THE REV. T. T. MATTHEWS.

Title: Thirty years in Madagascar

Author: Thomas T. Matthews

Release date: February 23, 2023 [eBook #70113]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: The Religious Tract Society, 1904

Credits: Peter Becker, Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THIRTY YEARS IN MADAGASCAR

OXFORD

HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

THE REV. T. T. MATTHEWS.

BY THE REV. T. T. MATTHEWS

OF THE LONDON MISSIONARY SOCIETY

WITH

SIXTY-TWO ILLUSTRATIONS

FROM PHOTOGRAPHS

AND SKETCHES

SECOND EDITION

LONDON

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

4 BOUVERIE STREET AND 65 ST. PAUL’S CHURCHYARD

1904

[3]

For the facts of the historical introduction I am mainly indebted to the writings of earlier writers and missionaries, and to unpublished native accounts of the earlier years of the mission and of the persecutions; for mine would have been almost impossible had it not been for the labours of those other workers in the same field, and for the native sources I have mentioned. Without such knowledge as this introduction gives no correct conception can be formed of Madagascar and the Malagasy, of the work done for and among them, the present condition and future prospects of the people, and of the future of Christian work in the island.

I have been also indebted to a long course of reading on mission work at large, and on the work in Madagascar in particular. Much of this has become so mingled with my own thoughts that I cannot now possibly trace all the sources of it; but I have tried, as far as I could, to make acknowledgement of all the sources of information to which I have been indebted, and special acknowledgement of those more recent sources of information not alluded to in any other book on Madagascar. There are many things in this book derived from native sources that have not been utilized before.

Believing that ‘a plain tale speeds best being plainly told,’ I have tried to tell my story in plain and pointed language, and I hope I have also been able to tell it graphically enough to make it interesting. My great difficulty has been condensation; very often paragraphs have had to be reduced to sentences, and chapters to paragraphs.

One who has spent thirty years in the hard, and often very weary, work of a missionary in Central Madagascar—not to mention the arduous and exhausting duties of deputation work while on furlough—with all the duties, difficulties, and anxieties involved in the superintendence of large districts, with their numerous village congregations and schools, could hardly be expected to have much spare time to devote to the cultivation of the graces of literature or an elegant style. I have tried to tell my story in a warm-hearted way, being anxious only that my meaning should be clearly expressed, whatever might be its verbal guise. I have never been able to understand why, without flippancy or irreverence, religious topics may not be treated at times ‘with innocent playfulness and lightsome kindly humour.’ Why, too, should the humorous side, and even humorous examples, be almost entirely left out of records of foreign mission work? Such incidents sometimes help to relieve the shadows by the glints of sunshine, and for this reason I have ventured to describe the bright, and even humorous, as well as the dark side of missionary work. I have tried to set forth the joy and humour as well as the care, the sunshine as well as the shadow.

John Ruskin says: ‘A man should think long before he invites his neighbours to listen to his sayings on any subject whatever.’ As I have been thinking on the subject of missions for forty years, and have been engaged in mission work for thirty, if my thoughts are not fairly mature on the subject now, and my mind made up on most points in relation to missions and mission work, they are never likely to be. At the same time, when an unknown writer asks the attention of the Christian public upon such an important theme as foreign missions, he is at least expected to show that he has such a thorough and practical acquaintance with them as fairly entitles him to a hearing. I hope the following pages will prove my claim to this consideration. If they help to create interest in the great cause of foreign missions in some quarters, and to deepen it in others, I shall feel well repaid for all the trouble the preparation of them has cost me.

I am deeply indebted to friends for their valuable help and advice, and render them my very hearty and sincere thanks.

[7]

| PAGE | |

|---|---|

| Chapter I. | |

| A Land of Darkness | 13 |

| Chapter II. | |

| ‘The Killing Times’ | 42 |

| Chapter III. | |

| From Darkness to Dawn | 69 |

| Chapter IV. | |

| The Morning Breaking | 87 |

| Chapter V. | |

| Breaking up the Fallow Ground | 107 |

| Chapter VI. | |

| Early Experiences | 123 |

| Chapter VII. | |

| Shadow and Sunshine | 142 |

| Chapter VIII. | |

| District Journeys and Incidents | 168 |

| Chapter IX. | |

| Development and Consolidation | 183 |

| Chapter X. | |

| The Dead Past | 202[8] |

| Chapter XI. | |

| Progress all along the Line | 213 |

| Chapter XII. | |

| Gathering Clouds | 229 |

| Chapter XIII. | |

| Bible Revision and ‘an Old Disciple’ | 248 |

| Chapter XIV. | |

| The Light Extending | 267 |

| Chapter XV. | |

| The Conquest of Madagascar | 291 |

| Chapter XVI. | |

| Trials, Triumphs, and Terrors | 314 |

| Chapter XVII. | |

| The End of the Monarchy | 352 |

| Chapter XVIII. | |

| The Triumph of the Gospel | 369 |

| INDEX | 381 |

[9]

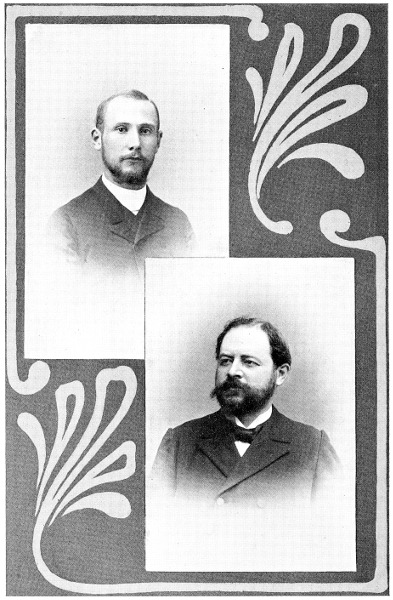

| The Rev. T. T. Matthews | Frontispiece | |

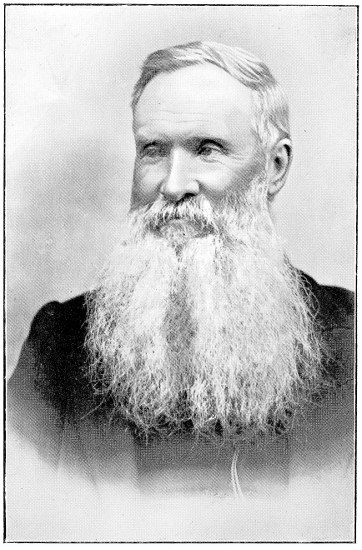

| Map of Madagascar | To face page | 13 |

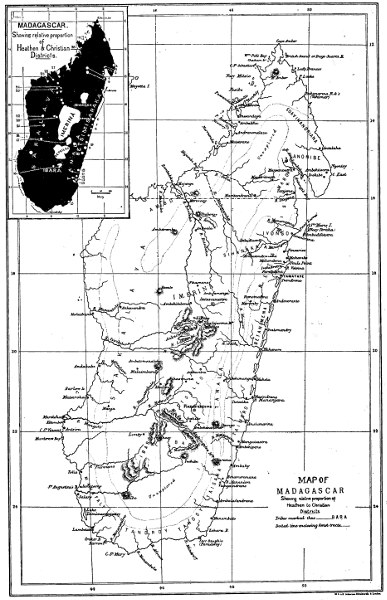

| Malagasy Hair-dressing | „ | 28 |

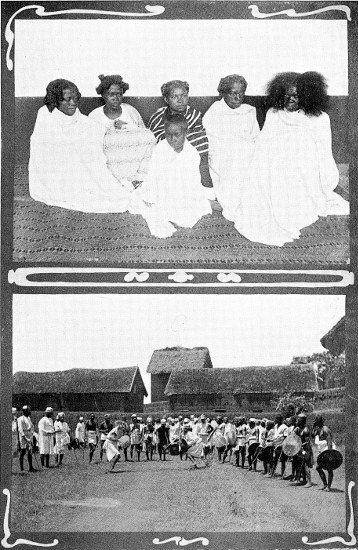

| A Heathen War-dance | „ | 28 |

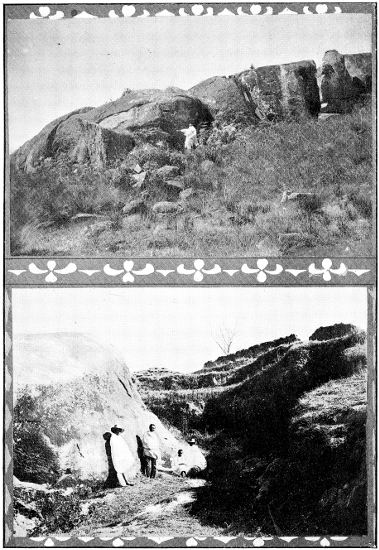

| The Cave in which the Bible was hid for Twenty Years | „ | 44 |

| The Fosse in which Rasalama was speared | „ | 44 |

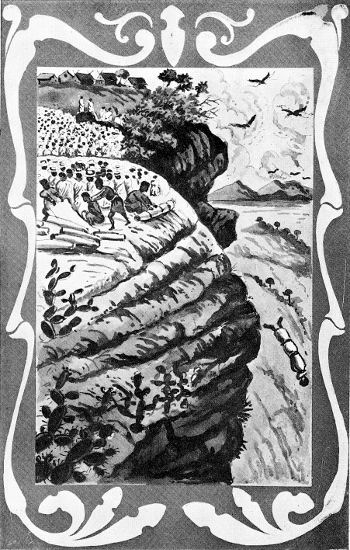

| The Martyrdoms at Ampamarinana | „ | 51 |

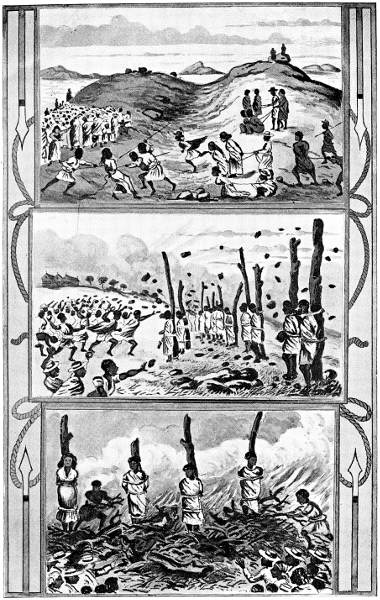

| The Spearing at Ambohipotsy | „ | 60 |

| The Stoning at Fiadanana | „ | 60 |

| The Burning at Faravohitra | „ | 60 |

| Criminals in Chains, illustrating how the Martyrs were treated | „ | 64 |

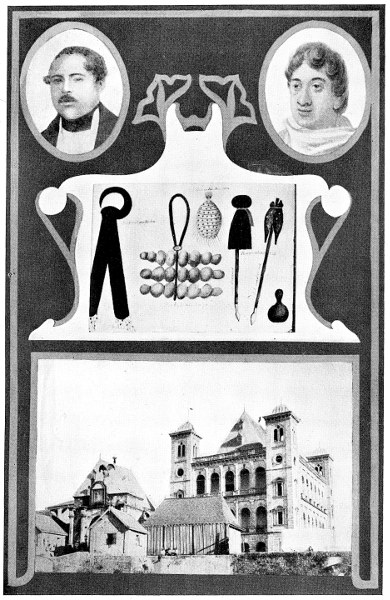

| Radama I. Radama II | „ | 74 |

| The Royal Idols of Madagascar | „ | 74 |

| The Palace, Antananarivo | „ | 74 |

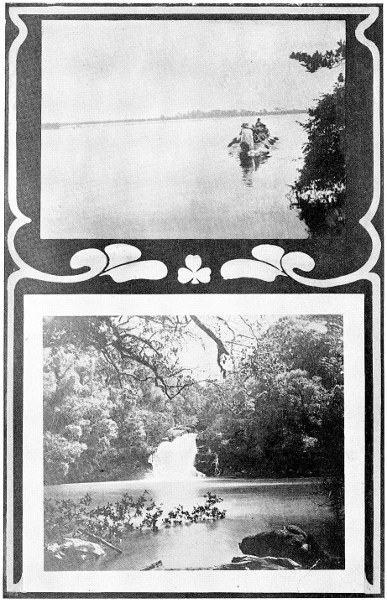

| A River Scene and a Forest Scene in Madagascar | „ | 83 |

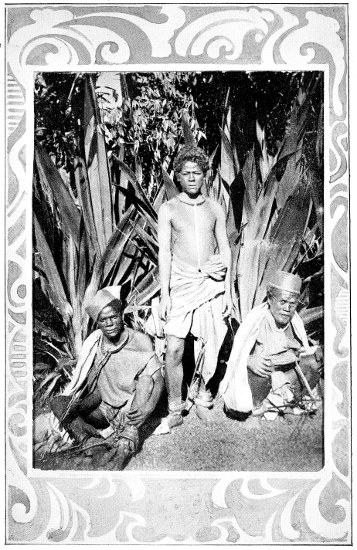

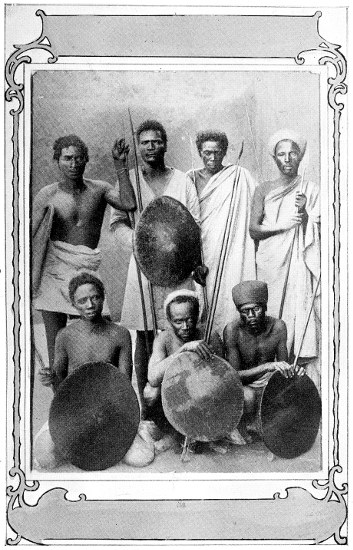

| Heathen Malagasy | „ | 110[10] |

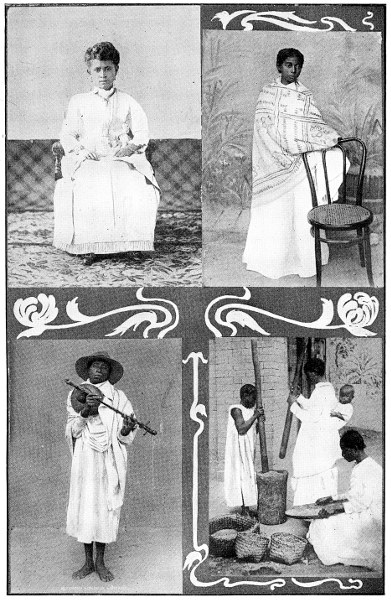

| Malagasy Types: A Hova Princess. A Hova Christian. A Minstrel. Malagasy pounding Rice | „ | 112 |

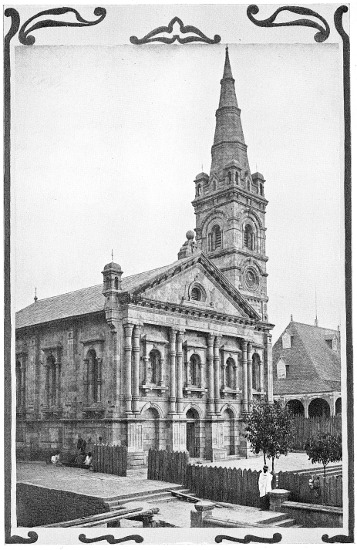

| The Palace Church, Antananarivo | „ | 119 |

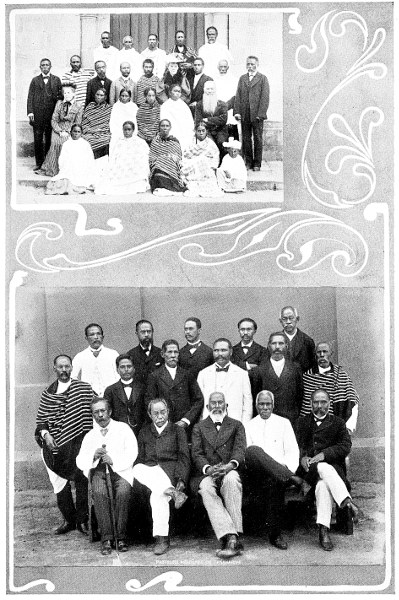

| Malagasy Christian Workers | „ | 144 |

| A Group of Native Preachers and Evangelists | „ | 144 |

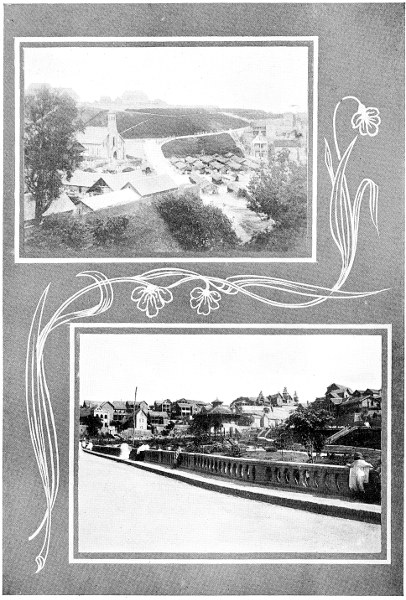

| Analakely: Church and Market-place | „ | 164 |

| The Piazza, Andohalo | „ | 164 |

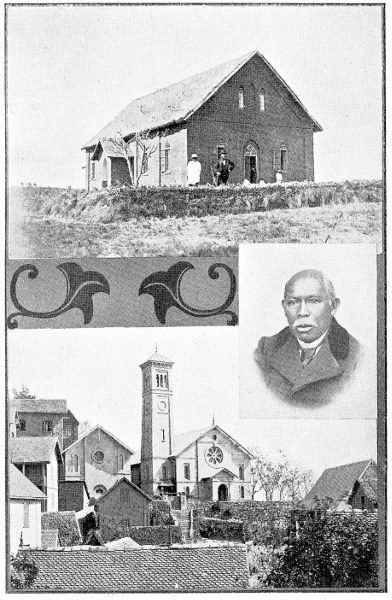

| Martyrs’ Memorial Church, Fihaonana | „ | 186 |

| The Spurgeon of Madagascar | „ | 186 |

| Martyrs’ Memorial Church, Ampamarinana | „ | 186 |

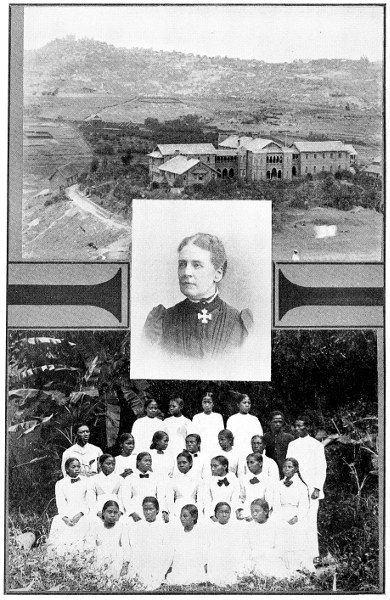

| The Mission Hospital. Miss Byam, the Matron. A Group of Nurses | „ | 195 |

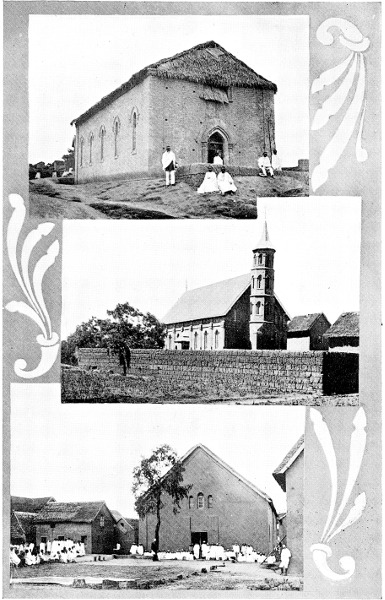

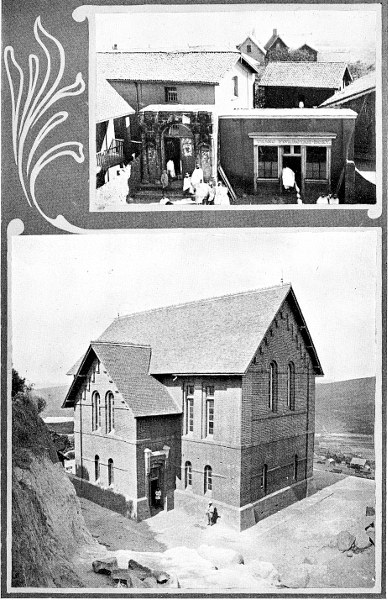

| Suburban Church, Old Style | „ | 201 |

| Suburban Church, New Style | „ | 201 |

| Imerimandroso Church | „ | 201 |

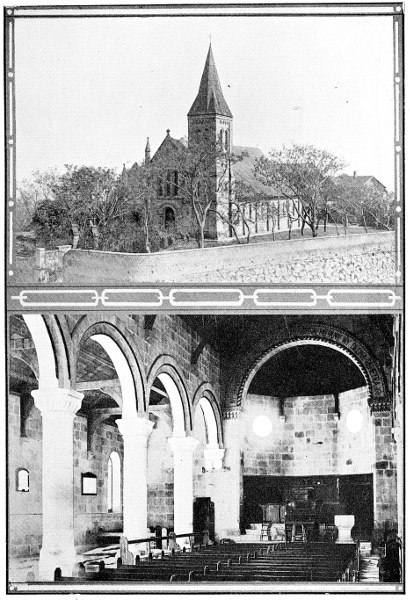

| Memorial Church, Ambatonakanga | „ | 230 |

| Interior of the Church | „ | 230 |

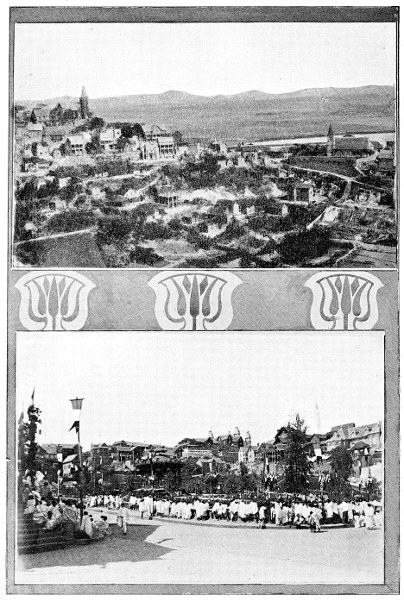

| Ambatonakanga from Faravohitra | „ | 237 |

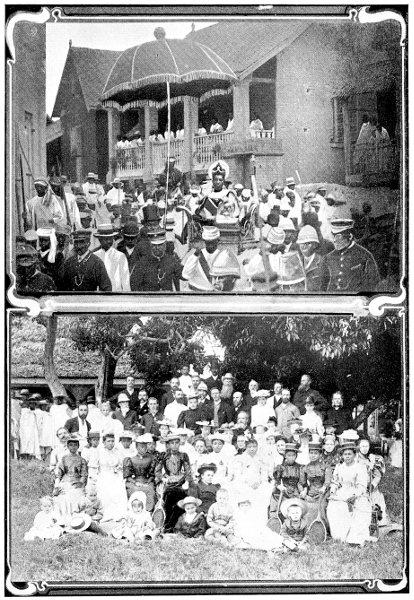

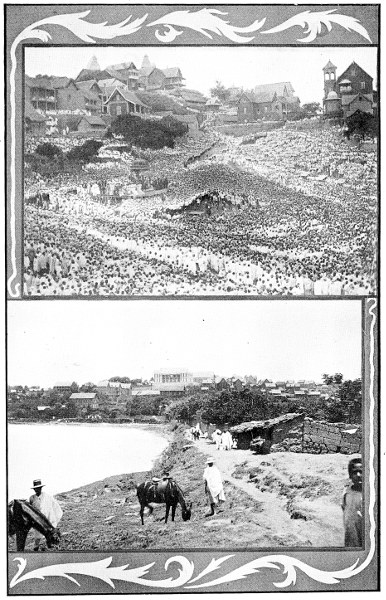

| Antananarivo on a Fête Day | „ | 237 |

| The Queen of Madagascar on the Way to the Last Review | „ | 245 |

| A Garden Party at the Queen’s Gardens | „ | 245[11] |

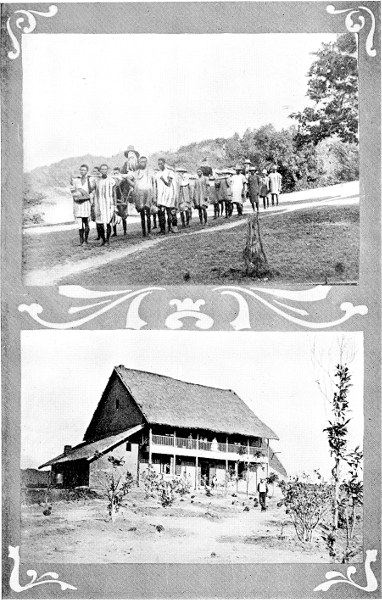

| The Author travelling in Palanquin. The Manse at Fihaonana | „ | 250 |

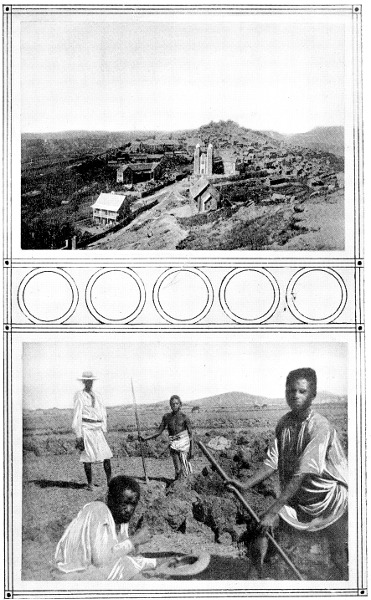

| Fianarantsoa, Capital of Betsileo | „ | 267 |

| Malagasy working the Soil | „ | 267 |

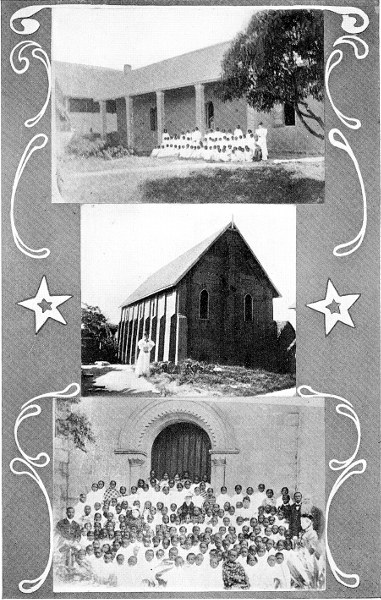

| The Old School, Ambatonakanga | „ | 279 |

| The New School, Ambatonakanga | „ | 279 |

| Group of Scholars, Teachers, and Christian Workers | „ | 279 |

| The Last Kabary | „ | 291 |

| The Queen’s Lake, Antananarivo | „ | 291 |

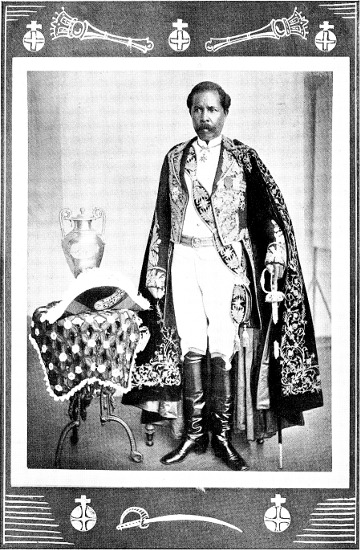

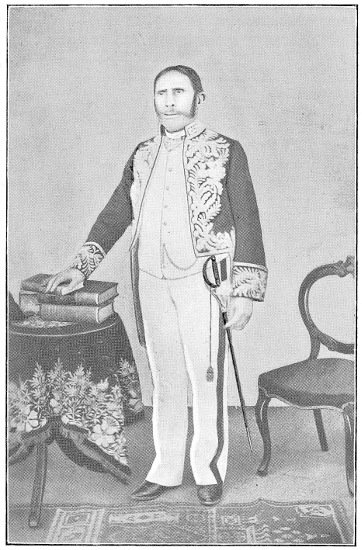

| Rainilaiarivony, the Last Prime Minister of Madagascar | „ | 300 |

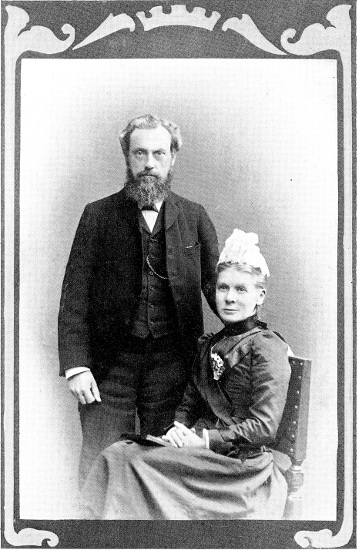

| William and Lucy Johnson | „ | 305 |

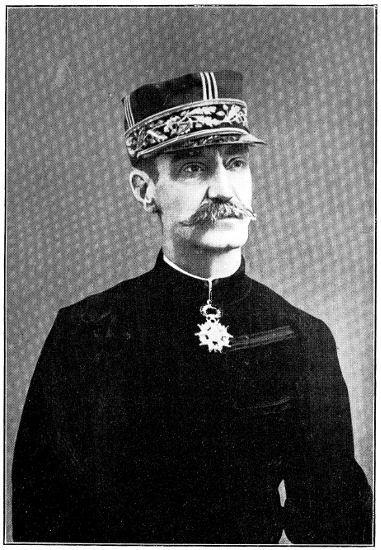

| General Gallieni | „ | 320 |

| B. Escande. P. Minault | „ | 353 |

| The Last Queen of Madagascar | „ | 359 |

| The London Missionary Society Printing-office | „ | 364 |

| The Normal School | „ | 364 |

| The Governor of Tamatave | „ | 374 |

MAP OF MADAGASCAR.

[13]

THIRTY YEARS IN MADAGASCAR

‘He brought them out of darkness.’—Psalm cvii. 14.

Madagascar is the third largest island in the world, about 1,000 miles long, by 375 at its widest part, with an average breadth of about 250 miles. It has an area of about 230,000 square miles, so that it is almost four times the size of England and Wales, or two and a half times that of Great Britain and Ireland, or seven times the size of Scotland!

This important island is situated in the Indian Ocean, and separated from the east coast of Africa by the Mozambique Channel, which is some 250 miles broad. It lies between latitude 12° 2’ to 25° 18’ south of the line, and longitude 44° to 50° east of Greenwich, about 550 miles to the north-west of the island of Mauritius—the far-famed ‘key of the Indian Ocean’—some 950 miles to the north-east of Port Natal, and 750 to the south-east of Zanzibar.

‘Although visited by Europeans only within the last 400 years, Madagascar has been known to the Arabs for many centuries, probably a thousand years at least, and also, although perhaps not for so long a time, to the Indian traders of Cutch and Bombay.’ Moreover, some of the great classical writers of Greece and Rome, such as Aristotle, Pliny (the elder), and Ptolemy, seem[14] to have heard of Madagascar; though until a few years ago this had escaped notice, owing to the fact that the island was known to them by different names.

There is perhaps some ground for supposing that the Jews may have known of Madagascar, and that the sailors of Solomon, in their voyages in the ‘ships of Tarshish,’ may have visited that island. ‘Ages before the Arabian intercourse with Madagascar, it is highly probable that the bold Phoenician traders’ ventured as far to the south, or at least obtained information about this great island.

The fact that the Ophir of Scripture, from which came the famous ‘gold,’ is now believed by most high authorities to have been on the east coast of Africa, renders it highly probable that these ‘ships of Tarshish,’ with Solomon’s sailors on board, may have visited Madagascar. If so, it is easy to account for the close resemblance between certain Malagasy and Jewish customs, such as the scape-goat and the sprinkling of blood, or rather their practice of soaking a piece of bulrush in the blood of the bullock killed at the annual festival of the Fàndròana, i. e. ‘the bath,’ and placing it above the lintel of the door of the hut for its sanctification and protection from evil influences. The killing of a bullock at the annual festival of the Fàndròana seems to suggest some slight connexion with the Jewish sacrifice of a bullock on the day of Atonement. Quarrels were made up, and binding engagements entered into, over the body of a slain animal. The Jewish forms of marriage, the practice of levirate marriage, the Jewish law as to bankruptcy, under which the bankrupt and his wife and family were sold into slavery for the behoof of his creditors—there is a Malagasy proverb which says: ‘Pretentious, like a slave of Hova parentage’—and[15] other usages seem all to point in the direction of Jewish influences.

There are fifteen different tribes in Madagascar, but the Hova tribe—that occupies the central province of Imèrina, Ankòva (the land of the Hova)—was for about a century the dominant one. The Hovas were not the aborigines of Central Madagascar; these were a tribe or people called the Vazìmba, who were dislodged by the ancestors of the Hovas, and who have been extinct for ages. In their heathen state the Hovas worshipped at the tombs of the Vazìmba, and offered sacrifices to their shades to propitiate them, as they believed they could harm them or do them good. The Hovas might be called the Anglo-Saxons of Madagascar, a race of foreigners who entered the island 1,000, perhaps 2,000, years ago, and who, strange to say, belong to the Malay portion of the human family, and are thus allied to the South Sea Islanders.

How the ancestors of the Hovas came to Madagascar is a mystery, as the nearest point from which it is believed they could have come is the neighbourhood of Singapore, upwards of 3,000 miles away. Hova tradition states that their forefathers landed on the north-east coast of the island, fought their way gradually up into the interior, and finally took possession of the central province of Imèrina. That is probably as near the truth as will ever be discovered.

‘About the seventh century, the Arabs of Mecca took possession of the Comoro Islands, lying to the north-west of Madagascar, and extended their commerce all over the coasts of that great island; and it was to a marked extent their language, civilization, and religion which for centuries dominated the north-west of the island. The great Arab geographer Edresi, who lived in A.D. 1099, has left[16] among his writings a description of Madagascar, which he calls Zaledi. The same author refers to the emigration of Chinese and Malays, who settled in Madagascar at an epoch which unfortunately cannot now be precisely determined, but which at least is not so very remote; these were probably the ancestors of the Hovas.’

Madagascar was first made known to modern Europe by the celebrated Venetian traveller Marco Polo, in the thirteenth century. He, however, had never seen or visited the island, but had heard during his travels in Asia various accounts of it under the name of Magaster, or Madagascar. He devotes a chapter of his most interesting book of travels to a description of the island; but he seems to have confounded it with Magadoxo on the adjoining coast of Africa, as much of what he relates is evidently confused with accounts of the districts on the mainland of Africa, and of the island of Zanzibar, since he says that ivory is one of its chief products, and that it contained elephants, camels, giraffes, panthers, lions, and other animals which never existed in Madagascar. The ‘rock’ or ‘rukh,’ a gigantic bird which he describes, is in all probability the aepyornis, the original of the huge bird of Sinbad the Sailor, long deemed fabulous. The aepyornis, now extinct, was a struthious bird allied to the New Zealand moa. It produced an egg which would fill a gentleman’s silk hat.

It was not until the beginning of the sixteenth century that any European set foot on Madagascar. Towards the end of the fifteenth century the adventurous Portuguese navigators, Bartholomew Diaz and Vasco da Gama, reached the southernmost point of Africa, and rounded the Cape of Good Hope, thus discovering the sea route to India and the far East. On the Mozambique coast[17] da Gama found numbers of Arabs trading with India, and well acquainted with the island of Madagascar. In A.D. 1505, King Manoel of Portugal sent out a fleet to the Indies, under the command of Don Francisco de Almeida, who in the following year sent back to Portugal eight ships laden with spices. On their way they discovered, on February 1, A.D. 1506, the east coast of Madagascar. Joas Gomez d’Abrew discovered the west coast of the island in the same year, on August 10, St. Laurence’s Day, from which circumstance it was called the Island of St. Laurence, a name which it retained for more than a hundred years.

During the early times of French intercourse with Madagascar, in the reign of Henry IV, it was known as the île Dauphiné; this name was never accepted by other nations. There is, however, every reason for believing that the name Madagascar is not a native name, but one given to the island by foreigners. ‘Nòsindàmbo’ (the isle of wild hogs) was a name sometimes given to Madagascar; but when the Malagasy themselves spoke of the whole island, they usually called it Izao rehètra izao, or Izao tontòlo izao (the universe). The Malagasy, like many other islanders, probably thought that their island home, if not the whole universe, was certainly the most important part of it, and that the Arabs and other foreigners came from some insignificant spots across the sea. Another name used by the Malagasy for their island is Ny anìvon’ny rìaka (what is in the midst of the floods), a name that might be fairly applied to most islands. This name, it is said, was engraved on the huge solid silver coffin of Radàma I, the King of Madagascar, or rather King of the Hovas. On it he was called Tòmpon’ny anìvon’ny rìaka (Lord of what is in the midst of the floods).

[18]

As might be expected, the accounts given of Madagascar by early voyagers and writers are full of glowing and extravagant language as to the fertility and natural wealth of the island. Although these are certainly very great, they have been much exaggerated.

The earliest known English book on Madagascar was written by Walter Hammond, surgeon, and published in 1640. The same author published another book in 1643, dedicated to the Hon. John Bond, Governor and Captain-General of the island of Madagascar; but who this Hon. John Bond was, or what right he had to that title, no one seems to know. In the latter part of the seventeenth century a book on Madagascar was published by a Richard Boothby, merchant in London. From the preface of his book we learn that two years before its publication there had been a project to found an English colony, or plantation, as it was called in those days, in Madagascar.

Doubtless there were many who mourned over the failure of this project, just as there are many, and the writer among them, who regret that the British flag does not wave over Madagascar to-day. Such a state of matters, they think, would be better for the world at large, and for Madagascar in particular. In their opinion the British flag, like the American, represents justice, mercy, and equal rights to all men of whatever clime or colour. This cannot be said to the same extent for all symbols of dominion. British and American statesmen seem still to have a belief—even although at times it may suffer partial eclipse—that ‘Righteousness exalteth a nation; whereas sin is a reproach to any people.’ Nations, civilized or uncivilized, cannot permanently be governed by falsehood and chicanery.

Until 1810 Madagascar seems to have been almost lost[19] sight of by European nations. In that year the islands of Mauritius and Bourbon, or Réunion, were captured from the French by the British, under Sir Ralph Abercromby. When the peace of 1814 was arranged, the island of Réunion was restored to France; but the island of Mauritius remained in the possession of Great Britain. Shortly afterwards a proclamation was issued by Sir Robert Farquhar, then Governor of the lately acquired colony of Mauritius, taking possession of the island of Madagascar as one of the dependencies of Mauritius. This proceeding, prompted by the belief that Madagascar was such a dependency, was discovered to be a mistake, and all claim to the island was given up.

The slave trade was at that time in full operation in Madagascar. Malagasy slaves supplied the islands of Mauritius and Bourbon, while shiploads were conveyed to North and South America, and even to the West Indies. Slaves could be bought on the coast of Madagascar in those days at from six to twelve pounds, and sold at from thirty to sixty pounds for a man, and at from forty to eighty pounds for a woman; and hence the trade proved a very tempting one to many. It reflects lasting honour on the British nation that no sooner had Madagascar come, to some extent, under the influence of Great Britain, through her possession of Mauritius, than a series of efforts were put forth to annihilate this vile traffic in human flesh. The attitude of British officers, consuls, and other officials towards man-stealing has ever been most uncompromising. Not even their bitterest enemies have ever dared to accuse them of selling the protection of their country’s flag to Arab slavers. And it was due, in the first instance, to the exertions of Sir Robert Farquhar, the able and humane Governor of[20] Mauritius, that the slave trade with Madagascar was abolished.

At the close of the year 1816 Sir Robert Farquhar sent Captain Le Sage on a mission to Madagascar, to induce Radàma I to send two of his younger brothers to Mauritius to receive an English education. They were sent, and placed under the care of Mr. Hastie, the governor’s private secretary, who afterwards took them back to Madagascar; and ultimately became himself the first British Agent to that island, and one of its best and noblest friends, a friend who has never been forgotten, notwithstanding all that has taken place in recent years. A most favourable impression was made on the mind of Radàma I by the way in which his brothers and he had been treated by Sir Robert Farquhar and the British.

Advantage was taken of this impression, and Mr. Hastie had instructions to negotiate a treaty with Radàma I for the abolition of the slave trade. This he ultimately accomplished by promising an annual subsidy from the British government of some two thousand pounds; and a present of flint-locks and soldiers’ old clothes for the king’s army. No act of Radàma’s life shed such lustre on his reign, or will be remembered with so much gratitude, as his abolition of the slave trade. Sir Robert Farquhar, however, contemplated not merely the civilization of Madagascar, but also its evangelization. With this in view, he wrote to the Directors of the London Missionary Society suggesting Madagascar as a field for missionary enterprise, and giving them every encouragement to enter upon it.

At one of the earliest meetings of the Directors of the Society in 1796 the subject of a mission to Madagascar was taken up; and when the subsequently famous[21] Dr. Vanderkemp left England in 1796 for South Africa, he had instructions to do all in his power to further the commencement of missionary operations among the Malagasy. The propriety of his paying a visit to the island to learn all he could for the guidance of the Directors was suggested. In 1813 Dr. Milne, whose name was destined to be so honourably connected with China, was also instructed to procure in Mauritius, on his way to China, all available information regarding the contemplated sphere of labour.

But it was not until 1818 that the first two London Missionary Society missionaries left our shores for Madagascar. In November of that year the Rev. D. Jones with his wife and child landed at Tàmatàve, and in January, 1819, the Rev. T. Bevan with his wife and child arrived, only to find that Mrs. Jones and her child were already dead of fever, while Mr. Jones lay very dangerously ill with it. Mr. Bevan at this seems to have lost heart. His child died on January 20, he himself on the 31st, and his wife on February 3. Thus within a few weeks of landing on the coast of Madagascar, five of the mission party of six had passed away, and the sole survivor was at the gates of death! They did not then know, what we know now, the proper season for landing on the coast of Madagascar. They landed just at the beginning of the fever season, and having no quinine they were but imperfectly equipped for fighting so dire a foe as Malagasy fever.

When able to travel, Mr. Jones returned to Mauritius to recruit his strength, and in September, 1820, he returned to Madagascar, along with Mr. Hastie, the first British Agent appointed to the court of Radàma I. The king received them very kindly, and when he understood the object of Mr. Jones’s coming, he sent a letter[22] to the Directors of the London Missionary Society, in which he said: ‘I request you to send me, if convenient, as many missionaries as you may deem proper, together with their families, if they desire it, provided you send skilful artisans, to make my people workmen as well as good Christians.’

Accordingly between 1820 and 1828 the Directors of the London Missionary Society sent fourteen missionaries to Madagascar—six ordained men and eight missionary artisans. Among the latter were a carpenter, a blacksmith, a tanner, a cotton-spinner, and a printer. Thus almost all that the Malagasy know to-day of the arts and industries of civilized life, in addition to the knowledge of ‘the way of Salvation,’ they owe to the missionaries of the London Missionary Society. The best of the Malagasy people have always been grateful to the Society for all it has done through its agents for their temporal and spiritual welfare.

Recently, however, another and a very different version of Malagasy history has been produced. It begins by casting reflections upon our work in Madagascar. We are told that the British missionaries have never done anything for the Malagasy, except to teach them to sing a few hymns and make hypocrites of them! We are seriously asked to believe that the Malagasy owe all their knowledge of civilization, and of the various arts and handicrafts of civilization, to a French sailor, who was wrecked on the coast of the island, found his way up to the capital, and there became the very intimate friend (or more, as some French writers maintain) of Rànavàlona I, the persecuting queen. Voltaire is credited with saying that he could ‘write history a great deal better without facts than with them.’ This ‘New Version of Malagasy History’ fully conforms[23] to his ideal—the facts are lacking. This ‘old man of the sea’ is a myth like his prototype.

Whatever else they may have done, it cannot be denied that the British missionaries were the first to reduce the language to writing. When the missionaries arrived in Madagascar the people had no written language. The king had four Arabic secretaries, and, but for the advent of the missionaries, in all probability the characters used in the language of Madagascar would have been Arabic, which of course would have made the acquisition of the language much more difficult to foreigners than it is. When the king saw the Roman characters, he said: ‘Yes, I like these better, they are simpler, we’ll have these.’ And so the character in which the language of Madagascar was to be written and printed was settled by the despotic word of the king under the influence of the missionaries.

When the language was mastered, and reduced to writing, the first task the missionaries undertook was the translation of the Scriptures. Here lies the radical distinction between Protestant and Roman Catholic missionaries. The former always give the people as soon as possible the Word of God in their own tongue; the latter never give it. There have been Roman Catholic missionaries in various parts of Madagascar since 1641; but they have never yet translated the Scriptures into Malagasy, and are not likely to do so. When the missionaries had translated and printed the Gospel of St. Matthew they sent up a copy to the king. It was read to him by one of his young noblemen whom the missionaries had taught to read. The king did not seem particularly interested in the Gospel until the account of the Crucifixion was reached, when he asked: ‘Crucifixion, what is that?’ It was explained to him.[24] ‘Ah!’ he said, ‘that’s a capital mode of punishment; I will have all my criminals crucified for the future. Call the head-carpenter.’ He was called, and ordered to prepare a number of crosses. I was very intimate for fourteen years with a Malagasy native pastor who had seen some of those crosses. During the dark and terrible times of persecution, tyranny, and cruelty under the rule of Rànavàlona I, some criminals, it is said, were really crucified.

When there was an addition to his family, Radàma I used to proclaim an Andro-tsì-màty—a day of general and unrestrained licentiousness. The whole country, and the capital in particular, was turned into a pandemonium of bestiality. Similar licence attended the great gatherings for the ceremony of circumcision. Mr. Hastie, the British Agent, compelled Radàma to put a stop to these orgies. He threatened, if another were proclaimed, to publish the proclamation in every gazette in Europe, and thus expose and hold him and his court and people up to the execration of Christendom. This had the intended effect. The king was always anxious to stand well with the nations of Europe; but when his wife came to the throne, she, being herself a shameless and outrageously licentious woman, restored these hideous customs.

Some years ago a missionary on the Congo stated in Regions Beyond that moral purity was quite unknown where he was labouring. A girl morally pure over ten years of age could not be found. It was the same in Madagascar, and is the same there to-day among the tribes that have not yet been reached by Christianity. Heathenism presents an indescribable state of things, and yet it never was so bad in Madagascar as in some other lands. A missionary from Old Calabar declared[25] some years ago that in the sphere where he laboured he did not know a woman either in the Church or out of it who, in the days of heathenism, had not murdered from two to ten of her own children. The dark places of the earth are not only the habitations of cruelty, but of every unutterable abomination.

Radàma I was an extraordinary man. He has been called the ‘Peter the Great’ of Madagascar, and from some points of view perhaps he deserved the title. Some called him the ‘Noble Savage’; but he hardly deserved the epithet of ‘noble,’ for he was ruthless and cruel. At his first interview with Mr. Hastie and Mr. Jones he seems to have been so pleased with them that he invited them back to dine with him next day. They accordingly went to the palace, and while they were seated at table a slave bringing in a tureen stumbled and spilt a little soup on it. Radàma turned and looked at one of the officers who stood behind him, and the latter left the room. When Mr. Hastie and Mr. Jones quitted the presence of the king, they saw the headless body of the poor slave lying in the yard. He had had his head struck off for insulting the king by spilling soup on the table in the presence of the sovereign and his guests! On another occasion, in 1826, the king went down to the port of Tàmatàve to see a British man-of-war. While at Tàmatàve he sent a slave up to the capital with a message, giving him six days to go up and return. It is still regarded as a hard journey either to go up to the capital or to come down in six days. This poor slave must have run every hour of those nights and days; and yet because he did not return on the evening of the sixth day, but the morning of the seventh, he was killed! Terrible as such things are, they are mild compared[26] with some of the enormities perpetrated in heathen countries.

Radàma died in 1828, a victim to his own vices. Rabòdo, his wife, or rather one of his wives, for he had twelve, by the aid of a number of officials, who were most of them opposed to Christianity and to the changes introduced by Radàma I, had herself proclaimed queen as Rànavàlona I. She soon made her position secure by murdering all the lawful heirs to the throne. Radàma had designated Rakòtobè, his nephew, the eldest son of his eldest sister, as his successor. He was a young man of intelligence who had been trained by the missionaries in their schools. He and his father and mother were put to death, as were also a number of the more enlightened officials. Andrìamihàja, a young Malagasy nobleman who had been a very great favourite with the queen, and had been mainly instrumental in placing her on the throne, and who was believed to be the father of her child, the future Radàma II, soon fell under her displeasure and was murdered. He had been considerably attracted towards Christianity, and at the time when his executioners reached his house he was reading the recently translated New Testament.

The original plan had been to banish all Europeans at once; but on the ground that they were useful in the work of education and civilization, he had secured their continuance for a time in the island, and had also aided and encouraged the work of the artisan missionaries. The queen sent to the missionaries to say that she did not mean to interfere with them or their work, as she was no less anxious than her late husband that the people should learn to be ‘wise and clever.’ The missionaries therefore thus continued to labour, and such[27] great progress was made that they and their converts very soon got into trouble.

Rànavàlona I was an able, unscrupulous woman. Her subjects regarded her with terror. She combined the worst vices of barbarism with the externals of semi-civilization. Brutal amusements and shameless licentiousness were conspicuous at her court. Her extravagance was great, yet her subjects condoned this, and even her acts of cruelty, on account of her extraordinary capacity for government. She had her rice picked by her maids of honour, grain by grain, so that no atom of quartz or stone might be found in it. If a single particle of grit reached Her Majesty’s tooth, it cost the offending maid of honour her life.

‘Among those who had gained a slight knowledge of the doctrines of Christianity before the missionaries were expelled in 1836 was Rainitsìandàvaka, in some respects a remarkable man. He was then a middle-aged man, of extra sanguine temperament. He did not belong to the congregation of Ambàtonakànga. He had never been baptized, but he had conversed with some of the church members and with some of the missionaries. After a time he began to make a stir in and around his own village in the north, teaching the people that Jesus Christ was to return to the earth, when all men would be blessed and perhaps never die; that there would be no more slavery, for all men would then be free; that there would be no more war, and that cannons, guns, and spears would be buried. Even spades might be buried then, for the earth would bring forth its fruits without labour. The idols, he said, were not divinities, but only guardians.

‘He and his followers formed themselves into a procession, and went up to the capital to tell the queen the glorious news. The queen appointed some of her[28] officers to hear his story. They returned and reported it to Her Majesty. She sent back to ask him if she, the Queen of Madagascar, and the Mozambique slave would be equal in those days? “Yes,” he replied. When this was told the queen she ordered the prophet and his chief followers to be put into empty rice-pits, boiling water to be poured over them, and the pits to be covered up[1].’

Such is heathenism! Missionaries are sometimes charged with a tendency to give only the bright side of things without much reference to the other. The charge is unjust. Common decency forbids more than a suggestion of what heathenism implies. The missionaries are the ‘messengers of the churches,’ whose task it is to make the darkness light, and their narratives must necessarily bear upon the results of their labours. By God’s good help and blessing, what has been done in Central Madagascar, in the islands of the South Seas, in New Guinea, in Central Africa, in Manchuria, in Livingstonia, and in other parts of the mission field, can be told; while that which the Gospel has supplanted may well be left to be the unspeakable hardship of those who have to face it in the name of their Lord, and of our common Christianity and civilization.

A famous missionary once attempted to tell his experiences as to heathenism, and got himself into trouble for his pains. Missionaries give their hearers credit for Christian common sense, and for the knowledge that there is a dark and dreadful side to missionary work, such as to justify the sacrifices of the churches and their agents in undertaking it. One significant fact may be mentioned here. While there was a name for every beast, and bird, and blade of grass, and tree, and stone, [29]and creeping thing, there was not in the language of Madagascar a word for moral purity. Such a thing had no existence until the people received the Gospel, and learned from it to value the things that are pure, lovely, and of good report.

MALAGASY HAIR-DRESSING.

A HEATHEN WAR-DANCE.

In 1823 the work of translating the Scriptures into Malagasy was begun, and in 1824 Radàma I gave the missionaries permission to preach the Gospel in the vernacular. The natives were not a little amazed to hear a European declaring to them with fluency in their own tongue the wonderful works of God. The mission made very rapid progress for a few years. There were about a hundred schools established in the provinces of Imèrina and Vònizòngo, and some four thousand children gathered into them. These schools were not centres where a large amount of secular and a small amount of religious education was given; they were also preaching stations, visited periodically by the missionaries, where the Gospel was preached and the Scriptures were explained. The truth thus found entrance into many benighted souls, laying hold of them in a way that nothing had ever done before, proving that it was still the power of God unto salvation unto every one that believeth. Many had grown weary of their old heathenism, and were feeling after God, if haply they might find Him.

The people had often spoken of Andrìamànitra[2] Andrìanànahàry (God the Creator) as existing, and the people had been told in their proverbs, with which all were familiar, that ‘God looks from on high and sees what is hidden’; that they were ‘Not to think of the[30] silent valley’ (that is, as a place in which it was safe to commit sin); ‘for God is over our head.’ They were told that ‘God loves not evil’; and also that ‘It is better to be condemned by man than to be condemned by God’; and again that ‘The waywardness of man is controlled by God; for it is He Who alone commands.’

In their proverbs God was also acknowledged as ‘the Giver to every one of life.’ This confession is found in the ordinary phrase used in saluting the parents of a newly born child, which was, ‘Salutation! God has given you an heir’; while His greatness is declared in another proverb which says, ‘Do not say God is fully comprehended by me.’ He was recognized as the rewarder both of good and evil; and hence their proverb, ‘God, for Whom the hasty won’t wait, shall be waited for by me.’ God’s omniscience was recognized in the proverb, ‘There is nothing unknown to God, but He intentionally bows down His head’ (that is, so as not to see); a rather remarkable parallel to the Apostle Paul’s words, ‘The times of ignorance, therefore, God overlooked.’ One proverb says, ‘Let not the simple or foolish one be defrauded, God is to be feared’; while another tells that, ‘The first death may be endured, but the second death is unbearable.’

In the Malagasy proverbs and folk-lore you have some few of the ‘fossilized remains of former beliefs’; and in these the people were told something of God and goodness, of right and wrong, while hints were given of a life beyond the grave, where good men would be rewarded and wicked men punished.

These, however, were but ragged remnants of former beliefs, which, while they might be enough to show that God had not left Himself without witness, had lost most of their meaning for the people, and almost all[31] their power over them. They were in no way guided by the fear of God in their daily life and conduct. God was not in all their thoughts, for He was a name and nothing more to the vast majority of the people.

The Malagasy were under the baneful sway of the most degrading superstitions. Hence polygamy, infanticide, trial by the poison ordeal, and all the attendant horrors of heathenism were everywhere rampant. The people were goaded on to commit the most cruel and heartless crimes against their nearest and dearest by the Mpanàndro (the astrologers), or the Mpìsikìdy (the workers of the oracle), and the Òmbiàsy (the diviners or witch-doctors). They and theirs were harmed or made ill, as they thought, by the Mpàmosàvy (the wizards or witches). They thought that all disease arose from bewitchery, and hence medicine was known as Fànafòdy, i. e. that which removes or takes off the Òdy, the charm or witchery. The far-famed Òdi-mahèry (powerful-charm) for which Vònizòngo, my own district during my first term of ten years in Madagascar, was once so famous, was mainly composed of the same ingredients as the witches’ broth in Macbeth—the leg of a frog, the tongue of a dog, the leg of a lizard, the head of a toad, and such like. The great poet says that ‘One touch of nature makes the whole world kin,’ and the same may be said of the touch of superstition.

The people had been sunk for ages in ignorance, and formed a counterpart to the heathen world which the Apostle Paul describes as ‘having the understanding darkened, being alienated from the life of God through the ignorance that was in them, because of the hardening of their heart. Being past feeling, they gave themselves over unto lasciviousness, to work all uncleanness with greediness.’ This made them mere playthings in the[32] hands of the ‘astrologers,’ ‘workers of the oracle,’ and ‘diviners’; for without their assistance they regarded themselves as completely at the mercy of the much feared Mpàmosàvy (the wizards or witches).

Everything—marriages, business, journeys—could be happy or successful only if undertaken on an auspicious day, and hence the proper authorities had to be paid to find out the lucky days. If a child was born on an unlucky day, or during the unlucky month of Àlakàosy, it had to be put to death, otherwise it was believed it would grow up to be a curse to its parents and its country. Of a child born on one of the so-called unlucky days, or during the so-called unlucky month, the diviner would at once say: ‘This child must die, or it will grow up to be a curse to the country, Mànana vìntan-dràtsy ìzy (it has a bad destiny hanging over it).’

There were different ways of putting these unfortunate innocents to death. If they were born during the unlucky month, they were placed in the evening at the gateway of the village, to be trampled to death by the cattle as they were being driven into the village for the night. If the gods inspired the cattle to step over the infant, its life was generally, though not always, spared. The Malagasy are very fond of their children—the parents would kneel by the pathway, the father on the one side, the mother on the other, pleading, with strong crying and tears, that the gods would spare their little one. Sometimes the cattle, with more sense than the people, when they came up to the babe, would sniff at it and step over it, and thus its life might be spared. This was the case, it is said, with Rainilàiàrivòny, the late prime minister of Madagascar, who was born during the unlucky month. It was not so often that male children were exposed in this way, some excuse[33] was usually found by the ‘diviners’; but as a rule the female children were thus exposed. Twins, whether male or female, were always put to death.

A child was not always spared even when the cattle had stepped over it. The diviner would sometimes say: ‘A mistake has been made; this child is not to die in that way, but by the Ahòhoka.’ Water was poured into a large wooden platter, called a sahàfa. The child was taken, turned over, and its face held in the water until the poor innocent was suffocated. Some diviners were more exacting than others. Instead of effecting death by suffocation, they would cause a round hole to be dug in the ground, in which the child was placed, and covered with earth up to the waist; boiling water was then poured over it until death relieved the poor child of its torments, after which the pit was filled up with earth and pounded over. Thus thousands upon thousands of children fell victims to this superstition, and do so still in those parts of the island unreached by the benign influence of the Gospel of Christ. Members of my own congregation at Fìhàonana, Vònizòngo, had seen such atrocities as those I have just described committed, if they had not themselves actually taken part in them.

The standard of morality was by no means high in heathen Madagascar. A man might be a drunkard, dishonest, a liar, or quarrelsome and given to fighting, and as such be regarded by his neighbours as a bad man, that is a bad member of society; but in other respects he might be utterly immoral without earning that title. A man’s morals were not regarded as having anything whatever to do with his personal character they were regarded as his own private affair. The community passed no judgement upon him.

[34]

I have said a man, because a woman was not really regarded as having any place in society. Women were viewed as little more than chattels necessary for the furnishing of a man’s house. They were the slaves of their lord and master. They were spoken of as àmbin-jàvatra, that is, surplus belongings. Under these circumstances the marriage relationship was not regarded as of much consequence, and before 1879 a man had only to say to his wife, in the presence of a witness, Misàotra anào, màndehàna hìanào, ‘Thanks, go!’ and she was divorced. Marriage was said not to be a binding tie, but only a knot out of which you could slip at any time. With such views of the highest and holiest relationship in life, with divorce easy, and polygamy rampant, the condition of society may be better imagined than described. Yet it could not exactly be said of the Malagasy that the ‘emblems of vice’ had been ever ‘objects of worship,’ or that ‘acts of vice’ had ever been regarded by them as ‘acts of public worship,’ as can be said of the people of some heathen lands.

Such a state of things, of which many were wearied, paved the way, in a measure, for the new teaching. The work of the mission made rapid progress. The Gospel effected a marvellous change in the lives of the people, and numbers were baptized on profession of faith and received into church fellowship. The old heathen party became alarmed at this, and rose in arms against the New Religion. As Samuel Rutherford said: ‘Good being done, the devil began to roar.’ This he did with a vengeance, making use of all who had vested interests in immorality and superstition, and especially of the keepers of the royal idols. The converts were charged with refusing to worship the gods[35] of their forefathers, and to pray to the spirits of their departed ancestors, and with praying instead to ‘the white man’s ancestor, Jesus Christ.’

History was repeating itself. The keepers of the royal idols frightened the queen by telling her that the gods were getting exasperated, and that if they once were enraged they would send fever, and famine, and pestilence, and all kinds of calamities. Although a strong-minded woman, and in some respects unusually shrewd, the queen was very superstitious, and the idol-keepers and the heathen party were able to work upon her fears, and, as the issue proved, with deadly effect.

‘She determined to introduce important changes in the government of the kingdom. She gave notice to the British Agent, and all Europeans, of her withdrawal from the treaty which Radàma I had made with the British government for the abolition of the foreign slave trade. She picked a quarrel with the British Agent because he had ridden on horseback into the village where a celebrated idol was kept, drove him from the capital, and ultimately from the island[3].’ Things had seemingly reached a crisis, and the missionaries felt that they might soon have to follow the British Agent; but this was for a time prevented by a rather singular incident.

There was no soap of any kind in Madagascar in those days. The queen had come into possession of some English soap, and thought it desirable to get the white teachers to make soap from the materials found in her own island, and instruct some of her young noblemen to make it. This is not exactly noblemen’s[36] work, as we should think; but in those days, and in that land, every one had to do as the queen commanded, or have their heads cut off. To attain her object she resolved to keep the gods and the royal idol-keepers quiet for a time, until some of her young noblemen had learned the mystery of soap-making.

She had already proposed to the missionaries that they should confine their efforts to mere secular education, which, however, they had politely but firmly declined to do. The influence of the artisan missionaries had been of immense service to the Madagascar Mission in those early days of its existence; and mainly to their teaching must be attributed much of the skill of the Malagasy workmen to this day. There can be no doubt that the manifest utility of their work did much to win for the mission a large measure of tolerance, as this incident of the soap-making shows.

‘Having driven the British Agent from the capital and the island, and wishing next to get rid of the missionaries, the queen sent and asked them all to meet at the house of the senior missionary, as she had a communication to make to them. The queen’s messengers met them, and in her name thanked them for all they had done and all they had taught the people. The queen wished to know, they said, if there was anything they could still teach her people. The missionaries replied that they had only taught the very simplest elements of knowledge, and that there was still many things of which the Malagasy were quite ignorant, and they mentioned sundry branches of education, among which were the Greek and Hebrew languages, which had been partially taught to some. The messengers carried this answer to the queen, and when they came[37] back they said that the queen did not care for the teaching of languages that nobody spoke; but she would like to know, they said, whether they could not teach her people something more useful, such as the making of soap from materials to be found in the country[1].’

This was rather an awkward question to address to theologians, and the ministerial members of the mission were much perplexed. Instruction in soap-making had not been part of their college training, and they knew little about it. ‘After a short pause, the senior member of the mission asked Mr. J. Cameron whether he could give an answer to that question. Mr. Cameron replied: “Come back in a week, and we may give an answer to Her Majesty’s inquiry.” At the end of the week they returned, and Mr. Cameron presented them with two small bars of tolerably good soap made entirely from materials found in the island[4].’ This incident, along with the conversations which the missionaries had with Her Majesty’s messengers, arrested for a time the backward trend of things. It revealed to Her Majesty and her heathen advisers their want of knowledge about the most common things, and their need of the most elementary education, and led to further inquiries about various matters. The tone adopted towards the missionaries and the treatment of them and their converts became more gentle and considerate.

The queen herself was so pleased with the soap that, on condition that Mr. Cameron would undertake a contract to supply the palace and the government with a certain amount of soap, and teach some of the young noblemen how to make it, things were to be allowed[38] to go on; and the missionaries were not to be interfered with in their work. Mr. Cameron and Mr. Chick, another of the artisan missionaries, undertook contracts for soap-making and the production of other useful articles. The government wanted them to undertake a contract for making gunpowder; but this they declined. It took nearly five years to fulfil this agreement. Perhaps their brethren had given Messrs. Cameron[5] and Chick a hint to deal out their instruction as to the soap-making in homoeopathic doses, so that they might be able to accomplish as much as possible of their higher service to Madagascar before the end of the period at which the contracts expired. One most important result to the mission from these contracts was a fresh impulse to the work of education throughout the central province. New schools were allowed to be established, and, although the queen and government would have much preferred to patronize merely secular education, had the missionaries agreed to separate it from religious teaching, they were constrained for the sake of the secular instruction to sanction and countenance the religious education.

[39]

The education of the young naturally formed an important element in the work of the mission from its commencement, and under the patronage of Radàma I the work flourished greatly. Radàma never became a Christian. ‘My Bible,’ he would say, ‘is within my own bosom.’ But he was a shrewd and clever man, and his ideas had been much broadened through intercourse with foreigners, and especially through his constant intercourse with Mr. Hastie, the British Agent, and he clearly saw that the education of the children would be an immense gain to his country. Thus he did all in his power to further this branch of missionary work, and both he and Mr. Hastie showed great interest in the prosperity of the schools.

In the year 1826 about thirty schools had been founded, and there were nearly 2,000 scholars; in 1828 the schools were forty-seven, but the number of scholars had fallen to 1,400. At one time the missionaries reported 4,000 as the number of scholars enrolled, though there were never so many as this actually receiving instruction. During the fifteen years the mission was allowed to exist (1820–1835) it was estimated that from 10,000 to 15,000 children passed through the schools; so that when the missionaries were compelled to leave the island there were thousands who had learned to read, and who had by the education they had received been raised far above the mass of their heathen fellow countrymen.

The direct spiritual results of the missionaries’ work were of slow growth, and it was not till eleven years after Mr. Jones’s arrival in the capital that the first baptisms took place. This was on the Sabbath, May 29, 1831, in Mr. Griffiths’s chapel at Ambòdin-Andohàlo, when twenty of the first converts were baptized in[40] the presence of a large congregation. On the next Sabbath, June 5, eight more were baptized by Mr. David Johns in the newly erected chapel at Ambàtonakànga.

From this time the growth was comparatively rapid and encouraging, and by the time of the outbreak of persecution two hundred had been received into church membership.

During the carrying out of the contracts the missionaries were hard at work on their translation of the Scriptures. They knew very well that what had taken place was but a calm before the storm, which they saw approaching, and that when it burst they would all be expelled from the island. They were most anxious to be able to leave the completed translation of the Word of God with the people. In March, 1830, a first edition of 3,000 copies of the New Testament was completed. Messrs. Cameron and Chick used to go down for a few hours in the morning to the Government Works at Ampàribè, to see to the soap-making and other work going on there; and after that they and the other artisan members of the mission went up in turns to help at the printing-office. The ministerial brethren would be there with their translation, and, under the guidance of the superintendent of the press, one member of the mission put up the type, while another brought the paper, another inked the type, and the rest took their turn at working the press. When, as was latterly the case, no labourers could be got to do it, even the ladies of the mission sometimes helped at this heavy task.

Thus these devoted men and women often worked to the small hours of the morning printing off the Scriptures. Before their task was finally accomplished the[41] New Testament, and also single books of both the Old and New Testaments, were bound up and set in circulation. Single sheets even of the Gospels, tracts, leaves of the Pilgrim’s Progress, and of the small hymn-book found their way all over the island; and some of these, as late as 1871, I found in the possession of the people in Vònizòngo.

[42]

‘Yea, and all that will live godly in Christ Jesus shall suffer persecution.’—2 Tim. iii. 12.

The edict of Queen Rànavàlona I against the Christian religion was published on March 1, 1835. To effect a return to absolute heathenism at all costs was the settled policy of the queen and her advisers. Christianity and heathen barbarism could not exist together. Very soon, however, to the astonishment of the queen and her advisers, it was found that although the missionaries had been expelled, and the Bible and other religious books burned, a stop had not really been put to the ‘praying.’ They had not been able to expel the Spirit of God from the hearts of the people. The good seed of the Kingdom began through persecution to strike its roots deeper, and under the influence of the dews of Heaven to spring up and yield fruit. Midnight prayer-meetings were begun in the capital itself, within gunshot of the palace. At one of those midnight prayer-meetings, when discovery meant certain death, a young man, Razàka, and his wife from Vònizòngo were baptized. He had been a scholar in the mission school at Fihàonana, and afterwards became the native pastor of the mother-church at Fihàonana, which office he held for more than twenty years. Not only so; he became the Apostle[43] of Vònizòngo, and founded some forty of the village congregations in that district.

The queen, thus thwarted, became more incensed than ever, and severer measures were resorted to in order to exterminate the hateful ‘praying.’ Death was the penalty of the slightest act of disobedience; but still the people continued to pray, and the Kingdom of God to make quiet but sure progress. The queen discovered, as other persecutors had done before, that the more she persecuted the people of God the more they increased and grew. Had the queen taken Christianity under her patronage, after the expulsion of the missionaries, she might have stifled it, or made it a mere name; but in persecuting the Christian faith she did it the best service possible. Persecution rooted and grounded Christianity in the hearts of the Hova people in a way that nothing else could have done. And not only so, but her cruelties did service to the cause of Christ in other lands besides Madagascar; for it was by the light of those martyr fires, which she in her cruelty had kindled, that thousands in this and other lands saw Madagascar, and were roused to take interest in the island and in Christian missions. Thus once more did God make the wrath of man to praise Him.

‘At the time when the missionaries left the capital severe persecution was directed against Rafàravàvy, a woman of rank who had become a convert prior to the proscription of Christianity. Her family, and she among them, had once been devoted in an exceptional degree to the service of the national idols. She was accused of “praying,” but upon the day they left Antanànarìvo she was pardoned on payment of a fine, and warned that if she was again found guilty her life would be forfeited. About a year later, with ten others[44] she was again accused of praying and allowing others to pray in her house. When arrested she refused to betray those who had been associated with her. The officers entrapped a young woman named Ràsalàma, who had been included in the same impeachment, into revealing the names of seven Christians hitherto unknown to the officials. Among these was a former diviner, Ràinitsìhèva by name, memorable in Madagascar annals by his name of Paul. Rafàravàvy would have been executed, and thus have become the first Christian martyr in Madagascar, but for a great fire on the eve of the day fixed for her execution. This led to a postponement of her execution. Ràsalàma, while in prison, grieved by the weakness which had led her to betray others, uttered words which, on being reported to the commander-in-chief, determined him to put her to death.

‘She was ordered for execution next morning, and the previous afternoon was put in irons, which, being fastened to the feet, hands, and neck, confined the whole body in a position of excruciating pain. In the early morning she sang hymns, as she was borne along to the place of execution, expressing her joy in the knowledge of the Gospel, and on passing the chapel in which she had been baptized, she exclaimed: “There I heard the words of the Saviour.” After being borne more than a mile farther, she reached the fatal spot—a broad, dry, shallow fosse or ditch, strewn with the bones of previous criminals, outside what was formerly a fortification, at the southern extremity of the hill on which the city stands. Here, permission being granted her to pray, Ràsalàma calmly knelt on the earth, committed her spirit into the hands of her Redeemer, and fell with the executioner’s spears buried in her body.

THE CAVE IN WHICH THE BIBLE WAS HID FOR TWENTY YEARS.

THE FOSSE IN WHICH RÀSALÀMA WAS SPEARED.

[45]

‘So suffered, on August 14, 1837, Ràsalàma, the first who died for Christ of the martyr Church of Madagascar, which thus, in its early infancy, received its baptism of blood. Heathenism and hell had done their worst. Some few of the bystanders, it was reported, cried out: “Where is the God she prayed to, that He does not save her now?” Others were moved to pity for one whom they deemed an innocent sufferer; and even the heathen executioners declared: “There is some charm in the religion of the white people, which takes away the fear of death.” Most of her more intimate companions were either in prison or in concealment; but one faithful and loving friend, who witnessed her calm and peaceful death, when he returned, exclaimed: “If I might die as tranquil and happy a death, I would willingly die for the Saviour too[6].”’

‘Ràsalàma was accused of praying, one of her own servants being the accuser. She was taken to the house of one of the high officers in Andòhàlo. This officer made use of bad language towards her, when Ràsalàma severely reproved him, saying: “Take care what you say, for we shall meet again face to face at the last day.” The officer replied: “I shall not meet you again, you silly young woman.” “You cannot avoid doing so,” said Ràsalàma, “for we must all appear at the judgement seat of God on the last day; and every idle word spoken by men shall be revealed to them on the day of judgement.”

‘Just before her martyrdom, Ràsalàma wrote a letter to one of the missionaries who had taught her, in which she said: “This is what I beg most earnestly from God—that I may have strength to follow the words of Jesus[46] which say: ‘If any one would come after Me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow Me.’ Therefore I do not count my life as a thing worth mentioning, that I may finish my course, that is, the service which I have received from my Lord Jesus.... Don’t you missionaries think that your hard work here in Madagascar for the Lord has been, or will be, of no avail. No! that is not, and cannot be the case; for through the blessing of God your work must be successful.”

‘She also called to mind the words of Scripture which say: “Precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of His saints[7].”’

‘After the death of Ràsalàma, 200 Christians were sold into slavery. Rafàravàvy was also sold, but her owner, so long as she did her allotted task, allowed her much personal liberty. Among those who had witnessed Ràsalàma’s martyrdom was the young man referred to above, named Rafàralàhy, who had been in the habit of receiving Christians for worship at his house near the capital. This man was betrayed by a former friend, an apostate who owed him money, and took this means of cancelling his debt.

‘After being confined in heavy irons for three days, he was taken out for execution. On the way he spoke to the officers of the love and mercy of Christ, and of his own happiness in the prospect of so soon seeing that divine Redeemer Who had loved him and died to save him. Having reached the place of execution, the same spot on which Ràsalàma had suffered nearly a twelvemonth before, he spent his last moments in supplication for his country and his persecuted brethren, and in commending his soul to his Saviour. As he rose from[47] his knees, the executioners were preparing, as was the custom, to throw him on the ground, when he said that was needless, he was prepared to die; and, quietly laying himself down, he was instantly put to death, his friends being afterwards allowed to inter his body in the ancestral tomb.

‘Rafàralàhy’s wife was seized, cruelly beaten, and compelled to name those who had frequented his house. Rafàravàvy, one of these, fled, and by the aid of native friends finally reached Tàmatàve. There, by the aid of sympathetic friends among the Europeans, with six other Christians, she escaped to Mauritius in safety. Five of these, including Rafàravàvy, visited England, and were present at a great meeting at Exeter Hall on June 4, 1839. Their presence centred extraordinary interest upon Madagascar, and indirectly upon the general work of the Society. The refugees were accompanied by Mr. Johns. They returned to Mauritius in 1842, and undertook work there among the many Malagasy slaves then in that island[8].’

The measures taken to destroy Christianity were not at all times equally severe; there were lulls in the storm, during which the persecuted had comparative quietness, and even gleams of sunshine. The years that stand out with special prominence in the annals of the persecution are 1835–37, 1840, 1849, and 1857. The next series of martyrdoms occurred in 1840. David Griffiths had been allowed to return to Antanànarìvo as a trader, and he, in connexion with Dr. Powell, whom business took to Madagascar, did all in their power to aid those whose Christian faith brought their lives into jeopardy. In May, 1840, sixteen of the proscribed made an attempt[48] to reach the coast. Unhappily, they were betrayed, captured, and, five weeks after their flight, they were brought back. Two managed to escape. Of the rest, on July 9, 1840, nine were executed.

Many of the native converts fled to the forests, where they died of fever; or to the mountains, where they lived among the dens and the caves of the earth; or to distant parts of the island, such as to the Ankàrana in the north, or to the Bètsilèo country in the south, or to the Sàkalàva tribe who occupy some six hundred miles of the west side of the island—where the most of them were murdered as Hova spies.

The province of Vònizòngo, being about forty miles to the north-west of the capital, having no governor, and very few government officials, became a hiding-place for many of the persecuted Christians. Midnight prayer-meetings were held there for years—first in the house of Ràmitràha, who was afterwards burned at Fàravòhitra, and afterwards in the house of Razàka. The converts travelled twenty, thirty, and even forty miles to attend those meetings. At Fìhàonana they had one of the few Bibles that had been saved. This was a well in the desert, for the ‘Word of God was precious in those days.’ The converts met and spent the night in reading the Scriptures and prayer; and on the very dark nights of the rainy season they ventured on singing a hymn to refresh their weary hearts and souls, trusting the noise of the falling rain would drown their voices, as it might well do. On such nights the queen’s spies did not venture abroad.

Many of the persecuted fled from the capital and other parts to Vònizòngo, and hid there for months, and some for years. The rice-pits under the floors of the huts were favourite hiding-places, while refuge was also found[49] among the rocks, in ravines on the hill-sides, and in the ‘cave,’ used as a small-pox hospital. Some of the rice-pits had underground passages connecting them with pits in the neighbouring huts, from which a passage led to the outside, so that if any in hiding in the first rice-pit were searched for, they could crawl into the pit in the adjoining hut, and thence find their way outside.

On one occasion Rafàravàvy Marìa, who afterwards escaped from the island and was brought to England, was in hiding in a hut in Vònizòngo, when an officer sent to search for her arrived in the village. He had come so suddenly that she had not had time to get into the rice-pit or outside into the fosse; she had barely time to crawl under a low wooden bedstead, and the woman of the house had only time to draw the mat on the bed down in front of it to hide her. She put some baskets with rice and manioc on the bedstead, to keep the mat from slipping down, when the officer entered the hut. He said: ‘Have you Rafàravàvy here?’ The woman of the house answered: ‘Look and see.’ He just looked round the hut, did not look under the bedstead, and went away. When he left the village to seek for her elsewhere Rafàravàvy escaped to a place of safety.

When very strict search was made by the queen’s orders for Bibles and other Christian books—for she more than suspected that they had not all been given up—the Christians in Vònizòngo were very much afraid they might lose their copy of the Scriptures. They said: ‘If we lose our Bible what shall we do?’ A consultation was held as to how and where the Bible was to be hidden to ensure its safety; and it was agreed that the best and safest place in which to hide the Bible was the small-pox hospital. The officers dreaded small-pox too much to venture there.

[50]

A little to the north-east of the village of Fihàonana a hill rises, and near the foot of it stands a cluster of large boulders. Inside that cluster, during the lulls in the persecution, from ten to thirty of the converts used to hold a Sabbath morning service. Underneath one of the largest of the boulders, at the foot of the hill, there is an artificial cave, dug out by the people to serve as a small-pox hospital for the village: in the dark corner of this cave the Bible was hidden between two slabs of granite. The queen’s officers arrived at the village, as it was expected they would, to search for the Bible and other Christian books, which the queen and government had reason to believe, from the reports of spies, were to be found there. A bootless search was made in the huts of the suspected, in the rice-pits, and in the village fosse; and then the officers directed their way to the cluster of boulders on the hill-side. As they were about to enter the cave where the Bible lay, some one said: ‘I suppose you know that this is the small-pox hospital?’ ‘We did not,’ they said, starting back in horror. ‘Wretch! why did you not tell us sooner? Why did you let us come so near?’ The officers beat a hasty retreat, and the Bible was safe. This particular copy is now, and for many years has been, in the library of the British and Foreign Bible Society, Queen Victoria Street, London.

Razàka lay for over two years in hiding in that cave, and during that time he seemed to have learnt most of the Bible by heart. After the martyrdom of Ràmitràha the queen had sent to have him arrested as the ringleader of the ‘prayers’ in Vònizòngo. Had he been caught, he would have been put to death. He had before that been sold into slavery for his religion; but, as a distant relative bought him, his slavery was of a mild type. He heard that the officers had been [51]sent out to arrest him, and went into hiding. A report was spread that he had escaped to the Sàkalàva tribe in the west, and the search was given up.

THE MARTYRDOMS AT AMPAMARINANA.

(From a Native Sketch.)

On a dark night he returned to the cave, and there began his long concealment of two years. At night his wife took him rice; in the daytime, when it was safe, he lay at the mouth of the cave and read and re-read the Bible. How many times he read it through I do not know, but I do know that he had the most extraordinary knowledge of the Scriptures of any man I have met. This qualified him for the honour afterwards conferred upon him of becoming native pastor of the mother-church at Fihàonana and the Apostle of the Vònizòngo district.

I have been unable to discover the number of church members in the Vònizòngo district when the persecution began, in 1835; but in a letter written in 1856 it was stated that there were then 193. I was told, however, in 1871, by Razàka, that when the persecution began, there were thirty-six church members at Fihàonana, ten of whom were then alive. Of the twenty-six dead, two died as martyrs. One, Ràmitràha, was burned at Fàravòhitra Antanànarìvo; the other, Rakòtonomè, was thrown over the rocks at Ampàmarìnana. These men were preachers at Fihàonana.

Ràmitràha was chief of the village and district of Fihàonana—his younger brother was chief in our time; their mother had been the first convert to Christianity in the Vònizòngo district. Ràmitràha seems to have been a very remarkable man. After the outbreak of the persecution, and when it became known that there were many Christians in the Vònizòngo district, several officers and men were sent to bring them to the capital. While the officers were on their way there, Ràmitràha was[52] informed of their coming, and that he was specially named as being a leader, and because midnight prayer-meetings had been held in his house. He was advised to flee; but he nobly refused. ‘Where could I flee to?’ he said. ‘If I flee to the west, I shall be speared by the Sàkalàvas as a Hova spy. If I flee to the forest, I shall die of fever. If I flee to the mountains or to the wilderness, I shall die of famine or fever; and if I am to die, I prefer to die for my faith.’ He was carried to the capital, along with some three hundred others, of whom the majority did not stand the test. To save their lives they took the oath to worship the idols and pray to the spirits of their ancestors and the departed sovereigns. Ràmitràha stood firm, and died for his faith in the flames at Fàravòhitra, while his fellow labourer, Rakòtonomè, was rolled down the precipice at Ampàmarìnana.

‘All through this period (from 1835 to 1849) accused Christians were often compelled to drink the tangèna, and many of them died. But it was not until 1849 that another fierce wave of persecution rolled over the infant church. On February 19, 1849, two houses belonging to Prince Ramònja, which had been used for Christian worship, were destroyed, and eleven Christians cast into prison. A kabàry was held at Andohàlo (the central piàzza of Antanànarìvo), and once again Christians were ordered to accuse themselves. In Vònizòngo a noble named Ràmitràha and others refused to worship the idols, and eighteen were condemned to death at Anàlakèly[9].’

‘Ràmitràha, a noble and a descendant of one of the most distinguished chiefs of the province of Vònizòngo, replied—when asked to take the oath invoking the idols—“God has given none to be worshipped on the[53] earth, nor under the heavens, except Jesus Christ.” “Fellow,” exclaimed the officer, “will you not pray to the spirits of the departed sovereigns, and worship the sacred idols that raised them up?” To which the steadfast confessor replied: “I cannot worship any of them; for they were sovereigns given to be served, but not to be worshipped. God alone is to be worshipped for ever and ever, and to Him alone I pray.” This faithful man sealed his testimony to Jesus Christ in the flames.

‘On February 25, 1849, the accused Christians were gathered at Andohàlo for examination and trial. They were asked: “What is the reason that you will not forsake this new religion, and that, notwithstanding threats of severe punishment and even death, you keep on earnestly practising it? Speak out and tell the truth, don’t lie.” They answered, one by one, but the substance of what was said was: “This is the reason why we love it: we can pray to the true God for the queen, the kingdom, and for ourselves who work; and thank Him for redemption and the blessings received at His hands. We know that true religion benefits the kingdom, because in the Word of God, which we accept, there are good laws which benefit the subjects and bless them; and these laws are not opposed to the laws of the land.”

‘During the first week of March, the Christians throughout the central provinces were ordered to accuse themselves at the appointed place in each district. “I give these ‘prayers’ time to accuse themselves,” said the queen’s message; “but not for their own sakes do I give them time, but for the sake of Imèrina; and were it not so, I would put them all to death; for they persist in doing what I hate[10].”’

[54]

‘On March 21 and 22, 1849, the Christians were gathered at Anàlakèly, and were again subjected, not to examination as to their rigid adherence to the new religion, but whether they would take the prescribed oath or not. One by one they were asked the following questions, and all gave similar answers.

‘The Officer: “Do you still practise prayer?”

‘Christian: “Yes, I still pray.”

‘Officer: “Will you not pray to the twelve sacred mountains, and the sacred idol that raised up and sanctified the twelve sovereigns?”

‘Christian: “The mountains are but earth to be trodden upon, and the idols are but wood from which houses are built, quite lifeless, the work of God’s hands—hence we cannot pray to them or worship them.”

‘Officer: “Will you not pray to Andrìanampòinimèrina and Radàma?”

‘Christian: “Andrìanampòinimèrina and Radàma were worthy of reverence as sovereigns while here on earth; but as to worshipping them, that cannot be done, as the objects of worship cannot be increased.”

‘Officer: “Will you not worship Her Majesty Rabòdonàndrìanampòinimèrina?”

‘Christian: “Rabòdonàndrìanampòinimèrina is the sovereign appointed by God to be served and obeyed; but she is only human, hence we cannot worship her, we can only worship God.”

‘Officer: “Won’t you take the oath?”

‘Christian: “We cannot do so, and we have vowed not to do so.”

‘Officer: “Do you still regard the Sabbath day as sacred, and abstain from all work on it?”

‘Christian: “The Sabbath is a day set apart for the service of God; during the six days we labour[55] and do all our work, but we still hold the Sabbath sacred.”

‘Officer: “Why do you say that you will not worship or pray to any one except God; and yet you worship and pray to Jehovah and Jesus Christ?”

‘Christian: “Jehovah and Jesus Christ are God under different names.”