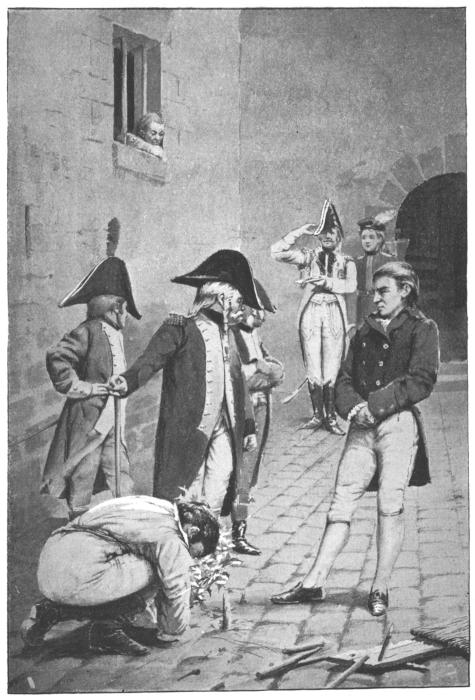

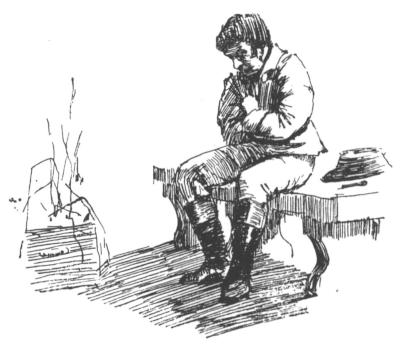

The stay of proceedings.

Title: Picciola

The prisoner of Fenestrella or, captivity captive

Author: X.-B. Saintine

Illustrator: Ferdinand-Joseph Gueldry

Release date: May 27, 2023 [eBook #70871]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: D. Appleton and Company, 1893

Credits: Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

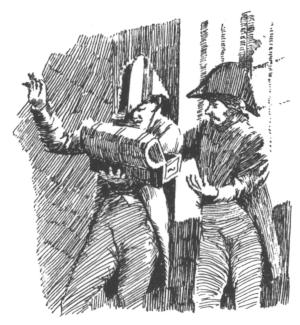

The stay of proceedings.

THE PRISONER OF FENESTRELLA

OR, CAPTIVITY CAPTIVE

BY

X. B. SAINTINE

ILLUSTRATED BY J. F. GUELDRY

NEW YORK

D. APPLETON AND COMPANY

1893

Copyright, 1893,

By D. APPLETON AND COMPANY.

Electrotyped and Printed

at the Appleton Press, U.S.A.

| FACING PAGE | |

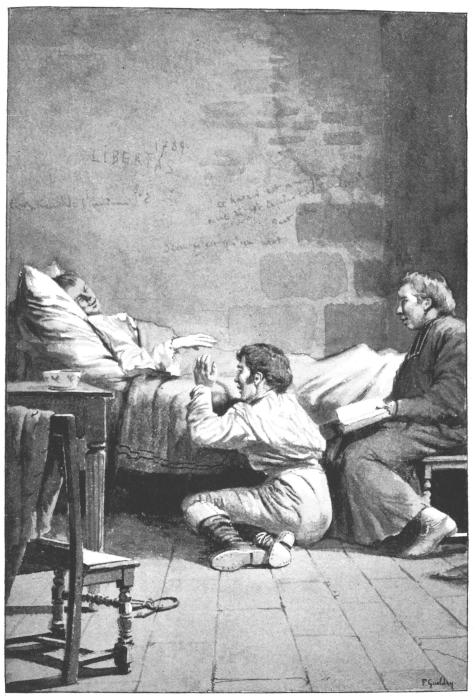

| The stay of proceedings | Frontispiece |

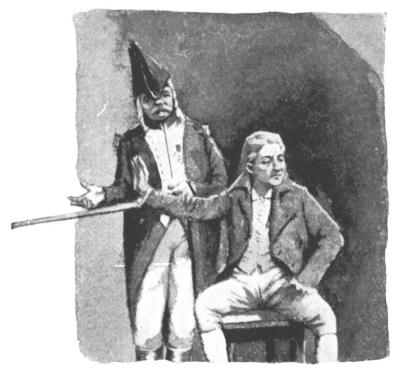

| The priest at Charney’s bedside | 40 |

| A reverie | 61 |

| Napoleon reviewing the troops | 96 |

| Teresa before the Empress | 116 |

| The farewell | 212 |

WITH HEAD AND TAIL PIECES FOR EACH CHAPTER AND NUMEROUS VIGNETTES.

I have reread my book, and I tremble in offering it to you; yet who can appreciate it better? You like neither romances nor dramas; my work is neither a romance nor a drama.

The tale which I have related, madam, is simple; so simple, indeed, that perhaps never has pen laboured on a subject more utterly restricted. My heroine is so unimportant! Not that I wish beforehand to throw the fault of failure on her; for if the action of my little history is thus meagre, its principle is lofty, its aim is elevated; and if I fail in attaining my purpose, it will be that my strength is insufficient. Yet I am not careless as to the fate of my labour, for in it are the deepest of my convictions; and believe me that, more from benevolence than vanity, I hope, though the crowd of ordinary readers may pass over my work with carelessness, that still for some it may possess a charm, for others, utility.

Do you find interest in the truth of a story? If so, I offer that to you to compensate for what you may not find in the story itself.

You remember that lovely woman, so lately dead, the Countess de Charney, whose expression, though mournful, seemed already to breathe of Heaven. Her look, so open, so sweet, which seemed to caress while wandering over you, and to make the heart swell as it lingered; from which one turned away only to be drawn again within its enchantment; you[vi] have seen it, at first timid as that of a young girl, suddenly become animated, brilliant, and self-possessed, exhibiting all its native energy, power, and devotion. Such was the woman; a marvellous union of tenderness and courage, of the weakness of sense and the strength of soul.

Such have I known her; such did others know her, long before me, when her soul was excited only by the affections of a daughter and of a wife. You understand the pleasure with which I dwell with you on such a woman; I may not often again have the opportunity. Still, she is not the heroine of my story.

In the only visit which you made her at Belleville, where was the tomb of her husband, and now, alas! her own, you more than once seemed surprised with what you saw. You were struck with an old, white-haired man, who sat next her at table, whose appearance and manners were coarse, even for his class. You saw him speak familiarly with the daughter of the countess, who, beautiful as her mother had been, answered him with kindness, and even with deference, giving him the name of godfather, which, indeed, was the relation he bore to her. Perhaps you have not forgotten a flower, dried and colourless, in a rich case; and, also, that when you asked her concerning it, a saddened look stole over the countenance of the widow, and your questions remained unanswered. This answer you now have before you.

Honoured with the confidence and affection of the countess, more than once, before that simple flower, between her and the venerable man, have I listened to long and touching details. Besides this, I hold the manuscripts of the count, his letters, and his two prison journals.

I have carefully retained in my memory those precious details; I have attentively perused those manuscripts; I have made important extracts from those letters; and in those journals have I found my inspiration. If, then, I succeed in rousing in your soul the feelings which have agitated mine in presence of these relics of the captive, my fears for my little book are vain.

One word. I have given throughout to my hero his title of count, even during a time in which such dignities were obsolete. This is because I have always heard him so called, in French and in Italian; and in my memory his name and his title are inseparably connected.

You now understand me, madam. You will not expect in this book a history of important events, or the vivid details of love. I have spoken of utility; and of what use is a love-story? In that sweet study, practice is worth more than theory, and each one needs his own experience: each one hastens to acquire it, and cares little to seek it already prepared in books. It is useless for old men, moralists by necessity, to cry, “Shun that dangerous rock, where we have once been shipwrecked!” Their children answer them, “You have tempted that sea, and we must tempt it in turn. We claim our right of shipwreck.”

Yet is there in my story something still of love; but, before all, of a man’s love for——shall I tell you? No, read, and you will learn.

X. B. Saintine.

Charles Veramont, Count de Charney, whose name is not wholly effaced from the annals of modern science, and may be found inscribed in the mysterious archives of the police under Napoleon, was endowed by nature with an uncommon capacity for study. Unluckily, however, his intelligence of mind, schooled by the forms of a college education, had taken a disputatious turn. He was an able logician rather than a sound reasoner; and there was in Charney the composition of a learned man, but not of a philosopher.

At twenty-five, the count was master of seven languages; but instead of following the example of certain[2] learned Polyglots, who seem to acquire foreign idioms for the express purpose of exposing their incapacity to the contempt of foreigners, as well as of their own countrymen, through a confusion of tongues, as well as intellect, Charney regarded his acquirements as a linguist only as a stepping-stone to others of higher value. Commanding the services of so many menials of the intellect, he assigned to each his business, his duty, his fields to cultivate. The Germans served him for metaphysics; the English and Italians for politics and jurisprudence; all for history; to the remotest sources of which he travelled in company with the Romans, Greeks, and Hebrews.

In devoting himself to these serious studies, the count did not neglect the accessory sciences. Till at length, alarmed by the extent of the vast horizon, which seemed to expand as he advanced; finding himself stumble at every step in the labyrinth in which he was bewildered—weary of the pursuit of Truth—(the unknown goddess,)—he began to contemplate history as the lie of ages, and attempted to reconstruct the edifice on a surer foundation. He composed a new historical romance, which the learned derided from envy, and society from ignorance.

Political and legislative science furnished him with more positive groundwork; but these, from one end of Europe to the other, were crying aloud for Reform; and when he tried to specify a few of the more flagrant abuses, they proved so deeply rooted in the social system—so many destinies were based on a fallacious principle, that he was actually discouraged. Charney had not the strength of mind, or insensibility of heart, indispensable to overthrow, in other nations, all that the tornado of the Revolution had left standing in his own.

He recollected, too, that hosts of estimable men, as learned, and perhaps as well-intentioned as himself, professed theories in total opposition to his own. If he were to set the four quarters of the globe on fire for the mere satisfaction of a chimera? This consideration, more startling than even[3] his historical doubts, reduced him to the most painful perplexity.

Metaphysics afforded him a last resource. In the ideal world, an overthrow is less alarming; since ideas may clash without danger in infinite space. In waging such a war, he no longer risked the safety of others; he endangered only his own peace of mind.

The farther he advanced into the mysteries of metaphysical science, analyzing, arguing, disputing—the more deeply he became enveloped in darkness and mystery. Truth, ever flying from his grasp, vanishing under his gaze, seemed to deride him like the mockery of a will-o’-the-wisp, shining to delude the unwary. When he paused to admire its luminous brilliancy, all suddenly grew dark; the meteor having disappeared to shine again on some remote and unexpected point; and when, persevering and tenacious, Charney armed himself with patience, followed with steady steps, and attained the sanctuary, the fugitive was gone again! This time he had overstepped the mark! When he fancied the meteor was in his hand—grasped firmly in his hand—it had already slipped through his fingers, multiplying into a thousand brilliant and delusive particles. Twenty rival truths perplexed the horizon of his mind, like so many false beacons beguiling him to shipwreck. After vacillating between Bossuet and Spinoza—deism and atheism—bewildered among spiritualists, materialists, idealists, ontologists, and eclectics, he took refuge in universal skepticism, comforting his uneasy ignorance by bold and universal negation.

Having set aside the doctrine of innate ideas, and the revelation of theologians, as well as the opinions of Leibnitz, Locke, and Kant, the Count de Charney now resigned himself to the grossest pantheism, unscrupulously denying the existence of one high and supreme God. The contradiction existing between ideas and things, the irregularities of the created world, the unequal distribution of strength and endowment among mankind, inspired his overtasked brain with the[4] conclusion that the world is a conglomeration of insensate matter, and Chance the lord of all.

Chance, therefore, became his God here, and nothingness his hope hereafter. He adopted his new creed with avidity—almost with triumph—as if the audacious invention had been his own. It was a relief to get rid of the doubts which tormented him by a sweeping clause of incredulity; and from that moment Charney, biding adieu to science, devoted himself exclusively to the pleasures of the world.

The death of a relation placed him in possession of a considerable fortune. France, reorganized by the consulate, was resuming its former habits of luxury and splendour. The clarion of victory was audible from every quarter; and all was joy and festivity in the capital. The Count de Charney figured brilliantly in the world of magnificence, elegance, taste, and enlightenment. Having attracted around him the gay, the graceful, and the witty, he unclosed the gates of his splendid mansion to the glittering divinities of the day—to fashion, bon ton, and distinction of every kind. Lost in the giddy crowd, he took part in all its enjoyments and dissipations; amazed that amid such a vortex of pleasures he should still remain a stranger to happiness!

Music, dress, the perfumed atmosphere surrounding the fair and fashionable, were the chief objects of his interest. Vainly had he attempted to devote himself to the society of men renowned for wit and understanding. The ignorance of the learned, the errors of the wise, excited only his compassion or contempt.

Such is the misfortune of proficiency! No one reaches the artificial standard we have created. Even those who are as learned as ourselves are learned after some other fashion; and from our lofty eminence we look down upon mankind as upon a crowd of dwarfs and pigmies. In the hierarchy of intellect, as in that of power, elevation is isolated—to be alone is the destiny of the great.

Vainly did the Count de Charney devote himself to sensual pleasures. In the infancy of a social system so long[5] estranged from the joys of life, and still defiled by the blood-stained orgies of the Revolution, attired in rags and tatters of Roman virtue, yet emulating the licentious excesses of the regency, he signalized himself by his prodigality and dissipation. Labour lost. Horses, equipages, a splendid table, balls, concerts, and hunting-parties, failed to secure Pleasure as his guest. He had friends to flatter him, mistresses to amuse his leisure; yet, though all these were purchased at the highest price, the count found himself as far as ever from the joys of love or friendship. Nothing availed to smooth the wrinkles of his heart, or force it into a smile; Charney actually laboured to be entrapped by the baits of society, without achieving captivation. The syren Pleasure, raising her fair form and enchanting voice above the surface of the waters, fascinated the man, but the eye of the philosopher could not refrain from plunging into the glassy depths below, to be disgusted by the scaly body and bifurcal tail of the ensnaring monster.

Truth and error were equally against him. To virtue he was a stranger, to vice indifferent. He had experienced the vanity of knowledge; but the bliss of ignorance was denied him. The gates of Eden were closed against his re-entrance. Reason appeared fallacious, joy apocryphal. The noise of entertainments wearied him; the silence of home was still more tedious; in company, he became a burden to others; in retirement, to himself. A profound sadness took possession of his soul!

In spite of all Charney’s efforts, the demon of philosophical analysis, far from being exorcised, served to tarnish, undermine, contract, and extinguish the brilliancy of every mode of life he selected. The praise of his friends, the endearments of his loves, seemed nothing more than the current coin given in exchange for a certain portion of his property, the paltry evidence of a necessity for living at his expense.

Decomposing every passion and sentiment, and reducing all things to their primitive element, he, at length, contracted a morbid frame of mind, amounting almost to aberration of intellect.[6] He fancied that in the finest tissue composing his garments, he could detect the exhalations of the animal of whose fleece it was woven—on the silk of his gorgeous hangings, the crawling worm which furnishes them. His furniture, carpets, gewgaws, trinkets of coral or mother-of-pearl, all were stigmatized in his eyes as the spoil of the dead, shaped by the labours of some squalid artisan. The spirit of inquiry had destroyed every illusion. The imagination of the sceptic was paralyzed!

To such a heart as that of Charney, however, emotion was indispensable. The love which found no single object on which to concentrate its vigour expanded into tenderness for all mankind; and he became a philanthropist!

With the view of serving the cause of his fellow-creatures, he devoted himself to politics, no longer speculative, but active; initiated himself into secret societies, and grew a fanatic for freedom, the only superstition remaining for those who have renounced the higher aspirations of human nature. He enrolled himself in a plot—a conspiracy against nothing less than the sovereignty of the victorious Napoleon!

In this attempt, Charney fancied himself actuated by patriotism, by philanthropy, by love of his countrymen! More likely by animosity against the one great man, of whose power and glory he was envious! An aristocrat at heart, he fancied himself a leveller. The proud noble who had been robbed of the title of count, bequeathed him by his ancestors, did not choose that his inferior in birth should assume the title of emperor, which he had conquered at the point of his sword.

It matters little in what plot he embarked his destinies; at that epoch, there was no lack of conspiracies! It was one of the many hatched between 1803 and 1804, and not suffered to come to light: the police—that second providence which presides over the safety of empires—was beforehand with it! Government decided that the less noise made on the occasion, the better; they would not even spare it so much as a discharge of muskets on the Plaine de Grenelle,[7] the scene of military execution: but the heads of the conspiracy were privately arrested, condemned, almost without trial, and conveyed away to solitary confinement in various state prisons, citadels, or fortresses, of the ninety-six departments of consular France.

