Title: Military Reminiscences of the Civil War, Volume 1: April 1861-November 1863

Author: Jacob D. Cox

Release date: November 1, 2004 [eBook #6961]

Most recently updated: December 30, 2020

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Steve Schulze, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team. This file was produced from images generously

made available by the CWRU Preservation Department Digital Library.

MILITARY

REMINISCENCES

OF THE CIVIL WAR

BY

JACOB DOLSON COX, A.M., LL.D.

Formerly Major-General commanding Twenty-Third Army Corps

VOLUME I.

APRIL 1861--NOVEMBER 1863

PREFACE

My aim in this book has been to reproduce my own experience in our Civil War in such a way as to help the reader understand just how the duties and the problems of that great conflict presented themselves successively to one man who had an active part in it from the beginning to the end. In my military service I was so conscious of the benefit it was to me to get the personal view of men who had served in our own or other wars, as distinguished from the general or formal history, that I formed the purpose, soon after peace was restored, to write such a narrative of my own army life. My relations to many prominent officers and civilians were such as to give opportunities for intimate knowledge of their personal qualities as well as their public conduct. It has seemed to me that it might be useful to share with others what I thus learned, and to throw what light I could upon the events and the men of that time.

As I have written historical accounts of some campaigns separately, it may be proper to say that I have in this book avoided repetition, and have tried to make the personal narrative supplement and lend new interest to the more formal story. Some of the earlier chapters appeared in an abridged form in "Battles and Leaders of the Civil War," and the closing chapter was read before the Ohio Commandery of the Loyal Legion. By arrangements courteously made by the Century Company and the Commandery, these chapters, partly re-written, are here found in their proper connection.

Though my private memoranda are full enough to give me reasonable confidence in the accuracy of these reminiscences, I have made it a duty to test my memory by constant reference to the original contemporaneous material so abundantly preserved in the government publication of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Where the series of these records is not given, my references are to the First Series, with the abbreviation O. R., and I have preferred to adhere to the official designation of the volumes in parts, as each volume then includes the documents of a single campaign.

J. D. C.

NOTE.--The manuscript of this work had been completed by General Cox, and placed in the hands of the publishers several weeks before his untimely death at Magnolia, Mass., August 4, 1900. He himself had read and revised some four hundred pages of the press-work. The work of reading and revising the remaining proofs and of preparing a general index for the work was undertaken by the undersigned from a deep sense of obligation to and loving regard for the author, which could not find a more fitting expression at this time. No material changes have been made in text or notes. Citations have been looked up and references verified with care, yet errors may have crept in, which his well-known accuracy would have excluded. For all such and for the imperfections of the index, the undersigned must accept responsibility, and beg the indulgence of the reader, who will find in the text itself enough of interest and profit to excuse many shortcomings.

WILLIAM C. COCHRAN. CINCINNATI, October 1, 1900.

CONTENTS

THE OUTBREAK OF THE WAR

Ohio Senate, April 12--Sumter bombarded--"Glory to God!"--The

surrender--Effect on public sentiment--Call for troops--Politicians

changing front--David Tod--Stephen A. Douglas--The insurrection must be

crushed--Garfield on personal duty--Troops organized by the States--The

militia--Unpreparedness--McClellan at Columbus--Meets Governor

Dennison--Put in command--Our stock of munitions--Making

estimates--McClellan's plan--Camp Jackson--Camp Dennison--Gathering of

the volunteers--Garibaldi uniforms--Officering the troops--Off for

Washington--Scenes in the State Capitol--Governor Dennison's

labors--Young regulars--Scott's policy--Alex. McCook--Orlando Poe--Not

allowed to take state commissions.

CAMP DENNISON

Laying out the camp--Rosecrans as engineer--A comfortless

night--Waking to new duties--Floors or no floors for the huts--Hardee's

Tactics--The watersupply--Colonel Tom Worthington--Joshua Sill--Brigades

organized--Bates's brigade--Schleich's--My own--McClellan's

purpose--Division organization--Garfield disappointed--Camp

routine--Instruction and drill--Camp cookery--Measles--Hospital

barn--Sisters of Charity--Ferment over re-enlistment--Musters by Gordon

Granger--"Food for powder"--Brigade staff--De Villiers--"A Captain of

Calvary"--The "Bloody Tinth"--Almost a row--Summoned to the field.

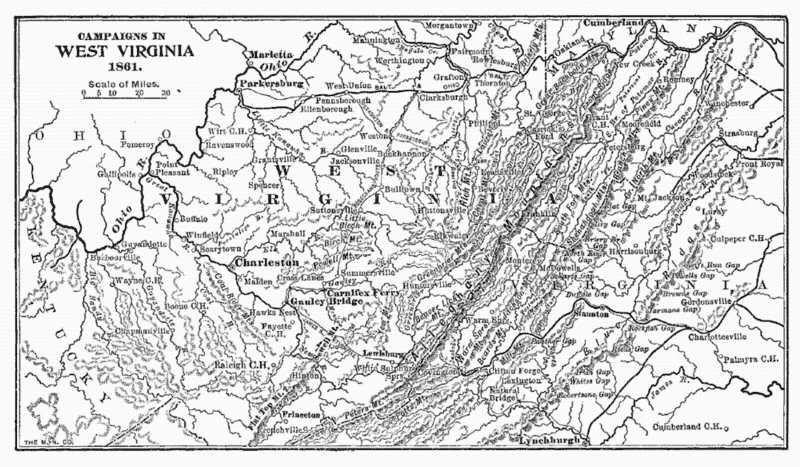

McCLELLAN IN WEST VIRGINIA

Political attitude of West Virginia--Rebels take the

initiative--McClellan ordered to act--Ohio militia cross the river--The

Philippi affair--Significant dates--The vote on secession--Virginia in

the Confederacy--Lee in command--Topography--The mountain

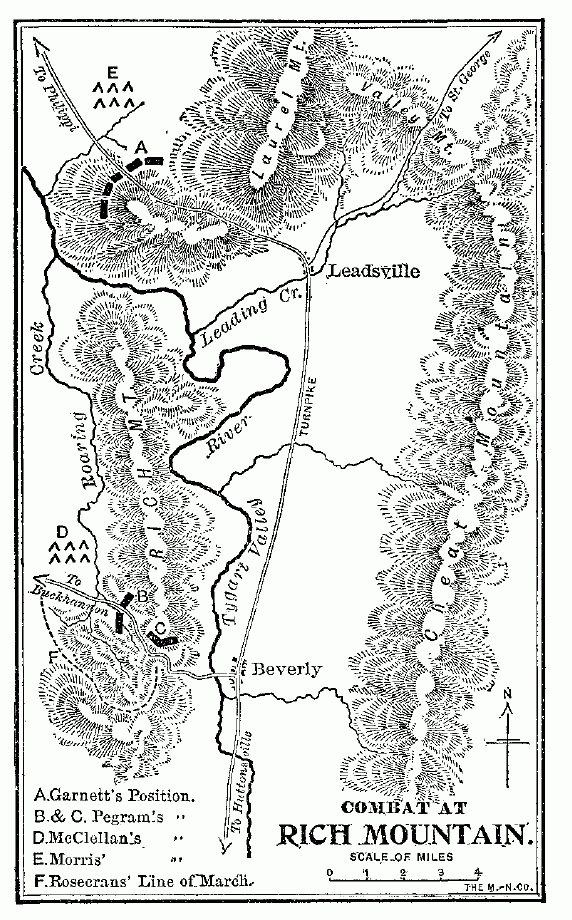

passes--Garnett's army--Rich Mountain position--McClellan in the

field--His forces--Advances against Garnett--Rosecrans's proposal--His

fight on the mountain--McClellan's inaction--Garnett's retreat--Affair

at Carrick's Ford--Garnett killed--Hill's efforts to intercept--Pegram

in the wilderness--He surrenders--Indirect results

important--McClellan's military and personal traits.

THE KANAWHA VALLEY

Orders for the Kanawha expedition--The troops and their

quality--Lack of artillery and cavalry--Assembling at

Gallipolis--District of the Kanawha--Numbers of the opposing

forces--Method of advance--Use of steamboats--Advance guards on river

banks--Camp at Thirteen-mile Creek--Night alarm--The river

chutes--Sunken obstructions--Pocotaligo--Affair at Barboursville--Affair

at Scary Creek--Wise's position at Tyler Mountain--His precipitate

retreat--Occupation of Charleston--Rosecrans succeeds McClellan--Advance

toward Gauley Bridge--Insubordination--The Newspaper

Correspondent--Occupation of Gauley Bridge.

