Title: In the tiger's lair

Author: Leo E. Miller

Illustrator: Paul Bransom

Release date: December 10, 2022 [eBook #69515]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921

Credits: Tim Lindell, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Illustrated by Paul Bransom

THE HIDDEN PEOPLE

A Story of a Search for Hidden Treasure

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

“Quizquiz, Inca, Child of the Sun ... commands that you

appear before his sacred person”

[Page 95

IN THE TIGER’S LAIR

BY

LEO E. MILLER

AUTHOR OF

“IN THE WILDS OF SOUTH AMERICA,”

“THE HIDDEN PEOPLE”

ILLUSTRATED BY PAUL BRANSOM

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1921

Copyright, 1921, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

COPYRIGHT, 1921, BY THE CURTIS PUBLISHING CO.

THE SCRIBNER PRESS

TO THE MEMORY

OF

LITTLE ROBERT

“In The Tiger’s Lair” is the story of the return of Stanley Livingston and Ted Boyle to the Andes Mountains of Peru to complete their search for the hidden treasure of the Incas. It is a separate and complete story in itself—one may read and understand it without having read “The Hidden People.”

Leo E. Miller.

Floral Park,

Stratford, Conn.,

Sept. 1, 1921.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE END OF THE UNDERGROUND RIVER | 1 |

| II. | SKY HIGH | 11 |

| III. | THE RETURN TO THE LAND OF THE INCAS | 24 |

| IV. | THE RIVALRY OF THE AIRMEN | 32 |

| V. | IN QUEST OF THE HIDDEN TREASURE | 43 |

| VI. | THE CROWNING MISFORTUNE | 55 |

| VII. | IN THE TIGER’S LAIR | 66 |

| VIII. | THE INCA’S THREAT | 80 |

| IX. | SONCCO’S SHREWDNESS | 92 |

| X. | THE PRISONERS CAPTURE THE KING | 105 |

| XI. | THE COUNSEL OF THE WISE MEN | 116 |

| XII. | THE VILLAINY OF VILLAC UMU | 128 |

| XIII. | STANLEY’S PLAN | 140 |

| XIV. | SONCCO’S AID TO THE PLOTTERS | 151 |

| XV. | THE TERROR OF DARKNESS AT MIDDAY | 165 |

| XVI. | THE COMING OF THE TIGERS | 180 |

| XVII. | ANIMALS OF A BYGONE AGE | 193 |

| XVIII. | THE MAN IN THE CRATER | 205[x] |

| XIX. | THE BREACH IN THE MOUNTAIN IS CLOSED | 221 |

| XX. | THE KING IS CROWNED | 233 |

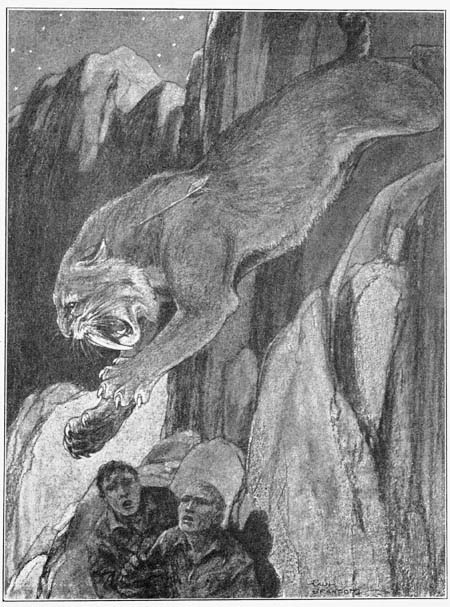

| “Quizquiz, Inca, Child of the Sun ... commands that you appear before his sacred person” | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

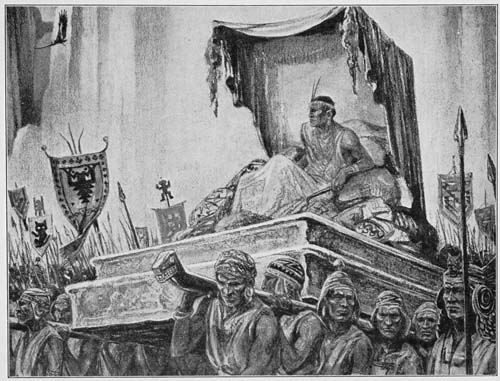

| Very obviously the Inca had carefully planned to impress the visitors | 82 |

| It was a bushmaster, the deadliest and the most feared of all South American snakes | 170 |

| An instant later a huge, dark form catapulted past the crouching men | 210 |

IN THE TIGER’S LAIR

Two years had passed since that day when Stanley Livingston and Ted Boyle, accompanied by the giant negro, Moses, faced the perils of the underground river rather than suffer a lingering death on the dismal shores of the lagoon beyond the wall at Uti.

Having finished their course at college, Livingston and Boyle, or Stanley and Ted, as they were better known, had decided upon a novel way of spending a few months’ vacation before entering their more serious professional careers. They went to look for the hidden treasure of the Incas that was known to lie somewhere in the vast ranges of the Andes Mountains of Peru. They well understood the difficulties of such an undertaking; there were snow-clad peaks to climb and steaming jungles to penetrate, and dangerous animals and still more formidable wild people to combat. But all these things simply added to the attraction of the venture.

[2]They had gone in quest of adventure, and their desire was gratified beyond their wildest expectations. Shipwreck, the burning thirst of a desert land, battles with fierce monkey-men, and the dread fevers of the lowlands were their lot during the first months of the journey. Then—the Hidden Valley where the Inca Huayna Capac lived and ruled the remnant of the once-great nation in all the magnificence and splendor of ancient times. The great king received them, not unkindly, made them princes, and surrounded them with every luxury. From the beginning, however, Quizquiz, son of the Inca and heir to the throne, had conspired against them, and in the end he had succeeded in securing their conviction on the charge of treason. They were condemned to exile beyond the great wall that divided the valley from Uti, the abode of the evil spirits. It was Timichi, previously banished to the dismal place, who showed them the gold-filled cavern where the vast treasure reposed and who later pointed out to them the underground river just as all hope of escape seemed gone. They had accepted the last, desperate chance and had emerged in the outer world rich in gold and in experience.

And now, after a period of two years, they found themselves back in the drooping wilderness, encamped[3] at the outer end of the underground river, preparing to remove the vast treasure their former efforts had revealed.

“We might have left this place only yesterday, so far as appearances are concerned,” Stanley said as they stood on the edge of the open, park-like place flanked by the abrupt cliffs on one side and the heavy jungle on the other. “Everything looks just the same as it did then. The deer are grazing just as peacefully and—I distinctly remember seeing that one with the lame fore leg. It speaks well for the neighborhood; the monkey-men have not invaded it yet, or the deer would not be so tame.”

“Yes, it surely does not seem as if two years have passed since we were here. The only thing lacking is Moses, but that is not our fault. We tried our best to find him. But, I wish we had him just the same, because we need him.”

“Poor old Moses. I miss him too. He saved our lives, and no one but a giant like him could have done it. But for him we should never have gotten out of the valley. If we ever succeed in locating him we shall have to divide up the gold we are going to get now. He shared all the hardships and he is entitled to a share of the spoils.”

“You are right, and no matter how much we give[4] him we shall always be in debt to him for what he did for us.”

They started across the open plot toward the little stream that wended its way through the centre. The deer stopped grazing, looked up at them with startled eyes, and then bounded into the protecting forest. When the men reached the watercourse, they followed it to the base of the stone escarpment, the top of which was hidden by the belt of yellowish, poisonous vapor that served as such an effectual barrier between the outer world and the Hidden Valley. Laving the foot of the stone wall was the pool, and opening into it was the black cavern that in reality was the mouth of the underground river.

“One would hardly suspect it of being such a magic river to-day,” Ted said, throwing himself on the short grass; “the water is flowing neither way; it is standing still. Wonder what Timichi would say to that, were he alive; but I have no doubt he has been dead a good many months.”

