Woodstock,

Feast of the Assumption, 1903.

Title: The great inquiry

Author: Hilaire Belloc

Illustrator: G. K. Chesterton

Release date: April 7, 2023 [eBook #70495]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Duckworth & Co, 1903

Credits: Benjamin Fluehr, Tim Lindell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

With the good taste that characterises our political life (how different from the howling bear-gardens of the Continent!), these minutes were officially communicated, as they appeared, to the Speaker, from whose pages they are now collected in this the

ONLY, FINAL, AND AUTHORISED EDITION.

Sir,

I am instructed by the Secretary of State for the Colonies to acknowledge the receipt of your letter and of the enclosed report. He desires me particularly to thank you for Mr. Vince’s pamphlet. He has not yet heard of Mr. Vince, but is bound to express his admiration for his lucid and patriotic argument.

Pray note that the Secretary of State for the Colonies will reply (through me) to all further communications as to “A Working-man correspondent:” a long political career has convinced him, etc.

BRITONS!

LOOK ON THIS PICTURE

“I AM LEAN AND LIVELY.”

AND ON THIS.

“I AM TOO FAT.”

THE GREAT INQUIRY

(ONLY AUTHORISED VERSION)

FAITHFULLY REPORTED

By H. B.

REPORTER TO THE COMMITTEE,

AND ORNAMENTED WITH SHARP CUTS DRAWN ON THE SPOT

By G. K. C.

DUCKWORTH & CO.,

3 HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C.

With its Conclusions, Majority and Minority Report, etc.

Printed by Order of the Committee.

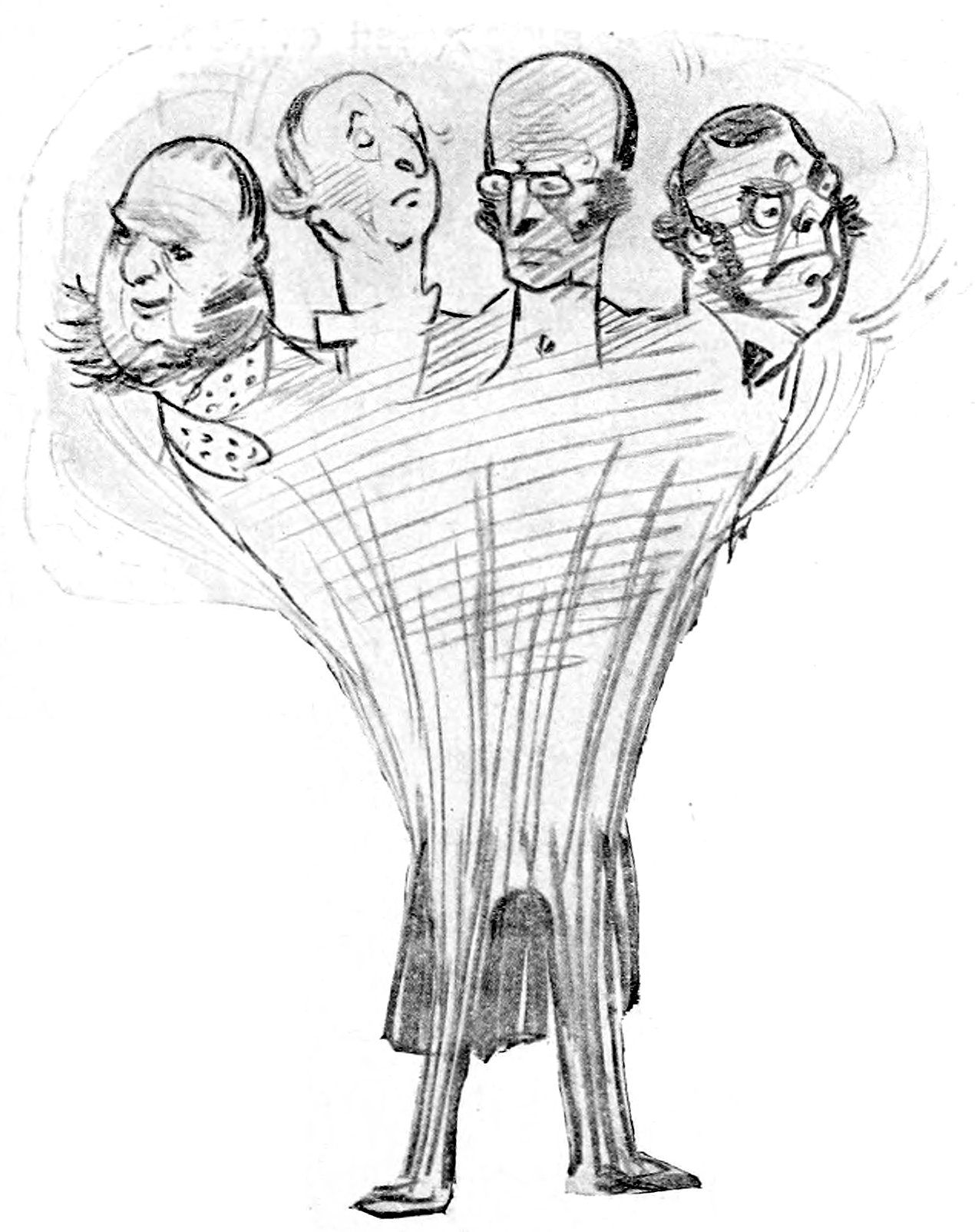

Your Inquiring Body, or Commission of Inquest, has been formed of a section of the Cabinet, with power to add to their number.

Of this power they have availed themselves sparingly and judiciously, as the following list will show:

These gentlemen, your Committee, having been sworn, in the Scotch manner, “that they would well and truly bolt out the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, such as would profit and serve this Our realm of England, the Channel Islands, and all Our dominions beyond the seas, so help them God,” the proceedings opened by a prayer that the wisdom of this world might be turned into foolishness, and that the false pride of Reason might be humbled, and the insolence of philosophers confounded.

Upon which was called Mr. Baines, of Middlesbrough, a gentlemanly-looking person, who deposed that:

The country was upon the verge of ruin. In the iron trade, competition with America, and latterly with Belgium and Germany, had been felt very severely. Mrs. Baines and self had passed through many anxious moments since 1892. The extravagance of their eldest son William at the University, which, under normal circumstances, would have caused them no uneasiness, had driven them almost distracted and had led to a most regrettable coolness between parent and child. For the last eight years he had found it impossible to spend more than one month, or at the most six weeks, in London during the season, and that in a hired house. In the worst year, 1897, Mrs. Baines had been compelled to take lodgings. It was only by an unstinted and harassing attention to detail that the business had been kept going. His hair, which twenty years ago had been of a rich nut-brown colour, was now quite grey, and growing very thin and patchy.

“A gentlemanly-looking person.”

Mr. Gerald Balfour, who had followed the business side of the argument very closely, here asked what remedy Mr. Baines proposed for this state of things?

Mr. Baines replied that there seemed to be but two courses to follow. The best way would be for the Government to pay him quarterly not less than 25s. for every ton of pig-iron he might manufacture. If, for party reasons, it was impossible to grant him such a sum, the second course would be to impose a duty on all other iron which would raise his, Mr. Baines’, iron by a similar amount.

Asked by Mr. Chamberlain whether it was his opinion that the wages of his hands would rise under such a system, Mr. Baines looked a trifle puzzled, and confessed that he did not understand the drift of the question.

Mr. Chamberlain (smiling pleasantly): “I will put my question in another form. Would you offer your employés a portion of the profit so acquired?”

Mr. Baines (bewildered): “Why should I?”

The Postmaster-General: “Let me tackle him, father....” (To Mr. Baines): “I take it all your men have a vote?”

Mr. Baines: “Yes, all except Ben Gailey, who did time for ghurling.”

“What is ghurling?”

Mr. Balfour (with great interest): “What is ghurling?”

The Postmaster-General (hurriedly): “That’s all right. Well, now, the question is this: if we give you £1 down for every ton of pig iron you shove on the market, and we make it a condition that you pay at least 5s. of it in extra wages, will you clinch?”