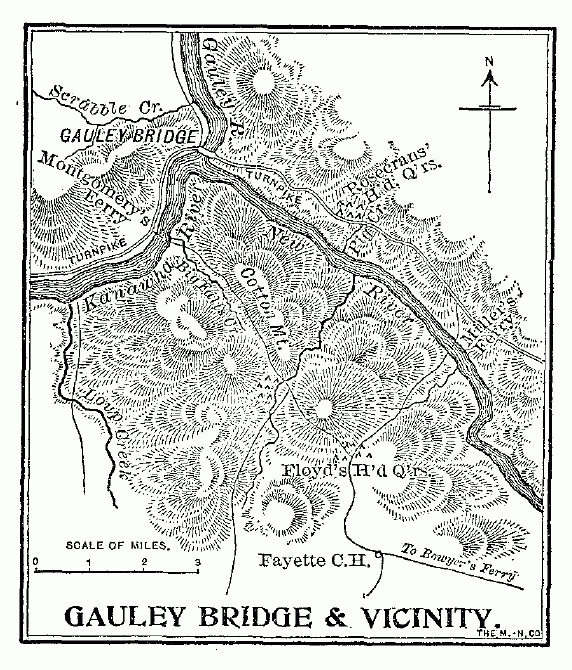

GAULEY BRIDGE

The gate of the Kanawha valley--The wilderness beyond--West Virginia

defences--A romantic post--Chaplain Brown--An adventurous

mission--Chaplain Dubois--"The river path"--Gauley Mount--Colonel

Tompkins's home--Bowie-knives--Truculent resolutions--The

Engineers--Whittlesey, Benham, Wagner--Fortifications--Distant

reconnoissances--Comparison of forces--Dangers to steamboat

communications--Allotment of duties--The Summersville post--Seventh Ohio

at Cross Lanes--Scares and rumors--Robert E. Lee at Valley

Mountain--Floyd and Wise advance--Rosecrans's orders--The Cross Lanes

affair--Major Casement's creditable retreat--Colonel Tyler's

reports--Lieutenant-Colonel Creighton--Quarrels of Wise and

Floyd--Ambushing rebel cavalry--Affair at Boone Court House--New attack

at Gauley Bridge--An incipient mutiny--Sad result--A notable

court-martial--Rosecrans marching toward us--Communications

renewed--Advance toward Lewisburg--Camp Lookout--A private sorrow.

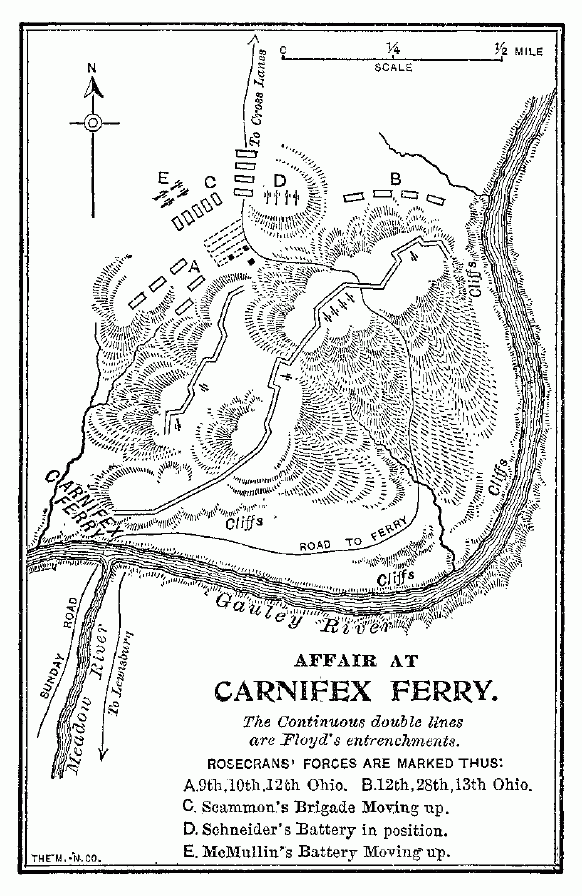

CARNIFEX FERRY--TO SEWELL MOUNTAIN AND BACK

Rosecrans's march to join me--Reaches Cross Lanes--Advance against

Floyd--Engagement at Carnifex Ferry--My advance to Sunday

Road--Conference with Rosecrans--McCook's brigade joins me--Advance to

Camp Lookout--Brigade commanders--Rosecrans's personal

characteristics--Hartsuff--Floyd and Wise again--"Battle of

Bontecou"--Sewell Mountain--The equinoctial--General Schenck

arrives--Rough lodgings--Withdrawal from the mountain--Rear-guard

duties--Major Slemmer of Fort Pickens fame--New positions covering

Gauley Bridge--Floyd at Cotton Mountain--Rosecrans's methods with

private soldiers--Progress in discipline.

COTTON MOUNTAIN

Floyd cannonades Gauley Bridge--Effect on Rosecrans--Topography of

Gauley Mount--De Villiers runs the gantlet--Movements of our

forces--Explaining orders--A hard climb on the mountain--In the post at

Gauley Bridge--Moving magazine and telegraph--A balky

mule-team--Ammunition train under fire--Captain Fitch a model

quartermaster--Plans to entrap Floyd--Moving supply trains at

night--Method of working the ferry--Of making flatboats--The Cotton

Mountain affair--Rosecrans dissatisfied with Benham--Vain plans to reach

East Tennessee.

WINTER-QUARTERS

An impracticable country--Movements suspended--Experienced troops

ordered away--My orders from Washington--Rosecrans objects--A

disappointment--Winter organization of the Department--Sifting our

material--Courts-martial--Regimental schools--Drill and picket duty--A

military execution--Effect upon the army--Political sentiments of the

people--Rules of conduct toward them--Case of Mr. Parks--Mr.

Summers--Mr. Patrick--Mr. Lewis Ruffner--Mr. Doddridge--Mr. B. F.

Smith--A house divided against itself--Major Smith's journal--The

contrabands--A fugitive-slave case--Embarrassments as to military

jurisdiction.

VOLUNTEERS AND REGULARS

High quality of first volunteers--Discipline milder than that of the

regulars--Reasons for the difference--Practical efficiency of the

men--Necessity for sifting the officers--Analysis of their defects--What

is military aptitude?--Diminution of number in ascending scale--Effect

of age--Of former life and occupation--Embarrassments of a new

business--Quick progress of the right class of young men--Political

appointments--Professional men--Political leaders naturally prominent in

a civil war--"Cutting and trying"--Dishonest methods--An excellent army

at the end of a year--The regulars in 1861--Entrance examinations for

West Point--The curriculum there--Drill and experience--Its

limitations--Problems peculiar to the vast increase of the

army--Ultra-conservatism--Attitude toward the Lincoln

administration--"Point de zêle"--Lack of initiative--Civil work of

army engineers--What is military art?--Opinions of experts--Military

history--European armies in the Crimean War--True generalship--Anomaly

of a double army organization.

THE MOUNTAIN DEPARTMENT--SPRING CAMPAIGN

Rosecrans's plan of campaign--Approved by McClellan with

modifications--Wagons or pack-mules--Final form of plan--Changes in

commands--McClellan limited to Army of the Potomac--Halleck's Department

of the Mississippi--Frémont's Mountain Department--Rosecrans

superseded--Preparations in the Kanawha District--Batteaux to supplement

steamboats--Light wagons for mountain work--Frémont's plan--East

Tennessee as an objective--The supply question--Banks in the Shenandoah

valley--Milroy's advance--Combat at McDowell--Banks

defeated--Frémont's plans deranged--Operations in the Kanawha

valley--Organization of brigades--Brigade commanders--Advance to Narrows

of New River--The field telegraph--Concentration of the enemy--Affair at

Princeton--Position at Flat-top Mountain.

POPE IN COMMAND--TRANSFER TO WASHINGTON

A key position--Crook's engagement at Lewisburg--Watching and

scouting--Mountain work--Pope in command--Consolidation of

Departments--Suggestions of our transfer to the East--Pope's Order No.

11 and Address to the Army--Orders to march across the

mountains--Discussion of them--Changed to route by water and

rail--Ninety-mile march--Logistics--Arriving in Washington--Two

regiments reach Pope--Two sent to Manassas--Jackson captures

Manassas--Railway broken--McClellan at Alexandria--Engagement at Bull

Run Bridge--Ordered to Upton's Hill--Covering Washington--Listening to

the Bull Run battle--Ill news travels fast.

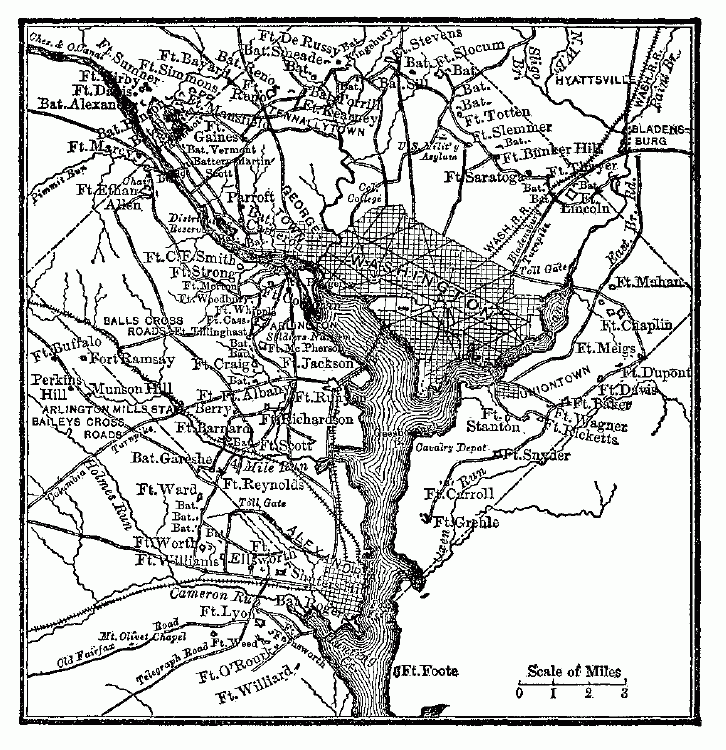

RETREAT WITHIN THE LINES--REORGANIZATION--HALLECK AND HIS SUBORDINATES

McClellan's visits to my position--Riding the lines--Discussing the

past campaign--The withdrawal from the James--Prophecy--McClellan and

the soldiers--He is in command of the defences--Intricacy of official

relations--Reorganization begun--Pope's army marches through our

works--Meeting of McClellan and Pope--Pope's characteristics--Undue

depreciation of him--The situation when Halleck was made

General-in-Chief--Pope's part in it--Reasons for dislike on the part of

the Potomac Army--McClellan's secret service--Deceptive information of

the enemy's force--Information from prisoners and citizens--Effects of

McClellan's illusion as to Lee's strength--Halleck's previous

career--Did he intend to take command in the field?--His abdication of

the field command--The necessity for a union of forces in

Virginia--McClellan's inaction was Lee's opportunity--Slow transfer of

the Army of the Potomac--Halleck burdened with subordinate's

work--Burnside twice declines the command--It is given to

McClellan--Pope relieved--Other changes in

organization--Consolidation--New campaign begun.

