Title: An Englishwoman's adventures in the German lines

Author: Ann Gladys Lloyd

Release date: July 7, 2023 [eBook #71135]

Most recently updated: November 6, 2023

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: C. Arthur Pearson, 1914

Credits: MWS, Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Page 13—Grendarmerie changed to Gendarmerie

Page 83—govermental changed to governmental

An Englishwoman’s Adventures

In the German Lines

By

Gladys Lloyd

London

C. Arthur Pearson Ltd.

Henrietta Street, W.C.

1914

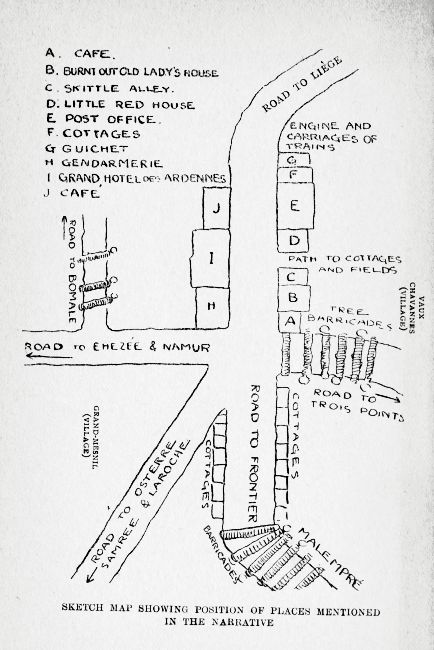

SKETCH MAP SHOWING POSITION OF PLACES MENTIONED IN THE NARRATIVE

| PAGE | |

| War! | 7 |

| Getting Ready | 10 |

| How the Uhlans came | 16 |

| Anything for Bread | 23 |

| Fiction v. Fact | 25 |

| The “Terrible” French | 28 |

| Spies Ahoy | 31 |

| Threatened with Death | 34 |

| To Leave or not to Leave | 41 |

| What the Uhlans think | 45 |

| The Sign of the Red Cross | 50 |

| On the Road | 55 |

| Rushing the Mails through | 61 |

| A Teuton Feast | 67 |

| Coals of Fire | 72 |

| In Danger | 75[6] |

| Maps and Mines | 78 |

| In the Bar | 80 |

| In the Woods | 82 |

| Prisoners of War | 86 |

| A Disturbed Night | 94 |

| The Plot Thickens | 97 |

| The March Past | 100 |

| Arrested! | 104 |

| “It’s a long, long way——” | 109 |

| Homeward Bound | 120 |

“Albert has gone.”

I jump down from the little vicinal (light railway) train, which always stops so obligingly in Manhay Street opposite the inn, and press Madame Job’s hand in silent sympathy.

“To Liège?” I ask after a pause.

“He is in the forts, Mademoiselle,” she answers tearfully.

So Madame’s son Albert, the baker, is a soldier too. Well, he will do his duty like all these Belgians. But who will bake for the countryside?

I greet the young Lepouses, Mademoiselle Irma, the pretty eldest daughter, the sixteen-year-old Louisa, Messieurs Floribert and Alfred, the stalwart sons. Last of all, the inn’s proprietor, wrinkled kindly Monsieur Job. I am introduced to M. le Précepteur,[A] the postmaster, at the post office,[8] and his wife and children. Together we sit out on the terrasse and discuss the one and only topic.

[A] M. le Précepteur is a descendant of the owners of Hougomont.

“Caught in the war. A nice ending to my summer’s holiday,” I say cheerfully.

“You had better return to England to-day—it will be your last chance,” says a dispatch carrier, a khaki-clad, dusty figure standing before us in the village street.

“The trains are taken for the soldiers. Besides, I have only Belgian paper money—unnegotiable now.”

“Walk then.”

“Too far,” I protest.

“Please yourself, Mademoiselle. But in war-time, a little hotel, on a high road, with the post office opposite and the Gendarmerie next door, is not the place of residence I should personally choose. Good-bye, Mademoiselle; good-bye, all. I must be off.”

The dispatch carrier mounts his machine, bends over the handle bars in best professional style, and is quickly lost to view in a cloud of dust.

We remain chatting out-of-doors for a little while. There is a careworn look on the faces of the women, a certain quiet determination in the eyes of the men. I understand. At midnight, in a [9] neighbouring village, I had heard the dreaded Tocsin sound out the call to arms. The tones of the harsh, crude bell, mingled with the agonised cries of sorrow-stricken women. No one slept. Some were helping loved ones to make their preparations for departure, others were quietly watching the ceaseless stream of men pass by. Hour after hour they came pouring into the village from outlying hamlets, summoned by beacon fires from the surrounding hills. Many paused to admire the long queue of patient, fly-tormented horses waiting to be shoed by the maréchal. In five hours the last message had been delivered, the last good-bye said. The men were gone. But the memory of their going is not easily effaced....

[10]

“Les Prussiens, les Prussiens!” These words are uttered in hoarse whispers under my window while I dress. They send a nervous tremor down my spine. At breakfast I am informed that the Germans are only a day’s march distant. They have already crossed the frontier and are advancing on us. Bombarded Liège is safer than Manhay, situated on one of the high roads from the frontier. The blindest Teuton could not miss this short, straight line of white-washed houses.

I join the crowd of peasants standing in a cluster at the cross-roads. Everyone is busy advising, gesticulating, prophesying. Other peasants are pouring in from the neighbouring villages for directions and news. Any stranger at once forms the nucleus of an entranced group. There is much chattering but little real excitement. These people who live on the edge of big events are never unprepared.

M. le Précepteur is busy in the post office trying to decipher governmental wires. Several malle-postes,[11] like two-horsed roofed-in wagonettes, are waiting about, their drivers ready to take round letters—the last batch, who knows!—to the scattered villages around. A very small girl, fortified by a very large dog, is deftly steering back some wandering cows from the direction of Malempré. The village idiot has been trying to get up a game in the skittle alley, but is promptly squelched.

Motor-cyclists are coming and going in the direction of Liège. Cars shoot through every few minutes at a break-neck speed carrying men in uniform. The Commandant, peaked hat and uniform complete, lolls at the door of the Gendarmerie. His horse is being walked up and down by a farmer’s boy.

He disappears into a back room to answer the telephone, but when he returns he does not impart his news to the gaping crowd. The little vicinal train puffs noisily down the street from its shed at the end of the village. The peasants of the 13th and 14th classes, called up to-day, climb in. They are very workmanlike in their dirty-white trousers, short belted coat, and “bonnet rond.” They carry necessaries in a small parcel. How I admire the plucky air of confidence on their manly faces as they lean over the side of the little car which[12] is to take them down to the railway ... to Liège ... perhaps to God.

They bend from the train to shake their relatives’ hands with something of the Commandant’s calm nonchalance. Matters are worse than I imagined. Men with pitchforks are even being called up to help guard the frontier. Too late! M. le Directeur is here in a khaki suit. The brave man. He is about to take dispatches. His motor-cycle needs petrol. The entire village hurls itself on the machine. We are all panting to be useful.

“Doucement, doucement, mes braves gens. Ce n’est pas un Allemand.” (Quietly, my good people! I am not a German), he says, laughing.

The spirit of the peasants obviously delights him. He breaks into a Walloon song. They all shout the chorus, beating time with their hands. Then he is off.

One thing is decided on. The magnificent avenues of trees which line the undulating roads must be decimated to bar the route against the German troops. To keep them back a few days, a few hours, will be something. Already knots of villagers in wideawake hats and stout corduroys are stealing away, axe hooked to shoulder, lengths of rope coiled round their left arms. They look[Pg 13] bored and indifferent, so I know they will work like demons. A bored-looking Belgian is a man to be feared.... Soon one hears the steady hack-hack, followed by a swirl and crash as some huge fir or oak falls prone across the great white road. There is something about the sound which makes one’s blood run cold. It comes as a foretaste of death.

A car drives up with four busbied officers. The Belgian guides. The Commandant speaks to them a moment. They drive on. He re-enters the Gendarmerie, comes out a moment later, locks the door and casts a lingering, almost affectionate glance at the yellow, black and red flag floating proudly from the masthead. He is wondering, perhaps, if he will ever see it again. Mounting his horse, he waves his hand to the villagers, and is off on his sixty-mile ride to Arlon. Brave Commandant of the nonchalant mien, but not brave enough to face those last good-byes. How I feel for you!

The day wears on. Already the end of the high road where it turns to Malempré is piled high with trees. The Noah’s-ark firs on the highway to Bomale have come toppling down like ninepins. My thoughts turn to weapons. I never dream for[14] an instant but that the peasants will fight the common enemy from behind those bulwark barricades. It seems the only natural and proper thing to do. I know nothing of the duties of non-combatants.

A man from a neighbouring village drives up in his cart. He gets down and feeds his horse with hunks of black bread which he tears from the loaf. I feel ashamed not to be armed. He may help. I approach him.

“Have you a spare rifle?” I ask wistfully.

He stares at me stupidly. “A rifle? No,” he says. “Why?”

“I could help to shoot the Germans,” I suggest.

“It’s a pity,” he answers, and his mouth twists in a grin as he turns back to feed his horse.

I have never held a rifle in my hands. But I feel convinced that the mere sight of a loathsome Teuton would make the most difficult and antiquated weapon go off of its own accord.

Madame Job’s little girl, Rosa, was sent back from Liège some days ago. The school is turned into a hospital, and the good nuns are acting as nurses for the wounded. Rosa’s German fellow-pupils are left behind. They will presently enjoy the novel sensation of being shelled by their own countrymen.

[15]

Rosa runs about the house like an elf and sings. For a pupil of the Sisters at the Orphelinat de St. Joseph she is very lively. Youth has the happy knack of living in the present. She and Louisa take it in turns to act at “Prussien,” the fashionable game. They submit with a good grace to be chased and well thumped on capture by Victor and René, the aubergiste’s son.

To-night we all sit out on the terrasse at the little white tables. The whole family are here. M. and Mme Job-Lepouse, Floribert, Alfred, Louisa, Irma, and Rosa. M. le Précepteur and his wife come over from the post office. The postman and the picturesque poacher lounge against the wall. In the distance the old Maids of Manhay are enjoying their evening chase after the elusive pig, and the skeleton dog is giving a series of infuriated yaps at his own enforced detention. The fair unknown comes out of the red doll’s house opposite and waters the rosier with rather tremulous grace. This will be our last night of peace....

[16]

“It never rains but it pours,” is as true of the Ardennes as of more distant lands. It has been pouring all night. It is pouring now. In the silence between the pitiless showers, we can hear the roar of the siege guns already bombarding Liège.

More trees have been cut down during the dark hours. A great wall of wood bars the road opposite the Gendarmerie leading to Vaux Chavannes. Numberless recumbent tree-trunks are making great dark tracks across the long and tortuous route towards the frontier. We have done our share. We can but wait events.

Everything is curiously quiet this morning ... in the village. For rustic sounds one only hears the Manhay pig grunting as he wallows with a furious enjoyment in the churned-up mud of a distant field, and the yapping of the miserable imprisoned dog from his box-kennel chained to an old wall. I sit out on the terrasse and begin to sew. Germaine is brought along in her nurse’s[17] arms and looks at me nervously. It is ironing day, and her mother is busy collecting the washing from the garden hedge. Victor plays the good old game of follow-my-leader up and down the street with little René.

Madame Job comes out of the inn and leans one hand for a moment on the back of my chair. The other steals up to her eyes.

“I can’t help thinking of Albert,” she says apologetically, “my Albert in the forts there below.” She gazes in the direction of Liège, which is hidden behind the distant wooded hills.

“Why fear for him?” I ask. “Is he not lucky to be in the forts, the forts-which-are-so-strong.”

I know the comforting phrase by heart now.

“The forts-which-are-so-strong.” She repeats the words after me like a child. A gleam of hope dawns for an instant on her kindly face, then fades away. “Supposing he is not fed!” she says with bitter emphasis. To the Walloon mind, hunger is almost worse than death.

Comforted by my fibs, she goes back to cook the dinner over the black oven. The oven and Madame are indivisible. I always think of them together.

I sew on. Suddenly steps are heard approaching from the direction of Vaux Chavannes. They[18] cease. Something is worming its way with a curious brushing noise round that piled-up barrier of trees. “It” turns the corner into the Manhay Street. A peasant is running towards me full tilt. His face is scarlet, his mouth open with the tongue sagging over the lips. He rolls from side to side as if drunken; reaching me he throws up his hands.

“Les Prussiens, les Prussiens!” he shouts, and falls on his face as though possessed.

We bring him water, we fan him. He revives.

“Three hundred Prussians are at Vaux Chavannes,” gasps the messenger.

The peasants disperse as though scattered by a shell. The village idiot takes cover in the pig-sty. Germaine is dropped by an agitated and diminutive nurse and immediately begins to scream. She is forcibly dragged to shelter. A scuttling and jabbering ensues. One hears the swish of skirts, the quick tramp-tramp of heavy boots, the sound of creaking stairs. I drag the fainting man into the hotel, quickly close and bolt the door, prop him against the wall, and go to the open dining-room window.

Manhay might stand as a model for “The Deserted Village.” The inn is silent as the grave, the family of Job-Lepouse is doubtless in the fields. With me[19] curiosity overrides fear. Even if it entails certain death I must see the Uhlans come. There is a sharp clitter-clatter of horses’ hoofs along the Vaux Chavannes road. It stops abruptly at the barricade. I hear a volley of very German curses, the crash-crash of weapons and then a mutilated bicycle comes hurtling through the air. I hear the cry of a man in pain. Some poor devil has been caught....

The Uhlans are in our street. They mass by the Gendarmerie, glare fiercely round. They have learned the feeling of the countryside in those barred tree-trunks which have crossed their path. They suspect a plot and are keen to fight. Charging down the road they come, lance out, heads erect, the sun glinting a thousand sparks from the rim of their metal helmets where it is left unprotected by the light cloth shield. They are not quite so smart as when parading last before their adoring women-kind. Their horses’ flanks are streaming, their uniforms dusty. “What splendid men they are!” is my first impression. “This is just like comic opera,” is my second. But when, at closer range, my eyes meet those long, sharp lances and that Teuton glare, I confess my third is funk!

[20]

I shall never forget that first moment of invasion. The forest of lances, the grey steel of pointed revolvers, sobbing women and frightened children. The desertion of the little village street and the scuttling of agonised peasants into their houses. The banging and locking of doors, the sudden silence as they scatter in the stable ... cellar ... fields. I can see it now.... I shall see it always.

One peasant is not fortunate enough to escape. A Uhlan with an over-developed (Teuton) sense of humour, pricks him in the fleshy part of the shoulder with the point of the lance. Having secured a good hold, the German gallops up and down the village, driving the unlucky man before him at a furious speed.

The remainder of the troop form up and charge towards us down the road. They interrupt their dash at the post office. The officer points a revolver at M. le Précepteur’s head in the ingratiating German way and asks some question. I swear that M. le Précepteur’s hair is standing on end in the manner hair so frequently assumes in novels, so very seldom in real life.

Something grey and cold intercepts itself between me and the sun. Something cold and grey touches[21] my forehead and a gleaming face comes on a level with my own. The first contact of that revolver makes my knees tremble and gives me a cold sensation down my spine. But I do not budge. My captor neither addresses me nor I him. We simply stare stupidly at one another. A wasp, attracted by the bright metal helmet rim, plays about his face. The hand that holds the revolver trembles. I am almost but not quite amused. Suddenly the weapon is withdrawn. The troop gather up their reins, canter on through the village and halt in consultation at the head of the street.

A curious intuition tells me that the Uhlans are afraid ... of our fear, that those tightly barricaded doors and closed windows suggest plots—perhaps armed resistance. It occurs to me that it would be wiser to show ourselves, to feign indifference. In times like these men are shot for showing the white feather.

I rush out and call the peasants by name. One or two stare stupidly from the windows, the rest do not budge. Many are in the fields, some probably in the cellars. I sit down on the terrasse and draw the little white chair close up to the painted white table. The moustached postman in the dirty white ducks comes to my side, so does[22] the poacher, unshaven but ever picturesque in his brown corduroys.

The order has been given to charge. They are coming back, the gallant Uhlans! Will they shoot us down? We shall know soon enough. I lift my glass of bock with a rather shaky hand while the postman puffs at his pipe and the poacher half smiles. He is a feckless, fearless rascal. Here they come, lances and all. The foremost misses my head by half an inch. I wince. The soldiers look unutterably fierce as they clatter past. The last few cover us with their revolvers until they turn the corner of the road. Clitter-clatter—fainter—then silence. The postman, ever solemn, turns to me and reaches over an enormous hand.

“Vous êtes—bon soldat, Mademoiselle,” he says, as he rises abruptly and saunters away down the street, puffing at his everlasting pipe.

[23]

The Uhlans are no longer a novelty, they are a frightful bore. One cannot take two steps outside the village without a soldier in that grey-greeny-blue uniform popping up from behind a tree or appearing as if marionetted down from the cloudless sky. Whenever I see one I have to repress a devouring wish to run.

The war has already taught me one lesson. That there is nothing more dangerous than a frightened soldier. The funk of a scared German oozes into his rifle—not his boots....

All the roads from the frontier, in fact the entire Ardennes are being patrolled by these creatures. To-day we have had armoured cars passing to and fro at break-neck speed, manned by soldiers and positively bristling with rifles.

Boom—boom—boom! It has been going on all day and all night, for the last three days and nights—that horrible cannon at Liège. Madame Job can hardly drag herself down this morning. She feels that each sound may mean the annihilation[24] of her dear Albert. Mlle Irma is crying gently too. My soup is decidedly watery and my omelette impossible. C’est la guerre!

A straggling procession of women visits the inn. Most of them have baskets. They have walked many miles in the burning heat. They need bread. Alas! Albert in the fort there below has other things than baking to think about. Besides, there is very little flour. Only just enough for M. le Directeur, the château on the hill and ourselves.

Madame Job stands out in the street and wrinkles her forehead at the sight of the familiar words, “Boulangerie Lepouse.” She does not mind the villagers, but suppose the dreaded Uhlans interpret the sign. What will happen to those six black loaves so snugly concealed in the postmaster’s cupboard? M. Alfred mounts a ladder and sploshes out the offending letters till nothing but a few black smudges and a hooded cart in the backyard tell of their once thriving trade in bread.

[25]

We have had no Prussians in the village for quite four-and-twenty hours, so the peasants are becoming almost their normal selves. We walk freely about the street and dare to laugh. Laughter is a rare sound in Manhay these days. We even affect to despise the Germans for not coming on in greater numbers.

“Nous avons vu les échantillons, mais où sont les marchandises?” (We have seen the samples, but where are the goods?) asks one village wit.

M. Floribert puts his tongue in his cheek and says the Walloon equivalent of “let ’em all come.”

René and Victor are showing their contempt for the foe by lassoing imaginary Prussians up and down the street, René as usual acting the unfortunate Teuton who is lassoed, hanged, decapitated, in whirlwind fashion, turn by turn.

A group of women sit out under the shady trees in the orchard and talk together as they mend their socks. Some of the older men stroll over to us and spin yarns. An Ardennois legend is spoken[26] of. Anyone could weave a legend round a spider’s web in the Ardennes. But legend-making is really rather out of fashion. Instead we have become military experts in minutiæ. We splay our fingers convincingly upon our tattered maps and say here ... and here ... are the English, there ... there ... and there are the French. They will advance so, and the Germans will retreat so ... until our audience fades away from sheer boredom and we are left to strategise alone.

The jade Rumour mocks our faith at every turn. We begin by swallowing each new idea with delicious open-mouthed credulity. The Germans have already conquered Antwerp ... England ... the world. Our cruisers have been sunk en masse. All the French generals have been shot. Someone has launched a projectile from an aeroplane and destroyed the entire Teuton army at one fell stroke. We sit out boldly on the hotel terrasse after this last glorious item of news and sip our coffee with brave show. Only the entry of some noisy Uhlans suffices to scatter us and rumour at the same time....

“Do be quiet!” says M. Job testily later in the day. He is worried by his children’s nervous chatter as they wander restlessly about the dimly[27] lighted rooms. He has been working in the nursery garden all through the hot hours and is a little annoyed not to find his supper ready.

Mdlle. Rosa slips a soft white hand into her mother’s wrinkled one and rubs her slender nose affectionately against the elder woman’s cheek. Even in war-time she does not forget the teaching of the Good Sisters of the Orphelinat de St. Joseph. She repeats in a dreamy childish voice: “Te souviens, Maman. Qui que le bon Dieu garde, eh bien il le garde ... bien” (Remember, Mamma, he whom God watches over He guards well). So we go to bed consoled.

[28]

This is a gala day. Company to lunch! The Tax-collector has walked here from a small town thirty miles away, en route for Aywaille, another twenty, where he intends to fetch his son from school.

“Quelle désastre que cette guerre,” is his opening remark as we fraternise over the vegetable soup.

I agree.

He draws something from his pocket and throws it across to me. It is a bullet. He shows me a large blister on his finger. “I was over-zealous for that keepsake this morning,” he says, laughing, “and tried to pick it up when it was red hot. There was a fight raging round my little house before I left. Picture to yourself a patrol of Uhlans breakfasting in the hotel-barn opposite. A company of French ride up and demand if the enemy is within. The innkeeper answers, trembling, ‘No.’ ‘The truth!’ thunder the Frenchmen, covering him with revolvers. He confesses. Mon Dieu! What[29] a scene! The French force the innkeeper and his son to set fire to their own barn, and when at length the Germans come out, one by one, stifled with smoke, they calmly pot them off, as if they were so many rabbits. Stay! One Frenchman rushes in before the fire has done its work. He dies a moment later, shot through the heart. I found on him two letters, to his mother and his sweetheart. Such letters!”

“The French are very brave,” I say.

“I tell you they fight—not like men but—comme les démons. They don’t ride up as the Uhlans do. They just ‘appear’ like lightning or earthquake or any other phenomenon and then—phew—le déluge.”

“Every German who comes in here says that the Belgians have cut off the ears and gouged out the eyes of their wounded before Liège,” I say. “We on our side are horrified at the tale of German atrocities. Each time a German enters this village we feel that the tragedy of Visé may be enacted over again.”

The Tax-collector shrugs his shoulders as he fingers a cigarette.

“You must remember it is against the rules of warfare for non-combatants to fire,” he murmurs.

“Have they?”

[30]

He flicks an infinitesimal spot of dust from the table-cloth, and does not answer me.

Yet if one’s country be invaded who shall say that one may not avail oneself of any means to oust the hated foe?

The nostalgia of war seizes me. I know a country where such things could not be. Shall I ever see England, dear England again? Involuntarily I breathe the words aloud. The Tax-collector leans across to me and speaks firmly but very gently as one would address a tired child, “You will never see England again, never, Mademoiselle. Make up your mind to that.”

I scrape my chair back along the wooden boards and rise in a flurry because “it is so hot, so hot”—and escape to my room to dream of what might have been but never can be now——

[31]

Chasse-aux-espions! A governmental order has come through that we are to arrest any suspicious-looking person who passes through the village. We suspect ourselves. We suspect everybody. We are only deterred from action by one thought. The horror of shooting in cold blood a poor, blindfolded, unarmed human thing.

The village is thrilled with excitement this morning. A tourist in tweed suit and knicker-bockers has arrived. He hangs up his soft felt hat in the hall and follows up his breakfast order with comments on the war. He has come from Vielsalm. He has spoken with the Germans. The peasants cluster round him.

“Nice kind fellows the Germans seem,” he says casually, as he walks into the dining-room and takes his seat.

That is sufficient. The men nudge each other and direct mysterious glances towards the door. I am invited to arrest him! I murmur that M. le Directeur and the Bourgmestre have the prior right[32] but that I shall be delighted to assist. On one condition. If found guilty the miscreant must be despatched round the corner and not before my eyes. The Bourgmestre when sent for will not come; I fetch M. le Directeur. “All unconscious of his fate” the spy is enjoying an excellent meal of bacon and eggs. He starts up as we enter and turns rather white. When challenged he opens his pocket-book and shows us his papers with admirable composure.

Dreadful error! On his card I read, “Monsieur Jottrand, Premier Avocat-Général à la Court d’Appel, Bruxelles.”

There is a burst of merriment from the peasants. They surge round him. M. le Directeur shakes him warmly by the hand. I rush to hide myself behind the big black stove in the kitchen.

The “spy” follows me in a moment later. “I congratulate myself, Mademoiselle,” he says. “I have never had the pleasure of being arrested by an Englishwoman before!”

M. Jottrand is tramping his way back to Brussels. He has lost all his luggage but is quite cheerful. So far he has escaped with his life. That is something these days.

Soon after he leaves us, German troops arrive in[33] the village and knock at the doors of every house in Grand-Mesnil. “We give you one hour,” they say, “to remove those trees on the Bomale and Vielsalm roads.”

A hurried conference takes place between the peasants. I interrogate one of them in the street next day. “How about those trees?” I ask.

“Oh, we removed them all right,” he answers. “Not quite as the Prussians intended, however. Un pas de gattes (goat’s path). On a modest estimate it will take the German army about three years to pass along in single file!”

[34]

“Sauvez-vous, sauvez-vous!” This warning yelled in strident, horrified tones is not the most cheerful awakener on a hot summer’s morning.

I hastily throw on some clothes. With my hair scruntled up in a little bun I rush to the window.

A German officer is standing before the house opposite, pointing a revolver at M. Job’s head. He issues orders in a harsh voice.

As he turns away to address his men, M. Job leaps across the road like a hare, his little sun-dried face pale as death.

“Save yourselves, my children. They are going to shoot us all down and set fire to the village. We have only a moment to escape. Sauvez-vous, sauvez-vous.”

He dashes headlong into the house. A second later the entire Job family are scuttling in and out of the inn back door, in a concerted arrangement to convey some of their things to a safe hiding-place in the fields before it is too late.

I rush back to my room, secrete my jewellery and[35] a treasured letter or two under my dress, make a small packet of soap, toothbrush and other necessaries. Then I go to the front window and peer through.

The officer is still in the same position, revolver in hand, addressing his men in rather angry tones. He has begun no violence as yet.

They are outside the door of a poor old woman who is quite alone. She understands no German and must be dying of fear.

I lean from the dining-room window and say with what firmness I can muster:

“What are you doing?”

“Go indoors,” says a soldier, motioning me imperiously back.

“The peasants have fired on us, so we shall shoot most of you and burn the village,” says the officer, covering me with his revolver.

“Our orders,” adds a soldier nonchalantly.

“But we have no——” (I cannot for the life of me remember “weapon” in German, so I act the word in dumb show, one clenched hand to my shoulder, the other in a straight line but further away. I shut one eye and look along my fists to be more convincing.) “There is not one in the village,” I assure him.

[36]

I wish my voice wouldn’t tremble so. It sounds cowardly.

He turns away and calls to the inhabitants of the little cottage before which he stands to come out. The old lady is alone there and I would bet my life she is hiding under the bed at this moment. So I run into the street and the sunshine and, quite beside myself, almost implore the officer not to do this thing.

Disregarding my entreaties he stands with uplifted revolver before the cottage door.

“Come out,” he says again.

No answer.

Before I can move, he lifts his weapon once more. With the gestures of a chef d’orchestre in the opening bars of his favourite orchestra, he strikes the glass panes of the door this way and that with the cold steel. The glass shatters in a thousand fragments on the square stone step. There is something so cruel and calculating in the expression of his hard face. With a smile of satisfaction the officer fires once, twice, thrice into the recesses of the room. One would think a mouse could not escape.

He throws something which must be a hand grenade into the midst of the mysterious still gloom. In an instant smoke and flames seem to[37] rise from the very ground before my horrified eyes. Then he calmly shoots once—twice again into the seething darkness to make sure that he has missed nothing. He turns away to look for the next victim.

I can’t help the tears running down my cheeks, but I say again:

“Indeed, indeed we have never fired. If you search the village through you will find we have nothing to fire with.”

“I heard them,” he says sternly.

In the distance a woman is scuttling along, trying to reach a neighbour’s house in safety. She is so terror-stricken, her progress is like the gait of a sick fowl. A living example is to hand. I point towards her. “Look at that,” I say. “The poor women are so frightened they cry all day long. Besides the women there are only old men and boys. Their one wish is to get the harvest in in peace. Is that a crime?”

A conference takes place between the soldiers I gather that our fate is in the balance. We must be born under a lucky star. We are saved again. The officer remounts his horse. He and his troop ride off briskly in the direction of Grand-Mesnil.

[38]

They are scarcely round the corner before the entire population of the village has rushed out carrying every bucket and jug they can lay their hands on. The old lady, not dead as I expected, but considerably stupefied by smoke, is saved from the burning house and set under the hedge to recover. The rest of us form a line and pass bucket after bucket of water from the pump, in the best workmanlike, fireman style.

The flames have got a good hold and the smoke is stifling, but we all work with a will and soon subdue them.

A young Belgian, just arrived on a motor-bicycle, says “salle cochons” under his breath, but does not help in the work of rescue. Later he confides to me that he is a Belgian spy carrying dispatches. Two days ago he was at Louvain talking with an officer of the “men in skirts.” My heart leaps to think they are so near.

“This morning I have come from Liège,” he says. “The German dead were piled up each side of my path, ghastly lolling corpses, one on the top of each other.” He puts his hand up higher than his head. “It was the most awful sight I have ever seen, and then the odour....” And the poor spy is literally sick in the village street.

[39]

I go back to the burnt cottage. Already willing hands have pulled out odds and ends of still smouldering furniture. The old lady’s cat, disturbed in early morning slumber, has once more resumed its accustomed position on the blackened doorstep. Its expression is cynical and its back arched in a definite anti-Prussian hump. I have no reason whatever to doubt the accuracy of its language when the next Uhlan comes along. The young Job-Lepouses who have been foremost in helping to extinguish the fire, return with me to breakfast. I have leisure to study their appearance.

Yesterday they were of reasonable size. To-day they look as though they had undergone a sudden fattening process which has taken effect in the most unlikely places. For instance, Mdlle Rosa’s right shoulder appears to be afflicted with a monstrous and most unsightly hump. Madame Job’s instep almost equals in size the girth of her waist. M. Floribert has a forearm which would not disgrace a Hackenschmidt. The secret is soon explained.

“Ha-ha, j’ai mes petites économies,” cries Mlle Louisa, dragging a fat leather bag from under her skirt.

[40]

M. Floribert smiles anxiously. He has numerous treasures up his sleeves, including his Sunday ties.

Madame Job lets down her stocking with the utmost sang-froid and displays a leg bound with Belgian paper money and bandaged with some nice old lace.

The house was stripped bare in those few minutes of pregnant danger. Linen, books and even bread were transferred to the most remote and sheltered corner of the vegetable garden. Here they were deposited in the camion or hooded cart in which M. Albert in the happy days, now gone, used to distribute the crisp, round loaves to the countryside. Here, too, hid Mdme la Précepteur, the children and Mdme Job until the danger had passed by....

[41]

People are leaving the village in ones and twos. It is pathetic to watch them come out of their houses, gently turn the key in the lock and then, with slow, sad step, walk quietly away along the high road, turning their backs for ever on their little world. They carry their most cherished possessions in a square cotton sack-bag of enormous check design slung from their shoulders. In their hands are little parcels or perhaps a straw basket packed with a medley of quaint treasures. Small, sturdy, brown-faced children run at their heels.

The peasants visualise mentally the awful atrocities at Visé and tremble at the knowledge that many men have been shot in the surrounding countryside. They say to themselves, “What happens there will happen here to-morrow.” They are afraid. They leave. If they stay it will be in a famine-stricken, Uhlan-haunted country. As they go ... well, I hope they have somewhere to go to!

As refugees they will earn the sympathy of all.[42] But charity, compensation, re-instatement, will never make them amends for the loss of lands and relatives and the dreadful agony of mind they have endured.

The lady of the rosier has fled. The watering-can is thrown carelessly in a corner and the rosier is already beginning to fade. The curtains are drawn and the doors locked at the red house opposite. The old maids of Manhay are suspected of planning a similar flight or their pig is very out-of-hand. He has been caught executing weird manœuvres in the street village, including the charging of ten tired Uhlans who coldly rebuffed him at the point of the lance.

Stragglers have come in from the frontier on their way from here to nowhere. They have the weary, listless air of people who have lost all interest in their lives. They carry their possessions in a small brown parcel and have the inevitable children dragging behind them. One can only offer them food and drink (we have not too much to spare) and speed them on their way.

Refugeeing seems in the air. I am amazed to find the house of Job-Lepouse, at least the feminine portion, is now thinking of retreat. I come upon Madame Job, the two little girls and Messieurs[43] Alfred and Floribert, all busy packing things in the backyard. A huge malle-poste with two horses is drawn up near the stables, a large, wide-mouthed washing-basket on the roof, lashed to the sides by stout cords, is being filled with an extraordinary medley of food, clothes, linen, books and articles of all kinds.

Madame Job, ever tearful, informs me that they are leaving for a retired little farm in the country, near Esneux, where they will be away from this dreadful high road and comparatively safe.

“You will come too, Mademoiselle?” she implores.

I demur. Any change will only mean out of the frying-pan into the fire. We may be slaughtered en route or arrested as spies. While I hesitate Madame la Précepteur rushes over attired as for a journey, carrying the little Germaine in cloak and bonnet. She is followed by Victor, dressed in sailor clothes. Their belongings are tied up in a large bag.

“The inn will have to be kept open or it will be sacked,” I say. “I think I will stay here, Madame.”

Mdlle Irma links her arm in mine and voices her determination to stay too.

[44]

The others are just about to take their seats in the great rambling vehicle when M. le Précepteur comes running across the road, white faced and agitated.

“They have caught a postman,” he says, “and torn up and scattered his letters over the forest.”

No need to ask who “they” are!

“Another postman has escaped by throwing his bicycle down by the roadside and plunging into the heart of the woods.”

No one seems to know whether the first man was killed, though rumour surmises he is injured. The point is, these encounters take place on the very road the malle-poste has to traverse.

Afraid to stay, afraid to go, poor Madame Job is in a sad plight. Finally the huge washing-basket with its moorings of cord is safely transferred to the cemented kitchen floor. The Précepteur, his wife and children, the Job-Lepouses and numerous villagers who had turned in to bid them good-bye, have a kind of second breakfast of black bread and coffee round that inevitable big black stove which I always, in my own mind, call “the peasants’” friend.

[45]

A furious fight is going on in the village street. Fists and tongues striving to outdo each other. Les Prussiens, of course. I think if the earth opened and swallowed us up we should at once attribute it to German atrocities! But this time the aubergiste is cuffing the picturesque poacher for something that gentleman has done.

“Brave garçon,” sneers a passer-by.

“Malain,” retorts the poacher fiercely.

The peasants fling themselves on the malcontents and proclaim a truce. They argue rightly that only fools quarrel in war-time.

Truth will out. There is method in the aubergiste’s madness. The poacher has confessed that he was responsible for our recent danger. Yesterday, it seems, he shot at a hare in the woods three miles away.

A slender thread of evidence on which to convict us of treason, but apparently any excuse is sufficient for these arrogant Germans.

I add my voice to the storm of eloquent advice,[46] “Tickle trout, trap hares, lay night-lines, make use of any and every device known to the poaching mind, but do not shoot.”

The culprit slinks meekly round the corner, still puffing at his curved-stem pipe. But I think he has learnt his lesson and will not be seen on the hills for some time to come....

The Uhlans are certainly a queer lot. We have ample opportunities of studying them, as they are for ever pushing forward, on their mission of patrolling the countryside. No sooner have we become accustomed to one troop and may congratulate ourselves our lives are safe, than another arrives to take its place. Sometimes they return in the evening, half without horses, or with the full complement of horses but the riders gone.

Of one patrol which went out scouting yesterday to Laroche, only the officer came back. Someone informed the French cavalry at a village near, and they cunningly laid an ambuscade in the wood at Samrée and cut them off. The greeny-grey uniform saved the German officer. He threw himself flat in the pine dust and managed to escape and make his way back to Manhay, footsore and weary. I saw him sitting on the bank by the roadside near the village last night, writing a letter to his mother.[47] He was little more than a lad. “I shall never see her again,” he said, crying. No more he will. He was killed to-day....

The Germans, though brave, seem inferior to the French in their scouting methods. Time and again small French patrols would cut them off, exercising superior finesse. One day in a skirmish outside the village, however, the Uhlans beat the French. An officer was triumphantly borne away prisoner to Werboumont. How thrilled we were at the sight of the culotte rouge. If there had only been more of them and free!

No one speaks of the men in skirts any more. The continuous stream of trains that was carrying the Highlanders into Liège have gone the way of all myths. The enthusiasm for the English is slightly on the wane. “They ought to come soon,” the peasants mutter discontentedly. “Without doubt they have their plan of campaign,” says little M. Job, who is always trusting.

Early morning and late at night is the time when we have the Uhlans mostly with us. It is nothing for them to call at 6 a.m. for breakfast, and they arrive in boisterous spirits (when they have suffered no losses) and call for beer at night.

They seem to have an extraordinary love for[48] music—or noise. They do not know in the least what they are going to war about, but most of them ask for a piano. The wheezy hotel gramophone affords them sheer delight. They must make music to-day if they die to-morrow. “À Paris, à Paris!” is the cry of the more enthusiastic, but “I’d rather be at home” is the qualifying statement of not a few.

One soldier confesses he feels the cord tightening round his neck each day. “Every advance means more danger,” says another gloomily. A third shows me his cartridge case. “Four for the enemy, one for the Kaiser,” is his pithy comment. There is an infectious air of gaiety about the frontier-sheltered lads, which is lacking in those who have once been shot over. As for the men with sad faces, it is enough to see their hands. They usually wear a wedding ring on the third finger.

The soldiers have remarkable ideas on the subject of the present campaign. Many honestly believe, and have probably been told so by their officers, that Belgium wantonly declared war on Germany. They say gleefully, “all the world is against us,” and tick off the various countries on their fingers. They simulate nothing but contempt for all concerned—except the French. Of them[49] they have a wholesome awe. Perhaps they are right. A man’s punch must have an extra kick in it when backed by three decades of hate....

“Russia! The Cossacks look fierce, but they run away,” say the Uhlans. “England. A mere handful of men. What are a hundred and fifty thousand to us.” They jerk their thumbs over the shoulders as though casting England to the deuce. “The French, yes. Terrible men, the French. But we shall win.”

I hope they will meet the English soon and get their ideas put right, as they surely will....

[50]

We no longer inhabit a cheerful Belgian village. In an unaccustomed country we must train ourselves to meet new laws. On Sunday we go to church. After service from the good Curé, M. le Directeur reads out to us a list of rules.

We must not collect in crowds, nor speak more than three in the village street.

We must not hide in the houses, but go about our ordinary avocations when the soldiers pass, or they will suspect a plot.

We must never run away—unless we want a bullet in the back—but throw up our hands when called upon to do so.

We must never do this and we must remember that, or we may expect to be bowled over as lightly as the wood blocks in that skittle alley which is the “distraction” of the Ardennois Sunday.

A German officer has frankly told us that the very smallest reprisal for any inimical act will be house-burning. Should a civilian dare to fire on[51] the German troops, well, that village may expect to be decimated of its remaining men. Besides this the Teutons do not trust our word. Twice to-day an officer has forced me to drink first from his glass of beer. The young Job-Lepouses have to do the same. A suspicious Uhlan intends to run no unnecessary risk.

No peace for the wicked! There is the air peril to contend with. A sound often heard here, like a hundred threshing machines in full swing, made me think at first that the peasants were working in the fields. The mystery is solved when glancing far, far up where sky and cloud seem to meet, an aeroplane is seen buzzing slowly overhead. Sometimes we see it near enough to recognise its white body with the black tail-planes and tips to wings. German, of course, always German. We never have any other here. I watch the machine as it begins to descend at an acute angle. A thousand feet down, it hovers for a while. Finally, it planes earthwards like some great, ominous magpie until hidden from sight in the hollow of a distant field.

“One for sorrow.”

Another machine comes sailing majestically towards us from the nebulous distance.

“Two for mirth.”

[52]

It will take us all our time to derive any amusement from these bomb-dropping fiends....

A brain-wave has passed over the village. The word “red-cross” is mentioned. M. le Directeur suggests with admirable sense that the inn should be turned into a hospital for the wounded soldiers. Wonderful the enthusiasm this idea has evoked. Extraordinary the unanimity with which it is received by the peasants.

M. le Précepteur wishes to hang a flag out of his window too. His step becomes more elastic, his expression brighter at the mere idea. This seems to him an opportune way of staving off the awful, possible hour of arrest. He is actuated, too, by that beautiful sense of compassion which makes the Belgian nature so attractive.

The burnt-out old lady is quite vociferous with joy at the prospect of nursing the enemy. It never occurs to her that she will thereby heap coals of fire on the miscreants who so basely tried to destroy her little home. At this moment she is sitting out in the potato-patch industriously picking over the flock in her mattress. The adjacent hedge is hung with odds and ends of half-burnt coverlets and clothes. I know she is scheming in[53] her generous Walloon brain how much of her slender household stock can be spared for the use of the wounded soldiers.

These flags—the great red cross on the white ground—are produced in the shortest space of time. We breathe more freely when they float out majestically from the hotel windows. We are as afire with first-aid enthusiasm as any ignorant sixteen-year-old Miss who has volunteered for the front. Every woman in the village has offered her help. She will insist on giving it too. I pity the first victim who arrives. He is likely to be pulled into a thousand pieces!

Scarcely any Uhlans have passed through to-day. Those who did were well behaved. This fact and the Red Cross flag have combined to make us quite jovial. The skittle alley is in use again. A group of villagers is gathered on the terrasse telling war-tales which would make our English fishermen green with envy.

One tale no one tells, however, out of respect to Madame Job. That is the tale of the Liège forts. We are all under a solemn pledge to believe that they are still intact. We know better. Anyone would know better after the awful cannonade of the last few days. But in our common humanity[54] we cannot bear that Madame Job should know before she must, that her Albert “in-the-forts-there-below” is dead, safe though she thought him in those forts, “the-forts-which-are-so-strong.”...

[55]

The village is parched for news. Only the black, yellow and red flag floating majestically above the Gendarmerie wall and the dull boom-boom of the cannon which, night and day, still comes from the direction of Liège, remind us that we are in Belgium, an integral part of that gallant little land. We have been without letters and papers for a week. We know nothing. Scarcely a living soul dares to find his way along the Uhlan-infested roads.

The engines of the little vicinal train are still packed away in their sheds in tidy rows. The ticket office is deserted. The workmen sit quietly at home, watching the starvation ghoul tread nearer day by day. The two-horsed malle-postes which feed the surrounding villages with letters from our central Manhay office have ceased running.

We are athirst for truth. Most would give all they possess (it is not worth much!) for just one word of encouragement about the campaign.[56] It is terrible to hear the cannon dealing out slaughter to your loved ones, to know that your houses, your food, your very lives are in hourly jeopardy, to be “in” the war and yet more ignorant of its events and trend than the people of India in all likelihood.

Yet the peasants never curse the enemy. That is the most wonderful thing. This very day I have seen a very poor villager give all the drink he had in his little house to some Uhlans whom he thought looked tired. He refused payment with indignation. It was a gift.

We are all suffering from Prussian eye. We see Uhlans everywhere. Behind the hedges, under the shade of the trees, popping out of cottage doors, springing Jack-in-the-box-like from beneath a bridge. We dream Uhlan, we talk Uhlan, we taste Uhlan. I think a fine should be inflicted on any villager who mentions the hated word more than once in twenty-four hours.

A peasant deserter has been discovered in an adjacent village. He ought to have joined the 13th Classe by rights when it was called up. Poor fellow! He has a wife and three young delicate children and is, I fancy, none too strong himself. What torture to remain there in disgrace among[57] the old men and young boys. And the penalty for him at the end is death....

Heroic M. le Directeur and his wife. I often think of them in their little country house near by. The vicinal railway which has opened up this exquisite corner of the world is due to his initiative. The peasants look to him as to a father.

His wife goes quietly about her business during this dreadful time as though there were no such thing as war. “Il faut feindre” (one must make-believe), she says to me. She does it well. No one would guess that her mother is in the burning village of Visé and the rest of their relations shut up in Liège. How hard it is for them to possess their souls in patience when loved ones are suffering so few—so very few miles away.

Like Madame Job they are thirsting for news. But unlike her they keep the longing to themselves. Madame Job has, I believe, a sneaking hope that Albert may turn up one day outside the little white-washed inn. I suspect she would rather have her beloved Albert a live coward than a dead hero.

A wire has come from Erezée, ten miles away, to say that packets of letters have arrived. A system of hand-messengers has been successful in bringing them through from Namur without[58] mishap. Who will volunteer to rush them to Manhay through our Uhlan-infested country?

The postmen refuse because of the trouncing their comrades received yesterday. M. A—— and I agree to have a try. He harnesses the hotel horse and we start off in the light spring dog-cart. Behind we have two refugees from Gouvy. They own no luggage beyond a bird-cage, so we are not over-loaded.

Gouvy is a frontier town which the Germans are fortifying in case of their enforced retreat. They have installed several regiments there and made the inhabitants’ lives unbearable. The station-master, postmaster and other civilians have been sent off as prisoners of war to Berlin after the pleasant Teuton fashion. These poor refugees are going to their parents at Barvaux, near Namur. May they find peace there as they expect. Personally I doubt it!

The drive to Erezée is uneventful. We suspect a Uhlan behind every tree-trunk but none appears. No living soul is on the road. As we enter the village street the peasants run out of the houses to welcome us. It is almost a royal progress. We realise how isolated these villages now are from one another.

[59]

A tiny Belgian flag is flying from the church at the top of the hill. Evidently the best the village could provide; it must have taken the choir, the Curé and all his merry, merry men to hoist it to its present height. As a decorative item that flag is beneath contempt. Its slender flag-pole is of such curved dimensions as to make it stick out from the belfry quite lop-sidedly. But as a moral factor it is beyond all praise....

We alight by the picturesque old pump. A crowd, including the gypsies from a travelling caravan, gathers round us anxious to hear the news.

In return they tell us theirs. One story interests me. At Hotton, near Melreux, a few miles away, the Colonel of an invading troop called on the doctor’s wife and politely asked her for the address of the Bourgmestre.

The doctor’s wife, not to be outdone in civility, sent her little girl along to show him.

In a short while the Colonel returned with the Bourgmestre in tow as prisoner.

“Where is your husband?” he demanded of the doctor’s wife.

“Out visiting patients,” she replied.

“Out when I ask for him!” shrieked the[60] infuriated officer, “I will have him shot for disobeying orders!”

This gross piece of injustice was happily not perpetrated. The Colonel graciously forgave the doctor, for, when the soldiers went to fetch him, he was found tending the German wounded with tender care....

[61]

Conventionality dies an easy death in time of war. Erezée is new to me, but in less than half an hour I have talked to more people than I do in England in a twelve-month. They all have the same tale to tell of sleepless nights, of ever-present horror at what may be at any moment. But so far they have been spared atrocities.

There is a sudden scuttle of every able-bodied person in the direction of the post office. The long-awaited post is in. An enterprising postman, “en vélo,” who has rushed them through is congratulated on every side. A crowd surges round the open window, stretching out eager hands to the clerks who are swiftly sorting the numerous piles of letters. The counter has long been appropriated by wrinkled peasants whose one anxiety is for news of the husbands and brothers who are so gallantly fighting for their rights at Liège.

Someone tears off a wrapper. The thin broad sheets of a Brussels evening paper flutter in the breeze. Old men and women, young boys and[62] girls gather round the owner with uplifted, expectant faces. Some do not know how to read, others have their eyes too full of tears. Besides, good news is so much more convincing when read aloud. The audience listens entranced. The gallantry of these Belgian troops—peasants like themselves—their valour is almost past belief! The work-worn, tired, rough-hewn faces turn to meet each other transfigured into beauty by their mutual look of pride....

We cannot, dare not wait to hear it all. The Uhlans may be here at any moment. I climb into the high dog-cart. The dépêches are put under the seat, even under my feet. I sit on a heap of them.... So does my companion. They are for Vaux Chavannes, Grand-Mesnil, all the little villages around, extending to Aywaille, twenty kilomètres away.

Carefully masking every sign of paper with a thick blue rug, we start off on the homeward journey. Not without tremors, for if we fall into the Uhlan hands anything may happen.

When we pass the last of the little cottages, and the last watching peasant has waved us farewell, I begin to fear.

Six solid miles of thick woods stretch before us[63] rolling down to the roadside on either hand. Here it was they caught the facteur yesterday. I suddenly loathe the sight of those green, feathery branches; they may cover up so much.

I glance at M. A——. His round happy face is rounder and happier than usual. He is even lighting a cigarette, though he finds it difficult, as he is trying to hold the reins and watch the horse and the woods at the same time.

Never have I seen an Ardennois without a pipe or cigarette in his mouth. I think a true son of the soil would start to light one with the death-rattle in his throat!

I imagine a dreaded Prussian behind every tree-trunk and under every bush for some miles. Then I clear my throat and ask mildly as we jog along (it would look suspicious to increase our pace):

“Supposing, just supposing we did happen to run across any Germans, and they did threaten to shoot us unless we delivered up the letters, which would you do?”

“Deliver up the letters, of course,” he says matter-of-factly, puffing at his cigarette.

I breathe a sigh of relief. After all, a whole skin is a more precious possession than much fine writing!

[64]

Providence watches over us again. As we near the beautiful avenue of fir trees which connects the Bomale road with Manhay, a peasant scout rushes out to warn us that Uhlans are ahead. We have just time to escape into a little lane.

More peasants come running up presently to tell us the road is clear. There is always the danger of being covered by field-glasses from some wooded hill, with its sequence of surprise attack, so we jog slowly along and drive into the yard instead of drawing up at the post office. Three minutes later a company of Hussars passes through without drawing rein. They are in high good humour, chattering, laughing, quite unsuspicious that the peasants they despise have been quick-witted enough to get the mails through under their very eyes!

Willing men are posted at intervals round the street and even in the fields to prevent an attack. M. le Précepteur saunters over from the post office and sets to work sorting letters in the back kitchen. It is safer there....

The dining-room blinds are drawn down, and we all collect by the little French window leading into the yard. The papers are taken round, and[65] unfolded. An enormous headline sweeps the page from end to end:

LA GUERRE VA DE MIEUX EN MIEUX.

Like most newspapers the contents are optimistic as regards their own side.

Mlle Irma reads the news aloud. She begins with the heroic defence of Liège.

As she reads, we hear the cannon booming, booming across the distant wooded hills.

To judge from the printed page, the gallant little Belgians have defeated the entire German army to a man. Several regiments have already covered themselves with imperishable glory, notably the 11th and 14th Foot. Albert is in the 14th.

A man named Desmoulins has rushed out of a fort and slain four Germans with his own hands before darting back safely to shelter. The enemy’s losses are enormous. I notice that in war they usually are. The Belgian casualties are described as so small that they are, seemingly, scarce worth mentioning.

“The chief losses,” reads Mlle Irma in her clear, pretty voice, “were sustained by the 11th” ... a slight pause quickly slurred over, “and the 32nd.”

[66]

“And the names!”

“There are no names as yet,” she returns quietly and goes on with the notes of a speech, “ce cher monsieur Askveeth,” had delivered in the English parliament only yesterday.

But Madame Job is not to be deceived. “It was the 14th which has been so cut up,” she says, putting up her apron to her eyes and beginning to cry again. “I know Albert is dead. Mon pauvre Albert in that terrible Liège!”

“Don’t fuss, Maman,” says M. Alfred the peacemaker. “It will be all right now the men in skirts are there....”

[67]

Friday.—Two men of the Brandenburger Cuirassiers come into the inn before breakfast. I am brought forward, as usual, to interpret. The shorter of the two, a square-jawed, swashbuckling kind of fellow, demands hay. I reply with superb mendacity, “We have no hay.” He follows this up with enquiries as to the disposition of the enemy. My face becomes vacant, my German resolves itself into a fluent mass of unintelligible sounds.

Woe is me! At that moment the door into the yard opens, and M. Alfred is seen crossing the clean wide space, bearing stablewards half a hayrick on a long pitchfork.

The Cuirassier gives a growl, thrusts his pug-nosed, underbred face almost into mine, and lands me a blow that knocks me up against the wall.

“Isn’t that hay?” he asks fiercely, pointing.

“Hay, but for us,” I answer calmly.

“You lie!” He prods at my left shoulder with[68] his bayonet, but he either fears to strike hard or the padded arrangement worn under my dress with a view to such contingencies does its work well. My wound is nothing but an abrasion of the skin.

The swashbuckler swaggers into the yard and coolly appropriates the hayrick. His friend, a gentle-faced, blond giant looks down at me with regret.

“You need not fear. I will see that you come to no harm. My friend there is a wild fellow,” he murmurs apologetically.

“Fear. Ich bin Engländerin,” I answer simply.

He laughs. “You are as brave as your brave little army. But—such a mere handful of men. How can it stand up against us!”

The swashbuckler returns. They leave the inn together and later appear before the Gendarmerie with the weird medley of weapons which every cavalryman seems to carry. They hammer at the stable door. It is smashed and their horses feeding in the empty stalls in less time than it takes to relate. Their next step is to batter at the door of the Gendarmerie itself. I go to the back of the house whence a narrow window commands a view of the place. Perfidious people! They have no[69] respect for the sanctity of home. The Commandant’s little treasures are quickly found. They run from room to room, opening drawers and rummaging through the contents, even overturning furniture. One man gets hold of a pile of letters, tied with ribbon. Love-letters perhaps.

Downstairs they go and bring up a ham, bread, some wine. A “pique-nique” in war-time is huge fun. They thoroughly enjoy their impromptu meal in the back bedroom. The remains of food are left scattered about the uncarpeted floors; some of it is trodden carelessly under the soldiers’ feet.

Everything is tossed about as green hay in the harvest field. The very sheets are torn from the beds and lie in little white ghostly heaps on the dark-stained boards. The Brandenburgers come out into the street where a row of stalwart bayoneting Cuirassiers are keeping order. My nice blond giant has a huge cigar between his teeth, the Commandant’s cigar, so has my swashbuckling bully.

They both lunch at the inn and fall to as if they had had nothing to eat for the last ten months. I am made to translate and can scarcely speak for anger. I suspect them of every crime.

[70]

Saturday.—The blond giant comes in at all hours. Everyone in the village likes him now in spite of his behaviour at the Gendarmerie. He seems gentle, mild-eyed and very courteous. We have been used to different treatment. He arranges everything so nicely, too. For instance, he begs us all not to put our noses out of the houses after twilight, under any pretext. “I can’t bear to think of your being frightened; my sentries might make a mistake,” he says, smiling pleasantly. The poor literal peasants don’t see that this is an euphuism for shooting us on sight. Orders, no doubt.

Sunday.—I get up early and go to Mass with Mlle Irma, having first obtained permission from the soldiers. We walk along the sides of the road, under the shadow of the trees, a wise precaution these days. Osterre chapel is packed to the doors. I have a curious feeling that those paint and plaster saints high up on their little pedestals are alive. St. Antoine’s nose looks longer and more pinched than ever, and he is gazing down as though ashamed to be of so little use to us in our hour of need. St. Christopher is mild, so is St. Joseph; the Madonna seems to smile at us with a modest kind of shrinking sympathy across pots of flaming geraniums.

[71]

Osterre chapel is packed. The sheep-and-goats division of the sexes appears to obtain in the Ardennes. The women’s side is over-crowded. We could hang out “standing room only” and be merely truthful. The men’s scarcely less so. All the women are as scrupulously neat in their Sunday silk blouses and flower-trimmed hats as though they had never heard of such a thing as war. One or two of the black-bonneted old peasants are making their rosaries damp with tears. I can see the beads, so brightly reflected against the polished wooden seats, shaking a little. At the end of the service, a box like a newly opened sardine tin, at the end of a long pole, is thrust before me by a tiny acolyte. Then we rise and go home comforted. We have shifted the burden of our troubles to other—wiser shoulders.

[72]

The Tax-collector is resting here for a few hours on his way home. He has brought with him his son, who looks dead tired with his twenty-mile walk. The lad’s luggage has all been left behind. But Aywaille was too near Liège to be safe. The Tax-collector will be glad to reach his journey’s end.

“All day long yesterday I watched the German troops march through the town,” he tells me. “It was pitiable to see those columns of splendidly equipped men, simply dropping from fatigue. Some could scarcely put one foot before the other.”

“They are our enemies.”

“My sister stood in the street for hours, refilling buckets of water from which the exhausted men swilled their necks and arms. She cut them tartine after tartine until all our bread was gone and she could hardly stand herself.”

“They are probably going down to shoot the peasants’ fathers, sons and brothers in Liège,” I remark coldly.

[73]

“From my sister’s point of view, they are suffering and they are men. That is enough....”

Compassion is evidently a Belgian vice!

Even Madame Job is breaking out in an unexpected quarter. She is satisfied for the moment as to Albert’s safety, so I am surprised to find her this evening occupying her favourite position on the lowest step of the kitchen stairs with her blue check apron over her head.

