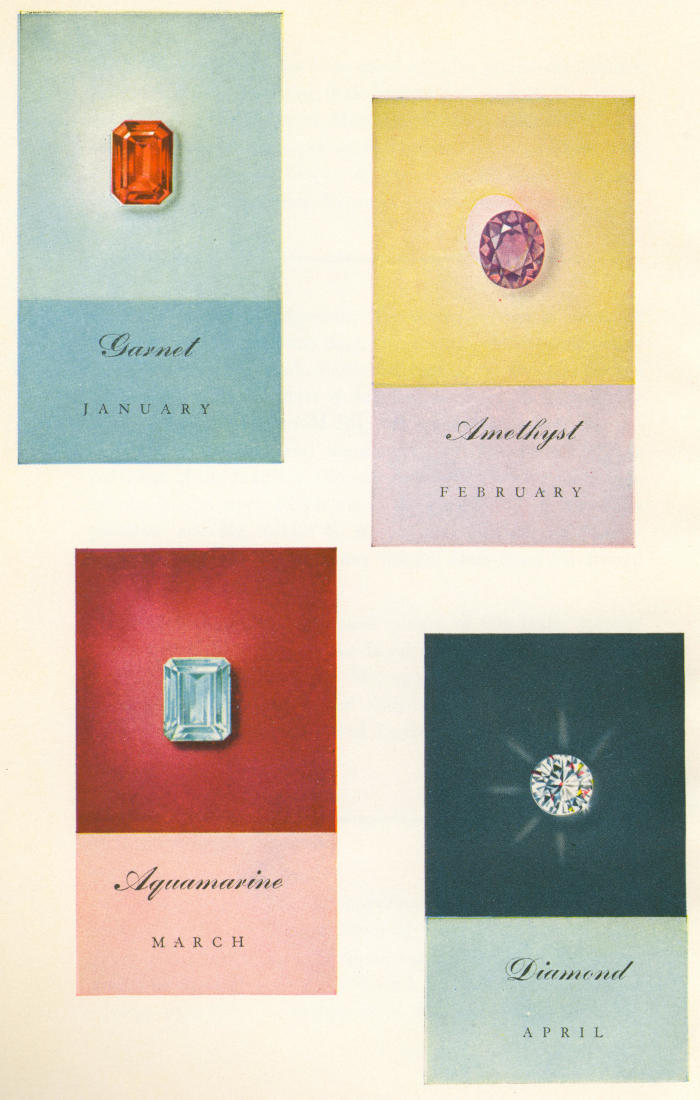

| Garnet JANUARY |

Amethyst FEBRUARY |

| Aquamarine MARCH |

Diamond APRIL |

Title: Jewels and the woman: The romance, magic and art of feminine adornment

Author: Marianne Ostier

Release date: September 25, 2022 [eBook #69046]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Horizon Press, 1958

Credits: Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

by Marianne OSTIER

JEWELS and the WOMAN

The Romance, Magic and Art of Feminine Adornment

HORIZON PRESS New York

Note: For centuries it has been the custom for jewelers to identify their designs by stamping their hallmark on jewels. The reproduction on page 20 is of Marianne Ostier’s hallmark. Unless otherwise noted in the captions, jewels here reproduced have been designed by Marianne Ostier. All jewels are illustrated in actual size, with the exception of the portraits and Illustration 17.

Credits and Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank all the people who have given time, information and encouragement to the work on this book. Particular thanks are due Mr. George D. Skinner of N. W. Ayer & Son Inc. for supplying invaluable information; Miss Dorothy Dignam, of the same firm, for her inspiring enthusiasm and knowledge; Mr. Lansford F. King, publisher of the Jewelers’ Circular Keystone, for his endless confidence in the work which made the completion of this book possible; and Mr. Albert E. Haase, president of the Jewelry Industry Council, for the many helpful facts from his special fund of knowledge.

For contributing to the visual quality of this book, grateful acknowledgment is made to the Jewelry Industry Council for the frontispiece colorplates; The Metropolitan Museum of Art for Illustrations 1 through 8; the British Information Service for Illustrations 11, 12 and 15; and Trude Fleischmann for Illustrations 28 and 29.

©1958 by Marianne Ostier

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 58-10224

Manufactured in the United States of America

All original designs as well as the text by Marianne Ostier are protected by copyright and may not be copied or reproduced without permission in writing from the author and publisher.

| Garnet JANUARY |

Amethyst FEBRUARY |

| Aquamarine MARCH |

Diamond APRIL |

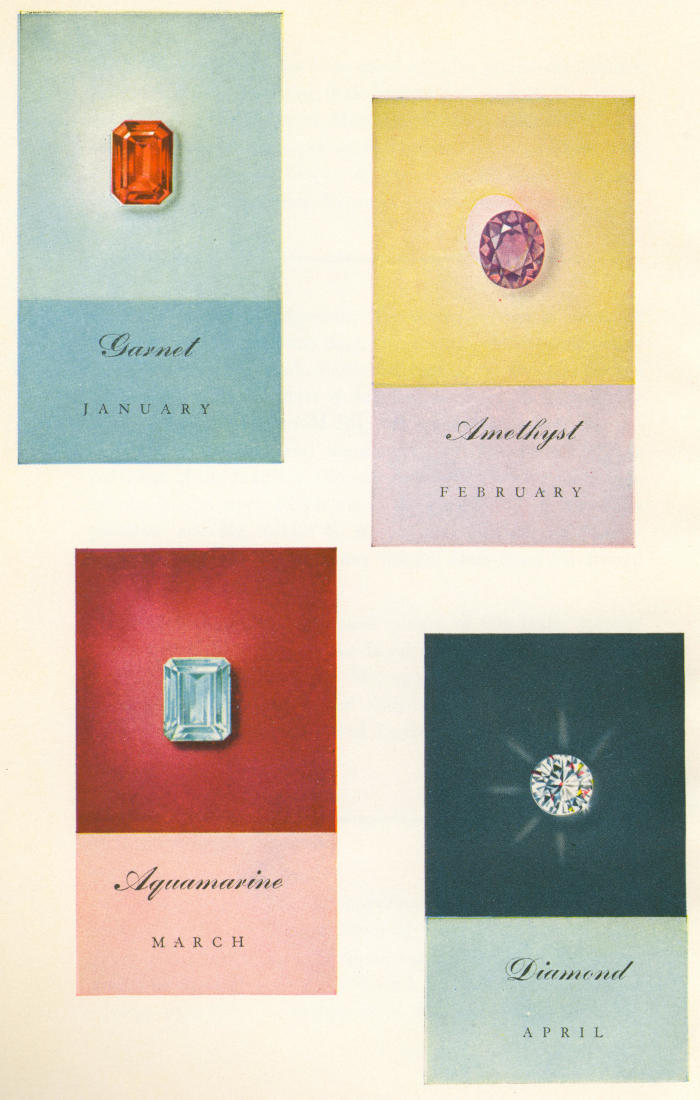

| Emerald MAY |

Pearl Alexandrite JUNE |

| Ruby JULY |

Peridot AUGUST |

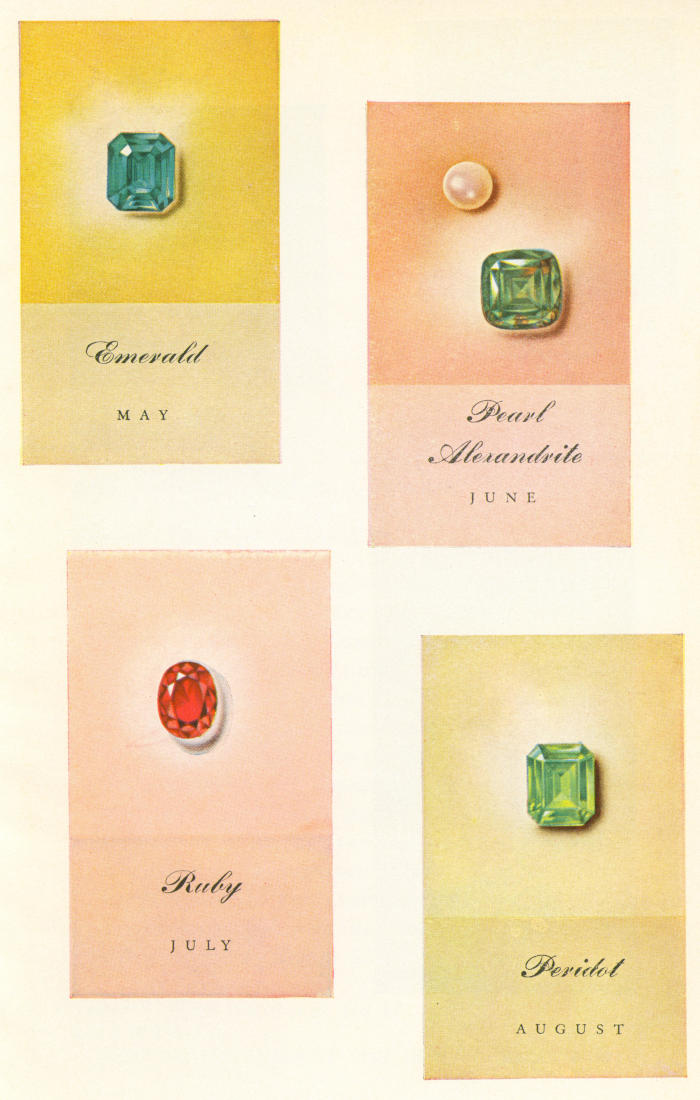

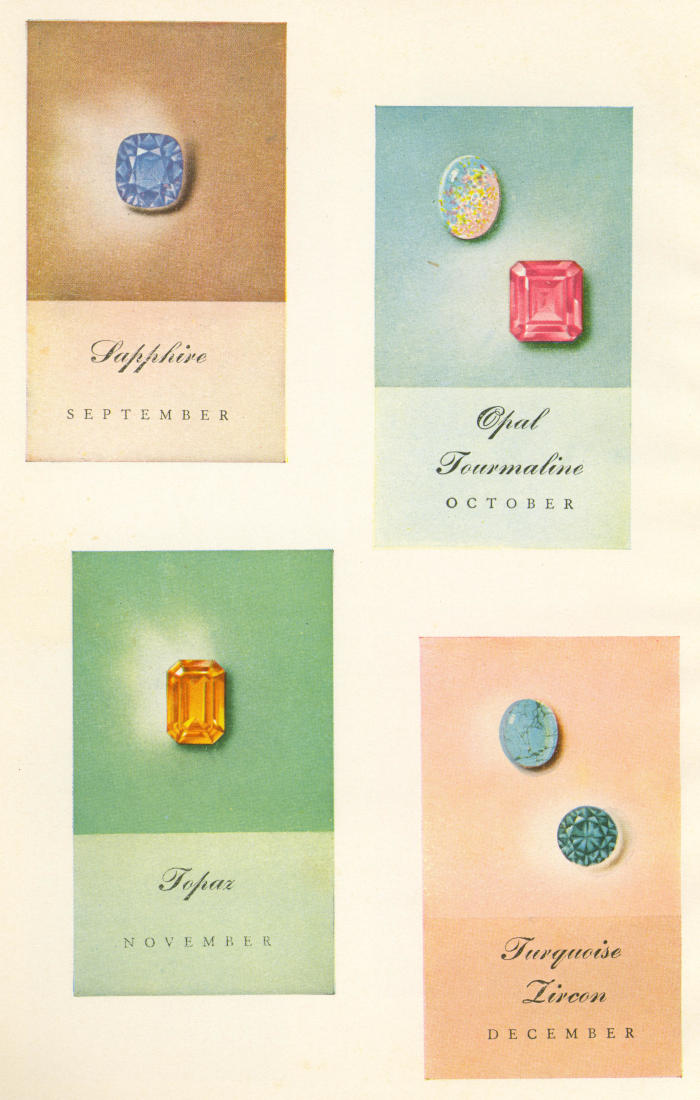

| Sapphire SEPTEMBER |

Opal Tourmaline OCTOBER |

| Topaz NOVEMBER |

Turquoise Zircon DECEMBER |

| Foreword | 17 |

| PART 1: Jewels: History, Character, Magic | |

| Chapter 1: The Story of Jewels | 23 |

| THE EARLIEST USES 23 EGYPT AND THE NEAR EAST 26 WESTWARD TO THE GREEKS 29 ETRUSCAN ACHIEVEMENTS 30 THE ROMAN CONQUEST 31 THE VOGUE OF THE PEARL 41 ROMAN LUXURY 42 THE TIDE TURNS EAST 42 EASTWARD TO INDIA 43 OVER THE CHINESE WALL 44 DARK AGE OF THE DIAMOND 45 TRIBES TO THE NORTH 45 THE CELTS AND THE EMERALD ISLE 46 THE ANGLO-SAXONS 47 JEWELS IN ENGLISH HISTORY 47 EDWARD THE CONFESSOR’S JEWELS 48 GROWTH OF THE GOLDSMITHS’ GUILD 48 THE ITALIANS IN THE RENAISSANCE 49 THE RENAISSANCE ACROSS EUROPE 50 THE REFORMATION 51 THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY 52 ON THE ROMANTICS 53 INTO THE NINETEENTH CENTURY 54 THE TWENTIETH CENTURY 55 | |

| Chapter 2: What the Stones Are | 57 |

| WHAT THE STONES ARE 57 THE GEMS 58 DIAMOND 58 [6] RUBY 60 SAPPHIRE 62 EMERALD 63 PEARL 64 OTHER STONES 67 ALEXANDRITE 68 AMETHYST 68 AQUAMARINE 69 BERYL 69 CARNELIAN 70 CAT’S-EYE 70 CHALCEDONY 71 CHRYSOBERYL 71 CHRYSOLITE 71 CHRYSOPRASE 72 CITRINE 72 CORAL 72 GARNET 73 HYACINTH 74 JACINTH 74 JADE 74 JASPER 75 JET 75 KUNZITE 76 LAPIS LAZULI 76 MALACHITE 77 MOONSTONE 77 ONYX 77 OPAL 78 PERIDOT 79 QUARTZ 79 SARD 80 SARDONYX 80 SPINEL 80 TOPAZ 81 TOURMALINE 81 TURQUOISE 82 ZIRCON 82 | |

