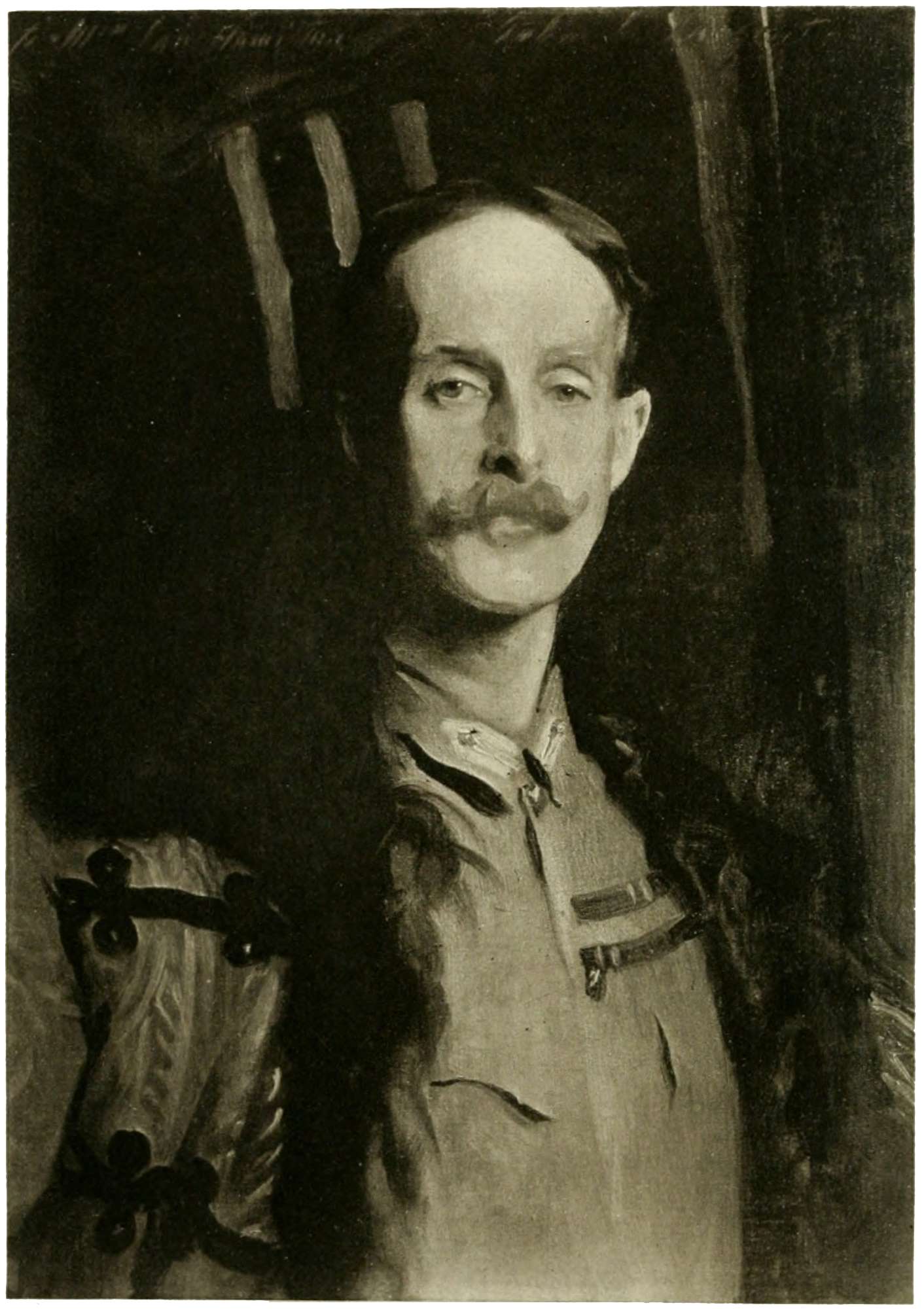

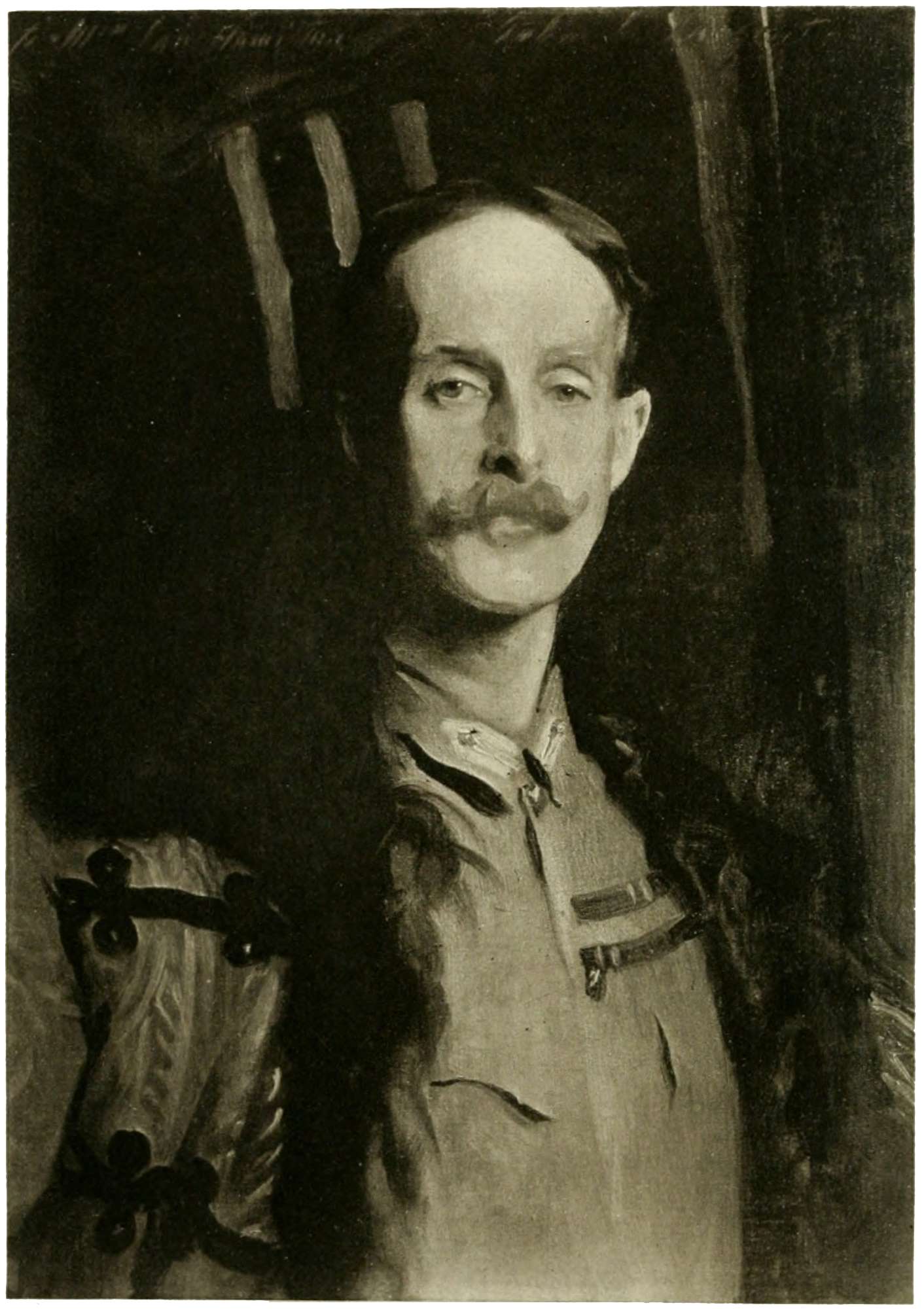

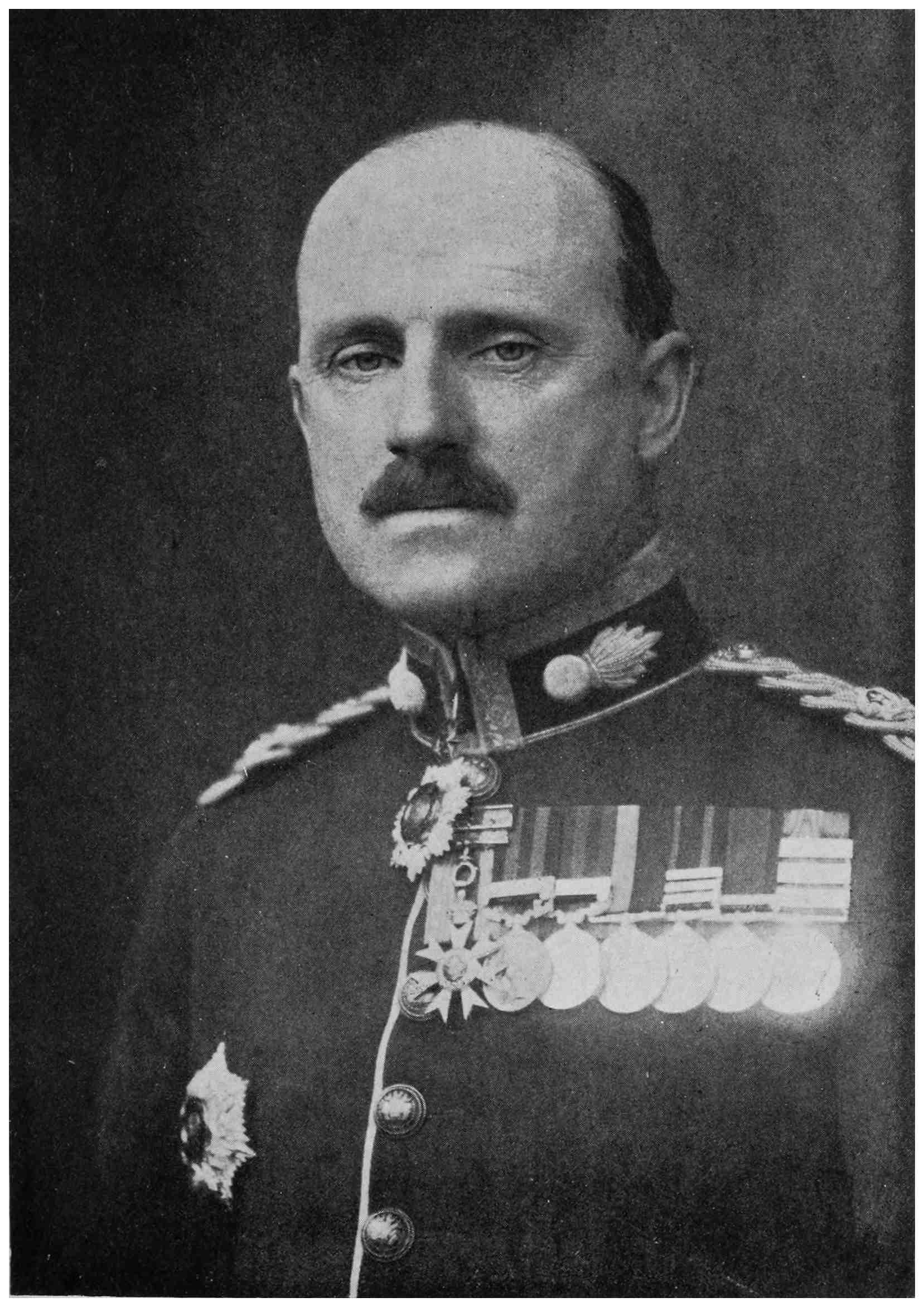

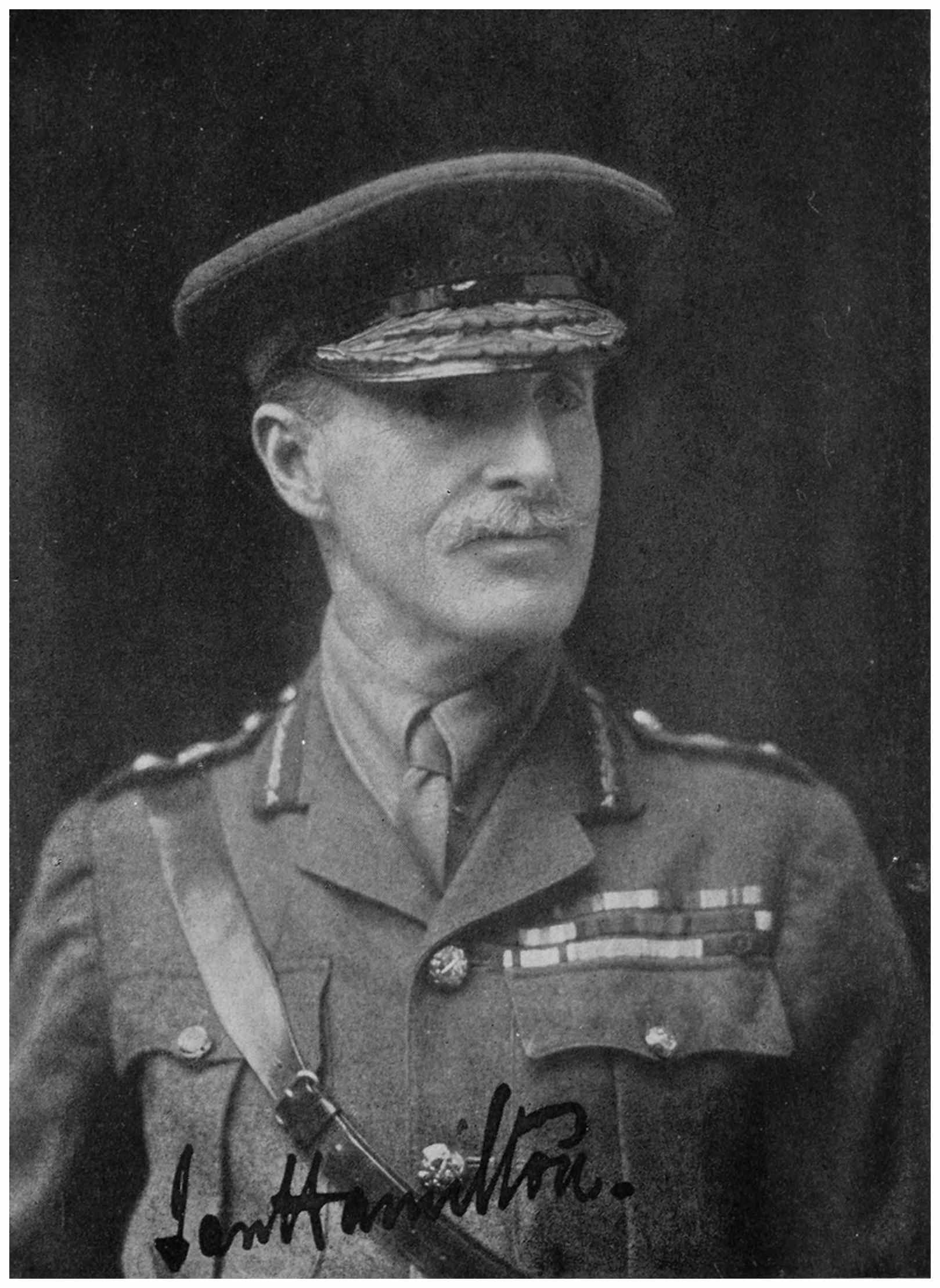

GENERAL SIR IAN HAMILTON. G.C.B., D.S.O.

FROM A PORTRAIT BY JOHN S. SARGENT. R.A.

Title: The Dardanelles campaign

Author: Henry Woodd Nevinson

Release date: June 13, 2023 [eBook #70969]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Nisbet & Co, 1920

Credits: Peter Becker, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

By the same Author

ESSAYS IN

REBELLION

7/6 net

The Spectator says:

“We have enjoyed it immensely.”

The Bookman says:

“More than engrossing ... to read it is to add to one’s mental equipment.”

The Westminster Gazette says:

“Interested and delighted us.”

Punch says:

“A gallant book.”

Nisbet & Co. Ltd.

NEIGHBOURS OF OURS: Scenes of East End Life.

IN THE VALLEY OF TOPHET: Scenes of Black Country Life.

THE THIRTY DAYS’ WAR: Scenes in the Greek and Turkish War of 1897.

LADYSMITH: A Diary of the Siege.

CLASSIC GREEK LANDSCAPE AND ARCHITECTURE: Text to John Fulleylove’s Pictures of Greece.

THE PLEA OF PAN.

BETWEEN THE ACTS: Scenes in the Author’s Experience.

ON THE OLD ROAD THROUGH FRANCE TO FLORENCE: French Chapters to Hallam Murray’s Pictures.

BOOKS AND PERSONALITIES: A Volume of Criticism.

A MODERN SLAVERY: An Investigation of the Slave System in Angola and the Islands of San Thomé and Principe.

THE DAWN IN RUSSIA: Scenes in the Revolution of 1905–1906.

THE NEW SPIRIT IN INDIA: Scenes during the Unrest of 1907–1908.

ESSAYS IN FREEDOM.

THE GROWTH OF FREEDOM: A Summary of the History of Democracy.

GENERAL SIR IAN HAMILTON. G.C.B., D.S.O.

FROM A PORTRAIT BY JOHN S. SARGENT. R.A.

THE DARDANELLES

CAMPAIGN

BY

HENRY W. NEVINSON

THIRD AND REVISED EDITION

London

NISBET & CO. LTD.

22 BERNERS STREET W. 1

| First Published | November 1918 |

| Second Edition | December 1918 |

| Third and Revised Edition | March 1920 |

DEDICATED TO

THOSE WHO FELL ON THE

GALLIPOLI PENINSULA

Beside the ruins of Troy they lie buried, those men so beautiful; there they have their burial-place, hidden in an enemy’s land.

The Agamemnon, 453–455.

Ἀνδρῶν ἐπιφανῶν πᾶσα γῆ τάφος, καὶ οὐ στηλῶν μόνον ἐν τῇ οἰκείᾳ σημαίνει ἐπιγραφὴ, ἀλλὰ καὶ ἐν τῇ μὴ προσηκούσῃ ἄγραφος μνήμη παρ᾽ ἑκάστῳ τῆς γνώμης μᾶλλον ἢ τοῦ ἔργου ἐνδιαιτᾶται.

Of conspicuous men the whole world is the tomb, and it is not only inscriptions on tablets in their own country which chronicle their fame, but rather, even in distant lands, unwritten memorials living for ever, not upon visible monuments, but in the hearts of mankind.

Pericles’ Funeral Speech;

Thucydides, ii. 43.

From the outset the Dardanelles Campaign attracted me with peculiar interest. The shores of the Straits were the scene of the Trojan epics and dramas. They were explored and partly inhabited by a race whose legends and history had been more familiar to me from boyhood than my own country’s, and more inspiring. They belonged to that beautiful part of the world with which I had become personally intimate during the wars, rebellions, and other disturbances of the previous twenty years. But, above all, I was attracted to the Campaign because I regarded it as a strategic conception surpassing others in promise. My reasons are referred to in various chapters of this book, and indeed they were obvious. The occupation of Constantinople would have paralysed Turkey as an ally of the Central Powers; it would have blocked their path to the Middle East, and averted danger from Egypt, the Persian Gulf, and India; it would have released the Russian forces in the Caucasus for action elsewhere; it would haveviii secured the neutrality, if not the active co-operation, of the Balkan States, and especially of Bulgaria, not only the most resolute and effective of them, but a State well disposed to ourselves and the Russian people by history and sentiment; by securing Bulgaria’s friendship, it would have delivered Serbia from fear of attack upon her eastern frontier, and have relieved Roumania from similar apprehensions along the Danube and in the Dobrudja; it would have confirmed the influence of Venizelos in Greece, and saved King Constantine from military, financial, and domestic temptations to Germanise; above all, it would thus have secured Russia’s left flank, so enabling her to concentrate her entire forces upon the Lithuanian, Polish, and Galician frontiers from the Memel to the Dniester.

The worst apprehensions of the Central Powers would then have been fulfilled. Blockaded by the Allied fleets in the Adriatic, and by the British fleet in the Channel and the North Sea, they would have found themselves indeed surrounded by an iron ring, and, so far as prophecy was possible, it seemed likely that the terms which our Alliance openly professed as our objects in the war might have been obtained in the spring of 1916. The subsidiary and more immediate consequences of success in the Dardanelles, such as the supply of munitions to Russia, and of Ukrainian wheat to our Alliance, were also to be considered. The saying of Napoleon,ix in May, 1808, still held good: “At bottom the great question is—Who shall have Constantinople?”

Under the prevailing influence of “Westerners” upon French and British strategy, these probable advantages were either disregarded or dismissed, and to dwell upon them now is a useless speculation. The hopes suggested by the conception in 1915 have faded like a dream. The dominant minds in our Alliance either failed to imagine their significance, or were incapable of supplying the power required for their realisation while at the same time pressing forward the proposed offensive in France. The international situation of Europe, and indeed of the world, is now changed, and the strategic map has been completely altered. Early belligerents have disappeared from the field, and new belligerents have entered the shifting scene. Already, in 1918, the Dardanelles Expedition has passed into history, and may be counted among the ghosts which history tries in vain to summon up. It is as an episode of a vanished past that I have attempted to represent it—a tragic episode enacted in the space of eleven months, but marked by every attribute of noble tragedy, whether we consider the grandeur of theme and personality, or the sympathy aroused by the spectacle of heroic figures struggling against the unconscious adversity of fate and the malign influences of hostile or deceptive power.

