Title: Essays on the Latin Orient

Author: William Miller

Release date: September 21, 2022 [eBook #69026]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Cambridge, University Press, 1922

Credits: Turgut Dincer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

C. F. CLAY, Manager

LONDON: FETTER LANE, E.C. 4

| NEW YORK: | THE MACMILLAN CO. | |

| BOMBAY | } | MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. |

| CALCUTTA | } | |

| MADRAS | } | |

| TORONTO: | THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. | |

| TOKYO: | MARUZEN·KABUSHIKI·KAISHA |

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

ESSAYS

ON

THE LATIN ORIENT

BY

WILLIAM MILLER, M.A. (Oxon.)

HON. LL.D. IN THE NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF GREECE: CORRESPONDING

MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND ETHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF GREECE:

AUTHOR OF THE LATINS IN THE LEVANT

CAMBRIDGE

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1921

“You imagine that the campaigners against Troy were the only heroes, while you forget the other more numerous and diviner heroes whom your country has produced.”

Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana, III. 19.

This volume consists of articles and monographs upon the Latin Orient and Balkan history, published between 1897 and the present year. For kind permission to reprint them in collected form I am indebted to the editors and proprietors of The Quarterly Review, The English Historical Review, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Die Byzantinische Zeitschrift, The Westminster Review, The Gentleman’s Magazine, and The Journal of the British and American Archæological Society of Rome. All the articles have been revised and brought up to date by the light of recent research in a field of history which is no longer neglected in either the Near East or Western Europe.

W. M.

36, Via Palestro, Rome.

March, 1921.

| CHAP. | PAGE | ||

| I. | THE ROMANS IN GREECE | 1 | |

| II. | BYZANTINE GREECE | 29 | |

| III. | FRANKISH AND VENETIAN GREECE | 57 | |

| 1. | THE FRANKISH CONQUEST OF GREECE | 57 | |

| 2. | FRANKISH SOCIETY IN GREECE | 70 | |

| 3. | THE PRINCES OF THE PELOPONNESE | 85 | |

| APPENDIX: THE NAME OF NAVARINO | 107 | ||

| 4. | THE DUKES OF ATHENS | 110 | |

| APPENDIX: THE FRANKISH INSCRIPTION AT KARDITZA | 132 | ||

| 5. | FLORENTINE ATHENS | 135 | |

| APPENDIX: | |||

| NOTES ON ATHENS UNDER THE FRANKS | 155 | ||

| THE TURKISH CAPTURE OF ATHENS | 160 | ||

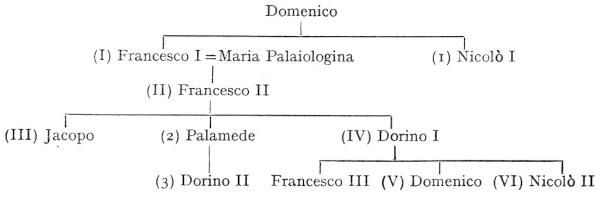

| 6. | THE DUCHY OF NAXOS | 161 | |

| APPENDIX: THE MAD DUKE OF NAXOS | 175 | ||

| 7. | CRETE UNDER THE VENETIANS (1204-1669) | 177 | |

| 8. | THE IONIAN ISLANDS UNDER VENETIAN RULE | 199 | |

| 9. | MONEMVASIA | 231 | |

| 10. | THE MARQUISATE OF BOUDONITZA (1204-1414) | 245 | |

| 11. | ITHAKE UNDER THE FRANKS | 261 | |

| 12. | THE LAST VENETIAN ISLANDS IN THE ÆGEAN | 265 | |

| 13. | SALONIKA | 268 | |

| IV. | THE GENOESE COLONIES IN GREECE | 283 | |

| 1. | THE ZACCARIA OF PHOCÆA AND CHIOS (1275-1329) | 283 | |

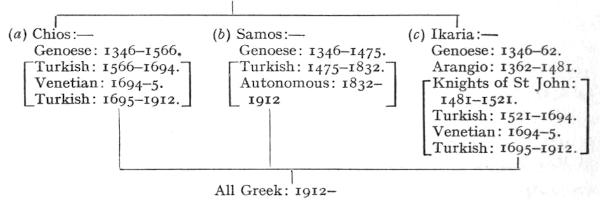

| 2. | THE GENOESE IN CHIOS (1346-1566) | 298 | |

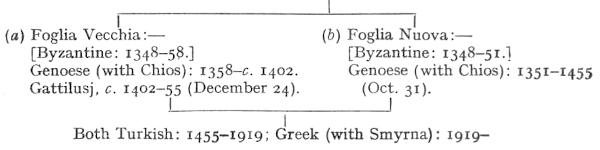

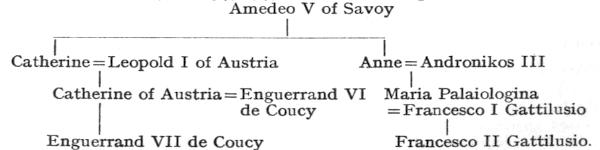

| 3. | THE GATTILUSJ OF LESBOS (1355-1462) | 313 | |

| V. | TURKISH GREECE (1460-1684) | 355 | |

| VI. | THE VENETIAN REVIVAL IN GREECE (1684-1718) | 403[viii] | |

| VII. | MISCELLANEA FROM THE NEAR EAST | 429 | |

| 1. | VALONA | 429 | |

| 2. | THE MEDIÆVAL SERBIAN EMPIRE | 441 | |

| APPENDIX: THE FOUNDER OF MONTENEGRO | 458 | ||

| 3. | BOSNIA BEFORE THE TURKISH CONQUEST | 460 | |

| 4. | BALKAN EXILES IN ROME | 497 | |

| 5. | THE LATIN KINGDOM OF JERUSALEM (1099-1291) | 515 | |

| 6. | A BYZANTINE BLUE STOCKING: ANNA COMNENA | 533 | |

| PLATE | FIGS. | TO FACE PAGE | |

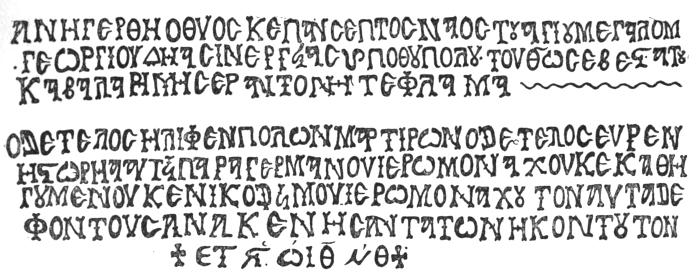

| I. | 1 & 2. | The Church of St George at Karditza | 134 |

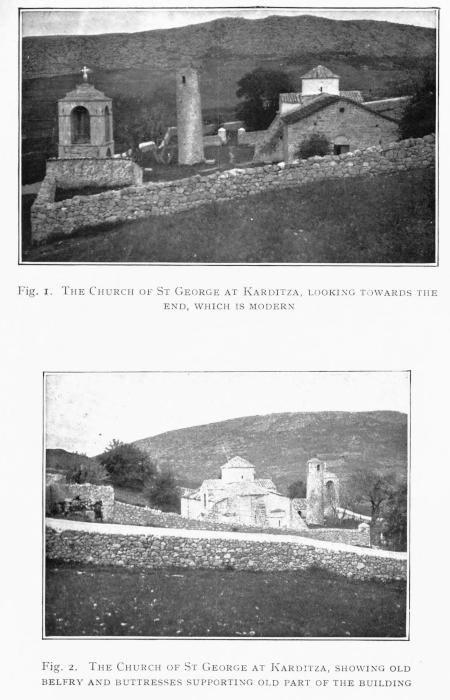

| II. | 1. | Monemvasia from the Land | 234 |

| 2. | Monemvasia. Entrance to Kastro | 234 | |

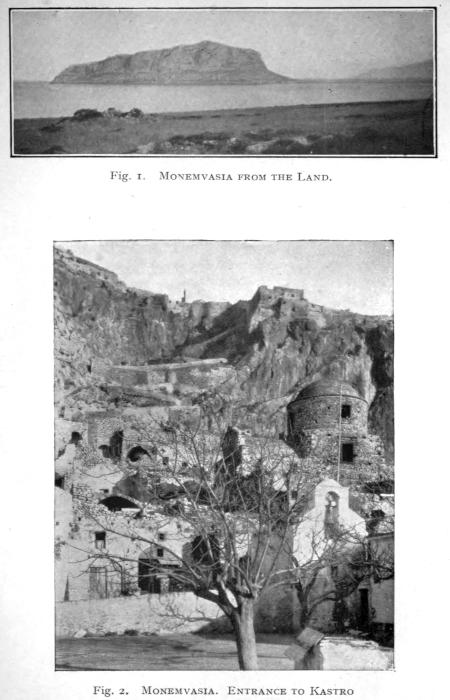

| III. | 1. | Monemvasia. Παναγία Μυρτιδιώτισσα | 235 |

| 2. | Monemvasia. Ἁγία Σοφία | 235 | |

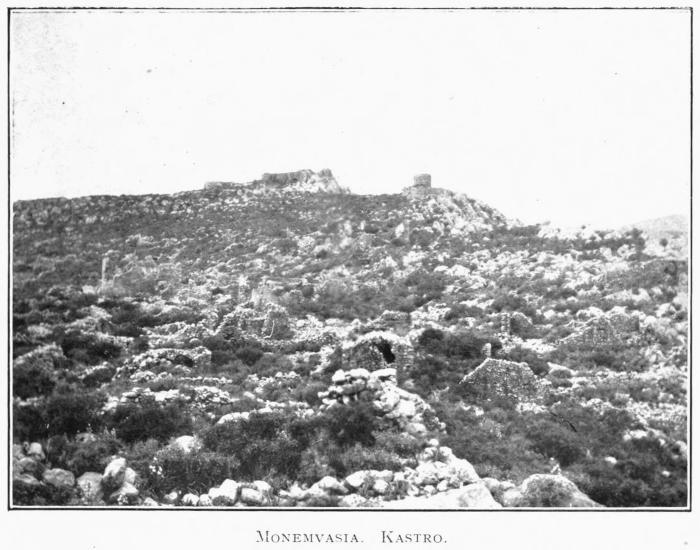

| IV. | Monemvasia. Kastro | 240 | |

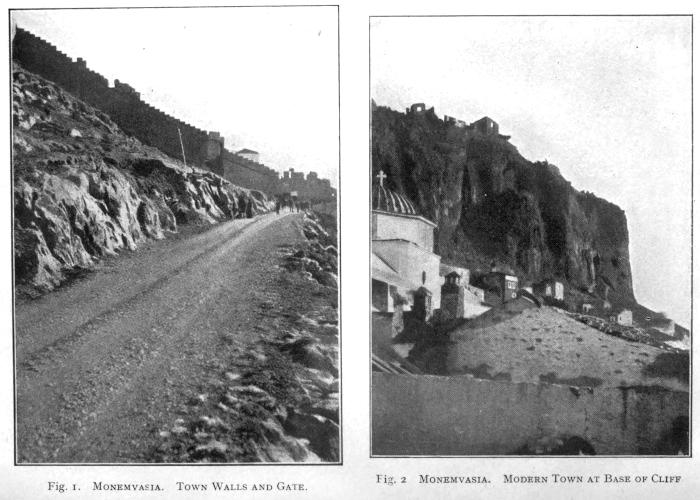

| V. | 1. | Monemvasia. Town Walls and Gate | 241 |

| 2. | Monemvasia. Modern Town at Base of Cliff | 241 | |

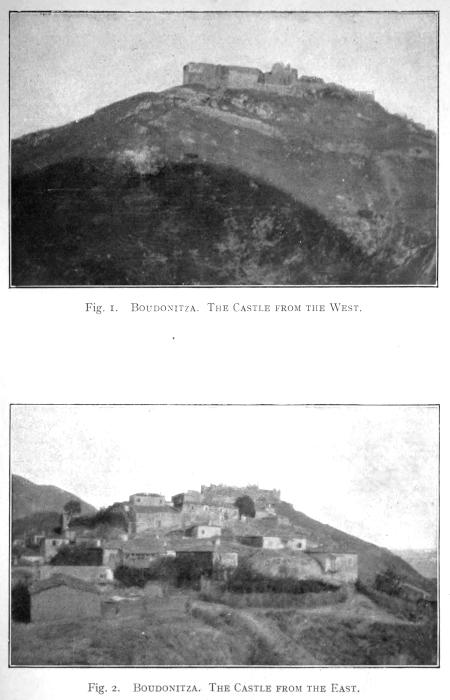

| VI. | 1. | Boudonitza. The Castle from the West | 246 |

| 2. | Boudonitza. The Castle from the East | 246 | |

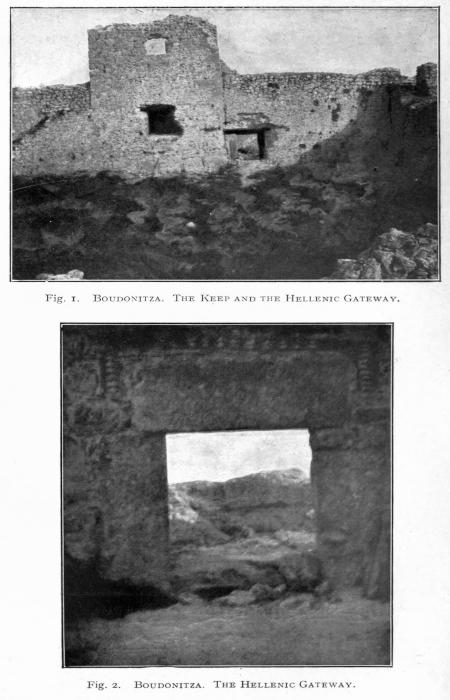

| VII. | 1. | Boudonitza. The Keep and the Hellenic Gateway | 247 |

| 2. | Boudonitza. The Hellenic Gateway | 247 |

| ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT | ||

| Fig. 1. | Inscription on the Church at Karditza | 133 |

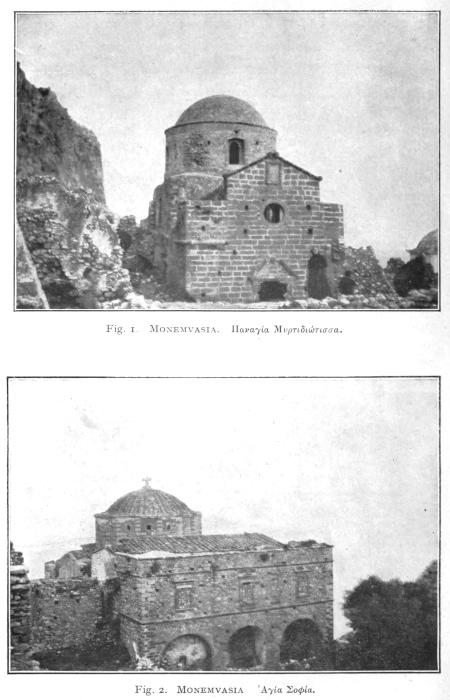

| ” 2. | Arms on Well-Head in the Castle at Monemvasia | 242 |

| MAP | |

| The Near East in 1350 | BETWEEN PAGES 282 AND 283 |

From the Roman conquest in 146 B.C. Greece lost her independence for a period of nearly two thousand years. During twenty centuries the country had no separate existence as a nation, but followed the fortunes of foreign rulers. Attached, first to Rome and then to Constantinople, it was divided among various Latin nobles after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1204, and succumbed to the Turks in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. From that time, with the exception of the brief Venetian occupation of the Peloponnese, and the long foreign administration of the Ionian Islands, it remained an integral part of the Turkish Empire till the erection of the modern Greek kingdom. Far too little attention has been paid to the history of Greece under foreign domination, for which large materials have been collected since Finlay wrote his great work. Yet, even in the darkest hours of bondage, the annals of Greece can scarcely fail to interest the admirers of ancient Hellas.

The victorious Romans treated the vanquished Greeks with moderation, and their victory was regarded by the masses as a relief from the state of war which was rapidly consuming the resources of the taxpayers. Satisfied to forego the galling symbols, provided that they held the substance, of power in their own hands, the conquerors contented themselves with dissolving the Achaian League, with destroying, perhaps from motives of commercial policy, the great mart of Corinth, and with subordinating the Greek communities to the governor of the Roman province of Macedonia, who exercised supreme supervision over them. But these local bodies were allowed to preserve their formal liberties; Corfù, the first of Greek cities to submit to Rome, always remained autonomous, and Athens and Sparta enjoyed special immunities as “the allies of Rome,” while the sacred character of Delphi secured for it practical autonomy. A few years after the conquest the old Leagues were permitted to revive, at least in name; and the land tax, payable by most of the communities to the Roman Government, seemed to fulfil the expectation of the natives that their fiscal burdens would be diminished under foreign rule. The historian Polybios[1], who successfully pleaded the cause of his countrymen at this great crisis in their history, has contrasted the purity of Roman financial[2] administration with the corruption of Greek public men, and has cited a saying current in Greece soon after the conquest: “If we had not perished quickly, we should not have been saved.” While this was the popular view, the large class of landed proprietors was also pleased by the recognition of its social position by its new masters, and the men who were entrusted with the delicate task of organising the conquered country at the outset of its new career wisely availed themselves of the disinterested services of Polybios, who enjoyed the confidence of both Greeks and Romans. Even Mummius himself, the destroyer of Corinth, if he carried off many fine statues to deck his triumph, left behind him the memory of his gentleness to the weak, as well as that of his firmness to the strong, and might have been taken as the embodiment of those qualities which Virgil, more than a century later, held up to the imitation of his countrymen.

