Title: Chicago and the Old Northwest, 1673-1835

Author: Milo Milton Quaife

Release date: October 31, 2022 [eBook #69274]

Most recently updated: July 27, 2025

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The University of Chicago Press, 1913

Credits: Tom Cosmas compiled from materials generously provided by The Internet Archive and are placed in the Public Domain.

- i -

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

Agents

THE CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

LONDON AND EDINBURGH

THE MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA

TOKYO, OSAKA, KYOTO

KARL W. HIERSEMANN

LEIPZIG

THE BAKER & TAYLOR COMPANY

NEW YORK

- ii -

MARQUETTE AT THE CHICAGO PORTAGE

From the bas relief by H. A. MacNeil

(Courtesy of the Chicago Historical Society)

- iii -

1673-1835

A STUDY OF THE EVOLUTION OF THE

NORTHWESTERN FRONTIER, TOGETHER

WITH A HISTORY OF FORT DEARBORN

By

Professor of History in the Lewis Institute

of Technology

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO, ILLINOIS

- iv -

Copyright 1913 By

The University of Chicago

All Rights Reserved

Published October 1913

Composed and Printed By

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago, Illinois, U.S.A.

- v -

There are many histories of Chicago in existence, yet none of them supplies the want which has induced the preparation of the present work. It has been written under the conviction that there is ample justification for a comprehensive and scholarly treatment of the beginnings of Chicago and its place in the evolution of the old Northwest. I have endeavored to produce a readable narrative without in any way trenching upon the principles of sound scholarship. To what extent, if any, I have succeeded must be for the reader to judge. I may, however, claim the negative virtue of entire freedom from the motives of commercial gain and family partisanship, which enter so largely into our local historical literature.

In preparing the work I have made as diligent a study of the sources as practicable, at the same time availing myself freely of the studies of others in the same field. With one exception acknowledgment of my obligations to the latter is made in the footnotes. The manuscript of a lecture by the late Professor Charles W. Mann on the Fort Dearborn massacre was put at my disposal. I have used it as far as it served my purpose without attempting to cite it in the footnotes.

In many places I have broken new ground and I can scarcely expect my work to be entirely free from error. I am particularly conscious of this in connection with chap, xiii on the Indian Trade, a subject to which a volume might well be devoted. In controversial matters I have written without fear or favor from any source. If in many cases my conclusions seem to differ from those of other writers, I can only say that the words of a recent historian with reference to history writing in the Middle Ages, "Recorded events were accepted without challenge, and the sanction of tradition guaranteed the reality of the occurrence," apply with almost equal force to much of the literature pertaining to early Chicago.

- vi -

I desire to express my obligation for courtesies rendered, or facilities extended, to the Chicago Historical Society, the Wisconsin State Historical Society, the Detroit Public Library, the Division of Manuscripts of the Library of Congress, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the War Department. I am indebted also for many favors to Miss Caroline McIlvaine, librarian, and Mr. Marius Dahl, record clerk, of the Chicago Historical Society; to Mr. C. M. Burton, of Detroit; to the descendants of Nathan Heald, Mr. and Mrs. Thomas McCluer and Mrs. Arthur McCluer, of O'Fallon, Mo., Mrs. Lillian Heald Richmond and Dr. and Mrs. Ottofy of St. Louis, and Mr. and Mrs. Wright Johnson, of Rutherford, N.J.; and to my wife and to my father-in-law, Rev. G. W. Goslin, for unwearied assistance in the preparation and revision of the manuscript. Finally I wish to record my deep obligation to Dr. Otto L. Schmidt, president of the Illinois State Historical Society, for much sympathetic advice and encouragement.

M. M. Quaife

Chicago

September, 1913

- vii -

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Chicago Portage | 1 |

| II. | Chicago in the Seventeenth Century | 21 |

| III. | The Fox Wars: A Half-Century of Conflict | 51 |

| IV. | Chicago in the Revolution | 79 |

| V. | The Fight for the Northwest | 105 |

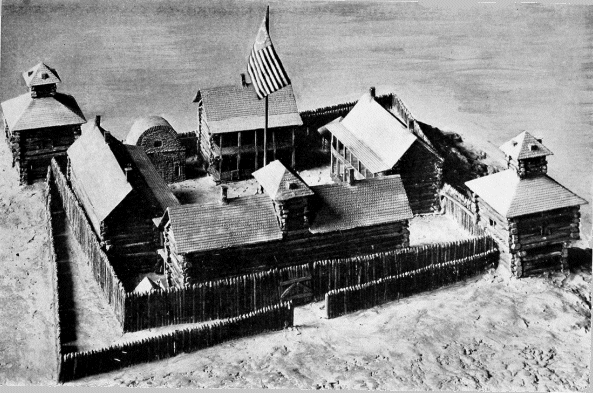

| VI. | The Founding of Fort Dearborn | 127 |

| VII. | Nine Years of Garrison Life | 153 |

| VIII. | The Indian Utopia | 178 |

| IX. | The Outbreak of War | 195 |

| X. | The Battle and Defeat | 211 |

| XI. | The Fate of the Survivors | 232 |

| XII. | The New Fort Dearborn | 262 |

| XIII. | The Indian Trade | 285 |

| XIV. | War and the Plague | 310 |

| XV. | The Vanishing of the Red Man | 340 |

| Appendix I: | Journal of Lieutenant James Strode Swearingen | 373 |

| Appendix II: | Sources of Information for the Fort Dearborn Massacre | 378 |

| Appendix III: | Nathan Heald's Journal | 402 |

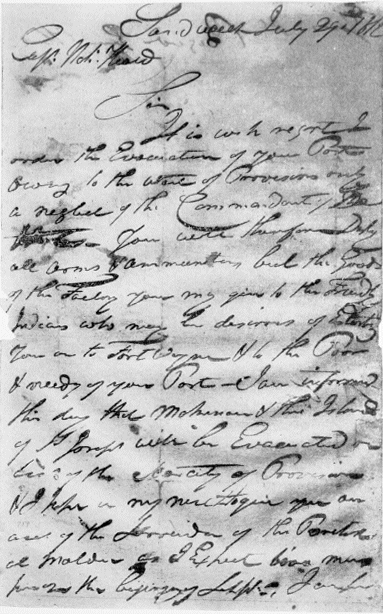

| Appendix IV: | Captain Heald's Official Report of the Evacuation of Fort Dearborn | 406 |

| Appendix V: | Darius Heald's Narrative of the Chicago Massacre, as Told to Lyman C. Draper in 1868 | 409 |

| Appendix VI: | Lieutenant Helm's Account of the Massacre | 415 |

| Appendix VII: | Letter of Judge Augustus B. Woodward to Colonel Proctor concerning the Survivors of the Chicago Massacre | 422 |

| Appendix VIII: | Muster-Roll of Captain Nathan Heald's Company of Infantry at Fort Dearborn | 425 |

| Appendix IX: | The Fated Company: A Discussion of the Names and Fate of the Whites Involved in the Fort Dearborn Massacre | 428 |

| Bibliography | 439 | |

| Index | 459 | |

- 1 -

The story of Chicago properly begins with an account of the city's natural surroundings. For while her citizens have striven worthily, during the three-quarters of a century that has passed since the birth of the modern city, to achieve greatness for her, it is none the less true that Nature has dealt kindly with Chicago, and is entitled to share with them the credit for the creation of the great metropolis of the present day. If in recent years the enterprise of man rather than the generosity of Nature has seemed chiefly responsible for the growth of Chicago, in the long period which preceded the birth of the modern city such was not the case; for whatever importance Chicago then possessed was due primarily to the natural advantages of her position.

Since this volume is to tell the story of early Chicago, concluding at the point where the life of the modern city begins, it is not my purpose to dwell upon the natural advantages which today contribute to the city's prosperity. Her central location with respect to population, surrounded by hundreds of thousands of square miles of country as fair, and supporting a population as progressive, as any on the face of the globe; her contiguity to the wheat fields of the great West; her situation in the heart of the corn belt of the United States; the wealth of coal fields and iron mines and forests poured out, as it were, at her feet; her unrivaled systems of transportation by lake and by rail; how all these factors, reinforced by the daring energy of her citizens, have combined to render Chicago the industrial heart of the nation is a matter of common knowledge. That in the days before the coming of the railroad or the settler, when for hundreds of miles in every direction the wilderness, monotonous and unbroken, stretched away, inhabited only by the wild beast and the wild Indian; when only at infrequent intervals were its - 2 - forest paths or waterways traversed by the fur trader or the priest, the representatives of commerce and the Cross, the two mightiest forces of the civilization before the advance of which the wilderness was to give way; that even in this far-away period Nature made of Chicago a place of importance and of concourse, the rendezvous of parties bent on peaceful and on warlike projects, is not so commonly understood.

The importance of Chicago in this early period was primarily due to the fact of her strategic location, whether for the prosecution of war or of commerce, at the head of the Great Lakes on one of the principal highways of travel between the two greatest interior waterway systems of the continent, those of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence and the Mississippi River. The two most important factors in the exploration and settlement of a country are the waterways and mountain systems—the one an assistance, the other an obstacle, to travel.[1] The early English colonists in America, settling first in Virginia and Massachusetts and gradually spreading out over the Atlantic coastal plain, were shut from the interior of the continent by the great wall presented by the Allegheny Mountains. The French, securing a foothold about the same time at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River, found themselves in possession of a highway which offered ready access into the interior. The importance of the rivers and streams as highways of travel in this early period is difficult to realize today. The dense forests which spread over the eastern half of the continent were penetrated only by the narrow Indian trail or the winding river. The former was passable only on foot, and even by pack animals but with difficulty.[2] The latter, however, afforded a ready highway into the interior, and the light canoe of the Indian a conveyance admirably adapted to the exigencies of river travel. By carrying it over the portages separating the headwaters of the great river systems the early voyageurs could penetrate into the heart of the continent.

- 3 -

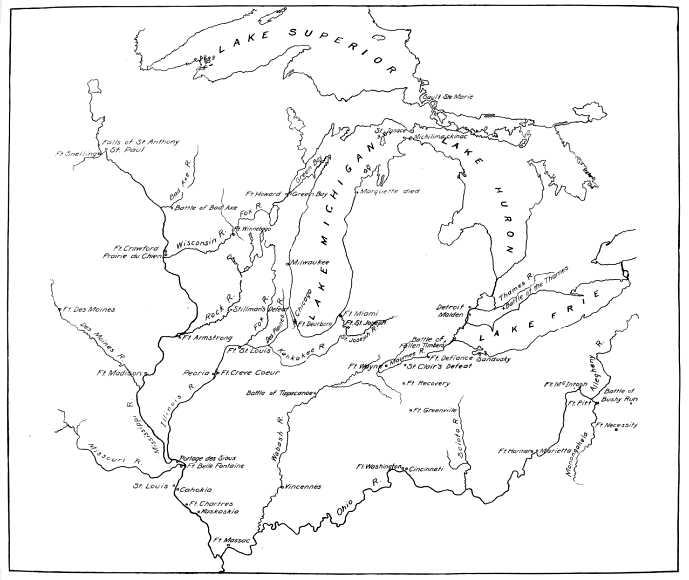

Proceeding up the St. Lawrence, the French colonists early gained the Great Lakes. Their advance rested here for a time, but in the last quarter of the seventeenth century, by a great outburst of exploring activity, the upper waters of the Mississippi were gained and eagerly followed to their outlet in the Gulf of Mexico. Thus New France found a second outlet to the sea, and thus, even before the English had crossed the Alleghenies, the French had fairly encircled them, and planted themselves in the heart of the continent. From the basin of the Great Lakes to that of the Mississippi they early made use of five principal highways.[3] On each, of course, occurred a portage at the point where the transfer from the head of the one system of navigation to the other occurred. One of these five highways led from the foot of Lake Michigan by way of the Chicago River and Portage to and down the Illinois. The Chicago Portage thus constituted one of the "keys of the continent," as Hulbert, the historian of the portage paths, has so aptly termed them.[4]

[3] Winsor, Narrative and Critical History of America, IV, 224.

[4] Hulbert, Portage Paths: The Keys of the Continent.

The comparatively undeveloped state of the field of American historical research is well illustrated by the fact that despite the historical importance of the Chicago Portage, no careful study of it has ever been made. The student will seek in vain for even an adequate description of the physical characteristics of the portage. Winsor's description, a paragraph in length, is perhaps the best and most authoritative one available.[5] Yet, aside from its brevity, neither of the two sources to which he makes specific reference can be regarded as reliable authorities - 4 - upon the Chicago Portage. Moll, the cartographer, notable for his credulous temperament,[6] relied for his knowledge of the Great Lakes region upon the discredited maps of Lahontan.[7] James Logan, whose description of the portage is quoted,[8] was a reputable official of Pennsylvania, but, in common with the seaboard English colonists generally, his knowledge of the geography of the interior was extremely hazy. This is sufficiently shown by the fact that he located La Salle's Fort Miami, which had stood during the brief period of its existence at the mouth of the St. Joseph River, on the Chicago.

[5] "What Herman Moll, the English cartographer, called the 'land carriage of Chekakou' is described by James Logan, in a communication which he made in 1718 to the English Board of Trade, as running from the lake three leagues up the river, then a half a league of carriage, then a mile of water, next a small carry, then two miles to the Illinois, and then one hundred and thirty leagues to the Mississippi. But descriptions varied with the seasons. It was usually called a carriage of from four to nine miles, according to the stage of the water. In dry seasons it was even farther while in wet times it might not be more than a mile; and, indeed, when the intervening lands were 'drowned,' it was quite possible to pass in a canoe amid the sedges from Lake Michigan to the Des Plaines, and so to the Illinois and the Mississippi."—Winsor, Mississippi Basin, 24. For similar descriptions see Hulbert, Portage Paths, 181; Jesuit Relations, LIX, 313-14, note 41.

[6] Winsor, Mississippi Basin, 80, 104, 111, 163.

[7] Moll's map in his Atlas Minor is simply an English copy of Lahontan's map of 1703. For the latter see Lahontan, New Voyages to North America (Thwaites ed.), I, 156.

[8] For the substance of Logan's report see the British Board of Trade report of September 8, 1721, printed in O'Callaghan, Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York, V, 621. This will be cited henceforth as New York Colonial Documents.

That there should be confusion and misconception in the secondary descriptions of the Chicago Portage is not surprising, in view, on the one hand, of the unusual seasonal variations in its character, and, on the other, of the dispute which very early arose concerning it. None of the other portages between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi—if indeed any in America—were subject to such changes as this one. The dispute over its character goes back to the beginning of the French exploration of this region. When Joliet returned to Canada from his famous expedition down the Mississippi in 1673, filled with enthusiasm over his discoveries, he gave out a glowing account of the country he had visited. In particular he seems to have dwelt upon the ease of communication between the Great Lakes and the Gulf of Mexico by way of the Chicago and Illinois rivers to the Mississippi. Joliet's records were lost, but both Frontenac, the governor of New France, and Father Dablon have left accounts of his verbal report.[9] Frontenac stated that a bark could go from the St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, with only a portage of half a league at Niagara. Dablon, who seems to have appreciated the situation more intelligently than Frontenac, said that a bark could go from - 5 - Lake Erie to the Gulf if a canal of half a league were cut at the Chicago Portage.

[9] Winsor, Cartier to Frontenac, 246-47; Jesuit Relations, LVIII, 105.

Probably Dablon's report represents more nearly than that of Frontenac what Joliet actually said, for it seems unlikely that he would ignore utterly the existence of the portage at Chicago. Even so, however, his description of the ease of water communication between the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River was unduly optimistic. Its accuracy was sharply challenged by La Salle upon his visit to Chicago several years later. Joliet passed through Illinois but once, rather hurriedly, knowing nothing of the country aside from what he learned of it on this trip. He was ill-qualified, therefore, to describe accurately the Illinois-Chicago highway and portage; at the most he could describe only the conditions prevailing at the time of his hasty passage. La Salle, on the other hand, was operating in the Illinois country from 1679 to 1683, seeking to establish a colony with its capital at the modern Starved Rock, one hundred miles from Chicago. He was greatly interested in developing the trade of this region, and, while he looked forward ultimately to securing a southern outlet for it, for the present he must find such outlet by way of Canada. In the course of his Illinois career he passed between his colony and Canada several times, and from both necessity and self-interest became thoroughly familiar with the routes of communication which could be followed. He himself ordinarily came by the Great Lakes to the foot of Lake Michigan and thence by the St. Joseph River and portage or the Chicago to the Illinois, but he became convinced that it would not be practicable to carry on commerce between his Illinois colony and Canada through the upper lakes, and that a route by way of the Ohio River and thence to the lower lakes and Canada was more feasible.

In discussing this subject La Salle was led to take issue with Joliet as to the feasibility of navigation between Lake Michigan and the Illinois, and so to state explicitly what the hindrances were.[10] The goods brought to Chicago in barges must be - 6 - transshipped here in canoes, for, despite Joliet's assertions, only canoes could navigate the Des Plaines for a distance of forty leagues. At a later time La Salle reverted to this subject, and in this connection gave the first detailed description we have of the Chicago Portage.[11] From the lake one passes by a channel formed by the junction of several small streams or gullies, and navigable about two leagues to the edge of the prairie. Beyond this at a distance of a quarter of a league to the westward is a little lake a league and a half in length, divided into two parts by a beaver dam. From this lake issues a little stream which, after twining in and out for half a league across the rushes, falls into the Chicago River, which in turn empties into the Illinois.

[10] Margry, Découvertes et établissements des Français dans l'ouest et dans le sud de l'Amérique septentrionale, II, 81-82. This collection will be cited henceforth as Margry.

[11] Margry, pp. 166 ff.

The "channel" was the main portion and south branch of the modern Chicago River. The lake has long since disappeared by reason of the artificial changes brought about by engineers; in the early period of white settlement at Chicago it was known as Mud Lake. La Salle's "Chicago River," into which Mud Lake ordinarily drained, was, of course, the modern Des Plaines.

Continuing his description of the water route by way of the Chicago and Des Plaines, La Salle pointed out that when the little lake in the prairie was full, either from great rains in summer or from the vernal floods, it discharged also into the "channel" leading to Lake Michigan, whose surface was seven feet lower than the prairie where Mud Lake lay. The Des Plaines, too, in time of spring flood, discharged a part of its waters by way of Mud Lake and the channel into Lake Michigan. La Salle granted that at this time Joliet's proposed canal of half a league across the portage would permit the passage of boats from Lake Michigan to the sea. But he denied that this would be possible in the summer, for there was then no water in the river as far down as his post of St. Louis, the modern Starved Rock, where at this season the navigation of the river began. Still other obstacles to the feasibility of Joliet's proposed canal were pointed out. The action of the waters of Lake Michigan had created a sand bank at the mouth of the Chicago River which the force - 7 - of the current of the Des Plaines, when made to discharge into the lake, would be unable to clear away. Again, the possibility of a boat's stemming the spring floods of the Des Plaines, "much stronger than those of the Rhone," was doubtful. But if all other obstacles were surmounted, the canal would still have no practical value because the navigation of the Des Plaines would be possible for but fifteen or twenty days at most, in time of spring flood; while the navigation of the Great Lakes was rendered impossible by the ice until mid-April, or even later, by which time the flood on the Des Plaines had subsided and that stream had become unnavigable, even for canoes, except after some storm.

Thus there was initiated by La Salle a dispute over the character of the water communication from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi by way of the Chicago Portage which has been revived in our own day, and in the decision of which property interests to the value of hundreds of thousands of dollars are involved.[12] Of the essential correctness of La Salle's description there can be no question. Considering its early date and the many cares with which the mind of the busy explorer was burdened, it constitutes a significant testimonial to his ability and powers of observation. It may well be doubted whether any later writer has improved upon—if, indeed, any has equaled—La Salle's description of the Chicago-Des Plaines route. From its perusal may be gathered the clue to the fundamental defect in the descriptions of the Chicago Portage which modern historians have given us. Overlooking the fact that the Des Plaines River was subject to fluctuation to an unusual degree, they err in assuming that the portage ceased when the Des Plaines was reached. The portage was the carriage which must be made between the two water systems. Hulbert is quite right in saying, as he does, that none of the western portages varied more in length than did this one.[13] In fact his words - 8 - possess far more significance than the writer himself attaches to them; for the length of the carriage that must be made at Chicago varied from nothing at all to fifty miles or, at times, to even twice this distance. At times there was an actual union of the waters flowing into Lake Michigan with those entering the Illinois River, permitting the uninterrupted passage of boats from the one system to the other. At other times the portage which must be made extended from the south branch of the Chicago to the mouth of the Vermilion River, some fifty miles below the mouth of the Des Plaines.

[12] The United States of America vs. The Economy Light and Power Company. The evidence taken in this case constitutes by far the most exhaustive study of the character and historical use of the Chicago Portage that has ever been made.

[13] Hulbert, Portage Paths, 181.

It is doubtless true that "truth, crushed to earth, will rise again," but the converse proposition of the poet that error dies amid its worshipers requires qualification. Certainly in the matter under discussion La Salle as early as 1683 dealt the errors of Joliet with respect to the Chicago Portage a crushing blow. Yet these self-same errors were destined to "rise again," and in the early nineteenth century it was again commonly reported that a practicable waterway from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi could be attained by the construction of a canal a few miles in length across what for convenience may be termed the short Chicago Portage, from the south branch of the Chicago River through Mud Lake to the Des Plaines. Even capable engineers threw the weight of their opinion in support of this fallacy.[14] But the young state of Illinois learned to her cost, in the hard school of experience, the truth of La Salle's observations. The canal of half a league extended in the making to a hundred miles and required for its construction years of time and the expenditure of millions of dollars.

[14] E.g., Major Stephen H. Long. For his report see the National Register, III, 103-98.

We may now consider the dispute between Joliet and La Salle over the character of the Chicago Portage in the light of the information afforded by the statements of later writers. It will follow from what has already been said that the secondary statements, whether of travelers or of gazetteers and other compendiums of information, made in the early part of the nineteenth century, must be subjected to critical examination. - 9 - The only way in which this may be done is by a resort to the sources; and our conclusions concerning the Chicago-Illinois Portage and route must be based upon the testimony of those who actually used it, or were familiar with the use made of it by others. A study of these sources makes it clear that the Des Plaines River was subject to great fluctuation at different seasons, or even as between periods of drought and periods of copious rainfall, and that the length and character of the portage at any given time depended entirely upon the stage of water in the Des Plaines. During the brief period of the spring flood boats capable of carrying several tons might pass between Lake Michigan and the Des Plaines and along the latter stream without meeting with obstacles other than those incident to the high stage of the water. The extreme range of the fluctuation was many feet.[15] Its effect upon the character of the Des Plaines was to cause it to pass through all the gradations from a raging torrent to a stream with no discharge, dry except for the pools which marked its course. There were times, then, in connection with these fluctuations, when the stream might be navigable for canoes, although it would not permit the passage of boats of greater draft.

[15] Schoolcraft estimated its depth in the seasons of periodical floods at eight to ten feet (Summary Narrative of an Exploratory Expedition to the Sources of the Mississippi River, in 1820, 398). See also Marquette's description of the spring flood of 1675, in Jesuit Relations, LIX, 181.

The duration of the spring flood was put by La Salle at fifteen or twenty days. At this time the flood was heavier than that of the Rhone, and a portion of it found its way through Mud Lake and the south branch of the Chicago River into Lake Michigan. The effect of this on the portage, obvious in itself, is described in many of the sources. Marquette, who was flooded out of his winter camp on the South Branch in the latter part of March, 1675, found no difficulty, aside from the obstacles presented by the floating ice, in passing from that point down the Des Plaines.[16] He reports the water as being twelve feet higher than when he passed through here in the late - 10 - summer of 1673. In 1821, in a time of high water, Ebenezer Childs passed up the Illinois and Des Plaines rivers to Chicago in a small canoe.[17] No month or date is given for this trip, but Childs expressly states that there had been heavy rains for several days before his arrival at the Des Plaines. He was unable to find any signs of a portage between the Des Plaines and the Chicago. When he had ascended the former to a point where he supposed the portage should begin he left it and taking a northeasterly course perceived, after traveling a few miles, the current of the Chicago. The whole intervening country was inundated, and not less than two feet of water existed all the way across the portage. Two years later Keating, the historian of Major Long's expedition to the source of the St. Peter's River, which passed through Chicago in early June, 1823, was informed by Lieutenant Hopson, an officer at Fort Dearborn, that he had crossed the portage with ease in a boat loaded with lead and flour.[18] Of similar purport to the testimony of Childs and Hopson is the account given by Gurdon S. Hubbard of his first ascent of the Des Plaines with the Illinois "brigade" of the American Fur Company in the spring of 1819.[19] The passage from Starved Rock up the river to Cache Island against the heavy current was difficult and exhausting. From this point, with a strong wind blowing from the southwest, sails were hoisted and the loaded boats passed rapidly up the Des Plaines and across the portage to the Chicago, "regardless of the course of the channel."

[16] Marquette's Journal, Jesuit Relations, LIX, 181.

[17] Wisconsin Hist. Colls., IV, 162-63.

[18] Keating, Expedition to the Source of St. Peter's River, ... in the Year 1823, 1, 166.

[19] Hubbard, Gurdon Saltonstall, Incidents and Events in the Life of, 60. MS in the Chicago Historical Society library. This work will be cited henceforth as Life.

With the subsidence of the spring flood the Des Plaines fell to so low a stage as to become unnavigable, even by the small boats ordinarily employed by the fur traders and travelers, except at such times as the river was raised by rains. According to La Salle, it was "not even navigable for canoes" except after the spring flood, and it would be easier to transport goods - 11 - from Lake Michigan to Fort St. Louis by land with horses, than by the use of boats on the river.[20]

[20] Margry, II, 168.

This statement of La Salle is corroborated by many other observers. St. Cosme's party of Seminary priests which passed from Chicago down the Illinois in the early part of November, 1698,[21] was compelled to portage eight leagues or more[22] along the Des Plaines, in addition to the three leagues across from the Chicago to that stream, and almost two weeks were consumed in passing from Chicago to the mouth of the Des Plaines, a distance of about fifty miles.[23] In describing the journey St. Cosme states that from Isle la Cache to Monjolly, a space of seven leagues, "you must always make a portage, there being no water in the river."

[21] Shea, Early Voyages Up and Down the Mississippi, 45 ff.

[22] The distances given in St. Cosme's detailed account total this amount. La Source's general statement is that the party portaged fifteen leagues (ibid., 83), but this, apparently, included the distance between the Chicago River and the Des Plaines.

[23] The party left Chicago October 29, and reached the mouth of the Des Plaines November 11.

In September, 1721, Father Charlevoix, touring America for the purpose of reporting to his king the condition of New France, came to the post of St. Joseph. His ultimate destination was lower Louisiana; from St. Joseph to the Illinois River proper two alternative routes were presented for his consideration, the one by way of the St. Joseph Portage and down the Kankakee River, the other around the southern end of Lake Michigan to Chicago and thence down the Des Plaines. His first intention was to follow the latter, but this was abandoned in favor of the route by the Kankakee, partly because of a storm on Lake Michigan, but also for the additional reason that since the upper Illinois, the modern Des Plaines, was a mere brook, he was told it did not have, at this season, water enough to float a canoe.[24] In his passage down the Kankakee the traveler observed at the mouth of the Des Plaines a buffalo crossing the - 12 - stream. Although sixty leagues from its source, Charlevoix noted that the Des Plaines was still so shallow that the water did not rise above the middle of the animal's legs.[25]

[24] Charlevoix, Histoire et description génerale de la Nouvelle France, avec le journal historique d'un voyage fait par ordre du roi dans l'Amérique septentrionale, VI, 104.

[25] op. cit., 118.

A hundred years after Charlevoix's passage down the Illinois, in midsummer, 1821, Governor Cass and Henry R. Schoolcraft came up that stream in a large canoe en route for Chicago. The observant Schoolcraft has left a careful and detailed narrative of their experiences, and a description of the Illinois River as continued in the Des Plaines.[26] The party was compelled to abandon the canoe at Starved Rock, and the remainder of the journey to Chicago was made on horseback. The route taken was in general along the banks of the river, although the actual channel was observed only occasionally. The result of this observation was the conclusion that the "long and formidable rapids" seen by the travelers completely intercepted navigation at this sultry season. This conclusion was further confirmed by meeting several traders on the plains who were transporting their goods and boats in carts from the Chicago River. They thought it practicable to enter the Des Plaines at Mount Joliet, thus necessitating a portage of about thirty miles, but Schoolcraft in recording this opinion points out that his own party had experienced difficulties far below this point. Although himself an enthusiast on the subject of the future commercial importance of Chicago, and of the utility of a canal connecting the Chicago and Illinois rivers, Schoolcraft's experience on this journey led him to call attention to the error of those who supposed a canal of only eight or ten miles in length would be sufficient to provide a navigable highway between Lake Michigan and the Illinois. This opinion was approved by Thomas Tousey of Virginia, another enthusiast on the subject of the canal, who explored the route of the Des Plaines on horseback in the autumn of 1822.[27] Although the water was uncommonly - 13 - high for the season, Tousey's investigation, while imbuing him with a "more exalted" opinion of the country and the proposed canal communication, convinced him that it would be attended with greater expense to open than he had formerly supposed.

[26] Schoolcraft, Travels in the Central Portions of the Mississippi Valley, 313 ff.

[27] Schoolcraft, Personal Memoirs of a Residence of Thirty Years with the Indian Tribes on the American Frontiers, 179-80.

The conditions encountered by John Tanner in a journey from Chicago down the Illinois River in the year 1820[28] were similar to those described by Schoolcraft the following year. Tanner was traveling from Mackinac to St. Louis in a birch-bark canoe. Some Indians who were accompanying him turned back before reaching Chicago, on receiving from others whom they met discouraging accounts of the stage of the water in the Illinois. Tanner, however, persevered in his enterprise. After a period of illness at Chicago he engaged a Frenchman, who had just returned from hauling some boats across the portage, to take him across also. The Frenchman agreed to transport Tanner sixty miles, and if his horses, which were much worn from the previous long journey, could hold out, one hundred and twenty miles, the length of the portage at the present stage of water. With his canoe in the Frenchman's cart and Tanner himself riding a horse belonging to the latter, the overland journey began. Before the first sixty-mile stage had been completed the Frenchman became ill. He turned back, therefore, and Tanner and his one companion attempted to put their canoe in the water and continue their journey. The water was so low that the members of the party themselves were compelled to walk, the men propelling the canoe by walking, one at the bow and the other at the stern. After three miles had been laboriously traversed in this fashion a Pottawatomie Indian was engaged to take the baggage and Tanner's children on horseback as far as the mouth of the Yellow Ochre River,[29] while Tanner and his companion continued to propel the now lightened - 14 - canoe as before. On reaching the Yellow Ochre a sufficient depth of water was found to permit the further descent of the Illinois in the loaded canoe.

[28] Narrative of the Captivity and Adventures of John Tanner, 256-59. This work will be cited henceforth as Tanner's Narrative.

[29] The similarity of names and distance from Chicago render it probable that Tanner here refers to the Vermilion River.

Perhaps the most interesting account of the passage of the portage in the dry season, and in some respects the most detailed, is the one contained in the autobiography of Gurdon S. Hubbard.[30] Beginning with 1818, for several years, with a single exception, Hubbard accompanied the Illinois "brigade" of the American Fur Company on its annual autumnal trip from Mackinac by way of Lake Michigan and the Chicago Portage to the lower Illinois River. Only the first crossing of the portage, in October, 1818, is described in detail. Leaving Chicago the party, comprising about a dozen boat crews, camped a day on the South Branch near the present commencement of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, preparing to pass the boats through Mud Lake to the Des Plaines. Mud Lake drained both ways, into the Des Plaines, and through a narrow, crooked channel into the South Branch, and only in very wet seasons, Hubbard states, did it contain water enough to float an empty boat. The mud was very deep and the lake was surrounded by an almost impenetrable growth of wild rice and grass.

[30] Hubbard, Life, 39-41.

From the South Branch the empty boats were pulled up the channel leading from Mud Lake. In many places where there was a hard bottom and absence of water they were placed on short rollers, and in this way were propelled along until the lake was reached. Here mud, thick and deep, was encountered, but only at rare intervals was there any water. Four men stayed in the boat while six or eight more waded in the mud alongside. The former were equipped with boat-poles to the ends of which forked branches of trees had been fastened. By pushing with these against the hummocks, while the men in the mud lifted and shoved, the boat was jerked along. The men in the mud frequently sank to their waists, and at times were forced to cling to the boat to prevent going over their heads. Their limbs were covered with bloodsuckers which caused intense agony - 15 - for several days, and sleep at night was rendered hopeless by the swarms of mosquitoes which assailed them. Yet three consecutive days of toil from dawn until dark under such conditions were required to pass all the boats through Mud Lake and reach the Des Plaines River.

The passage down the Des Plaines and the Illinois as far as the mouth of Fox River consumed almost three weeks more. Until Cache Island was reached the journey was comparatively easy, although even in this portion of the Des Plaines progress was frequently interrupted by the necessity of making portages or passing the boats along on rollers.[31] From Cache Island to the Illinois River the goods were carried on the men's backs most of the way, while the lightened boats were pulled over the shallow places, often being placed on poles and thus dragged over the rocks and shoals. In the autumn of 1823 Hubbard was sent to a post on the Iroquois River. To shorten his journey and "avoid the delays and hardships of the old route by way of Mud Lake and the Des Plaines" he resolved to travel to his destination by way of the St. Joseph Portage and the Kankakee River. A year later he was placed in charge of the Illinois River posts of the American Fur Company. He thereupon proceeded to execute a plan he had long urged upon his predecessor. The boats were unloaded on their return from Mackinac to Chicago, and scuttled in the swamp to insure their safety until they should be needed for the return voyage to Mackinac laden with furs the following spring. The goods and furs were transported between Chicago and the Indian hunting-grounds on pack horses. Thus "the long, tedious, and difficult passage" through Mud Lake into and down the Des Plaines was avoided.

[31] Ibid.

It is evident, then, that the chief factor in determining the character and length of the Chicago Portage was the Des Plaines River, and that during a large part of the year the portage that must be made extended much farther than simply from the Chicago to the Des Plaines. Schoolcraft and Cass in 1821 were compelled to abandon their canoe at Starved Rock, almost- 16 - one hundred miles from Chicago. The traders whom they met in the course of their horseback journey were apparently planning to put their boats into the Des Plaines at Mount Joliet, after a portage of thirty miles. Whether, in view of Schoolcraft's own experience, they succeeded in entering the river at this point may well be doubted. The transcript of names from the account books kept by John Kinzie at Chicago[32] contains several entries of charges for assisting traders over the portage; some of these show that the portage was made from Mount Joliet, while one, in June, 1806, shows that it extended to the "forks" of the Illinois. Tanner's experience presents the extreme example, if his statement of distances can be relied on, of a portage of one hundred and twenty miles.[33] The varying length of the portage necessary at different seasons is well described in an official report made in 1819 by Graham and Phillips.[34] At one season there is an uninterrupted water communication between Lake Michigan and the Mississippi; at another season a portage of two miles; at another a portage of seven miles, from the Chicago River to the Des Plaines; and at still another, a portage of fifty miles, extending to the mouth of the Des Plaines.

[32] Barry, Rev. Wm., Transcript of Names in John Kinzie's Account Books, MS in the Chicago Historical Society library. This will be cited henceforth as the Barry Transcript.

[33] If, as suggested above, the Yellow Ochre was the same stream as the Vermilion River, the distance from Chicago to its mouth was about one hundred miles.

[34] State Papers, Doc. No. 17, 16th Congress, 1st Sess. Senator Benton claimed in 1847 that he had written this report from data supplied him by Graham and Phillips (Niles' Register, LXXII, 309).

These fluctuations in the state of the Des Plaines and in the length of the portage influenced materially the plans of the traders and travelers who had occasion to traverse this route. For obvious reasons in times when the Des Plaines was known to be low and the portage correspondingly long the Chicago route would be avoided if practicable. Thus Charlevoix preferred the Kankakee to it in 1721. A hundred years later, the Indians who had set out with Tanner upon learning of the low stage of the water in the Illinois, abandoned the journey and- 17 - returned to their homes. St. Cosme's party in 1698 sought to reach the Illinois from Lake Michigan by the Root and Fox rivers, desisting from the effort only under the belief that this would necessitate a portage of forty leagues. Compelled to follow the Chicago route, the prospect of the long and difficult passage down the Des Plaines to navigable water on the Illinois induced them to leave all of their goods but one boat-load at Chicago in charge of a member of the party. This made necessary a return from the lower Mississippi for them the following spring, but even this was preferred to the arduous undertaking of transporting them over the long portage at Chicago in the dry season.

More significant, perhaps, is the fact that those who had occasion to cross the Chicago Portage, and were informed concerning the seasonal fluctuations of the Des Plaines, planned their business so as to take advantage, as far as possible, of the seasons of high water. Colonel Kingsbury, who in 1805 conducted a company of soldiers from Mackinac to the Mississippi by way of the Illinois River to establish Fort Belle Fontaine, was ordered to proceed to Chicago with them on the first vessel in the spring.[35] The Illinois River traders in the employ of the American Fur Company in the period from 1818 to 1824 so planned their business as to bring their boats laden with furs up the Des Plaines in the season of the spring flood.

[35] Cushing to Lieutenant-colonel Kingsbury, February 20, 1805. This letter belongs to the collection of letter books, letters, and other papers of Jacob Kingsbury in the Chicago Historical Society library. Kingsbury was in command of Detroit, Mackinac, and other northwestern posts from 1804 on, and for a time was the superior authority in charge of a group of posts including Fort Wayne, Fort Dearborn, Mackinac, and Detroit. His letters and papers constitute a source of prime importance for this period of northwestern history. They will be cited henceforth as the Kingsbury Papers.

La Salle had early contended that it was more feasible to transport goods between Chicago and Starved Rock with horses than by boats on the river. There arose very early a demand for another means of transportation between the two places at such times as the use of the Des Plaines in boats was impracticable, whether from excess or from deficiency of water. Lahontan- 18 - represents, in his famous narrative of his Long River expedition,[36] that he returned by way of the Illinois River and Chicago Portage. To lessen the drudgery of "a great land carriage of twelve great leagues," he engaged four hundred Indians to transport his baggage from the Illinois village to Lake Michigan, "which they did in the space of four days." Historians have long agreed in denouncing the pretended Long River discovery as fraudulent, but there is nothing improbable about the statement of the necessity of a land carriage of twelve great leagues at the Chicago Portage.

[36] Lahontan, Voyages, I, 167 ff.

Whether Lahontan ever in fact employed four hundred Indians to transport his baggage over the Chicago Portage may well be doubted; but that other travelers employed Indians in a similar capacity is certain. The companions of Cavelier, La Salle's brother, who passed from Fort St. Louis to Lake Michigan in September, 1687, employed a dozen Shawnee Indians to carry their goods to the lake, because there was no water in the river at this season of the year.[37] Unable to make their way from Chicago to Mackinac they returned to the fort to pass the winter. In this same autumn of 1687, some Frenchmen en route from Montreal to Fort St. Louis with three canoes loaded with merchandise and ammunition were halted at Chicago on account of lack of water in the Des Plaines.[38] Upon information of this being brought to Tonty he engaged the services of forty Shawnee Indians, women and men, by whom the goods were transported to the fort.

When horses were first employed on the Chicago Portage cannot, of course, be stated. We have seen that La Salle advocated their employment, but he himself was never in a position to use them. That such use began very early, however, is indicated by a tradition preserved by Gurdon S. Hubbard of an adventure of a trader named Cerré on the Des Plaines.[39] The Indians sought to force him to pay toll to them, but he defied them;- 19 - the controversy ended happily, however, and the Indians transported Cerré's goods on their pack horses from Cache Island to the mouth of the Des Plaines. The date of this incident is not recorded, but Cerré first came into the Illinois country in 1756. If the Indians were accustomed thus early to use pack horses to transport the goods of travelers it is not improbable that the practice may have originated long before.

[39] Hubbard, Life, 41-43.

The demand for transportation facilities at the portage was thus coeval with the advent of the French in this region. In the early nineteenth century the satisfaction of this demand afforded employment and a livelihood to some of the inhabitants of Chicago. The transporting of travelers and their baggage across the portage formed part of the business of John Kinzie. That it was Ouilmette's principal occupation, at least for a considerable period, seems probable.[40] Major Stoddard stated in 1812 concerning the Chicago Portage that in the dry season boats and their cargoes were transported across it by teams kept at Chicago for this purpose.[41] Several years later Graham and Phillips reported that there was a well-beaten road from the mouth of the Des Plaines to the lake, over which boats and their loads were hauled by oxen and vehicles kept for this purpose by the French settlers at Chicago.[42] Schoolcraft and Cass procured horses to convey them to Chicago from the point near Starved Rock where they abandoned their canoe. John Tanner's narrative shows that the Frenchman who carried him a distance of sixty miles from Chicago to the Illinois River in the preceding year was commonly engaged in this business. Probably this man was Ouilmette, although Tanner does not give his name. If it was someone other than Ouilmette, it is evident that at least two Chicago residents were engaged in this business.

[40] See Post, pp. 143-44; Tanner's Narrative, 257; Barry Transcript.

[41] Stoddard, Sketches, Historical and Descriptive, of Louisiana, 368 ff.

[42] State Papers, Doc. No. 17, 16th Congress, 1st Sess.

The project of Joliet of a canal to connect Lake Michigan with the Illinois River was revived early in the nineteenth century. After numerous investigations and reports had been- 20 - made, the work of construction was at last begun, amid great enthusiasm, in the year 1836. Twelve years later the Illinois and Michigan Canal was completed, and therewith the Chicago Portage ceased to be. Even without the construction of the canal its old importance and use were about to terminate. The advance of white settlement sounded the death knell of the fur trade. With the advent of the railroad, trade and commerce sought other channels and another means of transportation. The waterways lost their old importance and the Chicago Portage passed into history. Ere this time, however, the New Chicago had been born and her future, with its marvelous possibilities, was secure.

- 21 -

It seems quite probable that Chicago was an important meeting-place for Indian travelers long before the first white men came to the foot of Lake Michigan. The portage of the Indian preceded the canoe of the white man, and the Indian trail was the forerunner of the white man's road. Who the first white visitor to Chicago was cannot be stated with certainty. The chief incentive to the exploration of the Northwest was the prosecution of the fur trade, and it is probable that wandering coureurs de bois had visited this region in advance of any of the explorers who have left us records of their travels. Coming to the domain of recorded history we encounter, on the threshold as it were, the master dreamer and empire builder, La Salle.

Already interested in the subject of western exploration, in the summer of 1669 he set out from his estate of Lachine in search of a river which flowed to the western sea.[43] His course to the western end of Lake Ontario is known to us, but from this point his movements for the next two years are involved in mist and obscurity. It is believed by some that he descended the Ohio to the Mississippi in 1670, and that the following year he traversed Lake Michigan from north to south, crossed the Chicago Portage, and descended the Illinois River till he again reached the Mississippi. But the claim that he reached the Mississippi during these years is rejected by most historians. Probably the exact facts as to his movements at this time will never be known. We are here interested, however, primarily in the question whether he came to the site of Chicago. Even this cannot be stated with certainty, but the preponderance of- 22 - opinion among those best qualified to judge is that he probably did.[44]

[43] For this expedition and the subsequent movements of La Salle see Winsor, Cartier to Frontenac; Parkman, La Salle and the Discovery of the Great West; Winsor, Narrative and Critical History, IV, 201 ff.

[44] Margry was convinced of this and Parkman thought it entirely probable. Winsor thought that La Salle came to the head of Lake Michigan, but was in doubt whether he entered the Chicago River or the St. Joseph. Shea, who constantly belittles La Salle's achievements, believed he "reached the Illinois or some other affluent of the Mississippi." See the references given in note 43.

The pages of history might be scanned in vain for a more fitting character with which to begin the annals of the great city of today. La Salle is noted, even as it is noted, for boundless energy, lofty aspiration, and daring enterprise. He combined the capacity to dream with the resolution to make his visions real. "He was the real discoverer of the Great West, for he planned its occupation and began its settlement; and he alone of the men of his time appreciated its boundless possibilities, and with prophetic eye saw in the future its wide area peopled by his own race."[45]

[45] Edward G. Mason, "Early Visitors to Chicago," in New England Magazine, New Ser., VI, 189.

In strong contrast with the masterful La Salle succeeds, in the early annals of Chicago, the gentle, saintly Marquette. For a number of years vague and indefinite reports had been carried to Canada of the existence, to the west of the Great Lakes, of a "great river" flowing westwardly to the Vermilion Sea, as the Gulf of California was then known. These reports roused in the French the hope of finding an easy way to the South Sea, and thence to the golden commerce of the Indies.

Spurred on by the home government Talon, the intendant of Canada, took up the project of solving the problem of the great western river.[46] It chanced that for several years Marquette, a Jesuit missionary, had been stationed on the shore of Lake Superior. Here he heard from his dusky charges stories of the great river and of the pleasant country to the westward. In consequence he became imbued with the double ambition of solving the geographical question of the ultimate direction of the river's flow, and of seeking in this new region a more fruitful field of labor.[47] In the summer of 1672 Talon- 23 - appointed Louis Joliet, a young Canadian who had already achieved something of a reputation as an explorer, to carry out the new task, and the projected exploration of the great river was launched. Joliet proceeded that autumn to Mackinac—the Michilimackinac of the French period—where he spent the winter preparing for the enterprise. Hither Marquette had come two years before, and here he had established the mission of St. Ignace. Proximity and a common interest in the projected enterprise combined to draw the two together; so that when the expedition set out from Mackinac in May, 1673, the party was composed of Joliet, Marquette, and five companions. Though Joliet was the official head of the expedition, it has come about, through the circumstance that his records were lost almost at the end of his toilsome journey, that we are chiefly indebted to the journal of Marquette for our knowledge of it, and have come insensibly to ascribe the credit for it to him.

From Mackinac the party passed, in two canoes, to the head of Green Bay, and thence by way of the Fox-Wisconsin River route to the Mississippi, which was reached a month after the departure from the mission of St. Ignace.[48] Down its broad current the voyagers paddled and floated for another month. Arrived at the mouth of the Arkansas, they were told by the natives that the sea was distant but ten days' journey, and that the intervening region was inhabited by warlike tribes, equipped with firearms, and hostile to their entertainers. This information led the explorers to take counsel concerning their further course. Deeming it established beyond doubt that the river emptied into "the Florida or Mexican Gulf," and fearful of losing the fruits of their discovery by falling into the hands of the Spaniards, they decided to turn about and begin the homeward journey.

[48] Marquette's Journal of the expedition is printed in Jesuit Relations, Vol. LIX. For standard secondary accounts see the works of Parkman and Winsor.

On reaching the mouth of the Illinois they learned that they could shorten their return to Mackinac by passing up that river. A pleasing picture is drawn by Marquette of the country through- 24 - which this new route led them. They had seen nothing comparable to it for fertility of soil, for prairies, woods, "cattle," and other game. The Indians received them kindly, and obliged Marquette to promise that he would return to instruct them. Under the guidance of an Indian escort the voyagers passed, probably by way of the Chicago Portage and River,[49] to Lake Michigan, whence they made their way to Green Bay by the end of September.

[49] It was the contention of Albert D. Hagar, a former secretary of the Chicago Historical Society, that on both this expedition and that of 1675 Marquette passed from the Des Plaines River to Lake Michigan by way of the Calumet Portage and River. (Andreas, History of Chicago, I, 46.) The evidence, however, seems to me to point to the route by way of the Chicago Portage and River. Hagar's argument is refuted by Hurlbut in Chicago Antiquities, 384-88.

The following year Joliet continued on his way to Quebec to report to Count Frontenac the results of his expedition. Marquette remained at Green Bay, worn down by the illness that was shortly to terminate his career. In the autumn of 1674, the disease having temporarily abated, he undertook the fulfilment of his promise to the Illinois Indians to return and establish a mission among them. Late in October he began the journey,[50] accompanied by two voyageurs, Pierre Porteret and Jacques, one of whom had been a member of the earlier expedition. The little party was soon increased by the addition of a number of Indians, and all together made their way down Green Bay and the western shore of Lake Michigan, to the mouth of the "river of the portage"—the Chicago. Over a month had been consumed in the journey, owing to frequent delays caused by the stormy lake. The river was frozen to the depth of half a foot and snow was plentiful. Ten days were passed here, when, Marquette's malady having returned, a camp was made two leagues up the river, close to the portage, and it was decided to spend the winter there. Thus began in December, 1674, the first extended sojourn, so far as we have record, of white men on the site of the future Chicago. There has been much loose writing concerning the character of their habitation. Even- 25 - Parkman states that they constructed a "log hut," and other writers have made similar assertions. There is no warrant for this in the original documents, and all the circumstances of the case combine to render it improbable.[51] Marquette was too sick to travel, and he had but two companions to assist him. They made two camps, one at the entrance of the river, and the other, a few days later, at the portage. It was already the dead of winter, and they could not have been equipped with heavy tools. It seems entirely probable that in place of a "log hut" they constructed the customary Indian shelter or wigwam.[52]

[50] For Marquette's Journal of this expedition see Jesuit Relations, Vol. LIX. Parkman and Winsor have written standard secondary accounts.

Marquette found that two Frenchmen had preceded him in establishing themselves in the Illinois country. He designates them as "La Taupine and the surgeon," and says that they were stationed eighteen leagues below Chicago, "in a fine place for hunting cattle, deer, and turkeys."[53] They were supplied with corn and other provisions, and were engaged in the fur trade. Apparently their location was selected either because it was "a fine place for hunting," or else because of its advantages as a trading station, for it is evident from the narrative that they were in close proximity to the Indians.

[51] The French word used by Marquette, cabannez, was commonly employed, whether as a verb or a noun, to designate the ordinary temporary encampment of travelers and the wigwam of the Indian. In Marquette's Journal of his first expedition (Jesuit Relations, LIX, 146), the word is used to designate the cover of sailcloth erected over the voyagers' canoes to protect them from the mosquitoes and the sun while floating down the Mississippi. Later, on the second expedition, when Marquette, hastening along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan toward Mackinac, found himself at the point of death, his companions hastily landed and constructed a "wretched cabin of bark" to lay him in (ibid., 194). Numerous other instances of the habitual use of the word to indicate a temporary camp might easily be cited.

[52] For a further development of this subject see H. H. Hurlbut's pamphlet, Father Marquette at Mackinac and Chicago, 13-14.

[53] Jesuit Relations, LIX, 174-76.

Who were these French pioneers of the upper Illinois Valley? We know concerning La Taupine—the mole—that he was a noted fur trader whose real name was Pierre Moreau;[54] that he was an adherent of Count Frontenac, the governor of New- 26 - France; and that he was accused by the intendant with being one of the Governor's agents in the prosecution of an illicit trade with the Indians. He had been with St. Lusson at the Sault Ste. Marie in 1671, and doubtless was possessed of all the information current among the French concerning the region beyond the Great Lakes. In what year he pushed out into this region and established the first habitation and business of a white man in northern Illinois will probably forever remain unknown.

[54] Ibid., 314; Mason, "Early Visitors to Chicago," cited in note 45.

The little that Marquette tells us of the companion of La Taupine serves only to whet our curiosity. Though these first residents were lawbreakers, they were not without redeeming qualities. In anticipation, apparently, of Marquette's arrival at their station they had made preparations to receive him, and had told the savages "that their cabin belonged to the black robe."[55] As soon as they learned of the priest's illness at Chicago the surgeon came, in spite of snow and bitter cold,[56] a distance of fifty miles to bring him some corn and blueberries. Marquette sent Jacques back with the surgeon to bear a message to the Indians who lived in his vicinity, and the traders loaded him, on his return, with corn and "other delicacies" for the sick priest. Furthermore, the surgeon was a devout man, for he spent some time with Marquette in order to perform his devotions. Clearly here is a character who improves with closer acquaintance. But such acquaintance is denied us. As a ship passing in the night the surgeon flashes across Chicago's early horizon; whence he came, whither he went, even his name will doubtless remain forever a mystery.

[55] Jesuit Relations, LIX, 176.

[56] The Journal records that the Indians were suffering from hunger because the cold and snow prevented them from hunting.

Meanwhile, how fared the winter with the three Frenchmen in their primitive camp near the portage? The picture of their life as painted in the pages of Marquette's Journal is not, on the whole, unattractive. The fraternal spirit manifested for them by the traders has already been noted. The Indians were- 27 - equally friendly. When those living in a village six leagues away learned of Marquette's plight, they were so solicitous for his welfare, and so fearful that he would suffer from hunger, that, notwithstanding the cold, Jacques had much difficulty in preventing the young men from coming to the portage to carry away to their village all Marquette's belongings.

The Indians' fears, however, proved groundless. Deer and buffalo abounded, partridges, much like those of France, were killed, and turkeys swarmed around the camp. The traders sent corn and blueberries, and the Indians brought corn, dried meat, and pumpkins. The severe winter produced its effect upon the game, some of the deer that were killed being so lean as to be worthless. But "the Blessed Virgin Immaculate," Marquette's celestial queen, took such care of them that there was no lack of provisions, and when the camp was broken up in the spring there was still on hand a large sack of corn and a supply of meat.

An intense spirit of religious devotion animated Marquette throughout the winter. It was his zeal in the service of his Heavenly Master that had led him, in his illness, to brave the rigors of a winter in the wilderness. Despite his bodily affliction, the observance of religious exercises was maintained. Mass was said every day throughout the winter, but they were able to observe Lent only on Fridays and Saturdays. On December 15 the mass of the Conception was celebrated. Early in February a novena, or nine days' devotion to the Virgin, was begun, to ask God for the restoration of Marquette's health. Shortly afterward his condition improved, in consequence, as he believed, of these devotions. An opportunity to give his religion a practical application was afforded him in the latter part of January. A deputation of Illinois Indians came bringing presents, in return for which they requested, among other things, a supply of powder. Marquette refused this, saying he had come to instruct them and to restore peace, and did not wish them to begin a war with their neighbors, the Miamis.

- 28 -

Toward the end of March the ice began to thaw, but on breaking up it formed a gorge, causing a rapid rise in the river. The camping-place was suddenly flooded, the occupants having barely time enough to secure their goods upon the trees. They themselves spent the night on a hillock, with the water steadily gaining upon them. The following day the gorge dissolved, the ice drifted away, and the travelers prepared to resume their journey to the village of the Illinois.

Eleven days were consumed in this journey, during which Marquette suffered much from illness and exposure.[57] According to Father Dablon he was received by the Indians "as an angel from Heaven." He preached to them and established his mission, and then, feeling the hand of death upon him, began his return journey to the distant mission of St. Ignace.

[57] Marquette's Journal ends abruptly at this point, his last entry being made on April 6 while the little party was waiting at the Des Plaines River for the subsidence of the ice and the cold winds to permit them to descend. For the remainder of the story we are indebted to the narrative of Father Dablon, Marquette's superior, whose information was derived from the two companions of Marquette. Dablon's narrative is printed in Jesuit Relations, Vol. LIX.

And now we come to what may be regarded as the next scene in the annals of Chicago. A crowd of the Illinois accompanied Marquette, as a mark of honor, for more than thirty leagues, vying with each other in taking charge of his slender baggage. Then, "filled with great esteem for the gospel," they took leave of him, and continuing his journey he shortly afterward reached Lake Michigan.[58] The route followed from this point was by way of the eastern side of the lake. But the missionary's life was to terminate sooner than the voyage. On May 19 he died, on the lonely shore of the lake, and was- 29 - buried near the mouth of a small river in the state of Michigan which was long to bear his name.

[58] The route followed by Marquette and his escort from the Illinois village to Lake Michigan is not certainly known. From the fact that after reaching the lake Marquette sought to reach Mackinac by following around its eastern shore, it has been argued that he ascended the Kankakee to reach Lake Michigan. The evidence seems to me, however, to favor the route by the Des Plaines and Chicago. Marquette had gone this way on the return from his first expedition, and had returned to the Illinois the same way. If he now followed this route, the thirty leagues which the Indians accompanied him would have brought them to the vicinity of the portage between the Des Plaines and the Chicago. In the period when travel was chiefly by water portages were natural meeting (and parting) places. The one argument in support of the Kankakee route is the fact that the further route of the party was along the eastern shore of the lake. But this fact does not obviate the possibility of a return to the lake by the Des Plaines and Chicago. Furthermore, by the Kankakee route from the point where the Indians turned back Marquette would still have to travel upward of one hundred and fifty miles to reach the lake. Yet the narrative states that he reached it "shortly after" they left him—a statement which harmonizes with the supposition that the leave-taking occurred at or near the Chicago Portage. For these reasons I have chosen to consider this an event in early Chicago history.

A successor to Marquette at the mission of the Illinois was found in the person of Father Claude Allouez, who was then stationed at the mission of St. Francis Xavier at Green Bay. In October, 1676, with two companions he set out in a canoe for his new field of work.[59] The winter closed down early, however, and before they had proceeded far they were compelled to lie over until February with some Pottawatomie Indians. Then they proceeded once more, in a way "very extraordinary"; for instead of putting the canoe into the water, they placed it upon the ice, over which a sail and a favoring wind "made it go as on the water." When the wind failed they drew it along by means of ropes. New obstacles to their progress arose, however, so that not until April did they enter "the river which leads to the Illinois." At its entrance they were met by a band of eighty Illinois Indians who had come from their village to welcome Allouez. The ceremony of reception which ensued may well be set forth in the words of the missionary himself, in whose honor it was staged.

[59] The narrative of Allouez is printed in Jesuit Relations, Vol. LX. The quotations from it which follow are from the Thwaites translation there given.

"The captain came about 30 steps to meet me, carrying in one hand a firebrand and in the other a Calumet adorned with feathers. Approaching me, he placed it in my mouth and himself lighted the tobacco, which obliged me to make a pretense of smoking it. Then he made me come into his Cabin, and having given me the place of honor, he spoke to me as follows:

'My Father, have pity on me; suffer me to return with thee, to bear thee company and take thee into my village. The meeting I have had today with thee will prove fatal to me if I do not- 30 - use it to my advantage. Thou bearest to us the gospel and the prayer. If I lose the opportunity of listening to thee, I shall be punished by the loss of my nephews, whom thou seest in so great number; without doubt, they will be defeated by our enemies. Let us embark, then, in company, that I may profit by thy coming into our land.'"

It is not to be supposed that the exact words of the "Captain" have been preserved, though it may well be that the general tenor of his remarks is here set forth. The speech concluded, they set out together, and "shortly after" arrived at the Chief's abode. We have no clue, further than this, to the location of the Indian camp. Probably it was in the vicinity of the portage; for aside from the fact that this furnished a logical stopping-place Marquette tells us that during his sojourn here, two years before, Indians were encamped in his vicinity during a portion of the winter.

After a brief stay among the Indians on the Illinois, where his labors met with great success, Allouez left them, returning again the next year. We have no details of these journeys, however, and our next account of the presence of white men in this region involves us in the schemes and deeds of the masterful La Salle.

La Salle conceived the ambitious design of leading France and civilization together into the valley of the Mississippi.[60] But vast obstacles interposed to hinder him in its execution. Canada must be his base of operations, and Canada abounded in hostile traders and priests who jealously sought to checkmate him at every opportunity. The initiation of his design involved the establishment of a colony in the Illinois country. In 1678 he sent out in advance a party of men to engage in trade for him and ultimately to go to the Illinois country and prepare for his coming. Meanwhile he himself was busied with further preparations for the execution of his project; a sailing vessel was constructed close above Niagara Falls, and in August, 1678, its- 31 - sails were spread upon Lake Erie for the voyage around the upper lakes. Arrived at Green Bay, the vessel was loaded with furs and started on its return, while La Salle and fourteen followers, in four canoes, continued their way down the western shore of Lake Michigan. The party laboriously made its way past the site of the modern cities of Milwaukee and Chicago and around the southern end of the lake to the mouth of the St. Joseph River. This had been agreed upon as the place of rendezvous with Tonty, La Salle's faithful lieutenant, who with twenty men was toiling, meanwhile, down the eastern side of the lake from Mackinac. Tonty had been delayed, and La Salle employed the period of waiting for him in building Fort Miami on an eminence near the mouth of the river. This became, therefore, the oldest fort in this region, and constituted an important base of operations for the prosecution of his designs.

[60] For the original documents pertaining to La Salle's work see Margry's collection. For standard secondary accounts see the works of Parkman and Winsor. I have drawn freely upon these in preparing this portion of my own narrative.

At last Tonty arrived, bringing news which rendered probable the loss of La Salle's sailing vessel, the "Griffin," with her cargo of furs. Early in December the combined party ascended the St. Joseph River to the portage leading to the Kankakee, near the site of the modern city of South Bend. Down the latter river they passed and into the Illinois, until they came to the great Indian village, in the vicinity of Starved Rock, where Marquette and Allouez had labored as missionaries during the past five years. The place was deserted, however, the inhabitants having departed for their annual winter hunt. The journey was resumed, therefore, as far as Lake Peoria, near which place a village of the Illinois was found.

A parley was held with the Indians, in the course of which La Salle unfolded his design of building a fort in their midst, and a "great wooden Canoe" on the Mississippi, which would go down to the sea, and return thence with the goods they so much desired. La Salle was successful in overcoming alike the suspicions of the natives, the intrigues of his enemies, and the disloyalty of his own men. A site suitable for a fort was selected, and here in the dead of winter was constructed the first civilized habitation of a permanent character in the modern state of- 32 - Illinois; the Indians gave to the fort the name of Checagou, but by La Salle it was christened Fort Crevecoeur.

La Salle had thus established himself in the heart of the Mississippi Valley, and had initiated the work of carving out what was to become the imperial domain of French Louisiana. But the major portion of that work lay yet before him, and difficulties were to succeed one another in its prosecution until the leader's death at the hands of a hidden assassin was to terminate his life in seeming failure. It is not our purpose here to attempt a history of La Salle's career; rather our aim is to sketch such of its salient features as may be pertinent to the unfolding of the story of the genesis of Chicago. The loss of the "Griffin" imposed upon La Salle the necessity of returning to Fort Frontenac for supplies. Having urged forward the construction of his fort and arranged for the departure of Hennepin and his associates on what eventuated in their famous exploration of the upper waters of the Mississippi, La Salle left Tonty in command at Fort Crevecoeur, and himself, in March, 1680, set forth on his long and terrible journey. In its course he again paused near Starved Rock, noted the ease with which it might be defended, and passing on to Fort Miami, dispatched orders to Tonty to occupy and fortify it. He then crossed on foot the trackless waste of southern Michigan in the season of spring floods, and came at last to his destination. He spent some months in setting his affairs in order, and in August, 1680, set out on the return to Illinois, passing by way of Mackinac and thence down the eastern side of Lake Michigan to Fort Miami.

Meanwhile, what of Tonty and affairs at Fort Crevecoeur? Faithful to his orders, Tonty, on receipt of the dispatch which La Salle had sent forward from Fort Miami, set forth to occupy Starved Rock. In his absence the men left at Fort Crevecoeur, spurred on by the tales of financial disaster to La Salle related by the new arrivals, rose in mutiny. They destroyed the fort, stole its provisions, and writing on the side of the unfinished vessel the legend Nous sommes tons sauvages—"We are all- 33 - savages"—departed. Upon the heels of this disaster succeeded a still greater menace to La Salle's designs. It was essential to their success that the Illinois Indians should retain peaceable possession of their territory. But now came against them a war party of the terrible Iroquois. They assailed and destroyed the village at the Rock and pursued the fleeing Illinois until the scattered survivors found refuge across the Mississippi.

The indomitable Tonty, almost alone in this sea of savagery, had done what he could to save the Illinois from destruction. His efforts proved vain, and with his few followers he fled from impending destruction. Their goal was distant Mackinac, and their route was up the Illinois and the Des Plaines to Lake Michigan and thence northward along its western shore. Doubtless the forlorn little party passed by Chicago, though we have no direct details as to this portion of their journey. Hardships and dangers in abundance were endured before the survivors found refuge with a band of friendly Pottawatomies at some point to the southward of Green Bay.

Shortly after the destruction of the Illinois La Salle, in ignorance of what had happened, came from Fort Miami to the relief of Tonty. In the ghastly remains of the village at Starved Rock he read the story of this new disaster to his plans. Failing to find the bodies of Tonty and his companions among them, he followed in the track of the pursued and pursuing savages until he reached the Mississippi. Concluding at last that Tonty had not come this way he retraced his steps to the junction of the Kankakee with the Des Plaines, and turning up the latter stream soon found traces of Tonty's party. It was now the dead of winter. Convinced of Tonty's escape, La Salle abandoned the canoes, which he had dragged with him on sledges thus far and made his way overland through extreme cold and deep snow to Fort Miami, where he arrived at the end of January.

The design was now conceived by La Salle of welding the western tribes into a confederation, which, under the guidance of himself and his French followers, should oppose the marauding incursions of the Iroquois into the West. The year 1681- 34 - was devoted to the furthering of this project and to the gathering of La Salle's scattered resources for a renewal of his attempt at establishing himself in the Mississippi Valley. Late in the year he was again at Fort Miami with a considerable party of French and Indians, ready for the exploit which has given him his greatest fame—the descent of the Mississippi to its mouth.