Title: The Ohio Naturalist, vol. II, no. 2, December, 1901

Creator: Ohio State University. Biological Club

Release date: August 31, 2023 [eBook #71531]

Language: English

Original publication: Columbus, OH: The Biological Club of the Ohio State University, 1900

Credits: Richard Tonsing and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

| Volume II. | DECEMBER, 1901. | Annual Subscription, 50 cts. |

| Number 2. | Single Number, 10 cts. |

“The Best of Everything Laboratorial.”

For every division of Natural Science.

Bookkeeping taught here as books are kept. All entries made from vouchers, bills, notes, checks, drafts, etc. The student learns by doing. Thorough, interesting and practical.

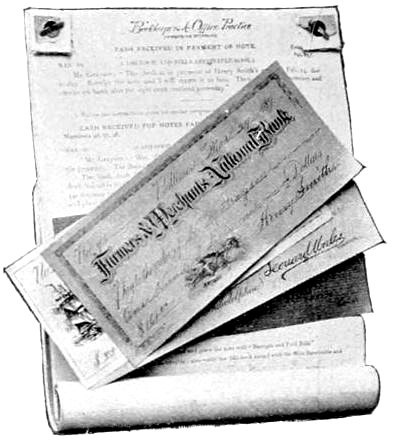

We are pioneer teachers of Gregg’s Light-Line Shorthand, a simple, sensible, legible, rapid system. Learned in half the time required by other systems. Send postal for first lesson.

A LESSON IN GREGG’S SHORTHAND.

If you are at present employed, write us regarding our Home Study work.

Same thorough instruction as given in the class room.

EVERY SCHOOL should have a collection of Natural History specimens. Why not

of the Birds or Mammals of your county or state, or enrich a present collection by the addition of some well mounted specimens? Costs so much? Perhaps so, but WRITE TO ME FOR PRICES and you will be surprised how little such a collection will cost after all. Think of the interest that will be awakened in your school in the

to reward you for trouble and outlay.

I mount to order

and solicit your patronage. If you are interested, you should not lose an opportunity to examine the novel collection of Ohio birds, prepared by myself, in the museum of Zoology, Ohio State University.

TAUGHT BY MAIL.—I give instructions in the Art of Taxidermy, personally, or BY MAIL. You can learn to collect and prepare your own birds, thus reducing the cost of a collection to a minimum.

A journal devoted more especially to the natural history of Ohio. The official organ of The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. Published monthly during the academic year, from November to June (8 numbers). Price 50 cents per year, payable in advance. To foreign countries, 75 cents. Single copies, 10 cents.

No typewriter is worth $100. We have made a mechanically excelling machine, and sell it for $35. We claim that it is the superior of any typewriter made. This is a broad but carefully weighed statement, and it is the truth.

Awarded gold medal at the Paris Exposition, 1900, in open competition with all other makes of typewriters.

Our descriptive matter tells an interesting story. Send for it and learn something about a high-grade typewriter sold at an honest price.

| PUBLISHED BY | ||

| The Biological Club of the Ohio State University. | ||

| Volume II. | DECEMBER. 1901. | No. 2. |

| Tyler—Meeting of the Biological Club | 147 |

| Meeting of the Ohio State Academy of Science | 156 |

| Kellerman—Fifty Additions to the Catalogue of Ohio Plants | 157 |

| Kellerman—Botanical Correspondence, Notes and News for Amateurs, I | 159 |

| Kellerman—Note and Correction to Ohio Fungi Exsiccate | 161 |

| Griggs—Notes of Travel in Porto Rico | 162 |

| Morse—Salamanders Taken at Sugar Grove | 164 |

| Williamson—Fishes Taken Near Salem, Ohio | 165 |

| Hine—Collecting Tobanidae | 167 |

| Hine—Observations on Insects | 169 |

The Biological Club met in Orton Hall and was called to order by the president, Prof. Osborn. As it is customary to elect new officers at the November meeting each year, the Nominating Committee presented the following names: For president, Mr. Mills; for vice-president, Mr. Morse; for secretary, Mr. Tyler. Prof. Lazenby moved that the secretary be instructed to cast the unanimous ballot of the members present for the names proposed. Carried. Messrs. J. C. Bridwell, M. T. Cook and Harvey Brugger were elected members.

The retiring president, Prof. Osborn, presented a very interesting address, an abstract of which follows:

It has been the custom in this society, following a mandate of its constitution, for the president on retiring from the chair to give an address, and it is presumed that such an address will either bring to your attention the results of some special investigation, summarize the work in some field of research or outline the progress and problems with which biology has to do.

When a year ago you were so kind as to honor me with this office, two things I think came especially to my mind; one the 148success of the club particularly in the new enterprise of publishing a journal; the other the duty, honor and privilege of preparing an address for this occasion. I presume you have all had the experience of contemplating some distance in the future a certain duty, debating the most suitable theme or method, and perhaps seen the time grow shorter and shorter with little real accomplishment. If I were to enumerate the various topics that have come to my mind as suitable for this occasion it would exhaust quite a part of our time; if I could reproduce the current of thought that has flowed from time to time along the pathways of such topics, I am sure you would experience a weariness that I should regret to occasion.

The parts of biology which we may make thoroughly our own are very few. It may be profitable, therefore, occasionally to take a general survey of the field to see what its sphere of influence may be, what phases of life are being advanced by its discoveries or by the distribution of knowledge which follows. It has seemed to me therefore that it would be appropriate this evening to attempt some such survey of biology, even though it be fragmentary and inadequate.

For convenience in arrangement we may group this survey along the lines of practical applications of service to mankind, such as occur in medicine, agriculture and kindred industries, domestic and social life, and those which have to do with the acquisition of knowledge and with education.

Applications of biology in medical science, in agriculture and in domestic life have in many cases assumed such intimate and essential character that we often look upon them as applied sciences more than in any other way.

While biology has been the foundation of all rational systems of medicine and the constant servant of this most beneficent of human professions, the forms of its uses and the wide reach of its service have so increased in recent years that we almost have excuse in feeling that it is a modern acquisition.

Could the ancient disciples of Esculapius, with their views of physiology and anatomy, have seen the present scope of these subjects and the marvelous results in cure and control of diseases by the discoveries and applications in bacteriology, I doubt if they would have recognized it as any part of their biology. Still harder would it have been to appreciate the relations of malarial parasite, mosquito and man whereby a serious disease in the latter is occasioned. Intimate relations of two kinds of life, as evidenced in the common parasites, must have been familiar from early times and their effects duly recognized, though their means of access and necessary life cycles were long misunderstood. But such relations as are found to exist in the production of malaria, Texas fever and yellow fever have been so recently discovered 149that we count them among the triumphs of our modern science. Indeed the discovery of such a relationship may be considered as having been impossible until the methods of modern research and the basis of knowledge as to life conditions were acquired, and which made it possible to put the disjointed fragments together. With the fragments thus related the riddle seems so simple that we wonder it was not solved before, but we must remember that it is knowledge which makes knowledge possible.

These direct advantages in medical science are however but part of the great gift to modern methods of disease control, for the possibilities in the control of disease by sanitation, quarantine, vaccination, etc., and other methods are all based on biological data.

In speaking of these recent acquisitions I would not disparage those important, in fact essential subjects of longer growth. Modern medicine would be a fragile structure without its basis of comparative anatomy, physiology, materia medica and therapeutics, which have for long years furnished a basis for rational methods in surgery and medication.

With all this knowledge at hand it is grievous to observe how general the delusion that disease may be eradicated by some much emblazoned nostrum, that some vile ‘Indian compound’ will be thought to have more virtue than the most accurately proportioned prescription which represents the best that modern science can do in the adaptation of a particular remedy to a particular ailment. That the patent medicine business is a most gigantic fraud and curse will I believe be granted by every scientific man who has made himself acquainted with the subject. Its immense profits are attested by the square miles of advertisements that disgrace the modern newspaper and magazine. Fortunes made from the fortunes spent in such advertising, along with the commissions to the lesser dealers, are drawn from a credulous people who not only receive no value in return, but in most cases doubtless are actually injured as a result.

That no student of biology can be deluded by such preposterous claims as characterize these compounds, in fact by any system of cure not based on sound biological principles, seems only a logical result of his training. I do not recall ever seeing the name of a biologist among the host of those who sing the praises of some of these rotten compounds. Mayors, congressmen, professors, clergymen and other presumably educated parties appear along with the host of those who fill this guilty list, a list that should be branded as a roll of dishonor. I believe that educated men owe some measure of effort toward the abatement of this plague. Naturally the medical profession is thought to be the rightful source for action, but among the uninformed any effort there is attributed to selfish motive. Certainly some 150measure of reform in this direction would be a service to mankind, and while no sensational crusade may be necessary, each one who knows enough of the laws of life to appreciate the monstrous folly of this business has it in his power to discourage it within the sphere of his individual influence at least. Newspapers are mostly choked off by the immense revenue derived from advertising, in fact I have known some which depended upon this as their main source of support, and have heard the candid statement that they could not have existed without it. All the more honor therefore to the few, and there are a few, which absolutely refuse to allow such advertisements in their columns.

That the modern physician must have a thorough knowledge of biology has become more and more apparent. He has to deal with life, and life thus far at least cannot be rendered into mere mechanical, physical or chemical factors. The activities of the human machine have much that must be studied from the basis of organic nature. If we do not know all the factors or forces of life we do know that there is a complex or combination of forces radically different from any single force of inorganic nature. Chemical affinity, physical attraction and repulsion, mechanical forces may furnish many aids, but the study of life activities must go still further. To do this we must recognize the laws of organic life, the forces of growth and nutrition, of reproduction, of evolution, in fact a host of forces which have no counterpart in the inorganic world.

Modern agriculture and horticulture are so dependent on the principles of biology that to dissociate them does violence to thought. Indeed this relation has existed through all recorded history, but in no period has the utility of biologic laws been so intimately blended with all the processes of cultivation.

The determination of the zones of greatest productivity for different crops, their soil requirements, the introduction and acclimatization of species belonging to other faunal or floral regions, the essentials of animal and plant nutrition, the control of disease or abatement of noxious forms of plant or animal, all these and more are embraced in the service of biologic science to agriculture in its various forms and thus to human interests.

Among special cases cited, but which cannot be printed here in detail, were various plant diseases, and particularly various insect pests, and the discoveries which have brought them more or less under control.

Aside from the sources of food supply, which come under the general term of agriculture, we derive many articles of diet from sources dependent on animal or plant life. The various fishery industries and oyster culture which have been so wonderfully promoted by biological investigations are excellent examples of the service of science to mankind. Game laws for the protection 151of certain forms of life of utility to man and the possible sources of food from various animals or plants not yet utilized may be mentioned here. Clothing comes in for its share, as in the methods for protection of silkworms, the saving of fur seals and other fur-bearing animals from extinction, and the use of various fibre plants. The successful growth of sponges, of pearls and many other articles of domestic comfort or ornament are connected in one way or another with biological problems, and their fullest development dependent on rational measures possible when the biological conditions are known.

In another way these questions enter into our social and commercial life. The rights of property in the migrant or semi-migrant forms of life have biologic as well as legal basis and some quite peculiar legal decisions would doubtless have been very different had the biology been appreciated. The classification of turtles as ‘vermin’ since they are neither fish nor fowl may be given as a case in point. Equally absurd and sometimes more disastrous are some of the rulings by customs officers whose knowledge of biology was doubtless derived from a Greek lexicon or some equally good authority. Such quarantine restrictions as have been imposed upon certain products by some governments show total lack of knowledge as to the possible conditions of injurious transportation or else the misapplication of them to serve some special end.

The exclusion of American pork and American fruits from certain countries, the controversy over the fur seals in Alaska, the inconsistent laws of states or nations regarding game, are some of the instances where it is evident that the law-making power and the agents of diplomacy need to be re-enforced with definite biological knowledge.

But there is another phase quite distinct from the purely utilitarian. Biological science opens up to us the facts of life and solves some of the questions of the greatest interest to mankind. What is life? What its origin? What are the factors that have controlled its development and the wonderful complexities which we observe in its distribution and adaptations? Are the forces that operate in the living organism merely physical, mechanical and chemical or are there activities inherent in life itself or that operate only in the presence of the life containing complex? Certainly, in no other branch of science are there problems more inviting. In no other has present knowledge given greater inspiration or greater intellectual service to mankind.

The field for acquisition of knowledge widens with each new discovery. We no sooner gain foothold in some hitherto unexplored realm than we become conscious that beyond this lie still 152other realms, knowledge of which has been dependent on knowledge of the routes by which they may be reached.

Thus structure must be known to understand function, and function known enables us to interpret structure. Evolution could not be demonstrated until after there had been gathered the necessary materials to show relations of different organisms, past and present. But, evolution known, and vast arrays of structure become intelligible. Without the knowledge of organic distribution no laws of distribution could be framed, but without the explanation of distribution afforded by evolution the facts are an unmeaning puzzle. So, too, without an effort at systematic arrangement of plant and animal forms no fundamental law of relationship could have been discovered, but given a law of relationship and systematic biology assumes a totally different aspect. Recognition of the multitudinous forms of nature are but one step then in the presentation of the vast concourse in their proper relations.

No doubt biologists will persist till every form of life has been adequately described and some means of designating it adopted. So much may be expected from the enthusiasm of the systematist. Some centuries of effort must, of course, be expected to elapse before the task is done. But it is evident that the modern biology is much less concerned in the mere recognition of these innumerable forms of life, these remotest expressions of the force of evolution, than in the gaining of some adequate conception of their relations, the forces of adaptation that have fitted them for their particular niche in the realm of nature, their relation to the other organisms with which they are associated and which constitute for them a source of support or a menace to existence. That is, modern biology concerns itself not only with the elements of structure in the organism, with the means it has of performing its varied functions with the aggregate of individuals which constitute its species, but goes on to its relations to all the influences and forces which have made it what it is and which sustain its specific existence. Less than this is too narrow a view of the province of biology. Here is unlimited scope for the student who pursues knowledge for love of knowledge.

As an inspiration to the general student the field of biology has always held an important place, and in these modern times its fascination is as potent as ever. Men have attacked the problems of life from many different viewpoints with greatly different aim and great difference in preparation and method in their work. Some of these have sought merely for inspiration for literary effort, but so far as their records have been exact and truthful they are contributions to science, when mixed with “vain imaginings” they become literature and not science, although their right to rank here may depend on literary merit. Every gradation 153from pure fiction to pure science may be found and every grade of literary merit as well. White and Goldsmith, Wood and Figuier, Kipling and Seton-Thompson, with many others that could be cited, illustrate this wide divergence among writers who have written to the entertainment and the greater or less profit of their readers. The value of such works as these is rather hard to estimate, especially from the scientific standpoint and particularly when one is under the hallucination of a beautiful piece of literary creation. They furnish entertainment and cultivate imagination, some of them stimulate observation and awaken an interest in nature, but unfortunately many of them contain so much that is inexact or erroneous that they may sadly encumber the minds of their readers.

But I would like to call attention here to what appears to me a fundamental condition of scientific work and thereby a necessary result of scientific training. Science is naught if not exact. Accurate observation, accurate record, accurate deduction from data, all of which may be reduced to simple, plain honesty. Anything else is error, not science. It is not that “honesty is the best policy,” but that in science honesty is the only possible policy. Hence, scientific training should give to every student this one at least of the cardinal virtues, and we may claim with justice this advantage as one of the results to be derived from pursuing scientific studies. In fact the relation of science and biological science, no less than any other, to general schemes of education, has been one of its most important contributions to humanity.

Biology has influenced modern education both in the matter taught and the method of its presentation. It has gone farther and farther into the mysteries of nature and opened up wider fields of knowledge. It has insisted that the student should be trained not only in the facts and the accurate interpretation of facts, but in the methods by which facts may be obtained, thus providing for the continuous growth of the substance from which its principles may be verified and definite conclusions reached.

In recent years there has been a wide demand for the more general distribution of knowledge of nature, and “nature study” has had a prominent place in the discussions of educators. I must confess to some fear for the outcome of well meant efforts to crowd such studies into the hands of unprepared teachers, though surely no one could wish more heartily for a wider extension of such work well done. It is encouraging to note steady progress in this line and we should be content not to push ahead faster than conditions will warrant.

Our science is an evergrowing one, and I wish to mention briefly some of the conditions of biological research and the conditions essential to its successful prosecution. The time has 154passed when it is possible for the isolated individual to accomplish much of anything of value in the growth of science. Such instances as the cobbler naturalist can not well be repeated under present conditions, and biological workers must expect that some part at least of their time is spent where libraries, museums and scientific workers are to be found. I recall meeting some years ago in an obscure little village, with a young man who was following a trade, but whose ardent love for nature had brought him to take up the study of a certain group of insects, and in this group he had conceived the idea of preparing a work covering the geographical distribution for the world. With scarcely the beginning of a library, with no access to general collections, apparently with no conception of the stupendous nature of the task he was so ambitiously undertaking, there was perhaps little danger of his discovering the hopelessness of his case. He doubtless gained much pleasure and individual profit in the quest, but for the progress of science, how futile such attempts. Isolated work is often necessary, often the only way in which certain data can be secured, but if isolation be permanent, if it means to be cut off from the records of what has already been done in one’s line of study, progress is painfully slow and results of little value. Access then to the world’s storehouses of knowledge, to libraries and museums where one may determine the conditions of progress on any given problem is an imperative condition to satisfactory research.

Another condition almost as imperative is time for extended and consecutive work. There are comparatively few places where, after passing the stages of preparation, one may have the opportunity to give uninterrupted time to pure research, but fortunately such opportunities are increasing.

Another factor is necessary equipment, a condition varying indefinitely with the problem undertaken. Studies of some of the simpler processes of life may be successfully carried on with barely any apparatus whatever, while others require the most costly and complex of machinery. Deep sea investigations, for example, are possible only with a suitable vessel and elaborate apparatus for dredging and other operations, and such expeditions as that of the Challenger, the Blake, the Albatross and others involve such vast outlays that only the liberality of nations or of the very wealthy render them possible.

However, the modest student without a dollar to invest in these expensive undertakings may have the opportunity to work as diligently and effectively as any. So, too, the costly equipments of marine stations, of universities, of national and state museums are open to every earnest worker.

Still another condition related to the best effort in research is a satisfactory outlet for publication. Probably no investigator 155enters on an elaborate extended research without the expectation that such results as he may obtain, especially such as are novel and important to the growth of science, shall at some time be given a public hearing and a permanent record in the annals of science. However much this ambition may be overworked and abused, it must be considered the logical and legitimate outcome of research, valuable as an incentive to work, essential to the progress of science.

The output of scientific laboratories is always pressing hard upon the organs of publication, and though we have numerous periodicals open to all, many society proceedings and transactions devoted to their membership, university bulletins intended primarily for the staff and students of each institution, still adequate publication facilities are often wanting. Especially is this true regarding the suitable illustration of papers which depend largely on plates or drawings for the elucidation of the text. Our own modest effort in The Naturalist is an attempt to meet one phase of this demand, but you all appreciate, I think, that it is insufficient for the needs of our own institution. Some of the more extended papers resulting from the work of either students or faculty must suffer oblivion, delay or inadequate presentation. Evidently a publication fund is one of our pressing needs.

Opportunities for research have been much increased within recent years, and now it is possible for one to look forward with some assurance to a career in research pure and simple if that is his desire. As many of those present doubtless anticipate such career, it may not be amiss to mention some of the opportunities that now present. Positions in connection with universities and colleges now as for a long time past offer some of the most available openings. Fellowships, and positions as assistants with comparatively light duties with expectation that the holder will devote himself to investigation that will advance his branch of science are offered in many places and their value is shown by the numerous candidates for each position. Many government positions in Department of Agriculture, Geological Survey and Fish Commission demand a high degree of training and offer exceptional opportunities for research.

The first few years following graduation are golden days of opportunity in the way of research. For the majority, perhaps, these are the days when the greatest amount of original study may be possible and under conditions favoring the greatest productivity. As time passes and duties and responsibilities increase the opportunity for uninterrupted work grows less and less. Of course original work should follow necessary preparation but can not be postponed indefinitely, in hopes of a more favorable season, if the individual hopes to accomplish anything of value in his chosen science. Too early publication however is 156to be discouraged. Most good things will keep for a time at least, and the opportunity to test and verify investigations before publishing is desirable. It is unwise to attempt to harvest a crop of glory, in scientific fields at least, before the seed has had time to germinate. The extremes of too hasty publication and indefinite delay are both to be avoided.

But this disjointed address must be brought to a close, I have indulged in a medley rather than pursuing a connected theme, but it has been in my mind to show how the influence of modern biology has been felt in every phase of human life and modified every phase of human thought. It touches history and illumines it as a record of human activities, the modifications and adaptations of the most dominant organism of earth. It touches language and infuses it with life as the highest evolution of all means of communication among animals. It enters the sphere of human relations and we see society, government, law, as the most complex expression of forces operative all along the line of organic life.

We may gain inspiration in our work from the thought that our field of labor gives opportunity for the highest service in the advancement of human interests and the intellectual uplift of the race.

The club extended Prof. Osborn a vote of thanks for his valuable address.

The Ohio State Academy of Science held its eleventh annual meeting at the Ohio State University in this city on November 29th and 30th. Between thirty and forty papers were given and the attendance was considerably above the average. On the evening of the 29th a joint meeting was held with the Modern Language Association of Ohio, which held its annual session at the University on the dates mentioned above. The committee arranged an interesting and appropriate program for the evening and a large and appreciative audience responded. The Academy meetings have been held heretofore during the Christmas vacation, therefore holding it at this time was an experiment, but judging from the program, attendance, and enthusiasm manifested, the meeting this year may be said to be one of the best the society has ever held.

It is of more than ordinary interest to be able to record the taking of specimens of the European ruff, Pavoncella pugnax (Linn.) in Ohio. Two male specimens are in the Dr. Jasper collection at the Ohio State University, one taken April 28th, 1879, at Columbus, the other November 10th, 1872, at the Licking Reservoir.

The plants listed below have been found growing in the State without cultivation. A large number of them are adventive species but not hitherto recorded in the Ohio list. Three of the names occurred in the old lists and were noted in the Catalogue of 1893 by Kellerman and Werner, but were discarded in the Fourth State Catalogue, published in 1899. These here referred to and which are below restored to the Ohio list, are Nos. 683a, 1423b, and 1990½a. No. 893a was included in L. D. Stair’s list of Railway Weeds. All the others are wholly new to the listed flora. While several persons have contributed to this increase, special thanks are due to Mr. Otto Hacker, who formerly as well as at present, contributed largely to a fuller knowledge of the State flora. Mr. Hacker has furnished specimens of all the species credited to him below and these are deposited in the State Herbarium. The rich field for adventive species in the region of Painesville may be understood when it is stated that the extensive and long-established nursery grounds of Storrs and Harrison are located at this place.

1a. Botrychium lunaria (L.) Sw. Moonwort. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

201a. Apera spica-venti (L.) Beauv. Silky Bent-grass. Wild-straw. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

201b. Aira caryophyllea L. Silvery Hair-grass. Rarely escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

253a. Festuca myuros L. Rat’s-tail Fescue-grass. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

272a. Hordeum sativum Jessen. Common Barley. Occasionally escaped.

272b. Hordeum distichum L. Two-rowed Barley. Rarely escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

470a. Lemna cyclostasa (Ell.) Chev. (L. valdiviana Phil.) Valdivia Duckweed. Richmond, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

557a. Gemmingia chinensis (L.) Kuntze. Blackberry Lily. Escaped. Franklin Co. J. H. Schaffner.

557b. Crocus vernus All. Crocus. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

568a. Limnorchis hyperborea (L.) Rybd. (Habenaria hyperborea (L.) R. Br.) Canton. Mrs. Theano W. Case.

670a. Quercus alexanderi Britton. Alexander’s Oak. “Ohio;” N. L. Britton, Manual of Flora, 336. This was formerly confused with, or included in Q. acuminata, and like the latter is not uncommon in Ohio.

683a. Urtica urens L. Small Nettle. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

158754a. Acnida tamariscina prostrata. Uline and Bray. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

762a. Portulaca grandiflora Hook. Garden Portulaca. Sun Plant. Escaped; Roadsides. St. Marys, Auglaize Co. A. Wetzstein.

775a. Lychnis vesicaria L. Lychnis. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

886a. Fumaria parviflora Lam. Small Fumitory. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

893a. Sisymbrium altissimum L. Tall Sisymbrium. L. D. Stair in List of Railroad Weeds. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

894a. Myagrum perfoliatum L. Myagrum. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

921a. Camelina microcarpa Andrz. Small-fruited False-flax. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

984a. Rubus neglectus Peck. Purple Wild Raspberry. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

985a. Rubus phoenicolasius Maxim. Japan Wineberry. Escaped from cultivation; comes freely from seed, and propagates by tips. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1004a. Potentilla pumila Poir. Dwarf Five-finger. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1026b. Sorbus aucuparia L. European Mountain Ash. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1051a. Prunus mahaleb L. Mahaleb. Perfumed Cherry. Columbus, Franklin Co. W. A. Kellarman. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1054a. Acuan illinoensis (Mx.) Kuntze. (Desmanthus brachylobus Benth.) Illinois Mimosa. New Richmond, Clermont Co. A. D. Selby.

1071a. Trifolium dubium Sibth. Least Hop-Clover. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1091a. Coronilla varia L. Coronilla, Axseed, Axwort. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1122a. Vicia augustifolia Roth. Smaller Common Vetch. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1171a. Euphorbia cuphosperma (Englem.) Boiss. Warty Spurge. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1195a. Euonymus europaeus L. Spindle-tree. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1265a. Viola odorata L. English or Sweet Violet. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1301b. Kneiffia linearis (Mx.) Spach. Narrow-leaf Sun-drops. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1423b. Spigelia marylandica L. Indian Pink or Carolinia Pink. Fl. M. V. A. P. Morgan. North Madison, Lake Co. D. W. Talcott.

1502a. Asperugo procumbens L. German Madwort. Catchweed. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1591534a. Scutellaria parvula ambigua Fernald. “Ohio,” Nuttall. Greene Co., E. L. Moseley; Montgomery Co., W. U. Young; Franklin Co., E. E. Bogue; Gallia Co., J. W. Davis.

1556a. Salvia lanceolata Willd. Lance-leaf Sage. By roadside near Columbus. W. A. Kellerman.

1586a. Mentha longifolia (L.) Huds. Horse Mint. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1600a. Physalis francheti Mast. Chinese Lantern Plant. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. D. W. Talcott.

1609½a. Datura metel L. Entire-leaf Thorn-apple. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1611b. Kickxia spuria (L.) Dumort. (Elatinoides spuria Wetzst.) Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1690a. Diodia teres Walt. Rough Button-weed. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1702a. Asperula hexaphylla All. Asperula. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1712a. Viburnum lantana L. Wayfaring Tree. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1732a. Valeriana officinalis L. Garden Valerian. Escaped. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1756a. Arnoseris minima (L.) Dumort. Lamb Succory. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1756b. Hypochaeris glabra L. Smooth Cat’s-ear. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1766c. Lactuca virosa L. Strong-scented Lettuce. Confused with L. scariola according to Britton, being the commoner of the two species. (A. D. Selby, Meeting Ohio Academy of Science, November, 1901.)

1775a. Hieracium pilosella L. Mouse-ear Hawkweed. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

1990½a. Tanacetum vulgare crispum DC. Tansy. Painesville, Lake Co. Otto Hacker.

Item 1. It has been asked how many species of plants occur in Ohio. Only a guess can at present be made. In the Catalogue of Ohio Plants, by Kellerman and Werner, prepared in 1893, there were listed 1,925 Spermatophytes, 68 Pteridophytes, 335 Bryophytes, and 1,400 Thallephytes. The Fourth Catalogue, by the writer, published in 1899, gave 2,025 species of Pteridophytes and Spermatophytes. While many additions to the previous list were included, very many species formerly 160reported were excluded because unauthenticated by herbarium specimens, and others were undoubtedly extra-limital for Ohio. Two Annual Supplements to this catalogue have been issued, bringing the number of species of the vascular plants, nearly all authenticated, up to about 2,150. The mosses, the higher fungi and the lichens have been listed with some degree of fullness, but most of the other lower plants have been very incompletely placed on record, though large collections, only partially worked up as yet, are now in the herbarium of the State University.

Item 2. Miss Ruth E. Brockett, of Rio Grande, Gallia County, Ohio, has found the Showy Skullcap, Scutellaria serrata Andr., previously unreported for this State. The distribution, as given in Britton’s Flora, is New York and Pennsylvania to North Carolina, Illinois and Kentucky. In the Rio Grande region many interesting or new plants for the Ohio list have hitherto been detected by Miss Brockett, as the Fringe Tree (Chionanthus virginica), the Purplish Buckeye (Aesculus octandra hybrida), and others too numerous to mention.

Item 3. An interesting and suggestive study has been published by Herman Dingler (Muenchen) on the organs for wind-dispersal (flug-organe) in the Vegetable Kingdom. The title of the book is “Ein Beitrag zur Physiologie der passiven Bewegungen im Pflanzenreich.” After describing fully the mechanics involved, and the methods of investigation, the author enumerates the Chief Types of the flight organs as follows (prefixing to the word “flyer” the descriptive words, 1, dust; 2, granule; 3, bubble; 4, hair; 5, pan; 6, umbrella; 7, sail; 8, disk-twist; 9, barrel-twist; 10, plain-twist; 11, screw, and 12, screw-twist):

Item 4. The recent death of Thomas Meehan, horticulturist and botanist, removes from the list of active American workers one whose numerous, accurate and original observations contributed greatly to the advancement of botanical science.

A critical inspection of the nomenclature used for the first Fascicle of the Ohio Fungi might seem to warrant the conclusion that the judgment of more recent workers is sometimes ignored and that a too conservative course has been adopted. But it should be remembered that the main purpose is to furnish Ohio material accompanied by names (occasionally synonyms) that were undoubtedly applied to the species represented. I have preferred to use for the Rust on Sunflower, Puccinia helianthi, rather than P. tanaceti—recent work on other species suggesting that with this also when fully studied, a physiological distinction may supplement the too insignificant morphological difference. Again, I have used Aecidium album, which Clinton applied to the first stage of the Uredine found on Vicia, not ignorant of the fact that Dietel gives this as a stage of Uromyces albus—but should not this first be substantiated by cultures? It is to be added that through inadvertency Peck’s later name (Aecidium porosum) was used, hence here follows a corrected label with both Clinton’s and Peck’s descriptions:

“Aecidium album Clinton, spots none; peridia scattered, short, white, the margin subentire; spots subglobose, white, about .0008 inches in diameter.” Report on the State Museum, State of New York, 26:78. 1873.

“Aecidium porosum, Pk. Spots none; cups crowded, deep-seated, broad, wide-mouthed, occupying the whole lower surface of the leaf to which they give a porous appearance; spores orange-colored, subangular, .0008–.001 inch in length.” Botanical Gazette, 3:34. April, 1878.

By its configuration, Porto Rico is divided into two parts very distinct from each other in almost every respect and of primary importance in all the affairs of the island. The north side, which comprises about two-thirds of the total area, is kept constantly wet with almost daily rains. On the south it has been known not to rain for a whole year in some places. On the north side grows an abundance of luxuriant, tropical vegetation; on the south in many localities are barren hills covered only with scrub brush. But throughout the island there is great local variation in all the climatic and physical conditions.

Along most of the north side there stretches a low, coast plain, out of which rise numberless, small, steep hills. This plain, everywhere well watered, is in most places very fertile, but in the vicinity of Vega Baja it becomes a sandy waste. This sand desert is one of the most peculiar places it has ever been my fortune to visit. There is no grass (turf-making grass is almost unknown in the tropics), neither are there large trees. Everywhere are low bushes not much more than ten feet tall. The sand beneath them is bare in many places, but is covered in others with various forms of herbage, most of which, instead of being composed of desert forms, as would be expected, is made up of the most typical water-loving plants, among which, Sphagnum (two species) and Utricularia are noteworthy. Imagine, if you can, a sphagnum bog shading into loose sand in a distance of only ten feet with no change in level. The explanation of this peculiar fact is, however, not hard to find. The rainfall is so copious that wherever there is any means of holding it, the hydrophytes take hold and spread, themselves acting as water holders when once started, while in other places the water quickly soaks into the sand and leaves it as dry as ever.

The plain on which this sand desert is located is separated in most places from the sea by low hills. It is very level and was probably once covered with water out of which projected many rocky islands—the limestone hills of to-day. These hills are a very characteristic feature of the country. From an incoming vessel they are plainly seen projecting like saw teeth all along the coast; from an eminence back in the country they appear to have no system or regularity whatever, but stick up anywhere sharp and rugged as though shaken out of a dice box onto a board. Further inland they are closer together with no plain between, though in other respects like those of the coast. It is as though they were eroded when the sea stood lower than it does to-day, perhaps very much lower; then the valleys were 163filled up during a period when the sea was slightly higher than at present, whence it has receded and left the island of to-day. They are covered with a characteristic jungle, rising conspicuously out of which is the “Llume” palm (Acria attenuata) whose graceful stem, only about half a foot thick at the base, attains a height of a hundred feet, tapering till it is only three or four inches thick at the top. It is nearly white and at a distance entirely invisible, so that the crown of leaves looks as though it were floating around in the air above the surrounding vegetation.

Further inland the limestone hills give way to others of red clay. The clay, like the limestone, is very deeply eroded. In most places it is so continually washed down that the sides of the hills stand always at the critical angle and are ready to slide from under the feet of the explorer. Indeed it would be impossible to climb them were it not for the numerous bushes everywhere standing ready to lay hold on. Here abound ferns, Melastomaceae and other plants of humid regions. Tree ferns are very common; the largest belong to one species of Cyathia. Its beauty is simply beyond description. Imagine, you who have never seen it, a trunk thirty feet tall surmounted by a crown of a dozen or fifteen great leaves made up of a score or two pinnae of the size and grace of ordinary ferns and you have the components—not the ensemble—of the tree fern.

This red clay region is the land of coffee. Everywhere the novice thinks the hillside covered with jungle, which turns out to be only poorly kept coffee plantations. The coffee region is coextensive with the range of several plants. Two or three species of the pepper family, with large peltate or round leaves, are found only here; and with one or two exceptions the Melastomaceae occur only in this wet country. They are a very large group of plants common throughout the tropics, but represented in the northern states by the common Rhexia. Its members may be known anywhere by their three-nerved leaves, many of which are beautifully patterned and marked so that even among other tropical plants they are conspicuous for their beauty.

When we cross the summit we come upon a different sort of vegetation; cacti take the place of tree ferns, and instead of wet jungles we have dry scrub brush full of spiny and thorny shrubs with almost every sort of prickle one can think of. One who has never encountered them can scarcely appreciate the abundance and effectiveness of tropical thorns. These thickets of brush extend over most of the undisturbed portion of the south side. Everywhere through them there are scattered cacti of several sorts; but near Guayanilla, a few miles west of Ponce, these become relatively much more numerous so as to form a veritable cactus desert. Only here is the largest form present. It is a large Opuntia with a bare stem and long arms radiating in one 164or two whorls near the top. Besides it there are several species of Cereus and another small Opuntia similar to the common prickly pear, together with a species of the same group cultivated for its fleshy branches which are eaten. All through this dry region agaves or century plants are very common. There seem to be several species, but they are such terrors to botanists that it is hard to tell anything about them.

From this brief sketch it will be seen what a diversified flora Porto Rico offers to the student. There are opportunities for several ecological studies of surpassing interest, and on the systematic side the work has only been begun. At present there are scant facilities for the student, but with the fuller occupation of the island by American government and customs, we may hope that some of our enterprising universities will establish there a school of tropical agriculture and botany, fields now white for the harvest but almost without workers.

Washington, D. C., October 30, 1901.

On May 25, 1901, Prof. Hine, while collecting in the hills at Sugar Grove, Fairfield County, O., found a salamander under a piece of pine log on the slope of a hill, about a hundred yards from water. It was, for the time, put in a jar along with several individuals of Desmognathus fusca Raf., which were taken in, or within a few feet of the rivulets which flow down the valley. Aside from this specimen taken on the hillside, all the specimens were found not farther than a half dozen feet from the water. When the collections were examined in the laboratory it was found that the single specimen just mentioned differed in many respects from the others. This led to investigation and it was found that it corresponded closely with the description of D. ochrophæa Cope. Thus, the posterior portion of the mandible was edentulous; no tubercle in canthus ocelli; belly paler than in any of D. fusca taken; length nearly three-fourths of an inch shorter than the others; a light bar from eye to corner of mouth; tongue free behind; parasphenoid teeth separated behind. The specimen was kindly examined by Dr. J. Lindahl, of the Cincinnati Society of Nat. Hist., who is acquainted with the form. He agreed that it corresponded with the description of Cope. Whether the characters as given above are sufficient to place the specimen under ochrophæa is a matter hard to decide. Cope gives the range of ochrophæa as “in the Alleghenies and their outlying spurs.” Dr. Lindahl has a specimen from Logansport, Ind., taken November 10, 1900.

The present short list is published, not because of any records of special interest, but in order that a record may be made of the fish known certainly from the headwaters of Beaver Creek. In the case of fish the most logical and significant way to indicate distribution is certainly by streams, and a very small contribution to the ichthyology of the above named stream is here presented.

About three-fifths of Columbiana County is drained by Beaver Creek, one-fifth by the Mahoning River and streams leaving the county to the west, while the remainder enters the Big Yellow and Little Yellow Creeks. Beaver Creek is practically confined to Columbiana County, though it empties into the Ohio River in Pennsylvania at Smith’s Ferry, just above the state line. The relation of Beaver Creek to the Mahoning River is interesting, the two being in general, arcs of concentric circles with the Mahoning outside. A person going directly west from Salem crosses Middle Fork of Beaver Creek first, then the Mahoning, and the same is true if he goes directly north or directly east. South-west of Salem the small streams empting into the Mahoning have not been seined. From one of these Herman McCane has taken a specimen of Ichthyomyzon concolor which is preserved in the Salem High School collection with the other species here recorded. All the other streams in close proximity to Salem are part of the system of the Middle Fork of Beaver Creek, with the exception of Cold Run, which flows almost directly south into the West Fork of Beaver Creek, the stream thus formed soon being augmented by the waters of the North Fork.

Seining has been done only near Salem in small tributaries and where Middle Fork has an average width of not more than ten or twelve feet. Mr. Albert Hayes, Mr. J. S. Johnson and Mr. F. W. Webster have helped me draw the seine. Mr. Webster has also given me many valuable suggestions as to suitable localities.

Mr. A. J. Pieters, Assistant Botanist in the U. S. Dept. of Agriculture, has written an interesting and useful article[1] on the plants of western Lake Erie. This report should be read by all who are interested in the hydrophytes of Ohio, or in the flora and fauna of Lake Erie. In addition to some introductory remarks, the paper treats of the plants in Put-in-Bay, in Squaw Harbor, near Gibraltar Island, in Hatchery Bay and in the open lake, and the plants of East Harbor. The swamp vegetation is also discussed, including the plants in the Portage River swamps and in the swamps about Sandusky Bay. The ecological conditions and the ecological adaptations of the flora are treated quite fully, and at the end are given alphabetical lists of the plants studied, including angiosperms, stoneworts and desmids.

1. A. J. Pieters. “The Plants of Western Lake Erie, with Observations on their Distribution.” Bull. U. S. Fish Commission, 1901, pp. 57–79. Pls. 11–20.

The habits of flies belonging to the family Tabanidæ, commonly called horse-flies or gad-flies, furnish much material for study and observation. I take this opportunity to record some of the notes which I have taken in the last few years while endeavoring to collect and study the local species of the family. Although the eggs, larvæ and pupæ of many species have been studied, what I have to say in this paper pertains wholly to the adults. Members of the family are usually taken by every entomologist who does general collecting, but as a usual thing males are seldom taken; in fact this sex is so poorly represented in collections that no key has been published for identifying the males of our American species. The student must use the key to the females as far as possible and guess at the rest. In very many cases the male is not even described, so that sometimes, when the sexes are unlike, they can be associated only by observations in the field. By careful collecting and observation we have procured practically all of our local species in both sexes, and the derived benefit, satisfaction and enjoyment have paid us fully for our time and pains.

In the first place the mouthparts of the two sexes are different—the male lacks the mandibles which are present in the female. This makes it necessary for them to procure their food from different sources, the male obtains his from flowers, while the female lives by puncturing the skin and sucking the blood of warm-blooded vertebrates. Thus it is evident that during the time spent in procuring food the sexes cannot remain together. From an economic standpoint the female most concerns the student and she is often taken for study without an attempt being made to procure the male.

At this point I can say collect females around horses, cattle and other animals, and males on flowers; but this is not enough, for knowing the general habits of insects we are certain that there is a common ground where the two sexes may be found together. One finds this common ground in the vicinity of water, where their transformations take place and where their eggs are laid, also in various other places, which we shall take occasion to discuss as we proceed.

The females of all our local species of Chrysops with Tabanus pumilus and nivosus come buzzing around the collector in numbers, and at such times may be taken easily with a net. Other species of Tabanus come near enough that the sound of their wings is recognizable, but are so active that it is almost impossible to procure them.

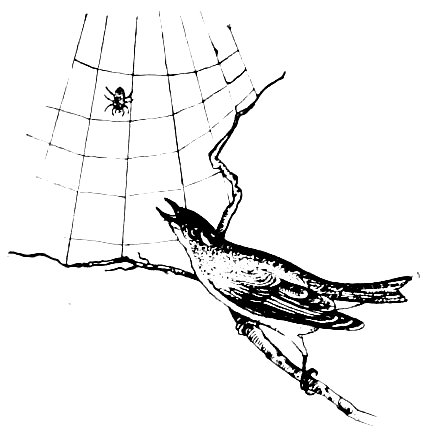

168During the time the female is ovipositing the male is often sitting near by on the foliage. At Georgesville, Ohio, June 4th, I observed C. mœchus ovipositing on foliage overhanging a mill-race; soon after specimens of the male sex were observed resting on the upper leaves of the same plant on which females were ovipositing. In a few minutes collecting, a dozen or more specimens of each of the sexes were procured. The only males of C. indus I have ever taken were procured at Columbus, on the border of a small pond, where the females were ovipositing.

The sexes of many species of Tabanus often alight on the bare ground of paths or roads that run through or along woods. At Cincinnati, June 10th, in company with Mr. Dury, we procured large numbers of the sexes of different species resting on some furrows that were plowed around a woods to prevent the spread of fire. We also took the same species resting in paths and roads that ran through the woods. Some of these same species were also taken from low-growing foliage in sunny places among the trees. At Medina, Ohio, males and females of T. vivax and trimaculatus were taken while resting in a road that ran through a dense woods.

One of the best places I have ever found to get the sexes of Chrysops and Tabanus is in the tall grass that skirts the marshes of Sandusky Bay. This grass is the Phragmites of botanists and grows to a great height by July 1st. On July 6th, at Black Channel, when the wind was high I went into a patch of this grass that was so dense that I could not use a net to advantage. Here I saw an abundance of flies and found that by approaching them very slowly I could readily pick the specimens off with my fingers. The male and female of T. stygius, nivosus, C. æstuans and flavidus and the male of T. affinis and bicolor were taken in this way. I found that this same species of grass afforded excellent collecting wherever found, but most material was procured when the wind was high. On the same date and near the same place the male of C. flavidus was taken from the flowers of the common spatter-dock, and this and æstuans were procured by sweeping in the adjacent low-growing herbage. R. C. Osburn informs me that he has had excellent success in collecting Tabanids from tall grass near water in his experience.

Tabanus sulcifrons Macq. is an abundant species in northern Ohio during the latter part of July and all of August. So common that by actual count twenty-eight specimens were taken from a cow in ten minutes, while a few that alighted on the animal during that time were not procured. August 1st of the present year I was at Hinckley, Medina County, and spent the day taking observations on this species. In the morning about nine o’clock I went to the border of a woods where I had often observed the species before. Here males and females were found 169in abundance crawling over the trunks and foliage of trees, on the fence along the woods and flying about generally. One pair was observed in copulation on the fence, and I am of the opinion that the presence of so many flies in the locality at the time is explained on the ground that it was the general mating place of the sexes. On several occasions I have made observations which lead me to believe that the sexes of various species of the family copulate among foliage often high up in the trees. As Tabanids are not easily procured with a net from the surface of a rough rail, I tried the experiment of picking the specimens off with my fingers and found that it was surprisingly successful, if the movement toward them was made very slowly until just ready to touch them when the fingers were gripped quickly. Near a watering trough where a herd of cattle drank daily I found males in numbers resting on the ground where the turf had been tramped off. Along Rocky River I observed both sexes fly down to the water and dip several times in succession and then away to alight on a stone on the bank or disappear from sight altogether.

On July 29th I rode from Sandusky to Cleveland by boat. Although we were from two to five miles off shore all the time, males and females of T. sulcifrons often came on board and alighted on the canvas and rigging of the boat. From this it is evident that this species at least may fly for some distance over water.

We have taken Goniops chrysocoma on several occasions. It has a habit which is of value to the collector. At Hinckley, Medina County, I took several females and observed that they have the habit of stationing themselves on the upper side of a leaf, where by vibrating their wings rapidly and striking the upper surface of the leaf at each downward stroke, make a rattling noise which can be heard plainly several feet away. At Vinton last spring Mr. Morse and myself identified the characteristic sound of the species and were guided by it to procure specimens.

I have taken the male of Pangonia rasa on blossoms of sumac at Medina, Ohio, in August.

Agromyza setosa Loew—The larvæ of several species of the genus Agromyza are known to mine the leaves and stems of various plants. Cabbage, potatoes, corn, clover, strawberries, verbenas, chrysanthemums and sunflowers are among the cultivated plants from which various species of the genus have been reared; while plantain, round-leaved mallow, golden-rod, aster, cocklebur, 170rag-weed and wild-rice are given as their food-plants. In some cases a single species of fly has been reared from a half dozen or more different plants. Agromyza setosa Loew, as determined by Coquillett, was reared in numbers from leaves of wild-rice, Zizania aquatica, at Sandusky during August of each of the years 1900 and 1901. Professor Osborn studied the species and its work in 1900, while my observations were made a year later. Although I include the notes taken by both of us, many points are needed before a detailed account of the habits and life history of the species can be given.

The eggs are conspicuous on account of their abundance and white color, and are deposited chiefly on the upper surface of the leaves of the food plant.

The larvæ upon hatching bore into the leaf and feed beneath its upper covering. When full grown they measure about 6 mm. in length, are white, or greenish on account of chlorophyl taken in with their food, and are furnished with strongly chitinous mouth parts. The mines which they make in the leaves are irregular in width and extend for varying lengths on one side or the other of the mid-rib. These variations in extent are usually explainable from the fact that a variable number of larvæ occupy the different mines. The work of the larvæ is apparent from the first on the upper side of the leaf, and may be seen beneath after a few days because of the fact that the parts beneath the mine sooner or later turn yellow.

The pupa is to be found either in the mine or clinging to the surface of the leaf. It is brown in color, with two prominences anteriorly where the attachment with the leaf is effected, and is contained within the last larval skin so that the legs and wing-pads are at no time visible from the outside.

Bibio albipennis Say—Larvæ observed in colonies under fallen logs, and boards which were lying on the ground. Specimens taken April 4th pupated May 5th and the adults appeared May 13th. The adults were unable to fly for several hours after they emerged on account of their wings remaining soft. I observed the first males flying out of doors on the 23d of May.

Chrysopila ornata Say—Larva about an inch and a half in length, white in color, cylindrical, with an enlargement at the posterior end bearing a number of fleshy elongations which are about the length of their basal breadth. Found under rotten wood May 1st. Pupa brown, last segment armed with six spinose teeth, the two on the ventral side arising from the same base, the remaining abdominal segments furnished with a circlet of spines near the posterior third. The adult emerged the 18th of June.

Six Colleges well equipped and prepared to present the best methods in modern education. The advantages are offered to both sexes alike.

Agriculture, Agricultural Chemistry, American History and Political Science, Anatomy and Physiology, Architecture and Drawing, Astronomy, Botany, Chemistry, Civil Engineering, Clay Working and Ceramics, Domestic Science, Economics and Sociology, Education, Electrical Engineering, English Literature, European History, Geology, Germanic Languages and Literatures, Greek, Horticulture and Forestry, Industrial Arts, Latin, Law, Mathematics, Mechanical Engineering, Metallurgy and Mineralogy, Military Science, Mine Engineering, Pharmacy, Philosophy, Physical Education, Physics, Rhetoric and English Language, Romance Languages, Veterinary Medicine and Zoology and Entomology.

The large mushrooms, Puffballs and other Fungi; Abnormal growths and interesting specimens of shrubs and trees. Also herbarium specimens of Algae, Fungi, Mosses and Ferns as well as flowering plants. Address

Will exchange Hudson, Corniferous and Carboniferous fossils. Address

Birds, Insects, Reptiles, etc. We wish to make our collections representative for the fauna of the state and will greatly appreciate all contributions to that end.

Ohio State University, Lake Laboratory. Located at Sandusky on Lake Erie. Open to Investigators June 15 to September 15. Laboratory courses of six and eight weeks beginning June 30, 1902. Write for special circular.

Process and Wood Engraving, Electrotypers and Manufacturers of Stereotyping and Engraving Machinery.

Prepared under the direct supervision of W. T. HARRIS, Ph.D., LL.D., United States Commissioner of Education, assisted by a large corps of competent specialists and editors.

☞ The International was first issued in 1890, succeeding the “Unabridged.” The New Edition of the International was issued in Oct., 1900. Get latest and best.

Students graded on their daily recitations and term examinations. Large class rooms designed for the recitation system. Laboratories are large, well lighted and equipped with modern apparatus. Abundant clinical facilities in both Medical and Dental Departments. CONSIDERING SUPERIOR ADVANTAGES FEES ARE LOW.

MEDICAL AND SURGICAL CLINICS AT FOUR WELL EQUIPPED HOSPITALS. ❧ ❧ ❧ ❧