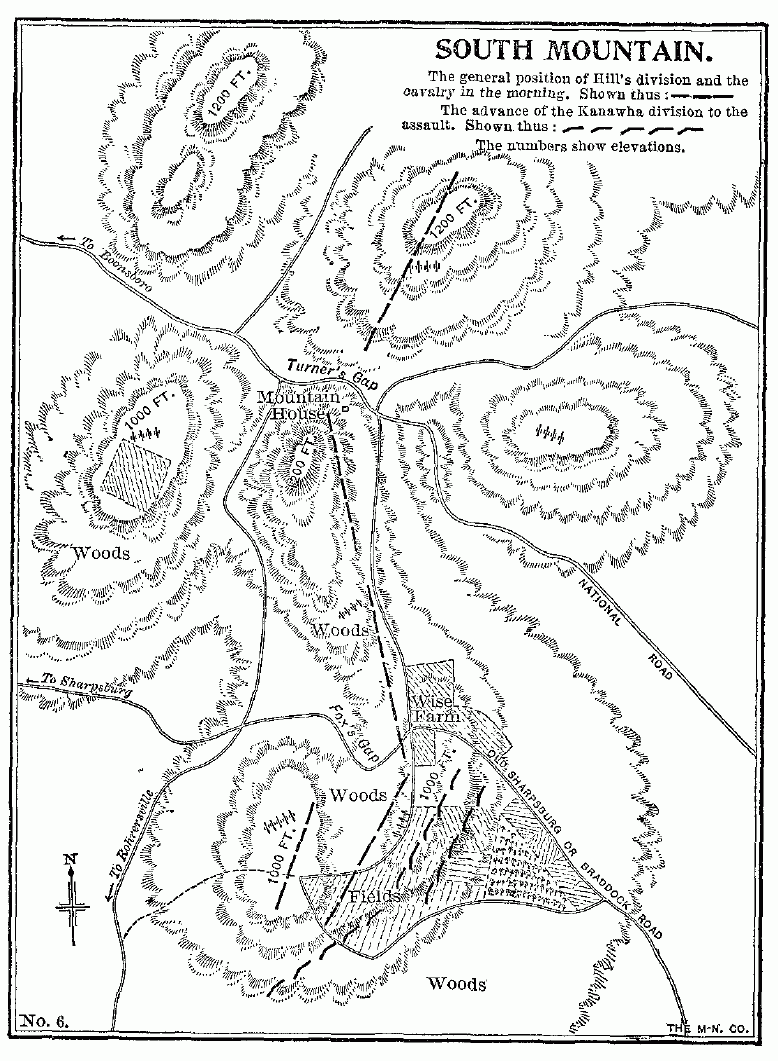

SOUTH MOUNTAIN

March through Washington--Reporting to Burnside--The Ninth

Corps--Burnside's personal qualities--To Leesboro--Straggling--Lee's

army at Frederick--Our deliberate advance--Reno at New Market--The march

past--Reno and Hayes--Camp gossip--Occupation of Frederick--Affair with

Hampton's cavalry--Crossing Catoctin Mountain--The valley and South

Mountain--Lee's order found--Division of his army--Jackson at Harper's

Ferry--Supporting Pleasonton's reconnoissance--Meeting Colonel Moor--An

involuntary warning--Kanawha Division's advance--Opening of the

battle--Carrying the mountain crest--The morning fight--Lull at

noon--Arrival of supports--Battle renewed--Final success--Death of

Reno--Hooker's battle on the right--His report--Burnside's

comments--Franklin's engagement at Crampton's Gap.

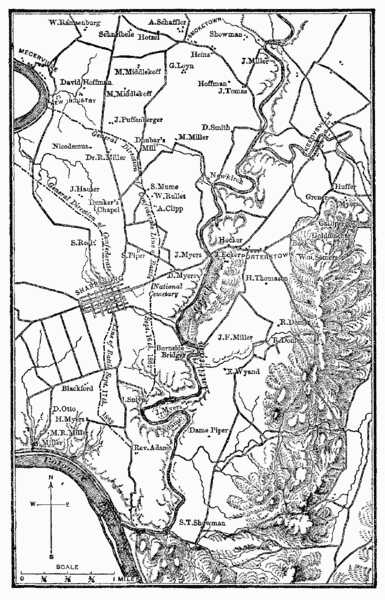

ANTIETAM: PRELIMINARY MOVEMENTS

Lee's plan of invasion--Changed by McClellan's advance--The position

at Sharpsburg--Our routes of march--At the Antietam--McClellan

reconnoitring--Lee striving to concentrate--Our delays--Tuesday's

quiet--Hooker's evening march--The Ninth Corps command--Changing our

positions--McClellan's plan of battle--Hooker's evening

skirmish--Mansfield goes to support Hooker--Confederate

positions--Jackson arrives--McLaws and Walker reach the field--Their

places.

ANTIETAM: THE FIGHT ON THE RIGHT

Hooker astir early--The field near the Dunker Church--Artillery

combat--Positions of Hooker's divisions--Rocky ledges in the

woods--Advance of Doubleday through Miller's orchard and garden--Enemy's

fire from West Wood--They rush for Gibbon's battery--Repulse--Advance of

Patrick's brigade--Fierce fighting along the turnpike--Ricketts's

division in the East Wood--Fresh effort of Meade's division in the

centre--A lull in the battle--Mansfield's corps reaches the

field--Conflicting opinions as to the hour--Mansfield killed--Command

devolves on Williams--Advance through East Wood--Hooker wounded--Meade

in command of the corps--It withdraws--Greene's division reaches the

Dunker Church--Crawford's in the East Wood--Terrible effects on the

Confederates--Sumner's corps coming up--Its formation--It moves on the

Dunker Church from the east--Divergence of the divisions--Sedgwick's

passes to right of Greene--Attacked in flank and broken--Rallying at the

Poffenberger hill--Twelfth Corps hanging on near the church--Advance of

French's division--Richardson follows later--Bloody Lane reached--The

Piper house--Franklin's corps arrives--Charge of Irwin's brigade.

ANTIETAM: THE FIGHT ON THE LEFT

Ninth Corps positions near Antietam Creek--Rodman's division at

lower ford--Sturgis's at the bridge--Burnside's headquarters on the

field--View from his place of the battle on the right--French's

fight--An exploding caisson--Our orders to attack--The hour--Crisis of

the battle--Discussion of the sequence of events--The Burnside

bridge--Exposed approach--Enfiladed by enemy's artillery--Disposition of

enemy's troops--His position very strong--Importance of Rodman's

movement by the ford--The fight at the bridge--Repulse--Fresh

efforts--Tactics of the assault--Success--Formation on further

bank--Bringing up ammunition--Willcox relieves Sturgis--The latter now

in support--Advance against Sharpsburg--Fierce combat--Edge of the town

reached--Rodman's advance on the left--A. P. Hill's Confederate division

arrives from Harper's Ferry--Attacks Rodman's flank--A raw regiment

breaks--The line retires--Sturgis comes into the gap--Defensive position

taken and held--Enemy's assaults repulsed--Troops sleeping on their

arms--McClellan's reserve--Other troops not used--McClellan's idea of

Lee's force and plans--Lee's retreat--The terrible casualty lists.

McCLELLAN AND POLITICS--HIS REMOVAL AND ITS CAUSE

Meeting Colonel Key--His changes of opinion--His relations to

McClellan--Governor Dennison's influence--McClellan's attitude toward

Lincoln--Burnside's position--The Harrison Landing letter--Compared with

Lincoln's views--Probable intent of the letter--Incident at McClellan's

headquarters--John W. Garrett--Emancipation Proclamation--An

after-dinner discussion of it--Contrary influences--Frank

advice--Burnside and John Cochrane--General Order 163--Lincoln's visit

to camp--Riding the field--A review--Lincoln's desire for continuing the

campaign--McClellan's hesitation--His tactics of discussion--His

exaggeration of difficulties--Effect on his army--Disillusion a slow

process--Lee's army not better than Johnston's--Work done by our Western

army--Difference in morale--An army rarely bolder than its

leader--Correspondence between Halleck and McClellan--Lincoln's

remarkable letter on the campaign--The army moves on November 2--Lee

regains the line covering Richmond--McClellan relieved--Burnside in

command.

PERSONAL RELATIONS OF McCLELLAN, BURNSIDE, AND PORTER

Intimacy of McClellan and Burnside--Private letters in the official

files--Burnside's mediation--His self-forgetful devotion--The movement

to join Pope--Burnside forwards Porter's dispatches--His double refusal

of the command--McClellan suspends the organization of wings--His

relations to Porter--Lincoln's letter on the subject--Fault-finding with

Burnside--Whose work?--Burnside's appearance and bearing in the field.

