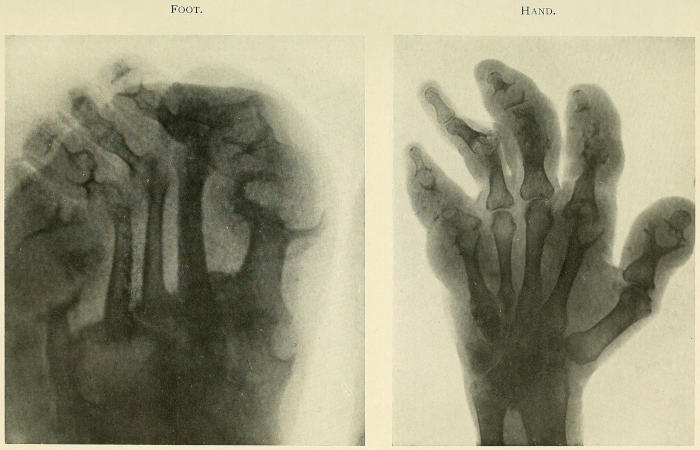

Gouty Arthritis.

Note large tuberous swellings on knuckle and metacarpo-phalangeal joints due to uratic deposits.

Title: Gout, with a section on ocular disease in the gouty

Author: Llewellyn J. Llewellyn

Contributor: W. M. Beaumont

Release date: January 24, 2023 [eBook #69874]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: C. V. Mosby Company, 1921

Credits: Mark C. Orton and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Gouty Arthritis.

Note large tuberous swellings on knuckle and metacarpo-phalangeal joints due to uratic deposits.

BY

LLEWELLYN JONES LLEWELLYN, M.B. Lond.

GOVERNOR AND SENIOR PHYSICIAN, ROYAL MINERAL WATER HOSPITAL, BATH;

FELLOW OF ROYAL SOCIETY OF MEDICINE; AUTHOR OF “ARTHRITIS DEFORMANS”;

CO-AUTHOR OF “FIBROSITIS”; CO-AUTHOR OF “MALINGERING, OR THE SIMULATION

OF DISEASE”; CO-AUTHOR OF “PENSIONS AND THE PRINCIPLES OF THEIR

EVALUATION”; CONTRIBUTOR TO LATHAM AND ENGLISH’S “SYSTEM OF TREATMENT,”

ALSO TO “OXFORD ENCYCLOPÆDIA OF TREATMENT” AND TO “STUDENT’S

TEXT-BOOK OF SURGERY.”

WITH A SECTION ON

OCULAR DISEASE IN THE GOUTY

BY

W. M. BEAUMONT

CONSULTING OPHTHALMIC SURGEON TO THE SOUTH-WESTERN

REGION OF THE MINISTRY OF PENSIONS; AUTHOR OF “INJURIES

OF THE EYES OF THE UNEMPLOYED, PROBLEMS IN PROGNOSIS,” ETC.

ST. LOUIS

C. V. MOSBY COMPANY

1921

Printed in Great Britain.

Dedicated

TO

MY WIFE

“A knowledge of the real nature of gout ... is, in my opinion, at the very foundation of all sound pathology,” wrote Todd many years since; and the passing years have but invested his reflection with deeper significance and something of prophetic insight. For who can doubt that he who would elucidate the pathological groundwork of gout must be at once a clinical physician, a bio-chemist, a bacteriologist, a morbid anatomist? and well may we ask, Who is sufficient for all this?

How vivid the light thrown upon the problems of clinical medicine by the bio-chemists! The story of the fate of protein and purin substances in the animal body, at one time a medley of guesses and gaps, is gradually evolving into one of relative certitude and completeness. Revolutionary, in truth, the change, and many a cherished shibboleth has been ruthlessly cast aside! With admiration not unmingled with awe we see them laying well and truly the foundations upon which in the ultimate scientific medicine must inevitably rest.

Of these the very corner-stones are chemical physiology and chemical pathology, the rapid evolution of which is profoundly altering our conceptions of health and disease. Those vital processes of the organism that but yesterday we saw “as through a glass, darkly,” are now in great part illumined, and the distortions wrought in them by disease made more manifest.

How pregnant, too, with warning their findings! Processes that to our untutored minds seem simple are revealed as infinitely complex. Through what a maze must we thread our way if we would disentangle the intricacies of metabolism! Intricate enough, forsooth, in health, but how much more so in disease! For, as Sir Archibald Garrod eloquently phrases it, “it is becoming evident that special paths of metabolism exist, not only for proteins, fats, and carbohydrates as such, but that even the individual primary fractions of the protein molecule follow their several katabolic paths, and are dealt with in successive stages by series of enzymes until the final products of katabolism are formed. Any of these paths may be locked while others remain open.”

It is with chastening reflections such as these that we may best approach our study of gout, that riddle of the ages upon which so many physicians from time immemorial have expended their dialectic skill. But, vast though the increase in our knowledge[viii] of the chemical structure of uric acid and its allies, uncertainty still dogs our steps, and, doubtful of the pathway to solution of the pathological mystery of gout, we must perforce approach the problem in a more strictly catholic attitude.

Uric acid has apparently failed us as the causa causans. Neither this substance nor its precursors can be held responsible for the fever, local inflammation and constitutional disturbances in gout, being, as they are, practically non-toxic. Albeit, though I hold this view, I do not for one moment suggest that uric acid has nothing whatever to do with gout. The fact that tophi, its pathognomonic stigmata, are compounded of biurate of soda, would per se stamp such an attitude as untenable. On the other hand, uric acid must be viewed at its proper perspective as a concomitant or sequel of gouty inflammation, the essential cause of which must be sought elsewhere.

“The old order changeth, giving place to new,” and happily with the advent of bacteriology our views, or rather our hazards, as to the nature of joint diseases underwent profound modification. But, strange to say, though quick to apprehend the significance of infection, its causal relation to other joint disorders, we still seem unaccountably loth to discard our timeworn conception of “gouty” arthritis as of purely metabolic origin. This to my mind is the more remarkable in that the onset, clinical phenomena, and course of acute gout, and no less the life history of the disorder as a whole, are emphatically indicative of the intrusion of an infective element in its genesis.

The extreme frequency with which infective foci are met with in the victims of gout, the frequency, too, with which exacerbations of the disorder are presaged by acute glandular affections of undeniably infective source, is by no means adequately realised. For our forefathers gout began, and, forsooth, often ended, in the “stomach,” or it was the “liver” that was impeached. But the portal to the alimentary canal was for them only a cavity, the contained structures of which, albeit, to their mind often betrayed evidences of a “gouty diathesis.” They distinguished “gouty” teeth, “gouty” tonsillitis, “gouty” pharyngitis, even “gouty” parotitis; but all these they classed as tokens or sequelæ of gout, not possible causes or excitants thereof.

Now as to the true significance of these acute glandular affections held by clinicians of repute to be of “gouty” origin. What of “gouty” tonsillitis, pharyngitis, parotitis? Still more, what of our deductions regarding the relationship of these same when met with in association with non-gouty forms of arthritis? Do we not hold them each and all as evidences of infection? and, we may well ask, why not in gout?

The marvel then is that even to-day many still hold that the tonsillitis, pharyngitis, even the gingivitis, like the subsequent articular lesions, are one and all attributable to the underlying gout. We certainly should not do so in the case of any arthritis other than “gouty,” and to my mind the time is ripe for a change of attitude.

The “gouty” throats, like the “gouty” teeth, should be regarded not as symptomatic of gout, but etiologically related thereto. We should cease to talk of “gouty” throats, teeth, etc., should renounce the prefix, for there is nothing specific of gout either in the tonsillar, pharyngeal, or dental lesions. We should instead view these various local disorders in their true perspective as foci of infection, causally related to the subsequent and secondary “gouty” arthritis.

Similarly, when we come to analyse the component elements of an acute paroxysm of gout, how strongly indicative of the intrusion of an infective element the following features: the onset, temperature curve, character of local articular changes of the disorder, the presence of leucocytosis, with secondary anæmia and enlargement of the lymphatic glands! Again, how suggestive the occasional complication of acute gout by lymphangitis and phlebitis! Of like significance, too, the paroxysmal nature and periodicity of the disorder, and the compatibility of the morbid anatomical changes and the cytological content of the aspirated joint fluid with their genesis by infection.

As to correlation of the metabolic phenomena of gout with the postulated infective element, I would suggest that, although abnormalities of metabolism form an integral part of gout, they are of themselves inadequate to achieve its efflorescence. As we shall see when we come to consider those elemental manifestations of gout, i.e., uratic deposits, or tophi, neither the purely physical nor the purely chemical theory of their origin will suffice, nor, for that matter, can any solution of their formation be gleaned from even a blend of the twain. In short, such hypotheses are too mechanical.

The intrusion of some other factor, “something vital, something biological,” seems essential for the elucidation of uratosis, i.e., uratic deposition. For this, not uricæmia, is the specific characteristic phenomenon of gout. If we cannot explain uratosis on physical or chemical grounds, then how much less, in view of the non-toxicity of uric acid, can we on this basis account for the inflammatory phenomena of the disorder!

Now inflammatory reaction is, I hold, an invariable antecedent in all gouty processes, whether of articular or ab-articular site. Granted that inflammatory reaction is a necessary prelude, the[x] specificity of gout is attested by the fact that the same is followed by local deposition of urates. But while this sequential uratic deposition invests all forms of “gouty” inflammation with a specific character unshared by any other disease, it follows that the cause of the said inflammation must, if possible, be ascertained.

