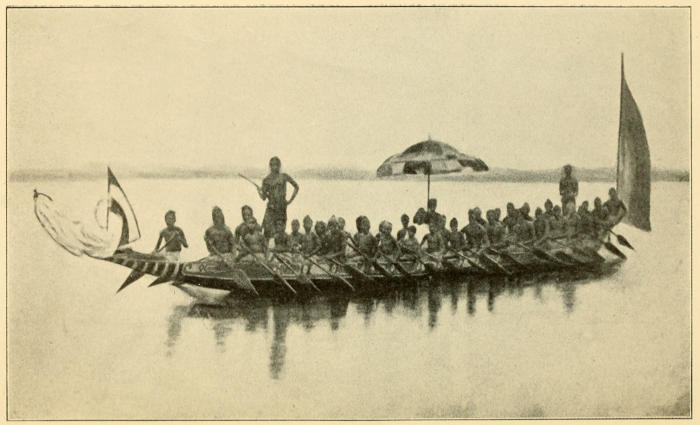

CANOE OF A CHIEF ON THE CAMERON RIVER. (See page 354)

Title: The jungle folk of Africa

Author: Robert H. Milligan

Release date: October 27, 2023 [eBook #71970]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Fleming H. Revell company, 1908

Credits: Peter Becker and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE JUNGLE FOLK OF AFRICA

BY

ROBERT H. MILLIGAN

The Jungle Folk of Africa

Illustrated, 8vo, cloth, net $1.50

“As one reads, the mystery and terror of the jungle seem to penetrate his soul, yet he reads on reluctant to lay down a book so grimly fascinating.”—Presbyterian.

Fetish Folk of West Africa

Illustrated, 8vo, cloth, net $1.50

“Mr. Milligan has written interestingly and vividly of the people among whom he labored, telling of their ways and habits, repeating some of their legends and beliefs and pointing out their failings as well as their good qualities.”—N. Y. Sun.

CANOE OF A CHIEF ON THE CAMERON RIVER. (See page 354)

The Jungle Folk of Africa

By

ROBERT H. MILLIGAN

ILLUSTRATED

New York Chicago Toronto

Fleming H. Revell Company

London and Edinburgh

Copyright, 1908, by

FLEMING H. REVELL COMPANY

Second Edition

New York: 158 Fifth Avenue

Chicago: 17 North Wabash Ave.

Toronto: 25 Richmond Street, W.

London: 21 Paternoster Square

Edinburgh: 100 Princes Street

“In the realm of the unknown, Africa is the absolute,” said Victor Hugo. Since the time of Hugo the civilized world has become better acquainted with African geography; but the Africans themselves are still a people unknown.

A certain noted missionary, while on furlough in America, after delivering a masterly and brilliant lecture on Africa to an audience of coloured people, gave an opportunity for persons in the audience to ask him questions pertaining to the subject. He was rather abashed when an elderly negro, who had been deeply interested in the lecture, called out: “Say, Mistah S., is they any colo’ed folks ovah thah?” Most people know that there are a goodly number of “colo’ed folks” in Africa; but the knowledge of the majority extends only to the colour of the skin. And if in this book I endeavour to make the Africans known as they really are, it is because I believe that they are worth knowing.

In the generation that has passed since the books of Du Chaillu were the delight of boys—old boys and young—the African has received but scant sympathy in literature. Du Chaillu had the mind of a scientist and the heart of a poet. He never understated the degradation of the African nor exaggerated his virtues, but he recognized in him the raw material out of which manhood is made. He realized that the African, like ourselves, is not a finality, but a possibility—“the tadpole of an archangel,” as genius has phrased it. But, then, Du Chaillu lived among the Africans long enough to speak their[10] language, to forget the colour of their skin, and to know them, mind and heart, as no passing traveller or casual observer can possibly know them.

In more recent books the African is usually and uniformly presented as physically ugly, mentally stupid, morally repulsive, and never interesting. This is by no means my opinion of the African. Kipling’s characterization, “half child, half devil,” is very apt. But what in the world is more interesting than children—except devils?

This book is an attempt to exhibit the human nature of the African, to the end that he may be regarded not merely as a being endowed with an immortal soul and a candidate for salvation, but as a man whose present life is calculated to awaken our interest and sympathy; a man with something like our own capacity for joy and sorrow, and to whom pleasure and pain are very real; who bleeds when he is pricked and who laughs when he is amused; a man essentially like ourselves, but whose beliefs and whose circumstances are so remote from any likeness to our own that as we enter the realm in which he lives and moves and has his being we seem to have been transported upon the magic carpet of the Arabian fable, away from reality into a world of imagination—a wonderland, where things happen without a cause and nature has no stability, where the stone that falls downwards to-day may fall upwards to-morrow, where a person may change himself into a leopard and birds wear foliage for feathers, where rocks and trees speak with articulate voice and animals moralize as men—a world running at random and haphazard, where everything operates except reason and where credulity is only equalled by incredulity. Elsewhere it is the unexpected that happens: in Africa it is the unexpected that we expect.

A knowledge of the jungle folk of Africa will include some acquaintance with their jungle home, their daily[11] life, their work, their amusements, their social customs, their folk-lore, their religion, and, among the rest, it will include their response to missionary effort. Of these several subjects, those which receive scant treatment in this book will be more fully presented in a second book on Africa, which is now in course of preparation.

I have avoided generalizations and abstractions, in the belief that the concrete and the personal would be not only more interesting but also more informing. This book is, therefore, in the main, a narration of the particular incidents of my own experience and observation during seven years in Africa; incidents, many of which, at their occurrence, moved me either to laughter or to tears, and sometimes both in alternation. For, nowhere else in the world does tragedy so often end in comedy, and comedy in tragedy.

I am indebted to Mr. Harry D. Salveter for his kindness in furnishing me with many photographic illustrations, including the best of my collection.

Robert H. Milligan.

New York.

| I | |

| The Voyage | 19 |

| Dreadful alternatives—A pork and cabbage saint—The outfit—A parting pain—Canary Islands—The change to the tropics—Sierra Leone—The native yell—Deck passengers—A meal of potato-peelings—Liberia—Shipboard conversation—A shrewd decision. | |

| II | |

| The Coast | 36 |

| Wet and dry seasons—The climate—The trader—Old Calabar—The crocodile—The most beautiful place in West Africa—The ugliest place in the world—Mount Cameroon—A ride on a mule—Landing in the surf. | |

| III | |

| Bush Travel | 55 |

| Where no white man had been—The greatest forest in the world—The caravan—Outfit—African roads—Bridges—The worst of the road—Blessings in disguise—The art of walking—The arrival in camp—The misery of morning—Rubber stomachs. | |

| IV | |

| Bush Perils | 73 |

| The road at the worst—Tired out—A palaver with the carriers—Elephants—A caravan astray—A long night—A borrowed shirt—The sullen forest—Accident the constant factor—A last journey—Advantage of breakfast before daylight. | |

| V | |

| The Camp-Fire | 89 |

| The camp—African mimics—The lemur’s cry—Legend of the snail—The chimpanzee and the ungrateful man—A fable of the turtle—Why the leopard walks alone—A “true” story—A magic fight—Discovering a thief—A spirit who spreads disease—A shadow-slayer—A witch discovered—Lying awake at night. | [14] |

| VI | |

| A Home in the Bush | 107 |

| Efulen—The “white animal” performs—Africa no solitude—The mail—The first fever—Yearning for a shirt—A vivid account of my funeral—The first house—Cooks and cooking—The medical layman—Mrs. Laffin’s visit. | |

| VII | |

| The Bush People | 131 |

| The Bulu tribe—“Better-looking than white people”—Dress—Ornamentation—A sociable queen—The white man’s origin—Our fetishes—A magic letter—Buying and selling—Chief Abesula. | |

| VIII | |

| After a Year | 148 |

| Killed by mistake—A woman stolen—A passion for clothes—The Batanga church—Expectoration a fine art—Romantic career of a nightshirt—Bekalida—Keli, the incorrigible—Death of Dr. Good. | |

| IX | |

| The Kruboys | 170 |

| The Kru tribe—The “real thing”—Kru English—The Kruboy’s superstition—The ship’s officers—Dressing with much assistance—Loading mahogany—The Kruboy and the surf—The white man out of his element. | |

| X | |

| White and Black | 195 |

| St. Paul de Loanda—Canine passengers—Portuguese slavery—An American problem—A health-change—Boma—Belgian atrocities—Matadi—Stanley—What I heard at Matadi—The apathy of the nations. | |

| XI | |

| The Fang | 217 |

| Gaboon—The village—The house—The door—The kiss unpopular, and no wonder—Marriage customs—A woman tortured—An elder brother—Immoral customs—The Gorilla Society—War—A troublesome sister—A blessing that resembled a curse—A strange war-custom—Music—Dancing—Story of the elephant and the gorilla—Fable of the sun and moon. | [15] |

| XII | |

| Fetishes | 249 |

| The conception of God—Dreams—Ancestor-worship—The conception of nature—The fetish proper—A wonderful medicine-chest—Various fetishes—A case of discipline—Witchcraft—A convicted witch—Wives and witchcraft—The white man and witchcraft. | |

| XIII | |

| A Boat Crew | 273 |

| The Evangeline—Makuba—An un-dress ball—Ndong Koni—A saint that lied—Capsized and rescued—A dying slave—Dressed in a table-cloth—Flogging a chief—A story of true love. | |

| XIV | |

| A School | 302 |

| The language difficulty—Lacked nothing but the essentials—The late M. de la R.—One of Macbeth’s witches—Death of Nduna—Bojedi—More candid than kind—The racial weakness—A royal romance—Marriage ceremonies—A penitent—A fall. | |

