Title: History of my pets

Author: Grace Greenwood

Illustrator: Hammatt Billings

Release date: August 30, 2023 [eBook #71523]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1871

Credits: David E. Brown and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

KETURAH THE KITTEN.

BY

GRACE GREENWOOD.

WITH ENGRAVINGS FROM DESIGNS BY BILLINGS.

NEW EDITION, REVISED AND ENLARGED.

BOSTON:

JAMES R. OSGOOD AND COMPANY,

(Late Ticknor & Fields, and Fields, Osgood, & Co.)

1871.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1850,

BY SARA J. CLARKE,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1871,

BY JAMES R. OSGOOD & CO.,

in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

University Press: Welch, Bigelow, & Co.,

Cambridge.

Re-dedicated

TO

MARCEL, FRED, FANNY, AND FRANK BAILEY,

OF WASHINGTON, D. C.

| PAGE | |

| KETURAH, THE CAT | 1 |

| SAM, THE COCKEREL | 17 |

| TOBY, THE HAWK | 23 |

| MILLY, THE PONY, AND CARLO, THE DOG | 34 |

| CORA, THE SPANIEL | 49 |

| JACK, THE DRAKE | 58 |

| HECTOR, THE GREYHOUND | 67 |

| BOB, THE COSSET | 79 |

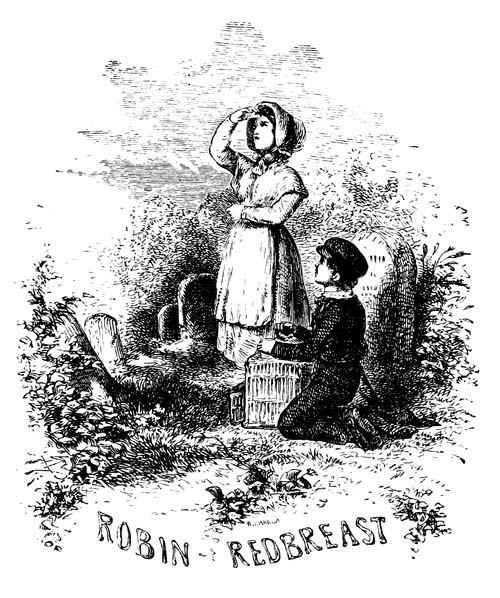

| ROBIN REDBREAST | 86 |

| TOM | 98 |

| SUPPLEMENTARY STORIES. | |

|---|---|

| FIDO THE BRAVE | 109 |

| CAT TALES. | |

| FAITHFUL GRIMALKIN | 117 |

| OBEDIENT THOMAS | 120 |

| KATRINA AND KATINKA | 124 |

| FEATHERED PETS.[vi] | |

| OUR COUSINS THE PARROTS | 135 |

| THE BENEVOLENT SHANGHAI | 151 |

| THE GALLANT BANTAM | 153 |

| THE DISOWNED CHICKS | 157 |

HISTORY OF MY PETS.

The first pet, in whose history you would take any interest, came into my possession when I was about nine years old. I remember the day as plainly as I remember yesterday. I was going home from school, very sad and out of humor with myself, for I had been marked deficient in Geography, and had gone down to the very foot in the spelling-class. On the way I was obliged to pass a little old log-house, which stood near the road, and which I generally ran by in a great hurry, as the woman who lived there had the name of being a scold and[2] a sort of a witch. She certainly was a stout, ugly woman, who drank a great deal of cider, and sometimes beat her husband,—which was very cruel, as he was a mild, little man, and took good care of the baby while she went to mill. But that day I trudged along carelessly and slowly, for I was too unhappy to be afraid, even of that dreadful woman. Yet I started, and felt my heart beat fast, when she called out to me. “Stop, little girl!” she said; “don’t you want this ’ere young cat?” and held out a beautiful white kitten. I ran at once and caught it from her hands, thanking her as well as I could, and started for home, carefully covering pussy’s head with my pinafore, lest she should see where I took her, and so know the way back. She was rather uneasy, and scratched my arms a good deal;—but I did not mind that, I was so entirely happy in my new pet. When I reached home, and my mother looked more annoyed than pleased with[3] the little stranger, and my father and brothers would take no particular notice of her, I thought they must be very hard-hearted indeed, not to be moved by her beauty and innocence. My brother William, however, who was very obliging, and quite a mechanic, made a nice little house, or “cat-cote,” as he called it, in the back-yard, and put in it some clean straw for her to lie on. I then gave her a plentiful supper of new milk, and put her to bed with my own hands. It was long before I could sleep myself that night, for thinking of my pet. I remember I dreamed that little angels came to watch over me, as I had been told they would watch over good children, but that, when they came near to my bedside, they all turned into white kittens and purred over my sleep.

The next morning, I asked my mother for a name for pussy. She laughed and gave me “Keturah,”—saying that it was a good Sunday name, but that I might call her Kitty, for short.

[4]Soon, I am happy to say, all the family grew to liking my pet very much, and I became exceedingly fond and proud of her. Every night when I returned from school, I thought I could see an improvement in her, till I came to consider her a kitten of prodigious talent. I have seen many cats in my day, and I still think that Keturah was very bright. She could perform a great many wonderful exploits,—such as playing hide and seek with me, all through the house, and lying on her back perfectly still, and pretending to be dead. I made her a little cloak, cap, and bonnet, and she would sit up straight, dressed in them, on a little chair, for all the world like some queer old woman. Once, after I had been to the menagerie, I made her a gay suit of clothes, and taught her to ride my brother’s little dog, as I had seen the monkey ride the pony. She, in her turn, was very fond of me, and would follow me whenever she could.

It happened that when Kitty was about[5] a year old, and quite a sizable cat, I became very much interested in some religious meetings which were held on every Wednesday evening in the village church, about half a mile from our house. I really enjoyed them very much, for I loved our minister, who was a good and kind man, and I always felt a better and happier child after hearing him preach, even though I did not understand all that he said. One evening it chanced that there were none going from our house; but my mother, who saw that I was sadly disappointed, gave me leave to go with a neighbouring family, who never missed a meeting of the sort. But when I reached Deacon Wilson’s, I found that they were already gone. Yet, as it was not quite dark, I went on by myself, intending, if I did not overtake them, to go directly to their pew. I had not gone far before I found Kitty at my heels. I spoke as crossly as I could to her, and sent her back,—looking after her till she was out[6] of sight. But just as I reached the church, she came bounding over the fence, and went trotting along before me. Now, what could I do? I felt that it would be very wicked to take a cat to meeting, but I feared that, if I left her outside, she might be lost, or stolen, or killed. So I took her up under my shawl, and went softly into church. I dared not carry her to Deacon Wilson’s pew, which was just before the pulpit, but sat down in the farther end of the first slip, behind a pillar, and with nobody near.

I was very sorry to find that it was not our handsome, young minister that preached, but an old man and a stranger. His sermon may have been a fine one, for the grown-up people, but it struck me as rather dull. I had been a strawberrying that afternoon, and was sadly tired,—and the cat in my lap purred so drowsily, that I soon found my eyes closing, and my head nodding wisely to every thing the minister said. I tried every way to keep awake,[7] but it was of no use. I finally fell asleep, and slept as soundly as I ever slept in my life.

When I awoke at last, I did not know where I was. All was dark around me, and there was the sound of rain without. The meeting was over, the people had all gone, without having seen me, and I was alone in the old church at midnight!

As soon as I saw how it was, I set up a great cry, and shrieked and called at the top of my voice. But nobody heard me,—for the very good reason that nobody lived anywhere near. I will do Kitty the justice to say, that she showed no fear at this trying time, but purred and rubbed against me, as much as to say,—“Keep a good heart, my little mistress!”

O, ’twas a dreadful place in which to be, in the dark night!—There, where I had heard such awful things preached about, before our new minister came, who loved children too well to frighten them but who chose rather to talk about our[8] good Father in Heaven, and the dear Saviour, who took little children in his arms and blessed them. I thought of Him then, and when I had said my prayers I felt braver, and had courage enough to go and try the doors; but all were locked fast. Then I sat down and cried more bitterly than ever, but Kitty purred cheerfully all the time.

