Title: The girls of Rivercliff School; or, Beth Baldwin's resolve

Author: Amy Bell Marlowe

Illustrator: Walter S. Rogers

Release date: December 5, 2022 [eBook #69478]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Grosset & Dunlap, 1916

Credits: David Edwards, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

By AMY BELL MARLOWE

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated. Price per volume,

60 cents, postpaid

THE OLDEST OF FOUR

Or Natalie’s Way Out

THE GIRLS OF HILLCREST FARM

Or the Secret of the Rocks

A LITTLE MISS NOBODY

Or With the Girls of Pinewood Hall

THE GIRL FROM SUNSET RANCH

Or Alone in a Great City

WYN’S CAMPING DAYS

Or The Outing of Go-Ahead Club

FRANCES OF THE RANGES

Or The Old Ranchman’s Treasure

THE GIRLS OF RIVERCLIFF SCHOOL

Or Beth Baldwin’s Resolve

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

Mabel Poured from a Waste-basket a Veritable

Shower of Small Parcels

“SHAME! SHAME!” CRIED A DOZEN VOICES.

Frontispiece (Page 150)

THE GIRLS OF

RIVERCLIFF

SCHOOL

OR

BETH BALDWIN’S RESOLVE

BY

AMY BELL MARLOWE

AUTHOR OF

A LITTLE MISS NOBODY, THE GIRLS OF

HILLCREST FARM, ETC.

Illustrated

NEW YORK

GROSSET & DUNLAP

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1916, by

GROSSET & DUNLAP

The Girls of Rivercliff School

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | “The Grapes that Hang High” | 1 |

| II. | Larry’s “Coming Out” Party | 11 |

| III. | Great-Grandmother Lomis’ Corals | 23 |

| IV. | The Sacrifice | 32 |

| V. | The “Water Wagtail” | 40 |

| VI. | An Adventure in Midstream | 48 |

| VII. | Cynthia Fogg | 61 |

| VIII. | Queer Talk | 68 |

| IX. | Rivercliff Landing | 74 |

| X. | A New World | 91 |

| XI. | “The Glass of Fashion” | 102 |

| XII. | Finding Her Place | 111 |

| XIII. | The Sunny Side | 123 |

| XIV. | A Great Deal to Learn | 133 |

| XV. | The Red Masque | 142 |

| XVI. | No Martyr’s Crown | 152 |

| XVII. | Flint and Steel | 162 |

| XVIII. | Another Barrier | 171 |

| XIX. | Mr. Dennis Montague | 181[vi] |

| XX. | Something Unexpected | 191 |

| XXI. | The Burial of Friendship | 204 |

| XXII. | A Renewed Resolve | 211 |

| XXIII. | Suspicion Hovers | 225 |

| XXIV. | The Traitor’s Blow | 235 |

| XXV. | Before the Judgment Seat | 242 |

| XXVI. | Rounding Out Another Year | 249 |

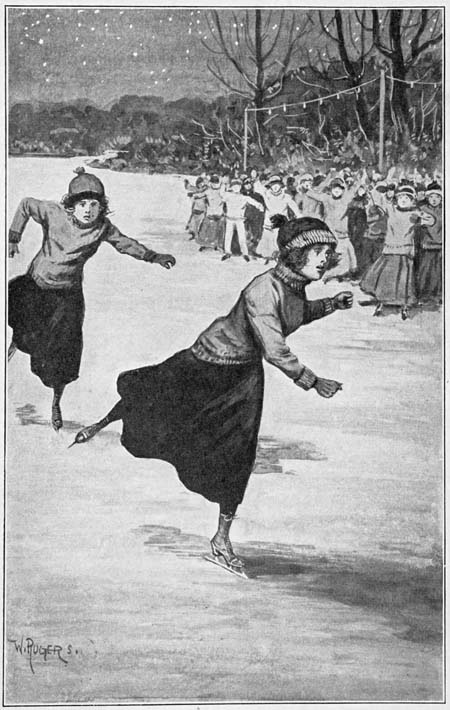

| XXVII. | The Ice Carnival | 258 |

| XXVIII. | Miss Freylinghausen | 274 |

| XXIX. | The “Perfect Number” in Aunts | 283 |

| XXX. | Vocational | 301 |

THE GIRLS OF RIVERCLIFF SCHOOL

“Beth! Beth Baldwin! Oh, B. B.! Do, for pity’s sake, stop! Do you expect me to chase you all over town such a hot day as this? It’s cruelty to animals to make me run in this awful sun,” and Mary Devine finally reached Elizabeth Baldwin’s side, and clung to her school friend’s arm, panting.

“Cruelty to how many animals, Mary?” asked Beth, laughing. “Are you a whole menagerie? You remind me of our Marcus when he was a little fellow. There was a ‘cat concert’ in our back yard one night, and Marcus put his head out of the door to see the participants.

“‘Oh, Mamma!’ he called, ‘there’s a million cats out here,’ and when mamma reproved him for exaggerating, he defended himself by saying: ‘Well, anyway, there’s our old cat and another one!’”

Mary had regained her breath now, and giggled over Beth’s little story, but was not to be sidetracked.[2] She had something to tell. News was Mary Devine’s over-mastering passion. To know what went on all over Hudsonvale, and to distribute her information generously, “free, gratis, for nothing,” was the height of her enjoyment.

Mr. Baldwin said one evening, after Mary had been calling on Beth: “They did think some of starting a local paper here in Hudsonvale; but they heard of that Devine girl and gave it up. No need of a newspaper with her in town.”

Now Mary gasped to her friend:

“Oh, Beth! I’ve got something to tell you. You’d never guess!”

“That’s good of you, dear,” Beth said, her black eyes dancing. “I hate conundrums. Tell me.”

“Larry Haven has hired an office in the Hudsonvale block.”

“Why, Mary! that certainly is news,” Beth cried. “I never would have guessed that. Has he hung out his shingle?”

“He’s going to,” declared Mary, who knew all about it, for her father was janitor of Hudsonvale’s one brick office building. “He’s taken the room next to Dr. Coldfoot’s, the dentist’s, suite. Larry told father that the screams of the dentist’s patients would not bother him, for he expected his clients would scream quite as loud when he separated[3] them from their money,” and Mary giggled again. “And oh, Beth! he’s just as handsome!”

“Who is—Dr. Coldfoot?” asked her friend, innocently.

“Goodness no! You are well aware, Beth Baldwin, that I meant the village pride, Mr. Lawrence Haven, just returned from the law school with his sheepskin.”

Beth laughed again. “I do hope he’ll be successful,” she said. “His father was a prominent lawyer, you know.”

“Goodness! I hope he can dance,” responded Mary. “There’s a great dearth of good dancers among the boys here in Hudsonvale. You know, Beth, at graduation last month we girls had to dance together at our party. Oh dear! I wish we were going to have it over again! What fun!”

“Larry Haven is no longer a boy,” Beth said slowly.

Mary laughed. “Of course not. He’s an old man,” she said saucily. “He’s twenty-two.”

“That is seven years our senior,” said Beth, reflectively.

“Six, in my case, if you please,” said Mary, smartly. “And what’s six years in a boy? He could be a lawyer forty times over and I wouldn’t be afraid of him.”

[4]“You have more assurance than most, Mary,” said Beth, smiling. “I don’t know that I shall dare even speak to Larry now.”

“Humph! you and he used to be as ‘sticky’ on each other as two molasses cocoanut balls—you know you used. He was the white-headed little boy who used to pull you to school on his sled,” said Mary, airily.

“But that was a long time ago,” said Beth, with laughter. “I haven’t seen Larry since last winter’s holidays—and then scarcely more than to wave my hand to him. He’s grown quite away from us Hudsonvale girls and boys since his sophomore year at college.”

“My! how he did puff himself and walk turkey his first two years at college,” said the slangy Mary. “The only boy from Hudsonvale who ever went to a real, big school, I guess.”

“But Larry wasn’t spoiled,” Beth hastened to say. “He’s so sweet-tempered.”

“Oh! you know how sweet he is if anybody does,” chuckled Mary. “Well! I must turn off here. Where are you going, Beth?”

“Just across town on an errand,” her friend said evasively; for it was the gossipy girl’s nature to repeat to the next person she talked with anything she had learned from her previous companion, no matter how trivial.

[5]“Not that I would mind if the whole town knew I was going to old Mrs. Crummit’s for a dozen fresh eggs,” thought Beth, with inward laughter. “But I do wish Mary Devine was not such a ‘Babbling Bess.’”

The girl’s mind, however, was filled with thoughts springing from the bit of news her school friend had told her. She and Mary had but recently graduated from the high school. And Larry Haven, the only son of the widowed Mrs. Euphemia Haven, had recently returned to his home with his diploma as a lawyer. Beth knew he had already been admitted to the county bar.

Beth’s mother and Euphemia Griswold had been bosom friends in girlhood. At first, after Euphemia Griswold had married Mr. Haven, the leading lawyer of the county and a scion of one of the oldest, if not one of the wealthiest, families in the State, she and Priscilla Baldwin, who had married a foreman in the Locomotive Works, remained very good friends.

The Haven baby carriage was often pushed along the pleasantly shaded walks of Hudsonvale side by side with the more plebian carriage containing the Baldwins’ first little one, who later had died. The two young women remained inseparable friends for some years.

Then had come the death of her first child, and[6] for a long period of time after this Mrs. Baldwin mingled but little with her friends. This was followed by a long illness. But, after a few years, Beth, now the oldest of her brood, came to give the foreman’s wife a new and better interest in life.

Meanwhile, her old-time chum had grown away from her. Mr. Haven had become a corporation lawyer and was fast growing rich. He and his family had always had entrance into the most exclusive society of the State. Had he not died suddenly when Larry was ten years old, he might have been a national figure in politics.

In dying, he had left Mrs. Euphemia Haven and her only child fairly well-to-do. The property had to be conserved with some shrewdness, perhaps; but the widow lived in one of the finest old houses in Hudsonvale, entertained well, and seemed to have everything her heart desired. Larry was given an excellent education; and it was understood that he was to follow in his father’s footsteps, for he must earn his own living now that he was of age, his mother having full rights in the property as long as she lived.

Mrs. Haven was not a snob. Although now the acknowledged leader of such society as there was in Hudsonvale (which was really a sprawling river-town surrounding the Locomotive Works[7] and coal-tar Dye Factory), she had often come to see her old friend, Mrs. Baldwin, while Larry was still small. So it was that the soft-spoken, gentle boy, with the watchful gray eyes and firm mouth, came to be a companion of Beth Baldwin’s while she was little.

He took her to school on her first day; and sat beside her and held her plump little hand for an hour, too, because she was afraid. He had drawn Beth to school on his sled, as Mary Devine said. Larry was as much at home in the Baldwin house when a child as he was in his own. Perhaps more at home, for there was more gaiety in the little cottage on Bemis Street, which soon began to be crowded with young life after Beth was born.

There was Marcus, two years Beth’s junior; Ella, now a flyaway child of eleven; Prissy—named after her mother—as sweet and loving as a child could be; and Fred and Ferd, the twins, six years old. They had all looked on Larry Haven as almost an elder brother.

For two years, however, as Beth had intimated to Mary Devine, Larry had not been much at the Baldwin home. Indeed, he had been in Hudsonvale but seldom. His summers had been spent in preparing for the law school, for he was very desirous to get ahead. His exceeding industry had brought results. He was a very young man, indeed,[8] to have succeeded in securing his diploma and entering upon public life as he now had.

As Beth Baldwin went her way, these thoughts weaved through her mind. And, too, she compared her own lot to that of her whilom playmate and confidant. When Beth learned that Larry was to go to college and finally enter the law school, she had expressed her intention of getting the maximum amount of education to be secured by a girl—and Larry had encouraged her to try for it.

Beth had stood well in her classes all through her high-school course. She had graduated among the first ten pupils in the class. She possessed a deep longing to continue her course. But——

“There’s about as much chance of my going to Rivercliff as there is of my getting an aeroplane and soaring in it to the Heights of Parnassus,” Beth told herself, with a little laugh and a little sigh. She was not of a melancholy disposition, and even the seriousness of her desire to learn and to achieve, in her way, as much as Larry had achieved in his, could not make her gloomy.

Mr. Baldwin earned three dollars and seventy-five cents a day as foreman of the erecting shop in the Hudsonvale Locomotive Works. The family had often “figured and refigured” that sum; but they could not make it come to more than twenty-two dollars and fifty cents a week.

[9]Marcus, although but thirteen, was already talking bravely about going to work. In another half year he could get his certificate and become an aid in the family’s support.

“While I,” thought Beth, shaking her head, “am desirous of adding to its burdens for three years to come. But then—if I only could—I know I could pay them all back,” she sighed.

It was Beth’s desire to take a normal and teacher’s course in a very thorough boarding school up the river. Having a diploma from Rivercliff would enable her to obtain a certificate to teach in the State schools. That was her aim—to be self-supporting, as well as to obtain an education the equal of that Larry Haven had secured.

She had surreptitiously dipped into Larry’s college textbooks when he was at home during his freshman and sophomore years, and she was sure that such studies were not beyond her comprehension.

“Dear me,” thought Beth, “the grapes that hang highest are always the sweetest. How am I ever going to get admission to Rivercliff School; or, once admitted, how am I to remain there the necessary three years? Dear me! if Larry——”

Just then she looked up before crossing the street and gazed directly into the calm, rather proud face of Larry’s mother who, in her little[10] electric runabout, was just drawing in to the opposite curb.

Mrs. Euphemia Haven was tall, of good figure, with beautiful hair, beginning to be touched with gray, that her maid dressed more becomingly than was any other woman’s hair in Hudsonvale. She had a good complexion, with a tinge of natural pink in the cheeks and lips. Her teeth were even and white, without the defects of gold showing the handiwork of the dentist. She dressed exquisitely, Beth thought.

Mrs. Haven drove her runabout with the assurance of a boy. She had steady nerves, a cordial laugh, a smile that was charming, and knew always how to put one at his ease. She beckoned now to Beth as the latter crossed the street, crying:

“Elizabeth! Beth! Come here, please! You are just the person I must see.”

Mrs. Euphemia Haven was very careful in her choice of words. Not that her diction was better or worse than most people’s; but she was very exact in saying just what she meant to say.

Instead of calling to Beth Baldwin that she “wished” to see her or “needed” to see her, she said “I must.” Behind that expression lay a rather sharp controversy between her son, Larry, and herself at the breakfast table that very morning. It was seldom that there was any friction at all between Mrs. Haven and her son, for she was a very indulgent mother and Larry was quite unspoiled, despite every chance in the world for his having been so affected.

She never interfered with his pleasures, seldom with his associates, and never balked his plans. He, on the other hand, never gave his mother a moment’s uneasiness, for she was assured that he was a Haven and would do nothing to smirch the family name.

Mrs. Haven did not blame her son for having[12] been so friendly with the family on Bemis Street. She, herself, had loved Priscilla Lomis with all her rather narrow heart when they were young. That Priscilla had married a mechanic was her mistake; and Mrs. Euphemia had condoned that mistake for years. But now she had to think of her son’s future. There were some past associations which she felt might better be ignored by him now that he was a man. The silly plans in her own and Priscilla Baldwin’s heads when they were young married women, each with a brand new baby to think of and talk about, Mrs. Haven long since had thought best forgotten.

She feared, however, that Priscilla might have remembered. Of course, that first dear little girl baby of her old friend’s had died; but here was another girl born into the family of the mechanic——

“And goodness!” thought Mrs. Haven, as Beth Baldwin crossed the street and drew near at her call, “what a perfect little beauty she is growing to be!”

Mrs. Euphemia Haven was one of those women who manage a lorgnette very well indeed. She caught it up now and looked at Beth through it—not because she really needed this aid to sight, but to cover a sudden slight confusion that she felt.

[13]“Mercy, Beth! how really pretty you have grown!” was her first audible comment. “And what a big girl! The other day you were only a little thing and Larry was playing nurse-girl to you. I expect he remembers you now as the little black-eyed tot he used to be so devoted to.”

“I presume so, Mrs. Haven,” replied Beth, composedly.

“Why, you must be through school,” went on Mrs. Haven. “Are you working or do you help your mother?”

“It is work helping in a family of eight, Mrs. Haven,” laughed Beth. “I have finished high school. But I hope to go to a more advanced school in the fall.”

“That will be rather difficult, will it not?” suggested Mrs. Haven, with raised eyebrows.

Beth knew that it was an intimation that Mrs. Haven fully understood the Baldwin’s financial circumstances. It was not said unkindly; yet, somehow, Beth felt that it was antagonistic. Her pretty head came up and she looked rather proudly into the fine eyes of Larry’s mother.

“Yes; it will be very difficult,” she admitted. “But I mean to get a better education if I have to earn the money myself to pay my way through school.”

“Dear me!” said Mrs. Haven, smiling. “What[14] a very determined girl! But—in your case, my dear—is an advanced education really worth while?”

“I think it is,” and this time Beth flushed. She recognized the critical note in her questioner’s voice, and she knew what it meant. “Don’t you think it was worth while for Larry to go to college?”

“Oh!” ejaculated the startled lady. “He—he is a boy.”

“And I am a girl,” Beth laughed. “But I think I have just as much ambition as any boy.”

The lady laughed too, and said:

“That brings me to the reason I had for hailing you, my dear. Now that Larry is home for good I want to give him a nice party. The young folk of Hudsonvale, I am afraid, have almost forgotten him. And, too, he is ambitious to take his father’s place in the community as a lawyer. We must introduce him to the older generation likewise. So, when we were talking it over this morning, he remembered you and told me to be sure to invite ‘that little Baldwin girl.’ Why!” and Larry’s mother laughed easily, as though she did not know she had conveyed a sting, “he will scarcely know you, you have grown so.”

“How kind of him to remember me,” Beth said sweetly.

[15]“Oh, Larry has always looked upon you as a little sister, I fancy—having been denied any of his own. Now, you will come, of course? Next Tuesday evening. There will be dancing.”

Mrs. Haven had managed to make Beth feel that she was being patronized; but the girl was too sensible to take offence. She believed Larry had really said that he wanted her at his party, and she would not disappoint her old playfellow.

“I will surely come, Mrs. Haven. Thank you,” she said, as the lady’s car started.

As Beth told her mother when she arrived home with the eggs, she had nothing but her graduation dress to wear to Larry’s “coming out” party, as Beth laughingly designated it, and that frock had been made with the view to its being her “best-Sunday-go-to-meeting” attire for two years to come. A new dress was an event in the Baldwin household.

“It’s not just the thing for an evening party, Mamma,” she said cheerfully. “But we’ll make it do.”

“I really would like to have you look your best when you go to Euphemia Haven’s,” Mrs. Baldwin answered.

“Of course! I shall scrub my face real clean and comb all the tangles out of my hair, Mother mine,” laughed Beth. “Why strive to amaze Mrs.[16] Haven with my fine appearance more than anybody else?”

“Why? Oh well! I want her to see what a very nice girl you are.”

“Thank you, Mamma! She has already told me I am pretty,” and Beth made a little face at the thought of Mrs. Euphemia Haven’s patronizing way.

Nevertheless, Beth had a desire to look her best if she attended the “coming out” party. But she wished to astonish another person rather than the rather haughty Mrs. Euphemia Haven.

That dress had to be thought about—and there were only four days before the date of the party. Beth was glad she had worn it only on graduation day. It would not be familiar to anybody but her classmates; and she fancied that if any of them were at Larry’s party they would be likely to appear in their graduation dresses, too. For Hudsonvale was not a very fashionable place.

The frock in question was of a good quality of cream-colored poplin—then a very popular fabric. It had been made high in the neck, for low-cut frocks for day wear were not approved in Hudsonvale. Evening wear was different. Decolleté was expected of any one who was invited to an evening party.

For a girl of her age Beth Baldwin’s taste was[17] admirable. Yet, because of her complexion, she could “carry off” oddities in style and colorings that scarcely any other girl in the village would have dared attempt.

She was handy, too, with her needle, and she decided to make some changes and adapt her dress for evening wear. She removed the long sleeves, and her mother gave her the lace out of her own wedding gown—so long laid away in camphor—with which she fashioned a soft, full, puff-like sleeve which reached only half way to her elbow. After removing the collar and the vest of the frock, she filled in over the shoulders and across the bust with some of the same pretty lace. Between the lace and the material of the dress she put beading, and in this she ran narrow cherry-colored ribbon. She put a rosette on each shoulder, a large one with streamers over her heart, other ribbons with very tiny rosettes to tie the puff-like sleeves, and made ready a sash of broad ribbon of the same hue.

The effect might be a trifle bizarre; but it was very becoming, indeed, to Beth, and when she put on the frock Monday evening and “tried it out” on the family, they thought her charming.

“Some class to you,” said the slangy Marcus. “Cricky! you’re the niftiest looking girl in the town—isn’t she, Pop?”

[18]“She’s what her mother was over again,” said Mr. Baldwin, proudly, lowering his paper to “peck” at his pretty daughter’s cheek.

“Oh, Mamma! I don’t see why you didn’t have me a dark and delirious beauty,” groaned Ella, “instead of a washed-out, flaxen-haired, inconsequential looking little dowdy! I hate to go anywhere with our Beth; she makes me look like just nothing.”

The family laughed at the flyaway’s plaint, and Ella added:

“Anyway, I hope Beth will get married long before I get any beaux. I know I couldn’t keep ’em a minute if they came here and saw Beth.”

“Mercy, Ella!” gasped her mother. “What are you talking about—a child of eleven?”

Mr. Baldwin laughed heartily. He usually did at his flaxen-haired daughter’s nonsense. But Ella added:

“I don’t care, Mamma. It should be against the law for one sister to be so much prettier than the others. Poor little Prissy and me—why, we haven’t any chance at all!”

“‘Handsome is as handsome does,’ daughter,” quoted Mrs. Baldwin, contemplating her eldest child with her head on one side.

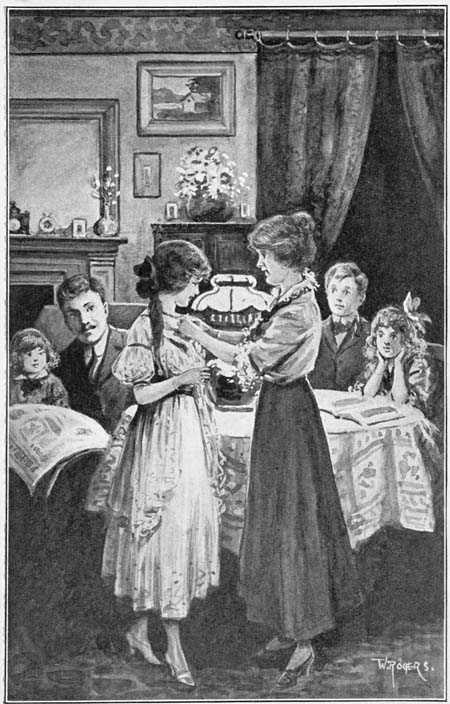

SHE SNAPPED THE BEAUTIFULLY CARVED NECKLACE

AROUND BETH’S THROAT.

Page 21.

“Oh, yes! that’s what Mr. Monkey said to the poor little Hippopotamus baby. He found little[19] Hippo crying beside a still pool,” said the vivacious Ella, “and asked him what the matter was.

“‘Oh, nuffin,’ said the Hippo, ‘only I never saw myself in a mirror before!’

“And, of course, Mr. Monkey said just what you did now, Mamma. But poor little Hippo knew that he couldn’t act handsome enough in a thousand years to overcome the handicap of the awful looks Nature had given him.”

Through the laughter of Mr. Baldwin and Marcus, Ferd, the blond twin, spoke up stoutly:

“I don’t care if they do call me ‘Blondy.’ I wouldn’t be black, like Fred.”

“I’m certainly glad I’m a bruin, like our Beth,” said his twin, loftily.

“‘Bruin!’”

“A bear that boy certainly is!”

“Goodness, Frederick,” said Ella, amid the laughter of the family. “You mean brunette.”

Fred did not take laughter kindly. “I know what I mean,” he growled. “I’m glad my complexion is like Beth’s.”

“Goodness, it isn’t!” cried the flyaway sister, suddenly. “You haven’t washed your face since supper, Frederick Baldwin! Come out to the kitchen sink with me this very minute!”

Mrs. Baldwin had left the room while this conversation was in progress. Now she returned[20] with a little square box that the children seldom saw. It was usually locked away in the safe in the bedroom occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin.

“Oh, Mamma!” gasped Beth, suspecting what was coming.

“Hello, Mother!” said Mr. Baldwin, with twinkling eye. “Getting out the ‘family jewels?’”

“Oh, Mamma!” shrieked Ella, racing in from the kitchen, dragging Fred with one hand and waving the washcloth in the other like a very limp banner. “Not Great-grandmother Lomis’ corals?”

Beth flushed and paled, her eyes shining like stars as she watched her mother unlock the little box with the key that always hung about her neck under her gown. Great-grandmother Lomis’ corals was the one heirloom that had been handed down to Mrs. Baldwin’s generation. They were as precious in the eyes of her daughters as the Queen of Sheba’s pearls.

“You’re never going to let me wear those to Larry’s ‘coming out’ party?” Beth finally gasped.

Her mother’s face was serious. “You are the eldest, my dear. The corals will be yours some day—yours to do with just what you please. Great-grandmother Lomis declared in her will that the corals should always be given to the eldest daughter, and from her to her eldest daughter.[21] This is an entail that the male heirs have nothing to do with,” and she laughed.

“They may be sold or otherwise disposed of for the benefit of the eldest daughter of each generation. If Beth wants to wear them to Euphemia’s—— There!”

She snapped the thin, beautifully carved, blood-red necklace around Beth’s throat. The deeper hue of the corals contrasted beautifully with the brighter ribbons, and against the dark loveliness of Beth’s skin the necklace had never shone to better advantage.

There was a pin, too; and Mrs. Baldwin swiftly snipped off the big rosette at Beth’s bosom and caught the filmy lace together there with the beautiful pin instead.

The corals set off the girl’s beauty wonderfully. There was an alluring, Eastern quality to it that now, enhanced by the old-fashioned jewelry, made Beth seem more mature than she really was.

Yet she was only a simple, sweet child, after all. She possessed a better figure than most girls of her age, and had a demure, self-possessed manner that might have led strangers to think her older than she was. In mind and heart, however, though thoughtful to a degree, Beth was a child.

“That’s mighty scrumptious—that’s what I call it,” declared Marcus.

[22]Perhaps Mr. Baldwin thought so too; for the next evening, when Beth was ready to start for the Haven house, a taxicab stopped at the door.

“Papa Baldwin! What extravagance!” exclaimed his wife.

“It’s not considered quite the thing, I believe,” he said drily, “for a young lady to walk to a party wearing three or four hundred dollars’ worth of jewelry.”

Not until then did Mrs. Baldwin wonder if she were doing wrong to allow Beth to wear the family heirloom. But it was too late to say no. Beth kissed her hand to the watching family from the taxicab—the man shut the door, and in a moment the machine rolled away from the little cottage on Bemis Street.

Beth Baldwin felt that this was really her first “grown-up” party. She knew that few of the girls who had graduated with her from high school had been invited to the Haven house on this evening; and few of the younger guests would be brought to the door, she was likewise sure, in any vehicle. There were but four taxicabs in the town.

Beth knew that to the very nicest parties in town most people went afoot, carrying their dancing slippers under their arms. But now the girl was set down before the Haven door, under an awning and on a well-worn strip of carpet, both of which led up to the wide-open and brilliantly lighted doorway of the mansion.

The Haven place was a fine old house; there was none better for the purpose of entertaining in town. Almost the whole of the lower floor could be used for dancing. The broad stairway, bordered by potted plants, offered plenty of “nestling corners” for tired dancers; palms hid the rear of the reception hall where the musicians were stationed.[24] Already, when Beth timidly entered, the lights, the moving couples, the tinkle of music, the murmur of voices, were quite confusing.

She saw Mrs. Euphemia Haven’s stately figure just within the drawing-room doorway. A few couples swung in time to the music across the hall in the huge dining-room, from which all the furniture had been taken. There were people going up and down the stairway whom she had never even seen before. She had not stopped to think until now that, after all, Larry Haven lived in a world quite apart from the Baldwins.

Her mother’s very good cravanette hid Beth’s frock from throat to slippers. She wore no head-covering save the waves of her pretty black hair. For Beth was one of those fortunate girls who possess soft looking, wavy hair, adaptable to any style of hair-dressing.

She was directed to the dressing rooms above, and mounted the stairs. There a maid showed her to one of the large bedrooms, now set apart for the women to use as a dressing room.

Five minutes later Beth descended the stairway. She saw at its foot a group of people looking up at her. Mrs. Haven was not one of them. Indeed, Beth thought she knew none of the group—at least, none of the women.

She imagined that they were whispering about[25] her. The suspicion heightened the color in her cheeks; but she could not afford to be panic-stricken now. Beyond this group—wavering a little in her sight because Beth saw her through a mist—she knew Mrs. Haven stood.

She stepped from the lower tread of the stairway, and—— Who was this who met her, both hands outstretched, lips smiling, gray eyes dancing? Such a tall young man, strikingly handsome, Beth thought, in his evening clothes, his shock of straw-colored hair brushed back from his brow, giving him a remarkably wide-awake appearance.

“Larry!” she said, almost in a whisper, giving him her hands.

“You howling little beauty!” he responded, in a tone equally confidential. “Mother did not prepare me for this change. Goodness, Beth! you’ve grown up!”

“No, no. But you have,” she said, flutteringly.

He laughed. Then he tucked Beth’s plump little hand under his arm and led her into the drawing-room.

“Mater,” he said, for she chanced to be alone at the moment, “I introduce you to the ‘belle of the ball.’ What do you know about our little ‘Saint Elizabeth?’ Hasn’t she grown up?”

“Mercy, child!” murmured Mrs. Haven, and the lorgnette came into play to rescue her from absolute[26] confusion. “I told you, Larry, how really pretty she had grown. In a few years, Beth, you will set the young men’s hearts aflame. Introduce her to some of the others—do, Larry. So she will not feel lonesome,” and the lady patted Beth’s arm with her lorgnette.

“And your Great-grandmother Lomis’ corals. I always envied your mother those beauties,” said the matron. “But I had no idea Priscilla had kept them all these years.”

“Why,” gasped Beth, finally stung to self-defense, “they are heirlooms!”

“Oh—yes—of course,” Mrs. Haven said. “But it isn’t every one who can afford to keep heirlooms, you know.”

Beth felt the sting in every word Larry’s mother uttered. She knew Mrs. Haven was antagonistic to her. Why?

“Do introduce her to some of the young folk, Larry,” his mother said impatiently.

“Not till I’ve danced once with her myself, Mater,” said the young man, laughing. “I can see plainly that if I don’t take my chance to do so right now, I’m likely to have none. Our little Beth is going to cut a wide swath to-night.”

“Mercy!” murmured his mother. “What are these children coming to?”

“You must not treat me as though I were grown[27] up, Larry,” Beth said, laughing, as the orchestra struck up again.

“Know this?” he asked quickly.

“Oh, yes,” said Beth, glad she had learned some of the new steps.

“Then come on—and tell me all about yourself while we dance,” Larry rejoined.

“Oh no! You are the interesting subject just now. Think! a full-fledged lawyer,” she told him.

“Yes—‘full-fledged,’ indeed,” he agreed. “And likely to get well plucked the first time I appear in court.”

“Does the thought of your first case scare you?” she asked roguishly.

“No. The fear that there won’t be a first case is what is troubling me. They tell me fledgling lawyers sometimes starve to death and are swept up with the dust in their offices and thrown out.”

“I’ll have Mary Devine watch over you. Her father is janitor of the block, you know. If you are seen to become emaciated, we will try to smuggle you in some food,” laughed Beth.

“I don’t know how long I shall be at it,” the young man said, with more seriousness; “but I mean if possible to make the name of Haven known—and respected—as it used to be among the ‘legal lights.’”

“Oh, I hope so, Larry!” she declared, with[28] warmth. “We all at our house will ‘boost’ for you.”

“And all the kids are well?” he asked, looking down at her with frank admiration.

“Lovely. And fast growing up. You should see Ella! She is going to be a regular ash-blonde.”

“I never did fancy light-complexioned people,” said Larry, laughing at her. “You suit me, Beth.”

“‘Thank you kindly, sir, she said,’” returned Beth, courtesying. “But remember, please, that my mother considers me a child.”

“Pooh! pooh! and a couple of fudges! You are a stunner, Beth.”

“I am a schoolgirl; you must not turn my head with compliments.”

“Got through the high, Elizabeth?” he asked.

“Yes.”

“And going in for the higher-ed., of course?”

“Just as sure—as sure!” she said firmly. “I don’t know just how, yet; but I mean to go to Rivercliff in the autumn.”

“Whew! That’s some school. I met some girls at college who had been there. Co-eds, you know.”

“Nice girls?”

“Awfully nice,” he declared. “They took two years at Rivercliff after high and then came to college. But the full course up there would put[29] you ahead a whole lot, Beth. These girls I speak of were preparing for particular lines of work. If a girl wanted to be a teacher——”

“That is my goal, Larry,” Beth interrupted, so earnestly that she missed her step. “I must be a teacher. You know—papa isn’t rich. We have to scrimp a good deal. If I could teach I could help a lot.”

“Sure you could,” he agreed, with answering enthusiasm. “And, besides, a girl doesn’t get anywhere at all now if she hasn’t a pretty good education. You know how it is—a fellow likes to talk to a girl that can discuss the same things he can, and discuss them intelligently. Why, Beth,” and he laughed, “our great-grandmothers, who only knew how to sew and knit and bake and be domestic, would never get a chance to marry nowadays.”

“What nonsense you talk,” said Beth, dimpling. “Papa says that the nearest way to a man’s heart is through his stomach. I fancy that not all young men of our generation are dyspeptic and have to live on predigested health foods.”

“That is all right,” Larry said seriously. “But a fellow can hire a cook. He wants a wife who can be his mental companion.”

“Good-ness me!” drawled Beth. “Hear the boy! When are you going to get married, Larry Haven? How soon?”

[30]“Just as soon as I find the right girl,” he returned, laughing at her.

“Do you expect her to starve to death in your law offices, too?” she demanded, quizzically.

The question brought him to a stop. He gazed down at her for a moment. “Got me there, Elizabeth—got me there,” he admitted. “I didn’t think of that. She will have to be supported—the future Mrs. Haven—won’t she?”

“And a cook hired for her, too,” Beth responded wickedly. “By the time you are able to do that, Larry Haven, on your income as an attorney, I shall be principal of a young ladies’ seminary at five thousand a year.”

He laughed delightedly. She was just as bright as he remembered her to have been when she was little.

He handed her over to Major Whipple after this dance. The major, although a bachelor of over fifty, still possessed a discriminating eye for beauty. And he could dance well, too. Beth was enjoying herself. Larry did not let her sit idle a single dance. And the boys, young men, middle-aged men, were all ready to be partners with her.

Larry said to his mother: “What did I tell you, Mater? Beth is the belle of the evening.”

“You will turn that child’s head, Larry. I warn you,” his mother said seriously.

[31]“Well! she talks a whole lot more sensibly than most of the young women I have talked with this evening,” he declared.

“Ah! she is wiser than I thought,” murmured Mrs. Haven. “And I would like to own those corals of her Great-grandmother Lomis.”

“But why did she try to make me appear so young?” Beth asked her mother, as they sat side by side busily sewing the afternoon following Larry’s party. “Really, I felt hurt. I cannot understand Mrs. Haven.”

Mrs. Baldwin looked at her eldest daughter thoughtfully—as though, however, her mind were a great way off.

“Why did she, Mother?” repeated Beth.

“I can understand Euphemia,” said Mrs. Baldwin, quietly. “You must not mind her, my dear.”

“But I cannot see why she wants me to seem childish, even if you do, Mother mine,” the girl said, somewhat impatiently.

“I fear one meaning is, that Euphemia feels that Larry would better remember you only as his playfellow when he, too, was a child,” Mrs. Baldwin said. “He is a man now, you know, and must have a man’s feelings as he has a man’s duties to perform.”

“Why, what nonsense, Mother!” exclaimed the[33] girl, throwing back her head and laughing delightedly. “He is only a great, big boy—that’s all Larry Haven is.”

Mrs. Baldwin shook her head, gravely. “You do not understand the difference between fifteen and twenty-two,” she said.

“Yes, Ma’am, I do,” the girl responded smartly. “I know my arithmetic. It’s seven years—just seven years, Mother mine.”

“That is not the real difference, Beth,” her mother pursued. “The difference is not to be measured by time——”

“No! One would think it were eternity to hear you,” laughed Beth.

Her mother laughed too; yet she was more serious than Beth could see any occasion for.

“There is a freshness and a boyishness about young men—and some men when they become older—that make them seem less mature than quite young girls,” Mrs. Baldwin said, finding it a little difficult to impress her daughter with the change in her whilom playmate.

“Larry Haven has stepped over the line from boyhood to manhood, whether you realize it or not, Beth. There is a vast difference now between you two. You look forward to study and the acquirement of text-book knowledge——”

“Oh! how much!” murmured Beth.

[34]“While he looks back upon his school course. The difference between knowledge wished for, and knowledge attained, is vast. It isn’t measured by mere time, as I said before. It is a difference in the attitude of one’s mind toward most things in the world. However much Larry may seem just the same as he used to be, he is not the same. He is a man grown, and you are only a girl.”

“Oh, Mamma! That is a sharp one,” said Beth, laughing placidly. “I really can’t see that being fifteen instead of twenty-two makes much difference between Larry and me. I can still make him say just the thing I want him to say—I always could. And I can still get the best of him in an argument.”

Mrs. Baldwin had to laugh, although it was not a very cheerful laugh. “Your being able to argue did not come from your studies in school, child, that is sure. You have always been good at that. You would argue now that you and Larry were equal.”

“Oh! I realize our inequality, Mamma,” Beth said sadly. “It’s the difference in our education, not our ages, that troubles me. He may be only a boy, but he’s got something in his head that I haven’t. And oh, Mamma! I want it so!”

“My dear girl!”

“I know. It is wicked, but I must say it. I[35] told Larry last night that I meant to go to Rivercliff this September. And I mean to! It seems to me that I would sacrifice almost anything for the chance to go there. I must go!”

“My dear!”

“Yes. It sounds dreadful, doesn’t it? I just get desperate when I think of how badly I want to learn. And if I don’t become a teacher, what is to become of me? Am I to go into the dye factory to earn my living? Dear Mother! I must earn my living somehow. The children are getting bigger, and need more and more. They must be educated, too. If I could get my teacher’s certificate in three years I could help you all.”

“I know—I know, child,” said her mother. “You would help us if you could.”

“Now I’ve made you cry! I’m so sorry! Do forgive me! But it isn’t that I would help the family if I could. It is that I must! Don’t you see it, Mamma? Papa is getting no younger. Already Marcus talks of going to work. Am I better than my brother? The family needs my help as much as it needs his. And I should be able to do more than he.”

“But, my dear——” cried Mrs. Baldwin, surprised by the girl’s earnestness. She began to doubt if her daughter was quite as childish as she had supposed.

[36]“At least,” went on Beth, ignoring her mother’s half-spoken protest, “you must let me go to work this summer to see if I can earn enough, somehow, to pay for my first half, if no more, at Rivercliff.”

“And what after that, daughter?” asked Mrs. Baldwin.

“I don’t know. I am reckless—or inspired!” and Beth laughed shakingly. “A way may be opened. I’ll take a chance.”

“Where can you get work for the summer?” her mother asked gravely.

“Well—I would go into the factory for a short time——”

“Oh, no! what would Larry say? You cannot do that,” her mother cried, with an energy that quite surprised Beth.

“Indeed!” sniffed the girl. “I guess you mean, what would Larry’s mother say? I am not beholden to Mrs. Haven.”

“No,” said Mrs. Baldwin, seriously. “But you would not wish to offend Larry’s mother.”

Beth showed herself puzzled. “Why, not deliberately,” she said. “Of course not. Nor Larry either. But why worry about them more than our other friends? Lots of folks who know us, and in no better circumstances than we are, either, will turn up their noses at me if I go to work in the dye factory. But you know how it is,[37] Mamma. A position in a store or an office is awfully hard to find in Hudsonvale. You wouldn’t want me to go to a summer hotel to be a waitress or a chambermaid?”

“Mercy me, Beth! What are you thinking of?” almost screamed Mrs. Baldwin.

“I’m thinking of making money to pay for my schooling at Rivercliff,” laughed her daughter. “I’ve read of lots of girls who earn their tuition fees by doing those things.”

“But you!”

“Who am I?” asked Beth. “Better than other girls? You’ve taught me to sweep, to dust, to make beds, and to be tidy.”

“Oh, yes,” Mrs. Baldwin hastened to say. “Every girl should learn the domestic duties.”

Beth began to giggle at that. “Larry says not. He’s going to hire a cook when he gets married. He forgets that the cook may leave suddenly. I believe they have a way of doing that.”

“For goodness’ sake!” gasped her mother. “What didn’t you and Larry talk about last night?”

“Why—lots of things. We didn’t have much time to really talk. We’ll wait till he comes here to see us to have a really old-fashioned confab together,” Beth said laughing. “But he’s a funny boy!”

[38]“I tell you he is a boy no longer,” Mrs. Baldwin said, a little worried.

“Oh, wait till you see him. He’s just the same old sixpence of a Larry. You’ll see, Mamma. But he is handsome in his dress suit. Doesn’t look at all like an undertaker.”

Mrs. Baldwin, shaking her head, rejoined:

“For you to go to work at any domestic service is out of the question. And your father would never hear to your working in the factory.”

“What shall I do then, Mamma? Peddle? Be an agent? Go from house to house and try to make people buy what they don’t want and don’t need and really would be better off without?” and Beth laughed gaily. “Or shall I go right out with a mask and a club and become a highway robber?”

Her mother had to laugh again at this suggestion. Really, Beth was practical in her ideas. “Much more so than most girls of her age,” thought the troubled mother, with a sigh.

She could not but be impressed with the earnestness of Beth’s desire for an education. She had already had quite as much schooling as Mrs. Baldwin—and Mrs. Euphemia Haven—had been given when they were girls.

“But the world is different now,” sighed the foreman’s wife. “And more is expected of girls. If Euphemia——”

[39]She did not finish her speech—there were some things she could not admit even to herself. But the next afternoon she dressed herself and went out. “Calling,” she told the curious girls. But she refused to say on whom she was to call.

After a sleepless night Mrs. Baldwin had made up her mind that Beth should have her desire if it were possible. By a sacrifice that she could not bring herself to tell even Mr. Baldwin about, she would raise sufficient money to pay for Beth’s first year at Rivercliff. She was quite sure Euphemia Haven would buy her Grandmother Lomis’ corals. For years she had wanted them. And Euphemia would give four hundred dollars for them.

“It is Beth’s sacrifice, not mine,” the mother thought, wiping her eyes before she mounted the walk to the Haven mansion. “And it is to benefit Beth. I am sure the child would rather have a year at school than the jewelry.”

She rang the bell and was admitted by the butler.

“I obtained the money from a friend. Payment of the loan need not be considered until your education at Rivercliff is finished, Beth. This sum will carry you through your first year in comfort. Meanwhile, as you say yourself, a way may be opened for you to continue your course there. ‘Sufficient unto the day.’ Ask no questions.”

Thus said Mrs. Baldwin, in family assembled, when the outcry was made regarding the suddenly and mysteriously acquired funds with which Beth was to storm the heights of Rivercliff School.

Mr. Baldwin looked at his wife oddly, but he asked no question—then or at any subsequent time. When Mrs. Baldwin was as firm as she looked now, the others dared not be inquisitive.

But as delighted as Beth was at the sudden opening of her prospects, she felt that a sacrifice of some kind had been made. She feared her mother and father had done some hard thing for which they might be troubled all through her school years. She had no suspicion of the truth—not for a moment.

[41]“But I will learn from other girls at school how to earn money to pay my way. And I’ll pay mamma back, too,” Beth thought, with but faint appreciation, after all, of how huge a sum four hundred dollars is, and how long it would take to earn and save it in any way open to a girl of fifteen.

Of course, the whole of it did not have to go for tuition and board. There would be a small sum for what Ella called her older sister’s “trousseau,” and for pocket-money and incidentals. Rivercliff was a more expensive school than one or two others Beth had thought of and she wished she could gain the advantages she craved in some other institution.

However, a girl with a diploma from Rivercliff had a distinct advantage over applicants from other schools with the State Board of Education. And for good reason. Rivercliff was more than a preparatory school in the usual acceptation of the term. A girl who faithfully took the courses laid down by Miss Hammersly, the principal, was well fitted for most places in life.

The summer was not spent idly by Beth. She had not merely resolved to obtain an education at her parents’ expense. She was ready and willing to do all in her power to help bring the much desired thing to pass.

[42]She obtained the opportunity of posing on several occasions for an illustrator for the magazines, who came each summer to a rustic studio she had built near Hudsonvale. Beth had done this work before, and the artist paid her fifty cents an hour. It was not an easily won fifty cents by any means. Retaining the poses as was desired strained the muscles and tired the mind more than most other work Beth had ever done.

She could crochet, too; but the payment she received for a baby’s bootees “a fly would starve to death on,” Ella declared—and with some apparent truth. However, Beth kept busy and happy. That is, she told herself she was quite, quite happy. But there was one thing that troubled her mind in secret. Larry Haven had never come to the little cottage on Bemis Street to see her.

From Mary Devine Beth heard much about Larry. He had established himself in the office next to Dr. Coldfoot, and——

“Such scrumptious furniture, Beth, you never did see. They say his mother made him a present of it all—furnished his office right up to the minute. And he’s got a very splendid sign,” added Mary, with enthusiasm.

Beth had seen the sign.

“And he comes downtown as brisk as a drug clerk every morning,” giggled Mary, “and shuts[43] himself into that office—oh, dreadfully busy, he is!”

“I hope he will be,” said Beth, laughing.

Nobody said anything to her about Larry’s not coming to the house. The children were all busy, and had become so used to his absence that they did not note its continuance after Larry returned from the law school.

That her old playmate was busy might be an excuse for his seldom calling; but there was absolutely no excuse, that Beth could imagine, for his never coming to see them. After the first fortnight following his party, Beth ceased to mention Larry in the family’s hearing. She was a girl who could hide her deeper feelings if she so chose; and she chose now to lead her mother to believe that thought of Larry never troubled her mind.

However, it did. More than once tears wet her pillow at night while she lay and wondered why Larry had forsaken her. She did not believe it could be the seven years’ difference in their ages.

“I don’t care if he does think me a little girl,” she told herself; “he might, at least, be polite.”

But, in truth, she laid the defection of Larry Haven to his mother. The why of this was no more clear to her girlish mind than Larry’s neglect; but she had felt Mrs. Haven’s antagonism so[44] deeply that she could not fail to take it into consideration now.

Beth was one of those loyal souls who seldom make friends save after due consideration, and who cling to their friendships, once made, through fair weather and foul. She felt about Larry just as she would have felt about an older brother. He was just as necessary to her complete happiness as Marcus was.

After their intimate talk at the party, Beth felt that her mind and Larry’s were a good deal in accord—especially on the question of the advancement of her schooling. So she hoped he would continue to show his interest in the wonderful (to her) prospect of Rivercliff. She had no assurance that Larry even knew she was surely going to school until the afternoon came for her departure from Hudsonvale.

It was an event, indeed, for one of the Baldwins to go away by the river boat. The Water Wagtail was one of the finest of the fleet plying up and down the Nessing River, and Mr. Baldwin had obtained for Beth one of the staterooms for the trip.

The county paper, which ran a page of Hudsonvale news (“in spite of Mary Devine,” Mr. Baldwin said), had printed a note of Beth’s proposed departure for school, and the date. Was[45] that how Larry knew? For when Beth went down to the dock and aboard the Water Wagtail, the steward had just taken a box of cut flowers to her stateroom.

“I declare for’t, Missy,” said the shining-faced negro, “yo’ friend suttenly has sent yo’ a heap o’ posies.”

“Let me see the card, steward,” she said quickly.

It was Larry’s, and Beth knew that flowers like these grew only in his mother’s garden—in Hudsonvale, at least.

Her family had trooped aboard after her—with Mary Devine and a dozen other girls who had been Beth’s friends at the high school. They made a noisy and jolly party. And how they wondered and exclaimed over the flower-filled stateroom.

“Why!” cried Mary Devine, “it’s just like a bridal tour you’re starting on. Aren’t you lucky, B. B.?”

“I surely am,” admitted Beth, smiling.

“But where’s the groom?” asked one of the other girls, slily. “Did he send the flowers?”

“How ridiculous!” rejoined Mary, scornfully. “It’s the best man who sends the flowers, not the groom. He has to help smell ’em!”

The party remained on deck while the freight[46] was being run aboard below. Beth’s glance often swept the littered dock as she talked gaily to her friends or to the children or to her mother and father. Suddenly her eyes fixed their gaze upon a tall figure striding down to the dock from Water Street.

It was Larry. Beth’s heart leaped and the color came and went in her cheeks. Had there not been so much going on, her excitement must have been noticed. As it happened, however, not even the girls chanced to see Larry till he was aboard the boat and was approaching the group.

By that time Beth had quite regained her self-control. She welcomed Larry with just the degree of warmth her mother displayed—by no means as joyfully as did Mary Devine. He had to be introduced to the other girls—re-introduced in some cases. With Mr. and Mrs. Baldwin he was delightfully cordial. The children—even the twins—welcomed Larry nicely. Nothing was said about his previous neglect.

When the warning whistle sounded and the party arose to leave, Larry manoeuvered to get Beth by herself for a moment. They took the outer deck on one side of the glass-enclosed cabin, while the rest of the party went the other way to the stair-well.

“Go to it, Beth. I glory in your resolve,”[47] Larry said, in reference to her plunge into boarding-school life. “Get all there is for you at Rivercliff.”

“I mean to, Larry,” she said composedly. “And thank you for the flowers—they are beautiful.”

“Oh, they were the Mater’s idea,” he said hurriedly. “But I have something here——”

He fumbled in his pocket and brought forth a little box—a jeweler’s box, Beth knew.

“You won’t want to wear those jolly old corals that belonged to your Great-grandmother Lomis at every party you go to up there,” Larry said, more boyish in his confusion than ever, Beth thought. “Here’s something you can wear right along—to remember me by.”

He thrust the box into her hand. The children came racing to join them. Beth hid the box quickly in her bag—she knew not why.

She pressed Larry’s hand in farewell. She kissed her mother, her father, and “all the tribe,” as Ella called the family. The girls waved their handkerchiefs from the shore.

Larry did not wait as the Water Wagtail pulled out into the stream. It was his tall form, however, striding up the dock when the steamboat was really under way that Beth last saw.

Beth had left the door of her stateroom wide open. When she went into the passage out of which it opened, she saw a girl looking in at the flowers, admiringly.

She was a merry-eyed girl, with short, fine, brown hair that had been blown about her face by the fresh, river breeze. This fact made her seem a little untidy; but she had a winning smile, was well dressed, and Beth found herself interested in the stranger even before the merry one spoke.

“How jolly!” she cried. “You certainly must have heaps and heaps of friends.”

“Why so?” asked Beth, demurely.

“Because they’ve just about filled your room with flowers. Or were they so glad to see you go that they over-speeded the parting guest?” added the girl, roguishly.

Beth laughed as she went by the other into the room and seized a bunch of roses. “Here,” she said, thrusting the flowers into the strange girl’s[49] hands. “I must divide with somebody. And my friends were not speeding the parting guest. I am going to school.”

“Bless us! so am I,” said the other, burying her rather retroussé nose in the fragrant blossoms. “But they didn’t waste any lovely flowers on poor little Molly—nay, nay, Pauline!”

“My name is not ‘Pauline,’” interposed Beth, her eyes dancing. “It’s Beth.”

“Oh, how jolly!” cried the other. “I never knew a girl named Beth outside of a story-book.”

“It’s my real name,” Beth said demurely.

“And are you going to school?”

“Yes.”

“Not to Rivercliff?”

“Yes; I am,” Beth said, her own eagerness increasing. “Are you?”

“How jolly!” ejaculated this rather exclamatory girl. “I certainly am going to Miss ’Ammersly’s hestablishment, as it would have been called in ‘dear hold Hengland,’ had she remained there to conduct her school.”

“Oh! is the principal English?” asked Beth.

“The nicest kind. And Madam Hammersly! Wait till you see her! She wears the cunningest caps.”

“Who is she?” asked the puzzled Beth.

