Title: The Danube

Author: Walter Jerrold

Illustrator: Louis Weirter

Release date: June 14, 2023 [eBook #70968]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Methuen and Co, 1911

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Amber Black and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

THE DANUBE

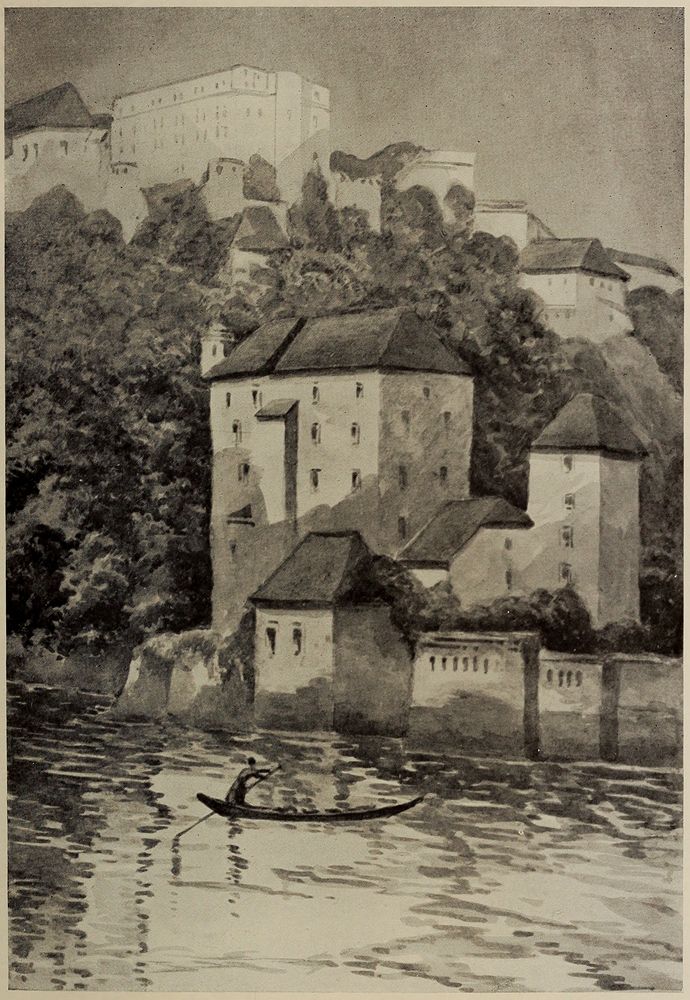

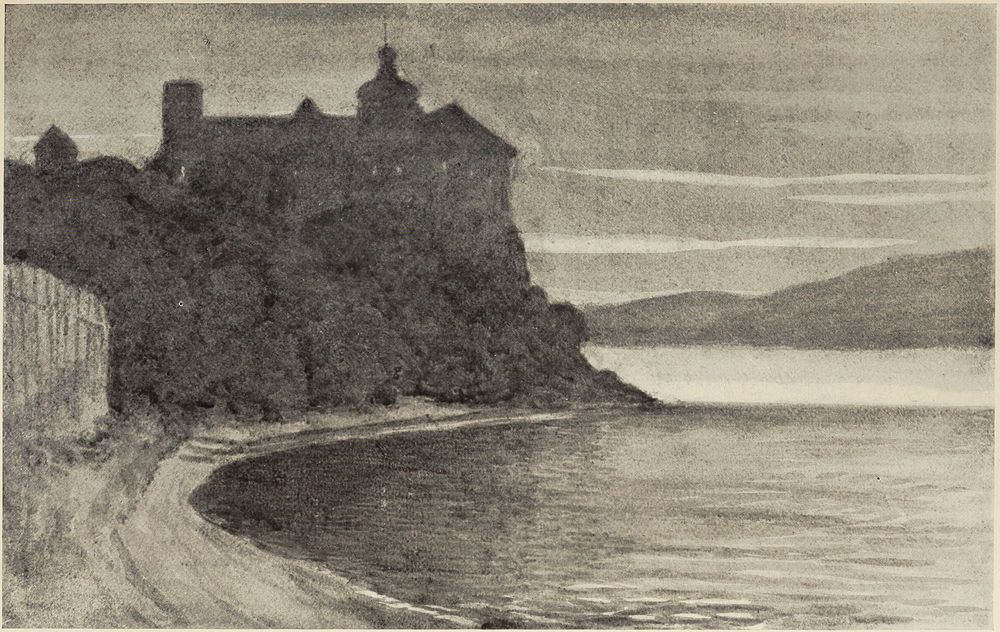

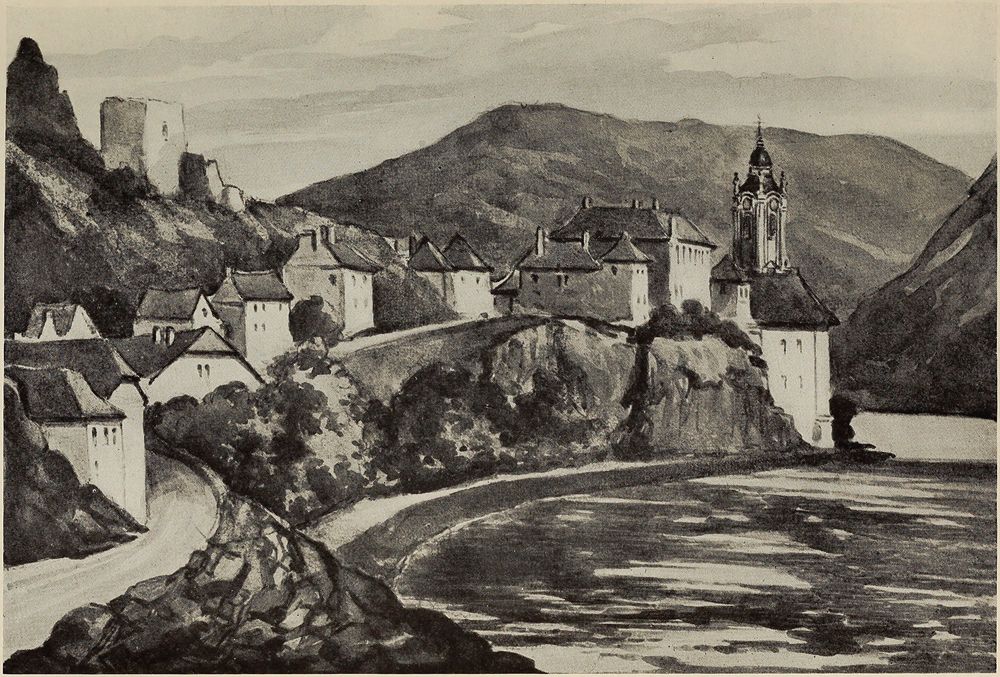

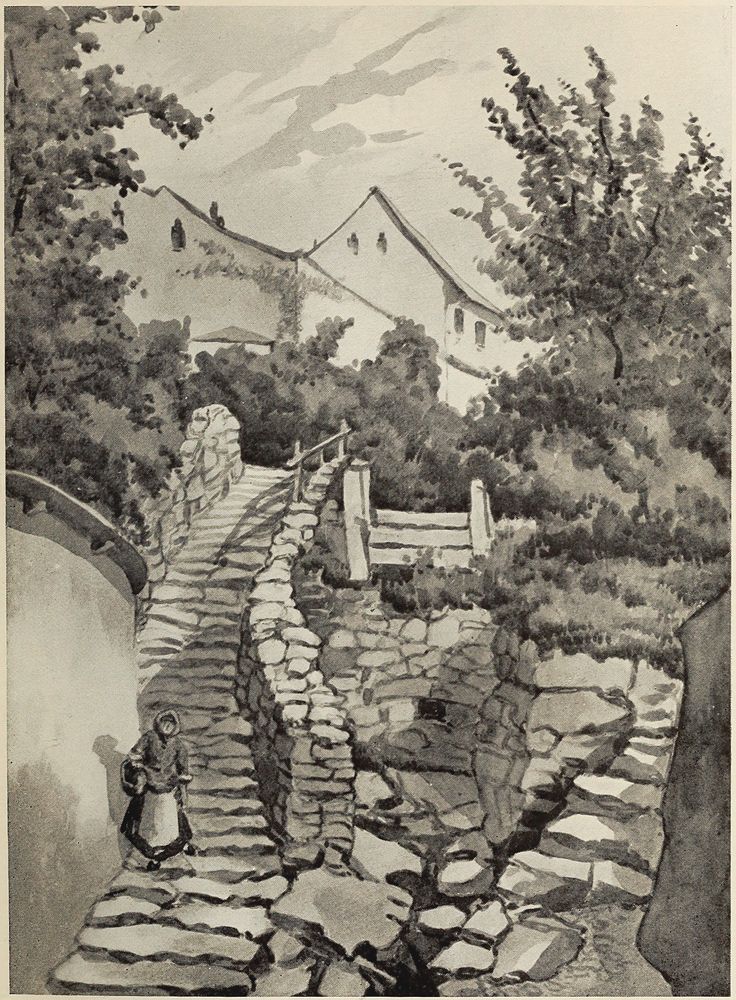

WEITENEGG CASTLE FROM THE WEITENBACH

BY

WALTER JERROLD

WITH THIRTY ILLUSTRATIONS BY

LOUIS WEIRTER, R.B.A.

OF WHICH TWELVE ARE IN COLOUR

METHUEN & CO. LTD.

36 ESSEX STREET W.C.

LONDON

[Pg v]

First Published in 1911

The Rhine appears to have been one of the earliest of Continental “playgrounds” for British tourists—to have been such, indeed, long before Switzerland had been exploited. In the days of our grandfathers “everybody” went to the Rhine—it had become as it were the last relic of the grand tour which to earlier generations had been regarded as a necessary finishing off to every gentleman’s education. The past popularity of the Rhine is emphasized by the fact that the great river was utilized by both Thackeray and Hood as scenic background for literary purposes. What the Rhine was, the greater, the more beautiful, the grander and more fascinating Danube should become in these days of improved means of communication. Probably in the past its difficulty of access made the enthusiasm of travellers less effective in attracting English visitors to the Danube. As early as 1827, J. R. Planché, poet, dramatist, and historian of costume, made a Descent of the Danube from Ratisbon to Vienna, and duly published an account of the journey in the following year. Twenty years later another writer, who had “scribbled successfully for the stage,” John Palgrave Simpson, published Letters from the Danube, describing a journey by steamer from Ratisbon to[Pg vi] Budapest. Then, in 1853, “two briefless barristers and a Cambridge undergraduate” journeyed in a Thames rowing-boat from Kelheim to Budapest, and one of their number, R. B. Mansfield, chronicled their adventures in The Water Lily on the Danube: being a brief account of a Pair-Oar during a voyage from Lambeth to Pesth. Some years earlier William Beattie had gathered various legends of the Danube to accompany Bartlett’s series of engravings of The Beauties of the Danube. Thus it will be seen that in days when the river was more distant than it is now it was not wanting panegyrists. In later years it has been curiously neglected, except in the way of casual references and the compact compilations of guide-books. This, however, may be said, so far as I have been able to ascertain, nobody who has journeyed along both the Rhine and the Danube—if we except the pardonable partiality of those who have a patriotic regard for the former—but finds the Danube almost incomparably the more variously fascinating stream.

From the time of the Romans onwards, from the time when our authentic chronicles begin, this mighty river has along its many hundreds of miles been the scene of so much history-making that to present the full story of the Danube would be to re-tell a large part of the history of the Continent during two thousand years. Such, it need scarcely be said, is not my aim or intention. To bring within the compass of a single volume some indication of the manifold beauties of the river, some hint of the romance that attaches to its castled crags, its villages, towns and cities, some suggestion of the great happenings of the past, some hint of the fascination of the present, is all that I can hope to do. And even so I am primarily concerned with presenting something of the story of the “scenic” Danube—that great stretch of the river which runs[Pg vii] from near Ratisbon in Bavaria to the Iron Gate between Rumania and Servia, the stretch of which, from voyaging in steamers, from tramping along the river-side roads, and from journeying along it by railway, I have a personal knowledge. In applying the word “scenic” to this greater part of the great river, it is not intended to suggest that the upper waters above Kelheim and the lower waters below the Iron Gate have not also much to offer the traveller, but the portion indicated is that which comprises the most famously picturesque parts of the Danube. It includes the beautiful mountainous stretches above and below Passau in Bavaria and Austria, where the river runs at the foot of the southern slopes of the Böhmer Wald; it includes the wonderful Wachau of Lower Austria, and the finely varied extent of the Hungarian Danube, with the grand Kazan defile, where the river forms a natural barrier between Hungary and Servia. Along the greater part of the great extent which lies between the limits named, comfortable passenger steamers run all through the summer season, and in these steamers the traveller may continue through Rumania and Bulgaria down to the Black Sea, and all the colour and glamour of the Orient. In the upper parts of the river, before we can get afloat on it, the Danube is as it were but an incident in the scenery, but, when once we reach the parts navigable by passenger steamers, the scenery becomes the setting or framework for the mighty stream.

The fact that the Danube is known to empty itself into the Black Sea makes many people regard it as a river at so great a distance as not to come within the range of a practical holiday policy; and if we give the Black Sea its ancient name of the Euxine, we make it seem more distant still. Yet the fact is that much of the beauty of the Upper Danube may[Pg viii] be explored by the holiday-maker who has but a fortnight or three weeks to spend, for the river has a length of nearly two thousand miles from where it rises in the duchy of Baden to where it joins the Black Sea, crossing or bordering in its course the States of Bavaria, Würtemburg, Austria, Hungary, Servia, Rumania and Bulgaria, and touching at the northernmost of its various mouths the vast territory of the Russian Empire. In parts the river is of course familiar to many people: those who go to Vienna, for example, see one of the least attractive bits it has to show; those who go to Budapest see it at its city best; while those who go to Ulm, Ratisbon, and other Bavarian towns know it in part. But I hope to show that it is by no means the best of the river that is seen by sojourners in any of the larger towns. It is to the visitor who likes to linger in out-of-the-way places that the Danube has most to offer, and in the hundreds of miles of beauties that it has to show there is little fear of places being overrun. That a goodly number of British visitors have “discovered” the river I learned from the captain of one of the steamers, who told me that “some seasons there are many English, but as a rule more Americans.” Yet the artist and I, on our journey down by boat, and on our river-side wanderings coming back, came across none of our compatriots, or of our transatlantic cousins, except in Vienna.

My thanks are due to numerous friends, known and unknown, who afforded me cordial assistance during a journey made yet more memorable by the many kindnesses shown to a travelling stranger. Special thanks, too, must be accorded to my friend Mr. James Baker, F.R.G.S., whose John Westacott might be described as a romance of the Danube, for it was he who first inspired me with the wish to journey down the great river, who brought home to me the fact,[Pg ix] which this volume seeks to enforce, that the Danube is not only an easily accessible but a well-nigh inexhaustibly delightful holiday ground.

