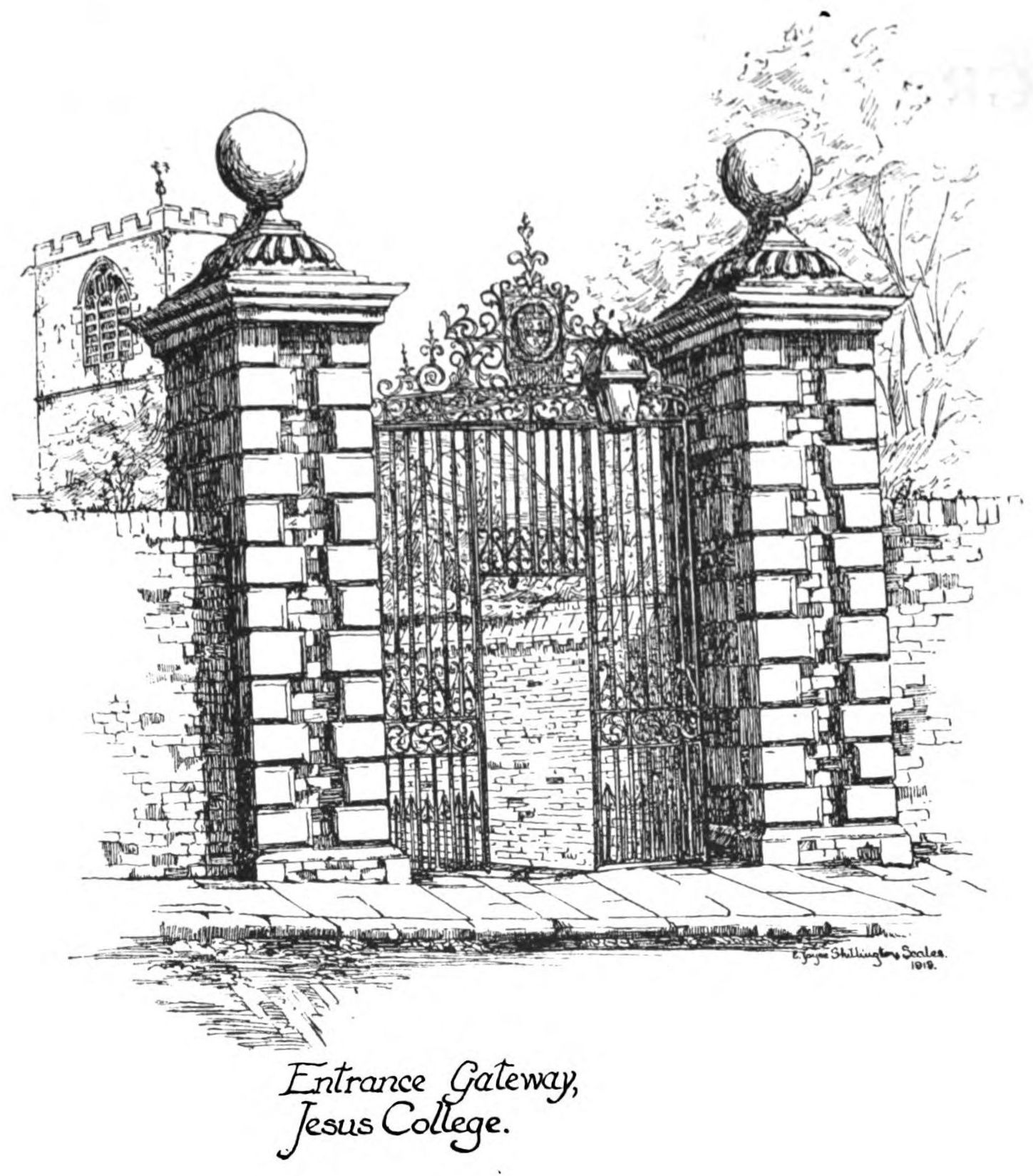

E. Joyce Shillington Scales

1919.

Entrance Gateway, Jesus College.

Title: Tedious brief tales of Granta and Gramarye

Author: Arthur Gray

Illustrator: E. Joyce Shillington Scales

Release date: November 28, 2022 [eBook #69438]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: W. Heffer & Sons Ltd, 1919

Credits: Emmanuel Ackerman and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

E. Joyce Shillington Scales

1919.

Entrance Gateway, Jesus College.

TEDIOUS BRIEF TALES OF

GRANTA AND GRAMARYE

BY

“INGULPHUS”

(ARTHUR GRAY, Master of Jesus College)

With illustrations by

E. JOYCE SHILLINGTON SCALES

“Merry and tragical, tedious and brief:

That is hot ice and wondrous strange snow.”

A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Cambridge:

W. Heffer & Sons Ltd.

London: SIMPKIN, MARSHALL, HAMILTON, KENT & Co. Ltd.

First Published, December, 1919.

For permission to reprint these tales, which originally appeared in The Cambridge Review, The Gownsman and Chanticlere (the Jesus College Magazine), the writer thanks the editors and proprietors of those papers.

In London lanes, uncanonized, untold

By letter’d brass or stone, apart they lie,

Dead and unreck’d of by the passer-by.

Here still they seem together, as of old,

To breathe our air, to walk our Cambridge ground,

Here still to after learners to impart

Hints of the magic that gave Faustus art

To make blind Homer sing “with ravishing sound

To his melodious harp” of Oenon, dead

For Alexander’s love; that framed the spell

Of him who, in the Friar’s “secret cell,”

Made the great marvel of the Brazen Head.

Marlowe and Greene, on you a Cambridge hand

Sprinkles these pious particles of sand.

[Pg 1]

There is a chamber in Jesus College the existence of which is probably known to few who are now resident, and fewer still have penetrated into it or even seen its interior. It is on the right hand of the landing on the top floor of the precipitous staircase in the angle of the cloister next the Hall—a staircase which for some forgotten story connected with it is traditionally called “Cow Lane.” The padlock which secures its massive oaken door is very rarely unfastened, for the room is bare and unfurnished. Once it served as a place of deposit for superfluous kitchen ware, but even that ignominious use has passed from it, and it is now left to undisturbed solitude and darkness. For I should say that it is entirely cut off from the light of the outer day by the walling up, some time in the eighteenth century, of its single window, and such light as ever reaches it comes from the door, when rare occasion causes it to be opened.

Yet at no extraordinarily remote day this chamber has evidently been tenanted, and, before it was given up to darkness, was comfortably fitted, according to the standard of comfort which was known in college in the days of George II. There is still a roomy fireplace before which legs have been stretched and wine and gossip have circulated in the days of wigs and brocade. For the room is spacious and, when it was lighted by the window looking eastward over the fields and common, it must have been a cheerful place for a sociable don.

Let me state in brief, prosaic outline the circumstances which account for the gloom and solitude in which this room has remained now for nearly a century and a half.

In the second quarter of the eighteenth century the University possessed a great variety of clubs of a social kind. There were clubs in college parlours and clubs in private rooms, or in inns and[Pg 2] coffee-houses: clubs flavoured with politics, clubs clerical, clubs purporting to be learned and literary. Whatever their professed particularity, the aim of each was convivial. Some of them, which included undergraduates as well as seniors, were dissipated enough, and in their limited provincial way aped the profligacy of such clubs as the Hell Fire Club of London notoriety.

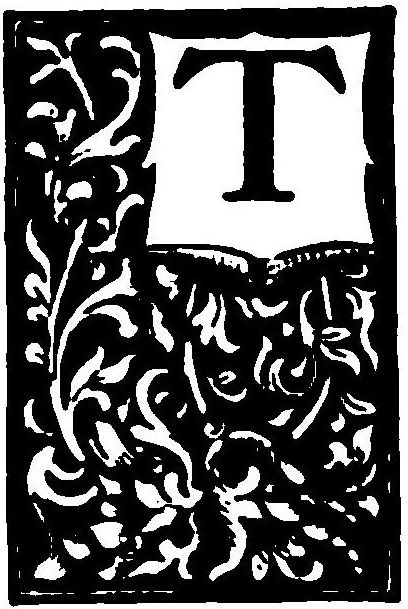

Among these last was one which was at once more select and of more evil fame than any of its fellows. By a singular accident, presently to be explained, the Minute Book of this Club, including the years from 1738 to 1766, came into the hands of a Master of Jesus College, and though, so far as I am aware, it is no longer extant, I have before me a transcript of it which, though it is in a recent handwriting, presents in a bald shape such a singular array of facts that I must ask you to accept them as veracious. The original book is described as a stout duodecimo volume bound in red leather and fastened with red silken strings. The writing in it occupied some 40 pages, and ended with the date November 2, 1766.

The Club in question was called the Everlasting Club—a name sufficiently explained by its rules, set forth in the pocket-book. Its number was limited to seven, and it would seem that its members were all young men, between 22 and 30. One of them was a Fellow-Commoner of Trinity: three of them were Fellows of Colleges, among whom I should specially mention a Fellow of Jesus, named Charles Bellasis: another was a landed proprietor in the county, and the sixth was a young Cambridge physician. The Founder and President of the Club was the Honourable Alan Dermot, who, as the son of an Irish peer, had obtained a nobleman’s degree in the University, and lived in idleness in the town. Very little is known of his life and character, but that little is highly in his disfavour. He was killed in a duel at Paris in the year 1743, under circumstances which I need not particularise, but which point to an exceptional degree of cruelty and wickedness in the slain man.

I will quote from the first pages of the Minute Book some of the laws of the Club, which will explain its constitution:—

“1. This Society consisteth of seven Everlastings, who may be Corporeal or Incorporeal, as Destiny shall determine.

[Pg 3]

2. The rules of the Society, as herein written, are immutable and Everlasting.

3. None shall hereafter be chosen into the Society and none shall cease to be members.

4. The Honourable Alan Dermot is the Everlasting President of the Society.

5. The Senior Corporeal Everlasting, not being the President, shall be the Secretary of the Society, and in this Book of Minutes shall record its transactions, the date at which any Everlasting shall cease to be Corporeal, and all fines due to the Society. And when such Senior Everlasting shall cease to be Corporeal he shall, either in person or by some sure hand, deliver this Book of Minutes to him who shall be next Senior and at the time Corporeal, and he shall in like manner record the transactions therein and transmit it to the next Senior. The neglect of these provisions shall be visited by the President with fine or punishment according to his discretion.

6. On the second day of November in every year, being the Feast of All Souls, at ten o’clock post meridiem, the Everlastings shall meet at supper in the place of residence of that Corporeal member of the Society to whom it shall fall in order of rotation to entertain them, and they shall all subscribe in this Book of Minutes their names and present place of abode.

7. It shall be the obligation of every Everlasting to be present at the yearly entertainment of the Society, and none shall allege for excuse that he has not been invited thereto. If any Everlasting shall fail to attend the yearly meeting, or in his turn shall fail to provide entertainment for the Society, he shall be mulcted at the discretion of the President.

8. Nevertheless, if in any year, in the month of October and not less than seven days before the Feast of All Souls, the major part of the Society, that is to say, four at the least, shall meet and record in writing in these Minutes that it is their desire that no entertainment be given in that year, then, notwithstanding the two rules last rehearsed, there shall be no entertainment in that year, and no Everlasting shall be mulcted on the ground of his absence.”

[Pg 4]

The rest of the rules are either too profane or too puerile to be quoted here. They indicate the extraordinary levity with which the members entered on their preposterous obligations. In particular, to the omission of any regulation as to the transmission of the Minute Book after the last Everlasting ceased to be “Corporeal,” we owe the accident that it fell into the hands of one who was not a member of the society, and the consequent preservation of its contents to the present day.

Low as was the standard of morals in all classes of the University in the first half of the eighteenth century, the flagrant defiance of public decorum by the members of the Everlasting Society brought upon it the stern censure of the authorities, and after a few years it was practically dissolved and its members banished from the University. Charles Bellasis, for instance, was obliged to leave the college, and, though he retained his fellowship, he remained absent from it for nearly twenty years. But the minutes of the society reveal a more terrible reason for its virtual extinction.

Between the years 1738 and 1743 the minutes record many meetings of the Club, for it met on other occasions besides that of All Souls Day. Apart from a great deal of impious jocularity on the part of the writers, they are limited to the formal record of the attendance of the members, fines inflicted, and so forth. The meeting on November 2nd in the latter year is the first about which there is any departure from the stereotyped forms. The supper was given in the house of the physician. One member, Henry Davenport, the former Fellow-Commoner of Trinity, was absent from the entertainment, as he was then serving in Germany, in the Dettingen campaign. The minutes contain an entry, “Mulctatus propter absentiam per Presidentem, Hen. Davenport.” An entry on the next page of the book runs, “Henry Davenport by a Cannon-shot became an Incorporeal Member, November 3, 1743.”

Doorway, Cow Lane.

The minutes give in their own handwriting, under date November 2, the names and addresses of the six other members. First in the list, in a large bold hand, is the autograph of “Alan Dermot, President, at the Court of His Royal Highness.” Now in October Dermot had certainly been in attendance on the Young[Pg 6] Pretender at Paris, and doubtless the address which he gave was understood at the time by the other Everlastings to refer to the fact. But on October 28, five days before the meeting of the Club, he was killed, as I have already mentioned, in a duel. The news of his death cannot have reached Cambridge on November 2, for the Secretary’s record of it is placed below that of Davenport, and with the date November 10: “this day was reported that the President was become an Incorporeal by the hands of a french chevalier.” And in a sudden ebullition, which is in glaring contrast with his previous profanities, he has dashed down “The Good God shield us from ill.”

The tidings of the President’s death scattered the Everlastings like a thunderbolt. They left Cambridge and buried themselves in widely parted regions. But the Club did not cease to exist. The Secretary was still bound to his hateful records: the five survivors did not dare to neglect their fatal obligations. Horror of the presence of the President made the November gathering once and for ever impossible: but horror, too, forbade them to neglect the precaution of meeting in October of every year to put in writing their objection to the celebration. For five years five names are appended to that entry in the minutes, and that is all the business of the Club. Then another member died, who was not the Secretary.

For eighteen more years four miserable men met once each year to deliver the same formal protest. During those years we gather from the signatures that Charles Bellasis returned to Cambridge, now, to appearance, chastened and decorous. He occupied the rooms which I have described on the staircase in the corner of the cloister.

Then in 1766 comes a new handwriting and an altered minute: “Jan. 27, on this day Francis Witherington, Secretary, became an Incorporeal Member. The same day this Book was delivered to me, James Harvey.” Harvey lived only a month, and a similar entry on March 7 states that the book has descended, with the same mysterious celerity, to William Catherston. Then, on May 18, Charles Bellasis writes that on that day, being the date of[Pg 7] Catherston’s decease, the Minute Book has come to him as the last surviving Corporeal of the Club.

As it is my purpose to record fact only I shall not attempt to describe the feelings of the unhappy Secretary when he penned that fatal record. When Witherington died it must have come home to the three survivors that after twenty-three years’ intermission the ghastly entertainment must be annually renewed, with the addition of fresh incorporeal guests, or that they must undergo the pitiless censure of the President. I think it likely that the terror of the alternative, coupled with the mysterious delivery of the Minute Book, was answerable for the speedy decease of the two first successors to the Secretaryship. Now that the alternative was offered to Bellasis alone, he was firmly resolved to bear the consequences, whatever they might be, of an infringement of the Club rules.

The graceless days of George II. had passed away from the University. They were succeeded by times of outward respectability, when religion and morals were no longer publicly challenged. With Bellasis, too, the petulance of youth had passed: he was discreet, perhaps exemplary. The scandal of his early conduct was unknown to most of the new generation, condoned by the few survivors who had witnessed it.

On the night of November 2nd, 1766, a terrible event revived in the older inhabitants of the College the memory of those evil days. From ten o’clock to midnight a hideous uproar went on in the chamber of Bellasis. Who were his companions none knew. Blasphemous outcries and ribald songs, such as had not been heard for twenty years past, aroused from sleep or study the occupants of the court; but among the voices was not that of Bellasis. At twelve a sudden silence fell upon the cloisters. But the Master lay awake all night, troubled at the relapse of a respected colleague and the horrible example of libertinism set to his pupils.

In the morning all remained quiet about Bellasis’ chamber. When his door was opened, soon after daybreak, the early light creeping through the drawn curtains revealed a strange scene. About the table were drawn seven chairs, but some of them had[Pg 8] been overthrown, and the furniture was in chaotic disorder, as after some wild orgy. In the chair at the foot of the table sat the lifeless figure of the Secretary, his head bent over his folded arms, as though he would shield his eyes from some horrible sight. Before him on the table lay pen, ink and the red Minute Book. On the last inscribed page, under the date of November 2nd, were written, for the first time since 1742, the autographs of the seven members of the Everlasting Club, but without address. In the same strong hand in which the President’s name was written there was appended below the signatures the note, “Mulctatus per Presidentem propter neglectum obsonii, Car. Bellasis.”

The Minute Book was secured by the Master of the College, and I believe that he alone was acquainted with the nature of its contents. The scandal reflected on the College by the circumstances revealed in it caused him to keep the knowledge rigidly to himself. But some suspicion of the nature of the occurrences must have percolated to students and servants, for there was a long-abiding belief in the College that annually on the night of November 2 sounds of unholy revelry were heard to issue from the chamber of Bellasis. I cannot learn that the occupants of the adjoining rooms have ever been disturbed by them. Indeed, it is plain from the minutes that owing to their improvident drafting no provision was made for the perpetuation of the All Souls entertainment after the last Everlasting ceased to be Corporeal. Such superstitious belief must be treated with contemptuous incredulity. But whether for that cause or another the rooms were shut up, and have remained tenantless from that day to this.

[Pg 9]

As this narrative of an occurrence in the history of Jesus College may appear to verge on the domain of romance, I think it proper to state by way of preface, that for some of its details I am indebted to documentary evidence which is accessible and veracious. Other portions of the story are supplied from sources the credibility of which my readers will be able to estimate.

On the 8th of November, 1538, the Priory of St. Giles and St. Andrew, Barnwell, was surrendered to King Henry VIII. by John Badcoke, the Prior, and the convent of that house. The surrender was sealed with the common seal, subscribed by the Prior and six canons, and acknowledged on the same day in the Chapter House of the Priory, before Thomas Legh, Doctor of Laws.[1]

Dr. Legh and his fellows, who had been deputed by Cromwell to visit the monasteries, had too frequent occasion to deplore the frowardness of religious households in opposing the King’s will in the matter of their dissolution. Among many such reports I need only cite the case of the Prior of Christ Church, Canterbury, mentioned in a letter to Cromwell from one of his agents, Christopher Leyghton.[2] He tells Cromwell that in an inventory exhibited by the Prior to Dr. Leyghton, the King’s visitor, the Prior had “wilfullye left owte a remembraunce of certayne parcells of silver, gold and stone to the value of thowsandys of poundys”; that it was not to be doubted that he would “eloyne owt of the same howse into the handys of his secret fryndys thowsandes of poundes, which is well knowne he hathe, to hys comfort hereafter”; and[Pg 10] that it was common report in the monastery that any monk who should open the matter to the King’s advisers “shalbe poysenyde or murtheryde, as he hath murthredde diverse others.”

Far different from the truculent attitude of this murderous Prior was the conduct on the like occasion of Prior John Badcoke. Dr. Legh reported him to be “honest and conformable.” He furnished an exact inventory of the possessions of his house, and quietly retired on the pittance allowed to him by the King. He prevailed upon the other canons to shew the same submission to the royal will, and they peaceably dispersed, some to country incumbencies, others to resume in the Colleges the studies commenced in earlier life.

John Badcoke settled in Jesus College. The Bursar’s Rental of 1538-39 shows that his residence there began in the autumn of the earlier year, immediately after the surrender of the monastery. Divorced from the Priory he was still attached to Barnwell, and took up the duties of Vicar of the small parish church of St. Andrew, which stood close to the Priory gate. So long as Henry VIII. lived, and the rites of the old religion were tolerated, he seems to have ministered faithfully to the spiritual needs of his parishioners, unsuspected and unmolested.

More than twelve months elapsed before the demolition of the canons’ house was taken in hand, and, for so long, in the empty church the Prior still offered mass on ceremonial days for the repose of the souls of the Peverels and Peches who had built and endowed the house in long bygone days, and were buried beside the High Altar. In the porter’s lodge remained the only occupant of the monastery—a former servant of the house, who, from the circumstance that in his secular profession he was a mason, had the name of Adam Waller. Occasional intruders on the solitude of the cloister or the monastic garden sometimes lighted on the ex-Prior pacing the grass-grown walks, as of old, and generally in company with a younger priest.

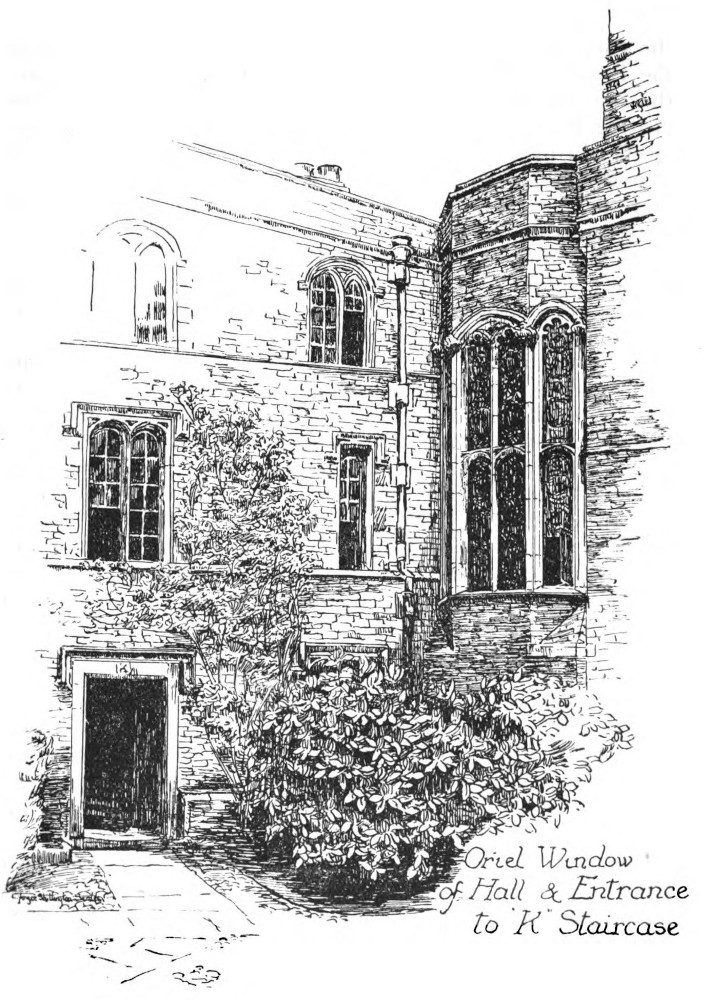

Oriel Window of Hall & Entrance to ‘K’ Staircase

This companion was named Richard Harrison. He was not one of the dispossessed canons, but came from the Priory of Christ Church, Canterbury, of which mention has been made. He was[Pg 12] the youngest and latest professed of the monks there, a nephew of the Prior, as also of John Badcoke. He had not been present at the time of Dr. Leyghton’s visitation, as he happened then to be visiting his uncle at Barnwell. As the Canterbury monks were ejected in his absence he had remained at Barnwell, and there he shared his uncle’s parochial duties. He, too, became a resident at Jesus, and he occupied rooms in the College immediately beneath those of Badcoke.

Late in the year 1539 the demolition of Barnwell Priory was begun. Adam Waller was engaged in the work. One incident, which apparently passed almost unnoticed at the time, may be mentioned in connection with this business. The keys of the church were in the keeping of Waller, who had been in the habit of surrendering them to the two ecclesiastics whenever they performed the divine offices there. On the morning when the demolition was to begin, it was found that the stone covering the altar-tomb of Pain Peverel, crusader and founder of the Priory, had been dislodged, and that the earth within it had been recently disturbed. Waller professed to know nothing of the matter.

The account rolls of the College Bursars in the reigns of Henry VIII. and Edward VI. fortunately tell us exactly the situation of the rooms occupied by Badcoke and Harrison, and as, for the proper understanding of subsequent events, it is necessary that we should realise their condition and relation to the rest of the College, I shall not scruple to be particular. They were on the left-hand side of the staircase now called K, in the eastern range of the College, and at the northern end of what had once been the dormitory of the Nuns of St. Radegund. Badcoke’s chamber, which was on the highest floor, was one of the largest in the College, and for that reason the Statutes prescribed that it should be reserved “for more venerable persons resorting to the College”; and Badcoke, being neither a Fellow nor a graduate, was regarded as belonging to this class. Below his chamber was that of Harrison, and on the ground-floor was the “cool-house,” where the College fuel was kept. Between this ground-floor room and L staircase—which did not then exist—there is seen at the present day a rarely opened door. Inside[Pg 13] the door a flight of some half-dozen steps descends to a narrow space, which might be deemed a passage, save that it has no outlet at the farther end. On either side it is flanked, to the height of two floors of K staircase, by walls of ancient monastic masonry; the third and highest floor is carried over it. Here, in the times of Henry VIII. and the Nunnery days before them, ran or stagnated a Stygian stream, known as “the kytchynge sinke ditch,” foul with scum from the College offices. Northward from Badcoke’s staircase was “the wood-yard,” on the site of the present L staircase. It communicated by a door in its outward, eastern wall with a green close which in the old days had been the Nunnery graveyard. In Badcoke’s times it was still uneven with the hillocks which marked the resting-places of nameless, unrecorded Nuns. The old graveyard was intersected by a cart-track leading from Jesus Lane to the wood-yard door. The Bursar’s books show that Badcoke controlled the wood-yard and coal-house, perhaps in the capacity of Promus, or Steward.

Now when Badcoke and Harrison came to occupy their chambers on K staircase, Jesus, like other Colleges in those troublous times, had fallen on evil days. Its occupants comprised only the Master, some eight Fellows, a few servants, and about half-a-dozen “disciples.” Nearly half the rooms in College were empty, and the records show that many were tenantless, propter defectum reparacionis; that is, because walls, roofs and floors were decayed and ruinous. Badcoke, being a man of means, paid a handsome rent for his chambers, not less than ten shillings by the year, in consideration of which the College put it in tenantable repair; and, as a circumstance which has some significance in relation to this narrative, it is to be noted that the Bursar—the accounts of the year are no longer extant—recorded that in 1539 he paid a sum of three shillings and fourpence “to Adam Waller for layyinge of new brick in yᵉ cupboard of Mr. Badcoke’s chamber.” The cupboard in question was seemingly a small recessed space, still recognisable in a gyp-room belonging to the chambers which were Badcoke’s. The rooms on the side of the staircase opposite to those of Badcoke and Harrison were evidently unoccupied; the Bursar[Pg 14] took no rent from them. The other inmates of the College dwelt in the cloister court.

In this comparative isolation Badcoke and Harrison lived until the death of Henry VIII. in 1546. In course of time Harrison became a Fellow of the College; but Badcoke preferred to retain the exceptional status of its honoured guest. To the Master, Dr. Reston, and the Fellows, whose religious sympathies were with the old order of things, their company was inoffensive and even welcome. But trouble came upon the College in 1549, when it was visited by King Edward’s Protestant Commissioners. It stands on record, that on May 26th “they commanded six altars to be pulled down in the church,” and in a chamber, which may have been Badcoke’s, “caused certayn images to be broken.” Mr. Badcoke “had an excommunicacion sette uppe for him,” and was dismissed from the office, whatever it was, that he held in the College. Worse still for his happiness, his companion of many years, Richard Harrison, was “expulsed his felowshippe” on some supposition of trafficking with the court of Rome.[3] He went overseas, as it was understood, to the Catholic University of Louvain in Flanders.

In 1549 Badcoke must have been, as age went in the sixteenth century, an old man. His deprivation of office, the loss of his friend, and the abandonment of long treasured hopes for the restitution of the religious system to which his life had been devoted, plunged him in a settled despondency. The Fellows, who showed for him such sympathy as they dared, understood that between him and Harrison there passed a secret correspondence. But in course of years this source of consolation dried up. Harrison was dead, or he had travelled away from Louvain. With the other members of the College Badcoke wholly parted company, and lived a recluse in his unneighboured room. By the wood-yard gate, of which he still had a key, he could let himself out beyond the College walls, and sometimes by day, oftener after nightfall, he was to be seen wandering beneath his window in the Nuns’ graveyard, his old feet, like Friar Laurence’s, “stumbling at graves.” An occasional visitor, who was known to be his pensioner, was Adam[Pg 15] Waller. But, though Waller was still at times employed in the service of the College, his character and condition had deteriorated with years. He was a sturdy beggar, a drunkard, sullen and dangerous in his cups, and Badcoke was heard to hint some terror of his presence. At last the Master learnt from the ex-Prior that he was about to quit the College, and none doubted that he would follow Harrison to Louvain.

Shortly after this became known, Badcoke disappeared from College. He had lived in such seclusion that for a day or two it was not noticed that his door remained closed, and that he had not been seen in his customary walks. When the door was at last forced it was discovered that he had indeed gone, but, strangely, he had left behind him the whole of his effects. Adam Waller was the last person who was known to have entered his chamber, and, being questioned, he said that Badcoke had informed him of his intention to depart three days previously, but, for some unexplained reason, had desired him to keep his purpose secret, and had not imparted his destination. Badcoke’s life of seclusion, and his known connection with English Catholics beyond sea, gave colour to Waller’s story, and, so far as I am aware, no enquiries were made as to the subsequent fate of the ex-Prior. But a strange fact was commented on—that the floor of the so-called cupboard was strewn with bricks, and that in the place from which they had been dislodged was an arched recess of considerable size, which must have been made during Badcoke’s tenancy of the room. There was nothing in the recess. Another circumstance there was which called for no notice in the then dilapidated state of half the College rooms. Two boards were loose in the floor of the larger chamber. Thirty feet below the gap which their removal exposed, lay the dark impurities of the “kytchynge sinke ditch.”

Adam Waller died a beggar as he had lived.

A century after these occurrences—in the year 1642—the attention of the College was drawn by a severe visitation of plague to a much-needed sanitary reform. The black ditch which ran under K staircase was “cast,” that is, its bed was effectually cleaned out, and its channel was stopped; and so it came about that from that[Pg 16] day to this it has presented a clean and dry floor of gravel. Beneath the settled slime of centuries was discovered a complete skeleton. How it came there nobody knew, and nobody enquired. Probably it was guessed to be a relic of some dim and grim monastic mystery.

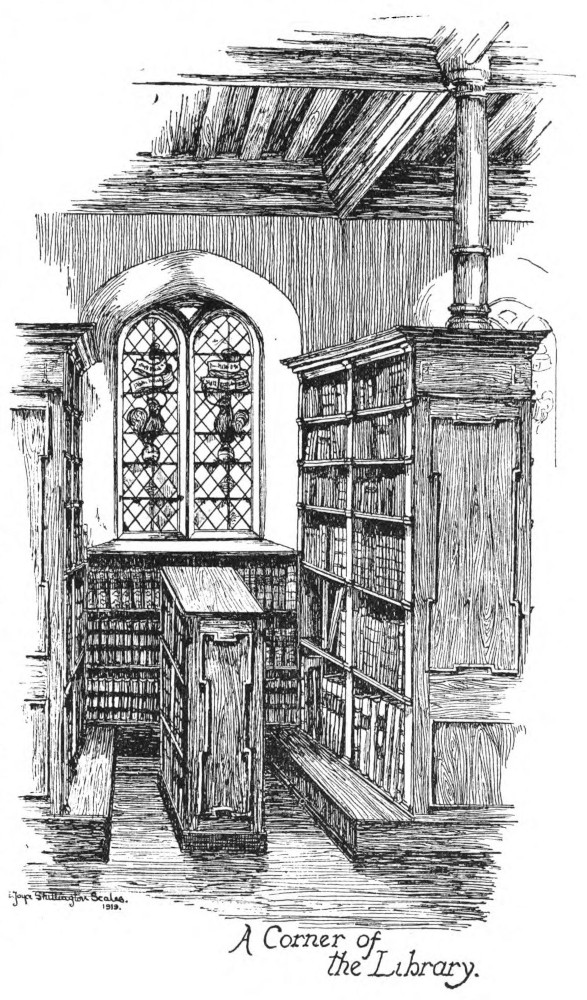

Now whether Adam Waller knew or suspected the existence of a treasure hidden in the wall-recess of Badcoke’s chamber, and murdered the ex-Prior when he was about to remove it to Louvain, I cannot say. One thing is certain—that he did not find the treasure there. When Badcoke disappeared he left his will, with his other belongings, in his chamber. After a decent interval, when it seemed improbable that he would return, probate was obtained by the Master and Fellows, to whom he had bequeathed the chief part of his effects. In 1858 the wills proved in the University court were removed to Peterborough, and there, for aught I know, his will may yet be seen. The property bequeathed consisted principally of books of theology. Among them was Stephanus’ Latin Vulgate Bible of 1528 in two volumes folio. This he devised “of my heartie good wylle to my trustie felow and frynde, Richard Harrison, if he shal returne to Cambrege aftyr the tyme of my decesse.” Richard Harrison never returned to Cambridge, and the Bible, with the other books, found its way to the College Library.

Now there are still in the Library two volumes of this Vulgate Bible. There is nothing in either of them to identify them with the books mentioned in Badcoke’s will, for they have lost the fly-leaves which might have revealed the owner’s autograph. Here and there in the margins are annotations in a sixteenth-century handwriting; and in the same handwriting on one of the lost leaves was a curious inscription, which suggests that the writer’s mind was running on some treasure which was not spiritual. First at the top of the page, in clear and large letters, was copied a passage from Psalm 55: “Cor meum conturbatum est in me: et formido mortis cecidit super me. Et dixi, Quis dabit pennas mihi sicut columbae, et volabo et requiescam.” (My heart is disquieted within me: and the fear of death is fallen upon me. And I said, O that I had wings like a dove: for then would I fly away, and be at rest.) Then, in lettering of the [Pg 18]same kind, came a portion of Deuteronomy xxviii. 12: “Aperiet[Pg 17] dominus thesaurum suum, benedicetque cunctis operibus tuis.” (The Lord will disclose his treasure, and will bless all the works of thy hands.) Under this, in smaller letters, were the words, “Vide super hoc Ezechielis cap. xl.”

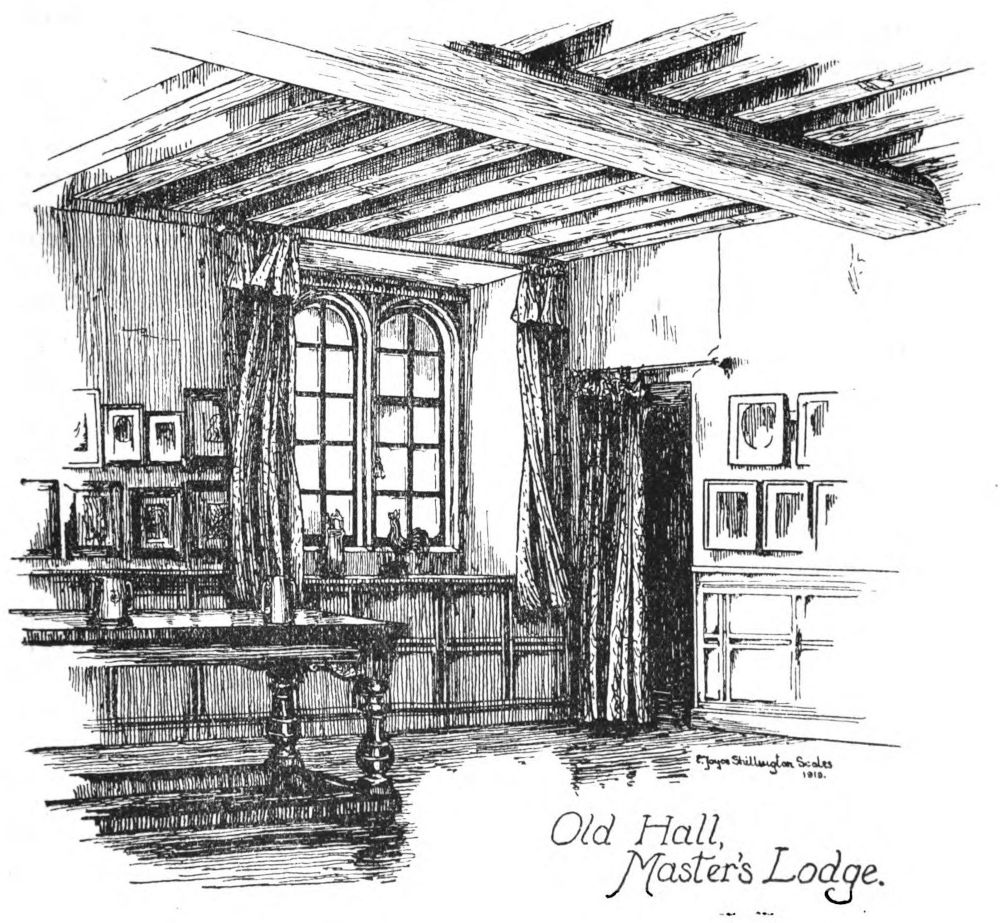

Old Hall, Master’s Lodge.

If in the same volume the chapter in question is referred to, a singular fact discloses itself. Certain words in the text are underscored in red pencil, and fingers, inked in the margin, are directed to the lines in which they occur. Taken in their consecutive order these words run: “Ecce murus forinsecus ... ad portam quae respiciebat viam orientalem ... mensus est a facie portae extrinsecus ad orientem et aquilonem quinque cubitorum ... hoc est gazophylacium.” This may be taken to mean, “Look at the outside wall ... at the gate facing towards the eastern road ... he measured from the gate outwards five cubits (7¹⁄₂ feet) towards the north-east ... there is the treasure.”

The outer wall of the College, the wood-yard gate and the road through the Nuns’ cemetery must at once have suggested themselves to Richard Harrison, had he lived to see his friend’s bequest, and he must have taken it as an instruction from the testator that a treasure known to both parties was hidden in the spot indicated, close to Badcoke’s chamber. And the first text cited must have conveyed to him that his friend, in some deadly terror, had transferred the treasure thither from the place where the two friends had originally laid it. But the message never reached Harrison, and it is quite certain that no treasure has been sought or found in that spot. If the Canterbury or any other treasure was deposited there by Badcoke it rests there still.

To those who are curious to know more of this matter I would say: first, ascertain minutely from Loggan’s seventeenth-century plan of the College the position of the wood-yard gate; and, secondly, which indeed should be firstly, make absolutely certain that John Badcoke was not mystifying posterity by an elaborate jest.

[1] Cooper, Annals, I., p. 393.

[2] The Suppression of the Monasteries (Camden Society’s Publications), p. 90.

[3] Cooper, Annals, II. p. 29.

[Pg 19]

The world, it is said, knows nothing of its greatest men. In our Cambridge microcosm it may be doubted whether we are better informed concerning some of the departed great ones who once walked the confines of our Colleges. Which of us has heard of Anthony Ffryar of Jesus? History is dumb respecting him. Yet but for the unhappy event recorded in this unadorned chronicle his fame might have stood with that of Bacon of Trinity, or Harvey of Caius. They lived to be old men: Ffryar died before he was thirty—his work unfinished, his fame unknown even to his contemporaries.

So meagre is the record of his life’s work that it is contained in a few bare notices in the College Bursar’s Books, in the Grace Books which date his matriculation and degrees, and in the entry of his burial in the register of All Saints’ Parish. These simple annals I have ventured to supplement with details of a more or less hypothetical character which will serve to show what humanity lost by his early death. Readers will be able to judge for themselves the degree of care which I have taken not to import into the story anything which may savour of the improbable or romantic.

Anthony Ffryar matriculated in the year 1541-2, his age being then probably 15 or 16. He took his B.A. degree in 1545, his M.A. in 1548. He became a Fellow about the end of 1547, and died in the summer of 1551. Such are the documentary facts relating to him. Dr. Reston was Master of the College during the whole of his tenure of a Fellowship and died in the same year as Ffryar. The chamber which Ffryar occupied as a Fellow was on the first floor of the staircase at the west end of the Chapel. The staircase has since been absorbed in the Master’s Lodge, but the doorway through[Pg 20] which it was approached from the cloister may still be seen. At the time when Ffryar lived there the nave of the Chapel was used as a parish church, and his windows overlooked the graveyard, then called “Jesus churchyard,” which is now a part of the Master’s garden.

North West Corner of Cloisters.

Ffryar was of course a priest, as were nearly all the Fellows in his day. But I do not gather that he was a theologian, or complied more than formally with the obligation of his orders. He came to Cambridge when the Six Articles and the suppression of the monasteries were of fresh and burning import: he became a Fellow in the harsh Protestant days of Protector Somerset: and in all his time the Master and the Fellows were in scarcely disavowed sympathy with the rites and beliefs of the Old Religion. Yet in the battle of creeds I imagine that he took no part and no interest. I should suppose that he was a somewhat solitary man, an insatiable student of Nature, and that his sympathies with humanity were starved by his absorption in the New Science which dawned on Cambridge at the Reformation.

When I say that he was an alchemist do not suppose that in the middle of the sixteenth century the name of alchemy carried with[Pg 21] it any associations with credulity or imposture. It was a real science and a subject of University study then, as its god-children, Physics and Chemistry, are now. If the aims of its professors were transcendental its methods were genuinely based on research. Ffryar was no visionary, but a man of sense, hard and practical. To the study of alchemy he was drawn by no hopes of gain, not even of fame, and still less by any desire to benefit mankind. He was actuated solely by an unquenchable passion for enquiry, a passion sterilizing to all other feeling. To the somnambulisms of the less scientific disciples of his school, such as the philosopher’s stone and the elixir of life, he showed himself a chill agnostic. All his thought and energies were concentrated on the discovery of the magisterium, the master-cure of all human ailments.

For four years in his laboratory in the cloister he had toiled at this pursuit. More than once, when it had seemed most near, it had eluded his grasp; more than once he had been tempted to abandon it as a mystery insoluble. In the summer of 1551 the discovery waited at his door. He was sure, certain of success, which only experiment could prove. And with the certainty arose a new passion in his heart—to make the name of Ffryar glorious in the healing profession as that of Galen or Hippocrates. In a few days, even within a few hours, the fame of his discovery would go out into all the world.

The summer of 1551 was a sad time in Cambridge. It was marked by a more than usually fatal outbreak of the epidemic called “the sweat,” when, as Fuller says, “patients ended or mended in twenty-four hours.” It had smouldered some time in the town before it appeared with sudden and dreadful violence in Jesus College. The first to go was little Gregory Graunge, schoolboy and chorister, who was lodged in the College school in the outer court. He was barely thirteen years old, and known by sight to Anthony Ffryar. He died on July 31, and was buried the same day in Jesus churchyard. The service for his burial was held in the Chapel and at night, as was customary in those days. Funerals in College were no uncommon events in the sixteenth century. But in the death of the poor child, among strangers, there was something[Pg 22] to move even the cold heart of Ffryar. And not the pity of it only impressed him. The dim Chapel, the Master and Fellows obscurely ranged in their stalls and shrouded in their hoods, the long-drawn miserable chanting and the childish trebles of the boys who had been Gregory’s fellows struck a chill into him which was not to be shaken off.

Three days passed and another chorister died. The College gates were barred and guarded, and, except by a selected messenger, communication with the town was cut off. The precaution was unavailing, and the boys’ usher, Mr. Stevenson, died on August 5. One of the junior Fellows, sir Stayner—“sir” being the equivalent of B.A.—followed on August 7. The Master, Dr. Reston, died the next day. A gaunt, severe man was Dr. Reston, whom his Fellows feared. The death of a Master of Arts on August 9 for a time completed the melancholy list.

Before this the frightened Fellows had taken action. The scholars were dismissed to their homes on August 6. Some of the Fellows abandoned the College at the same time. The rest—a terrified conclave—met on August 8 and decreed that the College should be closed until the pestilence should have abated. Until that time it was to be occupied by a certain Robert Laycock, who was a College servant, and his only communication with the outside world was to be through his son, who lived in Jesus Lane. The decree was perhaps the result of the Master’s death, for he was not present at the meeting.

Goodman Laycock, as he was commonly called, might have been the sole tenant of the College but for the unalterable decision of Ffryar to remain there. At all hazards his research, now on the eve of realisation, must proceed; without the aid of his laboratory in College it would miserably hang fire. Besides, he had an absolute assurance of his own immunity if the experiment answered his confident expectations, and his fancy was elated with the thought of standing, like another Aaron, between the living and the dead, and staying the pestilence with the potent magisterium. Until then he would bar his door even against Laycock, and his supplies of food should be left on the staircase landing. Solitude for him was neither unfamiliar nor terrible.

[Pg 23]

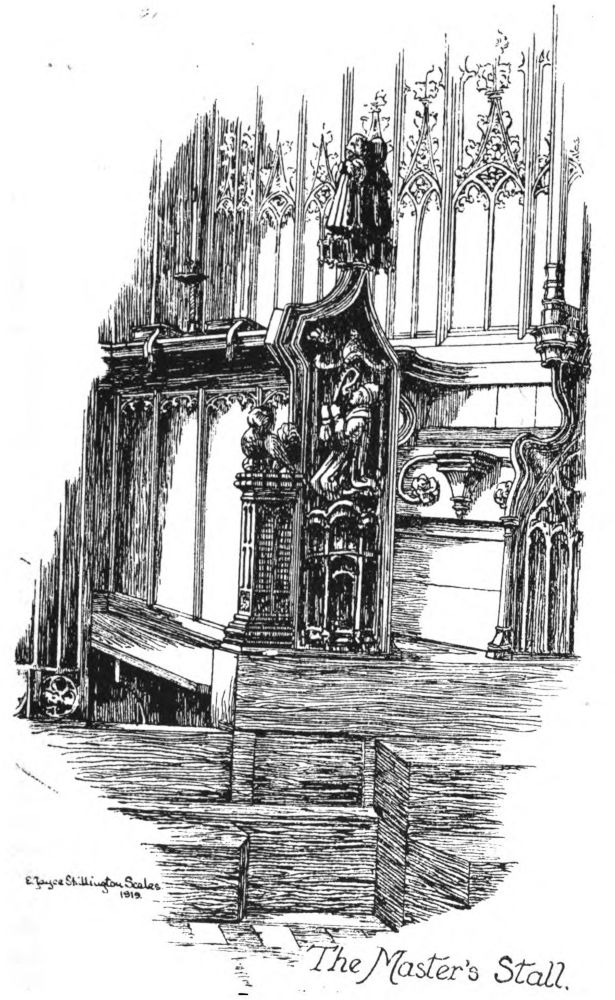

The Master’s Stall.

[Pg 24]

So for three days Ffryar and Laycock inhabited the cloister, solitary and separate. For three days, in the absorption of his research, Ffryar forgot fear, forgot the pestilence-stricken world beyond the gate, almost forgot to consume the daily dole of food laid outside his door. August 12 was the day, so fateful to humanity, when his labours were to be crowned with victory: before midnight the secret of the magisterium would be solved.

Evening began to close in before he could begin the experiment which was to be his last. It must of necessity be a labour of some hours, and, before it began, he bethought him that he had not tasted food since early morning. He unbarred his door and looked for the expected portion. It was not there. Vexed at the remissness of Laycock he waited for a while and listened for his approaching footsteps. At last he took courage and descended to the cloister. He called for Laycock, but heard no response. He resolved to go as far as the Buttery door and knock. Laycock lived and slept in the Buttery.

At the Buttery door he beat and cried on Laycock; but in answer he heard only the sound of scurrying rats. He went to the window, by the hatch, where he knew that the old man’s bed lay, and called to him again. Still there was silence. At last he resolved to force himself through the unglazed window and take what food he could find. In the deep gloom within he stumbled and almost fell over a low object, which he made out to be a truckle-bed. There was light enough from the window to distinguish, stretched upon it, the form of Goodman Laycock, stark and dead.

Sickened and alarmed Ffryar hurried back to his chamber. More than ever he must hasten the great experiment. When it was ended his danger would be past, and he could go out into the town to call the buryers for the old man. With trembling hands he lit the brazier which he used for his experiments, laid it on his hearth and placed thereon the alembic which was to distil the magisterium.

Then he sat down to wait. Gradually the darkness thickened and the sole illuminant of the chamber was the wavering flame of the brazier. He felt feverish and possessed with a nameless uneasiness which, for all his assurance, he was glad to construe as fear: better[Pg 25] that than sickness. In the college and the town without was a deathly silence, stirred only by the sweltering of the distilment, and, as the hours struck, by the beating of the Chapel clock, last wound by Laycock. It was as though the dead man spoke. But the repetition of the hours told him that the time of his emancipation was drawing close.

Whether he slept I do not know. He was aroused to vivid consciousness by the clock sounding one. The time when his experiment should have ended was ten, and he started up with a horrible fear that it had been ruined by his neglect. But it was not so. The fire burnt, the liquid simmered quietly, and so far all was well.

Again the College bell boomed a solitary stroke: then a pause and another. He opened, or seemed to open, his door and listened. Again the knell was repeated. His mind went back to the night when he had attended the obsequies of the boy-chorister. This must be a funeral tolling. For whom? He thought with a shudder of the dead man in the Buttery.

He groped his way cautiously down the stairs. It was a still, windless night, and the cloister was dark as death. Arrived at the further side of the court he turned towards the Chapel. Its panes were faintly lighted from within. The door stood open and he entered.

In the place familiar to him at the chancel door one candle flickered on a bracket. Close to it—his face cast in deep shade by the light from behind—stood the ringer, in a gown of black, silent and absorbed in his melancholy task. Fear had almost given way to wonder in the heart of Ffryar, and, as he passed the sombre figure on his way to the chancel door, he looked him resolutely in the face. The ringer was Goodman Laycock.

Ffryar passed into the choir and quietly made his way to his accustomed stall. Four candles burnt in the central walk about a figure laid on trestles and draped in a pall of black. Two choristers—one on either side—stood by it. In the dimness he could distinguish four figures, erect in the stalls on either side of the Chapel. Their faces were concealed by their hoods, but in the tall form which[Pg 26] occupied the Master’s seat it was not difficult to recognise Dr. Reston.

The bell ceased and the service began. With some faint wonder Ffryar noted that it was the proscribed Roman Mass for the Dead. The solemn introit was uttered in the tones of Reston, and in the deep responses of the nearest cowled figure he recognised the voice of Stevenson, the usher. None of the mourners seemed to notice Ffryar’s presence.

The dreary ceremony drew to a close. The four occupants of the stalls descended and gathered round the palled figure in the aisle. With a mechanical impulse, devoid of fear or curiosity, and with a half-prescience of what he should see, Anthony Ffryar drew near and uncovered the dead man’s face. He saw—himself.

At the same moment the last wailing notes of the office for the dead broke from the band of mourners, and, one by one, the choristers extinguished the four tapers.

“Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine,” chanted the hooded four: and one candle went out.

“Et lux perpetua luceat ei,” was the shrill response of the two choristers: and a second was extinguished.

“Cum sanctis tuis in aeternum,” answered the four: and one taper only remained.

The Master threw back his hood, and turned his dreadful eyes straight upon the living Anthony Ffryar: he threw his hand across the bier and held him tight. “Cras tu eris mecum,”[4] he muttered, as if in antiphonal reply to the dirge-chanters.

With a hiss and a sputter the last candle expired.

The hiss and the sputter and a sudden sense of gloom recalled Ffryar to the waking world. Alas for labouring science, alas for the fame of Ffryar, alas for humanity, dying and doomed to die! The vessel containing the wonderful brew which should have redeemed the world had fallen over and dislodged its contents on the fire below. An accident reparable, surely, within a few hours; but[Pg 27] not by Anthony Ffryar. How the night passed with him no mortal can tell. All that is known further of him is written in the register of All Saints’ parish. If you can discover the ancient volume containing the records of the year 1551—and I am not positive that it now exists—you will find it written:

“Die Augusti xiii

Buryalls in Jhesus churchyarde

Goodman Laycock }

Anthony Ffryar }of yᵉ sicknesse”

Whether he really died of “the sweat” I cannot say. But that the living man was sung to his grave by the dead, who were his sole companions in Jesus College, on the night of August 12, 1551, is as certain and indisputable as any other of the facts which are here set forth in the history of Anthony Ffryar.

[4] Samuel xxvii. 19.

[Pg 28]

This is a story of Jesus College, and it relates to the year 1643. In that year Cambridge town was garrisoned for the Parliament by Colonel Cromwell and the troops of the Eastern Counties’ Association. Soldiers were billeted in all the colleges, and contemporary records testify to their violent behaviour and the damage which they committed in the chambers which they occupied. In the previous year the Master of Jesus College, Doctor Sterne, was arrested by Cromwell when he was leaving the chapel, conveyed to London, and there imprisoned in the Tower. Before the summer of 1643 fourteen of the sixteen Fellows were expelled, and during the whole of that year there were, besides the soldiers, only some ten or twelve occupants of the college. The names of the two Fellows who were not ejected were John Boyleston and Thomas Allen.

With Mr. Boyleston this history is only concerned for the part which he took on the occasion of the visit to the college of the notorious fanatic, William Dowsing. Dowsing came to Cambridge in December, 1642, armed with powers to put in execution the ordinance of Parliament for the reformation of churches and chapels. Among the devastations committed by this ignorant clown, and faithfully recorded by him in his diary, it stands on record that on December 28, in the presence and perhaps with the approval of John Boyleston, he “digg’d up the steps (i.e. of the altar) and brake down Superstitions and Angels, 120 at the least.” Dowsing’s account of his proceedings is supplemented by the Latin History of the college, written in the reign of Charles II. by one of the Fellows, a certain Doctor John Sherman. Sherman records, but Dowsing does not, that there was a second witness of the desecration—Thomas Allen. Of the two he somewhat enigmatically remarks:[Pg 29] “The one (i.e. Boyleston) stood behind a curtain to witness the evil work: the other, afflicted to behold the exequies of his Alma Mater, made his life a filial offering at her grave, and, to escape the hands of wicked rebels, laid violent hands on himself.”

That Thomas Allen committed suicide seems a fairly certain fact: and that remorse for the part which he had unwillingly taken in the sacrilege of December 28 prompted his act we may accept on the testimony of Sherman. But there is something more to tell which Sherman either did not know or did not think fit to record. His book deals only with the college and its society. He had no occasion to remember Adoniram Byfield.

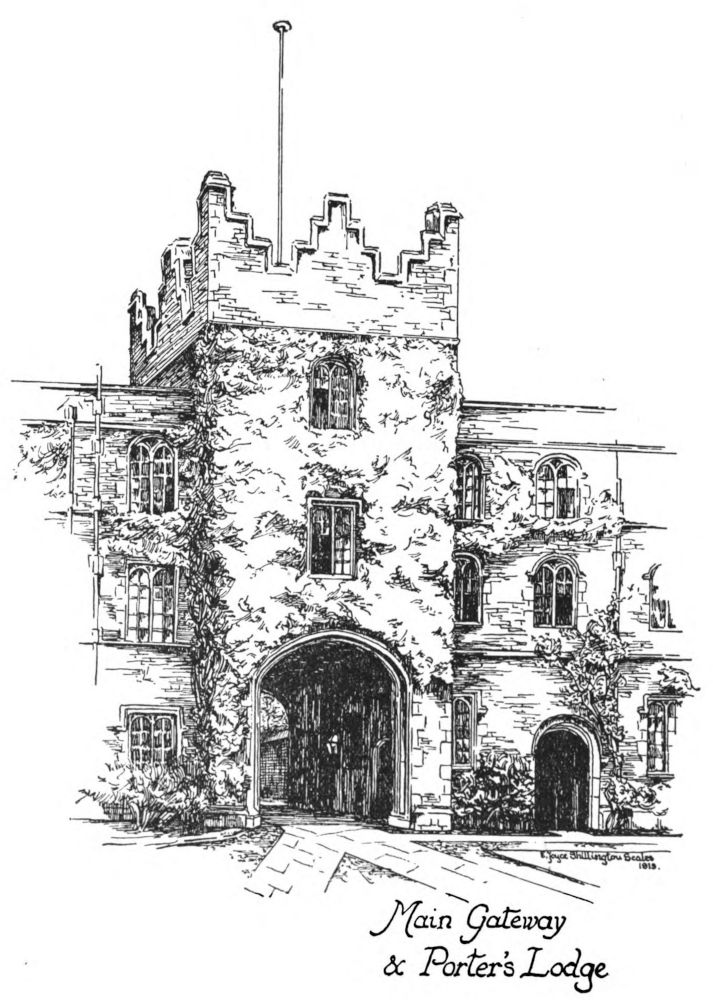

Byfield was a chaplain attached to the Parliamentary forces in Cambridge, and quarters were assigned to him in Jesus College, in the first floor room above the gate of entrance. Below his chamber was the Porter’s lodge, which at that time served as the armoury of the troopers who occupied the college. Above it, on the highest floor of the gate-tower “kept” Thomas Allen. These were the only rooms on the staircase. At the beginning of the Long Vacation of 1643 Allen was the only member of the college who continued to reside.

Some light is thrown on the character of Byfield and his connection with this story by a pudgy volume of old sermons of the Commonwealth period which is contained in the library of the college. Among the sermons which are bound up in it is one which bears the date 1643 and is designated on the title page:

A faithful admonicion of the Baalite sin of Enchanters & Stargazers, preacht to the Colonel Cromwell’s Souldiers in Saint Pulcher’s (i.e. Saint Sepulchre’s) church, in Cambridge, by the fruitfull Minister, Adoniram Byfield, late departed unto God, in the yeare 1643, touching that of Acts the seventh, verse 43, Ye took up the Tabernacle of Moloch, the Star of your god Remphan, figures which ye made to worship them; & I will carrie you away beyond Babylon.

The discourse, in its title as in its contents, reveals its author as one of the fanatics who wrought on the ignorance and prejudice against “carnal” learning which actuated the Cromwellian soldiers[Pg 30] in their brutal usage of the University “scholars” in 1643. All Byfield’s learning was contained in one book—the Book. For him the revelation which gave it sufficed for its interpretation. What needed Greek to the man who spoke mysteries in unknown tongues, or the light of comment to him who was carried in the spirit into the radiance of the third heaven?

Now Allen, too, was an enthusiast, lost in mystic speculation. His speculation was in the then novel science of mathematics and astronomy. Even to minds not darkened by the religious mania that possessed Byfield that science was clouded with suspicion in the middle of the seventeenth century. Anglican, Puritan, and Catholic were agreed in regarding its great exponent, Descartes, as an atheist. Mathematicians were looked upon as necromancers, and Thomas Hobbes says that in his days at Oxford the study was considered to be “smutched with the black art,” and fathers, from an apprehension of its malign influence, refrained from sending their sons to that University. How deep the prejudice had sunk into the soul of Adoniram his sermon shows. The occasion which suggested it was this. A pious cornet, leaving a prayer-meeting at night, fell down one of the steep, unlighted staircases of the college and broke his neck. Two or three of the troopers were taken with a dangerous attack of dysentery. There was talk of these misadventures among the soldiers, who somehow connected them with Allen and his studies. The floating gossip gathered into a settled conviction in the mind of Adoniram.

For Allen was a mysterious person. Whether it was because he was engrossed in his studies, or that he shrank from exposing himself to the insults of the soldiers, he seldom showed himself outside his chamber. Perhaps he was tied to it by the melancholy to which Sherman ascribed his violent end. In his three months’ sojourn on Allen’s staircase Byfield had not seen him a dozen times, and the mystery of his closed door awakened the most fantastic speculations in the chaplain’s mind. For hours together, in the room above, he could hear the mumbled tones of Allen’s voice, rising and falling in ceaseless flow. No answer came, and no word that the listener could catch conveyed to his mind any intelligible sense. Once the voice[Pg 32] was raised in a high key and Byfield distinctly heard the ominous ejaculation, “Avaunt, Sathanas, avaunt!” Once through his partly open door he had caught sight of him standing before a board chalked with figures and symbols which the imagination of Byfield interpreted as magical. At night, from the court below, he would watch the astrologer’s lighted window, and when Allen turned his perspective glass upon the stars the conviction became rooted in his watcher’s mind that he was living in perilous neighbourhood to one of the peeping and muttering wizards of whom the Holy Book spoke.

Main Gateway & Porter’s Lodge.

An unusual occurrence strengthened the suspicions of Byfield. One night he heard Allen creep softly down the staircase past his room; and, opening his door, he saw him disappear round the staircase foot, candle in hand. Silently, in the dark, Byfield followed him and saw him pass into the Porter’s lodge. The soldiers were in bed and the armoury was unguarded. Through the lighted pane he saw Allen take down a horse-pistol from a rack on the wall. He examined it closely, tried the lock, poised it as if to take aim, then replaced it and, leaving the lodge, disappeared up the staircase with his candle. A world of suspicions rushed on Byfield’s mind, and they were not allayed when the soldiers reported in the morning that the pistols were intact. But one of the sick soldiers died that week.

Brooding on this incident Adoniram became more than ever convinced of the Satanic purposes and powers of his neighbour, and his suspicions were confirmed by another mysterious circumstance. As the weeks passed he became aware that at a late hour of night Allen’s door was quietly opened. There followed a patter of scampering feet down the staircase, succeeded by silence. In an hour or two the sound came back. The patter went up the stairs to Allen’s chamber, and then the door was closed. To lie awake waiting for this ghostly sound became a horror to Byfield’s diseased imagination. In his bed he prayed and sang psalms to be relieved of it. Then he abandoned thoughts of sleep and would sit up waiting if he might surprise and detect this walking terror of the night. At first in the darkness of the stairs it eluded him. One night, light in[Pg 33] hand, he managed to get a glimpse of it as it disappeared at the foot of the stairs. It was shaped like a large black cat.

Far from allaying his terrors, the discovery awakened new questionings in the heart of Byfield. Quietly he made his way up to Allen’s door. It stood open and a candle burnt within. From where he stood he could see each corner of the room. There was the board scribbled with hieroglyphs: there were the magical books open on the table: there were the necromancer’s instruments of unknown purpose. But there was no live thing in the room, and no sound save the rustling of papers disturbed by the night air from the open window.

A horrible certitude seized on the chaplain’s mind. This Thing that he had caught sight of was no cat. It was the Evil One himself, or it was the wizard translated into animal shape. On what foul errand was he bent? Who was to be his new victim? With a flash there came upon his mind the story how Phinehas had executed judgment on the men that were joined to Baal-peor, and had stayed the plague from the congregation of Israel. He would be the minister of the Lord’s vengeance on the wicked one, and it should be counted unto him for righteousness unto all generations for evermore.

He went down to the armoury in the Porter’s lodge. Six pistols, he knew, were in the rack on the wall. Strange that to-night there were only five—a fresh proof of the justice of his fears. One of the five he selected, primed, loaded and cocked it in readiness for the wizard’s return. He took his stand in the shadow of the wall, at the entrance of the staircase. That his aim might be surer he left his candle burning at the stair-foot.

On ‘A’ Staircase.

In solemn stillness the minutes drew themselves out into hours while Adoniram waited and prayed to himself. Then in the poring darkness he became sensible of a moving presence, noiseless and unseen. For[Pg 34] a moment it appeared in the light of the candle, not two paces distant. It was the returning cat. A triumphant exclamation sprang to Byfield’s lips, “God shall shoot at them, suddenly shall they be wounded”—and he fired.

With the report of the pistol there rang through the court a dismal outcry, not human nor animal, but resembling, as it seemed to the excited imagination of the chaplain, that of a lost soul in torment. With a scurry the creature disappeared in the darkness of the court, and Byfield did not pursue it. The deed was done—that he felt sure of—and as he replaced the pistol in the rack a gush of religious exaltation filled his heart. That night there was no return of the pattering steps outside his door, and he slept well.

Next day the body of Thomas Allen was discovered in the grove which girds the college—his breast pierced by a bullet. It was surmised that he had dragged himself thither from the court. There were tracks of blood from the staircase foot, where it was conjectured that he had shot himself, and a pistol was missing from the armoury. Some of the inmates of the court had been aroused by the discharge of the weapon. The general conclusion was that recorded by Sherman—that the fatal act was prompted by brooding melancholy.

Of his part in the night’s transactions Byfield said nothing. The grim intelligence, succeeding the religious excitation of the night, brought to him questioning, dread, horror. Whatever others might surmise, he was fatally convinced that it was by his hand that Allen had died. Pity for the dead man had no place in the dark cabin of his soul. But how was it with himself? How should his action be weighed before the awful Throne? His lurid thought pictured the Great Judgment as already begun, the Book opened, the Accuser of the Brethren standing to resist him, and the dreadful sentence of Cain pronounced upon him, “Now art thou cursed from the earth.”

In the evening he heard them bring the dead man to the chamber above his own. They laid him on his bed, and, closing the door, left him and descended the stairs. The sound of their footsteps died away and left a dreadful silence. As the darkness[Pg 35] grew the horror of the stillness became insupportable. How he yearned that he might hear again the familiar muffled voice in the room above! And in an access of fervour he prayed aloud that the terrible present might pass from him, that the hours might go back, as on the dial of Ahaz, and all might be as yesterday.

Suddenly, as the prayer died on his lips, the silence was broken. He could not be mistaken. Very quietly he heard Allen’s door open, and the old, pattering steps crept softly down the stairs. They passed his door. They were gone before he could rise from his knees to open it. A momentary flash lighted the gloom in Byfield’s soul. What if his prayer was heard, if Allen was not dead, if the events of the past twenty-four hours were only a dream and a delusion of the Wicked One? Then the horror returned intensified. Allen was assuredly dead. This creeping Thing—what might it be?

For an hour in his room Byfield sat in agonised dread. Most the thought of the open door possessed him like a nightmare. Somehow it must be closed before the foul Thing returned. Somehow the mangled shape within must be barred up from the wicked powers that might possess it. The fancy gripped and stuck to his delirious mind. It was horrible, but it must be done. In a cold terror he opened his door and looked out.

A flickering light played on the landing above. Byfield hesitated. But the thought that the cat might return at any moment gave him a desperate courage. He mounted the stairs to Allen’s door. Precisely as yesternight it stood wide open. Inside the room the books, the instruments, the magical figures were unchanged, and a candle, exposed to the night wind from the casement, threw wavering shadows on the walls and floor. At a glance he saw it all, and he saw the bed where, a few hours ago, the poor remains of Allen had been laid. The coverlet lay smooth upon it. The dead necromancer was not there.

Then as he stood, footbound, at the door a wandering breath from the window caught the taper, and with a gasp the flame went out. In the black silence he became conscious of a moving sound. Nearer, up the stairs, they drew—the soft creeping steps—and in panic he shrank backwards into Allen’s room before their advance.[Pg 36] Already they were on the last flight of the stairs; and then in the doorway the darkness parted and Byfield saw. In a ring of pallid light that seemed to emanate from its body he beheld the cat—horrible, gory, its foreparts hanging in ragged collops from its neck. Slowly it crept into the room, and its eyes, smoking with dull malevolence, were fastened on Byfield. Further he backed into the room, to the corner where the bed was laid. The creature followed. It crouched to spring upon him. He dropped in a sitting posture on the bed and as he saw it launch itself upon him, he closed his eyes and found speech in a gush of prayer, “O my God, make haste for my help.” In an agony he collapsed upon the couch and clutched its covering with both hands. Beneath it he gripped the stiffened limbs of the dead necromancer, and, when he opened his eyes, the darkness had returned and the spectral cat was gone.

[Pg 37]

On a certain morning in the summer of the year 1510 John Eccleston, Doctor in Divinity and Master of Jesus College in Cambridge, stood at the door of his lodge looking into the cloister court. There was a faint odour of extinguished candles in the air, and a bell automatically clanked in unison with its bearer’s step. It was carried by a young acolyte, who lagged in the rear of a small band of white-robed figures who were just disappearing from sight at the corner of the passage leading to the entrance court. They were the five Fellows of the newly-constituted College.

As they disappeared, the Master, with much deliberation, spat into the cloister walk.

To spit behind a man’s back might be accounted a mark of disgust, contempt, malice—at least of disapproval. Such were not the feelings of Dr. Eccleston.

It is a fact known all over the world, Christian and heathen, that visitants from the unseen realm cannot endure to be spat at. The Master’s action was prophylactic. For supernatural visitings of the transitory, curable kind the rites of the Church are, no doubt, efficacious. In inveterate cases it is well to leave no remedy untried.

With bell, book and candle the Master and Fellows had just completed a lustration of the lodge. The bell had clanked in the Founder’s Chamber and in the Master’s oratory. The Master’s bedchamber had been well soused with holy water. The candle had explored dark places in cupboards and under the stairs. If It was there before it was almost inconceivable that It remained there now. But one cannot be too careful.

Two days previously a funeral had taken place in the College. It was a shabby affair. The deceased, John Baldwin, late a brother of the dissolved Hospital of Saint John, was put away in an obscure[Pg 38] part of the College churchyard—now the Master’s garden—behind some elder bushes which grew in the corner bounded by the street and the “chimney.” The mourners were the grave-digger, the sexton and the parson of All Saints’ Church. Though brother John had died in a college chamber the society of Jesus marked its reprobation of his manner of living by absenting themselves from his obsequies.

Brother John had been a disappointment: uncharitable persons might say he was a fraud. He had got into the College by false pretences. In life he had disgraced it by his excesses, and, when he was dead, he had perpetrated a mean practical joke on the society. It is not well for a man in religious orders to joke when he is dead.

How did it come that brother John Baldwin, late Granger of the Augustinian Hospital of Saint John, died in Jesus College?

The Hospital of Saint John was dissolved in the year 1510, to make room for the new college designed by the Lady Margaret. Bishops of Ely for three centuries and more had been its patrons and visitors, and dissolute James Stanley, bishop in 1510, fought stoutly for its maintenance. But circumstances were too strong for the bishop. The ancient Hospital was hopelessly bankrupt. The buildings were ruinous: there was not a doit in the treasury chest: the household goods were pawned to creditors in the town. The Master, William Tomlyn, had disappeared, none knew whither, and only two brethren were left in the place. One of them was John Baldwin: the other was the Infirmarer, a certain Bartholomew Aspelon.

On the eve of the dissolution, bishop Stanley wrote a letter to the Master and Fellows of the other Cambridge society of which he was visitor, namely, Jesus College. He commended to their charitable care brother John Baldwin, an aged man of godly conversation who was disposed to bestow his worldly goods for the comfort and sustenance of the Master and Fellows in consideration of their maintenance of him in College during the remaining years of his earthly pilgrimage. It was a not uncommon practice in those days for monasteries and colleges to accept as inmates persons,[Pg 39] clerical or lay, who wished to withdraw from the world and were willing, either during life or by testamentary arrangements, to guarantee their hosts against pecuniary loss.

Report said that, though the Hospital was penniless, brother John in his private circumstances was well-to-do and even affluent. It did not befit the Master and Fellows to enquire how he had come by his wealth. They were wretchedly poor, and the bishop’s certificate of character was all that could be desired. They thanked the bishop for his prudent care for their interests and covenanted to give the religious man a domicile in the College with allowance for victuals, barber, laundress, wine, wax and all other things necessary for celebrating Divine service, as to any Fellow of the College. Brother John promptly transferred himself to his new quarters, which were in a room called “the loft,” on the top floor above the Founder’s Chamber in the Master’s lodge.

The Master and Fellows were disappointed in brother John’s luggage. It consisted simply of two brass-bound boxes, heavy but unquestionably small, even for a man of religion. An encouraging feature about them was that they bore the monogram of Saint John’s Hospital. Brother John and his former co-mate of the Hospital, Bartholomew Aspelon, constantly affirmed that the missing Master, William Tomlyn, had decamped with the contents of the Hospital treasury. But the society of Jesus hoped that they were not telling the truth. Brother John kept the two boxes under his bed. They were always carefully locked, but brother John threw out vague hints that their contents were destined for a princely benefaction to his hospitable entertainers.

In other respects brother John’s equipment was not such as would betoken a man of wealth. Rather it savoured of monastical austerity. His only suit of clothing was ancient, and even greasy. It was never changed, night or day. Brother John was apparently under a religious obligation to abstain from washing.

As a man of godly conversation brother John was unfortunate in his personal appearance. It was presumably a stroke of paralysis which had drawn up one side of his face and correspondingly depressed the other. His mouth was a diagonal compromise with[Pg 40] the rest of his features. One eye was closed, and the other was bleared and watery. His nose was red, but the rest of his face was of a parchment colour.

Brother John was an elderly person, and continued ill health unfortunately confined him to his chamber, above the Master’s. He expressed a deep regret that he could not share the society of the Fellows in the Hall at their meals of oatmeal porridge, salt fish, and thin ale. His distressing ailments necessitated a sustaining diet of capons and oysters, supplied to him in his chamber by the College. He was equally debarred from attending services in the Chapel, but the wine with which the society had covenanted to supply him was punctually consumed at the private offices which he performed in his chamber. A suitable pecuniary compensation was made to him on the ground that his domestic arrangements rendered the services of the College laundress unnecessary.

Bartholomew Aspelon, who lodged in an alehouse in the town, was the constant and affectionate attendant at brother John’s sick bed: for, indeed, he seldom got out of it. From a neighbouring tavern he brought to him abundant supplies of the ypocras and malmsey wine which were requisite for the maintenance of the invalid’s failing strength. Brother Bartholomew was an individual of a merry countenance and gifted with cheerful song. In the sick room the Fellows would often hear him trolling a drinking catch, to which the invalid joined a quavering note. So constant and familiar was the lay that John Bale, one of the Fellows, remembered it thirty years afterwards, and put it in the mouth of a roystering monk whom he introduced as one of the characters in his play, King Johan. The words ran thus:

Wassayle, wassayle, out of the mylke payle,

Wassayle, wassayle, as whyte as my nayle,

Wassayle, wassayle, in snow, frost and hayle,

Wassayle, wassayle, with partriche and rayle,

Wassayle, wassayle, that much doth avayle,

Wassayle, wassayle, that never wyll fayle.

The invasion of the college silences by this unusual concert was marked by the Fellows with growing disapproval: and they[Pg 41] were not comforted when they discovered that the new robe which they had contracted to supply to their guest had been pledged to the host of the Sarazin’s Head in part payment of an account rendered. But they possessed their souls in patience as they noted that the health of their venerable guest was declining with obvious rapidity. With some insistence they pointed out to the Master the desirability of having a prompt and clear understanding about brother John’s testamentary dispositions. Dr. Eccleston was entirely of the Fellows’ mind in the matter.

Fireplace in Master’s Lodge.

One evening in June, some three months after brother John had begun his residence in the College, it seemed to Dr. Eccleston that the time had come to sound him about his intentions. The patient was very low, and brother Bartholomew was much depressed.[Pg 42] With inkhorn and pen the Master went upstairs to the sick man’s chamber. Nuncupatory wills were in those days accepted as legal obligations, and the Master was minded that he would not leave brother John until he had obtained, from his dictation, a statement of his intentions as to the disposal of his goods.

Obviously brother John’s mind was wandering when the Master entered the room, for he greeted his arrival with a snatch of the old scurvy tune,

Wassayle, wassayle, that never wyll fayle,

and feebly added “Art there, bully Bartholomew? Bear me thy hand to the bottle, for I am dry.”

“Brother John, brother John,” said the Master, “bestir thee, and think of thy state. It is time for thee to consider of thy world’s gear and how thou wilt bestow it according to thy promise to our poor company, for their tendance of thee.” Brother John raised himself in his bed and opened his serviceable eye. Something like a grin puckered up his sloping mouth. “Art thou of that counsel, goodman Doctor?” said he: “then have with thee. I were a knave if I did not thank you for your kindness, and, trust me, ye shall not be the losers for your pains. Take quill and write. I will dictate my will in two fillings of thy pen. Write”: and the Master wrote.

“To the Master and Fellows of Jesus College I give and bequeath that chest that lieth beneath my bed and is marked with a great letter A, and all that is in it. To brother Bartholomew Aspelon, late of the Hospital of Saint John, in like manner I bequeath that other chest that is marked B.”

“Is that all?” asked the Master. “Gogswouns, it is all I have,” said brother John. “Yet stay, good Master. Nothing for nothing is a safe text. Thou shalt write it as a condition, on pain of forfeiting my bequest, that ye shall bury me in the aisle of your church, immediately before the High Altar: that ye shall keep my obit, or anniversary, with placebo and dirige and mass of requiem; and that once each week a Fellow that is a priest shall pray and sing for the soul of John Baldwin, the benefactor of the College. Is it rehearsed, master doctor?” “It is written,” said the Master.[Pg 43] “Ite, missa est,” said the invalid, “and fetch me a stoup of small ale, good Master.”

A few days later John Baldwin made his unimproving, unregretted end. Brother Bartholomew carried off his portion of the legacy. The other chest was deposited on the table in the Founder’s Chamber and opened by the Master before the assembled Fellows.

It contained half a dozen bricks, a fair quantity of straw and shavings, and nothing else—nothing except a small scrap of torn and dirty paper at the bottom of the box. With one voice the Master and Fellows decreed that their unworthy guest should be buried in the least respectable portion of the churchyard. Which thing was done, as I have already mentioned.

Of course the dirty paper under the straw was scrutinized by the Master and Fellows. But it was of no importance. It looked like a deed or a will, in which the deceased, in return for nursing in sickness, proposed to give some unspecified property to his disreputable friend, Aspelon, and apparently stipulated that he should be buried in the choir of the Hospital chapel. But it was not witnessed: it had obviously been torn up, and all that was left of it was the part on the scribe’s right hand. It ran thus:

ego Johannes Baldewyn nuper frat

rigiam do lego et confirmo domino

u pro mea in egritudine relevaci

domino Bartolomeo Aspelon confrat

ne quod habeat uter prior invener

am in tumulo sepultus subter quen

parte chori in sacello Hospitalis

theshede

The last word, if rightly read, was unintelligible.

But the College had by no means done with brother John. On the evening after his burial, as the Master and Fellows were leaving the Chapel, their steps were suddenly arrested as they heard the familiar Wassail stave raised in a thin and tuneless voice. It came from the open window of the deceased brother, and unquestionably the voice was not Aspelon’s. In consternation they listened till it died ineffectually away in an attempted chorus strain.[Pg 44] After brief deliberation they resolved to visit the “loft” in a body—Master, Fellows, “disciples” and servants—and see what this thing might mean. They found the place as blank and silent as it remained when the deceased had been taken out to his burial. But before they reached the stair-foot in their descent the thin piping strain fell on their ears again, and this time none were bold enough to go back. After that, at all times of night and day, the interminable ditty was fitfully renewed, and panic held the College. At night the “disciples” huddled in one room, and the Fellows lay two in a bed.

Unfortunately for Dr. Eccleston, he was condemned to the solitude of the lodge, deserted even by his famulus, the sizar who attended him. He sat up all night and studied works of divinity, in the hope that theology, if it did not put the songster to rout, would at least distract his own thoughts from the devilish roundelay in the garret above his head. On the second night he began to congratulate himself on the success of his experiment, for the singer relapsed into silence. In his exhaustion he might even have slept, but that the door of his study had a gusty habit of flying open unexpectedly and closing with a bang. He had actually begun to drowse over his folio when a sharp pressure on his right shoulder aroused him. Hastily turning his head he saw the papery countenance of the dead brother gazing on him with all the affection that one eye could testify, the chin planted on the Master’s shoulder, and the mouth slewed into a simulation of innocent mirth. Dr. Eccleston read no more divinity that night.