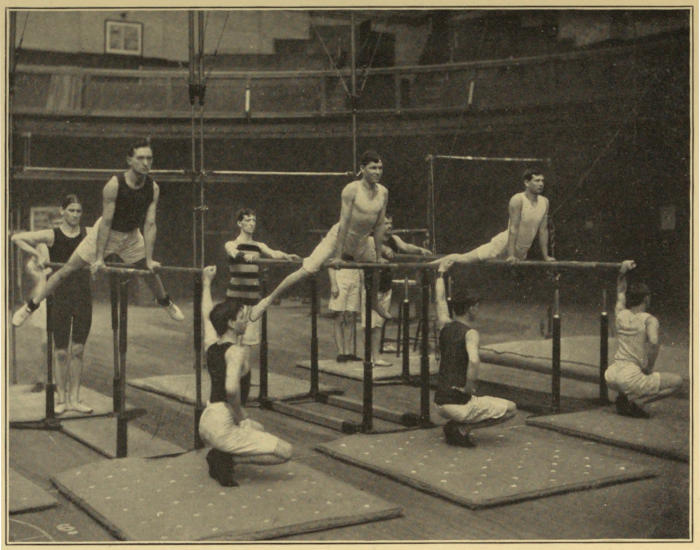

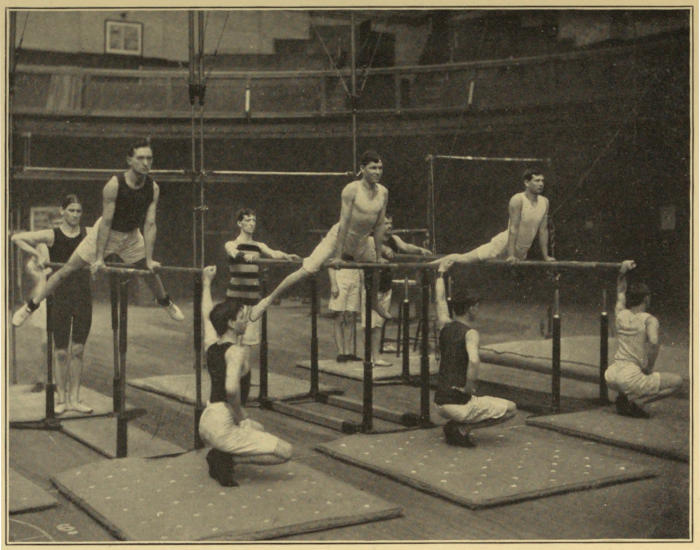

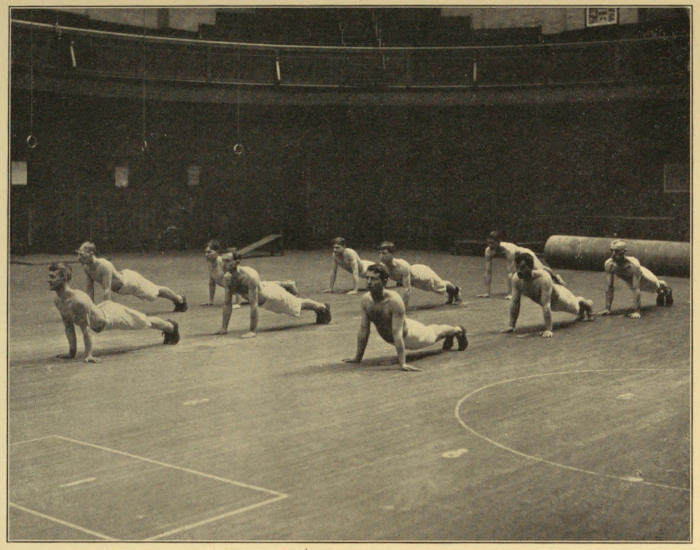

Showing a group of the soldiers at work in the gymnasium.

Title: Physiological economy in nutrition, with special reference to the minimal proteid requirement of the healthy man

Author: R. H. Chittenden

Release date: November 28, 2022 [eBook #69439]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

PHYSIOLOGICAL ECONOMY

IN

NUTRITION

WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE MINIMAL

PROTEID REQUIREMENT OF THE

HEALTHY MAN

AN EXPERIMENTAL STUDY

BY

RUSSELL H. CHITTENDEN,

Ph.D., LL.D., Sc.D.

DIRECTOR OF THE SHEFFIELD SCIENTIFIC SCHOOL OF YALE UNIVERSITY

AND PROFESSOR OF PHYSIOLOGICAL CHEMISTRY; MEMBER OF THE

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES; PRESIDENT OF THE

AMERICAN PHYSIOLOGICAL SOCIETY; MEMBER OF

THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL SOCIETY, ETC.