The pax Romana, which the Roman conquest seemed likely to confer upon the jealous Greeks, was occasionally broken in the early decades of the new administration. The sacred isle of Delos, which was then subordinate to Athens, and which had become the greatest mart for merchandise and slaves in the Levant since the destruction of Corinth, and the silver-mines of Laurion, which had of old provided the sinews of naval warfare against the Persian host, were the scenes of servile insurrections such as that which about the same time raged in Sicily, and a democratic rising at Dyme not far from Patras called for repression. But the participation of many Greeks in the quarrel between Rome and Mithridates, King of Pontus, entailed far more serious consequences upon their country. While the warlike Cretans, who had not bowed as yet beneath the Roman yoke, sent their redoubtable archers to serve in his ranks, the Athenians were seduced from their allegiance by the rhetoric of their fellow-citizen, Athenion, or Aristion, a man of dubious origin, who had found the profession of philosopher so paying that he was now able to indulge in that of a patriot. Appointed captain of the city, he established a reign of terror, and included the Roman party and his own philosophic rivals in the same proscription. He despatched the bibliophile Apellikon, who had purchased the library of Aristotle, with an expedition against Delos, which failed; but a similar attempt by the Pontic forces was successful, and the prosperity of the island was almost ruined by their ravages. When the armies of Mithridates reached the mainland, there was a great rising against the Romans, and for the second time the plain of Chaironeia witnessed a battle, which on this occasion, however, was indecisive. A great change now took place in the fortunes of the war.[3] Sulla arrived in Greece, routed the Athenian philosopher and his Pontic colleague in a single battle, cowed most of the Greeks by the mere terror of his name, and laid siege to Athens and the Piræus, which offered a vigorous resistance. The groves of the Academy and the Lyceum furnished the timber for his battering rams; the treasuries of the most famous temples, those of Delphi, Olympia and Epidauros, provided pay for his soldiers; the remains of the famous “long walls,” which had united Athens with her harbour, were converted into siegeworks. The knoll near the street of tombs, on which a tiny church now stands, is supposed to be part of Sulla’s mound, and the bones found there those of his victims. An attempt to relieve the besieged failed; and, as their provisions grew scarce, the Athenians lost heart and sought to obtain favourable terms from the enemy. In the true Athenian spirit, they prayed for consideration on the ground that their ancestors had fought at Marathon. But the practical Roman replied that he had “not come to study history, but to chastise rebels[2],” and insisted on unconditional surrender. In 86 B.C. Athens was taken by assault, and many of the inhabitants were butchered; but, in spite of his indifference to the glories of Marathon, the conqueror consented to spare the fabric of the city for the sake of its ancient renown. The Akropolis, where Aristion had taken refuge, still held out, and the Odeion of Perikles, which stood at the south-east corner of it, perished by fire in the siege. Want of water at last forced the garrison to surrender, and the evacuation of the Piræus by the Pontic commander made Sulla master of that important position also. To the Piræus he showed as little mercy as Mummius had shown to Corinth. While from Athens he carried off nothing except a few columns of the temple of Zeus Olympios, a large sum of money which he found in the treasury of the Parthenon, and a fine manuscript of Aristotle and Theophrastos, he levelled the Piræus with the ground, and inflicted upon it a punishment from which it did not recover till the time of Constantine. Then he marched to Chaironeia, where another battle ended in the rout of the Pontic army, and the Thebans atoned for their rebellion by the loss of half their territory, which the victor consecrated to the temples of Delphi and Olympia as compensation for what he had taken from them. A fresh Pontic defeat at Orchomenos in Bœotia ended the war upon Greek soil, but the struggle long left its mark upon the country. Athens still retained her privileges, and the Cappadocian King Ariobarzanes II, Philopator and his son, restored the Odeion of Perikles[3], but many[4] of her citizens had died in the siege, and the rival armies had inflicted enormous injuries on Attica and Bœotia, the chief theatre of the war. Some small towns never recovered, and Thebes sank into a state of insignificance from which she did not emerge for centuries.

The pirates continued the work of destruction, which the first Mithridatic war had begun. The geographical configuration of the Ægean coasts has always been favourable to that ancient scourge of the Levant, and the conclusion of peace between Rome and the Pontic king let loose upon society a number of adventurers, whose occupation had ceased with the war. The inhabitants of Cilicia and Crete excelled above all others in the practice of this lucrative profession, and many were their depredations upon the Greek shores and islands. One pirate captain destroyed the sanctuaries of Delos and carried off the whole population into slavery; two others defeated the Roman admiral in Cretan waters. This last disgrace resulted in the conquest of that fine island by the Roman proconsul Quintus Metellus, whose difficult task fully earned him the title of “Creticus.” The islanders fought with the desperate courage which they have evinced in all ages. Beaten in the open, they retired behind the walls of Kydonia and Knossos, and when those places fell, a guerilla warfare went on in the mountains, until at last Crete surrendered, and the last vestige of Greek freedom in Europe disappeared in the guise of a Roman province. Meanwhile, Pompey had swept the pirates from the seas, and established a colony of those marauders at Dyme, the scene of the previous rebellion[4]. Neither before nor since has piracy been put down with such thoroughness in the Levant, and Greece enjoyed, for a time at least, a welcome immunity from its ravages.

But the administration of the provinces in the last century of the Roman Republic often pressed very heavily upon the unfortunate provincials. Even after making due deduction for professional exaggeration from the charges brought by Cicero against extortionate governors, there remains ample evidence of their exactions. The notorious Verres, the scourge of Sicily, though he only passed through Greece, levied blackmail upon Sikyon and plundered the treasury of the Parthenon, and bad governors of Macedonia, like Caius Antonius and Piso, had greater opportunities for making money at the expense of the Greeks. As Juvenal complained at a later period, even when these scoundrels were brought to justice on their return home, their late province gained nothing by their punishment, and Caius Antonius, in exile on Cephalonia, treated that island as if it were his private property. The Roman[5] money-lenders had begun, too, to exploit the financial necessities of the Greeks, and even so ardent a Philhellene as Cicero’s correspondent, Atticus, who owed his name to his long sojourn at Athens and to his interest in everything Attic, lent money to the people of Sikyon on such ruinous terms that they had to sell their pictures to pay off the debt. Athens, deprived of her commercial resources since the siege by Sulla, resorted to the sale of her coveted citizenship, much as some modern States sell titles, and subsisted mainly on the reputation of her schools of philosophy. It became the fashion for young Romans of promise to study there; thus Cicero spent six months there and revisited the city on his way to and from his Cilician governorship, and Horace tells us that he tried “to seek the truth among the groves of Academe[5].” Others resorted to Greece for purposes of travel or health, and the hellebore of Antikyra (now Aspra Spitia) on the Corinthian Gulf and the still popular baths of Ædepsos in Eubœa were fashionable cures in good Roman society. Moreover, a tincture of Greek letters was considered to be part of the education of a Roman gentleman. Cicero constantly uses Greek phrases in his correspondence, and Latin poets borrowed most of their plumes from Greek literature.

The two Roman civil wars which were fought on Greek soil between 49 and 31 B.C., were a great misfortune for Greece, whose inhabitants took sides as if the cause were their own. The struggle between Cæsar and Pompey was decided at Pharsalos in Thessaly, and most of the Greeks found that they had chosen the cause of the vanquished, whose exploits against the pirates and generous gift of money for the restoration of Athens were still remembered. But Cæsar showed his usual magnanimity towards the misguided Greeks, with the exception of the Megareans, whose stubborn resistance to his arms was severely punished. Most of the survivors of the siege were sold as slaves, and one of Cæsar’s officials, writing to Cicero a little later, says that as he sailed up the Saronic Gulf, the once flourishing cities of Megara, the Piræus and Corinth lay in ruins before his eyes[6]. It was Cæsar, however, who in 44 B.C., raised the last of these towns from its ashes. But the new Corinth, which he founded, was a Roman colony rather than a Greek city, whose inhabitants were chiefly freedmen, and whose name was at first associated with a lucrative traffic in antiquities, derived from the plunder of the ancient tombs. Had he lived, Cæsar had intended to dig a canal through the Isthmus—a feat reserved for the reign of the late King George. On Cæsar’s death, his murderer, Brutus, was enthusiastically welcomed by the Athenians, who erected[6] statues to him and Cassius besides those of the ancient tyrannicides, Harmodios and Aristogeiton. The struggle between him and the Triumvirs was decided at Philippi in Greek Macedonia, near the modern Kavalla, but had little effect upon the fortunes of Greece, though there were Greek contingents on either side. After the fall of Brutus, Antony spent a long time at Athens, where he flattered the susceptible natives by wearing their costume, amused them by his antics and orgies on the Akropolis, gratified them by the gift of Ægina and other islands, and scandalised them by the presence of Cleopatra, upon whom he expected them to bestow the highest honours. When the war broke out between him and Octavian for the mastery of the Roman world, Greece for the second time became the theatre of her masters’ fratricidal strife. At no previous time since the conquest had the unhappy country suffered such oppression as then. The inhabitants were torn from their homes to serve on the ships of Antony, the Peloponnese was divided into two hostile camps according to the sympathies of the natives, and in the great naval battle of Aktion the fleeing ship of Cleopatra was pursued by a Lacedæmonian galley. The geographer Strabo, who passed through Greece two years later, has left us a grim picture of the state of the country. Bœotia was utterly ruined; Larissa was the only town in Thessaly worth mentioning; many of the most famous cities of the Peloponnese were barren wastes; Megalopolis was a wilderness, Laconia had barely thirty towns; Dyme, whose citizens had taken to piracy again, was falling into decay. The Ionian Islands and Tegea formed pleasant exceptions to the general misery, but as an instance of the wretched condition of the Ægean, the islet of Gyaros was unable to pay its annual tribute of £5. The desolation of Greece impressed Octavian so deeply that he founded two colonies for his veterans on Hellenic soil, one in 30 B.C. on the spot where his camp had been pitched at the battle of Aktion, which received the name of Nikopolis (“City of victory”) in memory of that great triumph, the other at Patras, a site most convenient for the Italian trade. In both cases the numbers of the Roman colonists were augmented by the compulsory immigration of the Greeks who inhabited the neighbouring cities and villages. This measure had the bad effect of increasing the depopulation of the surrounding country, but it imparted immediate prosperity to both Patras and Nikopolis, and the factories of the former gave employment to numbers of women, while the celebration of the “Aktian games” at the latter colony attracted sight-seers from other places. Augustus, as Octavian was now called, made an important change in the administration of Greece, separating it from the Macedonian[7] command, with which it had hitherto been combined, and forming it in 27 B.C. into a separate senatorial province of Achaia, which was practically identical with the boundaries of the Greek kingdom before 1912, and of which Cæsar’s recently founded colony of Corinth was made the capital. But this restriction of the limits of the province did not affect the liberties of the different communities, though here and there Augustus altered their respective jurisdictions. Thus, in order to give Nikopolis a share in the Amphiktyonic Council, he modified the composition of that ancient body, and he enfranchised the Free Laconians who inhabited the central promontory of the Peloponnese, from Sparta; thus founding the autonomy which that rugged region has so often enjoyed[7]. But Athens and Sparta both continued to be “allies of Rome,” Augustus made a Spartan Prince of the Lacedæmonians, and honoured them by his own presence at their public meals. If he forbade the Athenians to sell the honour of citizenship, he allowed himself to be initiated in the Eleusinian mysteries, and his friend, Agrippa, presented Athens with a new theatre. As a proof of their loyalty and gratitude, the Athenians dedicated a temple on the Akropolis “to Augustus and Rome,” a large fragment of which may still be seen, and erected a statue of Agrippa, the pedestal of which is still standing in a perilous position at the approach to the Propylæa. It was in further honour of the master of the Roman world, that an aqueduct was constructed from the Klepsydra fountain to the Tower of the Winds, which the Syrian Andronikos had built at a somewhat earlier period of the Roman domination. The adjoining gate of Athena Archegetis was raised out of money provided by Cæsar and Augustus, a number of friendly princes proposed to complete the temple of Olympian Zeus, while an inscription still preserves the generosity of another ruler, Herod, King of the Jews, towards the home of Greek culture.

The land now enjoyed a long period of peace, and began to recover from the effects of the civil wars. A further boon was the transference of Achaia from the jurisdiction of the Senate to that of the Emperor soon after the accession of Tiberius, who, whatever his private vices may have been, was most considerate in his treatment of the provincials. He sternly repressed attempts at extortion, kept his governors in office for long terms, and, when an earthquake injured the city of Aigion on the gulf of Corinth, excused the citizens from the payment of taxes for three years. The restriction of the much-abused right of asylum[8] in various temples, such as that of Poseidon on the island of Tenos, and the delimitation of the Messenian and Lacedæmonian boundary, showed the interest of the Roman Government in Greek affairs; and the cult of the Imperial family, which was now developed in Greece, was perhaps due to gratitude no less than to the natural obsequience of a conquered race. The visit of the Emperor’s nephew, Germanicus, to Athens delighted the Athenians and scandalised Roman officialdom by the Imperial traveller’s disregard of etiquette; and it was insinuated by a prejudiced Roman even at that early period that these voluble burgesses, who talked so much about their past history, were not really the descendants of the ancient Greeks, but “the offscourings of the nations.” So deep was the impression made by the courtesy of Germanicus that, several years later, an impostor, who pretended to be his son Drusus, found a ready following in Greece, which he traversed from the Cyclades to Nikopolis. It became the custom, too, to banish distinguished Romans, who had incurred the Emperor’s displeasure, to an Ægean island, and Amorgos, Kythnos, Seriphos, and Gyaros were the equivalent of Botany Bay. The last two islets in particular were regarded with intense horror, and Juvenal has selected them as types of the worst punishment that could befall one of his countrymen[8]. Caligula, less moderate than Tiberius in his treatment of the Greeks, carried off the famous statue of Eros from Thespiæ, for which his unaccomplished plan of cutting the Isthmus of Corinth was no compensation. Claudius restored the stolen statue, and in 44 A.D. handed over the province of Achaia to the Senate—an arrangement which, with one brief interval, continued to be the practice of the Roman Government for the future. Meanwhile, alike under Senatorial and Imperial administration, the Greeks had acquired Roman tastes and had even adopted in many cases Roman names. If old-fashioned Romans complained that Rome had become “a Greek city,” where glib Hellenic freedmen had the ear of the Emperor and starving Greeklings were ready to practise any and every profession, the conservatives in Greece lamented the introduction of such peculiarly Roman sports as the gladiatorial shows, of which the remains of the Roman amphitheatre at Corinth are a memorial. The conquering and the conquered races had reacted on one another; the Romans had become more literary; the Greeks had become more material.

It was at this period, about 54 A.D., that an event occurred which profoundly modified the future of the Greek race. In, or a little before,[9] that year St Paul arrived at Athens, and, stirred by the idolatry of the city, delivered his famous speech in the midst of the Areopagos. The unvarnished narrative of the Acts of the Apostles does not disguise the failure of the great teacher’s first attempt to convert the argumentative Greeks, to whom the new gospel seemed “foolishness.” But “Dionysios the Areopagite and a woman named Damaris, and others with them,” believed, thus forming the small beginnings of the Church which grew up there in later days. From Athens the Apostle proceeded to Corinth, where he stayed “a year and six months.” The capital of Achaia and mart of Greece was a fine field for his missionary labours. The Roman colony, which had now been in existence almost a century, had become the home of commerce and the luxury which usually accompanies it. The superb situation, commanding the two seas, had attracted a cosmopolitan population, including many Jews, and the vices of the East and the West seemed to meet on the Isthmus—the Port Said of the Roman Empire. We may trace in the language of the two Epistles, which the Apostle addressed to the Corinthians later on, the main characteristics of the seat of Roman rule in Greece. The allusions to the fights with wild beasts, to the Isthmian games, to the long hair of the Corinthian dandies, to the easy virtue of the Corinthian women, all show what was the daily life of the most flourishing city of Greece in the middle of the first century. Yet even at Corinth many were persuaded by the arguments of the tent-maker, and a Christian community was founded at the port of Kenchreæ on the Saronic Gulf. At the outset the converts were of humble origin, like “the house of Stephanas, the first fruits of Achaia”; but Gaius, Tertius, Quartus, and “Erastus, the chamberlain of the city,” were persons of better position. That a man like Gallio, the brother of Seneca the philosopher and uncle of Lucan the poet, a man whom the other great poet of the day, Statius, has described as “sweetness” itself, was at that time governor of Achaia, shows the importance attached by the Romans to their Greek province. St Paul had not the profound classical learning of the governor’s talented family, but the two Epistles to the Thessalonians, which he wrote during this first stay at Corinth, have conferred an undying literary interest on the capital of Roman Greece. Silas and Timotheus joined the Apostle at that place; and after his departure the learned Alexandrian, Apollos, carried on the work of Christianity among the Corinthians. But the germs of those theological parties, which were destined later on to divide the Greek Christians, had already been planted in the congenial soil of Achaia. The Christian community of Corinth, with the fatal tendency to faction[10] which has ever marked the Hellenic race, was soon split up into sections, which followed, one St Paul, another Apollos, another the supposed injunctions of St Peter, another the simple faith of Christ. Even women, and that, too, unveiled, like the Laises of Corinth, had taken upon themselves to speak at Christian gatherings, and drinking and the other sensual crimes of that luxurious city had proved temptations too strong for some of the new converts. This state of things provoked the two Epistles to the Corinthians and the second visit of the Apostle to the then Greek capital, where he remained three months, writing on this occasion also two Epistles from Greece—that to the Romans and that to the Galatians. For the sake of the greater security which the land route afforded, he returned to Asia through Northern Greece, accompanied among others by St Luke, whose traditional connection with Greece may be traced in the wax figure of the Virgin, said to be his work, in the monastery of Megaspelæon, and in the much later Roman tomb venerated as his, at Thebes. With the exception of his delay at Fair Havens on the south coast of Crete, we are not told by the writer of the Acts that St Paul ever set foot on Greek territory again; but he left Titus in that island “to ordain elders in every city,” and contemplated spending a winter at Nikopolis. A tradition, unsupported, however, by good evidence, has been preserved to the effect that he was liberated from his Roman imprisonment, and it has been supposed that he employed part of the time that remained before his death in revisiting Corinth and Crete. His “kinsmen,” Jason and Sosipater, bishops of Tarsus and Ikonium, preached the Word at Corfù, where one of them was martyred, and where one of the two oldest churches of the island still preserves their names[9]. The Greek journey of the pagan philosopher, Apollonios of Tyana, who tried to restore the ancient life of Hellas and to check the Romanising tendencies of the age, took place only a few years after the first appearance of the Apostle of the Gentiles in Greece.

