Title: Post mortem: Essays, historical and medical

Author: C. MacLaurin

Release date: October 1, 2022 [eBook #69078]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: 1922: George H. Doran Company, 1923

Credits: MWS, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

[Photo, Anderson.

THE EMPEROR CHARLES V.

From a portrait by Titian (Madrid, Prado).

Post Mortem

Essays, Historical and Medical

C. MacLaurin

M.B.C.M., F.R.C.S.E., LL.D.

Lecturer in Clinical Surgery

University of Sydney, etc.

New York:

George H. Doran Company

Made and Printed in Great Britain by Butler & Tanner, Frome and London

WHETHER the “great man” has had any real influence on the world, or whether history is merely a matter of ideas and tendencies among mankind, are still questions open to solution; but there is no doubt that great persons are still interesting; and it is the aim of this series of essays to throw such light upon them as is possible as regards their physical condition; and to consider how far their actions were influenced by their health. There are many remarkable people in history about whom we know too little to dogmatize, though we may strongly suspect that their mental and physical conditions were abnormal when they were driven to take actions which have passed into history; for instances, Mahomet and St. Paul. Such I have purposely omitted. But there were far more whose actions were clearly the result of their state of health; and some of these who happen to have been leaders at critical epochs I have ventured to study from the point of view of a doctor. This point of view appears to have been strangely neglected by historians and others. If the background against which it[8] shows its heroes and heroines should appear unsentimental and harsh, at least it appears to medical opinion as probably true; and it is our duty to seek Truth. If it appears to assume an iconoclastic attitude towards many ideals I am sorry, and can only wish that the patina cast upon their characters were more sentimental and beautiful.

Jeanne d’Arc and the Emperor Charles V were undoubtedly heroic figures who have been almost worshipped by many millions of people; yet undoubtedly they were human and subject to the unhappy frailties of other people. This in no way detracts from their renown. I must apologize for treating Don Quixote as a real person; he was quite as much a living individual as anyone in history. Through his glamour we can get a real glimpse of the character of Cervantes.

In Australia we have no access to the original sources of European history; we must rely upon the “printed word” as it appears in standard monographs and essays.

I owe many thanks to Miss Kibble, of the research department of the Sydney Public Library, without whose help this work could never have been undertaken.

Sydney, 1922.

| PAGE | |

| The Case of Anne Boleyn | 13 |

| The Problem of Jeanne d’Arc | 34 |

| The Empress Theodora | 65 |

| The Emperor Charles V | 88 |

| Don John of Austria, Cervantes, and Don Quixote | 114 |

| Philip II; and the Arterio-Sclerosis of Statesmen | 144 |

| Mr. and Mrs. Pepys | 157 |

| Edward Gibbon | 180 |

| Jean Paul Marat | 191 |

| Napoleon I | 204 |

| Benvenuto Cellini | 226 |

| Death | 232 |

[10]

| The Emperor Charles V | Frontispiece |

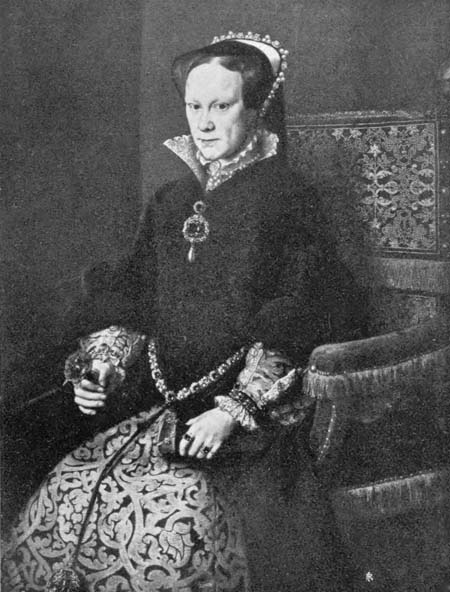

| Mary Tudor | Face p. 16 |

| The Empress Theodora | ” 72 |

| Perseus and the Gorgon’s Head | ” 228 |

[12]

THERE is something Greek, something akin to Œdipus and Thyestes, in the tragedy of Anne Boleyn. It is difficult to believe, as we read it, that we are viewing the actions of real people subject to passions violent indeed yet common to those of mankind, and not the creatures of a nightmare. Yet I believe that the conduct of the three protagonists, Henry, Catherine, and Anne, can all be explained if we appreciate the facts and interpret them with the aid of a little medical knowledge and insight. Let us search for this explanation. Needless to say we shall not get it in the strongly Bowdlerized sketches that most of us have learnt at school; it is a pity that such rubbish should be taught, because this period is one of the most important in English history; the actors played vital parts; and upon the drama that they played has depended the history of England ever since.

In considering an historical drama one has to remember the curtain of gauze which Time has drawn before us, and to allow for its colour and density. In the case of Henry VIII and his time, though the actual materials are enormous,[14] yet everything has to be viewed through an odium theologicum that is unparalleled since the days of Theodora. In the eyes of the Catholics, Henry was, if not the actual devil incarnate, at all events the next thing; and their opinion has survived among many people who ought to know better to the present day. Decidedly we must make a great deal of allowance.

Henry succeeded to the throne, nineteen years of age, handsome, rather free-living, full of joie-de-vivre, charming, and with every promise of greatness and happiness. He died at fifty-five, unhappy, worn down with illness, at enmity with his people, with the Church, and with the world in general, leaving a memory in the popular mind of a murderous concupiscence that has become a byword. About the time that he was a young man, syphilis, which is supposed to have been introduced by Columbus’ men, ran like a whirlwind through Europe. Hardly anyone seems to have escaped, and it was said that even the Pope upon the throne of St. Peter went the way of most other people, though it is possible that this accusation was as unreliable as many other accusations against the popes. Be that as it may, the foundations were then laid for that syphilization which has transformed the disease into its present mildness. It is impossible to doubt that[15] Henry contracted it in his youth[1]; the evidence will become clear to any doctor as we proceed.

The first act of his reign was to marry for political reasons Catherine of Aragon, who was the widow of his elder brother Arthur. She was daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain, and, though far from beautiful, proved herself to possess a great and noble soul and a courage of well-tempered steel. The English people took her to their hearts, and when unmerited misfortune fell upon her never lost the love they had felt for her when she was a happy young woman. Though she was six years older than Henry, the two lived happily together for many years. Seven months after marriage Catherine was delivered of a daughter, still-born. Eight months later she had a son, who lived three days. Two years later she had a still-born son. Nine months later she had a son, who died in early infancy, and eighteen months afterwards the infant was born who was to live to be Queen Mary. Henry was intensely disappointed, and for the first time turned against his wife. It[16] was all important to produce an heir to the throne, for it was thought that no woman could rule England. No woman had ever ruled England, save only Matilda, and her precedent was not alluring. So Henry longed desperately for a son; nevertheless as the little Mary grew up—a sickly child—he became passionately devoted to her. She grew up, as one can see from her well-known portrait, probably an hereditary syphilitic. For a time Henry had thought of divorcing Catherine, but his affection for Mary probably turned the scale in her mother’s favour. Catherine had several more miscarriages, and by the time she was forty-two ceased to menstruate; it became clear that she would have no more children and could never produce an heir to the throne.

[Photo, Anderson.

MARY TUDOR.

From a portrait by Moro Antonio (Madrid, Prado).