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

1907

Copyright, 1904,

By Frederick A. Stokes Company

Published in November, 1904

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

| Facing page | |

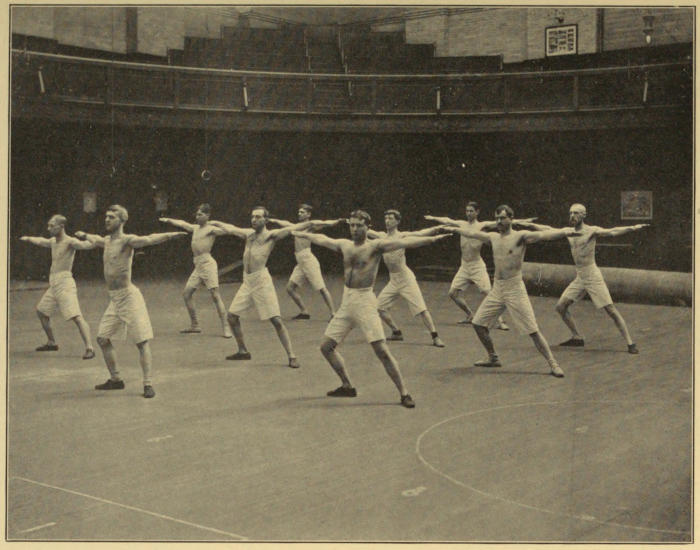

| Group of soldiers at work in the Gymnasium | 136 |

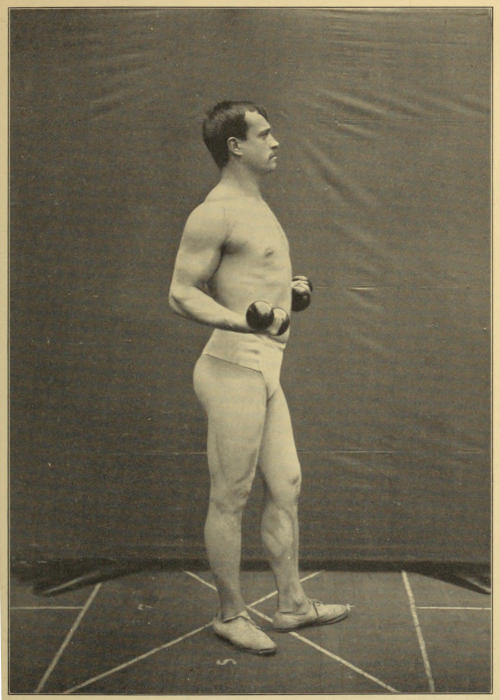

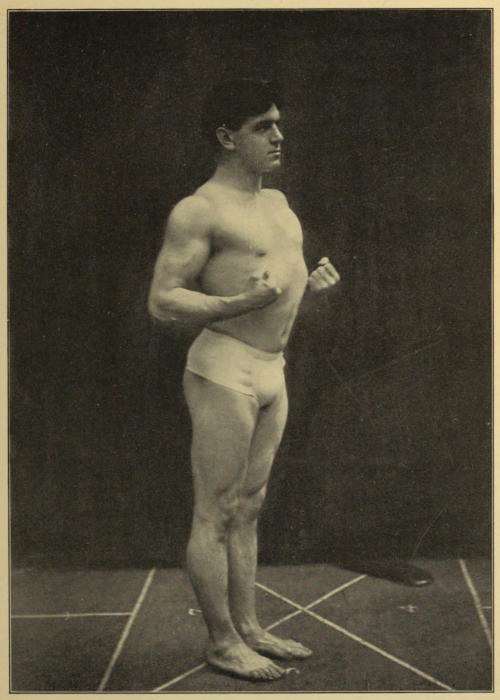

| Side view of Fritz | 198 |

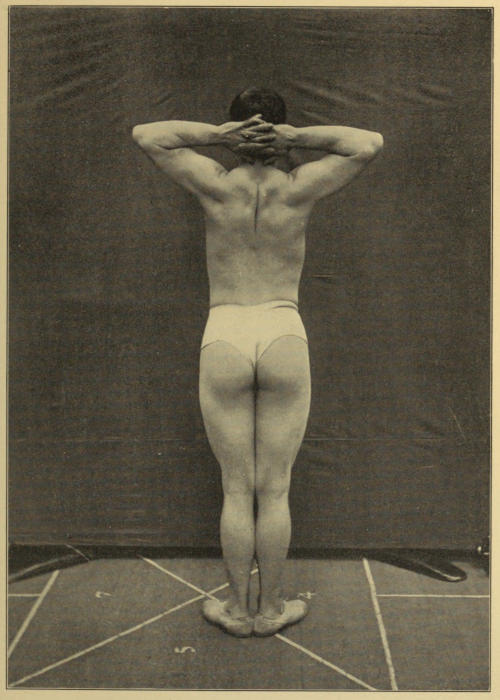

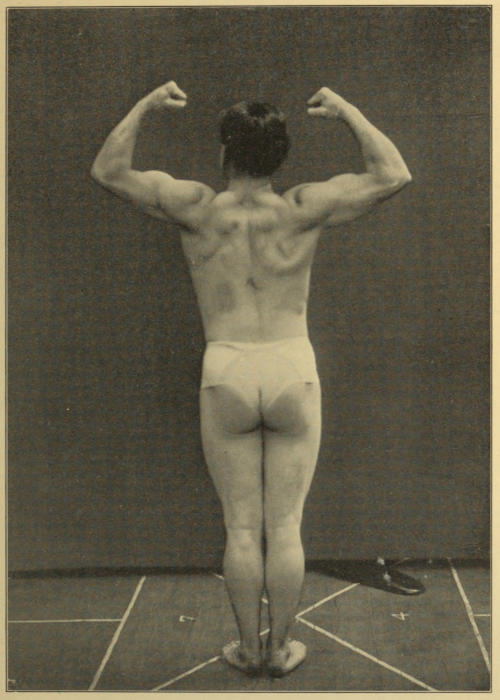

| Back view of Fritz | 204 |

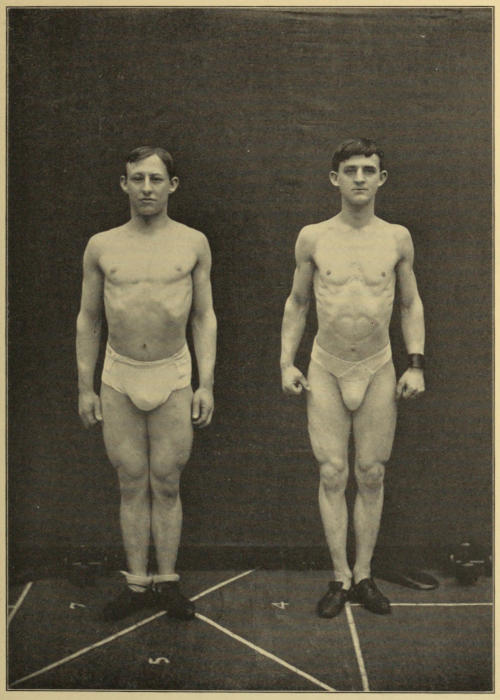

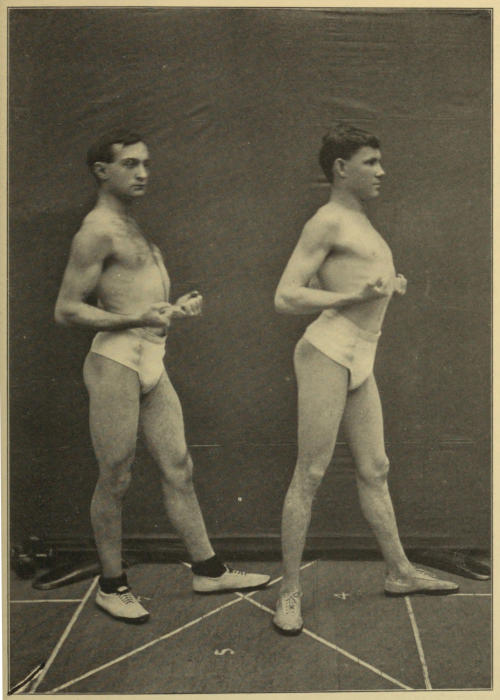

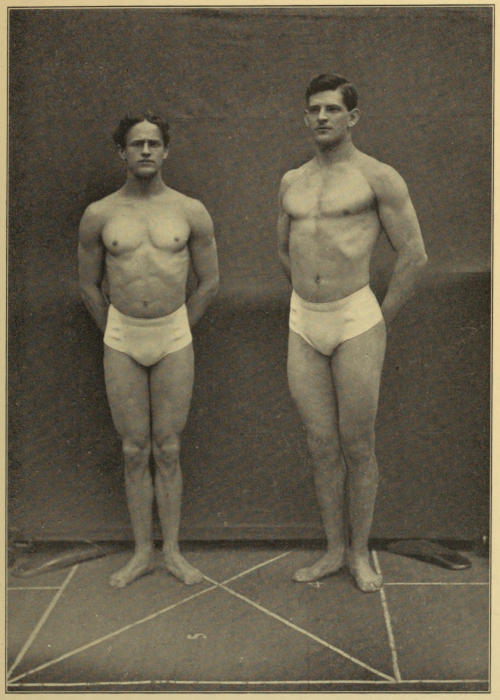

| Front view of Coffman and Steltz | 212 |

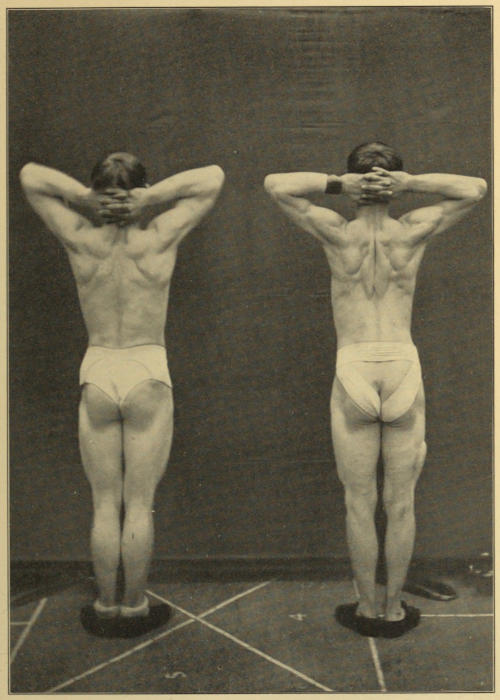

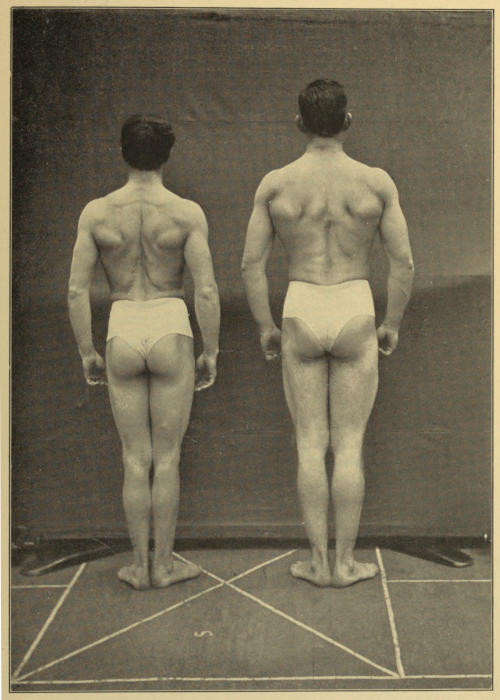

| Back view of Coffman and Steltz | 220 |

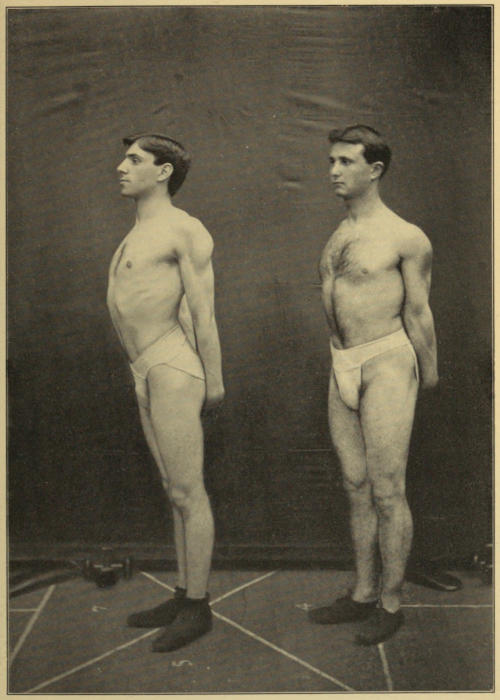

| Side view of Zooman and Cohn | 234 |

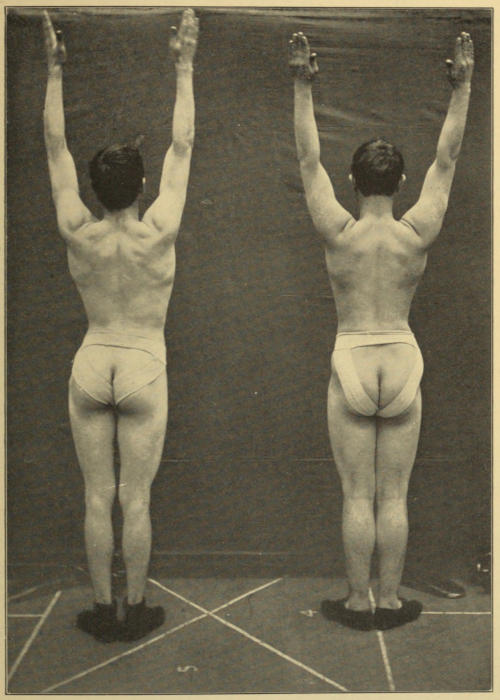

| Back view of Zooman and Cohn | 240 |

| Side view of Loewenthal and Morris | 258 |

| Group of soldiers exercising in the Gymnasium | 262 |

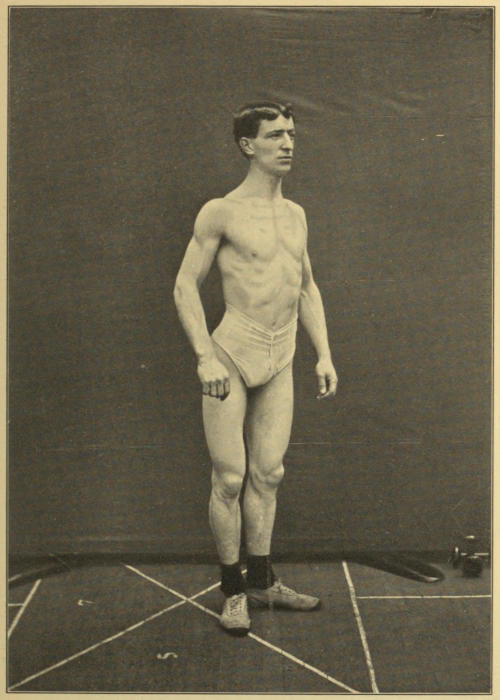

| Front view of Sliney | 272 |

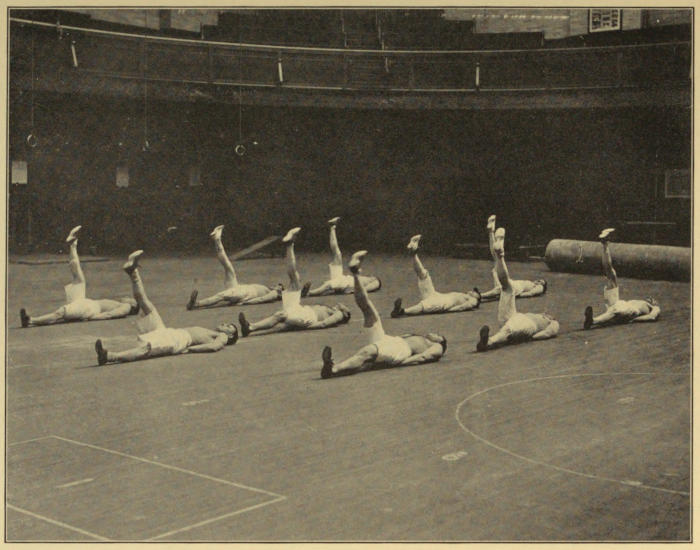

| Soldiers exercising in the Gymnasium | 284 |

| Soldiers exercising in the Gymnasium | 296 |

| Side view of Stapleton | 328 |

| Back view of Stapleton | 366 |

| Front view of W. L. Anderson and Bellis | 440 |

| Back view of W. L. Anderson and Bellis | 442 |

The writer has been most generously aided by substantial grants from the Bache Fund of the National Academy of Sciences, and from the Carnegie Institution of Washington; also by large donations from Mr. Horace Fletcher of Venice, and from Mr. John H. Patterson of Dayton, Ohio. In addition, the War Department of the United States met in large measure the expense of maintaining at New Haven the Detachment of Volunteers from the Hospital Corps of the United States Army, detailed here through the courtesy of Surgeon-General Robert Maitland O’Reilly.

