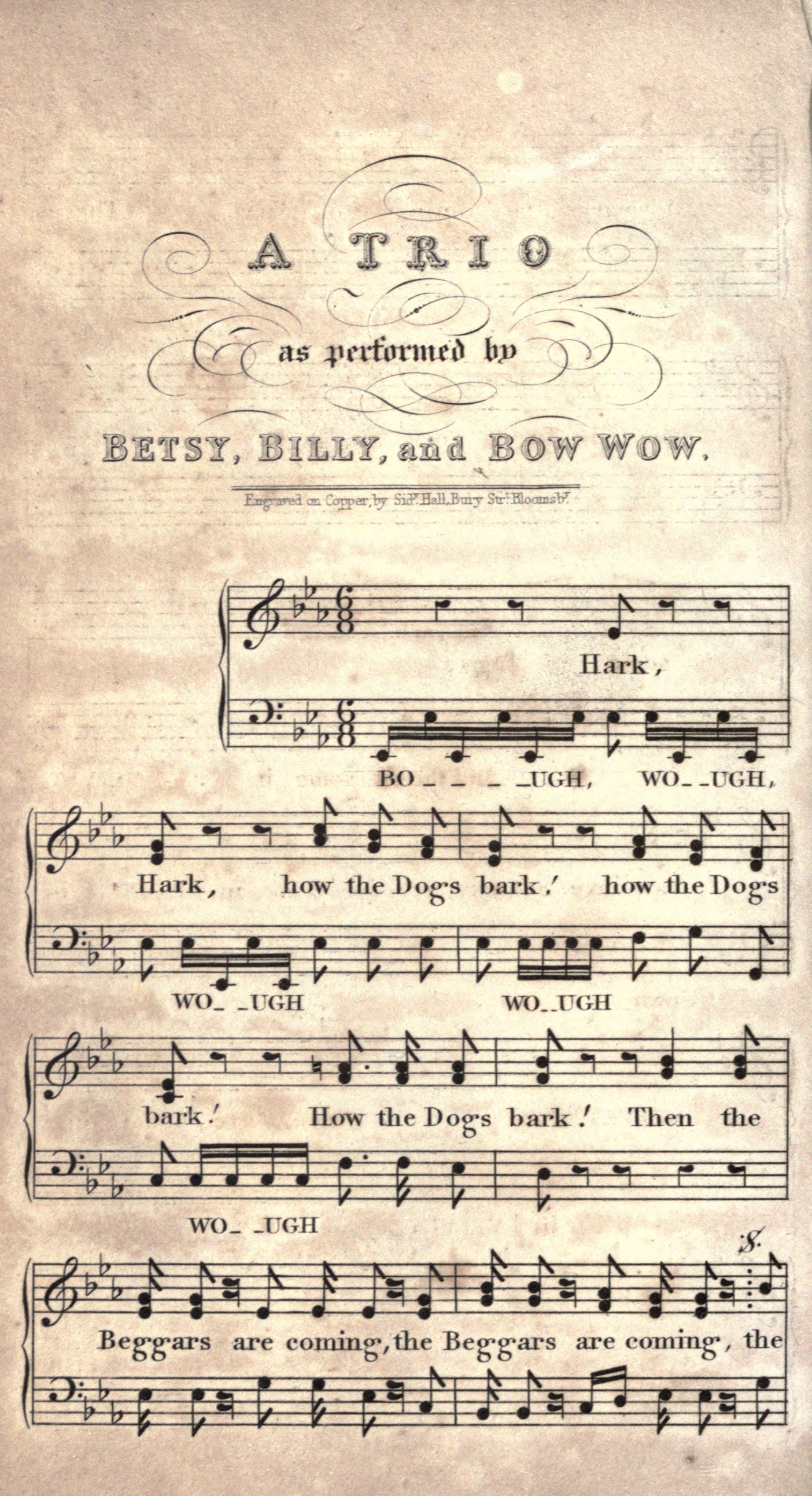

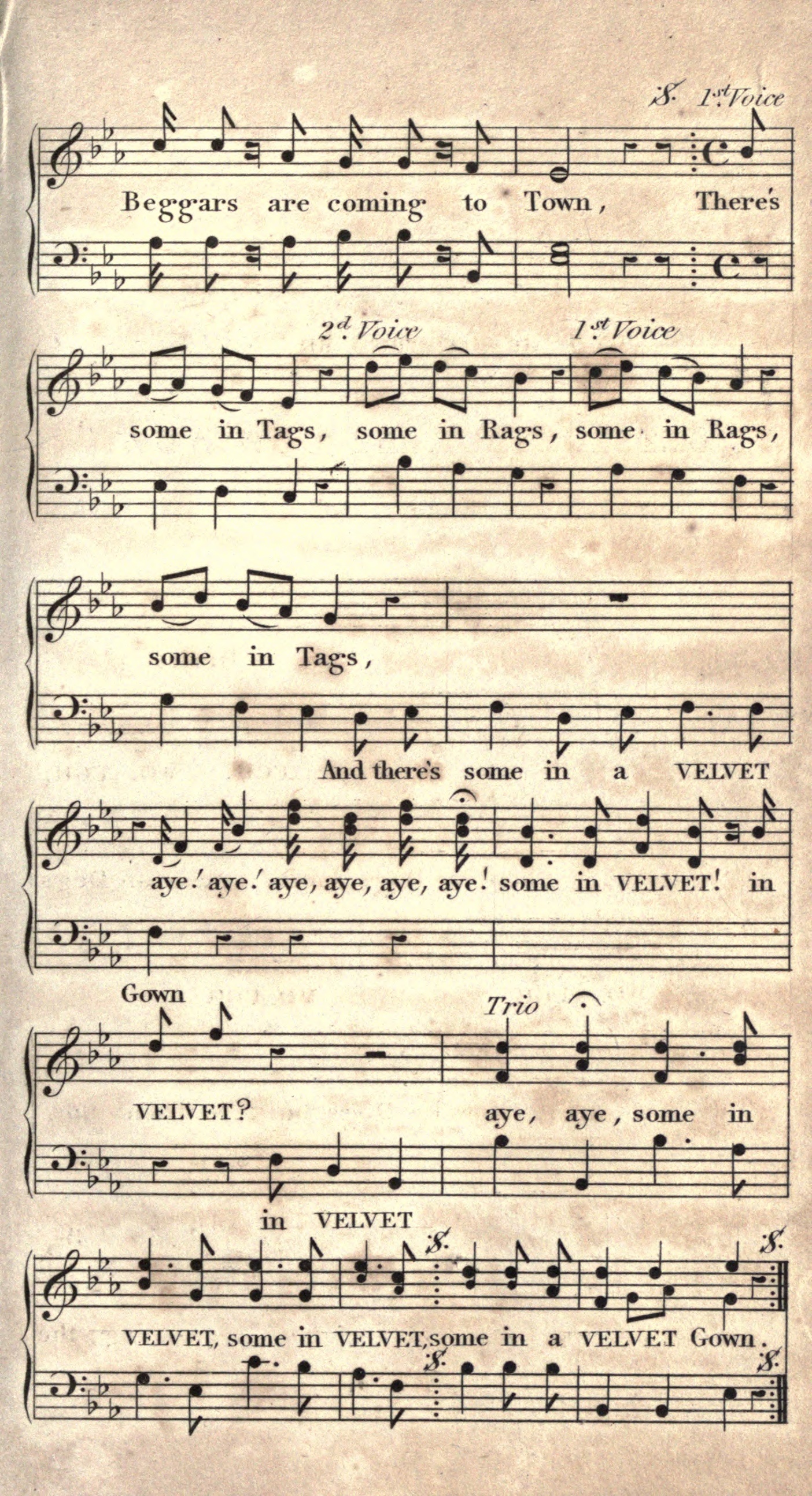

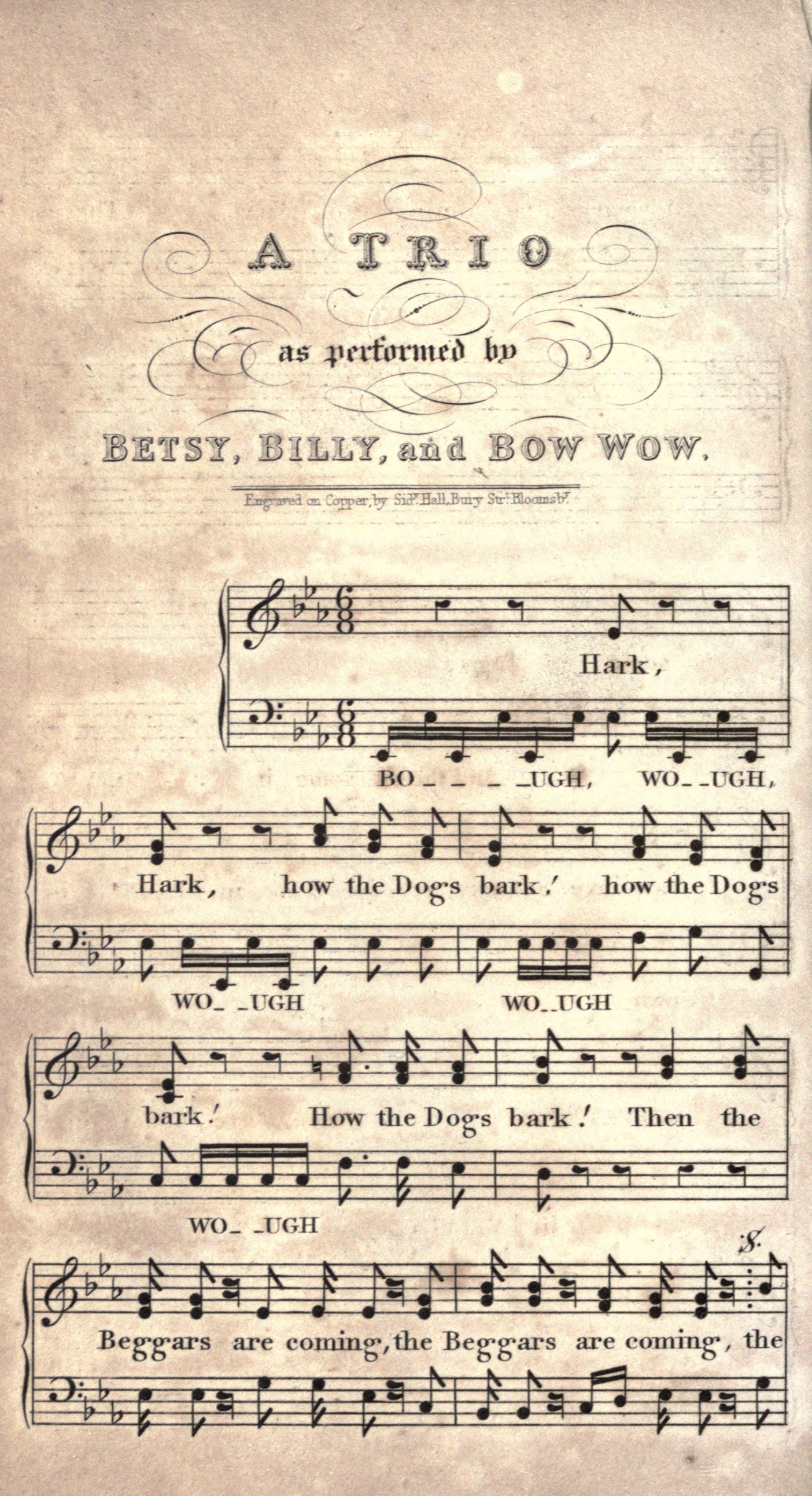

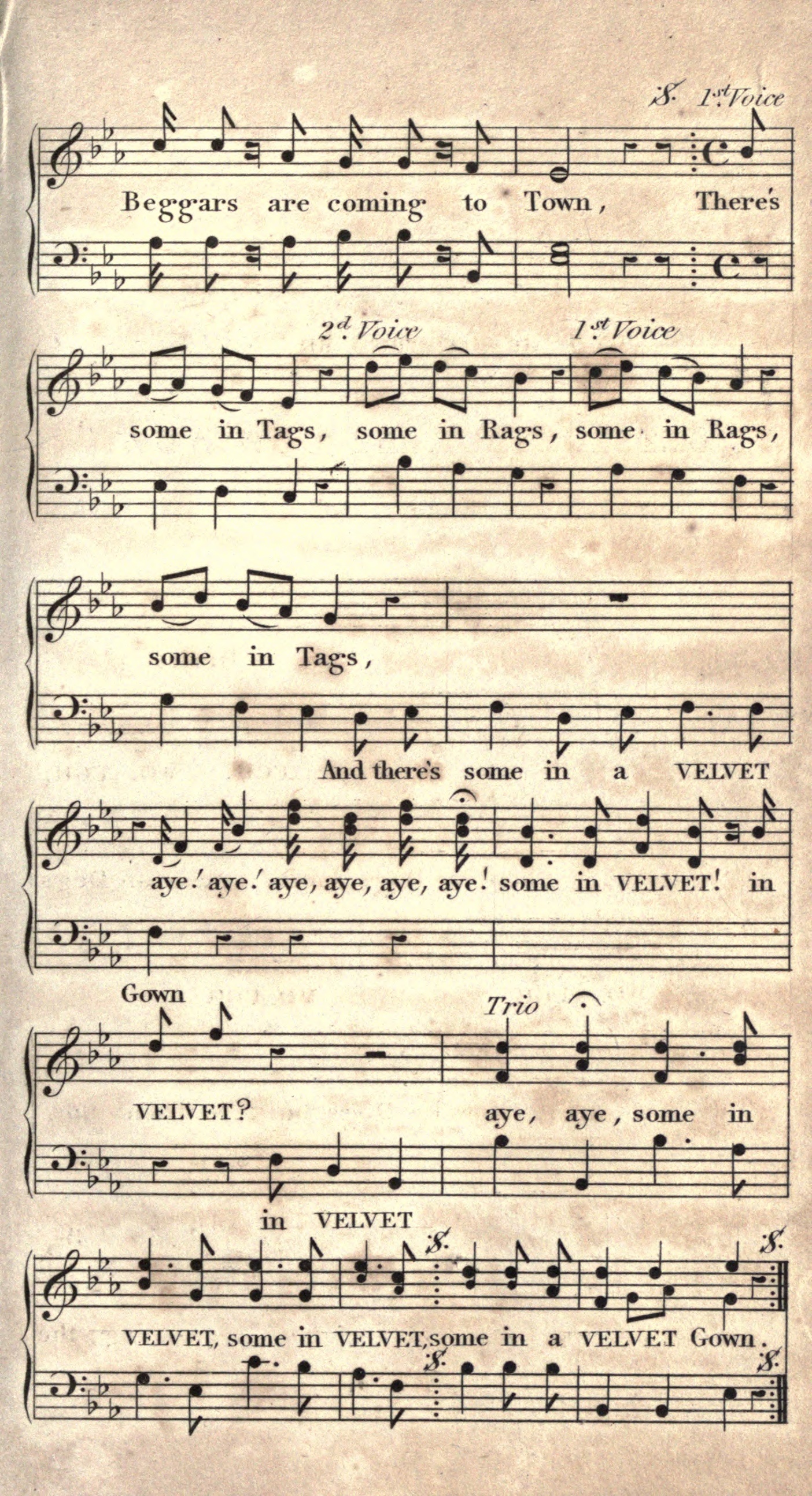

A TRIO

as performed by

BETSY, BILLY, and BOW WOW,

Engraved on Copper, by Sidy. Hall, Bury Strt. Bloomsby.

[ | Download [MusicXML]

Title: The traveller's oracle; or, maxims for locomotion, part 2 (of 2)

Containing precepts for promoting the pleasures and hints for preserving the health of travellers

Author: John Jervis

Editor: William Kitchiner

Release date: May 9, 2023 [eBook #70726]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Henry Colburn, 1827

Credits: Julia Miller, Krista Zaleski and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned images of public domain material from the Google Books project.)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation and accents have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

Click on the [Listen] link to hear the music and on the [MusicXML] link to download the notation. As of the date of posting, these links to external files will work only in the HTML version of this e-book.

OR,

MAXIMS FOR LOCOMOTION:

CONTAINING

PRECEPTS FOR PROMOTING THE PLEASURES,

AND

HINTS FOR PRESERVING THE HEALTH

OF

TRAVELLERS.

PART II.

COMPRISING THE

HORSE AND CARRIAGE KEEPER’S ORACLE;

RULES FOR PURCHASING AND KEEPING OR JOBBING HORSES AND CARRIAGES;

ESTIMATES OF EXPENSES OCCASIONED THEREBY;

AND AN EASY PLAN FOR

ASCERTAINING EVERY HACKNEY-COACH FARE.

By JOHN JERVIS,

AN OLD COACHMAN.

THE WHOLE REVISED

By WILLIAM KITCHINER, M.D., &c.

SECOND EDITION.

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, NEW BURLINGTON STREET.

1827.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY J. MOYES, TOOK’S COURT, CHANCERY LANE.

THE

HORSE AND CARRIAGE KEEPER’S

ORACLE;

OR,

RULES FOR PURCHASING AND KEEPING

OR

JOBBING HORSES AND CARRIAGES;

ACCURATE ESTIMATES

OF

EVERY EXPENSE OCCASIONED THEREBY;

AND

AN EASY PLAN

FOR

ASCERTAINING EVERY HACKNEY-COACH FARE.

| Introduction | 3 |

| Estimate of Keeping a Groom and one Horse in your own Stable | 11 |

| Estimate of the Expense of Keeping one Horse at a Livery Stable | 15 |

| Estimates of various Carriages | 16 |

| Expense of Keeping a Coachman, a Carriage, and two Horses in your own Coach-House and Stable | 19 |

| Liberal Plan of Keeping a Carriage | 33 |

| Estimate of Hiring a Carriage for any short Period | 39 |

| Estimate of Jobbing Horses | 44 |

| Estimate and Description of a Handsome Town Chariot | 50 |

| Carriages and Coachmaking | 59 |

| Of the Construction of a Chariot | 65 |

| Of Axle-Trees | 93 |

| Of the Wheels | 99 |

| The Ornaments of Carriages | 104 |

| Cautions against Purchasing of Cheap Second-hand Carriages | 112 |

| Of the Harness | 119 |

| Of Second-hand Harness | 121 |

| Travelling Carriages | 123 |

| Description of Buonaparte’s Travelling Chariot | 127 |

| Duties on Male Servants, Carriages, and Horses | 131 |

