Title: Brothers and sisters

Author: Abbie Farwell Brown

Illustrator: Ethel C. Brown

Release date: January 10, 2023 [eBook #69760]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1906

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

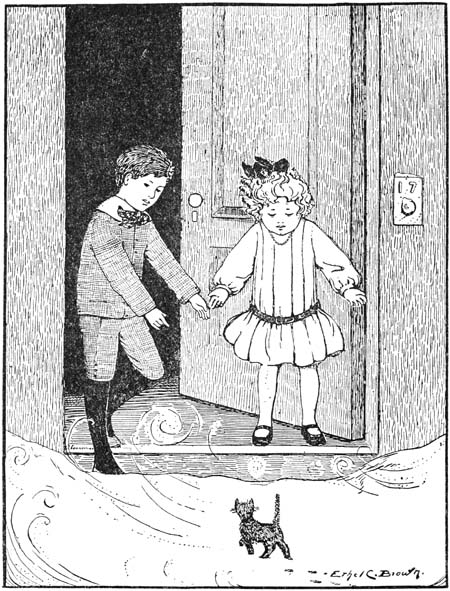

“POOR LITTLE KITTY, HOW COLD SHE MUST BE”

(Page 6)

BROTHERS AND

SISTERS

BY

ABBIE FARWELL BROWN

ILLUSTRATED BY

ETHEL C. BROWN

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

1906

COPYRIGHT 1906 BY ABBIE FARWELL BROWN

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published September 1906

For permission to reprint the several chapters of this volume thanks are due to The Churchman,—“The Garden of Live Flowers,” “April Fool,” “The Dark Room,” “The Pieced Baby,” “The Alarm;” to The Congregationalist,—“The Japanese Shop,” “Brothers and Sisters;” to Good Housekeeping,—“Buried Treasure;” and to The Kindergarten Review,—“The Christmas Cat.”

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Christmas Cat | 1 |

| II. | The Christmas Cat’s Present | 10 |

| III. | The Japanese Shop | 19 |

| IV. | April Fool’s Night | 28 |

| V. | The April Fool | 38 |

| VI. | The April-Fool Journey | 48 |

| VII. | The Dolls’ May-Party | 57 |

| VIII. | The Dark Room | 66 |

| IX. | The Garden of Live Flowers | 86 |

| X. | Buried Treasure | 97 |

| XI. | The Pieced Baby | 106 |

| XII. | The Alarm | 120 |

| XIII. | Brothers and Sisters | 131 |

| XIV. | Tommy’s Letter | 145 |

| “Poor little kitty, how cold she must be” (page 6) | Frontispiece |

| “See what Santa has brought the Christmas cat” | 16 |

| The littlest baby white rabbit | 24 |

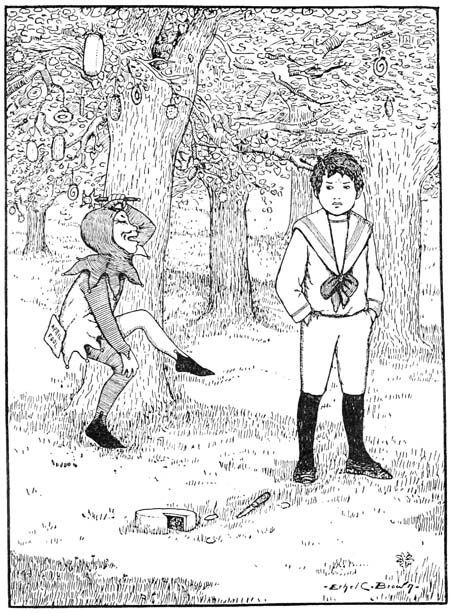

| “I am April Fool” | 40 |

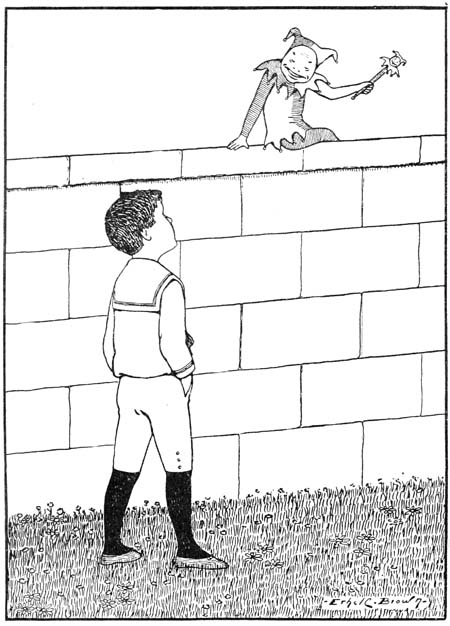

| Kenneth found that it was a wall of glass | 44 |

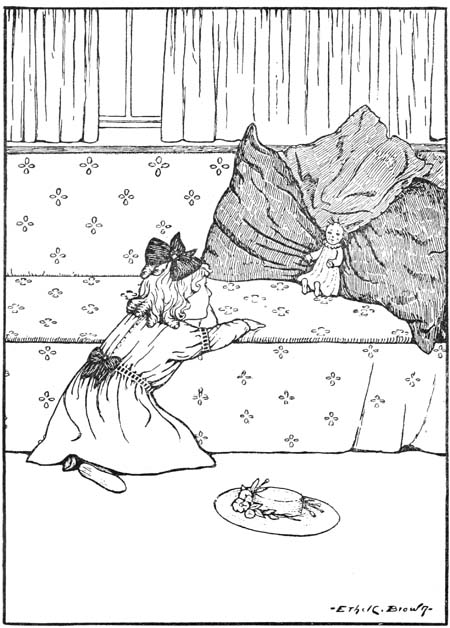

| She lifted poor Matilda and set her up on the window seat | 64 |

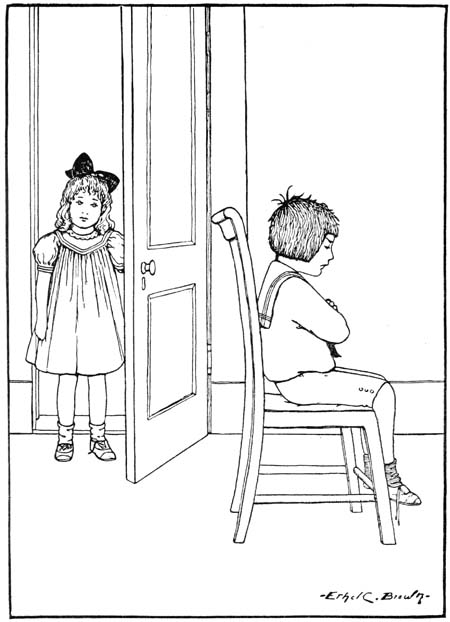

| In tiptoed a little figure | 74 |

| Living flowers | 92 |

| The sand stretched out like a great sheet of paper | 98 |

| Awakened by a little silvery laugh | 108 |

| They were Tommy and Mary Prout | 122 |

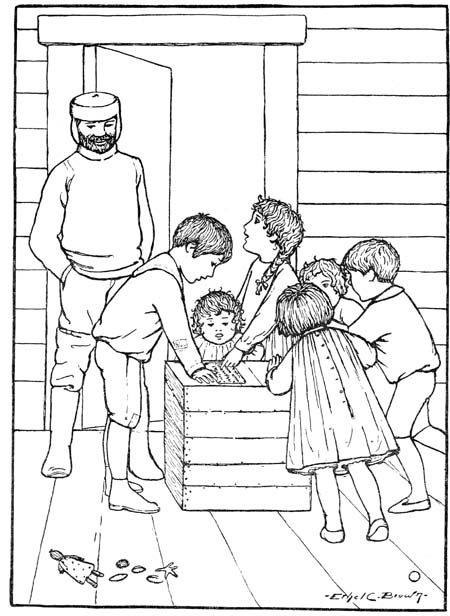

| What a shriek of joy went up | 142 |

BROTHERS AND SISTERS

IT was the day before the day before Christmas, and there came a big snowstorm, so that Kenneth and Rose were shut up in the house. Now that was a very hard thing to bear, for as every one knows, the last two days before Christmas are the longest, slowest days in the whole year. But if one has to stay in the house and just think, it seems as though the time would never go by.

If it had been a pleasant day they could have gone out of doors to skate, or to coast, or to play any number of jolly games which they now remembered sadly. Perhaps they would have gone to their cousin Charlie’s house, which was in the next block but one beyond theirs. Perhaps their papa would have taken[2] them down town for a last look at the Christmas shops, and the wonderful toys, some of which they hoped Santa Claus would remember to bring to the Thornton house. There were ever so many nice things which they could have done to make the time pass away, if only it had been a pleasant day. But now there seemed nothing in the world to do.

Kenneth and Rose wandered dismally about the house. They peeped into the play-room, where the toys were lying about looking very lonely, as though they would say,—

“O Kenneth! Do come and play with us. Please, Rosie, don’t go away and leave us all alone!”

But Kenneth and Rose were tired of all the old toys, they had played with them so many, many times. They hoped that Santa would bring them some new ones on Christmas morning, if Christmas morning would ever, ever come!

In the dining-room Rose’s old doll, Matilda, was lying face downward on the sofa, quite[3] heart-broken because she had been so long deserted. Rose looked at her, then she turned her back sadly.

“Matilda is growing very ugly,” she said. “No wonder she hides her face, with only one eye and a broken nose. I still love her very much, but I do so hope that Santa will not forget how much I need a new dollie.”