The successful carrying out of the experiments in all their details, especially the chemical work, has been rendered possible by the active and continuous co-operation of the writer’s colleague, Lafayette B. Mendel, Ph.D., Professor of Physiological Chemistry in the Sheffield Scientific School.

Efficient aid in the routine chemical and other work of the laboratory in connection with the experiments has been rendered by Frank P. Underhill, Ph.D., Arthur L. Dean, Ph.D., Harold C. Bradley, B.A., Robert B. Gibson, Ph.B., Oliver E. Closson, Ph.B., and Charles S. Leavenworth, Ph.B.

Dr. William G. Anderson, Director of the Yale Gymnasium, with the co-operation of his assistants, has rendered valuable aid in looking after the physical development of the men[vi] under experiment, in arranging for frequent strength tests, as well as in prescribing the character and extent of their work in the Gymnasium. The greater portion of the training of the soldiers was under the personal supervision of William H. Callahan, M.D., Medical Assistant at the Gymnasium, while Messrs. William Chase, Anton Muller, John Stapleton, and H. R. Gladwin, Assistant Instructors in the Gymnasium, led the drills and looked after the actual muscular training of the men.

In the study of “Reaction Time” and other matters of psychological interest the work was under the direction of Charles H. Judd, Ph.D., in charge of the Yale Psychological Laboratory, aided by Warren M. Steele, B.A., and Cloyd N. McAllister, Ph.D.

In the morphological study of the blood, etc., Dr. Wallace DeWitt, Lieutenant in command of the Army detail, rendered valuable aid. Dr. DeWitt likewise co-operated in all possible ways during his stay in New Haven to maintain the integrity of the conditions necessarily imposed on the soldier detail in an experiment of this character.

Further, acknowledgments are due the several non-commissioned officers of the Hospital Corps for their intelligent co-operation and interest. Finally, to the men of the Hospital Corps who volunteered for the experiment, our thanks are due for their cheerful compliance with the many restrictions placed upon them during their six months’ sojourn in New Haven, and for the manly way in which they conducted themselves under conditions not always agreeable.

To the students of the University who volunteered as subjects of experiment our acknowledgments are due for their intelligent co-operation, keen interest, and hearty compliance with the conditions imposed.

There is no subject of greater physiological importance, or of greater moment for the welfare of the human race, than the subject of nutrition. How best to maintain the body in a condition of health and strength, how to establish the highest degree of efficiency, both physical and mental, with the least expenditure of energy, are questions in nutrition that every enlightened person should know something of, and yet even the expert physiologist to-day is in an uncertain frame of mind as to what constitutes a proper dietary for different conditions of life and different degrees of activity. We hear on all sides widely divergent views regarding the needs of the body, as to the extent and character of the food requirements, contradictory statements as to the relative merits of animal and vegetable foods; indeed, there is great lack of agreement regarding many of the fundamental questions that constantly arise in any consideration of the nutrition of the human body. Especially is this true regarding the so-called dietary standards, or the food requirements of the healthy adult. Certain general standards have been more or less widely adopted, but a careful scrutiny of the conditions under which the data were collected leads to the conclusion that the standards in question have a very uncertain value, especially as we see many instances of people living, apparently in good physical condition, under a régime not at all in harmony with the existing standards.

Especially do we need more definite knowledge of the true physiological necessities of the body for proteid or albuminous foods, i. e., those forms of foods that we are accustomed to speak of as the essential foods, since they are absolutely requisite for life. If our ideas regarding the daily quantities of these foods necessary for the maintenance of health and[viii] strength are exaggerated, then a possible physiological economy is open to us, with the added possibility that health and vigor may be directly or indirectly increased. Further, if through years and generations of habit we have become addicted to the use of undue quantities of proteid foods, quantities way beyond the physiological requirements of the body, then we have to consider the possibility that this excess of daily food may be more or less responsible for many diseased conditions, which might be obviated by more careful observance of the true physiological needs of the body.

First, however, we must have more definite information as to what the real necessities of the body for proteid food are, and this information can be obtained only by careful scientific experimentation under varying conditions. This has been the object of the present study, and the results obtained are now placed before the public with the hope that they will prove not only of scientific interest and value, but that they will also serve to arouse an interest in the minds of thoughtful people in a subject which is surely of primary importance for the welfare of mankind. That the physical condition of the body exercises an all-powerful influence upon the mental state, and that a man’s moral nature even is influenced by his bodily condition are equally certain; hence, the subject of nutrition, when once it is fully understood and its precepts obeyed, bids fair to exert a beneficial influence not only upon bodily conditions, but likewise upon the welfare of mankind in many other directions.

In presenting the results of the experiments, herein described, the writer has refrained from entering into lengthy discussions, preferring to allow the results mainly to speak for themselves. They are certainly sufficiently convincing and need no superabundance of words to give them value; indeed, such merit as the book possesses is to be found in the large number of consecutive results, which admit of no contradiction and need no argument to enhance their value. The results presented are scientific facts, and the conclusions they justify are self-evident.

| Page | |

| Acknowledgments | v |

| Preface | vii |

| Introductory | 1 |

| I. Experiments with Professional Men. |

|

| Chittenden: Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc. | 24 |

| First Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, amount and character of the daily food | 34 |

| Second Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 43 |

| Mendel: Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc. | 53 |

| First Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, amount and character of the daily food | 60 |

| Second Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 67 |

| Underhill: Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc. | 79 |

| First Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, composition of the daily food, etc. | 87 |

| Second Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 93 |

| Dean: Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc. | 98 |

| Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, amount and character of the daily food | 103 |

| Beers: Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc. | 111 |

| First Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, amount and character of the daily food | 114 |

| Second Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 121 |

| Summary of Results; True Proteid Requirements | 127 |

| II. Experiments with Volunteers from the Hospital Corps of the United States Army. |

|

| Description of the Men | 134 |

| Daily Routine of Work | 135[x] |

| Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc., for each of the thirteen men under experiment | 139 |

| Average Daily Output of Nitrogen | 199 |

| Nitrogen Metabolized per kilo of Body-Weight | 201 |

| Changes in Body-Weight during the Experiment | 202 |

| First Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, amount and character of the daily food | 203 |

| Second Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 223 |

| Third Nitrogen Balance, with composition of daily food, etc. | 242 |

| Summary regarding Nitrogen Requirement | 254 |

| Physical Training of the Men—Report by Dr. Anderson of the Yale Gymnasium | 255 |

| Body Measurements | 261 |

| Strength or Dynamometer Tests | 262 |

| Comparison of the Total Strength of the Men at the beginning and end of the Experiment | 274 |

| Reaction Time Experiments—Report by Dr. Judd of the Yale Psychological Laboratory | 276 |

| Character and Composition of the Blood | 283 |

| General Conclusions | 285 |

| Daily Dietary of the Soldier Detail | 288 |

| III. Experiments with University Students, trained in Athletics. |

|

| Consumption of Proteid Food by Athletes | 327 |

| Description of the Men | 329 |

| Daily Record of Nitrogen Excretion, etc., for each of the eight men under Experiment | 332 |

| Average Daily Excretion of Metabolized Nitrogen | 364 |

| Metabolized Nitrogen per kilo of Body-Weight | 365 |

| Daily Diet Prescribed | 366 |

| Nitrogen Balance, with comparison of income and output, and amount and character of the daily food, etc. | 375 |

| The Physical Condition of the Men | 434 |

| Strength or Dynamometer Tests | 436 |

| Report by Dr. Anderson of the Yale Gymnasium | 439 |

| Reaction Time—Report by Dr. Judd of the Yale Psychological Laboratory | 442 |

| General Summary; True Physiological Requirements for Proteid Food | 454[xi] |

| IV. The Systemic Value of Physiological Economy in Nutrition. |

|

| Diseases due to Perversion of Nutrition | 455 |

| Waste Products of Proteid Metabolism may be Dangerous to Health | 456 |

| Origin and Significance of Uric Acid | 458 |

| Modification of Uric Acid Excretion by diminishing the amount of Proteid Food | 463 |

| Tables showing Excretion of Uric Acid by the three groups of men under observation; Uric Acid per kilo of Body-Weight, etc. | 467 |

| V. | |

| Economic and Sociological Importance of the Results | 471 |

| VI. | |

| General Conclusions | 474 |

| VII. | |

| Description of Illustrations | 477 |

Note.—For the benefit of lay readers, metabolism, a word frequently made use of, may be defined as a term applied to the collective chemical changes taking place in living matter. When these metabolic changes are constructive, as in the building up of tissue protoplasm from the absorbed food material, they are termed anabolic; when they are destructive, as in the breaking down of living matter or in the decomposition of the materials stored up in the tissues and organs, they are termed katabolic. Proteid metabolism, or more exactly proteid katabolism, therefore, means the destructive decomposition of proteid or albuminous matter in the living body and is practically synonymous with nitrogenous metabolism, since the entire nitrogen income is mainly supplied by the proteids or albuminous matters of the food. The chief carbon income, on the other hand, is supplied by fats and carbohydrates, such as starches and sugars.

As the result of many years of observation and experiment certain general conclusions have been arrived at regarding the requisite amounts of food necessary for the maintenance of health and strength. Certain dietary standards have been set up which have found more or less general acceptance in most parts of the civilized world; standards which have been reinforced and added to by man’s aptitude for self-indulgence. Carl Voit, of Munich, whose long and successful life as a student of Nutrition renders his conclusions of great value, considers that an adult man of average body-weight (70-75 kilos) doing moderate muscular work requires daily 118 grams of proteid or albuminous food, of which 105 grams should be absorbable, 56 grams of fat, and 500 grams of carbohydrate, with a total fuel value of over 3000 large calories, in order to maintain the body in equilibrium. The Voit standard or daily diet is accepted more or less generally as representing the needs of the body under normal conditions of life, and[2] the conclusions arrived at by other investigators along these same lines have been more or less in accord with Voit’s figures. In confirmation of this statement the following data may be quoted:

AVERAGE DIETS.

| Moleschott. | Ranke.[1] | Forster. | Hultgren[2] and Landergren. | Atwater. | Studemund.[3] | Schmidt.[4] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| grams | grams | grams | grams | grams | grams | grams | |

| Proteid | 130 | 100 | 131 | 134 | 125 | 114 | 105 |

| Carbohydrates | 550 | 240 | 494 | 523 | 400 | 551 | 541 |

| Fats | 40 | 100 | 68 | 79 | 125 | 54 | 63 |

| Fuel value (calories)[5] | 3160 | 2324 | 3195 | 3436 | 3315 | 3229 | 3235 |

In many of these diets it is to be noted that the proteid requirement is placed at even a higher figure than Voit’s standard. Similarly, Erisman, studying the diets of Russian workmen having a free choice of food and doing moderately hard work, found the daily diet to be composed of 131.8 grams of proteid, 79.7 grams of fat, and 583.8 grams of carbohydrate, with a total fuel value of 3675 large calories. Further, Hultgren and Landergren[6] found that Swedish laborers doing hard work had as their daily diet 189 grams of proteid, 110 grams of fat, and 714 grams of carbohydrate, with a total fuel value of 4726 large calories. Voit found that German soldiers on active service consumed daily 145 grams of proteid, 100 grams of fat, and 500 grams of carbohydrate, with a total fuel value[3] of 3574 large calories. Lichtenfelt,[7] studying the nutrition of Italians, states that an Italian laborer doing a moderate amount of work requires 110.5 grams of proteid and a total fuel value for the daily food of 2698 calories, while at hard labor he needs 146 grams of proteid daily, with carbohydrates and fat sufficient to give 3088 large calories. In our own country Atwater,[8] who has made many valuable observations upon the dietetic habits of different classes of people and under different conditions of life, has stated that a somewhat more liberal allowance of proteid would seem desirable, say 125 grams, with a total fuel value of 3500 large calories for a man doing severe muscular labor.

In what is perhaps the latest book on alimentation, Armand Gautier,[9] writing of the French people, states that the ordinary man in that climate needs daily 110 grams of albuminous food, 68 grams of fat, and about 423 grams of amylaceous or saccharine food. It is possible, however, says Gautier, that the quantity of albuminous food can be reduced, if necessary, to 78 grams per day in case a man is not doing work and takes in addition at least 50 grams of fat and 485 grams of carbohydrate food. Where, however, an individual works eight to ten hours a day, the ration, says Gautier, must be increased to at least 135 grams of albuminous food, with 85 to 100 grams of fat, and with from 500 to 900 grams of starchy food.

While these figures may be taken as showing quite conclusively the dietetic standards adopted by mankind, there is no evidence whatever that they represent the real needs or requirements of the body. We may even question whether simple observation of the kinds and amounts of food consumed by different classes of people under different conditions of life have any very important bearing upon this question. They[4] throw light upon dietetic habits, it is true, but such observations give no information as to how far the diets in question serve the real needs of the body. We may find, for example, that under certain given conditions of diet the people in question have the appearance of being well nourished, and that they do their work with apparent ease and comfort; but might not these same results follow with smaller amounts of food? If so, there must of necessity be a certain amount of physiological economy under the more restricted diet, and a consequent ultimate gain to the body through diminished wear and tear of the bodily machinery.

Indeed, experimental work and observations scattered through the last few years have suggested the possibility of much lower standards of diet sufficing to meet the real physiological needs of the body. Thus, Hirschfeld,[10] in 1887, found in experimenting on himself (24 years of age and weighing 73 kilos) that it was possible to maintain nitrogen equilibrium on a diet containing only 5 to 7.5 grams of nitrogen per day, or 35 to 45 grams of proteid, for a period of ten to fifteen days. The amount of non-nitrogenous food consumed, however, was fairly large, especially the amount of butter,—frequently 100 grams a day—the average fuel value ranging from 3750 to 3916 large calories daily. In 1888 Hirschfeld,[11] again experimenting on himself, maintained nitrogen equilibrium for several days on 7.5 grams of nitrogen per day, with fats and carbohydrate sufficient to yield a total fuel value of 3462 large calories as the daily average. The chief criticism of Hirschfeld’s experiments is that he failed to obtain in all cases definite analytical data of the food-stuffs employed and failed to determine the nitrogen of the fæces. Still his results are of value as indicating the possibility of maintaining nitrogenous equilibrium for a brief time at least on a low proteid intake.

Kumagawa,[12] studying especially the diet of the Japanese and experimenting on himself (27 years old and weighing 48 kilos), found with a purely vegetable diet, containing per day 54.7 grams of proteid, 2.5 grams of fat, and 569.8 grams of carbohydrate, that he showed for a period of nine days a plus balance of nitrogen, indicating that his body was laying on about 4 grams of proteid per day. The nitrogen excreted per urine and fæces amounted to 8.09 grams per day, while the nitrogen in the daily food amounted to 8.75 grams. It is interesting to observe in these experiments, as indicating the degree of absorption of the vegetable food (composed in large measure of rice) that the daily average of nitrogen in the urine amounted to 6.069 grams and in the fæces 2.029 grams. In other words, of the 54.7 grams of nitrogen-containing food only 37.8 grams were absorbed, 12.69 grams passing out with the fæces. The total fuel value of the absorbed food per day was 2478 large calories. Similarly, Hirschfeld[13] has called attention to the fact that with many vegetable foods especially, not more than 75 per cent of the ingested proteid can be digested and absorbed, thus emphasizing the necessity of paying heed to the character of the proteid food in considering the nutritive value of a given diet.

In some experiments reported by C. Voit[14] in 1889, on the diet of vegetarians, E. Voit and Constantinidi found that nitrogenous equilibrium was established in one man with about 8 grams of nitrogen, corresponding to 48.5 grams of proteid as the daily diet, with large amounts of starchy foods and some fat. Similarly, Nakahama[15] in the same year, studying the diet (mostly vegetable) and nutritive condition of thirteen German laborers in Leipzig, found that their daily[6] food contained on an average 85 grams of proteid, but Carl Voit criticising these results states that the men were of comparatively light body-weight—about 60 kilos—and not well nourished.

Kellner and Mori,[16] studying the nutrition of a Japanese (weighing 52 kilos and 23 years of age) state that on a purely vegetable diet containing 11.34 grams of nitrogen, of which only 8.58 grams were digested, there was a distinct loss of body-weight, with a daily loss to the body of 1.16 grams of nitrogen. On a mixed diet, however, containing fish, it was possible to establish nitrogenous equilibrium with a daily diet containing 17.48 grams of nitrogen, of which 15.27 grams were digested and utilized. Similarly, Caspari,[17] 29 years old and weighing 66.2 kilos, found that while he could maintain his body in nitrogenous equilibrium on 13.26 grams of nitrogen per day, he could not accomplish it on 10.1 grams of nitrogen, though his daily food contained 3200 large calories.

Other investigators, however, have found no great difficulty in establishing nitrogenous equilibrium in man with much lower quantities of proteid food. Thus, Klemperer[18] found in the case of two young men of 64 and 65.5 kilos body-weight respectively, in an experiment lasting eight days, that nitrogenous equilibrium was established on 4.38 and 3.58 grams of nitrogen per day, but with a daily diet containing in addition to the small amount of proteid 264 grams of fat, 470.4 grams of carbohydrate, and 172 grams of alcohol, with a total fuel value of 5020 large calories.

Peschel,[19] too, has reported experimental results showing that he was able to establish nitrogenous equilibrium for a[7] brief period with 7 grams of nitrogen daily, 5.31 grams appearing in the urine and 1.58 grams in the fæces.

Caspari and Glaessner,[20] in a five-days’ experiment with two vegetarians, found that the wife consumed daily, on an average, 5.33 grams of nitrogen, with fats and carbohydrates to equal 2715 calories, while the man took in 7.82 grams of nitrogen and 4559 calories. Both persons laid on nitrogen in spite of the low intake of proteid food.

Siven’s[21] experiments, however, are perhaps worthy of more careful consideration. Of 60 kilos body-weight and 30½ years of age, his experiments conducted on himself extended through thirty-two days with establishment of nitrogenous equilibrium on 6.26 grams of nitrogen. Moreover, in another experiment he was in nitrogen equilibrium for a day or two at least on 4.5 grams of nitrogen. In Siven’s experiment, the most noticeable feature is the added fact that the total intake of food per day was comparatively low, with a fuel value of only 2444 large calories. In this connection we may call attention to the recent experiments of Landergren,[22] who found with four individuals fed on a daily diet containing only 2.1 to 2.4 grams of nitrogen, but with a large amount of carbohydrate, some fat and alcohol, that on the fourth day of this “specific nitrogen hunger” only 3 to 4 grams of nitrogen were metabolized and appeared in the urine. In other words, a healthy adult man having a sufficient intake of non-nitrogenous food seemingly need not metabolize more proteid than suffices to yield 3 to 4 grams of nitrogen per day.

Such data as these, of which many more might be quoted, surely warrant the question, how far are we justified in assuming the necessity for the rich proteid diet called for by the Voit standard? Voit, however, with many other physiologists[8] would apparently object to any diminution of the daily 118 grams of proteid for the moderate worker, on the ground that an abundance of proteid in the food is a necessity for the maintenance of physical vigor and muscular activity. This view is certainly reinforced by the customs and habits of mankind; but we may well query whether our dietetic habits will bear criticism, and in the light of modern scientific inquiry we may even express doubt as to whether a rich proteid diet adds anything to our muscular energy or bodily strength.

How far can our natural instinct be trusted in the choice of diet? We are all creatures of habit, and our palates are pleasantly excited by the rich animal foods with their high content of proteid, and we may well question whether our dietetic habits are not based more upon the dictates of our palates than upon scientific reasoning or true physiological needs. There is a prevalent opinion that to be well nourished the body must have a large excess of fat deposited throughout the tissues, and that all bodily ills and weaknesses are to be met and combated by increased intake of food. There is constant temptation to increase the daily ration, and there is almost universal belief in the efficacy of a rich and abundant diet to strengthen the body and to increase bodily and mental vigor. Is there any justification for these beliefs? None, apparently, other than that which comes from the customs of generations of high living.

It is self-evident that the smallest amount of food that will serve to keep the body in a state of high efficiency is physiologically the most economical, and hence the best adapted for the needs of the organism. Any excess over and above what is really needed is not only uneconomical, but may be directly injurious. This is especially true of the proteid or albuminous foods. It is, however, quite proper to question whether a brief experiment of a few days in which nitrogenous equilibrium is perhaps established at the low level of 4 to 5 grams of nitrogen, the equivalent of 25 to 35 grams of proteid, is to be accepted as fixing the daily requirements of the healthy man, offsetting the customs or habits of a lifetime. Voit himself,[9] however, has clearly emphasized the general principle that the smallest amount of proteid, with non-nitrogenous food added, that will suffice to keep the body in a state of continual vigor is the ideal diet. Proteid decomposition products are a constant menace to the well-being of the body; any quantity of proteid or albuminous food beyond the real requirements of the body may prove distinctly injurious. We see the evil effects of uric acid in gout, but there are many other nitrogenous waste products of proteid katabolism, which with excess of proteid food are liable to be unduly conspicuous in the fluids and tissues of the body, and may do more or less damage prior to their excretion through the kidneys. Further, it requires no imagination to understand the constant strain upon the liver and kidneys, to say nothing of possible influence upon the central and peripheral parts of the nervous system, by these nitrogenous waste products which the body ordinarily gets rid of as speedily as possible. They are an ever present evil, but why increase them unnecessarily? This question brings us back to the starting-point. What is the minimal proteid requirement for the healthy man, or rather, how far can we safely and advantageously diminish our proteid intake below the commonly accepted standards?

The question of safety is a pertinent one. Thus, Munk[23] some years ago (1893) sounded a warning on this point which was later confirmed by Rosenheim.[24] Both of these observers reported that in dogs fed for some time on a low proteid diet, but with an abundance of carbohydrate and fat, there was after some weeks (6-8) a loss of the power of absorption from the alimentary tract, dependent not alone upon a changed condition of the epithelial cells of the intestine, but also upon a diminished secretion of the digestive juices, loss of body-weight, strength, and vigor, followed speedily by death. If[10] these results were really due to the low proteid diet, they suggest a grave danger which must not be lightly passed by. Jägerroos[25] has likewise observed, experimenting on dogs, that there was, after some months, a striking disturbance of the intestines on a low proteid intake, which, however, was eventually traced to a distinct infection, and probably in no manner connected with the diminished amount of proteid in the diet. In these various experiments on dogs carried out by Munk, Rosenheim, and by Jägerroos, there was of necessity great monotony in the diet, and in Munk’s experiments no fresh meat at all was fed, but simply dried food. In other words, if the diet was in any sense responsible for the poor health of the animals, it is fully as plausible to attribute the results to the abnormal conditions under which the animals were kept as to any specific effect due to the low proteid intake. It is very essential that the food of dogs, as of men, shall fulfil all ordinary hygienic conditions. It must be not only of sufficient quantity for the true needs of the body, but it should also have the necessary variety with reasonable degree of digestibility, and proper volume or bulk. When these qualities are lacking, it is not strange if deviations from the normal gradually develop. That the low intake of proteid food could be responsible for the condition existing in Munk’s and Rosenheim’s experiments is not plausible; a view which is strongly reinforced by many observations, notably those of Albu[26] on a woman thirty-seven years old and weighing 37.5 kilos, who had followed a vegetarian diet for six years, and who while under Albu’s care for two years consumed only 34 grams of proteid per day, the total fuel value of the food being only 1400 calories per day. This woman was in nitrogenous equilibrium on 5.4 grams of nitrogen, and on this diet had freed herself from the illness to which she had long been subject.

Voit’s[27] vegetarian is described by Voit himself as a man twenty-eight years old, weighing 57 kilos, well nourished, with well developed muscles, etc. He had lived on a purely vegetable diet for three years, and was found to be in nitrogenous equilibrium on 8.2 grams of nitrogen. No mention is made of any disagreeable effects connected with this low proteid ration, although persisted in for several years. Jaffa’s[28] experiments and observations on the fruitarians and nutarians of California “showed in every case (two women and three children) that though the diet had a low protein and energy value, the subjects were apparently in excellent health and had been so during the five to eight years they had been living in this manner.” In comparing the income and outgo of nitrogen on a diet composed mainly of nuts and fruits, it was observed in two subjects that 8 grams of nitrogen were sufficient to bring about nitrogen equilibrium, while with two other subjects on a like diet the nitrogen required daily for equilibrium was about 10 grams. The diet used in these experiments, however, was of necessity more or less restricted in variety, and was without doubt somewhat monotonous. Jaffa appears to agree with Caspari that the minimum amount of proteid required daily varies with the individual, and may even vary with the same individual at different times. Further, Jaffa, in harmony with Siven, believes that after the body has suffered a loss of nitrogen, there is at once an effort to attain nitrogenous equilibrium, and that any gain of nitrogenous body material is a comparatively slow process. If this is true, it is obvious that the living substance of the tissue protoplasm must be slowly formed from the proteid of the diet. This, says Jaffa, should serve as a warning to anyone contemplating any appreciable decrease in the proteid of the daily diet.

Another statement made by Jaffa may be quoted in this[12] connection, since it illustrates the attitude taken by many physiologists on this question. “Even if it could be proved,” says Jaffa, “by a large number of experiments that nitrogen equilibrium can be maintained on a small amount of protein, it would still be a great question whether or not it would be wise to do so. There must certainly be a constant effort on the part of the human organism to attain this condition, and with a low protein supply it might be forced to do so under conditions of strain. In such a case the bad results might be slow in manifesting themselves, but might also be serious and lasting. It has also been suggested that when living at a fairly high protein level the body is more resistant to disease and other strains than when the protein level is low.” While these suggestions demand careful consideration, it is equally evident that there is another side to the question, viz., the possible danger to the body from the physiological action of the larger amounts of nitrogenous waste products which result from an excess of proteid food, and which float about through the system prior to their excretion. In addition, we must not overlook the great loss of energy to the body in handling and getting rid of the surplus of unnecessary food of whatever kind introduced into the alimentary tract, to say nothing of the danger of intestinal putrefaction and toxæmia when from any cause the system loses its ability to digest and absorb the excess of food consumed. Further, the possible strain on the kidneys and other organs must not be overlooked. Hence we may well query on which side lies the greater danger. To an unprejudiced observer, one not wedded to old-time tradition, it would seem as if great effort was being made to sustain the claims of a high-proteid intake. It is surely well to be careful, but it is certainly not necessary to magnify imaginary dangers to the extent of suppressing all efforts toward the establishment of possible physiological economy.

In a paper read before the Physiological Section of the British Medical Association in 1901 by Dr. van Someren, claim is made of the existence of a reflex of deglutition, the proper working of which protects from the results of malnutrition[13] by preventing the intake of any excess of food. Thorough mastication and insalivation aid in the more complete utilization of the food and render possible great economy, so that body-weight and nitrogen equilibrium are both maintained on an exceptionally small amount of food. This principle had been worked out by Mr. Horace Fletcher on himself in an attempt to restore his health to a normal condition, with such beneficial results that he was speedily restored to a state of exceptional vigor and well-being. Deliberation in eating, necessitated by the habit of thorough insalivation, it is claimed results in the occurrence of satiety on the ingestion of comparatively small amounts of food, and hence all excess of food is avoided.

In the autumn of 1901, Mr. Fletcher and Dr. van Someren visited the physiological laboratories of Cambridge University, and as stated by Sir Michael Foster[29] the matter was more closely inquired into with the assistance of physiological experts. Observations were carried out on various individuals, and as stated by Professor Foster “the adoption of the habit of thorough insalivation of the food was found in a consensus of opinion to have an immediate and very striking effect upon appetite, making this more discriminating, and leading to the choice of a simple dietary, and in particular reducing the craving for flesh food. The appetite, too, is beyond all question fully satisfied with a dietary considerably less in amount than with ordinary habits is demanded.”... “In two individuals who pushed the method to its limits it was found that complete bodily efficiency was maintained for some weeks upon a dietary which had a total energy value of less than one-half of that usually taken, and comprised little more than one-third of the proteid consumed by the average man.” Finally, says Foster, “it may be doubted if continued efficiency could be maintained with such low values as these, and very prolonged observations would be necessary to establish the facts. But all subjects of the experiments who applied the principles[14] intelligently agreed in finding a very marked reduction in their needs, and experienced an increase in their sense of well-being and an increase in their working powers.”

In the autumn of 1902 and in the early part of 1903, Mr. Fletcher spent several months with the writer, thereby giving an opportunity for studying his habits of life. For a period of thirteen days in January he was under constant observation in the writer’s laboratory, when it was found that the average daily amount of proteid metabolised was 41.25 grams, his body-weight (75 kilos) remaining practically constant. Later, a more thorough series of observations was made, involving a careful analysis of the daily diet, together with analysis of the excreta. For a period of six days the daily diet averaged 44.9 grams of proteid, 38.0 grams of fat, and 253 grams of carbohydrate, the total fuel value amounting to only 1606 large calories per day. The daily intake of nitrogen averaged 7.19 grams, while the daily output through the urine was 6.30 grams and in the fæces 0.6 gram; i. e., a daily intake of 7.19 grams of nitrogen, with a total output of 6.90 grams, showing a daily gain to the body of 0.29 gram of nitrogen, and this on a diet containing less than half the proteid required by the Voit standard and having only half the fuel value of the Voit diet. Further, it was found by careful and thorough tests made at the Yale Gymnasium that Mr. Fletcher, in spite of this comparatively low ration was in prime physical condition. In the words of Dr. Anderson, the Director of the Gymnasium, “the case is unusual, and I am surprised that Mr. Fletcher can do the work of trained athletes and not give marked evidences of over-exertion.... Mr. Fletcher performs this work with greater ease and with fewer noticeable bad results than any man of his age and condition I have ever worked with.”[30] It is not our purpose here to discuss how far these results are due to insalivation, or the more thorough mastication of food. The main point for us is that we have here a striking illustration of the establishment of nitrogen[15] equilibrium on a low proteid diet and great physiological economy as shown by the low fuel value of the food consumed, coupled with remarkable physical strength and endurance.

With data such as these before us we see the possible importance of a fuller and more exact knowledge of true dietary standards. We find here questions suggested, the answers to which are of primary importance in our understanding of the nutritive processes of the body; greater ease in the maintenance of health, increased power of resistance to disease germs, duration of life increased beyond the present average, greater physiological economy and greater efficiency, increased mental and physical vigor with less expenditure of energy on the part of the body. All these questions rise before us in connection with the possibility of maintaining equilibrium on a lowered intake of food, especially nitrogenous equilibrium, with a diminished consumption of proteid or albuminous food. Is it not possible that the accepted dietary standards are altogether too high?

It is of course understood that there can be no fixed dietary standard suitable for all people, ages, and conditions of life. Dietary standards at the best are merely an approximate indication of the amounts of food needed by the body, but these needs are obviously changeable, varying with the degree of activity of the body, especially the amount of physical work performed, to say nothing of differences in body-weight, sex, etc. Further, it is doubtless true that there is what may be called a specific coefficient of nutrition characteristic of the individual, a kind of personal idiosyncrasy which exercises in some degree a modifying influence upon the character and extent of the changes going on in the body. Still, with due recognition of the general influence exerted by these various factors the main question remains, viz., how far the usually accepted standards of diet are correct; or, in other words, is there any real scientific ground for the assumption that the average individual doing an average amount of work requires any such quantity of proteid, or of total nutrients, as the ordinary dietetic standards call for? Cannot all the real physiological[16] needs of the body be met by a greatly reduced proteid intake, with establishment of continued nitrogenous equilibrium on a far smaller amount of proteid food than the ordinary dietary standards call for, and with actual gain to the body?

Just here we may emphasize why prominence is given to the establishment of nitrogenous equilibrium, and why the proteid intake assumes a greater importance than the daily amounts of fat and carbohydrate consumed. Fats and carbohydrates when oxidized in the body are ultimately burned to simple gaseous products, viz., carbonic acid and water. Hence, these waste products are easily and quickly eliminated and cannot exercise much deleterious influence even when formed in excess. To be sure, there is waste of energy in digesting, absorbing, and oxidizing the fats and carbohydrates when they are taken in excessive amounts. Once introduced into the alimentary canal they must be digested, otherwise they will clog the intestine or undergo fermentation, and so cause trouble. Further, when absorbed they may be transformed into fat and deposited in the various tissues and organs of the body; a process desirable up to a certain point, but undesirable when such accumulation renders the body gross and unwieldy. With proteid foods, on the other hand, the story is quite different. These substances, when oxidized, yield a row of crystalline nitrogenous products which ultimately pass out of the body through the kidneys. Prior to their excretion, however, these products—frequently spoken of as toxins—float about through the body and may exercise more or less of a deleterious influence upon the system, or, being temporarily deposited, may exert some specific or local influence that calls for their speedy removal. Hence, the importance of restricting the production of these bodies to the minimal amount, owing to their possible physiological effect and the part they are liable to play in the causation of many diseased conditions. Further, the elimination of excessive amounts of these crystalline nitrogenous bodies through the kidneys places upon these organs an unnecessary burden which[17] is liable to endanger their integrity and possibly result in serious injury, to say nothing of an early impairment of function.

The present experiments were undertaken to throw light upon this broad question of a possible physiological economy in nutrition, and with special reference to the minimal proteid requirement of the healthy man under ordinary conditions of life. The writer as a student of physiology has always maintained that man is disposed to eat far more than the needs of the body require, but his active interest in this problem was aroused especially by his observations of Mr. Fletcher and the marked physiological economy the latter was able to practice, not only without detriment, but apparently with great gain to the body as regards strength, vigor, and endurance, coupled with an apparent resistance to disease. While Mr. Fletcher and Dr. Van Someren would doubtless emphasize the importance of insalivation as a means of controlling the appetite and thereby regulating the consumption of food in harmony with the real needs of the body, it is of primary importance for the physiologist and for mankind to know definitely how far it is possible to reduce the intake of food with perfect safety and without loss of that strength, mental and physical, vigor, and endurance which are characteristic of good health. Further, it is equally plain that if there is possible gain to the body from a practice of physiological economy in diet, we should know how far this can be accomplished by simple restriction in the amount of food without complicating the problem by other factors.

In planning the conduct of this series of experiments the writer has clearly recognized that, while it may be possible, as previous experiments have shown, to maintain body equilibrium and nitrogen equilibrium on a low proteid diet for a brief period, this fact does not, as Munk has previously pointed out, by any means establish the view that such a diet will prove efficient in maintaining equilibrium for a long period, or that bodily strength and vigor can be kept up and the proper resistance to disease secured. Hence, it seemed[18] necessary to so arrange the experiments that they should continue not for a few days or weeks merely, but through months and years. Further, it is very questionable whether the restricted diet (restricted in variety) frequently made use of for convenience in ordinary metabolism experiments is well adapted for bringing out the best results. Hence, it was decided to avoid so far as possible any monotony of diet, giving due recognition to the psychical influences liable to affect secretion, digestion, etc., so admirably worked out by Pawlow in his classical experiments on these subjects; influences which are unquestionably of great importance in controlling and modifying, in some measure at least, the nutritive changes in the body. Again, it is evident that to have experiments of this character broadly useful, they must be tried upon a large number of people and under different conditions of life, in order to avoid so far as possible the influence of personal idiosyncrasy and thereby escape misleading conclusions.

The experiments have been conducted with three distinct types or classes of individuals:

1st. A group of five men of varying ages, connected with the University as professors and instructors; men who while leading active lives have not engaged in very active muscular work. They were selected as representatives of the mental worker rather than the physical worker, although several of them in the performance of their daily duties had to be on their feet in the laboratory a good portion of the day.

2d. A detail of thirteen men, volunteers from the Hospital Corps of the United States Army and representatives of the moderate worker; men who for a period of six months took each week day a vigorous amount of systematic exercise in the gymnasium, in addition to the routine work connected with their daily life as members of the United States Hospital Corps. These men were of different nationalities, ages, and temperaments.

3d. A group of eight young men, students in the University, all thoroughly trained athletes, and some of them with exceptional records in athletic events.

Before proceeding with a detailed account of the experimental work, it may be well again to emphasize that what is especially desired is to ascertain how far, if any, the intake of proteid food can be diminished without detriment to the body, i. e., with maintenance of nitrogen and body equilibrium and without impairment of bodily and mental vigor. Further, if a lower proteid standard than that generally adopted can be established, it is desirable to ascertain whether it can be maintained indefinitely, or for a long period of time, without loss of strength and vigor. Obviously, it is of primary importance that we should know quite definitely what the minimal proteid requirement of the healthy man per kilo of body-weight really is, and the experimental work about to be detailed has aimed especially to determine whether it is possible to materially lower the amount of daily proteid food, without detriment to the bodily health and with maintenance of physical and mental vigor.

The writer, fully impressed with his responsibility in the conduct of an experiment of this kind, began with himself in November, 1902. At that time he weighed 65 kilos, was nearly 47 years of age, and accustomed to eating daily an amount of food approximately equal to the so-called dietary standards. Recognizing that the habits of a lifetime should not be too suddenly changed, a gradual reduction was made in the amount of proteid or albuminous food taken each day. In the writer’s case, this resulted in the course of a month or two in the complete abolition of breakfast, except for a small cup of coffee. A light lunch was taken at 1.30 P. M., followed by a heavier dinner at 6.30 P. M. Occasionally, however, the heartier meal was taken at noontime, as the appetite suggested. It should be added that the total intake of food was gradually diminished, as well as the proteid constituents. There was no change, however, to a vegetable diet, but a simple introduction of physiological economy. Still, there was and is now a distinct tendency toward the exclusion of meat in some measure,[20] the appetite not calling for this form of food in the same degree as formerly. At first, this change to a smaller amount of food daily was attended with some discomfort, but this soon passed away, and the writer’s interest in the subject was augmented by the discovery that he was unquestionably in improved physical condition. A rheumatic trouble in the knee joint, which had persisted for a year and a half and which only partially responded to treatment, entirely disappeared (and has never recurred since). Minor troubles, such as “sick headaches” and bilious attacks, no longer appeared periodically as before. There was greater appreciation of such food as was eaten; a keener appetite and a more acute taste seemed to be developed, with a more thorough liking for simple foods. By June, 1903, the body-weight had fallen to 58 kilos.

During the summer the same simple diet was persisted in—a small cup of coffee for breakfast, a fairly substantial dinner at midday and a light supper at night. Two months were spent in Maine at an inland fishing resort, and during a part of this time a guide was dispensed with and the boat rowed by the writer frequently six to ten miles in a forenoon, sometimes against head winds (without breakfast), and with much greater freedom from fatigue and muscular soreness than in previous years on a fuller dietary. The test of endurance and fitness for physical work which the writer thus carried out “on an empty stomach” tended to strengthen the opinion that it is a mistake to assume the necessity for a hearty meal because heavy work is about to be done. It is certainly far more rational from a physiological standpoint to leave the hearty meal until the day’s work is accomplished. We seemingly forget that the energy of muscular contraction comes not from the food-stuffs present at the time in the stomach and intestinal tract, but rather from the absorbed material stored up in the muscles and which was digested and absorbed a day or two before. Further, it is to be remembered that the very process of digestion draws to the gastro-intestinal tract a large supply of blood, and that a large amount of energy is needed for the processes of secretion, digestion, absorption, and[21] peristalsis, which are of necessity incited by the presence of food in the stomach and intestine, thereby actually diminishing the amount of energy available at the place where it is most needed. Why, then, draw upon the resources of the body just at a time, or slightly prior to the time, when the work we desire to perform, either muscular or mental, calls for a copious blood supply in muscle or brain, and when all available energy is needed for the task that is to be accomplished?

We are too wont to compare the working body with a machine, the boiler, engine, etc., overlooking the fact that the animal mechanism differs from the machine in at least one important respect. When we desire to set machinery in operation we must get up steam, and so a fire is started under the boiler and steam is generated in proportion as fuel is burned. The source of the energy made use of in moving the machinery is the extraneous combustible material introduced into the fire-box, but the energy of muscular contraction, for example, comes not from the oxidizable food material in the stomach, but from the material of the muscle itself. In other words, in the animal body it is a part of the tissue framework, or material that is closely incorporated with the framework, that is burned up, and the ability to endure continued muscular strain depends upon the nutritive condition of the muscles involved, and not upon the amount of food contained in, or introduced into, the stomach. All physiologists will, I think, acknowledge the soundness of this reasoning, but how few of us apply the principle in practice. It is perfectly logical to begin the work of the day with a comparatively empty stomach,—after we have once freed ourselves from the habit of a hearty breakfast,—and in the writer’s experience both mental and physical work have become the easier from this change of habit. The muscle and the brain are given opportunity to repair the waste they have undergone, by the taking of food at times when the digestive processes will not draw upon the energy that in activity is needed elsewhere.

Further, it is easy to understand why on a restricted diet, especially of proteid foods, there should be a diminished sense[22] of fatigue in connection with vigorous or continued muscular work, and why at the same time there should be an increased power of endurance, with actual increase of strength. With a diminished intake of proteid food there is a decreased formation of crystalline nitrogenous waste products, such as uric acid and the purin bases, to say nothing of other bodies less fully known, which circulating through the system are undoubtedly responsible, in part at least, for what we term fatigue. We need not consider here whether the sense of fatigue is due to an action of these substances upon the muscles themselves, upon the motor nerves or their end-plates, or upon the central nervous system; it is enough for the present purpose to emphasize the probable results of their presence in undue amount. Lastly, we may emphasize what is pretty clearly evident to-day, viz., that the energy of muscular contraction comes preferably from the oxidation, not of the nitrogenous or proteid constituents of the muscles, but of the non-nitrogenous components of the tissue; another reason why excess of proteid food may be advantageously avoided. Moreover, proteid food stimulates body metabolism in general, and hence undue amounts of proteid in the diet augment unnecessarily the metabolism or combustion of the non-nitrogenous material of the muscle, thereby destroying what would otherwise be preserved as a source of energy in muscular contraction, when the muscles are called upon for the performance of their daily functions.

On the writer’s return to New Haven in the fall of 1903, he was surprised to find that his body-weight was practically the same as early in July. In the period between November, 1902, and July, 1903, the body had lost 8 kilos under the gradual change of diet, but from July to October, 1903, the weight had apparently remained stationary, from which it might fairly be assumed that the body had finally adjusted itself to the new conditions.

What now was the condition of the body as regards nitrogen metabolism? To answer this question the entire twenty-four hours’ urine was collected practically every day, from[23] October 13, 1903, to June 28, 1904, representing a period of nearly nine months. This daily output through the kidneys was analyzed each day with special reference to the total nitrogen,[31] as a measure of the amount of proteid material metabolized. Total volume of the urine, specific gravity, uric acid, phosphoric acid, indican, and other points were also considered, the more important results being indicated in the following tables.

Scrutiny of the tables shows that during this period of nine months the body-weight was practically constant. The daily volume of urine was exceptionally small and fairly regular in amount, the average daily output for the nine months being 468 c.c. It is a noticeable fact that with a diminished intake of proteid food there is far less thirst, and consequently a greatly decreased demand for water or other fluids. Further, in view of the small nitrogenous waste there is no need on the part of the body for any large amount of fluid to flush out the kidneys. The writer has not had a turbid urine during the nine months’ period. With heavier eating of nitrogenous foods, an abundant water supply is a necessity to prevent the kidneys from becoming clogged, thereby explaining the frequent beneficial results of the copious libations of mineral[31] waters, spring waters, etc., frequently called for after, or with, heavy eating. Obviously, a small volume of urine each day means so much less wear and tear of the delicate mechanism of the kidneys. Somewhat noticeable, in a general way, is the apparent relationship between the volume of the urine and the nitrogen output, in harmony with the well-known diuretic action of urea. The specific gravity of the urine shows variation only within narrow limits, the daily average for the nine months being 1027.

Uric acid is noticeably small in quantity, the average daily output for the nine months’ period, based upon the determinations made, being only 0.392 gram.

Chief interest, however, centres around the figures for total nitrogen, since these figures give for each day the extent of the proteid metabolism; i. e., the amount of proteid material broken down in the body each day in connection with the wear and tear of the bodily machinery. To fully grasp the significance of these data, it should be remembered that the prevalent dietary standards are based upon the assumption that the average adult must metabolize each day at least 16 grams of nitrogen. Indeed, that is what actual analysis of the urine indicates in most cases. If now we look carefully through the figures shown in the above tables, covering a period from October 13, 1903, to June 28, 1904, it is seen that the daily nitrogen excretion is far different from 16 grams. Indeed, the figures for nitrogen are exceedingly low, and, moreover, they vary little from day to day. The average daily output of nitrogen through the urine for the entire period of nearly nine months is only 5.699 grams.

For the first six months the average daily excretion amounted to 5.82 grams of nitrogen, while from April 12 to June 28 the average daily excretion of nitrogen was 5.40 grams, thus showing a slight tendency downward. On the whole, however, there is shown a somewhat remarkable uniformity in the daily excretion. Thus, the average daily excretion for the month of November was 5.79 grams of nitrogen, for the month of March 5.66 grams, thus showing very little[32] difference in the output of nitrogen through the kidneys in these two periods, three months apart. In other words, the extent of proteid katabolism was essentially the same throughout the entire nine months, implying that the amount of proteid food eaten must have been fairly constant, and that the body had adapted itself to this new level of nutrition from which there was no tendency to deviate. There was no weighing out of food and no attempt to follow any specified diet. The greatest possible variety of simple foods was indulged in, and the dictates of the appetite were followed with the single precaution that excess was avoided. In other words, it was temperance in diet, and not prohibition. Yet it is equally true, in the writer’s case at least, that the appetite itself unconsciously served as a regulator, since there was, as a rule, no necessity to hold the appetite in check to avoid excess. Doubtless, the writer’s knowledge of the general composition of food-stuffs has had some influence in the choice of foods, and thereby aided in bringing about this somewhat remarkable uniformity in the daily output of nitrogen for such a long period of time on an unrestricted diet.

What now do the nitrogen figures show regarding the amount of proteid material metabolized each day? It will be remembered that the Voit standard calls for 118 grams of proteid or albuminous food daily, of which 105 grams should be absorbable, in order to maintain the body in a condition of nitrogen equilibrium, and in a state of physical vigor and general tone. This would mean a daily excretion through the urine of at least 16 grams of nitrogen. The daily output of nitrogen in the case under discussion, however, was 5.699 grams for a period of nearly nine months. This amount of nitrogen excreted through the urine means only 35.6 grams of proteid metabolized, or about one-third the amount called for by the Voit standard, or the standards generally adopted as expressing man’s daily requirement of proteid food. But was the body in nitrogenous equilibrium on this small amount of proteid food? Naturally, this question might be answered in the affirmative, on the basis of the constancy in body-weight[33] for the period from October to June, but more decisive proof is needed. The question was therefore settled by a careful comparison of the income and output, in which all the food eaten was carefully weighed and analyzed, while the nitrogen of the urine and fæces was determined with equal accuracy. The first experiment of this character to be quoted is for the week commencing March 20, a period of six days.

Following are the diets made use of each day, the weights of the various food-stuffs being given in grams. Likewise is shown the nitrogen content of the several food-stuffs for each day, and also a comparison of the nitrogen intake with the output of nitrogen through the urine:

Sunday, March 20, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—One cup coffee, i. e., coffee 137.5 grams, cream 30.5 grams, sugar 9 grams.

Dinner, 1.30 P. M.—Stewed chicken 50 grams, mashed potato 131 grams, biscuit 49 grams, butter 13 grams, chocolate pudding 106 grams, one small cup coffee, i. e., coffee 64 grams, sugar 12 grams, cheese crackers 29 grams.

Supper, 6.30 P. M.—Lettuce sandwiches 56 grams, biscuit 35 grams, butter 6 grams, one cup tea, i. e., tea 170 grams, sugar 7 grams, sponge cake 47 grams, sliced oranges 82 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 64 + 137 = | 201.5 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.085 | gram. |

| Cream | 30.5 | × | 0.41 | = | 0.125 | ||

| Sugar | 12 + 9 + 7 = | 28.0 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Chicken | 50.0 | × | 4.70 | = | 2.350 | ||

| Mashed potato | 131.0 | × | 0.30 | = | 0.393 | ||

| Biscuit | 35 + 49 = | 84.0 | × | 1.49 | = | 1.251 | |

| Butter | 13 + 6 = | 19.0 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.019 | |

| Chocolate pudding | 106.0 | × | 0.86 | = | 0.911 | ||

| Cheese crackers | 29.0 | × | 2.54 | = | 0.737 | ||

| Lettuce sandwich | 56.0 | × | 0.92 | = | 0.515 | ||

| Tea | 170.0 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.082 | ||

| Sponge cake | 47.0 | × | 0.98 | = | 0.461 | ||

| Sliced orange | 82.0 | × | 0.073 | = | 0.060 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.989 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.910 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1708 calories.[32] |

Monday, March 21, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—Coffee 119 grams, cream 30 grams, sugar 9 grams.

Lunch, 1.30 P. M.—One shredded wheat biscuit 31 grams, cream 116 grams, wheat gems 33 grams, butter 7 grams, tea 185 grams, sugar 10 grams, cream cake 53 grams.

Dinner, 6.30 P. M.—Pea soup 114 grams, lamb chop 24 grams, boiled sweet potato 47 grams, wheat gems 76 grams, butter 13 grams, cream cake 52 grams, coffee 61 grams, sugar 10 grams, cheese crackers 16 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 119 + 61 = | 180 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.076 | gram. |

| Cream | 30 + 116 = | 146 | × | 0.41 | = | 0.600 | |

| Sugar | 9 + 10 + 10 = | 29 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Shredded wheat biscuit | 31 | × | 1.62 | = | 0.502 | ||

| Tea | 185 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.089 | ||

| Wheat gems | 33 + 76 = | 109 | × | 1.46 | = | 1.591 | |

| Butter | 7 + 13 = | 20 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.020 | |

| Cream cake | 53 + 52 = | 105 | × | 0.97 | = | 1.018 | |

| Pea soup | 114 | × | 1.00 | = | 1.140 | ||

| Lamb chop | 24 | × | 4.54 | = | 1.090 | ||

| Sweet potato | 47 | × | 0.18 | = | 0.085 | ||

| Cheese crackers | 16 | × | 2.54 | = | 0.410 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.621 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.520 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1713 calories. |

Tuesday, March 22, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—Coffee 97 grams, cream 26 grams, sugar 9 grams.

Lunch, 1.30 P. M.—Baked potato 83 grams, fried sausage 36 grams, soda biscuit 39 grams, butter 12 grams, tea 137 grams, sugar 10 grams, cream meringue 59 grams.

Dinner, 6.30 P. M.—Chicken broth 146 grams, bread 52 grams, butter 15 grams, creamed potato 76 grams, custard 76 grams, coffee 50 grams, sugar 11 grams, cheese crackers 10 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 97 + 50 = | 147 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.060 | gram. |

| Cream | 26 | × | 0.42 | = | 0.109 | ||

| Sugar | 9 + 10 + 11 = | 30 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Baked potato | 83 | × | 0.40 | = | 0.332 | ||

| Fried sausage | 36 | × | 3.06 | = | 1.101 | ||

| Soda biscuit | 39 | × | 1.66 | = | 0.647 | ||

| Butter | 12 + 15 = | 27 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.027 | |

| Tea | 137 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.066 | ||

| Cream meringue | 59 | × | 0.92 | = | 0.543 | ||

| Chicken broth | 146 | × | 0.78 | = | 1.138 | ||

| Bread | 52 | × | 1.66 | = | 0.863 | ||

| Creamed potato | 76 | × | 0.42 | = | 0.319 | ||

| Custard | 76 | × | 0.82 | = | 0.623 | ||

| Cheese crackers | 10 | × | 2.54 | = | 0.254 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.082 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.940 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1398 calories. |

Wednesday, March 23, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—Coffee 103 grams, cream 30 grams, sugar 10 grams.

Lunch, 1.30 P. M.—Creamed codfish 64 grams, potato balls 54 grams, biscuit 44 grams, butter 22 grams, tea 120 grams, sugar 10 grams, wheat griddle cakes 133 grams, maple syrup 108 grams.

Dinner, 6.30 P. M.—Creamed potato 85 grams, biscuit 53 grams, butter 15 grams, apple-celery-lettuce salad 50 grams, apple pie 127 grams, coffee 67 grams, sugar 8 grams, cheese crackers 17 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 103 + 67 = | 170 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.071 | gram. |

| Sugar | 10 + 10 + 8 = | 28 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Cream | 30 | × | 0.43 | = | 0.129 | ||

| Potato balls | 54 | × | 0.68 | = | 0.367 | ||

| Creamed codfish | 64 | × | 1.26 | = | 0.806 | ||

| Biscuit | 44 + 53 = | 97 | × | 1.66 | = | 1.610 | |

| Butter | 22 + 15 = | 37 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.037 | |

| Tea | 120 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.058 | ||

| Wheat griddle cakes | 133 | × | 1.32 | = | 1.760 | ||

| Maple syrup | 108 | × | 0.019 | = | 0.021 | ||

| Creamed potato | 85 | × | 0.53 | = | 0.450 | ||

| Cheese crackers | 17 | × | 2.54 | = | 0.431 | ||

| Apple-celery salad | 50 | × | 0.20 | = | 0.100 | ||

| Apple pie | 127 | × | 0.75 | = | 0.953 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.793 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.610 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1984 calories. |

Thursday, March 24, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—Coffee 100 grams, cream 25 grams, sugar 8 grams.

Lunch, 1.30 P. M.—Shredded wheat biscuit 29 grams, cream 118 grams, wheat gems 60 grams, butter 8 grams, tea 100 grams, sugar 7 grams, apple pie 102 grams.

Dinner, 6.30 P. M.—Milk-celery soup 140 grams, bread 15 grams, butter 1 gram, lettuce sandwiches 62 grams, tea 100 grams, sugar 10 grams, lemon pie 109 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 100 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.042 | gram. | |

| Cream | 25 + 118 = | 143 | × | 0.43 | = | 0.615 | |

| Sugar | 8 + 7 + 10 = | 25 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Shredded wheat biscuit | 29 | × | 1.76 | = | 0.510 | ||

| Wheat gems | 60 | × | 1.17 | = | 0.702 | ||

| Butter | 8 + 1 = | 9 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.009 | |

| Tea | 100 + 100 = | 200 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.096 | |

| Apple pie | 102 | × | 0.75 | = | 0.765 | ||

| Milk-celery soup | 140 | × | 0.42 | = | 0.588 | ||

| Bread | 15 | × | 1.36 | = | 0.204 | ||

| Lettuce sandwich | 62 | × | 1.02 | = | 0.632 | ||

| Lemon pie | 109 | × | 0.82 | = | 0.894 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 5.057 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 4.310 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1594 calories. |

Friday, March 25, 1904.

Breakfast, 7.45 A. M.—Coffee 100 grams, cream 25 grams, sugar 9 grams.

Lunch, 1.30 P. M.—Halibut with egg sauce 108 grams, mashed potato 89 grams, biscuit 48 grams, butter 10 grams, chocolate-cream cake 90 grams, tea 100 grams, sugar 9 grams.

Dinner, 6.30 P. M.—Milk-celery soup 121 grams, lettuce sandwiches 61 grams, creamed potato 65 grams, lettuce-apple-celery salad 74 grams, coffee 70 grams, sugar 10 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 100 + 70 = | 170 | × | 0.042 | = | 0.071 | gram. |

| Cream | 25 | × | 0.40 | = | 0.100 | ||

| Sugar | 9 + 9 + 10 = | 28 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Halibut, etc. | 108 | × | 3.02 | = | 3.262 | ||

| Mashed potato | 89 | × | 0.26 | = | 0.231 | ||

| Biscuit | 48 | × | 1.52 | = | 0.730 | ||

| Butter | 10 | × | 0.10 | = | 0.010 | ||

| Tea | 100 | × | 0.048 | = | 0.048 | ||

| Chocolate-cream cake | 90 | × | 0.99 | = | 0.891 | ||

| Celery-milk soup | 121 | × | 0.52 | = | 0.629 | ||

| Lettuce sandwich | 61 | × | 0.98 | = | 0.598 | ||

| Lettuce-apple salad | 74 | × | 0.21 | = | 0.155 | ||

| Creamed potato | 65 | × | 0.37 | = | 0.241 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.966 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.390 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1285 calories. |

NITROGEN BALANCE.—Chittenden.

| Nitrogen Taken in. |

Output. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nitrogen in Urine. | Weight of Fæces[33] (dry). | ||||||

| March | 20 | 6.989 | grams. | 5.91 | grams. | 3.6 | grams. |

| 21 | 6.621 | 5.52 | 0.0 | ||||

| 22 | 6.082 | 5.94 | 12.0 | ||||

| 23 | 6.793 | 5.61 | 18.5 | ||||

| 24 | 5.057 | 4.31 | 23.0 | ||||

| 25 | 6.966 | 5.39 | 16.9 | ||||

| 74.0 | grams contain 6.42% N. |

||||||

| 38.508 | 32.68 | + | 4.75 | grams nitrogen. | |||

| 38.508 | grams nitrogen. | 37.43 | grams nitrogen. | ||||

| Nitrogen balance for six days | = | +1.078 | grams. |

| Nitrogen balance per day | = | +0.179 | gram. |

Average Intake.

| Calories per day | 1613. |

| Nitrogen per day | 6.40 grams. |

Examination of the results shown in the foregoing balance makes it quite clear that the body was essentially in nitrogenous equilibrium. Indeed, there was a slight plus balance, showing that even with the small intake of proteid food the body was storing up nitrogen at the rate of 0.16 gram per day. The average daily intake of nitrogen for the six days’ period was 6.40 grams, equal to 40.0 grams of proteid or albuminous food. The average daily output of nitrogen through the urine and fæces was 6.24 grams. The average daily output of nitrogen through the urine for the six days’ period was 5.44 grams, corresponding to the metabolism of 34 grams of proteid material. When these figures are contrasted with the usually accepted standards of proteid requirement for the healthy man, they are certainly somewhat impressive, especially when it is remembered that the body at that date had been in essentially this same condition for at least six months, and probably for an entire year. The Voit standard of 118 grams of proteid, with an equivalent of at least 18 grams of nitrogen and calling for the metabolism of 105 grams of proteid, or 16.5 grams of nitrogen per day, makes clear how great a physiological economy had been accomplished. In other words, the consumption of proteid food was reduced to at least one-third the daily amount generally considered as representing the average requirement of the healthy man, and this with maintenance of body-weight at practically a constant point for the preceding ten months, and, so far as the writer can observe, with no loss of vigor, capacity for mental and physical work, or endurance. Indeed, the writer is disposed to maintain that he has done more work and led a more active life in every way during the period of this experiment, and with greater comfort and less fatigue than usual. His health has certainly been of the best during this period.

In this connection it may be well to call attention to the completeness of the utilization of the daily food in this six days’ experiment, as shown by the small amount of refuse discharged per rectum, indicating as it does the high efficiency of the digestive processes and of the processes of absorption.[42] The refuse matter for the entire period of six days amounted when dry to only 74 grams, and when it is remembered how large a proportion of this refuse must of necessity be composed of the cast-off secretions from the body, it will be seen how thorough must have been the utilization of the food by the system. The loss of nitrogen to the body per day through the fæces amounted to only 0.79 gram, and this on a mixed diet containing considerable matter not especially concentrated, and on some days with noticeable amounts of food, such as salads, not particularly digestible.

Finally, emphasis should be laid upon the fact that this economy of proteid food, this establishment of nitrogen equilibrium on a low proteid intake, was accomplished without increase in the daily intake of non-nitrogenous foods. In fact, the amount of fats and carbohydrates was likewise greatly reduced, far below the minimal standard of 3000 calories as representing the potential energy or fuel value of the daily diet. Indeed, during the balance period of six days just described the average fuel value of the food per day was only a little over 1600 calories.

As the experiment continued and the record for the months of April and May was obtained, it became evident from the nitrogen results that the rate of proteid katabolism was being still more reduced. A second balance experiment was therefore tried with a view to seeing if the body was still in nitrogen equilibrium, and also to ascertain whether the fuel value of the food still showed the same low calorific power. For a period of five days, June 23 to 27, the intake of food and the entire output were carefully compared, with the results shown in the accompanying tables.

Thursday, June 23, 1904.

Breakfast.—Coffee 123 grams, cream 50 grams, sugar 11 grams.

Lunch.—Omelette 50 grams, French fried potatoes 70 grams, bacon 10 grams, wheat gems 43 grams, butter 9 grams, strawberries 125 grams, sugar 20 grams, cream cake 59 grams.

Dinner.—Beefsteak 34 grams, peas 60 grams, creamed potato 97 grams, bread 26 grams, butter 17 grams, lettuce-orange salad 153 grams, crackers 43 grams, cream cheese 15 grams, coffee 53 grams, sugar 12 grams.

| Food. | Grams. | Per cent Nitrogen. | Total Nitrogen. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coffee | 123 + 53 = | 176 | × | 0.045 | = | 0.079 | gram. |

| Cream | 50 | × | 0.35 | = | 0.175 | ||

| Sugar | 11 + 20 + 12 = | 43 | × | 0.00 | = | 0.000 | |

| Omelette | 50 | × | 1.32 | = | 0.660 | ||

| French fried potatoes | 70 | × | 0.37 | = | 0.259 | ||

| Bacon | 10 | × | 3.43 | = | 0.343 | ||

| Wheat gems | 43 | × | 1.49 | = | 0.641 | ||

| Butter | 9 + 17 = | 26 | × | 0.13 | = | 0.034 | |

| Strawberries | 125 | × | 0.11 | = | 0.138 | ||

| Cream cake | 59 | × | 0.98 | = | 0.578 | ||

| Beefsteak | 34 | × | 4.14 | = | 1.408 | ||

| Peas | 60 | × | 0.97 | = | 0.582 | ||

| Creamed potato | 97 | × | 0.34 | = | 0.330 | ||

| Bread | 26 | × | 1.23 | = | 0.320 | ||

| Lettuce-orange salad | 153 | × | 0.15 | = | 0.230 | ||

| Crackers | 43 | × | 1.40 | = | 0.602 | ||

| Cream cheese | 15 | × | 1.62 | = | 0.243 | ||

| Total nitrogen in food | 6.622 | grams. | |||||

| Total nitrogen in urine | 5.260 | ||||||

| Fuel value of the food | 1863 calories. |

Friday, June 24, 1904.

Breakfast.—Coffee 96 grams, sugar 8 grams, milk 32 grams.

Lunch.—Creamed codfish 89 grams, baked potato 95 grams, butter 10 grams, hominy gems 58 grams, strawberries 86 grams, sugar 26 grams, ginger snaps 47 grams.