From a snapshot by Robert Vaucher.

Correspondent of the Paris L’Illustration.

Title: Six months on the Italian front

Author: Julius M. Price

Release date: October 11, 2023 [eBook #71851]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: E. P. Dutton & Co, 1917

Credits: Peter Becker, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

There is only one Footnote in this book, on page 166. This Footnote has been moved and placed directly under the paragraph that has its anchor [A].

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dashed blue underline.

WORKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR

FROM THE ARCTIC OCEAN TO THE YELLOW SEA

THE LAND OF GOLD

FROM EUSTON TO KLONDIKE

DAME FASHION

MY BOHEMIAN DAYS IN PARIS

MY BOHEMIAN DAYS IN LONDON

From a snapshot by Robert Vaucher.

Correspondent of the Paris L’Illustration.

SIX MONTHS ON

THE ITALIAN FRONT

From the Stelvio to the Adriatic

1915-1916

By

Julius M. Price

War-Artist Correspondent of the

“Illustrated London News”

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON & COMPANY

681 FIFTH AVENUE

1917

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

THE WESTMINSTER PRESS

411A HARROW ROAD

LONDON W

To the Italian Military Authorities

in recognition of the courtesy and many kindnesses

extended to me during my six months’ work with the

glorious Army of Italy.

NOTE

I am indebted to the Directors of the Illustrated London News for their kind permission to reproduce in this book the sketches and drawings I made for them whilst on the Italian Front, a great many of which have already been published.

As the reader will discover for himself, I have no pretensions to pose as a Military Expert. This book is the result of a few hasty impressions gathered over a period which, with all its minor inconveniences and little daily worries, I look back upon as among the happiest and best filled of a somewhat varied career. I have not yielded to the temptation to be interesting at the expense of veracity; to that fact the indulgent reader will, I trust, attribute many of the dull pages. If in the latter half of the book I have laid particular stress on the operations leading up to and culminating in the capture of Gorizia, I hope I may be forgiven, as I had the good luck to be the only foreign correspondent on the spot at these scenes of History-making. In my dedication I have paid a humble tribute to the many kindnesses I received at the hands of the Military Authorities, from His Excellency General Cadorna downwards. I can only repeat it here.

Julius M. Price.

21, Golden Square,

London, W.

January, 1917.

[Pg ix]

| CHAPTER I: | PAGE |

| Marching orders—I leave for Rome—Paris via Folkestone and Boulogne in war time—My campaigning kit—The war-correspondent’s list—Quaint item—Travelling “light”—A box of choice Havanas—Boulogne to Paris; well-intentioned ladies and their “Woodbines”—The one and only cigarette—Paris to Turin—Curious order on train—Method and prescience—Few soldiers on route—Arrival in Rome—A cheap room—No sign of excitement in streets—23rd May—Excitability of the Italian no longer noticeable—Rome unruffled—The declaration of war—On the Corso Umberto that evening—The Café Aragno—National stoicism—The Day—Business as usual—The general mobilisation—A triumph of organization—At the War Office | 3 |

| CHAPTER II: | |

| My credentials—The War Zone—Italy’s preparedness—The Press Censorship—General Elia’s advice—Disappointment—A pipe in the Pincio—An inspiration—I leave for Venice—Venice in war time—The lonely pigeons of the Place St. Marc—The Doge’s Palace—The bronze horses—Interior of St. Marc, strange spectacle—First act of war between Italy and Austria—Aeroplane bombs Venice—French Aviators—Treasures of Venice—Everyday life in Venice during daytime—After nightfall—On the qui vive—Extraordinary precautions—Dangers of the streets—Spy fever—Permis de séjour—The angry crowd—Defences against air attacks—Venice not a place forte—Nearest point of the Front—The British Vice-Consul, Mr. Beak—A good Samaritan—The letter of credentials—The Commandant of Venice—More advice—New Rescript of the Generalissimo—Reference to Correspondents—Decide attempt go to Udine—The language difficulty—The waiter at the Hotel Danielli—His offer to accompany me—Make arrangements at once—Introduced to Peppino Garibaldi—Amusing incident | 15 |

| CHAPTER III:[x] | |

| From Venice to Udine—Reservists rejoining—Interesting crowd—Delays en route—Endless procession of military trains—Drawn blinds—The Red Cross train—Arrived Udine—Scene on platform—In search of an hotel—A little incident—The well-dressed civilian—The obliging guide—My suspicions—Awkward questions—The best hotel in Udine—A little “Trattoria” close by—A cheap room—First impressions of Udine—At the Police Office—The permis de séjour—The Carabinieri and the local police—The fascination of the big guns—The “Military Commandant of Udine”—A difficult proposition—The luck of the undelivered letter—My guide has to leave me—I change my quarters—The Hotel “Tower of London”—Alone in Udine—An awkward predicament—A friend in need—Still more luck—Dr. Berthod—I am offered a studio—I accept—The delight of having this studio in Udine | 25 |

| CHAPTER IV: | |

| The wonderful system on which everything was worked—Udine “the Front”—The commencement of hostilities—The 24th May—The first day of operations auspicious for Italy—Redemption of the province of Friuli—New Italian Front—Cormons—The inhabitants of Italian origin—A good practical joke—The moral of the troops—Unpretentious attempts at wit—High spirits of the men—The road from Udine to Cormons—Wonderful sight—Italian flags everywhere—A mystery where they came from—Wild triumphant advance of the Italian troops—Women kiss the ground—But a lever de rideau—Italians cross the Isonzo—Austrians on Monte Nero—Monte Nero—The capture of Monte Nero—Incredible daring of the Alpini—The story of the great achievement—Number of prisoners taken—The prisoners brought to Udine—Their temporary prison—The tropical heat—An ugly incident—Austrian attempt to re-take Monte Nero—Success follows success—Capture of Monfalcone and Gradisca; Sagrado and Monte Corrada—Commencement of the attack on Gorizia—Subjects for my sketch book—Touches of human nature—High Mass in the mountains—The tentes d’abri—Cheerfulness of men in spite of all hardships | 37 |

| CHAPTER V:[xi] | |

| Udine the Headquarters of the Army—The King—His indefatigability—His undaunted courage—A telling incident—The King with the troops—Love and sympathy between Victor Emanuele and the men—Brotherhood of the whole Army—A pleasant incident—Men salute officers at all times—Laxity shown in London—Cohesion between rank and file—The Italians of to-day—The single idea of all—Udine crowded with soldiers—The military missions of the allied nations—Big trade being done—Orderly and sedate crowd—Restaurants—The food—The market-place—The Cinemas—Proximity of the fighting—The Café “Dorta”—Pretty and smartly-dressed women—An unexpected spectacle—The Military Governor—The streets at night—Precautions against “Taubes”—The signal gun—Curiosity of inhabitants—No excitement—Udine a sort of haven—I remain there six weeks—A meeting with the British Military Attaché, Colonel Lamb—My stay in Udine brought to an abrupt ending—The police officer in mufti—Am arrested—Unpleasant experience—An agent de la Sureté—At the police station—The commissaire—Result of my examination—Novara—Magic effect of the undelivered letter again—I write to General Cafarelli—My friends at the “Agrario”—General Cafarelli—His decision—The third class police ticket for the railway—Packed off to Florence—The end of the adventure | 49 |

| CHAPTER VI: | |

| Florence in war time—War correspondents to visit the Front—I receive a letter from Mr. Capel Cure of the Embassy—Return to Rome—Signor Barzilai, Head of Foreign Press Bureau—I am officially “accepted”—Correspondents to muster at Brescia—Rome to Brescia via Milan—The gathering of the correspondents—Names of those present—Papers represented—The correspondent’s armlet—Speech of welcome by General Porro—Plan of journey announced—Introduced to officers of Censorship—To leave war zone a conclusion of tour of Front—“Shepherding” the correspondents—Censorships established at various places—Correspondents’ motor cars—Clubbing together—Car-parties—My companions—Imposing array of correspondents’ cars—National flags—Cordiality amongst all correspondents and [xii] Censors—Good-fellowship shown by Italians—Banquet to celebrate the occasion | 63 |

| CHAPTER VII: | |

| Brescia—Rough sketch of arrangements—A printed itinerary of tour—Military passes—Rendezvous on certain dates—The “off-days”—Much latitude allowed—We make a start—Matutinal hour—First experience of freedom of action—Like schoolboys let loose—In the valley of Guidicaria—First impression of trenches on mountains—A gigantic furrow—Encampments of thousands of soldiers—Like the great wall of China—Preconceived notions of warfare upset—Trenches on summits of mountains—A vast military colony—Pride of officers and men in their work—Men on “special” work—“Grousing” unknown in Italian Army—Territorials—Middle aged men—“Full of beans”—Territorials in first line trenches—Modern warfare for three-year olds only—Hardy old mountaineers—Heart strain—The road along Lake Garda—Military preparations everywhere—War on the Lake—The flotilla of gun-boats—The Perils of the Lake—A trip on the “Mincio” gun-boat—I make a sketch of Riva—A miniature Gibraltar—Desenzano—Nocturnal activity of mosquitoes—Return to Brescia—Something wrong with the car—Jules Rateau of the Echo de Paris—Arrange excursion to Stelvio Pass—A wonderful motor trip—The Valley of Valtellino—The corkscrew road—Bormio—The Staff Colonel receives us—Permits our visiting positions—Village not evacuated—Hotel open—Officers’ table d’hôte—We create a mild surprise—Spend the night at hotel | 71 |

| CHAPTER VIII: | |

| On the summit of the Forcola—We start off in “military” time—Our guide—Hard climbing—Realize we are no longer youthful—Under fire—Necessary precautions—Our goal in sight—An awful bit of track—Vertigo—A terrifying predicament—In the Forcola position—A gigantic ant-heap—Unique position of the Forcola—A glorious panorama—The Austrian Tyrol—The three frontiers—Shown round [xiii] position—Self-contained arsenal—Lunch in the mess-room—Interesting chat—The “observation post”—The goniometre—Return to Bormio—Decide to pass another night there—An invitation from the sergeants—Amusing incident | 85 |

| CHAPTER IX: | |

| From Brescia to Verona—Absence of military movement in rural districts—Verona—No time for sightseeing—The axis of the Trentino—Roveretto, the focus of operations—Fort Pozzachio—A “dummy fortress”—Wasted labour—Interesting incident—Excursion to Ala—Lunch to the correspondents—Ingenious ferry-boat on River Adige—The Valley of the Adige—Wonderful panorama—“No sketching allowed”—Curious finish of incident—Austrian positions—Desperate fighting—From Verona to Vicenza—The positions of Fiera di Primiero—Capture of Monte Marmolada—The Dolomites—Their weird fascination—A striking incident—The attempted suicide—The Col di Lana—Up the mountains on mules—Sturdy Alpini Method of getting guns and supplies to these great heights—The observation post and telephone cabin on summit—The Colonel of Artillery—What it would have cost to capture the Col di Lana then—The Colonel has an idea—The idea put into execution—The development of the idea—Effect on the Col di Lana—An object lesson—The Colonel gets into hot water—The return down the mountain—Caprili—Under fire—We make for shelter—The village muck-heap—Unpleasant position—A fine example of coolness—The wounded mule—An impromptu dressing | 97 |

| CHAPTER X: | |

| Belluno—Venadoro in the heart of the Dolomites—A fine hotel—Tame excursions—Visit to Cortina d’Ampezzo—Austrian attempts to recapture it—305mm. guns on the Schluderbach—Long range bombardment—Austrian women and children in the town—Italians capture Monte Cristallo—Aeroplanes and observation balloons impossible here—Tofana in hands of Italians—Serenity of garrison—Cortina d’Ampezzo—General invites us to a déjeuner—Living at Venadoro—Delightful camaraderie—Evenings in the big saloon—From Belluno to Gemona—Description of Front in [xiv] this Sector—Our excursion to Pal Grande—The road—On mules up the mountain—A warning—Rough track—Peasant women carrying barbed wire up to the trenches—Pay of the women—Much competition for “vacancies”—The climb from Pal Piccolo to Pal Grande—A wonderful old man—“Some” climb—The entrenched position on Pal Grande—Spice of danger—Violent artillery duel—The noise of the passing shells—Magnificent view—Timau—The Freikoffel—Its capture by the Alpini—Wounded lowered by ropes—Capture of Pal Grande—Presence of mind of a doctor—A telling incident—Extraordinary enthusiasm of the troops—Food convoys—The soldier’s menu—Daily rations—Rancio; the plat du jour—Officers’ mess arrangements—An al fresco lunch on Pal Grande—The “mess-room”—“Pot Luck”—A wonderful meal—A stroll round the position—An improvised bowling alley—Use is second nature—In the trenches—A veteran warrior—The pet of the position—Gemona—The list of lodgings—My landlady—Good restaurants in Gemona—The Alpini quartered there—The military tatoo in the evenings—Reception by the Mayor—A delightful week | 115 |