A word or two should, perhaps, be said as to the spelling of place names adopted. Generally speaking, I have sought to use the names, and the spellings, used in the countries to which the places belong. In bilingual Hungary most places have two names, Magyar and German, in which cases I give the national name, followed by its German equivalent in parentheses. Where there are recognized English names, such as Vienna and Ratisbon, I have used these, as it would in such cases be the merest pedantry to render them Wien and Regensburg.

WALTER JERROLD

Hampton-on-Thames

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | v | |

| I | ||

| THE UPPER DANUBE | ||

| CHAP. | ||

| I. | FROM DONAUESCHINGEN TO DONAUWÖRTH | 3 |

| II. | DONAUWÖRTH TO RATISBON | 17 |

| III. | RATISBON TO PASSAU | 49 |

| II | ||

| THE AUSTRIAN DANUBE | ||

| IV. | PASSAU TO LINZ | 75 |

| V. | LINZ TO THE WACHAU | 99 |

| VI. | THE WACHAU | 129 |

| VII. | THE WACHAU TO DÉVÉNY | 159 |

| III | ||

| THE HUNGARIAN DANUBE | ||

| VIII. | FROM THE OLD CAPITAL TO THE NEW | 185 |

| IX. | THE HUNGARIAN CAPITAL | 204 |

| X. | BUDAPEST TO BELGRADE | 222 |

| XI. | BELGRADE TO ORSOVA | 243[Pg xii] |

| IV | ||

| THE LOWER DANUBE | ||

| XII. | THE IRON GATE TO RUSTZUK | 269 |

| XIII. | RUSTZUK TO THE BLACK SEA | 288 |

| INDEX | 309 |

| Weitenegg Castle from the Weitenbach (in colour) | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

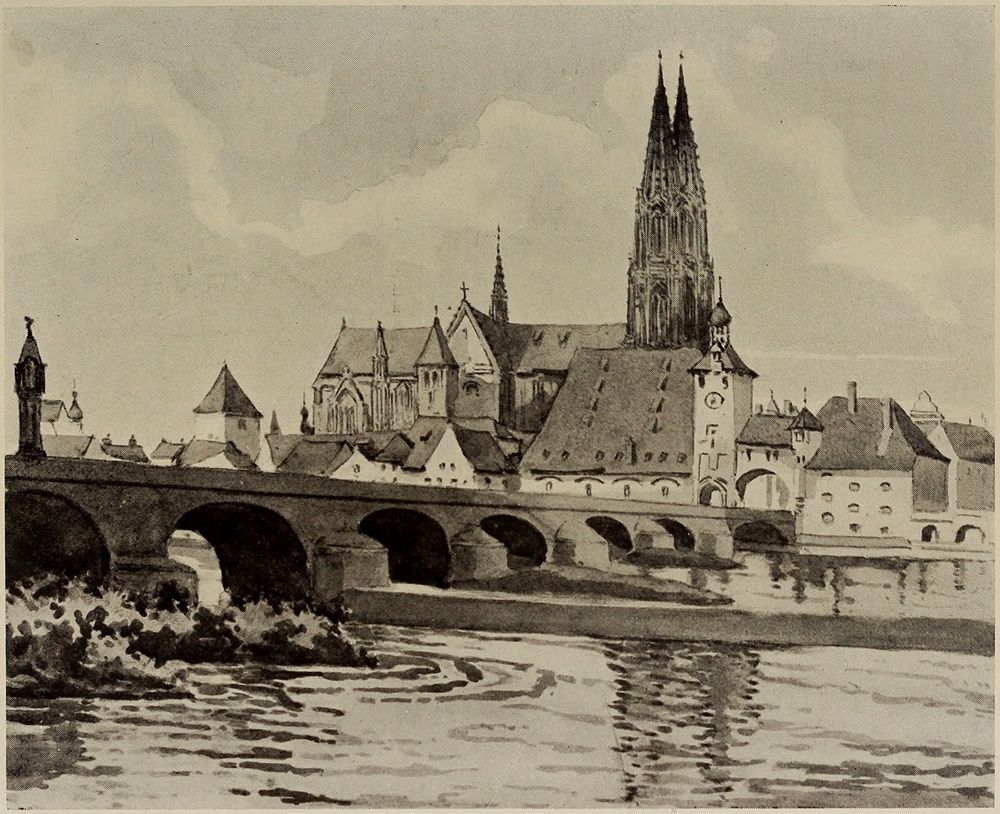

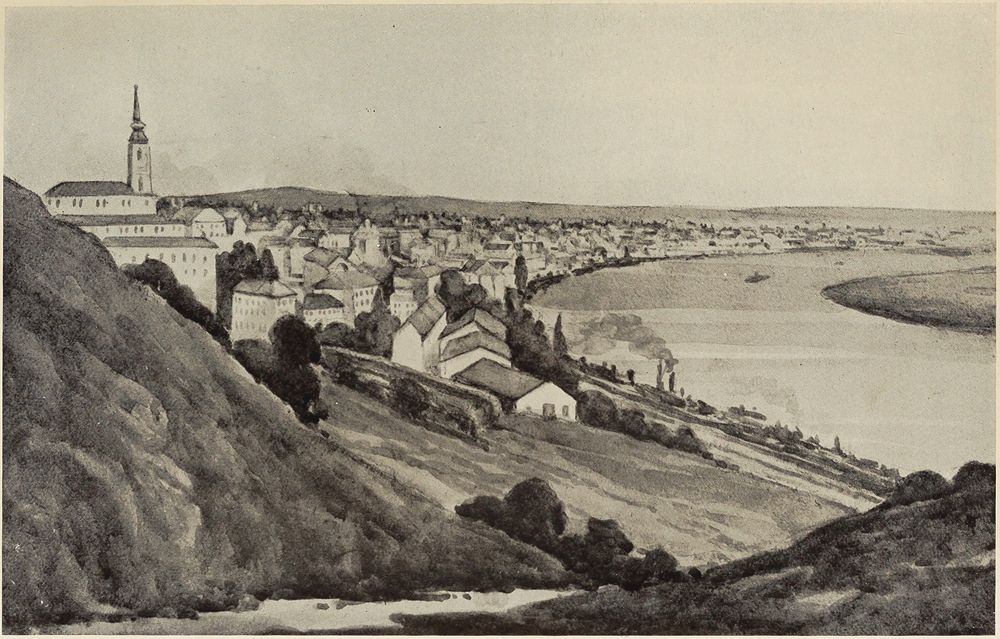

| Ratisbon | 28 |

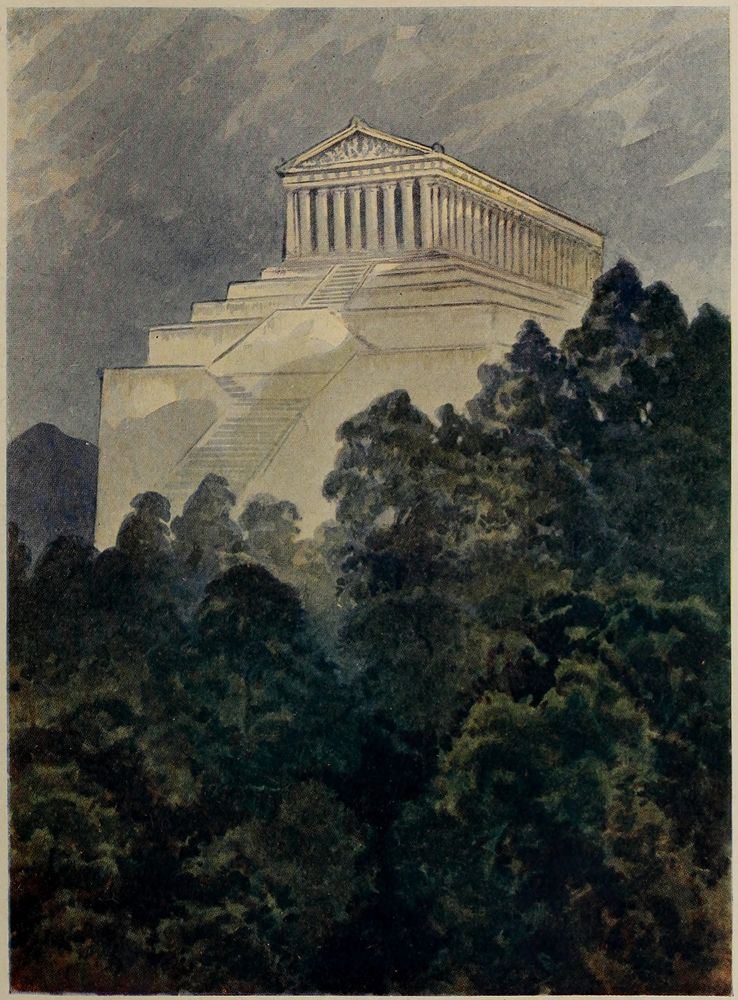

| The Walhalla (in colour) | 42 |

| Oberhaus and Niederhaus, Passau | 76 |

| The Strudel (in colour) | 110 |

| St. Nikola | 120 |

| Sarmingstein | 122 |

| Persenbeug | 126 |

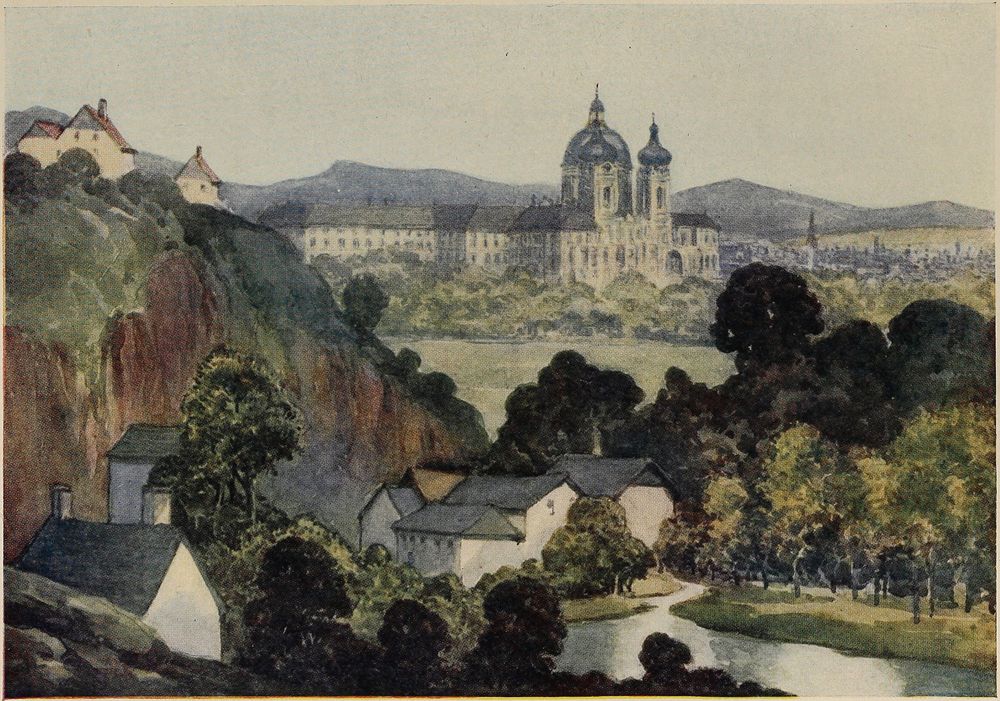

| Mölk (in colour) | 130 |

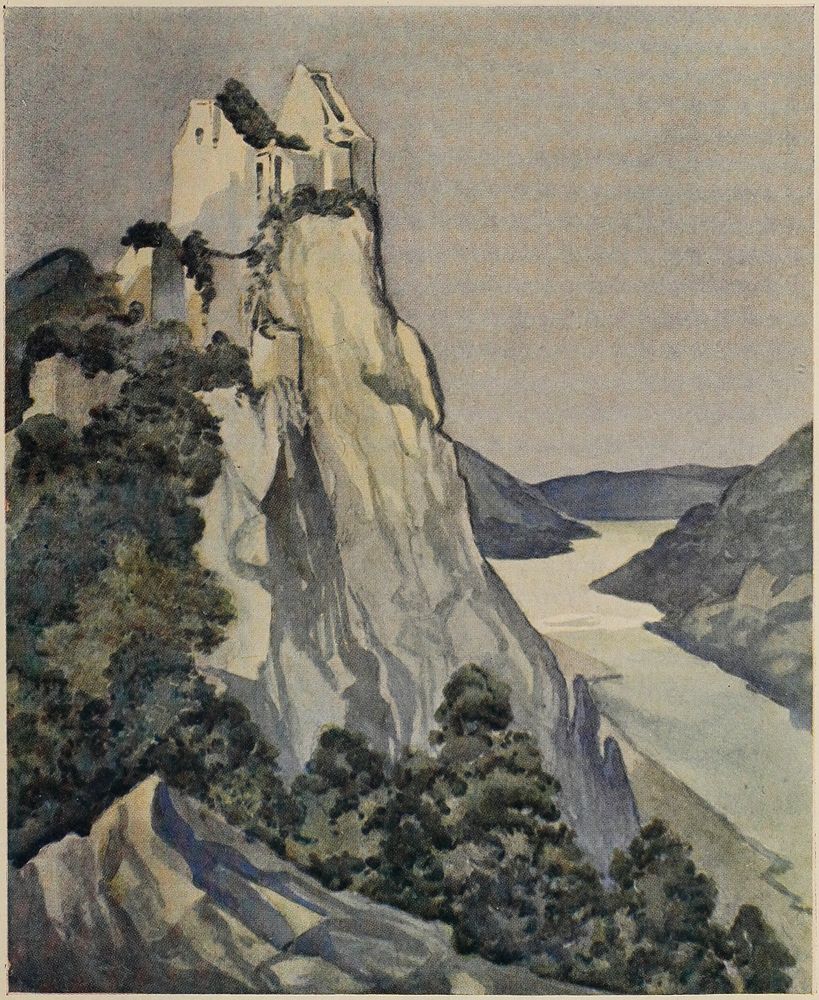

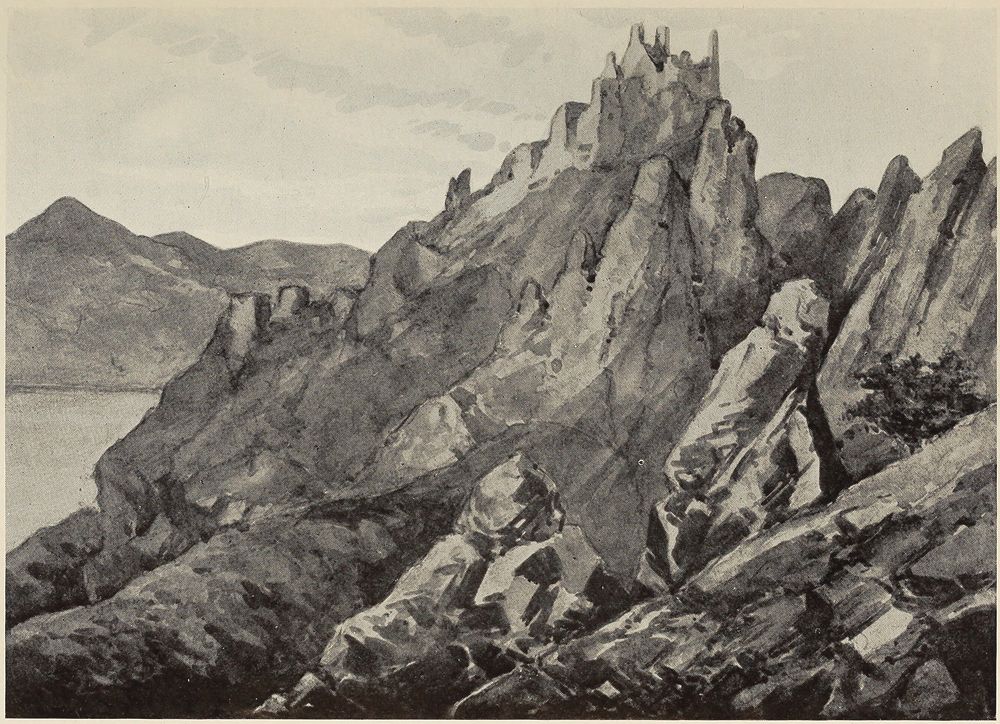

| Aggstein (in colour) | 134 |

| The Devil’s Wall | 138 |

| Spitz Vineyards | 140 |

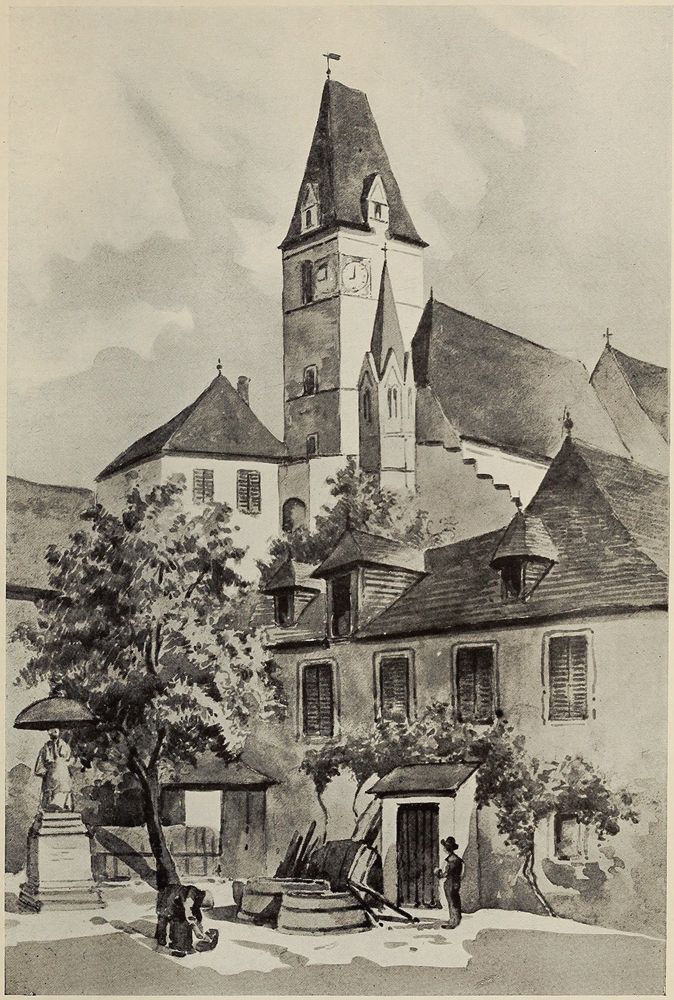

| Weissenkirschen | 142 |

| Dürrenstein | 148 |

| Dürrenstein Castle | 152 |

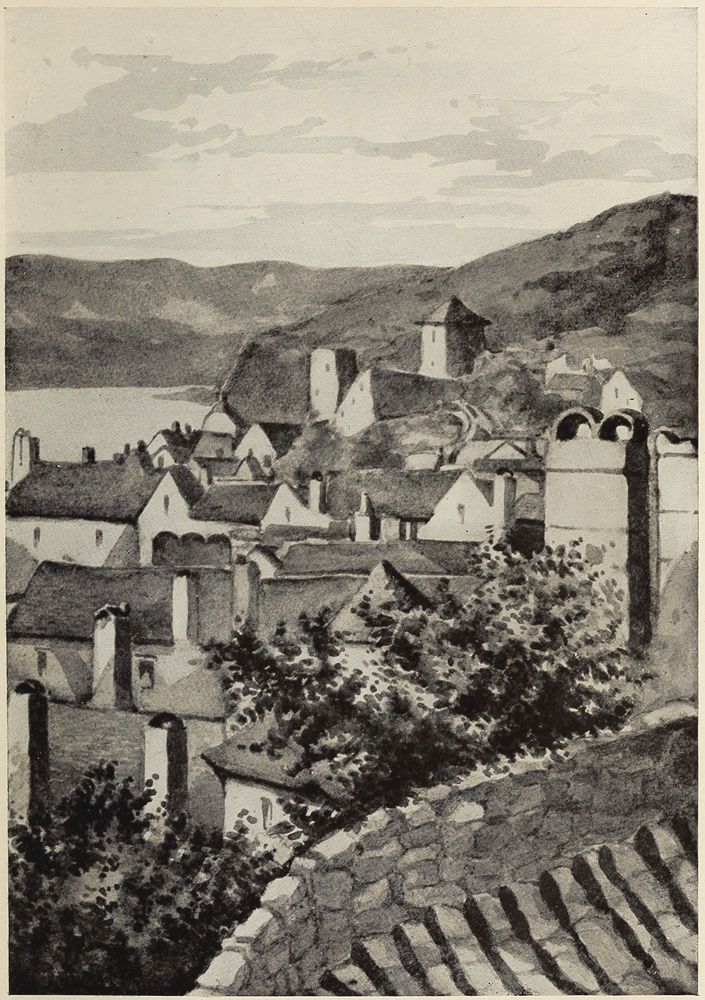

| Stein | 154 |

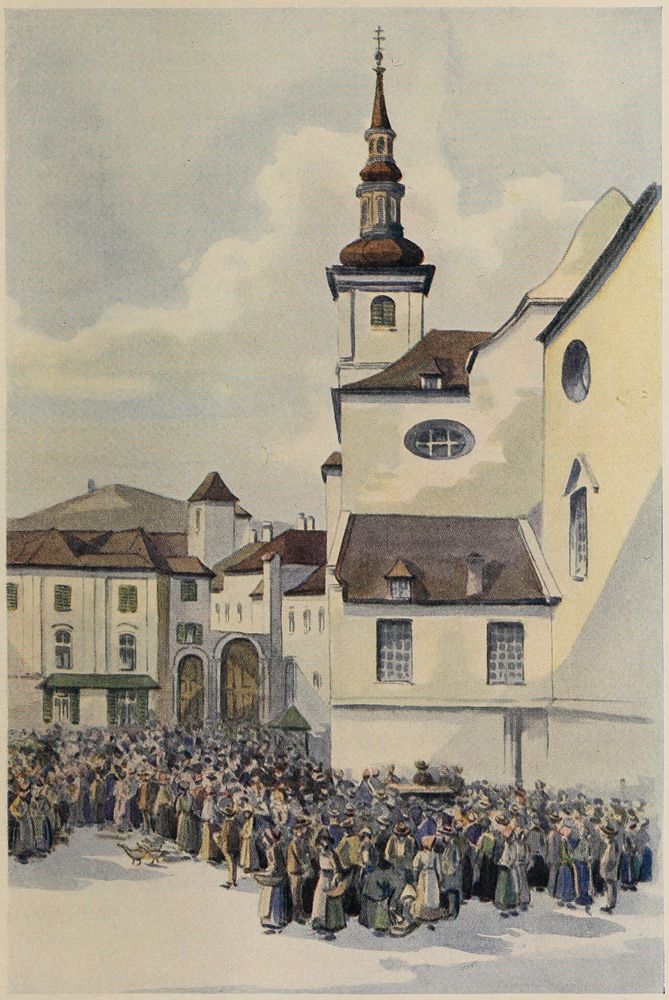

| The Market Place, Krems (in colour) | 156 |

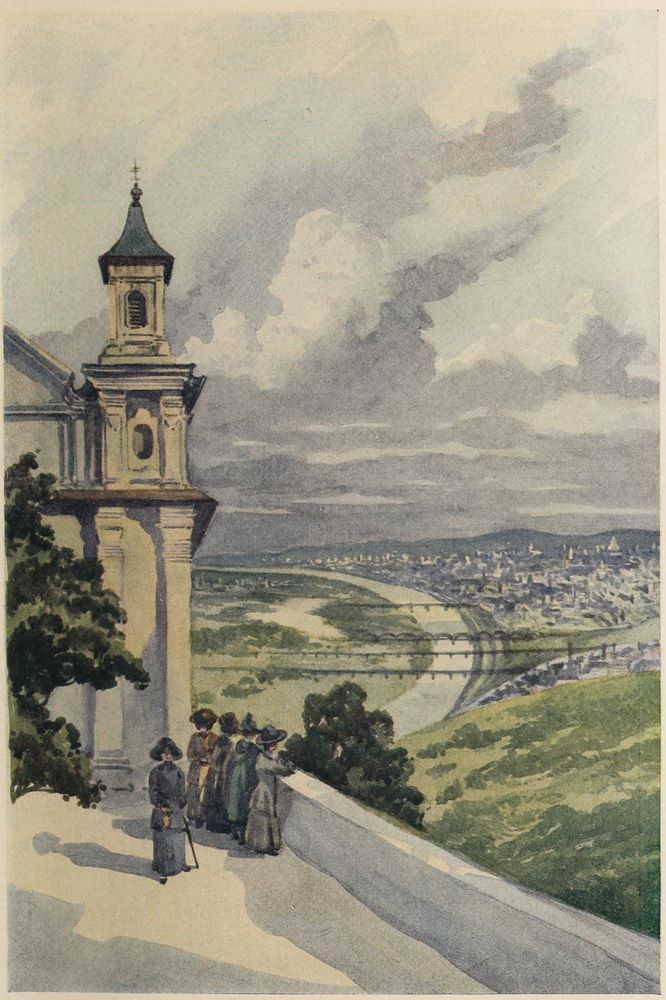