They went down into the kitchen, with a vague hope that Katie might find them something to do. But Katie was too busy baking the Christmas pies and cake to bother with children. She would not even give them a bit of dough to play with.

“Whisht!” she cried, flapping a dishcloth at them fiercely, “Rin out o’ me kitchen, you childer! I can’t have ye fussing about here this day, niver a bit. Rin off an’ play somewheres else, like a good little lad and lassie, now.”

Run off and play! Where should they run, and what should they play? There was no one to help them. Papa was down town in[4] spite of all the snow. Kenneth wished that he too was a big man who could go out of doors in spite of all the snow. Mamma was busy in the library with secrets of her own, and would not let them in. Rose wished that she too was a big lady who could have secrets all by herself. Then she would not mind however hard it might storm outside.

Kenneth flattened his nose against one dining-room window, and Rose flattened her nose against the other, and they stared out at the snow smoothly spreading itself over everything, just as Katie was frosting the cake downstairs. Big drifts were piling up beyond the curbstones, and in the doorways opposite. Now and then a sleigh floundered past, the horses making their way with difficulty. Supposing, oh, supposing that it should storm for two whole days, and the snow should grow so deep that even Santa Claus’s reindeer could not get through with the gifts for their Christmas stockings!

Suddenly Kenneth jumped right up in the[5] air and cried, “Look, Rose!” And at the same moment Rose pressed her nose even flatter on the window and said, “O Kenneth, what is it?”

Something tiny and black was moving along through the snow on the sidewalk. It gave little hops, each time sinking down almost out of sight, stopping to rest between jumps as though it were very tired. The children watched it breathlessly.

At last it came to the long flight of steps, which looked like a smooth toboggan-slide of snow. But the little black creature seemed to know what was underneath the cold white covering, for it hopped bravely up on the lowest step, then up and up, step by step, to the landing, where the snow was not so deep. And now the children could see it plainly.

“Why, it’s a poor little kitty!” cried Kenneth, almost pushing the glass out of the window with his small, cold nose, so eager was he to watch the little stranger.

“And she has come to our ownty-donty[6] steps!” echoed Rose. “Poor little kitty, how cold she must be!”

Just at that moment the wet little black thing looked up at the window where Rose stood, and just as if she had heard what Rose said, the poor kitty answered very sadly, “Mi-a-o-ow!”

All this time it had been snowing harder and harder, and already the tracks which the kitty had made in the snow were blotted out of sight. At the same moment Kenneth and Rose made a dash for the front door. “We mustn’t let the poor kitty stay there,” said Kenneth, “she will be all drowned in the snow, and frozen, too.”

“Yes, we must bring her in and make her nice and warm,” said Rose.

So they opened the front door, and stood at the head of the steps calling, “Kitty, kitty!” very gently, while the snow whirled in about their ankles.

“Mi-a-ow!” answered the black cat, but this time she spoke more cheerfully. “Thank[7] you!” she seemed to say. “May I really come in?”

“Come in,” said Kenneth.

“Poor kitty, do come in!” cried Rose, holding out her hand invitingly. And the black cat walked in.

She was very wet and draggly, but Kenneth took her in his arms and carried her upstairs. Rose ran before, and they knocked on the library door, where their mamma was hidden with her secrets.

“Mamma, Mamma! Come here a minute!” they cried. “Come and see what we have found. Come quick, Mamma!”

In a minute their mamma came hurrying, and opened the door just a tiny little crack, through which she peeped at them. But when she saw what Kenneth had in his arms she came out quickly, shuttling the door carefully behind her (to keep the Christmas secrets from running away, I suppose).

“What have you found, Kenneth?” she cried, holding up her hands.

[8]“A kitty, a poor kitty, lost in the snow,” said Kenneth.

“We had to take her in and make her warm and comfy at Christmas time, didn’t we, Mamma?” said Rose.

“Please, Mamma, you will let us keep her, won’t you?” they both pleaded.

Mrs. Thornton hesitated. The cat was very wet and homely. She had meant to give the children a pretty little kitten some day. But just then the poor hungry animal looked up and gave a pitiful “Mi-a-ow,” and Mrs. Thornton remembered how dreadful it was that any living creature should be miserable and cold and homeless at the happy Christmas time.

“Yes, you may keep her, children,” she said. “Keep her and make her have a merry Christmas.”

Kenneth and Rose took the little cat downstairs and gave her a good dinner. “But you shall have a better one on Christmas Day,” promised Kenneth. Rose found a tiny basket[9] and made a bed beside the fire in the dining-room. And there the black cat slept all the afternoon, she was so tired, and so glad to rest and to be warm. Rose sat beside her, stroking her soft fur, and Kenneth sat at the other side of the fireplace trying to think up a good name for the new kitty, so that the time went before they knew it, and they had forgotten to wish it were Christmas day.

“What have you named the little cat?” asked their papa when the children showed him their new pet that evening.

“Oh, Kenneth has thought of the loveliest name!” cried Rose, jumping up and clapping her hands. “We are going to call her Christine,—because she is a little Christmas cat. Isn’t that a beautiful name, Papa?”

And Papa said that he thought it was a very beautiful name indeed.

THE next morning when Kenneth and Rose awoke, it was bright and fair. The storm had cleared away, and the whole world was white and wonderful with spangled snow. Now the children could play out of doors as much as they liked, and the time went so fast that they almost forgot to wish Christmas would hurry up. Their cousin Charlie came over to play with them, and they built snow forts and snowballed one another; they made big statues of snow in the back yard and shoveled the sidewalks and the front steps nicely. Before they knew it it was evening again,—Christmas eve, and their mamma was inviting them to come and see her secret in the library.

And what do you think the secret was? When the folding doors were thrown open[11] there was a glare of light and a smell of woodsy green, and Kenneth and Rose and their cousin Charlie cried “Oh!” they were so surprised. For there stood a beautiful Christmas tree, glittering with spangles and icicles and silver balls and tiny candles.

Kenneth and Rose and Charlie danced around the tree, and they had a beautiful time finding the little bags of candy which were hidden for each of them among the green branches.

“It was a lovely, lovely secret,” whispered Rose in her mamma’s ear. “And when I grow up I will make one just like it for my dolls.”

When all the candles had sputtered and gone out, Charlie’s papa came to take him home. And after that it was time to go to bed. But first they must hang up their stockings for Santa Claus to fill. They tied them up over the fireplace in the library,—Kenneth’s long black stocking and Rose’s shorter brown one. Then Kenneth said,—

“Oh, Mamma, we must hang up a stocking[12] for Christine. I am sure Santa will want to remember the poor little Christmas cat.”

“I know!” cried Rose. “I will hang up one of my little summer socks. That will be just right for a little kitty-cat’s Christmas.”

So she brought one of her short white socks and they hung it up in the chimney-place right between the other two stockings,—between Kenneth’s and Rose’s. And Christine looked pleased. Then everybody said good-night, and the children went to bed.

It was very, very early in the morning when Kenneth opened his eyes and said out loud, “It is Christmas Day! Oh, at last it is Christmas Day!” Then his eyes opened very wide indeed, and he said nothing at all. The bedposts looked so queer!

Kenneth scrambled over and examined them. On each post at the foot of the bed was a big yellow orange. These were the first signs of Christmas, and they kept Kenneth busy for some minutes. But when he had eaten one of the oranges he could not wait any longer.

[13]He ran to Rose’s room and thumped on the door. “Merry Christmas, Rose! Wake up!” he cried, poking in his head. But already Rose was wide awake, and was sitting up in bed eating one of the oranges which had grown on her bedposts, too, during the night.

“Merry Christmas yourself,” cried Rose, jumping out of bed. “Let us run and wake up papa and mamma.”

So they trotted down the hall to mamma’s room and thumped on the door. “Merry Christmas, Mamma! Merry Christmas, Papa!” they cried. “We are going down to look at our stockings and see whether or not Santa really did come last night.”

Papa and mamma sighed a little, for they were still very sleepy. But mamma said, “Well, children, you may go down. But first you must put on your clothes, so that you will not take cold. Papa and I will be there in a little while.”

Kenneth was dressed first. He ran downstairs to the library, and sure enough! there[14] hung the three stockings, bulgy and knobby and queer. He shouted up the stairs, “Oh, Rose! Hurry, hurry! He really came, Santa Claus came, and he did not forget even Christine.”

In a minute down came Rose, with her shoes half buttoned and her curls all tangled. She could not wait this morning to make everything just right.

They seized their stockings and sat down on the floor to pull out the “plums,” like little Jack Horner. In Kenneth’s stocking he found a big red apple, and a bag of lovely marbles. Under these was a new game in a box, and a horn of candy. Kenneth dived down lower and found a toy cart, and a top, and a baby camera. At last he reached the toe of the stocking, where there was just one thing left. “I think it is a stick of candy,” said Kenneth. But when it came out, it was a jack-knife with four blades. You can imagine how pleased Kenneth was.

As for Rose, what do you suppose she[15] found in her stocking? She had a red apple, too, and a horn of candy. Then there was a cunning pocket-book, and a little coral necklace in a velvet box. There was a red rubber ball and a harmonica, and away down in the little brown toe of her stocking hid a tiny doll’s watch and chain. But the best gift of all poked its head out of the top of her stocking and smiled at her the very first thing. It was a lovely little doll, with yellow curls like Rose’s own, and blue eyes, and a white dress with blue ribbons.

