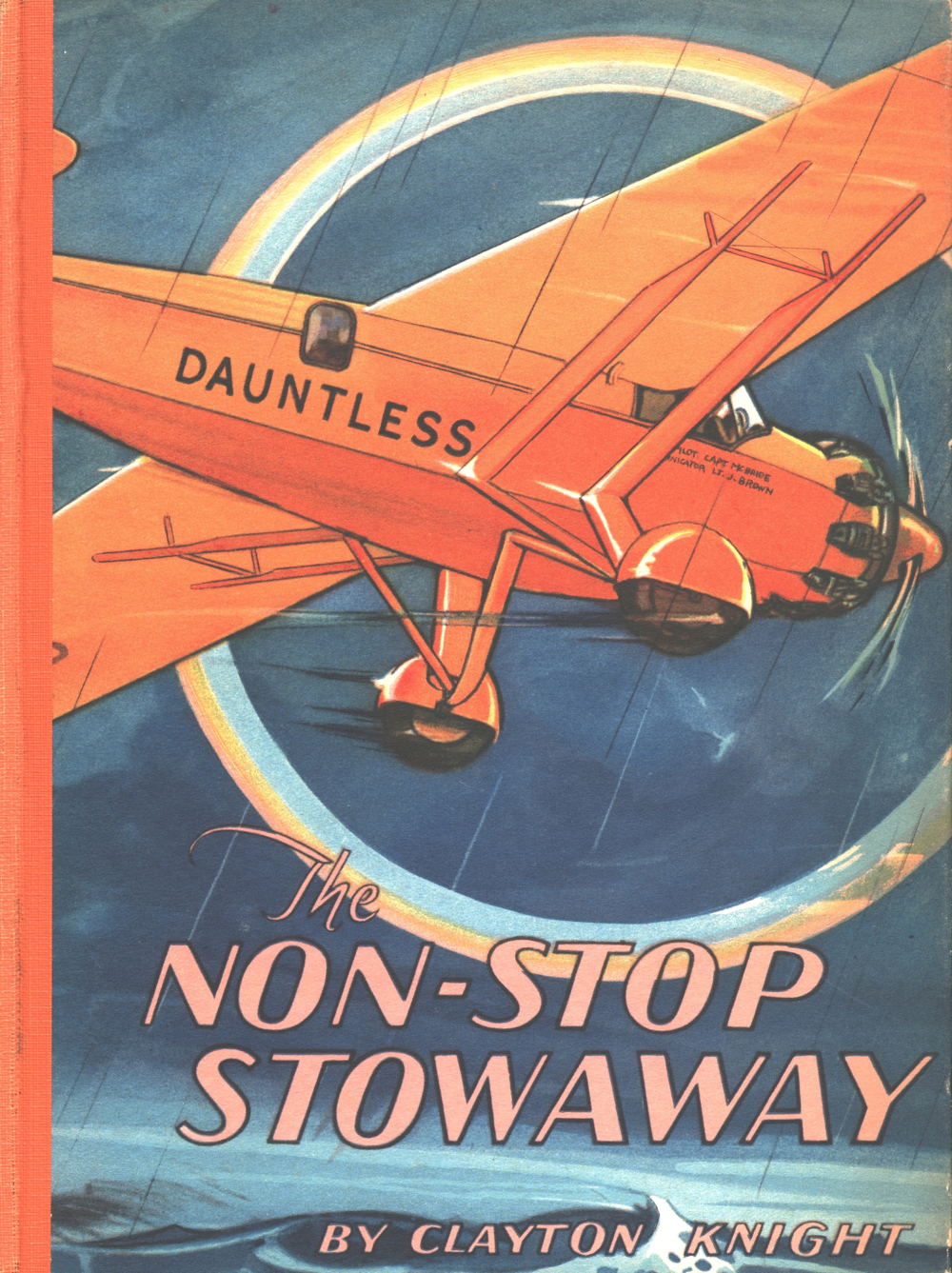

Title: The non-stop stowaway

The story of a long distance flight

Author: Clayton Knight

Release date: April 9, 2023 [eBook #70513]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: The Buzza Company, 1928

Credits: Steve Mattern , Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

THIS is a story for boys who want to know of the thrills and joys of Aviation. It is written by a war flyer who was a pilot with a squadron at the front and who there learned to know how he and other young men reacted to those dangerous moments when lightning-quick decisions were necessary.

He has seen many boys learning to fly, and observed how most of them, after they had learned, acted in a crisis with the utmost coolness whether it was the sing of a bullet or the miss of a motor that brought the warning of danger.

He knows that those flyers were wrong in their belief during the war that no flying in peace time could equal the thrill and tingle of the nervous excitement which they were then experiencing.

Since the war ended, the design of planes and engines has so far advanced that distances are being spanned now that they never then believed possible.

Nature has put dangers in the paths of our modern flyers, as great or greater than that of an enemy, for from the moments of the dangerous take-off with tremendous loads of fuel, until the landing on another Continent, there can be no relaxation.

And after watching the planes leave for long ocean flights where no safe landing can be made for many hours, we have come to realize and appreciate the strain these pilots are under.

When several of these bidders for long distance honors have failed to appear at their announced destination and when, after a frantic search has been carried on over land and sea, the world has been forced to admit that no trace—not even a stick of wood or a rag of fabric—can be found, then it is comforting to think, to hope, that somewhere, a safe landing has been made.

EDITOR.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | The Plane Tested | 9 |

| II | A Narrow Escape | 23 |

| III | Trouble Brews | 36 |

| IV | The Plane Is Christened | 45 |

| V | Ready to Hop | 53 |

| VI | The Flight Is On | 74 |

| VII | Mid-Atlantic | 88 |

| VIII | Conditions Change | 106 |

| IX | Another World | 116 |

| X | Kiwi Gets His Wings | 136 |

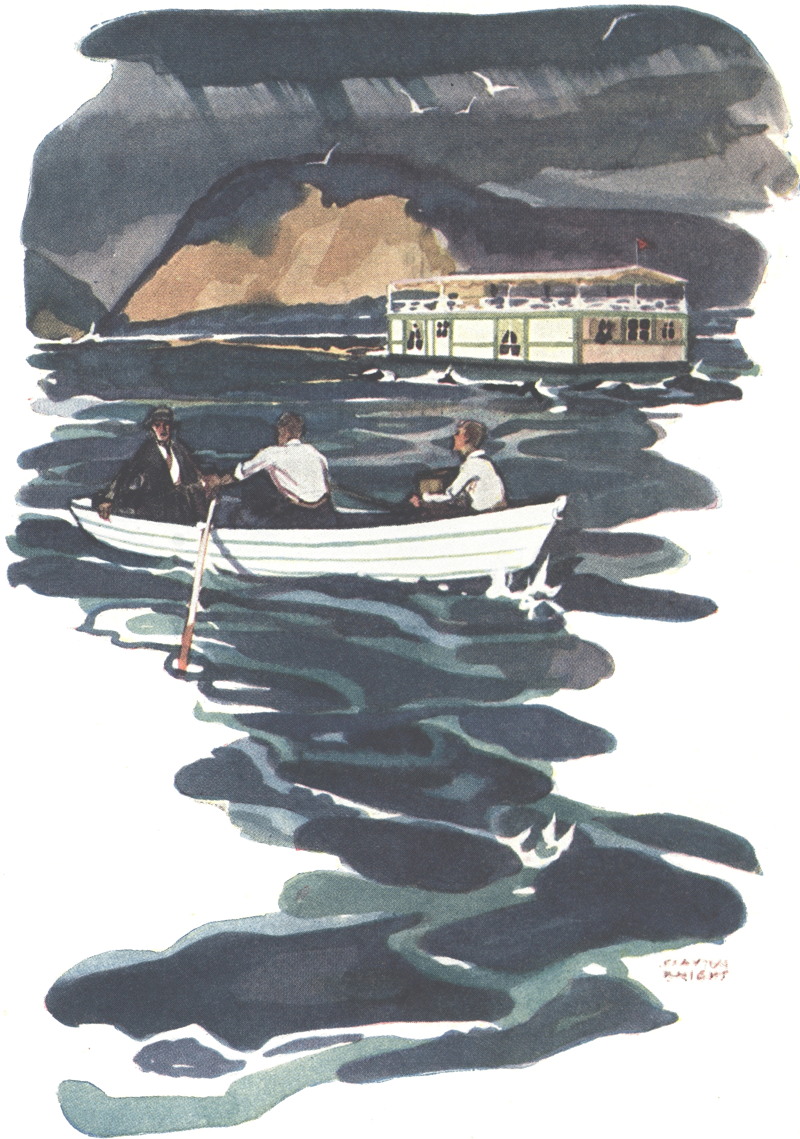

SUPPER was over. The man and the boy, although they had finished, seemed in no hurry to clear the table. Darkness had come, and through the windows of their little houseboat twinkling lights on the shore half a mile away were reflected in the quiet waters of the bay. All was still except for the putt-putt of a motor-boat a long way off. The man in blue trousers and white shirt with the collar open seemed to be listening for something. The boy tried hard to get him to talk.

“How long will Dad be, do you suppose?” “Will he come back by train, or will he fly back?” were some of his questions.

Jack’s reply to them all had been, “We’ll see.”

The boy thought to himself, “What a silly answer,” but that seemed to be all the silent sailor man would say. He looked little enough like a sailor now, and not nearly as grand and imposing as when he had met the boy and his father in New York as they stepped off the train on their arrival from the West nearly a month ago. At that time he had appeared in his uniform of blue with gold braid and 10gold wings. As they had driven out from the station across the crowded city with its strange noises and bewildering lights, there had been time to do little more than notice the slim straightness of him.

His Dad had said to Jack, after the first greetings were over, “Well, here’s the young fellow I wrote you about. I couldn’t leave him out West, and besides he will be a great help around the hangar.”

And Jack had replied, as he shook hands, “One more Kiwi for our camp.”

“Right,” said Dad, “but I have had to make him a promise that he won’t be a Kiwi for long.”

Kiwi was a good enough name in its way, and it did seem to stick to him wherever Dad went. All his boy friends knew him as Snub but, of course, the boys knew so little about flying and few of them knew where the name of Kiwi came from.

Dad had told him that during the war—and Dad had been there, so he should know—all of the officers who did not fly had come to be known as Kiwis, named after a bird from Australia or New Zealand “which had wings but did not fly.”

So Kiwi he was. There seemed a promise in the name that one of these days he would learn to fly, for, after all, a Kiwi did have wings. It was something to start with, and on all 11the flights he had gone on with Dad he had kept his eyes open and now felt that he understood all that had to be done to control the plane.

Often when they had landed after a flight, old war-time friends of Dad’s would come over with a loud “Well, Skipper, how’s the boy doing? Going to send him off solo[1] soon?”

1. After a pupil completes his training with an instructor, who has a duplicate set of controls, then he is sent on his first solo flight. To fly solo is to fly alone.

And Dad would reply, “Not yet awhile. He has a lot to learn and there’s plenty of time yet.”

So on that first meeting with Jack, as they rolled across the bridge to Long Island, Kiwi had wondered if this broad-shouldered sailor-flyer could be coaxed into teaching him.

Dad and Jack had been too busy talking to notice him. Dad was asking a thousand questions: how much had they got done on the ship? ... were the tanks installed yet? ... had the motor been shipped? Dad seemed upset that more had not been accomplished. “We must get a hustle on if we’re to get off by the 15th of June,” he had said.

After they had been riding for some time, Kiwi asked:

“Whose house are we going to, Dad?”

Dad turned to Jack, who hurriedly said, “Wait till you see. I have had a wonderful idea. You remember Old Bert who used to fly the pontoons over at Rockaway—who would loop any old crate they would let him fly? He has a shipyard over here and is building houseboats—two sizes—and he thought we would like to use one of the smaller ones—just one big room and a little kitchen and a porch. We can moor it where we like, sleep under the awning on top, and keep the car on the shore near by so that we can run back and 12forth to the field. That will only take about twenty minutes, and it means a good swim in the morning and another after mucking around the hangars all day. Does the Kiwi swim?”

“Like a fish.”

“Well, that’s settled then.”

A half hour later they swung down a long hill and into the main street of a little town, nestling in a deep valley, with a long, lake-like arm of the Sound coming nearly to the center of the village. They turned off and wound through a big yard where piles of boards and planks and beams rose up 13like top-heavy buildings along the narrow roads. The smell of cedar and pine hung in the air. They drew up at the wide-open door of a shed from which came the whine of buzz-saws and the pounding of hammers. They had hardly stopped when a sunburned man appeared at the door, evidently expecting them.