| Vienna from Leopoldsberg (in colour) | 174 |

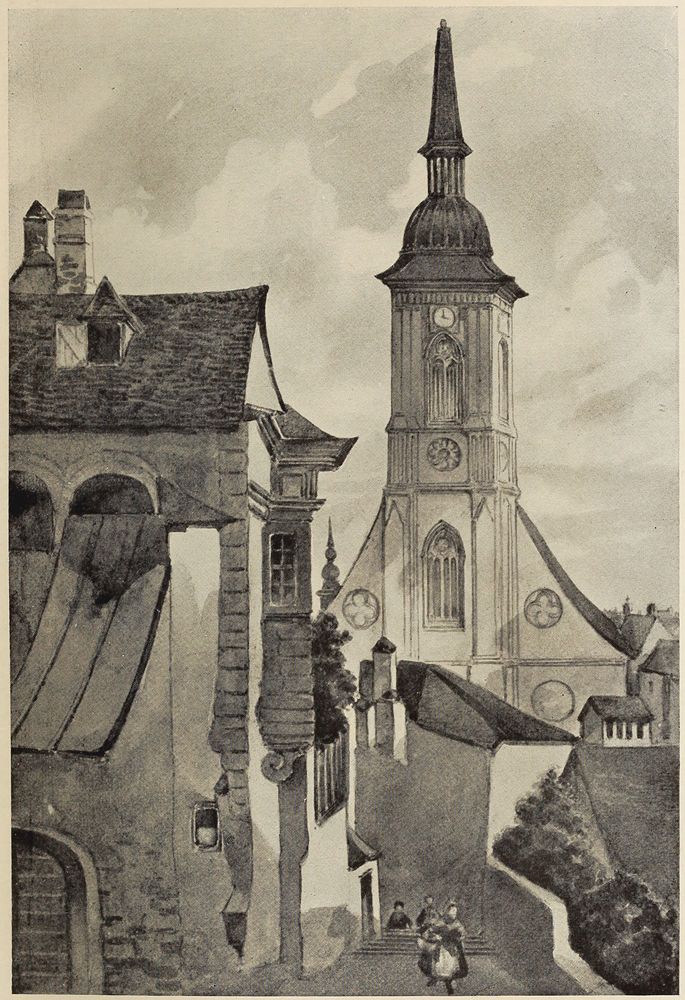

| The Cathedral, Pozsony | 188 |

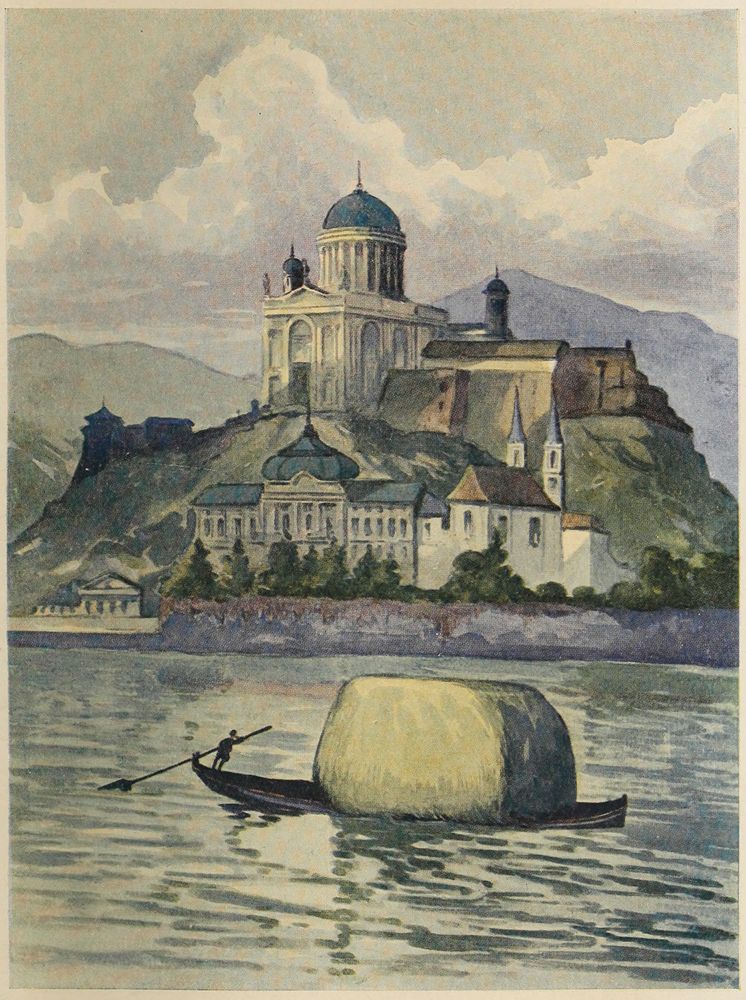

| Gran (in colour) | 200 |

| The Palace, Budapest (in colour) | 216 |

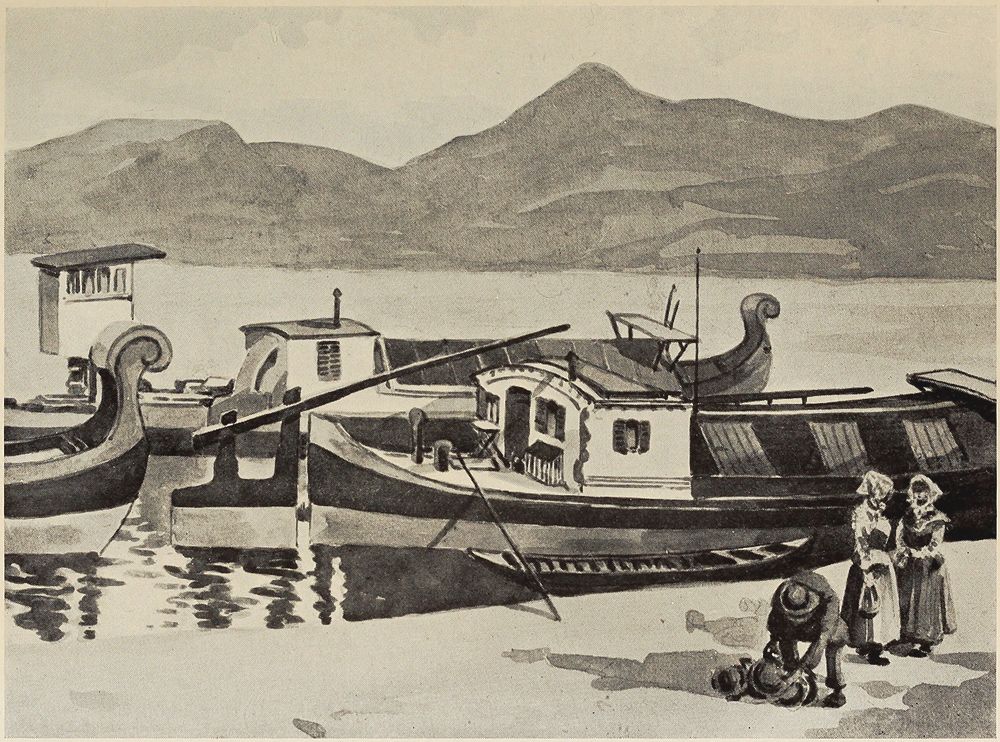

| Boats from Szegedin | 230 |

| Belgrade | 240 |

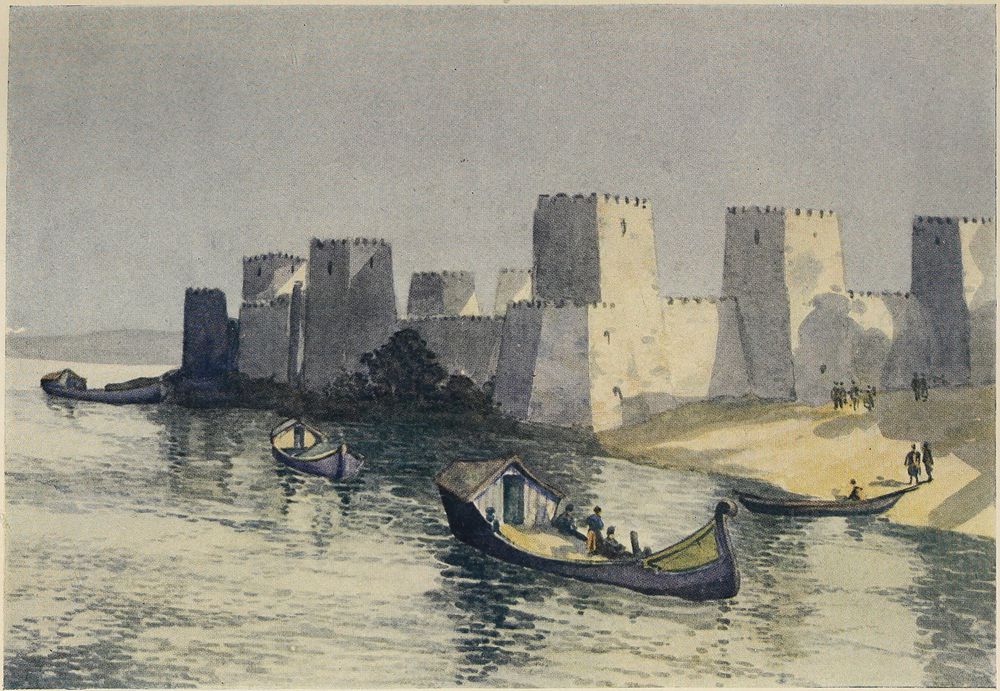

| Old Turkish Fort, Semendria (in colour) | 244 |

| Báziás | 246 |

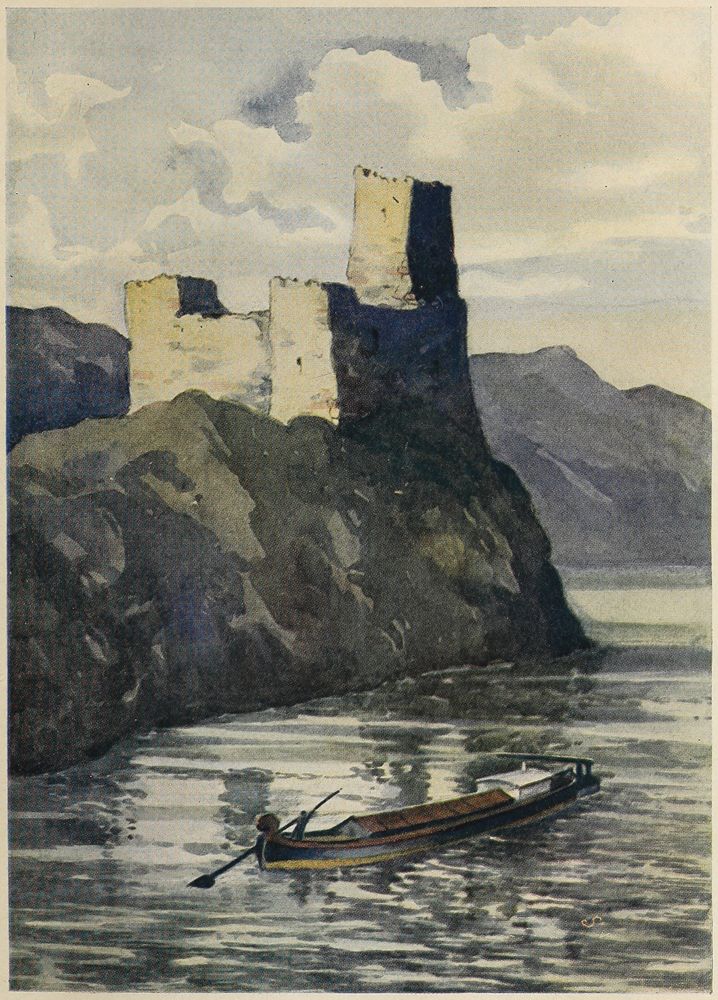

| Rama Castle (in colour) | 250 |

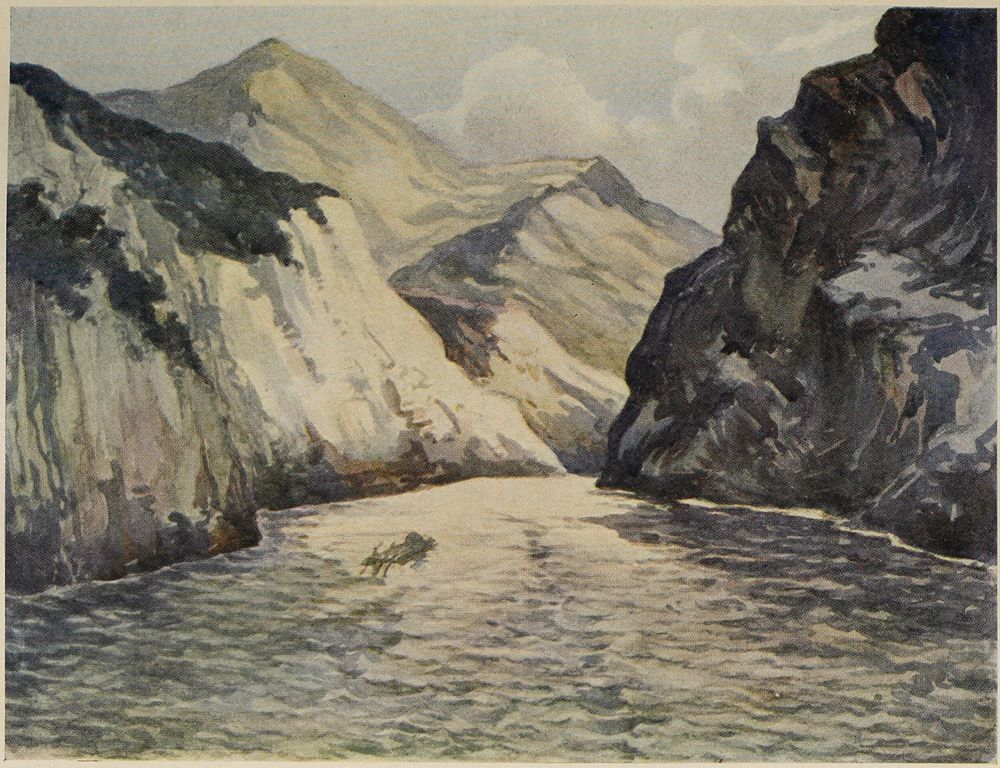

| The Kazan (in colour) | 256 |

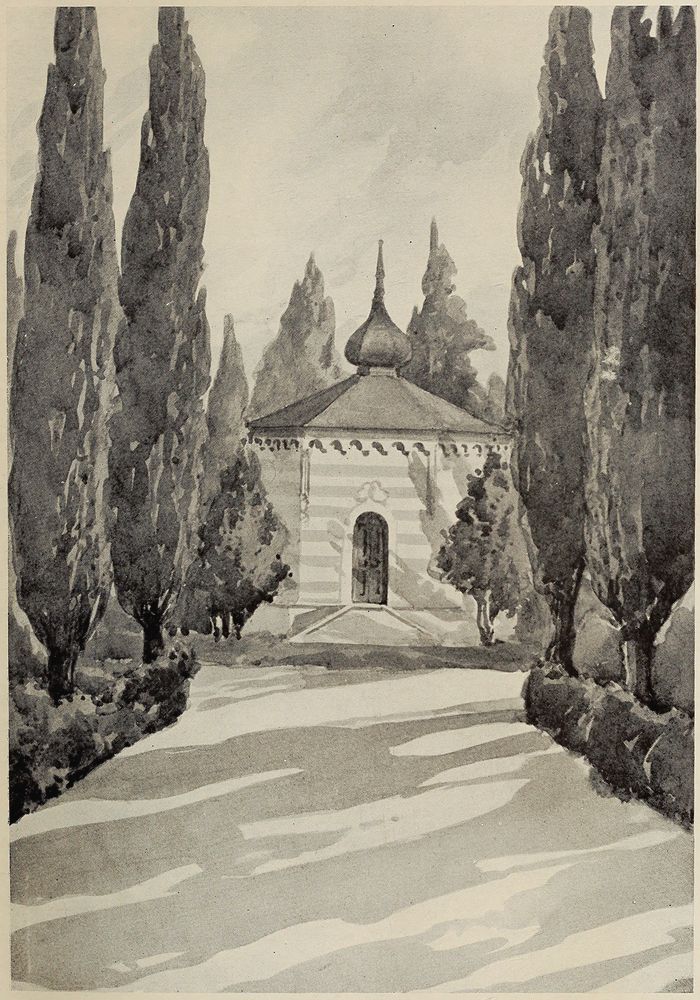

| The Crown Chapel, Orsova | 260 |

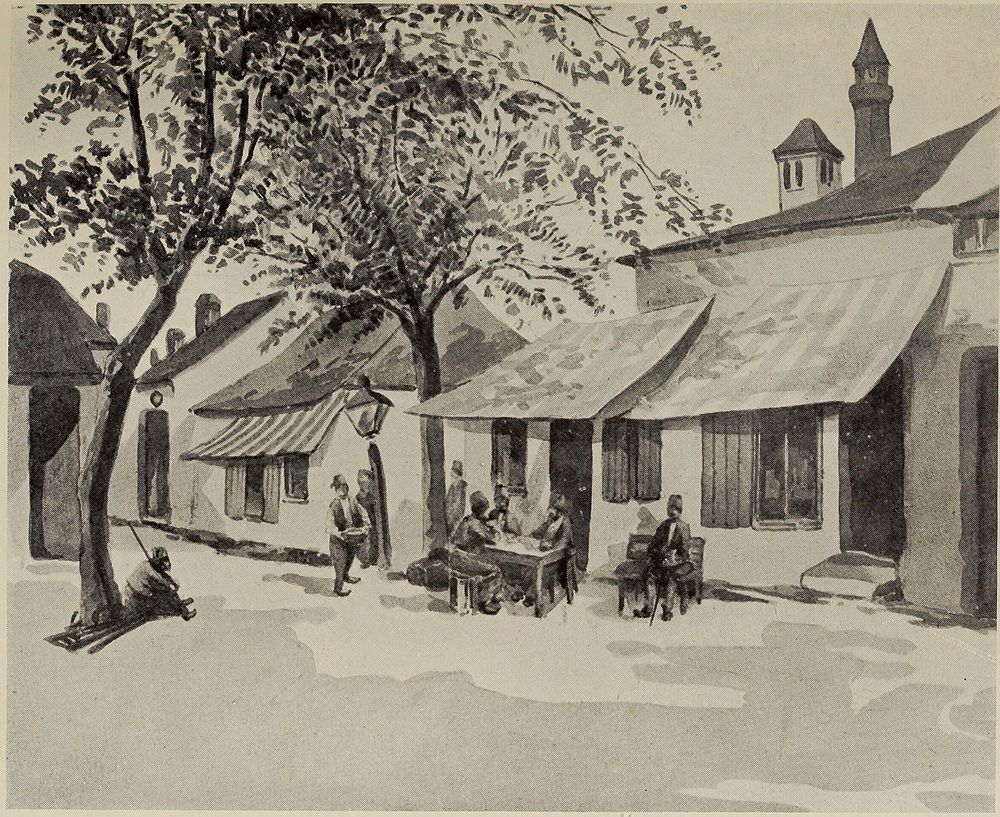

| A Café in Ada Kaleh | 262 |

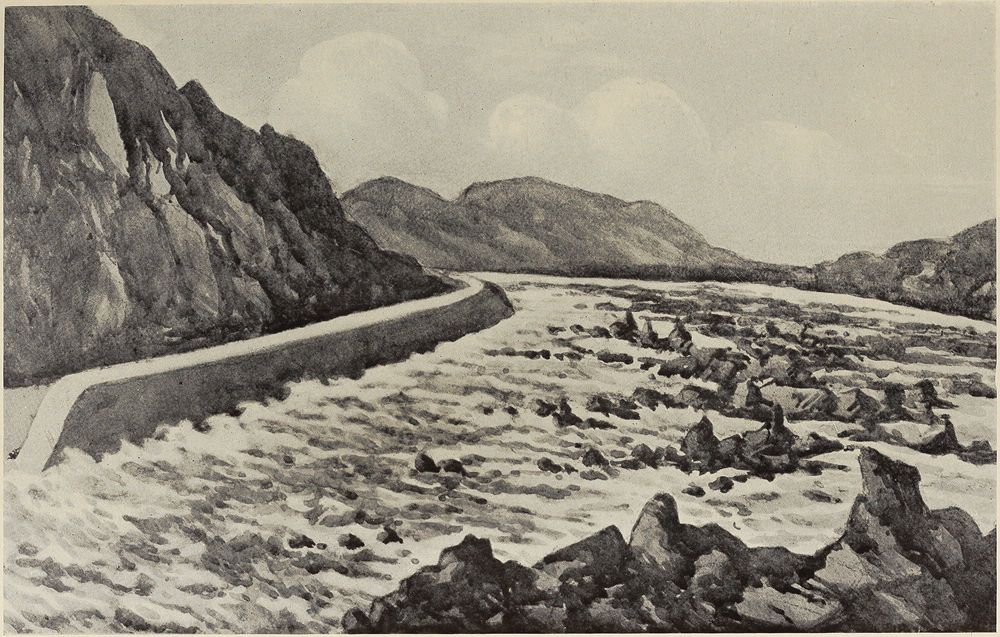

| The Iron Gate | 272 |

“The Danuby, the river sometimes of our merry passage”

Sir Henry Wotton

[Pg xv]

[Pg xvi]

[Pg 3]

THE DANUBE

If it cannot be said of the Danube as it was said of the Thames that it is “strong without rage, without o’erflowing full,” it can certainly be said that, like the Thames, two separate places claim to be the source of the river. These two places are St. Georgen and Donaueschingen—both of them in the Duchy of Baden, both of them in the district of the Black Forest (part of the great Hercynian forest, which in the time of Cæsar stretched from the neighbourhood of Basle into the boundless regions of the north), and both of them claiming that they are situated at the very place where the mighty river starts upon its long journey. Unfortunately for the claims of the former place, the stream that runs thence to Donaueschingen is named the Brigach; and it is only when that river joins with the Breg, which also rises not far from St. Georgen, that the name Donau or Danube is used. Geographically[Pg 4] perhaps, the source of a river being supposed to be that one of its streams which starts at the point furthest from its mouth, St. Georgen might be entitled to the honour, but custom and sentiment have long since granted it to Donaueschingen; and as that place embodies the river’s name, it is likely long to hold the honour—even as Thames Head will continue in the view of most people to have a better title to being considered the actual source of the Thames than Seven Springs.

The rivalry has not unjustly been described by one writer as a matter of Tweedledum and Tweedledee, for when the opposing advocates seek classical support the St. Georgenites can put Tacitus into the witness box, while the Donaueschingites can subpœna Strabo. It is a pretty little quarrel, and we may leave it at that. Another point that need not trouble us over its conflict of testimony is that of the derivation of the name, though it may be noted in passing that it has been variously derived from “Donner,” thunder; from “Tanne,” a fir tree; and from Celtic words “Do Na.” The last suggestion was surely put forward by an ingenious Donaueschingite, for once admit it, and the claims of St. Georgen are reduced to the ridiculous.

It is at the point where the Brigach and the Breg join that the Danube begins, and there at Donaueschingen is where our story of the river on its journey to the sea may also best begin. An old distich runs—

which may be Englished—

At the town in which is the “source” is a beautiful estate belonging to Prince Fürstenberg, a park which has been described as more like an English park than[Pg 5] any other on the Continent, and on the lake are many and various waterfowl including, says one veracious chronicler, swans which are the lineal descendants of the first ever introduced into Germany, it is supposed from Cyprus at the time of the Crusades. This is a curious statement seeing that swans are indigenous over the greater part of Europe. Museum, picture galleries and library are here, but for our present purpose the centre of interest is the spring or source, which has been enclosed, decorated with flowers and ornamented with allegorical statuary representing the Baar—the name of the parish—holding the young Danube in her arms “and whispering instructions for her journey.” Here, too, is an inscription recording the length of the river and the height of the source above the sea-level—

Steps lead down to the water, and there in accordance with an ancient custom the visitor is expected to drink of the Danube, though he is no longer expected to follow the mediæval plans either of leaping into the stream or pouring into it a cup of wine as an oblation or charm. From the source “the water, which is pure and limpid” is carried by a conduit to the Brigach, and at the point of junction the word “Donau” is inscribed—to remove any lingering doubts from the minds of those inclined to favour the St. Georgen heresy.

At Donaueschingen the ill-starred Austrian Princess Marie Antoinette, a child of fourteen, rested on her journey from Vienna to Paris—marriage and the guillotine.

Of the many hamlets, villages and small towns that the Danube passes, it will not be possible to say much, except where we pause to learn some ancient legend, some scrap of history, or to indicate things of special beauty or interest that are to be seen. In its first few[Pg 6] miles the course of the river takes us, as Mr. C. E. Hughes puts it, through “part of the Hegau, the land of towering, castle-crowned peaks, the land of legends and traditions innumerable;”[1] through Pfohren, with its Duck Castle, so named because it was built in the water, now fallen from its castle dignity, in a field near the river, and Geissingen with its old covered bridge. Most of the way from Donaueschingen to Ulm the railway closely follows the course of the river. Next comes Immendingen—whence the railway branches south through the mountains of the volcanic Hegau which forms the dividing watershed between the Danube and the Rhine where the two rivers most nearly neighbour each other.

A few miles below Immendingen is Möhringen, where some of the water of the Danube is supposed to percolate through the earth and reappear some distance to the south as the Aach, which flows into Lake Constance and so becomes part of the Rhine. Below Möhringen is Tuttlingen at the foot of the ruin-crowned Homberg, a prosperous town, and a good centre for excursions, but as an incident on the Danube, chiefly notable for a monument forming yet one more connexion with the Rhine; for here is to be seen a statue, erected nearly twenty years ago to Max Schneckenburger, author of the German national song Wacht am Rhein. Schneckenburger was born in 1819 at Thalheim, a village some miles to the west, and there he was buried thirty years later. From Tuttlingen the river follows a winding course to Mühlheim, on high ground to the right with a ruined pilgrimage church of Mariahilf beyond, and then, more tortuously still, crossed and recrossed by the railway to Fridingen. Beuron, the next place of any importance, is notable for its monastery of Benedictines which was originally founded in the[Pg 7] eleventh century by the Augustines, was suppressed at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and made over to the Benedictines about fifty years ago. On a height to the south of Beuron is a notable château, and also within easy reach of the village is a large grotto known as Peter’s Cavern.

Through a narrow and beautiful valley the river goes on by wooded hills and pleasant, picturesque villages, with ruined castles now and again standing boldly on the rocky heights. Near Gutenstein are the towering rocks of Rabenfels and Heidenfels. The river, winding to and fro among the hills, is more or less closely neighboured, as has been said, by the railway; while from Tuttlingen to Sigmaringen the course of the stream may be followed by the pedestrian who has leisure—and to him alone is it given to enjoy all the beauties of this picturesque stretch of the Danube. Sigmaringen itself is a town on the right bank that affords a fine centre for exploring the river up or down-stream, and among the things of interest to be seen here is Prince Hohenzollern’s Schloss, situated on a precipitous rock immediately above the Danube, with pleasant hills on the further side of the river. In the Schloss is an admirable museum and picture gallery. On the high Brenzkofer Berg, on the left side of the river, is a monument to the Hohenzollerns killed in the war of 1866 and the Franco-Prussian War and from it is to be had a good and extensive view.

After Sigmaringen is left behind the valley is less narrow, and the river goes on past small villages and old towns, each of which has no doubt its interest for the leisurely pedestrian. Beyond Reidlingen on the left bank is seen on the right the isolated hill of Bussen, from the summit of which is to be had a view embracing the whole of Upper Swabia and much of the Alps. On the hill is a pilgrimage church and a ruined castle The ruined castles are so numerous along parts of the[Pg 8] river that is not possible to pause at all; for it would appear as though in the good old times the population largely consisted of castle-dwelling barons. Zweifaltendorf has a stalactite cave; Rechtenstein, with another ruined castle, is a notably beautiful spot; Ober-Marchtal has a grand old Premonstratensian monastery; while Munderkirchen, built upon a rock islanded by the forking river, has a new stone bridge with an arch span of one hundred and sixty-four feet. Beyond this the valley is wider. At the village of Ehingen, the railway turns northward from the river, which between here and Ulm receives several affluents from the south, including just before Ulm the Iller, while at Ulm itself, the river Blau comes in from a delightfully wooded and rocky valley on the left.

Ulm, the frontier town of Würtemburg, is important in the story of the Danube for a variety of reasons. In the first place, it is here, fourteen hundred feet above sea-level, that the river becomes effectively navigable for flat-bottomed boats of about a hundred tons, and thus it is the centre of a brisk trade. Then it is a picturesque old city, with many ancient houses still to show, and it was long regarded as a strategic point of great importance, and, therefore, was maintained as a fortress of first rank. It was said, some years ago, that it was capable of sheltering within its fortifications a force of a hundred thousand men. Latterly, it has developed as an industrial and commercial centre, and the ramparts have been acquired by the town for peaceful purposes.

Among all that the city has to show the visitor, the ancient Gothic cathedral—the many striking features of which call for a guide-book’s help and cannot be touched upon in this gossiping chronicle—stands out most prominently. “Long before reaching Ulm the old cathedral, with its massive but unfinished towers, attracts[Pg 9] the attention of the traveller as seen from the road, and the first view of the dark rolling Danube which is obtained before reaching Ulm, is at first sight a grand and imposing object”—thus, in dubious English, wrote a traveller arriving from Augsburg some years ago. Since that was written, the beautiful great tower on the western side with its wonderful sculptured doorway, and wealth of figures has been completed in accordance with the fifteenth century design left by the last of the original architects. This work of completion occupied thirteen years (1877-1890) and now the tower, 528 feet in height, has the distinction of being one of the loftiest in the world—thirteen feet higher than that of Cologne cathedral and twenty-seven feet lower than the Washington Monument. From the tower is to be had an extensive view, said to take in the historic battleground of Blenheim, past which the Danube flows some thirty miles away. Writing seventy years ago, a visitor declared that if the tower could be completed, it would be one of the finest in Europe, and such it is now acknowledged to be. The cathedral itself is the second largest in the German Empire, being exceeded only by that at Cologne, and it is supposed to be capable of containing as many as thirty thousand persons.

As is fitting in a place regarded as of great military importance, Ulm figures in the annals of war. It was hence that the Elector of Bavaria set out for the famous battlefield of Blenheim some distance down the river, and it was here that the Austrian General Mack shut himself up with a force of over thirty thousand men to stay Napoleon’s rapid advance on Vienna in 1805. Despite the importance of Ulm, despite the formidable army he had with him—with ample provisions and ammunition—Mack surrendered the town almost without striking a blow; “yet somehow he was suffered to escape[Pg 10] the punishment of which he was thought to be richly deserving.”

If, thanks to the action of one man, the military annals of Ulm are thus in part inglorious, it has the distinction of remarkable association with one of the oldest of the arts of peace. It was here that the “Meistersänger” lingered longest, “preserving without text and without notes the traditional love of their craft.” It is true that the Meistersänger lacked on the whole the freshness and fascination of their forerunners the “Minnesänger,” but their story forms an interesting chapter in the history of the literature of their land, though a German historian of German literature has sneered at them as “chiefly burghers of towns ... prudent though uninspired votaries of the Muse,” and has declared that in their work “the real soul of Poetry was wanting.” It is, however, interesting to know that for nearly five centuries there were burghers to keep the idea of poetry alive if no more, and to know that here in Ulm there remained in 1830 a dozen of the Meistersänger. Nine years later there were but four, and they in 1839 formally made over their insignia and other guild property to a modern singing society. The last formal meeting of the Meistersänger had taken place in 1770.

Ancient Ulm was on the left bank of the Danube—the old city wall along the river front affords a pleasant walk—but now it may be said to include Neu Ulm on the right bank; indeed for military purposes the two were some years ago made one, though the old town is in Würtemburg and the new one in Bavaria.

It was at Elchingen, just below Ulm, that Marshal Ney won the victory that caused General Mack to surrender the city and gained for the victor, Napoleon’s brave des braves, the grand eagle of the Legion of Honour and the title of Duke of Elchingen. Beyond the scene of the battle of October 14, 1805, the river[Pg 11] traverses for many miles the extensive marshlands of Donaumoos and Donauriet, closely neighboured by the railway. About fifteen miles below Ulm, picturesquely situated on the right bank on a hill overlooking the extensive Donaumoos on the further side, is Gunzburg, on the site of the old Roman station of Guntia. This place should be additionally interesting to English visitors as having long possessed a nunnery, founded here, it is supposed after a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, by an English woman named Maria Ward. Lauingen and Dillingen are small, attractive old towns. The first was the birthplace of Albertus Magnus—a celebrated scholar whom we shall meet again on our downward journey along the river—of whom a bronze statue is to be seen in the market place.

The next places, Höchstäd and Blindheim, on the left bank, though small, loom large in history as the scenes of decisive battles. As long ago as the eleventh century two battles were fought here between the Emperor Henry IV., and the Bavarian Guelph I., when the latter was defeated and lost his dukedom. Then, in 1703, the Elector of Bavaria and Marshal Villars defeated the Austrians, and but a short interval elapsed before the Danube villages found themselves, in August, 1704, once more, thanks to the great military genius of the Duke of Marlborough, the scene of one of the “fifteen decisive battles of the world,” a battle on which, according to one historian, the fate, not only of Europe, but of progressive civilization depended. The village of Blindheim or Blenheim was strongly occupied by the French, and the French-Bavarian army occupied the ground on the north to beyond the village of Lutzingen, while on the eastern side of the slight valley of the Nebel, the little stream which runs into the Danube at Blenheim, were the allies under Marlborough. It is not necessary here to tell the story. Is it not told in all the[Pg 12] history books, and at length in the biographies of the great commander, and in Creasy’s “Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World”? It may, however, be well to recall the words in which Alison in his “Life of Marlborough” emphasizes the decisiveness of the battle.