| The Art of Managing Coachmen | 133 |

| Of Evening Parties | 136 |

| Of Coachmen and Orders | 142-150 |

| Of Punctuality | 151 |

| Of Lending your Carriage | 160 |

| The Fifteen Things which a good Coachman Won’t Do | 165 |

| Coachman’s Tools | 170 |

| Of the New Road and Regent’s Park | 173 |

| Of Driving | 184 |

| Of Care of the Carriage | 201 |

| Of Repairing Carriages | 212 |

| On Horses | 218 |

| Hints to Purchasers of Horses | 223 |

| To Preserve the Health of Horses | 238 |

| To Make a Horse have a Fine Coat | 246 |

| On the Food of Horses | 249 |

| On sending Horses to Grass | 257 |

| Colds of Horses | 261 |

| Of Stables | 266 |

| Management of Horses in case of Fire | 272 |

| Hints to Horsemen | 273 |

| On the Rough Shodding of Horses in Frosty Weather | 281 |

| Of the Comparative Expense of a Private Carriage and of Hiring of Hackney Coaches | 286 |

| An Easy Plan of Ascertaining every Fare of a Hackney Coach | 292 |

| When and How to Call a Coach | 312 |

| Hackney Coach and Chariot Fares | 318 |

| Specimen of Cary’s New Guide for Ascertaining Hackney Coach Fares | 324 |

| MUSIC TO PART II. | |

| Trio | to face page 90 |

[Pg 3]

The following Estimates of the Expense of keeping Horses and Carriages, are Accurate Statements, they cannot be well kept for less, and they need not cost more:—the Reader will have no difficulty in finding a Hackneyman, and a Coachmaker, who will furnish him with them on the terms herein set down; for we have adopted a mean between thoughtless Extravagance on the one hand, and rigid Parsimony on the other.

It is a very frequent, and a very just complaint, that the Expense of a Carriage is not so much its First Cost, as the charge of Keeping it in Repair. Many are deterred from indulging [Pg 4]themselves therewith, from a consciousness that they are so utterly unacquainted with the management thereof, they are apprehensive the uncertainty of the Expense, and the Trouble attending it, will produce Anxiety, which will more than counterbalance the Comfort to be derived from it.

Few Machines vary more in quality than Carriages, the charge1 for them varies as much;—the[Pg 5] best advice that can be offered to the Reader, is, to “Deal with a Tradesman of Fair Character, and established circumstances.—Such a person has every inducement to charge reasonably, and has too much at stake, to forfeit, by any silly Imposition, the Credit that he has been years in establishing by careful Integrity.”——Dr. Kitchiner’s Housekeeper’s Ledger, 8vo. 1826, p. 20.

Those Carriages which cost least, are not always the Cheapest, but often turn out, in the end, to be the Dearest.

Of Chariots, that appear to be equally handsome to a common Eye, which has not been taught to look minutely into the several parts of their machinery; One may be cheap at 250l., and Another may be dear at 200l.: notwithstanding, the Vender of the latter may get more Profit than the Builder of the former.