[17]During these years Henry’s morals had been no worse than those of any other prince in Europe; certainly better than Louis XIV and XV, who were to come after him, or Charles II. He met Mary Boleyn, daughter of a rich London merchant, and made her his mistress. Later on he met Anne Boleyn, her sister, a girl of sixteen, and fell in love. We have a very good description of her, and several portraits. She was of medium stature, not handsome, with a long neck, wide mouth, bosom “not much raised,” eyes black and beautiful and a knowledge of how to use them. Her hair was long, and it appears that she used to wear it long and flowing in the house. It was not so very long since Joan of Arc had been burnt largely because she went about without a wimple, and Mistress Anne’s conduct with regard to her hair was probably worse in those days than for a girl to be seen smoking cigarettes when driving a motor-car to-day. At any rate, she acquired demerit by it, and everybody was on the look-out for more serious false steps. The truth seems to be—so far as one can ascertain truth from reports which, even if unprejudiced, came from people who knew nothing about a woman’s heart—that she was a bold and ambitious girl who laid herself out to capture Henry, and succeeded. Mary Boleyn was thrust aside, and Henry paid violent court in his own enormous and impassioned way to Anne. We have some of his love letters; there can be no doubt of his sincerity, or that his love for Anne was, while it lasted, the great passion of his life. Had she behaved herself she might have retained that love. She repulsed him for several years, and we can see the idea of divorce gradually growing in his mind. He appealed to Pope Clement VII to help him. Catherine defended herself bravely, and stirred Europe in her cause. The Pope hesitated, crushed between[18] the hammer and the anvil, between Henry and the Emperor Charles V. Henry discovered that his marriage with Catherine had come within the prohibited degrees, and that she had never been his wife at all. It was a matter of doubt then—and I believe still is—whether the Pope’s dispensation could acquit them of mortal sin. Apparently even his Holiness’ influence would not have been sufficient to counterbalance the crime of marrying his deceased brother’s widow; nevertheless it was rather remarkable that, if Henry were really such a stickler for the forms of canon law as he now wished to make out, he never troubled to raise the question until after he had fallen in love with some one else. He definitely promised Anne that he would divorce Catherine, marry Anne, and make her Queen of England. Secure in his promise, Anne yielded to her lover, seeing radiant visions of glory before her. How foolish would any girl be who let slip the chance—nay, the certainty—of being the Queen! Yet she was to discover that even queens can be bitterly unhappy. Anne sprang joyfully into the unknown, as many a girl has done before her and since, trusting to her power to charm her lover; and became pregnant. Meanwhile the struggle for the divorce proceeded, the Pope swaying this[19] way and that, and Catherine defending her honour and her throne with splendid courage. The nurses and astrologers declared that the fœtus was a son, and the lovers, mad with joy, were married in secret, divorce or no divorce. The obliging Archbishop Cranmer pronounced that the marriage with Catherine was null and void, as the Pope would not do so.

The time came for Anne to fulfil her promise and provide an heir. King and queen anticipated the event in the wildest excitement. There had been several lovers’ quarrels, which had been made up in the usual manner; once Henry was heard to say passionately that he would rather beg his bread in the streets than desert her. Yet it is doubtful whether Anne Boleyn was ever anything more than an ambitious courtesan; it is doubtful whether she ever felt anything towards him but her natural wish to be queen. In due course her baby was born, and it was a girl—the girl who afterwards became Queen Elizabeth.

Henry’s disappointment was tragic, and for the first time Anne began to realize the terror of her position. She was detested by the people and the Court, who were emphatically on the side of the noble woman whom she had supplanted. She had estranged everybody by her vain-glory and arrogance in the hour of her triumph; and it[20] began to be whispered that even if her own marriage were legal while Catherine was still alive, yet it was illegal by the canon law, for Mary Boleyn, her sister, had been Henry’s wife in all but name. Canonically speaking, Henry had done no better by marrying her than by marrying Catherine. A horrible story went around that he had been familiar with her mother first, and that Anne was his own daughter, and moreover that he knew it. I think we can definitely and at once put this aside as an ecclesiastical lie; there is absolutely no evidence for it and it is impossible to conceive two persons more unlike than the little lively brunette and the great fresh-faced “bluff King Hal.” Moreover, Henry denied the story absolutely, and whatever else he was, he was a man who was never afraid to tell the truth. Most of the difficulties in understanding this complex period of our history disappear if we believe Henry’s own simple statements; but these suffer from the incredulity which Bismarck found three hundred years later when he told his rivals the plain unvarnished truth.

Let us anticipate events a little and narrate the death of Catherine, which took place in 1536, nearly three years after the birth of Elizabeth. The very brief and sketchy accounts which have survived give me the impression that she died[21] of uræmia, but no definite opinion can be given. Henry, of course, lay under the immediate charge of having poisoned her, but I do not know that anybody believed it very seriously. So died this unhappy and well-beloved lady, to whom life meant little but a series of bitter misfortunes.

After Elizabeth was born the tragedy began to move with terrible impetus towards its climax. Henry developed an intractable ulcer on his thigh, which persisted till his death, and frequently caused him severe agony whenever the sinus closed. He became corpulent, the result of over-eating and over-drinking. He had been immensely worried for years over the affair of Catherine; as a result his blood-pressure seems to have risen, so that he was affected by frightful headaches, which often incapacitated him from work for days together. He gave up the athleticism which had distinguished his resplendent youth, aged rapidly, and became a harassed, violent, ill-tempered middle-aged man—not at all the sort of man to turn into a cuckold.

Yet this is precisely what Anne did. Less than a month after Elizabeth was born—while she was still in the puerperal state—she solicited Sir Henry Norreys, the most intimate friend of the King, to be her lover. A week later, on October 17th, 1533, he yielded. During the[22] next couple of years Anne seems to have gone absolutely out of her senses, if the contemporary stories are true. She seems to have solicited several prominent men of the Court, and even to have stooped to one of the musicians; worst of all, it was said that she had committed incest with her brother, Lord Rocheford. Nor did she behave with the ordinary consideration for the feelings of others that might have brought her hosts of friends—remember, she was a queen!—should the time ever come when she should need them. It does not require any great amount of civility on the part of a queen to win friends. Arrogant and overbearing, she estranged everybody at Court; she acted like a beggar on horseback, and was left without a friend in the place. And she, who owed her husband such a world, behaved towards him with the same arrogance as she showed to others, and in addition jealousy both concerning other women whom she feared and concerning the King’s beloved daughter, Mary. She spoke to the Duke of Norfolk—her uncle on the mother’s side, and one of the greatest peers of the realm—“like a dog”; as he turned away he muttered that she was “une grande putaine.” The most polite interpretation of the French word is “strumpet.” When the Duke used such a word to his own niece, what sort[23] of reputation must have been gathering about her?

She had two more miscarriages. After the second the King’s fury flamed out, and he told her plainly that he deeply regretted having married her. He must have indeed been sorry; he had abandoned a good woman for a bad; for her he had quarrelled with the Pope and with many of his subjects; whatever conscience he had must have been tormenting him: all these things for the sake of an heir, which seemed as hopelessly unprocurable as ever. Both the women seemed affected by some fate which condemned them to perpetual miscarriages; this fate, of course, was Henry’s own syphilis, even supposing that neither wife had contracted it independently. (It is much to Anne Boleyn’s credit or discredit, that to a syphilitic husband she bore a daughter so vigorous as Elizabeth, though Professor Chamberlin does not appear to think very highly of her health.)

Meanwhile all sorts of scandalous rumours were flying about; and finally a maid of honour, whose chastity had been impugned, told a Privy Councillor that no doubt she herself was no better than she should be, but that at any rate her Majesty Queen Anne was far worse. The Privy Councillor related this to Thomas Cromwell; he,[24] the rumours being thus focussed, dared to tell the King. Henry changed colour, and ordered a secret inquiry to be held. At this inquiry the ladies of the bedchamber were strictly cross-examined, but nothing was allowed to happen for a few days, when a secret commission was appointed, consisting of the Chancellor, the judges, Thomas Cromwell, and other members of the Council. Sir William Brereton was first sent to the Tower, then the musician Smeaton. Next day there was a tournament at Greenwich, in the midst of which Henry suddenly rose and left the scene, taking Norreys with him. Anne was brought before the Commission next day, and committed to the Tower, where she found that Sir Francis Weston had preceded her. Lord Rocheford, her brother, joined her almost immediately on the charge of incest.

The Grand Juries of Kent and Middlesex returned true bills on the cases, and the Commission drew up an indictment, giving names, places, and dates for every alleged act. The four commoners were put on trial at Westminster Hall. Anne’s father, Lord Wiltshire, though he volunteered to sit, was excused attendance, since a verdict of guilty against the men would necessarily involve his daughter. One may read this either way, against or in favour of[25] Anne. Either Wiltshire was enraged at her folly, and merely wished to end her disgrace; or it may be that he thought he would be able to sway the Court in her favour. Possibly he was afraid of the King and wished to show that he at least was on his royal side, however badly Anne may have behaved. In dealing with a harsh and tyrannical man like Henry VIII it is difficult to assess human motives, and one prefers to think that Wiltshire was trying to do his best for his daughter. Smeaton the musician confessed under torture; the other three protested their innocence, but were found guilty and were sentenced to death. Thomas Cromwell, in a letter, said that the evidence was so abominable that it could not be published. Evidently the Court of England had suddenly become squeamish.

Anne was next brought to trial before twenty-five peers of the realm, her uncle the Duke of Norfolk being in the chair. Probably, if the story just related were true, the Duke’s influence would not be exerted very strongly in her favour, and she was convicted and sentenced to be hanged or burnt at the King’s pleasure; her brother was tried separately and also convicted. It is said that her father and uncle concurred in the verdict; they may have been afraid of their own heads.[26] On the other hand, it is possible that Anne was really guilty; unfortunately the evidence has perished. The five men were executed on Tower Hill in the presence of the woman, whose death was postponed from day to day. In the meantime Henry procured his divorce from her, while Anne, in a state of violent hysteria, continuously protested her innocence. On the night before her execution she said that the people would call her “Queen Anne sans tête,” laughing wildly as she spoke; if one pronounces these words in the French manner, without verbal accent, they form a sort of jingle, as who should say “ta-ta-ta-ta”; and this foolish jingle seems to have run in her head, as she kept repeating it all the evening; and she placed her fingers around her slender neck—almost her only beauty—saying that the executioner would have little trouble, as though it were a great joke. These things were put to the account of her light and frivolous nature, and have probably weighed heavily with posterity in attempting to judge her case; but it is clear that they were merely manifestations of hysteria. Joan of Arc, whose character was probably the direct antithesis of Anne Boleyn’s, laughed when she heard the news of her reprieve. Some people think she laughed ironically, as though a very simple peasant-girl could be ironical if she tried.[27] Irony is a quality of the higher intelligence. But cannot a girl be allowed to laugh hysterically for joy? Or cannot Anne Boleyn be allowed to laugh hysterically for grief and terror without being called light and frivolous? So little did her contemporaries understand the human heart. A few years later came one Shakespeare, who could have told King Henry differently; and the extraordinary burgeoning forth of the English intellect in William Shakespeare is one of the most wonderful things in our history. Before the century had terminated in which Anne Boleyn had been considered light and frivolous because she had laughed in the shadow of the block, Shakespeare had plumbed the depths of human nature.

Anne was beheaded on May 19th, 1536, in the Tower, on a platform covered thickly with straw, in which lay hidden a broadsword. The headsman was a noted expert brought over specially from St. Omer, and he stood motionless among the gentlemen onlookers until the necessary preliminaries had been completed. Then, Anne kneeling in prayer and her back being turned towards him, he stole silently forward, seized the sword from its hiding-place, and severed her slender neck at a blow. As she had predicted, he had little trouble, and she never saw either[28] her executioner or the sword that slew her.[2] Her body and severed head were bundled into a cask, and were buried within the precincts of the Tower; and Henry threw his cap into the air for joy. On the same day he obtained a special dispensation to marry Jane Seymour. He married her next day.

The chief authority for the reign of Henry VIII is contained in the Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII, edited by Brewer and Gairdner. This gigantic work, containing more than 20,000 closely printed pages, is probably the greatest monument of English scholarship; the prefaces to the different volumes are remarkable for their learning and delightful literary style. Froude’s history is charming and brilliant as are all his writings, but is now rather out of date, and is marred by his hero-worship of Henry and his strong Protestant bias. He sums up absolutely against Anne, and, after reading the letters which he publishes, I do not see how he could have done anything else. He believes her innocent of incest,[29] however, and doubtless he is right. Let us acquit her of this crime, at any rate. A. F. Pollard’s Life of Henry VIII is meticulously accurate, and is charmingly written; he thinks it impossible that the juries could have found against her and the court have convicted without the strongest evidence, which has not survived. P. C. Yorke sums up rather against her in the Encyclopædia Britannica; but S. R. Gardiner thinks the charges too horrible to be believed and that probably her own only offence was that she could not bear a son. Professor Gardiner had evidently seen little of psychological medicine, or he would have known that no charge is too horrible to believe. The “Unknown Spaniard” of the Chronicle of Henry VIII is an illiterate fellow enough, but no doubt of Anne’s guilt appears to enter his artless mind; he probably represents the popular contemporary view. He says that he took his stand in the ring of gentlemen who witnessed the execution. He gives an account of the arrest of Sir Thomas Wyatt the poet—the first English sonneteer—and the ipsissima verba of a letter which Wyatt wrote to Henry, narrating how Anne had solicited him even before her marriage in circumstances that rendered her solicitation peculiarly brazen and shameless. That Henry should have pardoned[30] him seems to show that the real crime of Anne was that she had contaminated the blood royal; a capital offence in a queen in almost all ages and almost every country. Before she became a queen Henry was probably complaisant enough to Anne’s peccadilloes; but afterwards—that was altogether different. “There’s a divinity doth hedge” a queen!

Lord Herbert of Cherbury, writing seventy years later, narrates the ghastly story with very little feeling one way or the other. Apparently the legend of Anne’s innocence and Henry’s blood-lust had not yet arisen. The verdict of any given historian appears to depend upon whether he favours the Protestants or the Catholics. Speaking as a doctor with very little religious preference one way or the other, the following considerations appeal strongly to myself. If Henry wished to get rid of a barren wife—barren through his own syphilis!—as he undoubtedly did, then Mark Smeaton’s evidence alone was enough to hang any queen in history from Helen downward, especially if taken in conjunction with the infamous stories related by the “Unknown Spaniard.” Credible or not, these stories show the reputation that attached to the plain little Protestant girl who could not provide an heir to the throne—the sort of reputation which[31] mankind usually attaches to a woman who, by unworthy means, has attained to a high position. Why should the King and Cromwell, both exceedingly able men, gratuitously raise the questions of incest and promiscuity and send four innocent men to their deaths absolutely without reason? Why should they raise all the tremendous family ill-will and public reprobation which such an act of bloodthirsty tyranny would have caused? Stern as they were they never showed any sign of mere blood-lust at any other time; and the facts that Anne’s father and uncle both appear to have concurred in the verdict, and that, except for her own denial, there is not a word said in her favour, seems to require a great deal of explanation.

We can thoroughly explain her conduct by supposing that she was afflicted by hysteria and nymphomania. There are plenty of accounts of unhappy women whose cases are parallel to Anne’s in the works of Havelock-Ellis and Kisch. There is plenty of indubitable evidence that she was hysterical and unbalanced, and that she passionately longed for a son; and it is simpler to believe her the victim of a well-known and common disease than that we should suppose the leading statesmen of England and nearly the whole of its peerage suddenly to be affected with blood-lust. It has been suggested that[32] Anne, passionately longing for a son and terrified of her husband’s tyrannical wrath, acted like one of Thomas Hardy’s heroines centuries later and tried another lover in the hope that she would gratify her own and Henry’s wishes. This course of procedure is probably not so uncommon as some husbands imagine and would satisfy the questions of our problem but for Anne’s promiscuity and vehemence in solicitation. If her sole object in soliciting Norreys was to provide a son, why should she have gone from man to man till the whole Court seems to have been ringing with her ill fame?

