Title: Rajah Brooke

the Englishman as ruler of an eastern state

Author: Sir Spenser St. John

Release date: May 3, 2023 [eBook #70688]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: T. Fisher Unwin, 1897

Credits: Bob Taylor, Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BUILDERS OF

GREATER BRITAIN

Edited by H. F. WILSON, M.A.

Barrister-at-Law

Late Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge

Legal Assistant at the Colonial Office

BUILDERS OF GREATER BRITAIN

1. SIR WALTER RALEGH; the British Dominion of the West. By Martin A. S. Hume.

2. SIR THOMAS MAITLAND; the Mastery of the Mediterranean. By Walter Frewen Lord.

3. JOHN AND SEBASTIAN CABOT; the Discovery of North America. By C. Raymond Beazley, M.A.

4. EDWARD GIBBON WAKEFIELD; the Colonization of South Australia and New Zealand. By R. Garnett, C.B., LL.D.

5. LORD CLIVE; the Foundation of British Rule in India. By Sir A. J. Arbuthnot, K.C.S.I., C.I.E.

6. ADMIRAL PHILLIP; the Founding of New South Wales. By Louis Becke and Walter Jeffery.

7. RAJAH BROOKE; the Englishman as Ruler of an Eastern State. By Sir Spenser St John, G.C.M.G.

8. SIR STAMFORD RAFFLES; England in the Far East. By the Editor.

Builders

of

Greater Britain

Brooke (signature)

RAJAH BROOKE

THE ENGLISHMAN AS RULER OF AN

EASTERN STATE

BY

Sir SPENSER ST JOHN, G.C.M.G.

AUTHOR OF

‘HAYTI; OR, THE BLACK REPUBLIC,’

‘LIFE IN THE FORESTS OF THE FAR EAST,’

ETC.

LONDON

T. FISHER UNWIN

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

MDCCCXCIX

Copyright by T. Fisher Unwin, 1897, for Great Britain and

the United States of America

[Pg xi]

I have undertaken to write the life of the old Rajah, Sir James Brooke, my first and only chief, as one of the Builders of Greater Britain. In his case the expression must be used in its widest sense, as, in fact, he added but an inappreciable fragment to the Empire, whilst at the same time he was the cause of large territories being included within our sphere of influence. And if his advice had been followed, we should not now be troubled with the restless ambition of France in the Hindu-Chinese regions, as his policy was to secure, by well defined treaties, the independence of those Asiatic States, subject, however, to the beneficent influence of England as the Paramount Power, an influence to be used for the good of the governed. Sir James thoroughly understood that Eastern princes and chiefs are at first only[Pg xii] influenced by fear; the fear of the consequences which might follow the neglect of the counsels of the protecting State.

The plan which the Rajah endeavoured to persuade the English Government to adopt was to make treaties with all the independent princes of the Eastern Archipelago, including those States whose shores are washed by the China Sea, as Siam, Cambodia and Annam, by which they could cede no territory to any foreign power without the previous consent of England, and to establish at the capitals of the larger States well-chosen diplomatic agents, to encourage the native rulers not only to improve the internal condition of their countries, but to inculcate justice in their treatment of foreigners, and thus avoid complications with other powers.

Sir James Brooke first attempted to carry out this enlightened policy by concluding treaties with the Sultans of Borneo and Sulu, to secure these States from extinction; the latter treaty was not ratified, however, owing to the timidity of a naval officer, foolishly influenced by a clever Spanish Consul in Singapore, who took advantage of the absence of the Rajah. In the forties and fifties the expansion of Great[Pg xiii] Britain, as is well known, was looked upon with genuine alarm by many of our leading statesmen.

Sir James Brooke, however, was not destined to see the fufilment of his ideas, as a ministry came into power in 1853 which cared nothing for the Further East, and in the hope of consolidating their majority in Parliament sacrificed their noble officer to appease the clamour raised by Joseph Hume and his followers, who, like other zealots, pursued their objects regardless of all the evidence which could be brought to refute their unfounded accusations. Joseph Hume may be called a libeller by profession, who began his career by making his fortune in the East India Company’s service in a very few years—a remarkable achievement; and who afterwards, when in Parliament, brought himself into notoriety by attacking first Sir Thomas Maitland, secondly Lord Torrington, and ultimately Sir James Brooke, whose shoe latchets he was unworthy to unloose.

Sir James had thus but a short career as an English official. He was named Confidential Agent in 1845, Commissioner and Consul-General in 1846, Governor of Labuan in[Pg xiv] 1847, and his return to England in 1851 practically closed his active political connection with England, though he did not resign all his offices until 1854.

But the Rajah did not thus conclude his own career; he returned to Sarawak and devoted all his energies to the development of his adopted country, and of the neighbouring districts. I shall have to relate what extraordinary vicissitudes of fortune he had to encounter, and how after many years of conflict he emerged triumphant, to leave to his successor, Sir Charles Brooke, a small kingdom, well organised as far as Sarawak was concerned, with strongly established positions reaching to Bintulu, which have but increased in influence and in power to further the well-being of the natives of every race and class; and to prove to all who care to interest themselves in the subject, what a gain to humanity has resulted from the old Rajah having had the courage and the forethought to found his rule in a wild country, whose inhabitants, with few exceptions, were till then inimical to Europeans, and mostly tainted by piracy. But he argued truly that these people knew very imperfectly what Englishmen were,[Pg xv] and he determined to show them that some, at all events, were worthy of their confidence, and could devote themselves without reserve to their welfare.

The peculiarity of the Rajah’s system was to treat the natives, as far as possible, as equals; not only equals before the law, but in society. All his followers endeavoured to imitate their chief, and succeeded in a greater or less degree, thus producing a state of good feeling in the country which was probably found nowhere else in the East, except in Perak, one of the Protected States in the Malay Peninsula, into which one of his most able assistants introduced his method of government. I am told that this good feeling, if not the old friendly intimacy between native and European, still exists to a considerable degree throughout the possessions of the present Rajah, which is highly honourable to him and to his officers.

I have not attempted to re-write my account of the Chinese Insurrection (see Chapter VI.). I wrote it when all the events were fresh in my mind, and no subsequent information has rendered it necessary to make any changes. It was a most interesting and important incident[Pg xvi] in the Rajah’s career, and it fixed for ever in the minds of his countrymen how wise and beneficent must have been his rule of the Malays and Dyaks, that they should have stood by him as they did when he appeared before them as a defeated fugitive.

How far-seeing were the Rajah’s views and plans is proved by the fact that his successor has found it unnecessary to change any phase of his policy, whether political or commercial, whether financial, agricultural or judicial; with the growth of the country in population and wealth all has been of course considerably augmented, but the lines on which this great advance has been made were laid by the first Rajah, and that this honour is due to him no one should deny.

As there was but one Nelson, so there has been but one Sir James Brooke. How admirable was the simplicity of his character! So kind and gentle was he in manner, that the poorest, most down-trodden native would approach him without fear, confident that his story would be heard with benevolent attention, and that any wrong would, if possible, be righted. And as[Pg xvii] for the purity of his private life, he was a bright example to all those around him.

It may be thought that I have exaggerated the grandeur of the Rajah’s personality, and the great benefits he conferred on the natives, and that I have been influenced in my views by the warm friendship which existed between us. If there be any who hold this opinion, I would refer them to Mr Alfred Wallace’s work, The Malay Archipelago, in which, after dwelling in a most appreciative manner on the Rajah’s rule in Sarawak, he adds these eloquent words, ‘Since these lines were written his noble spirit has passed away. But though by those who knew him not he may be sneered at as an enthusiastic adventurer, or abused as a hard-hearted despot, the universal testimony of everyone who came in contact with him in his adopted country, whether European, Malay or Dyak, will be that Rajah Brooke was a great, a wise and a good ruler, a true and faithful friend, a man to be admired for his talents, respected for his honesty and courage, and loved for his genuine hospitality, his kindness of disposition and his tenderness of heart.’

[Pg xviii]

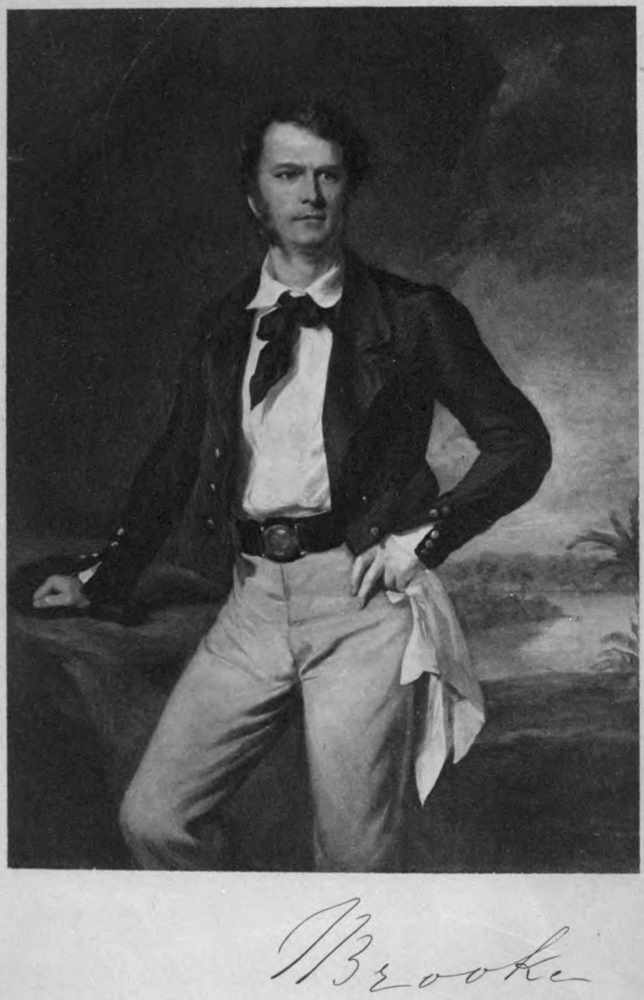

The portrait of Rajah Brooke facing the title page is taken from the picture by Sir Francis Grant, which is one of his best works. It is a most speaking likeness, and I have left it in my will to the Trustees of the National Portrait Gallery, if they will accept it.