“Oh, you dear doll!” cried Rose, hugging her tightly. “I knew that Santa would bring you to me! You are ever so much prettier than Matilda, and I shall call you Alice.”

Now Papa and Mamma came down, and they were eager to see what was in Christine’s stocking. “Let us take it down to the dining-room where Christine is,” said Mamma. “Katie tells me that there are some queer-looking bundles there for you, which Santa could not crowd into your stockings.”

[16]With a whoop of joy Kenneth ran down the stairs to the dining-room, and Rose followed as fast as she could, carrying the little white sock with the presents for the Christmas cat. She went up to the basket beside the fire, where Christine lay just as they had left her the night before.

“Oh, Kitty, see what Santa has brought you,” said Rose, holding out the little bulgy stocking. Then she stared hard into the basket where Christine lay. “Oh-h-h! Kenneth!” she cried. “Come here quick! See what Santa has brought the Christmas cat!”

For there, cuddled close up against Christine’s black fur, were two tiny round things mewing with baby voices; one little black kitten, and one as yellow as Rose’s curls, both with their eyes shut tight.

“Well, well!” said papa. “Santa could not get those into Kitty’s stocking, so he brought them here. Isn’t it a lovely present for a little Christmas cat?”

“SEE WHAT SANTA HAS BROUGHT THE CHRISTMAS CAT”

“Of course they both belong to Christine,”[17] said Kenneth, “but may I not call one of them mine, and the other one Rose’s?”

“I want the yellow one,” said Rose.

“I like the black one best,” said Kenneth, “so that is all right.” But Christine licked both the kittens with her pink tongue and purred happily.

“I like them both best, and they are both mine,” she seemed to say.

Then the children took out the presents from the little white sock. There was a pretty collar and a bow of ribbon,—yellow, which was Christine’s most becoming color. And there was a little bunch of catnip instead of candy. Santa seemed to know just what a little cat would best like. But nothing seemed to please Christine so much as the tiny balls of black and yellow fur in her basket. And the children did not blame her. For indeed, of all their Christmas gifts,—except Alice, the new doll, and Kenneth’s jack-knife,—they each liked best the kitten which they had chosen.

[18]“I shall call my kitten Buff,” said Rose, touching the little yellow ball gently.

“And mine shall be Fluff,” said Kenneth, who liked to make rhymes sometimes. “Oh, I am so glad that we took Christine in out of the snow, Rose! For if we hadn’t, perhaps Santa would never have thought of leaving us these dear little kittens.”

And I shouldn’t wonder if Kenneth was right.

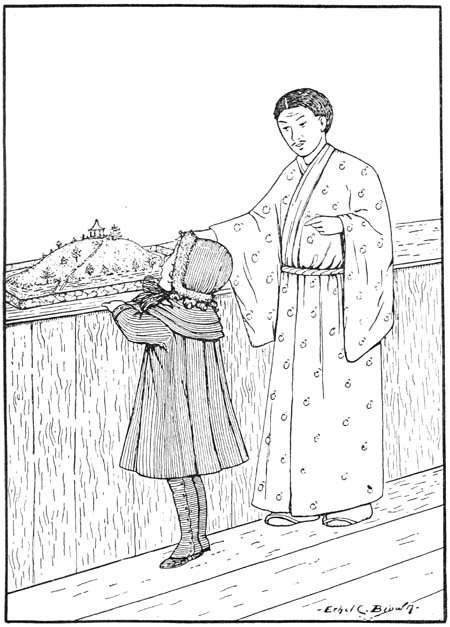

ONE day, not very long after Christmas, Mrs. Thornton said to Rose,—

“Rose, dear, I am going to the Japanese Shop to buy a wedding present, and I think you would like to go, wouldn’t you?”

“What is a Japanese Shop?” asked Rose.

“Oh, it is a very wonderful shop,” said her mamma. “I can’t begin to tell you about all the curious things which they sell in a Japanese Shop. You must come and see for yourself.”

So Rose put on her hat and coat and went with her mother to the Japanese Shop. What a wonderful place it was, indeed! Rose felt just as if she were in some strange, new kind of Fairyland, such as she had never before heard about. Everything was colored so bright and beautiful! There were such queer-shaped things sitting about on the floor and standing[20] up in the corners! Curious lanterns swung from the ceiling, and tall screens of black and gold, with pictures of wonderful long-legged birds flying across, made dark nooks, in which strange bronze animals lurked surprisingly. Everything smelt sweet and rich, too, almost with the Christmas-tree fragrance of mamma’s holiday secret.

Rose wandered about by herself while her mother was looking at the funny lamps hiding under colored umbrellas, which she called wedding presents, though Rose did not understand why. They did not interest her like Christmas presents, which were very different. But over in a corner, all by itself, Rose found something which she thought would make the loveliest Christmas present,—the most wonderful Christmas present that any little girl could have. And oh! how she wanted it for her very own!

It was a toy garden; the kind that is put into the guest-room of a Japanese house to amuse visitors.

[21]My! It was a wonderful little garden,—a real, truly live garden, with growing trees and plants and moss. But it was all so tiny that it could stand on a little table no wider than Rose’s arm was long. And though the trees were really, truly grown-up trees, a great deal older than Rose,—older even than her mamma, whom Rose thought very old indeed,—they were no taller than Rose’s little hand.

This is the way the garden looked. First, it was almost square and there was a little stone wall all around it, about an inch high. In the middle of the garden was a hill built of rocks, and on the top of the hill was a lawn of green moss, with a tiny pagoda, or Japanese house, no bigger than a match-box. The sides of the hill sloped down, very green and smooth, and at the foot was a little brook of real water, winding around the whole garden. The tiniest path of sand crept zig-zag down the hill to a bit of a red bridge that crossed the brook, for the people in the house at the top of the hill to use. And all along the brook grew little[22] baby plants, and the wonderful dwarf trees that I told you about. Pine-trees they were, most of them, and the pine needles had fallen on the ground and had turned rusty brown, just as everyday pine needles do. Only these were ten times smaller. Rose wondered who lived in the little house at the top of the hill, and she said to herself:—

“Oh, how I wish I were little enough to live in that dear little house, and play in that sweet little garden, and climb up into those darling little trees! Oh, how I wish I could be littler!” And that was something which Rose had never before wished.

Just then Rose heard a cough behind her, and looking around she saw that the funny Japanese Man who kept the store was standing close at her elbow. He was smiling very pleasantly, so Rose said to him:—

“Oh, Mr. Japanese Man! I think you can tell me who lives in the dear little house and plays in the dear little garden and paddles in the dear little brook. Will you, please?”

[23]The Japanese Man bowed and grinned, and looked at Rose for a minute without saying anything. Then he went away to the other end of the store. Presently he came back, and he had something in his hands. He set a little Somebody down beside the house on the top of the hill; and it was a tiny little old man made of china-stuff, in a long green gown, with a knob of hair on the back of his head, like a lady.

“He live in house, litty ol’ man,” said the Japanese. “And these, his animals; live in garden.” As he said this the Japanese Man set down on the bridge the littlest baby white rabbit, and in the brook a tiny-winy duck, which floated on the water, and under one of the trees a wee-wee mouse, with pink ears.

“Oh!” cried Rose, clapping her hands. “Oh! how I wish I could be little enough to play there with them. Are they alive, Mr. Japanese Man?”

The Man grinned more than ever. Then[24] he came close up to Rose and whispered behind his hand, as though it were a great secret:—

“No, not alive now. But after dark, when moon shines, and store all empty—all big folks gone away—then all come alive. My—my! Litty ol’ man walk down hill, go fishy in brook. Duck say ‘Quack quack!’ Litty rabbit hop so-so over bridge. Litty mouse cry ‘Wee, wee!’ and climb up pine-tree. My! Litty girl like to see?”

“Oh! Have you ever seen?” cried Rose with her eyes very wide.

But just then her mamma came back, with a bundle under her arm, which was probably a little Wedding Present, though Rose did not care enough about it to inquire. But she was very sorry when the Japanese Man bowed politely and walked away to the other end of the store. She had wanted to ask him a great many more questions.

“Come, Rose,” said her mother; “we must go home now.”

THE LITTLEST BABY WHITE RABBIT

[25]“O Mamma! I want it!” sighed Rose wistfully.

“Want what? The garden? Oh, my Dear! I cannot buy you that,” said her mamma sadly; “it costs dollars and dollars. But maybe I could buy you the mouse, or the duck, or the rabbit, or the little old gentleman up there. Would you like one of them, Dear?”

“Oh, no!” cried Rose. “It would be dreadful to take them away from their lovely garden. I wouldn’t have one of them for anything. Think how lonesome he would be when it grew dark and they all came alive!”

On the way home Rose told her mamma the great secret, which the Japanese Man had told her. And her mamma thought it was all very strange indeed, and said she wished that she too was little enough to play in the wonderful garden with Rose and that interesting family.

When they reached home Rose told Kenneth all about the toy garden, and the secret which the Japanese Man had told her. But[26] Kenneth only said, “Pooh! I don’t believe a word of it,” which was very disappointing. But, of course, Kenneth had not seen the garden, nor heard the Japanese Man tell the secret, which made a great difference.

When it was dark Rose went to bed, and in a little while her mamma came to kiss her good-night. Rose held her tightly by the hand and made her sit down on the edge of the bed, where the moonlight shone like silver.