| Chapter 3: Birthstones and the Magic of Gems | 83 |

| THE SEASONS 83 THE DAYS OF THE WEEK 84 SUNDAY 84 MONDAY 84 TUESDAY 85 WEDNESDAY 85 THURSDAY 85 FRIDAY 86 SATURDAY 86 THE MONTHS 87 TABLE OF BIRTHSTONES 87 JANUARY—GARNET 88 FEBRUARY—AMETHYST 89 MARCH—AQUAMARINE 90 APRIL—DIAMOND 91 MAY—EMERALD 92 JUNE—PEARL 94 JULY—RUBY 96 AUGUST—SARDONYX OR PERIDOT 97 SEPTEMBER—SAPPHIRE 99 OCTOBER—OPAL 100 NOVEMBER—TOPAZ 102 DECEMBER—TURQUOISE 104 SIGNS OF THE STARS 113 THE ZODIAC 113 ARIES, THE RAM 114 TAURUS, THE BULL 114 GEMINI, THE TWINS 115 CANCER, THE CRAB 115 LEO, THE LION 115 VIRGO, THE VIRGIN 115 LIBRA, THE SCALES 116 SCORPIO, THE SCORPION 116 SAGITTARIUS, THE ARCHER 116 CAPRICORN, THE GOAT 116 AQUARIUS, THE WATER CARRIER 117 PISCES, THE FISHES 117 | |

| PART 2: The Art of Feminine Adornment | |

| Chapter 4: The Art of Feminine Adornment | 121 |

| ROYAL CROWNS OF BRITAIN 122 EVERYWOMAN’S QUEEN 123 [7] A STONE’S BEST SETTING 123 TYPES OF WOMEN 124 THE MAJOR METALS 125 THE BASIC DESIGNS 125 | |

| Chapter 5: The Earclip | 127 |

| THE SUPREME IMPORTANCE OF THE EARCLIP 127 EARRINGS THROUGH THE AGES 127 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE EARS 129 THE EARCLIP AND THE FACIAL CONTOUR 130 THE SHAPE OF YOUR FACE 131 DETAILS OF THE FACE 132 VERSATILE EARCLIPS 133 THE HAIR AND THE EARCLIP 133 THE BRUNETTE 134 THE DARK-HAIRED 134 THE REDHEAD 135 THE BLONDE 135 AS THE HAIR TURNS GREY 136 IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS IN SELECTING EARCLIPS 136 | |

| Chapter 6: The Necklace | 139 |

| THE SYMBOLISM OF THE NECKLACE 139 THE GENERAL EFFECT 140 THE DIAMOND NECKLACE 141 THE RIVIÈRE 141 THE BAGUETTE NECKLACE 142 THE PEARL NECKLACE 142 THE COLORS OF THE PEARL 143 FOR THE BRUNETTE 143 FOR THE BLONDE AND THE REDHEAD 144 FOR A LONG NECK 144 FOR A WIDE NECK 145 SIZE OF PEARLS 145 THE PROPER STRINGING OF PEARLS 145 THE NECKLACE CLASP 146 DESIGNS FOR CLASPS 146 FOR FORMAL WEAR 147 THE SENTIMENTAL CLASP 148 FITTING THE PEARL NECKLACE 148 THE BEAD NECKLACE 149 FASHIONS FROM INDIA 149 OTHER NECKLACE JEWELS 150 THE NECKLACE OF GOLD 151 APPENDAGES: THE TASSEL 152 APPENDAGES: THE SINGLE DROP 152 TRANSFORMATIONS 153 MY OWN CONVERSIONS 153 WHAT A WOMAN WEARS, OTHERS SEE 154 | |

| Chapter 7: The Ring | 157 |

| THE GIVING OF A RING 157 CONSIDER THE HAND 158 [8] PROPORTIONS OF THE HAND 158 THE DIAMOND RING: THE ENGAGEMENT RING 159 THE WEDDING RING 160 THE WEARING OF THE BAND 161 THE PEARL RING 162 THE BLACK PEARL 162 DECORATIVE RINGS 163 MATCHED WITH EARCLIPS 164 INTERCHANGEABLE CENTERS 164 RING SIZES 165 RINGS AND NAIL POLISH 166 ABOUT WEARING A RING 166 | |

| Chapter 8: The Bracelet | 169 |

| EARLY USES 169 THE EMPERORS OF INDIA 169 VARIOUS MATERIALS 170 TYPES OF BRACELETS 170 FAVORITE SHAPES 171 THE SPECIAL CLASP 171 BRACELET WIDTH 172 FOR THE SLIM ARM 172 FOR THE HEAVIER WRIST 172 FITTING A BRACELET 173 GENERAL THOUGHTS 173 THE ANKLET 174 | |

| Chapter 9: Pins, Brooches and Clips | 175 |

| ELABORATE PINS 175 THE SIMPLER CLIP 176 ITS VERSATILITY 176 ITS PERSONALITY 185 THE CHANGE IN THE BROOCH 185 THE OLD DOUBLE CLIP 186 THE NEW DOUBLE CLIP 187 THE ABSTRACT DESIGN 187 THE FLOWER DESIGN 188 EARLIER FLOWERS 189 CURRENT VARIETIES 190 THE ROSE 190 THE SKINPIN 191 THE SCATTERPIN 191 THE JEWELLED HAIRPIN 192 THE MOBILE CLIP 192 THE SENTIMENTAL BROOCH 193 REPLICAS OF PETS 194 PINS HOLD MEMORIES 194 PRACTICAL PRINCIPLES 195 | |

| Chapter 10: Watches | 197 |

| QUEEN ELIZABETH I 197 PRINCESS SOPHIA 197 EARLY FORMS 198 WHERE TO WEAR THE WATCH 199 JEWELLED HOURS 200 IN FRONT OF YOUR MIRROR 202 [9] | |

| PART 3: The Etiquette of Wearing Jewels | |

| Chapter 11: The Etiquette of Wearing Jewels | 207 |

| EN ROUTE 208 WEEKEND 208 GARDEN PARTY 209 THE BEACH 209 ON THE GOLF COURSE 210 AT THE RACES 210 BUSINESS LUNCHEONS 211 THE CHARITY LUNCHEON 212 OPENING NIGHT 212 MATCHING THE GOWN 213 MATCHING THE MAN 213 SOME BASIC RULES 214 THE DINNER PARTY 215 THE WATCH 216 THE CIGARETTE CASE 216 THE HOSTESS 216 AT THE WHITE HOUSE 217 THE PRESIDENT’S DINNER 218 THE CAPTAIN’S DINNER 218 EMBASSY PARTIES 220 MEETING ROYALTY 221 CORONATION 221 A QUEEN’S CROWN 222 WHEN EVERY WOMAN IS QUEEN 223 THE BRIDESMAIDS 224 THE MOTHER OF THE BRIDE 225 THE WEDDING GUESTS 225 THE NEWBORN 226 THE ANNIVERSARY 227 TABLE OF ANNIVERSARY GIFTS 227 THE MORE SOLEMN TIME 228 AUDIENCE WITH THE POPE 229 IN MOURNING 229 OTHER OBSERVATIONS 230 COLOR COMBINATIONS 230 RESTRAINT 230 EYEGLASSES 231 THE LORGNETTE 231 THE CORSAGE 232 EMBROIDERY 232 MORE ABOUT BRACELETS 232 MORE ABOUT RINGS 234 GOLD JEWELS 234 IN THE SPOTLIGHT 234 | |

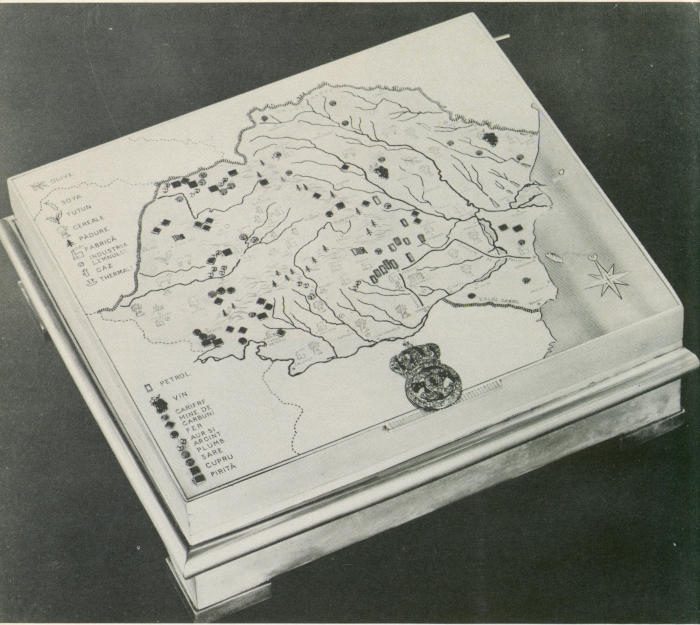

| Chapter 12: Jewels as Gifts | 237 |

| GIVE YOURSELF 237 GIFTS OF LASTING VALUE 238 GIFTS TO THE BABY 238 TO THE MOTHER TOO 239 AS THE CHILD GROWS 239 ST. VALENTINE’S DAY 239 COLLEGE DAYS 240 THE WEDDING DAY 240 FOR THE BRIDESMAIDS 241 FOR THE USHERS 241 OTHER GIFTS TO THE BRIDE 242 PARENTS’ DAYS 242 FOR LATER BIRTHDAYS 243 GIFTS FOR THE MAN 244 THE WIFE’S ROLE 244 THE RIGHT ACCESSORIES 245 THE PERSONAL [10] TOUCH 245 SPECIAL GIFTS 246 HISTORIC GIFTS 246 THE PRESENTATION OF A GIFT 247 | |

| PART 4: The Techniques and Care of Jewels | |

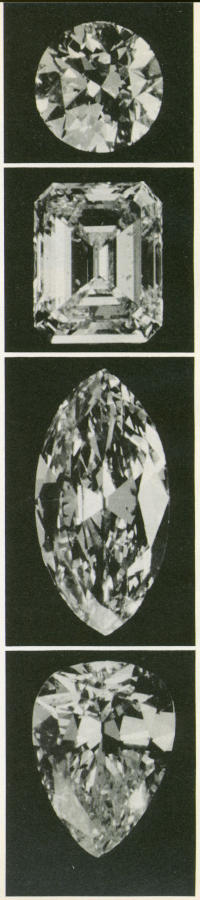

| Chapter 13: The Techniques of Gems | 259 |

| DEFINITIONS 259 LIGHT ON THE STONES 260 STAR GEMS 260 THE PEARL 261 CUTTING THE STONES 261 CABOCHON 262 FACETS 262 TYPES OF FACETING 263 HARDNESS OF THE STONES 264 QUALITIES OF A STONE 267 MEASUREMENT 268 THE PRECIOUS METALS 268 ALLOYS 269 | |

| Chapter 14: The Care of Jewels | 271 |

| HOW TO CARE FOR JEWELS 271 HOME CARE 271 CLEANING DON’TS 272 PEARLS 272 REMINDERS 273 MORE CAUTIONING 274 FOR TRAVEL 274 INSURANCE 275 THE TRAVELING CASE 275 REGISTERING JEWELS 276 TRAVELING CAUTIONS 277 | |

| Chapter 15: Jewelry Up to Date | 279 |

| THE OLD AND THE ANTIQUE 279 OLD JEWELRY WITH NEW POSSIBILITIES 280 THE CONTEMPORARY JEWELS 281 MODERN MOVEMENT 281 THE JEWELER AS ARTIST 283 VARIED STONES 283 VARIED TREATMENT 284 REMODELLING OF WATCHES 285 ADDING PEARLS 285 INFINITE RICHES IN A LITTLE ROOM 286 | |

| PART 5: The Story of Rings and Famous Stones | |

| Chapter 16: Romance of Rings | 289 |

| THE UNIVERSAL RING 289 THE MAGIC RING 289 DIVINING [11] RINGS 290 RENAISSANCE REMEDY RINGS 291 VISIBILITY RINGS 292 RELIGIOUS RINGS 293 PRACTICAL RINGS 294 POISON RINGS 295 HONORARY RINGS 296 POSIES AND LOVERS’ RINGS 296 THE NUPTIAL RING 298 LESS SOLEMN MARRIAGE RINGS 299 COUNTING FINGERS 301 MEMORIAL RINGS 302 | |

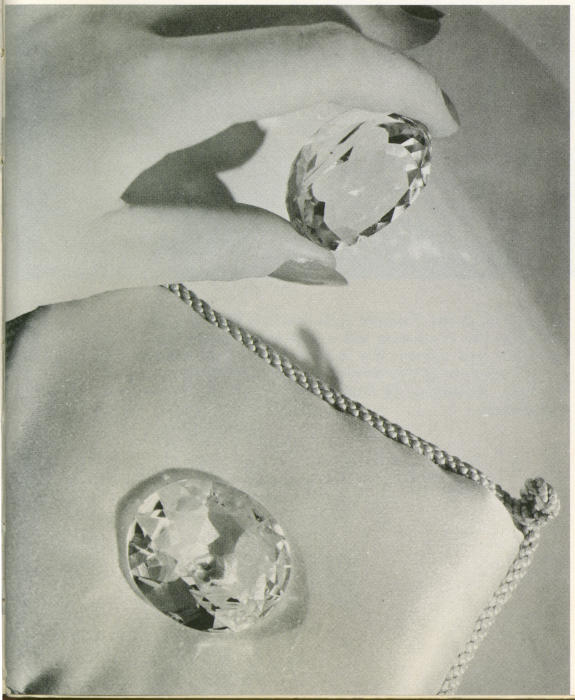

| Chapter 17: Some Famous Stones | 305 |

| THE BLACK PRINCE’S RUBY 305 OTHER PRECIOUS STONES 306 THE CRYSTAL PALACE 307 THE DIAMONDS 307 THE KOHINOOR 308 TAVERNIER 310 THE FLORENTINE 310 THE GREAT MOGUL 311 THE ORLOFF 311 THE SHAH OF PERSIA 312 THE GREAT TABLE 313 THE BLUE TAVERNIER 313 THE HOPE 314 THE JEHAN AKBAR SHAH 315 THE CULLINAN 315 THE EXCELSIOR 316 THE REGENT 316 THE SANCY 318 OUT OF THE EARTH 319 | |

