Title: A voice from Waterloo: A history of the battle fought on the 18th June, 1815

Author: Edward Cotton

Release date: December 31, 2022 [eBook #69670]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: B. Green, 1877

Credits: Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of each chapter.

Many minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

THE FIELD OF WATERLOO.

HOTEL DU MUSÉE,

AT THE FOOT OF THE LION MOUNT.

This Hotel, kept by a niece of the late Sergeant-Major Cotton, is situated in the very centre of the field of Waterloo, and is strongly recommended to visitors on account of its proximity to the scenes of interest connected with the great battle, and also for the excellent accomodation and comfort it offers at moderate charges.—See Bradshaw’s continental Guide.

Wines and Spirits of the best quality. Bass’s pale Ale;

London porter, etc.

N.B.—Guide Books,—“The voice from Waterloo” by Sergeant Cotton, the most correct and cheapest account of the battle published—Plans of the field views and Photographs of all noted places always on sale at the Hotel.

A Museum of Relics shewn to visitors.

Déposé selon la loi.

Entered at Stationers’ Hall.

BRUSSELS:

J. H. Briard, Printer, 4, Rue aux Laines.

A VOICE FROM

WATERLOO

A HISTORY OF THE BATTLE

FOUGHT ON THE 18TH JUNE 1815

WITH A SELECTION FROM THE WELLINGTON DISPATCHES, GENERAL ORDERS

AND LETTERS RELATING TO THE BATTLE.

ILLUSTRATED WITH ENGRAVINGS, PORTRAITS AND PLANS.

BY

SERGEANT-MAJOR EDWARD COTTON

(LATE 7TH HUSSARS).

“Facts are stubborn things.”

SIXTH EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED.

PRINTED FOR THE PROPRIETOR,

MONT-ST.-JEAN,

SOLD ALSO BY THE PRINCIPAL BOOKSELLERS IN BELGIUM.

LONDON

B. GREEN, PATERNOSTER-ROW.

1862

AS A TESTIMONY

of the profound admiration entertained for His Lordship by every British soldier,

THIS WORK IS HUMBLY DEDICATED

TO FIELD-MARSHAL THE MOST NOBLE

THE MARQUIS OF ANGLESEY, K.G., G.C.B., G.C.H.,

by His Lordship’s grateful servant,

E. COTTON, Sergeant-Major,

LATE 7TH HUSSARS.

TO THE SIXTH EDITION.

“A Voice from Waterloo” is the unassuming tale of an old soldier who was an eyewitness of and actor in many of the scenes he attempts to describe.

My having resided more than fourteen years on the field, as Guide, and Describer of the battle, may be considered as the parent of the present memoirs.

No one can be more convinced than I am, of my inability to do justice to the subject: but I have had great advantages in communicating personally on the spot with “Waterloo men” of every nation; all of whom, from the general to the private, have evidently considered it a duty and a pleasure to assist an old companion in arms. The inquiries and comments made by those gallant men, have afforded me opportunities of gleaning much information which no other person has obtained, and has enabled me to give a fuller and truer history of the battle, than a more talented man could have done, unless he had enjoyed the same privilege.

One of my objects in writing, is to correct opinions which have gone forth, and which are greatly at variance with facts: opinions so erroneous as to warrant the remark of general Jomini, that “Never was a battle so confusedly described as that of Waterloo.” It is certain that the hour of many occurrences on the field has been erroneously stated: such as of the arrival, or rather becoming engaged, of the different Prussian corps; the fall of La Haye-Sainte, defeat of the Imperial guard, etc.

After the publication of so many accounts of the battle of the 18th of June, it may be fairly asked on what grounds I expect to awaken fresh interest in a subject so long before the public. Can I reconcile the conflicting statements which have already appeared in print? Can I add to the information which most of my countrymen already possess concerning this memorable epoch? Or can I present that information in a compendious and lucid form, such as the general reader may still need? Something in all these ways, I hope I have accomplished.

Putting aside some of the French and English accounts as not only irreconcilable with facts, but as self-refuted by their inconsistencies and mutual contradictions,—using such of the French narratives as agree with those of their opponents, which, as Wellington observed of Napoleon’s bulletins, may be safely relied upon as far as they tell against themselves,—I have cleared up a great number of the points disputed by our own writers, who agree in the main, but differ in some circumstances involving not merely questions of time and locality of certain events, but even the claims of individuals, regiments and brigades to the honour attached to their deeds on that day. By my long residence at Mont-St.-Jean, constant study of the[ix] surface of the battle field, knowledge of the composition and even dress of the different bodies of the French troops which stood before us, and by paying close attention to the remarks made by many a gallant comrade revisiting the spot, I have in a great measure succeeded in reconciling discrepancies which perhaps no other person could explain.

I am also emboldened to think that my “Voice from Waterloo” presents to the general reader all the leading facts of this eventful struggle, in so concise a manner, and at so moderate a cost, as to secure it a preference over every other narration of the battle.

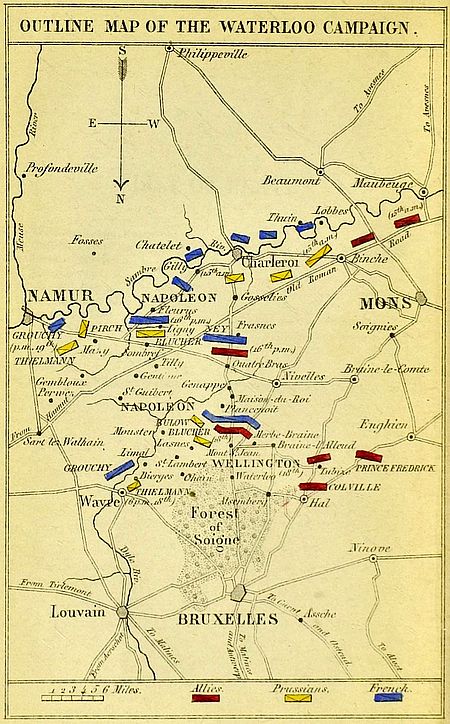

Although not strictly belonging to “A Voice from Waterloo,” I have added, as a connecting link in the narrative, an outline map, and a sketch of the military operations of the campaign of 1815.

Most anxious to avoid the imputation of having employed the materials of others without acknowledgment, I beg to state that, besides various military periodicals, I have made use of captain Siborne’s History of the War in France and Belgium: The Military Life of the Duke of Wellington, by Major Basil Jackson and Captain Rochfort Scott; The Wellington Dispatches and General Orders, by Colonel Gurwood; Fall of Napoleon, by Colonel Mitchell; Political and Military Life of Napoleon, and The Art of War, by General Jomini; History of the King’s German Legion, by Major Beamish; Prussian History of the Campaign of 1815, by General Grollman, etc., etc.

As to the manner in which I have executed my task, I know I am open to criticism. No doubt many of my remarks will be considered too digressive. Some persons will think I am too hard upon Napoleon: my authorities in this are more frequently French than English. Others[x] will judge me too partial to the immortal Wellington.

Waterloo was termed by Napoleon, “a concurrence of unexempled fatalities, a day not to be comprehended. Was there treason? or was there only misfortune?”

Wellington said, that “he had never before fought so hard a battle, nor won so great a victory.” If the reader derive the same impression from his attention to “A Voice from Waterloo,” I shall be satisfied, because I shall have succeeded.

Edward Cotton,

Waterloo Guide, and Describer of the Battle.

Mont-St.-Jean, February, 1849.