The witness, who was complimented by Lord Lansdowne on the manly and straightforward way in which he had given his evidence, then stood down.

Mr. Harry Gibbs, farmer of Goudhurst, questioned upon Hops, said that W’ops were in a turrible bad way, and all. He knew his own mind. He was a practical man. He said: “Let the Government prohibit all foreign W’ops, Sussex and all, and let brewers have a law, and let ’un buy Kentish W’ops. There was old Sir Charles Gorle, there was, member of Parliament and all, and he knew for certain as that old man in his brewery never bought none but Sussex, and he’d have a law....”

Mr. Chamberlain (sternly): “Stand down.”

Witness (loudly): “Ar! I’m a plain man and not to be druv, and I tell you....”

Lord Lansdowne: “Stand down, sir!”

Witness (more loudly): “I tell you if you let these dang Sussex W’ops....”

The whole Committee here rose and in chorus ordered the witness to stand down.

Witness: “You hear me! These Sussex W’ops, they have the vly; they aren’t....”

The police here removed the witness, who struggled violently, shaking his fist over his shoulder, and shouting:

“Ar, it’s stan’ down naow!... You wait till t’election.... Ar. You see which way I voät then.... Ar!”

Similar cries were heard in the passage without, until his voice was lost in the distance, or was perhaps gagged by the police.

This unpleasant scene was succeeded by the testimony of a very different witness, Lord Renton, who was of opinion that the good money should be kept in the country.... He, for his part, could see no kind of reason why we should buy from abroad what we could very well make for ourselves.... He was interested in butter.... He believed that the preservation of eggs was only a matter of time.

At this moment, Mr. Balfour observing that the Committee had sat for full twenty minutes, the inquiry was adjourned. Mr. Chamberlain went out with Lord Renton, and partook of his motor-car, as he was stopping with His Lordship from Saturday to Monday.

At the second weekly meeting of the Cabinet Committee of Inquiry into our Fiscal System, Lord Halsbury joined the Committee.

Mr. Manning, of East Ham, whose striking pamphlets, What We Really Eat and Not by Bread Alone, have brought him well-deserved fame, was asked to join, but declined on the ground of party loyalty.

“Mr. Manning, of East Ham.”

The Duke of Sutherland, who had also been invited to sit, had instructed his private secretary to write to the same effect, expressing an ardent sympathy with the objects of the Committee, but recalling the great part he had played in Liberal politics for many years, and pointing out that he could better serve the cause by remaining attached to a party which he hoped to leaven by his example and oratory.

Mr. Benjamin Kidd, the first witness, deposed on oath that he was a philosopher. He begged leave to give his testimony in metaphysical language, as he could speak no other. After some consultation leave was granted, and the sworn interpreter at Scotland Yard was summoned by telephone.

“The Official Interpreter.”

Thus relieved, the witness swore that the synthesis of an agglomeration, real or imaginary—in plain words, of all thinkable congeries—was informed by an appreciation of its organic or inorganic character. He was far from saying that the organic and inorganic were separated by any hard and fast line, but he did maintain⸺

Mr. Chamberlain: I think that point is clear.

Mr. Benjamin Kidd, continuing, deposed that a political entity was emphatically of the former kind as to its consciousness. And without consciousness where were they? He then maintained it demonstrable beyond argument that all truisms, including altruism, lead to one central principle, namely, that in all inequalities differences appeared, for if they did not, then where were they? Applying this primordial and cosmic truth to the particular region of international exchange, he could but conclude that all material increment of res mercatoriæ must and did connote diminution of eorundem facilitas and vice versâ.

The witness here sat down, and the interpreter, who had been taking notes, declared in a loud voice that Mr. Kidd’s speech meant, in English, that the excess of imports was paid for in gold. (Murmurs of applause.)

The Lord Chancellor (emphatically): I always said it!

Mr. Chamberlain (triumphantly to Mr. Balfour): What about Seddon now?

Mr. Balfour (in some confusion): I never said anything against Seddon, besides which, who knows but what Kidd—

Here Mr. Kidd was observed to break down and sob bitterly; willing hands supported him to the Carlton, where first aid to the wounded was skilfully rendered by Doctor Sir Conan Doyle, V.C.... On recovering consciousness he attributed his agony to severance from the Great Liberal Party, of which he had so long been the most brilliant ornament. The distinguished physician, who had himself suffered such pangs, soothed him as best he could, and conveyed the news to the Committee, who were profoundly moved.

Mr. Chamberlain (solemnly): If this man dies, the Opposition will have a heavy weight upon its soul.

[The Committee here murmured their approval, and the Inquiry proceeded.]

Mr. Balfour: It is now our task, I think, to find by what issue the gold escapes, and to stop the leak.

Mr. Charles Griggs (expert) deposed: That such a gold export would require fifty-six vessels, each 500 ft. long by 45 broad with a draught of 27 ft.

Peter Garry (Private Detective in the pay of the Birmingham Caucus): “I have watched all the ports, and can swear that no such vessel, let alone fifty-six, has cleared with gold since July, 1902.”

In view of the difficulties raised by this witness, it was determined to call further testimony:

Peter Cale (porter) deposed to hauling great sacks of something hard and heavy on to the passenger boats at Dover last April. These sacks might very well have contained gold. Cross-examined: They might have contained almost anything else. They had no smell.

Martha Quinn (labourer’s wife) swore that she had often heard people, especially her husband’s master, say that a power of money went abroad to pay for foreign kickshaws. She herself had paid a considerable sum last year for Norwegian matches, American tobacco, German sausage, foreign tea, and all. Cross-examined as to where the tea came from, she said, after some hesitation, that she thought it came from Lipton.

Mr. Chamberlain (sternly): That is within this Empire.

Martha Quinn (curtseying) begged the pardon of the Court. She was ordered to stand down.

Mr. Thomas Hepton, draper, of Regent Street, W., swore that he sold in the past year some 50,000 or 60,000 cases of foreign woven stuffs, every one of which had to be paid for. The profit only remained in England.

Cross-examined: He did not himself pay for the goods in gold, but he gave a cheque upon his bankers, who doubtless sent the money abroad in packing cases, and all that went to the ⸺ foreigner.

Lord Lansdowne: Moderate your language.

Mr. Hepton: I am sorry, my lord, but if you had sent case after case of solid gold away to France week after week for ten years, you would feel as I do.

Mr. Haywood of Bicester, Mr. Calm of Stroud, Mr. Merry of Lincoln, Mr. Bowse of Lichfield, Mr. Hopper of Lancaster, Mr. Grape of Shrewsbury, &c., bank managers, swore that their business consisted almost wholly of handing out large masses of bullion daily to offensive people, many of whom had the appearance of foreigners.

“With the appearance of foreigners”

Lord Halsbury: All this is hearsay evidence, and not worth the paper it is written on.

During a short altercation between the legal and non-legal members of the Committee, a person at the back of the room leapt to his feet and demanded to be heard. He was permitted to speak, and deposed:

That he had been gathering statistics in the employment of a politician whose name he must conceal.

Mr. Balfour: I am afraid we must have that name.

Witness: May I send it up on a piece of paper?

Lord Halsbury: Is he a peer?

Lord Halsbury: Well, is he a person of importance?

Witness (eagerly): Oh! yes, my lord.

Lord Halsbury (after consulting his colleagues): We do not think his name material. Proceed.

Witness (in an emphatic manner): The facts I have to produce are simple. They are well known. It is their meaning which has escaped the public. When the meaning is grasped it will amply account for our great annual loss of gold.

(Here the Committee betrayed an interest bordering on frenzy, leaning forward and fixing burning eyes on the witness, who continued:)

“The number of passenger tickets taken at the ports of this country is over 12 millions annually. (Sensation.) Ships’ crews (excluding coasters), fishermen running across to the continent, fugitive criminals, and King’s messengers bring the number up to 18 millions. (Sensation.) Not one of these 18 millions leaves without a sum of money ... many carry away immense sums ... our office can prove that the very clergy in their annual excursions will carry 20, 30, nay, 100 pounds a family. (Sensation.) How many return with any money at all? (Here the speaker made a dramatic pause.) ... I have little more to add. The total sum so lost by innumerable outlets amounts certainly to 200, possibly to 230, million pounds. England is a sieve.”

Witness here left the box, and the Committee rose in a state of seething excitement, several of the more commonplace members repeating mechanically, “A sieve!” “A regular sieve!” “Poor old England is a sieve!”

Mr. Chamberlain looked radiant in a black frock coat and top hat, with boots to match, and a flower of some kind in his buttonhole, while Mr. Balfour was quite cheerful and vivacious. As the Court rose the opinion was freely expressed that the day’s work has given the Cause a great lift forward.

The third meeting of the Grand Committee of Inquest, commissioned under the Privy Seal of Great Britain and Ireland and the Dominions beyond the Seas, met at Downing Street this week to further explore—we mean, to explore further—the Fiscal Conditions of this Realm of England.

The late arrival of the members of the Committee gave rise to some anxious talk in the passage which corresponds to the Lobby of the House in Downing Street. The wildest rumours were afloat. Some said that Mr. Chamberlain had resigned; others that he had committed suicide. The more sober would have it that the inquest was indefinitely postponed, and that the whole scheme for protecting or not protecting native industries, or food, or what-not, as the Inquiry might or might not have shown to be necessary, or unnecessary, or either, was to be dropped. Among the adherents of the latter (or former) opinion were several journalists, a bishop, four diplomats, and an economist.

All doubts were set at rest by the arrival at 3.35 or thereabouts of the first members of the Committee and two members of the Birmingham “gang.” Three-quarters of an hour later Mr. Balfour was towed up in his motor-car, and the Court opened.

The business before the Court this morning was to receive the testimony of some fifty-eight witnesses on the technical details of our chief industries, and to hear their views on special points; especially on the inroads made by foreign competition in matters of construction.

A definition having been asked of where “technical detail” began, the Prime Minister refused to define the matter, but he ventured so far as to ask a question—whether there were not foreigners in the habit of substituting in small but essential parts of machinery patterns to which we, being of a superior race, could not stoop without changing the very conditions of our psychology? It was more or less upon these lines (said the Prime Minister) that the questions—if they could be called questions—were, so to speak, to proceed; and he hoped that the answers they should receive, using the word “answers” in its most general sense, would on the whole conform to some such conception of the duties more or less before them. (Applause.)

The first witness to be called was the Times economist, who refused to reveal his real name. Being threatened with the torture, he confessed to several aliases. He admitted to having signed many letters before this above the pseudonym of “Verax,” and, more lately, above those of “A Conservative Working-Man” and “A Disgusted Liberal.” He was not specially paid for these articles: it was all in the day’s work.

Cross-examined: He admitted to having written for the Daily Telegraph; he was not “Maude” of Chit-Chat. Asked whether he were the “Revenue Officer” of pious memory, he denied the imputation—or, as he called it, the “soft impeachment”—with the utmost violence. He also denied any connection, direct or indirect, with the “Times Encyclopædia,” the “Times System of Payment by Instalments,” the “Parnell Letters,” the “Hawkesley Letters,” the “Jameson Raid,” the “Argument upon the Mortality in the Concentration Camps,” the recent “Roman Correspondence,” the Times “Dramatic Criticism,” and “The Industrial Freedom League,” and, indeed, everything else connected with that journal. The witness here swore with some heat, the ingenuous colour mounting to his cheeks, that he had never changed a date, nor forged nor garbled a letter, nor taken South African shares, nor suppressed evidence, nor done any of these things.

Counsel (suavely): My dear Mr. (I really do not know your name), when has there been a bare suggestion of anything of the kind?

Witness (hotly): I could see very well where your questions were driving.

When this little scene had come to an end, the witness proceeded to give evidence that the great mass of imported manufactured goods were loaded with damnable contraptions, with the undoubted object of destroying our own industry, and of supplanting them by that of the foreigner. He quoted statistics to show that the iron trade, the textile trade of Lancashire, the plain chair and kitchen table trade of High Wycombe, the boot, shoe, and slipper trade, the cork trade, the shipbuilding trade, the glue and gum trade, the fishbone manure trade, and the manufacture of cheese had declined during the last fifteen years from 10 to 30 per cent. He ascribed this deplorable breakdown partly to the ignorance of technical detail prevalent among politicians, but more to the devilish contrivances which gave foreign machinery a specious appearance of superiority to our own. He thought it could be proved that no one of these trades would have declined or disappeared had not Britain suffered from this most unjust and tricky form of competition. He was confident of one thing—that unless the greatest attention was given by the Committee to what he called “Spade-work,” uninteresting but essential matters of fact, it was all up with the Empire.

Mr. Balfour (with some hesitation): All this is mere assertion.

Witness (calmly): Upon assertion every great religion has been built.

Mr. Balfour (seraphically): You are quite right. I have always maintained that the analytical function, and even the quasi-postulated phenomena of the senses⸺

“I have always maintained”

A Voice: Shut up!

Lord Lansdowne (smartly): If any further expressions of private opinion are delivered from the well of the Court, I, for one, shall protest.

Mr. Chamberlain (to the unknown person): Ked!

The Court then proceeded to call further witnesses.

Mr. Henderson, Gentleman-Agriculturalist, deposed that it was the habit of foreigners, principally Frenchmen and Dutchmen, to arrive in his district of Norfolk every summer with great masses of vegetables, principally onions, which they had grown at least three weeks earlier than they could honestly be produced. There was less infamy of this kind in agriculture perhaps than in other trades—but it was there all the same. The witness mentioned melons and giant earlies, and alluded in passing to yellow kidneys, mammoths, Reading prides, and other vegetables, in proof of his contention. But the chief example was Hessian fly.

Cross-examined: Witness could not see what all this had to do with machinery. Perhaps he had mistaken the day.... Anyhow he was a practical man.

The witness then stood down with an inconclusive frown.

Mr. Lutworthy, of 236, Eton Square, and “The Knoll,” Birmingham, deposed that for the last fifteen years German hardware of all kinds had been flung at his head, and that it was not in human nature to withstand it. To give an example. Iron king-bolts with flange attachments selling in Newcastle at 35s. the imperial gross in 1897, by discount, were rebated on the margin—(here the Duke of Marlborough started violently, recovered himself, gazed wildly at the witness, and then began taking notes)—on the margin, he repeated, at a cover of 10 to 8 according to the higgling of the market. In 1898 the margin had risen to the minimum fifth, in spite of heavy buying from Russia. In 1899⸺

Lord Halsbury: Was not that before the little trouble in South Africa?

Mr. Lutworthy: Yes, my lord, but it was late in the year. Towards September futures were quoted at less than the old “Charles Henry Agreement” rate—excluding freights. In 1900⸺

Mr. Gerald Balfour (anxiously): Would you mind repeating that last sentence?

Mr. Lutworthy (pleasantly): Let me make it perfectly clear. (The whole Committee here leant forward with the utmost attention.) Let us suppose this (taking up the Book on which he had been sworn) to be a king-bolt. Each king-bolt has at the centre what is known as a flange attachment, as might be this. (The witness then constructed a complicated thing out of a piece of paper lying near, and stuck it all round the Book.) Now, to attach the flange attachment so as to be attachable and detachable, it is necessary to—(here the witness looked all round the table anxiously)—Oh! yes. There; that will do!—(picking up a pencil)—to affix either to it or to its bevel a catch, as might be this pencil, so. (The witness here suited the action to the word.) Now, the Germans, instead of that, which is the right way, they drop the counter, lift the main-ratch, and so get all the head-gear into one piece. (Here the witness paused with a set, angry face; several people in the well of the Court cried “Shame!” and Mr. Balfour’s hand trembled. Then Mr. Lutworthy added in a shaking voice): One can do nothing against that kind of hitting below the belt.

Mr. Chamberlain: And you took that lying down!

Mr. Lutworthy (despairingly): I had to. What could I do? If the bevel had been galvanised or plated, or even treated with mercury in the original patent, I might have shifted the catch myself. But as it was—(fiercely)—Oh! how I have struggled!

Lord Lansdowne (in a deep voice): It is not for long!

The witness here stood down with a bowed head.

Mr. Chamberlain (briskly): Next!

Sir Charles Castlegate, introduced between two policemen, deposed that: As the results of his bankruptcy were still at issue, he must speak guardedly.

“Between two policemen.”

Lord Halsbury (sympathetically): We quite understand, Sir Charles ... pray continue.

Sir Charles (hurriedly): I have been concerned, as a company-promoter and member of the Carlton Club, with gyroscopes, penny-in-the-slot machines, atmospheric double-gear brakes, man-lifting kites, clenched carrying chains, and many other labour-saving devices. I will deal first with the auto-motor-sheaf-binder. It was originally all British. (At this point Mr. Balfour handed a note marked “Urgent” to a messenger, who rushed from the room.) It was originally all British. Now, what happened? I will make myself clear. In every sheaf-binding machine the essential parts are a “binder” and a “clutch.” Now, the binder is familiar to you all ... (Here some clamour seemed to rise from the street) the clutch is more complicated. You must consider these in the clutch. Either the pick and the main-nut or (which is much the same) the spring, the oil-pan, and the “dagger.” I will draw a rough sketch.... (As the prisoner leant over the paper a loud cry of “Fire!” was raised without, several fire engines were heard ringing their bells and shouting down Whitehall. Immediately afterwards a four-inch stream of water burst into the room and played upon the Court.

The Committee rose in the utmost trepidation and alarm, and the whole Court poured down the historic staircase. Several young gentlemen were crushed, one beyond recovery, and a grave tragedy was only averted by the presence of mind of Mr. Balfour and Mr. Chamberlain, who escaped with dignity and composure by another entry, and so relieved the pressure. Nevertheless, the fruits of the day were, it is feared, wholly lost, and no conclusion was arrived at.)

At the fourth meeting of the Cabinet Committee, appointed by its own members, with right of co-option, to discover by what means our Fiscal Relations—suitable, no doubt, for an earlier age—might be brought into closer relation, or relations, with the modern, &c., &c.... All the members arrived most punctually, several peers waiting outside in the rain for some moments before the doors opened. (Paragraph.)

When the Bench was seated, silence was imposed by the voice of a herald, and Mr. Chamberlain rose:

He assured the Court he would detain them but a few moments. Lord Byron had wittily said that still waters ran deep, and he, for his part, after a long life spent in close, hard-headed bargaining, had noticed that the less a man said, the more he was worth. It was a rule he himself had always observed. In his conception of Empire, the silent man, who never spoke, but did, should rule until he reached the sky.

(Here Lord Lansdowne began muttering to himself, Lord Halsbury openly pulled out his watch, Mr. Balfour shut his eyes and crossed his legs, and the Duke of Marlborough said “Hear, hear!” in a subdued voice.)

Mr. Chamberlain, continuing in a manner which combined courtesy with firmness, and which was emphasised by his favourite gesture, said that he felt it his duty to mention two painful incidents. One was the premature announcement in the Daily Mail that he was backing down. He had no intention of backing down till next February, and there was an end of that. The second was the misadventure which had broken up last week’s sitting. He alluded to the false alarm of fire, and especially to the pouring of a four-inch stream of water into a building sacred to his own immortal predecessor, Mr. Pitt, the father of Lord Chatham and the Saviour of Europe—the man to whom we owed Gibraltar, and all that Gibraltar stood for.

“Courtesy and firmness”

Whoever gave that false alarm was unworthy of the name of Briton. A pro-Boer newspaper had gone so far as to ascribe it to a conspiracy against him among his own colleagues. (Here Mr. Chamberlain looked round, and was met by nervous laughter.) It was like a great deal else that such people said; it was a lie.

He had now passed several years in close intimacy with them all, and he could only say that a more honourable and courteous set of men he had never dealt with. He was sure they would reciprocate the feeling.

He could safely say this: After visiting in all its extent the majesty of the Empire, and returning to England, he could only ascribe what had been done in his absence to the loyal support of the men around him.

Mr. Chamberlain here sat down. He rose again, however, in a moment, with the words, “I shall detain you but a very few minutes,” and some time after closed an interesting and fruitful speech by saying that the practice of “Dumping” was universally admitted, and that the business before the Court that day would consist in hearing from witnesses the form which the process took in various industries.

The first witness to be called was—

Mr. Henry Salter, manager of Messrs. Garrant and Schüler. He was willing to turn King’s Evidence. (Murmurs.)

Mr. Chamberlain: I hope the witness will be heard with respect. He is doing his duty, as did our brave allies on the veldt, and as did my old friend Le Caron. (To witness) Mr. Salter, I am proud to shake you by the hand. I wish I had known you in 1886. Such men are rare.

Witness, continuing, deposed that for no less than eight years past his employers had given away their German bicycles free.

[Sensation. A furious voice from the well of the court cried, “Let me get at him!” and an Anglo-Saxon of huge stature was with difficulty prevented from making an ugly rush. He turned out to be a patentee of the old style of high bicycles, who had been ruined by the competition of safeties.]

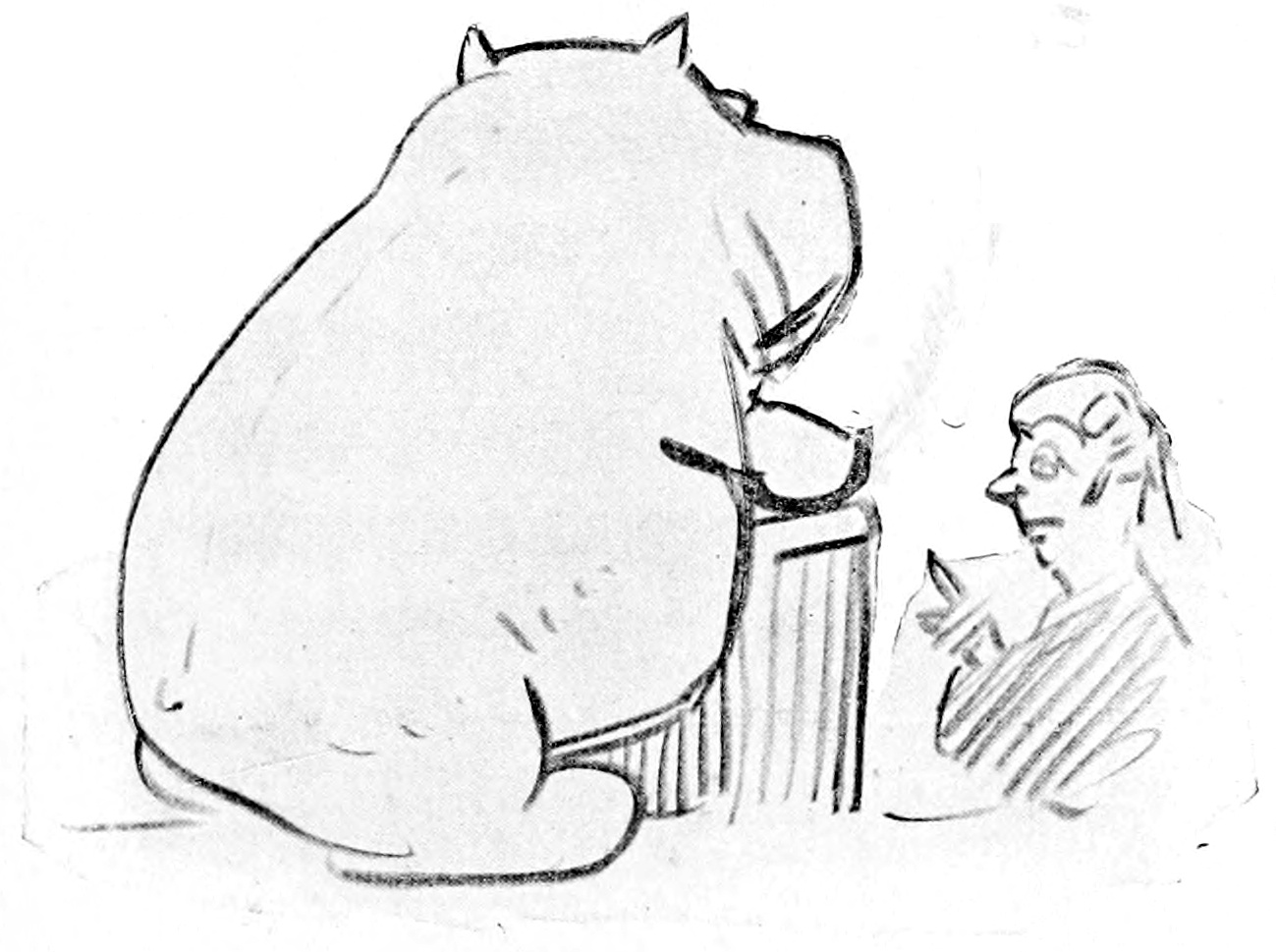

“An Anglo-Saxon of huge stature”

Witness, further examined, estimated the total number of bicycles he had thus offered free at a little over three millions.

Mr. Chamberlain (smiling): Oh, come, Mr. Salter, come!

Mr. Salter (shuffling uneasily): Business is business, my lord. (Loud laughter, in which Mr. Chamberlain joined.) There’s nothing to laugh at. Every man must make the best of himself.

Lord Lansdowne: How were these bicycles bestowed? Did you ask people to your country house, and give them by way of their private secretaries, or did you forget to send in the bill?

Mr. Salter: Neither, Sir Thomas; we put an advertisement in the papers, saying, a “£12 bicycle given away free.”

Mr. Balfour (with interest): I have seen such advertisements, but I never understood what they meant. The words alone seem to make no sense.

Mr. Salter (eagerly): They do, indeed, sir! All the competitors had to do was to send 1s. 6d. in stamps, and to get orders for ten other bicycles. (A pause, after which the witness added, anxiously) Am I free now?

Mr. Balfour (in confusion): Yes—I suppose so—you may go.

Mr. Salter: Yes. But I mean⸺They can’t do anything to me?

Lord Halsbury (peevishly): No! no! no! My good man! All this is privileged, of course.

[The witness, heaving a deep sigh of relief, walked slowly and rather insolently past two policemen, and sauntered into the street, where he was at once arrested.]

Mr. Chamberlain (briskly): That settles Bicycles. Now for Powder! Next!

[At the mention of “Powder” there stepped forward a most popular gentleman, with whom all members of the Committee warmly shook hands.]

Witness, examined, swore that while his discovery was still in the experimental stage, a hideous foreigner had appeared at his works, and had proposed “a deal.” This foreigner produced a sample of Powder which exploded practically at any moment the gunner might choose; at other times—in magazines or manufactories—the Powder would not explode. It kept in hot climates, and spread no disease aboard ship. It was certainly a most remarkable product. The foreigner proposed that they should furnish it to the Government as witness’s own, and share profits. (Indignation.)

Lord Lansdowne: And you refused?

Witness: Certainly I refused, Lansdowne! I was not given my monopoly to let in foreign spies!

Mr. Balfour: We owe you a profound debt of gratitude!

Witness (visibly affected): Thank you, Arthur. I can only repay you all by loyal service; and I think your kindness will be partly justified when I tell you that I am within sight of producing powder that explodes. Some has already gone off by accident in one of my sheds and killed a German.

[Witness here shook hands again warmly all round and went out.]

Mr. Elihu Z. Kapper swore that he was an American. In 1872 he first began to import mineral oil into this country. The people took kindly to it, and used it in a thousand ways. By 1880 he was importing 50,000 gallons a year of it. Meanwhile he was chiselled out by Mr. Rockefeller, and left to freeze. Mr. Rockefeller was a great man. He (witness) had then turned his attention to the English field, and had discovered vast lakes of oil in Devon, Norfolk, Denbigh, Cumberland, and Rutland. He had floated ten companies.

Mr. Balfour (aside): Wasted capital!

Witness: They had all gone bankrupt, and their bankruptcy was undoubtedly due to underselling from America. England had more undeveloped oil than any other country in the world.

Mr. Chamberlain: Now let me put you a practical question. If we prohibited the import of foreign oil, could you float an eleventh company?

Mr. Kapper (promptly): I have an eleventh floated already, Secretary—I could float a twelfth.

Witness was succeeded by young Mr. Garry, of Steynton Hall, Rugby, who swore that a foreigner, a Prince, had met him at the Savoy last June, and had given him several articles of foreign manufacture—a cane, a match-box, a dachshund, a wrist-watch, and a dozen of hock. In return he had given nothing. He had lent the Prince sums of money on various occasions, but it had all remained in the country.

The next witness was Lord Rustington. His lordship was visibly affected by illness, and his face, framed by great whiskers, bore an anxious and even irritable expression. He hobbled on a stick and said “thank you” to an assistant who offered him a chair. He had received the summons. He was willing to give evidence on dumping. It was a growing evil. At first (in his case) tin cans, packing boxes, and paper were the only things to complain of. Last year boots were found.

Mr. Gerald Balfour (puzzled): How “found”?

Witness (testily): Please let me finish what I was going to say!... Were found, I say, and occasionally empty bottles as well⸺

Mr. Chamberlain: But, surely⸺

Witness (angrily): Will you let me finish a sentence? Empty bottles, certainly, empty bottles. And this year it was awful. Old rakes, broken wheels, heaps of filthy hats, baskets, and—it might seem incredible—an old mowing-machine.

Cross-examined on the place of origin of these imports, witness said: It was the gipsies. They always camped near that corner of the home farm on the Pulboro’-road. They threw all sorts of things over the hedge⸺

Mr. Balfour (firmly): There is some error. This can have nothing to do with our inquiry. My dear Lord Rustentown⸺

Witness: Rustington!

[At this point the Committee consulted. After a little whispering Mr. Balfour explained with the utmost gentleness that there had been a mistake. The summons should have been sent to Lord Rustentown, the well-known ironfounder, money-lender, newspaper-proprietor, and supporter of the Government. If any apology of his⸺]

Witness in a towering passion declared that the fault lay with this Government and their accursed folly in flooding the country with new peers and letting them take any accursed name they fancied. In the course of his remarks witness struck his game foot with his stick, and thereupon became so violent that he was compelled to retire.

There succeeded a dignified silence of some few minutes, at the close of which Lord Halsbury said:

His lordship then rose to his full height and strode solemnly out of the room.

Mr. Gerald Balfour was the next to leave. He hurried through the door without a word. The Prime Minister followed him, talking to himself.

Lord Lansdowne smiled a little anxiously, looked right and left at his colleagues, tapped on the table with his fingers, and then got up in his turn and went out in a thoughtful manner.

Throughout this painful scene Mr. Chamberlain sat immovable, with a fixed stare and with set lips. At last, in a tone of characteristic energy and resource, he broke the silence with the cry of “Next!” But in the universal uncertainty and alarm no one responded to the summons.

The unnatural tension was relaxed by the abrupt departure of the three remaining members of the Court, Mr. Austen Chamberlain preceding his father, the Duke of Marlborough following his chief.

As the audience dispersed, the gloomiest forebodings arose upon the subject of the next sitting.

The fifth—and, in some respects, or, as Mr. Balfour has put it, “in many ways,” the most important—meeting of the Cabinet Committee appointed to Inquire upon the Causes of our National Decline, and to suggest some Remedy Therefor, was held at Downing Street in the usual place: the little room on the first floor to the left of the door.

The window, sketches of which have already appeared in the illustrated papers, may be distinguished by the new and perfectly clean panes of glass replacing those broken during the recent alarm of Fire.

A large crowd began to assemble at two o’clock outside the premises wherein the tragedy was to take place, and it was with difficulty that a number of policemen in plain clothes, but shod in the regulation boots, kept a lane open through the anxious though good-natured populace.

Mr. Chamberlain was the first to arrive, accompanied by the Postmaster-General. They came on foot, faultlessly dressed and apparently in the highest good humour.

Shortly afterwards the Duke of Marlborough appeared in the lowest good humour; he was on horseback, and bore several very large volumes precariously under one arm. The crowd waited in vain for the other members of the Committee; they did not come.

Meanwhile it was explained to the Court within that the three members present constituted a quorum, and the sitting was opened by

Mr. Chamberlain rising and saying he would detain them but a very few moments. He pointed out that his opponents were perpetually harping sordidly upon the mere economic evils which might follow the introduction of Preferential Free Trade. To reply to these criticisms might have baffled a man of less determination; he could not ask volunteers to come forward and submit themselves to the test, and his—he supposed he must call him his honourable—friend had refused to lend the Boer Prisoners still (he was glad to say) in captivity. He had surmounted those difficulties. He would call a number of living animals upon whom the whole scheme, from the recent procedure in Parliament to the effect of cheap tobacco upon the stomach, had been tried. (To the Door-keeper.) Let loose the⸺

The proceedings were here interrupted by Counsel for the Cobden Club, who rose and said he had a “replevin et demurrer” to lay before the Court. He believed such action to be cognisable under the writ “de Hæretico Comburendo,” and submitted, in all respect, that it was indictable by the Chartered Secretary of the S.P.C.F.C.H.H.[1] before the Justices in Eyre or in Chambers.

Mr. Chamberlain, holding in his hand a little slip of paper, spoke in his legal capacity as member of the Privy Council; still deciphering the said slip, he pointed out that the jurisdiction of the Courts Seizined was inferior to that of the Courts “En Plein” such as was this Court. He was sure of his facts. He would allow no interruption, contradiction, observation, Garrant in Warren or in Main, Bart, Blaspheme or Marraeny, under pain of contempt. He trusted his learned brother (turning to the Duke of Marlborough) would agree with him.

The Duke of Marlborough, rising with his hands clasped behind his back, spoke in so low a tone that he could hardly be heard. He was understood to say that it was all right.

Mr. Austen Chamberlain, speaking De Auctoritate Suâ, said they had heard the opinion of the greatest statesman and jurist in England, and also of one who, as one of the highest members of the Highest Court in the Realm—the House of Lords—was an unimpeachable authority.

The Court thus agreeing, Counsel for the Cobden Club was fined a hundred pounds for contempt, and the Inquiry proceeded.

The first witness to be called was a Horse.

As it was evidently impious to swear the animal, and impossible to take his affirmation with hand lifted over the head in the Agnostic style, he was allowed to pledge himself by proxy that he would do nothing for the sake of gain, prejudice, hate, love, favour, or worldly advantage.

The Trainer then explained that the horse would prove to demonstration that muzzling produced no ill effect upon living creatures.

Mr. Chamberlain: Have you tried the experiment upon Human Beings?

The Trainer: No.

Mr. Chamberlain: No what?

The Trainer: No, your worship.

Mr. Chamberlain (sternly): That is better.... (Gently) You have not tried it upon Human Beings because you thought an experiment in corporis viro would suffice?

The Trainer: ...? ...?

Mr. Chamberlain (testily): Do you hear me?

The Trainer (sulkily): Yus!

Mr. Chamberlain (to the Court, and especially to the Press): The Horse, you will observe, is free. He can whinny, neigh, or bite at will. Observe!

(At this word a gentleman called James ran a pin into the Witness, who thereupon lashed out a violent kick against the wall.)

Mr. Chamberlain: He shall now be muzzled.

(A large leathern bag completely enveloping its head and mane was put over the witness, who thereupon shuffled uneasily, as though bewildered.)

Mr. Chamberlain: Now!

(Mr. James again touched up the witness with the pin. Instead of kicking, the witness danced in an agitated manner and went through various contortions.)

Mr. Chamberlain: I think no further proof is needed of the advantage—or at any rate the innoxiousness—of the muzzle or gag. I trust the experiment will put an end to those foolish complaints in Parliament and the Press which have recently caused the continent itself to sneer. Next!

The next witnesses called were Two Pigs.

The Counsel for the Cobden Club, at the risk of his fortune, rose to protest. His disclaim was not so much against the Pigs themselves (porcs de soi), for the Court had allowed them, and he (emphatically) was not there to contradict the superior wisdom of the Court. It was rather against the presence of two witnesses in the box at the same time. It was wholly opposed to the spirit of Our English Law. Latterly that spirit had been attacked in a hundred ways: Prisoners could speak for themselves, even solicitors—he was ashamed to say—could plead in inferior Courts, but two witnesses in the same box was more, he thought, than the temper that produced an Eldon and a Halsbury could stand. Let alone the relaxation of the moral bond (for how could these two witnesses feel in common the awful meaning of an individual oath?) let alone the moral bond....

Mr. Chamberlain (suddenly): You are making a speech!

The Counsel for the Cobden Club was then taken off to prison. The Inquiry proceeded.

The Witnesses solemnly deposed by another’s mouth (as do infants in baptism) that they were born of one litter in the beautiful old-world village of....

Mr. Chamberlain: Go on! go on!

Witnesses, continuing, affirmed that they were reared in the same way to the age of six months. It was then determined to feed the one (Tom) in the Protectionist, the other (Bill) in the Free Trade spirit. All manner of food was stuffed into the latter at all hours; the former had a sparse meal once a week of honest English husks and bean-pods, with a little straw. Look at them now! “Kruger,” the free-trader pig, was so fat he could hardly walk. His life was a burden: he implored the release of death. “Roosevelt,” on the other hand, was a frisky, amiable, and active pig, capable of the most amusing tricks, and a fit companion for the best wits of the age.

The Witnesses then stood down after receiving the thanks of the Court.

A Ferret, two Dormice, and a Capercailzie having been heard to little effect,

A Boa-Constrictor was called to show that indirect taxation was capable of indefinite expansion, and a Hippopotamus to satisfy the Court that a broad basis was synonymous with stability.

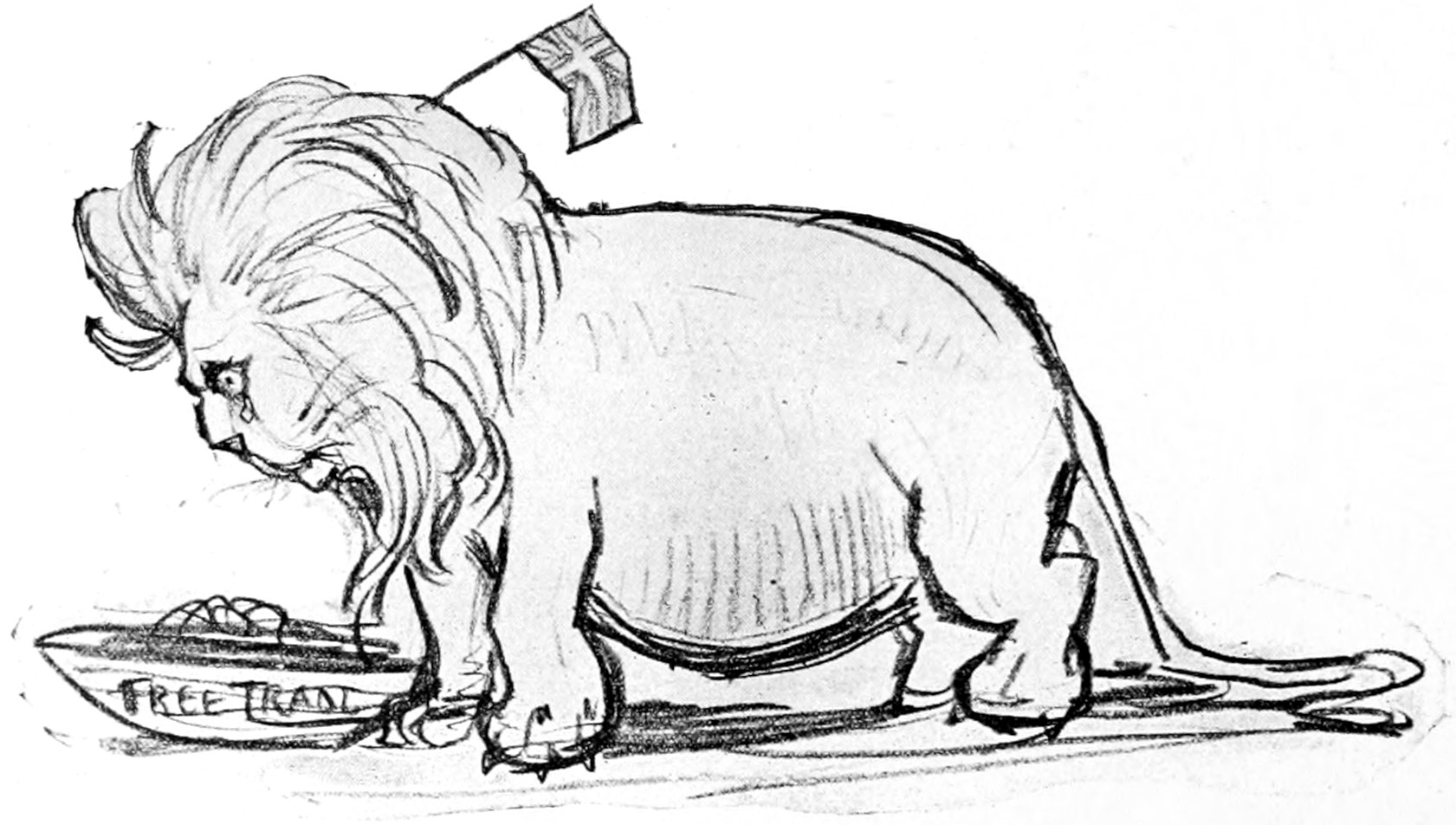

A Trained Lion was sworn, and showed, in the most amusing manner, under the artificial stimulus of a trainer with a whip, how in old age, with his teeth drawn and his spirit thoroughly broken, even so dangerous a beast could be put to the most useful work: such as rolling a log, balancing a see-saw, ploughing the sand, wiping something off a slate, doing a little spade work, and even roaring at command more loudly than in youth. The Imperial Brute was dressed in a large Union-Jack, and while it provided instruction afforded also entertainment to the company.

Many other witnesses, subpœnaed at enormous expense, carried conviction to all present, when Mr. Chamberlain ordered to be introduced the Elephant, presented by our Friend and Ally, the Maharajah of Gûm.

After some delay, during which the anxiety of the Court was terrible to behold, a Marabout arrived announcing that the Faithful Animal and Loyal Servant of the Empire had breathed its last that very hour in its Rooms at St. James’s! The Marabout, who elected to be sworn in the Hindoo manner, that is, formally and without prejudice, recounted with many sobs the last hours of the noble Pachyderm. It was chosen, he assured the Court, on account of its peculiar longevity; it being assumed by His Highness the Maharajah (here witness bowed once to the Court, once to the Royal Arms, and once to nothing in particular) that an animal which had outlived the Empire of the Great Mogul would survive the protracted Inquiry upon the Fiscal Relations of the &c., &c. Alas! Providence had otherwise disposed!

In a chastened and humble mood, and dwelling upon the vanity of human affairs, the Court solemnly adjourned. The Duke of Marlborough was heard to murmur, in the words of Burke, “What shadows we are, and what shadows we pursue!” a phrase which Mr. Chamberlain immediately entered in his pocket-book under the heading “p. 273, pop. quota.; mem. Latin original?”

The sixth and last sitting of the Inquiry upon the Fiscal (skip the rest) was remarkable in many ways, but especially for the fact that Mr. Chamberlain alone appeared.

The audience in the street outside, and the many experts and officials who were privileged to enter the court, were waiting in vain for the advent of at least the Duke of Marlborough or Mr. Austen Chamberlain, when the Colonial Secretary rose, and after remarking that he would detain them for but a very few moments, begged that they would not take alarm at the constitution of the court.

The absence of his colleagues was just the kind of thing that his more virulent opponents might put down to some difference within the Cabinet. Against malicious ignorance of that kind there was no weapon but direct contradiction. He would contradict it here and now, as he had successfully contradicted in the past his connection with the Jameson raid, the stupid story about the garden party at Lord Rothschild’s, and the legend of his having been a Free Trader and a Home Ruler, in some remote past which his enemies found it very difficult to discover. (Laughter.)

He did not think it seemly that a man should talk too much about himself. He would therefore make no allusion to the services he had rendered his country. Such as they were, they could never be more than the services of one man. A great man perhaps, a loveable man certainly, but after all, only one man.

Lord Beaconsfield had said that men imputed themselves. He was not quite clear what this meant, but,—....

(Here Mr. Chamberlain took up another little bit of paper, frowned, let drop his eye-glass, fiddled a little with his fingers, frowned again, replaced his eye-glass, and explained that he had mislaid some of his notes.)

Continuing in a more natural tone, and with far less fluency, he proceeded to give in detail the reasons for the absence of each of his colleagues.

The Prime Minister was occupied at Deptford, arguing with some Nonconformists.

“Arguing with Nonconformists.”

Lord Halsbury had retired into a monastery, to make his peace with God.

Lord Lansdowne had been suddenly called to the Foreign Office to translate some Frenchified stuff or other in the Sugar Convention.

The Duke of Marlborough was suffering from brain fever, and, in spite of the terribly contagious nature of the disease, Mr. Gerald Balfour was nursing him with all the tenderness of a woman.

His own son, Austen, had that very morning received a letter from a Mrs. Augusta Legge, of Tooting. It was addressed to the Postmaster-General, and complained that a box of fish, despatched by her ten days ago, had been lost in the post. The Postmaster-General always attended to these things himself. It was in the tradition of hard, silent self-denial in which he had himself been brought up, and in which he had brought up his family.

Under the circumstances he thought he would not call any witnesses ... something much more convincing than any number of witnesses was being prepared in the Horse Guards’ parade.

Mr. Chamberlain cordially invited those present to attend, and sat down after speaking two hours and thirty-four minutes, during the whole of which prodigious space of time he kept his audience entranced and speechless.

At the close of these proceedings, Lord Burnham came forward in his robes, his escutcheon borne by pages, and displaying as supporters, Hummim and Thummim, with the legend “Nec Nomina Mutant.” The Venerable Peer presented the Colonial Secretary with a pair of white gloves, according to an ancient and touching custom, which prescribes such a gift when a Court is happily spared the painful duty of delivering a verdict.

Mr. Chamberlain then disappeared through a little door to robe himself as a Roman Emperor, in which character he proposed to address the pageant.

On reaching the Horse Guards’ Parade an enormous crowd was discovered stretching as far as the eye could reach, but leaving between themselves and the grand stand a space, through which could defile the procession which had been arranged. At precisely fifteen minutes to six Mr. Chamberlain rose to address the crowd, and by a fine conception the brass band, the flags, and the various contingents of the procession began marching past at the same time.

It was perhaps on this account that his speech was not very clearly heard. The opening sentence, however, rang high and clear: “I shall detain you,” he said, “for but a very few moments.” What followed was drowned in a blast of trumpets preceding the arrival of⸺

A dozen miserable Unionist Free Traders. The unhappy men were gagged and driven forward, with their hands tied behind their backs, by a convoy of voters from Birmingham, arranged in blocks of five, and bearing banners ornamented with mottoes in their own dialect.

In the short interval following their passage, several of Mr. Chamberlain’s sentences could be plainly heard:

“I will tell the truth ... that has ever been ... Imperial race ... one united....”

At this moment the contingent of National Scouts, cheering wildly and galloping past the saluting point, drowned the master’s voice.

When the dust they had raised had somewhat fallen, his stern, impassive features were once more discernible, and a few more sentences could be caught above the din, though with increasing difficulty, as the mob were beginning to indulge in that loud horse-play which is inseparable from great popular movements.

“He was not often mistaken.... They could not point to any opinion which he had ... and which had not been....”

Though it was evident from the considerable distension of his mouth that the Great Statesman was still making history, nothing more could be heard: every word was swallowed up, as it were, in the increasing enthusiasm of the crowd.

An effigy of Mr. Winston Churchill, stuffed with straw, was dragged past the grand stand amid hoots and jeers, and finally burnt at the stake in the open space near the Duke of York’s steps.

Fifty-seven enormous vans, drawn by twelve strong horses each, and loaded to the height of at least forty feet with pamphlets and small handbooks, received perhaps a greater ovation than any other section of the procession, until, at its close, and, as though to emphasize that unity among all our fellow subjects, which has been the object of Mr. Chamberlain’s life, a number of Kaffirs, dressed as nearly as possible in the manner of the British working man, appeared on the extreme right, and marched past with colours flying.

When the approaching tramp and order of these brave men fell upon their ears, the crowd could no longer restrain themselves. Loud shouts of “Tweebosch!” and the names of other well-fought fields whereon they had fought and bled for us, rose from the three educated men who were to be discovered in that vast assembly. As the legion passed the stand itself, and turned eyes right to the majestic figure that had enrolled them in the common service of the Island Race, a great song, of which the words were at first indistinct, rose spontaneously from various parts of the parade: within a few seconds half a million undaunted voices were giving forth the great Song of Empire:

Spurred by such emotions, the crowd broke through the cordon which had hitherto been stoutly maintained by a body of Mr. Brodrick’s recruits, and made a rush for the grand stand; it unfortunately collapsed under the multitude of those attempting to honour their leader by a personal embrace. Perhaps no fitter termination could have been imagined for a scene which marked a turning point in the history of the Horse Guards’ Parade.

The Colonial Secretary, it need scarcely be added, did not remain to receive this last testimony to his popularity, but the beginning of the enthusiastic movement in the crowd was enough to convince him that he had thousands at his back, and, as Napoleon is reported to have said to his coachman after Waterloo, “With such numbers behind him a man should be capable of all things.”

APPOINTED TO

SIT HARD UPON

THE FISCAL CONDITIONS

OF THE

MOTHERLAND.

Made to the Cabinet in Full Session, crowned, robed, and regardant, and ordered to be enrolled among the Imperial Archives

Under the Great Seal, the Privy Seal, and the Mace Statuant.

Your Committee—

Did first consider whether they should pursue the course of stating their reasons before their conclusions; or, secondly, their conclusions before their reasons; or, thirdly, their reasons only; or, fourthly, their conclusions only; or, fifthly, a sort of rhodomontade in which there should be neither reasons nor conclusions, as is the more common practice. Your Committee divided upon each of these questions, when it appeared that—

It having thus arrived, in the heat of the moment, that Your Committee had by accident rejected all courses, and had nothing left to go upon—there being no precedent for such a misadventure—

Your Committee

Thereupon decided to begin de novo et ab ovo, and there was drawn up by

Your Committee, with the aid of an expert prose-writer, a majority report, in the following tenor:—

SECTION I. Your Committee are of opinion, after hearing all the evidence presented to them, that—

The Empire cannot go on like this. It is amply proved that not only Great Britain and Ireland, but the Colonies also, are and have been for many years increasing in wealth, population, and power, to the grave detriment of the Christian Virtues of Humility and Holy Dread. It is further proved beyond cavil that the cheapness of goods of all kinds has enabled the mass of the population to live riotously, has destroyed thrift, impaired industry, and even threatened that Sobriety which had hitherto been the chief mark of our race.

SECTION II. There is, however, another side of the picture. Not only Great Britain and Ireland, but the Colonies also, are on the verge of bankruptcy; their population is for the most part starving; in many districts, notably in Lancashire, the Isle of Thanet, Manitoba, and the Wagga-Muri country, N.S.W., the wretched populace subsist on grass like beasts of the field, and have lost all semblance of human form. Even the wealthy classes have felt the pinch. Three furnished houses in South Audley Street are untenanted, and it has been necessary to provide out-door relief for the clergy.

MADE IN POOR OLD KENT.

SECTION III. Gold has accumulated so rapidly of late years as at once to clog the main channels of business, and to make men lose all sense of the value of the precious metal. An increase of five million pounds a year in the circulating medium of the country cannot be regarded without alarm. Innumerable 10s. bits are carelessly mistaken for sixpences. Whole sovereigns are dropped in cabs, and capitalists of great prominence allow vast sums to be withdrawn by fraud from their balances at the banks. The precious metals are used in making cigarette cases, medals, and statuettes, and are even wantonly wasted upon objects of superstition in the churches. All these evils undoubtedly proceed from what Professor Macfadden has called “The Plethora of Gold.”

SECTION IV. Meanwhile there is an awful and hitherto irresistible drain of gold from every port in the kingdom. Most of our population, even those betraying every outward sign of prosperity, say that “they do not know where to turn for money.” The young men at our universities are all of them deeply in debt, and even the old men are often pretty dicky.

“The young men are all of them deeply in debt, and even the old men are often pretty dicky.”

Four Colonial loans have failed during the year.

Mr. Seddon informs us that a paltry reward offered him by a grateful nation had to be raised in no less than five instalments. Indeed, he was for a long time most anxious about the fifth.

It is extremely difficult to get change.

Numerous cases are on record in which gentlemen of good birth have found themselves in omnibuses without the means to pay their fare. Some of them have been thrown out with violence.

“Gentlemen of good birth”

Short temporary loans, such as could once be negotiated by friends for nothing, can now only be raised upon ruinous terms—sometimes as much as 60 per cent.—from total strangers.

Paper is everywhere creeping in in the place of metal, in the shape of cheques, bank-notes, stamps, I.O.U.s, and dunning letters: a state of affairs rather worthy of Spain than of a Race which has spread its language over half the new world.

All these evils are most undoubtedly caused by the drain of gold.

SECTION V. Foreign nations, in a fit of madness, are perpetually forcing presents upon us, to the ruin of our legitimate trade. Patriots who attempt to refuse these gifts are met by threats.

A well-known alderman, of Peckham, who persistently bought English wine in preference to foreign trash, has recently died in torment under the suspicion of poison.

A promising young clerk and poet, known as Balmy Jim, who dressed exclusively in clothes of his own manufacture, has been discovered hanging to a tree in Richmond Park.

The Rev. Charles Henty, Fellow of St. Barnabas, who broke a lot of glass in Kew Gardens to encourage English glazing, has been incarcerated.

SECTION VI. No less than fourteen professors of political economy have pointed out, in a very able manifesto, that they differ from some of the most remarkable of our politicians upon fiscal matters. This alone should show the intense interest aroused by the whole question, and the absurdity of pretending that an inquiry was not demanded.

SECTION VII. We are informed by our colleagues that they have been scurrilously attacked by no less than fourteen pedants, whom they believe to be in the pay of foreign powers. This is not the kind of accusation that can be proved or disproved. It suffices to show the importance of the issues before us.

SECTION VIII. The Editors of the Daily Mail, of the Spectator, of the Standard, and so forth, have suddenly turned nasty against the Editors of the Times, the Daily Express, the Globe, and what not, whoever they may be. This alone should show, &c., &c.

SECTION IX. The Duke of Devonshire has made some most irritating remarks, so has Sir John Gorst. This alone, &c., &c.

Your Committee are, therefore, totally unable to make up their minds what on earth should be done.

It is quite impossible to decide.

They are on the horns of a dilemma.

They are in the utmost perturbation.

They heartily wish you had not asked them to undertake this task.

And Your Commissioners will ever pray, &c.

Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to our Fellow Creatures However Humble.