SPENSER ST JOHN.

4 Chester Street, S.W.

Note.—I would wish to add a few words to explain why, in the course of this Life of Rajah Brooke, I have not dwelt on the controversy which raged for some years about the character of the Seribas and Sakarang Dyaks. The only person who, to a late period, held to his view that these tribes were not piratical was Mr Gladstone; but after reading my first Life of Rajah Brooke, in which I defended the policy of my old chief with all the vigour I could command, I received the following note from him, which rendered unnecessary any further discussion of the subject:—

February 25, 1880.

My dear Sir,—I thank you very much for sending me your Life of Sir James Brooke, which I shall be anxious to examine with care. I have myself written words about Sir James Brooke which may serve to show[Pg xix] that the difference between us is not so wide as might be supposed, and I fully admit that what I have questioned in his acts has been accepted by his legitimate superiors, the Government and the Parliament.—I remain, yours faithfully,

W. E. Gladstone.

His Excellency Spenser St John.

It is as well that I should publish another letter, to show that Mr Gladstone bore me no ill-will on account of the vigorous way I had attacked him whilst defending the policy of my old chief. I had applied to Lord Granville to be sent out as Special Envoy to renew relations with the Republic of Mexico, and the following is his Lordship’s reply:—

Foreign Office, May 28, 1883.

My dear Sir Spenser,—Many thanks for your note. I have availed myself of your offer, mentioning it to Gladstone, who highly approved (notwithstanding the hard blows you once dealt him), and I have submitted your name to the Queen, who, I feel sure, will sanction the step.—Yours sincerely,

Granville.

It is pleasant to place on record this generosity of feeling in one of our greatest statesmen, whose career has now been closed.

[Pg xxi]

| PAGE | |

| Preface, | xi |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Brooke’s Ancestors and Family—His Early Life—Appointed Ensign in the Madras Native Infantry—Campaign in Burmah—Is wounded and leaves the Service—Makes Two Voyages to China—Death of His Father—Cruise in the Yacht ‘Royalist,’ | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Expedition to Borneo—First Visit to Sarawak—Voyage to Celebes—Second Visit to Sarawak—Joins Muda Hassim’s Army—Brooke’s Account of the Progress of the Civil War—It is ended under the Influence of His active Interference—He Saves the Lives of the Rebel Chiefs, | 11 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Third Visit to Sarawak—Makota intrigues against Brooke—Visit of the Steamer ‘Diana’—He is granted the Government of Sarawak—His Palace—Captain Keppel of H.M.S. ‘Dido’ visits Sarawak—Expedition against the Seribas Pirates—Visit of Sir Edward Belcher—Rajah Brooke’s Increased Influence—Visit to the Straits Settlements—Is wounded in Sumatra—The ‘Dido’ returns to Sarawak—Further Operations—Negotiations with British Government—Captain Bethune and Mr Wise arrive in Sarawak, | 43 |

| CHAPTER IV[Pg xxii] | |

| Sir Thomas Cochrane in Brunei—Attack on Sherif Osman—Muda Hassim in Power—Lingire’s Attempt to take Rajah Brooke’s Head—Massacre of Muda Hassim and Budrudin—The Admiral proceeds to Brunei—Treaty with Brunei—Action with Pirate Squadron—Rajah Brooke in England—Is Knighted on His Return to the East—Visits the Sulu Islands—Expedition against Seribas Pirates, | 71 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Attacks on the Rajah’s Policy—Visits to Labuan, Singapore and Penang—Mission to Siam—The Rajah’s Return to England—Dinner to Him in London—His Remarkable Speech—Lord Aberdeen’s Government appoints a Hostile Commission—The Rajah’s Return to Sarawak—Commission at Singapore—Its Findings, | 103 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Chinese surprise the Town of Kuching—The Rajah and His Officers escape—The Chinese proclaim Themselves Supreme Rulers—They are attacked by the Malays—Arrival of the ‘Sir James Brooke’—The Chinese, driven from Kuching, abandon the Interior and retreat to Sambas—Disarmed by the Dutch, | 141 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Events in the Sago Rivers—The Rajah proceeds to England—Cordial Reception—First Paralytic Stroke—Buys Burrator—Troubles in Sarawak—Loyalty of the Population—The Rajah returns to Borneo—Settles Muka Affairs with Sultan—Installs Captain Brooke as Heir Apparent—Again leaves for England—Sarawak recognised by England—Life at Burrator—Second and Third Attacks of Paralysis—His Death and Will, | 177[Pg xxiii] |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Present Condition of Sarawak—Rajah an Irresponsible Ruler—Sarawak Council—General Council—Residents and Tribunals—Employment of Natives—Agriculture—Trade Returns—The Gold Reefs—Coal Deposits—Varied Population—Impolitic Seizure of Limbang—Missions—Extraordinary Panics—Revenue—Administration of Justice—Civil Service—Alligators—Satisfactory State of Sarawak, | 203 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Present Condition of North Borneo—Lovely Country—Good Harbours on West Coast—Formation of North Borneo Company—Principal Settlements—Telegraphic Lines—The Railway from Padas—Population—Tobacco Cultivation—Gold—The Public Service—The Police of North Borneo—Methods of Raising Revenue—Receipts and Expenditure—Trade Returns—Exports—Interference with Traders—A Great Future for North Borneo, | 232 |

| APPENDIX | |

| Mr Brooke’s Memorandum on His proposed Expedition to Borneo, Written in 1838, Reprinted from Vol. I. of ‘The Private Letters of Sir James Brooke, K.C.B., Rajah of Sarawak.’ Edited by J. C. Templer, Barrister-at-Law (Bentley, 1853), | 259 |

| Index, | 291 |

[Pg xxiv]

| Portrait of Sir James Brooke, after the Picture by Sir Francis Grant, P.R.A., in the possession of the Author, | Frontispiece |

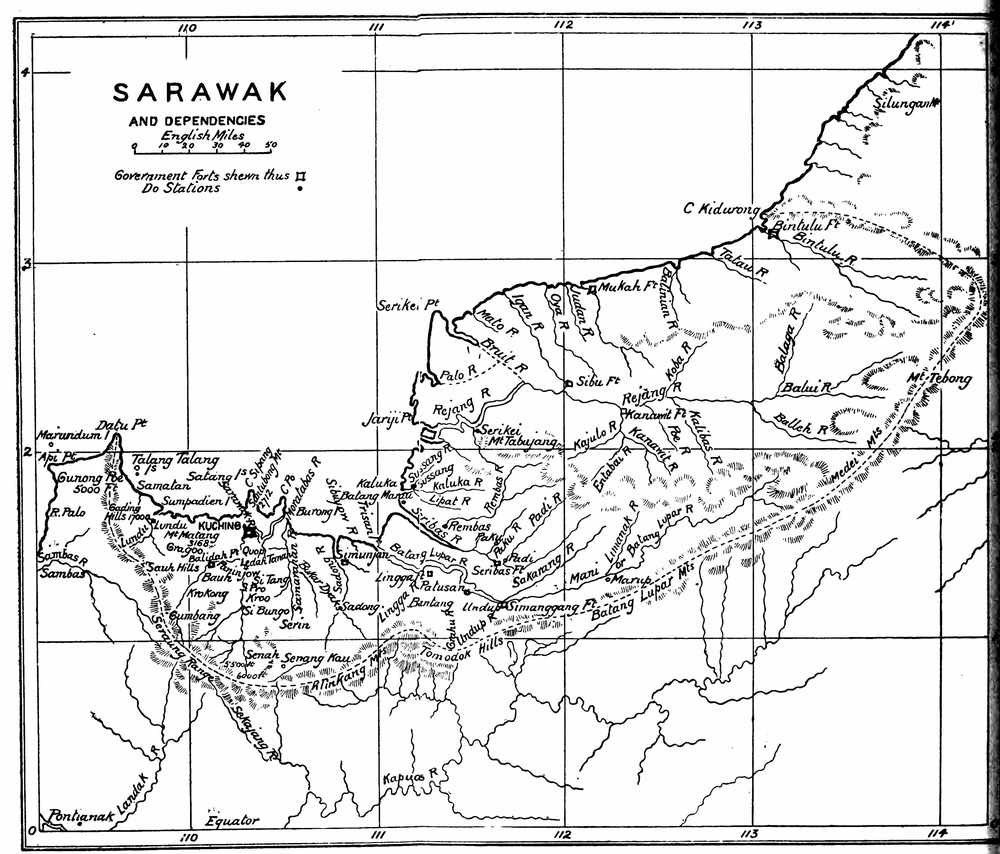

| Map of Sarawak and its Dependencies at the close of Sir James Brooke’s Government, | To face page 49 |

