Title: Christmas in Austria; or, Fritzl's friends

Author: Frances Bartlett

Illustrator: Bertha Davidson Hoxie

Release date: October 6, 2022 [eBook #69097]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Dana Estes & Company, 1910

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Krista Zaleski, Thiers Halliwell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

or

Fritzl’s Friends

BY

FRANCES BARTLETT

ILLUSTRATED BY

BERTHA D. HOXIE

BOSTON

DANA ESTES & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1910

By Dana Estes & Company

All rights reserved

CHRISTMAS IN AUSTRIA

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

On the snow covered stones of the Stephansplatz of Vienna, Fritzl and Tzandi danced joyously. The boy Fritzl because it was Christmas Eve. Because also in the rapid motion his little body forgot how poorly it was clad. While Tzandi, the terrier of “Schottisch” or Scottish ancestry, danced because anything his small master did was pleasing in his sight, and to be copied, if possible. Under Fritzl’s chin was tucked a violin; and as the boy danced he played snatches of melody: bits of Hungarian folk songs, and bars of the waltzes the Viennese love, which set the feet of the passers-by moving more swiftly. But not one kreutzer had been slipped into the boy’s hand, although it was Christmas Eve.

Now Fritzl and Tzandi had no home. For only that Christmas Eve, the cross old woman, of whose cellar they had made a pitiful refuge, had warned them of what they might expect, if they came within her house again. Indeed, neither Fritzl nor Tzandi could remember any home save the cellar, and before that, the attic where they had lived with the blind musician, who, dying, had left his cherished violin to the little boy, whose heart and fingers were overflowing with music. “I tell you what, Tzandi,” cried Fritzl, as toward midnight boy and dog sought shelter in one doorway after another of the Stephansplatz, only to be driven forth: “There’s a lovely corner by the Riesenthor! I forgot all about it till now. Let’s go there, it’s the very place! ’Course Santa Claus will go through that very door into the cathedral, and can hear us when we tell him we’re waiting for him. Why, just as easy, Tzandi!”

So they crept into one of the sculptured niches of the “Giant’s Gate,” where the great wings of the angels announcing the birth of the Christ Child made an insufficient shelter. Suddenly the carved portals opened, and one of the sacristans of the cathedral came forth, and looked about the now almost deserted square.

Then like two little spirits, Fritzl and Tzandi slipped into the porch, and from there into the solemn church.

Once Tzandi looked up anxiously into his master’s face, as if he feared that Santa Claus might not find them there. “Of course he will,” laughed Fritzl, answering the dog’s silent question; “Why, I’m surprised you didn’t know he’ll be sure to come in here to say ‘Merry Christmas’ to the Blessed Mother, first thing in the morning!”

Tzandi wagged his tail in relief, as if his last fear were quieted.

Like shadows, through the shadows of the vast nave passed boy and dog, straight to the statue of the Blessed Mother. And upon the pavement at her feet, safely hidden in the shelter made by the sculptures of her shrine, they nestled closely against each other.

“Now isn’t this the very beautifullest place in all the world to be in Christmas Eve?” asked Fritzl drowsily, dropping his head upon Tzandi’s shaggy hide.

And Tzandi, already half asleep, wagged his tail blissfully.

“Merry Christmas! Merry Christmas! It’s time to get up, little master,” barked Tzandi, as the first pale gleams of the Christmas sunrise crept through the painted window above the high altar of St. Stephans.

“Merry Christmas! Merry Christmas! So it is,” answered Fritzl sleepily; “but does your head too feel awful funny, Tzandi? All light and hot? And your feet all cold and heavy?” By a languid wag of his tail, Tzandi assured his master that all was indeed as he had said. “I tell you what it is,” said the boy; “we’re just hungry. And Santa Claus hasn’t come. I s’pose there are so many children in Vienna, he couldn’t help being late getting around to us. Oh, but don’t you wish he’d come!”

A frantic wagging of Tzandi’s tail, and the thrusting of his cold nose into his master’s hand, answered as plainly as words could have done. “Let’s go out to the Stephansplatz,” went on Fritzl, rising weakly to his feet; “and I’ll play, and you shall dance, and surely, Christmas morning, someone will give us some kreutzers. And—and—” The words trailed off drowsily.

The boy shook himself impatiently. “I never felt so sleepy as this before,” he thought; “and Christmas too!” Then after an awkward little “reverence” before the Blessed Mother, and a “Merry Christmas” whispered softly to her, Fritzl went down the broad nave to the Riesenthor, pushed open one of its portals slowly, and with his violin held closely to him, and followed by Tzandi, went without, and stood, a forlorn little figure, upon the broad stone step.

The hour for early mass had not yet come, but the Stephansplatz was already filled with people, singing Christmas carols. The booths were fringed with evergreen; every window was a blaze of color; and the people, as they walked or danced along, waved boughs of hemlock, so that the square looked almost as if the long vanished pine forests were once more growing in Old Vienna.

“Now what did I tell you, Tzandi,” Fritzl cried triumphantly, if somewhat shakily. “Just look at all those boys and girls! ’Course Santa Claus hasn’t forgotten us, but he couldn’t help being a bit late, Tzandi dear. Any minute now, he may come!”

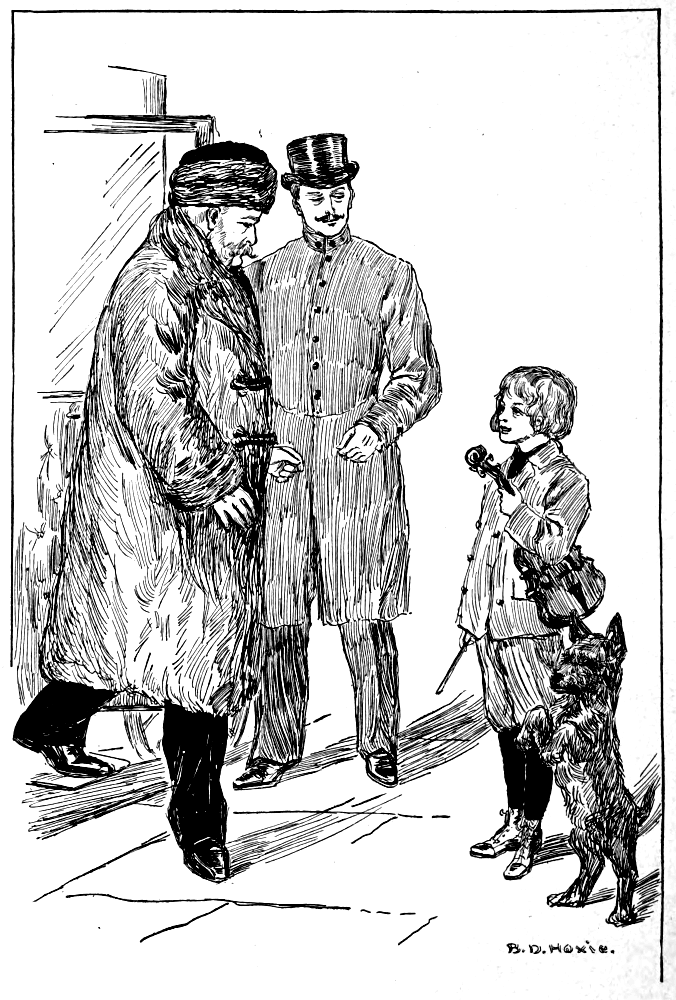

Suddenly, from the direction of the Graben, came the sound of cheering. The crowd opened, like great waves parted by some mighty wind, and into the Stephansplatz came a closed carriage drawn by two black horses. Slowly it passed along, the white-haired man within bowing kindly to right and left, straight to where Fritzl and Tzandi waited, at the Riesenthor. At the foot of the steps, the carriage stopped. A groom in quiet livery opened the door. And wrapped in furs from head to feet, the white-haired man stepped out. Beneath his bushy eyebrows, eyes as clear and blue as those of a child looked forth. And the lips under the heavy white moustache were smiling, as he mounted the steps.

Fritzl gave a little gasp of pure delight. Deaf to the words the crowd were crying, of the identity of the white-haired, fur-wrapped figure, he had no doubt.

It must be Santa Claus.

The relaxed little figure straightened; the thin little hands were outstretched; and lifting his happy eyes to the friendly ones looking straight into them, Fritzl cried:

“Tzandi, Tzandi, he’s come!”

And fell, a limp little heap, at the feet of “Unser Franz.”

Just about the time when Fritzl and Tzandi waked, that Christmas morning, two little children within the palace at Schönbrunn were welcoming the Christ Child’s Day.

One, a boy of eleven, known throughout Austria-Hungary as “the little lame Prince,” was the Archduke Maximilian. The other, a girl of nine, was the Archduchess Elizabeth. But to each other, and the imperial family at Vienna, they were known as “Max” and “Betty.”

Max had been the first to waken; but for a time he laid very still, cuddled within the soft blankets of his bed, his young heart beating happily, at the thought of what the day was to bring to him. Ever since he was born, the little Prince had been crippled. But for nearly two years, the famous surgeon of the Kinderspitzel of Vienna had been treating him; and this Christmas Day he was to walk, for the first time in his life. And all the great empire of Austria-Hungary was waiting for the test, almost as eagerly as he. For when the good Emperor, his grandfather, should cease to reign, Max would be “Unser Kaiser” to millions of people.

Suddenly there came a knock at the door.

“Merry Christmas, and come in, Betty!” called Max excitedly.

And a small girl, crying as excitedly, “Merry Christmas, Maxchen, and I knew perfectly well you’d say it first!” pushed open the door, and running across the room, threw herself down by Maxchen’s bed, flinging her soft arms around her brother’s neck.

“Oh, Betty, Betty,” he cried, as he nestled against her, “it seems almost too good to be true! Only it must come true, mustn’t it, Christmas Day?”

“’Course it must,” agreed Betty stoutly; “why, didn’t the Herr Doctor tell you it would come true, this very day?”

“Yes,” breathed Max softly.

“And there’s nothing in the world, the Herr Doctor doesn’t know,” declared Betty; “and I love him.”

“So do I,” cried Max; “almost as much as Grandpapa Franzchen!” For by that name, born of affection, was the august Emperor of Austria-Hungary known to his grandchildren.

“Betty,” the boy cried abruptly, “the very first race we’ll run will be from there,” pointing to the “Gloriette,” shining like a jewel in the sunrise light,—“straight to the edge of the lily pond. And—and—I’ll beat you, you little girl!”

“Can’t!” answered Betty, stretching out her slim straight legs, and looking at them with confidence.

“Can!” Max cried delightedly. And then they both laughed, and cuddled together more closely.

“Do you remember,” Max went on, “that boy we watched, in the rose garden, running races with his dog, one day last summer? The boy with a violin under his arm?”

Yes, Betty remembered.

“My, how he ran!” sighed Max, “and we called and called to him, and finally made ‘Goggles’” (this the most dignified of the tutors of the Prince) “go after him. But of course he couldn’t run fast enough, and the boy got quite away. I wish I could find that boy. Betty,” rising on one elbow, “when I walk, I will! I do so want that boy and that dog!”

“Why,” laughed matter-of-fact Betty, “you’ve heaps of boys to play with, and heaps of dogs!”

“But not one boy who can play the violin. And not one dog that can dance.”

“Well, that dog was a dear,” Betty agreed cordially; “and—why, Maxchen,” she went on, “we’ll ask Grandpapa Franzchen to get the boy and the dog for us, this very Christmas Day. We’ll—” But the little maid’s blithe voice was interrupted by the sound of footsteps in the corridor. The door opened softly, “His Majesty the Emperor and the Herr Doctor,” was solemnly announced. And into the sunlit room, two stately men came.

We know quite well how “Unser Franz” looked. We saw him, that very morning, speaking kindly to Fritzl and Tzandi, at the Riesenthor.

“Merry Christmas—Merry Christmas, dear Grandpapa Franzchen and dear Herr Doctor!” cried the children. And Betty slipped quickly to the floor, and curtsied demurely to the Emperor.

“Merry Christmas, Merry Christmas!” returned the Emperor and Doctor gaily, who had wisely given the children the longed-for chance to say it first.

Then the old Kaiser caught Betty up in his arms, and kissed her forehead. “Now God bless thee, Liebchen,” he said, seating himself in the great chair beside the bed, and bending over and kissing Max on both his cheeks. Then, with an arm around each grandchild, he looked up at the Herr Doctor, standing straight and tall beside him.

A very king of men was the Herr Doctor, with stalwart shoulders, and kindly grave eyes, the color of the sea, when the sky is clouded.

“Well, your Highness,” he said, in a voice as tender as his eyes, “all ready to walk to-night?”

“Yes, sir,” answered Max bravely, but nestling closer against his grandfather.

Then the Herr Doctor looked down into the anxious face of the old Emperor.

“Your Majesty need have no fear of the result of to-night’s test,” he said softly, “the little lad will walk.”

“And Grandpapachen,” cried Betty, breaking into the solemn pause which followed, “he’s going to run races with the boy and the dog! The boy with the fiddle, and the dog that can dance, you know,” she explained rapidly. “Why, Grandpapa Franzchen,” stroking his white hair with her dimpled hand, “Max wants that boy and that dog, so! Please get them for him, dear Grandpapa Emperor!”

When Betty commenced her story of the races to be run with a boy who carried a violin, and a little dog that could dance, a strange look had flashed into the Emperor’s eyes. This deepened to one of amazement, and then his whole face glowed with the thought within his heart.

It seemed that he was going to be able to give even more pleasure than he had hoped.

“Well, Maxchen,” he laughed, “thou hast set thy grandfather a hard task! To find, in his great city of Vienna, a boy who plays the fiddle and who has a dog that dances! But he will try, Liebchen,” patting his grandson’s head softly. “Would you know them, should you see them again, little ones?” he cried, quite as excited now as the children.

“Why, of course we would,” laughed Betty, for herself and Max too: “there are only—they—you know, Grandpapa dear!”

“I will commence to search for them this moment,” announced the Emperor gaily, lifting Betty to the floor and rising from his chair, “and the Herr Doctor shall help me! But what wilt thou do with them, beside run races, should I find them for thee?” he asked Max.

“I will make them happy,” said the little lame Prince.

As the two men were leaving the room, the Herr Doctor turned. “Your Highness,” he said, “where will you go first, when you walk to-night?”

“To my Emperor,” answered the boy proudly, raising one little hand in salute.

Fritzl lifted his heavy eyelids, and looked about him, first languidly, then wonderingly. Gone were the Riesenthor and the Stephansplatz, and in place of them was a quiet room, lined with books and hung with tapestries.

But the friendly eyes into which his gazed were still those of “Santa Claus,” and the friendly hand which had touched his bare head on the steps of the Giant’s Gate, held one of his own. His violin lay on the couch beside him, while a warm little tongue licking his hand, and the subdued but joyous thumping of a stubby tail against the polished floor, told that Tzandi was near.

So, all his fears relieved, Fritzl looked up happily to the man who sat beside him, and asked: “Is this your house, dear Santa Claus?”

“I shall have to tell him,” said “Unser Franz” to himself. Then aloud: “Yes, little lad, it is my house. But it is the palace of Schönbrunn, and I am only the Kaiser.”

“Well, I s’pose you can’t help it,” sighed Fritzl, “but I truly thought you were Santa Claus. You look exactly like him!”

“Thank you,” replied the Emperor meekly, “and I will try to be like him. Indeed, he sent me to thee, little lad, so do not be disappointed. Another year thou shalt surely see him. I—your Emperor—promise thee. And now, what wilt thou choose first as a gift from him?”

“Something to eat for Tzandi and me,” leapt the swift reply.

“Bless my heart,” laughed “Unser Franz,” ringing a silver bell on the table beside him. Then, as a servant appeared, he said, “Bring broth and bread and milk for the little lad.”

“Oh, yes,” he went on, answering the question in Fritzl’s eyes, “Tzandi has already eaten all that he possibly could.”

Then while Fritzl, propped with pillows on the broad lounge, ate hungrily, they talked together.

“What is thy name, little lad?”

“Fritzl, sir—I mean, Your Majesty,” remembering the words he had heard the servant use.

“Fritzl—and what else?”

“Nothing else,” firmly, “just Fritzl.”

“But who were thy father and mother?”

“I never had any,” the boy answered gravely. “Once there was Josef, the blind fiddler, but since he went to heaven, there’s only been just the violin and Tzandi and me.”

“And what art thou going to be, when thou art a man?”

“A great violinist!” flashed the prompt answer.

“And so thou shalt be, little Fritzl, if I can help thee to it.”

When the boy had eaten the broth and bread, “Unser Franz” rose.

“Now stay thou here, child, and rest,” he said; “after I have wished my own dear little ones ‘Merry Christmas,’ I will come back to thee.”

But the Emperor returned sooner than Fritzl had expected.

“For what dost thou think our Prince wishes most, this Christmas morning?” he said excitedly, “why, a little boy who can play the fiddle, and a little dog that can dance. Come thou with me straight to him, Fritzchen!”

Tucking his violin carefully under his arm, the boy slipped one small hand into the hand of the Emperor, and followed by Tzandi, they went from the room.

At the end of a long corridor, the Emperor stopped before a closed door.

“Go thou in alone, Fritzl,” he said softly, opening the door: “there are two little friends within who will welcome thee.”

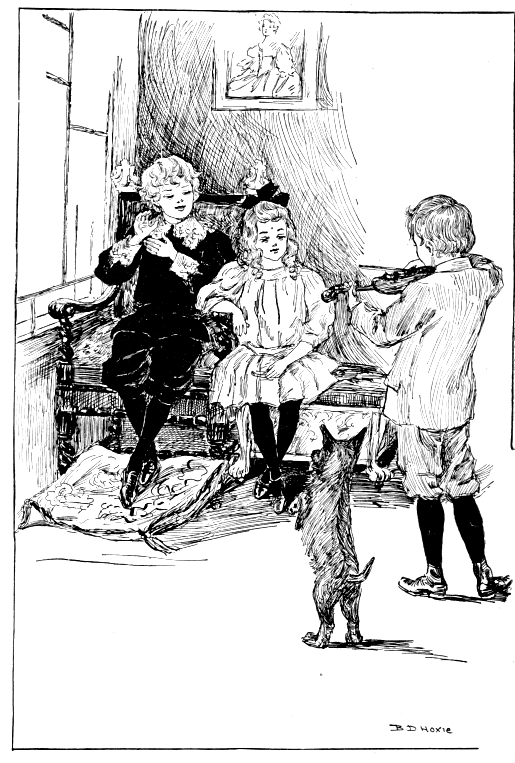

Very quietly, as if nothing more could surprise him, that day of miracles, Fritzl crossed the threshold, and stood within the room.

At one of the bay windows overlooking the terraced garden, sat the little lame Prince and his sister, their curly heads bent over a book.

“The dog looks something like the one that boy had,” Fritzl heard the Prince say wistfully.

“Only he hasn’t such a dear funny tail as—”

But Betty never finished her sentence.

Tzandi, having been quiet as long as seemed to him desirable, gave a soft little whine.

The brother and sister turned swiftly.

“It’s the boy with the violin!” cried Max.

“It’s the dog!” cried Betty.

“I told you so, Maxchen!” Betty announced triumphantly, as a half hour later, explanations having been finished, the three children and Tzandi clustered on the tiger skin, before the fire of pine logs. “I told you Grandpapa Franzchen would bring them to you. There isn’t anything in this world he can’t do. And now, Fritzl, commence at the very first beginning, and tell it all over again!”

“Oh, poor Fritzl,” she cried, slipping a warm hand into his, as he came to that part of his story, where Tzandi and he were driven out of the doorways, in which they had sought shelter, the night before.

“Poor little Fritzl,” echoed the Prince, “all cold and lonely!”

“I wasn’t exactly lonely,” said Fritzl loyally, looking down at Tzandi at his feet, sleeping the sleep of a well-fed dog, “but I was awful hungry!”

“Well,” cried the small Archduchess stoutly, “it was the very last time, Fritzl. You sha’n’t be hungry or cold any more, ever again!”

“Sit thou closer to me, Fritzchen,” commanded the Prince: “now I will tell thee my story.”

Then he told Fritzl how he had never been able to run or walk like other boys. How, for nearly two years, the famous surgeon had been treating him. How, that very Christmas night, he was to walk for the first time.

“But if he fail?” faltered Fritzl, tears of anxiety in his eyes and voice.

“He will not fail,” the Prince said proudly: “he never fails anyone—my Herr Doctor! And now, Fritzl,” all a boy’s love of fun flashing into his eyes, “make Tzandi dance!”

And how Tzandi danced!

Back and forth, up and down the room, while Fritzl fiddled merrily, and Max and Betty clapped their hands in delight.

For Tzandi realized that the time had come for him to do honor to his little master’s training, and never did a dog dance as he, that Christmas Day!

He was still waltzing blithely, his fore paws waving ecstatically in the air, when the Emperor came into the room. “I have come to hear thee fiddle, Fritzl,” he said, taking Betty into his arms, and seating himself in the great arm-chair beside the Prince. “Play me one of the dances my children of Hungary love.”

So Fritzl played, standing proudly yet very modestly before his Kaiser. And the old Emperor, closing his eyes, saw once more that village on the Danube, where, a boy about the age of the three children, he had been taught to dance the czardas; heard once more the chant of the pines, and the laughter of the Hungarian peasants, who had danced with him.

“Little lad,” he said, as the song died plaintively away, “God has given thee the greatest of his gifts. And now,” he went on, “play that which shall make these children think of the brave deeds of their ancestors.”

And Fritzl played: deep chords and crashing measures, underneath which was the tramp of feet, and the clash of sword blades.

“Grandpapa, Grandpapa,” cried Max excitedly, “canst thou not hear them? The tramp of the men and the tramp of the horses of Rudolph, going forth to victory over Ottokar of Bohemia?”

“Oh, and the sound of swords drawn swiftly,” Betty cried, nestling closer into her grandfather’s arms.

“And now,” said “Unser Franz” softly, “play thou that song which neither thou nor these other little orphaned ones ever heard. The song that mothers sing.”

Again Fritzl played: and the sound was like the ripple of quiet waters, like the rustle of rain-drenched poplar leaves, like the cadence of a woman’s voice, hushing her little child to sleep upon her breast.

Again the Emperor closed his eyes, and saw his mother’s face, and heard the song his beautiful wife used to sing to their only son, long dead.

Then, brushing the tears from his eyes, he cried cheerily to Fritzl: “Play thou the ‘Kaiser Hymn!’ And then,” kissing the forehead of the boy beside him, “the Prince must rest.”

Fritzl drew himself to his tallest, tucked his violin more firmly under his chin, and to its measures sang in his clear young voice, the other children joining eagerly,—

“Gott erhalte, Gott beschütze, unsern Kaiser, unser Land!”

In the “Blue Salon” of Schönbrunn, the imperial family awaited the coming of the Emperor and the Prince, talking together softly, not only of “Maxchen,” as they called him lovingly, but of Fritzl, whose story had spread throughout the palace.

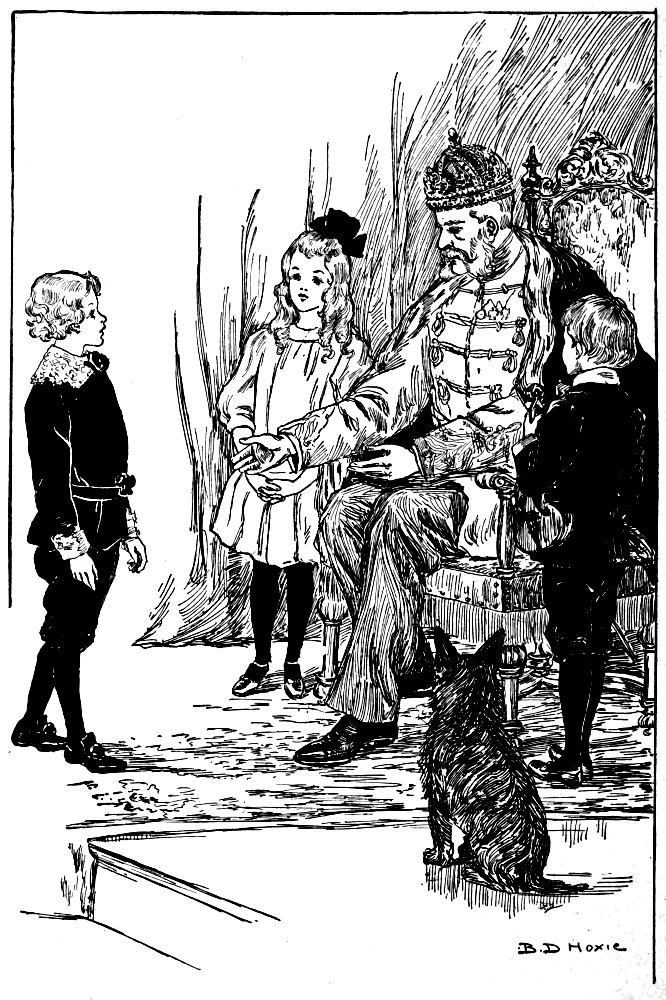

At last, the Hofmeister threw open impressively the east door of the salon, and across its threshold, and down the pathway made for him by his family, the Emperor passed slowly. Lightly holding his right hand, trying to walk demurely, but fluttering along like a white rosebud softly blown, was the little Archduchess Betty. Tightly clinging to his left hand, walked a boy, holding a violin. Behind, went the Archduke Max, in his wheeled chair, and beside him was the great surgeon.

At the dais, on one side of the salon, the three children and the Herr Doctor halted, while the Emperor mounted its steps, and bowing to those assembled, who curtsied and bowed deeply in return, took his seat upon the golden throne.

It was all very solemn and stately. And Fritzl felt rather lonely. He missed Tzandi, among all these strange and awe-inspiring people.

“I wonder,” he thought to himself, “if they’re both dreams—last night, in the Stephansplatz, and here, to-night!”

Now just at that moment there came the sound of subdued but excited voices at the east door of the salon. The dignified Hofmeister was seen to plunge wildly forward, in a vain attempt to bar the way. And then—and then—(as long as he lives, Fritzl says he can never forget the mingling of surprise and joy and shame which flooded his heart) a little terrier dog, ears and tail erect in the pride of victory, trotted through the door, and across the room to the three children, grouped at the foot of the throne. Looking up into Fritzl’s scarlet face, he wagged his stumpy tail joyously, and giving three sharp little barks of salutation, sat up on his hind legs, his fore paws waving politely. One ear erect, the other drooping in that deprecating fashion, which means that a little dog knows he is doing what he should not, but really can not help it.

How he reached his master remains a mystery unto this day. But there he was.

Laughing heartily with the rest, the Emperor said, “Although an uninvited, thou art a welcome guest, Monsieur Tzandi!” While Max and Betty patted his shaggy head, as he trotted from one to the other, licking their hands with his soft red tongue.

Suddenly, the Emperor nodded to the Herr Doctor.

The face of the little Prince grew white; but there was no trace of fear or doubt in the blue eyes, lifted to the great surgeon’s face.

Betty tried to smile bravely at him, creeping closer to Fritzl, and slipping her hand within his. While to Fritzl himself it seemed as if everyone must hear the beating of his heart, so frightened was he.

Then, very tenderly, the Herr Doctor lifted the Prince from his wheeled chair, and stood him carefully on the dais, a few feet from the Emperor’s throne. Involuntarily, both Betty and Fritzl moved nearer, each stretching out a trembling hand as if to help him. But Max stood steadily.

“Maxchen, Maxchen,” called softly the Emperor, his face as white as his snowy hair, “come thou to me, dear child!”

The boy gave a last look into the good Doctor’s eyes, which were strangely dim.

“Go thou, little lad,” said the surgeon gently.

Then the Prince walked bravely into his grandfather’s outstretched arms.

When the tumult of congratulation had somewhat subsided, and Max had walked proudly back to the great surgeon (happiest perhaps of all those present), the Emperor rose, and silence fell upon the room. His voice trembled a little, from excitement and relief, but the fresh color had come back to his kind face.

“Good friends and mine own people,” he said, “of that which the Herr Doctor has done for the Prince—for me—for you—for the empire—I can not speak. There are no words for that which is within my heart. Only my life henceforth can prove its gratitude.” Then beckoning to Fritzl, who mounted the steps of the dais fearlessly, and stood beside him, the Emperor continued: “Somewhat over a hundred years ago this Christmas night, a little lad, one Mozart, sat at yonder spinet, and played to our great Empress and her children. To-night, a little lad shall play to you. This little lad, Fritzl, whom I believe God means to become as great a musician, as became that child of long ago. He has known cold and hunger and neglect. But he has been a brave lad, and none of these things shall he ever know again.”

“Now Fritzchen, play to these thy friends,” he commanded kindly, reseating himself upon his golden throne.

Slim and straight, in his suit of black velvet, Fritzl stood beside him, looking about the brilliant room. At first he was timid and the little hand which raised the violin to his shoulder trembled. But looking into the gentle face beside him, and down at the smiling ones of the good Herr Doctor, Max and Betty and Tzandi, he thought of nothing but pleasing them.

So, wholly forgetting himself, he cuddled his violin closely under his chin, and whispering to it lovingly, played.

Played as he had played that afternoon, in the quiet chamber to the Emperor and his grandchildren; and all curiosity and indifference died away, and those who listened, held their breath in surprised delight. For he brought to them the cool sweet breath of pine woods, the ripple of April leaves, the sound of voices long unheard but never to be forgotten. And when at last, at the Emperor’s request, he played “the song that mothers sing,” into many eyes which for long had not felt them, crept tears. Then his bow dropped and he looked wistfully into the Emperor’s face. There was a moment of absolute silence, and then the room re-echoed with applause. It came with such a crash that once more Fritzl was frightened, and shrank closer to the Kaiser. Seeing the boy was overwrought, “Unser Franz” said quickly, “Now he shall play for you the noblest hymn our ‘Vater Haydn’ ever wrote. And then, the little ones shall dance!”

Once again, Fritzl lifted his shining bow. The voices of the people joined that of the violin, and “Gott erhalte, Gott beschütze” rang through the room, as it had never before been sung there. For every heart rejoiced that the little Prince could walk, and they knew that to the lad who played to them, God had given the gift of genius. Then the Emperor ordered the salon prepared for the children to dance.

The older members of the imperial family made their obeisances and departed. And at last, only the children of the house of Habsburg and a few of the younger matrons remained with the Emperor.

Once more the great Christmas tree blazed with candles, while about it danced the children hand in hand.

Then Fritzl tuned his violin carefully. “May I play for them to dance?” he said.

“Unser Franz” nodded a smiling consent.

Then, back and forth over the tense strings flew the gleaming bow, and the waltz the elder Strauss wrote for the music and dance loving Viennese, and which they love above all others—“Die Schöne Blaue Donau”—vibrated through the Blue Salon.

Back and forth, like butterflies, danced the children, curls and ribbons blowing, little feet twinkling on the polished floor, while the Emperor beat time on the arms of his throne and smiled happily, greeting them all as they fluttered by.

At the foot of the throne, two boys watched the dancing. The “little lame Prince,” lame no longer. The little “waif,” a waif no longer, and to-day, one of the world’s great violinists.

“Thou wilt be dancing with them, next Christmas, Liebchen,” said the Emperor, patting his grandson’s curly head.

“Ye-e-s, sir,” assented Max, without enthusiasm; “but oh, Grandpapa Franzchen,” he cried excitedly, “I’d rather run races in the garden with Betty and Fritzl and Tzandi!”

“Well, thou canst do both,” laughed “Unser Franz.”

“Oh dear me,” sighed Betty, as the candles having burnt low in the sconces, and upon the great tree, the last good nights were being said: “Christmas is all over!”

“It will come again next year, little sister, it always does,” consoled Max, “and next year it will be nicer for Fritzl, because he missed the Christmas tree last night, you know, Betty!”

“It couldn’t be nicer,” cried Fritzl, smiling gratefully at the little brother and sister: “it’s the very most beautifullest Christmas that ever was!” And Tzandi, whirling delightedly on his hind legs, barked an ecstatic assent.

The following corrections have been applied to the text: