Title: A pound of prevention

Author: G. C. Edmondson

Illustrator: Richard Kluga

Release date: October 13, 2023 [eBook #71870]

Language: English

Original publication: New York, NY: Royal Publications, Inc, 1958

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

By G. C. EDMONDSON

Illustrated by RICHARD KLUGA

They knew the Mars-shot might fail, as

the previous ones had. All the more

reason, then, for having one good meal!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Infinity April 1958.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

Without his hat General Carnhouser was just a tired old man. Three men sat at the other side of the table. "No use trying to gloss it over," he said.

The young men nodded. If this shot failed it might be a hundred years before Congress could be conned into another appropriation. The three young men had an even better reason not to fail. They were going to be in the rocket.

Hagstrom spoke. "There were no technical difficulties in the previous shots."

"Right," the general said. "Take-offs proceeded according to schedule. Orbital corrections were made; then everybody settled down for a four-month wait. When deceleration time came the shot was still in the groove."

"We know," van den Burg said tiredly. He worked a microscopic speck of dirt from under a fingernail. There was a loud snap as he snipped the nail off. He stared at the general, a lean forefinger to one side of his ascetic nose.

"I'm no expert," the general said wearily. "When you reach my age they turn you into an office boy."

Hagstrom lit a cigarette. "It's tomorrow, isn't it?"

The general nodded. "They're loading now."

The third man's slight build and bushy black hair belied his mestizo origins. "I still don't think much of those rations," he said.

Hagstrom laughed suddenly. "You aren't going to con me into eating pickled fire bombs for four months."

"If I lived on prune soup and codfish balls I'd make no cracks about Mexican food," Aréchaga grunted. "You squareheads don't appreciate good cooking."

"You won't get any good cooking in zero gravity," the general said. They got up and filed out the door, putting on their caps and military manners.

Outside, trucks clustered at the base of a giant gantry. Aréchaga shuddered as a fork lift dropped a pallet of bagged meat on the gantry platform. The meat was irradiated and sealed in transparent plastic, but the habits of a lifetime in the tropics do not disappear in spite of engineering degrees. All that meat and not a fly in sight, he thought. It doesn't look right.

Multiple-stage rockets had gone the way of square sail and piston engines when a crash program poured twenty-two mega-bucks into a non-mechanical shield. Piles now diverted four per cent of their output into a field which reflected neutrons back onto the pile instead of absorbing them. Raise the reaction rate and the field tightened. Those sudden statewide evacuations in the early years of the century were now remembered only by TV writers.

A liquid metal heat exchanger transferred energy to the reaction mass which a turbine pump was drawing from a fire hydrant. Since the hydrant was fed from a sea water still there was no need for purification.

The last load of provisions went up and an asepsis party rode the gantry, burdened with their giant vacuum cleaners and germicidal apparatus.

"They'll seal everything but the control room," the general said. "When you go aboard there'll only be one compartment to sterilize."

"I still think it's a lot of hog-wash," Aréchaga said.

"They can't have us carrying any bugs with us," van den Burg said tiredly.

"The Martians might put us in quarantine," Hagstrom added sourly.

"If there are any Martians—and if we get there," Aréchaga groused.

"Now boys," the general began.

"Oh, save it, Pop," Hagstrom said. "Let's be ourselves as long as the public relations pests aren't around."

"Anybody going to town?" van den Burg asked.

"I am," Aréchaga said. "May be quite a while before I get another plate of fried beans."

"Checkup at 0400," the general reminded.

Hagstrom went to B.O.Q. Van den Burg and Aréchaga caught the bus into town and lost each other until midnight when they caught the same bus back to the base.

"What's in the sack?" Hagstrom asked.

"Snack," Aréchaga said. "I can't stand that insipid slop in the B.O.Q. mess."

"Looks like a lot of snack to eat between now and daybreak."

"Don't worry, I've got quite an appetite."

At 0345 an orderly knocked on three doors in Bachelor Officers' Quarters and three young men made remarks which history will delete. They showered, shaved, and spat toothpaste. At 0400 they walked into the Medical Officer's door. A red-eyed corpsman reached for a manometer and the three men began taking their clothes off. Fifteen minutes later the doctor, a corpulent, middle-aged man in disgustingly good humor for 0400, walked in with a cheery good morning. He poked and tapped while the corpsman drew blood samples.

"Turn your face and cough," he said.

"You think I'm going to develop hernia from riding a nightmare?" Hagstrom growled. "You did all this yesterday."

"An ounce of prevention," the doctor said cheerfully.

"A pound of bull," van den Burg grunted.

"Now boys, what if that got in the papers?" asked a voice from the doorway.

"Damn the papers!" they greeted the general.

"Do we get breakfast?" Aréchaga asked.

"You'll take acceleration better without it."

"Tell my stomach that."

"Bend over the table," the doctor said.

"Oh, my aching back," Hagstrom moaned.

"That's not the exact target, but you're close. And awaaaay we go," the doctor chanted as he drove the needle home.

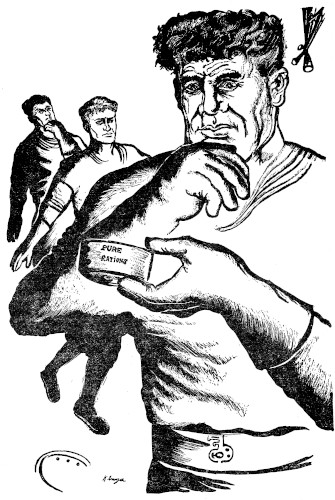

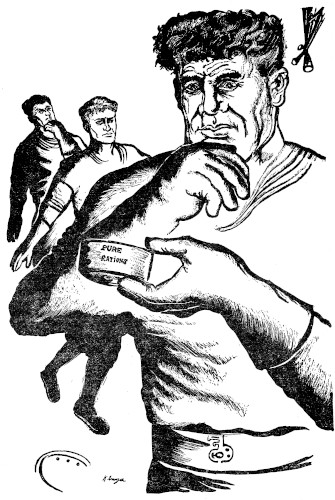

Each man received an injection of antibiotics and drank a paper cupful of anise-flavored liquid.

"Don't we get wrapped in cellophane?" Aréchaga asked.

"You'll be pure enough when that purgative goes through you."

They dressed and rode in the general's staff car to the base of the gantry. As the car stopped, the general said, "Well boys, I hope you don't expect a speech."

"We love you too, Pop," van den Burg said. They shook hands and stepped aboard the gantry platform. Hagstrom muttered and they faced a telescopic TV pickup with mechanical grins until the rising platform shielded them.

Each had his own control board and each was prepared to take over another's duties if necessary. They took off the baggy coveralls and tossed them into lockers. Aréchaga's made an odd clunk. He hitched up his shorts and turned quickly. They checked each other's instruments and settings, then went to their couches. A clock with an extra hand ticked the seconds off backward.

"We're ready," van den Burg muttered into a throat mike.

"So're we," a speaker answered tinnily.

The second hand began its final revolution in reverse. With blastoff it would begin turning in its proper direction. There was a clang as the water hose dropped its magnetic nipple. The rumbling became louder and the G meter climbed to 3.5. After several minutes the needle dropped suddenly to 2. Aréchaga tried to lift his head but decided it wasn't worth the effort. The rumbling stopped and he knew the sudden panic of free fall.

He made the adjustment which controlled arc flights and free fall parachute jumps had taught him and unstrapped. The speaker's tinny voice read off numbers which they transmuted into turns of two wheels with axes at right angles. Since the weight of the remaining reaction mass could not be calculated with exactitude they spun by trial and error the last few turns until a telescope parallel to the thrust axis zeroed on a third magnitude pinpoint whose spectroscope matched the tinny voice's demands.

"Why such a razzy speaker?" Hagstrom groused as he spun a wheel.

"A paper cone gets mush-mouthed in 3 G's," van den Burg grunted.

Aréchaga set the pump for 1.6 seconds at four liters. He nodded. Hagstrom pulled the rods. Weight returned briefly; then they floated again. Van den Burg belched. The tinny voice approved, and Hagstrom dropped the cadmium rods again. "Anybody for canasta?" Aréchaga asked.

The first day nobody ate. Overtrained, blasé—still, it was the first time and the stomach had yet to make peace with the intellect. The second day Aréchaga broke the pantry door seals and studied the invoices. He gave a groan of disgust and went back to sleep. With something solid strapped in on top it was almost easy.

On the third day van den Burg put bags of steak and string beans into the hi-fi oven and strapped himself into a chair. He used chopsticks to snare the globules of soup and coffee which escaped from hooded cups despite all precautions.

"How is it?" Hagstrom asked.

"It'd taste better if you'd come down and sit on the same side of the ship."

Human Factors had recommended that table and chairs be situated in one plane and resemble the real thing. The sight of one's fellow man at ease in an impossible position was not considered conducive to good digestion.

Hagstrom dived across the room and in a moment Aréchaga joined him. Aréchaga sampled the steak and vegetables and turned up his nose. He broke seals and resurrected pork, beef, onions, garlic, and sixteen separate spices. There was far too much sancoche for one meal when he was through.

"What'll you do with the rest of it?" Hagstrom asked.

"Eat it tomorrow."

"It'll spoil."

"In this embalmed atmosphere?" Aréchaga asked. He sampled the stew. "Irradiated food—pfui!" He went to his locker and extracted a jar.

"What's that?" van den Burg asked.

"Salsa picante."

"Literal translation: shredding sauce," Hagstrom volunteered. "Guaranteed to do just that to your taste buds."

"Where'd you get it?" van den Burg asked.

"Out of my locker."

"Not sterile, I presume."

"You're darn tootin' it ain't. I'm not going to have the only tasty item on the menu run through that irradiator."

"Out with it!" van den Burg roared.

"Oh, come now," Aréchaga said. He poured salsa over the stew and took a gigantic bite.

"I hate to pull my rank but you know what the pill rollers have to say about unsterilized food."

"Oh, all right," Aréchaga said morosely. He emptied the jar into the disposal and activated the locks. The air loss gave the garbage a gradually diverging orbit.

He began cranking the aligning wheels. When the stars stopped spinning, he threw a switch and began reading rapidly into a mike. Finished, he handed the mike to Hagstrom. Hagstrom gave his report and passed it to van den Burg.

Aréchaga rewound the tape and threaded the spool into another machine. He strapped himself before a telescope and began twiddling knobs. Outside, a microwave dish waggled. He pressed a trigger on one of the knobs. Tape screamed through the transmitter pickup.

"Make it?" Hagstrom asked.

"It began to wander off toward the end," Aréchaga said. He switched the transmitter off. The temperature had risen in the four minutes necessary to squirt and the sunward side was getting uncomfortable even through the insulation. Hagstrom began spinning the wheel.

Aréchaga fed tape into the receiver and played it back slowly. There was background noise for a minute then, "ETV One. Read you loud and clear." There was a pause; then a familiar voice came in, "Glad to hear from you, boys. Thule and Kergeulen stations tracked you for several hours. Best shot so far. Less than two seconds of corrective firing," the general said proudly.

Hagstrom and van den Burg returned to their books. Aréchaga snapped off the player and went into the pantry. The light dimmed and brightened as the spin exposed and occulted its accumulator. He filed the information subconsciously for his revision list and glared at the provisions.

Shelves were filled—meats, vegetables, fruits, all held in place by elastic netting. The skin-tight plastic was invisible in the dim light. Aréchaga began to feel prickly as the lack of ventilation wrapped him in a layer of steam. All that food right out in the open and no flies. It just isn't right, he thought. He shrugged and picked out three apples.

"Keep the doctor away?" he asked as he swam back into the control room. Hagstrom nodded and caught one.

"Thanks, I'm not hungry," van den Burg said. He put his book under the net and began taking his own pulse.

"Something wrong?" Aréchaga asked.

"Must have been something I ate," he grunted.

Hagstrom eyed his half-eaten apple with distaste. "I must have eaten some too." He threw the apple into the disposal and belched. Aréchaga looked at him worriedly.

Two days passed. Hagstrom and van den Burg sampled food fretfully. Aréchaga evacuated the disposal twice in six hours and watched them worriedly. "Are you guys thinking the same thing I am?" he asked.

Van den Burg stared for a moment. "Looks that way, doesn't it?"

Hagstrom started to say something, then dived for a bag and vomited. In a moment he wiped his mouth and turned a pale face toward Aréchaga. "This is how it started with the others, isn't it?" he said.

Aréchaga began talking into the recorder. He killed spin long enough to squirt. In a few minutes the razzy speaker again made them part of Earth. "—and hope for the best," the general was saying. "Maybe you'll adjust after a few days." The voice faded into background noise and Aréchaga turned off the player.

"Any ideas?" he asked. "You know as much medicine as I do."

Van den Burg and Hagstrom shook their heads listlessly.

"There's got to be a reason," Aréchaga insisted. "How do you feel?"

"Hungry. Like I hadn't eaten for two weeks."

"The same," Hagstrom said. "Every time I eat it lays like a ton of lead. I guess we just aren't made for zero grav."

"Doesn't seem to be hitting me as quickly as it did you two," Aréchaga mused. "Can I get you anything?" They shook their heads. He went into the library and began skimming through the medical spools.

When he returned the others slept fitfully. He ate a banana and wondered guiltily if his salsa had anything to do with it. He decided it didn't. The other crews had died the same way without any non-sterile food aboard. He floated back into the pantry and stared at the mounds of provisions until the mugginess drove him out.

Three more days passed. Hagstrom and van den Burg grew steadily weaker. Aréchaga waited expectantly but his own appetite didn't fail. He advanced dozens of weird hypotheses—racial immunity, mutations. Even to his non-medical mind the theories were fantastic. Why should a mestizo take zero grav better than a European? He munched on a celery stalk and wished he were back on Earth, preferably in Mexico where food was worth eating.

Then it hit him.

He looked at the others. They'll die anyway. He went to work. Three hours later he prodded Hagstrom and van den Burg into wakefulness and forced a murky liquid into them. They gagged weakly, but he persisted until each had taken a swallow. Thirty minutes later he forced a cup of soup into each. They dozed but he noted with satisfaction that their pulses were stronger.

Four hours later Hagstrom awoke. "I'm hungry," he complained. Aréchaga fed him. The Netherlander came to a little later, and Aréchaga was run ragged feeding them for the next two days. On the third day they were preparing their own meals.

"How come it didn't hit you?" van dan Burg asked.

"I don't know," Aréchaga said. "Just lucky, I guess."

"What was that stuff you gave us?" Hagstrom asked.

"What stuff?" Aréchaga said innocently. "By the way, I raised hell with the inventory getting you guys back in condition. Would you mind going into the far pantry and straightening things up a little?"

They went, pulling their way down the passage to the rearmost food locker. "There's something very funny going on," Hagstrom said.

Van den Burg inspected the stocks and the inventory list suspiciously. "Looks all right to me. I wonder why he wanted us to check it." They looked at each other.

"You thinking what I'm thinking?" Hagstrom asked.

Van den Burg nodded. They pulled themselves silently along the passageway back to the control room. Aréchaga was speaking softly into the recorder, his back to the entrance. Hagstrom cleared his throat and the black-haired little man spun guiltily. Van den Burg reached for the playback switch.

"It's just a routine report," Aréchaga protested.

"We're curious," Hagstrom said.

The recorder began playing. "—I should have figured it right from the start. If food is so lousy the flies won't touch it, then humans have no business eating it."

"What's the food got to do with it?" Hagstrom asked.

"Quiet!" van den Burg hissed.

"—got by all right on Earth where there was plenty of reinfection, but when you sealed us in this can without a bug in a million miles—" Aréchaga's voice continued.

"If food can't rot it can't digest either. Irradiate it—burn the last bit of life out of it—and then give us a whopping dose of antibiotics until there isn't one bug in our alimentary tracts from one end to the other. It's no wonder we were starving in the midst of plenty."

"Wait a minute. How come you didn't get sick?" Hagstrom asked.

Aréchaga flipped a switch and the recorder ground to a stop. "I reinfected myself with a swallow of salsa picante—good, old-fashioned, unsanitary chili sauce."

A horrible suspicion was growing in van den Burg's mind. "What did you give us?" he asked.

"You left me little choice when you threw out my salsa," Aréchaga said. "Why do you have to be so curious?"

"What was it?" van den Burg demanded.

"I scraped a little salsa scum from the inside of the disposal. It made a fine culture. What did you think I gave you?"

"I'd rather not answer that," van den Burg said weakly.