| CHAPTER XI: | |

| Gemona to Udine—Final stage of official journey—Regrets—Arrival at Udine—List of recommended lodgings—My room—My landlady an Austrian woman—I pay my respects to General Cafarelli—My friend Dr. Berthod—My old studio at the Agrario—The Isonzo Front—Many rumours—Off on our biggest trip; 245 kilometres in the car—Roads excellent and well-looked after—A great change—Cormons quite an Italian town—Same with other towns in conquered territory—Observatory on Monte Quarin—A splendid bird’s-eye view—The plain of Friuli—Podgora—The Carso—The hum of aeroplanes—The Isonzo Sector—The [xv] immense difficulties—Received by the General—A pleasant goûter—Lieutenant Nathan, Ex-Mayor of Rome—The Subida lines of trenches—Explanation of Italian successes everywhere—Caporetto via Tolmino—A desolate region—Road along the Isonzo—The mighty limestone cliffs of Monte Nero—The great exploit of its capture recalled—One mountain road very much like another—Nothing to sketch—Perfect organization—The fog of dust—Caporetto—Not allowed to motor beyond—Important strategic operations—Monte Rombon—Difficulty to locate Austrian guns—A glimpse of Plezzo—The situation here—Excursion to Gradisca via Palmanova, a semi-French town—Romans—Curious rearrangement of cars—Only two allowed proceed to Gradisca under fire—The Italian batteries at work—The deserted streets—The “observatory” room—The iron screens—View of Monte San Michele being bombarded—Stroll through the town—A big shell—Excursion to Cervignano, Aquileia and Grado—Peaceful country-side—Grado the Austrian Ostend—Fish-lunch at a café—The town continually bombarded by aircraft—Arrival of Beaumont, the French airman—Conclusion of official tour of Front—No permission given for correspondents to remain—Success of tour—Comments on organization, etc. | 131 |

| CHAPTER XII: | |

| Conclusion of Correspondents’ tour of Front—I return to London—Awaiting events—Brief official communiqués—Half Austrian Army held up on Italian Front—Harrying tactics—Trench warfare during the winter—Recuperative powers of the Austrians—Gorizia a veritable Verdun—Italian occupation of Austrian territory—Many thousand square miles conquered—A bolt from the blue—Serious development—Awakening Austrian activity—400,000 troops in the Trentino—Front from Lake Garda to Val Sugana ablaze—Totally unforseen onslaught—Towns and villages captured—Genius of Cadorna—Menace of invasion ended—I go and see Charles Ingram with reference going back to Italy—His journalistic acumen—My marching orders—Telegram from Rome—My journey back to Italy—Confidence everywhere—Milan in darkness—Improvement on the railway to Udine—Udine much changed—Stolid business air—Changes at the Censorship—Press Bureau and club for correspondents—The Censorship staff—Few accredited correspondents—Remarkable absence of Entente correspondents—Badges and passes—Complete freedom of action given me—I start for Vicenza en route for Arsiero—Scenes on road—From daylight into darkness—Hun [xvi] methods of frightfulness—Arsiero—Its unfavourable position—Extent of the Austrian advance—Rush of the Italians—Austrians not yet beaten—Town damaged by the fire and bombardment—Villa of a great writer—Rossi’s paper-mills—The town itself—The battlefield—Débris of war—A dangerous souvenir for my studio | 149 |

| CHAPTER XIII: | |

| The fighting on the Asiago plateau—Brilliant counter-offensive of General Cadorna—I go to Asiago—Wonderful organization of Italian Army—Making new roads—Thousands of labourers—The military causeway—Supply columns in full operation—Wonderful scenes—Approaching the scene of action—The forest of Gallio—The big bivouac—Whole brigades lying hidden—The forest screen—Picturesque encampments—The “bell” tent as compared with the tente d’abri—Our car stopped by the Carabinieri—“Nostri Canoni”—We leave the car—The plain of Asiago—The little town of Asiago in distance—The Austrian and Italian batteries and Italian trenches—Hurrying across—The daily toll of the guns—Asiago in ruins—Street fighting—Importance attaching to this point—An ominous lull—Regiment waiting to proceed trenches—Sad spectacle—The quarters of the divisional commandant—His “office”—Staff clerks at work—Telephone bells ringing—The commandant’s regret at our coming—Big artillery attack to commence—A quarter of an hour to spare—A peep at the Austrian trenches—A little, ruined home—All movements of troops to trenches by night—Artillery action about to commence—Not allowed go trenches—Adventure on way back—Attempt cross no man’s land at the double—My little “souvenir” of Asiago—Bursting shells—Ordered to take cover—The wounded soldiers and the kitten—Anything but a pleasant spot—The two Carabinieri—Cool courage—In the “funk-hole”—An inferno—My own impressions—Effect on soldiers and our chauffeur—The wounded sergeant—We prepare to make a start back—Irritating delay—A shrapnel—My companion is wounded—Transformation along road—Curious incident | 163 |

| CHAPTER XIV:[xvii] | |

| Slow but certain progress on the Trentino front—An open secret—The mining of the Castalleto summit—Carried out by Alpini—Recapture of Monte Cimone: also by Alpini—Heroic exploits—Udine one’s pied à terre—An ideal “News centre”—The Isonzo Front—The old days of the war correspondent as compared with the present conditions—Well to be prepared—Returning to Udine for lunch—Attracting attention—Unjustifiable—Things quiet at the Front—Unusual heat of the summer—Changeable weather at Udine—Early days of August—Increasing activity in the Isonzo Sector—Significant fact—Communiqué of August 4th—The communiqué of the following day—General attack by Italians all along this Front—Arrange start for scene of action—My car companions 6th August—Magnificent progress everywhere—Afternoon news—Capture of Monte Sabottina announced—We make for Vipulzano—On the road—Stirring scenes—“New” regiments—“Are we down-hearted”—The penchant for Englishmen—A cortège of prisoners—Like a huge crowd of beggars—Half-starved and terror-stricken strapping young fellows | 183 |

| CHAPTER XV: | |

| The commencement of the battle for Gorizia—We approach scene of action—Sheltered road—Curious “Chinese” effect—Headquarters of the 6th Corps d’Armée—Cottage of British Red Cross—Our cordial reception by General Capello—A glorious coup d’oeil—Wonderful spectacle—The Socialist Minister Leonida Bissolati—More good news received—The scene before us—Explanation of word “Monte”—Continuous line of bursting shells—Country in a state of irruption—No indication of life anywhere—Not a sign of troops—My motor goggles—Curious incidents—“Progress everywhere”—Colonel Clericetti announces good news—Capture of Gorizia bridge-head—Excited group of correspondents and officers—Arrange start at once with two confrères for fighting Front—Our plan—The thunder of the guns—The rearguard of advancing army—Our pace slackened—Miles and miles of troops—Wonderful spectacle of war—Mossa—Go on to Valisella—Machine guns and rifle fire—Ghastly radiance—General [xviii] Marazzi’s Headquarters—Not allowed proceed further—Decide make for Vipulzano—Arrive Arrive close on 10 o’clock—Bit late to pay visit—General invites us to dinner—Large party of officers—Memorable dinner—Atmosphere of exultation—News Austrians retreating everywhere—Thousands more prisoners—Dawn of day of victory—I propose a toast—On the terrace after dinner—Battle in full progress—Awe-inspiring spectacle—Little lights, like Will-o’-the-Wisps—Amazing explanation—Methodical precision of it all—Austrian fire decreasing gradually—Time to think of getting back to Udine and bed | 195 |

| CHAPTER XVI: | |

| The capture of Gorizia—Up betimes—My lucky star in the ascendant—I am put in a car with Barzini—Prepared for the good news of the capture—Though not so soon—A slice of good fortune—Our chauffeur—We get off without undue delay—The news of the crossing of the Isonzo—Enemy in full retreat—We reach Lucinico—The barricade—View of Gorizia—The Austrian trenches—“No man’s land”—Battlefield débris—Austrian dead—An unearthly region—Austrian General’s Headquarters—Extraordinary place—Spoils of Victory—Gruesome spectacle—Human packages—General Marazzi—Podgora—Grafenberg—Dead everywhere—The destroyed bridges—Terrifying Explosions—Lieutenant Ugo Oyetti—A remarkable feat—The heroes of Podgora—“Ecco Barzini”—A curtain of shell fire—Marvellous escape of a gun-team—In the faubourgs of Gorizia—“Kroner” millionaires—The Via Leoni—The dead officer—The Corso Francesco Guiseppe—The “Grosses” café—Animated scene—A café in name only—Empty cellar and larder—Water supply cut off—A curious incident—Fifteen months a voluntary prisoner—A walk in Gorizia—Wilful bombardment—The inhabitants—The “danger Zone”—Exciting incident—Under fire—The abandoned dog—The Italian flags—The arrival of troops—An army of gentlemen—Strange incidents—The young Italian girl—No looting—At the Town Hall—The good-looking Austrian woman—A hint—The Carabinieri—“Suspects”—Our return journey [xix] to Udine—My trophies—The sunken pathway—Back at Lucinico—The most impressive spectacle of the day | 219 |

| CHAPTER XVII: | |

| After Gorizia—Method and thoroughness of General Cadorna—Amusing story—Result of the three days fighting—Employment for first time of cavalry and cyclists—Udine reverts to its usual calm—Arrival of visitors—Lord Northcliffe and others—Whitney Warren—Changes along the fighting Front—Monte San Michele—A misleading statement—“Big Events” pending—A visit to Gorizia—My companions—Great change visible on road—Battlefield cleared away—Gorizia—Deserted streets—Rules and regulations for the inhabitants—The two cafés open—Rumours of counter-attack—The General’s Headquarters—Somewhat scant courtesy—A stroll round—We decide spend night in Gorizia—The deserted Hotel—We take possession of rooms—A jolly supper party—A glorious summer night—One long hellish tatoo—The Austrian counter-attack—A night of discomfort—The noise from the trenches—The cause of my “restlessness”—The “comfortable” beds—Gorizia in the early morning—Indifference to the bombardment—Back to Udine via Savogna, Sdraussina and Sagrado—Panorama of military activity—Monte San Michele—Looking for a needle in a bundle of hay—The cemeteries—The pontoon bridge—The Austrian trenches—The cavalry division—Renewed shelling of Gorizia | 237 |

| CHAPTER XVIII: | |

| Big operations on the Carso—General optimism—No risks taken—Great changes brought about by the victory—A trip to the new lines—Gradisca and Sagrado—A walk round Gradisca—Monte San Michele—Sagrado—Disappearance of Austrian aeroplanes and observation balloons—Position of Italian “drachen” as compared with French—On the road to Doberdo—Moral of troops—Like at a picnic—A regiment on its way to the trenches—The Italian a “thinker”—Noticeable absence of smoking—My first impression of the Carso—Nature in its most savage mood—The Brighton downs covered with rocks—Incessant [xx] thunder of guns—Doberdo hottest corner of the Carso—No troops—Stroll through ruins of street—Ready to make a bolt—A fine view—The Austrian trenches—Shallow furrows—Awful condition of trenches—Grim and barbarous devices—Austrian infamies—Iron-topped bludgeons, poisoned cigarettes, etc.—Under fire—A dash for a dug-out—The imperturbable Carabinieri—Like a thunderbolt—A little incident—Brilliant wit—The limit of patience—The Italian batteries open fire—No liberties to be taken—On the way back—Effect of the heavy firing—Motor ambulances—Magnified effect of shell fire on Carso—Rock splinters—Terrible wounds | 255 |

| CHAPTER XIX: | |

| Difficulties Italians have still to contend with on way to Trieste—Italian superior in fighting quality—Dash and reckless courage—Success reckoned by yards—Total number of prisoners taken—A huge seine net—The “call of the wild”—A visit to San Martino del Carso—My companion—Our route—The attraction of the road—Early morning motoring—On our own—The unconventional quarters of the divisional general—The Rubbia-Savogna railway station—The signalman’s cabin—An interesting chat with the General—At our own risk—The big camp on Monte San Michele—The desolate waste of the Carso—An incident—Nothing to sketch—“Ecco San Martino del Carso”—Shapeless dust-covered rubble—The Austrian trenches amongst the ruins—Under fire—Back to Udine—A pleasant little episode—Déjeuner to Colonel Barbarich at Grado—A “day’s outing”—The little “Human” touch—The “funk-hole” in the dining room—A trip in a submarine chaser—Things quiet in Udine—A period of comparative inactivity | 269 |

| CHAPTER XX: | |

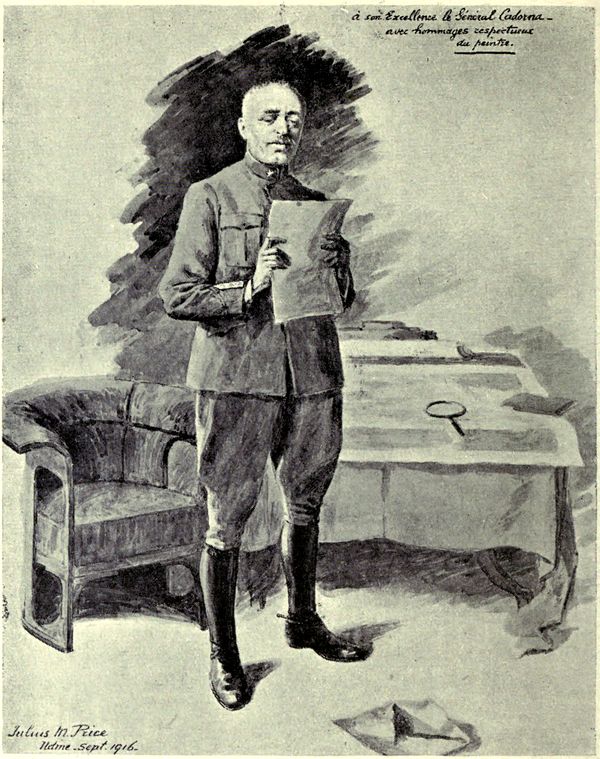

| Declaration of war between Italy and Germany—Effect of declaration at Udine—Interesting incident—General Cadorna consents to give me a sitting for a sketch—The curious conditions—Methodic and business-like—Punctuality and precision—A reminder of old days—I am received by the Generalissimo—His simple, unaffected manner—Unconventional chat—“That will please [xxi] them in England”—My Gorizia sketch book—The General a capital model—“Hard as nails”—The sketch finished—Rumour busy again—A visit to Monfalcone—One of the General’s Aides-de-camp—Start at unearthly hour—Distance to Monfalcone—Arctic conditions—“In time for lunch”—Town life and war—Austrian hour for opening fire—Monfalcone—Deserted aspect—The damage by bombardment—The guns silent for the moment—The ghost of a town—“That’s only one of our own guns”—A walk to the shipbuilding yards—The communication trench—The bank of the canal—The pontoon bridge—The immense red structure—The deserted shipbuilding establishment—Fantastic forms—Vessels in course of construction—A strange blight—The hull of the 20,000 ton liner—The gloomy interior—The view of the Carso and Trieste through a port-hole—Of soul-stirring interest—Hill No. 144—The “daily strafe”—“Just in time”—Back to Udine “in time for lunch”—Return to the Carso—Attack on the Austrian positions at Veliki Hribach—New Difficulties—Dense woods—Impenetrable cover—Formidable lines of trenches captured—Fighting for position at Nova Vas—Dramatic ending—Weather breaking up—Operations on a big scale perforce suspended—Return London await events | 281 |

[xxiii]

| FACING PAGE | ||

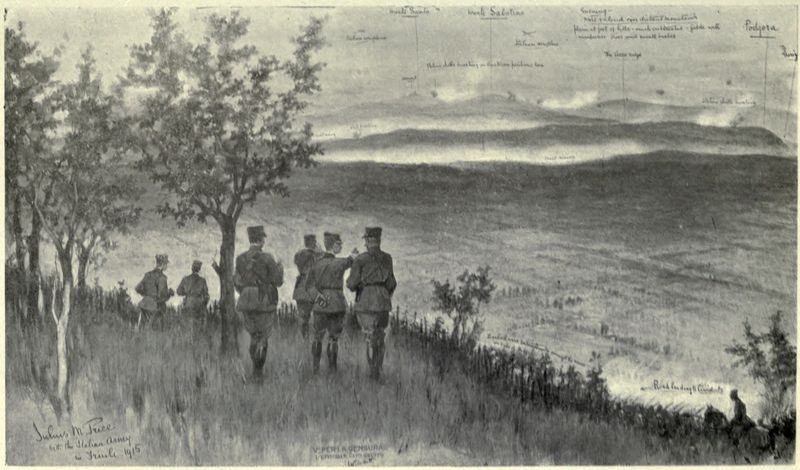

| The Author in San Martino del Carso | Frontispiece | |

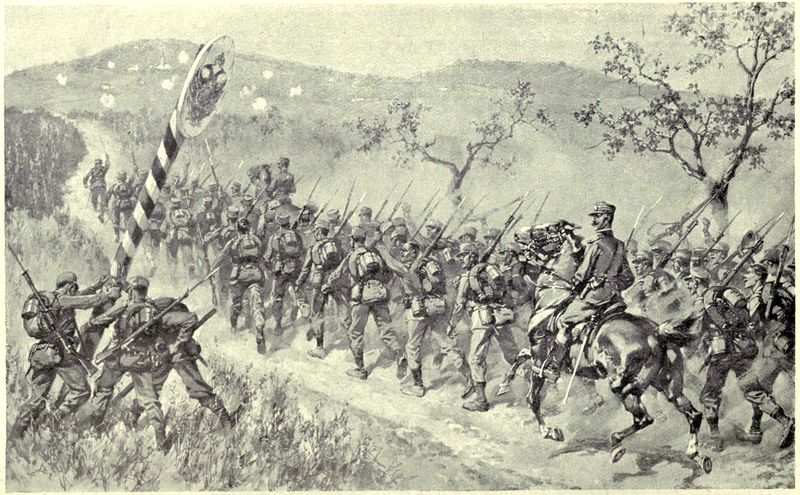

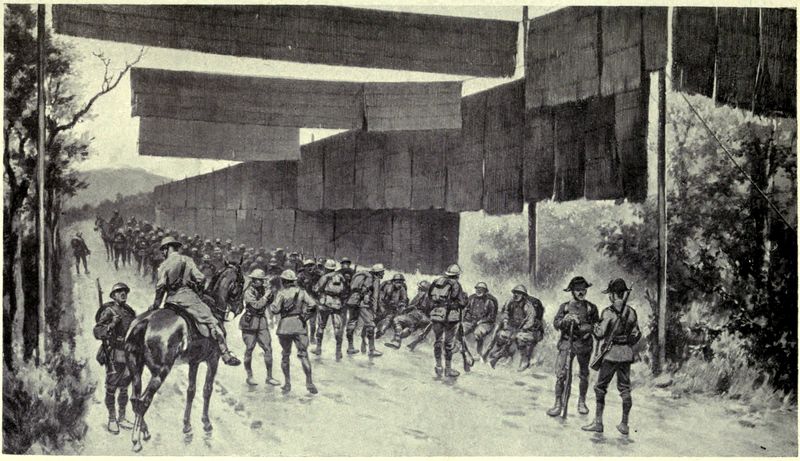

| During the entire day the onward march continued | 11 | |

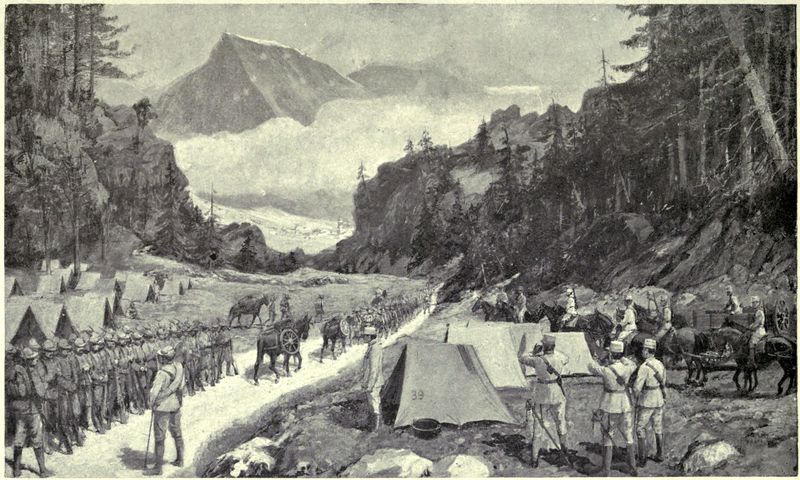

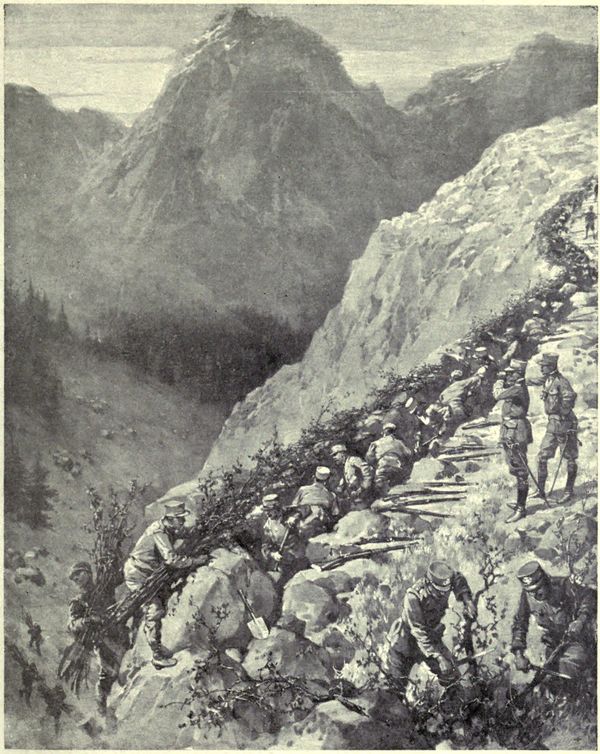

| Rugged and threatening, visible for miles around, is the frowning pinnacle of bare rock known as Monte Nero | 26 | |

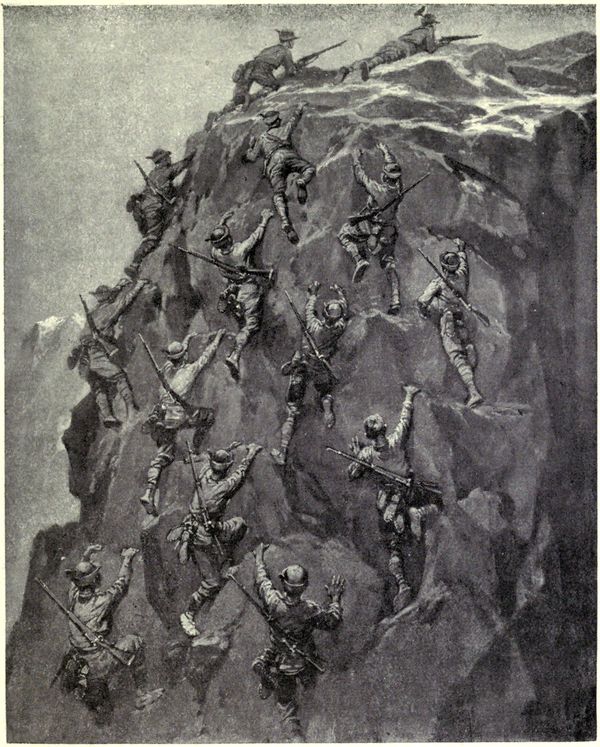

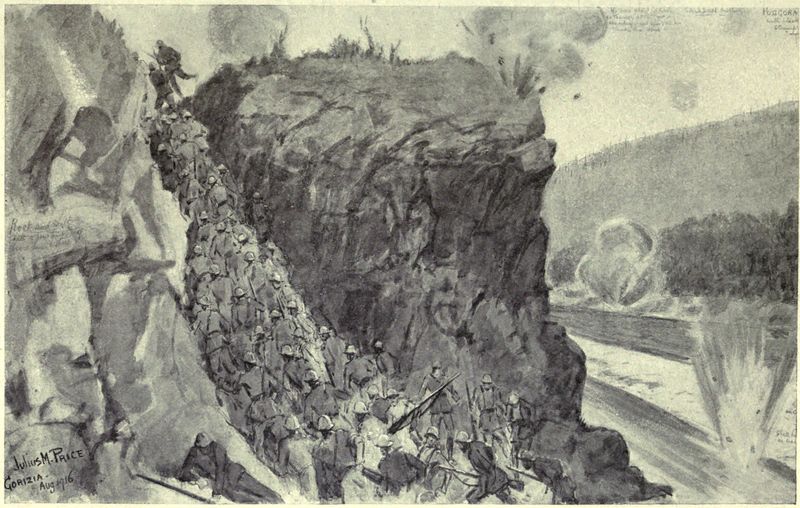

| It meant practically scaling a cliff of rock | 38 | |

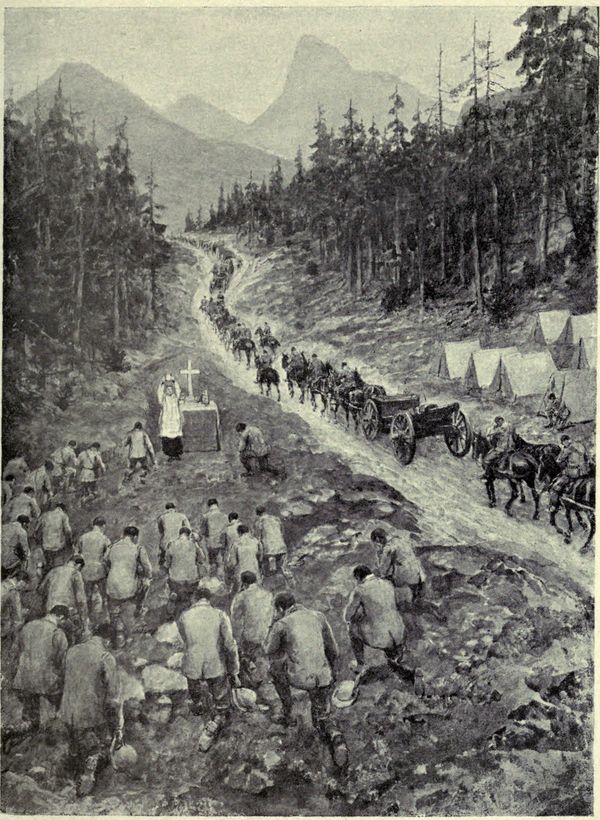

| A rude altar of rough boxes was set up | 50 | |

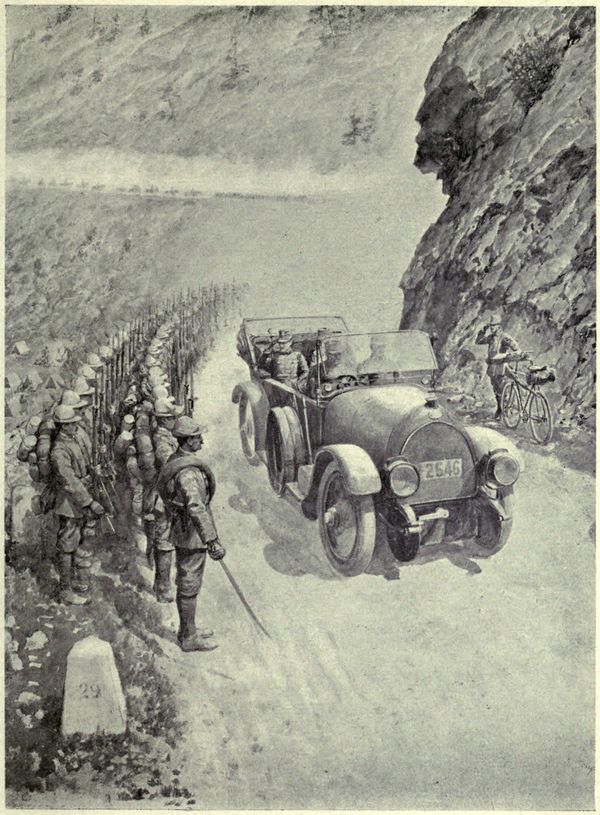

| The King appeared indefatigable and was out and about in all weathers | 62 | |

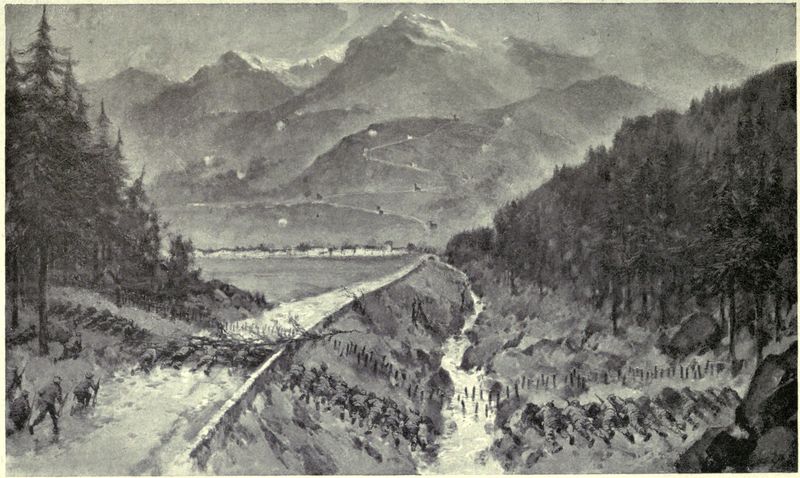

| Along the big military highway constructed by Napoleon | 74 | |

| As he whirled past in the big car | 88 | |

| The whole region was positively alive with warlike energy | 100 | |

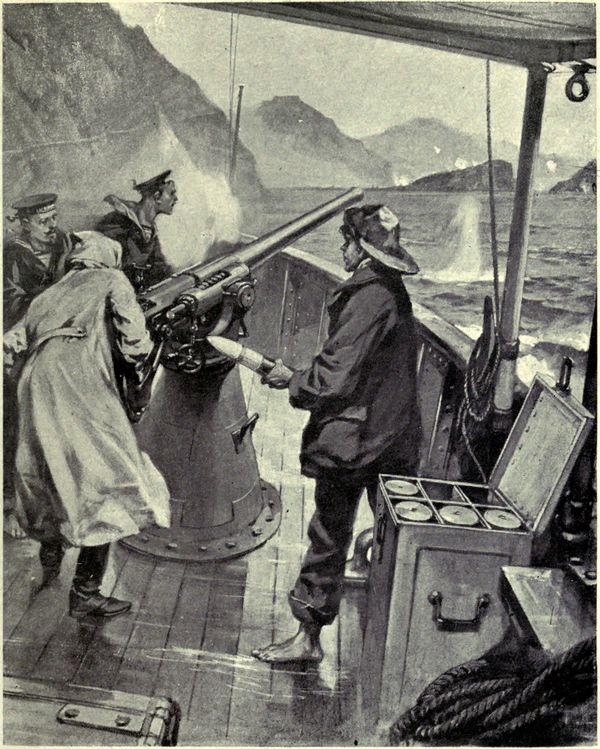

| A very useful-looking Nordenfeldt quick-firer mounted on the fore-deck | 112 | |

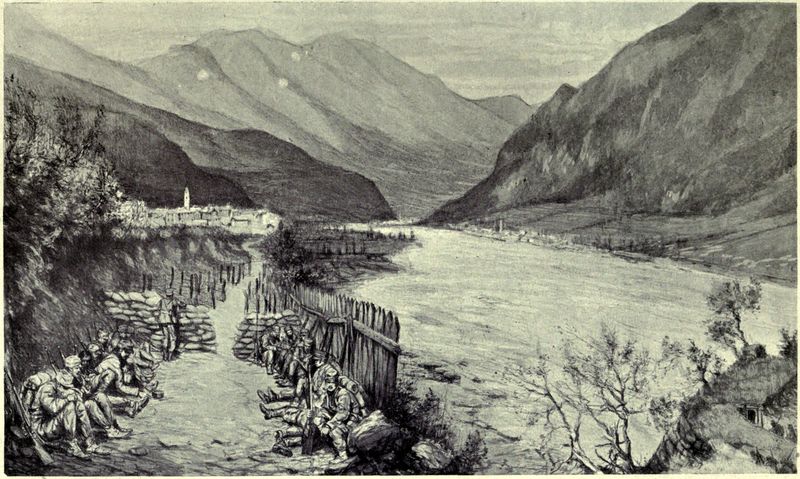

| Before us stretched the broad valley of the Adige | 124 | |

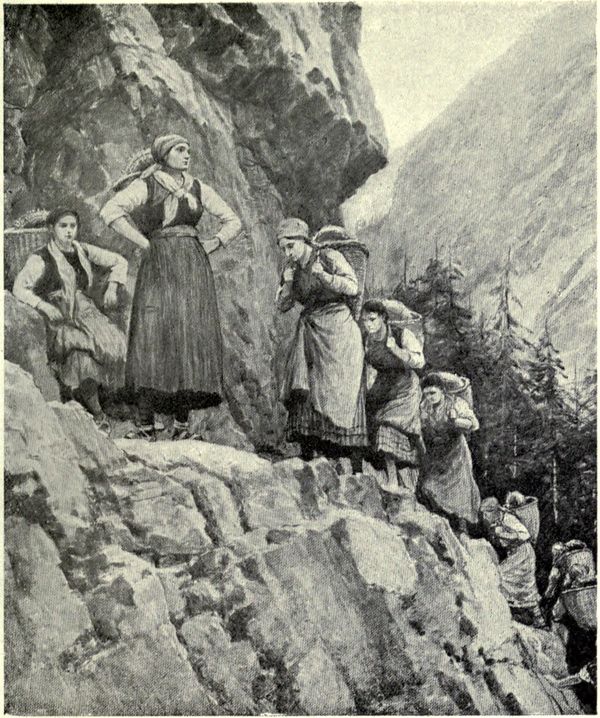

| On one of the worst portions we passed a gang of peasant women carrying barbed wire up to the trenches | 136 | |

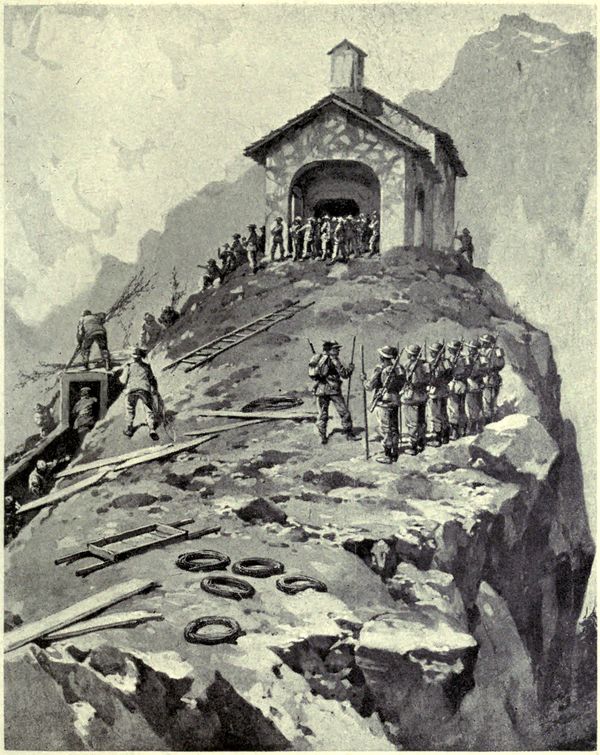

| One would have liked to spend an indefinite time in these scenes of warlike activity | 148 | |

