Title: History of Zionism, 1600-1918, Vol. 2 (of 2)

Author: Nahum Sokolow

Author of introduction, etc.: S. Pichon

Contributor: Israel Solomons

Release date: May 26, 2023 [eBook #70865]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Longmans, Green and Co, 1919

Credits: Richard Hulse, Tony Browne, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was provided by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Punctuation has been standardized.

Most abbreviations have been expanded in tool-tips for screen-readers and may be seen by hovering the mouse over the abbreviation.

The text may show quotations within quotations, all set off by similar quote marks. The inner quotations have been changed to alternate quote marks for improved readability.

This book was written in a period when many words had not become standardized in their spelling. Words may have multiple spelling variations or inconsistent hyphenation in the text. These have been left unchanged unless indicated with a Transcriber’s Note.

Index references have not been checked for accuracy.

The symbol ‘‡’ indicates the description in parenthesis has been added to an illustration. This may be needed if there is no caption or if the caption does not describe the image adequately.

Footnotes are identified in the text with a superscript number and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

Transcriber’s Notes are used when making corrections to the text or to provide additional information for the modern reader. These notes are identified by ♦♠♥♣ symbols in the text and are shown immediately below the paragraph in which they appear.

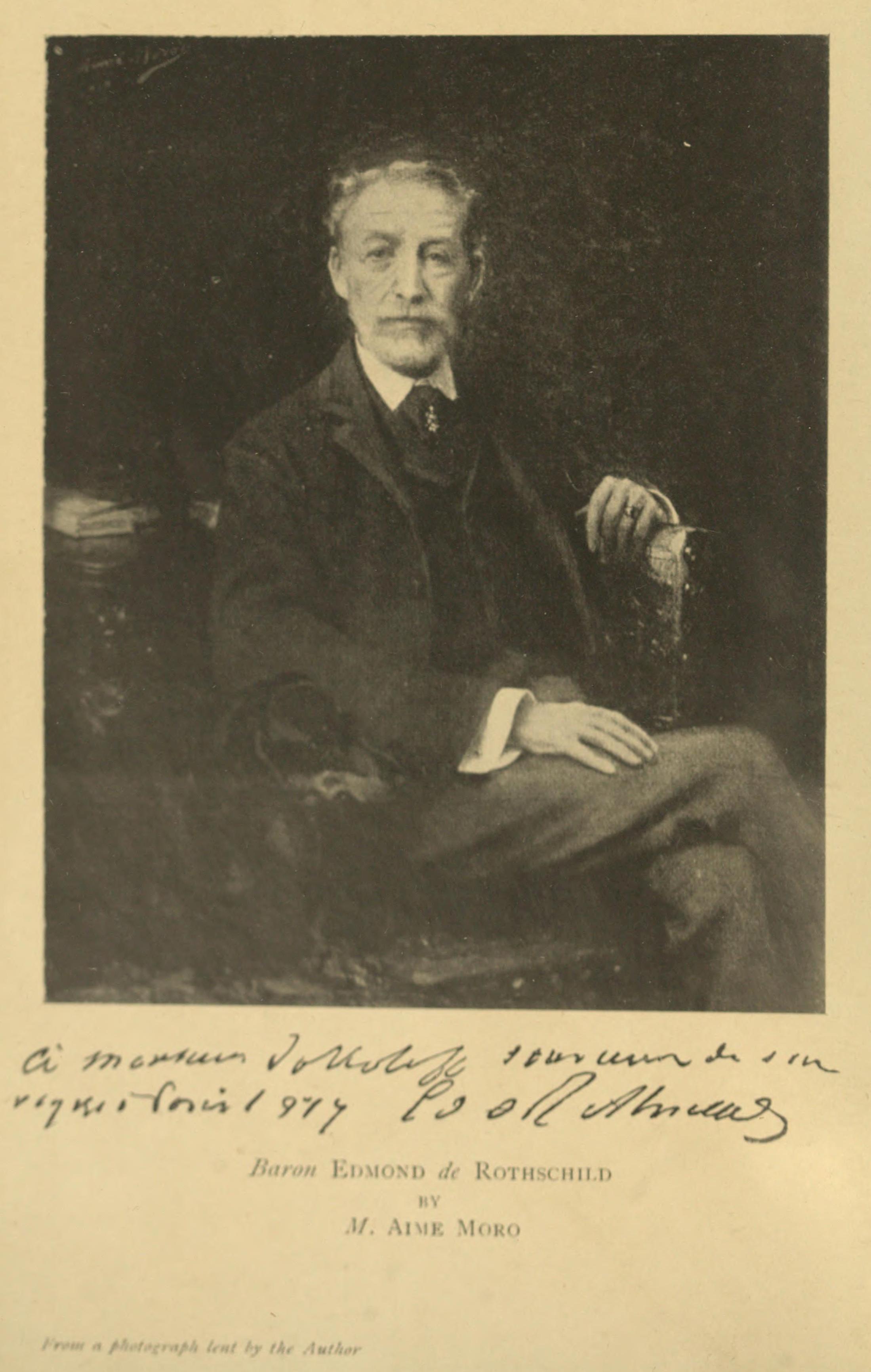

Baron Edmond de Rothschild

BY

M. Aime Moro

From a photograph lent by the Author

History of Zionism

1600‒1918

BY

NAHUM SOKOLOW

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

THE Rᵀ. HON. A. J. BALFOUR, M.P.

WITH NINETY PORTRAITS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY ISRAEL SOLOMONS

IN TWO VOLUMES

VOL II.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

M. STÉPHEN PICHON

MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS FOR FRANCE

LONGMANS, GREEN AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

FOURTH AVENUE & 30TH STREET, NEW YORK

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA AND MADRAS

1919

The present volume contains the continuation and documentation of Volume I.

After the conclusion of the historical review in its chronological order, it was considered desirable to supplement a portion of the narrative by adding further chapters, which will be found at the beginning of the present volume. These chapters bring the historical narrative up to the outbreak of the War in 1914.

The developments in the Zionist Movement during the War are dealt with in a separate account, which is not claimed to be, in the proper sense of the word, an historical study, but an account of recent activities up to the Peace Conference.

The present volume also contains an introduction, written by the French Ministre des Affaires Etrangères, M. Pichon, which arrived too late to be included in the first volume, and a character sketch of the late Sir Mark Sykes, whose death occurred while the present volume was in the press, to whose memory a tribute is offered.

The appendices contain not only the text of documents referred to in the body of the book, many of them hitherto unpublished, but also essays on subjects related to the main purpose of the work—for instance, Jewish art, and Hebrew literature—and notes of a bibliographical or critical character.

It is desired to point out that the nature of the subject with which this work deals rendered it inevitable that it should to some extent assume an encyclopædic rather than a narrative character. The innumerable sources from which Zionism draws its being, the geographical dispersion of the Jewish people, the many events and phenomena outside of the life of the Jewish people which have had and still have their bearing on the development of the Jewish National idea, give it inevitably the form that it has assumed. The author is well aware that the History of Zionism as narrated in these pages does not appear as altogether a symmetrical structure. Some periods dealt with in the story are somewhat disjointed, and as a necessary consequence the record of those periods reflects the same character. A writer who cared more for the form than for the correctness of the narrative would in such a case have recourse to his imagination in order to fill in the blanks. The present author has not, however, done so. He has attempted rather to let Zionism appear as it really was in the different countries and epochs with which he has dealt. Where his narrative is fragmentary events were fragmentary. In the earliest periods the different elements of Zionism were sometimes completely detached from one another. An exact description of these therefore takes necessarily an encyclopædic character. But Zionism develops as a unity, and at the end it will be found to offer to the reader a united picture.

The present book treats of the History of Zionism especially in England and France, but it has been found both impossible and also undesirable to exclude from the narrative all references to certain important events and personalities of other countries. Zionism in England and France, however, forms the main thesis of these volumes. Furthermore, this book is not only a history of the Zionist efforts among the Jews, it also narrates the history of similar efforts by non-Jews, in connexion with political events and literary manifestations in the countries in which they worked. At the same time the author has endeavoured as little as possible to cover ground that has already been repeatedly traversed, his intention being rather to break new ground and especially to bring to light hitherto unknown sources, old and forgotten prints, unpublished manuscripts and archives. These he has used to illustrate and document his narrative.

The plan which the author has followed falls under three headings:—

(I.)The special treatment of Zionism in England and France;

(II.)A particular consideration of the pro-Zionist efforts outside of Jewry; and

(III.)The publication of previously unknown literary and archival sources.

In accordance with this plan this history begins in the year 1600, although the history of Zionism in reality opened much earlier, even perhaps at the beginning of the Jewish history of the countries dealt with.

Material for a thorough treatment of the History of Zionism in other countries, including many monographs and historical notices which remain in the hands of the author, as well as further recent diplomatic and other documents relating to the most recent development of Zionism and in connexion with the Peace Conference of 1919, will be used as the basis of further volumes.

Publication of an index to the work might well have been deferred until these volumes had been completed, but the author thinks that he ought not to delay one any longer. At the end of the present volume, therefore, the reader will find a thorough index of persons and of subjects, for which Mr. Jacob Mann, M.A., is responsible and to whom he hereby tenders his thanks.

Finally, the author wishes to supplement the expression of thanks addressed to those of his friends who are mentioned in the Preface to the first volume of this work for the assistance they have rendered him in its preparation, and to mention in particular the good services of Mr. Albert M. Hyamson and M. André Spire.

Paris, June, 1919.

MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS FOR FRANCE

Fidèle aux traditions de son histoire, la France vient de montrer une fois de plus, au prix du sang de tant de ses fils, comment elle entend les devoirs que lui impose son rôle séculaire d’émancipatrice des opprimés. Elle sort aujourd’hui victorieuse d’une lutte décisive, soutenue au nom du Droit menacé par la brutalité d’un impérialisme sans scrupules. Champion des grandes idées qu’il a, plus que tout autre, semées à travers le monde, notre pays a puisé dans la conscience d’être un vivant symbôle de justice, la force de terrasser son adversaire. Il a, du moins aujourd’hui, le droit de se dire, non sans fierté, qu’il n’est plus au monde une race ou une nation qui ne puisse faire entendre ses légitimes aspirations, et qui ne sache qu’en France il y aura toujours un cœur pour les adopter.

