, sooner or later,” whispered Mark to Frank, while they were eating. “Perhaps it’s just as well to make the best[17] of it. It will be time enough to turn on him when he does something which is openly offensive.”

When it came time to settle the bill, the lank youth wished to pay for everybody, but the others would not allow this.

“Let everybody pay for himself,” said Darry. “Then there won’t be any trouble.”

“I can pay as well as not,” said Hockley, sourly.

“So can any of us,” returned Mark, dryly; and there the subject dropped.

The trip to Manhattan Beach and the fireworks were very enjoyable, and before the evening came to an end everybody was in a much better humor, although both Mark and Frank felt that they would have enjoyed the trip more had Hockley not been present.

Hockley was stopping at the Astor House, and left them near the entrance to the Brooklyn Bridge. He had wanted them to have a late supper with him, and had even mentioned wine, but all had declined, stating they were tired and wished to go to bed.

“He must be getting to be a regular high-flyer if he uses much wine,” remarked Frank when the four were on their way uptown. “What a fool he is with his money. He thinks that covers everything.”

[18]“He’ll be foolish to take to drink,” returned Darry. “It has ruined many a rich young fellow, and he ought to know it.”

“I think Hockley would be all right if it wasn’t for the high opinion he has of himself,” came from Sam. “But his patronizing way of talking is what irritates. He considers nobody as important as himself. In one way I think he’d be better off if he was poor.”

“The family haven’t been rich very long—only eight or ten years, so I’ve heard,” said Mark. “Poor Hockley isn’t used to it yet. It will be a lesson to him to learn that there are lots of other rich folks in this world who aren’t making any fuss and feathers about it.”

In the morning came a message from Professor Strong, stating that he had arrived, and was stopping at the Hotel Manhattan. He added that he would see Mr. Robertson and Mr. Newton that morning, and would be at the service of the boys directly after lunch.

“Now we won’t lose much more time,” cried Frank. “I declare I wish we were to sail for Venezuela to-day.”

“I fancy the professor has a good many arrangements[19] to make,” said Sam. “It’s quite a trip we are contemplating, remember.”

“Pooh! it’s not such a trip to Caracas,” returned Darry. “My father was down there once—looking at a coffee plantation.”

“A trip to Caracas wouldn’t be so much, Darry,” said Mark. “But you must remember that we are going further,—to the great lake of Maracaibo, and then around to the mouth of the Orinoco, and hundreds of miles up that immense stream. They tell me that the upper end of the Orinoco is as yet practically unexplored.”

“Hurrah! we’ll become the Young Explorers!” cried Darry, enthusiastically. “Say, I wonder if the professor will want us to go armed?”

“I don’t think so,” said Frank. “He’ll go armed, and as he is a crack shot I guess that will do for the lot of us.”

“Glummy showed me a pearl-handled pistol he had just bought,” put in Sam. “He said it cost him sixteen dollars.”

“He’d be sure to mention the price,” said Frank, with a sickly grin. “I’d like to see him face some wild beast—I’ll wager he’d drop his pistol and run for his life.”

[20]“Maybe somebody else would run, too,” came from Mark. “I don’t believe it’s much fun to stand up in front of a big wild animal.”

“Are there any such in Venezuela?”

“I don’t know—we’ll have to ask the professor.”

When the boys presented themselves at Professor Strong’s room at the Hotel Manhattan they found that worthy man looking over a number of purchases he had made while on his trip downtown.

“Glad to see you, boys,” he said, as he shook one and another by the hand. “I trust you are all feeling well.”

“Haven’t been sick a minute this summer,” answered Darry, and the others said about the same.

“I see you have your firearms with you,” remarked Mark, as he gazed at a rifle and a double-barreled shotgun standing in a corner. “We were wondering if we were to go armed.”

“I shouldn’t feel at home without my guns,” returned the professor with a smile. “You see that comes from being a confirmed old hunter. I don’t anticipate any use for them except when I go hunting. As for your going armed, I have already arranged with your parents about that. I shall take[22] a shotgun for each, also a pistol, for use when we are in the wilds of the upper Orinoco.”

“Will you lead us on a regular hunt?” asked Darry, eagerly.

“I will if you’ll promise to behave and not get into unnecessary difficulties.”

“We’ll promise,” came from all.

“I have been making a number of purchases,” continued Professor Strong. “But I must make a number more, and if you wish you can go along and help me make the selections.”

“Is Glummy—I mean is Jake Hockley coming up here?” questioned Mark.

“I expected him to come with you. Isn’t he stopping with one of you?”

“No, he’s stopping at the Astor House,” came from Frank.

There was an awkward pause, which was very suggestive, and the professor noted it. With his gun in hand he faced the four.

“I’m afraid you do not care much to have Master Hockley along,” he said, slowly.

“Oh, I reckon we can get along,” answered Darry, after the others had failed to speak.

“It is unfortunate that you are not all the best of[23] friends. But Hockley asked me about the trip a long while ago and when it came to the point I could not see how I could refuse him. Besides that, I was thinking that perhaps the trip would do him good. I trust you will treat him fairly.”

“Of course we’ll do that,” said Mark, slowly.

“I guess there won’t be any trouble,” said Frank, but deep in his heart he feared otherwise.

“Hockley has not had the benefits of much traveling,” continued the professor. “And traveling broadens the mind. The trip will do us all good.”

They were soon on their way to Fourteenth Street, and then Broadway, and at several stores the professor purchased the articles he had put down on his list. The boys all helped to carry these back to the hotel. On arriving they found Jake Hockley sitting in the reception room awaiting them.

The face of the lank youth fell when he saw that they had been out on a tour without him. “I’d been up earlier if you had sent me word,” he said to the professor. “I suppose I’ve got to get a lot of things myself, haven’t I?”

“You have your clothing, haven’t you?—I mean the list I sent to you?”

“Yes, sir.”