The faculty of Counting, too frequently, masters all the other Faculties, and is the grand source of deception which Speculating Shopkeepers are ever ready to take advantage of;—for catching the majority of Customers, Cheapness is the surest bait in the World,—how many [Pg 6]more people can count the difference between 20 and 25, than can judge of the Quality of the article they are about to buy?

Quantity strikes the eye at once.—It is recorded, that a certain King having commanded his Treasurer to give an Artist a Thousand Pounds for some work which his faithful Minister knew would be most liberally paid for with half that sum; the sagacious Treasurer ordered, Five Hundred Pounds in Silver to be laid upon a Table in a Room which he knew that his Majesty would pass through with him. On seeing the heap of Silver, the King exclaimed, “What’s all that Money for?” The Treasurer replied, “Sire, it is half of the Sum which your Majesty commanded me to give to the Artist.”—On which, the King said, “Hey, hey! a deal of Money—a deal of Money—Half of that will do!!!”

Quantity may be estimated by an uneducated Eye—to discern the Quality of things, requires Experience and Judgment—capital Guides; but with which the purchasers of Horses and Carriages are Years before they acquire sufficient acquaintance to derive any benefit from [Pg 7]them, and their chief security is, to deal with Persons who have justly acquired, and long maintained, an unblemished Reputation.

I must here protest against a Custom which it is high time was abolished, that of asking Guineas instead of Pounds,—as Guineas are coined no more, there is no pretence for continuing this trick of charging 5l. per Cent extra! Those who do it, know that nobody would give them 105 Pounds; but, under the jingle of 100 Guineas, they contrive to poke an additional Five Pounds out of your pocket!

As we have earnestly advised, that the Coachman may be made independent of the Coachmaker, so let the latter be entirely independent of the former.

Be not so perfunctory, as to permit your Coachman to order what he pleases. If you send a Carriage to be repaired, with the usual Message, “To do any little Jobs that are wanted,” you will most likely not have a little to pay.

When any Repair is required, desire your Coachman to tell you; examine it with your own Eyes, and with your own hand write the order to the Coachmaker, &c. for every thing that is wanted; and warn him you will not pay [Pg 8]for any Jobs, &c. not so ordered, and desire him to keep such Orders and return them to you when he brings his Bill, that you may see it tallies therewith, and you may keep a little Book yourself, into which you may copy such Orders.

Counsellor Cautious went one step further; and before any work was begun, required a Note, stating for how much, and in how long, the person would undertake to completely perform it.

However well built originally, the Durability of the Beauty and the Strength of Carriages, depends much upon how they are managed;—they are as much impaired by those to whose care they are entrusted, not understanding, or not performing, the various operations which preserve them, as they are by the Wear occasioned by Work.

In hiring a Coachman, his having a due knowledge of how to take care of a Carriage, is of as much importance as his experience in Horses, or his skill in Driving.

Persons who order Carriages, are frequently disappointed in the convenience and appearance of them, from not giving their Directions in terms sufficiently explicit;—when[Pg 9] those who buy Carriages make any such a mistake, it is said, that those who sell are not always remarkably anxious to rectify it, unless at the expense of the proprietor.

An Acquaintance of the Editor’s, ordered that the interior of a New Chariot should be arranged exactly like his former Carriage:—when it was finished, he found that there were several very disorderly deviations from the old plan, which were extremely disagreeable to him:—the Builder said, civilly enough, that he was exceedingly sorry, and would soon set it all right—which he did; but presented a Bill of Ten pounds for mending these mistakes, which having arisen entirely from his own Inattention to the fitting up of the Old Carriage, his Customer successfully resisted the payment of, having been prudent enough to have the Agreement for building the Carriage, worded, “That it should be finished in all respects to his entire satisfaction, by a certain Time, for a certain Sum.”

To the end of this work is added a Copious Glossary, and an Index, which will readily conduct the Reader to the various subjects, and be found extremely useful in explaining the Technical terms, &c. commonly used by Coachmakers.

[Pg 10]

The Editor has endeavoured to explain the various points in so plain a manner, that persons who are previously entirely unacquainted with the subject, may calculate exactly what will be the Expense, and ascertain pretty accurately the best manner of managing, and of estimating the pretensions of those they are about to employ, either to build or to take care of a Carriage, &c., in almost as little time as they can read this little Book; in which it is hoped that they will find Amusement blended with useful Instruction, and soon gain such a general knowledge of the subject, as will effectually protect them from Imposition:—at all events, the Editor is quite sure, that it will soon save the Purchaser more than double what he has been so good as to give his friend the old Coachman for the following advice.—Now Cent per Cent, even in these times, when it is said that Cash is scarce, is quite as large a profit as can be made by most Purchases! Therefore, the Editor sends Mr. Jervis’s Book to Press, with a contented conscience, and a hearty wish, that all who buy it may be able to invest all their Money to equal advantage.

[Pg 11]

EXPENSE OF KEEPING A GROOM AND ONE HORSE IN YOUR OWN STABLE.

A Saddle-Horse being but of little service during November, December, January, and February, during these four Months Economical Equestrians send their Nags to a Straw-Yard.

Sportsmen say, that nothing does a Horse more good than a Winter’s Run once in Two or Three years—it far exceeds turning to Grass in Summer, when the Flies are troublesome.

The Price at Straw-Yards varies from 3s. 6d. to 5s. a week, depending upon the Straw, which is contingent on the Corn Crops: some Horses sleep in at Night, and have Hay given them, or at least ordered for them, in which case, 7s. per Week is charged.

| £ | s. | d. | |

| The Straw-Yard for one Horse, for 17 Weeks, say at 4s. 6d. per Week, will be | 3 | 16 | 6 |

This Holiday is very beneficial to the Horse, especially to his Legs and Feet, which, when worn down by hard work, or cut up by flinty Roads or bad Shoeing, are thereby greatly refreshed and strengthened.

For the remaining 35 Weeks, the allowance of Provisions per week cannot be less than

| £ | s. | d. | |

| 1 Truss of Straw2, at 36s. per Load | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 Truss and a half of hay, at £5 per Load | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| ¾ peck of Oats per Day, is per Week 5¼ pecks, and at 25s. per Quarter | 0 | 4 | 2 |

| Food per Week | 0 | 9 | 4 |

| 35 | |||

| —————— | |||

| Food for 35 Weeks | 16 | 6 | 8 |

| Expense of Horse in Straw-Yard, brought forward | 3 | 16 | 6 |

| Taking to and from the Straw-Yard | 0 | 10 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| Annual Keep | 20 | 13 | 2 |

| A Saddle-Horse, on an average, is shod about Once in four weeks, and the set of Shoes costs 5s.; Nine Sets of Shoes | 2 | 5 | 0 |

| The Annual Duty | 1 | 8 | 9 |

| —————— | |||

| Annual Expense | £24 | 6 | 11 |

| —————— | |||

Obs.—This Allowance for Provision is hardly sufficient for Horses that do hard work, which require a Peck of Oats per Day, a Truss and a half of Straw, the same of Hay, with some good Chaff, and occasionally a little Bran; also a handful of Beans in Wet Weather, especially to Horses that work at Night.

A Hackneyman’s allowance for Two Horses is a Sack of Oats per week, which give, if good measure, Four good feeds a day; Country measure, will run nearly five feeds.

| £ | s. | d. | |

| The above is the Annual Expense—exclusive of Stable Rent—Interest of Money paid for the purchase of the Horses—Saddles—Bridles—Horse Cloths, &c.—Farrier’s Bills for Physic—Turnpikes—Travelling Expenses—Groom’s Wages and Livery, &c., which, excepting the difference of charge between a Coachman’s Box Coat, and a Groom’s Great Coat, and the difference of Rent and Taxes on a Single Stall Stable, (which it is often excessively difficult to obtain contiguous to your House), and on Two Stalls and a Coach-house, is, according to the[Pg 14] Expense of keeping a Groom or Coachman given in Estimate No. 4, about | 95 | 0 | 0 |

| Annual Keep | 24 | 6 | 11 |

| —————— | |||

| Total | £119 | 6 | 11 |

| —————— | |||

N.B.—The Hackneyman’s Charge for Jobbing a Saddle Horse, and finding Stabling, &c. is, per Annum, about £70.

[Pg 15]

EXPENSE OF KEEPING ONE HORSE AT A LIVERY STABLE.

At some Livery Stables, your Horses will be taken as much care of as they can be in your own: at others, they fare very sadly;—therefore, cautiously inquire into the Character of the person keeping them;—moreover, if his Rent is in arrear, your Carriage and Horses may be seized and sold by his Landlord.

| £ | s. | d. | |

| Four Feeds per Day, at £1. 1s. per Week | 54 | 12 | 0 |

| Hostler, 1s. or 1s. 6d. per Week—a Gratuity of a shilling now and then to the Under Hostler, who looks after the Chaise, or attends to the Horse, together, perhaps, equal to about | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Shoeing, and Duty per Annum | 4 | 13 | 9 |

| —————— | |||

| £63 | 5 | 9 | |

| —————— | |||

A CABRIOLET AND HARNESS,

| £ | s. | d. | |

| When quite new, if Jobbed, will be, for one Year, from £30 to | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax thereon | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| For Standing, and care at a Livery Stable, per Week, 1s. 6d. | 3 | 18 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| £47 | 3 | 0 | |

| —————— | |||

The Price of a new Two-Wheel One Horse Chaise—Dennett—Tilbury—Stanhope, &c. is from £40 to £90.

Of a Cabriolet, from £100 to £130.

Of a Four-Wheel One Horse Chaise, with head to it, from £100 to £150.

Of a Pair of the best Strong Gig Wheels, with Ash felleys and patent hoop tires, about £7.

Wheels, at first, want only new Shoeing, or turning the Tire, as they wear upon one edge principally: this is done for about 20s. or 25s., and they will last almost as long as at first.

[Pg 17]

New-tireing a Pair of Gig Wheels with Patent hoop-tire, costs about £2. 10s.

Mem.—When going to Drive, not only inquire, but give a look yourself at the Wheels, &c. before you set off—trust this to no one—make sure that the Bridle and the Bit fit easy to the Mouth, and see that the Collar and every part of the Harness fit comfortably:—if your Horse tosses his head up and down continually, he is not easy.

is at no time a better maxim than when preparing for a Journey.

“A Carriage with but two Wheels should be built so that the principal part of the weight is on the Axle-Tree, (instead of the Horse’s back), and the Carriage part of the Vehicle ought to be on Springs, as well as the Body: this prevents the Bolts and Nuts working loose, and the Joints opening, &c. The Lamps should be at the sides; but the Dashing Iron ought to have in front a socket on each side to place the Lamps in at Night, which will throw the light before the Horse’s head, and prevent any shadow from the Wheels—when they are used at the [Pg 18]Sides, you see your danger just too late. The Shafts should be plated underneath with Iron, or if your Horse falls, they are apt to break, which may occasion a dangerous fall to the Persons in the Vehicle.”—A. E.