| But nothing had stopped the rush of the Italians | 160 | |

| And came up with reinforcements hurrying forward | 172 | |

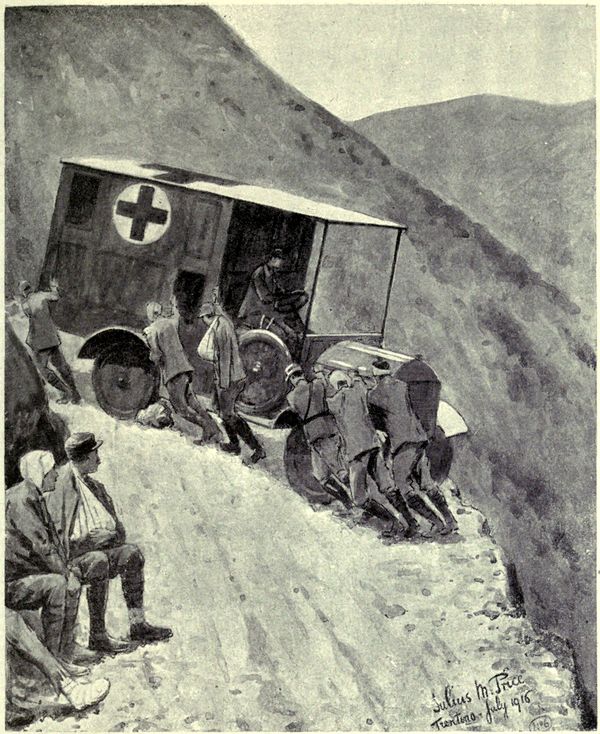

| The least severely wounded occupants jumped out of the wagon | 186 | |

| And day by day one heard of minor successes in Trentino | 198 | |

| The object of this being to hide movements of troops and convoys | 210 | |

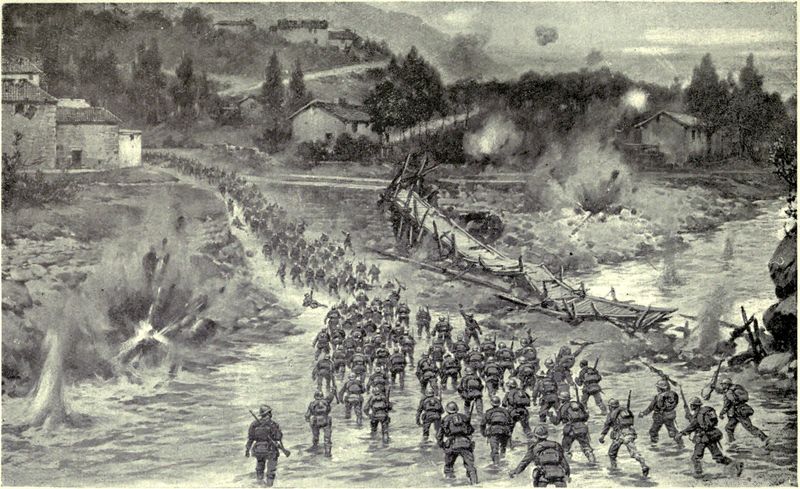

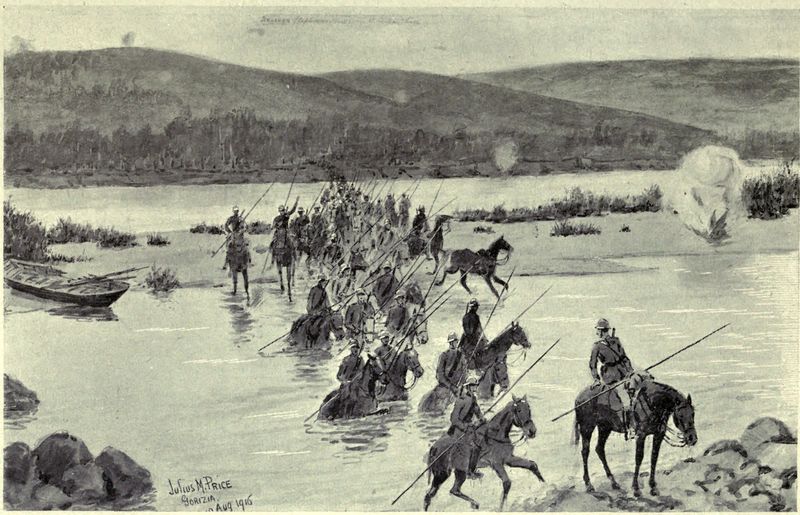

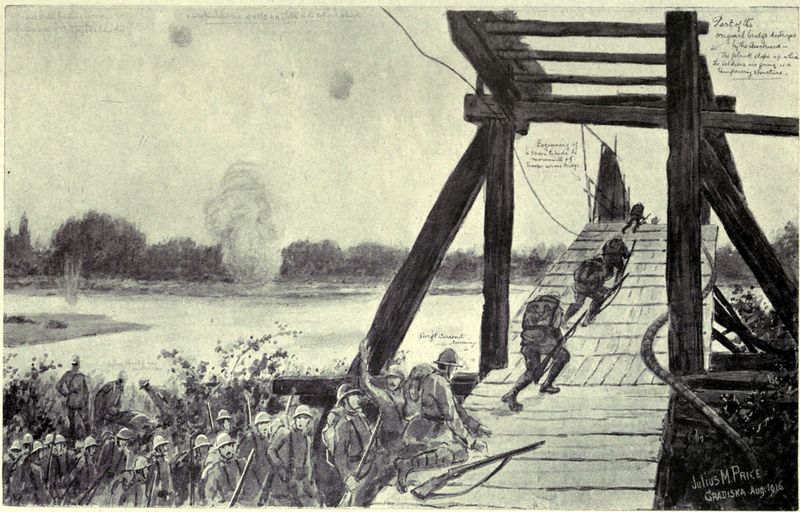

| Two infantry regiments, the 11th and 12th, forded and swam across the river [xxiv] | 222 | |

| The soldiers round us now began to move forward, and we were practically carried up the gully with them | 234 | |

| I was fortunate enough to get some interesting sketches of the cavalry crossing the river under fire | 246 | |

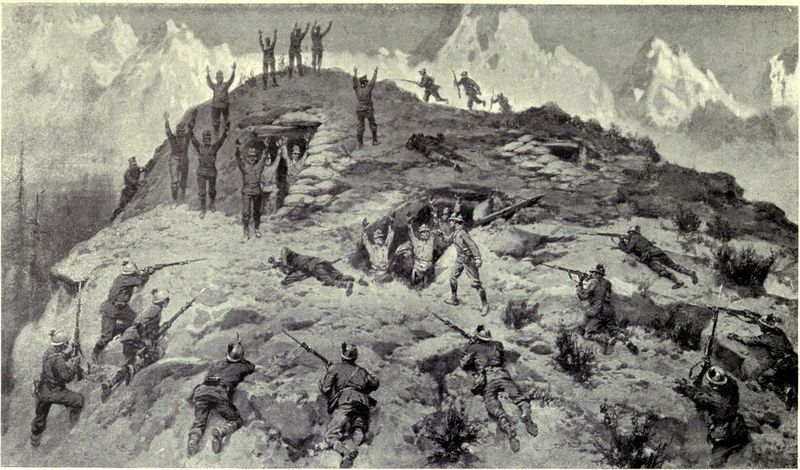

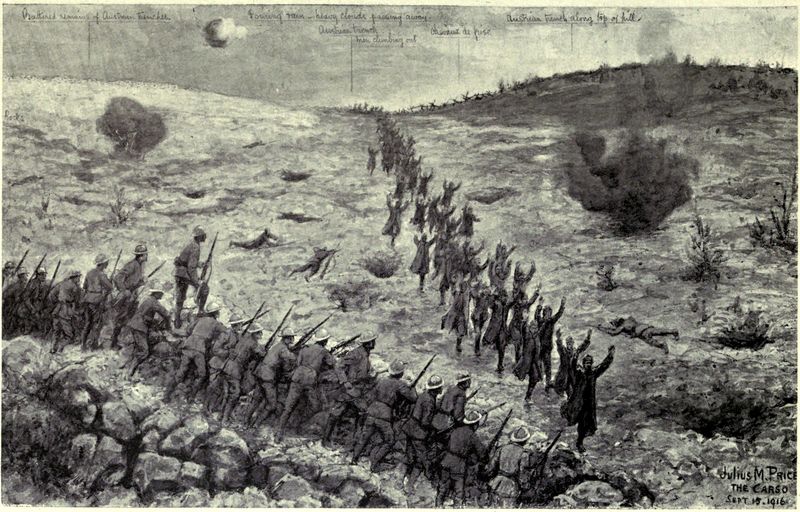

| The only difficulty the officers experienced was in getting them to advance with caution | 258 | |

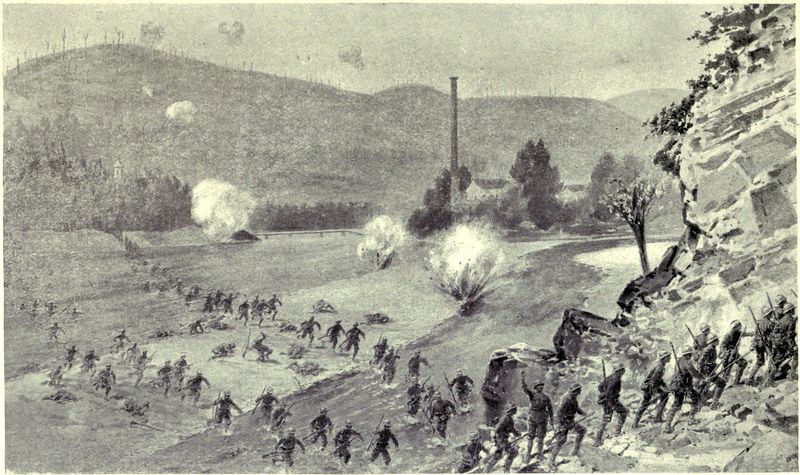

| They came racing across the stretch of “No Man’s Land” | 270 | |

| A grey-haired officer of medium height, whom I immediately recognized as the Generalissimo, was reading an official document | 283 | |

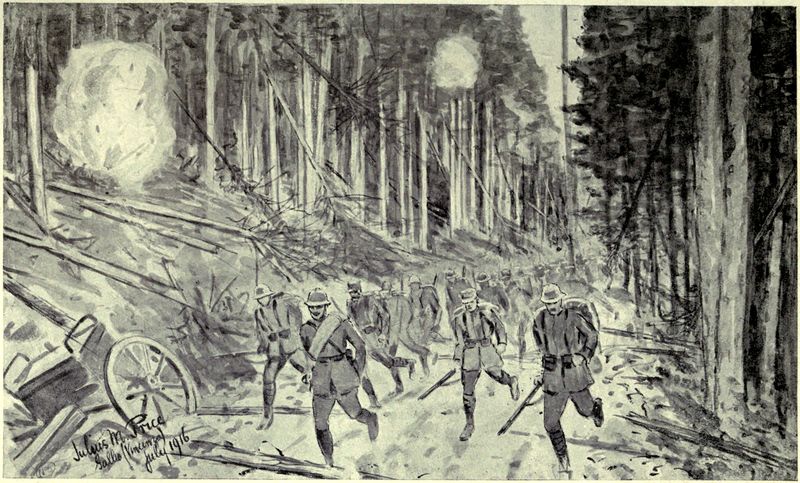

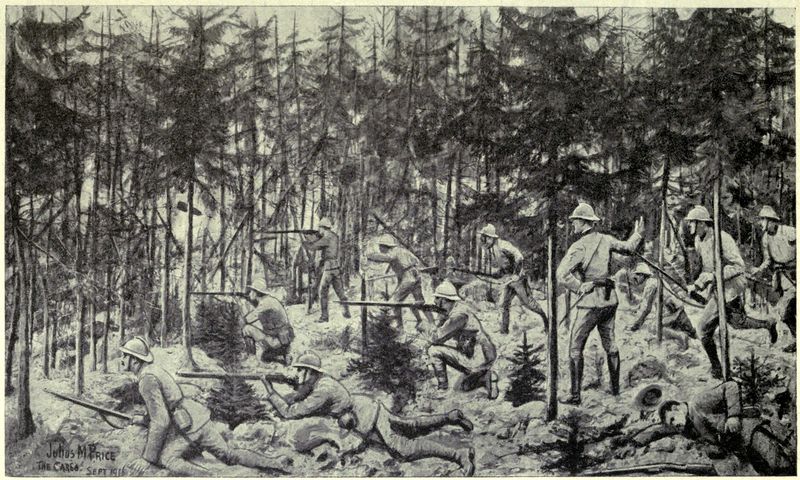

| To advance through the jungle called for all the cool, disciplined courage of the Italian soldier | 291 | |

[Pg 1]

Marching orders—I leave for Rome—Paris via Folkestone and Boulogne in war time—My campaigning kit—The war-correspondent’s list—Quaint item—Travelling “light”—A box of choice Havanas—Boulogne to Paris; well-intentioned ladies and their “Woodbines”—The one and only cigarette—Paris to Turin—Curious order on train—Method and prescience—Few soldiers on route—Arrival in Rome—A cheap room—No sign of excitement in streets—23rd May—Excitability of the Italian no longer noticeable—Rome unruffled—The declaration of war—On the Corso Umberto that evening—The Café Aragno—National stoicism—The Day—Business as usual—The general mobilisation—A triumph of organization—At the War Office.