[24]“Then you are all right, for I have the other things.”

From the professor the boys learned that the steamer for La Guayra, the nearest seaport to Caracas, the capital of Venezuela, would sail three days later.

“There is a sailing every ten days,” said Professor Strong. “The steamers are not as large as those which cross the Atlantic but they are almost as comfortable, and I have seen to it that we shall have the best of the staterooms. The trip will take just a week, unless we encounter a severe storm which drives us back.”

“I don’t want to meet a storm,” said Hockley.

“Afraid of getting seasick,” came from Frank.

“Not exactly,” snapped the lank youth. “Perhaps you’ll get seasick yourself.”

“Does this steamer belong to the only line running to Venezuela?” asked Sam.

“This is the only regular passenger line. There are other lines, carrying all sorts of freight, which run at irregular intervals, and then there are sailing vessels which often stop there in going up or down the coast.”

The three days to follow passed swiftly, for at the[25] last moment the professor and the boys found plenty of things to do. On the day when the steamer was to sail, Sam’s mother came down from Boston to see her son off, and the parents of Mark and Frank were also on hand, so that there was quite a family gathering. The baggage was already aboard, a trunk and a traveling case for each, as well as a leather bag for the guns and ammunition.

At last came the familiar cry, “All ashore that’s going!” and the last farewells were said. A few minutes later the gang-plank was withdrawn and the lines unloosened. As the big steamer began to move, something like a lump arose in Frank’s throat.

“We’re off!” he whispered to Mark. “Guess it’s going to be a long time before we get back.”

Mark did not answer, for he was busy waving his handkerchief to his folks. Frank turned to Sam and saw that the tears were standing in the latter’s eyes, for Sam had caught sight of his mother in the act of wiping her eyes. Even Darry and Hockley were unusually sober.

In quarter of an hour, however, the strain was over, and then the boys gave themselves up to the contemplation of the scene before them. Swiftly[26] the steamer was plying her way between the ferry-boats and craft that crowded the stream. Soon the Battery was passed and the Statue of Liberty, and the tall buildings of the great metropolis began to fade away in the blue haze of the distance. The course was through the Narrows to the Lower Bay and then straight past Sandy Hook Light into the broad and sparkling Atlantic.

“Take a good look at the light and the highlands below,” said the professor, as he sat beside the boys at the rail. “That’s the last bit of United States territory you’ll see for a long while to come—unless you catch sight of Porto Rico, which is doubtful.”

“Won’t we stand in to shore when we round Cape Hatteras?” asked Hockley.

“We shall not have to round Cape Hatteras, Hockley. Instead of hugging the eastern shore of the United States the steamer will sail almost due South for the Mona Passage on the west of Porto Rico. This will bring us into the Caribbean Sea, and then we shall sail somewhat westward for a brief stop at Curaçao, a Dutch island north of the coast of Venezuela. It is not a large place, but one of considerable importance. The submarine cable from Cuba to Venezuela has a station there.”

[27]“I’m going to study the map of Venezuela,” said Mark. “I know something about it already, but not nearly as much as I’d like to.”

“To-morrow I’ll show you a large map of the country, which I have brought along,” answered Professor Strong. “And I’ll give you a little talk on the history of the people. But to-day you had better spend your time in making yourselves at home on the ship.”

“I’m going to look at the engine room,” said Frank, who was interested in machinery, and down he went, accompanied by Darry. It was a beautiful sight, to see the triple expansion engines working so swiftly and yet so noiselessly, but it was frightfully hot below decks, and they did not remain as long as they had anticipated.

They were now out of sight of land, and the long swells of the Atlantic caused the steamer to roll not a little. They found Sam huddled in a corner of the deck, looking as pale as a sheet.

“Hullo, what’s up?” queried Frank, although he knew perfectly well.

“Nothing’s up,” was the reply, given with an effort. “But I guess there will be something up soon,” and then Sam rushed off to his stateroom,[28] and that was the last seen of him for that day.

Mark was also slightly seasick, and thought best to lie down. Hockley was strolling the deck in deep contempt of those who had been taken ill.

“I can’t see why anybody should get sick,” he sneered. “I’m sure there’s nothing to get sick about.”

“Don’t crow, Glum—I mean Jake,” said Frank. “Your turn may come next.”

“Me? I won’t get sick.”

“Don’t be too sure.”

“I’ll bet you five dollars I don’t get sick,” insisted the lank youth.

“We’re not betting to-day,” put in Darry. “I hope you don’t get sick, but—I wouldn’t be too sure about it.” And he and Frank walked away.

“What an awful blower he is,” said Frank, when they were out of hearing. “As if a person could help being sick if the beastly thing got around to him. I must confess I don’t feel very well myself.”

“Nor I,” answered Darry, more soberly than ever.

Dinner was served in the dining saloon at six o’clock, as elaborate a repast as at any leading hotel.[29] But though the first-class passengers numbered forty only a dozen came to the table. Of the boys only Frank and Hockley were present, and it must be confessed that Frank’s appetite was very poor. Hockley appeared to be in the best of spirits and ate heartily.

“This is usually the case,” said the professor, after having seen to it that the others were as comfortable as circumstances permitted. “But it won’t last, and that is a comfort. Hockley, if I were you, I would not eat too heartily.”

“Oh, it won’t hurt me,” was the off-hand answer. “The salt air just suits me. I never felt better in my life.”

“I am glad to hear it, and trust it keeps on doing you good.”

Frank and Mark had a stateroom together and so had Sam and Darry. Hockley had stipulated that he have a stateroom to himself, and this had been provided. The professor occupied a room with a Dutch merchant bound for Curaçao, a jolly, good-natured gentleman, who was soon on good terms with all of the party.

There was but little sleep for any of the boys during the earlier part of the night, for a stiff breeze was blowing and the steamer rolled worse than ever.[30] But by three o’clock in the morning the wind went down and the sea seemed to grow easier, and all fell into a light slumber, from which Mark was the first to awaken.