| To the Marquis of Anglesey | Page | V |

| Preface | VII | |

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Napoleon leaves Elba; lands in France.—Louis XVIII quits Paris.—Napoleon, joined by the army, arrives in Paris.—Hostile declaration of the great powers of Europe against Napoleon, which he treats with contempt, and prepares for war.—France soon appears one vast camp.—Allied armies assemble in Belgium.—The duke of Wellington arrives and takes the command; adopts precautionary measures.—In consequence of rumours, his Grace issues a secret memorandum, and draws the army together.—Strength, composition and distribution of the allied, Prussian, and French armies.—Continued rumours; and certain intelligence of the enemy’s advance.—Importance of holding Brussels.—Napoleon’s attempt to surprise us frustrated.—Blücher concentrates his forces.—Napoleon joins his army, and issues his order of the day; attacks the Prussian outposts, and takes Charleroi.—Intelligence reaches the Duke.—Distribution of the enemy.—The Duke orders the army to prepare, and afterwards to march on Quatre-Bras.—The duchess of Richmond’s ball.—The troops in motion at early dawn.—His Grace proceeds by Waterloo to Quatre-Bras, and from thence to Ligny, where he meets Blücher, whom he promises to support, and returns to Quatre-Bras.—Picton’s division and the Brunswickers arrive at Quatre-Bras, and are attacked by the French left column under Ney; more of our troops arrive.—Outline of the battles of Quatre-Bras and Ligny.—Observations. | 1 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Colonel Gordon’s patrol discovers the Prussians are retreating upon Wavre.—The allied army ordered to retire upon Waterloo.—The Duke writes to Blücher.—Retreat commenced, followed by the enemy.—Skirmishing.—Pressed by the lancers, who are charged by the 7th hussars; the latter are [xii] repulsed.—The life-guards make a successful charge.—Lord Anglesey’s letter, refuting a calumnious report of his regiment.—Allied army arrives on the Waterloo position.—The enemy arrive on the opposite heights, and salute us with round-shot, to which we reply to their cost.—Piquets thrown out on both sides.—Dismal bivac; a regular soaker.—The Duke and Napoleon’s quarters.—His Grace receives an answer from Blücher.—Probability of a quarrel on the morrow.—Orders sent to general Colville.—Description of the field of Waterloo; Hougoumont and La Haye-Sainte.—Disposition of the allied army, and the advantages of our position.—Disposition of the enemy, and admirable order of battle.—The eve of Waterloo.—Morning of the 18th wet and uncomfortable; our occupation.—The Duke arrives; his appearance, dress, staff, etc.—Positions corrected.—French bands play, and their troops appear; are marshalled by Napoleon, a magnificent sight, worth ten years of peaceful life.—Why tarries Napoleon with his grand martial display?—The Emperor passes along his lines; his troops exhibit unbounded enthusiasm; his confidence of victory. | 19 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| The Duke at Hougoumont, makes a slight change, returns to the ridge.—Battle commences at Hougoumont; Jérôme’s columns put in motion, drew the fire of our batteries upon them, to which theirs replied.—Close fighting at Hougoumont.—Our left menaced by the enemy’s cavalry.—Howitzers open upon the enemy in the wood of Hougoumont.—The enemy press on and approach the masked wall, from whence the crashing fusillade astounds them.—Our troops under lord Saltoun charge and rout the enemy; a portion of whom pass Hougoumont on their right, and enter the gate; a desperate struggle ensues.—Gallantry of colonel Macdonell, sergeant Graham, and the Coldstream.—The enemy’s light troops drive off our right battery.—Colonel Woodford, with a body of the Coldstream, reinforces Hougoumont.—Sergeant Graham rescues his brother from the flames.—Prussian cavalry observed.—Hougoumont a stumbling-block to the enemy, who now prepare to attack our left.—Napoleon observes apart of Bulow’s Prussian corps, and detaches cavalry to keep them in check.—A Prussian hussar taken prisoner; his disclosures to the enemy.—Soult writes a dispatch to Grouchy.—Oversight of Napoleon, who orders Ney to attack our left.—D’Erlon’s columns advance; terrific fire of artillery.—La Haye-Sainte and Papelotte attacked.—Picton’s division, aided by Ponsonby’s cavalry, defeat the enemy.—Shaw the life-guardsman killed.—Struggle for a colour.—A female hussar killed.—Picton killed.—Scots Greys and Highlanders charge together.—Two eagles captured, with a host of prisoners.—Our heavy cavalry get out of hand.—Ponsonby killed.—12th dragoons charge.—Our front troops drawn back.—Charge of Kellermann’s cuirassiers, repulsed by Somerset’s household brigade, who following up the enemy mix with Ponsonby’s dragoons on the French position.—Captain Siborne’s narrative of the attack upon our left and centre.—Heroism of lord Uxbridge. | 47 | |

| CHAPTER IV.[xiii] | ||

| Hougoumont reinforced, the enemy driven back.—The enemy’s cavalry charge, and are driven off.—Struggle in the orchard continued.—Advance of a column of French infantry, who suffer and are checked by the terrific fire of our battery.—Napoleon directs his howitzers upon Hougoumont, which is soon set on fire; notwithstanding, the Duke ordered it to be held at any cost.—La Haye-Sainte again assailed.—A ruse of the enemy’s lancers.—Fire of the enemy’s artillery increases.—Importance of our advanced posts.—Ney’s grand cavalry attacks; destructive fire of our guns upon them, and their gallantry.—After numerous fruitless attempts against our squares, the enemy get mixed; are broken, and driven back by our cavalry.—Their artillery again open fire upon us.—Extraordinary scene of warfare.—An ammunition waggon in a blaze.—The earth trembles with the concussion of the artillery.—Ney, reinforced with cavalry, continues his aggressions, and, as before, after repeated fruitless attacks, the assailants are driven off.—Terrific fire of artillery.—Not so many saddles emptied by our musketry as expected.—The enemy’s attacks less frequent and animated.—Captain Siborne’s lively description of Ney’s grand cavalry attack. | 73 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Difficulties encountered by the Prussians on their march from Wavre; a portion of them are about debouching.—Blücher encourages them by his presence.—The Duke had been in constant communication with the Prussians, who take advantage of Napoleon’s neglecting to protect his right.—Two brigades of Bulow’s corps advance upon the French right.—A Prussian battery opens fire.—Cavalry demonstrations.—Napoleon orders De Lobau’s (sixth) corps to his right, to oppose the Prussians, and brings the old and middle guard forward.—Bulow extends his line and presses on.—De Lobau’s guns exchange a brisk cannonade with the Prussian batteries.—La Haye-Sainte again assailed and set on fire, which was got under.—Loss of a colour.—Destructive fire of our battery upon the French cavalry.—Our artillery suffer dreadfully from that of the enemy.—Hanoverian cavalry quit the field.—A column of the enemy’s infantry advances and is driven back.—Chassé’s division called back from Braine-l’Alleud.—Lord Hill’s troops brought forward, a sight quite reviving.—Struggle at Hougoumont continued.—Adam’s brigade attacks, drives back the enemy, and takes up an advanced position.—La Haye-Sainte taken by the French.—The 52d regiment in line repulses a charge of cuirassiers.—General Foy’s eulogium on our infantry.—Napoleon’s snappish reply to Ney’s demand. | 85 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| La Haye-Sainte strengthened by the enemy, who drive our riflemen from the knoll and sand-pit, and throw a crashing fire upon our front troops, who return it with vigour.—The enemy push forward, between La Haye-Sainte and our position, some guns that fire grape, but are soon dislodged.—Destructive [xiv] fire of our rifles upon the cuirassiers.—Our guards and Halkett’s brigade assailed by skirmishers, who are driven off.—Prussian force in the field.—The Prussians approach Plancenoit.—De Lobau falls back.—Prussian round-shot fall at La Belle-Alliance.—The young guard sent to Plancenoit.—Blücher informed of Thielmann’s corps left at Wavre being vigorously attacked.—Desperate struggle at Plancenoit, which is reinforced by the enemy, when the whole Prussian force is driven back.—Onset follows onset.—The Duke, by aid of his telescope, looks for the Prussians.—Hougoumont continues a scene of carnage.—Our centre suffers dreadfully from the crowds of skirmishers who now press on in swarms.—French battery pushed forward, and dislodged by one of ours.—The 30th and 73d colours sent to the rear.—The Duke is coolness personified.—The troops murmur to be led on to try the effect of cold steel.—The Prussians keep up a cannonade.—Our line remains firm.—More Prussians swarming along.—Napoleon’s doom soon to be sealed.—Imperial guard formed into columns of attack.—Many of our guns rendered useless.—Disorder in our rear.—Our army much reduced; those left are determined to conquer or perish.—Vivian and Vandeleur’s brigades move from the left to the centre, which gives confidence to the few brave fellows remaining.—His Grace observes the enemy forming for attack, and makes preparations to receive the coming storm.—Colonel Freemantle sent in search of the Prussians.—Our centre continues a duelling ground.—Gallant conduct of the prince of Orange, who is wounded.—The Nassau-men and Brunswickers give way in confusion; Wellington gallops up, and aided by Vivian, Kielmansegge and other officers, puts all right again. | 97 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| Napoleon advances his Imperial guard; gives it up to Ney.—The Emperor addresses his men for the last time.—Blücher’s guns blazing away, the enemy replies.—Napoleon circulates a false report.—The French guards about to attack men who, like themselves, had never been beaten.—Tremendous roar of artillery.—Vandersmissen’s brigade of guns arrives.—The right or leading column of the Imperial guard, on ascending the tongue of ground, suffers dreadfully from our double-charged guns, which it appears to disregard.—Ney’s horse killed.—The attacking column crowns the ridge, well supported.—“Up, guards, make ready!”—The British guards, Halkett’s brigade, with Bolton’s and Vandersmissen’s batteries, open fire upon the head of the assailing column, which it returns.—Gallantry of sir Colin Halkett.—The enemy in confusion, charged by our guards and Halkett’s 30th and 73d regiments.—The first French column, after displaying the most heroic courage, gives way in disorder.—The second attacking column approaching, suffers from our batteries.—Our guards, ordered to retire, get into disorder, which soon sets to right again.—Halkett’s brigade in great confusion, but soon recovers.—D’Aubremé’s Netherlanders in the greatest disorder.—Our batteries, with the guards, open fire upon the head of the left attacking column, whilst the 52d and rifles assail its front and left flank; the French return the fire with vigour.—The crisis.—The enemy in confusion, charged in flank, gives way.—Pursued by Adam’s brigade.—Vivian’s hussars launched forward upon the enemy’s [xv] reserves; their disposition.—General disposition of the Prussian and French armies. | 111 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| As the Imperial guard retired in the greatest disorder, its retreat caused a panic throughout the French army.—The Prussians being relieved from the pressure of the enemy’s right en potence, their operations begin to take effect.—Wellington observing the state of things, determines to attack, and orders the advance of his whole line.—His Grace in front, hat high in air.—Vivian’s hussars get a message from the Duke; they form line, attack and drive off the enemy.—Colonel Murray’s dangerous leap.—Vandeleur’s brigade advanced.—Major Howard killed.—General Cambronne made prisoner.—Adam’s brigade attacks and drives off the rallied force of the Imperial guard.—Lord Uxbridge wounded; sir J. O. Vandeleur commands the cavalry.—Sir Colin Campbell begs the Duke not to remain under the heavy fire.—Adam’s brigade menaced by cuirassiers.—His Grace with but one attendant.—Adam’s brigade falls upon a broken column of the enemy.—Singular encounter and act of bravery.—Repugnance to the shedding of human blood unnecessarily.—Battery and prisoners captured.—Adam’s brigade in the line of fire of a Prussian battery.—The 71st capture a battery.—Prussian dispositions to attack Plancenoit and the French right.—Operations of the allies during this period.—Plancenoit the scene of a dreadful struggle.—Bravery of the young guard, who save their eagle.—Humane conduct of their general Pelet.—Napoleon in a square, much pressed.—Wellington and his advanced troops at Rossomme, where the pursuit is relinquished by us, and continued by the Prussians, who, busy in the work of death, press on and capture sixty guns.—On returning towards Waterloo, the Duke meets Blücher, who promises to keep the enemy moving.—His Grace is silent, sombre, and dejected for the loss of his friends.—Bivac.—Observations. | 123 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| Morning after the battle.—Extraordinary and distressing appearance of the field.—Solicitude for the wounded.—The Duke goes back to Brussels to consult the authorities and soothe the extreme excitement.—Humane conduct of all classes towards the wounded.—The allied army proceeds to Nivelles; joined by our detached force.—His Grace issues a general order.—Overtakes the army. On the 21st we cross the frontier into France.—Proclamation to the French people.—Napoleon abdicates in favour of his son.—Cambray and Péronne taken.—Narrow escape of the Duke.—Grouchy retreats upon Paris, closely pursued by the Prussians.—The British [xvi] and Prussian armies arrive before Paris.—Combat of Issy.—Military convention.—The allies enter the capital on the 7th of July.—Louis XVIII enters next day.—Napoleon surrenders at sea, July 15th.—He is exiled to St.-Helena, where he dies in 1821.—Reflections. | 137 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| English, Prussian and French official accounts of the battle.—Marshal Grouchy’s report of the battle of Wavre.—Returns of the different armies.—Position of the allied artillery.—Artillery, etc., taken at Waterloo.—Questions connected with the campaign; Wellington’s position at Waterloo.—Opinion of general Jomini.—The Duke’s plans and expectations.—His letter to lord Castlereagh.—Resolution of the allied powers, on receiving the intelligence of Napoleon’s flight from Elba.—Wellington’s letter to general Kleist.—The Duke’s decision.—His anticipations.—Obstacles which his Grace met with.—Conduct of the Saxon troops.—Blücher forced by them to quit Liège.—Wellington’s resolution concerning these troops. | 145 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| Napoleon’s plans of campaign.—His letter to Ney, and proclamation to the Belgians.—His sanguine expectations, and utter disappointment.—Opinions of French authors on the circumstance of Napoleon’s not reaching Brussels.—Their inconsistencies.—Desire of Napoleon to make his marshals responsible for errors he committed.—Opinion of M. de Vaulabelle.—Napoleon’s charges against Grouchy; impossibility of the latter’s preventing a portion of the Prussians reaching the field of Waterloo—The Emperor’s charges against Ney refuted.—Admirable conduct of Ney during the campaign.—Mode of history-writing at St.-Helena.—The battle not fought against the French nation.—Napoleon’s character.—Motley composition and equivocal loyalty of part of the allied army.—Refutation of the charge that the Duke was taken by surprise; credulity of some English writers on this subject.—His Grace’s admirable precaution.—Foreign statements, that the Prussians saved us, examined.—The tardy cooperation of the Prussians produced, not the defeat, but the total rout of the French.—Conversation of Napoleon at St.-Helena.—Gourgaud’s account.—Opinions of the Duke and lord Hill.—Ney’s testimony in the Chamber of Peers. | 177 | |

