Title: An elder brother

Author: Eglanton Thorne

Release date: October 24, 2023 [eBook #71948]

Language: English

Original publication: London: The Religious Tract Society, 1895

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

BY

EGLANTON THORNE

Author of "The Old Worcester Jug," "Worthy of his Name," etc.

London

THE RELIGIOUS TRACT SOCIETY

56 PATERNOSTER ROW AND 65 ST. PAUL'S CHURCHYARD

BUTLER & TANNER,

THE SELWOOD PRINTING WORKS,

FROME, AND LONDON.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

IV. MICHAEL MAKES A GOOD BARGAIN

VIII. THE BURDEN MAKES ITSELF FELT

XII. MICHAEL'S HOUSE BECOMES A HOME

AN ELDER BROTHER

OLD BETTS

THERE are persons for whom no shop has a greater attraction than a second-hand book-shop. It may be that they have a passion for collecting the old and rare, and love to turn over the well-thumbed, dusty volumes, in the hope of lighting upon a treasure in the form of a first edition, or a work long out of print. Or they may be drawn merely by a desire to acquire cheaply the coveted book which their poverty will not permit them to purchase fresh from the publisher. Whatever the nature of the attraction, the shop of Michael Betts, which stood a few years ago at the corner of a narrow, quiet street in Bloomsbury, had for such individuals, an irresistible fascination.

It was a small shop, but it had a high reputation of its kind, and its importance was not to be measured by its size. It lay several feet below the level of the street, and a flight of stone steps led down to the door. Every available inch of space within the shop was occupied by books. They crowded the shelves which lined the shop from floor to ceiling; they filled the storey above, and a great part of the tiny room at the back of the shop in which Michael took his meals; they overflowed into the street, and stood on a bench before the window, and were piled at the side of each step which led up to the pavement. They were books of all sorts and conditions, of various tongues and various styles.

Michael knew them perhaps as well as it was possible for a man to know such a mixed multitude. He was not a scholarly man, having received, indeed, but the most ordinary education; but in his leisure hours, he had managed to acquaint himself with most of the classics of our mother tongue. For the rest, by virtue of close observation, and, where possible, a little judicious skimming or dipping, he contrived to discover the nature of most books that came into his hands, and to pretty accurately determine their worth.

Michael Betts struck most persons as being an elderly man, though he was not so old as he appeared. Some of his customers were wont to describe him as "Old Betts." He did not feel himself to be old, however, and once when he happened to overhear some one so describe him, the term struck him as singularly inappropriate.

He was a man about the middle height, but inclined to stoop. His smooth, beardless face, surmounted by thick, wiry, iron-grey hair, which curled about his brows, was broad and of the German type. Its hue was pallid, rather as the result of the confined life he led in the close, ill-lighted shop, than from positive ill-health. His dark, deep-sunken eyes had often a dreamy, absent expression, but grew keen at the call of business, for Michael Betts was a shrewd man of business, and made few mistakes either in buying or selling.

He had kept that corner shop for nearly thirty years, and though his business had steadily grown during that period, he had managed it without assistance. It might be that he would have done better had he not attempted to carry it on single-handed. He was a young man when he started the business, but now that he was on the borderland of old age he might have found the help of a youth of much service. But Michael judged otherwise. He "was not fond of boys," he said. He felt that he had not the patience to train one.

He could not bear to have his nice, orderly, methodical ways upset by a careless youth. Moreover, from living constantly alone, he had become of such a reserved, suspicious, even secretive disposition, that the very thought of having any one constantly with him in the shop was hateful to him. For his shop was his all. He had no life behind or beyond it. He had no one to love him, or whom he could love. Even his books he did not love as they should be loved. Though he lived in them and with them, as well as by them, he prized them chiefly for the sake of what they brought him. But he did not care that another hand should meddle with them. Rather than that, he preferred to adhere to his old-fashioned plan, so behind the day, of locking his shop when he was called out on business, and affixing to the door a notice of the hour at which he might be expected to return.

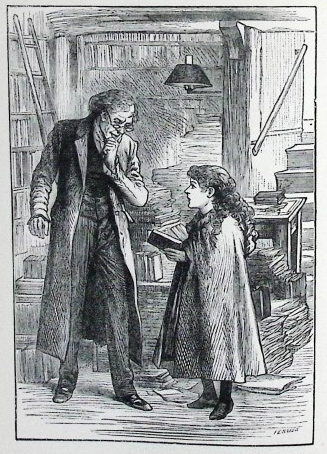

Early one gloomy afternoon in November, Michael was busy at the back of the shop, sorting, as well as he could in the dim light, a newly-acquired purchase. He looked round as the bell which hung at the door gave a little tinkle announcing the entrance of a customer; but though he looked he could not at once discern who it was who entered with such a light tread, and strange, irregular movements. He had to move to the other side of a high pile of books ere he perceived his customer, and then he was very much surprised. Such a pretty, dainty, wee one he had never seen in his shop before.

A little girl of six or seven years stood there alone, making a bright, fair spot in the midst of the gloom and dust and piles of dingy volumes. She wore a little serge cloak of a soft green shade, lined with pink silk, and a tiny, close-fitting velvet hood of the same green hue covered her golden locks, which, however, escaped from it wherever they could, hanging in ringlets down her cheeks and over her little shoulders. With her rosebud mouth, soft liquid blue eyes, and fair pink and white complexion, she was the sweetest picture imaginable; but she was a bewildering vision to Michael Betts. He stood looking at her in amazement, quite at a loss how to address her.

She, in her turn, regarded him gravely for a few moments; but she showed no sign of embarrassment. When she spoke, it was with the simple, unconscious dignity of childhood.

"Are you old Mr. Betts?"

"My name is Betts, certainly," replied Michael; "I don't know about the old. Can I do anything for you, missy?"

"Yes. I want a 'Pilgrim's Progress,' if you please. Noel and I want to have one for our very own. On Sundays, we are allowed to have mother's, which is a beautiful one, with such lovely pictures in it; but she will not let us have it in the nursery during the week, and we really must have one, for, you see, we like to play at being Christian and Faithful, and we want the book in order to know exactly what they do and say. We each like being Christian best, so we take it in turns. That is the fairest way, I think, don't you?"

"I can't say, I am sure, my dear," said Betts, looking very puzzled. "Do you wish me to see if I have a 'Pilgrim's Progress'?"

"Yes, please," said the child eagerly, with brightening face. "Father said he'd no doubt you would have one you could let us have for a shilling. He said he would see about it, but he generally forgets when he says that, so I thought I had better come myself. I have the shilling here," she added, fumbling in her glove. "It's in two sixpences: one sixpence is mine, and the other is Noel's."

"And who is your father, little missy?" asked Michael.

"Why, father is father, of course," said the wee girl, as if she considered the question rather unnecessary; adding, however, after a moment's reflection, "but perhaps you would call him Professor Lavers."

"Ah, to be sure," said Michael, nodding his head. He knew Professor Lavers well. He was one of his best customers. But it was difficult to think of the elderly, worn-looking professor as the father of this sweet little maiden.

"Father is a very learned man," said the child, nodding her head sagaciously; "mother says so. That's why they call him Professor. My name is Margery, you know, and Noel's is Noel. Noel means Christmas in French, and mother called him that because he was born on Christmas Day."

"Is Noel older than you?" asked Michael, who was beginning to feel interested in the child's frank confidences.

"Oh no. He is a year younger; but he's nearly as big as I am. That's because he is a boy. Mother says boys ought to be big. What lots and lots of books you have, Mr. Betts! My father has a great many books; but not nearly so many as you have."

"No. I've got another room full of them upstairs, little missy."

"Have you?" said Margery, in an awestruck voice. "And have you read them every one, Mr. Betts?"

"Oh dear no," said Betts, smiling as he shook his head; "life wouldn't be long enough for that, missy. But I think I know something about most of them, though."

"Do you?" Margery looked at him in wonder. "How clever you must be! It takes me such a time to find out what is in a book. But then you are very, very old. You have had a great many years to do it in."

"Humph!" said Betts, pushing his fingers through his thick, grizzly hair, and hardly knowing what to make of this remark.

"Can you read Greek, Mr. Betts?" asked Margery eagerly. "My father can read Greek—can you?"

