Title: Bromoil printing and bromoil transfer

Author: Emil Mayer

Translator: Frank Roy Fraprie

Release date: October 10, 2022 [eBook #69127]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: American photographic publishing co, 1923

Credits: Charlene Taylor and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BROMOIL PRINTING

AND

BROMOIL TRANSFER

BY

DR. EMIL MAYER

PRESIDENT OF THE VIENNA CLUB OF AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHERS

AUTHORIZED TRANSLATION

FROM THE SEVENTH GERMAN EDITION

BY

FRANK ROY FRAPRIE, S.M., F.R.P.S.

EDITOR OF AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHY

AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHIC PUBLISHING CO.,

BOSTON 17, MASSACHUSETTS

1923

Copyright, 1923

BY AMERICAN PHOTOGRAPHIC PUBLISHING CO.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Electrotyped and printed, March, 1923

THE PLIMPTON PRESS

NORWOOD·MASS·U·S·A

The bromoil process has always been one in which it has seemed difficult to attain success. Though many books and articles on the subject have been published, every writer seems to give different directions and every experimenter to have difficulty in following them. The consequence is that almost every successful experimenter with this process has developed methods of his own and has frequently been unable to impart them to others. One reason for this has been that each make of bromide paper varies in its characteristics from the others and that methods, which are successful with one, do not always succeed with another. Various bleaching solutions have been described, and, as the bleaching solution has two functions—bleaching and tanning, which progress with different speeds at different temperatures—a lack of attention on this point has doubtless been a frequent cause of unsuccess. Little attention has also been paid to the necessity for observing the temperature of the water used for soaking the print. The author of the present book has investigated these various points very carefully, and for the first time, perhaps, has brought to the attention of the photographic reader the need for an accurate knowledge of the effect of these different variables.

In the following book he describes only a single method of work, without variations until the process is learned, though he does describe various methods of[iv] work which may be used to vary results by the experienced worker. His method of instruction is logical and based on accepted educational principles. He describes one step at a time fully and carefully, explains the reasons for adopting it, and then proceeds to the next step in like manner. We feel sure that every reader, who will be reasonably careful in his methods of work and will follow these instructions literally, will learn how to make a good bromoil print. After attaining success in this way, the variations may be tried, if desired.

While the author gives instructions for testing out papers to see if they are suitable, it may be advisable to record here the results of some American and English workers. H. G. Cleveland in American Photography for February, 1923, recommends, in addition to the papers specially marked by their makers as bromoil grades, the following: Eastman Portrait Bromide; P. M. C., Nos. 7 and 8; and Wellington, Cream Crayon Smooth, Rough, or Extra Rough. He suggests that a rough test may be made of a new brand of paper by placing a small test strip in water at 120° to 140° Fahrenheit for a few minutes and then scraping the emulsion surface with a knife blade. If the coating is entirely soft and jelly-like, it will probably be suitable for the process. If it is tough and leathery, it will be unsuitable, and, if a portion of the coating is soft but the other portion tough, then it will also be unsuitable. His experience is that Wellington Bromoil paper is entirely suitable for the process. Chris J. Symes in The British Journal of Photography for December 1, 1922, recommends for bromoil the following English papers: Kodak Royal, white and toned; Vitegas, specially prepared for bromoil; Barnet Cream Crayon[v] Natural Surface, Rough Ordinary and Tiger Tongue. For transfer, he has found the following suitable: Kodak Royal, white and toned; Kodak Velvet; Barnet Smooth Ordinary; and Barnet Semi-matt Card.

The reader who is interested in bromoil transfer, will find the directions of Mr. Guttmann on this process slightly different from those of Dr. Mayer in minor points, but the worker who is far enough advanced to essay this difficult process will be able to recognize these discrepancies and choose the process which seems more useful to himself.

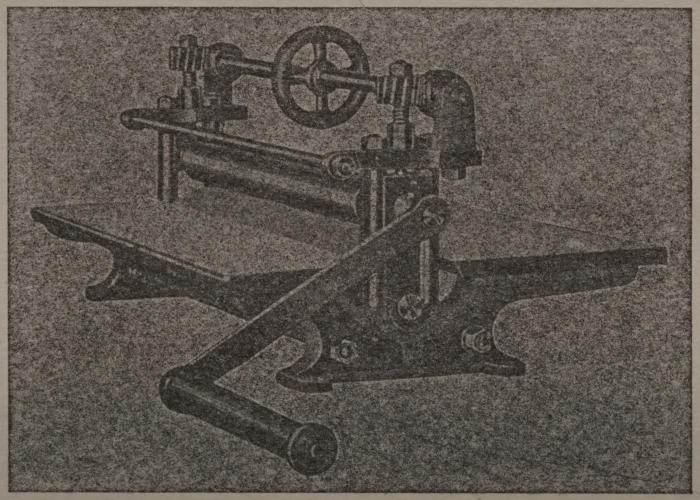

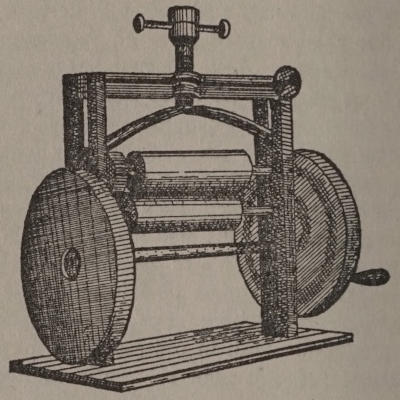

Metal etcher’s presses for transfer are sold at comparatively high prices in the United States, but second hand ones may often be found in the larger cities. Small wooden mangles with maple rolls may be had at fairly low prices from dealers in laundry supplies, and have been found to be useful.

Following the style of the German original, italics have been freely used for the purpose of calling attention to the most important stages of the process, rather than for the ordinary purposes of emphasis.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Mr. E. J. Wall for assistance in the first draft of the translation, and also in revision of the proofs.

Frank Roy Fraprie.

Boston, February, 1923.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | iii |

| Contents | vi |

| Preliminary remarks | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Production of the Bromide Print—Definition of Perfect Print—The Choice of the Paper—Development—Control of the Silver Bromide Print—Fixation | 10 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The Removal of the Silver Image—Bleaching—The Intermediate Drying | 29 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| The Inking-up—The Production of the Differential Swelling—The Properties of the Relief and Its Influence on the Character of the Picture—Effect of Warm Water—Effect of Ammonia—The Utensils—Brushes—The Inks—The Support—Removal of the Water from the Surface of the Print—The Brush Work—Use of Dissolved Inks—Use of Rollers—Resoaking of the Print during the Working-up—Removal of the Ink from the Surface—Failures—Alteration of the Character of the Picture by the Inking—The Structure of the Ink—Different Methods of Working—Hard Ink Technique (Coarse-grain Prints)—Soft Ink Technique—Sketch Technique—Large Heads—Oil Painting Style—Night Pictures—Prints with White Margins—The Swelled-grain Image—Mixing the Inks—Polychrome Bromoils | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| After-Treatment of the Finished Print—Defatting the Ink Film—Retouching the Print—Refatting of the Print—Application of Ink to Dry Prints | 104[vii] |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Transfer Methods—Simple Transfer—Combination Transfer with One Print-plate—Shadow Print—High Light Print—Combination Transfer from Two Prints | 115 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Oil vs. Bromoil | 134 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Bromoil Transfer, by Eugen Guttmann—The Bromoil Print—The Choice of the Paper—The Machine—Printing—Combination Printing with One Bromoil—The Value of Combination Printing—Retouching and Working-Up—Drying | 142 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Preparation of Bromoil Inks, by Eugen Guttmann—The Varnish—Powder—Colors—Tools—Practice of Ink Grinding—Ink Mixing—Permanency—Ink Grinding Machines | 176 |

We all know what great progress photography has made in the last few years. The most obvious sign of this advance is the fact that it has gradually escaped from the practice of literal reproduction of the objects seen by the lens, and slowly attained to the rank of a recognized means of artistic expression, so that it can justly be considered as a new branch which has grown out of the old tree of reproductive art. This pleasing development may primarily be ascribed to the fact that the practice of photography, which was originally confined almost exclusively to professional workers, has gradually spread and has become a means of recreation to the multitude in their leisure hours. It was the amateur who demanded new methods and apparatus and thus gave a new impulse to photographic manufacturing. Improvements of the most fundamental character were made in optical apparatus, in the construction of cameras of the most varied types, and in the fabrication of plates and films. An extraordinary number of novelties has appeared in these lines in the course of time; modern photographic apparatus makes possible the solution of problems which would not have been attempted a few years ago, and improvements are still appearing.

The situation in the matter of printing processes is quite different. We are provided with apparatus and sensitive material for the production of the photographic[2] negative, in a perfection which leaves nothing to be desired. To produce a print from the negative, however, we had until recently no positive processes which were not well-known to previous generations. This may be confirmed by a glance at any photographic textbook written around 1880. The various printing processes, platinum, bromide, carbon, and gum, which were until recently the alpha and omega of printing technique, had been known for decades. Compared with the methods for the production of negatives, printing methods showed practically no advance; they remained in complete stagnation. We can scarcely consider as an exception certain new methods brought forward in recent years, which proved unsuccessful and quickly disappeared from practice.

These facts can only be explained by remembering that the positive processes, which were available to photographers and with which they had to be satisfied, were rather numerous and offered a considerable variety of effects. Nevertheless, a single characteristic was common to all previously known photographic printing processes—their inflexibility. Each of these processes, in spite of its individual peculiarities, could do nothing more than exactly reproduce the negative which was to be printed. It was possible to produce certain modifications of the negative image as a whole, by printing it darker or lighter, or by using a harder or softer working process. Changes on the negative itself for the purpose of giving a more artistic rendering must, however, always be very carefully thought out in advance and effected by retouching, often difficult and not within the power of every photographer, or by other methods which change the negative itself. If such modifications of the[3] negative proved unsuccessful, it was irreparably lost; if they succeeded, the plate, as a rule, could no longer be used in any different manner. The possibility of undertaking radical changes which might realize the artistic intentions of the worker on the print itself, in order to save the negative, and especially of planning and carrying out the deviations from the original negative, which expressed the worker’s artistic feelings, during the printing, was not afforded by any previously known printing methods. A single exception was found in gum printing, if the production of the image was divided into a series of partial printings. Each of these phases, however, was in itself incapable of modification except for the possibility of doing a certain small amount of retouching; nevertheless, by means of efficient management of the single printings and by properly combining them, beautiful artistic effects could be obtained. This, however, required an extraordinary amount of practice and skill, and a very considerable expenditure of time, and it must also be remembered that the failure of one of the last printings often destroyed all the previous work. Also, in gum printing, to have a reasonable expectation of success, the work must be thought out from the very beginning and carried out in exact accordance with a plan from which it was scarcely possible to deviate during the work, even when it became apparent that the desired result could not be satisfactorily obtained.

The possibility of planning results during the course of the printing and carrying them out directly on the print itself did not previously exist.

The first process to bring us nearer to this ideal and make possible a freer method of working was oil printing. The technique of this process consisted in sensitizing[4] paper which had been coated with a layer of gelatine, by means of a solution of potassium bichromate, and of printing it under the negative. The yellowish image was then washed out; the bichromate had, however, produced various degrees of tanning of the gelatine, corresponding to the various densities of the silver deposit in the negative. The lighter portions, which had been protected from the action of light by the dense parts of the negative, retained their original power of swelling and could therefore later absorb water. The shadows, however, corresponding to the transparent parts of the negative, were tanned, had lost their absorptive power, and had become incapable of taking up water. Consequently, the high lights swelled up fully in water, the shadows remained unchanged, and the middle tones showed various degrees of swelling corresponding to the gradation of the negative. If the print was blotted off and greasy inks spread upon it by means of a properly shaped brush, the inks were entirely repelled by the swollen high lights which had absorbed water, and completely retained by the fully tanned shadows, while the middle tones, in proportion to the amount of tanning, retained or repelled the greasy ink more or less completely.

In this process, for the first time, there was found a possibility of changing various parts of the image absolutely at the worker’s will, even during the progress of the work. By the use of harder or softer inks it was possible to color the swollen high lights more deeply, or to hold back the shadows so that they did not take up all the ink that was possible. It was possible to leave certain parts of the print entirely untouched and work up other parts to the highest degree; in short, oil[5] printing opened the way to free artistic handling of the print.

Thus, the oil process was the first photographic printing process in which we were completely emancipated from the previous inflexibility which ruled in all printing.

Nevertheless, a number of disadvantages attach to oil printing which hinder its general use. The most important shortcoming of this process is that bichromated gelatine as a printing medium can only reproduce a comparatively short scale of tone values. The production of prints from contrasty negatives is therefore impossible, for the shadows are much overprinted before details appear in the high lights, or on the other hand, there is no detail in the lights if the shadows are fully printed. This difficulty can be only partly overcome by the most skilful use of inks of various consistency. It is indeed possible to ink up the lights by the use of very soft ink, but this does not replace the missing details; and overprinted shadows, which it is tried to improve by keeping down the quantity of ink applied, appear empty. Thus it happens that most of the oil prints yet exhibited show a certain muddy family likeness, which, at first, when the process was new, was considered to be advantageous on account of the novelty of the effect, but later received deserved criticism. A second disadvantage of the oil print is the fact that it is not possible to observe the progress of the printing on the bichromated gelatine film. The brownish image on a yellow background is very deceiving, and it is usually necessary to determine the proper amount of printing for each individual negative by actual experiment, and to make additional prints by means of a photometer.

Another inconvenience of other previously known[6] printing processes, to which oil printing is also subject, comes from the fact that the great majority of negatives are now made with small cameras. On account of the extraordinary perfection of modern objectives, the small negatives produced by modern hand cameras can be enlarged practically without limit. The advantages of a portable camera are so considerable that large and heavy tripod cameras have practically gone out of use, except for certain special purposes. On the other hand, however, direct prints from small negatives are, as a rule, entirely unsatisfactory from an artistic standpoint. If we desire to use any of the previously mentioned positive processes, including oil, to produce artistic effects, we must first make an enlarged negative. This requires, in the first place, the production of a glass transparency from the small negative, from which we may prepare the desired enlarged working negative.

Various workers held various views as to whether this requirement were a help or a hindrance, but it was universally accepted as a necessity. The way from the plate to the enlarged negative, nevertheless, always remained uncertain, tedious, and expensive. Simple as it may appear to be, it includes a whole series of stages where it is possible to come to grief. At every single step lurks the danger that undesired changes of gradation in the negative may result from inaccuracy in exposure and development, from the use of improperly chosen sensitive material, and from various other causes, and even if these factors are all correctly handled, there is still an unavoidable loss of detail. Therefore the path from the small original negative to the enlarged negative necessary in previously used processes is neither simple nor safe.

Naturally it was also necessary to travel this wearisome path in working the oil process, when it was desired to make large prints from small negatives.

When it was announced in England that Welborne Piper had discovered a process which started from a finished silver bromide print instead of from a gelatine film sensitized with bichromate, new vistas were opened. If the process should prove to be practically useful, we could consider that all the previously mentioned difficulties were overcome at a single stroke.

The principle of this process, bromoil printing, is the removal of the silver image from a finished silver bromide print by means of a bleaching solution while, simultaneously with the solution of the silver image, the gelatine film is tanned in such a way in relation to the previously present image that the portions of gelatine which represent the high lights of the image preserve their capability of swelling, while the shadows of the image are tanned.

Therefore the bromoil process is a modification of oil printing, based not upon a bichromated gelatine film, but upon a completed bromide print. This represents extraordinary progress. The two previously mentioned disadvantages of oil printing are completely avoided in the bromoil process. We now have at our command the far longer scale of tone values of bromide paper and we can use the great possibilities of modification allowed by the highly developed bromide process. The difficulties of printing are completely removed, for we have at our command a perfectly visible image as a starting point. A further advantage which can not be too highly estimated is inherent in the bromoil process: complete independence of the size of the original negative.

When I began my investigations in the field of bromoil printing, the process had, as far as practical value went, only a purely theoretical existence, as is the case in the early days of most photographic processes. The fact that it was possible to produce images on a bleached bromide print by the application of greasy inks was well established. The practical application of the process was absolutely uncertain and only occasionally were satisfactory results obtained. Most of the prints produced in this way were flat and muddy. It is easy to understand that the process could find no widespread popularity while it was so incompletely worked out. The researches, which I then began, showed that most bromide papers took up greasy inks after development by any method and subsequent bleaching of the image. The pictures thus obtained, however, were muddy, flat, and not amenable to control, and therefore were less satisfactory than the bromide prints from which I had started. During the course of my work, I have succeeded in obviating these difficulties, in the first place, by preparing a satisfactory bleaching solution, next, by determining what properties bromide paper must possess in order to give perfect bromoil prints, and, finally, by working out a series of other necessary conditions, which I have described in this book and which must be adhered to if the process is to work smoothly and certainly, and produce satisfactory results.

The bromoil process, which is now completely mastered, offers, in brief, the following advantages:

Simplicity, certainty and controllability of the printing material;

Independence of the size of the negative and easy production of enlarged artistic prints;

Freedom in the choice of basic stock and its surface;

The possibility of freely producing on the print any desired deviations from the negative, during the work;

Full mastery of the tone values without dependence on those of the negative;

Independence of daylight, both in printing and in working up the print;

The possibility of the most radical alterations of the print as a whole and in part during the work;

Freedom of choice of colors;

The possibility of preparing polychromatic prints with any desired choice of colors, and complete freedom in the handling of the colors;

The possibility of comprehensive and harmonious modifications of the finished print;

The possibility of producing prints on any desired kind of non-sensitized paper by the method of transfer.

The description of working methods will be divided into the following phases:

| I. | Production of the bromide print; |

| II. | Removal of the silver image; |

| III. | Application of the ink; |

| IV. | After-treatment of the finished print. |

Failures in the bromoil process in the great majority of cases can be ascribed to the fact that the basic bromide print was not satisfactory. Therefore the method of preparation of the bromide print or enlargement deserves the most careful consideration, for the bromide print is the most important factor in the preparation of a bromoil print. The beginner, especially, can not proceed too carefully in making his bromide print.

Because of the extraordinary importance of this point, we must first define what is here meant by a perfect bromide print.

In deciding how to produce a satisfactory bromide print as a basis for a bromoil, we must exclude from consideration esthetic or artistic grounds.

The bromide print must be technically absolutely perfect, that is, it must have absolutely clean high lights, well graded middle tones, and dense shadows. Especial stress must be laid on the brilliancy of the high lights. It is best to compare these high lights with an edge of the paper which has not been exposed and is not fogged or, even better, with the back of the paper. The highest lights should show scarcely a trace of a silver precipitate and must therefore be almost as white as the paper itself. Negatives which do not allow of the production of prints as perfect as this should not be used while the bromoil process is being learned.

This apparently superfluous definition of a perfect bromide print has to be given in this way, because it only too often occurs in practice that the worker himself is not clear as to what is meant by the expression, perfect bromide print. This may be partly ascribed to the fact that the silver bromide process—whether rightly or wrongly need not be determined here—has not been properly appreciated among amateurs who are striving for artistic results. Bromide printing has frequently been considered not to be satisfactory as an artistic means of expression, and has therefore been considerably neglected. In many quarters it is considered as just good enough for beginners.

Nevertheless, the bromide process is per se an uncommonly flexible method and gives, even with a very considerable amount of overexposure or underexposure, that is, even when very badly handled, results which are considered usable. It is even possible that an improperly made bromide print, one for instance, which is soft and foggy, might in some circles be considered as esthetically more interesting than a perfect print. This is an undeniable advantage of the process. It may also become a danger, if an imperfect bromide print is used as a starting point in the bromoil process. If anyone is not sure on this point, let him compare his own bromide prints with such samples as are frequently shown by manufacturers in window displays and sample books. He will then see what richness of tones and wealth of gradation are inherent in the process. If, however, an imperfect silver bromide print is used as a starting point for a bromoil, it can not be expected that the latter will display all the possibilities of this process. If the bromide print is muddy, the work of inking will be difficult,[12] and it will be impossible to obtain clean high lights. If it is underexposed and too contrasty, it can not be expected that the bromoil will show details in the high lights which were lacking in the bromide print. If the worker himself does not know that his silver bromide print is faulty, he is inclined to ascribe the difficulties which he finds in making the bromoil print and his dissatisfaction with the results, to the bromoil process itself. Most of the unsatisfactory results in bromoil work must be ascribed to the imperfect quality of the bromide print which is used, and this is the more important as this lack is not perceptible to the eye after the bleaching is completed. Whoever, therefore, desires to successfully practice bromoil printing, must first decide impartially and critically whether he actually knows how to make bromide prints, and must acquire full mastery of this process.

The technically perfect bromide print made from a properly graded negative can, as will later be described, have its gradations changed in the bromoil process without any difficulty, and thus be made softer or more contrasty. The advanced bromoil printer who is a thorough master of the technique of the process will therefore easily be able to work even with poor negatives; when making his bromide prints from such negatives, he will consider the ideas which he intends to incorporate in the bromoil print and will make his bromide print harder or softer than the negative and at the same time retain the necessary cleanness of the high lights.

The best starting point for a bromoil print, however, especially for the beginner, is and must be a bromide print as nearly perfect as possible.

A suggestion for the certain obtaining of such prints may be added here. When we are working with a negative with strong high lights, judgment as to the freedom of the bromide print from fog by comparison with an unexposed edge is not difficult. This is not the case with negatives which show no well marked high lights. In such cases it is advisable to determine what is underexposure by making test strips in which details in the high lights and middle tones are lacking and, working from this point, determine by gradual increase of exposure the correct time which gives a perfectly clean print.

The Choice of the Paper.—One of the most important problems is to find a suitable paper for the process. Not all of the bromide papers which are on the market will give satisfactory results. It is only possible to use papers whose swelling power has not been too completely removed in process of manufacture by the use of hardeners. The principle of the bromoil process is that a tanning of the gelatine shall occur simultaneously with the bleaching of the silver bromide image. As we have already remarked, this does not affect the high lights and leaves them still absorbent, while the shadows are tanned and therefore become incapable of taking up water. The half-tones are tanned or hardened to an intermediate degree and therefore can take up a certain amount of water. Therefore, in place of the vanished silver image, we get a totally or partially invisible tanned image in the gelatine film.

The variously hardened parts of the gelatine film, corresponding to the various portions of the vanished bromide image, display the property acquired through different degrees of tanning by the fact that the portions[14] of the gelatine which remain unhardened and which correspond to the high lights of the silver image formerly present, absorb water greedily. Consequently they swell up and acquire a certain shininess, because of their water content; in addition they generally rise above the other parts of the gelatine film, which contain little or no water, and give a certain amount of relief when they are fully swelled. The portions of the film in which the deep shadows of the bromide image lay are completely tanned through, can therefore take up no water, and remain matt and sunken. This graded swelling of the gelatine film becomes more apparent, the higher the temperature of the water in which the film is swollen.

If, however, the paper was strongly tanned in the process of manufacture, the gelatine has already lost all or most of its swelling power before it is printed and, although the bleaching solution in such cases can indeed remove the silver image, it can no longer develop the differences of absorptive power which are necessary for a bromoil print; for, although the bleaching solution can harden an untanned gelatine layer, it cannot bring back the lost power of swelling to a film which is already hardened through and through.

Therefore bromide papers which have already been very thoroughly hardened in manufacture show no trace of relief after bleaching, and very slight, if any, shininess in the lights. This is the case especially with those white, smooth, matt, heavyweight papers which are especially used for postcard printing. When such papers are taken out of the solutions, as a rule, these run off quickly and leave an almost dry surface. It is generally not possible to make satisfactory bromoil prints on such[15] papers. It is true that the image can be inked by protracted labor; it is, however, muddy and flat and, as a rule, cannot be essentially improved even by the use of very warm water. Other types of bromide paper which have not been so thoroughly hardened may show no relief after bleaching, yet, after the surface water has been removed, they do show a certain small amount of shininess in the high lights when carefully inspected sidewise. With such papers the necessary differences of swelling can generally be developed if, as will later be more completely described, they are soaked in very warm water or in an ammoniacal solution. It is rare to find in commerce silver bromide papers which have not been hardened at all, or only very slightly hardened, in their manufacture. Such papers, because their films are very susceptible to mechanical injury, are not likely to stand the wear and tear of the various baths. On the other hand, as a rule, they usually produce a strong relief even in cold water, and therefore tend to produce hard prints. The greatest adaptability for bromoil printing may be anticipated from bromide papers which are moderately hardened during manufacture.

To determine whether a given brand of bromide paper is suitable for bromoil work, an unexposed sheet of the paper should be dipped in water at a temperature of about 30° C. (86° F.) and the behavior of the gelatine film observed. If this swells up considerably and becomes slippery and shiny, the paper has the necessary swelling power and can be used with success.

On account of the great variety of bromide papers which are on the market, we have a very wide choice as regards the thickness and color of the paper and the structure of its surface. It may be remarked here that[16] papers of any desired surface, even rough and coarse grained papers, can be used for bromoil printing, as easily as papers with a smooth surface. The difficulties experienced with very rough surfaced papers in some other processes do not exist in bromoil. Because of the elasticity of its hairs, the brush carries the ink as easily into the hollows of the surface as to its high points.

The thickness of the paper is of no importance in bromoil printing, except that the handling of the thicker papers is easier, because they lie flatter during the work and distort less on drying; also, as a rule, thick papers are easier to ink.

Gaslight papers can also be used if their gelatine films satisfy the above mentioned requirements. Therefore we have the widest possible choice in the printing materials for bromoil.

A great number of bromide papers of different manufacturers are well suited for bromoil printing; it is, however, advisable to make a preliminary investigation as to the amount of hardening they have undergone, for it occasionally happens that different emulsions of the same brand show quite different grades of hardening, so that on one occasion it is possible to make bromoil prints on them without the least difficulty, while the same paper at another time may absolutely refuse to take the ink. On account of the great popularity of the bromoil process in recent years, it can be easily understood that some manufacturers might seek a wider sale for their products by claiming for them a special suitability for this process. It is therefore a wise precaution to previously test even those brands which are advertised as specially adapted for bromoil printing, and not to depend too much on such claims.

Development.—The processes of tanning in the film of a bromide print, produced by the bleaching of the silver image, which will be described later, are of an extremely subtle nature. We must therefore endeavor to avoid all causes for damage in this process and especially everything which tends to harden the whole film even to the slightest degree. Any tanning, which affects the whole gelatine film, has the same effect as general fog in a negative. It is well known that almost all the developers used in photography have more or less tendency to harden the gelatine film. A very considerable damage to the bromoil print through the use of a tanning developer might naturally be imperceptible to the eye. Yet this may at times manifest itself in a very undesirable and disturbing form, especially when the bromide paper has been so much hardened in manufacture that it possesses only just the necessary qualification for bromoil printing. It may then happen that the last remainder of swelling capacity can be taken from the paper by the use of a tanning developer. However desirable it might be and however it might simplify the process to be able to use any desired developer in producing the bromide print, to avoid trouble it must be observed that the use of developers which tan the film may seriously influence the result, even though it is possible to get some kind of prints in many cases. If the worker is absolutely sure that the bromide paper which he is using is not strongly hardened and is therefore well suited for bromoil printing, he may undertake development with any one of the ordinary developers which he prefers.

The developers, which do not exercise a hardening influence on the gelatine, are the iron developer and[18] amidol (diamidophenol hydrochloride). As the iron developer is not really suited to this purpose on account of certain unpleasant qualities inherent in it, it is advisable to use amidol for the development of bromide paper for bromoil printing whenever possible, and the best developer is composed as follows:

| Amidol | 1.7 | g | 12.3 | gr. |

| Sodium sulphite, dry | 10 | g | 77 | gr. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 16 | oz. |

The sodium sulphite is first dissolved in water, and the easiest way is to pour the necessary quantity of water into a developing dish and sprinkle the pulverized or granular dry sodium sulphite into it while the dish is constantly rocked; solution takes place almost instantly under these conditions. Larger lumps, which would stick to the bottom of the dish, must be immediately stirred up. As soon as the sodium sulphite is dissolved, the amidol should be added and this will also dissolve immediately. The addition should be made in the order described, for, if the amidol is dissolved first, the solution is often turbid. If dry sodium sulphite is not available, double the quantity of crystallized sulphite may be used.

The amidol developer should be freshly prepared each time that it is used, as it does not keep in solution. The measurement of the quantities of amidol and sulphite given above does not need to be made with the most painstaking care, as small variations in the quantities are unimportant.

In using amidol developer the greatest care must be taken to avoid allowing amidol powder, in even the[19] smallest quantity, to come into contact with the bleached print ready for bromoil printing. Even the finest particles of amidol, although invisible to the naked eye, will produce yellowish brown spots on the gelatine which penetrate through the film and into the paper itself. These dots and spots, especially if, as is usual, they occur in large numbers, will make the print completely useless, and it is impossible to remove them.

If amidol developer is not available, any other developer which is desired may be used. As we have already stated, however, certain possibilities of failure are to be anticipated, but will not necessarily occur.

Every effort should be made to produce a bromide print as perfect as possible, with clean high lights.

The best bromide prints or enlargements for bromoil printing are those which are correctly exposed, but are not developed out to the greatest possible density. A print which is thus fully developed is very satisfactory as a bromide but offers certain difficulties in bromoil printing, which will be described later. Therefore the development should be stopped as soon as the lights show full detail without any fog, but before the shadows have reached full density. The deepest shadows should then be of a deep greyish black, but should not be clogged up. When a bromide print is properly exposed, there is sufficient time between the appearance of the details in the lights and the attainment of the deepest possible black in the shadows to easily select the proper moment for cessation of development. It is, however, desirable not to go beyond this stage of development, for the reason that a very dense silver deposit distributed completely through the gelatine emulsion to the paper support is not easily bleached out. When this difficulty[20] occurs, the bleaching solution is generally, but incorrectly, blamed for it. If, in spite of this difficulty, complete bleaching is attained, the shadows of the image usually retain a yellowish color which cannot be removed by the baths which follow the bleaching. If it is intended to ink up the whole surface of such a print, this discoloration of the shadows is not important, for it will be completely covered by the ink. But if the print is to be treated in a sketchy manner, and some parts of its surface are not to be inked, this cannot be successfully done on account of the yellowish coloring of the shadows.

Underexposure must be carefully avoided, for details which are not present in the bromide print will, of course, not appear in the bromoil print.

Overexposure will occasionally give usable results, if the development of the overexposed print is stopped at the proper point. In such cases, we must usually expect some deposit in the high lights and consequently a certain fogging of the image, though this can often be overcome, at least partly, by swelling the print at a higher temperature. Perfect prints cannot be expected, if the basic print is lacking in quality. If the overexposure is not too great, the print can be improved to a certain extent by clearing it in very dilute Farmer’s reducer. Treatment with this reducer has no deleterious effect on the later processes. The Farmer’s reducer should only be used for a slight clearing up of too dark parts of the bromide print; for this purpose the parts of the moist print which are to be reduced should be gone over with a brush dipped in very dilute reducer and immediately plunged into plenty of water, to avoid any spreading of the reducer into other parts of the image.

Developing fog should naturally be avoided as much as possible. Fogging of the bromide print is caused by the formation of a more or less dense silver precipitate without any relation to the image over the whole surface of the print. As the bleacher takes effect wherever metallic silver is present in the film, the result in such cases is a general tanning of the film, which is detrimental to the production of the necessary differences in swelling power in the gelatine. The tanned gelatine image is then also fogged.

Consequently the best results may be obtained from very brilliant, but not excessively developed, bromide prints.

We must also avoid falling into the opposite extreme in the development of the bromide print, by getting too thin prints lacking in contrast. In prints which are too thin, only a very small quantity of metallic silver has been reduced in the development, and this lies wholly on the surface of the film. Such prints usually show full detail, but the contrasts between the lights and the shadows are too small. Since the tanning produced by the later bleaching occurs because of the presence of metallic silver in the film, and since its intensity depends on the quantity of this silver, we cannot obtain the necessary difference in swelling power by bleaching the film of prints which are too thin because of insufficient development. The result is a weak tanned image in the gelatine film; bromoil prints thus produced can consequently only exhibit a very short scale of tone values, and this cannot be essentially lengthened by the use of the bromoil process alone. Such bromide prints may find a special application in combination transfers, which will be described later. It is also possible,[22] under certain circumstances, to use incomplete development as a method for producing soft bromoil prints from contrasty negatives.

Control of the Silver Bromide Print.—Although in bromoil printing the most various renderings can be obtained from a perfect bromide print, by variation of the temperature of swelling and by proper handling of the inking, it is also possible, under some circumstances, to vary the final result by proper treatment during the making of the bromide print, especially when we are not dealing with normal negatives. If, for instance, we have to deal with a very thin negative, it is possible that even the extreme possibilities offered by the bromoil process are not sufficient to insure the attainment of the desired modulation, for, as will later appear, the possibility of increasing the difference in swelling in the film is limited by the limited resisting power of the gelatine. In such cases, we must take advantage of the accumulation of all possible aids and therefore, in making the bromide print, do all that is possible in order to bring out desired objects, which are only indicated in the negative and do not show sufficient detail.

Therefore, if we desire to increase the contrast of the negative in the final print, we should use a harder working paper and add potassium bromide to the developer.

If we desire to get soft prints from a contrasty negative, we may use different methods. The simplest way is the use of a very rapid and consequently soft working paper. Ordinarily, however, this method is not sufficiently helpful. We must therefore also use suitable methods in later steps of the process, such as making the difference in swelling in the gelatine layer as small[23] as possible in order to bring down the contrast, or inking up with soft inks.

A very reliable process for the production of soft prints or enlargements, even from contrasty negatives, is the following: the proper exposure for the densest portions of the negative should be first determined by means of a trial strip; then a full sized sheet of paper is exposed for exactly the time which has been determined, soaked in water until it is perfectly limp, and then placed in the developer. As soon as the first outlines of the image appear, the print is placed in a dish of pure water and allowed to lie there, film down. As soon as development has ceased, the print is taken out of water, dipped into the developer for an instant, and then immediately put back into the water. This method requires considerable time for full development, but produces prints or enlargements of especial softness. In this process, the developer which is absorbed by the film is soon exhausted in reducing the heavy deposit in the shadows, so that their development ceases, while enough developer still remains unexhausted in the other portions of the image to keep on developing. With very dense negatives, developer warmed to 25° C. (77° F.) can be used for the production of soft prints, but it must be very much diluted and carefully used, for development proceeds very quickly. Very soft prints may also be obtained by bathing the exposed bromide prints for about two minutes in a one per cent solution of potassium bichromate before development. This solution is thoroughly washed out of the print, and it is then developed.

Yet with very hard negatives all these remedies frequently fail, because the high lights are almost completely[24] opaque to light because of their density. In such cases the negative itself must be improved. The ammonium persulphate reducer usually recommended for such plates, which acts more strongly on the lights than on the shadows, is, however, too uncertain in its action and may imperil the negative. It is better to adopt Eder’s chlorizing method, which enables one to improve too contrasty negatives in a convenient and certain manner. The principle of this process is as follows: the metallic silver of the negative is converted into silver chloride, which is again developed. This redevelopment is accomplished in such a way that the silver chloride on the surface of the film is first reduced to metallic silver; if development is continued, the reduction is continued to the bottom of the film. The delicate details, lying on the surface of the film, are thus first developed, while development of the overdense high lights, in which the silver deposit extends right through to the glass, is finished only after some time. It is therefore possible to stop development at the instant at which the shadows and half-tones are completely redeveloped, while the overdense high lights are, for instance, only half developed, and therefore only half consist of metallic silver, the lower half being still silver chloride. If the development is interrupted at this stage and the negative placed in a fixing bath, the still undeveloped silver chloride is dissolved. The shadows and half-tones thus retain their original values, and only the overdense deposits in the shadows are reduced. If the development is not stopped at this stage, but is carried through to completion, the negative is obtained unaltered, and the process can be repeated. If the second development is stopped too soon, the[25] negative may be endangered and a very thin negative, lacking in contrasts, obtained.

The practical application of the chlorizing process is effected by bleaching the negative in the following solution:

| Cupric sulphate | 100 | g | 1 | oz. |

| Common salt | 200 | g | 2 | oz. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 10 | oz. |

As soon as the negative is completely bleached, which should be judged not only by transmitted light but also by examination from the glass side, it should be well washed and immersed in a slow-acting developer. All these processes can be carried out in daylight, and the second development of the negative is best controlled by frequent examination of the glass side. Development should be stopped when the shadows and half-tones are blackened, and there is still a whitish film of silver chloride in the high lights. Observation of the negative by looking through it is not advisable, for the negative very soon appears dense by transmitted light, because the metallic silver formed in development masks the silver chloride. As soon as the development is considered to have gone far enough, the plate should be rinsed and then fixed and washed in the usual manner. After a few trials, the judgment of the correct stage at which to stop development presents no difficulty.

I ordinarily use the chlorizing process in the following way, which practically excludes any possibility of failure: the negative is completely bleached in the solution just mentioned, and then washed for five minutes. It is then developed in any desired developer until it shows by transmitted light practically the same[26] density, though in a brownish color, as it had before chlorizing. It is then rinsed off, placed in a solution of hypo, not stronger than two per cent, and carefully watched by light passing through the plate; it is taken out as soon as the desired stage is reached, well washed, and dried. In this modification of the chlorizing process the condition of the plate can be observed at every stage. The final negative, to be sure, does not consist of pure metallic silver, but as a rule of a combination of silver and silver chloride; but such negatives are sufficiently permanent for making prints and enlargements on bromide paper.

It is also advisable to lessen the harsh contrasts in a normal negative, either by masking the more transparent parts on the glass side, or by holding them back in printing or enlarging. Briefly, every possible means should be employed in order to obtain as good and harmonious a bromide print as possible.

The beginner is strongly recommended, however, in his first trials with bromoil, to start as far as possible with normal negatives and correct, and especially very clean, bromide prints. The use of this process for the improvement of the results from difficult negatives should be left for more expert workers.

It is often desired to provide landscapes with clouds, and this can be easily attained if enlargements are used as the basis for bromoil prints. Acceptable results are given by a process, which has often been recommended. This is, after blocking out the sky on the negative, to enlarge the landscape, develop the print and again place it while still wet on the enlarging screen and expose for the clouds, disregarding the existing image, and then develop the clouds.

I might describe here another process for obtaining clouds, because it is especially suitable for the bromoil process. If there is no object in the negative which is cut by the upper edge of the plate, it is extremely easy to introduce clouds into such a landscape, and at the same time lengthen out the picture at the top. A cloud negative suitable for the landscape is chosen, and the relative exposures for the landscape and clouds found as accurately as possible by test strips. The landscape negative is then focused on the enlarging screen so that there is plenty of paper above the upper edge of the plate, and then the exposure is made while the upper part of the paper is covered with a card, which is kept moving constantly between the light source and the enlarging screen, so that the upper edge of the plate is not imaged on the screen. After the exposure is finished, the paper is shifted down on the screen until the upper edge of the paper comes at the place which was previously occupied by the edge of the plate, the landscape negative is changed for the cloud negative, and the clouds are exposed on the upper and hitherto unexposed part of the enlarging paper, while the landscape is protected from exposure by means of a piece of card, shaped like the previous one for the sky, and continually moved to avoid a sharp line of separation. In the subsequent development a perfectly uniform picture is obtained, in which there should be no visible trace of its compound nature.

Obviously, in the preparation of the bromoil print, it is advisable to employ to the utmost the many possibilities which bromide printing offers. Thus too thin parts of a negative may be held back by proper blocking out on the back and numerous other possible modifications,[28] which have been described in textbooks and technical journals, but which cannot be further dealt with here, may be profitably employed.

Fixation.—The developed bromide print should be well rinsed and fixed in the usual way. If the rinsing is omitted or is too superficial, complete or partial reduction phenomena may occur in the fixing bath, and make the print unusable.

The bromide print should be left in the hypo solution for about 10 minutes, and care should be taken, if several prints are simultaneously treated, that they do not stick to one another. Then should follow thorough washing for removal of the hypo; if traces of hypo remain in the film, the subsequent bleaching is rendered more difficult, as the image does not disappear but only turns brownish. While it is feasible to subject the bromide print to the bleaching process, as soon as it comes from the washing, an intermediate drying is an advantage; for the gelatine gains greater resistance by this drying.

Bleaching.—The bleaching process has the purpose of making the bromide print, correctly prepared according to the previously described method, suitable for the bromoil process. To this end the silver image must be made to disappear and in its place that condition of the gelatine produced which renders it possible for it to take up the greasy ink. The bleaching solution has, therefore, two functions: it must remove the metallic silver, imbedded in the gelatine film, which forms the bromide image, and at the same time cause a tanning of the gelatine film corresponding to the image that disappears. In the place of the silver image there then exists an invisible tanned image in the gelatine film.

There are a large number of chemical compounds known to photographic technique, which enable us to dissolve out the metallic silver imbedded in the gelatine film. Such are, for example, the many reducers which have found practical application. Many of these chemicals also cause changes in the gelatine simultaneously with the solution of the silver. But not one of the hitherto known bleaching solutions possesses the double power required of it: solution of the silver image and corresponding tanning of the film. Some produce too great a tanning which acts upon the whole film, and the result in inking-up is muddy flat prints, which do not lend themselves to artistic modification. With other[30] bleaching solutions a differential tanning of the gelatine is produced, but at the same time they so alter the surface of the gelatine that it becomes glossy all over, and only takes even soft inks with difficulty.

My experiments have led to the compounding of a bleach which completely fulfils the requirements set for it; the silver image is quickly and completely removed, while simultaneously a tanning of the film, strictly analogous to the disappearing image, is effected; easier and more certain inking-up is rendered possible, and besides this the advantage is obtained that the differences of relief, produced in the gelatine by the bleaching process, can be influenced to a wide degree by varying the temperature of the water. The composition of this bleaching solution, which prepares the gelatine film in the most perfect manner for the bromoil print, is as follows, three stock solutions being required:

| I. | Cupric sulphate | 200 | g | 2 | oz. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 10 | oz. | |

| II. | Potassium bromide | 200 | g | 2 | oz. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 10 | oz. | |

| III. | Cold saturated solution of potassium bichromate. | ||||

A concentrated bleach is made by mixing:

| Solution I. | 3 parts |

| Solution II. | 3 parts |

| Solution III. | 1 part |

To every 100 ccm of this mixture should be added 10 drops of pure hydrochloric acid (10 drops to 3½ oz.). This concentrated bleach will keep indefinitely and[31] should be diluted before use with three to four times its volume of water. The use of a more concentrated solution is not advisable, as irregularities frequently occur in consequence of too rapid bleaching, especially towards the margins of the prints.

The color of the concentrated bleach is green, or when diluted, yellowish; the solution must be absolutely clear. When the stock solutions are mixed there is usually some cloudiness, but this is cleared up by the hydrochloric acid. By standing for a long time at low temperatures a precipitate is sometimes formed, but this is of no moment. The compounding of this bleach should be made with the greatest accuracy. Inaccuracies or modifications in its composition are serious, because although the solution does not lose in bleaching power, yet the invisible tanning action is then often not completed in the desired manner. Too great an addition of hydrochloric acid for example, accelerates the process of bleaching, but the inking-up of prints thus bleached is frequently difficult. If the bleaching of the shadows of the bromide prints goes on slowly, the reason as a rule lies in the fact that the prints were overdeveloped and have an excessively dense silver deposit.

The bromide prints should be immersed in this bleaching solution, after previous soaking in cold water. If they have been correctly made, the image rapidly grows weaker and after a few minutes its greyish-black color changes into a pale citron yellow. If the bromide print was developed too far, the bleaching takes rather longer, as the shadows, developed right through to the base, require a lengthy period for solution. If several prints are to be bleached at once, the best procedure is to place one print in the solution and turn it film side[32] down when the first traces of bleaching are noticeable. Then the next print should be immersed with the film up and by thus proceeding gradually it is possible to bleach a large number of sheets simultaneously in the one dish. Continual movement will prevent the formation of air bells. If air bells adhere to the film, they protect those places from the action of the bleach and dark points or spots of unchanged metallic silver remain, the subsequent bleaching of which naturally prolongs the process. The same applies to prints which lie on top of one another.

With too slow bleaching, the hydrochloric acid may be gradually increased, at the most to double that prescribed; one should not hasten the bleaching process by warming the solution. The bleaching is rapidly effected in warm solutions; yet generally the film of moderately hardened papers is so altered that they swell up too much even in cold water and take the ink badly or not at all. The dilute bleaching solution will keep and may be used repeatedly as long as it acts; when it becomes exhausted, the slowing up of the bleaching cannot be hastened by the addition of hydrochloric acid. The chemical reactions in the bleaching bath are, according to Dr. P. R. von Schrott, as follows:

2CuBr₂ + Ag₂ = 2AgBr + Cu₂Br₂

The cuprous bromide, Cu₂Br₂, which is formed, reduces the bichromate as follows:

3Cu₂Br₂ + 6CrO₃ = 3CuBr₂ + 3CuCrO₄ + Cr₂O₃.CrO₃

It sometimes happens that bromide prints, in spite of[33] long immersion in the bleaching solution, apparently will not bleach and only change their color to brown.

The reason for this usually unimportant phenomenon is, as a rule, that such prints have not been sufficiently washed and still contain hypo.

It may also happen that prints which have lain on top of each other in washing are badly washed in parts; then the image bleaches, but the film shows dark patches or streaks at those places which still contain hypo. Such apparently unbleached prints should be left for about 10 minutes in the bleaching solution; the disturbing coloration, whether of the whole picture or only of parts, disappears completely in the subsequent baths, even when the image had apparently remained at full strength.

If such a print, apparently not bleached or spotty, is immersed in the sulphuric acid bath mentioned below, the discoloration of the film is quickly removed by its action; the print then often passes through a phase in which it appears to be a negative, the secondary image becoming visible on the yellow ground, and then bleaches out completely. With such prints it may also happen that it is only noticed after removal of the stain that unbleached traces of the silver image still remain. Then the bleaching must be repeated.

If the color of the bromide print only changes to brown even after protracted immersion in the bleaching solution, otherwise retaining full gradation, and remaining unchanged even in the sulphuric acid bath, though it bleaches out in the hypo, the print cannot be inked. The reason for this difficulty is improper composition of the bleaching solution, or occasionally improper development and fixation of the bromide print. It may[34] also be due to excessive use of the bleaching solution; 3 to 4 ccm (50 to 70 minims) of concentrated bleaching solution should be allowed for every 13 by 18 cm (5 by 7) print.

Obviously all these processes may be carried out by diffused daylight. The bleached-out prints should be repeatedly washed, until the drainings are quite clear, and should then be immersed in the following bath:

| Sulphuric acid, pure | 10 | ccm | 77 | min. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 16 | oz. |

In this bath any remaining color disappears quickly and completely, and prints, which have apparently wholly or partially resisted bleaching, are also very rapidly decolorized in this bath. Any spots and streaks also disappear. If, however, there is anything left, then the bleaching was not complete, and unreduced metallic silver remains in the film. After the sulphuric acid bath the prints should show the pure color of the paper base; the film side ought to be hardly different from the back in color. With prints that have been overdeveloped, a certain slight variation of color remains in the film, which, however, in no wise prejudices the inking-up. If there are still some spots, they are usually due to a slight precipitate lying on the surface of the film, which can be easily swabbed off. When this point of colorlessness is reached, and it usually requires only a few minutes, it is useless to leave the prints longer in the acid bath. They should be washed in repeated changes of water and immersed in the following fixing bath:

| Hypo | 100 | g | 1 | oz. |

| Water | 1000 | ccm | 10 | oz. |

The use of this fixing bath is essential and is based on the following considerations. During the bleaching process a secondary silver bromide image is formed in the gelatine film. This secondary image is not visible on white and yellowish bromide papers, because it is whitish-grey. If a bleached print, which has not been fixed, is exposed for a long time to daylight a distinctly visible blue-grey image is formed, which naturally is troublesome in the further operations. This secondary image of silver bromide is completely removed, however, by the fixing bath.

The ordinary acid fixing baths can also be used without disadvantage for fixing. If the sulphuric acid is not sufficiently washed out, decomposition of the fixing bath may ensue, which will be made apparent by the unpleasant smell, and which is prejudicial to the action of the bath. Care should be taken that the prints do not stick to one another in the fixing bath and that they are thoroughly fixed out, as the secondary bromide image that is not removed will make its appearance in insufficiently fixed places and may cause darker patches.

Washing then completes the preliminary preparation of the prints.

For the sake of completeness it should be mentioned that the prints may be immersed in the bleaching solution in the darkroom after the first development, and can be fixed after the solution of the silver image. This shortened process is, however, uncertain and can not be recommended.

The Intermediate Drying.—After the bleaching process outlined in the previous section the print must be dried without fail. While drying after the development and fixation of the bromide print is advisable but not absolutely necessary, the intermediate drying after bleaching is of the greatest importance. It is possible that the later operations may be successful in spite of neglect of this recommendation. As a rule, however, various mishaps occur when the intermediate drying is omitted. In many cases the ink can only be caused to adhere with difficulty, in others, not at all; sometimes the inking will proceed up to a certain point and then suddenly completely stop. Sometimes the image appears as a negative, that is to say, the ink is taken up by the high lights and rejected by the shadows. All these failures will be obviated by the intermediate drying at this stage. Whether this intermediate drying takes place rapidly or slowly is practically immaterial; naturally it ought not to be so prolonged that the gelatine suffers.

The prints thus prepared can either be again soaked in water and immediately worked up, or kept and treated at any time. It is very convenient, especially for an amateur, to have a stock of such ready prepared and dry prints, because he is then in a position to work when he finds time and opportunity. The prints, prepared and dried as has been described, will keep indefinitely. With correct treatment there can be seen on the gelatine film of the dry print scarcely a trace of the bleached-out image; only in the very deepest shadows a slight coloration of the film, tending to grey, can sometimes be noticed. It is advisable, therefore, to mark the print on the paper side before bleaching, as otherwise it is subsequently difficult to distinguish this.

Before we go any further, the whole preliminary process is summarized once more:

The Production of the Differential Swelling.—In the chapter on the bleaching we fully explained the processes which take place in the gelatine film under the action of the bleaching solution, and that the most important result of the bleaching process, aside from the disappearance of the silver image, is the formation of different degrees of swelling corresponding to the primary image, which in their totality form the tanned image produced in place of the photochemical image by the bleaching.

For the success of the bromoil print, it is now of the utmost importance that the different capabilities of swelling, now latent in the gelatine film, should be satisfactorily utilized. It is obviously possible to produce this swelling in very different degrees. The colder the water used for the swelling, the smaller the difference between the lights and shadows, while the warmer the water the more this difference is accentuated. If, for example, a print prepared for the bromoil process is placed in cold water and allowed to swell for some minutes, the existing capacity for swelling will only be excited to a slight degree. The high lights of the invisible image only take up a little water, and when dry are differentiated from the shadows under oblique visual examination by a very delicate gloss or not at all. If[39] this picture is now worked-up with greasy ink, a print is obtained with a short scale of gradation, and its tone values are usually less satisfactory than those of the original bromide print. If, on the other hand, the print is placed in very warm water, the swelling of the gelatine reaches a maximum. The high lights are very much swollen, even the half-tones are somewhat raised, and the shadows, which do not absorb water, appear sunken. The result of the swelling in such warm water in this case is the formation of a very pronounced relief, that is not only visible, but is almost perceptible to the touch. If such a picture is inked up, a bromoil print is obtained, the contrasts of which are much stronger than those of the original bromide print. Between these two extremes there is obviously a whole series of intermediate stages, the suitable employment of which permits of the most varied gradations.

As already mentioned, the capacity for swelling of the different makes of bromide papers is not the same in baths of the same temperature. This fact, however, argues neither for nor against the usefulness of the various bromide papers. It makes necessary, to be sure, a certain care in the use of a paper, the qualities of which are unknown. If one has to deal with such a paper, the prepared print should first be soaked in quite cold water; it should then be removed from the water, placed on a support, dried in the manner to be later described, and examined by oblique illumination as to whether the high lights show by a slight gloss that they have absorbed water. This will be the case if the image shows well swollen high lights; if they are not present, it will hardly be possible to find distinctly glossy places. In any case one may begin with the inking-up, prepared,[40] as will be explained later, to increase the swelling if necessary during the inking-up by immersion in warm water. If on the other hand, the print, when taken from the cold water, distinctly shows places where differences of swelling are shown by a gloss or even a delicate relief in the film, the work may be proceeded with, without further trouble.

Under any circumstance one should be careful at first in the production of the differential swelling. There should rather be no relief than too pronounced a one; for differences of swelling that are too small can be easily and satisfactorily increased during the work; on the other hand it is scarcely possible again to reduce too strong a relief. While learning, or when using an unfamiliar brand of paper, it is therefore advisable to allow the sheet to swell first in cold water and to carefully begin the inking-up. Only if this is not satisfactory, should a warmer bath be used and the inking again tried. This method is, however, dealt with more fully in the section of Chapter III, entitled “Different Methods of Working” (page 85).

The Properties of the Relief and its Influence on the Character of the Picture.—In order that the following explanations may be understood, an important property of the prepared and dried gelatine film must be mentioned.

The film of the prepared print, in which the differences of swelling necessary for the formation of the bromoil print are latent, develops variations of relief when it is placed in water. Then the untanned high lights absorb water, as already described, while the hardened shadows do not absorb it. The result of this process is the formation of those swellings, which, when they[41] have attained a certain degree, are characterized by the formation of a relief.

A definite degree of swelling corresponds to a definite temperature of water. This swelling disappears again if the film is dried. The gelatine has, however, acquired the property of again attaining the same degree of swelling when immersed in water at any time after drying, even if the temperature of this water be a good deal lower. A print, for example, on which a certain relief has been produced in water at 35° C. (95° F.) and which has given up this water again because of drying, again attains the same relief if immersed in ordinary tap water at 10° C. (50° F.). If, however, this print after drying is immersed in water at 40° C. (104° F.), that is in hotter water than that first used, a still higher relief is obtained, and again in a similar manner, after drying, it will attain this higher relief when immersed in water at any lower temperature.

The degree of swelling that is once attained can, therefore, so far as the resistance of the gelatine film will permit, be increased, but it cannot be reduced, if the print as a whole is not subjected to a tanning, as with formaldehyde, a process that is not easily controllable. This peculiarity of gelatine makes it necessary to go to work carefully in the formation of the relief, so as not to carry the latter too far. If the work is begun on a too low relief this can be easily increased to the necessary height, as will be shown later, absolutely without any regard to any inking up that may have been done. On the other hand, if the formation of the relief has once been carried too far, as a rule the print can not be used, although reduction of the excessive swelling by a tanning agent may be attempted.

The property of the gelatine film, just described, offers a further convenience for the bromoil worker; for he can bring the bleached and dried print to the necessary degree of relief in water of suitable temperature, and, if he does not wish to work it up at once, it can be dried and laid aside until needed. In working-up such prints he is then, as a rule, relieved of the necessity of obtaining warm water.

The question how far the swelling of the film has to go or in other words what kind of a relief should exist, if any, in order to obtain a harmoniously graduated bromoil print, is extremely difficult to answer. A few practical trials quickly give the ability to judge this correctly. If a well-modulated negative is used, one in which the differences of gradation between the high lights and the shadows are not too great, the swollen gelatine film after drying should show a very delicate but still noticeable relief; yet the high lights of the print should scarcely be raised above the shadows, and should not show too marked a gloss.

The visibility of the relief is essentially determined by the character of the print. The more contrasty the bromide print was, the more easily are the different degrees of swelling made apparent by the formation of a visible relief. A picture with sharp outlines and great contrasts, such as an architectural study, easily gives a distinct relief visible in all its details. Pictures with softer gradation, as, for instance, delicate portraits, behave differently. One can not expect a striking relief in such prints. If this should be forced by warming the water, the bromoil print may easily attain an undesirable harshness. With portraits, one should therefore be satisfied when the outline of the profile against[43] the background, the contours of the eyes and the mouth, are raised to a barely visible extent from the gelatine base. At the same time very dense parts, like a white collar, a lady’s light dress, lace, etc., may show a very distinct relief, even when the sharper lines of the face scarcely stand out in relief. Yet even in such cases the features can be recognized by the different gloss of the high lights and shadows under oblique observation. Naturally some attention must be paid here to the particular views of the operator. If strong contrasts are desired, greater differences of swelling must be used; if, on the other hand, softly modulated effects are sought, distinct relief must be avoided. In any case it is advisable not to attain this at once, but to get it as needed during the working-up by the use of water gradually increasing in temperature.

It must be laid down as an axiom that the efficiency of a relief should never be judged by the eye alone, but should always be carefully tested out by inking-up with the brush. The degree of swelling is correctly estimated at the first attempt when, in inking-up, the picture appears quite clearly after a little hopping, and this may happen if the character of the image is right, even though no relief could be seen.

The stronger the relief formed by warming the water, the more contrasty the bromoil print will be. Nevertheless there is a certain limit which should not be overstepped. If the print is warmed in the water bath so much that an excessive relief, which can almost be felt with the finger, is formed, in which deeply cut lines alternate with highly glazed places in relief, then the high lights are so saturated with water that under no circumstances will they take ink; even the softest inks[44] will not adhere to them. Thus we obtain harsh highlights without details, while the deeply sunken shadows literally fill up with ink and become sooty. If the formation of the relief has been driven so far, it is not advisable to treat the print with ink.

The forcing of the relief to the extreme possible limit is only justified when working with a flat negative, in order to obtain as rich a gradation as possible from a flat print. Also, this should not be done all at once before the commencement of the inking-up, but effected gradually during the work. Working in this way, extraordinarily successful results can be obtained and the contrast of the bromoil print can be made far more rich than that of the original bromide print. The limit lies only in the resisting power of the gelatine film and the flatter the bromide print was the sooner this is reached.

The upper limit of temperature permissible for the water can hardly be defined; it depends entirely on the hardness of the gelatine film. It may happen that it is necessary gradually to go almost to the boiling point. Films that are hardened right through will withstand even boiling water without forming a relief.

If, in warming the print, the melting point of the gelatine is approached, those parts which are but slightly tanned, such as the high lights, and especially any unexposed edges, begin to show a granular structure, and finally, when the heating is carried further, to melt.