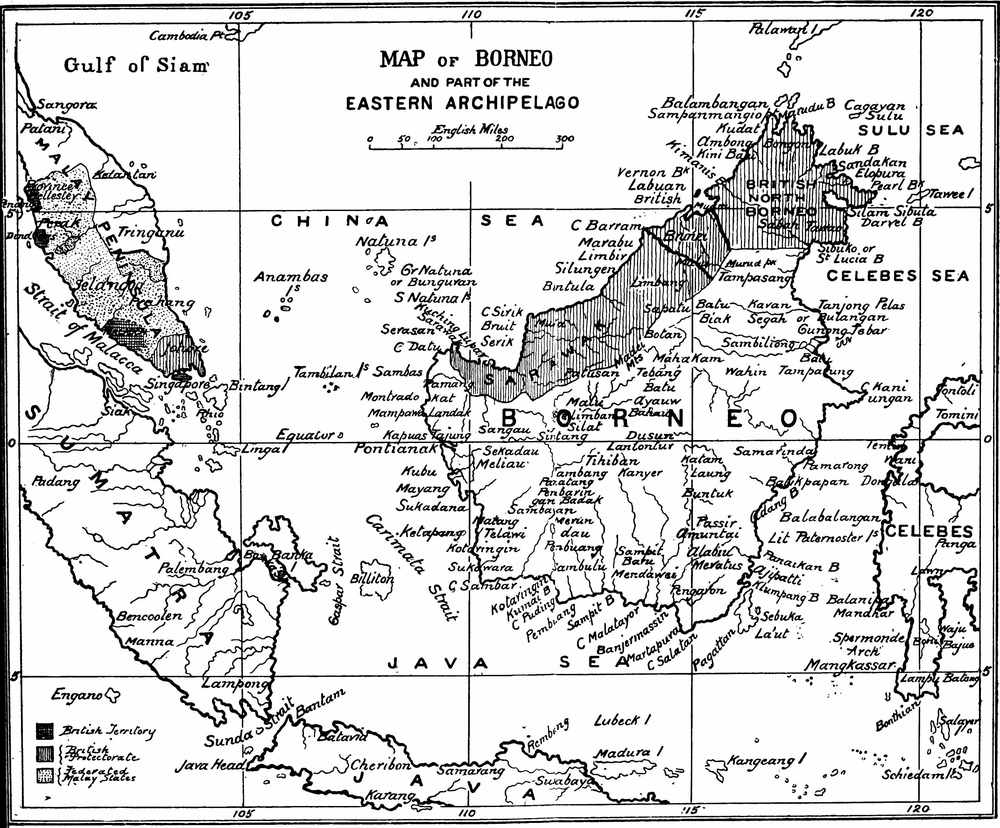

| Map of Borneo and part of the Eastern Archipelago, shewing British Territories, British Protectorates and Federated Malay States, | To face page 96 |

[Pg 1]

Rajah Brooke

BROOKE’S ANCESTORS AND FAMILY—HIS EARLY LIFE—APPOINTED ENSIGN IN THE MADRAS NATIVE INFANTRY—CAMPAIGN IN BURMAH—IS WOUNDED AND LEAVES THE SERVICE—MAKES TWO VOYAGES TO CHINA—DEATH OF HIS FATHER—CRUISE IN THE YACHT ‘ROYALIST’

James Brooke was the second son of Mr Thomas Brooke of the Honourable East India Company’s Bengal Civil Service, and of Anna Maria Stuart, his wife. Their family consisted of two sons and four daughters. One of the latter, Emma, married the Rev. F. C. Johnson, Vicar of White Lackington; another, Margaret, married the Rev. Anthony Savage; the eldest son, Henry, died unmarried after a short career in the Indian army.

Mr Thomas Brooke was the seventh in descent from Sir Thomas Vyner, who, as Lord Mayor of London, entertained Oliver Cromwell in the Guildhall in 1654; whilst his only son, Sir Robert Vyner,[Pg 2] who had taken the opposite side in those civil contests, received Charles II. in the city six years later. On the death of Sir Robert’s only son George the baronetcy became extinct, and the family estate of Eastbury, in Essex, reverted to the two daughters of Sir Thomas Vyner, from one of whom, Edith, the Brooke family is derived, as one of her descendants married a Captain Brooke, who was Rajah Brooke’s great-grandfather.[1]

Mr Thomas Brooke, though not distinguished by remarkable talent, was a straightforward, honest civilian, and his wife was a most lovable woman, who gained the affections of all those with whom she was brought into contact. She always enjoyed the most perfect confidence of her distinguished son. To her are addressed some of his finest letters, in which he pours forth his generous ideas for the promotion of the welfare of the people whom he had been called upon to govern.

James Brooke was born on the 29th of April 1803 at Secrore, the European suburb of Benares, and he remained in India until he was twelve years old, when he was sent to England to the care of Mrs Brooke, his paternal grandmother, who had established herself in Reigate. He shortly afterwards went to Norwich Grammar School, at that time under Dr Valpy, but he remained there only[Pg 3] a couple of years, as, after the freedom of his life in India, discipline was irksome to him, and he ran away home to his grandmother. I never heard him say much about the master, but he loved and was beloved by many of his schoolfellows, and showed even then, by his influence over the boys, that he was a born leader of men.

About this time his parents returned from India and settled at Combe Grove, near Bath, where they collected their children around them. A private tutor was engaged to educate young Brooke, but it could have been only for a comparatively short time, as in 1819 he received his ensign’s commission in the 6th Madras Native Infantry, and soon started for India. He was promoted to his lieutenancy in 1821, and in the following year was made a Sub-Assistant Commissary-General, a post for which, as he used to say, he was eminently unfitted.

When the war with Burmah broke out in 1824 Brooke found himself thoroughly in his element. As the English army advanced into Assam the general in command found himself much hampered in his movements by the want of cavalry. Brooke partly relieved him of this difficulty; his offer to raise a body of horsemen was accepted. By the orders of the general he called for recruits, who could ride, from the different regiments, and soon had under him an efficient body of men, who undertook[Pg 4] scouting duties. He found it difficult to keep them in hand, for the moment they saw an enemy they would charge, and then scatter in every direction where they thought a Burmese might be concealed.

During an action in January 1825 he performed very efficient service with his irregular cavalry, charging wherever any body of Burmese collected. He received the thanks of the general, and his conduct was mentioned in despatches as ‘most conspicuous.’ Two days later occurred an instance of what is almost unknown in our army. A company of native troops had been ordered to attack a stockade manned by Burmese; the English officer in command advanced until, on turning a clump of trees, he came well under fire; then, losing his nerve, he bolted into the jungle. Brooke arrived at that moment, saw the infantry wavering, threw himself from his horse, assumed the command, and thus encouraged they charged the stockade, but Brooke literally ‘foremost, fighting fell.’ Seeing their leader fall, the men were again about to retreat, when Colonel Richards, advancing with reinforcements, restored the fight, and in a few minutes the place was taken, though with heavy loss. No attempts were ever made to turn these strong stockades, and thus the army suffered severely and to no purpose.

I have often heard Sir James Brooke tell the[Pg 5] story. He had been sent out to reconnoitre; found the enemy strongly posted, and suspecting an ambuscade, galloped back to warn his superior officer, but too late, as firing had already commenced, and the infantry, without a leader, were confused. He placed himself at their head, but as he charged he felt a thud, and fell, losing all consciousness. After the action was over, his colonel, who had seen him fall, inquired about young Brooke, and was told that he was dead; but examining the fallen officer himself, found him still alive and had him removed to hospital. A slug had lodged in his lungs, and for months he lay between life and death. It was not, in fact, until August that he was strong enough to be removed, and then only in a canoe. He was paddled down a branch of the Bramapootra, rarely suffering from pain, but gazing pensively at the fast-running stream and the fine jungle that lined its banks; in after life it seemed to him as a dream.

On the Medical Board at Calcutta reporting that a change of climate was necessary, he was given a long furlough. He returned to England and joined his family at Bath. The voyage did him some good, but the wound continued very troublesome, and at times it appeared as if he could not recover. After the slug had been extracted, however, he gradually got better, so that in July 1829 he was enabled to embark on board the Company’s ship[Pg 6] Carn Brae; but fate was against his again joining the Indian army. This vessel was wrecked, and when, in the following March, he sailed for the East on board the Huntley Castle, she was so delayed by bad weather, that when she called in at Madras Brooke found that he could not join his regiment before the legal expiration of his leave. He consequently resigned the service and proceeded in the Huntley Castle to China.

