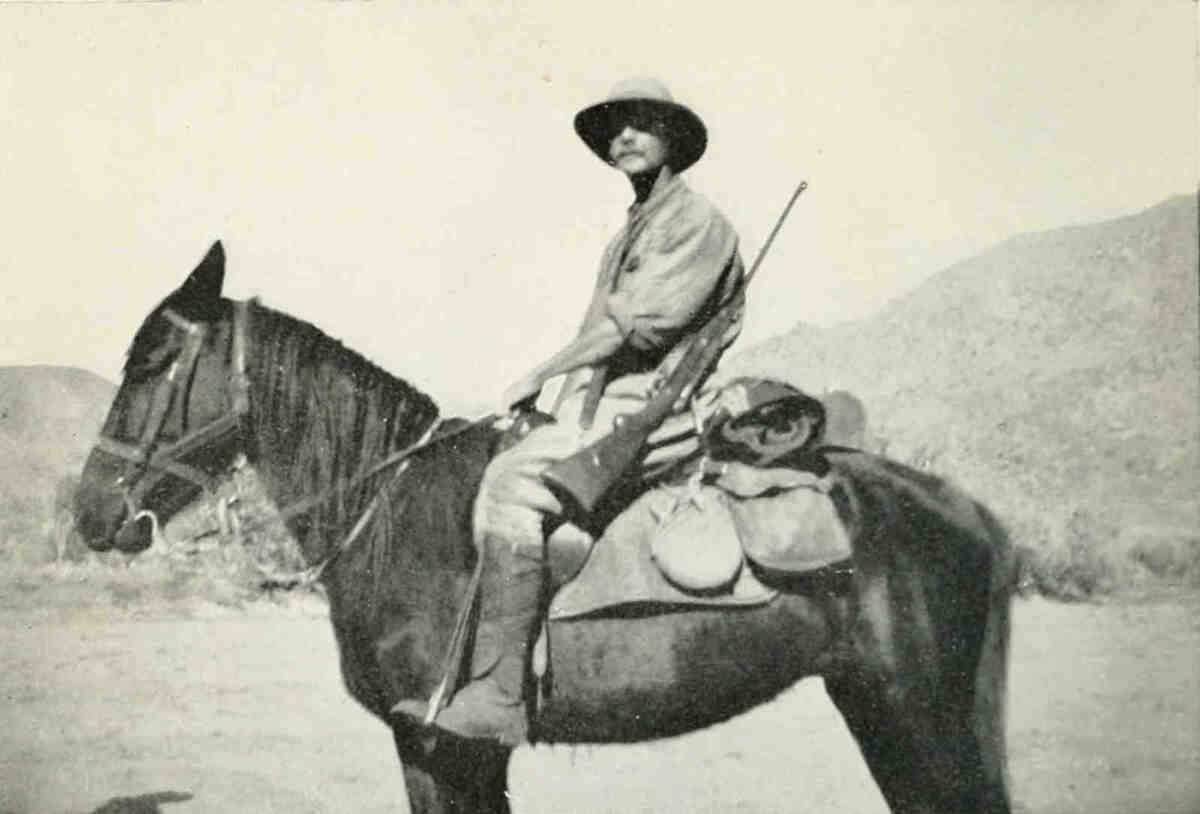

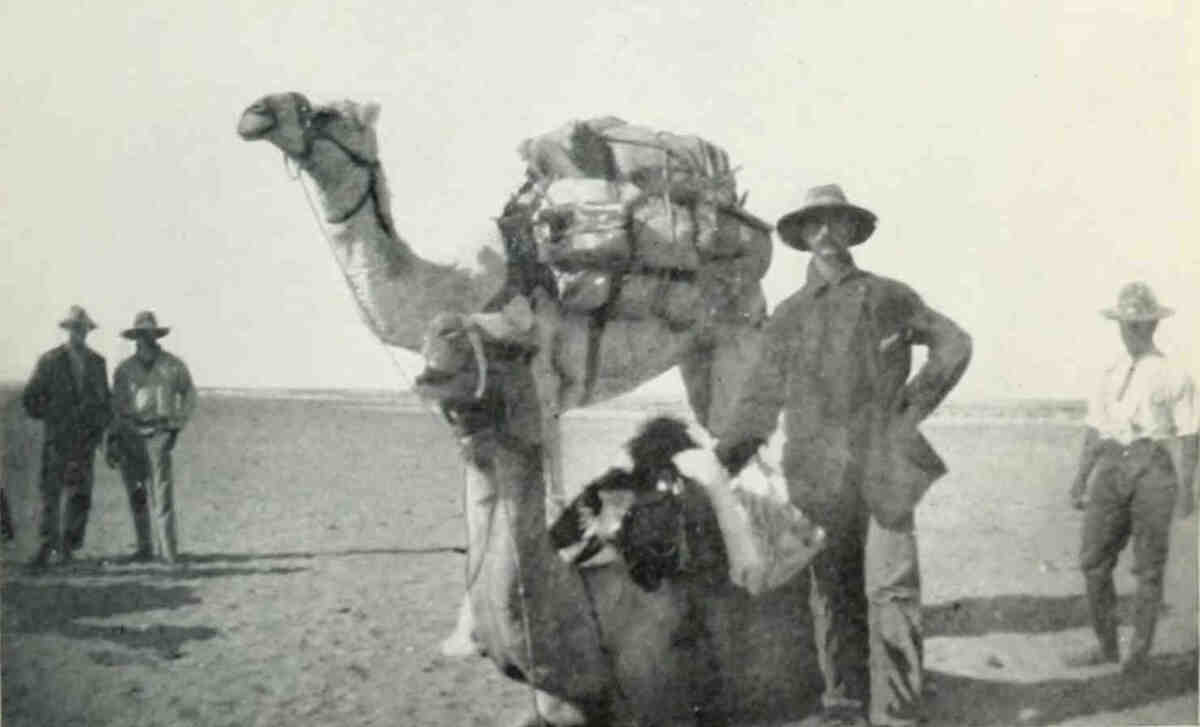

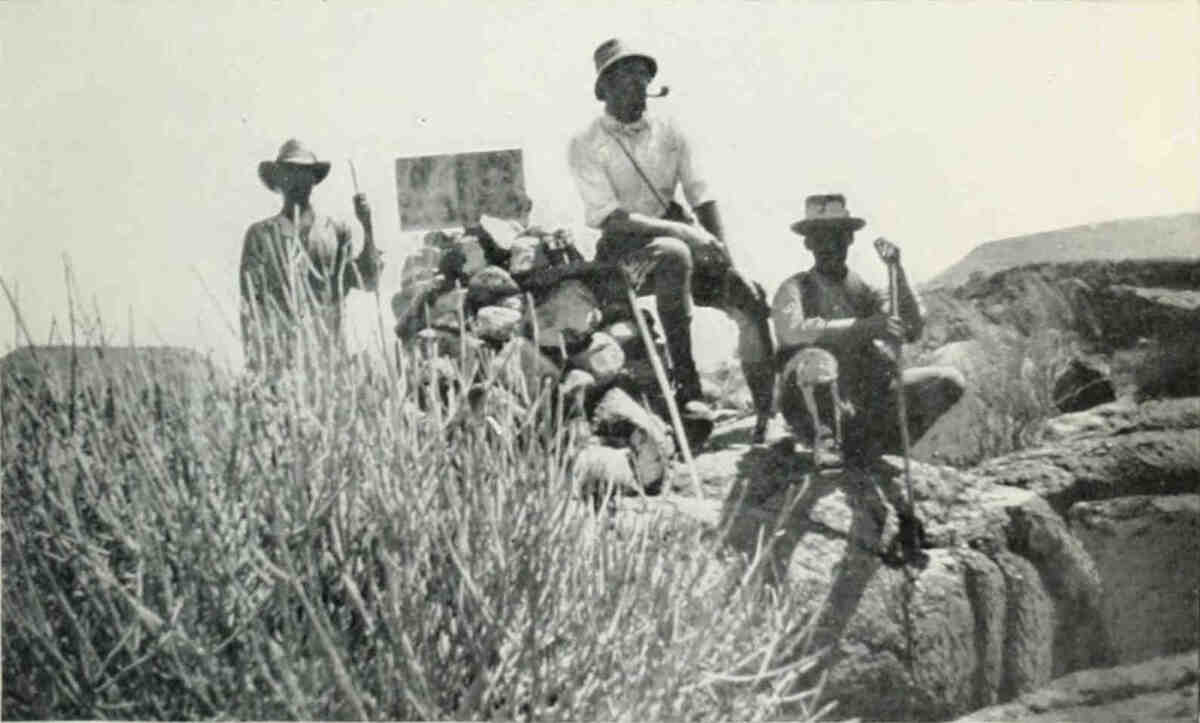

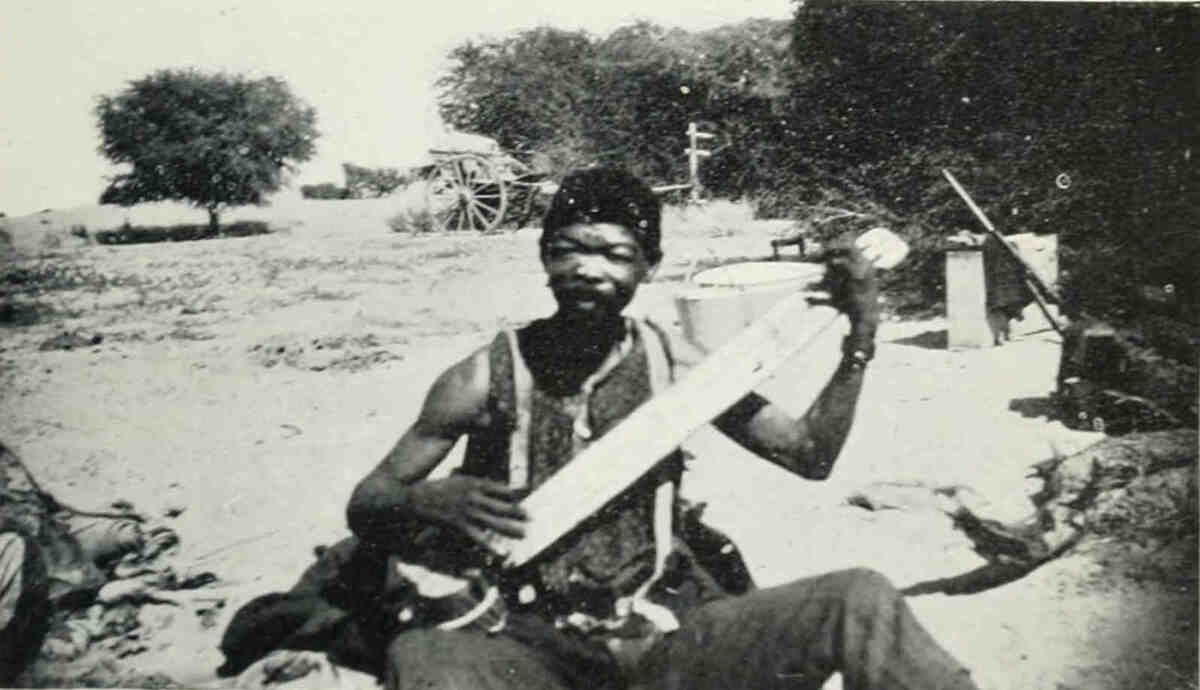

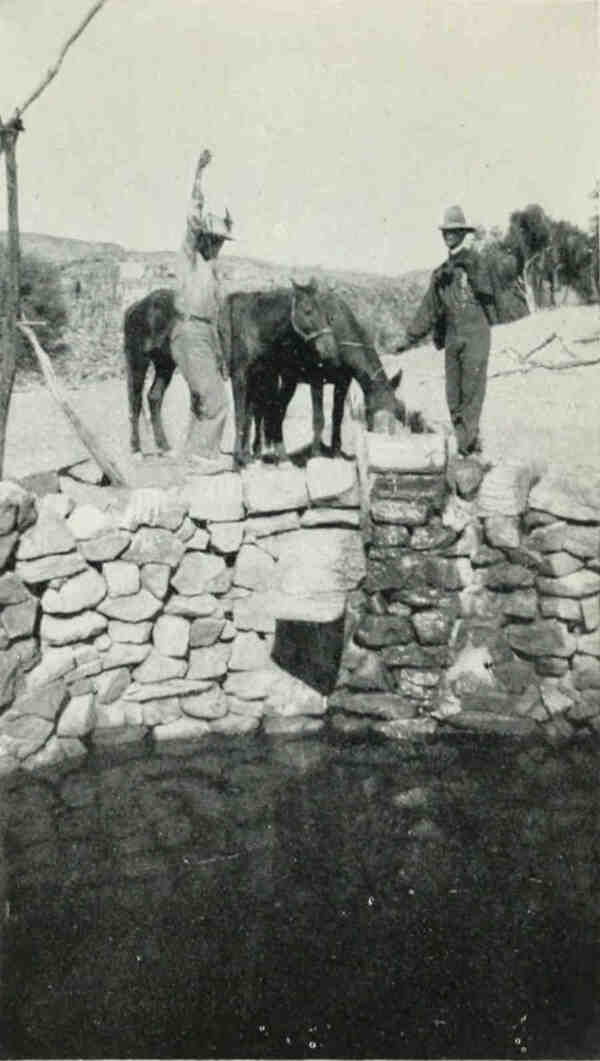

THE AUTHOR AT NAKOB, READY FOR A LONG TRIP.

Frontispiece.

Title: The glamour of prospecting

wanderings of a South African prospector in search of copper, gold, emeralds, and diamonds

Author: Fred C. Cornell

Release date: April 30, 2023 [eBook #70674]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd, 1920

Credits: deaurider, PrimeNumber and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

IN THE WILDS OF SOUTH

AMERICA

Six Years of Exploration in Colombia, Venezuela, British Guiana, Peru, Bolivia, Argentina, Paraguay, and Brazil. By LEO E. MILLER, of the American Museum of Natural History. First Lieutenant in the United States Aviation Corps. With 48 Full-page Illustrations and with maps. Demy 8vo, cloth.

This volume represents a series of almost continuous explorations hardly ever paralleled in the huge areas traversed. The author is a distinguished field naturalist—one of those who accompanied Colonel Roosevelt on his famous South American expedition—and his first object in his wanderings over 150,000 miles of territory was the observation of wild life; but hardly second was that of exploration. The result is a wonderfully informative, impressive, and often thrilling narrative in which savage peoples and all but unknown animals largely figure, which forms an infinitely readable book and one of rare value for geographers, naturalists, and other scientific men.

LONDON

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD.

THE AUTHOR AT NAKOB, READY FOR A LONG TRIP.

Frontispiece.

THE GLAMOUR

OF PROSPECTING

WANDERINGS OF A SOUTH AFRICAN PROSPECTOR

IN SEARCH OF COPPER, GOLD, EMERALDS, AND

DIAMONDS

BY

LIEUT. FRED C. CORNELL, O.B.E.

AUTHOR OF “A RIP VAN WINKLE OF THE KALAHARI,” ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND A MAP

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE

First published in 1920

(All rights reserved)

Most of this record of wanderings in wild parts of South Africa had been written and was ready for publication before the outbreak of war: and since then there has been a radical alteration in much of the country described; for, with the conquest of German South-West by General Botha, the Union Jack now floats over the huge tract of country between the lower Orange River, the twentieth degree of east longitude, Portuguese Angola, and the South Atlantic.

As a result also of that campaign, new railway lines have come into being, and with the linking-up of the railway between Prieska, Upington, and the captured German system at Kalkfontein, the traveller to-day can ride in comfort in a saloon carriage from Cape Town to the farthest extremities of the conquered territory.

And, incidentally, many of the wild spots I have described have been brought within easy reach. For instance, the lonely little police post at Nakob (described in the closing chapters, and the scene of the violation of Union territory by German troops) was, at the outbreak of war, separated by 250 miles of difficult, semi-desert country from the nearest British railway at Prieska. To-day the line runs close by where the post stood, and passes within sight of the hill in British territory the Germans then occupied.

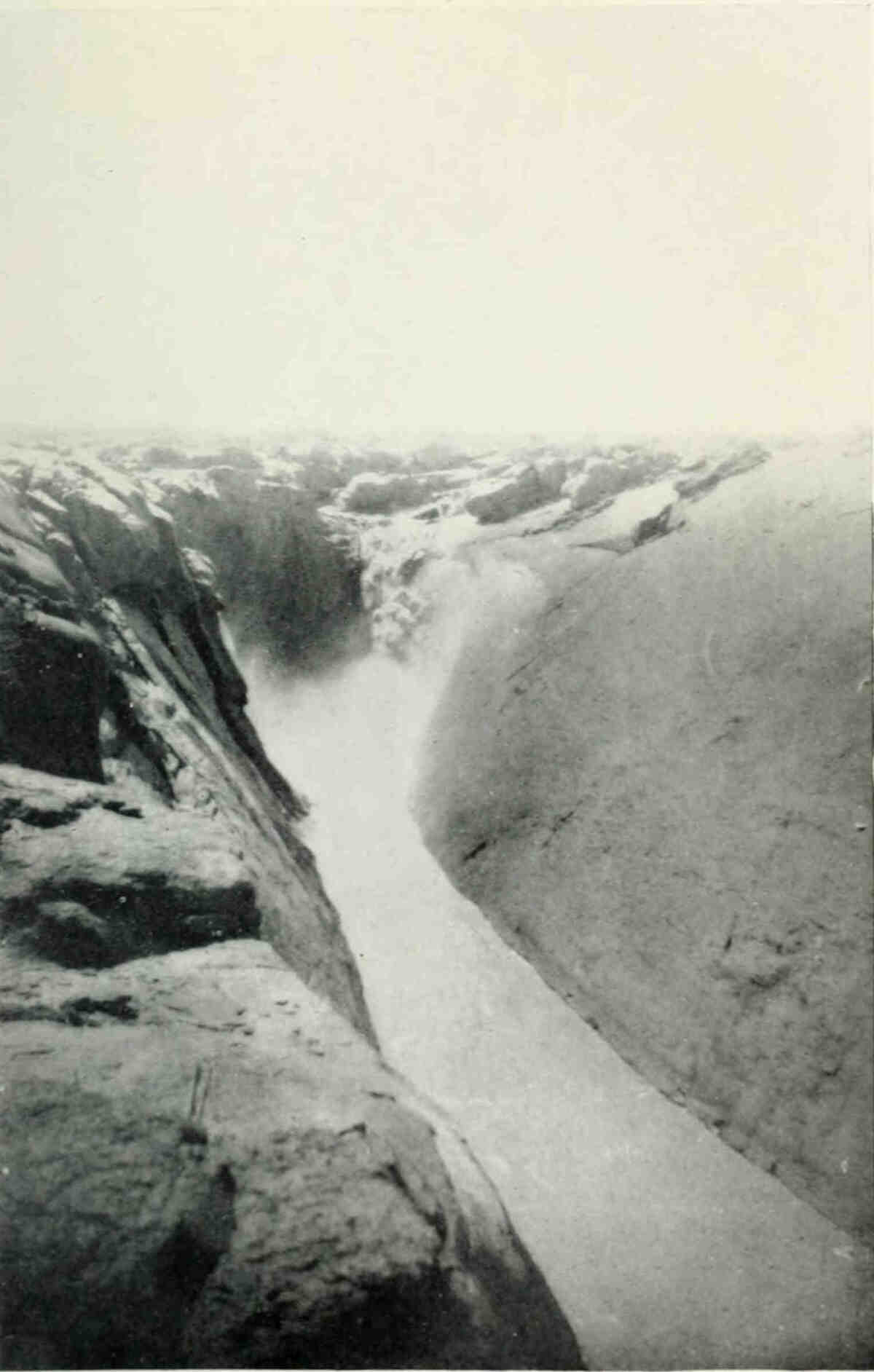

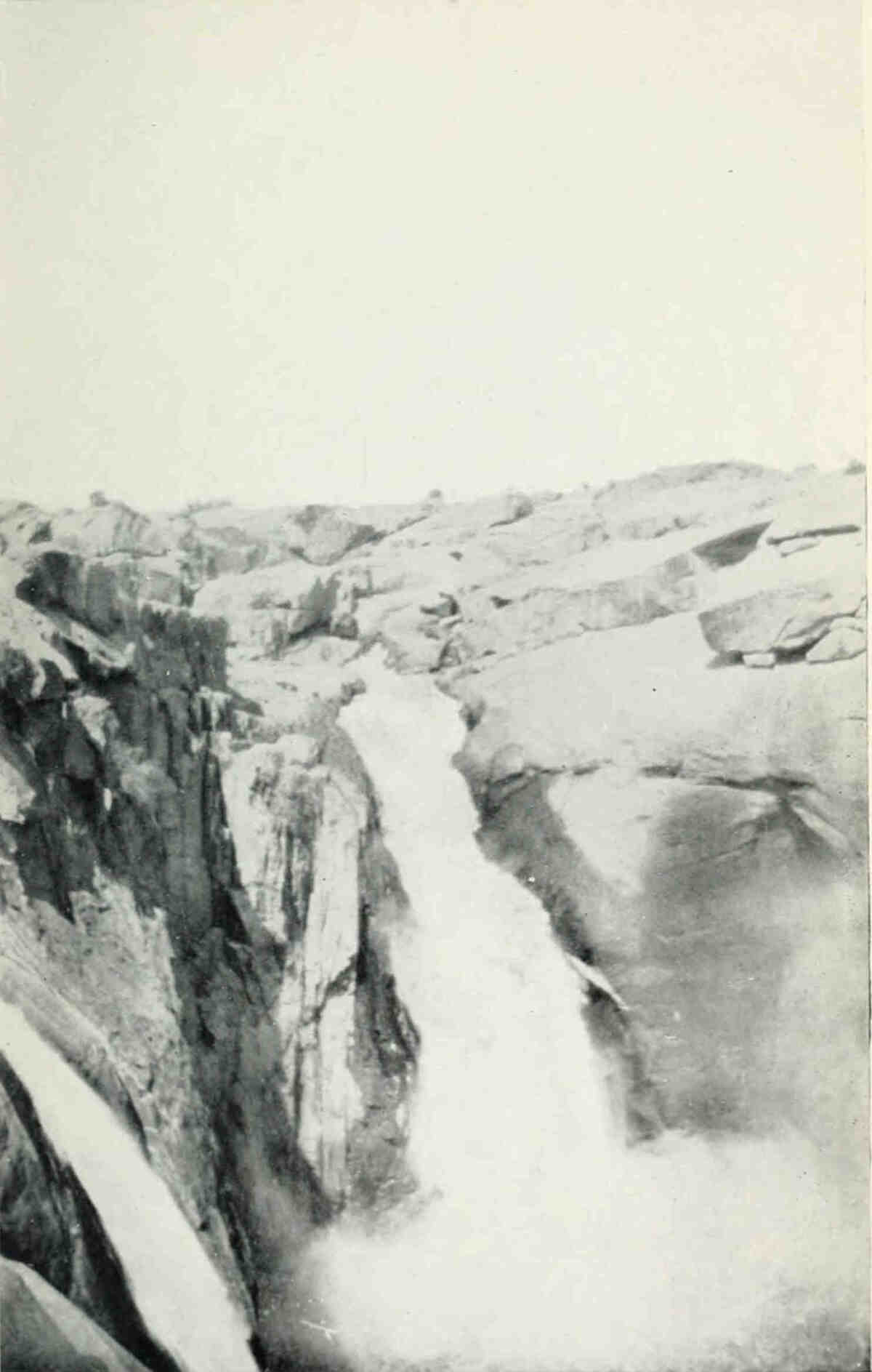

Upington, too, with a fine bridge spanning the Orange, has been brought into touch with the rest of South Africa; and, with the fertile oasis of the Orange River stretching on either hand and giving marvellous results in the growing of citrus and other fruits, cannot fail to become an important and thriving centre. There are rich mineral deposits in the vicinity, one of which (the “Areachap” copper-mine, mentioned in Chapter V) has, I believe, been reopened since the railway at Upington has rendered 150 miles of costly waggon transport unnecessary, and the marvellous “Great Falls of the Orange River,” ranking, with the Victoria Falls and Niagara, amongst the world’s greatest cataracts, is now within a day’s journey of the railway, and with the coming of peace, will undoubtedly be visited by thousands of visitors, and come to its own.

A railway has also been built to within easy distance of Van Ryn’s Dorp (mentioned in Chapter IV), and it is safe to predict that these new lines will be productive of a great accession of mineral wealth to the Union, wealth that has hitherto lain untouched and unexploited owing to its great distance from a railway.

These new lines, however, much as may be expected of them, still leave untapped vast spaces of the country I have described. Notably the mountainous Richtersfeldt region of Northern Klein Namaqualand (see Chapters VII to XI), with all its wealth of copper and other minerals, and which lies to-day as solitary and untrodden as when I left it. The Southern Kalahari, with its fine ranching possibilities and its remarkable “pans,” is still a huge “Royal Game Reserve,” forbidden to the farmer and the prospector; and though the dry Kuruman River (Chapter XVII) was the route for the flying invasion of German South-West (to the astonishment of the Germans, who believed the desert impossible by troops), the desert has long since claimed its own again: and the region is once more given over to the vast herds of gemsbok and a few wandering Bushmen.

To turn to the newly acquired territory of Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, much of the latter still remains practically unexplored, and although concessions over vast tracts of country were granted to various private companies by the German Administration, few attempts have been made to develop the great mineral wealth known to exist. There are exceptions, notably the rich copper deposits of Otavi and the Khan copper-mine, both having been worked to great advantage prior to the war, whilst the remarkable diamond discoveries on the coast have added enormously to the wealth of the country. But much of Northern Damaraland, Ovampoland, and Amboland, etc., has scarcely been scratched, and this is notably the case in the vast terra incognita of the north-western portion known as the “Kokoa Veldt.” Here but little prospecting has ever been allowed, but copper abounds, tin and gold have been found, and the former in abundance, and there are other valuable minerals and precious stones waiting the day when the territory in question is thrown open to individual enterprise.

In conclusion, let me point out that this book, though recording faithfully some of my own prospecting trips, is in no wise intended to serve as a handbook to the would-be prospector; indeed, he should carefully avoid doing many of the things herein recorded. But should he contemplate becoming a prospector, let him at any rate not be discouraged by reading of the few discomforts and hardships I have experienced, for these, after all, were richly compensated for by the glorious freedom and adventure of the finest of outdoor lives, spent in one of the finest countries and climates of the world. And far be it from me to do anything to discourage the prospector. He is, I maintain, the true pioneer; his pick and hammer open up the wild places of the earth (usually to the benefit of those who follow him more than to his own), and, in the rush for “fresh scenes and pastures new” which will inevitably follow the war, he will be a factor of importance.

The ideal prospector is born, not made. He may be versed in geology and mineralogy and excel with the blow-pipe, but unless he has the love of wild places in his bones he will never fulfil his purpose. He must be an “adventurer” in the older and honourable sense of the word; often, unfortunately, he “fills the bill” in the more sordid sense. He should be able to ride, shoot, walk, climb, and swim with the best; indeed, if he still exists in the future, he will probably also need to fly. And the wilds must call him. “Something hid behind the ranges! Go and look behind the ranges!” as Kipling has it. That is the true spirit of the prospector; he must love his work or he will never succeed in it. I have had men out with me who were good enough theoretically, but were quite useless to cope with the misadventures they had to encounter, and soon gave up the life for something easier. I have had others to whom the glamour of a life spent in the wilds, with the sand for a couch and the stars for a ceiling, outweighed all its little disadvantages.

Fred C. Cornell.

Cape Town, 1919.

SOME WILD-GOOSE CHASES—DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS IN GERMAN SOUTH-WEST AFRICA—BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NEW MANDATORY, LUDERITZBUCHT pp. 1-13

RUMOUR OF “HOTTENTOTS’ PARADISE”—UP THE COAST ON A SEALING CUTTER—WALFISH BAY pp. 14-29

THE NAMIEB DESERT, “SAM-PANS”—CAPE CROSS—SWAKOPMUND—WINDHUKpp. 30-43

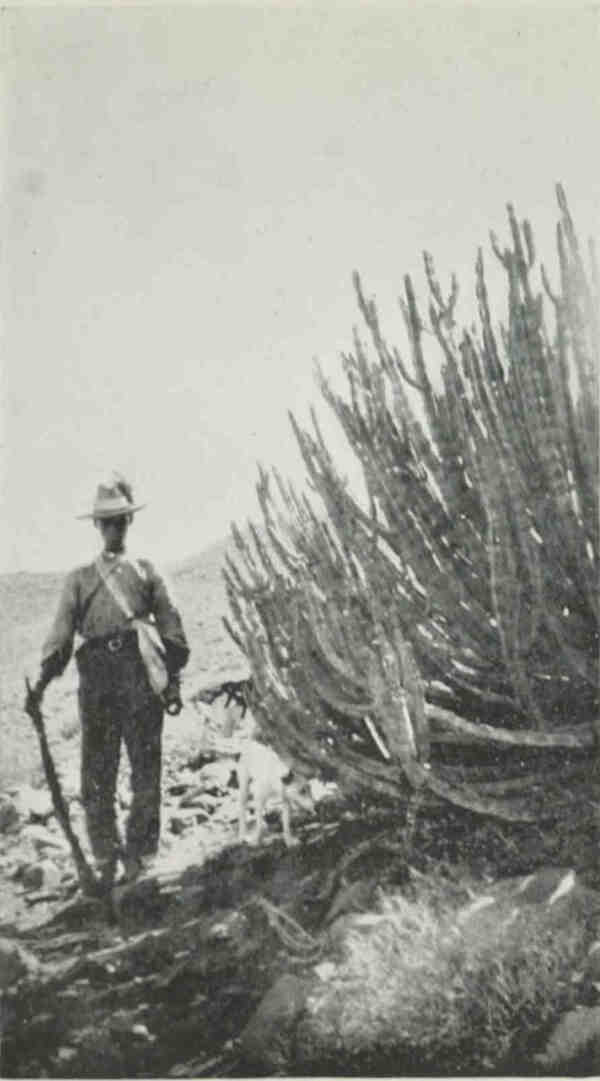

MORE DIAMOND RUMOURS—PROSPECTING IN A MOTOR-CAR—VAN RYN’S DORP—PROSPECTING IN EARNEST—A PATRIARCH—NEWS OF BUSHMAN’S PARADISE pp. 44-62

“ANDERSON’S DIAMONDS”—PRIESKA, UPINGTON—THE SOUTHERN KALAHARI pp. 63-75

ZWARTMODDER—THE MOLOPO—RIETFONTEIN—THE GAME RESERVE pp. 76-91

KLEIN NAMAQUALAND—RICHTERSFELDT—PORT NOLLOTH AND THE “C.C.C.”—STEINKOPF—WONDERFUL NAMAQUALAND FLOWERS—TREKKING TO RICHTERSFELDT—FLEAS!—MONOTONY OF THE COUNTRY—MOUNTAINS IN SIGHT pp. 92-103

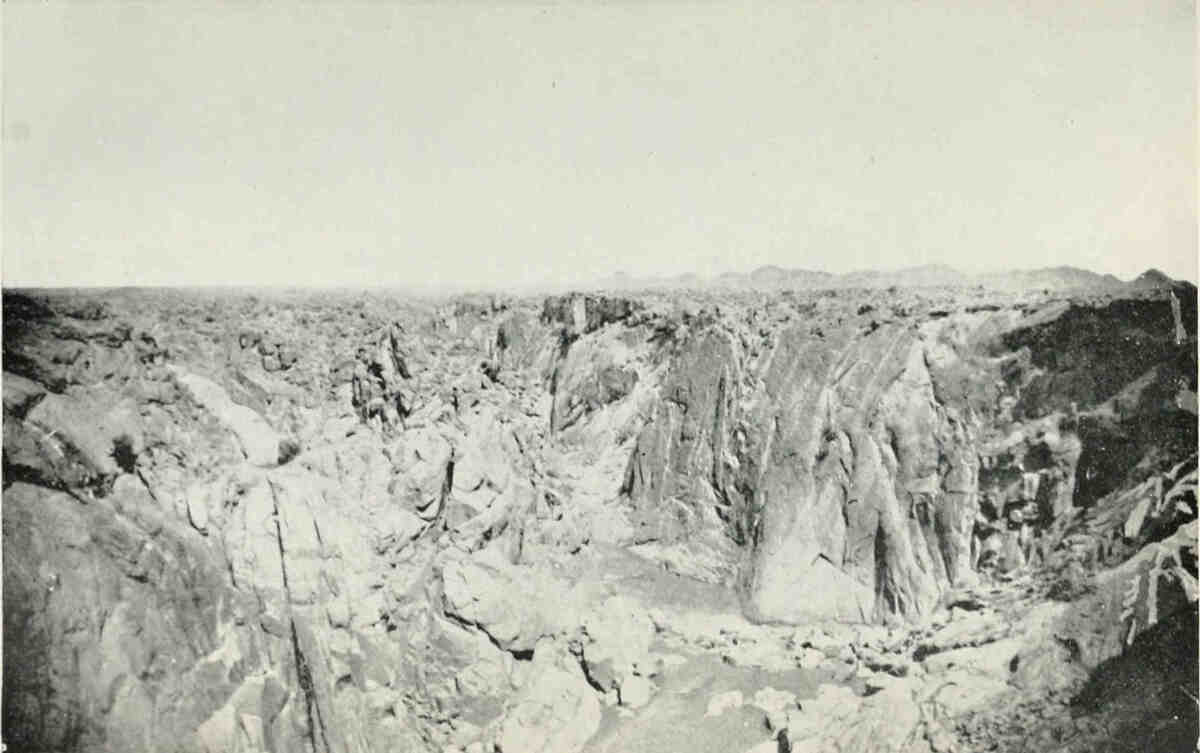

RICHTERSFELDT—ALEXANDER BAY—MOUTH OF THE ORANGE RIVER—“HADJE AIBEEP”—HELL’S KLOOF—A DESERTED COPPER-MINE—ROUGH GOING—A MAGNIFICENT VISTA OF PEAKS—AN OLD GOLD PROSPECT pp. 104-121

GOLD CAMP—THROUGH THE MOUNTAINS TO ARIEP—TATAS BERG AND COPPER PROSPECTS—A “MOUNTAIN” OF COPPER—THE GREAT FISH RIVER—THE “GROOT SLANG”—ZENDLING’S DRIFT pp. 122-144

ZENDLING’S DRIFT—JACKAL’S BERG—THE RESULT OF TOO MUCH WHYMPER—HUGE NUGGET OF NATIVE COPPER—A DIFFICULT PASS—KUBOOS—DEGENERATE NATIVES—BACK TO PORT NOLLOTH pp. 145-158

SECOND TRIP TO RICHTERSFELDT—SMASH-UP IN HELL’S KLOOF—CHRISTMAS AT KUBOOS—TESTING THE “BANKET”—A NEAR THING IN THE RAPIDS—AFTER A LEOPARD—NEW TRAILS—HOTTENTOT SUPERSTITION—STEWED FLAMINGO AND OTHER WEIRD DISHES—END OF THE TRIP pp. 159-184

BRYDONE’S DIAMONDS—THE GREAT FALLS OF THE ORANGE—MOUTH OF THE MOLOPO—BAK RIVER—THE GERMAN SOUTH-WEST BORDER—KAKAMAS—LITTLE BUSHMAN LAND pp. 185-212

GRAVEL TERRACES AT ZENDLING’S DRIFT—SECOND CHRISTMAS AT RICHTERSFELDT—GERMAN POST AT ZENDLING’S—MAKING A RAFT—HIPPO AT THE LORELEI MOUNTAIN pp. 213-223

PERMIT FOR THE FORBIDDEN GAME RESERVE—VAN REENEN AND THE SCORPION—SECOND VISIT TO THE GREAT FALLS—OLD GERT, OUR GUIDE—BUSHMAN ARROWS AND THEIR POISONS—BUSHMAN INOCULATION AGAINST SNAKE-BITE—ANTIDOTE FOR SNAKE-BITE—TALES OF “THE GREAT THIRST” pp. 224-236

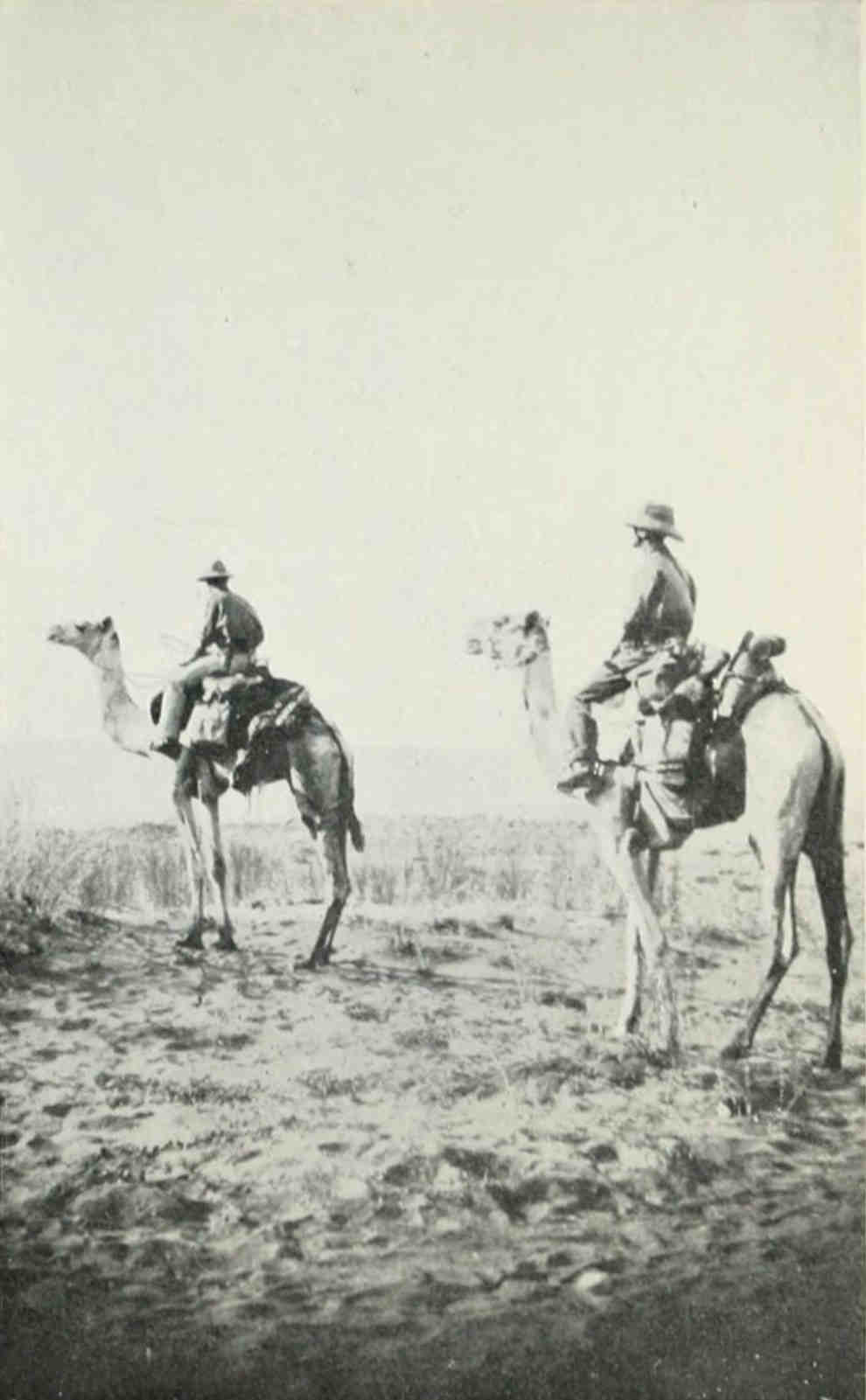

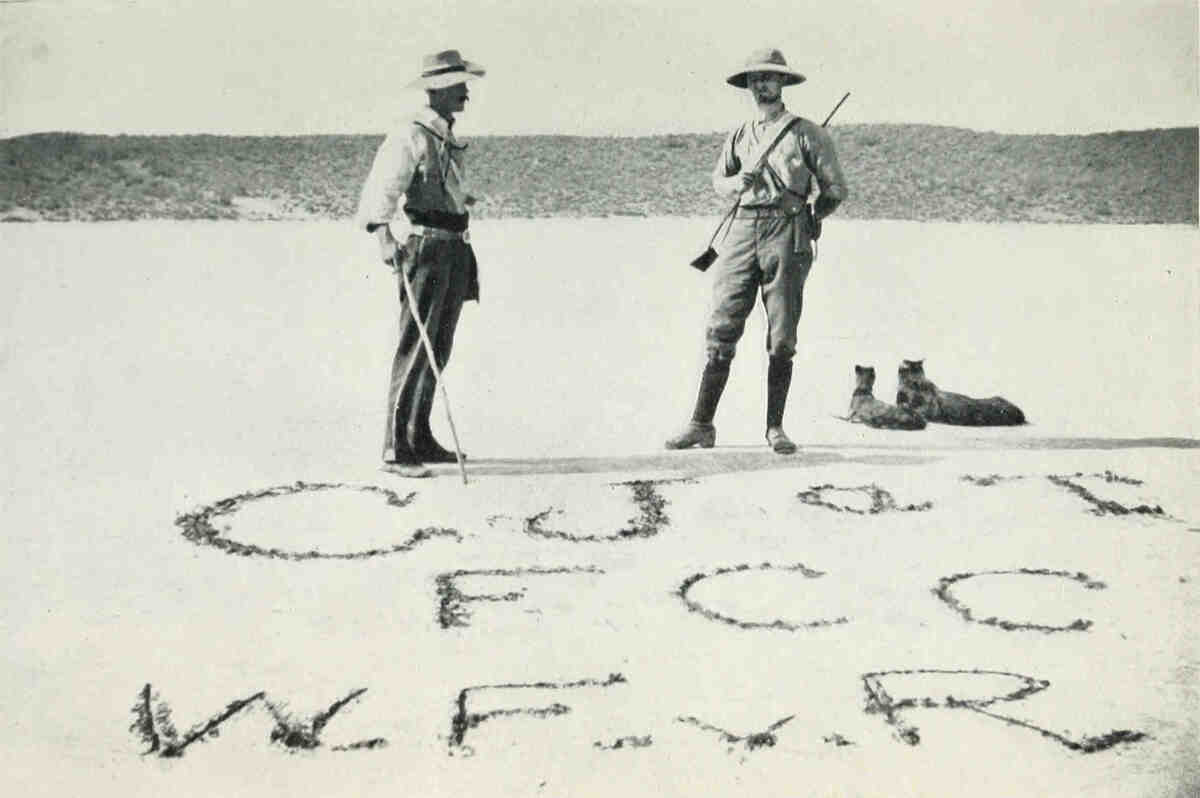

THE “PANS” OF THE KALAHARI DESERT—THE MOLOPO ROUTE—BOOMPLAATS—ENTERING THE RESERVE—SPOORS—THE WATER CAMP—THIRST—THE GREAT SALT PAN—LOST! pp. 237-259

FORMATION OF THE DUNES AND PANS—“KOBO-KOBO” PAN—RAIN IN THE DESERT—SCORPIONS—AAR PAN—MIRAGE AND “SAND-DEVILS”—KOICHIE KA—THE PIT AND THE PUFF-ADDER pp. 260-276

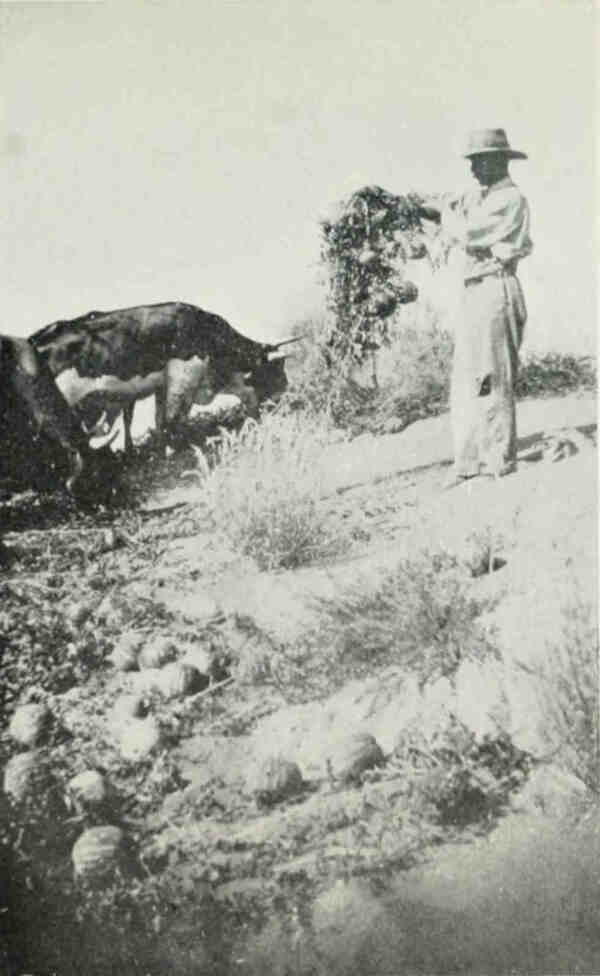

THE KURUMAN RIVER—WITDRAAI—AAR PAN AND EASTWARD—GEMSBOK AND T’SAMMA—DRIELING PAN—WILD DOGS—THIRSTY CAMELS—SEARCH FOR WOLVERDANSE—“NABA”!—BUSHMEN—END OF THE TRIP pp. 277-293

TRIP IN SEARCH OF “EMERALD VALLEY”—FEVER AND FAILURE—BACK TO GORDONIA—SECOND TRIP TO BAK RIVER—“SOME GUN!”—THE PACK-COW—SURLY NATIVES—“ROUGHING IT” pp. 294-307

RESULT OF KALAHARI TRIP—NAKOB—LACK OF POLICE ON FRONTIER—WORKING A KIMBERLITE PIPE—UKAMAS—DRUNKEN GERMAN OFFICERS—SLOW TREKKING—A BAD SMASH pp. 308-323

WAR!—VIOLATION OF BRITISH TERRITORY AT NAKOB—THE END pp. 324-334

[Page 1]

THE GLAMOUR OF

PROSPECTING

SOME WILD-GOOSE CHASES—DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS IN GERMAN SOUTH-WEST AFRICA—BRIEF HISTORY OF THE NEW MANDATORY, LUDERITZBUCHT.

What gave me “diamond fever” I don’t pretend to say. Certainly I have no love for the cut and finished article, and nothing would induce me to wear it; but for the rough stone, and for the rough life entailed in searching for it, I have always had a passion. Yet the luck attending many of my ventures has been but bad, or at the best, indifferent. The first tiny glittering crystal that I found at the bottom of my wooden “batea” in Brazil, many years ago, had cost me weeks of hard work and every penny I possessed; and the months of hard digging and perilous prospecting that followed that first “find,” and that led me through the diamond-fields of Diamantina and Minhas Geraes, left me none the richer except in experience. But the memory of those long-ago hardships is a faint thing compared with the glamour that still clings to that time; and even here in South Africa, the home of the diamond, not all the vicissitudes of years spent on the Vaal River Diggings, or of prospecting in far wilder spots, have taken away the fascination that, to me, lies in this most precarious of all professions. Still, the fruitless searches have been many, and I have often been called upon to make long and arduous trips where the quest of precious stones has proved nothing but a wild-goose chase.

[Page 2]

A stray diamond, very possibly dropped by an ostrich, and maybe the only one for a hundred square miles, has often led to a rush to where it was found, whilst, frequently, circumstantial tales of the finding of “precious” stones have been founded on the picking up of a beautiful but worthless quartz crystal.

At no period of late years were rumours as to the finding of diamonds more rife in South Africa than in 1907, when the sands of Luderitzbucht, in adjacent German territory, were found to be full of them, and when luck led me many hundreds of miles in another direction, and spoilt my chance of being one of the first in those new and wonderful fields.

Ever since the discovery of the first South African diamond in the Hopetown District in 1867, a belief has been prevalent among the thousands of diamond seekers scattered along the Vaal River Diggings that rich fields of a similar nature must exist far lower downstream. Yet, although the theory is logical enough, and many expeditions have from time to time searched the banks far beyond the confluence of Vaal and Orange, and a few have even reached the little-known lower reaches of the latter and located both promising gravel and even stray diamonds, nothing of a payable nature has so far been discovered in that direction.

In the latter part of 1907 I was shown an extremely beautiful stone of about twenty carats, that had been picked up by a transport rider some fifty miles below Prieska; and the accompanying gravel that this man brought in was so exactly a replica of the Vaal River “wash” that I came to terms with the finder and set about arranging a small expedition to accompany him and test the spot.

Before completing my arrangements, I went into Kimberley to try and find an old digger partner of mine, who had always been particularly anxious to explore the lower Orange River, and who, I thought, would be just the man to accompany me.

After some trouble I found him, and before I[Page 3] could even broach the subject of my visit he opened fire on me. “The very man I wanted to see,” he burst out; “in fact, I was just writing to you. Man, I’ve just seen a whole lot of diamonds from a new place entirely; they’re small, but the chap who found them swears you can pick them up by the handful where he got them.”

It appeared that the finder of these small stones was again a transport rider, who had been working in German South-West Africa, and had brought back a small phial full of these tiny stones, which he said could be had for the picking up anywhere in the sand near a certain bay he knew of. An hour later my friend had found him again, and I saw them for myself—nearly fifty small, clean, and brilliantly polished little diamonds, of good quality, astonishingly alike in size, and quite different from either “mine” or “river” stones in appearance.

The man’s story was circumstantial enough, and March, my former partner, was most anxious to accompany him back to German South-West, and tried hard to induce me to join him.

Now, for years rumours had been current among prospectors and diamond diggers, as to the existence of the precious gems in abundance somewhere along the desolate, wind-swept shores of the little-known country lying north and west of the Orange; but the region was too remote and too inhospitable to encourage expeditions in that direction, and the German régime of the country by no means added to its attractiveness. So that, tempting as the little “sandstones” were, I was not to be persuaded; moreover, I had committed myself to the other venture and consoled myself with the reflection that, after all, my one big diamond from the Orange River was worth more than the whole phialful brought from German territory. And when I told my tale in turn and spoke of the big twenty-carat beauty I had seen, not only did March promptly decide to come with me, but Du Toit, the discoverer of the German stones, immediately threw in his lot with us, arguing,[Page 4] doubtless, that it would be easier and quicker to fill bottles with big diamonds than with little ones. “Anyway,” he said, “the other place can wait; we can go there afterwards if we think it worth while.” And so it was agreed, and thereby we probably missed a fortune, for the place where Du Toit had found the diamonds is to-day one of the richest diamond-fields in South-West Africa.

Anyway, the decision once arrived at, we lost no time in getting under way, and a few days later we were on our way towards the spot where the twenty-carat stone had been found, and which we fondly hoped would prove as rich in big stones as Du Toit declared the sands of the German coast were in small.

Into the details of that disastrous trip I shall not enter here. Suffice it to say that four months later, ragged, footsore, broken in health and practically penniless, we tramped back into Prieska, having searched the southern bank of the river for nearly three hundred miles without having found a single diamond. Gravel there was in abundance, containing all the so-called “indications”—agates, jasper, chalcedony, banded ironstone—in fact, all the usual accompaniments of the diamond as they are found higher up the river, but never the diamond itself.

So good had these “indications” been that we were eternally buoyed up by the hope that sooner or later we must strike the right place, and so we had wandered on till the fine outfit we had started with had gone piecemeal to keep us in food; and it was only when our small funds were absolutely exhausted, and our tools and kit reduced to what we stood in and could carry, that we gave up the quest of the “Fata Morgana” that had led us on and on into the wild country near the “Great Falls” below Kakamas, and beyond all trace of civilisation.

For weeks we had had no news, and had not seen a newspaper or received a letter for months, and I well remember, when at long last we reached Prieska, with what eagerness we hastened to the little post-office for the budget we expected waiting for us.[Page 5] And the very first letter I opened told me what this particular wild-goose chase had cost us, for both it and numerous wires and newspapers of long weeks back told of the sensational discovery of diamonds in the sands of German South-West, and the fabulous finds that the lucky first-comers had made there.

Newspaper reports spoke of men picking them up by the handful, filling their pockets with them in an hour or two, of bucketsful lying in the Bank. In fact, it was Sinbad’s wonderful “Valley of Diamonds” over again; and, giving due allowance for the exaggeration usual to such discoveries, there still could be no doubt that we had missed a fortune by not going there with Du Toit four months back, instead of on our disastrous trip down the river.

I had always liked Du Toit, who was one of the best Afrikanders I ever met, but never did he show to such advantage as when he got this news; his sun-flayed face went a shade pale as he read it, but all he said was, “Ah, well, better luck next time, boys.”

But we didn’t get it.

At De Aar the little party divided, March and our guide of the last venture going back to the River Diggings, whilst Du Toit and myself returned to Cape Town, intent on getting up to German South-West Africa as soon as possible.

And as German South-West Africa, now a Mandatory of the Union of South Africa, will figure prominently in these pages, it may be as well to give a brief account of that extensive country, which, until the discovery of diamonds already alluded to, was very little known to the average man even in Cape Colony, its next-door neighbour.

As early as 1867, owing to reports of rich mineral deposits existing in the country then known as Great Namaqualand and Damaraland, the Cape Government proposed to the Imperial Government the annexation of the whole of the West African coastline from the Orange River to Portuguese Angola,[Page 6] but no definite action ensued. And, in spite of various “Resolutions” the Cape Government subsequently made in favour of this extension of territory, nothing happened till 1877, when a Special Commission was sent to Damaraland, where they received offers of submission from the principal chiefs of the country.

The Imperial Government was, however, adverse to taking over the whole of this vast coastline, with its then unknown hinterland, but sanctioned the hoisting of the British flag at Walfish Bay, the natural port of a huge stretch of country; and this tiny mouthful of territory, bitten as it were out of the surrounding country that so soon afterwards became German, has, much to the annoyance of Berlin, remained British ever since.

At the time this annexation took place the hinterland was well populated by various native tribes, the Damaras (also known as Hereros), a people of Bantu descent who came from the north, and the Namaquas, a Hottentot race who had gradually spread from the south.

The true aboriginals of the country were probably what are known to-day as “Berg Damaras,” a little people of Bushman characteristics, small in numbers, but ethnologically of far greater interest than either of the two invading races. On the irruption of the Namaquas, these aboriginals were mostly conquered and enslaved, but a few escaped to the mountains, and retain their national characteristics to this day. Herero and Namaqua eventually met somewhere about the vicinity of where Windhuk now stands, and for a time each treated the other with respect; but about 1840 the Namaquas, strengthened by the accession to their ranks of certain half-breed desperadoes who had fled from Cape Colony and who were well armed and mounted, attacked the Damaras to such purpose that they were soon completely conquered and enslaved, and Jager Afrikander, the chief refugee and desperado, became their chief. Between 1863 and 1870, however, the Damaras[Page 7] again rose and waged a war of independence, being, however, again crushed. Ten years later a rising again occurred, and the whole country was plunged in warfare. Meanwhile, however, the white man had arrived upon the scene, the British at Walfish Bay, and numerous white pioneers, including many Germans, had penetrated the country beyond it.

Prominent among the pioneers were several missionaries of the Rhenish Missionary Society, and upon their heels followed the traders, so that when in 1880 the above-mentioned native trouble broke out, a considerable number of white men were settled in the interior.

As British responsibility was conterminous with the boundaries of her Walfish Bay territory, these venturesome settlers had but little protection afforded them; and as German enterprise developed farther south and trading ventures were started, Germany asked the British Government for its protection for these pioneers. Certain negotiations followed, and by June 1884 Germany had made up its mind to extend its own protection to its subjects in Damaraland and Great Namaqualand, and incidentally to afford the cover of its sovereignty to an enormous concession of land near Angra Pequena which had been obtained by a wealthy Bremen merchant named Luderitz from certain native chiefs.

This bay of Angra Pequena, so named by the Portuguese who discovered it, is now known as Luderitzbucht; it lies about two hundred and fifty miles south of Walfish Bay, and, although vastly inferior to the latter port, also affords good anchorage. Here Luderitz started large trading stations; and in 1884, in pursuance of Bismarck’s scheme of colonial expansion, a belt of land twenty miles in width along the coast from the Orange River northward to Portuguese territory (excluding, of course, Walfish Bay) was placed under the protection of the German Empire.

From that time German expansion marched quickly,[Page 8] and in June 1885 the German dominion was extended over the whole of the vast hinterland up to the 20th parallel of east longitude, the Gordonia border of the present day.

Late in the day, but luckily just in time, the statesmen of Cape Colony realised that this was but a step towards driving a German barrier across South Africa from sea to sea; and as a counter-stroke, in 1885, Bechuanaland (lying east of the new territory) was annexed as far north as the Molopo River, and declared under British protection up to the northern confines of the Kalahari Desert.

The Germans, foiled in their design of further expansion, set about making the most they could of Damaraland. But red tape, officialism, and their harsh and overbearing methods, hampered them in their attempt at colonisation; moreover much of the land was practically desert and up to the time of the discovery of diamonds at Luderitzbucht the country had been run at a loss, and there had been a determined attempt by the Socialists in the Reichstag to force its abandonment.

The Herero and Hottentot rebellion in 1903 dragged on for years, and cost the Germans much blood and treasure, for they found themselves utterly unable to cope with the extraordinary mobility of the native commandos. These, excelling in guerilla warfare, harassed them incessantly, and, although in vastly inferior numbers, gave the raw German troops—fresh to the country—endless trouble before they were subdued or captured.

Towards the end of this costly campaign the warfare was waged with extreme bitterness, and indeed it ended in the virtual extermination of the Herero race.

With this slight, and, I hope, pardonable digression, I will return to Cape Town, where Du Toit and I at length embarked for Luderitzbucht.

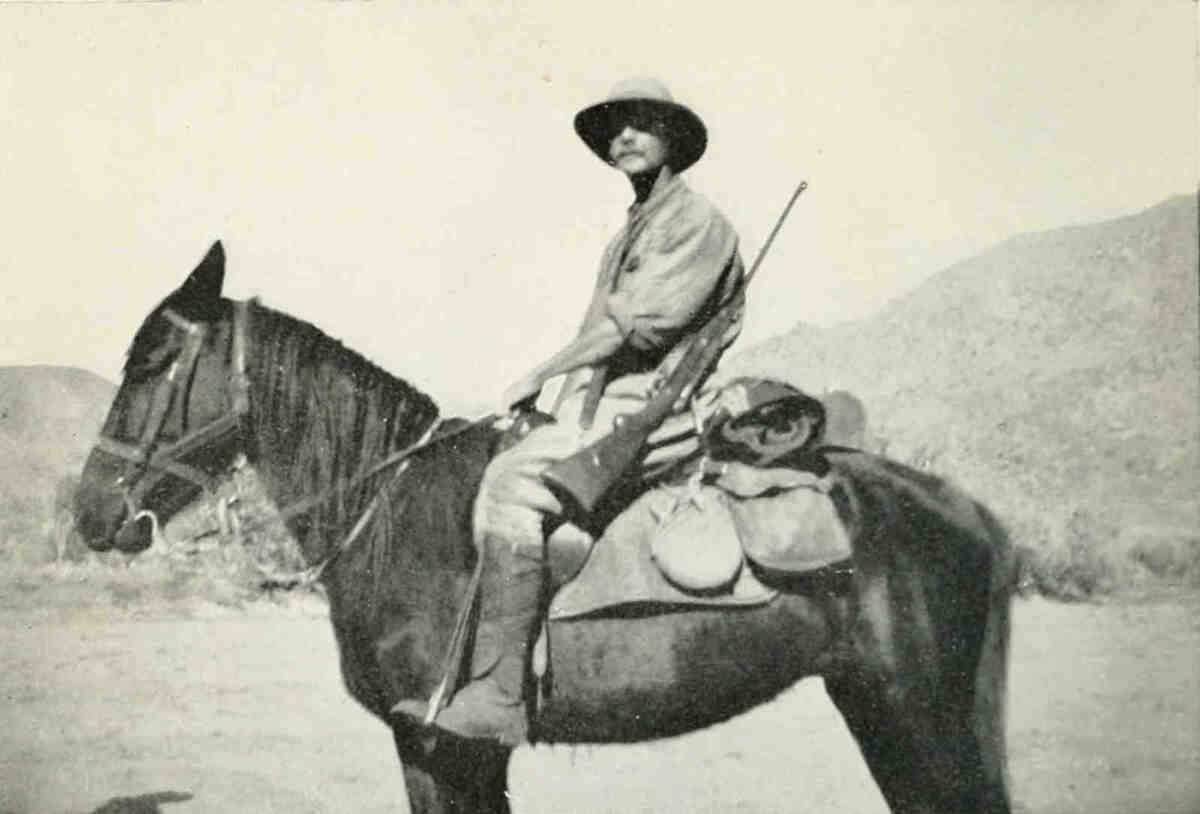

“BABYING” FOR DIAMONDS.

The machine is called a “baby” (or more correctly “bébé,” after the French digger who invented it), and is universally used by South African diamond diggers.

The Frieda Woerman took us up the coast in [Page 9]comfort. We passed Port Nolloth in a fog which showed us nothing of the forlorn little northern copper port, and fog clung to us till we reached Luderitzbucht.

These sea-fogs are a feature of the South-West African coasts, and on the British (Namaqualand) coast they are beneficial, as they distribute a certain amount of moisture to the scanty vegetation of the coastal belt; but at Luderitzbucht there is no vegetation for the fog to moisten.

For, north, south, and east of it there is nothing but sand and barren rocks, and this description applies to practically the whole of the coast belt for hundreds of miles in either direction.

Luderitzbucht, at the time of which I write, was little more than a forlorn collection of corrugated iron huts clustering around one or two of the more important buildings, dignified by the names of “hotel,” store, and Customs House. The streets were ankle deep in sand, and the first thing that struck me was the enormous number of empty bottles that lay piled and scattered about in all directions—principally beer bottles, of course, but also thousands of mineral-water bottles, for water was at that time extremely scarce. The very little obtained locally was of poor quality, had a vile alkaline taste, and often alarming medicinal effects upon the new-comer; moreover, it had never been sufficient even for the scanty population existing here before the discovery of diamonds. A large condensing plant had supplied the deficiency in an intermittent manner, for it frequently broke down or got out of order, and it was the usual thing in the early days to have cargoes of water brought by steamer from Cape Town.

With the discovery of diamonds came the influx of “all sorts and conditions of men” usual to “rushes” all over the world, and water rose to famine prices. Washing in sea-water, when tried by a few over-particular new-chums, was followed by extremely painful results, for the brine aggravated a hundredfold the painful sun-blisters inevitable in a[Page 10] country where the blazing rays of a sub-tropical sun beat back with redoubled fierceness from the glaring, scorching, all-pervading sand. A helmet, whilst absolutely essential, is after all but little protection from a glare that comes from the sand all around one as from a huge mirror. We soon found that, if this glare was to be borne at all, it was by using spectacles of smoked glass, and these, fitted with wire gauze side-protectors, are also essential in the blinding sand-storms that form a frequent variation of Luderitzbucht weather conditions.

We found the place so crowded that it was almost impossible to obtain even the roughest accommodation; the hotels were full, the stores were full, every shanty dignified by the name of a dwelling was crammed, men “pigging it” four and six in tiny rooms meant for a single occupant, and food, and above all water, at famine prices.

So great had been the rush, for a time, that the police had been quite unable to cope with it, and when I came to see more of the motley crowd of “fortune seekers” that had invaded the place, I easily forgave the irascibility of the stout, overfed and overheated German officials who had had to deal with them all. What a lot they were! Only a small minority were genuine prospectors, engineers, or mining-men with a legitimate interest in the diamond discoveries; the majority were shady “company promoters,” bucket-shop experts, warned-off bookmakers and betting-men (“brokers” they usually styled themselves), and sharpers of all sorts, on the lookout for prey in the shape of lucky diggers or discoverers. Then, too, there were a number of self-styled “prospectors,” runaway ships’ cooks, stewards, stokers, and seamen, the bulk of whom had never seen a rough diamond in their lives, and of course a modicum of genuine men of past experience—principally ex-“river-diggers”—men whose small capital was running away like water for bare necessities in this miserable dust-hole of creation.

[Page 11]

We soon found that most of the available land in the vicinity of Luderitzbucht had been taken up, and much of it had already changed hands two or three times. Companies and syndicates were being “floated” at a great rate, many of them by unscrupulous scoundrels of promoters, acting upon the “reports” of equally lying and unscrupulous “prospectors.”

Schurfscheinen (prospecting licences) were at that time transferable, and as they were daily becoming more difficult to procure, they often changed hands several times, and for quite large sums, before they were even used for their legitimate purpose of enabling the holder to locate and peg-off a claim. And often, when, as a result of an expensive expedition, ground was located and title secured, the diamonds shown to back up the “discoverer’s” or “promoter’s” highly coloured report would be the only ones ever seen by the gullible purchaser or shareholder.

The conditions under which diamonds were found made “salting” a very easy matter to carry out and a very difficult one to detect. The small and brightly polished little gems, usually running three or four to the carat—that is to say, about the size of hemp-seed—were generally found in the surface deposit of loose sandy shingle spread over much of the sand-belt near the coast, and differing from the sand of the country only in being slightly coarser. This loose deposit, in common with the sand, is in many places heaped up into small, wave-like ripples by the action of the prevailing wind, and wherever the diamonds exist these little ridges are exceptionally rich in them. The method of searching for them was simply by crawling along almost flat upon the ground, and turning over the shallow layer with a knife-point, though on some of the claims hand-washing in sea-water was being attempted. Most of the diamonds so far had come from a place known as “Kolman’s Kop,” a mile or two inland from the bay, and on the railway to Aus—indeed, the line ran right through this diamondiferous area—and it[Page 12] was here that Du Toit had picked up his stones. So plentiful were the little “crystals” that many a little bottleful of them had been brought into Luderitzbucht in the early days and given away as curiosities, without the slightest notion as to what they really were.

A few keen-eyed Kaffirs engaged in construction work on the railway, and who had worked in the Kimberley mines or on the Vaal River Diggings, first realised what they really were, and several of these “boys,” who afterwards came to Cape Town, and there attempted to sell the stones, were convicted and sentenced to various terms of imprisonment under the provisions of the “I.D.B.” Act of Cape Colony.

Few, if any, of those who read the report of their trials believed their story that they had picked up the stones in the sands of German South-West Africa, but the few who did believe and made investigation were amply repaid for their trouble, for the first-comers picked up diamonds by the handful.

A few days tramping the surrounding district soon convinced us that all the likely ground near Luderitzbucht had been taken up—and indeed much that was unlikely—and we decided to clear off to an outlying district where distance and want of water had thus far prevented “prospectors” from penetrating.

A general examination of the gravel, sand, and various deposits had shown to we old diggers the significant fact that, whatever the origin of the diamonds, there was some analogy between these fields and those of the Vaal River Diggings, for prominent everywhere were the familiar pebbles of striped agate, chalcedony, jasper, etc., we knew so well. Most of these pebbles were, however, very much smaller than those of the Vaal River; moreover the action of wind and water had “graded” the loose deposits to such an extent that whole acres appeared to have been worked by sieves of a uniform mesh.

[Page 13]

Now, this “grading” was also a feature of the diamonds themselves, for they were of a remarkably uniform size, and in this respect differed entirely from those of any other known deposit; for at Kimberley, or on the Vaal River Diggings, one of the fascinations of the precarious profession of diamond-digging lies in the fact that big and little stones are found together, and the next spadeful of ground may bring the digger a stone the size of a pea, or one the size of a potato. Now, the general theory as to how the diamonds came to be in the Luderitzbucht sands was that they had come from the sea, either from a rich pipe beneath it, or from a huge deposit washed down the Vaal and Orange Rivers during the course of countless ages, and out to sea, whence the north-setting current had brought the diamonds ashore. And we—pundits all—believed that, as the sea had obviously done the work of “grading” the stones, there must exist vastly heavier deposits somewhere along the coast, where, it should follow, we should also find vastly bigger diamonds. And those were what we wanted, the bigger the better.

[Page 14]

RUMOUR OF “HOTTENTOTS’ PARADISE”—UP THE COAST ON A SEALING CUTTER—WALFISH BAY.

At that time rumour was rife that, somewhere in the terrible wilderness of sand-dunes stretching north-east of Luderitzbucht, there existed an oasis where not only water was plentiful, but where diamonds, big ones, abounded. This fabled oasis was usually called the “Hottentots’ Paradise,” and tradition maintained that to this remote and inaccessible spot the remnant of that poor degenerate race of natives that had escaped extermination at the hands of the Germans in the recent rebellion had retreated. It was also rumoured that these men were well armed, that they had cattle and food in abundance, and that, cut off by a wilderness of waterless country, the Germans had hesitated to attack them. There were other versions; in fact, no two agreed exactly, except that the oasis was situated somewhere between Luderitzbucht, Walfish Bay, the high plateau of the interior, and the sea, and that there the diamonds were as big as they were abundant.

Already one or two abortive expeditions had started with the intention of searching for this place, but none of them had got far; thirst had in each instance conquered them; and at least one had lost every animal it started with.

One day, when we were looking round as to the best direction in which to make our own attempt, I was asked by a prospector to join an expedition just being outfitted to search for this place, and he put such a plausible tale before me that I hastened to consult Du Toit. He shook his head when I told him the way this expedition proposed travelling.[Page 15] “No water,” he said; “they’ll be back within a week, if they get back at all! There are only two ways of searching for the place: from the coast, having a boat with plenty of water waiting you, or with camels. These fellows talk of mules—well, let ’em go. I’ve heard of something better.”

Then he told me he had met a man he had known on the River Diggings who had turned sealer, and had for some years past plied his dangerous trade along this wind-swept coast in a little ten-ton cutter, and that this man had told him that north of Sylvia Heights there existed a wonderful beach where the pebbles were identical with those of the Vaal River Diggings, but that they were very much larger. He said they lay graded by the tide for miles and miles along the beach—agates, chalcedonies, jaspers, and banded ironstones (the bandtom of the digger); and that, when he had come back from a holiday in Europe and found all Luderitzbucht diamond-mad, he had resolved to go to this beach, where he believed he would find them lying thick, but that he had been in some trouble with the police and could not get a Schurfschein. As we both had obtained these valuable documents, he was quite prepared to run us up to this spot in his little cutter, sharing expenses, and sharing in all claims we might be able to peg.

Now, this seemed a perfectly God-sent opportunity for locating the “big stones” we all felt certain existed, and we set about getting in stores for the trip at once. These consisted principally of hard biscuit, “bully beef,” tea, coffee, and sugar, and above all water. Of the latter we had two fairly large breakers, and a miscellaneous collection of other utensils, ranging from big oil-drums to canvas water-bottles—in all, an ample supply for fifteen or twenty days. We went on board that very evening. Besides our pal the skipper, there were two other hands, men who, had they chosen to wash themselves, would probably have proved to be white, but who were so coated with seal oil and the accumulated grime of[Page 16] many voyages that it was impossible to say what colour was underneath it all. They spoke a jargon that they fondly imagined was English, but I believe they were Scandinavians of sorts. The little half-decked cutter barely held us and our belongings, and would have been none too comfortable even for a short trip such as we hoped for and anticipated.

And, unfortunately, our voyage was both long and disagreeable, for we had scarcely got clear of Luderitz Bay one fine evening than it came on to blow great guns, and so heavy did the weather become that our skipper had to run clean out to sea. Up to then I had fondly imagined I knew something about the sea, and was proof against such a very amateur malady as sea-sickness; but alas! I had a lot to learn. Indeed, I soon found that, in spite of a good deal of knocking about the sea at various times, I really knew nothing of bad weather. There was no snuggling down in a cosy cabin or the soft cushions of a big saloon about this experience, no looking at big seas through the comforting protection of thick plate-glass portholes. Here the huge waves were towering, threatening, imminent; and nothing but the coolest of heads, and strongest and steadiest of hands at the helm, could have kept the little cockle-shell from shipping a big sea and foundering. Portions of big seas she shipped repeatedly, and little seas in the intervals; in fact, for hours she appeared to consider herself to be a sort of submarine of which I suppose I must have been the periscope—for I was continually endeavouring to stand erect in my attempt to dodge the waves. Within an hour or two of leaving the bay I was wet through, and continued so till I got on shore again; and during that period of three nights and two days I had ample reason to know that sea-sickness is not nearly as laughable as it looks! They gave me rum and water, and it made me worse; they coaxed me with hard ship’s biscuit and fat bully beef, and somehow it failed to entice me. Once, in a comparatively dry interval, they managed to light a stove and make some alleged[Page 17] coffee. It tasted so of seal oil that it merely effected the apparently impossible by making me feel worse than I did before.

The skipper assured me that it was all my fancy when I told him that the coffee-pot must have been used for trying down seal, and offered to prove it by making another brew in the legitimate utensil used for that purpose, that I might taste the difference. The only consolation I had during the whole memorable sixty hours was that Du Toit was apparently even worse than myself. He did not even attempt to dodge the water as we shipped it, but lay with closed eyes and hands mechanically clutching the oily stays, just where the first spasm caught him, and except for groans, nothing coherent passed his lips but profanity during the whole voyage. We had left Luderitzbucht at sunset on Tuesday evening, and the gale that sprang up that night blew itself out sufficiently by Thursday afternoon to enable them to put the cutter about towards shore again. I did not witness the operation, but I heard some cryptic remarks thereto, and knew by the way the crew fell over me they were hurrying about something. Then the motion changed, and a wave went over me broadside instead of lengthways. The sail flapped furiously, and then she heeled over so that I rolled off my seat. And then a quite new motion began, a bobbing, jerking, wrenching movement that started fresh trouble. However, by dark that night we were in sight of land, and I began to have some faint hope that, after all, we might survive.

I was aroused from a broken and uneasy slumber by a chorus of quacks, and cackles, and grunts, sounding as though the cutter had run clean into a farmyard, and at this phenomenon I had just sufficient curiosity in me to open my eyes and sit up. Dawn was breaking and we were close to land, in comparatively smooth water, to the leeward of a small island, from which arose the hubbub I had heard. It was not a farmyard, however, but an island covered partly with big seals, and partly with penguins and[Page 18] other sea-fowl in such incredible swarms that they jostled each other for elbow-room. This was one of the many guano and sealing islands lying off the coast of German South-West Africa, all of which are British possessions belonging to Cape Colony. On several of them diamonds are supposed to exist, but they are prohibited ground to prospectors. I believe this to have been Hollam’s Bird Island, but had no chance to inquire as my sitting position immediately brought on the old trouble, and I had other urgent matters to attend to.

However, our troubles were almost over, for less than two hours later the cutter was deftly manœuvred into a little indentation where the water was comparatively smooth, and we got out the tiny dory that had filled up most of the cutter’s foredeck room and landed. And never were men more pleased than Du Toit and I, and we there and then agreed that one trip in that cutter was enough. Once we had found the diamonds, we would send it back to Luderitzbucht to charter a decent-sized boat to go back in; but as for travelling back ourselves in her—not much!

According to the skipper the beach he knew of lay about three or four miles down the coast, but this was the only safe landing-place and anchorage, and here we must camp. So we got our water and provisions ashore, and by the aid of a big bucksail and some driftwood we made a shelter to live and sleep in. This driftwood lay in abundance all along the sandy, desolate shore, and served excellently for fuel, though it was too dry and rotten to be of much service for anything else. The landing even of our few stores and belongings took up the best part of the day, and we decided not to make our first trip to our diamond beach till the morning; but just before sunset Du Toit and I went a short distance inland to where the first high dunes began, and climbed a prominent one for a look-round. And east, north, and south there was nothing but sand; not a tree anywhere, only here and there a stunted[Page 19] bush struggling forlornly against adversity; nothing but bare waves, mounds, and ridges of desolate dunes as far as the eye could reach, and to the west the equally (but not more) desolate ocean. No sign of life anywhere except a few gulls over the sea, though on our way back a jackal followed but a few paces behind, full of curiosity at the strange beings the like of whom he had probably never seen before. We saw several of these jackals during our stay there, and they were all quite fearless. Their spoors and those of the stronte woolfe, or brown hyena, were numerous, and the only spoors of any kind to be seen along the desolate shore, where these creatures probably picked up a precarious living from the dead fish occasionally stranded there. A short distance up the coast we found a flat space where the sand was comparatively hard, and where, apparently, in the past a shallow lagoon had existed. Here there were a few straggling bushes, thick-leaved and resinous, and scanty clumps of a sort of strong, wiry rush seemed to point to moisture at a short distance below the surface. Here, too, we found huge heaps of the shells of a species of large limpet, shell middens showing that at one time a people existed in the locality, probably the strand looper, the beach-roaming forerunner of both Bushman and Hottentot. But except for the shells, no vestige of him remained, nor of the water that he at one time drank at, though probably a few feet dug in the sand might have laid that bare.

I wanted badly to sleep that night, but apparently the others had different views. The sand was soft and dry, and a shallow hole scooped in it for my hip and a heap for my pillow, with a blanket spread over all, made a couch fit for a Sybarite, especially after the battering my bones had received on board the cutter. Du Toit was already snoring when I snuggled down, but I was far too used to his basso profondo to let that keep me awake, and was just dropping off when the skipper started an interminable argument with one of the other men on some weird technicality[Page 20] connected with the sealer’s craft, and kept it up apparently for hours. I did not like to interrupt them, but time after time, just as I got fairly under way, their voices woke me. I saw the big camp fire of driftwood sink and die down till nothing but a few embers remained; I saw the late moon rise and flood the wide solemn sea of dunes with mysterious light, saw the shadowy slinking forms of two or three jackals sneaking about, less than a stone’s throw away; heard the soft, soothing swish of the waves on the beach, and Du Toit’s solo; but above all came this incessant wrangle.

At last I called out to the skipper, “Look here, Jim, when are you fellows going to shut up? It must be nearly morning, and I want to sleep!”

“Sleep?” said he. “Great Scott! why, I thought you’d never want to sleep again! Why, man, you slept all the way from Luderitzbucht here! Sleep? Why, you never opened your eyes all the way!”

“That was sea-sickness,” I said, “not sleep—sea-sickness!”

“Must ha’ been sleeping-sickness,” he chuckled, and the two other asses chuckled too, and repeated his attempt at a witticism over and over again with fresh chuckles till I got too ratty to do anything but swear. And still they smoked, and talked, and yarned; until at length, in sheer desperation, I grabbed my blankets and, with a parting benediction that must have kept them warm till morning, cleared away out of earshot, scraped a fresh couch out with a swipe of my foot, snuggled up in my blankets and went to sleep instantly.

I awoke shivering, for as usual along the coast the early morning had brought a dense sea-fog that enveloped everything, and had soaked my blankets through and through. It had been to guard against this drenching “Scotch mist” of a fog that we had erected the bucksail shelter, from which Jim and his co-idiots had driven me, and under which I now found them snoring in feeble opposition to Du Toit. They were snug and dry, but the big sail above hung[Page 21] bellying down with its soaking weight of accumulated moisture, whilst the guy-ropes were stretched taut for the same reason.

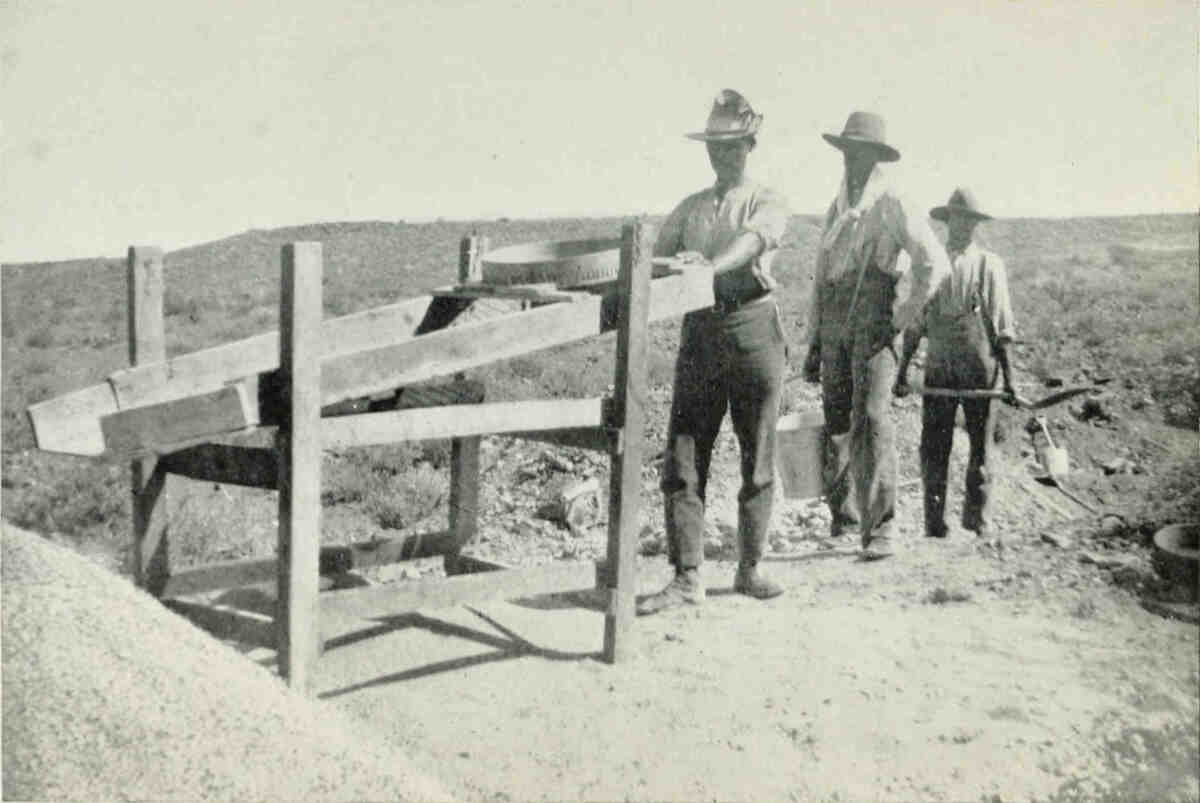

SEALERS AT OLIFANTS ROCKS.

The only white man (Irish) is the man standing behind.

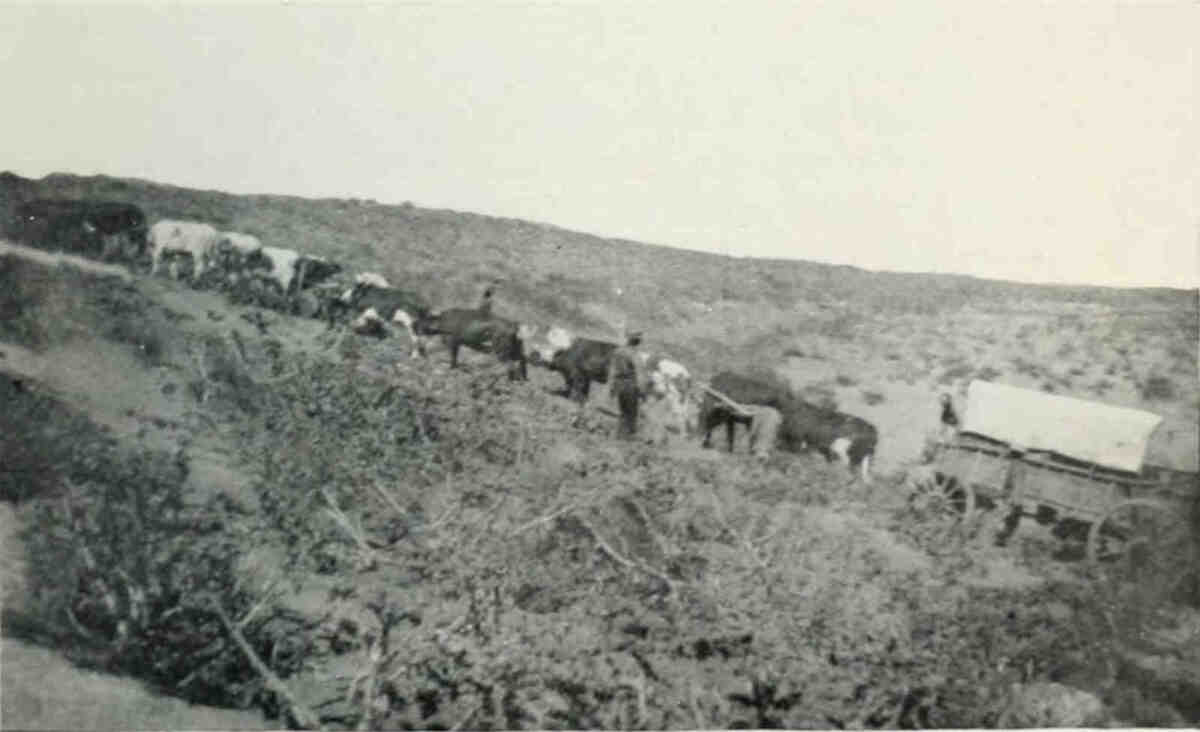

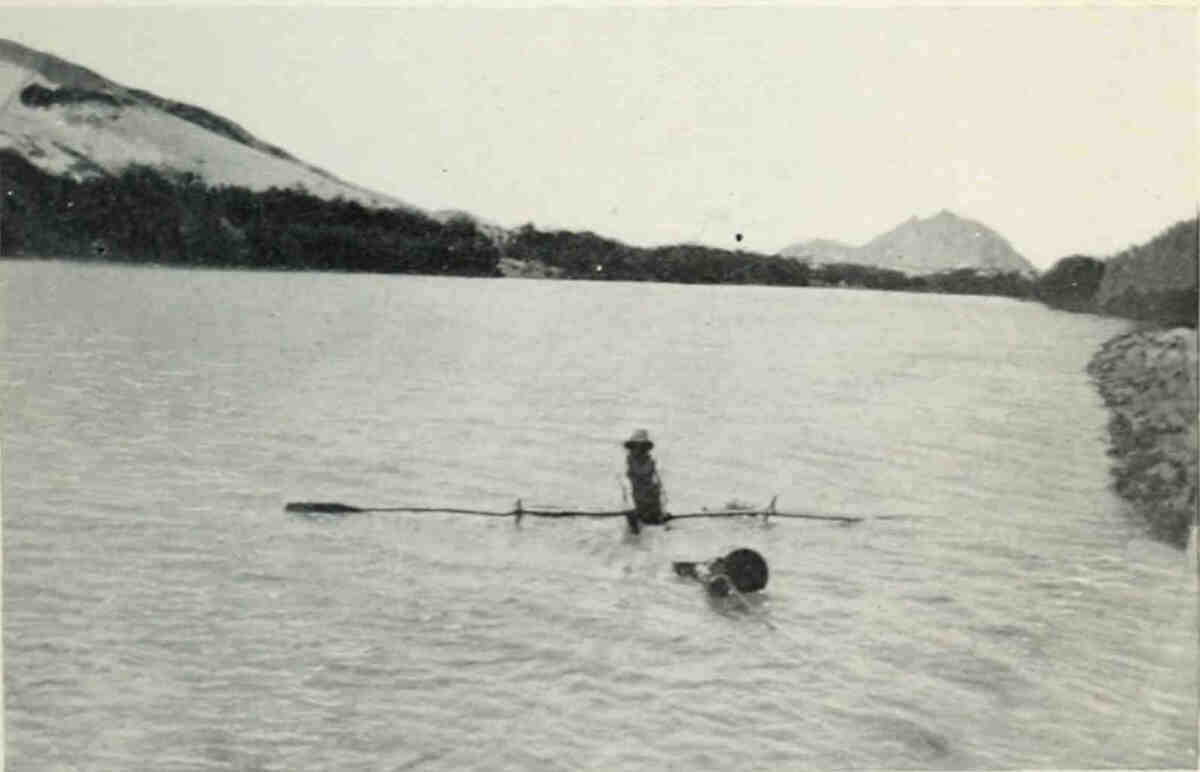

TAKING THE HORSES ACROSS OLIFANTS RIVER.

Of course I simply had to do it—they were too snug and dry and warm, and I was too wet and cold, to allow of any other course of action! So I just snicked the guy-ropes slightly in a weak spot and hurried back and turned in again in my wet blankets, hoping for the best. It came soon—a muffled squelch—followed by a perfect bedlam of polyglot profanity. I heard someone get mixed up with the pots and buckets and make disparaging remarks about them; I heard another’s periods cut short by a sound impossible to write, but that conveyed a pleasant picture of an attempt to get rid of a full mouthful of sand—in fact, though I could see nothing, I could hear enough to conjure up a vivid picture of what was happening under that extremely wet and extremely heavy bucksail.

At length they struggled out, as I could visualise by the storm of recrimination and accusations.

“You donder!” I heard Du Toit snort (I found later his nose was badly bashed by a bucket). “I knew you didn’t tie the verdomte touw properly!”

“Oh, blazes!” retorted Jim’s voice, “here’s a slab-sided son of a zand-trapper, that don’t know a rope from a reim, trying to tell a sailor-man how to tie knots. H——! Why, you snored the blamed thing down! Where’s your partner anyway? Asleep, I s’pose, under all that. Well! what did I say about sleeping-sickness?”

They then appeared to search for me; and then one of the incoherent gentlemen made a remark to Jim.

“So he did,” I heard him agree; “cleared out when we were talking. I’d clean forgotten. He’ll be asleep somewhere. Sleep!”

Then they came and found me, and of course found me asleep, and made fitting remarks.

I relate this little incident at full length because it happened to be the only cheerful happening of that disastrous trip.

[Page 22]

Directly the fog lifted and we had re-erected the tent and had some breakfast, we took a sieve and a spade or two and started towards the beach, leaving one of the crew to watch tent and cutter. It was probably nearer four miles south than three—a long, wearisome drag through heavy sand for the most part, for the tide was high and we could not follow the water’s edge.

At length we came to it, and I must confess that when I first set eyes upon that beautiful stretch of clean and polished gravel I felt that Jim had been right, and that here, if anywhere in German South-West, we should find the “big stones” in plenty.

For this mile-long beach looked like a vast débris heap of all the fancy pebbles the “new-chum” digger usually collects during his first month or so on the River Diggings: striped agates of all shades, jaspers, cornelians, chalcedonies, and above all the yellow-and-black striped banded ironstone, band-toms of the digger.

And along that most disappointing beach we searched day after day, always hoping and expecting to find, and always in vain. We tried the larger-graded pebbles farther from the water first, hoping for Cullinans or at least Koh-i-noors, and by degrees we worked down to the water’s edge, where the grit was but little coarser than that of Luderitzbucht; but all to no avail.

We sank prospecting-pits 5 or 6 feet in depth at regular intervals, always finding the same promising material, always getting the same disappointing result. We turned over the big stones by hand, we “gravitated” the small stuff by sieve, as we had learnt to do years before; there were no diamonds there.

The sun flayed us, for the heat during the day was terrific, and the nights were correspondingly cold and damp with the heavy sea-fog, that came down always towards morning. We grudged ourselves time for food and sleep, so obsessed were we with the idea that the diamonds must be there somewhere.[Page 23] Moreover, the little food we did get was of bad quality, and the water abominable. A good deal of knocking about South Africa had inured me to drinking bad water—alkaline, stagnant, full of animalcules, etc.—but this stuff was different, and I soon found that Jim had been right when he had protested that the coffee-pot was not generally used for seal oil. It was not the pot that the taste came from, it was the water itself. Every beaker, every cask, every drum, every utensil was impregnated with oil, there was absolutely no getting away from it. And yet so soaked in the same unctuous, all-pervading liquid were the three sealers that they could not taste it; in fact, they could not understand my own and Du Toit’s repugnance to drinking it, in the least! But to me, as water, this liquid was quite undrinkable, as coffee I swallowed it with an effort and kept it down with a greater one, and as tea I never had the pluck to try it more than once.

One morning, after an exceptionally heavy fog, a drop or two of water percolating through the bucksail and falling on my nose not only awakened me, but gave me a brilliant idea. “What an ass!” I thought, as I jumped up there and then. “Why, I could have had a pint or two of rain-water every day had I thought of it!” I cleared out with a dipper and pail, and sure enough there was quite a pint of water caught in the slack of the sail. And I scooped it out, and raked the embers together, and put my own tin “billy” on to boil and promised myself a cup of tea made with pure water, not oil! And I went and woke Du Toit and told him, and he came and sat by the fire to watch me brew it. Of course we’d no milk, but we had sugar, and I poured out two “beakers” (enamelled mugs) of it, and set them to cool. Du Toit was in a hurry; he blew his. “Smells good,” he said, and took a big gulp.

“Scalded you a bit, eh?” I asked, as I noticed the tears come to his eyes in a valiant attempt to swallow what he’d supped. He nodded, didn’t seem to trust his voice somehow! Then I took mine, first[Page 24] pouring it from cup to cup to cool it, and taking a mighty draught “at one fell swoop.”... As soon afterwards as I was able I went over to Jim and roused him gently but firmly. “Jim,” I asked, “how did you make this bucksail waterproof?” “Oh!” he replied enthusiastically, “she’s a real good ’un is that bucksail! I took a lot of trouble with her. Soaked her in paraffin first of all, then went over her with raw linseed oil. She still leaked a bit, and a feller at the whaling-station at Saldanha Bay gave me some whale oil for her, and I soaked that into her. Then, when I heard what you fellows wanted up here, I bunged some good old seal oil into her, and now she’d take a lot of beating!”

And “she” would have—for she tasted of all the lot—I haven’t forgotten that tea yet!

We spent ten days incessantly searching the gravel, and at length gave it up in despair. Jim advised us that we had only about water enough for six days, and, bad as it was, we knew we could not do without it, and the only question was whether to return to Luderitzbucht, or to try our luck at another place a lot farther up the coast. One of the Scandinavians suggested the latter. He said he had been there but once, but that the gravel was identical with that we had been trying. Only there was much more of it. It was a long way off, however, somewhere near Cape Cross, north of Walfish Bay and Swakopmund, and if we decided to go we should have to call at Walfish Bay for water. But, Jim continued, we were nearer the latter place than Luderitzbucht, the wind would probably be more in our favour; and we voted en masse for these fresh fields. Before sailing, however, Du Toit and I went about four miles inland into the dunes to an extremely high and prominent one, a real sand-mountain about 200 feet high, from which we hoped to get a view of the sandy wastes generally, as we had still a lingering hope that we might yet find a similar deposit to that of Kolman’s Kop, with plenty of small stones, even though we could not find the big ones.

[Page 25]

From this huge, bare dune—the sand on the crest of which lay piled for the crowning 10 feet in an almost sheer wall—we had a fine panorama of the terrible waterless waste surrounding us, treeless, bare, and horrible in the glaring sun, awful in its featureless monotony of huge wave after wave of verdureless sand. Away south, in the far distance, we could see higher land near the coast, probably “Sylvia’s Heights,” and inland, faintest of faint cobalt against the glare, the outline of a long range of mountains, between which and the farthest distinguishable sand-dunes danced a lake of shimmering mirage, seldom absent in these wide spaces of the desert. Here and there, among the long ridges of the dunes, spaces could be noted which appeared to be covered with low bush, and towards one of these “pans” I made my way, whilst Du Toit struck out for a similar one in an opposite direction. The going was extremely difficult, for the dunes here lay in long parallel lines, very close together, very high and steep, and naturally with very deep corresponding valleys between; and my way lay across them. The distance appeared nothing, but each successive dune I climbed seemed to bring me no nearer the pan I was aiming for, and which was only visible for a second or two as I reached the crest of each big sand-wave. Anything more tedious than this crossing of the bare dunes it is impossible to imagine, though slower progress might conceivably be made in an attempt to cross a closely built city by climbing up, over and down the houses instead of using the streets.

However, I reached the pan at last and found it to be an oval-shaped “floor,” strewn thickly with water-worn pebbles and quite free from sand. Scattered bush grew here and there upon it, and near the centre I saw larger trees growing. These I found to be tall thorn-trees, called locally cameel doorn, a species of thorny acacia which is usually found in or near watercourses; and at this time of the year they were covered with little yellow balls of bloom, scenting the air deliciously with the smell of cowslips.[Page 26] And here, in the middle of this sea of dunes, they lined a watercourse, and though it was bone-dry, there was evidence that at one time a considerable quantity of water had flowed there. Many of the larger trees, the girth of a man, were dead, and much larger blackened stumps were plentiful. This dry watercourse disappeared under the sand-dunes at either end of the pan, and a closer inspection of the whole extent of the latter showed that it was the remaining trace of what had at one time undoubtedly been the wide bed of a river of considerable extent, of which the narrow tree-lined watercourse in the centre had been the last surviving trickle. Later, I found many of these beds among the dunes, all choked with sand and long dead and extinct, but showing indisputably that this country was not always the waterless desert it is to-day. In some cases water still flows deep in their sand-choked beds, and can be obtained by digging.

An hour or two spent in this spot convinced me that there were no diamonds to be picked up, and I turned back coastwards, after being rejoined by Du Toit. He had been to a similar pan still farther inland, and his conclusion had been that of myself, that it formed part of an ancient river-bed overwhelmed and choked by the dunes. He also said that from a high dune there, through his glasses, he had seen a very much wider expanse of country of a similar nature through a break in the dunes inland, and that it had appeared to be quite thickly wooded. He had also seen moving objects in that direction, but whether gemsbok or cattle he could not say. At any rate it was apparently an oasis, and quite possibly the “Hottentots’ Paradise” we had heard so much about. At least, so thought Du Toit. “But it’s a long way, and the dunes seem to get worse in that direction. It would take us a day and a half to reach it; that means we’d have to take water for three days, for we could not depend on finding water there. And if it is the place, there are a lot of well armed Hottentots there, and we’ve no [Page 27]rifles, and we’ve no trade goods to barter with. No, it’s not worth the risk; but, man, if the yarns we’ve heard are true, there must be piles of diamonds there!”

DRIFTWOOD ON THE DESOLATE BEACH NEAR CAPE VOLTAS.

The low point in the distance.

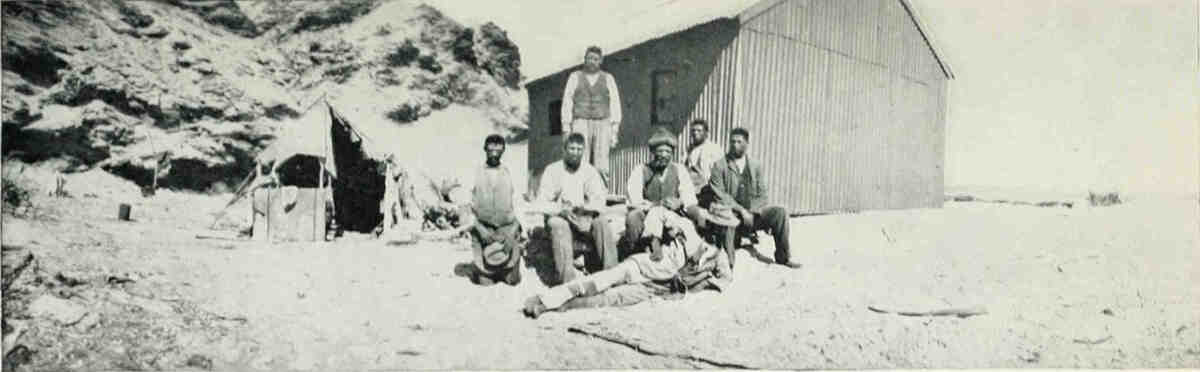

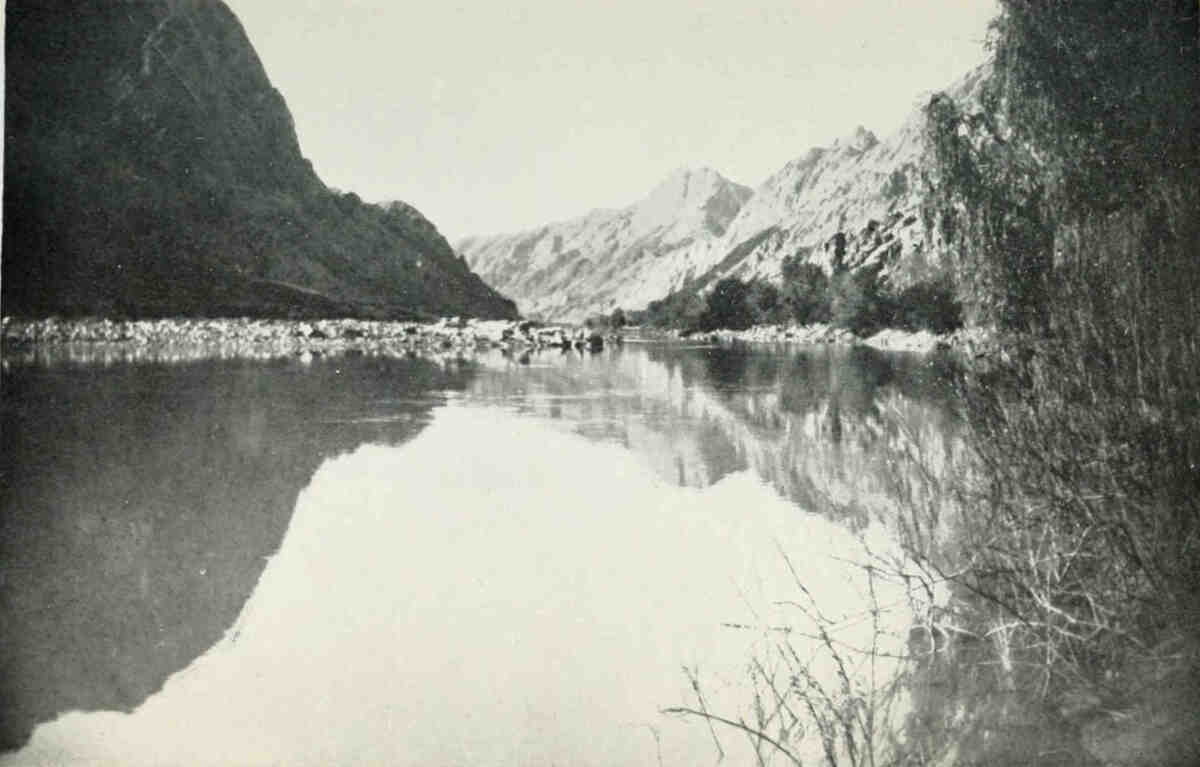

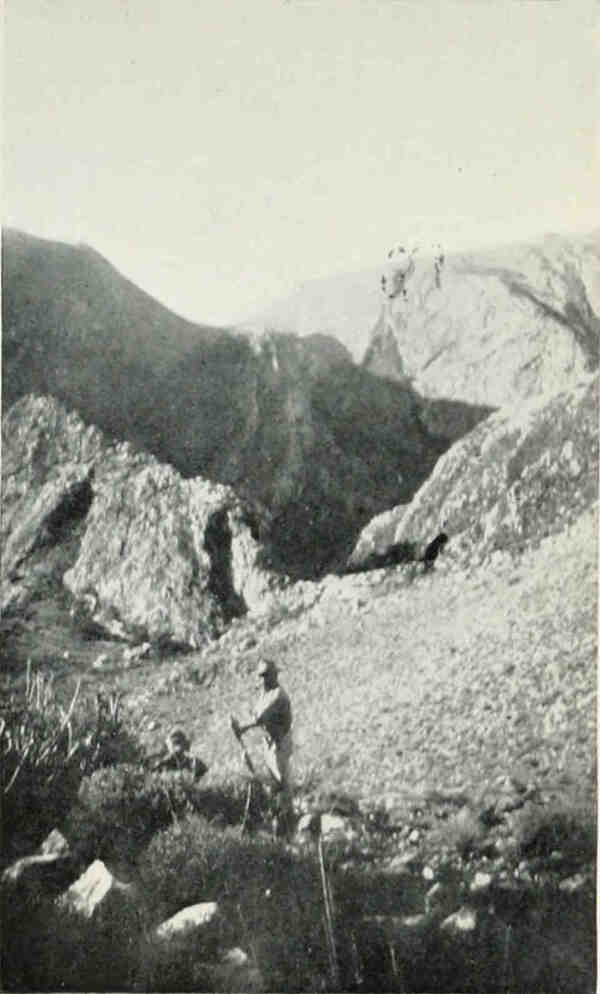

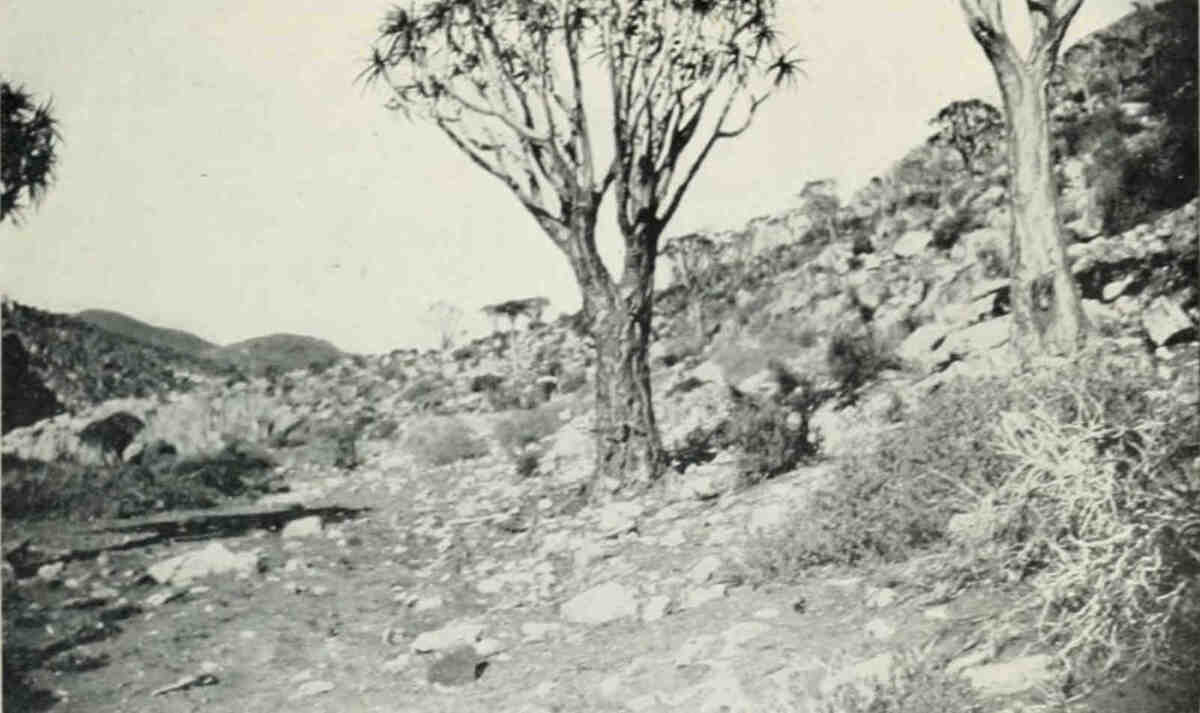

PROSPECTING PARTY NEARING THE MOUNTAIN OF RICHTERSFELDT, NAMAQUALAND.

So we turned our backs reluctantly on that unknown oasis—which may indeed have been no oasis at all, and nothing more than a big pan similar to those we had examined—and toiled back to the coast.

No matter how good a walker a man may be in the ordinary way, he will find the first few days’ walking in the dunes a most painful and exhausting experience. Wading through loose sand up to the ankle, climbing up it at a steep angle, and plunging down it on the other side of the dune, only to repeat the process, ad infinitum, exercise a terrific strain upon muscles scarcely called into play in ordinary walking; and ten miles a day across country like this is a severe strain upon a new hand at the game. With practice, of course, he can do double, and with experience he falls into a peculiar shuffling gait which is the most noticeable feature about the farmer and others who dwell in these sandy districts and who are nicknamed “Zand-trappers.” All of which Du Toit imparted to me as we walked back to the coast.

“You lift your feet too high,” he said, “like these blooming Germans do when they’re goose-stepping. Walk like this.”

I told him I should be sorry to, and he appeared annoyed; but I found that, though I could beat him easily on the hard flat, I stood no chance with him in the sand, and what I had always put down to bunions or sore feet was really this “zand-trapping” gait that he had acquired in his youth, and never got rid of. Most men who live among the sand wear low veldtschoens, without socks. These schoen are easily kicked off and emptied of their accumulation of sand periodically; whilst many adopt the practice of cutting a small hole in the sole near the toe, through which they occasionally shake out the dusty contents. Ordinary boots last but very little time, as the sand has an extraordinary abrading action[Page 28] upon the leather, cutting the stitching holding sole and upper together in a few days.

We got back and told Jim about what we had seen, and he put finality to the matter by declaring that if we were mad enough to try to reach the oasis we could walk back to Luderitzbucht with the diamonds, as he’d be “somethinged” if he’d wait for us! Moreover, he’d packed everything on to the cutter, and if we wanted to beat up to Walfish Bay and Cape Cross we’d better get on board at once.

I had hoped for a good night’s rest that night, but instead, like a lamb to the slaughter, I was led to that wretched cutter, where again, to a modified extent, what Jim called my “sleeping-sickness” floored me. However, this time the weather was fine and the breeze was fair, and two days later we ran into Walfish Bay.

A magnificent stretch of water, perfectly protected from the prevailing winds, and capable of accommodating an enormous fleet, it is certainly the key of the huge German hinterland; and it was a very far-seeing policy on the part of England not only to secure it for herself, but to hold tight to it against all the wiles and blandishments of German diplomacy.

For had England given it up, the Germans would have undoubtedly transformed it into a most powerful naval base, which would have been not only a menace to the Cape mail route, but to all British possessions farther south, and would incidentally have forced the maintenance of a powerful fleet at or near the Cape.

Important as the place is strategically, however, England (or rather Cape Colony, of which it forms an integral part) has done little to develop this small slice of territory. A fairly good pier and a few forlorn-looking corrugated iron buildings looking as though they had been dumped down, forgotten and deserted, constitute the settlement, which stands forlornly on the bare sand.

A resident magistrate, a few born-tired officials, a [Page 29]“hotel”- and store-keeper—in all a handful of the slackest white people I ever saw—constituted the population. The condensing gear on which they relied principally for water was out of repair, which (according to Jim’s remarks about it) appeared to be its normal state; and here we had to wait four days before we could fill our miscellaneous collection of water “tanks.”

THE NAMIEB DESERT, “SAM-PANS”—CAPE CROSS—SWAKOPMUND—WINDHUK.

Meanwhile a local acquaintance of Jim’s asked Du Toit and me to go with him a day’s journey up the Khuisiep River, to a place in the Namieb Desert, where he believed that tin existed, and I jumped at the opportunity. We had good horses and travelled light, with a few roster-kooks and some biltong by way of provisions, and a water-bottle each. Riding south from the forlorn-looking settlement, we followed the thin line of vegetation denoting the river-bed, which, when it contains water, empties itself into the lagoon terminating the southern extremity of the bay. Thence, striking inland, the bed widens till it becomes a long stretch of wooded country offering the most striking contrast to the barren desert and sandhills that hem it in on either side. But, in spite of the thick verdure and fine trees, there is no water to be met with along the whole route, except immediately after rains, and at one or two spots where pits have been sunk.

What a treat those trees were, though! The eye, aching with the red-hot glare of a whole landscape of bare, scorching sand, turned to their beautiful greenery with a wonderful sense of rest and relief.

Most of them were varieties of acacia, cameel doorn, such as I have described, and others covered with huge, bean-like pods, and most striking among them were fine, majestic trees resembling big oaks in outline, and giving the whole well-wooded expanse a beautiful park-like aspect.

There was plenty of welcome shade, especially from a smaller but thicker-leaved tree of a variety[Page 31] of wattle; grass and creeping plants made a verdant carpet, butterflies flitted about among brilliant flowers, and bright-plumaged birds called to each other in the trees. In fact, to us, fresh from sand and sea and “sleeping-sickness,” it was Paradise. And I said so to Du Toit as we off-saddled for a bite at midday, knee-haltering our ponies and taking our snack under the shade of a big mimosa. I said to him, “Let’s stop here! Anyway, if we find diamonds or tin, let’s stop here! What can we want more? Green trees, birds, flowers, grass, shade for the seeking, water for the digging! This is Paradise, and it’s good enough for me. I’m going to sleep.”

And I did, Du Toit, with unwonted consideration, offering to keep an eye on the horses, and wake me when it was time to trek again. But I did not sleep long. I awoke with the pleasant sensation of being stabbed all over with red-hot needles. One eye was too swollen to work, but the other advised me of the fact that it was not needles that were troubling me, but a small yet most iniquitous insect that had sampled me before in other sandy parts, but that, in my delight at the beautiful trees and beautiful shade, I had forgotten. This was the “sam-pan.” I had seen him before, but this time I had evidently found him at home, where he lived! He was all over me—a small, pernicious infliction ranging in size from a pin’s head to a shirt-button, flat, almost circular in shape, and with legs all around his perimeter. Entomology is not my strong point, but that’s how he looks, and he feels as though he had a mouth on each foot. And in this case he had caught me just as he might have caught the most abject greenhorn: lying asleep in the shade of a tree where there were obvious signs that cattle, or big buck, had been in the habit of standing.

These horrible little pests are one of the biggest scourges of the desert. They are a species of tick that breed in the droppings of animals, and burrow in the sand of the immediate vicinity, lying low till some juicy, full-blooded victim comes along for[Page 32] them to perform upon. For this reason they are always plentiful under certain shady trees, favoured by oxen and big game as a resting-place in the heat of the day. Choose one of these spots and sit down in the pleasant shade and watch the sand around you. Not a sign of insect life for the first few minutes—and then! A tiny eruption in the sand near your elbow, and there, scratching his way to daylight—and you—comes the pioneer, followed by others till the whole earth is alive with them. And bite! So poisonous are they to some people that to be bitten badly leads to blood-poisoning, and in any case the intolerable itching from their bites spoils a man for sleep or anything else but scratching and inventing new profanity for days and days after he has been victimised. All of which I had known, and still Du Toit and his companion in crime had caught me beautifully, with the enticing shade of that big tree. They lay sleeping peacefully, a bare twenty yards away, under a bush thick enough to shade them and too small to have harboured oxen—or sam-pans.

We followed the Khuisiep till late that evening, when we came to a water-hole where our horses drank, and near which we slept that night, not too near, for the immediate vicinity was literally buzzing with mosquitoes. The stagnant water was also full of their larvæ—so full that we strained it through a handkerchief before boiling a billy of it for coffee, and got a spoonful of larvæ to each billy. Still it was quite drinkable as coffee, much better than the oleaginous liquid Jim provided us with.

The following morning we left the Khuisiep and turned up a tributary watercourse (dry) coming from the desert eastward; a few miles up which we left the sand behind and came into rocky, broken country, sterile and quite without vegetation. Here there were many outcrops of granite, and in certain parts of the dry stream-bed garnets were lying by the bucketful. They were a constituent of the granite, but in many instances had been mistaken for ruby tin. Black titaniferous iron-sand also abounded in[Page 33] this stream-bed, and in many of the small quartz reefs large crystals of jet-black tourmaline were to be seen—some of them huge specimens as thick as one’s wrist. Unfortunately, real prospecting was out of the question, as we had neither tins nor tools; but the country is a most interesting one, and it is quite possible that some day a valuable discovery of tin may be made there. Want of water—that great handicap to prospecting in South Africa—prevented us even “panning” the river-bed; but certain sand and gravel, which I took back to the nearest water that night and panned there, yielded both tin and copper, and a fine “tail” of gold. This spot was just over the border of British territory, but the unnamed river apparently came from the mountains, plainly visible in German territory eastward. Our trip back was uneventful, and we arrived at Walfish Bay the following evening, where we solved the water question and found Jim ready to start. Before doing so I indulged in the extravagance of purchasing a small cask for water for my own use; a procedure that called forth such an amount of elaborate sarcasm from Jim and Co. that I soon regretted it, more so as I found on broaching it that the contents tasted as strongly of tar as the other had done of oil.

Again the cutter had favourable winds, and this time neither Du Toit nor myself was seasick, a fact Jim commented upon most ungraciously, as he said we took up less room and were far less in the way when suffering from “sleeping-sickness” than we were doing now we thought we were sailors. There’s no pleasing some people!

We landed at a spot some seventy miles up the coast, and not far distant from Cape Cross, where Diego Cam, one of John of Portugal’s intrepid old navigators, placed a padrâo, or stone cross, when he first landed there in 1460 or thereabouts. This cross, from which the Cape takes its name, has long since disappeared, but according to Jim the sculptured socket in which it was set can still be seen on[Page 34] a prominent point of the rock. Probably it was the only part of the monument that the early souvenir-hunters could not take away with them.

However, much as I wished to see it, we did not get to Cape Cross that journey. We landed in a little cave within a short walk of the beach we were in search of, a beach identical with that one we had prospected lower down the coast, and which yielded identical results. We searched it for a week and found no diamonds.

Moreover we wandered inland, for the interior here, though barren and inhospitable, did not present the difficulties of the huge sand-dunes we had encountered lower down. Flat sandy wastes there were, devoid of vegetation, but easily traversed, and these were also broken by frequent barren kopjes, whilst but a few miles inland we saw high, flat-topped mountains. In many of the dry watercourses and on certain spots on the sand-flats we found likely-looking gravel, but never any diamonds, and at the end of ten days we decided to return to Swakopmund, from whence we could pick up a steamer to Luderitzbucht. Jim suggested this course to us, whilst offering, if we so wished, to carry out his original offer to land us there himself. “But,” said he, “if you’re not keen on it, I’ll just drop you at Swakopmund, where you’ll get a boat easier than you would at Walfish Bay. We’ve got something else on up here that might be worth our while—if you really are not keen!” We quite fell in with Jim’s view, for we neither of us relished beating back against headwinds all the way to Luderitzbucht in the cutter; besides, Jim had proved himself a white man right through, and we didn’t want to stand in the way of that mysterious “something else” he had on. We never asked him what it was, but some funny things could be told about those sealing cutters’ doings along the coast in those days—when none of them were particularly keen about the German Customs regulations! Well, good luck [Page 35]to Jim and his “crew” anyway—they were good sorts!

So they landed us at Swakopmund, and before leaving again Jim told us that he expected to be back in Luderitzbucht in about a month, and, if we were still there and cared to do it, he would take us down to a place not far north of the Orange River mouth where he had heard diamonds had been picked up.

But our late experience had shaken our faith in promising-looking gravel patches, and so we omitted to follow up this clue, which, as events proved later, might very probably have led us to discover the famous and fabulously rich Pomona fields. So, with a vague promise to meet again somewhere, we parted from Jim, who cleared away up the coast—ostensibly at least—on his mysterious errand, and whom I never saw again.

The officials at Swakopmund were both surly and suspicious, but luckily our papers were in order, and we could show sufficient funds to satisfy the immigration authorities; and as we found we should have to wait ten days for a steamer, we decided to run up to the capital, Windhuk, after first having a good look round Swakopmund and the immediate vicinity. Disappointed in their efforts to obtain the country’s natural port at Walfish Bay, the Germans had done their best to construct a harbour at Swakopmund, which is really the mouth of the Swakop, or more correctly “Tsoachaub” river. This river, in common with all others of this country, only flows during the summer months, but water can be obtained in abundance almost all along its course by digging in the sand. From a few miles inland its banks are covered with vegetation, and indeed these long dry river oases are a frequent and pleasant feature of this part of the Protectorate.

Although large sums of money must have been spent upon the attempt at a harbour at Swakopmund, it appears to be a very qualified success. There is a stone jetty that offers some protection to tugs in fine weather, but ships have to lie in the roadstead, and when the prevailing gales are blowing landing is both difficult and dangerous. The township boasts[Page 36] quite a number of good buildings, and is a credit to the orderly ideas of German officialism. A good deal of ore was being brought down by rail from Otavi, a copper-mine some 250 miles north-west, connected by a 2-feet gauge line. This and the landing of a tremendous amount of army stores, waggons, and artillery made the port quite a busy one. And an Englishman whom we met at the hotel told us that the amount of stores landed during the latter part of the recent Hottentot and Herero rebellion had been enormous, and that depôts were being built all over the country inland to allow of their storage. Considering that the two races were practically wiped out at the time peace was declared, it is difficult to understand what all these stores and munitions of war are needed for.

We went to Windhuk on the third day, a slow and tedious journey of 237 miles which took us over twenty-four hours to accomplish.