Title: Pen and pencil sketches of Faröe and Iceland

With an appendix containing translations from the Icelandic and 51 illustrations engraved on wood by W. J. Linton

Author: Andrew James Symington

Illustrator: W. J. Linton

Translator: Ólafur Pálsson

Release date: October 23, 2023 [eBook #71936]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Longman, Green, Longman, and Roberts, 1862

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Gísli Valgeirsson, Bryan Ness and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

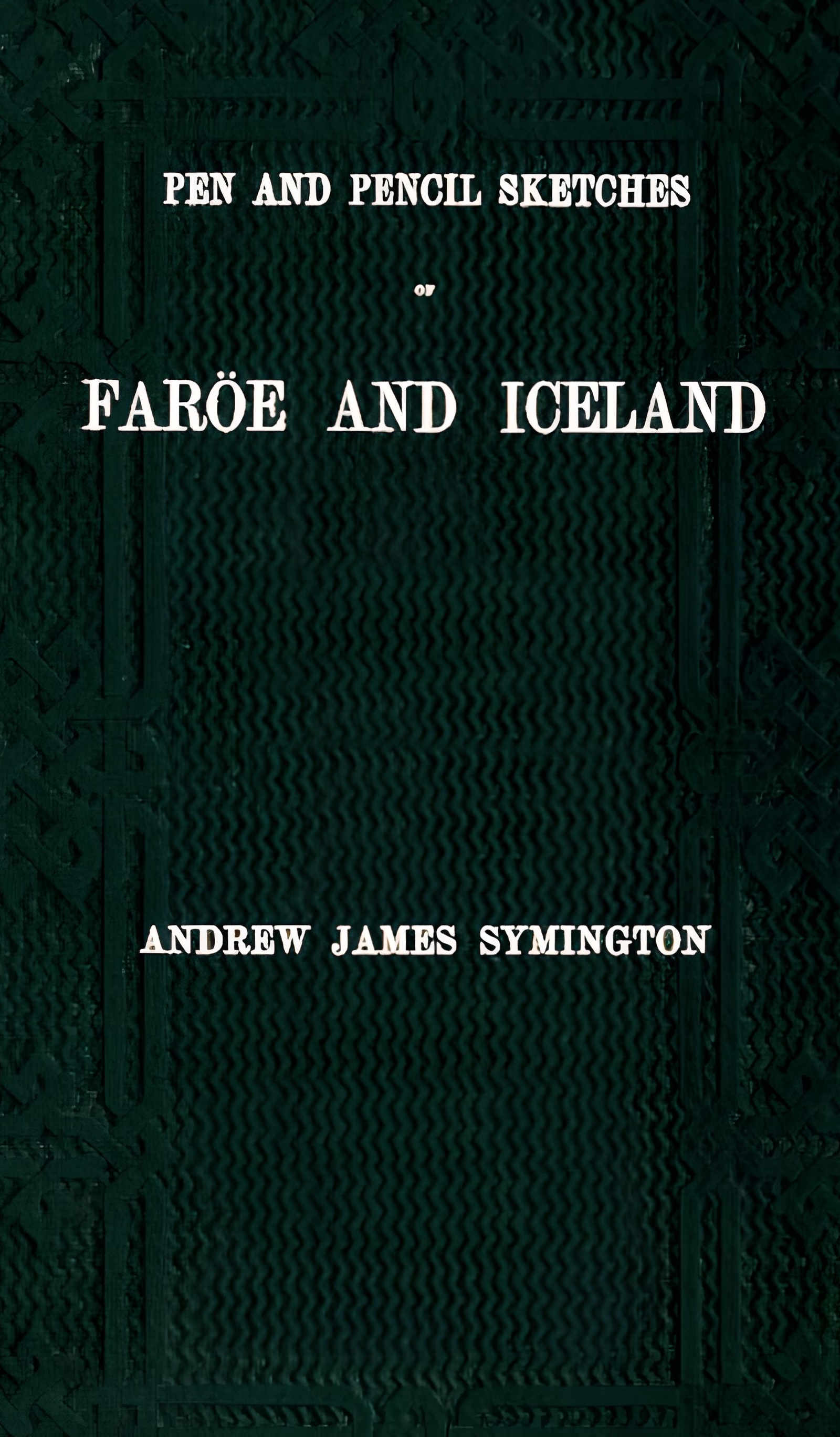

THE GREAT GEYSER IN ERUPTION.—See page 117.

May 1862.

The greater part of this volume consists of a diary jotted down in presence of the scenes described, so as to preserve for the reader, as far as possible, the freshness of first impressions, and invest the whole with an atmosphere of human interest.

The route taken may be thus shortly indicated: Thorshavn; Portland Huk; the Westmanna Islands; Reykjavik; the Geysers; then, by sea, round the south coast of the island, with its magnificent Jökul-range of volcanoes; along the east coast, with its picturesque Fiords, as far north as Seydisfiord; and thence home again, by the Faröe Isles.

The aim, throughout, has been both to present pictures and condense information on matters relating to Faröe and Iceland. In obtaining the latter I have had the advantages of frequent intercourse with Icelanders, both personal and by letter, since my visit to the North in the summer of 1859, and would here mention, in particular, the Rev. Olaf Pálsson, Dean and Rector of Reykjavik Cathedral; Mr. Jón Arnason, Secretary to the Bishop, and Librarian; Mr. Gísli Brynjúlfsson, the Icelandic poet and M.P.; Mr. Sigurdur Sivertsen, a retired merchant, and Mr. Jacobson.

And so too with the Faröese.

I acknowledge obligations to Dr. David Mackinlay of Glasgow, Dr. Lauder Lindsay of Perth, and several other friends who have visited Iceland and rendered vime assistance of various kinds. Thanks are also due to Mr. P. L. Henderson, for transmitting, by the Arcturus, letters, books and newspapers to and from the north.

The Appendix comprises thirteen Icelandic stories and fairy tales translated by the Rev. Olaf Pálsson; specimens of old Icelandic poetry; poems on northern subjects in English and Icelandic; information for intending tourists; a glossary; and lastly, a chapter on our Scandinavian ancestors—treating of race, history, characteristics, language and tendencies. This paper, originally intended for an introduction, may be perused either first or last, at the option of the reader. There is also a copious Index to the volume.

The illustrations, engraved by Mr. W. J. Linton, are all from original drawings by the writer, with the exception of half a dozen,[1] taken from plates in the large French folio which contains the account of Gaimard’s Expedition.

Should these pages induce photographers and other artists to visit this strange trahytic island resting on an ocean of fire in the lone North Sea, or students to become familiar with its stirring history and grand old literature, I shall feel solaced, under a feeling almost akin to regret, that this self-imposed task—which, in spite of sundry vexatious delays and interruptions, has afforded me much true enjoyment—should at length have come to an end.

May 1862.