Another visitor of a very different kind next arrived in the classic land. Nero had already displayed his taste for the fine arts by despatching an emissary to Greece with the object of collecting statues for the adornment of his palace and capital. Delphi, Olympia and Athens, where, in the phrase of a contemporary satirist, “it was easier to meet a god than a man,” furnished an ample booty, and the Thespians again lost, this time for ever, the statue of Eros. But Nero was not content with the sculpture of Greece; he yearned to display his manifold talents before a Greek audience, “the only one,” as he said, “worthy[11] of himself and his accomplishments.” Accordingly, in 66, he crossed over to Kassopo in Corfù, and began his theatrical tour by singing before the altar of Zeus there. Such was the zeal of the Imperial pot-hunter, that he commanded all the national games to be celebrated in the same year, so that he might have the satisfaction of winning prizes at them all in the same tour. In order to exhibit his musical gifts, he ordered the insertion of a new item in the time-honoured programme at Olympia, where he built himself a house, and at Corinth broke the Isthmian rules by contending in both tragedy and comedy. As a charioteer he eclipsed all previous performances by driving ten horses abreast, upsetting his car and still receiving the prize from the venal judges; as a victor, he had the effrontery to proclaim his own victory, and the number of his wreaths might have done credit to a royal funeral. In return for their compliance, the Greeks were informed by the voice of the Emperor himself on the day of the Isthmian games that they were once more free from the jurisdiction of the Senate and exempt from the payment of taxes[10]. The name of freedom and the practical advantage of fiscal immunity appealed with force to the patriotic and commercial sides of the Greek character, and outweighed the extortions of the Emperor and his suite to such a degree that Nero became a popular hero, in whose honour medals were struck and statues erected. To signalise yet further his stay in Greece, he bade the long projected canal to be dug across the Isthmus. This time the work was actually begun, and a prominent philosopher, who had incurred the Imperial displeasure, was seen digging away with a gang of other convicts. Nero himself dug the first sod with a golden spade, and carried away the first spadefuls of earth in a basket on his shoulders. But the task, of which traces may still be seen, was soon abandoned, and the dangers which threatened his throne recalled the Emperor to Italy. But first he consulted the Oracle of Delphi, which fully maintained its ancient reputation for obscurity and accuracy, but was bidden henceforth to be dumb. The two most celebrated seats of Greek antiquity, Athens and Sparta, he left, however, unvisited—Sparta, because he disapproved of its institutions; Athens, because he, the matricide, feared the vengeance of the Furies, whose fabled shrine was beneath the Areopagos[11].

The civil war, which raged in Italy between the death of Nero and the accession of Vespasian, had little influence upon Greece, except that it gave an adventurer, who bore a striking resemblance to the late[12] Emperor and shared his musical tastes, the opportunity of personating him. But this pretender, who had made himself master of the island of Kythnos, was soon suppressed[12], and Vespasian, as he visited Greece on his way from the East to Rome, could calmly study the condition of that country. The stern old soldier, who, in spite of his Greek culture, had fallen asleep during Nero’s recitations, had no sympathy with Greek antiquities, and maintained that the Hellenes did not know how to use their newly-restored freedom, which had involved the impoverished Roman exchequer in the loss of the Greek taxes. He accordingly restored the organisation and fiscal arrangements which had been in force before Nero’s proclamation, only that the province of Achaia under the Flavian dynasty no longer included Thessaly, Epeiros, and Akarnania. For a long time Greece had no political history; but we know that Domitian, like Tiberius, was as considerate towards the provincials as he was tyrannical to the Roman nobles; that he cherished a special cult for the goddess Athena; and that he deigned to allow himself to be nominated as Archon Eponymos of Athens for the year 93—an instance which shows the continuance of an institution which had been founded nearly eight centuries earlier. Trajan’s direct connection with Greece was limited to a stay at Athens on the way to the Parthian war, but he counted among his friends the most celebrated Greek author of that age, the famous Plutarch, who passed a great part of his time in the small Bœotian town of Chaironeia, where his so-called “chair,” obviously the end seat of one of the rows in the theatre, may still be seen in the little church. Like Polybios in the first period of the Roman conquest, Plutarch served as a link to unite the Greeks and their masters. At once an Hellenic patriot and an admirer of Rome, he combined love of the past independence of his country with a shrewd sense of the advantages of Roman rule in the existing circumstances. True, the Greece of his time was very different from that of the Golden Age. While the single city of Megara had sent 3000 heavy armed men to the battle of Platæa, the whole province of Achaia could not raise a larger number in his days. Depopulation was going on apace; Eubœa was almost desolate, and the inland towns of the mainland were mostly losing their trade, which was gravitating to the coasts. The expenditure of the Greek taxes at Rome led to the want of funds for public objects, and the Roman system of making immunity from taxation a principle of Roman citizenship divided the Greeks into two classes, the rich and the poor. The former led luxurious lives, built expensive houses, added acre to acre, and fell into the[13] hands of the foreign money-lenders of Corinth or Patras. The latter sank lower and lower in the social scale, and it was noticed that, while the Greek women had become more beautiful, the classic grace of Hellenic manhood had declined. But Greece continued to exercise her perennial charm on the cultured traveller. In spite of the Thessalian brigands, tourists journeyed to see the Vale of Tempe, and a race of loquacious guides arose, whose business it was to explain the history of Delphi. Men of the highest rank were proud to be made Athenian citizens, and one of them, Antiochos Philopappos, grandson of the last king of Kommagene, was commemorated in the last years of Trajan by the monument which is to-day one of the most conspicuous in all Athens.

The reign of Hadrian was a very happy period for the Greeks. A lover of both ancient and contemporary Hellas, which he visited several times, the Imperial traveller left his mark all over the country. We may gather from Pausanias, whose own wanderings began at this period, that there was scarcely a single Greek city of importance which had not received some benefit from this Emperor. Coins of Patras describe him as “the restorer of Achaia,” Megara regarded him as her “second founder,” Mantineia had to thank him for the restoration of her classical name. Alive to the want of through communication between the Peloponnese and Central Greece, he built a safe road along the Skironian cliffs, where now the tourist looks down on the azure sea from the train that takes him from Megara to Corinth. He provided the latter city with water by means of an aqueduct from Lake Stymphalos, and began the aqueduct at Athens which was completed by his successor. But this was only one of his many Athenian improvements. His affection for Athens, where he lived as a Greek among Greeks and had held the office of Archon Eponymos, like Domitian, led him to assign the revenues of Cephalonia to the Athenian treasury, to regulate the oil-trade, that important branch of Attic commerce, his edict about which may still be read on the gate of Athena Archegetis, to repair the theatre of Dionysos, and to present the city with a Pantheon, a library, contained within the Stoa which still bears his name and of which part is still standing, and a gymnasium. He also built there a temple of Hera, and completed that of Zeus Olympios, which had been begun by Peisistratos more than six centuries before and had provided Sulla with spoil. The still standing columns of this magnificent building formed the nucleus of the “new Athens,” which he founded outside “the old city of Theseus,” and to which the Arch of Hadrian, as the inscriptions upon it show, was intended as the[14] entrance. With another of his foundations, the temple of Zeus Panhellenios, was connected the institution of the Panhellenic festival, which represented the unity of the Greek race and, like the more ancient games, had a religious basis. Hadrian called into existence a synod of “Panhellenes,” composed of members of the Greek communities on both sides of the Ægean, who met at Athens and whose treasurer was styled “Hellenotamias,” or “steward of the Hellenes”—a title borrowed from the classical Confederacy of Delos. In name, indeed, the golden age of Athens seemed to have returned, and the enthusiastic Athenians heaped one honour after another upon the head of the great Philhellene. They adored him as a god, and the President of the Panhellenic synod became his priest; his statues rose all over the city, his name was bestowed upon one of the months, a thirteenth tribe was formed and called after him, and the thirteen wedges of the repaired theatre of Dionysos contained each a bust of Hadrian; even an unworthy favourite of the Emperor was dubbed a deity with the same ease that we convert a charitable tradesman into a peer.

Hadrian’s two immediate successors continued his Philhellenic policy. Antoninus Pius erected new buildings for the use of the visitors to that fashionable health-resort, the Hieron of Epidauros; and in graceful recognition of the legend, according to which the founders of the first settlement on the Palatine were emigrants from Pallantion in Arkadia, raised that village to the rank of a city, with the privileges of self-government and immunity from taxes. Marcus Aurelius seemed to have realised the Utopian ideal of Plato, that philosophers should be kings or kings philosophers. The Imperial author of the Meditations wrote in Greek, had sat at the feet of Greek teachers, and greatly admired the products of the Greek intellect. But his reign was disturbed by warlike alarms, and it is noteworthy that at this period the first of those barbarian tribes from the North, which inflicted so much injury upon Greece in later centuries, penetrated into that country. The Greeks showed, however, that they had not in the long years of peace, forgotten how to defend themselves. At Elateia the Kostobokes—such was the name of the marauders—received a check from a local force and withdrew beyond the frontier[13]. In spite of his distant campaigns, Marcus Aurelius found time to visit Athens, restored the temple at Eleusis, was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries, and founded in 176 the Athenian University. It was, indeed, the heyday of Academic life, and Athens was under the Antonines the happy hunting-ground of professors, who received salaries from the Imperial exchequer, and[15] enjoyed the privilege of exemption from costly public duties. One of their number, Herodes Atticus of Marathon, has, by his splendid gifts to the city, perpetuated his fame to our own time. His vast wealth, united to his renown as a professor of rhetoric, not only made him the most prominent man in Athens, where he held the post of President of the new Panhellenic synod, but gained him the Roman consulship, the friendship of Hadrian, and the honour of instructing the early years of Marcus Aurelius. When Verus, the colleague of the latter in the Imperial dignity, visited Athens, it was as the guest of the sophist of Marathon; when the University was founded, it was Herodes who selected the professors. The charm of his villas at Kephisia, then, as now, the suburban pleasaunce of the dust-choked Athenians, and in his native village, has been extolled by one of his pupils, while the Odeion which still bears his name was erected by him to the memory of his second wife[14]. He also restored the Stadion, which had been built by Lykourgos about five centuries earlier, and within its precincts his body was interred. There still exist remains of his temple of Fortune, a goddess of whom he had varied experiences. For his vast wealth and the sense of their own inferiority caused the Athenians to revile their benefactor, and as many of them owed him money, he was naturally regarded as their enemy until his death. Many other Greek cities benefited by his liberality; he built a theatre at Corinth and restored the bathing establishment at Thermopylæ; and he was even accused of making life too easy for his fellow-countrymen because he provided Olympia with pure water by means of an aqueduct, of which the Exedra is still visible.

