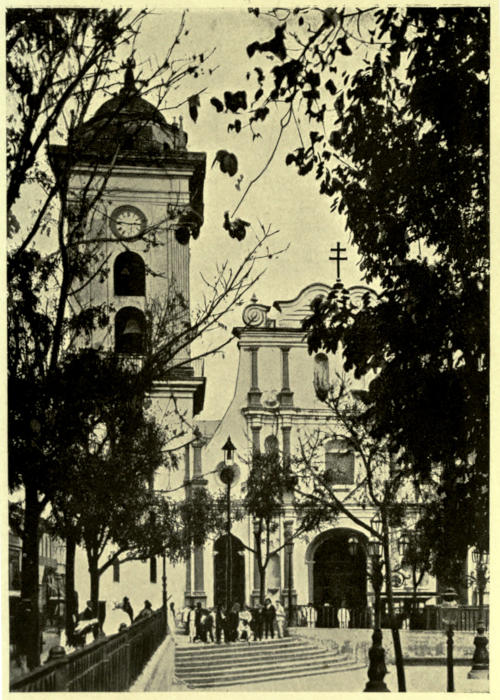

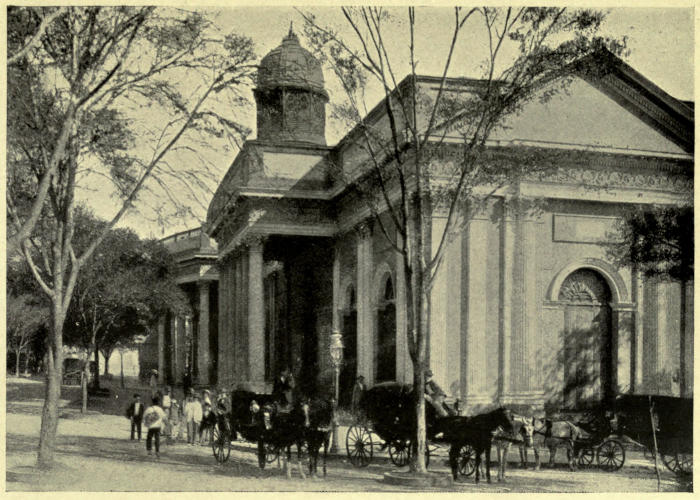

CATHEDRAL: CARÁCAS.

Title: Venezuela

Author: Leonard V. Dalton

Release date: June 22, 2023 [eBook #71020]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: T. Fisher Unwin, 1912

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE SOUTH AMERICAN SERIES

VENEZUELA

CATHEDRAL: CARÁCAS.

VENEZUELA

BY

LEONARD V. DALTON, B.Sc. (Lond.)

FELLOW OF THE GEOLOGICAL AND ROYAL GEOGRAPHICAL

SOCIETIES, ETC.

WITH A MAP AND 34 ILLUSTRATIONS

T. FISHER UNWIN |

|

LONDON: |

LEIPSIC: |

1912 |

|

(All rights reserved.)

TO

D. R. R.

The author is desirous of expressing his appreciation of the continued courtesy and kindness rendered during his stay in Venezuela by the British Chargé d’Affaires, Mr. W. E. O’Reilly, by Mr. E. A. Wallis, and other British residents, as well as the warm reception accorded by the Venezuelan officials throughout the parts of the country he visited.

Mr. F. A. Holiday, A.R.C.S., F.G.S., has made himself responsible for much of the information on the Llanos, and has assisted largely in the preparation of the tables in Appendix B. Mr. J. D. Berrington, of El Callao, also furnished details relating to the Guayana goldfields and their surroundings.

The author is greatly indebted to Mr. N. G. Burch, F.R.G.S., for reading the manuscript and for many valuable suggestions and criticisms. He would also thank Mr. G. T. Wayman, of Carácas, for many useful documents and items of interest regarding recent developments.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY NOTE | 9 |

| CHAPTER I PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION OF THE UNITED STATES OF VENEZUELA |

25 |

| Situation—Area—Population—Main physical divisions—The Guayana Highlands—Mountains, rivers, and forests The Llanos—Selvas—Mesas—Rivers and cienagas—The Delta—Caños—The Caribbean Hills—Serrania Costanera—Serrania Interior—Rivers—Segovia Highlands—Drainage—Vegetation—The Andes—Portuguesa Chain—Cordillera of Mérida—The Sierra Nevada—Mountain torrents—Vegetation—Páramos—The coastal plain—Lake of Maracaibo—Coro and Paraguana lowlands—Climate—“White-water” and “black-water” rivers—Seasons—Tierra caliente, templada, and fria—Temperature and seasons—“St. John’s little summer”—Health. | |

| CHAPTER II THE GEOLOGICAL HISTORY OF VENEZUELA |

38 |

| Ancient land of Guayana—Comparison with Scottish Highlands—Gneisses, schists, and granite—Dykes—Roraima Series—Strange peaks—The Caribbean Series—“All that glitters is not gold”—La Galera—Segovia Group—Natural castles—Capacho Limestone—The “Golden Hill”—Cerro de Oro Series—Formation of mountains—Early outlet of Orinoco—Cumaná Series—Shoals and islands—Llano gravels—Cubagua Beds—Igneous rocks—Earthquakes—Hot springs—A natural kettle—Coal—Iron—Gold—Copper—Lead—Petroleum and asphalt—Sulphur—Salt—Urao—Ornamental stones—Wealth in minerals. | [12] |

| CHAPTER III THE PLANTS AND ANIMALS OF VENEZUELA |

47 |

| The glamour of the South American forests—Hidden treasures—Temples of Nature—“A dim religious light”—Bejucales—Forest giants—Brazil nuts—Tonka-beans—Rubber—Quinine—Arctic and tropic forms—The Llanos—Tierra caliente—Natural hothouses—Colour and coolness Páramo plants—Monkeys—An old friend—Cannibalism—Vampires and bats—“Tigers” and “lions”—“Handsome is as handsome doesn’t”—Wild horses—Dolphins—Prickly mice—The “water-hog”—Sloths—Birds—Many-coloured varieties—Umbrella-bird—“Cock-of-the-rock”—Toucans—Cuckoos—Humming-birds—“Who are you?”—Oil-birds—Parrots and macaws—Eagles and vultures—A national disgrace—Game-birds—Snakes—Lizards—From the Orinoco to a city dinner—A cup-tie crowd—Ferocious fish—When is a mosquito not a mosquito?—Agricultural ants—Gigantic spiders—Ticks—A pugnacious crustacean—A rich field. | |

| CHAPTER IV VENEZUELA UNDER SPANISH RULE AND BEFORE |

61 |

| Pre-Columbian times—No great empire—Primitive Venezuelans—Picture rocks—Invasions—The Guatavitas and the legend of El Dorado—Amalivaca—An Inca prince?—Ancient roads—The discovery of Tierra firme, 1498—Alonso de Ojeda—The name “Venezuela”—A great geographical fraud—Discovery of the treasures of the west—Arrival of the conquistadores—The slave trade—Treacheries of the Cubagua colonists—Gonzalez de Ocampo—Las Casas—First cities of the New World—Settlement of Coro—The Welsers—Alfinger—Ingratitude of Charles V.—New Andalusia—Exploration of the Orinoco—Cruelties of Alfinger—Exploration of the Llanos—First Bishop of Venezuela—Destruction of New Cadiz—Faxardo and the Carácas—Cities of Western Venezuela—The rebellion of Aguirre—Foundation of Carácas—Pimentel moves his capital to the new city—Capture of Carácas by English buccaneers—Inaccuracies of Spanish historians—Explorations of Berrio in Guayana—Raleigh and El Dorado—Attempts to civilise the Indians—Missions—University of Carácas—Guipuzcoana Company—Revolution of Gual and España—Miranda—The last Captain-General—The Junta—Appeals to England—The Declaration of Independence. | [13] |

| CHAPTER V THE REPUBLIC, 1811-1911 |

84 |

| Local character of revolution—Declaration of a Constitution—Centralised government—Troubles of the young republic—The Church and the patriots—Miranda—Dictatorship and downfall—Drastic measures of Monteverde—Youth and parentage of Simon Bolivar—The guerra a muerte—Dictatorship of Bolivar—Monteverde murders four prisoners—The Mestizos—Massacre of Spaniards—Murmurings—Retirement of Bolivar—Royalist victories and reinforcements—Morillo’s barbarities—Return of Bolivar to Venezuela—Indecisive campaign—Renewed discontent—Bolivar withdraws to Haiti, but returns—Mariño’s insubordination—Massacre of Barcelona—Campaign in the Llanos—Arrival of the British Legion—Congress of Angostura—The march to Bogotá—The republic of great Colombia—Change of allegiance of the Mestizos—Armistice of Trujillo—Negotiations with Spain—Recommencement of hostilities—Battle of Carabobo—End of Spanish power in Venezuela—Position of Venezuela in Colombia—Separatist movement—Death of Bolivar—Páez first President of Venezuela—Vargas—Folly of Mariño—Progress of the country—Public honours to Bolivar—Recognition of republic by France and Spain—Commerce and prosperity of the country—Tyranny of Tadeo Monágas—Abolition of slavery—Revolution of Julian Castro—Capital temporarily removed to Valencia—Federalists and Centralists—Falcón—Convenio de Coche—Federal Constitution—Guzman Blanco—Development under his government—Revolution of Crespo—British Guiana boundary dispute—Cipriano Castro—The Matos revolution—Coup d’état of General Gomez—Centenary celebrations—Present prospects. | |

| CHAPTER VI MODERN VENEZUELA |

106 |

| Boundaries—Frontier with Brazil—Colombia—British Guiana—Internal subdivision—States and territories with their capitals—Density of population—Constitution—Departments of the Executive—Jefes Civiles—Legislature—Senators and deputies—Administration of justice—Laws[14] relating to foreigners—Marriage—Public health—Philanthropic institutions—Education—Coinage—Multiplicity of terms—Towns—Typical houses—Furniture—Hospitality—Food—Clothing—Army and navy—Insignia—Busto de Bolivar—The Press. | |

| CHAPTER VII THE ABORIGINES |

119 |

| The Goajiros—Lake dwellings—Appearance—Territory—Villages—Government—Burial customs—Religion—Medicine-men—The Caribs—A fine race—Cannibalism—Headless men of the Caura—The Amazons—Industries—Religion—Marriage customs—The aborigines of Guayana—Tavera-Acosta on languages—The Warraus—Appearance—Houses—Food—Clothing—Marriage customs—Birth—Death—Religion—Treatment of sick—The Banibas—Appearance—Customs—Religion—Celebration of puberty of girls—Marriage customs—The Arawaks—Religion—Early missions amongst Indians—Wanted, a twentieth-century apostle. | |

| CHAPTER VIII THE STATES OF THE “CENTRO”: DISTRITO FEDERAL, MIRANDA, ARAGUA, AND CARABOBO |

135 |

| La Guaira—Heat—Port-works—The Brighton of Venezuela—Sugar plantations—Streets and botiquins—Guarapo—La Guaira-Carácas Railway—A great engineering feat—Carácas—Climate—Population—Streets—Buildings—The Salón Elíptico—El Calvario—El Paraiso—“La India”—Water supply—Trams and telephones—Lighting—Industries—The Guaire valley—Coffee—Miranda—Ocumare del Tuy—Petare—Central Railway—Vegetable snow—Carenero Railway—Rio Chico—Los Teques—Great Venezuelan Railway—La Victoria—Sixteen-fold wheatfields—Maracay—Grazing lands—Cheese—President Gomez’s country house—Villa de Cura—An epitome of the State—Lake of Valencia—Cotton—Carabobo—Valencia—Cotton mills—Montalbán—Deserted vineyards—Wild rubber—Puerto Cabello Railway—The port—Meat syndicate—Club—Ocumare de la Costa—What is bad for man may be good for cocoa—Mineral resources. | [15] |

| CHAPTER IX ZULIA |

149 |

| The Lake of Coquibacoa in the sixteenth century and now—Wealth and importance of the State—Area and population—Waterways—Forests—Mineral wealth—Savannahs—Maracaibo—Harbour and dredging schemes—Cojoro—Wharves and warehouses of Maracaibo—Exports—Population—German colony—Buildings—Industries—Tramways—Coches—Lake steamers—Ancient craft—The comedy of the bar—Railways—Communication with Colombia—Altagracia—Santa Rita—A western Gibraltar—An eventful history—San Carlos de Zulia—Sinamaica—Vegetable milk—Timber—Copaiba—Fisheries—The “Maracaibo Lights.” | |

| CHAPTER X THE ANDINE STATES: TÁCHIRA, MÉRIDA, AND TRUJILLO |

157 |

| Access—Roads versus railways—Mineral wealth—“Maracaibo” coffee—Forests—San Cristobal—Water supply—Industries—Roads—Rubio—Táchira Petroleum Company—San Antonio—Lobatera—Colón—Interrupted communications—Pregonero—El Cobre—Old mines—La Grita—Seboruco copper—Mérida—The Bishop and the Bible—Eternal snows—Earthquakes—Electric light—Road schemes—Gold and silver—Lagunillas—Urao—Wayside hospitality—Puente Real—Primitive modes of transport—Las Laderas—The Mucuties valley—Tovar—Mucuchíes—The highest town in Venezuela—The páramos—Timotes—Trujillo—Valera—Water supply—La Ceiba Railway—Betijoque and Escuque—Boconó—Santa Ana—Carache—Unknown regions—Possibilities of the Andes. | |

| CHAPTER XI LARA, YARACUY, AND FALCÓN |

171 |

| The original Venezuela—Ancient cities—Communications—Barquisimeto—Fortified stores—Productions—The Bolivar Railway—Duaca—Aroa copper-mines—A precarious house-site—In the mine—Bats and cockroaches El Purgatorio—Blue and green stalactites—San Felipe—The Yaracuy valley—Nirgua—Yaritagua—Tocuyo—The “coach” to Barquisimeto—Quíbor—Minas—Carora—An[16] ill-advised scheme—Siquisique—Steamboats on the Tocuyo—San Luis—Coro—The first cathedral of South America—Goat-farms—Fibre—La Vela—Capatárida tobacco—Curaçao—A fragment of Holland—A mixed language—Trade—Sanitation—The islands. | |

| CHAPTER XII IN THE “ORIENTE.” NUEVA ESPARTA, SUCRE, PART OF MONÁGAS, AND THE DELTA TERRITORY |

181 |

| Restricted use of term “Oriente”—Margarita—Asunción—Porlamar and Pampatar—Macanao—A primitive population—The priests, the comet, and the people—Cubagua—Pearl fisheries—Coche—Cumaná—Las Casas—A diving feat—Petroleum and salt—Fruit—The Manzanares—Cumanacoa—In the hills—San Antonio and its church—The Guacharo cave—Humboldt—Virgin territory—Punceres—Oil-springs—The Bermudez asphalt lake—Carúpano—Ron blanco—Sulphur and gold—Rio Caribe—Peninsula of Paria—Cristobal Colón—An ambitious project—The Delta—The Golfo Triste—Pedernales—Asphalt and outlaws—In the caños—Tucupita—Barrancas—Imataca iron-mines—Canadian capital for Venezuela—Guayana Vieja. | |

| CHAPTER XIII THE LLANOS. MONÁGAS, ANZOÁTEGUI, GUÁRICO, COJEDES, PORTUGUESA, ZAMORA, AND APURE |

193 |

| The great plains—An ocean without water—“Bancos” and mesas—Drought and flood—A living floor—Streams which flow upwards—Heat—Cattle and horses—Imported butter—Methods of milking—Civil wars—Future prospects—A mean annual temperature of 90° F.—Barcelona—History—The massacre of the Casa Fuerte—Survivors—Guanta—Coal of Naricual—Aragua de Barcelona—Maturín—Low death rate—Caño Colorado—Bongos—Athletic boatmen—Casitas—Travelling on the Llanos—An hato—Areo—An ancient cotton press—The men of Urica—Churches and wayside shrines—A gruesome monument—Calabozo—Barbacoas—Ortiz—Zaraza and Camaguan—San Carlos—Barinas—Guanare—Past prosperity and future prospects. | [17] |

| CHAPTER XIV THE CITY AND STATE OF BOLIVAR |

211 |

| An enormous area—How to reach it—Ciudad Bolivar—Climate—San Felix—Falls of the Caroni—Trade of San Felix—Quality of “roads”—Upata—Guasipati—Balatá industry—Extravagant exploitation—Former importance—The goldfields—El Callao—The discovery—Callao Bis—Big dividends—The common pursuit—Venamo valley High freights—Poor quality of labour—Unsystematic working—Goldfields of Venezuela, Ltd.—Savannahs—Stock-farming—Sugar—Old settlements—An ancient bridge—Tumeremo and the balatá forests—Killing the goose that lays the golden eggs—The Caroni—An opportunity for a pioneer—Up the Orinoco—The “Gates of Hell”—The Caura—Rice and tonka-beans—“Lajas”—Rubber of the Nichare—Falls of Pará—André’s journeys—Mountains of the upper Caura—The Waiomgomos—Reticence regarding names—Ticks—Caicara—The Cuchivero—Savannahs and “Sarrapiales”—Sarsaparilla—Climate of the Orinoco valley. | |

| CHAPTER XV THE AMAZONAS TERRITORY |

223 |

| Area—General character—San Fernando de Atabapo—The upper Orinoco—Communication with outside world—Atures and Maipures rapids—Humboldt’s description—The Compañía Anónima de Navegacion Fluvial y Costanera—General Chalbaud—Railway projects—The Piaroas—Curare—Savannahs—Rubber—Brazil-nuts—Wild cocoa—Mineral wealth—Water power—Rubber prospectors—Method of working—Esmeralda—The place of flies—Mt. Duida—Gold possibilities—The Raudal de los Guaharibos—The limit of exploration—The Ventuari—An old Spanish road—A midnight massacre—Stock-raising lands—The Maquiritare—Trading with gold dust—The Casiquiare bifurcation—Life of the natives—Eau de Cologne in the wilds—The Guainia and Rio Negro—Maroa—Cucuhy—The Atabapo—Lack of population—Education—Colonisation—General prospects. | [18] |

| CHAPTER XVI THE DEVELOPMENT OF VENEZUELA |

235 |

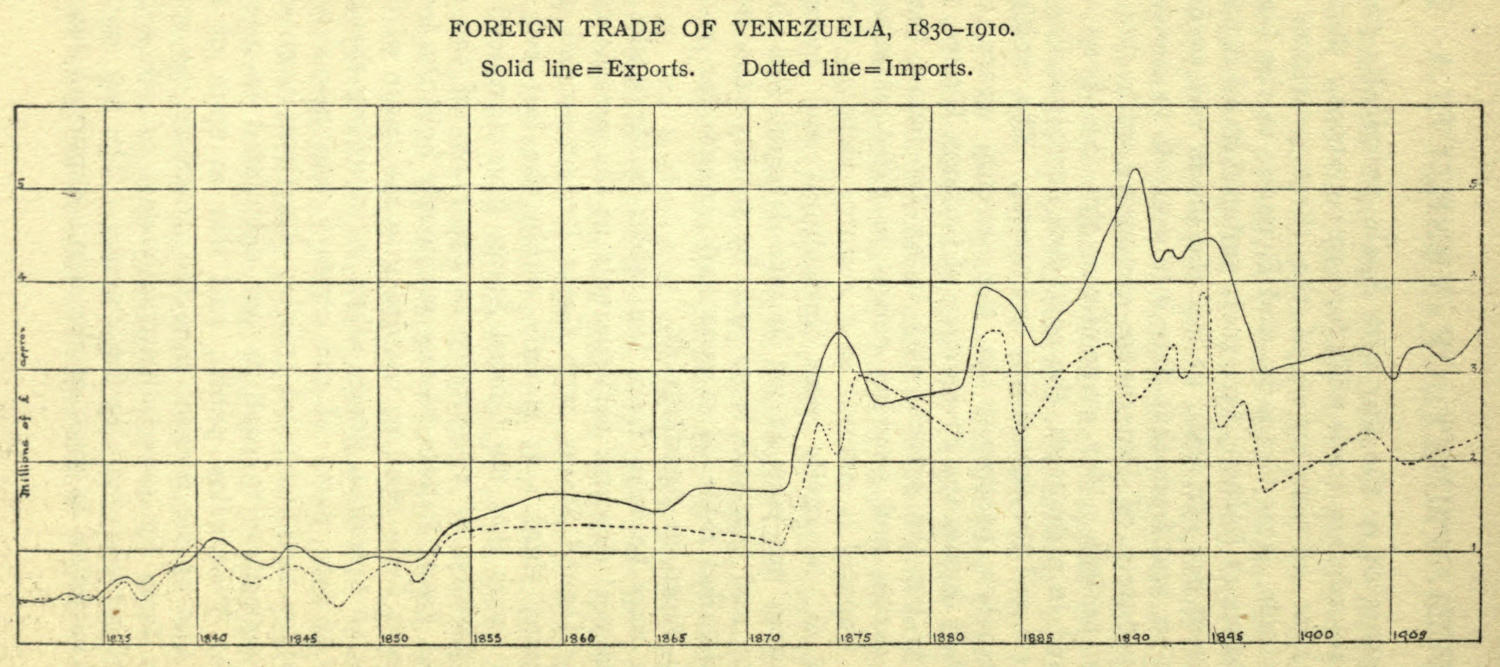

| Commerce—Early history—Pearls and gold—The Guipuzcoana Company—The republic—Years of struggle—Separation from Colombia—Guzman Blanco—British, American, and German trade—Opportunities—Currency—Banking—Banco de Venezuela—Banco Carácas—Banco de Maracaibo—National Debt—Natural resources—Large returns on capital—Coal—Iron—Salt—Asphalt and petroleum—Sulphur—Copper—Gold—The Llanos—Stock-raising—Possibilities of the industry—The Venezuelan Meat Products Syndicate—Agriculture—Coffee—Cocoa—Sugar—Tobacco—Cotton—Rubber—Tonka-beans, balatá, sernambi and copaiba—Fisheries—Pearls—Industries—Chocolate—Cotton-mills—Tanning—Matches, glass, and paper—Cigarettes and beer—Arts and sciences—Academy of History—Universities—Surveys. | |

| CHAPTER XVII COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSPORT |

252 |

| Lack of adequate means—Postal service—A small but growing system—Methods of carriage—Unusual uses of mailbags—Telegraphs—Telephones—Railways—Bolivar Railway—Later lines—Tramways—Abundant water-power—“Roads”—Carreteras—Bridle-paths—P.W.D.—Waterways—Less than they seem—Importance—The Orinoco—Ports—Shipping—Steamship lines. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII THE FUTURE OF VENEZUELA |

261 |

| A great opportunity—The Panama Canal—The Llanos—Petroleum-fields—Liquid fuel—Position of Venezuela—Guayana—Possibilities—Colonisation—Government—The military-political class—The disgrace of labour—Better conditions—Vargas—The “Matos” revolution—General Gomez—Hopes to be realised—Honesty and justice—Development—Roads—Railways—Education—Consular service—Great Britain’s trade with Venezuela—A poor third—British capital—The people’s responsibility—An opportunity. | [19] |

| APPENDICES | |

| APPENDIX A | 269 |

| Population of States and districts under the Constitution of 1909 according to the census of 1891 | |

| APPENDIX B | 274 |

| Imports (by classes)—Imports (by countries)—Exports (by products)—Imports (classes and countries)—Exports (by products and ports) | |

| APPENDIX C | 281 |

| Population, altitude, mean annual temperature and death rate of principal Venezuelan cities—Heights of principal mountains | |

| APPENDIX D | 283 |

| Government finance—Revenue—Expenditure | |

| APPENDIX E | 285 |

| The National Debt of Venezuela—Internal debt—Foreign debt | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 287 |

| General Works—Geographical—Geological—Botanical and Zoological—Historical—Ethnological—Carácas and the “Centro”—Zulia—The Andes, Falcón, &c.—The “Oriente”—The Llanos—Bolivar City and State—The Territorio Amazonas—Resources, commercial development, communications, &c. | |

| INDEX | 314 |

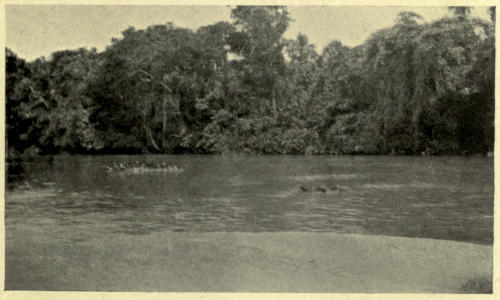

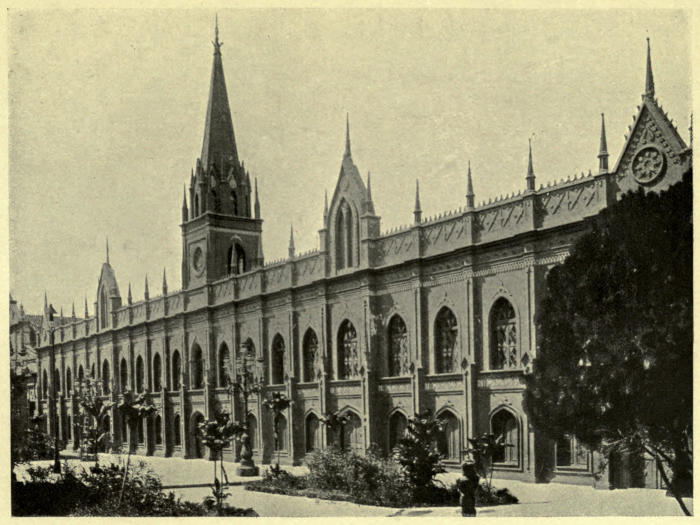

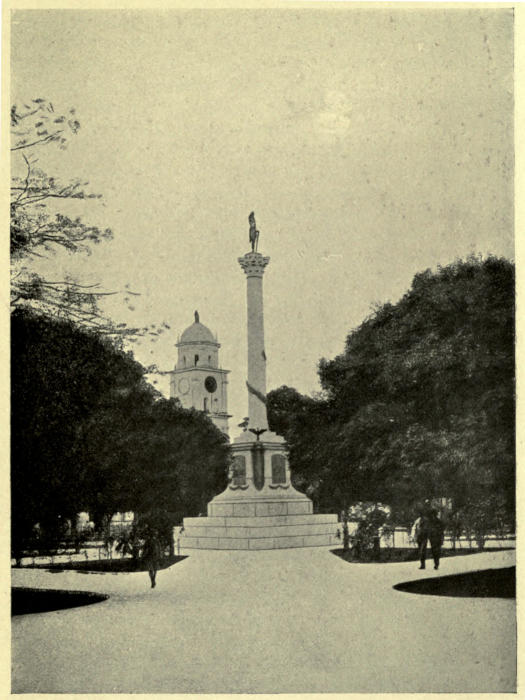

| CATHEDRAL: CARÁCAS | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

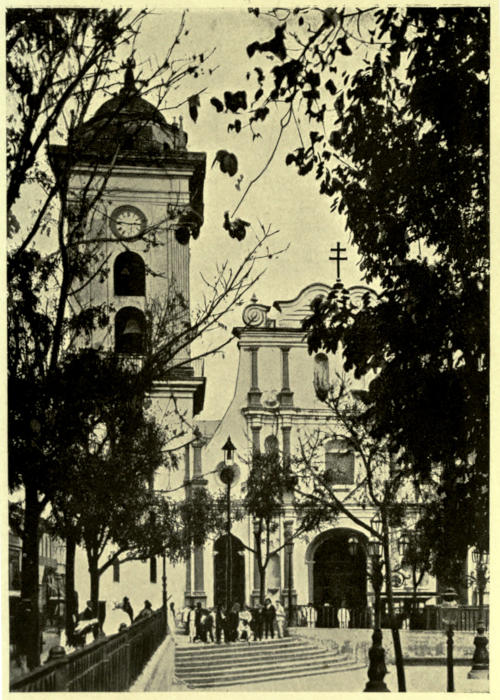

| PENINSULA OF PARIA FROM TRINIDAD | 28 |

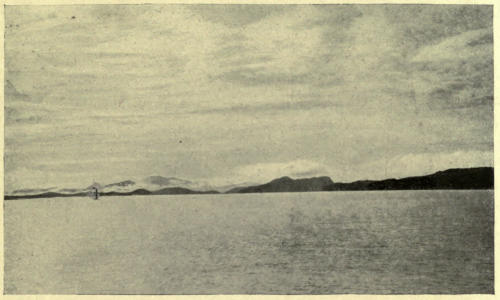

| IN THE DELTA | 28 |

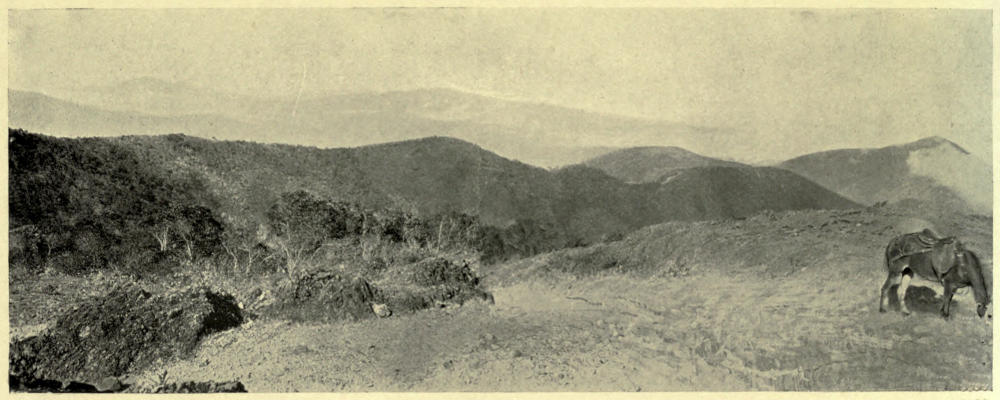

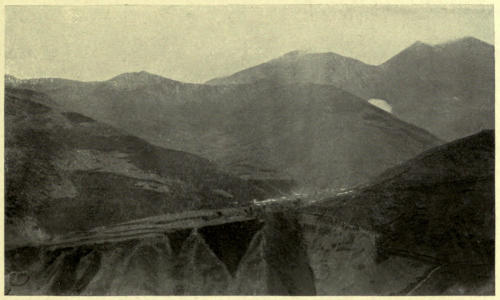

| PANORAMA OF THE ANDES FROM NORTH OF CARACHE | 36 |

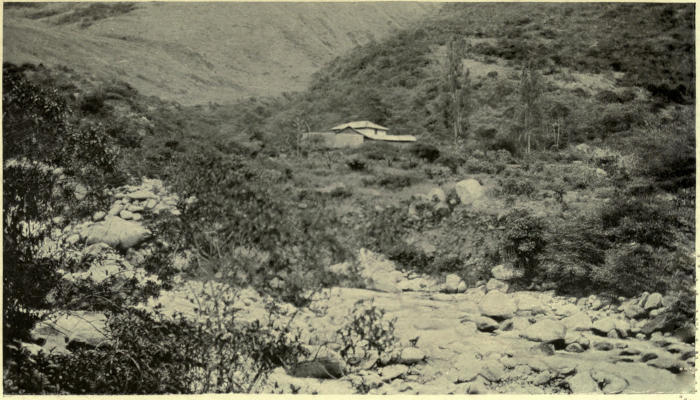

| IN THE UPPER TEMPERATE ZONE: THE CHAMA VALLEY | 50 |

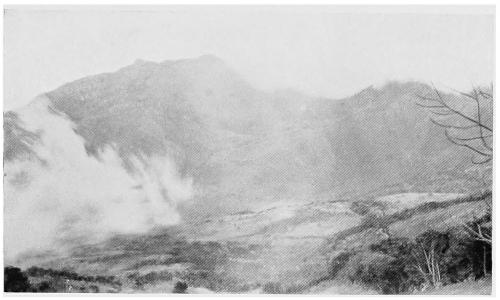

| CLOUD DRIFTS IN THE ANDES | 58 |

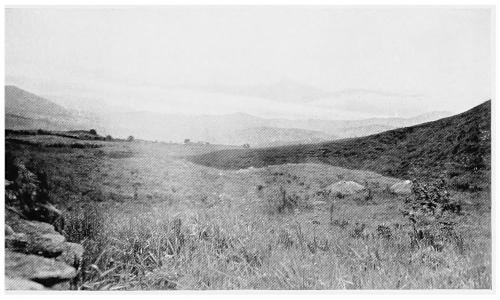

| TORBES VALLEY AND THE COLOMBIAN HILLS | 58 |

| THE CHAMA VALLEY ABOVE MÉRIDA | 68 |

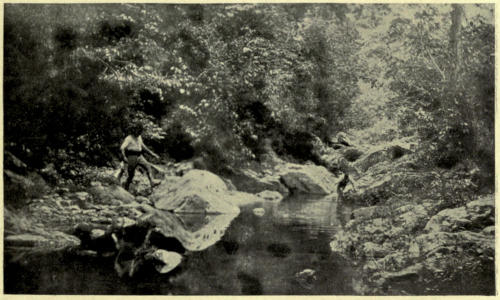

| MOUNTAIN STREAM NEAR CUMANACOA AND CUMANÁ | 68 |

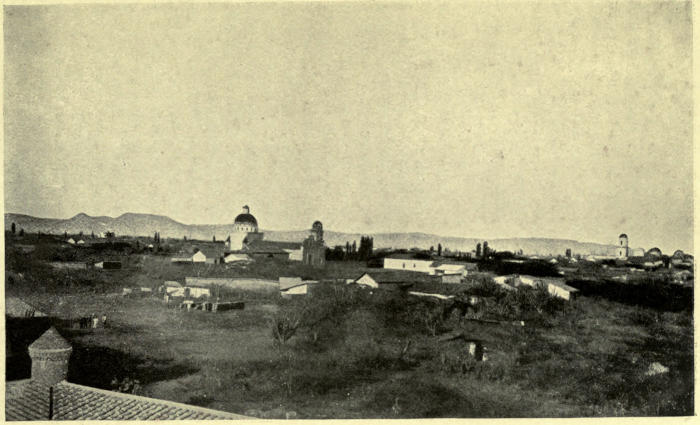

| BARQUISIMETO | 78 |

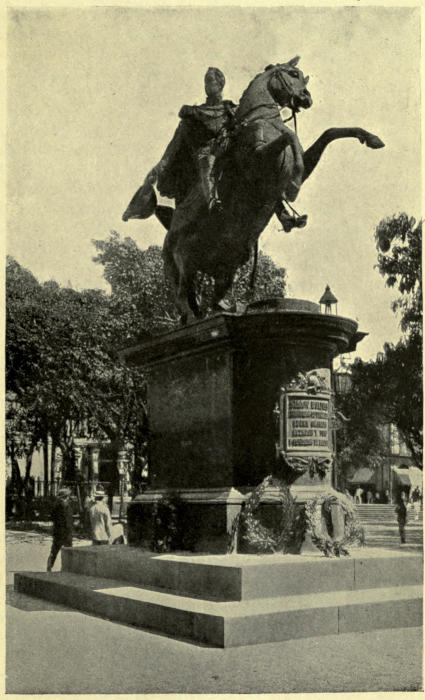

| STATUE IN PLAZA BOLIVAR: CARÁCAS | 88 |

| THE UNIVERSITY: CARÁCAS | 98 |

| THE FEDERAL PALACE: CARÁCAS | 108[22] |

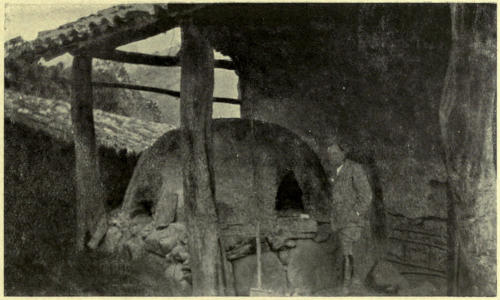

| OVEN: LA RAYA | 116 |

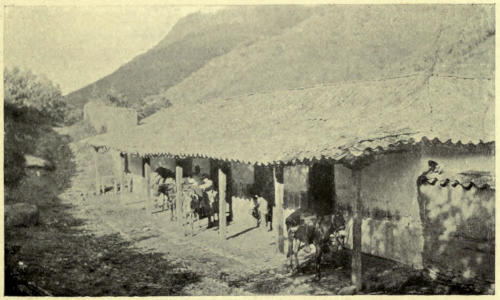

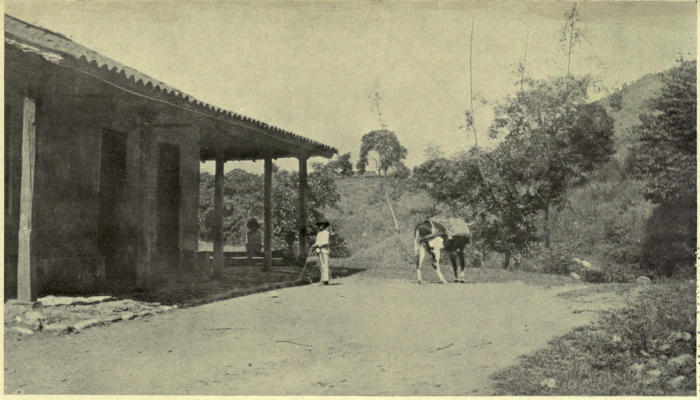

| AN ANDINE POSADA: LA RAYA | 116 |

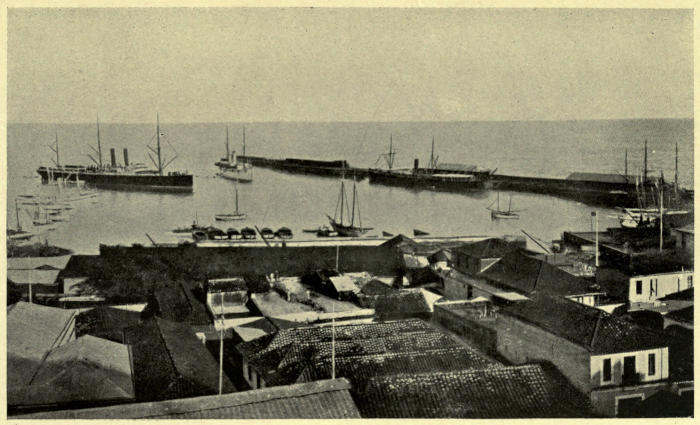

| LA GUAIRA HARBOUR | 128 |

| PLAZA BOLIVAR: VALENCIA | 138 |

| MARACAIBO BAY | 148 |

| SAN TIMOTEO: LAKE OF MARACAIBO | 148 |

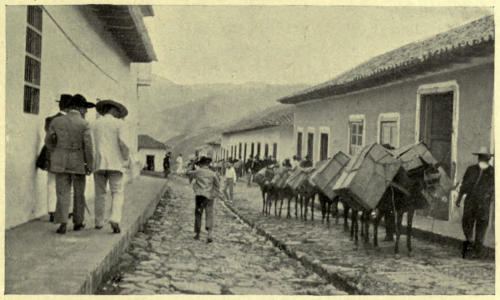

| A STREET IN LA GRITA | 158 |

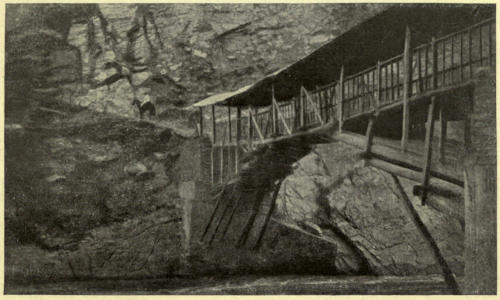

| PUENTE REAL: GORGE OF THE CHAMA | 158 |

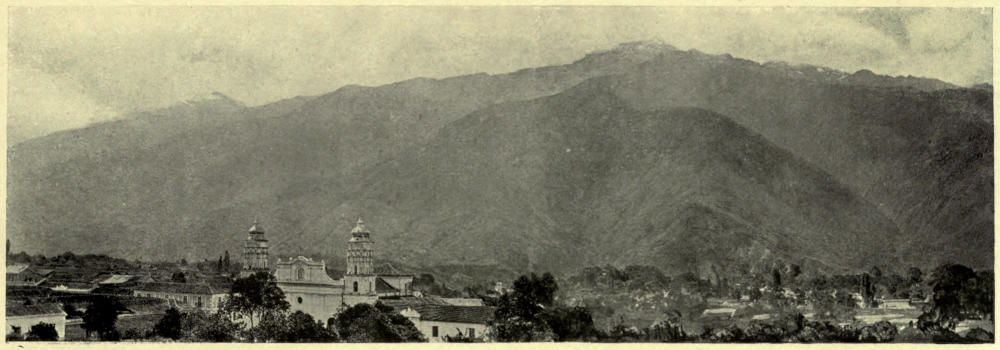

| THE SIERRA NEVADA AND CATHEDRAL OF MÉRIDA | 168 |

| WILLEMSTAD: CURAÇAO | 178 |

| THE HARBOUR: WILLEMSTAD | 178 |

| PUERTO CRISTOBAL COLÓN | 188 |

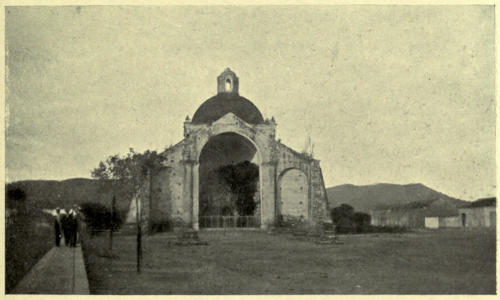

| RUINED CHURCH: BARCELONA | 198 |

| CASA FUERTE: BARCELONA | 198 |

| MESA OF ESNOJAQUE: TRUJILLO | 208 |

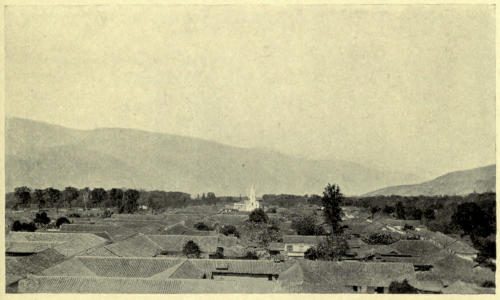

| MÉRIDA: LOOKING SOUTH FROM UNIVERSITY | 208 |

| CARRYING TILES ON OX-BACK: NEAR TOVAR | 218[23] |

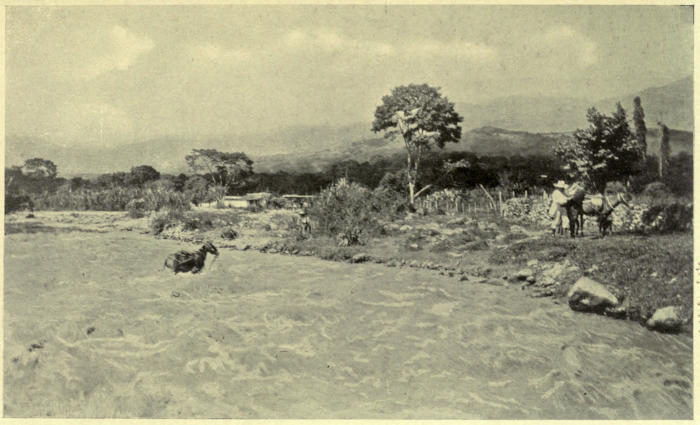

| CROSSING THE TORBES IN FLOOD | 228 |

| THE “PITCH” LAKE: TRINIDAD | 244 |

| COUNTRY COACH: BARQUISIMETO | 256 |

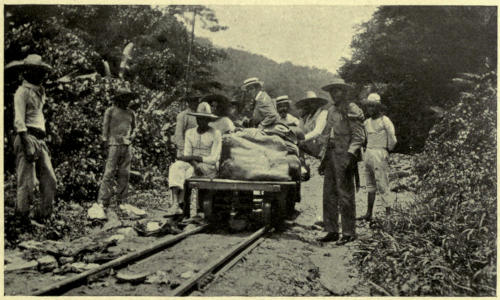

| ON THE BOLIVAR RAILWAY | 256 |

The frontispiece and the illustrations facing pages 78, 88, 98, 108, 128, 138 are taken from “Venezuela,” by N. Veloz-Goiticoa, by permission of the Bureau of South American Republics, Washington, U.S.A.

Situation—Area—Population—Main physical divisions—The Guayana Highlands—Mountains, rivers, and forests—The Llanos—Selvas—Mesas—Rivers and cienagas—The Delta—Caños—The Caribbean Hills—Serrania Costanera—Serrania Interior—Rivers—Segovia Highlands—Drainage—Vegetation—The Andes—Portuguese chain—Cordillera of Mérida—The Sierra Nevada—Mountain torrents—Vegetation—Páramos—The Coastal Plain—Lake of Maracaibo—Coro and Paraguana Lowlands—Climate—“White-water” and “black-water” rivers—Seasons—Tierra caliente, templada, and fria—Temperature and seasons—“St. John’s little summer”—Health.

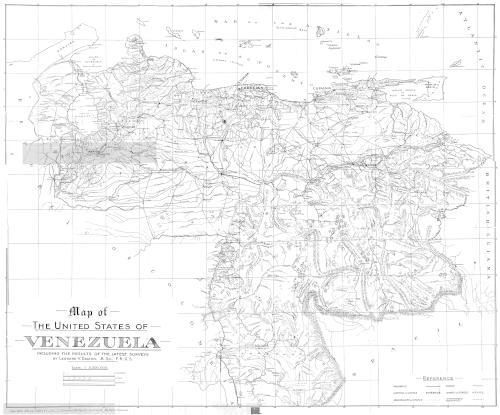

If we take a map of South America on which the political boundaries are clearly shown, Venezuela will be observed as a wedge of territory immediately to the east of the most northerly point of the continent, separating Colombia from our colony of British Guiana.

The United States of Venezuela, as this republic is officially called, lie wholly within the tropical zone, between latitude 0° 45´ N. and 12° 26´ N. and longitude 59° 35´ W. and 73° 20´ W. (from Greenwich). The area within these limits is some 1,020,400 square kilometres, or 394,000 square miles, according to the Statistical Year Book for 1908, published in Carácas[26] in 1910. The total population, according to the same authority, is 2,664,241, these being the figures of the last census, that of 1891.

Turning to our map once more, it will be seen that the wedge is not a regular one, but suggests rather the lower half of a human head, with the Lower Orinoco as the line of the jaw. The features are easily observed to separate the territory of the republic into four main divisions: (1) the Guayana Highlands, including all the region corresponding to the part of the head below the jaw-line, i.e., south and east of the Orinoco; (2) the great central area of plains or Llanos, bounded on the north and west by (3) the north-eastern branch of the great Andine chain, and in the north-west of the country (4) a smaller low-lying region round the Lake of Maracaibo. Each of these divisions includes somewhat varying types of land surface, but has its main features of uniform character.

As already defined, the Guayana Highlands include the whole of that vast, more or less unexplored, tract of Venezuela lying on the right bank of the Orinoco and round the head-waters of that river. The area is primarily one huge elevated plateau about 1,000 feet or more above the sea, and from this rise a few principal mountain ranges, with some peaks over 8,000 feet high, while smaller hills and chains link up the larger systems. The highest ground is found on the Brazilian frontier, beginning at Mount Roraima (8,500 feet), where the three boundaries of Venezuela, British Guiana, and Brazil meet, and extends thence in the Sierras Pacaraima and Parima westward and southward to the head-waters of the Orinoco. From Roraima the Orinoco-Cuyuni watershed extends northward within Venezuela, along the Sierras Rincote and Usupamo and the Highlands of Puedpa, to the Sierra Piacoa, and thence south-east along the[27] Sierra Imataca to the British limits again. The Sierra Maigualida forms the watershed between the Caura and the Ventuari.

The whole area, which amounts to some 204,600 square miles, is well watered by the upper Orinoco and the Ventuari, with the other great tributaries, the Cuchivero, Caura, Aro, Caroni, and their affluents. Large as these rivers are, they are so broken by rapids that travel along them is only possible for much of their length in small portable craft, and even then the passage is fraught with danger. Save for the districts in the immediate neighbourhood of the Orinoco, and scattered areas elsewhere, the whole region is thickly covered with forests of valuable timber, containing rubber, tonka-beans, brazil-nuts, copaiba, and all the varied natural produce of the South American tropics.

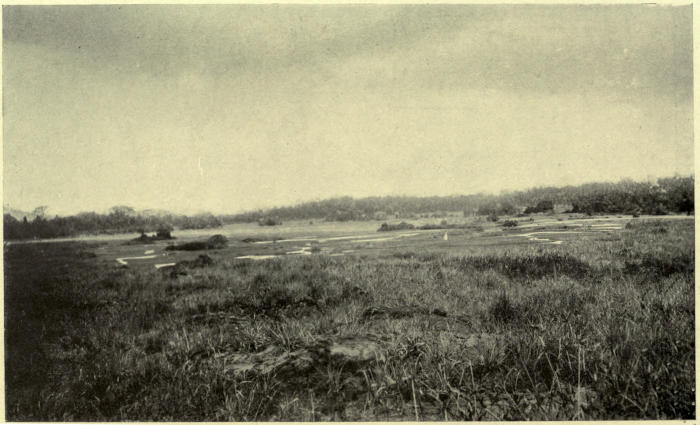

The great plains or Llanos of the Orinoco extend from the banks of the Meta in a broad arc parallel to the course of the Orinoco along its left bank. Westward they are bounded by the Cordillera of Mérida, and northward by the Cordillera of Carácas and the hills of Sucre, but between these ranges, at Barcelona, they virtually reach the sea for a short distance. To the east they merge into the low-lying tract of the Orinoco Delta. The total area of the Llanos proper is in the neighbourhood of 108,300 square miles, so that we have in these two thinly populated tracts about 80 per cent. of the territory of the republic.

Vast areas of the Llanos remain, for all practical purposes, still unexplored, and their general character can only be inferred from that of the regions bordering on the “roads.” The typical areas are wide grass plains, often stretching to the horizon on all sides without a break, but generally interrupted by little groups of palms and small trees, especially near the banks of the rivers. At some four or five points[28] near the northern edge there are great forests or selvas, relics possibly of an earlier, more extensive woodland.

The elevation of the Llanos ranges up to 650 feet, and more than this in the mesas of the central region, these being gravel-capped plateaux, of varying extent, beginning in the west with the Mesa de Santa Clara, northward of Caicara, and extending thence in a continuous series eastward and northward to form the watershed between the Orinoco and the Unare-Aragua basin, which drains into the Caribbean Sea west of Barcelona. The lowest part of the Llanos is situated westward of this chain of tablelands, in the valley of the Portuguesa, the lower part of which has large tracts less than 300 feet above sea-level. East of the Mesa de Guanipa the ground falls comparatively rapidly to the Delta.

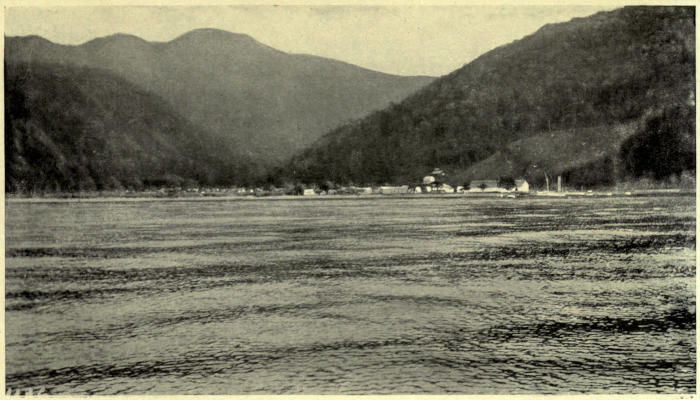

PENINSULA OF PARIA FROM TRINIDAD.

IN THE DELTA.

While severe drought is experienced over much of the Llano region in summer, the heavy rains, particularly in the western districts, produce floods over the low-lying plains, the mesas being dry at all times. The whole area is traversed by numerous streams and rivers, which rise either on the southern slopes of the Cordillera or in the mesas. North of the Meta, in addition to the large number of smaller streams which here and there broaden out into marshy lakes or cienagas, we have the navigable rivers Arauca (the main waterway to eastern Colombia) and Apure, flowing from the Andes to the Orinoco in an easterly direction. The Apure receives many tributaries on its left bank from the Venezuelan Andes, most important of which are the Portuguesa, rising in the plains of the same name south of Barquisimeto and joining the Apure at San Fernando, and the Guárico, whose mouth is east of the same town, flowing from south of Carácas through the State to which it gives its name, and receiving from the east the waters of the Orituco, whose source is less than thirty miles[29] from the coast in longitude 66°. Of the Orinoco tributaries from the north beyond the Apure the most important is the Manapire, all the streams east of this rising in the mesas and having but short courses. The greater part of the eastern Llanos drains northward by the Unare and Aragua into the Caribbean Sea. A few large rivers rise on the east of the mesas, but flow for short distances only through the plains, emptying, not into the Orinoco itself but the caños of the Delta. This last-mentioned region of inundated forest, savannah and mangrove swamp, occupies about 11,500 square miles, bringing the total area of the central plains up to 119,800 square miles.

The third great tract, the north-eastern spur of the Andes, divides itself naturally into three parts—the Caribbean Hills, along the shores of the sea of the same name; the Segovia Highlands, linking the former to the higher mountains of western Venezuela; and the Cordillera of Mérida, or the Venezuelan Andes. The total area occupied by these mountain and hill tracts is about 41,800 square miles.

The Caribbean Hills give to the Venezuelan coast its splendid and almost unique aspect, for, save for the interruption near Barcelona, the range extends without much decrease in average height from west of longitude 68° to the east end of the peninsula of Paria, less than 62° west of Greenwich. Two main lines of elevation are plainly discernible in the Carácas region, known as the Serrania Costanera and the Serrania Interior; they continue throughout the range, but are less distinct in the Cumaná Hills. The greatest elevation of the outer line is reached near Carácas itself, a considerable area west of the city rising to over 6,500 feet, while to the east are the famous peaks of La Silla (de Carácas) and Naiguatá (8,620 feet and 9,100 feet respectively). In the inner range the greatest elevation is round Mount Turimquiri, south of Cumaná; the eastern[30] portion of the coast range, in the peninsulas of Araya and Paria, does not rise above 3,200 feet. On the northern side the complex is drained only by mountain torrents falling rapidly throughout their short courses to the sea, while on the south are the head-waters of the Orinoco tributaries. Between the two ranges, however, we have longitudinal valleys with rivers of more or less importance—the Aragua, flowing westwards from Carácas into the lake of Valencia or Tacarigua, which overflows into the Paito, a tributary of the Portuguesa; and the Tuy, with its affluent the Guaire, flowing eastwards to the sea south of Cape Codera. In the Cumaná Hills we have the Manzanares and other smaller streams emptying their waters into the Gulf of Cariaco, and on the east the Lake of Putucual, though small, is similar in situation to that of Valencia, and its overflow forms the River San Juan, which empties into the Gulf of Paria, forming virtually part of the Orinoco drainage. The lower slopes of all these ranges, and the valleys, are clothed with rich forests, excepting the dry, barren coasts near Carácas, while the heights are bare, save for grass and a few small temperate trees.

Between the western extremity of the Caribbean Hills and the northern spurs of the Venezuelan Andes there is an elevated region, which, though subject to variations of level, possesses the main features of a tableland, and this type of surface extends in a broad belt northward through the States of Lara and Falcón. Their main extent is in the State of Lara, whose capital, Barquisimeto, had as its original name, before any territorial limits were defined round it, Nueva Segovia; it seems appropriate, therefore, to distinguish this area as the Segovia Highlands.

The level of most of the area so designated ranges from 1,500 to 3,500 feet, but the plateau type is best developed in the Barquisimeto region, the dry, barren plains of which, with their cactus[31] vegetation, suggest by their general features the dry bed of an ancient lake, in whose waters the small scattered hills formed islands, while the Andine spurs to the south and the Sierra de Aroa and similar mountain masses north of Barquisimeto, constituted its limits. Beyond the latter, and north of the Tocuyo River, while the larger part of the area maintains its more or less uniform elevation, three well-defined ranges rise from the plateau, in the Cordilleras of Baragua, Agua Negra, and San Luis; the last named is the largest, and extends for 110 miles parallel to the Coro coast, overlooking the Gulf of Venezuela. Practically the whole of this region is drained by the Tocuyo and its tributaries, the other rivers rising merely on its outer edges and falling direct to the sea; from this generalisation should be excepted a small area round Barquisimeto, in the catchment area of the river of the same name, which contributes its waters to the volume of the Portuguesa, and so enters the Orinoco. The Tocuyo, whose principal affluents are the Carora and the Baragua on its left bank, rises in the Andes and flows for some 330 miles in a northerly direction, changing to easterly in the lower river, before it empties itself into the Caribbean. While the southern part of this area is barren, all the lower slopes of the northern hills are forest clad and fertile, with llanos in the Carora Valley and grass-covered summits above.

To the south we have the Venezuelan Andes, stretching for some 300 miles south-westward to the Colombian frontier, and forming the highest land in the whole country.

There are two main divisions of this mountain group, the Portuguesa chain south of Barquisimeto, and the Cordillera of Mérida constituting the more important and higher part. The Portuguesa chain reaches its greatest elevation (13,100 feet) in the[32] south near the sources of the Tocuyo, the northern portion rising only to about 5,000 feet. A slight break in the mass is caused by the valley of the Boconó, beyond which the Cordillera of Mérida begins with peaks of nearly 13,000 feet on the north, rising to their maximum in the centre, where the summits of the Sierra Nevada of Mérida have an elevation of about 16,400 feet, and the top of the highest of all, La Columna, is 16,423 feet above sea-level. Southwards the elevations decrease again, until on the borders of Colombia the watershed is less than 5,000 feet above the sea. The streams of this chain, with its steep outer flanks so characteristic of the Andes, naturally belong for the most part to the catchment area of the Orinoco or the Maracaibo Lake, but there is a succession of longitudinal valleys within the chain which may be considered as pertaining more particularly to the Andes. The chief of these rivers are the Motatán, which, rising north of Mérida, flows northwards through Trujillo to the Lake of Maracaibo; the Chama, whose sources are in the same snows that supply the Motatán, though the stream flows southward past Mérida, bending then sharply northward to reach the south shore of the lake opposite the mouth of the Motatán; and the Torbes, flowing south-westward by San Cristobal, and turning there to the east to fall into the Uribante, a tributary of the Apure. Every type of vegetation occurs within this Andine tract, varying according to the geology of the ground and its elevation. At some points there are fertile valleys with tropical flora, others with temperate cereals; sometimes bare mountain slopes and hot gorges supporting only cactus and acacia, and little of these; sometimes grass-clad slopes and summits, with the peculiar heather-like and resinous plants of the “páramos,” and, lastly, the eternal snows of the peaks of the Sierra Nevada.

North of the mountain region of Venezuela lies what may be considered as the coastal plain, including the alluvial area of the Lake of Maracaibo, the Coro and Paraguana lowlands, and such few tracts of flat ground as may be found along the coast, with the numerous islands in the Caribbean which belong to Venezuela. The area of this division may be estimated as about 27,800 square miles. The lake has many points of similarity to the Delta, both in hydrography and general character. The southern part has innumerable rivers comparable to the caños, with open lagoons and swamps, bordered by dense forests more or less inundated in the rains. On the east and west shores to the north there are stretches of higher ground between the swamps, and frequent grass plains like the Llanos; the western side is bounded by the Sierra de Perija, forming the frontier of Colombia. Chief of the rivers traversing these plains are the Motatán and Chama, already mentioned as rising in the Andes, the Escalante, and the Catatumbo; the mouths of all are of a deltaic character, and all are navigable to a greater or lesser extent. The largest and most important is the Catatumbo, which, with its great tributary, the Zulia, rises in Colombia.

The Coro and Paraguana lowlands form a stretch of open, sandy, more or less barren and low hills, extending from the neighbourhood of the port of Maracaibo along the coast to Coro, and into the Paraguana peninsula; with them may be grouped the islands, which are similar in character, except Margarita, whose mountains resemble those of the Caribbean chain, though the open, cactus-covered lower ground is a repetition of the western coast (and Curaçao).

The climate of the 394,000 square miles naturally varies greatly according to latitude, elevation, and vegetation. The Guayana region, here also, stands[34] by itself, both from its southern position and comparatively uniform elevation, so that over a wide area the temperature and rainfall are more or less the same. Naturally in those parts of Guayana where mountain ridges rise above the general level of the plateau the temperature is lower than the average, but these must constitute a small part of the whole. There is a marked difference in the meteorological conditions in the various river-valleys of the Orinoco basin, where the “white-water”—i.e., the swiftly flowing but muddy streams, with rocky beds—are always accompanied by a clear sky overhead, and mosquitoes and crocodiles abound; on the “black water”—the deep and slow rivers—the sky is continually clouded, but the air is free from mosquitoes. The Orinoco represents the former type, the Rio Negro the latter. The rainy season in Guayana begins in April and lasts till November; the remaining four months are fairly dry.

The better known region of the north is generally considered as divided, qua climate, into three regions, in common with tropical South America generally—that is to say, the hot, temperate, and cold zones. The hot zone or Tierra caliente is generally considered as ranging from sea-level to an elevation of 1,915 feet, where the mean annual temperature varies from 74° to 91° Fahr. The intermediate or temperate zone, the Tierra templada, lies between 1,915 and 7,030 feet above sea-level, and within those limits the mean annual temperature may fall as low as, or even lower than, 60° Fahr. The Tierra fria, or cold zone, including the highest peak of Venezuela, 16,423 feet, has mean annual temperatures ranging from 60° to below zero.

The Tierra caliente includes (in addition to the greater part of Guayana) the Llanos, the coastal plains, and the region of the Lake of Maracaibo, the lower slopes and part of the central valleys of the[35] mountains, part of the Segovia Highlands, and the Caribbean islands. The higher ground naturally has a climate varying with elevation, but the typical hot country, the Llanos are the warmest, the islands the coolest. On the Llanos the central, northern, and eastern regions are cooler than the southern and western, the highest mean annual temperature being recorded in San Fernando de Apure. Over this area the rainfall is heavy, and the wet season lasts from April to November. Maracaibo has the highest temperature of the cities of the coastal region, and, while the rains in the greater part of the area last through the same months as in Guayana and the Llanos, the area round the lake is comparatively free from rain until August and September, when the heaviest falls are recorded. The Segovia highlands and the islands alike have a lower mean temperature and rainfall than the remainder of the zone, the position of the one region, behind the coastal range which has precipitated the moisture of the easterly winds, being paralleled by the distance of the islands from these heights in the opposite direction.

The Tierra templada includes the greater part of the inhabited region of the hills, in which the climate necessarily varies greatly according to situation, the bottoms of some of the Andine valleys within the zone being more oppressive than parts of the low countries.

In the eastern part of the Caribbean Hills the rains last during the same months as in the Llanos, but in the Andes, particularly to the south, the seasons vary, and it is generally considered that there are two rainy seasons; the first light rains from April to June, separated by “St. John’s little summer” (El Veranito de San Juan) from the later heavy rains which last from August to November; this arrangement applies rather to the eastern side of the watershed, the western side having an increasing similarity[36] in seasons to the Llanos as one descends towards those plains.

Only the higher peaks and ridges of the Caribbean Hills are included in the Tierra fria, but between Tocuyo and the Colombian frontier the greater part of the area is situated above 7,030 feet. The prevalent strong winds and the sparse vegetation of the upper areas render them too unattractive to have become extensively colonised, but the products of the temperate zone grow readily in the lower parts below the timber-limit. Only the peaks of the Sierra Nevada are permanently snow-covered, the line having, it is said, retreated upwards of late years. The snow is apparently more abundant in the hotter months of the year, when the clouds which are dropping rain on the plain hide the peaks for many hours of the day, and then, lifting suddenly, show them white with snow far below the normal point, which is about 14,700 feet above sea-level. A very short period of exposure to the sun’s rays restores the mountains to their usual aspect.

PANORAMA OF THE ANDES FROM NORTH OF CARACHE.

From the point of view of health, Venezuela must be looked upon as holding a good record for a country in its latitude, where malaria is to be expected to prevail. The death-rate for the whole republic in 1908 is given in the Anuario Estadístico as 25·1 per 1,000, and of the 56,903 deaths in that year, about one-third were infants under four years of age, while malaria (paludismo) accounts for 8,239. Tuberculosis and gastric and nervous diseases are the most prevalent causes of death. Yellow fever, once so prevalent, is now rare, thanks to improved sanitary conditions. The Delta region and the lower parts of the Guayana valley are the most unhealthy from a general point of view, while the death-rate of the cities shows that the Llanos are by far the healthiest district, with the Andes next, followed by the Caribbean Hills. In some of the[37] low-lying coast towns, where mangrove swamps abound in the neighbourhood, the death-rate is high, but as a general rule the northern coast, with its dry atmosphere and sea breezes, while hot, appears to be markedly healthy.

Ancient land of Guayana—Comparison with Scottish Highlands—Gneisses, schists, and granite—Dykes—Roraima Series—Strange peaks—The Caribbean Series—“All that glitters is not gold”—La Galera—Segovia Group—Natural castles—Capacho Limestone—The Golden Hill—Cerro de Oro Series—Formation of mountains—Early outlet of Orinoco—Cumaná Series—Shoals and islands—Llano gravels—Cubagua beds—Igneous rocks—Earthquakes—Hot springs—A natural kettle—Coal—Iron—Gold—Copper—Lead—Petroleum and asphalt—Sulphur—Salt—Urao—Ornamental stones—Wealth in minerals.

A certain interest, often described as spurious but none the less common, generally attaches to the ancient for the sake of its antiquity, and we may, hope, therefore, that the story of the rocks of Venezuela will appeal even to non-geological readers.

The Guayana Highlands appear not only to be formed of the oldest rocks in Venezuela, but from such scanty study as has been made of parts of the region, to represent one of the most ancient land-surfaces in the world. Different as they are in appearance, they offer many analogies with the north-western highlands of Scotland from a geological point of view; and here it is known that the processes of building-up and breaking-down have preserved for us glimpses of a land which stood, as it now stands, long ages ago when living organisms, if there were any, had not reached such a stage in their development[39] as to leave their traces in the deposits of the time.

The great elevated platform from which rise the peaks and mountain chains of Guayana appears everywhere to be composed of similar rocks, gneisses, hornblende schists, and granites, all containing evidence of great antiquity in geological time. This Guayana complex, as it may be called, has been considered by geologists as more or less equivalent in age to the Lewisian gneiss of Scotland, and therefore one of the oldest members of the Archæan system.

What may have been the original condition of the rocks it is impossible now to say, but one of the agencies which has brought them to their present form has left its traces in the form of “dykes” of quartz-porphyries and felsite, which were once forced in a molten condition into crevices and joints of the then less solid deposits.

After the cooling of these intrusions and wearing down of the whole mass by atmospheric influences, the movements of the earth’s crust produced a shallow sea or series of lakes over what is now Guayana, and in these waters a series of beds of red and white sandstones, coarse conglomerate, and red shale were laid down to a thickness of about 2,000 feet. Later the area was again elevated into dry land, the sediments were consolidated, and again veins or dykes of basalt, dolerite, and similar dark, heavy rocks in a molten condition forced themselves into the fractures of gneisses and sandstones alike. These sandstones are here named the Roraima Series, from their occurrence in that mountain, and they now remain as isolated peaks or chains of hills all over Guayana, which, since that far-off period when the series was first consolidated, seems to have been always dry land.

The points at which the Roraima beds have been[40] left as upstanding masses of horizontally stratified material, in place of being completely denuded from the ancient foundation of gneiss, appear to have been determined in many cases by the presence of exceptional accumulations of molten igneous rock, which has hardened and remained as a cap to protect the softer sandstones below from the effects of atmospheric weathering. Where this has been the case the strange vertical-sided, flat-topped mountains of Guayana are the result.

While in all probability northern Venezuela has no rocks quite so ancient as those of Guayana, the geological history of this part of the country has been much more eventful, and the number of earthquakes suggest that even yet the form of the earth’s crust in this region is undergoing comparatively violent changes.

As is commonly the case, to find the oldest rocks we have to search the hills, and because the masses of gneiss, silvery mica-schist, marble, and so on, which form the highest parts of much of the mountain region, were first studied by Mr. G. P. Wall in the Caribbean Hills in 1860, he named the whole the Caribbean Series. The beds which make up the series may have been deposited at a period corresponding to that of the ancient Silurian rocks of Wales, but it seems very possible that they are older in some parts than in others. They form the central region of the Venezuelan Andes, where there is a core of granite which probably cooled at a date subsequent to the consolidation of the gneiss and schists. The silvery mica-flakes of the latter are very often mistaken by the inhabitants for gold or silver ores, and the author had more than one pretty but valueless specimen offered for sale, with its locality to be revealed as a secret of great worth! The same rocks extend all the way along the coastal range across the Boca del Draco into Trinidad, and[41] northward in Margarita the mountains are formed of similar gneisses and schists. In the Llanos north of El Baúl there is a peculiar elevated plateau known as La Galera, from which rise many hills of gneiss and granitic rock, but these may perhaps be an outlying island of the Guayana complex.

After the deposits of the Caribbean Series had been consolidated and elevated into dry land, but before they had been thrown into high mountains such as they form to-day, perhaps at the same time that the granite of the Sierra Nevada of Mérida was being pushed up under them in a molten condition, the seas around were receiving deposits of quartz sand, mud, and lime, which were later consolidated to form a series of red and yellow sandstones, shales, slates, and black bituminous limestones, which now outcrop along the Sierras, and chiefly in the Segovia Highlands, suggesting for the whole the name Segovia Group. The animals which inhabited the seas of those times left their shells and remains in the rocks, and the forms (Ammonites, Inoceramus, &c.) which have been found by various travellers show that these deposits were formed at a period approximately corresponding to that of the lowest parts of our chalk or of the Cretaceous System generally.

Here and there throughout the mountains of northern Venezuela, the traveller is sure to be struck by the sight of great cliffs and castle-like masses of limestone rock, which add greatly to the effect of the scenery where they occur. From their position it is clear that these were originally parts of a more or less continuous accumulation of lime in a deep, still sea, after more turbulent waters had deposited the Segovia Group. The German traveller Dr. Sievers called this limestone the Capacho Limestone, from Capacho in Táchira. The fossils are similar to those of the period of the higher parts of the chalk.

After the deposition of the Capacho Limestone the earth’s crust, which had in this region remained tranquil for a considerable period, again underwent some changes, and in the new shallower sea thus formed sand and mud, with some lime, were alternately laid down. The resulting sandstones, shales, and limestones were named by Dr. Sievers the Cerro de Oro Series, from a hill formed of these rocks in Táchira, and called Cerro de Oro, or Golden Hill, because the very abundant iron pyrites in it were mistaken for the precious metal. Many fossils have been found in the group, and from these it seems that in Venezuela, instead of the break between Cretaceous and Tertiary which we have in England, there was a continuous series of deposits, so that at the base we have chalk fossils, and higher up Eocene forms, the general character of the animal life changing gradually from one to the other.

With the consolidation of the Cerro de Oro beds we have a new period of disturbance, in which the mountain chains of northern Venezuela began to be formed as we know them to-day, and the waters of the Orinoco began to flow into the Atlantic more or less by the present mouth of the river. Alongside the newly formed hills, or islands as they would then be, sandstones and shales were deposited to a considerable thickness. They are found outcropping now along the coast and under the Llanos, as well as round the Lake of Maracaibo. The first fossils from them were collected by Mr. G. P. Wall from Cumaná, and it seems fitting to distinguish the whole as the Cumaná Series.

After the deposition of the Cumaná Series, and the crust movements which led to the consolidation and folding of these rocks, the physical features of Venezuela must have been very much what they are to-day, save that many of the smaller islands and parts of the coast were still submerged as shoals,[43] whilst the Llanos seem to have been a great swampy or submerged plain, with deep water in parts, over which the Orinoco sediments gradually accumulated in the form of current-bedded sands and clays surmounted by gravels, which we may term the Llano deposits. At the same time, along the coast and on the shoals shell-beds were being formed, and can now be seen at Cabo Blanco, west of La Guaira, and similar places, while practically the whole surface of the Island of Cubagua is formed of them, suggesting the name Cubagua Beds. About this period some volcanic rocks were thrust up and cooled both in the Peninsula of Paraguana and near San Casimiro, south of Carácas. In the mountains great masses of gravels containing huge boulders and some Megatherium and other bones were being piled up by the rivers. Last of all we have the still-accumulating recent alluvium of the modern streams, attaining its widest extent in the Delta and round the Lake of Maracaibo.

No volcanoes, active or recently extinct, are known in Venezuela, but the country has, like most of South America, been continually subject to earthquake shocks of greater or less intensity. Some of these are historic, but of the many others recorded not a few had far-reaching effects on the population. The first important tremor noticed after the discovery and settlement of the shores of the Caribbean was that of 1530, which shook the city of Nueva Cadiz on the Island of Cubagua and destroyed the fortress of Cumaná, thus checking for some time the colonisation of the mainland in this region. Thirteen years later New Cadiz was visited again by earthquake and hurricane, and so disastrous were the results that from that day to the present Cubagua has been, what it was before the arrival of the Spaniards, a desert island. The many shocks experienced in the course of the seventeenth and eighteenth[44] centuries seem to have been generally unaccompanied by much loss of life or property, but this period of comparative quiescence was followed by one of the historical examples of severe earthquake early in the nineteenth century. In March, 1812, a shock destroyed great parts of Carácas, La Guaira, Barquisimeto, Mérida, and other towns, and in the capital alone ten thousand people were killed. The great earthquake which, on August 13, 1868, made itself felt all over South America, so much affected some of the Venezuelan rivers that their waters over-flowed the banks, and even remained for a short time in new channels. In 1894 Mérida and other towns in the Andes suffered much damage, houses and churches being shaken down; the destruction was in some cases extraordinarily complete. Since that time only slight tremors have been felt.

The internal heat in the north-eastern spur of the Andes, which traverses Venezuela, manifests itself at many points in the form of hot springs. One, containing much sulphur, is found at Las Trincheras, between Valencia and Puerto Cabello. The temperature of this spring varies, but in 1852 it was found by Karsten to be only a few degrees below the boiling point of water; in general, however, it does not exceed 195° F. or 17° below boiling point. Wall found one south of Carúpano actually boiling. All along the flanks of the coastal Cordillera there are mineral springs, generally at fairly high temperatures, and many more are known throughout the Andes. Nearly all these springs have been used in the treatment of various diseases, though none has achieved especial popularity.

While hot springs may be interesting to the visitor, they are hardly valuable assets to a country such as Venezuela, but this part of the world has always, and with much justice, held the reputation of being rich in minerals. There is coal of fairly[45] good quality in more than one of the Cretaceous and Tertiary groups of strata, near Barcelona, Tocuyo, Coro, and Maracaibo, as well as in the Andes, but the often-associated iron is only found in large quantities in the Guayana gneiss south of the Orinoco Delta.

Gold, that great lure for the early European ventures to the west, may be said to occur in almost every State of Venezuela, but it has only been worked with profit in Guayana, even though samples of a quartz-reef near Carúpano are said to have assayed 7 oz. to the ton. When Sir Robert Dudley visited the coast of the Gulf of Paria in 1595, he heard of a goldmine near Orocoa (Uracoa), on the eastern side of the Llanos, which may mean that the gravels are occasionally auriferous, but unfortunately he failed to reach the place. Placer workings are the chief source of the precious metal in the Guasipati goldfields in Guayana, but the reefs from which it is derived have been discovered and worked at odd times. In British Guiana, where the conditions are similar, Mr. Harrison says that the gold is generally found along the later intrusive dykes, the smallest dykes being the richest, while most gold is found where a basalt intrusion crosses one of the older ones.

The ores of copper are fairly common in the northern Cordillera, and the mines of Aroa in Yaracuy have been worked for many years. Here the pyrites veins occur in the Capacho Limestone, not far from where it has been invaded by a mass of granite. In the Andes it seems to occur in the more ancient rocks, as near Seboruco in Táchira, and Bailadores in Mérida. A mine near Pao seems to be in Cretaceous rocks.

Many other metallic ores occur at various points, notably galena in the Andes, but one of the most common minerals of northern Venezuela is petroleum, known in its desiccated form as “Bermudez asphalt”[46] over half the world. Boring for the original mineral oil has only recently been undertaken. Sulphur is one of the less valuable minerals which occur in considerable quantities, but the so-called salt-mines are not strictly mines at all, and are described in Chapter XVI. Humboldt had heard of the strange mineral lake near Lagunillas, which contains a large proportion of urao or sesqui-carbonate of soda, a mineral not usually found in nature, and here apparently supplied from springs rising in the Segovia rocks. It is used locally for mixture with tobacco juice to make a chewing mixture called chimo, but there have been projects to obtain the salt in large quantities for the manufacture of caustic soda.

In addition to those already mentioned, all the following minerals or ornamental stones have been found in one part or another of Venezuela, viz., marble, kaolin, gypsum, calcium phosphate, opal, onyx, jasper, quartz, felspar, talc, mica, staurolite, asbestos, and ores of antimony, silver, and tin.

The minerals of Venezuela have merely been mentioned casually in this place, an account of the extent to which they have been exploited being deferred to the chapter on the general development of the country. It is evident, however, when one considers their number and the extent of their distribution, that the geological changes which have played their part in the building up of the physical features of the country have left Venezuela in possession of splendid assets in this respect.

The glamour of the South American forests—Hidden treasures—Temples of Nature—“A dim religious light”—Bejucales—Forest giants—Brazil nuts—Tonka-beans—Rubber—Quinine—Arctic and tropic forms—The Llanos—Tierra caliente—Natural hothouses—Colour and coolness—Páramo plants—Monkeys—An old friend—Cannibalism—Vampires and bats—“Tigers” and “lions”—“Handsome is as handsome doesn’t”—Wild horses—Dolphins—Prickly mice—The “water-hog”—Sloths—Birds—Many-coloured varieties—Umbrella-bird—“Cock-of-the-rock”—Toucans—Cuckoos—Humming-birds—“Who are you?”—Oil-birds—Parrots and macaws—Eagles and vultures—A national disgrace—Game-birds—Snakes—Lizards—From the Orinoco to a city dinner—A cup-tie crowd—Ferocious fish—When is a mosquito not a mosquito?—Agricultural ants—Gigantic spiders—Ticks—A pugnacious crustacean—A rich field.

Most of us, if possessed of imaginative faculties, have been impressed in our youth by the thought of those vast virgin forests of South America, inhabited, as we often used to think, only by huge boa-constrictors and anacondas which lived to an immense age and continued to grow throughout their lifetime; and even in later years, when experience at first or second hand has taught us that the supposed silent forest of the tropics is generally noisy with the chattering of monkeys and birds or the perpetual hum and chirp of insects, and is often far from a desirable place on account of these last, the glamour of the[48] vastness and fertility of these great untrodden temples of nature remains with us.

More than half of Venezuela is covered by forest, and, indeed, comes within the forest area of South America; what botanical treasures and zoological curiosities may yet be discovered, when some explorer is found to succeed Humboldt and Schomburgk, are not to be guessed at, and it is not our purpose to give a scientific account of what has been done towards classifying and enumerating the many plants and animals already known to live in Venezuela, but to briefly describe what is most interesting and important to the general reader who may be interested in the country as a whole.

Richest in quantity, and probably in variety, of vegetable life is the little-known land of Guayana, with its vast forests, hot climate, and heavy rainfall. Within it the plants range from the alpine shrubs and reindeer moss of some of the higher plateaux and hills to the bamboos and orchids of the river banks. The simile which compares the tropical forest to those darkened lofty cathedrals of Europe has been often used, and is, perhaps, somewhat trite, but its aptness is incontrovertible. The huge timber-trees grow fairly close together, and their spreading tops, fifty, eighty, or a hundred feet from the ground, with the abundant hanging lianes and flowering creepers, keep all but a feeble light from the ground, whence it comes that the under-growth is usually sparse or absent, and progress on foot is comparatively easy. Sometimes, however, there are stretches of bejucal, full of tangled ground creepers, and it may take a day to cut a path for one mile through such growth as this.

Of all the forest giants of Guayana, Schomburgk considered the mora the most magnificent; the average diameter of the trunk is about three feet, and it seldom branches at less than forty feet from[49] the ground. The dark-red, fine-grained wood is said to be excellent for shipbuilding purposes. Mahogany or caoba, the palo de arco, whose wood is very like mahogany in colour, and a big tree called in Venezuela rosewood, which it resembles, are among the timber trees of the region known to us in Europe. The huge ceibas, with their buttress-like roots, have a soft, easily worked wood, excellent for the dug-out canoes of the Indians, and the equally large mucurutu or cannon-ball tree furnishes a beautiful but hard and fine-grained timber. Unfortunately, the very fertility of the soil becomes a drawback in the exploitation of these timber resources, for all trees grow with equal freedom, and the particular kind for which the lumber-man is searching may only be found at rare intervals; on a large scale, when all the valuable woods are utilised, this difficulty would, to some extent, disappear.

There are two fruit-trees whose products are well known in European markets, and though these grow all over Guayana, they are particularly abundant in certain regions. The Brazil nut was first described by Humboldt, but since his time it has become a common article of merchandise in Europe; the tree which bears it is itself large, and the fruit, with its fifteen or twenty nuts, is tremendously heavy, and generally breaks in falling from the tree when ripe, not infrequently cracking the shells inside, when the birds and monkeys are able to enjoy the oily kernel; otherwise the exterior usually proves too hard. The other fruit we have referred to is the sarrapia, or tonka-bean, not so well known to the general public of to-day as formerly, though extensively used in perfumery. The trees grow in greatest abundance and excellence, according to André, in the Caura and Cuchivero valleys. The gums and resins of Guayana include the balatá, copaiba-balsam, and rubber-producing trees, the latter chiefly varieties of[50] Hevea, while cinchona or quinine with innumerable creepers and trees possessed of medicinal or toxic properties are found everywhere. The 2,450 species of plants referred to by Schomburgk have since been added to, and it is obvious that in such an assembly there must be many of value, as yet undiscovered and unused.

The vegetation of the higher exposed peaks and plateaux is quite different from that of the forests, and here Schomburgk found such an alpine, or rather Arctic, form as reindeer-moss, associated with semi-tropical rock-orchids and aloes.

The forest plants and trees of Guayana also flourish in the Delta region and in the forests bordering the Llanos of Maturín, but the vegetation of northern Venezuela is generally very different from that of the south.

The great green or brown plain of the Llanos is often beautified by small golden, white, and pink flowers, and sedges and irises make up much of the small vegetation. Here and there the beautiful “royal” palm, with its banded stem and graceful crown, the moriche, or one of the other kinds, forms clumps to break the monotony, and along the small streams are patches of chaparro bushes, cashew-nuts, locusts, and so forth. The banks of the rivers often support denser groves of ceibas, crotons, guamos, &c.; the last-named bears a pod covered with short, velvety hair, within which, around the beans (about the size of our broad beans), is a cool, juicy, very refreshing pulp, not unlike that of the young cocoa-pod. Along the banks of the streams in front of the trees are masses of reeds and semi-aquatic grasses, which effectually conceal the higher vegetation from a traveller in a canoe at water-level.

IN THE UPPER TEMPERATE ZONE: THE CHAMA VALLEY.

As might be expected, when we enter the region of the Cordilleras, we find very different types of vegetation in the various zones. The tierra caliente[51] has generally a heavy rainfall, and then supports thick forest, but along the coast there are barren stretches with only cactus, acacia, croton, and similar plants, picturesque, but hardly beautiful. The mangroves and their associated forms line the shore in a belt of varying width, but behind follow, according to the climate and soil, lowland forests or plains and hills covered with cactus of all shapes and sizes, some being so large that the woody stems are used locally in building.

In the tierra caliente we have the plantations of cacao, sugar, bananas, plantains, maize, and cassava, which produce the staple foods of the inhabitants, and the highly profitable coconuts, if not cultivated, are at least encouraged and exploited. In addition, there are the many valuable products of the forests, chief of which are the dye-woods and tanning barks, including logwood, dividive, mangrove, indigo, and many others. A good deal of valuable timber grows in parts of the forest, the chief woods exported being mahogany and “cedar.”

As we rise into the cooler regions, we find, naturally, a mixture of the hot-country plants and those of the mountains; particularly is this so in the case of cultivated kinds. One may see in the same valley, within a short distance of one another, bananas, potatoes, sugar-cane, wheat, yuca or cassava, peas, maize, cotton, cocoa, and coffee, all flourishing, and a single orchard may contain guavas and apples, peaches and oranges, papayas and quinces, not to mention many other fruits; the garden adjoining will have a mixture of roses, carnations, violets, and dahlias with bougainvilleas, dragon’s blood, magnolias, and other tropical flowers. Strawberries, mint, bulrushes, nasturtiums, and other of our garden plants have been successfully naturalised in these mountain regions within 10° of the equator.

The higher part of the tierra templada exhibits[52] the greatest variety of plants peculiar to this zone. As one travels along the mountain roads, in addition to new kinds of palms, one sees screw-pines and beautiful tree-ferns, splendid white rock-orchids and purple parasitic varieties, red and white rhododendrons and heaths, cranberries, blackberries, ivy, passion-flowers, yews, quinine-trees, aloes of all kinds, small bamboos, silver-ferns, and all manner of beautiful flowering shrubs and plants, for it is here and not in the hotter tropical regions that we have the greatest variety of colour and the most beautiful floral scenery.

Nor is the tierra fria of the Cordilleras without its beauty and interest to the botanist. The small woods of the temperate zone gradually die out, and towards the snow-line we have the alpine grasses, heaths, and lichens of the páramos, amongst which are scattered those peculiar white or yellow, thick-leaved, aloe-shaped plants which, strangely enough, have lumps of resin clinging to their roots, and seem in this respect to supply the place of the pines and firs which are not found in Venezuela.

There is at least one animal found in the forests of Guayana which is familiar even to the untravelled Cockney, namely, the prehensile-tailed capuchin monkey or sapajou, of which several species are known in Venezuela, while they are the most common tame kind brought to Europe. Humboldt’s woolly monkey, which is nearly allied, is dark grey, the capuchin being generally reddish; its flesh is said to be excellent eating for those who feel no qualms at nearing the verge of cannibalism. Many other kinds are found in the forests, including the black thumbless spider-monkeys, but the variegated spider-monkey, of which the first specimen brought alive to England came from the Upper Caura in 1870, is a gorgeous beast, with black back, white cheeks, a band of bright reddish-yellow across the forehead, and[53] yellow under-surface to body and limbs. The banded douroucouli also occurs in southern Venezuela, and Mr. Bates has described how, on the banks of the Amazon, a person passing by a tree in which a number of them are concealed may be startled by the apparition of a number of little striped faces crowding a hole in the trunk. Their ears are very small. The graceful little squirrel-monkeys, with dark fur shot with gold, the titi, reddish-black, with a white spot on the chest, the white-headed and other sakis, and the abundant and very noisy howlers are all denizens of the Guayana forests. Nor must we omit to mention the pretty little marmosets, which are often kept as pets.

Bats, and their objectionable cousins, the vampires, are abundant in Venezuela, but the true blood-sucking vampire does not seem to be very common.

There are, of course, no tigers or lions, properly so called, in the New World, but the names have been usurped by similar beasts, the jaguar and the puma. The tan-coloured fur of the former, with its large rosette-like spots, is very beautiful, and quite equals that of the tiger in large specimens, while for agility it more than rivals its Asiatic relative, being credited with climbing trees and living there in times of severe flood, to the great danger and annoyance of the usual inhabitants, the monkeys. The tawny puma is also said to chase the monkeys in the tree-tops, even in ordinary times. The other large cats of Venezuela include the ocelot, jaguarondi, and margay, and there is the one fox-like “Azara’s” dog.

The peculiar-looking “spectacled bear” is found up in the Andes, and the kinkajou represents the raccoon tribe, while the weasels include the tayra and grison, and their relative, the handsome but most objectionable skunk, occasionally pollutes the atmosphere with his presence. The big Brazilian otter,[54] with chocolate-brown fur, is found in the rivers of the Llanos.

Amongst the hoofed animals, the red Brazilian and Ecuador brockets represent the deer, and there are two species of vaquira or peccary, in addition to the now acclimatised European pig. Horses and donkeys live in a semi-wild state on the Llanos, though their nearest relative native to the country is the tapir or danta, a very different beast in appearance.

The nailless manati of the Orinoco mouth is fairly common, and higher up the river there is a fresh-water dolphin: the author observed a fish-like beast in the Lake of Maracaibo, which may be the same species, though out in the salt water of the Caribbean the common dolphin is found, as well as the cachalot, and another species of whale is said to have been seen there.

The rodents include a number of species of great scientific interest, but for the ordinary individual one rat or shrew is much like another, and the squirrels, mice, rabbits, hedgehogs, and allied animals are very similar to those of Europe. One of the mice has flattened spines mingled with the fur, and the coypu or perro de agua has a very harsh coat, though it is rather like a beaver in appearance and habits, while some near relatives of smaller size have the same peculiar flattened spines on the back. The peculiar Brazilian tree-porcupine is a Guayana species. The gracefully formed aguti or acure is common in the Venezuelan forests, and its near relative, the aguchi, is found there with the lappa or paca, the flesh of which is excellent eating. The big “water-hog,” chiguire or capybara, familiar to Zoo visitors, occurs in Guayana and elsewhere.

There are several sloths common in the low-lying parts of the Guayana forests and similar regions of northern Venezuela, and the great-maned ant-eater or[55] “ant-bear,” with the lesser ant-eater, is as often seen in Venezuela as in any part of South America, while Guayana is the centre of the small district in which the peculiar two-toed ant-eater is found. The cachicamos or armadillos are much esteemed as food in the forest districts.

The marsupials are represented by the rabipelados or opossums and the perrito de agua or water-opossum.

The birds, being more commonly seen, are perhaps of greater interest than the mammals, and certainly many of the Venezuelan birds are beautiful, though, as frequently happens, what they gain in plumage they lose in song, and few have even a pleasant note.

Beautifully coloured jays, the peculiar cassiques, with their hanging nests, starlings, and the many violet, scarlet, and other tanagers, with some very pretty members of the finch tribe, are all fairly abundant in Venezuela. Greenlets, some of the allied waxwings, and thrushes of various kinds, with the equally familiar wrens, are particularly abundant, nor does the cosmopolitan swallow absent himself from this part of the world. The numerous family of the American flycatchers has fifty representatives in Venezuela, and the allied ant-birds constitute one of the exceptions to the rule, in possessing a pleasant warbling note. The chatterers include some of the most notable birds of Venezuela, and we may specially notice the strange-looking umbrella-bird which extends into the Amazon territory, known from its note as the fife-bird; the variegated bell-bird, which makes a noise like the ringing of a bell; the gay manikins, whose colour include blue, crimson, orange, and yellow, mingled with sober blacks, browns, and greens; the nearly allied cock-of-the-rock is one of the most beautiful birds of Guayana, orange-red being the principal colour in its plumage,[56] while its helmet-like crest adds to its grandeur; the hen is a uniform reddish-brown. The wood-hewers are more of interest from their habits than the beauty of their plumage.

The beautiful green jacamars, the puff-birds, and the bright-coloured woodpeckers are found all over Venezuela in the forests, but their relatives the toucans are among the most peculiar of the feathered tribe. With their enormous beaks and gaudy plumage they are easily recognised when seen, and can make a terrible din if a number of them collected together are disturbed, the individual cry being short and unmelodious. Several cuckoos are found in Venezuela, some having more or less dull plumage and being rare, while others with brighter feathers are gregarious. With the trogons, however, we come to the near relatives of the beautiful quezal, all medium-sized birds, with the characteristic metallic blue or green back and yellow or red breasts. The tiny, though equally beautiful, humming-birds are common sights in the forest, but a sharp eye is needed to detect them in their rapid flight through the dim light; some of the Venezuelan forms are large, however, notably the king humming-bird of Guayana; and the crested coquettes, though smaller, are still large enough to make their golden-green plumage conspicuous. The birds which perhaps most force themselves, not by sight but by sound, upon the notice of travellers are the night-jars; the “who are you?” is as well known in Trinidad as in Venezuela. The great wood night-jar of Guayana has a very peculiar mournful cry, particularly uncanny when heard in the moonlight. The kingfisher-like motmots have one representative in Venezuela, but the other member of the group, which includes all the preceding birds, constitute a family by itself. This is the oil-bird or guacharo, famous from Humboldt’s description of the cave of Caripe in which[57] they were first found. The young birds are covered with thick masses of yellow fat, for which they are killed in large numbers by the local peasantry. They live in caves wherever they are found and only come out to feed at dusk.

Other birds which are sure to be observed even by the least ornithological traveller are the parrots and macaws which fly in flocks from tree to tree of the forest, uttering their discordant cries. The macaws have blue and red or yellow plumage, but the parrots and parraquets are all wholly or mainly of a green hue. The several owls are naturally seldom seen, and, in the author’s experience, rarely heard.

There are no less than thirty-two species of falcons or eagles known from Venezuela, and of these many are particularly handsome, such as the swallow-tailed kite and the harpy eagle of Guayana. Their loathsome carrion-eating cousins, the vultures, have four representatives.

In the rivers and caños of the lowlands there are abundant water-birds, and the identified species include a darter, two pelicans, several herons or garzas, the indiscriminate slaughter of which in the breeding season for egret plumes has been one of the disgraces of Venezuela, as well as storks and ibises. Among the most beautiful birds of these districts are the rosy white or scarlet flamingoes, huge flocks of which are sometimes seen rising from the water’s edge at the approach of a boat or canoe. There are also seven Venezuelan species of duck.

The various pigeons and doves possess no very notable characteristics, and one or two of the American quails are found in the Andes. Other game-birds include the fine-crested curassows of Guayana, the nearly allied guans, and the pheasant-like hoatzin. There are several rails, and the finfeet are represented. The sun bittern is very common on[58] the Orinoco. There are members of the following groups: the trumpeters (tamed in Brazil to protect poultry), plovers, terns, petrels, grebes, and, lastly, seven species of the flightless tinamous.

Descending lower in the scale, we come to the animals which are, or used to be, most often associated in the mind with the forests of South America. The snakes are very numerous, but only a minority are poisonous. Of the latter the beautiful but deadly coral-snake is not very common, but a rattlesnake and the formidable “bushmaster” are often seen. Of the non-poisonous variety the water-loving boas and tigres or anacondas are mainly confined to the Delta and the banks of the Guayana rivers. The cazadora (one of the colubers) and the Brazilian wood-snake or sipo, with its beautiful coloration, are common; the blind or velvet snake is often found in the enclosures of dwellings.

One of the lizards, the amphisbæna, is known in the country as the double-headed snake, and is popularly supposed to be poisonous, but there are many species of the pretty and more typical forms, especially in the dry regions, while the edible iguana is common in the forests. There are eleven species of crocodiles, of which the caiman infests all the larger rivers and caños. The Chelonidæ include only two land tortoises, but there are several turtles in the seas and rivers, and representatives of this family from the Gulf of Paria often figure on the menus of City companies.

There are some six genera of frogs and toads to represent the Amphibians, and the evening croaking of the various species of the former on the Llanos is very characteristic of those regions; one, in particular, emits a sound like a human shout, and a number of them give the impression of a crowd at a football match.

CLOUD-DRIFTS IN THE ANDES.

TORBES VALLEY AND THE COLOMBIAN HILLS.

Fish abound in rivers, lakes, and seas, but, considering[59] their number, remarkably little is known about them. Some are regarded as poisonous, and others are certainly dangerous, such as the small but ferocious caribe of the Llano rivers, which is particularly feared by bathers, as an attack from a shoal results in numbers of severe, often fatal, wounds. The temblador or electric eel is very abundant in the western Llanos, and is as dangerous in its way as the caribe.