Title: The French Revolution 1789-1795

Author: Bertha Meriton Gardiner

Release date: September 19, 2023 [eBook #71688]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1921

Credits: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them. Larger, more detailed versions of the maps may be seen by clicking "Larger" beneath those maps.

This ebook contains sidenotes. Most of them have been positioned at the beginnings of the paragraphs they summarize. In a few cases, the original sidenotes were printed well into the middle of their paragraphs, and in those cases, they appear here in similar positions. To distinguish mid-paragraph sidenotes from regular text, the .epub and .mobi versions of this book surround those sidenotes in diamond symbols: ♦sidenote text♦.

Additional notes will be found near the end of this ebook.

HISTORICAL WORKS FOR SCHOOLS.

EPOCHS OF ANCIENT HISTORY.

EDITED BY THE

Rev. Sir G. W. COX, Bart., M.A., and by C. SANKEY, M.A.

THE GRACCHI, MARIUS, AND SULLA. By A. H. Beesly, M.A. With 2 Maps.

THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE, from the Assassination of Julius Cæsar to the Assassination of Domitian. By the Rev. W. Wolfe Capes, M.A. With 2 Maps.

THE ROMAN EMPIRE OF THE SECOND CENTURY, or the Age of the Antonines. By the Rev. W. Wolfe Capes, M.A. With 2 Maps.

ROME TO ITS CAPTURE BY THE GAULS. By Wilhelm Ihne. With Map.

THE ROMAN TRIUMVIRATES. By Charles Merivale, D.D., late Dean of Ely. With Map.

ROME AND CARTHAGE, the PUNIC WARS. By R. Bosworth Smith, M.A. With 9 Maps and Plans.

THE GREEKS AND THE PERSIANS. By the Rev. Sir G. W. Cox, Bart., M.A. With 4 Maps.

THE ATHENIAN EMPIRE, from the Flight of Xerxes to the Fall of Athens. By the Rev. Sir G. W. Cox, Bart., M.A. With 5 Maps.

THE RISE OF THE MACEDONIAN EMPIRE. By Arthur M. Curteis, M.A. With 8 Maps.

EPOCHS OF ENGLISH HISTORY.

Edited by MANDELL CREIGHTON, D.D., LL.D.

LATE BISHOP OF LONDON.

EARLY ENGLAND TO THE NORMAN CONQUEST. By L. York Powell, M.A.

ENGLAND A CONTINENTAL POWER, 1066–1216. By Mrs. Mandell Creighton.

THE RISE OF THE PEOPLE AND THE GROWTH OF PARLIAMENT. 1215–1485. By James Rowley, M.A.

THE TUDORS AND THE REFORMATION. 1485–1603. By Mandell Creighton, D.D., LL.D.

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST ABSOLUTE MONARCHY, 1603–1688. By Mrs. S. R. Gardiner.

THE SETTLEMENT OF THE CONSTITUTION, 1689–1784. By James Rowley, M.A.

ENGLAND DURING THE AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN WARS. 1765–1820. By the Rev. O. W. Tancock.

EPOCHS OF ENGLISH HISTORY. Complete in One Volume, with 27 Tables and Pedigrees and 23 Maps. Fcp. 8vo.

THE SHILLING HISTORY OF ENGLAND: being an Introductory Volume to the Series of Epochs of English History. By Mandell Creighton, D.D., LL.D. Fcp. 8vo.

LONGMANS, GREEN & CO., 39 Paternoster Row,

London, New York, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras.

Epochs of Modern History.

Edited by EDWARD E. MORRIS, M.A., J. SURTEES

PHILLPOTTS, B.C.L., and C. COLBECK, M.A.

Fcp. 8vo.

The BEGINNING of the MIDDLE AGES. By the Very Rev. Richard William Church, M.A. &c., late Dean of St. Paul’s. With 3 Maps.

The NORMANS in EUROPE. By the Rev. A. H. Johnson, M.A. With 3 Maps.

The CRUSADES. By the Rev. Sir G. W. Cox, Bart., M.A. With a Map.

The EARLY PLANTAGENETS. By W. Stubbs, D.D., late Bishop of Oxford. With 2 Maps.

EDWARD the THIRD. By the Rev. W. Warburton, M.A. With 3 Maps and 3 Genealogical Tables.

The ERA of the PROTESTANT REVOLUTION. By F. Seebohm, LL.D. With 4 Maps and 12 Diagrams.

The AGE of ELIZABETH. By Mandell Creighton, D.D., LL.D., late Bishop of London. With 5 Maps and 4 Genealogical Tables.

The FIRST TWO STUARTS and the PURITAN REVOLUTION, 1603–1660. By Samuel Rawson Gardiner. With 4 Maps.

The THIRTY YEARS’ WAR, 1618–1648. By Samuel Rawson Gardiner. With a Map.

The ENGLISH RESTORATION and LOUIS XIV. 1648–1678. By Osmund Airy, LL.D.

The FALL of the STUARTS; and WESTERN EUROPE from 1678 to 1697. By the Rev. Edward Hale, M.A. With 11 Maps and Plans.

The AGE of ANNE. By E. E. Morris, M.A. With 7 Maps and Plans.

FREDERICK the GREAT and the SEVEN YEARS’ WAR. By F. W. Longman. With 2 Maps.

The WAR of AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE, 1775–1783. By J. M. Ludlow. With 4 Maps.

The FRENCH REVOLUTION. 1789–1795. By Mrs. S. R. Gardiner. With 7 Maps.

The EPOCH of REFORM, 1830–1850. By Justin McCarthy.

LONGMANS, GREEN & CO., 39 Paternoster Row,

London, New York, Bombay, Calcutta, and Madras.

Epochs of Modern History

EDITED BY

C. COLBECK, M.A.; EDWARD F. MORRIS, M.A.;

AND J. SURTEES PHILLPOTTS, M.A., B.C.L.

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

B. M. GARDINER

CENTRAL EUROPE 1789

Longmans, Green & Co., London, New York, Bombay, Calcutta & Madras.

v

Epochs of Modern History

BY

BERTHA MERITON GARDINER

SIXTEENTH IMPRESSION

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

FOURTH AVENUE & 30TH STREET, NEW YORK

BOMBAY, CALCUTTA, AND MADRAS

1921

All rights reserved

In writing this handbook on the French Revolution, it has been my endeavour to give a correct and impartial account of the most important events of the revolutionary period, and of the motives by which the leading characters were actuated. Much has necessarily been omitted which finds a place in larger works. Those who wish to pursue the subject further, and have time at their disposal, would do well to study, besides general histories, some of the many books lately published which deal with special branches of the subject, and often enable the reader to form a more independent judgment both of men and events than is possible from the perusal of works of the former class alone. Amongst general histories those of Michelet and Louis Blanc will probably be found most serviceable. No satisfactory account of the relations of France with other countries is to be found in the French tongue, partly because French historians still write with bias, partly, also, because they hitherto either have been unacquainted with, or have ignored the results of German research. Professor Von Sybel’s well-knownvi book, ‘Geschichte der Revolutionszeit,’ contains the fullest and best account of the relations which existed between the different States of Europe, but it is not an impartial one. Hermann Hüffer’s books are valuable contributions to our knowledge of diplomatic relations, and, being written from an opposite point of view, should be studied by all readers of Von Sybel. The history of the foreign policy of England during this period has still to be written. M. Sorel has lately published in the pages of the ‘Révue Historique’ a full account of the foreign policy pursued by the Committee of Public Safety after Robespierre’s fall, and of the negotiations leading to the treaties of peace signed in 1795 between France and Prussia and France and Spain. Much fresh information regarding the internal condition of France during the revolutionary period is to be found scattered in local and special histories of various kinds. Amongst such may be specially mentioned Mortimer Ternaux’s ‘Histoire de la Terreur,’ and ‘La Justice Révolutionnaire,’ by Berriat St. Prix. M. Taine in his great work has collected a large number of extracts from documents lying in the archives of the departments, but entire absence of classification, and the strong political bias of the writer, makes this work of less value to the student than others of less pretensions. Amongst the best of local histories are the works of M. Francisque Mège, which reveal the course taken by the Revolution in the province of Auvergne. Biographical works are numerous. Mirabeau’s character will best be learnt from his correspondence with the Count de la Marck. M. D’Héricault’s ‘Révolution devii Thermidor’ contains a detailed account of the policy pursued by Robespierre after the expulsion of the Girondists. Danton’s life and character can best be studied in the works of M. Robinet. Schmidt’s ‘Pariser Zustände während der Revolutionszeit’ contains the best existing account of the economic condition of Paris between 1789 and 1800. As it is improbable that those for whom this book is in the first place intended will have any idea of the amount represented by so many thousand or million livres, I have invariably given the English equivalent of the French money, following the table inserted by Arthur Young in his ‘Travels in France.’ After the introduction of the revolutionary calendar, I have in giving dates followed the table in ‘L’Art de vérifier les Dates.’ In consequence of the different system of intercalation pursued in the two calendars, the correspondence of dates varies from year to year, and in consequence of leaving this fact unnoticed even French historians sometimes give the date in the old style wrongly. I have only further to add that the purple lines upon the map of France in provinces represent the frontiers where customs duties were levied under the old Monarchy. They are copied from a map published with Necker’s works. It will be seen that Alsace and Lorraine, as well as Bayonne and Dunkirk, were allowed to trade freely with the foreigner. Marseilles enjoyed the same privilege.

ix

| CHAPTER I. | |

| FEUDALISM AND THE MONARCHY. | |

| PAGE | |

| The Monarchy in France | 1 |

| Social condition of France | 3 |

| Feudal rights | 4 |

| Condition of the Church | 6 |

| Government and administration | 7 |

| The privileged classes | 8 |

| Taxation | 9 |

| Condition of the People | 11 |

| Interference with trade | 13 |

| Public opinion in France | 13 |

| Voltaire and his followers | 13 |

| The Encyclopædists | 14 |

| The Church and Christian Theology attacked | 15 |

| The Economists | 16 |

| Rousseau | 16 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| FRANCE UNDER LOUIS XVI., 1774–1789. | |

| The Ministry of Turgot | 18 |

| Opposition raised to his reforms | 19 |

| Character of Louis XVI. | 19x |

| Character of Marie Antoinette | 20 |

| 1776. Dismissal of Turgot | 21 |

| Movement of Reform extends over Europe | 21 |

| Condition of England | 23 |

| Pitt in Office | 24 |

| Reaction after Turgot’s dismissal | 25 |

| Ministry of Necker | 25 |

| Necker opposed by the Parliaments | 25 |

| 1781. He resigns office | 26 |

| Desire for political liberty | 26 |

| 1776. American Declaration of Independence | 26 |

| 1783. Ministry of Calonne | 27 |

| 1787. The Assembly of Notables | 27 |

| Ministry of Brienne | 27 |

| General disaffection | 28 |

| 1788. Second Ministry of Necker, and calling of the States General | 29 |

| Pamphlets and Cahiers | 29 |

| Siéyès’ Pamphlet—What is the Third Estate? | 30 |

| Double Representation of the Third Estate | 31 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| THE ASSEMBLY AT VERSAILLES, 1789. | |

| May 5, 1789. Meeting of the States General | 33 |

| Relation of the King to the Revolution | 33 |

| Question whether the States were to sit as one or as three chambers left undecided | 33 |

| Evil consequences of the Royal policy | 34 |

| Character and policy of Mirabeau | 35 |

| Title of National Assembly adopted by the Third Estate | 37 |

| Excitement and disorder in Paris | 38 |

| Louis takes part with the Upper Orders | 39 |

| June 20. Tennis Court Oath | 40 |

| Royal Sitting of June 23 | 40 |

| The States constituted as one Chamber | 41 |

| July 14. The fall of the Bastille | 43xi |

| Establishment of a Municipality and of a National Guard in Paris | 46 |

| Visit of Louis to the Capital | 47 |

| Risings in the Provinces | 48 |

| Decrees of August 4 | 49 |

| Composition of the Assembly | 51 |

| The Reactionary Right | 51 |

| The Right Centre | 52 |

| The Centre and Left | 52 |

| The Extreme Left | 53 |

| Causes giving ascendency to the Left | 54 |

| Policy of Mirabeau | 56 |

| Declaration of the Rights of Man | 58 |

| New Constitution; Legislature to be formed of one House; Veto given to the King | 58 |

| Scarcity of Bread | 59 |

| Character of the National Guard of Paris | 60 |

| October 6. The King and Queen brought to Paris | 60 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THE CONSTITUTION, 1789–1791. | |

| Results of the Movement of October 6 | 63 |

| The Jacobins | 64 |

| The Constitution; Administrative Changes; Establishment of 44,000 Municipalities | 65 |

| Judicial Reforms | 66 |

| Increase of the State debt | 67 |

| Church Property appropriated by the State | 67 |

| Creation of Assignats | 68 |

| Civil Constitution of the Clergy | 69 |

| Feast of the Federation | 69 |

| Emigration of the nobles | 70 |

| Embitterment of the Relations between nobles and peasants | 71 |

| Weakness of the Central Government | 72 |

| Mutinies in the Army | 73 |

| Imposition of an Oath on the Clergy; Schism in the Church | 74xii |

| The Constitution decried by the Ultra-Democrats | 76 |

| Brissot | 76 |

| Desmoulins | 77 |

| Marat | 78 |

| Sources of influence exercised by the Ultra-Democrats | 79 |

| Influence exercised by Jacobin Clubs | 80 |

| September 1790. Resignation of Necker | 81 |

| The Commune of Paris; Composition of its Municipality | 81 |

| Mirabeau’s policy; his Death, April 2, 1791 | 84 |

| Position of the Constitutionalists | 85 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE FALL OF THE MONARCHY, 1791–1792. | |

| Unpopularity of Marie Antoinette | 87 |

| June 20, 1791. Flight of the Royal Family | 88 |

| Ultra-Democrats seek the Establishment of a Republic | 91 |

| July 17. Massacre of the Champ de Mars | 91 |

| Attempt to revise the Constitution | 93 |

| The work of the National Assembly; legal and financial reforms | 93 |

| Creation of Assignats of small value | 94 |

| Plans of the Queen | 94 |

| Policy of territorial aggrandisement pursued by the Great Powers | 96 |

| Austria and Russia at war with Turkey | 97 |

| Death of Joseph II. | 97 |

| Treaty of Reichenbach | 97 |

| Declaration of Pilnitz | 98 |

| Designs of Catherine II. on Poland | 98 |

| Leopold II. unwilling to engage in war with France | 98 |

| The new Legislative Assembly; its composition | 99 |

| Policy of the Girondists | 100 |

| Ecclesiastical policy of the Legislature | 101 |

| Emigrants encouraged by Princes of the Empire | 101 |

| Growth of a warlike spirit in the Assembly | 102 |

| The French Revolution is more than a National movement | 104xiii |

| Commencement of war with Austria and Prussia | 105 |

| The Jacobins embody a spirit of suspicion | 106 |

| Robespierre’s character | 107 |

| Administrative anarchy | 109 |

| Troubles at Avignon | 110 |

| The Girondists hope for the best | 111 |

| Lafayette denounces the Jacobins | 112 |

| The mob invades the Tuileries on June 20 | 113 |

| The Country declared in danger; Manifesto of the Duke of Brunswick | 114 |

| Preparations made for an insurrection | 115 |

| Insurrection of August 10; Suspension of the King | 117 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| THE FALL OF THE GIRONDISTS, 1792–1793. | |

| Formation of the new Commune of Paris | 119 |

| The September massacres | 121 |

| The defence of the Argonnes | 123 |

| The meeting of the Convention, and the abolition of Monarchy | 124 |

| The Girondists and the Mountain | 125 |

| Weakness of the Centre | 128 |

| Re-election of the Commune | 129 |

| Conquest of Savoy, Mainz, and Belgium | 130 |

| Question of the annexation of Belgium | 131 |

| The Opening of the Scheldt, and the order to the Generals to proclaim the Sovereignty of the People | 134 |

| Objects of the Allies | 135 |

| Pitt’s ministry in England | 136 |

| Views taken of the French Revolution in England | 137 |

| Trial and Execution of Louis XVI. | 139 |

| War with England; the French expelled from Belgium | 141 |

| Establishment of the Revolutionary Court; Defeat of Neerwinden | 143 |

| Party strife in the Convention | 144 |

| Establishment of the Committee of Public Safety | 145xiv |

| Deputies in mission | 146 |

| Laws against Emigrants and Nonjurors | 147 |

| Policy of the Mountain | 148 |

| The economical situation | 149 |

| Popular remedies opposed by the Girondists | 151 |

| The Commune leads a movement against the Girondists | 153 |

| Expulsion of the leading Girondists | 155 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE COMMUNE AND THE TERROR, 1793. | |

| State of public feeling | 156 |

| Girondist and Royalist movements; Resistance in Lyons and Toulon | 157 |

| General submission to the Convention | 158 |

| War in La Vendée | 159 |

| Successes of the Vendeans | 160 |

| Successes of the Allies | 161 |

| Coolness between Austria and Prussia | 162 |

| Assassination of Marat | 163 |

| Sanguinary tendencies of the Government | 165 |

| Growing strength of the Committee of Public Safety | 166 |

| Power of the Commune | 167 |

| Views of Hébert and Chaumette | 168 |

| Introduction of the conscription | 170 |

| Maximum laws | 171 |

| Laws against speculation | 172 |

| Depression of trade and agriculture | 173 |

| Law of ‘Suspected Persons’ | 175 |

| Increased activity of the Revolutionary Court | 176 |

| Execution of the Queen and the Girondists | 177 |

| Worship of Reason | 178 |

| Introduction of the Revolutionary calendar | 180 |

| Surrender of Lyons | 181 |

| Destruction of the Vendean army | 182 |

| The Terror in the Departments | 183 |

| The Terrorists a small minority | 186xv |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE FALL OF THE HÉBERTISTS AND DANTONISTS, 1793–1794. | |

| Condition of the Army | 188 |

| Carnot’s military reforms | 189 |

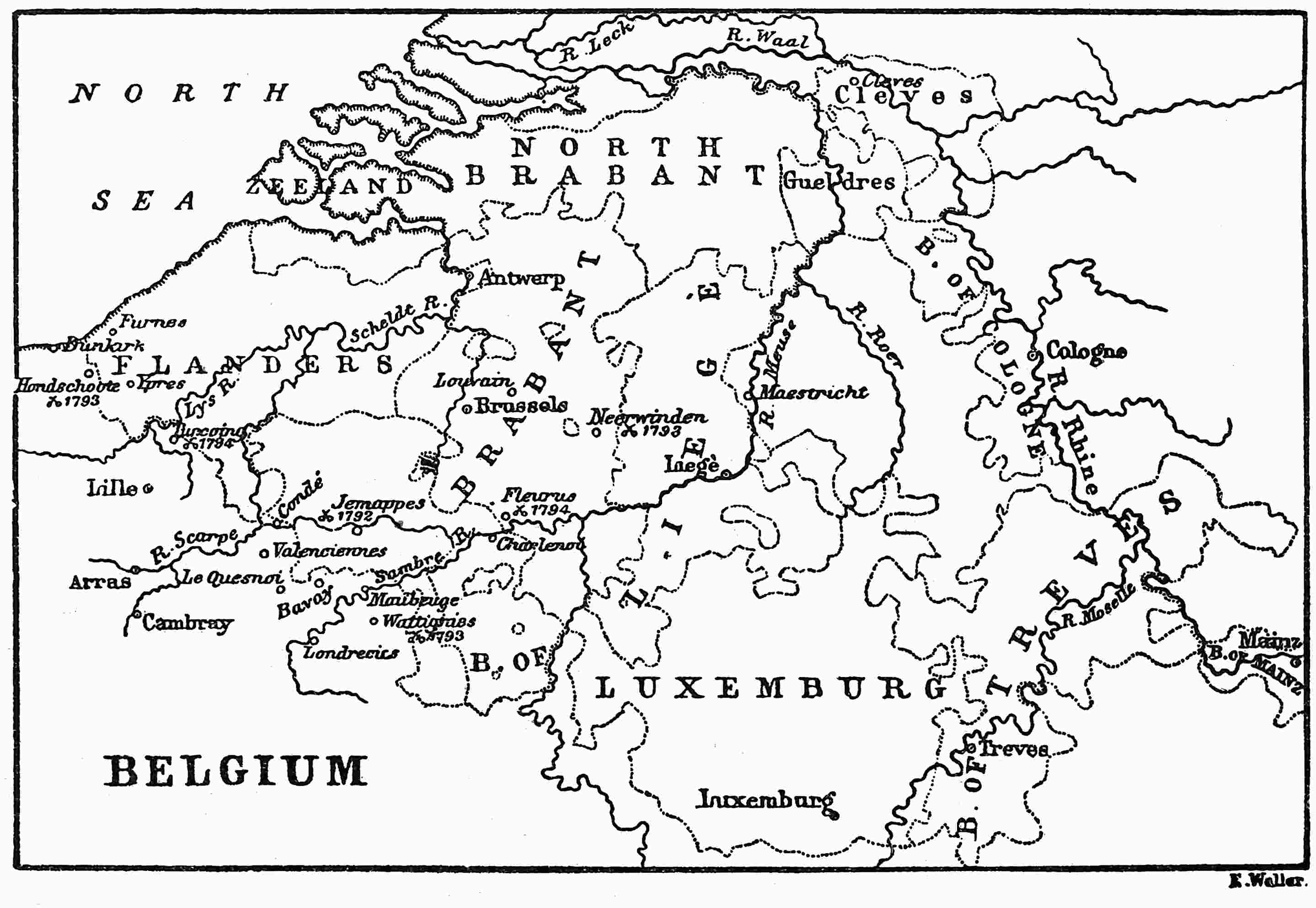

| Campaign in Belgium and the Rhine; Victories of Hondschoote and Wattignies | 191 |

| The Allies expelled from Alsace by Hoche and Pichegru | 192 |

| Legislation of the Convention | 193 |

| Cambon’s financial measures | 195 |

| Growing feeling against the Commune | 196 |

| Robespierre attacks the Hébertists | 197 |

| The Old Cordelier | 199 |

| The Hébertists attack the Dantonists | 200 |

| Robespierre’s influence over the Jacobins | 201 |

| Robespierre abandons the Dantonists | 202 |

| Execution of the Hébertists and Dantonists | 204 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE FALL OF ROBESPIERRE, 1794. | |

| Despotism of the Committee of Public Safety | 204 |

| Aims of Robespierre | 205 |

| Aims of St. Just | 206 |

| Financial object of the continuation of the Terror | 207 |

| The Terror systematised | 208 |

| Renewal of the War in La Vendée | 209 |

| Treaty of the Hague between England and Prussia | 209 |

| Insurrection in Poland | 210 |

| Differences between England and Prussia | 211 |

| The Allied Forces driven from Belgium | 212 |

| Worship of the Supreme Being instituted by Robespierre | 214 |

| Increased activity of the Revolutionary Court | 215 |

| Position of Robespierre | 216 |

| Discords break out within the Committee of Public Safety | 217 |

| Insurrection of Thermidor | 219 |

| Execution of the Robespierrists | 220xvi |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| FALL OF THE MONTAGNARDS, 1794–1795. | |

| Reactionary Movement in Paris and in the Departments | 221 |

| Parties in the Convention | 222 |

| Readmission of the expelled Girondist Deputies to the Convention | 223 |

| Repeal of Maximum Laws, and suffering in Paris | 225 |

| Insurrection of Germinal 12 | 226 |

| Reaction in Paris, and in the Departments | 227 |

| The public exercise of all forms of worship permitted by the Convention | 228 |

| The White Terror | 229 |

| Insurrection of Prairial 1 | 230 |

| Proscription of Montagnards | 231 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE TREATY OF BASEL AND THE CONSTITUTION OF 1795. | |

| Conquest of Holland by Pichegru | 232 |

| Foreign policy of the Convention | 233 |

| Foreign policy of Thugut | 235 |

| Foreign policy of Catherine II.; Alliances between Russia and Austria | 236 |

| English foreign policy; Successes at Sea, and conquest of French Colonies | 237 |

| Prussian foreign policy; Peace made at Basel between Prussia and France | 238 |

| Position of Spanish Government; Treaty of Peace between France and Spain | 240 |

| War in the West; Hoche appointed Commander-in-Chief | 242 |

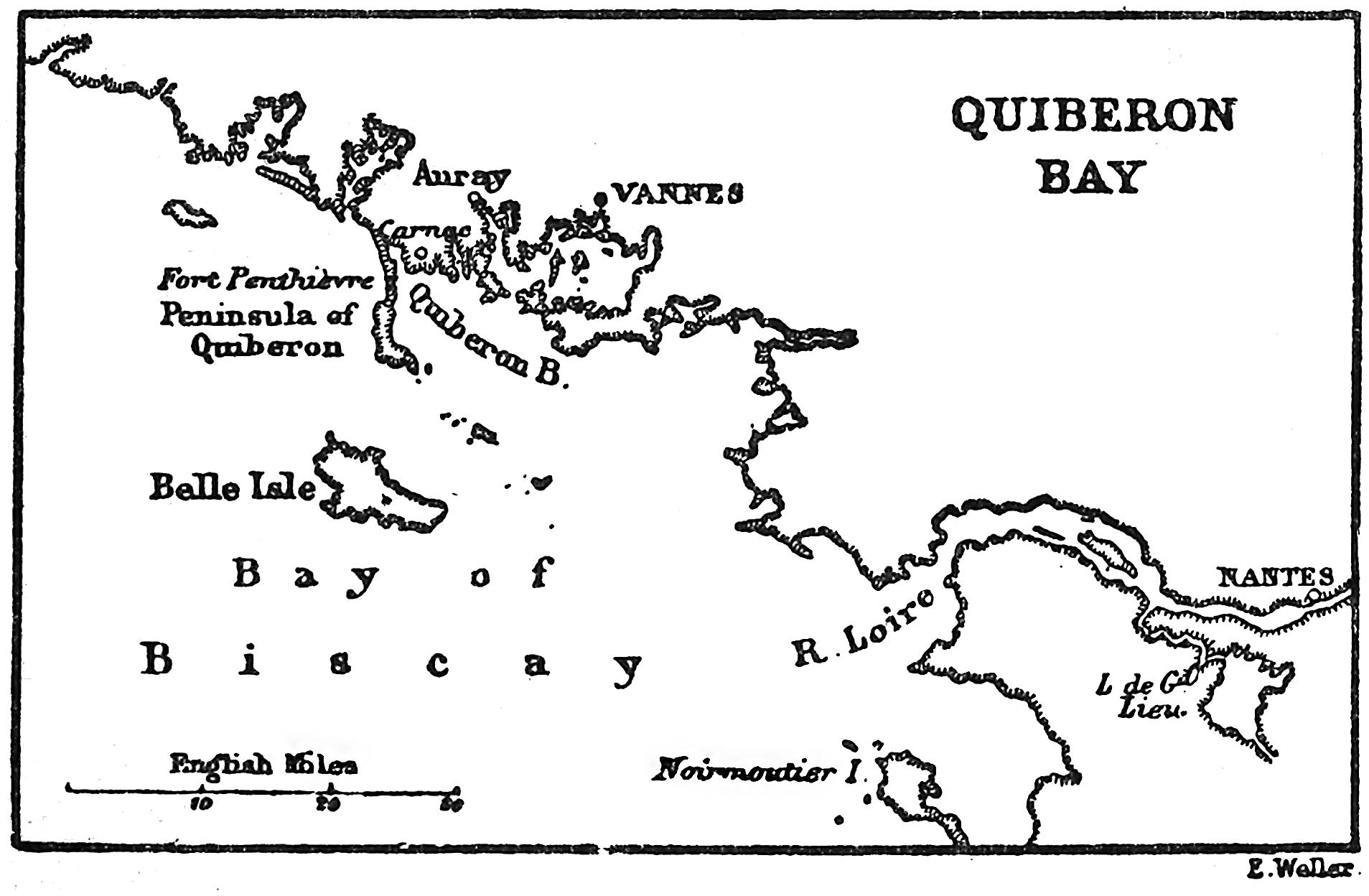

| Expedition of Emigrants to Quiberon | 243 |

| Position of the Convention; its unpopularity | 245 |

| Death of the Dauphin | 245 |

| The Convention sanctions the use of Churches for Catholic worship | 246 |

| Position of the Clergy; Parties amongst them | 247 |

| The Convention frames the Constitution of 1795 | 248xvii |

| Special Laws passed to maintain the Republican Party in Power | 249 |

| Insurrection of Vendémiaire 13 suppressed by Napoleon Bonaparte | 250 |

| Law of Brumaire 3, excluding relations of Emigrants from Office | 250 |

| The Five Directors; Position of the New Government | 251 |

| INDEX | 255 |

MAPS.

| Europe in 1789 To face title page | |

| Map of France in Provinces | 9 |

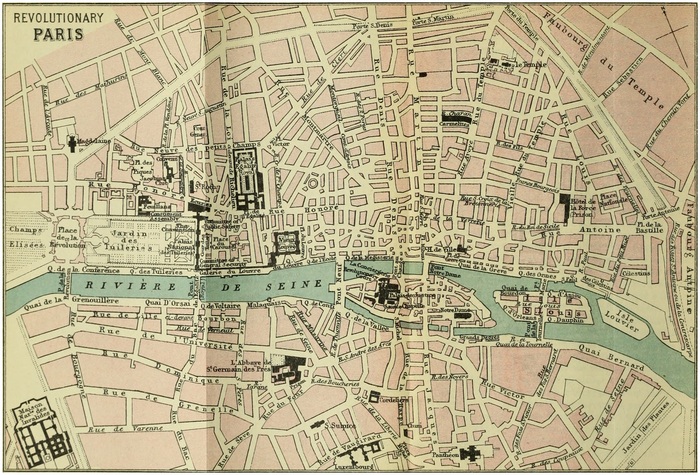

| Revolutionary Paris | 43 |

| Map of France in Departments | 65 |

| Map of Belgium | 132 |

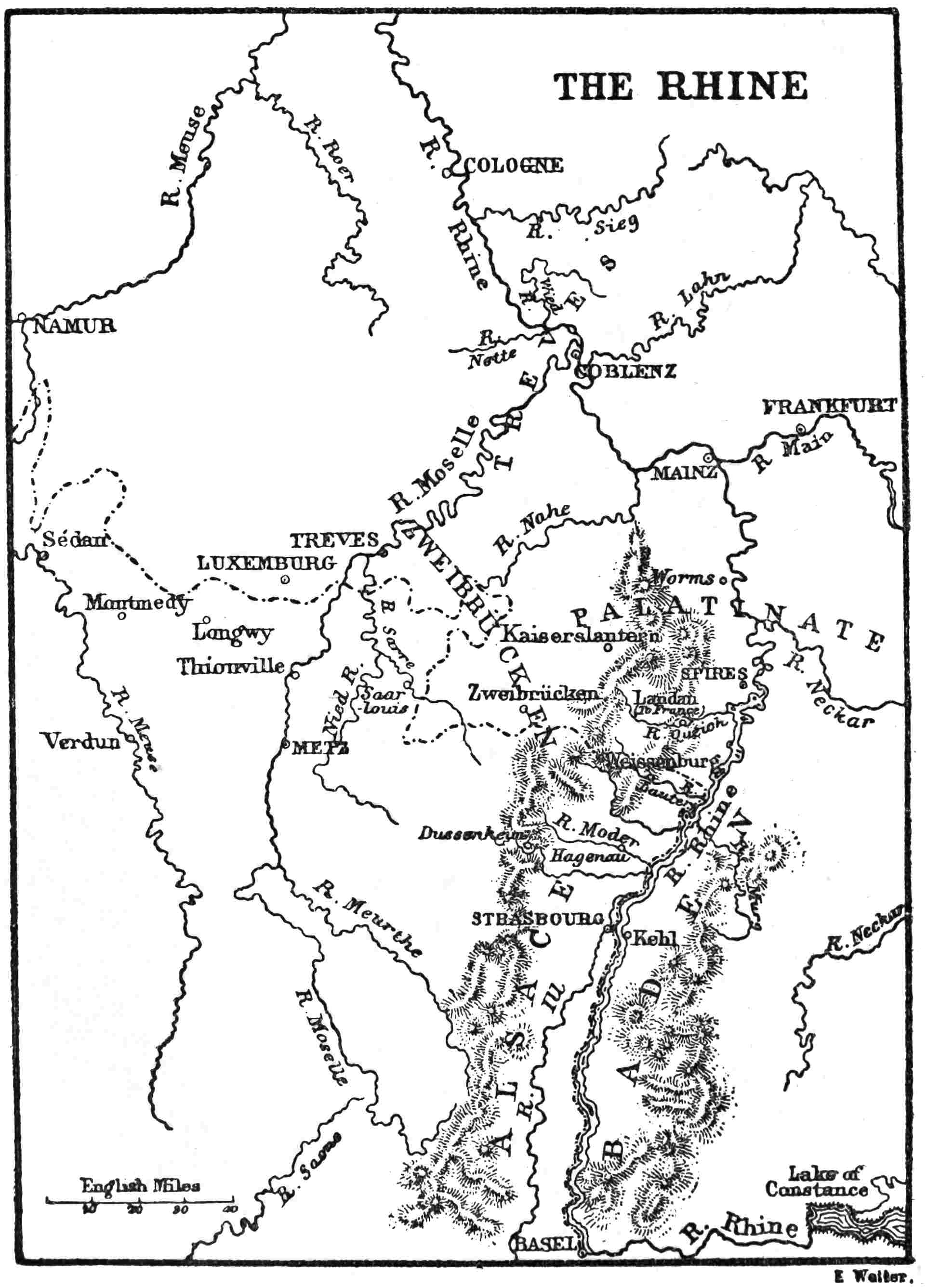

| Map of the Rhine | 190 |

| Map of Quiberon | 241 |

REVOLUTIONARY CALENDAR.

| Vendémiaire | Sept. | Oct. |

| Brumaire | Oct. | Nov. |

| Frimaire | Nov. | Dec. |

| Nivose | Dec. | Jan. |

| Pluviose | Jan. | Feb. |

| Ventose | Feb. | March |

| Germinal | Mar. | April |

| Floréal | April | May |

| Prairial | May | June |

| Messidor | June | July |

| Thermidor | July | Aug. |

| Fructidor | Aug. | Sept. |

xviii

Dates relating to military or foreign affairs are given in italics in order that the attention of the reader may be drawn to the relation between them and the domestic occurrences.

| 1774 | |

| Accession of Louis XVI.—Ministry of Turgot. | |

| 1776 | |

| Dismissal of Turgot—Ministry of Necker—American Declaration of Independence. | |

| 1778 | |

| France allies itself with America. | |

| 1781 | |

| Resignation of Necker. | |

| 1783 | |

| Calonne’s Ministry. | |

| 1787 | |

| The Assembly of Notables—Brienne’s Ministry. | |

| 1788 | |

| Necker’s Second Ministry. | |

| 1789 | |

| May 5. | Meeting of the States General. |

| June 17. | Adoption of the title of National Assembly. |

| June 20. | The Tennis Court Oath. |

| June 23. | The King comes to the Assembly to command the separation of the Orders. |

| July 14. | Capture of the Bastille. |

| Aug. 4. | Abolition of feudal rights. |

| Oct. 6. | The King brought to Paris.xix |

| 1790 | |

| July 14. | Feast of the Federation. |

| Nov. 27. | Oath imposed on the Clergy. |

| 1791 | |

| April 2. | Death of Mirabeau. |

| June 20. | The Flight to Varennes. |

| July 17. | The Massacre of the Champ de Mars |

| Aug. 27. | Declaration of Pilnitz. |

| Sept. 30. | End of the Constituent Assembly. |

| Oct. 1. | Meeting of the Legislative Assembly. |

| 1792 | |

| April 20. | Declaration of War against the King of Hungary and Bohemia, entailing also a War with Prussia. |

| June 13. | Dismissal of the Girondist Ministers. |

| June 20. | The King mobbed in the Tuileries. |

| July 26. | The Duke of Brunswick’s Manifesto. |

| Aug. 10. | Overthrow of the Monarchy. |

| Aug. 24. | Surrender of Longwy. |

| Sept. 2–7. | The September Massacres. |

| Sept. 20. | The Cannonade of Valmy. |

| Sept. 21. | Meeting of the Convention. |

| Sept. 22. | Proclamation of the Republic. |

| Nov. 6. | Victory of Jemmapes, followed by the occupation of Belgium, Savoy, Nice, and Mainz. |

| Nov. 19. | The Convention offers assistance to all Peoples desirous of freedom. |

| Dec. 2. | The French driven out of Frankfort. |

| Dec. 15. | The Convention orders its Generals to revolutionise the Foreign Countries in which they are. |

| 1793 | |

| Jan. 21. | Execution of the King. |

| Feb. 1. | Declaration of War against England and Holland. |

| Mar. 3. | Miranda driven from Maestricht. |

| Mar. 9. | Establishment of the Revolutionary Court. |

| Mar. 18. | Defeat of Neerwinden, followed by the loss of Belgium. |

| April 6. | Constitution of the Committee of Public Safety.xx |

| June 2. | Expulsion of the Girondists. |

| July 3. | Assassination of Marat. |

| July 8. | Surrender of Mainz, Condé, and Valenciennes. |

| Aug. 23. | The Levy of all men capable of bearing arms decreed. |

| Sept. 8. | Victory of Hondschoote. |

| Sept. 17. | The great Maximum Law and the Law against Suspected Persons. |

| Oct. 7. | Capture of Lyons. |

| Oct. 16. | Execution of the Queen. |

| Oct. 16. | Victory of Wattignies. |

| Oct. 31. | Execution of the Girondists. |

| Nov. 10. | Worship of Reason at Notre Dame. |

| Dec. 10. | Capture of Toulon. |

| Dec. 12. | Destruction of the Vendean Army at Le Mans. |

| 1794 | |

| Mar. 24. | Execution of the Hébertists. |

| April 5. | Execution of the Dantonists. |

| April. | Insurrection in Poland. |

| April 18. | Victory of Turcoing. |

| June 1. | Battle of June 1. |

| June 8. | Feast in honour of the Supreme Being. |

| June 26. | Victory of Fleurus, followed by the evacuation of Belgium by the Allies. |

| July 28. | Execution of the Robespierrists. |

| Nov. 12. | Jacobin Club closed. |

| Dec. 8. | Seventy-three Deputies of the Right readmitted into the Convention. |

| Dec. 24. | Repeal of Maximum Laws. |

| 1795 | |

| Jan. | Invasion of Holland. |

| Mar. 8. | Readmission to the Convention of survivors of Girondist Deputies proscribed on June 2, 1793. |

| April 1. | (Germinal 12) Insurrection of Lower Classes against the Convention. |

| Feb. 22. | Public exercise of all forms of worship permitted by the Convention. |

| May 20. | (Prairial 1) Second insurrection by Lower Classes against the Convention.xxi |

| April 5. | Treaty of Peace made at Basel between France and Prussia. |

| June 8. | Death of the Dauphin. |

| July 12. | Treaty of Peace between France and Spain. |

| July 21. | Defeat of Emigrants at Quiberon. |

| Sept. 23. | Proclamation of the Constitution of the Year III. (1795). |

| Oct. 5. | (Vendémiaire 13) Insurrection of the Middle Classes against the Convention. |

| Oct. 26. | (Brumaire 4) Meeting of the New Legislature. |

xxii

1

Like the rest of Western Europe, France, in the Middle Ages, was ruled by a feudal nobility, holding their lands of the king. Nowhere in Western Europe in the tenth century was the power of the king less, or the power of the nobles greater. The weight of their authority, therefore, fell heavily upon the peasants on their estates, and upon the inhabitants of the little towns scattered over the country. A feudal noble, if he were a seigneur, answering to our lord of the manor, ruled all dwellers on his estate. Their claims to property were heard in his courts, and they were amenable to his jurisdiction for crimes committed, or alleged to have been committed, by them. The seigneur may not have been a worse tyrant than many kings and princes of whom we read in history; but he was always close at hand, whilst Nero or Ivan the Terrible was far off from the mass of his subjects. He knew all his subjects by sight, had his own passions to gratify amongst them, and his vengeance to wreak upon those whom he personally disliked. To be free from this domination must have been the one thought of thousands of miserable wretches.

To shake off the yoke by their own efforts was an2 impossibility. The nearest ally on whom they could count was the king. He too was opposed to the domination of the nobles, for as long as they could disregard his orders with impunity, he was king in name alone. He was, in fact, but one nobleman amongst many, with a higher title than the rest.

Dwellers in towns could more readily coalesce and resist the authority of the seigneurs than dwellers in the country. By trade they acquired wealth, and with wealth influence. In the twelfth century they formed themselves into municipal communities, and, bidding defiance to their seigneurs, called upon their king to aid them in achieving independence. From that time to the end of the seventeenth century the power of the Monarchy grew stronger with every succeeding generation. The king was the dispenser of law and order, while the enemies of law and order were the feudal nobles. When Louis XIV. took the government into his own hands, in 1661, his will was law. Justice was administered by parliaments or law courts acting in the name of the king. The affairs of the provinces were administered by intendants, acting by his commission. No nobleman, however wealthy or highly placed, dared to resist his authority. With the frank gaiety of their nation the nobles themselves accepted the position, and crowded to his court or confronted death in his armies. He was able to say, without fear of contradiction, ‘I am the State.’

Unhappily for his people, he could not say ‘I am the Nation.’ In him the Monarchy had been victorious over its enemies, but it had not accomplished its task. The nation wanted more work from its kings, wanted simply that they should go on in the path which had been trodden by their ancestors. The national wish was too feebly expressed to reach the ears of Louis. He was thinking of military glory and courtly display, not of the3 grievances of his people. He had overthrown the power of the nobility so far as it threatened his own. He did not care to inquire whether there was enough left to produce cruel wrong far off from the splendid palace of Versailles. His great-grandson, the vile, profligate Louis XV., had even less thought for the exercise of the duties of a king, as father of his people. The Monarchy was in its decline, not because it was intentionally tyrannical, but because it had ceased to do its duty. The French people were not Republican. They needed a government, and government in any true sense there was none.

In consequence of the king thus deserting the path trodden by his ancestors, a state of things arose in France such as was found in no other country. Nowhere did the nobility as a class do so little for the service of their countrymen, yet nowhere were they in possession of more social influence or greater privileges. Nowhere were the mercantile and trading classes comparatively more wealthy and intellectual, yet nowhere was the distinction between the noble and the plebeian or bourgeois more rigorously maintained. Finally, in no other country where, as was the case in France, the mass of peasants were free men, did the owners of fiefs retain so many rights over the dwellers on their estates, and yet live in such complete separation from them.

After the nobles had lost political power they were cut off from all healthy communication with their fellow subjects. In France all sons and daughters of noblemen were noble, and their families did not blend with those of other classes like the family of an English peer. Nobles contemned the service of the administration as beneath their birth; on the contrary, no one who was not of noble birth could hold the rank of an officer4 in the army. The great lords flocked to Paris and Versailles, where they wasted their substance in extravagant living; the lesser nobles, men who in England would have occupied the position of country gentlemen, were often through poverty compelled to reside in their châteaux, where they lived in isolation, having no common interests with their neighbours, while clinging tenaciously to the possession of their rights as proprietors and feudal lords. ♦Feudal rights.♦ These feudal rights varied in every province, but were of three general kinds. (1) Rights which had their origin when the seigneur was also ruler—as, for instance, the right of administering justice, though this he now almost invariably farmed to the highest bidder; the right of levying tolls at fairs and bridges; and the exclusive right of fishing and hunting. (2) Peasants in the position of serfs were only to be found in Alsace and Lorraine; but rights still existed all over the country which betrayed a servile origin. Thus, the farmer might not grind his corn but at the seigneur’s mill, nor the vine-grower press his grapes but at the seigneur’s press; and every man living on the fief must labour for the seigneur without return so many days in the year. (3) Finally, the courts ruled that wherever land was held by a peasant from the owner of a fief, there was a presumption that the owner retained a claim to enforce cultivation and the payment of annual dues. Land so held was termed a censive—resembling an English copyhold. The granting of land on these terms never stopped from the close of the Middle Ages down to the Revolution. The dues retained were often petty. One tenant might pay a small measure of oats; another a couple of chickens. Yet the payments were often sufficiently numerous to form the chief maintenance of many of the nobles. The holders of these censives possessed however, all the rights of proprietors. They could not be dispossessed so long5 as they paid the dues to which they were liable, and they could sell and devise the land without the consent of the owners of the fief. Properties held on these terms abounded in all parts of France, and though the extent of each censive was often no more than a couple of acres, it is probable that before the Revolution at least a fifth of the soil had by these means passed into the possession of the peasantry.

The existence of feudal rights produced three results exceedingly detrimental to the national prosperity. It impeded a good cultivation of the soil; it prevented the country from being inhabited by men of the middle class, who preferred to reside in towns rather than recognise the social superiority claimed by the seigneur; and, finally, it was an incessant source of irritation to the whole rural population. By the rights due to a seigneur as ruler, and by those of servile origin, all dwellers upon the fief were affected, whether occupiers of land or not. The cultivator suffered at every turn—in the prohibition to plant what crops he pleased; in the prohibition to destroy the seigneur’s deer and rabbits that roamed at will over his fields and devoured his green corn; in the toll he paid for leave to guard his crops while growing, and to sell them after they were gathered in; and in many other ways. Such a system had become in the course of centuries both excessively complicated and wholly unsuited to existing social conditions. Sometimes half-a-dozen different persons claimed dues from the same piece of land. The proprietorship of fiefs and the ownership of feudal rights, or the greater part of them, were constantly separated. Poverty induced the resident seigneur to sell his rights, which, bought by a townsman, passed from hand to hand in the market, like any other property, and were the more sought after because their possession was held a sign of social superiority.6 Non-resident owners farmed them, and middle-men were harsh and exacting in their collection. The peasant, ignorant and poor, but thrifty and cunning, and fondly attached to his plot of ground, disputed claims made upon him to pay dues now to this man, now to that, in virtue of concessions of which, in a vast number of cases, the origin was completely lost. Innumerable lawsuits resulted, which left stored up in the peasant’s mind bitter feelings of resentment against both judge and seigneur, one of whom he accused of partiality, the other of rapacity and extortion.

The maintenance of feudal relations between classes, when neither government nor society rested on the same bases as in feudal times, could only be productive of harm. In right of birth privileges and advantages were claimed by nobles without regard to principles of justice or of public utility. On every side, in the army, the navy, the profession of the law, distinction between the nobleman and the bourgeois still prevailed. But no institution suffered in consequence of the privileges of the nobility so great moral detriment as the Church. The Church was a rich, self-governed corporation, in possession of an annual revenue of more than 8,750,000l., providing for about 130,000 persons, including monks and nuns. This great wealth was unfairly distributed, and to a large extent misapplied. As a rule, all higher posts were reserved for portionless daughters and younger sons of noble families. Bishops and abbots, who revelled in wealth, were nobles; parish priests, who had barely enough for subsistence, were bourgeois and peasants. Thus the Church teemed with abuses, and exerted little moral influence. Her wealth excited the jealousy of the middle classes, whilst the luxurious and profligate lives led by many prelates and holders of sinecures brought disgrace on the ecclesiastical profession.7 Of reform there was no hope, since the lower clergy, who had interest in effecting it, were excluded from all part in Church government.

Such abuses called aloud for the hand of a reformer. The material result of social disorder was impoverishment and decay. ‘Whenever you stumble on a grand seigneur,’ wrote an English traveller, ‘you are sure to find his property a desert.... Go to his residence, wherever it may be, and you will probably find it in the midst of a forest very well peopled with deer, wild boars, and wolves. Oh! if I were the legislator of France for a day, I would make such great lords skip.’ The king had acquired power in right of the services he rendered the nation. When he ceased to do good, as had been the case since Louis XIV. plunged the nation into a series of wars of ambition, it was inevitable that he should do harm. The welfare of the masses was dependent on the action of the central government, and the central government sacrificed their welfare for the sake of obtaining favour with the upper classes. Hence administration was in a chaos, and the government, in appearance all powerful, was in reality strong only when it had to deal with the crushed and helpless peasant and artisan. The States-General, which in some sort answered to our English Parliament, had last met in 1614. For the past two centuries the royal council had been engaged in undermining local liberties, and establishing a centralised system of administration. The work in all essentials was so thoroughly done, that no parish business, down to the raising of a rate or the repairing of a church-steeple, could be effected without authorisation from Paris. Absolute and centralised, the government was also excessively arbitrary. On plea of State necessity it repudiated debts, broke contracts, over-ruled laws, and set aside proprietary rights without8 scruple. The issue of warrants, called lettres de cachet sealed letters, ordering the imprisonment of the person designated in some state fortress, was an ordinary mode of inflicting punishment. Yet, however harsh and arbitrary in treatment of individuals, the government sought to avoid collision with the upper classes as a body. On all sides it left standing institutions of the Middle Ages, local functionaries, and municipal assemblies, of which the existence in many instances increased the weight of local charges and impeded attempts to ameliorate the condition of the working classes. In the same way the upper law courts, the Parliaments, were suffered as of old to meddle in administrative matters. Privileges, so far from being assailed, were respected. Whatever special rights provinces, towns, or classes possessed were suffered to remain and were often extended.

The wars of Louis XIV. and the orgies of Louis XV. absorbed more and more money. On the labouring classes, already overtaxed, an increased weight of taxation was always being laid. Hence, of these classes the king became the oppressor, and the oppression was the greater because the upper classes, who were best able to pay taxes, contributed much less than their fair share of the burden.

The nobles and clergy, styled the two upper orders, stood, in right of their privileges, both pecuniary and honorary, apart from the rest of the nation. Nobles did not pay any direct taxes in the same proportion as their fellow subjects, and in the case of the taille, a heavy property tax, their privilege approached very nearly to entire exemption. The clergy, except in a few frontier provinces, paid personally no direct taxes whatever. The bourgeoisie was regarded as an inferior class. Those who were able acquired by purchase the rank and privileges of nobles, and in this way had come into existence a nobility9 of office and royal creation, which, although looked down upon by the old nobility of the sword, enjoyed the same pecuniary immunities. Those left on the other side of the line deeply resented the social superiority claimed by the nobility in right of its privileges. The upper section of the bourgeoisie was, however, itself privileged to no inconsiderable extent. By living in towns, merchants, shopkeepers, and professional men were able to avoid serving in the militia and collecting the taille, from which in the country nobles alone were exempt. They also purchased of the government petty offices, created in order that they might be sold, to which no serious duties were attached, but the possession of which conferred on the holders partial exemption from payment of the taille and of excise duties, and other privileges of like character.

FRANCE IN PROVINCES 1769–1789.

Longmans, Green & Co., London, New York, Bombay, Calcutta & Madras.

Oppressive as taxation was, owing to its weight alone, and to its unjust distribution between classes, it was rendered yet more so by want of administrative unity, by the nature of some of the taxes and the method of their assessment and collection. Internal custom-houses and tolls impeded trade, gave rise to smuggling, and raised the price of all articles of food and clothing. It took three and a half months to carry goods from Provence to Normandy, which, but for delays caused by the imposition of duties, might have travelled in three weeks. Customs duties were levied with such strictness that artisans who crossed the Rhône on their way to their work had to pay on the victuals which they carried in their pockets. Excise duties were laid on articles of commonest use and consumption, such as candles, fuel, wine, and even on grain and flour. Some provinces and towns were privileged in relation to certain taxes, and as a rule it was the poorest provinces on which the heaviest burdens lay. One of the most iniquitous of the taxes10 was the gabelle, or tax on salt. Of this tax, which was farmed, two-thirds of the whole were levied on a third of the kingdom. The price varied so much that the same measure which cost a few shillings in one province cost two or three pounds in another. The farmers of the tax had behind them a small army of officials for the suppression of smuggling, as well as special courts for the punishment of those who disobeyed fiscal regulations. These regulations were minute and vexatious in the extreme. Throughout the north and centre of France, the gabelle was in reality a poll tax; the sale of salt was a monopoly in the hands of the farmers; no one might use other salt than that sold by them, and it was obligatory on every person aged above seven years to purchase seven pounds yearly. This salt, however, of which the purchase was obligatory, might only be used for purely cooking purposes. If the farmer wished to salt his pig, or the fisherman his fish, they must buy additional salt and obtain a certificate that such purchase had been made. Thousands of persons, either for inability to pay the tax, or for attempting to evade the laws of the farm, were yearly fined, imprisoned, sent to the galleys, or hanged. The chief of the property taxes, the taille, inflicted as much suffering as the gabelle, and was also ruinous to agriculture. Over two-thirds of France the taille was a tax on land, houses, and industry, reassessed every year not according to any fixed rate, but according to the presumed capacity of the province, the parish, and the individual taxpayers. The consequence was that, on the smallest indication of prosperity, the amount of the tax was raised, and thus parish after parish, and farmer after farmer, were reduced to the same dead level of indigence.

Under the state of things here described, France had retrograded in wealth and population. Intense misery11 prevailed amongst the working classes. Artisans were unable to live on their wages; farmers and small proprietors were constantly being reduced to beggary; ignorance grew more dense. The government, by its own frequent setting aside of laws, and by its intolerance and cruelty, helped to render the people lawless, superstitious, and ferocious. Protestants were subjected to persecuting laws. Thousands of them had been driven from the country, or shot down by troops. The penal code was barbarous, and the brutal breaking on the wheel was an ordinary mode of putting criminals to death. It was only by very rough usage that fiscal regulations were maintained, and the taxes gathered in. If the taille and the gabelle were not paid, the defaulter’s goods were sold over his head, and his house dismantled of roof and door. In all cases in which the administration was concerned, whatever justice peasant and artisan received was meted to them by administrative officials who were themselves parties in the cause. Famine was like a disease which counted its victims by hundreds. As a rule, the farmer was a poor and ignorant peasant, living from hand to mouth, miserably housed, clothed, and fed.

An Englishman, Arthur Young, travelling in France in the years 1788–1789, reports how he passed over miles and miles of country once cultivated, but then covered with ling and broom; and how within a short distance of large towns no signs of wealth or comfort were visible. ‘There are no gentle transitions from ease to comfort, from comfort to wealth; you pass at once from beggary to profusion. The country deserted, or if a gentleman in it, you find him in some wretched hole, to save that money which is lavished with profusion in the luxuries of a capital.’ The same traveller tells us how, as he was walking up a hill in Champagne, he was12 joined by a poor woman who complained of the hardness of the times. ‘She said her husband had but a morsel of land, one cow and a poor little horse, yet he had a franchar (42 lbs.) of wheat and three chickens to pay as a quit rent to one seigneur, and four franchars of oats, one chicken, and one shilling to pay another, besides very heavy tailles and other taxes. She had seven children, and the cow’s milk helped to make the soup. It was said, at present, that something was to be done by some great folks for such poor ones, but she did not know who nor how, but God send us better, “car les tailles et les droits nous écrasent.” This woman, at no great distance, might have been taken for sixty or seventy, her figure was so bent and her face so furrowed and hardened by labour, but she said she was only twenty-eight.’

Since, owing to the weight of taxation, no profits were to be made by farming, it was impossible that there should be a good cultivation of the soil. The amount of capital employed on land in England was at least double that employed in France. Hence, while in England famine was unknown, in France production barely equalled consumption, and scarcities were of incessant occurrence. A single bad season would force the farmer to desert his land, and with his family beg or steal. Whenever bread rose above three halfpence the pound men starved. Bread riots constantly took place in one or another province, and the country swarmed with beggars, brigands, poachers, and smugglers. Thousands of these outcasts were imprisoned, sent to the galleys, or hanged; but no severity could lessen their number, while the causes producing them remained unremoved. Adequate means of providing for the destitute there were none. A few hospitals and other charitable institutions existed. Bishops, great seigneurs, and monasteries often kept alive hundreds in seasons of scarcity. Hospitals,13 however, were little better than plague houses, where the sick and infirm were taken in to die, whilst private charity was partial and insufficient. There was no general system of poor relief. With the object of keeping bread at a price within the people’s reach, the corn trade was subject to a variety of regulations and restrictions. Occasionally the government made purchases of foreign corn, which was resold under price. Sometimes the prices of corn and other articles of food were fixed. In towns the price of bread was ordinarily regulated according to the price of corn by police officers, a not unnecessary precaution when the baking trade was in the hands of a close corporation. A more vicious mode of relief could hardly have been devised, but to abandon it was no easy matter. The arbitrary means taken to reduce the price of corn often had the effect of raising it, and, when successful, only tended to lessen production and lead to greater scarcities, since cutting down the profit of the already overweighted corn grower was, in reality, casting an additional tax upon him. On the other hand, it was no less true that so long as the existing order continued, a slight rise in the price of the pound of bread meant sheer starvation for the mass of artisans, and for thousands of agricultural labourers and small proprietors who were not corn growers. Accustomed to look to the government to provide them with cheap bread, in every season of scarcity these clamoured for a reduction in price, and unless authorities were complaisant, resorted to riot and pillage.

The misery of the working classes presented in itself reason enough for revolution; but revolution only comes when there are men of ideas to lead the unlettered masses. In France the educated classes entertained revolutionary ideas, and the men of letters who promulgated those ideas became the leaders of opinion, and exerted enormous influence over their14 own and the following generations. First came the Voltairians, led by Voltaire (1694–1778). During the century rapid advance was being made in all branches of study—in history, jurisprudence, mathematical and physical science. The idea of progress was definitely conceived, and knowledge upheld as the chief factor in producing virtue and happiness. For the increase and diffusion of knowledge the recognition of two principles was indispensable—religious toleration and the freedom of the press. Both these principles were, however, in direct antagonism to the principles on which the authority of the Roman Catholic Church was based—unity of faith and worship, the subordination of philosophy and science to theology, the submission of reason to the teaching of tradition. Protestant clergymen were put to death as late as 1762; while in 1765 a lad convicted of sacrilege was hanged, and his body afterwards burned. Such acts of intolerance and cruelty were, however, condemned by public opinion, and, between the Church and the exponents of the new ideas, violent collision inevitably ensued. Voltaire made it the work of his life to destroy belief in revealed religion. In verse and in prose, in historical works, in letters and pamphlets by the dozen, with rude licence or sham respect, he held up the Church to derision, indignation, and contempt, as the great enemy of enlightenment and humanity. ‘The most absurd of empires,’ he wrote, ‘the most humiliating for human nature, is that of priests; and of all sacerdotal empires, the most criminal is that of priests of the Christian religion.’

Voltaire himself was a sceptic. Behind him followed men who denied belief in a personal God and the immortality of the soul. Diderot (1713–1784) and D’Alembert (1717–1783), with indefatigable energy published the ‘Encyclopædia,’ or dictionary of universal knowledge, inculcating, at least indirectly,15 atheistical opinions, and designed, by the destruction of ignorance and superstition, to undermine the whole fabric of Christian theology. Before the end of his long life, in 1778, Voltaire was the most eminent man in France, and sceptical and atheistical opinions were commonly held and openly professed by men and women of the upper and middle classes. The triumph of the new philosophy was not, indeed, due merely to the powers of irony or the reasoning of its advocates. The scandalous abuses within the Church had prepared the way for its reception. The attacked had no efficient weapon with which to repel their assailants. The Church was without reforming energy or proselytising zeal. On the arm of the State she could not rely for support with the same confidence as in former times. The government was incapable of stamping out the new movement, nor was it prepared seriously to make the attempt. The official class, which came out of the middle class, was, like all others, permeated with the new ideas. The occasional arrest of authors and printers, and seizure of types and presses, did but increase the virulence of the attack, and made the forbidden books more eagerly sought after. The clergy were the more open to attack because they were interested in the maintenance of privileges and abuses which inflicted cruel wrongs on the working classes, while the new philosophy aimed at destroying whatever stood in the way of material progress and the happiness of the masses. In opposition to the Church’s doctrine of the natural depravity of human nature, its adherents taught that man is born good, and that wrong-doing is the result of ignorance; inculcated the importance of educating all classes, and refused to recognise limits to the improvement of which both individuals and the race are capable. Often accompanied by a sensual view of life, which accorded with the profligacy common16 amongst the upper classes at the time, this high opinion of human nature developed a respect for man as man, regardless of social position, race, or creed, and a passionate hatred of inequalities founded on such distinctions. ♦Economists.♦ A school of political economists, starting from the theory that all men originally had equal rights, and every man liberty to employ his time, his hands, and his brains according to his own advantage, demonstrated the principles of free trade, and declared entire liberty of agriculture, entire liberty of commerce and industry, entire liberty of the press to be the true foundations of national prosperity. Appealing to abstract principles of justice, humanity and right, Voltairians and Economists joined in opening a fire of scathing criticism on existing laws, customs, and institutions. They exposed the abuses and sufferings incident to the use of torture, serfdom, and the slave trade, to excessive centralisation and interference with trade and agriculture, to close guilds, feudal duties, internal custom-houses, to the taille and the gabelle, and demanded the carrying out of reforms which should set trade and industry free, destroy class and provincial privileges, introduce unity in the administration, and equality of rights between man and man.

The Voltairians were specially characterised by their attack upon the Church and Christianity; the Economists by the importance which they attached to individual liberty. Neither regarded the ignorant and oppressed masses as able to act for themselves, and both looked to the royal power, enlightened by a free press, as the instrument through which reform must be effected. Rousseau was a writer of a different stamp. Instead of idolising knowledge he declared the untaught peasant and artisan the superiors of the philosopher and man of culture. They alone, he said, had retained that17 natural goodness of heart which men had in times long since gone by, when social inequalities along with idleness and luxury were unknown. Rousseau opposed also the atheistic tendencies of the day, declaring belief in a personal God and the immortality of the soul requisite to make life endurable to the oppressed. His indifference to knowledge and culture caused him to regard the masses themselves as alone able to regenerate France, if indeed regeneration were still possible. Society, according to him, was originally based on a contract by which every citizen in return for protection of person and property placed himself under the general will. Laws, therefore, were the expression of the general will; kings were merely the servants of the people, and not they but the people sovereign. Whatever was amiss in France, or in other countries, the fault lay purely with society and government, and should ever idleness and luxury disappear and the people recover their lost sovereignty, then and then only, as in primitive times, would men be happy and virtuous. ‘Man is born free,’ were the opening words of the ‘Social Contract,’ the book in which these theories were maintained, ‘and everywhere he is in chains.’

When the necessity of reform had been demonstrated by a band of powerful and brilliant writers, whose works were the popular reading of the day, it was inevitable that desire for change should grow, as the new ideas spread over wider circles, and sufferers from abuses became more and more alive to their wrongs. Undermined by18 public opinion, the existing order could not endure for long, and the vital question before France was, by what means change should be accomplished. The Voltairians called on the King to take the work in hand, and on the death of Louis XV. in 1774, it appeared possible that the young Louis XVI. would endeavour to regain the path that his predecessors had abandoned, and, by relieving the people from their burdens, seek the welfare of the entire nation. ♦Turgot’s Ministry.♦ Turgot, the new Controller-General, who exercised the functions both of Minister of Finance and Minister of the Interior, represented the party of reform, and was in all his actions inspired by a strong love of knowledge and by a passionate desire to benefit his fellow-men. He was not, like the writers of his time, a mere theorist, but also a practised and successful administrator, who for thirteen years had been Intendant of the poor province of Limousin. Now that he was invested with higher authority, it was Turgot’s aim to ameliorate the condition of the people throughout France, by the introduction of reforms based on those principles of equality and individual liberty which Voltairians and Economists proclaimed. His chief reforms were the abolition of restrictions on the internal trade in corn and wine; the abolition of the corvée, or forced unpaid labour of the peasants for repair of roads, for which he substituted a land-tax payable by all proprietors whether privileged or not; and finally, the abolition of guilds, giving liberty to every one, however poor, to exercise what trade he pleased and to raise his condition according to his capacity. Besides these, his most important measures, Turgot carried out many lesser reforms tending to set labour and industry free, to cheapen food and clothing, and to lessen the burdens of the poor by the equalisation of taxation, and by the abolition of the fiscal abuses and sinecure19 offices which enriched the monied aristocracy of Paris and the court nobility. The reforms, however, which Turgot accomplished were but a small portion of those which he had in contemplation. He aimed at the remodelling of the whole system of taxation, the removal of all custom-houses to the frontier, the abolition of the gabelle, and the substitution for the taille of a new tax to be imposed on the land of all proprietors without exception, the gradual abolition of feudal dues, the grant of civil rights to Protestants, and, finally, the decentralisation of administration by the establishment of provincial assemblies, to be elected by all landed proprietors without distinction of rank. His work was no sooner begun than it was prematurely cut short. A violent opposition party was at once formed, which comprised the court nobility, the upper clergy, the nobility of office, farmers of the gabelle and other indirect taxes, judges in Parliament, masters of guilds and state officials—in a word, all those who made profit out of existing abuses, and whose special privileges were assailed. ‘Everybody fears,’ a friend of Turgot wrote to him, ‘either for himself, or for his brother, or for his friend.’

Whether Turgot was to stand or fall depended entirely on the resolution of the King. Louis XVI. was well-intentioned, conscientious, and sincerely desirous of ruling for the good of his subjects, but he lacked the qualities which are requisite to a prince called on to govern at a great national crisis. He was without self-confidence, irresolute in action, and incapable of judging the real value of men, or of grasping the real bearing of events and measures. He could not even rule his own court. Simple in his tastes, and shy and reserved by disposition, his happiest hours were spent in the hunting field, or in the company of a blacksmith, mastering the art of making locks. It was20 no wonder that such a King should be driven to and fro between conflicting opinions, when those who surrounded his throne, and with whom he came in daily contact, accused his Minister of violence and injustice, and of entertaining projects destructive to monarchical government. ‘The King,’ said Turgot, ‘is above all, for the good of all.’ Louis could never rise to this conception of his position. Turgot would have made him ruler of men equal before the law, and in possession of equal rights as citizens. Desirous as Louis was to ease the lower classes of their burdens, he was never able to conceive of the noble as being on the same footing as the common man. ♦Marie Antoinette.♦ The only person in whom he reposed confidence was his wife, Marie Antoinette, a daughter of the Empress Maria Theresa, and with fatal weakness he often yielded to her desires in opposition to his own better judgment. She had been married to him while still a child, and left to grow up uninstructed and without guides in the corrupt atmosphere of the court of Versailles. At the age of nineteen, when she became Queen, she was a bright and vivacious, but ignorant and thoughtless woman, whose days were spent in a never ceasing round of formalities and dissipation. She employed her influence over her husband to obtain for her friends pensions and offices, without any sense of what was due to her position as Queen in the midst of a frivolous and intriguing court, or of what she owed to the starving and suffering masses who were deprived of their hard-won earnings for the enrichment of an idle and spendthrift nobility. When ministers sought to put a check on her extravagance, or in any way thwarted her inclinations, they provoked her resentment, dangerous in proportion to the power that she was able to exercise over the King. Her aversion to Turgot was the cause which finally produced his dismissal from office. The Austrian ambassador, Mercy, informing21 Maria Theresa of the event, used words of more pregnant meaning than he was himself aware. ‘The Controller-General,’ he said, ‘is of high repute for integrity, and is loved by the people; and it is therefore a misfortune that his dismissal should be in part the Queen’s work. Such use of her influence may one day bring upon her the just reproaches both of her husband and of the entire nation.’

Turgot was the greatest statesman that France had seen since Richelieu. He had a clear comprehension of the economical and social evils under which the country suffered, and of the remedies to be applied to them. The best ideas of the age found room in his capacious mind, and all that he attempted to do had ultimately to be accomplished, though by other means than those which he contemplated. Louis had shown his incapacity to see that it was his first duty to make himself the repairer of wrong and injustice, and truly a representative king, who could say, ‘I am the nation.’ After Turgot’s failure, revolution, that is to say change accompanied by violence and convulsion, became inevitable.

The reforming movement, of which in France Turgot was the representative, was not confined to that country, but was, in fact, an European movement, of which the influence was felt, however faintly, even in the most backward States. Kings and statesmen, under the influence of Voltairian ideas, held sceptical opinions, and took interest in the material condition of their subjects. It was perceived that if monopolies enriched individuals they prevented the development of commerce and industry; that if duties were levied between the provinces of the same kingdom, exchange of commodities could only with difficulty be effected; that if nobles did not pay their fair share of taxation, the revenue of the State suffered, and the working classes were overburdened. Jealous eyes were cast22 upon the territorial wealth of the Catholic Church, and protests were raised against the multiplication of monasteries, and the idle lives led by their inmates. In many States efforts were made to increase the authority of the king by the destruction of provincial and class privileges. The idea that the sovereign reigned for the good of the nation was accepted, at least in theory, by the most autocratic of European princes. In Russia Catherine II., in Prussia Frederick II., invited to their courts and patronised French philosophers. In Spain Aranda, in Tuscany Manfredini, in Portugal Pombal endeavoured to lessen the privileges of nobles and clergy, and to loosen the bonds in which industry and commerce were held. In Savoy feudal charges were abolished, compensation being given to the proprietors. In Parma, in Brunswick, and in other Italian and German states, similar tendencies were manifested. But although the reforming movement, on the lines laid down by Voltaire and the Economists, was not confined to France, nowhere else was there to be found amongst the people any strong desire for reform. In Germany, in Spain, in Italy, the new views were confined to a few theorists and statesmen, and did not penetrate beneath the surface of society. The cause lay in the difference of social conditions. Outside France, nobles, as a rule, lived at home on their estates, still administering justice to peasants and serfs. The middle class took no interest in matters of government, but devoted its energies to scientific and literary pursuits. The lower classes, being still in dependence on the upper, entertained no lively resentment of their privileges. Hence reforming princes could never accomplish more than a few isolated changes without danger of rousing rebellion. Nobles and clergy, the moment their privileges were threatened, offered opposition; the middle class did not care to render support; the lower classes were more ready to follow the23 lead of nobles and clergy than the lead of the government. Of all the princes of his time the Emperor Joseph II. was the boldest innovator. In his hereditary dominions he offended the nobles by the abolition of provincial states, the clergy by closing monasteries and upholding principles of toleration, the people by alterations in their religious services. An insurrection broke out in Belgium under the leadership of nobles and clergy (1789). Both in Galicia and Hungary the nobles threatened to take up arms, and for a time it seemed as if the Austrian dominion would fall to pieces.

In England the same ideas prevailed as on the Continent, but the social and political condition of the country was such as to enable reforms to be accomplished more gradually and with far less violent change than was possible either in France or Austria. The English people had for centuries formed an united nation. No sharp lines of division divided one class from another. The laws were the same for all: younger sons of noblemen ranked as commoners, and country gentlemen sat in Parliament by the side of merchants and traders. A free press prepared the way for change by allowing the discussion of questions of general interest, and free institutions gave political experience, and taught the governing classes the necessity of yielding in time to public opinion. Parliament, which represented only the landed and commercial interests, legislated selfishly, and was slow to admit or redress wrong done to the unrepresented classes; but gross oppression of the lower orders, such as existed in France, was unknown in England. Country gentlemen looked after the affairs of parish and county. The body of the rural population consisted of agricultural labourers maintained by poor-rates when wages fell short. Charges on land due to the lord of the manor, though far from being extinct, existed24 mainly in the form of money payments, affecting only a comparatively small number of persons. Although the same protective principles which prevailed on the Continent prevailed also in England, whatever restraints were laid either on persons in the selection of their calling, or on industry, commerce and agriculture, there was to be found far more liberty than elsewhere. The country was the most flourishing in Europe, and wealth was being rapidly accumulated. Special advance was made in the system of farming by the introduction of the rotation of crops and artificial manures. Wages rose, and bread was cheap, and all classes for a time shared in the general prosperity.

In England a large body of eminent men, philosophers, statesmen, and philanthropists, entertained the new ideas and sought to bring them into practice. In 1776, Adam Smith published the ‘Wealth of Nations,’ in which the principles of free trade were promulgated. The younger Pitt, who took office in 1783, was his disciple. He proposed to abolish restrictions on the trade of Ireland with England, and intended to lessen the power of the aristocracy by a reform of the electoral system. In 1787 a Treaty of Commerce was concluded between England and France, designed to increase trade between the two countries. The most important measures brought forward by Pitt were not, however, carried through Parliament. This was in part owing to the factious opposition of the Whigs, in part to the strong Conservative instincts of the governing classes, but in part also because little discontent or desire for change existed among the people at large.

If, however, England was slow to move, reforms once made rested on a sure foundation. Such was not the case with those made in the name of absolute princes on the Continent. After Turgot’s dismissal, fifty out of25 seventy of the guilds which he had abolished were revived, and the peasants were compelled by blows to resume their labours on the roads. Necker, a Genevese banker, was Turgot’s successor (October 1776). He was not a statesman, like Turgot, with definite aims in view, but he was an able financier and a humane man, holding the philanthropic sentiments of the day, and eager to relieve the condition of the masses. A war with England increased the difficulties of the government. In 1778 Louis, reluctantly following public opinion, assisted the English colonies in America in their struggle for independence. There were only three means of meeting the expenses of the war: increased taxation, economy, and loans. The first was impossible; the second only possible to a limited extent; and Necker, therefore, was compelled to borrow. The loans that he opened were quickly filled up, because men of the middle class, who were the chief lenders, believed that their interests were safe while he directed the finances. But the public debt was greatly increased, and the prospect of the future, with reforms uneffected in the system of taxation, rendered them more dark. Although Necker did not attempt to introduce radical measures such as had excited opposition against Turgot, his abolition of sinecures and other administrative changes gave offence to the same classes. The Parliament of Paris, whose lead was followed by the twelve provincial Parliaments, formed the chief organ of resistance. These Parliaments or law-courts were, in fact, powerful legal corporations to which many hundred persons were attached. The judges belonged to the nobility of office, and were independent of the government, since they held their offices in right of purchase, and might not be dispossessed without proof of misconduct. They exercised, besides judicial, a certain political function, since edicts of the26 King’s council did not have the force of law until they had been registered by the Parliaments. This right of registration in the time of Louis XIV. had been a mere form. If the Parliament of Paris hesitated to carry out his wishes, he held a so-called bed of justice when he came to the court in person, and on his command registration was compulsory. But now that the royal authority had fallen into contempt, the Parliaments offered prolonged resistance, and before the Government could obtain registration of its edicts, intimidation and even the use of military force were resorted to. Necker, when he sought to effect reform, necessarily became involved in quarrels with the Parliaments, and, finding that the King gave but a half-hearted support, he resigned office (1781).

Louis could relieve himself from momentary inconvenience by abandoning a Minister of whom he was weary, but had no power to stay the course of events. Those who had lent money to the government deeply resented Necker’s fall, because they believed him able to secure regular payment of the interest on the national debt. Desire for social change was accompanied by desire for political change also. Rousseau had said that the people was sovereign, and as the incompetency of the crown to carry out the national will became with each successive ministry more manifest, ideas long since vaguely floating in men’s minds gathered strength and consistency. The cause of the American colonies was taken up with immense enthusiasm. The Declaration of Independence (July 4, 1776), which, in accordance with the principles laid down in the ‘Social Contract,’ asserted that all men were created equal and endowed with the natural right of overthrowing an unjust government, was hailed as the enunciation of an universal truth, of which Frenchmen as well as the27 colonists might reap the benefit. Meanwhile government in France grew yearly more utterly weak and helpless. The war with England ended in 1783, but financial embarrassments increased. ♦Calonne.♦ Calonne, who became Controller-General the same year, pursued Necker’s system of borrowing without his justification, and retained office by abstaining from acts calculated to offend the privileged classes. The demands of the Queen and the Court were complied with, and abuses destroyed by Necker again called into existence. ‘If it is possible, madam,’ said the obsequious Minister, on an occasion when the Queen pressed him for money, ‘it shall be done; if it is impossible, it shall be done.’ But such squandering of the revenue could not last for ever. Calonne’s credit broke down, and he was driven as a last resource to propose the reform of the entire system of administration and taxation. By publicity he hoped to overcome resistance. He called together an extraordinary council or assembly of notables, nominated by the King (February 1787), and laid his propositions before them, thinking that in the existing state of opinion they would not venture to refuse support. But this assembly, composed almost entirely of privileged persons, proved recalcitrant. The majority were against the reforms proposed, while the few who approved them were determined that they should be made by an assembly representative of the nation.