[3]

CHAPTER I

“Gerrard 2575?”

“Hello—Hello!”

“That you, Julius Price? Charles Ingram speaking—When are you starting for Italy?”

I had only received my marching orders from the office the previous day, so the thought came to my mind “Early next week,” but I hadn’t the pluck to give expression to it. Instead, I compromised lamely with “As soon as possible.”

“Rubbish!” snapped the voice, “Get off at once.”

I had known my Charles Ingram—best of chiefs—most loyal of friends—too long to attempt to argue. I had started on too many journeys for The Illustrated London News not to realize that a War-Artist must have no collars to buy—no friends to bid farewell to—so there was only one stereotyped answer possible—“All right, I’ll leave to-morrow morning.”

“Well, goodbye and good luck to you.”

8.30 the following morning therefore saw me at Charing Cross, duly passported and baggaged, bound for Rome.

Although Italy had not yet officially declared her intention of joining in with the Allies, it was well known that it was but a matter of a few days before she would do so. The War fever all over Italy was at its height, and there seemed no possibility of anything occurring to influence adversely the decision of the King. The sands of time were rapidly running out, while Count Berchtold, the Austrian Chancellor, was deliberately—for the Allies, fortunately—playing with the destiny of his nation.

[4]

The centre of interest at the moment was obviously the Capital, so I was anxious to reach it in time to witness the historic scenes of the near future. Rumour had it that so eager was the nation to get to grips with its hereditary foe that a revolution would ensue were the King to hesitate as to his course of action, while it had been an open secret for some weeks that a general mobilisation of the Army and Navy had been in active progress since the commencement of the period of tension. Italy, therefore, was the point de mire of the entire world on the 20th of May, 1915, when I left London, and I could congratulate myself that, thanks to the journalistic flair of Charles Ingram, I should be on the spot in time for anything that might happen.

At that date one was still able to reach Paris via Folkestone and Boulogne—England was only just awakening to the fact she was at war—the popular short sea-passage route had not yet been taken over by the military authorities, and although the examination of passports and passengers was severe, there was nothing like the difficulty and delay one now experiences in getting across the Channel. The scheduled time from London to Paris was a mere matter of twelve hours, which, of course, was not excessively long under the circumstances, while as compared with the time the journey occupies to-day via Southampton and Havre, it was rapidity itself.

It had been a bit of a rush to get through all I had to do in the twenty-four hours I had at my disposal before leaving London. Consuls will not be hurried even for War-Correspondents, and one’s passport nowadays is far and away the most important article of one’s belongings. There are, moreover, always a hundred and one things that must be done before starting on an expedition of indefinite duration. I know of nothing more irritating when “on the[5] road” than suddenly to discover you have forgotten to bring with you some insignificant but invaluable object which can be easily procured in London but which is unobtainable abroad.

In common with most Correspondents, I have always made it a habit to have my kit kept more or less packed ready for emergency, but not to the extent of one of the brotherhood, who, in order to obviate the danger of finding something missing from his trunks while on the war-path, had lists of the various items pasted in the lid of each trunk which he would carefully verify before starting. An excellent idea, and even amusing in places, as on the occasion when his old soldier-servant had described one of the important items in the list, “False tooth (Supernumerary).”

That the selection of every detail of one’s baggage when travelling “light” is an all important matter is incontrovertible, but personal experience and individual fancy can be the only guide to what one is likely really to want on a hazardous journey. For myself, I have contrived to sort things down to an irreducible minimum, which will go in a car or the luggage rack of a railway carriage. This, together with a small attaché case for my books, papers and spare pipes, constitutes my entire baggage, of which I never lose sight.

Two pals came to see me off, and one, a connoisseur in these matters, brought me a box of his choicest Havanas to smoke en route, and delighted though I was at his kind thought, I felt I was going to have trouble with this unexpected addition to my luggage. And it started when I found that my bags were so full up that I could find no immediate home for a box of 100 big cigars, much as I could appreciate them. I could not help feeling that had my friend given me a leg of mutton to carry to Rome it would have been a less awkward parting gift.

[6]

The trouble I had with those cigars makes me smile even now when I think of it—they seemed to get everywhere—rather than carry the box, I endeavoured to distribute them in various pockets—with the result that I was simply overwhelmed with Corona Coronas, and although I smoked hard all the way it seemed to make no impression on the supply, and the thought of what might happen at the Italian frontier became a positive obsession.

I had already spent six months on the French front, so was pretty familiar with the warlike scenes that presented themselves on the other side of the Channel, but to most of my fellow travellers they were quite new.

Several well-intentioned ladies in the train from Boulogne to Paris had provided themselves with big supplies of “Woodbines,” and all the way to Etaples, whenever we passed soldiers along the line, they were busy throwing the small packets of cigarettes out of the windows to English and French indiscriminately.

It was Voltaire, I believe, who asserted that England has sixty religious sects but only one sauce. I fancy that the French “Poilu” would now substitute “cigarette” for “sauce,” but whether they prefer the “one and only” to their more robust “Caporals” is a matter of doubt. For my own part, I was too busy that day getting through with my Coronas to trouble much about either.

I should have liked to have spent a few hours in dear old Paris, but the exigency of the situation in Italy did not permit me to entertain the idea for a moment. I just had sufficient time to drive to the Gare de Lyon, dine at a restaurant near the Station, and catch the Rome express.

The train was not crowded, and the journey till we reached Turin was quite featureless with the[7] exception, as far as I could judge, that everyone was discussing the situation in Italy.

At the frontier station of Modane, where the examination of luggage was quite perfunctory, some important news had just come through. The Parliament, on reassembling, had given to the Salandra Cabinet by an overwhelming majority a vote of confidence, which amounted to a declaration of war against Austria.

At Turin, where we arrived in the afternoon, the station was buzzing with rumours that war had already been declared—this, as it turned out, was not the case, but it showed how acute was the crisis and the excited state of popular opinion.

This was borne strongly upon me by a curious order given to the passengers on the train leaving Turin. In broad daylight all blinds had to be drawn down and kept down till we had passed a certain station further on. The reason for this did not transpire, but it was rigorously enforced.

It was a typical Italian summer afternoon, so the discomfort thus entailed in the stuffy carriages may be better imagined than described; but it brought home to you the seriousness of the situation and the fact that whatever the outcome the Government was taking no chances. What was happening in the district through which we were passing was none of our business, and they let us know it—thus.

This was actually the first indication of the nearness of war, and also an illuminating insight of the “method” and prescience of the war department. What struck you everywhere was the small number of soldiers one saw, and you could but conclude that if movement of troops were taking place they were perhaps being carried out in the zone where the blinds had to be drawn, though Turin was so far from any prospective front that this seemed an excessive precaution.

[8]

Rome, if not exactly deserted, was much emptier than usual for the time of year; but as it was 84° in the shade that may have had something to do with it.

At the Grand Hotel, where I proposed staying, all the upper floors were closed.

The white waistcoated manager showed me a fine room on the second floor, and on my enquiring the price, asked me, as I thought with diffidence, whether I thought six lires a day was too much. As I knew the charge in normal times would not have been less than three times that amount, I told him I did not—and took it.

A stroll through the principal streets in the cool of the evening, when one might have expected some indication of popular feeling, revealed absolutely no sign of anything abnormal. It was outwardly the Rome of peace times, not as you would have expected to find it on the eve of war; yet the Press was full of the gravity of the impending crisis, and in the Capital, as on the journey towards it, one was struck by the remarkable absence of soldiers everywhere.

The following day, Sunday, the 23rd of May, it was evident from the tenor of the morning papers that the ultima ratio was in sight, and that it was now only a question of hours, or even minutes, when the momentous decision of the King would be announced. There was a significant calm everywhere that one could not fail to notice, though nobody appeared to have any doubt as to what was pending.

Strangely enough all the old characteristics of the Latin race seem to be dying out—the excitability, the hotheadedness, the volubility of the Italian of the days of yore are no longer en evidence. The men of Italy of to-day are of a different fibre, and though the old-time mettle remains, it is shown differently.[9] There is a growing tendency amongst all classes towards the imperturbability and placidity one associates with Northern races. Events are accepted more dispassionately, and there is far less of the garrulity and dramatic gesture of twenty years ago.

As was generally anticipated, the fateful decision was made known towards evening, and the papers appeared announcing the declaration of war, and that Baron von Macchio, the Austrian Ambassador, had been handed his passports at 3.30.

Even then, when one would have expected the pent up feelings of the people to display themselves in some form of demonstration, there was no commotion whatever.

Along the Corso Umberto the gaily-dressed crowds strolled as leisurely as ever, and the laughter and merriment were the same as on any ordinary Sunday evening. There were perhaps more people about than usual, but this was probably because it was a delightfully cool evening after an exceptionally hot day.

The Café Aragno, which is the hub of the political, journalistic and social life of the Capital, was, of course, packed, as it always is on Sundays. Groups of people were standing about in the roadway and on the pavement reading and discussing the news. “Extra Special” Editions of the evening papers, with fresh details of the situation, seemed to be coming out every few minutes, and the paper boys did a big trade.

If, however, I had not seen it for myself I should never have believed that such composure in such exceptional circumstances could be possible. I could not help contrasting in my mind this quite remarkable absence of excitability in Rome with what I had seen in Paris on the first day of the mobilisation. When the streets resounded to the cheers of the Reservists and everywhere was wild excitement.

[10]

It may have been that the event had been so long anticipated in Italy that when the actual moment arrived its effect was discounted; but nevertheless stoicism of this remarkable character certainly struck one as being quite an unexpected trait of the national temperament.

I was, I must admit, the more surprised and disappointed, as my instructions from my Editor were to get to Rome as quickly as possible and make sketches of the scenes that would doubtless be witnessed in the streets as soon as war was declared, but there was no more to sketch in Rome on that Sunday evening than one would see any day in London, and there were certainly far fewer soldiers about.

In fact, it is probably no exaggeration to state that it was with a sigh of relief that the Italians learned that hostilities were about to commence against Austria.

“The Day” that had been looked forward to for forty-nine years, since peace was forced upon Italy by Prussia and Austria in 1860 after the Battle of Sadowa, had at last come, and found the nation united in its determination to endure anything and stand any sacrifice in its resolve to conquer its hereditary foe once and for all.

The absence of outward sign of feeling amongst the populace was as much marked in the days following the declaration of hostilities. The object of the war was well understood, and therefore popular with all classes—in the Capital at any rate, and there was in consequence no flurry or appearance of undue restlessness anywhere—business went on as usual, and except for the shouting of the newsboys, one could scarcely have known that war had commenced.

To face page 11

All this was, of course, due to the fact that the general mobilisation had been gradually and quietly taking place for some time previously. There were[11] therefore none of the heartrending scenes such as one witnessed in the streets and round the railway stations in Paris after the first flush of excitement had worn off, for most of the Reservists were well on the way to the Frontier by the time war was declared.

It was a veritable triumph of organisation, and reflected the greatest credit on all concerned.

I had occasion to go to the War Office several times, and found an air of solid business on all sides that was very impressive. Everything appeared to be going on as though by clockwork—a wonderful testimony to the efficiency of the different departments. There was not the slightest indication that anything had been left to chance or to luck in “muddling through somehow.”

Of course it is incontrovertible that those in charge of the destinies of the nation had had ample time to get ready and to profit by the lessons of the war elsewhere, but this does not alter the fact that it was only the wonderful state of preparedness in Italy that enabled her to take the initiative directly war was declared. It certainly revealed an intuitive power of grasping the exigencies of the situation on the part of the Chiefs of the War department that to my mind presaged victory from the outset.

[13]

My credentials—The War Zone—Italy’s preparedness—The Press Censorship—General Elia’s advice—Disappointment—A pipe in the Pincio—An inspiration—I leave for Venice—Venice in war time—The lonely pigeons of the Place St. Marc—The Doge’s Palace—The bronze horses—Interior of St. Marc, strange spectacle—First act of war between Italy and Austria—Aeroplane bombs Venice—French aviators—Treasures of Venice—Everyday life in Venice during daytime—After nightfall—On the qui vive—Extraordinary precautions—Dangers of the streets—Spy fever—Permis de séjour—The angry crowd—Defences against air attacks—Venice not a place forte—Nearest point of the Front—The British Vice-Consul, Mr. Beak—A good Samaritan—The letter of credentials—The Commandant of Venice—More advice—New Rescript of the Generalissimo—Reference to Correspondents—Decide attempt go to Udine—The language difficulty—The waiter at the Hotel Danielli—His offer to accompany me—Make arrangements at once—Introduced to Peppino Garibaldi—Amusing incident.

[15]

CHAPTER II

I arrived in Rome armed with sufficient credentials and recommendations, apparently, to frank me through every barrier to the Front, but I was not long discovering that in spite of the courtesy with which I was received by the officials to whom I had introductions, it was hopeless to expect any relaxation, for the time being, of the stringent decree with regard to the War Correspondents that had been issued by the Generalissimo.

A “War Zone” was declared at once, and the most rigorous precautions taken to insure its being guarded against intrusion. Within its confines were several important cities, as for instance, Brescia, Venice, Verona, Vicenza, Belluno, Bologna, Padua and Udine and the entire area was considered as in a state of war, and immediately placed under what was practically martial law. No railway tickets were obtainable unless one had a permit to travel on the line.

It is of interest to mention all these conditions ruling at the very beginning of the war as affording an object lesson in the “method” and foresight which were displayed in every move of General Cadorna even to the smallest details.

Italy took a long while making up her mind to throw in her lot with the Allies, but there was no losing time once she made a start, as was soon proved, and her preparedness was evidenced in every direction.

A censorship of the most drastic character was established at once, and it looked at one time as if correspondents were going to have a bad time of it, and see even less, if possible, than in the other areas of the war.

[16]

“Go and make a journey through Italy; there is lots to see that will interest you as an artist, and come back in about three months from now; then perhaps some arrangements will have been made with reference to correspondents going to the Front.” This was all I could get from General Elia, the genial Under-Secretary of State for War, who speaks English fluently—when at last, through the kindly intervention of the British Embassy I managed to see him and begged to be permitted to accompany the troops.

This could scarcely be construed as encouraging, and as I came away from the interview I must admit I felt the reverse of elated. I had already spent a week trying to get permission to go to the Front, and I certainly had not the slightest intention of playing the “tourist” for the next few months, nor of idling away my time in Rome if I could help it. But what was to be done?

I could hardly speak a word of Italian, so knew I was handicapped terribly for getting about alone. I strolled up to the solitude of the Pincio, and lighting my pipe, sat down under the trees to think it out. I forgot to mention that the decree placing Venice and other towns within the War Zone was not to come into force for another twenty-four hours.

Suddenly an idea occurred to me. I knew Venice well, why not go there; at any rate I should be quite near the Front, and with luck I might manage to make my way there. Anyhow it could not fail to be more interesting so close to the scene of operations than in Rome.

I made up my mind to start that day if possible, and, going to Cooks’ office near the hotel, found that I was in luck’s way—there was a train that afternoon, and there was not the least difficulty in getting a ticket, but this was the last opportunity of doing so without a permit, I was told.

[17]

The next day therefore saw me in Venice and amidst familiar scenes. But it was a very altered place from the Venice of peace time. It looked very dreary and lifeless. The week that had elapsed since the commencement of hostilities had brought about a great change.

There were no visitors left—only one hotel was open, Danielli’s—the Grand having been taken over by the Red Cross Society; the canals, those delightful arteries of Venetian life, appeared almost deserted, although the steam launches were running as usual; the pigeons had the place St. Marc practically to themselves, workmen were busy removing the glorious windows from the Doge’s Palace and bricking up the supporting arches.

The chapel at the base of the Campanile was shrouded in thick brickwork; the famous bronze horses on the portico of St. Marc had been taken down at once; the interior of the church itself presented a curious spectacle, as it had several feet of sand on the floor, and was hidden by a big bastion of sandbags.

It is perhaps of interest to mention that the first act of war between Austria and Italy took place at Venice. At 3.30 on the morning of the 24th May the inhabitants were aroused by the loud boom of a signal gun—this was immediately followed by the screech of all the steam whistles in the City and on the boats.

In a very few minutes the batteries of the Aerial-Guard Station and machine guns and rifles were firing as rapidly as they could at the intruders—several Taubes flying at a great height—without effect, unfortunately, as they managed to drop several bombs and get away unscathed. Two of the bombs fell in the courtyard of the Colonna di Castelpo, one in the Tana near the Rio della Tana, another in the San Lucia, and a fourth in the Rio del Carmini.

It was said that an enormous parachute, to which[18] was suspended incandescent matter to light up the ground, was released from one of the aeroplanes, but this was not corroborated; it is certain though that the bomb that fell in San Lucia was incendiary and spread lighted petroleum, without effect happily. Austria, therefore, lost no time in beginning her war of vandalism.

Every precaution possible was being adopted while I was there, to protect the city against any further aeroplane attacks, and there was a contingent of French aviators—amongst whom was Beaumont—staying at the hotel, who were constantly patrolling over the city.

Unfortunately, in a place like Venice, which is such a veritable conglomeration of artistic treasures, it is obviously very difficult to protect all, and with a thoroughly ruthless and barbaric enemy like Austria it is to be feared that a lot of irreparable damage will be done before the end of the war.

Life in Venice during the daytime was practically normal—sunshine engenders confidence; it was after nightfall that you realised the high state of tension in which everyone was living; it could scarcely be described as terror, but a “nervy,” “jumpy” condition, which was very uncanny. Everyone seemed to be on the qui vive, though curiously enough the fear of the Venetians, as far as I could judge, was not so much for themselves as for the safety of their beloved city.

The most extraordinary precautions were taken to ensure its being shrouded in impenetrable obscurity at night—a ray of light shewing through a window meant instant arrest for the occupant of the room. Even smoking out of doors at night was strictly forbidden. The doorways of restaurants, cafés, and shops were heavily draped with double curtains, and after eight o’clock the electric light was turned off and only candles allowed.

[19]

It would be difficult to describe the weird effect of Venice in total darkness on a moonless night.

It is said that more people have lost their lives by falling into the canals than through aeroplane bombs, and I can quite believe it, for it was positively dangerous to go a yard unless one was absolutely certain of one’s whereabouts.

Added to this was the risk of being mistaken for a spy. One had to get a permis de séjour from the Police, but even with this in your pocket one was never really safe, for they had “spy fever” very badly indeed when I was there, and even old and well-known inhabitants were not immune from suspicion at times.

I heard of several cases of hair-breadth escapes from the clutches of the angry crowd which would gather on the slightest suggestion. To be heard speaking with a foreign accent was often sufficient to attract unpleasant attention, so you were inclined to be chary of venturing far from the Place St. Marc at any time, however much your papers might be en règle.

Apart from the defensive work that was being undertaken to protect Venice from Austrian air attacks, there was nothing of interest in the way of military or naval activity to be seen. Destroyers and torpedo boats occasionally came into the lagoon, but seldom remained long.

The position of Venice makes it a sort of cul de sac, and of no importance whatever from the point of view of land and sea operations, and it is quite at the mercy of Austrian aeroplanes or seaplanes operating from Pola or Trieste.

The sole object the Austrians can have in attacking it therefore is to cause wanton damage to its historic buildings and art treasures, for it is not a place forte in any sense of the word; and if there is one thing more than another calculated to stiffen[20] the backs of the Italians against their enemy and to make them the more determined to do all in their power to crush Austria for ever, it is this cold-blooded onslaught on their national artistic heirlooms, for which there is no military justification whatever.

At that time the nearest point of the Front was some 40 miles from Venice, in Friuli, and after a few days marking time, I decided that this was where I must make for if I wanted to see anything of what was going on in this early stage of the war.

The courteous and genial British Vice-Consul, Mr. Beak, who had just taken over the post, proved a veritable good Samaritan, and did his best to help me.

I have not mentioned, I think, that when in Rome I had been given an important letter of credentials by the British Embassy recommending me for any facilities the Italian military authorities might be prepared to grant me, and the letter now proved invaluable. Mr. Beak got a translation made of it, to which he affixed the consular stamp, and, armed with this, I paid a visit to the Commandant of Venice, at the Arsenal.

He received me with the utmost cordiality, but when I suggested his giving me permission to go to the Front he informed me that he had no power to do this; that my best plan would be to go direct to Headquarters at Udine, where doubtless I would get what I wanted on the strength of my letter from the Embassy. I said nothing, but with the recollection of what General Elia had told me in Rome, I had my doubts. Anyhow, it gave me the idea of going to Udine and trying my luck; if the worst came to the worst, I could but be sent back, and in the meantime I should have seen something of the Front.

The following day a new rescript of the Generalissimo appeared in the papers to the effect that until[21] further orders no correspondents were allowed in the War Zone. This was awkward for me, as, of course, I was already in it, but I made up my mind to run the further risk of getting up to the actual Front if it were possible. But how, without speaking Italian, for, of course, the “interpreter” element had disappeared from Venice since there were no longer any tourists to interpret for.

My ever faithful pipe as usual helped me to solve the difficulty (what I owe to Lady Nicotine for ideas evolved under her sway I can never be sufficiently grateful for).

There was a very intelligent young waiter at the hotel who spoke English fluently, and it occurred to me that he would make a useful guide if he would go with me. He not only jumped at the idea, but actually offered to come for a few days for nothing if he could get permission from the manager, and if I paid his expenses, so anxious was he to see something of the military operations.

There was no difficulty in getting the consent of the manager as the hotel was practically empty; and then my friend, the Vice-Consul, again good-naturedly came to my assistance by giving me a letter to the Military Commandant of Udine, in which he stated fully my object in coming to the front, and the fact that I was carrying a special letter of credentials from the Embassy.

These two important documents, together with my passport, were, I felt, sufficient to frank me some distance unless unforseen trouble arose; so I made arrangements to start at once; and in order not to be hampered with baggage, as I did not know where my venture would take me, decided to leave my bulky luggage behind at the hotel, only taking with me what I could carry on my back in my “ruksak.”

Before I left I was introduced to a very nice[22] fellow who had just arrived in Venice, and a somewhat amusing incident occurred. I did not catch his name at first, and, as he spoke English so fluently and looked so much like an Englishman, I was somehow under the impression that he was a correspondent of a London paper. He appeared mystified when, after a few casual remarks, I asked him how long he had been in Italy.

“How long?” he exclaimed. “Why, I live here.” “But you are not an Italian?” “Well, you see my grandfather was,” he replied with a touch of humour which I was only able to appreciate, when I heard later that my “English journalist” was Peppino Garibaldi, a nephew of the great patriot. He had just come from the Front, where he had been to see the King to offer his services in raising a regiment of volunteers similar to the one he had recently commanded on the French front in the Argonne. His offer, it appeared, was not accepted, but afterwards I learned he was given a commission in the Army, and he has since so distinguished himself in action that he has risen to the rank of Colonel. I believe his brothers have also done equally well in the Army, thus proving that they are all real “chips of the old block.”

[23]

From Venice to Udine—Reservists rejoining—Interesting crowd—Delays en route—Endless procession of military trains—Drawn blinds—The Red Cross train—Arrival Udine—Scene on platform—In search of an hotel—A little incident—The well-dressed civilian—The obliging guide—My suspicions—Awkward questions—The best hotel in Udine—A little “Trattoria” close by—A cheap room—First impressions of Udine—At the Police Office—The permis de séjour—The Carabinieri and the local police—The fascination of the big guns—The “Military Commandant of Udine”—A difficult proposition—The luck of the undelivered letter—My guide has to leave me—I change my quarters—The Hotel “Tower of London”—Alone in Udine—An awkward predicament—A friend in need—Still more luck—Dr. Berthod—I am offered a studio—I accept—The delight of having this studio in Udine.

[25]

CHAPTER III

The train service between Venice and Udine was apparently running as usual, and there was no difficulty in getting tickets in spite of the drastic regulations with regard to passengers. Possibly it was assumed that anyone already inside the War Zone had permission to be there, so no further questions were asked.

My guide, of course, got the tickets, so I had no trouble in that matter; perhaps if I had gone to the booking office myself with my limited vocabulary of Italian it would have been different. As it was, it all seemed ridiculously simple, and there appeared to be no difficulty whatever.

In Venice they are so accustomed to Englishmen, and artists are such “common objects of the seashore,” that I attracted no particular notice, in spite of my rucksack and my Norfolk jacket, breeches and leggings.

The train left Venice at 8 o’clock in the morning, and was crowded with officers in uniform and reservists in civilian attire, going to join their regiments. Every class of Italian life was to be seen amongst them—from the peasant with his humble belongings in a paper parcel to the smart young man from Venice with his up-to-date suit case and other luggage.