CARRIAGES WITH TWO3 WHEELS

Are the cheapest, and have the advantage over all others for Lightness and Expedition; but Mem. If the Horse be ever so sure-footed, and the Driver be ever so skilful and steady, they are still but Dangerous Vehicles—which will only be used by those who are compelled to sacrifice Safety to Celerity, and Comfort to Cheapness:—if risks, however, are incurred by this mode of conveyance, Expense is certainly diminished, for the rate of charges in Travelling is considerably less in proportion for one Horse and Two Wheels, than for two Horses and Four Wheels.

[Pg 19]

EXPENSE OF KEEPING A COACHMAN, AND A CARRIAGE AND TWO HORSES, IN YOUR OWN COACH-HOUSE AND STABLE.

| £. | _s._ | _d._ | |

| A Peck of _Oats_ per Day for each Horse, when Corn is 25_s._ per Quarter; say 24 Quarters per Annum | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| A Quarter of a Truss of Hay for each Horse per Day, at £5 per Load; say 5½ Loads per Annum | 27 | 10 | 0 |

| One Truss of Straw each Horse per week; say three Loads per Annum, at 36_s._ | 5 | 8 | 0 |

| _Beans_, which are only wanted when Horses are worked very hard; and _Physic_, which (excepting the _Persuader_ prescribed--see Index) is as little wanted by a Horse, as it is by a Man. See OBS. _to Estimate No. I._ | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Twenty-eight sets of _Shoes_, at 5_s._ per set | 7 | 0 | 0 |

| _Farriers’ Bills_,--the Risk of your Horses turning out unsound and inefficient,--the[Pg 20] Expense of hiring other Horses while your own are Ill, &c., and the Interest of the Money paid for the purchase of the Horses, &c., cannot be estimated at less than £20. per Annum for each Horse | 40 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 113 | 18 | 0 | |

Those Persons who are most dependent upon their Carriage, frequently require it to carry them only a Mile or Two, and may save the expense of hiring another Horse while one of their own is Ill, or is in want of a Day’s rest, by having a pair of Shafts made to fit on, and so use it with only one Horse—which will do all the work required by many infirm persons, almost as easily as Two:—we wonder that more Chariots are not so constructed.

The preceding Calculation shews that the Expense of keeping Two Horses, and the Risk of loss by Horses, &c. cannot well be set down at less than £113. 18s. per Annum.

A Hackneyman will furnish a pair of Horses, take all the Hazards, and bear all the expenses [Pg 21]enumerated above; at from £135. to £160. per Annum, according to the quantity of Work, and the Age, Colour, and Quality of the Horses required.

If a Pair of Horses are hired for a Year, and they are given up at any time within that period, it is customary to give a couple of months’ notice, or a couple of months’ money. Have a written agreement about this.

The following is my Agreement for hiring Horses:—

“Memorandum. Mr. Thurston agrees to furnish Dr. Kitchiner with a Pair of Horses at £140. per Annum, to be paid Quarterly; and if Dr. K. wishes to give them up, he must give two months’ notice, or two months’ money: i. e. £24.

“From January 5th, 1827.

Wm. Kitchiner.

Jas. Thurston.”

I would not recommend a Carriage Horse to be less than Seven years old, especially if to be driven in Crowded Streets:—Horses that [Pg 22]have not been taught how to behave in such situations, are extremely awkward and unmanageable, and often occasion Accidents.

As I have said, the Price charged for Job Horses varies as the goodness of the Horses, and as the Work required, does. Some persons do not Exercise their Horses enough;—others require Two Horses to do as much Labour as should be done by Three. Again, the price of Horses varies from less than £80. a Pair, to twice £80. a piece.

If you keep Horses for useful purposes, you must not be too nice about either their Colour, or the condition of their Coats.

The ordinary Town Carriage Work can be done just as well by a Pair of Horses, which may be had for £70. or £80. as with those that cost three times that Sum; indeed it will most likely be done better. If you have Horses worth an hundred pounds a piece, you will be afraid of using them when you most want them; i. e. in Cold and Wet Weather, for fear of their catching Cold and breaking their Coats, &c. Moreover, the Elegance of an Equipage, in the Eyes of most [Pg 23]people, depends more upon the Carriage, Harness, and Liveries, than upon the Horses:—all can judge of the former, but few of the latter; and, provided they are the same Size and of the same Colour, the Million will be satisfied.

Horses in Pairs are sometimes worth double what they are, singly—and Horsedealers do not like to buy any but of the most common Colours; i. e. Bays and Browns; because of the ease in matching them. Horses of extraordinary Colours may be purchased at a proportionably cheap rate, unless they are in Pairs, and happen to be an extraordinary good match, when they will sometimes bring an extravagant price.

An Ancient Equestrian gives the following advice; and also gave us all those Paragraphs to which are affixed the initials A. E.:—

“If you have occasion to match your Horse, do not let the Dealer know you are seeking for a Match Horse, or he will demand a higher price; nor do not send your servant to select for you.”—See [Pg 24]the “Hints to Purchasers of Horses,” in Chap. IV.

If you will be contented with the useful Qualities of your Horses, i. e. their Strength and Speed, and are not too nice about their matching in Colour, you may be provided with capital Horses, at half the cost of those who are particular about their Colour; and moreover, you may easily choose such as will do double the service.

The Judgment and Liberality of the Proprietors are not so questionable on account of the Horses (which all the Wit and all the Wealth in the World cannot always procure exactly what may be wished) as they are about those works of Art, a Carriage and a Livery; these, good Taste and Liberality can always command. The difference in the charge for the hire of an elegant New Carriage and a shabby Old one, does not exceed £25. per Annum; and £10. per Annum more will defray all the extra expense incurred by giving a handsome Livery; so there is not 10 per Cent saved in the Shabbiest turn out.

[Pg 25]

As most people Job their Carriage Horses, we shall continue our Estimate, and set down—

| £. | _s._ | _d._ | |

| For a Pair of Jobbed Horses (the lowest price at present) | 135 | 0 | 0 |

| The Duty on Two Horses | 4 | 14 | 6 |

| On a Four-Wheeled Carriage | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| On the Coachman | 1 | 14 | 0 |

| Wages4 of the Coachman, not less than 10_s._ per week | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Board, ditto, ditto, at 14_s._ per week [Pg 26] | 36 | 8 | 0 |

| N.B. If there are no Lodging Rooms over the Coach-house, it is customary to allow a Coachman about 4_s._ per Week, _i. e._ about £10. per Year, to pay his Lodging. |

|||

| Allowance for Oil and Grease, Towels and Leathers, to clean the Carriage, _at least_ 1_s._ per Week | 2 | 12 | 0 |

| Rent of Coach-house and Stable | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax on ditto | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 240 | 8 | 6 | |

| —————— | |||

The advice of our great Dramatic Bard cannot be quoted more aptly than in the following Maxim for choosing a Livery:—

Shakespeare.

[Pg 27]

We recommend a Blue, Brown, Drab, or Green Livery, the whole of the same Colour. To have a Coat of one Colour, and lined with another, a Waistcoat of another, and the other Clothes of another Colour, claims the Poet’s censure—it is “Gaudy”—unless for a full Dress Livery on a Gala Day:—we equally disapprove of the Capes of a Box Coat being alternately Blue and Yellow, or Brown and Red, &c.

Coachman’s Livery.

Those who affect an elegant Equipage, usually give their Coachman annually, say Two handsome Suits of what is termed the best Second Cloth (what is called Livery Cloth is a little cheaper, but much coarser, and not half so serviceable).

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Brought forward | 240 | 8 | 6 |

| Light Blue Cloth Double-breasted Coat, edged with Crimson, and lined

with Shalloon same colour as the Coat, with Gold-laced Collar and Button Holes— Waistcoat, Blue Kerseymere, with Shalloon Sleeves; Plush Breeches, lined, and gilt Knee Buckles |

14 | 14 | 0[Pg 28] |

| 30 Large and 18 Small Buttons with Crest5 and Motto, &c. thereon | 0 | 13 | 6 |

| Working Dress, (once a Year), Drab Cord Breeches, Coat, Waistcoat, and Overalls (Drab Fustian, lined,) &c. | 3 | 13 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 259 | 9 | 0 | |

For those who make but little use of their Carriage, One Livery a Year, or Two in Three Years, is enough, especially if you give a Working-dress, as the Livery is then worn merely when he mounts the Box to drive.

Those who give only One Livery in a Year, should do that in April, so that they [Pg 29]may have the credit of it during the Summer months, while it is seen: during the Winter it is almost always covered by the Box Coat; when the Coat the man does his work in, will do as well as any. If a Livery Coat has a Laced Collar, wearing the Box Coat over it, will soon cut it to pieces.

Counsellor Cautious never gave a Coachman a Livery till he had served him for Three Months. Some Persons, instead of a Livery, allow 3s. or 4s. per Week extra, and the Coachman finds his own Clothes, a plain Blue Coat; they giving him only a Hat and Great Coat.

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Brought forward | 259 | 9 | 0 |

| A good full-made Box Coat, with six real Capes, and lined with Shalloon, about £7. (according to the number of Capes and the quality of the Cloth, the price varies from £5. to £8.), once in Three Years, at the end of which it is given to the Coachman, per Annum | 2 | 7 | 0 |

Plain Liveries, without Lace, &c. one-third less, i. e. about £5. per Suit. |

|||

| Two Plain Hats[Pg 30] | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| £264 | 6 | 0 | |

With Gold Lace Binding, and a neat narrow Gold Band, they cost about double the above sum.

Some give, Annually, one plain Hat for common use, and one edged with Gold Lace and a Gold Band as a Dress Hat.

Those who like to see their Coachman neat and nice, give him a Clothes Box as well as a Clothes Brush, or, which is infinitely better, a Cupboard six feet high, about three feet deep, and three feet wide, with pegs to hang his Box Coat, Hat, and other Clothes on, which, without such a case, are soon spoiled by the Dust of the Hay Loft.

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Brought forward | 264 | 6 | 0 |

| The Yearly hire of a handsome new Chariot or Coach and Harness, from £70. to £84.: if it is hired for only three or four Years, and fitted up with Under-springs, Collinge’s Axles, &c., and finished in the best style, as described in Estimate No 9, it will be about | 84 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| Total | 348 | 6 | 0 |

To the above Estimate is to be added the charges of Turnpikes—Short Baits6—Travelling Expenses, &c., extra Visiting, and numerous other Expenses, which would not be incurred without a Carriage to carry you to them: these will make the total amount of outgoings from keeping a Carriage come up to not less than £400 per Annum.