RETURN TO WEST VIRGINIA

Ordered to the Kanawha valley again--An unwelcome surprise--Reasons

for the order--Reporting to Halleck at Washington--Affairs in the

Kanawha in September--Lightburn's positions--Enemy under Loring

advances--Affair at Fayette C. H.--Lightburn retreats--Gauley Bridge

abandoned--Charleston evacuated--Disorderly flight to the Ohio--Enemy's

cavalry raid under Jenkins--General retreat in Tennessee and

Kentucky--West Virginia not in any Department--Now annexed to that of

Ohio--Morgan's retreat from Cumberland Gap--Ordered to join the Kanawha

forces--Milroy's brigade also--My interviews with Halleck and

Stanton--Promotion--My task--My division sent with me--District of West

Virginia--Colonel Crook promoted--Journey westward--Governor

Peirpoint--Governor Tod--General Wright--Destitution of Morgan's

column--Refitting at Portland, Ohio--Night drive to Gallipolis--An

amusing accident--Inspection at Point Pleasant--Milroy ordered to

Parkersburg--Milroy's qualities--Interruptions to movement of troops--No

wagons--Supplies delayed--Confederate retreat--Loring relieved--Echols

in command--Our march up the valley--Echols retreats--We occupy

Charleston and Gauley Bridge--Further advance stopped--Our forces

reduced--Distribution of remaining troops--Alarms and minor

movements--Case of Mr. Summers--His treatment by the Confederates.

WINTER QUARTERS, 1862-63--PROMOTIONS AND POLITICS

Central position of Marietta, Ohio--Connection with all parts of

West Virginia--Drill and instruction of troops--Guerilla

warfare--Partisan Rangers--Confederate laws--Disposal of

plunder--Mosby's Rangers as a type--Opinions of Lee, Stuart, and

Rosser--Effect on other troops--Rangers finally abolished--Rival

home-guards and militia--Horrors of neighborhood war--Staff and staff

duties--Reduction of forces--General Cluseret--Later connection with the

Paris Commune--His relations with Milroy--He resigns--Political

situation--Congressmen distrust Lincoln--Cutler's diary--Resolutions

regarding appointments of general officers--The number authorized by

law--Stanton's report--Effect of Act of July, 1862--An excess of nine

major-generals--The legal questions involved--Congressional patronage

and local distribution--Ready for a "deal"--Bill to increase the number

of generals--A "slate" made up to exhaust the number--Senate and House

disagree--Conference--Agreement in last hours of the session--The new

list--A few vacancies by resignation, etc.--List of those dropped--My

own case--Faults of the method--Lincoln's humorous comments--Curious

case of General Turchin--Congestion in the highest

grades--Effects--Confederate grades of general and

lieutenant-general--Superiority of our system--Cotemporaneous reports

and criticisms--New regiments instead of recruiting old ones--Sherman's

trenchant opinion.

FAREWELL TO WEST VIRGINIA--BURNSIDE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF THE OHIO

Desire for field service--Changes in the Army of the

Potomac--Judgment of McClellan at that time--Our defective

knowledge--Changes in West Virginia--Errors in new

organization--Embarrassments resulting--Visit to General Schenck--New

orders from Washington--Sent to Ohio to administer the draft--Burnside

at head of the department--District of Ohio--Headquarters at

Cincinnati--Cordial relations of Governor Tod with the military

authorities--System of enrolment and draft--Administration by Colonel

Fry--Decay of the veteran regiments--Bounty-jumping--Effects on

political parties--Soldiers voting--Burnside's military plans--East

Tennessee--Rosecrans aiming at Chattanooga--Burnside's business

habits--His frankness--Stories about him--His personal

characteristics--Cincinnati as a border city--Rebel sympathizers--Order

No. 38--Challenged by Vallandigham--The order not a new

departure--Lincoln's proclamation--General Wright's circular.

THE VALLANDIGHAM CASE--THE HOLMES COUNTY WAR

Clement L. Vallandigham--His opposition to the war--His theory of

reconstruction--His Mount Vernon speech--His arrest--Sent before the

military commission--General Potter its president--Counsel for the

prisoner--The line of defence--The judgment--Habeas Corpus

proceedings--Circuit Court of the United States--Judge Leavitt denies

the release--Commutation by the President--Sent beyond the

lines--Conduct of Confederate authorities--Vallandigham in

Canada--Candidate for Governor--Political results--Martial

law--Principles underlying it--Practical application--The intent to aid

the public enemy--The intent to defeat the draft--Armed resistance to

arrest of deserters, Noble County--To the enrolment in Holmes County--A

real insurrection--Connection of these with Vallandigham's speeches--The

Supreme Court refuses to interfere--Action in the Milligan case after

the war--Judge Davis's personal views--Knights of the Golden Circle--The

Holmes County outbreak--Its suppression--Letter to Judge Welker.

BURNSIDE AND ROSECRANS--THE SUMMER'S DELAYS

Condition of Kentucky and Tennessee--Halleck's instructions to

Burnside--Blockhouses at bridges--Relief of East Tennessee--Conditions

of the problem--Vast wagon-train required--Scheme of a railroad--Surveys

begun--Burnside's efforts to arrange co-operation with Rosecrans--Bragg

sending troops to Johnston--Halleck urges Rosecrans to

activity--Continued inactivity--Burnside ordered to send troops to

Grant--Rosecrans's correspondence with Halleck--Lincoln's

dispatch--Rosecrans collects his subordinates' opinions--Councils of

war--The situation considered--Sheridan and Thomas--Computation of

effectives--Garfield's summing up--Review of the situation when

Rosecrans succeeded Buell--After Stone's River--Relative

forces--Disastrous detached expeditions--Appeal to ambition--The

major-generalship in regular army--Views of the President

justified--Burnside's forces--Confederate forces in East

Tennessee--Reasons for the double organization of the Union armies.

THE MORGAN RAID

Departure of the staff for the field--An amusingly quick

return--Changes in my own duties--Expeditions to occupy the

enemy--Sanders' raid into East Tennessee--His route--His success and

return--The Confederate Morgan's raid--His instructions--His reputation

as a soldier--Compared with Forrest--Morgan's start delayed--His

appearance at Green River, Ky.--Foiled by Colonel Moore--Captures

Lebanon--Reaches the Ohio at Brandenburg--General Hobson in

pursuit--Morgan crosses into Indiana--Was this his original

purpose?--His route out of Indiana into Ohio--He approaches

Cincinnati--Hot chase by Hobson--Gunboats co-operating on the

river--Efforts to block his way--He avoids garrisoned posts and

cities--Our troops moved in transports by water--Condition of Morgan's

jaded column--Approaching the Ohio at Buffington's--Gunboats near the

ford--Hobson attacks--Part captured, the rest fly northward--Another

capture--A long chase--Surrender of Morgan with the remnant--Summary of

results--A burlesque capitulation.

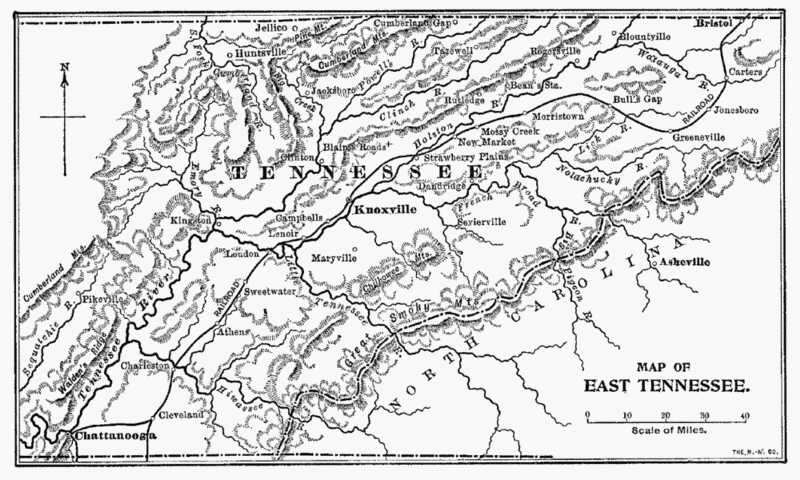

THE LIBERATION OF EAST TENNESSEE

News of Grant's victory at Vicksburg--A thrilling scene at the

opera--Burnside's Ninth Corps to return--Stanton urges Rosecrans to

advance--The Tullahoma manoeuvres--Testy correspondence--Its real

meaning--Urgency with Burnside--Ignorance concerning his situation--His

disappointment as to Ninth Corps--Rapid concentration of other

troops--Burnside's march into East Tennessee--Occupation of

Knoxville--Invests Cumberland Gap--The garrison surrenders--Good news

from Rosecrans--Distances between armies--Divergent lines--No railway

communication--Burnside concentrates toward the Virginia line--Joy of

the people--Their intense loyalty--Their faith in the future.

BURNSIDE IN EAST TENNESSEE

Organizing and arming the loyalists--Burnside concentrates near

Greeneville--His general plan--Rumors of Confederate

reinforcements--Lack of accurate information--The Ninth Corps in

Kentucky--Its depletion by malarial disease--Death of General Welsh from

this cause--Preparing for further work--Situation on 16th

September--Dispatch from Halleck--Its apparent purpose--Necessity to

dispose of the enemy near Virginia border--Burnside personally at the

front--His great activity--Ignorance of Rosecrans's peril--Impossibility

of joining him by the 20th--Ruinous effects of abandoning East

Tennessee--Efforts to aid Rosecrans without such abandonment--Enemy

duped into burning Watauga bridge themselves--Ninth Corps

arriving--Willcox's division garrisons Cumberland Gap--Reinforcements

sent Rosecrans from all quarters--Chattanooga made safe from attack--The

supply question--Meigs's description of the roads--Burnside halted near

Loudon--Halleck's misconception of the geography--The people imploring

the President not to remove the troops--How Longstreet got away from

Virginia--Burnside's alternate plans--Minor operations in upper Holston

valley--Wolford's affair on the lower Holston.

