![[The image of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

Title: The chase

a poem

Author: William Somerville

Author of introduction, etc.: William Bulmer

Engraver: Thomas Bewick

Illustrator: John Bewick

Release date: September 14, 2023 [eBook #71644]

Most recently updated: September 30, 2023

Language: English

Original publication: London: W. Bulmer and Co, 1802

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

![[The image of the book's cover is unavailable.]](images/cover.jpg)

BY

WILLIAM SOMERVILE, ESQ.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY W. BULMER AND CO.

Shakspeare Printing Office,

CLEVELAND-ROW.

1802.

The following Address was prefixed to the Quarto Edition of the Chase, published in 1796.

TO THE PATRONS OF FINE PRINTING.

When the exertions of an Individual to improve his profession are crowned with success, it is certainly the highest gratification his feelings can experience. The very distinguished approbation that attended the publication of the ornamented edition of Goldsmith’s Traveller, Deserted Village, and Parnell’s Hermit, which was last year offered to the Public as a Specimen of the improved State of Typography in this Country, demands my warmest acknowledgments; and is no less satisfactory to the different Artists who contributed their efforts towards the completion of the work.

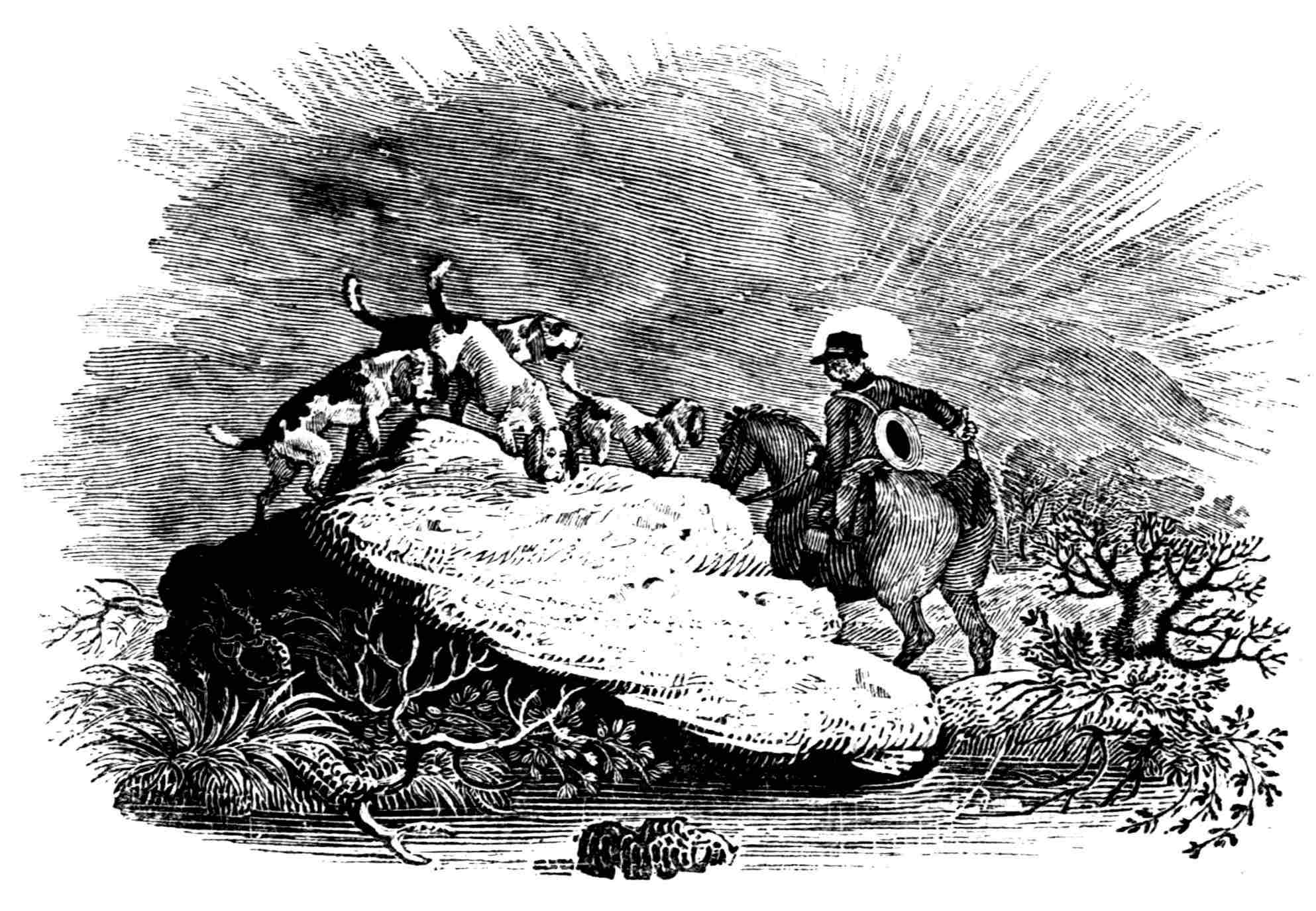

The Chase, by Somervile, is now given as a Companion to Goldsmith; and it is almost superfluous to observe, that the subjects which ornament the present volume, being entirely composed of Landscape Scenery and Animals, are adapted, above all others, to display the beauties of Wood Engraving.

Unfortunately for his friends, and the admirers of the art of Engraving on Wood, I have the painful task of announcing the death of my early acquaintance and friend, the younger Mr. Bewick. He died at Ovingham, on the banks of the Tyne, in December last, of a pulmonary complaint. Previously, however, to his departure from London for the place of his nativity, he had prepared, and indeed finished on wood, the whole of the designs, except one, which embellish the Chase; they may therefore literally be considered as the last efforts of this ingenious and much to be lamented Artist.

In executing the Engravings, his Brother, Mr. Thomas Bewick, has bestowed every possible care; and the beautiful effect produced from their joint labours will, it is presumed, fully meet the approbation of the Subscribers.

W. BULMER.

Shakspeare Printing Office,

May 20th, 1796.

{v}{iv}

That celebrity has not always been the attendant on merit, many mortifying examples may be produced to prove. Of those who have by their writings conferred a lasting obligation on their country, and at the same time raised its reputation, many have been suffered to descend into the grave without any memorial; and when the time has arrived, in which their works have raised a curiosity to be informed of the general tenour, or petty habits of their lives, always amusing, and frequently useful, little more is to be collected, than that they once lived, and are no more.

Such has been the fate of William Somervile, who may, with great propriety, be called the Poet of the Chase; and of whom it is to be regretted that so few circumstances are known. By the neglect of friends while living, and the want of curiosity in the publick, at the time of his death, he has been deprived of that portion of fame to which his merits have entitled him; and though the worth of his works is now universally acknowledged, his amiable qualities, and he is said to have possessed many,{vi} are forgotten and irrevocably lost to the world. In the lapse of more than half a century, all his surviving friends, from whom any information could be derived, are swept away. The little which has been hitherto collected concerning him, will be found, on examination, not perfectly satisfactory; and of that little, some part is less accurate than our respect for so excellent a writer leads us to wish it had been.

He was of a family of great antiquity in the county of Warwick. His ancestor came into England with William the Conqueror, and left two sons. The eldest, from whom our poet was descended, had Whichnour, in the county of Stafford, for his inheritance; and the other, the ancestor of Lord Somervile, settled in the kingdom of Scotland. The eldest branch afterwards removed to Ederston, in the county of Warwick; which manor Thomas Somervile became possessed of, by marrying Joan, daughter and sole heir of John Aylesbury, the last heir male who owned that estate. This Thomas died in the year 1501, leaving one son, Robert, who also left one son, John, who was the father of William Somervile, whose only son, Sir William Somervile, Knight, left a posthumous son, William, who died in 1676, having married Anne, daughter of John{vii} Viscount Tracey, of the kingdom of Ireland, by whom he had eleven sons and five daughters. Of this numerous progeny, none seem to have survived except Robert, who married Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Sir Charles Wolseley, and by her became the father of three sons; 1. our author; 2. Robert, who was killed in India; and, 3. Edward, who was of New College, Oxford; where he took the degree of B. C. L. December 7, 1710, and D. C. L. April 26, 1722, and died between the years 1733 and 1742.