“Miss Hammersly’s mother. And such a dear![50] She is really the housekeeper and general manager—and, oh! so particular! No end! But she’s a jolly old dear, at that.”

Beth saw that this girl overworked at least one word in the English language. But it was impossible to look at her without thinking of that very word. She was jolly, indeed.

Naturally, Beth Baldwin was greatly interested in this, the first of her future schoolmates whom she met and not a little curious about her. She learned at once that Molly Granger had been to Rivercliff for two years already, having entered what Miss Hammersly called the “primary department.”

“But I shall be a full-fledged first-grade with you ‘freshies’ this fall. I shall be in your classes,” she said cheerfully. “I believe I am going to like you a lot, Beth. And that’s more than I can say for some of the girls who have been with me as ‘primes’ and now will be in our grade too. There’s Maude Grimshaw, for instance. That girl would try the patience of a Jobess.”

“A what?” gasped Beth.

“A Jobess. Female for Job. Isn’t that right?” asked Molly, her eyes dancing.

Beth laughed. Then she said suddenly:

“Oh, wait!” and, seizing some more of the flowers from Mrs. Euphemia Haven’s garden, she[51] darted out of the stateroom. She had been watching for several moments a girl who stood in plain view in the cabin and who had been staring at the flowers.

She was a slim, freckled girl, rather oddly dressed, Beth thought; but her big, dark eyes expressed a longing for the flowers that could not be mistaken.

“You’ll have some, won’t you?” demanded Beth, offering the flowers to this stranger, as she had to Molly Granger. “I have so many of them!”

Then she realized that the freckled girl’s eyes were blue. A shadow seemed to lift from them as she smiled. Whereas they had been dusky before, they shone as she looked first at the flowers and then at Beth.

“Oh, thank you!” she said, and her voice was delightfully gentle—“cultured,” Beth would have said, had that expression not so badly fitted the strange girl’s appearance. She wore a very odd combination of garments.

Her smile and her speech repaid Beth for her act. The freckled-faced girl crossed the cabin—she walked gracefully—and sat down upon a divan with the flowers. Before Beth turned back to her new friend, Molly Granger, the blue eyes had become clouded again and the tall figure of the[52] girl drooped over the handful of flowers. Beth whispered to Molly:

“I wonder who she is?”

“Haven’t the first idea,” said the jolly girl, carelessly.

“Do you think she is going to school with us?”

“To Rivercliff? I should say not!” gasped Molly. “Say! you don’t know what you’re up against there, Beth. Why, we girls of Rivercliff stand for the ‘acme of style.’ The only magazines we read are the fashion magazines—and we only look at the pictures in those. Maude Grimshaw could wear diamonds to each class recitation—and royal ermine, I presume, too—whatever that is,” and Molly laughed.

“Oh!” exclaimed Beth, greatly taken aback.

“Only, you see, Miss Hammersly won’t have it. She is for plain frocks in school. What the girls wear in the evenings or on holidays does not so much bother her. We’re all supposed to be from families who roll in wealth—whatever that may mean,” and Molly giggled again.

“Are—are you?” asked Beth, somewhat timidly.

“Am I what, my dear?” returned Molly.

“From a rich family?”

“Goodness, no! My aunts send me to Rivercliff. I’m a poor, lone orphan. My poor, dear[53] mother must have taken one look at me, have seen what an awful, ugly little sprite I was, and thankfully ceased to live. My father was a missionary and died of fever in Canton. There you have my history, saving that seven aunts—all my father’s sisters (do you wonder he went missionarying?)—took upon themselves the task of bringing up and educating ‘poor lil’ Molly.’ If I hadn’t a well developed sense of the ridiculous, it would have killed me long ago.”

Molly rattled on so recklessly that Beth was more than a little startled at first. Then it began to impress the girl from Hudsonvale that here was a person who had really never had a mother or a father, and had never learned the actual need of parents. Therefore, she could talk so indifferently about them.

Another thought was, however, buzzing in Beth’s brain.

“What do you suppose these wealthy girls at Rivercliff will say to my dresses?” she asked. “I’ve only one better than this—and that’s for evening wear.”

“Goodness! How long is a string?” demanded the other girl.

“What?”

“How long is a string?” repeated Molly, laughing. “You might as well ask me that as to ask[54] me how Maude Grimshaw and that tribe will look on you and your clothes. And I guess there’s no answer to that old wheeze.”

“Oh, yes there is,” said Beth, laughing too. “My sister Ella says the answer is ‘from here to there.’”

It did not take much to keep these two new friends laughing. And, at the moment, it did not seem a great trouble to Beth whether the wealthy girls at Rivercliff liked her and her clothes or not.

She carried most of Larry’s donation of flowers out into the cabin and told the stewardess to arrange them on one of the writing tables. Then she locked her stateroom door and went with Molly on a tour of the boat.

“You see, I’ve been up and down the river on this boat a dozen times,” said the jolly orphan. “I come from Hambro, ’way down the river. I started early this morning. We’ll get to the Rivercliff landing to-morrow evening—if the freight traffic isn’t too heavy. The Water Wagtail staggers from one side to the other of the river, picking up freight at the landings, and sometimes the trip is delayed long beyond sched. But never mind! school doesn’t really open till Monday. We’ve got three perfectly good days before us.”

Twice Beth noticed the freckled girl as they passed through the cabin. She still sat in her[55] melancholy attitude, and the flowers had dropped into her lap. Beth knew she must be in some trouble or sorrow; but she scarcely saw how she could help the stranger.

Molly Granger kept up a running fire of comment upon everybody and everything. The steamboat stopped at two small towns before dark, and the new chums watched the busy scenes on the docks and talked about the new faces they saw. Beth found Molly the very best of company; for while she was light-hearted and full of fun and mischief, she was sound at the root and had no unkindness or meanness in her make-up. Indeed, Beth Baldwin had never met one of her own age before whom she liked so well on such short acquaintance.

Left to herself for a short while, Beth was going over in her mind all the adventures of this busy and exciting day. How much had happened—and how much unexpected—since she had started from the little cottage on Bemis Street.

Then, for the very first time since she had slipped it into her bag, Beth thought of Larry’s present. Something in a jeweler’s box! How had she forgotten it for so long?

“That proves that this has been an exciting time,” murmured the girl, getting her bag and opening it. “Ah! here is the box.”

[56]It was neatly wrapped and tied, and her fingers were engaged in untying the string for a minute or so. Then she opened the box. A puffy mass of pink cotton met her gaze. She pulled this aside.

“Oh! O-o-o-oh!” she breathed. “The beauty! The beauty!”

She took out the pin. It was delicately wrought of platinum and studded with diamond chips and tiny half-pearls. It was not very expensive; but it showed skilled workmanship and was an ornament that would surely attract attention. Yet it was simple enough to look well if worn by a young girl.

Larry Haven’s taste could not be criticized. If he had selected the pin himself (and Beth believed he had, from what he had said at its presentation), it showed that he thought of her—that he still considered Beth his little friend and comrade.

Yet, if so, why had he neglected coming to the Bemis Street cottage all summer? This still puzzled and troubled the girl.

At supper time Beth and Molly went up to the saloon deck and the captain of the waiters found the two friends seats at a pleasant table. Beth looked for the freckled girl but did not see her. Yet Beth was sure she had not gone ashore at either of the landings.

While the girls ate and enjoyed their supper,[57] a mist arose and enfolded the steamboat and enshrouded the face of the river. When they came out on the open deck again, the clammy breath of the mist fanned their cheeks, and all they could see of the banks on either hand were occasional twinkling lights—either on scattered farmsteads or in tiny villages or ferry-houses.

“B-r-r-r-r! It’s going to be a nasty night,” said Molly Granger. “I shall go to bed early. No fun sitting up unless the moon shines. Then it is lovely to be out here and watch the shores. The old steamer won’t stop again till we reach Marbury—about midnight.”

“I was hoping for a moonlit night,” said Beth, disappointedly.

“Better to get a good sleep, for to-morrow will be a long day,” said Molly, showing a streak of good sense that Beth had not known she possessed. “We may not get to bed to-morrow night till late; for we may be delayed in reaching Rivercliff. I’ve been as late as eleven o’clock getting off this boat at that landing.”

“I guess you know best, Molly,” agreed Beth.

But she was not sleepy herself—not even when Molly bade her a warm good-night and went into her own stateroom, which was not far from Beth’s. The latter encircled the outer main deck again. The Water Wagtail was in midstream. She was[58] a side-wheeler, and the splashing of her buckets and the creak of her walking-beam, added to the hiss! hiss! of the spray from overside, played an accompaniment to Beth’s thoughts.

Her first night away from home! Never had she slept from under her parents’ roof before. Her own little room, shared with Ella, was the only chamber in which the girl had ever spent the night.

Little wonder that she felt nervous, if not apprehensive. There were two berths in her room—an upper and lower. She would have been glad to share the stateroom with Molly Granger; but she shrank from admitting to even that easy-going, jolly chum that she felt the need of company at night.

She shrank, too, from going to her stateroom and locking herself in.

Instead, she wandered about the boat again. She spent more than two hours going from deck to deck—sitting a while in one place, then getting up and wandering about, wrapped well in her raincoat to keep out the thick mist.

Several times she saw the freckled-faced girl. Either she had no stateroom, or else, with Beth, she did not feel like going to it. And her expression of countenance and deeply despondent manner troubled the girl from Hudsonvale.

[59]“I wish I could do something for her,” thought Beth. “She must be poverty poor with that get-up. Dear me! I haven’t any too much money myself; but if a little would help her——”

She finally started toward the strange girl, determined to accost her; but just then the latter arose from her seat and approached one of the uniformed officers of the boat, then just passing through the cabin.

“Are we near Brakelock, yet?” Beth heard the girl ask.

“We’re not far from that landing, Miss; but we stop there only on the down trip unless we’re signalled to take passengers. Nothing doing to-night, Miss.”

“Thank you,” said the girl, quietly.

The man went about his business. The girl immediately descended the stairs to the lower, or freight, deck. Beth, hesitating whether she should speak to her or not, followed unobserved.

Nobody seemed to be about. The way was open aft to the outer deck behind the paddle-wheels. The tall girl went swiftly to the port side, slid open one of the doors, and stepped out upon the misty, open deck. Beth went out by another door. There was nobody aft but herself and that other girl—not another soul.

The girl did not see Beth and the latter hesitated[60] again. What should she say to her? How accost her?

And then—the discovery set Beth’s heart to beating madly—she saw that the strange girl was leaning far over the rail of this lower deck, so close below which the black water hissed and gurgled. In a moment she had a knee upon the flat top of the rail, flinging up her tight skirts with an impatient kick to free her limbs of their entanglement.

She was teetering—almost head downward—on the rail, about—it seemed—to plunge into the swift current of the river!

Beth had learned something about vigorous play at basket-ball under the direction of the instructor in physical culture at the Hudsonvale high school. Besides, she had not played with Marcus and the other boys—even with Larry in years gone by—without learning what is meant by a low tackle.

So, when she jumped for the girl who seemed about to throw herself into the river from the stern of the Water Wagtail, she “tackled low.” She seized the reckless girl about her knees, locking her legs tightly in her arms.

“You can’t! I sha’n’t let you!” Beth gasped, as the other struggled. “Oh! what a wicked thing you are doing!”

The freckled girl squealed—no other word could exactly express the startled sound she made when Beth seized her. Then she attempted to turn around and face her rescuer, as the latter dragged her down and away from the rail.

“What are you doing? Stop it!” sputtered the[62] tall girl. “Goodness! how strong you are! Do let me be!”

“I won’t!” cried the excited Beth. “I won’t! You sha’n’t do such a dreadful thing! I’ll shout for help!”

“Oh! don’t do that,” begged the other girl. “They’ll do something awful to me.”

“Then promise you won’t do that——”

“What?”

“It would be dreadful——”

“What would be dreadful?” repeated the strange girl, in some heat. “They’d have got the boat back again. I wasn’t going to steal it.”

“Steal it?” murmured Beth, startled and confused.

“Yes. I’d have left it tied along shore there. No harm would have come to it.”

“Oh, my dear!” gasped Beth. “Is there a boat there?”

“Of course there is. Didn’t you see it dragging just astern? They forgot to hoist it in. I noticed it before dark. Say!” exclaimed the other, her strange eyes suddenly shining in the mist as she stared at Beth. “What did you think I was trying to do when I was hauling in on that painter?”

“I—I thought you wanted to drown yourself,” whispered the confused Beth.

“My aunt!” exclaimed the girl, and laughed[63] shortly. “No. I’m not quite so desperate as all that.”

“But you might fall overboard getting into that boat,” said Beth.

“I can swim. But the current’s swift here in midstream,” and she shuddered. “Now you’ve knocked the courage all out of me. Oh, dear!”

“Why do you want to leave the boat in such a crazy fashion?” demanded Beth, regaining her self-possession.

“I’ve got to get away before the Water Wagtail stops at Marbury,” said the other, hastily.

“Why?” repeated Beth.

“Oh—because!”

“But you wouldn’t dare take that boat. You might fall overboard from it. You would be lost in this fog,” Beth urged.

“I know. I wouldn’t dare now,” said the other, gloomily.

“If I hadn’t stopped you something dreadful might have happened.”

“Nothing more dreadful than will happen when we reach Marbury.”

“What do you mean?” asked the curious and sympathetic Beth.

“They know I am on this boat,” confessed the girl, with sudden desperation. “And they’ll come aboard of her and take me back.”

[64]“Back where?”

“I can’t tell you. It’s awful! I haven’t a living soul I can call my own—not a real relative——”

“You are an orphan?” asked Beth, thinking at once of an asylum or an institution to which she supposed poor girls without parents or relatives have to go. Besides, the awful clothing this girl wore bore out this supposition of Beth’s—that she had run away from a charitable establishment of some kind.

“Of course, I’m an orphan,” said the other girl, quickly.

“Can’t I help you?” suggested the sympathetic Beth.

“How?”

“What is your name, please?” asked Beth. “Mine is Beth Baldwin.”

“Cynthia—Cynthia Fogg,” mumbled the other girl, and so hesitatingly that Beth half believed that the last name, at least, was born of the thick river mist out into which the wonderful blue eyes were staring. Nevertheless, Beth said nothing to betray her doubt.

“You say these—these people will search the boat for you?” she asked.

“Yes.”

“People from the—the institution from which you have run away?”

[65]Cynthia turned her head quickly so that Beth could no longer see her face, replying in a muffled tone: “Yes; from the institution.”

“How do you know they are on board?” continued the practical Beth.

“Somebody that knows me saw me at that last landing—just as the steamboat was pulling out,” replied Cynthia. “I know he’ll telephone up the river to Marbury. And I’ll never get away from them now.”

“You may escape them,” said Beth, kindly. When Cynthia looked back at the dragging boat, she added hastily: “Oh, not by that means. There must be a less perilous way.”

Without any thought of the possible consequences, Beth had given her heart and hand to the strange girl’s cause. It meant little to her that this girl had run away from some public institution. She did not stop to ask why she had run away.

“How, I’d like you to tell me?” said Cynthia.

“Surely those who look for you will not arouse the passengers and make a disturbance in the middle of the night? We don’t get to Marbury till midnight, I understand.”

“That’s right.”

“Then,” said the generous Beth, “why not come to my stateroom?”

[66]“Yours? Why! you don’t know me,” said the other girl, rather astounded.

“Surely, we’ve just introduced ourselves,” laughed Beth. “I am alone in my stateroom. There are two berths. They’ll never look for you there.”

“Oh, my aunt!” ejaculated Cynthia Fogg, with such sudden animation, that her strange eyes sparkled again. “That would be great!”

Beth thought the girl an odd combination of characteristics. One moment she was morose; the next she brightened up and was all life and gaiety. But the girl from Hudsonvale was bent only on helping Cynthia.

“Will you come to my room?” she repeated.

“Surely I will—if you think they’ll let me.”

“Who?”

“Why, the steamboat people,” said Cynthia.

“I guess they won’t stop us. But we’d better not let anybody see us together. When the boat gets to Marbury, somebody may remember having seen you with me, and then they’ll suspect where you are hidden,” said the practical Beth.

“My aunt! so they will,” admitted Cynthia.

“So we’ll go singly. Don’t let the stewardess see you,” said Beth, warningly. “I’ll go first. You’ll surely follow?”

“Of course I will,” said the other girl, warmly.

[67]“And no trying to go overboard—into a boat or not?” added Beth, smiling.

“I’m afraid now,” confessed the other. “You’ve scared me.”

“Then I’ll take care of you,” promised Beth, laughing again.

“You are a nice little thing,” repeated Cynthia Fogg.

“Thank you. My room is Number Fifty-three.”

“I know,” said the other. “I saw those flowers. I’ll wait till you get there before I come upstairs.”

Beth re-entered the enclosed part of the boat and went up to the main deck at once. She had been in her stateroom ten minutes before she heard a quiet little rustle outside her door. She had left it unlocked, but now she turned the knob invitingly.

The freckled girl pushed it open and glided in, closing it noiselessly behind her.

“Here I am,” she said.

The dress of this unfortunate in whose fate Beth had taken such a strong interest, had already made the girl from Hudsonvale wonder. Such a shocking combination of color and tawdry finery Beth had seldom seen, even in a mill village, which Hudsonvale was.

Yet the tall, freckled girl wore the incongruous garments with utter unconsciousness. She never seemed to give her dress a thought.

On a green straw hat of the season’s mode, was a purple feather, which had plainly seen service in the rain. She wore a ragged feather boa and a rather soiled brown silk waist much worn under the arms and evidently originally built for a much fuller figure.

A black serge skirt of very narrow proportions seemed shrunk upon her, and was spotted and shiny. Low brown shoes and spats completed the costume.