Dans la paix comme dans la guerre, la France, étroitement unie à ses Alliés, veut demeurer fidèle à sa parole. Elle a promis aux nationalités naguère asservies de défendre leurs intérêts et de faire respecter leurs droits. Elle ne reniera pas une promesse dont la réalisation, en inaugurant une ère nouvelle de l’histoire du monde, justifiera les sacrifices consentis à la cause commune. Elle ne laissera se commettre aucune injustice, d’où qu’elle vienne, et qu’elle qu’en soit la victime. Elle ne saurait permettre, en particulier, sans protester hautement, qu’une majorité ethnique ou confessionnelle puisse désormais abuser impunément de sa force à l’égard d’autres éléments voisins, plus faibles ou plus dispersés.

C’est dire l’écho que ne pourra manquer d’éveiller chez les Français la voix éloquente du représentant le plus autorisé du Sionisme. Monsieur Sokolow, mettant au service de son idéal, un talent qui n’en est plus à son premier essai, s’attache à nous retracer l’histoire des doctrines au triomphe desquelles il n’a cessé de consacrer le meilleur de ses forces. Sachant combien il importe, aujourd’hui, de démontrer historiquement les origines et les antécédents des idées que l’on professe, il a voulu nous exposer les titres que possède le Sionisme à s’imposer à l’attention des Alliés, au moment où ceux-ci procèdent à une reconstitution du monde entier. Monsieur Sokolow, dont la foi dans le succès final de nos armes ne connut jamais de défaillances, possède une foi au moins égale dans l’esprit de justice qui préside à l’œuvre de la Conférence de la Paix. Les sympathies et les concours précieux qu’il a su trouver chez nos amis Britanniques, et dont Mr. Balfour lui renouvelle ici-même l’assurance la plus formelle, sont aux protagonistes du Sionisme un sûr garant de l’accueil que la France réserve à leur généreuse initiative.

Non seulement, en effet la race juive n’a cessé d’être, au cours des siècles, persécutée, décimée, poursuivie sans trêve par une haine incapable de désarmer; plus malheureuse encore que tant d’autres peuples opprimés, qui ont pu conserver au moins un symbôle de leur grand passé, les Juifs n’ont pu sauver ce dernier vestige. D’autres qu’eux mêmes sont devenus les maîtres de la Judée. Dispersés à travers le monde, beaucoup aspirent aujourd’hui plus que jamais à reprendre la chaîne brisée par tant de conquérants successifs, de leurs traditions ethniques et religieuses: ils pensent aussi qu’une telle restauration n’est possible qu’appuyée sur des réalités, c’est à dire, en l’espèce, sur un foyer moral national reconstitué au milieu des ruines de l’antique Judée. Qui donc, sans avoir perdu les plus élémentaires sentiments d’humanité et de justice, pourrait refuser aux exilés de revendiquer leur place, au même titre que les autres éléments indigènes, dans cette Palestine où un contrôle collectif des Puissances européennes assurera désormais à chacun le respect de ses droits les plus sacrés?

Entrée en guerre pour assurer la victoire définitive du Droit sur la force, la France se félicite de l’appui que le Sionisme a rencontré chez elle et chez ses Alliés. Une doctrine qui a pour elle, outre la justice, l’éloquence d’avocats tels que M. Sokolow est assurée de succès. Je suis heureux de l’occasion qui m’est offerte de réitérer les vœux que le Gouvernement de la République n’a cessé de faire pour le triomphe final d’une cause qui rallie tant de sympathies françaises.

INTRODUCTION by M. Stéphen Pichon

CHAPTER XLIXA. From the Second to the Fourth Congress

Chovevé Zion and Zionists in England—Louis Loewe—Nathan Marcus Adler—Albert Löwy—Abraham Benisch—The Rev. M. J. Raphall—Dr. M. Gaster—Rabbi Samuel Mohilewer—English representation at the Second and Third Congresses—The Fourth Congress in London.

CHAPTER XLIXB. The Death of Herzl

England and Zionism—Sir B. Arnold in the Spectator—Cardinal Vaughan—Lord Rosebery—The death of Herzl—David Wolffsohn—Prof. Otto Warburg—Zionism in the smaller states.

CHAPTER XLIXC. The Pogroms

The year 1906—Pogroms—Emigration—Conder and his activities—An Emigration Conference—The Eighth Congress—The question of the Headquarters.

CHAPTER XLIXD. The Death of Wolffsohn

1910‒14—The Tenth and Eleventh Congresses—Death of Wolffsohn.

CHAPTER XLIXE. On the Eve of the War

Baron Edmond de Rothschild in Palestine—Sir John Gray Hill—Professor S. Schechter—South African Statesmen—A Canadian Statesman—Christian religious literature again.

ZIONISM DURING THE WAR, 1914‒1918—

⭘ General Survey

⭘ Zionist Propaganda in Wartime

⭘ Conferences

⭘ The Jewish National Fund

⭘ Zionism and Jewish Relief Work

⭘ The Russian Revolution

⭘ Political Activities in England and the Allied Countries

⭘ Conference of English Zionist Federation in 1917

⭘ Zionism and Public Opinion in England

⭘ Co-ordination of Zionists’ Reports

⭘ The British Declaration and its Reception

⭘ London Opera House Demonstration

⭘ Manifesto to the Jewish People

⭘ Declarations of the Entente Governments

APPENDICES—

| I. | The Prophets and the Idea of a National Restoration |

| II. | Rev. Paul Knell: Israel and England Paralleled |

| III. | Matthew Arnold on Righteousness in the Old Testament |

| IV. | “Esperança de Israel,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| V. | “Spes Israelis,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| VI. | “Hope of Israel—Ten Tribes ... in America—מקוה ישראל—De Hoop Van Israel,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| VII. | The Humble Addresses of Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| VIII. | “Vindiciæ Judæorum,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| IX. | Enseña A Pecadores |

| X. | “De Termino Vitæ—of the Term of Life,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| XI. | “נשמת חיים—De Immortalitate Animæ,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

| XII. | “Rights of the Kingdom,” by John Sadler |

| XIII. | “Nova Solyma,” edited by the Rev. Walter Begley |

| XIV. | “Præadamitæ—Men before Adam,” by Isaac de La Peyrère |

| XV. | Isaac Vossius |

| XVI. | “Doomes-Day” |

| XVII. | “Restauration of All Israel And Judah” |

| XVIII. | “Apology for the Honorable Nation of the Jews—Apologia por la Noble Nacion de los Ivdios—Verantwoordinge voor de edele Volcken der Jooden,” by Edward Nicholas |

| XIX. | “A Word for the Armie,” by Hugh Peters |

| XX. | Isaac da Fonseca Aboab |

| XXI. | Dr. Abraham Zacutus Lusitanus |

| XXII. | Jacob Judah Aryeh de Leon |

| XXIII. | Thesouro Dos Dinim |

| XXIV. | “Rettung der Juden,” by Manasseh Ben-Israel |

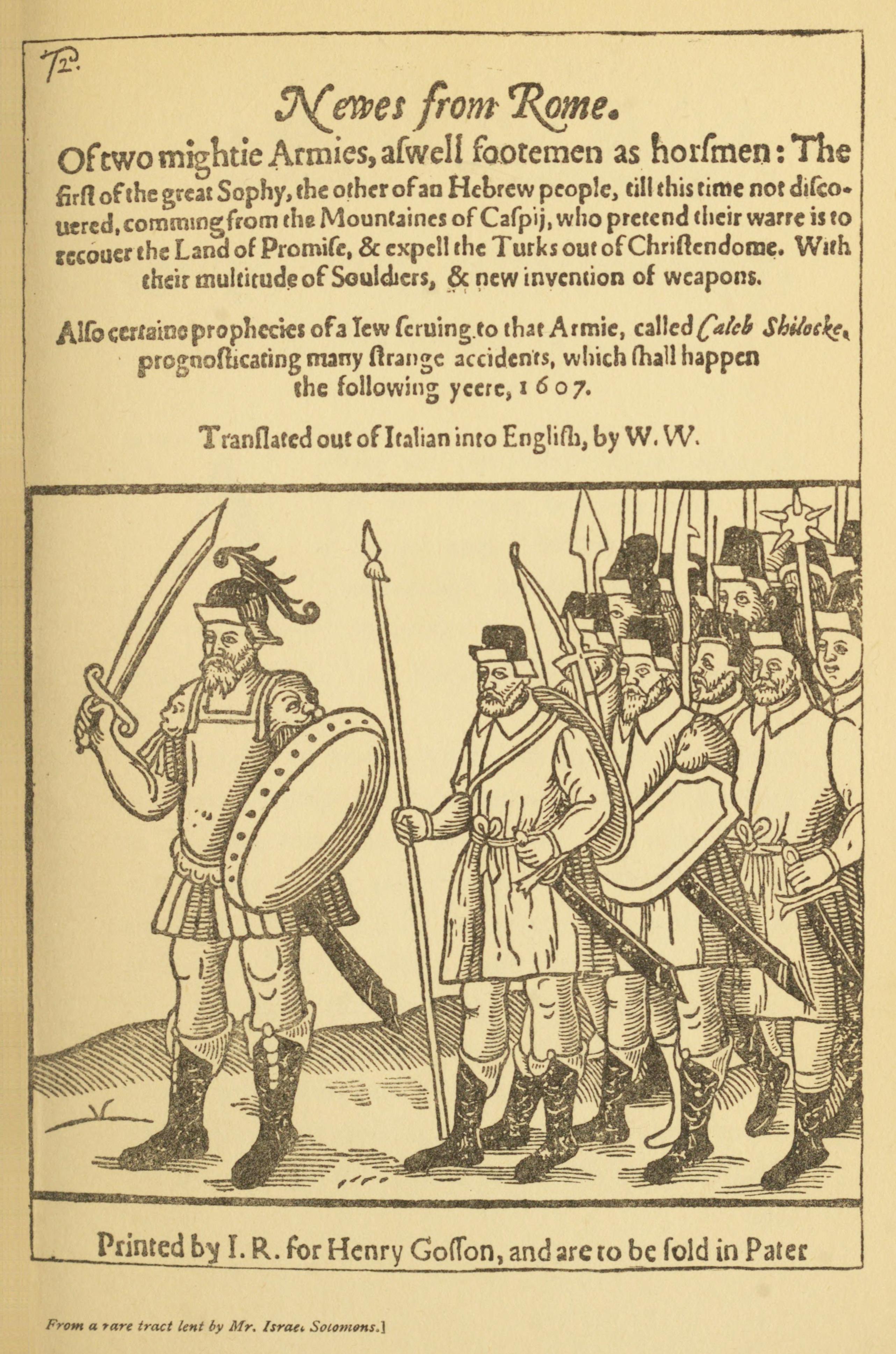

| XXV. | Newes from Rome |

| XXVI. | “The World’s Great Restauration,” by Sir Henry Finch |

| XXVII. | “The World’s Great Restauration”—continued |

| XXVIII. | Philip Ferdinandus |

| XXIX. | Petition of the Jewes Johanna and Ebenezer Cart(en) (w)right |

| XXX. | “The Messiah Already Come,” by John Harrison |

| XXXI. | “Discourse of Mr. John Dury to Mr. Thorowgood—Jewes in America,” by Tho. Thorowgood—“Americans no Jews,” by Hamon l’Estrange |