Now, as I believe, “gouty” subjects are ab initio victimised by innate tissue peculiarities, doubtless reflected in corresponding obliquities of tissue function and metamorphosis, and through their medium the general resistance of the body to invasion by infections is lowered; in other words, under the influence of these morbific agencies the latent morbid potentialities of the gouty become overt and manifest. For in the gouty, as Walker Hall observes, “a slight injury or indiscretion of diet, an overloaded intestine, or increased toxicity of the intestinal flora, may be followed by a disturbance of the general nuclein metabolism and a local reaction in certain tissues.”

Enough has been said to disclose the dominant trend of this work, and although there are many aspects of the subject in regard to which I hold somewhat iconoclastic views, yet exigencies of space forbid me even to allude to them in this foreword. I hasten therefore to discharge the pleasing duty of acknowledging my great indebtedness to the acumen and discrimination which has been brought to bear on this subject by a long succession of eminent physicians, in proof of which I need only adduce the names of those giants of the past the illustrious Sydenham, Sir Thomas Watson, Sir Charles Scudamore, Jonathan Hutchinson, not to mention Trousseau, Charcot, Lecorche, and Rendu. But I should fail in my duty did I not in a special sense express my deep indebtedness to the classic and epoch-making work of Sir Alfred Garrod. For the rest, too, I have derived much enlightenment from Sir Dyce Duckworth’s treatise and the various works on the subject by Luff, Lindsay, and others.

From the bio-chemical aspect I owe much to the researches of Walker Hall, and to those of our American confrères Folin, Denis, Benedict, Pratt, McLeod, Walker Jones, Gideon Wells, etc.

Reverting to my own colleagues at the Royal Mineral Water Hospital, Bath, I would tender my deep thanks to the Honorary Physicians, Drs. Waterhouse, Thomson, Lindsay, and King Martyn, for the uniformly generous manner in which they afforded me opportunities for studying cases under their care.

To Dr. Munro, our senior pathologist, I am especially beholden for invaluable, nay indispensable, help in the matter of blood examinations, the cytological study of joint fluids, and the microscopic verifications of tophi. To Dr. MacKay also my[xi] cordial thanks are due for the skiagraphs contained in this work.

For the section dealing with the ocular disorders met with in the gouty my most sincere thanks are due to Mr. W. M. Beaumont, of Bath, whose singularly wide experience in this sphere renders him unusually equipped to deal with this highly controversial aspect of gout. To Drs. Cave and Gordon, of Bath, also I am indebted for many valuable suggestions kindly afforded me while writing this volume. To my brother Dr. Bassett Jones I am under deep obligation for unwearying assistance in our joint endeavour to ascertain the exact relationship of gout to lumbago, sciatica, and other types of fibrositis.

For the preparation of the index of this work I would proffer my grateful thanks to Mr. Charles Hewitt and to Miss Donnan and Miss Crosse for having undertaken the arduous task of typing the manuscript thereof.

Lastly, I would express my thanks to my publisher, Mr. Heinemann, for much consideration and many courtesies.

LL. J. LL.

31, Upper Brook Street, W. 1.

| CHAPTER I HISTORICAL AND INTRODUCTORY |

|

| The Antiquity of Gout. Prevalence of Gout in the Anglo-Saxon Period. Views of the Humoralist. The Aphorisms of Hippocrates. Introduction of the Word Gout. Early Views as to the Nature of Tophi. The “Honour of the Gout.” That Gout confers Immunity from other Disorders. Growing Infrequency and Attenuation of Gout | pp. 1-13 |

| CHAPTER II THE PEDIGREE OF GOUT |

|

| Tardy Dissociation of Chronic Gout. Identification of Muscular Rheumatism. Differentiation of Chronic Gout from Arthritis Deformans. Cleavage of Arthritis Deformans into Two Types. Elimination of the Infective Arthritides | pp. 14-20 |

| CHAPTER III EARLIER THEORIES OF PATHOGENESIS |

|

| Garrod’s Theory. Antagonistic Views. Histogenous Theories. Antecedent Structural Changes. Hepatic Inadequacy. Hyperpyræmia. Nervous Theories. Growing Scepticism as to Garrod’s Pathogeny of Gout | pp. 21-34 |

| CHAPTER IV DEFINITION, CLASSIFICATION, ETIOLOGY, AND MORBID ANATOMY |

|

| Definition. Classification. Suggested Classification of Articular Gout. Etiology and Morbid Anatomy. Bodily Conformation and Individual Temperament. Locality, Race, Climate. Food, Drink, Occupation. Lead Poisoning. Mental and Physical Over-exertion. Summary. Morbid Anatomy | pp. 35-58 |

| CHAPTER V PATHOLOGY OF GOUT-PROTEIN METABOLISM |

|

| Revelations of the Bio-chemist. The Formation of Urea. Fate of the Amino-acids. Seat of Formation of Urea. Amino-acids in Relation to Gout. The Glycocoll Theory of Gout. Urea Excretion in Gout. Creatine and Creatinine. Inborn Errors of Metabolism | pp. 59-70 |

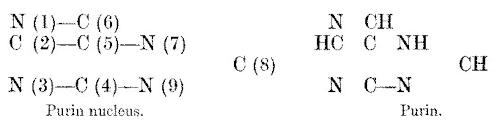

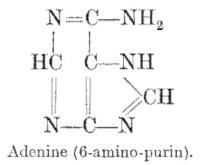

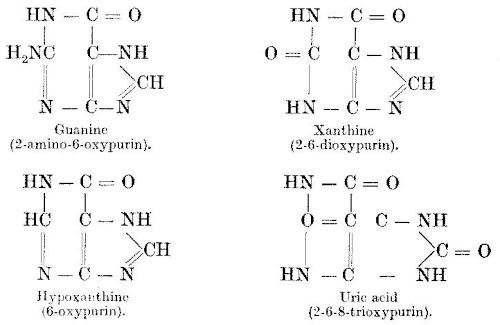

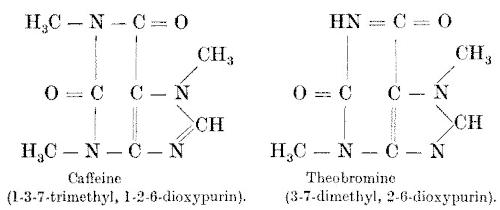

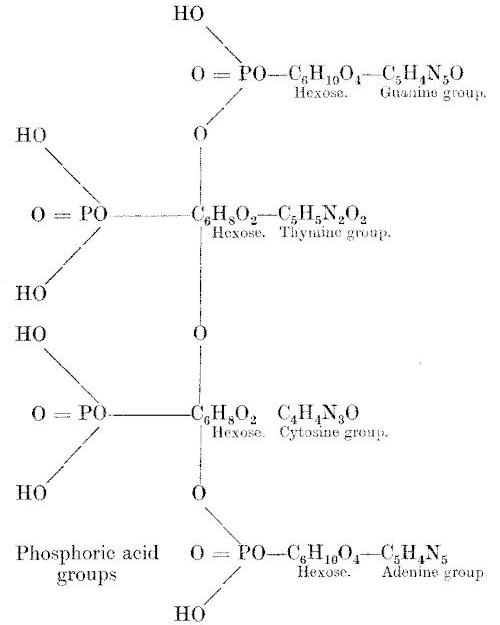

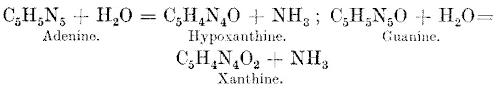

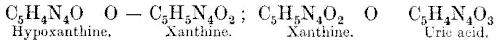

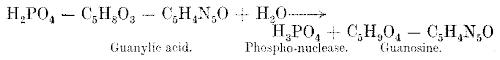

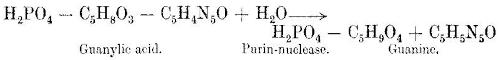

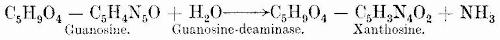

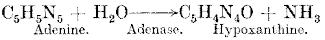

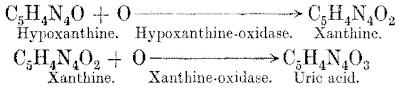

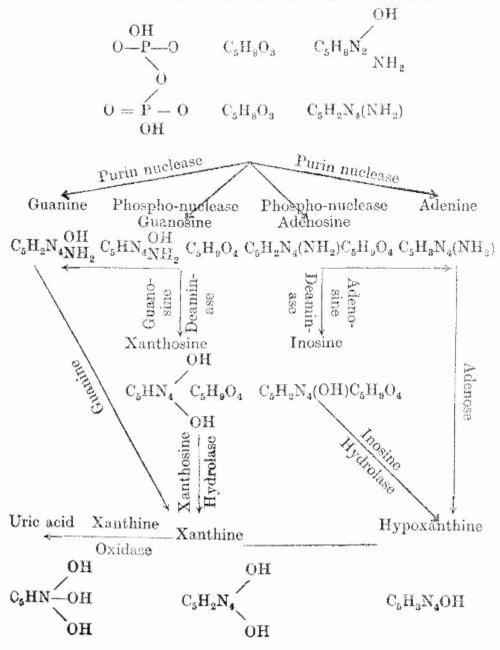

| CHAPTER VI NUCLEIN METABOLISM |

|

| The Isolation of Nucleic Acid. Researches on Spermatozoa. The Discovery of Purins. Uric Acid a Derivative of Nucleic Acid. The Chemistry of Uric Acid and the Purin Bodies. Chemical Constitution. Properties of Uric Acid. Uric Acid in the Blood. Gudzent and Schade’s Theories. Organic Combinations. Complexity of the Problem | pp. 71-82[xiv] |