“I feel better, although pretty weak,” he said, with an attempt at a smile. “How is it with you, Frank?”

“Oh, I didn’t catch it very badly.”

“Did Glummy get sick?”

“No.”

“He’s in luck. How he will crow over us.”

“If he starts to crow we’ll shut him up,” answered Frank, firmly.

They were soon dressed and into the stateroom occupied by Sam and Darry.

“Thanks, I’m myself again,” said Darry. “And why shouldn’t I be? I’m so clean inside I feel fairly polished. I can tell you, there’s nothing like a good dose of mal de mer, as the French call it, to turn one inside out.”

“And how are you, Beans?” asked Mark.

“I think I’m all here, but I’m not sure,” came from Sam. “But isn’t it a shame we should all be sick and Hockley should escape?”

[31]“Oh, he’s so thick-skinned the disease can’t strike through,” returned Frank.

He had scarcely uttered the words when Darry, who had stepped out into the gangway between the staterooms came back with a peculiar smile on his face.

“He’s got ’em,” he said.

“He? Who? What has he got?” asked the others in a breath.

“Glummy. He’s seasick, and he’s in his room doing more groaning than a Scotch bagpipe. Come and listen. But don’t make any noise.”

Silently the quartet tiptoed their way out of the stateroom and to the door of the apartment occupied by Hockley. For a second there was silence. Then came a turning of a body on a berth and a prolonged groan of misery.

“Oh, why did I come out here,” came from Hockley. “Oh dear, my head! Everything’s going round and round! Oh, if only this old tub would stop rolling for a minute—just a minute!” And then came another series of groans, followed by sounds which suggested that poor Hockley was about as sick as a boy can well be.

[32]“Let’s give him a cheer, just to brace him up,” suggested Frank, in a whisper.

“Just the thing,” came from Darry. “My, but won’t it make him boiling mad!”

But Mark interposed. “No, don’t do it, fellows, he feels bad enough already. Come on and leave him alone,” and this advice was followed and they went on deck. Here they met the professor, who wanted to know if they had seen Hockley.

“No, sir, but we heard him,” said Sam. “He’s in a bad way, and perhaps he’d like to see you.”

At this Professor Strong’s face became a study. Clearly he knew what was in the boys’ minds, but he did not betray it. Yet he had to smile when he was by himself. He went to see Hockley, and he did not re-appear on deck until two hours later.

“Supposing we now look at that map of Venezuela and learn a little about the history of the country,” said Professor Strong, immediately after the lunch hour and when all was quiet on board the steamer. “We can get in a corner of the cabin, and I don’t think anybody will disturb us.”

Ordinarily the boys would not have taken to anything in the shape of a lecture, but they were anxious to know something more of the locality they were to visit, and so all readily agreed to follow Professor Strong to the nook he had selected. Hockley was still absent, and the others asked no questions concerning him. The professor hung up his map and sat on a chair before it, and the lads drew up camp chairs in a semi-circle before him.

“As you will see by the map, Venezuela lies on the north coast of South America,” began Professor Strong. “It is bounded on the north by the Caribbean Sea, on the east by British Guiana, on the south[34] by Brazil and on the west by Colombia. It is irregular in shape, and its greatest length is from south-east to north-west, about twelve hundred miles, or by comparison, about the distance from Maine to Minnesota or California to Kansas.”

“Phew! that’s larger than I thought,” came from Frank, in an undertone.

“Many of the South American republics are larger than most people realize,” went on the professor. “Venezuela has an estimated area of nearly 598,000 miles—to give it in round figures. That is as large as all of the New England States and half a dozen other States combined. The country has over a thousand rivers, large and small, over two hundred of which flow into the Caribbean Sea, and four hundred helping to swell the size of the mighty Orinoco, which, as you already know, is the second largest river in South America,—the largest being the Amazon of Brazil. The Orinoco is a worthy rival of our own Mississippi, and I am afraid you will find it just as muddy and full of snags and bars.”

“Never mind, we’ll get through somehow,” put in Darry, and his dry way of saying it made even the professor laugh.

[35]“Besides the rivers, there are a number of lakes and bays. Of the former, the largest is Lake Maracaibo, with an area of 2,100 square miles.”

“That must be the Maracaibo coffee district,” suggested Mark.

“To a large extent it is, for the lake is surrounded by coffee and cocoa plantations. In the interior is another body of water, Lake Valencia, which possesses the peculiarity of being elevated nearly 1,700 feet above the ocean level. All told, the country is well watered and consequently vegetation is abundant.”

“But I thought it was filled up with mountains?” came from Sam.

“A large part of the country is mountainous, as you can see by the map, but there are also immense plains, commonly called llanos. The great Andes chain strikes Venezuela on the west and here divides into two sections, one running northward toward the Caribbean Sea and the other to the north-eastward. Some parts of these chains are very high, and at a point about a hundred miles south of Lake Maracaibo there are two peaks which are each over 15,000 feet high and are perpetually covered with snow.”

[36]“I guess we won’t climb them,” observed Sam.

“I hardly think so myself, Samuel, although we may get a good view of them from a distance, when we visit Lake Maracaibo. Besides these chains of mountains there are others to the southward, and here the wilderness is so complete that it has not yet been thoroughly explored. It is a land full of mountain torrents, and one of these, after flowing through many plains and valleys, unites the Orinoco with the Amazon, although the watercourse is not fit for navigation by even fair sized boats.”

“What about the people?” asked Mark, after a long pause, during which all of them examined the map more closely, and the professor pointed out La Guayra, Caracas, and a dozen or more other places of importance.

“The people are of Spanish, Indian and mixed blood, with a fair sprinkling of Americans and Europeans. There has been no accurate census taken for a number of years, but the population is put down as over two and three quarters millions and of this number about three hundred thousand are Indians.”

[37]“Are those Indians like our own?” questioned Darry.

“A great deal like the Indians of the old south-west, excepting that they are much more peaceful. You can travel almost anywhere in Venezuela, and if you mind your own business it is rarely that an Indian or a negro will molest you. And now let me ask if any of you know what the name Venezuela means?”

“I don’t,” said Frank, and the others shook their heads.

“The name Venezuela means Little Venice. The north shore was discovered by Columbus in 1498. One year later a Castilian knight named Ojeda came westward, accompanied by Amerigo Vespucci, and the pair with their four ships sailed from the mouth of the Orinoco to the Isthmus of Panama. They also explored part of Lake Maracaibo, and when Vespucci saw the natives floating around in their canoes it reminded him of Venice in Italy, with its canals and gondolas, and he named the country Little Venice, or Venezuela. When Vespucci got home he wrote an elaborate account of his voyage, and this so pleased those in authority they immediately[38] called the entire country America, in his honor, and America it has been ever since.”

“Yes, but it ought to be called Columbia,” put in Frank, as the professor paused.

“Perhaps you are right, Newton, but it’s too late to change it now. The Spaniards made the first settlement in Venezuela in 1520, and the country remained true to Spain until 1811. Ojeda was first made governor of all the north coast of South America, which soon took the name of the Spanish Main. Pearls were found in the Gulf of Paria, and the Spaniards at Santo Domingo rushed into South America and treated the innocent natives with the utmost cruelty. This brought on a fierce war lasting over forty years. This was in the times of Charles V, and he once sold the entire country to the Velsers of Augsburg, who treated the poor natives even worse than they had been treated by the Spaniards. In the end, between the fighting and the earthquakes which followed, the natives were either killed off or driven into the interior. Then came another Castilian knight, who in 1567 founded the city of Caracas, so called after the Indians who used to live there.”

[39]“I have often read stories of the Spanish Main,” said Mark. “They must have been bloody times.”

“They were, for piracy and general lawlessness were on every hand. The Spaniards ruled the people with a rod of iron, and everything that the country produced in the way of wealth went into the pockets of the rulers. At last the natives could stand it no longer, and a revolution took place, under the leadership of Simon Bolivar, and a ten years’ war followed, and the Spanish soldiery was forced to leave the country.

“At first Venezuela, with New Granada, (now Colombia) and Ecuador formed the Republic of Colombia. Simon Bolivar, often called the George Washington of South America, was the President of the Republic. At Bolivar’s death Venezuela became independent, and has remained independent ever since. Slavery was abolished there in 1854.”

“They were ahead of us in that,” observed Frank.

“So they were, and the credit is due to Jose Gregorio Monagas, who suffered a martyr’s death in consequence. The freeing of the slaves threw the country into another revolution, and matters were not settled until 1870, when Antonio Guzman Blanco[40] came into power and ruled until 1889. After this followed another series of outbreaks, one political leader trying to push another out of office, and this has hurt trade a good deal. At present General Castro is President of Venezuela, but there is no telling how long his enemies will allow him to retain that office.”

“I hope we don’t get mixed up in any of their revolutions,” said Sam.

“I shouldn’t mind it,” put in Darry. “Anything for excitement, you know.”

“Venezuela has been divided into many different states and territories at different times,” continued Professor Strong. “In 1854 there were thirteen provinces which were soon after increased to twenty-one. In 1863 the Federalists conquered the Unionists, and the provinces were re-named states and reduced to seven. But this could not last, for fewer states meant fewer office holders, so the number was increased to twenty states, three territories and one federal district. What the present government will do toward making divisions there is no telling.”

“I should think they would get tired of this continual fighting,” said Darry.

“The peons, or common people, do get very tired[41] of it, but they cannot stop the ambitions of the political leaders, who have the entire soldiery under their thumb. These leaders have seen so much of fighting, and heard of so much fighting in their sister republics, that it seems to get in their blood and they can’t settle down for more than a few years at a time. But as outsiders come in, with capital, and develop the country, I think conditions will change, and soon South America will be as stable as North America or Europe.”

“Now I feel as if I knew a little more than I did before,” observed Frank to Mark, after the professor’s talk had come to an end and the teacher had gone to put away his map. “It’s a pretty big country, isn’t it?”

“It is, Frank, and at the best I suppose we can see only a small portion of it. But it would be queer if we got mixed up in any of their fighting, wouldn’t it?”

“Do you really think we shall?”

“I don’t know. But just before we left New York I saw a long article in one of the newspapers about affairs in Venezuela, Colombia and on the Isthmus. It seems that the Presidents of the two Republics are unfriendly, and as a consequence the President of Venezuela has given aid to the rebels in Colombia, while the President of Colombia is doing what he can to foment trouble in Venezuela. Besides that Nicaragua and Ecuador are in the mix-up.[43] The papers said that fighting has been going on in some places for years and that thousands of lives have been lost, especially in the vicinity of the Isthmus.”

“It’s a wonder the professor didn’t speak of this.”

“Oh, I guess he didn’t want to scare us. Perhaps the soldiery doesn’t interfere with foreigners, if, as he says, the foreigners mind their own business.”

The day was all that one could wish and the boys enjoyed it fully, for the seasickness of the day before had done each good. Mark and his chums wondered how Hockley was faring, and at last Sam went to the professor to inquire.

“He is a very sick young man,” said Professor Strong. “His over-eating has much to do with it. But I hope to see him better in the morning.”

“Do you think he would like to see any of us?” asked Sam. “We’ll go willingly if you think best.”

“No, he said he wished to see no one but myself, Winthrop. You will do best to let him alone, and when he comes out I wouldn’t say anything about the affair,” concluded the professor.

To while away the time the boys went over the steamer from end to end, and an obliging under-officer explained the engines, the steering gear and[44] other things of interest to them. So the time passed swiftly enough until it was again the hour to retire.

Hockley appeared about ten o’clock on the following morning, thinner than ever and with big rings under his eyes. He declined to eat any breakfast and was content to sit by himself in a corner on deck.

“I suppose you fellows think I was seasick,” he said, as Sam and Darry passed close to him. “But if you do, you are mistaken. I ate something that didn’t agree with me and that threw me into a regular fit of biliousness. I get them every six months or so, you know.”

“I didn’t know,” returned Darry, who had never seen Hockley sick in his life. “But I’m glad you are over it,” he went on, kindly.

“I suppose Frank and Mark are laughing in their sleeves at me,” went on the lank youth, with a scowl.

“I don’t believe they are thinking of it,” answered Sam. “We’ve been inspecting the ship from top to bottom and stem to stern, and that has kept us busy. You ought to go around, it’s really very interesting.”

“Pooh! I’ve been through ’em loads of times—on[45] the regular Atlantic liners,—twice as big as this,” grumbled Hockley.

A few words more followed, and Sam and Darry passed on. “He’s all right again,” observed Darry. “And his seasickness didn’t cure him of his bragging either.”

The steamer was now getting well down toward the Mona Passage, and on the day following land was sighted in the distance, a series of somewhat barren rocks. A heavy wind was blowing.

“Now we are going to pass through the monkey,” said Darry, after a talk with the professor.

“Pass through the monkey?” repeated Frank. “Is this another of your little jokes, Darry?”

“Not at all. Mona means monkey, so the professor told me.”

“Will we stop?”

“No, we won’t go anywhere near land. The next steamer stops, I believe, but not this one.”

“I wouldn’t mind spending some time in Porto Rico and Cuba,” put in Mark. “There must have been great excitement during the war with Spain.”

“Perhaps we’ll stop there on our way home,” said Sam. “I should like to visit Havana.”

The Mona Passage, or Strait, passed, the course[46] of the steamer was changed to the south-westward. They were now in the Caribbean Sea, but the waters looked very much as they had on the bosom of the Atlantic. The wind increased until the blow promised to be an unusually severe one.

“My, but this wind is a corker!” ejaculated Frank, as he and Mark tried in vain to walk the open deck. “Perhaps we are going to have a hurricane.”

“You boys had better come inside,” said Professor Strong as he hurried up. “It’s not safe to be here. A sudden lurch of the steamer might hurl you overboard.”

“All right, we’ll come in,” said Mark.

He had scarcely spoken when an extra puff of wind came along, banging the loose things in the open cabin right and left. The wind took Frank’s cap from his head and sent it spinning aft.

“My cap!” cried the youth and started after it.

“Be careful of yourself!” came from the professor, but the fury of the wind drowned out his voice completely.

Bound to save his cap Frank followed it to the rail. As he stooped to pick it up the steamer gave a sudden roll to the opposite side and he was thrown[47] headlong. At the same moment the spray came flying on board, nearly blinding him.

“Stay where you are!”

“He’ll go overboard if he isn’t careful!” ejaculated Mark, and ran after his chum.

“You be careful yourself,” came from Professor Strong, as he too rushed to the rescue.

Before either could reach Frank the youth had turned over and was trying to raise himself to his feet. But now the steamer rolled once more and in a flash Frank was thrown almost on top of the rail. He caught the netting below with one hand but his legs went over the side.

“Oh!” burst out Mark, and could say no more, for his heart was in his throat. He thought Frank would be washed away in a moment more. The spray still continued to fly all over the deck and at times his chum could scarcely be seen.

“Stay where you are,” called out Professor Strong, to Mark. Then he turned and in a moment more was at the rail and holding both Frank and himself. Following the advice given, Mark held fast to a nearby window.

By this time a couple of deck hands were hurrying to the scene, one with a long line. One end of the line was fastened to the companionway rail and[48] the other run out to where the professor and Frank remained. The boy was all out of breath and could do but little toward helping himself. But Professor Strong’s grip was a good one, and it did not relax until one of the deck hands helped the lad to a place along the rope. The deck hand went ahead and the professor brought up the rear, with Frank between them. In a moment more they were at the companionway and Frank fairly tumbled below, with the others following him.

“Gracious, but that was a close shave!” panted the boy, when able to speak. “I hadn’t any idea the steamer would roll so much.”

“After this when it blows heavily you must remain in the cabin,” said Professor Strong, rather severely. “And if your cap wants to go overboard—”

“I’ll let it go,” finished Frank. “I won’t do anything like that again for a train load of caps, you can depend on that.”

The storm increased, and by nightfall it was raining heavily. The boys had expected a good deal of thunder and lightning, but it did not come, and by sunrise wind and rain were a thing of the past and[49] the steamer was pursuing her course as smoothly as ever.

On board the ship were half a dozen passengers bound for Curaçao, including Herr Dombrich, the merchant who occupied a portion of Professor Strong’s stateroom. One of the number going ashore at the little island was a man from Baltimore, a fellow with Dutch blood in his veins, who had formerly been in the saloon business, and who was far from trustworthy. His name was Dan Markel, and, strange as it may seem, he had formed a fairly close acquaintanceship with Jake Hockley.

“I wish I had the money you have,” said Dan Markel to Hockley, one afternoon, as the two were sitting alone near the bow of the steamer. “There are lots of openings in Curaçao for a fellow with a little capital. The Dutchmen down there don’t know how to do business. With five hundred dollars I could make ten thousand in less than a year.”

“Haven’t you got five hundred dollars?” asked Hockley, with interest.

“Not now. I had a good deal more than that, but I was burnt out, and there was a flaw in my insurance papers, so I couldn’t get my money from the[50] company.” Dan Markel told the falsehood without a blush.

“But what do you expect to do in Curaçao without money—strike some sort of job?”

“I’ve got a rich friend, who has a plantation in the interior. I think he will give me a place. But I’d rather establish myself in the town. He wrote to me that there was a good opening for a tobacco shop. If I could get somebody to advance me five hundred dollars I’d be willing to pay back a thousand for it at the end of six months.”