All were in the highest possible spirits, and it gave me more the impression of a holiday outing of some big manufacturing company than a troop-train as it virtually was.

I now began to realize how handicapped I was in not speaking Italian; it would have been so interesting to have been able to chat with these enthusiastic young fellows.

[26]

It was supposed to take three hours to get to Udine, but we were two hours and a half longer, as we were continually being held up for trains with troops, artillery and every description of materiel to pass. It was an endless procession, and the soldiers in them seemed as happy as sand-boys, and cheered lustily as they passed us.

The blinds of our windows and doors had to be kept drawn down the whole way, and no one except the officers was allowed to get out of the train at the stations under any pretext. Still there was not much that we did not see; the blinds did not fit so tight as all that.

At one place we passed a long Red Cross train full of badly-wounded men just in from the Front. This was the first time there had been any evidence of the fighting that was taking place on ahead. It was almost a startling sight, and came in sharp contrast to the cheering crowds of healthy boys in the troop trains that had gone by a few minutes previously.

There was a big crowd of officers and soldiers on the platform at Udine, which was the terminus of the line, and one realised at once that it was an important military centre. Outside was a large assemblage of vehicles, motor waggons, and ambulance cars, and altogether there was a scene of military activity that presented a sharp contrast to sleepy Venice.

To face page 26

The station is some little distance from the town, so we set off in search of a small hotel we had been recommended to where we could get quiet lodgings for a day or two as I did not want to put up anywhere where we should attract undue attention. I had thought it would be advisable to drop the “War Correspondent” for the time being and to call myself simply a wandering artist in search of Military subjects, and my intelligent young guide quite entered into my idea—it was only a harmless little[27] fib after all.

A few hundred yards from the station a little incident occurred which, curiously enough, turned out to be the commencement of the run of luck which, with one exception, of which I shall tell later, I had during the whole of my stay in Udine. It came about in this wise.

A good-looking, well-dressed man in civilian attire caught us up as we were walking along, and, noticing that we seemed uncertain which way to take, asked pleasantly if we were looking for any particular street. My companion unhesitatingly told him we had just arrived in Udine, and were looking for lodgings.

The stranger, noticing I could not speak Italian, addressed me in a very good French, and obligingly offered to accompany us part of the way. I could not well refuse, but I recollect how the thought instantly flashed through my mind that he was perhaps a police official in mufti or a detective, and my suspicions seemed to be confirmed by a question he put to me bluntly.

“Are you journalists?” he enquired suddenly.

My first impulse was to ask what business it was of his what we were, when it flashed through my mind that it was better not to resent his query, which might after all mean no harm. So I replied that I was a travelling artist in search of military subjects, and that my companion was my interpreter. “But why do you ask if we are journalists?” I continued.

“Because journalists are forbidden to come to Udine, and only yesterday the famous Barzini himself was arrested and sent back to Milan for coming here without permission. Of course there may be no objection to you as an artist if all your papers are in order.”

[28]

I assured him they were, but nevertheless I did not feel very reassured after what he had told me; it seemed a sort of hint that unless I was very sure of my position I had better not think of taking lodgings at Udine, otherwise I was asking for trouble. However, I had weighed all this in my mind beforehand, and was well aware of the risk I was taking.

It makes me smile even now when I recall how curtly I answered him, and how every remark he made only increased my early doubts as to his bona-fides, for he turned out to be as good and genuine a fellow as I ever met, and had it not been for this chance meeting, my early impressions of Udine would have been very different to what they were, apart from the result it had on my work whilst there, but of all this more anon.

The modest hotel we had been recommended to put up at was merely modest in comparison with Danielli’s at Venice, for it was the Hotel d’Italie, one of the best and most frequented in Udine, and the very last place I should have chosen for seclusion. As it turned out, they had not a room vacant, so we had perforce to seek accommodation elsewhere.

Meanwhile the obliging stranger had left us to our own devices, much to my relief, as I was not over keen on his knowing where we put up.

There happened to be a little “trattoria” close by, and we went in to get something to eat. It was late for lunch, so we had it to ourselves, and the proprietor, seeing we were strangers, came and had a chat with us.

It turned out that he had a room to let for 1.50 per night with two beds in it; it was large and very clean, so, to avoid walking about trying to find something better, I told him that I would take it. But it was more easily said than done.

“You must go to the Questura (the police) and[29] get their permission to stay in Udine before I can let you have it,” he told us. This was a bit awkward, but there was no help for it but to go at once and get the ordeal over, so we made our way at once to the police station.

We had to pass through a main street, and I realised at once that Udine, although the “Front” and the Headquarters of the Army, was only a small Italian garrison town, with perhaps more soldiers about than there would have been in normal times.

Considering how close it was at that moment to the actual opening operations of the war, it was distinctly disappointing from my point of view, considering I was looking for military subjects. In this respect it was even less interesting than many of the French towns such as, for instance, Epinal or Langres, I had been in during the early days shortly after the commencement of hostilities.

This was my first impression of Udine—I had reason to modify it considerably in a very short time, in fact during the first day I was there. The echo of the big guns convinced me that although life in Udine was outwardly normal, the war was very near indeed.

At the Questura, to my surprise, the Commissaire made but little difficulty in giving me a permis de séjour, on seeing my passport and my last permis from Venice, and on my guide explaining that I might be remaining some little time, he readily made it out for one month.

As I came away I could not help wondering why it should have been so easy for me to obtain this permission to remain in Udine when Barzini had been arrested and sent away a couple of days previously.

I had yet to learn that in the War Zone the civil authorities and the local police take a very back seat,[30] and that the permis de séjour I had just been given would prove of no value whatever if the Carabinieri—i.e., the military police—took exception to my being in Udine. Fortunately I did not learn this until some days later, and in the meantime, confident in the possession of my police permit, I had no hesitation in walking about the town freely.

The sound of the big guns, however, which one heard unceasingly, soon began to exercise the curious fascination over me that they always have, and I was not long making up my mind that I must lose no time in Udine.

It was a delightfully quaint old town, with cafés and restaurants, and altogether a pleasant place to spend a few days in, but this was not what I had come for. So I immediately set about making enquiries for the quarters of the “Military Commandant of Udine” in order to present my letter from the Consul, and ask for permission to go out to the scene of operations.

It seemed on the face of it a perfectly simple matter to find out where he was staying, but we spent several hours going from place to place without success.

The long official envelope with “On His Majesty’s Service” on it proved an open sesame everywhere, and I was received with marked courtesy by all the staff officers I showed it to, and the envelope itself seemed to inspire respect, but not one of them could (or as I thought “would”) give me the information of the Commandant’s whereabouts. It struck me as being very strange all this mystery as it appeared.

Well, after having spent two hours going from one staff building to another, we had to give it up as a bad job—it was evidently a very difficult proposition to present a letter to the “Military Commandant of Udine”—and the envelope was beginning to show signs of wear after being handled[31] so much, so there was nothing for it but to have the letter always handy and chance coming across him sometime—in the meantime, if any questions were asked me as to the reason of my being in Udine I felt I had always the excuse of this document which I was waiting to hand personally to the “Military Commandant.”

As it turned out I owed all my luck in remaining in Udine as long as I did to this undelivered letter in its official envelope. Whenever I was asked any awkward questions as to why I was there, out it would come, and the mere sight of it seemed to afford me protection. It was a veritable talisman. How its spell was eventually broken I will narrate in due course.

To get out to the scene of operations without a permit appeared hopeless, for the moment; one realised it would take some time to work it, so the only thing to do was to chance it and to remain on in the hope of something turning up—that Udine was the place to stay in if one could was evident. I therefore decided not to budge till they turned me out, and I never had cause to regret my decision.

My guide had only been given a few days holiday, so when he saw that there was no immediate chance of getting out to see anything of the fighting he told me he thought he had better return to Venice.

This, of course, meant my remaining on alone—a somewhat dreary prospect, since I knew no one, and, as I said, could scarcely make myself understood, but there was no help for it.

Before he left I managed, with his assistance, to find a better room in a small hotel in the main street (curiously enough the hotel was named “The Tower of London”), and arranged to have my luggage sent from Venice.

It would be difficult to describe my feelings when I found myself alone outside the station after my[32] guide had gone. I felt literally stranded, but my lucky star was in the ascendant, and in a few minutes a little incident occurred that made me feel that I might get used to Udine after all.

There is a tramcar running from the station to the town, so I got on it as a sort of first attempt at finding my way about without assistance, but when the conductor apparently asked me where I wanted to go I was at once non-plussed, and could only gesticulate my ignorance and offer him a lire to take the fare out of.

I might have been in an awkward predicament and have attracted more attention than I desired, when a big stout man, who was also standing on the platform of the car, turned to me and in excellent English asked me where I was going and if he could be of any assistance since he saw I was an Englishman and could not speak Italian.

Needless to add, that this led to a conversation, and I learned that he had lived for many years at Cairo, hence his speaking English so well. He was a very genial fellow, and a genuine admirer of the English nation and our methods in Egypt.

Before we parted it was arranged that I should meet him the following day at the principal café in the town, and that he would introduce me to a young fellow, a friend of his, who also spoke English fluently, and who would doubtless be glad to show me around. So within five minutes of the departure of my guide I had fallen on my feet.

My luck even then was not out: just as I got off the tram I ran into the affable stranger who had walked with us from the station on the day of our arrival. He seemed so genuinely pleased to meet me again that my suspicions of him vanished at once, and I unhesitatingly accepted his offer of an “Americano” at the café close by; the fact of my being alone seemed to interest him immensely, and[33] he expressed astonishment at my risking remaining in Udine without understanding Italian.

In the course of conversation I learned he was Dr. Berthod, the President of an Agrarian Society, with a big warehouse and office in Udine. He asked me where I proposed to do my work, and when I said in my bedroom at the hotel, he told me that in his building there was a large room with a north light which he, speaking on behalf of his members, would be pleased if I would make use of as a studio whilst I was in Udine.

This was so unexpected that I was quite taken aback—such friendliness from a stranger quite overwhelmed me.

He would take no refusal, and insisted on my going with him to see if it would suit me.

It turned out to be a capital room, and I told him it would answer my purpose admirably, so he got some of his workmen to clear it out for me at once, in readiness for me to commence work, and promised to find me an easel and everything I required.

He refused to discuss the idea of my paying anything for it, saying they were only too pleased to help an Englishman, and that they would be delighted if I would consider it as my studio as long as I was in Udine. This was eighteen months ago, and the room is still reserved for me.

Without this studio, as I soon realised, life up at the Front for any length of time would have been terribly fatiguing and monotonous. It is difficult to convey an idea of the delight it was, having a quiet place to come back to work in after rushing about in a car for hours and probably having been under fire all the time.

To get away for a while from the turmoil of war when you were in the midst of it was a relief, like going from blazing sunshine into the cool interior of a cathedral.

[35]

The wonderful system on which everything was worked—Udine “the Front”—The commencement of hostilities—The 24th May—The first day of operations auspicious for Italy—Redemption of the province of Friuli—New Italian Front—Cormons—The inhabitants of Italian origin—A good practical joke—The moral of the troops—Unpretentious attempts at wit—High spirits of the men—The road from Udine to Cormons—Wonderful sight—Italian flags everywhere—A mystery where they came from—Wild triumphant advance of the Italian troops—Women kiss the ground—But a lever de rideau—Italians cross the Isonzo—Austrians on Monte Nero—Monte Nero—The capture of Monte Nero—Incredible daring of the Alpini—The story of the great achievement—Number of prisoners taken—The prisoners brought to Udine—Their temporary prison—The tropical heat—An ugly incident—Austrian attempt to re-take Monte Nero—Success follows success—Capture of Monfalcone and Gradisca; Sagrado and Monte Corrada—Commencement of the attack on Gorizia—Subjects for my sketch book—Touches of human nature—High mass in the mountains—The tentes d’abri—Cheerfulness of men in spite of all hardships.

[37]

CHAPTER IV

Everything seemed to go as though by routine in the early operations, and from the moment war was declared and the Italian army made its “Tiger spring” for the Passes on the night of May 23rd-24th it was manifest that General Cadorna had well-matured plans, and, that they were being carried out without a hitch anywhere.

During the six weeks I managed to stay in Udine I had ample opportunity of observing the wonderful system on which everything was worked, and how carefully pre-arranged were the movements of troops and material. Certainly no army—not even excepting the German—ever started a war under better conditions.