| CHAPTER VII SOURCES OF URIC ACID |

|

| Exogenous Purins. Exogenous Uric Acid Excretion. Fate of the Unexcreted Purins. Endogenous Purins. Source of Endogenous Purins. Proteins and their Derivatives. Amino-acids and Dicarboxylic Amino-acids. Endogenous Uric Acid Excretion. Factors influencing Endogenous Uric Acid Excretion. Physiological Conditions. Pathological States. Ingestion of Certain Drugs. Synthetic Formation of Uric Acid | pp. 83-97 |

| CHAPTER VIII FORMATION AND DESTRUCTION OF URIC ACID |

|

| Distribution of the Enzymes. Stages in Disruption of Nucleic Acid. Destruction of Uric Acid | pp. 98-106 |

| CHAPTER IX URIC ACID IN RELATION TO GOUT |

|

| Uric Acid Excretion in Gout. Uric Acid Variations in Acute Gout. Uric Acid Variations in Chronic Gout. Retarded Exogenous Uric Acid Output. Lowered Endogenous Uric Acid Output. Other Anomalies in Excretion in Gout. Purin Metabolism in other Disorders. Purin Metabolism in Chronic Alcoholism and Plumbism | pp. 107-116 |

| CHAPTER X THE RENAL THEORY OF GOUT |

|

| Anomalies in Uric Acid Excretion in Gout. Uricæmia in Nephritis. The Relationship, if any, between the Amounts of Uric Acid and of Urea, and Total Non-protein Nitrogen in Human Blood. Uricæmia not necessarily due to Renal Defect. Uricæmia not Peculiar to Nephritis. Uricæmia does not necessarily Portend Gout. To what may be ascribed the Deficient Eliminating Capacity of the Kidney for Uric Acid. Uratic Deposits in Nephritis. Differentiation of Uratic Deposits in Gout and Nephritis. Clinical Associations of Gout and Granular Kidney | pp. 117-132 |

| CHAPTER XI URICÆMIA IN GOUT |

|

| Folin and Denis’s Method. Uric Acid a Normal Constituent of Blood. Effect of Exogenous Purins. Uric Acid Content of Blood in Gout. Hyperuricæmia in Non-gouty Arthritis. Variations in Uric Acid Content of Blood independently of Diet. What Relationship, if any, Exists between the Uric Acid Content of the Blood and Attacks of Gout. Discussion of the Foregoing Data. The Significance of Uricæmia. Sources of Fallacy in Uric Acid Estimation. Disabilities of Modern Tests. Need for further Investigations | pp. 133-148 |

| CHAPTER XII URATOSIS IN RELATION TO GOUT |

|

| Constitution of Tophi. Mode of Formation. Localisation of Uratic Deposits. The Causation of Tophi. Solubilities of Uric Acid. Tophi in Relation to Uricæmia. Tissue Affinities for Uric Acid. Retention Capacity of Tissues for Uric Acid. Clinical Evolution of Tophi. The Cause of the Inflammatory Phenomena. Non-toxicity of Uric Acid. Are the Precursors of Uric Acid Toxic? | pp. 149-170[xv] |

| CHAPTER XIII THE RISE OF THE INFECTIVE THEORY |

|

| Boerhaave’s Forecast of the Infective Theory. Ringrose Gore on Infective Origin. Leucocytosis in Acute Gouty Polyarthritis. Chalmers Watson’s Researches on Gout in a Fowl. Trautner’s Suggestion of a Specific Infection | pp. 171-176 |

| CHAPTER XIV GOUT AS AN INFECTION |

|

| Local Foci of Infection: Dental, Nasal, Pharyngeal, etc. Gastro-intestinal Disorders. Variation in Free HCL. Intestinal Disorders. Infection or Sub—infection | pp. 177-187 |

| CHAPTER XV GOUT AS AN INFECTION (continued) |

|

| Analysis of the Acute Paroxysm. The Evolution and Life History of Gout. Analogies between Gout and the Specific Infective Arthritides. Correlation of the Metabolic Phenomena of Gout with the Postulated Infective Element | pp. 188-199 |

| CHAPTER XVI CLINICAL ACCOUNT |

|

| Acute Localised Gout. Prodromal Symptoms. Dyspepsia. Premonitory Symptoms of Tophus Formation. Premonitory Articular Pains. The Acute Paroxysm. Detailed Consideration of Phenomena. Mode of Onset. Localisation. Nature of Pain. General Phenomena. Pyrexia. Changes in the Blood. Uric Acid Excretion. Local Phenomena. Tophus Formation | pp. 200-213 |

| CHAPTER XVII CLINICAL ACCOUNT (continued) |

|

| Acute Gouty Polyarthritis. Mode of Invasion. Distribution of Lesions. Local Characters. Constitutional Symptoms. Changes in the Blood. Leucocytosis. Collateral Phenomena of Gout. Lumbago, Sciatica, etc. Incidence of Gouty Stigmata in Various Types of Fibrositis | pp. 214-224 |

| CHAPTER XVIII CLINICAL ACCOUNT (continued) |

|

| Chronic Articular Gout. The Joint Deformities of Chronic Gout. Tophi: Their Evolution and Distribution. Other Sites of Tophi. Affinities between Gout and other Diseases. Gout in Relation to Glycosuria. Gout in Relation to Phlebitis. Cutaneous Disorders. Gout and Nephritis. Prognosis in Gout | pp. 225-246 |

| CHAPTER XIX ETIOLOGICAL AND CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS. |

|

| Articular Gout. Etiological Diagnosis. Clinical Diagnosis. Introductory Remarks. The Diagnostic Status of Tophi. Tophi in Relation to Arthritis. Frequency of Tophi in True Gouty Arthritis Underestimated. Difficulty of Detecting Tophi | pp. 247-257[xvi] |

| CHAPTER XX CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS (continued) |

|

| Acute Articular Gout. Localised Variety. Differential Diagnosis. Infections. Acute Gonococcal Arthritis. Traumatic Lesions. Acute Osteoarthritis. Static Foot Deformities. Hallux Valgus with Inflamed Bunion. Hallux Rigidus. Metatarsalgia. Gout in the Instep. Gonococcal Arthritis. Tuberculosis and Syphilitic Disease of the Tarsal Joints or the Related Joints. Pes Planus. Gout in the Heel. Referred Pain. Local Sources of Fallacy. Post-calcaneal Bursitis. Synovitis of the Tendo Achillis. Gout in the Sole. Plantar Neuralgia. Erythromelalgia. Anomalous Sites for Initial Outbreaks | pp. 258-267 |

| CHAPTER XXI CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS (continued) |

|

| Acute Gouty Polyarthritis. Differential Diagnosis. Acute Articular Rheumatism. Acute Gonococcal Arthritis. Etiology. Onset. General Symptoms. Distribution of Lesions. Local Characters. Associated Phenomena. Secondary Syphilitic Arthritis. Acute Rheumatoid or Atrophic Arthritis. Age and Sex. Onset. General Symptoms. Distribution of Lesions. Local Characters. Associated Phenomena. Infective Arthritis of Undifferentiated Type | pp. 268-274 |

| CHAPTER XXII CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS (continued) |

|

| Chronic Articular Gout. Chronic Monarticular Gout. Monarticular Gout in Large Articulation a Rarity. Chronic Gout of Oligo-articular Distribution. Its Confusion with Chronic Villous Synovitis. Villous Synovitis Static and Non-gouty in Origin. Clinical Symptoms of Villous Synovitis. Bilateral Hydrarthrosis. Peri-synovial and Peri-bursal Gummata. Chronic Gout of Polyarticular Distribution. Differential Diagnosis. Osteoarthritis. Local Characters of Joint Swellings. Rheumatoid Arthritis. Local Characters of Joint Swellings. Nerve Arthropathies. Hæmophilic Arthritis | pp. 275-285 |

| CHAPTER XXIII CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS (continued) |

|

| Skiagraphy. Significance of Local Areas of Rarefaction. The Radiographic Types of Gouty Arthritis. Differential Diagnosis. Infective Arthritis. Hypertrophic or Osteoarthritis. Rheumatoid or Atrophic Arthritis | pp. 286-292 |

| CHAPTER XXIV IRREGULAR GOUT |

|

| Historical Account. Murchison’s Views. Retrocedent Gout. Gout in the Stomach. Cardiac and Cerebral Forms. Other Irregular Manifestations. Conclusions. Infantile Gout | pp. 293-307 |

| CHAPTER XXV OCULAR DISEASE IN THE GOUTY |

|

| Evidence of Gout in the Eye. Deposition of Urates. Gouty Diathesis. Significance and Location of Tophi. Relative Incidence of Iritis. Metastasis. Arthritic Iritis. Gouty Iritis not a Clinical Entity. Ocular Symptoms in Hyperuricæmia. False Gout. Retinal Hæmorrhage. Neuro-retinitis. Glaucoma. Conclusions | pp. 308-326[xvii] |

