Nº. 1. Vol. 6.

Sketch

of the

CATALONIAN OPERATIONS

1813-14

with the Plan of a

position at

CAPE SALOU

proposed by

GENL. DONKIN

to

SIR S. MURRAY.

London, Pubd. by T. & W. BOONE, 1840. Drawn by Col. Napier

Title: History of the war in the Peninsula and in the south of France from the year 1807 to the year 1814, vol. 6

Author: William Francis Patrick Napier

Release date: February 6, 2023 [eBook #69964]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Thomas & William Boone, 1840

Credits: Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

This is volume 6 of 6. Similar to volumes 4 and 5, this volume had a date (Year. Month) as a margin header on most pages. This information about the chronology of the narrative has been preserved as a Sidenote to the relevant paragraph on that page, whenever the header date changed.

With a few exceptions noted at the end of the book, variant spellings of names have not been changed.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

Volume 1 of this series can be found at

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/67318

Volume 2 of this series can be found at

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/67554

Volume 3 of this series can be found at

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/68187

Volume 4 of this series can be found at

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/68536

Volume 5 of this series can be found at

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/69220

AND IN THE

SOUTH OF FRANCE,

FROM THE YEAR 1807 TO THE YEAR 1814.

BY

W. F. P. NAPIER, C.B.

COLONEL H. P. FORTY-THIRD REGIMENT, MEMBER OF THE ROYAL SWEDISH

ACADEMY OF MILITARY SCIENCES.

VOL. VI.

PREFIXED TO WHICH ARE

SEVERAL JUSTIFICATORY PIECES

IN REPLY TO

COLONEL GURWOOD, MR. ALISON, SIR WALTER SCOTT,

LORD BERESFORD, AND THE QUARTERLY REVIEW.

LONDON:

THOMAS & WILLIAM BOONE, NEW BOND-STREET.

MDCCCXL.

LONDON:

MARCHANT, PRINTER, INGRAM-COURT, FENCHURCH-STREET.

| Notice and Justification, &c., &c. | Page i |

| BOOK XXI. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Lord Wellington blockades Pampeluna, besieges St. Sebastian—Operations on the eastern coast of Spain—General Elio’s misconduct—Sir John Murray sails to attack Taragona—Colonel Prevot takes St. Felippe de Balaguer—Second siege of Taragona—Suchet and Maurice Mathieu endeavour to relieve the place—Sir John Murray raises the siege—Embarks with the loss of his guns—Disembarks again at St. Felippe de Balaguer—Lord William Bentinck arrives—Sir John Murray’s trial—Observations | Page 1 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Danger of Sicily—Averted by Murat’s secret defection from the emperor—Lord William Bentinck re-embarks—His design of attacking the city of Valencia frustrated—Del Parque is defeated on the Xucar—The Anglo-Sicilians disembark at Alicant—Suchet prepares to attack the allies—Prevented by the battle of Vittoria—Abandons Valencia—Marches towards Zaragoza—Clauzel retreats to France—Paris evacuates Zaragoza—Suchet retires to Taragona—Mines the walls—Lord William Bentinck passes the Ebro—Secures the Col de Balaguer—Invests Taragona—Partial insurrection in Upper Catalonia—Combat of Salud—Del Parque joins lord William Bentinck who projects an attack upon Suchet’s cantonments—Suchet concentrates his army—Is joined by Decaen—Advances—The allies retreat to the mountains—Del Parque invests Tortoza—His rear-guard attacked by the garrison while passing the Ebro—Suchet blows up the walls of Taragona—Lord William desires to besiege Tortoza—Hears that Suchet has detached troops—Sends Del Parque’s army to join lord Wellington—Advances to Villa Franca—Combat of Ordal—The allies retreat—Lord Frederick Bentinck fights with the French general Myers and wounds him—Lord William returns to Sicily—Observations | 33 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Siege of Sebastian—Convent of Bartolomeo stormed—Assault on the place fails—Causes thereof—Siege turned into a blockade, and the guns embarked at Passages—French make a successful sally | 65 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| Soult appointed the emperor’s lieutenant—Arrives at Bayonne—Joseph goes to Paris—Sketch of Napoleon’s political and military situation—His greatness of mind—Soult’s activity—Theatre of operations described—Soult resolves to succour Pampeluna—Relative positions and numbers of the contending armies described | 86 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Soult attacks the right of the allies—Combat of Roncesvalles—Combat of Linzoain—Count D’Erlon attacks the allies’ right centre—Combat of Maya—General Hill takes a position at Irueta—General Picton and Cole retreat down the Val de Zubiri—They turn at Huarte and offer battle—Lord Wellington arrives—Combat of the 27th—First battle of Sauroren—Various movements—D’Erlon joins Soult who attacks general Hill—Second battle of Sauroren—Foy is cut off from the main army—Night march of the light division—Soult retreats—Combat of Doña Maria—Dangerous position of the French at San Estevan—Soult marches down the Bidassoa—Forced march of the light division—Terrible scene near the bridge of Yanzi—Combats of Echallar and Ivantelly—Narrow escape of lord Wellington—Observations | 109 |

| BOOK XXII. | |

| CHAP. I. | |

| New positions of the armies—Lord Melville’s mismanagement of the naval co-operation—Siege of St. Sebastian—Progress of the second attack | 179 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Storming of St. Sebastian—Lord Wellington calls for volunteers from the first fourth and light divisions—The place is assaulted and taken—The town burned—The castle is bombarded and surrenders—Observations | 197 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Soult’s views and positions during the siege described—He endeavours to succour the place—Attacks lord Wellington—Combats of San Marcial and Vera—The French are repulsed the same day that San Sebastian is stormed—Soult resolves to adopt a defensive system—Observations | 218 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| The duke of Berri proposes to invade France promising the aid of twenty thousand insurgents—Lord Wellington’s views on this subject—His personal acrimony against Napoleon—That monarch’s policy and character defended—Dangerous state of affairs in Catalonia—Lord Wellington designs to go there himself, but at the desire of the allied sovereigns and the English government resolves to establish a part of his army in France—His plans retarded by accidents and bad weather—Soult unable to divine his project—Passage of the Bidassoa—Second combat of Vera—Colonel Colborne’s great presence of mind—Gallant action of lieutenant Havelock—The French lose the redoubt of Sarre and abandon the great Rhune—Observations | 239 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Soult retakes the redoubt of Sarre—Wellington organizes the army in three great divisions under sir Rowland Hill, marshal Beresford, and sir John Hope—Disinterested conduct of the last-named officer—Soult’s immense entrenchments described—His correspondence with Suchet—Proposes to retake the offensive and unite their armies in Aragon—Suchet will not accede to his views and makes inaccurate statements—Lord Wellington, hearing of advantages gained by the allied sovereigns in Germany, resolves to invade France—Blockade and fall of Pampeluna—Lord Wellington organizes a brigade under lord Aylmer to besiege Santona, but afterwards changes his design | 271 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Political state of Portugal—Violence, ingratitude, and folly of the government of that country—Political state of Spain—Various factions described, their violence, insolence, and folly—Scandalous scenes at Cadiz—Several Spanish generals desire a revolution—Lord Wellington describes the miserable state of the country—Anticipates the necessity of putting down the Cortez by force—Resigns his command of the Spanish armies—The English ministers propose to remove him to Germany—The new Cortez reinstate him as generalissimo on his own terms—He expresses his fears that the cause will finally fail and advises the English ministers to withdraw the British army | 295 |

| BOOK XXIII. | |

| CHAP. I. | |

| War in the south of France—Soult’s political difficulties—Privations of the allied troops—Lord Wellington appeals to their military honour with effect—Averse to offensive operations, but when Napoleon’s disasters in Germany became known, again yields to the wishes of the allied sovereigns—His dispositions of attack retarded—They are described—Battle of the Nivelle—Observations—Deaths and characters of Mr. Edward Freer and colonel Thomas Lloyd | 326 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Soult occupies the entrenched camp of Bayonne, and the line of the Nive river—Lord Wellington unable to pursue his victory from the state of the roads—Bridge-head of Cambo abandoned by the French—Excesses of the Spanish troops—Lord Wellington’s indignation—He sends them back to Spain—Various skirmishes in front of Bayonne—The generals J. Wilson and Vandeleur are wounded—Mina plunders the Val de Baygorry—Is beaten by the national guards—Passage of the Nive and battles in front of Bayonne—Combat of the 10th—Combat of the 11th—Combat of the 12th—Battle of St. Pierre—Observations | 363 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Respective situations and views of lord Wellington and Soult—Partizan warfare—The Basques of the Val de Baygorry excited to arms by the excesses of Mina’s troops—General Harispe takes the command of the insurgents—Clauzel advances beyond the Bidouze river—General movements—Partizan combats—Excesses committed by the Spaniards—Lord Wellington reproaches their generals—His vigorous and resolute conduct—He menaces the French insurgents of the valleys with fire and sword and the insurrection subsides—Soult hems the allies right closely—Partizan combats continued—Remarkable instances of the habits established between the French and British soldiers of the light division—Shipwrecks on the coast | 410 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| Political state of Portugal—Political state of Spain—Lord Wellington advises the English government to prepare for a war with Spain and to seize St. Sebastian as a security for the withdrawal of the British and Portuguese troops—The seat of government and the new Cortez are removed to Madrid—The duke of San Carlos arrives secretly with the treaty of Valençay—It is rejected by the Spanish regency and Cortez—Lord Wellington’s views on the subject | 425 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Political state of Napoleon—Guileful policy of the allied sovereigns—M. de St. Aignan—General reflections—Unsettled policy of the English ministers—They neglect lord Wellington—He remonstrates and exposes the denuded state of his army | 440 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| Continuation of the war in the eastern provinces—Suchet’s erroneous statements—Sir William Clinton repairs Taragona—Advances to Villa Franca—Suchet endeavours to surprise him—Fails—The French cavalry cut off an English detachment at Ordal—The duke of San Carlos passes through the French posts—Copons favourable to his mission—Clinton and Manso endeavour to cut off the French troops at Molino del Rey—They fail through the misconduct of Copons—Napoleon recalls a great body of Suchet’s troops—Whereupon he reinforces the garrison of Barcelona and retires to Gerona—Van Halen—He endeavours to beguile the governor of Tortoza—Fails—Succeeds at Lerida, Mequinenza, and Monzon—Sketch of the siege of Monzon—It is defended by the Italian soldier St. Jaques for one hundred and forty days—Clinton and Copons invest Barcelona—The beguiled garrisons of Lerida, Mequinenza, and Monzon, arrive at Martorel—Are surrounded and surrender on terms—Capitulation violated by Copons—King Ferdinand returns to Spain—His character—Clinton breaks up his army—His conduct eulogised—Lamentable sally from Barcelona—The French garrisons beyond the Ebro return to France and Habert evacuates Barcelona—Fate of the prince of Conti and the duchess of Bourbon—Siege of Santona | 475 |

| BOOK XXIV. | |

| CHAP. I. | |

| Napoleon recalls several divisions of infantry and cavalry from Soult’s army—Embarrassments of that marshal—Mr. Batbedat a banker of Bayonne offers to aid the allies secretly with money and provisions—La Roche Jacquelin and other Bourbon partizans arrive at the allies’ head-quarter—The duke of Angoulême arrives there—Lord Wellington’s political views—General reflections—Soult embarrassed by the hostility of the French people—Lord Wellington embarrassed by the hostility of the Spaniards—Soult’s remarkable project for the defence of France—Napoleon’s reasons for neglecting it put hypothetically—Lord Wellington’s situation suddenly ameliorated—His wise policy, foresight, and diligence—Resolves to throw a bridge over the Adour below Bayonne, and to drive Soult from that river—Soult’s system of defence—Numbers of the contending armies—Passage of the Gaves—Combat of Garris—Lord Wellington forces the line of the Bidouze and Gave of Mauleon—Soult takes the line of the Gave de Oleron and resolves to change his system of operation | 505 |

| CHAP. II. | |

| Lord Wellington arrests his movements and returns in person to St. Jean de Luz to throw his bridge over the Adour—Is prevented by bad weather and returns to the Gave of Mauleon—Passage of the Adour by sir John Hope—Difficulty of the operation—The flotilla passes the bar and enters the river—The French sally from Bayonne but are repulsed and the stupendous bridge is cast—Citadel invested after a severe action—Lord Wellington passes the Gave of Oleron and invests Navarrens—Soult concentrates his army at Orthes—Beresford passes the Gave de Pau near Pereyhorade—Battle of Orthes—Soult changes his line of operations—Combat of Aire—Observations | 536 |

| CHAP. III. | |

| Soult’s perilous situation—He falls back to Tarbes—Napoleon sends him a plan of operations—His reply and views stated—Lord Wellington’s embarrassments—Soult’s proclamation—Observations upon it—Lord Wellington calls up Freyre’s Gallicians and detaches Beresford against Bordeaux—The mayor of that city revolts from Napoleon—Beresford enters Bordeaux and is followed by the duke of Angoulême—Fears of a reaction—The mayor issues a false proclamation—Lord Wellington expresses his indignation—Rebukes the duke of Angoulême—Recalls Beresford but leaves lord Dalhousie with the seventh division and some cavalry—Decaen commences the organization of the army of the Gironde—Admiral Penrose enters the Garonne—Remarkable exploit of the commissary Ogilvie—Lord Dalhousie passes the Garonne and the Dordogne and defeats L’Huillier at Etauliers—Admiral Penrose destroys the French flotilla—The French set fire to their ships of war—The British seamen and marines land and destroy all the French batteries from Blaye to the mouth of the Garonne | 580 |

| CHAP. IV. | |

| Wellington’s and Soult’s situations and forces described—Folly of the English ministers—Freyre’s Gallicians and Ponsonby’s heavy cavalry join lord Wellington—He orders Giron’s Andalusians and Del Parque’s army to enter France—Soult suddenly takes the offensive—Combats of cavalry—Partizan expedition of Captain Dania—Wellington menaces the peasantry with fire and sword if they take up arms—Soult retires—Lord Wellington advances—Combat of Vic Bigorre—Death and character of colonel Henry Sturgeon—Daring exploit of captain William Light[1]—Combat of Tarbes—Soult retreats by forced marches to Toulouse—Wellington follows more slowly—Cavalry combat at St. Gaudens—The allies arrive in front of Toulouse—Reflections | 603 |

| CHAP. V. | |

| Views of the commanders on each side—Wellington designs to throw a bridge over the Garonne at Portet above Toulouse, but below the confluence of the Arriege and Garonne—The river is found too wide for the pontoons—He changes his design—Cavalry action at St. Martyn de Touch—General Hill passes the Garonne at Pensaguel above the confluence of the Arriege—Marches upon Cintegabelle—Crosses the Arriege—Finds the country too deep for his artillery and returns to Pensaguel—Recrosses the Garonne—Soult fortifies Toulouse and the Mont Rave—Lord Wellington sends his pontoons down the Garonne—Passes that river at Grenade fifteen miles below Toulouse with twenty thousand men—The river floods and his bridge is taken up—The waters subside—The bridge is again laid—The Spaniards pass—Lord Wellington advances up the right bank to Fenouilhet—Combat of cavalry—The eighteenth hussars win the bridge of Croix d’Orade—Lord Wellington resolves to attack Soult on the 9th of April—Orders the pontoons to be taken up and relaid higher up the Garonne at Seilth in the night of the 8th—Time is lost in the execution and the attack is deferred—The light division cross at Seilth on the morning of the 10th—Battle of Toulouse | 624 |

| CHAP. VI. | |

| General observations and reflections | 657 |

| No. I. | |

| Lord William Bentinck’s correspondence with sir Edward Pellew and lord Wellington about Sicily | 691 |

| No. II. | |

| General Nugent’s and Mr. King’s correspondence with lord William Bentinck about Italy | 693 |

| No. III. | |

| Extracts from the correspondence of sir H. Wellesley, Mr. Vaughan, and Mr. Stuart upon Spanish and Portuguese affairs | 699 |

| No. IV. | |

| Justificatory pieces relating to the combats of Maya and Roncesvalles | 701 |

| No. V. | |

| Ditto ditto of Ordal | 703 |

| No. VI. | |

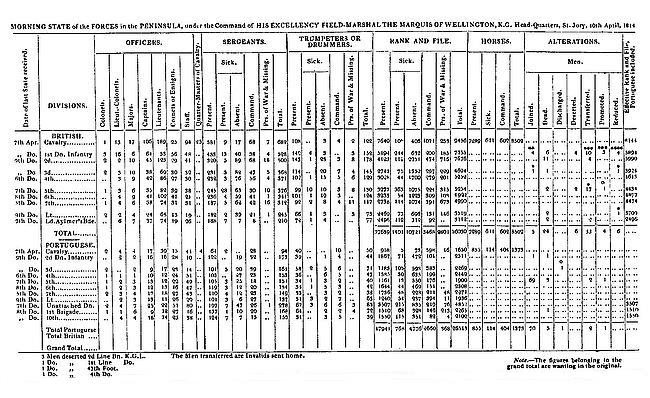

| Official States of the allied army in Catalonia | 704 |

| No. VII. | |

| Ditto of the Anglo-Portuguese at different epochs | 705 |

| No. VIII. | |

| Ditto of the French armies at different epochs | 707 |

| No. IX. | |

| Extract from lord Wellington’s order of movements for the battle of Toulouse | 709 |

| No. X. | |

| Note and morning state of the Anglo-Portuguese on the 10th of April, 1814 | 710 |

| No. 1. | Explanatory of the Catalonian Operations and plan of Position at Cape Salud. |

| 2. | Explanatory of Soult’s Operations to relieve Pampeluna. |

| 3. | Combats of Maya and Roncesvalles. |

| 4. | Explanatory Sketch of the Assault of St. Sebastian. |

| 5. | Explanatory Sketch of Soult’s and lord Wellington’s Passage of the Bidassoa. |

| 6. | Explanatory Sketch of the Battle of the Nivelle. |

| 7. | Explanatory Sketch of the Operations round Bayonne, and of the Battle. |

| 8. | Explanatory Sketch of the Battle of the Nive, and Battle of St. Pierre. |

| 9. | Explanatory Sketch of the Battle of Orthes, and the Retreat of Soult to Aire. |

| 10. | Explanatory Sketch of the Operations against Tarbes, and the Battle of Toulouse. |

| To follow Page 689. |

This volume was nearly printed when my attention was called to a passage in an article upon the duke of Wellington’s despatches, published in the last number of the “British and Foreign Quarterly Review.”

After describing colonel Gurwood’s proceedings to procure the publication of the despatches the reviewer says,

“We here distinctly state, that no other person ever had access to any documents of the duke, by his grace’s permission, for any historical or other purpose, and that all inferential pretensions to such privilege are not founded in fact.”

This assertion, which if not wholly directed against my history certainly includes it with others, I distinctly state to be untrue.

For firstly, the duke of Wellington gave me access to the original morning states of his army for the use of my history; he permitted me to take them into my possession, and I still have possession of them.

Secondly. The duke of Wellington voluntarily directed me to apply to sir George Murray for the “orders of movements.” That is to say the orders of battle issued by him to the different generals previous to every great action. Sir George Murray thought proper, as the reader will see in the justificatory pieces of this volume, to deny all knowledge of these “orders of movements.” I have since obtained some of them from others, but the permission to get them all was given to me at Strathfieldsaye, in the presence of lord Fitzroy Somerset, who was at the same time directed to give me the morning states and he did do so. These were documents of no ordinary importance for a history of the war.

Thirdly. Lord Fitzroy Somerset, with the consent of the duke of Wellington, put into my hands king Joseph’s portfolio, taken at Vittoria and containing that monarch’s correspondence with the emperor, with the French minister of war, and with the marshals and generals who at different periods were employed in the Peninsula. These also were documents of no slight importance for a history of the war, and they are still in my possession.

When I first resolved to write this History, I applied verbally to the duke of Wellington to give me papers in aid of my undertaking. His answer in substance was, that he had arranged all his own papers with a view to publication himself—that he had not decided in what form they should be given to the world, or when, probably not during his lifetime, but he thought his plan would be to “write a plain didactic history” to be published after his death—that he was resolved never to publish anything unless he could tell the whole truth, but at that time he could not tell the whole truth without wounding the feelings of many worthy men, without doing mischief: adding in a laughing way “I should do as much mischief as Buonaparte.” Then expatiating upon the subject he related to me many anecdotes illustrative of this observation, shewing errors committed by generals and others acting with him, or under him, especially at Waterloo; errors so materially affecting his operations that he could not do justice to himself if he suppressed them, and yet by giving them publicity he would ungraciously affect the fame of many worthy men whose only fault was dulness.

For these reasons he would not, he said, give me his own private papers, but he gave me the documents I have already noticed, and told me he would then, and always, answer any questions as to facts which I might in the course of my work think necessary to put. And he has fulfilled that promise rigidly, for I did then put many questions to him verbally and took notes of his answers, and many of the facts in my History which have been most cavilled at and denied by my critics have been related by me solely upon his authority. Moreover I have since at various times sent to the duke a number of questions in writing, and always they have been fully and carefully answered without delay, though often put when his mind must have been harassed and his attention deeply occupied by momentous affairs.

But though the duke of Wellington denied me access to his own peculiar documents, the greatest part of those documents existed in duplicate; they were in other persons’ hands, and in two instances were voluntarily transferred with other interesting papers to mine. Of this truth the reader may easily satisfy himself by referring to my five first volumes, some of which were published years before colonel Gurwood’s compilation appeared. He will find in those volumes frequent allusions to the substance of the duke’s private communications with the governments he served; and in the Appendix a number of his letters, printed precisely as they have since been given by colonel Gurwood. I could have greatly augmented the number if I had been disposed so to swell my work. Another proof will be found in the Justificatory Pieces of this volume, where I have restored the whole reading of a remarkable letter of the duke’s which has been garbled in colonel Gurwood’s compilation, and this not from any unworthy desire to promulgate what the duke of Wellington desired to suppress, but that having long before attributed, on the strength of that passage, certain strong opinions to his grace, I was bound in defence of my own probity as an historian to reproduce my authority.

W. F. P. NAPIER.

March 28th, 1840.

Having in my former volumes printed several controversial papers relating to this History, I now complete them, thus giving the reader all that I think necessary to offer in the way of answer to those who have assailed me. The Letter to marshal Beresford and the continuation of my Reply to the Quarterly Review have been published before, the first as a pamphlet, the second in the London and Westminster Review. And the former is here reproduced, not with any design to provoke the renewal of a controversy which has been at rest for some years, but to complete the justification of a work which, written honestly and in good faith from excellent materials, has cost me sixteen years of incessant labour. The other papers being new shall be placed first in order and must speak for themselves.

Some extracts from Alison’s History of the French Revolution reflecting upon the conduct of sir John Moore have been shewn to me by a friend. In one of them I find, in reference to the magazines at Lugo, a false quotation from my own work, not from carelessness but to sustain a miserable censure of that great man. This requires no further notice, but the following specimen of disingenuous writing shall not pass with impunity.

Speaking of the prevalent opinion that England was unable to succeed in military operations on the continent, Mr. Alison says:—

“In sir John Moore’s case this universal and perhaps unavoidable error was greatly enhanced by his connection with the opposition party, by whom the military strength of England had been always underrated, the system of[ii] continental operations uniformly decried, and the power and capacity of the French emperor, great as they were, unworthily magnified.”

Mr. Alison here proves himself to be one of those enemies to sir John Moore who draw upon their imaginations for facts and upon their malice for conclusions.

Sir John Moore never had any connection with any political party, but during the short time he was in parliament he voted with the government. He may in society have met with some of the leading men of opposition thus grossly assailed by Mr. Alison, yet it is doubtful if he ever conversed with any of them, unless perhaps Mr. Wyndham, with whom, when the latter was secretary at war, he had a dispute upon a military subject. He was however the intimate friend of Mr. Pitt and of Mr. Pitt’s family. It is untrue that sir John Moore entertained or even leaned towards exaggerated notions of French prowess; his experience and his natural spirit and greatness of mind swayed him the other way. How indeed could the man who stormed the forts of Fiorenza and the breach of Calvi in Corsica, he who led the disembarkation at Aboukir Bay, the advance to Alexandria on the 13th, and defended the ruins of the camp of Cæsar on the 21st of March, he who had never been personally foiled in any military exploit feel otherwise than confident in arms? Mr. Alison may calumniate but he cannot hurt sir John Moore.

In the last volume of sir Walter Scott’s life by Mr. Lockhart, page 143, the following passage from sir Walter’s diary occurs:—

“He (Napier) has however given a bad sample of accuracy in the case of lord Strangford, where his pointed affirmation has been as pointedly repelled.”

This peremptory decision is false in respect of grammar, of logic, and of fact.

Of grammar because where, an adverb of place, has[iii] no proper antecedent. Of logic, because a truth may be pointedly repelled without ceasing to be a truth. Of fact because lord Strangford did not repel but admitted the essential parts of my affirmation, namely, that he had falsified the date and place of writing his dispatch, and attributed to himself the chief merit of causing the royal emigration from Lisbon. Lord Strangford indeed, published two pamphlets to prove that the merit really attached to him, but the hollowness of his pretensions was exposed in my reply to his first pamphlet; theVide Times, Morning Chronicle, Sun, &c. 1828. accuracy of my statement was supported by the testimony of disinterested persons, and moreover many writers, professing to know the facts, did, at the time, in the newspapers, contradict lord Strangford’s statements.

The chief point of his second pamphlet, was the reiterated assertion that he accompanied the prince regent over the bar of Lisbon.

To this I could have replied, 1º. That I had seen a letter, written at the time by Mr. Smith the naval officer commanding the boat which conveyed lord Strangford from Lisbon to the prince’s ship, and in that letter it was distinctly stated, that they did not reach that vessel until after she had passed the bar. 2º. That I possessed letters from other persons present at the emigration of the same tenor, and that between the writers of those letters and the writer of the Bruton-street dispatch, to decide which were the better testimony, offered no difficulty.

Why did I not so reply? For a reason twice before published, namely, that Mr. Justice Bailey had done it for me. Sir Walter takes no notice of the judge’s answer, neither does Mr. Lockhart; and yet it was the most important point of the case. Let the reader judge.

The editor of the Sun newspaper after quoting an article from the Times upon the subject of my controversy with lord Strangford, remarked, that his lordship “wouldVide Sun newspaper 28th Nov. 1828. hardly be believed upon his oath, certainly not upon his honour at the Old Bailey.”

Lord Strangford obtained a rule to shew cause why a criminal information should not be filed against the editor for a libel. The present lord Brougham appeared for the[iv] defence and justified the offensive passage by references to lord Strangford’s own admissions in his controversy with me. The judges thinking the justification good, discharged the rule by the mouth of lord Tenterden.

During the proceedings in court the attorney-general, on the part of lord Strangford, referring to that nobleman’s dispatch which, though purporting to be written on the 29th November from H.M.S. Hibernia off the Tagus was really written the 29th of December in Bruton-street, said, “Every body knew that in diplomacy there were twoReport in the Sun newspaper copies prepared of all documents, No. 1 for the minister’s inspection, No. 2 for the public.”

Mr. Justice Bayley shook his head in disapprobation.

Attorney-general—“Well, my lord, it is the practice of these departments and may be justified by necessity.”

Mr. Justice Bayley—“I like honesty in all places, Mr. Attorney.”

And so do I, wherefore I recommend this pointed repeller to Mr. Lockhart when he publishes another edition of his father-in-law’s life.

In the eighth volume of the Duke of Wellington’s Despatches page 531, colonel Gurwood has inserted the following note:—

“Lieutenant Gurwood fifty-second regiment led the “forlorn hope” of the light division in the assault of the lesser breach. He afterwards took the French governor general Barrié in the citadel; and from the hands of lord Wellington on the breach by which he had entered, he received the sword of his prisoner. The permission accorded by the duke of Wellington to compile this work has doubtless been one of the distinguished consequences resulting from this service, and lieutenant Gurwood feels pride as a soldier of fortune in here offering himself as an encouraging example to the subaltern in future wars.”—“The detail of the assault of Ciudad Rodrigo by the lesser breach is of too little importance except to those[v] who served in it to become a matter of history. The compiler however takes this opportunity of observing that colonel William Napier has been misinformed respecting the conduct of the “forlorn hope,” in the account given of it by him as it appears in the Appendix of the fourth volume of his History of the Peninsular War. A correct statement and proofs of it have been since furnished to colonel William Napier for any future edition of his book which will render any further notice of it here unnecessary.”

My account is not to be disposed of in this summary manner, and this note, though put forth as it were with the weight of the duke of Wellington’s name by being inserted amongst his Despatches, shall have an answer.

Colonel Gurwood sent me what in the above note he calls “a correct statement and proofs of it.” I know of no proofs, and the correctness of his statement depends on his own recollections which the wound he received in the head at this time seems to have rendered extremely confused, at least the following recollections of other officers are directly at variance with his. Colonel Gurwood in his “correct statement” says, “When I first went up the breach there were still some of the enemy in it, it was very steep and on my arrival at the top of it under the gun I was knocked down either by a shot or stone thrown at me. I can assure you that not a lock was snapped as you describe, but finding it impossible that the breach from its steepness and narrowness could be carried by the bayonet I ordered the men to load, certainly before the arrival of the storming party, and having placed some of the men on each side of the breach I went up the middle with the remainder, and when in the act of climbing over the disabled gun at the top of the breach which you describe, I was wounded in the head by a musquet shot fired so close to me that it blew my cap to pieces, and I was tumbled over senseless from the top to the bottom of the breach. When I recovered my senses I found myself close to George,[2] who was sitting on a stone with his arm broken, I asked him how the thing was going on, &c. &c.”

Now to the above statement I oppose the following letters from the authors of the statements given in the Appendix to my fourth volume.

Major-General Sir George Napier to Colonel William Napier.

“I am sorry our gallant friend Gurwood is not satisfied with and disputes the accuracy of your account of the assault of the lesser breach at Ciudad Rodrigo as detailed in your fourth volume. I can only say, that account was principally, if not wholly taken from colonel Fergusson’s, he being one of my storming captains, and my own narrative of that transaction up to the period when we were each of us wounded. I adhere to the correctness of all I stated to you, and beg further to say that my friend colonel Mitchell, who was also one of my captains in the storming party, told me the last time I saw him at the commander-in-chief’s levee, that my statement was “perfectly correct.” And both he and colonel Fergusson recollected the circumstance of my not permitting the party to load, and also that upon being checked, when nearly two-thirds up the breach, by the enemy’s fire, the men forgetting their pieces were not loaded snapped them off, but I called to them and reminded them of my orders to force their way with the bayonet alone! It was at that moment I was wounded and fell, and I never either spoke to or saw Gurwood afterwards during that night, as he rushed on with the other officers of the party to the top of the breach. Upon looking over a small manuscript of the various events of my life as a soldier, written many years ago, I find all I stated to you corroborated in every particular. Of course as colonel Gurwood tells you he was twice at the top of the breach, before any of the storming party entered it, I cannot take upon myself to contradict him, but I certainly do not conceive how it was possible, as he and myself jumped into the ditch together, I saw him wounded, and spoke to him after having mounted the faussbraye with him, and before we rushed up the breach in the body of the place. I never saw him or spoke to him after I was struck down, the whole affair did not last above twenty-five or thirty minutes, but as I fell when about two-thirds up the breach I can only answer[vii] for the correctness of my account to that period, as soon after I was assisted to get down the breach by the Prince of Orange (who kindly gave his sash to tie up my shattered arm and which sash is now in my possession) by the present duke of Richmond and lord Fitzroy Somerset, all three of whom I believe were actively engaged in the assault. Our friend Gurwood did his duty like a gallant and active soldier, but I cannot admit of his having been twice in the breach before the other officers of the storming party and myself!

“I believe yourself and every man in the army with whom I have the honor to be acquainted will acquit me of any wish or intention to deprive a gallant comrade and brother-officer of the credit and honor due to his bravery, more particularly one with whom I have long been on terms of intimate friendship, and whose abilities I admire as much as I respect and esteem his conduct as a soldier; therefore this statement can or ought only to be attributed to my sense of what is due to the other gallant officers and soldiers who were under my command in the assault of the lesser breach of Ciudad Rodrigo, and not to any wish or intention on my part to detract from the distinguished services of, or the laurels gained by colonel Gurwood on that occasion. Of course you are at liberty to refer to me if necessary and to make what use you please of this letter privately or publicly either now or at any future period, as I steadily adhere to all I have ever stated to you or any one else and I am &c. &c.

“George Napier.”

Extract of a letter from colonel James Fergusson, fifty-second regiment (formerly a captain of the forty-third and one of the storming party.) Addressed to Sir George Napier.

“I send you a memorandum I made some time back from memory and in consequence of having seen various accounts respecting our assault. You are perfectly correct as to Gurwood and your description of the way we carried the breach is accurate; and now I have seen your memorandum I recollect the circumstance of the men’s arms not[viii] being loaded and the snapping of the firelocks.”—“I was not certain when you were wounded but your description of the scene on the breach and the way in which it was carried is perfectly accurate.”

Extract of a letter from colonel Fergusson to colonel William Napier.

“I think the account you give in your fourth volume of the attack of the little breach at Ciudad Rodrigo is as favorable to Gurwood as he has any right to expect, and agrees perfectly both with your brother George’s recollections of that attack and with mine. Our late friend Alexander Steele who was one of my officers declared he was with Gurwood the whole of the time, for a great part of the storming party of the forty-third joined Gurwood’s party who were placing the ladders against the work, and it was the engineer officer calling out that they were wrong and pointing out the way to the breach in the fausse braye that directed our attention to it. Jonathan Wyld[3] of the forty-third was the first man that run up the fausse braye, and we made directly for the little breach which was defended exactly as you describe. We were on the breach some little time and when we collected about thirty men (some of the third battalion rifle brigade in the number) we made a simultaneous rush, cheered, and run in, so that positively no claim could be made as to the first who entered the breach. I do not want to dispute with Gurwood but I again say (in which your brother agrees) that some of the storming party were before the forlorn hope. I do not dispute that Gurwood and some of his party were among the number that rushed in at the breach, but as to his having twice mounted the breach before us, I cannot understand it, and Steele always positively denied it.”

Having thus justified myself from the charge of writing upon bad information about the assault of the little breach I shall add something about that of the great breach.

Colonel Gurwood offers himself as an encouraging example for the subalterns of the British army in future wars; but the following extract from a statement of the late major Mackie, so well known for his bravery worth and modesty, and who as a subaltern led the forlorn hope at the great breach of Ciudad Rodrigo, denies colonel Gurwood’s claim to the particular merit upon which he seems inclined to found his good fortune in after life.

Extracts from a memoir addressed by the late Major Mackie to Colonel Napier. October 1838.

“The troops being immediately ordered to advance were soon across the ditch, and upon the breach at the same instant with the ninety-fourth who had advanced along the ditch. To mount under the fire of the defenders was the work of a moment, but when there difficulties of a formidable nature presented themselves; on each flank a deep trench was cut across the rampart isolating the breach, which was enfiladed with cannon and musquetry, while in front, from the rampart into the streets of the town, was a perpendicular fall of ten or twelve feet; the whole preventing the soldiers from making that bold and rapid onset so effective in facilitating the success of such an enterprize. The great body of the fire of defence being from the houses and from an open space in front of the breach, in the first impulse of the moment I dropt from the rampart into the town. Finding myself here quite alone and no one following, I discovered that the trench upon the right of the breach was cut across the whole length of the rampart, thereby opening a free access to our troops and rendering what was intended by the enemy as a defence completely the reverse. By this opening I again mounted to the top of the breach and led the men down into the town. The enemy’s fire which I have stated had been, after we gained the summit of the wall, confined to the houses and open space alluded to, now began to slacken, and ultimately they abandoned the defence. Being at this time in advance of the whole of the third division, I led what men I could collect along the street, leading in a direct line from the great breach into the centre of the town, by which street[x] the great body of the enemy were precipitately retiring. Having advanced considerably and passed across a street running to the left, a body of the enemy came suddenly from that street, rushed through our ranks and escaped. In pursuit of this body, which after passing us held their course to the right, I urged the party forwards in that direction until we reached the citadel, where the governor and garrison had taken refuge. The outer gate of the enclosure being open, I entered at the head of the party composed of men of different regiments who by this time had joined the advance. Immediately on entering I was hailed by a French officer asking for an English general to whom they might surrender. Pointing to my epaulets in token of their security, the door of the keep or stronghold of the place was opened and a sword presented to me in token of surrender, which sword I accordingly received. This I had scarcely done when two of their officers laid hold of me for protection, one on each arm, and it was while I was thus situated that lieutenant Gurwood came up and obtained the sword of the governor.

“In this way, the governor, with lieutenant Gurwood and the two officers I have mentioned still clinging to my arms, the whole party moved towards the rampart. Having found when there, that in the confusion incident to such a scene I had lost as it were by accident that prize which was actually within my reach, and which I had justly considered as my own, in the chagrin of the moment I turned upon my heel and left the spot. The following day, in company with captain Lindsay of the eighty-eighth regiment I waited upon colonel Pakenham, then assistant adjutant-general to the third division, to know if my name had been mentioned by general Picton as having led the advance of the right brigade. He told me that it had and I therefore took no further notice of the circumstance, feeling assured that I should be mentioned in the way of which all officers in similar circumstances must be so ambitious. My chagrin and disappointment may be easily imagined when lord Wellington’s dispatches reached the army from England to find my name altogether omitted, and the right brigade deprived of their just meed of praise.”—“Sir,[xi] it is evident that the tendency of this note” (colonel Gurwood’s note quoted from the Despatches) “is unavoidably, though I do him the justice to believe by no means intentionally upon colonel Gurwood’s part, to impress the public with the belief that he was himself the first British officer that entered the citadel of Ciudad Rodrigo, consequently the one to whom its garrison surrendered. This impression the language he employs is the more likely to convey, inasmuch as to his exertions and good fortune in this particular instance he refers the whole of his professional success, to which he points the attention of the future aspirant as a pledge of the rewards to be expected from similar efforts to deserve them. To obviate this impression and in bare justice to the right brigade of the third division and, as a member of it, to myself, I feel called on to declare that though I do not claim for that brigade exclusively the credit of forcing the defences of the great breach, the left brigade having joined in it contrary to the intention of lord Wellington under the circumstances stated, yet I do declare on the word of a man of honour, that I was the first individual who effected the descent from the main breach into the streets of the town, that I preceded the advance into the body of the place, that I was the first who entered the citadel, and that the enemy there assembled had surrendered to myself and party before lieutenant Gurwood came up. Referring to the inference which colonel Gurwood has been pleased to draw from his own good fortune as to the certainty and value of the rewards awaiting the exertions of the British soldier, permit me, sir, in bare justice to myself to say that at the time I volunteered the forlorn hope on this occasion, I was senior lieutenant of my own regiment consequently the first for promotion. Having as such succeeded so immediately after to a company, I could scarcely expect nor did I ask further promotion at the time, but after many years of additional service, I did still conceive and do still maintain, that I was entitled to bring forward my services on that day as a ground for asking that step of rank which every officer leading a forlorn hope had received with the exception of myself.

“May I, sir, appeal to your sense of justice in lending me your aid to prevent my being deprived of the only reward I had hitherto enjoyed, in the satisfaction of thinking that the services which I am now compelled most reluctantly to bring in some way to the notice of the public, had during the period that has since elapsed, never once been called in question. It was certainly hard enough that a service of this nature should have been productive of no advantage to me in my military life. I feel it however infinitely more annoying that I should now find myself in danger of being stript of any credit to which it might entitle me, by the looseness of the manner in which colonel Gurwood words his statement. I need not say that this danger is only the more imminent from his statement appearing in a work which as being published under the auspices of the duke of Wellington as well as of the Horse Guards, has at least the appearance of coming in the guise of an official authority,” “I agree most cordially with colonel Gurwood in the opinion he has expressed in his note, that he is himself an instance where reward and merit have gone hand in hand. I feel compelled however, for the reasons given to differ from him materially as to the precise ground on which he considers the honours and advantages that have followed his deserts to be not only the distinguished but the just and natural consequences of his achievements on that day. I allude to the claim advanced by colonel Gurwood to be considered the individual by whom the governor of Ciudad Rodrigo was made prisoner of war. It could scarcely be expected that at such a moment I could be aware that the sword which I received was not the governor’s being in fact that of one of his aide-de-camps. I repeat however that before lieutenant Gurwood and his party came up, the enemy had expressed their wish to surrender, that a sword was presented by them in token of submission and received by me as a pledge, on the honour of a British officer, that according to the laws of war, I held myself responsible for their safety as prisoners under the protection of the British arms. Not a shadow of resistance was afterwards made and I appeal to every impartial mind in the[xiii] least degree acquainted with the rules of modern warfare, if under these circumstances I am not justified in asserting that before, and at the time lieutenant Gurwood arrived, the whole of the enemy’s garrison within the walls of the citadel, governor included, were both de jure and de facto prisoners to myself. In so far, therefore, as he being the individual who made its owner captive, could give either of us a claim to receive that sword to which colonel Gurwood ascribes such magic influence in the furthering of his after fortunes, I do maintain that at the time it became de facto his, it was de jure mine.”

Something still remains to set colonel Gurwood right upon matters which he has apparently touched upon without due consideration. In a note appended to that part of the duke of Wellington’s Despatches which relate to the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo he says that the late captain Dobbs of the fifty-second at Sabugal “recovered the howitzer, taken by the forty-third regiment but retaken by the enemy.” This is totally incorrect. The howitzer was taken by the forty-third and retained by the forty-third. The fifty-second regiment never even knew of its capture until the action was over. Captain Dobbs was a brave officer and a very generous-minded man, he was more likely to keep his own just claims to distinction in the back-ground than to appropriate the merit of others to himself. I am therefore quite at a loss to know upon what authority colonel Gurwood has stated a fact inaccurate itself and unsupported by the duke of Wellington’s dispatch about the battle of Sabugal, which distinctly says the howitzer was taken by the forty-third regiment, as in truth it was, and it was kept by that regiment also.

While upon the subject of colonel Gurwood’s compilation I must observe that in my fifth volume, when treating of general Hill’s enterprise against the French forts at Almaraz I make lord Wellington complain to the ministers that his generals were so fearful of responsibility the slightest movements of the enemy deprived them of their judgment. Trusting that the despatches then in progress of publication would bear me out, I did not give my authority[xiv] at large in the Appendix; since then, the letter on which I relied has indeed been published by colonel Gurwood in the Despatches, but purged of the passage to which I allude and without any indication of its being so garbled. This omission might hereafter give a handle to accuse me of bad faith, wherefore I now give the letter in full, the Italics marking the restored passage:—

From lord Wellington to the Earl of Liverpool.

Fuente Guinaldo, May 28th, 1812.

My dear lord,

You will be as well pleased as I am at general Hill’s success, which certainly would have been still more satisfactory if he had taken the garrison of Mirabete; which he would have done if general Chowne had got on a little better in the night of the 16th, and if sir William Erskine had not very unnecessarily alarmed him, by informing him that Soult’s whole army were in movement, and in Estremadura. Sir Rowland therefore according to his instructions came back on the 21st, whereas if he had staid a day or two he would have brought his heavy howitzers to bear on the castle and he would either have stormed it under his fire or the garrison would have surrendered. But notwithstanding all that has passed I cannot prevail upon the general officers to feel a little confidence in their situation. They take alarm at the least movement of the enemy and then spread the alarm, and interrupt every thing, and the extraordinary circumstance is, that if they are not in command they are as stout as any private soldiers in the army. Your lordship will observe that I have marked some passages in Hill’s report not to be published. My opinion is that the enemy must evacuate the tower of Mirabete and indeed it is useless to keep that post, unless they have another bridge which I doubt. But if they see that we entertain a favourable opinion of the strength of Mirabete, they will keep their garrison there, which might be inconvenient to us hereafter, if we should wish to establish there our own bridge. I enclose a Madrid[xv] Gazette in which you will see a curious description of the state of king Joseph’s authority and his affairs in general, from the most authentic sources.

Ever, my dear lord, &c. &c.

Wellington.

The following statement of the operations of the fifth division at the combat of Muriel 25th October, 1812, is inserted at the desire of sir John Oswald. It proves that I have erroneously attributed to him the first and as it appeared to me unskilful disposition of the troops; but with respect to the other portions of his statement, without denying or admitting the accuracy of his recollections, I shall give the authority I chiefly followed, first printing his statement.

Affair of Villa Muriel.

On the morning 25th of October 1812 major-general Oswald joined and assumed the command of the fifth division at Villa Muriel on the Carion. Major-general Pringle had already posted the troops, and the greater portion of the division were admirably disposed of about the village as also in the dry bed of a canal running in its rear, in some places parallel to the Carion. Certain of the corps were formed in columns of attack supported by reserves, ready to fall upon the enemy if in consequence of the mine failing he should venture to push a column along the narrow bridge. The river had at some points been reported fordable, but these were said to be at all times difficult and in the then rise of water as they proved hardly practicable. As the enemy closed towards the bridge, he opened a heavy fire of artillery on the village. At that moment lord Wellington entered it and passed the formed columns well sheltered both from fire and observation. His lordship approved of the manner the post was[xvi] occupied and of the advantage taken of the canal and village to mask the troops. The French supported by a heavy and superior fire rushed gallantly on the bridge, the mine not exploding and destroying the arch till the leading section had almost reached the spot. Shortly after, the main body retired, leaving only a few light troops. Immediately previous to this an orderly officer announced to lord Wellington that Palencia and its bridges were gained by the foe. He ordered the main body of the division immediately to ascend the heights in its rear, and along the plateau to move towards Palencia in order to meet an attack from that quarter. Whilst the division was in the act of ascending, a report was made by major Hill of the eighth caçadores that the ford had been won, passed by a body of cavalry causing the caçadores to fall back on the broken ground. The enemy, it appears, were from the first, acquainted with these fords, for his push to them was nearly simultaneous with his assault on the bridge. The division moved on the heights towards Palencia, it had not however proceeded far, before an order came directing it to retire and form on the right of the Spaniards, and when collected to remain on the heights till further orders. About this time the cavalry repassed the river, nor had either infantry or artillery passed by the ford to aid in the attack, but in consequence of the troops being withdrawn from the village and canal a partial repair was given to the bridge, and small bodies of infantry were passed over skirmishing with the Spaniards whose post on the heights was directly in front of Villa Muriel. No serious attack from that quarter was to be apprehended until an advance from Palencia. It was on that point therefore that attention was fixed. Day was closing when lord Wellington came upon the heights and said all was quiet at Palencia and that the enemy must now be driven from the right bank. General Oswald enquired if after clearing the village the division was to remain there for the night. His lordship replied, the village was to be occupied in force and held by the division till it was withdrawn, which would probably be very early in the morning. He directed the first brigade under brigadier-general Barnes[xvii] to attack the enemy’s flank, the second under Pringle to advance in support extending to the left so as to succour the Spaniards who were unsuccessfully contending with the enemy in their front. The casualties in the division were not numerous especially when the fire it was exposed to is considered. The enemy sustained a comparative heavy loss. The troops were by a rapid advance of the first brigade cut off from the bridge and forced into the river where many were drowned. The allies fell back in the morning unmolested.

John Oswald, &c. &c. &c.

Memoir on the combat of Muriel by captain Hopkins, fourth regiment.

As we approached Villa Muriel the face of the country upon our left flank as we were then retrograding appeared open, in our front ran the river Carrion, and immediately on the opposite side of the river and parallel to it there was a broad deep dry canal. On our passing the bridge at Villa Muriel we had that village on our left, from the margin of the canal the ground sloped gradually up into heights, the summit forming a fine plateau. Villa Muriel was occupied by the brigadier Pringle with a small detachment of infantry but at the time we considered that it required a larger force, as its maintenance appeared of the utmost importance to the army, we were aware that the enemy had passed the Carrion with cavalry and also that Hill’s caçadores had given way at another part of the river. Our engineers had partly destroyed the bridge of Villa Muriel, the enemy attacked the village, at the time the brigadier and his staff were there,[4] passing the ruins of the bridge by means of ladders, &c. The enemy in driving the detachment from the village made some prisoners. We retired to the plateau of the heights, under a fire of musquetry and artillery, where we halted in close column; the enemy strengthened the village.

Lord Wellington arrived with his staff on the plateau, and immediately reconnoitred the enemy whose reinforcements[xviii] had arrived and were forming strong columns on the other side of the river. Lord Wellington immediately ordered some artillery to be opened on the enemy. I happened to be close to the head-quarter staff and heard lord Wellington say to an aide-de-camp, “Tell Oswald I want him.” On sir John Oswald arriving he said, “Oswald, you will get the division under arms and drive the enemy from the village and retain possession of it.” He replied, “My lord, if the village should be taken I do not consider it as tenable.” Wellington then said, “It is my orders, general.” Oswald replied, “My lord as it is your orders they shall be obeyed.” Wellington then gave orders to him “that he should take the second brigade of the division and attack in line, that the first brigade should in column first descend the heights on the right of the second, enter the canal and assist in clearing it of the enemy,” and saying, “I will tell you what I will do, Oswald. I will give you the Spaniards and Alava into the bargain, headed by a company of the ninth regiment upon your left.” The attack was made accordingly, the second battalion of the fourth regiment being left in reserve in column on the slope of the hill exposed to a severe cannonade which for a short time caused them some confusion. The enemy were driven from the canal and village, and the prisoners which they made in the morning were retaken. The enemy lost some men in this affair, but general Alava was wounded, the officer commanding the company of Brunswickers killed, and several of the division killed and wounded. During the attack lord Wellington sent the prince of Orange under a heavy fire for the purpose of preventing the troops exposing themselves at the canal, two companies defended the bridge with a detachment just arrived from England. The possession of the village proved of the utmost importance, as the retrograde movement we made that night could not have been effected with safety had the enemy been on our side of the river, as it was we were enabled to pass along the river with all arms in the most perfect security.

TO

GENERAL LORD VISCOUNT BERESFORD,

BEING

An Answer to his Lordships Assumed Refutation

OF

COL. NAPIER’S JUSTIFICATION OF HIS THIRD VOLUME.

My Lord,

You have at last appeared in print without any disguise. Had you done so at first it might have spared us both some trouble. I should have paid more deference to your argument and would willingly have corrected any error fairly pointed out. Now having virtually acknowledged yourself the author of the two publications entitled “Strictures” and “Further Strictures,” &c. I will not suffer you to have the advantage of using two kinds of weapons, without making you also feel their inconvenience. I will treat your present publication as a mere continuation of your former two, and then my lord, how will you stand in this controversy?

Starting anonymously you wrote with all the scurrility that bad taste and mortified vanity could suggest to damage an opponent, because in the fair exercise of his judgement he had ventured to deny your claim to the title of a great commander: and you coupled this with such fulsome adulation of yourself that even in a dependent’s mouth it would have been sickening. Now when you have suffered defeat, when all the errors misquotations and misrepresentations of your anonymous publications have been detected and exposed, you come forward in your own name as if a new and unexceptionable party had appeared, and you expect to be allowed all the advantage of fresh statements and arguments and fresh assertions, without the least reference to your former damaged evidence. You expect that I should have that deference for you, which your age, your rank, your services, and your authority under other circumstances might have fairly claimed at my hands; that I should acknowledge by my silence how much I was in error, or that I should defend myself by another tedious[xx] dissection and exposition of your production. My lord, you will be disappointed. I have neither time nor inclination to enter for the third time upon such a task; and yet I will not suffer you to claim a victory which you have not gained. I deny the strength of your arguments, I will expose some prominent inconsistencies, and as an answer to those which I do not notice I will refer to your former publications to show, that in this controversy, I am now entitled to disregard any thing you may choose to advance, and that I am in justice exonerated from the necessity of producing any more proofs.

You have published above six hundred pages at three different periods, and you have taken above a year to digest and arrange the arguments and evidence contained in your present work; a few lines will suffice for the answer. The object of your literary labours is to convince the world that at Campo Mayor you proved yourself an excellent general, and that at Albuera you were superlatively great! Greater even than Cæsar! My lord, the duke of Wellington did not take a much longer time to establish his European reputation by driving the French from the Peninsula; and methinks if your exploits vouch not for themselves your writings will scarcely do it for them. At all events, a plain simple statement at first, having your name affixed, would have been more effectual with the public, and would certainly have been more dignified than the anonymous publications with which you endeavoured to feel your way. Why should not all the main points contained in the laboured pleadings of your Further Strictures, and the still more laboured pleadings of your present work, have been condensed and published at once with your name? if indeed it was necessary to publish at all! Was it that by anonymous abuse of your opponent and anonymous praise of yourself you hoped to create a favourable impression on the public before you appeared in person? This, my lord, seems very like a consciousness of weakness. And then how is it that so few of the arguments and evidences now adduced should have been thought of before? It is a strange thing that in the first defence of your generalship, for one short campaign, you should have neglected proofs[xxi] and arguments sufficient to form a second defence of two hundred pages.

You tell us, that you disdained to notice my “Reply to various Opponents,” because you knew the good sense of the public would never be misled by a production containing such numerous contradictions and palpable inconsistencies, and that your friends’ advice confirmed you in this view of the matter. There were nevertheless some things in that work which required an answer even though the greatest part of it had been weak; and it is a pity your friends did not tell you that an affected contempt for an adversary who has hit hard only makes the bystanders laugh. Having condescended to an anonymous attack it would have been wiser to refute the proofs offered of your own inaccuracy than to shrink with mock grandeur from a contest which you had yourself provoked. My friends, my lord, gave me the same advice with respect to your anonymous publications, and with more reason, because they were anonymous; but I had the proofs of your weakness in my hands, I preferred writing an answer, and if you had been provided in the same manner you would like me have neglected your friends’ advice.

My lord, I shall now proceed with my task in the manner I have before alluded to. You have indeed left me no room for that refined courtesy with which I could have wished to soften the asperities of this controversy, but I must request of you to be assured, and I say it in all sincerity, that I attribute the errors to which I must revert, not to any wilful perversion or wilful suppression of facts, but entirely to a natural weakness of memory, and the irritation of a mind confused by the working of wounded vanity. I acknowledge that it is a hard trial to have long-settled habits of self satisfaction suddenly disturbed,—

It was thus the flattering muse of poetry lulled you with her sweet strains into a happy dream of glory, and none can wonder at your irritation when the muse of history awakened you with the solemn clangour of her trumpet to[xxii] the painful reality that you were only an ordinary person. My lord, it would have been wiser to have preserved your equanimity, there would have been some greatness in that.

In your first Strictures you began by asserting that I knew nothing whatever of you or your services; and that I was actuated entirely by vulgar political rancour when I denied your talents as a general. To this I replied that I was not ignorant of your exploits. That I knew something of your proceedings at Buenos Ayres, at Madeira, and at Coruña; and in proof thereof I offered to enter into the details of the first, if you desired it. To this I have received no answer.

You affirmed that your perfect knowledge of the Portuguese language was one of your principal claims to be commander of the Portuguese army. In reply I quoted from your own letter to lord Wellington, your confession, that, such was your ignorance of that language at the time you could not even read the communication from the regency, relative to your own appointment.

You asserted that no officer, save sir John Murray, objected at the first moment to your sudden elevation of rank. In answer I published sir John Sherbroke’s letter to sir J. Cradock complaining of it.

You said the stores (which the Cabildo of Ciudad Rodrigo refused to let you have in 1809) had not been formed by lord Wellington. In reply I published lord Wellington’s declaration that they had been formed by him.

You denied that you had ever written a letter to the junta of Badajos, and this not doubtfully or hastily, but positively and accompanied with much scorn and ridicule of my assertion to that effect. You harped upon the new and surprising information I had obtained relative to your actions, and were, in truth, very facetious upon the subject. In answer I published your own letter to that junta! So much for your first Strictures.

In your second publication (page 42) you asserted that colonel Colborne was not near the scene of action at Campo Mayor; and now in your third publication (page 48) you show very clearly that he took an active part in those operations.

You called the distance from Campo Mayor to Merida two marches, and now you say it is four marches.

Again, in your first “Strictures,” you declared that the extent of the intrigues against you in Portugal were exaggerated by me; and you were very indignant that I should have supposed you either needed, or had the support and protection of the duke of Wellington while in command of the Portuguese army. In my third and fourth volumes, published since, I have shown what the extent of those intrigues was: and I have still something in reserve to add when time shall be fitting. Meanwhile I will stay your lordship’s appetite by two extracts bearing upon this subject, and upon the support which you derived from the duke of Wellington.

1º. Mr. Stuart, writing to lord Wellesley, in 1810, after noticing the violence of the Souza faction relative to the fall of Almeida, says,—“I could have borne all this with patience if not accompanied by a direct proposal that the fleet and transports should quit the Tagus, and that the regency should send an order to marshal Beresford to dismiss his quarter-master-general and military secretary; followed by reflections on the persons composing the family of that officer, and by hints to the same purport respecting the Portuguese who are attached to lord Wellington.”

2º. Extract from a letter written at Moimenta de Beira by marshal Beresford, and dated 6th September, 1810.—“However, as I mentioned, I have no great desire to hold my situation beyond the period lord Wellington retains his situation, or after active operations have ceased in this country, even should things turn out favourably, of which I really at this instant have better hopes than I ever had though I have been usually sanguine. But in regard to myself, though I do not pretend to say the situation I hold is not at all times desirable to hold, yet I am fully persuaded that if tranquillity is ever restored to this country under its legal government, that I should be too much vexed and thwarted by intrigues of all sorts to reconcile either my temper or my conscience to what would then be my situation.”

For the further exposition of the other numerous errors and failures of your two first publications, I must refer the[xxiv] reader to my “Reply” and “Justification,” but the points above noticed it was necessary to fix attention upon, because they give me the right to call upon the public to disregard your present work. And this right I cannot relinquish. I happened fortunately to have the means of repelling your reckless assaults in the instances above mentioned, but I cannot always be provided with your own letters to disprove your own assertions. The combat is not equal my lord, I cannot contend with such odds and must therefore, although reluctantly, use the advantages which by the detection of such errors I have already obtained.

These then are strong proofs of an unsound memory upon essential points, and they deprive your present work of all weight as an authority in this controversy. Yet the strangest part of your new book (see page 135) is, that you avow an admiration for what you call the generous principle which leads French authors to misstate facts for the honour of their country; and not only you do this but sneer at me very openly for not doing the same! you sneer at me, my lord, for not falsifying facts to pander to the morbid vanity of my countrymen, and at the same time, with a preposterous inconsistency you condemn me for being an inaccurate historian! My lord, I have indeed yet to learn that the honour of my country either requires to be or can be supported by deliberate historical falsehoods. Your lordship’s personal experience in the field may perhaps have led you to a different conclusion but I will not be your historian: and coupling this, your expressed sentiment, with your forgetfulness on the points which I have before noticed, I am undoubtedly entitled to laugh at your mode of attacking others. What, my lord? like Banquo’s ghost you rise, “with twenty mortal murthers on your crown to push us from our stools.” You have indeed a most awful and ghost-like way of arguing: all your oracular sentences are to be implicitly believed, and all my witnesses to facts sound and substantial, are to be discarded for your airy nothings.

Captain Squire! heed him not, he was a dissatisfied, talking, self-sufficient, ignorant officer.

The officer of dragoons who charged at Campo Mayor![xxv] He is nameless, his narrative teems with misrepresentations, he cannot tell whether he charged or not.

Colonel Light! spunge him out, he was only a subaltern.

Captain Gregory! believe him not, his statement cannot be correct, he is too minute, and has no diffidence.

Sir Julius Hartman, Colonel Wildman, Colonel Leighton! Oh! very honourable men, but they know nothing of the fact they speak of, all their evidence put together is worth nothing! But, my lord, it is very exactly corroborated by additional evidence contained in Mr. Long’s publication. Aye! aye! all are wrong; their eyes, their ears, their recollections, all deceived them. They were not competent to judge. But they speak to single facts! no matter!

Well, then, my lord, I push to you your own despatch! Away with it! It is worthless, bad evidence, not to be trusted! Nothing more likely, my lord, but what then, and who is to be trusted? Nobody who contradicts me: every body who coincides with me, nay, the same person is to be believed or disbelieved exactly as he supports or opposes my assertion; even those French authors, whose generous principles lead them to write falsehoods for the honour of their country. Such, my lord, after a year’s labour of cogitation, is nearly the extent of your “Refutation.”

In your first publication you said that I should have excluded all hearsay evidence, and have confined myself to what could be proved in a court of justice; and now when I bring you testimony which no court of justice could refuse, with a lawyer’s coolness you tell the jury that none of it is worthy of credit; that my witnesses, being generally of a low rank in the army, are not to be regarded, that they were not competent to judge. My lord, this is a little too much: there would be some shew of reason if these subalterns’ opinions had been given upon the general dispositions of the campaign, but they are all witnesses to facts which came under their personal observation. What! hath not a subaltern eyes? Hath he not ears? Hath he not understanding? You were once a subaltern yourself, and you cannot blind[xxvi] the world by such arrogant pride of station, such overweening contempt for men’s capacity because they happen to be of lower rank than yourself. Long habits of imperious command may have so vitiated your mind that you cannot dispossess yourself of such injurious feelings, yet, believe me it would be much more dignified to avoid this indecent display of them.

I shall now, my lord, proceed to remark upon such parts of your new publication as I think necessary for the further support of my history, that is, where new proofs, or apparent proofs, are brought forward. For I am, as I have already shewn, exonerated by your former inaccuracies from noticing any part of your “Refutation” save where new evidence is brought forward; and that only in deference to those gentlemen who, being unmixed with your former works, have a right either to my acquiescence in the weight of their testimony, or my reasons for declining to accept it. I have however on my hands a much more important labour than contending with your lordship, and I shall therefore leave the greatest part of your book to those who choose to take the trouble to compare your pretended Refutation with my original Justification in combination with this letter, being satisfied that in so doing I shall suffer nothing by their award.

1st. With respect to the death of the lieutenant-governor of Almeida, you still harp upon my phrase that it was the only evidence. The expression is common amongst persons when speaking of trials; it is said the prisoner was condemned by such or such a person’s evidence, never meaning that there was no other testimony, but that in default of that particular evidence he would not have been condemned. Now you say that there was other evidence, yet you do not venture to affirm that Cox’s letter was not the testimony upon which the lieutenant-governor was condemned, while the extract from lord Stuart’s letter, quoted by me, says it was. And, my lord, his lordship’s letter to you, in answer to your enquiry, neither contradicts nor is intended to contradict my statement; nor yet does it in any manner deny the authenticity of my extracts, which indeed were copied verbatim from his letter to lord Castlereagh.

Lord Stuart says, that extract is the only thing bearing on the question which he can find. Were there nothing more it would be quite sufficient, but his papers are very voluminous, more than fifty large volumes, and he would naturally only have looked for his letter of the 25th July, 1812, to which you drew his attention. However, in my notes and extracts taken from his documents, I find, under the date of August, 1812, the following passage:—