It was at this period, too, that the traveller Pausanias wrote his famous Description of Greece, a work which gives a faithful account of that country as it struck his observant eyes. Compared with what it had been in Strabo’s time, the land seemed prosperous in the age of the Antonines, though some districts had never recovered from the ravages of the Roman wars. Much of Bœotia was still in the desolate state in which Sulla had left it; Ætolia had not been inhabited since Octavian carried off its population to Nikopolis; the lower town of Thebes was quite deserted, and the ancient name was then, as now, confined to the ancient Akropolis, while the sole occupants of Delos were the Athenians sent to guard the temple. But Delphi was in a flourishing condition, the Roman colonies of Patras and Corinth continued to prosper, and among the ancient cities of the Peloponnese, Argos and Sparta still held the foremost rank, while the much more[16] modern Megalopolis, upon which such high hopes had been built, shared the fate of Tiryns and Mycenæ. Moreover, despite the robbery of statues by Romans from Mummius to Nero, Pausanias found a vast number of ancient masterpieces all over the country, and even the paintings, with which Polygnotos had adorned the Stoa Poikile at Athens, were still visible. As for the relics of classical lore and prehistoric legend, they abounded in every city that could boast of a hero, and the remark of Cicero was as true in the time of Pausanias, that in a Greek town one came upon the traces of history at every step. In the second century, too, good Doric was still spoken by the Messenians; and, if the pure Attic of Plato had been somewhat corrupted at Athens by the presence of many foreign students, it was still preserved in all its glory by the peasants of Attica. The writings of Lucian at this period show how even a Syrian could, by long residence at Athens, acquire a masterly gift of Attic prose. The illusion of a classical revival was further kept up by the continuance of ancient institutions, even though they had lost the reality of power. Pausanias mentions the existence, and describes the composition, of the Amphiktyonic Council in his time, when it was still the guardian of the Delphic oracle. The Court of the Areopagos preserved its ancient forms at Athens; the Ephors and other Spartan authorities had survived the disapproval of Nero; the Confederacy of the Free Laconians, though reduced in size, still included eighteen cities; Bœotia and Phokis enjoyed the privilege of local assemblies. The great games still attracted competitors and spectators; the great oracles still found some believers, who consulted them; and the old religion, if it had little moral force, was, at least in externals, still that of the majority, though philosophers regretted it and enlightened persons like Pausanias inclined to a rational interpretation of the myths, and told stories of bribes administered to the Pythian priestess. Christianity had made little progress in Greece during the three generations that had elapsed since the last visit of St Paul. Mention is, indeed, made by the Christian historian, Eusebius, of large communities at Larissa, Sparta, and in Crete; but Corinth still remained the chief seat of the new faith, and the Corinthian Christians still retained that factious spirit which St Paul had rebuked. Athens, as the home of philosophy, was little favourable to the simplicity of the Gospel; but the celebrated Athenian philosopher, Aristides, was not only converted to Christianity, but presented an Apology for that creed to Hadrian during his residence in the city; while another Athenian, Hyginos, was chosen Pope in the age of the Antonines. Anacletos, the second (or, in other lists, fourth) Bishop of Rome after[17] St Peter, is said to have been a native of Athens, and a third, Xystos, perished, as Pope Sixtus II, in the persecution of Valerian. The tradition that Dionysios the Areopagite, became first Bishop of Athens[15], and there gained the crown of martyrdom, and that St Andrew suffered death at Patras, has been cherished, and in the case of Patras has had a considerable historical influence.

With the death of Marcus Aurelius the series of Philhellenic Emperors ended, and the Roman civil wars in the last decade of the second century occupied the attention of the Empire. Without taking an active part in the struggle, Greece submitted to the authority of Pescennius Niger, one of the unsuccessful candidates, and this temporary error of judgment may have induced the Emperor Septimius Severus to inflict a punishment upon Athens, the cause of which is usually ascribed to a slight which he suffered during his student days there. His successor, Caracalla, by extending the Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the Empire, gave the Greeks an opportunity, of which they were not slow to avail themselves. From that moment the doors of the Roman administration were thrown open to all the races of the Roman dominions, and the nimble-witted Greeks so obtained a predominance in that department such as they acquired much later under Turkish rule. From that moment, too, they considered themselves as “Romans,” and the name stuck to them long after the Roman Empire had passed away. But Caracalla, while he thus made them the equals of the Romans in the eyes of the law, increased the taxes which it had long been the privilege of Roman citizens to pay, while he continued to exact those which the provincials had paid previous to their admission to the citizenship. The reductions made by his successors, Macrinus and Alexander Severus, were to a large extent neutralised by the great depreciation of the currency, which began under Caracalla and continued for the next half century. The Government paid its creditors in depreciated money, but took good care that the taxes were paid in good gold pieces. The worst results followed: officials were tempted, like the modern Turkish Pashas, to recoup themselves by extortion for the diminution in their salaries; trade with foreign countries became uncertain, even the specially thriving Greek industries of marble and purple dye must have been affected, and possessors of good coin buried it in the ground. Amid this dismal scene of decay, Athens continued to preserve her reputation as a University town. Though no longer patronised by cultured Emperors, she still attracted numbers of pupils to her lecture rooms; and the name[18] of Longinus, author of the celebrated treatise, On the Sublime, adorns the scanty Athenian annals of this period. That the drama was not neglected is clear from the inscription which records the restoration of the theatre of Dionysos by the Archon Phaidros during this period. But the philosophers and playgoers of Athens were soon to be roused by the alarm of an invasion such as their city had not experienced for many a generation.

Hitherto, with the unimportant exception of the raid of the Kostobokes as far as Elateia, Greece had never been submitted to the terrors of a barbarian inroad since the Roman Conquest, The Roman Empire had protected Achaia from foreign attack, and even the least friendly of the Emperors had allowed no one to plunder the art treasures of the Greek cities except their own occasional emissaries. Hence the Greece of the middle of the third century preserved in many respects the same external appearance as that of the same country four hundred years earlier. But this blessing of peace, which Rome had conferred upon the Greeks, had had the bad effect of training up a nation which was a stranger to the arts of war. Caracalla, indeed, had raised a couple of Spartan regiments; but the local militia of the Greek cities had had no experience of fighting, and the fortifications of the country had been allowed to fall into ruin. Such was the state of the Greek defences when in 250 the Goths crossed the Balkans and entered what is now South Bulgaria. Measures were at once taken to defend the Greek provinces. Claudius, afterwards Emperor, was ordered to occupy the historic pass of Thermopylæ, but his forces were small and most of them had been newly enrolled. The death of the Emperor Decius, fighting against the Goths, increased the alarm, and the siege of Salonika thoroughly startled the Greeks. No sooner had Valerian mounted the Imperial throne, than they signalised his reign by repairing the walls of Athens, which had been neglected since the siege of Sulla[16], and it was perhaps at the same time that a fort and a new gate were erected for the defence of the Akropolis[17]. As a second line of defence the fortifications across the Isthmus were restored, and occupied, just as by Peloponnesian troops of old on the approach of the Persian host. But these preparations did not long preserve the country from the attacks of the Goths. Distracted by the rival claims of self-styled[19] Emperors, Valens in Achaia, and Piso in Thessaly, who had availed themselves of the general confusion to declare their independence, and visited by a terrible plague which followed in the wake of the Roman armies, the Greeks soon had the Gothic hosts upon them. A first raid was repulsed, only to be repeated in 267 on a far larger scale. This time the Goths and fierce Heruli arrived by sea, and, after ravaging the storied island of Skyros, captured Argos, Sparta, and the lower city of Corinth. Athens herself was surprised by the enemy, before the Emperor Gallienus, whose admiration for the ancient city had been shown by his initiation into the Eleusinian mysteries and his acceptance of the Athenian citizenship with the office of Archon Eponymos, could send troops to her assistance. But at this crisis in her history, Athens showed herself worthy of her glorious past. At that time one of her leading citizens was the historian Dexippos, whose writings on the Scythian wars, preserved now only in fragments, were favourably compared by a Byzantine critic with those of Thucydides[18]. But Dexippos, if a less caustic writer, was a better general, than the historian of the Peloponnesian war. He assembled a body of Athenians, addressed them in a fiery harangue, a fragment of which still exists[19], and reminded them that the event of battles was usually decided by bravery rather than by numbers. Marshalling his troops in the Olive Grove, he accustomed them little by little to the noise of the Gothic war cries and the sight of the Gothic warriors. The arrival of a Roman fleet effected a timely diversion, and the barbarians, taken between two hostile forces, abandoned Athens and succumbed to the Emperor’s arms on their march towards the North. Fortunately they seem to have spared the monuments of the city during their occupation, and we are told that the Athenian libraries were saved from the flames by the deep policy of a shrewd Goth, who thought that the pursuit of literature would unfit the Greeks for the art of war[20]. Dexippos, who proved by his own example the compatibility of learning with strategy, has been commemorated in an inscription, which praises his merits as a writer, but is silent about his fame as a maker, of history—known to us from a single sentence of the Latin biographer of Gallienus[21]. Yet at that moment Greece needed men of action rather than men of letters. For another Gothic invasion took place two years later, and from Thessaly to Crete the vessels of the barbarians harried the coasts. But the interval had been used to put the defences of the cities into[20] repair; and such was the ill-success of the invaders, who could not take a single town, that they did not renew the attack. For more than a century the land was spared the horrors of a fresh Gothic war. The great victory of the Emperor Claudius II over the Goths at Nish and the abandonment of what is now Roumania to them by his successor Aurelian secured the peace of Achaia. Although the three invasions had resulted in the loss of a considerable amount of moveable property and of many slaves, who had either been carried off as captives or had escaped from their Greek masters to the Gothic ranks, the recovery of Athens and Corinth seems to have been so rapid that seven years after the last raid they were among the nine cities of the Empire to which the Roman Senate wrote announcing the election of the Emperor Tacitus and bidding them direct any appeals from the Proconsul to the Prefect of the City of Rome—a clear proof of their civic importance.

But the Greeks soon looked for the fountain of justice elsewhere than on the banks of the Tiber. With the reign of Diocletian began the practice of removing the seat of Government from Rome, and that Emperor usually resided at Nicomedia. His establishment of four great administrative divisions of the Empire really separated the two Eastern, in which Greece was comprehended, from the two Western, and prepared the way for the foundation of Constantinople by Constantine and the ultimate division of the Eastern and Western Empires. Diocletian’s further increase in the number of the provinces, several of which were grouped under one of the Dioceses, into which the Empire was split up for administrative purposes, had the double effect of altering the size of the Greek provinces, and of scattering them over several Dioceses. Thus Achaia, Thessaly, “Old” Epeiros (as the region round Nikopolis was now called), and Crete, formed four separate provinces included in the Mœsian Diocese, the administrative centre of which was Sirmium, the modern Mitrovitz. The Ægean islands, on the other hand, composed one of the provinces of the Asian Diocese. The province of Achaia had, however, the privilege of being administered by a Proconsul, who was an official of more exalted rank than the great majority of provincial governors. Side by side with these arrangements, the currency reform of Diocletian and the edict by which he fixed the highest price of commodities cannot fail to have affected the trade of Greece, while his love of building benefited the Greek marble quarries.

After the abdication of Diocletian the Christians of Greece were visited by another of those persecutions, of which they had had experience under the Emperor Decius half a century earlier. But on[21] neither occasion were the martyrdoms numerous, except in Crete, and it would appear that Christianity in Greece was less prosperous, or less progressive, than the same creed in the great cities of the East, where the victims were far more numerous. Constantine’s toleration made him as popular with the Greek Christians as his marked respect for the Athenian University made him with the Greek philosophers, and it is, therefore, no wonder that in his final struggle against his rival, Licinius, he was able to collect a Greek fleet, which mustered in the harbour of the Piræus, then once more an important station, and forced for him the passage of the Dardanelles. But the reign of Constantine, although he found a biographer in the young Athenian historian, Praxagoras[22], was not conducive to the national development of Greece. Adopting the administrative system of Diocletian, he continued the practice of dividing the Empire into four great “Prefectures,” as they were now called, each of which was subdivided into Dioceses, and the latter again into provinces. The four Greek provinces of Thessaly, Achaia (including some of the Cyclades and some of the Ionian Islands), Old Epeiros (including Corfù and Ithake), and Crete (of which Gortyna was the capital), formed part of the Diocese of Macedonia in the Prefecture of Illyricum, whereas the rest of the Greek islands composed a distinct province of the Asian Diocese in the Prefecture of the Orient. Thus, the Greek race continued to be split into fragments, while at the same time the levelling tendency of Constantine’s administration gradually swept away those Greek municipal institutions, which had hitherto survived all changes, and thus the inhabitants of different parts of the country began to lose their peculiar characteristics. A few time-honoured vestiges of ancient Greek freedom existed for some time longer; thus the Areopagos and the Archons of Athens and the provincial assembly of Achaia may be traced on into the fifth century. But their place was taken by the new local senates, composed of so-called Decuriones, who were chosen from the richest landowners, and who had to collect, and were held personally responsible for, the amount of the land-tax. This onerous office was made hereditary, and there was no means of escaping it except by death or flight to a monastic cell; even a journey outside the country required a special permit from the governor, and the rich Decurio, like the mediæval serf, was tied down to the land which he was so unfortunate as to own. Even an Irish landlord’s lot seems happy compared with that of a Greek Decurio, nor was the provincial who escaped the unpleasant privilege of serving the State[22] in that capacity greatly to be envied. The exaction of taxes became at once more stringent and more regular—a combination peculiarly objectionable to the Oriental mind—and the re-assessment of their burdens every fifteen years led the people to calculate time by the “Indictions,” or edicts in which, with all the solemnity of purple ink, the Emperor fixed the amount of the imposts for this new cycle of taxation. That the ruler himself became conscious of the inequalities of his subjects’ contributions was evident half a century later when Valentinian I allowed the citizens of each municipality to elect an official, styled Defensor, whose duty it was to defend his fellow-citizens before the Emperor against the fiscal exactions of the authorities.

The transference of the capital to Constantinople, enormous as its ultimate results have proved to be, was at first a disadvantage to the inhabitants of Greece. We are accustomed to look on the centre of the Byzantine Empire as a largely Greek city, but it must be remembered that, at the outset, it was Roman in conception and that its language was Latin. Almost immediately, however, it began to drain Greece of its population, attracted by the prospects of work and the certainty of “bread and games” in the New Rome. In the days of Demosthenes Byzantium had been the granary of Athens; now Attica, always unproductive of wheat, began to find that Constantine’s growing capital had to import bread-stuffs for its own use, and the Athenians were thankful for an annual grant of corn from the Emperor. The founder wanted, too, Greek works of art to adorn his city, and 427 statues were placed in Sta Sophia alone; the Muses of Helikon were carried off to the palace of the Emperor; the serpent column, which the grateful Greeks had dedicated at Delphi after the battle of Platæa, was set up in the Hippodrome, where one of its three heads was struck off by the battle-axe of Mohammed II.

The conversion of Constantine to Christianity had the natural effect of bringing within the Christian ranks those lukewarm pagans who took their religious views from the Emperor. But the comparative immunity from persecution which the Christians of Greece had enjoyed under the pagan ascendancy led them to treat their opponents with the same mildness. There was no reaction, because there had been no revolution, and the devotees of the old and the new religion went on living peaceably side by side. The even greater temptation to the subtle Greek intellect to indulge in the wearisome Arian controversy, which so long convulsed a large part of the Church in the East, was rejected owing to the fortunate unanimity of the bishops who were sent from Greece to attend the Council of Nice.[23] Their strong and united opposition to the heresy of Arius was re-echoed by their flocks at home, and the Church, undivided on this crucial question, became more and more identified with the people. After Constantine’s death the harmony between the pagans and the Christians was temporarily disturbed. Under Constantius II the public offerings ceased, the temples were closed, the oracles fell into disuse; under Julian the Apostate a final attempt was made to rehabilitate the ancient religion. Julian seemed, indeed, to the conservative party in Greece to have restored for two brief years the silver age of Hadrian, if not the golden age of Perikles. The jealousy of Constantius, by sending him in honourable exile to Athens, had made him an enthusiastic admirer of not only the literature but the creed of the old Hellenes. It was at that time that he abjured Christianity and was initiated into the Eleusinian mysteries, and when he took up arms against Constantius it was to the Corinthians, Lacedæmonians, and Athenians that he addressed Apologies for his conduct. These manifestoes, of which that to the Athenians is still extant among the writings of Julian, had such an effect upon the Greeks, flattered no doubt by such an attention, that they declared in his favour, and on his rival’s death they had their reward. The temples were re-opened, the altars once more smoked with the offerings of the devout, the great games were revived, including the Aktian festival of Augustus, which had fallen into decline with the falling fortunes of Nikopolis. Julian restored that city and others like it, and the Argives did not appeal in vain for a rehearing of a wearisome law-suit with Corinth to an Emperor who was steeped to the lips in classic lore. At Athens he purged the University by excluding Christians from professorial chairs, Christian students were often converted, like the Emperor, by the genius of the place, and the University became the last refuge of Hellenism in Greece, when Julian’s attempted restoration of the old order of things collapsed at his death. Throughout this period, indeed, the University of Athens was not only the chief intellectual centre of the Empire—for Rome had ceased, and the newly founded University of Constantinople had not yet begun, to attract the best intellects—but it was the all-absorbing institution of the city. Athenian trade had gone on decaying, and under Constans, the son of Constantine, the people of Athens were obliged to ask the Emperor for the grant of certain insular revenues, which he allowed them to devote to the purchase of provisions. So Athens was now solely a University town, and the ineradicable yearning of the Greeks for politics found vent, in default of a larger opening, in such academic struggles as the election of a professor or the merits of the rival corps[24] of students. These corps, each composed as a rule of students from the same district, kept Athens alive with their disputes, which sometimes degenerated into pitched battles calling for the intervention of the Roman governor from Corinth. So keen was the competition between them, that their agents were posted at the Piræus to accost the sea-sick freshman as soon as he landed and enlist him in this or that corps. Each corps had its favourite professor, for whose class it obtained pupils, by force or argument, and whose lectures it applauded whenever the master brought out some fresh conceit or distorted the flexible Greek language into some new combination of words. The celebrated sophist Libanios, and the poetic divine, Gregory of Nazianzos, respectively the apologist and the censor of Julian, have left us a graphic sketch of the student life in their time at Athens, when the scarlet and gold garments of the lecturers and the gowns of their pupils mingled in the streets of the ancient city, which still deserved in this fourth century the proud title of “the eye of Greece.”