Spasmodic snuffles under the cotton screen warn me what to expect. I gently pull down the covering and stroke her face.

“We shall win,” I say consolingly.

At this Madame breaks down completely.

“Win? The poor, poor Prussians will be killed, all killed. There was one so young to-night, with eyes so sad.” (Snort and snuffle.) “Have they not also wives and mothers who will mourn their loss?”

I find no words in which to confute this obvious truth.

Madame soon revives. In her careful Walloon brain she has conceived what she calls “un plan.”

“If I care for the Prussians” (I know she is hoping that heaps and heaps will be brought in from the battlefield to test her word), “perhaps[74] they will care for my Albert should he be wounded in the forts there below....”

I do not dare to tell her that the Belgians have themselves blown up the Chaudfontaine forts and that her beloved Albert is doubtless numbered with the dead....

[75]

One of the Uhlans is quite communicative to-day. He shows us how the patrols are worked. It is very interesting, but far too red-tapey. “In twenty minutes,” he says, “I can summon a hundred and twenty Uhlans to my aid.” To get them, however, he has to write on his cross-barred paper his name, position, date, hour, regiment and extra details. This human document he places in an envelope which also has to be addressed and endorsed with date, hour, name, etc. Business-like but slightly superfluous when the enemy’s patrols are almost on you. I pity the Uhlan deputed to take the message.

The Cuirassier is in a soft mood this morning. He comforts Madame Job with the assurance that no great battle can take place in the Ardennes, where the wooded hills and valleys are ill-suited to such a scheme. He ridicules our idea of hiding in the woods as being a fatal plan for escaping the Germans. “You would be found and dragged out in a moment,” is his reassuring statement. Later he turns to me.

[76]

“You do not fear the Germans, Fräulein?”

All the Uhlans ask me that. They seem so amazed that we do not scuttle like rabbits at their approach.

“No, I am not afraid,” I answer.

“But you are in more danger here than my brother who is a prisoner in Russia,” he persists.

I translate this to the family of Job, who all tearfully implore me, as they have done a hundred times in the last week, to disguise myself as a peasant and pretend to be one of them....

It seems a skulking thing for a Britisher to do. I can’t face it.

“You see, Fräulein, there are many spies. They have shot women as well as men before Liège. There is short shrift for spies in war-time. You are alone too. So much the more suspicious.”

“I must take my chance.”

“Stay in your room then.”

Stay in my room, indeed, when ten, twenty times a day my help is sought in smoothing over difficulties, interpreting orders for the enemy or the peasants. A likely plan!

A Cuirassier speaks of himself and the family he never expects to see again.

“My five brothers are all serving in the army,”[77] he says, “the sixth is a prisoner in Russia. My two sisters’ husbands are soldiers too. My father an engineer, aged sixty-five and in weak health, has also been compelled to come forward and serve his country. My mother was like that when we came away,” he passes the back of his hand across his eyes.

I begin to pity the German women nearly as much as I pity the Belgian peasants. But then the former have suffered no atrocities—as yet.

[78]

One day I ask the Cuirassier why he has no markings on his shoulder straps. He coughs, blushes, then unbuttons one and turns it back to show a large N. surmounted by an Imperial crown embroidered in blood red.

“The Czar was our Colonel, Fräulein,” he says, in the horrified accents usually reserved for the mention of the Prince of Darkness.

The fact does not seem to me so awful. I hide a smile.

“Many of the men tore the straps off their uniforms before they would go on active service,” he says seriously.

I ask him why he is such friends with the swashbuckler.

“One does not choose one’s comrades in war-time, Fräulein.”

He brings out a map which seems to have every fir tree and blade of grass in the country accurately described on it and draws his finger along the page until he comes to Namur.

[79]

“The French have blown up every bridge over the Meuse.” He indicates the length of the river between Namur and Liège. “We shall build them again.” He goes on to tell me facts about the countryside which I thought only the peasants knew.

The network of patrols with which Germans enmesh the country so far in advance of the body of the army, seems to have done its work well.

I translate to the Job family, who listen amazed.

The Cuirassier tries to pump me, very deftly, very innocently.

“Have you heard anything of the number of French in Namur. Have they been strengthening the defences there during the last two weeks. Is it true that their food supply is inadequate to the needs of the town?”

It is amazing how obtuse I suddenly become. I forgot that the Job-Lepouses have dinned into my brain for the past fortnight the pleasing legend that a hundred and forty thousand Frenchmen, not to speak of Belgians, are defending Namur, and that every other tree in the country side has been cut down to pile up barricades. I swear I have no knowledge of the (possibly[80] true) assertion that the avant-garde of the French troops, two hundred men and officers, are at Laroche. I am duller witted all of a sudden than the village idiot who has, by the way, refuted the charge of idiotcy by keeping mostly to the fields since the Germans came.

Some infantry, I think they were Landwehr, on guard here to-day, were quite distressed at the sight of weeping women and children. Later in the day a little deputation of them waited upon me at the inn. “Would you please go round the village, Fräulein,” they said, “and tell the women and children that we mean them no harm? Have we not wives and children too?” One of them opened his wallet or pocket-book and showed me the photo of a pretty curly-headed German child. Needless to say, I did go round and reassure the people. The result was that the Landwehr were the richer that evening by the peasants’ last pots of appetising home-made jam.

I have to go into the bar and translate in my bad[81] German for the soldiers. Yesterday some of the Uhlans’ horses, picketed in the village street, put their heads through a front window of the inn. I was called in by both sides to assess the damage. It was rather embarrassing, especially as I had to make out the account in greasy German coin! The Uhlans paid up at once, as usual, but the tender-hearted hotel-keeper refused to ask anything approaching the value of the window. The soldiers are annoyed with me sometimes for not being able to procure them special kinds of German beer. Cognac is the drink they love, but the officers have particularly ordered they shall not be served with it.

This business of barter and exchange is often very trying. I had a terrible transaction to-day with a Prussian non-commissioned officer over a box of cigars. It nearly turned my hair grey! We ultimately sold it him for a franc. Anyway, I feel proud to have done my share towards the annihilation of the enemy. A few drops of Prussic acid would have been wholesome by comparison!

[82]

Monday—Notices have now been posted up in all the Belgian villages that, since the Belgian civilians, both men and women, have shot at the Germans and even killed their wounded, anyone who offers the slightest resistance will be at once shot down. The house to house search for arms is rigorously prosecuted. A man in the village is shot to-day. He was working in the fields and ran away instead of facing round and throwing up his arms when challenged.

In one village, so the Germans themselves tell me, they have shot twenty-nine men out of thirty-four. They assert that their soldiers were fired on as they entered the street.

The Kaiserliche regiment is encamped at Malempré, a mile away. They have taken an ox and one or two sheep and roasted them whole. They have also forced the peasants to dig up their own fields of potatoes for the soldiers and stood over them to ensure the order being carried out at once. The Germans give a bit of paper, in[83] exchange, a governmental I.O.U. redeemable at the end of the war ... if there is an end and the peasants are alive to see it!

“All will be paid,” says an orderly complacently, as he triumphantly carries off our last fresh eggs. But what is the use of German money or governmental I.O.U.’s when one cannot reach the town for fresh supplies.

“All will be paid.” What a mockery! Stay. They are right. All will be paid. With more than money. With blood and treachery and women’s tears....

I sat up all last night as usual. Paraffin and candles have long given out, but luckily there was a thrice-blessed moon. In the queer half-light, the sentries looked like so many demons pursued by their own shadows. Soldiers were sleeping all about the hard cobblestone street as though lying quietly in their beds at home. Only the Cuirassiers under my window kept up a constant noise. Their horses, too, were stamping and moving continually in the stables as though anxious to get away.

This morning I ask one of the more kindly-disposed soldiers if he is not afraid of death.

“I must do my duty,” he says simply. “But I feel the cord tightening round my neck each day.”

[84]

He looks pale and pinched, as though disease, not rifle fire, would be his end.

“I was out scouting in the woods last night, Fräulein,” he tells me later. “It is so cold, so eerie, and then one only gets a couple of hours’ sleep when the dawn comes. There are horrible things in the woods, Fräulein—shapes and monstrosities. The pine dust powders under the horse’s feet and the green boughs go “swish” in one’s face just as one turns on the electric torch, thinking to have spotted a rascally Frenchman——”

“—And you did?” I asked breathlessly.