“Hello, Bert,” they called.

He rushed over to the car, shook hands with Dad, and there was a great hubbub of questions and answers. He said their boat was waiting, and it would be a tip-top place to spend a cool hour or so hearing all the news.

They were rowed out, and Kiwi spent busy minutes exploring the little houseboat. He came into the sitting room in time to hear Dad say to Bert, “As soon as the backers came across with the money, I wired Burrows to start work on the plane as we had planned it and to rush it through so that we could make our tests and still get off in June while the weather was good. Then I turned heaven and earth trying to find Jack. I had no idea whether he was out East with the fleet or had come back. When I did locate him, he was able to get leave from the Navy to make the flight, and hopped a train for Washington and got right to work on weather maps. He seems to have the navigation part of our trip very thoroughly in hand. Tomorrow I will get over to the factory and see if they cannot be hurried with the plane.”

And from then on there had been endless conferences with old friends and new about equipment to be taken, routes to be followed, wind currents to dodge. The days had stretched into weeks, and still the plane was on the ground.

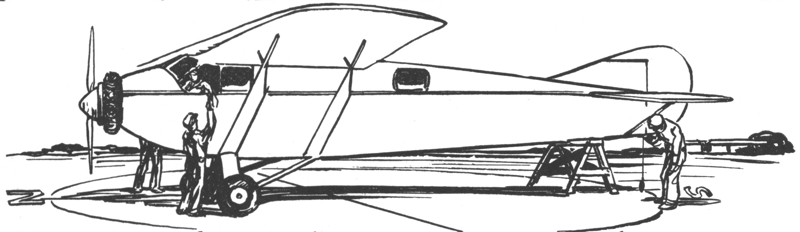

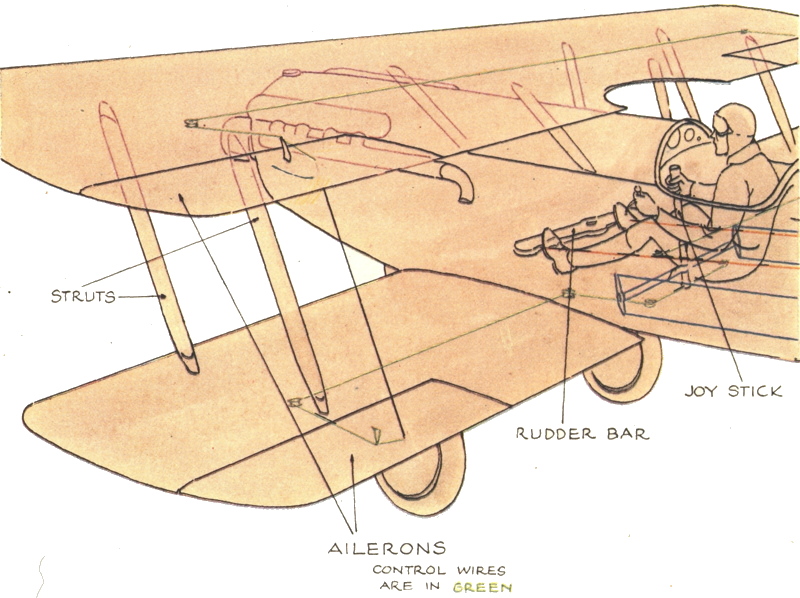

Kiwi had been taken to the factory twice. The plane looked 14enormous even in its unfinished state. The body of the machine still lacked its covering, but in its middle sat an enormous metal tank. Control wires seemed to run in all directions. The big wing also carried two tanks, and only the wing-tips were hollow. The engine was still missing. There were reports that it had been shipped, but for days after that it did not put in an appearance.

Nearly always Jack and Kiwi spent the day on the houseboat or driving over the winding country roads near by. Jack pored over maps and strange charts. He brought home queer instruments and tested them from the roof of their 15houseboat during the moonlight nights. They swam, and once or twice they went fishing.

At last the day came when the plane was finished, and must be taken up for its first test flight. Jack and Dad had talked it over the day before, and it was decided that Jack and Kiwi should stay on the boat and let Dad do the testing.

“You’ll get plenty of chances, Jack, later on, after I get the feel of it.”

So now Jack and Kiwi sat there on the houseboat after supper, impatiently waiting for the sound of oars. About nine o’clock they heard a little boat bump against their home, and both rushed out.

It was Dad.

“Jack, she flies—she really does! She lifted off the ground in about two hundred yards and handled like a dream. Of course, there are some things to be done, but they can be fixed when we get the plane over at our field. You and I will go after it tomorrow and start our own work on it.”

“May I go with you to bring it back, Dad?” Kiwi asked.

“Well, not this time. You’ll have other chances later on.”

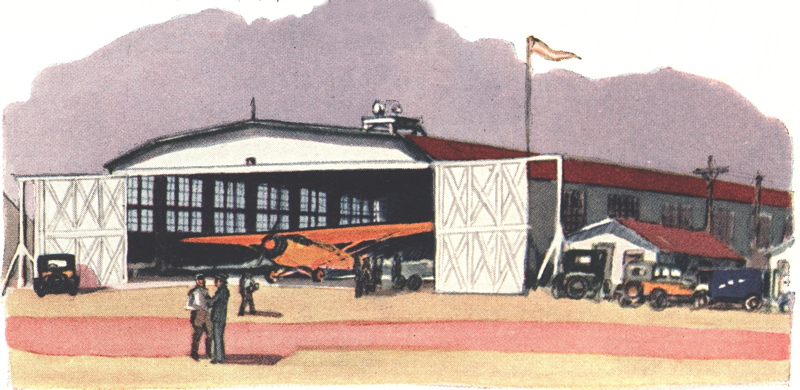

The day that Dad and Jack went after the plane dragged 16endlessly for Kiwi. He had been driven over to the airdrome early so that he could welcome them when they arrived. Ordinarily he would have been interested in the other planes that were busy about the fields. They were continually hopping off and landing, being fuelled up with gasoline and going up again. But today it was different. His mind was on Dad and Jack, and he was constantly on the lookout for their return.

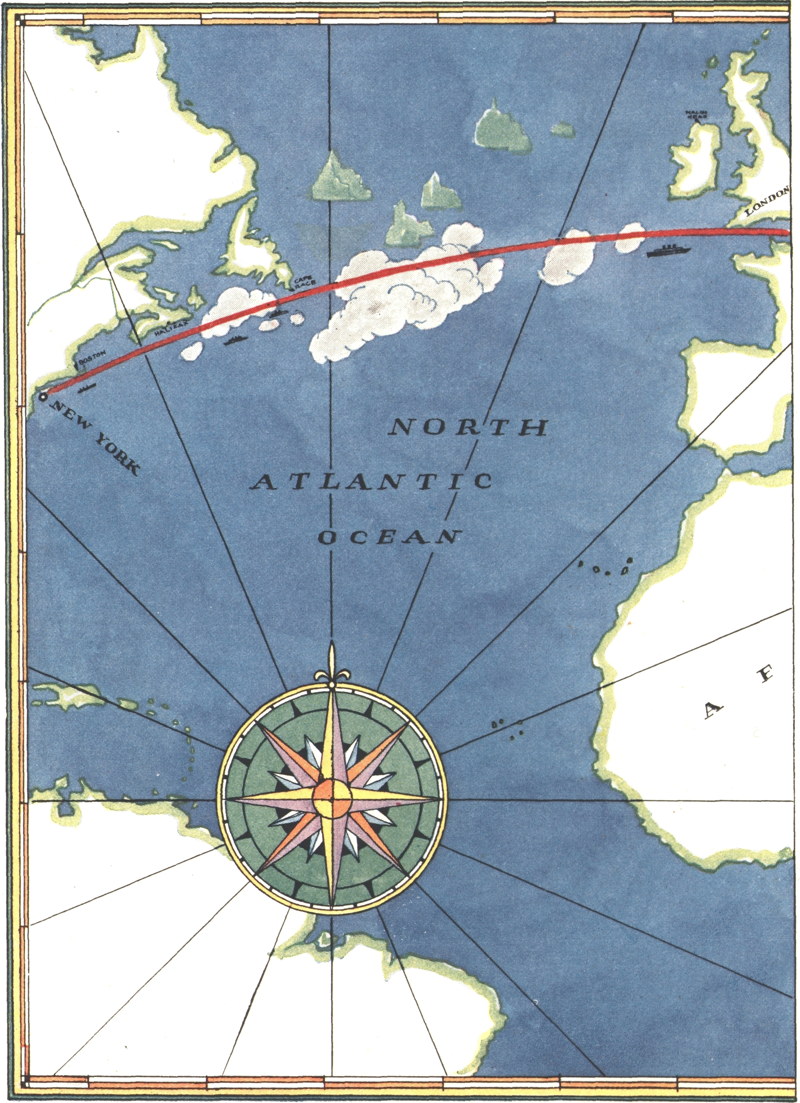

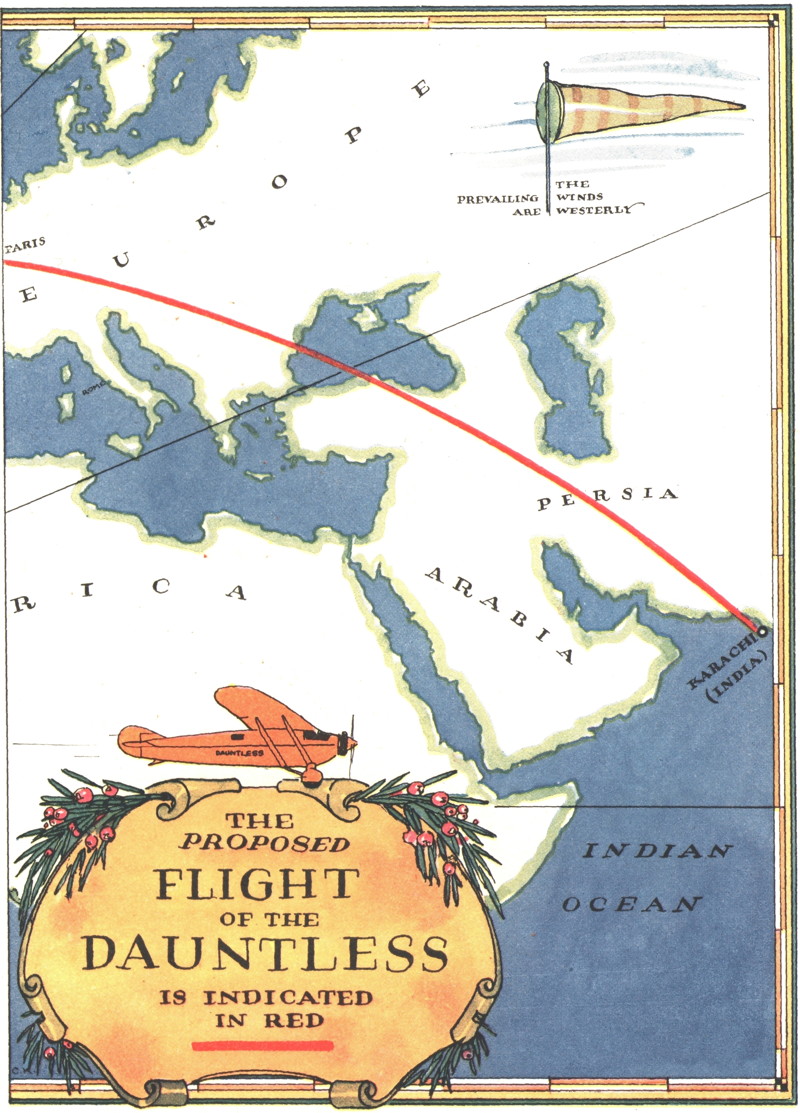

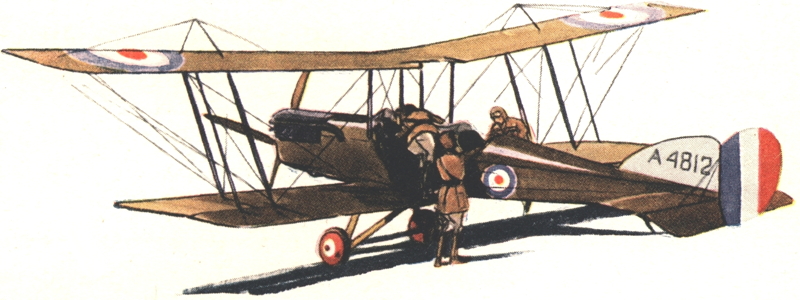

At last, late in the afternoon, the sound of a different motor drew the attention of the pilots and mechanics to a new plane coming in from the west. It circled the field several times, and came down to land at the far end. Wheels and tail skid gently touched, and the plane rolled along with scarcely a bump. It taxied up to the hangars and was soon surrounded by an excited group curious to see all the new features of this bird which was to attempt such a tremendous hop. For the word had traveled that here was a new challenger for the long distance record. Here was a machine, equipped with all the latest gadgets,[2] in which two experienced flyers were planning to leave New York and not touch their wheels again till they arrived in far off India.

2. A term used in referring to the instruments on a plane and the levers or buttons which control them.

Its single huge wing glistened in the sunlight. The pilot and navigator’s cockpit, covered with glass, was just in front of this wing and behind the huge radial engine which was even then slowly and smoothly turning the propeller. Just behind the wing in the body of the machine was a tiny window, through which those who were tall enough could peek in and see a small compartment behind the gas tank. 17The two wheels of the undercarriage[3] bore massive balloon tires and were further protected by large shock absorbers upon which the weight of the plane rested. The whole plane was painted a brilliant orange.

3. The undercarriage consists of two wheels and a frame-work which are attached to and support the body of the plane.

Switching off the engine, Dad stepped out with a happy smile. “So far, so good.”

Then came days of trying and testing. Fortunately they were favored with splendid weather. For a day or two it rained during the morning, but they were able to get in one or two flights before dark.

They took the machine up so that Jack could test his wireless. A Lieut. Connors flew over from Washington with a small, compact set which he hoped would be better than 18the one they already had in the machine. On one of the tests it seemed as though the ultimate in wireless transmission and reception had been accomplished for an airplane.

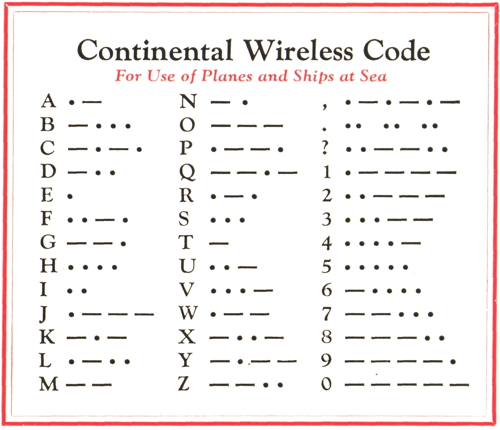

The machine went to two thousand feet, the wireless aerial was lowered, and Kiwi stood beside Lieut. Connors, who was manipulating the receiving set in the back of a small truck. Jack and Connors tested their signals both flying away from and toward the receiving set. The dots and dashes of the code came in equally strong either way.

Kiwi put on the head-phones to listen while Connors clicked out a message to those soaring above. Jack had taught Kiwi the wireless code for his name, and soon he was thrilled to hear “H-e-l-l-o K-i-w-i” come down from the air.

However, there were other days when the set seemed not to work so well, and it took hours of tinkering before all the troubles were found and adjusted. The set in the plane was finally moved to a place away from the main tank and the engine.

Then there was the compass to be corrected. Kiwi had not realized that correcting a compass was such a long operation, although Dad had told him that the magnetic compass in an airplane was a very sensitive instrument. There was much iron and steel in the motor, and there were many conflicting forces pulling the magnetic needle from its position toward the north magnetic pole.

To compensate for these forces, small metallic rods had to be added.

So Kiwi followed as the plane was wheeled out onto a cement circular platform on the ground away from the buildings. Marked on this circular platform were the north, 19south, east and west points. Pointing the plane due north, the bits of iron were placed in position in the compass to counteract the attraction of the motor and other metal parts. These bits of metal were about the size of the lead in a pencil, and were of various lengths. After they had been inserted in holes provided in the base of the compass, they were secured in place.

As soon as the needle pointed to the north as it should, the plane was wheeled around till it pointed east and the process was repeated until the compass had been corrected for each direction.

However, they knew that many times a pen-knife or some such similar object in the pockets of a pilot would serve to throw the compass off its proper direction.

Knowing the particularly delicate nature of compasses, the Skipper was very cautious about putting too much trust in them, and insisted that their compass be carefully checked.

They also had an earth inductor compass, which was more reliable, but which had to be adjusted by an expert from the factory.

The ride home from the field in the cool of the evening was usually taken up with long discussions about balanced rudders and whether they did not need more surface on the elevators.

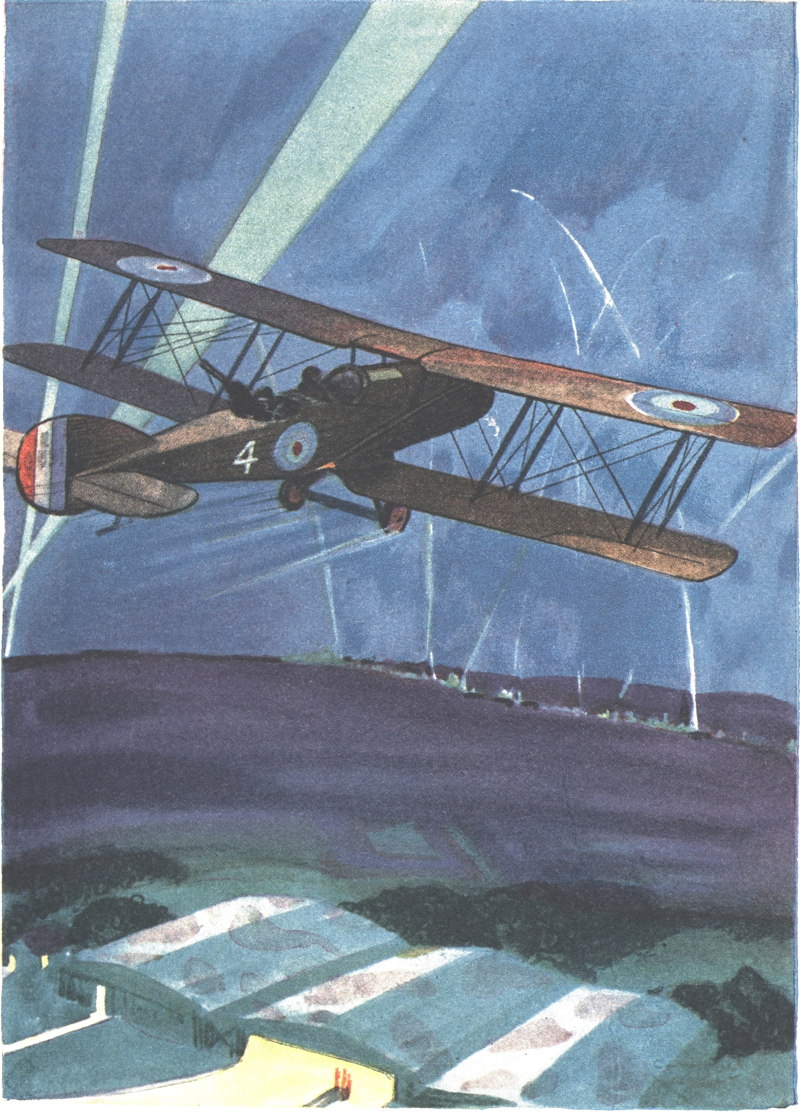

Later on, even the evenings, which Kiwi always looked 20forward to, were taken up with test flights. They tried out their navigation lights and landing by flares.

Many evenings Kiwi would go sound asleep in the back of the car until the voice of Jack awoke him suggesting that they rush home for their swim and supper.

During all this time, coax as he would, Kiwi had not been taken on his promised ride. Dad had always answered in that same hateful formula, “We’ll see.” Why were grownups so fond of those two words? He promised himself never to use that expression when he was grown up.

Kiwi had made many friends around the field—the men in greasy overalls who tinkered with the engines, Old Bill who kept the lunch stand at the end of the field and who had made his name famous for having packed the sandwiches for several earlier cross-Atlantic flights. But there was a scarcity of boys of his own age. There were plenty who were older and who seemed to be able to convince the instructors on the field that they could learn to fly.

Kiwi felt a lack of the proper arguments to use. He was sure he could fly if they would give him a chance. But as soon as he brought up the subject, they insisted on talking down to him as if he were a child.

Kiwi felt that it was Old Bill at the lunch wagon who eventually got him his first ride in the new plane. His father and Jack had dashed down for a hurried lunch, and Old Bill said to Kiwi, “Well, how does she handle?” Kiwi had blushed to the roots of his hair and admitted that he did not know. Whereupon Old Bill had turned to his Dad and said, “What, you haven’t taken this boy up yet?” And his father had answered, “He’ll get his ride—perhaps tomorrow.”

21That night, after considerable pestering, his father gave him a definite promise that if the next day were fine he’d get that first ride.

Old Bill

IN the morning, as Kiwi and the two men rowed away from the little houseboat, clouds hung low over the bay, the wind whipped up tiny whitecaps, and in the bow of the boat where Kiwi sat he felt the wavelets going slap-slap as they drew toward the shore. A sand bank showed yellow against the dark gray of the sky. Jack had received weather reports during the night from the wireless he had installed on their floating home and, with a quick look around, dismissed the threatening appearance of things with a curt, “This will all clear away by noon, I’m sure.”

Kiwi’s spirits rose, for it had begun to look as though his flight might be postponed again.

On the ride over to the field in the car, Jack said:

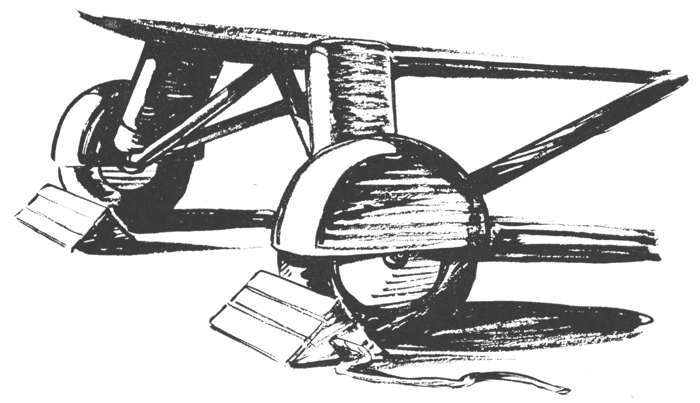

“Well, Skipper, do we try out your comic stream-lining on the wheels today? Not many pilots have any faith in them. I cannot see myself where they will add much to our speed.”

“Well,” replied the Skipper, “I’ll admit that they look 24like a pair of tin pants, but if they add even five miles an hour to the speed of our bus, that amount, spread over seventy hours, will mean a lot for our chances of arriving in India. At any rate, we’ll give them a try today if those mechanics have managed to get them installed.”

By the time they drew up in front of the hangar the weather looked more threatening. There was little activity outside the long row of hangars that lined the field. Old Bill had waved from the little window of his restaurant as they passed. Only one machine was standing on the line, and the mechanics were half-heartedly turning the propeller over.

At their own hangar the two smudgy mechanics were still busy with the stream-lining. There seemed little chance that the plane would be ready much before noon.

Kiwi wandered up the line of hangars to see what other excitement he could find. He liked to listen to the flying talk that was practically the only topic of conversation around the field. He had learned to respect those rather dingy buildings, some of which were now in a sad state of disrepair.

They had served other purposes during the war. Dad had even pointed out the deserted and dilapidated buildings that had been used for barracks, where he had eaten and slept before being sent overseas. He had also pointed out to Kiwi the building they had used as a kitchen, where he had washed dishes and peeled potatoes for twelve hours at a stretch as a punishment for being caught in his bed after the whistle for reveille had blown.

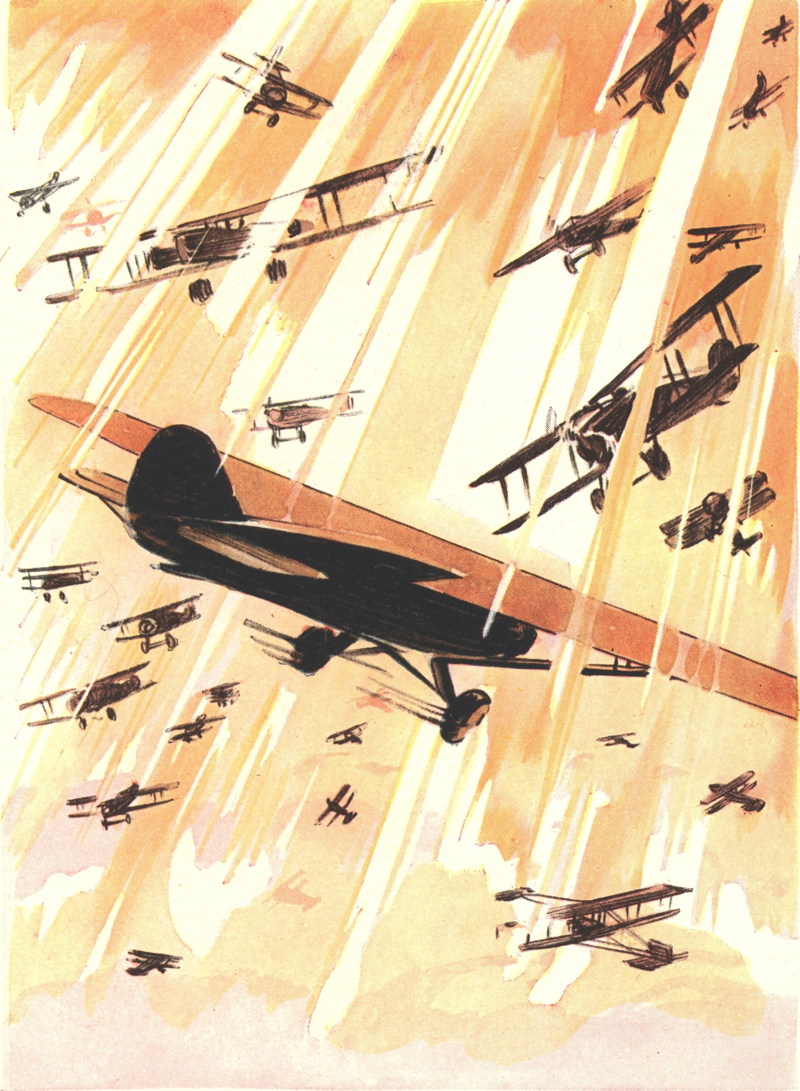

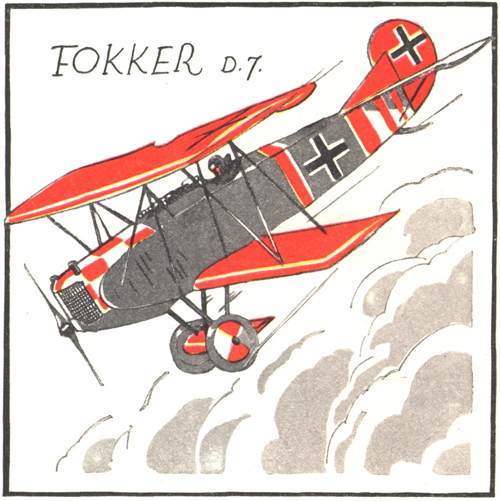

There was little now to make them glamorous—no uniforms to be seen, no sound of bugles, no high hopes for adventurous times across the seas. In fact, they seemed to Kiwi a 25bit too spooky even in daylight. He seldom stayed long in any one of them. Dad had given him the feeling that they were crowded with the unseen presence of rollicking young fellows who had once stayed there, who had gone away, and had never returned. They had learned to fly, had mounted into the high heavens, had come to know a world apart—a world of mountainous clouds, with the ground far below blue-gray in the early morning—a silent kingdom of its own, its silence sometimes shattered by the rattle of machine-guns and the bursts of anti-aircraft shells.

Just before noon, as the sky seemed to lighten somewhat, Kiwi noticed their machine being wheeled from the hangar with its new stream-lining in place.

He hurried back and was told that they would soon start. As chocks[4] were put under the wheels, he climbed up into 26the cockpit beside his Dad. It was a tiny place with just enough room for two men, crowded with instruments and wheels. Even the seat was a gasoline tank. For gasoline was to be the life of their flight, and every possible ounce had to be carried when the real hop-off came. During most of the tests the tanks were only partly filled.

4. Chocks are triangular blocks of wood placed in front of the two wheels of the undercarriage to prevent the plane from beginning to roll after the propeller has been started.

He watched Dad as he adjusted the levers, and as the mechanic said, “Switch off! Suck in!” Dad leaned out and repeated it after him. The mechanic turned the propeller over several times to get a rich mixture in each cylinder. Then as the mechanic called out “Contact!” Dad threw over his switches, and after a couple of false starts the engine roared into life.

For a few moments, as it warmed up, Dad watched the dial which told the number of revolutions his engine was making. Then, as he felt that all was ready, he opened wide the throttle and the whole plane quivered with the roar of the engine. As soon as his instruments showed him that the engine was developing its full power, he throttled back and motioned to Jack to hop in.

As Jack started to do so, he said, “We haven’t the wireless aerial. Connors is splicing on a new piece.”

“Never mind,” Dad replied, “we won’t need it this time.”

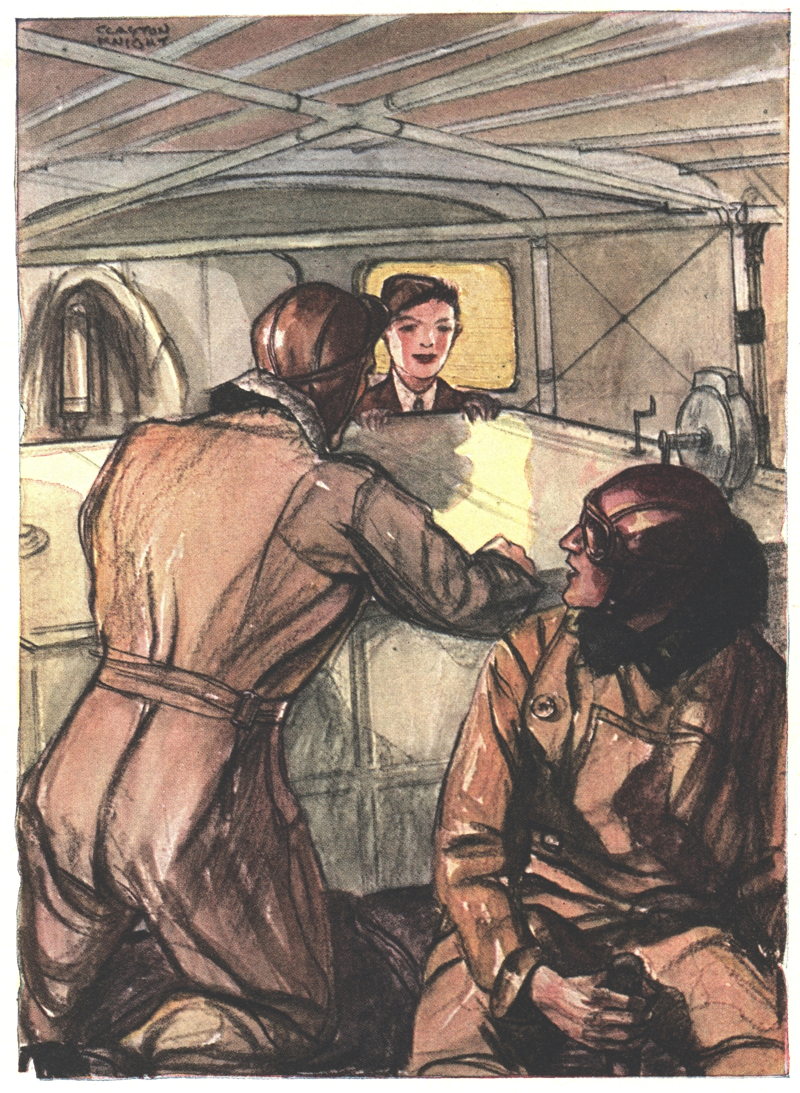

Dad’s invitation to Jack meant that there would be no room in front for Kiwi. But Dad said, “Kiwi, you slip over the tank and ride in the compartment in the back.”

There was scarcely room for him to squeeze through in the space between the top of the tank and the under side of the wing.

The chocks were withdrawn, and they went bumping out 27across the field to the far side and turned into the wind. Then, as the engine opened up, Kiwi felt the tail lift, they went rolling across the ground and, with a last gentle bump, were in the air.

Kiwi looked out to see the ground apparently falling away from him, and the hangars, houses and fields took on a toy-like appearance. He was now accustomed to this sensation, but he would always remember his first flight and how odd 28it had seemed to have the ground slip away from beneath him in this strange manner. He remembered the queer feeling he had had when they made their first turn. It seemed as though they were perfectly stationary, and that the whole earth had suddenly started to tilt up until it stood on edge.

Kiwi remembered, too, his first experience in clouds. The clouds were not very high, and he had motioned to Dad to go up through them. As they started up they were soon surrounded by a fog so dense that even the wing-tips faded from sight. They had flown on for what seemed to him an endless time, when Dad shook his head, motioned that the clouds were too thick, and started down.

Wires screamed with the vibration, and Kiwi kept a sharp lookout over the side for the first appearance of the ground. Surely they must see it soon! Then, with a sudden start, he looked over his shoulder to find the earth apparently above him. It took him some seconds to convince himself that this was really the ground in such an unusual place. There above him was this uncanny earth, with the trees lining the tiny roads, half hiding the toy-like houses.

Dad had afterwards explained to him that in trying to get up through the clouds he had lost all sense of direction; that when he had shut off his engine and pointed the plane to what he thought was down, they had fallen sideways rather than straight down, which accounted for the earth appearing in this unexpected quarter.

However, on this first flight in the new machine, he had no such experience; for they had taken off in a straight line and climbed to nearly a thousand feet before any turn was made. Also, being completely inclosed in his little compartment, 29he felt much more secure. He peered out of the windows, first on one side and then on the other. As they came back over the field, he looked down to see several figures rushing about and another plane taking off.

Dad headed out toward the ocean. It was Kiwi’s first view of the Atlantic, which extended far off toward the misty horizon, dotted here and there with busy ships going about their errands. A long trail of smoke marked a big liner heading for the port of New York. Its decks and life-boats showed dazzling white against the dark blue of the water.

Then Dad turned and they headed back toward the field. Suddenly, almost from nowhere, there appeared to Kiwi a plane with silver wings and blue body—the plane that he had noticed taking off a short time before. It came close and tried to fly level with them. Kiwi, fascinated, watched the pilot as he waved to them. He continued to wave, and then pointed to the side of his machine.

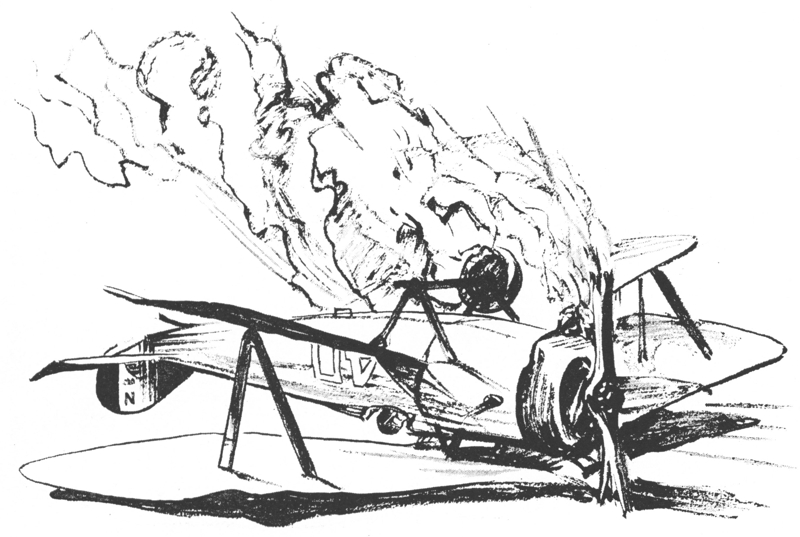

Kiwi noticed then in large white chalked letters the words, YOUR RIGHT WHEEL GONE.

The pilot of this machine seemed unable to catch up with them and so attract Dad’s and Jack’s attention.

30As they roared along, Kiwi crossed over to the right side, looked out of his little window, and there hanging down useless was the stream-lining and no sign of the wheel.

His first thought was, “Now Dad will shew them what it means to be a good pilot.” Then it crossed his mind, “Perhaps Dad doesn’t know it’s gone.”

He scrambled up onto the huge tank and wormed his way toward the front. Jack saw him coming and motioned him back. The roar of the motor drowned out Kiwi’s voice as he tried to tell them what had happened. But Jack did finally understand as Kiwi pointed frantically back toward the other plane still trying to overtake them.

Dad gave a startled glance toward the plane and read the message,

YOUR RIGHT WHEEL GONE.

He motioned to Jack to open his cockpit window and verify their predicament. There was a nodding of heads, showing that both understood.

When they got back to the field they flew low, while Dad waved his arm to let those on the ground know that they were aware of their plight. The news of their mishap had evidently traveled, for a crowd was gathering and more and more cars were arriving.

They made no attempt to land for they could see that another plane was about to take-off, and a mechanic was even then chalking a new message to them.

They circled around until this plane drew alongside, and against its dark background they read a longer message:

LAND AT MITCHEL. AMBULANCE THERE. NO CROWDS.

31Dad waved his arm to let them know he understood. Then he drew over toward the other field and circled around for several minutes, which came to seem like hours. They could see the activity on the ground as every preparation was made to take care of the inevitable crash.

To land a heavy plane such as theirs on one wheel was a thing that had been seldom, if ever, tried before. Kiwi had heard stories of pilots who had landed not knowing one wheel was off, and he knew that the consequences were often very serious. Planes turned over so quickly once the axle caught and dug into the ground. But he also knew that warned as they had been of the loss of their wheel, there was a good chance that Dad would pull them through.

32He thought of the hours of work that had been spent on this machine and of the high hopes they had that it would carry Dad and Jack thousands of miles across land and water, and he realized how dashed their hopes would be if there were irreparable damage.

Jack’s head appeared above the tank. He motioned Kiwi forward, and then explained to him by gestures how he must brace himself when the final moments of landing came.

Kiwi nodded and felt that here was his chance to show Dad and Jack that he had the necessary courage. He knew that he would prove equal to the test.

As he dropped back into his compartment, he looked down on the field. A group of men had marked a cross with wide strips of cloth in the middle of the field, showing the best place to land. In front of the Operations Office was a little group of people beside the ambulance, with a red cross on its side. As he looked farther along, he saw the red and the 34polished nickel of a fire truck. Men were hurrying to different parts of the field with what he knew to be fire-extinguishers.

The stage was set for the try.

As they circled around, heading into the wind, he felt Dad throttle back the engine and the long, slow glide to the field was started.

The spectators on the ground were no more tense than Kiwi, through the long seconds of this dive to uncertainty.

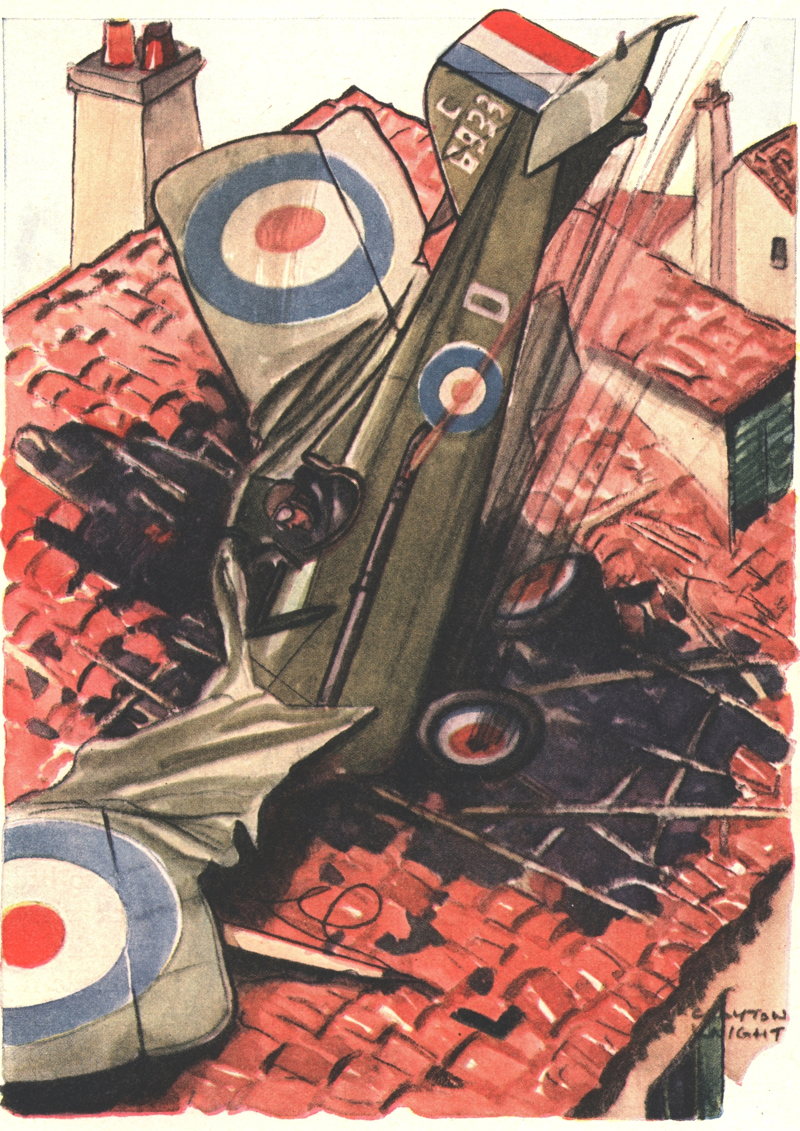

The silence, after the engine had been throttled down, was broken only by the rush of the wind through the struts. He braced himself. He felt Dad tip the plane over so that the left wheel would touch first. As the plane lost momentum, the other axle dropped, caught in the ground, and with a terrific crunching of metal they spun around and came to a stop.

He heard cheers and voices and saw Dad’s scared face come through the trap door in the bottom.

“Are you all right, Kiwi?”

Dad lifted him down with shaking arms, and they were at once surrounded by a group of people slapping Dad on the back and telling him what a wonderful job he had done.

They looked the precious plane over. Some damage had been done, but nothing that could not be fixed within a few days. One of the wing-tips had been slightly torn and they would need a new propeller.

It seemed no time at all until camera men appeared, and nothing would do but that Dad must pose with Kiwi on his shoulder and Jack smiling by his side.

Within a few minutes planes from the other field began arriving. The pilots were amazed to find all three unhurt, 35and were loud in their praise of the marvelous way in which Dad had made the landing. He stood there, cool and collected, smoking a cigarette, the color now back in his tanned cheeks, his wavy chestnut hair very much awry as he took off his helmet and goggles. There was nothing to show of the tense strain he had been under except a slightly drawn look about his gray eyes. He was shorter and less striking in appearance than Jack, but the crowd of pilots singled him out and gave him that praise which only one pilot can give to another.

They made a fuss over Kiwi, too, and he had the feeling that he had been weighed and not found wanting—that in this emergency he had kept his head and done the right thing.

For the first time Dad seemed to notice Kiwi’s nondescript clothes as the photographers were snapping pictures. True, very little attention had been paid to what he wore. There had seemed to be so many other more important things to be looked after. But as they were riding back to their old hangar, Dad said, “Kiwi, I think tomorrow would be a good time for you and me to make a trip into town and we will get you a new outfit. If you will insist upon getting your pictures in the papers, the folks back home will want to see you in the sort of clothes a young aviator should wear.”

“Will it be a uniform, Dad, like yours?” Kiwi had asked.

“Absolutely, if that’s what you want,” had been Dad’s promise.

THEY awoke the next morning to find that their adventure of the day before had made them famous. The newspapers all told of the fight for life over the flying fields of Long Island. They told of the real courage of the two men and the boy when an unforeseen mishap had so nearly ruined their plane and their chances for a long distance record.

A reporter from one of the newspapers had questioned the mechanics in charge of the plane, and hinted that one of them had been careless in reassembling the undercarriage after the new stream-lining had been put in place. This was most difficult to prove. Certainly Jack and the Skipper did their best to decide from an inspection of the wreckage of the broken axle what the trouble had been.

The Skipper had great confidence in the two mechanics, Cosgrave and Billings, who were looking after the plane, and felt quite sure of their loyalty. Jack was not so sure. He had taken a dislike to Cosgrave, and several times had voiced his distrust to the Skipper.

Billings

About Billings, who was an English engine expert, there could be no possible doubt. He had been the Skipper’s engine sergeant in France. There was nothing particularly handsome about him. He was rugged, square, had large ears and a shock of black hair hanging in his eyes. He was always covered with grease, and grit was ground into his hands. His finger-nails were always outlined in black. He was bandy-legged, and even in an army uniform he looked anything but soldier-like.

After the war Billings had gone back to England and had tried to keep busy, but times were hard and there was an over-supply of skilled mechanics. He had drifted over to America, and had been working for several years at the factory that had built the engine for the Skipper’s plane.

When the factory head had received the order for a specially built engine for a particularly long non-stop flight, he had sent for Billings and told him that here was an engine that must be watched through all its construction, from the tiniest nut and bolt, to the moment of its great trial. Nothing must be overlooked. Everything must be tested and re-tested.

“It will make or break our reputation, for I have every confidence in 38Captain McBride who is going to make the try,” he said.

Billings’ face lighted up.

“That wouldn’t be Skipper McBride—er—Captain Malcolm McBride—would it, sir?”

“Yes, that’s the man. A pilot with plenty of experience and the habit of being lucky.”

“Why, sir, I was with him in France for a year. He’ll do it, and there’s nobody would like to help him more than me. Is he here? Could I see him?”

“No, but if you want to write him, here’s his address. He hasn’t come East yet.”

So in the Skipper’s mail one morning a few days later was a letter from Billings:

“Capt. Malcolm McBride, D.F.C.,

Dear Sir:

I take my pen in hand to tell you that this is your old Sergeant Billings of No. 206 Squadron. You will remember me from the old days in France, especially the time you took me up for a ride and threw the old Bristol fighter about until I lost my false teeth, and had to get leave to go back to London to get a new set fitted.

I am working now for the company that is building your engine, and you can rest assured that I will watch it, Captain, until it is ready for delivery. What I was wondering was, wouldn’t you be needing some one to look after it until your hop-off? I would like nothing better than that job. I think I could get a leave to help you if you would write to Mr. Block.

Hoping this finds you “in the pink” as it leaves me,

Yours respectfully,

C. M. Billings. Ex-Sergeant R. A. F.”

39To say that the Skipper was pleased, is putting it much too mildly. Of course he remembered Billings. Billings had been with his squadron during all his flying days in France. Billings had been the last man he had seen as he left the ground each day, and the first man to greet him as he landed and taxied up to an open space in front of the old Squadron hangars.

“Engine all right, sir?” Billings would ask, even before the Skipper had swung his cramped legs out of the plane.

Billings’ personal interest in those engines had been almost motherly. Once, returning from a trip to the “lines,” the Skipper had been caught in an almost tropical downpour of rain, which made it necessary for him to land and spend the night at an airdrome about thirty miles away from his own. When he did get back to his own field, Billings had seemed about to take the whole engine apart just to make sure that it had not been mistreated while away.

Here, surely, was the sort of loyalty that would be needed in their new adventure. Therefore the Skipper lost no time in wiring East to make sure that Billings would come with the engine and help them off to their goal.

Of Cosgrave, both Jack and the Skipper knew very little. He had been recommended by the people who had built the plane, and had seemed to go about his work willingly and to do it well. He had apparently obeyed all their orders, and was ready to help at all times. He had even offered to bring over a cot and sleep in the hangar so as to “keep an eye on the plane.” This he had done, and was always there early and late.

Jack had said to the Skipper one night, “I like Cosgrave all right, but I can’t say as much for some of his friends.”

40The Skipper had thought little about this until the accident with the wheel. Then he began to wonder if Cosgrave were on the level or if there were something underhanded going on. The whole thing might bear a little watching. But surely no one could have any object in stopping their flight. True, there were others who would like to get the prize money and the prestige it would bring.

Another group of men with a plane almost as good as the Skipper’s were at a nearby field, and were getting a good deal of publicity. Every day the papers carried new stories about their plane. However, the gossip heard around the hangars told of quarrels and dissensions between the pilots and their powerful backers. Lawyers had been busy drawing up contracts and counter-contracts. It seemed hardly possible to the Skipper that their activities would carry them so far as definitely to try to interfere with him and Jack.

He dismissed the whole thing from his mind, and with his usual energy began to put the plane into shape with as little delay as possible. His confidence in his stream-lining idea for the wheels was unshaken. However, the few minutes they had been in the air had given them no check on their speed.

Repairs of a temporary nature had to be made quickly at the army field. A new propeller was ordered.

During the two days these repairs were going on, Kiwi had a chance to see and explore this new field. All during the day army planes fully equipped with guns were taking off and landing and practising close V formations over the field. The pilots’ uniforms with their silver wings were a welcome change from the golf clothes that most of the men at the other field wore.

41True to his promise, the Skipper took Kiwi into New York, where they went to a huge store on Madison Avenue and ordered a tunic and breeches to be made for him. Kiwi secretly hoped that Dad would buy him some field boots such as he wore, but Dad seemed to think that leather puttees would do as well. The salesman in the store had recognized the pair from their newspaper photographs, and they were the center of attraction during their stay.

The man who took Kiwi’s measure remarked about his straightness and his sturdy shoulders. He said it would take a week for the uniform to be finished, and Kiwi could hardly wait to see it.

However, the days passed. The new propeller was fitted. The plane was flown back to the old hangar and the tests went on.

It was finally established that the Skipper had been right—the new stream-lining had increased the speed of the plane by exactly eight miles an hour. There could be no question that it was an advantage.

Through one of Jack’s friends in the Navy, they met a chemist who was developing a new fuel, lighter in weight than gasoline and nearly twice as powerful. He was anxious for them to try it out on their flight to India. Their experiments with it had led the Skipper and Jack to believe that it was a real discovery, and they decided to test it out on a long flight before the big hop.

The tanks were nearly filled with the new fuel, and early one morning they took off for Washington. It was to be their longest test and would give them a good check on their speed and fuel consumption.

42Kiwi was not to go along, but Bert had promised to take him on a sailing picnic that day. Several times Kiwi had seen Bert in his sailboat, with a crowd aboard, sail off up the bay, and he was torn between the desire to go with Bert and the feeling that he did not want to miss a day at the flying field.

Dad and Jack had been gone about half an hour when Bert sailed alongside the houseboat and Kiwi hopped aboard. They spent a glorious day along the sunlit shore of the Sound, and at noon put in to Mattituck where they built a fire on the beach and had their lunch. They roasted potatoes, fried some bacon, and romped with a friendly dog who came to visit them. The shore was wide and sandy, and about an hour after lunch they had a swim in the cool waters of the Sound.

On the trip back the wind died down, and they lay becalmed for nearly an hour. Then a light wind sprang up from another quarter. The sun sank lower in the west. They were still some miles from home. Bert finally gave up trying to sail, started the auxiliary engine, and they slowly chugged up the bay.

It was dark as they drew abreast the houseboat and there were no lights showing. Bert wrote a note and left it for the Skipper, and carried Kiwi off to his own home for dinner.

The day in the open had made him ravenously hungry, and the meal, served in the wide, cool dining room facing the shore, was doubly welcome for its touch of home.

Bert’s wife, who was waiting as they drew up to the little dock, had embraced Kiwi with a great squeeze as Bert called out, “How about some food for that boy?” She had had only fleeting glimpses of Kiwi since the day of his arrival. 43He had seemed so busy with the men folks. However, she must have had some experience with small boys, for several times pies, cakes, and doughnuts had been sent out to him. He liked her cheery bustling about the dining room. It called to mind his mother who seemed to be somewhere in his shadowy past. He had missed her terribly after she had gone, and tonight, seeing Bert’s wife so busy about the house, brought it all back to him.

Dinner over, they had gone out on the wide veranda in time to see a new moon climb up from the hills.

Bert had telephoned the field, and came back with the report that Dad’s plane had circled Washington, had wirelessed that all was well, and had started for Norfolk early in the afternoon.

The minutes dragged. More calls to the field brought them little comfort. The plane had been seen over Cape May, but no wireless call had come from it.

About nine-thirty Kiwi was packed off to bed, and as he lay there he heard Bert at the phone still calling the flying field.

44Tucked into this strange bed in a spare room at the head of the stairs, he lay thinking about the plane. The cool white sheets, the chintz curtains at the window, the little knick-knacks on the dresser were unaccustomed and almost forgotten niceties. The wind and the sun during the day had made him drowsy, but he could not sleep for wondering what was happening to Dad and Jack.

It was so calm and peaceful there in the little room. The light breeze that stirred the window curtains only helped to emphasize this calm. Still, somewhere out along the coast, perhaps Dad and Jack were in trouble.

He tried to picture some adventure that might have befallen them. If they had had to land in the water, he remembered that they had no boat. The collapsible rubber one which they were to take on their trip across the ocean had not yet arrived. If they did have to land, he hoped that it might be near some farmhouse which would give them shelter for the night.

As he fell asleep, Bert’s voice came drifting up the stairs, repeating the words that had just come over the telephone, “No news.”

KIWI awoke with a dread feeling that something was wrong. It was daybreak—light was just beginning to come in the window. Then he remembered that Dad and Jack had not come back in the plane.

Hurriedly dressing, he tiptoed down the stairs, opened the door onto the porch, and without disturbing anyone made his way down the path. The robins and the grackles were making a great racket in an old pine tree near a little lake in Bert’s yard.

He followed the shore, hurried on through the lumber yard, and out to the road. The way to the field was by this time well known to him and he started off at a fast clip. He felt that he must get over to the field and get some news of Dad.

There were few people on the road, and he had gone perhaps half a mile before anyone overtook him. The first car whizzed by, but another, coming along soon after, pulled up beside him and the man leaned out and called:

46“Want a ride, Bub? How far are you going?”

Kiwi was not sure that he ought to get into this stranger’s car; but the man, dressed in dark clothes, a blue shirt and a cap with a shiny peak, seemed thoroughly friendly. So he hopped in. The car started off with a clatter and rattle as Kiwi said that he was going over to the flying field.

“That’s right on my way,” the man said. “I’m just going over to take out the 4:59.”

“Are you a flyer?” Kiwi asked.

“Well, not exactly. As a matter of fact I’m a fireman on the Long Island railroad. But I see lots of these flyers as my train passes by the field. One of these days I’m going to get one of them to take me up.”

“I’ve been up lots of times,” Kiwi replied, proudly.

They chattered on, and Kiwi told the man who he was and how his father was planning a non-stop flight to India.

The fireman said, a little incredulously, “Are you going, too?”

Kiwi had to admit, rather shamefacedly, that he wasn’t—at least Dad had said he wasn’t—“But I’d like to, and I’ve heard that India is a very nice place. Dad says they have elephants there the same as they have in the circus, except they are everywhere. The people wear turbans and bright-colored clothes, and even the men wear earrings.”

47The fireman looked a bit skeptical as to that. He had seen such things at the movies, but really did not believe they were true.

As they turned the corner into the road that led past the field, he stopped and let Kiwi out. As Kiwi thanked him for the ride, he said, “Tell your Dad I’m coming over for a ride one of these days.”

“I don’t think he’ll take you,” Kiwi answered. “You have to tease him a lot for rides.”

As the car started away, it came over Kiwi that he did not know where Dad was just then. He might be down, almost anywhere along the coast.

There seemed to be no one at the field. He followed the road down toward their hangar, clambered through the fence, and came up through the tall grass at the back.

He heard voices inside the hangar and stopped. It might be Dad. He heard Cosgrave saying something, and then a strange voice broke in, “But you are going it too fast, old fellow. They’ll catch on to you. Wait till just before they hop. That’s time enough.”

This sounded funny to Kiwi, and he wondered who could be talking to Cosgrave in this manner. He hurried around to the front, opened the little door and went into the empty hangar, making his way to the room partitioned off at the back. The wind carried the small front door to with a bang, and the voices he had heard suddenly ceased. As he opened the inner door, Cosgrave was just standing up and starting for it. Kiwi looked at the other man, but it was no one he had seen before. He was neatly dressed and had a tiny black mustache.

48Cosgrave said, in a strange voice, “Oh, hello, Kiwi. What are you doing around here so early?”

“I came over to find out what had happened to Dad.”

“Oh, he’s all right. We got a message during the night that he had landed near Trenton. Just some little vibration trouble with the engine, which they’ll fix up first thing this morning and probably be back here by noon.”

After a long pause the stranger lit a cigarette and said to Cosgrave, “Well, I’ll be running along. You phone me later, will you?” And with a backward glance at Kiwi, he walked out.

About two o’clock that afternoon the plane returned.

Dad said the plane had performed wonderfully until after they left Washington. They had been able to form a good idea of its speed and its new fuel consumption. They were flying a compass course over the clouds off Norfolk when a slight vibration had started in the engine. Since it had not been bad enough to worry them, they had kept on. However, as they had continued north, near Cape May, it had grown worse, and although it was dark when they reached Trenton, they decided to risk a landing at a strange field rather than strain the engine-bearers. They tried for some time to locate the airdrome, and finally concluded that they had better try to land on a large, flat field some miles out from the town. With the aid of one of their parachute flares, which they dropped, they had landed with little difficulty.

With flashlights they were able to locate the trouble. Two bolts, holding the engine to its frame, had become loosened and the cotter-pins from both were missing.

They had attracted the attention of a passing motorist who took Jack to a telephone, while Dad stayed with the plane. 49Jack had tried, without much success, to telephone through to Bert and to the field, and finally had sent telegrams instead. They tied the wing-tips of the plane to some fence posts, and a State policeman offered to watch it till morning. The policeman also directed them to a place where they spent the night.

In the morning, it was the work of but a few minutes to put the plane into good shape, and with a parting wave to the policeman and a few people who had gathered to see them take-off, they left. Without further difficulty they had landed at their own field.

This long test had reassured the Skipper and Jack on many points, and there seemed little more to do to the plane. The letters and the numbers of their license, NX-953, had been painted on the top of the right-hand and on the bottom of the left-hand wing and on the tail. The man who had done this had asked about a name, but Jack and the Skipper had been unable to agree on one.

The backers of the flight, having had word that the plane was nearly ready for the take-off, wrote the Skipper that they would be at the field by the end of the week. One of them suggested in the letter that there should be a formal christening. It would help the publicity. The fact that he had a very attractive daughter who photographed well may have put the idea into his head.

Kiwi’s excitement ran high at all these new preparations. His new uniform had been delivered, and he had strutted about the houseboat with it on. Both Dad and Jack were immensely pleased at his new appearance, and Jack promised to go with him to the barber for a last trimming up.

50The makers of Kiwi’s uniform had added a touch of their own, and had sewed on a small pair of embroidered wings. But on this point Dad was firm. The wings could not be worn. “For,” he said, “you are not a pilot, Kiwi, and until you have learned to fly, no wings.”

This started Kiwi off anew on his demands to be taught to fly. He had worked on Jack on every possible occasion to get a promise of instruction from him. But so far no definite promise had been made. Jack, at odd times, had been teaching him the wireless code. By now Kiwi knew it by heart, and every evening, when possible, Jack would get him to learn the sing of the letters. Tacked over Kiwi’s bed was this card with the dots and the dashes and the letters they stood for:

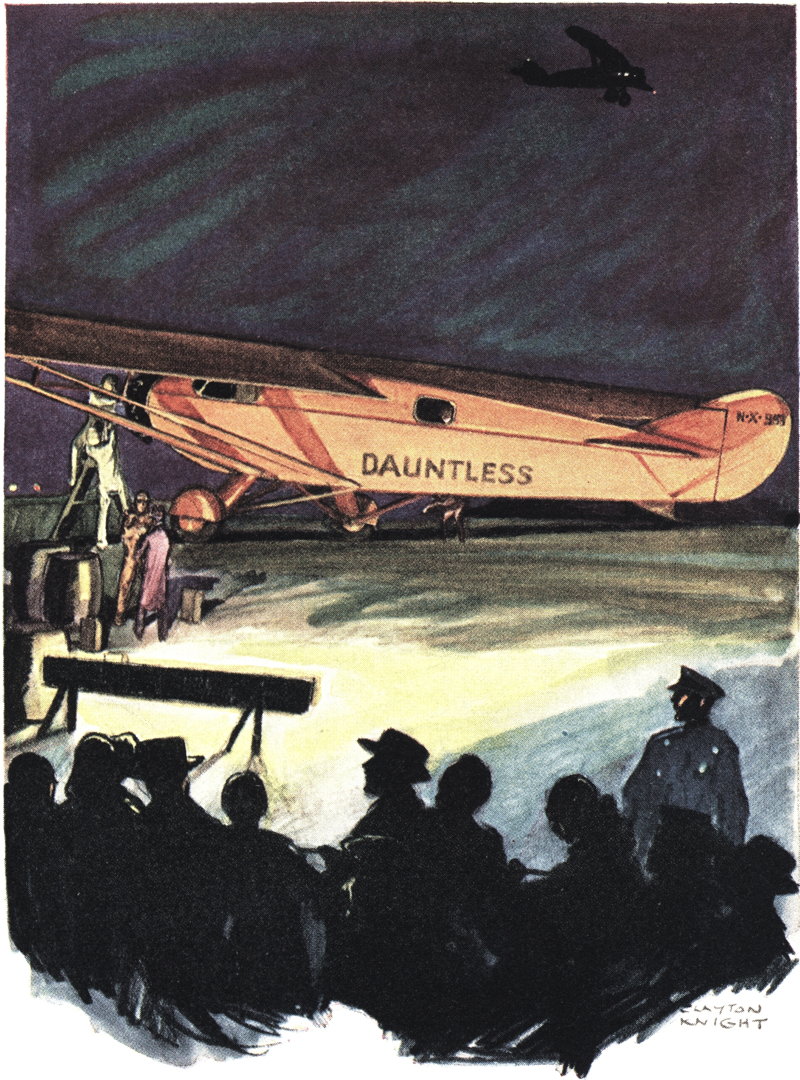

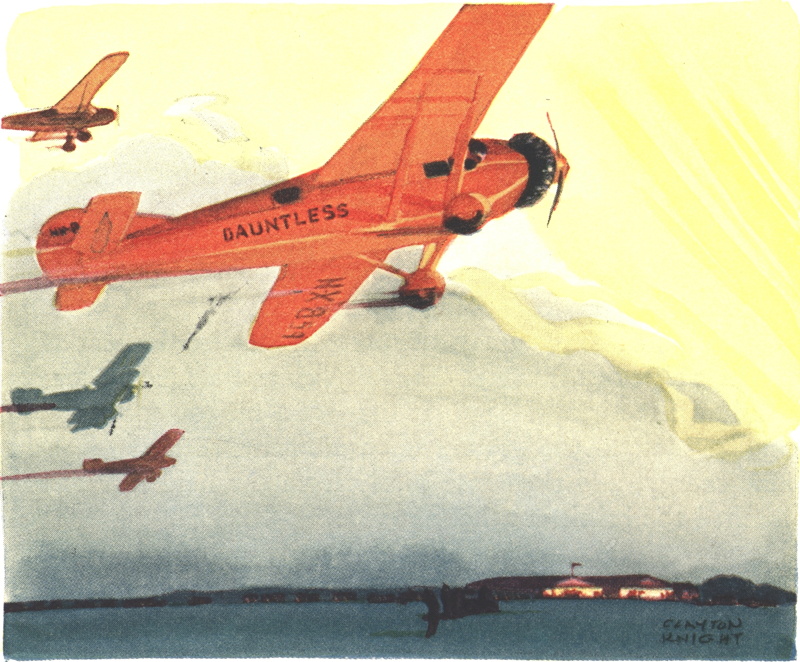

52On Saturday afternoon, the party arrived with the attractive daughter, her mother, and a bottle of what they hoped was pre-war champagne. The field was crowded. A small platform had been built and the machine wheeled up to it so that the attractive daughter could just reach the big propeller. Both Billings and Cosgrave had spent the whole morning cleaning and polishing the plane until it shone. Jack, the Skipper and Kiwi were all in their uniforms. As they stood on the little platform in the bright sun, to the tune of clicking movie cameras, the bottle of champagne was brought down smartly on the metal propeller, and the young girl said, in a clear voice:

“I christen thee ‘Dauntless’, and wish thee all the luck in the world for thy big adventure.”

The crowd cheered, and the golden liquid foamed and bubbled as it ran down the long blade of the propeller. Everyone was happy. Any doubt of their success seemed out of place on this bright, sunny afternoon. Dad and Jack’s confidence in their machine and in themselves radiated from them.

THE christening was over, and the publicity that it brought had added interest to their flight. In the days before the christening they had scarcely ever been bothered by crowds around the hangar.

Now things were changed. Whenever the plane was inside the hangar, the doors had to be kept closed, or ropes stretched, to keep the idle curious from interfering with the work in hand. Rumors were continually being broadcast that a surprise take-off was imminent, which brought throngs to the field at all hours of the day and night.

Reporters on special assignments were always bothering the Skipper and Jack with questions about the performance of the plane, how long they expected it would take them to get to India, and about incidents in their lives that the reporters thought would be of interest to the public.

From one source or another they found out about the Skipper’s war record—how he had gone to a ground school in this country, had been sent to England to finish his flying training, and, this completed, had waited in England for 54weeks for an assignment to an American Squadron; how the shortage of planes on the American front had prevented this; how the British, who had spent time and money in training American pilots, found themselves with plenty of planes and a scant supply of their own men to fly them; how the British government had finally asked and received permission from the American authorities to send some of these American pilots to France to work with the British flying corps; how the Skipper had gone out under this arrangement and fought with great distinction with his British comrades.

The newspaper men had also looked up stories about the Skipper that had been printed in his home papers during the war. These they reprinted—stories of the miraculous way in which he had come through months of hard flying with scarcely a scratch; of his spending a couple of weeks at one of the base hospitals in France, recovering from a slight wound made by a machine-gun bullet as he was diving on a balloon near Armentieres, and then, without waiting for the usual sick leave, of his hurrying back to his squadron and 55plunging once more into the daily round of patrols, shooting down two enemy planes the very day of his return.

During one fight, when he was within a hair’s breadth of adding one more enemy machine to his score, his engine had stopped in the midst of a zoom, and the enemy, realizing he was getting the worst of it, had streaked for home, leaving the Skipper several miles behind the enemy lines with just enough altitude to glide down to No Man’s Land, where he had scrambled from his machine into a shell hole. There he crouched while the enemy artillery battered his plane to pieces with shell fire. Getting his direction, in the failing light, from the line of enemy balloons, he had made his way, as soon as darkness came, to his own lines.

56Stumbling across the torn and broken country, he had come across a British Tommy badly wounded, and had dragged him to safety. For this and other of his exploits he had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, one of the highest British decorations given to airmen.

Then, when the Skipper’s leave to England had come around, after six months at the front, he, with several others, had been summoned to Buckingham Palace to be decorated by the King. He had nervously awaited his turn at the end of a long red carpet which led to the platform where the King stood. He had walked forward and saluted, more frightened than he had ever been in the midst of a scrap in the air. The King had pinned on the cross, had asked him one or two questions about his flying, had thanked him for his splendid services as an American with the British army, and before he knew it the interview was over and he was on his way out.

DISTINGUISHED

FLYING CROSS

The newspapers printed all this, and drew on their imagination for a great deal more.

They gave a full description of Jack’s training and work with the Navy and his flying ability. But most of all, they devoted many paragraphs to his development of a device which was a really practical drift indicator. This ingenious instrument, upon which they were going to rely during their long hop, seemed to solve the problem of correcting their 57drift, even in clouds and fog. Heretofore, pilots attempting to navigate over long distances of fog-obscured areas had found themselves unable to tell whether or not the wind was carrying them sideways off their course.

The story of Kiwi’s life and his adventures also became public property.

Billings was not much help to reporters. Naturally taciturn, he became even more so with newspaper men, and was almost surly in his refusal to help them out with their stories.

Cosgrave, however, liked the chance to talk, and did so on every occasion. The Skipper finally warned him he had better say little or nothing at all, and that if there were any information the papers should have, he, the Skipper, would give it.

One evening the Skipper had taken Billings back to the houseboat with him, and during supper he tried to draw him out about Cosgrave and what he, Billings, thought of him.

During the conversation, Kiwi suddenly remembered the things he had overheard, on the morning that Dad and Jack were at Trenton, in the back room of the hangar. He told Dad about it.

Dad frowned, and for several minutes seemed deep in thought. Then he said, “Billings, I don’t want to be unfair to Cosgrave—he may be all right. We have very little proof that he isn’t. But I am going to ask you to keep an eye on him. Watch his work on the plane, and if you see the slightest thing that looks suspicious, I want you to come and tell me.”

Billings had promised to do this, and the Skipper tried to dismiss from his mind the thought that there might be forces 58working against them other than the natural ones which they expected to have to contend with.

The Skipper and Jack pushed ahead with their preparations. Their collapsible boat was delivered and they tested it. When folded, it took up very little room. Attached to it was a metal cylinder containing compressed air, and it was the work of a moment to open the valve in this cylinder and inflate the boat. With it were two tiny oars and a water-tight pocket in which could be packed medical supplies and condensed food.

They inflated the boat, and Dad and Jack and Kiwi navigated their strange craft about the harbor, returning to the houseboat all too soon to please the boy who enjoyed this novel way of traveling.

The time before the hop-off was getting short, and there was still one detail that gave them considerable concern. They could not seem to prevent the vibration of the engine from interfering with the proper functioning of their instruments. It was annoying to have one or the other of their dials go wrong.

Jack finally decided to remove the whole thing, and regroup the instruments so that all those which had to do with navigation would be in one part of the board and the engine instruments in another. The compasses, the drift-indicator, the dial which registered their turn and climb were placed on one side, and in front of the Skipper were the oil-pressure, engine temperature, tachometer or engine revolution counter, the fuel gauges and the dial which showed their altitude.

The entire instrument board had to be protected in some way from the vibration, and it was Billings’ scheme to set it 59on four rubber blocks which he cut from ordinary rubber bath sponges.

All this took hours of Billings’ time, for each instrument had to be disconnected and replaced. However, late one night it was finished, and the Skipper decided that, inasmuch as the time was getting very short, they would test it at once.

As the plane was rolled out of the hangar, the news spread that they were about to go, and the crowds gathered. Their announcement that it was only a test flight was not believed.

When they were ready to leave the ground they found the field covered with people, and try as they would they could find no open space long enough to make the take-off safe. It was a warm summer night, and apparently everyone for miles around had driven to the field. The Skipper and Jack eventually had to abandon the night test and wait until morning.

A plan had been forming for some time in Kiwi’s mind. He had a queer sinking sensation every time he thought of Dad and Jack going off without him. He saw no reason why he, too, should not go when the plane left.

The stories he had heard of India made him want to land there, too. He liked to think of the warm, tropical days and nights in that strange country. Bert had brought him a book 60of stories about India which had thrilled him. These stories told of hunting wild animals from the backs of enormous elephants. He liked to imagine himself seated in one of the howdahs—the canopied, chairlike saddle strapped to the back of a richly decorated elephant.

He remembered one story of a playful elephant, said to be over a hundred years old, who pretended to be thoroughly frightened every time he crossed a stream of water for fear quicksands would suck him down.

He would picture himself wandering through the narrow streets of the cities, with vistas of temples ahead—their domes shining in the sunlight, covered with layers of pure gold that had been added to them through the centuries, until, on some of the oldest temples, the gold leaf was a quarter of an inch thick.

Kiwi had asked Dad a number of times to take him along, but Dad had always dismissed his request as being out of the question. However, in the darkness and confusion of that night attempt, Kiwi thought he saw how it could be accomplished. He was sure that if there were as much confusion at the actual take-off, it would be a simple matter for him, in the darkness, to crawl under the plane, open the trapdoor in the rear compartment, and slip in unobserved.

Kiwi realized that Dad would be upset about his disobedience, but he felt sure that he could make himself useful on the trip, and that both Dad and Jack would be glad he had come.

The more he thought about it, the more he knew he couldn’t bear to be left behind, and the more determined he was to go with them. During the next two or three days, as Dad and 61Jack were making the final test flights, he worked out in his mind all the necessary details.

Weather reports were taking up more and more of Jack’s time, but Kiwi kept up with his wireless practice. He could now send twelve words a minute and receive almost ten.