MILITARY

REMINISCENCES

OF THE CIVIL WAR

THE OUTBREAK OF THE WAR

Ohio Senate April 12--Sumter bombarded--"Glory to God!"--The surrender--Effect on public sentiment--Call for troops--Politicians changing front--David Tod--Stephen A. Douglas--The insurrection must be crushed--Garfield on personal duty--Troops organized by the States--The militia--Unpreparedness--McClellan at Columbus--Meets Governor Dennison--Put in command--Our stock of munitions--Making estimates--McClellan's plan--Camp Jackson--Camp Dennison--Gathering of the volunteers--Garibaldi uniforms--Officering the troops--Off for Washington--Scenes in the State Capitol--Governor Dennison's labors--Young regulars--Scott's policy--Alex. McCook--Orlando Poe--Not allowed to take state commissions.

On Friday the twelfth day of April, 1861, the Senate of Ohio was in session, trying to go on in the ordinary routine of business, but with a sense of anxiety and strain which was caused by the troubled condition of national affairs. The passage of Ordinances of Secession by one after another of the Southern States, and even the assembling of a provisional Confederate government at Montgomery, had not wholly destroyed the hope that some peaceful way out of our troubles would be found; yet the gathering of an army on the sands opposite Fort Sumter was really war, and if a hostile gun were fired, we knew it would mean the end of all effort at arrangement. Hoping almost against hope that blood would not be shed, and that the pageant of military array and of a rebel government would pass by and soon be reckoned among the disused scenes and properties of a political drama that never pretended to be more than acting, we tried to give our thoughts to business; but there was no heart in it, and the morning hour lagged, for we could not work in earnest and we were unwilling to adjourn.

Suddenly a senator came in from the lobby in an excited way, and catching the chairman's eye, exclaimed, "Mr. President, the telegraph announces that the secessionists are bombarding Fort Sumter!" There was a solemn and painful hush, but it was broken in a moment by a woman's shrill voice from the spectators' seats, crying, "Glory to God!" It startled every one, almost as if the enemy were in the midst. But it was the voice of a radical friend of the slave, who after a lifetime of public agitation believed that only through blood could freedom be won. Abby Kelly Foster had been attending the session of the Assembly, urging the passage of some measures enlarging the legal rights of married women, and, sitting beyond the railing when the news came in, shouted a fierce cry of joy that oppression had submitted its cause to the decision of the sword. With most of us, the gloomy thought that civil war had begun in our own land overshadowed everything, and seemed too great a price to pay for any good; a scourge to be borne only in preference to yielding the very groundwork of our republicanism,--the right to enforce a fair interpretation of the Constitution through the election of President and Congress.

The next day we learned that Major Anderson had surrendered, and the telegraphic news from all the Northern States showed plain evidence of a popular outburst of loyalty to the Union, following a brief moment of dismay. Judge Thomas M. Key of Cincinnati, chairman of the Judiciary Committee, was the recognized leader of the Democratic party in the Senate, [Footnote: Afterward aide-de-camp and acting judge-advocate on McClellan's staff.] and at an early hour moved an adjournment to the following Tuesday, in order, as he said, that the senators might have the opportunity to go home and consult their constituents in the perilous crisis of public affairs. No objection was made to the adjournment, and the representatives took a similar recess. All were in a state of most anxious suspense,--the Republicans to know what initiative the Administration at Washington would take, and the Democrats to determine what course they should follow if the President should call for troops to put down the insurrection.

Before we meet again, Mr. Lincoln's proclamation and call for seventy-five thousand militia for three months' service were out, and the great mass of the people of the North, forgetting all party distinctions, answered with an enthusiastic patriotism that swept politicians off their feet. When we met again on Tuesday morning, Judge Key, taking my arm and pacing the floor outside the railing in the Senate chamber, broke out impetuously, "Mr. Cox, the people have gone stark mad!" "I knew they would if a blow was struck against the flag," said I, reminding him of some previous conversations we had had on the subject. He, with most of the politicians of the day, partly by sympathy with the overwhelming current of public opinion, and partly by reaction of their own hearts against the false theories which had encouraged the secessionists, determined to support the war measures of the government, and to make no factious opposition to such state legislation as might be necessary to sustain the federal administration.

The attitude of Mr. Key is only a type of many others, and makers one of the most striking features of the time. On the 8th of January the usual Democratic convention and celebration of the Battle of New Orleans had taken place, and a series of resolutions had been passed, which were drafted, as was understood, by Judge Thurman. In these, professing to speak in the name of "two hundred thousand Democrats of Ohio," the convention had very significantly intimated that this vast organization of men would be found in the way of any attempt to put down secession until the demands of the South in respect to slavery were complied with. A few days afterward I was returning to Columbus from my home in Trumbull County, and meeting upon the railway train with David Tod, then an active Democratic politician, but afterward one of our loyal "war governors," the conversation turned on the action of the convention which had just adjourned. Mr. Tod and I were personal friends and neighbors, and I freely expressed my surprise that the convention should have committed itself to what must be interpreted as a threat of insurrection in the North if the administration should, in opposing secession by force, follow the example of Andrew Jackson, in whose honor they had assembled. He rather vehemently reasserted the substance of the resolution, saying that we Republicans would find the two hundred thousand Ohio Democrats in front of us, if we attempted to cross the Ohio River. My answer was, "We will give up the contest if we cannot carry your two hundred thousand over the heads of your leaders."

The result proved how hollow the party professions had been; or perhaps I should say how superficial was the hold of such party doctrines upon the mass of men in a great political organization. In the excitement of political campaigns they had cheered the extravagant language of party platforms with very little reflection, and the leaders had imagined that the people were really and earnestly indoctrinated into the political creed of Calhoun; but at the first shot from Beauregard's guns in Charleston harbor their latent patriotism sprang into vigorous life, and they crowded to the recruiting stations to enlist for the defence of the national flag and the national Union. It was a popular torrent which no leaders could resist; but many of these should be credited with the same patriotic impulse, and it made them nobly oblivious of party consistency. Stephen A. Douglas passed through Columbus on his way to Washington a few days after the surrender of Sumter, and in response to the calls of a spontaneous gathering of people, spoke to them from his bedroom window in the American House. There had been no thought for any of the common surroundings of a public meeting. There were no torches, no music. A dark crowd of men filled full the dim-lit street, and called for Douglas with an earnestness of tone wholly different from the enthusiasm of common political gatherings. He came half-dressed to his window, and without any light near him, spoke solemnly to the people upon the terrible crisis which had come upon the nation. Men of all parties were there: his own followers to get some light as to their duty; the Breckinridge Democrats ready, most of them, repentantly to follow a Northern leader, now that their recent candidate was in the rebellion; [Footnote: Breckinridge did not formally join the Confederacy till September, but his accord with the secessionists was well known.] the Republicans eagerly anxious to know whether so potent an influence was to be unreservedly on the side of the country. I remember well the serious solicitude with which I listened to his opening sentences as I leaned against the railing of the State House park, trying in vain to get more than a dim outline of the man as he stood at the unlighted window. His deep sonorous voice rolled down through the darkness from above us,--an earnest, measured voice, the more solemn, the more impressive, because we could not see the speaker, and it came to us literally as "a voice in the night,"--the night of our country's unspeakable trial. There was no uncertainty in his tone: the Union must be preserved and the insurrection must be crushed,--he pledged his hearty support to Mr. Lincoln's administration in doing this. Other questions must stand aside till the national authority should be everywhere recognized. I do not think we greatly cheered him,--it was rather a deep Amen that went up from the crowd. We went home breathing freer in the assurance we now felt that, for a time at least, no organized opposition to the federal government and its policy of coercion would be formidable in the North. We did not look for unanimity. Bitter and narrow men there were whose sympathies were with their country's enemies. Others equally narrow were still in the chains of the secession logic they had learned from the Calhounists; but the broader-minded men found themselves happy in being free from disloyal theories, and threw themselves sincerely and earnestly into the popular movement. There was no more doubt where Douglas or Tod or Key would be found, or any of the great class they represented.

Yet the situation hung upon us like a nightmare. Garfield and I were lodging together at the time, our wives being kept at home by family cares, and when we reached our sitting-room, after an evening session of the Senate, we often found ourselves involuntarily groaning, "Civil war in our land!" The shame, the outrage, the folly, seemed too great to believe, and we half hoped to wake from it as from a dream. Among the painful remembrances of those days is the ever-present weight at the heart which never left me till I found relief in the active duties of camp life at the close of the month. I went about my duties (and I am sure most of those I associated with did the same) with the half-choking sense of a grief I dared not think of: like one who is dragging himself to the ordinary labors of life from some terrible and recent bereavement.

We talked of our personal duty, and though both Garfield and myself had young families, we were agreed that our activity in the organization and support of the Republican party made the duty of supporting the government by military service come peculiarly home to us. He was, for the moment, somewhat trammelled by his half-clerical position, but he very soon cut the knot. My own path seemed unmistakably clear. He, more careful for his friend than for himself, urged upon me his doubts whether my physical strength was equal to the strain that would be put upon it. "I," said he, "am big and strong, and if my relations to the church and the college can be broken, I shall have no excuse for not enlisting; but you are slender and will break down." It was true that I looked slender for a man six feet high (though it would hardly be suspected now that it was so), yet I had assured confidence in the elasticity of my constitution; and the result justified me, whilst it also showed how liable to mistake one is in such things. Garfield found that he had a tendency to weakness of the alimentary system which broke him down on every campaign in which he served and led to his retiring from the army much earlier than he had intended. My own health, on the other hand, was strengthened by out-door life and exposure, and I served to the end with growing physical vigor.

When Mr. Lincoln issued his first call for troops, the existing laws made it necessary that these should be fully organized and officered by the several States. Then, the treasury was in no condition to bear the burden of war expenditures, and till Congress could assemble, the President was forced to rely on the States to furnish the means necessary for the equipment and transportation of their own troops. This threw upon the governors and legislatures of the loyal States responsibilities of a kind wholly unprecedented. A long period of profound peace had made every military organization seem almost farcical. A few independent military companies formed the merest shadow of an army; the state militia proper was only a nominal thing. It happened, however, that I held a commission as Brigadier in this state militia, and my intimacy with Governor Dennison led him to call upon me for such assistance as I could render in the first enrolment and organization of the Ohio quota. Arranging to be called to the Senate chamber when my vote might be needed upon important legislation, I gave my time chiefly to such military matters as the governor appointed. Although, as I have said, my military commission had been a nominal thing, and in fact I had never worn a uniform, I had not wholly neglected theoretic preparation for such work. For some years the possibility of a war of secession had been one of the things which would force itself upon the thoughts of reflecting people, and I had been led to give some careful study to such books of tactics and of strategy as were within easy reach. I had especially been led to read military history with critical care, and had carried away many valuable ideas from this most useful means of military education. I had therefore some notion of the work before us, and could approach its problems with less loss of time, at least, than if I had been wholly ignorant. [Footnote: I have treated this subject somewhat more fully in a paper in the "Atlantic Monthly" for March, 1892, "Why the Men of '61 fought for the Union."]

My commission as Brigadier-General in the Ohio quota in national service was dated on the 23d of April, though it had been understood for several days that my tender of service in the field would be accepted. Just about the same time Captain George B. McClellan was requested by Governor Dennison to come to Columbus for consultation, and by the governor's request I met him at the railway station and took him to the State House. I think Mr. Larz Anderson (brother of Major Robert Anderson) and Mr. L'Hommedieu of Cincinnati were with him. The intimation had been given me that he would probably be made major-general and commandant of our Ohio contingent, and this, naturally, made me scan him closely. He was rather under the medium height, but muscularly formed, with broad shoulders and a well-poised head, active and graceful in motion. His whole appearance was quiet and modest, but when drawn out he showed no lack of confidence in himself. He was dressed in a plain travelling suit, with a narrow-rimmed soft felt hat. In short, he seemed what he was, a railway superintendent in his business clothes. At the time his name was a good deal associated with that of Beauregard; they were spoken of as young men of similar standing in the Engineer Corps of the Army, and great things were expected of them both because of their scientific knowledge of their profession, though McClellan had been in civil life for some years. His report on the Crimean War was one of the few important memoirs our old army had produced, and was valuable enough to give a just reputation for comprehensive understanding of military organization, and the promise of ability to conduct the operations of an army.

I was present at the interview which the governor had with him. The destitution of the State of everything like military material and equipment was very plainly put, and the magnitude of the task of building up a small army out of nothing was not blinked. The governor spoke of the embarrassment he felt at every step from the lack of practical military experience in his staff, and of his desire to have some one on whom he could properly throw the details of military work. McClellan showed that he fully understood the difficulties there would be before him, and said that no man could wholly master them at once, although he had confidence that if a few weeks' time for preparation were given, he would be able to put the Ohio division into reasonable form for taking the field. The command was then formally tendered and accepted. All of us who were present felt that the selection was one full of promise and hope, and that the governor had done the wisest thing practicable at the time.

The next morning McClellan requested me to accompany him to the State Arsenal, to see what arms and material might be there. We found a few boxes of smooth-bore muskets which had once been issued to militia companies and had been returned rusted and damaged. No belts, cartridge-boxes, or other accoutrements were with them. There were two or three smooth-bore brass fieldpieces, six-pounders, which had been honeycombed by firing salutes, and of which the vents had been worn out, bushed, and worn out again. In a heap in one corner lay a confused pile of mildewed harness, which had probably been once used for artillery horses, but was now not worth carrying away. There had for many years been no money appropriated to buy military material or even to protect the little the State had. The federal government had occasionally distributed some arms which were in the hands of the independent uniformed militia, and the arsenal was simply an empty storehouse. It did not take long to complete our inspection. At the door, as we were leaving the building, McClellan turned, and looking back into its emptiness, remarked, half humorously and half sadly, "A fine stock of munitions on which to begin a great war!" We went back to the State House, where a room in the Secretary of State's department was assigned us, and we sat down to work. The first task was to make out detailed schedules and estimates of what would be needed to equip ten thousand men for the field. This was a unit which could be used by the governor and legislature in estimating the appropriations needed then or subsequently. Intervals in this labor were used in discussing the general situation and plans of campaign. Before the close of the week McClellan drew up a paper embodying his own views, and forwarded it to Lieutenant-General Scott. He read it to me, and my recollection of it is that he suggested two principal lines of movement in the West,--one, to move eastward by the Kanawha valley with a heavy column to co-operate with an army in front of Washington; the other, to march directly southward and to open the valley of the Mississippi. Scott's answer was appreciative and flattering, without distinctly approving his plan; and I have never doubted that the paper prepared the way for his appointment in the regular army which followed at so early a day. [Footnote: I am not aware that McClellan's plan of campaign has been published. Scott's answer to it is given in General Townsend's "Anecdotes of the Civil War," p. 260. It was, with other communications from Governor Dennison, carried to Washington by Hon. A. F. Perry of Cincinnati, an intimate friend of the governor, who volunteered as special messenger, the mail service being unsafe. See a paper by Mr. Perry in "Sketches of War History" (Ohio Loyal Legion), vol. iii. p. 345.]

During this week McClellan was invited to take the command of the troops to be raised in Pennsylvania, his native State. Some things beside his natural attachment to Pennsylvania made the proposal an attractive one to him. It was already evident that the army which might be organized near Washington would be peculiarly in the public eye, and would give to its leading officers greater opportunities of prompt recognition and promotion than would be likely to occur in the West. The close association with the government would also be a source of power if he were successful, and the way to a chief command would be more open there than elsewhere. McClellan told me frankly that if the offer had come before he had assumed the Ohio command, he would have accepted it; but he promptly decided that he was honorably bound to serve under the commission he had already received and which, like my own, was dated April 23.

My own first assignment to a military command was during the same week, on the completion of our estimates, when I was for a few days put in charge of Camp Jackson, the depot of recruits which Governor Dennison had established in the northern suburb of Columbus and had named in honor of the first squelcher of secessionism. McClellan soon determined, however, that a separate camp of instruction should be formed for the troops mustered into the United States service, and should be so placed as to be free from the temptations and inconveniences of too close neighborhood to a large city, whilst it should also be reasonably well placed for speedy defence of the southern frontier of the State. Other camps could be under state control and used only for the organization of regiments which could afterward be sent to the camp of instruction or elsewhere. Railway lines and connections indicated some point in the Little Miami valley as the proper place for such a camp; and Mr. Woodward, the chief engineer of the Little Miami Railroad, being taken into consultation, suggested a spot on the line of that railway about thirteen miles from Cincinnati, where a considerable bend of the Little Miami River encloses wide and level fields, backed on the west by gently rising hills. I was invited to accompany the general in making the inspection of the site, and I think we were accompanied by Captain Rosecrans, an officer who had resigned from the regular army to seek a career as civil engineer, and had lately been in charge of some coal mines in the Kanawha valley. Mr. Woodward was also of the party, and furnished a special train to enable us to stop at as many eligible points as it might be thought desirable to examine. There was no doubt that the point suggested was best adapted for our work, and although the owners of the land made rather hard terms, McClellan was authorized to close a contract for the use of the military camp, which, in honor of the governor, he named Camp Dennison.

But in trying to give a connected idea of the first military organization of the State, I have outrun some incidents of those days which are worth recollection. From the hour the call for troops was published, enlistments began, and recruits were parading the streets continually. At the Capitol the restless impulse to be doing something military seized even upon the members of the legislature, and a large number of them assembled every evening upon the east terrace of the State House to be drilled in marching and facing, by one or two of their own number who had some knowledge of company tactics. Most of the uniformed independent companies in the cities of the State immediately tendered their services, and began to recruit their numbers to the hundred men required for acceptance. There was no time to procure uniform, nor was it desirable; for these independent companies had chosen their own, and would have to change it for that of the United States as soon as this could be furnished. For some days companies could be seen marching and drilling, of which part would be uniformed in some gaudy style, such as is apt to prevail in holiday parades in time of peace, whilst another part would be dressed in the ordinary working garb of citizens of all degrees. The uniformed files would also be armed and accoutred; the others would be without arms or equipments, and as awkward a squad as could well be imagined. The material, however, was magnificent, and soon began to take shape. The fancy uniforms were left at home, and some approximation to a simple and useful costume was made. The recent popular outburst in Italy furnished a useful idea, and the "Garibaldi uniform" of a red flannel shirt with broad falling collar, with blue trousers held by a leathern waist-belt, and a soft felt hat for the head, was extensively copied, and served an excellent purpose. It could be made by the wives and sisters at home, and was all the more acceptable for that. The spring was opening, and a heavy coat would not be much needed, so that with some sort of overcoat and a good blanket in an improvised knapsack, the new company was not badly provided. The warm scarlet color, reflected from their enthusiastic faces as they stood in line, made a picture that never failed to impress the mustering officers with the splendid character of the men.