| XV | |

| A Little Scholar | 329 |

| A health-change—The brightest of his class—Rotten Elephant—Very sick—An object of wonder—Mount Teneriffe—Adventure with a stage-coach—Adventure with a donkey—The crisis—The Ashantee war—A burial at sea. | |

| XVI | |

| A Church | 354 |

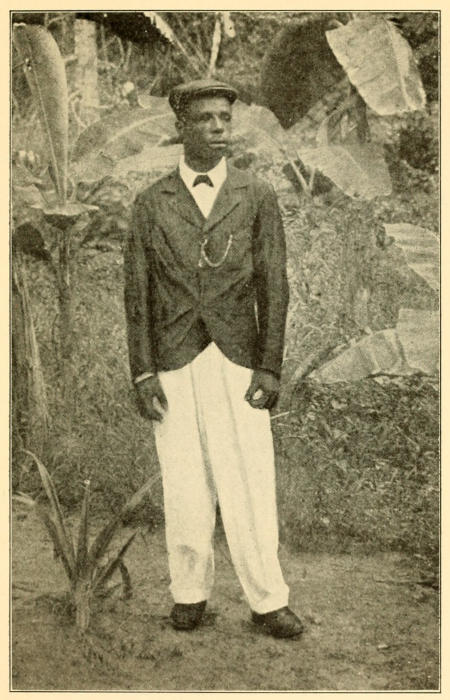

| Reality versus romance in missions—Arrival of the steamer—Adventure in a canoe—An Apollo Belvidere in ebony—A sensational call to worship—A white man’s foot—A prayer that caused a panic—Not wickedness, but worms—The right hand, or the left?—“Dawn of the Morning”—M’abune Jésu—Keeping the Sabbath—The harvest—The Jesuits—A building not made with hands—“O’er crag and torrent.” | |

