Title: French enterprise in Africa

the personal narrative of Lieut. Hourst of his exploration of the Niger

Author: Hourst

Translator: N. D'Anvers

Release date: September 14, 2023 [eBook #71649]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Chapman & Hall, Ld, 1898

Credits: Galo Flordelis (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

FRENCH ENTERPRISE IN AFRICA

The Exploration of the Niger

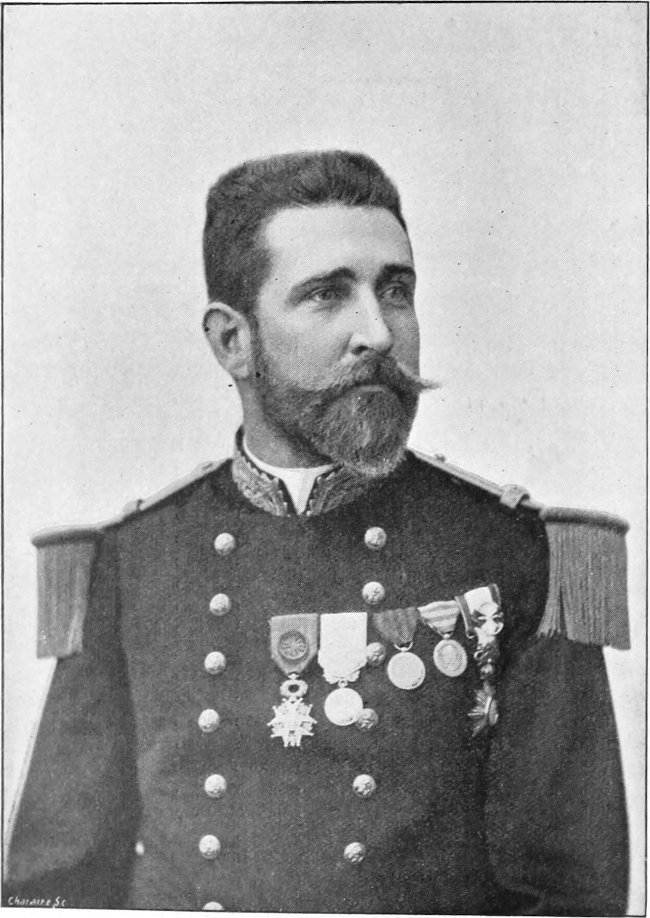

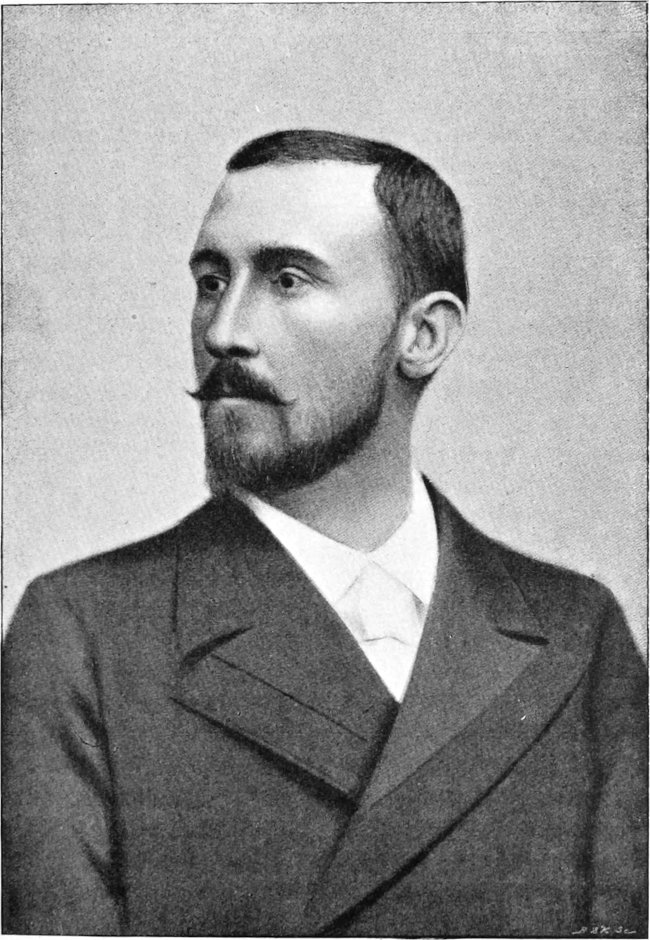

LIEUTENANT HOURST.

THE PERSONAL NARRATIVE OF LIEUT.

HOURST

OF HIS

Exploration

of the Niger

Translated by

Mrs. ARTHUR

BELL (N. D’Anvers)

AUTHOR OF ‘THE ELEMENTARY HISTORY OF ART,’

‘THE SCIENCE LADDERS,’ ETC.

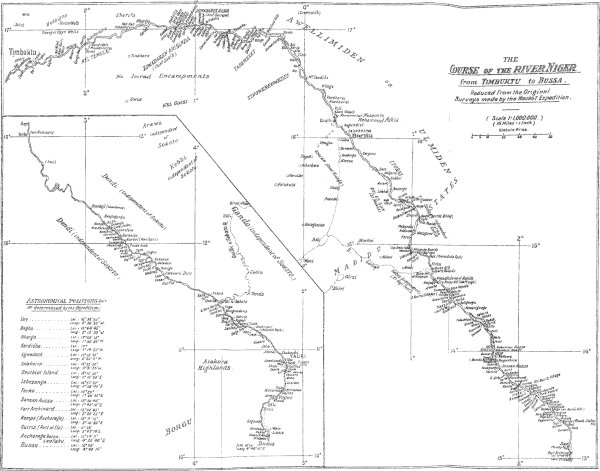

WITH 190 ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAP

![[Illustration]](images/i002.jpg)

LONDON: CHAPMAN & HALL, Ld.

1898

[All rights reserved]

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

The appearance of this brightly-written record of an adventurous voyage down the Niger, from Timbuktu to the sea, such as has never before been accomplished, is just now peculiarly opportune, when attention is so much concentrated on the efforts of the French to extend their influence in Africa, especially in the Western Sudan.

The author of the Exploration of the Niger is, of course, greatly prejudiced against England, and his jealous hostility to those he habitually calls “our rivals” peeps out at every turn, but for all that the work he has done is good and valuable work, adding much to the knowledge of the Niger itself, its basin, and the various tribes occupying the riverside districts. It is remarkable, that in spite of much opposition Lieutenant Hourst managed to keep the peace with the natives from the first start from Timbuktu to the arrival at Bussa. Whilst the footprints of too many of his predecessors were marked in blood, he and his party passed by without the loss of a single life, and in this most noteworthy peculiarity of his journey, the brave and patient young leader may claim to rank even with that great pioneer of African discovery, David Livingstone.

True the Lieutenant owed the good relations he was[viii] able to maintain with the chiefs to a fiction, for acting on the advice of a certain Béchir Uld Mbirikat, a native of Twat, whom he had met at Timbuktu, he passed himself off as the nephew of Dr. Barth, the great German traveller, who had everywhere won the love and respect of the people with whom he was brought in contact. Assuming the name of Abdul Kerim, or the Servant of the Most High, the Frenchman solved all the difficulties which threatened to stop his progress by the simple assertion that he was the nephew of Abdul Kerim, as Barth was and still is called in the Sudan. “I was thus able,” says Abdul Kerim, “to emerge safely from every situation, however embarrassing,” explaining that the natives do not distinguish between different European nationalities, but simply class all together as “the whites.”

Apart from this initial falsehood, of which the Lieutenant does not seem to be in the least ashamed, his dealings with the natives were marked by perfect straightforwardness; every promise, however trivial, made to one of them he faithfully performed, whilst from the officers under him and the coolies in his service he won the utmost devotion and love. He deserves indeed very great credit for the ever ready tact with which he turned aside rather than met the difficulties assailing him at every turn, and Dr. Barth would have had no cause to be ashamed of his relative if the young gentleman had indeed been his nephew.

Lieutenant Hourst’s chapter on the much misjudged Tuaregs is especially interesting, and, most noteworthy fact, full of hope for the future. He attributes their many excellent qualities to their reverence for their women.[ix] The husband of one wife only, the Tuareg warrior looks up to that wife with something of the chivalrous devotion of the knights of the Middle Ages, presenting in this respect a very marked contrast to his Mahommedan neighbours, of whom, by the way, the Frenchman has the lowest possible opinion; charging them with a total disregard of morality, beneath the cloak of an assumed religious zeal. On the so-called marabouts he is especially severe, giving many instances of the evil influence they exercise over the simple-minded natives.

It would be unfair to the author to spoil the interest of his narrative by any further revelations of its contents; suffice it to add, that in spite of his all too-evident bias against the English, he is unable to deny that he was kindly treated by the individual members of the Royal Niger Company, with whom he came in contact. His only wish, he naïvely remarks, is that some of the warm-hearted men who welcomed him back to civilization had belonged to his own nationality. There is something truly pathetic in the plea with which the courageous young explorer winds up his record of his year of arduous work, and yet more arduous waiting, hoping against hope for the instructions from home which never came. He knows, he says, that all the countries suitable for colonization—Australia was the last of them—are already occupied by “our rivals,” but there is still room, he thinks, for French “colonies of exploration,” where talented young men, unable to find a career in their native country, may usefully employ their energies in turning the natural wealth of French acquisitions to account. That is all he hopes for; but he cannot help adding a few touching[x] words of appeal to the French colonial authorities, asking them to cease from sending out expeditions only to abandon them to their fate, taking no notice of their requests for instructions or for help.

Reading between the lines of this record of a brave struggle against terrible odds, it is only too easy to realize that the policy of prevarication of the French Government in all matters colonial is a well-considered policy, as astute as it is unfair, alike to the gallant officers in command of abortive exploring expeditions as to the “rivals” so cordially disliked.

Nancy Bell.

Southbourne-on-Sea,

October 1898.

[xi]

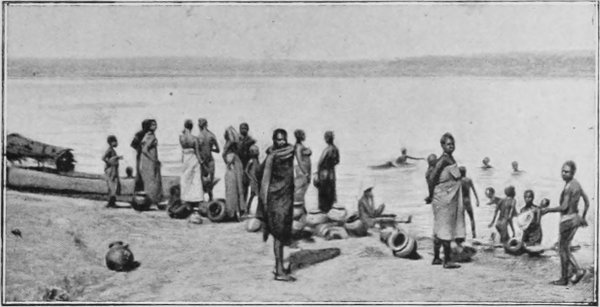

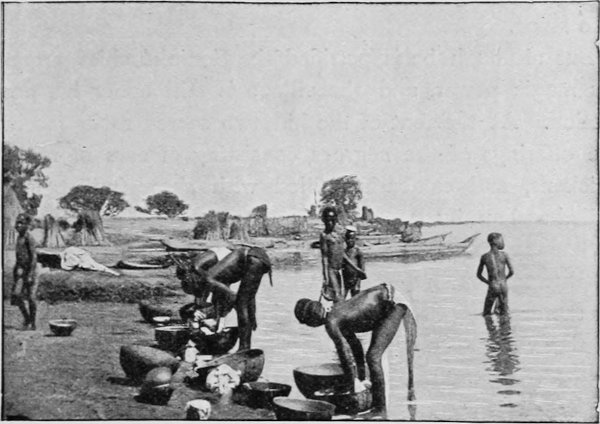

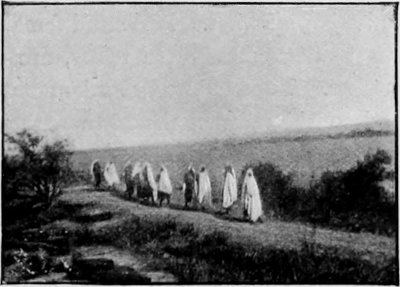

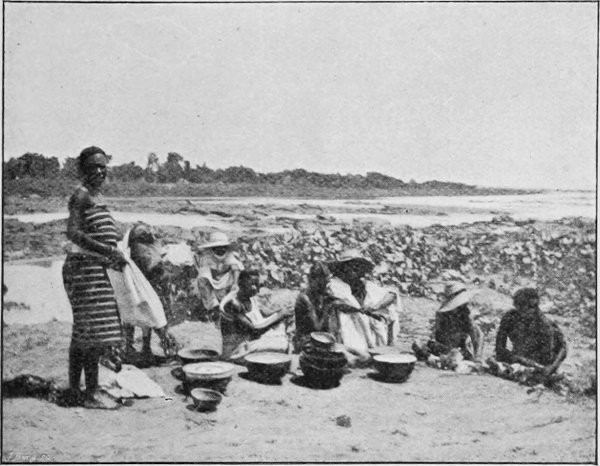

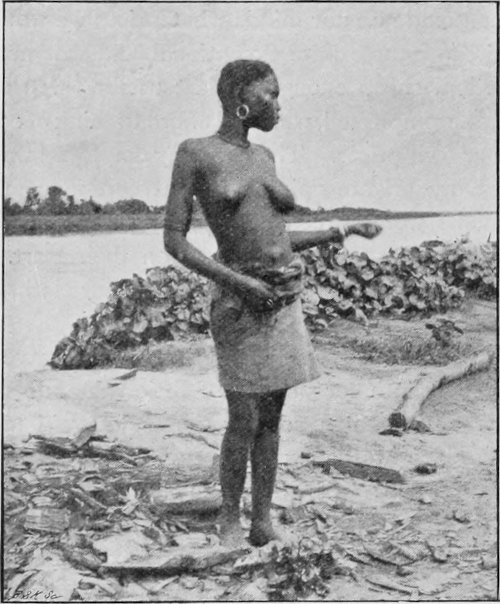

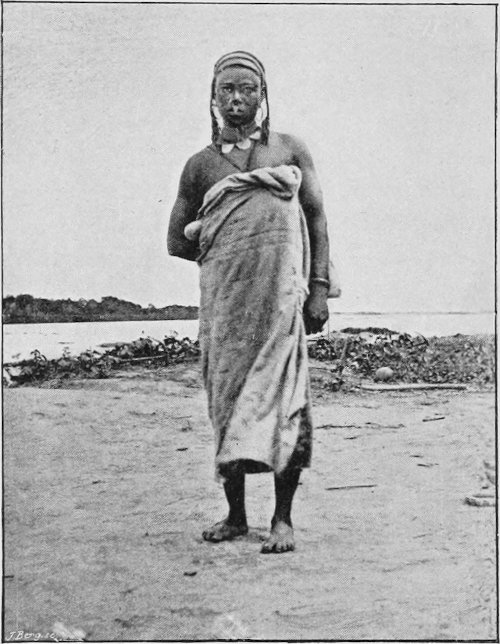

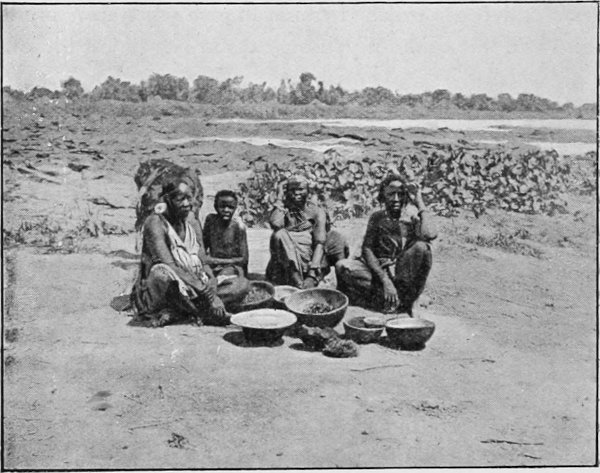

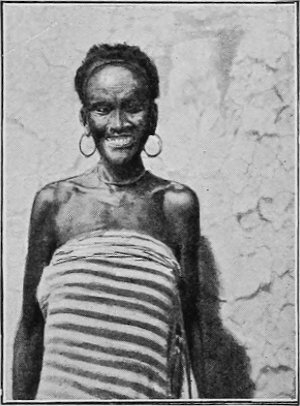

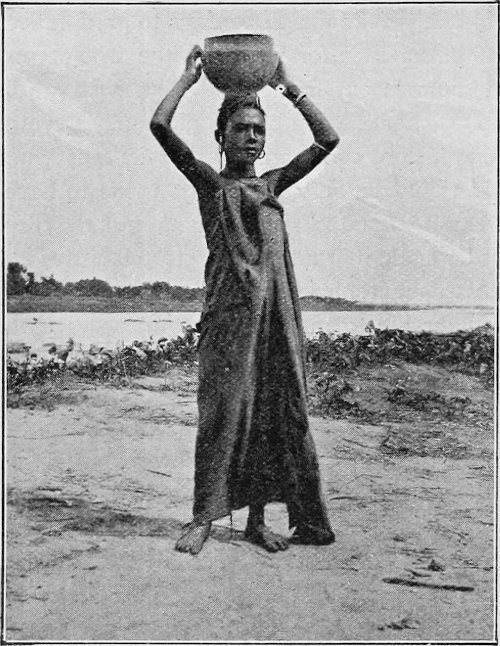

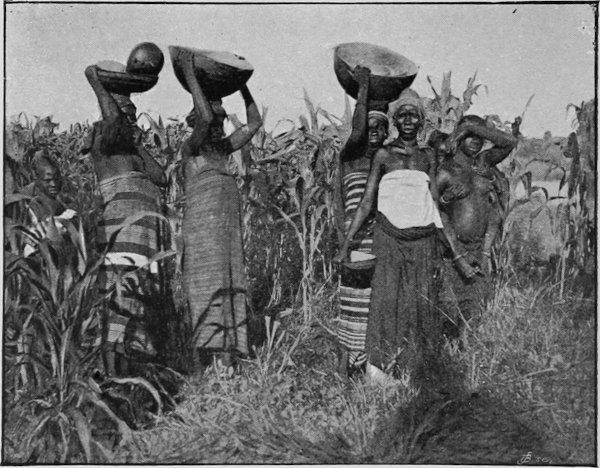

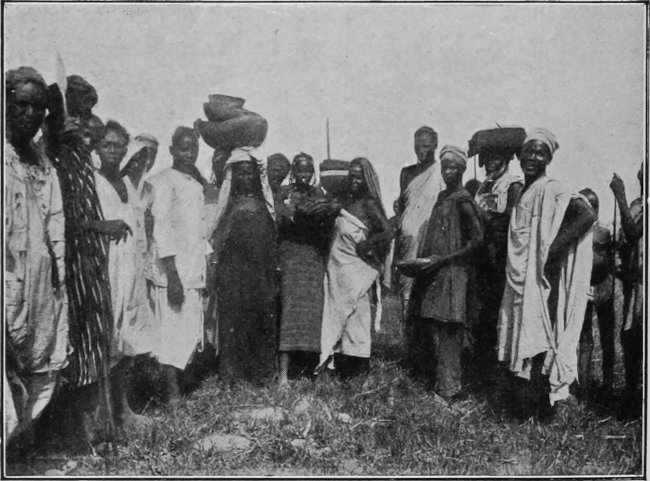

WASHERWOMEN OF SAY.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| TRANSLATOR’S NOTE. | vii | |