| Frontispiece | |

| THE BIRTHSTONES, COLORPLATES | |

| Following Page 32 | |

| 1. | GREEK EARRINGS, 5TH CENTURY B.C. |

| 2. | CYPRIOTE PENDANT, 8TH CENTURY B.C. |

| 3. | EARLY 18TH CENTURY ITALIAN BROOCH |

| 4. | EGYPTIAN BRACELET, 4TH CENTURY B.C. |

| 5. | ETRUSCAN RING |

| 6. | 18TH CENTURY ITALIAN RING |

| 7. | CYPRIOTE RING |

| 8. | ROMAN WREATH, 3RD CENTURY B.C. |

| 9. | INSIDE VIEW OF THE FAMOUS OLD TIFFANY STORE, NEW YORK, 1875 |

| 10. | THE CROWNING OF A QUEEN |

| 11. | THE BRITISH CROWN JEWELS |

| 12. | THE BRITISH CROWN JEWELS |

| 13. | REMODELLING THE IMPERIAL STATE CROWN |

| 14. | EMPRESS ELISABETH OF AUSTRIA[14] |

| Following Page 104 | |

| 15. | QUEEN ELIZABETH II |

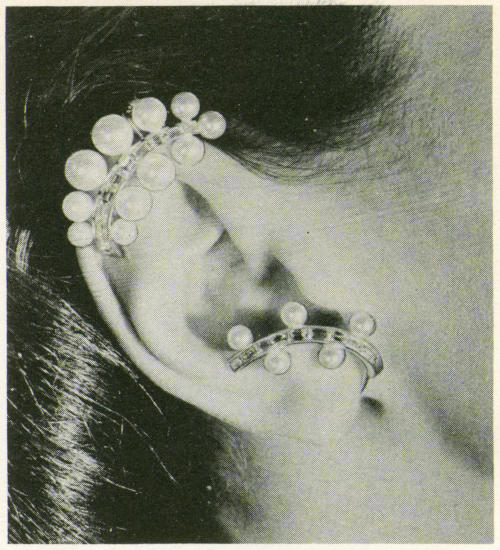

| 16. | PEARL AND BAGUETTE DIAMOND EARCLIPS |

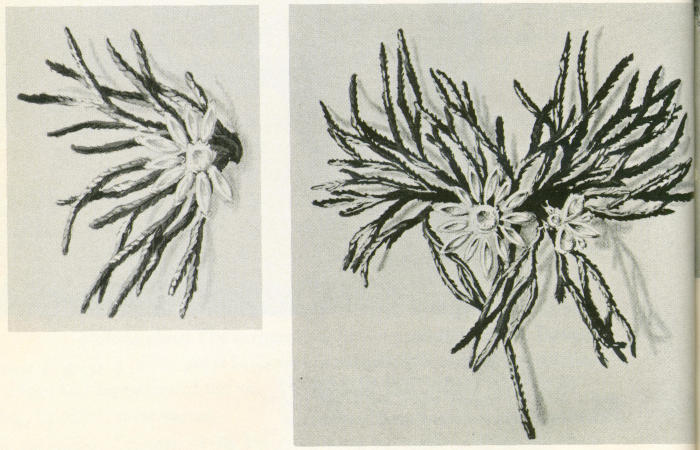

| 17. | DEEP SEA ALGAE |

| 18. | DOUBLE ROSE CLIP |

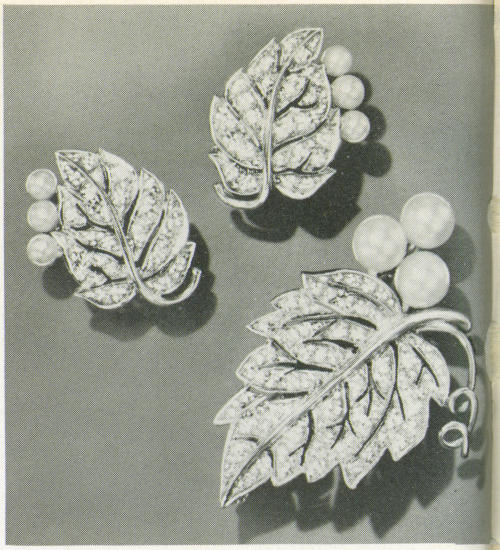

| 19. | DIAMOND AND PEARL LEAVES |

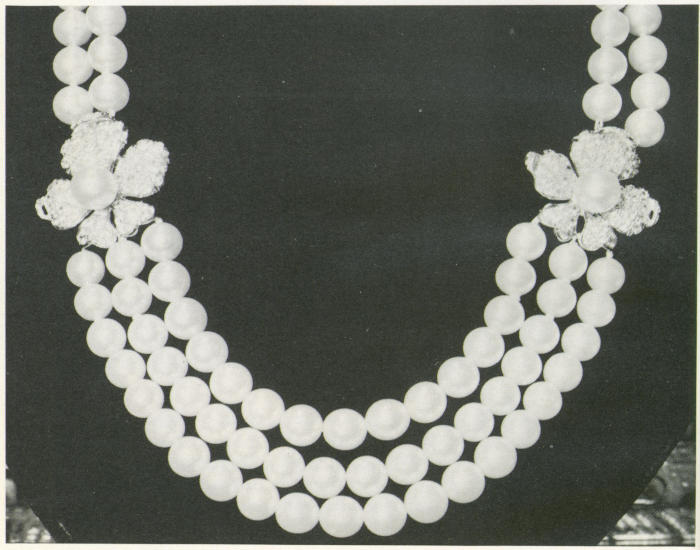

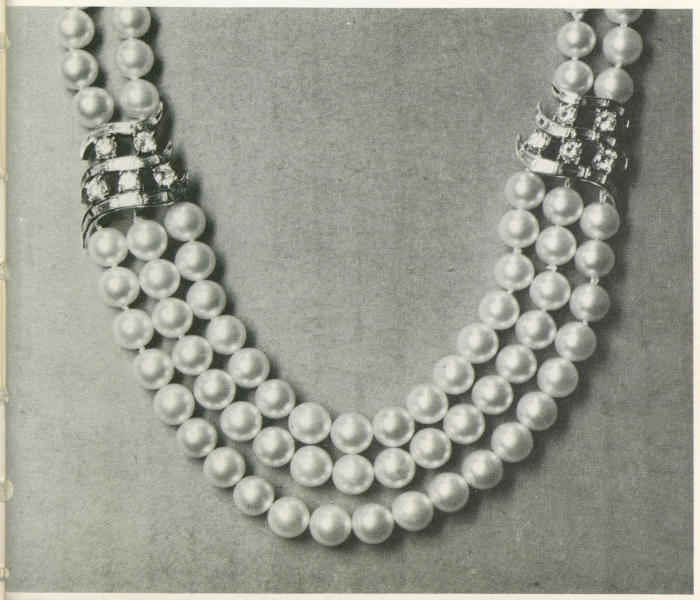

| 20. | PEARL AND DIAMOND NECKLACE |

| 21. | PEARL RING |

| 22. | QUEEN GERALDINE OF ALBANIA |

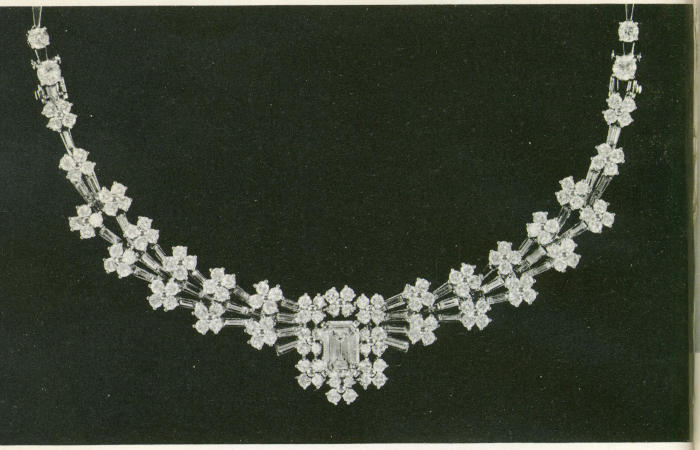

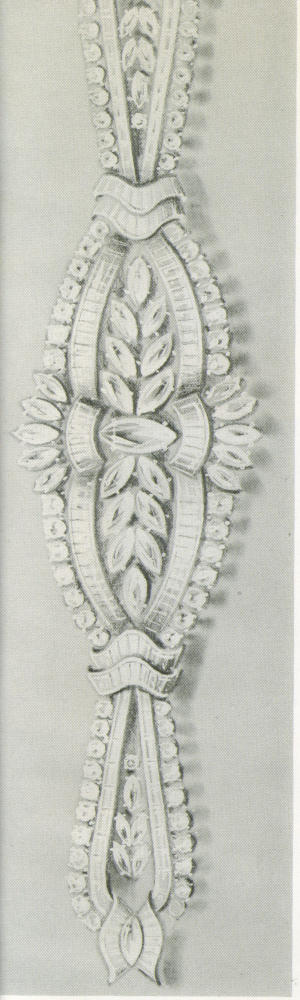

| 23. | DIAMOND NECKLACE |

| 24. | DIAMONDS CAUGHT IN A NET |

| 25. | NECKLACE FOR A BRIDE |

| 26. | DIAMOND PINCUSHION ORNAMENT |

| 27. | DIAMOND PINCUSHION ORNAMENT |

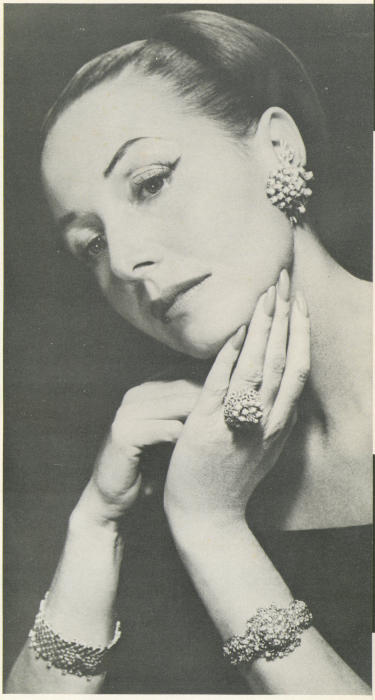

| 28. | MARIANNE OSTIER |

| Following Page 176 | |

| 29. | MRS. FREDERIC GIMBEL |

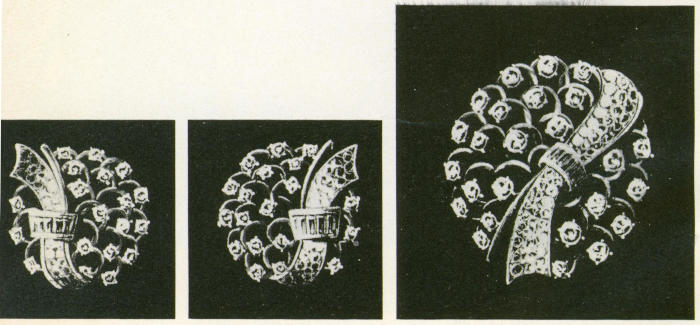

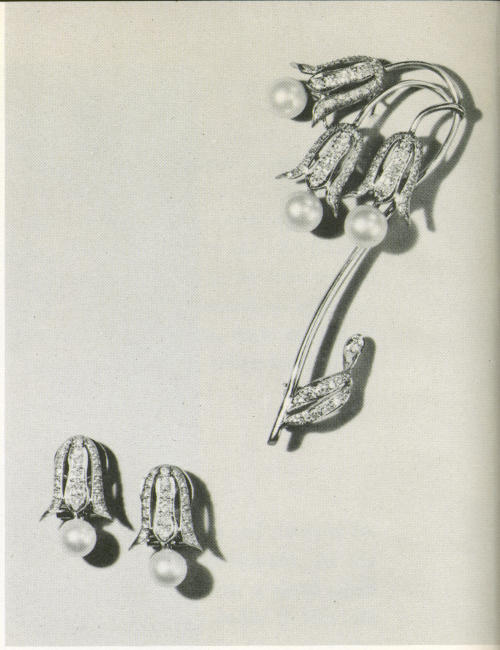

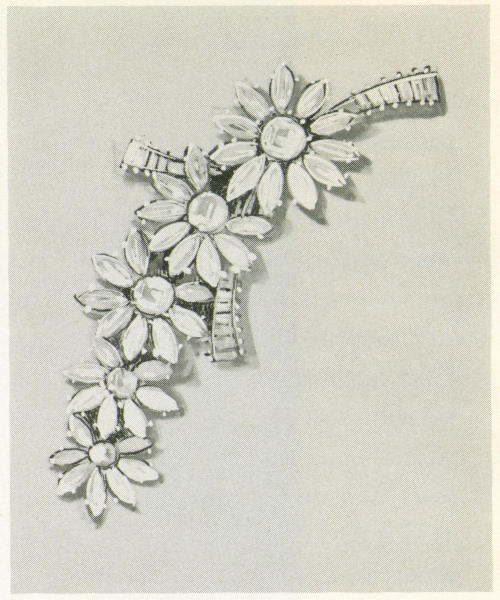

| 30. | BELLFLOWER BROOCH AND EARCLIPS |

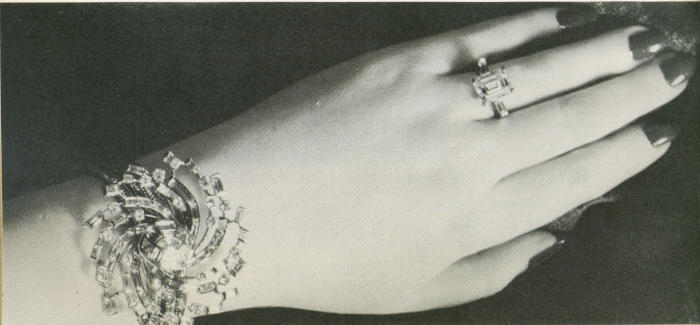

| 31. | BRACELET AND ENGAGEMENT RING |

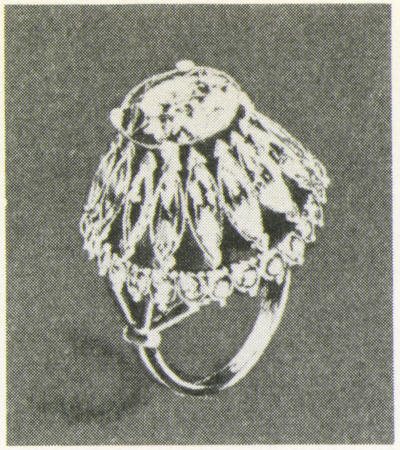

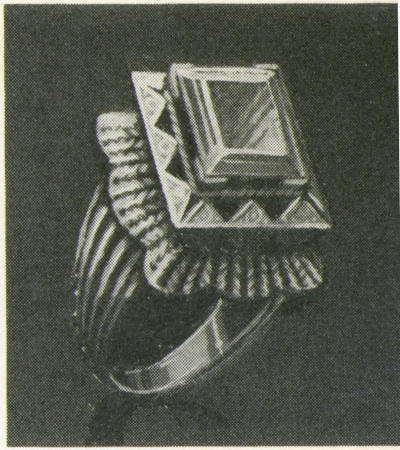

| 32. | DESIGN FOR A DIAMOND RING |

| 33. | DESIGN FOR A GOLD RING |

| 34. | DESIGN FOR A FORMAL DIAMOND AND PLATINUM BRACELET |

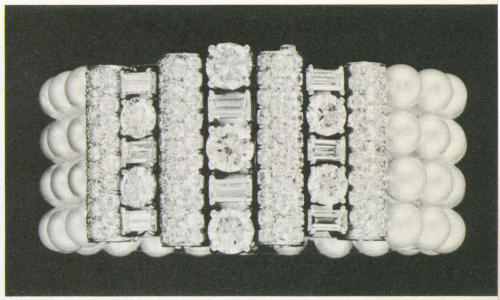

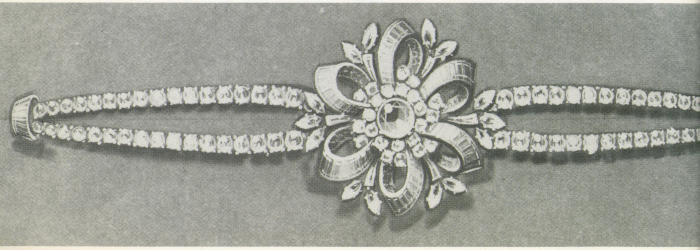

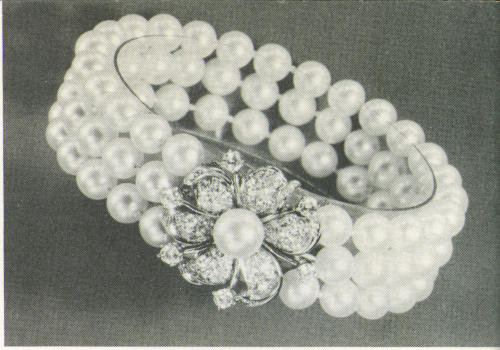

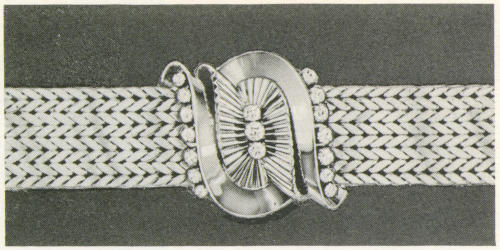

| 35. | DIAMOND AND PEARL BRACELET |

| 36. | DESIGN FOR A BRACELET |

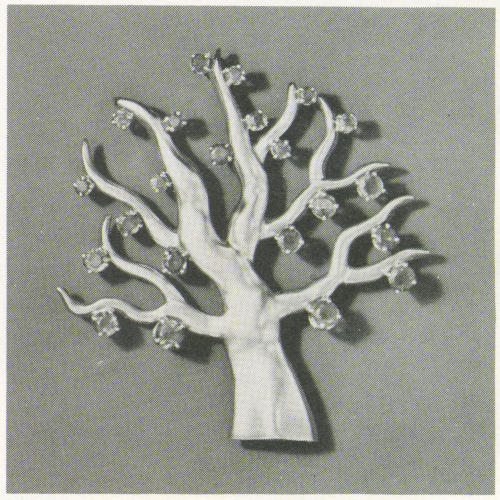

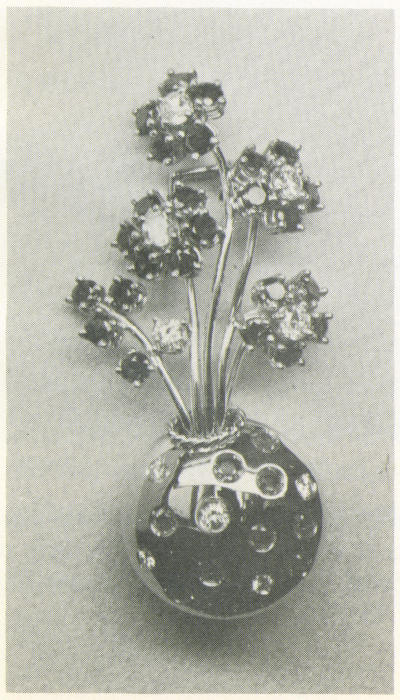

| 37. | TREE OF LIFE |

| 38. | DESIGN FOR A MULTI-PURPOSE JEWEL |

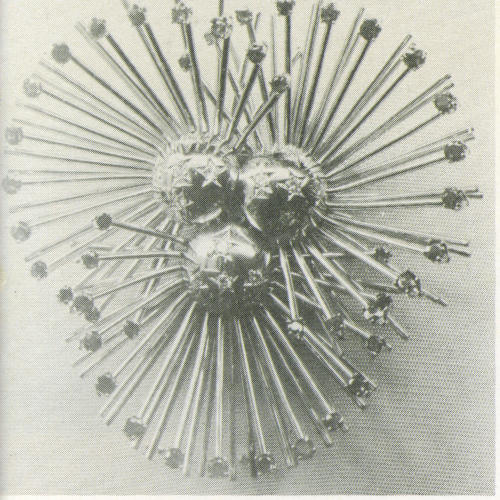

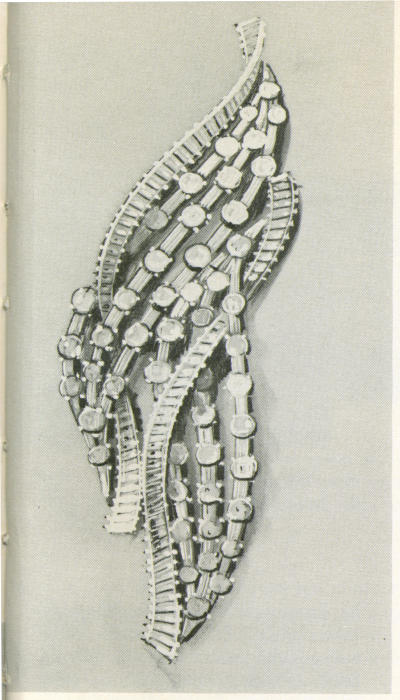

| 39. | AURORA BOREALIS |

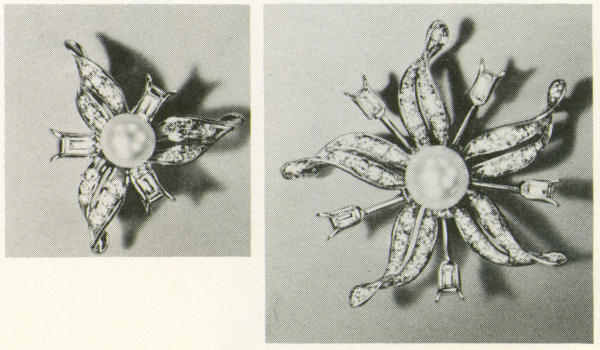

| 40. | FLOWER FANTASY |

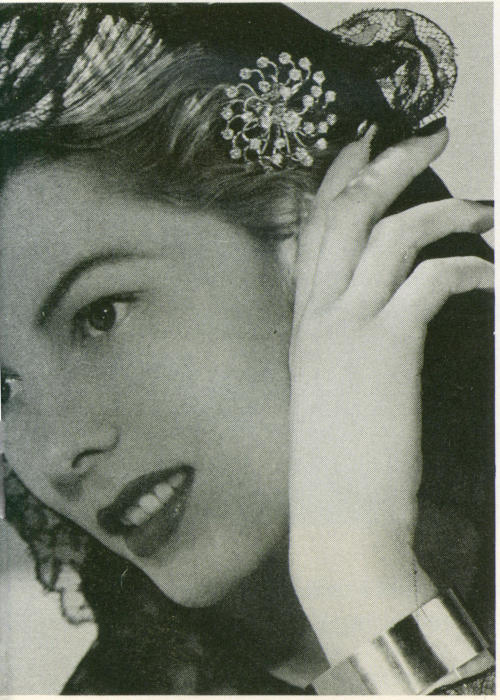

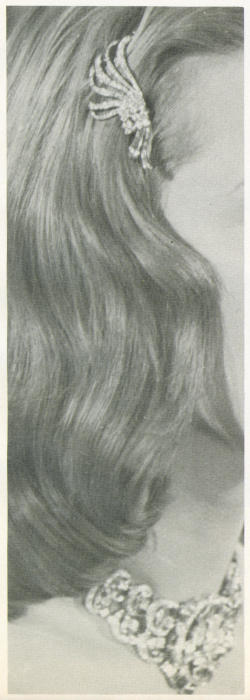

| 41. | DIAMOND HAIR ORNAMENT |

| 42. | THREE-STRAND PEARL BRACELET |

| 43. | MISS BLANCHE THEBOM[15] |

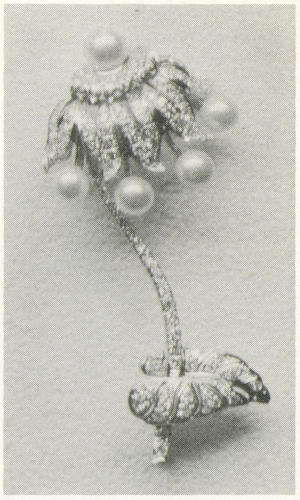

| 44. | CANTERBURY BELL |

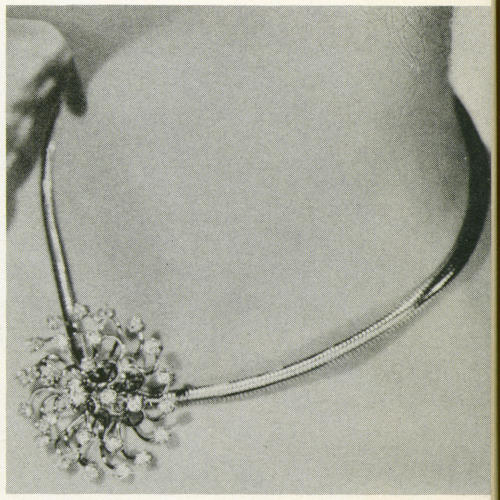

| 45. | GOLD SHELL FOR INFORMAL WEAR |

| 46. | FLOWER LAPEL BROOCH |

| 47. | MRS. TEX MC CRARY |

| Following Page 256 | |

| 48. | PORTRAIT OF H. H. INDIRA DEVI |

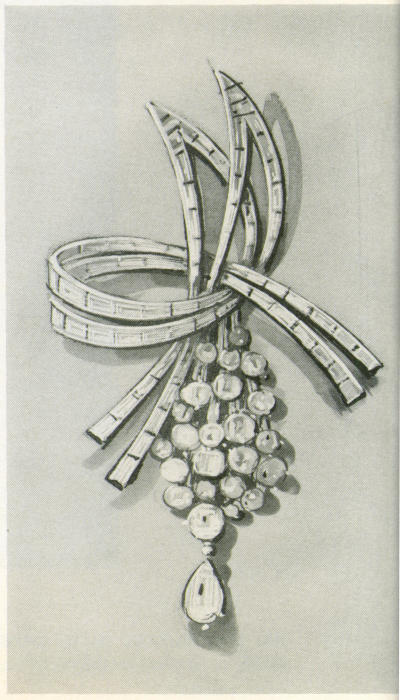

| 49. | SPRAY PIN DESIGN |

| 50. | DESIGN FOR A DIAMOND CUP |

| 51. | DESIGN FOR A DOUBLE CLIP |

| 52. | DESIGN FOR A GOLD AND DIAMOND PIN |

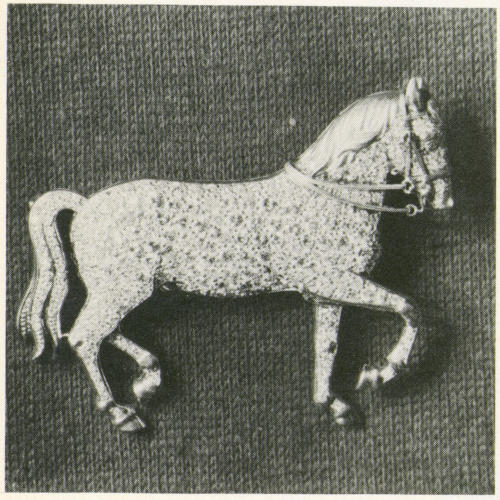

| 53. | PORTRAIT OF FLIPPY |

| 54. | FLORIAN |

| 55. | SET OF EARCLIPS AND BROOCH |

| 56. | GOLD AND DIAMOND WATCH |

| 57. | PEARL NECKLACE WITH TWO DIAMOND MOTIFS |

| 58. | TABLE OF DIAMONDS |

| 59. | MODELS OF THE KOHINOOR DIAMOND |

| 60. | GOLD CIGAR BOX |

