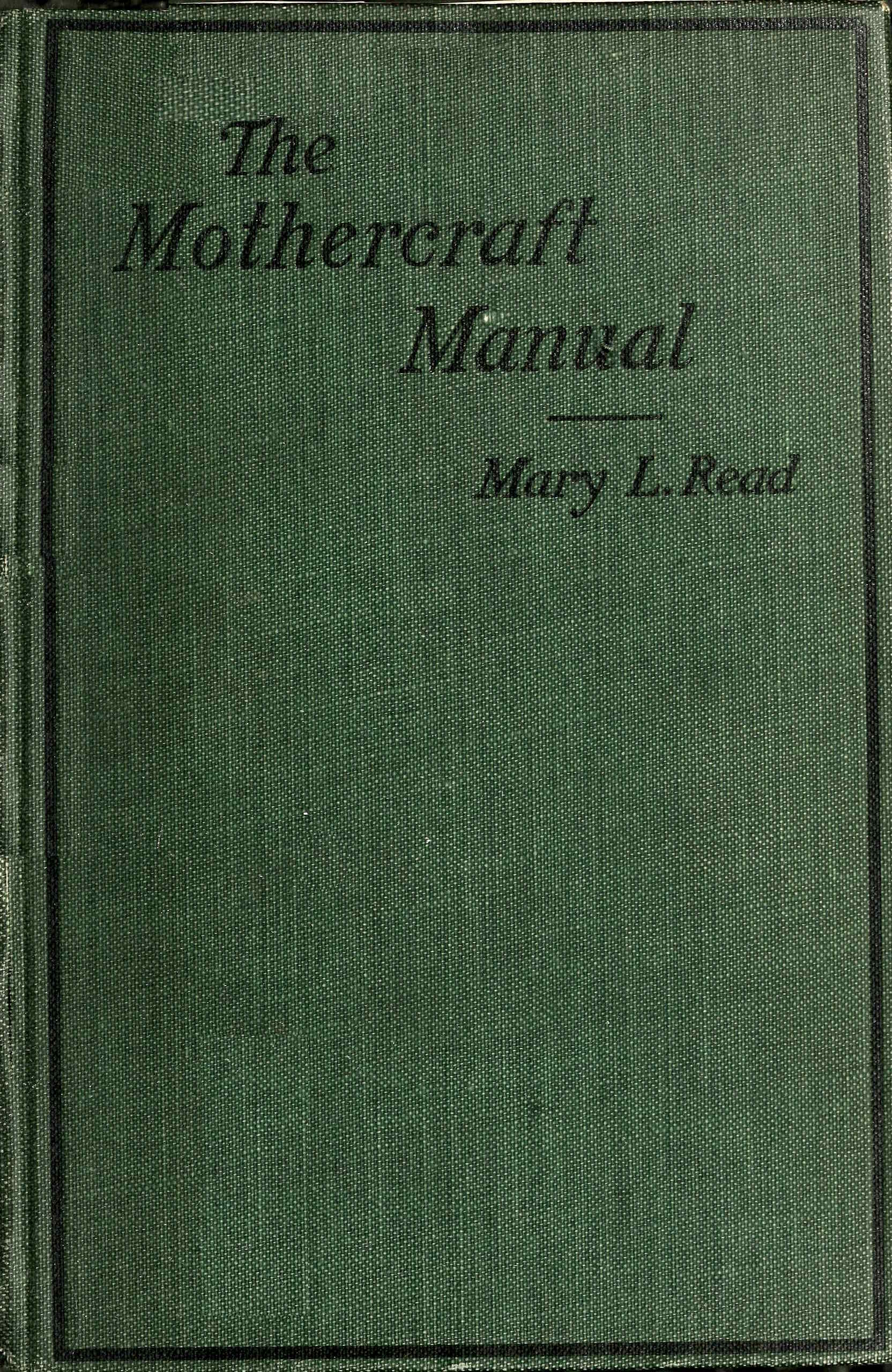

Title: The mothercraft manual

Author: Mary L. Read

Release date: May 31, 2023 [eBook #70887]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Little, Brown, and Company, 1916

Credits: Bob Taylor, ellinora and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

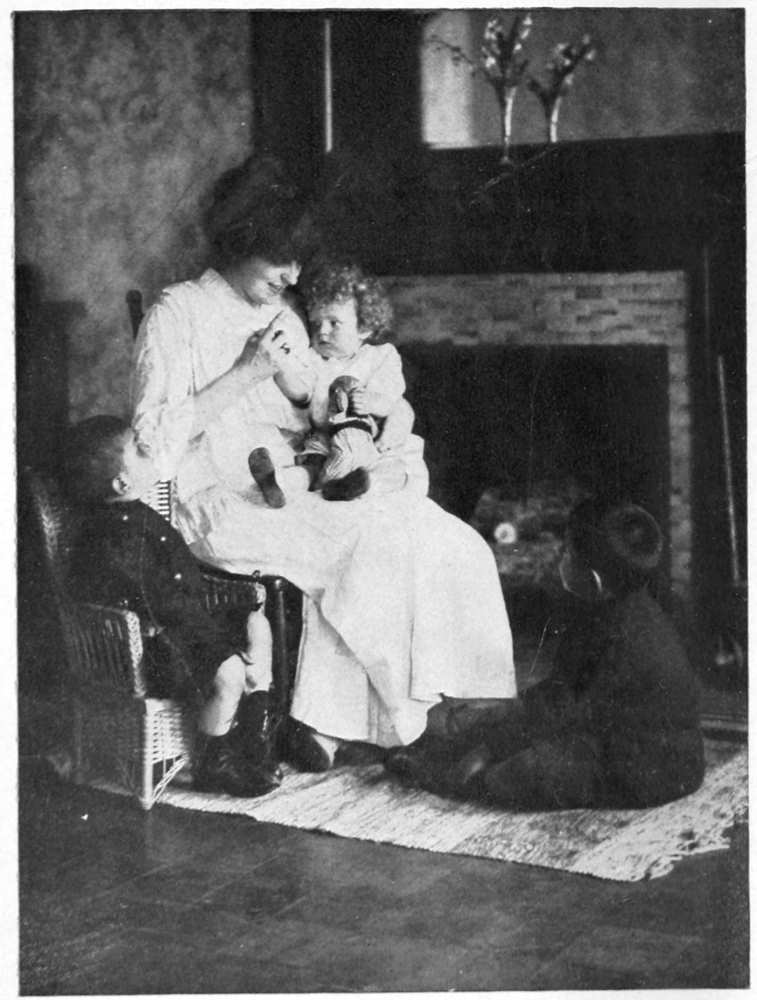

Training in Mothercraft, at the School of Mothercraft, New York City. Frontispiece.

THE

MOTHERCRAFT

MANUAL

BY

MARY L. READ, B.S.

ILLUSTRATED

BOSTON

LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY

1921

Copyright, 1916,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

INSCRIBED TO

MY MOTHER AND FATHER

[Pg vii]

“Seventy-five per cent. of the women of America are married, and most of these have children.” It is not conceivable that women entering into any other vocation of life would think of undertaking it without deliberate preparation. Motherhood is so precious and wonderful that we fear to think of it in terms of definite preparedness. We like to think that it comes natural to be good mothers and that to study in preparation for it or to analyze it might produce more harm than good.

Let me use my own case as an illustration of how ill-prepared even earnest women are for motherhood. I was married twenty-nine years ago. I wanted children with all my heart. My first baby came sixteen months after I was married. I bought all the literature I could find on my new occupation, kindergarten books beginning with Froebel and ending with Susan Blow and her contemporaries; I studied Spencer’s Education, William James’ chapters on habit and attention, and read biographies of great people. My first ambition was to be a good mother, and I was eager to learn all I could about it. My college studies for five years were Greek, Latin, and higher mathematics, with an occasional semester of botany, evidences of Christianity, physics, etc. I do not remember hearing a reference to motherhood during my college experience.

[Pg viii]

I have had six children, four of whom are living. Had I had the knowledge I now have, or know how to get, it seems that the little seven-months-old boy could have been saved. I was called a scientific mother, my babies were fed regularly, put to bed regularly, and were dressed as sensibly as babies are now, but at that time we did not have the knowledge about the physical care of babies which we now have. What I object to is the amount of time I had to give when my children were little to learn things which I ought to have known before motherhood came to me, so that I could have been free to give myself to them. I knew “education through play” only as a figure of speech. Last summer I took a year-old baby to camp. I had the care of her three consecutive months, and was responsible for her six months. I yielded to the impulse to play with her, and in gratifying this instinct I used all the store of knowledge which experience had brought to me. It was evident that she was learning things every day, and that progress was astonishingly rapid. Most of the things I taught her were taught by the use of signs and objects. I asked her if she wanted to come to me by holding out my hands to her. She understood, and soon asked me to take her by holding out her hands to me. I asked her where her eyes were, her mouth, nose, ears, by touching each in turn. She understood and touched each in turn. It was interesting to note when it was no longer necessary to use the sign, when she understood spoken language without the aid of gesture.

The phrase that “education begins at the cradle” took on a new significance. I felt that I was a teacher as well as a mother and the importance of my part in the education of this baby opened up amazingly. It was play, but it was also education. Those minutes with her when no one was near, when we were all in all to each other, were precious beyond words.[Pg ix] Through this love-relation there was intense joy in both learning and teaching. The reason the mother’s part in education is incomparable to any other is because of this love-relation.

We are told that during the first five years of life more is learned than during all the rest of life. The teachers during these years are primarily the mothers. The mother-teacher relation goes on after school days begin, but gradually is regarded less important, and the teacher’s part grows. Mother is forgotten as a teacher. She loses confidence in herself and forgets that no one can take her place.

It does not seem to me that any woman could have more earnestly desired and striven to be a good mother. I studied and worked as hard as I could, but it was not possible for me to secure the training that girls can get to-day. It now seems to me that it is about as rational for a woman to learn by experience with her own children to be a good mother, as it would be for a doctor to get his education merely by practising on his patients. Motherhood offers no less opportunities for success than do the professions of law or medicine. The preparation for it is just as definite and is more important. It has remained for Mary L. Read, with splendid devotion and university training, to put these matters together and to organize and conduct a “School for Mothercraft.”

The time is coming when women will no more go into physical and spiritual motherhood unprepared, trusting to “mother instinct”, than they will go into law or medicine, trusting to their sense of right and of sympathy with the sick to guide them.

CHARLOTTE V. GULICK.

[Pg xi]

Certain definite ideals have been constantly in mind in the preparation of the present volume, among these the following:

To write a handbook that is so definite, concrete, and clear that the least experienced person of average intelligence will find it practical.

To bring directly to those who have opportunity to use it,—the home-makers, present and prospective,—some of the wealth of present knowledge in biology, dietetics, hygiene, domestic efficiency, child psychology, education, that is stored in the laboratories, research reports, medical records, technical journals, and educational classics, translating these from the obscure tongue of technical language into the clearer speech of daily life.

To furnish a guide to more technical or detailed consideration of each subject.

To present fundamental principles and facts rather than mere rule of thumb procedure, so that the reader may act intelligently and make intelligent variations.

Not to compromise on half-way procedure that merely prevents disaster, but to make clear the means to greatest personal efficiency and social power.

To keep a progressive yet reserved attitude between conservative and radical theories.

[Pg xii]

To bring the spirit of sympathy and humanness, of love and child-nature and poetry into the teaching of home-making.

To lighten the burden and enlighten the minds and hearts of earnest young people so that with joy and satisfaction they may essay and find the home and family life that their hearts desire.

Froebel outlined, nearly a century ago, a thorough, practical training course for young women, preparatory to home-making or to vocational work as teachers or mothers’ assistants. At Pestalozzi-Froebel House in Berlin, half a century ago, under the administration of Frau Shrader and Miss Annette Schepel, such a course was organized. Echoes of it to-day are found in the German secondary schools and special schools for girls. The same idea spread to England a quarter of a century ago, and there to-day a score of special schools, and some girls’ high schools, provide such a training.

In America, the School of Mothercraft was opened in New York City in December, 1911, to work out experimentally a training course for educated young women.[1] Here has been developed a comprehensive, human, practical course including domestic science and art, and the care and training of babies and little children. The students work in a home atmosphere, under home conditions, using the household for their practice work, caring for the resident babies and children, educating and training them in the course of the day’s régime, and receiving their own training in personality and technique as well as in theory. Extension classes have been maintained for young mothers, brides, and engaged young women.

[Pg xiii]

It is work with young women and the children in the School of Mothercraft that has made possible the preparation of the present volume.

No book can take the place of the living teacher. No amount of discussion of theory can be a substitute for experience. Yet experience, without sound principles, is also of minor value. Any book presupposes a modicum of common sense and rational judgment in its readers.

In a volume of such limited compass only a few significant principles can be presented, and some of the important elementary facts and technique that more technical books may overlook. The present volume aims only to be an introduction to the many phases of home-making, child care, and child training, to furnish something of vision for these responsibilities, and a guide for further study.

No book can be a substitute for the personal advice of the physician, the hygienist, the psychologist, and the teacher. The reader of any book on applied science may easily make the mistake of interpreting statements out of proportion to their significance, or of misunderstanding directions so that they even become misleading. Only discussion with the living teacher will discover and correct such errors.

The reader must be open-minded to new discoveries, new theories, new methods. At the present time, as never before, extensive researches are being made in biology, hygiene, dietetics, child psychology, and pedagogy. Important discoveries as revolutionary as the discovery of the circulation of the blood, radio-activity, the cellular basis of life, may be made at any future time.