“O Mamma!” she whispered. “Think of the shop, all dark and empty now, with just one moonbeam shining on the little garden in the corner. And the little old man comes alive, pop! like that! Now he goes walking out of his house, down the little path over the hill. And the bunny-rabbit scampers in front of him, hoppity-hop! Can’t you see him, Mamma? Now they come to the little bridge; the funny duck says ‘Quack, quack!’ and swims away round and round the garden. Now the little old man sits down under one of the tiny pine-trees and begins to fish in the[27] brook. And the wee-wee mouse runs up and down the tree and nibbles the cheese which the old man has in his pocket for bait. O Mamma, I can see it all, just as plainly! I wish I were there.”

“I can almost see it, too,” said Mamma.

“O Mamma, I think I could grow little just as easily as they could come alive. Don’t you?” said Rose.

Her mother answered, “We-el, perhaps.”

But she would never take Rose to the Japanese shop after dark, to see whether or not it could be done. Maybe she was afraid that Rose might grow little and stay little always—which would have been a dreadful thing for her mamma. But Rose thinks that she herself would like it very well indeed,—to live always in that wonderful garden with the mouse and the duck and the rabbit and the funny little old man,—if only Kenneth would grow little, too. But Kenneth does not want to grow little. He is trying just as hard as he can, every day, to grow big.

ON the night of April Fool’s day Kenneth had a strange adventure. It was Kenneth’s way to direct his dreamland journey toward Fairyland, where, if he but knows the secret how, a child can have the pleasantest possible times. On this particular night Kenneth shut his eyes tight and said the magic words which are the ticket on the Fairy Railroad; and presto! as usual, he found himself spinning through space into the realm where he would be. He kept his eyes shut tight, however, for every wise child knows that he must not peep during that wonderful journey, nor try to find out how it is done, or he will never be able to go again. It was only when a soft little jounce told him that the trip was over that Kenneth opened his eyes and ventured to look around.

[29]Yes, there he was, sure enough! He remembered the glittering Christmas-tree avenue which led up from the station. He remembered the beautiful flower beds on either side of the path—fairy beds where the flowers could talk prettily, and answer any questions which a child might ask. He remembered the white marble palace which gleamed beyond the Christmas trees, a palace full of wonder and delight. He hastened toward it up the hill. Yes, this was certainly the Fairyland of his dreams, where he always had such a lovely, lovely time; where all that he wished came true in the most marvelous way, and where delightful surprises were continually happening to give him pleasure. Kenneth smacked his lips already at thought of the goodies he would have to eat, and his fingers wriggled eagerly, longing to clutch the wonder-toys which he knew were growing somewhere about for him, when he had time to look for them.

Now there was no one to meet him at the[30] station, and Kenneth thought this strange. For he had expected to find his usual guide, a pretty little gauze fairy in spangled white, with a wand and crown and all the dainty ornaments which fairies wear. Kenneth was not greatly troubled, however, for he had been to Fairyland so often that he knew the country very well indeed, and he was not at all bashful nor afraid to help himself if he should see anything which pleased him.

He began briskly to walk up the avenue, on either side of which the flowers nodded and smiled at him, saying, “Good evening, Kenneth. How are you to-night?”

Kenneth laughed and nodded back, thinking to himself, “How very pretty they look! I never before saw them so gorgeous and beautiful. They must be perfumed with extra sweetness; I will go and see.” And, stepping up to a great bed of lilies, he bent over them, giving a deep, deep sniff; for Kenneth loved dearly the fragrance of flowers.

“Achoo! Achoo! Achoo!” Kenneth[31] sneezed, and sneezed again, so that his head almost fell off. “Achoo! Achoo! Achoo!” He reeled and staggered as he turned away. And all the flowers laughed so that they nearly snapped their slender stalks. They seemed to find it a great joke.

“You dreadful flowers! You are full of snuff! Achoo!” he cried indignantly.

“Aha! Aha! You know all about it!” cried the flowers. “The trick is not new to you; but is it not funny? Aha! Aha!”

Kenneth did not think it at all funny as he ran on up the pathway, sneezing painfully at every step. At last he paused to wipe his eyes. “Achoo! Achoo!” Poor boy! He was fairly weak with his efforts, and spying a little seat near by under a tree, thought he would sit down to rest a minute and get his breath before going on his way. It was a funny little seat, like a great toadstool, and it looked very comfortable. But no sooner had Kenneth seated himself, than the wretched thing sank down into the ground, leaving[32] him with a bump on the gravel of the avenue.

“Aha! Aha!” cried the flowers, tittering foolishly when they saw Kenneth sprawling. “Oh, how funny you do look! What a good joke! How clever! We shall die laughing!”

“You are very silly flowers,” said Kenneth, pouting. “You laugh at nothing at all. I never knew you to be so disagreeable.” And, trying to look very dignified in spite of his dusty jacket, he jumped up and strode down the avenue. The inviting little round seats seemed to have sprung up everywhere like mushrooms since his last visit, but he was too cautious to sit down again, although he was very tired.

Kenneth walked so fast to escape the mortifying laughter which rang from the flower-bells, that he had almost passed the last Christmas tree before he remembered the magic fruit which they always bore for him.

“Hello!” he cried. “I meant to look for a new jack-knife. I always find just what I[33] want on these trees. Why, yes—there is one now, right over my head. Oh, what a beauty!” He reached up to grasp it as it swung about a foot above his nose. But at the very moment when Kenneth stretched out his hand, the tree gave a sudden jerk and up flew the knife quite out of reach.

“Oh!” cried Kenneth, stamping his foot angrily. “What made it do that?”

“Ha, ha!” snickered the flowers, who had been peeping at him from a distance. “What a joke! Try again, Kenneth.” And Kenneth tried again and again, jumping after the knife more frantically each time. But it was of no use. A malicious breeze, or some other cause, seemed to bend the tree away from him whenever he reached toward it. And at last he gave up in disgust.

“I wanted a fountain pen, too,” he said to himself. “There ought to be one on another tree. Yes, here it is.” And once more Kenneth reached eagerly for the shining black thing that dangled close by his hand.

[34]Pop! Kenneth was half blinded by a stream of water that spurted into his eye. It was no fountain pen, but a fountain pop-gun that had gone off when he touched it.

“Ha, ha!” shrieked the flowers, in a perfect madness of delight. Kenneth sat down on the grass to wipe his eyes and dry the little river that was running most uncomfortably up his coat sleeve. But my! How quickly he sprang up again! The grass that looked so tempting and soft was a cruel snare. For some one had wickedly planted it with pins or needles. Poor Kenneth! This was too much.

It is no fun to find one’s self a human pincushion. He began to cry, and even then he heard the voices of the flowers sounding faintly, and they were laughing still. He glanced toward them angrily, then tucked his hands into his pockets and resolved not to let them see him cry. He marched away up the avenue without a glance into the Christmas trees, although they dangled the most interesting[35] bundles before his face and seemed trying to tempt him to pluck their magic fruit. He also kept off the grass more carefully than if there had been a staring signboard to warn him.

Now just outside the palace grew a thicket of magic nut bushes. Here Kenneth always stopped on his way to the greater wonders inside, to crack a nut and to have a pleasant surprise. Yes, there at the foot of the marble steps was the thicket, green as usual, and full of brown nuts, mysteriously knobby and promising. Kenneth picked one and knelt down on the gravel to crack it with a stone. But instead of the beautiful velvet cloak, magically folded into a tiny parcel, or a dwarf pony which would quickly grow full-sized, or a picture-book with moving figures on its pages, such as he had found at other times, the nut was stuffed with dusty cobwebs, which were of no use to any one, least of all to Kenneth.

“Oh!” said Kenneth, in disappointment, and then he distinctly heard a queer voice[36] cry, “April Fool!” He looked up and around, but there was no one to be seen.

“April Fool!” cried the voice again. “Ha, ha! Kenneth has such a sense of fun! He is a great joker himself; ha, ha!” Kenneth thought it must be one of the flowers, though the voice sounded different. He wished the good Fairy would come to him. His chin began to quiver, when he heard the same queer voice tittering behind the thicket of nut bushes. There was a little summer-house close by, and into this Kenneth ran to hide the tears which would come into his eyes. What a disagreeable country it was, this Fairyland which he had loved so well! He came here to be happy; but all these ugly tricks fairly spoiled the pretty place. He said to himself that he would never come again. Just then he spied a large, square envelope fastened to the side of the summer-house by a thorn. It was addressed, “For Kenneth.”

“Why, that means me,” he cried, very much surprised. “Perhaps it is a letter from[37] my good Fairy to explain why she has not come to meet me.” And he tore it open eagerly.

It was a fat, bulky letter of several sheets. This was very exciting, for Kenneth had not received many letters in his short life. He unfolded the first sheet. From the middle of the page stared at him these words printed in huge red letters:—

APRIL FOOL!

KENNETH looked at it angrily, then turned over the other pages. They were just the same as the first one. He tore up the sheets and threw them on the ground. It was only an April Fool letter, after all!