“Diamonds,” the song goes, “are a girl’s best friend.” Take special note of the sex; it is significant. For only among humans has the female increasingly become the adorned sex. The mane of the lion or of the stallion gives the male a magnificence beyond the competence of the lioness or the mare. It is the peacock that spreads the studded glory of its tail—not the peahen. As among the birds and beasts, so primitive man was the resplendent sex, while his mate went about her task, in more subdued and humble tones. By the time of the Renaissance—it took that long in civilization’s climb—men and women were about equal in their adornment. In Europe, indeed, only men wore diamonds until 1444, when King Charles VII of France (whom Joan of Arc had placed upon the throne) was captivated by Agnes Sorel’s beauty and daring, when she appeared in a superb necklace of diamonds. The diamond at once became the prized gem of womankind.

The costumes and jewels of the courtiers of Elizabeth I of England were surpassed by those of the Queen only in the measure of her superior station. Since then, however, the attire of men has grown increasingly functional, sedate, and commonplace, while that of women has retained its freedom of color and flow. And the great world of jewelry is preeminently the woman’s domain.

Scientists in several fields have sought the reasons for this change; we may rest content with the fact. A man may be thought distinguished, or perhaps handsome; only a woman may be called beautiful. And by proper adornment of apparel and jewelry, every woman seeks to enhance her beauty.

Certain austere sects frown upon “artificial” aids to beauty. In the hills of Pennsylvania are honest women whose lips and cheeks have never been touched by added color. But such persons are outside the main path of human progress. For the quest of beauty—surely a legitimate and a desirable quest—has taken the same path as the other great adventures of man, which have placed him supreme among all living creatures.

Look at the problem of security. The bear can strike a tremendous blow with his paw. The tiger springs with fierce gash of fang and claw. The eagle pounces with deadly talon and beak. Beside these, how puny the fist of man! But the bear, the tiger, the eagle remain with but these weapons, while man closed his tiny hand around a club, then hurled a spear, then winged his bow with arrows, shot forth his bullets and his bombs. While the animals mark a dead end of evolution, man continued to evolve by “artificial” extensions of his powers.

The same is true in every field. The news of the victory of Marathon was borne by a runner, who coursed the twenty-four miles, gasped out his word of triumph, and dropped dead. Since then man has harnessed the ox, mounted the horse, and surpassed all other creatures in means of travel upon and within the waters, across the earth, high and higher in the air.

So in the realm of beauty. First man painted his naked body. Then he adorned himself with claws and teeth torn from the animals, with feathers plucked from the birds. Soon he discovered the sheen of precious metals, the sparkle of gems. The progress of adornment, from ancient Egypt to the twentieth century world, has been marked by the further discovery and refinement of metals and the design of jewels. Synthetic[19] gems and costume jewelry have given to every woman opportunities once limited to the wealthy few; the principles applicable to the wearing of costly jewels are the same for their less expensive cousins. And the pattern of the quest of personal beauty is in line with the general pattern of human evolution.

Although we have approached beauty through these somewhat solemn reflections, we must not forget that the best reflection of beauty is in the admiring eye of the beholder. It is a mutual pleasure; but it is a personal, an individual task. For it is every woman’s duty—not merely to herself but to those around—to present her fairest aspect to the world.