| XXXII. | “Whether it be Lawful to Admit Jews into a Christian Commonwealth,” by John Dury |

| XXXIII. | “Life and Death of Henry Jessey” |

| XXXIV. | “The Glory of Jehudah and Israel—De Heerlichkeydt ... van Jehuda en Israel,” by Henry Jesse |

| XXXV. | Of the Late Proceeds at White-Hall, concerning the Jews (Henry Jesse) |

| XXXVI. | Bishop Thomas Newton and the Restoration of Israel |

| XXXVII. | “A Call to the Christians and the Hebrews” |

| XXXVIII. | The Centenary of the British and Foreign Bible Society |

| XXXIX. | Lord Kitchener and the Palestine Exploration Fund |

| XL. | Bonaparte’s Call to the Jews |

| XLI. | Letter addressed by a Jew to his Co-religionists in 1798 |

| XLII. | “Transactions of the Parisian Sanhedrim,” by Diogene Tama |

| XLIII. | “Signs of the Times”—“A Word in Season”—“Commotions since French Revolution”—“History of Christianity”—“The German Empire”—“Fulfilment of Prophecy,” by Rev. James Bicheno |

| XLIV. | “Restoration of the Jews”—“Friendly Address to the Jews,” by the Rev. James Bicheno—“Letter to Mr. Bicheno,” by David Levi |

| XLV. | “Attempt to Remove Prejudices Concerning the Jewish Nation,” by Thomas Witherby |

| XLVI. | “Observations on Mr. Bicheno’s Book,” by Thomas Witherby |

| XLVII. | “Letters to the Jews,” by Joseph Priestley |

| XLVIII. | “An Address to the Jews on the Present State of the World,” by Joseph Priestley |

| XLIX. | “Letters to Dr. Priestley,” by David Levi |

| L. | “A Famous Passover Melody,” by the Rev. F. L. Cohen |

| LI. | “Reminiscences of Lord Byron ... Poetry, etc., of Lady Caroline Lamb,” by Isaac Nathan |

| LII. | “Selection of Hebrew Melodies,” by John Braham and Isaac Nathan |

| LIII. | Earl of Shaftesbury’s Zionist Memorandum—Scheme for the Colonisation of Palestine |

| LIV. | Restoration of the Jews |

| LV. | Another Zionist Memorandum—Restoration of the Jews |

| LVI. | Extracts from Autograph and other Letters between Sir Moses Montefiore and Dr. N. M. Adler |

| LVII. | The Final Exodus |

| LVIII. | Disraeli and the Purchase of the Suez Canal Shares |

| LIX. | Cyprus and Palestine |

| LX. | Disraeli and Heine |

| LXI. | Disraeli’s Defence of the Jews |

| LXII. | A Hebrew Address to Queen Victoria (1849) |

| LXIII. | An Appeal by Ernest Laharanne (1860) |

| LXIV. | Statistics of the Holy Land |

| LXV. | An Open Letter of Rabbi Chayyim Zebi Sneersohn of Jerusalem (1863) |

| LXVI. | The Tragedy of a Minority, as seen by an English Jewish Publicist (1863) |

| LXVII. | London Hebrew Society for the Colonization of the Holy Land |

| LXVIII. | An Open Letter of Henri Dunant (1866) |

| LXIX. | An Appeal of Rabbi Elias Gutmacher and Rabbi Hirsch Kalischer to the Jews of England (1867) |

| LXX. | Alexandre Dumas (fils) and Zionism |

| LXXI. | Appeal of Dunant’s Association for the Colonisation of Palestine (1867) |

| LXXII. | Edward Cazalet’s Zionist Views |

| LXXIII. | A Collection of Opinions of English Christian Authorities on the Colonization of Palestine |

| LXXIV. | Petition to the Sultan |

| LXXV. | (1) Chovevé Zion and Zionist Workers |

| ○ | (2) Modern Hebrew Literature |

| LXXVI. | Note upon the Alliance Israélite Universelle and the Anglo-Jewish Association |

| LXXVII. | An Appeal of the Berlin Kadima |

| LXXVIII. | The Jewish Colonies in Palestine |

| LXXIX. | The Manifesto of the Bilu (1882) |

| LXXX. | Zionism and Jewish Art |

| LXXXI. | Progress of Zionism in the West since 1897 |

| LXXXII. | The Institutions of Zionism |

| LXXXIII. | David Wolffsohn’s Autobiography |

| LXXXIV. | Some English Press Comments on the London Zionist Congress (1900) |

| LXXXV. | Colonel Conder on the Value of the Jewish National Movement (1903) |

| LXXXVI. | Lord Gwydyr on Zionism and the Arabs |

| LXXXVII. | Consular Reports |

| LXXXVIII. | “Advent of the Millennium” (Moore) |

| LXXXIX. | Crémieux’s Circular to the Jews in Western Europe |

| XC. | “The Banner of the Jews” (Emma Lazarus) |

| XCI. | “The Advanced Guard” |

○ Baron Edmond de Rothschild

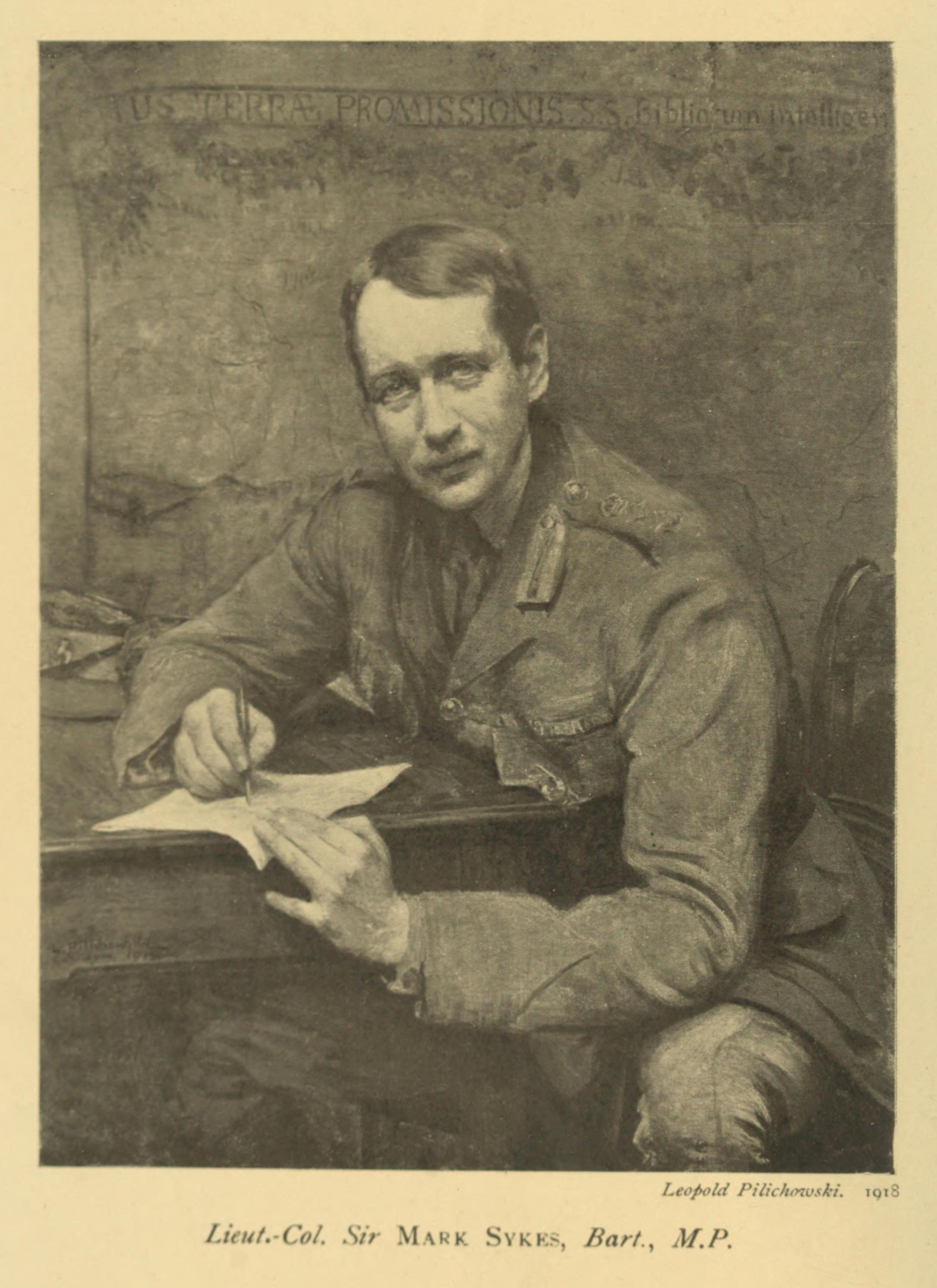

○ Lieut.-Col. Sir Mark Sykes, Bart., M.P.

○ Rt. Hon. Arthur J. Balfour, M.P.