“He clung to life a number of years even in that awful place, but I, too, think he must be dead now. He was nearly gone when we left him. Too bad there was nothing we could do for the poor fellow.”

They returned to camp and began to prepare supper.

[5]“Our provisions should last several weeks, not counting on the game we can get here,” Stanley observed as he looked over the supplies. “In that length of time we can bring out all the gold any one could possibly desire. We have only to hide it inside of sacks of ivory nuts, of which the jungle is full around here, cache it, and then one of us can stay on guard while the other goes back to Cuzco for peons to carry them out. No one will ever suspect.”

“It’s all so simple. And there is not a chance of failure,” Ted remarked between mouthfuls. “Just think, there are millions in gold on the other side of that wall, and it is all ours for the mere taking. Let’s do the job as quickly as possible; I want to get back home to make use of my wealth.”

“Don’t be too sure,” Stanley cautioned. “You know we haven’t got it yet.”

“But it is there. We know that, because we saw it and helped ourselves to all we could carry. And we know how to get in and out of the place too. So this one time I am dead sure that as much gold as we want will be ours in a few weeks, and I for one am going to treat myself generously.”

Remembering Moses’ experience with the deadly bushmaster, they made no attempt to sleep on the ground. But, going into the forest, cut a number of[6] stout poles and, tying the tops together to form tripods, slung their hammocks between them for the night.

Their first thought on the following morning was to see if there was any perceptible current in the river; but to their disappointment they found that the water was stationary, as before.

“Looks as if we might have to paddle the rafts through. We could do that easily enough if necessary, but it would help a good deal if the water were flowing in the right direction. But why worry? It will take at least two days to make the rafts, and by that time the current will doubtless set in again.”

They now began to work in earnest. Near the lower end of the open space where the river entered the forest, clumps of tall bamboo dotted both banks. Some of the great, jointed stems were fully eight inches in diameter and fifty feet high. Chopping them down and cutting them into ten-foot lengths was hard work, for they had only their machetes, or brush-knives, with which to work. Also, as each joint was full of water it had to be tapped and drained, after which the openings had to be plugged up again with gum; this made the stalks light and buoyant. They carried them to the water, one at a time, and lashed them together to form rafts. This required more time than they had[7] anticipated; in fact, four days passed before the two were completed.

“How much gold do you intend to take from the cave?” Ted asked one day when their task was nearly finished.

“As much as I can, of course. These rafts will carry several hundred pounds each in addition to our own weight, and we can make a dozen trips, or even more.”

“A ton for each is not too much. It is remarkable how much the yellow metal is worth. When we were here before, you guessed that each of our packs contained about ten thousand dollars’ worth, and you were nearly right. We got almost eleven thousand apiece, and the emerald necklaces were appraised at double that. I should not wonder but that there are many precious stones in the cave, too, hidden among the gold.”

“All the better for us. They are not so bulky or heavy. Think of all the good we can do when we get back home.”

“Yes! I intend to be very liberal with a certain college I think a lot of.”

“Hospitals is my hobby. You shall see.”

When the rafts were all ready they pushed them along the bank, and up to the mouth of the underground river.

[8]“It is strange that the water does not move,” Ted said, looking puzzled. “It looks black and stagnant—as if it has been standing still a long time.”

“Do not let that trouble you. If it does not flow by to-morrow morning we shall paddle through the tunnel. We have been through it before and know the way. Besides, we are well supplied with flash-lights now. There is nothing to it, so why worry?”

They hewed short, broad-bladed paddles out of a cottonwood branch and carefully covered all the things they did not intend to take with them on the following day with broad palm-leaves, to protect them if it rained.

When dawn came, it found them on their rafts, paddling into the mouth of the cave. Once inside, Stanley switched on one of the lights that had been tied to the front of his raft, and the bright glare revealed a passage from ten to twenty feet wide with an uneven ceiling of jagged rock fifteen feet above their heads. Swarms of bats, frightened by the unusual visitors, left their hiding-places overhead, and with a flutter of wings dashed out of reach of the circle of light and disappeared.

“We have been going over half an hour now,” Ted said, looking at his watch. “Of course we have not made very good time, but we should be nearing the end. Can you see daylight ahead?”

[9]“No! The opening is not in sight. But, what is this? Slow up so you won’t bump into me! The water seems to stop here.”

“Stop? There must be a bend in the river.”

“I can see none.”

“Still there must be some open channel. Didn’t we come through here before? Give me the light; perhaps the turn is back here.”

They focussed the bright rays in all directions, but to no avail.

“Ted!” Stanley cried in sudden consternation. “This was the opening, right here, but it is not here now. It has been blocked up.”

“Impossible,” Ted returned in dismay. “Do you mean that we cannot get back into the valley?”

“Come ahead and see for yourself.”

Ted pushed his way to the front of Stanley’s raft. The latter’s words were all too true, for the opening into the valley was filled with earth and stones of large size.

“They learned of our escape from Timichi,” Ted said bitterly, “and knew we would come back. Well, I am not ready to admit that all my visions and hopes are dead; but just now there is nothing but darkness ahead.”

“How about dynamite?” Stanley asked suddenly.[10] “We could blast away the rocks in the entrance and get in after all.”

“But what could we do against the Inca’s hordes once we were inside?”

“Come to think of it, I do not believe they had anything to do with this. They would not dare venture beyond the wall. There must have been a landslide on the slope above. In a region like this earthquakes occur frequently on account of the many volcanoes, and that would explain all this.”

They paddled back through the tunnel silently and sadly. All their dreams of wealth had suddenly vanished. It had never occurred to them that something might prevent them from securing the enormous treasure they had discovered. They knew its exact location; its value was so great that no man could estimate it, and to secure it required no further effort than to take it and carry it away. And then—their great disappointment.

“That is just what we will do,” Stanley said that night as they were eating their supper. “We have not lost a thing, only there will be a slight delay in carrying out our original plans. To-morrow we shall start back to Cuzco for the dynamite. The rest will be easy.”

Stanley had never been more mistaken in his life.

When the two reached Cuzco, after the long, difficult climb up the mountain-sides, they found news of a startling character awaiting them. Their own country had become involved in the World War. And with this intelligence came to them the realization of their duty.

The two lost no time in returning to the coast, and took the next steamer bound northward. Arrived in their homes, Ted applied for and was accepted in one of the officers’ training-camps, while Stanley enlisted in the aviation branch of the service.

Before long Ted began to regret his decision to join the infantry. It happened late one October afternoon when the company was returning, under full packs, from a lengthy hike into the country. The dust rose in clouds that threatened to suffocate the men and the sun still blazed unrelentingly on the weary, tramping forms. But even as they marched along the men sang with a good deal of spirit, although[12] any one who had heard them outward bound that morning could have easily recognized the difference in the vigor of their song.

From afar came a droning, buzzing sound, hard to locate but drawing rapidly nearer. A moment later some one shouted “airplane,” and a hundred and fifty pairs of eyes were eagerly scanning the sky; soon they succeeded in making out a small, dark speck high in the heavens, and as they gazed it grew larger and larger, until finally the trim outlines of the graceful craft could be distinguished clearly. Something seemed to go wrong with the machine when it was directly overhead. The steady purr of the motor stopped and the great speed at which the ship had been travelling began to slacken. Every one held his breath in anticipation of the tragedy that was about to take place. After a second’s pause, during which the airplane seemed to stand still, it plunged toward the earth in a bewildering succession of turns, nose down, tail pointed into the sky. Its antics gave one the impression that it might be sliding down some gigantic aerial corkscrew, and how long the craft continued in its spinning fall to destruction no one knew, but to the spectators below it seemed like minutes. Just as it appeared as if the next few turns must bring the fatal crash the machine stopped spinning, started[13] into a graceful, straight dive, and then with a startled roar of the exhausts swooped upward and away.

“I’d give anything in the world to be able to fly like that,” Ted confided to the cadet by his side.

“You are covering a lot of territory,” he replied. “The ground is good enough for me.”

“It will have to be for me, too, I guess, but think of those fellows playing among the clouds while we swallow dust on the road or wallow in knee-deep mud in the trenches. Think of the glory of fighting miles above the earth!”

“What’s the matter? Not feeling sorry for yourself, are you?”

Ted ignored this remark. His thoughts were high above in the ethereal blue, where the airplane had been manœuvring with such graceful ease but a few minutes before.

“I want to fly and do my fighting up there,” he said to himself more than to any one else in particular.

“And be shot down and hit the ground so hard it would take the whole police squad a week to dig you out,” Ted’s neighbor, whose name was Carter, interrupted. “Not for me! I’ll take mine down here, where I know there is something safe and solid under my two feet.”

The company reached the barracks with just fifteen[14] minutes in which to brush up for retreat. There was no time for discussion or conversation, but that night, just before taps, it was reported that a commission had arrived whose object it was to select men for the air service; several would be accepted from each company. That accounted for the sudden appearance of the air-ship that afternoon; it was part of the advertising plan to secure the necessary number of men.

Ted called on his captain immediately, and was told to report to the major in charge of the commission on the following morning.

There was no sleep for him that night. The hours dragged as he tossed restlessly on his hard bunk and listened to the heavy breathing of the other men, and when morning came he was so excited he was sure he should be rejected on that very account. But the major was inclined to make allowances, and informed Ted that he might expect to be transferred at no far-distant date.

The order releasing him from duty with the company and sending him southward to the ground school in Texas came two weeks later. And two days after that Ted was speeding toward his new station.

Then followed three months of the hardest kind of work; there were long lectures and hours of study[15] upon the organization of foreign armies, interspersed with periods of calisthenics and infantry drill; also instructions on topics connected with flying, such as motors, rigging, gunnery, and wireless. Every one worked at top speed to assimilate as much as possible of the knowledge with which he was being crammed; that occupied all the hours of daylight and part of the night, too, so there was little time to form close and lasting friendships. Everybody was so busy with his own problems that it was impossible to pay much attention to the other fellow.

But the three months were up at last, and Ted, standing near the head of his section, was promptly sent to flying school. Those who were not so fortunate in their marks were sent to concentration camps to wait weeks, even months, for their turn.

“Attention to orders,” called the section leader the morning after Ted and a number of others had reported for their new class of instruction. “Boyle, Currier, Davis, and Edwards report to Lieutenant Livingston, Ship Number 188. Green, Hammond, Jones, and Murphy report to Lieutenant Talbot, Ship Number 210,” and so on down the line, ending with a final “Fall out.”

Ted could not believe his ears. Was it possible that the Lieutenant Livingston who was to be his[16] instructor was Stanley? They had not communicated with one another since entering the service.

Ted hurried to Ship Number 188, which had been pointed out to him by one of the mechanics.

“Lieutenant Livingston, sir?” he inquired of the officer evidently in charge of the ship.

“Yes, what can I do for you? Why—if it isn’t Ted. What are you doing here? I am certainly glad to see you.”

Ted explained how he had been transferred from the infantry and had just completed his course at ground school; also that he had been assigned to Stanley for flying instruction.

“This is luck. Let’s get at it right away; we can talk more to-night. Hop into the rear seat and we’ll start right off.”

“What do I have to do?” Ted asked excitedly.

“This is just going to be a joy ride around the field. Don’t do or touch anything; sit as comfortably as you can and look around; watch the ground and the air and the other ships.”

So saying he helped Ted into his place and showed him how to adjust the buckle of his safety-belt across his lap. “You will hardly ever need the belt,” he said, “but it is just as well to get into the habit of fastening it.”

[17]Then he climbed into the forward cockpit and opened and closed the throttle a number of times, while the motor roared and slowed down alternately. At a signal to the crew chief, the men removed the blocks from under the wheels, and taking hold of the lower wings swung the ship around until it faced the flying-field, which was into the wind.

An instant later, with an increasing roar, the machine was tearing across the ground at a terrific speed. Ted looked down over the edges of the cockpit, and saw the grass rushing backward in a blurred, green streak. A frightful wind struck his face, cutting off his breath and making his eyes water. He ducked his head behind the little celluloid wind-shield to adjust his goggles more snugly, and when he looked again they had left the ground. He closed his eyes for a moment; there was no sensation of motion whatever; they seemed to be standing stock-still, like a kite at the end of a string, facing a cyclone of wind, but the thunder of the engine was deafening.

After climbing a thousand feet, they made a number of circuits of the field. Then Stanley throttled the motor and dipping the ship down at a steep angle, began the glide back to the landing-place. The propeller moved so slowly that the blades could easily be distinguished, and the wind shrieked through the[18] wires with a shrill wail. They levelled off at a few feet above the ground, and after skimming along a short distance, touched so gently that there was scarcely any shock; after that they slowed down and rolled up to the dead-line from which they had started.

The course of instruction continued daily, and under Stanley’s capable guidance Ted learned rapidly. When he had had six hours in the air he could fly the ship in a manner satisfactory to his teacher; so Stanley took it upon himself to include a few of the more commonly used stunts in the course. For this purpose, however, they always went some distance from the field, where they were safe from the observation from below of the officers in charge.

“I am going to show you a new one to-day,” Stanley said one afternoon, as they were taking their places for the flight. “Be doubly sure the belt is fastened; you will need it for once.”

“I can stand anything you can,” Ted replied. “Go as far as you like.”

Soon they were leaving the field behind, mounting as they soared into the distance. The aneroid needle pointed to two thousand, then three, four, five, and finally six thousand feet. Ted had never been so high before in the plane, and the earth below seemed new and strange. The patches of woods looked like[19] clusters of dark, green dots, and the fields reminded him of the squares of a checker-board. Banks of white, fluffy clouds rolled past, their upper edges tinted with glowing silver by the brilliant sunlight.

Stanley shut down the engine. “Is everything all right?” he called back.

“Yes!”

“I am going into a whip-stall. Be sure your belt is tight.”

He opened wide the throttle and nosed the plane down so that they attained a terrific speed; then he suddenly pulled it almost straight upward and shut off the engine. For a moment the ship seemed to stand still in the air in an upright position; then it whipped downward with tremendous force, sliding on the tail. Ted felt himself raised off his seat, but, thank heaven, the belt held, or he would have remained in mid-air while the plane hurtled away from beneath him. After falling some little distance Stanley again turned on the power and they swung out of the dive and levelled off gracefully.

But at that instant a burst of smoke was swept back by the blast of the propeller. The engine slackened its speed and a series of sharp, pistol-like reports came from the exhausts.

Ted was seized with consternation, for a thin[20] streamer of flame shot back from under the hood; the plane was afire.

Stanley saw the danger at the same moment and dove in an attempt to put out the fire, but this manœuvre, frequently successful in such an emergency, proved to be the worst possible thing in this case. With a roar the flame struck him full in the face; he tried to pull the ship out of the dive, but the fiery blast stifled him; the ground below, the sky above, and even the wings on either side of him seemed wrapped in a haze, and in an instant he was enveloped in complete darkness.

Ted saw the wilting figure in front of him droop out of sight; at the same time the plane began to quiver and lurch from side to side. Without a guiding hand to direct it the heretofore graceful craft became converted into a mass of steel and wood and cloth hurtling through space to certain destruction. He realized the frightfulness of the situation in a flash; Stanley had either fainted or was dead.

“I must get him down; I must save him,” he gasped, frantically grasping the controls in his own cockpit. He thought little of his own danger; it was his companion who filled his mind. He must get him to the ground and save him if it was not already too late.

The blaze was sweeping back directly over the top[21] of the twenty-gallon container resting between the engine and the front cockpit. “I must fan the flames to one side,” Ted thought. “If the gas catches, it will be the end.”

Responding to a savage turn of the wheel, the ship turned on edge and the streamer of fire darted out to one side. If only he could keep it there! Perhaps the rudder would help; he gave it a sharp kick, then felt that he had made a mistake, for he had pushed it in the direction opposite to the wheel. But the ship, tilted at a steep angle, started into a side-slip toward the ground, and that was exactly what he wanted. He must keep on slipping from side to side, like a falling leaf.