Brooke never cared much for the East India Company’s service, and as he had formed friendships on board the Huntley Castle he preferred continuing in her to remaining idle in India awaiting the Directors’ decision, which, even if favourable, could scarcely arrive before twelve months had expired. The decision was favourable; but as young Brooke had in the meantime left Madras the matter dropped. The Indiaman first touched at the Island of Penang, one of the Straits Settlements, and here Brooke had an opportunity of seeing what lovely islands there were in the Further East. It is not necessary to dwell on this voyage, as nothing of importance occurred during it; but his stay in China made a deep impression on Brooke’s mind. He saw how the Chinese ill-treated and bullied our countrymen, and how the East India Company submitted to every insult in order not to imperil their trade.

After the usual stay in the Canton River, the Huntley Castle returned to England, and Brooke found himself at home with no employment whatever.[Pg 7] He formed many projects; the favourite one, which he had discussed with the officers of the Huntley Castle, was to purchase a ship, load her with suitable goods, and sail for China or the adjacent markets. But as none of the friends had any capital, Brooke confided their views to his father, and naturally met with the objection that his son was not a trader and never could become one. However, in the end, the young fellow prevailed. The brig Findlay was bought, laden with goods, and with his partner, Kennedy, formerly of the Huntley Castle, and his friend, Harry Wright, also of the same vessel, he set sail for the Further East. This voyage was not destined to be a success. Brooke wished to introduce on board the easy discipline of a yacht, whilst Kennedy, who was captain, went to the other extreme and would insist upon the severe discipline of the navy, without its safeguards. Differences soon arose, and as they found trade by interlopers was not encouraged, Brooke went to see Mr Jardine, of the firm of Messrs Jardine, Matheson & Company, and laid the case before him. The shrewd man of business could not but smile at the idea of this elegant young soldier managing a trading speculation. He, however, agreed to buy vessel and cargo, and told the partners they had better leave the matter in his hands. No objection was raised, and Mr Jardine so judiciously invested in silks the amount he had arranged to pay, that in the end comparatively little loss accrued, none of which was allowed by Brooke to fall on Kennedy.

[Pg 8]

On his return to England Brooke wearied of continued leisure, and although he yachted about the Southern Coast and the Channel Islands, he longed for some sphere of action which could bring his great abilities into play. The death of his father, in December 1835, gave him complete independence. The fortune left was sufficient to provide for his wife, and to give to each of his children £30,000. Brooke now decided to carry out the plan he had formed since his first voyage to China, which was to buy a small vessel and start on a voyage of discovery. But this time there were to be no partners and no trade; he intended to be complete master in his own ship. He ultimately fixed his choice on the Royalist, a schooner yacht of about 142 tons burden. He was delighted with his purchase, and soon tried her qualifications by starting in the autumn of 1836 for a cruise in the Mediterranean. There he visited most of the principal cities, including Constantinople, which in after years afforded him a constant subject of conversation with the Malays, who interested themselves in every detail of his visit. ‘Roum’ to them is still the great city where dwells the head of the Mohammedan religion.[2] Among those who accompanied him on this cruise was his nephew, John Brooke[Pg 9] Johnson, afterwards known as Captain Brooke, and also John Templer, who was then and for many years afterwards one of his warm friends and enthusiastic admirers.

Though determined to make a voyage of discovery in the Eastern Archipelago, Brooke was not able to leave England till December 1838. He employed all his spare time in studying the subject, finding out what was already known, and drawing attention to his plans by a memoir he wrote on Borneo and the neighbouring islands, summaries of which were published in the Athenæum and in the Journal of the Geographical Society. He felt a great admiration for Sir Stamford Raffles, and ardently desired to carry out his views in dealing with the peoples of the Further East.

How well Brooke sums up the feelings which prompted him to undertake what was in every respect a perilous enterprise! ‘Could I carry my vessel to places where the keel of European ship never before ploughed the waters; could I plant my foot where white man’s foot had never before been; could I gaze upon scenes which educated eyes had never looked on, see man in the rudest state of nature, I should be content without looking to further rewards.’

It is difficult, even under the most favourable circumstances, to convey to the mind of a reader an exact portrait of the man whose deeds you desire to chronicle; but as I lived for nearly twenty years with James Brooke, I feel I know him well in all his strength and his weakness. Let me try to describe[Pg 10] him. He stood about five feet ten inches in height; he had an open, handsome countenance; an active, supple frame; a daring courage that no danger could daunt; a sweet, affectionate disposition which endeared him to all who knew him well. Those whom he attended in sickness could never forget his almost womanly tenderness, and those who attended him, his courageous endurance. His power of attaching both friends and followers was unrivalled, and this extended to nearly every native with whom he came in contact. His few failings were his too great frankness, his readiness to believe that men were what they professed to be, or should have been, and (for a short time in latter years) that the unsophisticated lower classes were more to be trusted and relied on than those above them in birth and education. His only weaknesses were, in truth, such as arose from his great goodness of heart and his confiding nature.

No painter ever succeeded better in conveying a man’s self into a portrait than Sir Francis Grant in his picture of Sir James Brooke. I have it now before me, and all I have said of his appearance may be seen at a glance. Although thirty years have passed since we lost him, he remains as much enshrined as ever in the hearts of his few surviving friends.

This brief preliminary chapter ended, I will now describe Brooke’s voyage to Borneo, and the events which succeeded that remarkable undertaking.

[1] These details are taken from Miss Jacob’s Life of the Rajah of Sarawak, Vol. I., page 1.

[2] When I first went to live in Brunei, the Sultan of Borneo’s capital, there was living there an old haji who was visiting Egypt at the time of Buonaparte’s invasion, and who remembered well the Battle of the Nile and the subsequent expulsion of the French by the English.

[Pg 11]

EXPEDITION TO BORNEO—FIRST VISIT TO SARAWAK—VOYAGE TO CELEBES—SECOND VISIT TO SARAWAK—JOINS MUDA HASSIM’S ARMY—BROOKE’S ACCOUNT OF THE PROGRESS OF THE CIVIL WAR—IT IS ENDED UNDER THE INFLUENCE OF HIS ACTIVE INTERFERENCE—HE SAVES THE LIVES OF THE REBEL CHIEFS

Brooke sailed from Devonport on December 16, 1838, in the Royalist, belonging to the Royal Yacht Squadron, which, in foreign ports, admitted her to the same privileges as a ship of war, and enabled her to carry a white ensign. As the Royalist is still an historic character in the Eastern Archipelago, I must let the owner describe her as she was in 1838. ‘She sails fast; is conveniently fitted up; is armed with six six-pounders, and a number of swords and small arms of all sorts; carries four boats and provisions for four months. Her principal defect is being too sharp in the floor. She is a good sea boat, and as well calculated for the service as could be desired. Most of the hands have been with me for three years, and the rest are highly recommended.’

[Pg 12]

Whilst the Royalist is speeding on prosperously towards Singapore, and calling at Rio Janeiro and the Cape, let me sum up in a few words the object of the voyage.

The memorandum[3] which Brooke drew up on the then state of the Indian Archipelago (1838), shows how carefully he had studied the whole subject. He first expounds the policy which England should follow if she wished to recover the position which she wantonly threw away after the peace of 1815; he then explains what he proposed to do for the furtherance of our knowledge of Borneo and the other great islands to the East. Circumstances, however, as he anticipated might be the case, made him change the direction of his first local voyage.

The Royalist arrived in Singapore in May 1839, and remained at that port till the end of July, refitting and preparing for future work. There Brooke received news which induced him to give up for the present the proposed voyage to Marudu Bay, the northernmost district of Borneo, and visit Sarawak instead. Rajah Muda Hassim, uncle to the Sultan of Brunei, was then residing there, and being of a kindly disposition, had taken care of the crew of a shipwrecked English vessel, and sent the men in safety to Singapore. This unlooked-for conduct on the part of a Malay chief roused the interest of the Singapore merchants, and Brooke was requested to[Pg 13] call in at Sarawak and deliver to the Malay prince a letter and presents from the Chamber of Commerce.

This was a fortunate diversion of his voyage, as at that time Marudu was governed by a notorious pirate chief. The bay was a rendezvous for some of the most daring marauders in the Archipelago, and nothing could have been done there to further our knowledge of the interior.

All being ready, and the crew strengthened by eight Singapore Malay seamen,[4] athletic fellows, capital at the oar, and to save the white men the work of wooding and watering, the Royalist sailed for Borneo on the 27th of July, and in five days was anchored off the coast of Sambas. All the charts were found to be wrong, so that every care had to be taken whilst working up the coast. A running survey was made, and on the 11th August Brooke found himself at the mouth of the Sarawak river.

When Brooke first arrived in Borneo, the Sultan Omar Ali claimed all the coast from the capital to Tanjong Datu, whilst further south was Sambas, under the influence of the Dutch; but the rule of Omar Ali was little more than nominal, as each chief in the different districts exercised almost unlimited power, and paid little or no tribute to the central Government.

At the time of Brooke’s first visit to Sarawak the[Pg 14] Malays of the country had broken out into revolt against the oppressive rule of Pangeran Makota, Governor of the district, and fearing that they might call in the aid of the Sambas Malays, and thus place the country under the control of the Dutch, the Sultan sent down Rajah Muda Hassim, his uncle and heir-presumptive, to endeavour to stifle the rebellion; but three years had passed, and he had done nothing. He could prevent the rebels from communicating with the sea, but he was powerless in the interior.