| CHAPTER XXVI TREATMENT OF GOUT |

|

| Radical Treatment of Local Foci of Infection or Toxic Absorption. Diet in Acute and Chronic Gout. The Fallacy of Fixed Dietaries. Thorough Physical Examination a necessary Prelude to Dieting. Need for Collaboration of Clinician and Bio-chemist | pp. 327-341 |

| CHAPTER XXVII TREATMENT OF GOUT (continued) |

|

| Regulation of Diet in the Gouty. The Individual Foodstuffs, Proteins, Carbohydrates, Fats, Vegetables, Fruits, Condiments. Special Dietaries. Amylaceous Dyspepsia. Hyperchlorhydria | pp. 342-371 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII MEDICINAL AND OTHER MODES OF THERAPY—ACUTE GOUT |

|

| Initial Purgation. Colchicum in Acute Gout. Method of Administration. Preparations and Dosage. Colchicine, Salicylate of Colchicine. Atophan. Alternative Remedies in Acute Gout. Salicylates. Alkalies. Quinine. Thyminic Acid. Anodynes in Acute Gout. Local Measures. Analgesics. Liniments, etc. Ionisation. Massage. Surgical Methods | pp. 372-388 |

| CHAPTER XXIX MEDICINAL AND OTHER MODES OF THERAPY (continued)—INTER-PAROXYSMAL PERIOD |

|

| Prophylactic Measures. Treatment of Atonic Dyspepsia. Hyperacidity due to Organic Acids. Treatment of Hypochlorhydria. Alkalies, Atophan, and Colchicum as Prophylactics | pp. 389-396 |

| CHAPTER XXX MEDICINAL AND OTHER MODES OF THERAPY (continued)—CHRONIC ARTICULAR GOUT AND ASSOCIATED MORBID CONDITIONS |

|

| Alkalies. Contrasts between Salts of Sodium and Potash. Differential Indications for their Usage. Alternatives. Salicylates. Benzoates. Hexamine. Iodides. Iodine. Albumen Compounds. Collosol Preparations of Iodine. Guaiacum. Local Measures in Chronic Articular Gout. Treatment of Tophi. Ionisation. Surgical Measures. Treatment of Associated Morbid Conditions. Fibrositis. Lumbago. Sciatica. Acute Brachial Fibrositis. Local Massage. Oxaluria. Glycosuria. Hyperchlorhydria. Gouty Phlebitis. Gouty Eczema. Gouty Nephritis | pp. 397-417 |

| CHAPTER XXXI CLIMATO-THERAPY, HYDRO-THERAPY, ETC. |

|

| Climate. Choice of Residence. Clothing. Exercise. Massage. General Hydro-therapy. Importance of thorough Physical Examination. Individual Reactive Peculiarities. Prophylactic Measures. Contra-indications and Untoward Complications. Methods of Application of General Hydro-therapy. Immersion Baths. Aix and Vichy Massage. Vapour Baths. Indications for Sub-thermal Baths. Local Hydro-therapy. Varieties of Douche. Treatment by Hyperæmia | pp. 418-430[xviii] |

| CHAPTER XXXII MINERAL SPRINGS AND CHOICE OF SPA |

|

| Difficulties of Definition and Classification. Radio-activity. General Principles of Spa Treatment. Physiological Action of Radium Emanation. Activation of Body Ferments. Influence of Uric Acid Metabolism. Increased Excretion of Uric Acid. Subjective Phenomena of Gout in Relation to Blood Content and Excretion of Uric Acid. Therapeutic Action and Application. Alimentary Disorders. Glycosuria. Raised Blood Pressure. Choice of Spa. The Spare and the Obese. Waters Suitable for Various Types of Dyspepsia. Bickel’s Experiments. Mineral Waters in Associated Morbid Conditions. Glycosuria. Oxaluria. Phlebitis. Respiratory Disorders. Fibrositis. Gouty Eczema. Uric Acid Gravel. Arterio-sclerosis. Chronic Nephritis. Concluding Remarks on Spa Treatment | pp. 431-465 |

| INDEX | pp. 457-469 |

“Teeth, bones, and hair,” quoth the Sage of Norwich, “give the most lasting defiance to corruption,” and were it not that “Time which antiquates antiquities and hath an art to make dust of all things hath yet spared these minor monuments,” it might perhaps have been inferred that gout was the primordial arthritic disease that afflicted mankind.

That it was the first articular affection to achieve clinical individuality may be allowed, but, from the aspect of antiquity, gout is relatively modern—the appanage of civilisation. True, Hippocrates, discoursing in the famous Asclepion at Cos, enunciated his aphorisms on gout some 300 years before the Christian Era, the dawn of which moreover found Cicero in his discussions at Tusculum lamenting its excruciating tortures “doloribus podagræ cruciari” and the peculiar burning character of its pains “cum arderet podagræ doloribus.”

But what of that? For did not Flinders Petrie in the hoary tombs of Gurob (dating back to the 28th Dynasty 1300 B.C.) find in mouldering skeletons of bygone civilisations unequivocal evidence of osteoarthritis.[1] But despite these sure though silent witnesses of the prevalence of this disorder among the ancient people of Egypt, yet in contrast with gout, no hint transpires in the writings of Greek or Roman physicians, nor those of much[2] later date, that the condition was recognised clinically, as a joint disorder, distinct from others of the same category.

Small call to marvel thereat, for how much more arresting the clinical facies of gout, with its classic insignia—tumor, robor, calor, et dolor—than of osteoarthritis, its etiolate tokens indicative rather of infirmity than of disease. Apart from this, it may well be that the early Egyptians owed their relative immunity from gout, and alike their proneness to osteoarthritis, to living hard laborious days, unenervated by that luxury and sloth, which in the first century A.D. drew upon the ancient Romans the caustic reproofs of Pliny and Seneca. For the old philosophers lamented the growing prevalence of the disorder, almost unknown in the early, more virile days of the Empire, rightly seeing in it but another harbinger of impending decadence, clearly attributable as it was to riotous living and debauchery.

Indeed, we have it on the authority of Galen that “In the time of Hippocrates there were only a few who suffered from podagra, such was the moderation in living, but in our own times, when sensuality has touched the highest conceivable point, the number of patients with the gout has grown to an extent that cannot be estimated.”

Nothing, in truth, seems more clearly established than this, that gout is the Nemesis that overtakes those addicted to luxurious habits and dietetic excesses. On the testimony of eminent travellers we are assured that amongst aborigines the disease is unknown. The indigenous native tribes of India are immune, but not so the immigrant flesh-loving Parsees. Strange to relate, Anglo-Indians of gouty habit, while resident in the Orient, seem exempt, some say, owing to cutaneous activity, but more probably because quâ Rendu “these are countries in which we cannot survive unless we are frugal.”

Nations too, like individuals, when fallen on hard times, lose their gout. Thus the Arabs, at the zenith of their mediæval Empire, were prone thereto, but in these latter days are almost exempt from its ravages. But, on the other hand, if we are to believe Professor Cantani, in no other disorder are the “sins of the fathers visited upon the children” with such pertinacity, claiming as he does that its marked incidence in Southern Italians is a direct heritage from the ancient Greeks and Romans.

Reverting to our own country, what evidences as to its antiquity are forthcoming? This much may at any rate be affirmed, that according to Mason Good “Gout is one of the maladies which seem to have been common in England in its earliest ages[3] of barbarism. It is frequently noticed by the Anglo-Saxon historian, and the name assigned to it is Fot-adl.”

Cockayne, in his “Leechdoms Wortcumming and Starcraft,” of early England, has it that the word “addle” appears to have been a synonym for ailment, thus “Shingles was hight circle addle.” That gout should have flourished so among our Anglo-Saxon forbears is perhaps a matter for regret but not for astonishment, when we recall their coarse Gargantuan feasts, washed down with doughty draughts of ale, “sack and the well spic’d hippocras.”

Gout, we see then, even in our own land, is full ancient, and the word, as Bradley as shown, may be traced in the English tongue right through the literature of the various periods.[2] This not only in the brochures of physicians, but also as in the days of Lucian in the works of historians, and the satires of poets, which indeed abound with allusions to the disease.

The Greek physicians, quite familiar as they were with the overt manifestations of gout, did not, as far as its nosology was concerned, commit themselves to any appellation that might imply their adherence to any theory as to its causation. They contented themselves with a mere topographical designation, terming the affection, podagra, chirargra, etc., according as foot or hand was the seat of the disorder, while for polyarticular types the generic term arthritis was invoked.

Nevertheless the old Greek physicians had their views as to its pathology. Thus the source of the peccant humours resided for them in the brain, which they had invested with all the functions of an absorbent and secreting gland. This hypothesis in time was displaced by the true humoral theory, according to which the[4] bodily fluids, those found in the alimentary canal, the blood stream, and the glandular organs, were the primordial agents of disease. No need, albeit, for gibes on our part, for how true much of their conception of the genesis of disease even to-day. Indeed, what else than a fusion of the foregoing views? the modern theory of Sir Dyce Duckworth, who would ascribe gout to the combined influence of neural and humoral factors. And now to consider briefly the individual views of the fathers of medicine.

In the eyes of the pioneer priest-physician, the disorder was attributable to a retention of humours, and many of his dicta have stood the corroding test of time. He noted, like Sydenham, its tendency to periodicity, its liability to recur at spring and fall. Also that eunuchs are immune and youths also, ante usum veneris, while in females its incidence is usually delayed until after the menopause.