| Facing Page | |

| Canoe of a Chief on the Cameroon River | title |

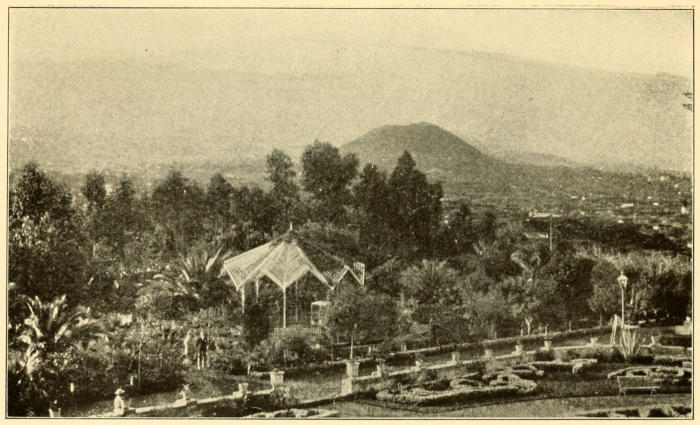

| Mount Teneriffe, Canary Islands | 24 |

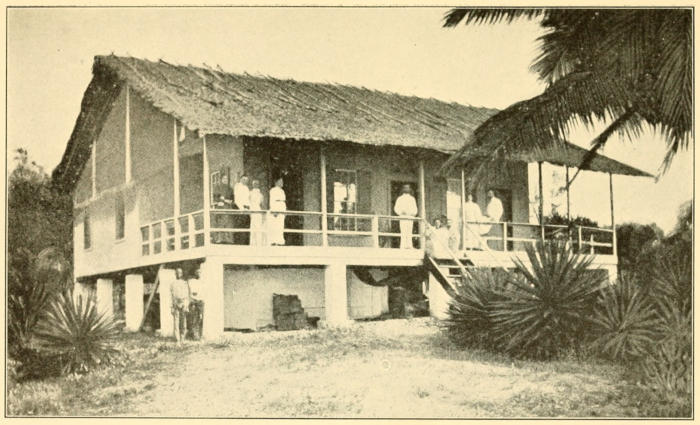

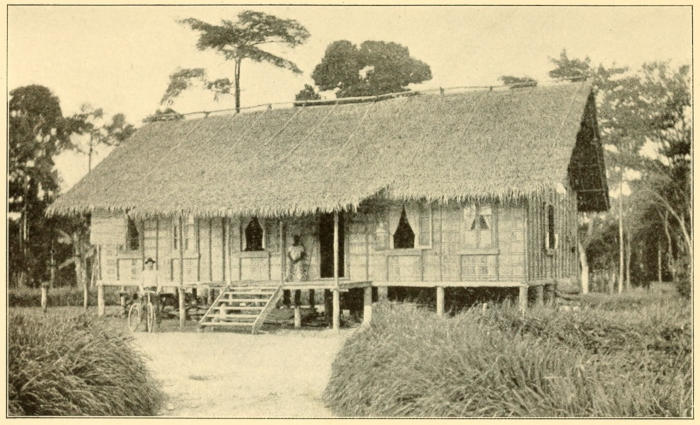

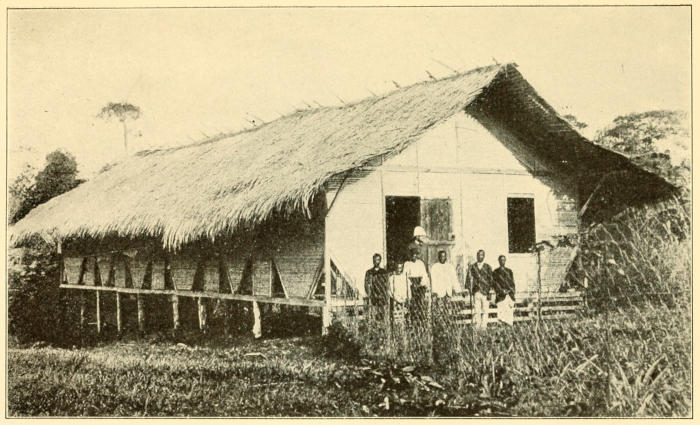

| Mission House at Batanga | 52 |

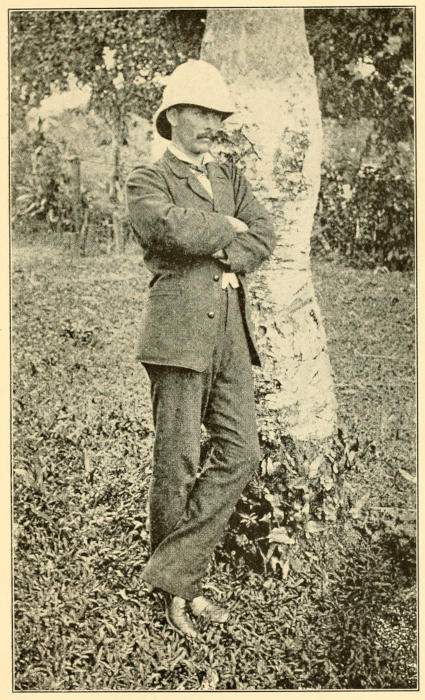

| Rev. A. C. Good, Ph. D. | 55 |

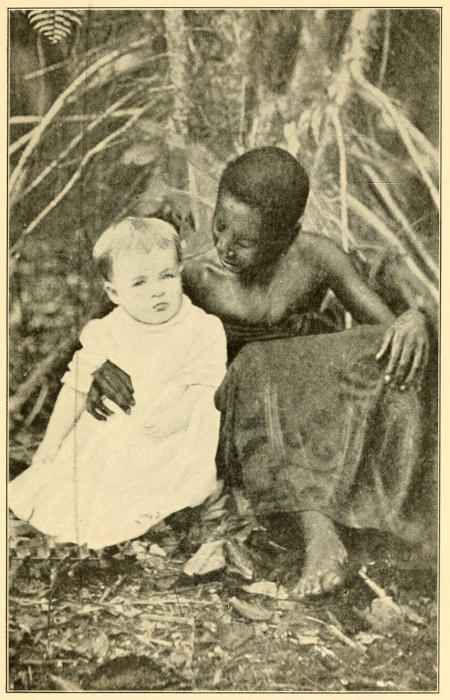

| Little Frances Born in Africa | 86 |

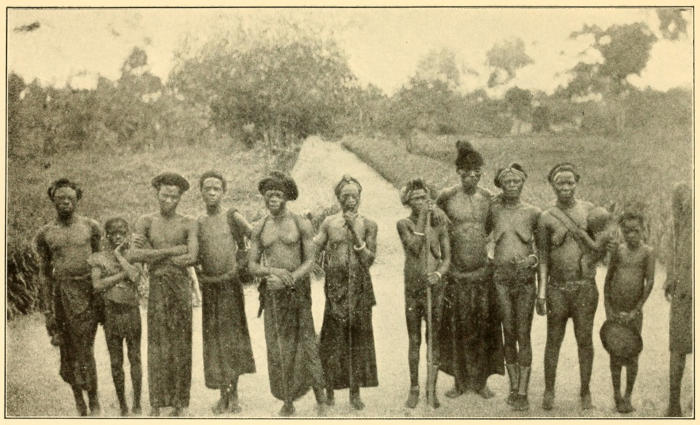

| A Group of Admiring Natives | 110 |

| An Improved Mission House at Efulen | 118 |

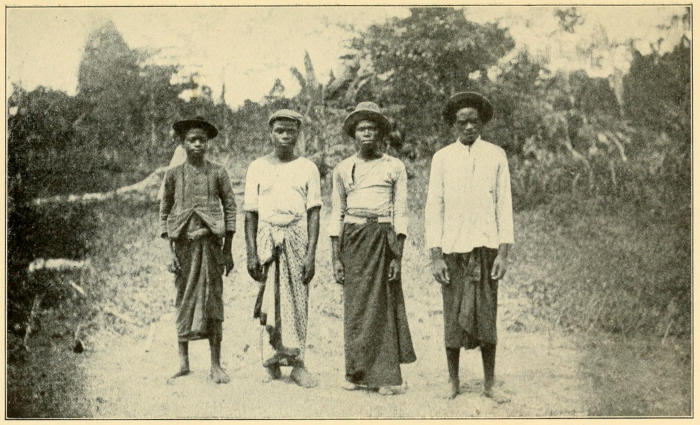

| The Passion For Clothes | 131 |

| The Old Church at Batanga | 154 |

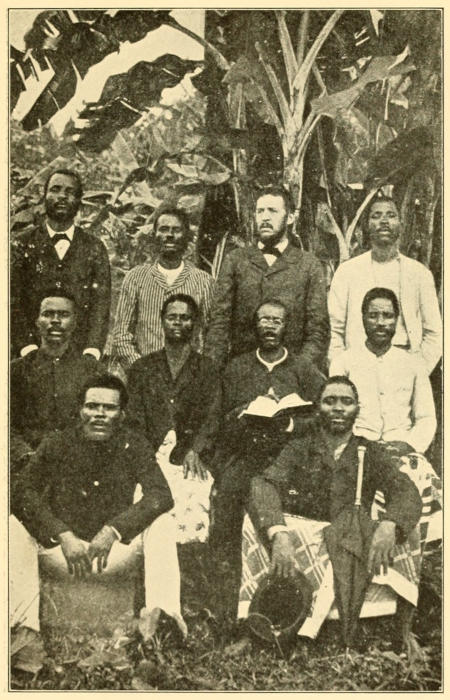

| Pastors and Elders of the Batanga Church | 160 |

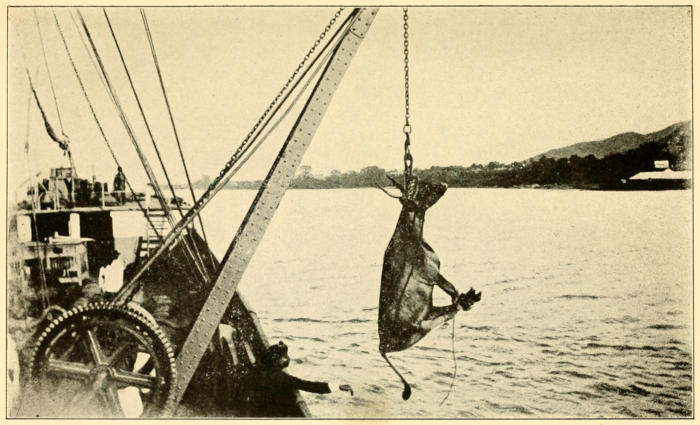

| The Debarkation of a Deck Passenger | 181 |

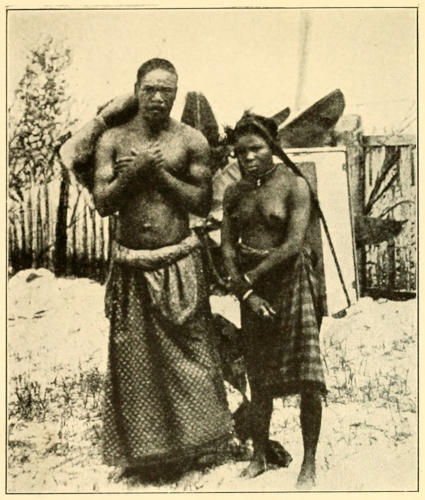

| Man and Wife | 224 |

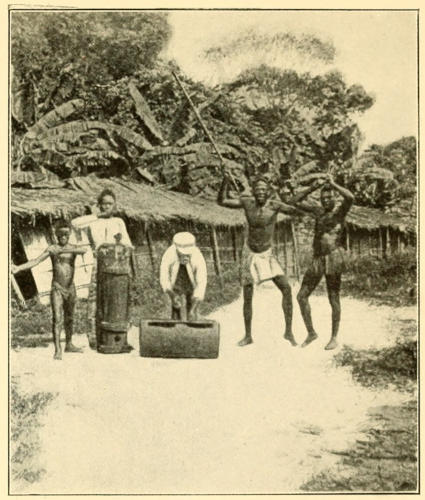

| Two Men Dancing | 224 |

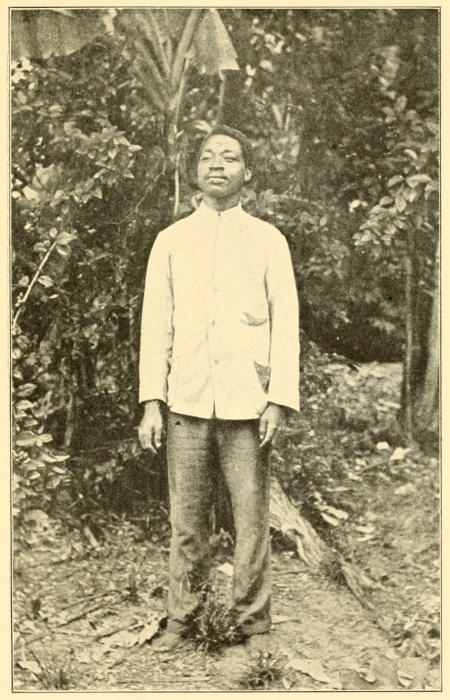

| Ndong Koni | 236 |

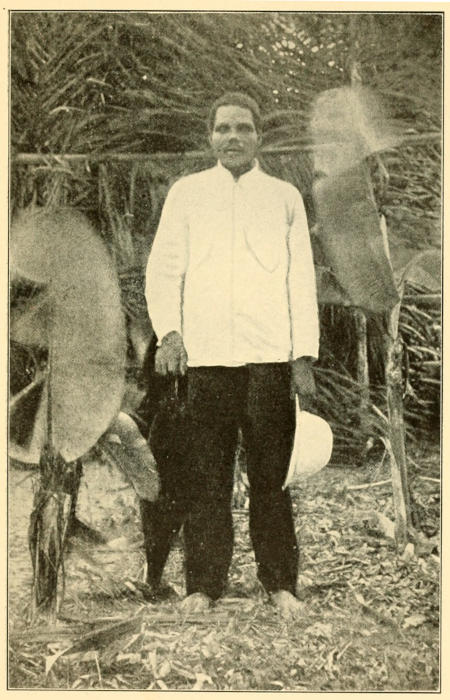

| Makuba, Captain of the Boat Crew | 276 |

| Bojedi, Teacher of Fang School | 314 |

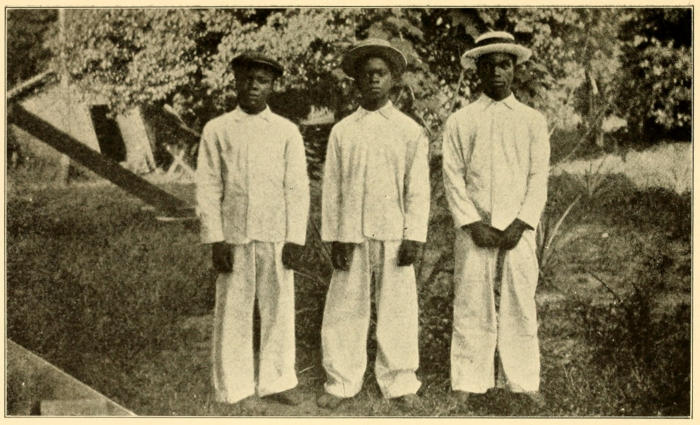

| Three Fang Boys | 378 |

When I was about to sail for Africa a friend read to me a thrilling incident which was supposed to be prophetic of my own fate. A cannibal maiden proposes marriage to a newly-arrived missionary. The missionary modestly declines her offer; whereupon, looking down at him with utmost complacency, she tells him that she will have him anyhow—either married, or fried. I have gone to Africa twice, and have lived there nearly seven years, yet I have escaped both of these dreadful contingencies. There is no longer any glamour of romance about the missionary life. It is not a life of hair-raising adventures and narrow escapes. In those seven years I was never frightened and seldom killed. Dull monotony is the normal experience and loneliness the besetting trial.

Neither are the sacrifices and privations of missionary life so great as many of us have supposed. The sacrifices of the missionary are more tangible, but not therefore greater, than those of the faithful minister at home; whose sacrifices are often more real because less obvious. A few days before I sailed the second time for Africa,[20] when I knew from former experience that the missionary life was no martyrdom, I was one day seated at a dinner-table where Africa and my going was the subject of conversation. The company had the most exaggerated ideas of the privations incident to missionary life. There was no use in a denial on my part; and to have disclaimed any of the fictitious virtues with which they loaded me would only have caused them to add the virtue of modesty to the rest.

A maiden lady across the table, who for some time had sat with abstracted countenance, at last, with upturned eyes and clasped hands, remarked: “Well, I think it is an appalling sacrifice.”

To have lived up to my part, my face at that moment should have worn a saintly expression of all the virtues rolled into one; but it happened that my mouth was quite full of pork and cabbage, with which my carnal mind was occupied, and I am sure I looked more like an epicure than an ascetic. Nothing but the pork and cabbage kept me from laughing outright.

Really, life in Africa is much the same as life anywhere else; and the “privations” only teach us how many things we can do without which we once thought were indispensable. This lesson is impressed the more deeply in such a land as Africa, where a human being may live for threescore years—comfortable, apparently happy, and at least healthy—with little else than a pot, a pipe and a tom-tom; the first ministers to his necessity, the second to comfort and the third to pleasure. If we will persist in regarding the missionary as a martyr, let us consider that the martyr does not differ essentially from other Christians. Martyrdom is potentially contained in the initial decision of each Christian. The consecration of a life to Christ implies the willingness to lay it down for Him. In an uncivilized land there is a likelihood[21] of unwonted hardships, and among savages some possibility of a violent death; but the latter is vastly improbable.

One can procure an outfit more conveniently and at less cost in Liverpool than in New York. A week at Liverpool is sufficient for this purpose. The outfit will depend somewhat upon whether one expects to live on the coast or in the bush where he will be cut off from the facilities of transportation by water. All transportation to the interior is by native porters, who carry sixty or seventy pounds on their backs, in loads as compact as possible. This excludes most furniture; and such furniture as can be transported is usually “knocked down.” An ordinary outfit will include several helmets of cork or pith, several white umbrellas lined with green, a dozen white drill suits, denim trousers, canvas shoes, leather shoes, rubber boots, cheese-cloth for mosquito-bars, rubber blankets, pneumatic pillows, hot-water bags, a supply of medicines (unless these are already on the field) especially quinine and castor-oil, a six-mouths’ supply of food—canned meats, vegetables and fruits—besides bedding and kitchenware, tableware, napery, etc., according to need, and guns and ammunition.

There is a romantic interest about this last week spent in the purchase of strange articles for an untried life, and in taking leave of civilization,—of such things as cities, society, music, fresh beef and fine clothes. The last evening in Liverpool I went to hear Tannhauser. Music had always been my pastime, and it was not an easy sacrifice to make. I therefore looked forward to that evening with peculiar interest, knowing that not again until my return, however long I might remain in Africa, would I hear any music worthy of the name. But Tannhauser proved to be not a sweet parting from civilization but an awful experience, by reason of some one in my neighbourhood[22] beating the time with his foot, as they so often do in England. I had one of the best seats in the house, but I exchanged it for another, only to find myself in a worse neighbourhood; for, in addition to a man on each side of me beating the time, a woman immediately behind “hummed the tune.” At the close of the performance I was in a condition of “mortal mind” that would have scandalized those who are disposed to canonize missionaries. But the sorrow of parting was thus mitigated as I reflected that civilization has its pains and savagery some compensations.

I went home and wrote the following to a friend: “Some one alluding to Macaulay’s knowledge of history and his unerring accuracy once said that infinite damnation to Macaulay would consist in being surrounded by fiends engaged in misquoting history while he was rendered speechless and unable to correct them; and I am thinking that my inferno would consist in being compelled to listen to some such exquisite melody as O Thou Sublime Sweet Evening Star, surrounded the while by fiends keeping time with their feet, and Beelzebub humming the tune.”

On my first voyage to Africa (having been appointed to the West Africa Mission, by the Board of Foreign Missions of the Presbyterian Church) I was four weeks on the way, from Liverpool, and landed at Batanga, in Cameroon, two hundred miles north of the equator. On the second voyage I was five weeks on the way, and landed at Libreville (better known as Gaboon) in the Congo Français, almost exactly at the equator. Libreville was the capital of the French Congo. Gaboon is properly the name of the bay or great estuary upon which Libreville is situated, and is one of the very few good harbours on the west coast. But long before the existence of Libreville, captains and traders had used the name Gaboon to designate the adjacent[23] settlement of native villages and trading-houses, and it is still the name in general use.

We made many calls along the way. Some of the places are very beautiful, such as the Canary Islands, Sierra Leone, Cape Coast Castle, Victoria, Fernando Po and Gaboon; and some are quite otherwise, for Africa is a land of extremes. Bonny is repulsive, and the Rio del Rey is a nightmare. Meanwhile, we are getting further and further away from all that is known and natural to our eyes, and nearer to a land of strange birds and beasts and trees, inhabited by tribes that to the white man are only a name, or have no name, and to whom he is perhaps an imaginary being, or the ghost of their dead ancestors.

At the Canary Islands, a week after leaving Liverpool, one may spend a day of interest and pleasure. On my first voyage we called at Las Palmas, in Grand Canary Island. On the second voyage we called at Santa Cruz on Teneriffe Island. The object of chief interest is the great Mount Teneriffe, seen sometimes a hundred miles at sea; probably the Mount Atlas of ancient fable, which was supposed to support the firmament. There are of course many mountain peaks in the world which rise to a greater height above the sea-level; but they are usually in ranges or on high table-lands far from the sea, and while the altitude is great, the individual peak may not be great. Teneriffe rises directly out of the sea, slowly at first but with increasing inclination, until at last it sweeps upward to the clouds and far above them, to a height of 12,500 feet. The sandy slopes upon the higher altitudes reflect the light with unequalled splendour. From the harbour of Las Palmas we saw the sun rising on Teneriffe. We stood on the deck before the dawn, and while darkness was all around us, saw the heights already struggling with the darkness, and the summit bathed in the light of the unrisen day. A heavy mist rolled down and spread[24] over the valleys, like a sea resplendent with every interchange of deepening and dissolving colour; while from below arose the increasing noise and tumult of a half-civilized city awaking from slumber. In a little while the clouds begin to assemble, and the peak is hidden throughout the day: so it is always. But in the evening, the clouds again are parted, like opening curtains, and the whole mountain is disclosed, majestic and beautiful in the light of the setting sun.

On the homeward voyage the steamers often take on an enormous deck-cargo of bananas. They are put in crates the size of barrels and are packed in straw. In the event of a severe storm before reaching Liverpool they are more than likely to be washed overboard. It is a pleasure to watch this loading from the upper deck. The Spanish workmen are neat and clean; they are skillful and work rapidly, as indeed they must in order to load the entire cargo in one day, which is usually the limit of time. All day long Spanish boys without clothes are crowded around the steamer in small boats, begging the passengers to throw pennies into the water and see them dive and get them. Many pennies and small silver coins are thrown over in the course of the day; and the boys seldom miss one.

A number of the passengers debark at the Canary Islands, and the rest have more room and more comfort. Immediately upon leaving the Islands double awnings are stretched over the decks; and the passengers and ship’s officers the next day don their tropical clothing. The sea is exceedingly calm as compared with the North Atlantic and the air soft and balmy. It recalled those lines of Keats—

MOUNT TENERIFFE, CANARY ISLANDS.

Probably the Mount Atlas of ancient fable, which was supposed to support the firmament.

The change to tropical life takes place in one day and it is like being suddenly transported into another world. The men nearly all are dressed in white drill suits, and most of them wear white caps and white canvas shoes. If they go ashore at various ports along the way they will exchange the cap for a cork helmet and besides will probably carry a white umbrella. The white suits if well made and well laundered look much more comfortable and becoming than any other clothing. They are usually made in military style with stitched collar, so as we go on further south the shirt of civilization may at length be dispensed with and the coat worn directly over an undershirt,—which latter ought to be of wool and medium weight. Except my first year, I wore no shirt at any time through all the years that I lived in Africa, not even at the French Governor’s annual reception at Gaboon. The English at Old Calabar on formal occasions make themselves ridiculous in black dress suits with the conventional area of shirt-front and collar. In these they swelter, vastly uncomfortable, while the starch dissolves and courses towards their shoes down back and breast. It is not only, nor chiefly, the high temperature but the extreme humidity that makes the atmosphere so oppressive. It seems to be seventy-five per cent, warm water.

On shipboard it is usually comfortable and pleasant while we are under way. The most delightful part of the voyage is the first few days after leaving the Canary Islands, when the course lies in the track of the northeast trade-winds. One thinks very differently, however, of this trade-wind in coursing against it on the homeward voyage after a length of time on the fever-stricken coast. It seems piercing cold, and, as Miss Kingsley says, one wishes that the Powers above would send it to the Powers below to get it warmed. It is in this zone that deaths most frequently occur on board. On the outward voyage[26] immediately after the most delightful part of the voyage comes the very worst part of it, as we pass beyond the trade-wind and close in to the coast near Cape Verde. For several days one is tempted to wish that he might turn back. There is a dead calm on board, and the heat is enough to curl one’s hair. It recalled Sydney Smith’s description of some such place, where “one feels like taking off his flesh and sitting in his bones.” But it continues only two or three days. During this time the “punka” is installed, a large fan suspended from the ceiling, the entire length of the table, worked by a rope, which a boy pulls with his hand.

A week after leaving the Canary Islands we reached our first African port, Sierra Leone. It has the finest harbour on the entire west coast. From the harbour it is very beautiful, with mountains of intense green standing like sentinels on either side and behind the town. The sound of the wind raging about these peaks, like the roaring of a lion, gives the name, Sierra Leone. Despite its attractive appearance, it is called The Whiteman’s Grave, and its history justifies the name. But as we proceed down the coast we find that every place which has any considerable number of white men is called The Whiteman’s Grave. The name Sierra Leone applies to the entire English colony; that of the town at this place is Freetown. It was originally a colony of freed slaves, which the English planted there during the suppression of the slave traffic. The first ship-load of colonists, between four and five hundred, was landed in 1787. Of these, sixty died on the way or within a fortnight after landing. Freetown has now a population of thirty thousand, and is prosperous. Along the wharf are warehouses with roofs of corrugated iron. The roofs of the traders’ houses also, both here and all along the coast, are of corrugated iron. Here and there among the colourless[27] huts of the natives there stands out boldly the frame houses of successful native traders, made of imported material and usually painted an impudent blue. Houses with floors are everywhere called deck-houses; for the decks of ships were the first floors ever seen by the natives.

So soon as we had anchored, the natives, in a score of boats, were crowding about the gangway, pushing back each other’s boats, fighting, cursing and yelling, in a general strife for the very lucrative privilege of rowing passengers ashore. However otherwise engaged in this scramble they are all yelling; and the resultant noise is the proper introduction to Africa. For, as noise is the first, so it will be the final and lasting impression. It is the grand unity in which other associations are gradually dislimned. We went ashore in the late afternoon. The people were all in the streets, moving about, but no one moving rapidly; all active, but no one very active. As there are no vehicles, pedestrians occupy the whole street, which is covered with grass. There is a great variety of dress and considerable undress. Many of the women wear a loose calico wrapper—a Mother Hubbard; and many of the men are dressed in the Mohammedan costume, which is more becoming, and more suitable for the climate, than any possible modification of European dress. It consists of a long white shirt with loose, flowing sleeves, and an outer garment somewhat like a university gown, of black or of blue. The ordinary man wears anything he may happen to have, from an eighth of a yard of calico to a rice-bag in which he cuts holes for his head and arms.

Ever so many were carrying loads on their heads—never any other way—and without touching them with their hands. Indeed, if their hands were engaged I am not sure whether they could talk; for when they talk[28] they gesticulate continually. Some were carrying beer bottles erect on their heads, some carried books, some of the women carried folded parasols; others carried fire-wood, or bananas, or large baskets of vegetables. They exchange the neighbourhood gossip as they pass, but without turning their heads; and sometimes they throw down their loads and seat themselves on opposite sides of the street to have “a friendly yell.” When we returned to the steamer we found on board, on the lower deck, about twenty native passengers. They have brought all their household goods, including chickens; and several of the women have babies strapped to their backs. They pay only for a passage on deck, taking the risk of the weather, and expect to yell their way to Fernando Po, in about two weeks. The number of deck passengers increases at each of the next several ports, until the deck is crowded; but they are never allowed on the upper deck.

The deck, formerly spacious and shining, is now covered with baggage, the abundance of which is only exceeded by its outlandish variety. The first mate is the ship’s general housekeeper. Cleanliness and order are a mental malady with him. If he could have his way the ship would carry no cargo, since the opening of the hatches and the discharging of it deranges the order of the lower deck and litters it with rubbish. Besides he would like to employ the boat-crews in holystoning one deck or another all the time instead of only once each morning. The sight of a dog affects him more seriously than seeing a ghost. Passengers are a great trial to him who carelessly place their deck chairs for comfort or for conversation with each other instead of leaving them in unneighbourly straight lines as he arranged them. He is rarely on speaking terms with the chief engineer, because the latter must frequently have coal carried from[29] the forehold; and there is a standing feud between him and the cook, whose grease-tub sits outside the galley door. The mate’s sole horror of a storm at sea is that the rolling of the ship spills the grease. Imagine the life this gentleman lives from the time that the native passengers begin to come aboard and fill the deck with their piles of miscellaneous baggage. He ages perceptibly. Disorder is precisely the weak point in the native character; and much of the mate’s time is spent in pitched battles with the native women, over the bestowment of their goods. No sooner has he, with the help of several deck-hands, arranged a lady’s goods in a neat square pile ten feet high and seated her children in a straight row than the lady orders all her children to get out of her way and proceeds to tear down the pile in order to get a cosmetic and a mirror that happen to be in two different boxes in the bottom. When the mate is not around the deck passengers seem very happy as they sit at random on their baggage and yell at each other. Here and there men in Mohammedan dress sit on the sunny deck in cross-legged tailor-fashion, reminding one of old Bible pictures. If they quarrel a great deal they also laugh a great deal, and the quarrels are no sooner ended than they are forgotten.

At Lagos several native men came out in a boat to meet a deck passenger and land his baggage. The natives are not allowed to use the gangway, and if the rope ladder is in use they pass up and down a single rope suspended over the ship’s side. On this occasion I observed one of the men from the boat alongside sliding down a rope and carrying a heavy box, by no means an easy thing to do. He expected that the others of his party would be waiting to receive him in the boat below. But they had drifted several yards away and were engaged in eating some potato peelings which a steward had thrown to them. He[30] called to them but they paid no attention:—they were eating. He yelled at them and cursed them, at the same time making with his legs impressive gestures of appeal and threat. But they sat indifferent until they had finished, while he with his load remained suspended in the air. Moreover, the sea at Lagos abounds with sharks. At last, having finished their repast, they came to his rescue. I was watching eagerly to see how many would be killed in the ensuing fight. But not a blow was struck, and the palaver did not last a minute. So forgetful are they of injuries. And though they are capable of great cruelty towards their enemies, their cruelty is callous rather than vindictive; not the cruelty that delights in another’s pain, but rather that of a dull imagination which does not realize it.

A few days after leaving Sierra Leone we anchored off Monrovia, the capital of Liberia, where we shipped eighty native men, Krumen, who were engaged by the ship as workmen for the discharging and loading of cargo. They are engaged for the round trip down the coast, three or four months, and are unshipped again on the homeward voyage. Of these Krumen I shall speak at some length in another chapter. They are the original native tribe of this part of the coast and are not to be confounded with the proper Liberians whose ancestors emigrated from America.

Liberia represents the philanthropic effort of America to restore to their native land the Africans carried to America by the slave trade. A large area of country was purchased from the native chiefs, and in 1820 the first settlement of colonists was established. Liberia is a country of possibilities. There is no richer soil on the entire west coast. It is especially suitable for coffee and cocoa; but it has remained undeveloped. The poor and ignorant colonists were not fit for self-government. America[31] should have done more or else less. The Liberians might far better have remained in America. During the several generations of their absence from Africa they seemed to have lost the power of resisting the malaria. The mortality among them was very great and they were pitiably helpless. The government of Liberia some one has said is a fit subject for comic opera. At one time becoming possessed of a little cash, by some wonderful accident, they provided themselves with a small gunboat by which they hoped to convince calling ships that theirs is a real government competent to collect dues, impose fines, and enforce the rules of quarantine and release that obtain at other ports, for which purpose it has proved as ineffective as a pop-gun. But they have used it successfully against the canoes of the Krumen in levying a heavy and unjustifiable duty upon these men when they return from the south voyage with their pay.

After two weeks on shipboard the immobility of life becomes agreeable and we are all content to be lazy. And in the evening when the social instinct is lively and men sit together at leisure in the balmy breeze, under the canvas roof, on a well-lighted deck, the sea so calm as to allay all apprehension, a wall of darkness around us, and the immensity of the sea beyond, as separate from the rest of the world as would be some tiny planet that has separated from the solid earth and rotates upon its own axis, then the charm of travel on the tropical sea is all that the imagination had preconceived,—a lazy, luxurious dream. When Boswell remarked to Johnson, “We grow weary when idle,” Johnson replied: “That is, sir, because others being busy, we want company; but if all were idle there would be no growing weary; we should entertain one another.” We were all equally idle and lazy, and wished we could be lazier. There were whole days when the conversation—until evening—contained[32] nothing more epigrammatic than “Please pass the butter,” or “Have a pickle?”

The company consists of traders, government officials and missionaries; and the captain is usually present. As our number diminishes at each successive port, we become better acquainted and more friendly. Men of antipodal differences are thus frequently brought into friendly and sympathetic relations, men who in ordinary life would seldom have been brought into contact with each other, and who never would have known that they had anything in common; and the experience is wholesome. I have learned to think more kindly of the African trader and to refrain from criticism because of some whom I have known intimately on these long voyages.

As we sit on deck in the evening the captain tells us that at Lagos, where we are due in a few days, he has seen the natives fight the sharks in the sea and kill them. The shark is the monster of the tropical seas, the incarnation of ferocity and hunger. The native takes a stout stick, six inches long and sharpened at both ends. With his hand closed tight around this he dives into the sea, and as the shark comes at him with its terrible mouth open, he thrusts the stick upright into its mouth as far as he can. There it remains planted in the upper and lower jaws of the shark, which, not being able to close its mouth, soon drowns and comes to the surface. It is a good story, and not incredible as a fact; for the native is brave enough and fool enough to do this very thing. But this is the same captain who tells of fearful storms which he has successfully encountered, when the ship rolled until she took in water through the funnels. He remarked to me one day, speaking of one of his officers who was not the brightest: “I always have to verify his reckoning; for he always mistakes east for west and invariably puts latitude where longitude ought to be.” He also tells of an invitation[33] he once received from a cannibal chief near Old Calabar, to come ashore and help him pick a missionary. He has seen the sea-serpent many a time and knows all about it. It is not dark green with brown stripes, as is generally supposed, but is bright yellow with blue spots, and is quite three hundred feet long. On one occasion it followed the captain’s ship for several days, at times raising one hundred and fifty feet of its length out of the water, and being prevented from helping itself to a sailor now and then only by great quantities of food which they threw over to it. This caused a famine on board, and they reached the nearest port in a half-starved condition. An affidavit goes with each of the captain’s stories. Most captains indulge in this entertaining hyperbole. Some are decidedly gifted with what has been called a “creative memory.” I have never yet known a captain who could not turn out as handsome a yarn as Gulliver.