| I. | AN ABORTIVE START | 1 |

| II. | FROM KAYES TO TIMBUKTU | 41 |

| III. | FROM TIMBUKTU TO TOSAYE | 93 |

| IV. | FROM TOSAYE TO FAFA | 151 |

| V. | THE TUAREGS | 199 |

| VI. | FROM FAFA TO SAY | 250 |

| VII. | STAY AT SAY | 295 |

| VIII. | MISTAKES AND FALSE NEWS | 356 |

| IX. | FROM SAY TO BUSSA | 403 |

| X. | FROM BUSSA TO THE SEA; CONCLUSION OF OUR VOYAGE | 446 |

| EPILOGUE | 498 | |

| INDEX | 513 |

| PAGE | |

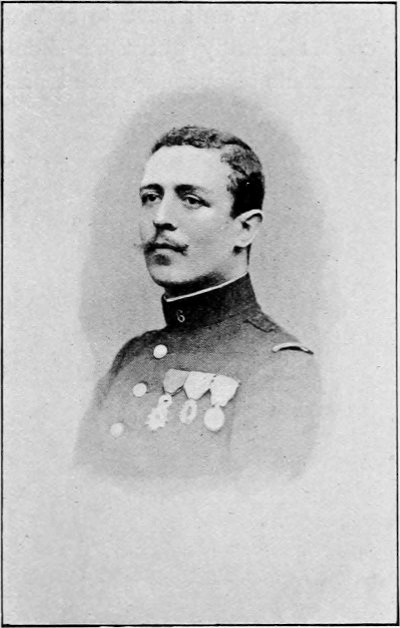

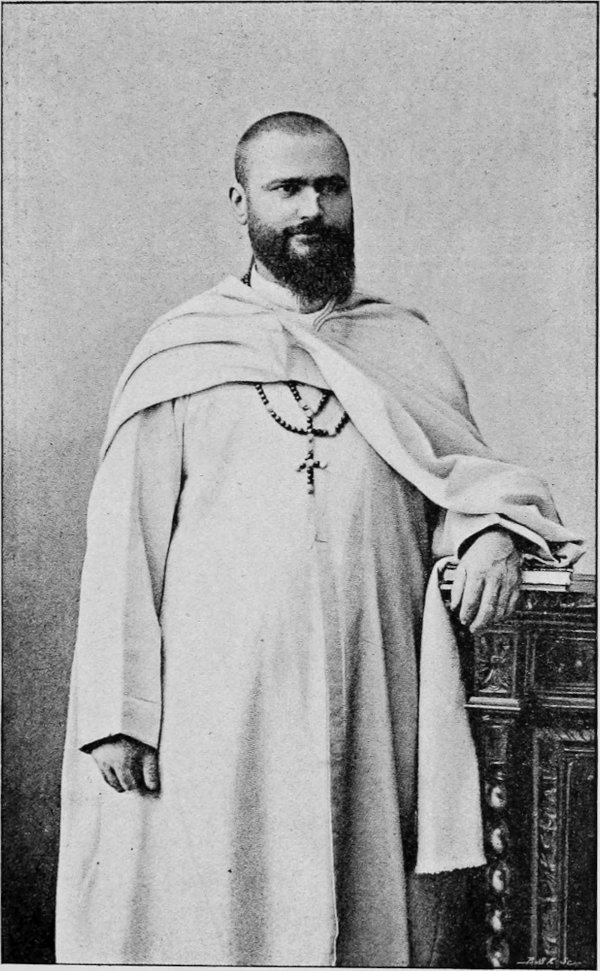

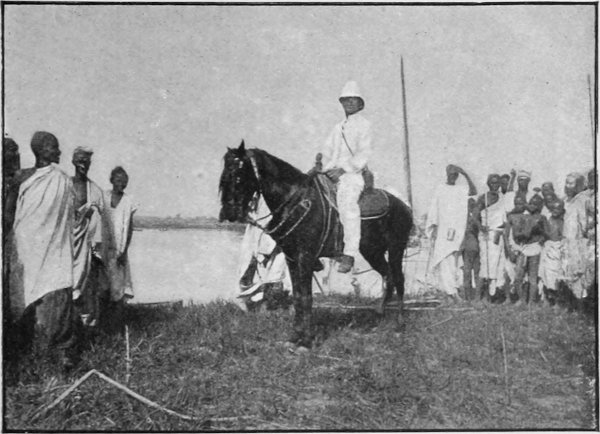

| LIEUTENANT HOURST | Frontispiece |

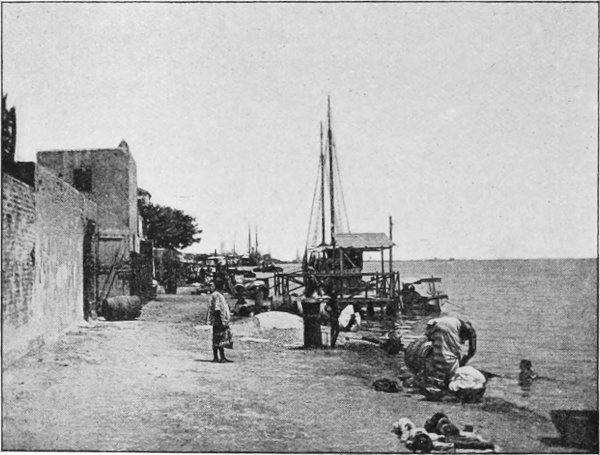

| WASHERWOMEN OF SAY | xi |

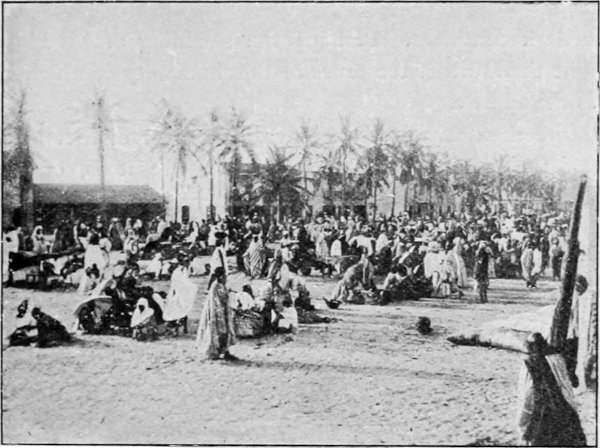

| MARKET PLACE, ST. LOUIS | 1 |

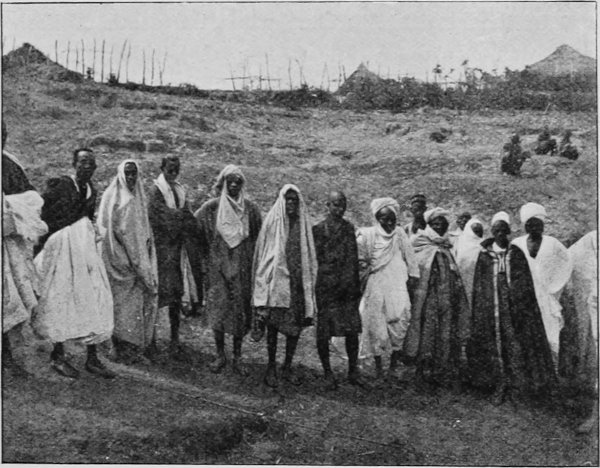

| NATIVES OF THE BANKS OF THE SENEGAL | 5 |

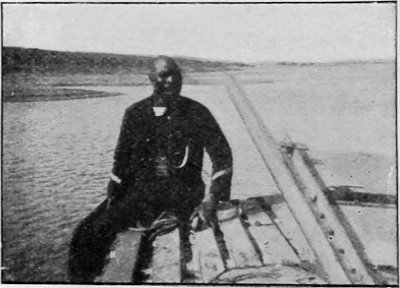

| NAVAL ENSIGN BAUDRY | 15 |

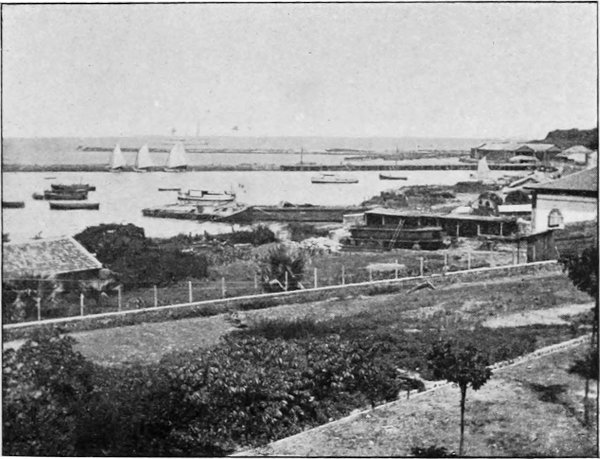

| THE PORT OF DAKAR | 21 |

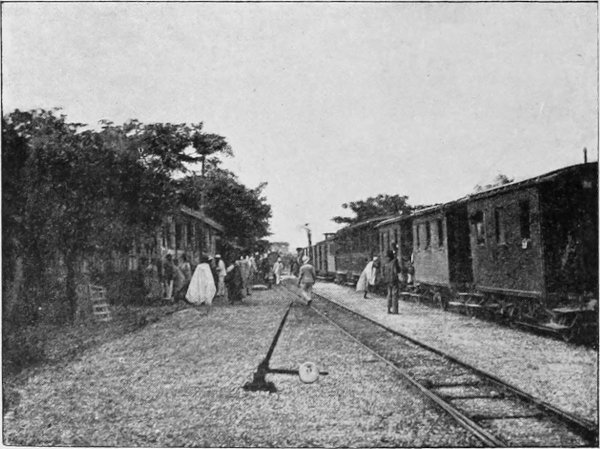

| PART OF THE DAKAR ST. LOUIS LINE | 24 |

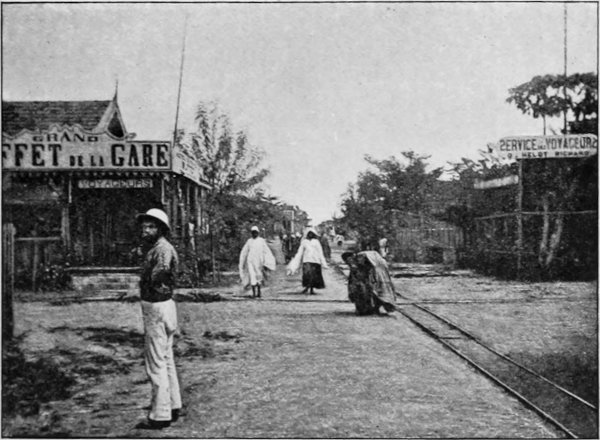

| RAILWAY BUFFET AT TIVIWANE | 25 |

| THE QUAY AT ST. LOUIS | 26 |

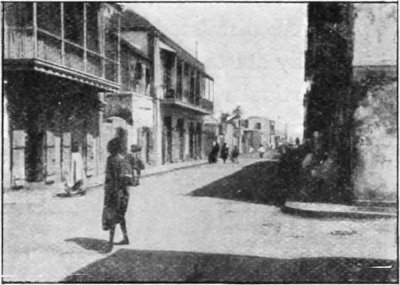

| A STREET IN ST. LOUIS | 27 |

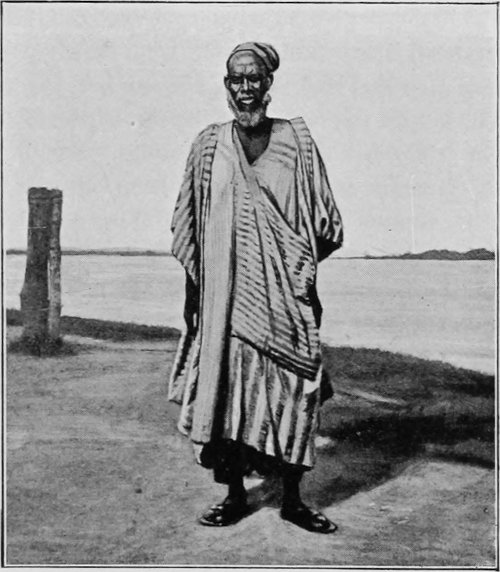

| BUBAKAR-SINGO | 27 |

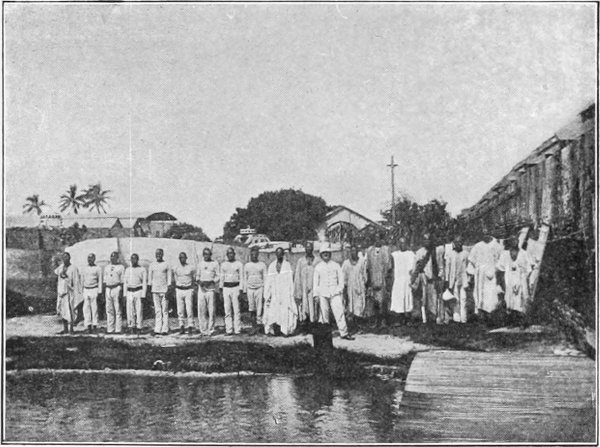

| THE COOLIES ENGAGED AT ST. LOUIS | 28 |

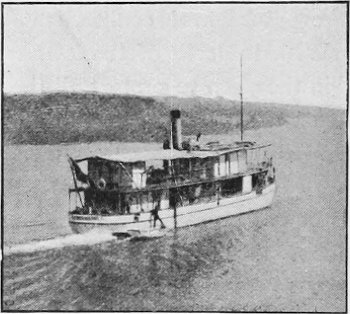

| THE ‘BRIÈRE DE L’ISLE’ | 30 |

| THE MARKET-PLACE AT ST. LOUIS | 31 |

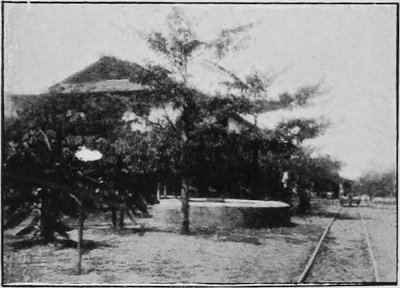

| GOVERNMENT HOUSE, KAYES | 32 |

| ON THE SENEGAL | 40 |

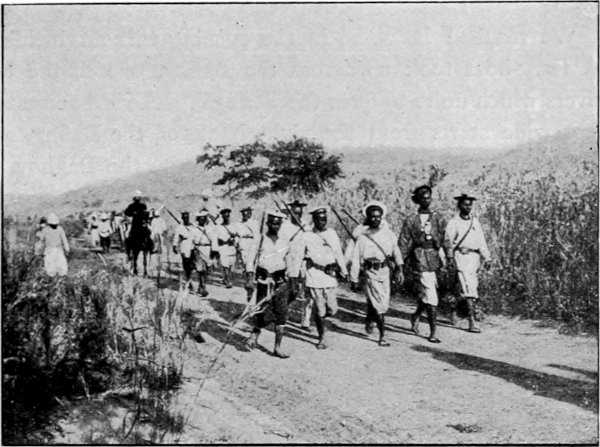

| EN ROUTE | 41 |

| LEFEBVRE CARTS UNHARNESSED | 42 |

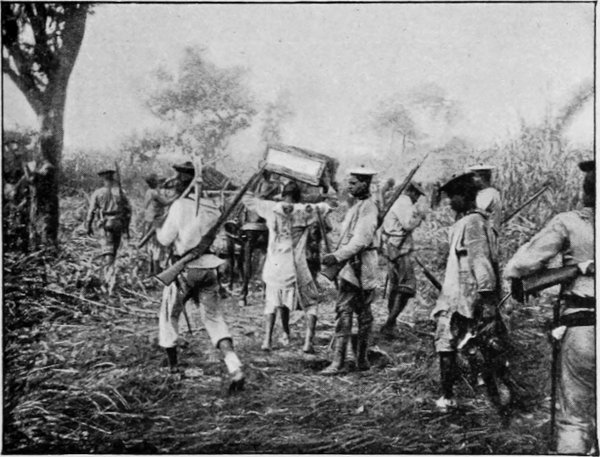

| LOADING OUR CONVOY | 43 |

| LIEUTENANT BLUZET | 45 |

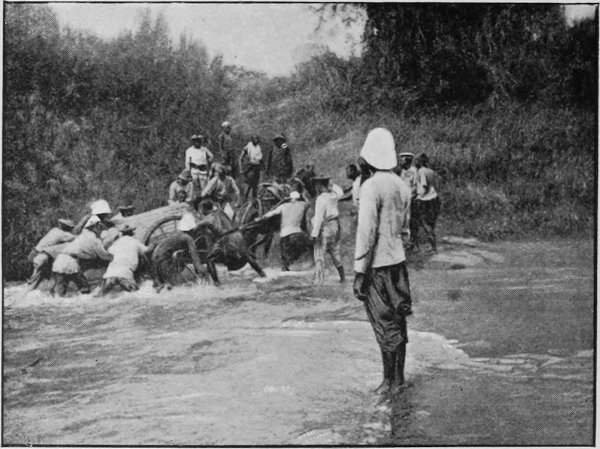

| CROSSING A MARIGOT | 46 |

| WE ALL HAVE TO RUSH TO THE RESCUE | 47 |

| OUR TETHERED MULES | 48 |

| DOCTOR TABURET | 51 |

| ARRIVAL AT KOLIKORO | 53 |

| BANKS OF THE RIVER AT KOLIKORO | 55 |

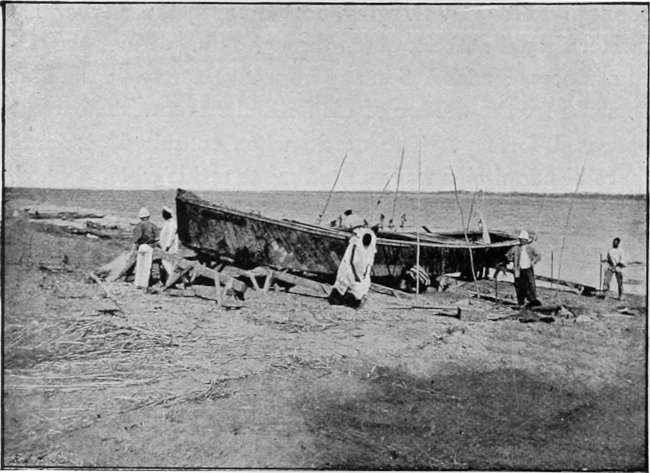

| REPAIRING THE ‘AUBE’ | 58 |

| TIGHTENING THE BOLTS OF THE ‘DAVOUST’ | 59 |

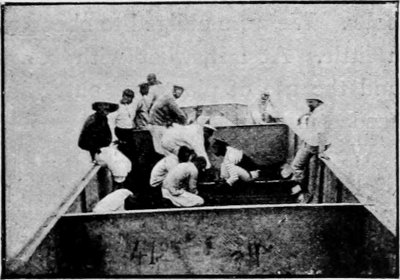

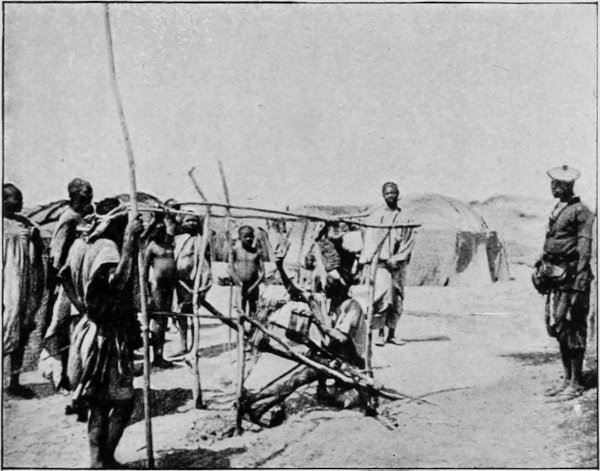

| PROCESSION OF BOYS AFTER CIRCUMCISION | 59 |

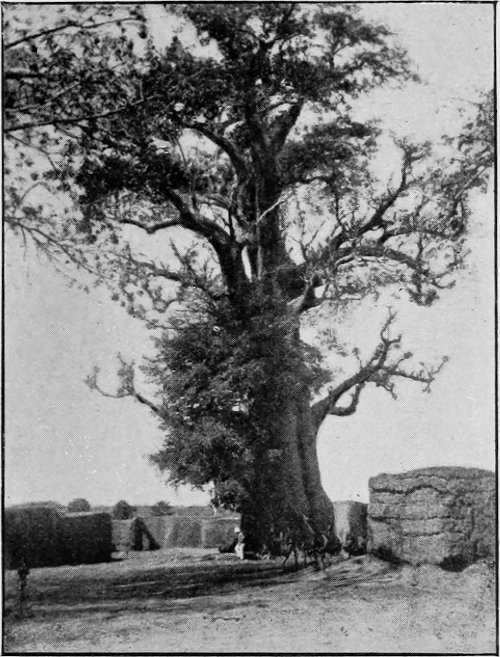

| THE SACRED BAOBAB OF KOLIKORO | 61 |

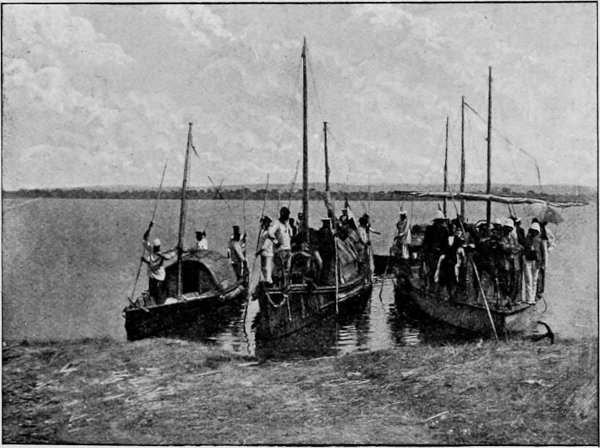

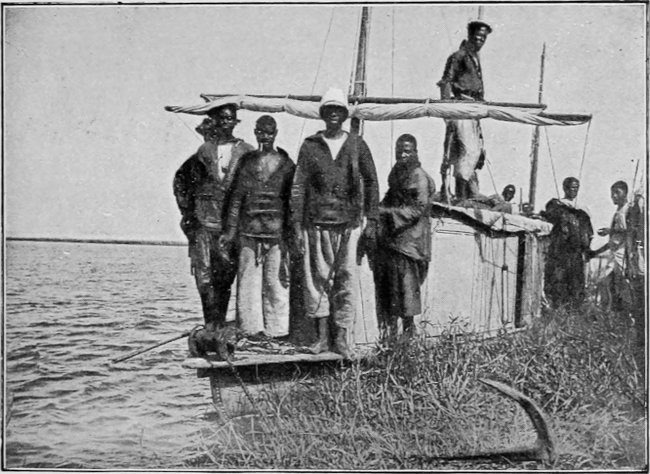

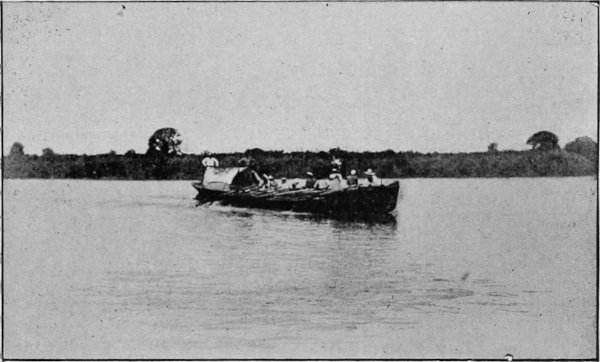

| THE FLEET OF MY EXPEDITION | 63 |

| DIGUI AND THE COOLIES OF THE ‘JULES DAVOUST’ | 65 |