“April Fool!” cried a voice, echoing the same hateful words. “April Fool! Ha! ha! What a joke!” It was a funny little voice, louder than those of the flowers, and, instead of being silvery sweet like theirs, it was harsh and disagreeable. Kenneth glanced up, and there, perched on the railing of the summer-house, was the queerest little fellow, making the most horrible faces. With a bound the figure sprang inside, and Kenneth saw him more clearly. He was certainly a fairy, for he had wings, gauzy and beautiful, growing from his shoulders. But his dress was unlike[39] that of any fairy whom Kenneth had met. It reminded him, however, of pictures that he had sometimes seen in books. This fairy wore a suit half of red and half of yellow; one leg and one shoe were red and the other yellow. His doublet was divided likewise, and likewise the funny hood which he wore about his shoulders. The borders of his costume were cut into points, and from every point hung a little bell that jingled and jangled mischievously whenever the imp moved about—which was continually. His cap had two long pointed ears, and in his hand he carried a wand, on the end of which was a copy of himself dressed in red and yellow, and tinkly with many bells. He was a very funny figure, and his mouth stretched from ear to ear in a grin which made Kenneth laugh, too. But Kenneth soon stopped laughing; for there was something about the imp’s smile that was not kindly, and that made one half afraid.

“Who are you?” asked Kenneth, trying to[40] seem very bold. “And what are you laughing at? I don’t see anything so very funny at this moment.”

“Oh, don’t you?” grinned the imp. “April Fool! I do. I am April Fool. Why, don’t you know me?” And turning around he showed Kenneth a large placard, such as he had himself often made, pinned to one of the points of the imp’s doublet. “April Fool!” it read. Kenneth began to understand.

“Oh, you are April Fool, are you?” he said. “I never saw you before.”

“Ho! You never saw me? No, but you have used my name often enough. You remember April Fool’s day every year? Aha! Those were good tricks you played, though to be sure most of them were old enough—old as I am, and that is old indeed, I can tell you, my little joker. But they are good jokes, are they not? One never tires of them, does one?” And again he grinned at Kenneth maliciously.

“I AM APRIL FOOL”

[41]“N-no,” said Kenneth, doubtfully, looking again at the pieces of the torn April Fool letter and rubbing his eyes, which still smarted from the snuff. “But I think jokes are funnier when one looks on, don’t you?”

“Ha! ha!” laughed the imp. “That is the best joke of all. Why, some folk seem to think as you do. But not I! Now I love a good joke for its own sake better than anything else in the world. I am always in it, for I am the joke itself. Ha, ha!”

“Then it is you who have made all these things happen to me,” said Kenneth angrily. “What do you mean by it?”

“Ha! ha! Don’t you know what night it is? To-morrow is the first of April! What can you expect in Fairyland except the very biggest of jokes? This is my night. But come, now, don’t be sulky. It is only a joke after all, and you are such a joker yourself that you ought to take these little matters very cheerfully. Come with me.”

“I don’t want to come with you,” said[42] Kenneth, hanging back. “I want to go home.”

“Nonsense, you cannot go home yet,” answered the imp. “It is not nearly morning. Now that you have come you must stay here until the time is up.”

“Then I want my good Fairy guide,” said Kenneth.

“Ho!” cried the other in scorn. “She is too silly-kind, too goody-goody. She has no real sense of fun, poor thing.”

“I like her fun best,” insisted Kenneth. “Please take me to her.”

“Oh, very well,” said April Fool carelessly. “If you insist I will bring you to her. But first you must have something to eat, for it is a long journey. Are you not hungry, poor boy?”

Kenneth confessed that he was very hungry. “Then we will go to the kitchen garden,” replied the imp; “and there you can feast as much as you like.”

“Oh, yes! I have been to the kitchen[43] garden,” cried Kenneth, brightening. “The good Fairy took me there; it is a lovely place!”

He followed April Fool out of the summer-house into a narrow path leading on and on and on between green hedgerows full of blossoms. Overhead the birds sang sweetly, and the sky was blue. Kenneth began to feel very happy. At last, in the distance, he caught sight of the kitchen garden, as he well remembered it, with its tall pie-fruit trees, its cooky bushes, its eclair plants, and its ice-cream fountains. The glimpse made him so hungry that he could hardly wait to be there, and he ran ahead, outstripping April Fool himself.

“That is right! Hurry, my boy!” cried the imp heartily. And Kenneth skipped on happily. But suddenly bump! went his head and his knee against something hard, and he came to a dizzy stop, hardly knowing what had happened. There lay the kitchen garden just beyond, but something had stopped him[44] and would not let him pass, something which he could not see.

“Ha! ha! April Fool again!” laughed the imp, holding his sides for merriment. “Don’t you see through this joke? Why, it is perfectly transparent.”

Sure enough! Kenneth put out his hand, and found that it was a wall of glass, which stretched across the path from hedge to hedge; a gateless wall which he could by no means climb over, but through which he could plainly see all the dainties on the other side. Kenneth groaned. “Oh, I am so hungry! What a cruel, cruel joke!”

“Jokes do seem cruel sometimes,” admitted April Fool; “but they are such fun! Oh, my, oh, my! How queer you did look when you bumped against that wall!” and he burst out laughing once more.

“Well, are you going to let me in?” asked Kenneth, trying to keep his temper, though he thought the joke in very poor taste, like most of April Fool’s tricks.

KENNETH FOUND THAT IT WAS A WALL OF GLASS

[45]“Oh, no, we cannot enter here,” said the imp. “This is only an impracticable window. We shall have to go around by another way, a détour of some miles. But this time I really promise to take you to the kitchen garden.”

Kenneth was very angry, but he began to suspect that he must let April Fool have his own way on this night. They turned back down the narrow path and began a long, tiresome journey round about and round about to the garden which they had already seen so near.

And what a journey that was! beset by so many surprises, shocks, and practical jokes that Kenneth was nearly frantic before they had seen the end. They were crossing a bridge over a pretty little stream, when in the middle—crash! The whole structure gave way, and down they fell, with a sickening sinking feeling—fully three feet! Then the bridge came to rest on the magic springs which were made to complete this jouncy joke. After this their way led through a pitch-black cavern,[46] which was so silent that Kenneth could hear his heart beat as he felt his way along. Suddenly there was an awful roar, like the growl of hundreds of wild beasts let loose. Kenneth screamed with fright, but the imp cried out, “April Fool!” And immediately the cave was filled with light, showing only an innocent sound-machine which had made all this commotion.

They came within sight of a broad brook, which the imp said they must cross. Kenneth took off his shoes and stockings to wade and stepped down to the margin. But what was his anger to find that it was only a wide mirror over which they were able to pass dry-shod. That was a famous joke, to judge by the imp’s shrieks of laughter when he saw Kenneth put out his foot to wade into the glassy stream. But Kenneth had become so tired of such fun that he did not even smile.

Kenneth grew thirsty, and they stopped to drink at a fountain which gushed clear and sparkling by the wayside. But at the first[47] draught Kenneth found his mouth full of horrid, briny water, such as one swallows by mistake when one is bathing in the sea. Poor boy! This made him all the thirstier, but he was resolved not to show April Fool how wretched and unhappy he really was.

AT last, however, when Kenneth was so tired and faint that he could hardly walk another step, they came to the kitchen garden. There were the pie trees and the raspberry shrubs, the caramel plants and the bonbon hedge, brown with luscious chocolates.

“Now, help yourself,” said the imp cordially. And without further invitation Kenneth fell to. A fine cream pie lay under one of the trees, from which it had just fallen. Kenneth cut a wedge out of it with the knife which was sticking conveniently in the tree-trunk, and began to eat it ravenously. But faugh! What dreadful stuff! It was frosted with soapsuds instead of whipped cream!

“April Fool!” cried the imp, dancing up and down, for this was the best joke of all.

[49]“Oh!” whimpered Kenneth, “I hope they are not all April-Fool goodies.” And he ran to the next tree. But a bite was all he needed to prove that he must not trust his eyes this April Fool’s night. The mince pies were made of sand and sawdust, with pebbles for plums. The sponge cake was indeed a real sponge. The doughnuts were of India rubber; they might be fine for a teething baby to bite, but they were a poor lunch for a hungry boy. The griddle-cakes were rounds of leather, nicely browned on both sides. The salad was made of tissue paper; the chocolates were stuffed with cotton wool and other horrid stuff; while the maple sugar, upon which Kenneth was perfectly sure he could rely, turned out to be yellow soap—clean, but not appetizing.

Even the eggs, growing innocently white upon the egg-plant, turned out to be hollow mockeries; some humorous little boy seemed to have blown their insides away, as a great joke. Once Kenneth would have thought that[50] a very funny idea. But now he sat down and cried and cried, he was so disappointed and so hungry.

“Boo hoo! Boo hoo!” sobbed Kenneth. “I want to go home. I don’t like Fairyland one bit!”

“Ha! ha!” laughed the imp. “April Fool! This isn’t Fairyland at all; this is April Fool Land, and you are It. But come, I really think you have had enough of it. I will take you to the true Fairyland, and give you over to your kind, good, serious Fairy guide. Shall we go? One, two, three—out goes he!” And with a snap of his fingers, Kenneth found himself outside the tantalizing kitchen garden, walking toward his good Fairy’s real, truly palace, which gleamed comfortingly through the trees.

At first he dared not think that it was really so; he suspected another joke of April Fool’s. But at last he spied the good Fairy herself, standing at the top of the long flight of marble steps which led up to the palace. Kenneth[51] ran forward and waved his hand eagerly, he was so anxious to exchange guides and to be rid of the hateful imp. But the Fairy did not seem to see him. She was shading her eyes with her hand and looking off over the Christmas trees, appearing troubled.

“Humph!” growled the imp. “There she is, looking for you. And how eager you are to leave me, now that you have enjoyed all the jokes I had to play. Well, good-by! You have only to walk up the staircase to your goody-goody Fairy, and you will be safe from me. I cannot pass into that palace, where the fun is of a different kind from mine.”

“It is a great deal nicer than yours, for it is always kind,” retorted Kenneth, “and yet it is just as funny.”

“Very well, go and look for it, then,” cried the imp, and without another word he disappeared.

Kenneth was much relieved to see him go. He set his foot on the lowest stair and eagerly began the ascent of the marble flight. But no[52] sooner had he lifted his foot to the second step than the staircase itself began to move under him, so that he had to step quickly to keep from falling. Horrible! What did this mean? “April Fool!” cried a voice behind him. “Ha! ha! It is my last joke, and it is a rare good one. You are on a treadmill staircase, Kenneth. You must climb fast or you will fall down and be ground up inside the machine. Hurrah! Step lively, please! Quicker, quicker! Maybe you will reach the top by to-morrow morning.”

Kenneth had to work his little legs faster and faster and faster, as the great staircase revolved under him. Yet however he strove he reached never a step nearer the top, but remained always in the same spot. And the Fairy still looked away over the tops of the Christmas trees, without seeing him.

“Ha! ha!” laughed the imp; but his voice was fainter than it had been, and Kenneth hoped it was fading away. The poor boy was so exhausted that he felt he could not keep[53] up for long. His legs ached and his head ached dizzily, and his poor back, bent over the whirling staircase, ached most of all. “I cannot bear it,” he said to himself, panting and out of breath. “I cannot move my legs any faster. I cannot breathe. I must sit down, even if I do go under to be ground into little pieces.”

Without more ado Kenneth sat down on the staircase, closing his eyes and shuddering with fear of what might happen next. But what happened? The staircase merely stopped with a jerk—and stood still.

“April Fool!” cried the far-off voice of the imp. “You might have done it long ago. April Fool—Fool—Fool!” and the voice faded away into a mere sigh of the breeze.

At the same moment Kenneth heard a sweet call from the top of the staircase. “Kenneth, Kenneth!” it said, in silvery tones quite unlike the imp’s harsh ones. And, looking up, he saw his good Fairy coming swiftly down the staircase toward him.

[54]“Oh, good Fairy,” sobbed Kenneth, “I have had such a dreadful time looking for you! Please stay by me, and do not let that bad, bad April Fool find me again.”

The good Fairy leaned over Kenneth and put her hand on his head. “Poor boy!” she said. “Has April Fool been playing his tricks on you? This was his night, you know. He said you were a friend of his, so we had to let him have his joke with you. He is indeed a horrid fellow, and I hope he is no longer your friend.”

“No, he will never be my friend again,” cried Kenneth.

“I like my own kind of jokes a great deal better,” said the Fairy: “pleasant surprises, unexpected kindnesses, pain turned into pleasure, and disappointment into joy. One can play those jokes all through the year. But it is too late for any of them to-night. You must go back home now, Kenneth.”

“I am quite ready to go,” said Kenneth wearily, for even a pleasant joke had no charms[55] for him now, he was so tired. The Fairy took him by the hand and led him back to the station. They passed the magic nut bushes, but Kenneth did not pause. They walked under the tempting Christmas trees, but he did not look up. They went between the rows of flowers, gently tittering on either side, but Kenneth did not so much as glance at them. The kind Fairy held his hand, and April Fool could play no tricks upon him now.

At the station the Fairy guide kissed Kenneth sweetly, and closed his eyes with her wand. “Come again to-morrow night,” she murmured, “and naughty April Fool will be gone for another year. Then you shall come into my palace and we will play some happy tricks.”

Then she spoke the magic words of his return ticket, and Kenneth, with his eyes closed, felt a spring, a rush, and a whirling about his head. But he never peeped until he felt once more the gentle jounce that told[56] him the end of his journey had come. Then with his fists he rubbed his eyes and, winking sleepily, opened them to find himself snugly lying in bed, with the morning sun shining into his window.

ALICE had never gone to a party before. Of course Rose, who was almost six years old, had gone to a great many. But Alice, who was her newest doll, was very young. She had come, you remember, on Christmas day, at the same time with Buff and Fluff; and the kittens had never yet been to a party either.

Matilda, who was Rose’s old doll, had been to almost as many parties as Rose herself. But Matilda was not invited to this party. Only the youngest and prettiest dolls were invited to this party, for it was to be a May-Party, where every one has to look as beautiful as possible. Poor Matilda had only one eye and a broken nose.

Ernestine, who was Lilian’s doll and who lived in the next block to Rose and Alice, sent[58] out the invitations to ten dolls and their little mammas. They were to come at two o’clock in the afternoon of May Day for a picnic at her house. And every one was to bring a luncheon in a little basket, just as if it were a really truly picnic in the summer woods, instead of a cold city May.

Rose dressed Alice in her prettiest white muslin gown, with a blue sash and the dear little watch which had come in the Christmas stocking. Alice’s yellow hair was curled and tied with a blue bow, and she looked so much like her little mother that Mrs. Thornton could not help laughing when they started for the picnic together. But Rose did not see anything very funny about it. Every one said that she looked like her own mother, and why should not Alice look like Rose?

At the very last moment, when they were starting for the party, Rose ran back upstairs to the play-room, where the old Matilda sat in her little chair by the fireplace.

“You poor dear old thing,” said Rose, hugging[59] her tight, “I never before went to a party without you, and it seems very cruel to leave you all alone. But please remember that I still love you dearly, though you have only one eye, and your nose is broken, and you aren’t pretty like Alice. I can’t take you to parties any more, because people would laugh at you. But you have had a great many good times, haven’t you, Matilda? while Alice hasn’t been yet to a single party. I must make Alice have a good time now, for she is my youngest child. Good-by, Matilda dear, and don’t you be lonesome while we are gone.”

Then Rose kissed the poor old doll and set her back in the little chair beside the fireplace. But Matilda looked very sad when the little mother went out of the door with the new doll in her arms, and it almost looked as if there was a real tear on her faded cheek under the one remaining eye.

When the front door banged behind them, Matilda fell forward onto the carpet and lay[60] there face downwards all the while that Rose and Alice were at the May-Party.

The party was held in Lilian’s dining-room. The floor was covered with a green rug which had flowers on it, and which looked like the real grassy out-doors of the country. In the middle of the room, instead of a dining-table, was a little May-pole, as tall as Rose’s head, with a wreath of flowers at the top and pretty colored ribbons hanging down all around it.

On one side was a throne with three little steps leading up to it, for the May Queen to sit on. And on top of the throne lay a beautiful crown of real flowers for the Queen to wear.

First of all, the dolls were stood up in a long row, so that the prettiest one might be chosen. There was Ernestine herself, the hostess, who was a fat wax doll as big as a real baby, with flaxen hair and four white teeth. Ernestine was very accomplished, for she could say “Papa” and “Mamma,” but[61] she was not nice and huggable and pretty like Alice. (At least, that was what Rose thought.)

Then there was Marjorie, who had black hair, and Helen-Grace-Antoinette, who wore a real satin dress that came from Paris; and Bébé, who was in long clothes and who was thought by all the little mothers, except her own, too babyish for a May-Party. There was Yo-San, who was a lovely Japanese lady; and Toto, a little boy sailor doll, the only gentleman present,—and of course he couldn’t be the May Queen! Then there were Blanche, and Beatrice, and Dinah who was black,—everybody wondered why she came to the party. Last of all, there was Alice. She was smaller than Blanche and Beatrice, but she wore a watch tucked into her sash. No other doll had a watch.

Each little girl wrote on a piece of paper the name of the doll which, next to her own, she thought prettiest. No one could vote for her own doll, for of course each little mother[62] would think her own child the best, and there would have to be ten queens.

Lilian’s mamma counted the votes. And what do you suppose? Alice was elected to be May Queen! It was all on account of the watch. You can imagine how proud Rose was.

They set Alice on the throne and put the crown of real flowers on her yellow curls, and she looked so pretty that Rose had to rush up and kiss her the very first thing. And all the other little girls wanted to kiss her, too.

Then the dolls danced around the May-pole, each one holding the end of one of the colored ribbons, till the pole was twisted all the way down and looked like a big stick of striped candy. The dolls seemed to enjoy it very much, but their mammas were a bit dizzy afterwards.

Then it was time for the picnic. Everybody sat down cross-legged on the green grass rug and opened the little lunch-baskets. First they spread a napkin on the grass, just[63] as one does at a real picnic, and set all the cakes and cookies and sandwiches on it, where every one could reach for herself. And they ate without any plates or knives or forks, which was great fun. But there were no ants to come and eat up the crumbs.

There were little cunning cakes, and figs and dates, grapes and apples, and some molasses candy. And there was lemonade to drink,—just like a grown-up picnic.

After they had eaten everything they played games around the May-pole until it was almost dark, and then it was time to go home. But before they went Ernestine, who gave the party, carried up to the throne a big tissue-paper basket full of flowers, and gave it to the May Queen, kneeling down before Alice on the lowest step of the throne, just as they do in plays. And Rose was so proud that her face turned as pink as one of the roses in the May Queen’s lovely basket. Each doll had a dear little nosegay to take home, but only the Queen had a whole basket full of flowers.

[64]“You dear, lovely Queen Alice!” cried Rose, as she hugged her dollie tight on the way home. “I am so proud of you, and I love you better than anything in the world except Papa and Mamma and Kenneth and Cousin Charlie,—oh, yes, and Matilda. I had almost forgotten poor Matilda.”

Rose was quiet for a minute, and then she whispered to Alice, “Don’t you think you ought to give some of these lovely flowers to poor Matilda, who didn’t go to the party and who isn’t pretty any more?”

Alice was a sweet little doll, and was quite willing to share her flowers. So as soon as the front door was opened Rose ran upstairs to the play-room with the May Queen on one arm and the basket of flowers on the other. There she found poor Matilda lying face downward on the carpet.

SHE LIFTED POOR MATILDA AND SET HER UP ON THE WINDOW SEAT

“Oh, you poor, poor dollie!” cried Rose. “Did you feel so badly as that? Well, don’t cry any more. Here is your dear little sister, the May Queen, who has come to share her[65] lovely flowers with you. We both love you so much that we are going to make you our Play-Room Queen. See!”

Then she lifted poor Matilda and set her up on the window seat, as if she were on a throne. And she took the beautiful flowers out of Alice’s basket and made a wreath which she placed on the old doll’s scraggly hair. And she pinned a lovely rose on Matilda’s dress.

“Now you look very nice and dear,” said Rose, as she kissed her on her battered cheek. “Good-night, Queen Matilda of the play-room. Isn’t this almost as good as being May Queen?”

And Matilda looked as if she thought it was. She seemed to be smiling with her ugly mouth. And when Rose softly shut the door of the play-room the old doll looked almost pretty,—in spite of her one eye and broken nose,—sitting there on the window seat, with Alice, the beautiful May Queen, at her feet.

IN the middle of June Kenneth came down with the scarlet fever. This was very unpleasant for Kenneth, and for Kenneth’s papa and mamma, who were just making ready to move the family down to the Island for the summer. It was very hard for Rose, too; for of course she could not play with Kenneth nor even see him for fear lest she too should catch the fever. It was a terrible thing for Rose not to see Kenneth for days and weeks.

They decided to send her away into the country, to the farm where Aunt Mary and Uncle John with Rose’s cousin Charlie Carroll had gone to live. Aunt Mary said that she would be glad to play for a while that Rose was her own little girl, for poor Aunt Mary had no little girl of her own. And Charlie[67] thought that it would be great fun to have a little sister; for you see he had never had one. And that is why he did not make a very good kind of brother at first.

Rose had not been in the country long before she began to miss Kenneth more than ever,—more even than she had expected. It was all Charlie’s fault.

Charlie had his naughty days,—every one has naughty days, sometimes, until he learns better. But it happened unfortunately that Charlie’s naughtiest time came the very day after Rose arrived in the country, when she was feeling especially lonesome, and before she was acquainted with the new house and the barn and the new pets and playthings. She began to be homesick almost as soon as her father said good-by to her and went away to the train which would carry him home to Mamma and Kenneth and the city. But she was still more homesick the next morning, when she woke up and remembered that she was not going to see Kenneth all that long,[68] bright, beautiful, out-of-doorsy day. So you see she needed very much that Charlie should be extra kind and good to her.

Charlie’s mamma lay awake that morning smiling to herself to think how nice it was that Rose was going to be Charlie’s little sister for a time, and how happy he would make her in this beautiful country, showing her the new kittens, and the rabbits, and old Brindle’s little calf, and the flower-garden,—all the things which Charlie had enjoyed so much since he had come into the county to live. But that was before she knew this was Charlie’s naughty day.

From the moment when he first opened his eyes and got out of the wrong side of the bed, Charlie was in trouble, and his mother had to speak to him so many times that she was ashamed to have Rose hear.

After breakfast, when Rose cried eagerly, “Oh, Charlie, now will you show me everything?” Charlie sulked and said, “Oh, bother!” And when Rose followed him out[69] into the garden, he tried to run away from her. But Rose could run fast too, and he soon found her panting at his heels.

“What makes you run so fast, Charlie?” she asked. “I can hardly keep up with you.”

“Well, I don’t want you to keep up with me,” he answered, turning his back on her and slapping his stick at a poor sunflower. “You had better go back to the house. I don’t want to play with you.”

Rose’s eyes filled with tears and she said, “What makes you so bad to me, Charlie? I haven’t seen you for a long time, but I thought you were a nice, pleasant boy, like Kenneth. Oh, how I wish I could go back to Kenneth!”

“Go home as soon as you please,” said Charlie rudely. “I don’t want you for a sister if you are so fussy and cross.”

“I am not fussy and cross!” cried Rose indignantly. “You have been very impolite and horrid to me, and I am ashamed of you!”

Then, I am sorry to say, Charlie did a very[70] naughty thing. He pushed Rose roughly, so that she fell down and bruised her poor little knee. She tried not to cry, but the tears would come. And when she saw Charlie disappear around the corner of the house with his hands in his pockets, as if he did not care at all, she began to sob.

“I wish I had not come to the country!” she whimpered.

Now from the parlor window Charlie’s mother had seen this last naughtiness, and straightway she went after her boy, who was kicking his toe against the piazza steps.

“Charlie, you have been a very naughty boy,” she said. “You have hurt your little cousin, and I must punish you. What makes you so bad to-day? I thought you and Rose would have such pleasant times together!”

“I don’t like girls,” said Charlie sulkily. “They are telltales and cry-babies. I am glad I pushed her.”

“Charlie!” exclaimed his mother, much shocked. “Go right up to the dark room[71] and sit down in a chair and stay there until you are sorry. When you are truly sorry you can come out and tell Rose.”

“I shan’t ever be sorry,” said Charlie obstinately. “And I will never tell her that I am.”

“Then you will have no supper to-night,” said his mother firmly. “Go, now. Do as I tell you, Charlie.”

Charlie knew that it was not safe to linger when his mother spoke in that tone. He stamped up the three flights of stairs and opened the door of the dark room. It was a spare chamber that was seldom used, save on Charlie’s naughty days. The blinds were closed tight, and not a ray of the beautiful summer sunshine could enter. Instead, there was a gloomy, greenish dimness, which was not at all pleasant. And the room was very, very still. The rest of the world seemed a long way off.

Charlie dragged a chair into the middle of the room and sat down, kicking the rungs with his feet. It was all Rose’s fault. He had given[72] her only a tiny push, and it could not have hurt her much. She was such a cry-baby and telltale! Of course it must have been she who had told his mother all about it. He could hear the faint sound of old Carlo barking outside, and fancied he caught echoes of Rose’s happy laughter. Yes, undoubtedly the mean little thing was playing with Carlo, enjoying herself in the beautiful sunshine as if nothing had happened, while he was shut up in the old dark room! Charlie thought of all the fine things he had planned to do this day, if something had not gone wrong from the very beginning.

A great fly buzzed against the window pane, and for a time Charlie was interested in watching it bump its foolish head again and again. But he soon grew tired of the sight and sound. What a stupid way to spend a beautiful day, watching an old fly in a dark room! How the minutes dragged that usually galloped away too fast! He had only to say that he was sorry, and he might come out. But he was not sorry, and he would never tell Rose so.

[73]The time dragged on. The fly had ceased to buzz, and Carlo to bark. There was no sound inside or outside the dark room. Probably Rose had gone to ride. Mamma had promised to take them to the lake, where they could learn to row. What fun that would have been! Now Rose was enjoying it alone. Selfish little thing!

Charlie began to fidget. The chair was hard and uncomfortable; he thought he must have been sitting there for hours. Luncheon time was over and gone. It must be almost evening. Surely it was growing even darker in the dark room. How could he ever bear to stay there all night alone—without any supper, too! He began to feel very hungry indeed. Suppose he should starve to death! That would make Rose feel badly enough. He hoped it would break her heart. A tear rolled down the side of his nose at the thought of his sad fate.

Just then he heard a sound outside the door. The knob turned, and in tiptoed a little figure[74] in white, with yellow hair and blue ribbons. It was Rose. Her face was tear-stained, and she looked piteously at him without speaking. Charlie frowned, and turned his head away. He was not sorry.

Rose stood first on one foot and then on the other, glancing shyly at Charlie, as if hoping that he would speak. But he only sulked and kicked the chair-rung harder. At last she dragged another chair from a corner of the room, placed its back to his, climbed up into it and sat down.

“H’m!” thought Charlie, “She has been naughty too. Now Mamma sees that I am not the only bad one. I wonder how long she will have to stay here.”

They sat silent for a long time, back to back. Then Charlie heard a sniff behind him. He knew that Rose was crying. “I am glad of it!” he said to himself. “I am glad she was naughty and had to be punished. Usually girls are not punished like boys. They are lucky, and manage to escape.”

IN TIPTOED A LITTLE FIGURE

[75]Another little sniff from Rose; then a long silence. At last she spoke, in a half-sobbing voice: “It is beautiful out of doors. But it is horrid in this dark room.” Charlie made no reply. Presently Rose tried again. “How long have you got to stay here, Charlie?”

“I don’t know,” he answered gruffly; “all night, perhaps.”

“Oh!” Rose’s tone was startled, and again there was a long silence.

“Aren’t you going to have any supper, Charlie?” she asked wistfully.

“No,” said Charlie. “Are you?”

“N-no,” said Rose hesitating, and then she gave a very long sigh.

Charlie chuckled. She had “told” of him. It was her fault. Since he had to suffer, it was some comfort to think that she must do so also. He was not a bit sorry.

“I wish we could have gone to the lake,” sighed Rose again. “I s’pect Aunt Mary went without us.” At this tantalizing thought Charlie retorted angrily:—

[76]“If you had not been a cry-baby and a telltale, mother wouldn’t have punished me, and we could both have gone.”

“I didn’t tell!” cried Rose indignantly. “I wouldn’t have told if you had broken my leg off. I can’t bear telltales, and I wouldn’t be one for anything.”

“Well, how did mother know, then?” asked Charlie, somewhat less crossly.

“I s’pose she looked out of the window and saw you push me, and I s’pose she saw that I was mis’able.”

“Cry-baby!” taunted Charlie scornfully.

“I am not a cry-baby,” said Rose, with a quaver in her voice. “It took all the skin off my knee—look!—and it hurts awfully when I bend it around, so. But I never told Aunt Mary, and she doesn’t know. I cried a little because—because you hurt my feelings; that was why.”

“Humph!” grunted Charlie, looking at the bruised, tender little knee. He tried to make light of it, but his cheeks reddened,[77] and he felt ashamed. Rose was such a little thing, after all.

Rose writhed in her seat. “Must you stay in the chair all the time?” she asked over her shoulder.

“Yes,” said Charlie briefly.

“It is so hard! I thought—if we could stand up, or sit down on the floor—maybe—but anyway we might play something else, some kind of quiet game; Twenty Questions, or—or something. Would you like to do that, Charlie?” She twisted about in the chair and eyed the back of his head wistfully. Charlie hardened his heart.

“No,” he said crossly. “I don’t want to play anything in this horrid old dark room.”

“It isn’t quite so lonesome now that I am here, is it?” asked Rose anxiously. Charlie made no reply. “I thought you might be glad for company,” she went on. “I don’t mind being here—much. But it is nicer outside. There is Carlo—hear him bark! And there are the sunshine and the birds and flowers—and[78] everything. Oh, it is lovely here in the country! I thought we would have such good times together, Charlie, as we used to do when you lived in the city, only here it is much nicer. You have so many lovely things to show me, Aunt Mary said. But now”— She stopped short as if afraid of hurting his feelings.

“How long have you got to stay here?” asked Charlie, wishing that she would go away.

“Oh, I don’t know,” she answered; “perhaps all night. But I hope not.”

“Why, what did you do that was so bad?” asked Charlie, turning half around, in surprised interest.

“I? Oh, I—I—I didn’t do anything,” stammered Rose.

“Then why did Mamma send you here?” he demanded.

“She didn’t send me. She doesn’t know I’m here. She thinks that I am in the summer-house with Carlo and my dolls, where she left me—hours ago.”

[79]“Then what did you come here for?” Charlie looked at her sternly. She dropped her eyes and fidgeted with the ruffle of her dress.

“I—I came because I didn’t want you to be punished all alone. P’rhaps if I hadn’t come to your house you would not have been naughty at all; so it was partly my fault. I am so sorry, Charlie! I shall stay here as long as you do.”

Charlie whirled around in his chair and sat back resolutely. He would not be sorry. Yes, it had been her fault; she had made him angry. Let her stay and be unhappy!

They sat very still for a time, then Charlie felt a little hand steal around the chair-back and touch his gently. But he jerked away.

“Are you angry, Charlie, because I came?” asked the soft little voice. “If you are very angry, I will go away. But I had much rather stay here in the dark with you. I—I am so lonesome without Kenneth, and you are all the brother I have now. Won’t you let me be your[80] little truly sister and do as I would if you were Kenneth? When I knew you were shut up here it made me so unhappy that I couldn’t play. I couldn’t even enjoy the sunshine and the flowers. If you go without your supper, so shall I. And if you stay here all night, I—I think I shall not be afraid to stay with you. But I hope Auntie will let you out before then.”

“No, she will not,” said Charlie, positively. “I know she will not.”

“Not if I ask her? Not if I tell her that it makes me very sad to have you here?” Rose’s voice trembled.

“No,” said Charlie, “I don’t think I shall ever come out.”

“Oh!” cried Rose in horror. “Then we shall die here together. We shall starve to death like the Babes in the Woods; but there will be no Robin Redbreasts to cover us with leaves. Oh, Charlie! Surely Aunt Mary would not be so cruel.”

Charlie could not bear to have any one[81] think so of his kind mother. “Mamma is not cruel,” he said. “If I stay here it is my own choice. I could come out now, if I chose to—to say—something.”

Rose clapped her hands. “Oh, say it, say it now, Charlie!” she cried.

At that moment a bell rang invitingly from downstairs. “Do say it, Charlie,” she begged. “There is the supper bell, and I am so hungry, aren’t you?”

Charlie was very hungry, but he bit his lip and answered, “No, I will not say it.”

“Oh, why not?” begged Rose. “What is it that you must say? Is it so very hard?”

“Well,—I must say that I am sorry because I pushed you.” Charlie blurted out the words with a gulp of shame.

“Oh, Charlie! And you are not sorry?” Rose pleaded.

“No, I am not sorry.”

“Not a little bit?”

“No, not one bit.”

Rose gave a little sigh and sank back in her[82] chair. “Well, then I s’pose we must stay here and be hungry. For of course you mustn’t say it unless you are really and truly sorry—not even for the sake of supper. But oh! I know there is going to be jelly-roll. I saw Maggie making it this morning.”

Charlie kicked the chair hard. “Let’s try to think about something else,” went on Rose cheerfully; “then perhaps we shall forget to be hungry. Let’s talk about—about Carlo.”

“Oh, do keep still!” grumbled Charlie. “I don’t want to talk at all.” Rose was silent for some minutes. Then she began to speak again, half to herself.

“I think I will go home to-morrow, if I don’t starve before that. I will go to Kenneth, who will be so glad to see me, even if he is sick. Maybe I shall catch the fever and die. But that would be better than living where I have no little brother to love me. After I am gone, Charlie can come out, for of course Auntie will not ask him to tell me he is sorry[83] if I am not here to listen. Then Carlo and the rabbits and Brindle and the calf will all be glad to see Charlie again, and no one will miss me, for I am only a silly little girl who spoils the beautiful country so that no one is happy here any more.” Here Rose gave a great sob. Charlie wriggled uncomfortably in his chair.

“I say, Rose, don’t talk like that. I don’t want you to go home. It wasn’t your fault. I was very bad to you,” he stammered.

“But it was my fault, too,” cried Rose eagerly. “I ought not to have said you were impolite and horrid. Even when you pushed me—”

“I am sorry I did that, Rose,” interrupted Charlie quickly. “I am, truly. I didn’t mean to hurt you.”

Once more the little hand stole around the chair-back and crept into his own. Charlie did not drop it this time. “You said it!” cried Rose. “Oh, Charlie! I am so glad! Now we can go down to supper.”

[84]Charlie stared. “Said it? What do you mean? What have I said?”

“Why, you said It; that you were sorry,” cried Rose, clapping her hands. “So it is all right now.”

Charlie looked rather silly. “I—I didn’t mean to say it,” he faltered. “I said I would never say it, and I meant what I said. But I am sorry, and now I am glad I said I was.” This sounded very queer, but Rose knew what he meant, and was quite satisfied.

At this moment the door opened and Charlie’s mamma appeared, looking anxious.

“Oh, here you are, Rose, my child,” she said. “Who would have thought to find you here! I was so worried. We have been looking for you all over the place. Have you been here all this beautiful afternoon, you poor little thing?” She looked reproachfully at Charlie.

“I wanted to stay here,” said Rose cheerfully. “But I am glad it is time to come out now.”

[85]“Come, then, Dearie; you must be very hungry,” said Charlie’s mother, taking Rose’s hand and leading her towards the door. But Rose hung back.

“You come too, Charlie,” she smiled.

“Mamma,” said Charlie bravely, “I am sorry I was naughty to Rose. I have just told her so. She is a brick, and I wish she was going to be my truly sister always. For the rest of her visit I am going to make her have the best time she ever knew.”

Then the supper bell rang again, anxiously, and the two children took hold of hands, scampering down the stairs like hungry puppies when they hear their master’s whistle.

AFTER Kenneth recovered from the scarlet fever and Rose came back to the city, the Thornton family went away for the summer to their island down in Maine, which the children loved better than any other place in the whole world.

It was a very wonderful island, and though Kenneth and Rose had gone down there as many years as they could remember, they were continually finding something new which they had never seen before. They liked to play that it was a desert island and that they were Robinson Crusoes who were exploring to see what they might find. And they were always hoping to come upon a mysterious footprint, or something like that.

One particular day they were scrambling about on the rocks, a long way from the foot[87] of the cliff on which perched their summer home. They had never before happened to climb down to this particular spot, because it was such a steep scramble. From the top of the cliff it did not look interesting at all. I dare say nobody had ever before been on that part of the island, except perhaps the Prout children, who lived not far away all the year round. It was a bad landing-place; no boat could ever come in from the sea on account of the big waves that dashed up on the sharp rocks. And nobody would ever have thought of scrambling down the cliff and over those rough boulders unless, like Columbus, he was an adventurous explorer looking to see what he might find. But you see, that is just what Kenneth and Rose were. They were explorers, and they had their eyes wide open to see what there might be in this new place.