The wind shrieked through the rigging with a terrifying scream and threatened to tear away the side of Ted’s face. He straightened out the plane, reversed his controls, and then began falling in the opposite direction. Back and forth they darted; the ground was rushing up to meet them at a furious speed. It was fascinating, this sight of the ground rushing upward, and as he looked at it he suddenly realized that they were almost directly above an open field—the landing-field, it must have been, for there were the white hangars in which the ships were kept; and the machines that had been out in the open were scurrying[22] in all directions. Vaguely he wondered how long it would be before they should crash in their midst.

After what seemed like ages, but which was in reality a matter of seconds, the ground loomed up close to them. The moment for the supreme test had come. Throwing the controls into neutral he brought the ship into an even glide. The hot blast struck his face and the fumes of burning oil made him cough and choke. But not for an instant did he relax to lower his head for a breath of air; he must see the thing through if it was the last thing he ever did.

Her speed gone, the ship settled rapidly; it was but ten feet from the ground. Ted pulled back the wheel cautiously to keep her nose up, as he had been told so often by Stanley, and the plane responded ever so feebly. The ship struck with a jolt, bounded, settled again, rolled forward a short distance, and came to a stop.

Ted snatched at the buckle of his belt, tore off his goggles, and jumped to the ground. His head was reeling and his throat was parched. The flames now extended in back of the hood and were reaching for the fuel-tank. It was only a question of seconds before the explosion that would deluge them with a shower of burning gasolene.

There was not time to try to rescue Stanley by pulling[23] him over the rim of the cockpit, and, besides, Ted had not the strength left for such an undertaking. So he clambered up on one wing and kicked in the linen side of the fuselage, after which he dragged the unconscious form of his companion through the hole. Then he tottered away with the limp body in his arms, how far he never knew.

A chorus of excited voices reached his ears in a confused murmur and helping hands relieved him of his burden. His head burned and a thousand needles seemed to stab through his chest. He clutched the air wildly and, gasping for breath, plunged headlong into darkness.

The exploits of Stanley and Ted in the great World War form no part of this story. It is enough to say that they saw extensive service on the Western Front and that they acquitted themselves in an entirely creditable manner.

The armistice was signed at last and the two, in common with thousands of others, were returned to their own country. They had attained the rank of first lieutenant. Now, their services being no longer urgently required, they tendered their resignations and received honorable discharges.

“I am beginning to feel as if I have had enough of a rest,” Ted said one night a few weeks afterward when Stanley dropped in at his home for one of his visits. They saw one another almost daily. “What do you say to making another attempt to get the treasure?”

“You know what I think about it,” Stanley replied. “If the folks had not been urging me to remain with[25] them a while longer, I should have suggested starting before now. They cannot forget what we went through on our first visit to the Hidden Valley; but they know we are determined to return to it. They are not discouraging me at all; only trying to put it off as long as possible.”

“We are losing a lot of time. The sooner we go back to Peru and have it over with the better. Think of the tons of gold lying in the cave waiting for us to carry them away.”

“I know. How do your people feel about it? I suppose they are not eager to have you go?”

“The situation is the same with me as with you. But I think we should start without further delay. There are so many things to be done when we get back, and time flies.” Then, after a moment’s thought: “I have been looking up the sailing dates. There is a good steamer for Panama next Tuesday—that is, a week from to-day. It will get us to the isthmus just in time to connect with the Panela of the Peruvian Line for Mollendo. Can you be ready then, or is that too soon?”

“I could be ready to-morrow. Waiting a whole week, now that we have actually decided to go, will seem like a year!”

“And,” said Ted as Stanley was leaving, “we had[26] better not take anything with us from here. We can get all the supplies and outfit we need in Cuzco.”

Arrived in Colon, they found the Panela scheduled to sail that same afternoon. There was barely sufficient time to transfer their baggage, comply with the customs formalities, and secure passage on the departing steamer.

Before long they had entered the muddy water of the canal, and soon after that the ship entered the locks and in an almost incredibly short time was raised to the level of Gatun Lake, with its vast expanse of murky water and its fringe of tree skeletons that stood like black monuments to mark the graveyard of the inundated forest. Darkness prevented the completion of the trip through the canal, so the ship was tied up for the night.

There was no moonlight, but the thousands of scintillating stars shed a soft radiance upon the torpid earth. The water was black and smooth as glass, save for the myriad points of reflected starlight. But in spite of the unruffled appearance of the surface the black depths were charged with life. One had only to drop some object overboard in order to excite to action the millions of jelly-fish that lurked below. When the water was agitated by the missile, no matter[27] how lightly, it blazed with patches and circles of greenish phosphorescence, so that the surface seemed aflame with a weird, unearthly fire. And occasionally there was a streak of the same uncanny light as one of the larger inhabitants of the deep cut the surface in a burst of speed in pursuit of some of the lesser fry.

With the coming of daylight the Panela was lowered through the locks at the far end of the canal and headed for the open ocean.

“No wonder this is called the Pacific,” said Ted as they stood on deck looking over the broad expanse of dark-blue water. The surface was so smooth that it might have been a sheet of glass; into this the prow of the ship cut a furrow crested with hissing white foam. Overhead the man-o’-war birds described great circles on motionless wings; they were marvels of grace and endurance, spanning the limitless blue day after day without stopping to rest. In the distance a number of whales rolled lazily in the briny water and blew thin jets of spray high into the air.

“If I were not so eager to finish our job down there I should say that this is the only life. I could keep sailing on forever. I certainly intend to do my share of travelling if this venture proves successful,” Stanley said.

“If?” Ted queried in surprise. “You mean when[28] the job is finished. There is no question in my mind but that we shall get the gold this time. We know exactly how to overcome the one little barrier that lies between us and the hidden millions.”

“You are right. When are we due to reach Mollendo?”

“Six days from now. Then three more days in which to get to Cuzco. Two or three days in which to gather our outfit together, and then for the trail. In a month from now, at the most, we shall be ferrying out the gold that has been concealed for so many centuries. The underground river will hum as we dash back and forth through it.”

“After that we shall be up against the hardest work of all; that is to get the gold out of the country and back home safely. But let’s not cross any bridges before we get to them. The future must take care of itself,” said Stanley.

“While we are so near to it, I wish we could take a peep into the Hidden Valley. Perhaps Huayna Capac, the Inca, is dead, and Quizquiz is king now. I am sorry for everybody in the valley if he is their ruler. The old king at least tried to be kind and generous, the best he knew how, but Quizquiz will be a tyrant in every sense of the word. He is conceited, arrogant, and cruel. I should hate to fall into his hands.”

[29]“And I, too,” said Stanley. “But there is no chance. He would not dare enter Uti, where the gold is hidden, and we shall certainly not trespass in his kingdom beyond the great wall. So we can simply guess at what is taking place in the Hidden Valley, and I am content to let it go at that.”

Stanley spoke with conviction, but he had no way of knowing what the future had in store for him. Just as the past years had brought the momentous events due to the World War, so there had been events of importance in the Hidden Valley, also. If Ted and Stanley could in some manner have obtained an inkling of what had happened behind those silent and unscalable mountains that surrounded the retreat of the last of the Incas, they doubtless should have refrained from making another attempt to secure the fabulous wealth that this same barrier also protected. Firmly resolved though they were not to enter the Hidden Valley proper again, it was not impossible that circumstances beyond their control might take them into the very region they were so eager to shun. And then—the terrible reckoning, with the pitiless, triumphant, and all-powerful Quizquiz as their captor and judge.

They landed in Mollendo just in time to take the early afternoon train into the mountains, and night[30] found them in the upland city of Arequipa. It required the greater part of another day to cover the distance to Puno, and on the morning after that the journey to Cuzco began.

As the train crept wearily over the high plateau and entered the outskirts of the city, Ted, who was gazing interestedly through the little window of their compartment, gave a cry of surprise.