The curability of the disease in its earlier stages was affirmed, but that after the deposit of chalk in the joints it proved rebellious to treatment, which for him resided in purgation and the local application of cooling agents.

In the first and second centuries Celsus, Galen, and Aretæus the Cappadocian recounted their views as to its nature and therapy, while the Augustan poet in his Pontic epistles, like Hippocrates, laments that his gouty swellings defy the art of medicine.

To Celsus, venesection at the onset of an attack seemed both curative and prophylactic. Corpulence of habit a state to be avoided, and conformably he prescribed frugality of fare and adequate exercise. Galen (130-200), more venturesome than his contemporaries, voiced his belief that tophi were compact of phlegm, blood, or bile, singly or in combination. For the rest, he enjoined bleeding and purgation and local applications, contravening, by the bye, Hippocrates’ claim as to the immunity of eunuchs in that in his (Galen’s) day their sloth and intemperance were such as readily begat the disorder.

About this period Lucian of Saramosta enumerated the various anti-gout nostrums vaunted as specifics in his day. Though in his comic poems, the Trago-podagra and Ocypus he rightly holds up to scorn the charlatanism rampant at the time, still it is quite clear that he possessed no mean knowledge of the clinical vagaries of gout and was quite alive to the mischief of too meddlesome treatment thereof.

Said the hero of the Trago-podagra:

Again, Seneca, in a jeremiad on the decadent habits of Roman ladies of the patrician order, observes: “The nature of women is not altered but their manner of living, for while they rival the men in every kind of licentiousness, they equal them too in their very bodily disorders. Why need we then be surprised at seeing so many of the female sex afflicted with gout.” That the old philosopher’s misgivings were but too well founded is obvious when we recall that so widespread were the ravages of gout among the Romans in the third century that Diocletian, by an edict, exempted from the public burdens those severely crippled thereby, in sooth a blatant illustration of political pandering to national vice.

But to return to the researches of physicians, those of Aretæus seem to have been the most enlightened of his time. A succinct account of the mode of invasion of gout and its centripetal spread in later stages to the larger joints is followed by enumeration of the exciting causes of outbreaks. Anent these, he quaintly notes the reluctance which the victims display to assigning the malady to its true cause—their own excesses—preferring to attribute it to a new shoe, a long walk, or an injury. Noting that men are more liable than women, he tells us, too, that between the gouty attacks the subject has even carried off the palm in the Olympic games. The white hellebore, to his mind, at any rate in early attacks, was the remedy par excellence. But, for the true nature of the disease, he, with humility and piety, avows that its secret origin is known only to the gods.

Not so his successor Cælius Aurelianus, who affirmed it to be not only hereditary but due to indigestion, over-drinking, debauchery, and exposure. Under their maleficent influence morbid humours were generated which sooner or later found a vent in one or other foot, with a predilection for tendons and ligaments; these structures he averred being the locus morbi. An abstemious dietary with exercise was his sheet anchor in therapy, with local scarification in preference to cupping and leeching, but violent purging and emetics he decried, and drugs to him made little appeal.

More ambitious than his predecessors, Alexander of Tralles, in the sixth century, held that there were many varieties of gout, some due to intra-articular effusions of blood, reminding us of Rieken’s view (1829) that hæmophilia is an anomalous variant of gout. Other cases, Alexander averred, were the outcome of[6] extravasation of bile or other peccant fluids between tendons and ligaments. Abstinence, especially from wine and blood-forming foods, was enjoined and a plentiful use of drastic purgatives, elaterium, etc., with local sinapisms and blisters. For the absorption of chalk stones he commended unguents containing oil, turpentine, ammoniacum, dragon’s blood, and litharge.

Aetius, a contemporary, is noteworthy in that during the intervals of attacks he highly eulogised the use of friction while, like Alexander of Tralles, he seems to have been much impressed with the virtues of colchicum, of which he says, “Hermodactylon confestim minuit dolores.” Planchon, in 1855, in his treatise, “De hermodactes au point de vue botanique et pharmaceutique,” claims to have proved that the hermodactylon of the ancients was Colchicum variegatum, of similar properties to the Colchicum autumnale.

Paulus Ægineta, like most of his confrères, regarded gout and rheumatism as the same disorder, differing only in their location. He subscribed whole heartedly to the prevailing humoral theory, but inclined to think the site of the discharged humours was influenced by weakness or injury of the parts. He noted, too, that mental states, sorrow, anxiety, etc., might act as determining causes.

Nor will any historical résumé rest complete without a reference to the numerous works of the Arabian physicians—Avicenna, Rhazes, Serapion, and Haly Abbas—who one or other all maintained gout to be hereditary, rare in women and due to peccant humours, developed in the train of depletions, debaucheries, and the like.

In the thirteenth century the Greek terms “podagra,” “chirargra,” etc., were to a large extent abandoned, and following Radulfe’s lead gave way to the use of the generic term “gout,” derived from the Latin “gutta.” Its adoption was doubtless traceable to the prevailing humoral views of the origin of the disorder, as due to some morbid matter exuding by “drops” into the joint cavities. Indeed, according to Johnson, the word “gut” was used as a synonym for “drop” by Scottish physicians even in his day.

In any case, the term found little difficulty in installing itself among all nations, taking in French the form “goutte,” in German “gicht,” in Spanish “gota,” etc. Trousseau thought it “an admirable name, because in whatever sense it may have been originally employed by those by whom it was invented, it is not now given to anything else than that to which it is applied.” In contrast[7] therewith, that trenchant critic Pye-Smith complained of the laxity with which the Germans invoked the word “gicht.” He says it is popularly credited with all the pains which are called “rheumatics” in England. “Sometimes ‘gicht’ is nothing but bad corns and is rarely true gout.” Albeit, Pye-Smith did not, as we shall see later, hold even his English confrères in this respect void of offence.

From these remote times onwards through the Middle Ages to the present day, an almost continuous series of historical records testify that not only has gout always been with us, but that its clinical characters throughout the ages have remained unaltered, conforming ever to the primitive type. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many physicians, both British and continental, ventilated their views as to the nature of gout, all swearing allegiance to the old humoral pathology, notably Sydenham, Boerhaave, Van Swieten, Hoffmann, Cadogan, etc.

The English Hippocrates, as Trousseau christened the illustrious Sydenham, displayed his catholic outlook by the pregnant words: “No very limited theory and no one particular hypothesis can be found applicable to explain the whole nature of gout.” A live-long martyr himself thereto, he brought all the strength of his dominating intellect to bear upon its elucidation. As to its causation, he held it to be due to a “morbific matter,” the outcome of imperfect “coctions” in the primæ viæ and in the secondary assimilating organs. He refrained from speculating as to the constitution of the materia peccans, but as Trousseau observes, “he made his morbi seminium play the part which modern chemistry attributes to the products it has discovered. Take it all in all,” he says, “the theory of the great English physician is much more medical than the theories of modern chemists.”

The word “tophus” or “tofus,” the Greek τοφος, seems to have been applied to rough crumbling rock, the disintegrated volcanic tufa. As to its constitution it is clear from the above quotation that Virgil evidently associated it with chalk, a shrewder guess than the fanciful hypothesis of Galen, though the views of Paracelsus (1493-1541) enunciated some centuries subsequently, were even more grotesque, a “mucous essence,” a “Tartarus” burning “like hell fire.”

Nevertheless, our contempt need be chastened when we recollect[8] that, up to the latter half of the eighteenth century, equally weird assumptions found acceptance. By some “various excrementitial humours,” by others “checked and decomposing sweat” were deemed the basis of tophi.

A mucilaginous extract, derived from the solid and liquid intake, appealed to some as an explanation of their formation, while to others, tophi were compounds of subtle and penetrating salts.

But the later view, doubtless the reflex of etiological hypotheses, was that tophi were of tartareous nature, closely similar to that encrusting the interior of wine casks. Hoffmann declared that the materies morbi actually was a salt of tartar circulating in the blood. His investigations of tophi and also of the stools, saliva, and urine of gouty subjects, convinced him that the peccant matter was tartar of wine.

Hoffmann’s views, however, were laughed to scorn by M. Coste as being obviously absurd, inasmuch as gout was not uncommon amongst those who had never partaken of wine, ergo, never of tartar. How infinitely more physicianly the inference of Sydenham, who, like some of the older humoralists held the tophus to be “undigested gouty matter thrown out around the joints in a liquid form and afterwards becoming hardened.”

So it went on until, alchemy being displaced by chemistry, uric acid was in 1775 discovered by Scheele, and in 1787 Wollaston established its existence in tophi, and to the further elaboration of our knowledge of this substance we shall allude later. Here we would only observe that Wollaston’s researches marked the coming substitution of the humoral and solidist theories by a chemical hypothesis as to the etiology of gout.

The absurd delusion, not wholly dissipated even to-day, that to have the gout, “Morbus Dominorum,” was highly creditable, a mark of good breeding, was firmly ingrained in our forefathers. We all recall the story of the old Scottish gentlewoman who would never allow that any but people of family could have bonâ fide gout. Let but the roturier aspire to this privilege, and she scouted the very idea—“Na, na, it is only my father and Lord Gallowa’ that have the regular gout.” As to the origin of this mistaken ambition, it most probably was the outcome of the fact that it was peculiarly an appanage of the great, the wealthy, and alas! those of intellectual distinction!