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | v | |

| LEITH TO THORSHAVN | 1 | |

| WESTMANNA ISLANDS—REYKJAVIK | 35 | |

| RIDE TO THE GEYSERS | 69 | |

| REYKJAVIK | 143 | |

| JÖKUL-RANGES AND VOLCANOES ON THE SOUTH COAST | 160 | |

| Kötlugjá’s Eruptions | 163 | |

| Icelandic Statistics | 180 | |

| Eruption of Skaptár Jökul | 187 | |

| Volcanic History of Iceland | 193 | |

| THE EAST COAST. BREIDAMERKR—SEYDISFIORD | 197 | |

| Seydisfiord, by Faröe, to Leith | 208 | |

| APPENDIX. | ||

|---|---|---|

| I. Icelandic Stories and Fairy Tales | ||

| Stories of Sæmundur Frodi called the learned. | ||

| I. The dark School | 219 | |

| II. Sæmund gets the living of Oddi | 221 | |

| III. The Goblin and the Cowherd | 222 | |

| IV. Old Nick made himself as little as he was able | 224 | |

| V. The Fly | 224 | |

| VI. The Goblin’s Whistle | 225 | |

| Fairy Tales | ||

| Biarni Sveinsson and his sister Salvör | 226 | |

| Una the Fairy | 235 | |

| Gilitrutt | 240 | |

| Hildur the Fairy Queen | 244 | |

| A Clergyman’s daughter married to a Fairy Man | 253 | |

| The Clergyman’s daughter in Prestsbakki | 256 | |

| The Changeling | 257 | |

| II. Specimens of old Icelandic Poetry | ||

| From the “Völuspá” | 260 | |

| From the “Sólar Ljód” or “Sun Song” | 262 | |

| From the Poems relating to Sigurd & Brynhild | 265 | |

| “The Hávamál” or “High Song of Odin” | 265 | |

| III. Poems on Northern Subjects | ||

| The Lay of the Vikings, by M.S.E.S. | 278 | |

| Do. Translated into Icelandic by the Rev. Olaf Pálsson | 279 | |

| The Viking’s Raven, by M.S.E.S. | 281 | |

| Death of the Old Norse King, by A.J.S. | 286 | |

| Do. Translated into Icelandic by the Rev. Olaf Pálsson | 287 | |

| IV. Information for intending Tourists | 289 | |

| V. Glossary | 292 | |

| VI. Chapter on Our Scandinavian Ancestors | 293 | |

| INDEX | 309 | |

| PAGE | |||

| 1. | The Great Geyser in Eruption | Frontispiece. | |

| 2. | Little Dimon—Faröe | 1 | |

| 3. | Foola | 10 | |

| 4. | Naalsöe | 15 | |

| 5. | Thorshavn, the capital of Faröe | 20 | |

| 6. | Fort, at Thorshavn | 23 | |

| 7. | From Thorshavn—showing Faröese Boats | 27 | |

| 8. | Hans Petersen; a Faröese boatman | 28 | |

| 9. | Basalt Caves—South point of Stromoe | 32 | |

| 10. | Portland Huk—looking south | 35 | |

| 11. | Needle Rocks or Drongs—off Portland Huk | 38 | |

| 12. | Bjarnarey | 43 | |

| 13. | Westmanna Skerries | 43 | |

| 14. | Cape Reykjanes—showing Karl’s Klip (cliff) | 45 | |

| 15. | Coast near Reykjavik | 45 | |

| 16. | Eldey | 46 | |

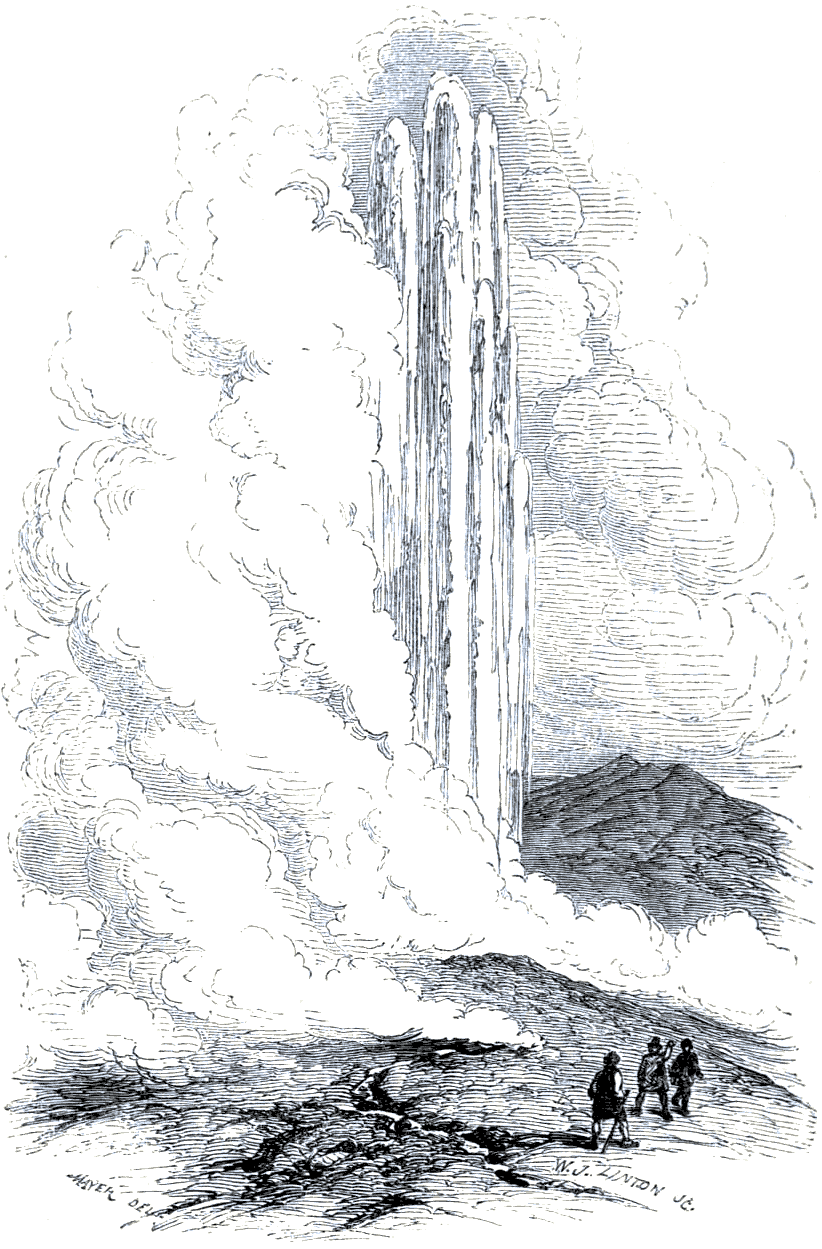

| 17. | Icelandic shoes, snuff-box, distaff, head-dress, & fishermen’s two-thumbed mits | 53 | |

| 18. | Reykjavik, from behind the town | 67 | |

| 19. | Icelandic Lady in full dress, from a Photograph | 68 | |

| 20. | View on the Route to Thingvalla | 69 | |

| 21. | Ravine | 73 | |

| 22. | Descent into the Almannagjá | 81 | |

| 23. | Almannagjá | 82 | |

| 24. | Fording the Oxerá | 83 | |

| 25. | Priest’s House at Thingvalla | 84 | |

| 26. | Althing and Lögberg from behind the church | 87 | |

| 27. | Lake of Thingvalla from the Lögberg | 89 | |

| 28. | Waterfall of the Oxerá as seen from the Lögberg | 90 | |

| 29. | Vent of Tintron | 94 | |

| 30. | Cinder-range of Vari-coloured Hills | 95 | |

| 31. | Crossing the Bruará | 104 | |

| 32. | The Great Geyser | 129 | |

| 33. | Skaptár Jökul | 134 | |

| 34. | Mount Hekla | 135 | |

| 35. | Lake of Thingvalla from the north-west | 139 | |

| 36. | Icelandic Farm, two hours’ ride from Reykjavik | 142 | |

| 37. | Music in an Icelandic home (playing the langspiel) | 145 | |

| 38. | Common Gull (Larus canus) | 159 | |

| 39. | Oræfa Jökul, the highest mountain in Iceland | 160 | |

| 40. | Snæfell Jökul, from fifty miles at sea | 161 | |

| 41. | Part of Myrdals Jökul and Kötlugjá range | 184 | |

| 42. | Oræfa Jökul, from the sea | 185 | |

| 43. | Entrance to Reydarfiord—east coast | 197 | |

| 44. | Near the entrance to Hornafiord | 198 | |

| 45. | Mr. Henderson’s Factory at the head of Seydisfiord | 202 | |

| 46. | Farm House, Seydisfiord | 206 | |

| 47. | Seydisfiord, looking east towards the sea | 207 | |

| 48. | Brimnæs Fjall | 208 | |

| 49. | Naalsöe—Faröe | 212 | |

| 50. | Entrance to the Sound leading to Thorshavn | 213 | |

| 51. | Stromoe—Faröe, looking north-east from below the Fort at Thorshavn | 216 | |

Can Iceland—that distant island of the North Sea, that land of Eddas and Sagas, of lava-wastes, snow-jökuls, volcanoes, and boiling geysers—be visited during a summer’s holiday? This was the question which for years I had vaguely proposed to myself. Now I wished definitely to ascertain particulars, and, if at all practicable, to accomplish such a journey during the present season.

2Three ways presented themselves—the chance of getting north in a private yacht—to charter a sloop from Lerwick—or to take the mail-steamer from Copenhagen. The first way seemed very doubtful; I was dissuaded from the second by the great uncertainty as to when one might get back, and the earnest entreaties of friends, who, with long faces, insinuated that these wild northern seas were not to be trifled with. However, the uncertainty as to time, and the expense, which for one person would have been considerable, weighed more with me than any idea of danger. Of the mail-steamer it was difficult to obtain any information.

One morning, when in this dilemma, my eye fell on an advertisement in the Times, headed “Steam to Iceland,” informing all whom it might concern that the Danish mail-steamer “Arcturus,” would, about the 20th of July, touch at Leith on its way north, affording passengers a week to visit the interior of the island, and would return to Leith within a month. I subsequently ascertained that it was to call at the Faröe and Westmanna Isles, and that it would also sail from Reykjavik round to Seydisfiord, on the east of Iceland, so that one might obtain a view of the magnificent range of jökuls and numerous glaciers along the south coast.

The day of sailing was a fortnight earlier than I could have desired, but such an opportunity was not to be missed. Providing myself with a long waterproof overcoat, overboots of the same material—both absolutely essential for riding with any degree of comfort in Iceland, to protect from lashing rains, and when splashing through mud-puddles or deep river fordings—getting together a supply of preserved meats, soups, &c. in tin 3cans, a mariner’s compass, thermometer, one of De La Rue’s solid sketch-books, files of newspapers, a few articles for presents, and other needful things, my traps were speedily put up; and, on Wednesday the 20th of July, I found myself on board the “Arcturus” in Leith dock.

It was a Clyde-built screw-steamer, of 400 tons burden. Captain Andriessen, a Dane, received me kindly; the crew, with the exception of the engineer, a Scotchman, were all foreigners. In the first cabin were eight fellow-passengers, strangers to each other; but, as is usual at sea, acquaintanceships were soon formed; by degrees we came to know each other, and all got along very pleasantly together.

There was only one lady passenger, to whom I was introduced, Miss Löbner, daughter of the late governor of Faröe, who had been south, visiting friends in Edinburgh. Afraid of being ill, she speedily disappeared, and did not leave her cabin till we reached Thorshavn. Of our number were Professor Chadbourne, of William’s College, Massachusetts, and Bowdoin College, Maine, U.S.; Capt. Forbes, R.N.; Mr. Haycock, a gentleman from Norfolk, who had recently visited Norway in his yacht; Mr. Cleghorn, lately an officer in the Indian army; Mr. Douglas Murray, an intelligent Scottish farmer, from the neighbourhood of Haddington, taking his annual holiday; Dr. Livingston, an American M.D.; and Capt. B——, a Danish artillery officer, en route from Copenhagen to Reykjavik.