On hearing of the arrival of the Royalist at the mouth of the river, Muda Hassim despatched a deputation to welcome the stranger and invite him to the capital—rather a grand name for a small village. Brooke soon got his vessel under weigh, and proceeded up the Sarawak, and after one slight mishap, anchored the next day opposite the rajah’s house, and saluted his flag with twenty-one guns.

Muda Hassim received Brooke in state, and the interview is thus described: ‘The rajah was seated in his hall of audience, which, outside, is nothing but a large shed, erected on piles, but within decorated with taste. Chairs were arranged on either side of the ruler, who occupied the head seat. Our party were placed on one hand, and on the other sat his brother Mahommed, and Makota and some other of the principal chiefs, whilst immediately behind him his twelve younger brothers were seated. The dress of Muda Hassim was simple, but of rich material, and[Pg 15] most of the principal men were well, and even superbly dressed. His countenance is plain, but intelligent and highly pleasing, and his manners perfectly easy. His reception was kind, and, I am given to understand, highly flattering. We sat, however, trammelled by the formalities of state, and our conversation did not extend beyond kind inquiries and professions of friendship.’ Brooke’s next interview was more informal, and closer relations were established, which encouraged him to send his interpreter, Mr Williamson, to ask permission to visit the Dyaks. This was readily granted, but before commencing his explorations, he received a private visit from Pangeran Makota. He was probably the most intelligent Malay whom we ever met in Borneo, frank and open in manner, but looked upon as the most cunning of the rajah’s advisers. He was much puzzled, as were indeed all the nobles, as to the true object of Brooke’s visit to Borneo, and confident in his power, determined to find it out. And though Brooke had in reality no object but geographical discovery, he could not convince his guest of that fact, who scented some deep intrigue under the guise of a harmless visit.

Brooke now took advantage of the rajah’s permission to explore some of the neighbouring rivers, and he was shown first the fine agricultural district of Samarahan, but only met Malays. His next visit was to the Dyak tribe of Sibuyows, who lived on the river Lundu, which discharged its waters not many miles[Pg 16] from Cape Datu, the southern boundary of Borneo proper.

From Tanjong Datu, as far as the river Rejang, the interior populations are called Dyaks—Land or Sea Dyaks—the former, a quiet, agricultural people, living in the far interior, plundered and oppressed by the Malays; they are to be found in Sarawak, Samarahan and Sadong. The Sea Dyaks were much more numerous, and though under the influence of the Malays and Arab adventurers, were too powerful ever to be ill-treated. They occupied the districts of Seribas and Batang Lupar, and those on the left bank of the Rejang, with a few scattered villages in other parts, such as this Sibuyow tribe on the Lundu.

The chief of this branch of the Sea Dyaks, the Orang Kaya Tumangong, was always a great favourite of the English officers in Sarawak. His was the first tribe that Brooke visited, and he then formed a high opinion of the brave man and his gallant sons, who were faithful unto death, and who were always the foremost when any fighting was on hand.

The village they occupied was, in fact, but one huge house, nearly six hundred feet in length, and the inner half divided into fifty separate residences for the fifty families that constituted the tribe. The front half of this long building was an open space, which was used by the inhabitants during the day for every species of work, and at night was occupied by the widowers,[Pg 17] bachelors and boys as their bedroom. The Sea Dyaks are much cleaner than the Land Dyaks, and the girls of Sakarang, for instance, looked as well washed as any of their sisters in May Fair.

The distinction of Land and Sea Dyaks was due to the fact that the former never ventured near the salt water, whilst the latter boldly pushed out to sea in their light bangkongs or war boats, and cruised along at least two thousand miles of coast. When the Royalist first arrived in Sarawak the majority of the Sea Dyaks were piratically inclined. This practice arose in all probability from their inter-tribal wars—the Seribas against the Lingas and Sibuyows—and from their custom of seeking heads—almost a religious observance. When a party of young men went out to search for the means of marrying, and had failed to secure the heads of enemies, we can easily imagine their not being too particular about killing any weaker party they might meet, even if they were not enemies, and, finding it met with no retaliation, continuing the practice. In this they were encouraged by the Malay chiefs who lived among them, and who obtained, on easy terms, the women and children captives who fell into the hands of the Dyak raiders. Although the Linga and Sibuyow branches of the Sea Dyaks hunted for heads, they were the heads of their enemies, whilst the Seribas, and, in a lesser degree, the Sea Dyaks of the Sakarang and the Rejang spared no one they could overcome.

[Pg 18]

Brooke’s next visit was to the river Sadong, to the north-east of Sarawak, and there he met Sherif Sahib, a great encourager of piracy of every kind. Sometimes he received the Lanuns,[5] the boldest marauders who ever invested the Far Eastern seas, bought their captives and supplied them with food, whilst at others he would aid the Seribas and Sakarangs in their forays on the almost defenceless tribes of the interior, or share their plunder acquired on the coasts of the Dutch possessions.

Finding that the rebellion in the interior of the Sarawak would prevent him from visiting it, Brooke decided to return to Singapore. After a friendly parting with Muda Hassim, whose last words were, ‘Do not forget me,’ the Royalist fell down the river. The night before Brooke had settled to sail he was joined by a small Sarawak boat with a dozen men, who were to pilot him out; but about midnight shouts were heard from the shore of ‘Dyak! Dyak’! In an instant a blue light was burnt on board the yacht and a gun fired, and then there came a dead silence. Brooke sprang into a boat and pushed off to the Malay prahu, to find half the crew wounded. It seemed that a cruising party of Seribas Dyaks had no doubt seen the fire lighted on the shore, and had noiselessly floated up with the flood tide and attacked the Malays, not[Pg 19] observing in the dark night the Royalist at anchor. This occurrence showed how necessary it was to be on one’s guard at all times.

The news brought by Brooke was well received in Singapore, as it opened up a new country to British commerce, and prevented the Dutch gaining a footing there, with their vexatious trade regulations, which practically debarred native vessels from visiting British ports.

As the Rajah Muda Hassim had assured his English visitor that the rebellion in the interior of Sarawak would collapse before the next fine season, he decided to pass the interval in visiting Celebes, a most attractive island, then but imperfectly known.

No part of Brooke’s journals is more interesting than the account of his experiences in Bugis land. They are, however, simple travels, without many personal incidents to be noted; but here, as elsewhere, he acquired the same ascendency over the natives, and the memory of his visit remained impressed on the minds of the Bugis rulers, who followed his advice in regulating their kingdoms, and especially listened to his counsels when he pointed out the danger of entering into armed conflict with their Dutch neighbours.

The following observations extracted from Brooke’s journals are remarkable: ‘I must mention the effect of European domination in the Archipelago. The first voyagers from the West found[Pg 20] the natives rich and powerful, with strong established governments and a thriving trade. The rapacious European has reduced them to their present position. Their governments have been broken up, the old states decomposed by treachery, bribery and intrigue, their possessions snatched from them under flimsy pretences, their trade restricted, their vices encouraged, their virtues repressed, and their energies paralysed or rendered desperate, till there is every reason to fear the gradual extinction of the Malay. Let these considerations, fairly reflected on and enlarged, be presented to the candid and liberal mind, and I think that, however strong the present prepossessions, they will shake the belief in the advantages to be gained by European ascendency, as it has heretofore been conducted, and will convince the most sceptical of the miseries immediately and prospectively flowing from European rule as generally constituted.’

The above observations naturally apply to the Dutch and Spanish systems, which at that time alone had sway in the Archipelago, as England, with its small trading depots, did not actively interfere with the native princes. Yet it must be confessed that Borneo proper, which had generally escaped interference from their European neighbours, fell from a position fairly important to the most degraded state, entirely owing to the incapacity of its native rulers and not to outside influences.

[Pg 21]

The visits to Sarawak and Celebes tended to confirm Brooke’s convictions that, if England would but act on a settled plan and on a sufficient scale, she could still save and develop the independent native states, without any necessity of occupying them.

In the year 1776 the Sultan of Sulu ceded to England all his possessions in the north of Borneo, and the East India Company formed a small settlement on the Island of Balambangan; this being on a very inefficient scale, was easily surprised by pirates and destroyed. Later on another attempt was made by the Company to establish themselves on the island, but it was soon abandoned.

Brooke, after carefully studying the subject, came to the same conclusion as Sir Stamford Raffles and Colonel Farquhar had done before him, that it was a mistake to take small islands; but that, on the contrary, this country should establish a settlement on the mainland of Borneo. As all the independent states of the Archipelago are filled with a maritime population, islands are not so safe from attack as the mainland, where the interior population is rarely warlike. He recommended that England should take possession of Marudu Bay, establish herself strongly there, be constantly supported by the navy, and from thence the Governor, with diplomatic powers, could visit all the independent chiefs and make such treaties with them as would prevent their being absorbed by[Pg 22] other European States. His policy was of the most liberal kind; he would have sought no exclusive trade privileges, but he would have preserved their political independence. He would have established in the more important states carefully-selected English agents, to encourage the chiefs in useful reforms and to prevent restrictions on commerce. On the mainland he would not have instantly established English rule, except in a well-chosen, central spot, and there he would have awaited the invitation of the chiefs to send an English officer to aid them in governing.

Had this great plan been executed on a suitable scale Brooke’s name would have been enshrined among the greatest builders of the British Empire. It is not too late even now; but where shall we find another Brooke to carry it out? North Borneo is at present under the protection of Great Britain, but it is owned and administered by a Chartered Company, and in these days cannot, under such conditions, hold the same position as a Crown colony.

The time seems propitious. The Spaniards have lost their hold over the Philippines, and Sulu and the great island of Mindanau will soon be free from their depressing influence; even the Dutch are acting on a more enlightened system, which would be encouraged, if England took an active interest in the Archipelago. The North Borneo Company would[Pg 23] scarcely refuse a proposal to place the country under our direct rule, and with another Sir Hugh Low it might be made a valuable possession, and would gradually dominate the whole of the Archipelago.

The Philippines will now be governed by one of the most progressive nations in the world, and the effect of their rule will be far-reaching. It would appear to be advisable that Great Britain should simultaneously take over North Borneo, as the conditions heretofore existing have so completely changed.

From Celebes Brooke returned to Singapore to refit. His plans were to visit Borneo again, then proceed to Manila, and so home by Cape Horn. He arrived at our settlement in May, left it again in August, and reached Sarawak on the 29th, to find himself cordially received by Muda Hassim. The war was not over, nor was the end of it in sight. A few half-starved Dyaks had deserted the Sarawak Malays, and come into the Bornean camp to be fed; but the route to Sambas was still open, and it was suspected that supplies were furnished by the Sultan of Sambas, who coveted the territory.

After considerable discussion and consideration, Brooke thought he would visit the headquarters of the army which was supposed to be besieging the enemy; but he found it seven miles below the principal hostile fort. The spot was called Ledah Tanah, or the tongue of land, where the two branches of the river meet. It was the site of the[Pg 24] old capital, and even when I was there some ten years later the iron-wood posts of the houses still existed, untouched by time, though over sixty years in use. As Brooke expected, Makota, at the head of the army, was doing nothing, and as he rejected the advice of his white visitor, and seemed determined not to advance nearer to the enemy, Brooke returned to Sarawak, and even announced his departure, as the North-East monsoon was coming on, and he did not wish to face it on his voyage to Manila. However, Muda Hassim appeared to feel his departure so acutely, that his heart smote him, and he agreed to visit the army once more, particularly as the Land Dyaks were now really leaving the rebels and joining the Bornean forces. He therefore returned to the camp, and by his energy compelled Makota to act. The stockade at Ledah Tanah was pulled down and moved to within a mile of the enemy’s chief fort, Balidah, and gradually stockade after stockade was built, until the most commanding one was erected within three hundred yards of the hostile fort. Brooke sent to the yacht for two six-pounders and a sufficient supply of ammunition, and, with the aid of his men, soon battered down the weak defences of the enemy, and then proposed an assault. But this bold advice was looked upon as insanity, and though promises to advance were freely given, when it came to action they all hung back. At length, wearied with this procrastination, Brooke, in spite of the entreaties of all[Pg 25] the native chiefs, embarked his guns and returned to the Royalist, and sent word to the rajah that his stay was utterly useless; but when Muda Hassim heard the decision, ‘his deep regret was so visible that even all the self-command of the native could not disguise it. He begged, he entreated me to stay, and offered me the country, its government and its trade, if I would only stop and not desert him.’

Though Brooke could not accept the grant then, as it would have been extracted from the rajah’s deep distress, he agreed to return to the army; and once more the guns were embarked in the boats, and every man who could be spared from the Royalist accompanied Brooke to the front. There he met Budrudin, Muda Hassim’s favourite brother, with whom he soon contracted a friendship which ended only with the Malay prince’s life. He was brave, frank and intelligent; he quickly appreciated the noble character of the white leader of men, and ever after he fully trusted him.

The episodes of the closing campaign of this civil war were so amusing, that although the story has been published several times, I cannot refrain from repeating it again in the words of the English chief.[6]

‘On the 10th December we reached the fleet and disembarked our guns, taking up our residence in a house, or rather shed, close to the water. The[Pg 26] rajah’s brother, Pangeran Budrudin, was with the army, and I found him ready and willing to urge upon the other indolent pangerans the proposals I made for vigorous hostilities. We found the grand army in a state of torpor, eating, drinking and walking up to the forts and back again daily; but having built these imposing structures, and their appearance not driving the enemy away, they were at a loss what to do next, or how to proceed. On my arrival, I once more insisted on mounting the guns in our old forts, and assaulting Balidah under their fire. Makota’s timidity and vacillation were too apparent; but in consequence of Budrudin’s overawing presence he was obliged, from shame, to yield his assent. The order for the attack was fixed as follows: our party of ten (leaving six to serve the guns) were to be headed by myself. Budrudin, Makota, Subtu and all the lesser chiefs were to lead their followers, from sixty to eighty in number, by the same route, whilst fifty or more Chinese, under their captain, were to assault by another path to their left. Makota was to make the paths as near as possible to Balidah, with his Dyaks, who were to extract the sudas and fill up the holes. The guns having been mounted, and their range ascertained the previous evening, we ascended to the fort about eight a.m., and at ten opened our fire and kept it up for an hour. The effect was severe. Every shot told upon their thin defences of wood, which fell in many places so as to leave storming[Pg 27] breaches. Part of the roof was cut away and tumbled down, and the shower of grape and canister rattled so as to prevent their returning our fire, except from a stray rifle. At mid-day the forces reached the fort, and it was then discovered that Makota had neglected to make any road because it rained the night before! It was evident that the rebels had gained information of our intentions as they had erected a fringe of bamboo along their defences on the very spot we had agreed to mount. Makota fancied the want of a road would delay the attack; but I well knew that delay was equivalent to failure, and so it was at once agreed that we should advance without any path. The poor man’s cunning and resources were now nearly at an end. He could not refuse to accompany us, but his courage could not be brought to the point, and pale and embarrassed he retired. Everything was ready—Budrudin, the Capitan China and myself, at the head of our men—when he once more appeared, and raised a subtle point of etiquette, which answered his purpose. He represented to Budrudin that the Malays were unanimously of opinion that the rajah’s brother could not expose himself in an assault; that the dread of the rajah’s indignation far exceeded their dread of death; and in case any accident happened to him, his brother’s fury would fall on them. Budrudin was angry, I was angry too, and the doctor most angry of all; but anger was unavailing. It was clear[Pg 28] they did not intend to do anything in earnest; and after much discussion, in which Budrudin insisted if I went he should likewise go, and the Malays insisted that if he went they would not go, it was resolved that we should serve the guns, whilst Abong Mia and the Chinese, not under the captain, should proceed to the assault. But its fate was sealed, and Makota had gained his object; for neither he nor Subtu thought of exposing themselves to a single shot. Our artillery opened and was beautifully served. The hostile forces attempted to advance, but our fire completely subdued them, as only three rifles answered us, by one of which a seaman was wounded in the hand, but not seriously. Two-thirds of the way the storming party proceeded without the hostile army being aware of their advance, and they might have reached the very foot of the hill without being discovered, had not Abong Mia, from excess of piety and rashness, began most loudly to say his prayers. The three rifles began then to play on them. One Chinaman was killed, the whole halted, the prayers were more vehement than ever, and after squatting under cover of the jungle for some time they all returned. It was only what I expected, but I was greatly annoyed by their cowardice and treachery—treachery to their own cause. One lesson, however, I learnt, and that was, that had I assaulted with our small party, we should assuredly have been victimised. The very evening of the failure the rajah came[Pg 29] up the river. I would not see him, and only heard that the chiefs got severely reprimanded; but the effects of reprimand are lost where cowardice is stronger than shame. Inactivity followed, two or three useless forts were built, and Budrudin, much to my regret and to the detriment of the cause, was recalled.

‘Amongst the straggling arrivals I may mention Pangeran Dallam, with a number of men, consisting of the Orang Bintulu, Meri, Muka and Kayan Dyaks from the interior. Our house, or, as it originally stood, our shed, deserves a brief record. It was about twenty feet long, with a loose floor of reeds and an attap or palm-leaf roof. It served us for some time, but the attempts at theft obliged us to fence it in and divide it into apartments—one at the end served for Middleton, Williamson and myself. Adjoining it was the storeroom and hospital, and the other extreme belonged to the seamen. Our improvements kept pace with our necessities. Theft induced us to shut in our house at the sides, and the unevenness of the reeds suggested the advantage of laying a floor of the bark of trees over them, which, with mats over all, rendered our domicile far from uncomfortable. Our forts gradually extended to the back of the enemy’s town, on a ridge of swelling ground, whilst they kept pace with us on the same side of the river on the low ground. The inactivity of our troops had long become a by-word amongst us. It was, indeed,[Pg 30] truly vexatious, but it was in vain to urge them on, in vain to offer assistance, in vain to propose a joint attack, or even to seek support at their hands; promises were to be had in plenty, but performances never.

‘At length our leaders resolved on building a fort at Sekundis, thus outflanking the enemy and gaining the command of the upper course of the river. The post was certainly an important one, and in consequence they set about it with the happy indifference which characterises their proceedings. Pangeran Illudin (the most active amongst them) had the building of the fort, assisted by the Orang Kaya Tumangong of Lundu. Makota, Subtu and others were at the next fort, and by chance I was there likewise; for it seemed to be little apprehended that any interruption would take place, as the Chinese and the greater part of the Malays had been left in the boats. When the fort commenced, however, the enemy crossed the river and divided into two bodies, the one keeping in check the party at Pangeran Gapoor’s fort, whilst the other made an attack on the works. The ground was not unfavourable for their purpose, for Pangeran Gapoor’s fort was separated from Sekundis by a belt of thick wood which reached down to the river’s edge. Sekundis itself, however, stood on clear ground, as did Gapoor’s fort. I was with Makota at the latter when the enemy approached through the jungle. The two[Pg 31] parties were within easy speaking distance, challenging and threatening each other, but the thickness of the jungle prevented our seeing or penetrating to them. When this body had advanced, the real attack commenced on Sekundis with a fire of musketry, and I was about to proceed to the scene, but was detained by Makota, who assured me there were plenty of men, and that it was nothing at all. As the musketry became thicker, I had my doubts when a Dyak came running through the jungle, and with gestures of impatience and anxiety begged me to assist the party attacked. He had been sent by my old friend the Tumangong of Lundu, to say they could not hold the post unless supported. In spite of Makota’s remonstrances, I struck into the jungle, winded through the narrow path, and, after crossing an ugly stream, emerged on the clear ground. The sight was a pretty one. To the right was the unfinished stockade, defended by the Tumangong; to the left, at the edge of the forest, about twelve or fifteen of our party, commanded by Illudin, whilst the enemy were stretched along between the points, and kept up a sharp-shooting from the hollow ground on the bank of the river. They fired and loaded and fired, and had gradually advanced on the stockade, as the ammunition of our party failed; and as we emerged from the jungle, they were within twenty or five-and-twenty yards of the defence. A glance immediately showed me the advantage of our position,[Pg 32] and I charged with my Englishmen across the padi field, and the instant we appeared on the ridge above the river, in the hollows of which the rebels were seeking protection, their rout was complete. They scampered off in every direction, whilst the Dyaks and Malays pushed them into the river. Our victory was decisive and bloodless; the scene was changed in an instant, and the defeated foe lost arms and ammunition either on the field of battle or in the river, and our exulting conquerors set no bounds to their triumph.

‘I cannot omit to mention the name of Si Tundu, a Lanun, the only native who charged with us. His appearance and dress were most striking, the latter being entirely of red, bound round the waist, arms, forehead, etc., with gold ornaments, and in his hand his formidable Bajuk sword. He danced, or rather galloped, across the field close to me, and, mixing with the enemy, was about to despatch a haji, or priest, who was prostrate before him, when one of our people interposed, and saved him by stating that he was a companion of our own. The Lundu Dyaks were very thankful for our support, our praises were loudly sung, and the stockade was concluded. After the rout, Makota, Subtu and Abong Mia arrived on the field; the last, with forty followers, had ventured half way before the firing ceased, but the detachment, under a paltry subterfuge, halted so as not to be in time. The enemy might have had fifty men at the attack. The defending party consisted[Pg 33] of about the same number, but the Dyaks had very few muskets. I had a dozen Englishmen, Subu, one of our Singapore boatmen, and Si Tundu. Sekundis was a great point gained, as it hindered the enemy from ascending the river and seeking supplies.

‘Makota, Subtu and the whole tribe arrived as soon as their safety from danger allowed, and none were louder in their own praise, but, nevertheless, their countenances evinced some sense of shame, which they endeavoured to disguise by the use of their tongues. The Chinese came really to afford assistance, but too late. We remained until the stockade of Sekundis was finished, while the enemy kept up a wasteful fire from the opposite side of the river, which did no harm.

‘The next great object was to follow up the advantage by crossing the stream, but day after day some fresh excuse brought on fresh delay, and Makota built a new fort and made a new road within a hundred yards of our old position. I cannot detail further our proceedings for many days, which consisted, on my part, in efforts to get something done, and on the others, a close adherence to the old system of promising everything and doing nothing. The Chinese, like the Malays, refused to act; but on their part it was not fear, but disinclination. By degrees, however, the preparations for the new fort were complete, and I had gradually gained over a party of the natives to my views; and, indeed, amongst the Malays,[Pg 34] the bravest of them had joined themselves to us, and what was better, we had Datu Pangerang and thirteen Illanuns, and the Capitan China allowed me to take his men whenever I wanted them. My weight and consequence was increased, and I rarely moved now without a long train of followers. The next step, whilst crossing the river was uncertain, was to take my guns up to Gapoor’s fort, which was about six or seven hundred yards from the town, and half the distance from a rebel fort on the river’s bank.

‘Panglima Rajah, the day after our guns were in battery, took it into his head to build a fort on the river’s side, close to the town in front, and between two of the enemy’s forts. It was a bold undertaking for the old man after six weeks of uninterrupted repose. At night, the wood being prepared, the party moved down, and worked so silently that they were not discovered till their defence was nearly finished, when the enemy commenced a general firing from all their forts, returned by a similar firing from all ours, none of the parties being quite clear what they were firing at or about, and the hottest from either party being equally harmless. We were at the time about going to bed in our habitation, but expecting some reverse I set off to the stockade where our guns were placed, and opened a fire upon the town and the stockade near us, till the enemy’s fire gradually slackened and died away. We then returned,[Pg 35] and in the morning were greeted with the pleasing news that they had burned and deserted five of their forts, and left us sole occupants of the left bank of the river. The same day, going through the jungle to see one of these deserted forts, we came upon a party of the enemy, and had a brief skirmish with them before they took to flight. Nothing can be more unpleasant to a European than this bush-fighting, where he scarce sees a foe, whilst he is well aware that their eyesight is far superior to his own. To proceed with this narrative, I may say that four or five forts were built on the edge of the river opposite the enemy’s town, and distant not above fifty or sixty yards. Here our guns were removed, and a fresh battery formed ready for a bombardment, and fire-balls essayed to ignite the houses.

‘At this time Sherif Jaffer, from Linga, arrived with about seventy men, Malays and Dyaks of Balow. The river Linga, being situated close to Seribas, and incessant hostilities being waged between the two places, he and his followers were both more active and warlike than the Borneans; but their warfare consists of closing hand to hand with spear and sword. They scarcely understood the proper use of firearms, and were of little use in attacking stockades. As a negotiator, however, the Sherif bore a distinguished part; and on his arrival a parley ensued, much against Makota’s will, and some meetings took place between Jaffer and a brother[Pg 36] Sherif at Siniawan, named Moksain. After ten days’ delay nothing came of it, though the enemy betrayed great desire to yield. This negotiation being at an end, we had a day’s bombardment, and a fresh treaty brought about thus: Makota being absent in Sarawak, I received a message from Sherif Jaffer and Pangeran Subtu to say that they wished to meet me; and on my consenting they stated that Sherif Jaffer felt confident the war might be brought to an end, though alone he dared not treat with the rebels; but, in case I felt inclined to join him, we could bring it to a favourable conclusion. I replied that our habits of treating were very unlike their own, as we allowed no delays to interpose; but that I would unite with him for one interview, and if that interview was favourable we might meet the chiefs at once and settle it, or put an end to all further treating. Pangeran Subtu was delighted with the proposition, urged its great advantages, and the meeting, by my desire, was fixed for that very night, the place Pangeran Illudin’s fort at Sekundis. The evening arrived, and at dark we were at the appointed place and a message was despatched for Sherif Moksain. In the meantime, however, came a man from Pangeran Subtu to beg us to hold no intercourse; that the rebels were false, meant to deceive us, and if they did come we had better make them prisoners. Sherif Jaffer, after arguing the point some time, rose to depart, remarking that with such proceedings he[Pg 37] would not consent to treat. I urged him to stay, but finding him bent on going I ordered my gig (which had some time before been brought overland) to be put into the water—my intention being to proceed to the enemy’s kampong and hear what they had to say. I added that it was folly to leave undone what we had agreed to do in the morning because Pangeran Subtu changed his mind; that I had come to treat, and treat I would. I would not go away now without giving the enemy a fair hearing. For the good of all parties I would do it—and if the Sherif liked to join me, as we proposed before, and wait for Sherif Moksain, good; if not, I would go in the boat to the kampong. My Europeans, on being ordered, jumped up, ran out and brought the boat to the water’s edge and in a few minutes oars, rudder and rowlocks were in her. My companions, seeing this, came to terms, and we waited for Sherif Moksain, during which, however, I overheard a whispering conversation from Subtu’s messenger, proposing to seize him, and my temper was ruffled to such a degree, that I drew out a pistol, and told him I would shoot him dead if he dared to seize, or talk of seizing, any man who trusted himself from the enemy to meet me. The scoundrel slunk off, and we were no more troubled with him. This past, Sherif Moksain arrived, and was introduced into our fortress alone—alone and unarmed in an enemy’s stockade, manned with two hundred men. His bearing was firm; he advanced[Pg 38] with ease and took his seat, and during the interview the only sign of uneasiness was the quick glance of his eye from side to side. The object he aimed at was to gain my guarantee that the lives of all the rebels should be spared, but this I had not in my power to grant. He returned to his kampong, and came again towards morning, when it was agreed that Sherif Jaffer and myself should meet the Patingis and the Tumangong, and arrange terms with them. By the time our conference was over the day broke, and we descended to our boats to have a little rest.