"No, miss, that I can't," said Michael, looking as if he did not quite like to own his inferiority; "but now, about this book you want. I believe I have a 'Pilgrim's Progress' somewhere, if only I can lay my hand on it. Ah, I think I know where it is."

He drew forward his library steps, mounted them, and after a brief search amongst the books on an upper shelf came down with one in his hand, which he dusted carefully ere he showed it to Margery.

"Here's the book you want, missy," he said, bending down to her as he held it open. "The back's a bit shabby; but the reading is all right. And there are pictures, too."

"Oh, how lovely!" exclaimed Margery, in delighted tones. "I do love books with pictures, don't you? Ah, there is poor Christian with his burden on his back. Oh, weren't you glad, Mr. Betts, when his burden fell off?"

"I glad?" said Mr. Betts, looking puzzled. "I don't understand you."

He had once read the "Pilgrim's Progress," wading through it with difficulty, many years ago; but had found it a book he "could make nothing of."

"When you read about it, I mean," said Margery. "But p'raps it's so long ago that you have forgotten. Mother says the burden means sin, and every one has that burden to carry till Jesus takes it away. Have you lost your burden, Mr. Betts?"

"My burden?" repeated Betts, more puzzled than ever.

"Yes—your burden of sin. You're a sinner, aren't you?"

"Indeed, miss, you're under a mistake," said Michael stiffly. "I know there are plenty of sinners in London; but I am not to be counted amongst them. I can honestly say that I never did anything wrong in my life."

Margery stood looking at him, her blue eyes opened to their widest extent, expressing the utmost wonder.

"Oh, Mr. Betts! Never in all your life! And you have lived so many years! What a very, very good man you must be! Why, I am always doing naughty things, though I do try to be good. And I thought everybody did wrong things sometimes. But never in all your life—"

"Well, here's the book, little missy, if you like to take it," said Michael, finding her remarks embarrassing, and wishing to put an end to them. "The price is one shilling and fourpence."

"But I have only a shilling," said Margery, giving him her two sixpences; "that won't be enough, will it?"

"That'll do, thank you, miss. Any day that you're passing you may bring me the fourpence."

"Oh, thank you, Mr. Betts!" said Margery, delighted. "I won't forget. How pleased Noel will be! But I must go now, or nurse will be angry. I expect she will say it was naughty of me to come alone. Good-bye, Mr. Betts."

"Good day, missy."

He opened the door for her, and she passed out, shaking back her sunny curls. But when she was half-way up the steps she suddenly stopped, stood in thought for a moment, and then turned back.

"Mr. Betts," she said, thrusting her pretty head inside the door again.

"Well, missy?"

"I can't understand about your never doing wrong. Mother says Jesus died for sinful people, and I thought that every one had sinned. But if you've never done wrong, then Jesus can't have died for you. It's very strange."

"Is it, miss?" said Michael, with a grim smile. "Well, don't you trouble your pretty self about me. It's all right. There's some things, you know, that little folks can't understand."

"Oh, there are, I know, lots. I'm always finding that out. But it's horrid not to be able to understand. Well, good-bye."

She ran off again, and was quickly out of sight.

"What a little chatterbox!" said Michael to himself; "what an extraordinary child! But why should they stuff her head with those old-fashioned theological ideas? I suppose she was right in a sense about my being a sinner. These old theologians would say so, at any rate. And in church, people confess themselves miserable sinners, but not one in a hundred means it. Anyhow, I'm sure of this, that if there was no one worse than me in the world to-day, it would be a very different world from what it is. So that is Professor Lavers' little girl. I wonder if she'll remember the fourpence."

A NEIGHBOUR

THOUGH for many years, Michael Betts had lived in loneliness, his life had not always been so lonely. As a young man, he had had his widowed mother to care for, and a brother, some ten years younger than himself, had shared their home. There had been other children who had passed away in infancy. Only these two, the eldest and the youngest, remained, and the mother loved them passionately, if not wisely.

It was perhaps not strange that between brothers so widely parted by years, there should be no very close bond of sympathy. But the distinction between them was more marked than that which mere age would effect. Their characters were wholly different. The disposition of the elder brother had always been serious, his behaviour correct, his words and ways prudent and cautious beyond his years. The bearing of the other afforded a great contrast. Frank from boyhood was distinguished by wild spirits; he was restless and reckless in his ways, bent upon pleasure and regardless of its cost, and disposed to chaff his grave, prudent brother.

The two could not understand each other. Michael, conscious of his own rectitude, was keenly alive to his brother's faults, and disposed to think the very worst of him. He was vexed with his mother when she persistently found excuses for Frank's failings, and reiterated her fond belief that he "meant no harm," and would "come right some day."

Whilst she lived to keep peace in the home, there was no open breach between the brothers. Unhappily, she passed away ere Frank had fully attained to manhood. His mother's death was a grief to Michael. He had loved her truly, in spite of a sense of her incapacity and wrong-headedness on many points, notably on those which concerned her younger son. Sometimes it had almost seemed as if she loved Frank, in spite of all his faults, better than the son whose meritoriousness had ever been apparent.

Yet Michael meant well by his brother when their mother's death left them together. He had promised her when she lay dying that he would be as a father to Frank; and he intended to keep that promise. He would do his duty by Frank; he would care for him and look after his interests as an elder brother should. To be sure, he expected that Frank would respond as he should to his fraternal kindness, and show a fitting sense of what the bond between them entailed upon him. But such an expectation was most vain. Frank was what he had always been.

Shortly after his mother's death, Michael, who had been saving money carefully for years, whilst working diligently and acquiring business experience, was able to take the corner house and open a book-shop on his own account. He counted on Frank's assistance in working it. He thought the business would provide a future for his young brother as well as for himself. But it was a disastrous experiment he was now undertaking. Frank had little inclination to work steadily as his brother's assistant. His careless, irregular ways tried Michael's patience beyond endurance. He reproached his brother bitterly; but his rebukes only elicited insolence and defiance.

Frank left his brother in anger, and found a situation for himself elsewhere. He did not keep it long, however. From idle, he fell into sinful courses. Lower and lower he drifted, till Michael saw him only when he came to beg for relief from the starvation to which his profligacy had reduced him. Michael dreaded his appearance. He could not bear that any of his customers should know that such a disreputable man was his brother.

But he never refused Frank food or a night's lodging, till after one of these brief visitations he missed a valuable classic, and was convinced that his brother had stolen it. Then he vowed that he would do nothing more for Frank. If his brother dared to come near him again, thinking to lay thievish hands on his goods, he would give him in charge. No one could say that he had failed in his duty towards his brother. No, he had kept his promise to his mother as far as it was in his power to keep it. He could do no more. Frank must reap as he had sown.

Michael never had occasion to put his threat into execution. His brother, perhaps, divined too well what he might expect. However that might be, Michael saw his face no more, and was thankful not to see it. As years passed on and he heard no more of Frank, he was able to persuade himself that his brother was dead. And as this conviction deepened within him, it became easier and easier to banish from his mind the thought of his unhappy brother.

His business absorbed his whole attention. It prospered, and year by year he was able to lay by money. This result he found most satisfactory. Gradually, but surely, the love of gain became the chief passion of his soul. His own wants were few and simple, and he had no one besides himself on whom to spend money, so his savings grew apace, and he hugged to his heart the knowledge that he was making a nice little sum. He never asked himself what good the money was to do, or for whom he was saving it. He forgot that he was growing old, and that a time must soon come when he would have to leave all that he possessed. He loved to think that he was growing rich; never suspecting how miserably poor he was in all that makes the true wealth of human life.

It was rarely now that Michael gave a thought to his unhappy brother; but on the evening of the day which had surprised him by bringing such a quaint little customer to his shop, he found his mind strangely disposed to revert to his own early days. It was a most unusual thing for him to speak with a little child. He could not remember when he had done so before. Had he been asked if he liked children, he would have answered the question decidedly in the negative. He certainly detested the boys of the neighbourhood, who were wont to annoy him by hanging about his shop of an evening, and laying their careless fingers on his books, and who had very objectionable ways of retaliating when he reproved them. But a fair, dainty, blue-eyed, childlike Margery was quite another thing. Her sweet, rosy face, shaded by drooping curls, rose again and again before his mental vision, and her childish voice repeated itself in his ears as he sat patching and mending some of the shabbier of his books.

And somehow those sweet accents carried his memory back to the days of his own childhood. He remembered a little sister who had died; he recalled the bitterness of the tears he had shed as he looked on her still, marble face, lying in the little coffin; he saw his mother weeping as though her heart would break; he saw baby Frank looking in surprise from one to the other, wondering at their tears, but untouched by any sense of their sorrow. How vividly the scene rose before him again! His mother's face, the well-worn, shabby furniture, the very atmosphere of the old home seemed about him for the moment.

Yet how long ago it was! If the little sister had lived, she might now have been an anxious-looking mother herself, with grown-up children. And Frank—baby Frank—what had become of him? Dead, probably,—yes, surely he was dead, and better dead. But Michael heaved a sigh as he thought of his brother. He had not been so moved for years. Certainly the visit of that little maiden had exercised a softening influence upon him. How long it was since he had seen his brother!

His life altogether seemed long, as he looked back on it. Very, very old, the little girl had called him. She was wrong there; he was not so very old. But he was getting old. He could not deny that, and the thought caused him a throb of pain. For the first time, he felt his life to be narrow and contracted and unsatisfactory. He rose and walked up and down the limited space in which it was possible to move between the piled-up books. He drew aside the curtain which hung over the little door, and looked up at the stars shining brightly above the tall houses opposite. And he sighed again. What was making him feel so unlike himself to-night?

He half hoped that on the following day little Margery might again make her appearance in his shop. Would she forget her little debt to him? He hoped not. He did not care about the fourpence so much; but he did want to see the pretty little creature again. But throughout the day he looked for her in vain. Nor did she appear on the next, nor the next. He was conscious of disappointment. On the third day, however, he had news which concerned her.

A well-known customer entered the shop. But though he knew the man well as a customer, Michael knew very little of him. He was not interested in the lives of his customers, except where they touched his own. He knew this one to be a minister of some kind, and from the alacrity with which he dropped the theological books he desired, if their price were at all high, the bookseller imagined that money was not plentiful with him. The fact that this preacher often asked for works by Mr. Spurgeon proved nothing, since Michael's experience had taught him that the writings of that great preacher have a fascination for every species of religious teacher who tries to open his lips in public for the edification of his brother man.

"Good day, sir," said Michael, as his customer entered the shop. "What can I do for you to-day?"

"Good day, Mr. Betts. I really do not know that I want anything in particular, only, as I was passing close by, I could not resist the temptation to look in, just to see what you have. Your wares are always tempting to me."

"I'm glad to hear it, sir. Look round, and welcome. Take your time over it. There's a new lot of books here that I've purchased lately. Maybe you'd fancy some of them."

"Thanks, thanks," said the other, turning eagerly towards the books. He stood for some minutes examining them in silence. Suddenly he said, "Ah! Here is a book, I see, by Professor Lavers. It is very sad about him, is it not?"

"What about him, sir?" asked Michael, in surprise.

"What? You have not heard? How strange! And he, a neighbour of yours!"

"He lives in Gower Street, certainly, if that makes him a neighbour of mine," said Betts grimly; "but what is the matter with him, sir?"

"He is very ill indeed; the doctors think he cannot recover. It is a sad pity. A scientific man of such ability can ill be spared."

Michael made no reply. He stood dismayed. A curious sensation of pain smote him. He was not thinking of the loss to science. He was thinking of a certain little fair-haired, blue-eyed child, who would soon be fatherless, if this news were true.

"He was taken ill very suddenly, I believe," said the customer; "it is acute pneumonia. He has not been ill more than three or four days. Still, I wonder you have not heard, living so near."

"Such neighbourhood does not count for much in London, sir," replied Michael, rousing himself from his abstraction. "Persons may live next door to each other for years, and never learn each other's names. I should know nothing of Professor Lavers if he did not happen to be a customer of mine."

"I suppose that is so," said the minister thoughtfully. "I suppose nowhere can one attain such complete isolation as in this London. Its life must tend to harden human hearts into selfish indifference to the needs of others. Sad indeed were the life of man, if he were left to the mercies of his brother man. But it comforts me to think of the great love of God enfolding the sinful, sorrowful city, and the heart of God pitying the infinite struggles and woes of humanity. But I must not linger now. Good day, Mr. Betts."

"Good day," said Michael. He had hardly followed what the other was saying. It did not seem to him that the love of God in any perceptible degree brightened the life of man. But what could a man who was satisfied with himself, and never done anything wrong in his life, know of the love of God?

LITTLE MARGERY'S LOSS

"I WONDER if he is any better?" Michael Betts said to himself as he rose the next morning.

It was something new for him to give a thought to any one, save in the way of business. It was strange indeed that he should actually feel anxious concerning the health of a neighbour; but as he moved to and fro, coaxing his fire into a blaze, and preparing his solitary meal, Michael was exceedingly desirous of learning how the new day had found Professor Lavers.

When the woman arrived who came every morning at nine to clean up his place and do him such womanly services as he required, he broke through the reserve he was wont to maintain towards her, and asked her if she could tell him how Professor Lavers was.

"How who is?" she asked, with an air of surprise.

"Professor Lavers."

"And who's 'e? I never 'eard of 'im," she said.

"Oh," Michael answered, with some embarrassment, "he lives in Gower Street—No. 48. He's a very learned, noted man. I thought you might know about him."

"I never 'eard of 'im," she said again. "Is 'e ill, then? What's the matter with 'im?"

Michael answered her very curtly. Since she could not satisfy his curiosity, he was not disposed to gratify hers. He went back into the shop, and busied himself with his books.

About noon the bell over his door tinkled, and looking up he saw with pleasure that little Margery was entering the shop, accompanied by a servant maid, who carried several small parcels.

"Good morning, Mr. Betts," she said, in her clear, high tones. "I've come to pay you the fourpence I owe you."

"Thank you, missy," he said, looking with interest at the sweet childish face and the blue eyes lifted so frankly to his.

"It's for the 'Pilgrim's Progress,' you know. I dare-say you thought I had quite forgotten it, but I hadn't; only nurse would not let me come before."

"It was no matter, miss. You need not have troubled about it. And do you like the book as much as you thought you would?"

"Oh yes; the pictures are lovely. But it is such a pity: we can't have any nice plays now; we're in dreadful trouble at home. My father is very ill, and Noel has been sent away to Aunt Susie's because he would make a noise, and I'm all alone, and I don't like it."

"Dear, dear! I'm very sorry to hear that," said Michael, feeling more moved than he could have believed it possible that he would have been by a matter which did not concern himself in the least; "but I hope your father is a little better this morning, my dear."

"I don't think so," said the little girl, with unshed tears in her eyes as she lifted them to his, "for mother was crying this morning, and she would not have cried if father had been better. We're quite in the Slough of Despond at home, aren't we, Jane?"

Jane smiled in response to the child's quaint words, but her eyes had a troubled expression. She shook her head as she met Michael's inquiring glance.

"He's no better," she said in a low tone, "and I'm sore afraid he'll never be no better."

"It's horrid without Noel," said little Margery, as she sprang lightly on to the top of a pile of big lexicons and then back again to the floor. "I can't play alone, and Jane does not know how to play properly. Besides, we must not make a noise."

She stood for a moment with a troubled look on her pretty pink and white face. Then, as she looked up at the old bookseller, a new idea occurred to her.

"Had you ever a little brother or sister to play with you, Mr. Betts?—when you were a little boy, I mean. Of course it's a very long time ago."

"Well, yes, miss, I had a little brother once; but, as you say, it's a long time ago."

"Then I suppose he is grown-up now. Where is he?"

"I don't know, miss."

"You don't know?" repeated the child in amazement. "You don't know where your brother is?"

The face of old Betts flushed as he caught the surprise in her tones.

"It's true, missy; I don't know where he is. Maybe he is dead; but I can't say."

"Now, Miss Margery, it's time we were going," said Jane quickly. "You know you promised me you would not stay a minute if I let you come in."

"All right; I'm ready," responded Margery; but she turned again to Michael ere she left the shop.

"Do you live here all by yourself, Mr. Betts? It's very lonely for you, isn't it? But I suppose people don't mind that when they get old."

He made no reply, except to bid her good day; and the next minute the green cloak and long golden locks had floated on the wind round the corner, and he was alone once more.

Was it very lonely for him? He had not thought so before; but to-day, as he looked round on the dingy old shop, so closely packed with books, and later, as he sat eating alone with little appetite the ill-cooked, unsavoury meal which his charwoman had prepared for him, he had a vague sense that his life was empty, and dull, and unlovely, and that he wanted something more for happiness than his trade could give him, even though he was making a good thing of it.

Almost the first thing Michael Betts saw when he unfolded his newspaper the next morning was the announcement of the death of Professor Lavers. After he had read the brief notice more than once, he read nothing more for some time. He sat with his breakfast untasted before him, gazing abstractedly at the row of bookshelves opposite. But he did not see the titles printed on the dingy covers. He was seeing a wee, winsome face, half hidden by drooping curls, and hearing the music of a sweet, childish voice. When he roused himself, it was to sigh heavily, and say half aloud, "It's a sad pity. It's a sad pity for that sweet little maid."

MICHAEL MAKES A GOOD BARGAIN

SOME weeks passed by, and Michael saw nothing more of little Margery. He thought of her more than once, wondering how it was with her and her little brother, now that their father was no more. Sometimes when the sudden tinkling of the bell over the shop door warned him of the approach of a customer, he would look up, half hoping that he might see the wee figure in the green cloak and close-fitting velvet bonnet. But Margery did not come, and if she had, she would not have worn the green cloak. That had been exchanged for sombre black, which gave a new and pathetic beauty to her sweet, round, pink and white face.

More than a month had passed since the professor's death, when one evening the servant who had accompanied little Margery when she came to pay the fourpence entered the shop, and asked Michael if he could call at No. 48, Gower Street, on the following morning, as her mistress wished to see him. After a moment's reflection, Michael replied that he would come, and added an inquiry as to the health of the little lady who had accompanied her when she came before.

"Miss Margery is quite well, thank you," replied the maid, "and as much of a chatterbox as ever. I never knew such a child for asking you questions and saying queer things. There's no knowing how to answer her."

"Did she grieve much for her father?" asked Michael.

"Well, yes, she cried a great deal. She was fond of her father, was Miss Margery. And it upset her to see her mother crying. But she got over it sooner than you would think. Children quickly forget their troubles. If you could have seen her and her little brother playing together on the day their father was buried, you'd have been surprised. But, there, it wasn't to be expected they could miss their father, for they saw so little of him. He was always shut up in his study with his books. A regular bookworm he was. You couldn't call him nothing else."

Michael made no reply; but he wondered whether, if he had been the father of a sweet little girl like Margery, he would have been content to live shut up with his books all day.

"Then I may tell Mrs. Lavers that you will come to-morrow morning at ten o'clock?" said the maid as she turned to go.

Michael assented. He was not surprised that Mrs. Lavers should send for him. It frequently happened that his attendance was requested at houses where there had been a recent bereavement, necessitating considerable changes. The professor's widow doubtless wished to dispose of some or all of her husband's books.

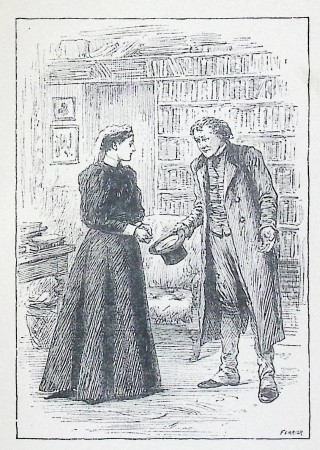

Michael was not mistaken. On his arrival at the house he was at once ushered into the late professor's library, and whilst he waited there, he feasted his eyes on the contents of the ample bookshelves, which were fully and richly stocked. He had time to form a good estimate of the value of the books ere Mrs. Lavers came into the room.

The professor's widow was a delicate, graceful woman of about thirty-five years of age. Her face was pale, and it had a very careworn, sorrowful expression; but it still bore the traces of past beauty, and the fair, rippling hair which showed beneath her widow's cap, and her soft blue eyes, reminded Michael of little Margery. As she addressed him, Michael knew instinctively that he had to deal with a true lady in the highest sense of the term. And she, glancing at him, was struck with his air of respectability, and believed that she might trust in his integrity.

"I sent for you, Mr. Betts," she said, "because I am obliged to part with my husband's books. I have to move into a very small house, into which I cannot take them. And indeed for other reasons I feel it my duty to sell them. I have been advised to show them to you; I have been told that I may trust you to give me a fair price for them."

"I can give you as good a price for them as any one in the trade, madam," replied Michael promptly. "Though I say it myself, it's true that I understand the second-hand book market as well as any one can. Do I understand that you wish to part with all the books in this room?"

"Yes, all of them," said the lady, with a sigh; "I have taken away such as I want to retain."

"Then with your permission, madam, I will make a brief inspection of the shelves, after which I shall be able to tell you the sum I can offer."

The lady made a sign of assent, and sank wearily into a large easy chair which stood by the hearth. She watched him with a melancholy expression on her face as he slowly directed his glance from shelf to shelf, occasionally pausing to jot down certain titles in his notebook.

Michael had already made up his mind as to the probable value of the books; but he was not going to commit himself till he had made a thorough survey of the shelves. When at last he had fully satisfied himself as to the number and character of the books, he turned to the lady and named the sum he was willing to give for them.

Mrs. Lavers' delicate cheek flushed as she heard it. She looked at him with troubled eyes. "No more than that!" she said. "It seems very little. Why, my husband spent pounds and pounds every year upon books."

"' I've no doubt he did, madam; but buying and selling are different things. I know what I may expect to make by these books, and I assure you it would not pay me to give more."

"No? Well, of course you know best." She looked disappointed and anxious. "I must think more about it before I decide."

"Certainly, madam. You may like to consult other dealers, perhaps; but I do not think any one in the trade will offer you more than I do."

With that he bade her good day, and went back to his shop.

Apparently his words proved true, and Mrs. Lavers found no one willing to give a larger price for the professor's books, for three days later she sent him an intimation that she was willing to part with them for the sum he had named. She requested that he would remove them as quickly as possible, as she was about to quit the house.

Michael Betts lost no time in sealing the bargain, from which he knew he should reap good profit. He promptly waited on Mrs. Lavers and handed her the sum he had agreed to give, and on the following evening he began to remove the books, engaging for this purpose the help of a man with a small hand-cart.

He did not see Mrs. Lavers ere he set about his task of dismantling the bookshelves. Doubtless she felt it a cruel necessity which forced her to dispose of her husband's books. It was little wonder if she shrank from the pain of seeing them carried out of the house, and therefore kept out of the way.

Michael had removed the books from several shelves, when he found lying on the top of a row of books, as if thrust there by chance, the copy of the "Pilgrim's Progress" which little Margery had purchased of him with such pleasure. He took it up and looked at it in surprise. He could not be mistaken in the book. He knew it by various tokens. Moreover, a glance at the fly-leaf showed him that Margery had written on it her own and her brother's name in a large, round, childish hand.

"Margery and Noel Lavers—the book of them both," she had written, that there might be no doubt as to the ownership of the volume.

Surely it was by accident that the book lay there! It could not be intended that he should carry it away with the others. The children could hardly have tired so soon of the book they had longed to possess. Persuaded that it was a mistake, Michael laid the book carefully aside in a safe place ere he went on with his task.

Presently he became aware of the sound of eager voices and noisy little feet on the stairs, then suddenly the door of the room in which he was working was flung back with a jerk, and little Margery ran in, followed by a little boy with dark, curly hair and dark eyes, who, however, started back on seeing a stranger, and sped away as quickly as he had come.

Margery looked astonished at finding the room occupied and books lying about in piles on the floor. She stood still for some moments, too surprised to utter a word. She wore a black frock, and black shoes and stockings covered her dainty feet and ankles; but a large white pinafore hid most of the frock, and over it her golden curls fell in rich profusion.

"Why, you're Mr. Betts, in whose shop I bought our 'Pilgrim's Progress,' she said at last. What are you doing here in my father's library?"

"I'm looking over the books, my dear," replied Michael; after a moment's hesitation. "Was that your little brother I saw just now?"

"Yes, that's Noel; but he always runs away when he sees anybody. It's riddiklus to be so shy. We were coming to look for a sermon book, because we are going to play at church, and I must have a book to read out of for the sermon—something with plenty of long, hard words. It doesn't matter if I don't say them properly, you know, for there's only Noel there."

"I see. So you play at going to church. That's a strange game."

"It's a very nice game," said Margery with eagerness. "I'm the clergyman, and Noel's the congregation. Sometimes Noel wants to preach; but he can't preach well. He means to preach when he is a man, though. He says he shall drive an omnibus all the week and preach on Sundays."

"Dear me!" said Michael, smiling, "that will be an unusual kind of life. But look here, little missy, see what I've found! Your 'Pilgrim's Progress!' You don't want to lose that, do you?"

"Oh, where did you find it?" exclaimed the child. "Noel and I have wanted it for days, and nurse said she did not know where it was."

"It was here on this shelf," said Michael, as he gave it to her.

"Oh, who could have put it there?" said little Margery, taking the book and beginning to turn over its pages. "Do you know, I like the pictures even better than I thought I should. See, here is Giant Despair. Doesn't he look horrid! But this is the picture I like best—'The Pilgrims Passing the River.' Mother says that father has crossed the river and gone to be with Jesus in the beautiful city. But I wish-oh, I do wish that he could have stayed here with us!"

The child's voice had suddenly grown mournful, and tears were dimming the blue eyes. A strange feeling came over Michael Betts—a curious, choking sensation which he could not understand. He longed to say something to comfort the child; but what could he say?

"Mother says we must all cross the river some day," continued little Margery, after a moment's silence. "We don't know when it will be. I should think you would cross soon, Mr. Betts, for you are so very old. You are older than my father was, aren't you?"

"I don't know, I am sure, miss," said Michael, turning hastily to the shelves and beginning to lift down the books without much heeding what he was doing.

"What are you going to do with those books, Mr. Betts?" demanded the child.

"I am going to take them away, missy. You see, your poor father won't want them any more, and they'd only be a trouble to your mother, especially as she is leaving this house, so I am going to take them to my shop."

Margery looked at him for a few moments in a troubled, bewildered way. Then big tears gathered again in her eyes.

"Oh, I can't bear it!" she cried suddenly. "Father is gone, and now his books are going, and everything will be different. I cannot bear it."

And then, to Michael's consternation, she threw herself face downwards on the rug and sobbed aloud with a child's passionate vehemence. He was in utter dismay, not knowing in the least what to say or do. It seemed to him quite a long time that he stood there, helpless and embarrassed; but in truth only a few minutes passed ere the door opened and a woman wearing a white cap and apron came quickly into the room.

"Come, come, Miss Margery, this won't do," she said, not unkindly, though in a tone of remonstrance, as she bent over the weeping child. "You mustn't give way like this. Come, come now."

And taking the child in her arms, she carried her from the room.

There were tears in Michael's eyes as he turned back to the bookshelves. The hands which tried to lift the books shook strangely. He hated his task now. He was thankful when he had got through with it, and the last load was conveyed to his shop.

He could not forget the child. He sat up late that night, still busied with the books, for it was not easy to find room for them all in the limited space which his premises afforded. Margery's words kept ringing in his ears—"I should think you would cross soon, Mr. Betts, for you are so very old. You are older than my father was, aren't you?"

The child was right, though how she knew he could not imagine. Michael had seen the professor's age recorded in the newspaper—he was fifty-one, whereas Michael was fifty-nine. But what of that?

No one but a child would think him old. Many men lived to be eighty, and some even to ninety. And he was so well and strong. No, he need not think yet of that dark, chill river of death, the very thought of which made him shiver. But he reflected, and the thought caused him to breathe more than one heavy sigh, that when his time came to pass that river there would be no one to go with him to the brink, no loving voice to bid him farewell, no child to mourn for him as little Margery mourned for her father. There had been no time in his hard-working, self-centred, business absorbed life to cultivate love; but Michael Betts was beginning to feel that its absence made a sore and woeful lack in his life.

UNRIGHTEOUS GAIN

ON the following day, Michael was still busy with the late professor's books. As he examined them more fully, he was disposed to congratulate himself on the bargain he had made. There were several valuable old books in the lot, and others which, if less aged, were much in request. Michael foresaw that he would make money by them. It was true his returns would come in slowly; but nevertheless, he must in time gain a handsome profit on the sum he had expended.

As he reflected on this, Michael's spirits rose. He forgot the gloomy thoughts which had troubled him on the previous evening. He ceased to think with pity of little Margery and her mother. After all, theirs was the common lot. Men must die, and women must weep. It was an ill wind which blew nobody any good, and their wind of trouble had brought him a good investment. Nothing pleased Michael more than a prospect of making money. He loved to think that he was accumulating capital.

He cherished the hope that he should die a rich man, though he had no one to whom he could leave his savings when death called him hence. He had never made a will. It seemed so unnecessary to trouble about that yet. Some day he would make one, of course. He had no intention of dying intestate and letting the Crown seize his hardly earned money. No, he thought he would leave his property to charities. He had a vague idea that in this way he might make amends for an uncharitable life. But it was rarely that he gave the matter a serious thought. Why should he, when death seemed so remote?

Michael began to realize money from the professor's books sooner than he could have anticipated. Only a few days later a gentleman came to the shop and asked for a copy of an old but still valuable encyclopædia. Michael remembered that there was one amongst his newly-acquired stock of books. He looked for the work, and soon brought forward the two strongly-bound, bulky volumes which formed it. He was half afraid that his customer would be frightened at the somewhat high price he felt obliged to ask for them. But the gentleman made no demur. He seemed so pleased to obtain them, indeed, that Michael half wished he had asked more.

"I'll take them with me, if you will just put a piece of paper round them," the gentleman said. "But, stay what is this?"

He had been turning over the pages of one volume when he came upon an envelope which seemed as if it had been slipped between the leaves to mark a place.

"That, sir? Oh, I don't suppose it's anything of consequence," said Michael, as he took it. As he turned it over in his hand, he perceived, to his astonishment, what appeared to be bank-notes within the envelope. With his instinctive caution, however, he said nothing, but thrust the envelope quickly out of sight. The gentleman concluded that he had found its contents to be trivial, and said nothing more about it; and as he waited whilst Michael did up the parcel, he gave not another thought to the matter.

But as soon as his customer had quitted the shop, Michael turned eagerly to the envelope. What was his amazement when he drew from it five Bank of England notes for ten pounds each! He could hardly believe his eyes. He looked at them carefully, holding each note up to the light. There could be no doubt that they were genuine. Fifty pounds! What a treasure to light upon!

But how did the notes come to be within the old book? Who had put them there? Had they belonged to Professor Lavers?

In the first surprise of his discovery, Michael had not a doubt as to the ownership of the money. His first impulse was to return them to Mrs. Lavers forthwith. She certainly had the first right to anything found within the books that he had purchased of her. The thing to be done was clear enough to Michael in the earliest moments which followed his great surprise.

But later, as he looked at the notes and shook them in his hand, and thought of all that might be done with them, various doubts and possibilities presented themselves to his mind. Who could say that the professor had put the notes where he found them? The notes were not fresh and crisp; they were soiled, and one was a little torn. They might have lain for years within the thick volume. They might have been there when Professor Lavers bought the encyclopædia. Michael knew that he bought many of his books second-hand. Besides, if he had left the notes there, they would have been missed, and questions asked and search made. Evidently no one had missed the money.

Why, then, Michael asked himself, need he proclaim what he had found? If a man found a sum of money, he had a right to keep it till some one claimed it, and could prove that it was his. If Mrs. Lavers came and told him that she had lost this money, he would restore it to her at once. But till then he had a perfect right to retain it. At any rate, he would do nothing hastily. He would wait and see what happened. So Michael locked the notes within his desk and tried to go on with his work as usual. But this was not easy. He could not forget that the notes were there, though he tried hard to do so. Nor, in spite of the many excellent arguments by which he strove to persuade himself that he was acting rightly, could he get the better of an uneasy sense that he was swerving from the path of rectitude.

A week passed by, and the roll of notes remained within Michael's desk. He was still trying to persuade himself that he was justified in retaining them, and he still found that the voice of conscience would not endorse his arguments. There were moments when that voice would say to him that his action in keeping money that was not his was little better than stealing.

One evening Michael Betts, goaded by these irritating suggestions, started to walk up Gower Street, with the half-formed intention of calling at Mrs. Lavers' house and asking to see her, that he might tell her what he had found in the old encyclopædia. The struggle within him was still so strong, the love of gain contending so fiercely with the love of integrity, that it is probable he would in any case have turned back when he reached Mrs. Lavers' house. But when he came to the door he found the steps littered with straw and paper; there was no light in the windows, and when he lifted the knocker, its fall resounded hollowly through the now empty house. Mrs. Lavers and her children had gone away, and the house was no longer a home.

Michael's feeling was one of relief.

"Now there's an end to the matter," he said to himself. "She's gone away, I don't know where, and it's not in my power to tell her. It's clear she knows nothing about the money, and she does not want it. I have therefore a perfect right to keep it."

And hugging this thought to his heart, and congratulating himself on the lucky thing he had done when he purchased the professor's library, Michael turned homewards.

As he approached his shop, he saw a girl standing beneath the lamp-post at the corner. She was a girl about fifteen years of age, with bright eyes showing beneath the thick black fringe which covered her forehead. Her cheeks were flushed by the cold wind, which, however, she did not seem to mind as she stood there. A large white apron covered her dark gown; she wore a violet woollen shawl crossed over her chest, and a hat with many feathers was on her head. She turned and looked curiously at Michael as he passed her, eyeing him so intently that he was conscious of her scrutiny, and resented it. As he was opening the door of his shop, she came to the head of the steps and called out in loud, clear tones:

"I say, are you Michael Betts?"

"That is my name, certainly," replied Michael, with dignity, "but I cannot see what business that is of yours."

"Maybe not. And yet, p'raps it is my business. Maybe I know more of you than you think for, Michael Betts."

"Then you know I'm a respectable man, and have nothing to say to a girl like you," returned Michael angrily.

"Respectable, indeed!" cried the girl hotly. "I don't know about your being so mighty respectable, but I'd have you know, other folks can be respectable besides yourself. You might practise a little civility along with your respectability."

Michael closed his door sharply, cutting short this tirade. The girl made an angry, defiant gesture in his direction, and then ran off.

"The hussy!" said Michael to himself. "How did she get my name so pat, I wonder? I hope none of the neighbours heard her calling it out. Anyhow, they all know me for a respectable man."

Suddenly with the thought his face flushed, and a pang of shame smote him. Was he indeed a respectable man? Would they respect him if they knew how he had kept the notes? Could he say that in that instance he had acted perfectly on the square? Alas! His conscience convicted him. He was no longer satisfied of his own probity. He had given his self-respect in exchange for those fifty pounds.

AN UNWELCOME ENCOUNTER

MICHAEL paid the fifty pounds into his bank, and had the satisfaction of seeing them entered in his pass-book. He was so much richer than he had expected to be, yet somehow he did not feel richer, but poorer. He had rather the feeling of one who had suffered loss. There was a stain upon his conscience, and a weight upon his mind; yet, with the strange perversity of human nature, he would not own this to himself. He still professed to believe himself justified in keeping the money he had found. He clung to it, and liked to think how it had swelled his balance at the bank, even whilst he knew that he should be filled with shame, if any one should ever learn how he had come by that money.

In Michael's lonely life there was no one save Mrs. Wiggins, the charwoman, to observe how he lived, and mark the variations in his moods. She began at this time to observe a change in the bookseller. He had never been what she would call a "pleasant-speaking" gentleman. She had always found him short of speech, irritable, and disposed to snub her whenever she attempted to inform him as to the gossip of the neighbourhood; but now he was positively surly in his manner towards her, and so quick of temper that it was almost more than she could "put up" with.

One morning, she thought she was giving him intelligence in which he could not fail to be interested, when she said:

"I've 'eard where that lady, the professor's widow, as you bought so many books of, 'as gone to live."

Her words startled Michael, and he turned his eyes on her without speaking. She took his silence as an encouragement to proceed.

"She's gone to live in Clarendon Gardens. That's not a very nice place, is it? And even there, she 'as only part of a 'ouse. It seems she's quite poor now she's lost 'er 'usband. She's sent away 'er servants, and keeps only a bit of a girl now. She washes and dresses the children 'erself, and does most of the cooking—and she such a lady, too! It's 'ard, ain't it? I 'eard it all from my cousin, who works for 'er landlady."

"I wish to goodness your cousin would mind her own business, or that you would keep her gossip to yourself!" exclaimed Michael angrily. "How can I help it, if Mrs. Lavers is poor and has to do without servants? I've done what I can for her in buying her books. What more can I do?"

"Oh, lor me! Nobody would expect you to do anything for her," exclaimed Mrs. Wiggins, with unconscious satire. "I just thought you might like to know about the poor lady. You need not turn so fiercely on me, Mr. Betts, for giving you a piece of news."

"Keep your news till it's wanted, and mind your own business," responded Michael crossly.

Mrs. Wiggins took up her dust-pan and brush, and retreated with much clatter into the back premises, muttering words which were not complimentary to her employer.

"Do, indeed! I'd like to see 'im ever do anything for anybody besides 'isself, the close-fisted old curmudgeon. I'd be sorry for a mouse that had to live on 'is leavings. The idea of 'is turning on me like that, as if a body couldn't speak about nothin'."

It was impossible for Mrs. Wiggins to understand how her words had for Michael the force of an accusation. She did not know of the secret consciousness which they awakened.

"So, then, it was a poor woman whom he had defrauded," said the voice of Michael's conscience.

"Defrauded! What an absurd idea!" the voice of his other self responded. "There was no fraud in the matter; the money had never been Mrs. Lavers'. A man had a right to keep what he found, unless he knew it to belong to some one else."

But reason as he might with himself, the information imparted by Mrs. Wiggins had disturbed Michael's mind.

An incident which occurred a few days later further destroyed its peace.

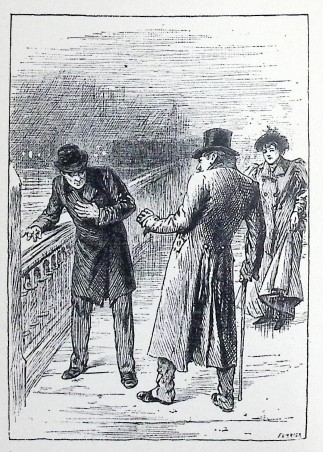

Business had taken Michael to the south side of the river, and he was returning late in the evening across one of the bridges on his way back to Bloomsbury, when his attention was arrested by the appearance of a man who stood leaning against one of the parapets and coughing violently. Michael started, and a thrill ran through him. He had so long thought of his brother as dead, that the sight of this man, who bore so striking a resemblance to him, affected him almost with terror, as though he conceived him to be a ghost.

To be sure, he had grey hair, and Frank's had been brown when Michael last saw him, and his form was pitifully bent and wasted; but still the resemblance was there, and so strong that Michael involuntarily stood still as he saw him, whilst his heart began to beat more painfully than was pleasant. The same instant the man ceased coughing; he lifted his head and saw by the light of the gas-lamp on the parapet above him the man who stood at his side. A low cry of wonder—and was it of pleasure?—escaped him. He moved a step nearer, exclaiming eagerly:

"Michael! Michael!"

"You don't mean to say it is you?" exclaimed the other, in tones which expressed no pleasure at the meeting. "You, Frank, after all these years! I thought you were dead."

"And perhaps hoped that I were," returned the other, retreating a step or two, whilst an air of hopelessness came over him again. "Well, it's no wonder. I'm not a brother you can be proud of."

Michael looked at him for a moment ere he made reply. The man appeared thin, and cold, and ill; but his was not one of the most abject-looking of the forms to be seen abroad in London. His clothes, though worn and threadbare, were decently tidy.

"You've only yourself to thank for being what you are," Michael said. "Drink and gambling and bad company bring a man to this."

"I've given up the drink, and gambling too, thank God!" said his brother. "I've been a teetotaler for more than a year, Michael."

"I'm glad to hear it," replied Michael, his tone implying that he doubted the statement. "But if that is so, how do you come to be in such low water? How do you live?"

"I can scarcely tell you how I live," returned the other. "I shouldn't live at all, if it were not for my little girl."

"Your little girl!" exclaimed Michael. "You don't mean to say that you've been so foolish as to marry?"

"I married many years ago, and I had one of the best of wives, though, God forgive me! I was often a brute to her. It was foolish of her to take me, no doubt, but I could never regret it. Whilst she lived, things were better with me; but when she died I went all wrong again. And now, when I fain would live a different life, I can't find any one willing to give me a chance."

"You could surely get work, if you exerted yourself."

"Could I? You don't know how hard it is to get work in London. And who would employ a man like me, when there are plenty of big, strong fellows to be hired? I haven't the strength to lift or carry. I'm good for very little now. I was in the Infirmary for three months. They patched me up a bit there, but I'm not much the better. If it were not for my little girl, I shouldn't be living now. She works at the match-making, and she keeps me more often than I keep her, bless her!"

A feeling of cold disgust was creeping over Michael Betts. There was no room for pity in his heart. He was conscious only of intense annoyance that such a being as this should be his brother.

"I'm sorry for you," he said loftily, "but it's your own fault. You made your bed, and you must lie upon it. I did what I could for you years ago, and ill you repaid me for what I did. Now I must wipe my hands of you. But here is a shilling for you."

He held out the coin as he spoke, but the chilled fingers of the other made no attempt to take it. The shilling fell from them to the pavement, and the ill-clad man did not pick it up.

"I don't want your money, Michael," he said hoarsely. "I could not help speaking to you when I saw you by my side; but don't think that I should ever have sought you out or asked you to do anything for me again. I know too well that I deserve nothing from you."

"That is well," said Michael coldly. "I must confess that had you come, you would not have found a welcome from me, since the last time you were at my place, you left me with good cause to regret your visit."

He turned on his heel without giving another glance at his unhappy brother.

"Michael, Michael," the weak voice called after him.

But Michael strode on and paid no heed. He did not slacken speed till he was the length of several streets from the river. Then he paused and drew a deep breath as he wiped the heat from his forehead.

"To think that he should turn up again!" he said to himself. "And I thought he was dead! But no, here he is again, and in the same deplorable plight. A pretty sort of a brother!"

And Michael knew that in his heart, he wished that his brother were dead.

"Of course, it's the same old story," he continued. "He's a sorry scamp, and always will be. It's all gammon about his becoming a teetotaler and trying to lead a better life. I don't believe a word of it. No, that won't go down with me. I only hope he'll keep away from me, as he says!"

Thinking thus, Michael arrived at his shop. It could hardly be called his home. He drew out his key, unlocked the door, and went in. He struck a match and kindled a lamp which he had placed just inside the door. Seen by its dim light the shop looked gloomy indeed. He passed through to the little room at the back. This, too, was littered with books. The fire had fallen out, and the place looked unhomelike and cheerless. Michael shivered. He became conscious of weariness and depression. He placed the lamp on the table and looked about for some means of rekindling the fire. The flame flickered feebly. Mrs. Wiggins had forgotten to replenish the oil.

As he looked about him in the dim light, Michael's eyes fell on the old leathern armchair which stood beside the fireplace. He had known that ancient piece of furniture as long as he had known anything. His mother, as her health grew feeble, had sat in it constantly, and now, as Michael glanced at it in the uncertain light, it suddenly appeared to him that he saw her form seated again in the old armchair. Most vividly, he seemed to see her sitting there with her white muslin cap resting on the dark hair which had been untouched by silver when she died, her little grey shawl upon her shoulders, and her hands busied with the socks she was perpetually knitting for her sons. Only an instant, it was ere the lamp flame leaped up, and he knew that he had been deceived by his fancy, but that instant left its impression. He sank on to a chair, shaken in body and mind.

How his mother would have grieved if she could have foreseen what Frank's future would be! Her darling son, a poverty-stricken tramp wandering about in search of a job! And he, Michael, had promised her that he would always be good to Frank. Had he kept that promise? Was he keeping it when he turned away from his brother on the bridge, telling him that he had made his bed and he must lie on it?

Michael sat for some minutes absorbed in painful thought. Then, resolutely turning his back on the old armchair which had awakened such unwelcome reflections, he began to pace to and fro the floor, for his limbs had grown benumbed by the chill of that fireless room.

"No," he said, half aloud, "I have not failed in my duty towards my brother. I have done all that could be expected of me. No one would do more. I've helped him again and again, only to be repaid by the basest ingratitude. Now, I will do no more."

IN THE GRIP OF PAIN

MICHAEL went to bed that night feeling thoroughly chilled in body and miserable in mind. Sleep would not come to him, nor could he get warm, though he put all the wraps he could find upon his bed. As he turned and tossed upon the mattress throughout the night, unable to find ease, the form of his brother as he had seen him on the bridge was ever before his eyes. What a wretched thing Frank had made of his life! It was all his own fault, for he had had a good chance when he was young. And then to think of his marrying, when he had not enough to keep himself! What improvidence!

Michael wondered what the little girl was like of whom his brother had spoken. With the thought, the image of the professor's sunny-faced, winsome little daughter rose before his mind. But it was not likely that his niece was at all like her. A girl who worked at match-making! Well, it was hard on a respectable, hard-working man to have relatives of such a description. Michael wished that he had taken another way home than the way that had led him across that bridge. He had been so much more comfortable under the persuasion that his brother was dead.

When Michael woke from the brief sleep that visited him towards dawn, it was past the hour at which he usually rose. But when he would fain have bestirred himself in haste, he found it impossible to do so. His back and limbs seemed to have grown strangely stiff, and when he tried to move, an agonising pain shot through them. He struggled against the unwelcome sensations, and did his best to persuade himself that he was suffering only from a passing cramp. But the pain was terrible. He felt as if he were held in a vice. How to get up he did not know; but he must manage to do so somehow. It was necessary that he should get downstairs to open the door for Mrs. Wiggins. Setting his teeth together and often groaning aloud with the pain, he managed at last to drag himself out of bed and to get on his clothes. It was hard work getting downstairs. He felt faint and sick with pain, when at length he reached the lower regions. It was impossible to stoop to kindle a fire. He sank into the old armchair and sat there bolt upright, afraid to move an inch, for fear of exciting fresh pain, till he heard Mrs. Wiggins' knock. Then he compelled himself to rise, and painfully dragged himself forth to the shop door, where he presented to the eyes of the charwoman such a spectacle of pain and helplessness as moved her to the utmost compassion of which she was capable.

"Dear me! Mr. Betts, you do look bad. It's the rheumatics, that's what it is. I've 'ad 'em myself. Is it your back that's so very bad? Then it's lumbago, and you'd better let me iron it."

"I'll let you do nothing of the kind!" cried the old man angrily. "Do for pity's sake keep away from me; I can't bear a touch or a jar. Make haste and light me a fire, and get me a cup of tea. That's all I want."

"You ought to be in bed, that's where you ought to be," said Mrs. Wiggins. "Just let me help you upstairs, now do, and then I'll bring you a cup of tea, all hot and nice."

"How can I go to bed?" he asked impatiently. "Who is to look after the shop if I go to bed?"

"Oh dear! That's a bad look out. Have you no one to whom you could send to come and take your place? Have you no brother now who would come to you?"

"Of course I have not!" he cried, annoyance betraying him into a quick movement, which was followed by a groan of pain. "I do wish you would attend to your business, and not ask me stupid questions."

"Stupid or not, you're not fit to stand in that shop to-day. Why, you couldn't lift a book without wincing. Ah me! It's bad enough to be lonesome when you're well, but it's sad indeed when you're ill to have no one to do a thing for you."

"Do be quiet," he cried; but Mrs. Wiggins, excited by the sight of his suffering, was not disposed to hold her tongue till she had fully relieved her mind. She began to suggest one patent remedy after another, and showed a remarkable acquaintance with all the quack medicines of the day. But Michael refused to try any of them. He had hardly ever been ill in his life, and he did not in the least know what to do with himself, or how to bear his pain.

It grew worse as the day wore on, and though Mrs. Wiggins made him a good fire, and he sat over it, he could not get warm. It was hopeless to think of attending to business. He was obliged to give in at last, and allow the shop door to be closed, whilst he was ignominiously helped up to bed by Mrs. Wiggins.

"Now you'd better let me send for a doctor," she said.

"No, indeed," he replied with energy. "I want no doctor yet. You don't suppose I can afford to send for a doctor every time I have an ache or pain?"

"Maybe not," she said, "but it seems to me you're pretty bad now."

"Folks don't die of rheumatics," he said.

"Oh, don't they?" she returned. "I've known a many cases in which they 'ave. Rheumatics is no joke. They're apt to seize on the 'eart, don't you know?"

And with this comforting reflection she left him.

As Michael lay there in pain and misery, he was reminded of a childish voice, which had said:

"I should think you would cross soon, Mr. Betts, for you are so very old."

Could it be that he was drawing near to the hour when he would have to cross that river of death?

The pain grew worse. From shivering, he passed into burning fever. Mrs. Wiggins felt very uneasy when the time came for her to go home.

"I don't like to leave you, Mr. Betts, I don't indeed," she said. "I can't think it's right for you to be all alone in this house. If you was to be took worse—"

"I shall not be worse," he said hoarsely; "the pain can't be worse than it is now, and it would not make it any better to have some one else in the house."

"But I wish you'd let me stay with you," she suggested. "Just let me go and tell my 'usband, and come back directly."

"No, no, no," he said, for he was weary of her attentions. "Take the house key with you, and lock the door on the outside, and come as early as you can in the morning. But first bring a big jug of cold water, and set it here beside the bed. I'm so thirsty, I could drink the sea dry, I believe."

"Ah, you've got fever, that's what you've got," replied Mrs. Wiggins. "Well, I suppose you must have your way."

So she did what he told her, and then went home.

But she was so impressed with the fact of his being very ill that she bestirred herself unusually early the next morning, and was at Mr. Betts' shop quite an hour before the time at which she generally appeared. She unlocked the door and let herself into the shop. Already the place seemed to have a deserted look. The dust lay thick on the books. Mrs. Wiggins went quickly up the steep staircase and knocked at the door of the attic, which was Michael's bedroom. She knocked, but there was no response to her knock. She knocked again more loudly, but Mr. Betts did not bid her enter, only she could hear his voice talking in strange, far-off tones. After a little hesitation she turned the handle and entered the room. Michael Betts lay on the bed, his face flushed with fever, his brows contracted with pain, his eyes wild and dilated. He was talking rapidly and incoherently.

"Well, Mr. Betts," she said, as she approached the bed, "and 'ow do you find yourself this mornin'?"

But he paid no heed to her words. They fell on unconscious cars. He went on talking rapidly; but she could not understand what he was saying. As she bent nearer, she could catch a few words now and then; but there seemed no connection in them.

"The river—it's cold and deep—there's a little girl on the other side—Oh, the pain—the awful, burning pain!—Oh, water—give me water—there's water in the river—I don't care if he is my brother. Give me water—water, I say. What are you telling me about the money?—It's mine—I have a perfect right to it. Oh, this pain! The water—the river."

"Lor' bless me! He's right off 'is 'ead," said Mrs. Wiggins; "'e's in a raging fever. It's no good speakin' to 'im. I must just fetch a doctor, whether 'e likes it or not."

A little later, a doctor stood beside Michael's bed. He pronounced it a severe case of rheumatic fever, made some inquiries respecting the circumstances of his patient, prescribed for him and departed, saying that he would send a nurse to look after him, since he needed good nursing more than medicine. The doctor showed his wisdom in so acting, for had Michael been left to the tender mercies of Mrs. Wiggins, well-meaning though they were, he would probably never have risen from his bed. As it was, he had a hard struggle ere the force of life within him overcame the power of disease. He was very ill, and at one time, the medical man had but faint hope of his recovery.

He was confined to his bed for weeks, and the little book-shop remained closed the while, for Michael was far too ill to give any directions as to what should be done about the business. After the fever left him, he was as weak as a baby: too weak to care about anything, so weak that every effort was painful, and he felt as if he had not the heart to struggle back to life again. Yet he shrank from the thought of death, and one of the first questions he asked his nurse, when he was able to think and speak connectedly, was if she thought he would recover.

"Yes," she said cheerfully, "you've turned the corner now. All you need is feeding up. Every day will see a change for the better now, if you're good and do as I tell you."

"I'll try," said Michael, quite meekly. "You've been very good to me, nurse."

"I should be a poor kind of nurse, if I hadn't been good to you," she replied. "It's my business to look after people when they're ill, and I have to take the greatest possible care of them, or things would go seriously wrong."

"I never had any one do as much for me as you've done," said Betts; "not since I lost my mother, I mean."

"Then you never had a wife?"

"No. I've never had time to think about getting one."

The nurse laughed.

"You're a strange man," she said; "but now eat some of this jelly."

"It is good," said Michael; "really I don't know as I ever tasted anything better."

"It's real, strong calf's-foot jelly, and it was made by a lady on purpose for you."

"That can't be," said Michael, looking at her in surprise; "there's no lady would make jelly for me. You must be making a mistake."

"Indeed I am not. You have more friends than you think. She came here and gave it into my very hands, so I must know. She said she'd heard from the doctor that you were ill, and she felt sorry for your being all alone. She said she'd done business with you, and when she saw the shop shut up, she asked about you."

"Well, I never!" said Michael. "I can't imagine who it could be."

"She said her name was Lavers."

"What?" exclaimed Michael in amazement. "What name did you say?"

"Lavers—Mrs. Lavers."

Michael gave a groan.

"What is the matter?" asked the nurse, turning to look at him; "have you the pain again?"

"No," he muttered, "not that sort of pain; but I wish she had not done it."

"Why, you ungrateful man!" exclaimed the nurse.

Michael made no reply. A hot flush of shame was dyeing his cheeks, and mounting to his forehead. The nurse observed it with some anxiety. She took his hand to feel his pulse. Was the fever about to return?

THE BURDEN MAKES ITSELF FELT

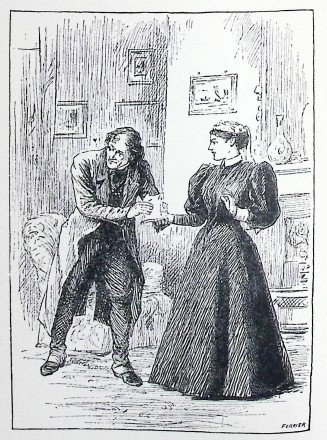

"MR. BETTS," said the nurse, three days later, as she came into the room, "that lady is downstairs, and she wants to know if you would like to see her."

"What lady?" asked Michael, though he thought he knew.

"The lady who made you the jelly—Mrs. Lavers, of course."

"Oh no," said Michael, shrinking down and drawing the bedclothes closer about him, as if he would fain hide himself; "I don't want to see her. I can't have her coming here. Tell her so, please."

"Don't you think that seems rather ungrateful, when she has been so kind to you?" asked the nurse. "Shall I say that you do not feel strong enough to see her to-day, but you hope to do so in a day or two?"

"No, no, no!" cried Michael vehemently. "Say nothing of the kind. I can't see her, I tell you. I can't and I won't, so there!"

"You're a strange man," said the nurse; and she went away, perhaps to repeat the same remark below stairs.

When she came back into the room a little later, Michael's eyes were fixed on her anxiously.

"Has she gone?" he asked.

"Yes, she has gone."

"What did she say?"

"Oh, she was sorry you would not see her, and she asked me to give you this." And the nurse held out to him a little bunch of sweet violets.

But Michael recoiled as if she were offering him something disagreeable.

"I wish she hadn't," he said.

"Well, you are ungrateful," said the nurse. "Catch me ever giving you flowers! And why you couldn't have let her come up to see you, I can't think. She would have read a chapter of the Bible to you, perhaps, and that would have done you good."

"I can read one to myself," said Michael.

"You're hardly strong enough for that yet. Have you a Bible?"

"Of course I've got a Bible," replied Michael indignantly. "What do you take me for? There is one somewhere that belonged to my mother, and there are plenty of them in the shop. Pretty old some of them are, too. The older they are, the more precious they are, you know."

"The Bible is precious anyhow," said the nurse. "It is a grand comfort, especially when one is weak and low. But you're thinking only of the binding, and the paper, and the print, Mr. Betts."