William Somervile, our poet, was born in the year 1677, at Ederston, “near Avona’s winding stream,” as he himself records in one of his poems. At the age of thirteen, in the year 1690, he was admitted a scholar of Winchester College, and continued there until the year 1694, when he was sent to New College, Oxford. It does not appear, as Dr. Johnson observes, that in the places of his education, he exhibited any uncommon proofs of genius or literature. He is said, by the same author, to have been elected a Fellow of New College; but as he does not seem to have taken any degree at the university, that assertion may be doubted. It is more probable, that he soon quitted the college for the country,{viii} where his powers were first displayed, and where he was distinguished as a poet, a gentleman, and a skilful and useful justice of the peace.

How soon he began to write verses we are not informed, there being few dates in his poems; but it is certain that he was no early candidate for literary fame. He had reached the age of fifty years, before he presented any of his works to the publick, or was the least known. In the year 1727, he published his first volume of Poems; the merit of which, like most collections of the same kind, is various. Dr. Johnson says, that, “though, perhaps, he has not, in any mode of poetry, reached such excellence as to raise much envy, it may commonly be said, at least, that he ‘writes very well for a gentleman.’ His serious pieces are sometimes elevated, and his trifles are sometimes elegant. In his verses to Addison, the couplet which mentions Clio, is written with the most exquisite delicacy of praise: it exhibits one of those happy strokes that are seldom attained. In his Odes to Marlborough, there are beautiful lines; but in the second ode, he shows that he knew little of his hero, when he talks of his private virtues. His subjects are commonly such as require no great depth of thought,{ix} or energy of expression. His fables are generally stale, and therefore excite no curiosity. Of his favourite, the Two Springs, the fiction is unnatural, and the moral inconsequential. In his tales, there is too much coarseness, with too little care of language, and not sufficient rapidity of narration.” To the justice of this estimate, it may be doubted whether an unreserved assent will be readily given. Dr. Johnson has often dealt out his praise with too scanty and parsimonious a hand.

His success as an author, whatever were his merits at that time, was however sufficient not to discourage his further efforts. In the year 1735, he produced the work now republished: a work, which has scarce ever been spoken of but to be commended, though Dr. Johnson, whose habits of life, and bodily defects, were little calculated to taste the beauties of this poem, or to enter into the spirit of it, coldly says, “to this poem, praise cannot be totally denied.” He adds, however, “he (the author,) is allowed by sportsmen to write with great intelligence of his subject, which is the first requisite to excellence; and though it is impossible to interest common readers of verse in the dangers or the pleasures of the chase, he has done all that{x} transition and variety could easily effect; and has, with great propriety, enlarged his plan by the modes of hunting used in other countries.” Dr. Warton observes, that he “writes with all the spirit and fire of an eager sportsman. The description of the hunting the hare, the fox, and the stag, are extremely spirited, and place the very objects before our eyes: of such consequence is it for a man to write on that, which he hath frequently felt with pleasure.”

Many other testimonies might be added; but its best praise, is the continued succession of new editions since its original publication.

As Mr. Somervile advanced in life, his attention to literary pursuits increased. In the year 1740, he produced “Hobbinol, or the Rural Games;” a burlesque poem, which Dr. Warton has classed among those best deserving notice, of the mock heroick species. It is dedicated to Mr. Hogarth, as the greatest master in the burlesque way; and at the conclusion of his preface, the author says, “If any person should want a key to this poem, his curiosity shall be gratified. I shall in plain words tell him, ‘it is a satire against the luxury, the pride, the wantonness, and quarrelsome{xi} temper of the middling sort of people,’ As these are the proper and genuine cause of that barefaced knavery, and almost universal poverty, which reign without control in every place; and as to these we owe our many bankrupt farmers, our trade decayed, and lands uncultivated, the author has reason to hope, that no honest man, who loves his country, will think this short reproof out of season; for, perhaps, this merry way of bantering men into virtue, may have a better effect than the most serious admonitions, since many who are proud to be thought immoral, are not very fond of being ridiculous.”

He did not yet close his literary labours. In the year 1742, a few months only before his death, he published Field Sports; a poem addressed to the Prince of Wales; and from Lady Luxborough’s letters we learn, that he had translated Voltaire’s Alzira, which, with several other pieces not published, were in her possession. One of these, written towards the close of life, is so descriptive of the old age of a sportsman, and exhibits so pleasing a picture of the temper and turn of mind of the author, we shall here insert. It is an “Address to his Elbow Chair, new clothed.{xii}”

To those who have derived entertainment or instruction from Mr. Somervile’s works, the information will be received with pain, that the latter part of his life did not pass without those embarrassments which attend a deranged state of pecuniary circumstances. Shenstone, who in this particular much{xiv} resembled him, thus notices his lamentable catastrophe. “Our old friend Somervile is dead! I did not imagine I could have been so sorry as I find myself on this occasion. Sublatum quærimus. I can now excuse all his foibles; impute them to age, and to distress of circumstances: the last of these considerations wrings my very soul to think on. For a man of high spirit, conscious of having (at least in one production,) generally pleased the world, to be plagued and threatened by wretches that are low in every sense; to be forced to drink himself into pains of the body, in order to get rid of the pains of the mind, is a misery which I can well conceive; because I may, without vanity, esteem myself his equal in point of economy, and, consequently, ought to have an eye to his misfortunes.” Dr. Johnson says, “his distresses need not to be much pitied; his estate is said to have been fifteen hundred a year, which by his death devolved to Lord Somervile of Scotland. His mother, indeed, who lived till ninety, had a jointure of six hundred.” This remark is made with less consideration than might have been expected, from so close an observer of mankind. Such an estate, incumbered in such a manner, and perhaps{xv} otherwise, frequently leaves the proprietor in a very uneasy situation, with but a scanty pittance; and it is evident, that our author was by no means an economist. Shenstone says, “for whatever the world might esteem in poor Somervile, I really find, upon critical inquiry, that I loved him for nothing so much as his flocci-nauci-nihili-pili-fication of money.” Lady Luxborough declares him to have been a gentleman who deserved the esteem of every good man, and one who was regretted accordingly.

He died July 19, 1742, and was buried at Wotton, near Henley on Arden. He had been married to Mary, daughter of Hugh Bethel, of Yorkshire, who died before him, without leaving any issue. By his will, proved the third of September, 1742, he remembered New College, the place of his education, by leaving to the master and fellows, fifteen volumes of Montfaucon’s Antiquities, and Addison’s works, for their library; and, apparently to encourage provincial literature, he bequeathed twenty pounds to purchase books for the parish library of the place of his residence.{xvii}{xvi}

The old and infirm have at least this privilege, that they can recall to their minds those scenes of joy in which they once delighted, and ruminate over their past pleasures, with a satisfaction almost equal to the first enjoyment; for those ideas, to which any agreeable sensation is annexed, are easily excited, as leaving behind them the most strong and permanent impressions. The amusements of our youth are the boast and comfort of our declining years. The ancients carried this notion even yet further, and supposed their heroes, in the Elysian fields, were fond of the very same diversions they exercised on earth: death itself could not wean them from the accustomed sports and gaities of life.

I hope, therefore, I may be indulged, even by the more grave and censorious part of mankind, if, at my leisure hours, I run over, in my elbow-chair, some of those chases, which were once the delight of a more vigorous age. It is an entertaining, and, as I conceive, a very innocent amusement. The result of these rambling imaginations will be found in the following poem; which if equally diverting to my readers, as to myself, I shall have gained my end. I have intermixed the preceptive parts with so many descriptions, and digressions, in the Georgick manner, that I hope they will not be tedious. I am sure they are very necessary to be well understood by any gentleman, who would enjoy this noble sport in full perfection. In this, at least, I may comfort myself, that I cannot trespass upon their patience more than Markham, Blome, and the other prose writers upon this subject.

It is most certain, that hunting was the exercise of the greatest{xix} heroes of antiquity. By this they formed themselves for war; and their exploits against wild beasts were a prelude to their future victories. Xenophon says, that almost all the ancient heroes, Nestor, Theseus, Castor, Pollux, Ulysses, Diomedes, Achilles, &c. were MαΘηζαὶ Kυνηγεδιῶν, disciples of hunting; being taught carefully that art, as what would be highly serviceable to them in military discipline. Xen. Cynegetic. And Pliny observes, those who were designed for great captains, were first taught, “certare cum fugacibus feris cursu, cum audacibus robore, cum callidus astu:”—to contest with the swiftest wild beasts in speed; with the boldest in strength; with the most cunning, in craft and subtilty. Plin. Panegyr. And the Roman emperors, in those monuments they erected to transmit their actions to future ages, made no scruple to join the glories of the chase to their most celebrated triumphs. Neither were their poets wanting to do justice to this heroick exercise. Beside that of Oppian in Greek, we have several poems in Latin upon hunting. Gratius was contemporary with Ovid; as appears by this verse,

But of his works only some fragments remain. There are many others of more modern date. Among these Nemesianus, who seems very much superiour to Gratius, though of a more degenerate age. But only a fragment of his first book is preserved. We might indeed have expected to have seen it treated more{xx} at large by Virgil in his third Georgick, since it is expressly part of his subject. But he has favoured us only with ten verses; and what he says of dogs, relates wholly to greyhounds and mastiffs:

And he directs us to feed them with butter-milk.—“Pasce sero pingui.” He has, it is true, touched upon the chase in the fourth and seventh books of the Æneid. But it is evident, that the art of hunting is very different now, from what it was in his days, and very much altered and improved in these latter ages. It does not appear to me, that the ancients had any notion of pursuing wild beasts, by the scent only, with a regular and well-disciplined pack of hounds; and therefore they must have passed for poachers amongst our modern sportsmen. The muster-roll given us by Ovid, in his story of Actæon, is of all sorts of dogs, and of all countries. And the description of the ancient hunting, as we find it in the antiquities of Pere de Montfaucon, taken from the sepulchre of the Nasos, and the arch of Constantine, has not the least trace of the manner now in use.

Whenever the ancients mention dogs following by the scent, they mean no more than finding out the game by the nose of one single dog. This was as much as they knew of the “odora canum vis.” Thus Nemesianus says,{xxi}

Oppian has a long description of these dogs in his first book, from ver. 479 to 526. And here, though he seems to describe the hunting of the hare by the scent, through many turnings and windings, yet he really says no more than that one of those hounds, which he calls ἰχνευτῆρες finds out the game. For he follows the scent no further than the hare’s form; from whence, after he has started her, he pursues her by sight. I am indebted for these two last remarks to a reverend and very learned gentleman, whose judgment in the belles-lettres nobody disputes, and whose approbation gave me the assurance to publish this poem.

Oppian also observes, that the best sort of these finders were brought from Britain; this island having always been famous, as it is at this day, for the best breed of hounds, for persons the best skilled in the art of hunting, and for horses the most enduring to follow the chase. It is, therefore, strange that none of our poets have yet thought it worth their while to treat of this subject; which is, without doubt, very noble in itself, and very well adapted to receive the most beautiful turns of poetry. Perhaps our poets have no great genius for hunting. Yet, I hope, my brethren of the couples, by encouraging this first, but imperfect essay, will shew the world they have at least some taste for poetry.

The ancients esteemed hunting, not only as a manly and{xxii} warlike exercise, but as highly conducive to health. The famous Galen recommends it above all others, as not only exercising the body, but giving delight and entertainment to the mind. And he calls the inventors of this art wise men, and well-skilled in human nature. Lib. de parvæ pilæ exercitio.

The gentlemen, who are fond of a jingle at the close of every verse, and think no poem truly musical but what is in rhyme, will here find themselves disappointed. If they will be pleased to read over the short preface before the Paradise Lost, Mr. Smith’s Poem in memory of his friend Mr. John Philips, and the Archbishop of Cambray’s Letter to Monsieur Fontenelle, they may, probably, be of another opinion. For my own part, I shall not be ashamed to follow the example of Milton, Philips, Thomson, and all our best tragic writers.

Some few terms of art are dispersed here and there; but such only as are absolutely requisite to explain my subject. I hope, in this, the criticks will excuse me; for I am humbly of opinion, that the affectation, and not the necessary use, is the proper object of their censure.

But I have done. I know the impatience of my brethren, when a fine day, and the concert of the kennel, invite them abroad. I shall therefore leave my reader to such diversion, as he may find in the poem itself.

The subject proposed. Address to his Royal Highness the Prince. The origin of hunting. The rude and unpolished manner of the first hunters. Beasts at first hunted for food and sacrifice. The grant made by God to man of the beasts, &c. The regular manner of hunting first brought into this island by the Normans. The best hounds and best horses bred here. The advantage of this exercise to us, as islanders. Address to gentlemen of estates. Situation of the kennel, and its several courts. The diversion and employment of hounds in the kennel. The different sorts of hounds for each different chase. Description of a perfect hound. Of sizing and sorting of hounds; the middle-sized hound recommended. Of the large deep-mouthed hound for hunting the stag and otter. Of the lime hound; their use on the borders of England and Scotland. A physical account of scents. Of good and bad scenting days. A short admonition to my brethren of the couples.

Of the power of instinct in brutes. Two remarkable instances in the hunting of the roebuck, and in the hare going to seat in the morning. Of the variety of seats or forms of the hare, according to the change of the season, weather, or wind. Description of the hare-hunting in all its parts, interspersed with rules to be observed by those who follow that chase. Transition to the Asiatick way of hunting, particularly the magnificent manner of the Great Mogul, and other Tartarian princes, taken from Monsieur Bernier, and the History of Gengis Cawn the Great. Concludes with a short reproof of tyrants and oppressors of mankind.

Of King Edgar, and his imposing a tribute of wolves’ heads upon the kings of Wales: from hence a transition to fox-hunting, which is described in all its parts. Censure of an over-numerous pack. Of the several engines to destroy foxes, and other wild beasts. The steel-trap described, and the manner of using it. Description of the pitfall for the lion; and another for the elephant. The ancient way of hunting the tiger with a mirror. The Arabian manner of hunting the wild boar. Description of the royal stag-chase at Windsor Forest. Concludes with an address to his Majesty, and an eulogy upon mercy.

Of the necessity of destroying some beasts, and preserving others, for the use of man. Of breeding of hounds; the season for this business. The choice of the dog, of great moment. Of the litter of whelps. Of the number to be reared. Of setting them out to their several walks. Care to be taken to prevent their hunting too soon. Of entering the whelps. Of breaking them from running at sheep. Of the diseases of hounds. Of their age. Of madness; two sorts of it described, the dumb, and outrageous madness: its dreadful effects. Burning of the wound recommended, as preventing all ill consequences. The infectious hounds to be separated, and fed apart. The vanity of trusting to the many infallible cures for this malady. The dismal effects of the biting of a mad dog, upon man, described. Description of the otter-hunting. The conclusion.

Printed by W. Bulmer and Co.

Cleveland-row, St. James’s.