At last I remembered that I had seen one of the back-windows open that evening,—perhaps I might get out through that. So I groped my way up the broad aisle, breathing hard with awe and fear. As I was passing the pulpit, there came a clap of thunder which jarred the whole building, and the great red Bible, which lay on the black velvet cushions of the desk, fell right at my feet! I came near falling myself, I was so dreadfully scared; but I made my way to the window, which I found was open by the rain beating in. But though I stretched myself up on tiptoe, I could not quite reach the[9] sill. Then I went back by the pulpit and got the big Bible, which I placed on the floor edgeways against the wall, and by that help I clambered to the window. I feared I was a great sinner to make such use of the Bible, and such a splendid book too, but I could not help it. I put Kitty out first, and then swung myself down. It rained a little, and was so dark that I could see nothing but my white kitten, who ran along before me, and was both a lantern and a guide. I hardly know how I got home, but there I found myself at last. All was still, but I soon roused the whole house; for, when the danger and trouble were over, I cried the loudest with fright and cold. My mother had supposed that Deacon Wilson’s family had kept me for the night, as I often stayed with them, and had felt no anxiety for me.

Dear mother!—I remember how she took off my dripping clothes, and made me some warm drink, and put me snugly[10] to bed, and laughed and cried, as she listened to my adventures, and kissed me and comforted me till I fell asleep. Nor was Kitty forgotten, but was fed and put as cosily to bed as her poor mistress.

The next morning I awoke with a dreadful headache, and when I tried to rise I found I could not stand. I do not remember much more, except that my father, who was a physician, came and felt my pulse, and said I had a high fever, brought on by the fright and exposure of the night previous. I was very sick indeed for three or four weeks, and all that time my faithful Kitty stayed by the side of my bed. She could be kept out of the room but a few moments during the day, and mewed piteously when they put her in her little house at night. My friends said that it was really very affecting to see her love and devotion; but I knew very little about it, as I was out of my head, or in a stupor, most of the time. Yet I remember how the good creature frolicked about[11] me the first time I was placed in an arm-chair, and wheeled out into the dining-room to take breakfast with the family; and when, about a week later, my brother Charles took me in his strong arms and carried me out into the garden, how she ran up and down the walks, half crazy with delight, and danced along sideways, and jumped out at us from behind currant-bushes, in a most cunning and startling manner.

I remember now how strange the garden looked,—how changed from what I had last seen it. The roses were all, all gone, and the China-asters and marigolds were in bloom. When my brother passed with me through the corn and beans, I wondered he did not get lost, they were grown so thick and high.

It was in the autumn after this sickness, that one afternoon I was sitting under the shade of a favorite apple-tree, reading Mrs. Sherwood’s sweet story of “Little Henry and his Bearer.” I remember how I cried[12] over it, grieving for poor Henry and his dear teacher. Ah, I little thought how soon my tears must flow for myself and my Kitty! It was then that my sister came to me, looking sadly troubled, to tell me the news. Our brother William, who was a little mischievous, had been amusing himself by throwing Kitty from a high window, and seeing her turn somersets in the air, and alight on her feet unhurt. But at last, becoming tired or dizzy, she had fallen on her back and broken the spine, just below her shoulders. I ran at once to where she lay on the turf, moaning in her pain. I sat down beside her, and cried as though my heart would break. There I stayed till evening, when my mother had Kitty taken up very gently, carried into the house, and laid on a soft cushion. Then my father carefully examined her hurt. He shook his head, said she could not possibly get well, and that she should be put out of her misery at once. But I begged that she might be[13] allowed to live till the next day. I did not eat much supper that night, or breakfast in the morning, but grieved incessantly for her who had been to me a fast friend in sickness as in health.

About nine o’clock of a pleasant September morning, my brothers came and held a council round poor Kitty, who was lying on a cushion in my lap, moaning with every breath; and they decided that, out of pity for her suffering, they must put her to death. The next question was, how this was to be done. “Cut her head off with the axe!” said my brother Charles, trying to look very manly and stern, with his lip quivering all the while. But my brother William, who had just been reading a history of the French Revolution, and how they took off the heads of people with a machine called the guillotine, suggested that the straw-cutter in the barn would do the work as well, and not be so painful for the executioner. This was agreed to by all present.

[14]Weeping harder than ever, I then took a last leave of my dear pet, my good and loving and beautiful Kitty. They took her to the guillotine, while I ran and shut myself up in a dark closet, and stopped my ears till they came and told me that all was over.

The next time I saw my poor pet, she was lying in a cigar-box, ready for burial. They had bound her head on very cleverly with bandages, and washed all the blood off from her white breast; clover-blossoms were scattered over her, and a green sprig of catnip was placed between her paws. My youngest brother, Albert, drew her on his little wagon to the grave, which was dug under a large elm-tree, in a corner of the yard. The next day I planted over her a shrub called the “pussy-willow.”

After that I had many pet kittens, but none that ever quite filled the place of poor Keturah. Yet I still have a great partiality for the feline race. I like nothing[15] better than to sit, on a summer afternoon or in a winter evening, and watch the graceful gambols and mischievous frolics of a playful kitten.

For some weeks past we have had with us on the sea-shore a beautiful little Virginian girl,—one of the loveliest creatures alive,—who has a remarkable fondness for a pretty black and white kitten, belonging to the house. All day long she will have her pet in her arms, talking to her when she thinks nobody is near,—telling her every thing,—charging her to keep some story to herself, as it is a very great secret,—sometimes reproving her for faults, or praising her for being good. Her last thought on going to sleep, and the first on waking, is this kitten. She loves her so fondly, that her father has promised that she shall take her all the way to Virginia. We shall miss the frolicsome kitten much, but the dear child far more.

SAM, THE ROOSTER.

The next pet which I remember to have had was a handsome cockerel, as gay and gallant a fellow as ever scratched up seed-corn, or garden-seeds, for the young pullets.

Sam was a foundling; that is, he was cast off by an unnatural mother, who, from the time he was hatched, refused to own him. In this sad condition my father found him, and brought him to me. I took and put him in a basket of wool, where I kept him most of the time, for a week or two, feeding him regularly and taking excellent care of him. He grew and thrived, and finally became a great house-pet and favorite. My father was[18] especially amused by him, but my mother, I am sorry to say, always considered him rather troublesome, or, as she remarked, “more plague than profit.” Now I think of it, it must have been rather trying to have had him pecking at a nice loaf of bread, when it was set down before the fire to raise, and I don’t suppose that the print of his feet made the prettiest sort of a stamp for cookies and pie-crust.

Sam was intelligent, very. I think I never saw a fowl turn up his eye with such a cunning expression after a piece of mischief. He showed such a real affection for me, that I grew excessively fond of him. But ah, I was more fond than wise! Under my doting care, he never learnt to roost like other chickens. I feared that something dreadful might happen to him if he went up into a high tree to sleep; so when he grew too large to lie in his basket of wool, I used to stow him away very snugly in a leg of an old pair of pantaloons, and lay him in a warm place under[19] a corner of the wood-house. In the morning I had always to take him out; and as I was not, I regret to say, a very early riser, the poor fellow never saw daylight till two or three hours after all the other cocks in the neighbourhood were up and crowing.

After Sam was full-grown, and had a “coat of many colors” and a tail of gay feathers, it was really very odd and laughable to see how every evening, just at sundown, he would leave all the other fowls with whom he had strutted and crowed and fought all day, and come meekly to me, to be put to bed in the old pantaloons.

But one morning, one sad, dark morning, I found him strangely still when I went to release him from his nightly confinement. He did not flutter, nor give a sort of smothered crow, as he usually did. The leg of which I took hold to pull him out, seemed very cold and stiff. Alas, he had but one leg! Alas, he had no head at all! My poor Sam had been murdered[20] and partly devoured by a cruel rat some time in the night!

I took the mangled body into the house, and sat down in a corner with it in my lap, and cried over it for a long time. It may seem very odd and ridiculous, but I really grieved for my dead pet; for I believed he had loved and respected me as much as it is in a cockerel’s heart to love and respect any one. I knew I had loved him, and I reproached myself bitterly for never having allowed him to learn to roost.