Her spasms of violent temper after her marriage, her fits of jealousy, her foolish arrogance and insolence to her friends, are all mental signs which go with nymphomania, and the fact that her post-nuptial incontinence seems to have begun while she was still in the puerperal state after the birth of her only living child seems highly significant. It is not uncommon for sexual desire to become intolerable in nervous and puerperal women. The proper place for Anne Boleyn was a mental hospital.

Henry VIII’s case, along with those of his children, deserve a paper to themselves. Henry himself died of neglected arterio-sclerosis just in the nick of time to save the lives of better men[33] from the executioner; Catherine Parr, who married him probably in order to nurse him—it is possible that she was really fond of him and that there was even then something attractive about him—succeeded in outliving him by a remarkable effort of diplomatic skill and courage, though had Henry awakened from his uræmic stupor probably her head would have been added to his collection. On the whole, one cannot avoid the conclusion that his conduct to his wives was not all his fault. They seem to have done no credit to his power of selection. The first and the last appear to have been the best, considered as women.

Inexorable Nemesis had avenged Catherine. The worry of the divorce left her husband with an arterial tension which, added to the royal temper, caused great misery to England and ultimately death to himself; and her mean little rival lay huddled in the most frightful dishonour that ever befell a woman. Decidedly there is something Greek in the complete horror of the tragedy.

IN 1410-12 France was in the most dreadful condition that has ever affected any nation. For nearly eighty years England had been at her throat in a quarrel which to our minds simply exemplifies the difference between law and justice; for it seems that the King of England had mediæval law on his side, though to our minds no justice; the Black Death had returned more than once to harass those whom war had spared; no man reaped where he had sown, for his crops fell into the hands of freebooters. Misery, destitution, and superstition were man’s bedfellows; and the French mind seemed open to receive any marvel that promised relief from its intolerable agony. Into this land of terror was born a little maid whose mission it was to right the wrongs of France; a maiden who has remained, through all the vicissitudes of history, extraordinarily fascinating, yet an almost insoluble problem. It is undeniable that she has exercised a vast influence upon mankind, less by her actual deeds than by the ideal which she set up; an ideal of courage, simple faith, and unquenchable loyalty which has inspired both her[35] own nation and the nation which burnt her. When the English girls cut their hair short in the worst time of the war;[3] when the French soldiers retook Fort Douaumont when all seemed lost: these things were done in the name of Joan of Arc.

The actual contemporary sources from which we draw our ideas are extraordinarily few. There is of course the report of the trial for lapse and relapse, which is official and is said not to be garbled. It is useful, not only for the Maid’s answers, which throw a good deal of light on her mentality, but for the questions asked, which appear to give an idea of reports that seem to have been floating about France at the time.[36] The only thing which interested her judges was whether she had imperilled her immortal soul by heresy or witchcraft, and from that trial we shall get few or no indications of her military career or physical condition, which are the things that most interest modern men. About twenty years after her execution it occurred to her king, who had repaid her amazing love and self-sacrifice with neglect, that since she had been burnt as a witch it followed that he must owe his crown to a witch; moreover, her mother and brother had been appealing to him to clear her memory, for they could not bear that their child and sister should still remain under a cloud of sorcery. King Charles VII, who was now a great man, and very successful as kings go, therefore ordered the case to be reopened, in which course he ultimately secured the assistance of the reigning Pope. Charles could not restore the Maid to life, but he could make things unpleasant for the friends of those who had burned her; and so we have the so-called Rehabilitation Trial, consisting of reports and opinions, given under oath, from many people who had known her when alive. As King Charles was now a great man, some of the clerics who had helped to condemn her crowded to give evidence in the poor child’s favour, attributing the miscarriage[37] of justice in her case to people who were now dead or hopelessly unpopular; some friends of her childhood came forward and people who had known her at the time of her glory; and, perhaps most important, some of her old comrades in arms rallied round her memory. We thus have a fairly complete account of her battles, friendships, trials, character, and death; if we read this evidence with due care, remembering that more than twenty years had elapsed and the mentality of mediæval man, we may take some of the statements at their face value. Otherwise there is absolutely no contemporary evidence of the Maid; Anatole France has pricked the bubble of the chroniclers and of the Journal of the siege of Orleans. But there is so much of pathological interest to be found in the reports of the trials that I need no excuse for a brief study of them in that respect.

The record of the life of Jeanne d’Arc is all too short, and the main facts are not in dispute. It is the interpretation of these facts that is in dispute. She was born on January 6th, 1412; the year is uncertain. Probably she did not know herself. In the summer of 1424 she saw a great light on her right hand and heard a voice telling her to be a good girl. This voice she knew to be the voice of God. Later on she heard the[38] voices of St. Michael the Archangel, of St. Catherine, and of St. Margaret. St. Michael appeared first, and warned her to expect the arrival of the others, who came in due course. All three were to be her constant companions for the rest of her life. At first their appearances were irregular, but later on they came frequently, especially at quiet moments. Sometimes, when there was a good deal of noise going on, they appeared and tried to tell her something, but she could not hear what they said. These she called her Council, or her Voices. Occasionally the Lord God spoke to her himself; Him she called “Messire.”

As Jeanne grew more accustomed to her heavenly visitors they came in great numbers, and she used to see vast crowds of angels descending from heaven to her little garden. She said nothing to anybody about these unusual events, but grew up a brooding and intensely religious girl, going to church at every possible opportunity, and apparently neglecting her ordinary duties of looking after her father’s sheep and cattle. She learned to sew and knit, to say her Credo, Paternoster, and Ave Maria; otherwise she was absolutely ignorant, and very simple in mind and honest. She was dreamy and shy; nor did she ever learn to read or write.

Later on the voices told her to go into France, and God would help her to drive out the English.[39] She continually appealed to her father that he should send her to Vaucouleurs, where the Sieur Robert de Baudricourt would espouse her cause. Ultimately he did so; and at first Robert laughed at her. He was no saint; in his day he had ravaged villages with the best noble in the land; and he was not convinced that Jeanne was really the sent of God that she claimed. When she returned home she found herself the butt of Domremy; nine months later she ran away to Vaucouleurs again, and found Robert more helpful. He had for some time felt sympathy with the dauphin Charles, and had grown to detest the English and Burgundians; and he now welcomed the supernatural aid which Jeanne promised; she repeated vehemently that God had sent her to deliver France, and that she had no doubt whatever that she would be able to raise the siege of Orleans, which was then being idly invested by the English.

Robert sent her to the Dauphin, who lay at Chinon. He was no hero, this Dauphin, but a poverty-stricken ugly man, with spindle-shanks and bulbous nose, untidy and careless in his dress, and for ever blown this way and that by the advice of those around him. Weak, and intensely superstitious, he would to-day have been the prey of every medium who cared to attack him;[40] he received Jeanne kindly, and ultimately sent her to Poitiers to be examined as to possible witchcraft by a great number of learned doctors of the Church, who could be relied upon to discern a witch as soon as anybody.

She was deeply offended at being suspected of witchcraft, and was not so respectful to her judges as she might have been; occasionally she sulked, and sometimes she answered the reverend gentlemen quite saucily. She is an attractive and very human little figure at Poitiers as she moves restlessly upon her bench, and repeatedly tells the doctors that they should need no further sign than her own deeds; for when she had relieved Orleans it would be obvious enough that she was sent directly from God. At Poitiers she had to run the gauntlet of the inevitable jury of matrons, who were to certify to her virginity, because it was well known that women lost their holiness when they lost their virginity. The matrons and midwives certified that she was virgo intacta; how the good ladies knew is not certain, because even to-day, with all our knowledge of anatomy and physiology, we often find it difficult to be assured on this point. However, there can be little doubt that they were correct; probably they were impressed with Jeanne’s obvious sincerity and purity of mind. All[41] women seem to have loved Jeanne, which is a strong point in her favour. The spiritual examination dragged on for three weeks; these poor doctors were determined not to let a witch slip through their hands, and it speaks well for their patience and good temper, considering how unmercifully Jeanne had “cheeked” them, that they ultimately found that she was a good Christian. Any ordinary man would have seen that at once; but these gentlemen knew too much about the wiles of the Devil to be so easily influenced; and it was a source of bitter injustice to Jeanne at her real and serious trial for her life that she was unable to produce their certificate.

The Dauphin took her into his service and provided her with horse, suit of armour, and banner, as befitted a knight; also maidservants to act propriety, page-boy, and a steward, one Jean d’Aulon. All that we hear of d’Aulon, in whose hands the honour of the Maid was placed, is to his credit. A witness at the Rehabilitation Trial said that he was the wisest and bravest man in the army. We shall hear more of him. Throughout the story, whenever he comes upon the scene we seem to breathe fresh air. He was the very man for the position, brave, simple-hearted, and passionately loyal to Jeanne. There is no reason to doubt that in spite of his close[42] companionship with her there was never any romantic or other such feeling between them; he said so definitely, and he is to be believed. His honour came through it all unstained; and he let himself be captured with her rather than desert her. It is clear from his evidence that the personality of the Maid profoundly affected him. After Jeanne’s death he was ransomed, and was made seneschal of Beaucaire.

Jeanne was enormously impressed by her banner, which was made by a Scotsman, Hamish Power by name; she described it at her trial.

“I had a banner of white cloth, sprinkled with lilies; the world was painted there, with an angel on each side; above them were the words ‘Jhesus Maria.’” When she said “the world” she meant God holding the world up in one hand and blessing it with the other. Later on she does not seem very certain whether “Jhesus Maria” was above or at the side; but she is very certain that she was tremendously proud of the artistic creation—yes, “forty times” prouder of her banner than of her sword; even though the sword was from St. Catherine herself, and was the very sword of Charles Martel centuries before. When the priests dug it up without witnesses and rubbed it their holy power cleansed it immediately of the rust of ages.

[43]When she arrived at Orleans she found the English carrying on a leisurely blockade by means of a series of forts between which cattle and men could enter or leave the city at will. The city was defended by Jean Dunois, Bastard of Orleans. The title Bastard implies that he would have been Duc d’Orleans only that he had the misfortune to be born of the wrong mother. There have been several famous bastards in history, and the kindly morality of the Middle Ages seems to have thought little the worse of them for their misfortune. It is only fair to state that there is some doubt as to whether Jeanne was sent in command of the army, or the army in command of Jeanne; indeed, all through her story it is never easy to be certain whether she was actually in command, and Anatole France looks upon her as a sort of military mascotte rather than a soldier. Nor has Anatole France ever been properly answered. Andrew Lang did his best, as Don Quixote did his best to fight the windmills, but Mr. Lang was an idealist and romanticist, and could not defeat the laughing irony of M. France. Indeed, what answer is possible? Anatole France does not laugh at the poor little Maid; he laughs through her at modern French clericalism. Nobody with a heart in his breast could laugh at Jeanne d’Arc! Anatole France simply said that[44] he did not believe the things which Mr. Lang said that he believed; he would be a brave man who should say that M. France is wrong.

When she reached Orleans a new spirit at once came into the defenders, just as a new spirit came into the British army on the Somme when the tanks first went forth to battle—a spirit of renewed hope; God had sent his Maid to save the right! In nine days of mild fighting, in which the French enormously outnumbered the English, the siege was raised. The French lost a few score men; the English army was practically destroyed.

Next Jeanne persuaded the Dauphin to be crowned at Rheims, which was the ancient crowning-place for the French kings. In this ancient cathedral, in whose aisles and groined vaults echoed the memories and glories of centuries, he was crowned; his followers standing around in a proud assembly, his adoring peasant-maid holding her grotesque banner over his head; probably the most extraordinary scene in all history. After Jeanne had secured the crowning of her king, ill-fortune was thenceforth to wait upon her. She was of the common people, and it was only about eighty years since the aristocracy had shuddered before the herd during the Jacquerie, the premonition of the Revolution of 1789. Class feeling ran strongly, and the nobles[45] took their revenge; Jeanne, having no ability whatever beyond her implicit faith in Heaven, lost her influence both with the Court and with the people; whatever she tried to do failed, and she was finally captured in a sortie from Compiêgne in circumstances which do not exclude the suspicion that she was deliberately sacrificed. The Burgundians held her for ransom, and locked her up in the Tower of Beaurevoir. King Charles VII refused—or at any rate neglected—to bid for her; so the Burgundians sold her to the English. When she heard that she was to be given into the hands of her bitterest enemies she was so troubled that she leaped from the tower, a height of sixty or seventy feet, and was miraculously saved from death by the aid of her friends—Saints Margaret and Catherine. It is easier to believe that at her early age—she was then about nineteen or possibly even less—her epiphyseal cartilages had not ossified, and if she fell on soft ground it is perfectly credible that she might not receive worse than a severe shock. I remember a case of a child who fell from a height of thirty feet on to hard concrete, which it struck with its head; an hour later it was running joyfully about the hospital garden, much to the disgust of an anxious charge-nurse. It is difficult to kill a young person by a fall—the bones and muscles[46] yield to violent impact, and life is not destroyed.

Jeanne having been bought by the English they brought her to trial before a court composed of Pierre Cauchon, Lord Bishop of Beauvais, and a varying number of clerics; as Anatole France puts it, “a veritable synod”; it was important to condemn not only the witch of the Armagnacs herself but also the viper whom she had been able to crown King of France. If they condemned her for witchcraft they condemned all her works, including King Charles. If Charles had been a clever man he would have foreseen such a result and would have bought her from the Duke of Burgundy when he had the chance. But when she was once in the iron grip of the English he could have done nothing. It was too late. If he had offered to buy her the English would have said she was not for sale; if he had moved his tired and disheartened army they would have handed her over to the University of Paris, or perhaps the dead body of one more peasant-girl would have been found in the Seine below Rouen, and Cauchon would have been spared the trouble of a trial. Therefore we may spare our regrets on the score of some at least of King Charles’s ingratitudes. It is possible that he did not buy her from the Burgundians because he was too stupid, too poor, or too parsimonious; it is more[47] likely that his courtiers and himself began to believe that her success was so great that it could not be explained by mortal means, and that there must be something in the witchcraft story after all. It could not have been a pleasant thing for the French aristocrats to find that when a little maid from Domremy came to help the common people, these scum of the earth suddenly began to fight as they had not fought for generations. Fully to understand what happened we must remember that it was not very long since the Jacquerie, and that the aristocratic survivors had left to their sons tales of unutterable horrors.

However, Jeanne was put on her trial for witchcraft, and after a long and apparently hesitating process—for there had been grave doubts raised as to the legality of the whole thing—she was condemned to death. Just before the Bishop had finished his reading of the sentence she burst into tears and recanted, when she really understood that they were even then preparing the cart to take her to the stake. She said herself, in words which cannot possibly be misunderstood, that she recanted “for fear of the fire.”

The sentence of the court was then amended; instead of being burned she was to be held in prison on bread and water and to wear woman’s clothes. She herself thought that she was to be[48] put into an ecclesiastical prison and be kept in the charge of women, but there is nothing to be found of this in the official report of the first trial. As she had been wearing men’s clothes by direct command of God her sin in recanting began to loom enormous before her during the night; she had forsaken her God even as Peter had forsaken Jesus Christ in the hour of his need, and hell-fire would be her portion—a fire ten thousand times worse than anything that the executioner could devise for her. She got up in the morning and threw aside the pretty dress which the Duchess of Bedford had procured for her—all women loved Jeanne d’Arc—and put on her war-worn suit of male clothing. The English soldiers who guarded her immediately spread abroad the bruit that Jeanne had relapsed, and she was brought to trial for this contumacious offence against the Holy Church. The second trial was short and to the point; she tried to show that her jailers had not kept faith with her, but her pleadings were brushed aside, and finally she gave the responsio mortifera—the fatal answer—which legalized the long attempts to murder her. Thus spoke she: “God hath sent me word by St. Catherine and St. Margaret of the great pity it is, this treason to which I have consented to abjure and save my life! I have damned myself[49] to save my life! Before last Thursday my Voices did indeed tell me what I should do and what I did then on that day. When I was on the scaffold on Thursday my Voices said to me: ‘Answer him boldly, this preacher!’ And in truth he is a false preacher; he reproached me with many things I never did. If I said that God had not sent me I should damn myself, for it is true that God has sent me; my Voices have said to me since Thursday: ‘Thou hast done great evil in declaring that what thou hast done was wrong.’ All I said and revoked I said for fear of the fire.”