| MADEMBA | 67 |

| YAKARÉ | 70 |

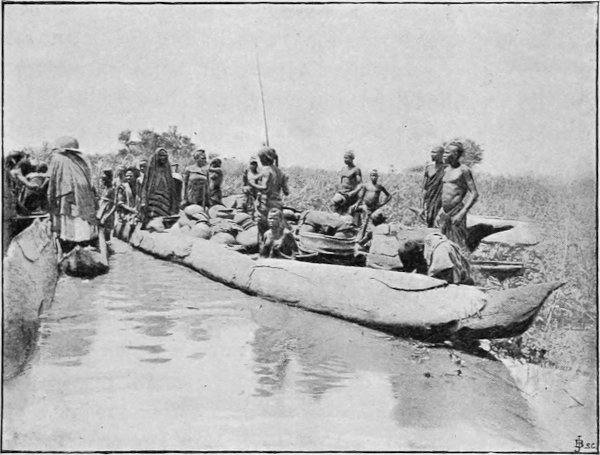

| LARGE NIGER CANOES | 72 |

| THE TOMB OF HAMET BECKAY AT SAREDINA | 76 |

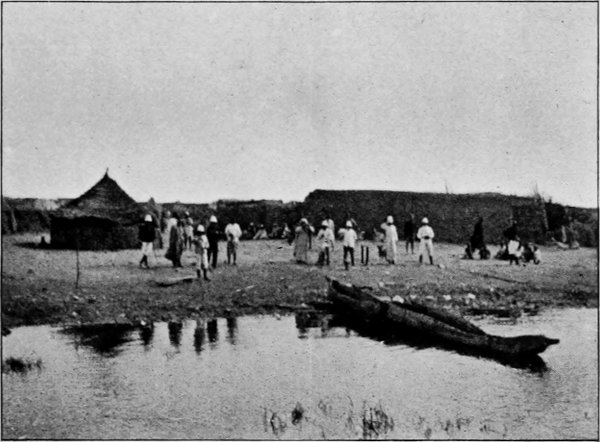

| SARAFÉRÉ | 77 |

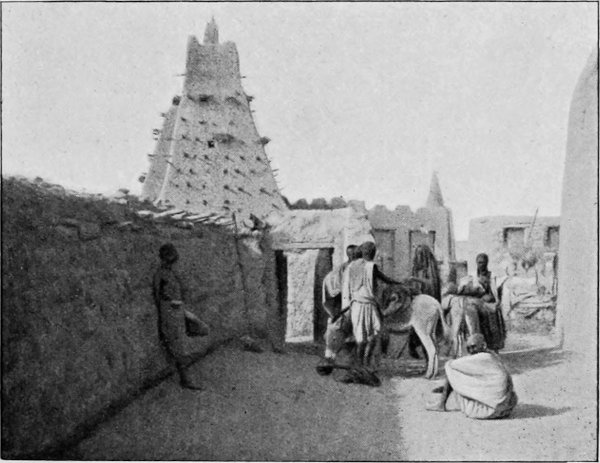

| A MOSQUE AT TIMBUKTU | 83 |

| [xiv]FATHER HACQUART | 85 |

| WE LEAVE KABARA | 91 |

| AT TIMBUKTU | 92 |

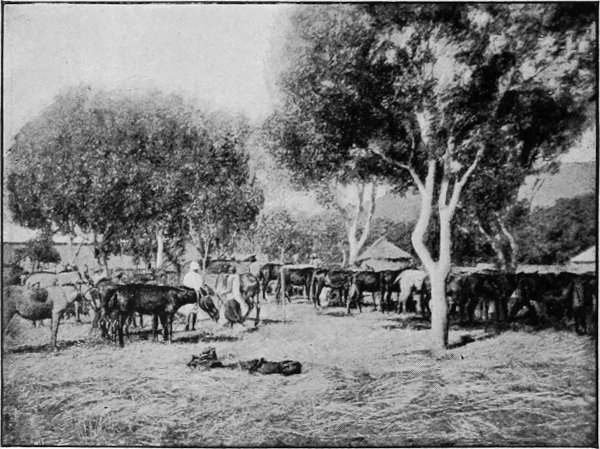

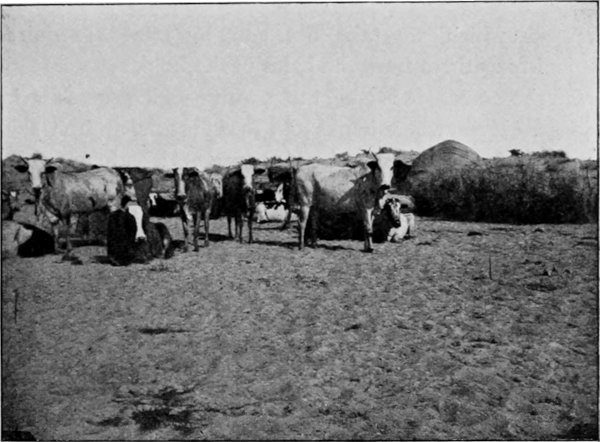

| DROVE OF OXEN | 93 |

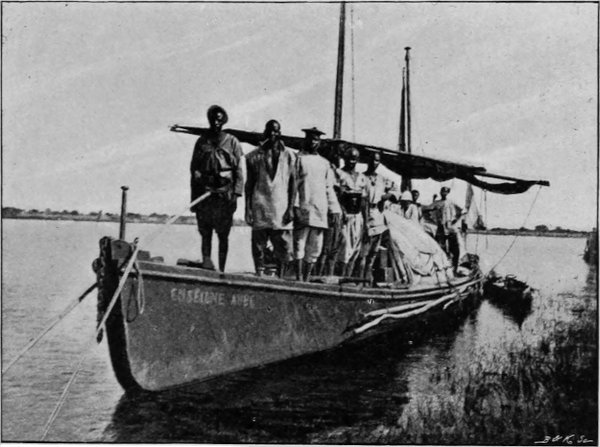

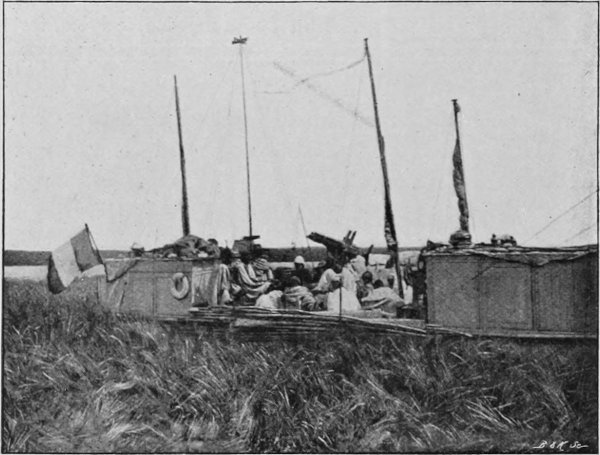

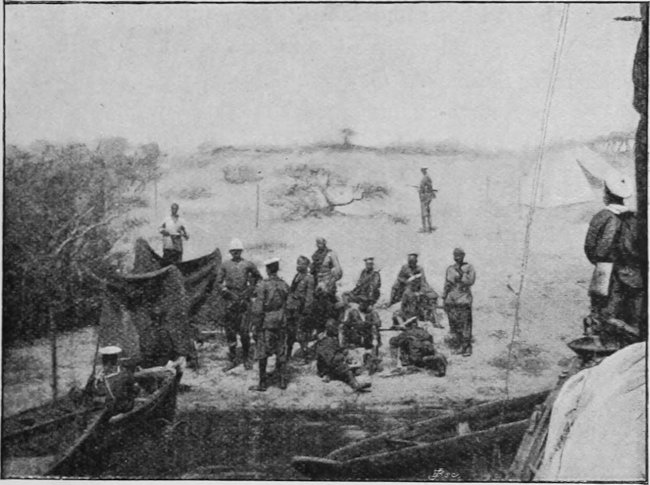

| THE ‘AUBE’ AND HER CREW | 95 |

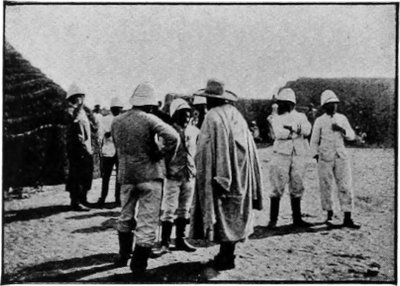

| INTERVIEW WITH ALUATTA | 108 |

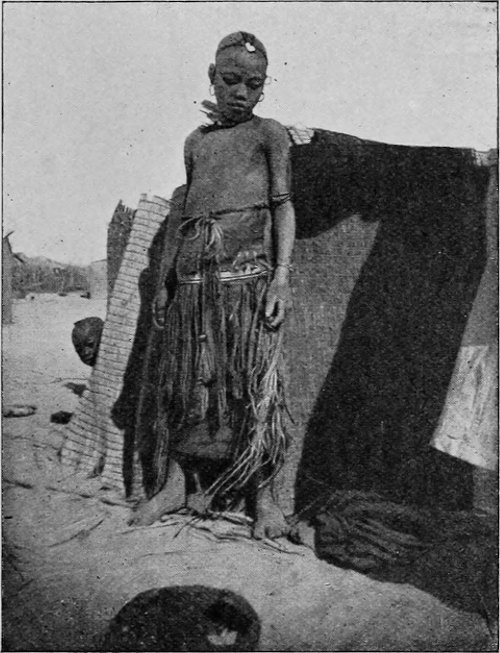

| A LITTLE SLAVE GIRL OF RHERGO | 109 |

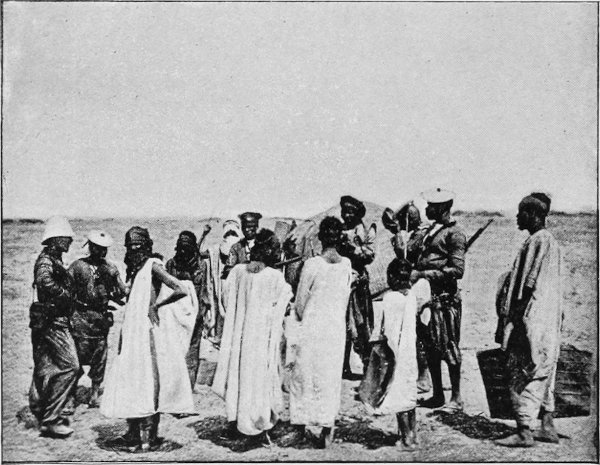

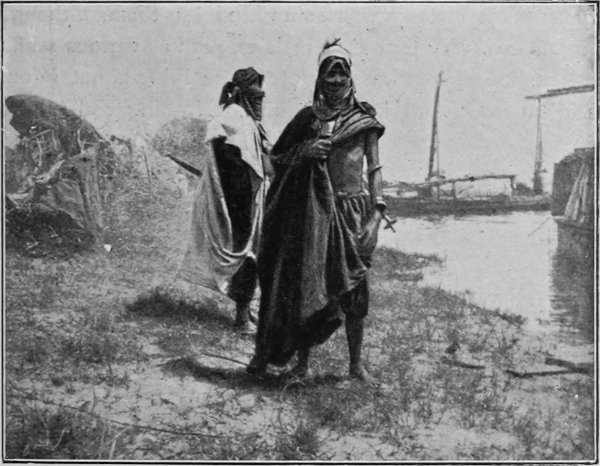

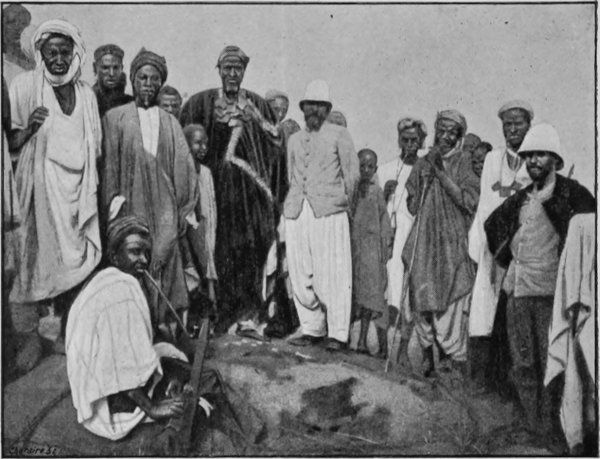

| TUAREGS AND SHERIFFS AT RHERGO | 110 |

| OUR PALAVER AT RHERGO | 111 |

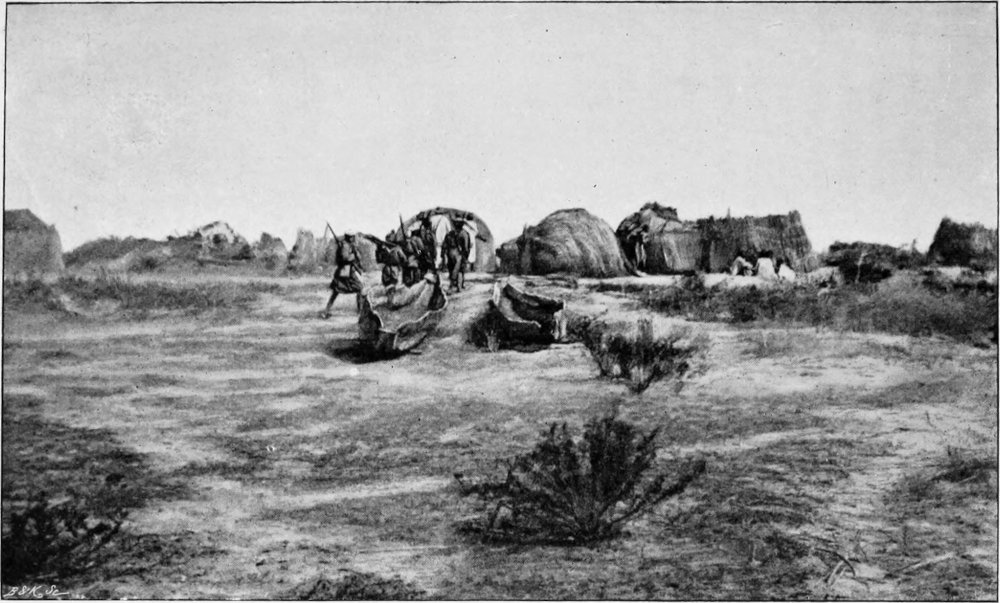

| ARRIVAL AT THE VILLAGE OF RHERGO | 113 |

| TRADERS AT RHERGO | 115 |

| SO-CALLED SHERIFFS OF RHERGO | 116 |

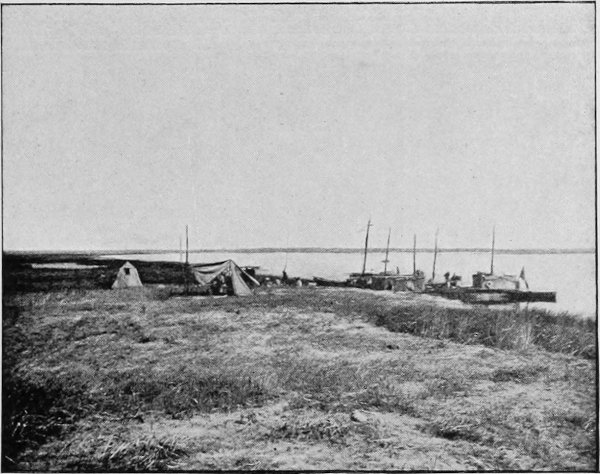

| THE ‘DAVOUST’ AT ANCHOR OFF RHERGO | 117 |

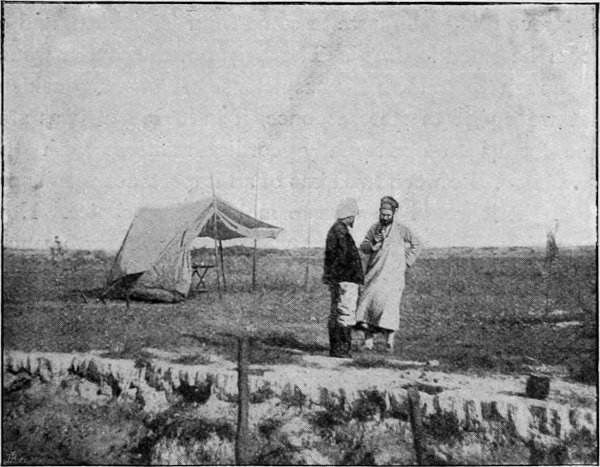

| POLITICAL ANXIETIES | 119 |

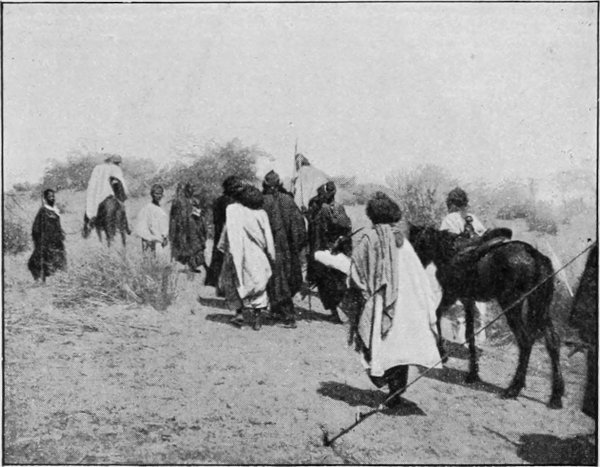

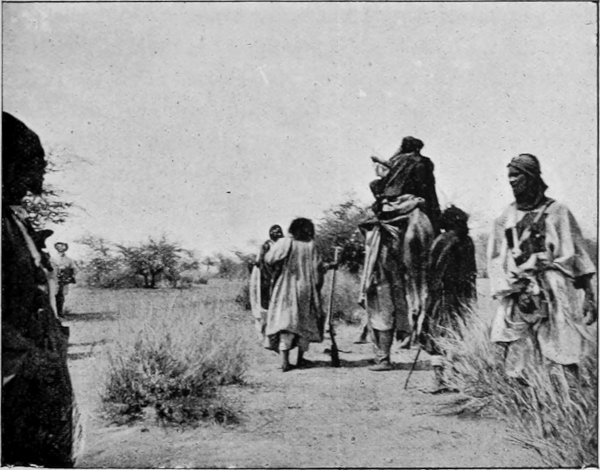

| SAKHAUI’S ENVOYS | 124 |

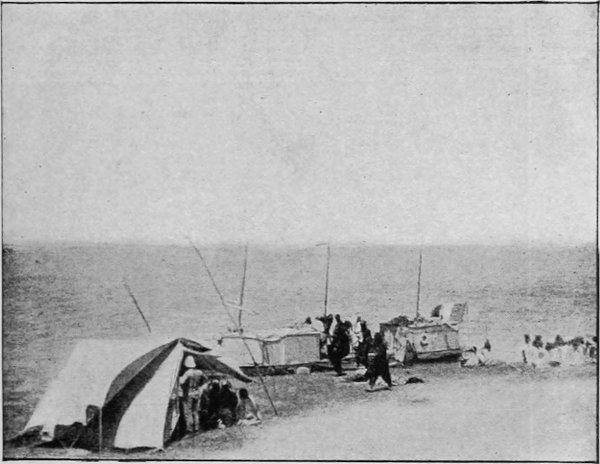

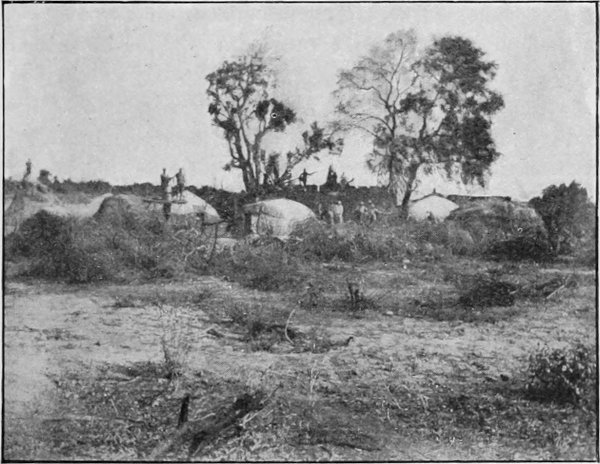

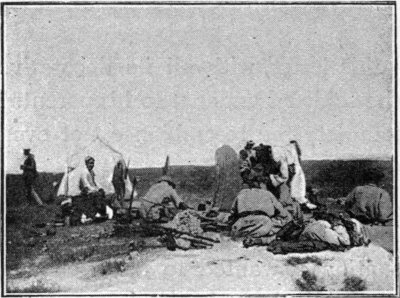

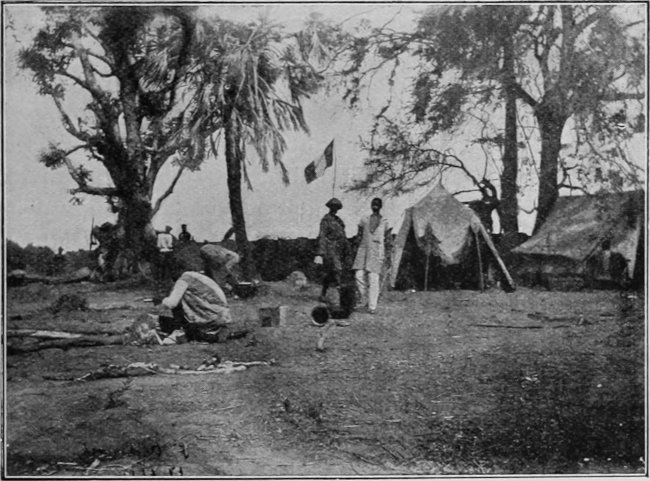

| OUR COOLIES’ CAMP AT ZARHOI | 127 |

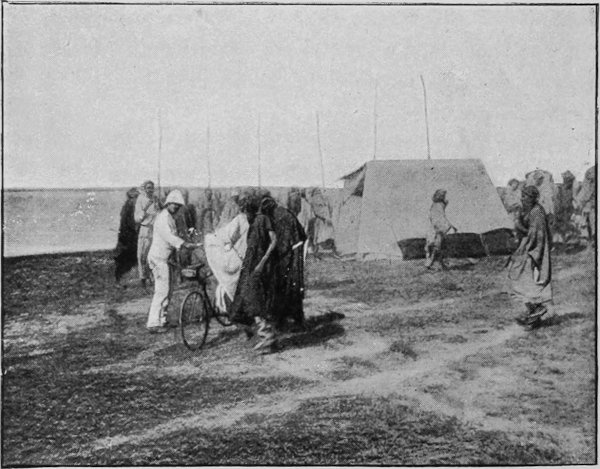

| OUR BICYCLE SUZANNE AMONGST THE TUAREGS | 132 |

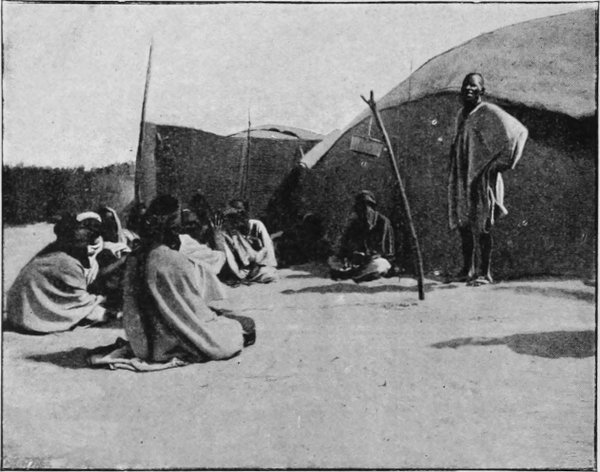

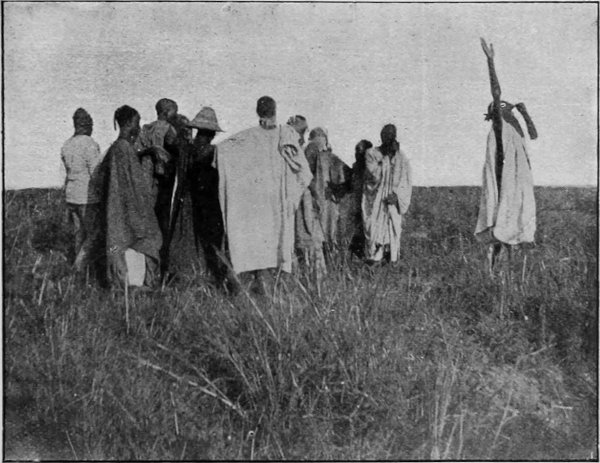

| OUR PALAVER AT SAKHIB’S CAMP | 133 |

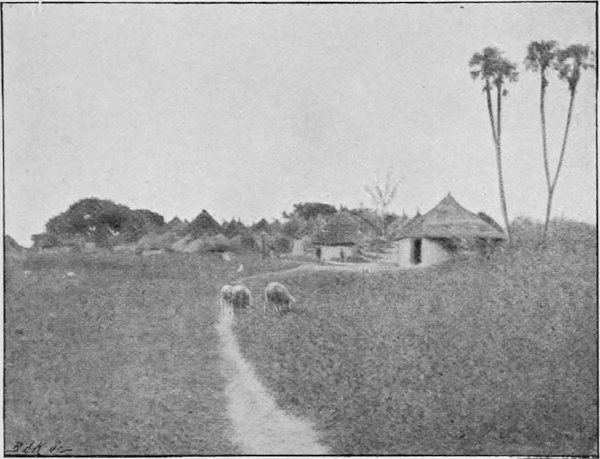

| THE VILLAGE OF GUNGI | 135 |

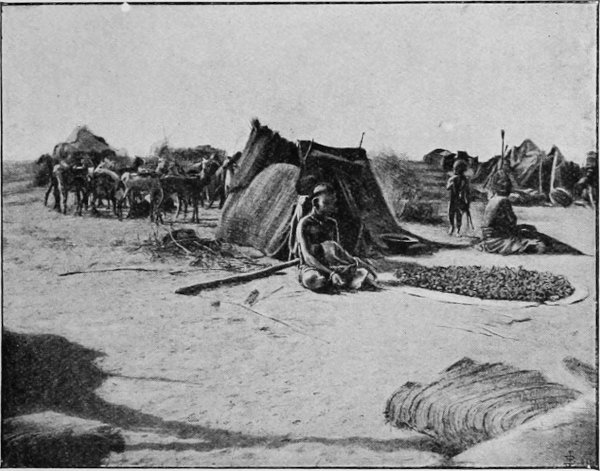

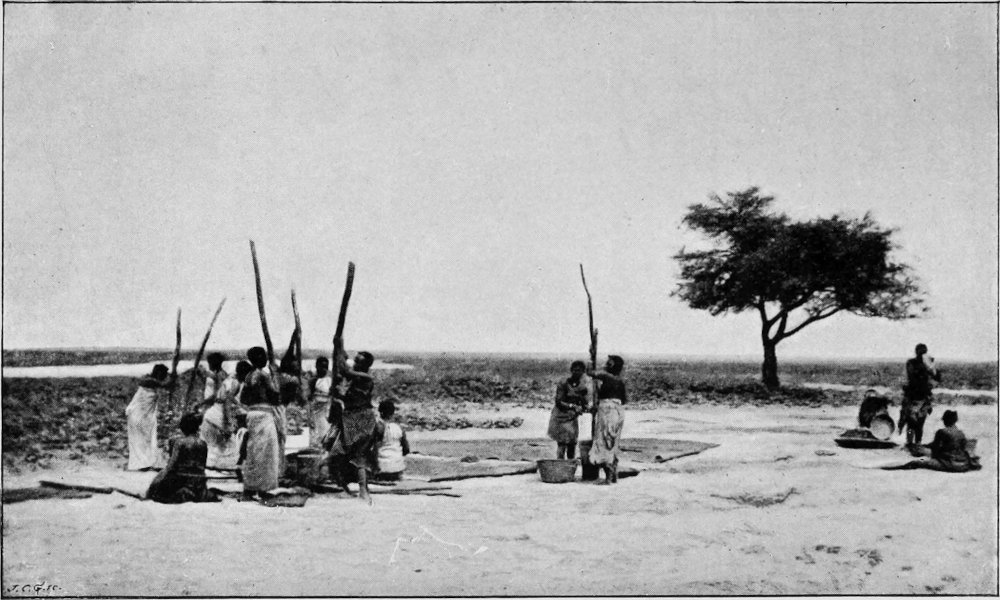

| OUR PEOPLE SHELLING OUR RICE AT GUNGI | 137 |

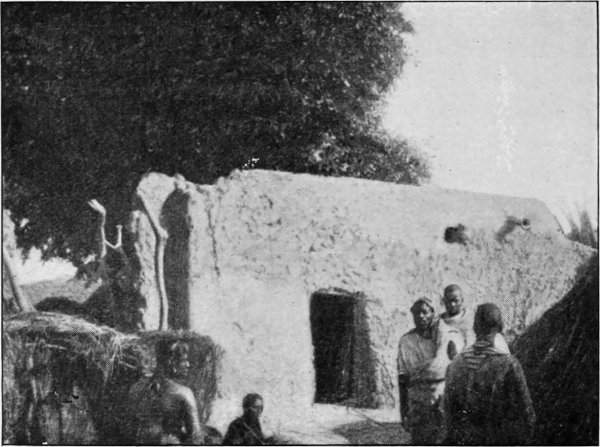

| SHERIFF’S HOUSE AT GUNGI | 139 |

| WEAVERS AT GUNGI | 141 |

| FATHER HACQUART AND HIS LITTLE FRIEND | 143 |

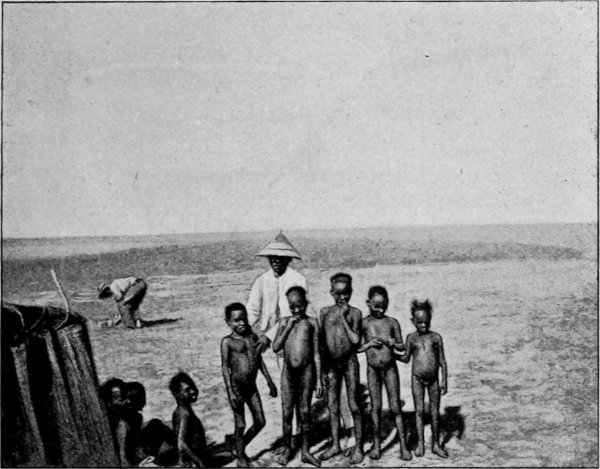

| LITTLE NEGROES AT EGUEDECHE | 145 |

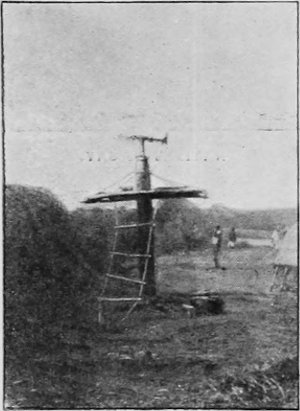

| TAKING ASTRONOMICAL OBSERVATIONS | 150 |

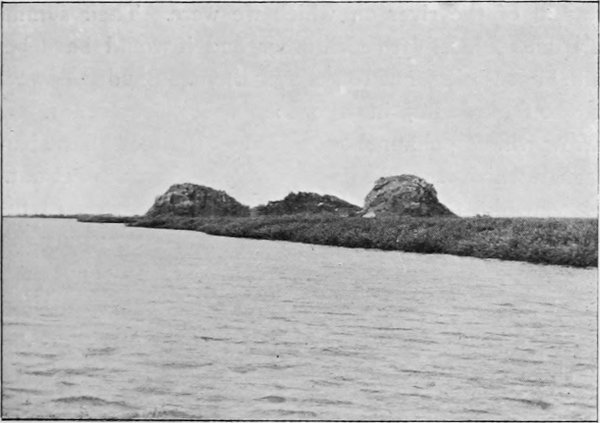

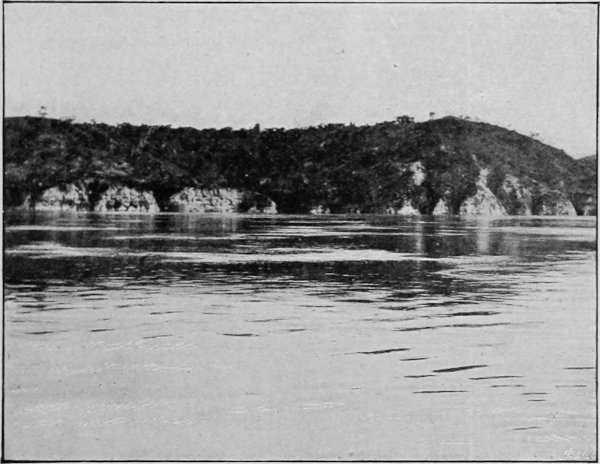

| TOSAYE, WITH THE BAROR AND CHABAR ROCKS | 151 |

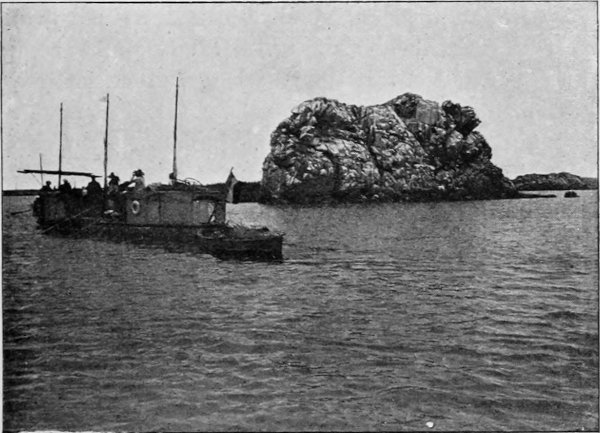

| THE ROCK BAROR AT TOSAYE | 155 |