“Things have certainly been happening here since we last saw this place,” he said. “Look!”

Stanley, too, peered through the window. A number of long, wide, wooden buildings had been erected along one side of a level field. There were also narrower and higher structures and a small cluster of tents. Men in uniform were drilling near the group of buildings; and a detachment of other soldiers was signalling with large white panels that were spread out on the ground.

“Ted,” he said suddenly, “that aviation-field has been put there for a purpose. It may mean that the war fever has spread even to these remote countries; or it may be only the beginning of a preparedness campaign. I can’t say why, but I feel in my bones that we are going to get mixed up in whatever it is before very long.”

“I hope not. We can’t afford to let anything sidetrack[31] us from getting that gold. If we keep putting it off something may happen to prevent our getting it altogether.”

“But that is just what I am thinking,” Stanley protested. “Everything we do must be a step toward the big goal.”

“I don’t see the connection.”

“Well, then, let me tell you. It takes many days of walking over the most difficult trail to reach the underground river. And heaven only knows how hard it will be to carry the gold back up the mountainside. Now, in an airplane the distance cannot be very great, and instead of work it would be fun. Now do you see what I mean?”

“Stanley!” Ted’s face beamed. “Do you think we could arrange it?”

“There is nothing impossible if you do not want it to be. We are going to get into the treasure-ground by the air-route this time, even if we have to steal one of those planes to do it.”

Just then the train rolled into the station and Ted and Stanley gathered up their baggage and followed the crowd along the platform and out into the street.

“Sir, the colonel presents his compliments and commands you to report to him at once.”

Ted and Stanley had just finished breakfast and were crossing the open little courtyard between the dining-room of the inn and their own quarters when the orderly stepped briskly in their path, saluted, and delivered his message.

“What?” Ted asked, stopping in his tracks.

“Colonel who?” from Stanley, “and what does he want with us?”

“Colonel José Antonio de Estrella, commanding officer of the First Aero Squadron.”

“Why this great honor? We do not know the colonel and cannot imagine why he wishes to see us. But of course if he insists, we shall be happy to pay him a visit. Only he should invite, not command, us; we have put up with enough ‘commanding and ordering’ in our own army to last us a long, long time.”

“Are not the señores the flyers who have been expected the past month? The colonel has been very impatient of the delay.”

[33]“No, we know nothing of the gentlemen you mention, but perhaps we can be of service, anyway. Take us to the colonel. I guess we can see him right away.”

The youth saluted and started away at a fast walk, the two Americans following.

“I told you we were going to get mixed up in that aviation proposition,” Stanley said. “I knew it the minute I saw that field.”

“Who knows what it may lead to? but I cannot see much to it just yet. We are being mistaken for some one else, and that is about all that is clear so far. So soon as the colonel sees us he will recognize his mistake, apologize profusely, and tell us to go our way.”

“Now that is exactly what we must avoid. We have an opening to do the very thing that will help us and we must manage to take advantage of it. Instead of our going to them to beg for a job, they have sent for us in error, it is true, but what is to prevent us from profiting by it?”

“You are right, and I only hope we can see the thing through. How much hard work it would save us if we could fly to the Hidden Valley, to say nothing of the time we should save!”

They reached the camp in a little over half an hour[34] and were immediately taken to headquarters, where the adjutant, a second lieutenant in a brilliant uniform, lost no time in ushering them into the colonel’s office.

The latter officer was of rather short build but of distinguished appearance. His hair and long mustaches were snowy white; his eyes were black. A number of medals and military decorations were pinned to his coat in a neat row, but one of the first things the Americans observed was that the wings of a flying officer were lacking.

“It is I who have made a big mistake,” he said as the two entered. “For the last four weeks I have been expecting two officers from Europe, but they do not come. Last night, when I heard that two strangers had arrived in the city, I concluded it must be they. I now see and acknowledge my mistake and I apologize for troubling the gentlemen.”

“The colonel owes us no apology,” said Stanley in a respectful manner. “Quite the contrary. It is a great pleasure for us to visit him. If we can be of service it will please us to help in any way we can. Both my companion and I have had considerable experience with airplanes.”

“You mean to say you are aviators?” the colonel asked, rising from his chair. “When and where did[35] you learn to fly and what has been your experience? Sit down and tell me all about it.”

Ted and Stanley did as they were asked, and for an hour they related to the officer their various experiences so far as aeronautics were concerned. He listened intently to all they had to say and asked many questions.

“It is indeed fortunate for me that you came,” he said when they had finished, “for I need your help and can offer you good positions. The manœuvres take place in two months and we must have ships in the air by that time. Now, when can you begin work? Remember, there is need of great haste.”

“Will you tell us exactly what is expected of us?” Ted asked. “And then we shall want to talk the matter over between ourselves. And what is the remuneration?”

“Your work will be to assemble the machines and to test them thoroughly before turning them over to the instructors. That will not be an easy undertaking and, as you know, it is not without danger, for I shall insist that the test flights be very conclusive; they will include trips across country of several hours’ duration. I want the planes to be as safe as possible before we begin taking up students. You will be subject to my orders only as civilian employees. And[36] the pay is five hundred soles a month, which is about two hundred and fifty dollars in the money of your country.”

They thanked the colonel for his offer and returned to the inn.

“What do you think of that for luck?” Ted fairly shouted. “Things are coming our way so fast it is hard to keep track of them.”

“We could not wish for a better arrangement,” Stanley agreed. “It is almost too good to be true. Every time we make one of those long test flights the colonel insists upon, we can drop into Uti and bring out a load of gold, as much as the ship will carry, and that is considerable. When we have enough we can resign and go home. We have not been asked to enlist for any given period of time, so we can quit when we want to, provided, of course, we give them reasonable notice, so they can get some one else to take our places.”

That afternoon they sent word to the colonel that they should be ready to start work on the following morning, and shortly after daybreak a cart arrived to take their effects to camp, as they were henceforth to occupy quarters on the military reservation.

The two reported to the officer soon after, and were at once sent to the hangars, where a number of crates[37] and boxes were stored. These containers held wings, bodies, and motors, just as they had been packed for shipment by the manufacturers in the United States. A detachment of some twenty odd mechanics were placed at their disposal. These men had been well trained in the theory of aeronautics, and while they lacked practical experience, showed unbounded enthusiasm for the work, combined with intelligence and adaptability. Before long the tasks in hand began in earnest.

Ted and Stanley went about the matter in a systematic, businesslike way. They called the men together and then divided them into sections, or crews, and explained in detail what the duties of each would be. A leader or chief was appointed for each crew. The Americans were to give orders to the chiefs, and the latter would be held responsible that these orders were carried out promptly by the men in their charge.

First they examined the bills of lading and invoices. Then they selected certain of the boxes, checked them off the lists, and had them removed to the largest hangar, which stood not far away. This required all of the first day.

The second day they opened the packages and removed the various parts, subjecting them to inspection,[38] checking them against the lists, and noting minor breaks that had to be repaired. They also visited the supply-tent, looked over the tools and materials available, and made out requisitions for such things as would be needed but which were lacking.

“It’s beginning to look like business now,” Stanley commented that night. “The first thing is always to work out a system; after that everything is easy.”

“Two days is a short time, but it is surprising how many things one can do. Of course we had a good foundation to build on, for the colonel had made a good beginning. Too bad there is not a flying officer in charge of the field; he could understand the whole proposition more clearly and make allowances for the difficulties we are up against,” Ted returned.

“So far the colonel has been a prince. He has given us a free hand, and so long as he continues in that spirit we shall get along all right. If he were a flyer he would want to boss everything and show us how to do things, probably in a way different from the one we are accustomed to.”

“Right. I never thought of that.”

It was exactly four weeks later that the first of the planes had been assembled ready to roll out of the hangar for the final adjustments and tuning up. The[39] ships were of the two-seater type, similar to the JN4H’s so commonly used on American flying-fields, and of sturdy, dependable construction. They had two-hundred-horse-power eight-cylinder engines, and were rated as capable of making an air-speed of ninety miles an hour. There were radio sets and machine-guns, the latter mounted one above the engine and the other on a turret in the rear cockpit.