To me this is the most poignant thing in the whole trial, which I have read with a frightful interest many times. It seems to bring home the pathos of the poor struggling child, and her blind faith in things which could not help her in her hour of sore distress.

Jules Quicherat published a very complete edition of the Trial in 1840, which has been the basis for all the accounts of Jeanne d’Arc that have appeared since. An English translation was published some years ago which professed to be complete and to omit nothing of importance. But this work was edited in a fashion so vehemently on Jeanne’s side, with no apparent attempt to ascertain the exact truth of the judgments, that I ventured to compare it with[50] Quicherat, and I have found some omissions which to the translator, as a layman, may have seemed unimportant, but which, to a doctor, seem of absolutely vital importance in considering the truth about the Maid. These omissions are marked in the English by a row of three dots, which might be considered to mark an omission,—but on the other hand might not. Probably the translator considered them too indecent, too earthly, too physiological, to be introduced in connexion with the Maid of God. But Jeanne had a body, which was subject to the same peculiarities and abnormalities as the bodies of other people; and upon the peculiarities of her physiology depended the peculiarities of her mind.

Jean d’Aulon, her steward and loyal admirer, said definitely in the Rehabilitation Trial, in 1456:—

“Qu’il oy dire a plusiers femmes, qui ladicte Pucelle ont veue par plusiers foiz nues, et sceue de ses secretz, que oncques n’avoit eu la secret maladie de femmes et que jamais nul n’en peut rien cognoistre ou appercevoir par ses habillements, ne aultrement.”

I leave this unpleasantly frank statement in the original Old French, merely remarking that it means that Jeanne never menstruated. D’Aulon must have had plenty of opportunities for knowing[51] this, in his position as steward of her household in the field. He guards himself from innuendo by saying that several women had told him. Jeanne’s failing to become mature must have been the topic of amazed conversation among all the women of her neighbourhood, and no doubt she herself took it as a sign from God that she was to remain virgin. It is especially significant that she first heard her Voices when she was about thirteen years of age, at the very time that she should have begun to menstruate; and that at first they did not come regularly, but came at intervals, just as menstruation itself often begins. Some months later she was informed by the Voices that she was to remain virgin, and thereby would she save France, in accordance with a prophecy that a woman should ruin France, and a virgin should save it. Is it not probable that the idea of virginity must have been growing in her mind from the time when she first realized that she was not to be as other women? Probably the delusion as to the Voices first began as a sort of vicarious menstruation; probably it recurred when menstruation should have reappeared; we can put the idea of virginity into the jargon of psycho-analysis by saying that Jeanne had well-marked “repression of the sex-complex.” The mighty forces which should have manifested[52] themselves in normal menstruation manifested themselves in her furious religious zeal and her Voices. Repression of the sex-complex is like locking up a giant in a cellar; sooner or later he may destroy the whole house. He ended by driving Jeanne d’Arc to the stake. That was a nobler fate than befalls some girls, whom the same giant drives to the streets; nobler, because Jeanne the peasant was of essentially noble stock. Her mother was Isabel Romée—the “Romed woman”—the woman who had had sufficient religious fervour to make the long and dangerous pilgrimage to Rome that she might acquire the merit of seeing the Holy Father; Jeanne herself made a still more dangerous pilgrimage, which has won for her the love of mankind at the cost of her bodily anguish. Madame her mother saved her own soul by her pilgrimage, and bore an heroic daughter; Jeanne saved France by her courage and devotion to her idea of God. And this would have been impossible had she not suffered from repression of the sex-complex and seen visions therefore.

Another remarkable piece of evidence has been omitted from the English translation. It was given by the Demoiselle Marguerite la Thoroulde, who had taken Jeanne to the baths and seen her unclothed. Madame la Thoroulde said, in the Latin[53] translation of the Rehabilitation Trial which has survived: “Quod cum pluries vidit in balneo et stuphis [sweating-bath] et, ut percipere potuit, credit ipse fore virginem.”

That is to say, she saw her naked in the baths and could see that she was a virgin! What on earth did the good lady think that a virgin would look like? Did she think that because Jeanne did not look like a stout French matron she must therefore be a virgin? Or did she see a strong and boyish form, with little development of hips and bust, which she thought must be nothing else but that of a virgin? That is the explanation that occurs to me; and probably it also explains Jeanne’s idea that by wearing men’s clothes she would render herself less attractive to the mediæval soldiery among whom her lot was to be cast. An ordinary buxom young woman would certainly not be less attractive because she displayed her figure in doublet and hose; Rosalind is none the less winsome when she acts the boy; and I should have thought that Jeanne, by wearing men’s clothes, would simply have proclaimed to her male companions that she was a very woman. But if the idea be correct that she was shaped like a boy, with little feminine development, the whole mystery is at once solved. It is to be remembered that we know absolutely[54] nothing about Jeanne’s appearance[4]; the only credible hint we have is that she had a gentle voice.

In the Rehabilitation Trial several of her companions in arms swore that she had had no sexual attraction for them. It is quaint to read the evidence of these respectable middle-aged gentlemen that in their hot and lusty youth they had once upon a time met at least one young girl after whom they had not lusted; they seem to consider that the fact proved that she must have come from God. Anatole France makes great play with them, but it would appear that[55] his ingenuity is in this direction misplaced. Is it not possible that Jeanne was unattractive to men because she was immature—that she never became more than a child in mind and body? Even mediæval soldiery would not lust after a child, especially a child whom they firmly believed to have come straight from God! It must be remembered that to half of her world Jeanne was unspeakably sacred; to the other half she was undeniably a most frightful witch. Even the executioner would not imperil his immortal soul by touching her. It was the custom to spare a woman the anguish of the fire, by smothering her, or rendering her unconscious by suddenly compressing her carotids with a rope before the flames leaped around her. But Jeanne was far too wicked for anybody to touch in this merciful office; they had to let her die unaided; and afterwards, so wicked was her heart, they had to rescue it from the ashes and throw it into the Seine. Is it conceivable that men who thought thus would have ventured hell-fire by making love to her? Yet more—it is quite possible that she had no bodily charms whatever; we know nothing of her appearance. The story that she was charming and beautiful is simply sentimental legend. Indeed, it is difficult not to become sentimental over Jeanne d’Arc.

[56]A noteworthy feature in her character was her Puritanism. She prohibited her soldiers from consorting with the prostitutes that followed the army; sometimes she even forced them to marry these women. Naturally the soldiers objected most strongly, and in the end this was one of the causes that led to her downfall. Jeanne used to run after the prohibited girls and strike them with the flat of her sword; in one case the girl was killed. In another the sword broke, and King Charles asked, very sensibly, “Would not a stick have done quite as well?” This is believed by some people to have been the very sword of Charles Martel which the priests had found for her at St. Catherine’s command, and naturally the soldiers, deprived of their female companions, wondered what sort of a holy sword could it have been which could not even stand the smiting of a prostitute? When people suffer from repression of the sex-complex the trouble may show itself either by constant indirect attempts to find favour in the eyes of individuals of the opposite sex, or sometimes by actually forbidding all sexual matters; Puritanism in sexual affairs is often an indication that all is not quite well with a woman’s subconscious mind; nor can one confine this generalization to one sex. It is not for one moment to be thought[57] that Jeanne ever had the slightest idea of what was the matter with her; the whole of her delusions and Puritanism were to her quite conscious and real; the only thing that she did not know was that her delusions were entirely subjective—that her Voices had no existence outside her own mind. Her frantic belief in them led her to an heroic career and to the stake. She did not consciously repress her sex; Nature did that for her.

Women who never menstruate are not uncommon; most gynæcologists see a few. Though they are sometimes normal in their sexual feelings—sometimes indeed they are even nymphomaniacs or very nearly so—yet they seldom marry, for they know themselves to be sterile, and, after all, most women seem to know at the bottom of their hearts that the purpose of women is to produce children.

But there is still more of psychological interest to be gained from a careful reading of the first trial. It is possible to see how Jeanne’s unstable nervous system reacted to the long agony. We had better, in order to be fair, make quite certain why she was burned. These are the words uttered by the good Bishop of Beauvais as he sentenced her for the last time:—

“Thou hast been on the subject of thy pretended divine revelations and apparitions lying, seducing, pernicious, presumptuous, lightly believing,[58] rash, superstitious, a divineress and blasphemer towards God and the Saints, a despiser of God Himself in His sacraments; a prevaricator of the Divine Law, of sacred doctrine and of ecclesiastical sanctions; seditious, cruel, apostate, schismatic, erring on many points of our Faith, and by these means rashly guilty towards God and Holy Church.”

This appalling fulmination, summed up, appears to mean—if it means anything—that she believed that she was under the direct command of God to wear man’s clothes. To this she could only answer that what she had done she had done by His direct orders.

Theologians have said that her answers at the trial were so clever that they must have been directly inspired; but it is difficult to see any sign of such cleverness. To me her character stands out absolutely clearly defined from the very beginning of the six weeks’ agony; she is a very simple, direct, and superstitious child struggling vainly in the meshes of a net spread for her by ecclesiastical politicians who were determined to sacrifice her to serve the ends of brutal masters. She had all a child’s simple cunning; when the Bishop asked her to repeat her Paternoster she answered that she would gladly do so if he himself would confess her. She thought[59] that if he confessed her he might have pity on her, or, at least, that he would be bound to send her to Heaven, because she knew how great was the influence wielded by a Bishop; she thought that she might tempt him to hear her in the secrets of the confessional if she promised to repeat her Paternoster to him! Poor child—she little knew what was at the bottom of the trial.

She sometimes childishly boasted. When she was asked if she could sew, she answered that she feared no woman in Rouen at the sewing; just so might answer any immature girl of her years to-day. She sometimes childishly threatened; she told the Bishop that he was running a great risk in charging her. She had delusions of sight, smell, touch, and hearing. She said that the faces of Saints Catherine and Margaret were adorned with beautiful crowns, very rich and precious, that the saints smelled with a sweet savour, that she had kissed them, that they spoke to her.

There was a touch of epigram about the girl, too. In speaking of her banner at Rheims, she said: “It had been through the hardships—it were well that it should share the glory.” And again, when the judges asked her to what she attributed her success, she answered, “I said to my followers: ‘Go ye in boldly against the English,’ and I went myself.” The girl who said[60] that could hardly have been a mere military mascotte. Yet, in admitting so much, one does not admit that she may have been a sort of Amazon. As the desperation of her position grew upon her she began to suffer more and more from her delusions; while she lay in her dungeon waiting for the fatal cart she told a young friar, Brother Martin Ladvenu, that her spirits came to her in great numbers and of the smallest size. When despair finally seized upon her she told “the venerable and discreet Maître Pierre Maurice, Professor of Theology,” that the angels really had appeared to her—good or bad, they really had appeared—in the form of very minute things[5]; that she now knew that they had deceived her. Her brain wearied by her long trial of strength with the Bishop, common sense re-asserted its sway, and she realized—the truth! Too late! When she was listening to her sermon on the scaffold in front of the fuel destined to consume her, she broke down and knelt at the preacher’s knees, weeping and praying until the English soldiers called out to ask if she meant to keep them there for their dinner; it is pleasing to know that one of them broke his lance into two pieces, which he tied into[61] the form of a cross and held it up to her in the smoke that was already beginning to arise about her.

Her last thoughts we can never know; her last word was the blessed name of Jesus, which she repeated several times. In public—though she had told Pierre Maurice in private that she had “learned to know that her spirits had deceived her”—she always maintained that she had both seen and believed them because they came from God; her courage was amazing, both physical and moral. She was twice wounded, but she said that she always carried her standard so that she would never have to kill anybody—and that in truth she had never killed anybody.

Her extraordinary accomplishment was due to the unbounded superstition of the French common people, who at first believed in her implicitly; it was Napoleon, a French general, who said that in war the moral is to the spiritual as three is to one; our Lord said, “By faith ye shall move mountains”; and it must not be forgotten that she went to Orleans with powerful reinforcements which she herself estimated at about ten to twelve thousand men. This superstition of the French was more than equalled by the superstition of the English, who looked upon her as a most terrifying witch: one witness at the Rehabilitation Trial said that the English were a very[62] superstitious nation, so they must have been pretty bad. Indeed, most of the witnesses at that trial seem to have been very superstitious; one must examine their evidence with care lest one suddenly finds that one is assisting at a miracle.

She seems to have been hot-tempered and emphatic in her speech, with a certain tang of rough humour such as would be natural in a peasant girl. A notary once questioned the truth of something she said at her trial; on inquiry it was found that she had been perfectly accurate; Jeanne “rejoiced, saying to Boisguillaume that if he made mistakes again she would pull his ears.” Once during the trial she was taken ill with vomiting, apparently caused by fish-poisoning, that followed after she had eaten of some carp sent her by the Bishop. Maître d’Estivet, the promoter of the trial, said to her, ‘Thou paillarde!’ (an abusive term), ‘thou hast been eating sprats and other unwholesomeness!’ She answered that she had not; and then she and d’Estivet exchanged many abusive words. The two doctors of medicine who treated her for this illness gave evidence, and it is pleasing to see that they seem to have been able to rationalize a trifle more about her than most of her contemporaries. But, taken all through, her evidence gives the impression of being exceedingly[63] simple and straightforward—just the sort of thing to be expected from a child.

It is noteworthy that a great many witnesses at the Rehabilitation Trial swore that she was “simple.” Did they mean that she was half-witted? Probably not. More probably it was true that she always wanted to spare her enemies, when, in accordance with the custom of the Hundred Years’ War, she should rather have held them for ransom if they had been noble or slain them if they had been poor men. To the ordinary brutal mediæval soldiery such conduct would appear insane. Possibly, of course, the term “simple” might have been used in opposition to the term “gentle.”

May I be allowed to give a vignette of Jeanne going to the burning, compiled from the evidence of many onlookers given at the Rehabilitation Trial? She assumed no martyresque imperturbability; she did not hold her head high in the haughty belief that she was right and the rest of the world wrong, as a martyr should properly do. She wept bitterly as she walked to the fatal cart from the prison-doors; her head was shaven; she wore woman’s dress; her face was swollen and distorted, her eyes ran tears, her sobs shook her body, her wails moved the hearts of the onlookers. The French wept for sympathy, the English laughed for joy. It was a very human[64] child who went to her death on May 30th, 1431. She was nineteen years of age—according to some accounts, twenty-one—and, unknown to herself, she had changed the face of history.

THIS famous woman has been the subject of one of the bitterest controversies in history; and, while it is impossible to speak fully about her, it is certain that she was a woman of remarkable beauty, character, and historical position. For nearly a thousand years after her death she was looked upon as an ordinary—if unusually able—Byzantine princess, wife of Justinian the lawgiver, who was one of the ablest of the later Roman Emperors; but in 1623 the manuscript was discovered in the Vatican of a secret history, purporting to have been written by Procopius, which threw a new and amazing light on her career.