| THE TADEMEKET ON A DUNE ON THE BANKS OF THE NIGER | 159 |

| PANORAMA OF GAO ON THE SITE OF THE ANCIENT GARO | 169 |

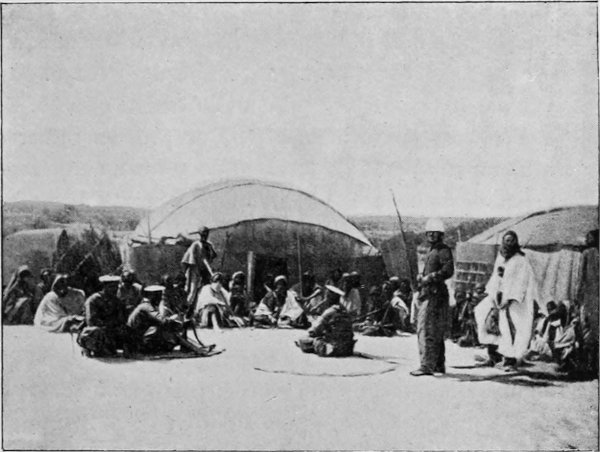

| PALAVER AT GAO | 171 |

| BORNU | 180 |

| BABA, WITH THE ROCKS ABOVE ANSONGO | 181 |

| THE KEL ES SUK OF ANSONGO REFUSE TO SUPPLY US WITH GUIDES | 183 |

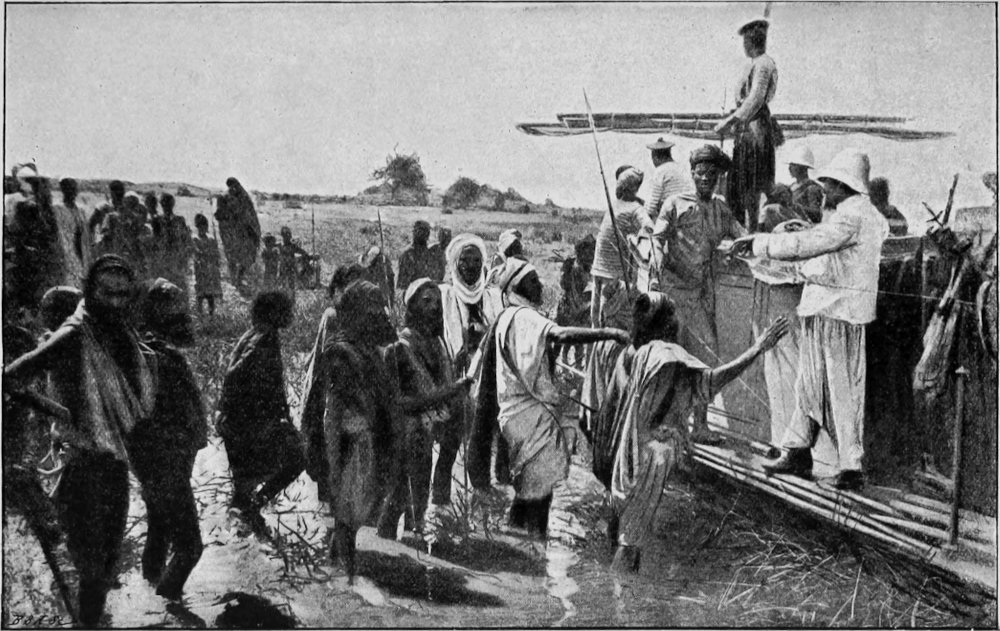

| DISTRIBUTION OF PRESENTS TO THE TUAREGS AT BURÉ | 187 |

| THE ‘DANTEC’ EXPLORING THE PASS | 188 |

| BURÉ | 189 |

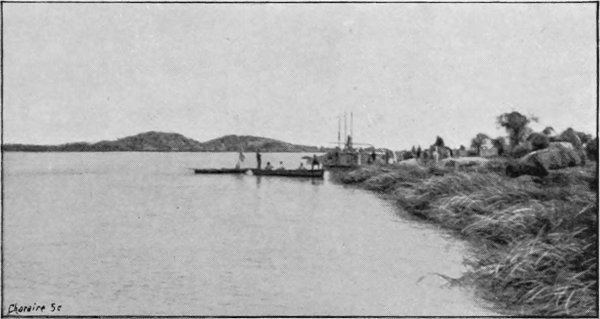

| CANOES AT BURÉ | 190 |

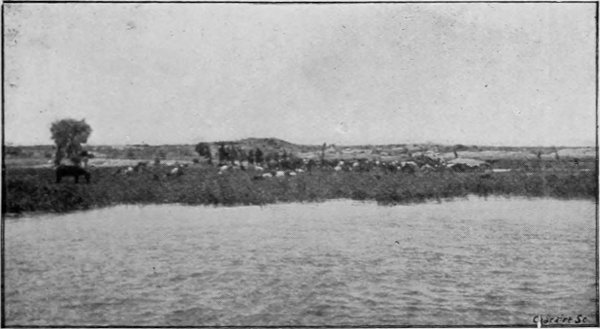

| FLOCKS AND HERDS AT BURÉ | 191 |

| GUIDES GIVEN TO US BY IDRIS | 192 |

| PALAVER WITH DJAMARATA | 195 |

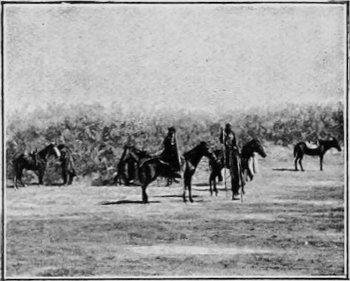

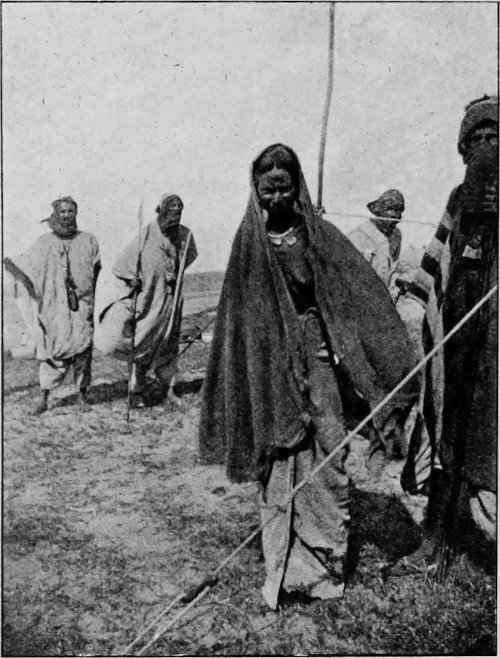

| TUAREGS | 198 |

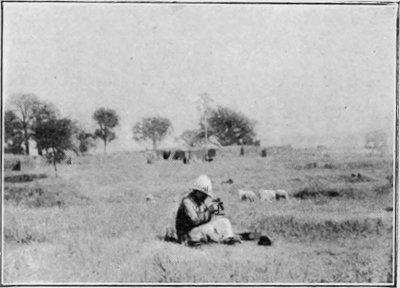

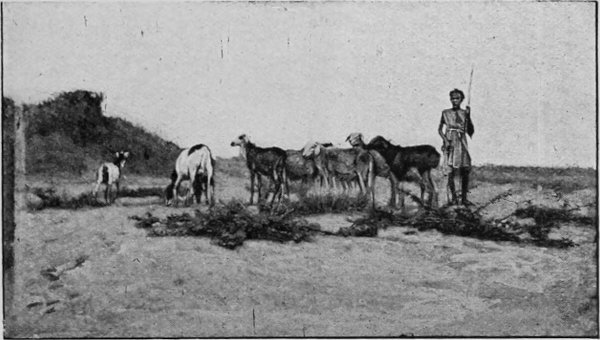

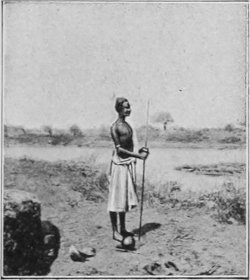

| AN AMRI SHEPHERD | 199 |

| TUAREGS | 203 |

| A GROUP OF TUAREGS | 208 |

| TUAREGS | 211 |

| A TUAREG WOMAN | 220 |

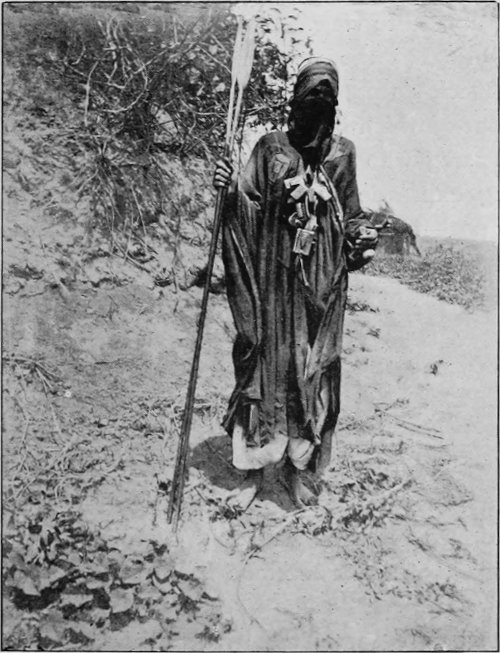

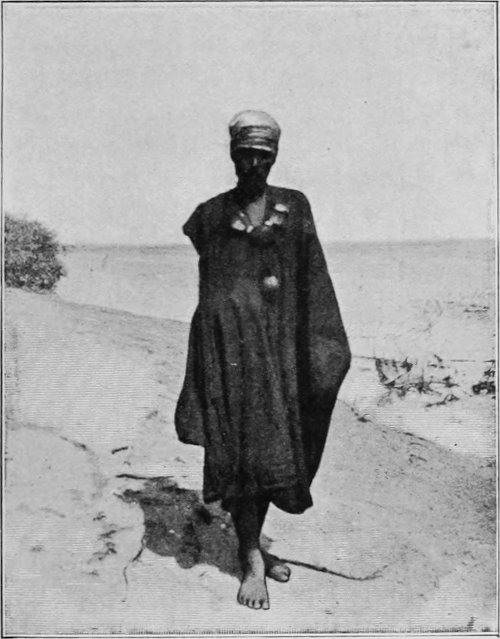

| A TUAREG IN HIS NATIONAL COSTUME | 223 |

| TUAREGS | 227 |

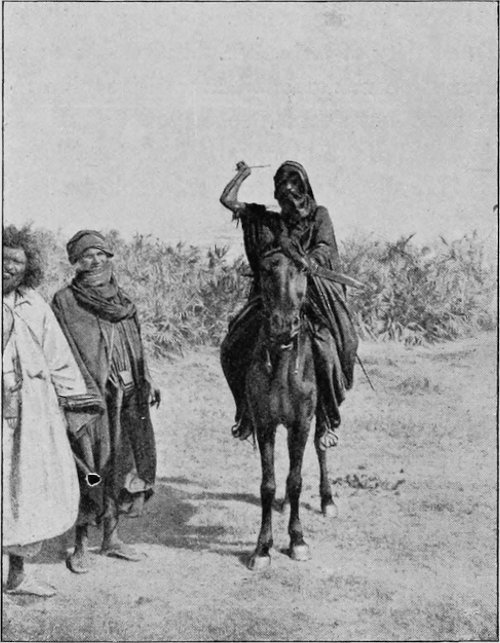

| TUAREG HORSEMAN | 232 |

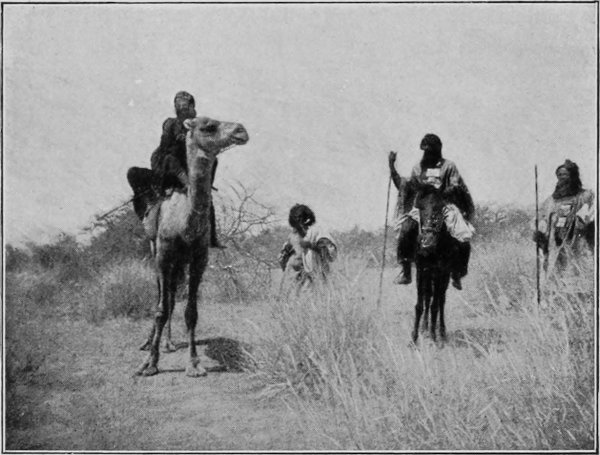

| [xv]MOORS AND TUAREGS | 234 |

| A YOUNG TUAREG | 239 |

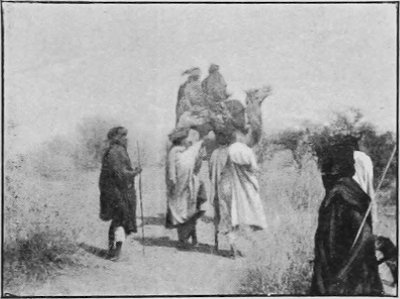

| TUAREGS | 245 |

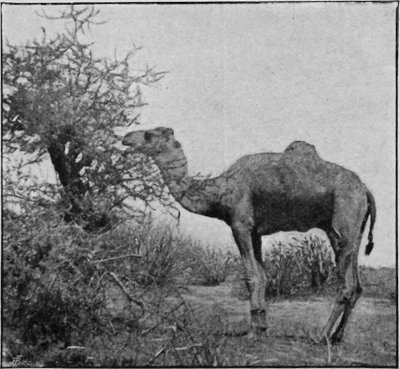

| AN AFRICAN CAMEL | 249 |

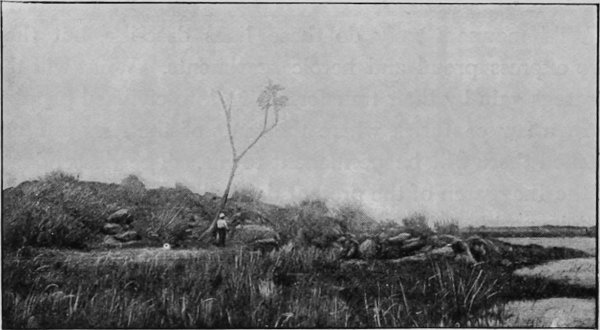

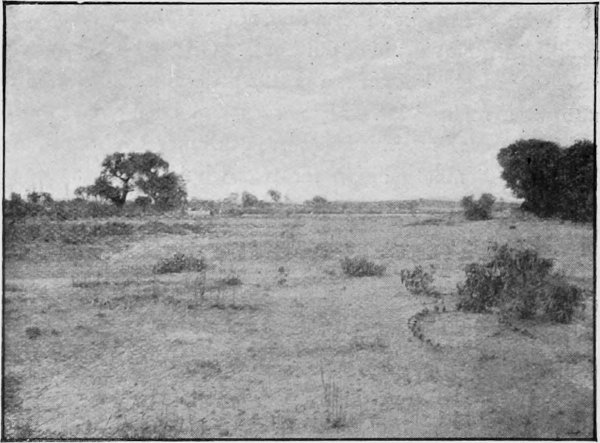

| AN ISOLATED TREE AT FAFA | 250 |

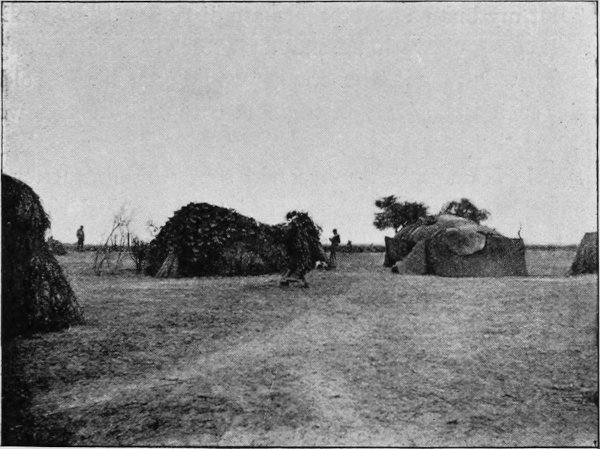

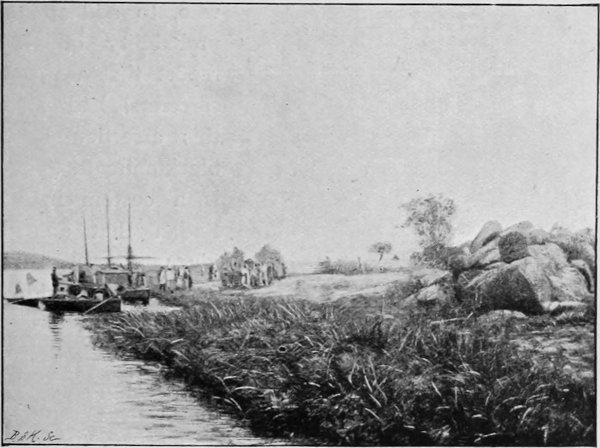

| FAFA | 251 |

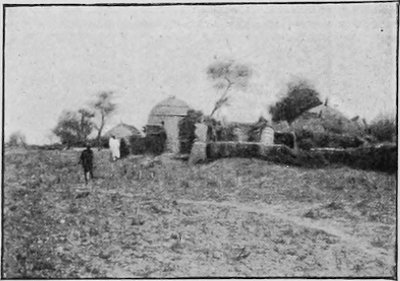

| KARU WITH MILLET GRANARIES | 252 |

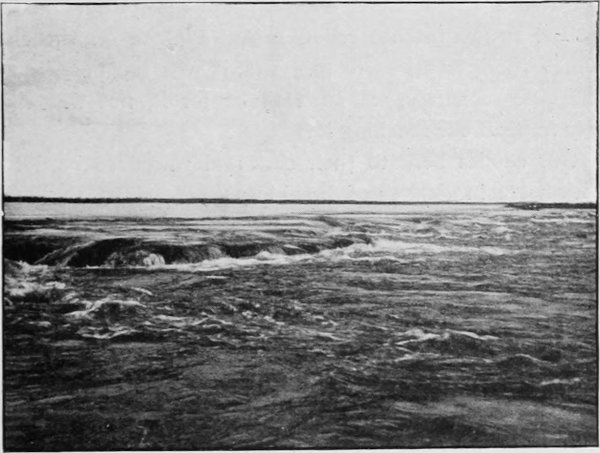

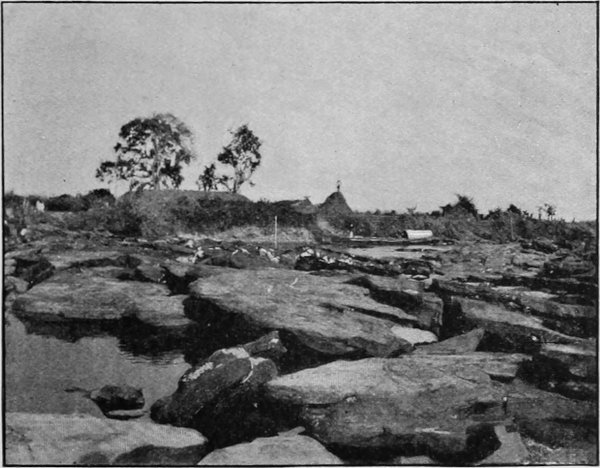

| THE LABEZENGA RAPIDS | 253 |

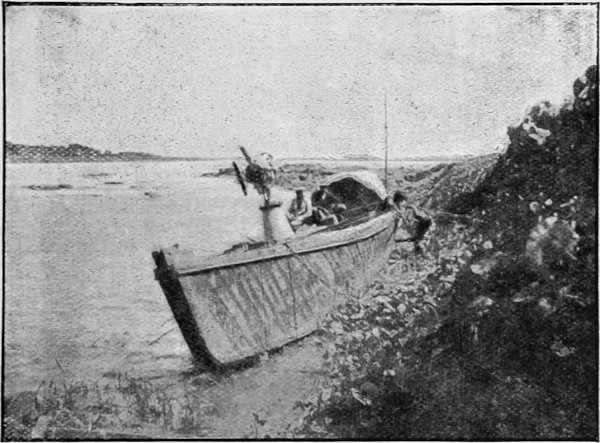

| THE ‘AUBE’ IN THE RAPIDS | 258 |

| THE ‘AUBE’ IN THE LAST LABEZENGA RAPID | 262 |

| LOOKING UP-STREAM FROM KATUGU | 263 |

| THE CHIEF OF AYURU | 264 |

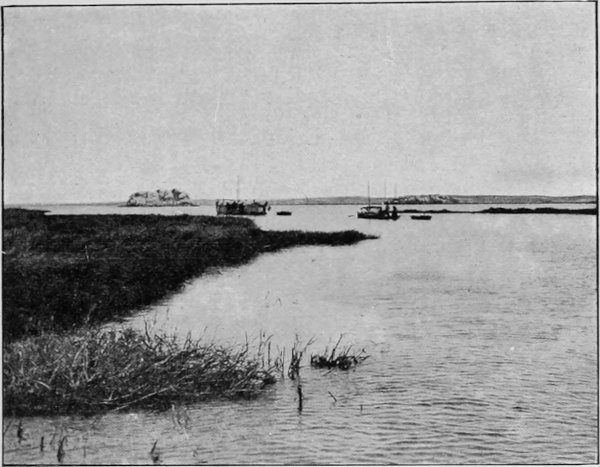

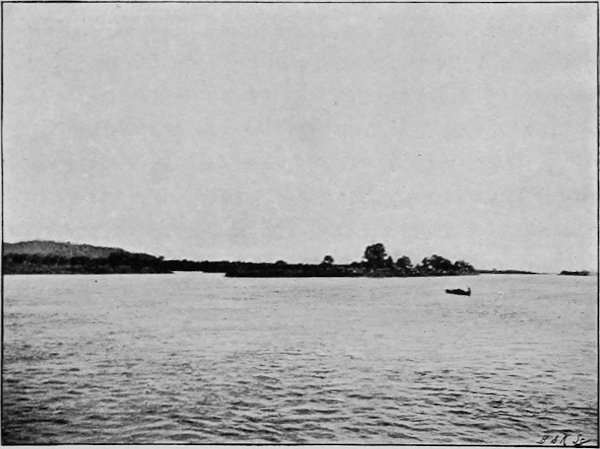

| AN ISLAND BETWEEN AYURU AND KENDADJI | 266 |

| A ROCKY HILL NEAR KENDADJI | 267 |

| FARCA | 274 |

| OUR SINDER GUIDES | 276 |

| AT SANSAN-HAUSSA | 279 |

| THE BOBO RAPIDS | 283 |

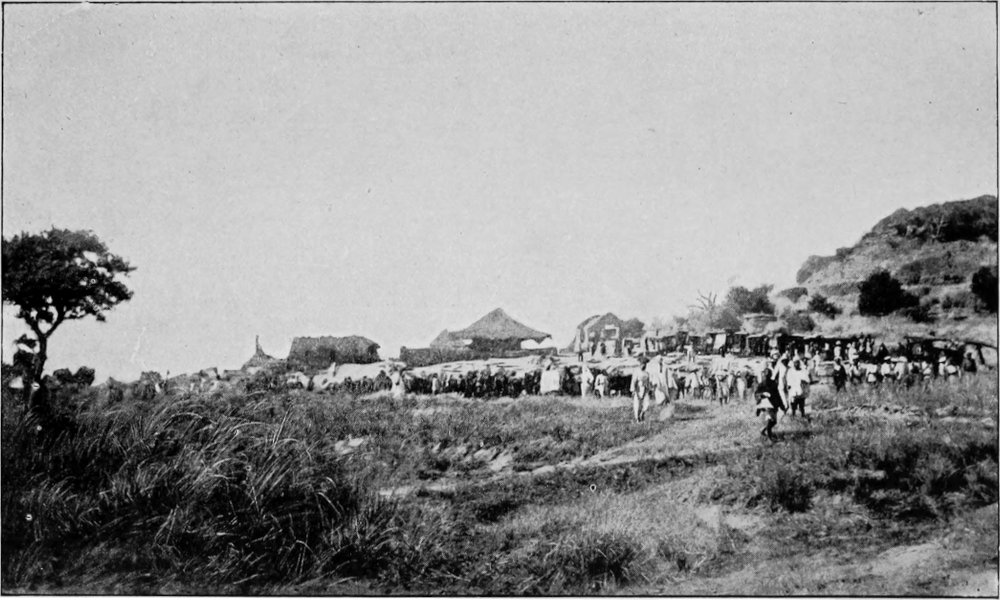

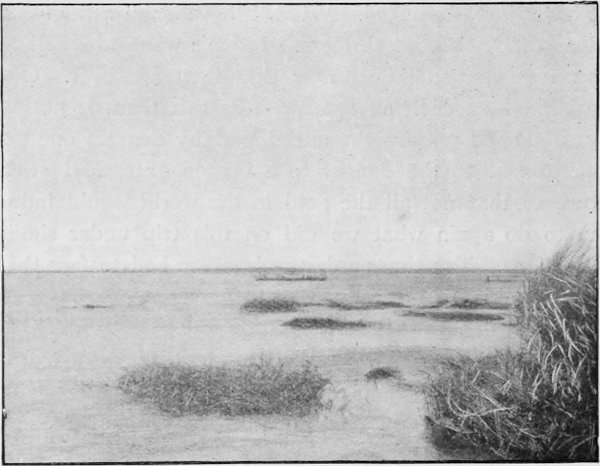

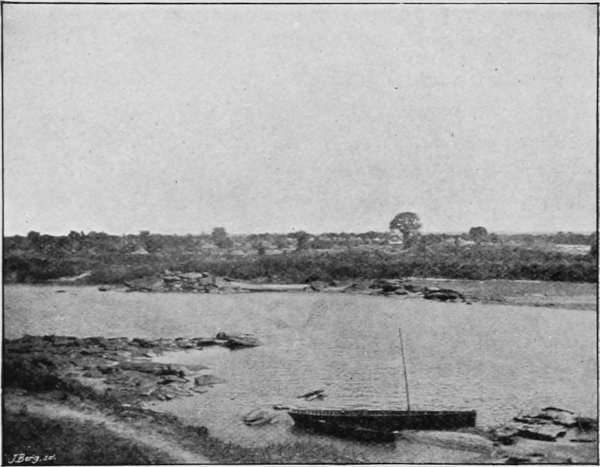

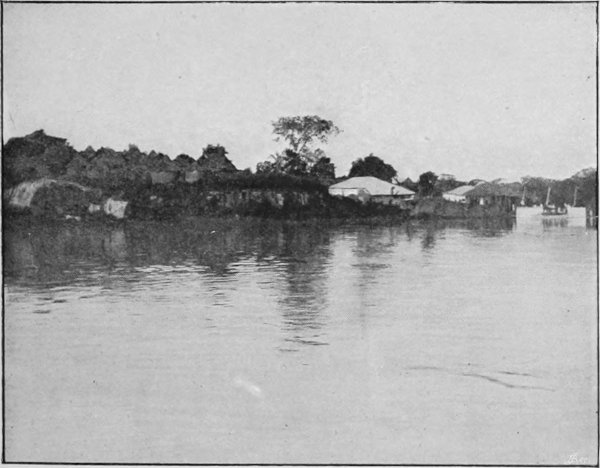

| VIEW OF SAY | 287 |

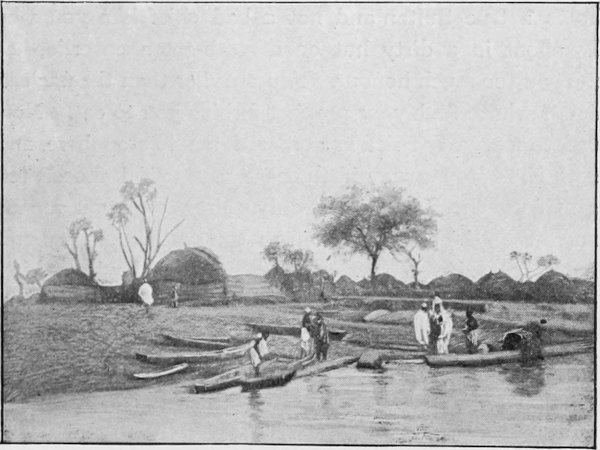