As the company become better acquainted conversation is more intimate and varied. Now we are discussing some subject of continental magnitude, and again, with equal interest, some infinitesimal triviality. Detached from the rest of the world, and with no daily budget of news, our interest becomes torpid, and things great and small appear without perspective on a flat surface of equality. We avowed our disbelief in the infallibility of the pope, and pronounced against his claim to temporal authority. We anticipated all the conclusions of the Hague Conference, and discussed the imminence of the “yellow peril.” We resolved that the Crown Colony system was a failure and had never been a success, and we devised an elaborate substitute but could not agree upon the details. We agreed that the English aristocracy had long been effete, and that the Duke of X, related to the queen, was a “hog.” We reached the amicable conclusion[34] that the thirteen colonies should never have rebelled, and that the blame was all on the side of England. We left posterity nothing to say on the relative merits of the republican and the monarchic forms of government, and decided that the enfranchisement of the negro was a mistake.

In juxtaposition to these discussions, one man occupied the company a part of an evening recounting the entire history of his corns; but I regret that I have forgotten their number and disposition. Another disclosed the fact that he always wore safety-pins instead of garters, and descanted upon his preference with such enthusiasm that he made at least one convert that I know of. I was carefully told how to mix a gin cocktail (though I may never have any practical use for this valuable knowledge) and how to toss a champagne cocktail from one glass to another in a beautiful parabolic curve; also how many cocktails a man might drink in a day without being chargeable with intemperance: in short, if there is anything about “booze” that I do not know it must be because I have forgotten.

One night (but this was another voyage and a different kind of captain) we put in practice the principle of arbitration of which we were all adherents; and the result was my discomfiture. An argument had arisen among us as to which was the more simple of the two currency systems, dollars and cents, and pounds, shillings and pence—as if there were logical room for difference of opinion! At last, the captain arriving, we decided to refer the matter to him and to surrender our judgment to his arbitrament. The captain (an Englishman of the very stolid sort), after a period of reflection replied very slowly, and with all the gravity of a judge: “Pounds, shillings and pence is the simpler system; for, don’t you know, that when you are told the price of a thing in dollars and cents[35] you always, in your mind, convert it into pounds, shillings and pence.”

“Of course, Captain,” said I; “I had not thought of that until you mentioned it; neither had I recalled the well-known fact that a Frenchman, while speaking French in the streets of Paris, is really thinking in English. Your decision is as shrewd as it is impartial.”

But the pleasure of the voyage depends largely upon the season. The wet and the dry seasons are distinctly divided. There is a long wet season of four months and a short wet season of two months each year, and corresponding long and short dry seasons. The rains generally follow the course of the sun as it moves between the northern and southern solstice. The regularity of the seasons is modified by local influences such as the proximity of mountains. The seasons at Batanga, for instance, are not so distinctly divided as at Gaboon. I am most familiar with the climate of Gaboon, which is practically at the equator. The long wet season begins in September, when the sun is coursing from the equator towards the southern solstice, and continues nearly four months. The long dry season begins in May and continues for four months. Those are the delightful months of the year. We are accustomed to associate a dry spell with heat and glaring sunshine. But there the brightest sunshine is in the wet season between the showers. The dry season is both cool and shady; so cool that the natives find it uncomfortable, while the sun is sometimes not seen for a week. It always seems to be just about to rain. A stranger to the climate would not risk going half a mile without taking an umbrella. But he is perfectly safe. There is not the least danger of rain between May and September. Often in the dry season I have travelled through the midday hours in a canoe, lying full length on a travelling rug with my face towards the sky; for there[37] is no glare: the mellow light has the quality of moonlight.

But a strong wind prevails during the dry months, and it is the season when the surf rages wildly on the open coast; when surf boats with cargo are often broken on the beach and the native crews lose their limbs and sometimes their lives. The ground though very dry does not become parched. The rustling of the palms or of the thatch roof at the close of the season is like the heavy pattering of rain, so much so that sometimes one is deceived in spite of himself. The dry season is healthiest for white men, but not for the native. They are not sufficiently protected against the wind, and pneumonia is common. However much we prefer the dry season, yet we weary of it towards the close, and like the natives we fairly shout for joy at the first shower.

The wet season is very disagreeable. The rain falls in streams, and, as Miss Kingsley says, “does not go into details with drops.” There are several torrential downpours each day and night. In the intervals during the day the sky is swept clear of clouds and the sun shines the strongest. The atmosphere is extremely humid and sultry. With the least exertion, or with no exertion, one perspires profusely, and there is no evaporation. One ought to change his clothing several times a day; but most of us cannot afford to devote so much time to comfort. Frequent tornadoes often cool the air in the evening.

The most uncomfortable of all places during the rain is on shipboard. The rain will at length find its way through any thickness of awning, and the delightful deck must be deserted for the stifling saloon. Our paradise is transformed to a purgatory. The rain is accompanied by a heavy mist and as it dashes upon the surface of the sea it lifts a cloud of spray that hides the water beneath and[38] we seem to be drifting courseless through cloudland, with our horizon immediately around us. As it continues day after day everybody becomes depressed; and as for the captain, it is scarcely safe to speak to him. One day when I was travelling in the wet season, the captain lost a whole day prowling up and down the coast looking for a place which was completely hidden in the rain and mist. He was angry; and an angry captain is a fearsome object. He is accustomed to being obeyed, and is master of everything else but the fourth element, which occasionally thwarts his plans and derides his authority. At a moment when the rain slackened from a torrent to a heavy shower, a passenger put his head out on deck and remarked: “It’s not raining, Captain.”

“Well, if that is not rain,” thundered the disgusted captain, “it is the best imitation of rain that I have ever seen.”

The subject upon which conversation dwells longest and to which it ever returns with gruesome interest is the African fever. The news that is brought on board at each port is like a death bulletin. To the new comer it is all very trying and very tragical. But he cannot escape from it; for the Old Coaster (and a man who has been out once before is an Old Coaster) assumes the grave responsibility of impressing deeply upon the mind of the tenderfoot the serious conditions which he is about to confront. It is impressed upon him that the fever is inevitable, and that the young and healthy die first; that temperate habits instead of being a defense are a snare, and that not to drink is simply suicide. Missionaries die like flies. But then of course it comes to the same thing in the end; there is no escape; and to worry about it, or to expect it, will bring on a fever in two days. Exposure to the sun is sure to induce fever; and yet none die so quickly as those who carry umbrellas. Quinine is useless[39] except to brace the mind of those who believe in it; but it isn’t any good. And when you get fever, you can’t escape, by leaving the coast in a hurry, even if there should be a steamer in port, which is very unlikely; for a man going aboard with fever is sure to die. Perhaps it is the horror of being buried at sea that kills him.

“How is that new clerk whom I brought out for you last voyage?” asks the captain, of a trader who has come aboard for breakfast.

“Poor chap!” says the trader, “he didn’t live two weeks. Another came on the next steamer, and he pegged out in three weeks. They ought to be sent out two at a time.”

“You remember so-and-so,” says another; “well, poor chap! (and as soon as he says “poor chap” we know the rest) he was found dead in bed one morning since you were here. They had used up all the lumber that they had laid away for coffins, so they took half the partition out of his house, to make a coffin; and then they didn’t get it long enough. The next fellow is now living alone in that same house with half the partition gone, and of course he can’t help reflecting that there is just enough left to make another coffin; and, indeed, to judge by the way he was looking when I saw him last they may have used it by this time.”

“Have you heard about the poor chap that so-and-so sent up country? Well, he died a few weeks ago. He was all alone except for the native workmen, and as soon as he died they ran away in fear. The agent got word of it and started up country immediately; but the rats had found him first.”

It is only when one reflects that all these “poor chaps” were somebody’s sons, and somebody’s brothers, that one realizes the tragedy of the coast. These little conversations[40] on board seem like the final obsequies performed for those who are dead.

“Do men ever die of anything except fever?” asks a new comer.

“O yes,” says the Old Coaster. “Let me see: there’s dysentery,—poor C died of that last week; and there’s enlarged spleen, abscesses, pneumonia, consumption (one falls into consumption here very quickly, and often when he least expects it), kraw-kraw and smallpox (smallpox has just broken out at Fernando Po: that’s our next port), not to speak of seven or eight varieties of itch, which some men have all the time; but itch doesn’t kill. By the way, I suppose you know that in this climate it is necessary that bodies be buried a few hours after death.”

In the speech of the coast there is no such thing as reticence, and soon enough we all learn to speak with brutal bluntness. The only comfort held out to the new comer is the hope that he will receive, as a sort of obituary, the kindly designation, “Poor Chap.”

I have never argued for the salubrity of the African climate; nor am I disposed to protest the general opinion that it is “the worst climate in the world.” The white man never becomes acclimatized, and never will until he develops another kind of blood. One lives face to face with the constant and proximate possibility of death as long as he is on the coast. It is an unnatural consciousness, which, when prolonged through years, tends to become fixed and permanent even when one has removed from the circumstances that were its occasion. And yet, the conversation of the Old Coaster is liable to make an exaggerated impression. In the first place, the impression is natural that the climate being so unhealthful must also be uncomfortable. But, in reality, while several months of the year are extremely uncomfortable, the[41] greater part of the year is tolerably comfortable and there are several months of exceedingly pleasant weather. Neither is the heat so great as is generally supposed. With the greatest effort on my part, I never succeeded in disabusing my friends of the notion that I was slowly roasting to death in Africa. With every hot spell in America, when the thermometer was standing at 100°, their thoughts turned towards me in profound sympathy. While I have at times suffered with the heat and there have been times on the river, between high banks, cut off from the breeze, when I nearly fainted, and one occasion upon which I was quite overcome, yet as a rule I lived comfortably by day; and the nights are always cool. The maximum temperature on the coast is from 86° to 88°, Fahrenheit, and even such a temperature is rare. One ought to add, however, that owing to the extreme humidity this temperature in Africa is incomparably hotter than the same temperature in America. It is the sultriness of the hottest weather that makes it insufferable. West Africa is heated by steam and without the medium of radiators. The uniformity of the climate is pleasurable, and is very strange to us of northern latitudes. One may reckon upon the weather to a certainty. Within the limits of a given season there is scarcely any variation from day to day.

The insalubrity is due to the deadly malaria of the reeking, mosquito-infested swamps. Mr. Henry Savage Landor, after a journey across Africa, announces to the world that he is a strong disbeliever in the mosquito theory of malaria. But, that the mosquito is the agent of the malaria bacillus, medical science no longer regards as theory, but as fact, a fact established by the most elaborate and painstaking series of experiments ever conducted in the interest of medical science. Mr. Landor also tells us that he and his men were frequently attacked[42] by malarial fever, becoming so weak that they could not raise their hands; but in every case a dose of castor-oil effected a cure in a few hours. He is therefore a strong advocate of castor-oil, but disbelieves in quinine. The use of castor-oil is no new discovery. Every man who has had any experience in West Africa takes it at the approach of a fever. But there is no substitute for quinine. And the medical men of the coast will agree in saying that life depends always upon the judicious use of it.

In recent years there has been such progress in the knowledge of malaria, and how to meet malarial conditions, that the record of West Africa is continually improving. Then again, missionary societies, following the example of the various European governments, have ceased to make war upon the inevitable and have greatly reduced the term of service. In American missions the term is generally three years; in English missions it is a year and a half or two years; and in the government service the term is usually much shorter than in the missions. My first experience in Africa was not a fair test of the climate. We were engaged in opening a new mission station in the bush, and the conditions were the most unhealthful. Our food was the coarsest,—it was several mouths before we tasted bread; our accommodations were the poorest,—part of the time we lived in a tent that did not protect us against the heavy rains; and besides there were forced journeys to the coast in the wet season with incidental hardships. After a succession of fevers and sensational recoveries I fled from the coast with broken health at the end of a year and a half.

But the second time, when I lived at Gaboon, I stayed five and a half years,—far too long. During the first three years at Gaboon T had fever once every two or three months. I became very familiar with its preceding[43] symptoms—physical exhaustion for several days, such that the least effort induced painful weariness and a frequent heavy sigh; aching of head and limbs; chills alternating rapidly with feverish heat, and a terrible temper. At the end of the third year I had a very severe fever which, instead of yielding to quinine the third day, became much worse, and the natives carried me in a hammock to the French hospital. There I remained for five weeks. But after that I had no more fever, not even once, though I remained in Africa more than two years longer, which would have been absolutely impossible if the fevers had continued. The difference was in my use of quinine. At first I took quinine only with the attacks of fever, and then I took an enormous quantity. But in the later period I kept myself immune by taking it daily whether I was ill or not. I took five grains every night for those several years. People are usually greatly surprised at this and ask if such an amount of quinine was not a terrible strain upon the constitution. It was, without doubt; but not so great a strain as malarious blood, and frequent fevers, and the shock of very large doses of quinine at such times. If I had not been in greatly reduced health before I began to take it regularly it is not likely that I should have required nearly so much. But this is anticipating; for we are still on the outward voyage.

In general the coast of West Africa is not beautiful; although it has a weird fascination for those who have once lived on it. It is low-lying, straight and monotonous: a gleaming line of white surf, a golden strip of sandy beach, a dark green line of forest—and that is all, for days and days and days, and for some two thousand miles, only broken at long intervals by the great estuary that is a peculiar characteristic of African rivers, and by low hills far away on the horizon. Many of the traders are living, not in the white settlements, but in single trading-houses[44] and far apart along this lonely shore. They like it or they hate it. To some it is an idle dream-life that they enjoy, and to others it is a nightmare that they abhor. Some of those who came aboard looked like haunted men. Each day is exactly like all the others, and the natural surroundings never vary however far they may wander along the beach—three endless lines of colour stretching away to eternity, the dull green forest front, the yellow strip of sand, the white surge of the foaming surf, and beyond it the boundless sea. Even in the darkest night the forest still shows as a blacker rim against the darkness, and the surf-line is white with a whiteness that no night can obscure. The unceasing sound of it is like low thunder, and unless one loves it he must often think what a relief it would be if it would stop but for one brief moment, and how the silence would “sink like music on his heart.”

In such places, and in the bush, the traders sometimes wear only pajamas, by day as well as night. There are natives enough around, and there is always noise enough; but it is the noise that only emphasizes solitude. And one were better to live entirely alone than to be subjected to the influence of African degradation without the moral restraints of home and the society of equals, unless his religious belief be something more than a mere acceptance of tradition, and his principles something more than conventional morality. There is a better class of natives whose society might relieve loneliness, but the trader, as a rule, does not gather this class around him.

Some are pleased to say very hard things about the traders. But he who would judge justly must have a mind well attempered to the claims of morality on the one hand, and on the other, to the allowance due to the frailty of human nature when placed in circumstances of unparalleled temptation. No man ever realizes the moral[45] restraints of good society until they are all withdrawn; nor how insidious the influence even of the most repulsive vices when they have become so common to our eyes that they cease to shock: the moral safety of most men is in being shocked. Of course there are bad men among the traders, and some very bad; and the rumshop which, wherever the white man has penetrated, rises like a death-spectre in the landscape, is an abomination to which it would be difficult to do injustice. But it is not chiefly the trader who is responsible for the rum traffic. Many of them would be thankful if the various governments would entirely prohibit its importation. Moreover, they sell a thousand things besides rum,—as many useful things, and necessary to civilization, as the native is willing to buy. The traders are all men of courage—we can at least admire them for that—and many are honest and many are kind; and it were far better to refrain from condemning the dissolute than that in so doing one should soil the reputation of an honest man.

We called at Cape Coast Castle, Accra, Lagos, Monrovia and several other places where there are no harbours, and where the surf is so violent that passengers rarely go ashore unless these places are their destination. The longest stop on the voyage was at Old Calabar, sixty miles up the Calabar River, where we stayed five days. Old Calabar when I was there first was the English capital of the Oil Rivers Protectorate, which afterwards became a part of Nigeria. The heat was insufferable; for, while it is possible to keep cool on the hills where the white men live, it is not possible in the low channel of the river, and especially in the cabin of a steamer. The name Old Calabar has a fine far-away sound, like Cairo or Bagdad, and suggests a place of romantic and legendary interest. And indeed the tales of the Arabian Nights scarcely surpass the real history of the native despots that[46] have ruled at Old Calabar even down to the death of King Duke in our own times, when, despite the presence of the English, it is said that five hundred natives were stealthily put to death to furnish the king a seemly retinue in the other world.

The run up the Calabar River is a pleasant variety after the long weeks on the sea. Here we first saw the crocodile, which abounds in all the largest rivers of Africa. It is the ugliest beast in the world. Lying on a bank of mud, its head always towards the water, and among old logs and roots, it looks itself like some gnarled and slimy log, and is difficult to discern. But at the sound of a gun or the near approach of the steamer it slides down into the water quick as a flash. Most of the passengers get their guns and take a few shots at them. In every case the passenger declares that he has shot the crocodile without a doubt; and as the creature disappears into the water there is of course no way of disproving the statement. But when we were coming down the river there seemed to be as many as ever.

The Spanish Island of Fernando Po is the most beautiful place in West Africa. Seen from the harbour in the early morning light or in the soft glow of the evening it is a fairy-land of tropical beauty. The bottom of the semicircular harbour is the crater of an extinct volcano and is very deep. The bank is covered down to the water with a lavish growth of ferns, and trailing vines, and flowers of many colours; while above the palm tree is abundant—the most graceful of all trees, and the billowy bamboo tosses in the breeze. In the middle and extending backwards is the white town of Saint Isabel, and behind the town stands a great solitary mountain of green, which rises to a height of ten thousand feet. Like other fairy-lands it requires the illusion of distance. It appears best from the harbour, and that is true of most[47] tropical beauty. The soil is the most fertile in West Africa. I have seen plantains there full twice as large as any that I have seen elsewhere. For some years it has been producing large quantities of cocoa, most of which is shipped to Spain and thence over the world in the form of chocolate.

Africa is a land of extremes. From Fernando Po crossing again to the mainland we went fifteen miles up the Rio del Rey to the ugliest place in the world. I have also been in the Rio del Rey several times on the homeward voyage, when the steamers usually spend a day there taking on palm-oil and rubber,—a coast steamer would go to Hades for palm-oil and take all the passengers along with it. There is no native village here. The three trading houses receive the produce which the natives bring down the river. All around is one vast mangrove swamp, an ideal mosquito-incubator. The trading-houses are erected upon a foundation made with the ashes of passing steamers, which were saved and deposited here.

The foliage of the mangrove is thin, and at a distance resembles our poplar. But the greater part of the mangrove is a solid mass of roots, almost wholly above ground and more nearly vertical than horizontal. The trees seem to be standing on stilts, six or eight feet long, as if they were trying to keep out of the water. There are also aerial roots, long, leafless and straight, depending from all the branches, even the highest, which as they reach the water spread into several fingers. At the high tide the roots are submerged and the ugliness of the swamp concealed for a while. But as the tide ebbs the roots appear dripping and slimy until they are completely exposed: and as the water still recedes long stretches of fœtid mud-bank appear. The smell has been accumulating for ages. A low-lying mist rises from the oozing[48] banks, and now and then stretches a stealthy arm out over the river, or creeps from root to root. Some one standing near exclaimed: “O heavens, what a place!” I could only wonder at the geographical direction of his thoughts; for my thoughts were of Gehenna and the river Styx. The mangrove swamp is surely the worst that nature has ever been known to do. My feeling of disgust was intensified by many experiences of after years. Sometimes approaching a town at the ebbing tide, a strong native has carried me on his back from the boat to the solid bank, across a waste of sludge, and sometimes he has fallen in the act. Other times, when one could not wade, they have thrown me a line and have dragged me across in a canoe; and I felt that if the canoe should capsize I would sink almost forever; or, perhaps be dug up twenty thousand years hence and exhibited as a pre-historic specimen. “Every prospect pleases,” reads the hymn, “and only man is vile.” But the worst débris of humanity is not half so vile as the prospect of a mangrove swamp at low tide.