In the present volume no attempt has been made to present controversial points of view, but a consistently constructive régime and programme has been given. The novice in any art must first learn to work constructively[Pg xiv] and rather dogmatically, until he has learned to apply one set of principles efficiently. Then he may begin to modify details according to some rational principle, instead of by mere whim, and to compare his method with other possibilities. The basis and the special authorities for the régime here presented will be found in the final chapter on bibliography.

July, 1916.

MARY L. READ.

[Pg xv]

[1] The word “mothercraft” was coined by the author to express the comprehensive scope of the training. The word has since come into use in England in a narrower sense, including merely infant care. It is hoped that in America the use of the word may be retained in its larger significance.

The author begs to acknowledge indebtedness and gratitude to many who have participated in the making of the book.

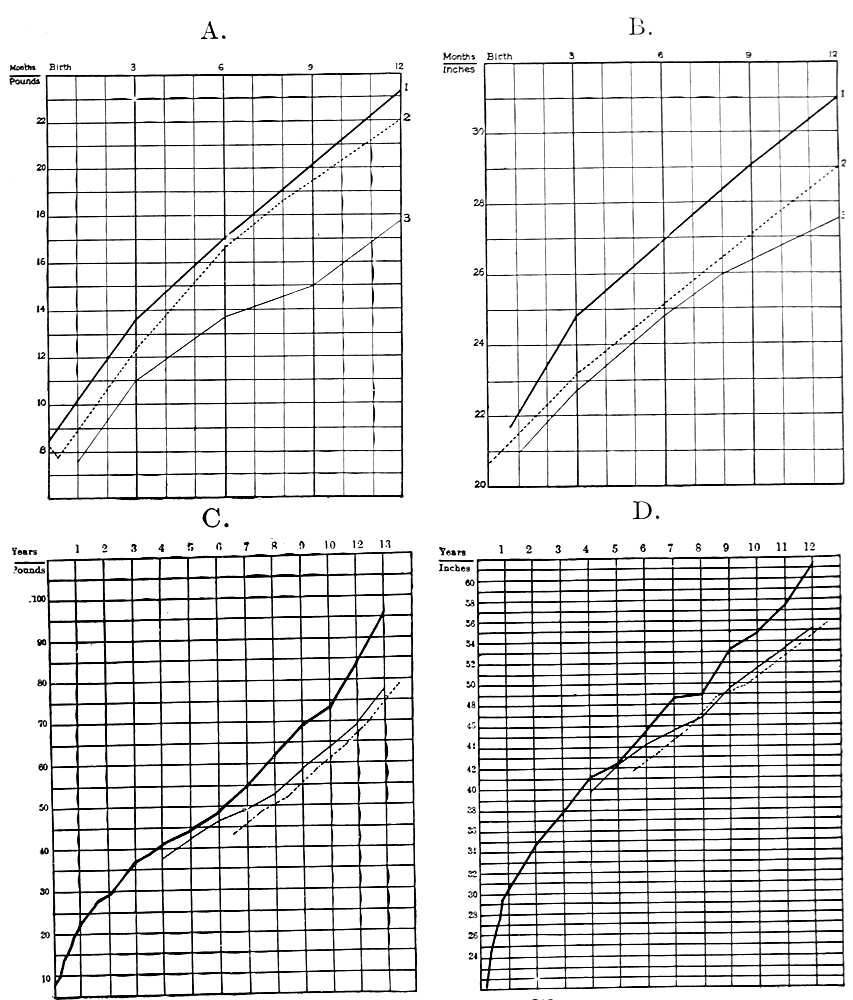

To the Messrs. Macmillan Co., Ginn Company, F. A. Stokes Co., and D. Appleton & Co., for permission to quote from their publications; to the American Medical Association Press and Dr. Roland G. Freeman for use of the graphs on growth; to Mr. William S. Bailey and The Nurse Studio for many of the photographs taken specially for this work.

Especially the author begs to tender sincere thanks for many criticisms, suggestions, and reviewing of manuscript to Dr. David Starr Jordan, Dr. William F. Snow, Professors Rudolph M. Binder, Willystine Goodsell, Robert M. Yerkes, and Mr. Paul Popenoe, on the sections dealing with the home and the family; to Dr. Josephine H. Kenyon for sections on maternity and infancy, Drs. Henry I. Bowditch, William Shannon, and William H. Burnham, for sections on hygiene and growth; to physicians and nurses at Battle Creek Sanitarium for assistance in the sections on nursing and nutrition; to Dr. William H. Park for revising data on communicable diseases, and to Professors Henry C. Sherman and Mary S. Rose for suggestions and for unpublished data on nutrition. Mrs. Anna Martin[Pg xvi] Crocker and Miss Sunnyve Carlsen have kindly given literary assistance. Helpful suggestions on the reading list have been furnished by science teachers of Horace Mann, Ethical Culture, Francis Parker, and the University of Chicago Elementary Schools. Miss Helen O. Rider and Miss Mary Scott Allen have rendered invaluable aid in criticism and clerical details. To the many others who have furnished technical data or read portions of the manuscript, the author here expresses thanks. Finally, the author would gratefully acknowledge the unfailing patience and kindly encouragement of the publishers. For such errors as may be found the author alone is responsible. Criticisms or suggestions from readers, which may improve the helpfulness or accuracy of the Manual, will be gratefully received.

MARY L. READ.

July, 1916.

[Pg xvii]

| PAGE | ||

| Introduction | vii | |

| Preface | xi | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I | Mothercraft: Its Meaning, Scope, and Spirit | 1 |

| II | Establishing the Home | 10 |

| III | Finding the Means for Mothercraft | 20 |

| IV | Founding a Family | 29 |

| V | Growth and Development | 41 |

| VI | Preparing for the Baby | 62 |

| VII | Care of the Baby | 85 |

| VIII | The Physical Care of Young Children | 119 |

| IX | The Feeding of Children | 155 |

| X | The Education of the Little Child | 196 |

| XI | Studying the Individual Child | 223 |

| XII | A Curriculum for Babyhood and Early Childhood | 246 |

| XIII | Play | 264 |

| XIV | Games | 275 |

| XV | The Toy Age | 285 |

| XVI | Story-telling | 299[Pg xviii] |

| XVII | Science and History | 309 |

| XVIII | Handwork | 317 |

| XIX | Music and Art | 329 |

| XX | Home Nursing and First Aid in the Nursery | 337 |

| Appendix | 365 | |

| Bibliography | 381 | |

| Index | 425 |

[Pg xix]

| Training in Mothercraft, at the School of Mothercraft, New York City | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

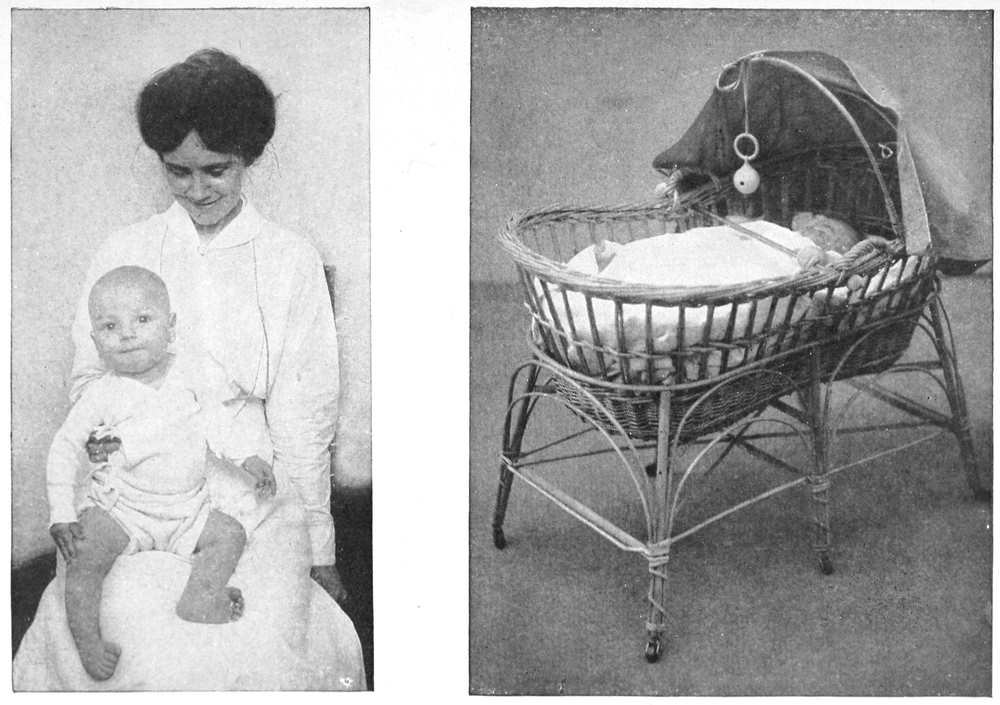

| Approved Baby Clothing and Bassinet | 62 |

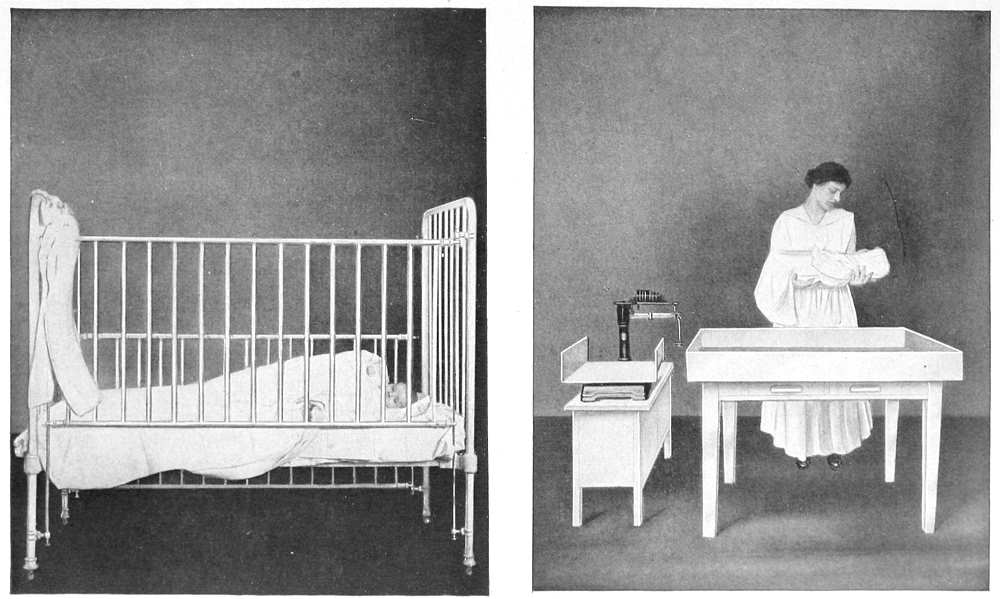

| Approved Crib, Scales, Nursery Table. Holding the Baby, Supporting Head and Back | 74 |

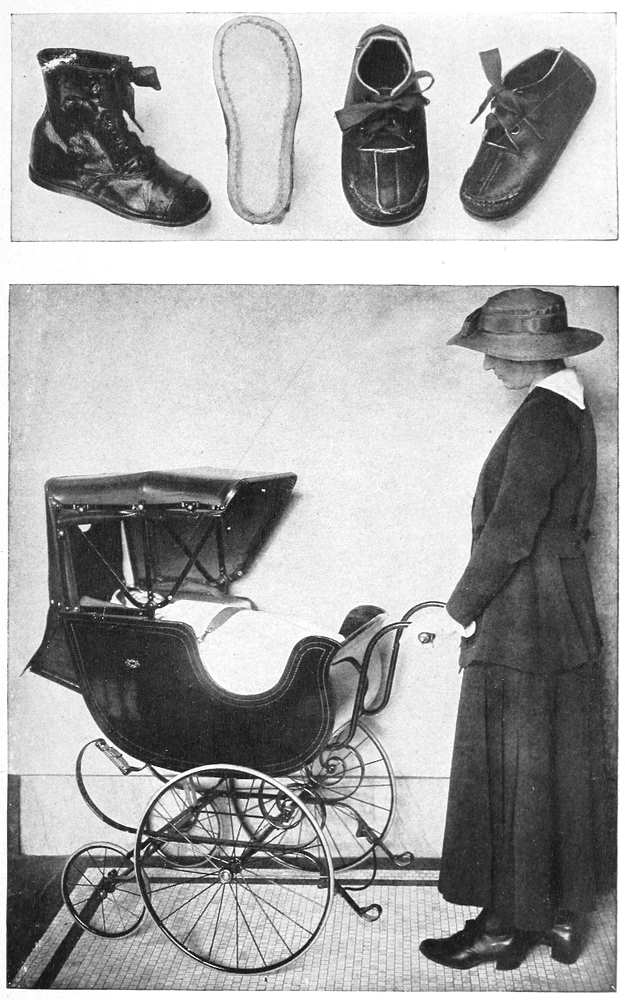

| Approved Baby Carriage and Shoes | 76 |

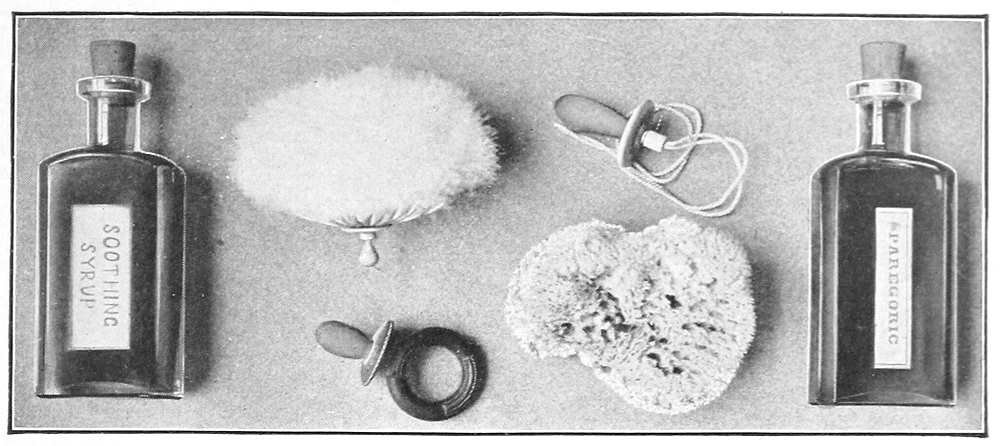

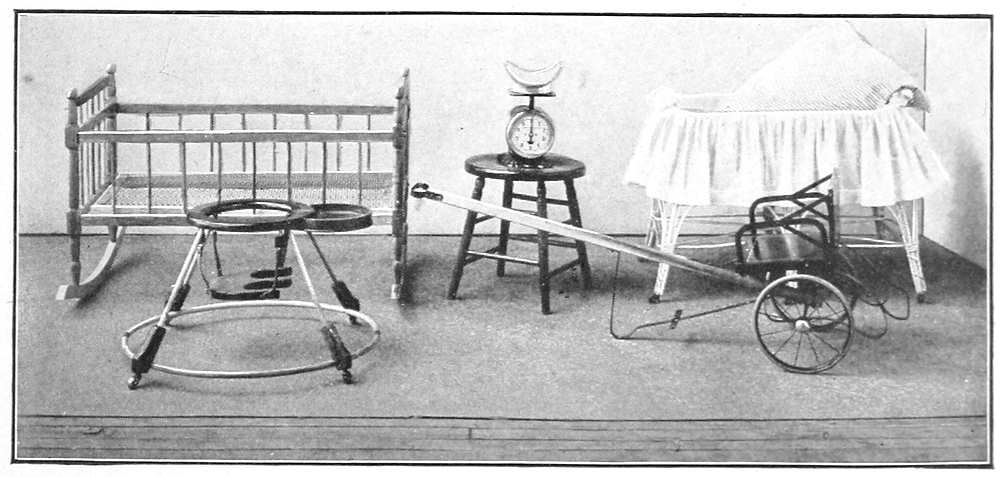

| Drugs and Unsanitary Appliances. Unhygienic Equipment and Unsatisfactory Scales | 80 |

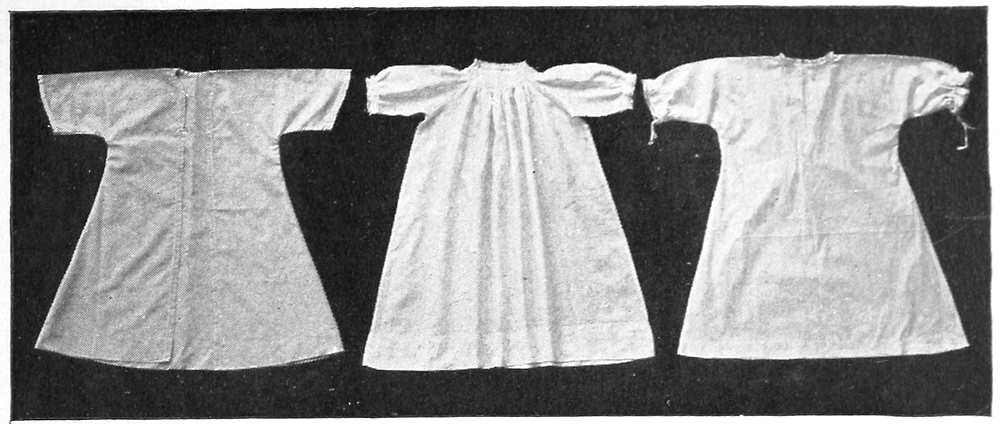

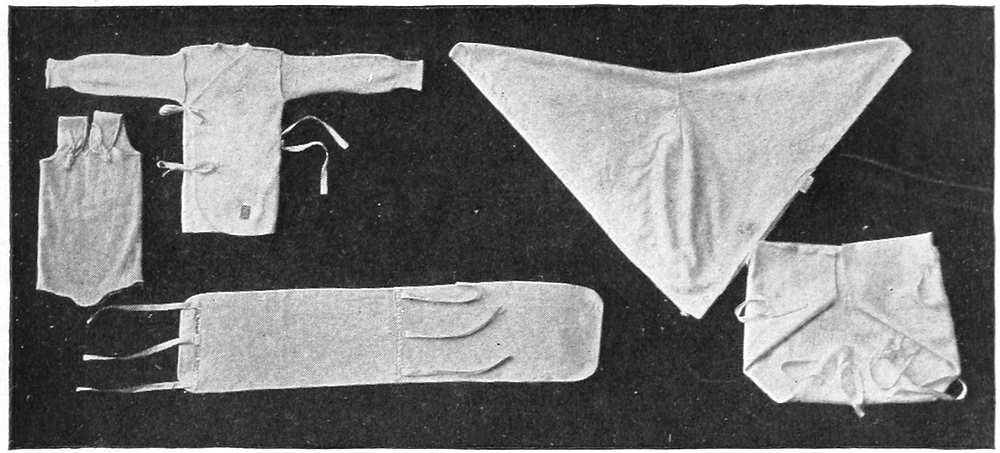

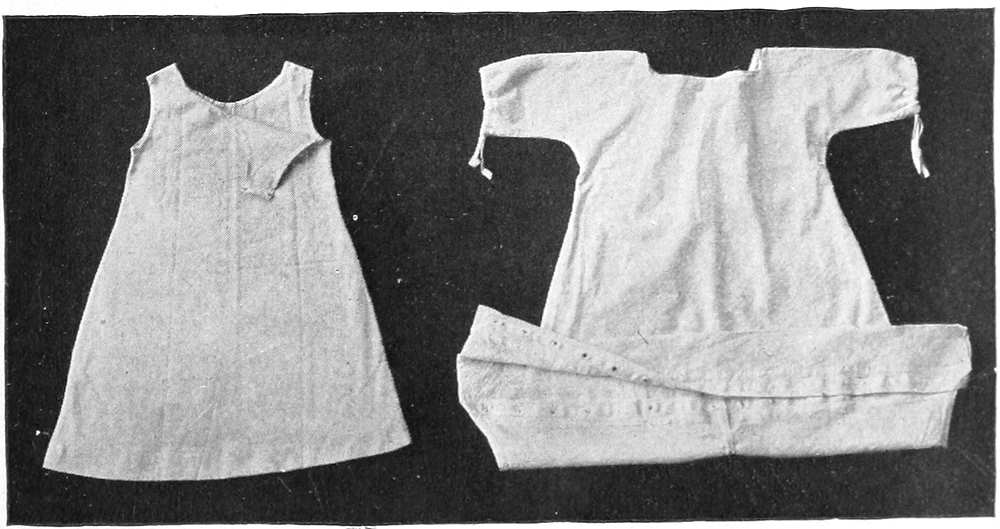

| For the Layette | 82 |

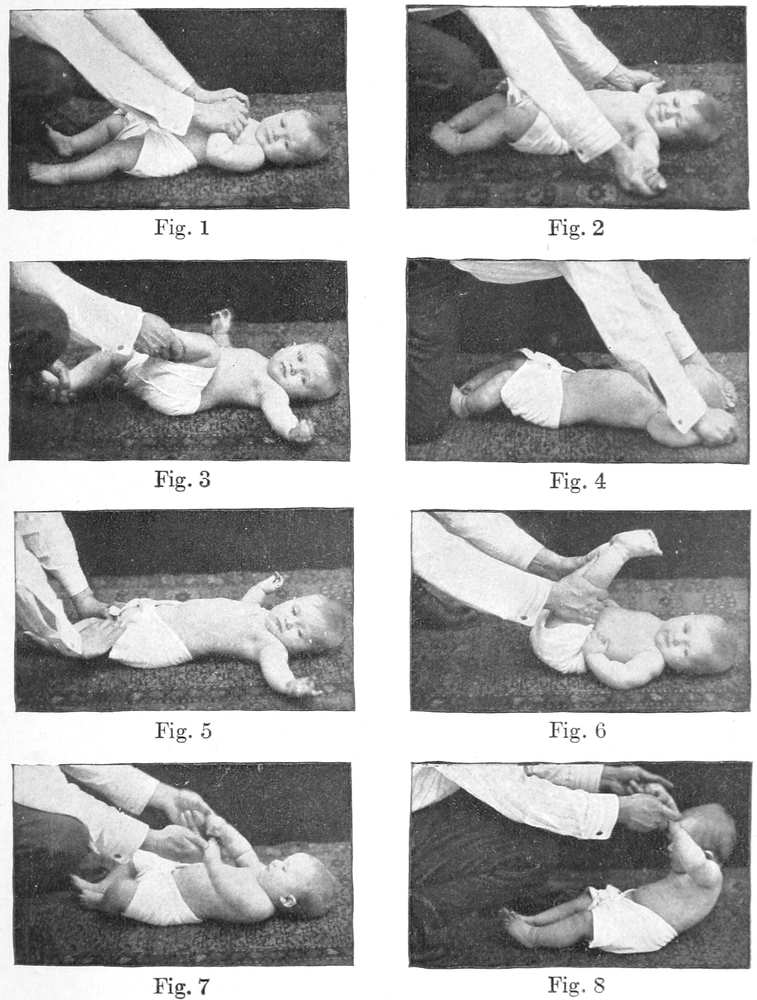

| Exercises for the Baby | 114 |

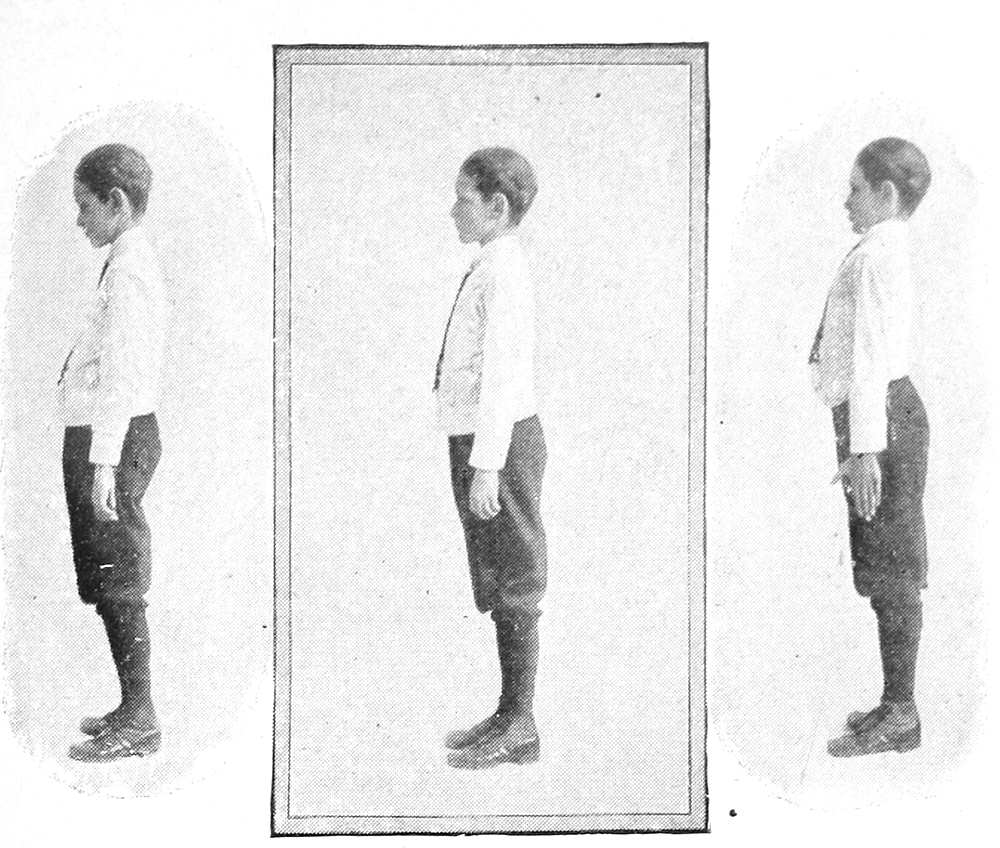

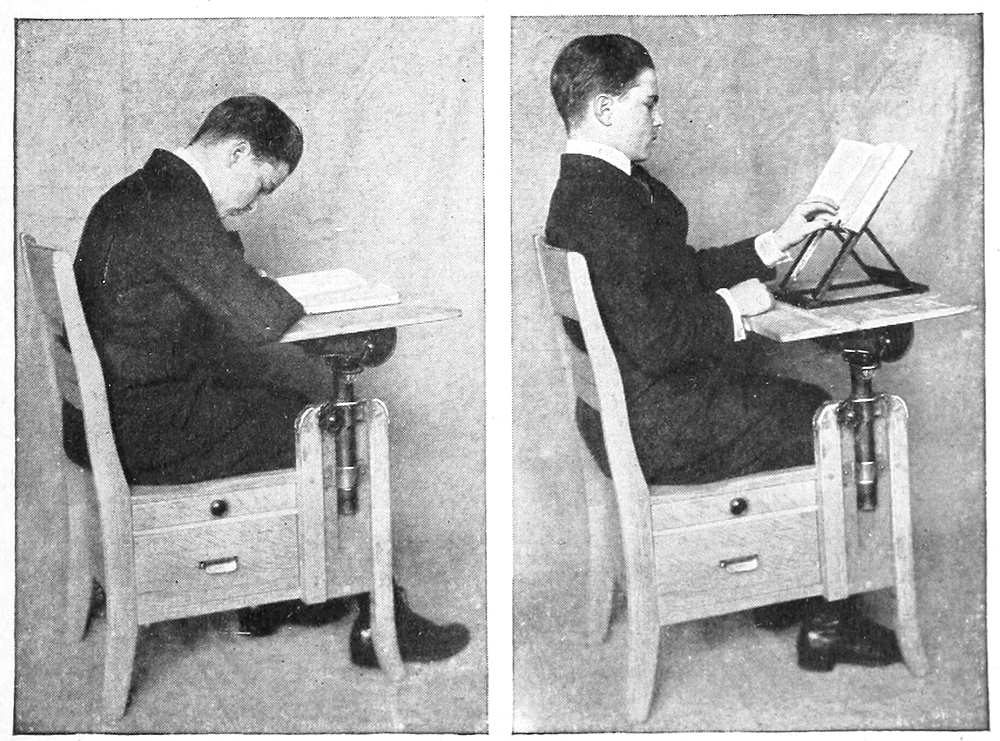

| Good and Bad Postures | 142 |

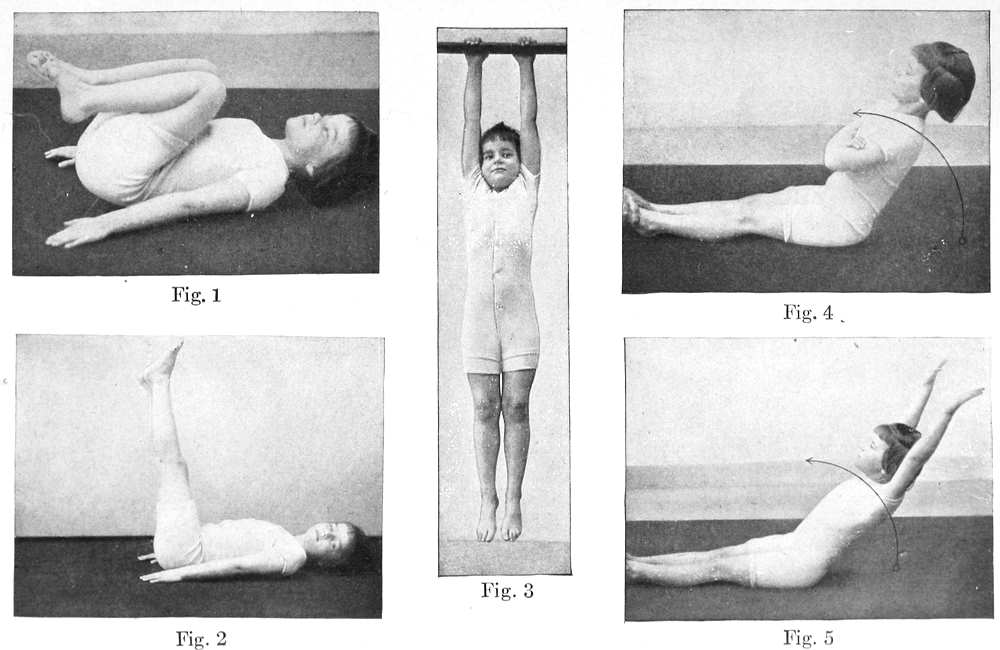

| Exercises for Trunk, Chest and Back | 144 |

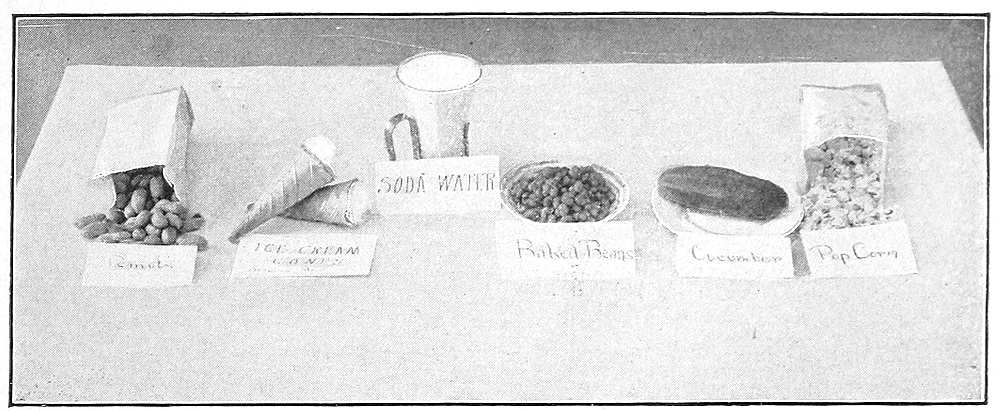

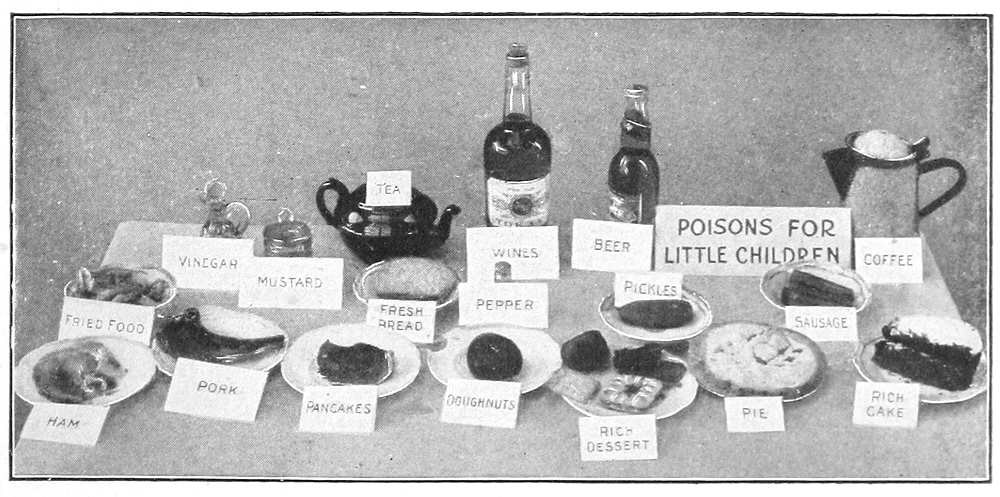

| Some Especially Dangerous Foods for Children under Six. Poisons for Little Children | 164 |

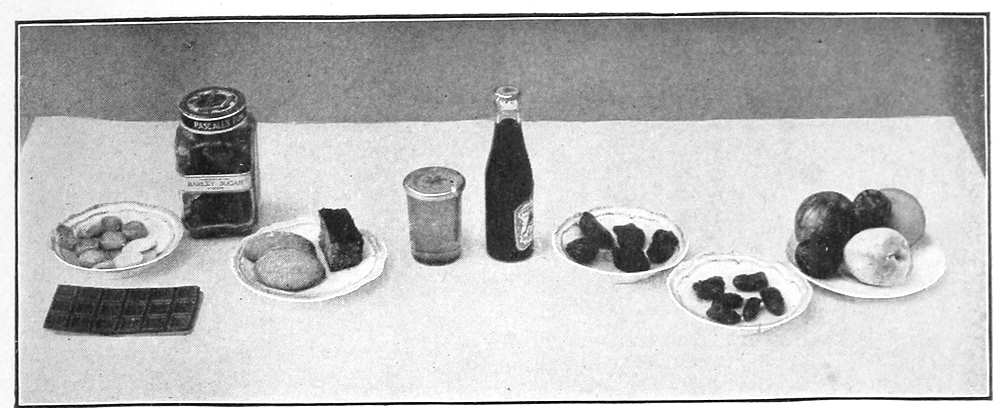

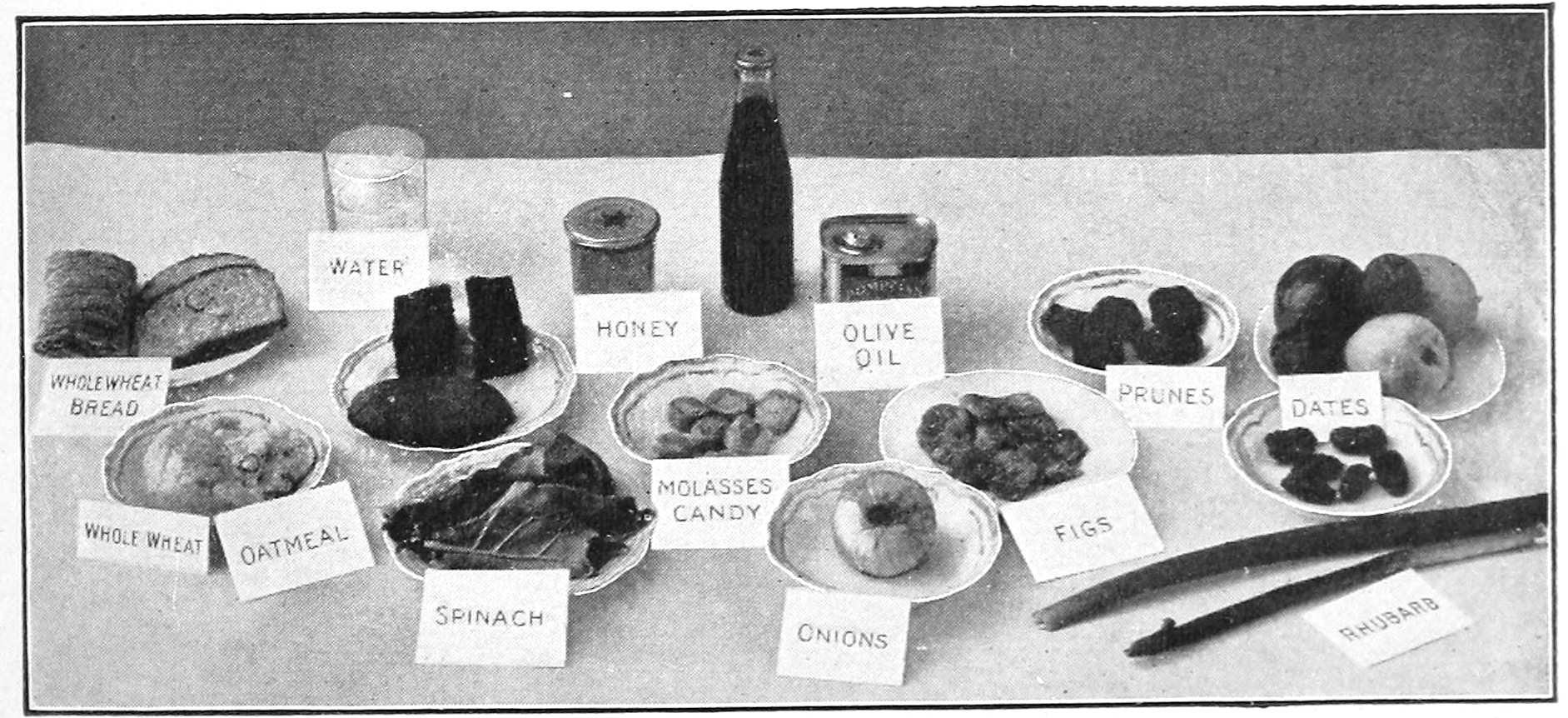

| Wholesome Sweets at Suitable Ages. Laxative Foods | 174 |

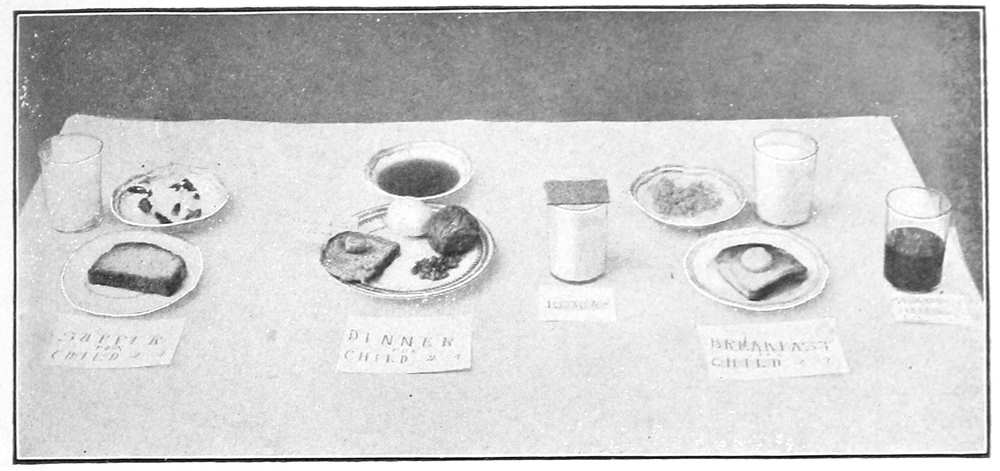

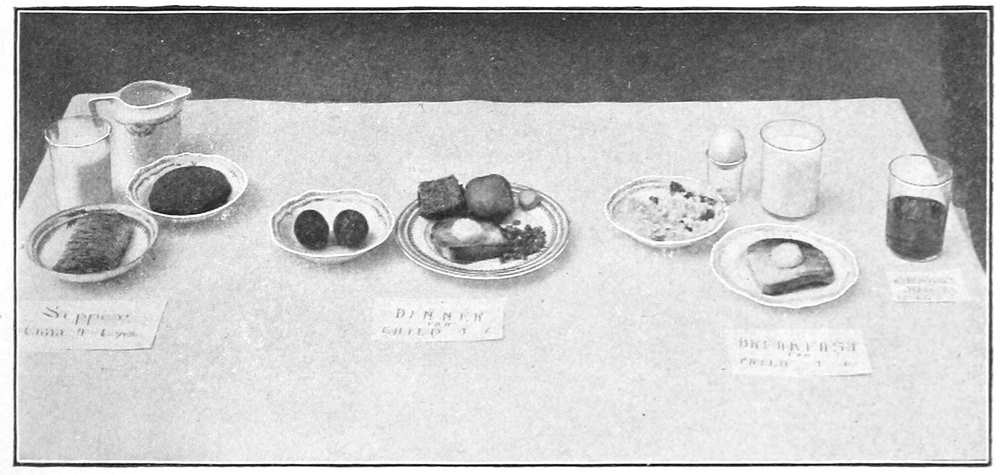

| Day’s Menu for Child Two to Four Years. Day’s Menu for Child Four to Six Years | 182 |