The Editor is aware that the foregoing Computations are rather higher than those random-guess Estimates, which some inexperienced persons have published: however, his Calculations[Pg 32] are neither more nor less than the actual amount which he has himself paid; and he does not believe that the business can be done properly for less than the Sums set down;—therefore,

[Pg 33]

The former is The Usual and Liberal Plan of Keeping a Carriage—it cannot be kept so comfortably on any other; but we must also tell our Readers The Cheapest Plan, which is about £100 per Annum less.

| £. | s. | d. | |

| 1st. Instead of giving £84 per Annum for a New Carriage and Harness, made in the best style, as per Estimate No. 9, you may hire an inferior, or a vamped-up second-hand one for about | 60 | 0 | 0 |

| A Hackneyman will supply a Pair of Horses, and keep them, &c. in his Livery Stables, for | 135 | 0 | 0 |

| Standing of Carriage, and charge for cleaning and greasing, &c. as in Estimate No. 6, per annum, not less than | 11 | 16 | 0 |

| Duty on Horses and Carriage | 10 | 14 | 6[Pg 34] |

| A Grand managing Economist informed me that he pays the Hostler at a Livery Stable 8s. per week additional, i. e. £20 per annum, to do all the work usually done by the Coachman, except driving the Carriage—he comes for orders as a Coachman does, and brings the Carriage to the Door, when his Man Servant, who acts as Coachman7, mounts the Box and drives it; on its return, the Footman drives it to the Stables, and the Hostler does all the rest of the business usually done by a Coachman | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Extra Wages to a Footman for Driving, and Box Coat, &c. not less than, per annum | 8 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 245 | 10 | 6 | |

| —————— | |||

Obs.—Few People but those who have either a very Strong Purse, or a very Weak Person, really require a Carriage every day.

[Pg 35]

Twice, or Thrice in a week would be quite enough for many;—such will do wisely, to find a Friend who will pay half of the Expense, and use the Equipage on alternate days—and on Sundays let it rest.

[Pg 36]

For those who wish for a Carriage merely as a matter of occasional Parade, rather than of continual Convenience, and hardly require it perhaps Two days in a Week, the cheapest plan is to purchase a Carriage, and keep it at a Stable Yard, where, as often as they wish, they can hire a pair of Horses: but a good Carriage must not stand in a Public Yard, unless it is put into a private Coach-house, where it can be carefully locked up:—if you pay a little extra for this, it is money well spent.

| £. | s. | d. | |

| The Expense then will be, the Interest of the Money paid for the purchase of the Carriage and Harness, (which we will suppose may be bought second hand for about £200), and keeping it in Repair, which, as it is but[Pg 37] seldom used, may be set down together at (not less than,) per annum | 30 | 0 | 0 |

| Standing of it, at 3s. per week, per annum | 7 | 16 | 0 |

| For Oil and Grease, and to the Hostler for cleaning the Carriage, from 1s. to 1s. 6d. per week, per annum | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Tax | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 47 | 16 | 0 | |

And £1. 1s. per Day for Hire of Horses, and 5s. the Coachman. See Estimate No. 7.

Thus, it appears, To keep a Carriage, and to use it once in a Year, costs £48. 2 s.!!!

The Hackneyman’s Charge for a Pair of Horses for three or four hours in the middle of the Day, say from One till Five o’clock, is about 15s.

From Four till Twelve at Night, that is, to take you to the Theatre or out to Dinner, and to bring you Home after, is 12s.

The Coachman’s fee for these Short Jobs, is about 2s. 6d.

Many people do not require a Carriage more than twice in a Week; nor then, more than [Pg 38]for Three or Four hours: to such, the Saving will be very great.

| £. | s. | d. | |

| Standing charges of the Carriage, &c. as per Estimate above | 47 | 16 | 0 |

| Horses and Coachman, for Four Hours, Twice a Week, at 17s. 6d. each time | 91 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| Per Annum | 138 | 16 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

HIRING FOR A SHORTER PERIOD THAN A YEAR.

If a Carriage be hired for a Day, a Week, or a Month, or for any time less than a Year, the person who let it out pays the Duty.

The customary charge for those common Carriages, whether of Two or Four Wheels, which are let out, is about 5s. per Day, or £5. per Month (28 Days).

Open Carriages are charged higher, as the whole Year’s Duty is paid upon them, though they are only used for a few Months.

When Coaches or Chariots are let by the Day or Week, the Harness is not included in the charge for them. Harness for a Pair of Horses is charged 1s. per Day, or 5s. per Week.

Hired Carriages are expected to be turned out clean, greased, and fit for immediate use:—examine them well before you take them; for[Pg 40] if any part breaks while in your use, you will be expected to pay for the Repair thereof, unless you make a previous Agreement that it shall be done by the person letting it.

Tell the person you hire of, how long you want the Carriage, and how far you are going to travel:—he has then no excuse for not giving you a sufficient Carriage.

The price of a Job during the dear Months, when the Town is full, i. e. in April, May, and June, for a Chariot or Coach, a Pair of Horses and Coachman, his Wages and Board Wages, the standing at the Hackneyman’s, &c., and all charges included, is, (a little more or less, according to the quality of the Horses and the Carriage), per Month, (reckoning 28 Days), about £26.

The usual sum for the Hire of a Coach or Chariot and Harness, is, according to the condition thereof, from £5. to £7. per Month:—if you hire them of a Coachmaker, you will have more choice, and may get a better Carriage.

A Glass Coach, or Chariot and Horses, not to travel beyond eight miles from Town, may be hired, per Day, for from £1. 1s. to £1. 5s.

[Pg 41]

The Coachman’s Fee is 5s.

If he is employed all Day, especially if you go into the Country, it is usual to give the Driver his Dinner.

For a distance exceeding eight miles from the place of letting, the charge is 1s. 6d. per Mile out, and half that sum in returning.

For Three or Four Hours in the middle of the Day, 18s.

The Coachman will expect about Half-a-Crown.

From Four till Twelve in the Evening, to take you out to Dinner, and to bring you Home, 15s.—Coachman, 2s. 6d.

In either of the above cases, if you find the Carriage, the charge will be from 3s. to 5s. less.

We subjoin a List of the charges for these things in Ireland.

MEETING OF THE COACH PROPRIETORS AND POST-MASTERS OF DUBLIN.

The Job Coach Proprietors and Post-Masters respectfully beg leave to inform the Nobility, Gentry, their Friends, and the Public, that at a Meeting of their Trade, held on Tuesday, the 25th of July, 1826, it was

[Pg 42]

Resolved—That in order to meet the exigency of the Times, the change of Currency, and the advanced price of every article necessary for their Trade, particularly forage, that from and after the 1st of August next, the prices of Posting and Job Carriages will be as follow, in British Currency.

POSTING.

| s. | d. British. | ||

| Chaise and Pair, with one or two passengers | 1 | 1 | per Mile. |

| Chaise and Pair, with three passengers | 1 | 4 | ditto. |

| Chaise and Four | 2 | 2 | ditto. |

| Coach and Four | 2 | 6 | ditto. |

| Pair of Horses to Gentlemen’s Chaise, one or two passengers | 1 | 4 | ditto. |

| Ditto, with three passengers | 1 | 6 | ditto. |

| Ditto Gentleman’s Coach | 1 | 6 | ditto. |

| Four Horses to ditto | 2 | 6 | ditto. |

| Four Horses to Chaise | 2 | 2 | ditto. |

JOB CARRIAGES.

| Carriage and Pair for Town, from ten until five, evening | 12 | 0 |

| Ditto, ditto, until twelve at night | 17 | 0 |

| Ditto, from six in the evening until twelve at night | 12 | 0 |

| Pair of Horses to Gentlemen’s Carriages, same rates. | ||

Resolved—That the sum of Ten Pence, [Pg 43]demanded by Messengers sent to us for Carriages, be discontinued.

Resolved—That we will not hire or employ any Coachman who has not a written recommendation from his last employer to produce.

Resolved—That the foregoing List of Prices, together with the Resolutions, be published in The Dublin Evening Mail, &c.

[Pg 44]

JOBBING HORSES.

We think that it is quite as Cheap, and are sure it is by far the most Comfortable plan, to Job Horses:—if one of them falls sick or lame, the Hackneyman immediately furnishes you with another—and you avoid a vast deal of Inconvenience and Anxiety. This begins to be so generally understood now, that not only Coach, but Cart and Waggon Horses are Jobbed by the Year,—and Carts and Waggons also.

To Job Horses, is particularly recommended to persons who are ambitious of having an elegant Equipage;—a pair of fine Horses that match exactly are always expensive to purchase; and if one of them dies, it is sometimes, to a private Gentleman, extremely difficult to find a fellow to it.

Horses cannot work equally, nor at ease to[Pg 45] themselves, if they are not nearly of the same Size, of the same Temper, and of the same Strength, and have the same Pace, and Step well together.

A Hackneyman or Horsedealer, who is in an extensive way of business, has so many opportunities of seeing Horses, that he can match a Horse with much less Expense, and more exactly, than any Gentleman or any Groom may hope to do: therefore, those who are particular about the match of their Horses, will find it not merely more expensive, but much more troublesome, to Buy than it is to Job.

Job Masters, in general, Sell, as well as Let Horses;—therefore, stipulate in your Agreement, that you shall, be supplied with various Horses till you are suited to your satisfaction; and then, that neither of them shall be changed without your consent:—for this, a Hackneyman may demand, and deserves, a little larger price; but it is Money paid for the purchase of Comfort,—is the only way to be well served, and prevents all disputes. If you do not make such an Agreement, and your Hackneyman happens to be offered a good price for one of your Horses, he may take it; and Your’s, like many other Carriages[Pg 46] in London, will be little better than a Break:—nothing is more disagreeable, nay, dangerous, than to be continually drawn by strange Horses.

While the Job is travelling in the Country, the Hackneyman is allowed what is called Night, or Hay Money, i. e. an addition of 1s. 6d. per Night for each Horse, every Night the Horses are out.

This is considered as a compensation for the increased price charged for Corn at Inns, which is much more than it costs the Hackneyman at Home.

Mem.—Make some previous agreement in Writing about all these things.

Some people who wish their Horses to be in high condition, yet desire to avoid all Risk and Trouble, &c. hire Horses, and find them in Corn, &c. themselves. A good Pair of Horses, without keep, are charged about £70. per Annum.

The Old Proverb tells us, that “The Eye8 of the Master makes the Horse Fat.”

[Pg 47]

“The next care a man should take, after he has found a Horse to his mind, and purchased him, should be to provide a Stable so situated, with respect to his house, that he may see him very frequently, and to have his Stall so contrived, that it may be as difficult a task to steal his Horse’s provender out of the Manger, as to take his own victuals out of the Larder.”—From Zenophon’s Treatise on Horsemanship, translated in Berenger’s Entertaining and Instructive Book upon Horsemanship, 4to. 1771. p. 231.

If you have valuable Nags, do not think it time lost, occasionally to visit the Stable, and see that they are comfortably taken care of, have their proper allowance of Corn, and are well bedded, &c., and see that the Corn be not brewed.—A smart Son of the Whip says, that “some Hostlers are so clever, that they can turn Oats into Ale.”

The Word Hostler, I find in the most learned Lexicon in our Language, which explains some [Pg 48]thousands of words more than Johnson, is written Oat-stealer—which this learned lexicographer says it must be allowed appears to be the true word.

The Dictionary above alluded to is a very deep work:—instead of its containing more words by thousands than are in Johnson,—Johnson does not give us ten words that are in it—nor does it contain much above ten words that are in Johnson: this admirable and elegant Dictionary is entitled “A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, by F. Grose, Esq., F.R.S. &c.”

Some people fancy that they have made a capital Bargain, by stipulating that the Hackneyman shall let their Carriage and Horses stand in his Livery Yard, and so save part of the charge of a private Coach-house and Stable:—if Hackneymen have plenty of Room, they have sometimes no objection to this; however, you must take into the reckoning, that your Carriage, while standing in an open Coach-house, and even while being cleaned in a Public Yard, is unavoidably exposed to continual danger from being carelessly run against by other Carriages passing [Pg 49]to and fro: moreover, it is often injured by the dirty Mops and Cloths, and by the careless manner in which it is cleaned. If you wish your Carriage to be turned out in nice condition, you must have your own Coach-house and Stable; it is much more advisable, not only for your own Advantage, but for the Comfort of your Coachman, which you will consider also, if you expect him to consider your Interest.

It is extremely desirable to have Stables, &c. adjoining your House; because a Coachman, when your Carriage is not wanted, has many spare hours in which he may be very useful in carrying Messages, &c.

[Pg 50]

DESCRIPTION OF AND ESTIMATE FOR A HANDSOME TOWN CHARIOT.

A Chariot built with the very best Materials and of the best Workmanship,—the Body made with convex sides, lined with fine cloth and silk lace, and lace Footman’s holders, Morocco head Cushions and Squabs, colour of Lace Cloth and Morocco, &c. to choice: handsome Venetian Blinds, best lute-string Spring Curtains, double folding steps trimmed with black Spanish Leather, lined with Cloth, and concealed in Doors; best Brussels Carpet to the bottom of Body, and Steps and Oak seat box.

The Body hung on a Carriage with compass perch, best Town-made Springs and Iron work; the Wood work of Carriage beaded and carved; Axle-trees turned and case hardened with solid pipe boxes; Wheels with the best seasoned [Pg 51]Ash felleys, and Patent hoop-tire rivetted: Barouche Dickey Coach Box set on a Boot and attached to the Carriage by handsome Iron Work, and made to take off in case of travelling; trimmed with the best patent Leather borders, and lined with Cloth; large splashing Iron in front of Body, covered with double patent leather; Mail Lamps; brass moulding to Body; Swage Door handles; the Body, Carriage, and Wheels painted to fancy; Arms painted in ornamented shields on Doors; and the best plate Glasses to Windows; the whole made of the best materials, and finished in the most complete manner,

| £. | s. | d. | |

| 240 | 0 | 0 | |

| If the following Extras are required:— | |||

| Handsome C springs with carved blocks, stays, &c. &c. | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Handsome carved hind Standards | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Under-Springs | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| Collinge’s Patent Axle-trees | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| New Pair of very Handsome Harness, with Patent Leather Water decks complete | 36 | 15 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 341 | 15 | 0 | |

| —————— | |||

The Coachmaker will keep the above Carriage [Pg 52]and Harness in Repair, and find Wheels, &c. for four Years, for £10. per Annum: this, at the end of that time, would make its expense £381. 15s., and it might then be worth about £100.; so that if you purchase, it will cost at least £70. per Annum, besides the Interest of the Money advanced: moreover, you will have more than common luck, if you get £100. for it at the end of Four Years.

If such a Chariot, with its appendages and Harness, as explained in the above Estimate, be taken on a Job, (the longer the period you hire it for, the less will be the annual charge,) for Four Years, the charge is about £84. per Annum. It is not advisable to agree to take a Carriage for a longer period than it will look well without being repainted, &c. After three or four Years, Carriages that are in continual use require to go into Dock for a thorough repair.

A Landaulett or a Landau is charged £10. per Annum more.

A Landau is a Carriage in the form of a Coach, the upper part of which may be opened for the advantage of air and prospect in [Pg 53]Summer time, and is principally intended for Country use, and is the most convenient Carriage of any, as so many persons may be accommodated with the pleasure of an Open and a Close Carriage in one, without the care of Driving, as in other Open Carriages, or the expense and incumbrance of keeping Two.

A Landau or Landaulett is not only more expensive to build, but more troublesome to keep nicely clean; and its Leather Roof much sooner wears shabby, than the Japanned Roof of a Coach or Chariot.

Nota Bene. It is customary for the Builder to warrant his Work for the first Twelvemonths, and to undertake to make good all failures happening within that time, which arise from the Timber or Iron work’s breaking, but not those decays which necessarily follow from reasonable use and wear, or damages by Accident. However, to prevent all Misunderstanding, insert the following lines in your Contract for Building:—also, that “after the Carriage has been out about two or three months, and the Varnish has got thoroughly[Pg 54] dry, the Builder shall Polish it free of further expense.” This process can be performed much better after a few months have elapsed, than it can when the carriage first comes out, as the Varnish is not then sufficiently hardened.—See Cautions on Building Carriages, at p. 65 et seq. of this Work.

TO JOB OR HIRE A CARRIAGE

Is the most convenient and cheapest way of proceeding.

Carriages are usually hired for such a time as they may be expected to last in Fashion, that is for about four or five years.

A One Horse Chaise with Two Wheels may be jobbed for £20. to £40. per Annum.

A Four Wheel Chaise from £30. to £50.

The present charge for the hire of a Coach or Chariot, (see Estimate No. IX.), Landau or Landaulett, and Harness, per Annum, is from £60. to £100. One year of which is paid in advance.

Coachmakers will build a New Carriage for this purpose, and finish it to your own fancy; [Pg 55]exactly the same as if you were to purchase it, and will paint it at the end of two or three years, if you hire it for a longer period.

Persons who constantly require the use of a Carriage will do wisely to Hire, and not for a longer period than Three or Four Years. The frequent Repairs which are constantly wanting to Older Carriages, occasion many Inconveniences, although the expenses of them are avoided by Hiring.

Carriages are never better built than those which are made expressly to be let on a Job. A Coachmaker takes care to choose materials and workmen of the best kind for his own sake, to avoid those subsequent charges, which, as has been observed before, constitute the evil of inferior Carriages.

Mem. In the Agreement for Hiring, stipulate for the option of purchasing the Carriage at the end of the First Year, at a certain Sum, i. e. if the original price was £300., and you paid £80. per Annum, for £220. After a Year’s wear, you will be able to see pretty clearly what kind of a Carriage you have got, and whether it is worth purchasing.

[Pg 56]

Harness is usually engaged with the Carriage, which is kept in Wheels and all Repairs, excepting those which are required from Accidents.

When Carriages are let by the Year, the following engagement is usually entered into by the contracting Parties:—

COPY OF AGREEMENT.

Articles of Agreement made and entered into this 13th Day of April, 1826, between A. B., Gent., of in the county of on the one part, and C. D., Coachmaker, of in the county of on the other; and this certifies that the said C. D. doth agree to build, and preserve in good and substantial repair, a Carriage with Harness for the use of the said A. B. until the full expiration of Four Years, from the date hereof, after the following manner:—(here is to be inserted the manner in which the Carriage is to be built, see Estimate No. IX., with all the particulars of keeping the same in repair, the time of New Painting, New Green silk Blinds, Hammerclothing, &c.):—to furnish New [Pg 57]Wheels when the said A. B. desires them, and to supply him with a good Chariot while this is repairing—and that A. B. shall have the option of purchasing the said Carriage and Harness at the end of the first Year for the sum of .

In consideration whereof the said A. B. doth agree to pay, or cause to be paid, to the said C. D. the sum of annually; the First Year’s payment on the receipt of the said Carriage and Harness, the Second on the commencement of the Second Year, and each Year’s hire to be paid in advance; and at the expiration of the Four Years, the said Carriage with Harness to be returned to the said C. D. with Glasses whole, and every part of the said Carriage and Harness complete and whole, excepting such deficiencies as may be expected from reasonable use and wear, provided always, and on condition, that if the said A. B. shall, during the said term of four Years, pay the said C. D. the sum of thirty Guineas, and give up the said Chariot and Harness complete, then this Agreement shall be void, any thing to the contrary notwithstanding.

[Pg 58]

In witness hereof, each party hath set their hands and Seals this day of

A. B.

C. D.

Witness, F. G.

This agreement must be on a Stamp, or Stamped within fourteen days; or if a question arise, and it should come into Court, the Stamping then would cost £20.

[Pg 59]

The Art of Coachmaking within these last Thirty Years, has been improved greatly in Beauty, Strength, and Convenience; and a Carriage is now considered as a distinguishing mark of the taste of its Proprietor.

There are few works of Art which require the aid of so many different Artists as the constructing of a Carriage; there are Wheel-wrights,—Spring,—Axle-tree,—Step,—and Tire,—Black and White Smiths,—Brass Founders,—Engravers,—Painters,—Carvers,—Carpenters,—Joiners,—Trimmers,—Lace Makers,—Lamp Makers,—Curriers,—Collar Makers,—Harness Makers, &c. &c.; and upon the quality of the Materials, and the capacity of these Workmen to execute their respective parts in a perfect manner, and upon the taste and skill of the Coachmaker in combining them, depends the Beauty and the Durability of the Carriage.

[Pg 60]

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF CARRIAGES.

The best time to bring out a New Carriage, is about April or May, before the extreme heat comes on; moreover, the Taxes are reckoned from one 5th of April to another: and if you enter a Carriage on the 5th of March, you will have to pay for a whole Year, for only one Month’s use of it.

If you have any thing peculiar about a Carriage, it will require much more time in building, than if you are contented with merely ordering “a fashionable Vehicle.” In the former case, do not hope to get it under Three, nor be surprised if you wait Four Months for it.

However, if you have no particular desire to be disappointed, summon to your assistance the aid of those powerful refreshers of a perfunctory Memory, the Goose, the Calf, and the Bee;9 i. e. take Mr. Jervis’s advice, and bind the Builder in a written contract, made by your Attorney, and duly Stamped, Signed, [Pg 61]Sealed, and Witnessed, &c., to deliver the Carriage, Harness, &c. completely finished on a certain day—or that he shall forfeit, and that day shall pay to You, One Hundred Pounds, and keep his Carriage himself.

Be careful that your Contract contains a full and very particular description of every part; for

Mem.—If you order the least Alteration or Addition afterwards, it will be charged Extra, unless you discreetly insert a sweeping clause, that the Whole shall be completed to your entire satisfaction, for the Money, and at the Time agreed upon.

An Honest Man will have no more objection to sign a written Agreement than to make a Verbal Promise, and a Prudent Man will never take the latter when he can get the former:—the Expense of a written Agreement is Money expended in preventing Anxiety, which is like sacrificing a Pebble to preserve a Diamond:—those who wish to avoid disappointments and litigation, will not stir one step without a Written Agreement—’tis a pretty bit of Paper, that makes men Honest, and keeps them so.

After you have settled what is to be the price of the New [Pg 62]Carriage—then, before you sign the Agreement respecting it, make your Bargain as to what Sum the Builder shall allow you for your Old One, provided you do not previously otherwise dispose of it.

The Money allowed for an Old Carriage, is less than a Novice will expect. I sold one Chariot, which I had in use only Five years, for only £15., nor could I get more for it, although I kept it for several Weeks.

I sold another Chariot, which had been in wear about the same time, for £30.,—and it is not often that a Builder will allow much more for a Carriage that has been in use for five or six Years:—by that time, the shape of the Body is out of Fashion, the Lining is shabby, and before it can be sold again to a particular person, it must be thoroughly repaired, which will cost a considerable Sum.

The following is an Estimate which was given to the Gentleman who bought my last Chariot.

AN ESTIMATE OF REPAIRING A CHARIOT

| £. | s. | d. | |

| And putting in all New wood work, neatly carved—fresh fitting, filing, and fixing the old Iron Work with new bolts—taking the[Pg 63] Springs to pieces—fresh fitting the plates, and re-fixing Springs with new rivets and bolts—altering the Iron work of the Barouche seat—putting a New Foot-board and fresh hanging it and the Body | 26 | 0 | 0 |

| Handsome new Patent Lamps | 2 | 8 | 0 |

| Repairing braces, pole-pieces, &c., new covering roller, bolts, and pole with New Leather | 1 | 14 | 0 |

| Altering and re-fixing the frame of Dash Iron, and covering it with New Leather | 4 | 12 | 0 |

| Covering the whole of the inside with new cotton false lining | 5 | 10 | 0 |

| New Carpets to the Bottom and the Steps | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| New Plating the Commode Handles and rivetting the Door Handles | 1 | 6 | 0 |

| New pair of Web Holders | 0 | 14 | 0 |

| New Painting the Body of a Chariot | 14 | 0 | 0 |

| New Wheels | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| New Lining | 35 | 0 | 0 |

| Fresh Stringing and Painting Blinds | 1 | 15 | 0 |

| New covering Glass Frames | 1 | 15 | 0 |

| New Silk to Green Curtains | 1 | 5 | 0 |

| Under-Springs | 25 | 0 | 0 |

| —————— | |||

| 137 | 7 | 0 | |

| —————— | |||

Now, if the Body had not been a beautiful piece of Work, it would not have been worth [Pg 64]while to have bestowed this large sum in renewing the Carriage part: but the whole of the exterior of the Old Body, although it had been built some Years, was more sound and unwarped, than most new Bodies are on the first day they are turned out; it was elegantly formed, and the Interior so admirably constructed for Comfort, that from it I learned the dimensions, &c. which I have given in the following description of what I think a Chariot ought to be.

Coachmakers sometimes shew Drawings of Carriages for their Customers to choose from,—it is more satisfactory, not only to see, but to take a ride in a pattern Carriage; this your Coachmaker can take you to see, or, if you see a Carriage which pleases your Eye, your Coachman can easily learn where it is put up; go with your Coachmaker and see it, and have a written Particular of all its peculiarities, an exact Measurement of its dimensions, and an Estimate in Writing of the cost thereof, similar to the one given in Chap. I. Estimate No. 9.

[Pg 65]

The Novice in these things may think that the following description is unnecessarily minute, and that he need only go to a Coachmaker and order “a Chariot,” and that Word will procure him all he wishes.

The form of Carriages is as absurdly at the mercy of Fashion, as the Cut of a Coat is;—however, if the Reader is willing to let the Builder please himself with the form of the Exterior, he will perhaps not be quite so polite as to submit the construction of the Interior entirely to the caprice of his Coachmaker.—If “as easy as an old Coat” be a true Aphorism, “as easy as an Old Carriage” is equally so:—by riding three or four Years in one, you become so used to it, that any change is extremely unpleasant—and if the Elbows or the Seat are too high, or too low, or too narrow, or too wide, &c. when the Body is built, it is always difficult, and [Pg 66]often impossible, to alter it; therefore, if you like your Old Body, measure it, and order your New one accordingly.

If you build a Body, pay a visit to your Coachmaker while it is in progress, especially just before it is put into the hands of the Painter.

All Coachmakers, do not, always, go to the expense of covering the Roof, Back, and Sides with one piece of Leather, as they ought to do;—the common practice is to cover the Roof only with Leather, and leave the Upper sides and back of pannel board, with a groove run in the Roof where the Leather is nailed in covering the nails and filling up the groove with Putty, which the Summer’s Sun and Winter’s Rain will soon crack, and the Water entering will soil the Lining, and the Inside of the Body will become damp:—the whole of the upper part of a Body should be enveloped in one large hide of strong Leather, and neatly worked in, so that it is one solid surface of Leather to paint on, which neither Heat nor Wet can affect for many Years.

[Pg 67]

The Breadth of a Body, to contain three persons comfortably, should not be less than 4 feet 3 inches.

From Back to Front, 4 feet are enough.

The Height of the Seat from the bottom, about 1 foot.

From the Seat to the Roof, not less than 3 feet 6 inches; the Cushions, which are commonly about three inches in thickness, not included.

A few Inches in Width and Breadth add but a few Pounds to the Weight, but contribute greatly to the Convenience of a Carriage, especially to well-grown and full-fed persons.

The little thoroughly-ugly humpty-dumpty Chariot, which looked something like a Champion Potatoe set on wheels, but which was the grand rage with Children of the Largest Growth about 30 Years ago, would not admit a small person to sit with his hat on, nor a tall one with his Hat off:—these foolish little wee Vehicles weighed only a few pounds less than the large commodious Chariots, in which the Lords and Ladies of the Creation transport themselves in at the present day.

The Elbows should not be more than 6 inches[Pg 68] above the Cushion, and should be so entirely in recess, that you may lean comfortably against the side of the Carriage:—in some ill-contrived modern bodies, they are placed too high, and project out, and as often as you loll towards them, remind you that you should not, and force you back into your perpendicular, by giving you a Punch in your Side.

In a Chariot Body of the size just described, there should be a Front Seat about 10 inches in width, which will occasionally carry Two persons:—this addition is especially desirable in a Travelling Chariot, as by sitting in one corner of the Carriage, you may put your Legs upon it, and take a Nap very comfortably. This Front Seat is doubly better than the old fashioned Bodkin Seat which drew out from the centre; and when you have Two fellow Travellers, in order to induce one of them to sit upon this accommodation seat, you may tell them that they will sit three times as comfortably there as on the front seat; for if they sit on that, they will be crowded themselves, and crowd two other persons also; but if one sits on the other seat, all may ride [Pg 69]comfortably enough:—it should be fixed on with Slip-Hinges, so that it may be taken off at pleasure.

The Door Lights or Windows are sometimes contracted on the Seat side about 4 inches; however, some people like them as large as possible, and besides, have the back of the Carriage stuffed eight or ten inches deep, which is exceedingly convenient for those who are anxious to exhibit themselves like Articles for sale in a Shew Glass.

Take care that the Glasses are of the best Quality, well Polished, White, and as free as possible from Specs and Veins.

These Glasses are commonly bound with Cloth of the same Colour that the Carriage is lined with, or with Black Velvet, which wears better, and works in the grooves more pleasantly than any binding:—the most elegant binding is Lace like that of the Glass-holders, or in which the Crest or Arms are woven.

The present fashion of Stuffing is preposterous; it reduces a Large Body to the size of a small One: however, if you like to ride about for the benefit of public inspection, as your friends, my [Pg 70]Lady Look-about,—the Widow Will-be-seen,—and Sir Simon Stare, do, pray study Geoffrey Gambado on the Art of sitting politely in Carriages with the most becoming attitudes, &c. and choose wide Door Lights and full Squabbing;—if you wish to go about peaceably and quietly, like Sir Solomon Snug, and are contented with seeing without being seen, adopt the contracted Lights and common Stuffing, which, among others, have this great advantage, that when you sit back, you may have the side Windows down, and a thorough Air passing through the Carriage, without its blowing in directly upon you: this, to Invalids who easily catch Cold, is very important.

The Back Light must not be more than 27 inches from the surface of the Cushions, or it will be too high for a person to look through it without rising up—it is convenient to have this made to Open, as it affords an easy opportunity of giving directions to the person behind the Carriage, and is a desirable aperture for admitting Air in very hot weather:—tell the Builder to give you a fine clear plate for this purpose, and not to glaze it with a [Pg 71]semidiaphanous “Old Accident,”—a technical term for those “Odds and Ends” of broken Coach Glasses which are sometimes used for this purpose, and which having been continually cleaned every day for thirty or forty years, have become so scratched, that you can hardly see through them.

I recommend the Lining to be Green, with Lace to correspond, and the Green silk Sun shades of the same Colour—Green is pleasant to the Eye, and Superfine Cloth or Tabinet, is, during nine months out of the twelve, much more comfortable in this Cold climate, than the chilling Leather which has lately been the fashion: in Summer this may be covered with what is commonly called a False Lining, which is generally made of Gingham, and is equally useful to preserve a New or hide an Old Trimming:—it should only be applied to the back and those parts of the sides that are leaned against; the Front, Roof, and Doors, should be left uncovered.

The Elegance of the Interior of a Carriage depends much upon the pattern and breadth of the Lace with which the Lining is bordered, [Pg 72]of which there are a great variety.—Lace-making is a distinct branch of Manufactory; and as “every Eye makes its own Beauty,” the person who builds a Carriage should desire his Coachmaker to furnish him with some patterns to choose from:—there are several Coach Lace-makers in Long Acre.

Some Carriages are fitted up with Squabs, i. e. Cushions stuffed with Wool and covered on one side with Cloth, and on the other with Silk, Linen, or Leather; the former side for Winter, the latter for Summer use.

The Seat Cushions should be covered on one side with Leather, and on the other with Cloth.

Let the Stuffing at the Back be no thicker than necessary to make it easy, i. e. about 2½ inches in thickness.

Have the Lid of the Sword Case to fall down with the back attached, instead of lifting up, being much easier to put in a parcel without troubling the passengers to rise.

The Seats, which are usually boarded, I would recommend to be, on one side, Caned or Girt-webbed, for ease in Sitting—the other half may be fitted up with a Case for containing Grog and Prog, &c. for a [Pg 73]Rusticating Party:—they should be about 22 inches deep—not more, or Short people cannot sit upon them comfortably:—they will be much easier if made on a bevil, and about an inch lower behind than they are before: if not originally so constructed, the stuffing of the Cushions may be easily adjusted so as to produce that effect.

The Green Silk Spring Sun Shades should be fixed upon the Doors; this saves the trouble of putting them up every time you open the Door, which must be done when they are fixed to the Body;—if the Blinds are fixed on the Door, take care to shut it when you get out of the Carriage in Wet Weather, or they will be spoiled:—when the Silk becomes faded, if it is turned upside down, the part most in sight will look almost as well as new.

If the Ground Colour of the Body is good, New Varnishing will sometimes do almost as well as New Painting.

I am told that the best Colour for Wear is Midgley’s Chrome Yellow. In consequence of the vivid brilliancy of this pigment, in all the variety of its shades, from the pale Lemon [Pg 74]colour to the full Orange, it has of late come into general use. When properly prepared, it possesses all the desiderata of perfect Colours, Smoothness, Body, Extensibility, and ready Mixture with Oil or Water, and dries well and blends well.

Venetian Blinds are delightful shades in warm Weather, as they admit the Air while they exclude the Sun; and when closed, serve as a shutter to prevent dust from soiling the Carriage while it is standing by. They should be painted on the Inside, of a Verdigrise Green, and on the Outside of the same Colour as the Carriage.

If these are not made of extremely well-seasoned Wood, they rattle very much in Dry, and swell in Damp weather.

These Blinds should have Bolts affixed to them, which, when fastened within, if you have Locks on the Carriage Doors, enable you to fasten up the interior of your Carriage completely.

There is a great deal of Rain falls during the warmest months in this Country, and our Chariots very much want an Exterior Blind (a [Pg 75]Hood as it were) in the front, which would exclude Rain, while it would admit Air:—many of our Wet days are so warm, that our Carriages are a shower Bath if the Windows are open, and a Vapour Bath if they are Shut!

The Handle of the Door Latch should be double—that is, it should have an additional Handle within side, the position of which will afford you the satisfaction of seeing that the Door is properly fastened, and also the power of easily opening it in case of an Accident, &c.

It is a very great convenience to have the power of opening the Door from the inside. This Handle should be made to turn towards the Door, so as to be within the Door when the Door is opened, it will then be out of the way of being struck against the Body in shutting; which, if it turns to the Right, will sometimes happen when the Door is shut by perfunctorious persons.

The spindles of these Handles during the first Year, till time has worn them a little, will occasionally move too stiffly: the remedy for this is a drop of Oil.

Never permit officious Strangers to shut [Pg 76]your Carriage Door; in order to save their own time and trouble, and to accomplish this at once, some idle and ignorant people will bang it so furiously, one almost fancies that they are trying to upset the Carriage, the pannels of which are frequently injured by such rude violence; therefore, desire your Coachman to be on the watch, and the moment he sees any one prepare to touch your Door, to say loudly and imperatively “Don’t meddle with the Door!”

Have Locks to the Doors—they are very necessary when travelling, or when your Carriage is waiting for you at Night: a Latch inside that will fasten the Door so that it cannot be opened on the outside, is also desirable, especially in Travelling Chariots.

In Landaulets the door opening without the window frame, particular directions to the Footman are necessary that he observe the Glass is entirely down before he attempts to open the Door, or the pane will be infallibly broken. When the glass is quite up there is no danger, for in rising it releases a Spring which fastens the Door; the blind does the [Pg 77]same; so that if the Servant keep the blinds up while the Carriage is waiting, a lock may be dispensed with. I would recommend the addition of this contrivance to Coaches and Chariots.

A Town Carriage should not be more than three feet from the Ground, so as to require only One Step; to which should be fixed a Strap, by which any person within the Carriage may very easily pull it up, and with the help of the Inside Handle, may, with equal facility, finish the Footman’s Work, and fasten the Door.

The above is an invaluable contrivance, and well deserves to be called “a Dumb Footman;” it entirely prevents the necessity of the Coachman’s leaving his Box; from which rash act, many lives have been lost, and many Carriages destroyed by the Horses running away10:—All [Pg 78]will adopt it, excepting those persons who are so unfortunate, as to be more Proud than Prudent. Mr. Jervis was extremely earnest in recommending these excellent appendages; and to impress the importance of them upon the imagination of the Editor as strongly as possible, he closed his arguments by averring, that for a Coachman to leave his Reins would be as desperate an act of rashness as for a Cook to leave her Kitchen while her Spit was going round, and equally likely to produce the most tremendous and irreparable Evils!

If such a plan be adopted, the Body must not be hung further than twenty-two inches from the Dickey, i. e. near enough to the Coach Box to allow the Coachman to put his hand on the top of the Door when it is opened, and hold it so while the Passengers get in and[Pg 79] out. Till the Hinges are worn a little, they will occasionally get rusty and move too stiffly, and require a little Oil.

The present fashionable Door Handle is too big by half, and is also extremely inconvenient on account of the Hinge in it, which requires an additional action, which in the course of a little wear becomes ricketty and rattles, and you can hardly tell to a certainty whether it fastens the Door completely or not.

The simple Handle without a Hinge, which was in vogue some years ago, is infinitely more convenient and safe, because its single action is more certain.

The Crest or Arms in the Centre, is an elegant ornament for the Head of the Handle.

A Boot or Budget fixed on the fore Carriage between the front Springs is useful to carry Horse Cloths, Luggage, &c.

Hind Standards are very useful for town work, to keep the Horses and Pole of other Carriages from injuring your Hind Pannels; but as they are a heavy weight, they should be made to take off for the country.

A Dickey Coach Box is the most convenient;[Pg 80] it is less impediment to the view of those who are inside the Carriage, and more comfortable to the Coachman. They should be fixed on the Boot, and entirely detached from the Body. Let it be large enough to contain Two persons. It is not quite so easy as the Body; but for those who love Air and Exercise, and a view of the Country, it is in Summer the pleasantest place.

The Seat thereof to hold Two persons, should be thirty Inches wide and twenty Inches deep, inside measurement. The Cushion should be of equal thickness, and not higher on the Driving side, as it is in a Gig, because when only the Coachman is on the Box, he should sit in the middle of it. There should be a Pocket on each side in the lining, for putting Tickets in.

This kind of Coach Box may be so made as to take off, and fix on behind the Carriage. Under the Seat, for the Coachman, should drop in a Box to serve as a Tool Budget, and contain a few spare Bolts, Nuts, Linch-Pins, Nails, a Wrench, a Winch that will fit your axle, Hammer, Chisel, a Pair of Pincers, &c.; [Pg 81]by help of which, a trifling accident on the Road may be remedied without delay.

Take care that your Coach Box is strongly and properly fixed on, and frequently examine the state of the Bolts and Nuts, &c. For want of sufficient strength, or of the efficient state of the supports to it, many dreadful accidents have happened; one of which we relate as a warning:—

“On Tuesday morning last, while the Coachman and the Footman, in the service of F. P. Ripley, Esq., 12, Woburn Place, Russell Square, were driving their Master’s carriage along Tavistock Place, Tavistock Square, the box on which they were sitting broke down, and precipitated them to the ground. The carriage wheels passed over the right leg of the Coachman and the left breast of the Footman. They were conveyed to their master’s with the greatest alacrity, where they received such treatment as their situations required. The coachman’s leg is bruised and lacerated extremely. The footman, on being raised from the ground, was excessively convulsed. We [Pg 82]are sorry to add there are no hopes of his recovery.”—Times, June 2, 1826.

Spikes to fix on the Hind Standards.

These spikes may be so contrived as to be put on and off very easily, with Three Nuts, in as few minutes;—the Footman’s Step should be fixed on in the same manner.

Do not permit Strangers to place themselves behind your Carriage at any time, or under any pretence whatever. There are innumerable instances of Carriages having been disabled from proceeding, and Travellers robbed and finished, by allowing such accommodation. The Collectors of Check Braces, and Footmen’s Holders, assume all kind of Characters, and are so expert, that they will take these articles off in half the time that your Coachman can put them on; and will rob you of what you cannot replace for a Pound, though they cannot sell them for a Shilling.

Therefore, Spikes are indispensable when you have not a Footman; otherwise, you will be perpetually loaded with idle people, i. e. unless [Pg 83]you think that two or three outside passengers are ornamental or convenient, or you like to have your Carriage continually surrounded by Crowds of Children, incessantly screaming, “Cut! Cut behind!” Why do not the Street Keepers prevent this Nuisance? These officers should be stationed in Sentry Boxes, as they are in the Parish of Bloomsbury, i. e. the same as the Watchmen are at Night; where, when not going their Rounds, they should remain.

The multitude of Strayed Dogs which are perpetually prowling and howling, and barking and biting at Horses’ heels, and making them start, and those which are carried about in Carts, also frequently frighten Horses and occasion Accidents, and are barbarous and dangerous Public Nuisances, which “the Street Keepers” should suppress.

Let it be enacted—that all Dogs, Fowls, and any other Beasts and Birds, found in the Streets, not having a Collar on, on which is engraven the Name and place of abode of the Owner thereof, shall henceforth be seizeable by any Constable, or Street Keeper, or Watchman, or any person who finds them; which[Pg 84] they shall have power to dispose of as their own property; and those with a Collar also, unless their owners immediately pay a fine of five shillings; one moiety of which shall be to the person finding them, the other to the Poor of the Parish. For want of such salutary Regulations, some of the Streets of London are like a Dog Kennel or a Poultry Yard.

These Beasts and Birds are seldom kept except by petty Housekeepers, who are perpetually applying to be excused paying Taxes. Surely such persons should not be permitted to annoy their neighbours, who by duly paying Parish rates, in fact, contribute to their maintenance.

Dogs out of Doors are horribly noisy, especially on Moon-light Nights, when they will turn up their Noses, and

for an hour together. They seldom give Tongue when inside of a House, except when shut in by themselves in an Empty house. There are certain Manufacturers who having more cunning than conscience, to evade paying [Pg 85]the Taxes upon their Warehouse, instead of letting somebody sleep in it, which would subject them to the Taxes, turn in a Dog as a Watchman, who barks and howls incessantly all night long. Surely such shirking Gentry are not entitled to the privilege of annoying a score or two of quiet Neighbours, who honestly pay the Taxes imposed by their Country! They and their Cur-Watchman should be indicted and amerced sans cérémonie.