| CANOES AT SAY | 291 |

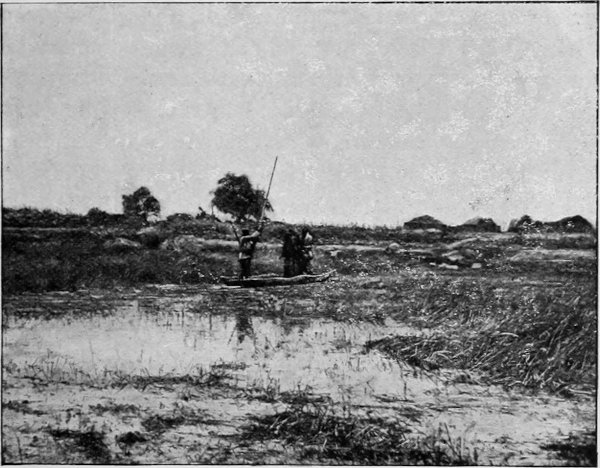

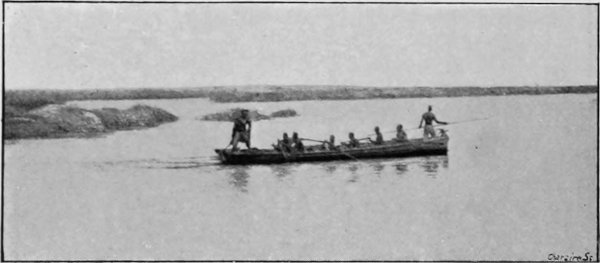

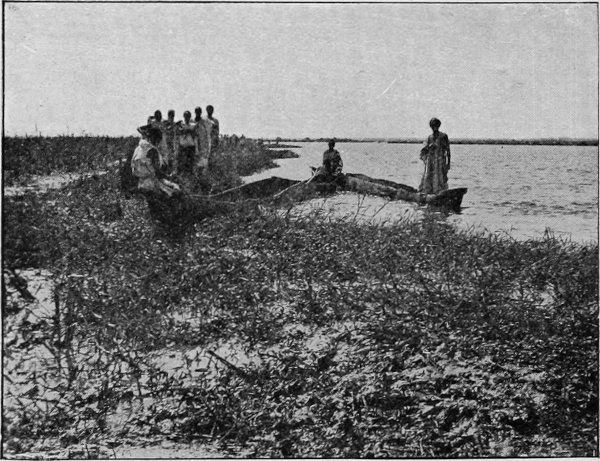

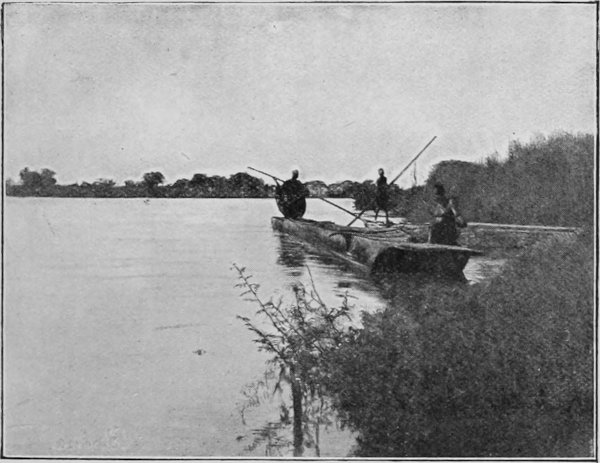

| OUR GUIDES’ CANOE | 294 |

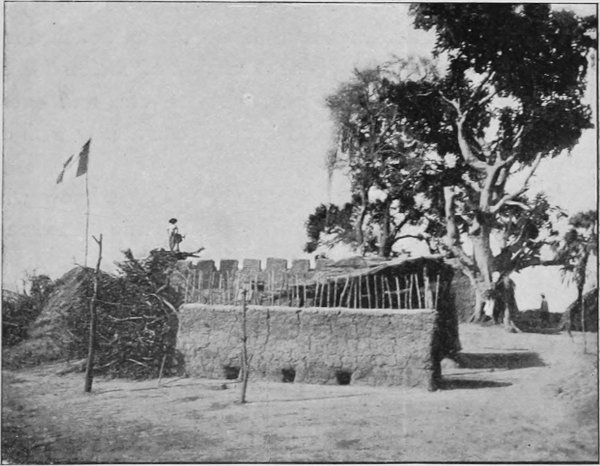

| THE ‘AUBE’ AT FORT ARCHINARD | 295 |

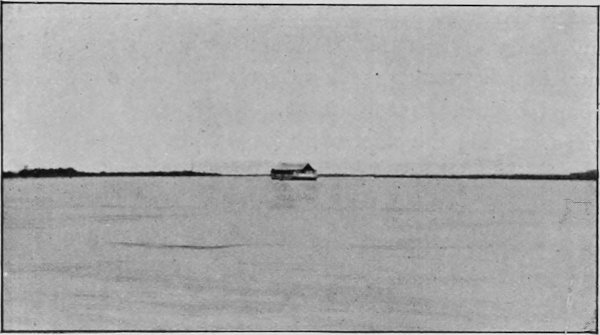

| VIEW OF OUR ISLAND AND OF THE SMALL ARM OF THE RIVER | 297 |

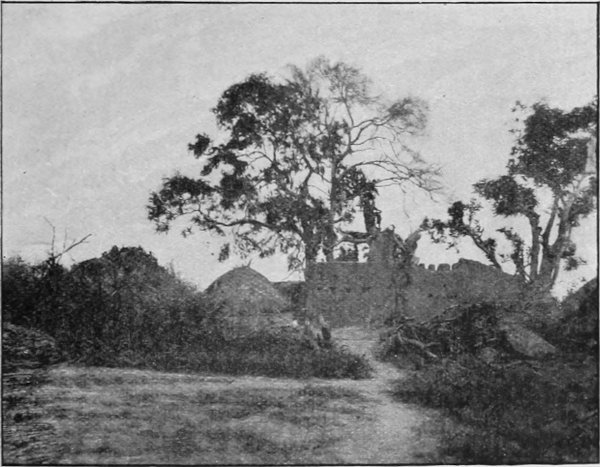

| FORT ARCHINARD | 301 |

| FORT ARCHINARD | 303 |

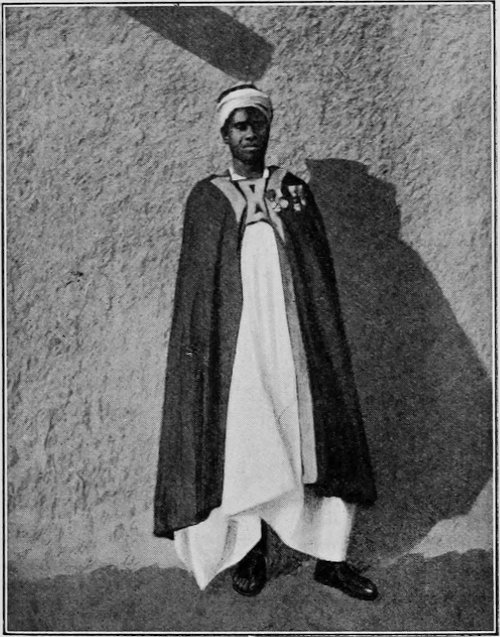

| OSMAN | 305 |

| PULLO KHALIFA | 308 |

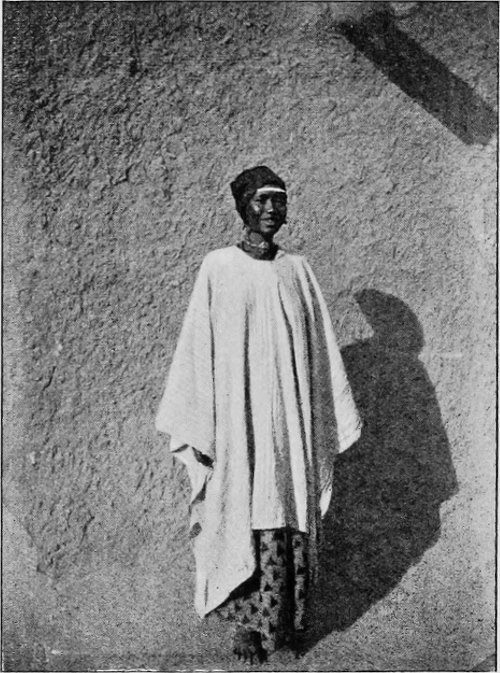

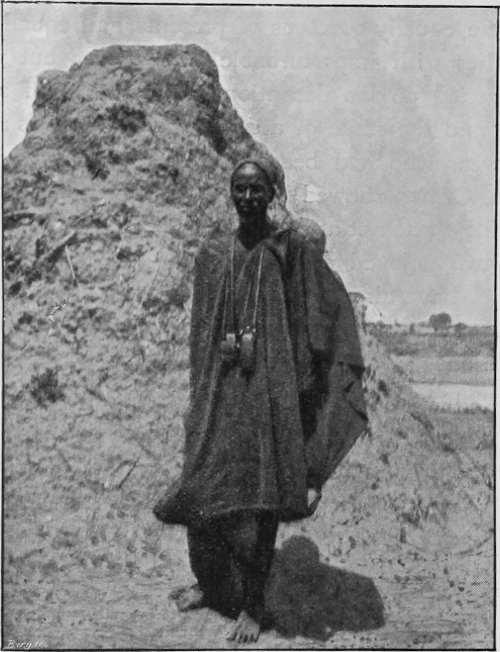

| A TYPICAL KURTEYE | 309 |

| THE ARABU | 310 |

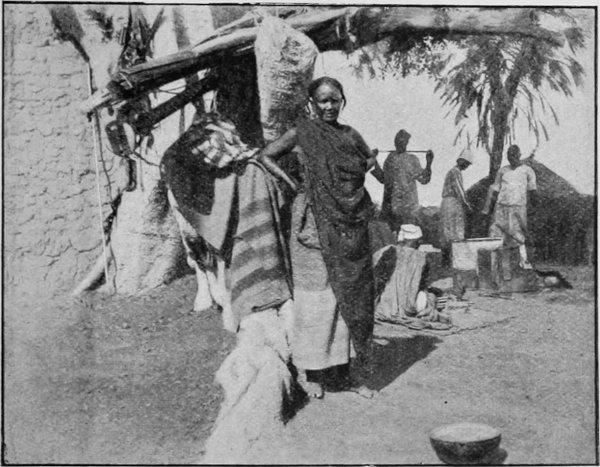

| A FEMALE TUAREG BLACKSMITH IN THE SERVICE OF IBRAHIM GALADIO | 315 |

| REPAIRING THE ‘AUBE’ | 319 |

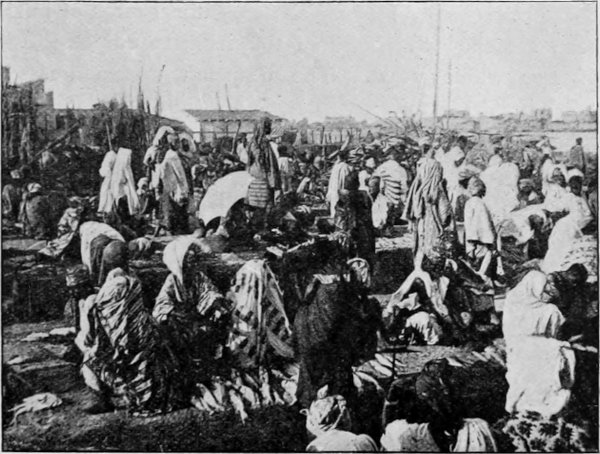

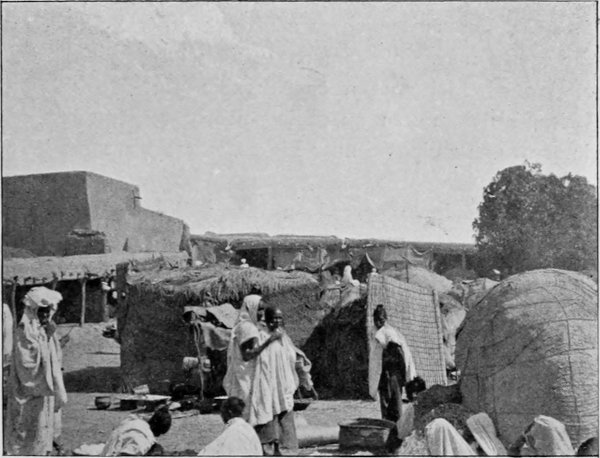

| OUR MARKET AT FORT ARCHINARD | 321 |

| MARKET AT FORT ARCHINARD | 322 |

| A YOUNG GIRL OF SAY | 324 |

| TYPICAL NATIVES AT THE FORT ARCHINARD MARKET | 326 |

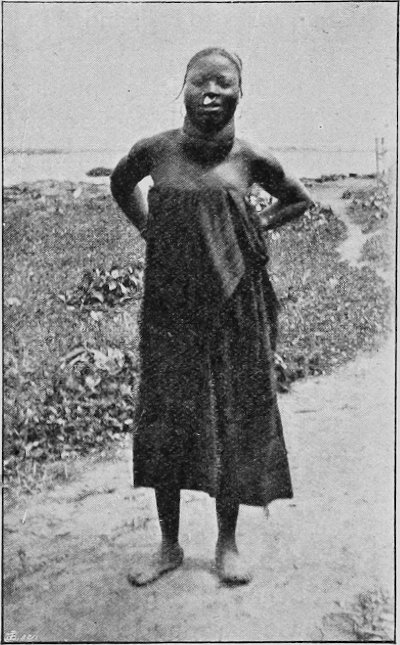

| WOMEN OF SAY | 330 |

| FORT ARCHINARD | 335 |

| OUR COOLIES AT THEIR TOILETTE | 338 |

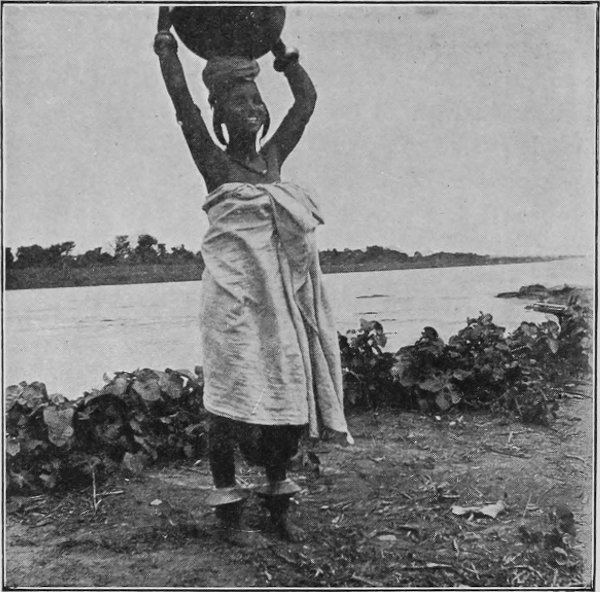

| A WOMAN OF SAY | 340 |

| A NATIVE WOMAN WITH GOITRE | 342 |

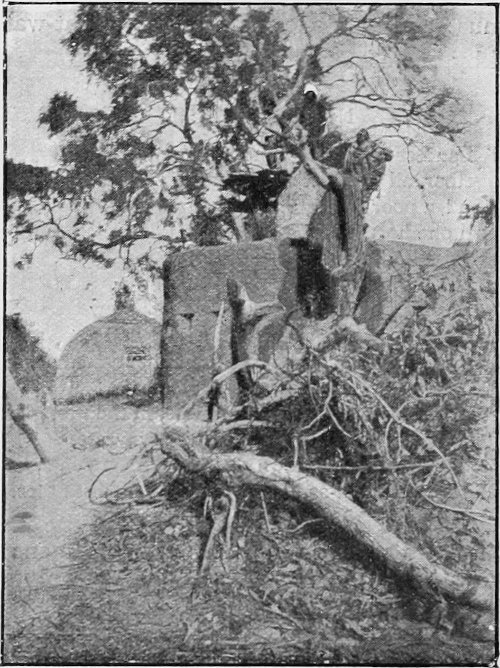

| A TOWER OF FORT ARCHINARD | 346 |

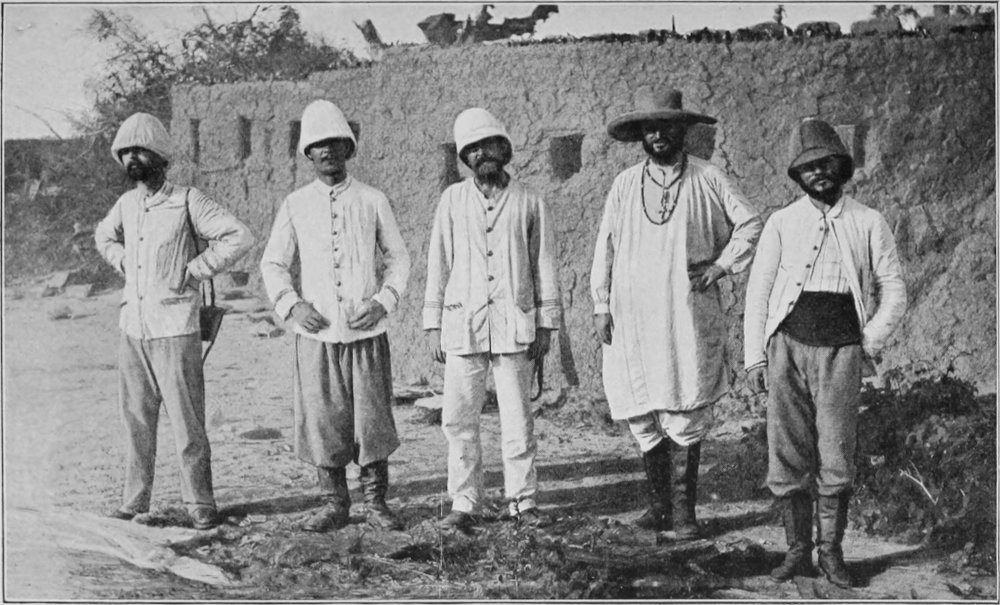

| THE MEMBERS OF THE EXPEDITION AT FORT ARCHINARD | 349 |

| OUR QUICK-FIRING GUN | 355 |

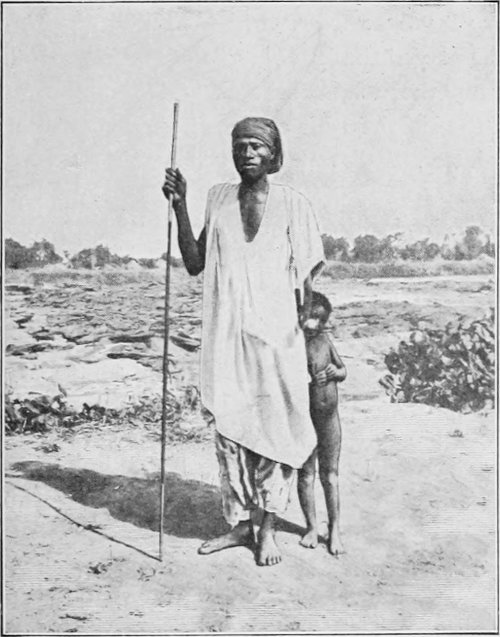

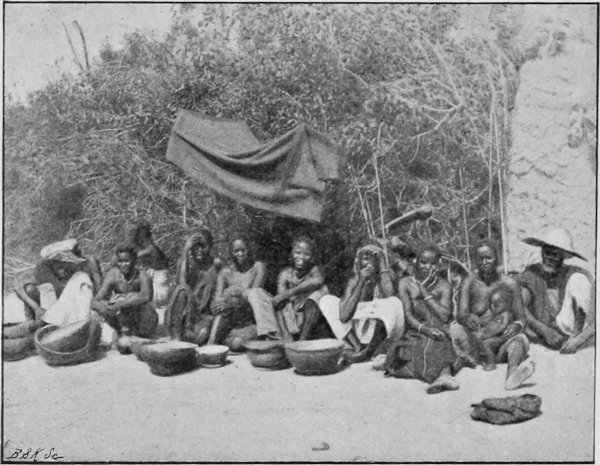

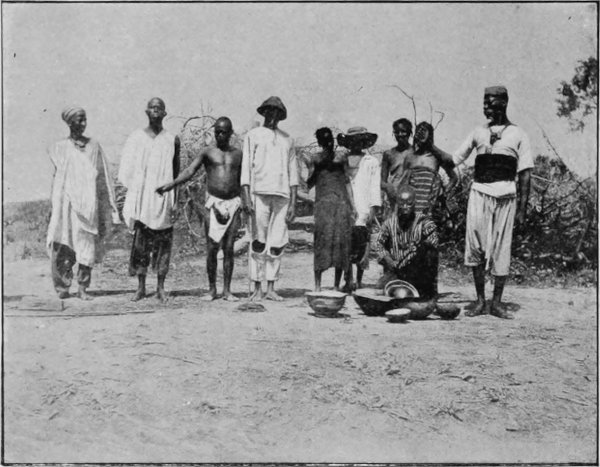

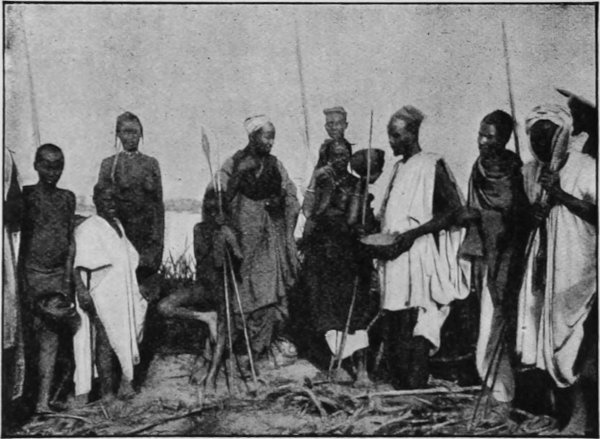

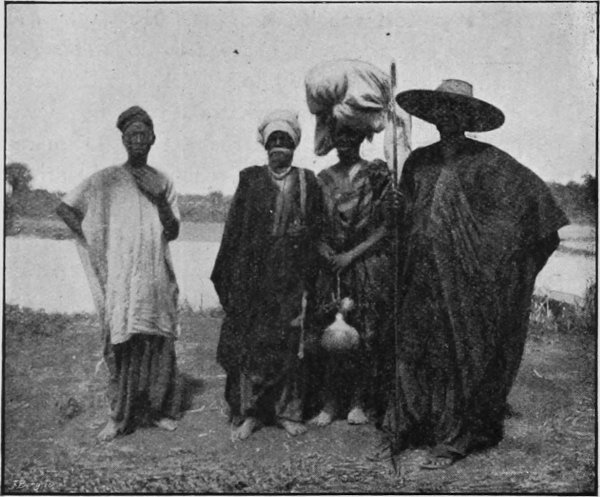

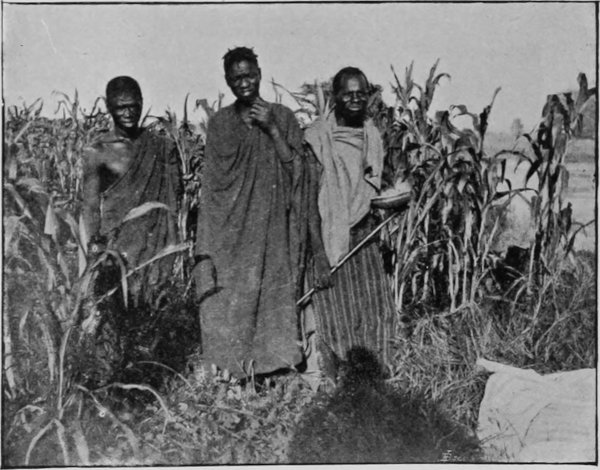

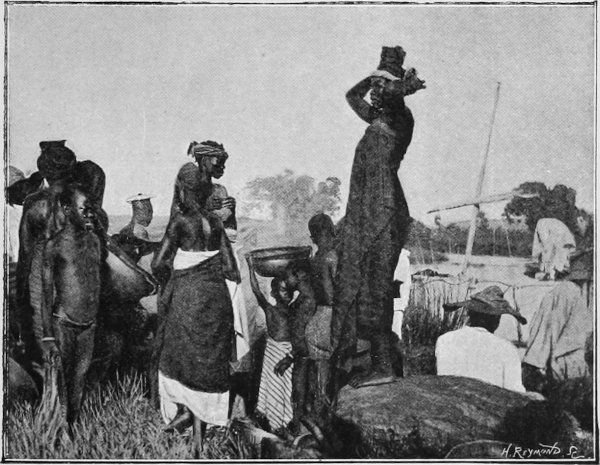

| NATIVES OF SAY | 356 |

| TALIBIA | 360 |

| TALIBIA | 362 |

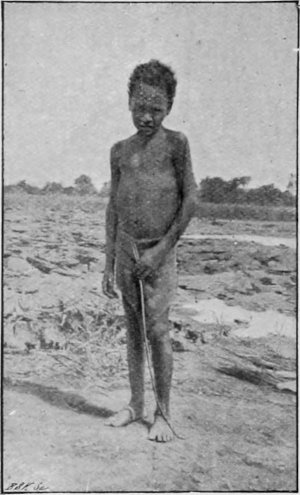

| GALADIO’S GRANDSON | 365 |

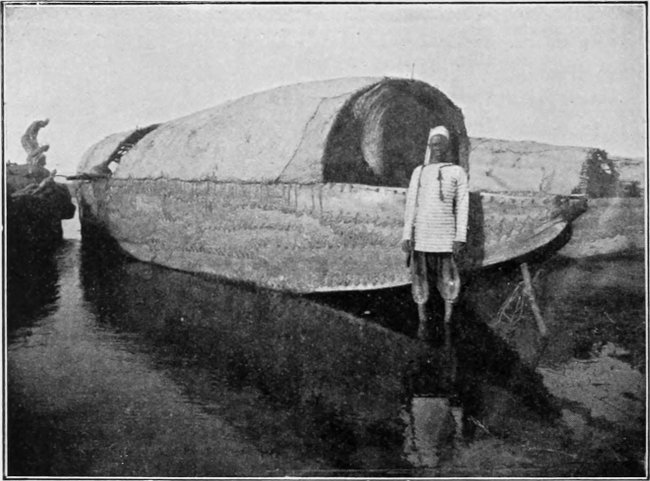

| THE ‘DAVOUST’ IN HER DRY DOCK | 370 |

| [xvi]TYPICAL MARKET WOMEN | 375 |

| THE MARKET AT FORT ARCHINARD | 376 |

| A WOMAN OF SAY | 378 |

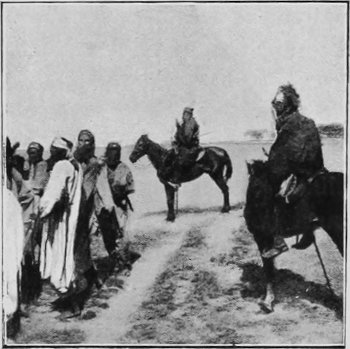

| ENVOYS FROM THE CHIEF OF KIBTACHI | 380 |

| A COBBLER OF MOSSI | 383 |

| FORT ARCHINARD | 385 |

| A MARKET WOMAN | 387 |

| A FULAH WOMAN | 389 |

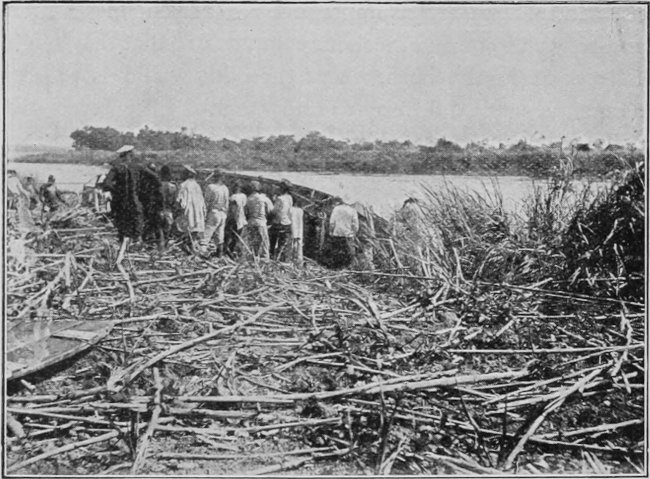

| LAUNCHING OF THE ‘AUBE’ AT SAY | 392 |

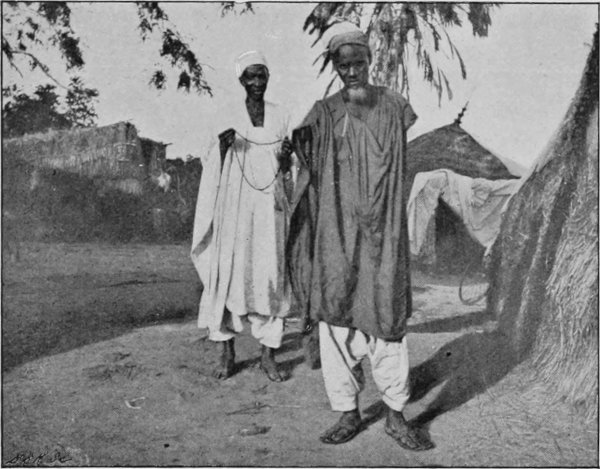

| TAYORO AND MODIBO KONNA | 394 |

| A YOUNG GIRL AT FORT ARCHINARD | 396 |

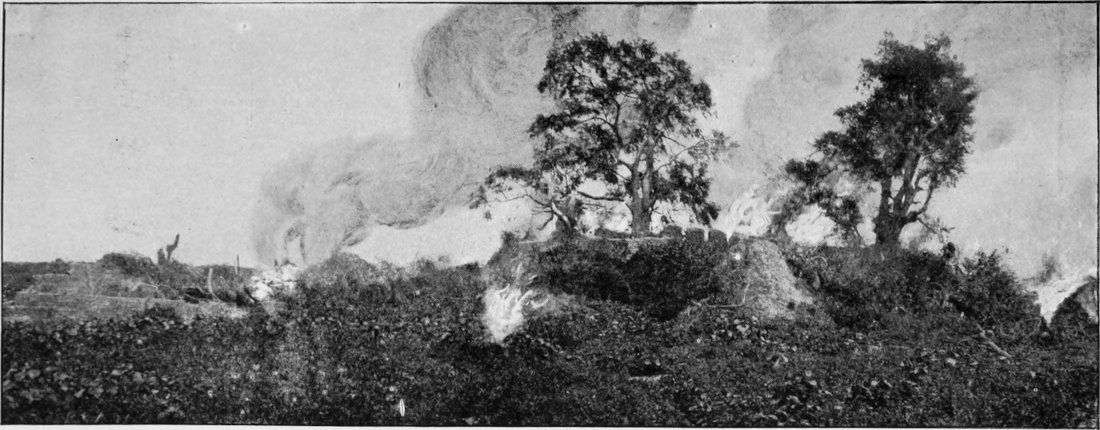

| THE BURNING OF FORT ARCHINARD | 401 |

| A YOUNG KURTEYE | 402 |

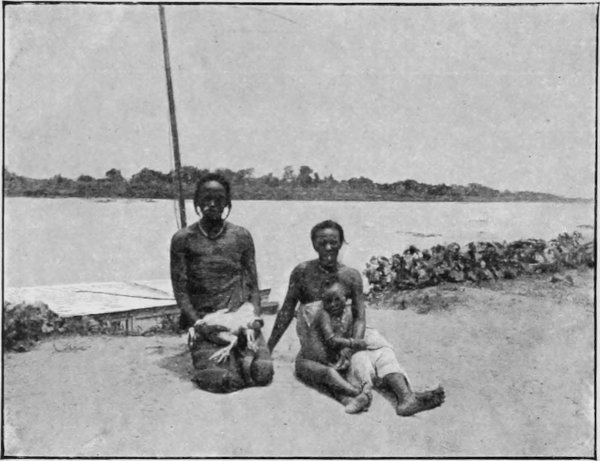

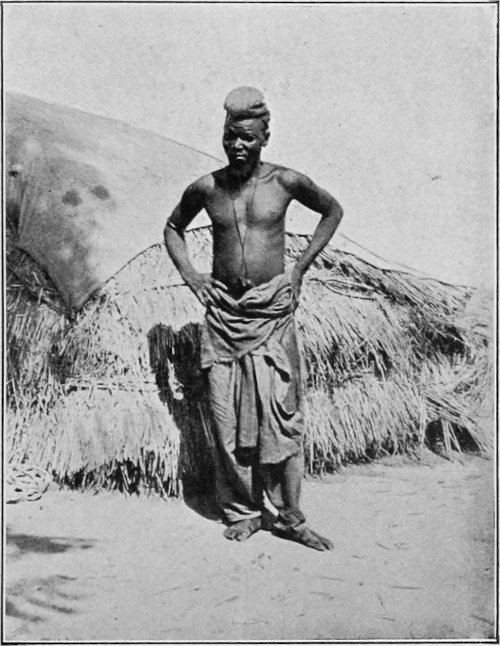

| NATIVES OF MALALI | 403 |

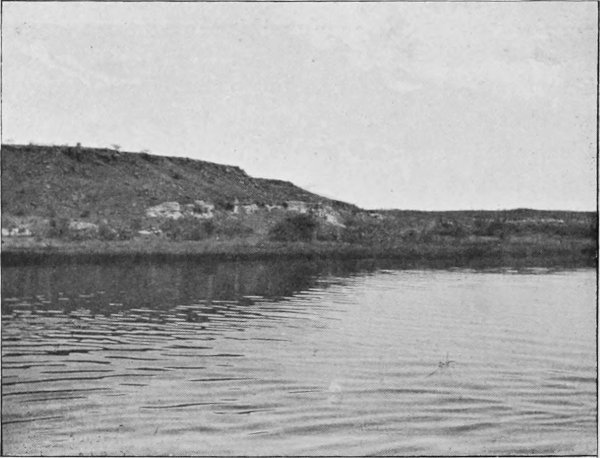

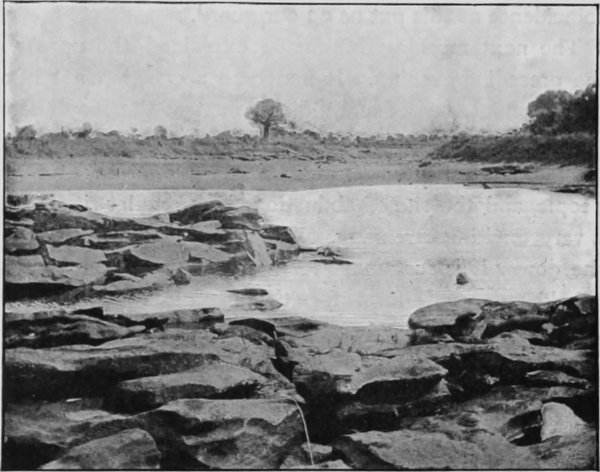

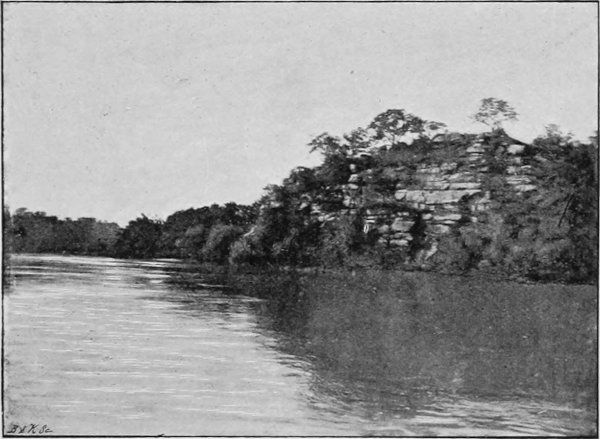

| ROCKY BANKS ABOVE KOMPA | 405 |

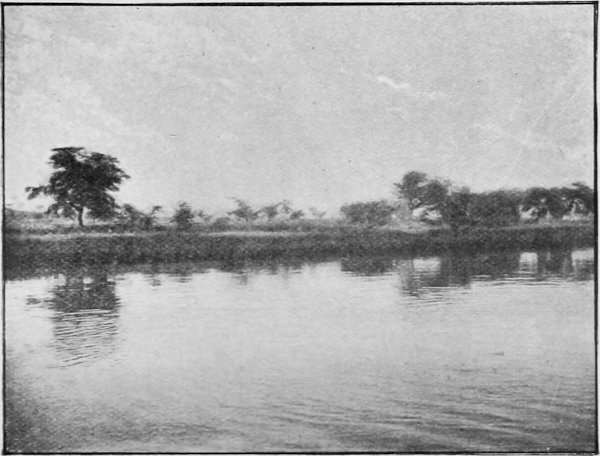

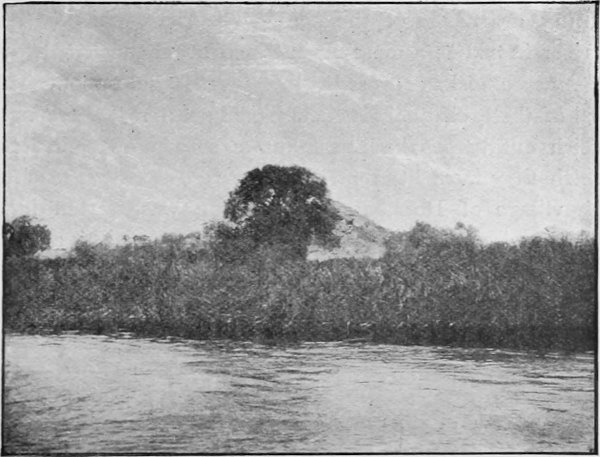

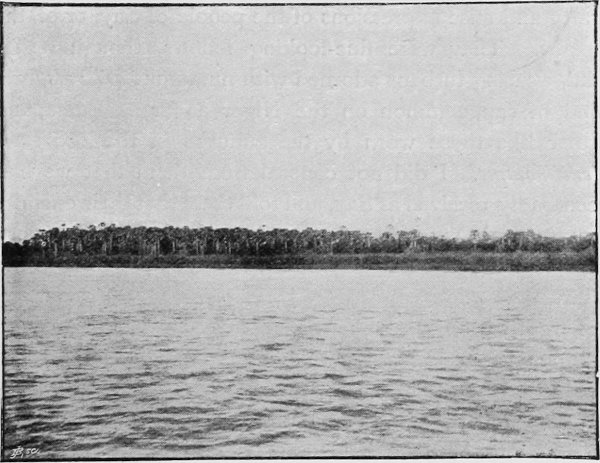

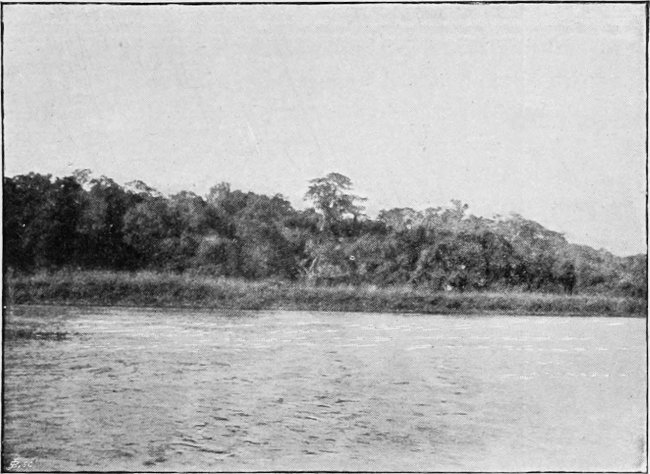

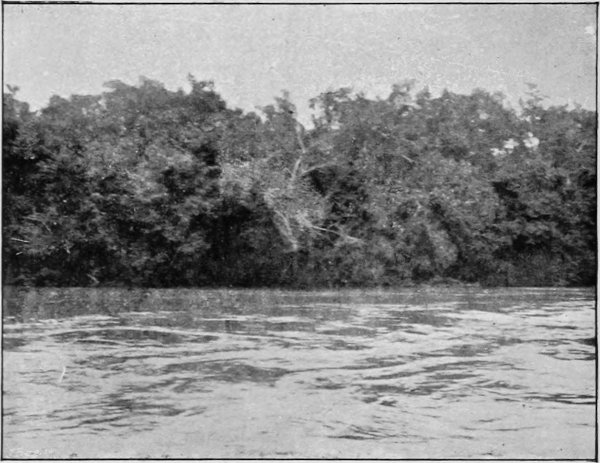

| A FOREST ON THE BANKS OF THE NIGER | 407 |

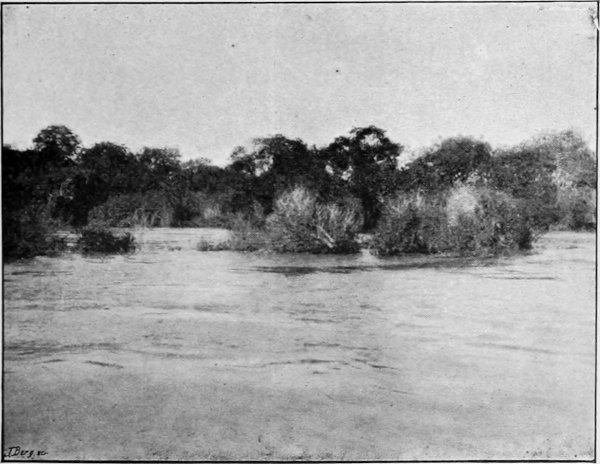

| THE BANKS OF THE NIGER NEAR KOMPA | 409 |

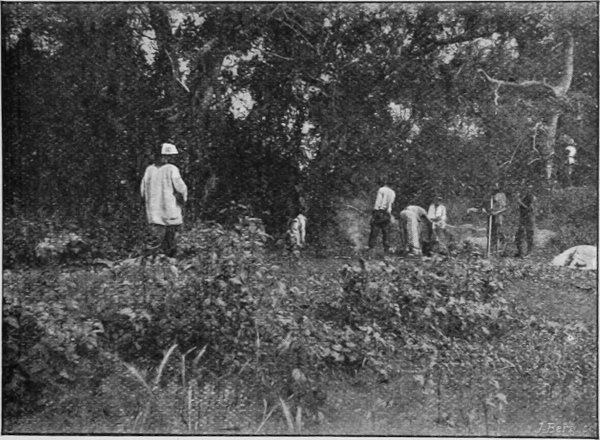

| OUR COOLIES WASHING THEIR CLOTHES | 415 |

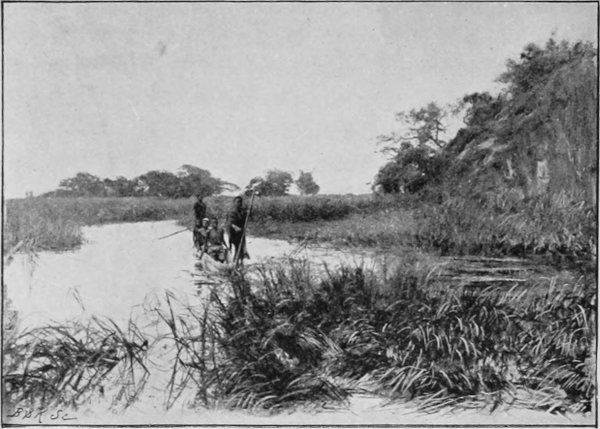

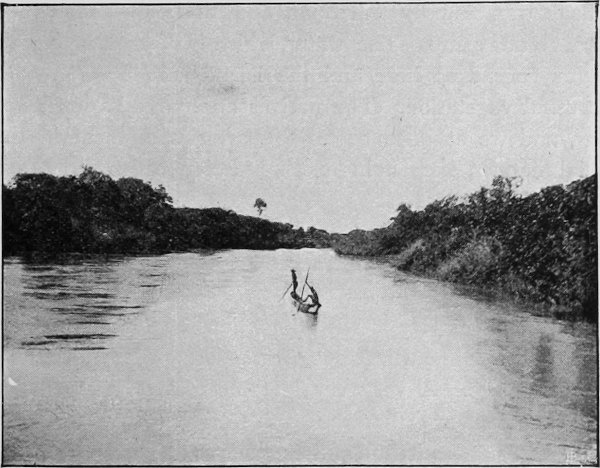

| THE MARIGOT OR CREEK OF TENDA | 418 |

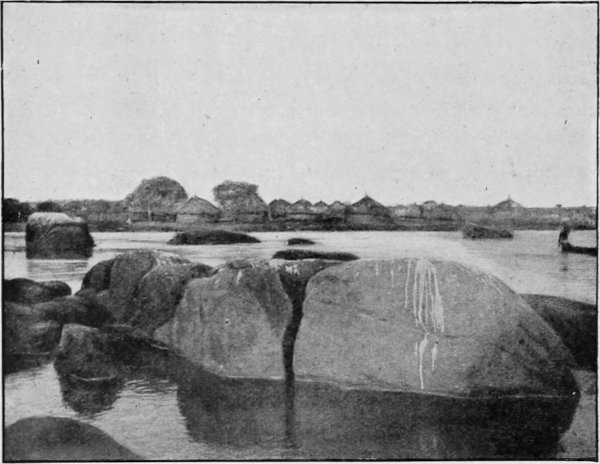

| GIRRIS | 426 |

| GIRRIS CANOES | 431 |

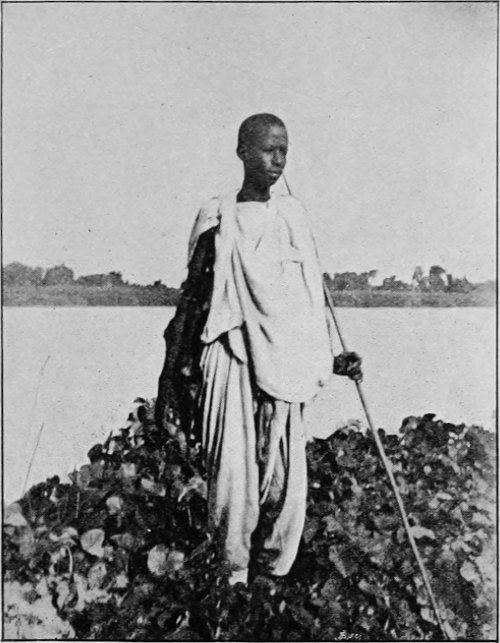

| OUR GUIDE AMADU | 437 |

| DJIDJIMA | 441 |

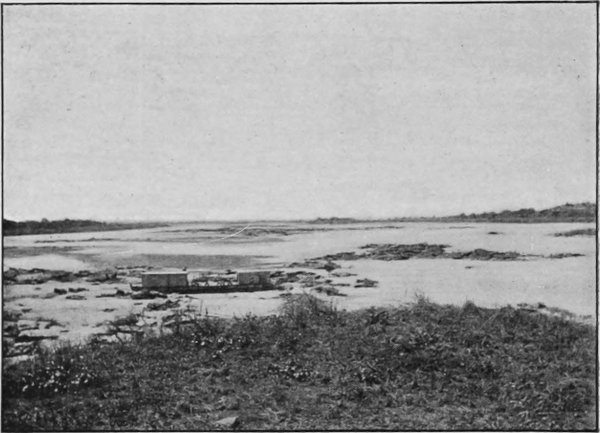

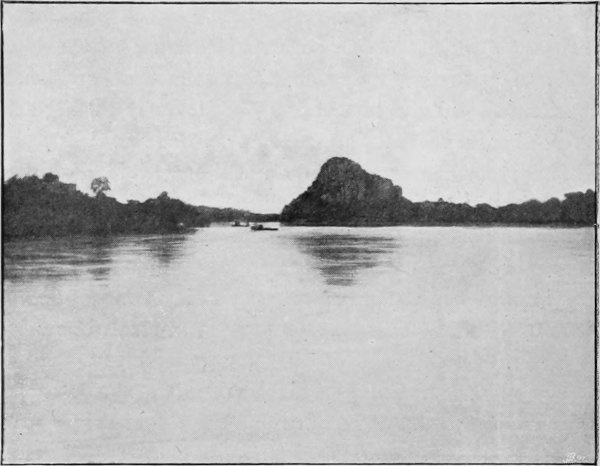

| THE NIGER BELOW RUPIA | 443 |

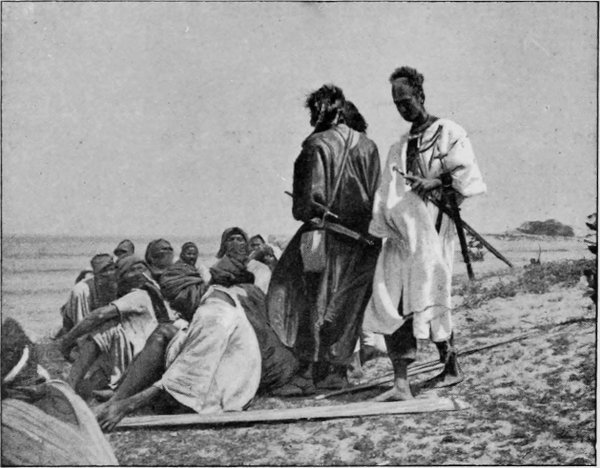

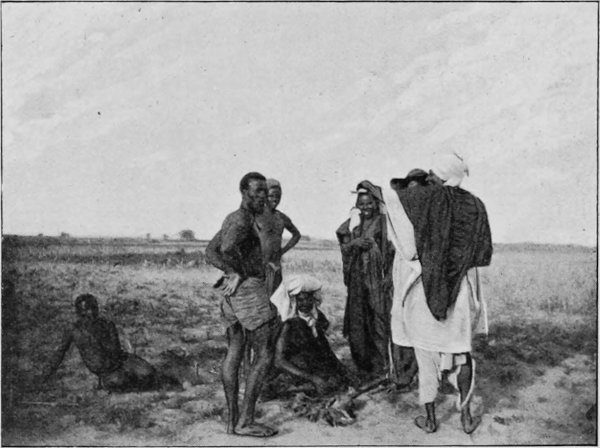

| A PALAVER | 445 |

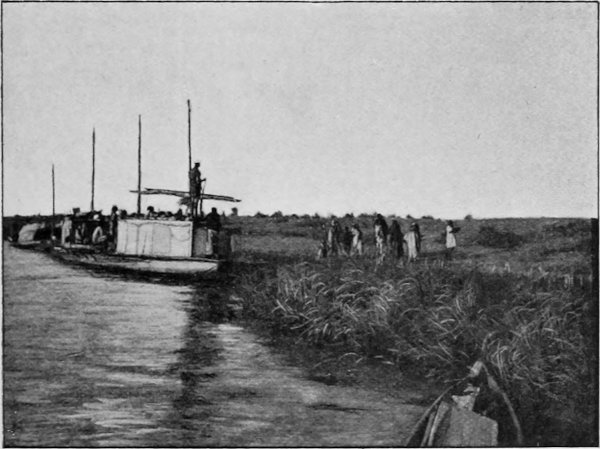

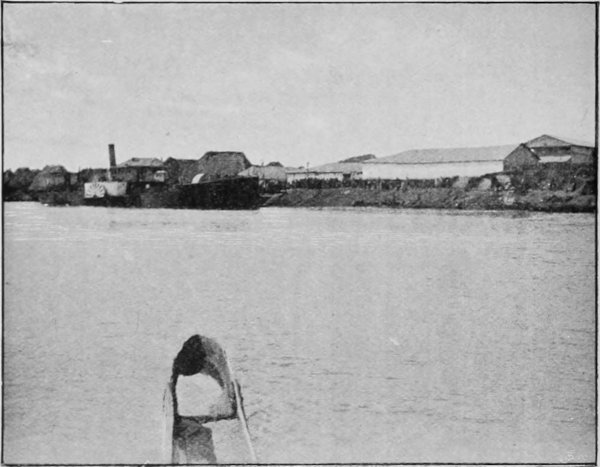

| THE SO-CALLED NIGRITIAN, THE OLD PONTOON OF YOLA | 446 |

| VIEW OF BUSSA | 447 |

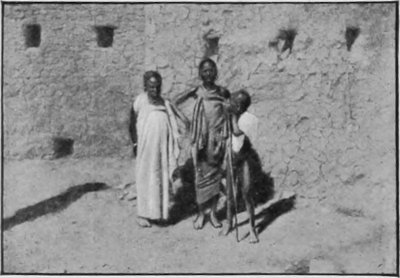

| NATIVES OF BUSSA | 448 |

| CANOES AT BUSSA | 449 |

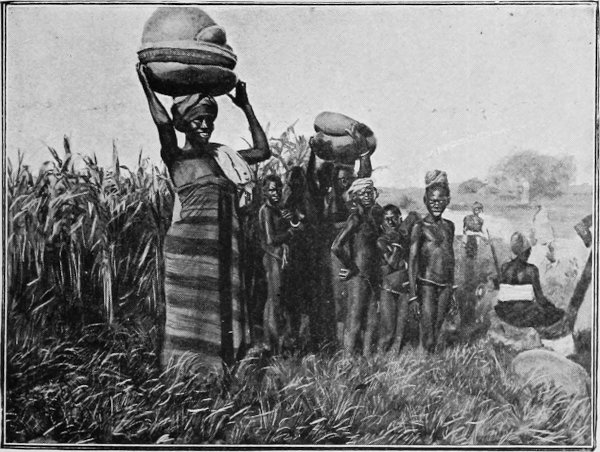

| WOMEN OF BUSSA | 450 |

| WOMEN OF BUSSA | 451 |

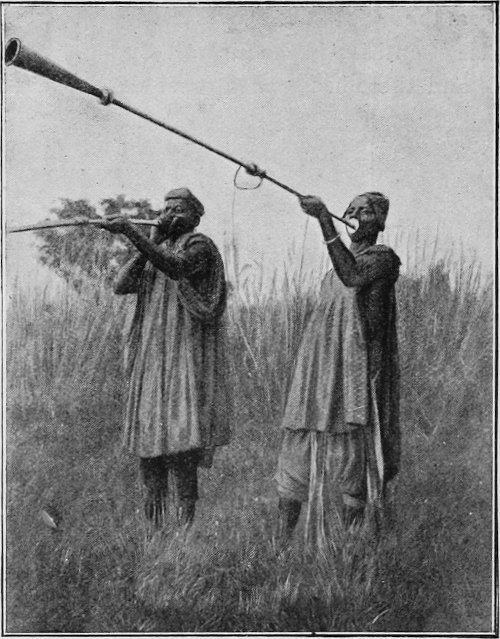

| TRUMPETERS OF BUSSA | 452 |

| WOMEN OF BUSSA | 455 |

| AMONG THE RAPIDS | 458 |

| THE RAPIDS BELOW BUSSA | 461 |

| AMONG THE RAPIDS | 463 |

| GEBA | 472 |

| RABBA | 477 |

| IGGA | 478 |

| MOUNT RENNEL ABOVE LOKODJA | 485 |

| NATIVES OF AFRICA | 497 |

| MEDAL OF THE FRENCH SOCIETY FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE | 501 |

| MEDAL OF THE ‘SOCIÉTÉ D’ALLIANCE FRANÇAISE’ | 503 |

| MEDAL OF THE LYONS GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY | 505 |

| MEDAL OF THE MARSEILLES GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY | 507 |

| MEDAL OF THE CHER GEOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY | 509 |

| NATIVES OF SANSAN HAUSSA | 510 |

| GRAND MEDAL OF THE PARIS SOCIETY OF COMMERCIAL GEOGRAPHY | 511 |

[1]

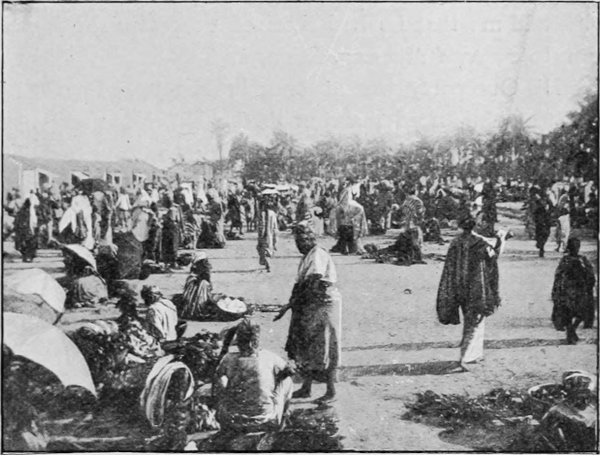

MARKET PLACE, ST. LOUIS.

THE EXPLORATION OF THE NIGER

Dr. Henry Barth, the greatest traveller of modern times, our illustrious predecessor on the Niger, was a prisoner at Massenya. Loaded with chains, and in hourly expectation of death, he was still devoted to his work, and had the superb courage to write—“The best way of winning the blacks from their barbarism is to create centres on the great rivers. The civilizing influence will then spread naturally, following the water-highways.”

In his generous dream, which might be his last, he consoled himself in thinking that soon the ideas of tolerance and progress would advance by the river-roads, by the “moving paths,” as he called them, to the very heart of[2] the dark continent. Perhaps the shedding of his blood might then further the cause of that humanity of which he was the apostle.

More than any other, perhaps, the Niger district lends itself to this idea of Dr. Barth’s. There it is, on the banks of the river, fertilized by timely inundations, that life appears to be concentrated. It is by following the streams and rivers, and crossing the lakes, that the forward march must proceed. The Niger, with its affluents and its lacustrine systems, still partially unknown, gives, even when only seen on the map, the impression of an organism complete in itself. As in the human body, the blood-vessels and the nerves carry the life and transmit the will of their owner, so does a mighty river with its infinite ramifications, seem to convey to the remote confines of a continent, commerce, civilization, and those ideas of tolerance and of progress which are the very life and soul of a country.

To utilize this gigantic artery—and this is a task which we Frenchmen have undertaken, for, at the demand of France, these countries have been characterized as under French influence—it was necessary first of all to know it.

It is to this task we have devoted ourselves, my companions and I. Providence has aided us, Providence has willed our success, in spite of difficulties of every kind. We had the great joy of returning with ranks unbroken, all safe and sound. Yet more rare, our journey did not cost a single human life, not even amongst those who were hostile to us and opposed our passage.

This I consider the greatest honour of the expedition of which I was in command.

Moreover, logic as well as humanity demanded that we should, in every case, as far as possible pursue a pacific policy.[3] What could men, whether negroes or others, think of the civilization we endeavour to introduce amongst them, if its first benefits are volleys of bullets, blood-shed—in a word, war?

The reader must not, however, misunderstand me. It has often been necessary, it will still long be necessary, even in conformity with our most honourable and elevated sentiments, to have recourse in certain cases to war, to enforce our ideas of justice. In the present state of barbarism of African races, especially where the false civilization of Islam has penetrated, the moral elevation of the lower classes is injurious to the material interests of directors, chiefs, sorcerers, or marabouts; and against them, of course, force must be used.

The motto chosen by the Royal Niger Company—was it in irony, or for the sake of rhythm?—“Pax, Jus, Ars,” is certainly most beautiful, most complete, most suitable, for a people who dream of combining venal profits with humanitarian ameliorations in their colonization of native districts. This motto cannot, however, be acted upon without some trouble and conflict. Peace? How about the successful slave raids undertaken under the cloak of religion, on which the Samorys, the Amadus, the chief of Sokoto and their bands depend for their livelihood? Justice? Suppose the races oppressed because of their very gentleness, ground down because of their productiveness, refuse to obey their conquerors, Toucouleurs, Fulahs, or whoever they may be; will the captive find himself the equal of the master? Art? the Knowledge and the Toil which should win freedom? Grant them, and what will become of the sorcerers, and the starving marabouts with their impostures and their mummeries? There have been, there inevitably will be again, prolonged and obstinate resistance. That resistance must be overcome, and the[4] struggle must cost bloodshed, but that bloodshed will increase the future harvest.

It is altogether different, however, with an exploring expedition. Its mission is not to dictate, but to persuade—not to conquer, but to reconnoitre. This, however, scarcely lessened the difficulty of our task. In a new country, ignorance alone, rather than actual ill-will founded on serious reasons, is enough to make the natives hostile. They look upon the traveller as a malevolent intruder, a sorcerer, a devil. They want to hinder his progress, to make him turn back, and when they despair of doing that they try to pillage and to destroy him.

Weapons of precision, discipline, a single blow may perhaps sometimes break through the obstacle, and the traveller will pass on. But afterwards?

Afterwards, the road will be closed before him. One tribe after another will rise, and if the explorer has any armed followers, it will be with him as it was with Stanley in his blood-stained course, the path behind him will be marked by corpses.

Afterwards, moreover, the road behind him will also be barred—closed for long years to every pacific attempt. This sort of thing means, in fact, difficulties increased, sometimes indeed rendered positively insurmountable to those who would resume or complete the task begun.

True, I cannot claim to have left behind me tribes entirely devoted to us, or districts completely won over to our ideas, to which France has but to send her traders and her directors; but I think I can say that where our passage did nothing to ameliorate the situation, it at least made it no worse; and of this I am proud.

Briefly stated, what we did on our expedition was, to ascend the Senegal, reach the Niger at its highest navigable point, and go down it to the sea.

[5]This was not a new idea. My friend Felix Dubois claims, not unjustly, that the same thing occurred to Colbert. For all that, however, scarcely a century ago no one knew the exact position either of the source or the mouth of the Niger; and those who were anxious to learn something about its geography, had only Herodotus, Ibn Batuta, and Leo Africanus to guide them.

But we must do justice to our rivals: the English were the first to attempt to realize the dream of Colbert. In 1797, the Scotchman Mungo Park reached the Upper Niger by way of Guinea. “Are there then no streams, no rivers, no anything in your country,” a chief of Kasso said to him, “that you come at the peril of your life to see the Joliba?” (the Upper Niger). Park stopped at Silla, near our present settlement at Sansanding, and renewing his attempt a few years later, he met his death—how, no one knows exactly, somewhere near Bussa.

NATIVES OF THE BANKS OF THE SENEGAL.

[6]Although very celebrated in England, Mungo Park was quite unknown to the French, even in their colonies. I give the following well-known anecdote from memory. “In 1890 a highly educated person said to M. X———, a French colonial officer of high rank, ‘There is a future before the Niger districts. See what Mungo Park says about them;’ and he followed this up with a lot of quotations from Park’s book. ‘Oh, that is all very interesting,’ said the other; ‘if Mungo Park is in Paris, you had better take him to the Minister.’ Then when the death of Park in 1805 was explained, M. X——— cried, thinking he had found an unanswerable argument, ‘I bet your Park died of fever!’”

Perhaps after all he confused him with the Parc Monceau, the healthiness of which had lately been called in question.

Our journey was accomplished just one century after Mungo Park’s first attempt. We started from about the same point, too, as did the great Scotch traveller, only from the Senegal instead of the Gambia, but our attempt was crowned by success.

Of course, it will be said, that we had fewer unknown districts to go through. Since 1805, Europeans have conquered half the continent of Africa. We stepped from a French colony into an English Protectorate. Moreover, earlier travellers than ourselves explored certain sections of our route, whilst Park had everywhere to work his way through virgin territory.

Perhaps, however, all these supposed advantages in our favour really only added to our difficulties.

Happening to find myself in Paris in October 1893, on the eve of my return to my Staff duties in the French Sudan, I one day met Colonel Monteil. “Go,” he said to me, “and find Monsieur Delcassé” (then Under Secretary of State for the Colonies), “he has something to say to you.”[7] The next day I presented myself at the Pavillon de Flore. “You are leaving for the Sudan,” said Monsieur Delcassé; “what are you going to do there?” “It is not quite decided yet,” I replied. “I heard some talk of a hydrographic exploration of the courses of the Bafing and the Bakhoy” (two streams which meet at Bafulabé, to form the Senegal). “You no doubt know more about it than I do.” “Well!” he replied, “I would rather you went down the Niger, in accordance with the project Monteil spoke to me about, and which you, it seems, submitted to my predecessor.”

“I should prefer it too,” I said; “it is just what I have been asking for for the last five years.”

“Well, then, that is settled; send me a report and an estimate of expenses.”

Thus in two minutes the exploration of the Niger was decided upon.

It is, in fact, true (see Report of December 1888) that I suggested such an expedition five years ago; but it is really ten years since a similar plan was proposed by another, and that other my venerated chief, my friend, and my master in all things connected with the Sudan, Naval Lieutenant Davoust. He died in harness.

After the occupation of Bamaku, Naval Ensign Froger, a man of immense energy, endurance, and indomitable perseverance, whose name comes in whenever there is any talk of French work in the Sudan, took a French gunboat, piece by piece, to the Niger. God only knows at what cost. There he put her together, launched her, and since 1884 she has remained on the river. This gunboat, baptized the Niger, was commanded, on the retirement of Froger, by Davoust, who in accepting the appointment, hoped to take his vessel up to Timbuktu. As a logical consequence, of course, he asked permission to go down to the opening of[8] the navigable portion of the great river, or, if it were possible, to the sea itself, but the authorization was refused. He was stopped at Nuhu in Massina. Weakened by dysentery and fever, he was compelled, greatly against his will, to return to France, without having even reached Timbuktu.

That honour was reserved for his successor, Caron, who, with Sub-Lieutenant Lefort and Dr. Jouenne, reached Koriomé, the port of the mysterious town; but the intrigues of the Toucouleurs and the merchants of the north made the Tuaregs hostile. He was unable to enter the ancient capital of the Sahara, but he brought back with him a magnificent map on the scale of ¹⁄₅₀₀₀₀ of the course of the river, such as had, perhaps, never before been made of any river of Africa. It proved beyond a doubt, that from Kulikoro to Timbuktu, that is to say, for a length of about 500 miles, the Niger is perfectly navigable, free from obstacles, everywhere accessible to small craft, and nearly always to steamers and barges of considerable draught.

Davoust returned to the charge in 1888, when he did me the honour of taking me as his second in command, and it was decided that we should go down the river, until the absolutely insuperable obstacles in our path barred our progress.

Alas! it was decreed that Davoust should never realize success.

What happened? Just as we were going to start came an order that we were to do nothing. We wintered at Manambugu, a terribly unhealthy spot, and there, with infinite trouble, we constructed a few wretched huts of straw and loam, to protect ourselves and our goods. Under such conditions, death soon wrought havoc in our ranks. We white men numbered eighteen when we started; less than a year later we were but five. The rest we had[9] buried along our path as we returned, or in our little cemetery at Manambugu.

Poor Davoust reached Kita but to die. The order forbidding us to start had been his death-blow. Until then he had, however, kept up only by force of his intense determination. It was but his hope of success which sustained him; he existed only for the sake of his great scheme. “Merely having failed to descend the Niger,” he exclaimed to me one day, “made Mungo Park famous, but we, we shall succeed.”

He could not bear to see all his long-cherished plans upset for no real reason, on the very eve of realization. It was too severe a blow for the little strength which remained to him. He nevertheless continued to help me in fitting out the Mage, a gunboat like the Niger, which we had brought from France; he even made some trial trips; but in the month of December he set off for home, to try and regain his strength in his native land, and buoyed up with the hope of being able to win over our colonial authorities to his views.

He never reached France; he rests at Kita. When we thought all was lost, and our mission hopelessly compromised, we gathered round his tomb. Perhaps it was our doing so which brought us good fortune at last.

How many, aye, some even greater men than he, have fallen thus! Alas! it has been with the dead bodies of our countrymen that the soil of the French Sudan, which we hope will some day yield so rich a harvest, has been fertilized! Dare we add, that those who went there in the hope of winning gold braid and crosses, got “crosses” indeed, but they consisted only of two bits of wood clumsily nailed together by some comrade, and set up in the corner of a field of millet, beneath the shade of some baobab tree; poor ephemeral crosses, soon eaten up by white ants,[10] incapable even of preserving the memory of the brave fellows buried beneath them.

But we must not bemoan too much the fate of these noble dead. We must honour them and follow their example.

Well then, Davoust being dead, without having accomplished his task, I vowed that a boat bearing his name should descend the river. This promise I made in 1888, but it was not until 1896 that I was able to redeem it. Now I have fulfilled my vow.

There is no doubt that it would have made all the difference in the political results of my mission, if it could have been undertaken eight or ten years earlier. For instance, in the negotiations which took place in 1890, and were so inauspicious for our influence on the Lower Niger, our plenipotentiaries would have been able to assert, that the rapids at Burrum existed only in the imagination of Sir Edward Malet, a fact not without its importance.

But we will not trouble ourselves with what the expedition ought to have done—we will merely record what it did do.

My project, adopted by M. Delcassé, was that of Davoust, slightly modified. Instead of employing gunboats drawing about three feet of water, I found it best to employ barges of very slight draught worked with oars. An attentive study of Dr. Barth’s narrative reveals how very great were the difficulties of navigation, at least on those parts of the river he himself explored; for it must be remembered that he never spoke by hearsay. Of course a boat drawing a foot or so only of water would easily pass over rapids, where such vessels as the Mage and the Niger must inevitably come to grief.

Moreover, a steam-boat needs fuel, and that fuel would have to be wood. Then we must go and cut that wood, which would give the natives opportunities for hostility.[11] Moreover, the machinery might get out of order. Of course, rowing is slower than steaming, but it is much safer. Then, too, we had the current in our favour; we had but to let ourselves go and we should certainly arrive at some goal, if not at a good port. The stream would carry our barges down, with us on or under them, as Spartan mothers would have said.

Besides, there was something graceful about this mode of progression. To row down the Niger at the end of the nineteenth century, was not only amusing, but there was really something audacious about it, when it might have been done so differently, and, after all, I was right; for never could gunboats have passed where my plucky little boat, the Davoust, made her way.

This resolution come to, the next thing was to build the boat which was to be the inseparable companion of our journey. “As you make your bed you must lie upon it,” I thought, and I gave my whole mind to the matter.

She must be strong but light, and easily taken to pieces; she must not exceed the minimum space needed to hold us all; she must be capable of carrying eight to ten tons, and she must not be difficult to steer.

During the year 1893, it happened that great progress had been made in the working of aluminium, and Monteil had actually ventured to employ that metal in the construction of a little boat intended for use on the Ubangi. It seemed, however, rather hazardous to follow his example, for, after all, what could be done with aluminium had not been actually put to the test, and our very lives depended almost entirely on the durability of our boat. Still, I had to take into account the fact that the craft would sometimes have to be carried overland, and then the lightness of the metal would be immensely in its favour.

In a word, I decided for aluminium. Truth to tell,[12] however, I confess I am not very proud of the decision I came to. The material was not hard enough; it was easily bent; it staved in at the slightest shock, and I often wished I had decided on a steel boat. At the same time, it should be admitted that its chief quality—that of lightness—was never really put to the test; for throughout the journey we never once had to take our craft to pieces, for the purpose of carrying it in sections, over otherwise insurmountable obstacles. As she was launched at Kolikoro, so she arrived at Wari. This was perhaps as well; for I really do not know whether the bolts once taken out of their strained sockets would ever have fitted properly again. To sum up, however, the Davoust, an aluminium boat, reached the mouth of the Niger, which was really all that was expected of her.

Now let me introduce my Davoust properly. She is not exactly a handsome craft. She looks more like a wooden shoe or a case of soap than anything; that is to say, the stern is square, whilst the bow runs up into a point. This pointed bow, I must remark en passant, will be very useful for jumping on shore from without wetting our feet.

She is about 98 feet long by 7½ feet wide, and only draws about a foot and a quarter of water, which does not prevent her from carrying nine tons. Two water-tight partitions divide her into three compartments, the central one of which forms the hold, where are stowed all our valuables, food, ammunition, and bales of goods. The hold is covered in with steel plates, which serve as a deck, and at the same time greatly add to the general strength of the craft.

The other two compartments, covered in by thin planking, serve as cabins. The planks, as will be readily understood, are but little protection against the heat of the sun and in storms; but, of course, it was impossible for me to add needlessly to the weight of the boat, merely for the sake of comfort. In the centre is placed a machine gun. In the[13] fore part of the steel deck will sit the oarsmen, or, to be strictly nautical, the rowers.

Three sails, two triangular and one square, will help us along when the wind is favourable. True, this rig-out of sails on a vessel the size of ours is not exactly what is generally seen in the Navy, but what does that matter in the wilds of Africa, with no companions and no engineers to make fun of my innovation? How well it will sound, too, will it not, when we reach their territories if the English telegraph to Europe, “A French three-master has descended the Niger from Timbuktu!”

All this finally settled, the next thing to do was to divide the boat into sections. The problem was, how to manage to do this so that these sections could be carried on the heads of our porters, no one of them weighing more than from about 55 to 66 lbs. This is really all we can expect of a black porter who was not brought up in the ship-building trade.

To begin with, I divide my boat longitudinally from bow to stern into two equal sections, which are afterwards sub-divided. These two sections are to be bolted on to a sheet of steel which will serve as a keel. The joints are of leather. The heaviest piece, that is to say, the stern, weighs some 81 lbs., but two porters can carry it together.

This flat-bottomed craft of ours will be steered by means of a long rudder, the wheel of which is placed at the threshold of my cabin, so that I shall have it close at hand. On my cabin roof is the steering compass, and the tent to protect us in the day, which tent is made of brown and red striped cloth with a scalloped edge. We fancy ourselves on the beach of Normandy when we are in it. The roof of my cabin will serve me as a table on which to work at my hydrographical observations.

The Davoust was just big enough to hold us all. She[14] could be handled easily enough; she contained only what was absolutely indispensable, and all I asked of her was that she should carry us safely to our goal.

It would not do for me to embark alone to descend the Niger. The next thing was, therefore, to choose my crew. Of all the lucky chances which marked the course of our trip, and contributed to its success, there was one for which I ought to have been more grateful to Providence than I was, and that was, that He gave me just the companions who went with me.

All who know from experience what the sun of Africa is, who are aware of the combined effects of illness and privations, such as the want of sufficient nourishment, of perpetual danger, of never-ceasing responsibility, who have themselves suffered from working with uncongenial companions, whose worst faults come out under the stress of suffering and fatigue, who know what the unsociability of the tropics often is, will realize the force of what I have said.

We started five companions, we returned five friends: that is the most astonishing part of what we did!

First of those who joined me, who shared all my hardships as well as my success, was Naval Ensign, now Lieutenant Baudry.

One of those who had laboured in the vineyard from the first, M. Baudry had begged me to take him with me, should the chance ever occur, long before my expedition was decided on. He happened to be in Paris at the time, for, like myself, he was about to start for the Sudan on Staff duty. He too had been bitten by the Colonial tarantula, causing a serious illness, only to be cured by an actual journey to the colonies. A few minutes after the decision of the Under Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs the matter was settled: he was to go with me.

[15]

NAVAL ENSIGN BAUDRY,

Second in command of the Hourst Expedition.

[17]He has been my comrade in happy and in dreary hours. Together we suffered from the events which kept us imprisoned, so to speak, in the French Sudan for nearly two years before we could really make a start. He adopted my ideas, he made them his own, and set to work immediately to carry them into action. It is but just that I should speak of him first of all in these terms of praise, for always and everywhere I was secure of his help and co-operation.

We made up the rest of our party at St. Louis, for Baudry and I were at first the only two white men in the expedition. We had to choose eight Senegal coolies, one of whom was a non-commissioned officer lent to us by the naval authorities. I knew that I should be able to engage any number of brave and sturdy fellows, faithful to the death down there, and so it proved.

The grave question of the choice of a native interpreter still remained to be solved. I had my man in my mind, but I did not know whether I could secure him. I lost no time in asking the authorities at Senegal to place Mandao Osmane at my disposal.

I had known and learnt to value Mandao on the Niger flotilla; he and his family had already rendered more devoted services to France than I could count. Well-read, intelligent, very brave, very refined, and very proud, Mandao was the type of an educated negro. He would have been a valuable assistant and a trusted friend to us. I knew that it was his great ambition to be decorated like his father, who had been one of General Faidherbe’s most valued auxiliaries. He was to die on the field of honour, killed during the Monteil expedition.

If some inquirer asks you, “What is the first thing to do to prepare for an exploring expedition to Central Africa?” answer without hesitation, “Buy some of the things which are being sold off in Paris.” And this is why. The usual[18] currency on the Niger is the little cowry found on the coast of Mozambique. Five thousand represent about the value of a franc. As will at once be realized, this means a very great weight to lug about, as heavy, in fact, as the Spartan coinage, and besides, it is not known everywhere even in Nigritia. In many villages everything is sold by barter. “How much for that sheep?” you ask, and the answer is “Ten cubits” (about six yards) “of white stuff, or fifty gilt beads, so many looking-glasses, so many sheets of paper, or so many bars of salt,” according to what the seller wants most.

One must provide oneself with the sort of things required.

Besides all this, presents are needed, and all sorts of unexpected articles come in usefully for them. Black-lead sold in tubes is used for blackening and increasing the brilliance of the eyes of Fulah coquettes; curtain-loops are transformed into shoulder ornaments or belts to hold the weapons of warriors; whilst the various dainty articles used in cotillons are much appreciated by native belles, who are also very fond of sticking tortoise-shell combs into their woolly locks. Take also some pipes, tobacco-pouches, fishing-tackle, needles, knives and scissors, a few burnouses made of bath-towels, china and glass buttons, coral, amber, cheap silks, tri-coloured sunshades, etc.

We had to give powerful chiefs such things as embroidered velvet saddles, weapons, costly garments, and valuable stuffs. Tastes change from one generation to another; the fashion is different in different villages; besides, we were expected, it was specified in our instructions, to open commercial relations with the natives for the travellers who should succeed us. So we were bound to have with us as great a variety of samples of our wares as possible.

Moreover, Tuaregs and negroes alike are only big[19] children. They fight just to amuse themselves when they happen to have a sword or a gun. They would play just as happily with a mechanical rabbit, a peg-top, or a doll which says “Papa.” So we must take some toys with us, such as crawling lizards, jumping frogs, musical boxes, even a miniature organ which plays the quadrille à chahut,[1] as it consumes yards of perforated paper. And even now I have not enumerated all the things we took.

Face to face with this very incoherent programme, suppose for carrying it out you have two naval officers, one just come back from the Sudan, the other from China, and you say to them, giving them the necessary funds, “Now you go and settle things up.” Well, you will soon see what they can do, but if they are up to their work they will go straight away and secure the help of Léon Bolard, a commercial agent who is a specialist in providing for exploring expeditions. And then these two will amuse themselves like a couple of fools for a month at least; that is what we did.

Long shall I remember these prowlings in furnishing shops, where the owners were not always very civil, for we turned their premises upside down sometimes for mere trifles. Some days we tramped for eighteen miles along the pavements of Paris, measured by the pedometer.

Our most amusing experiences were when we went in search of bargains at sales. Slightly soiled stuffs and remnants are first-rate treasure trove for explorers who are at all careful of the coffers of the State; but how one has to walk, and how one has to climb to fourth and fifth storeys to realize these economies! We once got about 1600 yards of velvet for nineteen sous, and we picked up knives with handles representing the Eiffel Tower, with others bearing political allusions to Panama, etc.

[20]At the end of a month Baudry and I were quite knocked up. Bolard alone continued indefatigable. But we had bought twenty-seven thousand francs’ worth of merchandise, which was all piled up in the basement of the Pavillon de Flore. Such an extraordinary heap it made; bales of calico on top of cavalry sabres, Pelion on Ossa.

We received several distinguished visitors there, too. M. Grodet, just appointed Governor of the French Sudan, came to see us, and was very amiable, seeming to take a great interest in what we were doing. Quantum mutata . . .

Next came the packing, which was anything but an easy task. An explorer ought to be also an experienced packer of the very first rank. No package must exceed 55 lbs. in weight. To begin with, all the luggage must be absolutely water-tight, easily handled, and of a regular geometrical shape, so as to be stowed away in our hold without much difficulty. Then the various articles making up each package must be so arranged as not to get damaged by rubbing against each other or shifting about. Lastly, and this was the greatest difficulty of all, the bales must be made up so that we could easily get out what we wanted without constantly opening them all. And what a responsibility the whole thing was!

Then we had certain things with us which were sure to strike the imagination of the natives, notably Baudry’s bicycle, some Geissler’s vacuum tubes, and an Edison phonograph—the cinematograph was not then invented. Our instrument was, in fact, one of the first which had been seen even in France. It would repeat the native songs, and I relied on it to interest the chiefs and the literati, for to amuse them would, I hoped, make them forget their hostile designs.

For weapons the Minister of War gave us ten Lebel[21] rifles of the 1893 pattern, ten revolvers of the very latest pattern, with ten thousand cartridges, which represented one thousand per man, more than enough in my opinion. Lastly, the naval authorities let us have a quick-firing Hotchkiss gun, with ammunition and all accessories.

On December 25 all was ready, except that the Davoust was not quite finished. On Christmas Day Baudry started for Bordeaux, with the larger portion of our stores, and on January 5, I, in my turn, embarked on the steamship Brazil of the Messageries Maritimes, taking with me my boat in sections.

THE PORT OF DAKAR.

Dakar lies low at the extremity of the bay on which it is built, at the foot of the heights, which together form Cape Verd. It has inherited the commercial position of Fort Goree, and looks like an islet of verdure framed amongst sombre rocks and gleaming sands.

Alas! if Dakar were English, what a busy commercial[22] port it would be! Into what an impregnable citadel, what a well-stocked arsenal, our rivals would have converted it.

But Dakar is French, and although we cannot deny that it has made progress, there is no shutting our eyes to the fact that the progress is slow. Yet it would be simply impossible to find a better site on the western coast of Africa. It is a Cherbourg of the Atlantic. The roadstead is very safe, it can be entered at any time, the anchorage is excellent, the air comparatively healthy, and there is plenty of water.

And what a splendid position too from a military point of view!

When war is declared, and the Suez Canal is blocked, the old route to India and the far East will resume its former importance, and Dakar will become, as Napoleon said of Cherbourg, “a dagger in the heart of England.” Well stored with coal, and provided with good docks and workshops, etc., Dakar might in the next great war become a centre for the re-victualling of a whole fleet of rapid cruisers and torpedo boats, harassing the commerce of England. It will also be the entrenched camp or harbour of refuge in which our vessels will take shelter from superior forces. Let us hope that this vision will be realized. Meanwhile the rivalry between St. Louis, Dakar, and Rufisque is not very beneficial to any one of the three towns.

Dakar is of special importance to the Niger districts, and this is why I have dwelt a little on its present position and probable future. Some day no doubt it will become the port of export of the trade of the Sudan, which will, I think, become very considerable when Kayes is connected with St. Louis and Badombé with Kolikoro by the great French railway of West Africa.

Dakar interested me for yet another reason. It was there I set foot once more on African soil after an absence of two[23] long years. I flattered myself that now I should have to contend face to face with material difficulties only, before I realized my schemes; so that when I saw all my bales and packages and the sections of the Davoust, with absolutely nothing missing, lying symmetrically arranged on the quay of the Dakar St. Louis railway, it was one of the happiest hours of my life. It has often been said that the most difficult part of an expedition is the start. Well, I thought I had started, and was now sure of success. Alas! what a humbling disillusioning was before me!

Thanks to the hearty co-operation of everybody, including the Governor, M. de Lamothe, and the Naval Commander, M. Du Rocher, Baudry had got everything ready for me.

There was, however, no time to be lost. An accident to her screw had delayed the Brazil three days, and we must start immediately for the Upper Niger, so we were off for St. Louis the very next morning. The sections of the Davoust were of an awkward shape, and being only hastily packed and tumbled on board anyhow at Bourdeaux, danced a regular saraband in the open wagons of the line, and I felt rather anxious about my poor vessel. But never mind, she would have plenty of bumping about later, and I wasn’t going to make myself miserable about her on this auspicious day.

Just a couple of words about the Dakar St. Louis railway. The Cayor, as the country it traverses is called, is slightly undulating, badly watered, and dreary looking. The natives living in it were hard to subdue. In continual revolt, they more than once inflicted real disasters on the French by taking them by surprise. At Thies the whole garrison was massacred, at M’ Pal a squadron of Spahis perished, for the Cayor had chiefs such as the Damels, Samba-Laobe and Lat-Dior, the last champions of resistance who became illustrious in the annals of Senegambia—real[24] heroes, who made us regret that it was impossible to win them over to our side.

The successive governors of Senegambia struggled in vain against the resistance of Cayor to their authority, and the constant insubordination of the natives. But what Faidherbe, Vinet-Laprade, and Brière de l’Isle, to name but the most celebrated, failed to achieve was accomplished peacefully by the railway in a very few years. Nor is that all, for many tracts, previously barren and uncultivated, now yield large crops of the Arachis hypogea, or pea-nut, which are taken away by the trains in the trading season.

PART OF THE DAKAR ST. LOUIS LINE.

Does not this prove how true it is that peace and commerce advance side by side; that the best, indeed the only way to pacify a country, and to conciliate the inhabitants, is to give them prosperity by opening up outlets for their commerce?

[25]Hurrah, then, for the Dakar St. Louis line! Three cheers for it, in spite of the delays and mistakes which were perhaps made when it was begun.

To say that it has every possible and desirable comfort would of course be false. In the hot season especially it is one long martyrdom to the traveller, a foretaste of hell, and the advice given to new-comers at Dakar still holds good—“Take ice, plenty of ice, with you, you will find it of double use, to freshen up your drinks by the way and to put in a handkerchief on your head under your helmet. With plenty of ice you may perhaps escape without getting fever or being suffocated.”

RAILWAY BUFFET AT TIVIWANE.

The trip by this line, which no European would care to take for pleasure, is really to the negroes a treat, who go by the train as an amusement. The directors did not count upon receipts from the blacks when they started the line, especially after a train which ran off the metals smashed up[26] a whole carriage full of natives against a huge baobab tree. Of course, when that happened no one thought the negroes would patronize the railway again. But it turned out quite the contrary. From that day they came in crowds, but they had provided themselves with talismans!

The marabouts, who do a brisk business in charms, had simply added a new string to their bow, for they sold gris-gris against the dangers of the iron road!

THE QUAY AT ST. LOUIS.

This is the negro all over. If he has but confidence in his gris-gris, he will brave a thousand dangers. If he has but confidence in his chief, he will follow him without hesitation, and without faltering to the end of the world. Inspire him then with that confidence, and you will be able to do anything with him.

Baudry had come to meet me on the line, and with him was a negro wrapped up in a tampasendbé, or native shawl. This man was Mandao, the interpreter I had asked for.[27] He had decided to go with us without a moment’s hesitation. This was yet another trump card for us, and all would now go well.

A STREET IN ST. LOUIS.

We reached St. Louis at six o’clock in the evening on January 17. An officer on the Staff of the Governor was waiting for me. M. de Lamothe, who was, by the way, an old friend of mine, received me most graciously, and was ready to do everything in his power to help me.

The Brière de l’Isle of the Deves and Chaumet company was to start on the 19th for the upper river. She was, however, already overloaded. What should we do? Time was pressing!

BOUBAKAR-SINGO.

On the morning of the 18th I engaged the coolies who were to follow us. Most of them were Sarracolais, whose tribe lives on the Senegal between Bakel and Kayes. From amongst a hundred candidates Baudry had already picked out twelve, and to these had been added a second master pilot belonging to the local station. All these were experienced campaigners, who had long been in the French service; they were sturdy, well-built fellows,[28] eager for adventure. I had but to eliminate three, and to confirm Baudry’s choice of the others, for we were limited to eight men, including their leader. After all, however, the coolies were dismissed by order of Governor Grodet before we actually started, so there is no need to introduce them more particularly. Boubakar-Singo, the second leader, who became pilot of the Davoust, alone deserves special mention. He was a splendid-looking Sarracolais, a first-rate sailor, who, when a storm came on, would jump into the water stark naked intoning all the prayers in his repertory.

THE COOLIES ENGAGED AT ST. LOUIS.

Our coolies engaged, we had not only to equip, but to dress them. We set them to work at once, for we had already solved the difficulty of how best to transport our stores. The governor lent us a thirty-five ton iron lighter, into which we stowed away everything, and the Brière de l’Isle took her in tow.

[29]It was not, however, without considerable trouble that we managed the stowing away of all our goods, but we succeeded somehow in being ready in good time. On the evening of the 19th the Brière weighed anchor, and we started for the upper river; our friends at St. Louis, the Government officials, the sailors, the tradespeople waving their hats and handkerchiefs in farewell, and shouting out “Good luck.”

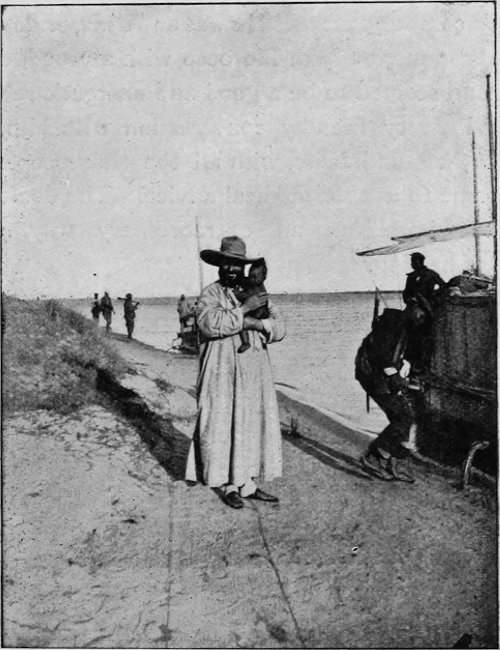

What a Noah’s ark was this thirty-five ton barge of ours, and what a mixed cargo she carried, with our bales and her sails, not to speak of the passengers! coolies, stately Moors, sheep and women. With the sails of the Davoust we rigged up a kind of shed in the stern to protect all these people, who, with nothing to do all day, crept about on the sloping roof sunning themselves like lizards. We turned the two days during which we were towed along to account by going over our numerous bales yet once more. Strange to say, almost incredible indeed, nothing was missing. It was worth something to see Bilali Cumba, a herculean coolie, pick up the instruments, weighing in their galvanized case more than 240 lbs., as easily as a little milliner would lift a cardboard box.

It was Bilali who made me the following sensible answer the other day, when we had given out wooden spoons to the men for their own use. Of course, like all negroes, they ate with their fingers, making their porridge up into a ball, and rolling it till it was quite hard before putting it into their mouths. I was laughing at Bilali about this when he said, “Friend, tell me what is the good of your spoon?” then spreading out the palms of his toil-worn hands he added, “What is good to work with is good to eat with.”

As Joan of Arc with her flag, he dedicated his hands to toil and honour too.

Our trip did not pass off without certain little accidents;[30] the constant splashing of the water loosened the joints of the barge, and we had to stick them together as best we could. However, we arrived on the 23rd at Walaldé, then the highest navigable point of the river. Probably it would be possible to go much further up, as far as Kaheide, in fact, at all times of the year, but it would have to be in boats with a different kind of keel to that now in use, and we have not got to that yet.

The Brière de l’Isle now left us to descend the river again.

THE ‘BRIÈRE DE L’ISLE.’

Henceforth we were to fly with our own wings. Painfully and slowly we made our way in our thirty-five ton barge, towed along by a rope from the bank, the river gradually widening out as we passed Kaheide, Matam, Saldé.

Then, alas! we got one piece of bad news after another.

At Saldé we heard of the death of Aube; at Bakel of the massacre of Colonel Bonnier and his column.

Too much fuss has been made about these glorious deaths, say many foolish critics. Over the ashes of soldiers killed in battle, there has been too much heated discussion. Well, at least, hyænas only do their terrible work at night!

As for me, I lost a chief whom I loved, and many old comrades with whom I had been under fire or in garrison. Hastily we pushed on for Bakel and Kayes, eager for further news, not only plunged in the deepest grief, but somewhat anxious about what was in store for ourselves.

On February 13 we arrived at Kayes. I went at[32] once with Baudry and Mandao to the Governor, M. Grodet, who told me that he had received despatches authorizing him to suspend my expedition, and to employ us as he liked! Our party was at once broken up. Baudry was sent to make forced marches to the Niger to escort some convoys of provisions on their way to re-victual Timbuktu. I should be disposed of later, and, as a matter of fact, I was eventually sent to take command of the Niger flotilla.

THE MARKET-PLACE AT ST. LOUIS.

THE MARKET-PLACE AT ST. LOUIS.

GOVERNMENT HOUSE, KAYES.

I must quote the actual words of this despatch, so fatal to us, for not long since M. Grodet was defending himself from the charge of having been somehow the cause of the delay to our expedition of two whole years. The despatch was addressed—“Colonies à Gouverneur, Sudan,” and ran thus—“Autorise surseoir Mission Hourst, et disposer de cet officier.”[2]

As will be observed, the Governor of the Sudan was authorized, that is to say, he could do as suggested or not, to suspend, that is to say, to stop us, for the limited time which seemed desirable to him. But any further disputing about it would do no good now.

One remark, however, I must make: we were stationary for two years on the banks of the Niger above Timbuktu, doing no particular service to our country. Decœur, Baud, and others were marching on Say from Dahomey. Can one fail to see what immediate political and diplomatic[33] advantages would have accrued to France from a junction which would have united the hinterlands of the two colonies?

It is true that Decœur and Baud were not starting from the Sudan, but from Dahomey, where Governor Ballot was sending out exploring expeditions, not stopping them.

But I have done. It is worse than useless to dwell on the endless petty mortifications, annoyances, and disappointments we had to endure. Useless indeed to recall all our own bitter experiences, which could but damp the enthusiasm of future explorers as eager to advance as we were. We succeeded in spite of everything in making ourselves useful. Even whilst re-victualling Timbuktu, which was threatened with famine—here again the responsibility rested with very highly placed officials—I was able to survey the whole of the system of lakes extending on the west of the town.

The most important of these lakes, Faguibine, is a regular inland sea, with its islets, its promontories, and its storms. It is a vast basin nearly 68 miles long by 12 broad, with a depth, which we sounded, exceeding here and there 160 feet. It is fed by the Niger when that river is in flood. We made a peaceful raid on this fine sheet of water in the Aube, a boat I shall introduce to you later, whilst the terrible Ngouna chief of the hostile Kel Antassar tribe retreated from us along its banks. Here for the first time I came into actual contact with the Tuaregs.

Baudry meanwhile explored the Issa-Ber (already visited by Caron) in his barge, and proved the navigability of the river at high tide.

I feel full of respectful gratitude to the military authorities of Timbuktu, especially Colonels Joffre and Ebener, for the almost affectionate consideration with which they treated me, and for being willing to employ us, for giving[34] us something definite to do to relieve the monotony and ennui of our detention. This was really an immense consolation to us, the best that any officer can hope for.

In May 1895 I received orders to return to France. Baudry, who, I am happy to say, was worn out mentally rather than physically, had preceded me by two months. As already stated, our coolies had been disbanded—from motives of economy, said the order. Our stores, too, were dispersed. Our boat was still at Bafulabé, and, mon Dieu, in what a state! One might have sworn that its sections had been intentionally twisted out of shape with blows from a hammer. Our chronometers—little torpedo-boat watches, regular masterpieces of precise time-keeping, made by that true artist M. Thomas—were being used at Badumbé in the telegraph office. Our bales, of the charge of which I had never been relieved, had been sent to Mopti for the Destenave expedition, which had been allowed to start. My friends in France, to whom I had addressed despairing appeals, remained silent; even Baudry gave not a sign of life.

Everything seemed finally lost. My expedition had not been superseded, it had been dissolved, destroyed.

I confess that when I embarked once more in the winter to make my way, by slow stages, back to France, I did for the first time despair of my unlucky schemes, and as I dwelt upon them, I believed that they were at an end for ever.

I had at least the consolation, as Davoust had had before me, of having struggled to the last.

On July 20, when I was halting at Bafulabé, and gazing with inward rage though outward calm at the dented sections of my Davoust, a telegram was handed to me. It was from Colonel De Trentinian, who had—at last!—succeeded M. Grodet as Governor of the French Sudan.

[35]It said, “The Colonial Minister resumes the original project of your expedition.”

I have had a few minutes of wild joy and happiness in my life. But not even on the day when, after I had been struggling nearly a month against fearful odds in the revolted district of Diena, I saw the column of succour approaching; nor again, last December, when, as we embarked at Marseilles, I thought all our difficulties were surmounted and all our dangers were left behind, did I experience such an immense sense of relief and delight as now. I could keep my oath after all! and by successful action put to confusion those who, either because they were badly advised or unscrupulous, had thrown obstacles in our way.

This is what had happened.

In France they say the absent are always in the wrong, and our story goes to prove it. Of all those who, when I left, had protested their devotion, had congratulated me in advance, who had even warmly embraced me, scarcely any—I had almost said not one—had taken our part or pleaded for us. In France, scientific societies, geographical and others, spring up like mushrooms, and form little cliques, hating each other like poison, and losing no opportunities of abusing each other in their speeches and declamations at their various banquets. Without running any risk themselves, or making any special exertion, their big-wigs—I was nearly saying their shareholders—get a lot of notoriety and patting on the back, through the work of a few members who are toiling far away from home.

If you ask their help in your difficulties, or even their moral support, they take absolutely no notice of you; but later, when you return, and have extricated yourself from your troubles by your own unaided efforts, and if you are also very docile, they will make no end of noisy fuss over you.

[36]I have often thought of these scientific swells when I have watched negro chiefs marching along followed by their satellites. They strut about, playing on the flute or the fiddle, beating their drums and shouting out compliments in a deafening manner. Every epithet seems suitable to their chief; he is their sun, their moon, and all the rest of it. “Thou art my father, thou art my mother, I am thy captive!” they shout.

But when adversity overtakes this flattered chief of theirs, when he is in trouble of any kind, gets the worst of it in some skirmish, for instance, what becomes of all the toad-eating satellites? They melt away, to go and offer their incense of flute and violin playing and bell-ringing to some more fortunate favourite of the hour.

Oh, these self-interested sycophants, how well I know them!

I have, however, a grateful pleasure in adding that there are exceptions to the rule. I will mention but one here. My dear and venerated friend, M. Gauthiot, chief secretary of the Société de Géographie Commerciale, was always ready to cheer us in our hours of discouragement, to aid us in our hopeful days; putting at our disposal all his influence, all his persuasive power, and exercising on our behalf the undoubted authority he possessed in all things geographical and colonial.

Directly he reached Paris Baudry went to seek him, not of course without some arrière pensée. “Well, how goes the mission?” he asked at once. “Done for, unless you can save us,” was the reply. “I’ll see about it,” said M. Gauthiot at once.

Then he went to my old friend Marchand, who was expected to do such great things on the Congo. “And Hourst and the descent of the Niger?” “You see what has come of that,” was the answer. “Well, perhaps something may yet be done.”

[37]Both did their utmost for us, but it was M. Gauthiot who took the last redoubt. The money question appeared to be the greatest difficulty, for they were trying to cut down the expenditure budget as much as possible. “Monsieur le Ministre,” said my friend, “I have come with my hands full!” And five thousand francs were in fact voted for my exploring expedition by the Comité de l’Afrique Française.

In a word, the efforts of our new allies turned the scale in our favour.

At that time M. Chautemps was, fortunately for us, Colonial Minister, whilst M. Chaudie was Governor-General of French West Africa, and Colonel (now General) Archinard Director of Colonial Defence, and it was on these three that the final order depended. I need only add, that they, with M. Gauthiot, became the four sponsors of the re-organized expedition, and we are full of respectful gratitude to them all.

“All I had to do in the matter,” said Baudry to me, “was simply to put in an appearance.”

I alluded above to the question of funds. Well, the whole thing was re-arranged on a fresh footing, otherwise the conditions were less favourable than they had been two years before. Nothing had changed with regard to the Tuaregs, but news had come by way of the Sudan that Amadu Cheiku, the dethroned Sultan of Sego, was trying to re-establish an empire on the banks of the Niger. Then the Toutée expedition was already on its way; no news had been received from it, and it is often more difficult to be second than first in traversing a new district.

Colonel Archinard, therefore, wished to increase the strength of our expedition considerably. To begin with, we were to have three barges instead of one, and that meant twenty coolies instead of eight. Then Lieutenant Bluzet, who, though still of low rank in the service, was quite an old[38] and experienced officer of the French Sudan, was to take charge of the military training of our men. “Take a doctor too,” said the Colonel, “he will make one more gun at least;” and I choose Dr. Taburet, who had been my medical adviser with the Niger flotilla, engaging his services by telegram.

All this of course added to the expense, and it was no easy matter to balance the accounts of so big an expedition with so very small a budget. However, we managed to do it somehow: Bluzet and Baudry made advances from their pay, and Bolard went on campaign once more with all his usual zeal and energy.

“You start four,” said Marchand to Baudry, when he saw him off at the Orleans station, “only one will return!”

Thank God, however, we all came back!

Directly I received the telegram from Colonel de Trentinian I set to work without losing a moment. I had to collect all our scattered stores again at Bafulabé from here, there, and everywhere. The Davoust had to be got into working order, and the only way to do that was to put her together and launch her, there would then be no unnecessary delay when the time for starting came. I was aided in this by a quarter-master with a turn for mechanics, a man named Sauzereau, who had already rendered me great service when I had charge of the Niger flotilla. It was hard work, but we succeeded, and it was a happy day when we baptized our boat by her already chosen name of Davoust at the little station of Bafulabé. It was the first time she had been afloat since we tried her near the Pont Royal in Paris. A missionary from Dinguira had come over at considerable inconvenience on purpose to pronounce a benediction over her. Colonel de Trentinian was good enough to travel from Kayes to be present, and I can tell you my Davoust presented a very fine[39] appearance on the Bakhoy. I would rather see her there than on the Seine. Digui, who had been second master pilot on the Niger flotilla, and whom I had chosen as Captain in place of Bubakar, dismissed, was delighted with his boat.

When all was counted over, there were many missing loads. Fortunately Captain Destenaves had only brought a few of the valuable bales to Mossi, the rest were at Sego, but of the tins of preserves and other provisions nothing was left but one case of fine Cognac, which, taken in very small doses, was our greatest luxury. There was still a little left a year later when we were at Fort Archinard. See how temperate we were! Baudry’s bicycle, which we had baptized Suzanne, I don’t know why, was in a pitiable state when we found her again. But Sauzereau was a specialist in such cases, and she was soon rolling along the Badumbé road, to the great astonishment of the blacks.

I had now nothing more to do but to wait for Baudry at Kayes. I went down there, and one fine morning he flung himself into my arms with Bluzet and twenty coolies behind him. Of course with regard to the coolies I speak figuratively. With a view to economy these coolies had not been rigged out, and they really looked like a band of brigands. Still they impressed me very favourably. I knew several of them, who had already served under me. They were not, it is true, quite equal to those I had engaged at first, and been obliged to disband by order of the Governor, but they were not bad fellows, and they would get into good working order by the way.

All had gone well with Baudry and Bluzet; they had even found time on board the boat, which had brought them up from St. Louis, to make up some rhymes, and in the evening, after copious libations—I mean copious for[40] Africa—we had the honour of listening to a sonnet of which they were the joint authors. Here it is:

ON THE SENEGAL.

[41]

EN ROUTE.

On October 10, 1895, we finally left Kayes. Our packages had been piled up the evening before in three railway wagons, and our party now took their places in the carriages. Baudry, Bluzet, and Sauzereau our engineer, who were to go up in the Davoust, remained, and the rest of my staff were the following: the second master pilot, Samba Amadi, generally called Digui, a man of colossal height and herculean strength, but more remarkable still for his zeal, his fidelity, and his nautical skill; the native interpreter Suleyman Gundiamu, who had been to Timbuktu with Caron as one of his coolies; the Arabic translator, Abdulaye Dem, a cunning and intelligent little Toucouleur, more cultivated than most of the negro marabouts; and twenty coolies, or native sailors.

[42]We reached Bafolabé in the evening without incident. A ferry-boat took us across the Bafing, one of the two rivers which unite to form the Senegal. A road some two feet wide starts from the right bank of the Bafing, and follows the course of the other affluent, the Bakhoy, to the village of Djubeba, where we camped on the evening of the 13th.

Thus far our journey had been effected by the aid of very civilized means of transport. On leaving Djubeba, however, our difficulties were to begin.

LEFEBVRE CARTS UNHARNESSED.

The carriage, or rather cart, which is used in the French Sudan for taking down provisions and other necessaries to our different stations on the Niger is of the kind known as the Lefebvre, about which there was so much talk during the Madagascar expedition. It consists of a big case of sheet iron mounted on a crank axle, and provided with two wheels. It is drawn by a mule.

[43]Is it an ideal equipage? or is it as bad as it is painted? I do not venture to decide the question. The truth, perhaps, lies between the two extremes. On the one hand, these carts were always able to follow our troops in the Sudan; but on the other, their intrinsic weight might very well be lessened. The chief advantage of metal rather than of wooden carts, is that they are watertight, and that when unloaded they can be floated across streams or rivers, but as I have never seen a Lefebvre cart execute this manœuvre, I feel a little sceptical about it still.

LOADING OUR CONVOY.

When the packages to be carried are small, compact, and about the same size and shape, it is easy enough to stow them away, but this was by no means the case with ours, and our large packages would be fearfully difficult to arrange and balance in the heavy metal carts.

On the 14th the mules arrived, some of which were to[44] be harnessed to the carts, whilst others were to carry pack-saddles. The whole of that day and the next were occupied in the arranging and loading.

The sections of the Davoust could not, of course, have been carried in carts in any case. I had asked for seventy porters to take charge of them, and these porters arrived in the evening. There was nothing now to prevent our starting.

The route from the French Sudan, so often traversed to re-victual our stations, has been too many times described for me to pause to speak of the stages by which the traveller passes from the banks of the Senegal to those of the Niger. For us, the usual difficulties were increased by the variety of our means of transport, including as they did carts, mules with pack-saddles, and porters. Moreover, ours was the first convoy which had passed over the route since the winter, and the road had not yet been mended all the way. The first few days were very tiring, and men and animals were all alike done up when we reached our first halting-place a little after noon. But every one did his best, and became more skilful at managing, so that in three days after the start our black fellows were as well up to their work as we were ourselves.

This was our general mode of dividing the day. At two o’clock in the morning the blowing of a horn roused everybody; the drivers gave the animals their nose-bags containing a few handfuls of millet to keep up their strength on the road; Bluzet, to whose special care I had confided the porters, collected his people, whilst our cook quickly warmed for each of us a cup of coffee which had been prepared overnight. An hour later we were off, the porters leading the way, our path lighted by torches of twisted straw, the fitful gleam of which made our negroes look like a troop of devils come to hold their sabbat in Central Africa.

[45]Bluzet rides at the head of the caravan, looking back every now and then, whilst two or three coolies run in the rear or on the flanks of our little column, like sheep dogs keeping a flock together. About a hundred yards behind the carts come jolting along on their rumbling iron wheels, whilst the pack animals bring up the rear.

LIEUTENANT BLUZET.

For one moment we file silently through the hush and calm of the tropical night, only broken by the cry of some bird, or the tap-tap of the Sudan woodpecker. But presently we come to a big hole in the ground, there is a shout of “Attention—Kini bulo!” (to the right), and from one leader to another the cry Kini bulo! is repeated, and[46] averts a catastrophe by letting every one know how to avoid the obstacle. A great galloping now ensues to catch up the leading cart, and this time the difficult place is passed without accident; but often enough a wheel slips into the bog, and in spite of all the poor mule’s tugging at her collar there it sticks. We all have to rush to the rescue, drivers and coolies literally put their shoulders to the wheel, and with shouts of encouragement and oaths they finally extricate it. It is out again at last, and we resume our march.

CROSSING A MARIGOT.

Then we come perhaps to what is called a marigot in West Africa, that is to say, a little stream which is dried up part of the year, and is a characteristic feature of the country. Before the rainy season it has probably been bridged roughly over, and a few planks have been thrown down at its edge, but in the torrential downpours of rain of the winter the planks have sunk, and the bridge has[47] been partially destroyed. We have to call a halt; to cut wood and grass to mend the bridge, and carry stones and earth to make stepping-stones, etc., so that it is often an hour or two before we can get across.

But now the horizon begins to glow with warm colour. The sun is rising, and as it gradually appears, its rays, which are not yet powerful enough to scorch us, softened as they are by the mists of the early morning, give a fresh impulse to the whole caravan. One of the drivers gives a loud cry, alike shrill and hoarse: it is the beginning of a native chant, in which the names of chiefs and heroes of the past, such as Sundiata, Sumanguru, Monson, and Bina Ali, occur again and again. The singer’s comrades take up the refrain in muffled tones. Then another negro brings out of his goat-skin bag a flute made of a hollow bamboo stem, and for hours at a time keeps on emitting from it six notes, always the same. The porters also have their music, and[48] our griot[3] Wali leads them on a kind of primitive harp with cat-gut strings, made of a calabash and a bit of twisted wood, from which hang little plaques of tin, which tinkle when the instrument is played.

WE ALL HAVE TO RUSH TO THE RESCUE.