Now Hockley was carrying five hundred dollars with him, which an indulgent father had given to him for “extras,” as he expressed it, for Professor Strong was to pay all regular bills. The money was in gold, for gold is a standard no matter where you travel. Hockley thought of this gold, and of how he would like it to be a thousand instead of five hundred dollars.

“I’ve got five hundred dollars with me,” he said, in his bragging way. “My father gave it to me to have a good time on.”

“Then you must be rich,” was the answer from the man from Baltimore.

“Dad’s a millionaire,” said Hockley, trying to[51] put on an air of superiority. “Made every cent of it himself, too.”

“I suppose you’ve got to pay your way with the money.”

“No, old Strong pays the bills.”

“Then you’re in luck. I suppose you don’t want to put that money out at a hundred per cent. interest,” went on Dan Market, shrewdly. “It would be as safe as in a bank, my word on it.”

“I want to use the money, that’s the trouble. I intend to have a good time in Venezuela.”

“You ought to have it, on that money. I wish I had your chance. Caracas is a dandy city for sport, if you know the ropes.”

“Then you have been there?”

“Yes, four years ago,” answered Markel, and this was another falsehood, for he had never been near South America in his life. He had spent his time in drifting from one city in the United States to another, invariably leaving a trail of debts behind him.

“And you know the people?”

“Yes, some of the very best of them. And I can show you the best of the cock fighting and the bull fighting, too, if you want to see them.”

[52]“That’s what I want,” answered Hockley, his eyes brightening. “No old slow poke of a trip for me. I suppose Professor Strong expects to make us toe the mark everywhere we go, but I don’t intend to stand it. I came for a good time, and if I can’t get it with the rest of the party I’m going to go it on my own hook.”

“To be sure—that’s just what I’d do.” Dan Markel slapped Hockley on the back. “Hang me if you ain’t a young man after my own heart. For two pins I’d go down to Caracas with you, just to show you around.”

“I wish you would!” cried Hockley.

“The trouble is while I can spare the time I can’t spare the money. I’d take you up in a minute if it wasn’t for that.”

“Never mind the money—I’ll foot the bill,” answered Hockley, never dreaming of how his offer would result. “I’d like to have a companion who had been around and who knew where the real sport lay. You come with me, and you can return to Curaçao after our crowd leaves Caracas.”

A talk of half an hour followed. Markel pretended to be unwilling to accept the generous offer at first, but at length agreed to go with Hockley and[53] remain with him so long as the Strong party stopped at Caracas. He was to show Hockley all the “fancy sports” of the town and introduce him to a number of swells and “high rollers.” On the strength of the compact he borrowed fifty dollars on the spot, giving his I. O. U. in exchange, a bit of paper not worth the ink used in drawing it up.

“Hockley has found a new friend,” observed Mark to Sam that afternoon. “A man a number of years older than himself, too.”

“So I’ve noticed, Mark. I must say I don’t quite fancy the appearance of the stranger.”

“Nor I. He looks rakish and dissipated. I wonder where he is bound?”

“I heard him speaking about getting off at Curaçao. If that’s the case we won’t have him with us after to-morrow.”

“Do we stop at the island to-morrow?”

“Yes, we’ll be there before noon, so the professor says.”

Just then Darry appeared and joined them. He had been in the cabin, and Hockley had introduced Dan Markel to him.

“Mr. Markel is a great talker, but I don’t take stock in much he says,” said Darry. “Hockley[55] evidently thinks him just all right. He was going to stop at Curaçao but has changed his mind and is going right through to Caracas. He says he knows Caracas like a book.”

“Perhaps he intends to take Hockley around,” suggested Sam.

“It was my impression we were all to go around with the professor,” came from Mark.

“That was the plan,” said Darry. “He’d have a good deal of bother if he allowed everyone to run off where he pleased. I don’t believe Hockley liked it much because I didn’t seem to care for his new friend.”

“Let him think as he pleases—we haven’t got to put ourselves out for his benefit,” said Mark; and there the subject was dropped for the time being.

In the meantime Frank had met Hockley and Dan Markel coming out of the stateroom the latter occupied. Markel had asked the lank youth to come below and take a drink with him, and Hockley had accepted, and a first drink had been followed by two more, which put Hockley in rather an “elevated” state of mind, even though he was used to drinking moderately when at home.

“My very best friend, Frank,” he called out.[56] “Mr. Dan Markel. Mr. Markel, this is one of our party, Frank Newton, of New York city.”

“Happy to know you,” responded Market, giving Frank’s hand a warm shake. “It’s a real pleasure to make friends on such a lonely trip as this.”

“I haven’t found it particularly lonely,” said Frank, stiffly. He was not favorably impressed by the appearance of the man from Baltimore.

“That’s because you have so many friends with you, my boy. With me it was different. I didn’t know a soul until Mr. Hockley and myself struck up an acquaintanceship.”

“But now it’s all right, eh?” put in Hockley, gripping Markel’s shoulder in a brotherly way.

“To be sure it’s all right,” was the quick answer. “We’ll stick together and have a good time. Perhaps young Newton will join us?”

“Thank you, but I shall stick to my chums,” answered Frank, coolly, and walked off, leaving Markel staring after him.

“The little beggar!” muttered Hockley, when Frank was out of hearing. “I’d like to wring his neck for him.”

“Why, what’s the trouble?”

“Oh, nothing in particular, but somehow he and[57] the rest of the crowd seem to be down on me, and they are making it as unpleasant as they can at every opportunity.”

“You don’t say! It’s a wonder Professor Strong permits it.”

“They take good care to be decent when he’s around, and of course I’m no tale bearer, to go to him. But I would like to fix young Newton.”

“Is he worse than the others?”

“Sometimes I think he is. Anyway, if I got square on him it might teach the others a lesson.”

Frank joined his chums and told what had taken place. At the next meal Markel was introduced to the others, but all ignored him, and even Professor Strong showed that he did not like the idea of Hockley picking up such an acquaintance.

The fact that he had been snubbed made Dan Markel angry, and feeling that Hockley was now his friend and would back him up, he let out a stream of abuse, in the privacy of his stateroom, with the lank youth taking it in and nodding vigorously.

“You are right, that little cub is the worst,” said Markel, referring to Frank. “He needs taming down. I wish I had him under my care for a week or two, I’d show him how to behave.”

[58]“I’ve been thinking of an idea,” retorted Hockley, slowly. “It would be a grand scheme if we could put it through.”

“What is it?”

“We are going to land at Curaçao to-morrow. I wish I could arrange it so one of the other fellows would be left behind to paddle his own canoe. It would take some of the importance out of him.”

“Well, that might be arranged,” returned Markel, rubbing his chin reflectively. “Perhaps we might fix it so that all of them were left there stranded.”

“How long will the steamer stay there?”

“Six hours, so I heard the captain tell one of the other passengers.”

“The trouble is we’ll all have to go ashore with the professor, if they let us go ashore at all.”

“Well, we’ll try to think up some scheme,” said the man from Baltimore; and then the subject was changed.

Curaçao is the largest and most important of the Dutch West Indian Islands, with a population of about 25,000 souls. The island is largely of a phosphate nature, and the government derives a handsome[59] income from the sale of this product. To the east of Curaçao is Bonaire, another Dutch possession, and to the west Aruba, all of which are likely to become a part of United States territory in the near future. The islands are of considerable importance, and trade not alone in phosphate of lime but also in salt, beans, dyewoods and fruits.

Early in the morning the dim outlines of Curaçao could be seen and about ten o’clock the steamer glided into the bay of St. Anna, upon which Willemstad, the capital city is located. The harbor is a commodious one, and ships displaying the flags of many nations were on every hand.

“What a pretty town!” exclaimed Mark, as he surveyed the distant shore with a glass. “I declare it looks like some of these old Dutch paintings.”

“This island is famous in history,” said Professor Strong, who stood by. “It was discovered by the Spaniards in 1527. About a hundred years after that the Dutch took it and held it for nearly two hundred years. Then the English came over and wrested it from the Dutch, but had to give it back eight years later, in 1815. The pirates and[60] buccaneers used to find these islands excellent stopping places, and many a political refugee has ended his days on them.”

“Is the capital very large?”

“About fifteen thousand inhabitants.”

“How about going ashore and taking a look around?” questioned Darry. “I’d like first rate to stretch my legs on land once more.”

“Oh, yes, do let us go ashore?” pleaded Frank. “The steamer is going to stay five or six hours, and that will give us loads of time for looking around.”

“I will see what can be done when we anchor,” said the professor. “They may be very strict here—I do not know.”

Soon the big steamer was close up to the wharf where she was to discharge part of her cargo and passengers. One of the first parties to leave was Herr Dombrich, who shook hands cordially with the professor.

“It has been von great bleasure to sail mit you,” said the Dutch merchant. “I vos hobe ve meet again, not so?”

“I’m thinking of taking the boys ashore,” said the professor. “They would like to see the city.”

[61]“Yes, yes, surely you must do dot,” was the reply. “I vould go mit you, but I must on pisiness go to de udder side of de island. Goot py!” and in a moment Herr Dombrich was ashore and lost in a crowd. Then Mark caught a glimpse of him as he was driven away in an old-fashioned Dutch carriage which had been waiting for him.

An interview was had with some custom house and other officials, and the party obtained permission to go ashore and roam around the place until the steamer should set sail for La Guayra. In the meantime Dan Markel had already disappeared up one of the long docks.

The man from Baltimore was in a quandary. He had borrowed fifty dollars from Hockley, and he was strongly inclined to hide until the steamer should sail and then use the money to suit himself. But he realized that his capital, which now represented a total of eighty dollars, would not last forever, and a brief look around Willemstad convinced him that it was not at all the city he had anticipated.

“I’d starve to death here, after the money was gone,” he reasoned. “I’ll wager these Dutchmen are regular misers. The best thing I can do is to go[62] to Caracas with that crowd and then squeeze that young fool out of another fifty, or maybe a couple of hundred.”

He had come ashore after another talk with Hockley, in which he had promised to lay some plan whereby one or another of the boys might be left behind. He had been told by the captain of the steamer that the vessel would sail at five o’clock sharp. If he could only manage to keep somebody ashore until ten or fifteen minutes after that hour the deed would be done.

The day was hot and, as was usual with him, Markel was dry, and he entered the first wine shop he discovered. Here he imbibed freely, with the consequence that when he arose to go his mind was far from being as free as it had been.

“I guess I’ll go and see a little more of the town on my own hook before I try to make any arrangements,” he muttered to himself, and strolled on until another drinking place presented itself. Here he met another American, and the pair threw dice for drinks for over an hour. Then the man from Baltimore dozed off in a chair, and did not awaken until a number of hours later.

Leaving the steamer, our friends proceeded to the main thoroughfare of Willemstad, a quaint old street, scrupulously clean—a characteristic of every Dutch town—and with buildings that looked as if they had been moved over from Amsterdam. Not far off was the home of the governor of the island, a mansion with walls of immense thickness. The place fronted the bay and near by was something of a fortress with a few ancient cannon. Here a number of Dutch soldiers were on duty.

“I will see if I cannot get carriages, and then we can drive around,” said Professor Strong, and this was done, and soon they were moving along slowly, for no Dutch hackman ever thinks of driving fast. Besides it was now the noon hour, and the hackmen would rather have taken their midday nap than earn a couple of dollars. The boys soon discovered that in the tropics to do anything, or to have anything done for you, between the hours of eleven to three[64] is extremely difficult. Merchants close their places of business and everybody smokes and dreams or goes to sleep.

“I see a lot of negroes,” observed Mark, as they moved along.

“The population is mostly of colored blood,” answered the professor. “The colored people are all free, yet the few Dutchmen that are here are virtually their masters. The negroes work in the phosphate mines, and their task is harder than that of a Pennsylvania coal miner ten times over. If we had time we might visit one of the phosphate works, but I hate to risk it.”

“For such a small place there are lots of ships here,” put in Sam.

“That is true and I think the reason is because this is a free port of entry. The ships bring in all sorts of things, and some say a good deal of the stuff is afterwards smuggled into Venezuela and Colombia.”

They drove on, past the quaint shops and other buildings, but in an opposite direction to that taken by Dan Markel. During the drive Hockley had little or nothing to say. He was worried over the non-appearance of the man from Baltimore, and[65] looked for him eagerly at every corner and cross road.

“He’s made a mess of it,” he thought. “We’ll be driving back soon and that will be the end of it.” And then he thought of the fifty dollars and began to suspect Markel, and something like a chill passed over him.

“If he cheated me I’ll fix him, see if I don’t!” he told himself. Yet he felt that he was helpless and could do nothing, for the loan had been a fair one.

“There is a curious story connected with the Island of Curaçao,” said the professor, as they passed along through the suburbs of the capital. “It is said that in years gone by some of the old Spanish pirates filled a cave in the interior with gold and then sprinkled a trail of salt from the cave to the sea. Some time after that the pirates were captured and all made to walk the plank. One of them, in an endeavor to save his life, told of the treasure and of the trail that had been left. Those who had captured the pirates immediately sailed for the island, but before they could reach here a fearful hurricane came up, washing the land from end to end and entirely destroying the trail of salt, so that the treasure has not been unearthed to this day.”

[66]For the greater part the road was hard, dusty and unshaded. But in spots were beautiful groves of plantains and oranges, while cocoanut palms were by no means lacking. The houses everywhere were low, broad, and with walls of great thickness, and in between them were scattered the huts of the poorer class, built of palm thatch and often covered with vines.

On the return they passed an old Dutch saw-mill, where a stout Dutchman was directing the labors of a dozen coal-black natives. The natives droned a tune as they moved the heavy logs into the mill. They appeared to be only half awake, and the master threatened them continually in an endeavor to make them move faster.

“They are not killing themselves with work,” observed Sam.

“They never work as fast in the tropics as they do in the temperate zone of our own country,” answered Professor Strong. “The heat is against it. Even the most active of men are apt to become easy-going after they have been here a number of years.”

The drive took longer than anticipated and when they again reached the docks the steamer was ready to sail. They were soon on board, and a little later[67] St. Anna harbor was left behind and the journey to Venezuela was resumed.

“What’s up?” asked Mark, of Hockley, when he saw the lank youth walking through the cabins looking in one direction and another. “Lost anything?”

“No,” was the curt answer, and then with a peculiar look in his eyes, Hockley continued: “Have you seen anything of Mr. Markel since we came on board?”

“I have not. He got off at Willemstad.”

“I know it. But he was going through to La Guayra and Caracas.”

“Well, I haven’t seen him,” answered Mark, and moved on.

Hockley continued his search for over an hour and then went to the purser, and from that individual learned that Markel had taken no stateroom for the coming night nor had he paid passage money to be carried to La Guayra.

“That settles it,” muttered Hockley to himself, as he walked off. “He has given me the slip and I am out my fifty dollars. What a fool I was to trust him! And I thought he was such a fine fellow!” And he gripped his fists in useless rage.[68] He fancied that he had seen the last of the man from Baltimore, but he was mistaken.

That night the boys went to bed full of expectations for the morrow, for the run from Curaçao to La Guayra, the nearest seaport to Caracas, is but a short one.

“My, but it’s getting hot!” observed Frank, while undressing. “It’s more than I bargained for.”

“You must remember we are only twelve degrees north of the equator,” answered Mark. “Wait till we strike the Orinoco, then I guess you’ll do some sweating. That stream is only about seven or eight degrees above the line.”

Nevertheless the boys passed a fairly comfortable night and did not arise until it was time for breakfast. Then they went on deck to watch for the first sight of land.

“Hurrah! There’s land!” was Darry’s cry, some hours later. He held a glass in his hand. “My, what a mountain!”

One after another looked through the glass, and at a great distance made out a gigantic cliff overhanging the sea. As the steamer came closer they made out the wall more plainly, and saw the lazy[69] clouds drifting by its top and between its clefts. At the foot of the gigantic cliff was a narrow patch of sand with here and there a few tropical trees and bushes. Upon the sand the breakers rushed with a low, booming sound, and in spots they covered the rocks with a milklike foam.

“I don’t see anything of a town,” said Frank.

“We have got to round yonder point before you can see it,” answered an under-officer standing near. “It’s not much of a place, and it’s tucked away right under the mountain.”

An hour later they rounded the point that had been mentioned and at a distance made out La Guayra, which is located on a narrow strip of land between the great cliff and the sea. They could see but little outside of several long and narrow streets running parallel with the mountain. At one end of the town was a small hill, with several long, low government buildings and a church or two.

“When I was here before, one had to be taken ashore in a small boat,” said Professor Strong. “The ocean ran with great swiftness along the beach. But now they have a breakwater and some first-class docks and there is little trouble.”

[70]“The town seems to be hemmed in,” said Sam. “How do they get anywhere excepting by boat?”

“There is a road over the mountain and a railroad track, too. But it’s up-hill climbing from beginning to end.”

“What’s that thing on yonder hillside?” asked Mark, pointing to a somewhat dilapidated building, one side of which was set up on long sticks.

“That is the old bull fighting ring. In days gone by they used to have very fierce fights there and much money used to be wagered on the contests. But the folks are beginning to become civilized now and the bull fighting doesn’t amount to much.”