| No. I. | |

| Wellington’s Secret Memorandum.—General orders for the movements of the army. | 209 |

| No. II.[xvii] | |

| Letters from lord Wellington, connected with the campaign: To Sir Charles Stuart, and the duc de Berry; dated three o’clock in the morning, 18th June, 1815.—To the earl of Aberdeen, the duke of Beaufort, and Marshal prince Schwarzenberg; expressing his grief for the loss of some friends on the field.—To general Dumouriez, the earl of Uxbridge, prince de Talleyrand, and lord Beresford; on his conviction that Napoleon had received his death-blow.—To lord Bathurst, saying that he would not be cajoled by the diplomatists, to suspend hostilities until Napoleon was secured from exciting fresh troubles.—The Duke informs the French commissioners, that he cannot consent to any suspension of hostilities.—His Grace insists upon sparing Napoleon’s life, prevents the bridge of Jena being destroyed, and protects Paris from Prussian vengeance.—To the French commissioners, stating his desire to save their capital.—Continued mediation with Blücher, to spare the Parisians’ pockets, and preserve them from humiliation; for which the French were most ungrateful, as the subsequent letters show.—Memorandum respecting marshal Ney.—Proclamation of Louis XVIII.—To Scott, Esq., on the loss of La Haye-Sainte, recommending him to leave the battle of Waterloo as it is.—To the duke of York, and lord Bathurst, on the expediency of granting medals. | 213 |

| No. III. | |

| Summary of Wellington’s career. | 233 |

| No. IV. | |

| Returns of the strength and loss of the British army.—List of British officers killed and wounded. | 236 |

| No. V. | |

| Marshal Blücher to baron Müffling.—Note of general Gneisenau.—The prince de la Moskowa to the duc d’Otrante. | 252 |

| No. VI. | |

| Anecdotes relative to the Waterloo campaign. | 258 |

| No. VII. | |

| List of officers who afforded the author information.—Testimonials and presents he has received relating to the battle. | 272 |

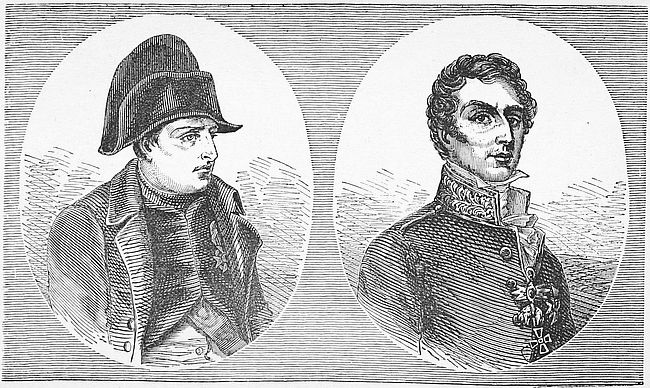

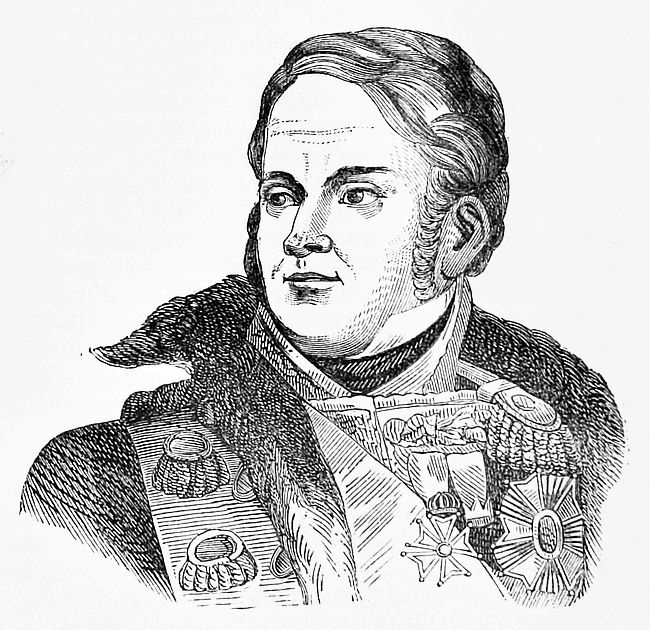

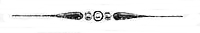

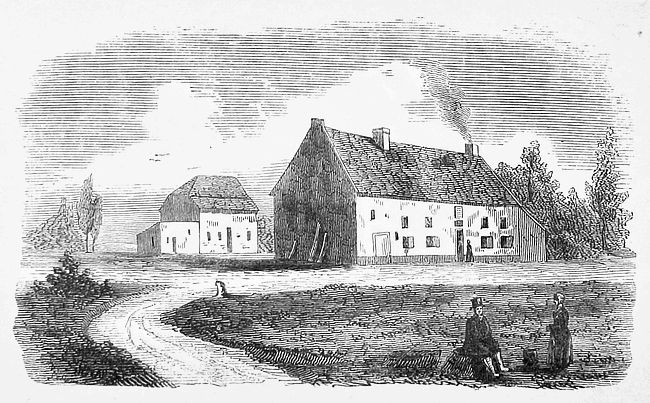

| 1. Wellington and Napoleon | Frontispiece. |

| 2. Outline Map of the campaign | facing page 1 |

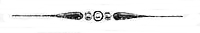

| 3. Field of Waterloo | 26 |

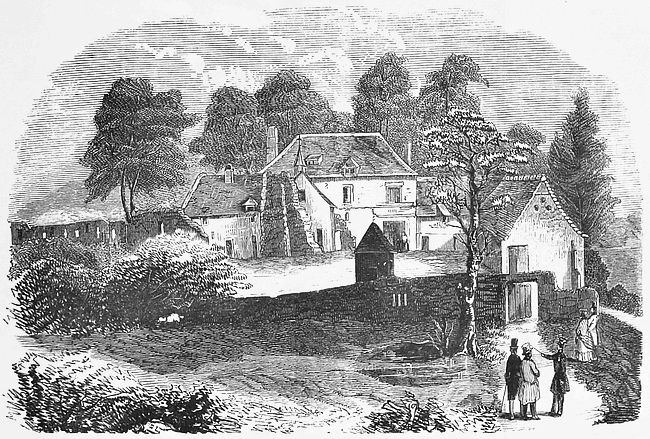

| 4. Hougoumont | 28 |

| 5. Marshal Ney | 52 |

| 6. Sir Thomas Picton | 58 |

| 7. Lord Uxbridge | 70 |

| 8. Field-Marshal Blücher | 86 |

| 9. Lord Hill | 93 |

| 10. La Belle-Alliance | 99 |

| 11. Napoleon | 190 |

| 12. Plan of the Field of Waterloo, towards sun-set, on June 18th | at the end. |

click here for larger image.

click here for larger image.

Drawn for Cotton’s Voice from Waterloo.

A VOICE

FROM

WATERLOO.

Napoleon leaves Elba; lands in France.—Louis XVIII quits Paris.—Napoleon, joined by the army, arrives in Paris.—Hostile declaration of the great powers of Europe against Napoleon, which he treats with contempt, and prepares for war.—France soon appears one vast camp.—Allied armies assemble in Belgium.—The duke of Wellington arrives and takes the command; adopts precautionary measures.—In consequence of rumours, his Grace issues a secret memorandum, and draws the army together.—Strength, composition and distribution of the allied, Prussian, and French armies.—Continued rumours; and certain intelligence of the enemy’s advance.—Importance of holding Brussels.—Napoleon’s attempt to surprise us frustrated.—Blücher concentrates his forces.—Napoleon joins his army, and issues his order of the day; attacks the Prussian outposts, and takes Charleroi.—Intelligence reaches the Duke.—Distribution of the enemy.—The Duke orders the army to prepare, and afterwards to march on Quatre-Bras.—The duchess of Richmond’s ball.—The troops in motion at early dawn.—His Grace proceeds by Waterloo to Quatre-Bras, and from thence to Ligny, where he meets Blücher, whom he promises to support, and returns to Quatre-Bras.—Picton’s division and the Brunswickers arrive at Quatre-Bras, and are attacked by the French left column under Ney; more of our troops arrive.—Outline of the battles of Quatre-Bras and Ligny.—Observations.

On the 26th of February 1815, Napoleon, accompanied by about a thousand of his guards, and all his civil and military officers, secretly left the isle of Elba, and landed the 1st of March, near Cannes, on the coast of Provence. The Emperor immediately marched towards the French capital; and arrived[2] in Paris on the evening of the 20th; the same day that Louis XVIII set out for Ghent.

Joined by all the troops which had been sent to oppose him, Napoleon was enabled to re-establish his authority in France. Amongst those who rejoined him, was marshal Ney, “le Brave des Braves;” he who had so warmly expressed himself in favour of the restoration of the Bourbons, and who, when appointed to the command of a body of troops to oppose his former master, declared, whilst kissing the king’s hand, that “he would bring back Napoleon in an iron cage.” Ney and the iron cage was the chief topic of conversation in Paris, when the news of his having joined Napoleon with his corps d’armée reached that capital[1].

The great powers of Europe, then assembled in congress at Vienna, instantly declared, that Napoleon, by breaking the convention which established him as an independent sovereign at Elba, had destroyed the only legal title on which his political existence depended, placed himself without the pale of the law, and proved to the world, that there could neither be truce nor peace with him. The allied powers, in consequence, denounced Napoleon as the enemy and disturber of the tranquillity of Europe, and resolved immediately upon uniting their forces against him and his faction, to preserve, if possible, the general peace.

Notwithstanding the hostile declaration of the allied sovereigns, they were utterly unable to put their armies in motion without that most powerful lever, English gold, the real sinews of war. Britain’s expenditure in 1815, was no less than 110,000,000l. sterling; out of which immense sum 11,000,000l. were distributed as subsidies amongst the contracting powers: Austria received 1,796,220l.; Russia, 3,241,919l.; Prussia, 2,382,823l.; and Hanover, Spain, Portugal,[3] Sweden, Italy and the Netherlands, with the smaller German states, shared the remainder amongst them.

Menacing as the position of the allies towards Napoleon appeared to be, and imposing as were their armies assembling to oppose him, he assumed a bold and resolute posture of defence. The general aspect of France at that time was singularly warlike; nearly the whole nation appeared to be electrified, and buckled on its armour to join the messenger of war. The exaltation of Napoleon was soon however sobered down by the arrival in Paris of the declaration of the allied powers, which document was little calculated to produce a favourable impression as to the ultimate success of the Emperor’s enterprise. The war-cry of nearly every state in Europe was, To arms! Draw the sword, throw away the scabbard, until the usurper shall be entirely subjugated and his adherents put down.

Napoleon, however, appeared undismayed, and endeavoured, by every means, to conceal the determined resolution of Europe from the French nation, who, for the most part, cheerfully responded to their leader’s call. Troops were organized, as if by magic, all over the country. The scarred veterans of a hundred battles, they who had followed their “petit caporal” through many a gory fight, heard with joy the voice of their idolized Emperor, summoning them again to glorious war and the battle field. There was a generation of fierce, daring, war-breathing men, ever ready to range themselves under the Imperial banners. Davoust states that France, on Napoleon’s return, was overrun with soldiers just released from the prisons of Europe, most of whom counted as many battles as years, and who quickly flocked round the Imperial eagles. Transports of artillery, arms, ammunition waggons, with all the materials of war, were to be seen moving from every point towards the frontiers. France, in a short time, bore the appearance of one vast camp.

To completely surround Paris with fortifications, as Louis-Philippe has since done, was also the desire of Napoleon, who inquired of Carnot, how much time and money it would require. “Three years and two hundred millions,” replied the minister, “and when finished, I would only ask for[4] sixty thousand men and twenty-four hours to demolish the whole.”

Early in April 1815, the allied troops began to assemble in Belgium. The Anglo-Hanoverian army, commanded by the prince of Orange, (afterwards William II,) had occupied the Low-Countries for the protection of Belgium and Holland, which had been constituted by the congress of Vienna a new monarchy, under the name of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. This army comprised about 28,000 men, 15,000 being British and German troops; a part of these were the remains of lord Lynedoch’s army, and the remainder young Hanoverians. 20,000 Dutch-Belgians were raised to act in concert with these troops. The general appearance of the army is thus described by sir Henry, now lord Hardinge, in a letter to lord Stewart: “This army is not unlike lord Randscliff’s description of a French pack of hounds: pointers, poodles, turnspits, all mixed up together and running in sad confusion.”

The duke of Wellington arrived in Brussels from the congress of Vienna on the night of April 4th, and took the command of the allied army; but the Dutch-Belgian army had not been placed immediately under the Duke’s command. His Grace being strongly convinced that his power of regulating the movements of the Dutch-Belgian troops ought not to be left open to any cavil or dispute, demanded the most unequivocal statement upon this matter from the king of the Netherlands. Nothing less than this measure could have made those troops serviceable to the cause of their country; such was still the fascinating power of Napoleon’s name over countries in which his rule and conscriptions had subdued and enervated the minds of men. On the 4th of May, Wellington received copies of the king’s decrees, making him field-marshal in his service, and placing the Dutch-Belgian army entirely under his command[2]. The Duke immediately put matters in a better condition, and instructed the prince of Orange how to keep up the necessary communications[3]. He transferred[5] prince Frederick’s corps to lord Hill[4], warned the Prussian commandant at Charleroi, the duke of Berry, and all others concerned, to be on the alert; he also gave them exact accounts of the movements and strength of the enemy between Valenciennes and Maubeuge. All this was accomplished by the Duke before the 10th of May. On the 11th, he wrote to sir Henry Hardinge, then attached to the Prussian head-quarters for the purpose of communication, that he reckoned the enemy’s strength on the frontiers at 110,000 men; and was glad that Blücher was drawing his forces nearer to the British. His Grace adopted the most effective measures for placing all the fortified towns and strong places in a condition to embarrass the enemy; and notwithstanding the objections made, by interested parties, to the necessary inundations, he was firm in ordering them, wherever the general security required it. The Duke sent able engineers to limit, as much as possible, the injury arising from letting out the waters, and to inundate with fresh instead of salt water, when practicable. For this timely care of the general interests, and even, as far as it was possible, of private property, the return he met with was unceasing complaints from the authorities of the several towns, where these measures had been applied. But the Duke did his duty firmly, and, after some expostulation with unreasonable grumblers, compelled them to do theirs. On the 7th of June, he issued his orders for the defence of the towns of Antwerp, Ostend, Nieuport, Ypres, Tournay, Ath, Mons and Ghent. The governors of these respective towns were required to declare them in a state of siege, the moment the enemy should put his foot on the Belgian territory: the towns were to be defended to the utmost; and if any governor surrendered before sustaining at least one assault, and without the consent of his council, he should be deemed guilty, not only of military disobedience, but of high treason. Such decisive measures were rendered necessary, in consequence of the equivocal loyalty of many who held municipal and military rank in the Netherlands. The king had prudently invested Wellington with these important[6] powers, and no man could have exercised them more effectively.

The French court (Louis XVIII and his suite) received advice how to save themselves by retiring to Antwerp, in case the enemy should succeed in turning the British right: they were desired to be in no alarm, nor to be startled by mere rumours, but to await positive information. Having thus provided for the military wants, and even for the fears of those behind him, the Duke devoted his whole attention to the army; and in proportion as the storm approached, repeated his warnings to the Prussians, by incessant dispatches to sir Henry Hardinge. He also sent frequent instructions to his own officers who were the nearest to the enemy, to keep on the alert.

The regiment I belonged to disembarked at Ostend on the 21st of April, and we soon found there was work in hand. Swords were to be ground and well pointed, and the frequent inspections of arms, ammunition, camp equipage, etc., plainly announced that we were shortly about to take the field. The army, soon after our arrival, had, in consequence of a secret memorandum[5] issued by the duke of Wellington to the chief officers in command, drawn closer together, in the probable expectation of an attack, and our great antagonist was not the sort of man to send us word of the when and the where. Louis XVIII, with his suite and a train of followers, being with us at Ghent, we were not destitute of information. Napoleon was as well informed of all that transpired in Belgium as if it had taken place at the Tuileries.

Things continued in this state until June, when, from various rumours, we began to be more on the alert.

At the commencement of operations, the duke of Wellington’s army comprised about 105,000 men, including the troops in garrison, and composed of about 35,000 British, 6,000 King’s German legion, 24,000 Hanoverians, 7,000 Brunswickers, and 32,000 Dutch-Belgians and Nassau-men, with a hundred and ninety-six guns. Many in the ranks of the last-named troops had served under Napoleon, and there still prevailed[7] amongst them a most powerful prejudice in his favour; it was natural, therefore, that we should not place too strong a reliance upon them, whenever they might become opposed to their old companions in arms.

The Anglo-allied army was divided into two corps, of five divisions each. The first was commanded by the prince of Orange; its head-quarters being Braine-le-Comte. Those of the second corps, under lord Hill, were at Grammont. The cavalry, divided into eleven brigades, was commanded by the earl of Uxbridge, now marquis of Anglesey; head-quarters Ninove. His Grace’s head-quarters were at Brussels, in and around which place was our reserve of all arms, ready to be thrown into whatever point of our line the enemy might attack, so as to hold the ground until the rest of the army could be united.

The Prussian army, under the veteran prince Blücher, consisted of about 115,000 men, divided into four corps, each composed of four brigades. The head-quarters of the 1st, or Zieten’s corps, were at Charleroi; the 2d, Pirch’s, at Namur, which was also Blücher’s head-quarters; the 3d, Thielmann’s, at Ciney; and the 4th, Bulow’s, at Liège.

Each corps had a reserve cavalry attached, respectively commanded by generals Röder, Jurgass, Hobe, and prince William. Their artillery comprised three hundred and twelve guns.

The Prussian army was posted on the frontier upon our left, from Charleroi to Maestricht. Our left, communicating with Blücher’s right, was at Binche; and our right stretched to the sea.

A large proportion of the British troops was composed of weak second and third battalions, made up of militia and recruits, who had never been under fire[6]; most of our best-tried Spanish infantry, the victors of many a hard-fought field, were on their way from America. The foreign troops, with the exception of the old gallant Peninsular German legion, were chiefly composed of new levies, hastily embodied, and[8] very imperfectly drilled; quite inexperienced in war, raw militia-men in every sense of the word, and wholly strangers to the British troops and to each other. Nor was the Prussian army what it had been; it was no longer the old Silesian one: many soldiers had just been embodied, and thousands had fought under the Imperial eagles.

The French army of the North, commanded by the Emperor in person, and destined to act against Belgium, early in June, was divided into six corps, and cantoned: the 1st, or D’Erlon’s, at Lille; the 2d, or Reille’s, at Valenciennes; the 3d, or Vandamme’s, at Mézières; the 4th, or Gérard’s, at Metz; and the 6th, or Lobau’s, at Laon. The Imperial guard was in Paris. The reserve cavalry, commanded by generals Pajol, Excelmans, Milhaut, and Kellermann, cantoned between the Aisne, the Meuse and the Sambre. There were three hundred and fifty pieces of artillery.

On the 16th of May, we received intelligence of there being 110,000 French troops in our front. On the 1st of June, it was rumoured that we were to be attacked; Napoleon was to be at Laon on the 6th, and extraordinary preparations were being made for the conveyance of troops in carriages from Paris to the frontiers. Intelligence reached the Duke, on the 10th of the same month, that Napoleon had arrived at Maubeuge, and was passing along the frontier. On the 12th, it was ascertained, for certain, that the French army had assembled and was about to cross the frontiers[7]; but the Duke, for reasons we shall hereafter give, did not think proper to move his troops until quite satisfied as to the point where Napoleon would make his attack; that point proved to be Charleroi, on the high-road to Brussels, on the left of the allied and right of the Prussian armies, said to be the most favourable for defeating the two armies, in detail; which I am inclined to doubt. Situated as the allied and Prussian armies were, Napoleon, by attempting to wedge his army in between the two, was pretty certain of having both upon him: he could not[9] aim a blow at one enemy without being assailed in flank or rear by the other.

Brussels, the capital of Belgium, lies in the very centre of that country, which was declared by general Gneisenau, chief of the Prussian staff, to be a formidable bastion, flanking efficaciously any invasion meditated by France against Germany, and serving at the same time as a tête de pont to England.

Napoleon had numerous partisans and friends in Belgium, who secretly espoused his cause, and who, no doubt, would have seconded him in his attempt to again annex that country to the French Empire. The people also were by no means reconciled to the union forced upon them by the congress of Vienna, a union with a country differing from them in religion and customs; and the dense population and troops of Belgium might probably have made a movement in favour of the French, had Napoleon obtained possession of the capital. From the tenor of Napoleon’s letter to Ney, and his proclamations to his army and to the Belgians[8], it is quite evident that the Emperor expected a manifestation of this kind. This would certainly have added to his cause that moral force of which it stood so much in need, and have induced thousands to rally round the Imperial eagles.

Brussels was our main line of operations and the line of communication with Ostend and Antwerp, the dépôts where our reinforcements and supplies were landed. The Duke, in consequence, saw clearly, it was of the utmost importance, both in a military and political point of view, to preserve an uninterrupted communication with those ports, and that the enemy should not, even for a moment, obtain possession of Brussels[9].

By the Emperor’s masterly arrangements his army was assembled on the frontiers with astonishing secrecy; but his intention of taking the two armies by surprise was defeated, on the night of the 13th, by the Prussian outposts, in advance of Charleroi, having observed the horizon illumined by the reflection of numerous bivac fires in the direction of Beaumont[10] and Maubeuge, which announced that a numerous enemy had assembled in their immediate front; this intelligence was forthwith transmitted to both Wellington and Blücher.

Zieten, the Prussian commander at Charleroi, received intelligence, on the afternoon of the 14th, that the enemy’s columns were assembling in his front, the certain prelude to an attack, probably the next day. Blücher, apprized of this about ten o’clock the same evening, immediately sent off orders for the concentration of the Prussian army at Fleurus, a preconcerted plan between the two commanders. When the order was first sent to Bulow at Liège, to move to Hannut, had the most trifling hint been given him of the French being about to attack, he would probably have been up in time to share in the battle of Ligny, which might have changed the aspect of affairs.

After dispatching orders for the concentration of the Grand army, Napoleon left Paris on the 12th, and, as he himself states, under a great depression of spirits, aware he was leaving a host of enemies behind, more formidable than those he was going to confront. He slept at Laon, and arrived at Avesnes on the 13th, near which place he found his army assembled, amounting, according to his own account, to 122,400 men and three hundred and fifty guns. Their bivacs were behind small hills, about a league from the frontier, situated so as to be concealed, in a great measure, from the view of their opponents.

The Emperor’s arrival amongst his devoted soldiers raised their spirits to the highest degree of enthusiasm, and on the 14th he issued the following order:

“Imperial head-quarters, 14th June, 1815.

“Napoleon, by the grace of God and the constitution of the Empire, Emperor of the French, etc.

“Soldiers! this day is the anniversary of Marengo and of Friedland, which twice decided the fate of Europe. Then, as after Austerlitz, as after Wagram, we were too generous: we believed in the protestations and in the oaths of princes, whom we left on their thrones. Now, however, leagued together,[11] they aim at the independence and most sacred rights of France; they have commenced the most unjust of aggressions. Let us then march to meet them: are they, and we, no longer the same men?

“Soldiers! at Jena, against those same Prussians, now so arrogant, you were one to three, and at Montmirail one to six. Let those amongst you, who have been captives to the English, describe the nature of their prison ships, and the frightful miseries you endured.

“The Saxons, the Belgians, the Hanoverians, the soldiers of the Confederation of the Rhine, lament that they are compelled to use their arms in the cause of princes, the enemies of justice, and of the rights of nations. They know that this coalition is insatiable: after having devoured twelve millions of Italians, one million of Saxons, and six millions of Belgians, it now wishes to devour the states of the second rank in Germany. Madmen! one moment of prosperity has bewildered them: the oppression and humiliation of the French people are beyond their power: if they enter France, they will find their grave.

“Soldiers! we have forced marches to make, battles to fight, dangers to encounter; but with firmness, victory will be ours.

“The rights, the honour and the happiness of the country will be recovered.

“To every Frenchman who has a heart, the moment is now arrived to conquer or to die[10].”

About four o’clock in the morning of the 15th of June, Napoleon attacked the Prussian outposts in front of Charleroi, at Thuin and Lobbes[11]. The Prussians fell back, slowly and with great caution, on their supports. By some unaccountable neglect Willington was not informed of the attack until after three o’clock in the afternoon, although the distance from[12] Thuin and Lobbes to Brussels is but forty-five miles[12]. Had a well arranged communication been kept up, the Duke could have been informed of the first advance of the French by ten o’clock A.M., and of the real line of attack by four P.M.

The French were in possession of Charleroi by eleven o’clock. The Prussians retired to a position between Ligny and St.-Amand, nearly twenty miles from the outposts. At three o’clock in the afternoon, the 2d Prussian corps had taken position not far from Ligny; Blücher had established his head-quarters at Sombreffe. The advanced posts of the French left column were at Frasnes, three miles beyond Quatre-Bras, from which the advanced posts of the allies had been driven. Ney’s head-quarters were at Gosselies, with a part of his troops only, whilst D’Erlon’s corps and the cavalry of Kellermann were on the Sambre. The centre column of the French army lay near Fleurus, the right column near Châtelet, and the reserve, composed of the Imperial guard and the 6th corps, between Charleroi and Fleurus.

The duke of Wellington, although apprized of the advance of Napoleon and his attack on the Prussian outposts, would make no movement to leave Brussels uncovered, until certain of the real line of attack, as such attacks are often made to mask the real direction of the main body of the enemy. But orders were immediately transmitted to the different divisions to assemble and hold themselves in readiness to march, some at a moment’s notice, and some at day-light in the morning[13].

Lord Uxbridge was ordered to get the cavalry together at the head-quarters (Ninove) that night, leaving the 2d hussars of the King’s German legion on the look-out between the Scheldt and the Lys.

The troops in Brussels, composed of the 5th, or Picton’s division, the 81st regiment, and the Hanoverian brigade of the 6th division, called the reserve, were to be in readiness to march at a moment’s notice.

After the Duke had completed his arrangements for the concentration of the army, his Grace, with many of our officers, went to the celebrated ball, given, on the eve of the memorable engagement at Quatre-Bras, by the duchess of Richmond, at her residence, now Nº 9, Rue des Cendres, Boulevard Botanique, near the Porte de Cologne. The saloons of the duchess were filled with a brilliant company of distinguished guests. The officers in their magnificent uniforms, threading the mazy dance with the most lovely and beautiful women. The ball was at its height, when the duke of Wellington first received positive intelligence that Napoleon had crossed the Sambre with his whole army and taken possession of Charleroi. The excitement which ensued, on the company being made acquainted with Napoleon’s advance, was most extraordinary. The countenances which, a moment before, were lighted up with pleasure and gaiety, now wore a most solemn aspect. The duke of Brunswick, sitting with a child (the present prince de Ligne) on his knees, was so affected, that in rising he let the prince fall on the floor. The guests little imagined that the music which accompanied the gay and lively dances at her Grace’s ball, would so shortly after play martial airs on the battle field, or that some of the officers present at the fête would be seen fighting in their ball dresses, and, in that costume, found amongst the slain.

At about the same time, his Grace also received information from his outposts in front of Mons, and from other sources, which proved that the enemy’s movement upon Charleroi was the real point of attack, and he immediately issued the following orders:

“Brussels, 15th June, 1815.

“AFTER-ORDERS.—TEN O’CLOCK, P.M.

“The 5th” (Picton’s) “division of infantry, to march on Waterloo at two o’clock to-morrow morning.

“The 3d” (Alten’s) “division of infantry, to continue its movement from Braine-le-Comte upon Nivelles.

“The 1st” (Cooke’s) “division of infantry, to move from Enghien upon Braine-le-Comte.

“The 2d” (Clinton’s) “and 4th” (Colville’s) “division[14] of infantry, to move from Ath and Grammont, also from Audenaerde, and to continue their movements upon Enghien.

“The cavalry, to continue its movement from Ninove upon Enghien.

“The above movements to take place with as little delay as possible.

“Wellington.”

Picton’s division and the Hanoverian brigade marched from Brussels about two o’clock A.M., on the 16th, taking the road to Waterloo by the forest of Soigne; near which they halted to refresh, and to await orders, to march either on Nivelles or Quatre-Bras, (the roads branching off at Mont-St.-Jean,) according as the Duke might direct, upon his becoming acquainted with the real state of affairs in front. Shortly after they were joined by the Brunswickers.

While halting, the duke of Wellington, who had left Brussels between seven and eight o’clock, passed with his staff, and gave strict orders to keep the road clear of baggage, and everything that might obstruct the movements of the troops. The duke of Brunswick dismounted, and seated himself on a bank on the road side, in company of his adjutant-general, colonel Olfermann. How little did those who observed this incident, think, that in a few hours the illustrious duke would, with many of themselves, be laid low in death! and numbers truly there were amongst the slain ere the sun set.

About twelve o’clock, orders arrived for the troops to proceed on to Quatre-Bras, leaving the baggage behind; this[15] looked rather warlike, but as yet nothing was known for certain. The Duke galloped on, and, after a hasty glance at the Waterloo position, rode to Quatre-Bras, where he conversed with the prince of Orange respecting the disposition of the troops as they arrived. His Grace well reconnoitred the enemy’s position. Seeing the latter were not in great force, he rode on to hold a conference with Blücher, whom he found about half-past one o’clock P.M. at the wind-mill at Bussy, between Ligny and Bry, where towards noon, by great activity and exertion, three corps of the Prussian army, about 85,000 men, had been put in position, but so disposed as to draw from the Duke his disapprobation of the arrangements. His Grace saw that the enemy were strong in Blücher’s front, and promising to support his gallant and venerable colleague, shook hands and returned to Quatre-Bras, where he arrived at about half-past two o’clock, soon after which time Napoleon began his attack upon Blücher.

Marshal Ney, who commanded the French troops at Quatre-Bras, commenced his attack upon Perponcher’s Dutch-Belgian division under the prince of Orange. About two o’clock, Picton’s division came up, composed of Kempt’s brigade, the 28th, 32d, 79th Highlanders, and 1st battalion 95th rifles, and of Pack’s brigade, the 1st Royal, 44th, 42d and 92d Highlanders, with Best’s Hanoverian brigade; soon after, the Brunswickers arrived incomplete, and some Nassau troops. Towards six o’clock, sir Colin Halkett’s brigade, the 30th, 33d, 69th, and 73d regiments, also Kielmansegge’s Hanoverian brigade, most opportunely reached the scene of action. Pack’s noble fellows were by this time so hard pressed, so much exhausted, and their ammunition was so nearly expended, that sir Denis Pack applied for a fresh supply of cartridges, or assistance, to sir Colin Halkett, who immediately ordered the 69th to push on and obey any orders given by Pack; the latter then galloped forward to a commanding point, and soon discovered the formation of a large force of cuirassiers preparing for attack. He spurred off to his brigade to prepare them for the coming storm, and in passing by the 69th, ordered colonel Morice to form square, as the enemy’s cavalry was at hand. The formation was nearly completed,[16] when the prince of Orange rode up, and, by a decided misconception, most indiscreetly directed them to reform line, which they were in the act of doing, when the rushing noise in the high corn announced the arrival of the enemy’s cuirassiers, who charged them in flank, rode right along them, regularly rolling them up. A cuirassier carried off the 69th’s colour, in defence of which cadet Clarke, afterwards lieutenant in the 42d, received twenty-three wounds, one of which deprived him of the use of an arm for life.

The duke of Wellington was nearly taken prisoner, and owed his escape to an order which he promptly gave to a part of the 92d, who were lining a ditch, to lie down whilst he galloped over them.

A little before seven o’clock, sir G. Cooke’s division, composed of the 1st brigade, under major-general Maitland, (the second and third battalions of the 1st foot-guards,) and of the 2d brigade, under sir J. Byng, (now lord Strafford,) composed of the 2d battalions of the Coldstream and the 3d foot-guards, came up, and soon drove the enemy back. Ney’s attacks were maintained with the greatest impetuosity during the first hours, but they became fewer and feebler as our reinforcements joined us, and towards the close of the day conducted with greater caution. Soon after sun-set, Ney fell back upon Frasnes, and the desperate struggle terminated. The duke of Wellington then advanced his victorious troops to the foot of the French position, when piquets for the night were thrown forward by both parties. Thus ended the action of Quatre-Bras, during which our troops were fully employed, and the Duke prevented from rendering his promised aid to the Prussians. It was only through the greatest personal exertions of our gallant chief and the most determined resistance on the part of his troops, that the enemy’s attacks were repulsed, and our communication with Blücher at Ligny by the Namur road kept open. The Emperor’s instructions to Ney to drive back the English, whom he supposed to be at that point in no great numbers, and afterwards to turn round and envelop the Prussian right flank, were completely frustrated. Our force in the field towards the close of the day was about 29,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and sixty-eight guns; that of[17] the enemy, about 16,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, with fifty guns.

To the fortunate circumstance of the marching and countermarching of D’Erlon’s corps (Ney’s reserve) between Frasnes, Ligny and Quatre-Bras, without pulling a trigger, we may probably attribute our success on the 16th. An additional force of 25,000 men, either at Ligny or Quatre-Bras, might have gained Napoleon a decisive victory.

The action at Quatre-Bras possessed its own peculiar and important merits, which, with our masterly retreat to the Waterloo position, would have been sounded by the trumpet of fame, but for the glorious achievement that immediately followed on the field of Waterloo.

In no battle did the British infantry display more valour or more cool determined courage than at Quatre-Bras. Cavalry we had none that could stand the shock of the French; the Brunswick and Belgian cavalry, it is true, made an attempt, but were scattered like chaff before the wind by the veteran cuirassiers, who, to render them the more effective, had been mounted on horses taken from the gendarmes throughout France. The British cavalry had had a long march, some nearly forty miles, and consequently did not arrive until the battle was over. The gallant Picton, seeing the cavalry driven back, led on our infantry in squares into the centre of the enemy’s masses of cavalry; faced with squares the charging squadrons, and in line, the heavy columns of infantry. What may not be effected by such troops, led by such a general? The duke of Brunswick fell, while rallying one of his regiments that had given way. Colonel sir Robert Mac Ara of the 42d, and colonel Cameron of the 92d, were also killed.

During our struggle at Quatre-Bras, Napoleon had attacked the Prussians at Ligny, and between nine and ten o’clock in the evening, their centre was broken, and they began a retreat upon Wavre[15]. The horse of marshal Blücher,[18] a beautiful grey charger, presented to him by our Prince Regent in 1814, was shot under him, and, while lying on the ground, the field-marshal was twice charged over by the enemy’s cavalry. Sir Henry Hardinge, attached to the Prussian head-quarters, lost his left hand at Ligny; and about eight thousand Prussians deserted, and returned home.

The battle of Ligny may be considered as a series of village fights, and had the impetuous old hussar, the gallant Blücher, then seventy-three years of age, not drawn troops from his centre, to strengthen his right, and to enable him to attack the enemy’s left, he might probably have maintained his position; but immediately Napoleon perceived that Blücher had withdrawn his troops from his centre, he made a dash at it, forced it, and thus gained the victory. Notwithstanding the Prussians were defeated, they highly distinguished themselves by their audacity and valour. The battle of Ligny was a fierce and sanguinary contest, and little or no quarter given by either side. Both parties were excited by deadly animosity, and the helpless wounded became the victims. The Prussian loss was about fifteen thousand men and twenty-five guns, exclusive of the eight thousand men that disbanded themselves. The French loss was rather less.

Colonel Gordon’s patrol discovers the Prussians are retreating upon Wavre.—The allied army ordered to retire upon Waterloo.—The Duke writes to Blücher.—Retreat commenced, followed by the enemy.—Skirmishing.—Pressed by the lancers, who are charged by the 7th hussars; the latter are repulsed.—The life-guards make a successful charge.—Lord Anglesey’s letter, refuting a calumnious report of his regiment.—Allied army arrives on the Waterloo position.—The enemy arrive on the opposite heights, and salute us with round-shot, to which we reply to their cost.—Piquets thrown out on both sides.—Dismal bivac; a regular soaker.—The Duke and Napoleon’s quarters.—His Grace receives an answer from Blücher.—Probability of a quarrel on the morrow.—Orders sent to general Colville.—Description of the field of Waterloo; Hougoumont and La Haye-Sainte.—Disposition of the allied army, and the advantages of our position.—Disposition of the enemy, and admirable order of battle.—The eve of Waterloo.—Morning of the 18th wet and uncomfortable; our occupation.—The Duke arrives; his appearance, dress, staff, etc.—Positions corrected.—French bands play, and their troops appear; are marshalled by Napoleon, a magnificent sight, worth ten years of peaceful life.—Why tarries Napoleon with his grand martial display?—The Emperor passes along his lines; his troops exhibit unbounded enthusiasm; his confidence of victory.

Our bivac was quiet during the night, except that the arrival of cavalry and artillery caused an occasional movement.

About two o’clock in the morning, a cavalry patrol got between the piquets, and a rattling fire of musketry began, which brought some of our generals to the spot; Picton was the first that arrived, when it was found that no attempt to advance had been made, and all was soon quiet again. After which the stillness of the enemy quite surprised his Grace, and drew the remark, “They are possibly retreating.”

The Duke, who had slept at Genappe, was early at Quatre-Bras. Up to this time we had no satisfactory intelligence of the Prussians. His Grace consequently sent a patrol along the Namur road to gain intelligence; captain Grey’s troop of the 10th hussars was sent on this duty, accompanied by lieutenant-colonel[20] the Hon. sir Alexander Gordon, one of the Duke’s aides-de-camp. Shortly afterwards, captain Wood, of the 10th, who had been patrolling, informed the Duke that the Prussians had retreated. Gordon’s patrol discovered, on the right of the road, some of the enemy’s vedettes and a piquet; they fell back hurriedly before the patrol, who turned off the high-road to their left, about five miles from Quatre-Bras, and about an hour afterwards came up with the Prussian rear. After obtaining the required information, the patrol returned to head-quarters at Quatre-Bras, where they arrived about seven o’clock A.M., reporting that the Prussians were retreating upon Wavre[16].

The Duke immediately issued the following orders:

To General Lord Hill, G.C.B.

“QUATRE-BRAS, 17th June, 1815.

“The 2d division of British infantry, to march from Nivelles on Waterloo, at ten o’clock.

“The brigades of the 4th division, now at Nivelles, to march from that place on Waterloo, at ten o’clock. Those brigades of the 4th division at Braine-le-Comte, and on the road from Braine-le-Comte to Nivelles, to collect and halt at Braine-le-Comte this day.

“All the baggage on the road from Braine-le-Comte to Nivelles, to return immediately to Braine-le-Comte, and to proceed immediately from thence to Hal and Brussels.

“The spare musket ammunition to be immediately parked behind Genappe.

“The corps under the command of prince Frederick of Orange will move from Enghien this evening, and take up a position in front of Hal, occupying Braine-le-Château with two battalions.

“Colonel Erstorff will fall back with his brigade on Hal, and place himself under the orders of prince Frederick.”

An officer from the Prussian head-quarters, bearing dispatches, written, no doubt, in secret characters, or the French would have immediately discovered the direction in which the Prussians retreated, had been waylaid and made prisoner in the night. But a second officer afterwards arrived at our head-quarters, and confirmed colonel Gordon’s statement that the Prussians had fallen back upon Wavre. The Duke immediately wrote to Blücher, informing him of his intention to retreat upon the position in front of Waterloo, and proposing to accept battle on the following day, provided the Prince would support him with two corps of his army.

The first hint to Picton of the Duke’s intention to retreat, was an order conveyed to him, to collect his wounded; when he growled out, “Very well, sir,” in a tone that showed his reluctance to quit the ground his troops had so bravely maintained the day before.

The Duke commenced the retrograde movement, masked as much as possible from the enemy, who followed us with a large force of cavalry, shouting, Vive l’Empereur!

The first part of the day (the 17th) was sultry, not a breath of air to be felt, and the sky covered with dark heavy clouds. Shortly after the guns came into play, it began to thunder, lighten, and rain in torrents. The ground very quickly became so soaked, that it was difficult for the cavalry to move, except on the paved road: this, in some measure, checked the advance of the French cavalry, who pressed us very much.

The regiment to which I belonged covered the retreat of the main columns. As we neared Genappe, our right squadron, under major Hodge, was skirmishing. By this time the ploughed fields were so completely saturated with rain, that the horses sunk up to the knees, and at times nearly up to the girths, which made this part of the service very severe. Our other two squadrons cleared the town of Genappe, and formed on the rising ground on the Brussels side. Shortly after, the right squadron retired through the town, and drew up on the high-road in column, when a few straggling French lancers, half tipsy, came up and dashed into the head of the column; some were cut down, and some made prisoners. The head of the French column now appeared debouching from the town,[22] and lord Uxbridge being present, he ordered the 7th hussars to charge.

The charge was gallantly led by the officers, and followed by the men, who cut aside the lances, and did all in their power to break the enemy: but our horses being jaded by skirmishing on heavy ground, and the enemy being chiefly lancers, backed by cuirassiers, they were rather awkward customers to deal with, particularly so, as it was an arm with which we were quite unacquainted. When our charge first commenced, their lances were erect, but upon our coming within two or three horses’ length of them, they lowered the points and waved the flags, which made some of our horses shy. Lord Uxbridge, seeing we could make no impression on them, ordered us about: we retired, pursued by the lancers and the cuirassiers intermixed. We rode away from them, reformed, and again attacked them, but with little more effect than at first. Upon this, lord Uxbridge brought forward the 1st life-guards, who made a splendid charge, and drove the cuirassiers and lancers pell-mell back into Genappe; the life-guards charging down hill, with their weight of men and horses, literally rode the enemy down, cutting and thrusting at them as they were falling. In this affair my old regiment had to experience the loss of major Hodge and lieutenant Myer, killed; captain Elphinstone[17], lieutenant Gordon and Peters, wounded; and forty-two men, with thirty-seven horses, killed and wounded. We were well nigh getting a bad name into the bargain.

Reports, as false as they were invidious, having been propagated by some secret enemy of the 7th hussars, it may not be uninteresting to the military world to be made acquainted with the opinion of their colonel, the marquis of Anglesey[18], as conveyed in the following letter:

“Brussels, 28th June 1815.

“MY DEAR BROTHER OFFICERS,

“It has been stated to me, that a report injurious to the[23] reputation of our regiment has gone abroad, and I do not therefore lose an instant in addressing you on the subject. The report must take its origin from the affair which took place with the advance-guard of the French cavalry, near Genappe, on the 17th inst., when I ordered the 7th to cover the retreat. As I was with you and saw the conduct of every individual, there is no one more capable of speaking to the fact than I am. As the lancers pressed us hard, I ordered you, (upon a principle I ever did, and shall act upon,) not to wait to be attacked, but to fall upon them.

“The attack was most gallantly led by the officers, but it failed. It failed because the lancers stood firm, had their flanks completely secured, and were backed by a large mass of cavalry.

“The regiment was repulsed, but it did not run away: no, it rallied immediately. I renewed the attack; it again failed, from the same cause. It retired in perfect order, although it had sustained so severe a loss; but you had thrown the lancers into disorder, who being in motion, I then made an attack upon them with the 1st life-guards, who certainly made a very handsome charge, and completely succeeded. This is the plain honest truth. However lightly I think of lancers under ordinary circumstances, I think, posted as they were, they had a decided advantage over the hussars. The impetuosity however and weight of the life-guards carried all before them, and whilst I exculpate my own regiment, I am delighted in being able to bear testimony to the gallant conduct of the former. Be not uneasy, my brother officers; you had ample opportunity, of which you gallantly availed yourselves, of avenging yourselves on the 18th for the failure on the 17th; and after all, what regiment, or which of us, is certain of success?

“Be assured that I am proud of being your colonel, and that you possess my utmost confidence.

“Your sincere friend,

“Anglesey, lieutenant-general.”

The 23d light dragoons, supported by the life-guards,[24] covered our retreat, and we arrived at a position on which was exhibited as noble a display of valour and discipline, as is to be found either in our own military annals, or in those of any other nation. This position was in front of and about two miles and a half from Waterloo, where most of our army was then drawn up.

The French advance-guard halted on the heights near La Belle-Alliance, when Napoleon said, he wished he had the power of Joshua to stop the sun, that he might attack us that day.

They opened a cannonade upon our line, but principally upon our centre behind the farm of La Haye-Sainte: our guns soon answered them to their cost, and caused great havock amongst the enemy’s columns, as they arrived on the opposite heights between La Belle-Alliance and the orchard of La Haye-Sainte. It was now getting dusk, and orders were given to throw out piquets along the front and flanks of the army.

Our left squadron, under captain Verner, was thrown into the valley in front of the left wing; the rest of my regiment bivacked near where Picton fell the next day.

The spirit of mutual defiance was such, that in posting the piquets, there were many little cavalry affairs, which, although of no useful result to either side, were conducted with great bravery, and carried to such a pitch, that restraint was absolutely necessary. Captain Heyliger, of the 7th hussars, (part of our piquet,) with his troop, made a spirited charge upon the enemy’s cavalry, and when the Duke sent to check him, his Grace desired to be made acquainted with the name of the officer who had shown so much gallantry. A better or more gallant officer, than captain Heyliger, never drew a sword; but he was truly unfortunate: if there was a ball flying about, he was usually the target. I was three times engaged with the enemy, serving with the captain, and he was wounded on each of those occasions: the first time, foraging at Haspereen; next, at the battle of Orthez; and thirdly, at Waterloo. The ball he received on the last occasion was extracted at Bruges, in 1831.

Our bivac was dismal in the extreme; what with the thunder,[25] lightning and rain, it was as bad a night as I ever witnessed, a regular soaker: torrents burst forth from the well charged clouds upon our comfortless bivacs, and the uproar of the elements, during the night preceding Waterloo, seemed as the harbinger of the bloody contest. We cloaked, throwing a part over the saddle, holding by the stirrup leather, to steady us if sleepy: to lie down with water running in streams under us, was not desirable, and to lie amongst the horses not altogether safe. A comrade of mine, Robert Fisher, a tailor by trade, proposed that one of us should go in search of something to sit on. I moved off for that purpose, and obtained two bundles of bean-stalks from a place that I now know as Mont-St.-Jean farm. This put us, I may say, quite in clover. The poor tailor had his thread of life snapped short on the following day.

The duke of Wellington established his head-quarters opposite the church at Waterloo, (now the post-house and post-office;) while his Imperial antagonist, Napoleon, pitched his tent near the farm of Caillou, about five miles from Waterloo, on the left of the Genappe road, in the parish of Old-Genappe. The Imperial baggage was also at this farm.

Most of the houses in the villages adjacent Waterloo were occupied by our generals, their staff, and the superior officers. Their names and rank were chalked on the doors, and legible long after a soldier’s death had snatched many of them from the field of their prowess and glory.

In the course of the evening the Duke received a dispatch from Blücher, in answer to his letter sent from Quatre-Bras, requesting the support of two corps of the Prussian army. The officer bearing this dispatch was escorted from Smohain, to Waterloo, by a party of the 1st King’s German hussars. Blücher’s reply was:

“I shall not come with two corps only, but with my whole army, upon this condition, that should the French not attack us on the 18th, we shall attack them on the 19th.”

The Duke therefore accepted battle only under these circumstances; Napoleon’s lauded plan of operations enabling his Grace to ultimately place the author of those brilliant conceptions between two fires. Blücher appeared most anxious[26] to fight side by side with the allies and their chief, deeming an Anglo-Prussian army invincible; while Wellington, after having defeated most of Napoleon’s best marshals, was no doubt desirous of measuring swords with their mighty master himself, the hero of a hundred battles.

There is every reason to believe that the Duke was more apprehensive of being turned by Hal on his right, and of Brussels being consequently taken by a coup de main, than about any other part of his position. This fact is confirmed by the following orders, dated

“Waterloo, 17th June, 1815.

“The army retired this day from its position at Quatre-Bras, to its present position in front of Waterloo.

“The brigades of the 4th division at Braine-le-Comte are to retire at day-light to-morrow morning upon Hal.

“Major-general Colville must be guided by the intelligence he receives of the enemy’s movements, in his march to Hal, whether he moves by the direct route, or by Enghien.

“Prince Frederick of Orange is to occupy with his corps the position between Hal and Enghien[19], and is to defend it as long as possible.

“The army will probably continue in its position, in front of Waterloo, to-morrow.

“Lieutenant-colonel Torrens will inform lieutenant-general sir Charles Colville of the position and situation of the armies.”

The field of Waterloo is an open undulating plain; and, on the day of the battle, was covered with splendid crops of rye, wheat, barley, oats, beans, peas, potatoes, tares and clover; some of these were of great height. There were a few patches of ploughed ground. The field is intersected by two high-roads which branch off at Mont-St.-Jean; these are very wide: the one on the right, leading to Nivelles and Binche, since planted with trees, is straight as an arrow for miles; that on the left, lying in the centre of both armies, leading south to Genappe, Charleroi and Namur, is not so[27] straight as the former: about eleven hundred yards in advance of the junction, is a gently elevated ridge which formed a good natural military position.

Nearly a year before these events, the Duke had written to lord Bathurst, enclosing “a Memorandum on the defence of the Netherlands,” in which he says:

“About Nivelles, and between that and Binche, there are many advantageous positions; and the entrance of the forêt de Soigne, by the high-road which leads to Brussels from Binche, Charleroi and Namur, would, if worked upon, afford others[20].”

The great advantage was that the troops could rest in rear of the crest of the ridge, screened in a great measure from the enemy’s artillery and observation, whilst our guns were placed at points, from whence they could sweep (they are wonderful brooms) the slope that descends to the valley in front. Upon the crest is a cross-road running east and west, intersecting the Genappe road at right angles, about two hundred and fifty yards on this side of the farm of La Haye-Sainte. The cross-road marks the front of the allied position. Near where the Lion now stands, the cross-road or line runs curving forward a little for about six hundred yards, when it first gently and then abruptly falls back into the Nivelles road, near the termination of the ridge, where it takes a sweep to the rear.

This point was at first our right centre, but became our right when lord Hill’s troops were brought forward into the front line, between four and five o’clock P.M.