MRS. ROBINSON AS "PERDITA."

Title: George Romney

Author: George C. Williamson

Release date: October 25, 2022 [eBook #69228]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: George Bell & Sons, 1901

Credits: Al Haines

Bell's Miniature Series of Painters

BY

ROWLEY CLEEVE

LONDON

GEORGE BELL & SONS

1908

First Published, 1901.

Reprinted, 1904, 1908.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Some of the Chief Books on Romney

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Mrs. Robinson as Perdita ... Frontispiece

The Countess-Duchess of Sutherland

George Granville, afterwards Duke of Sutherland

George Romney was a Cumberland lad, born in 1734, of parents who were in humble circumstances living at Dalton in the Fells.

His father was an ingenious man who lived on his own farm as a yeoman, but who followed also the pursuits of a joiner and cabinet-maker, and who was one of the first persons in the north to see and make use of the newly imported wood mahogany, from which he made a chest of drawers out of a sailor's chest brought from the West Indies.

Romney inherited much of his father's ingenuity, and as a lad set about making a fiddle, which he completed in later years and retained all his life. It was a sound instrument of really good tone, and the artist himself played well upon it.

As a lad Romney was sent to a small local school; but he made very slight progress with his studies, and preferred to spend his time in sketching or in copying the pictures that he found in papers or books.

His father, finding that he was making so little progress, took him away from school before he was eleven, and placed him in his own workshop, where he soon began to learn how to ply the tools and to make a creditable use of his new accomplishment.

Still, however, his spare time was filled up by painting, and he made very careful copies of the illustrations in a monthly magazine which one of his father's workmen, who boarded in the house, lent him regularly as it appeared.

He was also asked by a person in the village to paint her portrait, and succeeded in performing the commission in so creditable a way, that it was quite clear to the elder Romney that his son was intended by nature to be an artist.

Accordingly, yielding to the persuasions of the lad himself, backed up as they were by those of many friends, he took steps to apprentice him to an itinerant painter, who was at that time in their neighbourhood, named Steele.

Here he was employed in the more menial work of the craft, grinding colours and preparing the palette; but Steele, although a poor painter himself, had been well trained in Paris, and was able to teach his young pupil much that was of the greatest use to him in his after career.

Steele afterwards eloped with a young lady who was one of his pupils, and Romney had to assist him in his arrangements. They were difficult, and involved a vast amount of trouble and exposure to night air at a time when the youth was far from strong; and after the gay couple had escaped to Gretna Green, Romney fell ill of a fever, and was nursed by a domestic servant named Mary Abbott. With this young person the artist fell violently in love, and on recovering from his illness married her on October 14th, 1756, when only twenty-two years old, and without any means of his own on which to live.

He had to leave his wife very soon after marriage, as Steele had gone to York, where he expected Romney to join him; but after a while the roving life that his master led, and his improvident habits and constant difficulties as to money, disheartened Romney, and he agreed with Steele that, if he would cancel his indenture, Romney would forgive him a debt that he had incurred of £10 from the young apprentice.

This course was adopted, and Romney returned to Kendal, where his wife had been residing.

Here he commenced his own work as a portrait-painter, and from at first painting signboards he soon became known as a clever worker, and was employed by the persons of quality in the neighbourhood to paint their portraits.

Many of the neighbouring landowners employed him, and at this time the artist set about painting historical scenes also and landscapes, in order to turn his time to profitable account. Many of these he sold at Kendal Town Hall by a system of lottery that was then very popular.

By such work the young couple were enabled to save £100, and with some of this money Romney determined to make his way up to London, as he felt that the limited scope that he had in the north was cramping his powers and that he was capable of greater things.

He had but two children, a son and a little daughter, and his wife, who loved him profoundly, was quite prepared to sacrifice herself in order that her husband might prosper. Therefore, taking with him but £30 of their joint savings, and leaving the remainder for her and the children, Romney left his native county for the great and distant city on March 14th, 1762.

The little daughter whom he left behind him died in the following year, and Mrs. Romney, with her son, removed to the house of her father-in-law, John Romney, with whom she continued to live.

During the whole time of his sojourn in London, which, with the exception of brief visits in 1767 and 1779, lasted till 1799, Romney appears to have continued on terms of the closest affection with his wife, and to have remitted to her constantly such sums of money as she required; but he never brought her up to London, and, as has been stated, only visited her in Kendal twice during the thirty-seven years which he spent in London.

This is the incident in the life of the artist upon which much stress has been laid by malevolent writers, and hard things have been said without number about Romney for his so-called desertion of his wife.

It must be remembered, however, that Romney's son and biographer does not say any hard things about his father in this matter, nor does he upbraid him for leaving his wife far away in the Fells. Mrs. Romney did not write letters of expostulation to her husband, or demand that she should be brought up to London; and when her husband returned to her as an invalid, she received him lovingly and nursed him with great devotion till his death. She in no way suffered pecuniary loss by his absence, as he regularly sent sums of money to her; and when their son was old enough to come to town, Romney had him to his house, treated him with the greatest affection, and took him about with him.

Surely it ill beseems those who consider the life of this gifted artist so to condemn his action, when those who were the ones best fitted to blame him specially abstained from doing so!

Mrs. Romney, be it remembered, came of very humble parentage, and was a homely person of but slight education. She appears to have had her own circle of friends in the places where she lived, to have been a person of simple tastes, not anxious to mix in the world of fashion or to receive its comments and its sneers. She would have been in all probability unhappy in London, have in no wise enjoyed the life that her husband lived, and have been an encumbrance to him and a clog on his progress; and Romney very possibly feared to expose her simplicity to the contempt of the people of fashion whom he met and whose portraits he painted.

She may have desired to avoid such society and have preferred her quiet at home, and it may have been a refinement of kindness on his part which led him to shelter her from the troubles which he knew would await her in London.

There is nothing which, with any degree of accuracy, can be stated against the moral character of Romney whilst he was away from her, and all such charges against him fall to the ground by reason of the absence of proof, and it seems clear that it was no such cause that kept him from sending for his wife. Even the reports as to Romney and Lady Hamilton, to which reference is made in a succeeding chapter, are gainsaid by the letters of Lady Hamilton herself which are in the Morrison collection, and no one has ever been able to produce one single piece of evidence in support of the statements that have been too wildly made. Mrs. Romney from the very first showed her deep attachment to her husband by sacrificing herself for his advancement; and she continued, as her letters show, throughout her life, to act in the same way for him, and to give him her deepest and tenderest affection: and we are therefore justified in accepting as normal a state of affairs as to which the chief persons concerned made no complaint, and in declining to attribute to the artist any unworthy motives for his conduct.

Romney did not come to London provided with references or introductions, nor with much money, and the consequence was that for the first ten years of his life in town it was a struggle for him to do any more than keep himself and remit small sums to his wife in Kendal.

He seems to have known only two persons in London, neither of whom was in a position to do much to assist him.

His first important effort proved a disappointment to him in its result. He competed for a premium offered by the Society of Arts, and his picture of The Death of General Wolfe, sent in 1763, received the second prize of fifty guineas. Later on, however, it was stated that the picture was not painted at all by this unknown artist, but by someone else, and that a fraud had been practised; and then, when that was disproved, the costume of the picture, which was not the usual one adopted at the time, was objected to; and it was further claimed that the event was not strictly historical, having only so recently happened. The prize was accordingly taken away from Romney; but, in consideration of the merits of the work, an ex-gratia payment was made to the artist by the Council of the Society of twenty-five guineas. The leading artists of the day had in this way given a slight to this new-comer which he never in after years forgot.

Whether, as has been stated, Sir Joshua Reynolds was at the head of this movement to crush the young artist we cannot tell; but it seems likely that the bitter jealousy which existed between the two men in after years, and which Reynolds never lost an opportunity of increasing, took its rise at this time, and certain it is that Reynolds hated to hear Romney praised, and was ever ready to say and do things that would annoy and irritate his rival.

Romney had always been convinced that the study of the great artists of the Continent was needful for him before he would be able to accomplish what he felt was within him, and he made every effort to get to Italy in order to study the Old Masters.

At this time he was unable to accomplish his cherished desire for want of funds, but he saved all that he could, and contented himself with a journey to Paris.

Here he copied all the works that appealed strongly to him, and spent every hour of his time in visiting galleries and churches and feasting his eyes on the treasures which they contained. His acquaintance with Vernet was of great service to him at this issue.

On his return to London after some seven weeks' absence he again set valiantly to work, and in 1765 carried off a premium from the Society of Arts of fifty guineas against all his competitors.

Then, in 1767, he went down to see his wife, and when he returned to London he brought with him his brother Peter, hoping to be able to assist him in some measure. Peter was not, however, steady or industrious, and, although he sat to his cleverer brother more than once, he did not remain with him long, but drifted away and eventually settled down to a more or less precarious life in Manchester.

Romney now made close friends with Richard Cumberland, who was known at that time as a writer of odes and a man of no small literary grace. Cumberland wrote about his new friend and also introduced him to many other persons, and in this way the artist obtained commissions for portraits from several notable personages.

Another important friend whom he made at this time was the miniature-painter Ozias Humphrey, with whom he made several excursions, and who was one of his closest friends for many years.

Two more efforts he made at this time to visit Italy, which was ever the goal of his desire; but on neither occasion was he able to start. The death of a friend on one occasion and his own serious illness on another prevented his leaving England, but in 1773 the long-desired visit took place.

The two friends, Romney and Humphrey, set out on March 20th, and after resting at Knole, near Sevenoaks, as the guests of the Duke of Dorset, to whom both artists were well known, they left England by water and arrived in Rome on June 18th.

He was provided this time with the best of introductions, especially bearing with him a letter to the reigning Pope Clement XIV., who received him most graciously, and allowed him to have scaffolding specially erected in the Vatican that he might study the works of Raphael.

Other introductions which the artist took with him were from Sir William Hamilton and his nephew Greville.

Romney was not yet a man of any means, and he supported himself whilst in Rome by painting portraits and some historical works, and by copying the great masterpieces which he found in the Eternal City; but he had to make every effort to be economical, as his pictures did not meet with a ready sale in Italy, and he desired to visit many other cities whilst in the country besides Rome.

He actually did see Venice, Bologna, Florence, Padua, Castel-franco, and even some of the smaller cities, as Modena, Reggio and Mantua. Then he slowly made his way back to England by way of Aix and Paris, arriving in London after two years' absence in high spirits, full of ideas, and overwhelmed with enthusiasm for all he had seen, but in a pecuniary condition poorer than he had ever been in his life.

He had, in fact, had to borrow money to carry him through France, and almost to starve himself in his journey, as his small means had long ago vanished, and he had withdrawn all the money that he had banked ere he left Italy.

When he arrived he was met by demands for immediate assistance on the part of his clever but ne'er-do-well brother Peter, but was for the moment unable to assist him.

He found, however, that his own fame had increased during his absence, and the demand for work from his brush was considerable, so much so that he was overwhelmed with the commissions that flowed in.

He felt now that he was in a position to take a larger house in a more fashionable neighbourhood than he had possessed before; and accordingly, as Francis Cotes, R.A., the painter in pastel, had died, and his house in Cavendish Square was still vacant, Romney took it and moved in on Christmas Day, 1775.

Cotes had died in 1770, and the sale of his effects took place in February, 1771; but after that the house stood vacant for a long time, and when Romney took it needed some considerable repair.

Romney had ever a fondness for bricks and mortar, and was delighted at the prospect of altering and adding to the house.

He bought the lease, which had some thirty years to run, and was subject to a rental of £105 per annum; and, although there was already a good studio attached to the premises in the form of a double room with sky-light and domed ceiling, yet the artist must needs set about building another and adding to the accommodation of the house, and so again exhausting his savings.

He also foolishly declined many of the commissions sent him, because he did not possess a studio which was, according to his ideas, fit for the reception of his clients, and in this way an idea got about that he was not desirous of doing any more work. The public taste accordingly veered round, and for a short time Romney found himself deserted by the crowds of would-be-sitters who had just before poured in upon him.

Then the Duke of Richmond, who had befriended the artist before, and had opened his gallery of sculpture to his use at any time, looked in upon him at his new residence and gave him several commissions, besides bringing with him many of his own friends, and was delighted to have the artist for a while practically to himself and his own circle of acquaintance. This turned the tide once more in the artist's favour, and prosperity never again deserted him.

ELIZABETH, COUNTESS-DUCHESS OF SUTHERLAND.

He now became the serious rival of Reynolds, who spoke of him in slighting manner as "the man in Cavendish Square," pretending, with studied insult, to have entirely forgotten his name.

All the world of fashion and wealth sat to the artist, and his list of portraits reads like a page from the fashionable gazette of the day, including as it does all the persons who were then well known in town and who constituted the cream of society.

The opportunity now arose for Romney to show how indifferent he was to the slights and contempt of his fellow-artists who ranged themselves around Sir Joshua.

The Royal Academy had at this time sprung into being, and its members desired to include all the chief artists in their ranks, and to show that those outside their membership were not worthy of attention. All their efforts, however, to include the name of the most fashionable artist of the time, or to hang his pictures on the walls of the exhibition, were in vain.

Romney was begged by his great friend Jeremiah Meyer, one of the leading miniature-painters and an original member of the new Academy, to come within its shelter. He was also approached by Mrs. Moser, by Humphrey, and by Angelica Kauffmann, all of whom desired him to exhibit his works. But it was in vain, and never did Romney send a single picture to the exhibitions of the Royal Academy. He completely ignored it, would not suffer it to be mentioned in his presence, considered that it was not worthy of any recognition, and went on painting pictures of all the loveliest women of society, but declining to allow a single one of them to be shown in the exhibitions of the Academy.

This determination was partly dictated, no doubt, by modesty, as there is every evidence that Romney was a modest, retiring, shy man, and even at the very zenith of his fame was not found in the brilliant society in which the President delighted. He was fond of his home and of his son, and was not a gay but a quiet man; but there is little doubt that his refusal to share in the glories of the Academy was also partly the result of his wish to show to those who had been bitter and who were still jealous of his fame that he was quite able to stand alone, and did not require the aid of any Academy to render his works popular or to enhance his fame.

The determination cost him the patronage of the Court and of a certain select group of persons who followed the lead of the King and did not select for themselves, but it is probable that in the long run the artist did not really suffer thereby.

He was a self-respecting and unassuming man at all times, and was not in the habit of forcing his way into any society or of appealing for commissions from his friends.

No flattery escaped his lips, no adulation of those who could assist him by their introductions and so render him the aid which he required; and in all these ways he was the reverse of those who were around him, and who used every artifice to bring themselves into popular notice and shrank from no ignoble effort to obtain patronage.

In 1779 he seems to have paid one of his infrequent visits to his wife in Kendal, and to have refreshed himself by a sight of his native county; but he was soon back again and hard at work.

It was perhaps at about this time that he first made the acquaintance of William Hayley, a poet, who had a great celebrity at that time, but whose chief work, "The Triumphs of Temper," is now never read.

The influence of this man upon Romney was not good, and of it his son, the Rev. John Romney, in after years spoke with much bitterness. Romney was, as has been already stated, fond of building work, and pleased to see an opportunity of increasing a house or studio; and this propensity of his was encouraged by Hayley, who loved to make a sensation and to live in a large house; and although Hayley was fond of Romney and brought him many commissions, yet on the whole the judgment of later days is certainly to the effect that it would have been better for Romney if he had never met this attractive friend.

For over twenty years the two men continued fast friends, and Romney used often to go down to stay with Hayley at Eartham, near Chichester, and spent some weeks during each autumn with him. He decorated part of the house, painting some delightful pictures to be placed in the new library that Hayley built; and he met there many pleasant friends, amongst whom were the poet Cowper and his friend Mrs. Unwin, in connection with whom is the chief claim that Hayley has for remembrance, and also the young sculptor Flaxman, for whom Romney acquired a deep friendship.

Hayley was a man of fine taste, personal fascination and amiability, and fond of associating with men of culture and quality; and it is for his friends rather than for any work that he himself did that his memory is kept in honour. Romney is said to have first met him when, returning from Kendal, he stopped awhile at Tabley as the guest of Sir John Leicester; and, as they were all of them great admirers of Pope, the acquaintance began which lasted for so many years, brought them into contact with Cowper and with Gibbon, and eventually made Hayley one of the biographers of Romney.

In 1790 Romney again went to Paris, this time accompanied by his friend Hayley and by the Rev. Thomas Carwardine, whose portrait he had painted.

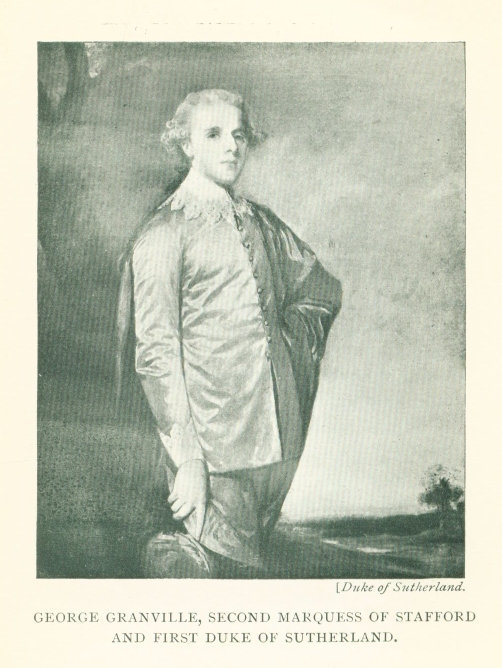

They were well received in that city, and visited many of the chief galleries, with introductions from the English Ambassador, who at the time was Lord Gower, afterwards second Marquess of Stafford and first Duke of Sutherland.

During this visit Hayley is said to have obtained the first of several loans that he got from Romney and never repaid. In this case it was £100.

On his return to London he was again almost overwhelmed with work, as more than ever he had become the fashion, and his portraits were desired by all who could afford to sit to him. The strain, however, of such constant work was beginning to tell upon the artist, who by this time was sixty years old, and he was glad of any excuse to leave town for a while to rest himself in the country.

He took a little cottage at Hampstead, to which he could retire for quiet; he stayed more and more with Hayley at Eartham, desiring some of his clients to come to him there, that in the quiet of that restful spot he might do fuller justice to their charms than he was able to do amid the turmoils of London life.

Whilst there he often rode over to Petworth, where he was painting portraits for Lord Egremont, and in these ways he got the country air and rest that were out of the question when he was in town. He did not, however, improve in mental vigour; but the old mania for building came on with greater force than ever, and unfortunately Hayley did not scruple to encourage it for his own ends.

In 1796 he was found one day by his son busy with extravagant ideas and designs for a great mansion in Edgware Road, and it was only the fact that his son was able to point out the folly of such an idea which dissuaded him from its accomplishment. The proposed purchase was eventually broken off, and Mr. John Romney records in his volume most gratefully his thankfulness to the solicitor, who behaved very handsomely in this matter.

Romney was, however, determined to leave Cavendish Square, and, acting on the advice of his son to buy a ready-built house rather than to erect one, he purchased an old dwelling-house near Holly Bush Hill, Hampstead, now identified with that known as The Mount, Heath Street, Hampstead, close to where he had been in the habit of lodging for some little while, and where he found the quiet and retirement which he desired.

This happened in 1796, and Romney let the residence in Cavendish Square and went to reside at Hampstead.

The accommodation did not, however, content him, and he acquired two copyhold plots of ground at the back of the house, on which he forthwith erected what Hayley describes as "a singular fabric," but which Cunningham calls a "strange new studio and dwelling-house."

He adds that it "cost £2,733, and was an odd whimsical structure, in which there was nothing like sufficient domestic accommodation, though there was a wooden arcade for a riding house in the garden, and a very extensive picture and statue gallery."

There is little doubt that this structure forms part of what is at present the Constitutional Club, the large room being Romney's picture gallery, although considerable additions have been made to the building.

In 1798 he had sold his London house to Mr., afterwards Sir Martin Shee, and, as this strange structure was ready, he moved into it, and let off to a Mrs. Rundell the old adjacent house in which he had been residing.

The new "whimsical" structure was not really complete when the artist went to live in it. The walls were not dry, the roof let in water; but the artist insisted on moving into his fanciful residence, and on taking with him the vast stock he had of his own pictures and those by other artists which he had collected.

Many of them were quickly injured by the damp of the house, and others by being placed in the open arcade; and Flaxman in a letter records the distress that he felt at seeing so fine a collection of works perishing.

Romney was now more than ever under the influence of Hayley, which was being used to its full and baneful extent, and other persons were taken into the house on the advice of the poet to assist the artist and to look after him, who were all more or less creatures of Hayley.

Hayley was considerably in Romney's debt, and was anxious, it is clear, that no one of repute should look into the affairs of the painter, but that his influence should reign supreme.

In 1798, however, Romney broke away from this state of affairs, and, accompanied by his son, who was devoted to him, and whose absence at his religious duties was the only reason which prevented his dwelling always with the artist, visited the north of England, not, however, as far as can be ascertained, going to Kendal.

A pleasant holiday was spent in the Lake district, but the mental vigour of the old artist did not gain much increase of strength by the change, and when he returned to London his health had completely broken down.

The following year he was again at Eartham with Hayley, but for the last time. Hayley's good nature towards his friends, his extravagant habits and his luxurious life, combined with utter neglect of monetary matters, had brought about the necessity for stern retrenchment, and Eartham was to be sold. He removed to Felpham, where he built a cottage near the sea, and there he and his son resided till the death of the latter, shortly afterwards; but at the earnest advice of Flaxman and his wife, coupled with the entreaties of his son, Romney went north back again to his wife, of whom he had seen so little for many years. She received him gladly and with open arms, and nursed him to the end with the most touching tenderness.

The last event of his life was the return from India of his brother, Colonel James Romney, to whom he had always been greatly attached, and for whom he had suffered some privations in order that the requisite sum needful for the Colonel's advancement might be sent him many years before.

The aged artist was, however, hardly able to recognize his beloved brother. He soon afterwards became completely childish in mind, and never again regained his intellectual powers.

He died on November 15th, 1802, at the age of sixty-eight, passing away in the arms of his wife, who devoted herself entirely to him up to the moment of his death. She survived him for many years.

In any consideration of the life and art of George Romney, however brief, it is impossible to leave out the name of Lady Hamilton, as she was so constantly painted by him.

It will be well, therefore, for a short section of this little book to be devoted to a story of the life of this fascinating person, who was fated to exercise so strong an influence upon the painter. It is hardly possible for the most imaginative romancer to tell a story more chequered in its events, more thrilling in its emotions, and more sad in its end.

Emma Lyon was the daughter of a smith in Cheshire, a humble man, who died in 1761, after a very short married life, and left his widow and infant daughter wholly without support.

The widow moved at once from Neston, where her husband had died, to Hawarden, her native place, and here by the aid of her relatives, almost equally poor with herself, she managed to bring up her child and send her to a dame's school in the village.

When about twelve Emma went as nursery-maid to the family of a Mr. Thomas, a doctor of Hawarden, whose son afterwards became an eminent surgeon.

At sixteen she left and came to London, and became housemaid to a tradesman in St. James's Street; and then later on, probably in 1778, became nursemaid in the family of another doctor, one Dr. Budd, a physician in St. Bartholomew's Hospital.

From here she migrated out to the west end, taking a place as lady's-maid in the house of a lady of fashion whose dwelling was a favourite resort of the gayest persons of the day, and where she had ample opportunity of reading as many books as she desired, of dressing in a style which made her more attractive, and of receiving a great deal of praise for her beauty and the quality of her voice.

The first slip which she made in her career was occasioned by her going to plead with Admiral Payne for the release of a cousin who had been forcibly pressed into the navy, and whose family were, without his assistance, unprovided for. Emma undertook this mission out of good nature and gained her petition; but in return the admiral, who was much struck by the beauty of her face, became her suitor, and she entered his house as his mistress. This life lasted for a very short time, as a wealthy baronet, Sir Harry Featherston, who visited Admiral Payne, begged her to leave him and come to Up Park as its mistress.

The admiral, who was shortly going on board his ship, consented to part with the fair Emma, who was much attached to her latest lover, and she went off with Sir Harry to Up Park, where she resided in the midst of every luxury for some months. Here she learned to ride on horseback, and succeeded in attaining to great proficiency in this accomplishment.

The affection, however, shown her by Sir Harry Featherston, lasted but a short time, and soon he began to weary of his toy. He brought his mistress to London, but was ashamed to let her be seen with him in public, and so gradually neglected her; and at the end of 1781 they separated, as Emma was not one to put up tamely with neglect, and was ambitious of yet greater conquests. They always remained friends, and corresponded to the end of their days; but another field of opportunity was now opening, and Emma was ready to avail herself of it.

The notorious and unscrupulous quack Dr. Graham was at that time in the height of his fame, and he had opened in 1779 his so-called Temple of Health in the Adelphi.

He was on the point of removing to more important premises when Emma Lyon left Up Park, and when, therefore, the Temple of Hymen, as the new imposture was named, was opened at Schomberg House, Pall Mall, in the residence afterwards occupied by Richard Cosway, R.A., and by Gainsborough, it was Emma Lyon who, as Hebe and the model of perfect beauty, health and happiness, was one of the greatest attractions of the place.

This wonderful woman, who was so lovely in face and form, and was withal so graceful in attitude, exhibited herself at the command of the quack in the most becoming of costumes of light drapery, posing as a goddess and attracting numerous admirers. Her beauty drew to the exhibition many of the noted painters and sculptors of the day, who were anxious to perpetuate the features and form of the fair Emma, and to draw her in the attitudes and characters which she so cleverly assumed.

She had no compunctions as to what character she assumed, whether it was Venus or a Bacchante, provided that she was admired and received the praise which was the very breath of her existence.

It was, however, only for a short time that she remained with Dr. Graham, as Mr. Charles Greville, the second son of the Earl of Warwick, to whom all her past history was unknown, and who fondly imagined that she was, as she represented herself to be, a paragon of virtue, fell deeply in love with her, and after a while gained her affection in return.

Greville was a man of the most cultivated taste, and he set about the education of the fair Emma with great zeal, training her in music, in dancing, in the love of the fine arts, and in the duties and accomplishments that befitted her new position.

He found out, after a short time, that she loved to be admired, and was ready to do anything that would obtain for her that gratification; but so successful was she in retaining her conquest of the man who appears to have honestly loved her, that for many years they lived together with considerable apparent affection on both sides.

When with Greville she sent for her mother, who from that moment and for some twenty years remained with her, assuming first the name of Cadogan, and then later on that of Hart, and she conducted herself with so much propriety that when Greville died he left her an annuity of £100 per annum.

Emma was now known as Mistress Hart, and it was under that name that Greville first introduced her to Romney in 1782, when he was himself sitting to the artist for his portrait.

During all the time when she first sat to Romney she was living with Greville and was attached to him, and there is absolutely no evidence whatever that the relationship between her and the artist was any other than that of a beautiful and accomplished woman sitting to a clever artist in numerous delightful scenes and characters.

Few works in which she is represented are more beautiful than the Circe, in which her fair girlish form is seen advancing toward the spectator full of the knowledge of that power of fascination that she had in so supreme a degree.

In 1784 another set of circumstances came into play. Greville had been extravagant in his method of living, and his affairs were somewhat embarrassed. He had seen a lady of quality with ample means whom he had thoughts of marrying; and at this moment his uncle, Sir William Hamilton, who was Ambassador to the King of Naples, arrived in London upon a long leave of absence.

Sir William was fascinated by the mistress of his nephew, and a curious agreement seems to have been entered into between the two men. Greville gave up his mistress to his uncle on the understanding that he took her to Naples, provided securities for the payments of Greville's debts, and made such arrangements as to his property as constituted Greville his heir.

Sir William was, on his part, to provide properly for Emma, who, with her mother, was to follow him to Naples under the excuse that she might there complete her training in music and singing under his care, and return to Greville when his means allowed him to provide for her.

She appears to have left England in complete ignorance that she had been transferred to Sir William Hamilton, and, from her pathetic letters to her old lover, to have been most anxious to leave Naples and return to him.

This was, however, impossible, and Greville, who was, it is clear, attached in some measure to her, and somewhat ashamed of his part in the bargain, had to make it clear to her that their connection was at an end, and that she had better yield to the persuasions of his uncle. Eventually she did so, but later on, in 1791, prevailed upon him to marry her, and they were married at Naples.

He then brought her back to London, as it was needful that she should be married according to the rites of the Church of England and presented at Court in order that she should take the position that was now rightfully hers as the wife of an English ambassador; and accordingly they were again married, and this time in Marylebone Church, on September 6th, 1791.

Then again she sat to Romney as Joan of Arc, as Cassandra and as The Seamstress, before she returned to Naples as Lady Hamilton.

Into the long history of her life in Naples there is no need to enter in these pages, nor to relate the story of the attachment which, as the wife of Sir William Hamilton, she formed for Nelson. She exercised great influence and power at Naples during the war, and was of the greatest assistance to Nelson, who for her sake deserted and cast off his wife, and entered into a close connection with Lady Hamilton, who was, it is clear, the mother of his child Horatia.

After the recall of the ambassador when the conduct of his wife had become notorious, Nelson took up his residence in the same house as that occupied by the Hamiltons; and when Sir William died in 1802 she went to reside with Nelson at Merton with the distinct understanding that so soon as Lady Nelson was dead he would make her his wife.

Nelson, however, died before his wife, and by his will left to Lady Hamilton certain property; but her extravagant manner of living soon exhausted her means, and as the nation did nothing of importance for her, an execution was put in and Merton and all its contents were sold. She then retired to a smaller house, and later on to lodgings, but was arrested for debt; and when she was able to do so she left the country and went to Calais, where, in 1814, she settled down, first in a farmhouse and then in apartments.

Her means were by this time greatly reduced, as she had only the interest of the money settled upon her daughter and the wreck of her own estate; but, as her daughter stated in later years, although "certainly under very distressing circumstances, she never experienced actual want." Her loveliness had left her, the beauty of her form had given place to corpulence, and it was in distress of mind and body that she died, attended only by her faithful daughter and by a rough hired servant, in her lonely apartments in the Rue Française, Calais, on January 15th, 1815.

She had some years before become a Catholic, and was at the very last attended by a priest and was buried with full Catholic rites outside Calais in the cemetery; but the land has for many years ceased to be used as a burying-place, and all trace of her grave has been lost. Her daughter survived her, and as the wife of the Rev. P. Ward died in March, 1881, at the age of eighty-one years.

Romney is almost exclusively known as a painter of portraits, his historical scenes attracting but little attention. In their way they were remarkable, but they were forced in their conception and over-sentimental in their design, as was the fashion of the day. In his portraits he struck a much truer note and by them his repute will stand.

It is almost impossible, taking into consideration the time in which he lived, to avoid comparing him with his great rivals Reynolds and Gainsborough, and perhaps it is well that it should be so, as by thinking of him in connection with these two men it will be possible to obtain a better impression of his capabilities and a knowledge of his faults.

He was, it is quite certain, a far less important man than Gainsborough, who must certainly be reckoned as the greatest of the three.

He lacked the colour sense that distinguished that great artist; he was by no means his equal in technical merit; and he had no ability to produce landscape-work that gave so great a charm to the pictures of the Sudbury artist.

The wonderful poetry that streamed from the brush of Gainsborough and refined all his works, the delicacy, the grace and the sweetness of his figures are all superior qualities to those which Romney possessed, whilst as a colourist Gainsborough stood head and shoulders above both his rivals.

When we come to draughtsmanship we are, however, on a different footing, as Romney was the superior both of Reynolds and Gainsborough in ability to draw with accuracy and truth, and he also surpassed both of them in the manner in which he obtained his effects.

Where Reynolds laboured Romney achieved the same effect with the greatest ease and simplicity; and, in fact, the word "simplicity" may be taken as the key-word in anything like a critical survey of Romney's work.

He was not so varied as was Reynolds. His pictures have a certain monotony about them which is more apparent than real. It is not that Romney, as has been unwisely said, made all his women alike, for that is not so; but the charm that constituted one of the chief merits of the artist was dependent to a great extent upon tricks of posture, glance and costume, and, having ascertained what these were, there was a danger on Romney's part of repeating them. There is further a certain monotony about his colouring, as he so greatly favoured the rich golden browns and deep roses that distinguish his best works.

He was, however, a true artist and could not avoid making his pictures beautiful. He had a keen sense of beauty, a passionate love of warm, rich, sunny colour, and when he came to deal with historical or dramatic scenes a very powerful imagination; but he was careless and wasteful of his powers, and was so overwhelmed with commissions that he did not put his best work into many of the pictures that he painted. They, however, always charm, and they are always pleasing and generally poetic, although they are in other respects very frequently open to grave criticism.

There are instances in which his ability reaches a very high plane. Some of his portrait figures are really sublime, and the superb dignity of such portraits as those of Lady Hamilton as Circe and Cassandra will not be easy to exceed.

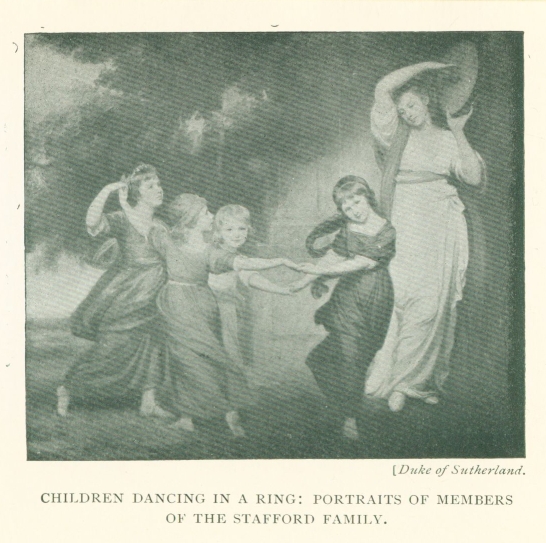

Other important characteristics of this great artist were his love of children and his ability to paint them in all their brisk childish humour. The delicious piquancy of the bright little faces, so full of charm, delight all who behold them, and there is also an irresistible grace and sweetness about the figures of his children that is very noteworthy.

Mark how cleverly he depicts motion, how easily in the Stafford and Clavering groups of children the young people move, and in what graceful attitudes the artist has represented them. They hardly touch the ground as they gracefully glide around through the figures of the mazy dance, and the happiness of their faces and the grace of their postures are alike most charming.

Romney had a very real sense of grace. His ideas were circumscribed by the fashion for classic attire which ruled the day, and the delight which his sitters had in being represented, not in their usual garb and posture, but as some goddess or mythological creation, and clothed in the robes of Greece or Rome.

CHILDREN DANCING IN A RING: PORTRAITS OF

MEMBERS OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY.

Whatever position or costume, however, he adopted, it was always graceful, refined and decorous; but some of his sweetest pictures were those where the simplest of gowns and the most natural of attitudes were selected, as, for example, The Seamstress.

Lady Hamilton, by her ingenuity in placing herself in the most becoming and graceful of attitudes, and by the marvellous power of expression that she possessed, enabling her to show in her countenance the very thoughts of the creation that she was representing, delighted Romney, and over and over again he posed her in various ways, and painted with increasing delight her lovely face.

She, who lived upon adulation, and desired above all that her beauty should be admired, was never tired of sitting to the artist who above all men had the desire and the power to express her features in their wonderful sweetness, and so the memory of the graceful sitter and clever artist are handed down together.

There is no doubt that the fame alike of sitter and artist served to make more popular the Grecian style of costume seen in the pictures, and so served to banish the more formal long-waisted style of dress that had been so popular a short time before. Classic ideas became more and more the vogue, and to the grace of the drapery is to be attributed some of the charm of the pictures. Once this was realized it was not easy for the artist to alter his original suggestion, and all the great ladies of the day had to be painted in the style that suited Lady Hamilton, but was not bound to suit the different styles of beauty of those who desired to follow her example and be painted by the fashionable artist.

One of the great advantages which the portraits of Romney have over those of Reynolds consists in the fact that the colours in them have stood the test of time. Even in Reynolds's own time the colours were beginning to fly from many of his works, and it is recorded that, having displeased the great connoisseur Horace Walpole, by some disparaging remarks upon a picture of Henry VII. that had been shown to the President, Walpole had his revenge by saying that Sir Joshua was not very likely to admire any picture in which the colours had stood.

Even Hayley, addressing Sir Joshua in poetry, desires him to "teach but thy transient tints no more to fly," and so draws attention thus early to what is the great blemish of the art of the President.

Romney avoided the constant experiments which were the bane of his great rival. Reynolds was never satisfied with the result that he obtained, but desired something finer and richer, and he was therefore always experimenting with new media, fresh colours and subtle underpainting, in order to produce some unusually brilliant effect. Romney was of far simpler mind. He was able to obtain all the effect he desired in the plainest and most simple means, and, having found a scheme of colouring which delighted him and a technique which he considered sufficient, he rested content.

The use by Reynolds of such ephemeral colours as lake and carmine in his flesh tints had no attraction for Romney. He was never bitten with the desire which characterized the President to use bitumen or asphaltum in his backgrounds and shadows, or to employ wax in his medium; and by the avoidance of all these pitfalls he was able to secure for his colours that quality of secure tenure which those used by the President so lacked.

Doubtless the search by the President after greater excellence was a characteristic in his favour, and the regular method adopted by his rival was not so praiseworthy, but the result has been to the satisfaction of the present generation; and where the works of Reynolds are but wrecks of what they once were (especially in the early and middle parts of his career), albeit they are notable wrecks, those of Romney are as fresh to-day as when first painted.

There is also, it must be acknowledged, a greater force and brilliance in the faces of Romney's sitters than in those of Reynolds.

The President loved to express the aristocratic composure, the deep thoughtfulness, the calm placidity of many of his fair women, and the dignity, reserve and autocracy of the men of the day; but Romney's faces are more piquant, more brilliant, full of action in many instances, and running over with life and delight.

His colouring, as has already been noted, is very frequently the rich harmony of gold and brown with flushes of full rose in which he so delighted; but he was not afraid of painting the primary colours when it was desirable that he should do so, and in one of the National Gallery pictures this capability can be well seen.

There is a melting quality, a charming manner of soft modelling that is also characteristic, an agreeable manner by which each colour composes itself into its adjacent tint without any hardness of outline; but even this suavity could be replaced by a certain hard, even rugged force, if desirable, and the picture just mentioned will also represent this harshness of outline.

On the whole he possessed to an unusual degree the power to thrill and to delight. His pictures are melodious, charming, graceful. His grouping is delightful and expressive of the highest genius; his draperies are simply and slightly painted; while the modelling of the features is full of consummate dexterity.

He attached great importance to the painting of fingers and hands, and gave much expression to them. His faces are quiet, and have often a look of the deepest pathos about them, a look which even approaches to melancholy; but, on the other hand, the sprightliness of youthful joy was well expressed by him, and if in a phrase his qualities are to be summed up, they may be so by the words "grace, melody, sunshine and sweetness."

From the National Gallery we have selected two: a portrait of Mrs. Mark Currie and the portrait called The Parson's Daughter.

Mrs. Mark Currie represents a life-size, nearly full-length figure. The lady is dressed in a simple white muslin dress with short sleeves, and an elaborate fichu of the same material. Round her waist is a silk sash of pale red, and the ribbons which trim her sleeves and fichu are of the same pale tint. Her fair hair, slightly powdered, falls in full clusters around her shapely shoulders.

Her face wears a quiet thoughtful expression, with a lurking look of humour about the eyes. The background is slightly suggested landscape and trees.

The lady was a Miss Elizabeth Close, who married Mr. Mark Currie, a goldsmith and banker, in January, 1789, and gave her first sitting for the portrait on the 7th of May of the same year.

It is not known whom The Parson's Daughter represents, nor why it bears that name.

It is a very charming circular portrait of a young lady with dark eyes and auburn hair, which is powdered and bound with a green ribbon. She wears a brown dress and white handkerchief.

The modelling on the face is very dexterously painted, and the tender thoughtful expression of the dark eyes quite beautiful.

The hair is painted in very broad, powerful fashion, and the draperies over the bust indicated lightly and put on with a wonderful sliding movement which is notable. On the whole Romney seldom did a more pleasing piece of work than the portrait of this quiet and refined dainty girl.

The Clavering Children, which we have the special permission of the owner (Rev. J. W. Napier-Clavering) to reproduce, is a very happy example of Romney's ability to depict children in movement and to give the effect of rapid motion.

Mark how lightly the two children tread the ground, with what easy step they move forward, seeming to come right out of the canvas towards the spectator. Notice how the scarf, which forms part of the dress of the girl, streams out in the wind, and see how lightly and with what a graceful movement the lad holds in the two dogs.

Romney was at his very best in this delightful group. The faces of both boy and girl are painted with unusual care, the clear eyes of the manly lad seeming to look right into the spectator; while the downcast lids of the girl's face serve but to reveal through their clear semi-transparency the brown eyes which they hide.

Much attention has in this work been given to the hands, which Romney rightly believed were indicative of character. The grasp of the sturdy fingers of the boy contrasts well with the long slender fingers which grasp the dog in loving embrace, and the same pleasing idea of divergence can be seen in the modelling of the faces and in the posture and shape of the feet. The dogs are painted in very natural positions: the darker spaniel, which is leaping up to the lad, is evidently in a favourite posture and full of enthusiasm towards his young master; while the tiny puppy which the girl hugs to her breast, and which the parent dog is most anxious to have back again into her care, is a fat little comic beast, quite young, and very ready to be caressed.

THOMAS JOHN CLAVERING, AFTERWARDS EIGHTH

BARONET, AND HIS SISTER, CATHERINE MARY.

The scene has no studio atmosphere about it. It was clearly unpremeditated, and has been happily seized by the artist at the right moment and perpetuated in this work. There is no elaborate underpainting in this picture, all the effects of it being obtained in the simplest manner. The sky and ground afford a sufficient foil in the way of scenery, and the two children come dancing towards the person who looks at the picture with the most artless grace and charm, attended as they are by their canine companions.

The boy was afterwards Sir Thomas John Clavering, the eighth baronet, of Axwell Park, where the family still reside, and was the grand-son of the sixth baronet, Sir James. He was born in 1771, married in 1791, succeeded his uncle in the family estates and title, and died in 1853. His sister, Catherine Mary, died unmarried in 1785.

The picture is a large one, as the figures are life-size, and it has been engraved; and hardly any of the works of Romney is more worthy of praise than this vivacious and graceful creation.

The wonderful eyes which distinguished the features of Lady Hamilton can be well appreciated in the portrait which we give from the National Portrait Gallery. The face is not altogether a pleasing one. It reveals some of the desire to fascinate which distinguished the lady's character.

There is a purpose in the gaze which these eyes extend to the observer, and the attitude, although intended to be a natural one, is quite evidently studied and assumed. It is intended to give full play to the face and eyes, and to reveal the graceful curves of the arms and the slender beauty of the fingers. The very roundness of the face is accentuated against the angles of the fingers in their half-closed position, and there is a studied grace in the arrangement of the draperies and in the muslin bands which form the head-dress. In all these respects it is a fitting representation of the famous beauty, who in a less natural pose would not have so amply revealed her power of charm.

The painting of the features with all their delicate and slight modelling is a triumphant success, and the eyes, which burn down into the very consciousness of the spectator, are superbly represented. The picture, small as it is, and showing but little of the graceful form, is yet a masterpiece, and is a delineation of character unsurpassed in its effect by any other portrait by the same hand.

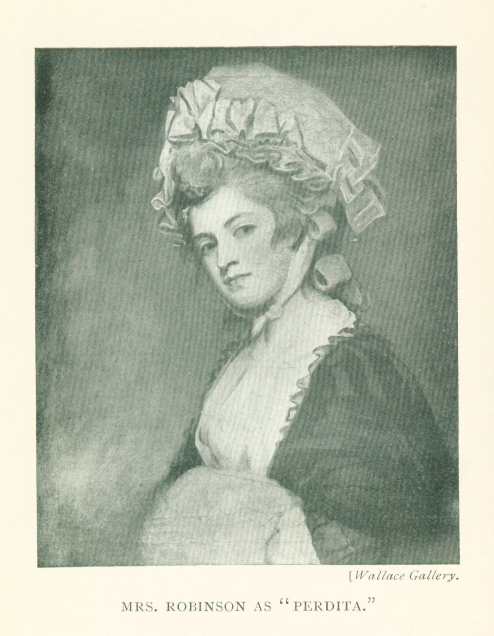

There is in the Wallace Gallery an interesting Portrait of Mrs. Robinson, the beautiful actress, in the character of Perdita, the daughter of Leontes in "The Winter's Tale," which she made so peculiarly her own.

Mrs. Robinson first took the part in the performance on December 3rd, 1779, at Drury Lane, in the presence of their Majesties King George III. and Queen Charlotte, and also before the youthful Prince of Wales, whose affection was afterwards to have such an effect upon her life.

She was at that time just over twenty-one years old, married to a man who systematically insulted and neglected her and spent his time with the lowest and most degraded of the women of his acquaintance. The Prince of Wales was in his eighteenth year, very susceptible, and he was at once attracted by this lovely woman, little more than a girl, who acted superbly and with such artless grace. In this way an acquaintance was commenced, Viscount Malden being employed as an intermediary, and ripened into a closer affection.

She, however, hardly met the Prince until he had his separate establishment in Buckingham House, as during the time when he lived at Kew he was kept under the strictest regulations. From the 1st of January, 1781, he was, however, his own master, and Mrs. Robinson shared his establishment, and was at the height of her beauty and position.

The attachment only continued for some two years, when the Prince, having vowed perpetual devotion to his Perdita, and made her many presents and more promises, suddenly transferred his affection to Mrs. Grace Dalrymple Elliott and absented himself from Mrs. Robinson.

He paid no attention to her misery, nor in any way assisted her in her distress, though he had given her a bond for £20,000 when she quitted the theatre at his desire to live with him. She eventually, however, obtained, through Charles James Fox, an annuity of £500 a year, and devoted herself to literature.

She had a very devoted daughter who lived with her, and in the presence of this daughter she died in December, 1800, and was buried at Old Windsor by her own particular desire.

In the picture in the Wallace Gallery she is represented in the walking costume which she assumed when she played the part of Perdita, wearing a handsome lace bonnet and carrying a huge muff. The face is one of peculiar sweetness, and the eyes have an arch look, mingled with thoughtful pathos, which is peculiarly attractive.

The face is wonderfully painted, the modelling being subtle and very dexterous; while the harmony of the whole work is most noticeable. The picture is one of Romney's most successful works in its charm of colour and sweetness of expression.

The remaining three of our illustrations are taken from the gallery of the Duke of Sutherland at Trentham, and are reproduced by kind permission of their noble owner, and of his Grace's representative, Mr. Bagguley.

The chief of the three is the important portrait group of Children dancing in a Ring, one of the most famous groups that Romney ever executed. The tall lady with the tambourine is Lady Anne Leveson-Gower, third daughter of the Earl Gower who afterwards became first Marquess of Stafford, by his second wife, Lady Louisa Egerton. She became eventually the wife of Vernon Harcourt, Archbishop of York.

The four dancing children are her step-sisters and step-brother, the children of the earl by his third wife, Lady Susan Stewart—the Ladies Georgiana, Charlotte, and Susan Leveson-Gower, who became respectively Lady G. Eliot, the Duchess of Beaufort, and the Countess of Harrowby. The young lad is Lord Granville Leveson-Gower, afterwards elevated to the peerage as the first Earl Granville, the father of the late well-known statesman of the same name.

The picture is a charming example of the skill of the artist, both in expressing lightness and grace in attitude, and also in power of grouping and composition. The children are moving with the utmost daintiness and freedom, and are all of them admirably well drawn.

The tall figure is, if anything, a little too tall, but adds dignity to the group, while the artless expression on the faces of the girls is beyond praise. There is a peculiar sweetness and happiness in the faces of all the little ones, and they are evidently in full enjoyment of health and spirits, and have no feeling of formal grouping or stilted posing about them.

GEORGE GRANVILLE, SECOND MARQUESS OF STAFFORD

AND FIRST DUKE OF SUTHERLAND.

The colour scheme is delightful. The white dress of the tall sister and of the boy, with the same hue in the columns, is charmingly contrasted with the green, plum colour and red of the other dresses, and with the increase of colour that the scarves of brown and purple give. All is harmony and grace without artifice, and the technique of the picture is of the very simplest order.

As an example of dignity and restraint, the Portrait of George Granville will be appreciated. He was the eldest son of the same Earl Gower who afterwards in his turn became second Marquess of Stafford and then first Duke of Sutherland. He was, of course, the brother of the tall girl with the tambourine in the last picture.

By his marriage with the lady who was Countess of Sutherland in her own right, he became a person of vast importance and the owner of enormous estates, which he managed admirably and laid the foundation for the position now occupied by his successors.

He stands quietly before the spectator, dressed in a yellow silk jacket with deep lace collar and cuffs, has a red robe thrown over his shoulders, and bears in his hand his gray hat with black feathers.

It is well to mark the extreme care with which the hand of the young aristocrat is painted, and how expressive it is—perhaps as much as the serious and somewhat haughty face—of the position and influence of the lad.

There is a composure and a stateliness in this portrait which are a sure index to the mind of the young nobleman, and few painters could so well have represented the mind of his sitter as Romney has done in this work. The child was assuredly father to the man, and thus early he foreshadowed in his features the calm dignity, reserve and power which in after life distinguished him as Duke.

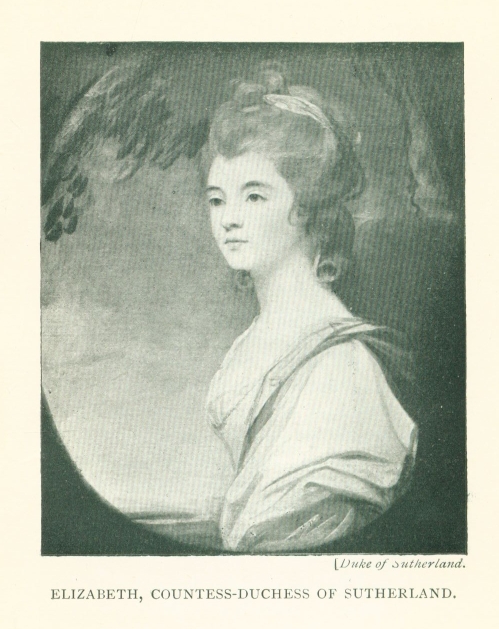

The third portrait is that of his wife, generally known as the Countess-Duchess of Sutherland.

Elizabeth was the only daughter and surviving child of the seventeenth and last Earl of Sutherland, and became, on the death of her father, Countess in her own right. Her mother was a great beauty, and she inherited all the exquisite features and charm of that parent, who died in the same year as the Earl of Sutherland, placing this bright girl, at the tender age of two years, in possession of the vast estates and the title of the earldom. Her beauty attracted the loyalty of all her tenants to her, and Sir Walter Scott records many a story of her charm and kindness.

The portrait records her appearance soon after she was married, when somewhat more than twenty years of age, and in the heyday of her sweet and thoughtful beauty. She is dressed in white and gold, her dark brown hair tied with ribbon, the background being foliage and a distant landscape.

There is all the effect of power, dignity and determination about the mouth and eyes; the face is a distinct oval, the form rather thin and slight, and the composure of the expression very marked. It is a striking portrait of a beautiful girl of high lineage and important position, and is a triumph of art as a portrait which is at once lovely in itself and a delineation of the mind of the person who is depicted in it.

NATIONAL GALLERY, LONDON.

Study of Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante, about 1786. (312)

The Parson's Daughter. A portrait. A circular bust portrait of a young lady. See page 45. (1068)

Portraits of Mr. and Mrs. Wm. Lindow. A life-size group. Bought in 1893. Strong in colour, and more definite and hard than is the artist's usual manner. (1396)

Portrait of Mrs. Mark Currie. A portrait of a lady seated on a terrace. See page 44. Painted in May, 1789. Romney received sixty guineas for this picture, which was bought for a very large sum by the Trustees from the family in 1897. (1651)

Portrait of a Lady and Child. (1667)

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERY, LONDON.

Portrait of Wm. Cowper, the poet.

Portrait of R. Cumberland, the dramatist.

Portrait of John Flaxman, R.A., designer and sculptor, represented modelling the bust of his friend Hayley, author of "The Triumphs of Temper," whose son, T. A. Hayley, is also introduced as a spectator. The son was a pupil of Flaxman.

Portrait of Lady Hamilton. A half-length, resting her elbows on the table, and with her face turned somewhat to the right. See page 47.

Portrait of James Harris, M.P. for Christchurch, a writer of treatises on art, music, painting and poetry, and of other works. His son became Earl of Malmesbury.

Portrait of the artist himself, unfinished. It was done in 1782, and bought at Miss Romney's sale in 1894.

THE WALLACE GALLERY, LONDON.

Portrait of Mrs. Robinson, the actress, in her favourite character of Perdita. See page 49. (37)

ROYAL INSTITUTION, LIVERPOOL.

A series of fine cartoons by the artist.

BIRMINGHAM ART GALLERY

A portrait of Lady Holte.

The foregoing represent the chief works of the artist that are in public and accessible galleries; but the greatest works still remain in private hands, and many of them are from time to time exhibited in London and the provinces.

Amongst notable collections may be mentioned that of the Duke of Sutherland, in which are the portraits of Elizabeth, Duchess of Sutherland, the second Marquess of Stafford, the five children of the Earl of Sutherland dancing in a ring, and the Countess of Carlisle. See pages 51-55.

The Rev. J. W. Napier-Clavering also owns some of the choicest works of Romney, namely, Maria Margaret Clavering, afterwards Lady Napier, Colonel Thomas Thornton, and the delightful group of Sir Thomas Clavering and his sister. See page 45.

Mr. Lockett Agnew owns the portraits of Miss Hay, Miss Leyborne Popham with her dog, Miss Popham, Lady Mary Parkhurst and Mr. Charles Parkhurst, all of them important pictures.

The Marquess of Lansdowne has the portraits of Lord Henry Petty and of Lady Louisa Fitzpatrick, both fine works, besides others of lesser importance; and other fine portraits belong to Mr. Beebe, Mr. R. Biddulph Martin, who has two, Sir Cuthbert Quilter, who has the splendid portrait of Mrs. Jordan, Sir Edward Newdigate-Newdegate, whose portrait of Lady Newdigate is well known, and Mr. Makins.

Other portraits belong to Earl Granville, Lord de Tabley, the Earl of Cawdor, the Earl of Normanton, Lord Berwick, Lord Thurlow, and to several members of the Rothschild family.

"George Romney and His Art," by Hilda Gamlin, 1894.

"Romney and Lawrence," by Lord Ronald Sutherland-Gower, 1882.

"Memoirs of Lady Hamilton," annotated by Long, 1891.

"Lady Hamilton," by Hilda Gamlin, 1894.

Cunningham's "Painters," 1879.

"Illustrated Catalogue of a Collection of Portraits exhibited at Birmingham in 1900."

"Memoirs of Romney," by Hayley, 1809.

"Memoirs of Romney," by his son, the Rev. John Romney, 1830.

The Catalogues of the Romney Exhibition in the Grafton Galleries in 1900 and 1901, with Notes by Nash.

"The Life of Mrs. Robinson," by Molloy, 1894.

1734. Birth of Romney.

1756. His marriage.

1757. His indenture cancelled.

1762. He starts for London.

1763. Paints The Death of General Wolfe for a premium offered by the Society of Arts.

1764. Journey to France.

1773. Journey to Italy, notably to Rome.

1775. Settled in Cavendish Square.

1782. First met Mistress Hart, afterwards Lady Hamilton.

1797. Removed to Hampstead.

1799. Returns to his wife.

1802. His death.

CHISWICK PRESS: CHARLES WHITTINGHAM AND CO.

TOOKS COURT, CHANCERY LANE, LONDON.

Bell's Miniature Series of Painters.

Edited by G. C. WILLIAMSON, Litt.D.

Pott 8vo, with 8 Illustrations, issued in cloth or in

limp leather, with Photogravure frontispiece.

ALMA TADEMA. By H. Zimmern.

ROSA BONHEUR. By Frank Hird.

BOTTICELLI. By R. H. Hobart Cust, M.A.

BURNE-JONES. By Malcolm Bell.

CONSTABLE. By Arthur B. Chamberlain.

CORREGGIO. By Leader Scott.

FRA ANGELICO. By G. C. Williamson, Litt.D.

GAINSBOROUGH. By Mrs. Arthur Bell.

GREUZE. By Harold Armitage.

HOGARTH. By G. Elliot Anstruther.

HOLBEIN. By Arthur B. Chamberlain.

HOLMAN HUNT. By G. C. Williamson, Litt.D.

LANDSEER. By McDougall Scott, B.A.

LEIGHTON. By G. C. Williamson, Litt.D.

LEONARDO DA VINCI. By R. H. Hobart Cust.

MICHELANGELO. By Edward C. Strutt.

MILLAIS. By A. Lys Baldry.

MILLET. By Edgcumbe Staley, B.A.

MURILLO. By G. C. Williamson, Litt.D.

RAPHAEL. By Mcdougall Scott, B.A.

REMBRANDT. By Hope Rea.

REYNOLDS. By Rowley Cleeve.

ROMNEY. By Rowley Cleeve.

ROSSETTI. By H. C. Marillier.

RUBENS. By Hope Rea.

TITIAN. By Hope Rea.

TURNER. By Albinia Wherry.

VAN DYCK. By E. R. Dibdin (In The Press).

VAN EYCK (Hubert and Jan). By P. G. Konody.

VELAZQUEZ. By G. C. Williamson, Litt.D.

WATTEAU. By Edgcumbe Staley, B.A.

WATTS. By Malcolm Bell.

WHISTLER. By Mrs. Arthur Bell.