The triumph of paganism ceased with the death of Julian; but his successor Jovian, though he ordered the Church of the Virgin to be erected at Corfù out of the fragments of a heathen temple opposite the royal villa[23], proclaimed universal toleration. His wise example was followed by Valentinian I, who repealed Julian’s edict which had made the profession of paganism a test of professorial office at Athens, and allowed his subjects to approach heaven in what manner they pleased. The Greeks were specially exempted from the law forbidding nocturnal sacrifices because it would “make their life unendurable.” The Eleusinian mysteries were permitted to be celebrated, and Athens continued to derive much profit from those festivals. It was fortunate for the Greeks that, at the partition of the Empire between him and Valens in 364, the Prefecture of Illyricum, which included the bulk of the Greek provinces, was joined to the Western half, and thus fell to his share. His reign marked the last stage of that peaceful development which had gone on in Greece since the Gothic invasion of the previous century. A few years after his death the Emperor Theodosius I publicly proclaimed the Catholic faith to be the established creed of the Empire, and proceeded to stamp out paganism with all the zeal of a Spaniard. The Oracle of Delphi was closed for ever, the temples were shut, and in 393 the Olympic games, which had been the rallying point of the Hellenic race for untold centuries, ceased to exist. As a[25] token of their discontinuance the statue of Zeus, which had stood in the temple of the god at Olympia, was removed to Constantinople, and the time-honoured custom of reckoning time by the Olympiads was definitely replaced by the prosaic cycle of Indictions. Yet Athens still remained a bulwark of the old religion, and the preservation of that city from the great earthquake which devastated large parts of Greece in 375 was attributed to the miraculous protection of the hero Achilles, whose statue had been placed in the Parthenon by the venerable hierophant of the Eleusinian mysteries.

But a worse evil than earthquakes was about to befall the Greeks. After more than a century’s peace, the Goths crossed the Balkans and defeated the Emperor Valens in the battle of Adrianople. The Greek provinces, entrusted for their better defence to the strong arm of Theodosius, escaped for the moment with no further loss than that caused by a Gothic raid in the North and by the brigandage which is the natural result of every war in the Balkan Peninsula. But, on the death of that Emperor and the final division of the Roman Empire between his sons, Honorius and Arcadius, in 395, the Goths, under their great leader, Alaric, attacked the now divided Prefecture of Illyricum. The evil results of the complete separation of the Eastern from the Western Empire were at once felt. The Greek provinces, which had just been attached to the Eastern system, might have been saved from this incursion if the Western general, Stilicho, had been permitted by Byzantine jealousy to rout the Goths in Thessaly. As the arm of that great commander was thus arrested in the act of striking, Alaric not only was able to penetrate into Epeiros as far as Nikopolis, which at that time almost entirely belonged to St Jerome’s friend, the devout Paula, but he marched over Pindos into Thessaly, defeated the local militia, and turned to the South upon Bœotia and Attica. The last earthquake had laid many of the fortifications in ruins, the Roman army of occupation was small, and its commander unwilling to imitate the conduct of Leonidas at Thermopylæ. The monks facilitated the inroad of a Christian army. The famous fortifications of Thebes had been restored, but they did not check the course of the impetuous Goth, who, leaving them unassailed, went straight to Athens. A later pagan historian has invented the pleasing legend that Pallas Athena and the hero Achilles appeared to protect the city from the invaders. But the Goths, who were not only Christians but Arian heretics, would have been little influenced by such an apparition. Athens capitulated, and Alaric, who bade spare the holy sanctuaries of the Apostles when, fifteen years later, he entered Rome, abstained from destroying the[26] artistic treasures of which Athens was full. But the great temple of the mysteries at the town of Eleusis, and that town itself, so intimately associated with that ancient cult, were sacrificed either to the fanaticism of the Arian monks who followed the Gothic army, to the cupidity of the troops, or to both. The last hierophant seems to have perished with the shrine, of which he was the guardian, and a pagan apologist saw in his fall the manifest wrath of the gods, angry at the usurpation of that high office by one who did not belong to the sacred family of the Eumolpidæ. Henceforth the Eleusinian mysteries ceased to exist, and the home of those great festivals is now a sorry Albanian village, where ruins still mark the work of the destroyer. Megara shared the fate of Eleusis, the Isthmus was left without defenders, and Corinth, Argos, and Sparta were sacked. Those who resisted were cut down, their wives carried off into slavery, their children made to serve a Gothic master. Even a philosopher died of a broken heart at the spectacle of this terrible calamity. Fortunately, Alaric’s sojourn in the Peloponnese was shortened by the arrival of Stilicho with an army in the Gulf of Corinth. The Goths withdrew to the fastnesses of Mount Pholoe, between Olympia and Patras, and it seemed as if Stilicho had only to draw his lines around them and then wait for hunger to do its work. But from some unexplained cause—perhaps a court intrigue at Constantinople, perhaps the negligence of the general—Alaric was allowed to escape over the Gulf of Corinth into Epeiros. After devastating that region he was rewarded by the Government of Constantinople with the office of Commander-in-Chief of the Imperial forces in the Eastern half of Illyricum, which comprised the scenes of his recent ravages. The principle of converting a brigand into a policeman has often proved successful, but there were probably many who shared the indignant feelings of the poet Claudian[24] at this sudden transformation of “the devastator of Achaia” into her protector. But Alaric could not rebuild the cities, which he had destroyed; he could not restore prosperity to the lands, which he had ravaged. We have ample evidence of the injury which this invasion had inflicted upon Greece in the legislation of Theodosius II in the first half of the next century. Two Imperial edicts remitted sixty years’ arrears of taxation; another granted the petition of the people of Achaia that their taxes might be reduced to one-third of the existing amount on the ground that they could pay no more; while yet another relieved the Greeks from the burden of contributing towards the expenses of the public games at Constantinople. There is proof, too, in the pages of a contemporary[27] historian, as well as in the dry paragraphs of the Theodosian Code, that much of the land had been allowed to go out of cultivation and had been abandoned by its owners. Athens, however, had survived the tempest which had laid waste so large a part of the country. True, we find the philosopher Synesios, who visited that seat of learning soon after Alaric’s invasion, writing sarcastically to a correspondent, that Athens “resembled the bleeding and empty skin of a slaughtered victim,” and was now famous for its honey alone. But the disillusioned visitor makes no mention of the destruction of the buildings, for which the city was renowned. Throughout the vicissitudes of the five and a half centuries, which we have traversed since the Roman Conquest, one conqueror after another had spared the glories of Athens, and even after the terrible calamity of this Gothic invasion she remained the one bright spot amid the darkness which had settled down upon the land of the Hellenes.

The period of more than a century which separated Alaric’s invasion from the accession of Justinian was not prolific of events on the soil of Greece. But those which occurred there tended yet further to accelerate the decay of the old classic life. Scarcely had the country begun to recover from the long-felt ravages of the Goths, than the Vandals, who had now established themselves in Africa, plundered the west and south-west coasts of Greece from Epeiros to Cape Matapan. But at this crisis the Free Laconian town of Kainepolis showed such a Spartan spirit that the Vandal King Genseric was obliged to retire with considerable loss. He revenged himself by ravaging the beautiful island of Zante, and by throwing into the Ionian Sea the mangled bodies of 500 of its inhabitants[25]. Nikopolis was held as a hostage by the Vandals till peace was concluded between them and the Eastern Empire, when their raids ceased. Seven years afterwards, in 482, the Ostrogoths under Theodoric devastated Larissa and the rich plain of Thessaly. In 517 a more serious, because permanent enemy, appeared for the first time in the annals of Greece. The Bulgarians had already caused such alarm to the statesmen of Constantinople that they had strengthened the defences of that city, and it was probably at this time that the fortifications of Megara were restored. On their first inroad, however, the Bulgarians penetrated no further into Greece than Thermopylæ and the south of Epeiros. But they carried off many captives, and, to complete the woes of the Greeks, one of those severe earthquakes to which that country is liable laid Corinth in ruins.