In treatment, I have made no attempt to rivalx my friend John Masefield’s Gallipoli—that excellent piece of work, at once so accurate and so brilliantly illuminated by poetic vision. Mine has been the humbler task of simply recording the events as they occurred, with such detail as seemed essential to complete the history, or was accessible to myself. In this endeavour, I have trusted partly to the books and documents mentioned below, partly to information generously supplied to me by many of the principal actors upon the scene; also to my own notes, writings, and memory, especially with regard to the nature of the country and the events of which I was a witness. Accuracy and justice have been my only aims, but in a work involving so much detail and so many controverted questions mistakes in accuracy and justice are scarcely to be avoided. I know the confusion of mind and the distorted vision so frequent in all great crises of war, and I know from long experience how ignorant may be the criticism applied to any soldier from the Commander-in-Chief down to the private with a rifle.

The mention of the private with a rifle suggests my chief regret. The method I have followed, in treating divisions or brigades or, at the lowest, battalions as the units of action, almost obliterates the individual soldier from consideration. Divisions, brigades, and battalions are moved like pieces on a board, and Commanding Officers must regardxi each of them only as a certain quantity of force acting under the laws of time and space. Yet each of the so-called units is made up of living men—men of distinctive personality and incalculably varying nature. Men are the actual units in war as in the State, and I do not forget the “common soldiers.” I do not overlook either their natural failures or their astonishing performance. In various campaigns and in many countries I have shared their apprehensions, their hardships, their brief intervals of respite, and their laborious triumphs. They, like the rest of mankind, have always filled me with surprised admiration or poignant sympathy. Among the soldiers of many races, but especially among the natives of these islands, whom I could best understand, I have always found the fine qualities which distinguish the majority of hardworking people, all of whom live perpetually in perilous hardship. I have found a freedom from rhetoric and vanity, a simple-hearted acceptance of life “in the first intention,” taking life and death without much criticism as they come, and concealing kindliness and the longing for happiness under a veil of silence or protective irony. But a book of this kind has little place for the mention of them, and that is my regret. Like a general, I have been obliged to consider forces mainly in the mass, and must leave to readers the duty of remembering, as I never cease to remember, that all divisionsxii and all platoons upon the Peninsula were composed of ordinary men like ourselves—individual personalities subject to the common sufferings of hunger, thirst, sickness, and pain; filled also with the common delight in life, the common horror of death, and the desire for peace and home. As in the case of general mankind, it was their endurance, their courage, self-sacrifice, and all that is implied in the ancient meanings of “virtue,” which excited my wonder.

Among those who have given me very kind assistance either on the Dardanelles Peninsula or in London, I may mention with gratitude General Sir Ian Hamilton, G.C.B., etc.; General Sir William R. Birdwood, K.C.B., K.C.S.I., etc.; Major-General Sir Alexander Godley, K.C.B., etc.; Major-General Sir A. H. Russell, K.C.M.G., etc.; the late Lieut.-General Sir Frederick Stanley Maude, K.C.B.; Major-General Sir W. R. Marshall, K.C.B.; Major-General H. B. Walker, C.B.; Major-General Sir William Douglas, K.C.M.G.; Major-General F. H. Sykes, C.M.G.; Major-General Sir D. Mercer, K.C.B.; Brigadier-General Freyberg, V.C.; Colonel Leslie Wilson, D.S.O., M.P.; and Lieut. Douglas Jerrold, R.N.V.D.; Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes, K.C.B., etc.; Rear-Admiral Heathcote Grant, C.B., etc.; Captain A. P. Davidson, R.N.; Captain the Hon. Algernon Boyle, R.N.; Staff-Surgeon Levick, R.N.; and the Rev. C. J. C. Peshall, R.N. It would indeedxiii be difficult to draw up a complete list of the Naval and Military officers to whom I owe my thanks.

Having taken many photographs on the Peninsula, I posted them, as I was directed, to the War Office, and never saw them again. I can only hope that any one into whose possession they may happen to have come upon the route, may find them as useful as I should have found them in illustrating this book. My friend, Captain C. E. W. Bean, has generously supplied me with some of his own photographs in their place. For the rest I am permitted to use official pictures, taken by my friend, Mr. Brooks. They are of course far superior to any I could have taken, but some are already familiar.

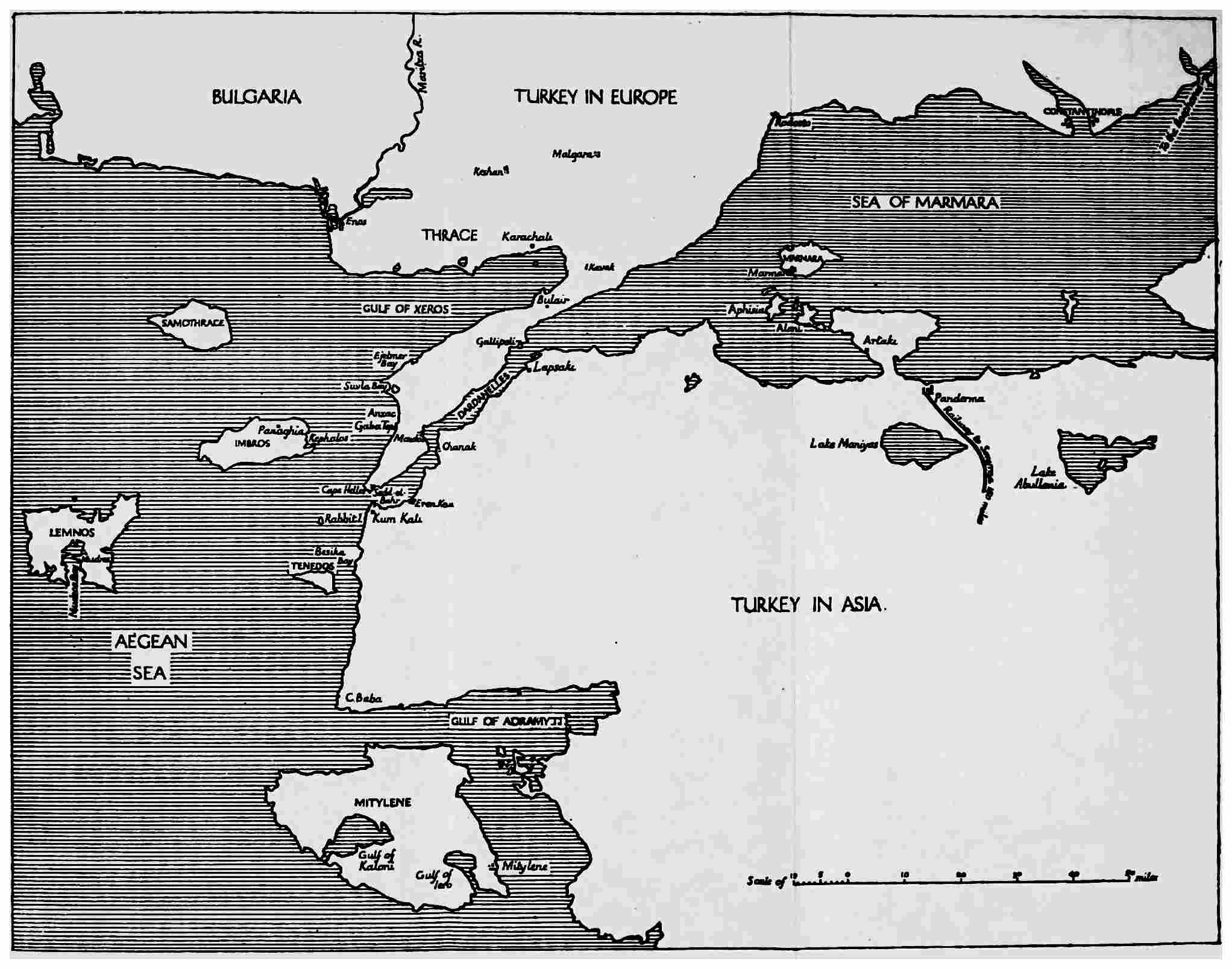

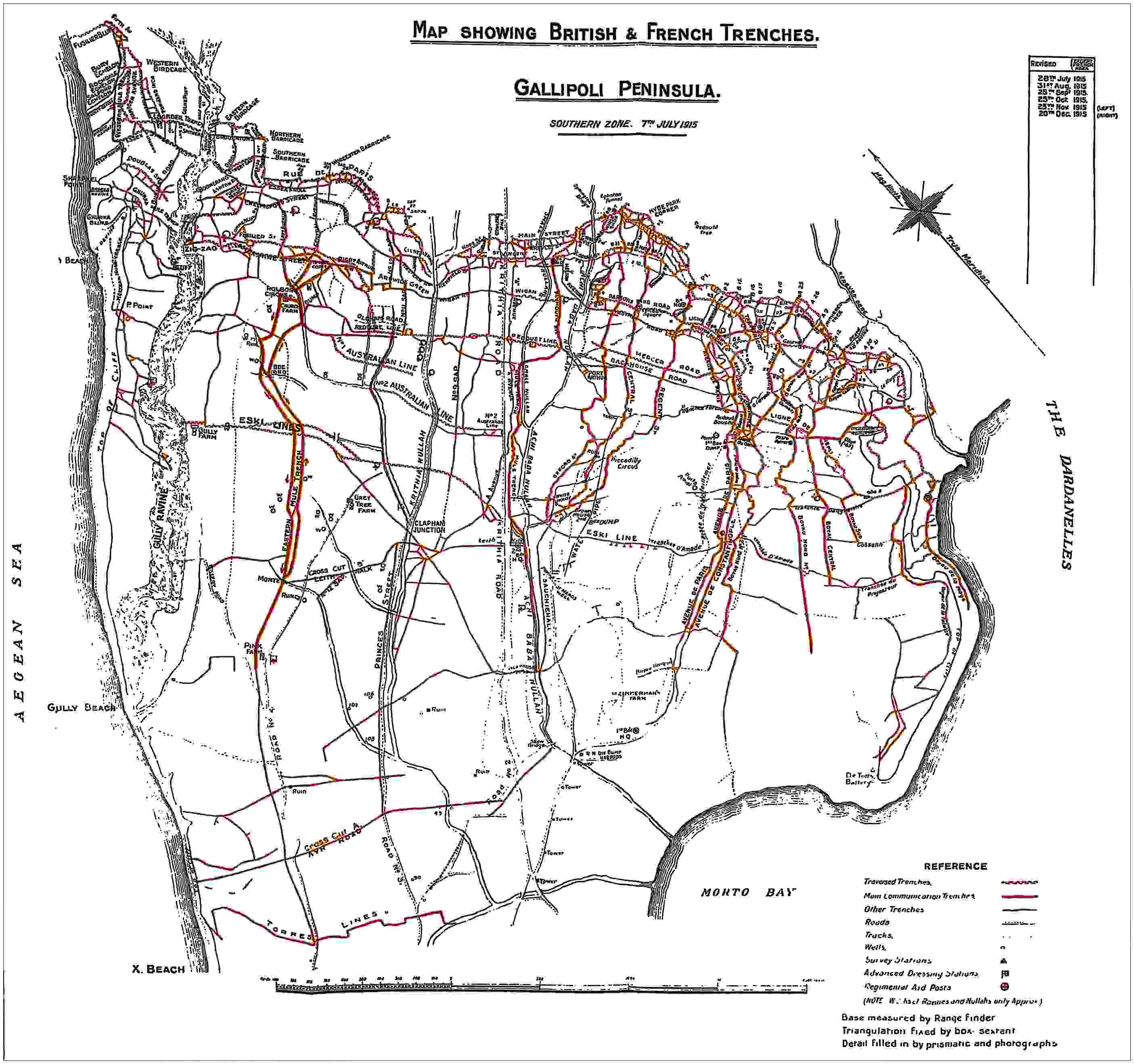

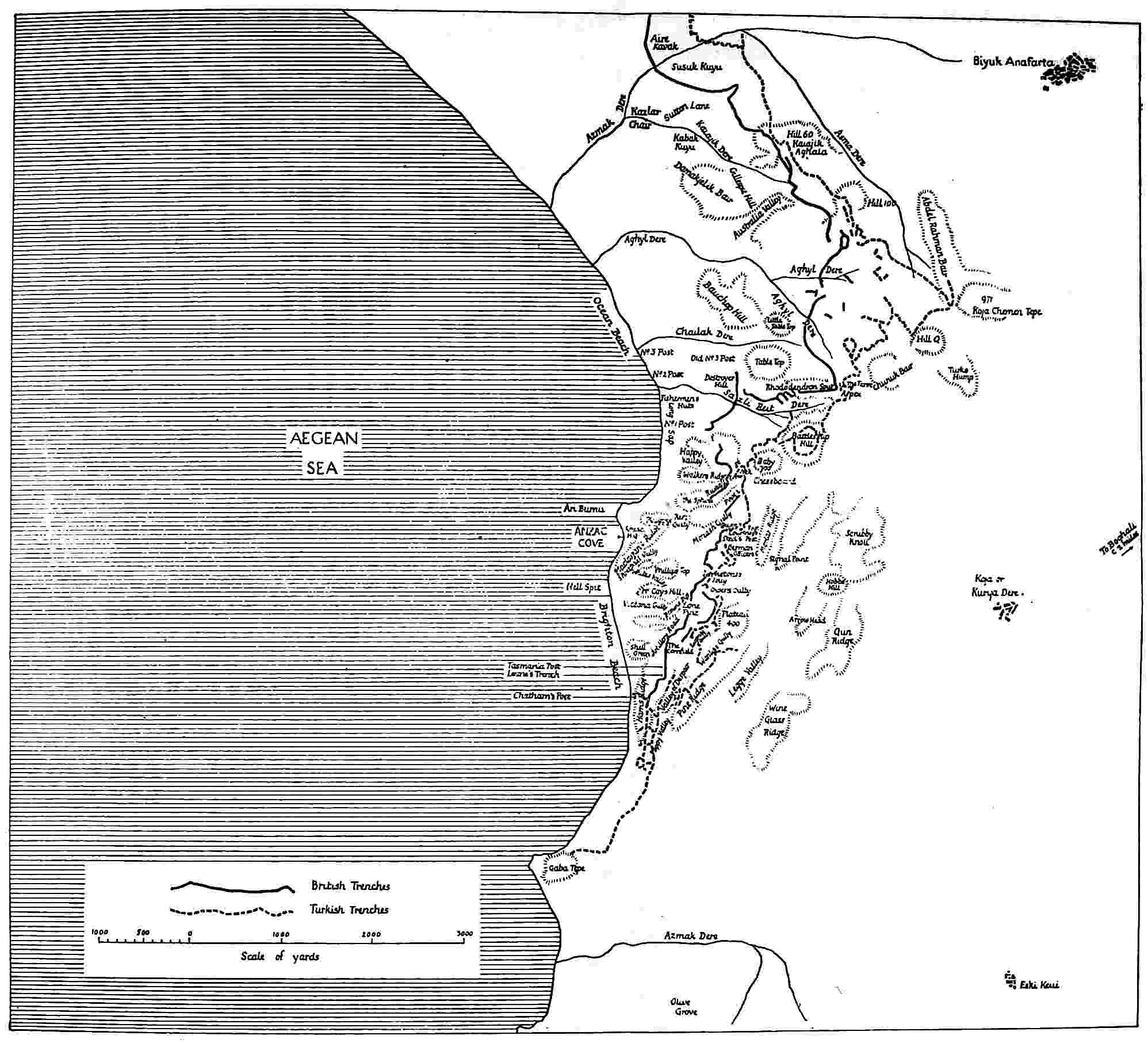

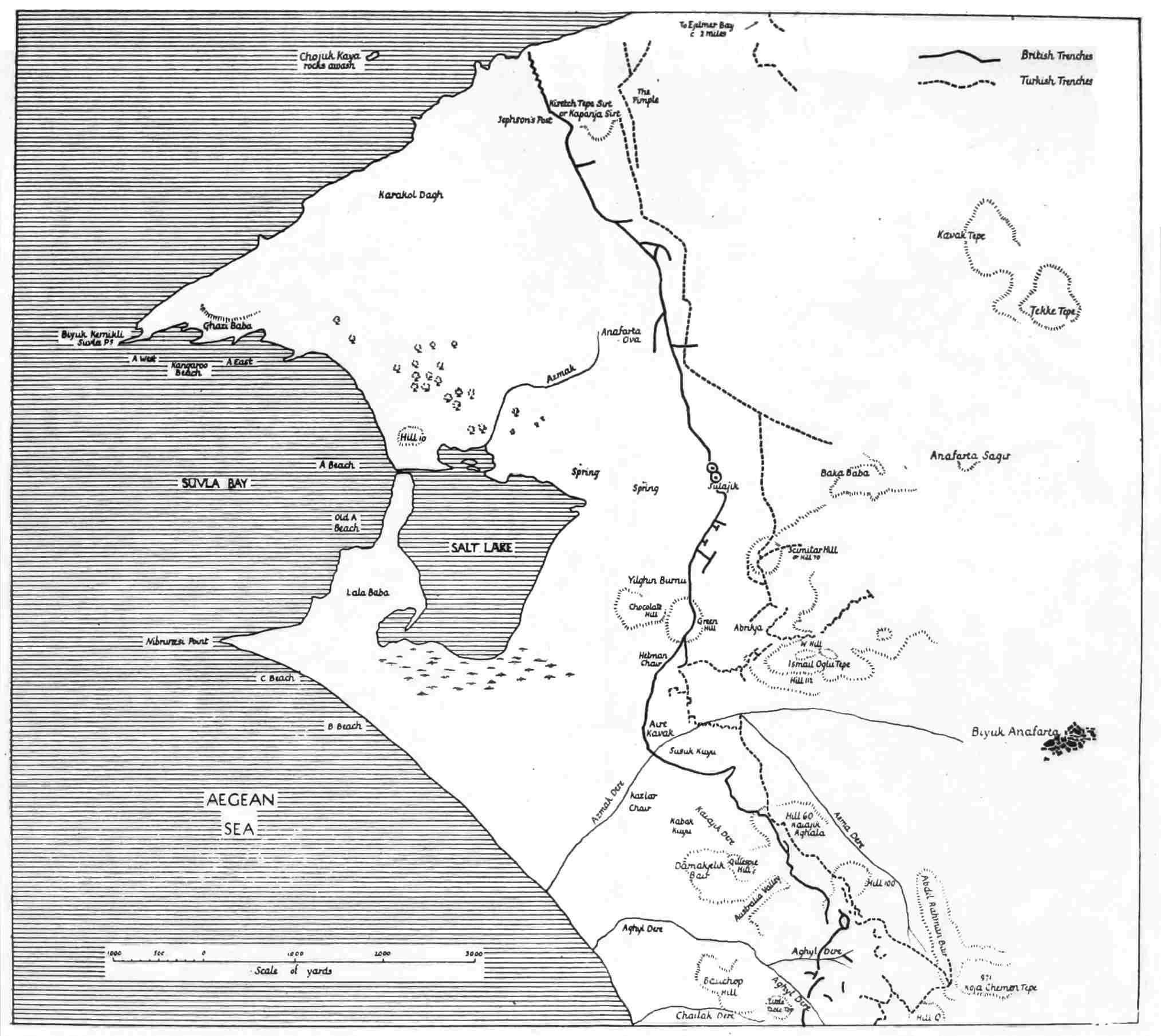

The maps are for the most part constructed from the Staff Maps (nominally Turkish, but mainly Austrian I believe) used by the G.H.Q. upon the Peninsula. Some also are derived from drawings by Generals and Staff Officers. For the larger maps of Anzac and Suvla I am indebted to the assistance of Captain Treloar and the Australian Staff in London, with permission of Sir Alexander Godley, and Brigadier-General Richardson (formerly of the Royal Naval Division); and to Mr. S. B. K. Caulfield.

The following is a list of the chief books and documents which I have found useful:—

Sir Ian Hamilton’s Dispatches.

Sir Charles Monro’s Dispatch on the Evacuation.

The Dardanelles Commission Report, Part I.

xiv

With the Twenty-ninth Division in Gallipoli, by the Rev. O. Creighton, Chaplain to the 86th Brigade (killed in France, April 1918).

The Tenth (Irish) Division in Gallipoli, by Major Bryan Cooper, 5th Connaught Rangers.

With the Zionists in Gallipoli, by Lieut.-Colonel J. S. Patterson.

The Immortal Gamble, by A. J. Stewart, Acting Commander, R.N., and the Rev. C. J. E. Peshall, Chaplain, R.N.

Uncensored Letters from the Dardanelles, by a French Medical Officer.

Australia in Arms, by Phillip F. E. Schuler.

The Story of the Anzacs. (Messrs. Ingram & Sons, Melbourne.)

Mr. Ashmead Bartlett’s Dispatches from the Dardanelles.

What of the Dardanelles? by Granville Fortescue.

Two Years in Constantinople, by Dr. Harry Stürmer.

Inside Constantinople, by Lewis Einstein.

Nelson’s History of the War, by Colonel John Buchan.

The “Times” History of the War.

The “Manchester Guardian” History of the War.

H. W. N.

London, 1918.

Secrets of the Bosphorus, by Henry Morgenthau (1919), especially illustrate pp. 144–145.

An interview with General von Sanders, by Mr. G. Ward Price, of the Daily Mail, in Constantinople (Nov. 13, 1918), contains points of military interest.

(Note to Second Edition.)

xv

| CHAPTER I | |

| THE ORIGIN | |

| PAGE | |

| Naval Bombardment, November 1914—Causes of German-Turkish Alliance—Germany’s Eastern aims—Mistakes of British diplomacy—The Goeben and Breslau—The position of Greece—Turkey declares war | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| THE INCEPTION | |

| Mr. Churchill first suggests attack on Gallipoli—Russia’s appeal for aid—A demonstration decided upon—The War Council—Lord Kitchener—Mr. Asquith—Mr. Churchill—Objects of his scheme—Lord Kitchener’s objections—Admirals Fisher and Arthur Wilson—Their duty as advisers—Lord Fisher’s opinion—Admiral Jackson’s view—Admiral Carden on the scheme—War Council orders a naval attack—Lord Fisher’s opposition—He gives reluctant assent—Decision for a solely naval expedition | 12 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| THE NAVAL ATTACKS | |

| Council’s hesitation renewed—A military force prepared—The 29th Division detained—Description of the Dardanelles—Mudros and the islands—Formation of the fleet—Bombardment of February 19—Renewed on February 25—Further attacks in early March—Effect on Balkan States—Mr. Churchill urges greater vigour—Admiral de Robeck succeeds to command—The naval attack of March 18—Losses and comparative failure—Purely naval attacks abandoned | 40 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| THE PREPARATION | |

| Sir Ian Hamilton’s appointment—His qualifications—Misfortune of delay—Transports returned for reloading—Sir Ian in Egypt—The forces there—The “Anzacs”—Possible lines of attack considered—The selected scheme—Chief members of Sir Ian’s staff—Available forces—Sir Ian’s address—Rupert Brooke’s death | 64xvi |

| CHAPTER V | |

| THE LANDINGS | |

| The Start from Mudros—Landing at De Tott’s Battery—Seddel Bahr and V Beach—The River Clyde—Landing at V Beach—Night there—W Beach or Lancashire Landing—Landing at X Beach—Y2 and Y Beaches—Landing at Y Beach—Its failure—Landing at Anzac—The positions won there—Feint off Bulair—Captain Freyberg’s exploit—French feint at Kum Kali | 88 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| THE TEN DAYS AFTER | |

| Sir Ian’s decision to hold Anzac—Advance from V Beach—Death of Doughty-Wylie—The French at V Beach—Position of Krithia—Advance of April 28—Turkish attack of May 1—Reinforcements arrive—Position at Anzac—Casualties—Underestimate of wounded—Unhappy results | 123 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| THE BATTLES OF MAY | |

| State of Constantinople—Our submarines—Sir Ian’s reduced forces—The guns—May 6 at Helles—May 7—May 8—The Australian charge—The 29th Division—Trench warfare—Death of General Bridges at Anzac—May 19 at Anzac—Armistice at Anzac—Loss by hostile submarines—G.H.Q. at Imbros—Hope of Russian aid abandoned—Mr. Churchill and Lord Fisher resign | 144 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| THE BATTLES OF JUNE | |

| Situation on Peninsula—June 4 at Helles—French Colonial troops—Arrival of General De Lisle—June 6 to 8 at Helles—Losses—Want of guns—June 28 at Helles—The Gully Ravine—Turkish proclamations—Position at Anzac—June 29 at Anzac—Discouragement—General Gouraud wounded—The war in Poland and Italy | 171 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| THE PAUSE IN JULY | |

| Local Turkish attacks—Turkish reinforcements—Our attacks of July 12 and 13 at Helles—General Hunter-Weston invalided—General Stopford’s arrival—Description of Helles—Rations—Description of Anzac—The Aragon at Mudros—Arrival of General Altham—The Saturnia—Arrival of Colonel Hankey—The monitors, “blister ships,” and “beetles”—The 10th, 11th, and 13th Divisions—The 53rd and 54th Divisions—Total forces in August—New scheme of attack considered | 195xvii |

| CHAPTER X | |

| THE VINEYARD, LONE PINE, AND THE NEK | |

| Feints and arrangement of forces—August 6 at Helles—August 7 to 13—Fight for the Vineyard—Leane’s trenches at Anzac—Lone Pine—Assault of August 6—Continuous fighting till August 12—Assault on German officers’ trenches—Assault on the Nek, August 7 | 224 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| SARI BAIR | |

| Description of the range—Nature of the approaches—General Godley’s force—His dispositions—Evening August 6 to evening August 7—Capture of Old No. 3 Post—Capture of Big Table Top—Capture of Bauchop’s Hill—Ascent of Rhododendron Ridge—General Monash on Aghyl Dere—Evening August 7 to evening August 8—Fresh dispositions—Summit of Chunuk Ridge reached—Death of Colonel Malone—Attempt at Abdel Rahman—Evening August 8 to evening August 9—Error of Baldwin’s column—Major Allanson on Hill Q—View of the Dardanelles—Party driven off by shells—Turks regain the summit—Baldwin at the Farm—Party on Chunuk Ridge relieved—Evening August 9 to evening August 10—Fresh party on Chunuk Ridge destroyed—Turks swarm over summit—Fighting at the Farm—Death of General Baldwin—Turks driven back to summit—Causes of comparative failure | 247 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| SUVLA BAY | |

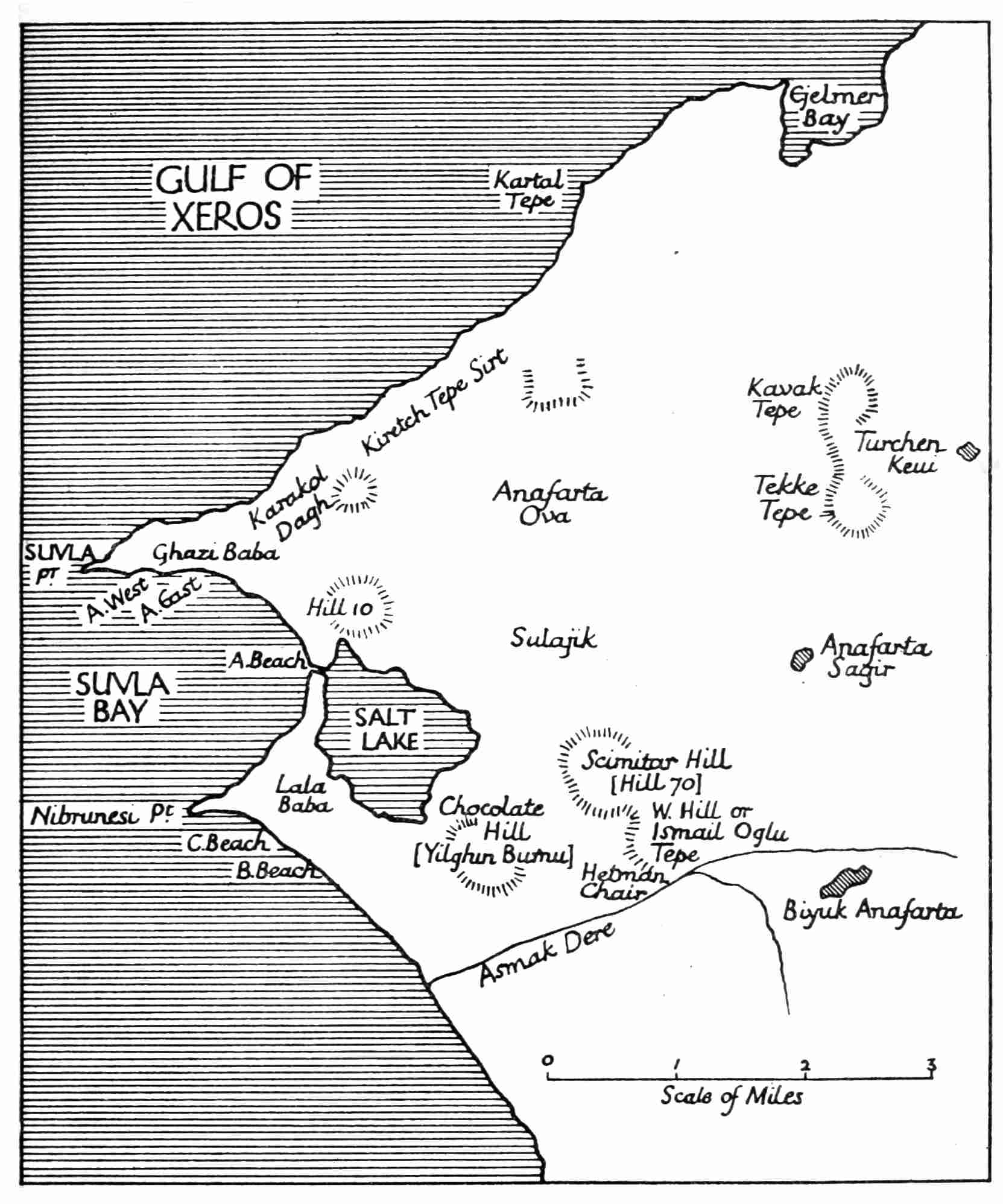

| Description of the bay and surrounding country—General Stopford and IXth Corps—Divisional Generals—Evening August 6 to evening August 7—The embarkation—Work of the Navy—The landing beaches—Capture of Lala Baba—Ill-luck of 34th Brigade—Delay and confusion of Brigades and Divisions—Hill’s Brigade (31st)—Its advance round Salt Lake—Capture of Chocolate Hill—General Mahon on Kiretch Tepe Sirt—Evening August 7 to evening August 8—Silence at Suvla—Failure of water distribution—Sir Ian visits Suvla—His orders to General Hammersley—Scimitar Hill abandoned by mistake—Evening August 8 to evening August 9—Turks reinforced return to positions—Failure of our attack on Scimitar Hill—Sir Ian proposes occupation of Kavak and Tekke Tepes—He sends his last reserve to Suvla—Evening August 9 to evening August 10—Renewed attack on Scimitar Hill—Its failure—General Stopford ordered to consolidate line—Evening August 10 to evening August 11—Landing of 54th Division—Confusion of front lines—Battalions reorganised—Evening August 11 to evening August 12—Sir Ian again urges occupation of Kavak and Tekke Tepes—Disappearancexviii of 5th Norfolks—General Stopford’s objections—The 10th Division on Kiretch Tepe Sirt (August 15)—Failure to maintain advance—General De Lisle succeeds General Stopford temporarily in command of IXth Corps—Other changes in command | 286 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| THE LAST EFFORTS | |

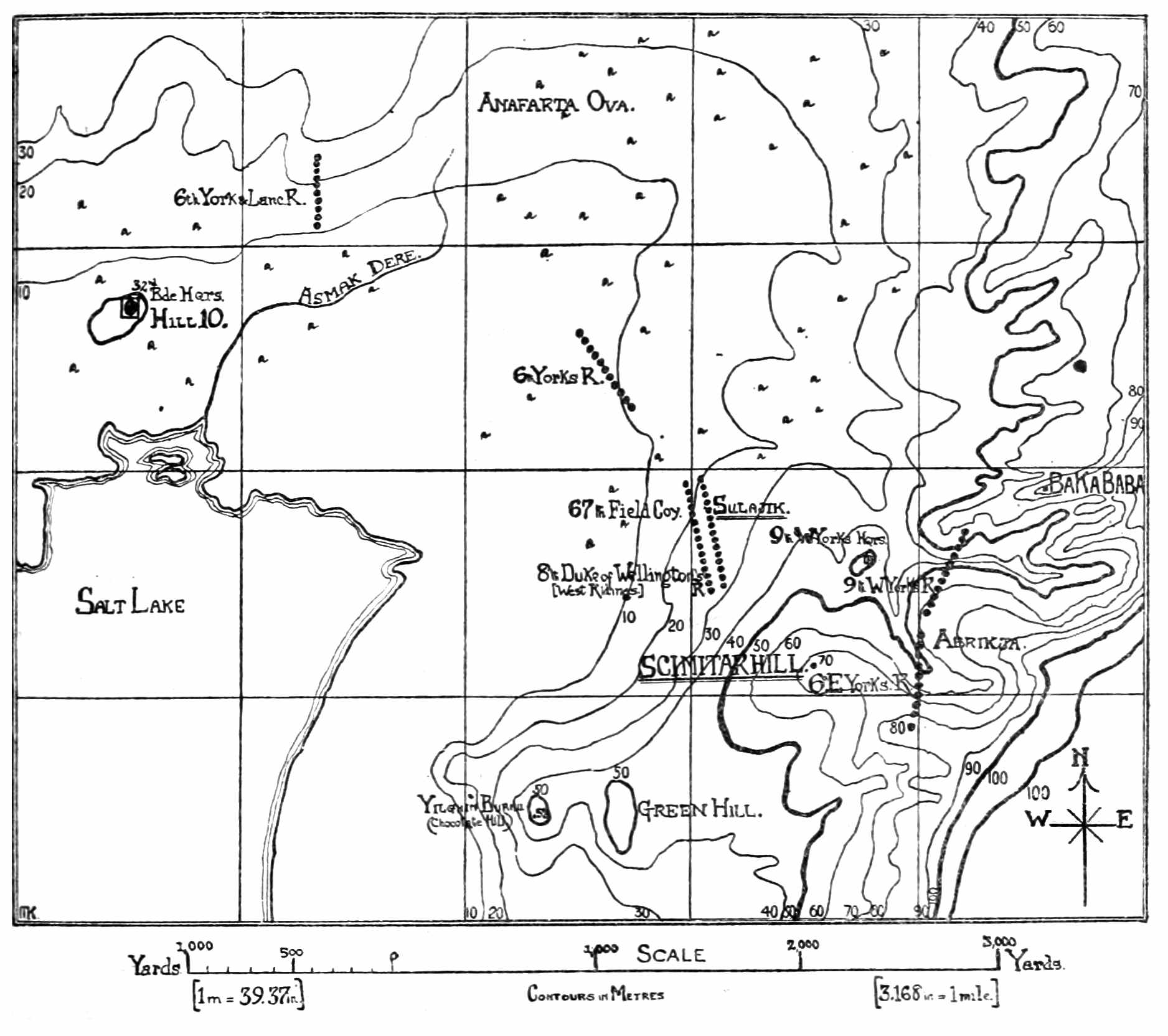

| Causes of the failure in August—Advantages gained—Approximate losses—Adequate reinforcements refused—Arrival of Peyton’s mounted Division—Renewed attempt against Scimitar Hill (August 21)—Mistakes in the advance on right—The 29th Division in centre—Advance of the Yeomanry—Failure to occupy the hill—Attack on Hill 60 from Anzac—Kabak Kuyu (August 21)—Connaught Rangers—Slow progress of attack—Second attack (August 27)—Third attack (August 29)—Last battle on the Peninsula | 333 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| SIR IAN’S RECALL | |

| Sickness increases during September—Monotonous food—Regret for dead and wounded—New drafts—Fears of winter—Sir Julian Byng commands IXth Corps—Events in France, Poland, and the Balkans—Attitude of Bulgaria and Greece—The 10th Division and one French sent to Salonika—Bulgaria declares war—Venizelos resigns—Serbia invaded—Salonika expedition too late, but destroys hope of Dardanelles—Lord Kitchener inquires about evacuation—Sir Ian’s reply—He is recalled | 356 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| THE FIFTH ACT | |

| Sir Charles Monro arrives—His report—The advocates of evacuation—Lord Kitchener visits the Peninsula—General Birdwood appointed to command—Storm and blizzard of November—General Birdwood ordered to evacuate Suvla and Anzac—Estimate of Turkish forces—Our ruses—Arrangements at Suvla—Risks of the final nights—Embarkation at Suvla—Problem at Anzac—Final arrangements—Evacuation of Anzac—Uncertainty about Helles—Evacuation ordered—Turkish attacks—Final withdrawal (January 8, 1916)—Recapitulation of causes of failure—Concluding observations—The end | 374 |

| INDEX | 413 |

xix

| General Sir Ian Hamilton | Frontispiece | |

| From a portrait by John S. Sargent, R.A. | ||

| FACING PAGE | ||

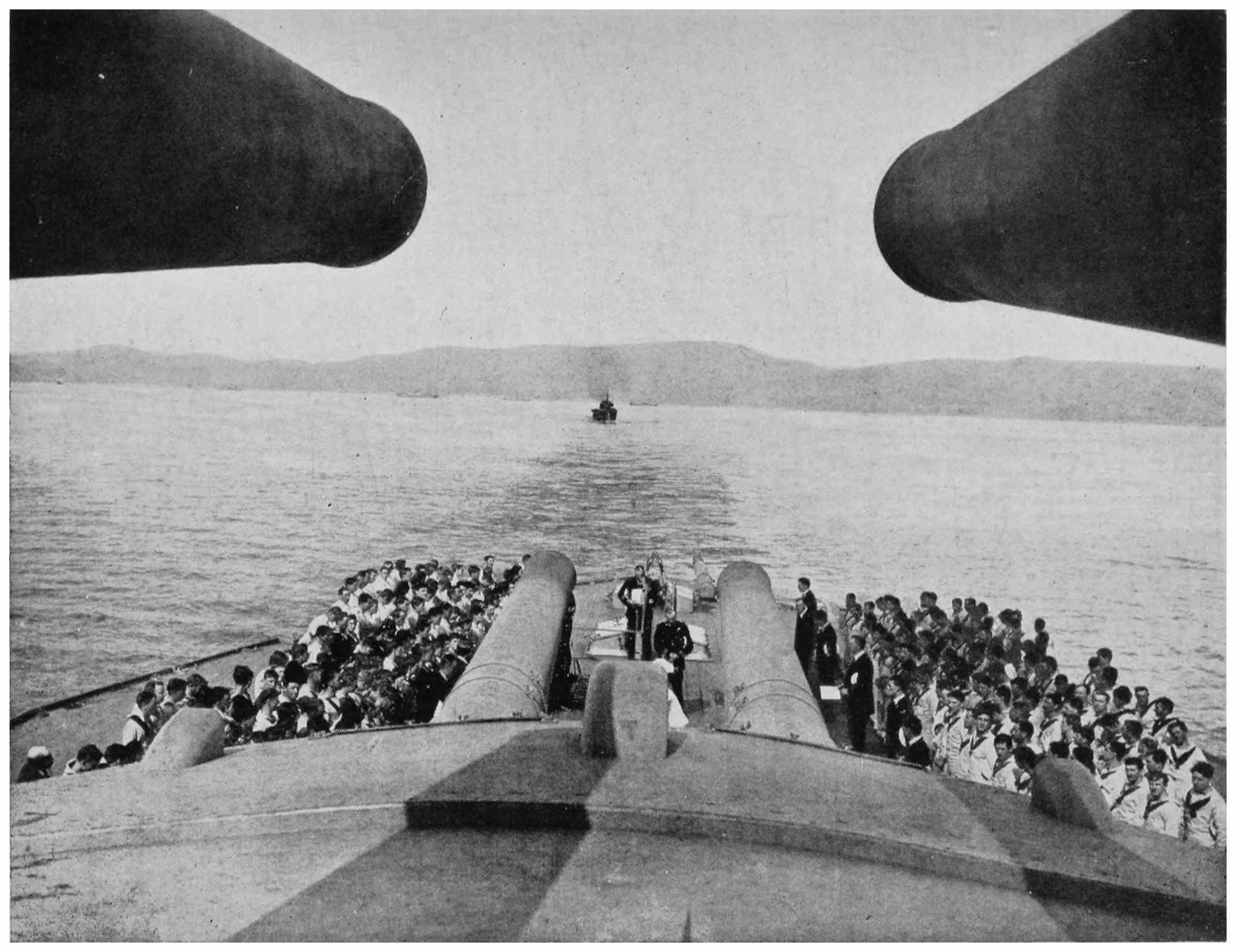

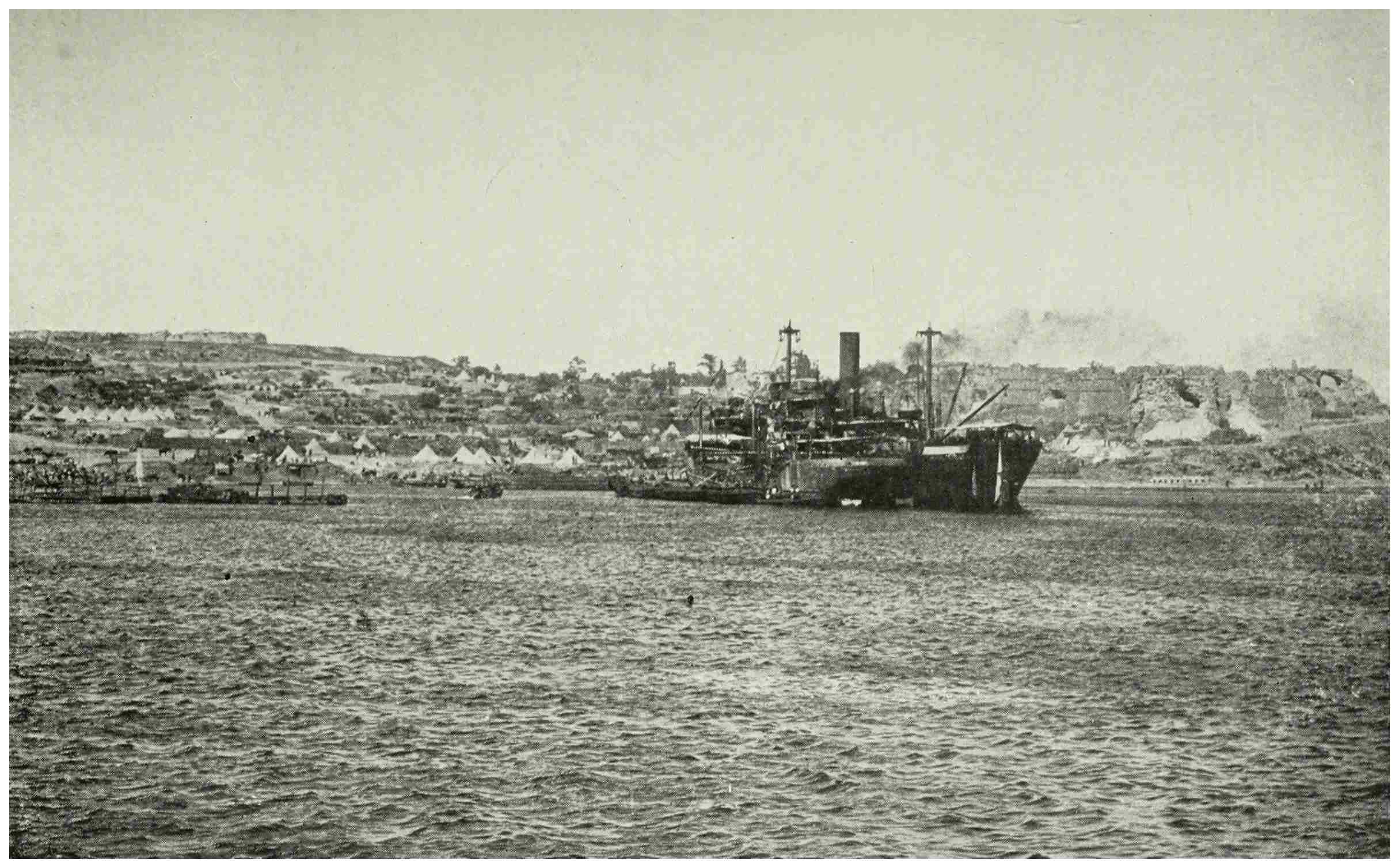

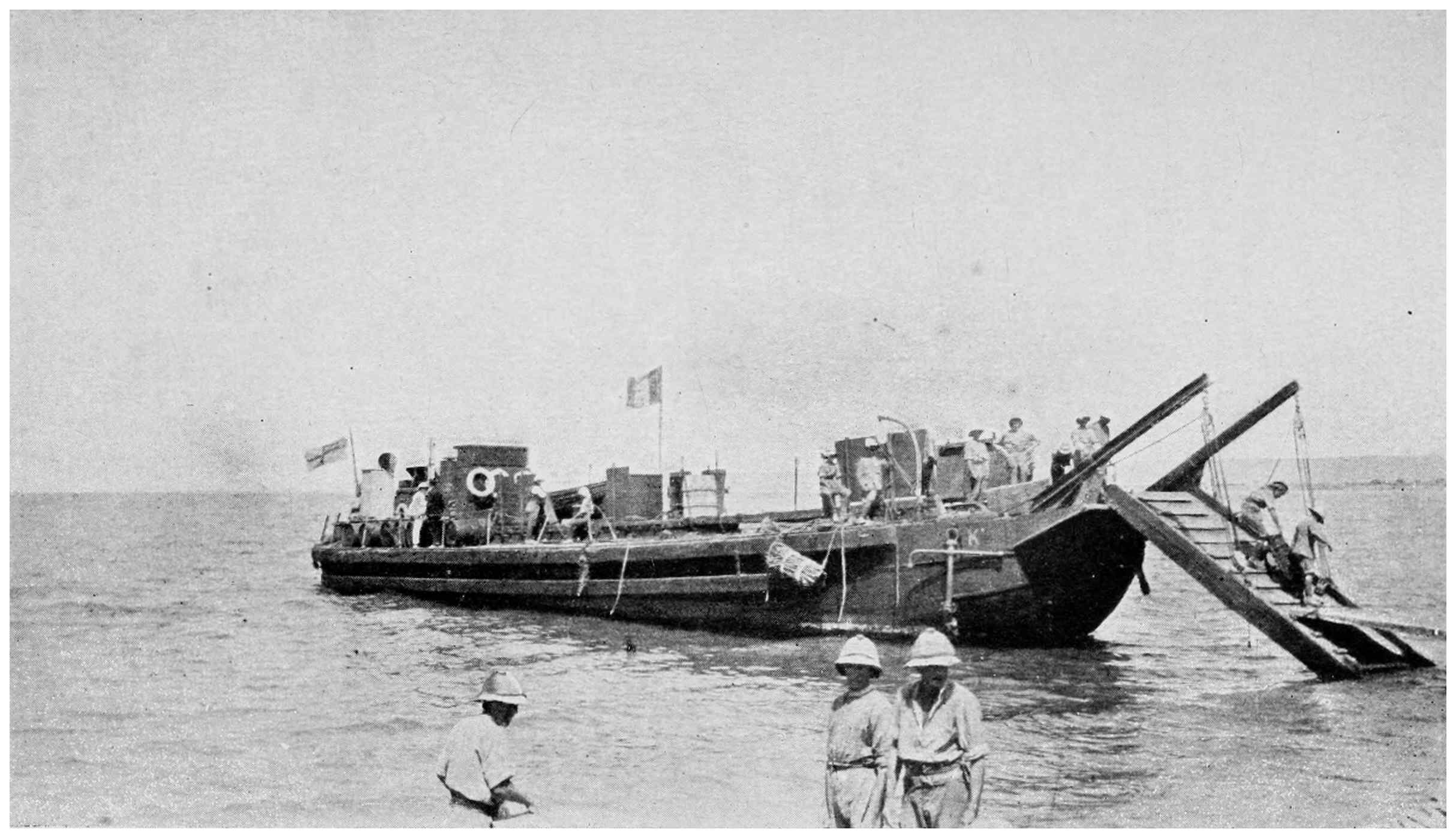

| Service on Board the Queen Elizabeth | 24 | |

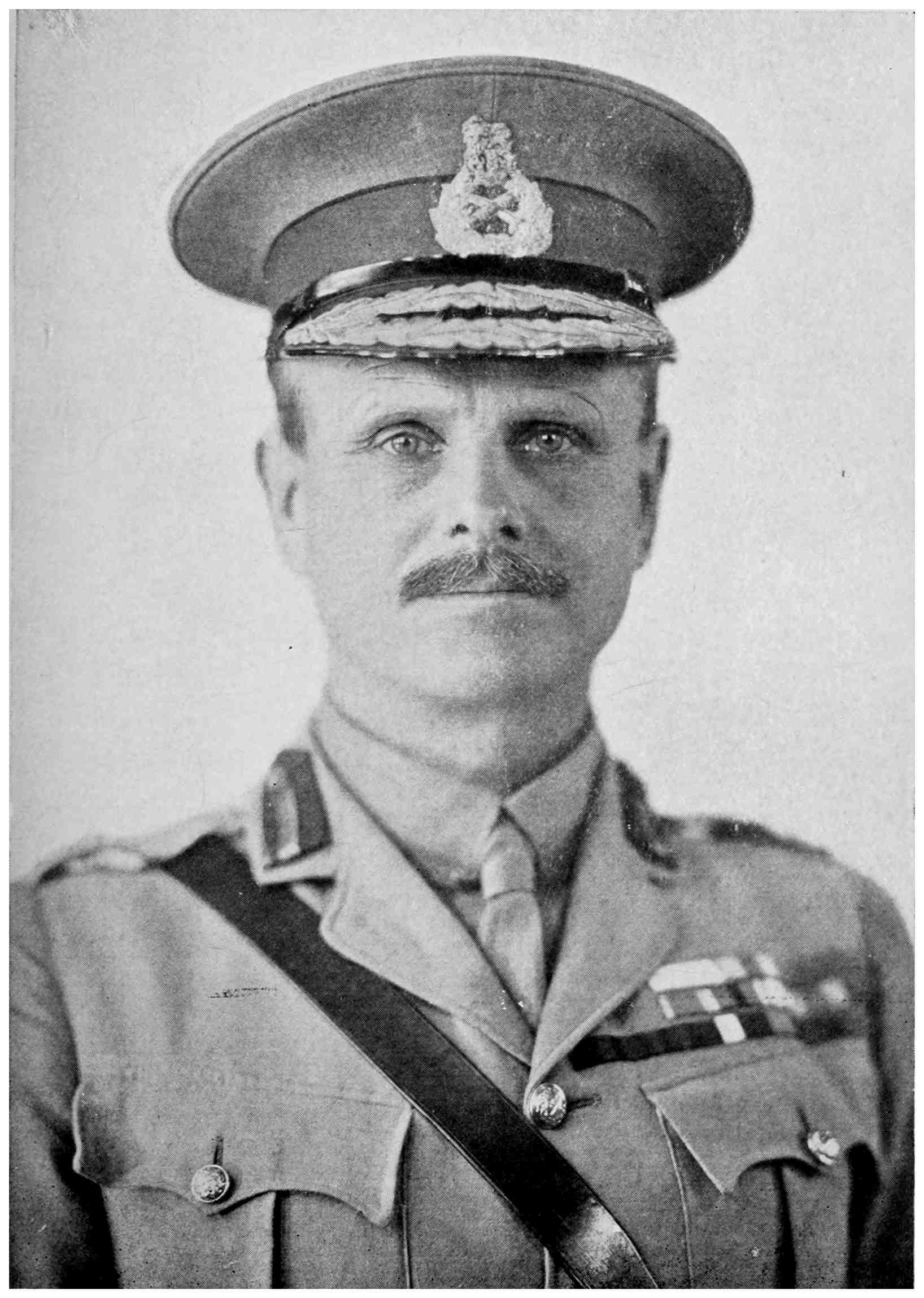

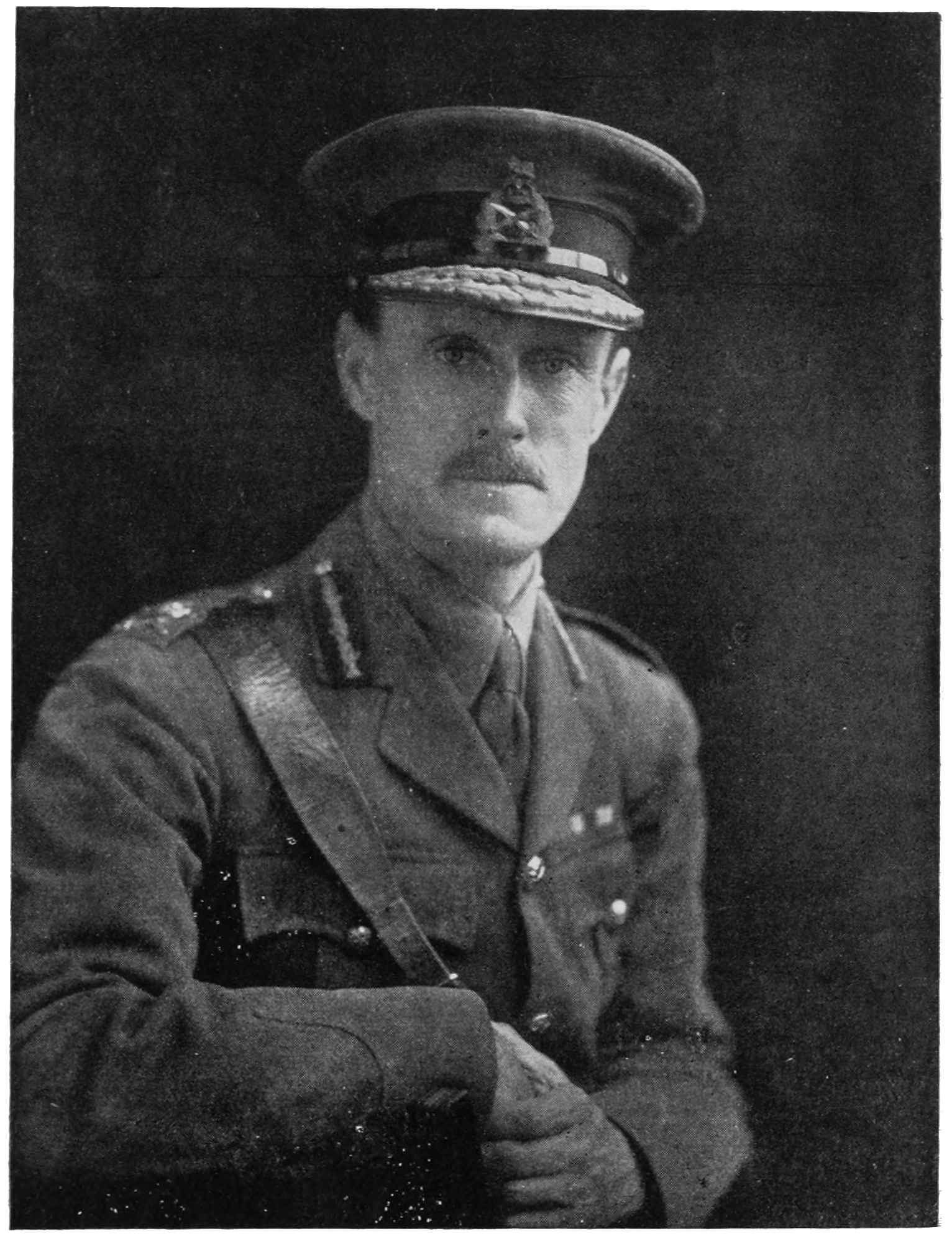

| General Sir William Birdwood | 44 | |

| The River Clyde, “V” Beach, and Seddel Bahr | 94 | |

| Lieut.-Col. C. H. H. Doughty-Wylie | 128 | |

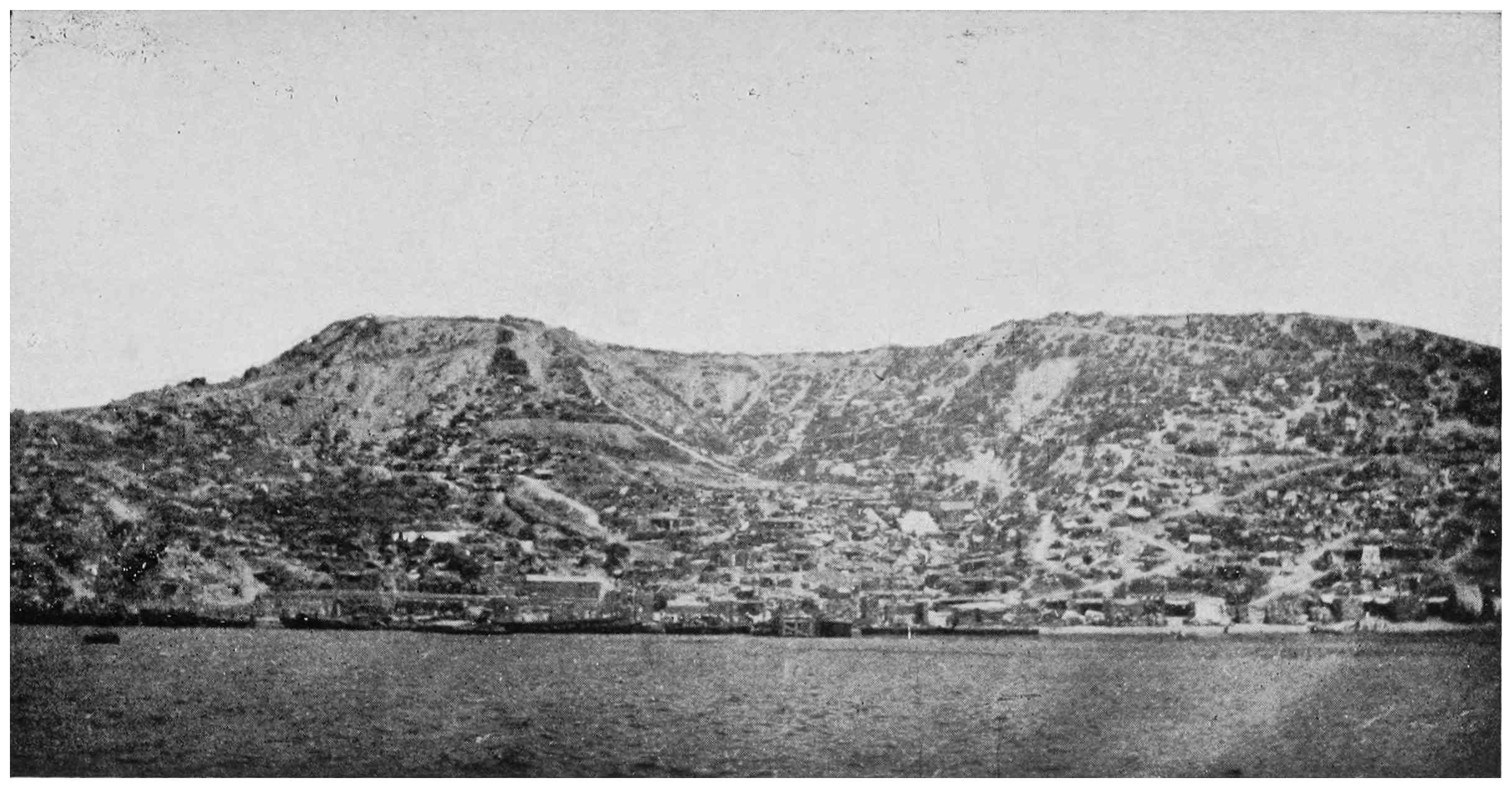

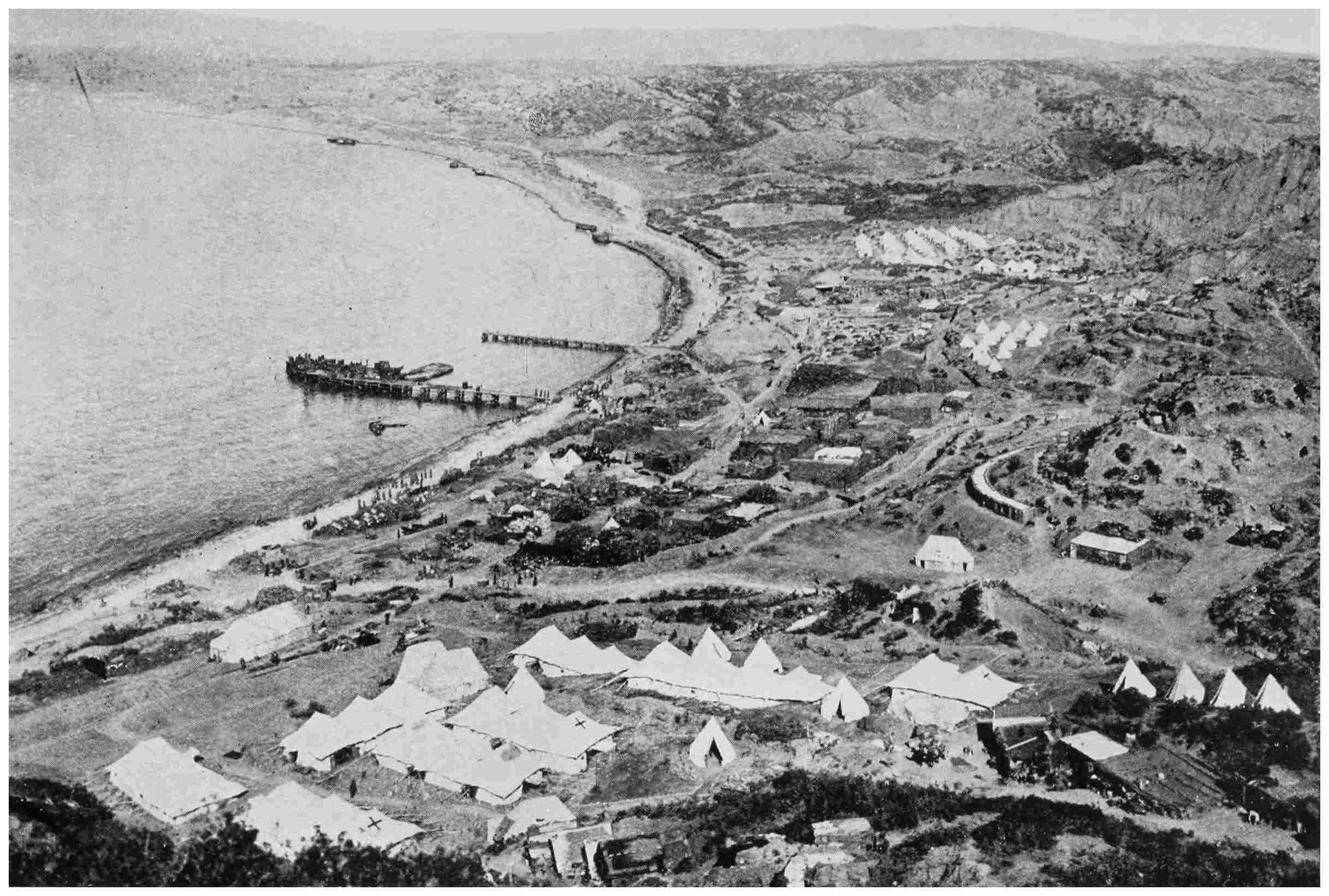

| Anzac Cove | 138 | |

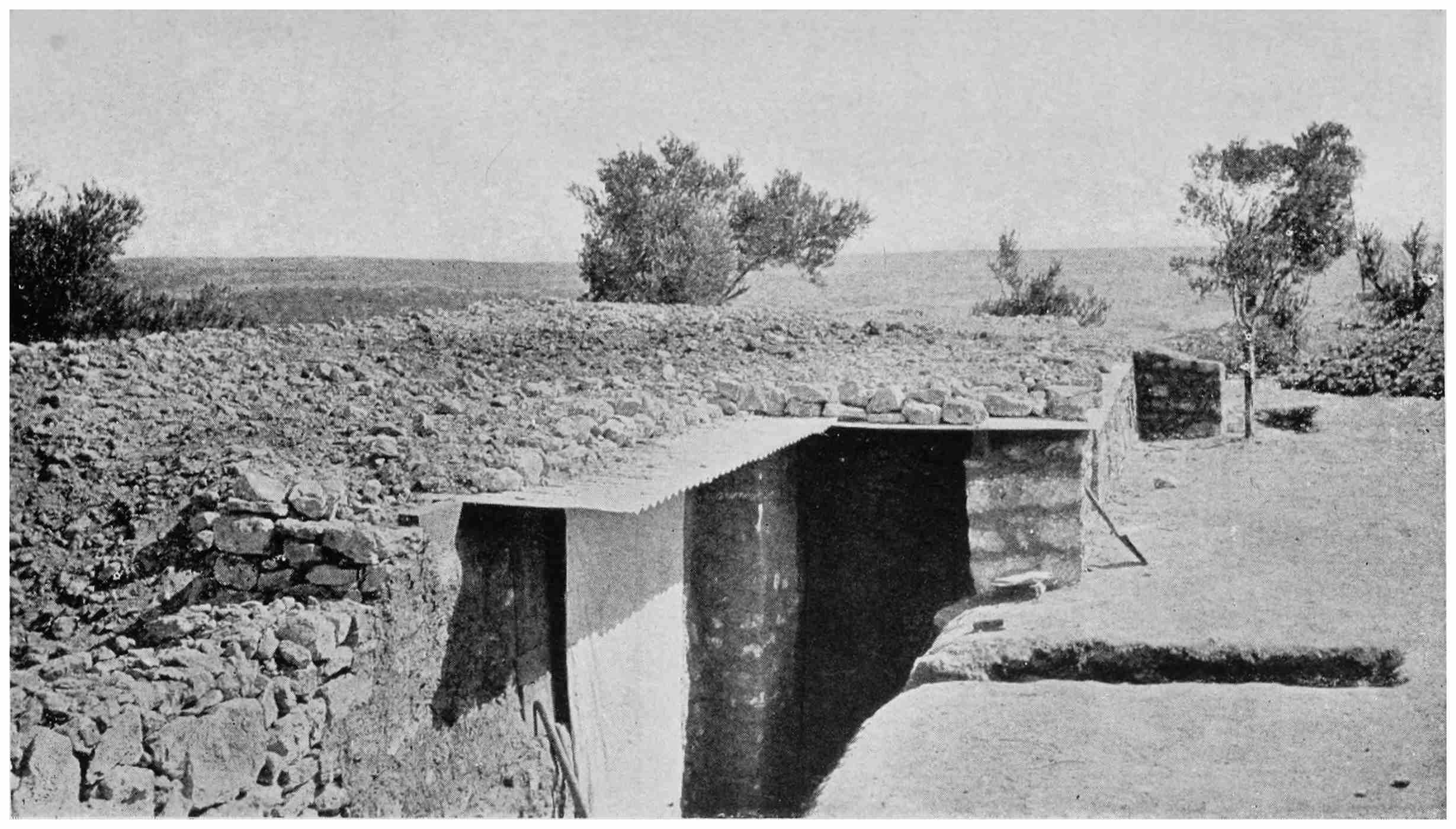

| French Dug-out at Helles | 174 | |

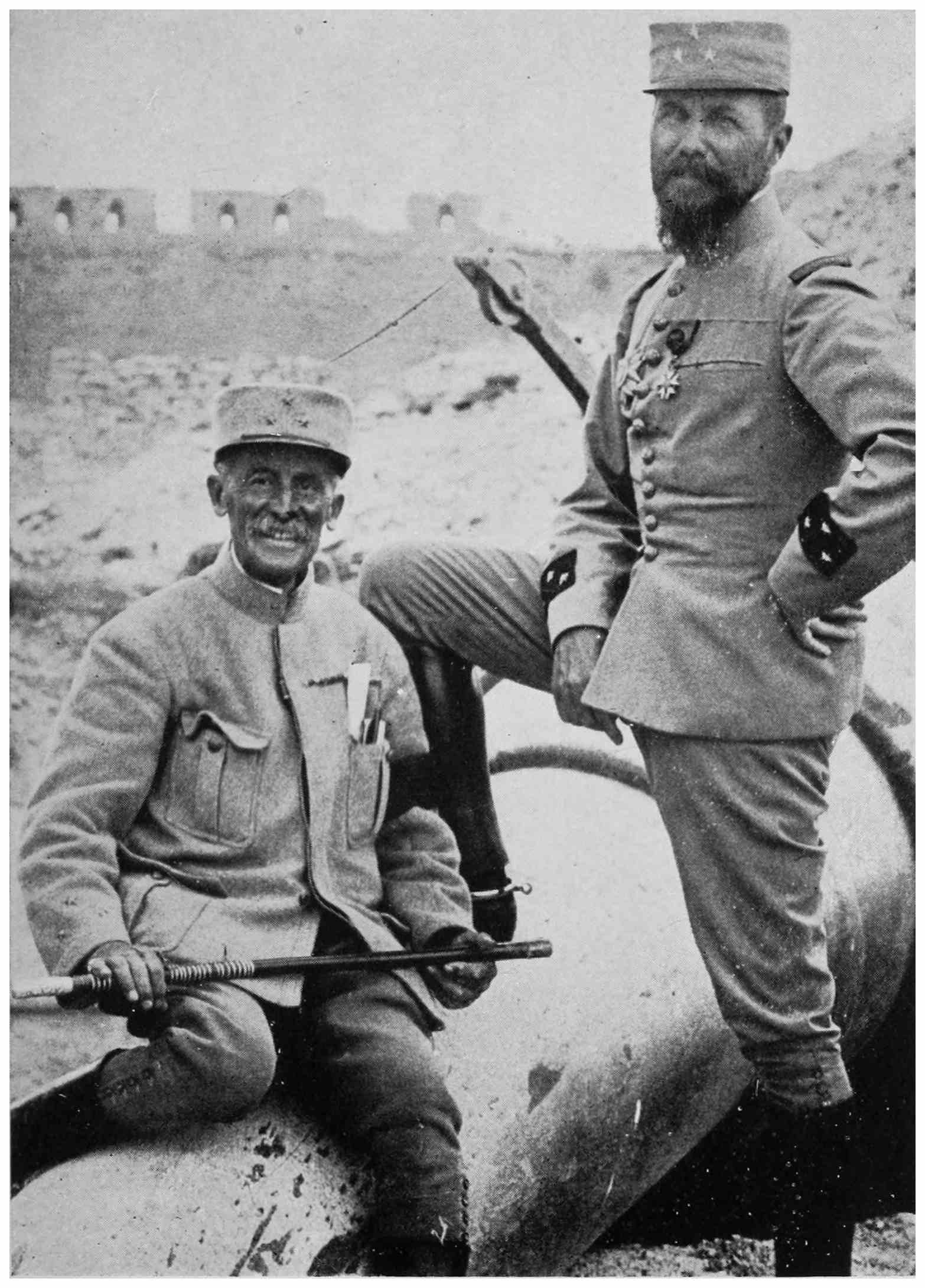

| General Gouraud standing with General Bailloud | 194 | |

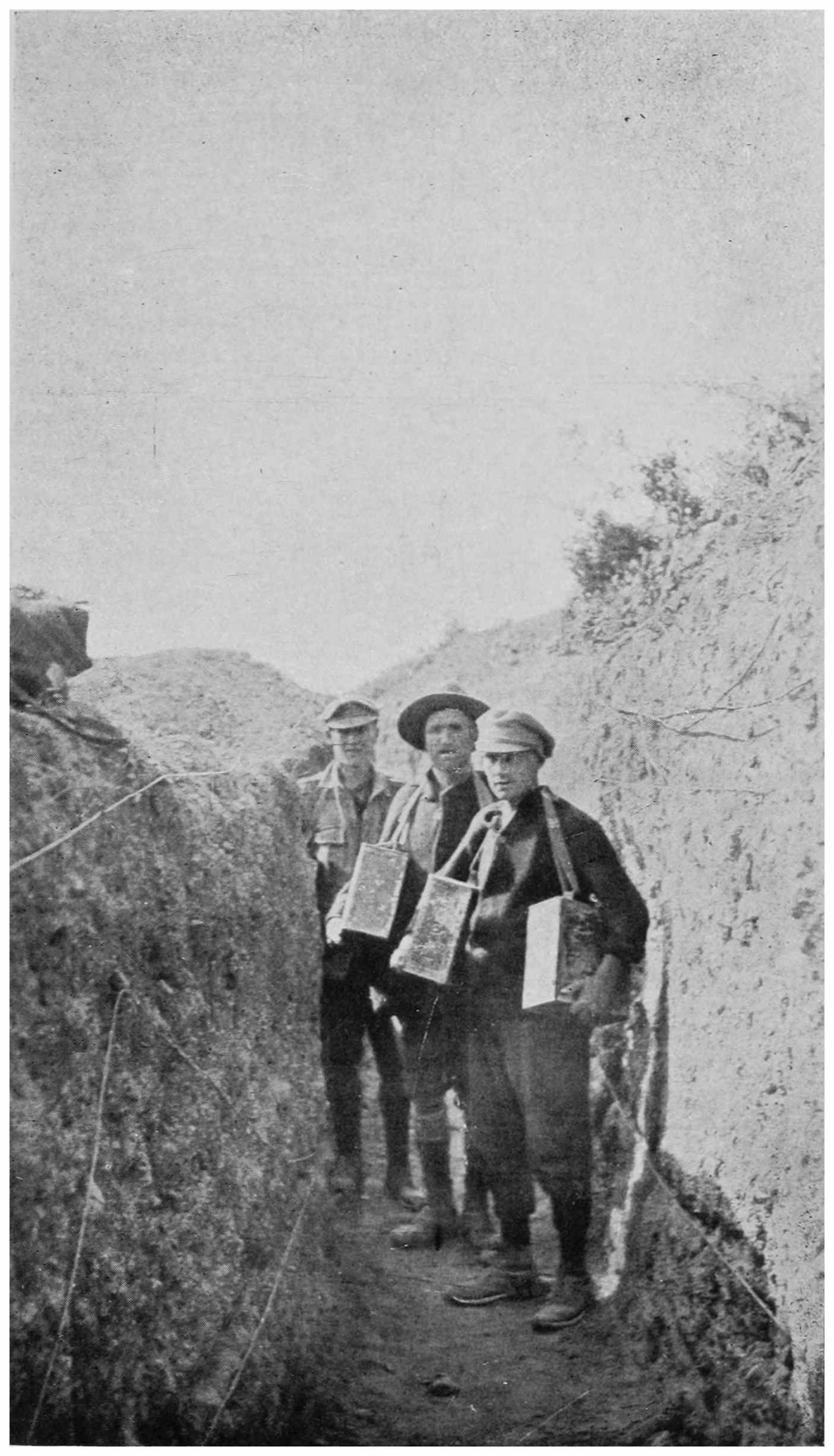

| Water-Carriers at Anzac | 206 | |

| A “Beetle” | 214 | |

| General Sir Ian Hamilton (1918) | 228 | |

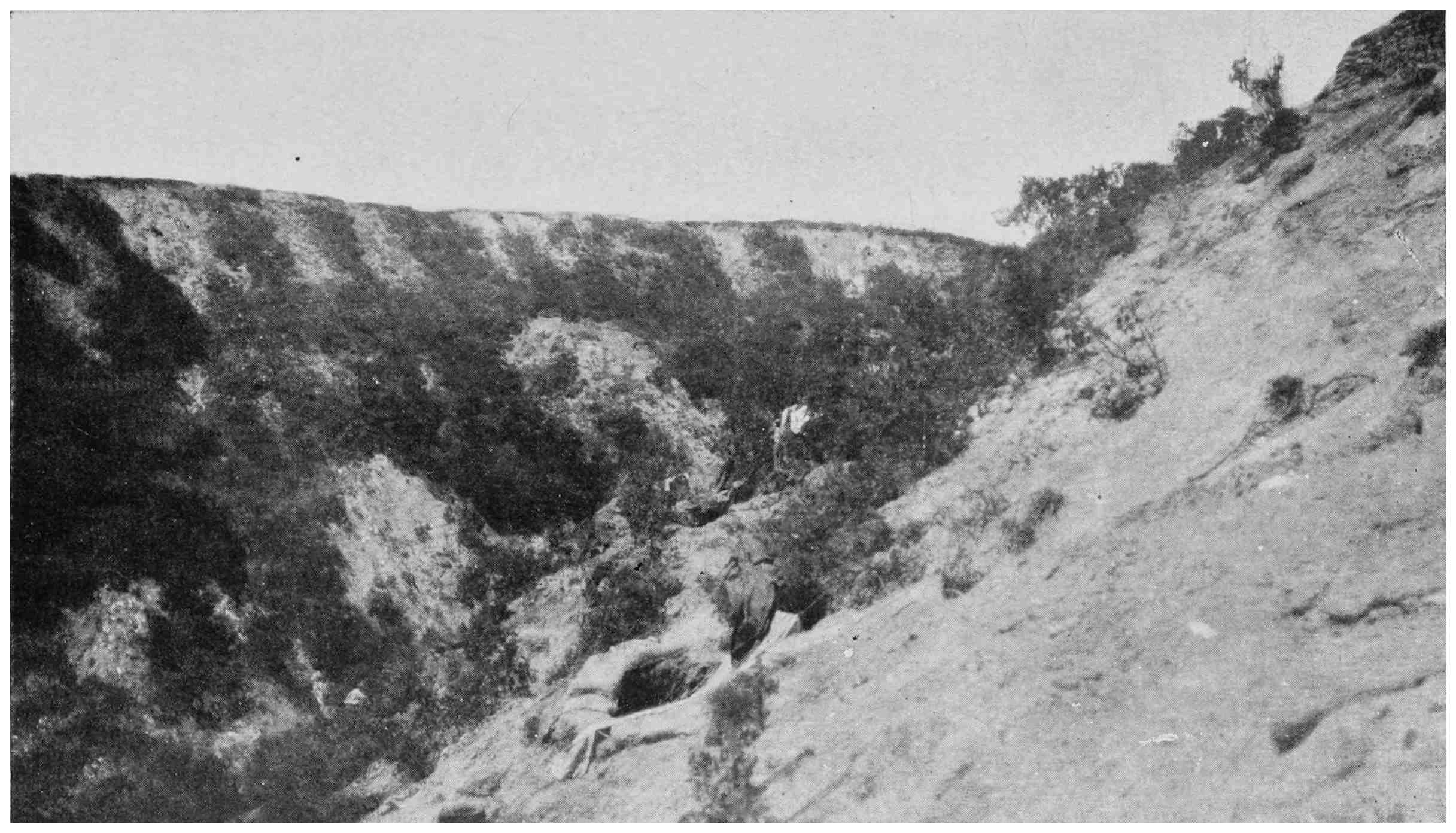

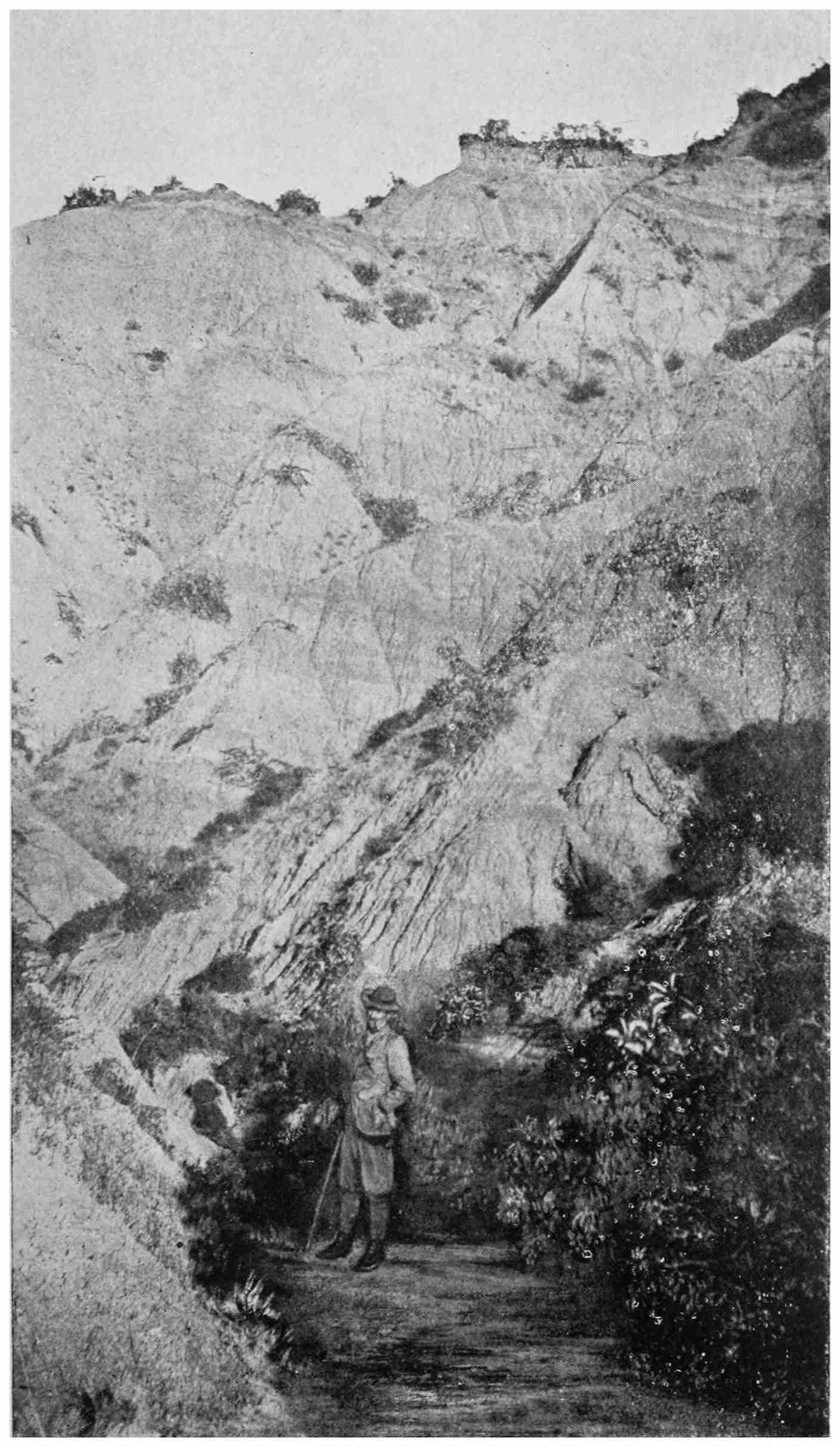

| Monash Gully | 244 | |

| Major-General Sir Alexander Godley | 256 | |

| Big Table Top | 260 | |

| Ocean Beach | 284 | |

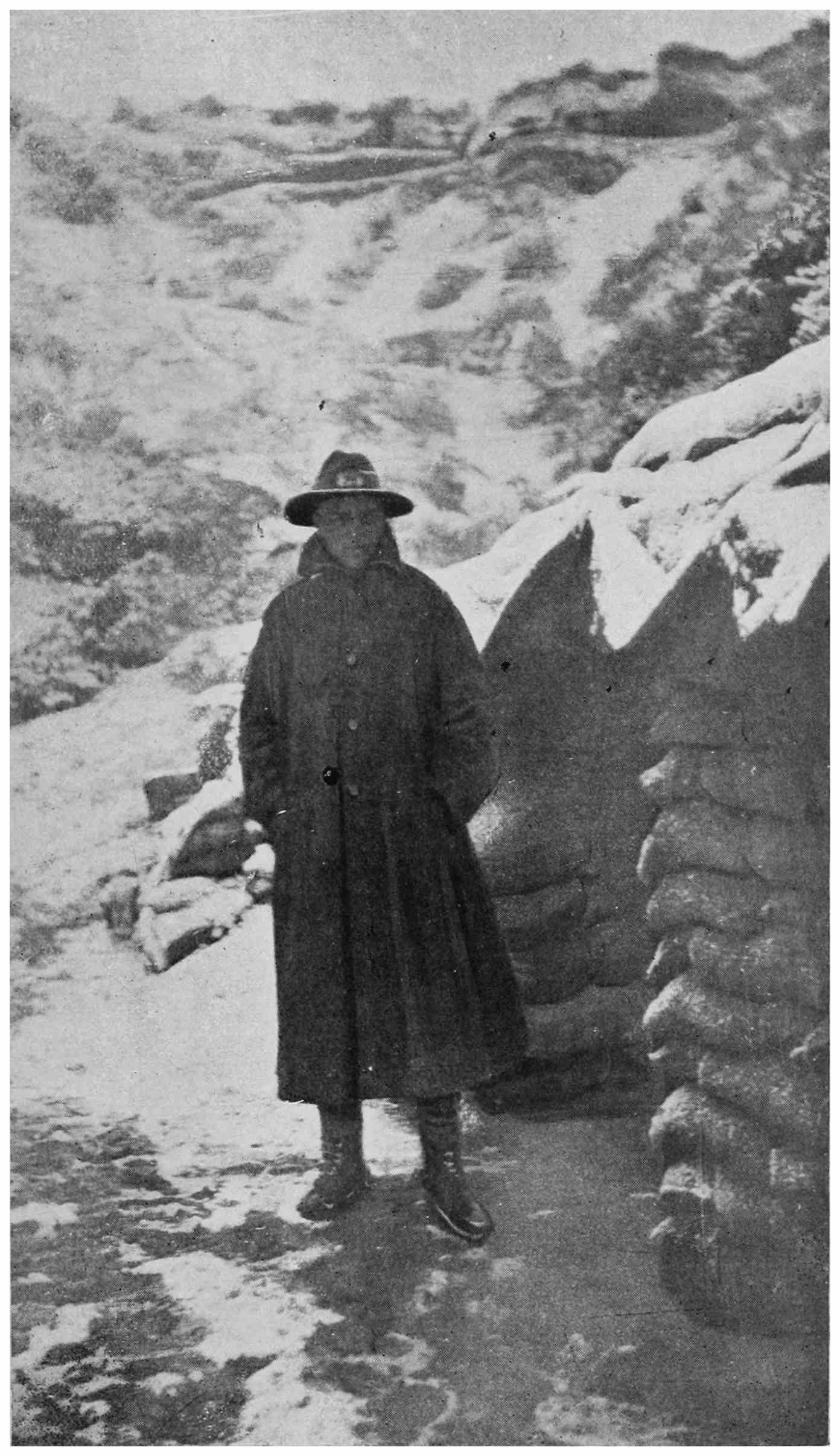

| Anzac in Snow | 384 | |

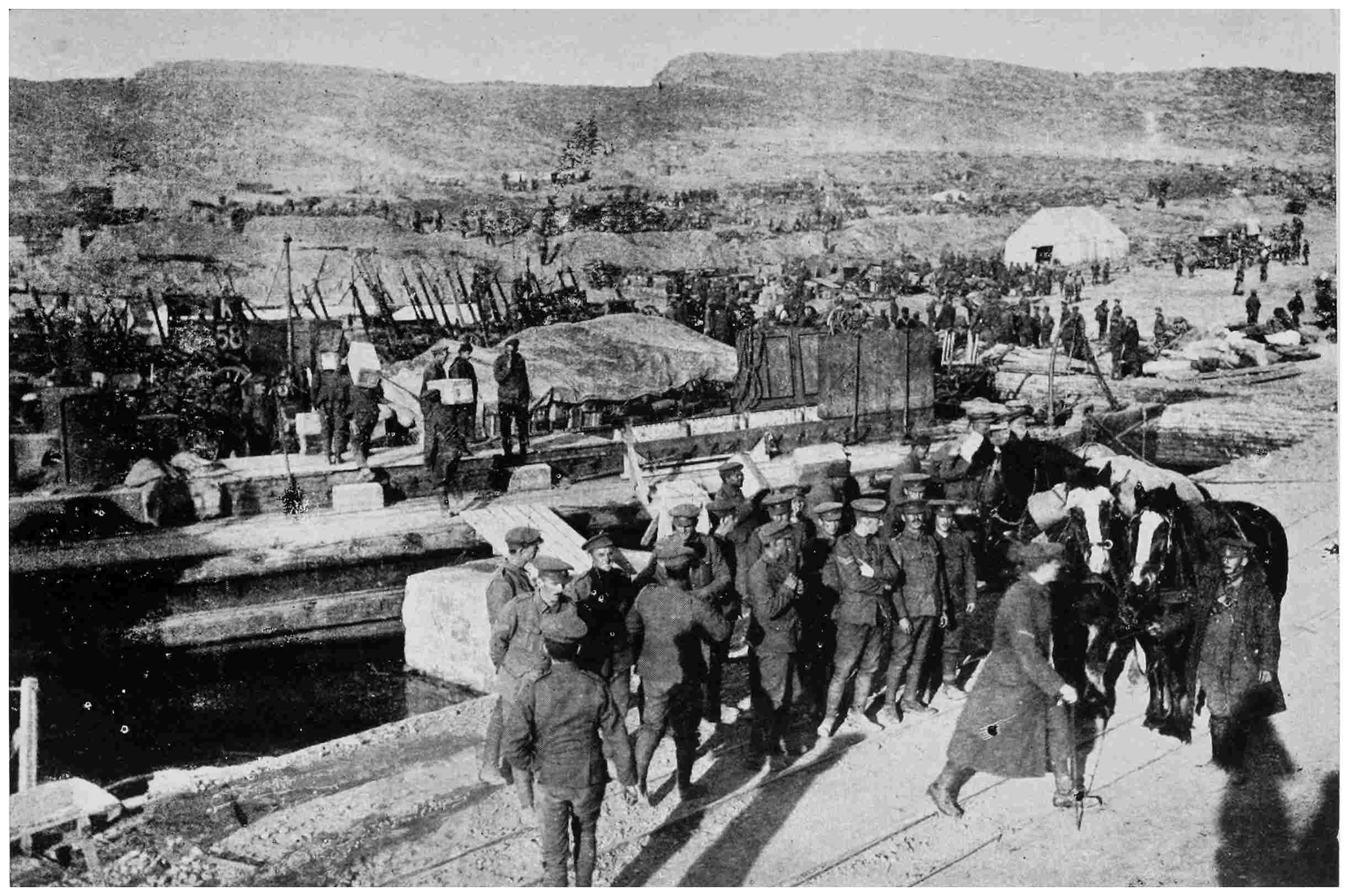

| Scene on Suvla Point | 394xx | |

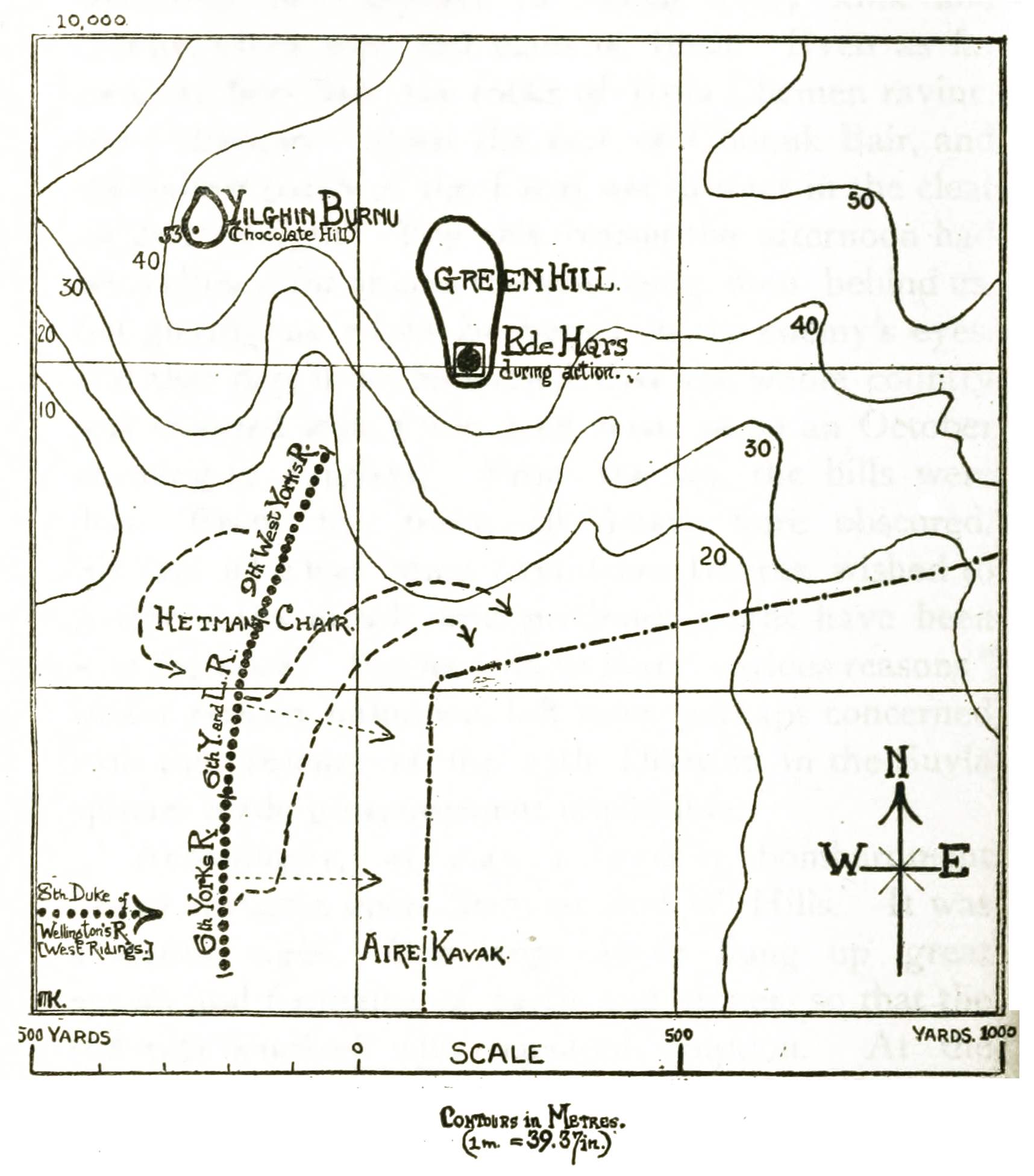

| MAPS | ||

| FACING PAGE | ||

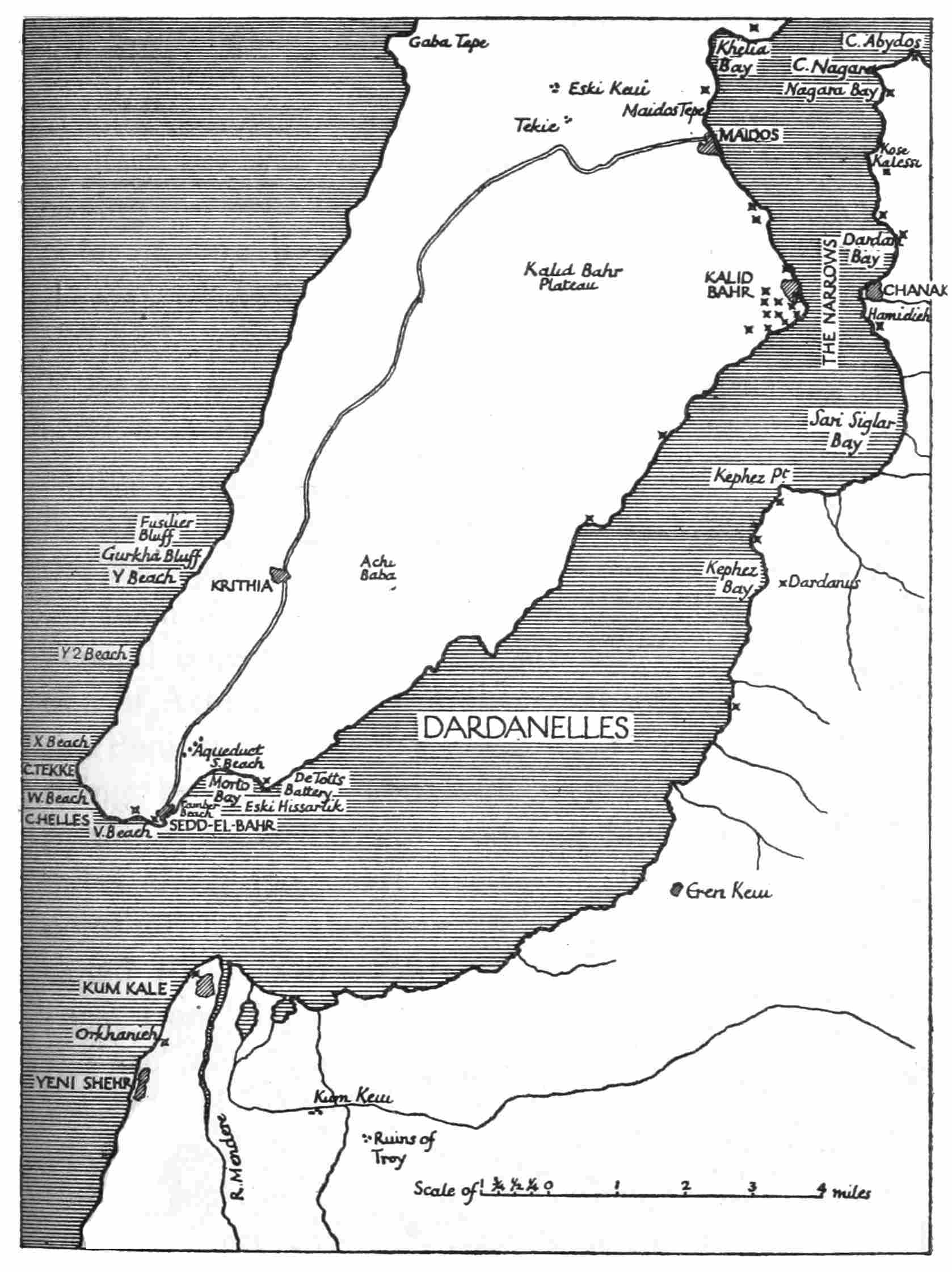

| Helles and the Straits | 78 | |

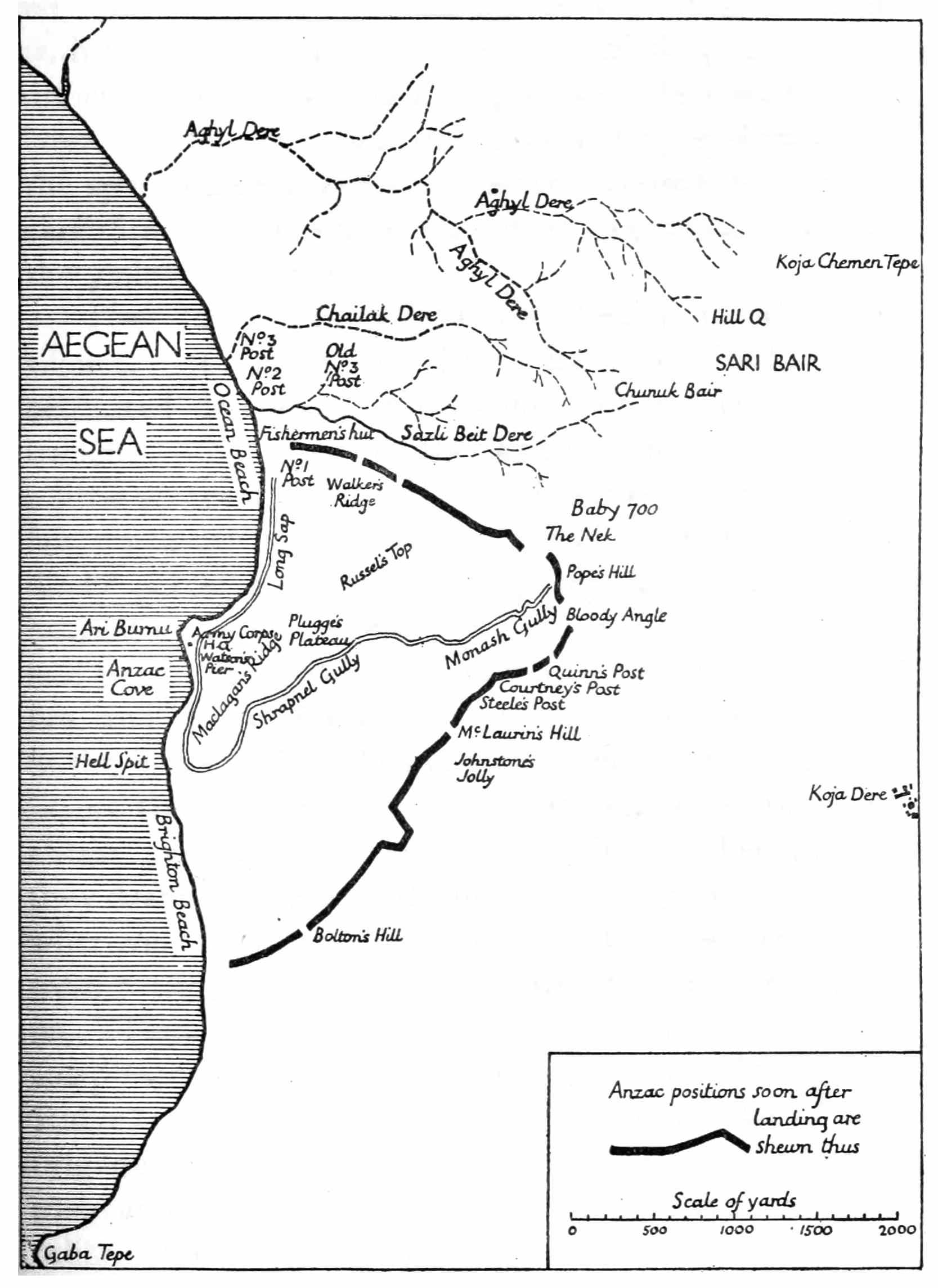

| Positions at Anzac | 112 | |

| Suvla Landing | 286 | |

| 32nd Brigade, August 8 | 316 | |

| 11th Division, August 21 | 341 | |

| At End of Book | ||

| 1. The Peninsula, the Straits, and Constantinople. | ||

| 2. British and French Trenches at Helles. | ||

| 3. Positions at Anzac (end of August). | ||

| 4. Positions at Suvla (end of August). | ||

1

On November 3, 1914, the silence of the Dardanelles was suddenly broken by an Anglo-French naval squadron, which opened fire upon the forts at the entrance of that historic strait. The bombardment lasted only ten minutes, its object being merely to test the range of the Turkish guns, and no damage seems to have been inflicted on either side. The ships belonged to the Eastern Mediterranean Allied Squadrons, commanded by Vice-Admiral Sackville Carden, and the order to bombard was given by the Admiralty, Mr. Winston Churchill being First Lord. The War Council was not consulted, and Admiral Sir Henry Jackson, Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean, in his evidence before the Dardanelles Commission described the bombardment as a mistake, because it was likely to put the Turks on the alert. Commodore de Bartolomé, Naval Secretary to the First Lord, also said he considered it unfortunate, presumably for the same reason.1 Even Turks, unaided by Germans,2 might have foreseen the ultimate necessity of strengthening the fortification of the Straits, but at the beginning they would naturally trust to the long-recognised difficulty of forcing a passage up the swift and devious channel which protects the entrance to the Imperial City more securely than a mountain pass.

War between the Allies and Turkey became certain only three days before (October 31), but from the first the temptation of the Turkish Government to throw in their lot with “Central Europe” was powerful. It is true that, during three or four decades of last century, Turkey counted upon England for protection, and that by the Crimean War and the Treaty of Berlin England had protected her, with interested generosity, as a serviceable though frail barrier against Russian designs. But the British occupation of Egypt, the British intervention in Crete and Macedonia, and perhaps also the knowledge that a body of Englishmen fought for Greece in her disastrous campaign of 1897, shook Turkish confidence in the supposed protection; while, on the other hand, Abdul Hamid’s atrocious persecution of his subject races proved to the British middle classes that, though the Turk was described as “the gentleman of the Near East,” he still possessed qualities undesirable in an ally of professing Christians. Besides, within the last eight years (since 1906), the understanding between England and Russia had continually grown more definite, until it resulted in open alliance at the outbreak of the war; and Russia had long been Turkey’s relentless and insatiable foe. For she had her mind3 steadily set upon Constantinople, partly because, by a convenient and semi-religious myth, the Tsars regarded themselves as the natural heirs of the Byzantine Emperors, and partly in the knowledge that the possession of the Bosphorus and the Dardanelles was essential for the development of Russia’s naval power.

Germany was not slow in taking up the part of Turkey’s friend as bit by bit it fell from England’s hand. If, in Lord Salisbury’s phrase, England found in the ’nineties that at the time of the Crimean War she had put her money on the wrong horse, Germany continued to back the weak-kneed and discarded outsider. Germany’s voice was never heard in the widespread outcry against “the Red Sultan.” German diplomacy regarded all Balkan races and Armenians with indifferent scorn. It called them “sheepstealers” (Hammeldiebe), and if Abdul Hamid chose to stamp upon troublesome subjects, that was his own affair. With that keen eye to his country’s material interest which, before the war, made him the most enterprising and successful of commercial travellers, Kaiser Wilhelm II., repeating the earlier visit of 1889, visited the Sultan in state at the height of his unpopularity (1898), commemorated the favour by the gift of a deplorable fountain to the city, and proceeded upon a speculative pilgrimage to Jerusalem, which holy city German or Turkish antiquarians patched with the lath and plaster restorations befitting so curious an occasion.

The prolonged negotiations over the concession of the Bagdad railway ensued, the interests of Turkey and Germany alike being repeatedly thwarted by England’s opposition, up to the very eve of the4 present war, when Sir Edward Grey withdrew our objection, providing only for our interests on the section between Bagdad and the Persian Gulf.2 During the Young Turk revolution of 1908–1909, English Liberal opinion was enthusiastic in support of the movement and in the expectation of reform. But our diplomacy, always irritated at new situations and suspicious of extended liberties, eyed the change with a chilling scepticism which threw all the advantage into the hands of Baron Marschall von Biberstein, the German Ambassador in Constantinople. His natural politeness and open-hearted industry contrasted favourably with the habitual aloofness or leisured indifference of British Embassies; and so it came about that Enver Pasha, the military leader of Young Turkey, was welcomed indeed by the opponents of Abdul Hamid’s tyranny at a public dinner in London, but went to reside in Berlin as military attaché.

Germany’s object in this astute benevolence was not concealed. With her rapidly increasing population, laborious, enterprising, and better trained than other races for the pursuit of commerce and technical industries, she naturally sought outlets to vast spaces of the world, such as Great Britain, France, and Russia had already absorbed. The immense growth of her wealth, combined with formidable naval and military power, encouraged the belief that such expansion was as practicable as necessary. But the best places in the sun were now occupied. She had secured pretty5 fair portions in Africa, but France, England, and Belgium had better. Brazil was tempting, but the United States proclaimed the Monroe doctrine as a bar to the New World. Portugal might sell Angola under paternal compulsion, but its provinces were rotten with slavery, and its climate poisonous. Looking round the world, Germany found in the Turkish Empire alone a sufficiently salubrious and comparatively vacant sphere for her development; and it is difficult to say what more suitable sphere we could have chosen to allot for her satisfaction, without encroaching upon our own preserves. Even the patch remaining to Turkey in Europe is a fine market-place; with industry and capital most of Asia Minor would again flourish as “the bright cities of Asia” have flourished before; there is no reason but the Ottoman curse why the sites of Nineveh and Babylon should remain uninhabited, or the Garden of Eden lie desolate as a wilderness of alternate dust and quagmire.

But to reach this land of hope and commerce the route by sea was long, and exposed to naval attack throughout its length till the Dardanelles were reached. The overland route must, therefore, be kept open, and three points of difficulty intervened, even if the alliance with Austria-Hungary permanently held good. The overland route passed through Serbia (by the so-called “corridor”), and behind Serbia stood the jealous and watchful power of the Tsars; it passed through Bulgaria, which would have to be persuaded by solid arguments on which side her material interests lay; and it passed through Constantinople, ultimately destined to6 become the bridgehead of the Bagdad railway—the point from which trains might cross a Bosphorus suspension bridge without unloading. There the German enterprise came clashing up against Russia’s naval ambition and Russia’s rooted sentiment. There the Kaiser, imitating the well-known epigram of Charles v., might have said: “My cousin the Tsar and I desire the same object—namely, Constantinople.” There lay the explanation of Professor Mitrofanoff’s terrible sentence in the Preussische Jahrbücher of June 1914: “Russians now see plainly that the road to Constantinople lies through Berlin.” The Serajevo murders on the 28th of the same month were but the occasion of the Great War. The corridor through Serbia, and the bridgehead of the Bosphorus, ranked among the ultimate causes.

The appearance (Dec. 1913) of a German General, Liman von Sanders, in Constantinople shortly after the second Balkan War, if it did not make the Great War inevitable, drove the Turkish alliance in case of war inevitably to the German side. He succeeded to more than the position of General Colman von der Goltz, appointed to reorganise the Turkish army in 1882. Accompanied by a German staff, the Kaiser’s delegate began at once to act as a kind of Inspector-General of the Turkish forces, and when war broke out they fell naturally under his control or command. The Turkish Government appeared to hesitate nearly three months before definitely adopting a side. The uneasy Sultan, decrepit with forty years of palatial imprisonment under a brother who, upon those terms only, had borne his existence near the throne, still retained the Turk’s traditional respect for England and7 France. So did his Grand Vizier, Said Halim. So did a large number of his subjects, among whom tradition dies slowly. With tact and a reasonable expenditure of financial persuasion, the ancient sympathy might have been revived when all had given it over; and such a revival would have saved us millions of money and thousands of young and noble lives, beyond all calculation of value.

But, most disastrously for our cause, the tact and financial persuasion were all on the other side. The Allies, it is true, gave the Porte “definite assurances that, if Turkey remained neutral, her independence and integrity would be respected during the war and in the terms of peace.”3 But similar and stronger assurances had been given both at the Treaty of Berlin and at the outbreak of the first Balkan War in 1912. Unfortunately for our peace, Turkey had discovered that at the Powers’ perjuries Time laughs, nor had Time long to wait for laughter. Following upon successive jiltings, protestations of future affection are cautiously regarded unless backed by solid evidences of good faith; but the Allies, having previously refused loans which Berlin hastened to advance, had further revealed the frivolity of their intentions the very day before war with Germany was declared, by seizing the two Dreadnought battleships, Sultan Osman and Reshadie, then building for the Turkish service in British dockyards. Upon these8 two battleships the Turks had set high, perhaps exaggerated, hopes, and Turkish peasants had contributed to their purchase; for they regarded them as insurance against further Greek aggression among the islands of the Asiatic coast. Coming on the top of the Egyptian occupation, the philanthropic interference with sovereign atrocity, the Russian alliance, and the refusal of loans, their seizure overthrew the shaken credit of England’s honesty, and one might almost say that for a couple of Dreadnoughts we lost Constantinople and the Straits.4

With lightning rapidity, Germany seized the advantage of our blunder. At the declaration of war, the Goeben, one of her finest battle-cruisers, a ship of 22,625 tons, capable of 28 knots, and armed with ten 11-inch guns, twelve 5·9-inch, and twelve lesser guns, was stationed off Algeria, accompanied by the fast light cruiser Breslau (4478 tons, twelve 4·1 inch guns), which had formed part of the international force at Durazzo during the farcical rule of Prince von Wied in Albania. After bombarding two Algerian towns, they coaled at Messina, and, escaping thence with melodramatic success, eluded the Allied Mediterranean command, and reached Constantinople through the Dardanelles, though suffering slight damage from the light cruiser Gloucester (August 8 or 9). When Sir Louis Mallet and the other Allied Ambassadors demanded their dismantlement, the Kaiser, with constrained but calculated charity, nominally sold or presented them to Turkey as a gift, crews, guns, and all. Here, then, were two fine ships, not merely9 building, but solidly afloat and ready to hand. The gift was worth an overwhelming victory to the foreseeing donor.5

Germany’s representatives pressed this enormous advantage by inducing the Turkish Government to appoint General Liman Commander-in-Chief, and to abrogate the Capitulations. They advanced fresh loans, and fomented the Pan-Islamic movement in Asia Minor, Egypt, Persia, and perhaps in Northern India. They even disseminated the peculiar rumour that the Kaiser, in addition to his material activities, had adopted the Moslem faith. The dangerous tendency was so obvious that, after three weeks’ war, Mr. Winston Churchill concluded that Turkey might join the Central Powers and declare war at any moment. On September 1 he wrote privately to General Douglas, Chief of the Imperial General Staff:

“I arranged with Lord Kitchener yesterday that two officers from the Admiralty should meet two officers from the D.M.O.’s (Director of Military Operations) Department of the War Office to-day to examine and work out a plan for the seizure, by means of a Greek army of adequate strength, of the Gallipoli Peninsula, with a view to admitting a British Fleet to the Sea of Marmora.”

Two days later, General Callwell, the D.M.O.,10 wrote a memorandum upon the subject, in which he said:

“It ought to be clearly understood that an attack upon the Gallipoli Peninsula from the sea side (outside the Straits) is likely to prove an extremely difficult operation of war.”

He added that it would not be justifiable to undertake this operation with an army of less than 60,000 men.6

Here, then, we have the first mention of the Dardanelles Expedition. It will be noticed that the idea was Mr. Churchill’s, that he depended upon a Greek army to carry it out, and that General Callwell, the official adviser upon such subjects, considered it extremely difficult, and not to be attempted with a landing force of less than 60,000 men.

In mentioning a Greek army, Mr. Churchill justly relied upon M. Venizelos, at that time by far the ablest personality in the Near East, entirely friendly to ourselves, and Premier of Greece, which he had saved from chaos and greatly extended in territory by his policy of the preceding five or six years. But Mr. Churchill forgot to take account of two important factors. After the Balkan Wars of 1912 and 1913, King Constantine’s imaginative but unwarlike people had acclaimed him both as the Napoleon of the Near East and as the “Bulgar-slayer,” a title borrowed from Byzantine history. Priding himself upon these insignia of a military fame little justified by his military achievements from 1897 onward, the King of Greece posed as the plain, straightforward soldier,11 and, perhaps to his credit, from the first refused approval of a Dardanelles campaign, though he professed himself willing to lead his whole army along the coast through Thrace to the City. The profession was made the more easily through his consciousness that the offer would not be accepted.7 For the other factor forgotten by Mr. Churchill was the certain refusal of the Tsar to allow a single Greek soldier to advance a yard towards the long-cherished prize of Constantinople and the Straits.

Turkish hesitation continued up to the end of October, when the war party under Enver Pasha, Minister of War, gained a dubious predominance by sending out the Turkish fleet, which rapidly returned, asserting that the ships had been fired upon by Russians (Oct. 28)—an assertion believed by few. On the 29th, Turkish torpedo boats (at first reported as the Goeben and Breslau) bombarded Odessa and Theodosia, and a swarm of Bedouins invaded the Sinai Peninsula. Turkey declared war on the 31st. Sir Louis Mallet left Constantinople on November 1, and on the 5th England formally declared war upon Turkey.

12

The breach with Turkey, so pregnant with evil destiny, did not attract much attention in England at the moment. All thoughts were then fixed upon the struggle of our thin and almost exhausted line to hold Ypres and check the enemy’s straining endeavour to command the Channel coast by occupying Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne. The Turk’s military reputation had fallen low in the Balkan War of 1912, and few realised how greatly his power had been re-established under Enver and the German military mission. Egypt was the only obvious point of danger, and the desert of Sinai appeared a sufficient protection against an unscientific and poverty-stricken foe; or, if the desert were penetrated, the Canal, though itself the point to be protected, was trusted to protect itself. On November 8, however, some troops from India seized Fao, at the mouth of the Tigris-Euphrates, and, with reinforcements, occupied Basrah on the 23rd, thus inaugurating that Mesopotamian expedition which, after terrible vicissitudes, reached Bagdad early in March 1917.

These measures, however, did not satisfy Mr. Churchill. At a meeting of the War Council on November 25, he returned to his idea of striking at the Gallipoli Peninsula, if only as a feint. Lord13 Kitchener considered the moment had not yet arrived, and regarded a suggestion to collect transport in Egypt for 40,000 men as unnecessary at present. In his own words, Mr. Churchill “put the project on one side, and thought no more of it for the time,” although horse-boats continued to be sent to Alexandria “in case the War Office should, at a later stage, wish to undertake a joint naval and military operation in the Eastern Mediterranean.”8

On January 2, 1915, a telegram from our Ambassador at Petrograd completely altered the situation. Russia, hard pressed in the Caucasus, called for a demonstration against the Turks in some other quarter. Certainly, at that moment, Russia had little margin of force. She was gasping from the effort to resist Hindenburg’s frontal attack upon Warsaw across the Bzura, and the contest had barely turned in her favour during Christmas week. In the Caucasus the situation had become serious, since Enver, by clever strategy, attempted to strike at Kars round the rear of a Russian army which then appeared to threaten an advance upon Erzeroum. On the day upon which the telegram was sent, the worst danger had already been averted, for in the neighbourhood of Sarikamish the Russians had destroyed Enver’s 9th Corps, and seriously defeated the 10th and 11th. But this fortunate and unexpected result was probably still unknown in Petrograd when our Ambassador telegraphed his appeal.

On the following day (January 3, 1915) an answer, drafted in the War Office, but sent through the Foreign Office, was returned, promising a demonstration14 against the Turks, but fearing that it would be unlikely to effect any serious withdrawal of Turkish troops in the Caucasus. Sir Edward Grey considered that “when our Ally appealed for assistance we were bound to do what we could.” But Lord Kitchener was far from hopeful. He informed Mr. Churchill that the only place where a demonstration might have some effect in stopping reinforcements going East would be the Dardanelles. But he thought we could not do much to help the Russians in the Caucasus; “we had no troops to land anywhere”; “we should not be ready for anything big for some months.”9

So, by January 3, we were bound to some sort of a demonstration in the Dardanelles, but Lord Kitchener regarded it as a mere feint in the hope of withholding or recalling Turkish troops from the Caucasus, and he evidently contemplated a purely or mainly naval demonstration which we could easily withdraw without landing troops, and without loss of prestige. In sending this answer to Petrograd, he does not appear to have consulted the War Council as a whole. His decision, though not very enthusiastic, was sufficient; for in the conduct of the war he dominated the War Council, as he dominated the country.

The War Council had taken the place of the old Committee of Imperial Defence (instituted in 1901, and reconstructed in 1904). The change was made towards the end of November 1914, but, except in one important particular, it was little more than a change in name. Like the old Committee, the15 Council were merely a Committee of the Cabinet, with naval and military experts added to give advice. The main difference was that the War Council, instead of laying its decisions before the Cabinet for approval or discussion, gave effect even to the most vital of them upon its own responsibility, and thus gathered into its own hands all deliberative and executive powers regarding military and naval movements. Sir Edward Grey, as Foreign Secretary, Mr. Lloyd George, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, and Lord Crewe, as Secretary for India, occasionally attended the meetings, and Mr. Balfour was invited to attend. But the real power remained with Mr. Asquith, the Prime Minister, Lord Kitchener, the Secretary for War, and Mr. Winston Churchill, First Lord of the Admiralty. In Mr. Asquith’s own words: “The daily conduct of the operations of the war was in the hands of the Ministers responsible for the Army and Navy in constant consultation with the Prime Minister.”10

This inner trinity of Ministers was dominated, as we said, by Lord Kitchener’s massive personality. In his evidence before the Dardanelles Commission, Mr. Churchill thus described the effect of that remarkable man upon the other members:

“Lord Kitchener’s personal qualities and position played at this time a very great part in the decision of events. His prestige and authority were immense. He was the sole mouthpiece of War Office opinion in the War Council. Every one had the greatest admiration for his character, and every one felt fortified,16 amid the terrible and incalculable events of the opening months of the war, by his commanding presence. When he gave a decision, it was invariably accepted as final. He was never, to my belief, overruled by the War Council or the Cabinet in any military matter, great or small. No single unit was ever sent or withheld contrary, not merely to his agreement, but to his advice. Scarcely any one ever ventured to argue with him in Council. Respect for the man, sympathy for him in his immense labours, confidence in his professional judgment, and the belief that he had plans deeper and wider than any we could see, silenced misgivings and disputes, whether in the Council or at the War Office. All-powerful, imperturbable, reserved, he dominated absolutely our counsels at this time.”11

These sentences accurately express the ideal of Lord Kitchener as conceived by the public mind. His large but still active frame, his striking appearance, and his reputation for powerful reserve, in themselves inspired confidence. His patient and ultimately successful services in Egypt, the Soudan, South Africa, and India were famed throughout the country, which discovered in him the very embodiment of the silent strength and tenacity, piously believed to distinguish the British nature. Shortly before the outbreak of war, Mr. Asquith as Prime Minister had taken the charge of the War Office upon himself, owing to Presbyterian Ulster’s threat of civil war, and the possibility of mutiny among the British garrison in Ireland, if commanded to proceed against that rather self-righteous population. When war with Germany was declared, it so happened that Lord Kitchener was in England, on the point of returning to Egypt,17 and Mr. Asquith handed over to him his own office as Secretary for War. The Cabinet, and especially Lord Haldane (then Lord Chancellor, but Minister of War from 1905 to 1912), the most able of army organisers, urged him to this step. But he needed no persuasion. He never thought of any other successor as possible. As he has said himself:

“Lord Kitchener’s appointment was received with universal acclamation, so much so indeed that it was represented as having been forced upon a reluctant Cabinet by the overwhelming pressure of an intelligent and prescient Press.”12

By the consent of all, Lord Kitchener was the one man capable of conducting the war, and by the consent of most he remained the one man, though he conducted it. Yet it might well be argued that the public mind, incapable of perceiving complexity, accepted a simple ideal of their hero which he himself had deliberately created. A hint of the mistake may be found in Mr. Asquith’s speech.13 He admitted that Lord Kitchener was a masterful man; that he had been endowed with a formidable personality, and was by nature rather disposed to keep his own counsel. But he maintained that he “was by no means the solitary and taciturn autocrat in the way he had been depicted.” One may describe him as shy rather than aggressive, genial rather than relentless, a reasonable peacemaker rather than a man of iron. Under that unbending manner, he studiously concealed a love of beauty, both human and artistic. Under a rapt appearance of far-reaching designs, his18 mind was much occupied with inappropriate detail, and could relax into trivialities. He was distinguished rather for sudden flashes of intuition than for reasoned and elaborated plans. During the first year of the war, his natural temptation to occupy himself in matters better delegated to subordinates was increased by the absence in France of experienced officers whom he could have trusted for staff work. He became his own Chief of Staff,14 and diverted much of his energy to minor services. At the War Council he acted as his own expert, and Sir James Murray, who always attended the meetings as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, was never even asked to express an opinion. The labours thus thrown upon Lord Kitchener, or mistakenly assumed, when he was engaged upon the task of creating new armies out of volunteers, and organising an unmilitary nation for war while the war thundered across the Channel, were too vast and multifarious for a single brain, however resolute. It is possible also that the course of years had slightly softened the personal will which had withstood Lord Milner in carrying through the peace negotiations at Pretoria, and Lord Curzon in reforming the Viceroy’s Council at Simla. Nevertheless, when all is said, all-powerful, imperturbable, reserved, Lord Kitchener dominated absolutely the counsels of the war’s first year, and his service to the country was beyond all estimate. It raises his memory far above the reach of the malignant detraction attempted after his death by certain organs of19 that “intelligent and prescient Press” which had shrieked for his appointment.15

Second in authority upon the War Council and with the nation, but only second, stood Mr. Asquith. For six years he had been Prime Minister—years marked by the restlessness and turbulence of expanding liberty at home, and abroad by ever-increasing apprehension. Yet his authority was derived less from his office than from personal qualities which, as in Lord Kitchener’s case, the English people like to believe peculiarly their own. He was incorruptible, above suspicion. His mind appeared to move in a cold but pellucid atmosphere, free alike from the generous enthusiasm and the falsehood of extremes. Sprung from the intellectual middle-class, he conciliated by his origin, and encouraged by his eminence. His eloquence was unsurpassed in the power of simple statement, in a lucidity more than legal, and, above all, in brevity. The absence of emotional appeal, and, even more, the absence of humour, promoted confidence, while it disappointed. Here, people thought, was a personality rather wooden and unimaginative, but trustworthy as one who is not passion’s slave. No one, except rivals or journalistic wreckers, ever20 questioned his devotion to the country’s highest interests as he conceived them, and, as statesmen go, he appeared almost uninfluenced by vanity.

Balliol and the Law had rendered him too fastidious and precise for exuberant popularity, but under an apparent immobility and educated restraint he concealed, like Lord Kitchener, qualities more attractive and humane. Although conspicuous for cautious moderation, he was not obdurate against reason, but could sing a palinode upon changed convictions.16 Unwavering fidelity to his colleagues, and a magnanimity like Cæsar’s in combating the assaults of political opponents, and disregarding the treachery of most intimate enemies, surrounded him with a personal affection which surprised external observers; while his restrained and unexpressive demeanour covered an unsuspected kindliness of heart. In spite of his lapses into fashionable reaction, most supporters of the Gladstonian tradition still looked to him for guidance along the lines of peaceful and gradual reform, when suddenly the war-cloud burst, obliterating in one deluge all the outlines of peace and progress and law. The Tsar who, with assumed philanthropy, had proposed the Peace Conferences at The Hague; the ruler to whom the ambition of retaining the title of “Friedenskaiser” was, perhaps honestly, attributed; the President who had known how passionately France clung to peace; the Belgian King who foresaw the devastation of his wealthy country; the stricken Emperor who, through long years of disaster following disaster, had hoped his distracted heritage might somehow21 hang together still—all must have suffered a torture of anxiety and indecision during those fateful days of July and August 1914. But upon none can the decision have inflicted deeper suffering than upon a Prime Minister naturally peaceful, naturally kindly, naturally indisposed to haste, plagued with the scholar’s and the barrister’s torturing ability to perceive many sides to every question, and hoping to crown a laborious life by the accomplishment of political and domestic projects which, at the first breath of war, must wither away. Yet he decided.

Third in influence upon the War Council (that is to say, upon the direction of all naval and military affairs) stood Mr. Winston Churchill. In his evidence before the Commission, Mr. Churchill stated:

“I was on a rather different plane. I had not the same weight or authority as those two Ministers, nor the same power, and if they said, This is to be done or not to be done, that settled it.”17

The Commissioners add in comment that Mr. Churchill here “probably assigned to himself a more unobtrusive part than that which he actually played.” The comment is justified in relation to the Dardanelles, not merely because it is difficult to imagine Mr. Churchill playing an unobtrusive part upon any occasion, but because, as we have seen, the idea of a Dardanelles Expedition was specially his own. It was one of those ideas for which we are sometimes indebted to the inspired amateur. For the amateur, untrammelled by habitual routine, and not easily appalled by obstacles which he cannot realise, allows22 his imagination the freer scope, and contemplates his own particular vision under a light that never was in office or in training-school. In Mr. Churchill’s case, the vision of the Dardanelles was, in truth, beatific. His strategic conception, if carried out, would have implied, not merely victory, but peace. Success would at once have secured the defence of Egypt, but far more besides. It would have opened a high road, winter and summer, for the supply of munitions and equipment to Russia, and a high road for returning ships laden with the harvests of the Black Earth. It would have severed the German communication with the Middle East, and rendered our Mesopotamian campaign either unnecessary or far more speedily fortunate. On the political side, it would have held Bulgaria steady in neutrality or brought her into our alliance. It might have saved Serbia without even an effort at Salonika, and certainly it would have averted all the subsequent entanglements with Greece. Throughout the whole Balkans, the Allies would at once have obtained the position which the enemy afterwards held, and have surrounded the Central Powers with an iron circle complete at every point except upon the Baltic coast, the frontiers of Denmark, Holland, and Switzerland, and a strip of the Adriatic. Under those conditions, it is hardly possible that the war could have continued after 1916. In a speech made during the summer of the year before that (after his resignation as First Lord), Mr. Churchill was justified in saying:

“The struggle will be heavy, the risks numerous, the losses cruel; but victory, when it comes, will make amends for all. There never was a great subsidiary23 operation of war in which a more complete harmony of strategic, political, and economic advantages has combined, or which stood in truer relation to the main decision which is in the central theatre. Through the Narrows of the Dardanelles and across the ridges of the Gallipoli Peninsula lie some of the shortest paths to a triumphant peace.”18

The strategic design, though not above criticism (for many critics advised leaving the Near East alone, and concentrating all our force upon the Western front)—the design in itself was brilliant. All depended upon success, and success depended upon the method of execution. Like every sane man, professional or lay, Mr. Churchill favoured a joint naval and military attack. The trouble—the fatal trouble—was that in January 1915 Lord Kitchener could not spare the men. He was anxious about home defence, anxious about Egypt (always his special care), and most anxious not to diminish the fighting strength in France, where the army was concentrating for an offensive which was subsequently abandoned, except for the attack at Neuve Chapelle (in March). He estimated the troops required for a Dardanelles landing at 150,000, and at this time he appears hardly to have considered the suggested scheme except as a demonstration from which the navy could easily withdraw.

Mr. Churchill’s object was already far more extensive. Like the rest of the world, he had marvelled at the power of the German big guns—guns of unsuspected calibre—in destroying the forts of Liége and Namur. In his quixotic attempt to save Antwerp24 (an attempt justly conceived but revealing the amateur in execution) by stiffening the Belgian troops with a detachment of British marines and the unorganised and ill-equipped Royal Naval Division under General Paris, he had himself witnessed another proof of such power. For he was present in the doomed city from October 4 to 7, two days before it fell. Misled by a false analogy between land and sea warfare, he asked himself why the guns of super-Dreadnoughts like the Queen Elizabeth should not have a similarly overwhelming effect upon the Turkish forts in the Dardanelles; especially since, under the new conditions of war, their fire could be directed and controlled by aeroplane observation, while the ships themselves remained out of sight upon the sea side of the Peninsula. It was this argument which ultimately induced Lord Kitchener to assent, though reluctantly, to a purely naval attempt to force the Straits, for he admitted that “as to the power of the Queen Elizabeth he had no means of judging.”19

But, for the moment, Mr. Churchill contented himself with telegraphing to Vice-Admiral Carden (January 3):

“Do you think that it is a practicable operation to force the Dardanelles by the use of ships alone?... The importance of the results would justify severe loss.”

At the same time he stated that it was assumed that “older battleships” would be employed, furnished with mine-sweepers, and preceded by colliers or other25 merchant vessels as sweepers and bumpers. On January 5 Carden replied:

“I do not think that the Dardanelles can be rushed, but they might be forced by extended operations with a large number of ships.”

Next day Mr. Churchill telegraphed: “High authorities here concur in your opinion.” He further asked for detailed particulars showing what force would be required for extended operations.20

Among the “high authorities,” Carden naturally supposed that one or more of the naval experts who attended the War Council were included. These naval experts were, in the first place, Lord Fisher (First Sea Lord) and Sir Arthur Wilson, Admirals of long and distinguished service. Both were over seventy years of age, and both were regarded by the navy and the whole country with the highest respect, though for distinct and even opposite qualities. Lord Fisher had been exposed to the criticism merited by all reformers, or bestowed upon them. Especially it was argued that his insistence upon the Dreadnought type, by rendering the former fleet obsolete, had given our hostile rival upon the seas the opportunity of starting a new naval construction on almost equal terms with our own. But, none the less, Lord Fisher was recognised as the man to command the fleet by the right of genius, and his authority at sea was hardly surpassed by Lord Kitchener’s on land. The causes of the confidence and respect inspired by Sir Arthur Wilson are sufficiently suggested by his invariable nickname of “Tug.” Both Admirals26 were members of the War Staff Group, instituted by Prince Louis of Battenberg in the previous November,21 and both attended the War Council as the principal naval experts. Admiral Sir Henry Jackson and Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Oliver (Chief of the Staff) were also present on occasion.

The expert’s duty in such a position has been much disputed. The question, in brief, is whether he acts as adviser to his Minister only (in this case, Mr. Churchill), or to the Council as a whole. Lord Fisher and Sir Arthur Wilson, supported by Sir James Wolfe Murray, Chief of the Imperial General Staff under Lord Kitchener (who was always his own expert), maintained they were right in acting solely as Mr. Churchill’s advisers. Though they sat at the same table, they did not consider themselves members of the War Council. It was not for them to speak, unless spoken to. They were to be seen and not heard. The object of their presence was to help the First Lord, if their help was asked, as it never was. In case of disagreement with their chief, there could be “no altercation.” They must be silent or resign. Their office doomed them, as they considered, to the old Persian’s deplorable fate of having many thoughts,27 but no power.22 In this view of their duties, they were strongly supported among the Dardanelles Commissioners by Mr. Andrew Fisher (representing Australia) and Sir Thomas Mackenzie (representing New Zealand). Following official etiquette, they were, it seems, justified in holding themselves bound by official rules to acquiesce in anything short of certain disaster rather than serve the country by an undisciplined word.23

If this attitude was technically correct, it is the more unfortunate that the Ministers most directly concerned, as being members of the War Council, should have taken exactly the opposite view, though masters of parliamentary technique. In his evidence before the Commission, Mr. Churchill, the man most closely concerned, protested:

“Whenever I went to the War Council I always insisted on being accompanied by the First Sea Lord and Sir Arthur Wilson, and when, at the War Council, I spoke in the name of the Admiralty, I was not expressing simply my own views, but I was expressing to the best of my ability the opinions we had agreed upon at our daily group meetings; and I was expressing these opinions in the presence of two naval colleagues and friends who had the right, the knowledge, and the power at any moment to correct me or dissent from what I said, and who were fully cognizant of their rights.”24

Mr. Asquith said “he should have expected any28 of the experts there, if they entertained a strong personal view on their own expert authority, to express it.”25 Lord Grey, Lord Haldane, Lord Crewe, Mr. Lloyd George, and Colonel Maurice Hankey, the very able Secretary to the War Council, gave similar evidence. Mr. Balfour said: “I do not believe it is any use having in experts unless you try and get at their inner thoughts on the technical questions before the Council.”26 In the House of Commons, at a later date, Mr. Asquith maintained:

“They (the experts) were there—that was the reason, and the only reason, for their being there—to give the lay members the benefit of their advice.... To suppose that these experts were tongue-tied or paralysed by a nervous regard for the possible opinion of their political superiors is to suppose that they had really abdicated the functions which they were intended to discharge.”27

These views appear so reasonable that we might suppose them unofficial, had not the speakers occupied the highest official positions themselves. The result of this difference of opinion regarding the duty of expert advisers was disastrous. The War Council assumed the silence of the experts to imply acquiescence, whereas it sprang from obedience to etiquette. Before the Commission, Lord Fisher stated that from the first he was “instinctively against it” (i.e. against Admiral Carden’s plan);28 that he “was dead against the naval operation alone because he knew it must be a failure”; and he added, “I must reiterate that as29 a purely naval operation I think it was doomed to failure.”29 It may be supposed that these statements were prophecies after the event, and the Commissioners observe that Lord Fisher did not at the time record any such strongly adverse opinions. Nevertheless, on the very day when a demonstration was first discussed, he wrote privately to Mr. Churchill:

“I consider the attack on Turkey holds the field, but only if it is immediate; however, it won’t be. We shall decide on a futile bombardment of the Dardanelles, which wears out the invaluable guns of the Indefatigable, which probably will require replacement. What good resulted from the last bombardment? Did it move a single Turk from the Caucasus?”30

Two days later he sent Mr. Churchill a formal minute, saying that our policy must not jeopardise our naval superiority, but the advantages of possessing Constantinople and getting wheat through the Black Sea were so overwhelming that he considered Colonel Hankey’s plans for Turkish operations vital and imperative, and very pressing. The object of these plans (circulated to the War Council on December 28, 1914) was to strike at Germany through her allies, particularly by weaving a web around Turkey; and for this purpose Lord Fisher sketched a much wider policy requiring the co-operation of Roumania, Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia.31 The scheme was not identical with another design of naval strategy which was already occupying Lord30 Fisher’s mind, and the frustration of which by the Dardanelles Expedition ultimately caused his resignation (in May). But the evidence here quoted shows that Lord Fisher could not be included among the “high authorities” referred to by Mr. Churchill as concurring with Admiral Carden’s opinion. Mr. Churchill said in his evidence that he did not wish to include either Lord Fisher or Sir Arthur Wilson (who throughout agreed with Lord Fisher in the main). He was thinking of Admirals Jackson and Oliver. Yet to Admiral Carden’s mind Lord Fisher would naturally be suggested as one of the high authorities; and was suggested.32

So soon as a demonstration of some sort was decided upon, Mr. Churchill asked Admiral Jackson to prepare a memorandum, which the Admiral described as a “Note on forcing the passages of the Dardanelles and Bosphorus by the Allied fleets in order to destroy the Turko-German squadron and threaten Constantinople without military co-operation.” The last three words are important, for it is evident that, though Admiral Jackson expressed no resolute opposition at the time, he was strongly opposed to the idea of a merely naval attack. In this memorandum he pointed out facts which even a layman might have discerned: that the ships, even if they destroyed the enemy squadron, would be exposed to torpedo at night, to say nothing of field-guns and rifles in the Straits, and would hold no line of retreat unless the shore batteries had been destroyed; that, though they might dominate the city, their position would not be enviable without a large military31 force to occupy it; that the bombardment alone would not be worth the considerable loss involved; that the city could not be occupied without troops, and there was a risk of indiscriminate massacre.33

The dangers of an unsupported naval attack were so obvious that Admiral Jackson can have needed no further authority in urging them. Yet he may have recalled a memorandum drawn up by the General Staff (December 19, 1906), stating that “military opinion, looking at the question from the point of view of coast defence, would be in entire agreement with the naval view that unaided action by the Fleet, bearing in mind the risks involved, was much to be deprecated.”34

Admiral Jackson’s discouraging memorandum of January 5 was not shown to the War Council. Yet it was of vital importance. In his evidence, Admiral Jackson insisted that he had always stuck to this memorandum:

“It would be a very mad thing,” he said, “to try and get into the Sea of Marmora without having the Gallipoli Peninsula held by our own troops or every gun on both sides of the Straits destroyed. He had never changed that opinion, and he had never given any one any reason to think he had.”

Long afterwards, Mr. Churchill suggested that32 what Admiral Jackson meant by a mad thing was an attempt to rush the Straits without having strong landing-parties available, and transports ready to enter when the batteries were seen to be silent.35 It is just possible to put that interpretation on the words, but both they and the memorandum itself appear naturally to imply a far larger military force than landing-parties as essential.

On January 11 Vice-Admiral Carden telegraphed a detailed scheme for gradually forcing the Dardanelles by four successive stages, the operations to cover about a month. The plan was considered by the War Staff Group at the Admiralty, and in subsequent evidence all agreed that they were very dubious, if not hostile. Lord Fisher said he was instinctively against it. Sir Arthur Wilson said he never recommended it. Admiral Oliver and Commodore Bartolomé said they were definitely opposed to a purely naval attempt. But all agreed that the operations could not lead to disaster, as they might be broken off at any moment.36 Admiral Jackson (not a member of the Group) also drew up a detailed memorandum upon all stages of the plan, “concurring generally,” and suggesting that the first stage should be approved at once, as the experience gained might be useful. He insisted in evidence that he recommended only an attack on the outer forts. He accepted the policy of a purely naval attack solely on the ground that it was not for him to decide. His responsibility was limited to his staff work, which he performed.37

33

The two decisive meetings of the War Council on January 13 and January 28 followed. At the former meeting Mr. Churchill explained the details of Admiral Carden’s plan, adding that, besides certain older ships, two new battle-cruisers, one being the Queen Elizabeth, could be employed.38 He thus revived his Antwerp experience of big-gun power against fortresses. When the exposition of the whole design was completed, Lord Kitchener gave it as his opinion that “the plan was worth trying. We could leave off the bombardment if it did not prove effective.” In this delusive belief the War Council arrived at the momentous decision:

“The Admiralty should prepare for a naval expedition in February to bombard and take the Gallipoli Peninsula, with Constantinople as its objective.”39

Although the word “take” is used, the Council had no intention at this time of employing a military force. It was assumed that none was available. The same meeting sanctioned Sir John French’s plan for an offensive in France (the offensive which degenerated into the attack on Neuve Chapelle in March). In case of a naval failure, the ships could be withdrawn; in case of success, there was talk of a revolution in Constantinople, and upon that hope the Council gambled.40

During this meeting Lord Fisher, together with Admiral Wilson and Sir James Murray, sat dumb as34 usual, and his silence was as usual taken for assent. When the Council had arrived at their resolution, he considered his sole duty was to assist in carrying it out. The very next day he signed a memorandum from Mr. Churchill strongly advising that we should devote ourselves to “the methodical forcing of the Dardanelles,”41 and he added the two powerful battleships Lord Nelson and Agamemnon to the fleet allotted for this operation. But his underlying difference of opinion became steadily stronger. In evidence, Mr. Churchill said he “could see that Lord Fisher was increasingly worried about the Dardanelles situation. He reproached himself for having agreed to begin the operation.... His great wish was to put a stop to the whole thing.... I knew he wanted to break off the whole operation and come away.”42 On January 25 Lord Fisher took the unusual course of writing to Mr. Asquith and stating his objections. He considered the Dardanelles would divert from another large plan of naval policy which he had in mind; further, that it was calculated to dissipate our naval strength, and to risk the older ships (besides the invaluable men) which formed our only reserve behind the Grand Fleet.43

Mr. Churchill replied in a similar memorandum to the Prime Minister, defending his Dardanelles plan on the plea of its value, even at a cost which, after all, would be relatively small. In hope of obtaining some agreement, Mr. Asquith invited Lord Fisher and Mr. Churchill to his room just before the meeting of the War Council on January 28—the35 second decisive meeting. After discussion, the Prime Minister expressed his satisfaction with Mr. Churchill’s view, and all three proceeded to the Council. It was a fairly full meeting, Sir Edward Grey and Mr. Balfour being present, besides the three dominating members and the experts. Mr. Churchill pressed his plan with eloquent enthusiasm. “He was very keen on his own views,” said Sir Arthur Wilson in evidence; “he kept on saying he could do it without the army; he only wanted the army to come in and reap the fruits ... and I think he generally minimised the risks from mobile guns, and treated it as if the armoured ships were immune altogether from injury.”44 Mr. Churchill re-stated the political and strategic advantages of success. He said that the Grand Duke Nicholas had replied with enthusiasm, and that the French Admiralty had promised co-operation.45 He said the Commander-in-Chief in the Mediterranean believed it could be done in three weeks or a month. The necessary ships were already on their way.

All the members of the War Council were won by these persuasive arguments. They needed little persuasion, and no persuasion is so strong as an enterprise begun. But Lord Fisher for once broke silence. He said he had not supposed the matter would be raised that day, and that the Prime Minister was well aware of his views. When he found that a final decision was to be taken, he got up to leave the36 room, intending to resign. But Lord Kitchener intercepted him, and taking him to the window strongly urged him to remain, pointing out that he was the only dissentient and it was his duty to carry on the work of his office as First Sea Lord. Whereupon Lord Fisher reluctantly yielded to the entreaty and returned to his seat.46

It is remarkable that at a meeting of such decisive moment no mention was made of Lord Fisher’s memorandum, nor of Mr. Churchill’s reply, nor of their conference with the Prime Minister an hour before. None the less, not only Mr. Asquith and Mr. Churchill knew of Lord Fisher’s opposition. Lord Kitchener knew of it; so did Sir Edward Grey. Yet the opinion of the chief naval authority in England was overruled. Mr. Asquith subsequently stated that “the whole naval expert opinion available to us (the War Council), whether our own or the French, was unanimously and consentiently in favour of this as a practical naval operation. There was not one dissentient voice.” As to Lord Fisher, he continued, it was quite true that he expressed on the morning of that day an adverse, or at least an unfavourable opinion, but not upon the ground of its merits or demerits from a technical naval point of view:

“Lord Fisher’s opinion and advice were not founded upon the naval technical merits or demerits of this operation, but upon his avowed preference for a wholly different objective in a totally different sphere.”

No doubt Lord Fisher insisted mainly upon that different objective as being the more important cause37 of his opposition. But it seems evident that from the first he was also opposed to a merely naval attack and bombardment. His letter to Mr. Churchill on January 2 (quoted above) proves this. And so does the following clause in his memorandum to the Prime Minister on January 25:

“The sole justification of coastal bombardments and attacks by the fleet on fortified places, such as the contemplated prolonged bombardment of the Dardanelles forts by our fleet, is to force a decision at sea, and so far and no further can they be justified.”47

Yet, in this case, there was no suggestion or possibility of forcing a decision at sea.

In the afternoon of the same day (January 28) Mr. Churchill had a private interview with Lord Fisher, and “strongly urged him to undertake the operation.” Lord Fisher definitely consented. Mr. Churchill says that if he had failed to persuade him, there would have been no need to altercate, or to resign, or even to argue. He would have gone back to the War Council and told them they must either appoint a new Board of Admiralty or abandon the project. “For the First Sea Lord has to order the fleets to steam and the guns to fire.”48 Lord Fisher, on the other hand, insisted in evidence that he had taken every step, short of resignation, to show his dislike of the proposed operations; that the chief technical advisers of the Government ought not to resign because their advice is not accepted, unless they think the operations proposed must lead to38 disastrous results; and that the attempt to force the Dardanelles as a purely naval operation would not have been disastrous so long as the ships employed could be withdrawn at any moment, and only such vessels were employed as could be spared without detriment to the general service of the fleet.49

The divergence of opinion here is not so complete as it seems; for by admitting that the War Council could have appointed a new Board of Admiralty if Lord Fisher had refused to carry out their decision, Mr. Churchill showed that, though the First Sea Lord could order the fleets to steam and the guns to fire, the ultimate control did not lie with him. The ultimate control lay with the Government (in this case the War Council), and Lord Fisher was undoubtedly right in thinking his constitutional duty consisted in carrying out the Council’s decisions or resigning his office. He did not resign at this time, because he thought the naval attack did not necessarily imply disaster. He agreed to undertake the charge. He considered it his duty simply to carry out the Council’s decision as best he could. With Mr. Churchill he attended another Council meeting later in the afternoon, and there the fateful, if not fatal, step was taken. It was decided that an attack should be made by the fleet alone, with Constantinople as its objective.50