To the old remark: Love is blind, the cynic has added: But marriage is an eye-opener. Of course, neither statement is true. While love may fasten upon and prize other qualities, the lover is usually keenly aware of the measure of his beloved’s beauty. He takes increasing pride and pleasure as she finds fresh ways of enhancing her natural gifts. There is a lesson hidden in the statement that if a woman is beautiful at fifteen she may thank God, but if she is beautiful at fifty she has herself to thank. The lesson is that a woman can learn what is seemly, what is becoming, what adds to her beauty.

One may look at precious stones and magnificent jewels ranged in a museum or in a store. When they are being worn, we look not so much at them as at the ensemble they help to create of a live alluring woman. The Crown Jewels in the Tower of London are imposing. When they are worn on occasions of state, the court regalia combine to keep them imposing still: it is less a person than a position that they adorn. But with the rest of us mortals, as even with queens in less stately hours, the jewels must fit the person and the personality, as well as the occasion.

What looks most attractive against the dark velvet on a counter may fail to harmonize with golden glinting hair. The[20] size of the earlobe, the figure of the woman, the color of the dress, the activity of the evening, all are factors in determining which jewels one should wear. Jewels have a long history, but always an immediate test of use. In both aspects, they hold an ever present allure.

MARIANNE OSTIER

Jewels:

History, Character, Magic

There are as many guesses about the origin of adornment as about the origin of language. The most popular theories might be called the functional, the magical, and the aesthetic.

When man first felt cold, says the functional theory—or when he first felt shame and hid his shame with the fig leaf—he had to find some way of fastening his garments. The leaves, the furs, the hides, would slip off unless adequately held together, especially when the man was running in swift hunt, or the woman bending under domestic burdens. The first fastenings were probably strands of vinestalks, lashes of interlaced leaves. Then pins made of long thorns, of wood, or of the bones of animals came into use. Pins of the last sort have been found in prehistoric caves. Naturally, iron, bronze, silver and gold pins followed, as the use of these metals became known. Crude safety pins, in form essentially the same as those we use today, have been unearthed in the most ancient tombs.

The transition from bone to metal may be observed in the word fibula, the early Latin word for a clasp. For the long outer leg bone is also called the fibula, and it looks like the tongue of a clasp, for which the other bone, the tibia, is the holder. And the word fibula comes from the Latin verb fivere, meaning to fasten.

On even the earliest pins, however, and especially on the domed backs of safety pins and clasps, there are curious carvings of dots and circles and other forms, which give scope to the second theory of the origin of adornment, the magical. For along with these fasteners are found necklaces of beads and other adornments that served no practical end—except the very important purpose of placating the gods, of warding off evil.

The telling of rosary beads, widespread today in Moslem as in Catholic lands, is a milder modern aid to prayer; in primitive times the need for protection was no less frequent and more desperate. Those of us who carry a rabbit’s foot or other charm, who put an amulet in our automobile to help us drive safely, who still “knock wood” to keep away mischance, need not smile at our far-off ancestors who engraved their beads with potent symbols or wore a scarab, preferably carved of precious stone, to keep all ills away. Charms and amulets were on every neck and arm. The devils were all about; they whirled in the tempest; they sprang suddenly in the form of a wild beast; they twisted one’s ankle as a jungle vine. And every stone-age child knew that the agate protected one against thunder and against tiger bite. If the agate was ringed like an eye, especially a tiger’s eye, it could outstare and drive away the fiercest fiend. To turn away the fangs of the venomous hidden snake, what better charm than lapis lazuli? Thus each of the colored stones known to the ancients had its special powers, or could be carved with symbols and signs of might—and jewels were worn to ward off all misfortune. Even among the ancient Greeks, it was recognized that (as the slave in Aristophanes’ play Plutus observes) there is no amulet that can save one from “the bite of a sycophant.”

The third theory of the origin of adornment, the aesthetic, declares that man is born with a love of beauty. There is no[25] question—and if there were, modern research has answered it—that the bright trinket attracts the babe. When one is happy one wants to sing; when one sees beauty, one wants to experience it with the gift of sight or, if it is tangible, to put it on. And ever to increase earth’s store of beauty. We cannot snare a sunrise, but we can make a garland of spring flowers. Even before he fashioned beads, primitive man adorned himself with necklaces of shells, of bears’ claws, stags’ teeth—probably also of many colored berries, but these have crumbled in the caves. Such findings are so widespread that Carlyle declared: “The first spiritual want of a barbarous man is decoration.”

Since the question of origins is buried in surmise, it seems fair to follow that eminent advocate of the middle way, Sir Roger de Coverley, and allow that there is something to be said for all three theories. Each impulse, to hold up clothing, to ward off evil, to enjoy beauty—power, protection, pleasure—may have had a share in the birth of adornment. It is true that there are paintings and statues, in the early tombs, of women clad only in their jewels. But while queens, and the concubines of kings might be thus untrammeled in their quest of beauty, humbler folk at work needed workaday attire. And always the magicians, the medicine men, then the priests, wove their holy spells, with mitre and chalice and ring inscribed with the secret words of power. A monarch of early times was an impressive sight, as not only his rings, his armlets and neckpiece, but his breastplate, the buckle of his belt, and the hilt of his sword were carved with sacred symbols and crusted with precious stones. Here were protection, power, and grandeur intertwined.

Perhaps the earliest jewelry to which we can attach an owner’s name was in the find unearthed in 1901 by Flinders Petrie in the royal tombs at Abydos. It is a bracelet of golden[26] hawks, rising from alternate blocks of turquoise and gold, and it belonged to the Egyptian Queen of Zer back in 5400 B.C. Somewhat later lived the Princess Knumit, whose mummy was adorned with all manner of jewels, anklets, bracelets, armlets, headbands, including a serpent necklace of beads of gold, silver, carnelian, lapis lazuli, and emerald, and hieroglyphics wrought in gold with inlaid gems. From Chaldea, as early as 3000 B.C., we have beads, and jewelry of lapis lazuli, and headdresses of finely beaten gold.

A panel in one of the pyramids gives us a realistic picture of the interior of a jeweler’s shop of long ago. The master craftsman, his bookkeeper, his workers and his apprentices are all busy at their tasks. We see them selecting, cutting, grinding, firing, shaping, setting, polishing, with tools that have changed little in 3000 years. The jewels we know today are all present there: diadems, earrings, brooches, bracelets, rings, girdles, anklets. The necklace seems to have been, in most cases, a wide tight band, almost a collar; on many a mummy such a “choker” has been preserved, studded with jewels, the gold between often in the shape of a falcon, or a lotus, or a sphinx. Favorite among the designs, of course, was the scarab; in the mummy itself, a scarab was inserted to take the place of the heart.

Two ornaments common in ancient Egypt are not found in use today. One is the pectoral, a great bejeweled breastpiece, usually hung from the neck. The other is the golden wig cover. The great men and women of the eighteenth century B.C. wore long black wigs (in contrast to the great men of the eighteenth century A.D.; George Washington’s inaugural wig, was, of course, powdered white). Close-fitting over these[27] black wigs were joined rows of gold bands or medallions, beaten fine, fastened together, forming a complete cover that reached to the shoulders. The bands bore hieroglyphics, the medallions were usually shaped like heads of man or beast. One other difference from later times: for the snuffbox of the eighteenth century A.D., or the cigarette lighter of the twentieth, society folk in ancient Egypt carried a perfume box.

The Egyptians had many rings, including signet rings. These were intaglios; that is, the design was cut into, hollowed out of, the metal or stone, so that when the ring was pressed on clay or wax it would leave a raised design like a cameo. The design might be a god, or a sacred animal such as a scarab or a sphinx, usually with an indication of the identity of the owner. Thus the King’s seal, and especially the King’s signet ring if borne by a messenger, carried the royal authority. Jezebel, wife of Ahab, King of the Israelites, used the seal of her royal spouse on the letters she wrote to destroy Naboth, whose vineyard they coveted.

The Israelites, indeed, wore rings on their fingers, in their nostrils, in their ears, and we are told that when they walked there was a tinkling about their feet. They also wore a gem pressed into the soft side of the nostril, a favorite spot for display through the Near East, still adorned by a gem among the Bedouins and the Hindus of today. The Israelites gave of these jewels in great quantity to adorn the Tabernacle that was built in the wilderness—and also for the making of the Golden Calf.

Legend has it that Solomon’s wisdom emanated from a magic ring. One day he carelessly left this ring behind him at the bath, and with the water of his bath it was thrown into the sea. Solomon retained enough wisdom to suspend his legal court for forty days, after which the ring came back to him in the stomach of a fish served at his table. A similar story of a jewel returned in the belly of a fish is told by[28] Polycrates, tyrant of Samos in 530 B.C. Like stories occur in The Thousand and One Nights; and the coat of arms of the city of Glasgow contains a salmon with a ring in its mouth, memorializing the occasion when St. Kentigern from the fish’s mouth restored to an early queen her ring and her reputation.

Oriental tales have many accounts of magic rings. One of the most elaborate deals with Gyges, a Lydian noble to whom King Candaules, proud of the possession of a beautiful wife, displayed her in her undraped beauty. The resourceful Gyges descended into a chasm of the earth, where he found a brazen horse with a human carcass in its belly. From the body Gyges took a ring which, when he turned the stone inward, made him invisible. Thus fortified, Gyges entered the palace and murdered the king. The widow, Nyssia, married him; he reigned thirty-eight years, from 716 to 678 B.C., with the help of the ring becoming so powerful and so rich that men spoke proverbially of “the wealth of Gyges.”

Another ring, as remembered by Chaucer in The Squire’s Tale, gave a man the power to understand the language of the birds. The reader may remember that the messenger between King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba was a bird that whispered in their ears. We gather such stories from early days literally through a fabulous thousand and one nights.

Although jewelry was a preeminent concern of the Egyptians, because they must be adorned not only in this world but in the next, it was a lively preoccupation throughout the Near East, the cradle of civilization. Babylonian and Assyrian tombs yield treasures in splendidly mounted jewels. A description of the goddess Ishtar, descending through the Seven Gates to the ultimate world, pictures her at each gate putting aside a separate jewel, finger rings, toe rings, necklace, earrings, armlet, brooch, girdle: she passes through the final gate in unadorned beauty.

Among the jewels of ancient Persia, from the fourth century B.C., is a great necklace of three rows of pearls, almost 500 pearls in all, half of them still well preserved across the flight of twenty-five centuries.

There exist some examples of Greek art in early times. A gold and silver brooch in the form of a flower may have been shaped about 1400 B.C. Perhaps 500 years later, by the time of the Trojan War, there were inlays, intaglios, even small plaques of gold with hooks to fit the ear. In the fifth century, when the great dramatists filled the theatres, Greek lapidaries were making filigree and enamels of fruit and flowers—a bit later, of the fair feminine form. By this time, too, the Greeks were copying the designs they saw on, or bought from, Egyptian and Phoenician traders; the sphinx and the scarab appear in Hellenic workmanship.

Originators are held by their new problems to a sort of modesty in design. Imitators often—striving to outdo—overdo. The Greeks grew far more elaborate than their predecessors. The great Greek sculptors were delighted with the human figure which posed sufficient problems, either bare or simply draped. But outside of statuary, and after the great fifth and fourth centuries, the wealthy Greeks in their ways of life had caught the fever of display. Their jewelry must surpass that of the eastern barbarians to whom they were bringing the benefits of Greek culture. From every medallion of a necklace, for example, might hang a pendant. And this pendant might be a tiny golden vase, which contained perfume—each vase a different fragrance—or which might open to reveal a series of figures—as, later, baroque rosary beads[30] opened to reveal, in minute carving, episodes in the life of the Virgin Mary.

A portrait of Alexander the Great was a favorite figure, in many materials and forms. Although Alexander gave one artist exclusive right to reproduce his likeness after his death, as this monopoly lapsed there was a boom on “good luck” jeweled representations of the man who wept because there were no more worlds for him to conquer.

The Greeks did not ape all the antics of the Phoenicians, some of whose high-born ladies pierced the entire rim of their ears, as well as the lobe, each jewel in its eyelet supporting a pendant stone. The Greeks used but one ornament per ear; but these grew larger and larger, more and more weighted with metal and studded with jewels, and so were finally worn suspended from a diadem or a cloth band.

Alexander’s conquests having taken the Greeks into farther lands and introduced them to unsuspected splendors of the Orient, they carried home gems that before had been unfamiliar to them: the topaz, the amethyst, the aquamarine.

In Italy, meanwhile, the Etruscans had brought the work of the goldsmith and the lapidary to a high peak of artistry. They developed the swivel ring, in which the mounted gem or special charm might be turned about, so that any face of it could be displayed. Thus the carvings on the belly of a scarab became as important as the design on its back.

The Etruscans also made circular or oval bands of earrings and necklaces, within which a pendant might hang free, a gently swinging precious stone or golden charm. From their necklaces often hung a hollow pendant, in which an amulet[31] might be placed. They made many headpieces, bands, wreaths, and pins of beaten or granulated gold.

Especially deft was the work of the Etruscans in granulated gold. Onto a metal surface they soldered tiny specks of gold, almost as fine as powder, producing the effect of a rich grain. The artistry of the Etruscan work was so superb that when it was recovered during the Renaissance, Benvenuto Cellini (1500-1571), the greatest goldsmith of his time, despaired of making successful copies of the Etruscan pieces and decided to shape designs of his own devising, “inferior as they may be.”

The whole Etruscan civilization gave way before the splendor that was Rome. Home from their conquests the Romans brought great stores of jewels, treasures of the Orient. Before the crowding and gaping throngs of the imperial city, the “triumphs” of their rulers marched for hours through the streets of Rome, while foreign potentates pulled chariots bearing their conquerors and carts with the loot of their palaces. At Pompey’s third triumph, in addition to countless gold and silver cases bestudded with gems, there were three dining-couches adorned with pearls, and a great chessboard, three feet by four, wrought of two precious stones, with a golden moon, weighing thirty pounds.

The Romans also brought home artisans, metal workers and jewelers, from whom after a time the natives learned their craft. Again we find the victors trying to outdo the vanquished whom they naturally despised. The adornments of men and women grew more and more massive. Women’s hairpins were eight and ten inches long. Rings were worn upon every finger. Great thumb rings were set with jewels[32] or made of gold in various designs, especially the heads of animals. Some of the bands of gold were very large but hollow; down the ages echo complaints that, in accident or brawl, a golden ring was crushed. The wealthy, of course, insisted on rings of solid gold. These became so heavy that some had to be worn in cold weather only, lighter ones being designed for summer wear. A specialty among the patricians came to be the key ring, a golden band with the key devised to lie flat along the finger, thus keeping with the master the safety of his treasures. Often a large iron key ring was worn by the chief steward of an estate; this opened the strongbox, which might hold the dinner plate and other daily valuables, and within a recess of which nestled the treasure chest of the golden key.

So great was the jeweled extravagance of the late Republic that Cato the Censor (234-149 B.C.) sought by legislation to limit the amount of jewelry one might wear. He also restricted the use of metal in rings, assigning iron, silver, or gold according to rank. Gold was reserved for the official ring of the Senator, which he himself might wear only when on duty. Naturally such restrictions could not be binding for long. Censorship usually produces an exaggeration of what it has tried to curb. In the early days of the Empire everyone worth his salt manifested his worth with adornments.

The citizens favored bright colors in their jewels: reds, yellows, blues. The drivers at the chariot races wore different colors; spectators bet on the red, the yellow, or the blue, and many a precious stone changed hands according to the speed of the horses and the drivers’ skill. If a lapidary could not secure precious stones large enough, or in quantities to meet the ever increasing demand, he made imitations of colored glass. Although Pliny cried out against the practice of making false gems, the usual purchaser had few tests to show when he was cheated.

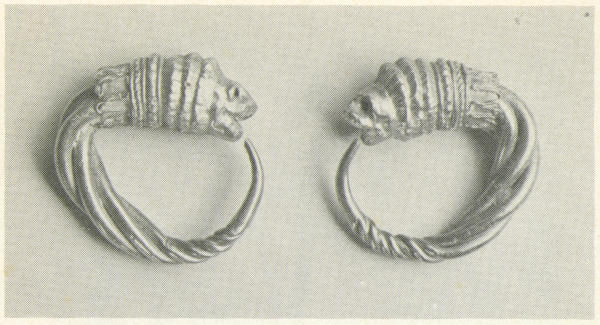

1. GREEK EARRINGS, 5TH CENTURY B.C. Wrought in gold, these ancient loops end in lions’ heads. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

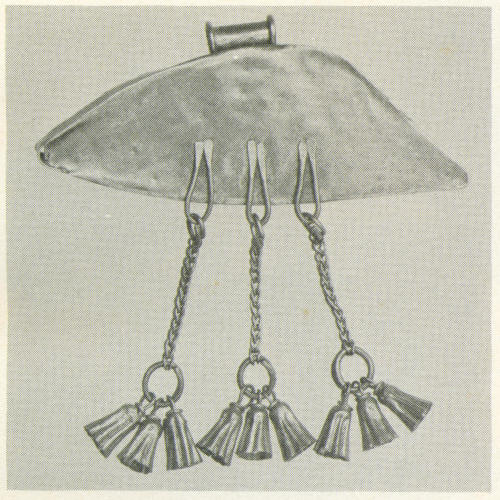

2. CYPRIOTE PENDANT, 8TH CENTURY B.C. This gold pendant with chains is an excellent example of the simple beauty found in the jewelry of ancient Cyprus. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

3. EARLY 18TH CENTURY ITALIAN BROOCH. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

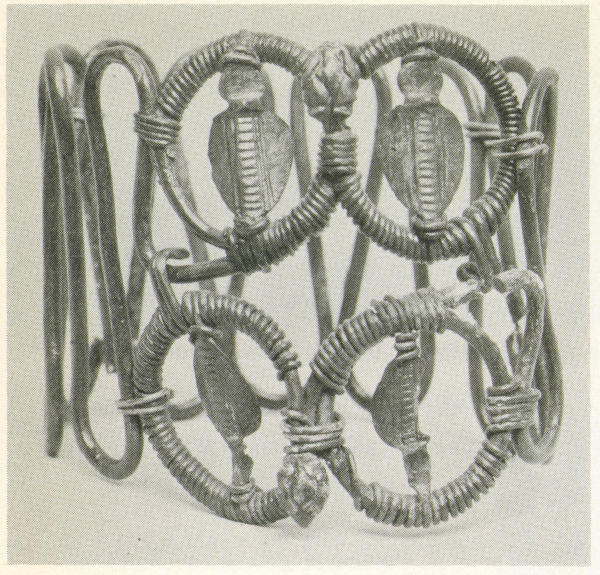

4. EGYPTIAN BRACELET, 4TH CENTURY B.C. “Costume jewelry” from the Ptolemaic Period. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

5. ETRUSCAN RING. This handsome gold ring is set with a banded agate which has been engraved with a satyr and a goat. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

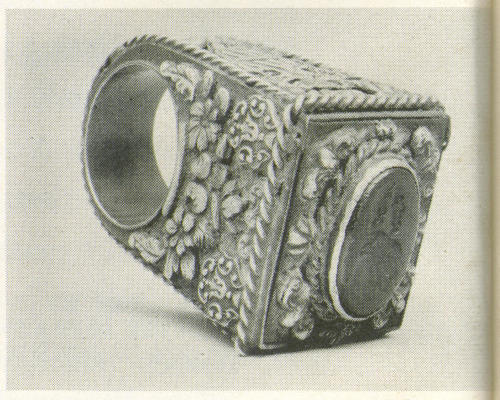

6. 18TH CENTURY ITALIAN RING. The seal on this silver ring is probably an effigy of one of the popes. The plaques represent St. George and the dragon, and the crest of Pope Clement XII. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

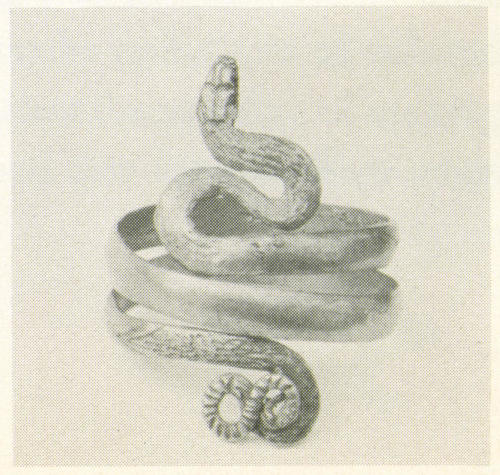

7. CYPRIOTE RING. Ancient gold worked in a spiral to produce an unusual piece of jewelry. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

8. ROMAN WREATH, 3RD CENTURY B.C. The expert craftsmanship of Roman metalwork can be seen in this gold wreath of ivy leaves. (Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)

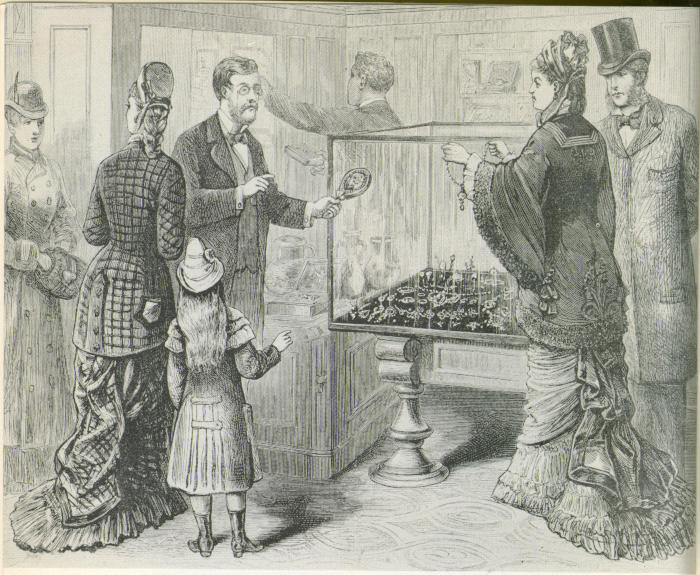

9. INSIDE VIEW OF THE FAMOUS OLD TIFFANY STORE, NEW YORK, 1875.

10. THE CROWNING OF A QUEEN. Queen Mary wears four of the magnificent gems cut from the Cullinan, the biggest diamond ever mined. On her bodice, pinned to the ribbon of the Order of the Garter, is the 317-carat Cullinan II with the 530-carat Great Star of Africa below it. These two gems normally are in the State crown and the Scepter respectively. At the base of her diamond collar are the Cullinan IV, a cushion-cut diamond of 64 carats and the Cullinan III, a pearshape-cut diamond of 95 carats.

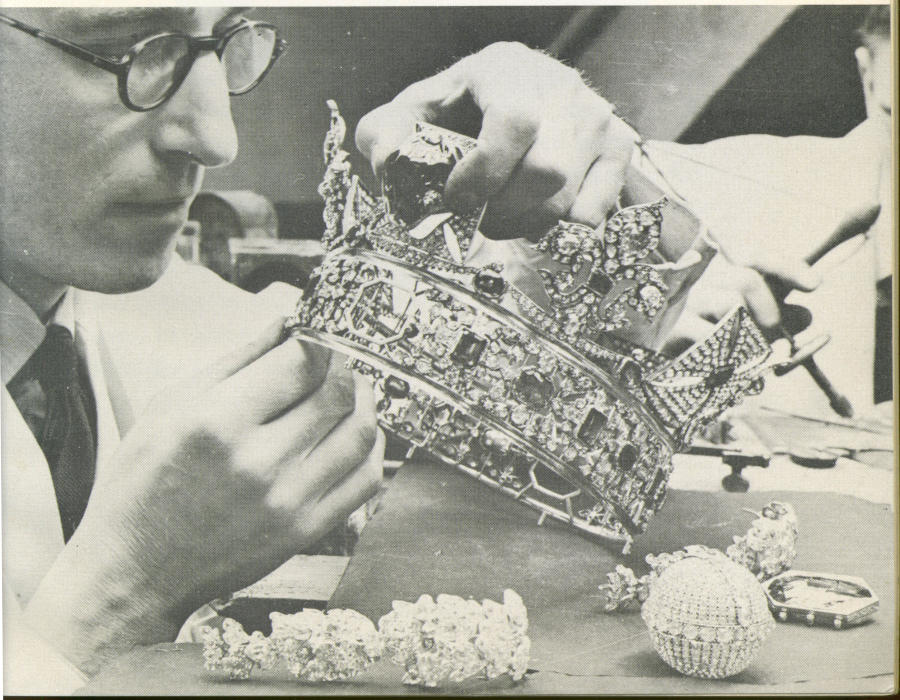

11, 12. THE BRITISH CROWN JEWELS. Left: The Crown of England, known as St. Edward’s Crown because it was copied, in the time of Charles II, from the ancient crown worn by Edward the Confessor, has been used by many of England’s monarchs for their coronation. Right: The Imperial State Crown is worn by the reigning monarch on all State occasions. Made in 1838, it embodies many historical gems, including the Black Prince’s Ruby, a sapphire from the ring of Edward the Confessor and the second Star of Africa. In all, the crown contains 2,783 diamonds, 277 pearls, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds and five rubies. (Courtesy of the British Information Services)

13. REMODELLING THE IMPERIAL STATE CROWN. Remodelling work in progress at the Goldsmiths & Silversmiths Company in London.

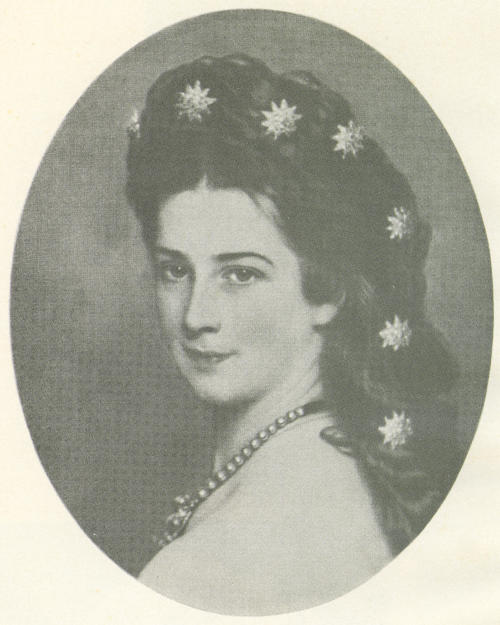

14. EMPRESS ELISABETH OF AUSTRIA. This portrait of one of the beauties of 19th century Europe shows the young Empress wearing hair ornaments of diamond stars which have quivering centers.

The notorious pearl-drinking dare of Cleopatra caught the fancy of the Romans. The serpent of the Nile dissolved a union (the Roman word for pearl was unionem, in this case truly symbolic) worth half a million dollars, and drank it as a pledge to her Antony. Cleopatra killed herself rather than walk in the triumph of Emperor Augustus, but the Emperor’s favorite, Agrippa, we are told, secured the mate to Cleopatra’s pearl. She had this great pearl halved, for the ears of the statue of Venus in the Pantheon.

The vogue of the pearl swept over Rome. This “disease of the oyster,” with its blush of rainbow colors over white, with its tint of beauty and its hint of underwater mystery, had indeed always been regarded as the queen of jewels. The Romans affected it to the degree of vulgar display. The historian Pliny (23-79 A.D.), who railed upon many customs of the time, commented on Pompey’s having a portrait of himself made in pearls and borne by slaves in his triumph. “Unworthy!” cried the satirist, “and a presage of the anger of the gods.” Pliny also recorded that a young bride was “covered from head to foot with pearls and emeralds.” He waxed indignant at the fact that women had pearls set in their shoes. But so did the Emperor Caligula, while the Emperor Nero, fond of the theatre, had pearls adorn his favorite players’ masks.

Not to be outdone by an Egyptian, Clodius—whose father was a favorite tragic actor—invited a great company to a feast; he dissolved and drank a large pearl, said that he enjoyed the flavor, and fed a similar gem to every guest.

The vogue of the pearl did not bring about the neglect of other gems. The Senator Nonius owned a great opal, valued at two million sesterces, approximately $150,000. The Emperor Augustus coveted the stone; rather than yield it to him, Nonius withdrew into exile.

Lollia Paulina, wife of the Emperor Caligula, possessed a great chain of emeralds and pearls worth over two million dollars.

It is significant of the change in Roman ways that when the Emperor Tiberius once more tried to limit the wearing of gold rings, he based his restrictions not on rank but on riches. Only those citizens might wear rings of gold, he ordained in 22 A.D., whose fathers and grandfathers held property valued at 400,000 sesterces, $30,000. Jewels, always the property, were thus also made the prerogative of the hereditary rich.

Back from Rome toward the East, with Constantine in 330 A.D., went the flowering fashions, to riot in Byzantine luxury. The Eastern capital exceeded the declining city of the West—abandoned to the barbarians and the popes—in extravagance, in colorful splendor and elaborate intricacy of design. Gems, no longer reserved for the showy jewels, were sewn upon or woven into the very texture of garments. In all this profusion, the crafts of the goldsmith and the lapidary continued to thrive, while the West lapsed into the dun rigor of the Dark Ages.

More or less independently of the western world, the making of fine jewels flourished in the Far East. In India the code of Manu, about 250 B.C., prescribed fines for poor workmanship and for the debasing of gold. A drama of the same period describes a workshop, with pearls and emeralds, and artisans to grind lapis lazuli, to cut shells, to pierce coral, and to make the filigree and other ornaments that have persisted in that part of the world unchanged to our day.