Statesmen, warriors, literary men and poets loom large amongst its victims. Lord Burleigh suffered greatly therefrom, and good[9] Queen Bess on that account always bid him sit in her presence, and was wont to say, “My Lord, we make much of you, not for your bad legs, but for your good head!” With more humour, Horace Walpole complained, “If either my father or mother had had it I should not dislike it so much! I am herald enough to approve it, if descended genealogically, but it is an absolute upstart in me, and what is more provoking, I had trusted in my great abstinence for keeping it from me, but thus it is!”[3]

Of warriors, Lord Howe, Marshal Saxe, Wallenstein, and Condé were among its victims; while of literary men and poets thus afflicted may be mentioned Milton, Dryden, Congreve, Linnæus, Newton, and Fielding. Of physicians, the great Harvey was a martyr to gout, and was wont to treat it after the following heroic fashion. Sitting, in the coldest weather, with bare legs on the leads of Cockaine House, he would immerse them in a pail of water until he nearly collapsed from cold. Mrs. Hunter, wife of John Hunter, in a letter to Edward Jenner about her distinguished husband, dated Bath, September 18th, 1785, laments that “He has been tormented with the flying gout since last March!” In short, the disorder, with a notable frequency, figures in the life history of some of the ablest men in all ages, hence the complacency with which lesser men, often without good reason, affect to have the gout.

“But nothing,” as Sir Thomas Watson says, “can show more strongly the power of fashion than this desire to be thought to possess, not only the tone and manners of the higher orders of society, not their follies merely and pleasant vices, but their very pains and aches, their bodily imperfections and infirmities. All this is more than sufficiently ludicrous and lamentable, but so it is. Even the philosophic Sydenham consoled himself under the sufferings of the gout with the reflection that it destroys more rich men than poor, more wise men than fools.”

“At vero (quod mihi aliisque licet, tam fortunæ quam Ingenii dotibus mediocriter instructis, hoc morbo laborantibus solatio esse possit) ita vixerunt atque ita tandem mortem obierunt magni Reges, Dynastæ, exercituum classiumque Duces, Philosophi, aliique his similes haud pauci.

“Verbo dicam, articularis hicce morbus (quod vix de quovis alio adfirmaveris) divites plures interemit quam pauperes, plures sapientes quam fatuos.”

The Scotch at one time regarded gout as fit and meet punishment for the luxurious living of the English. But, as was pointed out, the cogency of the moral was somewhat spoilt by the fact that the disorder was found to exist even among the poor and[10] temperate Faroe Islanders. In truth, although “the taint may be hereditary, it may be generated by a low diet and abstinence carried to extremes.”

The fallacy that longevity and freedom from other maladies was ensured by gout was prevalent among our forefathers. In satire of this, one Philander Misaurus issued a brochure entitled “The Honour of the Gout,” and purporting to be writ, “Right in the Heat of a violent Paroxysm; and now publish’d for the common Good” (1735). “Bless us,” says he, “that any man should wish to be rid of the Gout; for want of which he may become obnoxious to fevers and headache, be blinded in his understanding, loose the best of his Health and the Security of his Life”; and forthwith in his zeal for the common good gives us the following invocation:—

He quaintly suggests that Paracelsus, if he would ensure men against death, had but to inoculate them with gout. Gout, indeed, was held to be a jealous disorder, intolerant of usurpation by any other disease, recalling the remark of Posthumus to his gaolers:—

Still the fallacy that gout was salutary died hard, and although it seems incredible, yet, Archbishop Sheldon is said not only to have longed for gout but actually to have offered £1,000 to any one who would procure him this blessing; for he regarded gout as “the only remedy for the distress in his head.” How ingrained the notion may be gathered from the fact that in the early part of the last century, M. Coste in his “Traité Pratique de la Goutte,” observed: “A popular error, which I wish to expose in a few words, is this prejudice, which has already lasted more than two[11] thousand years, and which has reached even the thrones of princes, where the disease commonly shows itself, viz., that gout prolongs life (que la goutte prolonge la vie). This error,” says he, “has taken the surest method of introducing itself, by making flattering promises, by persuading its victims that there is a singular advantage in having gout, and that the malady drives away all other evils, and that it ensures long life to those whom it attacks.”

In like refrain, our own countryman Heberden deplores that people “are neither ashamed nor afraid of it; but solace themselves with the hope that they shall one day have the gout; or, if they have already suffered it, impute all their other ails, not to having had too much of that disease, but to wanting more. The gout, far from being blamed as the cause, is looked up to as the expected deliverer from these evils.” Such deluded views being prevalent, it is hardly a matter for surprise that misguided persons deliberately courted a “fit of the gout” by resorting to excess and intemperance.

But alas, while the initial visitations of gout, after their passing, may leave behind them a renewed sense of well-being, it is no less certain that, when once installed, the intervals of respite grow shorter and shorter. Crippledom grows apace, the general health breaks and untimely senescence overtakes the worn-out victim, and, as Heberden puts it, “that gout causes premature death, when all the comforts of life ...

are destroyed, and the physical powers either insensibly undermined or suddenly crushed by an attack of paralysis or apoplexy, should hardly be reckoned among the misfortunes attending the disease.”

But for our encouragement it may be observed that not always does gout carry with it such a terrible Nemesis. “Gout is the disease of those who will have it,” said a wise physician, and though the inbred gouty tendency may be so strong as to cast defiance at abstinence, yet it is by no means always so. A man may inherit gout, but he need not foster it by self-indulgence. Much less need he, as so often happens, acquire it by depraved habits of life. In no disease do sobriety and virtuous living ensure so great a reward. As Sir Thomas Watson long since said to those inheriting this unwelcome legacy: “Let the son of a rich and gouty nobleman change places with the son of a farm servant, and earn his temperate meal by the daily[12] sweat of his brow, and the chance of his being visited with gout will be very small.”

So accurate and graphic were the clinical pictures of gout depicted by the ancient physicians that there is no doubt the gout of to-day conforms to the primitive type as met with among the Greeks and Romans. This certainly as regards the arthritic phenomena of the disease; for in those remote ages little or no account seems to have been taken of its irregular or ab-articular manifestations. While disregard of the latter group renders more credible their claims as to the widespread prevalence of the affection, nevertheless, I think there can be no doubt that the frequency of gout amongst the ancient Greeks and Romans was probably over-estimated.

Can it be questioned that a large percentage of the cases of gout in those bygone times consisted of undifferentiated infective forms of arthritis. Syphilis and gonorrhœa must have existed then as now, and their specific forms of arthritis, how easily confused with “rich man’s gout!” Surely too, they, like ourselves, must have suffered with states of oral sepsis, pyorrhœa alveolaris, etc., not to speak of infective disorders, with their correlated arthritides. In short, the differentiation of arthritic disorders was then hardly in its infancy, and it is in light of this disability that we must appraise their clearly extravagant assertions as to the widespread ravages of gout in their day.

But passing to more recent times, there is little doubt that the classical type of podagra is very much rarer to-day than, say, in the time of Sydenham. Indeed, it may be said to be becoming progressively infrequent. Thus, writing in 1890, Sir Dyce Duckworth tells us that some twenty-six years prior to that date, Sir George Burrows informed him that “he then saw fewer cases of acute gout than he was accustomed to see in his earlier practice.” It may be recalled, too, that Sir Charles Scudamore, in retrospect of his own experience, of still earlier date, was led to much the same conclusion. Moreover, not only is the disorder less frequent, but its virulence seems to have suffered attenuation, and this to a marked degree.

Again, Ewart, writing in 1896, observed that “goutiness” is becoming relatively more common than declared gout. This, he thought, by reason of the increasing attenuation in transmission of the “gouty” taint. In this, as well as the more mitigated[13] character of the arthritic manifestations, he saw hope of “an ultimate extinction of the bias in ‘gouty’ families.” For, as he rightly says, side by side with “the tendency to a reproduction of morbid parental peculiarities, there is a yet stronger tendency in Nature to reproduce the healthy type of the race in each successive generation.”

But while there is a general consensus of opinion as to the growing rarity of acute regular gout, on the other hand, many, as if loth to part with the disorder, claim that pari passu with the decline of regular types the incidence of irregular manifestations grew proportionately.

In my experience the incidence of regular gout has appreciably diminished during the past twenty years. Moreover, such examples as one has met with incline much more in character to the asthenic than to the sthenic variety of podagra. But, in contrast to many, I have observed no increase in the irregular manifestations of gout. On the contrary, a steady diminution in the nebulous content of this category, but to this vexed subject we shall recur in a subsequent chapter dealing with the propriety or not of retaining this ill-defined term in medical nomenclature.

My conclusion, then, is that not only is arthritic gout becoming less prevalent, but that the type of the disease also has suffered attenuation. Probably this dual change is the outcome of many factors, not the least of these an increase in national sobriety. For as Sir Alfred Garrod long since observed, “There is no truth in medicine better established than the fact that the use of fermented liquors is the most powerful of all the predisposing causes of gout; nay, so powerful, that it may be a question whether gout would ever have been known to mankind had such beverages not being indulged in.

Under the vague term “articulorum passio” or “arthritis” the physicians of antiquity handed down to posterity the clinical description of a disease in the varied symptomatology of which we may descry at one time the features of gout and anon those of rheumatism. But centuries had to elapse before gout became differentiated from rheumatism. For there is no doubt that not only the Greek and Roman physicians, but those also of the Græco-Arabian school, confounded these two disorders, or more accurately failed to differentiate rheumatism.