In traversing the Alps on my way to Italy—an humble tourist, with my staff in my hand, and my wallet on my shoulder, I remember pausing to contemplate, near the pass of Rodoretto, a torrent swollen by the melting of the glaciers. The tumultuous sounds produced by its course, the foaming cascades into which it burst, the varying colors and hues created by the movement of its waters, yellow, white, green, black, according to its channel through marl, slate, chalk, or peat earth—the vast blocks of marble or granite it had detached without being able to remove, around which a thousand ever-changing cataracts added roar to roar, cascade to cascade; the trunks of trees it had uprooted, of which the still foliaged branches emerging from the water were agitated by the winds, while the roots were buffeted by the waves; fragments of the very banks clothed with verdure, and driven like floating islands against[9] the trees, as the trees were driven in their turn against the blocks of granite—all this, these murmurs, clashings, and roarings, confined between narrow and precipitous banks, impressed me with wonder and admiration. And this torrent was the Clusone!

Skirting its shores, I pursued the course of the stream into one of the four valleys retaining the name of “Protestant,” in the memory of the Vaudois who formerly took refuge in their solitudes. There, my torrent lost its wild irregularity; and its hundred roaring voices were presently subdued. Its shattered trees and islands had been deposited on some adjacent level; its colours had resolved themselves into one; and the material of its bed no longer distinguishable on the tranquil surface. Still strong and copious, it now flowed with decency, propriety, almost with coquetry: affecting the airs of a modest rivulet as it bathed the rugged walls of Fenestrella.

It was then I visited Fenestrella, a large town celebrated for peppermint water, and the fortress which crowns the two mountains between which it is situated, communicating with each other by covered ways, but partly dismantled during the wars of the Republic. One of the forts, however, was repaired and refortified when Piedmont became incorporated into France.

In this fortress of Fenestrella, was Charles Veramont, Count de Charney, incarcerated, on an accusation of having attempted to subvert the laws of government, and introduce anarchy and confusion into the country.

Estranged by rigid imprisonment, alike from men of[10] science and men of pleasure, and regretting neither—renouncing without much effort his wild projects of political regeneration—bidding a forced farewell to his fortune, by the pomps of which he had been undazzled—to his friends, who were grown tiresome, and his mistresses, who were grown faithless; having for his abode, instead of a princely mansion, a bare and gloomy chamber—the jailer of Charney was now his sole attendant, and his imbittered spirit his only companion.

But what signified the gloom and nakedness of his apartment? The necessaries of life were there, and he had long been disgusted with its superfluities. Even his jailer gave him no offence. It was only his own thoughts that troubled him!

Yet what other diversions remained for his solitude—but self-conference? Alas! none! Nothing around him or before him but weariness and vexation of spirit! All correspondence was interdicted. He was allowed no books, nor pens, nor paper; for such was the established discipline at Fenestrella. A year before, when the count was intent only on emancipating himself from the perplexities of learning, this loss might have seemed a gain. But now, a book would have afforded a friend to consult, or an adversary to be confuted! Deprived of every thing, sequestered from the world, Charney had nothing left for it, but to become reconciled to himself, and live in peace with that natural enemy, his soul. For the cruelty with which that unsilenceable monitor continued to set before him the desperateness of his condition, rendered conciliation necessary. His case was indeed a hard one! A man to whom nature had been so prodigal, whose cradle society had surrounded with honours and privileges—he to be reduced to such abject insignificance—he to have need of pity and protection, who had faith neither in the existence of a God nor the mercy of his fellow-creatures!

Vainly did he strive to throw off this frightful consciousness, when in the solitude of his reveries it alternately chilled and scorched his shrinking bosom: and once more, the unhappy[11] Charney began to cling for support to the visible and material world—now, alas! how circumscribed around him. The room assigned to his use was at the rear of the citadel, in a small building raised upon the ruins of a vast and strong foundation, serving formerly for defence, but rendered useless by a new system of fortification.

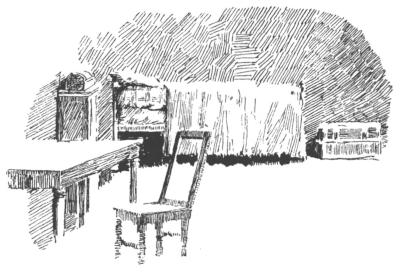

Four walls, newly whitewashed, so that he was denied even the amusement of perusing the lucubrations of former prisoners, his predecessors; a table, serving for his meals; a chair, whose insulated unity reminded him, that no human being would ever sit beside him there in friendly converse; a trunk for his clothes and linen; a little sideboard of painted deal, half worm-eaten, offered a singular contrast to the rich mahogany dressing-case, inlaid with silver, standing there as the sole representative of his former splendours. A clean, but narrow bed, window-curtains of blue cloth (a mere mockery, for, thanks to the closeness of his prison bars and the opposite wall rising at ten feet distance, there was little to fear from prying eyes or the importunate radiance of the sun). Such was the complement of furniture allotted to the Count de Charney.

Over his chamber was another, wholly unoccupied; he had not a single companion in that detached portion of the fortress.

The remainder of his world consisted in a short, massive, winding stone staircase, descending into a small paved court, sunk into what had been a moat, in the earlier days of the[12] citadel, in which narrow space he was permitted to enjoy air and exercise during two hours of the day. Such was the ukase of the commandant of Fenestrella.

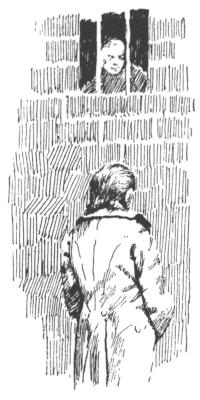

From this confined spot, however, the prisoner was able to extend his glance towards the summits of the mountains, and command a view of the vapours rising from the plain; for the walls of the ramparts, lowering suddenly at the extremity of the glacis, admitted a limited proportion of air and sunshine into the court. But once shut up again in his room, his view was bounded by an horizon of solid masonry, and a surmise of the majestic and picturesque aspect of nature it served to conceal. Charney was well aware that to the right rose the fertile hills of Saluces; that to his left were developed the last undulations of the valley of Aorta and the banks of the Chiara; that before him lay the noble plains of Turin; and behind, the mighty chain of Alps, with its adornment of rocks, forests, and chasms, from Mount Genevra to Mount Cenis. But, in spite of this charming vicinage, all he was permitted to behold was the misty sky suspended over his head by a frame-work of rude masonry; the pavement of the little court, and the bars of his prison, through which he might admire the opposite wall, adorned with a single small square window, at which he had once or twice caught glimpses of a doleful human countenance.

What a world from which to extract delight and entertainment! The unhappy Count wore out his patience in the attempt![13] At first, he amused himself with scribbling with a morsel of charcoal on the walls of his prison the dates of every happy event of his childhood; but from this dispiriting task he desisted, more discouraged than ever. The demon of scepticism next inspired him with evil counsel; and having framed into fearful sentences the axioms of his withering creed, he inscribed them also on his wall, between recollections consecrated to his sister and mother!

Still unconsoled, Charney at length made up his mind to fling aside his heart-eating cares, adopt, by anticipation, all the puerilities and brutalization which result from the prolongation of solitary confinement. The philosopher attempted to find amusement in unravelling silk or linen; in making flageolets of straw, and building ships of walnut-shells. The man of genius constructed whistles, boxes, and baskets, of kernels; chains and musical instruments, with the springs of his braces; nay, for a time, he took delight in these absurdities; then, with a sudden movement of disgust, trampled them, one by one, under his feet!

To vary his employment, Charney began to carve a thousand fanciful designs upon his wooden table! No school-boy ever mutilated his desk by such attempts at arabesque, both in relief and intaglio, as tasked his patience and address. The celebrated portal of the church of Candebee, and the pulpit and palm trees of St. Gudula at Brussels, are not adorned with a greater variety of figures. There were houses upon houses, fishes upon trees, men taller than steeples, boats upon roofs, carriages upon water, dwarf pyramids, and flies of gigantic stature,—horizontal, vertical, oblique, topsy-turvy, upside down, pell-mell, a chaos of hieroglyphics, in which he tried to discover a sense symbolical, an accidental intention,[14] an occult design; for it was no great effort on the part of one who had so much faith in the power of chance, to expect the development of an epic poem in the sculptures on his table, or a design of Raphael in the veins of his box-wood snuff-box.

It was the delight of his ingenuity to multiply difficulties for conquest, problems for solution, enigmas for divination; but even in the midst of these recreations, ennui, the formidable enemy, again surprised the captive.

The man whose face he had noticed at the grated window might have afforded him food for conjecture, had he not seemed to avoid the observation of the Count, by retiring the moment Charney made his appearance; in consequence of which, he conceived an abhorrence of the recluse. Such was his opinion of the human species, that the stranger’s desire of concealment convinced him he was a spy, employed to watch the movements of the prisoners, or, perhaps, some former enemy, exulting over his humiliation.

On interrogating the jailer, however, this last supposition was set at rest.

“’Tis an Italian,” said Ludovico, the turnkey. “A good soul—and, what is more, a good Christian; for I often find him at his devotions.”

Charney shrugged his shoulders: “And what may be the cause, pray, of his retention?” said he.

“He attempted to assassinate the Emperor.”

“Is he, then, a patriot?”

“A patriot! Rubbish! Not he. But the poor soul had once a son and daughter: and now he has only a daughter. The son was killed in Germany. A cannon-ball broke a tooth for him. Povero figliuolo!”

“It was a paroxysm of selfishness, then, which moved this old man to become an assassin?”

“You have never been a father, Signor Conte!” replied the jailer. “Cristo Santo! if my Antonio, who is still a babe, were to eat his first mouthful for the good of this empire of the French (which is a bantling of his own age, or thereabouts), I’d soon—— But basta! I’ve no mind to take up my lodging at Fenestrella, except as it may be with the keys at my girdle or under my pillow.”

“And how does this fierce conspirator amuse himself in prison?” persisted Charney.

“Catching flies!” replied the jailer, with an ironical wink.

Instead of detesting his brother in misfortune, Charney now began to despise him. “A madman, then?” he demanded.

“Perche pazzo, Signor Conte? Though you are the last comer, you excel him already in the art of hacking a table into devices. Pazienza!”

In defiance of the sneer conveyed in the jailer’s remark, Charney soon resumed his manual labors, and the interpretations of his hieroglyphics; but, alas! only to experience anew their insufficiency as a kill-time. His first winter had expired in weariness and discontent: when, by the mercy of Heaven, an unexpected object of interest was assigned him.

One day, Charney was breathing the fresh air in the little court of the fortress, at the accustomed hour, his head declining, his eyes downcast, his arms crossed behind him, pacing with slow and measured steps, as if his deliberation tended to enlarge the precincts of his dominion.

Spring was breaking. A milder air breathing around, tantalized him with a vain inclination to enjoy the season of liberty, as master of his time and territory. He was proceeding to number, one by one, the stones paving the courtyard, (doubtless to verify the accuracy of former calculations—for it was by no means the first time they had put his arithmetic to the test), when he perceived a small mound of earth rising between two stones of the pavement, cleft slightly at its summit.

The Count stopped short—his heart beat hurriedly without any rational grounds for emotion, except that every trivial incident affords matter of hope or fear to a captive. In the most indifferent objects, in the most unimportant events, the prisoner discerns traces of a mysterious project for his deliverance.

Who could decide that this trifling irregularity on the surface[17] might not indicate important operations under ground? Subterraneous issues might have been secretly constructed, and the earth be about to open and afford him egress towards the mountains! Perhaps his former friends and accomplices had been sapping and mining, to procure access to his dungeon, and restore him to light and liberty!

He listened! he fancied he could detect the low murmur of a subterraneous sound. He raised his head, and the loud and rapid clang of the tocsin saluted his ear. The ramparts were echoing with the prolonged roll of drums, like the call to arms in time of war. He started—he passed his trembling hand over his forehead, on which cold dews of intense agitation were already rising. Is his liberation at hand? Is France submitted to the domination of a new ruler?

The illusion of the captive vanished as it came. Reflection soon restored him to reason. He no longer possesses accomplices—he never possessed friends! Again he lends a listening ear, and the same noises recur; but they mislead his mind no longer. The supposed tocsin is only the church bell which he has been accustomed to hear daily at the same hour, and the drums, the usual evening signal for retreat to quarters. With a bitter smile, Charney begins to compassionate his own folly, which could mistake the insignificant labors of some insect or reptile, some wandering mole or field-mouse, for the result of human fidelity, or the subversion of a mighty empire.

Resolved, however, to bring the matter to the test, Charney, bending over the little hillock, gently removed the earth from its summit; when he had the mortification to perceive that the wild though momentary emotion by which he had been overcome, was not produced by so much as the labors of an animal armed with teeth and claws! but by the efforts of a feeble plant to pierce the soil—a pale and sickly scatterling of vegetation. Deeply vexed, he was about to crush with his heel the miserable weed, when a refreshing breeze, laden with the sweets of some bower of honeysuckles, or syringas, swept past, as if to intercede for mercy towards the[18] poor plant, which might perhaps hereafter reward him with its flowers and fragrance.

A new conjecture conspired to suspend his act of vengeance. How has this tender plant, so soft and fragile as to be crushed with a touch, contrived to pierce and cleave asunder the earth, dried and hardened into a mass by the sun, daily trodden down by his own footsteps, and all but cemented by the flags of granite between which it was enclosed? On stooping again to examine the matter with more attention, he observed at the extremity of the plant a sort of fleshy valve affording protection to its first and tenderest leaves, from the injurious contact of any hard bodies they might have to encounter in penetrating the earthy crust in search of light and air.

“This, then, is the secret?” cried he, already interested in his discovery. “Nature has imparted strength to the vegetable germ, even as the unfledged bird which is able to break asunder with its beak the egg-shell in which it is imprisoned; happier than myself—in possession of unalienable instruments to secure its liberation!” And after gazing another minute on the inoffensive plant, he lost all inclination for its destruction.

On resuming his walk the next day, with wide and careless steps, Charney was on the point of setting his foot on it, from inadvertence; but luckily recoiled in time. Amused to find himself interested in the preservation of a weed, he paused to take note of its progress. The plant was strangely grown; and the free light of day had already effaced the pale and sickly complexion of the preceding day. Charney was struck by the power inherent in vegetables to absorb rays of light, and, fortified by[19] the nourishment, borrow, as it were, from the prism, the very colours predestined to distinguish its various parts of organization.

“The leaves,” thought he, “will probably imbibe a hue different from that of the stem. And the flowers? what colour, I wonder, will be the flowers? Nourished by the same sap as the green leaves and stem, how do they manage to acquire, from the influence of the sun, their variegations of azure, pink, or scarlet? For already their hue is appointed. In spite of the confusion and disorder of all human affairs, matter, blind as it is, marches with admirable regularity: still blindly, however! for lo, the fleshy lobes which served to facilitate for the plant its progress through the soil, though now useless, are feeding their superfluous substance at its expense, and weighing upon its slender stalk!”

But, even as he spoke, daylight became obscured. A chilly spring evening, threatening a frosty night, was setting in; and the two lobes, gradually rising, seemed to reproach him with his objections, by the practical argument of enclosing the still tender foliage, which they secured from the attacks of insects or the inclemency of the weather, by the screen of their protecting wings.

The man of science was better able to comprehend this mute answer to his cavilling, because the external surface of the vegetable bivalve had been injured the preceding night by a snail, whose slimy trace was left upon the verdure of the cotyledon.

This curious colloquy between action and cogitation, between the plant and the philosopher, was not yet at an end. Charney was too full of metaphysical disquisition to allow himself to be vanquished by a good argument.

“’Tis all very well!” cried he. “In this instance, as in others, a fortunate coincidence of circumstances has favoured the developement of incomplete creation. It was the inherent[20] qualification of the nature of the plant to be born with a lever in order to upraise the earth, and a buckler to shelter its tender head: without which it must have perished in the germ, like myriads of individuals of its species which proved incapable of accomplishing their destinies. How can one guess the number of unsuccessful efforts which nature may have made, ere she perfected a single subject sufficiently organized! A blind man may sometimes shoot home; but how many uncounted arrows must be lost before he attains the mark? For millions of forgotten centuries, matter has been triturating between negative and positive attraction. How then can one wonder that chance should sometimes produce coincidence? This fleshy screen serves to shelter the early leaves. Granted! But will it enlarge its dimensions to contain the rest as they are put forth, and defend them from cold and insects? No, no; no evidence of the calculating of a presiding Providence! A lucky chance is the alpha and omega of the universe!”

Able logician!—profound reasoner! listen, and Nature shall find a thousand arguments to silence your presumption! Deign only to fix your inquiring eyes upon this feeble plant, which the munificence of Heaven has called into existence between the stones of your prison! You are so far right that the cotyledon will not expand so as to cover with its protecting wings the future progress of the plant. Already withering, they will eventually fall and decay. But they will suffice to accomplish the purpose of nature. So long as the northern wind drives down from the Alps their heavy fogs or sprinkling of sleet, the new leaves will find a retreat impermeable to the chilly air, caulked with resinous or viscous matter, and expanding or closing according to the impulse of the weather; finally distended by a propitious atmosphere, the leaflets will emerge clinging to each other for mutual support, clothed with a furry covering of down to secure them against the fatal influence of atmospheric changes. Did ever mother watch more tenderly over the preservation of a child? Such are the phenomena, Sir Count, which you might long ago have[21] learned to admire, had you descended from the flighty regions of human science, to study the humble though majestic works of God! The deeper your researches, the more positive had been your conviction; for where dangers abound, know that the protection of the Providence which you deny is vouchsafed a thousand and a thousand fold in pity to the blindness of mankind!

In the weariness of captivity, Charney was soon satisfied to occupy his idle hours by directing his attention to the transformations of the plant. But when he attempted to contend with it in argument, the answers of the vegetable logician were too much for him.

“To what purpose these stiff bristles, disfiguring a slender stem?” demanded the Count. And the following morning he found them covered with rime: thanks to their defence, the tender bark had been secured from all contact with the frost.

“To what purpose, for the summer season, this winter garment of wool and down?” he again inquired. And when the summer season really breathed upon the plant, he found the new shoots array themselves in their light spring clothing; the downy vestments, now superfluous, being laid aside.

“Storms may be still impending!” cried Charney, with a bitter smile; “and how will these slender and flexile shoots resist the cutting hail, the driving wind?” But when the stormy rain arose, and the winds blew, the slender plant, yielding to their intemperance, replied to the sneers of the Count by prudent prostration. Against the hail, it fortified itself by a new manœuvre; the leaves, rapidly uprising, adhered[22] to the stalks for protection; presenting to the attacks of the enemy the strong and prominent nerves of their inferior surface; and union, as usual, produced strength. Firmly closed together, they defied the pelting shower; and the plant remained master of the field; not, however, without having experienced wounds and contusions, which, as the leaves expanded in the returning sunshine, were speedily cicatrized by its congenial warmth.

“Is chance endowed then with intelligence?” cried Charney. “Must we admit matter to be spiritualized, or humiliate the world of intelligence into materialism?”

Still, though self-convicted, he could not refrain from interrogating his mute instructress. He delighted in watching, day by day, her spontaneous metamorphoses. Often, after having examined her progress, he found himself gradually absorbed in reveries of a more cheering nature than those to which he had been of late accustomed. He tried to prolong the softened mood of mind by loitering in the court beside the plant; and one day, while thus employed, he happened to raise his eyes towards the grated window, and saw the fly-catcher observing him. The colour rose to his cheek, as if the spy could penetrate the subject of his meditations; but a smile soon chased away the blush. He no longer presumed to despise his comrade in misfortune. He, too, had been engaged in contemplating one of the simplest creations of nature; and had derived comfort from the study.

“How do I know,” argued Charney, “that the Italian may not have discovered as many marvels in a fly, as I in a nameless vegetable?”

The first object that saluted him on his returning to his chamber, after this admission, was the following sentence, inscribed by his own hand upon the wall, a few months before:

“Chance, though blind, is the sole author of the creation.”

Seizing a piece of charcoal, Charney instantly qualified the assertion, by the addition of a single word—“Perhaps.”

Charney had long ceased to find amusement in these gratuitous mural inscriptions; and if he still occasionally played the sculptor with his wooden table, his efforts produced nothing now but germinating plants; each protected by a cotyledon, or a sprig of foliage, whose leaves were delicately serrated and prominently nerved. The greater portion of the time assigned him for exercise was spent in contemplation of his plant—in examining and reasoning upon its developement. Even after his return to his chamber, he often watched the little solitary through his prison-bars. It had become his whim, his bauble, his hobby—perhaps only to be discarded like other preceding favourites!

One morning, as he stood at the window, he observed the[24] jailer, who was rapidly traversing the courtyard, pass so close to it that the stem seemed on the point of being crushed under his footsteps; and Charney actually shuddered! When Ludovico arrived as usual with his breakfast, the Count longed to entreat the man would be careful in sparing the solitary ornament of his walk; but he found some difficulty in phrasing so puerile an entreaty. Perhaps the Fenestrella system of prison discipline might enforce the clearing of the court from weeds, or other vegetation. It might be a favour he was about to request, and the Count possessed no worldly means for the requital of a sacrifice. Ludovico had already taxed him heavily, in the way of ransom, for the various objects with which it was his privilege to furnish the prisoners of the fortress.

Besides, he had scarcely yet exchanged a word with the fellow, by whose abrupt manners and character he was disgusted. His pride recoiled, too, from placing himself in the same rank with the fly-catcher, towards whom Ludovico had acknowledged his contempt. Then there was the chance of a refusal! The inferior, whose position raises him to temporary consequence, is seldom sufficiently master of himself to bear his faculties meekly, incapable of understanding that indulgence is a proof of power. The Count felt that it would be insupportable to him to find himself repulsed by a turnkey.

At length, after innumerable oratorical precautions, and the exercise of all his insight into the foibles of human nature, Charney commenced a discourse, logically preconcocted, in hopes to obtain his end without the sacrifice of his dignity—or, to speak more correctly, of his pride.

He began by accosting the jailer in Italian; by way of propitiating his natural prejudices, and calling up early associations. He inquired after Ludovico’s boy, little Antonio; and, having caused this tender string to vibrate, took from his dressing-box a small gilt goblet, and charged him to present it to the child!

Ludovico declined the gift, but refused it with a smile; and Charney, though somewhat discountenanced, resolved to[25] persevere. With adroit circumlocution, he observed, “I am aware that a toy, a rattle, a flower, would be a present better suited to Antonio’s age; but you can sell the goblet, and procure those trifles in abundance with the price.” And, lo! à propos of flowers, the Count embarked at once into his subject.

Patriotism, paternal love, personal interest, every influential motive of human action, were thus put in motion in order to accomplish the preservation of a plant! Charney could scarcely have done more for his own. Judge whether it had ingratiated itself into his affections!

“Signor Conte!” replied Ludovico, at the conclusion of the harangue, “riprendi sua nacchera indorata! Were this pretty bauble missing from your toilet-case, its companions might fret after it! At three months old, my bantling has scarce wit enough to drink out of a goblet; and with respect to your gilly-flower—”

“Is it a gilly-flower?” inquired Charney, with eagerness.

“Sac à papious! how should I know? All flowers are more or less gilly-flowers! But as to sparing the life of yours, eccellenza, methinks the request comes late in the day. My boot would have been better acquainted with it long ago, had I not perceived your partiality for the poor weed!”

“Oh! as to my partiality,” interrupted Charney, “I beg to assure you—”

“Ta, ta, ta, ta! What need of assurance,” cried Ludovico. “I know whereabouts you are better than you do. Men must have something to love; and state prisoners have small choice allowed them in their whims. Why, among my boarders here, Signor Conte (most of whom were grand gentry, and great wiseacres in their day, for ’tis not the small fry they send into harbour at Fenestrella), you’d be surprised at what little cost they manage to divert themselves! One catches flies—no harm in that; another—” and Ludovico winked knowingly, to signify the application—“another chops a solid deal table into chips, without considering how far I may be responsible for its preservation.” The Count vainly[26] tried to interpose a word: Ludovico went on: “Some amuse themselves with rearing linnets and goldfinches; others have a fancy for white mice. For my part, poor souls, I have so much respect for their pets, that I had a fine Angora cat of my own, with long white silken hair, you’d have sworn ’twas a muff when ’twas asleep!—a cat that my wife doated on, to say nothing of myself. Well, I gave it away, lest the creature should take a fancy to some of their favourites. All the cats in the creation ought not to weigh against so much as a mouse belonging to a captive!”

“Well thought, well expressed, my worthy friend!” cried Charney, piqued at the inference which degraded him to the level of such wretched predilections. “But know that this plant is something more to me than a kill-time.”

“What signifies? so it serves but to recall to your mind the green tree under which your mother hushed your infancy to rest, per Bacco! I give it leave to overshadow half the court. My instructions say nothing about weeding or hoeing, so e’en let it grow and welcome! Were it to turn out a tree, indeed, so as to assist you in escalading the walls, the case were different! But there is time before us to look after the business—eh! eccellenza?” said the jailer, with a coarse laugh. “Not that you hav’n’t my best wishes for the recovery of the free use of your legs and lungs; but all must come in course of time, and the regular way. For if you were to make an attempt at escape—”

“Well! and if I were?” said Charney, with a smile.

“Thunder and hail!—you’d find Ludovico a stout obstacle in your way! I’d order the sentry to fire at you, with as little scruple as at a rabbit! Such are my instructions! But as to doing mischief to a poor harmless gilly-flower, I look upon that man they tell of who killed the pet-spider of the prisoner under his charge, as a wretch not worthy to be a jailer! ’Twas a base action, eccellenza—nay, a crime!”

Charney felt amazed and touched by the discovery of so much sensibility on the part of his jailer. But now that he had begun to entertain an esteem for the man, his vanity[27] rendered it doubly essential to assign a rational motive for his passion.

“Accept my thanks, good Ludovico,” said he, “for your good-will. I own that the plant in question affords me scope for a variety of scientific observations. I am fond of studying its physiological phenomena.” Then (as Ludovico’s vague nodding of the head convinced him that the poor fellow understood not a syllable he was saying) he added, “More particularly as the class to which it belongs possesses medicinal qualities, highly favourable to a disorder to which I am subject.”

A falsehood from the lips of the noble Count de Charney! and merely to evade the contempt of a jailer, who, for the moment, represented the whole human species in the eyes of the captive.

“Indeed!” cried Ludovico; “then all I have to say is, that if the poor thing is so serviceable to you, you are not so grateful to it as you ought to be. If I hadn’t been at the pains of watering it for you now and then, on my way hither with your meals, la povera picciola would have died of thirst. Addio, Signor Conte!”

“One moment, my good friend,” exclaimed Charney, more and more amazed to discover such delicacy of mind so roughly enclosed, and repentant at having so long mistaken the character of his jailer. “Since you have interested yourself in my pursuits, and without vaunting your services, accept, I entreat you, this small memento of my gratitude! Should better times await me, I will not forget you!”

And once more he tendered the goblet; which this time Ludovico examined with a sort of vague curiosity.

“Gratitude, for what, Signor Conte?” said he. “A plant[28] wants nothing but a sprinkling of water; and one might furnish a whole parterre of them in their cups, without ruining oneself at the tavern. If la picciola diverts you from your cares, and provides you with a specific, enough said, and God speed her growth.”

And having crossed the room, he quietly replaced the goblet in its compartment of the dressing-box.

Charney, rushing towards Ludovico, now offered him his hand.

“No, no!” exclaimed the jailer, assuming an attitude of respect and constraint. “Hands are to be shaken only between equals and friends.”

“Be my friend, then, Ludovico!” cried the Count.

“No, eccellenza, no!” replied the turnkey. “A jailer must be on his guard, in order to perform his duties like a man of conscience, to-day, to-morrow, and every day of the week. If you were my friend, according to my notions of the word, how should I be able to call out to the sentinel, Fire! if I saw you swimming across the moat? I am fated to remain your keeper, jailer, e divotissimo servo!”

In the course of his solitary meditations, after Ludovico’s departure, Charney was compelled to admit that, in his relations with the jailer, the man of genius and education had fallen below the level of the man of the people. To what wretched subterfuges had he descended, in order to practice upon the feelings of this kind-hearted and simple being! He had even soiled his noble lips with an untruth.

He was startled to discover the services recently rendered by Ludovico to the “povera picciola.” The boor, the jailer, morose only when invited to a breach of duty, had actually watched him in secret, not to exult over his weakness, but to render him a service; nay, by his obstinate disinterestedness, the man persisted in imposing an obligation on the Count de Charney.

In his walk next morning, the Count hastened to share,[30] with his little favourite, the cruise of water allotted to his use; not only watering the roots, but sprinkling the plant itself, to refresh its leaves from dust or insects. While thus occupied, the sky became darkened by a thunder-cloud, suspended like a black dome over the turrets of the fortress. Large rain-drops began to fall: and Charney was about to take refuge in his room, when a few hail-stones mingling with the rain, pattered down on the pavement of the court. La povera picciola seemed on the point of being uprooted by the whirlwind which accompanied the storm. Her dishevelled branches and leaves shrinking up towards their stalks for protection against the chilling shower, trembled with every driving blast of wind that howled, as if in triumph, through the court.

Charney paused. Recalling to mind the reproaches of Ludovico, he looked eagerly around for some object to defend his plant from the storm; but nothing could be seen. The hail-stones came rattling down with redoubled force, threatening destruction to its tender stem; and, notwithstanding Charney’s experience of its power of resistance against such attacks, he grew uneasy for its safety. With an effort of tenderness, worthy of a father or a lover, he stationed himself between his protegée and the wind, bending over her, to secure her from the hail; and, breathless with his struggles against the violence of the storm, devoted himself, like a martyr, to the defence of la picciola.

At length the hurricane subsided. But might not a recurrence of the mischief bring destruction to his favourite at some moment when bolts and bars divided her from her protector? He had already found cause to tremble for her safety, when the wife of Ludovico, accompanied by a huge mastiff, one of the guardians of the prison, occasionally traversed the yard; for a single stroke with its paw, or a snap of its mouth, might have annihilated the darling of the philosophical captive; and Charney accordingly passed the remainder of the day in concocting a plan of fortification.

The moderate portion of wood allowed him for fuel,[31] scarcely supplied his wants in a climate whose nights and mornings are so chilly, in a chamber debarred from all warmth of sunshine. Yet he resolved to sacrifice his comfort to the safety of the plant. He promised himself to retire early to rest, and rise later; by which means, after a few days of self-denial, he amassed sufficient wood for his purpose.

“Glad to see you have more fuel than you require,” cried Ludovico, on noticing the little stock. “Shall I clear the room for you of all this lumber?”

“Not for the world,” replied Charney, with a smile. “I am hoarding it to build a palace for my lady-love.”

The jailer gave a knowing wink, which signified, however, that he understood not a word about the matter.

Meanwhile, Charney set about splitting and pointing the uprights of his bastions; and carefully laid aside the osier bands which served to tie up his daily fagots. He next tore from his trunk its lining of coarse cloth; out of which he drew the strongest threads: and his materials thus prepared, he commenced his operations the moment the rules of the prison and the exactitude of the jailer would admit. He surrounded his plant with palisades of unequal height, carefully inserted between the stones of the pavement, and secured at the base by a cement of earth, laboriously collected from the interstices, and mortar and saltpetre secretly abstracted from the ancient turret-walls around him. When the labours of the carpenter and mason were achieved, he began to interlace his scaffolding at intervals with split osiers, to screen la picciola from the shock of exterior objects.

The completion of his work acquired, during its progress, new importance in his eyes, from the opposition of Ludovico. The jailer shook his head and grumbled when first he noticed the undertaking. But before the close of the performance the kind-hearted fellow withdrew his disapprobation; nay, would even smoke his pipe, leaning against the wicket of the courtyard, and watching, with a smile, the efforts of the unpractised mechanic; interrupting himself in the enjoyment of[32] his favourite recreation, however, to favour Charney with occasional counsels, the result of his own experience.

The work progressed rapidly; but, to render it perfect, the Count was under the necessity of sacrificing a portion of his scanty bedding; purloining handfuls of straw from his palliasse, in order to band up the interstices of his basket-work, as a shelter against the mountain wind, and the fierceness of the meridian sun, which in summer would be reflected from the flint of the adjacent wall.

One evening, a sudden breeze arose, after Charney had been locked in for the night—and the yard was quickly strewn with scattered straws and slips of osier, which had not been worked in with sufficient solidity. Charney promised himself to counteract next day the ill effects of his carelessness; but on reaching the court at the usual hour, he found that all the mischief had been neatly repaired: a hand more expert than his own had replaced the matting and palisades. It was not difficult to guess to whom he was indebted for this friendly interposition. Meanwhile, thanks to her friend—thanks to her friends, the plant was now secured by solid ramparts and roofing: and Charney, attaching himself, according to the common frailty of human nature, more tenderly to the object on which he was conferring obligation, had the satisfaction to see the plant expand with redoubled powers, and acquire new beauties every hour. It was a matter of deep interest to observe the progress of its consolidation. The herbaceous stem was now acquiring ligneous consistency. A glossy bark began to surround the fragile stalk; and already, the gratified proprietor of this gratuitous treasure entertained eager hopes of the appearance of flowers among its leaves. The man of paralysed nerves—the man of frost-bound feelings, had at length found something to wish for! The action of his lofty intellect was at last concentrated into adoration of an herb of the field. Even as the celebrated Quaker, John Bartram, resolved, after studying for hours the organization of a violet, to apply his powers of mind to the analysis of the vegetable kingdom, and eventually acquired high eminence[33] among the masters of botanical science, Charney became a natural philosopher.

A learned pundit of Malabar is said to have lost his reason in attempting to expound the phenomena of the sensitive plant. But the Count de Charney seemed likely to be restored to the use of his by studies of a similar nature; and, sane or insane, he had at least already extracted from his plant an arcanum sufficiently potent to dispel the weariness of ennui, and enlarge the limit of his captivity.

“If it would but flower!” he frequently exclaimed, “what a delight to hail the opening of its first blossom! a blossom whose beauty, whose fragrance, will be developed for the sole enjoyment of my eager senses. What will be its colour, I wonder! what the form of its petals?—time will show! Perhaps they may afford new premises for conjecture—new problems for solution. Perhaps the conceited gipsy will offer a new challenge to my understanding? So much the better! Let my little adversary arm herself with all her powers of argument. I will not prejudge the case. Perhaps, when thus complete, the secret of her mysterious nature will be apparent? How I long for the moment! Bloom, picciola! bloom—and reveal yourself in all your beauty to him to whom you are indebted for the preservation of your life!”

“Picciola!” Such is the name, then, which, borrowed from the lips of Ludovico, Charney has involuntarily bestowed upon his favourite! “Picciola!” la povera picciola, was the designation so tenderly appropriated by the jailer to the poor little thing which Charney’s neglect had almost allowed to perish.

“Picciola!” murmured the solitary captive, when every morning he carefully searched its already tufted foliage for indications of inflorescence; “when will these wayward flowers make their appearance!” The Count seemed to experience pleasure in the mere pronunciation of a name uniting in his mind the images of the two objects which peopled his solitude—his jailer and his plant!

Returning one morning to the accustomed spot, and, as[34] usual, interrogating Picciola branch by branch, leaf by leaf, his eyes were suddenly attracted towards a shoot of unusual form, gracing the principal stem of the plant. He felt the beatings of his heart accelerated, and, ashamed of his weakness, the colour rose to his cheek, as he stooped for re-examination of the event. The spherical shape of the excrescence which presented itself, green, bristly, and imbricated with glossy scales, like the slates of a rounded dome surmounting an elegant kiosk, announced a bud! Eureka! A flower must be at hand!

The fly-catcher, who occasionally made his appearance at his grated window, seemed to take delight in watching the assiduities of Charney towards his favourite! He had observed the Count compose his cement, weave his osier-work—erect his palisades; and, admonished by his own long captivity of the moral influence of such pursuits, readily conjectured that a whole system of philosophy was developing itself in the mind of his fellow-prisoner.

One memorable day, a new face made its appearance at the window—a female face—fair, and fresh, and young. The stranger was a girl, whose demeanour appeared at once timid and lively; modesty regulated the movements of her well-turned head, and the brilliancy of her animated eyes, whose glances were veiled by long silken eyelashes of raven darkness.[36] As she stood behind the heavy grating, on which her fair hand bent for support, her brow inclining in the shade as if in a meditative mood, she might have stood for a chaste personification of the nymph Captivity. But when her brow was uplifted, and the joyous light of day fell on her lovely countenance, the harmony and serenity of her features, her delicate but brilliant complexion, proclaimed that it was in the free air of liberty she had been nurtured, not under the dispiriting influence of the bolts and bars of a dungeon. She was, perhaps, one of those tutelary angels of charity, whose lives are passed in soothing the sick and solacing the captive?—No!—the instinct which brought the fair stranger to Fenestrella was still more puissant—even that of filial duty. Only daughter to Girardi the fly-catcher—Teresa had abandoned the gay promenades and festivities of Turin, and the banks of the Doria-Riparia, to inhabit the cheerless town of Fenestrella, not that her residence near the fortress afforded free access to her father: for some time she found it impossible to obtain even a momentary interview with the prisoner. But to breathe the same air with him—and think of him nearer to herself, was some solace to her affliction. This was her first time of admittance into the long-interdicted citadel; and such is the origin of the delight which Charney sees beaming in her eyes, and the colour which he observes mantling on her cheek. Restored to the arms of her father, Teresa Girardi has indeed a right to look gay, and glad, and lovely!

It was a sentiment of curiosity which attracted her to the window; a feeling of interest soon attaches her to the spot. The noble prisoner and his occupation excite her attention; but finding herself noticed in her turn, she tries to recede from observation, as if convicted of unbecoming boldness. Teresa has nothing to fear! The Count de Charney, engrossed by Picciola and her flower-bud, has not a thought to throw away on any rival beauty!

A week afterwards, when the young girl was admitted to pay a second visit to her father, she turned her steps, almost[37] unconsciously, towards the grated window for a glimpse of the prisoner; when Girardi, laying his hand upon her arm, exclaimed, “My fellow-prisoner has not been near his plant these three days. The poor gentleman must be seriously ill.”

“Ill; seriously ill!” exclaimed Teresa, with emotion.

“I have noticed more than one physician traversing the court: and from what I can learn from Ludovico, they agree only to a single point—that the Count de Charney will die.”

“Die!” again reiterated the young girl, with dilating eyes, and terror rather than pity expressed in her countenance. “Unhappy man—unhappy man!” Then turning towards her father, with terror in her looks, she exclaimed, “People die, then, in this miserable place!”

“Yes, the exhalations from the old moats have infected the citadel with fever.”

“Father, dearest father!”

She paused—tears were gathering under her eyelids; and Girardi, deeply moved by her affliction, extended his hand tenderly towards her. Teresa seized and covered it with tears and kisses.

At that moment Ludovico made his appearance. He came to present to the fly-catcher a new captive whom he[38] had just arrested—neither more nor less than a dragon-fly with golden wings, which he offered with a triumphant smile to Girardi. The fly-catcher smiled, thanked his jailer, and, unobserved by Ludovico, set the insect at liberty; for it was the twentieth individual of the same species, with which he had furnished him during the last few days. He profited, however, by the jailer’s visit to ask tidings of his fellow-prisoner.

“Santissimo mio padrono! do you fancy I neglect the poor fellow?” cried Ludovico, gruffly: “though still under my charge, he will soon be under that of St. Peter. I have just been watering his favourite tree.”

“To what purpose—since he is never to behold its blossoms?” interrupted the daughter of Girardi.

“Perche, damigella—perche?” cried the jailer, with his accustomed wink, and sawing the air with a rude hand, of which the forefinger was authoritatively extended; “because, though the doctors have decided that the sick man has taken an eternal lease of the flat of his back, I, Ludovico, jailer of Fenestrella, am of a different opinion. Non lo credo—trondidio!—I have notions of my own on the subject.”

And turning on his heel he departed; assuming, as he left the room, his big voice of authority, to acquaint the poor girl, that only twenty-two minutes remained of the time allotted for her visit to her father. And at the appointed minute, to a[39] second, he returned, and executed his duty of shutting her out.

The illness of Charney was indeed of a serious nature. One evening, after his customary visit to Picciola, an attack of faintness overpowered him on regaining his room; when, rather than summon assistance, he threw himself on the bed, with aching brows, and limbs agitated by a nervous shivering. He fancied sleep would suffice for his restoration.

But instead of sleep, came pain and fever; and on the morrow, when he tried to rise, an influence more potent than his will nailed him to his pallet. Closing his eyes, the Count resigned himself to his sufferings. In the face of danger, the calmness of the philosopher and the pride of the conspirator returned. He would have felt dishonoured by a cry or murmur, or an appeal to the aid of those by whom he was sequestered from the breathing world—contenting himself with instructions to Ludovico respecting the care of his plant, in case he should be detained in bed, the carcere duro which was to render still harder his original captivity. Physicians were called in, and he refused to reply to their questioning. Charney seemed to fancy that, no longer master of his existence, he was exempted from all care for his life. His health was a portion of his confiscated property; and those who had appropriated all, might administer to that among the rest. At first, the doctors attempted to overcome his spirit of perversity; but finding the sick man obstinately silent, they began to interrogate his disorder instead of his temper.

The pathognomonic symptoms to which they addressed themselves, replied in various dialects and opposite senses; for the learned doctors invested their questions, each in the language of a different system. In the livid hue of Charney’s lips, and the dilated pupils of his eyes, one saw symptoms of putrid fever; another, of inflammation of the viscera; while the third inferred, from the coloration of the neck and temples, the coldness of the extremities, and the rigidity of the[40] countenance, that the disorder was paralytic or apoplectic—protesting that the silence of the patient was involuntary, the result of the cerebral congestion.

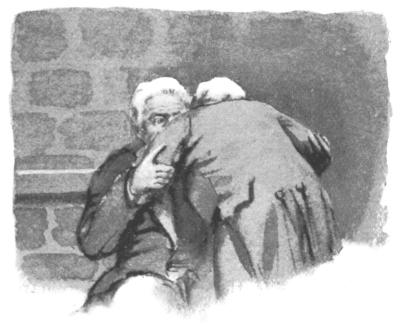

Twice did the captain-commandant of the fortress deign to visit the bedside of the prisoner. The first time to inquire whether the Count had any personal requests to make—whether he was desirous of a change of lodging, or fancied the locality had exercised an evil influence over his health; to all which questions Charney replied by a negative movement of the head. The second time, he came accompanied by a priest. The Count had been given over by his doctors as in a hopeless state. His time was expired; it became necessary to prepare him for eternity; and the functions of the commandant required that he should see the last consolations of religion administered to his dying prisoner.

Of all the duties of the sacerdotal office, the most august, perhaps, are those of the ordinary of a prison—of the priest whose presence sanctifies the aspect of the gibbet! Yet the scepticism of modern times has flung its bitter mockeries in the face of these devoted men! “Hardening their hearts under the cuirass of habit,” says the voice of the scorner, “these officials become utterly insensible. They forget to weep with the condemned—they forget to weep for them; and the routine of their professional exhortations has neither grace nor inspiration in its forms of prayer.”

Alas! of what avail were the most varied efforts of eloquence—since the exhortation is fated to reach but once the ear of the victim? Alas! what need to inveigh against a calling which condemns the pure and virtuous to live surrounded by the profligate and hard-hearted, who reply to their words of peace and love, with insults, imprecations, and contempt? Like yourselves, these devoted men might have tasted the luxuries and enjoyments of life—instead of braving the contact of the loathsome rags of misery, and the infected atmosphere of a dungeon. Endued with human sensibilities, and that horror of sights of blood and death inherent in all mankind,[41] they compel themselves to behold, year after year, the gory knife of the guillotine descend on the neck of the malefactor; and such is the spectacle, such the enjoyment, which men of the world denounce as likely to wear down their hearts to insensibility!

The priest at Charney’s bedside.

In place of this “man of sorrows and acquainted with grief,” devoted for a lapse of years to this dreadful function, in place of this humble Christian, who has made himself the comrade of the executioner, summon a new priest to the aid of every criminal! It is true, he will be more deeply moved; it is true, his tears will fall more readily—but will he be more capable of the task of imparting consolation? His words are rendered incoherent by tears and sobs; his mind is distracted by agitation. The emotion of which he is so deeply susceptible, will communicate itself to the condemned, and enfeeble his courage at the moment of rendering up his life a sacrifice to the well-being of society. If the fortitude of the new almoner be such as enables him to command at once composure in his calling, be assured that his heart is a thousand times harder than that of the most experienced ordinary.

No—cast not a stone at the prison priest; throw no additional obstacles in the way of so painful a duty! Deprive not the condemned of their last friend. Let the cross of Christ interpose, as he ascends the scaffold, between the eyes of the criminal and the fatal axe of the executioner. Let his last looks fall upon an object proclaiming, trumpet-tongued, that after the brief vengeance of man comes the everlasting mercy of God!

The priest summoned to the bedside of Charney was fortunately worthy of his sacred functions. Fraught with tenderness for suffering humanity, he read at once, in the obstinate silence of the Count, and the withering sentences which disfigured his prison walls, how little was to be expected of so imperious and scornful a spirit; and satisfied himself with passing the night in prayers by his bedside, charitably officiating with Ludovico in the services indispensable to the sufferer.[42] The Christian priest waited, as for the light of dawning day, an auspicious moment to brighten with a ray of hope the fearful darkness of incredulity!

In the course of that critical night, the blood of the patient determining to the brain, produced transports of delirium, necessitating restraint to prevent the unfortunate Count from dashing himself out of bed. As he struggled in the arms of Ludovico and the priest, a thousand incoherent exclamations and wild apostrophes burst from his lips; among which the words “Picciola—povera Picciola!” were distinctly audible.

“Andiamo!” cried Ludovico, the moment he caught the sound. “The moment is come! Yes, yes, the Count is right; the moment is come,” he reiterated with impatience. But how was he to leave the poor chaplain there alone, exposed to all the violence of a madman? “In another hour, it may be too late!” cried Ludovico. “Corpo di Dio! it will be too late. Blessed Virgin, methinks he is growing calmer! Yes, he droops! he closes his eyes! he is sinking to sleep! If at my return he is still alive, all’s well. Hurra! reverend father, we shall yet preserve him, hurra, hurra!”

And away went Ludovico, satisfied, now the excitement of Charney’s delirium was appeased, to leave him in the charge of the kind-hearted priest.

In the chamber of death, lighted by the feeble flame of a flickering lamp, nothing now was audible but the irregular breathing of the dying man, the murmured prayers of the priest, and the breezes of the Alps whistling through the grating of the prison-window. Twice, indeed, a human voice mingled in these monotonous sounds—the “qui vive?” of the sentinel, as Ludovico passed and repassed the postern on his way to his lodge, and back to the chamber of the Count. At the expiration of half an hour, the chaplain welcomed the return of the jailer, bearing in his hand a cup of steaming liquid.

“Santo Christo! I had half a mind to kill my dog!” said Ludovico, as he entered. “The brute, on seeing me, set up[43] a howl, which is a sign of evil portent! But how have you been going on here? Has he moved? No matter! I have brought something that will soon set him to rights! I have made bold to taste it myself—bitter, saving your reverence’s presence, as five hundred thousand diavoli! Pardon me! mio padre!”

But the priest gently put aside the offered cup.

“After all,” said Ludovico, “’tis not the stuff for us. A pint of good muscadello, warmed with a slice or two of lemon, is a better thing for sitters-up with the sick—eh, Signore Capellano? But this is the job for the poor Count; this will put things in their places. He must drink it to the last drop; for so says the prescription.”

And, as he spoke, Ludovico kept pouring the draught from one cup to another, and blowing to cool it; till, having reduced it to the proper temperature, he forced the half-insensible Count to swallow the whole potion, while the chaplain supported his shoulders for the effort. Then, covering the patient closely up, they drew together the curtains of the bed.

“We shall soon see the effects,” observed the jailer to his companion. “I don’t stir from hence till all is right. My birds are safe locked in their cages; my wife has got the babe to keep her company. What say you, Signore Capellano?”

And Ludovico’s garrulity having been silenced by the almoner, by a motion of the hand, the poor fellow stationed himself in silence at the foot of the bed, with his eyes fixed on the dying man; retaining his very breath in the anxiousness of his watchfulness for the event. At length, perceiving no sign of change in the Count, he grew uneasy. Apprehensive of having accelerated the last fatal change, he started up, and began pacing the room, snapping his fingers, and addressing menacing gestures to the cup, which was still standing on the table.

Suddenly he stopped short, and fixed his eyes on the livid face of Charney.

“I have been the death of him,” cried he, accompanying the apostrophe with a tremendous oath. “I have certainly been the death of him.”

The chaplain raised his head, when Ludovico, unappalled by his air of consternation, began anew to pace the room, to stamp, to swear, to snap his fingers with all the energy of Italian gesticulation, till, tired out by his own impetuosity, he threw himself on his knees beside the priest, hiding his head in the bedclothes, and murmuring his mea culpa, till, in the midst of a paternoster, he fell asleep.

At dawn of day the chaplain was still praying, and Ludovico still snoring; when a burning hand, placed upon the forehead of the latter, suddenly roused him from his slumbers.

“Give me some drink,” murmured the faint voice of Charney.

And, at the sound of a voice which he had supposed to be for ever silenced, Ludovico opened his eyes wide with stupefaction to fix them on the Count, upon whose face and limbs the moisture of an auspicious effort of nature was perceptible. The fever was yielding to the effect of the powerful sudorific administered by Ludovico; and the senses of Charney being now restored, he proceeded to give rational directions to the jailer concerning the mode of treatment to be adopted; then, turning towards the priest, still humbly stationed on his knees at the bedside, he observed—

“I am not yet dead, sir! Should I recover (as I have every hope of doing), present the compliments of the Count de Charney to his trio of doctors, and tell them I dispense with their further visits, and the blunders of a science as idle[45] and deceptions as all the rest. I overheard enough of their consultations to know that I am indebted to chance alone for my recovery.”

“Chance!” faltered the priest—“chance!”—And, having raised his eyes to Heaven in token of compassion, they fell upon the fatal inscription on the wall—

“Chance, though blind, is the sole author of the creation.”

The chaplain paused, after perusing this frightful sentiment; then, having gathered breath by a deep and painful inspiration, he added, in a solemn voice, the last word inscribed by Charney—

“Perhaps!”

And ere the startled Count could address him, he had quitted the apartment.

Elated by success, Ludovico lent his ear, in a sort of idiotic ecstasy, to every syllable uttered by the Count. Not that he comprehended their meaning:—There, luckily, he was safe. But his dead man was alive again; had resumed his power of speaking, thinking, acting—a sufficient motive of exultation and emotion to the delighted jailer.

“Viva!” cried he; “viva, evviva. He is saved. All’s well! Che maraviglia! Saved!—and thanks to whom?—to what?”