‘On the 20th December we met the chiefs on the river, and they expressed themselves ready to yield, without conditions, to the rajah, if I would promise that they should not be put to death. My reply was that I could give no such promise; but if they surrendered, it must be for life or death, according to the rajah’s pleasure, and all I could do was to use my influence to save their lives. To this they assented after a while; but then there arose the more difficult question, how they were to be protected until the rajah’s orders arrived. They dreaded both Chinese and Malays, especially the former, who had just cause for angry feelings, and who, it was feared, would make an attack on them directly their surrender had taken from them their means of defence. The Malays would not assail them in a body, but would individually plunder them, and give occasion for disputes and bloodshed. Their apprehensions were[Pg 39] almost sufficient to break off the hitherto favourable negotiations, had I not proposed to them myself to undertake their defence, and to become responsible for their safety until the orders of their sovereign arrived. On my pledging myself to this they yielded up their strong fort of Balidah, the key of their position. I immediately made it known to our own party that no boats were to ascend or descend the river, and that any person attacking or pillaging the rebels were my enemies, and that I should fire upon them without hesitation.

‘Both Chinese and Malays agreed to the propriety of the measure, and gave me the strongest assurances of restraining their respective followers; the former with good faith, the latter with the intention of involving matters, if possible, to the destruction of the rebels. By the evening we were in possession of Balidah, and certainly found it a formidable fortress, situated on a steep mound, with dense defences of wood, triple deep, and surrounded by two enclosures, thickly studded on the outside with ranjaus. The effect of our fire had shaken it completely, now much to our discomfort, for the walls were tottering and the roof as leaky as a sieve. On the 20th December, then, the war closed. The very next day, contrary to stipulation, the Malay pangerans tried to ascend the river, and when stopped began to expostulate. After preventing many, the attempt was made by Subtu and Pangeran Hassim in three large boats, boldly pulling towards us.[Pg 40] Three hails did not check them, and they came on, in spite of a blank cartridge and a wide ball to turn them back. But I was resolved, and when a dozen musket balls whistled over and fell close around them, they took to an ignominious flight. I subsequently upbraided them for this breach of promise, and Makota loudly declared they had been greatly to blame, but I discovered that he himself had set them on.

‘I may now briefly conclude these details. I ordered the rebels to burn all their stockades, which they did at once, and deliver up the greater part of their arms, and I proceeded to the rajah to request from him their lives. Those who know the Malay character will appreciate the difficulty of the attempt to stand between the monarch and his victims. I only succeeded when, at the end of a long debate—I soliciting, he denying—I rose to bid him farewell, as it was my intention to sail directly, since, after all my exertions in his cause he would not grant me the lives of the people, I could only consider that his friendship for me was at an end. On this he yielded. I must own that during the discussion he had much the best of it; for he urged that they had forfeited their lives by the law, as a necessary sacrifice to the future peace of the country; and argued that in a similar case in my own native land no leniency would be shown. On the contrary, my reasoning, though personal, was, on the whole, the best for the rajah and the people. I explained my extreme reluctance to have the blood[Pg 41] of conquered foes shed; the shame I should experience in being a party, however involuntarily, to their execution, and the general advantage of a merciful line of policy. At the same time I told him that their lives were forfeited, their crimes had been of a heinous and unpardonable nature, and that it was only from so humane a man as himself, one with so kind a heart, that I could ask for their pardon; but, I added, he well knew that it was only my previous knowledge of his benevolent disposition, and the great friendship I felt for him, which had induced me to take any part in the struggle. Other stronger reasons might have been brought forward, which I forbore to employ, as being repugnant to his princely pride, viz., that severity in this case would arm many against him, raise powerful enemies in Borneo proper, as well as here, and greatly impede the future right government of the country. However, having gained my point, I was satisfied.

‘Having fulfilled this engagement, and being, moreover, with many of my Europeans, attacked with ague, I left the scene with all the dignity of complete success. Subsequently the rebels were ordered to deliver up all their arms, ammunition and property; and last, the wives and children of the principal people were demanded as hostages and obtained. The women and children were treated with kindness and preserved from injury or wrong. Siniawan thus dwindled away. The poorer men stole off in canoes, and were[Pg 42] scattered about, most of them coming to Kuching. The better class pulled down the houses, abandoned the town and lived in boats for a month when, alarmed by the delay in settling terms and impelled by hunger, they also fled—Patingi Gapoor, it was said, to Sambas, and Patingi Ali and the Tumangong amongst the Dyaks. After a time it was supposed they would return and receive their wives and children. The army gradually dispersed to seek food, and the Chinese were left in possession of the once renowned Siniawan, the ruin of which they completed by burning all that remained and erecting a village for themselves in the immediate neighbourhood. Sherif Jaffer and many others departed to their respective homes, and the pinching of famine succeeded to the horrors of war. Fruit, being in season, helped to support the wretched people, and the near approach of the rice harvest kept up their spirits.’

Thus ended the great civil war, which is so renowned in local history. The three chiefs mentioned—Patingi Gapoor, Patingi Ali and the Tumangong—with their sons and relatives, will appear again as some of the principal actors in the history of Sarawak. All except Patingi Gapoor remained faithful to the end, or are still among the main supports of the present Government. I knew them all, with the exception of Patingi Ali, who was killed whilst gallantly heading an attack on the Sakarang pirates during Captain Keppel’s expedition in 1844.

[3] See Appendix.

[4] I knew one of them, Subu, the favourite of every foreigner in Sarawak.

[5] The Lanuns came from the great island of Mindanau, in the Southern Philippines, which was a nominal possession of Spain, and cruised in well-armed vessels.

[6] Voyage of the Dido, Vol. I., page 172, et seq.

[Pg 43]

THIRD VISIT TO SARAWAK—MAKOTA INTRIGUES AGAINST BROOKE—VISIT OF THE STEAMER ‘DIANA’—HE IS GRANTED THE GOVERNMENT OF SARAWAK—HIS PALACE—CAPTAIN KEPPEL OF H.M.S. ‘DIDO’ VISITS SARAWAK—EXPEDITION AGAINST THE SERIBAS PIRATES—VISIT OF SIR EDWARD BELCHER—RAJAH BROOKE’S INCREASED INFLUENCE—VISIT TO THE STRAITS SETTLEMENTS—IS WOUNDED IN SUMATRA—THE ‘DIDO’ RETURNS TO SARAWAK—FURTHER OPERATIONS—NEGOTIATIONS WITH BRITISH GOVERNMENT—CAPTAIN BETHUNE AND MR WISE ARRIVE IN SARAWAK

Peace being again restored to the country, Brooke was enabled to study the position. Muda Hassim occasionally mentioned his intention of rewarding his English ally for his great services by giving him the government of Sarawak; but nothing came of it, as when the document for submission to the Sultan was duly prepared it proved to be nothing but ‘permission to trade.’ However unsatisfactory this might be,[Pg 44] Brooke accepted it for the moment, and it was agreed that he should proceed to Singapore, load a schooner with merchandise, and return to open up the resources of the place. In the meantime the rajah was to build a house for his friend, and prepare a shipload of antimony ore as a return cargo for the schooner.

While in Singapore Brooke wrote to his mother concerning his plans, and he now added, ‘I really have excellent hopes that this effort of mine will succeed; and while it ameliorates the condition of the unhappy natives, and tends to the promotion of the highest philanthropy, it will secure to me some better means of carrying through these grand objects. I call them grand objects, for they are so, when we reflect that civilisation, commerce and religion may through them be spread over so vast an island as Borneo. They are so grand, that self is quite lost when I consider them; and even the failure would be so much better than the non-attempt, that I could willingly sacrifice myself as nearly as the barest prudence will permit.’

Many, perhaps, could write such words, but Brooke really felt them, and fully intended to carry out his views, whatever obstacles might stand in his way; and they were many, for on his return to Sarawak in the Royalist, with the schooner Swift laden with goods for the market, he found no house built and no cargo of antimony ready. A house in Sarawak could be built in ten days or a fortnight, as the materials are all[Pg 45] found in the jungle and the natives are expert at the work.

The antimony was procurable, but, as Brooke afterwards found, it was the product of forced labour, almost always unpaid. One cannot but smile at Brooke’s first attempt at trade. Without sending up to see whether the antimony was ready, he accepted Muda Hassim’s word, and then handed over to him the whole of the cargo of the Swift. What might have been expected followed. No sooner had the Malay rajah secured the goods than the most profound apathy was shown as to the return cargo. The same system was followed with regard to the government of the country; every attempt to discuss it was evaded, and I believe that Makota did his best to persuade Muda Hassim that the Englishman was but a bird of passage, who would soon get tired of waiting, and would sail away without the return cargo, and drop all thoughts of governing the country.