At last, my brothers came to me, and very kindly and gently persuaded me to let Sam be buried out of my sight. They dug a little grave under the elm-tree, by the side of Keturah, laid the body down, wrapped in a large cabbage-leaf, filled in the earth, and turfed over the place. My brother Rufus, who knew a little Latin, printed on a shingle the words, “Hic jacet Samuelus,”—which mean, Here lies Sam,—and placed it above where the[21] head of the unfortunate fowl should have been.

I missed this pet very much; indeed, every body missed him after he was gone, and even now I cannot laugh heartily when I think of the morning when I found him dead.

A short time after this mournful event, my brother Rufus, who was something of a poet, wrote some lines for me, which he called a “Lament.” This I then thought a very affecting, sweet, and consoling poem, but I have since been inclined to think that my brother was making sport of me and my feelings all the time. I found this same “Lament” the other day among some old papers, and as it is quite a curiosity, I will let you see it:—

TOBY, THE HAWK.

About the queerest pet that I ever had was a young hawk. My brother Rufus, who was a great sportsman, brought him home to me one night in spring. He had shot the mother-hawk, and found this young half-fledged one in the nest. I received the poor orphan with joy, for he was too small for me to feel any horror of him, though his family had long borne rather a bad name. I resolved that I would bring him up in the way he should go, so that when he was old he should not destroy chickens. At first, I kept him in a bird-cage, but after a while he grew too large for his quarters, and had to have a house built for him expressly. I[24] let him learn to roost, but I tried to bring him up on vegetable diet. I found, however, that this would not do. He eat the bread and grain to be sure, but he did not thrive; he looked very lean, and smaller than hawks of his age should look. At last I was obliged to give up my fine idea of making an innocent dove, or a Grahamite, out of the poor fellow, and one morning treated him to a slice of raw mutton. I remember how he flapped his wings and cawed with delight, and what a hearty meal he made of it. He grew very fat and glossy after this important change in his diet, and I became as proud of him as of any pet I ever had. But my mother, after a while, found fault with the great quantity of meat which he devoured. She said that he eat more beef-steak than any other member of the family. Once, when I was thinking about this, and feeling a good deal troubled lest some day, when I was gone to school, they at home might take a fancy to cut off the head of my pet[25] to save his board-bill, a bright thought came into my mind. There was running through our farm, at a short distance from our house, a large mill-stream, along the banks of which lived and croaked a vast multitude of frogs. These animals are thought by hawks, as well as Frenchmen, very excellent eating. So, every morning, noon, and night, I took Toby on my shoulder, ran down to the mill-stream, and let him satisfy his appetite on all such frogs as were so silly as to stay out of the water and be caught. He was very quick and active,—would pounce upon a great, green croaker, and have him halved and quartered and hid away in a twinkling. I generally looked in another direction while he was at his meals,—it is not polite to keep your eye on people when they are eating, and then I couldn’t help pitying the poor frogs. But I knew that hawks must live, and say what they might, my Toby never prowled about hen-coops to devour young chickens. I taught him[26] better morals than that, and kept him so well fed that he was never tempted to such wickedness. I have since thought that, if we want people to do right, we must treat them as I treated my hawk; for when we think a man steals because his heart is full of sin, it may be only because his stomach is empty of food.

When Toby had finished his meal, he would wipe his beak with his wing, mount on my shoulder, and ride home again; sometimes, when it was a very warm day and he had dined more heartily than usual, he would fall asleep during the ride, still holding on to his place with his long, sharp claws. Sometimes I would come home with my pinafore torn and bloody on the shoulder, and then my mother would scold me a little and laugh at me a great deal. I would blush and hang my head and cry, but still cling to my strange pet; and when he got full-grown and had wide, strong wings, and a great, crooked beak that every body else was[27] afraid of, I was still his warm friend and his humble servant, still carried him to his meals three times a day, shut him into his house every night, and let him out every morning. Such a life as that bird led me!

Toby was perfectly tame, and never attempted to fly beyond the yard. I thought this was because he loved me too well to leave me; but my brothers, to whom he was rather cross, said it was because he was a stupid fowl. Of course they only wanted to tease me. I said that Toby was rough, but honest; that it was true he did not make a display of his talents like some folks, but that I had faith to believe that, some time before he died, he would prove himself to them all to be a bird of good feelings and great intelligence.

Finally the time came for Toby to be respected as he deserved. One autumn night I had him with me in the sitting-room, where I played with him and let[28] him perch on my arm till it was quite late. Some of the neighbours were in, and the whole circle told ghost-stories, and talked about dreams, and warnings, and awful murders, till I was half frightened out of my wits; so that, when I went to put my sleepy hawk into his little house, I really dared not go into the dark, but stopped in the entry, and left him to roost for one night on the hat-rack, saying nothing to any one. Now it happened that my brother William, who was then about fourteen years of age, was a somnambulist,—that is, a person who walks in sleep. He would often rise in the middle of the night, and ramble off for miles, always returning unwaked. Sometimes he would take the horse from the stable, saddle and bridle him, and have a wild gallop in the moonlight. Sometimes he would drive the cows home from pasture, or let the sheep out of the pen. Sometimes he would wrap himself in a sheet, glide about the house, and appear at our bedside like[29] a ghost. But in the morning he had no recollection of these things. Of course, we were very anxious about him, and tried to keep a constant watch over him, but he would sometimes manage to escape from all our care. Well, that night there was suddenly a violent outcry set up in the entry. It was Toby, who shrieked and flapped his wings till he woke my father, who dressed and went down stairs to see what was the matter. He found the door wide open, and the hawk sitting uneasily on his perch, looking frightened and indignant, with all his feathers raised. My father, at once suspecting what had happened, ran up to William’s chamber and found his bed empty; he then roused my elder brothers, and, having lit a lantern, they all started off in pursuit of the poor boy. They searched through the yard, garden, and orchard, but all in vain. Suddenly they heard the saw-mill, which stood near, going. They knew that the owner never worked there at night, and supposed that[30] it must be my brother, who had set the machinery in motion. So down they ran as fast as possible, and, sure enough, they found him there, all by himself. A large log had the night before been laid in its place ready for the morning, and on that log sat my brother, his large black eyes staring wide open, yet seeming to be fixed on nothing, and his face as pale as death. He seemed to have quite lost himself, for the end of the log on which he sat was fast approaching the saw. My father, with great presence of mind, stopped the machinery, while one of my brothers caught William and pulled him from his perilous place. Another moment, and he would have been killed or horribly mangled by the cruel saw. With a terrible scream, that was heard to a great distance, poor William awoke. He cried bitterly when he found where he was and how he came there. He was much distressed by it for some time; but it was a very good thing for all that, for he never walked in his sleep again.

[31]As you would suppose, Toby, received much honor for so promptly giving the warning on that night. Every body now acknowledged that he was a hawk of great talents, as well as talons. But alas! he did not live long to enjoy the respect of his fellow-citizens. One afternoon that very autumn, I was sitting at play with my doll, under the thick shade of a maple-tree, in front of the house. On the fence near by sat Toby, lazily pluming his wing, and enjoying the pleasant, golden sunshine,—now and then glancing round at me with a most knowing and patronizing look. Suddenly, there was the sharp crack of a gun fired near, and Toby fell fluttering to the ground. A stupid sportsman had taken him for a wild hawk, and shot him in the midst of his peaceful and innocent enjoyment. He was wounded in a number of places, and was dying fast when I reached him. Yet he seemed to know me, and looked up into my face so piteously, that I sat down by him, as I[32] had sat down by poor Keturah, and cried aloud. Soon the sportsman, who was a stranger, came leaping over the fence to bag his game. When he found what he had done, he said he was very sorry, and stooped down to examine the wounds made by his shot. Then Toby roused himself, and caught one of his fingers in his beak, biting it almost to the bone. The man cried out with the pain, and tried to shake him off, but Toby still held on fiercely and stoutly, and held on till he was dead. Then his ruffled wing grew smooth, his head fell back, his beak parted and let go the bleeding finger of his enemy.

I did not want the man hurt, for he had shot my pet under a mistake, but I was not sorry to see Toby die like a hero. We laid him with the pets who had gone before. Some were lovelier in their lives, but none more lamented when dead. I will venture to say that he was the first of his race who ever departed with a clean[33] conscience as regarded poultry. No careful mother-hen cackled with delight on the day he died,—no pert young rooster flapped his wings and crowed over his grave. But I must say, I don’t think that the frogs mourned for him. I thought that they were holding a jubilee that night; the old ones croaked so loud, and the young ones sung so merrily, that I wished the noisy green creatures all quietly going brown, on some Frenchman’s gridiron.

When I was ten or eleven years of age, I had two pets, of which I was equally fond, a gentle bay pony and a small pointer dog. I have always had a great affection for horses, and never knew what it was to be afraid of them, for they are to me exceedingly obliging and obedient. Some people think that I control them with a sort of animal magnetism. I only know that I treat them with kindness, which is, I believe, after all, the only magnetism necessary for one to use in this world. When I ride, I give my horse to understand that I expect him to behave very handsomely, like the gentleman I[35] take him to be, and he never disappoints me.

MILLY the pony & CARLO the dog.

Our Milly was a great favorite with all the family, but with the children especially. She was not very handsome or remarkably fleet, but was easily managed, and even in her gait. I loved her dearly, and we were on the best terms with each other. I was in the habit of going into the pasture where she fed, mounting her from the fence or a stump, and riding about the field, often without saddle or bridle. You will see by this that I was a sad romp. Milly seemed to enjoy the sport fully as much as I, and would arch her neck, and toss her mane, and gallop up and down the little hills in the pasture, now and then glancing round at me playfully, as much as to say, “Aint we having times!”

Finally, I began to practise riding standing upright, as I had seen the circus performers do, for I thought it was time I should do something to distinguish myself.[36] After a few tumbles on to the soft clover, which did me no sort of harm, I became quite accomplished that way. I was at that age as quick and active as a cat, and could save myself from a fall after I had lost my balance, and seemed half way to the ground. I remember that my brother William was very ambitious to rival me in my exploits; but as he was unfortunately rather fat and heavy, he did a greater business in turning somersets from the back of the pony than in any other way. But these were quite as amusing as any other part of the performances. We sometimes had quite a good audience of the neighbours’ children, and our schoolmates, but we never invited our parents to attend the exhibition. We thought that on some accounts it was best they should know nothing about it.

In addition to the “ring performances,” I gave riding lessons to my youngest brother, Albert, who was then quite a little boy. He used to mount Milly behind[37] me, and behind him always sat one of our chief pets, and our constant playmate, Carlo, a small black and white pointer. One afternoon, I remember, we were all riding down the long, shady lane which led from the pasture to the house, when a mischievous boy sprang suddenly out from a corner of the fence, and shouted at Milly. I never knew her frightened before, but this time she gave a loud snort, and reared up almost straight in the air. As there was neither saddle nor bridle for us to hold on by, we all three slid off backward into the dust, or rather the mud, for it had been raining that afternoon. Poor Carlo was most hurt, as my brother and I fell on him. He set up a terrible yelping, and my little brother cried somewhat from fright. Milly turned and looked at us a moment to see how much harm was done, and then started off at full speed after the boy, chasing him down the lane. He ran like a fox when he heard Milly galloping fast behind him, and when he looked[38] round and saw her close upon him, with her ears laid back, her mouth open, and her long mane flying in the wind, he screamed with terror, and dropped as though he were dead. She did not stop, but leaped clear over him as he lay on the ground. Then she turned, went up to him, quietly lifted the old straw hat from his head, and came trotting back to us, swinging it in her teeth. We thought that was a very cunning trick of Milly’s.

Now it happened that I had on that day a nice new dress, which I had sadly soiled by my fall from the pony; so that when I reached home, my mother was greatly displeased. I suppose I made a very odd appearance. I was swinging my bonnet in my hand, for I had a natural dislike to any sort of covering for the head. My thick, dark hair had become unbraided and was blowing over my eyes. I was never very fair in complexion, and my face, neck, and arms had become completely browned by that summer’s exposure.[39] My mother took me by the shoulder, set me down in a chair, not very gently, and looked at me with a real frown on her sweet face. She told me in plain terms that I was an idle, careless child! I put my finger in one corner of my mouth, and swung my foot back and forth. She said I was a great romp! I pouted my lip, and drew down my black eyebrows. She said I was more like a wild, young squaw, than a white girl! Now this was too much; it was what I called “twitting upon facts”; and ’twas not the first time that the delicate question of my complexion had been touched upon without due regard far my feelings. I was not to blame for being dark,—I did not make myself,—I had seen fairer women than my mother. I felt that what she said was neither more nor less than an insult, and when she went out to see about supper, and left me alone, I brooded over her words, growing more and more out of humor, till my naughty heart became so hot[40] and big with anger, that it almost choked me. At last, I bit my lip and looked very stern, for I had made up my mind to something great. Before I let you know what this was, I must tell you that the Onondaga tribe of Indians had their village not many miles from us. Every few months, parties of them came about with baskets and mats to sell. A company of five or six had been to our house that very morning, and I knew that they had their encampment in our woods, about half a mile distant. These I knew very well, and had quite a liking for them, never thinking of being afraid of them, as they always seemed kind and peaceable.

To them I resolved to go in my trouble. They would teach me to weave baskets, to fish, and to shoot with the bow and arrow. They would not make me study, nor wear bonnets, and they would never find fault with my dark complexion.

I remember to this day how softly and slyly I slid out of the house that evening.[41] I never stopped once, nor looked round, but ran swiftly till I reached the woods. I did not know which way to go to find the encampment, but wandered about in the gathering darkness, till I saw a light glimmering through the trees at some distance. I made my way through the bushes and brambles, and after a while came upon my copper-colored friends. In a very pretty place, down in a hollow, they had built them some wigwams with maple saplings, covered with hemlock-boughs. There were in the group two Indians, two squaws, and a boy about fourteen years old. But I must not forget the baby, or rather pappoose, who was lying in a sort of cradle, made of a large, hollow piece of bark, which was hung from the branch of a tree, by pieces of the wild grape-vine. The young squaw, its mother, was swinging it back and forth, now far into the dark shadows of the pine and hemlock, now out into the warm fire-light, and chanting to the child some Indian lullaby.[42] The men sat on a log, smoking gravely and silently; while the boy lay on the ground, playing lazily with a great yellow hound, which looked mean and starved, like all Indian dogs. The old squaw was cooking the supper in a large iron pot, over a fire built among a pile of stones.

For some time, I did not dare to go forward, but at last I went up to the old squaw, and looking up into her good-humored face, said, “I am come to live with you, and learn to make baskets, for I don’t like my home.” She did not say any thing to me, but made some exclamation in her own language, and the others came crowding round. The boy laughed, shook me by the hand, and said I was a brave girl; but the old Indian grinned horribly and laid his hand on my forehead, saying, “What a pretty head to scalp!” I screamed and hid my face in the young squaw’s blue cloth skirt. She spoke soothingly, and told me not to be afraid, for nobody would hurt me. She then took[43] me to her wigwam, where I sat down and tried to make myself at home. But somehow I did’nt feel quite comfortable. After a while, the old squaw took off the pot, and called us to supper. This was succotash, that is, a dish of corn and beans, cooked with salt pork. We all sat down on the ground near the fire, and eat out of great wooden bowls, with wooden spoons, which I must say tasted rather too strong of the pine. But I did not say so then,—by no means,—but eat a great deal more than I wanted, and pretended to relish it, for fear they would think me ill bred. I would not have had them know but what I thought their supper served in the very best style, and by perfectly polite and genteel people. I was a little shocked, however, by one incident during the meal. While the young squaw was helping her husband for the third or fourth time, she accidentally dropped a little of the hot succotash on his hand. He growled out like a dog, and struck her across the[44] face with his spoon. I thought that she showed a most Christian spirit, for she hung her head and did not say any thing. I had heard of white wives behaving worse.

When supper was over, the boy came and laid down at my feet, and talked with me about living in the woods. He said he pitied the poor white people for being shut up in houses all their days. For his part, he should die of such a dull life, he knew he should. He promised to teach me how to shoot with the bow and arrows, to snare partridges and rabbits, and many other things. He said he was afraid I was almost spoiled by living in the house and going to school, but he hoped that, if they took me away and gave me a new name, and dressed me properly, they might make something of me yet. Then I asked him what he was called, hoping that he had some grand Indian name, like Uncas, or Miantonimo, or Tushmalahah; but he said it was Peter. He was a pleasant[45] fellow, and while he was talking with me I did not care about my home, but felt very brave and squaw-like, and began to think about the fine belt of wampum, and the head-dress of gay feathers, and the red leggins, and the yellow moccasons I was going to buy for myself, with the baskets I was going to learn to weave. But when he left me, and I went back to the wigwam and sat down on the hemlock-boughs by myself, somehow I couldn’t keep home out of my mind. I thought first of my mother, how she would miss the little brown face at the supper-table, and on the pillow, by the fair face of my blue-eyed sister. I thought of my young brother, Albert, crying himself to sleep, because I was lost. I thought of my father and brothers searching through the orchard and barn, and going with lights to look in the mill-stream. Again, I thought of my mother, how, when she feared I was drowned, she would cry bitterly, and be very sorry for what she had[46] said about my dark complexion. Then I thought of myself, how I must sleep on the hard ground, with nothing but hemlock-boughs for covering, and nobody to tuck me up. What if it should storm before morning, and the high tree above me should be struck by lightning! What if the old Indian should not be a tame savage after all, but should take a fancy to set up the war-whoop, and come and scalp me in the middle of the night!

The bell in the village church rang for nine. This was the hour for evening devotions at home. I looked round to see if my new friends were preparing for worship. But the old Indian was already fast asleep, and as for the younger one, I feared that a man who indulged himself in beating his wife with a wooden spoon would hardly be likely to lead in family prayers. Upon the whole, I concluded I was among rather a heathenish set. Then I thought again of home, and doubted whether they would have any family worship that night,[47] with one lamb of the flock gone astray. I thought of all their grief and fears, till I felt that my heart would burst with sorrow and repentance, for I dared not cry aloud.

Suddenly, I heard a familiar sound at a little distance,—it was Carlo’s bark! Nearer and nearer it came; then I heard steps coming fast through the crackling brushwood, then little Carlo sprang out of the dark into the fire-light, and leaped upon me, licking my hands with joy. He was followed by one of my elder brothers, and by my mother! To her I ran. I dared not look in her eyes, but hid my face in her bosom, sobbing out, “O mother, forgive me! forgive me!” She pressed me to her heart, and bent down and kissed me very tenderly, and when she did so, I felt the tears on her dear cheek.

I need hardly say that I never again undertook to make an Onondaga squaw of myself, though my mother always held that I was dark enough to be one, and I[48] suppose the world would still bear her out in her opinion.

I am sorry to tell the fate of the faithful dog who tracked me out on that night, though his story is not quite so sad as that of some of my pets. A short time after this event, my brother Charles was going to the city of S——, some twenty miles away, and wished to take Carlo for company. I let him go very reluctantly, charging my brother to take good and constant care of him. The last time I ever saw Carlo’s honest, good-natured face, it was looking out at me through the window of the carriage. The last time, for he never came back to us, but was lost in the crowded streets of S——.

He was a simple, country-bred pointer, and, like many another poor dog, was bewildered by the new scenes and pleasures of the city, forgot his guide, missed his way, wandered off, and was never found.

The pet which took little Carlo’s place in our home and hearts was a pretty, chestnut-colored water-spaniel, named Cora. She was a good, affectionate creature, and deserved all our love. The summer that we had her for our playmate, my brother Albert, my sister Carrie, and I, spent a good deal of time down about the pond, in watching her swimming, and all her merry gambols in the water. There grew, out beyond the reeds and flags of that pond, a few beautiful, white water-lilies, which we taught her to bite off and bring to us on shore.

Cora seemed to love us very much, but there was one whom she loved even more.[50] This was little Charlie Allen, a pretty boy of about four or five years old, the only son of a widow, who was a tenant of my father, and lived in a small house on our place. There grew up a great and tender friendship between this child and our Cora, who was always with him while we were at school. The two would play and run about for hours, and when they were tired, lie down and sleep together in the shade. It was a pretty sight, I assure you, for both were beautiful.

It happened that my father, one morning, took Cora with him to the village, and was gone nearly all day; so little Charlie was without his playmate and protector. But after school, my sister, brother, and I called Cora, and ran down to the pond. We were to have a little company that night, and wanted some of those fragrant, white lilies for our flower-vase. Cora barked and leaped upon us, and ran round and round us all the way. Soon as she reached the pond, she sprang in[51] and swam out to where the lilies grew, and where she was hid from our sight by the flags and other water-plants. Presently, we heard her barking and whining, as though in great distress. We called to her again and again, but she did not come out for some minutes. At last, she came through the flags, swimming slowly along, dragging something by her teeth. As she swam near, we saw that it was a child,—little Charlie Allen! We then waded out as far as we dared, met Cora, took her burden from her, and drew it to the shore. As soon as we took little Charlie in our arms, we knew that he was dead. He was cold as ice, his eyes were fixed in his head, and had no light in them. His hand was stiff and blue, and still held tightly three water-lilies, which he had plucked. We suppose the poor child slipped from a log, on which he had gone out for the flowers, and which was half under water.

Of course we children were dreadfully[52] frightened. My brother was half beside himself, and ran screaming up home, while my sister almost flew for Mrs. Allen.

O, I never shall forget the grief of that poor woman, when she came to the spot where her little dead boy lay!—how she threw herself on the ground beside him, and folded him close in her arms, and tried to warm him with her tears and her kisses, and tried to breathe her own breath into his still, cold lips, and tried to make him hear by calling, “Charlie, Charlie, speak to mamma! speak to your poor mamma!”

But Charlie did not see her, nor feel her, nor hear her any more; and when she found that he was indeed gone from her for ever, she gave the most fearful shriek I ever heard, and fell back as though she were dead.

By this time, my parents and a number of the neighbours had reached the spot, and they carried Mrs. Allen and her drowned boy home together, through the twilight. Poor Cora followed close to[53] the body of Charlie, whining piteously all the way. That night, we could not get her out of the room where it was placed, but she watched there until morning.

Ah, how sweetly little Charlie looked when he was laid out the next day! His beautiful face had lost the dark look that it wore when he was first taken from the water; his pretty brown hair lay in close ringlets all around his white forehead. One hand was stretched at his side, the other was laid across his breast, still holding the water-lilies. He was not dressed in a shroud, but in white trousers, and a pretty little spencer of pink gingham. He did not look dead, but sleeping, and he seemed to smile softly, as though he had a pleasant dream in his heart.

Widow Allen had one other child, a year younger than Charlie, whose name was Mary, but who always called herself “Little May.” O, it would have made you cry to have seen her when she was brought to look on her dead brother. She laughed[54] at first, and put her small fingers on his shut eyes, trying to open them, and said, “Wake up Charlie! wake up, and come play out doors, with little May!” But when she found that those eyes would not unclose, and when she felt how cold that face was, she was grieved and frightened, and ran to hide her face in her mother’s lap, where she cried and trembled; for though she could not know what death was, she felt that something awful had happened in the house.