The officering of these new troops was a difficult and delicate task, and so far as company officers were concerned, there seemed no better way at the beginning than to let the enlisted men elect their own, as was in fact done. In most cases where entirely new companies were raised, it had been by the enthusiastic efforts of some energetic volunteers who were naturally made the commissioned officers. But not always. There were numerous examples of self-denying patriotism which stayed in the ranks after expending much labor and money in recruiting, modestly refusing the honors, and giving way to some one supposed to have military knowledge or experience. The war in Mexico in 1847 was the latest conflict with a civilized people, and to have served in it was a sure passport to confidence. It had often been a service more in name than in fact; but the young volunteers felt so deeply their own ignorance that they were ready to yield to any pretence of superior knowledge, and generously to trust themselves to any one who would offer to lead them. Hosts of charlatans and incompetents were thus put into responsible places at the beginning, but the sifting work went on fast after the troops were once in the field. The election of field officers, however, ought not to have been allowed. Companies were necessarily regimented together, of which each could have but little personal knowledge of the officers of the others; intrigue and demagogy soon came into play, and almost fatal mistakes were made in selection. After a time the evil worked its own cure, but the ill effects of it were long visible.

The immediate need of troops to protect Washington caused most of the uniformed companies to be united into the first two regiments, which were quickly despatched to the East. It was a curious study to watch the indications of character as the officers commanding companies reported to the governor, and were told that the pressing demand from Washington made it necessary to organize a regiment or two and forward them at once, without waiting to arm or equip the recruits. Some promptly recognized the necessity and took the undesirable features as part of the duty they had assumed. Others were querulous, wishing some one else to stand first in the breach, leaving them time for drill, equipment, and preparation. One figure impressed itself very strongly on my memory. A sturdy form, a head with more than ordinary marks of intelligence, but a bearing with more of swagger than of self-poised courage, yet evidently a man of some importance in his own community, stood before the seat of the governor, the bright lights of the chandelier over the table lighting strongly both their figures. The officer was wrapped in a heavy blanket or carriage lap-robe, spotted like a leopard skin, which gave him a brigandish air. He was disposed to protest. "If my men were hellions," said he, with strong emphasis on the word (a new one to me), "I wouldn't mind; but to send off the best young fellows of the county in such a way looks like murder." The governor, sitting with pale, delicate features, but resolute air, answered that the way to Washington was not supposed to be dangerous, and the men could be armed and equipped, he was assured, as soon as they reached there. It would be done at Harrisburg, if possible, and certainly if any hostility should be shown in Maryland. The President wanted the regiments at once, and Ohio's volunteers were quite as ready to go as any. He had no choice, therefore, but to order them off. The order was obeyed; but the obedience was with bad grace, and I felt misgivings as to the officer's fitness to command,--misgivings which about a year afterward were vividly recalled with the scene I have described.

No sooner were these regiments off than companies began to stream in from all parts of the State. On their first arrival they were quartered wherever shelter could be had, as there were no tents or sheds to make a camp for them. Going to my evening work at the State House, as I crossed the rotunda, I saw a company marching in by the south door, and another disposing itself for the night upon the marble pavement near the east entrance; as I passed on to the north hall, I saw another, that had come a little earlier, holding a prayer-meeting, the stone arches echoing with the excited supplications of some one who was borne out of himself by the terrible pressure of events around him, whilst, mingling with his pathetic, beseeching tones as he prayed for his country, came the shrill notes of the fife, and the thundering din of the inevitable bass drum from the company marching in on the other side. In the Senate chamber a company was quartered, and the senators were there supplying them with paper and pens, with which the boys were writing their farewells to mothers and sweethearts whom they hardly dared hope they should see again. A similar scene was going on in the Representatives' hall, another in the Supreme Court room. In the executive office sat the governor, the unwonted noises, when the door was opened, breaking in on the quiet business-like air of the room,--he meanwhile dictating despatches, indicating answers to others, receiving committees of citizens, giving directions to officers of companies and regiments, accommodating himself to the wilful democracy of our institutions which insists upon seeing the man in chief command and will not take its answer from a subordinate, until in the small hours of the night the noises were hushed, and after a brief hour of effective, undisturbed work upon the matters of chief importance, he could leave the glare of his gas-lighted office, and seek a few hours' rest, only to renew the same wearing labors on the morrow.

On the streets the excitement was of a rougher if not more intense character. A minority of unthinking partisans could not understand the strength and sweep of the great popular movement, and would sometimes venture to speak out their sympathy with the rebellion or their sneers at some party friend who had enlisted. In the boiling temper of the time the quick answer was a blow; and it was one of the common incidents of the day for those who came into the State House to tell of a knockdown that had occurred here or there, when this popular punishment had been administered to some indiscreet "rebel sympathizer."

Various duties brought young army officers of the regular service to the state capital, and others sought a brief leave of absence to come and offer their services to the governor of their native State. General Scott, too much bound up in his experience of the Mexican War, and not foreseeing the totally different proportions which this must assume, planted himself firmly on the theory that the regular army must be the principal reliance for severe work, and that the volunteers could only be auxiliaries around this solid nucleus which would show them the way to perform their duty and take the brunt of every encounter. The young regulars who asked leave to accept commissions in state regiments were therefore refused, and were ordered to their own subaltern positions and posts. There can be no doubt that the true policy would have been to encourage the whole of this younger class to enter at once the volunteer service. They would have been the field officers of the new regiments, and would have impressed discipline and system upon the organization from the beginning. The Confederacy really profited by having no regular army. They gave to the officers who left our service, it is true, commissions in their so-called "provisional army," to encourage them in the assurance that they would have permanent military positions if the war should end in the independence of the South; but this was only a nominal organization, and their real army was made up (as ours turned out practically to be) from the regiments of state volunteers. Less than a year afterward we changed our policy, but it was then too late to induce many of the regular officers to take regimental positions in the volunteer troops. I hesitate to declare that this did not turn out for the best; for although the organization of our army would have been more rapidly perfected, there are other considerations which have much weight. The army would not have been the popular thing it was, its close identification with the people's movement would have been weakened, and it perhaps would not so readily have melted again into the mass of the nation at the close of the war.

Among the first of the young regular officers who came to Columbus was Alexander McCook. He was ordered there as inspection and mustering officer, and one of my earliest duties was to accompany him to Camp Jackson to inspect the cooked rations which the contractors were furnishing the new troops. I warmed to his earnest, breezy way, and his business-like activity in performing his duty. As a makeshift, before camp equipage and cooking utensils could be issued to the troops, the contractors placed long trestle tables under an improvised shed, and the soldiers came to these and ate, as at a country picnic. It was not a bad arrangement to bridge over the interval between home life and regular soldiers' fare, and the outcry about it at the time was senseless, as all of us know who saw real service afterward. McCook bustled along from table to table, sticking a long skewer into a boiled ham, smelling of it to see if the interior of the meat was tainted; breaking open a loaf of bread and smelling of it to see if it was sour; examining the coffee before it was put into the kettles, and after it was made; passing his judgment on each, in prompt, peremptory manner as we went on. The food was, in the main, excellent, though, as a way of supporting an army, it was quite too costly to last long.

While mustering in the recruits, McCook was elected colonel of the First Regiment Ohio Volunteers, which had, I believe, already gone to Washington. He was eager to accept, and telegraphed to Washington for permission. Adjutant-General Thomas replied that it was not the policy of the War Department to permit it. McCook cut the knot in gallant style. He immediately tendered his resignation in the regular army, taking care to say that he did so, not to avoid his country's service or to aid her enemies, but because he believed he could serve her much more effectively by drilling and leading a regiment of Union volunteers. He notified the governor of his acceptance of the colonelcy, and his coup-de-main was a success; for the department did not like to accept a resignation under such circumstances, and he had the exceptional luck to keep his regular commission and gain prestige as well, by his bold energy in the matter.

Orlando Poe came about the same time, for all this was occurring in the last ten days of April. He was a lieutenant of topographical engineers, and was stationed with General (then Captain) Meade at Detroit, doing duty upon the coast survey of the lakes. He was in person the model for a young athlete, tall, dark, and strong, with frank, open countenance, looking fit to repeat his ancestor Adam Poe's adventurous conflicts with the Indians as told in the frontier traditions of Ohio. He too was eager for service; but the same rule was applied to him, and the argument that the engineers would be especially necessary to the army organization kept him for a time from insisting upon taking volunteer service, as McCook had done. He was indefatigable in his labors, assisting the governor in organizing the regiments, smoothing the difficulties constantly arising from lack of familiarity with the details of the administrative service of the army, and giving wise advice to the volunteer officers who made his acquaintance. I asked him, one day, in my pursuit of practical ideas from all who I thought could help me, what he would advise as the most useful means of becoming familiar with my duties. Study the Army Regulations, said he, as if it were your Bible! There was a world of wisdom in this: much more than I appreciated at the time, though it set me earnestly to work in a right direction. An officer in a responsible command, who had already a fair knowledge of tactics, might trust his common sense for guidance in an action on the field; but the administrative duties of the army as a machine must be thoroughly learned, if he would hope to make the management of its complicated organization an easy thing to him.

Major Sidney Burbank came to take McCook's place as mustering officer: a grave, earnest man, of more age and more varied experience than the men I have named. Captain John Pope also visited the governor for consultation, and possibly others came also, though I saw them only in passing, and did not then get far in making their acquaintance.

CAMP DENNISON

Laying out the camp--Rosecrans as engineer--A comfortless night--Waking to new duties--Floors or no floors for the huts--Hardee's Tactics--The water-supply--Colonel Tom. Worthington--Joshua Sill--Brigades organized--Bates's brigade--Schleich's--My own--McClellan's purpose--Division organization--Garfield disappointed--Camp routine--Instruction and drill--Camp cookery--Measles--Hospital barn--Sisters of Charity--Ferment over re-enlistment--Musters by Gordon Granger--"Food for powder"--Brigade staff--De Villiers--"A Captain of Calvary"--The "Bloody Tinth"--Almost a row--Summoned to the field.

On the 29th of April I was ordered by McClellan to proceed next morning to Camp Dennison, with the Eleventh and half of the Third Ohio regiments. The day was a fair one, and when about noon our railway train reached the camping ground, it seemed an excellent place for our work. The drawback was that very little of the land was in meadow or pasture, part being in wheat and part in Indian corn, which was just coming up. Captain Rosecrans met us, as McClellan's engineer (later the well-known general), coming from Cincinnati with a train-load of lumber. He had with him his compass and chain, and by the help of a small detail of men soon laid off the ground for the two regimental camps, and the general lines of the whole encampment for a dozen regiments. It was McClellan's purpose to put in two brigades on the west side of the railway, and one on the east. My own brigade camp was assigned to the west side, and nearest to Cincinnati. The men of the two regiments shouldered their pine boards and carried them up to the line of the company streets, which were close to the hills skirting the valley, and which opened into the parade and drill ground along the railway.

A general plan was given to the company officers by which the huts should be made uniform in size and shape. The huts of each company faced each other, three or four on each side, making the street between, in which the company assembled before marching to its place on the regimental color line. At the head of each street were the quarters of the company officers, and those of the "field and staff" still further in rear. The Regulations were followed in this plan as closely as the style of barracks and nature of the ground would permit. Vigorous work housed all the men before night, and it was well that it did so, for the weather changed in the evening, a cold rain came on, and the next morning was a chill and dreary one. My own headquarters were in a little brick schoolhouse of one story, which stood (and I think still stands) on the east side of the track close to the railway. My improvised camp equipage consisted of a common trestle cot and a pair of blankets, and I made my bed in the open space in front of the teacher's desk or pulpit. My only staff officer was an aide-de-camp, Captain Bascom (afterward of the regular army), who had graduated at an Eastern military school, and proved himself a faithful and efficient assistant. He slept on the floor in one of the little aisles between the pupils' seats. One lesson learned that night remained permanently fixed in my memory, and I had no need of a repetition of it. I found that, having no mattress on my cot, the cold was much more annoying below than above me, and that if one can't keep the under side warm, it doesn't matter how many blankets he may have atop. I procured later an army cot with low legs, the whole of which could be taken apart and packed in a very small parcel, and with this I carried a small quilted mattress of cotton batting. It would have been warmer to have made my bed on the ground with a heap of straw or leaves under me; but as my tent had to be used for office work whenever a tent could be pitched, I preferred the neater and more orderly interior which this arrangement permitted. This, however, is anticipating. The comfortless night passed without much refreshing sleep, the strange situation doing perhaps as much as the limbs aching from cold to keep me awake. The storm beat through broken window-panes, and the gale howled about us, but day at last began to break, and with its dawning light came our first reveille in camp. I shall never forget the peculiar plaintive sound of the fifes as they shrilled out on the damp air. The melody was destined to become very familiar, but to this day I can't help wondering how it happened that so melancholy a strain was chosen for the waking tune of the soldiers' camp. The bugle reveille is quite different; it is even cheery and inspiriting; but the regulation music for the drums and fifes is better fitted to waken longings for home and all the sadder emotions than to stir the host from sleep to the active duties of the day. I lay for a while listening to it, finding its notes suggesting many things and becoming a thread to string my reveries upon, as I thought of the past which was separated from me by a great gulf, the present with its serious duties, and the future likely to come to a sudden end in the shock of battle. We roused ourselves; a dash of cold water put an end to dreaming; we ate a breakfast from a box of cooked provisions we had brought with us, and resumed the duty of organizing and instructing the camp. The depression which had weighed upon me since the news of the opening guns at Sumter passed away, never to return. The consciousness of having important work to do, and the absorption in the work itself, proved the best of all mental tonics. The Rubicon was crossed, and from this time out, vigorous bodily action, our wild outdoor life, and the strenuous use of all the faculties, mental and physical, in meeting the daily exigencies, made up an existence which, in spite of all its hardships and all its discouragements, still seems a most exhilarating one as I look back on it across a long vista of years.

The first of May proved, instead, a true April day, of the most fickle and changeable type. Gusts of rain and wind alternated with flashes of bright sunshine. The second battalion of the Third Regiment arrived, and the work of completing the cantonments went on. The huts which were half finished yesterday were now put in good order, and in building the new ones the men profited by the experience of their comrades. We were however suddenly thrown into one of those small tempests which it is so easy to get up in a new camp, and which for the moment always seems to have an importance out of all proportion to its real consequence. Captain Rosecrans, as engineer, was superintending the work of building, and finding that the companies were putting floors and bunks in their huts, he peremptorily ordered that these should be taken out, insisting that the huts were only intended to take the place of tents and give such shelter as tents could give. The company and regimental officers loudly protested, and the men were swelling with indignation and wrath. Soon both parties were before me; Rosecrans hot and impetuous, holding a high tone, and making use of General McClellan's name in demanding, as an officer of his staff, that the floors should be torn out, and the officers of the regiments held responsible for obedience to the order that no more should be made. He fairly bubbled with anger at the presumption of those who questioned his authority. As soon as a little quiet could be got, I asked Rosecrans if he had specific orders from the general that the huts should have no floors. No, he had not, but his staff position as engineer gave him sufficient control of the subject. I said I would examine the matter and submit it to General McClellan, and meanwhile the floors already built might remain, though no new ones should be made till the question was decided. I reported to the general that, in my judgment, the huts should have floors and bunks, because the ground was wet when they were built,--they could not be struck like tents to dry and air the earth, and they were meant to be permanent quarters for the rendezvous of troops for an indefinite time. The decision of McClellan was in accordance with the report. Rosecrans acquiesced, and indeed seemed rather to like me the better on finding that I was not carried away by the assumption of indefinite power by a staff officer.

This little flurry over, the quarters were soon got in as comfortable shape as rough lumber could make them, and the work of drill and instruction was systematized. The men were not yet armed, so there was no temptation to begin too soon with the manual of the musket, and they were kept industriously employed in marching in single line, by file, in changing direction, in forming columns of fours from double line, etc., before their guns were put in their hands. Each regiment was treated as a separate camp, with its own chain of sentinels, and the officers of the guard were constantly busy teaching guard and picket duty theoretically to the reliefs off duty, and inspecting the sentinels on post. Schools were established in each regiment for field and staff and for the company officers, and Hardee's Tactics was in the hands of everybody who could procure a copy. It was one of our great inconveniences that the supply of the authorized Tactics was soon exhausted, and it was difficult to get the means of instruction in the company schools. An abridgment was made and published in a very few days by Thomas Worthington, a graduate of West Point in one of the earliest classes,--of 1827, I think,--a son of one of the first governors of Ohio. This eccentric officer had served in the regular army and in the Mexican War, and was full of ideas, but was of so irascible and impetuous a temper that he was always in collision with the powers that be, and spoiled his own usefulness. He was employed to furnish water to the camp by contract, and whilst he ruined himself in his efforts to do it well, he was in perpetual conflict with the troops, who capsized his carts, emptied his barrels, and made life a burden to him. The quarrel was based on his taking the water from the river just opposite the camp, though there was a slaughter-house some distance above. Worthington argued that the distance was such that the running water purified itself; but the men wouldn't listen to his science, vigorously enforced as it was by idiomatic expletives, and there was no safety for his water-carts till he yielded. He then made a reservoir on one of the hills, filled it by a steam-pump, and carried the water by pipes to the regimental camps at an expense beyond his means, and which, as it was claimed that the scheme was unauthorized, was never half paid for. His subsequent career as colonel of a regiment was no more happy, and talents that seemed fit for highest responsibilities were wasted in chafing against circumstances which made him and fate seem to be perpetually playing at cross purposes. [Footnote: He was later colonel of the Forty-sixth Ohio, and became involved in a famous controversy with Halleck and Sherman over his conduct in the Shiloh campaign and the question of fieldworks there. He left the service toward the close of 1862.]

A very different character was Joshua W. Sill, who was sent to us as ordnance officer. He too had been a regular army officer, but of the younger class. Rather small and delicate in person, gentle and refined in manner, he had about him little that answered to the popular notion of a soldier. He had resigned from the army some years before, and was a professor in an important educational institution in Brooklyn, N. Y., when at the first act of hostility he offered his services to the governor of Ohio, his native State. After our day's work, we walked together along the railway, discussing the political and military situation, and especially the means of making most quickly an army out of the splendid but untutored material that was collecting about us. Under his modest and scholarly exterior I quickly discerned a fine temper in the metal, that made his after career no enigma to me, and his heroic death at the head of his division in the thickest of the strife at Stone's River no surprise.