The lavishness of Oriental potentates is proverbial; their collections of precious stones and elaborate jewels have been as fabulous as their incalculable wealth. Almost to our own generation birthday gifts to maharajahs have matched the monarch’s weight in gold or precious stones. At the greatest period of Indian art, during the reign of the Mogul Shah Jehan, who died in 1666, the art of jewelry almost merged with that of architecture. In addition to the celebrated Peacock Throne, the Shah built the Great Mosque at Delhi, and at Agra the Pearl Mosque and that triumph of beauty, the Taj Mahal. This was erected as a mausoleum for his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahall, who was called “the adornment of the palace.”

In addition to the designs and patterns of tile that are a feature of the mosques, the Taj Mahal is adorned with great treasures of the East: “jasper from the Punjab, carnelians from Broach, turquoises from Tibet, agates from Yemen, lapis lazuli from Ceylon, coral from Arabia, garnets from Bundelcund, diamonds from Punnah, rock crystal from Malwar, onyx from Persia, chalcedony from Asia Minor, sapphires from Colombo.” It took thirteen years, from 1632 to 1645, to collect these treasures and construct the mausoleum. The memory of a woman may be buried there, but a beauty beyond description is preserved.

Still farther east, in China, a more restrained and delicate beauty was developed. Piety and filial devotion taught the Chinese to limit their display. They cultivated the economy of good taste. The world’s largest known emerald, found in China, was carved into the figure of Kwan Yin, goddess of mercy. Jewels were not worn indiscriminately; they served not only to adorn but to signify station. A mandarin of the first rank wore ruby or red tourmaline; a mandarin of the second, coral or garnet; of the third, beryl or lapis lazuli; of the fourth, rock crystal; and of the fifth, other stones of white.

Beyond all other stones the Chinese prized “the divine stone,” jade. While this occurs in various shades, even of blue, of red, of brown, it was, and still is, especially sought in ivory white and in the shades of green, from light apple to the dark “imperial jade.” This was, legend whispered, a crystallization of the spirit of the sea. Its possession conferred longevity, man’s prolonged moment in the eternity of the gods.

A perfect piece of jade is left uncarved. As a pendant, brooch, or ring, it stands alone, in simple beauty. A cultured Chinese was likely to have one with him unmounted, just the stone, to cherish it and finger it and feel its silken surface. There were experts who could tell the quality, the very color, of a piece of jade, without looking at it, just from the feel.

Treasured through the centuries in China, jade has come to be prized in the West as well. The Emperor Kuang-hou sent Queen Victoria, for her Jubilee, a sceptre of jade. The deep green of the richest jade, the divine stone, makes it a fit companion for the diamond, the monarch of gems.

The diamond was not mentioned, in this summary narrative, until the description of the Taj Mahal. This greatest of precious stones—hardest of gems, and the only one that consists of a single element—was little known in the ancient world, and but slowly won appreciation in the West. At the height of the Renaissance, Cellini in 1568 set down the values of the precious stones, of flawless stones one carat in weight. A ruby of such specifications was worth 800 gold crowns; an emerald, 400; a diamond, but 100. (The more common sapphire was a far fourth, at ten gold crowns a carat.)

The Dark Ages in southern Europe were not especially bright with gems. Individual rulers made some display, on crown, on hilt of sword, and ecclesiastical splendor was slowly gathering, along with decorated frames and representations of the Virgin Mary. On the other hand, the medieval Church frowned upon unseemly extravagance of display, and some monarchs, even Charlemagne when he doffed his rich crown of state, were sober and plain in their attire.

In the more northerly lands, and among the tribes that in the fourth, fifth, and sixth centuries pressed upon and twice overran Rome, there was meanwhile more than a crude attempt at jeweled adornment. The Ostrogoths made some magnificent brooches, mainly with animal designs. The Visigoths were fond of garnets, often set on a background of cloisonné. Their crowns and coronets were elaborately wrought; one of these, belonging to the Spanish-Gothic King Reccesvinthus (649-672) was given as a votive offering to the church of Santa Maria near Toledo.

The warlike and otherwise austere Franks took pride in their jeweled buckles. Their brooches were circular, or formed in the shape of birds. In Belgium, in the Fifth century, there was considerable carving of chips, a practice that migrated to Scandinavia. In Sweden there was also an abundance of circular pendants, beaten of thin gold, and decorated with animals.

Among the Celtic peoples were found armlets and fibulas, the latter not so short in the arch, nor so exquisite, as the Greek pins, nor yet so long and heavy as the Roman. The Celts had large, crescent-shaped head ornaments, attached near the ears and standing straight up on either side like the horned moon. They made heavy gold torques, necklaces of twisted metal usually tight as a collar. Some of the torques, especially those in Ireland, were much longer and hung down in massive twists across the chest. Ireland is called “the Emerald Isle” not from any pride in its deep green verdure, but from the ring sent by Pope Adrian to Henry II of England in 1170, a ring set with an emerald, for the King’s investiture with the dominion of Ireland.

The Scotch, because of the way they wore their plaid, grew to have exceptionally splendid brooches. A fine one of these, preserved in the British Museum, is known as the Loch Buy brooch; it is of rock crystal cut in a convex mound, in a circle of ten projecting turrets each topped with a pearl. A noteworthy brooch design is that of the pin with arms: a straight bar down the center, enclosed in two arcs of a circle of beaten gold.

Although most of their gold designs were hammered down into the metal, the early Celts also grew expert in répoussé, a[47] process in which, on a thin sheet of metal, the design is hammered upward from underneath.

Among the Anglo-Saxons, especially those that settled in Kent, a greater variety was manifest. They made beads in many shapes and shades of glass and amber. They were fond of the amethyst set in pure gold. They adorned their hair with pins tipped with figures of animals and fantastic birds. They took great pains with the art of enamel, which they fashioned cloisonné.

The finest known piece of Anglo-Saxon days is the Alfred Jewel, a gold plaque of cloisonné enamel found in 1693 at Newton Park. It is an oval two inches long, a little over an inch high, and an inch deep. At the tip of the oval is a boar’s head. Rock crystal covers the main plaque of translucent enamel, blue, white, green, and brown, shaped in the head of a man. Some think this may represent a saint, or the Christ; some say it is a portrait of Alfred the Great, for along the edge in gold are the letters: Aelfred mec heht gewyrcan, “Alfred had me worked.”

Among other treasures of early England are examples of filigree, such as a Kentish brooch set with garnets, of the sixth century, and brooches of granular gold.

One of the three Royal Crowns of the British monarch is supposedly that of Edward the Confessor, who was buried in Westminster in 1101, but whose shrine was opened and the jewels taken forth for future kings. The royal treasures of the English realm, however, were broken up by the Roundheads under Cromwell.

Life at its longest is fleeting, but beauty is an enduring symbol: the destroyers of the royal treasure are scorned today almost more than the regicides. The current Crown of Edward the Confessor, therefore, is a replica, even if the old one was authentic. Less suspect is the great sapphire, which Edward wore in his coronation ring, and which today is the central stone in the cross atop the British Imperial Crown of State.

Less than a century after Edward, in the reign of Henry II, the first Plantagenet ruler of England, the Goldsmiths’ Guild was formed. By 1380, two hundred years later, it was one of the most powerful guilds in the country, with rigid rules for admittance and for the quality of materials and workmanship. Although the artists worked for the king and the nobles, the bulk of their production was for ecclesiastical and general religious use. As a result, they developed greater refinements and further elaborations in this field. We have already noticed the rosary beads that open, disclosing scenes of the life of Christ or the Virgin Mary. But a cardinal without succumbing to the sin of pride might wear a jeweled pendant if the hanging box of gold opened upon a crucifix, or adorn his robe with a rich chain of gold if its links were medallions designed with holy scenes. Cardinal Wolsey, whose kitchen boasted twenty-two[49] specialty chefs, vied with his lusty monarch, Henry VIII, in many ways, but he could never hope to match the King’s jewels which included almost 250 rings, well over 300 brooches, and one of whose diamonds, an observer reports, was bigger than “the largest walnut I ever saw.”

The Italian Renaissance started earlier than and outshone the English. The great jewel collections of ancient times, of the Emperors Julius Caesar and Hadrian of Maecenas were dwarfed by the collections of the Medici and the Borgias. The styles favored in those days are still vivid in the portraits of the period. Many of the painters and sculptors, indeed—Donatello (1386-1466), Pollaiuolo (1429-1498), Botticelli (1444-1510), Cellini, to name but four—began their careers as goldsmiths and jewelers. They fashioned works with painstaking devotion and venturesome skill for their generous but exacting patrons.

Lorenzo de Medici collected the antique cameos and intaglios freshly unearthed in Italian soil; under the spur of his interest, intaglio jewels achieved a new delicacy. Metal was worked with greater deftness, flat, chased, or répoussé. Faience, the art of painting and glazing ceramics, was added to the colorful arts of enameling.

Enseignes became popular, badges of dignity in the form of a gold adornment on a man’s hat, with the nobleman’s crest or other identification caught into the design. All over the continent, and even among the Italianate Englishmen of Elizabeth’s court and James’, the enseigne was worn as a clasp to hold the plume, while from one ear beneath dangled a golden ring or a pear-shaped pearl.

Rings of all sorts were again in demand, especially signet[50] rings, fede (clasped hands) friendship rings, gimmals or gemmels (twin rings that could be separated for two lovers to wear)—and poison rings.

Particularly popular was the pendant, in many forms and positions. Pendant earrings again grew, until almost too large to wear. Even larger pendants, many opening on cameos, dangled upon the breast. Pendants of all sorts hung from the girdles, utilitarian in the shape of golden keys or scissors, religious in the shape of a crucifix or the relic of a saint, along with purely aesthetic medallions of animals or flowers, or golden spheres—so many as to make a tinkling when one walked.

A new fashion in the pendant was introduced, a jewel on the forehead, hung from a hair band or adornment; in India, similar pendants had for centuries hung from the veil. This new pendant was called the ferronière, from La Ferrionière (“the ironmonger’s wife”) whose portrait survives, probably painted by Leonardo da Vinci when she was mistress of Francis I of France.

When Cellini went to France, he gave impetus to the art work there. In Spain, the goldsmiths fashioned reliquaries; they wrought pendants on which they hung the emeralds new-garnered from Peru; they favored bow-shaped brooches of many jewels, the ruby vying with the emerald. The great international bankers, the Fuggers, dealt also in jewels and gems. Hans Holbein the painter, while in England, made many designs for jewels. The painter Albrecht Dürer, son of a goldsmith, fashioned a pendant for Henry VIII, with the initials E R (Enricus Rex) and three large drops.

At the same time, the sons of wealthy merchants, the young[51] bloods of the cities, with spangled chain and jeweled dagger hilt, aped the sons of nobles. Restrictive regulations did little to curb their display. As wealth was not yet evenly distributed, not everyone could afford the genuine precious stones, and the trade in paste flourished. Milan was the center of this manufacture. In addition to the ordinary glass used for imitation gems, strass glass was developed. Invented by Josef Strasser, this mixes lead or flint with the usual vitreous substance and obtains a greater lustre. Either type of glass often had placed beneath it, cunningly hidden in the setting, a tiny bit of quicksilver or tinfoil, to make the glass reflect more light and thus seem to sparkle with its own fire.

The Renaissance no more than earlier times had skill to know the genuine from the imitation. Cellini chuckles over the fact that Henry VIII of England, bargaining with a shrewd dealer of Milan for a fine set of jewels, received what he felt was one of his best buys—in paste.

The ease of working in these various modes overreached itself. The designs again grew more and more elaborate. Enseignes, medallions, love tokens, memorials of saints, grew heavier than the hats, than the heads, they were intended to adorn. Rings and bracelets were fashioned to be worn outside of gloves; gloves were fashioned with slits to display bracelets and rings within. Extravagance of ornament, though a minor cause, contributed to the revulsion against the many abuses of the day that led to the two reformations. The Church itself embarked on a housecleaning campaign, which included simplicity of dress and paucity of adornment.

The seventeenth century in Europe, in the field of jewels, was one of timid venturing. The Portuguese came to the fore[52] with delicate work, golden sprays of leaves and flowers with tiny gems, ribbons and knots of gold. In France the sévigné appeared, a simple golden bow or rosette worn on the breast, named after the Marquise de Sévigné, a noted blue-stocking and one of the greatest letter writers of her day. The sévigné, at first rather plain, was elaborated during the eighteenth century into a massive brooch, or even a gemmed stomacher. The aigrette also appeared at this time, in the form of feather-like thin movable stalks of gold tipped with tiny gems set in enamel; these vibrated as the wearer moved.

In the eighteenth century greater attention was again paid to adornment. The aigrette became more popular, used mainly as an ornament for the hair. Thin silver stalks like stems of wheat were banded just below the center, with a slide for fastening; the tips were set with diamonds. Some pins for the hair and some brooches were fashioned with birds or butterflies, again on thin stalks so that they flitted as the wearer walked. This vibration of the aigrette added to the sparkle of the gems. I have made a variation of this jewel, as a flower, to fit the taste of the twentieth century.

A new type of pendant earring was the girandole. This appeared in two main forms. In one, from a large circular stone at the ear lobe hung three pear-shaped pendants, sometimes amethysts or other colored stones, but usually diamonds. In the other type, from the top stone was suspended an oval hoop of gold, within which a single large diamond hung loose.

More and more as the nineteenth century came near, the fashion in precious stones demanded diamonds. If not in the center of a jewel, they were used to set off the main one. They were worn in the new marquise ring, the gold of which[53] was fashioned to hold a large oblong stone surrounded by diamonds. They were an essential element of the parure, the set of matching jewels, which developed in this century in France. Thus milady might have, in a parure, a bracelet, necklace, earrings, aigrette, and sévigné, all ordered together and made of the same metals and precious stones, patterned for their respective purposes in a concordant, harmonizing whole.

For a time, under the influence of the rococo style, and the Gothic tendency in the other arts, it looked as though jewelry designs, becoming more and more elaborate and extravagant, might again approach the eccentric and achieve the inept. In 1755, however, the ruins of Pompeii were unearthed, with their treasures of antique style, and a classical simplicity became the order of the day, fostered for a time by the “return to nature” of the Romantics. It was felt, for instance, that the diamond, now prized beyond all other precious stones, shone most effulgent when it stood alone in a simple setting.

The wars toward the end of the eighteenth century, culminating in the French Revolution and the campaigns of Napoleon, shifted the ownership but did not stem the manufacture or the collection of jewels. The inventory of Mlle. Mars, taken in 1828, listed over sixty items, many of them treasures in themselves. Notable among these were: a necklace of two rows of brilliants (diamonds), forty-six in the first row, forty-eight in the second. Eight bunches of sprigs of wheat tipped with brilliants (that is, eight aigrettes) totaling about 500 brilliants weighing 57 carats; a garland of brilliants that could be worn as one bouquet or divided into three flower brooches, totaling 709 brilliants and 85¾ carats; a sévigné—mounted in colored gold a central large topaz was surrounded by brilliants,[54] with three drops of opals also surrounded by brilliants, the whole set in gold studded with rubies and pearls; a pair of girandole earrings of brilliants—in each, from the large stud brilliant were suspended three pear-shaped brilliants, united by four smaller ones; a pair of earrings—from the large stud brilliant of each hung a cluster of 14 smaller brilliants, like a bunch of grapes; a parure of opals, consisting of a necklace, a sévigné, two bracelets, earrings, and a belt-plate. And Mlle. Mars, though a noted comic actress and a favorite of Napoleon, was by no means the outstanding society woman of her day.

By 1840 many new designs—frets, crescents, stars—were employed to show off the popular diamonds. These were still preeminent in the magnificence of the marriage of Napoleon III in 1853, but his Empress Eugénie revived the use of strings of pearls for the evening. Diamonds were then worn in similar strings, called rivières, necklaces of a succession of single stones, matched or graduated, with a very large stone in the center. A stone of ten carats was no longer considered large; the diamond must be at least fifteen carats, and preferably nearer forty. The large solitaire became popular, not only for engagement rings, but as the clip-stone on a pin or pendant, from the diamond often hanging a pear-shaped pearl.

The late nineteenth century developed an electicism, a freedom of choice among the various modes of the past, that continues into the jewelry design of our own day. Toward the end of the century, perhaps as a by-product of the school of les diaboliques in literature and art, there developed a desire to shock the bourgeoisie, and with it a certain desire for novelty,[55] manifested in such bizarre items as live beetles worn as pins, or brooches of a live tortoise with gems set in its shell.

A central ground of common sense and classical design was firmly maintained by Peter Carl Fabergé and the House of Fabergé, which designed many of the jewels at the turn of the century and continued popular among the Edwardians. The great World’s Fair in Paris in 1900 showed a fresh interest in design, and the use of such materials as translucent enamel, ivory, and horn. The influence of the Orient showed in these materials; it was also evident in larger and more colorful earrings and the multiplicity of bracelets.

Hair styles played their part in the shaping of jewelry. The pompadour in front, with chignon, increased the output of tortoise-shell combs, often studded with diamonds, and of fourches, large two-pronged hairpins similarly adorned. After 1914, the vogue of bobbed hair shifted production from combs to diamond slides. At the same time, the exposed ears made ear ornaments de rigueur. As many persons objected to having their ear lobes pierced for earrings, the earclip became popular; today it is almost universal in feminine fashion.

About this time, too, short sleeves led to an increased use of bracelets, often worn several on one arm. Especially popular has been the bangle bracelet, a band of gold from which are suspended coins, figures of men and animals, and other tokens and mementos. Sometimes golden disks are engraved with sentimental designs or sayings; sometimes the words are humorous, the figures grotesque.

Platinum and more recently palladium have been increasingly used as basic metals for the new jewelry, along with the now less frequent silver and the constant gold.

Spurred by René Lalique, the impetus of modern art has been felt in jewelry design. Cubic, non-representational, and other modes of abstract form have helped shape the modern bracelet, earclip, watch, and the case for powder, cigarettes, lighter, or the watch. While some jewels thus manifest the modern modes, others draw freely on the beauty of the past, as stimulus to the creation of fresh patterns of beauty for our day.

On the basis of beauty, stones cannot be divided into precious and semiprecious for, from stone to stone, there is continuous range of color and glow. Nor indeed can price be the one criterion, for here many elements produce variety. Although the term “gem of the first water” is reserved for the flawless blue-white diamond, as the carats of the single stone increase the flawless ruby and the emerald become even more costly; and varieties and special specimens of other stones, such as the fire opal and imperial jade, move up into comparable range. For certain individuals, of course, a particular stone will have associations of sentiment that render it more precious—in the nontechnical sense—than another stone in the category of “precious.” It is, then, tradition rather than any inherent value that sets a secondary label, “semiprecious,” on all but five of the stones used for human adornment. Let us call these five the gems, to distinguish them from the other stones.

There is no doubt that the five gems—diamond, ruby, emerald, sapphire, and pearl—have grown more fully than all others into our ways of living. They have become, as I shall indicate in this chapter, adornments not only of our persons but of our speech and writing. They are used not only in figures of jewelry but in figures of speech, to express human beauty, or eminence, or virtue. The poet and the orator, as well as the monarch and the lover, have utilized the glamour of the gem.

Supreme in human imagination is the diamond, the hardest of all stones. The word diamond captures this significance, for it is from Greek adamas, meaning unconquerable, the tameless stone.

The diamond is also the only gem that is entirely composed of a single element. It is carbon, which also appears in its more common and less costly forms as soot, jet, and coal. The diamond is pure carbon crystallized in regular octahedrons, eight-sided figures.

For a long time, one word was used to mean both the diamond and the lodestone, the natural magnet. In French today, the gem is diamant, and the magnet is aimant—which also means loving. Perhaps the word changed because the natural magnet, attracting things to it, was thought of as “the loving stone.” The diamond is the beloved stone.

Most diamonds at their best are colorless, with perhaps a bluish glow. They may also be blue, green, violet, less often red—and black. The black diamond is usually unwanted for[59] jewelry, but is used by lapidaries and others for cutting, grinding, and polishing hard stones.

If a jeweler speaks of a Matura diamond or a Ceylon diamond, he is using an old trade name for a zircon. Similarly, a Welsh, Irish, Cornish, Quebec, or California diamond is likely to be an attractive piece of rock crystal.

True diamonds were known in Asia at least as far back as 900 B.C. India was the homeland of the gem for many years. The best stones in the sixteenth century were those cut in Hyderabad, India, in the famed city of Golconda. Rich findings were made about 1720 in Brazil; in Borneo in 1738; elsewhere, diamonds were discovered in less significant amounts. But by far the richest hoards were unearthed in 1867 in South Africa, which is still the world’s greatest source of diamonds.

Although the lozenge is the characteristic shape of its crystal surface, the rough diamond stone is found in many shapes and cut into great variety. Because of the tears that the great tragic actress Sarah Bernhardt wrung from the audiences at his melodramas, Victor Hugo presented her with a tear-shaped diamond.

Among the many literary references to the diamond, the Elizabethan playwrights were particularly fond of the expression “diamond cut diamond”, meaning in that aristocratic age, when great man matched with great. In the more democratic nineteenth century, particularly with regard to those most democratic of spirits, the pioneers—such as the Americans opening up the West—it became popular to speak of an uncouth, unpolished but fundamentally fine fellow as “a diamond in the rough.”

Lovers at all times have linked this most brilliant of stones with their fair one’s sparkling eyes. One said that, wherever he went in the world, he found only his beloved:

There are several sayings which, though they refer to the diamond, by indirection speak of mankind. Thus there is a warning to the person who is heedless of dress or decor, or of the furnishing of office or home, in the remark: “A fine diamond may be ill set.” There is, on the other hand, a challenge to pretense, or perhaps a warning to a person about to select an employee—or a mate—in the Chinese proverb: “A diamond with a flaw is better than a perfect pebble.”

The ruby is a variety of corundum. The Sanskrit word kuruvinda was limited to the ruby, but we today use the word corundum to mean any form of aluminum oxide, chemically Al₂O₃. Corundum is next in hardness (though far inferior) to the diamond, and a hard granular form of it is used in grinding and polishing. In its pure, transparent form it is, according to its color, the ruby, the sapphire, the Oriental amethyst, or the Oriental topaz.

The Latin word ruber means red, and the crystalline corundum that is a ruby takes shades from pale rose-pink to a deep crimson that borders on the purple. The color is determined by the nature of the oxide, and the gem sometimes has a light silken sheen. A flawless deep red ruby is one of the rarest and most costly of gems.

Because of its great value, the ruby has often been used as a term of comparison for human worth, implying the highest excellence. The Scottish poet William Dunbar used it in pious[61] thought: “Hail, redolent ruby, rich and radious! Hail, Mother of God!”

Among precious rubies, greatly desired is the star ruby, a gem so flawed that it catches the light as a sun with six out-shooting rays. “The sun is fair,” said the poet Drummond of Hawthorne on a fine summer’s morning, “when he with crimson crown and flaming rubies leaves his eastern bed.” The star ruby, with its three crossbars making six rays of light, has been thought by these lines of light to signify Faith, Hope, Charity, Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Thus it is doubly prized, for its good fortune and for its beauty.

The deep rubies of “pigeon’s blood” or ox-blood red come from Burma; those from Siam may be purplish brown; from Ceylon, more probably pink; a Brazilian ruby, a topaz; a Siberian ruby, a tourmaline; and a Balas ruby, a spinel.

Most frequent of all comparisons with gems are references to the “ruby lips” of beauty. Close after these come allusions to the rich red of wine, as when Fitzgerald tells us, in his translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam:

Robert Herrick, the poet of youth and springtime, who advises us to enjoy lovely things while they are here—“Gather ye rosebuds while ye may”—in a note of more solemn warning says to a fair maid:

What the maiden answered is not on record, but it is sadly pleasant to think, three hundred years later, that somewhere today that ruby is still beautiful and still enjoyed.

Sapphire is the current form of a Sanskrit word meaning dear to Saturn, an olden god whose reign was regarded as the golden age. The stone has been known since earliest times, although what the ancients called sapphire was probably the lapis lazuli, our sapphire being called by them the hyacinth. It is hard to tell, however, just what gem is intended when in the Song of Songs the Queen of Sheba sings of Solomon, her beloved: “His hands are as gold rings set with beryl; his belly is as bright ivory overlaid with sapphires.”

Our sapphire is a bluish transparent variety of native crystalline aluminum oxide, the same corundum that when it is red we call a ruby. The sapphire may be sky blue or cornflower blue, and shade through the lighter hues to an almost colorless stone, called white or water sapphire.

The sapphire is often used as a figure for the stars or for blue eyes: “Those eyes, those sparkling sapphires of delight”... “Now glowed the firmament with living sapphires.” This last line is by Milton, from Paradise Lost, which he dictated to his daughters when he was blind. The poet Gray pictures Milton as becoming blinded by his great vision:

While the sapphire at its best still captures the blue of a cloudless sky, it brings with it today a vision of more serene beauty.

The emerald is the most precious of the large beryl group of stones. It has been deemed precious from ancient times. Cleopatra’s emerald mines are still being worked. A flawless deep green emerald of good size is extremely rare. Such a gem, normally, is table cut. The emerald also may be pierced for use as a bead, or engraved. In Egypt, the usual carving was a scarab—Cleopatra possessed one; in India, the carving often was a god.

The word emerald, before the sixteenth century, was esmeraldus and smaragdus; the Sanskrit word for the gem was marakta. As recently as the last century, Ralph Waldo Emerson summed up the chief sensuous impressions of the Orient: “Color, taste, and smell: smaragdus, sugar, and musk.”

There are few colors at once as striking and as restful as the green of an emerald. It seems to have the depths of the pure rays in a calm ocean. Coleridge in The Ancient Mariner used it for another form of the ever-changing waters:

Tennyson used it for the widespread carpet of the land.

In a lighter vein, it has been used to suggest the color of unripe fruit, as in Eugene Field’s verses on the peach:

The green of the emerald makes it, in many minds, the most beautiful of colored gems.

The pearl is the only one of the five gems that is the product of life. It gives body to the eternal paradox that out of evil springs good; out of deformity, beauty. For these reasons, the pearl is most frequently, of all gems, woven into symbols of man’s activity. “Honesty dwells like a miser, sir, in a poor house,” said Shakespeare, “as your pearl in a foul oyster.”

A pearl, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it, is a nacreous concretion formed within the shell of various bivalve molluscs around some foreign substance (i.e., a grain of sand), composed of filmy layers of carbonate of lime interstratified with animal membrane.

Trying to isolate the intruding irritant, the oyster secretes a sticky fluid. The fluid hardens, another layer of it is secreted, and the pearl grows. The genuine pearl oyster is the meleagrina margaritifera. Margaritifera means pearl-bearing from which comes the name Margaret meaning pearl. Other molluscs may also form pearls, though not usually the varieties served in the months with an “R”.

Freshwater pearls come from mussels, of the kind called unionidae. Unionem is the Latin word for pearl—also for onion, which like the pearl is made up of layer upon layer. Mary Queen of Scots had a necklace of fifty-two graduated pearls, all of them fetched out of Scottish rivers.

Pearls are prized because of the beautiful lustre that glows upon them, pink or even bluish-grey, an iridescence over the basic white. Rarest are the large black pearls, which make a beautiful center drop on a brooch or a necklace. The pearl is hard and smooth in texture, beautiful to see and pleasant to feel.

The usual shapes in which a pearl grows are round, button, pear, and baroque (which in this use merely means irregular). The round pearls are used mainly for necklaces, which must[65] be threaded in silk or plastic or other such material; any metal may darken and dull the beauty of a pearl. Button pearls are used in earclips, studs, brooches and rings. Pear-shaped pearls are attractive as pendants. The use of baroque pearls depends upon their shape and size.

Pearls are assorted and matched with great care, according to their size, shape, and color. The matching of a string of pearls may be a quest of twenty years. Sometimes a jeweler will hold the pearls until he has a matched necklace, graduated or of equal size; but it is also a challenge to a woman who enjoys jewels to buy a few pearls she can wear in various ways while watching for enough of their peers to form a string.

The lustrous inside of the oyster shell, formed of the same material as the gem, is called mother of pearl. A blister pearl is a flattish excrescence that, instead of being inside the soft oyster, adheres to the shell; it may be detached and used. Seed pearls are very tiny pearls, weighing less than a quarter of a grain.

For ages one of the most highly prized and priced of gems, the pearl has become less costly not because of changing taste or of successful simulation, but because man has learned the secret of the stimulation of the oyster to make it create a pearl. The best natural pearls come from the Persian gulf and the waters of Australia; but it is the Japanese who have most fully developed the technique of inserting a foreign body in the oyster, so that it then carries on, under its own living power, the process of making a real—but what is called a cultured—pearl. Man proposes and the oyster disposes.

From the “gates of pearl” through which Saint Peter allows the elect to enter Heaven, to the guardians—“of Orient pearl a double row”—of the smiling mouth, the pearl has been caught into proverb and poem. At the beginning of this century, the pearl figured in a popular song:

For some reason, all of Shakespeare’s references to the pearl are linked with sadness. The song in The Tempest tells:

And it is after Othello has killed his faithful wife Desdemona and has discovered that his clouding suspicions were untrue, that he calls himself:

As far back as the Bible a thing of supreme quality was referred to as a pearl of great price; and the same book (Matthew) issues the famous warning: “Neither cast ye your pearls before swine.”

In other ways the pearl has been used as a symbol. The poet Swinburne, in sentimental mood, exclaimed:

The rarity of the stone, and the difficult task of the pearl-diver, are used symbolically in an epigram by Dryden:

The American poet, William Russell Lowell (father of the Supreme Court Justice of the same name), wrote in his copy of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam: