IF YOU FIGHT, FRED, I SHALL SUSPEND YOU

Title: The high school rivals

or, Frank Markham's struggles

Author: Frank V. Webster

Release date: July 30, 2023 [eBook #71306]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Cupples & Leon Company, 1911

Credits: David Edwards, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Or

Fred Markham's Struggles

BY FRANK V. WEBSTER

AUTHOR OF "THE BOYS OF BELLWOOD SCHOOL," "THE NEWSBOY PARTNERS," "THE YOUNG TREASURE HUNTER," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1911, by

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

Printed in U. S. A.

BOOKS FOR BOYS

By FRANK V. WEBSTER

ONLY A FARM BOY

TOM, THE TELEPHONE BOY

THE BOY FROM THE RANCH

THE YOUNG TREASURE HUNTER

BOB, THE CASTAWAY

THE YOUNG FIREMEN OF LAKEVILLE

THE NEWSBOY PARTNERS

THE BOY PILOT OF THE LAKES

TWO BOY GOLD MINERS

JACK, THE RUNAWAY

COMRADES OF THE SADDLE

THE BOYS OF BELLWOOD SCHOOL

THE HIGH SCHOOL RIVALS

AIRSHIP ANDY

BOB CHESTER'S GRIT

BEN HARDY'S FLYING MACHINE

DICK, THE BANK BOY

DARRY, THE LIFE SAVER

"Nineteen hundred and twelve to the top steps! We're Second Form now! Top steps belong to the Second Form!" shouted four boys, redolent with health and life, as they dashed up the tree-lined walk leading to the Baxter High School, mounted the lower steps, and threw themselves into the coveted positions.

It was the opening day of school, and the spacious, shady grounds were alive with happy, wide-awake boys, and merry, laughing girls, renewing old acquaintances and closely scrutinizing all newcomers.

As the rallying cry rang out, other members of the Second Form broke away from those with whom they were talking and hastened to join the four leaders whom they hailed by the nicknames of Taffy, Soda, Lefty and Buttons, reminders of past exploits.

With envious glances at the proud Seconds, the Lower Form scholars gathered at the foot of the steps, eager to witness any fun that might transpire.

Conspicuous among them was a tall, thin boy, who carried a large bunch of books under his arm.

"Is that the meeting-place of the Second Form?" asked this lad, of the one nearest him.

"Uhuh."

"Thank you. I think I will join them."

"You'd better n——" began his informer, but before he could finish his warning, a hand was clapped over his mouth and warm lips whispered in his ears, "Let him go. He must be taught respect for the Upper Forms. Wait till Soda sees him."

Interference was now too late, had the Lower Form boy wished to finish his advice. For no sooner had the newcomer emerged from the ranks of the others standing at the foot of the steps than a girl, brunette, and very pretty, nudged her companion, who, though just as attractive, was of the blonde type, and giggled:

"Oh, Grace, look at that coming up the steps!"

This exclamation, being audible to the others, all the boys and girls turned their eyes in the direction of the new student, and watched his approach in a silence portentous in its intensity.

Even the newcomer felt its significance, and, as he reached the fourth step from the top, paused, hesitatingly.

Taking advantage of his evident embarrassment, the lad nicknamed Soda, making his voice very deep, demanded:

"What dost thou wish, Clothespin?"

The nickname was so appropriate that the boys and girls roared with laughter, adding still more to their victim's discomfiture.

Twice he cleared his throat, but the grinning faces of the boys and the mischievous eyes of the girls stifled his words and sent hot flushes to his cheeks.

"He's mine! I saw him first!" exclaimed another of the Second Formers, noting the newcomer's embarrassment. "Now, Clothespin, what is it you desire? Speak, or forever hold your tongue."

To the new student, the bantering seemed terribly real, and, after gulping several times, he stammered:

"Is this the Second Form?"

"Yea, verily, Clothespin, this is the Second Form—that is, the best part of it," returned Soda.

But if the students had been amazed by the newcomer's temerity in mounting the steps, they were dumfounded by his reply, as he bowed gravely:

"I am glad to meet you all. My name is James Appleby Bronson. I have passed my examinations to the Second Form."

An instant the students on the top step gazed from their new member to one another, then Soda arose, and, with a mocking wave of his hand, bowed low and commanded:

"Second Formers, rise and salute your fellow member, Mr. James Appleby Bronson, called Clothespin for short."

As though moved by a spring, the twenty-two members of the Second Form stood up and chorused:

"Welcome, Clothespin."

"Then I can sit with you?" asked the newcomer, looking toward Soda.

"You can sit on the top step, there by the railing," replied the leader, pointing to a place at the opposite side of the porch. "There are a few formalities to be settled before you can be really one of us."

Relieved that his torture was over for the moment, yet wondering what the "formalities" could be, Bronson started to take the seat by the rail, when the lad called Taffy exclaimed:

"Where are your credentials?"

"Credentials?" repeated the new student in surprise.

"Yes, your credentials. Didn't the Head give you a card?"

"Why, no. Mr. Vining said all I need do was to meet my instructors and enroll in the classes."

"It was very wrong in the Head to misinform you," began Taffy in mock solemnity, when he was interrupted by a voice shouting: "Here comes Bart Montgomery!"

Instantly cries of welcome greeted the announcement, and in the confusion Bronson was forgotten.

Glancing at the boy whose arrival had spared him further badgering, Bronson saw a tall, lithe fellow, with dark-hued, handsome face.

"Who is Montgomery?" he asked of the boy next him.

"What, you coming to Baxter and don't know Bart Montgomery?" returned the other. "Don't let anybody else hear you say so. He made the hit that won over Landon School last spring—the first time in four years. He's the best baseball and football player at Baxter, that's who Bart Montgomery is."

"No, he isn't, either," interposed another boy.

"Who's better?" demanded Bart's champion.

"Fred Markham."

"Don't you believe him, Clothespin!"

"Well, I don't know about his athletic standing, but I do know I don't like Mr. Montgomery's eyes," rejoined the latter; "he can't look you in the face."

This dispute had passed unnoticed in the welcoming of Bart. As he took his seat in the center of the Second Form students, Lefty exclaimed:

"Now we're all back."

"Not yet," returned Buttons.

"Who's missing?"

"Fred Markham."

"Oh, he'll not be back," sneered Bart Montgomery.

"Why?" chorused several of the boys, while all the others gathered closer.

"You know his father failed, don't you?" demanded Bart.

"Sure," said Buttons, "but how does that affect Fred?"

"He can win the Second Form Scholarship in Science—that'll give him cash enough, if he's short of money," protested another.

"Oh, it isn't lack of rocks that will keep him away," asserted Bart contemptuously.

"Then what will?" persisted Buttons.

All the former students who had returned to Baxter were aware that a rivalry had sprung up the previous year between Fred Markham and Bart Montgomery, due to the former's increasing ability, both in his studies and in athletics, which threatened to wrest the Form leadership from Bart. But they had supposed it to be an honest, schoolboy rivalry, and the tone in which Bart spoke of Fred surprised them.

As both boys were popular, they had many followers among their own and the Third Form students, and unconsciously these divided, Fred's supporters gathering about Buttons, who was championing their absent leader, the others about Bart.

Noticing that he had by far the most numerous following, Bart's pride got the better of his discretion and he retorted:

"If you want to know so much, I'll tell you. You know some men fail in order to make money."

"You mean Fred Markham's father failed dishonestly?" demanded Buttons.

So pointed was the insinuated accusation that, young people though they were, the other students realized its seriousness, and with solemn faces awaited Bart's reply.

The attention of all the scholars hanging upon the answer, none of them had noticed the approach of a well-built, manly young fellow, whose open, honest face and frank blue eyes were in striking contrast to the crafty, though handsome, features of Bart. As a result, the late-comer had reached the edge of the crowd just as Bart exclaimed:

"That's just what I mean. My father was the principal creditor. So I guess I know."

At these words there was a sharp intaking of breath by the divided groups, and Buttons retorted:

"I don't believe it. Fred Markham's father is an honest man."

"Thank you, Buttons," exclaimed a strained voice.

At the words, all eyes were turned in the direction whence they came, and as the boys recognized the speaker, shouts of "Here's Fred! Hello, Cotton-Top! Now say that to his face, you Bart!" filled the air.

"Who said my father was dishonest?" demanded Fred.

"Bart did!" chorused several.

Striding to where the calumniator stood, Fred looked straight in his face.

"Did you say my father was dishonest?"

But the accuser did not have the courage to say in the presence of the son what he had said in his absence, despite the fact that he overtopped Fred by a good two inches, and temporized:

"I said there was something queer about your father's failure. My father said so."

"You are right, Bart Montgomery. There was something 'queer' about it—but not on my father's side!"

"What do you mean?" snarled Bart.

"Anything you want to think," returned Fred.

Drawing back his right hand, Bart hissed:

"I'll teach you to say things about my father, you puppy! Even before yours failed mine could buy him and sell him."

"Because your father had more money doesn't make mine dishonest," retorted Fred, squaring himself to ward off the expected blow.

But before it could be delivered, a stern voice exclaimed:

"Boys, what does this mean?"

"The Head! The Head!" gasped several of the onlookers, and like magic the crowd of students melted away, leaving Mr. Vining, for it was the principal of the school, with Fred and Bart. A moment he gazed from one to the other of the lads.

"Second Formers should set an example of good behavior, not bad," he said. "Bart, come to my office at once. Fred, I shall expect you at the end of thirty minutes."

From behind trees and other points of vantage, scores of eyes had watched the headmaster, as, silent and with the gentle dignity that endeared him to his students, he entered the school building, followed by the unwilling Bart.

The town of Baxter would never have been distinguished from countless other prosperous country villages had it not been for the High School. And Mr. Vining's personality had made that institution what it was—the best in the county.

Never for an instant did the headmaster forget that he had once been a boy himself, wherefore he had been able to look with indulgence upon the harmless pranks of the lads and girls under his charge. It had been his good fortune to attract assistants who held the same general ideas, and, as a result, the one hundred and twenty pupils in the school were more like a big, happy family than anything else.

For the most part, the students lived in Baxter, but each year saw more and more scholars come from other towns.

Due to his understanding of young people, Mr. Vining had established the policy of allowing them to settle their differences themselves, only interfering in cases of unusual seriousness.

But fighting in public was tabooed—and because they knew this, the students had fled when his unheralded arrival had put a stop to the quarrel between Fred and Bart.

No sooner had he disappeared within the building, however, than the scholars emerged from their hiding places.

Swarming about Fred, they looked at him like one about to receive condign punishment.

"You're a nice one, you are, to get Bart in trouble on the very first day of school," came from the lad called Taffy.

"Then he shouldn't have said such things about my father," retorted Fred.

"And he called you a puppy," chimed in another.

"It isn't a nice word, but it doesn't seem to me as mean as saying such things about Mr. Markham," asserted the new Second Former to his neighbor.

"It don't, eh?" ejaculated the other. "Well, it's a good deal worse. 'Puppy' is the fighting word at Baxter."

Fortunately for Bronson, his remark had not been heard by any except the boy next him, or he would have been drawn into the wrangle which was growing serious again as Taffy exclaimed:

"Fiddlesticks! I'll bet you saw the Head coming or you'd never dared to face Bart. You know he can whip——"

"You know better than that, Taffy Brown," rejoined Fred, flushing at the charge.

"Besides, Bart can't whip Fred," interposed Buttons.

"He can't, eh? Bart Montgomery can whip any boy in the Second Form, and all but Sandow Hill in the First," returned Taffy.

"Guess again," derided several of Fred's followers.

"I'll go sodas for the entire Form that Fred can lick Bart!" Soda exclaimed.

The size of the wager for a moment dampened Taffy's ardor, and he growled:

"If Fred wanted to fight Bart, why didn't he wait till after school?"

"I'll tell you why, Taffy Brown," retorted Fred hotly. "I'm not going to stand by and let any one make such a statement about my father, no matter where it is or who is 'round."

These words, backed by the defiant determination expressed by Fred's face and attitude, brought a cheer from his supporters, while Bart's howled in derision.

"If you think I am afraid of Bart, I'll fool you!" exclaimed Fred, flushing. "I'll meet him to-night at seven, at The Patch."

"And I'll wager sodas for the Second Form, girls barred, against Taffy!" cried Soda.

"I'll just go you, but it's a shame to take your money, Soda. You'd better have any one who believes in Fred chip in, so you won't have to lose so much; sodas for ten Seconds will cost one dollar."

"Which you will have to pay," rejoined Fred's champion.

"Hooray! Here's Bart now!" shouted somebody who had seen the boy emerge from the building.

Instantly all eyes were focused upon the tall form of the boy who had just left the headmaster, while many were the surmises as to what had transpired at the interview. As Bart drew near, the scholars noticed that his swarthy face was flushed.

"I'll bet the Head gave him a fierce trimming," whispered Soda. But his remark was lost in the babel of voices that demanded to know what Mr. Vining had said.

Bart, however, was in no mood to gratify their curiosity, and, with only unintelligible mumbles in response to the questions, stalked moodily away among the trees, looking neither to the right nor to the left.

"My eye! but the Head must have scorched him!" commented Buttons.

"Well, he ought to," asserted Soda.

"It was Bart's fault, anyway. He had no business to——"

The opinion was never expressed, however, for suddenly a voice called:

"Fred, why don't you come to me when I send for you?"

And turning toward the direction whence it came, the boys beheld the headmaster standing on the porch of the building.

"I didn't know you had sent for me, Mr. Vining," responded Fred, pushing aside his fellows. "I thought you did not want me for half an hour."

"I asked Bart to tell you to come right in."

"I didn't hear him, sir. I am sorry."

"That shows just how white Fred is," declared Buttons vehemently. "He wouldn't say Bart didn't tell him—just said he didn't hear him."

"And it shows how mean Bart is," added Soda.

Regardless of their support of the two leaders of the Second Form, Baxter boys and girls were noted for their love of fair play, and this exhibition of pettiness by Bart surprised them into silence, which lasted until the headmaster and Fred were lost to sight within the school building.

Mr. Vining's office was on the right of the hallway, near the entrance, and although it was tastefully furnished, so intimately associated was it with reprimands and explanations that none of the scholars ever noticed how comfortable and attractive it was.

Pointing to a bench, the headmaster indicated to Fred to be seated, and himself dropping into a Morris chair, he studied the boy's face a moment before saying:

"Did I understand you to say that Bart did not tell you to come to me?"

"I said I did not hear him, sir."

"But you would have, had he done so?"

"The boys were calling out to him, so I couldn't hear very well."

"You're the same Fred, aren't you?" smiled Mr. Vining at the boy's refusal to implicate one of his fellow students. "Now tell me how the trouble started."

"I can't, sir!"

"Why?"

"Because I was not there when it began."

But Fred did not hesitate to describe his own actions.

"I'm sorry," commented the headmaster, when the recital was finished. "I'm afraid you will be obliged to hear a good many unpleasant——"

"But my father is not dishonest," interrupted Fred.

"It is natural for you to think so," returned Mr. Vining noncommittally. "As I said when I came upon you and Bart, you Second Form boys should set an example by obeying the rules. You know fighting in front of the school is forbidden, don't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then why were you going to?"

"Because I shall defend my father's name anywhere, Mr. Vining."

"H'm! Baxter rules are made to be obeyed, Fred. To prevent a recurrence of this morning's scene, I must ask you to give me your word not to fight with Bart."

"I can't, sir."

"Why?"

"Because when the boys said I only stood up against Bart after having seen you coming——"

"Is that true?" interrupted Mr. Vining.

"No, sir. I was too busy watching Bart to see any one else."

"H'm. Go on."

"I said I would fight him to-night at seven."

IF YOU FIGHT, FRED, I SHALL SUSPEND YOU

Several minutes the headmaster gazed at the serious, manly face of the boy before him, then said:

"If you fight, Fred, I shall suspend you. Now you may go."

It was with lagging feet and heavy heart that Fred left the office of the headmaster.

Bart's aspersions on his father had hurt him deeply, and Mr. Vining's refusal to agree with his own opinion of his parent's honesty had surprised him. But the deepest cut of all was the threat to suspend him should he fight with Bart. If he obeyed the headmaster, he knew all too well that his fellow students—that is, all except Margie—would attribute his action to fear of Bart, and he was also familiar enough with the nature of his rival to realize he would lose no opportunity to twist events to his own advantage.

Such a combination of circumstances was enough to perplex an older head than Fred's, and as he descended the steps, he felt a keen resentment against the headmaster for placing him in such a position. It was with relief, however, that he saw Margie had drawn the other girls off to a spot where they would be out of earshot, for he dreaded their scrutiny more than the rough comments of his fellows.

"He looks as solemn as an owl," exclaimed Buttons, who with Soda and his other staunch supporters had been awaiting his coming.

"The Head must be in a fierce frame of mind to-day," commented another.

"No wonder, with Fred and Bart getting into a mix-up at the very opening of school," returned Soda.

"Well, let's show Fred we intend to stand by him," exclaimed Buttons.

This suggestion met with ready response, and, with a rush, Fred's adherents gathered about him.

"Get a trimming?" queried one of them.

"Worse than that," responded Fred soberly. "I can't defend my father and myself against Bart."

"Whe-ew! How Bart and his crowd will crow!" lamented Soda. And from the expressions on the faces of the others it was evident he had voiced their sentiments.

"But why can't you? What did the Head say?" demanded Buttons.

Eagerly the others looked toward Fred.

"I will be suspended if I fight."

"Jumping grasshoppers! but that is a bad one!"

It had been the proud boast of Baxter that never but once had a student been suspended, whereas in the rival school of Landon suspensions were of almost yearly occurrence. The boys grew silent in the contemplation of the penalty.

It was at this juncture that the First Form students, led by Sandow Hill, reached the steps. With the majority of them Fred was a favorite, and as they noticed the serious expressions on the faces of the Second Form boys, several of them asked:

"What's the trouble? Why so glum, Cotton-Top?"

"He and Bart had a row. The Head came along, and now he's threatened Fred with suspension if he fights Bart," poured forth Buttons, going into details in reply to further questioning.

"Fred ought to be thankful," exclaimed one of the girls. "That big bully would make mincemeat of him."

"You girls go along into school," snapped Sandow. Then, turning to Fred, he asked: "Was there any limit set to where you couldn't fight?"

"Why, no," returned the boy, puzzled by the question.

"Then cheer up," laughed the leader of the First Form. "So long as the Head didn't set any specific limit, you can have your go with Bart anywhere not on school grounds."

This solution of the problem elicited shouts of approval from Fred's followers, but the boy most concerned did not share in the glee.

"I don't think that would be honorable," he interposed. "Mr. Vining said he would suspend me if I mixed it up with Bart."

"But he can't control your actions off school grounds," asserted Hal Church, another First Former.

The tone in which the words were uttered, together with their implication that Fred was not any too anxious to meet his larger rival, produced just the effect Hal had intended.

"I told Mr. Vining I would defend my father's name anywhere," flashed back Fred. "And I will. What he said to Bart, I don't know. But if you can persuade Bart to be at The Patch at seven to-night, I'll show him I'm not afraid of him."

"If we can persuade him?" ejaculated Taffy, who had joined the group just in time to hear Fred's challenge. "Say, it's all Lefty and I could do to keep him from coming back to have it out with you right here now."

"Good. Then have your man ready at seven, Taffy. Buttons, you have Fred on hand. I'll referee the go. Mum's the word. I'll make life unhappy for the boy who carries word of this to the Head," declared Sandow.

"Don't worry about us," asserted Buttons, while Taffy sneered: "You'd better have a doctor handy—or an ambulance. Fred'll need 'em."

Just then the ringing of the bell, calling the scholars to the general assembly room, made the boys forget the quarrel, and, trooping into the building, they took the benches on the right side, while the girls sat on the left, all facing the platform where the Head and his three assistants were seated.

After a short prayer, Mr. Vining welcomed his former students back, and then dilated upon the ideals of Baxter, laying particular stress upon submission to rules. At this reference to obedience, the boys looked at Bart and Fred, and many a face broke into a grin.

"And now we will have the drawing of desks," announced the headmaster, concluding his words of advice, and reaching for a box, into which he dropped some square pieces of paper. "As you know, the First and Second Forms sit together in Room one, and the Third and Fourth Forms in Room two. The three back rows of desks belong to the First and Third Forms, respectively.

"First Form, come forward. The numbers on the cards indicate the desk you can call your own for this school year. Miss Ayres, you may draw first."

Quickly the girl stepped to the platform, thrust her hand into the box, drew out a piece of paper and handed it to the headmaster.

"You have drawn number three, Miss Ayres. Church, you are next."

Rapidly the First Form made their drawings, and then more slips were placed in the box for the Seconds.

"I think we might be allowed to select our own desks," grumbled Bart, and, as the possibility of the two rivals drawing adjacent desks was thus suggested, the others became all attention.

Though he gave no indication of the fact, the headmaster had overheard Bart's remark, and for that reason called Fred to make the first selection, announcing "seventeen" as he read the slip the youth handed him.

"That's the best desk in the Second Form section," whispered several of the boys, while Buttons and Soda patted their chum lovingly on the back when he returned to his seat between them.

As one name after another was called, Bart became more and more glum, his sober face evidencing that he felt slighted at being compelled to wait.

"There's Clothespin, the new boy," murmured Soda, as Bronson walked awkwardly forward. "Wouldn't it be rich if he drew a better desk than Bart?"

"Eighteen," announced Mr. Vining. And the allotment proceeded till only Bart was left.

Eagerly the students had listened as one number after another was called and such close attention did they pay that it was not necessary for them to hear the figure "thirty-three" read to know that the only desk remaining for Bart was in the front row.

"I won't sit there!" growled the rich lad, as the fateful number was announced. "If a newcomer can force me into the front row, I'll do my studying at home."

"That is not the Baxter spirit, my boy," chided the headmaster. "You had an equal chance with the rest. Furthermore, it is very impolite to Mr. Bronson."

"I don't care. I won't sit way up front," retorted Bart, his ungovernable temper making him regardless of consequences.

This challenge of authority drove the kindly expression from Mr. Vining's face, and he cleared his voice to speak when Fred stood up, exclaiming:

"Montgomery can have my desk, and I'll sit up front."

"Thank you, Fred. Bart, because of Fred's sacrifice, you can have number seventeen. Bronson, I regret you should have suffered such rudeness at the hands of any Baxter boy."

This open rebuke to the haughty Bart delighted Fred's champions, and when the desks for the two other Forms had been assigned, they gloated over it as they filed outdoors.

In passing out it so happened that Fred and Bart were brought face to face.

"Grand-stand player!" hissed the bully.

"I don't play to grand stands, and you know it, Bart Montgomery. I was only thinking of the honor of Baxter," retaliated Fred.

"A Markham talking of honor," rejoined Bart.

Unknown to the boys, Mr. Vining had come up behind them, and, as he heard the bully's unkind words, he said:

"Fred, you may forget what I told you this morning."

To Fred the lifting of the ban against his defending his father's name seemed the solution of all his troubles. In his joy he forgot to thank Mr. Vining, and when his remissness occurred to him he saw the form of the headmaster just entering his office.

"That sure was white of him," the boy muttered to himself. "I don't believe he realized what his threat of suspension meant to me."

Several of the boys had noticed Mr. Vining speaking to Fred, and as soon as the former had passed them, turned back, eager to learn what he had said.

Fred, however, was not disposed to gratify their curiosity, and vouchsafed them only a smile, tantalizing in its mystery.

"It must be good news," asserted Buttons, when his most diplomatic attempts to obtain the desired information had failed. "A few minutes ago your face was as long as a yardstick, and now you're grinning like a cat full of chicken."

"It is good news," laughed Fred, and then the sight of the boy for whom he had sacrificed his desk suggesting an avenue of escape from his too solicitous friends, he called: "Oh, you Bronson. Come and I'll show you where you will sit. Sandow Hill had seventeen last year, so you'll probably have a lot of cleaning out to do."

"It's lucky for you, Cotton-Top, that Sandow didn't hear you say that," came from a First Former. "But I shall tell him, and he'll attend to you, never fear. I don't know what Baxter is coming to when Second Formers can criticize their betters."

The austerity of the First Form student frightened Bronson.

"Do you suppose Mr. Hill will be angry at what you said?" he asked in a whisper.

"He may pretend to be," returned Fred, "but he won't be, really. The Firsts always put on a lot of airs. If you let them, they'll make your life miserable. Just don't take what they say seriously. But there's one thing you must remember—don't talk back to them. It's one of Baxter's unwritten laws that Lower Formers must not talk back to the Firsts."

"Are there many of these unwritten laws?" asked Bronson, alarmed at this constant outcropping of Baxter traditions. He was anxious not to violate any of them, and his own reception had been such as to convince him that unless he soon learned them, he would be in constant hot water.

"No-o, not so very many."

"Are they very hard to learn?"

"Oh, you'll catch on to them soon. Just keep your eyes open and you'll learn them. There's another, though, you should know, or you'll have to stand treat to the whole First Form. When the Firsts are going to classes or coming out, you must never walk in front of them. They have the right of way, just as we Seconds do over the other forms."

"Thank you, I'll remember."

"You'd better. Being new, some candy-loving girl will try to get you in front of her."

"But how can I help it?"

"Just step to one side, and say, 'After you, my dear First Former.' It makes 'em ripping mad."

Room No. 1, being located at the rear of the school building, had a separate entrance, and in reaching it, the boys were obliged to cross one end of the campus. As Fred and Bronson made their way to it, they saw several of the students kicking footballs.

"Are you on the team?" asked the newcomer.

"No, only Firsts make the School team. But I hope to make my Form team."

"Then how is it Montgomery could make the ball team and win the Landon game?"

"Because it's different with baseball. Any one can try for that. The Head says it isn't so dangerous."

By this time the two had reached No. 1, which was already swarming with students busily moving their belongings from their old desks to the ones they had just drawn.

"This will be a good chance for you to meet the Form," said Fred. And he introduced Bronson to Margie Newcomb, Grace Darling, Taffy Brown, Soda Billings, Shorty Simms and Ned Tompkins.

"You mustn't take what we do too seriously, Mr. Bronson," said Margie, as she cordially shook the newcomer's hand. "You will soon get accustomed to us. Oh, Alice," she cried, as the girl who had first espied Bronson when he mounted the steps entered the room, "Come here a minute."

But the girl, noting the presence of the new student, turned on her heel and went out.

At this snub, Margie bit her lip.

"Alice is miffed because Fred has more manners than her brute of a brother," explained Grace. "You'd better leave her and Mary alone, Marg."

"So she's Mr. Montgomery's sister?" asked Bronson, an amused light shining in his eyes. "They do seem alike."

"Oh, don't mind her. That's just the Montgomery way," interposed Fred. "She's really a mighty nice girl—when you know her. Come on, and I'll show you through the building."

After inspecting all the recitation rooms, the laboratory, and the gymnasium in the basement, the boys returned to No. 1.

As Fred and Bronson reached a spot whence they could see the latter's desk, both were surprised to behold an envelope attached thereto by a clothespin.

"Wonder what that is?" exclaimed Fred. Seizing the envelope, he glanced at the address, then handed it to his companion.

"A letter for me?" murmured the newcomer, in surprise. "Whom do you suppose it's from?"

"Why not open it and find out?" suggested Fred, striving to restrain a smile, for he had recognized the round, flourishing writing of Soda.

Quickly Bronson did this, his face assuming a look of perplexity as he scanned the contents. Twice he read the note, then asked:

"Who are the 'Big Six,' and where is 'The Witches' Pool'?"

Recognizing a plot of his chums to have fun with the newcomer, Fred said, ignoring the questions:

"Let me see the note."

But Bronson refused to give it to him.

"How can I tell who sent it, if I can't see the handwriting?" demanded Fred, surprised at such action.

"But I can't show it to you."

"Why?"

"The note says I mustn't."

"Look here, Bronson, you mustn't take things so seriously. This note is just to scare you. It doesn't mean anything. If you don't let me see it, we can't get back at the boys who sent it."

A moment more Bronson hesitated, then reluctantly handed it to Fred. The note ran as follows:

"Clothespin, bring your credentials to the Witches' Pool by eight o'clock to-night. By order of the Big Six. Show this to Cotton-Top at your peril."

"That's some of Soda's doings," said Fred. "I'm not surprised he didn't want you to let me know about it. But I wonder what he means by your credentials?"

"Why, the papers I must get to show I am a member of the Second Form, I suppose."

"What papers? Who's been telling you such stuff?"

"Soda." And briefly Bronson related to his new friend the incidents of his reception when he introduced himself.

So absorbed had both boys been in the note that not until the creaking of a door, cautiously opened, reached his ears did Fred realize the conspirators were on the lookout to see when the note was discovered. But at the tell-tale sound, he grabbed Bronson by the arm, and with a whispered "Come with me," led him rapidly out the side door and round to the back of the building.

"Where are you going?" eagerly inquired his companion, as Fred slackened his pace.

"To get even with Soda, of course."

"But he hasn't done anything to you."

"Oh, yes, he has. He knows I am showing you around, so anything he does to you is the same as though he did it to me; see?"

"Yes, I see," returned Bronson slowly, adding quickly, "I wonder if the other boys would have been so decent to me, if you hadn't taken me in tow?"

"Of course they would."

But Bronson held a different opinion, though he did not say so, and all the way to the village store, whither Fred led him, he thanked his lucky stars that the fair-haired boy had taken him under his protection.

Arrived at the store, Fred walked to the back part and asked of the clerk:

"Got any very smelly limburger cheese?"

"Sure."

"How much is it?"

"Fifty cents a pound."

"Then give me half a pound of the very smelliest."

"I'll pay for it," said Bronson, as the package was delivered to them, adding, in fear that Fred might think his offer reflected on his position, "it's only fair, you know, because you are helping me out of a hole."

"All right. Now, we'll get a box, and you write on a card, 'My Credentials—Clothespin,' then we'll have it wrapped up."

When this had been done, Fred persuaded the clerk to address the package to "The Big Six, Care of Mr. Soda Billings, Baxter High School."

"I wish we could be there when they open it," exclaimed Bronson, as they returned to the school building.

"We'll be in on the fun, don't worry. Just stay outside, here, and I will deliver your credentials."

Cautiously Fred entered No. 1, laid the box on Soda's desk, and bolted out of the door.

To the waiting boy the reappearance of his friend seemed instantaneous.

"Quick! To the campus; They mustn't see us near the building!" breathed Fred.

To gain the football field was but the work of a few seconds, and when Soda and his fellow conspirators rushed from the building, the two boys were watching the punting and tackling of team aspirants to the apparent oblivion of all else.

Not long did it take Buttons to descry Fred's yellow head, however, and with a whoop, he dashed at him, followed by his companions, one of whom bore the odoriferous box.

"What shall we do now?" asked Bronson nervously, as the shout reached his ears.

"Nothing. It's their move. Pretend to be interested in the practice—only keep your weather-eye open."

But though the newcomer tried to appear indifferent, when the cessation of the footbeats and the sound of heavy breathing announced the arrival of Soda and the others, he could not keep from looking around to see what they were doing.

"Ha! ha! His guilty conscience makes him fearful!" cried Buttons gleefully. "Clothespin, I'm surprised at you—not to say deeply grieved."

Determined to make amends for having allowed his curiosity to get the better of him, Bronson, ignoring the remark, looked at Fred.

"Who did you say that fellow with the ball is?" he asked.

"That's Tom Perkins, the best full back ever at Baxter," replied Fred, with a wink of approval, never turning his head.

"But how can you tell when only Firsts are allowed to try for the team?"

"Oh, you can get a line on the men from their work on their Form teams. Tom has played full back ever since he came to Baxter."

Surprised at their reception, Buttons and his companions stood quietly until Fred began a history of football at Baxter, relating the most exciting incidents of the annual games with Landon, and then launched into the chances of the various candidates for making the 1912 team.

"Look here, Clothespin, it is customary at Baxter to answer when you are spoken to," exclaimed Soda, as soon as Fred paused for breath.

"Beg pardon, did you address me?" asked Bronson, with a well-feigned look of astonishment. "I was so interested in what Fred Markham was telling me that I did not hear you. What did you say?"

"Good boy, Clothespin," exclaimed Fred between laughs, as he danced with glee at Bronson's simulated surprise. "It isn't very polite, Soda, to interrupt when I am telling a new member of our Form about the team, especially when you smell so."

"Oh, shut up, Cotton-Top," snapped Soda. "Nobody's talking to you. Our business is with Clothespin."

"Business?" repeated the latter innocently.

"Yes, business," broke in Buttons. "We received your credentials. They are certainly strong. After due deliberation, however, we have decided that as you did not deliver them in accordance with instructions, you will not be accorded the privileges of the Second Form unless you eat them."

As he uttered the last words, Buttons took the odoriferous limburger from the box and started to jam it into Bronson's mouth.

But before he could do so, Fred caught his arm.

"Keep out of this, you Cotton-Top!" cried the other boys, jumping for Fred. "This is none of your affair."

"Oh, yes, it is," grinned Fred, throwing aside Soda and skillfully dodging the others who charged at him. Then sniffing loudly, he continued: "I say, Buttons, you'd better run and take a bath."

"Bath nothing," retorted Buttons angrily. "It's this cheese."

Even his fellow-conspirators could not keep from laughing at the indignation with which he repelled the charge.

"I'll stand treat for sodas if you'll come down to the store," exclaimed Bronson, deeming the moment opportune to try to make friends with his tormentors. "That is, if we can go without missing classes."

"Sure we can go. There are no classes till afternoon," chorused several.

Laughing and talking, the boys started for the village, when Buttons suddenly cried:

"I say, let's put the cheese in Bart's desk. He's gone home, and it will make him furious."

The suggestion met with hearty approval, and after due consideration, Shorty Simms was selected as the one to hide the limburger.

"We'll all go in," declared Soda, "then if any instructor sees us, he won't be able to tell who did it, as he would if Shorty went alone."

Readily agreeing, the boys swarmed in a troop into the building, and while Shorty, watching his chance, dodged to Bart's desk, opened the top and placed the limburger as far back as possible, smearing some of it in the cracks.

Gleefully the others watched, filing innocently from the room when the deed was accomplished.

"Wow! but Bart'll raise an awful rumpus," opined several.

"Never mind about Bart. Come on to the store," exclaimed Soda. And, linking his arm through Bronson's, as though fearful he might escape, Soda hurried through the hall, the others following close behind.

But as they started down the steps, they were confronted by a group of Firsts.

"Hey, you Seconds! Back to Number one and clean our desks for us."

At a glance Fred realized that he and his companions were outnumbered by the Upper Formers, and, with that quickness of decision which was destined to make him so good a football player, he whispered:

"The side door!"

Laughing derisively, thee Seconds turned and rushed into No. 1, hastily swarming out the window and through the door.

So unexpected was the refusal to clean their desks, that for a moment the Firsts stood motionless at the foot of the steps, then charged up.

But that moment of hesitation had been sufficient for Fred and his followers to make good their escape, and as the Firsts rushed into No. 1, the last boy reached the campus and with a mocking wave of his hand, Buttons shouted:

"Try the Thirds! They're slow but tame!"

Bronson's action in standing treat for Buttons and his crowd did much to establish him in their good graces, and the lads soon became better acquainted.

"I say, have you picked out your boarding-place, Clothespin?" Soda asked presently. "If you haven't, we may be able to save you getting into one of the 'Old Ladies' Homes.'"

"That's the Baxter name for several boarding-houses managed by elderly maiden ladies," explained Fred. "They——"

But he was interrupted by Soda's announcement:

"The lunacy commission will now consider the sad case of Fred Markham, star athlete of the Second Form, who is so far out of his head as to call the harpies that collect the rent and dish out the prunes at the 'Old Ladies' Homes' maiden ladies. It——"

"I realize that all sense of politeness and respect for your elders is lacking in you, Soda," broke in Fred, "but you must remember that Bronson has been accustomed to associating with well-bred people."

This retort, interpreted in the spirit in which it was uttered, evoked howls of delight from all but the victim of Fred's sarcasm, and Shorty expressed their sentiments by saying:

"That ought to hold you for some time, Soda. Now, don't begin to talk back. Remember, children should be seen and not heard."

"Your conversation may be edifying, but it is not enlightening as to a boarding-house for Bronson," retorted Soda.

"I am deeply moved by your kind consideration of my welfare," smiled Bronson, "and I thank you heartily. But that I may save you further bother, I will tell you I have already arranged for quarters."

"Bet you're stung," declared Shorty, while the others chorused: "Where?"

"With Mr. Vining."

"The Head?" gasped the boys, flashing significant glances to one another, the rising inflection of their voices proclaiming their incredulity.

"Yes, he is an old friend of my family."

"Take me by the hand, somebody, and lead me away," groaned Soda. "Here we invited Bronson to a party at the Witches' Pool, and he lives with the Head."

Though the words were spoken in jest, the expressions on the boys' faces showed that they were wondering whether or not their new Form member would prove a spoil-sport.

Divining their thoughts, Bronson hastened to say:

"I hope the fact that I live with Mr. Vining will make no difference in our relations. It was arranged between mother and him that I should not be quizzed, no matter what happens at school."

"My eye! I wish I could live with the Head," lamented Shorty. "I was quizzed by either him or Gumshoe regularly once a week—if not oftener—all last year."

"We'll petition him to adopt you," cried Soda. "Who'll sign?"

But before the suggestion could be carried out, the blowing of a noon whistle sent the boys to their respective homes for dinner.

The fun with the cheese, and the escape from the Firsts, had distracted Fred's mind from the unpleasant events attendant upon his arrival at school, but as he approached his unpretentious but comfortable home, his rival's remarks recurred to him. Consequently it was a very sober boy who entered the dining room of the Markham homestead.

Instantly realizing that her son's quietness—in striking contrast to his usual good spirits—betokened something serious, Mrs. Markham was about to ask the cause when Fred forestalled her by inquiring:

"Where's father?"

"He's gone to Manchester."

"Why?"

It was the hope of both Mr. and Mrs. Markham that they might keep the full import of the failure from Fred, and in accordance with the plan agreed upon between husband and wife when the former set out on his trip—taken in reality to obtain a position—the woman replied:

"Your father has gone on business, Fred." And then, in an effort to divert his mind from such dangerous ground, she continued: "How did school start? Are there any new boys in your Form?"

Fred, however, was not turned so easily from his object, and, without reply to his mother's questions, said:

"But if he has failed, I don't see how he has any business."

Realizing that her attempt to change the conversation was futile, Mrs. Markham replied:

"He has gone to obtain a position, if possible."

This information appeared to Fred partially to confirm what his rival had said, and it was with a very shaky voice he murmured:

"I'm sorry he went without talking to me."

During this conversation, neither mother nor son had more than tasted the delicious dinner that was growing cold on the table before them, and in one more attempt to divert Fred's thoughts, Mrs. Markham said:

"You will never make your football team if you don't eat."

The words suggested to Fred that he could not afford to sacrifice any strength for his bout with Bart Montgomery by abstaining from food, and, though it was with little relish, he ate his dinner.

When finished, he returned to his questioning, almost taking his mother's breath away by asking:

"Did father make money by his failure?"

An instant Mrs. Markham was too amazed to speak. Then, quickly recovering herself, she replied indignantly:

"No, indeed! Who put such an idea into your head?"

"Bart Montgomery."

Suppressing the groan this reply brought to her lips, for she was well aware of the Montgomery family's pride and trouble-stirring tongues, intuitively her mother's heart felt all her son would be made to suffer by his rich Form mate, and, desirous of knowing the worst, Mrs. Markham asked:

"What did that bully say?"

"He said father failed dishonestly, that his father was the principal creditor, so he ought to know."

"The contemptible brute! Do you suppose if your father had made money by his failure he would now be trying to find a position in order to earn money with which to support us. Fred, your father is an honest man—which is more than Bart Montgomery's mother can say about his father, with all his wealth!"

"Hooray for you, mother! I wish I'd thought of that to say to Bart this morning," exclaimed Fred. "But I'll say it the next time I see him."

Mrs. Markham's anger at the imputation her husband was dishonest had carried her beyond the bounds of her customary caution, and, regretting her indiscretion, she shook her head.

"You mustn't do anything of the sort, Fred. Promise me you won't."

"Why?" he demanded, surprised at this sudden change in his mother, without replying to her request.

"Because it will only make it harder for your father."

"How?"

For several minutes Mrs. Markham was silent, evidently considering whether or not the time had come when Fred should be told all the ramifications of the failure. Finally deciding such a course would be the wisest, she parried:

"If I tell you, will you promise not to make that remark to Bart?"

"I won't do so if it will hurt father."

This answer seeming satisfactory, Mrs. Markham said:

"Being business, there are some points I don't understand myself. But I know enough to give you a general idea.

"When your father started his automobile supply business, he was obliged to borrow some money for which he gave notes.

"People all said your father would not succeed. But when he did, several of them grew jealous, and strove to make trouble for him by buying up his notes.

"Mr. Montgomery heard about it, and, coming to your father, offered him enough funds to pay off the notes, agreeing to accept interest and let your father pay off the principle as he could.

"Believing the offer made in good faith, your father gratefully accepted it. But it was not long before he discovered he was mistaken.

"Mrs. Montgomery has a sister who married Charles Gibbs. Being eager to have her sister with her in Baxter, she asked her husband to start Mr. Gibbs in business.

"Seeing your father's success, Mr. Montgomery decided to ruin your father and set up his brother-in-law in the automobile supply business.

"Accordingly, he came to your father and told him he was sorry but he must have his money. Your father protested, but Mr. Montgomery was firm.

"In despair your father tried to obtain money from the banks in nearby towns, but, when inquiry was made, Mr. Montgomery said your father had obtained the loan from him by misrepresentation and the banks refused to lend."

"The sneak!" flashed Fred, his hands clenching as he thought of such treachery to his father.

"As a last resort, your father tried to mortgage our house, but when his title to the property was examined, it was found there was some flaw in the deed.

"Your father insisted some one had tampered with the records, but to no avail.

"Refused money on all sides, there was nothing left for him to do and he was forced into bankruptcy."

In silence Fred digested the story for several minutes.

"I don't see how they can call father dishonest for that. He certainly wouldn't change the deed," he said finally.

"That is the part I don't understand. They said your father had some money on deposit in the Baxter National Bank, which had been withdrawn before Mr. Montgomery could attach it."

"They mean father is hiding this money?"

"Yes."

"But why shouldn't he withdraw it?"

"The law says a bankrupt must not dispose of nor conceal any property from his creditors."

"What does father say?"

"That he never signed the check on which the money was paid."

"Then he never did!" asserted Fred emphatically. "I'll bet Charles Gibbs and Thomas Montgomery are mixed up both in the deed and the check transaction."

"Hush, dear, you mustn't say such things! Both your father and I believe as you do, but Mr. Montgomery is so powerful we can do nothing, unless we have absolute proof," exclaimed Mrs. Markham, looking anxiously about in fear that some one might have entered and heard the remark.

"Don't worry, mother," exclaimed Fred, jumping from his chair and running to her, as he saw the tears fall on her cheek when she finished the story, "I'll get the proof!"

As Fred uttered the manly words, his mother raised her tear-stained face, the light of hope shining in her eyes, threw her arms about him and, her head resting on his shoulder, murmured, between her sobs:

"Oh, if you only could, my boy!"

"I will find the proof, if there is any," asserted Fred confidently, "so cheer up, Momsy."

This sharing of his parents' burden seemed to Fred to draw him nearer to them, and in this closer understanding he and his mother talked matters over, during the course of which the clash with Bart, the drawing of the desks and the joke with the cheese were related.

At the recounting of Bart's rudeness in refusing to occupy the desk he had drawn, Mrs. Markham exclaimed:

"There is no saying so true, my son, as that gentleness is bred in the bone. Gentle birth is a thing no money can buy. So long as it was a Montgomery who was so insolent, I am glad that it was a Markham who made amends. You must bring Bronson to the house."

Further confidences between mother and son were prevented, however, by a loud rap on the side door—which opened into the dining room—followed immediately by the entrance of a tall figure.

"How do you do, Mrs. Markham? Ready, Fred?" came from the newcomer.

"Sandow Hill, you'll scare the life out of me some day, coming in so suddenly," cried Mrs. Markham, as she recognized the boy who had entered so unceremoniously.

"I hope not, but I am so in the habit of running in here I almost forgot to knock. You should give me credit for that, at least."

"Oh, you mustn't think I meant what I said seriously, Sandow, but now that Mr. Markham has gone away, I am a bit nervous."

The leader of the First Form was about to comment upon this announcement, when a significant glance from Fred warned him not to, and instead he said:

"Ready for school, Cotton-Top? I thought I'd call and walk along with you. I want to talk about organizing the Second Form football team."

"Yes, I'm ready," Fred replied, accepting the remark at its face value, although he was well aware it was about his affair with Bart that Sandow meant. "Wait until I get my cap." And going into the hall, he quickly returned, his face aglow with pleasure, in his hand a dark blue cap with the letters "S. F." worked in gold braid on the front.

"Thank you, Momsy," he cried, putting his arm around her waist and kissing her affectionately. "It's a beauty. I was going to ask you to make one and here you've given it to me as a surprise. Isn't it swell, Sandow?"

"It sure is," asserted the leader of the Firsts, thus appealed to. "I wish you'd make me one, Mrs. Markham, with the First's colors, crimson with white initials."

"I shall be pleased to, Sandow. I believe I have some cloth of the exact shade, so I can do it this very afternoon."

"That will be fine, Mrs. Markham, and it will help me out of a bad hole. Several of the girls have offered to make my cap and I don't want to decide between them. But I'd be delighted to wear one you made."

Smiling at the boy's ingenuous frankness, Mrs. Markham renewed her promise to make his Form cap, adding:

"Sandow, won't you come to supper to-night? And Fred, you may bring your new Form mate. I'll ask Sallie Ayres, Margie Newcomb and Dorothy Manning."

At any other time, the boys would have hailed with delight the prospect of an evening with the girls, for Sandow was very fond of Sallie Ayres and Dorothy Manning, while Fred thought there was no one quite so attractive as Margie Newcomb. But under the circumstances, the suggestion filled them with consternation and they looked at one another in blank dismay, which was no whit allayed by Mrs. Markham's saying:

"So you're planning some mischief for to-night, are you? I thought there was something in the wind when you called for Fred, Sandow. Of course, if you prefer your pranks, why I will tell the girls not to come."

"Then you've asked them?" blurted Sandow.

"Yes, this morning."

"But how did you happen to ask three?" inquired Fred, suspecting that his mother, who looked upon the opening day of school with dread because of the hazing that was usually indulged in, had proposed the supper party in the hope that she could keep him at home. "You didn't know about Bronson."

"Oh, yes, I did," returned Mrs. Markham, with a smile, "and I've already invited him."

"When did you meet him?"

"I haven't met him, yet. I saw Mrs. Vining this morning on the street, and she told me about his boarding with her and said she hoped you and he would be friends. Just then the girls came along and I thought it would be pleasant for Mr. Bronson if he could meet them. So I asked them and sent him an invitation."

"Momsy, you're a fox! You mean you thought you could keep Sandow and me at home where you could watch us," laughed Fred.

"Well, shall I tell the girls you prefer your skylarking to their society?" inquired Mrs. Markham.

"If she does, your goose will be cooked with Margie," blurted Sandow, and then, as he realized how disrespectful the voicing of his thoughts sounded, he added, blushing:

"I beg your pardon, Mrs. Markham. I spoke without thinking."

"Never mind, Sandow," laughed Fred's mother. "But I agree with you that Margie will resent such action on Fred's part."

Confronted by such an embarrassing situation, the boy who was to meet Bart in defense of his father's honor, was doing some rapid thinking.

"We'll have the party, Momsy," he replied. "Only please have supper at seven instead of six." And without giving his parent the opportunity to ask the reason for the late hour, Fred kissed her and dashed out the door, followed by his schoolmate.

"Jiminy crickets! but this is a pretty mess!" lamented Sandow, as he and Fred settled into a rapid walk. "How do you intend to get around Bart? Put it off until to-morrow?"

"Not much! I'll meet him at five instead of seven."

"He won't agree, if he thinks it will be an accommodation to you."

"Oh, won't he?" returned Fred, smiling in a superior manner. "You just wait and see. He'll jump at the chance!"

"Go ahead and tell me; I'm not good at puzzles."

"There's no mystery. I'll simply tell him that I'm going to a party and want to get through with him first. He'll think he can give me a couple of black eyes and shame me before the girls."

"Great head, Cotton-Top!—provided he doesn't close your peepers. Bart's some scrapper. He told Hal he'd been taking boxing lessons during the summer. It's because I wanted to give you a few points I dropped in for you. Have you any idea how you are going at him?"

"Sure. The way Phil Thomas got him in our Form game with Landon last year."

While the leader of the Firsts realized that Fred was strong and agile, he had no idea the boy had already mapped out his plan of campaign, and he asked in surprise:

"How do you mean?"

"Why, make his nose bleed. After Thomas hit Bart on the nose, he lost his nerve."

Though the plan appealed to the First, he did not wish to say so, lest Fred become overconfident, and he replied:

"But it's getting in the good blow that will be the difficulty."

"That's the truth," asserted a third voice. And turning, Fred and Sandow were surprised to see Buttons close beside them.

"It's lucky it was you!" declared the First. "Guess we'd better change the subject. I didn't realize we were so near the school. You two run along and I'll arrange with Hal."

"Thought everything was fixed," remarked Buttons, as Sandow left them.

"Going to change the hour, that's all." And Fred told his chum about the party, adding: "Can't you get Grace Darling and come over in the evening?"

"Guess so. I promised to let her know how things came out."

"But she'll tell Marg."

"What of it."

"Marg'll tell Momsy and she'll worry her head off."

"Well, there's no use crying over what can't be helped. There's Bart now. Will you ask him to change the time or shall I arrange with Taffy?"

"I will."

No sooner had Fred spoken than he started toward his rival.

By this time, a score or more boys were in sight and as they saw Fred heading for Bart, they hastened their steps, keeping their eyes on both.

Bart Montgomery had also seen the boy he hated coming toward him and, though he wondered what could be the reason, pretended not to notice him, and it was not until Fred hailed him, with an "I say, Bart, just a moment," that he looked in his direction.

"Well?" drawled the rich bully, as his rival came closer.

"I'm giving a supper to-night and I'd be obliged if you'd meet me at five instead of seven. When I set the hour this morning, I did not know about it."

As Fred spoke, the other boys had formed a circle about the two and eagerly they awaited the bully's response.

For a moment, Bart was on the point of refusing. Then, as Fred had hoped, he saw the chance of humiliating his rival before his friends and sneered:

"You, giving a supper? Who's going?"

"That's none of your business, Bart Montgomery. Will you meet me at five—or are you afraid to?"

"I afraid to meet you? Say, if you'll take my advice, you'll postpone your supper. You'll be more fit for bed and a doctor than a supper."

This taunt drew shouts of approval from Bart's followers.

"Thank you. Five it is," said Fred, ignoring the others. And he walked away to find Bronson, to whom he extended in person the invitation sent by his mother.

Usually the forming of the classes and the assignment of lessons on the opening day was a period of terror for the headmaster and the instructors, but on this occasion, the boys were too excited over the outcome of the quarrel between the rivals to cause any trouble. Thus the tasks were soon completed, and the boys hastened to the campus, while Fred and Bart were spirited away by Buttons and Taffy, respectively.

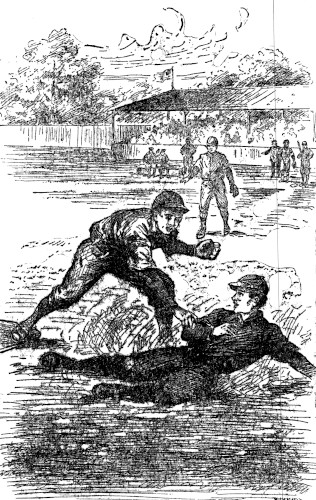

The scene of the combat between the rivals was a tree-enclosed patch of ground back of Hal Church's barn, beside the cattle run, and as the hour of five approached forms of boys could be seen seeking the spot cautiously, dodging out of sight at every sound.

Then followed a silence, broken now and again by subdued exclamations, and finally the appearance of Fred and Buttons from between the trees, showing that the fight was at an end.

"Why are we going this way?" asked Fred, as his chum led him along the cattle run. "It looks as if I were afraid to be seen."

"Well, you're not exactly a fit exhibit for a beauty show," grinned his chum, and then he suddenly gave three whistles, which were followed immediately by the appearance of two girls from behind the bars at the end of the cattle run.

"What in the world?" began Fred, then, recognizing the figures, he exclaimed: "Why, it's Marg and Grace!"

"My, but you're the fine little guesser," chuckled Buttons. "Who did you think they were, Alice and Mary Montgomery?"

His chum's sarcasm was lost on Fred, however, as, thinking only of the position of the girls, he hastened toward them.

"Marg, you mustn't stay here! You never should have come!" he cried.

"But, I couldn't help it, Fred. I was so worried. Are you—did you—oh! You're all blood! Did that big brute of a Bart get the best of you?"

The look that he read in the girl's eyes was so delightful to the conflict-stained boy that he forgot all else and simply drank it in.

"For goodness sake! Speak, one of you, and relieve our anxiety. Marg has been making my life miserable for the last hour," exclaimed Grace.

"An hour?" repeated both boys, in surprise.

"If not longer," smiled Grace. "I told her the thing wouldn't begin till five, but that didn't make any difference. So please tell us how it came out."

"No, don't," protested Margie, her eyes on Fred's bespattered face. "I can tell—and I don't want to hear it." Then, her affection asserting itself, she put her hand on Fred's arm and breathed: "I'm so sorry! But we won't care. He's bigger than you are, anyway."

"Um-m! You ought to be willing to take a licking every day if Marg would talk like that to you," grinned Buttons.

"Well, I would," retorted the girl, a blush suffusing her pretty face, as she realized the significance of her avowal. "I——"

Something about the expression on Buttons' face, however, suggested to Grace that her chum's sympathy was wasted and she interrupted:

"Don't say another word, Marg. The boys are just drawing you on. I believe Fred won."

But neither boy made any response.

"If you don't tell us, I'll never speak to either of you again," flashed Grace.

Alarmed at the prospect of such a dire calamity, Buttons said:

"Sure he won!"

A moment the girls looked at one another, then Marg exclaimed, looking into Fred's face:

"Really? Did you really beat that big brute of a bully, Fred?"

"Yes."

"Oh, I'm so glad!" cried the girl.

"I think you're a couple of mean things, to tease us so," declared Grace. "Why didn't you tell us in the first place?"

"Because you talked so much we didn't have the chance, and then when he saw you were so sure Bart won, we thought we'd let you have your own way," grinned Buttons.

"Smarty!" snapped Grace.

But Margie was so proud to think the boy of her preference had defeated the rich bully, that she did not share her chum's pique, declaring:

"I'm so happy, I don't mind your not telling us. Indeed, I think it's pleasanter to find we were wrong."

A moment Buttons looked at the happy couple, then seized Grace by the arm and started away, laughing:

"Come on, girlie, this is no place for us. Besides, you ought to be nice to me. I was Fred's second."

Her anger being only simulated, Grace readily allowed herself to be led away and as they went, Fred called:

"Come on back here! If you don't mind the invitation being a little late, I want you both to come home to supper with me."

"Very kind of you, I'm sure," grinned Buttons, "but your mother invited us this afternoon."

"But—why——"

"Your mother sent an invitation by me, when she learned about your fight," exclaimed Grace.

"Then she knows?" gasped Fred.

"Evidently," grinned Buttons.

"Come on, then, quick! We must let Momsy know I won. She'll be worrying her heart out," exclaimed the victor, as he seized Margie's hand and broke into a run, followed by the others.

The arrival at the house affording Margie the first chance to catch her breath long enough to speak, she put her face close to Fred's and whispered:

"One of the reasons I like you is that you are so thoughtful of your mother. Another is because you were not afraid of that Bart Montgomery."

To the surprise of the happy four, they found the other boys and girls awaiting them, and Fred was subjected to merry bantering for his remissness in not being at home to welcome his friends.

"I didn't know you were coming to spend the afternoon," he laughed in return, gazing significantly toward the clock whose hands pointed to ten minutes before seven.

"My, but isn't he the stickler for form," commented Sandow. "Does your majesty wish us to go out and wait until seven and then come in?"

"I told Mr. Hill I thought we would be too early," interposed Bronson apologetically.

"You mustn't mind Fred, Mr. Bronson," quickly exclaimed Mrs. Markham. "When you are better acquainted with him, you will know, he is always joking. Besides, supper is ready, so, as you are all here, we can begin just as soon as Fred makes himself presentable."

Flushing at this reminder of his uncouth appearance, the lad made his excuses and started for his room.

"You're more than forgiven," smiled Sallie Ayres, and from this remark the boy realized that the result of the affair with Bart had been made known to his mother and guests.

No sooner had Fred left the room than the girls offered to assist Mrs. Markham in placing the food on the table.

"I say, Mrs. Markham, isn't there something we fellows can do, too?" asked Sandow, following the girls to the kitchen. "We don't want to be left in there alone."

"Let's make them put on aprons and wait on the table," suggested Dorothy.

But Mrs. Markham laughingly protested, and so the boys were forced to content themselves with watching the preparations.

"Oh, I wish we had something funny to put at Fred's plate," exclaimed Margie, when the food was on the table. "Haven't you anything you can think of, Mrs. Markham?"

"Dear me, I don't believe I have," replied the youth's mother, after a moment's reflection.

"Bronson's got something," announced Sandow. "He made me wait for him on the way over."

Expectantly the eyes of the others were turned upon their new schoolmate.

"Oh, what is it?" cried Margie eagerly.

"I'm afraid it's rather silly," apologized Bronson.

"Never mind. Do hurry and show us before Fred comes," urged Grace.

Blushing profusely, Bronson put his hand in his pocket, drew forth a paper bag and handed it to Mrs. Markham.

"Quick! Quick!" breathed the others, clustering around her, eager to see the contents.

"O-oh! it's a candy Teddy Bear!" exclaimed Sallie.

"Fine!" chuckled Buttons. "Here, Mrs. Markham, please let me have that bag. Sandow, you get a match."

Taking the bag, the boy tore out a small piece of paper, hastily wrote on it, "You're all to the candy," thrust the match through the paper, set the Teddy Bear on Fred's plate and then fixed the match in its arms in such a way as to give the effect of a banner.

"But what does that expression mean?" asked Mrs. Markham, to whom the slang was as so much Sanskrit.

"It means Fred's all right," interpreted Sandow. "Now, come away, I hear him."

With hurried steps, the young people made their way to the other end of the table, which they reached just as the fair-haired boy entered the room.

"What's up? Why are you all in here?" Fred inquired, looking from one to another of his friends.

"The girls wanted to help me put the supper on the table and Sandow and Buttons could not bear to be separated from Sallie and Grace for so long," smiled Mrs. Markham.

"I can understand that," returned Fred. "But there's something else. Every one of you has a guilty expression."

"Hungry, you mean," corrected Buttons. "For pity's sake, take your seat and don't keep us waiting any longer. My mouth's been watering for some of Mrs. Markham's pumpkin pie ever since I was asked to supper. Bronson, I told you this morning, you ought to let us select your boarding place for you. Mrs. Markham's the best cook in Baxter. That's why Fred always looks so sleek and superior."

Pleased and laughing at the boyish compliment, Fred's mother bade them be seated.

So intent was the fair-haired boy in assisting Margie, that it was several moments before he noticed his own plate.

"WELL, OF ALL THINGS," HE EXCLAIMED

"Well, of all things!" he exclaimed, as his eyes rested on the sugared sweetmeat. Then, as he caught sight of the inscription, he added, recognizing the writing: "Buttons, I know it was your diffidence in company that prevented you giving this to Grace. So permit me to do so for you.

"You see, I know both their characteristics and sentiments, Bronson," added their tormentor, as he set the candy bear, with its banner, beside Grace's plate.

Merrily the others laughed, while the boy and girl most concerned blushed furiously.

"Just you wait, Cotton-Top," growled Buttons. But the threat was accepted as the jest it was meant to be.

Healthy young people all, the evident relish with which they ate bore eloquent testimony to the savoriness of Mrs. Markham's cooking.

"Now, go into the other room and amuse yourselves," said the happy woman, when the meal was finished. But the young people refused, declaring they would wash and wipe the dishes, which they did, despite Mrs. Markham's protest.

With games, singing and dancing, the evening quickly passed and, all too soon, the clock struck ten.

"Oh, dear, it seems as though I'd only just come," sighed Margie.

"Never mind, there'll be other nights," laughed Sandow.

"Yes, indeed. I hope you'll all come around often," smiled Mrs. Markham.

"Oh, wouldn't it be jolly to form a supper club," exclaimed Dorothy. "Just we eight. We can take turns meeting at each other's house, once a week."

Enthusiastically the others received the idea. To Mrs. Markham, however, the suggestion was alarming, for she realized that it would tax her already straitened circumstances severely, were she obliged to provide supper for eight young people, even as often as once in two months.

"I think once in two weeks would be often enough," she proposed.

"Yes, I think that would be better," agreed Margie, divining the reason. "Mother said that I must give more attention to my music, if I wanted to keep on with it, and evenings are the only time to practice that I have."

"Then, we'll make it every two weeks," declared Fred, with a promptness that evoked laughter from the others.

"As I suggested the idea, I invite you all to my house for the next meeting," said Dorothy; and after bidding their hostess "Good-night," the young people discussed the club as they walked home.

All their homes were in the center of the village, save Margie's, for which she and Fred had usually been glad. Indeed, as he walked along, the boy was anticipating the pleasure of being alone with the girl of his choice—when they were all startled to hear hurried footsteps behind them.

"Look out for tricks," whispered Buttons. "This is hazing night."

Quickly each boy braced himself to shield, to the best of his ability, the girl he was escorting.

Suddenly, the footsteps seemed to stop. Puzzled, the boys looked at one another.

"There they go, on the grass next the road!" exclaimed Buttons excitedly.

Quickly the others turned, but so heavy were the shadows, that they were unable to distinguish the forms.

"How many did you see?" queried Sandow.

"Six."

"Recognize any of 'em?"

"Too dark."

The presence of six boys, who evidently did not wish to allow their faces to be seen, on the street so late suggested but one idea to all of the young people—that Bart was planning to waylay his rival, as he returned from taking Margie home.

"H'm. Guess we'll all walk home with you, Margie," observed Sandow.

The girl, however, had been doing some rapid thinking.

"Oh, I'm not going home to-night," she exclaimed, giving her chum's arm a significant pinch as she spoke, "I'm going to stay with Grace."

"What did you want to scare Marg for, Sandow?" snapped Fred, in none too pleasant a tone.

"He didn't scare me," flashed the girl. But in her heart she knew that only fear for Fred would have persuaded her not to go home.

"Your mother will be worried," asserted the boy.

"I'll telephone her."

All the others were relieved at this solution of the difficulty, for they were fond of Fred, and they understood, all too well, the significance of their being followed.

"Why won't all you girls stay at my house to-night?" asked Grace. "Sister's away, so there'll be plenty of room. You can telephone, you know."

For a moment, Sallie hesitated. But a nudge from Sandow caused her to acquiesce.

This arrangement decided upon, the young people resumed their way.

After leaving the girls at Grace's home, the boys walked to the Vinings' with Bronson, and then started back.

But not more than ten yards had they walked from the gate, when they heard a hoarse cry:

"Here they come!"

To the three boys, this cry was not surprising. Indeed, they had been expecting an attack ever since Buttons had espied the six figures sneaking through the shadows, and their only amazement was that they had been allowed to escort the girls and Bronson to their homes, without interference.

"Quick, link arms! Lower your heads, and we'll dash through them!" whispered Sandow. "Use your elbows, like you do in football."

"Strike hard and low," added Buttons. "They mean business—or they wouldn't have waited till we got the girls home."

Instinctively, each boy squared his shoulders at this voicing of the thoughts that had been uppermost in their minds, ever since they learned they were being followed.

"That's certain enough or there wouldn't be six of them to only three of us," returned Sandow. "Crouch down, and we may be able to upset 'em."

"I say charge 'em," breathed Fred. "Bart'll expect us to back up against the fence. So if we run hard, we can break through them."

That the rich bully was the leader of their pursuers, neither Sandow nor Buttons doubted. But, knowing his disposition, they feared the methods he might adopt under cover of darkness, realizing the attack would centre on Fred.

Accordingly, as the fair-haired boy made his suggestion of charging, Sandow whispered:

"Better make a wedge. You run in the lead, Cotton-Top, and Buttons and I will shove you along."

To decide upon their line of action took the boys less time than it does to describe it, and no sooner had the suggestion of the wedge been made than the trio charged.

This move surprised Bart, for he it was. So eager was he to fall upon his rival, that, in his excitement, his voice, when he gave the word of the boys' approach, had been louder than he realized. Moreover, his plan of attack, thoroughly in keeping with his nature, had been to fall upon Fred and his companions from the rear.

In consequence, when he heard the thudding of their footsteps, the bully lost his head.

"Out at them! Get Fred!" he snarled, leaping from his hiding place onto the sidewalk, as he spoke.

Either because they had other ideas of how they should proceed, or because the suddenness of their intended victims' action paralyzed them, Bart's followers did not immediately obey.

And their delay was their leader's undoing.

With great force, Fred, backed by Buttons and Sandow, struck the lone boy on the sidewalk, bowling him over as though he were a tenpin.

"There's no one else ahead," exclaimed Fred. "Guess we were too quick for 'em. No use running any more."

The impetus of his companions was such, however, that though the boy at the head of the wedge stopped running, as he spoke, the others carried him along for several yards.