“Had the French triumphed,” he says, “the Protestants might have been driven, like the Pagan heathens of old by the sons of Pepin, beyond the Elbe; the Stuart race, and with them Romish ascendancy, might have been re-established in England; the fire lighted by Latimer and Ridley might have been extinguished in blood; and the energy breathed by religious freedom into the Anglo-Saxon race might have expired. The destinies of the world would have been changed. Europe, instead of a variety of independent states whose mutual hostility kept alive courage, while their national rivalry stimulated talent, would have sunk into the slumber attendant on universal dominion. The Colonial Empire of England would have withered away and perished, as that of Spain has done in the grasp of the Inquisition. The Anglo-Saxon race would have been arrested in its mission to overspread the earth and subdue it. The centralized despotism of the Roman Empire would have been renewed on Continental Europe; the chains of Romish tyranny, and with them the general infidelity of France before the Revolution, would have extinguished or perverted thought in the British islands.” Voltaire summed up the battle of Blenheim which “dissipated for ever Louis the Fourteenth’s once proud visions of almost universal conquest” in the following words: “Such was the celebrated battle which the French call the battle of Hochstet (Höchstäd), the Germans Plentheim (Blindheim), and the English Blenheim. The conquerors had about five thousand killed, and eight thousand wounded, the greater part being on the side of Prince Eugene.[Pg 13] The French army was almost entirely destroyed: of sixty thousand men, so long victorious, there never reassembled more than twenty thousand effective. About twelve thousand killed, fourteen thousand prisoners, all the cannon, a prodigious number of colours and standards, all the tents and equipages, the general of the army, and one thousand two hundred officers of mark in the power of the conqueror, signalized that day.”

Recalling the effect of the great battle we may also call to mind the passage in which Addison describes it in his poem in laudation of Marlborough:—

The correct periods, the conventional epithets of the author of “The Campaign” somehow leave us less moved than does the simple episode presented by a later poet, for it must have been of the little Nebel stream that Southey was thinking when he wrote his simple satire on military glory in “The Battle of Blenheim”:—

[Pg 14]

The poet’s “Old Kaspar” had not had the advantage of studying history in the light of Alison, and his satire has, it is to be feared, had little effect on war. Indeed, two years after the ballad was first published, further fighting was to take place in this very neighbourhood, when in 1800 Moreau cut off the Austrians’ routes into Italy, and so facilitated Napoleon’s Italian campaign.

At Donauwörth, on the left bank, we still have news of battle, for this old “free city” was stormed by Gustavus Adolphus in 1632 and was captured by King Ferdinand two years later, while it also played an important part in the preliminaries that led up to the battle of Blenheim, seeing that it was in this neighbourhood that Marlborough defeated the Bavarians and cut them off from their French allies.

His own account of the engagement was sent to the States-General in the following terms:

“High and Mighty Lords.—

“Upon our arrival at Onderingen, on Tuesday, I understood that the Elector of Bavaria had despatched the best of the foot to guard the post of Schellenburg, where he had been casting up entrenchments for some days, because it was of great importance; I therefore resolved to attack him there; and marched yesterday morning by three o’clock, at the head of a detachment of six thousand foot and thirty squadrons of our troops, and three battalions of Imperial grenadiers; whereupon the army begun their march to follow us; but the way being very long and bad, we[Pg 15] could not get to the river Wertz till about noon, and ’twas full three o’clock before we could lay bridges for our troops and cannon, so that all things being ready, we attacked them about six in the evening. The attack lasted a full hour: the enemies defended themselves very vigorously, and were very strongly intrenched, but at last were obliged to retire by the valour of our men, and the good God has given us a complete victory. We have taken fifteen pieces of cannon, with all their tents and baggage. The Count D’Arco, and the other generals that commanded them, were obliged to save themselves by swimming over the Danube. I heartily wish your High Mightinesses good success from this happy beginning, which is so glorious for the arms of the allies, and from which I hope, by the assistance of heaven, we may reap many advantages. We have lost very many brave officers, and we cannot enough bewail the loss of the Sieurs Goor and Beinheim, who were killed in the action. The Prince of Baden and General Thungen are slightly wounded; Count Stirum has received a wound across his body, but it is hoped he will recover; the Hereditary Prince of Hesse-Cassel, Count Horn, Lieutenant-General, and the Major-Generals Wood and Pallandt are also wounded. A little before the attack begun, the Baron of Moltenburg, Adjutant-General to Prince Eugene, was sent to me by his Highness, with advice that the Marshals of Villeroy and Tallard were marched to Strasburg, having promised a great reinforcement to the Elector of Bavaria, by way of the Black Forest, and I had advice, by another hand, that they designed to send him fifty battalions and sixty squadrons of their best troops. Since I was witness how much the Sieur Mortagne distinguished himself in this whole action, I could not omit doing him the justice to recommend him to your High Mightinesses to make up to him the loss of his general;[Pg 16] wherefore I have pitched upon him to bring this to your High Mightinesses, and to inform you of the particulars.

“Marlborough”

Donauwörth grew to be a place of such importance that it was for a time the seat of the Dukes of Upper Bavaria, until Duke Louis the Severe, who in 1256 had his wife beheaded on an unfounded charge of infidelity, removed his capital to Munich. It is suggested that the change of capital was dictated by the duke’s guilty conscience. In the church attached to the suppressed Benedictine Abbey of the Holy Cross here, is to be seen the sarcophagus of the unhappy, Desdemona-like Duchess Mary. The story runs that no sooner had the deed been perpetrated than incontestable evidence of the duchess’s innocence was forthcoming, and the conscience-stricken husband became grey in a single night:—

FOOTNOTES:

[1] “The Black Forest,” p. 276 (Methuen).

[Pg 17]

From the old capital of the old dukedom to Ingoldstadt the river for nearly forty miles finds its way through part of the Bavarian plain, another broad-stretching Donaumoos, or marshland, which has, however, been largely reclaimed and brought under cultivation. On the left bank much of the ground is higher and well wooded. Near Lechsend, which is on the left bank, the river Lechs comes in on the right—and a little way inland in the same direction is the village of Rain, where in March, 1632, the aged Bavarian General Tilly was mortally wounded in seeking to stay the triumphant progress of Gustavus Adolphus. In the following month Tilly died of his wounds at Ingoldstadt.

The village of Oberhausen on the right bank as the river nears Neuberg is associated with the memory of a remarkable “common” soldier who fell near there on June 21, 1800, and to whose memory a monument has there been erected. This was La Tour d’Auvergne—presumably a member of the family which had given France one of her most famous military leaders in[Pg 18] Turenne. It is said of d’Auvergne that he was “the darling of the army, the model of modern chivalry—a second Bayard.” He refused to be anything more than a common soldier, being satisfied with the title granted him by Napoleon in consideration of his gallant exploits, of “first grenadier of the French army.” “I am only proud,” said he, “of serving my country; I care nothing for praise or honour; my reward is in the consciousness of performing my duty; but thus to be praised to my face, it hurts my feelings—that word ‘consideration’ will be the torment of my life.” Having retired into private life during a period of peace, d’Auvergne came forward when the son of one of his old friends was drawn as a conscript, and insisted upon taking his place. Thus it came about that he took part in the fight near Oberhausen when, rushing ahead of his comrades to cut down the Austrian colour-bearer, he was surrounded by the enemy and transfixed by a lancer who attacked him from behind. “For three days the drums were covered with crape, and on the first Vendémiaire, his sword of honour was suspended in the Church of the Invalides at Paris. The forty-sixth demi-brigade from that time forward carried his heart in a silver box suspended to the colours of the regiment; and on every muster his name was recalled in these terms—Remember La Tour d’Auvergne who died on the field of honour!” A scrap of verses quoted by Dr. Beattie suggests that there existed something of another romance than that of his death.

The next place of note is Neuberg, a pleasant old town situated a few miles below Oberhausen on hilly ground on the right. This was of old the capital of a small principality; the handsome old castle rising above the varied roofs on the lower part of the bank is now partly used as a barracks, while the newer western portion erected in the early part of the sixteenth century is utilised for housing the local archives. The town is picturesquely placed, and has many antiquities of interest. Beyond lie further stretches of the Donaumoos, the next point with a history being the old and interesting town of Ingoldstadt which was at one time a place of considerable importance as the seat of a large university, founded in the latter half of the fifteenth century. At the beginning of the nineteenth the university was removed to Landshut and some years later to Munich. There are a number of interesting old buildings in the town and in the Ober-Pfarr-Kirche (1439) are to be seen monuments to Tilly and to Dr. Johann Eck, the great controversial opponent of Martin Luther. I have seen it recorded somewhere that the Duke of Marlborough, visiting Ingoldstadt was presented with a portion of the skull of Oliver Cromwell. If the incident be true, and the relic genuine, it would seem as though the whole skull which was a few years ago much discussed as Cromwell’s could scarcely have been his.

Below Ingoldstadt we have Mehring on the right bank and then on the left Vohenburg, with a large ruined castle, at one time the seat of a Margravate where the tragic marriage of Albert and Agnes, of which we shall learn more at Straubing, took place. Then[Pg 20] comes Pförring on the left, and Neustadt on the right. At Pförring, Kriemhilda, bound for the kingdom of the Huns and her marriage with Etzel, took leave of her brothers:

Neustadt is a good railway centre for a beautiful and interesting stretch of the river. A little below it on the same bank is Eining, a small place at one time of great importance as having been for nearly five centuries a frontier station of the Roman Empire, under the name of Abrisina, and now worth visiting for its remains of that station. Here was the junction of the military roads which connected the Roman territory along the Danube with the Rhine and Gaul. On the opposite side of the river is Hienheim from near which starts up the steep hillside the great Limes Romanus—the wall which was built by the Emperor Probus from the Danube to the Rhine, a wall according to Gibbon nearly two hundred miles, and according to another authority nearly three hundred and fifty miles in length. Says Gibbon:

“The country which now forms the circle of Swabia, had been left desert in the age of Augustus by the emigration of its ancient inhabitants. The fertility of the soil soon attracted a new colony from the adjacent provinces of Gaul. Crowds of adventurers, of a roving temper and of desperate fortunes, occupied the doubtful possession, and acknowledged by the payment of tithes the majesty of the Empire. To protect these new subjects a line of frontier garrisons was gradually extended from the Rhine to the Danube. About the reign of Hadrian, when that mode of defence began to[Pg 21] be practised, these garrisons were connected and covered by a strong entrenchment of trees and palisades. In place of so rude a bulwark, the Emperor Probus constructed a stone wall of a considerable height, and strengthened it by towers at convenient distances. From the neighbourhood of Neustadt and Ratisbon on the Danube, it stretched across hills, valleys, rivers and morasses, as far as Wimpfen on the Neckar and at length terminated on the banks of the Rhine after a winding course of near two hundred miles. This barrier, uniting the two mighty streams that protected the provinces of Europe, seemed to fill up the vacant space through which the barbarians, and particularly the Allemanni, could penetrate with the greatest facility into the heart of the Empire. But the experience of the world, from China to Britain, has exposed the vain attempt of fortifying an extensive tract of country. An active enemy who can select and vary his points of attack must, in the end, discover some feeble spot, or some unguarded moment. The strength as well as the attention of the defenders is divided; and such are the blind effects of terror on the firmest troops, that a line broken in a single place is almost instantly deserted. The fate of the wall which Probus erected may confirm the general observation. Within a few years after his death, it was overthrown by the Allemanni. Its scattered ruins, universally ascribed to the power of the dæmon, now serve only to excite the wonder of the Swabian peasant.”[2]

The remains of this great wall where it started from the Danube, known in German as the Pfahl-Graben, and sometimes as the Devil’s Wall, are to be seen little more than a mile below Hienheim. From here we have for some miles a lovely bit of the Danube, with grand[Pg 22] forest-covered hills in the immediate neighbourhood, and the river following a winding course through them—part of the way between precipitous rocks rising ruggedly three or four hundred feet above the water. A short distance down on the right bank and close to the shore is the extensive Benedictine Monastery of Weltenburg dating from the eighth century, but turned in the middle of the nineteenth into a brewery. Dr. Beattie describes how, after some one had expatiated on the past glory of the place, a bystander said “It is written that Weltenburg shall rise again like a phœnix from its ashes; that the pilgrim shall again bow at its altar; that the abbot shall preside at its chapter; and——”

He was interrupted by a Bavarian sitting by with “Never! your abbots were mere men—sinners like others, and if they possessed any fervour, it was but the natural warmth of the grape. I have listened with much patience to what you have heard about the crusades, and so forth; but I also know a little of the history of the place; for, as ‘successor to the abbots,’ several documents have fallen into my hands, which assure me that they will never resume their old quarters; and one of the strongest reasons is, that the old cellars are empty; the old vineyard uprooted, and that our Bavarian beer is too cold for their stomachs.... Depend upon it, sir, if the abbots of old had restricted themselves to such virtuous potations, and been a little more chary of politics, I had not this day been the ‘brewing abbot of Weltenburg.’ These abbots, sir, were jovial fellows; most of them had worn casques in early life, and, although afterwards taking shelter under the cowl, ended with the cask at last. In my early days, one of their drinking songs was a special favourite at the Wirthshaus, and seems almost prophetic of the brewery that was to come. It is still a favourite.

[Pg 23]

As we near Kelheim a striking building takes the eye; this is the fine dome of the Befreiungshalle, which rises from woodland on the summit of the Michaelsberg on the rocky left bank. This grand classical edifice (the “complement” of the Walhalla which we shall see below Ratisbon) was built for Louis the First, of Bavaria. It was founded in 1842 and opened just twenty-one years later, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Leipzig. Its name, the Hall of Liberation, indicates the purpose for which it was erected—to commemorate the freeing of the country from foreign domination by the final overthrow of Napoleon. On the columned outer walls great female figures each nearly twenty feet high stand as emblems of eighteen German provinces, while within the great marble rotunda are thirty-four representations in Carrara marble of the Genius of Victory designed by Schwanthaler, between each pair being a bronze shield made from captured French guns and inscribed with the names of battles won. Other inscriptions include[Pg 24] the names of great generals and of captured fortresses. From the external gallery is to be had a grand view up and down this lovely bit of the Danube, over the town of Kelheim and the valley of the river Altmühl which here joins the Danube.

Between Weltenburg and Kelheim the abruptly rising rocks topped with trees that border the river have been given various names owing to their fancied resemblance to the thing from which they are named—the “Lion,” the “Bishop,” the “Crocodile,” the “Pulpit,” “Peter and Paul,” and so forth. This part of the river can only be explored by boat, which should be taken from Hienheim to Kelheim, and not in the reverse direction owing to the slowness with which boats can go up-stream. As there is no pathway by the river-side owing to the precipitous nature of much of the limestone cliffs which rise sheer from the water, the boatmen going up-stream through the Lange Wand, as the defile is named, have to pull themselves along by the aid of rings, fastened for that purpose in the rocky walls. There have not been wanting enthusiasts who describe this as the finest part of the river from its source to the Black Sea.

Kelheim, backed by the forest, is on the low land at the foot of the hill on which the Befreiungshalle stands, and at the junction of the Altmühl with the Danube. Here too the Ludwig Canal which joins the Main with the Danube, reaches the latter river, thus, as it were, enislanding the town. Kelheim is an old place with remains of an old Roman tower, a castle of the Dukes of Bavaria, now used for government offices, and other visible evidences of its one-time importance. From Kelheim to Ratisbon is about twenty miles—the railway keeps fairly close to the river for most of the distance—of pleasant scenery along the winding stream. The first half of the journey is flat, the second between[Pg 25] low hills. Opposite Kapfelberg with its limestone quarries on the left bank—whence was taken the stone of which Ratisbon cathedral and bridge are built—is the Teufelsfelsen. Shortly before reaching Abbach on the right is to be seen the memorial erected in 1794 to commemorate the making of the road along the river here. This memorial takes the form of a large tablet inscription on the rock face, with in front, on the bank raised upon massive pedestals, two large couchant lions carved in stone, “one looking into the river, the other apparently trying to make out the inscription.” Abbach itself is an attractive village amid greenery dominated by its slender-spired church, with the remains of an ancient castle—one of the “common objects” of a long Danube journey. This is Heinrichsburg, or King Henry’s Castle and is interesting as the birthplace of Henry the Second (canonized for his many benefactions to the Church) and as one of the seats of his splendour as King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor. In his age the monarch turned to the consolations of religion, in expiation it is suggested in the following lines of earlier crimes:

[Pg 26]

Oberndorf, a little distance below Abbach, is chiefly to be recalled for a tragic act of vengeance and its remarkable consequences. Hither Count Otto of Wittelsbach, who in 1208 had murdered the Emperor Philip at Bamberg, fled, and here he was overtaken and slain. The long story of the subsequent marvels may be summarized as follows. The murderer being killed, his head was cut off and thrown into the Danube, but either the river refused to accept the grisly object or Count Otto’s passion, strong in death, still animated the severed head, for “refusing to sink or move down with the current, it continued to gnash its teeth, and to fix its glaring eyes on the spectators with a menacing look, which none but the ‘black friar of Ebrach’ could withstand.” The friar, holding in his hand a black cross (which had been brought by an eagle from Calvary!) went to the river bank and addressed the floating head in the following awful words: “Dus. milabundus. Dom. infernis. presto, diabolorum!” on hearing which the head whirled round, shook its clotted locks, and sank, plump to the bottom of the river! The good people of Oberndorf fell upon their knees at the miracle, in thankfulness at having got rid of the uncomfortable spectacle. That night and the following day, however, blue flames were observed playing over the surface of the water where the head had unwillingly disappeared. The black friar of Ebrach was, however, again equal to the occasion, for he planted the black cross on the river bank opposite the manifestation, and in seven days the flames had entirely disappeared! The head having thus been finally disposed of, the body of the Count Otto was left exposed on a bare rock—thenceforward to be known as “the Murder Stone”—to pass into decay, the spot being duly respected as a haunted one:

Through a few miles of delightful and quietly picturesque scenery, the Danube winds on from this haunted spot towards Ratisbon. And as we near that city, beyond the suppressed Benedictine monastery of Prüfening, near where the railway crosses the Danube, the rapid stream passes round several small islands. Just beyond the railway bridge, the Naab comes in on the left from an attractive valley, and low hills on the same bank mark the journey round the next bend which brings us within sight of the bridges and towers of Ratisbon itself.

Most of the earlier describers of the Danube began the account of their downward journeying at Ratisbon—except the adventurous three who navigated the “Water Lily,” and they joined the great river by way of the Main and Danube Canal, and so reached the latter stream at Kelheim. If we look at the general map of Europe it is easy to recognize why this should be so, and even now, probably, most tourists intending to take the passenger steamers from where they start at Passau make first for Ratisbon, and they are all well rewarded by so doing. Though it is the many old houses and towers, the twin crocketed spires of delicate openwork of the cathedral, the many nooks and corners and amazingly artistic “bits” that impress us when we wander about the town, it is here the river that claims our first attention. The wonderful “blue” river, seen as I saw it here under heavy grey skies, shows of a warm green colour—a green on the yellow side of greenness. Strauss’s waltz has impressed the “blue” Danube on our minds most persistently, yet here again and again we find ourselves commenting on its greenness and even its greyness, and wondering why it should have got its reputation for blueness. Inquiry of the captain of a[Pg 28] Danube steamer settled the matter. “If you want to see the Danube really blue you must come to it in the winter,” said he.

When we stand in autumn on the fine old twelfth century stone bridge-built, says tradition, by the devil—or walk about the long islands Ober Wöhrd and Unterer Wöhrd—islands which are really one, being connected by a narrow spit of land—it is the wonderful yellowish greenness of the rapidly swirling water that strikes us, that and the rapidity of the current which, as it is forced into narrow channels by the isletted piers of the bridge, whirls and swirls onwards, breaking into white foam. The bridge rises gradually to where, about the centre of it, there is on the western parapet the statue of the “Brückenmännchen,” the “little bridge man,” or naked figure of a boy seated astride a wedge of stone, and with hand shading his eyes, looking at the cathedral spires. It is an ingenious piece of statuary, for even as if one person pauses in the street and looks upwards, other passers-by will inevitably do the same, having reached this point on the bridge we almost instinctively turn to look in the direction the “Mannchen” is ever looking, and doing so we get a beautiful view of the old town dominated by the beautiful spires, the Golden Tower and other high buildings rising from a grand medley of roofs, while in the foreground is the quaint old stone gateway through which we reach the bridge, close-neighboured by a fine steep stretch of dark tiled roof, broken by its little dormers—presumably for ventilating purposes. Looking up-stream from here, we have the Ober Wöhrd, largely covered with buildings, and on the further side of it a pleasant tree-grown branch of the river with low green hills and woodlands in the distance. From the nearer of these hills, by the village of Winzer, is to be had a beautiful general view over the whole of Ratisbon.

REGENSBURG

[Pg 29]

Looking down-stream, just below the bridge is the Unterer Wöhrd, also with many buildings on it, and a mill, the great wheel of which is seen incessantly turning with the ever hasting stream. Both up and down-stream the view is broken by an ugly iron bridge, for each of these islands is thus connected with the city. At the further end of the stone bridge is Stadtamhof, an old town which has suffered much in the course of the warfare of which Ratisbon has been so often the scene; it was destroyed by the Swedes during the Thirty Years’ War, and was burned down by the Austrians in 1809. It has thus nothing of special interest to show the visitor, though when the market of covered booths down the broad main street is in full swing, it is a picturesque and animated scene. Crossing the bridge one may justly recall Napoleon’s words: “ Votre pont est très désavantageusement bâti pour la navigation.”

While on the bridge it may be as well to repeat the full legend which ascribes its building to the devil. It runs that the architect of the cathedral had a particularly clever apprentice, to whom he delegated the task of erecting a stone bridge across the Danube. The young man set to work with great self-confidence, making a bet with his master that the bridge which he was about to begin would be completed before the coping-stone was laid on the cathedral which was already far advanced. The cathedral continued to grow with such rapidity that the bridge-builder began to despair about winning his bet, and to wish that he had not entered into so rash an engagement. Cursing his own slow progress he wished that the devil had the building of the bridge. No sooner were the words out of his mouth than a venerable seeming monk stood before him and offered at once to take charge of the work. “Who and what art thou?” inquired the young architect. “A poor friar,” responded the other, “who in his youth having learnt something of[Pg 30] thy craft would gladly turn his knowledge to the advantage of his convent.” “So!” said the young architect, looking at him more particularly, “I think I see a cloven hoof, and a whisking tail to boot! But no matter; since thou comest in search of employment, build me those fifteen arches before May-day, and thou shalt have a devil’s fee for thy pains.” “And what?” inquired the fiend. “Why,” replied the young man, “as thou hast a particular affection for the souls of men, I will ensure thee the first two—male and female—that shall cross this bridge.” “Say three—and done,” said the devil eagerly, and throwing off his friar’s habit. “Three be it,” said the architect, at which the devil set readily to work. Before nightfall the spandrels were set—the stone came to hand ready hewn, the mortar ready mixed. The devil was as good as his word, and on May-day morning the bridge was completed, and the obliging fiend lay in wait under the second arch ready to pounce upon his fee. A crowd had collected to see and try the bridge, but before any one could set foot on it the cunning architect called upon them to stop, saying that in the opening of the bridge there was a solemn ceremony to be performed before it could be pronounced safe for public use. He then called to his foreman. “Let the strangers take precedence,” and at his words a rough wolfdog, a cock and a hen were set at large and driven over the first arch. Instantly an awful noise was heard from beneath the bridge, and some of the people declared that they plainly heard the words, “Cheated! cheated, of my fee!” Needless to say that, after such an episode, a procession of monks and the sprinkling of holy water were necessary before the bridge could be regarded as really safe.

The bridge-builder’s cunning in making use of the devil and then outwitting him, according to the legend, had yet a tragic sequel for the young architect’s master,[Pg 31] finding himself beaten in their contest, threw himself from one of the towers of the cathedral. Should the incredulous want proof, one of the carven figures high on the edifice is said to be placed there as in the act of throwing itself down in witness to the truth of the tragedy, and, incidentally of course, also to the diabolic origin of the beautiful bridge.

Turning from the Danube itself to this most important of the towns on its banks that we have yet reached, it will be found that Ratisbon is a place full, at once of present fascination and of interesting association. The fascination can only be indicated, the associations only glanced at where the city must necessarily be compressed within the narrow limits of something less than a chapter. The buildings of this city of towers, in their variety and picturesqueness, offer an almost endless feast to the artist and the lover of old places. The magnificent cathedral, the quaint old Rathaus, the three old gateways—the Alte Kapelle, the Schotten Kirche, St. Emmeram’s Abbey Church, and numerous old houses take the attention in succession, while the narrow streets, the broad marketplaces with their animated crowds offer much of interest. The general impression remaining in the mind after wandering about is one of endlessly varied gables, of red-tiled roofs broken by tiny dormers, square towers and twinned spires.

The markets round about the cathedral, and in the open space on which the somewhat bleak-looking Neupfarrkirche stands are lively scenes with numerous peasant women exposing, in curious boat-shaped wooden boxes, in baskets, or on outspread sheets of newspaper, their fruit, vegetables and other produce; then, too, there are rows of stalls with umbrella-like awnings, and all the varied display of a continental market. Perhaps one of the most notable features (here, and in many other markets all along the course of the river) is the[Pg 32] extraordinary number of fungi, freshly gathered, and dry and wizened, which are offered for sale. The mushroom that we know—and to which in our ignorance or prejudice we limit ourselves—is not to be seen; but the variety of its congeners that are shown would delight the heart of any enthusiastic fungologist. Evidently those of the peasants who have not fruit or vegetables, eggs or fowls, butter or cream to sell, search the woods and fields for edible fungi, and from the quantity displayed, it may be assumed, find a ready sale for them in the towns.

Another market that is interesting is that at the eastern end of the Kepler Strasse, in which the fish caught in the Danube are exposed for sale, “all alive, oh.” They are kept crowded together in oblong tubs and long wooden troughs like feeding troughs, so crowded indeed, and with so little of their native element, that it is surprising that they keep alive at all. The fish I noticed included pike—up to about two feet in length—barbel, and a deep fish, fifteen to eighteen inches long, with curious horny-looking scales of a large size along the back and near the gills and tail.

The Cathedral of Ratisbon—“one of the finest Gothic churches in Germany” is a grand and beautiful pile, built between the years 1275 and 1534 (the spires were added in 1859-1869); and as the architects employed upon it during the two and a half centuries that it was a-building included the Roritzers, a father and two sons, the words which Longfellow used of Strasburg Cathedral are no less appropriate here:—

It was by one of the younger Roritzers, that the peculiar feature of the beautiful western front—the[Pg 33] triangular porch—was designed. Within the wonderfully proportioned building is much that is interesting to the student of ecclesiastical architecture. Such details, however, must be sought in the guide-books.[3] The small tower on the north is known as the Eselsturm or Donkey’s Tower, and it is said to have had that name given it because the winding inclined plane by which it is ascended was used during the building of the cathedral for donkeys to carry up loads of material required by the builders. The tower is part of the old Romanesque edifice which the present structure superseded and it has been suggested that it was probably the belfry of the older cathedral.

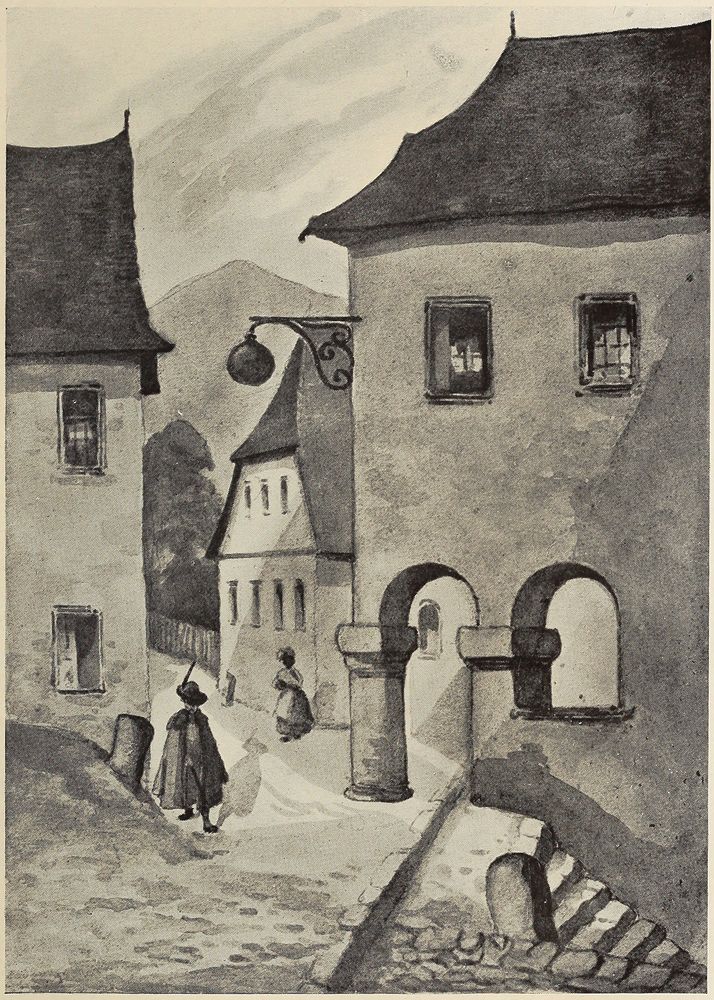

The old Rathaus (Town Hall), now a kind of museum of national and municipal relics, with its high-pitched tiled roof, its flower-bedecked windows, and its ornamental doorway in the corner of the Rathausplatz attracts attention before we learn that it is not only the old-time centre of Ratisbon civil life, but was for nearly a century and a half before 1806 the meeting place of the German Imperial Diet. The wholesome admonitory inscription which those proceeding to the Diet meetings were expected to read, mark, learn, and inwardly digest ran to the following effect: “Let every senator who enters this court to sit in judgment, lay aside all private affections; anger, violence, hatred, friendship and adulation! Let thy whole attention be given to the public welfare: for as thou hast been equitable or unjust in passing judgment on others, so mayst thou expect to stand acquitted or condemned before the awful tribunal of God.” The wooden ceiling, sixteenth century frescoes and old stained glass of the Diet Hall[Pg 34] or Reichssaal, are noteworthy features. In the Rathaus, too, are some grand old tapestries, and—for the delectation of those who sigh over the good old times—a very chamber of horrors in the torture chamber, with its rack, “Spanish donkey,” “Jungfrauenschoss,” and such-like witnesses to past manifestations of man’s inhumanity to man. The collection of these demoniacally ingenious instruments is a particularly good one, and should suffice to impress the least imaginative with “the horrors.”

St. Emmeram’s Abbey—of which the church is the main part now left, the site of the abbey being occupied by the palace of the Prince of Thurn and Taxis—lies on the south side of the town, with one of the four remaining town gates—the Emmeramer Tor—near by. The church is still worth a visit from those interested in ecclesiastical art and architecture, in older tombs and shrines of saints; here, too, they will find the tombs of King Childeric of France and other mediæval notables. The bridge gate we have already glanced at; the other two left standing when the town wall was demolished about half a century ago are the Prebrunntor on the west and the tall tile-roofed Ostentor. The Schottenkirche (or St. Jacob’s Church) has a fine pillared doorway chiefly remarkable for the number of quaintly carven figures of men and beasts about it. The many square towers that rise above the surrounding roofs on many of the streets are survivals, peculiar I believe to Ratisbon, of the old days when every nobleman had to be prepared to defend his house. And the story of Ratisbon suggests that such preparation was necessary, for in the course of nine hundred years the city had to withstand a siege fourteen times.

The highest of these towers, the Goldene Turm in the Wahlenstrasse, rises one hundred and seventy feet above the pavement; another is on the Haidplatz, and[Pg 35] yet another not far from the bridge, attached to a house on which is a gigantic mural painting of David attacking Goliath. It may well be that this subject arises from an episode in the history of Ratisbon, also made the subject of a house-wall painting. This episode was a fight between one of the citizens of the place and a giant. The story runs that in the year 930 a terrible combat was fought on the Haidplatz between a gigantic Hun, Craco by name, and Hans Dollinger, a valiant burgher of Ratisbon. The Hun had already flung forty knights out of the saddle when, in the presence of the Emperor, he was confronted by the dauntless Dollinger. The Emperor marked the champion twice over the mouth with the sign of the cross it is said, and to the virtue of the holy sign was attributed the final overthrow of the mighty pagan. Craco’s sword, nearly eight feet in length, was removed some centuries later to Vienna, and Ratisbon lost a remarkable relic.

On the wall of the house adjoining the tower on the Haidplatz the inn “zum Goldenen Kreuz” is a medallion of Ludwig the First with ornate decoration, and on the wall of the tower is another medallion with twenty-four lines of verse about a certain royal romance. The inscription appears to have been painted up recently, but whether replacing an older one I cannot say. It was to the charms of one Barbara Blomberg—who is said variously to have been landlady of the Golden Cross, a washerwoman and the daughter of a well-to-do citizen, that the Emperor Charles the Fifth succumbed during one of his visits to this part of his vast dominions. The story runs that Barbara was introduced to the Emperor that her singing might lessen the melancholy from which he suffered. On 24 February, 1545 the lady bore a son—tradition says in a room in this inn—who was to become known to fame as Don John of Austria, and the victor of Lepanto. In the following year the[Pg 36] Emperor closed the incident by marrying Barbara to one of his courtiers, and carried off the child to be brought up as befitted his high (but for some years unacknowledged) paternal origin. Among the other features are the many fountains in street and platz, notably the one in the Moltkeplatz, and the flower-decorated one opposite the western end of the cathedral. Just west of the bridge gate is another old stone fountain dated 1610. But of these details the interesting old city has much to show to the wanderer about its by-ways. Another thing which strikes the visitor is the way in which the chemists’ shops retain such old signs as were at one time familiar features of our London streets, but which with us only survive on inns. In Ratisbon the “Apotheken” are duly named the “Elephant,” the “Lion,” the “Eagle,” and so on.

Mention has been made of Kepler Strasse, and it should be added that the famous astronomer, John Kepler, was doubly associated with Ratisbon. Hither he came in 1613 to appear before the Diet as the advocate of the introduction of the Gregorian Calendar into Germany—an introduction which was, however, delayed owing to anti-papal prejudice. Seventeen years later Kepler journeyed from Sagan in Silesia on horseback that he might appeal to the Diet for arrears of payment due to him. But, reaching Ratisbon, he fell ill of a fever, and died there on 15 November, 1630. We shall hear something of the astronomer again lower down the river at Linz.

In this city of many ecclesiastical foundations the very horses are said to have been taken to church in past times, though, it is true, only once a year. On St. Leonard’s Day—6 November—the peasants from the surrounding country used to bring their horses, gaily bedecked, into the city and take them one at a time to peep into St. Leonard’s church—“a pious precaution[Pg 37] which was supposed to preserve them the year round from the staggers, and, indeed, every other disorder that horseflesh is heir to.”

When Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was here in 1716, she described Ratisbon as being full of “Envoys from different States,” and said that it might have been a very pleasant place but for the “important piques, which divide the town almost into as many parties as there are families ... the foundation of these everlasting disputes turns entirely upon rank, place, and the title of Excellency, which they all pretend to, and, what is very hard, will give it to nobody. For my part I could not forbear advising them (for the public good) to give the title of Excellency to everybody, which would include the receiving it from everybody; but the very mention of such a dishonourable peace was received with as much indignation, as Mrs. Blackaire did the motion of a reference.” In some of the churches—she does not specify which—Lady Mary was shown some curious relics, for she says: “I have been to see the churches here and had the permission of touching the relics, which was never suffered in places where I was not known. I had, by this privilege, the opportunity of making an observation, which I doubt not might have been made in all the other churches, that the emeralds and rubies which they show round their relics and images are most of them false; though they tell you that many of the Crosses and Madonnas, set round with these stones, have been the gifts of Emperors and other great Princes. I don’t doubt indeed but they were at first jewels of value; but the good fathers have found it convenient to apply them to other uses, and the people are just as well satisfied with pieces of glass amongst these relics. They showed me a prodigious claw set in gold, which they called the claw of a Griffin, and I could not forbear asking the Reverend Priest that[Pg 38] showed it whether the Griffin was a Saint. The question almost put him beside his gravity; but he answered they only kept it as a curiosity. I was much scandalized at a large silver image of the Trinity, where the Father is represented under the figure of a decrepit old man, holding in his arms the Son, fixed on the Cross, and the Holy Ghost, in the shape of a dove, hovering over him.”

History has so much to say of Ratisbon that here we can but glance at some of the details of a place which we are told has been known by twenty different names. In Germany it is Regensburg, the town situated at the point where the Regen joins the Danube, while we still know it by its old latinized name which has been said to indicate that it was recognized as a good landing place. This point is explained in some Latin lines quoted by Planché:—

In Roman times the town was known as Regina Castra and was probably one of the more important of the places along the frontier of Illyricum or those provinces of the Danube which, says Gibbon, were esteemed the most warlike of the empire. According to tradition it was the port at which many of the Western Crusaders commenced their voyage to the Holy Land, in evidence of which we have ballad testimony:—

[Pg 39]

After the decline and fall of the Roman Empire, Ratisbon was by no means allowed to fall back into a centre of peace, for history tells us, as has been said, that fourteen times was it besieged during something less than a thousand years. In the Thirty Years’ War its position made it a frequent storm centre, and thrice within eight years did it undergo bombardment. The wonder is that so much of the old place survives after such a record. The last of the fourteen attacks on it (21 April, 1809) is probably the best known, thanks to the mnemonic value of poetry, for it was then that the “Incident of the French Camp,” of which Robert Browning wrote, is supposed to have occurred.

Before leaving Ratisbon it may be recalled that it was here that Richard Cœur de Lion was sent as captive[Pg 40] to the Emperor Henry the Sixth to be re-delivered to his captor and arch-foe Duke Leopold of Austria, who duly incarcerated him in a lonely Danube castle more than two hundred miles further down the river.

Between six and seven miles below Ratisbon is the Walhalla, a modern building which no visitor to the ancient city should fail to see. It may be reached by the river, by the road which more or less closely follows the low right bank through the little village of Barbing, or by the light railway, the Valhallabahn, which starts in one of the Stadtamhof streets, crosses the Regen and runs between the low hills and the left bank of the river. The railway goes on to the Walhalla and beyond, but the temple can easily be reached from Donaustauf, a small town at the foot of the hill, on which stand the remains of a castle of the same name—ruins which, on a suitable day, afford a grand view, and to which attaches much history, and something of mystery. Through the long street of the village with its white houses is the way to the great Temple of Fame, but before visiting it, this ruined castle cresting the bluff rock above the town should be seen.

The original castle built on this commanding point is supposed to have been founded by Bishop (afterwards Saint) Tuto, who died in 930, and whose tomb is at St. Emmeram’s in Ratisbon. Whether it was founded by the saintly bishop or not, it was long used as the residence of the bishops of Regensburg, though its strength and position caused it to be coveted by lay rulers also. Henry the Proud having in 1132 taken it from the bishop of that day, the citizens of Regensburg not only besieged the castle, but actually succeeded in capturing it. It was besieged again in 1146 and yet again in 1159. It is not easy, looking across the closely cultivated plain towards Regensburg, to-day to realize the scenes of those strenuous Middle Ages. In the fourteenth century Donaustauf was[Pg 41] sold to Charles the Fourth of Bohemia, who maintained it as one of the barrier fortresses of his kingdom.

Of the time when the castle was the residence of the bishops of Regensburg, and should seemingly have been a centre of Christian peace and charity there are accounts that indicate that it had under some possessors quite another reputation. Here, for example, is one of the stories:

“A certain worthy Bishop of Regensburg, not contented with fleecing his flock, according to the approved and legitimate method, made it a point of conscience to waylay and plunder his beloved brethren whenever they ventured near the Castle of Donaustauf, in which he resided upon the banks of the Danube, a little below the town. In the month of November 1250,” says the chronicle, “tidings came to Donaustauf, that, on the following morning, the daughter of Duke Albert of Saxony would pass that way, with a gorgeous and gallant escort. The bait was too tempting for the prelate. He sallied out upon the glittering cortège, and seizing the princess and forty of her noblest attendants, led them captives to Donaustauf. The astonished remainder fled for redress, some to King Conrad, and others to Duke Otho, at Landshut, who immediately took arms, and carrying fire and sword into the episcopal territory, soon compelled the holy highwayman to make restitution and sue for mercy. Conrad, satisfied with his submission, forgave him; in return for which the bishop bribed a vassal, named Conrad Hohenfels, to murder his royal namesake; and accordingly, in the night of the 28th of December, the traitor entered the Abbey of St. Emmeram’s, where the king had taken up his abode, and stealing into the royal chamber, stabbed the sleeper to the heart; then running to the gates of the city, threw them open to the bishop and his retainers, exclaiming that the king was dead.[Pg 42] The traitors were, however, disappointed. Frederick von Ewesheim, a devoted servant of the king, suspecting some evil, had persuaded the monarch to exchange clothes and chambers with him, and the assassin’s dagger had pierced the heart, not of Conrad, but of his true and gallant officer. The bishop escaped the royal vengeance by flight; but the abbot of St. Emmeram’s, who had joined the conspirators, was flung into chains; and the abbey, the houses of the chapter, and all the ecclesiastical residences, were plundered by the king’s soldiery. The Pope, as might be expected, sided with the bishop and excommunicated Conrad and Otho; but the murderer, Hohenfels, after having for some time eluded justice, was killed by a thunderbolt!”

Another prelate who resided here is reputed to have had the enviable power of being in two places at once. This was no less a personage than Albertus Magnus, who succeeded the highwayman-bishop in the episcopate of Ratisbon. According to the chronicles, Albertus was able, while delivering his lectures in the Dominican Chapel in Regensburg itself, also to be closely engaged in study in his palace at Donaustauf, some miles away. A case surely in which even the system of pluralism would have been thoroughly justified.

THE WALHALLA

Coming down from the peaceful ruins to the village again, we may take one of two ways to the Walhalla, going straight on to the east where the front of the giant Grecian temple is seen above the trees on the brow of the hill to the left, and climbing the many steps to the front; or taking the left turning where the road forks, and going past the little hillside church of St. Salvator—built, it is said, in expiation of the sacrilegious crime of some soldiers, who dishonoured the Host—through woodland paths reach the western columned side of the great edifice, and come more or less suddenly on what is, if the weather[Pg 43] be clear, a grand “surprise” view. Behind us the oak woodland, in front the magnificent Parthenon-like white building, standing on the brow of the hill—

And to the right, green and turf and a view across the Bavarian plain. On a fine day the view is one to arrest the attention, while the grand building with its columned exterior is so satisfying to the eye, that we may well feel inclined to linger about before entering the great hall. Approaching from the back, we pass under the arcade of columns to the front, where massy tiers of steps lead down the hill to the river.

From the front here is a magnificent view if kindly weather prevails—its extent could be gauged even on such a grey wet day as that on which I visited it. The building stands three hundred and fifteen feet above the river—not in itself a great height—but the southern bank is the beginning of a great far-stretching plain, and it is said that, in the most favourable climatic conditions (which so rarely obtain in such cases) the distant Alps can be seen. Even if it fall short of that, the view is sufficiently extensive across the plain, back to Ratisbon and down the winding stream, island-divided, towards Straubing.

Before entering this Temple of Fame—more impressive than that imagined by Pope—it may be mentioned that the building was founded for the purpose which its name sufficiently attests, by Ludwig the First of Bavaria, owing to the great pleasure which he had had when studying at Jena in the society of Goethe. It is said that he then declared that if he ever succeeded to the throne he would erect a building which should serve as a Temple of Fame for the whole of Germany. Nobly did he fulfil that promise. The[Pg 44] architect was Leo von Klenze; the first stone was laid on October 18, by King Ludwig; and on the same date, twelve years later, the temple was solemnly dedicated by his Majesty, who said: “May the Walhalla contribute to extend and consolidate the feelings of German nationality. May all Germans of every race henceforth feel they have a common country of which they may be proud, and let each individual labour according to his faculties to promote its glory.” It had cost about two hundred thousand pounds, and thus honouring the great men of the German lands, the Bavarian king gained lasting honour for himself, for the building is one as perfect in taste as it is in form, to use the words of an early visitor. It is true that there have not been wanting critics who have objected to the incongruity of building a temple after a Greek plan to the honour of great Teutons and then naming it the Walhalla, but the objection is really an unimportant one, and we may well be satisfied with having a beautiful edifice dedicated to a beautiful purpose: we may remind the critics, too, that “the Doric order was peculiarly sacred to heroes and worthies.” Entering, we find ourselves in a grand and impressive hall: