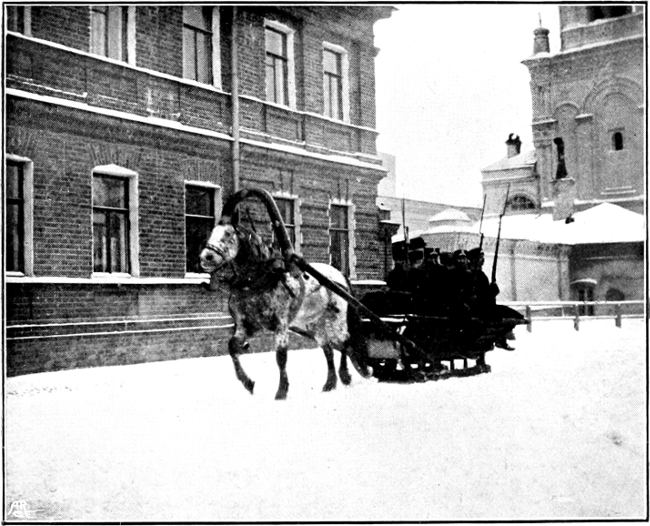

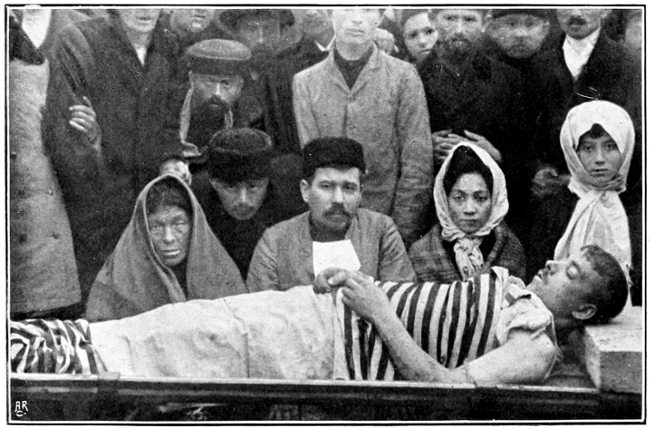

Art Reproduction Co.

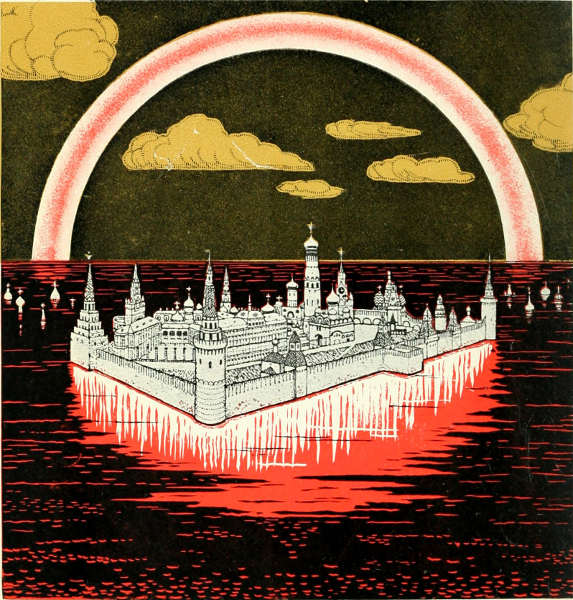

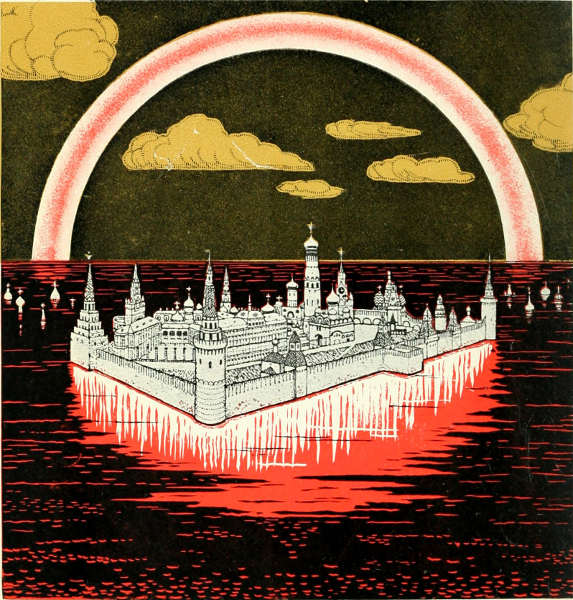

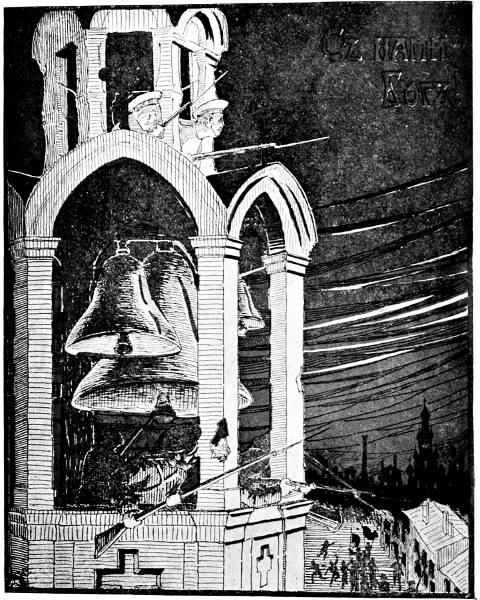

“PACIFICATION.”

The Kremlin of Moscow, Christmas, 1905.

From Sulphur (Jupel).

Title: The dawn in Russia

Author: Henry Woodd Nevinson

Release date: February 9, 2023 [eBook #69996]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Harper & brothers, 1906

Credits: Peter Becker, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE DAWN IN RUSSIA

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Neighbours of ours

In the Valley of Tophet

The Thirty Days’ War between Greece and Turkey

Ladysmith: The Diary of a Siege

The Plea of Pan

Between the Acts

A Modern Slavery

Art Reproduction Co.

“PACIFICATION.”

The Kremlin of Moscow, Christmas, 1905.

From Sulphur (Jupel).

OR

SCENES IN THE RUSSIAN

REVOLUTION

BY

HENRY W. NEVINSON

ILLUSTRATED

LONDON AND NEW YORK

HARPER & BROTHERS

45 ALBEMARLE STREET, W.

1906

[v]

| INTRODUCTION | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| Summary of chief events since the outbreak of the Japanese War, February 1904—Scandals of the War—Tolstoy’s protest—The Königsberg case—Assassination of Bobrikoff and Plehve—The Zemstvo Petition of Rights—The appearance of the workman—Father Gapon—Petition to the Tsar—Bloody Sunday—Trepoff—Assassination of Grand Duke Sergius—Promises of a State Duma—Outbreak in the Caucasus—The Moscow Zemstvoists—Death of Troubetskoy—End of the Japanese War—The railway strike—The general strike—The Manifesto of October 30, 1905—Restoration of Finland’s liberties—Mutiny at Kronstadt—Refusal of Zemstvoists to serve under Witte—Martial Law in Poland—Second general strike declared—Its failure—Manifesto to the Peasants | 1 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE STRIKE COMMITTEE | |

| The Hall of Free Economics—Description of Delegates—The Women—The Executive—Khroustoloff—The Eight-hours’ Day—The Russian “Marseillaise”—Meeting against Capital Punishment—Freedom in the balance—Beginnings of reaction—But [vi]hope prevailed | 25 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE WORKMEN’S HOME | |

| The Schlüsselburg Road—The River—The People and the Cossacks—Casual massacres—The Workmen’s Militia—The Alexandrovsky ironworks—The mills—The hours of labour—Wages—Prices and the standard of living—Standard of work and food—Housing and rent—Washing—Holidays and amusements—Connection of work-people with villages—Passion for the land—The Peasant’s Congress—The Sevastopol mutiny—The post and telegraph strike | 37 |

| CHAPTER III | |

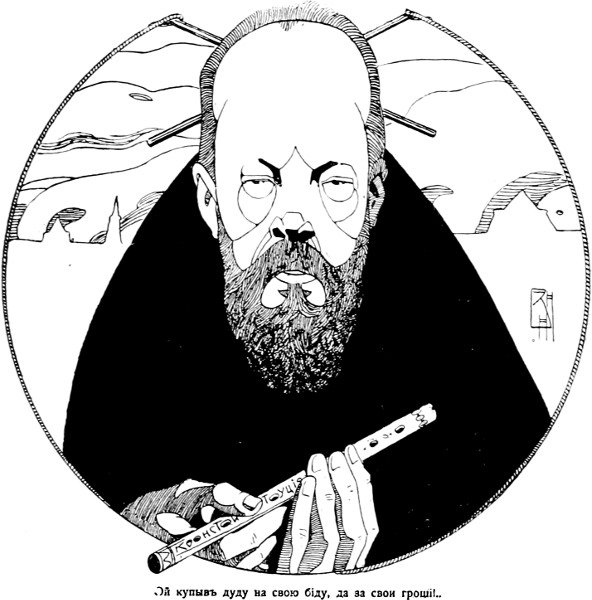

| FATHER GAPON AGAIN | |

| Meeting of December 4th—The Salt Town—Gapon’s followers—Barashoff, the Chairman—The Hymn of the Fallen—Russian music—Police spies—Russian Oratory—Moderate demands of the Gaponists—Opposition of the Social Democrats—Scarcity of Anarchists—Conversation with Father Gapon—His apparent Nature—Charges of Opportunism | 50 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE FREEDOM OF THE WORD | |

| Effect of the post strike—Volunteer sorters—Epidemic of strikes—Joy in public speaking—The power of speech—Sudden outburst of newspapers—The Russian Gazette—The New Life—The Son of the Country—The Beginning—Our Life—Russia—The Jewish Papers—The Reactionary Press—Novoe Vremya—The Citizen—The Word—The satiric papers and Cartoons—Character of Russian satire—The Social Revolutionists [vii]had no paper—Nor had the Radicals—The dangers of division—The split in a Polish restaurant—The joy of life—The assassination of Sakharoff—The protest of the Strike Committee against Government finance—Arrest of Khroustoloff and the Executive | 60 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE OPEN LAND | |

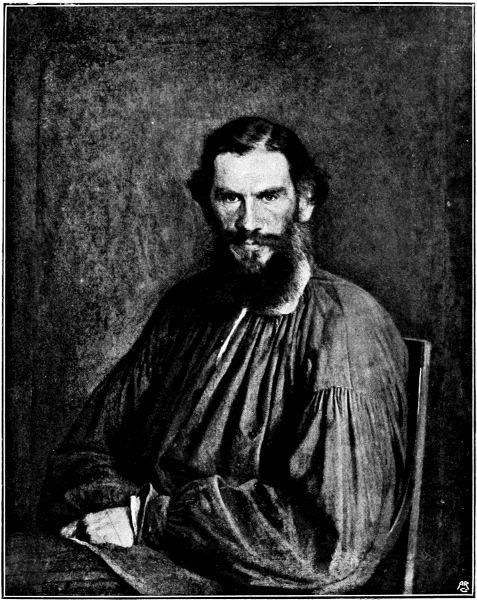

| The town of Toula—The road to the country—The travelling peasant—The wayside inn—A country house—Landowners at home—A typical village—A cottage interior—The stove and the loom—Doubts on the Mir—A beggar for scraps—Flogging for taxes—Tolstoy on the End of an Age—How Empires will now cease—The aged prophet—The restoration of the land—The rotting towns—New ideals of statesmanship—Indifference to poets and Shakespeare—The grace of sanctity and the limitations of logic | 81 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE STATE OF MOSCOW | |

| The return of the Army—How they were received—Fears and hopes about their return—Would the soldiers obey?—The Rostoff regiment—The Cossacks and the crowd—Instinct of mutual aid—The post strike—Private assistance—Formation of unions—The tea packers—The shop assistants—Failure of gaiety—University closed—Lectures for the Movement—Soldiers in revolt—The Zemstvoists—Miliukoff’s paper—A Moscow factory—The barrack system—Wages—The post strike and freedom of speech—Gorky on the rich and educated—The Children of the [viii]Sun—The street murders | 97 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE OLD ORDER | |

| St. Nicholas’ Day—Fears and expectations—The Black Hundred Perils of night—The new Governor-General—The sacred Banners—The crowd of worshippers—The procession—The bishops and the Iberian Virgin—The Krasnaya—Incitements to massacre—Appeal to Dubasoff—The stampede of the patriots | 120 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE DAYS OF MOSCOW—I | |

| My start for the Caucasus—The railway strike begins—The peasants on the train—General strike—Provisions cut short—Friendly discussions with soldiers—A red flag procession—A Cossack charge—Silence at night—Government preparations—Revolutionists unwilling to rise—The Government’s design to bring on the outbreak—The attack on Fiedler’s house—Revolutionary force and arms—Reported danger of English overseers—The guns begin—The district of fighting—The revolutionary plan—The barricades—Difficulties of the spectator in street fighting—Interest of the crowd—Casualties begin—The red cross—Assistance to the wounded—The Government guns | 129 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE DAYS OF MOSCOW—II | |

| Reports of the revolution—Guns on the Theatre Square—Explosion in a gun-shop—Increase in the fighting—Sledges refuse the wounded—The merciful soldier—A schoolboy killed—The revolutionist position—The barricade forts—Barricades never held—The revolutionist tactics—Varieties in barricade—The troops protect their right flank—Barricades still growing—Police [ix]in disguise | 155 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE DAYS OF MOSCOW—III | |

| The beginning of the end—My attempts at photography—Unsuspected presence of revolutionists—Search for revolvers—Labels for identification—Fresh fighting on the Government’s left—But the main movement was failing—Revolutionists appeal for volunteers—Official estimate of casualties—Assassination of the chief of secret police—The Sadovaya at dawn—The police receive rifles—The barricades destroyed—Business resumed by order—Relief of business people—Fighting continues in Presnensky District—Mills held for the revolution—Arrival of the Semenoffsky Guards—Bombardment of the district—The murder of Dr. Vorobieff for assisting the wounded—The district from the inside—Attempts to escape—End of the rising—Various estimates of dead and wounded—The executions—The slaughter of prisoners—The flogging of boys and girls—Christmas Day—The ceremony in the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour | 169 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| IN LITTLE RUSSIA | |

| Results of the rising—Revolutionists claim some success—Some gain in unity—But the movement lost prestige—Hopes of winning over troops proved vain—Reasons of this—Consequent elation of the Government—Hopes of a new loan—Witte laments his lost faith—My journey to Kieff—Harvest rotting on the platforms—Kieff as religious centre—Pilgrimages to the catacombs—An intellectual centre—Character of Little Russians—Their costume—No thought of separation—Apprehension of Poles—The Little Russian movement—The recent riots of Loyalists—Attack on the British Consulate—Persecution of Jews—Crowded prisons and typhus—The Black Earth—Grain as Russia’s chief export—Poverty [x]of the villages—Reasons for this—The country districts quiet | 198 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| THE JEWS OF ODESSA | |

| Joy over the Manifesto—Violent suppression—Trepoff and Neidhart—The days of massacre—Present state of Jewish quarters—Habits of Jews—Refusal of concealment—A type of Israel—Attempts at relief—Difficulties of organization—Flight of the rich and distress of their parasites—Dockers and their poverty—The Constitutional democrats—Their programme—The Jewish Bund—Jewish disqualifications—The English Aliens Act | 215 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| LIBERTY IN PRISON | |

| Murder of the student Davidoff—Precautions for the anniversary of Bloody Sunday—Strike Committee orders a memorial of silence—The day on the Schlüsselberg road—The Navy and telescopic sights—Silence in the workmen’s districts—The Vampire and Freedom—Wholesale arrests—Methods of imprisonment and sentence—The House of Inquiry—A letter from prison—The Peter-Paul fortress—Khroustoloff’s prison—The Cross prison—Imprisonments and executions—Why Russia has no Cromwell—The Schlüsselberg converted into a mint—Statistics of suppression—The committee of ministers—Siberian exile continued—Meetings of Constitutional Democrat delegates—Their methods and programme—Their leaders—Miliukoff still hopeful | 228 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| THE PRIEST AND THE PEOPLE | |

| Over the ice to Kronstadt—Father John and his shelter—The service of the altar—His blessing—His miraculous life and powers—His influence in reaction—A revolutionary concert—The proletariat of intellect—Russian democracy—The use of the parable—The bond of danger—The advantage of [xi]tyranny | 248 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| A BLOODY ASSIZE | |

| The Baltic Provinces—Lists of floggings and executions—Vengeance of the German landowners—They are weary of town life—Letts driven to execution—The Irish of Russia—Character of the people—Their songs—Their religion—Their buildings—Their isolated farms—Disaster of Russification—The burning of country houses—“We have condemned you to death”—Mixture of social and national grievances—Refusal of Germans to appeal to Berlin—The case of Pastor Bielenstein—A Lettish scholar—A rebel’s funeral—The assize in the country—Executions ordered by telephone—The case of a schoolmistress—Reprisals and rescues | 262 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| THE PARTIES OF POLAND | |

| Polish tendency to division—The reactionary position stated—Supposed beneficence of martial law—Suppression good for Poles—Absurdities of Socialists and Nationalists—Reconquest of Finland necessary—Poland essential as barrier against Germany—The Polish workman—Disasters in Polish trade—Loss of credit—The landless labourers—Education—Wages—Rent—Polish brides and demand for ancestral relics—The Realist party—The National Democrats—A meeting to practice for elections—A Nationalist programme—The Progressive Democrats—The National Socialists—The Social Democrats—The Proletariat Socialists—The Jewish Bund—Attempts to influence the Army—Executions of so-called Anarchists and Jews—The Warsaw citadel—Two brave Jewesses | 282 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| THE DRAMA OF FREEDOM | |

| The struggle between Freedom and Oppression—The early hopes—The [xii]Government’s uncertainty—The plot to overthrow Freedom—Its apparent success—The new loan secured—Difficulty of realizing the actual truth beneath abstractions—Persistence of the revolution—Summary of events—Finance and the elections—Execution of Lieutenant Schmidt—Victory of the Constitutional Democrats—Germany refuses to share in the loans, but France and England subscribe largely—Resignation of Count Witte—Reported death of Father Gapon—Attempt to assassinate Admiral Dubasoff—Assassination of General Jeoltanowski—Fundamental Law—New Ministers—Preparing for the Duma | 301 |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| THE FIRST PARLIAMENT | |

| Baleful prophecies—Provocations—Meeting of Constitutional Democrats broken up by police—Ministerial figureheads—Birthday of freedom—Trepoff’s precautions—Ceremony in Winter Palace—The Old Order confronted by the New—The Church intervenes—The Tsar’s address—“Unwavering firmness,” and the “Necessity of Order”—No promise of amnesty—Officials applaud—The people silent—The cry of the prisoners—The Duma assembles in the Taurida Palace—President elected by 426 to 3—Petrunkevitch speaks first—The demand for amnesty—A languid afternoon in the “Nobleman’s Assembly”—Golitzin greeted with holy kisses—Witte and Durnovo side by side—Prayers and compliments—The Duma at work—Taurida Palace closely guarded—Difficulties about procedure—Drafting the reply to the Tsar’s speech—An honourable impatience—Congratulations from many lands—Telegrams from imprisoned “politicals”—Russia’s representatives unanimous for amnesty—Freedom and Justice versus Tradition and the Sword | 317 |

[xiii]

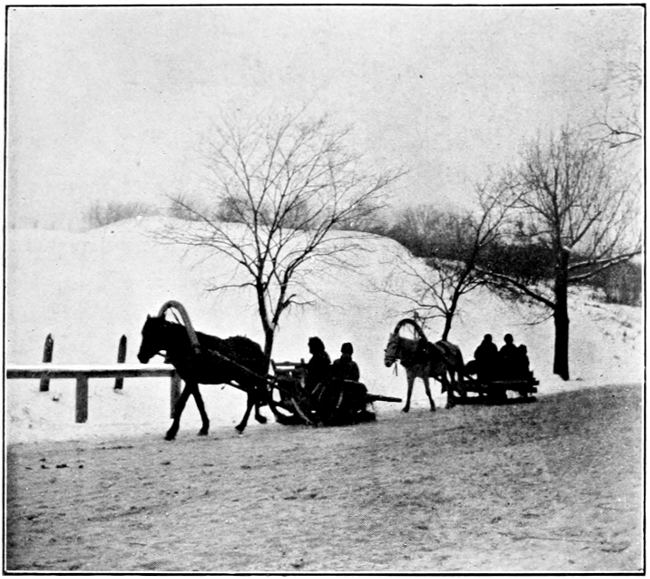

| “Pacification.” The Kremlin of Moscow, Christmas,

1905 From Sulphur (Jupel) |

Frontispiece |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

|---|---|

| A Demonstration by the Kazan Church, St. Petersburg From The Marseillaise |

2 |

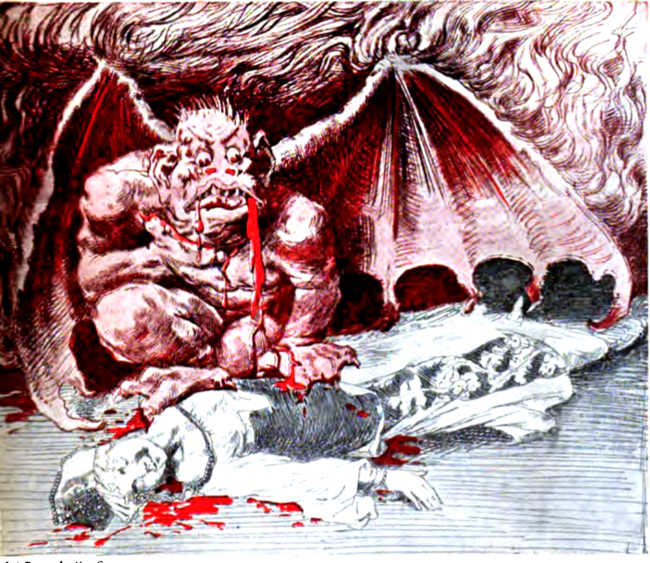

| “homunculus” and the S.D. (social Democratic) Rats From Burelom (The Storm) |

12 |

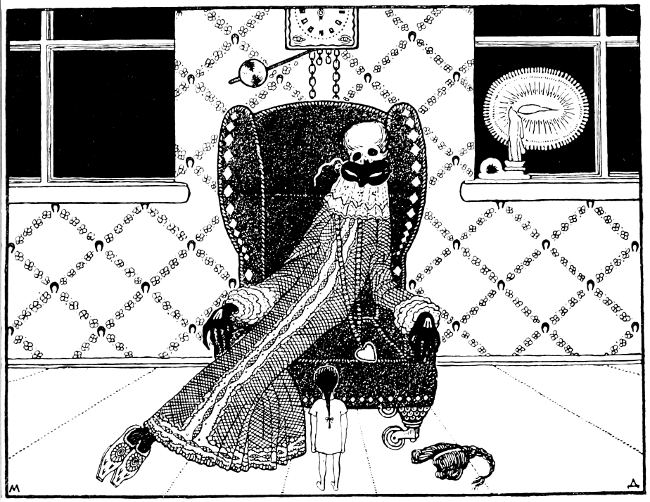

| “An Autumn Idyll” From Sulphur (Jupel) |

40 |

| Witte and the Constitution From Sprut |

72 |

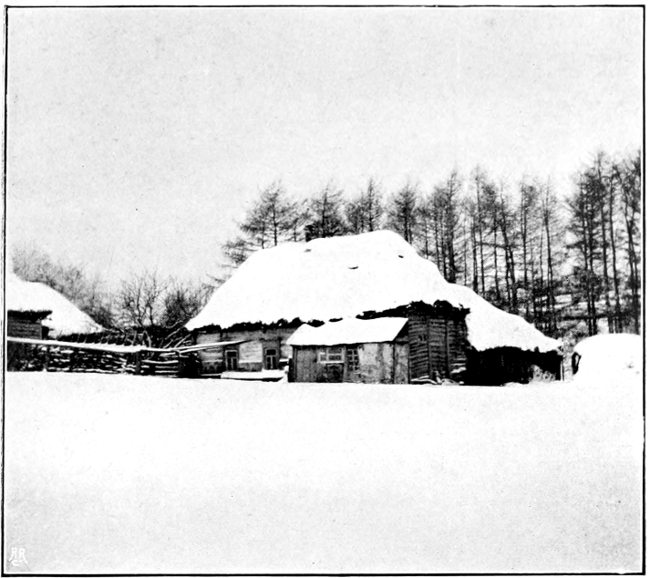

| Peasant Sledges | 80 |

| A Private Sledge | 80 |

| Tolstoy’s Home | 90 |

| Peasants | 90 |

| Tolstoy in Middle Age | 96 |

| Fiedler’s House | 140 |

| Effect of Shells | 140 |

| A Minor Barricade | 146 |

| A Military Post at Moscow | 146[xiv] |

| “God with us!” From Sprut |

152 |

| Barricades on the Sadovaya | 162 |

| “The New Era” From Sulphur (Jupel) |

176 |

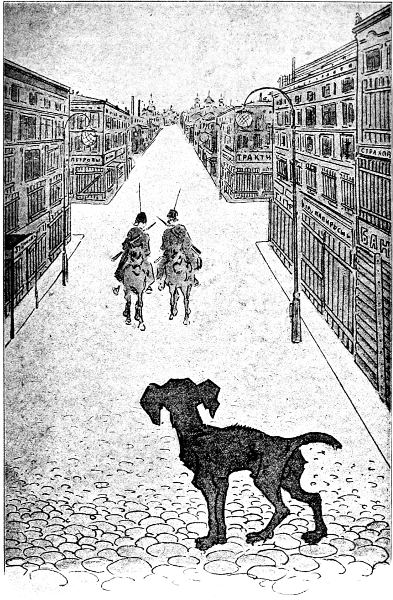

| “Intercourse is Resumed” From Streli (Arrows) |

182 |

| Dubasoff’s Roll Call From Burelom (The Storm) |

194 |

| A Little Russian | 206 |

| A Tramp | 206 |

| A Peasant’s Home | 212 |

| The Lavra at Kieff | 212 |

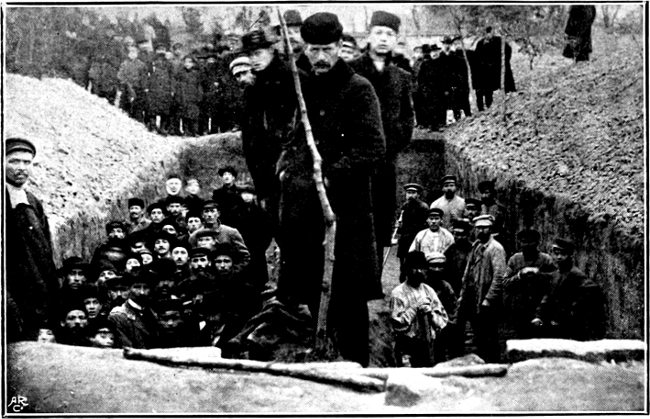

| The Jews’ Grave at Odessa | 216 |

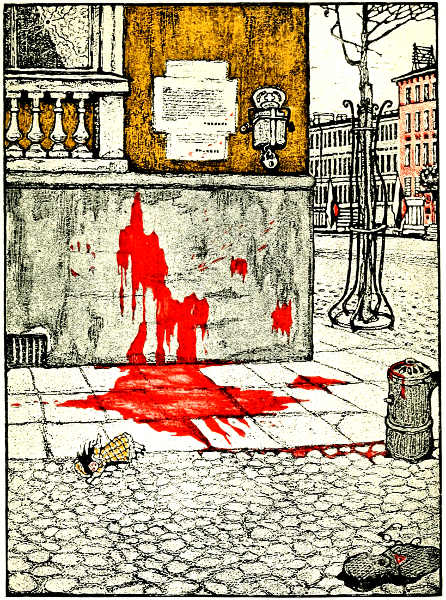

| After the Massacre | 216 |

| “I think she’s Quiet at Last” From the Vampyre |

232 |

| 1905–1906 From Sulphur (Jupel) |

300 |

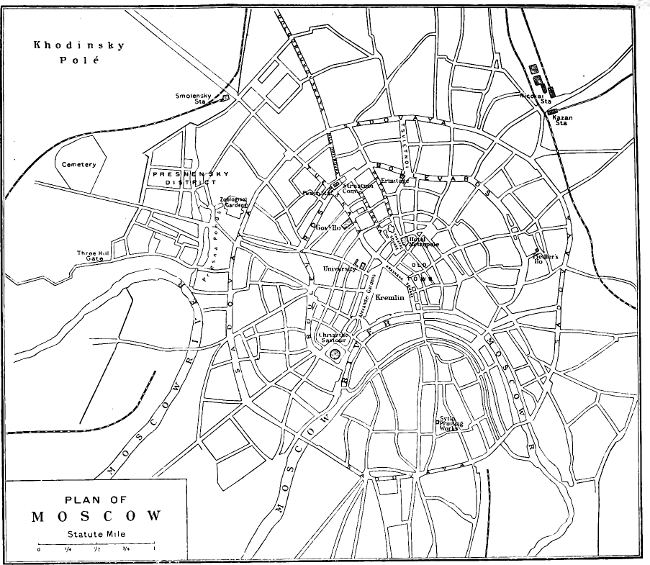

| Plan of Moscow | 350 |

The design on the cover is from a cartoon in the Russian revolutionary paper Pulemet (The Machine Gun).

The illustrations are from Russian cartoons and from photographs, most of which were taken by the author.

[1]

THE DAWN IN RUSSIA

OR

SCENES IN THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

I have not attempted in this book to do more than describe some of the scenes which I witnessed in Russia during the winter of 1905–1906, while I was acting there as special correspondent for the Daily Chronicle. For the most part, the descriptions are given in the same words which I wrote down at the time, either for my own memory or for the newspaper. But the whole has been re-arranged and rewritten, while certain scenes have been added for which a daily paper has no room. I have also inserted between the scenes a bare outline of the principal events that were happening elsewhere, so that the significance of what I saw may be more easily understood, and the dates become something better than mere numbers.

But to realize the meaning of the earlier chapters, a further introduction is necessary, and it is difficult[2] to know where to begin. For there is never any real break in a nation’s history from day to day, and the movement of 1905 was not the first sign of change, but only the brightest. The story of the undaunted struggle for freedom in Russia during the last fifty years has been admirably told by Stepniak, Kropotkin, Zilliacus, Miliukoff, and many other writers. In books that are easily obtained, any one may learn the course of that great movement—the changes in its aims and methods, the distinctions in its parties, and the martyrdoms of its recorded heroes. So for this present purpose of chronicling a few peculiar or unnoticed events and situations which would hardly have a place in history at all, perhaps it will be enough if I begin the skeleton annals with the outbreak of the war between Russia and Japan in February, 1904.

A DEMONSTRATION BY THE KAZAN CHURCH, ST. PETERSBURG.

From The Marseillaise.

It is true that for some time earlier the revolutionary movement had obviously been gathering strength. Within two years there had occurred outbreaks among the peasants, student risings in Moscow, and a demonstration in front of the great classic building called the Kazan Cathedral in St. Petersburg. Some soldiers at Toula had actually refused to kill the work-people. The Zemstvos, or District Councils of landowners and upper-middle classes, had ventured to recommend economic reforms, and a student from Kieff had assassinated Sipiaguine, the Minister of the Interior. To counteract [3]these evils, heightened by a period of industrial depression, Plehve had been promoted from the Governorship of Finland to the Ministry of the Interior; a manifesto had been issued (March 12, 1903), removing the responsibility of the village communes for individual taxation, and promoting religious toleration; and the Jews of Kishineff had been massacred, with the connivance of the Government, and probably at its direct instigation (April 20, 1903). The Armenian Church in the Caucasus was deprived of £3,000,000 of its funds, the public debt of Russia rose to £700,000,000, about half of the interest on which had to be paid to foreign countries, and Witte was appointed President of the Committee of Ministers, while his assistant Pleske succeeded him in what was then regarded as the far more important position of the Ministry of Finance.

It was obvious that the Government—which we may call Tsardom or Oligarchy as we please—had in any case entered upon the way to destruction, and that the revolution was already at work. Indeed, the Social Democrats had met in secret in 1903, and published a “minimum programme” demanding a Republic under universal adult suffrage. But still the disastrous war with Japan hastened these tendencies, and its outbreak may conveniently be taken to mark a period, for the dates of wars are definite and the results quick.

[4]

The course of that ruinous campaign, unequalled, I suppose, in history for the uninterrupted succession of its disasters, need not concern us now. It wasted many millions of money, borrowed by a country which is naturally and inevitably poor. It revealed an incompetence in the ruling classes worse than our own in South Africa, together with a corruption and a heartlessness of greed compared to which even the scandals of South Africa seemed rather less devilish. It kept from their work in fields and factories about a million grown men, who had to be fed and clothed, however badly, by the rest of the population, and it killed or maimed some two or three hundred thousand of them. Otherwise the war can hardly be said to have concerned the Russian people any more than ourselves, so general was their indifference both to its cause and to its failure. “It is not our war, it is the Government’s affair,” was the common saying. Tolstoy is a prophet, and the mark of a prophet is that he speaks with the voice of God and not with the voice of the people; but in his protest against the war (published in the Times of June 27, 1904) he uttered a denunciation of the Government with which nearly the whole of Russia’s population would have agreed. Of the head of that Government himself, he wrote:—

“The Russian Tsar, the same man who exhorted all the nations in the cause of peace, publicly announces that,[5] notwithstanding all his efforts to maintain the peace so dear to his heart (efforts which express themselves in the seizing of other people’s lands and in the strengthening of armies for the defence of those stolen lands), he, owing to the attack of the Japanese, commands that the same should be done to the Japanese as they had begun doing to the Russians—namely, that they should be slaughtered; and in announcing this call to murder he mentions God, asking the Divine blessing on the most dreadful crime in the world. This unfortunate and entangled young man, recognized as the leader of 130,000,000 of people, continually deceived and compelled to contradict himself, confidently thanks and blesses the troops which he calls his own for murder in defence of lands which he calls his own with still less right.”

While the myth of Russia’s military and naval power—a myth which for fifty years had misguided England’s foreign policy, checked any generous impulse on the part of our statesmen, and driven them to breach of national faith, callousness towards outrageous cruelty, and every moral humiliation that a proud and ancient people can suffer—while this overwhelming myth was being dissipated month by month in the Far East, the characteristic methods by which the Russian Tsar and Oligarchs sought to maintain their hold upon the wealth and privileges of State were being revealed in the so-called Königsberg case. It was discovered that even in a foreign capital like Berlin, the Russian Government employed a little army of spies, under a recognized and highly-paid official, to search the homes of Russian[6] Liberals, to watch their goings, and open their letters. It was also shown that, even under a comparatively civilized government like the German, the authorities were ready to bring their own subjects to trial for alleged verbal attacks upon the Tsar; while a Russian Consul, probably in obedience to orders from home, would tell any lie and garble any document to support the charge.

On June 17th the air was cleared by the assassination of General Bobrikoff, the Russian tyrant of Finland, and on July 8th that deed was followed by the assassination of Plehve. In all the history of political murder, I suppose, there has never been a case in which the victim received less pity, or the crime less condemnation. The pitiless hand of reaction was for the moment stayed. The birth of an heir to the uneasy crown inspired the Tsar with such amiability that, as father of his people, he abolished the punishment of flogging among his grown-up subjects. Prince Sviatopolk Mirski, who was justly regarded as something of a Liberal as princes go, succeeded Plehve at the Interior, released some political prisoners, advocated decentralization with the development of the Zemstvos, and promised better education, liberty of conscience, and freedom of speech.

Again the Zemstvoists, taking their courage as moderate Liberals in both hands, met secretly in St. Petersburg, and drew up a kind of Petition of Rights[7] to be presented to the Tsar. There were one hundred and six members present at the secret conferences, thirty-six of them belonging to the caste of the nobility, and their Petition began with the complaint that the bureaucracy had alienated the people from the Throne, and that by its distrust of self-government it had shown itself entirely out of touch with the people. In place of the bureaucratic system, the Petition demanded an elected Legislature of two Houses, together with freedom of conscience, the press, meeting, and association, equal civil and political rights for all classes and races, and similar methods of justice for the peasants as for other men.

The Zemstvo petition was issued on November 22, 1904. A month later (December 26th) it was repeated in still more direct and urgent terms by the Moscow Zemstvo, which had always taken the lead in reform, being inspired by its President, Prince Sergius Troubetzkoy, Professor of Philosophy in the University since 1888. But, in the meantime, student riots had again occurred in Moscow and St. Petersburg, the censorship had been renewed, and on the same day as the Moscow petition there appeared an Imperial manifesto proclaiming “the unshakable foundations of the Russian State system, consecrated by the fundamental laws of the Empire,” and announcing the Tsar’s determination to act always in accordance[8] with the revered will of his crowned predecessor, while he thought unceasingly upon the welfare of the realm entrusted to him by God. The manifesto went on to admit that when the need of this or that change had been proved to be mature, the Tsar was willing to take it into consideration, and upon this principle he undertook to maintain the laws, to give local institutions as wide a scope as possible, to unify judicial procedure throughout the Empire, to establish State insurance of workmen, and to revise the laws upon political crime, religious offences, and the press. But the tone of the whole manifesto was felt to be reactionary, and there was no guarantee that its promises would be observed. When our own Charles I. made concessions, the people shouted, “We have the word of a King!” But they soon found that assurance was a shifty thing to trust to, and since then the words of kings have counted for no more than the words of men.

But the opening of the next year (1905) was marked by the appearance of a new element in revolution. Certainly, there had been strikes and riots in the great cities before; there had been peasant risings and other forms of economic agitation in various parts. But as a whole the revolutionary movement as such had been inspired, directed, and even carried out by the educated classes—the students, the journalists, the doctors, barristers, and other[9] professional men. It had been almost limited to that great division of society which in Russia is called “The Intelligence.” The word is fairly well represented by our phrase “educated classes”—a phrase which embodies our greatest national shame. It includes all who are not workmen or peasants, and so is much wider in significance than the French term “The Intellectuals,” with which it is often confused. In England, for instance, it would include the House of Lords, the clergy, army officers, country gentlemen, and the leaders of society whom no Frenchman would dream of classing among the intellectual.

It was “the Intelligence” who hitherto had fought for the revolution. It was they who had suffered scourgings and exile and imprisonment and madness and violation and the gallows in the name of freedom. It was they who had endured the horror that most people feel in killing a man. And, above all, it was they who had devoted their lives, their careers, and reputations to going about among the peasants and working-people to show them that the misery and terror under which they lived were neither necessary nor universal. At length the firstfruits of their toilsome propaganda, continued through forty years, were seen, and the revolutionary workman appeared.

He was ushered in by Father George Gapon, at that time a rather simple-hearted priest, with a rather[10] childlike faith in God and the Tsar, and a certain genius for organization. His personal hold upon the working classes was probably due to their astonishment that a priest should take any interest in their affairs, outside their fees. We have seen the same thing happen in England, when Manning and Westcott won the reverence due to saints because they displayed some feeling for the flock which they were paid large sums to protect. Father Gapon, with his thin line of genius for organization, had gathered the workmen’s groups or trade unions of St. Petersburg into a fairly compact body, called “The Russian Workmen’s Union,” of which he was President as well as founder. In the third week in January the men at the Putiloff iron works struck because two of their number had been dismissed for belonging to their union. At once the Neva iron and ship-building works, the Petroffsky cotton works, the Alexander engine works, the Thornton cloth works, and other great factories on the banks of the river or upon the industrial islands joined in the strike, and in two days some 100,000 work-people were “out.”

With his rather childlike faith in God and the Tsar, Father Gapon organized a dutiful appeal of the Russian workmen to the tender-hearted autocrat whose benevolence was only thwarted by evil counsellors and his ignorance of the truth. The petition ran as follows:—

[11]

“We workmen come to you for truth and protection. We have reached the extreme limits of endurance. We have been exploited, and shall continue to be exploited under your bureaucracy.

“The bureaucracy has brought the country to the verge of ruin and by a shameful war is bringing it to its downfall. We have no voice in the heavy burdens imposed on us. We do not even know for whom or why this money is wrung from the impoverished people, and we do not know how it is expended. This is contrary to the Divine laws, and renders life impossible. It is better that we should all perish, we workmen and all Russia. Then good luck to the capitalists and exploiters of the poor, the corrupt officials and robbers of the Russian people!

“Throw down the wall that separates you from your people. Russia is too great and her needs are too various for officials to rule. National representation is essential, for the people alone know their own needs.

“Direct that elections for a constituent assembly be held by general secret ballot. That is our chief petition. Everything is contained in that.

“If you do not reply to our prayer, we will die in this square before your palace. We have nowhere else to go. Only two paths are open to us—to liberty and happiness or to the grave. Should our lives serve as the offering of suffering Russia, we shall not regret the sacrifice, but endure it willingly.”

On the morning of Sunday, January 22, 1905, about 15,000 working men and women formed into a procession to carry this petition to the Tsar in his Winter Palace upon the great square of government buildings. They were all in their Sunday clothes;[12] many peasants had come up from the country in their best embroideries; they took their children with them. In front marched Father Gapon and two other priests wearing vestments. With them went the ikons, or holy pictures of shining brass and silver, and a portrait of the Tsar. As the procession moved along, they sang, “God save our people. God give our Orthodox Tsar the victory.”

So the Russian workmen made their last appeal to the autocrat whom they called their father. They would lay their griefs before him, they would see him face to face, they would hear his comforting words.

But the father of his people had disappeared into space.

As the procession entered the square, the soldiers fired volley after volley upon them from three sides. The estimate of the killed and wounded was about 1500. That Sunday—January 9th in Russian style—is known as Bloody Sunday or Vladimir’s Day, after the Grand Duke Vladimir, who was supposed to have given the orders.

Next morning Father Gapon wrote to his Union: “There is no Tsar now. Innocent blood has flowed between him and the people.”

“HOMUNCULUS” AND THE S. D. (SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC) RATS.

From Burelom (The Storm).

Innocent blood has flowed before and tyrants still have reigned. They have been feared, they have won their way, and men have served them. Mankind will endure much in the name of government, [13]but to be governed by a coward is almost beyond the endurance of man.

On January 24th a new office of Governor-General of St. Petersburg was created, and Trepoff received the first appointment.

Disturbances continued in Warsaw, Lodz, and Sosnowice, the industrial centres of Poland, and on January 31st 200 work-people were killed and 600 wounded in the streets of Warsaw.

On February 17th the Grand Duke Sergius, Governor-General of Moscow, uncle to the Tsar, conspicuous for his cruelty, and, even among the Russian aristocracy, renowned for the peculiarity of his vices, was assassinated as he drove into the Kremlin.

This event and other outbreaks that were continually occurring in the great centres of industry, inspired a remarkable manifesto and rescript that appeared on March 3rd and were characteristic of the hesitating fugitive in Tsarkoe Selo. The manifesto took the form of a pathetic address to the people whom he had misgoverned with such disaster:—

“Disturbances have broken out in our country” (it said) “to the joy of our enemies and our own deep sorrow. Blinded by pride, the evil-minded leaders of the revolutionary movement make insolent attacks upon the Holy Orthodox Church and the lawfully established pillars of the Russian State....

“We humbly bear the trial sent us by Providence, and[14] derive strength and consolation from our firm trust in the grace which God has always shown to the Russian power, and from the immemorial devotion which we know our loyal people entertain for the Throne....

“Let all those rally round the Throne who, true to Russia’s past, honestly and conscientiously have a care for all the affairs of the State such as we have ourselves.”

In the rescript that followed on the same day a form of Legislative Assembly was promised in these words—

“I am resolved henceforth, with the help of God, to convene the worthiest men, possessing the confidence of the people and elected by them, to participate in the elaboration and consideration of legislative measures.”

Buliguine, who had now succeeded Mirski as Minister of the Interior, and was probably the author of the rescript, was appointed to organize the elections. But a counterblast of reaction swept over the distracted Tsar; Trepoff was made Assistant-Minister of the Interior and Chief of the Police, with full power to forbid all congresses, associations, or meetings, and Buliguine resigned, though he remained nominally in office till the end of October.

Outbreaks in the country became continually more serious. In June there was fierce rioting in Lodz, the great manufacturing town of Poland, and in the Baltic port of Libau. In the same month the great battleship Potemkin of the Black Sea fleet mutinied at Odessa, threw two big shells into the[15] town, burnt the docks, and steamed away to the mouth of the Danube for refuge.

Mid-August brought another manifesto, which began with the usual precepts of maudlin falsehood—

“The Empire of Russia is formed and strengthened by the indestructible solidarity of the Tsar with the people and the people with the Tsar. The concord and union of the Tsar and the people are a great moral force, which has created Russia in the course of centuries by protecting her from all misfortunes and all attacks, and has constituted up to the present time a pledge of unity, independence, integrity, material well-being, and intellectual development.

“Autocratic Tsars, our ancestors, constantly had that object in view, and the time has come to follow out their good intentions and to summon elected representatives from the whole of Russia to take a constant and active part in the elaboration of laws, attaching for this purpose to the higher State institutions a special consultative body, entrusted with the preliminary elaboration and discussion of measures, and with the examination of the State Budget.

“It is for this reason that, while preserving the fundamental law regarding autocratic power, we have deemed it well to form a State Duma, and to approve regulations for the elections to this Duma.”

This consultative Duma was to lay its proposals before the Council of State, which might submit them to the Tsar if it approved. The Duma was to meet not later than January, 1906, and was to consist of 412 members, representing 50 governments and the military province of the Don,[16] only 28 of the members representing towns. The members were to be paid £1 a day and fares, and were to sit for five years, unless the Tsar chose to dissolve them. Their meetings were to be secret, except that the President might admit the Press if he chose.

On September 7th a race-feud broke out between the Mohammedan Tartars and the Armenians at Baku, on the Caspian, and spread to Tiflis and all along the southern slopes of the Caucasus. The destruction of the great oil-works at Baku involved a loss of many millions of pounds, and further embarrassed the railways and manufacturing districts, which depended almost entirely on naphtha for their fuel.

On September 25th an assembly of 300 representatives of the Zemstvos of the empire was gathered in a private house at Moscow to consider their attitude towards the promised Duma, which was regarded as a concession to their previous representations during the year. They recognized that the Duma of the August manifesto would not be either a representative or legislative assembly, but, regarding it as a possible rallying-point for the general movement towards freedom, they agreed to obtain as many seats as possible, so as to form a united group of advanced opinion.

They further drew up a programme of their political aims, including the formation of a National[17] Legislative Assembly; a regular budget system; the abolition of passports; equal rights for all citizens, including peasants; equal responsibility of all officials and private citizens before the law; the liberation of the villager from the petty official (natchalnik); inviolability of person and home; and freedom of conscience, speech, press, meeting, and association.

The programme is important, as indicating what to the average Liberal politician in England would appear the most obvious abuses of the Russian system, because nothing is here demanded which has not long ago been obtained for our own country by the efforts of our upper and middle classes in the past.

As soon as the assembly broke up, Prince Sergius Troubetzkoy, the true leader of these Liberal or Zemski delegates, the President of the Moscow Zemstvo, and for a month past the Rector of the University, went to St. Petersburg to urge the Government to allow public meetings, and while speaking on behalf of free speech at the Ministry of Public Education, he suddenly died. He was only forty-three, and it is tempting to speak of him as the first of the Girondists to fall. But all through what I have seen in Russia, I have avoided even a mental reference to the French Revolution as carefully as I could. For history is a great hindrance in judging the present or the future.

[18]

The manifesto of October 19th, announcing the final conclusion of the peace with Japan, by which the Russian Government was compelled to abandon all for which it had striven during many years in the Far East, was hardly noticed in the gathering excitement of the days.

On October 21st, the workmen again appeared unexpectedly upon the scene, and delivered their first telling blow by declaring a general railway strike. The strength of the movement was that it disorganized trade, made the capitalist and commercial classes very uncomfortable, and, above all, that it prevented the Government from sending troops rapidly to any particular point of disturbance. The weakness was that, as in all strikes, the strikers were threatened with starvation while their employers suffered only discomfort; that the peasants, being unable to get their produce to market, began to regard the revolution with suspicion; and that the Government succeeded in running a military train between St. Petersburg and Moscow (only a ten hours’ journey) nearly all the time.

The objects of the strikers were in the main political, as could be seen from the demands presented to Witte by a deputation on October 24th—

“The claims of the working classes must be settled by laws constituted by the will of the people and sanctioned by all Russia. The only solution is to announce political guarantees for freedom and the convocation of[19] a Constituent Assembly, elected by direct, universal, and secret suffrage. Otherwise the country will be forced into rebellion.”

To this petition Witte’s reply was peculiarly characteristic—

“A Constituent Assembly is for the present impossible. Universal suffrage would, in fact, only give pre-eminence to the richest classes, because they could influence all the voting by their money. Liberty of the press and of public meeting will be granted very shortly. I am myself strongly opposed to all persecution and bloodshed, and I am willing to support the greatest amount of liberty possible.... But there is not in the entire world a single cultivated man who is in favour of universal suffrage.”

Undeterred by any fear of exclusion from the circle of culture, the workmen continued their demands for universal suffrage and a Constituent Assembly, and on October 26th the Central Strike Committee—or Council of Labour Delegates, as it was properly called—sitting in St. Petersburg, declared a general strike throughout Russia. About a million workers came out.

This was the second workmen’s blow, and it shook Tsardom from top to bottom.

Four days after the beginning of the strike, the famous Manifesto of October 30th (17th in Old Style) was issued, promising personal freedom and a constitution. The document began with the harmless necessary cant—

[20]

“The troubles and agitations in our capitals and numerous other places fill our heart with great and painful sorrow.... The sorrow of the people is the sorrow of the sovereign.... We therefore direct our Government to carry out our inflexible will in the following manner:—

“I. To grant to our people the immutable foundations of civil liberty, based on real inviolability of person, and freedom of conscience, speech, union, and association.

“II. Without deferring the elections to the State Duma already ordered, to call to participation in the Duma (as far as is possible in view of the shortness of time before the Duma assembles) those classes of the population now completely deprived of electoral rights, leaving the ultimate development of the principle of electoral right in general to the newly established legislature.

“III. To establish it as an immutable rule that no law can ever come into force without the approval of the State Duma, and that it shall be possible for the elected of the people to exercise a real participation in supervising the legality of the acts of authorities appointed by us.”

This manifesto was greeted by an outburst of joy unequalled in the melancholy annals of Russia. Righteousness and peace kissed each other upon the streets; and so did professors, students, and even working people. Red flags paraded the squares, generals saluted them, soldiers joined in the Marseillaise of labour. But the Central Strike Committee was not overcome by the general hallucination. They rightly refused to trust the Tsar without guarantees, and they continued to press their demands for a political amnesty and the[21] convocation of a Constituent Assembly. They also demanded the restoration of its old liberties to Finland, and the dismissal of Trepoff. When anti-Jewish riots broke out at Kieff, Warsaw, and especially at Odessa, they steadily and justly maintained that the “Black Hundred” or “Hooligans” of the massacre and pillage were encouraged by the police and the priests, who wished to make out that the Russian people were opposed to political liberties.

The panic of the Government continued. They could not measure the strength of this new force among the work-people, or of this new instrument, the general strike. They were uncertain, also, about the army, which, together with the police and officials, formed their sole protection from ruin. Pobiedonostzeff, the aged Procurator of the Holy Synod, and the embodiment of an obstinate and narrow tyranny in Church and State, resigned. On November 4th, an amnesty was proclaimed for political offenders, though certain qualifications and categories were added.

On the same day a manifesto restored the old liberties of Finland, abolishing the decree of February 15, 1899, by which the autocratic principle, the dictatorship, and the employment of Russian gendarmes had been imposed upon the duchy contrary to its original constitution, and repealing also the military law of July 12, 1901, which compelled recruits to serve outside their own country.

[22]

On November 9th Trepoff sent in his resignation, and Durnovo, since infamous for his brutality, took office. The same day a violent but ill-considered mutiny broke out among the sailors and gunners at Kronstadt.

From that moment the Government began to recover courage, and we may mark the gradual revival of reaction. Perhaps it was immediately due to the refusal of the Liberal Zemstvoists to take part in a ministry under Witte, unless the promises of the manifesto were guaranteed, and a Constituent Assembly convened. In any case the change was quite apparent in a manifesto of November 12th, declaring the present situation unsuitable for the introduction of reforms, which would only be possible when the country was pacified.

Next day a ukase proclaimed martial law in Poland, and excluded that country from the manifesto, on the pretence that the Poles were plotting against the integrity of the Russian Empire by establishing a separate nation of their own.

The Central Strike Committee answered this ukase on the morrow (November 14th) by declaring another general strike in sympathy with Poland, and Witte, on his side, retaliated by posting an appeal to the work-people, conceived in his most unctuous and fatherly style. It ran—

“Brothers! Workmen! Go back to your work and cease from disorder. Have pity on your wives and children,[23] and turn a deaf ear to mischievous counsels. The Tsar commands us to devote special attention to the labour question, and to that end has appointed a Ministry of Commerce and Industry, which will establish just relations between masters and men. Only give us time, and I will do all that is possible for you. Pay attention to the advice of a man who loves you and wishes you well.”

This appeal was immediately followed (November 17th) by a manifesto to the peasants, reducing their payments for the use of land by one-half after January, 1906, and abolishing it altogether after January, 1907. These payments were still being made under the land settlement that followed the emancipation of the serfs in the early sixties, and their nominal value to the Government was seven million pounds a year. But the apparent generosity of the remission is diminished by the consideration that the peasants had already paid the economic value of the land many times over, and pressure could still be brought upon them to make up the heavy arrears due to successive famines.

Three days later (November 20th), the Central Strike Committee declared the strike at an end. This second general strike was felt to have been a failure. People and funds were still exhausted by the first. Comparatively few of the great factories came out; the object of the strike was too remote from the workman’s daily life to persuade him to endure the starvation of his family for it. So the[24] strike failed. It produced nothing; it did not frighten or paralyse the Government.

Nevertheless, the Strike Committee remained the most powerful body of men in the Empire, and their order commanding the cessation of the strike called hopefully upon the working classes to continue the revolutionary propaganda in the army, and to organize themselves into military forces “for the final encounter between all Russia and the bloody monarchy now dragging out its last few days.”

Such was the situation when, on November 21st I landed at the revolutionary little port of Reval, and went on to St. Petersburg by the first train which had run since the strike ended.

[25]

Away in the western quarter of St. Petersburg, at some distance from the fashionable centre, stands a rather decrepit hall of debased classic. In England one would have put it down to George II.’s time, but in St. Petersburg everything looks fifty years older than it is, because fashions used to travel slowly there from France. Among the faded gilding of stucco pilasters and allegorical emblems of the virtues and the arts, are hung the obscure portraits of long-forgotten men—philosophers, governors, and generals—who were of importance enough in their day to be painted for the remembrance of posterity. Glaringly fresh among the others hangs the portrait of the hesitating gentleman whom the accident of birth has left Autocrat of Russia, whether he likes it or not. The hall was dedicated to the discussion of “Free Economics” by some scientific body, but never before had economics been discussed there with such freedom as during those November nights when the Central Strike Committee, or Council of Labour Delegates, chose it for their meetings.

[26]

Admission was by ticket only, and I obtained mine from a revolutionary compositor, hairy as John the Baptist, and as expectant of a glory to be revealed. On the first night that I went, the big chamber, with its ante-room half separated by plaster columns, was crowded with working people. So was the entrance hall, where goloshes are left, in Russian fashion, so that the floors may not be dirtied. Some of the men wore the ordinary dingy clothes of English or European factory-hands, making all as like as earwigs. Some had come dressed in the national pink shirt, with embroidered flowers or patterns down the front and round the collar. But most wore the common Russian blouse of dark brown canvas, buttoned up close to the neck, and gathered round the waist by a leather belt.

Many women were there, too, but as a rule they were not working women from the mills. Some may have been artisans or the wives of artisans, but most were evidently journalists, doctors, or students, from the intellectual middle classes, which in Russia produces the woman revolutionist—the woman who has played so fine a part in the long struggle of the past, and was now elated above human happiness by the hope of victory. For Russian women enjoy a working equality and comradeship with men, whether in martyrdom or in triumph, such as no other nation has yet realized.

The workmen were delegates from the various[27] trades of the capital and some of the provinces—railway men, textile hands, iron workers, timber workers, and others. About five hundred of them had been chosen, and each delegate represented about five hundred other workers. But round the long green table in the middle of that decrepit hall, under the eyes of the hesitating little Tsar’s portrait, sat the chosen few whom the delegates had appointed as their executive committee. Between twenty and thirty of them were there—men of a rather intellectual type among workers, a little raised above the average, either by education or natural power. A few wore some kind of collar, a few showed the finest type of Russian head—the strong, square forehead and chin, the thoughtful and melancholy eyes, the straight nose, not very broad, and the dense masses of long hair all standing on end. A few seemed to be bred just a trifle too fine for their work, as dog-fanciers say. There they sat and spoke and listened—the members of that Strike Committee which had won fame in a month—just a handful of unarmed and unlearned men, who had shaken the strongest and most pitiless despotism in the world.

In the middle, along one side of the table, was their president, the compositor Khroustoloff—or Nosar, as his real name was—a man of about thirty-five, pale, grey-eyed, with long fair hair, not a strong-looking man, but worn with excitement and[28] sleeplessness. For there was no time now for human needs, and his edge of collar was crumpled and twisted like an old rag. Yet he controlled an excited and inexperienced meeting with temper and ease, showing sometimes a sudden flicker of laughter for which there is very little room in Russian life. Neither for sleep, nor human needs, nor laughter, was there time, but in front of Khroustoloff and of all those men lay the prison or the grave, and in them there is always time enough.

That night, as long as I was there, the meeting was occupied with the discussion of the eight-hours’ day. One of the executive read out the reports received from all the factories represented by delegates as to the hours of labour at present. In some cases, the masters had conceded an eight-hours’ day after the first strike. In others, they had come down to nine, in others to ten. Most had absolutely refused a reduction. These reports, though monotonous and many, were listened to with the silence that characterizes a Russian meeting. It was broken only now and then by a little laughter or a murmur of anger. I have never heard a Russian speaker interrupted even by applause.

The evening before I had attended a meeting where a dull but deserving speaker, to whom no one wanted to listen, went on for an hour and twenty minutes in a silence like an African forest’s, with only an occasional whisper of breezy dresses[29] as the audience changed their position at the end of some uninteresting clause. Ages of dumb suffering have given these people the interminable patience of mountains, and a public meeting is so new to them that they find a fearful pleasure in speeches which our free-born electors would howl down in three minutes. Any meeting of British trade-unionists would have polished off the Strike Committee’s business in an hour, but when I came away, though it was past two in the morning and the meeting had begun at six in the afternoon, the discussion was still proceeding with healthy vigour, and there were plenty of other subjects of equal importance still to be settled. The Committee, in fact, sat almost in permanence night and day.

As soon as the reports were all read, the executive gathered up their papers and adjourned into an upper room to consider their decision. During their absence, the other delegates broke up into groups according to trades, for the discussion of their own affairs. Standing on a chair, a man would shout, “Weavers, this way, please!” “Engineers, here!” or “Railway-men, this way!” and the various workers clustered round in swarms. A fine hum of business arose, and a buzz of conversation with outbursts of laughter too, for all spirits still were high with success and the confidence of victory. At last, as the executive remained over an hour in conference, a yellow-haired young workman[30] with a voice like the Last Trumpet, raised the Russian “Marseillaise,” and in a moment the room was sounding to the hymn of freedom. Russian words—rather vague and rhetorical words—have been set to the old French tune, and even the tune has been altered at the end of the chorus, to make room for the words, “Forward, forward, forward!” which come in suddenly, like the beating of a drum. It was sung in all the streets of all the cities, but I heard it first in the midst of German territory, upon the Kiel canal. For as I was coming over, the only passenger upon the Russian boat, we met an emigrant ship bound for the refuge of freedom, as England still was at that time, and at the sight of our Russian flag the emigrants all burst into the song, the men waving their hats and the women their babes in defiance.

After the “Marseillaise,” the workmen turned to national songs, one of which was almost as magnificent, and was touched with the immense sorrow of Russia. All had one burden—the hatred of tyrants, the love of freedom, the willingness to die for her sake. To us, such phrases have come to bear an unreal and antiquated sound, for it is many centuries since England enjoyed a real tyranny, and the long comfort of freedom has made us slack and indifferent to evil. But in Russia both tyranny and revolt are genuine and alive, and at any moment a man or woman may be called upon to prove how far the[31] love of freedom will really take them on the road to death.

A few days before this workmen’s meeting, I had been at an assembly of the educated classes to protest against capital punishment. One speaker—a professor of famous learning—was worn and twisted by long years of Siberian exile. He was the worst speaker present, but it was he who received the deep thunder of applause. Another had, with Russian melancholy, devoted his life to compiling an immense history of assassination by the State. Before he began to speak, he announced that he was going to read the list of those who had been executed for their love of freedom since the time of Nicholas I. Instantly the whole great audience rose in silence and remained standing in silence while a man might count a hundred. It was as when a regiment drinks in silence to fallen comrades. But few regiments have fought for a cause so noble, and few for a cause in which the survivors still ran so great a risk.

The executive returned from their consultation, and at once the meeting was quiet. President Khroustoloff, in a clear and reasonable statement, announced that, in the opinion of the executive, a fresh general strike on the eight-hours’ question would at present be a mistake. The eight-hours’ day was an ideal to be kept before them; they must allow no master who had once granted it to[32] go back on his word; they must urge the others forward, little by little, and in the meanwhile organize and combine till they could confront both capitalism and autocracy with assurance. Another member of the executive spoke in support of this decision, and then the delegates of the opposite party had their turn. It was the old difference between the responsible opportunist, who takes what he can get, and the man of the ideal, who will take nothing if he cannot have all. The idealists pointed to the evident intention of Witte’s Government to thwart the workmen’s advance. They pointed, with good reason, to the gradual renewal of police persecution during the last few days, and to the encouragement given to masters who declared a lock-out. They urged that it was best to fight before the common enemy regained his full power, and that the general strike, so efficient before, was still the only weapon the workmen had. It was all true. Yet the recent strike had almost failed, and it was just because a general strike was the workmen’s only weapon that it should be sparingly used. A second failure within a fortnight would show the Government that freedom’s only weapon was not so dangerous after all. In the end the executive had its way; they were supported by three hundred votes against twenty; and there could be no question of the wisdom. The weapon of a general strike is too powerful[33] to be brought out, except for some special and all-important crisis. It is like an ancient king, more feared when little seen.

Freedom at that moment was just hanging in the balance. One almost heard the grating of the scales as very slowly the balance began to swing back again. Already things were not quite so hopeful as they had been, and many good revolutionists spoke of the future with foreboding. The first fine rapture of liberty was over, and people who had eagerly proclaimed themselves Liberals three weeks before, now began to feel in their pockets, to hesitate and look round. In subdued whispers commerce sighed for Trepoff back again, and the ancient security of a merchant’s goods. They pretended terror of peasant outbreaks, and the violence of “Black Hundred” mobs, organized by the police just to show the dangers of reform. But it was reform itself that they dreaded, and the name of Socialism was more terrible to them than the tyranny.

Day by day the police were becoming active again. As family men with a stake in the country, they could not be expected to see their occupation taken from them without a struggle. They had the same interest in the ancient régime as the Russian aristocracy in Paris or Cannes; and for their livelihood the misery of the people was equally essential. Whenever they dared, they planted themselves in[34] front of the doors and drove the audience away from a meeting; and the audience had to go, for except to bombs and revolvers there was no appeal. Every day I watched the police hounding groups of tattered and starving peasants or workmen along the streets, because they had ventured to come to St. Petersburg without passports, and had to be imprisoned till a luggage train could take them back to their starving homes. In spite of the manifesto, the censor of the post-office was active again. It is a terrible thing for a civil servant to feel that his work does not justify his pay. So the censor blacked out a cartoon in Punch representing the Tsar as hesitating between good and evil, and then he felt he could look the world in the face.

Already the people recognized that as yet they had no guarantee of freedom. As long as the Oligarchs controlled the police and the army, freedom existed only on sufferance. No one knew what the army would do, and no one knew what the fighting power of the revolution was. Those unknown factors alone terrified the Oligarchs into reform. But all the promises were only bits of paper. It had long been proved that the Tsar’s word went for nothing. At the birth of his son he had abolished flogging, but the taxes had been “flogged out” of the peasants just as before. Manifesto after manifesto had been issued without the[35] least result, beyond winning the applause of an English writer or two. So far the Tsar’s pledges of reform had been no more effectual than his Conference of Peace and he could only become harmless if he had no power to harm.

Yet the outward appearance of freedom surpassed all hope and imagination. Nothing like this had ever been seen in Russia before. Newspapers dared to tell the truth. Meetings were held which a few weeks before would have sent every speaker to the cells. The Poles gathered in a great assembly demanding the overthrow of absolutism and solidarity for the revolution among all the states of the Empire. Women and children taunted the patrols of Guards and Cossacks as they rode the streets. Ladies threw open their nice clean rooms for workmen to meet in. The students’ restaurants hummed with liberty. The air sounded with the “Marseillaise.”

“In Russia now, everybody thinks,” said a revolutionist to me, “and where people think, liberty must come.” Thought and liberty were to bring him death in a few weeks, but for the moment it seemed impossible that any reaction could bring the old order back. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men could not restore that ancient tyranny. The spring of freedom had come slowly up that way, but at last it was greeted as certain, and so it seemed to me when in the darkness of[36] early morning I left that workmen’s meeting still hot with discussion in the mouldering hall, and tramped home through slush and thawing snow, watching the rough floes of drifting ice as they settled down into their winter places upon the Neva.

[37]

The Schlüsselburg road runs nearly all the way beside the great stream of the Neva, which was still pouring down in flood in those November days, though it sounded incessantly with the whisper of floating ice. The road leads from St. Petersburg along the whole course of the river up to that ill-omened fortress in the Ladoga lake, where so many of the martyrs of freedom have enjoyed the imprisonment or death with which Russia rewards greatness. For six or seven miles the road passes through a series of villages, now united into one long and squalid street, inseparable from the city, though only a few hundred yards behind the mills and workmen’s dwellings lie flat fields, and woods, and dull but open country. This is the largest manufacturing district of the capital. Its factories had already become historic with bloodshed, and it was here that the workmen’s party was organized, and the Council of Labour Delegates first formed.

The mills stand on both sides of the river, but as a rule the work-people live on the south or left[38] bank, where the road runs; for there is no passable road on the other side. In summer they pay a farthing toll to steam ferry-boats. In winter they walk across the ice to work, guided by little rows of Christmas trees stuck on the ice, as is the Russian way. But between whiles, twice a year, there come a few days when they cannot go to work at all. Those days ought to have come by the time I visited the region first, but the frost was late.

Everything was strange that year. For months together no work had been done, and though some of the mills had just re-opened after the second general strike, the road was crowded with shabby men and women, who gathered at the corners, or trampled up and down in the filth, or sat stewing in the dirty tea-rooms, quieting their hunger with drink. Fully 60,000 of them were out of work, for in answer to the strike many masters had declared a lock-out.

Backwards and forwards among them marched little sections of six or seven soldiers, their bayonets fixed, their rifles loaded, their warm brown overcoats paid for by the work-people and the peasants. Groups of four or five Cossacks clattered to and fro with carbine and sword, while on the saddle, ready to the right hand, hung the terrible nagaika or Cossack whip, paid for by the work-people and the peasants. It is heavy and solid, with twisted hide, like a short and thicker sjambok; at the butt is a loop for the[39] wrist, and near the end of the lash a jagged lump of lead is firmly tied into the strands. When a Cossack rises in his stirrups to strike, he can break a skull right open, and any ordinary blow will slit a face from brow to chin, and cripple a woman or child for life.

The Manifesto had not changed the Cossack nature. A week before, at a workmen’s meeting held to discuss the strike, it was proposed to stop the steam trams which run along the road. But the Cossacks had received orders not to allow the trams to be stopped. So down they trotted to the meeting; a pistol shot is said to have been heard somewhere in the darkness, and in a moment the horses were plunging through the midst of a confused and helpless crowd, while swords and nagaikas hewed the people down. The number of killed and wounded was variously given, as is usual in massacres.

On one of my later visits down the road, I became acquainted with a man who had survived a scene even more terrible. As a small patrol of Cossacks was riding by, a little boy of eight, who had come to the mill with his mother, shook his tiny fist at them from a window. By command of their officer, the men rode into the mill yard, dismounted, entered the machinery rooms, bayoneted the child, and began firing at random upon the people at their work. Eight were killed where they stood. The man who told me of the deed escaped[40] through a side door, and hid himself under the boilers till the soldiers rode away elated with victory. Then the workmen dragged out the dead, and the boy’s body was given to his mother.

Tired of being slaughtered like fowls, the workmen themselves were collecting arms, and had organized a kind of volunteer service, or “militia,” as they called it. Armed groups crept through the fields and back lanes from one point of vantage to another. Even in the daytime, firing was common in the streets, and almost every night the workmen met the soldiers in sharp encounter. The factories, whether at work or not, were all guarded by sentries inside and out. The Alexandrovsky ironworks, which belong to Government, and had been shut down the day before I was there, were at once filled with troops, and the hands, some five thousand in number, remained outside to increase the shabby and indignant crowd upon the street.

Art Reproduction Co.

AN AUTUMN IDYLL.

From Sulphur (Jupel).

The ironworkers were the best paid of all the workmen in the district. The works are in an old red-brick factory, built originally for making guns, but long used for the locomotives on the straight line from St. Petersburg to Moscow. Many charming personages in Russian society had justly regarded that factory as the source of human happiness. But in their trepidation to enjoy, they had neglected the fount of enjoyment, and the place had long been sliding down to ruin. Already it was much cheaper [41]to buy new locomotives from Germany, Belgium, or Zurich, in spite of the high tariff, than even to repair the old engines here. At last, I suppose, just the one inevitable day had come when the thing became too ludicrous even for a Government’s methods of industry. The gates were shut, and the five thousand hands turned out to meditate on the source of human happiness.

It was thought at the time that, like the master of finesse who pays his tailor by ordering more clothes, the management would open again soon, because one per cent. of the wages had always been stopped for a pension fund. This fund was estimated at something like £2,000,000, and the Government might well prefer to go on paying out several thousands a year in dead loss rather than be called upon for a solid £2,000,000 when nothing more could be flogged out of the starving peasants, and France was beginning to look twice at a sou before lending it. What happened in the end I did not hear, but I passed down that road some months later, and the works were still shut up.

Other mills, which did not rest upon State credit (that is to say, on drink and the flogging of peasants), and were struggling not to keep shut, but to keep open, were naturally in a different position. There are cotton mills, wool mills, paper mills, and candle mills along the river, many of them run by English capital, and managed by English overseers. In most[42] of the textile mills, the machinery is also English, this being almost the only import in which England still rivals Germany. There is a greater spaciousness about the buildings and yards than in England, due, I suppose, to the cheapness of land; though, in fact, our old economic theories of rent are valueless here, for, in spite of the vast extent of uncultivated land in Russia, the rents in the capital towns are far higher than in London. But, apart from this spaciousness and a certain easy-going slackness in the labour, one might imagine one’s self in a Lancashire or Yorkshire mill. It was in mills like these that the labour questions arose which were really the causes of the strike that shook the Russian despotism. Of course, political questions came in—the war scandals, the demands for home rule, amnesty, universal suffrage, and a constituent assembly. But a revolution, like a war, goes upon its belly, and it is difficult to get working men to move if they are fairly content with their food and lodging. It is still more difficult to get working women to move.

Till ten years ago the hours in these mills were seventy-five a week, or twelve and a half a day, not counting the dinner hours. They then fell to sixty-seven, and the strike of last October brought them down to sixty-two and a half. For the first week of November (just after the manifesto), the hands proclaimed an eight-hours’ day, and walked out of[43] the mills when the time was up. After a week of that, the managers shut the gates, preferring to pay the hands the fortnight’s wages to which they are entitled on dismissal, and then to let the mills stand idle. About a fortnight later, the textile managers agreed to come down to sixty and a half hours a week, and on that arrangement the hands came in again. Thus in ten years the workmen had reduced their hours by nearly fifteen a week, and seven of these had been knocked off in two months, simply by combination in strikes. As I said, the general strike is a powerful weapon, though, unhappily, dangerous to those who use it.

At the time there was a general opinion that a nine-hours’ day would be enforced by an Imperial ukase. Even the employers believed it, and looked forward to making up the loss by increased duties on imports, and higher prices for their goods. The workmen would probably acquiesce, for a strike falls most heavily on themselves, and under the Russian factory laws any one who incites to a strike or joins in it may be imprisoned for four to eight months. Till December, 1904, all trade unions and meetings of workmen were also illegal. During his period of ill-omened power, Plehve had affected to encourage meetings in this very district, but his sole object was to ascertain who were the real leaders among the people, and who were the best speakers. When that was known, in the middle of the night, knocking[44] would be heard at a man’s door. He would open it to a group of soldiers or police, and from that moment he disappeared, spirited away, no one knew where. It was the Government’s method of protecting vested interests.

Wages nearly always go by piecework, and they vary according to skill. In the cotton mills a man may earn anything between 15d. and 4s. 4d. a day, and a woman between 10d. and 2s. 4½d. In the woollen mills a weaver makes about 3s. 5d. a day, and he has two assistants (generally girls) who make from 1s. 10d. to 2s. 4d. each. The ironworkers, as I said, get a rather higher wage, but the maximum, I think, in no case is over 30s. a week, and I doubt if the average, including women and girls, is over 15s.

The mere amount of money in wages is unimportant. A handful of bay-salt or three yards of cheap cotton may be good wages to an African native. All depends on what the payment can buy and what work it represents, and I am inclined to think from what 1 have seen in many lands that in reality the wage of the working class is much the same all the world over. The standard of tolerable existence certainly varies a little, but the wage is always regulated by the lowest standard that will be endured. Wherever I have consulted an overseer or mill-owner as to the standard of living in Russia, he has almost always told me that I must[45] not judge by English ideas, “because the people here are quite satisfied with black bread and cucumbers.” By cucumbers he meant the small pickled gherkins in barrels, such as form one peculiar ingredient in the smell of Petticoat Lane. At the same time all English overseers were agreed that the Russian workman’s standard of work is far lower than the English. A Russian will mind only two looms, they told me, where an Englishman will mind four or even six. It had not occurred to them that there might be some connection between the standard of food and the standard of work, nor, indeed, did that concern them much, for in the end they obtained about the same amount of work for the same amount of wage.

When I became more acquainted with the work-people’s life and had been into several of their homes, I found that, as long as they were in work, most of them had soup every day, because bad meat was cheap. Beyond the soup, black bread was the duty, pickled cucumber the pleasure; and the drink was almost unlimited tea—very weak and without milk, but syruppy with sugar—varied by an occasional debauch on the State’s vodka, which pays the greater part of the tyranny’s expenses.

On the Schlüsselburg road the work-people live in wooden huts built up wandering courts or lanes off the main street. I have not seen a family occupying more than one room. If they rent two[46] or three, they sub-let. A room costs from 15s. to 22s. a month, and the larger rooms are usually divided between two or more families. In some cases each of the four corners is occupied by a different family, separated by shawls or strings, and dwelling as though in tents, as used to be the fashion in the East End. Till quite lately a very large proportion of the work-people lived in special barracks built for them inside the mills, but during that year of strikes most of the overseers had cleared their work-people out because they were dangerously near to themselves and the machinery, and I did not see the “living-in” system really at work till I got to Moscow, where it was still general, though probably soon to disappear.

In the work-people’s rooms there was hardly ever any furniture beyond the bed, the table, some stools, and a chest for clothes. I never saw washing things of any kind. Even in winter the family clothes are washed in the river, the women cutting square holes in the ice and dipping the clothes into the water below. As to the people, in accordance with the one salutary rubric of the Orthodox Church, all men (I am not quite sure about women) must wash before they go to service. In preparation for this sacred duty, they pay a few pence at the public baths, sluice themselves down with hot water, and then lie steaming on shelves, brushing their skin with branches of birch. The effect is very satisfactory, and[47] the Russians as a whole are a cleanly people, both in themselves and their houses, compared to ourselves.

The work-people have the further advantage of twenty-three ecclesiastical holidays in the year, not counting Sundays, and the masters are obliged to provide a hospital or to pay for medical assistance, even for women with child. In an English mill across the river, a clubroom for lectures, concerts, and amusements had just been erected, but the revolution had arrested culture of that kind. It had also arrested football, which was just becoming popular. Cricket had been tried, but was found too mysterious and pedantic, too much like the British Constitution with all its growths and precedents. The only native amusements that I could find were cards, knucklebones, and the fortnightly debauch in vodka when the wages are paid. But at the time of my first visit, there was some chance that the vodka would be dropped, for on the previous Sunday night the Strike Committee had decided that the work-people should for the present give up spirits, tobacco, and other Government monopolies, not for abstinence but to deprive the Government of revenue. The truly Nationalist party has urged the same course in Ireland.