But Cora’s sorrow was also sad to see. When the body of Charlie was carried to the grave, she followed close to the coffin, and when it was let down into the grave, she leaped in and laid down upon it, and growled and struggled when the men took her out. Every day after that, she would go to that grave, never missing the spot, though there were many other little mounds in the old church-yard. She would lie beside it for hours, patiently waiting, it seemed, for her young friend to[55] awake and come out into the sunshine, and run about and play with her as he was used to do. Sometimes she would dig a little way into the mound, and bark, or whine, and then listen for the voice of Charlie to answer. But that voice never came, though the faithful Cora listened and waited and pined for it, through many days. She ate scarcely any thing; she would not play with us now, nor could we persuade her to go into the pond. Alas! that fair, sweet child, pale and dripping from the water, was the last lily she ever brought ashore. She grew so thin, and weak, and sick, at last, that she could hardly drag herself to the grave. But still she went there every day. One evening, she did not come home, and my brother and I went down for her. When we reached the church-yard, we passed along very carefully, for fear of treading on some grave, and spoke soft and low, as children should always do in such places. Sometimes we stopped to read[56] the long inscriptions on handsome tombstones, and to wonder why so many great and good people were taken away. Sometimes we pitied the poor dead people who had no tombstones at all, because their friends could not afford to raise them, or because they had been too wicked themselves to have their praises printed in great letters, cut in white marble, and put up in the solemn burying-ground, where nobody would ever dare to write or say any thing but the truth. When we came in sight of Charlie’s grave, we talked about him. We wondered if he thought of his mother, and cried out any when he was drowning. We thought that he must have grown very weary with struggling in the water, and we wondered if he was resting now, sleeping down there with his lilies. We said that perhaps his soul was awake all the time, and that, when he was drowned, it did not fly right away to heaven, with the angels, to sing hymns, while his poor mother was weeping, but[57] stayed about the place, and somehow comforted her, and made her think of God and heaven, even when she lay awake in the night, to mourn for her lost boy.

So talking, we came up to the grave. Cora was lying on the mound, where the grass had now grown green and long. She seemed to be asleep, and not to hear our steps or our voices. My brother spoke to her pleasantly, and patted her on the head. But she did not move. I bent down and looked into her face. She was quite dead!

I have hesitated a great deal about writing the history of this pet, for his little life was only a chapter of accidents, and you may think it very silly. Still, I hope you may have a little interest in it after all, and that your kind hearts may feel for poor Jack, for he was good and was unfortunate.

It happened that once, during a walk in the fields, I found a duck’s egg right in my path. We had then no ducks in our farm-yard, and I thought it would be a fine idea to have one for a pet. So I wrapped the egg in wool, and put it into a basket, which I hung in a warm corner by the kitchen-fire. My brothers laughed[59] at me, saying that the egg would never be any thing more than an egg, if left there; but I had faith to believe that I should some time see a fine duckling peeping out of the shell, very much to the astonishment of all unbelieving boys. I used to go to the basket, lift up the wool and look at that little blue-hued treasure three or four times a day, or take it out and hold it against my bosom, and breathe upon it in anxious expectation; until I began to think that a watched egg never would hatch. But my tiresome suspense finally came to a happy end. At about the time when, if he had had a mother, she would have been looking for him, Jack, the drake, presented his bill to the world that owed him a living. He came out as plump and hearty a little fowl as could reasonably have been expected. But what to do with him was the question. After a while, I concluded to take him to a hen who had just hatched a brood of chickens, thinking that, as he was a friendless[60] orphan, she might adopt him for charity’s sake. But Biddy was already like the celebrated

With thirteen little ones of her own, and living in a small and rather an inconvenient coop, it was no wonder that she felt unwilling to have any addition to her family. But she might have declined civilly. I am afraid she was a sad vixen, for no sooner did she see the poor duckling among her chickens, than she strode up to him, and with one peck tore the skin from his head,—scalped him,—the old savage! I rescued Jack from her as soon as possible, and dressed his wound with lint as well as I could, for I felt something like a parent to the fowl myself. He recovered after a while, but, unfortunately, no feathers grew again on his head,—he was always quite bald,—which gave him an appearance of great age. I once tried to remedy this evil by[61] sticking some feathers on to his head with tar; but, like all other wigs, it deceived no one, only making him look older and queerer than ever. What made the matter worse was, that I had selected some long and very bright feathers, which stood up so bold on his head that the other fowls resented it, and pecked at the poor wig till they pecked it all off.

While Jack was yet young, he one day fell into the cistern, which had been left open. Of course he could not get out, and he soon tired of swimming, I suppose, and sunk. At least, when he was drawn up, he looked as though he had been in the water a long time, and seemed quite dead. Yet, hoping to revive him, I placed him in his old basket of wool, which I set down on the hearth. He did indeed come to life, but the first thing the silly creature did on leaving his nest was to run into the midst of the fire, and before I could get him out, he was very badly burned. He recovered from this also, but with bare[62] spots all over his body. In his tail there never afterwards grew more than three short feathers. But his trials were not over yet. After he was full-grown, he was once found fast by one leg in a great iron rat-trap. When he was released, his leg was found to be broken. But my brother William, who was then inclined to be a doctor, which he has since become, and who had watched my father during surgical operations, splintered and bound up the broken limb, and kept the patient under a barrel for a week, so that he should not attempt to use it. At the end of that time, Jack could get about a little, but with a very bad limp, which he never got over. But as the duck family never had the name of walking very handsomely, that was no great matter.

After all these accidents and mishaps, I hardly need tell you that Jack had little beauty to boast of, or plume himself upon. He was in truth sadly disfigured,—about the ugliest fowl possible to meet in a long[63] day’s journey. Indeed, he used to be shown up to people as a curiosity on account of his ugliness.

I remember a little city girl coming to see me that summer. She talked a great deal about her fine wax-dolls with rolling eyes and jointed legs, her white, curly French lap-dog, and, best and prettiest of every thing, her beautiful yellow canary-bird, which sung and sung all the day long. I grew almost dizzy with hearing of such grand and wonderful things, and sat with my mouth wide open to swallow her great stories. At last, she turned to me and asked, with a curl of her pretty red lips, “Have you no pet-birds, little girl?” Now, she always called me “little girl,” though I was a year older and a head taller than she. I replied, “Yes, I have one,” and led the way to the back-yard, where I introduced her to Jack. I thought I should have died of laughter when she came to see him. Such faces as she made up!

I am sorry to say, that the other fowls[64] in the yard, from the oldest hen down to the rooster without spurs, and even to the green goslings, seemed to see and feel Jack’s want of personal pretensions and attractions, and always treated him with marked contempt, not to say cruelty. The little chickens followed him about, peeping and cackling with derision, very much as the naughty children of the old Bible times mocked at the good, bald-headed prophet. But poor Jack didn’t have it in his power to punish the ill-mannered creatures as Elisha did those saucy children, when he called the hungry she-bears to put a stop to their wicked fun. In fact, I don’t think he would have done so if he could, for all this hard treatment never made him angry or disobliging. He had an excellent temper, and was always meek and quiet, though there was a melancholy hang to his bald head, and his three lonesome tail-feathers drooped sadly toward the ground. When he was ever so lean and hungry, he would gallantly give up his dinner to the plump, glossy-breasted[65] pullets, though they would put on lofty airs, step lightly, eye him scornfully, and seem to be making fun of his queer looks all the time. He took every thing so kindly! He was like a few, a very few people we meet, who, the uglier they grow, the more goodness they have at heart, and the worse the world treats them, the better they are to it.

But Jack had one true friend. I liked him, and more than once defended him from cross old hens, and tyrannical cocks. But perhaps my love was too much mixed up with pity for him to have felt highly complimented by it. Yet he seemed to cherish a great affection for me, and to look up to me as his guardian and protector.

As you have seen, Jack was always getting into scrapes, and at last he got into one which even I could not get him out of. He one day rashly swam out into the mill-pond, which was then very high, from a freshet, and which carried him over the dam, where, as he was a very delicate fowl,[66] he was drowned, or his neck was broken, by the great rush and tumble of the water. I have sometimes thought that it might be that he was tired of life, and grieved by the way the world had used him, and so put an end to himself. But I hope it was not so; for, with all his oddities and misfortunes, Jack seemed too sensible for that.

ELEGY.

Hector the Grey-Hound

Hector was the favorite hound of my brother Rufus, who was extremely fond of him, for he was one of the most beautiful creatures ever seen, had an amiable disposition, and was very intelligent. You would scarcely believe me, should I tell you all his accomplishments and cunning tricks. If one gave him a piece of money, he would take it in his mouth and run at once to the baker, or butcher, for his dinner. He was evidently fond of music, and even seemed to have an ear for it, and he would dance away merrily whenever he saw dancing. He was large and strong, and in the winter, I remember, we used to harness him to a little sleigh, on[68] which he drew my youngest brother to school. As Hector was as fleet as the wind, this sort of riding was rare sport. At night we had but to start him off, and he would go directly to the school-house for his little master. Ah, Hector was a wonderful dog!

A few miles from our house, there was a pond, or small lake, very deep and dark, and surrounded by a swampy wood. Here my brothers used to go duck-shooting, though it was rather dangerous sport, as most of the shore of the pond was a soft bog, but thinly grown over with grass and weeds. It was said that cattle had been known to sink in it, and disappear in a short time.

One night during the hunting season, one of my elder brothers brought a friend home with him, a fine, handsome young fellow, named Charles Ashley. It was arranged that they should shoot ducks about the pond the next day. So in the morning they all set out in high spirits. In[69] the forenoon they had not much luck, as they kept too much together; but in the afternoon they separated, my brothers giving their friend warning to beware of getting into the bogs. But Ashley was a wild, imprudent young man, and once, having shot a fine large duck, which fell into the pond near the shore, and Hector, who was with him, refusing to go into the water for it, he ran down himself. Before he reached the edge of the water, he was over his ankles in mire; then, turning to go back, he sunk to his knees, and in another moment he was waist-high in the bog, and quite unable to help himself. He laid his gun down, and, fortunately, could rest one end of it on a little knoll of firmer earth; but he still sunk slowly, till he was in up to his arm-pits. Of course, he called and shouted for help as loud as possible, but my brothers were at such a distance that they did not hear him so as to know his voice. But Hector, after looking at him in his sad fix a moment, started off on[70] a swift run, which soon brought him to his master. My brother said that the dog then began to whine, and run back and forth in a most extraordinary manner, until he set out to follow him to the scene of the accident. Hector dashed on through the thick bushes, as though he were half distracted, every few moments turning back with wild cries to hurry on his master. When my brother came up to where his friend was fixed in the mire, he could see nothing of him at first. Then he heard a faint voice calling him, and, looking down near the water, he saw a pale face looking up at him from the midst of the black bog. He has often said that it was the strangest sight that he ever saw. Poor Ashley’s arms, and the fowling-piece he held, were now beginning to disappear, and in a very short time he would have sunk out of sight for ever! Only to think of such an awful death! My brother, who had always great presence of mind, lost no time in bending down a young tree[71] from the bank where he stood, so that Ashley could grasp it, and in that way be drawn up, for, as you see, it would not have been safe for him to go down to where his friend sunk. When Ashley had taken a firm hold of the sapling, my brother let go of it, and it sprung back, pulling up the young man without much exertion on his part. Ashley was, however, greatly exhausted with fright and struggling, and lay for some moments on the bank, feeling quite unable to walk. As soon as he was strong enough, he set out for home with my brother, stopping very often to rest and shake off the thick mud, which actually weighed heavily upon him. I never shall forget how he looked when he came into the yard about sunset. O, what a rueful and ridiculous figure he cut! We could none of us keep from laughing, though we were frightened at first, and sorry for our guest’s misfortune. But after he was dressed in a dry suit of my brother’s, he looked funnier than ever,[72] for he was a tall, rather large person, and the dress was too small for him every way. Yet he laughed as heartily as any of us, for he was very good-natured and merry. It seems to me I can see him now, as he walked about with pantaloons half way up to his knees, coat-sleeves coming a little below the elbows, and vest that wouldn’t meet at all, and told us queer Yankee stories, and sung songs, and jested and laughed all the evening. But once, I remember, I saw him go out on to the door-step, where Hector was lying, kneel down beside the faithful dog, and actually hug him to his breast.

When not hunting with his master Hector went with Albert and me in all our rambles, berrying and nutting. We could hardly be seen without him, and we loved him almost as we loved one another.

One afternoon in early spring, we had been into the woods for wild-flowers. I remember that I had my apron filled with the sweet claytonias, and the gay trilliums,[73] and the pretty white flowers of the sanguinaria, or “blood-root,” and hosts and handfuls of the wild violets, yellow and blue. My brother had taken off his cap and filled it with beautiful green mosses, all lit up with the bright red squaw-berry. We had just entered the long, shady lane which ran down to the house, and were talking and laughing very merrily, when we saw a crowd of men and boys running toward us and shouting as they ran. Before them was a large, brown bull-dog, that, as he came near, we saw was foaming at the mouth. Then we heard what the men were crying. It was, “Mad dog!”

My brother and I stopped and clung to each other in great trouble. Hector stood before us and growled. The dog was already so near that we saw we could not escape; he came right at us, with his dreadful frothy mouth wide open. He was just upon us, when Hector caught him by the throat, and the two rolled on the ground,[74] biting and struggling. But presently one of the men came up and struck the mad dog on the head with a large club,—so stunned him and finally killed him. But Hector, poor Hector, was badly bitten in the neck and breast, and all the men said that he must die too, or he would go mad. One of the neighbours went home with us, and told my father and elder brothers all about it. They were greatly troubled, but promised that, for the safety of the neighbourhood, Hector should be shot in the morning. I remember how, while they were talking, Hector lay on the door-step licking his wounds, every now and then looking round, as if he thought that there was some trouble which he ought to understand.

I shall never, never forget how I grieved that night! I heard the clock strike ten, eleven, and twelve, as I lay awake weeping for my dear playfellow and noble preserver, who was to die in the morning. Hector was sleeping in the next room, and[75] once I got up and stole out to see him as he lay on the hearth-rug in the clear moonlight, resting unquietly, for his wounds pained him. I went and stood so near that my tears fell on his beautiful head; but I was careful not to wake him, for I somehow felt guilty toward him.

That night the weather changed, and the next morning came up chilly and windy, with no sunshine at all,—as though it would not have been a gloomy day enough, any how. After breakfast—ah! I remember well how little breakfast was eaten by any of us that morning—Hector was led out into the yard, and fastened to a stake. He had never before in all his life been tied, and he now looked troubled and ashamed. But my mother spoke pleasantly to him and patted him, and he held up his head and looked proud again. My mother was greatly grieved that the poor fellow should have to die for defending her children, and when she turned from him and went into the house,[76] I saw she was in tears; so I cried louder than ever. One after another, we all went up and took leave of our dear and faithful friend. My youngest brother clung about him longest, crying and sobbing as though his heart would break. It seemed that we should never get the child away. My brother Rufus said that no one should shoot his dog but himself, and while we children were bidding farewell, he stood at a little distance loading his rifle. But finally he also came up to take leave. He laid his hand tenderly on Hector’s head, but did not speak to him or look into his eyes,—those sad eyes, which seemed to be asking what all this crying meant. He then stepped quickly back to his place, and raised the rifle to his shoulder. Then poor Hector appeared to understand it all, and to know that he must die, for he gave a loud, mournful cry, trembled all over, and crouched toward the ground. My brother dropped the gun, and leaned upon it, pale and distressed. Then came the[77] strangest thing of all. Hector seemed to have strength given him to submit to his hard fate; he stood up bravely again, but turned away his head and closed his eyes. My brother raised the rifle. I covered my face with my hands. Then came a loud, sharp report. I looked round and saw Hector stretched at full length, with a great stream of blood spouting from his white breast, and reddening all the grass about him. He was not quite dead, and as we gathered around him, he looked up into our faces and moaned. The ball which pierced him had cut the cord in two that bound him to the stake, and he was free at the last. My brother, who had thrown down his rifle, drew near also, but dared not come close, because, he said, he feared the poor dog would look reproachfully at him. But Hector caught sight of his beloved master, and, rousing all his strength, dragged himself to his feet. Rufus bent over him and called him by name. Hector looked up lovingly and forgivingly[78] into his face, licked his hand, and died. Then my brother, who had kept a firm, manly face all the while, burst into tears.

My brother William, who was always master of ceremonies on such occasions, made a neat coffin for Hector, and laid him in it, very gently and solemnly. I flung in all the wild-flowers which Albert and I had gathered on the afternoon of our last walk with our noble friend, and so we buried him. His grave was very near the spot where he had so bravely defended us from the mad dog, by the side of the way, in the long, pleasant lane where the elm-trees grew.

One cold night in March, my father came in from the barn-yard, bringing a little lamb, which lay stiff and still in his arms, and appeared to be quite dead. But my mother, who was good and kind to all creatures, wrapped it in flannel, and, forcing open its teeth, poured some warm milk down its throat. Still it did not open its eyes or move, and when we went to bed it was yet lying motionless before the fire. It happened that my mother slept in a room opening out of the sitting-room, and in the middle of the night she heard a little complaining voice, saying, “Ma!” She thought it must be some one of us, and so answered, “What, my child?”[80] Again it came, “Ma!” and, turning round, she saw by the light of the moon the little lamb she had left for dead standing by her bedside. In the morning it was found that the own mother of “Bob,” (for we gave him that name,) had died of cold in the night; so we adopted the poor orphan into our family. We children took care of him, and though it was a great trouble to bring him up by hand, we soon became attached to our charge, and grew very proud of his handsome growth and thriving condition. He was, in truth, a most amusing pet, he had such free manners with every body and was so entirely at home everywhere. He would go into every room in the house,—even mount the stairs and appear in our chambers in the morning, sometimes before we were up, to shame us with his early rising. But the place which of all others he decidedly preferred was the pantry. Here he was, I am sorry to say, once or twice guilty of breaking the commandment against stealing, by[81] helping himself to fruit and to slices of bread which did not rightfully belong to him. He was tolerably amiable, though I think that lambs generally have a greater name for sweetness of temper than they deserve. But Bob, though playful and somewhat mischievous, had never any serious disagreement with the dogs, cats, pigs, and poultry on the premises. My sister and I used to make wreaths for his neck, which he wore with such an evident attempt at display, that I sometimes feared he was more vain and proud than it was right for such an innocent and poetical animal to be.

But our trials did not really commence until Bob’s horns began to sprout. It seemed that he had no sooner perceived those little protuberances in his looking glass, the drinking-trough, than he took to butting, like any common pasture-reared sheep, who had been wholly without the advantages of education and good society. It was in vain that we tried[82] to impress upon him that such was not correct conduct in a cosset of his breeding; he would still persevere in his little interesting trick of butting all such visitors as did not happen to strike his fancy. But he never treated us to his horns in that way, and so we let him go, like any other spoiled child, without punishing him severely, and rather laughed at his sauciness.

But one day our minister, a stout, elderly gentleman, solemn-faced and formal, had been making us a parochial visit, and as he was going away, we all went out into the yard to see him ride off, on his old sorrel pacer. It seems he had no riding-whip; so he reached up to break off a twig from an elm-tree which hung over the gate. This was very high, and he was obliged to stand on tiptoe. Just then, before he had grasped the twig he wanted, Bob started out from under a large rose-bush near by, and run against the reverend gentleman, butting him so violently[83] as to take him quite off his feet. My father helped the good man up, and made a great many apologies for the impiety of our pet, while we children did our best to keep our faces straight. After our venerable visitor was gone, my father sternly declared that he would not bear with Bob any longer, but that he should be turned into the pasture with the other sheep, for he would not have him about, insulting respectable people and butting ministers of the Gospel at that rate.

So the next morning Bob was banished in disgrace from the house and yard, and obliged to mingle with the vulgar herd of his kind. With them I regret to say that he soon earned the name of being very bold and quarrelsome. As his horns grew and lengthened, he grew more and more proud of the consequence they gave him, and went forth butting and to butt. O, he was a terrible fellow!

One summer day, my brother Charles and a young man who lived with us were[84] in the mill-pond, washing the sheep which were soon to be sheared. I was standing on the bank, watching the work, when one of our neighbours, a hard, coarse man, came up, and calling to my brother, in a loud voice, asked if he had been hunting a raccoon the night before. “Yes, Sir, and I killed him too,” answered my brother. “Well, young man,” said the farmer, “did you pass through my field, and trample down the grain?” “I crossed the field, Sir, but I hope I did no great damage,” replied Charles, in a pleasant way. “Yes, you did!” shouted the man, “and now, you young rascal, if I ever catch you on my land again, day or night, I’ll thrash you!—I’ll teach you something, if your father won’t!” As he said this, stretching his great fist out threateningly toward my brother, he stood on the very edge of the steep bank. Just behind him were the sheep, headed by the redoubtable Bob, who suddenly darted forward, and, before the farmer could suspect what was coming,[85] butted him head over heels into the pond! My brother went at once to the assistance of his enemy, who scrambled on to the shore, sputtering and dripping, but a good deal cooled in his rage. I suppose I was very wicked, but I did enjoy that!

For this one good turn, Bob was always quite a favorite, with all his faults, and year after year was spared, when worthier sheep were made mutton of. He was finally sold, with the rest of the flock, when we left the farm, and though he lived to a good old age, the wool of his last fleece must long since have been knit into socks and comforters, or woven into cloth,—must have grown threadbare, and gone to dress scarecrows, or stop cellar-windows; or been all trodden out in rag-carpets.

I must now, dear children, pass over a few years of my life, in which I had no pets in whose history you would be likely to be interested.

ROBIN REDBREAST

At the time of my possessing my wonderful Robin, we had left our country home, my brothers were most of them abroad in the world, and I was living with my parents in the pleasant city of R——. I was a school-girl, between fifteen and sixteen years of age. That spring, I commenced the study of French, and, as I was never a remarkably bright scholar, I was obliged to apply myself with great diligence to my books. I used to take my grammar and phrase-book to my chamber,[87] at night, and study as long as I could possibly keep my eyes open. In consequence of this, as you may suppose, I was very sleepy in the morning, and it usually took a prodigious noise and something of a shaking to waken me. But one summer morning I was roused early, not by the breakfast-bell, nor by calling, or shaking, but by a glad gush of sweetest singing. I opened my eyes, and right on the foot-board of my bed was perched a pretty red-breasted robin, pouring out all his little soul in a merry morning song. I stole out of bed softly, and shut down the window through which he had come; then, as soon as I was dressed, caught him, carried him down stairs, and put him into a cage which had hung empty ever since the cat made way with my last Canary.

I soon found that I had a rare treasure in my Robin, who was very tame, and had evidently been carefully trained, for before the afternoon was over he surprised and delighted us all by singing the air of[88] “Buy a Broom” quite through, touching on every note with wonderful precision. We saw that it was a valuable bird, who had probably escaped, and for some days we made inquiries for its owner, but without success.

At night I always took Robin’s cage into my chamber, and he was sure to waken me early with his loud, but delicious, singing. So passed on a month, in which I had great happiness in my interesting pet. But one Saturday forenoon I let him out, that I might clean his cage. I had not observed that there was a window open, but the bird soon made himself acquainted with the fact, and, with a glad, exulting trill, he darted out into the sunshine. Hastily catching my bonnet, I ran after him. At first, he stayed about the trees in front of the house, provokingly hopping from branch to branch out of my reach, holding his head on one side, and eyeing me with sly, mischievous glances. At last he spread his wings and flew down[89] the street. I followed as fast as I could, keeping my eye upon him all the time. It was curious that he did not fly across squares, or over the houses, but kept along above the streets, slowly, and with a backward glance once in a while. At length, he turned down a narrow court, and flew into the open window of a small frame-house. Here I followed him, knocking timidly at the door, which was opened at once by a boy about nine years old. I found myself in a small parlour, very plainly, but neatly furnished. In an arm-chair by the window sat a middle-aged woman, who I saw at once was blind. A tall, dark-eyed, rather handsome girl was sitting near her, sewing. But I did not look at either of these more than a moment, for on the other side of the room was an object to charm, and yet sadden, my eyes. This was a slight girl, about my own age, reclining on a couch, looking very ill and pale, but with a small, red spot on each cheek, which told me that she was almost[90] gone with consumption. She was very beautiful, though so thin and weary looking. She had large, dark, tender eyes, and her lips were still as sweet as rose-buds. I think I never saw such magnificent hair as hers; it flowed all over her pillow, and hung down nearly to the floor, in bright, glossy ringlets.