○ Gen. Sir Edmund H. H. Allenby

○ M. S. J. M. Pichon

○ M. Jules Cambon

○ H.E. Paolo Boselli

○ H.E. Baron Sidney Sonnino

○ M. A. F. J. Ribot

○ M. G. E. B. Clemenceau

○ President Thomas Woodrow Wilson

○ Rt. Hon. David Lloyd George, M.P.

○ Laying Foundation Stone of the Hebrew University, Jerusalem

○ Newes from Rome.

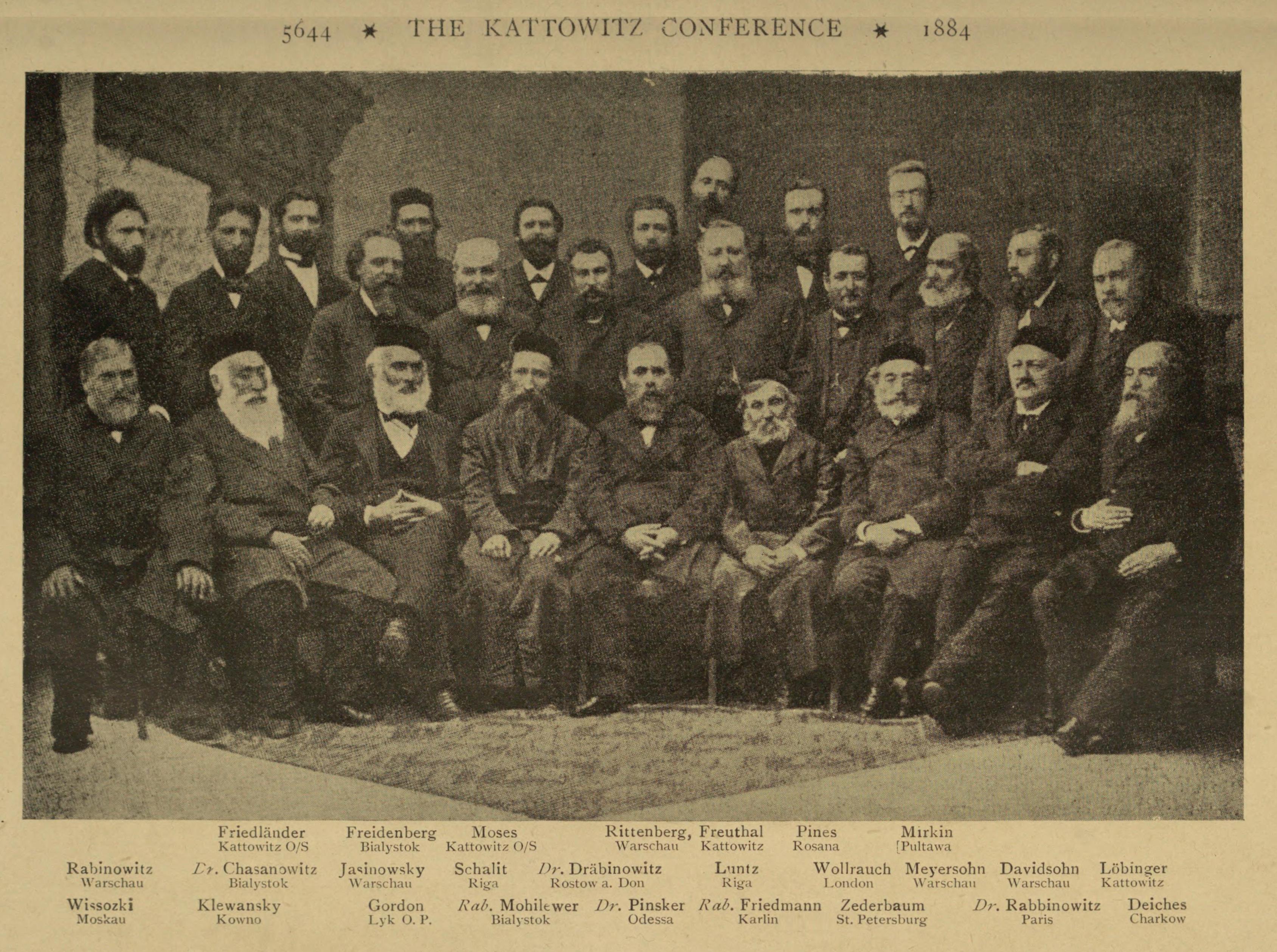

○ The Kattowitz Conference, 5644 = 1884

Leopold Pilichowski. 1918

Lieut.-Col. Sir Mark Sykes, Bart., M.P.

A most tragic event took place on the 16th of February, 1919, when the world lost one of the most valiant champions of Zionism, namely Sir Mark Sykes, Bart., M.P. He fell like a hero in the thick of the fight; he was suddenly extinguished, as it were a torch in full blaze. He stood towering above the crowd of sceptics and grumblers, viewing the promised land as from Pisgah’s height, his clear eye fixed on Zion. He was at once a sage and a warrior, a knight in the service of the sacred spirit of the national idea without fear or reproach, whom nothing could overcome but the doom of sudden and premature death. Sir Mark Sykes was but forty years old, physically a giant, a picture of perfect manhood, full of youthful vigour, a soldier and a poet, a fervid patriot and a kindly and self-sacrificing friend of humanity. He was one of the born representatives of that tradition which for centuries has inseparably united the genius of Great Britain with the Zionist ideal of the Jewish people. In him appeared to be harmoniously united the soaring imagination of Byron, the deep mysticism of Thomas Moore, the religious zeal of Cardinal Manning and the statesmanly and wide outlook of Disraeli.

The germs of Sykes’ Zionism lay latent in him in his earliest years. He was scarcely eight years old when his father took him for the first time to Jerusalem. He often related how when many years later he visited a certain spot in Palestine, an elderly Arab told him that years before an English gentleman had been there with a little boy, leaving behind him kindly memories. His father, a wealthy landowner in Yorkshire, was one of the principal churchbuilders in England of his time. He was a gentleman of the old style, a protector of the poor, fired with religious enthusiasm, who devoted untiring labour to the management of his family estate. Every foot of this extensive family estate with its churches and schools, its country houses and old and new farms and dwellings, with its great collections and its old and valuable library, bears the impress not only of marked diligence and refined taste, but also of an unusual sense of continuity and tradition. Long before the traveller from Hull reaches the estate, a high and slender tower strikes his eye. It is the monument that has been erected in memory of the grandfather, the old squire, an original character about whom Sir Mark was wont to tell so many amusing stories. Long after the introduction of railways he used to ride his steed to London, and on the way often used to stop, take the hammer from the navvies who were breaking road-metal, and perform their work for them for hours at a time. Now his statue is to be seen in a chapel-like recess crowned with a high tower on one of the main roads of the estate. His son, Sir Mark’s father, was not less of an original character. He had nothing of the tradition of feudal lords—the family was descended from an old and very rich shipbuilding family in Hull which flourished in the 16th century, had by the 17th century gained a great reputation, and later had business relations with Peter the Great—but he rather represented the type of a fanciful Maecenas, whose hobby it was constantly to remodel buildings or to erect new ones. His ancestors had built ships, he built houses. That amounted to a passion in him, a noble passion, a desire to build, endow and found. And as he was very religious he built churches. He also travelled widely and gathered large collections in his country house. His religion was nominally High Church, but he must have had strong leanings towards Catholicism. His wife, the mother of Sir Mark, was an ardent Catholic. Sir Mark was attached to his mother, and was brought up in the Catholic faith. On his mother’s side Sir Mark had a decided strain of Irish blood, but the English type was predominant in him. His features, however, were of extraordinary gentleness, his eyes large and clear blue in colour, and a wisp of hair would often fall over his brow. He was an English Catholic and cherished in his heart the memory of the not so far distant time when Catholics were persecuted, and restricted in their civil rights. He was a Catholic in a country where the Catholics constitute a small and weak minority, and often he remarked to me that it was his Catholicism that enabled him to understand the tragedy of the Jewish question, since not so long since Catholics had to suffer much in England. His Catholicism did not make him fanatical; it made him rather cosmopolitan, that is to say, catholic in the pure sense of the word. He received an exceptionally careful education and studied hard in Catholic schools before he took his course at Cambridge. The fact that in his early youth he had Jesuit priests among his teachers was often exploited by those who envied him, in a sense which suggested a leaning in him towards Jesuitism. If the term Jesuitism be taken to mean a zeal for Catholicism, then there can be no doubt that this assertion is correct, since Sir Mark was certainly very religious. But if this expression be taken in the customary sense, namely, as equivalent to clerical intrigue, hypocrisy and spiteful hate of other religions, nothing was more remote from the character, the mental outlook and all other attributes of Sir Mark than such a form of Jesuitism. He was incapable equally of dissembling or of servile conduct; he was proud without being arrogant, and was severe and inflexible when truth was at stake. His soul was an open book; he troubled himself neither of career nor of popularity. He possessed an ideal, and this ideal was the sole test of all his thought and actions. At heart he was pious, a good Christian and a good Catholic: he never prided himself upon his faith, which was a sacred thing to him: religious boast and propaganda were alike foreign to him: his relations with God were an intimate personal matter which concerned no stranger; but his faith was the moving force of his life which afforded him courage to go forward and strength to endure and to deny himself.

When I was with Sir Mark in Hull, where we came to speak at a great Zionist meeting last summer, the member for Hull disappeared from my sight for several hours on one occasion. I presumed that he had gone to the old Catholic cathedral to attend a service as he frequently did. On returning he told me that he had visited his old teachers, the Jesuit fathers, and that he had convinced them that it was the duty of Christians to atone for the crime that humanity has not ceased for many centuries to commit against the Jewish people in withholding their old native country from them. “This was not so difficult,” he added, “as one of these fathers is an avowed friend of the Jewish people. When, some years ago, a protest meeting was held in Hull against the Beilis trial (the trumped-up story of ritual murder that had emanated in Kiev from the Russian anti-Semites), this priest had appeared on the platform to declare in the name of his religion that the persecutions of the Jews that took place in Russia under the old régime were a blot upon civilisation.” The meeting which was to be held that same day was to be attended by Jews and Christians equally. He said with a humorous smile that his success with the fathers made him hope for equal success with the whole Christian audience at that meeting. “Perhaps people find fault with me,” he continued, “that I have neglected their local affairs. A member for Hull who gives all his time to Zionism may be rather a puzzle to the good people of Hull, but I think I shall manage them—will you be responsible for the Jews?” I replied, “Very well, I shall be responsible for the Jews, but only with your help; the Jews are more impressed by an English baronet who is a Christian than by a fellow Jew like me.” “It is to be regretted,” he said somewhat sadly, “that the Jews rather than follow leaders of their own race bow and scrape to Gentiles. How do you explain that?” I answered: “That is the spirit of the Exile, that can be combated only by means of Zionism.”

The meeting was most successful. There never had been such a Zionist triumph in Hull. The enthusiasm was shared by both the Christian representatives and the Jewish population, the latter but recently arrived for the most part from Eastern Europe. There was only one discordant note in the speeches, and that probably escaped the notice of most of those present, and did not detract in the least from the success of the meeting; this was an utterance that offended Sir Mark’s religious sentiment. “It is natural,” someone said, “for Sir Mark to be a friend of the Jews as he is such a good Christian, and must be conscious of the fact that the founder of Christianity belonged to the Jewish race; moreover, Sir Mark as a Catholic venerates the Holy Mother who was as we know a daughter of the Jewish people.” This utterance pained Sir Mark and hurt me very much. I afterwards had long talks with Sir Mark about this tactlessness, which could only have been committed by a quasi-assimilated Jew. The speaker may have meant it well, but a Zionist could never have made such a mistake, for to be a Zionist, means not only to desire immediate emigration to Palestine, but also to maintain the proper practical attitude to the non-Jewish world. This attitude is one neither of servility nor of arrogance, it is one of dignified yet modest and noble self-consciousness, self-respect and respect for others.

In order to understand the attitude of such as Sir Mark and others like him in his own and other nations, towards the Jewish problem, it is necessary to study the problem more closely than is common among the unthinking crowd who bandy about the words anti-Semitism and philo-Semitism, and, upon their superficial observations, condemn one man as an anti-Semite and laud another as a philo-Semite, according as whether they hate or love certain individual Jews. The crowd does not understand that one can be a great friend of the Jewish people and a great admirer of the Jewish genius and yet find such things ridiculous and repulsive as the apeing, the servility, the obtrusiveness, the hollowness and the empty display, the desire to intrude everywhere, the excessive zeal of the neophytes and all the unpleasant traits of some assimilated Jews. On the other hand, one may approve of all these qualities and rejoice that certain Jews have become rich, obtained titles or gained high office in so far as one desires the assimilation of the Jewish people and the extinction of the Jewish spirit.

Anti-Semitism is fractricidal in that it implies hatred and contempt for, and the desire to persecute a whole race. It is organised outrage, because it employs the brutal power of a majority to insult a defenceless minority and to deprive it of human rights. It is consciously calumnious because it instigates malice against the Jewish people or religion and exploits for this purpose actual weaknesses or failings belonging in reality to neither the race nor the religion. It is biassed and sophistical because it generalises from the faults of individuals and because it fixes itself upon the mote in another’s eye without perceiving the beam in its own.

Philo-Semitism in the true sense of the word resembles philhellenism. The latter does not mean simply friendly intercourse with parvenu Greeks, but sympathy for the Hellenic people as such, and with the spirit of Hellenism and an endeavour to aid these and to establish them. Of such a kind was the philo-Semitism of Sir Mark Sykes. I will speak plainly, and do not hesitate to state that he had no liking for the hybrid type of the assimilating Jew. He had no wish to interfere with such people; he emphatically condemned any attempt at suppression of rights or chicanery, but he did not like this type just because he was fond of the Jewish people. What was of the Jewish essence, of the Jewish tradition, was sacred to his religious sense and stimulating to his artistic sense. In this lay the secret, not exactly of our personal success with Sykes (for our cause is of too great an importance in the world’s history to be connected with personalities) but of the wonderful concord of minds which was the natural outcome of his outlook. The opposite poles attracted each other with irresistible force. Truly anglicised Jews could not have had the hundredth part of the same success with him, not because of their not being excellent patriots and capable men (for such many of them incontestably are and Sykes was fond of society and of making acquaintances and was amiable to all), but for him there were real Englishmen enough. Concerning English affairs, national questions and parliamentary matters he would discourse with anglicised Jews on the same footing as English non-Jews, but concerning the spirit of Jewish history, the ethos of Hebraism, the national sufferings and aspirations, that emerge only in national Hebrew literature, in the large centres of Jewish population in Eastern Europe and in the new settlements in Palestine—concerning all these matters he would and could seek information only from the fountain source. These are the things that have succeeded with Sykes and others and that will succeed further, not high diplomacy. There is no lack of this latter at the Foreign Office, which swarms with great diplomats, and it would be carrying coals to Newcastle to seek to add more trained specialists to the crowd of busy politicians in Downing Street. There could be no success with Sykes that way. He was, as it were, born to work with us Hebrews for Zionism.

The spirit of the East breathed in this Yorkshire gentleman. In his earliest youth he showed a keen interest for Arabia, for Islam and the Turkish Empire. At Cambridge he studied Arabic under Professor E. G. Browne, and there also he met the lady who was afterwards to be his wife and true helpmeet, a daughter of Sir John Gorst, who was at the time one of the members of parliament for the University. In the year 1898 Sykes, then a young student, undertook a second journey to the East, and stayed much of his time in the Hauran. He devoted himself with the entire freshness and sincerity of his youth (he was then but twenty years old) to his observations as a traveller. In the year 1900 appeared his first book, which recounts his impressions in an elegant style and light form.¹ In this book he ascribes to his guide, a Christian Arab named Isa, the following words apropos of the Jews there, that they were “dirty like Rooshan and robber like Armenian.”² Sykes himself had at that time no clear idea of Jews or of Armenians—of the two peoples for whom he strove and died nineteen years later. He cites an expression of opinion and repeats it in the bad English of an Arab guide. After his return from the East, he devoted his attention to military studies, in which he distinguished himself. He served in the South African War in 1900‒2. He gave a proof of his technical knowledge in his work on strategy and military training which he had compiled in collaboration with Major George d’Ordel.³ In the year 1904 he was travelling again, and the literary product of his later and earlier journeys was his second considerable book on Islam and the Orient.⁴ This book is dedicated to his fellow-soldiers in the South African War.⁵ In this work already speaks to us a young but mature man who had travelled much in four continents and had been through the South African Campaign. Here we already perceive the fundamentals of his later Zionism. As regards the future of the Orient he looks not to modern civilisation and capitalism, but to the latent force of national life. He was not deceived by the specious platitudes so dear to that deplorable product of modern European democracy ‘the man in the street’ as to ‘extending the blessing of Western civilisation’; he regarded rather with unconcealed apprehension the contingency of the Western Asiatics becoming ‘a prey to capitalists of Europe and America,’ “in which case a designing Imperial Boss might, untrammelled by the Government, reduce them to serfdom for the purpose of filling his pockets and gaining the name of Empire-maker.” (Prof. Browne’s Preface, Dar-ul-Islam, p. iv.). He had a great predilection for all national individualities, and detested the desire to imitate and assimilate. “He hated the hybrid Levantine ... and faithfully portrayed the Gosmopaleet (Cosmopolite)” (ibid.). He condemned interfering tutelage. “Orientals hate to be worried and hate to have their welfare attended to.... Oppression they can bear with equanimity, but interference for their own good they never brook with grace” (ibid.). He shows a profound historic sense: “he does not disguise his preference for countries with ‘a past’ over countries with ‘a future’” (ibid.), and finds in the nature of the Oriental the conditions for a true equality. “He recognises the fact that there is more equality because less snobbery and pretence in Asia than in Europe” (ibid.). The only feature that is wanting in this book is a knowledge of Jews and of Zionism. He makes but once mention of this matter, in a short sketch of the Jews at Nisibin. “The Jews at Nisibin ... their appearance is much improved by Oriental costume ... in which they look noble and dignified.” He then adds: “I trust that the Uganda Zionists will adopt my suggestion” (p. 141). One who believes in the assimilation of the Jews may snobbishly consider this also as anti-Semitic, but in fact it is only the harmless joke of an artist, for Sykes was essentially an artist. His drawings were excellent, he was also very musical, and had a great predilection for all true individuality, for the archaic, the original, the unadulterated, for race, nationality, genius loci, for everything racy and natural, and for everything that was not cliché, mechanical and snippety.

This was the foundation of his latent Zionism. From 1904 to 1911 he pursued his military studies, managed his estates and travelled much. In 1911 he entered Parliament as member for Hull. Although nominally a Tory, Sir Mark was at bottom no party man, but a man of convictions. Full of faith, greedy for work, energetic, confident, capable, quick of study, charmed with a fight. Equally ready to defend or attack, he was unselfish. Over the Irish question he fell out with the Conservatives; he was an outspoken champion of Home Rule, and throughout his life he remained a loyal friend of Irish nationalism. His speeches soon made him popular in Parliament; they were never long and yet never trite. He showed the same qualities in his letters to the Press. He had always something to say, some original thought which he expressed in his own individual style. He told me once, how he had learned public speaking at school. He had to prepare the outline of the speech and afterwards to state in short and simple terms the substance of his speech. The latter, he added, was the more difficult task, because a facile speaker can make long speeches, and yet find it impossible to repeat later the essential facts of his speeches. He was not a facile speaker in this sense; he never spoke quite extempore, but always prepared his speeches carefully, often by means only of simple key words or of a few pictures, resembling hieroglyphics, as, for example, the sun with streaming rays. He never spoke to the gallery, never flattered, never perverted the truth under the mask of sincerity, and never sought to create effects. His speeches were full of beauty and deep idealism with a breath of religious fervour, as he leant forward to address himself to the hearts of his audience. This practical man was at bottom a poet. He could tell most fascinating stories. He had not been brought up in the chilling atmosphere of severe Puritanism, but in the medieval glamour of Catholic cathedrals and under the sun of the East. Yet he had remained a proud and staunch Briton. He was a remarkable and extremely unusual combination of a blue-eyed, simple and modest Englishman of childlike sweetness, and of a medieval knight full of Oriental reminiscences, with ardent faith and picturesque imagination. We loved him and he loved us, because his nature was gentle, kind and sympathetic. He chatted freely: he told all about his enthusiasms, his “castles in the air,” his stories about dervishes, his travelling impressions, with a lively dramatic touch with appropriate gesture and expression, often drawing his round, brown stylo pen from his pocket in order to explain the matter more pointedly by means of a rapid sketch. How often I regretted that no shorthand writer was present. His ways were dignified and courteous, his modesty so natural and so frank that he gave the impression of being himself unconscious of it. When the talk took a jesting turn, there was no sting in his witticisms, his jests were easy and never offensive. When he was angered, his emotion lasted but a few seconds, and afterwards he was as light-hearted as a child.