About eleven o’clock one night, as Jack got his weather reports and checked them up from his chart, he called the Skipper over and said:

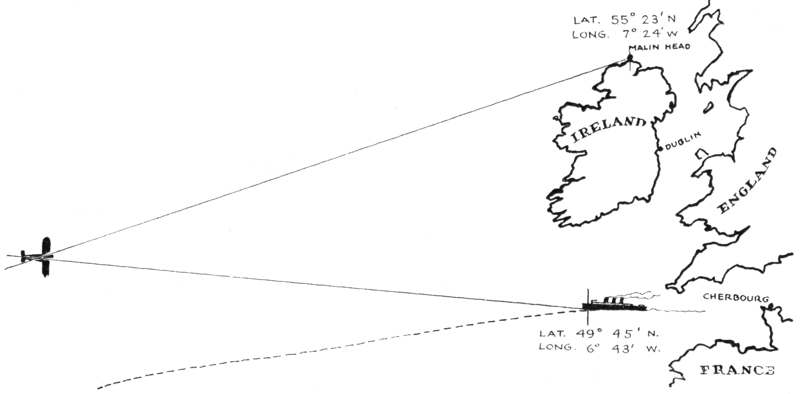

“Things look as favorable now as they have for some time. There is a storm near Chicago moving this way, but I don’t think it can possibly arrive until about eight in the morning. There is another one directly in our path in about the middle of the Atlantic; but from the reports I have it is moving northward and should be well out of our way by the time we get there. If you say the word, I’m for starting in the morning.”

The Skipper replied, “The plane is ready. The weather is up to you, Jack. Let’s go!”

Telephone calls were put through to the field and to the official who was to seal the barograph[5] before they started. They sent word to Old Bill at the lunch wagon to pack the food and to get the thermos bottles filled.

5. Barograph—An instrument which records on a chart the variations in height above sea level.

About twelve-thirty, when everything was packed and ready and they were about to start for the field, they got another report from the weather man. In the two hours that had elapsed since the previous report, conditions had changed for the worse. The mid-ocean storm which they had known about, had altered its course and was heading in toward Newfoundland.

62Jack and the Skipper talked it over and decided they had better put off the attempt until there was a better chance of having favorable conditions. This meant more telephone calls to tell of their change in plans.

When they talked to Billings on the phone, he said that the field was already covered with people and cars, and that it was more than likely the crowd would refuse to believe the take-off had been postponed. He said the plane was in perfect condition, and that he believed he would stay at the hangar the rest of the night.

The Skipper

It was a great disappointment to Kiwi, for his excitement had risen to fever pitch. However, he was packed off to bed, and for the next few days all their plans waited on favorable news from the weather man. Conditions over Long Island seemed perfect for the take-off. The moon was just approaching the full.

Kiwi, for the first time, realized how many others were helping in this tremendous undertaking. Wireless operators on many ships plunging across the ocean were flashing their news of conditions as they found them at sea. Other wireless operators in lonely places were sending their data of wind velocities, rain and sleet. All this information was being gathered and carefully analyzed 63for these two men who would soon come to know the vagaries of nature at first hand.

Kiwi was already in bed and asleep one night when an unusual bustle about the houseboat awoke him, and he sensed that something was up. Word had come through that the path was open for the great dash across the Atlantic.

Preparations to start were again made, with innumerable last things to be thought of. Kiwi was able to pack a tiny lunch and stuff it into his pocket unobserved.

Jack

They were rowing ashore to pick up Bert when Dad said to Kiwi:

“Now, boy, after we leave, you will be taking your orders from Bert. Everything is taken care of, and he will look after you until we come back. See that you always do what you know I would want you to do.”

Kiwi smiled, sheepishly, but could think of nothing to say.

The ride over to the field seemed to take hours. Neither Dad nor Jack talked much, but Bert managed to say to Kiwi:

“Well, they will soon be off, and then you and I will sit and wait for news of their arrival.”

As they drove onto the field they saw cars parked everywhere, and crowds thick about the entrance to the 64building. They pushed through them, and there in the lighted hangar stood the great bird ready for its flight.

It had been planned to start from the long runway on the adjoining field, and the greater part of their load of fuel had been stored there in readiness. Before the hangar doors were opened, all their kit had been stowed in the plane, even Kiwi finding an opportunity to hide away his little package of lunch in the rear compartment.

At last the hangar doors were opened, and ropes having been stretched to keep the crowd back, the plane was rolled out, its tail lashed to the rear of a truck and, followed by the crowd, it began its mile-and-a-half journey to the other field across the rolling ground. Its mighty wing bobbed and rocked about as if anxious to be off and away.

The moon was partly hidden by a thin layer of clouds so that the night seemed unusually dark. There was practically no wind.

Arriving at the far end of the runway on the other field, the tail of the plane was set on the ground, and flood lights were temporarily placed which threw a ghostly glow over the “Dauntless.”

Cosgrave and Billings started at once to pump in the precious supply of fuel. Jack went back to the hangar to get the last minute weather reports, while the Skipper, easily the coolest person in the crowd, chatted with the backers of his flight.

As the hours passed the crowd grew, but this time they were being held back behind lines by the police.

Old Bill from the restaurant came puffing up with the thermos bottles and sandwiches, and with a sly wink to 65Kiwi handed him a couple of oranges, saying, “You may need these, Kiwi.”

Kiwi became more and more confused. He began to wonder if it were going to be as easy as he had thought to stow away when the plane left. He had not counted on those blinding lights. But he stuck close to Dad and hoped for the best.

About four o’clock the tanks were filled. Fifteen spare cans, holding four gallons each, had been stowed in the rear compartment and lashed tight. The barograph was put aboard and sealed by the official from Washington.

Billings, in a fever of excitement, decided they’d better give the engine one more try; so the canvas tarpaulin over the engine and propeller was removed and the engine roared into life. Billings ran it long enough to satisfy himself that it was working perfectly, then turned it off.

The heavy silence that fell was almost oppressive. A meadow lark sprang into the air, with the exultant little song they sing at dawn. Everyone was tense with the thought of the great test that was soon to come.

Jack came back from the hangar with the report that conditions were as favorable as they had been at any time.

They waited for the daylight.

There was the sound of a motor overhead, and a plane with a news photographer aboard swept over them.

Still the darkness lingered.

The sun by now should have been lighting up the eastern horizon. Instead, came a patter of raindrops, and Billings rushed to cover up his precious engine and propeller to protect them from the dampness.

66It rained harder. Many of the crowd, seeing the engine covered up, decided that the flight was off for that day.

A little group stood under the protecting wing of the plane and waited to see how bad the storm would be.

Dad turned to Kiwi. “Kiwi, you had better look up Bert and go back to the hangar with him.”

Kiwi’s face fell. Plainly disappointed, he nodded his head and disappeared into the darkness toward the place where Bert’s car had been parked.

The crowd thinned with the usual remark that this was another false alarm.

As suddenly as it had started, the rain stopped.

Jack, who had expected these local showers, said he thought it would clear up soon. Not long after, a faint, gray light appeared in the east, telling of the approach of a new day.

The Skipper was impatient to get away. He told Billings to take the cover off the engine, and he and Jack made a last examination of the whole plane. They looked at the shock absorbers, noting that with the heavy load there was very little play left in them. The Skipper said, however, that there was enough.

By this time Billings was ready to start the motor. Before the eyes of the small group who had waited through the rain, Jack and the Skipper got into their flying suits.

The big moment had come.

In the excitement of the last minute preparations Kiwi had been missed, and although Dad asked several of the men about the plane if he had been seen, there were conflicting rumors. Some thought he had gone back to the hangars; others were not sure but that he had found shelter in one of the cars.

68Precious minutes were passing. The Skipper felt that the time had come to go and that saying good-bye to Kiwi would be too much of an ordeal for him. So he turned to Bert and said huskily:

“Say ‘good-bye’ to Kiwi for me. I am trusting you to take good care of him. As far as I can see, everything has been provided for, and I know he will be safe in your hands.”

Fearing to trust himself to say more, he hurriedly shook hands with his close friends, gripped Billings’ hand hard and slapped him on the back. Then he climbed up into the cockpit, where Jack was already waiting, and the motor was started.

As the engine was warming up, the crowd could see through the glass window the Skipper laughing nervously at some remark of Jack’s. Then he opened the throttle and the huge engine made a tremendous uproar as he gave it a final try.

Billings stood at one side, his practised ear listening for the slightest skip in its measured beat.

The Skipper throttled back the engine, leaned out of the window, and motioned for Billings. As he came up, the Skipper said, “How does it sound? All right?”

Billings, who had listened to many engines in his day, who had seen many men trusting their lives to them, and who had heard that same question asked many times before, felt a lump rise in his throat as he realized the tremendous responsibility that rested upon him and upon his answer. He gulped hard, and then choked out, “All right, Captain—and the best of luck to you,” waved to Jack, and motioned to Cosgrave to pull out the chock from under the wheel on his side.

Billings and Cosgrave stepped back, and for a few moments 69that were awful in their suspense they waited for the flight to begin.

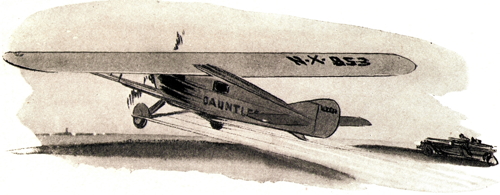

The engine opened up gradually, took hold, and the plane slowly started to roll along—the slow roll which was to start the Skipper and Jack off on an epoch-making flight that would carry them across the wide Atlantic, over the Mediterranean, and on to India. The engine had started, and for seventy hours it would have to keep up an uninterrupted flow of power.

The plane gathered speed, rocking gently as the tail left the ground.

Billings and Cosgrave had leaped onto the running-board of a fast car and were speeding after it, watching it gather momentum for the take-off.

Camera men took hurried pictures and scampered out of the path of the approaching plane.

The end of the runway was getting perilously near when the first sign of lift came. The Skipper was evidently coaxing her into the air, and the first lift was a bit too soon, for she settled back to the ground for a moment, seemed to gather new energy, and then rose surely from the field just as they reached the brink of a little ravine.

70They were off!

In the early morning light the plane was hard to follow. It could faintly be seen lifting its way upward.

Other planes, now that the “Dauntless” was up, soared alongside the big ship as it carefully made a turn and headed for the east and the rising sun. The entire group came back over the field at an altitude of about a thousand feet.

The crowd hoped that there would be a last fluttering good-bye from the cockpit, but both men were too busy to do more than glance out.

71The flight was on!

Billings and Cosgrave returned to the old hangar. Its vast emptiness oppressed them so that they could hardly speak. They would have to wait hours and hours to know what all their work would accomplish. They looked forward to the long wait with dread.

Bert came up in a car and asked if they had seen Kiwi. Surely by now he would have returned to the hangar. But no one had seen him since the rain storm that had seemed, for a time, to blot out the Skipper’s chances for a take-off. Bert hurried back to the other field with the hope that he might still be there.

In the small room at the back of the hangar, Connors was busy with his wireless set. With the earphones on he bent over his instruments at the table and tried to pick up the first message to come back from the plane. From time to time the click of his sending key could be heard through the partition.

72Both Billings and Cosgrave were absentmindedly picking up the scattered evidences of the hurried departure from the hangar. They had closed the big doors, when Billings, very tense, suddenly swung around and confronted Cosgrave.

“Cosgrave, you and me have been working hard on this job for a long time now, and there have been times when I thought you were up to some crooked business. The plane is off and away. If anything happens to those boys that I can trace to you, I’m going to make you the sorriest man that ever walked onto this field.”

Cosgrave turned a bright red at all this, but said nothing for a few minutes, while Billings glowered at him. Then, seeming to come to a decision, he said:

“Well, Limey, I think I can trust you. I don’t want you to mention this to no one, but when I have told you I think you will understand.

“At the beginning I was offered money—and a lot of it—to try and stop, or postpone, this flight. I was in a jam and needed money, and I thought I could do something—nothing serious, you understand—that would look accidental. But the longer I worked for those two men, the more I realized that I couldn’t go through with it.

“Then when the Kiwi started flying with them and came so close to getting cracked up the time they lost the wheel, I phoned the people who were trying to buy me and said, ‘Nothing doing.’ And Billings, you can believe me or not, but since that time I have worked even harder than you to make this flight a success. There is nothing about that plane now, as far as I know, that isn’t in perfect condition.”

Billings felt his anger rise during Cosgrave’s confession, 73and for a little time he could think of nothing but punishing the man. With his jaw set hard, he looked straight into Cosgrave’s eyes, trying to see through to his very soul, to discover if all he had confessed was the truth. Cosgrave’s gaze never wavered, and Billings at last decided that Cosgrave had done no harm and all was right with the plane.

TO the two men in the cockpit of the monoplane, the tense drama of hours had been packed into those few seconds of the take-off.