Procopius—or whoever wrote this most scurrilous history—states that the great Empress in early youth was an actress, daughter of a bear-keeper, and that she had sold tickets in the theatre; her youth had been disgustingly profligate: he narrates a series of stories concerning her which cannot be printed in modern English. The worst of these go to show that she was an ordinary type of Oriental prostitute, to whom the word “unnatural,” as applied to vice, had no meaning. The least discreditable is that the[66] girl who was to be Empress had danced nearly naked on the stage—she is not the only girl who has done this, and not on the stage either. She had not even the distinction of being a good dancer, but acquired fame through the wild abandon and indecency with which she performed. At about the age of twenty she married—when she had already had a son—the grave and stately Justinian: “the man who had never been young,” who was so great and learned that it was well known that he could be seen of nights walking about the streets carrying his head in a tray like John the Baptist. When he fell a victim to Theodora’s wiles he was about forty years of age. The marriage was bitterly opposed by his mother and aunts, but they are said to have relented when they met her, and even had a special law passed to legalize the marriage of the heir to the throne with a woman of ignoble birth; and, after the death of Justin, Theodora duly succeeded to the leadership of the proudest court in Europe. This may be true; but it does not sound like the actions of a mother and old aunts. One would have thought that a convenient bowstring or sack in the Bosphorus would have been the more usual course.

So far we have nothing to go by but the statements of one man; the greatest historian of[67] his time, to be sure—if we can be certain that he wrote the book. Von Ranke, himself a very great critical historian, says flatly that Procopius never wrote it; that it is simply a collection of dirty stories current about other women long afterwards. The Roman Empire seems to have been a great hotbed for filthy tales about the Imperial despots: one has only to remember Suetonius, from whose lively pages most of our doubtless erroneous views concerning the Palatine “goings on” are derived; and to recall the foul stories told about Julius Cæsar himself, who was probably no worse than the average young officer of his time; and of the last years of Tiberius, who was probably a great deal better than the average. Those of us who can cast their memories back for a few years can doubtless recall an instance of scurrilous libel upon a great personage of the British Empire, which cast discredit not on the gentleman libelled but upon the rascal who spread the libel abroad. It is one of the penalties of Empire that the wearer of the Imperial crown must always be the subject of libels against which he has no protection but in the loyal friendship of his subjects. Even Queen Victoria was once called “Mrs. Melbourne,” though probably even the fanatic who howled it did not believe that there was any truth in his insinuation.[68] And Procopius did not have the courage to publish his libels, but preferred to leave to posterity the task of finding out how dirty was Procopius’ mind. Probably he would not have lived very long had Theodora discovered what he really thought of her. He was wise in his generation, and had ever the example of blind Belisarius before him to teach him to walk cautiously.

Démidour in 1887, Mallet in 1889, and Bury also in 1889, have once more reviewed the evidence. The two first-mentioned go very fully into it, and sum up gallantly in Theodora’s favour; but Bury is not so sure. Gibbon, having duly warned us of Procopius’ malignity, proceeds slyly to tell some of the most printable of the indecent stories. Gibbon is seldom very far wrong in his judgments, and evidently had very little doubt in his own mind about Theodora’s guilt. Joseph Maccabe goes over it all again, and “regretfully” believes everything bad about her. Edward Foord says, in effect, that supposing the stories were all true, which he does not appear to believe, and that she had thrown her cap over the windmills when she was a girl—well, she more than made up for it all when she became Empress. After all, it depends upon how far we can believe Procopius; and that again depends upon how far we can bring ourselves[69] to believe that an exceedingly pretty little Empress can once upon a time have been a fille de joie. That in its turn depends upon how far each individual man is susceptible to female beauty. If she had been a prostitute it makes her career as Empress almost miraculous; it is the most extraordinary instance on record of “living a thing down,” and speaks volumes for her charm and strength of personality.

She lived in the midst of most furious theological strife. Christianity was still a comparatively new religion, even if we accept the traditional chronology of the early world; and in her time the experts had not yet settled what were its tenets. The only thing that was perfectly clear to each theological expert was that if you did not agree with his own particular belief you were eternally damned, and that it was his duty to put you out of your sin immediately by cutting your throat lest you should inveigle some other foolish fellows into the broad path that leadeth to destruction. Theodora was a Monophysite—that is to say, she believed that Christ had only one soul, whereas it was well known to the experts that He had two. Nothing could be too dreadful for the miscreants who believed otherwise. It was gleefully narrated how Nestorius, who had started the abominable[70] doctrine of Monophysm, had his tongue eaten by worms—that is, died of cancer of the tongue; and it is not incredible that Procopius, who was a Synodist or Orthodox believer, may have invented the libels and secretly written them down in order to show the world of after days what sort of monster his heretical Empress really was, wear she never so many gorgeous ropes of pearls in her Imperial panoply. It is difficult to place any bounds to theological hatred—or to human credulity for that matter. The whole question of the nature of Christ was settled by the Sixth Œcumenical Council about a hundred and fifty years later, when it was finally decided that Christ had two natures, or souls, or wills—however we interpret the Greek word Φύσις—each separate and indivisible in one body. This, and the Holy Trinity, are still, I understand, part of Christian theology, and appear to be equally comprehensible to the ordinary scientific man.

But it is difficult to get over a tradition of the eleventh century—that is to say, six hundred years before Procopius’ Annals saw the light—that Justinian married “Theodora of the Brothel.” Although Mallet showed that Procopius had strong personal reasons for libelling his Empress, one cannot help feeling that there must be something in the stories after all.

[71]Once she had assumed the marvellous crown, with its ropes of pearls, in which she and many of the other Empresses are depicted, her whole character is said to have changed. Though her enemies accused her of cruelty, greed, treachery, and dishonesty—and no accounts from her friends have survived—yet they were forced to admit that she acted with propriety and amazing courage; and no word was spoken against her virtue. In the Nika riots, which at one time threatened to depose Justinian, she saved the Empire. Justinian, his ministers, and even the hero Belisarius, were for flight, the mob howling in the square outside the Palace, when Theodora spoke up in gallant words which I paraphrase. She began by saying how indecorous it was for a woman to interfere in matters of State, and then went on to say: “We must all die some time, but it is a terrible thing to have been an Emperor and to give up Empire before one dies. The purple is a noble winding-sheet! Flight is easy, my Emperor—there are the steps of the quay—there are the ships waiting for you; you have money to live on. But in very shame you will taste the bitterness of death in life if you flee! I, your wife, will not flee, but will stay behind without you, and will die an Empress rather than live a coward!” Proud little woman—could[72] that woman have been a prostitute selling her body in degradation? It seems impossible.

The Council, regaining courage, decided for fighting; armed bands were sent forth into the square; the riot was suppressed with Oriental ferocity; and the Roman Empire lasted nearly a thousand years more. “Toujours l’audace,” as Danton said nearly thirteen hundred years later, when, however, he was not in imminent peril himself.

[Photo, Alinari.

THE EMPRESS THEODORA.

From a Mosaic (Ravenna, San Vitale).

In person Theodora was small, slender, graceful, and exquisitely beautiful; her complexion was pale, her eyes singularly expressive: the mosaic at Ravenna, in stiff and formal art, gives some evidence of character and beauty. She was accused, as I have said, of barbarous cruelties, of herself applying the torture in her underground private prisons; the stories are contradictory and inconsistent, but one story appears to be historical: “If you do not obey me I swear by the living God that I will have you flayed alive,” she said with gentle grace to her attendants. It is said that her illegitimate son, whom she had disposed of by putting him with his terrified father in Arabia, gained possession of the secret of his birth, and boldly repaired to Constantinople in the belief that her maternal affection would lead her to pardon him for the offence of having been born, and that thereby[73] he would attain to riches and greatness; but the story goes that he was never seen again after he entered the Palace. Possibly the story is of the nature of romance. She dearly longed for a legitimate son, and the faithful united in prayer to that end; but the sole fruit of her marriage was a daughter, and even this girl was said to have been conceived before the wedding.