There were also several passengers in the second cabin, some of whom were students returning home from their studies in the Danish universities.

4There was a large boat to be got on board, for discharging the steamer’s cargo at Iceland, which took several hours to get fastened aloft on the right side of the hurricane deck—with the comfortable prospect of its top-heaviness acting like a pendulum, and adding considerably to the roll of the ship, should the weather prove rough.

Shortly after seven P.M. we got fairly clear of the dock. Strange to think, as the last hawser was being cast off, that, till our return, we should hear no postman’s ring, receive no letters with either good tidings or annoyances—for we carry the mail,—and see no later newspapers than those we take with us! Friends may be well or ill. The stirring events of the Continent, too, leave us to speculate on changes that may suddenly occur in the aspect of European affairs, with the chances of peace, or declarations of war.

However, allowing such thoughts to disturb me as little as possible, and trusting that, under a kind Providence, all would be well with those dear to me, hopefully, and not without a deep feeling of inward satisfaction that a long cherished dream of boyhood was now about to be realised, I turned my face to the North.

A dense mist having settled on the Frith of Forth, the captain deemed it prudent to anchor in the roads. During the night it cleared off, and at five o’clock on Thursday morning, 21st July, our star was in the ascendant, and the “Arcturus” got fairly under way.

The morning, bright and clear, was truly splendid; the day sunny and warm; many sails in sight, and numerous sea-birds kept following the ship.

Breakfast, dinner, and tea follow each other in regular 5succession, making, with their pleasant reunions and friendly intercourse, a threefold division of the day. On shipboard the steward’s bell becomes an important institution, a sort of repeating gastronomical chronometer, and is not an unpleasant sound when the fresh sea-air has sharpened one’s appetite into expectancy.

The commissariat supplies were liberal, and the department well attended to by a worthy Dane, who spoke no English, and who was only observed to smile once during the voyage. Captain Andriessen’s fluent English, and the obliging Danish stewardess’ German, enabled us all to get along in a sort of way; although the conversation at times assumed a polyglot aspect, the ludicrous olla-podrida nature of which afforded us many a good hearty laugh.

The chief peculiarities in our bill of fare were lax or red-smoked salmon; the sweet soups of Denmark, with raisins floating in them; black stale rye-bread; and a substantial dish, generally produced thrice a day, which, in forgetfulness of the technical nomenclature, we shall venture to call beef-steak fried with onions or garlic—that bulb which Don Quixote denounced as pertaining to scullions and low fellows, entreating Sancho to eschew it above all things when he came to his Island. At sea, however, we found it not unpalatable. There must ever be some drawbacks on shipboard. One of these was the water produced at table, of which Captain Forbes funnily remarked, that it “tasted badly of bung cloth—and dirty cloth, too!” But, such as it was, the Professor and I preferred it to wine.

Thus much of culinary matters, for, with the exception of a few surprises, which, according to all our 6previous ideas, confused the chronology of the dishes—making a literal mess of it—and sundry minor variations in the cycle of desserts proper, the service of one day resembled that of another.

There was only wind enough to fill the mainsail, and in it, on the lea side of the boom, as if in a hammock, sheltered from the broiling sun, I lay resting for hours. Off Peterhead, we saw innumerable fishing boats—counted 205 in one fleet. Off Inverness, far out at sea, we counted as many, ere we gave in and stopped. Their sails were mostly down, and we, passing quite near, could observe the process of the fishermen shooting their nets; the sea to the north-east all thickly dotted with boats, which appeared like black specks. A steamer was sailing among them, probably to receive and convey the fish ashore.

Perilous is the calling of the fisherman! Calm to-day, squalls may overtake him on the morrow—

As the sun went down, from the forecastle we watched a dense bank of cloud resting on the sea; its dark purple ranges here and there shewing openings, with hopeful silver linings intensely bright—glimpses, as it were, into the land of Beulah. Then the lights and shadows grandly massed themselves, gradually assuming a sombre hue; while starry thoughts of dear ones at home rose, welling up within us, as the daylight ebbed slowly away over the horizon’s rim.

7Friday morning, July 22.—Rose at seven; weather dull; neither land, sky, nor sail, visible; our position not very accurately known. At four in the morning the engine had been stopped, the look-out having seen breakers a-head—no observation to be had. Our course to the North Sea lay between the Orkney and Shetland Islands. After breakfast it cleared, and on the starboard bow, we saw Fair Isle, so that our course was right, although we had not known in what part of it we were.

There was cause for thankfulness that the Orkneys had been passed in safety. Where the navigation is intricate and requires care at best, our chances of danger during the uncertainty of the night had doubtless been great. The south of the Shetland Isles also appeared to rise from the sea, dim and blue, resting on the horizon, like clouds ethereal and dreamlike.

At 11 o’clock A.M., sailing past Fair Isle, made several sketches of its varied aspects, as seen from different points. Green and fair, this lonely island lies about thirty miles south-west of the Shetland group, and in the very track of vessels going north.

It has no light-house, and is dreaded by sailors; for many are the shipwrecks which it occasions. Before now, we had heard captains, in their anxiety, wish it were at the bottom of the sea. Could not a light be placed upon it by the Admiralty, and a fearful loss of life thus be averted?

The island contains about a hundred inhabitants, who live chiefly by fishing and knitting. They are both skilful and industrious. During the winter months, the men, as well as the women, knit caps, gloves, and waistcoats; 8and for dyeing the wool, procure a variety of colours from native herbs and lichens.

True happiness, springing as it ever does from above and from within, may have its peaceful abode here among those lonely islanders quite apart from the noise and bustle of what is called the great world, although the stranger sailing past is apt to think such places “remote, unfriended, melancholy, slow.”[2]

Ere long we could distinguish the bold headland of Sumburgh, which is the southern extremity of Shetland; and a little to the north-west of it, by the aid of an opera-glass, Fitful Head,[3] rendered famous by Sir Walter Scott as the dwelling place of Norna, in “The Pirate.”

Last summer I visited this the most northern group of British islands, famed alike for skilful seamen, fearless fishermen, and fairy-fingered knitters; for its hardy ponies, and for that soft, warm, fleecy wool which is peculiar to its sheep.

Gazing on the blue outline of the islands, I now involuntarily recalled their many voes, wild caves, and splintered skerries, alive with sea gulls and kittiwakes. The magnificent land-locked sound of Bressay too, where her Majesty’s fleet might ride in safety, and where Lerwick—the capital of the islands, and the most northerly town in the British dominions—with its quaint, foreign, gabled aspect, rises, crowning the heights, from the very water’s edge, so that sillacks might be fished 9from the windows of those houses next the sea. Boating excursions and pony scamperings are also recalled; the Noss Head, with its mural precipice rising sheer from the sea to a height of 700 feet, vividly reminding one of Edgar’s description of Dover Cliff, in “Lear,” or of that which Horatio pictured to Hamlet—

Nor is the much talked of cradle forgotten, slung on ropes, for crossing the chasm between a lower cliff and the Holm of Noss;—a detached rocky islet, the top of which only affords pasture, during the summer months, for some half dozen sheep.

The curious and singularly-perfect ancient Pictish or Scandinavian Burgh, in the Island of Moosa, rises again before me; Scalloway Bay, with its old Castle in ruins, its fishermen’s cots, and fish-drying sheds. A high, long, out-jutting rocky promontory too, on which I had stood watching the “yeasty waves” far below, as they rolled thundering into an irregular cave, which, in the course of ages, they had scooped out among the basaltic crags, and, leaping up, scattered drenching showers of diamond spray. Every succeeding dash of the billows produced a loud report like the discharge of artillery, the reverberations echoing along the shore. In the black creek below, the brine seething like a caldron was literally churned into white foam-flakes, which, rising into the air on sudden gusts of wind, 10sailed away inland, high overhead, like a flock of sea-birds. These flakes were of all sizes, large masses of froth at times floating down, and alighting at our very feet, from so great a height that they had merely shewed as black specks against the bright sunlight. In lulls one could actually lift them bodily from the ground, upwards of two cubic feet in size; but when the wind rose, such masses of whipped sea-cream were again seized upon, swept aloft, divided into smaller portions, and carried away across the island. These and other pleasing memories presented themselves as we now gazed on the distant, dim-blue Shetland Isles.

Saw a large vessel disabled and being towed southwards from Shetland, where she appears to have come to grief. Topmasts gone, sides battered and patched with boards. She is high out of the water, so that the cargo must have been discharged. All our opera-glasses and telescopes are in requisition.

Sat on the boom for hours, the vessel rolling heavily over the great smooth Atlantic billows. In the afternoon passed the island of Foola, which has been called the St. 11Kilda of Shetland. It lies about sixteen miles west of Mainland, and is high and precipitous. The cliffs are tenanted by innumerable sea-fowls, which are caught in thousands by the cragsmen, and afford a considerable source of revenue to the inhabitants.

Blue and cloudlike the detached and isolated heights of Mainland, Yell, and Unst—the promontory of Hermanness, on the latter, being the most northerly point of the British islands—are fast sinking beneath the horizon. Ere long Foola, left astern, follows the others. No land in sight, not a sail on the horizon; all round is now one smooth heaving circular plain of blue water—the ever changing level producing a most singular optical effect.

In the evening walked the deck with Mr. Haycock, discoursing of Norwegian scenery, and of yacht excursions thither. The evening clear and pleasant, although the ground-swell continued to increase. Turned in, at half-past ten o’clock. The vessel rolled much during the night. Professor Chadbourne, Mr. Murray, and Mr. Cleghorn’s berths were in the same state-room as mine. The quarter-deck being elevated, one of our windows opened towards the deck, and could at all times afford good and safe ventilation; but the stewards always would shut it, watching their opportunity of doing so when we were asleep. We always opened it again, when on waking we found the deed had been done; and all of us made a point of shouting out ferociously when we caught them stealthily at it. This shutting and opening occurred several times every night, and seemed destined to go on, spite of all our remonstrances; a nuisance only relieved by a slight dash of the ludicrous. Danes don’t seem to like fresh air.

12Saturday morning, July 23.—No land in sight, open sea from Norway to America; heavy swell on the Atlantic, and wind changing from N.E. to N.W.; numerous whales blowing, quite close to the vessel; gulls and kittiwakes flying about.

At mid-day came in sight of the Faröe Islands rising above the horizon; fixed the first glimpse of them, and continued sketching their outline from time to time, as on nearing them it developed itself—watching with great interest the seeming clouds slowly becoming crags. Little Dimon, a lofty rock-island, somewhat resembling Ailsa, and purple in the distance, was, from the first, the most prominent and singular object on the horizon line.

The waves rolling so heavily that not only the hull, but the mast of a sloop, not very far off, is quite hid by each long swell. The Professor, Dr. Livingston, and Mr. Murray all agree in saying that they never had such heavy seas in crossing the Atlantic.

The Faröe group consists of twenty-two islands, seventeen of which are inhabited. A bird’s-eye view of them would exhibit a series of bare, steep, oblong hills, in parallel ranges; with either valleys or narrow arms of the sea between them, and all lying north-west and south-east. The name Faröe is said to be derived from faar or foer, the old word for a sheep; that animal having probably been introduced by the Norse sea-rovers long before these islands were permanently colonised in the time of Harold. However, fier—the Danish word for feathers—is more likely to be the correct etymology; for these islands are the native habitat of innumerable sea-birds.

They lie 185 miles north-west of the Shetland Isles, 13400 west of Norway, and 320 south-east of Iceland; population upwards of 3000, and subject to Denmark.

We are now approaching Suderoe, the most southerly of the islands. On our left lie several curious detached rocks, near one of which, called the Monk, is a whirlpool, dangerous in some states of the tide; although its perils, like those of Corrivreckan between Jura and Scarba in the Hebrides, have been greatly exaggerated. On one occasion I sailed over the latter unharmed by Sirens, Mermaids, or Kelpies; only observing an irregular fresh on the water, where the tide-ways met, and hearing nothing save a dripping, plashing noise in the cross-cut ripple, as if many fish were leaping around the boat.

In storms, however, such places had better receive a wide berth.

The approach to the Faröe group is very fine, presenting to our view a magnificent panorama of fantastically-shaped islands—peaked sharp angular bare precipitous rocks, rising sheer from the sea; the larger-sized islands being regularly terraced in two or more successive grades of columnar trap-rock. Some of these singular hill-islets are sharp along the top, like the ridge of a house, and slope down on either side to the sea, at an angle of fifty degrees. Others of them are isolated stacks.

The hard trap-rock, nearly everywhere alternating with soft tufa, or claystone, sufficiently accounts for the regular, stair-like terraces which form a striking and characteristic feature of these picturesque islands. The whole have evidently, in remote epochs, been subjected to violent physical abrasion, probably glacial, during the period of the ice-drift; and, subsequently, to the disintegrating crumbling influences of moisture, and of 14the atmosphere itself. Frost converts each particle of moisture into a crystal expanding wedge of ice, which does its work silently but surely and to an extent which few people would imagine.

We now pass that singular rock-island, Little Dimon, which supports a few wild sheep; and Store Dimon, on which only one family resides. The cliffs here, as also on others of the islands, are so steep that boats are lowered with ropes into the sea; and people landing are either pulled up by ropes, or are obliged to clamber up by fixing their toes and fingers in holes cut on the face of the rock. Sea-fowls and eggs are every year collected in thousands from these islets by the bold cragsmen. These men climb from below; or, like the samphire-gatherer—“dreadful trade”—are let down to the nests by means of a rope, and there they pursue their perilous calling while hanging in “midway air” over the sea. They also sometimes approach the cliffs at night, in boats, carrying lighted torches, which lure and dazzle the birds that come flying around them, so that they are easily knocked down with sticks, and the boat is thus speedily filled. As many as five thousand birds have been taken in one year from Store Dimon alone, and in former times they were much more numerous.

We watch clouds like white fleecy wool rolling past, and apparently being raked by the violet-coloured peaks; whilst others lower down are pierced and rest peacefully among them.

Having passed Sandoe, through the Skaapen Fiord, we see Hestoe, Kolter, Vaagoe, and other distant blue island heights in the direction of Myggenaes, the most western island of the group. We now sail between 15Stromoe on the west, and Naalsöe on the east. Stromoe is the central and largest island of the group, being twenty-seven miles long and seven broad. It contains Thorshavn, the capital of Faröe. Naalsöe, the needle island, is so called from a curious cave at the south end which penetrates the island from side to side like the eye of a needle—larger, by a long way, than Cleopatra’s. Daylight shews through it, and, in calm weather, boats can sail from the one side to the other. We observe a succession of sea-caves in the rocks as we sail along, the action of the waves having evidently scooped out the softer strata, and left the columnar trap-rock hanging like a pent-house over each entrance. These caves are tenanted by innumerable sea-birds. On the brink of the water stand restless glossy cormorants; along the horizontal rock-ledges above them, sit skua-gulls, kittiwakes, auks, guillemots, and puffins, in rows; and generally ranged in the order we have indicated, beginning with the cormorant on the lower stones or rocks next the sea, and ending with the puffin, which takes the highest station in this bird congress.

16If disturbed, they raise a harsh, confused, deafening noise; screaming and fluttering about in myriads. Their numbers are so frequently thinned, and in such a variety of ways, that old birds may, on these occasions, be excused for exhibiting signs of alarm.

The Faröese eat every kind of sea-fowl, with the exception of gulls, skuas, and cormorants; but are partial to auks, guillemots, and puffins. They use them either fresh, salted or dried. The rancid fishy taste of sea-birds resides, for the most part, in the skin only—that removed, the rest is generally palatable. In the month of May the inhabitants of many of the islands subsist chiefly on eggs. Feathers form an important article of export.

We watched several gulls confidingly following the steamer; one in particular, now flying over the deck as far as the funnel, now falling astern to pick up bits of biscuit that were thrown overboard to it. Long I stood admiring its beautiful soft downy plumage, its easy graceful motions, the great distance to which a few strokes of its powerful pinions urged it forward, or, spread bow-like and motionless, allowed it simply to float and at times remain poised in the air right over the deck, now peering down with its keen yet mild eyes, and leaving us to surmise what embryo ideas of wonder might now be passing through its little bird-brain.

The Danish officer raised, levelled his piece, and fired; the poor thing screamed like a child, threw up its wings, turned round, and fell upon the sea like a stone; its companions came flying confusedly in crowds to see what was wrong with it, and received another shower of lead for their pains.

Holding no peace-society, vegetarian, homeopathic &c. 17views, I do not object to the bona fide clearing of a country from dangerous animals; or to shooting, when rendered necessary for supplying our wants; but—from the higher, healthier platform of Christian manliness, reason and common sense—would most emphatically protest against thoughtless or wanton cruelty. Such barbarism could not be indulged in, much less be regarded as sport, but from sheer thoughtlessness in the best; while, under almost any circumstances, the destruction of animal life will, by the true gentleman, be regarded as a painful necessity.

Those who love sport for its own sake may be divided into three classes—the majority of sportsmen it is to be hoped belonging to the first of these divisions;—viz., the thoughtless, who have never considered the subject at all, or looked at any of its bearings; those whose blunted feelings are, in one direction, estranged from the beauty and joy of existence; and the third and last class, where civilization makes so near an approach to the depravity of savage natures, that a tiger-like eagerness to destroy life takes possession of a man and becomes a passion. He then only reckons the number of braces bagged, and considers not desolate nests, broken-winged pining birds, and the many dire tragedies wrought on the moor by his murderous gun.

A study of the habits of birds, taking cognizance of all the interesting ongoings of their daily lives, of their wonderful instincts and labours of love, would, we should think, make a man of rightly-constituted mind feel the necessity of destroying them to be painful; and he certainly would not choose to engage in it as sport. The fable of the boys and the frogs is in point, and the term 18“sport,” thus applied, is surely a cruel, and certainly a one-sided word. In low natures, sympathy becomes totally eclipsed and obscured by selfishness; and all selfishness is sin.

Although shocked at witnessing the needless destruction of the poor gull, for the sake of the officer, who was of a gentle kindly nature, doubtless belonging to the “first division,” we tried hard to palliate the deed; but that pitiful cry of agony haunts us yet!

Whales rising to the surface and spouting around the vessel; also shoals of porpoises tumbling and gambolling about; sometimes swimming in line so as closely to resemble the coils of a snake moving along; such an appearance has probably originated the mythic sea-serpent.

There are still many caves in the rocks close on the sea; innumerable birds flying out of them and settling on the surface of the heaving water close under the cliffs.

We now approach a little bay, surrounded by an amphitheatre of bare hills; the hollow, for a wonder, slopes down to the shore; we observe patches of green among the rocks, and a flag flying. Several fishing sloops lie at anchor, but there is no appearance of a town. Here we are told is Thorshavn, the capital of Faröe—the 19haven of Thor. As we approach, we discover that it is a town, the chief part of it built upon a rocky promontory which divides the bay; we can also distinguish the church and fort. The green tint we had observed is grassy turf—but it happens to be growing on the roofs of the wooden houses; and the houses are scattered irregularly among the brown rocks. On the promontory, house rises above house from the water’s edge; and the black, wooden church tower rising behind appears to crown them all. On an eminence, to the right of the town, is the battery or fort, with a flagstaff in front. All glasses in requisition, we curiously examine the place and discover several wooden jetties—landing places for fishing boats. Beneath the fort and all round, split fish are spread on the rocks to dry; many square fish-heaps also are being pressed under boards, with heavy stones placed above them.

The scenery around is not unlike that of Loch Long in Scotland, while the general aspect of Thorshavn itself resembles the pictures of old towns given in the corners of maps of the fifteenth century.

As we enter the bay with colours flying, the Danish flag is run up at the fort, displayed by the sloops, and flutters from the flagstaff at Mr. Müller’s house. This gentleman is one of the local authorities and also agent for the steamer. A cold wind blows down the ravine, boats are coming off, the steam-whistle rejoices on hearing itself echoed among the hills, and the anchor is let go. Now, that we are near it, the town appears really picturesque and carries one several hundred years back, with its veritable old-world, higgledy-piggledy quaintness.

Saturday night, 6 P.M.—Went on shore in the captain’s boat, called at Mr. Müller’s office—a comfortable new erection—and then separated into parties to explore the place. Crowds of men, women, and children, standing at every door, stare at us with undisguised child-like wonder; the men—middle-sized stalwart fellows with light hair and weathered faces—taking off their caps to us as we pass along returning their salutes.

“An ancient fishy smell,” together with a strong flavour of turf-smoke, decidedly predominate over sundry other nondescript odours in this strange out-landish town. The results of our exploration are embodied in the following jottings, which, at all events, participate so far in the spirit of the place as to resemble its ground-plan.

Houses, stone for a few feet next the ground, then wood, tarred or painted black, and generally two stories 21in height; small windows, the sashes of which are painted white; green turf on the roofs. The interiors of the poorer sort of houses are very dark; an utter absence of voluntary ventilation; one fire, and that in the kitchen, the chimney often only a hole in the roof. Yet even in these hovels there is generally a guest-room, comfortably boarded and furnished. In such apartments we observed chairs, tables, chests of drawers, feather-beds, down coverlets, a few books, engravings on the walls, specimens of ingenious native handiwork, curiosities, &c. This juxtaposition under the same roof was new to us, and struck every one as something quite peculiar and contrary to all our previous experiences. The streets of Thorshavn are only narrow dirty irregular passages, often not more than two or three feet wide; one walks upon bare rock or mud. These passages wind up steep places, and run in all manner of zigzag directions, so that the most direct line from one point to another generally leads “straight down crooked lane and all round the square.” Observed a man on the top of a house cutting grass with a sickle. Here the approach of spring is first indicated by the turf roofs of the houses becoming green. Being invited, we entered several fishermen’s houses; they seemed dark, smoky, and dirty; and, in all, the air was close and stifling. In one, observed a savoury pot of puffin broth, suspended from the ceiling and boiling on a turf fire built open like a smith’s forge, the smoke finding only a very partial egress by the hole overhead; on the wall hung a number of plucked puffins and guillemots; several hens seen through the smoke sitting contentedly perched on a spar evidently intended for their accommodation in the 22corner of the apartment; a stone hand-mill for grinding barley, such as Sarah may have used, lay on the floor; reminding one of the East, from whence the Scandinavians came in the days of Odin.

In passing along the street we saw strips of whale-flesh, black and reddish-coloured, hanging outside the gable of almost every house to dry, just as we have seen herrings in fishing-villages on our own coasts. When a shoal of whales is driven ashore by the boatmen, there are great rejoicings among the islanders, whose faces, we were told, actually shine for weeks after this their season of feasting. What cannot be eaten at the time is dried for future use. Boiled or roasted it is nutritious, and not very unpalatable. The dried flesh which I tasted resembled tough beef, with a flavour of venison. Being “blood-meat,” I would not have known it to be from the sea; and have been told that, when fresh and properly cooked, tender steaks from a young whale can scarcely be distinguished from beef-steak.

The costume of the men is curious, and somewhat like that of the Neapolitans;—a woollen cap, like the Phrygian, generally dark-blue or reddish; a long jacket and knee-breeches, both of coarse home-made cloth, blue or brown; long stockings; and thin, soft, buff-coloured lamb-skin shoes, made of one piece of leather, and without hard soles, so that they can find sure footing with them on the rocks, or use their toes when climbing crags almost as well as if they had their bare feet. There is less peculiarity in the female costume. The men and women generally have light hair and blue eyes. Honest and industrious, crime is scarcely known amongst them.

23Visited the Fort, which is very primitive; simply a little space on a hill-side, enclosed with a low rough stone wall; four small useless cannon lying on the grass, enjoying a sinecure—literally lying in clover; a wooden sentry-box in the corner; a flagstaff in front of it, and two little cottages behind, to accommodate several of the garrison, who prefer living there to lodging in the town, as their comrades do. There are only some eight or ten soldiers altogether; and these, with the commander, constitute the sole military establishment in Faröe. They appear to occupy themselves with fishing, &c., very much like the other inhabitants of the place.

Visited the library, which was established by a former Amptman or Governor. It occupies two rooms, which are shelved all round and comfortably heated with a stove. We observed many standard Danish, German, French and English books, several valuable folio works of reference, and many trashy modern novels. The 24Faröese are inquisitive and intelligent, show a taste for reading, but possess no native literature like the Icelanders.

Visited the church, which is built of wood. The service performed in it is the Lutheran, as in Denmark. It contains an altar-piece intended to represent “Joseph of Arimathea with the dead body of Christ,” two large candles, and a silver and ebony crucifix. The galleries, of plain unvarnished wood, are arranged like opera stalls, one above the other from the floor, and with green curtains to each. At the right side of the pulpit were three large sand-glasses, an old custom once common in all our churches; fronting the altar was the organ-loft. Everything about the church was neat, clean, and primitive. Flower-beds were planted so as to form wreaths or crosses on the graves in the churchyard; and all appeared to be carefully tended and kept in order by loving hands.

Went by invitation of Fraulein Löbner to drink tea at her mother’s, the Danish officer with me. We were ushered into a charming old-fashioned room with low panelled roof; everything in it was neat, scrupulously clean, and primitive. A valance of white Nottingham lace-curtain ran along the top of the diamond-paned lattice windows; while a row of flower-pots, with blooming roses and geraniums, stood in the window-sill. There were cabinets with rich old china-ware; several paintings on the wall, two of which were really excellent—one, a portrait in oil of her late father who had been Governor of Faröe; the other a portrait of her brother, also deceased. Her father was a Dane of German extraction; and her mother—a kindly old lady to whom we were now introduced—a native of Faröe.

25At tea we had preserves, made from rhubarb grown in their own garden; a silver ewer of delicious cream highly creditable to Faröese dairyship; and buns, tarts, almond-cakes, &c., baked by the one baker of Thorshavn, and quite as good as could be had in London.

While the officer was sketching from the window, our kind hostess wound up a musical box, at the same time expressing her regret that the piano-forte, which I had observed standing in the room, was under repair. She also showed us a folio of her own drawings, and many engravings. Here a lady of cultivated mind, and who has mingled in good society, is happy and content to dwell in this remote isle; for to her it possesses the magic of that endearing word—home!

She tells us that wool, fish, feathers, and skins form the chief articles of export; that barley is the only grain raised in Faröe, but the summer is so short that it has not time to ripen. The ears are plucked by the hand and dried in a kiln. The rye, of which their black bread is made, is imported chiefly from Denmark. The hay-harvest is of great importance to the inhabitants. There are numerous sheep in the islands—some individuals possessing flocks of from four to five hundred, besides a few ponies and cows. Dried, the mutton is serviceable for food during winter, when frequent storms interfere with fishing operations.

As in Shetland, the wool is collected from the sheep by the hand, at the season of the year when they are casting their fleeces; for shearing, besides being a more painful process, would deprive them of the long hair so necessary for their protection in an uncertain climate, and leave them to shiver exposed to the untempered 26fury of the northern blast. The sheep thus enables the islanders to supply their own home wants, and also annually to export many thousand pairs of knitted stockings and gloves, together with the overplus raw material.

Miss L. informs us that Thorshavn contains about eight hundred inhabitants. Of these, most of the men are fishers when the weather will admit of their going off. The people are very ingenious, and make knives of all sizes, with curiously inlaid wooden handles and sheaths. The wood for such purposes is obtained from logs of mahogany, which are frequently found as drift-wood among these islands. We were shewn a home-made fancy work-table, neatly put together in a very ingenious and workman-like manner.

Each man here is a sort of Jack-of-all-trades, from the mending of boats or nets, to the killing of sheep and drying them in sheds for the winter store of provisions; from the making of lamb-skin shoes to the building of houses, or the manufacture of implements.

Miss Löbner has kindly and obligingly undertaken to procure some specimens of these manufactures and local curiosities against my return from Iceland.

Gazing round, as we take leave of our kind entertainers, I fix in my mind’s eye the lady-like air and quaint point-devise costume of the elder lady, who, with silvery hair combed back from her brow, had moved about most assiduously performing all the sacred rites of hospitality to her guests; the mediæval aspect of everything in the room,—from the stove to the timepiece, from the polished wooden floor to the panelled ceiling; the diamond-paned lattice windows, with their old-world outlook on the town and the flat wooden bridge, close 27by, which crosses a brawling stream rushing impetuously over rocks from the gully behind; the absolute cleanness and polish of everything; and the monthly roses blooming freshly as of old;—all so vividly impress themselves upon my mind that the whole becomes a waking dream of other days; and it would not seem much out of keeping, or at all surprising, were the Emperor Charles V. himself to open the door and walk into the quaint old apartment we are now about to leave.

Nine P.M.—Wandered alone by the shore, and sketched the view, looking north, from beneath the fort; also made a drawing of the bay from the wooden jetty; while engaged on the latter, crowds of fishermen gathered around me making odd remarks of wonder, the general scope of which I could gather, as they recognised the steamer, boats, hills, &c., coming up on the paper; 28sketched one of the onlookers, an intelligent looking fellow, and here he is.

The fishing boats or skiffs, have all the high bow and stern of the Norwegian yawl; square lug-sails very broad and carried low are the most common. The weather is so very uncertain, the gusts so sudden and violent, that, preceded by a lull during which a lighted candle may be carried in the open air, they come roaring down the valleys or between the islands, bellowing with a noise like thunder, and sometimes strip the turf from the hill side, roll it up like a sheet of lead and carry it away into the sea, while the air is darkened by clouds of dust and stones.

Felt comfortably warm when sketching in the open air between ten and eleven P.M., for, though the climate 29is moist, the mean temperature is warmer than that of Denmark, and, on account of the gulf stream, not much below our own. Forchhammer states that at Thorshavn in mild years, it is 49·2°; in cold years, 42·3°; the average temperature being 45·4°. The greatest height of the thermometer during his observations was 72·5°, and the lowest 18·5°.

Shortly before eleven o’clock the soldiers of the fort manned their boat, and rowed us off to the steamer.

After narrating our various experiences on shore, had a pleasant quiet home-talk with Professor Chadbourne, read a few verses of the New Testament, and as the week was drawing to a close we retired to our berths, wishing each other a good night’s rest after all the novel excitement, wonder, and fatigues of the day.

Sabbath, July 24.—Wind high, and the lashing rain pouring down in torrents. Went ashore at ten o’clock to attend church; heard the pleasing sound of psalm-singing in various of the fishermen’s dwellings as we passed along. Called for Mr. Müller, who had invited me to his pew. The service was Lutheran, and began at eleven o’clock. The pastor was absent, but the assistant, M. Lützen, who is also schoolmaster and organist, officiated. All the people, singing lowly, joined in several fine old German chorales, led by the organist, who also played some of Sebastian Bach’s music with much taste and feeling—although little indebted to the instrument, which was old and infirm, piping feebly and tremulously in its second childhood.

The area of the church was entirely occupied by women, many of them with their bare heads, but most of them with a quaint little covering on the back part of the 30head for hair and comb; only saw two bonnets in the whole congregation. One old lady—with her hair combed back, a black silk covering on the back part of her head, and, from where it terminated behind her ears, a stiff white frill sticking right out—looked as if she had just stepped out from one of Holbein’s pictures; others resembled Gerard Dow’s old women. The men “were drest, in their Sunday’s best;”—long jackets and knee-breeches of coarse blue or brown cloth, frequently ornamented with rows of metal buttons; stockings of the same colours; and the never-varying buff-coloured lamb-skin shoes.

It was pleasing to see these stalwart descendants of the brave old Vikings “the heathen of the Northern sea,”—these men whose daily avocations exposed them to constant perils by sea and land, here, in the very haven of Thor, walking reverently into a Christian church, with their caps and Bibles in their hands, and quietly entering their pews to worship God.

Although the day was very wet, and the regular minister absent, there was present a congregation of about two hundred; and all seemed truly devotional during the service.

From the roof, between two old-fashioned brass chandeliers, was suspended a brig, probably the gift of some sailor preserved from shipwreck. The service began at eleven o’clock, and ended at half-past twelve. When it was over, I spoke with Skolare Lützen, who had officiated. He is a native of Copenhagen, speaks little English, but good German. He took me over the building, and into the pulpit. Altogether, the quaint appearance of the church, the organ, the singing of the people, 31the devout reading and simplicity of the service, and the curious old costumes carried one back to the time of the Reformation, and to me all was singularly interesting. One could fancy that here, if anywhere, the European world had stood still, and that Luther himself would not have detected the lapse of centuries, if permitted once more to gaze on such a scene as was here presented.

Two of us accompanied Mr. Müller to his house before going on board the steamer. His wife and daughter were hospitable and kind; and, as usual on a visit here, tarts, cakes, and wine were produced. His home resembles a museum, containing many stuffed birds, eggs, geological specimens and other natural curiosities collected in these islands. His little son’s name is Erasmus.

Captain Andriessen had wished to sail to-day, but could not get men to work on Sabbath discharging the cargo; at which I was well pleased, both for the right feeling it indicated on the part of the Faröese, and for our own sakes. Here we lie peacefully anchored in the bay, enjoying the Sabbath quiet, while the tempest is now howling wildly outside the islands, and the lashing pelting rain is pouring down on the deck overhead like a shower-bath.

The rain having abated, ere retiring for the night, walked the deck for half an hour. Thorshavn, as seen in the strong light and shade of evening from the steamer’s deck, has truly a most quaint old-world look—all the more so now that we know it from exploration—so very primitive that one can scarcely imagine anything like it. It is unique.

Monday morning, July 25.—From an early hour, all hands busily occupied discharging the cargo, heavily-laden boats following each other to the shore. At half-past one o’clock, the last boat pushes off, the steam-whistle is blown, and we sail away round the south point of Stromoe, shaping our course north-west through Hestoe Fiord. The coast of the islands is abrupt, mostly rising sheer from the sea; many basaltic columns, and a succession of wave-worn caves, in front of which countless sea-birds are flying, swimming and diving. The trap hills are regularly terraced like stairs. Clouds drifting among the hills, and from every gully cataracts leaping down in white foam to the sea. The general colour of the rocks is gray and brown, slightly touched here and there with green. These islands might be characterized as several groups or chains of hills, lying nearly parallel to each other and separated by narrow arms of the sea, which run in straight lines 33north-west and south-east. The summits of the larger islands reach an elevation of from one to two thousand feet; while the highest hill—Slattaretind, near Eide in Oesteroe—is two thousand nine hundred feet high.

The hills around still exhibit a succession of grassy declivities, alternating with naked walls of black or brown rock. The flat heights of these islands, we are told, are either bare rock or marshy hollows. There are also several small lakes, the largest of which, in Vaagoe, is only two miles in circumference, and lies surrounded by wild rugged mountain masses.

We count a dozen foaming cataracts, all in sight at once, and falling down over precipitous rocks around us into the sea. The wind perceptibly sways them hither and thither, and then dispersing the lower portion of the water raises it in silvery clouds of vapour on which rainbows play. They resemble the Staubach in Switzerland; and remind us of the wild mist-veil apparition of Kühleborn, in the charming story of Undine.

The tidal currents, in the long narrow straits which divide the northern islands from each other, are strong but regular; running six hours the one way and six hours the other. Boatmen must calculate and wait for the stream, as the oar is powerless against it.

The atmospheric effects are beautiful;—a bold headland, ten miles to the south, appears in the bright sunshine to be of the deepest violet colour; no magic of the pencil could approach such a tint. It is heightened too by the white gleaming sail of a fishing smack relieved against it.

When we got clear of the islands, the ground-swell 34became much heavier; for the storm of the preceding day had been terrific. Great heavy waves of smooth unbroken water, worse than Spanish rollers; boat tumbling and plunging about, with sail set to steady her; walked the deck for an hour and found use for my sea-legs.

Several gulls follow the ship; I never tire of watching their graceful motions, as, with white downy plumage and wings tipt with black, they fly forward round the mast, remain poised over the deck, or fall astern keeping in the steamer’s wake. Two of our companions have discovered a capital sheltered nook and sit smoking, perched up inside the large inverted boat which we are taking north with us.

An Icelander and a Dane are among the second-class passengers; got them to read aloud to me Icelandic and Danish, also Greek and Latin. In pronouncing the latter two, they follow the classic mode and give the broad vowel sounds, as taught in the German and Scottish universities but not at Oxford or Cambridge.

The dim Faröes are fast falling astern—

The vessel by the log makes eight knots—course, N. by W. and sails set.

The day lengthens as we go north, and at midnight I can now see to read large print, although the sky is very cloudy.

No land—no sail in sight; we heave over the billows of the lonely Northern Sea, and now all is clear before us for Iceland!

Tuesday morning, July 26. Open sea and not a sail visible, although we carefully scan “the round ocean.”

Tremendous rolling all night; everything turning topsy-turvy and being knocked about—my portmanteau, which was standing on the cabin floor, capsized. Only by dint of careful adjustment and jambing in the form of the letter z could we prevent ourselves from being shot out of our berths.

To-day we have the heaviest rolling I ever experienced. It is impossible even to sit on the hurricane deck without holding on by a rope, and not easy even with such assistance. Deck at an angle of 40 to 45°. The boat fastened aloft aggravates matters. A very little more, or the slightest shifting of the cargo, would throw us on our beam ends. The boat getting loose from its fastenings when we are on the larboard roll would break off the funnel. The Captain has hatchets ready, at once to send it overboard or break it up if requisite for our safety. 36The bell tolling with the roll of the ship, first on the one side, and then on the other; generally four or five times in succession. A series of large rollers alternate with lesser waves; the bell indicates the former. Waves without wind roll in from the N. and N.W., both on the starboard and port bow.

In the afternoon saw a piece of wreck—mast and cordage—floating past, most likely a record of woe; involving waiting weary hearts that will not die.

Not a speck on the whole horizon line; a feeling of intense loneliness would at times momentarily creep over us. Birds overhead flying south brought to mind Bryant’s beautiful poem addressed to “The Waterfowl,” which he describes as floating along darkly painted on the crimson sky:

The heavy rolling still continues. Hope the cargo will keep right, or we shall come to grief. Thought of the virtues of my friends. However, maugre a dash of danger, a group of us on the hurricane deck really enjoyed the scene as if we had been veritable Mother Carey’s chickens. One sang Barry Cornwall’s song 37“The Sea;” another by way of contrast gave us “Annie Laurie” and “Scots wha hae wi’ Wallace bled;” and towards evening we all joined in singing “York;” that grand old psalm tune harmonizing well with the place and time—

The gulf-stream and the rollers meeting make a wild jumble. Barometer very low—2810; low enough for a hurricane in the tropics. Stormy rocking in our sea-cradle all day and all night.

Wednesday, July 27.—Vessel still rolling as much as ever. Saw a skua—a black active rapacious bird, a sort of winged pirate—chasing a gull which tried hard to evade it by flying, wavering backwards and forwards, zig-zagging, doubling, now rising and now falling, till at last, wearied out and finding escape impossible, it disgorged and dropt a fish which the skua pounced upon, picking it up before it could reach the surface of the sea. The fish alone had been the object of the skua’s pursuit. The skua is at best but a poor fisher and takes this method of supplying its wants at second hand. Subsequently we often observed skuas following this their nefarious calling; unrelentingly chasing and attacking the gulls until they gave up their newly caught fish, when they were at once left unmolested and allowed to go in peace; but whether the sense of wrong or joy at escape predominated, or with what sort of feelings and in what light the poor gulls viewed the transaction, a man would require to be a bird in order to form an adequate idea.

We cannot now be far from Iceland, but clouds above and low thick mists around preclude the possibility of 38taking observations or seeing far before us. In clear weather we are told that the high mountains are visible from a distance of 100 or 150 miles at sea.

At half-past Three o’clock P.M., peering hard through the mist, we discover, less than a mile ahead, a white fringe of surf breaking on a low sandy shore for which we are running right stem on. It is the south of Iceland; dim heights loom through the haze; the vessel’s head is turned more to the west and we make for sailing, in a westerly direction with a little north in it, along the shore up the western side of the island which in shape somewhat resembles a heart.

The mist partially clears off and on our right we sight Portland Huk, the most southern point of Iceland. Here rocks of a reddish brown colour run out into the sea rising in singular isolated forms like castellated buildings; one mass from a particular point of view exactly resembles the ruins of Iona, even to the square tower; other peaks are like spires. Strange fantastic needle-like rocks or drongs shoot up into the air—the Witches’ fingers (Trollkonefinger) of the Northmen. The headland exhibits a great arched opening through which, we were told, at certain states of the tide, the steamer could sail if her masts 39were lowered. It is called Dyrhólaey—the hill door—and from it the farm or village close by is named Dyrhólar. Behind these curious rocks appeared a range of greenish hills mottled with snow-patches, their white summits hid in the rolling clouds.

There are numerous waterfalls; glaciers—the ice of a pale whity-green colour—fill the ravines and creep down the valleys from the Jökuls to the very edge of the water. Their progressive motion here is the same as in Switzerland, and large blocks of lava are brought down imbedded in their moraine. I perceived what I thought to be curved lines on the surface like the markings on mother-of-pearl, indicating that the downward motion of a glacier is greater in the centre than where impeded by friction at the sides.

On the shoulders of the range of heights along the coast, snow, brown-coloured patches and green-spots were all intermingled; while the upper mountain regions of perpetual snow were meanwhile for the most part hid in clouds which turban-like swathed their brows in fleecy “folds voluminous and vast.”

The steamer is running, at nine knots, straight for the Westmanna Islands, where a mail is to be landed. They lie off the coast nearly half way between Portland Huk, the south point, and Cape Reykjanes the south-west point of Iceland.

How gracefully the sea-birds skim the brine, taking the long wave-valleys, disappearing and reappearing amongst the great heaving billows. We note many waterfalls leaping from the mountain sides to the shore, and at times right into the sea itself, from heights apparently varying from two to four hundred feet.

40We now approach the Westmanna Islands, so called from ten Irish slaves—westmen—who in the year A.D. 875 took refuge here after killing Thorleif their master. They are a group of strange fantastically shaped islets of brown lava-rock; only three or four however have any appearance of grass upon them, and but one island, Heimaey—the home isle, is inhabited. The precipitous rock-cliffs are honeycombed with holes and caves which are haunted by millions of birds. These thickly dot the crevices with masses of living white; hover like clouds in the air, and swarm the waters around like a fringe—resting, fluttering, or diving, by turns.

Westmannshavn, the harbour of the islands, is a bay on the north-west of Heimaey where a green vale slopes down to the sea. It is sheltered by the islands of Heimaklettur on the North, and Bjarnarey on the East. We observed a flag flying, and a few huts scattered irregularly and sparsely on the slope. This place is called Kaupstadr—or head town—but there is no other town in the group. The roofs of the huts were covered with green sod and scarcely to be distinguished from the grass of the slope on which they stood save by the light blue smoke which rose curling above them from turf fires.

A row-boat came off for the mail, which, we were told, had never before been landed here from a steamer; the usual mode is to get it from Reykjavik in a sailing vessel. For those accustomed to at least half a dozen deliveries of letters every day, it was strange to think that here there were fewer posts in a whole year. These Islands have, on account of their excellent fisheries, from very remote periods been much frequented by foreign 41vessels. Before the discovery of Newfoundland, British merchants resorted hither, and also to ports on the west coast of Iceland, to exchange commodities and procure dried stock-fish. Icelandic ships also visited English ports. This intercommunication can be distinctly traced back to the time of Henry III.; but by the beginning of the fifteenth century it had become regular and had risen to importance. It was matter of treaty between Norway and England; but, with or without special licenses, or in spite of prohibitions—sometimes with the connivance and permission of the local authorities, and at other times notwithstanding the active opposition of one or both governments—the trade being mutually profitable to those engaged in it continued to be prosecuted. English tapestry and linen are mentioned in old Icelandic writings, and subsequently we learn that English strong ale was held in high estimation by the Northmen.

Edward III. granted certain privileges and exemptions to the fishermen of Blacknie and Lyne in Norfolk on account of their Icelandic commerce. In favourable weather the distance could be run in about a fortnight.

From Icelandic records we learn that in the year A.D. 1412, “30 ships engaged in fishing were seen off the coast at one time.” “In A.D. 1415 there were no fewer than 6 English merchant ships in the harbour of Hafna Fiord alone.”

Notwithstanding the proclamations and prohibitions both of Eric and Henry V. the traffic still continued to increase; and we incidentally learn that in the year A.D. 1419 “Twenty-five English ships were wrecked on this coast in a dreadful snow-storm.” Goods supplied to the natives then, as in later times, were both cheaper and 42better than could be obtained from the Danish monopolists. It will be remembered by the reader that when Columbus visited Iceland he sailed in a bark from the port of Bristol.

Gazing on this singular group of rocky Islands, on the coast of Iceland, so lone and quiet, and reverting to the early part of the thirteenth century, it was strange to realize that into this very bay had then sailed and cast anchor the ships of our enterprising countrymen—quaint old-fashioned ships, such as we may still see represented in illuminated MSS. of the period; and that their latest news to such English merchants or fishermen as had wintered or perhaps been stationed for some time at Westmannshavn—supposing modern facilities for the transmission of news—would not have been the peace of Villafranca but the confirmation of Magna Charta;—instead of the formation of volunteer corps, nobles hastening to join the fifth Crusade;—not the treading out of a Sepoy revolt, but Mongolian hordes overrunning the Steppes of Russia;—and instead of some important law-decision, celebrated trial, or case in Chancery, they might hear of an acquaintance who had perished in single combat, or who had indignantly and satisfactorily proved his or her innocence by submitting to trial by ordeal. These were the old times of Friar Bacon—the days of alchemy and witchcraft. Haco had not yet been crowned King of Norway; Snorre Sturleson was yet a young man meditating the “Heimskringla.” The chisel of Nicolo Pisano and the pencil of Cimabue were at work in Italy. Neither Dante nor Beatrice as yet existed; nor had the factions of Guelph and Ghibeline sprung into being. Chaucer was not born till the 43following century. Aladdin reigned; Alphonzo the Wise, King of Leon and Castile, had not promulgated his code of laws. Not a single Lombard moneylender had arrived to settle in London; and the present structure of Westminster Abbey had not then been reared.

On leaving Westmannshavn, sailing north between the islands of Heimaklettur and Bjarnarey, we saw two men rowing a boat deeply laden to the gunwale with sea-fowls, probably the result of their day’s work. The cliffs everywhere alive with birds, and the smooth sea beneath them, in the glorious light of the evening sun, dotted black as if peppered with puffins and eider-ducks.

Nine P.M. Sketched various aspects of the islands and several of the strange outlying skerries.

44When the Westmanna Islands are reckoned at fourteen, that number does not include innumerable little rocky stacks and islets of all fantastic shapes alone or in groups; some like Druidical stones or old ruins, others of them far out and exactly like ships in full sail, producing a strange effect on the horizon.

The island nearest the coast of Iceland on the east of Heimaey is called Erlendsey; that furthest north-west is Drángr; and the furthest west Einarsdrángr. On the south-west is an islet called Alsey; we have also an Ailsa in the frith of Clyde: both names probably signifying fire-isle. The islet furthest south is called Geirfuglasker. These names are necessarily altogether omitted on common small maps.

We witness a glorious sunset on the sea,—the horizon streaked with burning gold:

Although the surface of the sea is quite smooth, a heavy ground swell keeps rolling along. A bank of violet cloud lies to the left of the sun, while dense masses of leaden and purple-coloured clouds are piled above it. An opening glows like a furnace seven times heated, darting rays from its central fire athwart the sky, and opening up a burning cone-shaped pathway of light on the smooth heaving billows, the apex of which reaches our prow.

Such the scene, as we sail north-west between the northernmost out-lying skerries of the Westmanna group and the south-west coast of Iceland and silently 45watch the gorgeous hues of sunset. Strangely at such times “hope and memory sweep the chords by turns,” till the past, fused down into the present, becomes a magic mirror for the future.

The air is mild and warm; time by Greenwich twenty-minutes to eleven. The sun is not yet quite down, and—by the ship’s compass, without making any allowance for deviation—is setting due north. At a quarter-past 12 A.M. when we leave the deck, it is still quite light.

Thursday Morning, July 28. Rose early—we are sailing along the Krisuvik coast in the direction of Cape Reykjanes—smoky cape—which runs out from the south-west of Iceland. The low lying coast is of black lava; behind it rise serrated hill-ranges, and isolated conical mountains; some of a deep violet colour, others 46covered with snow and ice, the dazzling whiteness of which is heightened by contrast with the low dark fire-scathed foreground. White fleecy clouds are rolling among the peaks, now dense and clearly defined against the bright blue sunny sky—now hazy, ethereal, and evanescent. We observe steam rising from a hot sulphur spring on the coast. These are numerous in this neighbourhood, which contains the principal sulphur mines of the island. Here, where we sail, volcanic islands have at different times arisen and disappeared; flames too have sometimes been seen to issue from submarine craters; this latter phenomenon the natives describe as “the sea” being “on fire.”

On our left we pass Eldey—or the Fire Isle—a curious isolated basaltic rock resembling the Bass, but much smaller. It rose from the deep in historic times. The top slopes somewhat, and is white; this latter appearance has originated its Danish name “Maelsek,” which is pronounced precisely in the same way as “meal-sack” would be in the Scottish dialect;—in fact the words are the same. Many solan geese flying about; whales gamboling and spouting close to the vessel.

47Nine A.M., Greenwich time. Got first glimpse of Snæfells Jökul—the fifth highest mountain in Iceland—height 4577 feet—lying nearly in a north-west direction, far away across the blue waters of the Faxa Fiord. A pyramid covered with perpetual snow and ice, gleaming in the sun, its outline is now traced against a sky of deeper blue than any of us ever beheld in Switzerland or Italy.

The Faxa Fiord, situated on the south-west, is the largest in the island, and might be described as a magnificent bay, forming a semicircle which extends fifty-six miles from horn to horn; while its shores are deeply and irregularly indented by arms of the sea, or Fiords proper, which have names of their own, such as Hafnafiord, Hvalfiord, or Borgarfiord. Snæfell, on the north side of it, rises from the extremity of the long narrow strip of steep mountain promontory that runs out into the sea, separating the Faxa from the Breida Fiord—another large bay;—while on the south the Guldbringu Syssel, terminating with Cape Reykjanes, is a bare low-lying black contorted lava field.

The Faxa Fiord, then, sweeping in a semicircle from Snæfell to Reykjanes, contains several minor Fiords, and is crowded with lofty mountain-peaks, sharp, steep, and bare. The intense clearness of the northern atmosphere through which these appear, together with the fine contrast of their colours—reds, purples, golden hues, and pale lilacs; rosy-tinted snow or silvery-glittering ice—all sharply relieved against the blue sky, as if by magic confound southern ideas of distance, so that a mountain which at first glance appears to be only ten or fifteen miles distant, may in reality be forty or fifty, and perhaps considerably more.

48The capital of Iceland lies in the south-east of this great bay. We have been sailing due north from Cape Reykjanes to the point of Skagi, and, rounding it, we sail east by north right into the Faxa Fiord, cutting off the southern segment of the bay, and are making straight for Reykjavik.

Several low-lying islands shelter the port and make the anchorage secure; one of these is Videy on which some of the government offices formerly stood, but it is now noted as a favourite resort of eider ducks which are here protected by law in order to obtain the down with which their nests are lined.

Solitary fishermen are making for the shore in their skiff-like boats. A French frigate and brig, a Danish war schooner and several merchant sloops are seen lying at anchor, shut in by the islands and a low lava promontory. All are gaily decked with colours. On rounding the point, Reykjavik the capital of Iceland lies fairly before us. It is situated on a gentle greenish slope rising from the black volcanic sand of that “Plutonian shore.” There are grassy heights at either side of the town and a fresh water lake like a large pond behind it. The cathedral in the centre, built of brick plastered brown stone colour, and the windmill on the height to the left, are the two most prominent objects. The front street consists of a single row of dark-coloured Danish looking wooden houses facing the sea. These we are told are mostly merchants’ stores. Several of them have flag-staffs from which the Danish colours now flutter. All our glasses are in requisition. Numerous wooden jetties lead from the sea up to the road in front of the warehouses, and, on these, females like the fish-women 49of Calais, “withered, grotesque, wrinkled,” and seeming “immeasurably old,” with others younger and better looking, are busily engaged in carrying dried fish between the boats and the stores. Young and old alike wear the graceful Icelandic female head-dress—viz. a little black cloth scull-cap, jauntily fastened with a hair pin on the back part of the head. From the crown of this cap hangs a silver tube ornament, out of which flows a long thick black silk tassel falling on the shoulder.

Two streets run inland from the front street, and at right angles to it. That on the left contains the Governor’s house, and the residences of several officials. It leads to the house where the Althing or Icelandic Parliament now assembles, and where, in another part of the same building, Rector Jonson teaches in the one academy of the island. The other street on the right contains several shops, merchants’ dwelling houses, the residence of Jón Gudmundsson, president of the Althing, advocate, and editor of a newspaper. It leads to the hotel, and to the residence of Dr. Hjaltalin, a distinguished antiquarian and the chief physician of the island. In the same direction, a little higher up, is the lonely churchyard.

Between these two streets, houses stand at irregular intervals, and nearly all have little garden-plots attached to them.

On the outskirts, flanking the town, which in appearance is more Danish than Icelandic, are a few fishermen’s huts, roofed over with green sod; and these, we afterwards found, were more like the style of buildings commonly to be met with throughout the island.

As we cast anchor, the morning sunshine is gloriously 50bright and clear, sea and sky intensely blue, and the atmosphere more transparent than that of Switzerland or Italy. Beyond Reykjavik, wild bare heights rise all round the bay; here—mountains of a ruddy brown colour, deeply scarred and distinctly showing every crevice; there—snow-patches gleaming on dark purple hills; here—lofty pyramids of glittering ice; there—cones of black volcanic rock; while white fleecy clouds in horizontal layers streak the distant peaks, and keep rolling down the shoulders of the nearer Essian range.

The arrival of the steamer is quite an event to the Icelanders. A boat came off from the shore, and another from the French brig, to get the mail-bags. We brought tidings of the peace of Villafranca, and heard the cheering of the French sailors when the news was announced to them. Dr. Mackinlay, who had remained, exploring various parts of the island, since the previous voyage of the Arcturus, and for whom we had letters and papers, kindly volunteered to give us information about the Geyser expedition. From his habits of keen observation, patient research, and kind-heartedness, he was well qualified to do so.

He recommended Geir Zöga, who had accompanied him on board, as a good trustworthy guide. We wished to start at once, so as to make the most of our time, but the undertaking was a more serious affair than we had anticipated. Ultimately, before landing, we arranged to start next morning at eight o’clock, as the very best we could do.