Title: Escape from East Tennessee to the federal lines

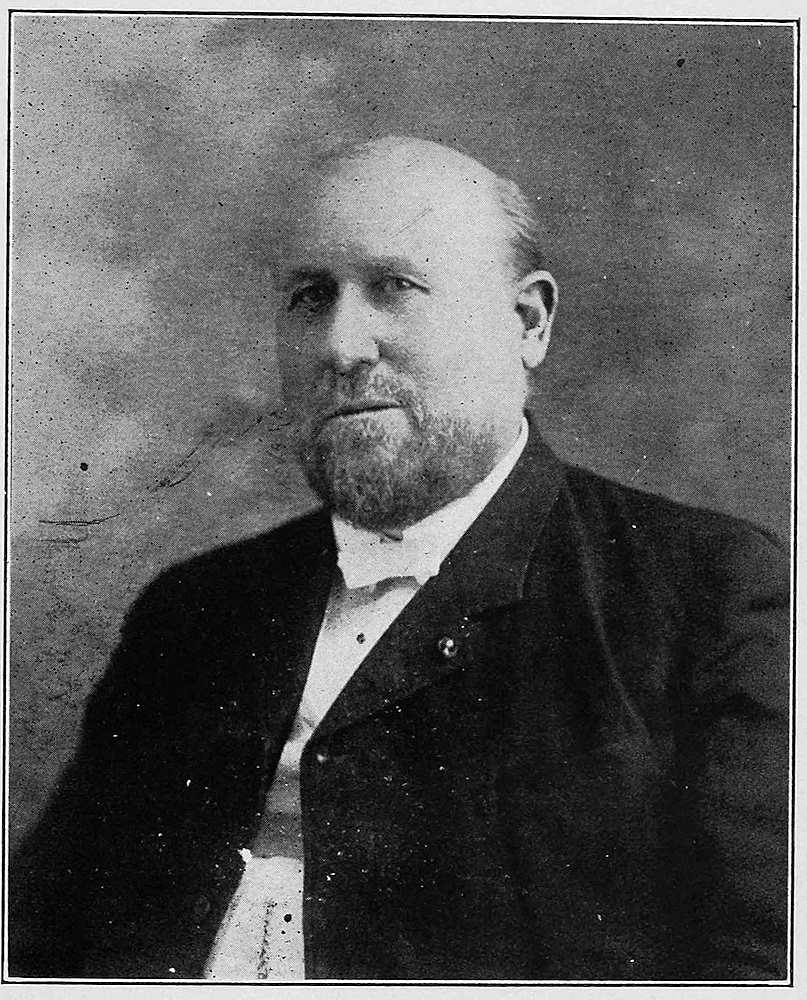

The history, given as nearly as possible, by Captain R. A. Ragan of his individual experiences during the war of the rebellion from 1861 to 1864

Author: Robert A. Ragan

Release date: June 16, 2023 [eBook #70992]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: James H. Dony, 1910

Credits: Bob Taylor, Carla Foust and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

CAPT. R. A. RAGAN IN 1863.

The History, given as nearly as possible, by Captain R. A. Ragan

of his individual experiences during the War of the

Rebellion from 1861 to 1864.

ILLUSTRATED.

WASHINGTON, D. C.

JAMES H. DONY, PUBLISHER.

1910.

Copyright 1910, by

R. A. RAGAN.

[Pg 3]

I lay no claim to literary attainments, but undertake to tell in simple words the story of my experiences, hardships and sufferings, lying out in the cold weather many nights, trying to make my way across the mountains and rivers to Kentucky, where the Union Army was encamped.

There have been a number of books written since the Civil War, dealing with the loyalty, heroism and suffering of the Union people of East Tennessee during that period, but few men have given their individual experience from 1861 to 1864.

I am, so far as I can ascertain, the only East Tennessee pilot living. I give the following names of those who piloted Union men through the lines: Daniel Ellis, James Lane, A. C. Fondren, James Kinser and David Fry. These men have all died since the War, except James Lane, who was killed at the foot of the Cumberland Mountain, in Powell’s Valley, while conveying men to Kentucky.

R. A. R.

[Pg 4]

ESCAPE FROM EAST TENNESSEE

I was born in Greene County, Tennessee, near the banks of the Nola Chucky River. My father moved in 1845 to the banks of the French Broad River, in Cocke County, Tennessee, shortly after I was born. I was the oldest of the six children, namely, myself, Alexander, Laura, Creed, Mary and James Ragan. My father was a county officer for years—in fact, until the late war. I grew up in the county, and attended muster.

In 1860 I was elected Lieutenant-Colonel of the Militia, and in the Fall of 1861 was in the employ of Frank Clark, who fattened hogs and every year drove them to South Carolina markets. At that time there were no railroads in East Tennessee leading to South Carolina. When we left East Tennessee there was no talk of war, but when we reached South Carolina, the people were excited and in a state of rebellion. Before reaching Spartanburg, Mr. Clark told me to be careful how I talked. He seemed to know the situation.

After we arrived at Spartanburg I was sick with jaundice for a few days, and confined to my bed. While in bed I could hear the rebels hallooing and riding through the streets, and the rattling of sabers.

In a few days I got out of my bed and went out into the streets. I was young, and hardly knew what it meant, for everything was calm when I left East Tennessee; but when I looked[Pg 5] up and saw the rebel flag, I felt a thrill of patriotism run through my veins, and then began to realize the fact that it was not the flag I had been used to all my life. At that moment I was a Union boy, and felt that I was in the wrong latitude.

If I had uttered a word against the South at that time I would have been hung to the first limb. The Negroes were excited and scared nearly to death. Some one would set a house on fire and accuse a Negro of the crime, and arrest the first one he came across, taking him out and hanging him. I saw two hung in this manner.

The next morning I said quietly to Mr. Clark, “I believe I will go back to East Tennessee.”

“All right,” he said.

I had, I think, the best saddle horse in the State; he was a fox trotter, only three years old, and his gait was smooth and easy. I bid Mr. Clark good-day, and started on my journey.

The farther I got from Spartanburg, the better I felt. I believe I rode sixty-two miles from early in the morning until dark. It seemed to me that the horse was a Union animal, for he “pulled for the shore.” I never put a spur or whip to his flesh. I was young, and will confess I was afraid the rebels were after me.

When I reached the top of the Blue Ridge, I looked back and it seemed to me that I could see the smoke of war. I then turned my face toward East Tennessee, and imagined I could see peace and harmony. I looked to my right and could see the Holston and Watauga Rivers running down through the valleys of East Tennessee, and the people going about their daily avocations;[Pg 6] and next was the Nola Chucky, where I was born, with her beautiful bottom lands extending for miles. Next came the French Broad, on the banks of which I was raised. Next was the Big Pigeon, which was made from the little streams gushing from the Great Smoky Mountain and the North Carolina Mountains. I imagined I could see all these rivers making their way in peace to the Tennessee River, which emptied into the Ohio above its junction with the great Mississippi. I did not think at that time that there were preparations being made by the North and the South for the greatest war that was ever fought in the world.

After I had rested on the top of this mountain, I continued my journey down through a part of North Carolina to Paint Rock, and then into East Tennessee. When I arrived at Newport, Cocke County, I found the people making preparations to sow wheat. I remember on my way from South Carolina I came to a farm on the banks of the French Broad. The men were plowing, some with mules, some with horses and others with yokes of oxen, turning over the land. They knew me, and asked how I had come out with my hogs, and how the times were over in South Carolina.

I said, “H— is to pay over there; they are fixing for war.”

They asked me who they were going to fight.

“The Yankees,” I said.

I told them that Fort Sumter had been fired upon. They asked me where Fort Sumter was. You see that the people in that locality had never heard of war, but in a short time they began talking about secession.

[Pg 7]

In February, 1861, the State of Tennessee voted against secession by the overwhelming majority of 68,000; but a military league, offensive and defensive, was entered into on the seventh day of May, 1861, between commissioners appointed by Governor Harris, on the part of the State of Tennessee, and commissioners appointed by the Confederate government, and ratified by the General Assembly of the State, whereby the State became a part of the Confederate States to all intents and purposes, although an act was passed on the 8th of June for the people to decide the question of separation and representation or no representation in the Confederate Congress.

In the meantime, troops had been organized and made preparations for war. The election was a farce, as the State had already been taken out of the Union and had formed an alliance with the other States of the Confederacy.

The leaders of the Union element, comprising the best talent of East Tennessee, had not been idle. The most prominent Union leaders at that time were Andrew Johnson, Thomas A. R. Nelson, W. B. Carter, C. F. Trigg, N. G. Taylor, Oliver P. Temple, R. R. Butler, William G. Brownlow, John Baxter and Andrew J. Fletcher. These men, with all their eloquence and ability, failed to accomplish the task of holding Tennessee in the Union.

[Pg 8]

The State commenced organizing troops, and as Lieutenant-Colonel of the Militia I was urged by the leading rebels of my county to make up a regiment for the rebel army. I refused to do so, and from that time on I was considered a Union man.

I was appointed by the School Board to teach school. When the Legislature met a law was passed exempting certain persons, such as school teachers, blacksmiths and millers from the Confederate service. Of course I came under the law and was exempt, and I wanted to keep out of the rebel army. I had just married and did not want to go North and leave my family until I was compelled to go. At that time very few men had left the State for the North.

In a short time the exemption law was repealed, and every man from eighteen to forty-five years of age had to join the rebel army or be conscripted. I was teaching school, but did not know of the repeal of the law; so in a day or two the rebel soldiers came to the school house and arrested me, and took me by way of my home, which was about two miles from the school house, in order that I might see my wife, as I requested.

When we reached my home my wife came to the door, and did not display any excitement. She was a brave Union woman, and knew that they had a hard customer, and that I would never fight for the Southern Confederacy. I wanted to have a private conversation with my wife, but they refused. I did not know when I would return, for they were killing men by hanging or shooting them every day, and taking others to Tuscaloosa. I just told my wife to go to her father and remain with him until I returned.

[Pg 9]

I will here relate a little incident that occurred while under arrest that evening, showing the way the rebels treated Union men. My brother-in-law was a rebel, but a nice man personally. He lived on a farm of about one hundred acres, adjoining the farm I lived on, and I can safely say that there was a cross-fence every two hundred yards through his farm, and no bars or gates to go through. I was on foot, and the rebel soldiers put me in front to lay down all these fences for them to pass through, and made me put them up afterward. Of course I obeyed orders, for every man was armed and wanted me to do something that they might have an excuse to shoot me.

When we passed out of the field into the woodland, we had to go through a deep hollow. When we reached the place, it was dark, although in the daytime. About the time we reached the middle of the hollow one of the soldiers, in a low voice, said to another, “Dave, this is a good place!” I listened, expecting to hear the command, “Halt!” but no reply was made to the remark. No one can imagine how I felt. I had just left my wife standing in the door of our little log cabin, watching the soldiers driving me through the field, taking down and putting up all the fences, as heretofore stated; I thought of my mother and my sisters, whom I should probably never see again. This was all in about a minute of time, but it was a terrible minute for me. However, the soldiers continued to drive me along until we came in the evening to the home of Henry Kilgore, the conscript officer, which was about two miles from our home. He took my name, and registered it on the conscript rolls. I was then considered a rebel soldier.

[Pg 10]

It was dark when we arrived at his house, and we had to remain until morning. There was a bed in the corner of the cabin, and I believe some beds on the second floor. The kitchen was about ten yards from the log cabin. They gave me my supper, but I had little appetite. I had known the conscript officer all my life, but he did not recognize me, and I will speak of him further on.

About eight o’clock I found they were going to have a “hoe-down” that night, and the men and women of the neighborhood were invited to come. They began to arrive about nine o’clock. I pretended to be sleepy, and an officer who was guarding me ordered me to get into the bed in the corner of the cabin. Of course I was under orders, and I crawled in—but no sleep for me.

They had a man with a violin, and commenced dancing, four at a time, face to face—a general hoe-down. They kept their drinks in the kitchen, which they visited often. They began to get tired and commenced singing

They danced and enjoyed themselves by running around in the house after each other, and the women would jump on my bed and trample over me. I thought at times I would be trampled to death, but I was pretty hard to hurt at that time and I was mad to the core.

[Pg 11]

Next day the soldiers got together and detailed three men to take me to Knoxville, Tenn. When we arrived there, about two o’clock in the morning, they took me out—I cannot tell where—and put me in the stockade with about three hundred poor ragged men who had declared themselves for the Union. When I went in, they raised a howl,

“There is another Lincolnite!”

I never saw such a sight in all my life. These men were half naked and barefooted, and some without hats. They had lost their apparel in the woods, trying to make their escape. I do not think they had washed their faces or hands since being captured.

In the morning a wagon drove up to the stockade, on the outside, and the driver commenced throwing old, poor beef over the stockade on the ground. I shall never forget seeing one of the men pick up a piece of beef and throw it against the wall to see if it would stick, but it was too poor. I never expected to eat or bite of it, and I never did.

My father, who was a cousin of John H. Reagan, Postmaster General of the Southern Confederacy, was on hand at Knoxville about the time I arrived. He telegraphed to Richmond that his son was under arrest, that he had committed no crime, and that he was a school teacher. The Richmond authorities telegraphed[Pg 12] back to Leadbeater, the commanding officer, directing him to release me. The next morning I passed out of the stockade and went back to my home, and commenced teaching school again.

In a few days word was sent to me that I was to be again arrested. I then disappeared, and for about eighteen months my whereabouts were only known by my family and the families of my wife, father, and an old uncle. All this time I was trying to get across to the Federal lines, but something happened to prevent my getting away. They were scouring the country for conscripts, and already had my name on the rolls, as I have heretofore stated.

Sometime about the first of 1862 I heard that a pilot was to be in Greene County, Tenn., to take Union men to the Federal lines. One Joseph Smith, who lived near my town, Parrottsville, went with me to Greene County, about twelve miles from our home, to the banks of the Nola Chucky River, and we remained there for a few days, lying in a straw stack and fed by an old Union lady, by the name of Minerva Hale.

News came that a “pilot” would be on hand about one mile from where we were. I do not know why, but something told me not to go. Joseph Smith left me, bidding me good-bye, and I never saw him again.

I started back home, twelve miles through the woods, and had to cross the Nola Chucky in the dark, and the rebels travelling all through the country, knowing that men were trying to cross to Kentucky. I reached home before daylight and let my wife know I had returned, then went out in the woods as usual and put up.

[Pg 13]

The next day news came to the neighborhood that the men Joseph Smith met were captured the night he left me, only three men making their escape—the pilot (William Worthington) and two others. They saved themselves by jumping into Lick Creek, a small but deep stream, and sinking themselves in the water, only allowing their faces above the water enough to breathe.

The rest of the men were taken to Vicksburg and put in the rebel army. Joseph Smith was shot in the foot while at Vicksburg, and gangrene set in, causing his death. The other men were never subsequently heard of.

I never slept in a house but three or four times during the time I was scouting. I travelled between what is called Neddys Mountain and Newport, Tenn., which is about twelve miles. I never travelled in a road, and always in the night.

I had an old uncle who lived in Newport, between the French Broad River and the Pigeon River, which were about four miles apart. I wanted to see him, and started out one night. It was dark and raining, but I always felt safer the harder it rained and the darker the night. I came to the French Broad, a good sized river. Of course I knew that I could not cross at the ferry, for I had heard that it was guarded by rebel soldiers. I had been raised in that section from a boy and was familiar with the river and the surrounding country. About two hundred yards below the ferry I crossed the river, wading part of the way and swimming the balance, with my clothes in a bundle on my head.

When I got over I went in the bushes and dressed. I had to be very careful, for the town was full of rebel scouts, but no regular regiment was stationed there.

[Pg 14]

I went on the north side of the town, and down a little alley to the back of my uncle’s house, and knocked at the kitchen door. Directly my cousin, Sarah Ragan, came to the door, and was dumbfounded to see me. She said, “Why, Cousin Bob, the town is full of rebel soldiers, and two are now in the parlor!”

She took me upstairs, and I remained there two days and nights. I could look out in the street and see the rebel soldiers going up and down. Of course they thought I was in the Northern Army, and nearly all the Union people thought the same.

I left the third night and went to my father’s, on the main road leading from Newport to Greeneville, Tenn., about three miles from Newport. This was a dangerous place for me to stop, but I wanted to see my mother and sister, and I always found such places about as safe for me as any, as the rebels never thought of me or any other Union man being in such places.

I remained there for a few days. The second day, about two o’clock, word came that a regiment of rebel soldiers were crossing the French Broad at Newport, the place I had left a few nights before. I was at a loss to know what to do.

A rebel family lived just a few hundred yards away, on the main road, and there was not a tree or bush to hide me. I knew the soldiers would stop at the house and probably search the building for Union men. I had but a few minutes to decide.

My mother was on hand and always ready to offer suggestions in time of danger. She said, “Bob, put on Laura’s dress and sun-bonnet, and cross the road.”

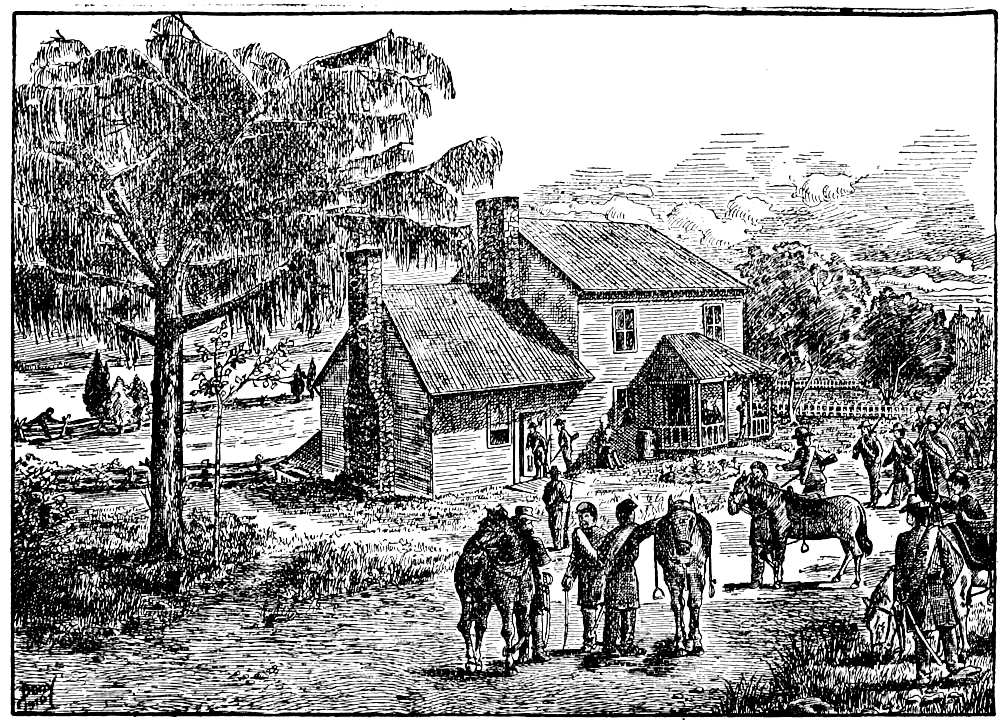

Capt. R. A. Ragan making his escape from the father’s home in 1862. See page 15.

My sister was well grown for her age, and in a few minutes I had the dress and bonnet on. The dress reached just below [Pg 15]my knees, but I crossed the road and passed the barn into an old field about three hundred yards away. I fell into a washout, and stuck my head out and saw the rebel regiment pass. Some of them stopped at the house.

This was the first rebel regiment I had seen, and of course it was a sight to me, and I felt more anxious to get to the Federal army. This regiment of rebel soldiers was on its way to Johnson, Carter and Cocke Counties, to look out for Union men making their way to Kentucky or to the Federal army.

I went back to the house after dark, and left that night for Neddys Mountain, in the neighborhood of my home, and remained there some time, visiting my home at nights, but never sleeping in the house.

I will here relate a little incident that occurred while on a visit to my father’s home, at the same place where I made my escape with the dress on. I was in the sitting room, talking to my mother, when some one knocked at the door, Of course we did not know who it was, so I got under an old-fashioned bed, with curtains to the floor. Our visitor was a lady who lived just below on the road, who was a strong rebel sympathizer, and had two brothers in the rebel army. She had come to spend the evening, and brought her knitting, as was the usual custom in that neighborhood. As she was busy talking to my mother, her ball of yarn rolled out of her lap and under the bed. As quick as lightning, mother ran and got the ball, by my kicking it back. In a few minutes she invited her visitor into another room.

[Pg 16]

At another time the same lady came while I was there, and she had a big bull dog with her. I heard that she was on the porch, and I went under the bed again. The dog came into the room and scented me. He stuck his head under the curtains, and I kicked him on the nose, and he went out yelping. The woman did not understand what it meant, but said nothing. I left that night, and never visited my father again during the war.

[Pg 17]

I remained around home and in the mountains, waiting for news to come for us to start for Kentucky. In a few tidings came that a “pilot” would start for the North about the first of May. Notice was given and preparations were made to meet on the north side of the Nola Chucky, in Greene Co., Tenn. I was to meet some men at a school house, about one mile from home. It was a dangerous time, as the rebels were scouting all over the country for Union men. That day, about three miles away, two Union men, Chris. Ottinger and John Eisenhour, were killed by the rebels.

On the 6th of May, 1863, I was at my father-in-law’s house, preparing to meet the party at the school house heretofore mentioned. About sun-down, my father-in-law went to the door on the north side of the house and, turning around, said,

“The rebels are coming up the lane to the house!”

He went out toward the barn, calling the horses, trying to draw the attention of the rebels, and knowing that I would try to get away. I was barefooted, bareheaded, and without a coat. I ran out of the house on the south side, and kept the house between myself and the rebels. I jumped over a high fence and passed the loom house, then jumped another high fence and lit on a lime-stone rock, cutting the ball of my left foot to the bone, but did not know it until I ran up close to the[Pg 18] barn and sat down in a briar thicket in a corner of the fence. I felt something sting, and putting my hand down, found the blood gushing from my foot. The reader can imagine how I felt. I was mad and ready to fight the entire Confederacy, but sat quietly, nursing my wrath and my wounded foot.

By this time it was quite dark, and the rebels had fed their horses and were going to the house for their supper which they had ordered. I got up and studied for a moment to know what to do, and finally decided to go back to the house the way I had ran out. I started back, and crawled along the side of a hedge fence on the south side of the house until I came to a gate that opened from the kitchen. There was a bright light shining through the window, and I could see all of the rebels seated at the table, there being about twenty of them.

Outside it was very dark by this time. I crawled along on all fours to the “big house” door and went in. The rebels had stacked their arms in the sitting room, and all of their accoutrements were lying on the floor. As there was no light in this room, it was very dark. A stairway led from this room to the second floor, and I knocked lightly on the stair railing. My sister-in-law came in and was shocked to find me in the house. I told her I had ruined my foot on a rock, and that I would go round on the north side of the house to the kitchen door, and that she should tell my wife to come out, as I wanted to speak to her; but my sister-in-law could find no chance to do so, for the rebels were watching the family.

[Pg 19]

I stood at the door a minute, and tapped lightly, just so my wife would hear it, for I could see through the window that she was standing at the door. She opened it just a little, and I whispered to her and said I would go out into the garden and remain there until the rebels left.

While in the room I was tempted to take up their guns and go to the window and shoot three or four of them, but I knew if I did they would kill the family and burn the house.

I remained in the garden until they left, but suffered fearfully with my wounded foot. I knew I had to meet the men at the school house. After the rebels departed, I went in and cut off the top of my shoe and washed the blood from my foot and bound it up the best I could. The family filled my haversack with provisions and I started for the school house, where I met the boys and related my troubles to them.

Men from all parts were making their way to the place on the north side of the Nola Chucky, some seven miles from home. We had to cross a cedar bluff on the north side of the river, and the night was dark and the country very rough.

As a man by the name of Alfred Timons was crossing the road alone, making his way to the place, he was fired upon by the rebels and shot through the head, the ball coming out through his right eye. He fell to the ground, but regained his strength and made his escape to the river, which he crossed and came to the camp. The boys dressed his wound the best they could, and he went to Kentucky, but lost the sight of his eye.

I suffered all night with my foot, and could hardly put it to the ground. There were about one hundred and twenty men[Pg 20] gathered there from all parts of the country, to go to Kentucky. We remained there that night and until about eight o’clock the next evening, when they started for that State.

I had to abandon the attempt to go this time, and was left alone on the bluff in a terrible condition—no one to help me back home, and if I should succeed in reaching home I could not stay in the house. I knew if I was captured I would be shot or hung to the first limb. The rebels had received word that we had crossed the river and were making our way to Kentucky.

I started for home that night, crossing the river in a canoe at the same place where I had crossed the night before. I travelled about three miles that night, and just before daylight I crawled into a barn, dug a hole in the hay, and remained there all day, suffering intensely with my foot. Some one came into the barn to feed the horses, but I knew who lived there, and did not dare to make my presence known. When the person came in the hay loft I was afraid whoever it was might stick the pitch fork in me. I could not tell whether it was a man or woman, for no word was spoken. I lay there all day, without anything to eat or drink, and suffering fearfully with my foot.

About eight o’clock that night I crawled out of the barn and started for home. I travelled about three miles, and before daylight I crawled into another barn. I had known the owner all my life. He was a German and a good Union man, but I could not let myself be known. No one came to the barn that morning, and I lay there all day. My foot had swollen so badly that my shoe had to be taken off, and I had to go barefooted.

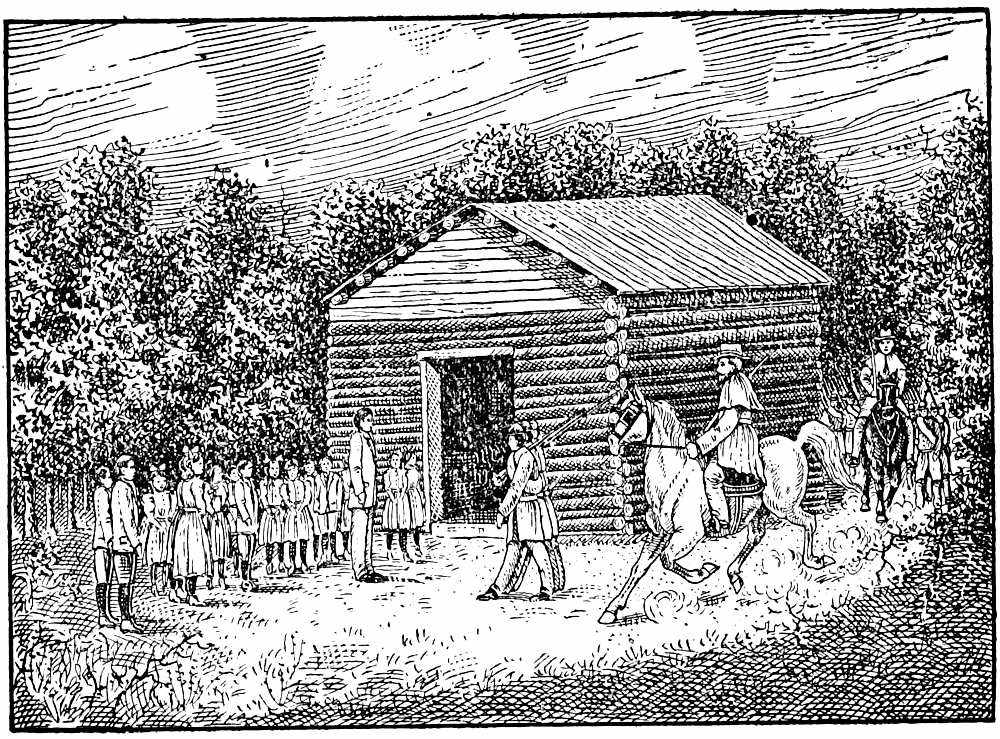

Capt. R. A. Ragan making his escape from his father-in-law’s home in 1862. See page 17.

[Pg 21]

The third night I crawled into the barn of Philip Easterly, who was my wife’s uncle. I did not let myself be known, but lay there all day as usual, and at night crawled out, having one mile and a half to travel to reach home.

I can safely say that I had to hop on one foot most of the way. I had no crutches and nothing but a stick that I had cut with a knife. When I arrived at my home, about three o’clock in the morning, my folks were surprised to see me, for they thought I could never walk on my foot in the condition it was in. I had my foot dressed for the first time since I was hurt. The blood had caked on it, and it looked as if amputation might be necessary; but my wife came to me two or three times a day and dressed it. I stayed in the barn at nights, and in the woods in the daytime. I had to remain in this condition for about six weeks, until I got so that I could begin to walk.

[Pg 22]

In July, 1863, the news came that George Kirk would meet some men in Greene County to take them to Kentucky. I was determined to go, if I had to crawl part of the way. We met in Greene County, with about a hundred men. We crossed Walden Ridge and the Watauga, Cumberland, Holston and Powell’s Rivers, encountering great hardships. Our provisions gave out, and the only way we could get anything to eat was to find a colored family. They were always loyal, and we could depend on them. They never would “give us away.”

When we reached Camp Dick Robinson, Kentucky, we found a great many East Tennessee men who had made their way through the mountains. Some had organized into companies.

Col. Felix A. Reeve, who is now Assistant Solicitor of the Treasury Department, was organizing the Eighth Tennessee Regiment of Infantry. I reported to him that there were a great many Union men in North Carolina and Cocke County, Tenn., that wanted to come to the Union army, and if he would give me recruiting papers I would attempt to cross the Cumberland Mountain into East Tennessee, and make up a company and bring them back with me. He was very anxious for me to try it, but said it was a very dangerous undertaking, for the rebel soldiers were guarding every road and path that had been traveled by the Union men. I concluded, however, to make the venture.

[Pg 23]

With my brother Alexander Ragan, Iranious Isenhour, James Kinser and James Ward, I started for East Tennessee. We crossed Cumberland Mountain, and it commenced raining, and when in the night we came to Powell’s River it was overflowing its banks. We had crossed at this place on our journey to Kentucky. The canoe was on the opposite side, and the night was so dark that we could not see across the stream. We knew that if we remained there until daylight we certainly would be captured and hung or shot. My brother and Eisenhour were good swimmers. They stripped off their clothes, and I never expected to see either of them again. I remember that my brother, while we were talking about who should swim over to get the canoe, said to me,

“I am not married, and if I get drowned it will not be so bad; if you were to get drowned, Emeline would be left alone.”

I have since thought thousands of times how noble it was in him to have such fraternal feeling for myself and my wife under circumstances of so trying a nature.

They both plunged in at the same time. The timber was running and slashing the banks on the other side. I held my breath, waiting to hear the result. In a few minutes I heard my brother say, “Here it is, Iranius.” So they brought the canoe over, and one by one we crossed to the other side. It was a frail little thing, and we thought every minute we would be drowned. We crawled up the steep bank to an old field, and as by this time it was daylight, we had to get into the woods and hide for the day. We had filled our haversacks with provisions when we left Camp Dick Robinson, but they were all wet and mixed up; yet we ate them all the same.

[Pg 24]

James Ward could not see a wink in the night. We did not know it until we had passed Cumberland Mountain. Of course we had to take care of him. He was like a moon-eyed horse; he was all right in the daytime, but we had to travel in the night, and we had to lead him half the time.

After a good many hardships, we reached Cocke County, Tenn. I do not think we met any one but an old man named Walker, whom I will mention later on. He gave us something to eat—in fact all he had, for the rebel soldiers had robbed him and left him destitute.

I went to my home in the night and made myself known, but did not sleep in the house.

While I was away, the rebels came to my father-in-law’s house and took him out to an old blacksmith shop and told him if he did not give up his money they would hang him. He would not tell them where the money was, and they put the rope around his neck and threw it over the joist of the blacksmith shop, and pulled him up by the neck. His daughter came and agreed to tell them where the money was, and they let the old man down, but he was so near dead that he could not stand. They took the money, some gold and some silver, and passed on. My father-in-law was Benjamin F. Neass, an unconditional Union man. These things I relate to show how Union men and families were treated.

In the meantime I sent for my father at Newport, whom I had not seen for a year, and told the messenger not to let him know who wanted to see him, but to meet me in a piece of woodland in a certain place on my father-in-law’s farm. The[Pg 25] next night he came. I asked him to send word to North Carolina, and every place where he could find out that there were Union men who wanted to go to Kentucky, but not to let a man know who was the “pilot.” He was Deputy Sheriff of the county, and was exempt from going into the rebel army at that time, but later on he had to leave the country.

In a few days word reached North Carolina and Greene and Cocke Counties, Tenn., that a “pilot” would be on hand at a place in the woods on my father-in-law’s farm at a certain date. On the appointed day, one, two and three at a time, they made their appearance. I did not make myself known, but had a man ready to meet them and keep them quiet, for the rebels were all through the country. I knew if they captured me it would be certain death, for they killed every “pilot” they could lay their hands on.

The Union women had been notified when we were to meet, and they had made haversacks and filled them with provisions for their husbands. The mothers and sisters had done the same thing for their sons and brothers who were single.

When the time came at nine o’clock for us to start, I came out and made myself known. There were about a hundred men present, and I had been acquainted with nearly all of them. They were surprised and glad to see me, and I swore in all who wanted to enlist. It was a sad sight. The wives bid their husbands good-bye, net knowing whether they would ever see them again or not, and some of them never did; but they were loyal women and were ready at all times to sacrifice all for their country.

[Pg 26]

Women in North Carolina and some parts of East Tennessee suffered themselves to be whipped, and everything taken from them, and yet they would not tell where their husbands were. I have known them to cut up the last blanket in the house, to make clothes for their husbands, who were lying out, waiting for a chance to reach the Federal army. The night I left, my wife had cut up a blanket and made for me a shirt and a pair of drawers. All these things go to show what the Union men and women of East Tennessee did to help save this Government when it was in danger of destruction.

We then started on the perilous undertaking, which was more dangerous at that time than upon the previous trip to Kentucky, for men all over East Tennessee had to leave, and the roads and river were guarded. Nearly all the men had old rifles or shotguns that they had rubbed up until they looked like army rifles. We reached the Nola Chucky, about twelve miles from our starting point, about midnight in a violent thunder storm, in the darkest night I had ever witnessed. As the lightning flashed we could see it run along the barrels of the guns. The river was very high, and there seemed to be a general war of the elements.

Each man had been instructed before we started to not speak above his breath, and if possible not to break a stick under foot. We halted in the lane in front of the house occupied by the man who kept the ferry, who was a Union man. His name was Reuben Easterly, six feet and two inches in height. I went to the door and knocked; he was slow to get up, but in a few moments came and opened the door.

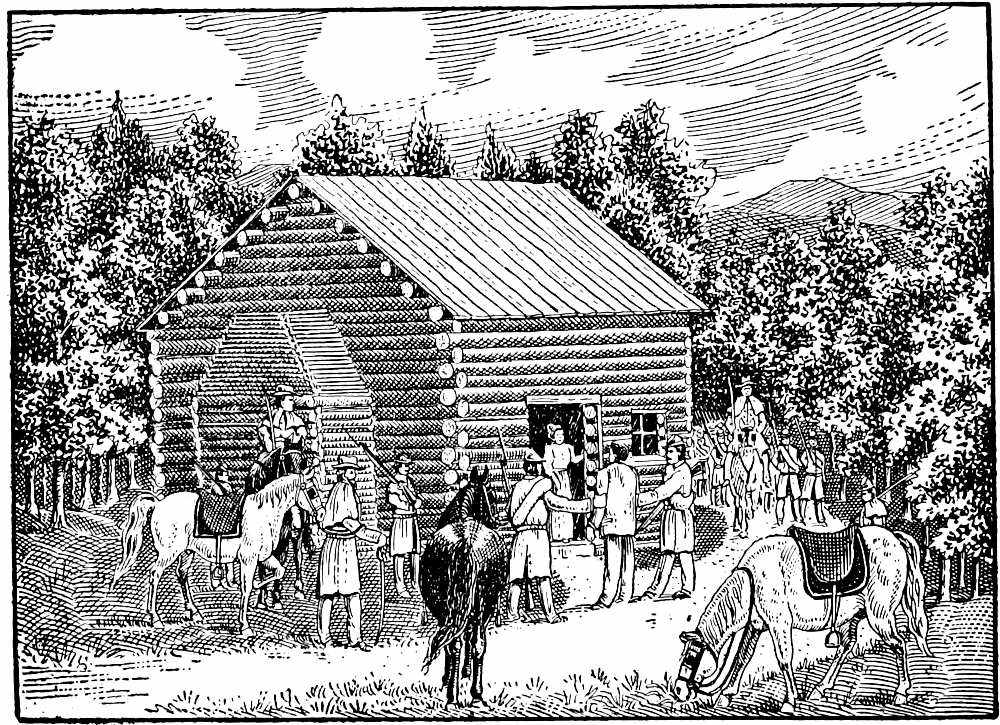

Capt. R. A. Ragan Arrested at the School House. See page 8.

[Pg 27]

I said in a low tone of voice, “One hundred and twenty Union men want to cross the river.”

He hesitated and said, “The river is up, and I am afraid you can’t cross.”

I said to him, “We have to cross, dead or alive. If we remain on this side until daylight, we will be captured and sent to Tuscaloosa.”

He finally agreed to try, as he was always ready to help Union men. He came out and about half of the men got into the flat-bottomed boat and ran up the river a hundred yards to get a start so as to reach the landing on the other side. We waited some time, and heard the old boat strike dirt on the safe side. In about half an hour the boat returned to our side, and the balance of us got in and were soon safely landed with the others. We asked old Reuben what he charged.

“Nothing,” said he, “and I wish you a safe journey to the promised land.”

Those kind words served to cheer us very much on our way.

After crossing the river we started for the Chucky Knobs, where we were to meet several Union men. When we reached the place, in a deep hollow, with no house within a mile, we found fifteen men waiting for us, including Judge Randolph, of Cocke County. A number of Union women had learned that we were to meet at this place, and that their husbands were going away, and they had prepared rations and haversacks to supply them on their dangerous journey. They bid them good-bye, and two of them never saw their husbands again.

We remained there all that day, and that night at eight[Pg 28] o’clock we started for good, with about one hundred and thirty men. All seemed to be in good spirits and glad that they were on their way to the “promised land,” as Reuben Easterly said when we crossed the Nola Chucky. We travelled about fifteen miles that night, and next day laid in the woods on the banks of the Watauga River.

When night came we crossed the river—some swimming and some crossing in an old canoe—and continued our journey. At daylight we came to the Holston River, at a point where no Union men had previously crossed on their way to Kentucky. I sent three men up the river to find a canoe, for some of the men could not swim and it was too deep to wade. They found an old canoe, and while some swam and others crossed in the canoe, it was nearly midnight when we all got across.

As the men reached the opposite side, they would lie down and go to sleep while the others were crossing. It was a level place on the opposite side, and stick weeds had grown up about five feet high. When the men had all crossed, they woke up those that were asleep, and we got in line and started. After travelling about half a mile, we heard some one howling at the top of his voice. I sent two of the boys back in haste to find out what was the matter. They found that Jimmie Jones was left asleep on the bank of the river, the boys having failed to awaken him. He said that he dreamed that the rebels were after him and he woke up and found we had gone, and the old man commenced howling like a lost dog. We were very uneasy about it, for fear the rebels had heard him, but evidently they had not and no unpleasant consequences resulted.

[Pg 29]

Next came Bays and Clinch Mountains, steep and rugged, over which we had to pass; and then came Clinch River, another dangerous place to cross, for the rebels were watching the paths and the rivers to prevent Union men from leaving the country and reaching the Federal lines.

We crossed Powell’s Mountain, tall, rough and rugged; then came Walden Ridge and the Wild Cat Mountain. The nights were so dark we could not see ten feet ahead of us. As we passed through these dark, narrow paths, we marched in single file, myself leading; the next one would take hold of my coat tail, and so on down the line. No man was allowed to speak above his breath. Sometimes men would fall and suffer themselves to be dragged for yards, but never spoke nor murmured a word.

We had some rations on hand that our wives had prepared for us, but they were getting scarce, from the fact that we had to keep away from houses and public roads. It was certainly strange that one hundred and thirty men could travel through a country two hundred miles, thickly settled in some places, and never be seen.

We continued on our march, the night being very dark and the country very rough. The men had become tired and worn out. Some were nearly barefooted, for their shoes were poor before they left home.

The next morning we came in sight of Powell’s River, and remained in a thick piece of woods for the day. We were in a dangerous part of the country—we were nearing Powell’s Valley, the most dangerous place in all our travels. When night[Pg 30] came we were a little refreshed, but were out of rations, and had been living on quarter rations all the way. We crossed Powell’s River that night, and started for the great task. We had to cross the “Dead Line” and Powell’s Valley the next night.

It was so dark we could not see ten steps ahead of us, and we lost our trail. When daylight came we found ourselves about two miles East of the regular trail. We halted in a deep hollow and had a consultation. I knew that I was “in for it,” if I failed to get them out. I was sure we were East of the home of old man Walker, the man who gave us something to eat on our way to Tennessee on our previous trip, and I thought I could find his house. I started West, and travelled two miles through the woods, in a rough country, with no houses near. It so happened that I came out of the woods at the rear of his house. I lay down in a patch of chinkapin bushes for some time, as I was not certain that I was at the right place, the house being a very ordinary log building.

I crawled to a low rail fence, and knocked on a rail of the fence with a small stone. In a moment Walker came out of the house, looking like a wild man, and seemed to know what was up. He went back and in a few minutes a company of rebel cavalry passed along the road. I waited until they got out of the way and then knocked again and he came out the second time.

He came slowly to where I lay, and said, “What’s the matter?” He recognized me, for it had been but a short time since we had a talk with him on our way from Kentucky to Tennessee. I told him that about one hundred and thirty men had got off the trail and had wandered about two miles East.

[Pg 31]

He said, “Don’t say a word; there have been several such cases.” He told me to go back in the thicket and not make any noise, for the rebels were travelling up and down the road; and he would bring the men out in a short time. In about two hours Walker returned, with the men trailing after him. I never saw men so happy, for they knew if they had remained there they would be captured and sent to Tuscaloosa.

We were all nearly starved, having eaten up all we had the day before. I asked Walker if he could get us something to eat. He said he did not have anything but Irish potatoes, and they were in the ground, and some apples that were on the trees, and nothing to make bread of. The rebels had taken nearly everything he had. He went to work and dug the potatoes and gathered the apples, and cooked them in some old tin buckets, the only things available. He cooked about two bushels each of the apples and potatoes.

It was about nine o’clock in the morning when he brought the men to his place, and at noon the “dinner” was ready. I got the men in line, and Walker passed the buckets along. As the men had no knives, forks or spoons, they had to use their hands, and some of them were so hungry that they burned their fingers in their eagerness to partake of the delicious and inviting repast. Our generous host continued to supply them until all was consumed.

The men were so famished that while he was cooking the apples and potatoes they peeled the bark off all the little trees and ate it. The whole thicket, about an acre, looked white after the trees had been thus denuded of their bark.

[Pg 32]

By this time it was two o’clock in the afternoon, and I told the men to lie down and try to sleep, for we had to cross the “Dead Line” and Powell’s Valley that night, and get into Cumberland Mountain, for I knew the rebels were on our trail.

While we were lying on the ground about three hundred yards from the main road, we could hear the rebels riding up and down the road. No man was allowed to make any noise. They obtained a few hours of sleep and rest, which was very much needed. I had two men detailed to keep them from snoring, for some of them you could hear a hundred yards. These men would go around and when a man would snore they would shake him or give him a kick.

When night came, the perilous task of crossing the “Dead Line,” which we had dreaded from the start, was before us. Several men had been killed at this place during the preceding ten days. I asked Walker if he knew a good Union man who could be relied upon to guide us to the road. He said there was a man in the neighborhood who had helped men to Powell’s Valley, and he would send a colored girl to see if the man could be found. By the time we were ready to start, about nine o’clock, he came. I questioned him and he seemed to be all right, so we started, he in the lead. I had been on the trail before, and after travelling about a mile I became a little suspicious and stopped the men. I thought we were too far West. I formed a hollow square, with this man in the center. I questioned him and found we were a mile off the trail. We put the man under arrest, and went back to where we had started and took up the right trail. I do not think this man intended to lead us into the rebels’ hands, but he became bewildered and scared.

Capt. R. A. Ragan at his home after Arrest. See page 8.

[Pg 33]

We reached Powell’s Valley about three o’clock in the morning, and halted on a little bank about ten feet above the level of the main road leading up and down the valley, which was called the “Dead Line.” I remember this experience as vividly as if it were but yesterday. The woods in which we were concealed were as dark as hell, and hell was in front of us. There were about one hundred and thirty men standing in single file, and I could not hear a man move or breathe. Even death itself could never be more still.

The valley we had to cross was about four hundred yards wide, and not a tree or bush in the valley. The road in front of us was dusty, and while we stood there we heard in the distance the rattle of sabers and the galloping of rebel cavalry. We stood motionless as they passed by, and the dust from the horses’ hoofs came up in the bushes and settled on our shoulders. What a time it was for us! It seemed that we were to cross the “Valley and shadow of death.”

When the rebel cavalry had passed, I cut off twenty-five men and said, “Now, boys, go!” and they did go. They crossed that valley like wild cattle. When I thought they were safely over, I cut off twenty-five more men, and they also landed safely. I waited awhile, and we could hear the rebel cavalry coming back. They passed down again, so we waited about ten minutes and then I said, “Boys, now follow me!” and we all crossed in safety and were at the foot of Cumberland Mountain, which was rough, steep, rocky and pathless. Every man had to pick his way until we nearly reached the top.

As we crossed the valley, the air was filled with the stench[Pg 34] of the decaying bodies of the men who had been killed a few days before. No one could venture to remove or bury them. I understood afterward that they attempted to cross in the daytime, and were killed.

When we reached the top of Cumberland Mountain we came to what was called Bailes’ Meadow, a name and place familiar to nearly every “pilot” and man who crossed the mountain. The boys were worn out, mostly all barefooted and nearly naked from crawling through bushes and briar thickets.

Some of them, when we reached the top of the mountain, looked back into the valley of East Tennessee and said, “Farewell to rebellion;” and they looked North and said, “I can see the Promised Land!” They were happy, but they had been so long hiding in the woods that they would only speak in whispers, and it was a long time before they could break themselves from the habit. You could trail them by the blood from their feet, but like brave men they marched along without a murmur.

James H. Randolph, of Newport, Tennessee, was with us. I was sorry for him as well as the others. His shoes were entirely worn out, and his feet were bleeding. I can remember the circumstances as distinctly as though it were but a few days ago. He looked at me and said, “Bob, when we get back to Tennessee we will give them H—, and rub it in!” He was mad, worn out, and nearly starved to death; but we were out of danger and began to realize that we were free once more.

We went down to the settlements in Kentucky, but could not see a man. It seemed that they had all gone to the Union[Pg 35] or the rebel army; but the farms appeared to be in good condition and well stocked, and the fields were full of corn. We came to a large farm at the foot of the mountain, with a large frame house, painted white, but could not see any one. There was quite a field of corn, just in roasting ears. We halted, and I told the boys we must have something to eat, for we were nearly starved. We had had nothing to eat since we ate the apples and potatoes at old man Walker’s.

I told four or five of the boys to go to the corn field and bring as many roasting ears as they could carry, and some five or six others to go out in the pasture where there was a nice flock of sheep and bring in a couple of fat bucks, and we would cook the mutton with the roasting ears. In the meantime others went to the house and got a wash kettle in which to cook the mutton and corn, and some salt for seasoning. By the time they returned the boys had arrived with the roasting ears. I looked out in the pasture and saw five boys, each pulling a sheep along. They were so hungry that they thought they could eat a sheep apiece; but we only killed two, and they were fine. We had men in the company who could equal any butcher in dressing a sheep. We filled the kettle with corn and mutton, and had a fine barbecue. We had no soap, and when the boys got through, their mouths, faces and hands were as greasy as a fat stand. I sent one of the boys to the house to tell the lady how much we had taken, and ask what she charged.

She said, “Nothing.” Some of the boys had a little gold and silver with them and wanted to pay her.

[Pg 36]

We reached Camp Dick Robinson in a few days, and remained there some time. Col. Reeve had his regiment nearly made up. We organized our company as Company K, which about completed the regiment. The company was mustered into the service, when the boys drew their uniforms and their new Enfield rifles. After they had shaved, cleaned up and put on their new uniforms, I met them several times and did not know them. They were the happiest men I ever saw.

[Pg 37]

The army was getting ready to start on the march for East Tennessee. I had bought my officer’s uniform, with my straps on my shoulders and a sword hanging by my side. I do not think that General Grant or General Sherman ever felt as big as I did. Of course we had been lying in the mountains of East Tennessee for nearly two years, and had been chased by rebels and in danger of our lives every minute of our time, and had to leave our families to be treated like thieves—why not feel good as we were going back to relieve them? I have known rebels to take women and whip them to make them tell where their husbands were.

About the first of August we were ordered to be ready to march at a minute’s notice, and in a few days the orders came for us to fall in line. The band struck up the tune, “Going back to Dixie;” the men cheered, and some shed tears of joy. The army concentrated at Danville, Ky., and General Burnside took command of the 23d Army Corps. We remained there a few days, and then took up our march in fact for East Tennessee. We had a pretty hard time getting across the mountains, as the roads were very bad, and the horses and mules were not used to traveling; a great many of them gave out, and a large number died.

We reached East Tennessee, below Knoxville, about the last of August, 1863, and marched in the direction of that city,[Pg 38] passing between it and Bean Station. We skirmished with the rebels on our way, and then camped at Bull’s Gap for a few days.

While at Bull’s Gap, I asked Col. Reeve for a detail of six men to go across the country about eighteen miles, to visit my home and find out if any rebels were lurking around in the neighborhood. When we got within a mile of Parrottsville, Cocke County, near where I lived, we sent a Union woman to the town, requesting her to see an old colored man by the name of Dave Rodman, who we knew had been living there all his life, and to tell him to come out to a piece of woodland just above the town.

About ten o’clock in the night we heard the old man coming in our direction. We met him and he informed us that Henry Kilgore (the man who conscripted me), Tillman Faubion and Cass Turner were in the town; that Kilgore was at his home, and the other two men were across the street at Faubion’s house. We went into the town, and George Freshour, who was a Sergeant in my company, and one other man and myself surrounded the Kilgore house, while the other three men went across the street to the Faubion house and captured Faubion and Cass Turner. Their horses were hitched to the fence, ready to mount and make their way to North Carolina. It was raining, and the night was very dark.

Freshour went to the front door and knocked; some one came to the door, and he asked if Kilgore was at home. They said that he had gone. As I was at the back kitchen door and the other man at the south door, we knew he had not passed out. Freshour insisted that Kilgore was in the house, and demanded[Pg 39] that the door be opened. Finally they let him in.

There was no light in the house. Freshour searched under the beds and every place that he thought a man could hide in, but failed to find his man. He then went into the kitchen and found Kilgore crouched behind some old barrels. We brought him out and took him across the street where the other two prisoners were. We then started down Clear Creek, which ran through the Knobs, and we had to cross it ten or fifteen times on foot logs that were narrow, smooth and slippery.

At the beginning of the Rebellion this man Henry Kilgore was a conscript officer, and gave Leadbeater’s Command, which was stationed at Parrottsville for the purpose of hunting Union men, all the information he could obtain as to where the Union men kept their corn, wheat, bacon and bee gum. He was a terror to the country.

Tillman Faubion was a nice man, and I never heard of him giving any information, but he was a strong rebel sympathizer.

Cass Turner lived between Sevierville and Newport, Cocke County, Tenn. He was a conscript officer, and one of the worst men in that section. While hunting Union men who were lying out in the hills, trying to get to Kentucky, he found that two or three men were hid in a cave in his neighborhood. He and two others went to the cave and found the men, and it was said he shot them and left their bodies in the cave.

I remember when we started with these three men, Sergt. Freshour walked behind Kilgore, and he insisted upon my giving him permission to kill Kilgore, but I would not let him do any harm to any of the men.

[Pg 40]

Cass Turner was a short man, weighing about two hundred pounds. He could not walk the foot-logs, and had to get down and slide across on his stomach. He and Kilgore pleaded with the boys to let them ride, but they refused.

About ten miles below where we captured these men we came to the home of a Mrs. Bible, whose husband had been captured by the rebels, taken to Tuscaloosa and died. Freshour asked her if she had any honey, and she replied that there was a bee hive in the barn that the rebels had not found. Freshour went to the bee hive, took out a pound of soft honey, put it in Kilgore’s tall white “plug” hat, and made him wear it. The honey ran down his face, eyes and ears. The cause of the Sergeant’s little act of “pleasantry” was the fact that Kilgore had sent the rebels to Freshour’s father’s house, and they took all of his bee hives, wheat, corn and bacon—in fact all he had. The rebel now had an opportunity to taste the “sweets of adversity.”

We took these men to Knoxville and turned them over to the authorities, and then returned to our command, at Bull’s Gap.

[Pg 41]

Preparations were being made at Missionary Ridge for battle, and the rebels were concentrating all their forces at that point. Burnside’s Corps returned to Knoxville and was besieged. After Grant defeated the rebel forces at Missionary Ridge, Longstreet’s army came up to Knoxville and attacked the Federal forces on the west end, but were repulsed with great loss. Longstreet’s defeated and demoralized forces took up their march to East Tennessee, making their way to Virginia. Burnside’s Corps followed them as far as Jonesboro, and then returned by way of Knoxville.

Grant and Sherman were getting their forces together, and making preparations for the great march to Atlanta. Burnside arrived at Red Clay and marched out to what is called Buzzard’s Roost and attacked the enemy, but they were too strongly fortified. We fell back, and Sherman commenced for the first time with his “flanking machine,” as the rebels called it. We marched around through Snake Creek Gap and formed in line of battle about a half mile from the rebel breastworks, our Division being in front. We marched down through a piece of woodland and up a hill about two hundred yards from the rebel works. The grape and canister would cut through our ranks, and we would close up the gaps. It was said that there were about five hundred pieces of artillery playing at the same time. It seemed that the earth was tottering to the center.

[Pg 42]

We were ordered to lie down within about one hundred yards of the rebel breastworks. A line of battle passed over us, a Colonel being mounted. His horse was shot from under him, but he never halted. The horse fell and rolled down the hill, about ten steps from our line.

General Sherman, knowing our condition and that we were losing hundreds of men, moved around on our extreme right and, getting the range of the rebel breastworks, turned loose his artillery and plowed the rebels out of the works. They retreated, and the day was ours.

When the battle was going on the cannon balls cut off the tops of the trees, and they fell in our ranks and killed many of our men. After the smoke of the battle had cleared away, I could see the rebel sharpshooters hanging in the trees. They had tied themselves to keep from falling if wounded, but some were dead. It was reported that the rebels obtained from some foreign country the long-range guns then used by the Southern sharpshooters, which seemed to be superior to the rifles in possession of our forces.

This little account is not intended to give the history of the War or the exciting campaign through Georgia, but only to give an insight into my personal experiences.

I will here relate one little occurrence at Cartersville, Ga., after we had driven the rebels across the Etowah River. I was detailed with about fifty men to go around a mountain and down to a large flour mill on the river, if we could, and burn it up with all its contents. We arrived on the side of a mountain just above the mill and halted. On the opposite side of[Pg 43] the river was a high bluff, from which we were fired upon by the rebels, but we sheltered ourselves behind trees.

I took eight or ten men and went back a few hundred yards to a little stream that flowed into a mill race leading to the mill. The race was quite large, and as the water overflowed on both sides it formed a screened pathway. We reached the mill, unseen by the rebels, and went from the basement to the upper floor, where we found four men sacking flour and corn meal and loading it in wagons in front of the mill. We arrested them and ordered them to help us carry the flour and meal back into the mill. We then unhitched the horses from the wagons, took off the wheels and rolled them into the mill, and then set the building on fire. When it was in full blast, we released the men and went back the same way we came. Finding that our men had silenced the rebels on the other side, we took up our march back to our command and made our report.

We crossed the Etowah River the next day, and found the rebels had formed a line of battle and built breastworks. We drove the rebel picket line in, and fortified within about five hundred yards from the enemy’s fortifications, which were on a ridge in a piece of woodland. Our picket line was deployed on the edge of an old field, about two hundred yards from the rebel breastworks. There were two small log cabins between the lines, about thirty feet apart, from which any of our men who exposed themselves were shot. I saw several men killed while trying to pass between these cabins. Being in charge of the brigade picket line, I received an order to charge the rebel[Pg 44] pickets and drive them into their works. I knew it was death to every man, for I had been there all day and understood the situation. I refused to make the charge, and one of Burnside’s Staff—I think it was Major Tracy—rode up and said to me, “Why did you disobey orders?” I told him if he remained where he was he would be shot. Just then a ball struck him in the breast, and he fell from his horse and was carried off the field. I received no more orders, and remained in charge of the picket line.

That night about twelve o’clock I heard a cow bell tinkling in front of us, sounding as if cattle were eating leaves off the bushes. I called the attention of Sergeant George Freshour to it. He belonged to my company, and was as brave a boy as ever lived. He said, “Captain, that is rebels, trying to make us think it is cattle.”

He handed me his gun, and said he would crawl down in the bushes and see what it meant. He was gone about ten minutes, when I heard him crawling out of the bushes, nearly out of breath, and in a low whisper he said, “Captain, the woods are full of rebels and they are advancing!”

I immediately passed the word along the line to get ready for a charge. In a few minutes I gave the order, “Charge!” and we did charge! We drove the rebel line back into their works, and returned to our former line. It was as dark as it could be, and they evidently thought the whole Federal army was after them

The next morning at daylight I was relieved, and we were congratulated for our action.

[Pg 45]

About four o’clock that evening the whole rebel line charged our works. The battle lasted about two hours, but we repulsed them and they fell back, leaving about three hundred dead and wounded on the field.

Sherman was moving on the extreme right, as usual, turning the rebels’ left flank, and they had to leave their works and retreat. We continued in pursuit of the enemy, skirmishing continuously, and when we reached the front of Atlanta we were on the extreme left near the breastworks, guarding the wagon train.

About two o’clock on the afternoon of July 22, 1864, the rebels attacked our left and drove our wagon train pell mell, forcing our left wing back. General James B. McPherson came up with his Staff, rode out through a piece of woodland in front of us, and ran into the rebel cavalry and was killed. I was within thirty yards of him at the time.

In about a half-hour General John A. Logan came up and took command. The evening after General McPherson was killed the rebels charged on our left, and it was said to be the hardest battle that was fought while we were at Atlanta.

Next morning we were ordered around to the extreme right of Atlanta, to tear up the railroad between Atlanta and Jonesboro. Our regiment was the first to reach the railroad. We took the rails off the cross ties and bent them, piled the cross ties on top of the rails and set them on fire. Two trains came up from the South, making their way to Atlanta, but discovered that the railroad was torn up, and backed out and disappeared.

[Pg 46]

On the sixth day of August we were about the center of the army, and were ordered to advance on the rebel works. There was an old field between our forces and the rebels. They had fortified on a ridge as usual, in the woods about three hundred yards from this old field, and they had cut down all the small timber in front of their works, the tops falling in our direction. They had sharpened the ends of the timber, forming an abbatis, of which we were not aware until we had reached within about twenty yards of their works. Some of our men succeeded in getting through these sharp limbs and up to their works, although they were killing our men by the dozen. Our color-bearer, a boy by the name of John Fancher, placed the flag on the rebel works, and they got hold of it and pulled him in. He was never heard of again until after the war, when the rebel records showed that he died in prison.

We had to fall back, leaving our dead and wounded on the ground. We lost ninety-three men wounded and killed out of our regiment. The officers who were killed were Capt. Bowers, Lieut. Johnson and Lieut. Fitzgerald. Lieut. Bible and Lieut. Walker were wounded.

There were five killed and wounded in my company. One of them, George Ricker, was killed in the fight and laid close to the edge of the old field. His mess-mate, William Smith, saw him lying dead as we fell back. After the battle was over, though the sharpshooters were still firing, Smith asked me to let him go back and get the body, and help bring it off the field. I said to him it was dangerous for him to go, but he insisted and I finally consented. He went to where Ricker was,[Pg 47] and just as he stooped down to raise him up a ball struck him in the side, and he fell dead on the body of his comrade. They were warm friends in life, and in death were not separated. Afterward the dead were buried, and the wounded cared for.

On the night of September 1, 1864, the rebels set fire to the arsenal and all the military implements in Atlanta, and it seemed the whole earth trembled with the explosions. The rebels evacuated the city, moving out southeast, and on the morning of September 2d our forces took possession, thus gaining the victory after a siege lasting over a month.

Next morning we followed the rebels to Jonesboro and had a hard battle, defeating them. After the battle was over we remained there for a few days, and then returned to Atlanta.

The rebel regiment that I was urged to make up in my county, heretofore mentioned, was captured in the Jonesboro fight, losing quite heavily in killed and wounded. Some of the men learned that my regiment was in the battle, and heard that I was there, and they sent for me. I found that fifteen or twenty of the boys with whom I had gone to school were prisoners, and several had been killed. Some of these were boys I had played with when we were children. I make this statement to show that fathers and brothers and neighbors and friends had fought against each other. This regiment that I speak of was paroled and went back to East Tennessee, and never returned to the rebel army.

After the war we were all good friends and good citizens. These boys went into the rebel army at the beginning of the war in 1861, and did not stay around home to rob and kill Union men, and hang them for their money.

[Pg 48]

In this closing chapter I desire to give some incidents, etc., pathetic, humorous and otherwise, associated with but not included in this somewhat disconnected and rambling account of my varied experiences.

The noble and patriotic women in East Tennessee, whose untold sufferings would fill a volume, most of whom have now passed beyond that bourne from whence no traveler ever returns, should have their names and deeds so far as possible recorded so that generations yet to come may honor them and reverence their memory.

No night was too dark, no danger too imminent, no task too arduous for these self-sacrificing women to perform when the opportunity was presented to them to lend a helping hand to the hunted, starving Union men.

What brave, loving mothers, wives and sisters of East Tennessee, who faced the tempests of hatred and persecution during the Civil War; whose willing hands were always ready to minister to the suffering and distressed; who carried food to the hunted and perishing Union men who wore the homespun clothes wrought by their own hands; who through waiting[Pg 49] years never faltered in love and faith and duty to friend or to country!

The deeds of the loyal men of East Tennessee, could they have been told individually in all their thrilling details and sufferings while they were living, would rival in patriotic interest the stories of Robert Bruce, William Wallace, or the brave Leonidas, who with his three hundred Spartans held the pass at Thermopylae against the hosts of Persian aggressors.

I recall another little incident that occurred in my travels from my home to my father’s, near Newport, Tenn. About midway on the route that I travelled, on the main road leading to Paint Rock, N. C., there lived a man by the name of John Hawk, who had two or three large bull dogs. I had travelled several times over this route, passing within two hundred yards of his house, and had never been molested by these dogs, for I was careful about making any noise. On one occasion I got too near the house, and happened to step on a stick in my path, which snapped loudly and the dogs heard it and started for me, yelping as they ran. I was fast on foot at that time, but the dogs seemed to be gaining on me. I looked for a tree to climb, but they were all too large. I knew the time was coming for me to make a fight for my life, for they were getting dangerously near. I picked up two knotty rocks as I ran, and soon reached a high cross fence that had been built in the woods. Beside the fence stood a small hickory tree, and I climbed up about ten feet just as the dogs reached the place. It was so dark I could hardly see them. They reared up and commenced barking as if they had treed a coon or a possum. I drew back[Pg 50] with one of the stones and struck one of the dogs squarely in the mouth, and I heard his teeth shatter. He raised a howl and ran away, with the other dog after him. After that time I kept that house at a greater distance. That night I made my way home, or in other words, to the mountains close by.

Old Uncle David’s Prayer.—This prayer was delivered by an old colored man before we crossed the Holston River. We found him living in a little log cabin on a farm. He was an old-fashioned preacher, and of course a Union man.

“O Lord God A’mighty! We is yo’ chil’n an’ ’spects you to hea’ us widout delay, cause we all is in right smart ob a hurry! Dese yer gemmen has run’d away from de Seceshers and dere ’omes, and wants to get to de Norf. Dey hasn’t got any time for to wait! Ef it is ’cording to de destination ob great Hebben to help ’em, it’ll be ’bout necessary fo’ de help to come right soon! De hounds an’ de rebels is on dere track! Take de smell out ob de dogs’ noses, O Lord! and let Gypshun darkness come ober de eysights ob de rebels. Confound ’em, O Lord! Dey is cruel, and makes haste to shed blood. Dey has long ’pressed de black man an’ groun’ him in de dust, an’ now I reck’n dey ’spects dat dey am a gwin’ to serve de loyal men de same way. Help dese gemmen in time ob trouble, an’ left ’em fru all danger on to de udder side ob Jo’dan dry shod! An’ raise de radiance ob yo’ face on all de loyal men what’s shut up in de Souf! Send some Moses, O Lord! to guide ’em fru de Red Sea ob Flickshun into de promis’ land! Send some great Gen’ral ob de Norf wid his comp’ny sweepin’ down fru dese yer parts to scare de rebels till dey flee like de Midians,[Pg 51] an’ slew dereselves to sabe dere lives! O Lord! bless de Gen’rals ob de Norf! O Lord! bless de Kunnels! O Lord! bless de Capt’ins! O Lord! bless der loyal men makin’ dere way to de promis’ land! O Lord, Eberlastin’! Amen.”

This prayer, offered in a full and fervent voice, seemed to cover our case exactly, and we could join in the “amen.” We then crossed the Holston River, but not dry shod.

Some time in 1862 the loyal men of Cocke County, East Tennessee, refused to go into the rebel army. They lived in what was called the Knobs. There were about four hundred of these men, some farmers, some mechanics and some blacksmiths, all loyal to the Government.

Leadbeater with his command was sent to Parrottsville, in the same county, and went into camp for the purpose of looking after these men, who had built breastworks on a high hill in that locality. They sawed off gum tree logs about the length of a cannon, and bored out holes in these logs large enough to load with tin cans full of large bullets and pieces of iron. They made iron bands out of wagon tires, and put them around the log cannons to keep them from exploding when fired. It was said that they could fire these wooden guns with accuracy.

The rebels heard of these preparations, and with a large force went into this Knob country and found the works, and captured about one hundred of these men and brought them to Parrottsville, where the army was in camp. They put them into a large one-story frame school-house, and placed a heavy guard around the prison, They kept them there for some time and treated them like brutes.

[Pg 52]

A man by the name of Hamilton Yett, who was a strong rebel, came into the prison and said he wanted “to look at the animals!” Such an expression from a man enraged the prisoners, and one of them, named Peter Reece, picked up a piece of brick from an old fire-place and threw it at Yett, striking him on the head and fracturing his skull. In a few minutes the soldiers came in the prison and took Reece out and hung him to a tree close to the prison, where he hung for three days. His wife and other women came and took the body down and hauled it away, no man being allowed to assist them.

Some of the men who were in this prison were taken to Tuscaloosa, some made their escape, and some were killed while trying to escape. There was a man by the name of Philip Bewley, who was a Methodist preacher, a good man and as strong a Union man as there was in East Tennessee. While in this prison he would pray for the success of the North and for the men who were with him in prison. He lived until after the war.

In this connection a little incident that occurred after the war may not be out of place in this small volume.

There was in our regiment a man by the name of Walker, who had one of his eyes shot out in the campaign in Georgia. When the war was over he came home, studied for the ministry and became a noted preacher.

In 1867 there was a big revival in the same town, Parrottsville, about three hundred yards from the old school-house in which Bewley and the other Union men were confined and where Reece was hung. While the revival was going on one[Pg 53] night at the church, Walker was praying the Lord to guide and direct the people in the way they ought to go, and that all might get to Heaven; Bewley rose up and said,

“Yes, thank the Lord, Brother Walker; there will be no rebels up there to shoot our eyes out!”

I heard this myself, and was not surprised, for he was the wittiest man I ever heard. It raised no excitement, for it was just after the war and prejudice was running high at that time; but, thank God, the war has been ended for forty-five years, and the North and the South have united, and we are now one people, one Nation, under one flag.

FIFTY YEARS AFTER THE WAR.