So it is that Charcot, reviewing the antiquity of gout, while he pays a graceful tribute to the ancient physicians for their masterly disquisitions thereon, at the same time deplored their silence on the subject of articular rheumatism.

This absence of allusion thereto is the more remarkable in that the term “rheumatism” or “rheumes” dates from a very remote period. Both words, in truth, were indifferently enlisted to denote all those diseases deemed attributable to the defluxion of some acrid humour upon one or other part of the body. Used by the ancients more in accordance with its etymological sense, the term “rheumes” or “rheumatism,” finds a place even in the writings of Pliny and Ovid. But our modern conception of the disorder differs widely from “the flux of humours” which the Greeks named rheumatism, or “the sharpe and eager flux of fleam” which for them characterised an attack of the “rheumes.”

The early English authors, too, invoked the word as a general term descriptive of various forms of disease. Sir Thomas Elyot, in his “Castel of Health,” so scoffed at by the faculty in his day, inculcates abstemiousness in those afflicted with the “rheumes,” and in “Julius Caesar,” Brutus is warned by Portia not to tempt “the rheumy unpurged ayre of night,” a clear indication that the term was used as a synonym for fluxions, humours and catarrhs of all sorts. But as to the malign articular forms of the affection, never a word; and this almost inexplicable silence led Sydenham, Haecker and Leupoldt to surmise that articular rheumatism was a modern disease unknown amongst the ancients.

Hallowed by tradition, this erroneous conception of the identity of gout and rheumatism endured until 1642, when Baillon, in his treatise “De Rheumatismo et Pleuritide,” effected a cleavage, at any rate between the acute varieties of these two diseases.

Dissociating the term “rheumatism” from its primitive interpretation, Baillon restricted its usage to that particular group of symptoms we now call acute articular rheumatism. In the same century Sydenham, in his “Classical Observations,” materially clarified the existing clinical confusion, defining with his customary lucidity the essential differences between the two disorders.

Bearing in mind the centuries that elapsed before the acute articular forms of gout and rheumatism were dissociated, one ceases to marvel that the task, incomparably more difficult, of discriminating between the chronic forms of these diseases is even now barely accomplished.

“Rheumatissimus agnatus podagræ” said our forefathers, the axiom postulating not the actual identity of the two affections, but a near relationship, and in this non-committal phrase we may, I think, descry the birth of that modern term “L’arthritisme,” so beloved of the French physicians. Even as late as the beginning of the nineteenth century Chomel at the Saltpetrière taught his pupils that gout and rheumatism were but clinical variants of an underlying “arthritic diathesis,” his successor Pidoux being still more insistent that the two disorders sprang from one common root. Even Charcot and Trousseau, convinced as they were of the essential distinctness of the two disorders, nevertheless admitted that at the bedside their chronic manifestations were with difficulty dissociated, the former pointing to the terms “rhumatisme goutteux” and “rheumatic gout” as tacit acknowledgments of our impotence.

Nor did this view that gout and alike rheumatism are the outcome of a basic arthritic diathesis fail of doughty supporters in this country. Thus Hutchinson, in his “Pedigree of Disease,” observes “gout is but rarely of pure breed, and often a complication of rheumatism. It so often mixes itself up with rheumatism, and the two, in hereditary transmission, become so intimately united, that it is a matter of considerable difficulty to ascertain how far rheumatism pure can go ... when this complication exists. It shows its power, we may suspect, by inducing a permanent modification of tissue, and it is to this modification that[16] the peculiarities in the processes (transitory rheumatic pains in joints, fasciæ, and muscles, chronic crippling arthritis, destructive arthritis with eburnation, lumbago, sciatica) are due. Hence the impossibility under many conditions of discriminating between gout and rheumatism.”

Laycock also subscribed to Charcot’s view, and Sir Dyce Duckworth confesses that the conception of “a basic diathetic habit of body called arthritic has well commended itself to my mind,” while as to the clinical commingling of the two disorders Sir Charles Scudamore spoke with no uncertain voice. That an individual may in youth suffer from acute articular rheumatism, and later in life develop gout, is undeniable, as also the reverse, that a gouty subject may be harassed by manifestations of chronic rheumatism or fibrositis. But this mutual trenching of the one upon the clinical territory of the other must not be allowed to impair our views as to the essential distinctness of gout and rheumatism. It is undeniable that the difficulty of differentiating between the chronic forms of these two disorders is great, for not even the revelations of skiagraphy, in the absence of a clinical history, will suffice to effect a discrimination. But to a further consideration of this vexed matter we refer the reader to the coming chapters on Diagnosis.

But to resume our thread, one great step forward we owe to Cullen, who not only differentiated acute from chronic articular rheumatism, but also clearly portrayed the clinical distinctness from both of muscular rheumatism. In so doing, he materially assisted in the differentiation of these same disorders from gout. But at the same time, owing to his immoderate advocacy of “chill” as the one great cause of rheumatism in all its forms, he undoubtedly retarded progress. For immediately there arose a cloud of witnesses who claimed a “rheumatic kinship” for a myriad visceral disorders, the victims of which had suffered exposure. Thus throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries many of the conditions now assigned to irregular gout were affiliated instead to rheumatism.

Apart from Cullen’s contribution the eighteenth century was unmarked by any further advance in differentiating the mass of heterogenous joint affections, indifferently classed as gout and[17] rheumatism. The physicians of this period, indeed, appear not only to have done little themselves, but had omitted to utilise the useful indications furnished by their predecessors.

Thus how much more swiftly would the clinical distinctness of chronic articular gout from rheumatoid arthritis have been realised had Sydenham’s dicta in the seventeenth century regarding this intricate problem been duly appreciated. Up to his time, the clinical descriptions of rheumatoid arthritis appeared now under gout, now under rheumatism. As for Sydenham himself, he placed the disorder, nosologically speaking, under chronic rheumatism, of which he believed it to be an apyretic variety. But the importance of his researches resides in this—he pointed out that it differed essentially from gout, but that, in resemblance thereof, it might endure throughout life, its course diversified by remissions and exacerbations. Also he tells us that its excruciating pains, even when of prolonged standing, sometimes cease spontaneously, noting also that the joints are, so to speak, turned over, and that there are nodosities, especially on the inside of the fingers.

Nevertheless, if we except Musgrave’s work (1703), “Arthritis ex Chlorosi,” which included some undoubted examples of rheumatoid or atrophic arthritis, no note was taken of Sydenham’s contention until a century afterwards. True, John Hunter in 1759 described the morbid anatomy of osteoarthritis or the hypertrophic forms of arthritis deformans, but not until 1868 was the true significance of Sydenham’s work appreciated, a most generous tribute being then accorded him by the great French physician Trousseau.

In 1800 Landre Beauvais published his clinical description of rheumatoid arthritis under the title “goutte asthenique primitif.” That Beauvais, as Sir Archibald Garrod contends, included under this title some cases of true gout is beyond doubt. But the words “Doit admettre une nouvelle espèce de goutte,” go far to justify Charcot in his claim that Beauvais, despite the title of his brochure, fully realised that the disease differed from gout.

A few years later (1804-1816), Heberden, in his Commentaries, insisted on the essential distinctness of rheumatoid arthritis from gout. Thus he wrote, “The disease called chronical rheumatism, which often passes under the general name of rheumatism and is sometimes supposed to be gout, is in reality a very different distemper from the genuine gout, and from the acute rheumatism, and ought to be carefully distinguished from both.” As to its salient features he noted its afebrile nature, the lack of redness in the skin over the affected joints, the relative absence of pain, and that it displayed no special tendency to begin in the feet. It was further marked by a protracted course involving severe crippling,[18] while the peculiar nodosities on the fingers are still associated with his name.

In 1805 Haygarth published his classical essay, “A Clinical History of the Nodosity of the Joints,” the opening sentence of which shows that, comparably with his successors, he lamented the laxity with which the term “rheumatism” was invoked and applied “to a great variety of disorders which beside pain, have but few symptoms that connect them together.” A purist in nosology, he equally deplored the term “rheumatick gout” as tending to perpetuate its confusion with gout and rheumatism, and suggested the term “Nodosities,” in the hope that “as a distinct genus it will become a more direct object of medical attention.”

Alas, even as late as 1868 Trousseau deplored the retention of the term “rheumatic gout” by Garrod and Fuller and his own countryman Trastour. But, in common justice to Garrod, it must be allowed that in the third edition of his work he definitely applied the term rheumatoid arthritis to the disorder in question. Nor can we refrain from recording Fuller’s words that “the natural history of rheumatic gout accords but little with that of acute rheumatism, and is equally inconsistent with that of true gout.”

In reviewing the researches of the foregoing writers it will be clearly seen that though they did yeoman service in differentiating broadly gout from the disorders grouped under Arthritis Deformans, there is little doubt that not for many years afterwards was their distinctiveness sufficiently realised. This may be in large part attributed to the fact that they still awaited the next great process of fission as applied to chronic joint disorders.

I allude in the first place to Charcot’s momentous discovery of the nerve arthropathies, and secondly, to the cleavage of arthritis deformans into the rheumatoid or atrophic, and the osteoarthritic or hypertrophic varieties.

It is to Vidal that we are indebted for the first clinical description of the atrophic type. Charcot in his lectures refers to it as the “Atrophic form of Vidal,” noting that in this variety “induration of the skin, a sort of scleroderma develops, the cutaneous covering is cold, pale, smooth, polished, and will not wrinkle, adding also that in such cases atrophy of the bones and muscles accompanies the wasting of the soft tissues.”

Notwithstanding this, Charcot, to our mind, unquestionably refers to the category of chronic articular gout certain of these examples of Vidal’s atrophic type of arthritis deformans. The[19] reasons he adduces for their gouty nature are, to say the least of it, both conflicting and unconvincing. On the one hand, he admits that they are clinically indistinguishable from Vidal’s type, in respect of their pronounced atrophic changes; on the other, he postulates them as gouty even though the uratic deposits “either do not exist at all, or only mere traces of them, or when only the articular cartilages are invaded by the urate of soda.” It must be conceded that chronic articular gout and rheumatoid or atrophic arthritis are totally distinct affections.

Now as to the hypertrophic variety, or osteoarthritis, which, of the twain, more closely resembles gout, and whose confusion therewith is far from infrequent even at the present time. Sir Dyce Duckworth, while he recognises with Charcot a tophaceous form of chronic articular gout, postulates the existence of another type, arthritis deformans uratica. Unlike Charcot, however, he seems only to have included under this term instances of the osteoarthritic or hypertrophic variety. But like Charcot, his claim that this particular variety is of gouty nature seems to rest on equally frail foundations, as witness his statement that they “may be complicated with visible or invisible tophaceous deposits!”

That osteoarthritis and gout may coexist in the same individual is certain, and equally sure is it that uratic deposits may supervene in joints the seat of osteoarthritis. But it is now, I think, generally conceded that, despite these coincidences, gouty arthritis and osteoarthritis are wholly distinct disorders, of wholly different origin.

At this period of our historical résumé we see that by the withdrawal of these three great groups—rheumatism, the nerve arthropathies and arthritis deformans—the domain of gout has, through these several allotments, undergone substantial shrinkage.

Yet again was the territory of gout destined to undergo further restriction, and this largely owing to the rise of the science of bacteriology. For in light of recent improvements in diagnostic methods, who can escape the conviction that under the term “gout” had been wrongfully included many forms of arthritis, now known to be due to specific infections. What, for example, of Hippocrates’ aphorism that gout was unknown in youths—ante usum veneris—who can doubt that some of his reputed cases of gout were examples of gonococcal or syphilitic arthritis?

What, too, of all the other infective arthritides—influenzal, pneumoccocal, scarlatinal, typhoidal, meningococcal—to mention only those actually affiliated to some specific organism. For gout,[20] be it noted, confers no exemption from other arthritic diseases, but how in time past were such to be differentiated therefrom?

Again, gouty subjects, as has been recently emphasised, are notoriously prone to pyorrhœa alveolaris, and how difficult, given the supervention of an arthritis in such to define the causal agent—gout or sepsis, which? Small wonder then, that the clinical content of gout, not only to ancient, but also to latter day physicians, loomed large, swollen as it undoubtedly was by the inclusion of infective arthritides, not to mention those of traumatic or static origin.

That more of these alien joint disorders—les pseudo-rheumatismes infectieux, as M. Bouchard terms them, were relegated to the “rheumatic” than to the “gouty” category, may perhaps be allowed, but still gout was undoubtedly allotted its full share and to boot. Moreover, if to “rheumatism” was wrongly affiliated the lion’s share of the infective arthritides, on the other hand to “gout” accrued a host of unrelated visceral disorders, not to mention affections of the nervous and vascular structures, etc.

In endeavouring to summarise the results of our brief retrospect, the somewhat chastening fact emerges, viz., that the isolation of articular gout has been achieved not so much by an increase in our knowledge as to what is gout, but through our growing perception of what is not gout. For of the causa causans of gout we are still as ignorant as in the days of Sydenham. But, in contrast, our enlightenment as to the clinical and pathological features of other forms of arthritis has steadily progressed. In this way, shorn of many alien joint disorders, gouty arthritis has slowly but surely asserted itself as a specific joint affection, distinct both from rheumatism and arthritis deformans.

In the course of our sketch, too, we have traced the evolution of the modern opinion that at least two separate conditions, “rheumatoid arthritis” and “osteoarthritis,” are comprised under arthritis deformans. This most tardily arrived at differentiation has done more than any other to clarify our conceptions as to what constitutes true “gouty arthritis.”

If to this be added the further differentiation, not only of the nerve arthropathies, but also of the infective arthridites—both specific and undifferentiated forms—it will be seen that the term “gouty arthritis,” once the most comprehensive perhaps in all medical nomenclature, has now been brought within, at any rate, reasonable distance of more or less exact definition.

The fanciful views of the humoralists as to the etiology of gout exercised almost undisputed sway up to the latter half of the eighteenth century. At that time the great Scottish physician, Cullen, took up arms against a doctrine which appeared to him unjustifiable in conception and baneful in practice. He inclined to the solidists rather than to the humoralists, claiming that gout was the outcome of a peculiar bodily conformation, and more especially of an affection of the nervous system. While he categorically denied that any materia peccans was the cause of gout, he yet admitted that in prolonged cases a peculiar matter appeared in gouty patients. But, in view of latter day revelations, Cullen, with singular prescience, maintained that the said matter was the effect and not the cause of gout.

Albeit, notwithstanding the almost universal deference accorded to Cullen, his theory, promulgated in 1874, though previously adumbrated by Stahl and afterwards reinforced by Henle, secured but few adherents. The source of this was not far to seek. For ever since the discovery of uric acid by Scheele in 1776, and its detection in tophi by Wollaston, an increasing body of opinion inclined to the view, that in some obscure way the life history of gout was bound up with that of uric acid.

Still, despite able advocacy in this country by Sir Henry Holland, Wollaston, and others, not to mention Continental authorities, such as Cruveilhier, it was felt that scientific proof of the truth of their contention was still lacking. But not for long were they left in doubt. For, in 1848, Sir Alfred Garrod’s momentous and epoch-making discovery of the presence of uric acid in the blood of the victims of gout allayed all doubts, and seemed then and for long after an all-sufficient explanation of the protean manifestations of the disease.

This distinguished physician enunciated his views in a series of propositions which embodied the result of his researches and incidentally laid the foundations of the uric acid theory.

This great physician held that, in true gout, uric acid in the form of urate of soda was, both prior to and during an attack, invariably present in the blood in abnormal quantities, and was moreover essential to its production; but with this reservation, that occasionally for a short time uric acid might be present in the circulating fluid without exciting inflammatory symptoms. This comparably with what obtains in lead poisoning, and on this account therefore he did not claim that the mere presence of uric acid therein would explain the occurrence of the gouty paroxysm.

He further averred that gouty inflammation is always accompanied by a deposition of urate of soda, crystalline and interstitial, in the inflamed part. Also that “the deposited urate of soda may be looked upon as the cause and not the effect of the gouty inflammation. Moreover, that the said inflammation tends to destruction of the urate of soda not only in the blood of the inflamed part, but also in the system generally.”

In addition, Garrod postulated implication of the kidneys, probably in the early, and certainly in the chronic stages of gout; and that the renal affection, though possibly only functional at first, subsequently became organic, with alterations in the urinary secretions.

As to the anomalous symptoms met with in gouty subjects, and alike those premonitory of a paroxysm, he ascribed them to the impure state of the blood, and due principally to the presence therein of urate of soda. Of causes predisposing to gout, if we except those attaching to individual peculiarities, they are either such as will lead to increased formation of uric acid or to retention of the same in the blood.

On the other hand, the determining causes of a gouty fit are those which induce a less alkaline condition of the blood, or which greatly augment for the time the formation of uric acid or such as temporarily check the eliminating powers of the kidneys. Lastly, his final axiom was that—in no disease but true gout is there a deposition of uric acid.

No tribute to Garrod’s masterly achievement could err on the side of generosity. A truly scientific physician, he built on the rock of sound clinical and pathological observations. For measured restraint, he stands out in pleasing contrast to those who, lacking his clinical acumen and sound judgment, brought not grist to the mill, but vain imaginings based on Garrod’s hard-won facts. His researches in truth constitute a landmark in the history of the pathology of gout, with their substitution of facts for pure hypotheses. True, though it was that, for half a century[23] before, there was a growing suspicion that lithic (uric) acid was the malign factor in the induction of gout, still it was not till Garrod’s discovery of uric acid in the blood and tissues of the “gouty,” that any definite step towards the elucidation of the problem presented by gout was attained.

One aspect of Garrod’s theory that much exercised the minds of his contemporaries was that for him uric acid was the alpha and omega of the disease, and as Ewart remarks, “If we are not over-anxious as to the stability of this mid-air foundation, everything is evolved smoothly from it on the lines of the theory.” Fortunately, however, for the progress of the art of medicine, men were over-anxious as to the why and wherefore of that accumulation of uric acid in the blood which Garrod held to be a necessary antecedent of gout. He himself, as we know, attributed it to a functional renal defect which may be inherited or acquired. To others, however, this assumption of renal inadequacy was not wholly satisfying, hence the origin of the many widely differing hypotheses from time to time advanced as to the pathogeny of the disorder.

Broadly speaking, the various conceptions proffered as to the causation of gout fall into one or other of the following categories. The primary alteration in gout is variously assumed to be:—

(1) In the blood or tissues, the so-called histogenous theories.

(2) In the bodily structures, either inborn or induced.

(3) In hepatic inadequacy.

(4) In hyperpyræmia.

(5) In the nervous system.