Such was the Mark Sykes of 1914 when the War broke out. He took up his part in the War with all his patriotism and with his idealistic faith in the victory of justice. In 1915 he was with his regiment busy in hard training and ready for the field. He often told me how it had come to pass that the East had become his sphere of action. One day Lord Kitchener said to him: “Sykes, what are you doing in France, you must go to the East.” “What am I to do there?” asked Sykes. “Just go there and then come back,” was Lord Kitchener’s answer. Sykes travelled to the East, made his way through accessible and inaccessible districts, and came back. His observations and experiences constituted the material upon which all the great things that afterwards happened were based. He then voluntarily entered the service of the Government as expert, as adviser, and as draughtsman of their policy. He was one of the pioneers of the new British War Policy in the East, one of the protagonists of the “Eastern School.” In the year 1916 he undertook with M. Georges Picot a journey to Russia. It was then the Czarist Russia with its eye fixed upon Constantinople; that was the occasion upon which the so-called Sykes-Picot agreement was signed. From the standpoint of Zionist interests in Palestine this agreement justly met with severe criticism; but it was Sykes himself who criticised it most sharply and who with the change of circumstances dissociated himself from it entirely. It was a product of the time, a time when there was as yet no decided plan formed of launching a definite campaign in the East, when the prime necessity was some sort of agreement, since otherwise no progress would have been made. This was long before Mr. Balfour’s declaration, and since at this time the Zionist interests in Palestine had as yet received no attention because they were unknown and not debatable, and also as it was essential to come to terms about Constantinople with the old regime in Russia, this agreement was a necessary prelude to action. This agreement Sykes regarded later as an anachronism.

Zionism had been at work in England for two full years without its coming to know anything of Sykes, who himself worked on his own lines for a year and a half, without knowing anything of Zionist organisation or a definite programme of Zionism. What happened resembled the construction of a tunnel begun at two sides at once. As the workers on each side approach one another they can hear the sound of blows through the earth. It seems at first a strange enough story; a certain Sir Mark appears, he makes some enquiries, and then expresses a wish to meet the Zionist leaders. Finally a meeting actually takes place and discussions are entered upon. Sir Mark showed a keen interest and wanted to know the aims of the Zionist Organisation, and who were its representatives. The idea assumed a concrete form; but this acquaintance, however, valuable as it was, had as yet no practical significance. Acquaintanceships were made and discussions took place during the years 1914‒16 by the hundred with influential people and with some who had more voice in affairs than Sir Mark ever had. They constituted certainly a most important introductory chapter, and one without which the book itself could not have been written, but they were naturally fragmentary, preliminary, without cohesion and without sanction. The work itself began only after the 7th of February, 1917.

The subsequent chapters describe this work in general outlines. A thousand details remain for the pen of some future historian, when the time comes for the archives of the Foreign Office, of the Ministries for Foreign Affairs of the other Entente Powers, and of the political offices of the Zionist Organisation in London and Paris to be made public. In the whole proceedings there are no secret treaties, no secret diplomacy, in fact neither diplomacy nor conspiracy; but they constitute a series of negotiations, schemes, suggestions, explanations, measures, journeys, conferences, etc., to which each of those who took a part gave something of the best in himself.

It is my duty both as historian and as one who took an active part in these negotiations and proceedings to record here that Sir Mark Sykes really gave of his best to this work. For more than two wonderful years we were in daily intercourse with him. Our friendship was of the most intimate. We shared in common all the delights and disappointments arising from the Zionist work. We instructed each other; he furnished his knowledge of the East, his profound understanding of the guiding political principles of Great Britain, his personal observations with reference to the possibilities of bringing our aims into harmony with the ideals of the Entente; we supplied Zionism, inspired by Jewish sufferings and hopes. It was not difficult for us to convince him what an excellent cultural type the Hebrew represents, since already in his youth, before he had the slightest idea of Jews and Zionism, he had intuitively perceived that the hybrid Levantine is hopeless in that direction. The idea was latent in him, and but awaited stimulus and direction into the proper channel. He was ready to understand what a great natural force the Jewish genius could be in the reawakening of Palestine, all the more because long before as a man of extraordinarily high culture—English to the last fibre of his thought, saturated with English tradition, English literature and English taste—and yet at the same time a broad-minded humanist, with great ideals not only for his own nation but for all other nations and races, he had seen that the ‘civilising’ of the East by assimilation was idle and superficial prating and a vain delusion. Deep sympathy of ideals had earlier formed an unconscious bond between us. When this sympathy ripened into consciousness through our meeting and soon after the commencement of our common work, the resulting harmony was not one of policy but one of outlook. The idea of a natural alliance between Jews, Arabs and Armenians as peoples of the Near East developed into something quite distinct and found in Sir Mark a convinced champion. He was an enthusiastic protagonist of the Jewish national renaissance in Palestine, an admirer of the Hebrew genius, who could not hear enough from me about national Hebrew literature, who took an interest in every detail of Jewish culture. At the same time he was a sincere friend of the Arabs and Armenians and made strenuous efforts to secure their liberation. We all worked together with him in this direction, but the main idea was his and remained his favourite project till the close of his life. Many superficial and petty individuals in our own ranks, who, not realising the great and difficult task and themselves taking no active part, busied themselves in spreading distrust and discontent, complained that Sykes was too much taken up with the Arabs. I am sure that among many Arabs of the same degree of political maturity Sykes was accused of being too much taken up by the Jews.

Our interchange of ideas resulted in a complete fusion of thought. But Sykes gave us his time and labour as well as ideas. It seemed as though in these two years his whole life’s energy reached its culminating point and spent itself. He worked at constant high pressure. But rarely he allowed himself a week-end in Sledmore with Lady Sykes and the children, and even there he was never idle. It was a constant round of church-going, of devotion to the estate and building repairs, of musicians, old French songs, and of hospitality. Holidays were out of the question. All his excursions were connected with political or Parliamentary business. Even prior to the commencement of his official connection with Zionism, Sir Mark was a man of extraordinarily wide activities. When on the 8th of February, 1917, one day after the first official meeting, our work began with the first conference with M. Georges Picot at Sir Mark’s private house, No. 9 Buckingham Gate, the latter place had already become an important centre for matters concerning the new and at that time scarcely completed plan of a kingdom of the Hedjaz, concerning Armenia and Mesopotamia, and was equipped with all such material as files of correspondence and telegraphic communications, etc. It was then that Zionism took its place in the system and came to dominate the situation more and more as our labours progressed. One was liable to be called upon at any moment, early in the morning or late at night. It became a joke with us to name his sudden telephone calls ‘brain-storms.’ Sir Mark had a ‘brain-storm’ which meant: danger in sight. This may appear as somewhat far-fetched to outsiders, but those who were in the thick of the work knew well what formidable obstacles stood in the way, and how well founded were Sir Mark’s doubts and fears. At every moment dangers had to be guarded against; there were elements that were in favour of the status quo ante in the Near East; vested economic interests that desired to uphold this status quo for their own ends; clerical, anti-Semitic and pan-Islamitic propaganda; certain Arab sections that opposed Zionism because, obsessed by fanaticism or misled by agitators or influenced by narrow and short-sighted considerations of the needs of the moment, they had no proper appreciation of the great idea of a Hebrew-Arabic national alliance; intrigues of certain Syrian concession-hunters who stormed with a ‘holy wrath’ against the Zionist idea; certain factions in England that would have nothing to do with an energetic policy in the East, and indeed ridiculed and belittled the importance of British interests in that region; a by no means small party that warned England against undertaking any new engagements; and finally, be it mentioned with regret, our Jewish circles of the assimilating school. The cause of Zionism was in the same dire case as Laocoon in the grip of snakes. Every day brought a fresh indication of some hostile movement, a new suspicion of enemy schemes each of which caused Sir Mark to sound a warning. These were the ‘brain-storms.’

I should like to record a few impressions of different occasions. The first was a day in April, 1917, in Paris. I was due at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to give information about Zionism. Sir Mark also came; he was a sincere friend of France and was anxious that Zionism should have the same appreciation in France as in England. He came in great haste by motor from the Front, where he had been making a visit, and went to the Hotel Lotti. He arrived early in the morning after a tiring night’s journey. At that time Doctor Weizmann was fully occupied with most important affairs in England. It fell to me to begin the official work in France, after we had together prepared all our plans. Sykes was impatient: in spite of his complete confidence in us, he could not refrain from remaining near me, always ready with advice and help. We worked together for some hours. I departed on my mission and we arranged for him to wait for me at the hotel. But as I was crossing the Quai d’Orsay on my return from the Foreign Office I came across Sykes. He had not had the patience to wait. We walked on together, and I gave him an outline of the proceedings. This did not satisfy him; he studied every detail; I had to give him full notes and he drew up a minute report. “That’s a good day’s work,” he said with shining eyes.

The second was a day in April, 1917, in Rome. Sykes had been there before me and could not wait my arrival. He had gone to the East. I put up at the hotel: Sykes had ordered rooms for me. I went to the British Embassy; letters and instructions from Sykes were waiting for me there. I went to the Italian Government Offices; Sykes had been there too; then to the Vatican, where Sykes had again prepared my way. It seemed to me as if his presence was wherever I went, but all the time he was far away in Arabia, whence I received telegraphic messages.

The third was at the London Opera House Meeting of the 2nd of December, 1917. It was a truly brilliant gathering in a packed house, a festive token of the bond of brotherhood between Great Britain and ancient Israel. Sykes modestly surveyed the assembly. The majority of the audience scarcely knew him, and only a few were aware that this was a great day in his life. When he began to speak the audience recognised that one was addressing them who had made Zionism a part of his life. He showed no flaring enthusiasm, but rather a quiet elation, a devotion to the subject. On leaving, he and I shook hands—no words were necessary because we understood each other.

The fourth was a mass meeting at the end of December in Manchester. In the morning there had been a small gathering with Sykes, and before the meeting a banquet in honour of Mr. C. P. Scott. The meeting itself was one of the largest that ever was held in Manchester. Sir Stuart Samuel was in the chair. Doctor Weizmann made one of his most brilliant speeches, and Mr. James de Rothschild roused the audience to enthusiasm. Then Sykes rose, and made a speech full of the dreamy poetry of an Eastern tale. The audience felt itself transported into another and better world. The poetry of the East diffused itself as a softening charm over the hard-cut lines of high political argument. After the meeting we sat down, tired out, to tea. Sykes hurried in in his rain-coat: he had no time to stay, as he had to catch the night train. He was due in London next morning to send urgent telegrams to Palestine.

The fifth was on a glorious June day in 1918 en route from Paris to London. Sykes insisted on my travelling with him. He was in company with a distinguished party containing nearly all the members of the Government. As there was no time to complete the passport formalities, he simply attached me to himself personally. I felt embarrassed and accepted his proposal with reluctance. But when he told me that it was necessary to remind people constantly of the Declaration, I made up my mind to venture flying if he should think it necessary. The journey almost assumed the form of a Zionist meeting. There were twenty-eight persons in all, the most prominent members of the Government. On deck the Prime Minister was talking with Jellicoe. The tall and imposing figure of Mr. Balfour, with his noble grey-haired head and the well-known small hat, stood above the rest. Sykes urged me to have a word with the Prime Minister. I seized the opportunity and in the course of our conversation I had from him the treasured words: that such a war as this would be in vain if we did not aim at succouring all peoples, the Zionist Jews included. I afterwards told this to Sykes, who was at the other end of the ship, but he knew already. “How, by an indiscretion?” “No, a favourable wind whispered it to me.” The ‘Favourable Wind’ was one of the company who had overheard the conversation.

Sir Mark’s work during the last few years falls into eight successive periods. (1) February‒March, 1917, the collaboration in London with M. Picot, and after the latter’s departure for France, with us; (2) March‒June, 1917, our journey to Paris; his journey to Egypt; (3) June‒November, 1917, preliminary work leading to the Balfour Declaration; (4) November, 1917‒March 1918, from the Declaration to the despatch of the Commission to Palestine; (5) March‒October, 1918, the work in London during the stay of the Commission in Palestine; (6) October‒December, 1918, the work after the return of the Commission; (7) December 1918‒February, 1919, the journey to Syria, and (8) February, 1919, the last days in Paris.

In the first period the foundations were laid; at that time Sir Mark was, so to speak, introduced into the world of Zionist ideas. The second was full of active negotiations with the Entente Governments. During the third Sykes was in busy relations with a number of the friends of our cause. In this period the work of Major Ormsby-Gore was of practically the same importance, as also during the fourth period. In the fifth period, during the time of the important work in Palestine of the Commission under the leadership of Doctor Weizmann, Major Ormsby-Gore was of great service there. The whole of the labours in London connected with the activity of the Commission and with a thousand other matters relating to Zionism fell upon Sykes, and necessitated daily work of an intensely difficult character.

To this period belong a number of most important measures which for the first time gave Zionism both internally and externally its proper position and its necessary prestige. Sir Mark had at that time his office in two rooms, afterwards partitioned into three, on the basement of the back wing of the Foreign Office, connected with the upper storeys by means of a lift, never used by Sir Mark, who mounted the stairs about twenty times daily at a lightning speed, which made it impossible for me to keep pace with him in spite of my most strenuous efforts. The first large room was dark because the big window was blocked with sandbags as a protection against possible air raids; it had long tables and was illuminated artificially. I had to be there often and for long periods at a time: my work, indeed, required my attendance there more than at the Zionist offices, and sometimes I had to go there three times a day and to remain there till late at night. On one of these occasions Sir Mark said to me, “Does not this subterranean room look like a medieval inquisition chamber, with those long tables upon which the victims of the Inquisition might be stretched for torture? Who knows,” added he humorously, “whether some of your forefathers had not to undergo treatment in chambers of this kind?” I answered, “Yes, as Scripture has it: ‘I will make the desolate valley into a door of hope.’” After that we often used to call this room the “Door of Hope.” This room opened into another where Sir Mark spent whole days at work except for the time at Westminster. The duties of Secretary were most ably filled by Mr. Dunlop, a young and energetic man; opposite, in the building in Whitehall Gardens, Sir Mark’s older colleague, the learned and highly experienced Mr. Beck, worked in conjunction with him. Between the two offices the faithful Serjeant Wilson, who accompanied Sir Mark everywhere on land and sea, passed to and fro. It was like a hive; there was a constant coming and going of Foreign Office men, M.P.’s, Armenian politicians, Mahommedan Mullahs, officers, journalists, representatives of Syrian Committees, and deputations from philanthropic societies. In the midst of this busy world Zionism maintained its prominent position. Everything had to pass through Sykes’ hands. In order to avoid confusion and divergence of effort he insisted upon what was readily conceded him, namely that he should pass an opinion on every question and every detail, and in this there was no hesitation, no delay. Among many others a couple of examples will suffice. The Oriental Jews, being Turkish subjects, were under the law regarded as alien enemies. They were certainly only technically such; at heart they were thoroughly pro-British and in any case politically harmless. Exceptions had already been made on the recommendations of personal standing, but no logical plan was followed. I maintained that the Zionist Organisation should be officially empowered to protect the Jews of Palestine and Syria, just as, for example, the Polish Committee protected the Poles from Galicia, who were also technically alien enemies. Sykes obtained this concession after considerable labour. This was an official recognition of the Zionist Organisation as competent authority. When at the time of the most strenuous military efforts, the later categories of the male population were called to the colours, the Zionist Organisation in England was threatened with losing the last of its secretaries, speakers, organisers, etc., and with seeing its activities restricted, if not completely interrupted. None were more patriotic than the Zionists, so many of whom were in the Army, but we had to deal with a number of men who could be of no value to the Army, and who, on the other hand, were indispensable to the Zionist Organisation. Previously some had been left with us, but now it was a question of large numbers. It was a generally recognised principle that people whose occupation was of national importance were allowed to continue at it. I insisted upon having this principle applied to Zionism. This matter could not be settled by any single individual or by any single tribunal. The question concerned a matter of principle, and had nothing to do with individuals. Since we had received the declaration of recognition from the British Government and the whole Entente, and as we had to prepare the field for the realisation of this declaration, this ought surely to have been regarded as a matter of national importance from the official standpoint. Sykes adopted this point of view and made strenuous efforts to have it realised. He was thoroughly convinced that our loyalty to Great Britain and her Allies was boundless, and that in all our demands the interests of both parties had been considered with equal devotion. On the other hand, we recognised that when he denied us something as inadmissible, though like any other man he might sometimes make mistakes, he was open to change of conviction upon good reason being shown, and that any stand taken by him against our proposals was due rather to the fact that he regarded the matter at issue as unfavourable in certain circumstances to Zionism, than that he had the interests of Zionism less at heart than we; thus a community of effort and a mutual trust was established, which led to a complete solidarity of aims. In this way our work in conjunction with Sykes became the foundation for our relations with the higher Government authorities, as also with Sykes’ colleagues and successors.

The most important and politically difficult task that had to be accomplished in London during the stay of the Commission in Palestine was to make possible the official laying of the foundation stone of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. The recommendations and the instructions carried by the President of the Commission, Doctor Weizmann, to Palestine were most valuable, and will stand as a lasting token of the generous and kindly feelings of the leading men in the British Government towards Zionism. The influence of the Commission, the excellence of their work, their splendid relations with the authorities had ensured complete success. Nevertheless it was found that, particularly with reference to the foundation-stone ceremony, the instructions had been of too general and too vague a character to overcome the formal and legal administrative obstacles. It is my duty to one who is gone, to record the great services of Sir Mark in this direction. It goes without saying that the final decision lay with a man in higher office. However, before Mr. Balfour gave his decision and before the most detailed instructions had been telegraphed, we had to work strenuously day after day for several weeks, by correspondence and by interviews, with such devotion and enthusiasm as only so magnificent an object as the Hebrew University in Jerusalem could inspire.

During the period that followed, namely the sixth as above described, the Zionist programme was being prepared. The end of the War was in sight, but the cessation of hostilities was not to be expected so very soon. Sykes decided, then, the whole of Palestine and Syria being in British hands, to travel thither to gather fresh information and to bring the results of his latter observations to the Peace Conference. I tried to dissuade him from this journey, because I thought his presence in Europe important: he, on the other hand, wanted me to go with him to Palestine. He finally went alone and wrote to me from there that I should come without delay. His stay in Palestine was, however, only a very short one: he soon passed to Syria and did strenuous work in the direction of restoring order in Aleppo. In the meantime the Peace Conference opened here. We were all of us already assembled—except Sykes. We thought of him every day.

One evening there was a telephone call. On taking up the receiver I heard Sykes’ voice telling me that he had just arrived in Paris, and was staying as usual at the Hôtel Lotti opposite us. I invited him at once to dinner, and he came. He was the same lovable fellow, full of life and humour, but now frightfully thin. He had lived the whole time on “German sausages” and had suffered much from digestive troubles. It only transpired later, that he had spent sixteen hours a day in Aleppo working under almost impossible conditions on behalf of the Arabs and Armenians. He was himself never in the habit of talking about his work. It was two hours after midnight when he left us,—he had so much to tell about the ordinary incapacity for proper administration of the local Syrian population and their marked capacity in that direction under suitable guidance, about the prospects for Palestine, about the steps he had taken against anti-Zionist intrigues in Syria and other matters. From that time forward we saw each other every day. Some days later he went to London to see his family and returned in three days with Lady Sykes. Immediately upon his arrival he was in touch with us. He had a thousand ideas, and had brought reports and instructions from Syria that had to be elaborated. Our days were filled with appointments for visits, interviews, etc. Then Lady Sykes was attacked by influenza, which caused a little dislocation and the postponement of an accepted invitation, but gave no cause for alarm. On the 13th of February, Sir Mark hastily entered my room, and on finding me indisposed, he shouted, “There’s no time now for being ill.” The following morning he sent word to me that Lady Sykes was better, but that he himself was taken ill. “I have got it,” he said to Serjeant Wilson when he went to bed. On the 15th Lady Sykes sent for me, and told me that her husband would have to remain in bed for a few days, that afterwards she intended to go to England for a week or so to recuperate. “To Sledmore?” I asked. “No,” said Lady Sykes, “it is too cold there. I think the South will be better. And my chief reason for troubling you,” she added, “is because my husband wants to know how Zionist matters went yesterday.” I gave full details to Lady Sykes. In the afternoon of the 16th Sir Mark died.

He died on the threshold of the Peace Conference which was destined to make his dream a living thing, died in a hotel in the midst of us, bound up with our deepest affections, a radiant form full of love and sincerity. His life was as a song, almost as a Psalm. He was a man who has won a monument in the future Pantheon of the Jewish people and of whom legends will be told in Palestine, Arabia and Armenia. Just returned from a difficult task in the service of humanity in the service of the idea of nationality, and about to perform great things for the Jewish people, he fell as a hero at our side.

There it ends! Shakespeare himself could use no more than the commonplace to express what is incapable of expression. “The rest is silence!”

We say: “The rest is immortality—in the annals of Zionism.”

Paris, April, 1919.

Chovevé Zion and Zionists in England—Louis Loewe—Nathan Marcus Adler—Albert Löwy—Abraham Benisch—The Rev. M. J. Raphall—Dr. M. Gaster—Rabbi Samuel Mohilewer—English representation at the Second and Third Congresses—The Fourth Congress in London.

The Chovevé Zion movement in England was not very powerful, yet it enjoyed a certain amount of popularity. If we examine, for instance, the records for 1892‒7—the years which preceded the First Zionist Congress (Basle, 1897)—we find among the leading representatives not only the Chief Rabbi of the Spanish and Portuguese Communities, Dr. M. Gaster, Mr. Herbert Bentwich, Rabbi Professor H. Gollancz, the late Colonel Albert Goldsmid, Dr. S. A. Hirsch, Mr. S. B. Rubenstein, Mr. E. W. Rabbinowicz and other English Jews of standing, who are even now more or less active in the Zionist Organization; but we read the names of the late Chief Rabbi of Great Britain, Dr. H. Adler, the late Lord Swaythling, Mr. Elkan Adler, Albert Jessel, Mr. Joseph Prag (who was one of the most active members), Joseph Nathan, Louis Schloss, Haim Guedalla, Captain H. Lewis-Barned, Bernard Birnbaum, Mr. Herman Landau and other distinguished members of the community, as among those of the prominent enthusiastic supporters of the Chovevé Zion movement who did not join the new Zionist Organization. The same phenomenon strikes us in France. There the new Zionism was confronted on the part of the Chovevé Zion by an opposition that was even stronger than in England.

An impartial historian, desirous of reviewing the facts as they were revealed in Jewish life and literature, would in vain endeavour to discover any essential difference between the Chovevé Zion and the Zionist fundamental principles. He could trace a complete and clear conception of political Zionism through centuries of English history or Jewish history in England, and on the other hand also efforts and undertakings in the direction of colonization pursued with great energy and care by forces that are generally found to be co-operating with political Zionism. A sober and dispassionate examination of all these ideas without regard to mere catchwords must lead to the conclusion that Sir Moses Montefiore’s representations to Mehemet Ali in 1838 were substantially the same as Herzl made to Abdul Hamid in 1898. However, both aimed at a legally assured home and both insisted that Palestine should belong to the Jewish people. And no real student of contemporary Jewish history will imagine that Sir Moses was an isolated dreamer. He never undertook anything in Jewish affairs without consulting the authorities of his time. One of his advisers was Louis Loewe, the well-known Jewish scholar and his secretary for many years.

Dr. Louis Loewe (1809‒88), who was educated at the Yeshibot of Lissa, Nikolsburg, Presburg, and at the University of Berlin, came to England in 1839 and was appointed by the Duke of Sussex to be his Orientalist. He then travelled in the East, where he studied languages. In Cairo he was presented to Mehemet Ali, for whom he translated some hieroglyphic inscriptions. On his return from Palestine he met at Rome Sir Moses and Lady Montefiore, who invited him to travel with them to Palestine. When, in 1840, Sir Moses went on his Damascus expedition, Loewe accompanied him as his interpreter. Since that time Loewe was attached to Sir Moses as his personal friend and secretary. He accompanied Sir Moses on nine different missions. He wrote several valuable works on oriental subjects: The Origin of the Egyptian Language, London, 1837; A Dictionary of the Circassian Language, 1859; a Nubian Grammar and several pamphlets—and translated J. B. Levinsohn’s Efes Damim (1871) and David Nieto’s Matteh Dan (1842). Dr. Loewe was an ardent supporter of all schemes in favour of Palestine and strongly assisted David Gordon, the editor of the Ha-Magid, who was an enthusiastic and outspoken political Zionist years before Herzl.

We have already mentioned to what an extent the Chief Rabbi, Dr. N. M. Adler, influenced Sir Moses’ works in Palestine. Nathan Adler was born at Hanover in 1803. He received his education at the Universities of Göttingen, Erlangen and Würzburg. Already as a youth his abilities proved him to be particularly adapted to the discharge of rabbinical functions. In 1829 he was appointed Chief Rabbi of Oldenburg; in 1830 his jurisdiction was transferred to Hanover and all its provinces. His fame spread beyond the Rhine and reached England just when the Jewish population there was in need of a spiritual leader. In 1844 the election took place for Chief Rabbi of the Ashkenazi Congregations of Great Britain and the choice fell on Dr. Adler. He was inducted into office on July 9th, 1845. His activity and influence during his lengthy career as Chief Rabbi proved a blessing and were attended with most invaluable results. His calling did not prevent him from contributing excellent literary productions, mostly in Hebrew, the principal of which is Nethino La-Ger’s commentary on the Targum of Onkelos. There is no doubt that this famous Rabbi and great Jew was in close touch with Sir Moses in all the steps the latter took for the colonizing of Palestine for a political as well as philanthropic purpose.

Many of the most important Jewish scholars arriving in England, and becoming in course of time the pride of English Jewry, were much attracted by the idea that England was the classical soil for a fruitful work in Palestine. It is worth noting that Dr. Albert Löwy belonged also to this group. He was born on the 10th of December, 1816, at Aussig in Moravia. After his barmizwah (attainment of his religious majority—the age of thirteen) he was sent to a public school at Leipzig. Later he attended the University and Polytechnic at Vienna. There he first met his lifelong friends, Moritz Steinschneider and Abraham Benisch. Löwy and his friends formed “Die Einheit,” a society whose object was to promote the welfare of the Jewish people. In order to realize this object the colonization of Palestine by the Austrian Jews was advocated. The first meeting of the new society was held in 1838, in Löwy’s room. The object, however, had to be kept secret for fear lest it would be defeated by the Government. England was regarded as the country likely to welcome the new movement, and, as an emissary of the Students’ Jewish National Society, Löwy was sent to London in 1841. Years afterwards he took a leading part in London in the foundation of a body with kindred objects, the Anglo-Jewish Association.

To the same group of noble-minded men who raised themselves to the height of a national and Zionist conception of a superior kind belonged also the afore-mentioned Abraham Benisch, one of the creators of the Anglo-Jewish Press, the author of the Jewish School and Family Bible (1851), the translator of Petahiah ben Jacob’s Travels (1856), and for many years editor of the Jewish Chronicle. If there ever was a Jewish nationalist, this important Anglo-Jewish writer was one beyond a doubt. He was a man of great abilities and learning, and rendered valuable assistance in the propaganda for and in the organization of the societies for the colonization of Palestine. In several leading articles written by him, with great tact and sagacity, he expounded—particularly in connection with the political events of 1856 and of 1861—the root principles of political Zionism.

Another remarkable Jewish scholar and pioneer of Zionism in his time was the Rev. M. J. Raphall, who was a brilliant writer and also a pioneer of the Anglo-Jewish Press. He edited the Hebrew Review and Magazine for Jewish Literature in 1837, which was resumed in 1859. Some years later he edited, together with the Rev. A. de Sola, the Voice of Jacob, which had been founded by Jacob Franklin in 1841. He afterwards settled in America and assisted there in the fifties of last century, together with some distinguished American Jews, in establishing in New York a society for the colonization of Palestine. He was later engaged in similar work in Canada. Essentially a student and a scholar, he devoted many years of his life to the propaganda of the Jewish national ideas.

It is impossible to conjure away all the facts showing, firstly, that the supposed differences between the Chovevé Zion movement and the new Zionism are mere phraseology, and, secondly, that the best representatives of Anglo-Jews were nationalist and Zionist. The refusal to accept the new Zionism on the part of some representatives of the Chovevé Zion movement for that reason can only be regarded as a temporary misunderstanding.

The new Zionism made headway in England especially through the efforts of the two organizations: the English Zionist Federation and the Ancient Order of Maccabeans.

The English Zionist Federation was formed in pursuance of a resolution passed by the Clerkenwell Conference of March, 1898, for the purpose of finding a common platform upon which Zionists of all shades of opinion could co-operate. A committee was appointed by the Conference to draw up a scheme, and that committee established the Federation. When the Federation was started it received support from eight societies, representing five towns: after six months, sixteen societies, representing nine towns, had joined: at the time of the Fourth Congress, thirty-eight societies, representing twenty-nine towns, were affiliated. This was the first stage of development prior to the London Congress of the Zionist Organization.

The appearance of English Zionist Delegates at the First Congress has already been alluded to. After the First Congress Dr. Gaster published the following letter in the Times of the 29th of August, 1897:—

“The movement aims at the solution of one of the most complex modern social problems in Europe, and the means which are to be employed towards the solution are the realization of deep-seated religious hopes and ideals. For this very reason men from all the ranks of Jewish society and all shades of Jewish religion are here united in the common, noble, lofty and humanitarian purpose—the restoration of Israel, which is, moreover, the true fulfilment of the words of our Prophets.