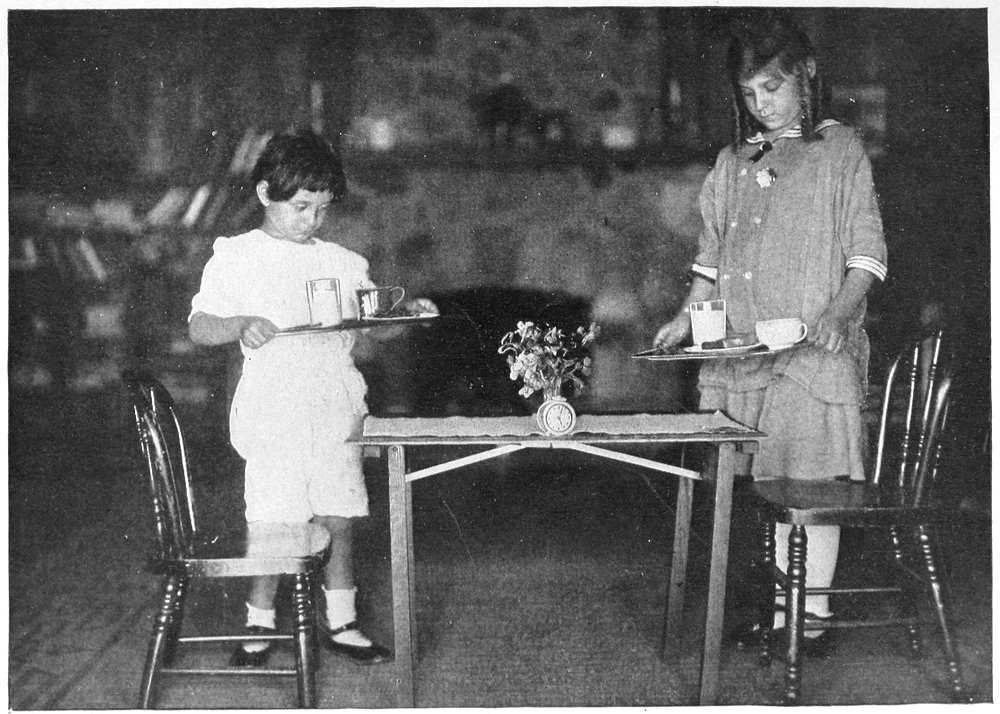

| Learning Self-reliance and Regularity. At the School of Mothercraft Summer Camp | 212 |

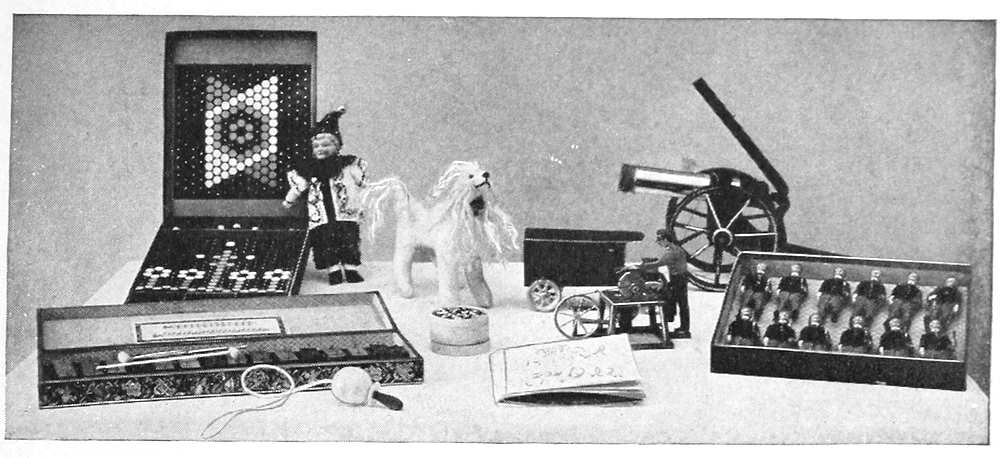

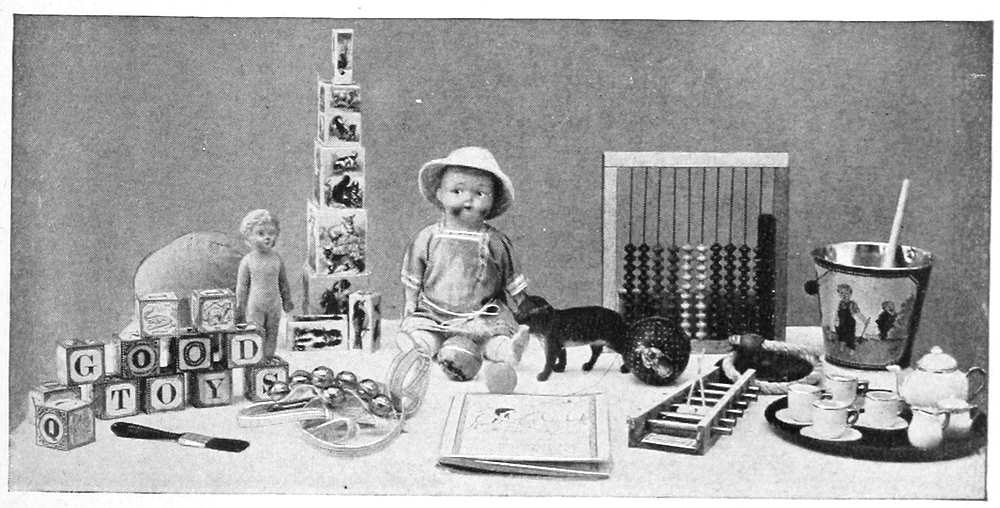

| Unhygienic, Inartistic, Anti-social Toys. Hygienic, Durable, Constructive, Social Toys | 290 |

| Handwork that Utilizes Fundamental Muscles. In the School of Mothercraft Child Garden | 320 |

| Height and Weight Charts | 370 |

[Pg 1]

THE MOTHERCRAFT MANUAL

“To know a child is to love it, and the more we know it, the better we love it.

“To know, love, and serve childhood is the most satisfying, soul-filling of all human activities.

“It rests on the oldest and strongest and sanest of all instincts.

“It gives to our lives a rounded-out completeness as does no other service.

“No other object is so worthy of service and sacrifice; and the fullness of the measure in which this is rendered is the very best test of a nation and race and a civilization.”

—G. Stanley Hall.

Mothercraft is the skilful, practical doing of all that is involved in the nourishing and training of children, in a sympathetic, happy, religious spirit. It is not merely the care of the little baby; that is a very small, though significant, part. Its practice is not dependent upon physical parenthood, but is part of the responsibility of every woman who has to do with children as teacher, nurse, friend, or household associate. It is no more an instinct than is gardening or building. It is not merely being with children. Its requisite is vital working knowledge of the fundamental principles of biology, hygiene, economics, psychology, education, arts. It is mothering—that oldest, steadiest, most satisfactory vocation to women always[Pg 2] and everywhere—made intelligent and efficient and joyous.

Mothercraft cannot be learned simply from books any more than can music, agriculture, carpentry, dentistry. The most important factor in the learning of mothercraft is the daily intelligent association with the children in their natural environment of home. A hospital with sick children is a place to learn its pathological phases.

No one of intelligence will dispute the theory that the most important period in the child’s life is the first seven years. It is in these years that the foundation of his physical life is settled (or unsettled); that the lifelong habits are formed; that the prejudices and the bases of his spiritual and social life are laid. The “gates of gifts”—his potentialities—are closed at birth, possibly when his parents are chosen. Whether one is an advocate of heredity or of environment as the most influential factor in the life of the individual, none will now gainsay that both the heredity and the environment of every individual can be controlled, and that each of these factors may be made vastly more efficient through the high ideals, the intelligence, and the foresight of parents present and potential.

In these days of radical change in the activities and education of women, mothercraft has not kept pace with the other vocations open to women. In a society where marriage is no longer an economic, domestic, or conventional necessity, there has developed a tacit assumption that youth would not marry, and therefore special preparation for home-making (and especially for child care) would be presumptuous and a waste of time. The school has left this part of a girl’s training for the home to give, and in a large proportion of homes there has not been the time or the intelligence or the foresight to give it. Girls have gone from elementary[Pg 3] school directly into industry, or to high school and college, or to finishing school and society. Educators and vocational guides have frequently overlooked it in educational and vocational conferences, exhibits, and guidebooks.

And yet to-day in America, the care and training of young children is chiefly in the hands of women. Seventy-five per cent. of women in America are married, and presumably most of them have the responsibility of children in their own homes.

There are ten million children under six years of age whose care and training is naturally in the entire control of their homes. There are fourteen million children between five and fifteen years of age who, on the average, spend thirty hours a week, for forty weeks a year, in school, while all the rest of their life—about seventy per cent. of their waking hours, as well as all their sleeping hours—is in the control of their mothers and fathers.

Nursing, within fifty years, has become a profession, and to-day it is almost impossible for a woman to find employment as a nurse unless she has had a special training for three years. Yet nursing has only to do with sick folk, usually in a hospital, which is still a far cry from the daily care, hygiene, and training of the normal child in a home. For an equal period, teachers of young children have been expected to take a special normal course of two to four years. Yet this training has had little to do, until recently in some quarters, with hygiene, biology, or the psychology of the child, but has concerned itself chiefly with subjects in the curriculum and with masses of children in an artificial grouping and environment, foreign to their native interests and inimical to their physical needs.

Only within the last twenty-five years has medicine developed pediatrics—the special study of children’s[Pg 4] treatment. Child-hygiene is still later as an exact science. Child-study, as an exact science, dates back to Froebel and the early nineteenth century, and is still a new field.

The mother in her home, herself with slight special preparation, busy with her children, could scarcely have been expected to keep pace with these developments and to teach them to her daughters, even had she the foresight. The higher institutions of learning, naturally among the most conservative forces of society, have not yet begun to perceive the significance of such a subject as mothercraft in the curriculum, although the beginnings of some phases are being made. The secondary and elementary schools, bound by the fetish of college requirements, are only beginning to show here and there indications of efforts to prepare for living instead of simply for college.

And the young woman—still immature, inexperienced, and therefore not appreciative of life’s values and impending responsibilities—has had neither the guidance of school and home, nor the educational opportunity, nor the personal foresight to prepare adequately for this vocation.

What is the consequence? A generation of women, the majority of whom are notoriously (and sometimes shamelessly) ignorant and unskilled in the most vital and significant human responsibilities. In millions of homes women are wasting their time and energy, losing the joy of their motherhood (and too often their little ones), perplexed, harassed, over-burdened, because they are bungling, stumbling blindly, groping at their vocation. And those they love most dearly are paying the penalty, in less happy homes, less efficient lives. Hundreds of thousands of self-supporting young women every year are going into industrial or commercial work or school teaching, not because they prefer it, but because opportunities[Pg 5] for acquiring the requisite skill are at hand, and conditions of work have been standardized. Hundreds of thousands of mothers with young children are seeking in vain for assistants of desirable personality and efficient training. For such workers there has been no adequate opportunity for training and no standardizing of working conditions. In all this, America is far behind both Germany and England.

What does mothercraft require in its practitioners? First, personality: love of children and sympathy with child-nature, responsibility, patience, thoroughness in the minute details day in and day out, self-control, good judgment, adaptability, the play spirit. Fundamental also are open-mindedness, spiritual vision, and the poise that results from a well-regulated physical régime and a firm apprehension of eternal verities.

Then knowledge: a sound foundation in the fundamental principles and vital facts of applied biology, psychology, sociology, ethics, economics, natural sciences, play, arts, as they relate to the home, the family, and childhood. Equally important is the scientific mind that knows how to approach new problems and receive new principles.

Then technique: the actual doing and practice of mothercraft. Knowledge is of no value until it is translated into efficient action. There must be little children to care for, tend, play with, educate.

What of fathercraft? Every child has two parents, equal in responsibility for his heredity and likewise for his rearing. Fathers could hardly be expected ordinarily to be versed in the intricacies of clothing, feeding, and bathing the baby. But why should not every man understand the principles of hygiene and foods as a matter of his general knowledge quite as much as for coöperation with the mother in the children’s régime? Why should he not with equal zest make a study of growth and development during childhood?[Pg 6] Even more, why should he not be intimately acquainted with child psychology and the fundamental principles of child training and education, that he may understand his own children and coöperate sympathetically in their upbringing? Is there any valid reason why he should not be equally acquainted with the sociology of the home, the meaning and principles of eugenics, the psychology of harmony in home life?

There is no profession open to either men or women that offers such opportunities for personal culture, individual expression, technical skill, scientific research, social contribution and welfare, as mothercraft. Perhaps the very comprehensiveness of it and its humanness have presented a problem so complex that it has baffled the educators and delayed its admission to academic dignity.

Through the channels of child welfare, eugenics, and pediatrics, a keener sense of responsibility toward the child unborn is developing. Through the increasing knowledge of heredity, child psychology, and education, a clearer vision is appearing to young men and young women of what they themselves might have been, and of what they may yet create and develop by combining wisdom with their great love. Philanthropists are realizing the futility of simply relieving immediate suffering, crime, inefficiency, for generation after generation. They are looking to the elimination of the causes: ignorance of the rudiments of living, poor heredity, neglect in childhood, unsanitary, ugly, unspiritual living conditions. “There is no wealth but life,” we are realizing with Ruskin. Statesmen and legislators are beginning to see that the stability of society and the State demand that the organizing of homes, the founding of families, the spending of family incomes, shall not be intrusted to novices and unskilled workers. As indications of this, we have the recently established Children’s Bureau, and the Smith-Lever[Pg 7] Bill with its appropriation for education that includes home-making.

In America, clubs, reading courses, and special correspondence for parents have been developed in the last quarter century by the International Congress of Mothers, Parent-Teachers’ Association, Home and School League, American Institute of Child Life. This is good and is helping many parents in meeting their perplexities, but as a national means of vocational training, its psychology and pedagogy is shortsighted and inefficient.

What banker would trust his ledgers to a youth just out of school, whose only special preparation for bookkeeping was a current reading course in business methods? What woman would permit a man to experiment on her garden if he was just beginning a correspondence course in agriculture? What business man wants to intrust his correspondence to a stenographer just out of a business course, even after months of such vocational training? All this is recognized as inefficient, wasteful, expensive in business; how much more so is it in the home, where precious human lives are the factors to be dealt with.

Slowly, but certainly, there is coming a new ideal in education. Children and young people are to be prepared for living. They are to know how to develop physical vitality and mental ability and spiritual power. They are to be prepared in spirit and intelligence, in skill and in science, in personality and technique for the responsibilities that most of them will assume, for the greatest responsibility any of them can assume—home-making and family rearing.

Both the school and the home are responsible for the preparation of these future parents. They must apply to this vocational problem all their knowledge of psychology and pedagogy. Right habits of regularity, responsibility, self-control, must be carefully[Pg 8] trained in those babyhood and early childhood stages; the manual phases of household work are to be taught in the manual stage before the teens; boys and girls are to be imbued with a wholesome, responsible spirit toward motherhood and fatherhood and the home which they are taught to look forward to as the goal for themselves; girls in their teens are to have companionship and experience with little children, learning the essential details and the significant guiding principles of their high calling in a practical, human, motherly way, under wise and sympathetic teachers. Girls, and boys likewise, will be encouraged to foresee the significance and values and responsibility of home and family, and to conduct themselves worthily of such a mission.

Secondary and elementary schools are beginning to give school credit for assistance at home. Domestic science and art are now taught in hundreds of schools. Their field as yet is narrowly restricted to the mechanics of the household, usually taught in an academic way. This, however, is an entering wedge for more practical, comprehensive, and human phases of home-making education whenever school administrators, teachers, and parents shall see that vision. The day seems not distant when colleges generally will give credit for all home-making branches, as a few do now for some phases. We may even yet see universities granting M.A. and Ph.D. degrees in mothercraft and fathercraft, as well as in philology, astronomy, history, or other more consequential branches of learning. College alumnæ themselves are making earnest appeals to their Alma Maters to prepare their students for home-making responsibilities. It is not unthinkable that the colleges, before many decades, might even include the preparatory work in these subjects among their entrance requirements, as they now do algebra and Latin. In that day “applied science” will be esteemed more[Pg 9] worthy than “pure science”, and ability to utilize more honorable than ability to memorize. By the next century, a mothercraft course may become as conventional a part of the curriculum of a finishing school as French or vocal training or æsthetic dancing; and its rudiments as requisite as a certificate of age for working papers; and preparedness in fathercraft as stringent a requirement for a marriage license as a medical certificate. Why not?

[Pg 10]

The Purpose of the Home. The cause, historically, and the reason, socially, for the home is the child and the family. Home is the great training school of life for parents as well as for children. It is not merely a place to eat and sleep; any boarding-house can provide that. The ideal home is a community of congenial spirits, a place of inspiration, comfort, rest of spirit as well as of body. Here dwell together two who have chosen each other as comrades in the complex problem of living, to share their fare, their mirth, their troubles, to give cheer in distress, encouragement in struggle, ambition for achievement, sympathy in trial and happiness, friendly criticism to refine; and to coöperate in their mutual desire, responsibility, joys, and trials of rearing a family.

As young men and women face squarely the possibilities in a home, as they perceive the causes of discord in family life, and study the basis of family stability and happiness, as they take the time before marriage to compare sincerely their ideals, tastes, standards, expectations, they will minimize the possibilities of later discord—even tragedy. If they cannot agree sincerely and heartily on economic, social, physiological, and psychological adjustments before the wedding ceremony, when each has the altruism of romance and the spur of the game, how can they expect to adjust themselves amicably afterwards, in the severe test of everyday needs and situations?

[Pg 11]

Marriage is the concern of the individual, because his happiness and his activity are involved. It is also the concern of the State, because property rights, social harmony, and future citizenship are involved. A brief study of the historical and social development of the home and family relations will give a surer basis for the rational discussion of this problem than would a theoretical discussion based merely on prejudices of individualism or altruism.

Evolution of Marriage. In the human species, infancy is prolonged over several years. From this mutual care by the mother and the father in primitive society, there evolved the mutual love for the little child and later for each other; and with this the permanent relationship which alone could produce the organization of the family. The beginnings of morality likewise developed from this sense of a community interest which called for a subordination of selfish desires.

For ages mankind has experimented with different forms of family relation and home organization, trying to discover which serve best to foster the child, conserve the State, and satisfy the men and women who form the family. Under different social and economic conditions, polygamy and polyandry (more than one wife or husband), promiscuity (several temporal husbands or wives) and monogamy (one husband or wife) have been tried.

Polygamy, in primitive society, developed where women were in excess, or their labor increased family income, or where a man’s fortune enabled him to support more than one wife and her children. The polygamous nature of man was accepted by Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Mohammedan religions, and its practice permitted by their statutes. The Jewish nation early evolved from polygamy to monogamy, and incorporated the latter into its religion and customs. Anglo-Saxon ideals were of monogamy. The teachings[Pg 12] of Christ emphasized monogamy. The early Christian teachers even carried this, as other ideals, to its farthest extreme, and preached the ideal of celibacy. It remained for Mormonism to sanctify polygamy and make it a duty. But polygamy, which was flatly opposed by the general sentiment of the United States, was short-lived in the territory of the Mormon Church. The local feeling on this issue at present may be summarized in the following sentiment, expressed by a distinguished citizen of Utah:

“Our citizenship must be world citizenship. It is a matter of common knowledge and comment that that citizen is most valuable to his town who can see the town’s needs in relation to those of his county; that he is of most value to his county who sees that county as a constituent part of the state and consents to nothing for his county that would hurt the state; that a state’s most valuable and serviceable citizen is the man who has the power in his thinking, reasoning, and acting to rise above sectionalism and act as a citizen of the nation. This is the test to which our citizenship must submit—the standard up to which it must measure.”

In primitive, as well as in civilized societies, the beginning of a new home is customarily celebrated with civil and religious ceremonies; customs and laws provide for the relative rights of the husband and wife to their persons, their children, their property, and the returns from their labor. Infidelity (particularly of the wife), common-law marriages (living as husband and wife without legal marriage), promiscuous relations, divorce, have generally been branded as anti-social and reprehensible, expressions of lack of self-control, altruism, and foresight.

Mankind is finding through the experience of the ages that monogamy best conserves child life, the home, the State, and individual happiness. It has found[Pg 13] that irresponsible parenthood, shallowness of marital or parental affection, promiscuous relations, all endanger the life and welfare of the child. It has learned that marriage customs and laws requiring considerable formality and therefore deliberation of the contracting parties, reduced the proportion of hasty, unsatisfactory, and temporary unions with their uncertain responsibility for the children, and their quarrels over property. Many factors have contributed to the establishment of the really monogamous family and home as the social ideal and the increasing social practice. The lengthening period of infancy, with the consequent longer period of mutual coöperation of parents in nurture and training; realization of the Christ spirit of love for others, of respect for the value and individuality of every human life; the consequent refinement of the emotional life and social feeling, and the sublimating of sex instincts to the development of a richer personality, to mental creative work and to social service; the democratization of education and social status; freedom in choice of a marriage partner—all have contributed a part.

Freedom of choice has been far less prevalent than capture, purchase, or family contract, in marriages of the past. It is wearisome to even try to imagine the procession of brides, since those early days of the cavemen, who had no choice in the matter of their husbands. For what countless millions of brides was the marriage arranged by barter between their fathers and their future household lords, sometimes the father requiring a purchase price, sometimes the bridegroom demanding a dowry. What millions of girls have been selected while mere children as the future wives and slaves of their husbands and the family drudges of the household. How many millions of brides and bridegrooms have never been consulted as to their personal feelings or desires, but have been[Pg 14] married because the elders of their families decreed it. Under all such conditions, if husband and wife developed affection for each other, that was so much of advantage to them from the combination; otherwise they must adapt themselves as best they could to the daily round of life in their common dwelling and throughout their family responsibilities.

Trial marriages have been an experiment in many societies. They are based upon suspicion and expectation of termination, instead of upon that whole-hearted confidence and expectation of endurance which is the basis of a permanent relation. Psychologically, therefore, their basis is false and weak. They presented a crude method of testing mutual adaptation and affection, which to-day may be gained by visiting a few weeks in each other’s families, by thorough preliminary discussion of problems of adjustment, and by consultation with a competent physician, biologist, and sociologist or a mature and thoughtful counsellor.

Thus has marriage evolved by stages from biological matings, based on physical attraction; to the business contract, based on economic relations; to the social contract, based on social advantage to the family, clan, or State; and finally to a spiritual relationship, based on mutual social and intellectual interests and ties. Romantic love as a general experience in marriage has developed only during the past few hundred years. No one of these phases—the biological, economic, social, or spiritual—can be ignored in marriage to-day without disaster, as divorce records and daily observation show so clearly. To ignore the higher relationships and base marriage simply on the biological or material is to revert back to a lower stage in human development. A marriage based simply on physical attraction soon loses its glamour, and is as a house built upon the sands. The enduring ties are those of spiritual comradeship. It is this spiritual-biological[Pg 15] love, evolving with the personality and soul of man, that has inspired the great wealth of spiritual creations in poetry, music, drama, and painting.

The American young woman of to-day, especially of the middle classes, is economically, socially, and religiously free to choose from among her suitors the one she finds most congenial and whom she really loves. Legislators are providing in many States for the woman’s equal rights in marriage to her person, property, and children. Churches, associations, and parents are awakening to their responsibility in providing natural and wholesome social opportunities for young men and women to become acquainted. If a woman does not find her ideal in the community where she lives, she is socially free to migrate to any part of the country, enter any one of a thousand occupations, and seek until she finds a suitable helpmeet. In this country, in contrast to Europe, there is an excess of some two million men in the population. She will find a large proportion of young men of her social class and education, whose standards and habits of life are as fine as Sir Galahad’s, who have the economic ability to make a comfortable living, and who are ready to coöperate intelligently and whole-heartedly in home-making. The young man of to-day will find an increasing proportion of young women who combine physical charm, social gifts, intellectual comradeship, home-making instincts, and preparation.

Why Homes Are Broken. In a country where divorce is easily obtained by either husband or wife, for serious cause, the proportion of divorces is an index (1) to the percentage of dissatisfied couples (which will always be considerably higher than the percentage of divorces); and (2) to the intelligence and forethought with which young people enter marriage. The census of 1910 estimated one marriage in twelve ending in divorce, and counted as direct parties about one half of one per[Pg 16] cent. of the population, something over three hundred thousand men and women, with children involved in about sixty per cent. of these families. The causes stated in the court records would, of course, be only those allowed in the laws as the legal grounds for granting a divorce. These, in the order of their frequency, were (1) desertion by the husband, (2) cruelty of the husband, (3) desertion by the wife, (4) non-support by the husband, (5) cruelty of the wife, (6) adultery. The most frequent real causes, as found by social investigation, are lack of self-control, lack of mutual ideals in regard to sex relations, ignorance of sex hygiene, use of alcohol, irresponsibility, economic extravagance, disagreement regarding the family income, hasty marriage after brief acquaintance. Among the other causes productive of discord are selfishness, insincerity, false pride, nagging, poor housekeeping, the husband’s lack of economic ability; marked differences in age, education, social status, religion; abnormal craving for social excitement; unnatural, crowded, unattractive homes.

How Homes Are Made Steadfast and a Benediction. The fundamental requisite of family happiness is love; not merely sex attraction, which may be wholly selfish, but love that is service, happier to give than to receive, willing to share. In some respects similarity between husband and wife is important in their social and intellectual tastes, moral standards, religious faith, refinement, love of children, rate of ability to progress, degree of seriousness or frivolousness, ardor and expression of affection. These make for congenial daily living. In some respects complementary qualities are desired. If one is impatient, the other may well possess a degree of patience and sense of humor to meet this; if one is extravagant, the other should be thrifty; if one is radical, the other may well be conservative, although marked extremes would always[Pg 17] clash. The degree of positiveness in the one should approximate that in the other; if equal, neither is willing to yield; if very unequal, one domineers the other. These complementary traits make for balance of family life. The qualities that each should possess would include responsibility, self-control, sincerity, kindliness; freedom from drugs, conscientious abstinence from alcohol and from vicious habits; a degree of maturity and experience equal to the responsibilities of home-making (usually not under twenty years for women and twenty-one for men), love of home life and of children; good health, freedom from any serious germ disease, a family history free from criminal tendencies, alcoholism, mental defects, tuberculosis. A gambler, spendthrift, flirt, vacillating or superficial man or woman, or one who is “sowing wild oats” has not the qualifications for establishing a home. The man should be able to earn a comfortable living, and the woman to administer the household efficiently and smoothly. Every woman should have some means of making her livelihood at the time she marries; it will greatly increase her husband’s respect for her and be a source of confidence to herself. She usually cannot do better, from the economic aspect, than to become thoroughly skilled in phases of home-making.

How the family income should be divided, what share the wife shall have for household use and for her personal use, is so diplomatic and acute a problem that it should be as sincerely and frankly discussed as all these other phases.

Whether the wife should undertake work besides managing the home-making is a moot question. Certainly her first responsibility is to make a home not only comfortable but inspiring. She needs to have such opportunity for relaxation, meditation, reading, personal development, that however weary and tense her husband may return in the evening, she can give rest,[Pg 18] good cheer, and refreshment of spirit, because of her reserve of vitality, and can send him each morning to his work with the courage and good spirits stimulated by her blitheness. She needs, also, to be storing reserve strength for her children.

The location of the house greatly affects the family life. Ideally, it should be a separate dwelling, with a porch for outdoor social life, a garden where all members of the family have room to work and play, with rooms enough for individual privacy; and it should be owned, not rented.

The minimum income on which two people may advisably marry will depend largely upon their degree of adaptability, patience, and sense of humor. Acquaintance before marriage may safely be not less than a year and preferably two, not only for thorough and sincere acquaintance, but for the possibility of the reaction and even repulsion that is so likely to follow a violent case of love on short acquaintance. If love is too ardent, it needs this discipline of patience and restraint. If it is deep enough to last through the rest of time, it will stand the test of waiting.

Having established their home, husband and wife may well cultivate their love wisely, seeing that it does not starve from lack of service in little thoughtfulnesses; that it is not surfeited by too much of sweetness or selfish expression; that it is protected by residence separate from relatives, friends, strangers; that both have individual social life and friends and pursuits so that they do not become wearisome to each other; that they busy themselves in some mutual objective interest—social welfare, club, lodge work or a reading course. The few minutes spent together each day in gaining inspiration, either in religious worship, or reading from some great book, or singing noble songs, will do much to keep the family life harmonious and to reduce the petty frictions. It is well to agree[Pg 19] on the first day—and carry through the agreement—that if misunderstanding or the least suspicion arises, it shall be frankly and thoroughly faced, discussed, and eliminated, remembering that it is “the little rift within the lute” that silences the music. Then, as the poet sings:

[Pg 20]

“Efficient housekeeping is the beginning of good citizenship.”

—Professor Martha van Rensselaer.

The Budget. Many young people hesitate to marry on a modest income, either through confessed inability to manage a small budget, or an unwillingness to begin humbly and live simply. Many mothers are sorely perplexed over the problem of finding time and energy from their household work for the education of and play with their children. Parents are perplexed over how to provide for and educate more than one or two children in what they consider a fitting manner.

Efficiency Methods. The whole complexity may be reduced to definite problems of philosophy, scientific efficiency, physics, and mathematics. The first step is to appreciate the relative value of life and of things, of genuine simplicity and vulgar show; of educating the children to share, to carry responsibility, to be self-reliant, or to be selfish, dependent, luxury-loving.

Second, all the labor-saving machinery in the world will but slightly reduce the output of time and energy in the household work unless the worker will apply her mind to the problem, adapt herself to new ways of performing a piece of work, and be willing to think.

Third, the individual problem must be studied. Have a regular monthly session to analyze seriously, with pencil and paper, the household situation, and to question every process of work and every expenditure.[Pg 21] Can the household régime be made simpler yet socially efficient? Where is there waste of energy, time, materials, income? How can the accumulation of dirt and dust be reduced? How can dishwashing and laundry work be reduced? How can time spent in cooking be decreased? How could any work be done in a less tiring position? Where could there be a reduction in the number of steps, trips, arm movements, duplications of work, arranging which requires later disarrangement? Where could pipes, drains, hose lines, faucets, pulleys, speaking tubes, signals, or other simple mechanical devices reduce time and labor? What work could be done by a part-time helper at an hourly or daily rate? What is the difference in cost between food cooked at home or purchased already cooked? What has been the loss from food wasted, spoiled, thrown away, improperly cooked? Could any foods be purchased directly from the producer, with a saving of cost? Are the dealers sending honest measures and correct bills? How could a reduction be made in the cost of fuel or of lighting?

Domestic engineers, housekeeping experiment stations, household efficiency laboratories already exist, but they are so new that the terms are not yet quite familiar. It may prove a great saving of time and energy to consult one of the new domestic engineers, whose business it is to analyze a kitchen or a house or a family budget, plan its rearrangement for economy of time, energy, and money, recommend labor-saving machinery, or organize a system of routine.

Fourth, begin at once to put efficiency principles into practice in the household work. Do not dawdle or potter over work. Analyze the work of the household into units, for example, preparation of breakfast, laying and clearing the dining table, care of a bedroom, washing the dishes. Specify the maximum amount of time each unit is worth, then see how this can be[Pg 22] reduced, using the fewest arm motions and least walking.

Saving Time and Energy. Learn to plan and organize work. Have a monthly, weekly, and daily schedule of work. It will often be necessary to vary this, but a well-planned schedule will nevertheless reduce the time otherwise wasted in unnecessary duplication and without definite purpose. “A stitch in time saves nine.” This applies to sanitation, plumbing, cleaning, gardening, colds, and sore throats, as well as to socks and frocks.

Study how to eliminate useless motions. Make exact studies, using a watch and a record pad. Observe how many trips were made in laying the table, and the length of time required. Discover ways of reducing this by half, through use of a tray, more convenient arrangement of supplies, fewer dishes, simpler service. Make similar studies with other processes, such as cleaning a room, or preparing a meal.

In an ordinary household, preparation of breakfast for a family of five persons should not require more than half an hour; lunch from twenty minutes to an hour; dinner from half an hour to two hours. The daily care of a bedroom should be completed in ten to twenty minutes. Washing of dishes, clearing of dining room and kitchen, should be finished in from twenty to sixty minutes after a meal. The weekly washing for such a family should be completed in four to six hours, and likewise the ironing. Five hours a week is enough to spend in baking, and only two should be necessary if bread is not made.

Make out the menus for a whole week, revising daily as necessary. This will assure better-balanced menus, more variety, economy of time and money in marketing, and will prevent the worry of unpreparedness. In marketing, purchase a two or four months’ supply of such staples as can be bought and stored advantageously.[Pg 23] Have a regular day weekly to inspect supplies and order staples. Have two or three regular days a week for purchasing fresh vegetables, fruits, meats.

The general architectural plan of a house, finish of walls and floors, construction of windows, doors, wainscoting, corners, mopboards, can make hours of difference in the week’s labor. Even when the general architecture cannot be altered, the floors may be improved. Carpeted or waxed floors are the most difficult to care for, while those painted or oiled are easiest. Useless bric-a-brac, carved and ornate furniture, all are dust and germ holders, and consume an extravagant amount of time for their care. For every unnecessary and useless piece of furniture, drapery, or utensil, the housekeeper must pay a tax of time and strength in handling. The Japanese have learned the beauty of simplicity in house furnishing.

Rearrange the plan of the kitchen until supplies, utensils, stove, water, sink are so placed that there are fewest steps and motions, and it is as convenient as an apartment house kitchenette. Tables, sinks, and ironing boards adjusted to the height of the worker will economize energy. A low stool to stand upon will reduce the height of work tables; a detached wooden frame or block on top of a low kitchen table or sink will often give the desired height without stooping. A cushioned stool or chair to sit upon while doing stationary work, or a soft rug under feet while standing, all add to comfort.

Electricity is the housekeeper’s man-of-all-work. It can heat, light, cook, supply the energy for the vacuum cleaner, washing machine, wringer, dishwasher. In some communities it is now furnished at a sufficiently low rate for such general use, and other communities can have the same low rates whenever the housekeepers organize and demand it.

[Pg 24]

Simple cooking is more digestible, nourishing, economical of labor, and, to a natural appetite, more appetizing. The most valuable part of potatoes and apples is next the skin, the removal of which before cooking is wasteful of time and materials. A coal stove is an enormous consumer of time and energy. An alcohol stove furnishes the cleanest method of cooking, quite practicable, with a fireless cooker and steam cooker, for a small family. Next in convenience, and more economical, are the gas or oil vapor stoves. A good fireless cooker vastly reduces the time required in the kitchen, and cuts the fuel bill in half.

In serving meals, labor is saved by using a tray, or better still a wheeled tray with several shelves, which may be drawn up to the table to hold the additional courses and the soiled dishes as removed. A special tray that will fit the cupboard shelf, to hold the constant accessories, will save handling.

Dishwashing is an ever-recurring, three-times-a-day problem. There are several fairly good dishwashing machines now on the market, both electric and hand-power. If dishes must be washed in the old-fashioned way, engineering efficiency can be put into it. After washing, scald the china in a wire basket such as business offices use for holding letters, and leave to dry without wiping, then place directly on trays to take to the table instead of placing on shelves only to take down again. In times of stress or of picnic spirit, papier-mâché or wooden dishes will save time.

For cleaning have a vacuum cleaner, carpet sweeper, hair floor brush, dustless mop, dustless dusters or cheesecloth dampened with kerosene, wax oil or furniture polish. It takes an hour or two after sweeping for dust to settle; this interval should be allowed before dusting furniture.

If good laundries, guiltless of injurious chemicals[Pg 25] and extravagant rates, are not available in the locality, a coöperative laundry providing these features may be organized and conducted by the women of the community, as in many places in Wisconsin. If laundry work must be done at home, an equipment of a good washing machine or even a hand vacuum washer, a wringer, stationary tubs, hose lines, running hot and cold water, with sewer connection for waste, greatly reduce the time and energy cost. A cold mangle or one heated by gas or charcoal costs but a few dollars and reduces by about seventy-five per cent. the labor of ironing flat work. Gas or electric irons are inexpensive and energy saving. Necessary laundry work may be greatly minimized by providing silk or cotton crepon for underwear and dresses, seersucker for children’s rompers, dresses, and aprons, with doilies or paper napkins in place of tablecloth, at least for breakfast and lunch, and paper towels for kitchen and bathroom.

The physical and mental condition of the worker is a very considerable factor in time and energy cost. Work attempted when one is fatigued, nervous, or tense consumes vastly more energy and time. Learn to relax at intervals; especially lie down for a few minutes about midday. “Never stand when you can sit; never sit when you can lie down.” If becoming nervous or tense, relax completely, and take long, slow, deep breaths of fresh air. Stand with the weight on the balls of the feet, head erect and chest expanded. Keep the house air in winter at efficiency point: between 65° F. and 68° F. in temperature, and sufficiently humid by well-filled water pans in furnace pipe or by large open dishes of water in room, and with a constant intake of fresh outside air.

Making the Most of the Family Income. Analyze the family income and spend it on paper many times before spending it over the counter. Train the family[Pg 26] to spend less than is planned, rather than more Ordinarily, for incomes up to three thousand dollars, the following is considered by economists a wise distribution, in a family with three children:

| Rent | 20% |

| Food | 25% |

| Operating expenses (heat, light, repairs, labor, supplies) | 15% |

| Clothing | 20% |

| Education, recreation, health, saving | 15-20% |

Personal ordering and selection of supplies, paying cash and keeping accounts, will furnish the greatest values for expenditures. Accurate scales and measures in the kitchen, with occasional tests of supplies sent, will check errors or dishonesty of marketmen. Cost of supplies may be reduced by keeping posted on market prices; buying in wholesale quantities where possible, in coöperation with other housekeepers; buying directly from the producer wherever possible; knowing the reliable grades and brands of package goods. A knowledge of the values of common foods and their comparative cost for equivalent food value is indispensable for efficiency. A reasonable allowance is two dollars to two dollars and a half a week for food supplies for each person. An ample quantity (eighteen hundred to two thousand calories a day) of nourishing food of limited variety can be purchased for one dollar a week. Luxuries should be had on a four dollar weekly allowance per person

The following table can be expanded by any housekeeper. For other food stuffs: Note calories per pound. (Given in Government Bulletin Number 28 or Rose’s Laboratory Manual in Dietetics) To find the number of calories for one cent, divide calories per pound by cost per pound. Fruits and green vegetables, although[Pg 27] furnishing few calories for one cent, are needed each day, for their vitamines, acids, and minerals.

Comparative Caloric Food Values and Cost

| Calories | Calories | |||

| Food | PER | Cost per | FOR | |

| Pound | Pound | One Cent | ||

| Oatmeal | 1803 | 4 | cents | 451 |

| Corn meal | 1613 | 4 | ” | 400 |

| Dried peas | 1612 | 8 | ” | 201 |

| White bread | 1174 | 6 | ” | 196 |

| Potatoes | 378 | 2 | ” | 189 |

| Milk, per qt | 675 | 9 | ” | 75 |

| Rice | 660 | 10 | ” | 66 |

| Flank steak | 1084 | 18 | ” | 60 |

| Shredded wheat | 1600 | 33 | ” | 48 |

| Salmon | 922 | 20 | ” | 46 |

| Sirloin | 957 | 28 | ” | 34 |

| Eggs (28 cents a doz ) | 672 | 21 | ” | 32 |

| Flounder | 128 | 7 | ” | 20 |

| Chicken | 289 | 25 | ” | 12 |

Locating the Home. Life in the open country, town, or suburb reduces the cost of living, as compared with the city, (a) by reducing the stimulation and excitement of daily life, and their energy cost; (b) reducing the temptations to extravagant and frivolous expenditure of money; (c) furnishing better air and more outdoor living, thus increasing the quality of life besides decreasing expenditures for illness; (d) providing a porch and yard where children may play in sight of mother at work, and where the family may find social life; (e) providing space for garden and poultry, whose care is healthful exercise, and whose products may reduce the expenditure for food. By purchasing staples at wholesale and organizing a coöperative marketing group for fruits and vegetables, as wide a variety and[Pg 28] as low a cost of food is possible as under most favorable city conditions. The provision of rural traveling libraries, art exhibits, educational picture films, the use of the schoolhouse as a social center, the improvement of education in the rural and suburban school with its ideal natural environment, all are part of that larger home-making for which every mother and father should feel a responsibility.

The Value of Life and of Things. “The things that are seen are temporal; the things that are not seen are eternal.” Do not mistake the means for the end in housekeeping. Orderliness, immaculate linen, garnished rooms are means. Good cheer, patience, kindliness, reserve force, poise are of vastly greater value. Often it is necessary to choose between the two. Cherish simplicity, beauty, courtesy, rather than conventionality, aping of passing modes, vulgar show, and ostentation in the house, equipment, household service, the clothing of the family. Train every member of the family to be responsible for the care of his own belongings and to wait upon himself as his share in social coöperation.

Let the children from toddling time help in the household duties and chores. It will be for their guardians a good training in patience, adaptability, and sympathy. What if their work is crude, with many mistakes and mishaps? They are learning motor coördinations, manual dexterity, a knowledge of homely routine, the meaning of labor and service, the joy of workmanship and creation, the satisfaction of self-reliance, the happiness of intimate comradeship with mother and father. Their character development is the great consideration, not the materials they are handling or the petty work they are accomplishing.

[Pg 29]

“The business of life is the transmission of the sacred torch of heredity undimmed to future generations. This is the most precious of all worths and values in the world.”

—G. Stanley Hall.

“The young people of the next and all succeeding generations must be taught the supreme sanctity of parenthood—that the highest profession and privilege they can aspire to is responsible fatherhood and motherhood.”

—C. W. Saleeby.

Solicitude for the Child as a Factor in Social Progress. The eugenic education of children is the real beginning. Parents can give to the little children in the home true ideals of parenthood, wholesome respect for maternity and paternity, training in the control of desires and appetites, a controlling sense of their personal and social responsibility, and true instruction regarding the origin and creation of life.

So to live that their children shall be strong and happy is a motive that a child can appreciate, and it can become the most powerful incentive for hygienic living, for industry, education, for social purity that is positive—noble in thought as well as restrictive in action. Trained thus through childhood, boys and girls will be prepared to meet with high-mindedness and moral stamina the storm and stress of adolescence; their ideals of sweetheart and lover will have a wholesome eugenic prejudice, and they will be prepared[Pg 30] to discuss with dignity, scientific spirit, and reverence this significant phase of their future home life.

There is no essential contradiction between romantic love and eugenics. Indeed, sincere, deep and enduring love of parents for each other and for their children is an essential in a eugenic ideal. A young woman knows a hundred young men, but is in love with only one (or possibly none) because the others do not embody the ideal that she has fashioned. Every young man and woman has such an ideal, perhaps only vaguely defined but certainly felt, with which they are in love, for which they search, and with which they sometimes invest an acquaintance only to discover later their illusion. This ideal is composed of the most alluring qualities and personalities they have known.

What young man would be likely to fall in love with a girl, however pretty, even charming, whom he knew could be the mother only of sickly, peevish, stupid children to inherit his name and perpetuate his family, or who would refuse to assume the burden of motherhood? What normal young woman would be attracted by any “fairy prince”, however romantic, wealthy, handsome, if she were aware that his children, should he have any, would be doomed to early death, weakness, or imbecility, and that she herself would be made a sufferer for life? The widespread tendency of young men and women of to-day to include beauty, vitality, and ability in their romantic ideal is itself sufficient evidence. Young men and women are generally too well balanced to marry simply from eugenic consideration without romantic love, although this is less reprehensible than marriage simply for title or livelihood, for social distinction, or personal creature comfort without consideration for either eugenics or romantic love. The prayer of Hector, as he lifted his little child in his arms in the tower of Troy, while the battle raged without the walls, is the prayer of the parent heart[Pg 31] everywhere, that the child shall be nobler and greater than the father.

The normal biological life for every man and woman is parenthood. The normal social relation between parents is mutual, abiding love. Only through the development of such a love has humanity evolved from the materialistic, individualistic stage of the animal to even the present stage of spiritual life and social relationships.

It is mutual solicitude for the child that places the biological relations of men and women on a wholesome, ethical, and spiritual plane. Historically, marriage and monogamy are the result of children. The social stigma upon illegitimacy is not artificial or unreasonable. It is the deep appreciation by the social experience of humanity that parental responsibility and solicitude is at the very foundation of society; that the selfish, reckless use of this creative power, or a cuckoo-like disregard for the child’s life, is undermining to society as well as to the character of the man, the woman, and their child. The far-sighted perceive, too, that the undermining influence of physical relations without spiritual purpose, of individualism that ignores social responsibilities, of blind, unreasoning following of any impulse, in this, as in any phase of life, is quite as destructive to the man, the woman, and society, even without the penalty of the unwelcome child; that usually the man is more blameworthy than the woman; that both are often the victims of ignorance, lack of ideals, and of early training in responsibility and self-control; and that similar selfish lack of solicitude for their child is equally reprehensible within and without marriage.

The child is the equal creation, responsibility, and satisfaction of both father and mother. The parent who willingly shirks the responsibility for the care of his or her own child is a coward, if not a knave or a[Pg 32] defective. The father who would voluntarily forego his share in the care and companionship of his child, or the mother who would demand this, are equally lacking in parental instinct.

Celibacy, marriage without love, parenthood without marriage, are equally undesirable. But if circumstances require a choice, celibacy is less miserable for the individual and less detrimental to society. It is part of the great social responsibility of parents and social administrators to remove the causes of celibacy by:

1. Providing academic, social, and moral education that prepares young men and women for congenial companionship and for home-making;

2. Making provision for wholesome recreational opportunities and acquaintance, for young men and women of similar intellectual and social interests;

3. Affording the economic opportunity for a family income for young men by their early twenties, through vocational training, regulation of the cost of commodities, direction of labor conditions;

4. Abolishing war, that fiendish Minotaur that not only interferes with Nature’s provision of an equal number of men and women in any generation, but that, more serious still, devours the ablest and strongest of the young men, depriving millions of women of their husbands and their children.

The Meaning and Significance of Eugenics. Eugenics, as defined by Sir Francis Galton, is “the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race and that develop these to their utmost advantage.” Wise men in former ages have perceived something of its possibilities.

Positive eugenics is concerned with whatever will enhance the inborn qualities of a new generation, therefore with social conditions that promote the mating of the physically, mentally, and morally able; with[Pg 33] conditions that improve the quality of the germ cells in the individual; with ideals that develop self-control and the spiritualizing of the instinct of race preservation.

Negative eugenics is concerned with the elimination of hereditary diseases and defects; with the prevention or correction of diseases, defects, poisons, and practices in the parent that have a harmful effect upon the germ cells and the unborn child; with the elimination of social and moral conditions that endanger the life or handicap the progress of unborn generations.

Genetics, the study of the laws of heredity, is the biological foundation of the science of eugenics; ethics and religion are the basis of practical eugenics.

In the past century great impetus was given to eugenic research and ideals by Sir Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin. Galton, indeed, coined the word “eugenics” from two Greek words meaning “well-born.” To quote from Galton’s own writings:

“Man is gifted with pity and other kindly feelings; he has also the power of preventing many kinds of suffering. I can conceive it to be within his power to replace Natural Selection by other processes that are more merciful and not less effective. This is precisely the aim of eugenics. Its first object is to check the birthrate of the unfit, instead of allowing them to come into being, though doomed in large numbers to perish prematurely. The second object is the improvement of the race by furthering the productivity of the most fit by early marriages and healthful rearing of their children. Natural Selection rests upon excessive production and wholesale destruction; eugenics on bringing into the world no more individuals than can be properly cared for and those only the best stock.”

Galton devoted his time and his fortune to the investigation of these principles and the propaganda of eugenic ideals. He made extensive studies of family[Pg 34] histories, especially to ascertain what evidence they gave of the inheritance of physical, mental, and moral traits. He organized the Eugenics Education Society, whose leaders include eminent scientists, sociologists, physicians, educators, and under whose auspices the First International Eugenics Congress was held in London in 1912.

Present Knowledge of Heredity. More has been learned about heredity in the past quarter century than in all previous history. Through the inspiration of Galton, extensive studies have been made of family histories in many countries, and not only has the certainty of inheritance been established, but some of the laws of heredity have been formulated. Through the laboratory studies made possible by the improvements in the compound microscope, important discoveries have been made of the physiological processes and the mechanism by which characteristics are inherited. This is the summary of our present knowledge:

Physical and mental characteristics are inherited.

Inheritance is of definite traits, such as eye color, height, musical genius, high or low resistance to a germ disease, for example, tuberculosis. Research work in genetics is at the present time especially concerned with discovering what are the unit characters and how each is transmitted.

Special cells, called germ cells, are the carriers of heredity; these contain the determining factors for physical and mental characteristics. These, like all the other cells of the body, are microscopic in size. The body of the individual is the temple in which the sacred cells of the race are protected.

Inheritance is not directly from the parent but from the germ cells, which may carry characteristics not found in the parent but in some of the other ancestors. An individual does not inherit what his parents are[Pg 35] but what is in the two germ cells, one from the mother, one from the father, that unite to form that individual.

With the union of the two germ cells the inborn characteristics of the individual are determined, “the gate of gifts is closed.” Environment and training may increase the strength, or minimize the force of inborn characteristics, or even suppress some of them, but it cannot add to them, or increase their force beyond their inherent limitations.

Some few characteristics are inherited only through the mother, or only through the father, or are transmitted only to the sons or only to the daughters; most characteristics are not thus limited, but may be transmitted by either parent to either son or daughter.

Acquired characteristics are not inherited. If a man loses his hand in an accident, his descendants cannot inherit one-handedness; if he masters a foreign tongue, his descendants cannot inherit his knowledge of that language.

No disease germ is inherited, in the genetic sense of being conveyed in the special germ cells. A child may be infected with a disease before its birth; this is not, strictly speaking, heredity but congenital (or prenatal) infection. Tuberculosis is sometimes thus conveyed from the mother, and syphilis very frequently when either the mother or the father has this disease even in latent form. What may be inherited is a tendency toward a disease, a weakness of specific organs or tissues, a lack of resistance to a specific disease.

Variations sometimes appear apparently spontaneously, as the result of some accident to the germ plasm, or an unusual combination in the two germ cells; such variations may be inherited.

Some characteristics are apparently persistent, and in the process of inheritance tend to predominate over their complementary characteristics. The former are called dominant, the latter recessive characteristics.[Pg 36] The law by which dominant and recessive traits are inherited was first formulated by Mendel, an Austrian monk, less than half a century ago. Biological research is being devoted at present to discovering what traits of human significance are subject to this Mendelian law, as it is called.

A characteristic found in both parents, or in both families, has a double possibility of appearing in their descendants, and some mental defects and abilities tend to appear with greater force and at an earlier age, in the descendants.

Every individual is born with all the germ cells he will ever possess.

These germ cells are highly susceptible to poisons in the circulation, especially to:

(1) alcohol, even in dilute quantities,

(2) fatigue poisons,

(3) opium, morphine, and similar drugs,

(4) lead and other poisonous metals,

(5) lack of nutrition due to anemic condition of the body.

If a germ cell is thus affected by poison at the time of the uniting of two cells, or during the subsequent development, the child is especially liable to:

(a) serious injury resulting in death before birth;

(b) low vitality resulting in death within a year after birth;

(c) defective development resulting in physical deformity or in mental defect, such as feeble-mindedness or idiocy.

If either parent is infected with syphilis, the germs most frequently attack the developing child and cause death before birth or during the first year; or the germs may attack any tissues, crippling, producing deformities, deafness, blindness, idiocy, manifest either at birth or later in life. If either parent is infected with gonorrhea, the eyes of the child will probably be infected at[Pg 37] birth, and blindness prevented only by immediate use of silver nitrate solution; or the mother may be made incapable of having a child.

Fitness for Parenthood. Even the minimum qualifications for parenthood are various. For the fullest welfare of the child the following qualifications are essential:

Spiritual: a sense of the responsibility of parenthood, love of children; love of harmony and mutual agreement between parents; self-control, unselfishness, patience.

Social: legal marriage, good moral character.

Economic: marketable skill, energy, adaptability; ability of father to earn a comfortable living, potential ability of mother to earn a living, ability to use income economically.

Mental: Maturity, experience, judgment to conduct one’s share of the family and household responsibility, ability to learn; for the mother, knowledge of at least the elements of hygiene, child-care and training, some experience in caring for little children.

Physical: physical and mental soundness; sound heredity, especially freedom from neuropathic taint, alcoholism, tuberculosis, venereal disease (syphilis or gonorrhea); freedom from poisons of alcohol, fatigue, worry, overwork; mother not less than twenty or more than forty-five; father not less than twenty, preferably past twenty-four; maximum vitality and physical energy.