Ted and Stanley surveyed their work with pride. The motor roared with an even, steady purr, or snorted and banged as the mechanician opened and closed the throttle, while the graceful machine tugged impatiently in its efforts to free itself from the grasp of the men clinging to the wings, and to leap the blocks that had been placed under the wheels.

“When shall we take the first spin?” Ted asked as he inspected the turnbuckles and hit the wire braces with his hand to gauge their tautness.

“To-morrow, if nothing goes wrong. Think of what a wonderful experience it will be to soar over the peaks of the Andes; and the first chance we get we will hop off to the Valley. All our dreaming and planning is about to bear fruit.”

Just then the colonel accompanied by two officers in strange uniforms approached.

The colonel introduced the new arrivals to the[40] Americans. “At last they are here,” he added. “They will have entire charge of the cadets. You gentlemen will work together in perfect harmony, I hope, in the best interests of the service.”

Ted and Stanley showed genuine pleasure at making the acquaintance of the two lieutenants, but the latter seemed cool and reserved, and after a casual examination of the throbbing ship followed the colonel into one of the hangars.

A moment later Ted went to the rear of the structure to get a wrench from the tool-box, and while pawing through the miscellaneous collection the chest contained, the sound of voices from within reached his ears.

“I have investigated them thoroughly,” the colonel was saying, “and I have learned that they have been in Cuzco at least twice before this. Each time they disappeared on some secret mission into the mountains, and it is said that they are searching for a lost mine or hidden treasure. But that is nothing against them; we should do the same if we had a reason to hope for success in such a venture. I have also examined their pilot’s books, for which they cabled voluntarily, and they showed an unusually large number of hours in the air and a record above reproach. Their work here has been done well. And, besides, they[41] came to my assistance when I needed them. I sent for them; they did not beg me for the places.”

“If the colonel will pardon my saying so, the lieutenant and I can now assume full charge of the work. We do not need the Americans. We ourselves should supervise the rigging of the ships we are to fly.”

“It is a part of their agreement that they must test the machines first, so they, not you, will take all the risks. There are enough duties to keep all of you occupied. Never forget that I am commanding officer and I shall not tolerate interference with my plans.”

With these words the colonel strode angrily away. For a minute neither of the two foreigners spoke.

“Those Americans are in everything,” one said finally. “What chance do we stand while they are here? They do not know the meaning of the word fear; I have often watched them on the battle-front and I know. If these two give such exhibitions here as their countrymen did over there, they and not we will attract all the attention. We must manage to keep them out of the air.”

“That is easy,” the other replied. “If we cannot keep them from going up, we can see to it that they come back down in an unexpected way. A loose pin, a defective strut, or any one of a dozen other things,[42] and they will not stand in our way again. And no one will ever suspect!”

Ted did not wait to hear more. With a face white with anger he hastened to where Stanley was clamping the Lewis gun to the iron bars of the turret.

Ted’s first impulse was to tell Stanley immediately of the conversation he had heard in the hangar. But the roar of the motor made this impossible. Then it occurred to him that the two officers might be watching them, so he decided to withhold the information until they were safely in their own quarters.

Stanley’s face was a puzzle as he listened to the story. He did not interrupt until the recital was completed.

“I am surprised that they should resent our presence here,” he said finally. “There is room enough for all of us, but these fellows must have come bent on being the whole show and are determined to have their way. Still, it is almost impossible to believe they were altogether in earnest. Perhaps they knew you were listening and tried to frighten us.”

“That is what they said, no matter what their real intention. I think the thing ought to be reported to the colonel.”

“Perhaps we should report it, but that would only make matters worse. Why not wait until we have[44] some proof of their intentions? Then we shall have a fair case against them. In the meantime I guess we can take care of ourselves.”

“We must take every precaution. There is too much at stake for us to make a break one way or the other.”

“Yes, we will be very careful. And we will let it go at that. I think we shall be able to tell without trouble if there has been any tampering with the ships. A strict watch must be kept, for one thing, and we shall make a most thorough inspection of our machine before each flight,” said Stanley. “Above all, we must work fast; that is, get into and out of our destination as soon as possible, and then we shall be at liberty to leave the country. If we speed up we may be able to forestall our rivals.”

“How about a test flight to-morrow? And then an attempt to reach the hidden place a few days later?”

“The very thing. Have a first trial flight to-morrow and then spend a few days making adjustments while we also make our other preparations. After that the dash for the mountains. But we may have to alter our plans greatly. With the opposition and competition we have now it will not be possible to make an unlimited number of flights. We might succeed in going once or twice without trouble, but if we[45] went too often and remained away for long periods of time they would become suspicious and either stop us or try to follow to see what we were doing.”

“I have a scheme we could try. Why not take a load of equipment on the first trip and cache it in one of the caves; then open up the underground river and take out as much gold as we want that way. If we have to discontinue flying before we bring out very much in the plane we can go back by the overland route and pick up what we have hidden in the forest. That will save a lot of time and trouble.”

“We could not improve on that if we tried,” Stanley agreed enthusiastically. “While I do the final tinkering on the machine you can be gathering the things together. Bring them to our hangar, load them at night, and we can hop away early the next morning.”

Somehow the news had spread that there was to be a trial flight on the following day, and a huge crowd, composed mostly of Indians, gathered on the outskirts of the field at daybreak. It was not until shortly after noon, however, that everything was in readiness for the initial attempt. The two donned their leather coats, helmets, and goggles, and climbed into the cockpits. At a signal from Stanley the crew removed the wooden blocks from under the wheels and swung the ship around into the wind. Stanley gradually[46] opened the throttle, and as the roar of the engine increased in volume the machine gathered speed and raced over the even ground. In a moment it had left the earth and was soaring upward at an appreciable angle. The crowd of onlookers waved their hats and burst into a wild cheer, and Ted, who was standing in the rear pit, leaned over the rim and waved his hand toward the ground as they sped into the distance.

Stanley carefully watched the braces, struts, and wings, but as there was no unusual vibration, he tried a number of turns, banking gently, dived and zoomed, and in other ways tested the craft. Its stability and balance were to his entire satisfaction. Then they ascended to a height of five thousand feet and performed a series of stunts that even the birds would not dare attempt. They side-slipped, dived, and spiralled, did wing-overs, and ended in a series of loops. After that they descended to the field in a long tail-spin, levelling off just in time to land easily and gracefully in front of their hangar.

The colonel was most enthusiastic and congratulated them heartily, but the two lieutenants kept in the background and offered no comments.

“There are only a few wires to tighten a little,” Stanley informed the commanding officer. “They are always liable to slacken somewhat during the first[47] flights. The fuselage is lined up perfectly. If the colonel so desires, we shall be glad to make a long cross-country flight next Sunday. That could serve as a final test, after which the ship would be ready to go into commission for the regular work of training cadets.”

“Splendid!” the colonel replied. “Go anywhere you like. Give the machine a most thorough trial. The instructors and pupils are waiting impatiently for their turn.”

Two days later, as they were going over the ship for a final inspection, Stanley suddenly noticed that the keys had been removed from the pins that fastened the right upper wing to the body. With a slight motion of his hand he indicated the fact to Ted.

“Now we shall find out who is responsible for that,” he said to Ted between his teeth.

They had the ship rolled out on the line and started the engines. The colonel and the two lieutenants were on the field as usual, watching the operations.

“Perhaps the lieutenants would like a flight to-day?” Stanley suggested pleasantly, approaching the trio. “With the colonel’s consent, and so far as we are concerned, the ship is at your disposal.”

The two began to look uncomfortable, and one of them stammered an excuse about not being prepared[48] with the proper clothing. The colonel promptly suggested that they might use the outfits of the Americans if they desired, but upon this the other one pleaded illness.

“Well,” Stanley said, looking straight at the two, “we thought we might go up for a few minutes, but I guess we had better not. If it is not safe for you, it is not safe for us.”

The colonel understood that there was some difficulty, but said nothing until the two instructors had gone. Then he questioned the Americans as to the meaning of the affair. They showed him the pins with the missing keys.

“But you have no evidence against any one!” he said slowly. “This is most serious, but I cannot accuse any one of such an act without proof.”

“No, but in the future the hangars must be guarded day and night. No one must be permitted to enter without a written pass from you.”

“That is a good idea. It shall be done. I shall immediately issue an order to that effect.”

The damage was soon repaired and the ship rolled back into the hangar.

Ted spent the greater part of the next morning making purchases in the city, and the packages were delivered to the field early in the afternoon. They had[49] been compelled to buy numerous things connected with their work during the previous weeks, so the arrival of the boxes caused no comment. Ted stored them in a corner of the hangar and covered them with a tarpauling.

That night they carefully studied their map, on which the location of the Hidden Valley had been marked as accurately as possible, as they had done so many times before. And at daybreak on the following morning Ted loaded the packages into the ship, while Stanley went for a conference with the colonel. When the latter, too, arrived on the field, the plane was on the line with the engine roaring.

Although the guards assured them that none had approached the hangar during the night, the two spent considerable time in a minute inspection of the machine. And when the sun was an hour high in the heavens they left the ground, circled the field until they had reached an altitude of several thousand feet, then headed straight to the north.

If their calculations were right, they should reach the valley in an hour, unless they encountered a strong head-wind. Allowing another hour for the return, there would be a leeway of a third hour, for the fuel-supply, counting that contained in the emergency-tank overhead, was ample for three hours.

[50]From directly above, the mountain-peaks appeared flattened out exactly like the plateaux and valleys, but they could be distinguished from the latter by the patches of snow and fields of black rocks. A wind from the south added greatly to their speed, so that the landscape beneath them moved back at a rapid pace. To their right, and far, far below, lay the sea of dark-green Amazonian jungle.

Here and there among the bleak mountain-peaks lay little green valleys with square, blocklike dots scattered about singly and in groups. To the casual observer they might have been mistaken for stones. But to the trained eye they were clearly Indian huts, distinguishable from the other objects by their regular outlines. And if Ted looked closely he could make out minute specks moving toward the houses; they were the Indians running to shelter, terrified, no doubt, by the roaring spectre in the sky.

“Keep your eyes open wide,” Stanley shouted back to his companion after he had throttled down the motor so that its roar did not drown the sound of his voice. “Look for the yellow vapor and the ring of volcanoes. The wall, too. What was that?”

A black form had passed them at great speed, its shadow blanketing one side of the craft.

Ted looked back, knowing that it could not have been a cloud, for the sky was clear.

[51]“It’s a condor,” he called at the top of his voice, just as Stanley opened the throttle. Even as he spoke the great bird was wheeling gracefully and heading in their direction. Master of the desolate mountain tops and of the air above them, the huge bird was evidently investigating or challenging this newcomer into its realm.

Ted pounded the linen side of the fuselage frantically with his gloved hand, and at the signal Stanley automatically pushed the control forward, ever so slightly, and the ship went into a steep dive. It was part of their old code, originated on the Western Front, and in the emergency both remembered it instantly.

They were not a moment too soon. The great bird shot past above them with a rush of wings audible above the slow throbbing of the throttled-down motor.

Just as Stanley brought the plane to a level keel, the bird wheeled, and again came toward them, from the front, but this time the pilot saw it in time. He must avoid collision with the audacious creature, for the impact of the heavy body against the struts of propeller would be enough to shatter them and send them crashing to the ground. His first impulse was to use the machine-gun in an attempt either to kill the bird or to cause it to swerve; but a second thought seemed better. He waited until the black form was[52] a scant hundred yards away; then he pulled hard on the control, and instantly the bird seemed to drop into space below them. What had really happened was that the ship had bounded upward in a steep zoom, passing high above the attacker, and before the latter could turn, Stanley had resumed the level course and opened wide the throttle. The ship started forward at such great speed that the bird, swift of wing though it was, could not overtake them; and they soon lost it in the distance, a black speck growing constantly smaller in the unclouded sky.

After that they flew at a lower altitude, so as not to arouse the ire of other condors that might be soaring at that dizzy height.

Ted was carefully scanning the ground, on which everything now appeared with startling distinctness. Below was an Indian trail on which a caravan of llamas had been wending its leisurely way. The leader of the file stopped and evidently sounded an alarm of some kind, for in a moment the panic-stricken animals were dashing down the trail, leaving a cloud of dust in their wake and scattering their packs by the wayside. After leaping a stone wall they disappeared into the doorway of a hut. At the same time a number of Indians, wearing bright-colored blankets, darted out of the rear doorway, routed from their[53] abode by the onrushing beasts, but no sooner had they gained the open than one of the group discerned the strange monster above them, and back they dashed into the hut.

Ted was watching the spot long after to see if any of the occupants of the shelter would appear after they had passed, when the engine again slowed down.

“That looks like the spot over there,” Stanley shouted, nodding toward the landscape in front of them.

Ted looked in that direction and nodded assent. Far ahead, and to one side, lay a circle of yellow vapor; it seemed to hug the earth in a solid ring, while columns and whisps rose into the sky to a great height. That could mean but one thing. It was the impenetrable barrier of poisonous gases arising from the chain of volcanoes surrounding the Hidden Valley. A quarter of an hour later they had crossed the margin of the ring. There it was, directly beneath them—the long valley with its winding river, Uti with the dismal lagoon glistening in the sunlight, and the great wall that separated the two places showing like a narrow gray ribbon. To the left was another valley with high, steep walls of rock hemming it in on all sides, but there was no vapor clinging to the rim of that enclosure.

[54]Stanley shut down the power and they began a rapid and almost noiseless descent in a series of graceful spirals. When down to five hundred feet above the ground, he again opened the throttle and circled a few times, while both craned their heads over the sides of the cockpits, looking for a suitable place to land. In a moment they recognized the level strip of beach on the border of the lake, the very spot, in fact, where their canoe had been stranded several years before; another spiral, then a long glide, and they had landed on the hard sand.

At last they were in the region of gold-filled caves, a mere stone’s throw from the place where the vast treasure of the Incas had lain untouched for so many centuries. The two scrambled out of their cramped quarters and jumped to the ground. Then, dashing their helmets and goggles aside, they started in a wild rush toward the cave.

Upon reaching the entrance to the underground chamber they stopped. The vision of Timichi, the demented, self-styled king they had encountered on their previous visit, loomed up before them. What if he were still alive and had observed their approach? It was not probable, for even years ago he had been very old and in ill health; but it was just barely possible that he still lived. In that event he would be awaiting them in the darkened passageway with some heavy weapon with which to attack them. He had every advantage, and that he would submit to the seizure of the treasure without putting up a fight was out of the question.

“Let’s call to him,” Ted suggested. “Perhaps he will recognize our voices or his name and come out—if he is in there.”

They called “Timichi,” then “Loco,” which latter was the name he had liked and which applied to him so well. But there was no response. Then they advanced slowly, but no sinister figure dashed out of the blackness to dispute their way.

A few steps and they had entered the treasure-chamber.[56] The light from the openings in the ceiling shone full upon their faces. They broke into a run in their eagerness to reach the shining heaps of yellow metal. Then they slackened their pace, stopped, and stared hard—first straight ahead and then at one another. Was it true? Could it be possible? Or were they dreaming? For a moment they were speechless, but Stanley finally managed to force the fateful words through his lips.

“It’s gone, it’s gone!” he cried hoarsely. “The gold is gone!”

“Yes, it’s gone!” Ted echoed. “There is not a speck of it left. All our trouble is for nothing.”

Stanley burst into a laugh almost hysterical in its sudden shrillness.

“Why, what a pair of chumps we are! Timichi must have taken it away. He was the only one this side of the wall. He got some foolish notion or other into his head and so carried away the treasure.”

“Of course! And being old and feeble, he could not have taken it very far. He took it to one of the neighboring caves, where we shall find it in a few minutes. It did give me a scare, though, to find the place empty.”

“Same here,” agreed Stanley. “For a minute I was thunderstruck. I could not even think straight.”

[57]They hurried from the cavern and began a systematic exploration of the numerous openings that led to subterranean chambers in the mountainside. Some were so dark that they had to make constant use of their flash-lights in finding their way about. Others were illuminated by shafts of daylight that entered through crevices overhead. Most of the caves bore no evidence of ever having been occupied; others had evidently been used as lairs by curious wild beasts of a bygone age, and their bones, mingled with those of the creatures on which they had preyed, strewed the earthen floor.

At last they came to the cave where Timichi had pointed out to them the rows of his silent subjects. They had avoided this place until the last, because they did not want to look upon the rows of dead. Now, as they had half expected, they found the remains of Timichi, dressed in his gorgeous finery, and sitting on a stone with his head resting against the wall, as if surveying his little kingdom of the departed. It was weird and pathetic and they did not stay long.

As for the gold, it had not been found. It had disappeared as completely as if the rumbling craters had opened and engulfed it with their fiery mouths.

“It’s the most mysterious thing I ever heard of.[58] There were tons of it, and it does not seem possible that Timichi could have carried it away at all.”

“I’ll bet he didn’t. Some one else has been here since we left. Let’s look around,” Ted replied.

The underground river occurred to them first of all. It was by this means that they had made their escape during their previous visit to the dismal place, just as it seemed they were condemned to a living death in company with the demented Timichi.

When, after a tedious journey along the murky margin of the lagoon, they finally reached the mouth of the subterranean stream, they found the entrance blocked by a mass of stones. Nor was the barrier the result of a landslide, as they had supposed when they tried to force their way through from the other side; the stones had been placed there by human hands. Some one had indeed anticipated their return and had tried to forestall them in every way.

Then they returned to the cave in which the gold had been concealed and carefully looked around for traces or clews of the one who had removed the treasure, and after a lengthy search their efforts were rewarded. A faint trail led from the entrance toward the great wall. They followed the indistinct path, breathless with anticipation; it ran straight to the point where the wall joined the abrupt mountainside.[59] And there, under the massive structure, a hole had been dug large enough for men to pass freely to and fro. The gold had been carried back into the Hidden Valley.

“Quizquiz!” both shouted in one breath. “It was he. No one else would have thought of it or had the cunning to put through such an undertaking.”

The hole had been partially blocked with a heap of earth and stones.

“Not even this place, which had the reputation of being the home of the devils, could stop Quizquiz,” Stanley said. “I see through it now. After our escape in the canoe he planned to get us back. He had the hole dug and found that we were gone. Then they saw the underground river. Putting two and two together, he could easily figure out how we got away. He knew we should return, so he had the river blocked and carried away the gold.”

“We are stumped, all right,” Ted admitted. “All my wonderful plans have gone soaring. We might as well go back and forget about the whole thing. But it is a bitter pill to swallow.”

They made their way to the plane slowly and suffering all the agony of keenest disappointment; their hopes and ambitions were not to be realized. Their dreams of the future had vanished in thin air.

[60]“Let’s have a bite to eat,” Stanley suggested. “I feel faint and weak. Then we can fly back to the field, give up our jobs, and get back home—soon, I hope; the sooner the better.”

“What about all the stuff we brought with us?” Ted asked. “We shall not need it.”

“No! We might as well dump it. No use to carry back the extra weight. And, by the way, what is in those boxes? They are awfully heavy. I could tell we had a big load aboard because I could not get the ship to climb fast.”

“That is the dynamite,” Ted said calmly.

“What?” in consternation.

“Dynamite. About a hundred pounds of it!”

“Do you mean to tell me those boxes are full of dynamite?”

“Certainly. We should have needed it to blow open the entrance to the underground river.”

“Good heavens!” Stanley fairly shrieked. “Think of carting along a load of dynamite in a country like this. If we had had a forced landing we should have blown into bits.”

“I thought of that. But a forced landing in a mountainous country would have meant our finish anyway. So what is the difference?”

“I guess you are right, but if I had known it I[61] should not have attempted to fly a single inch until we had taken it out. It is a good thing you did not tell me about it.”

“What shall we do with it?”

“Get rid of it as soon as we can.”

“But if any one from the valley should come here he would find it,” said Ted. “I have an idea. Let’s mark the boxes for Quizquiz and leave a note saying that if he hits them with his golden sceptre he will see all his forefathers; then shove the boxes through the hole under the wall.”

“It would serve him right, but they cannot read. Besides, we do not want to kill any one. We shall have to hide it or throw it into the lake.”

“No, not throw it into the lake,” Ted said, with a peculiar shudder. “We are not out of here yet; we might need it!”

“Are you predicting more trouble? Hasn’t enough happened to us already?”

“I don’t know. But something tells me not to throw it away. I feel queer; it might be my imagination, but it is true just the same.”

“All right; do anything you like with it. But we will take it out of the ship this very minute; and the other things, too. We cannot be bothered with useless baggage.”

[62]They unlashed and unloaded the boxes. Then they ate a light lunch.

“We can hide everything in one of the smaller caves,” Ted decided. “No one will go prowling around in any of them. And if—I almost said when—we need the things we shall know where to find them.”

When they had disposed of the packages they prepared to depart. It was mid-afternoon and they must lose no more time in returning to the field. The colonel, no doubt, was anxious about them already.

In order to take off properly they were compelled to head toward the great wall because a current of air came from that direction. But the distance was sufficient to enable them to clear it by an ample margin. They also wanted to circle above the valley a few times for a farewell glimpse of the hiding-place of the last of the once powerful Incan nation, for soon they should leave it, never to return.

With a steadily increasing roar of the engine the ship raced over the ground, and when it had gained enough headway Stanley pulled back the stick and the plane leaped into the air. In a moment they had cleared the wall by a hundred feet. Now they were skimming above the depression concealing the Inca’s stronghold.

[63]Ted leaned out over the rim of the gunpit in order to have a good view of the fleeting ground below them. There was the river down which Moses had steered their plunging canoe to safety on the night of their escape, spread across patches of velvet green; stone huts that looked like toy blocks were scattered over the barren places, some in rows, others in groups and villages. People, terrified by the monster thundering over their heads, were scurrying to cover behind stone walls and into doorways. Far, far in the distance was a great city; Ted recognized it as the Patallacta, or City on the Hill, where they had first met Huayna Capac, the old king. Nearer was another collection of buildings covering a large territory; that was the City of Gold, with its palaces, gardens, and the great temple of the sun. Ted remembered it, too, only too well, for it was there they had been tried and condemned because of Quizquiz’s treachery. But they had escaped, thanks to Moses! And here they were again, safe, high in the air, out of reach of their enemy.

Without warning there came a few loud explosions from the exhausts, the engine hesitated, picked up again for a moment, slowed down, faltered, and stopped. Stanley realized immediately that the fuel in the main tank was exhausted, so he quickly shut off the feed-valve and turned on the supply from the[64] second reservoir, after which he dived at a steep angle, so that the rush of air might spin the propeller and thus crank the engine. But the expected roar did not come. Apparently the gasolene did not flow, for while the propeller was turning, there was only the coughing sound of a dead engine. He looked at the indicator in alarm; the tank was full, there was no mistake about that.

Almost before he knew it he was so near the ground that there was not time for further efforts to determine the cause of the trouble. He barely succeeded in straightening out the diving craft before it struck the earth with a thud. They cavorted along over a rock-strewn field beside the river, bounding and threatening to upset, and when the ship finally came to a stop the two were too dazed for speech. For, in their wild sprint over the uneven ground the propeller had struck a boulder and one of the blades was shattered.

They were indeed in an unenviable predicament. Not for all of the gold of the Incas should they have entered the Hidden Valley voluntarily. Yet fate had decreed that they should find themselves there, and under the most distressing circumstances. The ship was as useless as if it had been broken into bits, and there was no other means of escape.