The death record of the Rio del Rey is appalling. Every time that I have been there—seven times—the traders that came on board looked like dying men; and often their limbs were bandaged for ulcers or kraw-kraw. I was once on board when an English missionary and his wife debarked at this place, expecting to go on up the river, beyond the swamps, to the mission station in the hills of the interior. The lady was becoming more and more fearful during the voyage, and the effect upon her of this lower river was such that she was almost hysterical. She remained on board all day until we were about to weigh the anchor. The first impression counts for much in the matter of health and resistance to the fever; and the sight of that shrinking woman going ashore in such a place was pitiable; for we all felt that she was[49] doomed. After a few months, however, she escaped with her life; but she was never able to return to Africa. The mangrove swamp stretches along the greater part of the coast of West Africa, and along the rivers where the water is salt or brackish because of the flow of the tide from the sea.

The next experience after the Rio del Rey was a greater contrast than ever. We proceeded forty miles southward and called at Victoria, in the German colony of Cameroon. The harbour at Victoria is divided from the sea by a semicircle of islands, some small and some larger. One of these islands, a large barren rock, when seen from a certain part of the beach, bears a singular though grotesque resemblance to Queen Victoria as she appeared when seated upon the throne. It is presumably from this that the place was given the name Victoria; for the English traders were there before Germany occupied the territory.

Immediately behind the harbour is the great Mount Cameroon, one of the greatest mountains in the world, a solitary peak, which rises immediately from the sea to a height of 13,700 feet; which is twelve hundred feet higher than Teneriffe. It was evening as we approached, and before we had entered the harbour it was night; for in the tropics day darkens quickly into night and there is no twilight. But on the top of the mountain, far above our night, we still saw the rose-red of the lingering day. The moon rose behind the mountain and we steered into the shadow of it closer and closer, for by night it seemed much nearer than it really was. The number of passengers had diminished to a very few, and they were silent; not a voice was heard on the deck. It was the strangest silence I have ever experienced; not the mere negation of sound, but like something positive, and diffused from the mountain itself; a silence more impressive than speech; the silence of an infinite comprehension. The[50] engines stopped: we were ready to cast the anchor, and I found myself wondering how the captain’s voice would sound when in a moment he would shout: “Let go.”

“How fit a place,” someone at length remarked, “for the sounding of the last trumpet and the final judgment! before this mountain which has looked down unchanged upon all the generations that have come and passed away since the world began.”

It is not always silent, however, for the natives, with some sense of its majesty, call it the “Throne of Thunder.” Fierce storms wage battle around its middle height, with terrific peals of thunder such as I have never heard elsewhere. Sometimes for many days it wraps itself in clouds and darkness, completely invisible. I was once a whole week at various ports within a few miles of it, and did not catch a glimpse of it. The clouds wrapped it about to the very base, and there was nothing to indicate that it was there except the unusual frequency of storm and thunder. Then, one day when we were at Victoria, the weather brightened so much that we expected soon to see the peak. I asked a native attendant, a young man, to watch for it and tell me if he saw it. At length, while I was sitting on deck watching for it myself, he exclaimed: “The peak! Mr. Milligan, the peak!”

“Where?” I said. “I don’t see it.”

“Look higher,” he exclaimed.

“I am looking as high as I can. I am looking as high as the sky.”

“Look higher than the sky,” he cried, with native simplicity; “the sky is not high.”

I lifted my eyes still higher towards the zenith, and there, through an expanding rift in the heavy cloud, I saw the peak, calm, bright and beautiful, just as it had been all the time, even when hidden by low-hanging clouds. I have often thought of it since. God is higher[51] than our highest thought, higher than our sky. Our habits of mind and heart, even our theology may hide Him from our sight, until by some unwonted experience these are shattered, and through the rent clouds of our former sky we see the living God.

A short time before I left Africa I spent ten days at a sanitarium of the Basle Mission, on the side of Cameroon, between three and four thousand feet high. I had then been in Africa for years and had tropical blood in my veins, and I suffered much with the cold. There was so much covering on my bed that I was fairly sore with the weight of it, and yet I was cold. The storms raged frequently, hiding the heavens from those below and the earth from us; for we were above the storm-cloud, and dwelt in light and sunshine. The detonation of thunder beneath us was like the muttering rumble of an earthquake.

The German government has built a splendid road from the base of the mountain up to the sanitarium. The road is well graded, and winds upwards like a continuous S, covering a distance of sixteen miles in the ascent. I was delighted when I found that the missionaries would provide me a mule upon which I could ride up to the sanitarium. I am a lover of horses, and often during those years in Africa I had been homesick for the sight of one. The mule, when he appeared, was sleek and strong; I put my arms around his neck and patted him and caressed him as if he were a long-lost friend. Then I mounted him and started up the road, an attendant following behind with another mule and carrying my baggage. The mule which I rode was deeply imbued with Longfellow’s sentiment: “Home-keeping hearts are happiest; to stay at home is best.” He climbed slowly and reluctantly, and by some mysterious operation of the law of gravitation his head had a persistent tendency to[52] turn about and swing down the grade. I soon realized that I could go faster without him, and that the strength which I was expending in keeping him in the path of duty was greater than that which I would require in going my way alone; and I had no strength to spare. Therefore after three or four miles in his company, finding his disposition fixed and unaspiring, I dismounted, and leaving him in the road for the guide, I walked the rest of the sixteen miles.

But ten days later, when I was returning to Victoria, the same mule was again put at my disposal, and I gladly accepted him. For I was much stronger, and I was going in the direction of his own desire; and besides it was down-hill all the way, and I knew that he was too lazy to hold back. The grade was not such that there was any danger to him from running; so I galloped the sixteen miles, and had the ride of my life. I could have shouted with delight. After a few miles I took a severe pain in my side. I dismounted and lay down on the ground. In a little while I was all right again, and taking off a pair of stout suspenders I tied them as tight as possible around my waist with a large clumsy knot at my side. I had already discarded my coat, and my only upper garment was a woolen undershirt with short sleeves. The suspenders around my waist gave me a new accession of strength and I galloped all the rest of the way, with the same pleasure, and entered Victoria where I made something of a sensation. My last association, therefore, with the great mountain, was not an impression of its solemn majesty, but the memory of a jolly good ride.

MISSION HOUSE AT BATANGA.

I was glad when at last we reached Batanga, and the long voyage was over. Our attention was drawn to the canoes in which men were fishing, and for which Batanga is famous. The quiet morning sea was dotted with them[53] within a radius of a mile around us, some of them being two miles from the shore. The Batanga canoe is the smallest on the entire coast. It is almost as light as bark; the men come to the beach in the morning carrying their canoes on their heads. It is quite an entertainment to see them going out through the surf, and I have seen a canoe capsized half a dozen times in the attempt. Later in the day, when the surf is heavier, they cannot get out at all. At sea the man straddles his canoe and lets his legs hang in the water; and in this fashion he sometimes ventures two miles from the shore.

We anchored nearly a mile from the beach and were sent ashore in a surf-boat manned by native Krumen. There is no harbour at Batanga, and the landing in the surf was the most exciting of my African experiences until that time. As we entered the surf the boat stood still for a moment, until caught up on the breast of a breaker, and—“Then, like a pawing horse let go, she made a sudden bound,” and we were carried towards the beach with violent speed that looked like destruction for us all. The crest of the breaker passed under us, however, when we were close to the beach, and immediately the Krumen leaped into the water, and with all their might ran the boat up on the beach far enough to escape the next wave. Then, while most of them placed themselves around the boat to steady it, the rest of them presented their backs to the passengers and yelled at them to jump on and ride ashore.

As the pitching boat was poised for a moment, standing on the gunwale, I seized a Kruman firmly by the hair with both my hands, and leaped upon him, astride his neck with my legs over his shoulders. I had put on a fresh white suit for the occasion, notwithstanding that I had been instructed by the Old Coasters that the Kruman, with his unique sense of humour, makes it a point to[54] drop the new comer into the surf and present him to his friends ashore as much bedraggled and beflustered as possible. I also had on the inevitable cork helmet, so bulky, and drooping over the eyes. Most men unaccustomed to them feel as awkward as they would in a Gainsborough hat. The Kruman, I am glad to report, did not drop me; perhaps because I kept so firm a hold on his hair that he did not know how much of it he might lose by a sudden or unexpected separation from me. It was probably my own fault, and not his, that when he stooped to deposit me, I missed the trick of lighting on my feet, which I afterwards learned. I reached the ground on all fours, in the wet sand. The white helmet fell from my head and rolled off towards the sea and I followed it, running quadrupedal fashion, and snatched it from an approaching wave.

A moment later I was exchanging greetings with a group of missionaries who had gathered on the beach.

At this landing on the beach I observed that we were standing under a cocoa-palm. I looked up, and lo, there was no snake hanging from it. Now, the most vivid impression—in fact the only impression of Africa that I had carried thus far through life, except that of sunny fountains rolling down golden strands, was made by a picture in the old-fashioned geography; in which there were crowded together, with contempt of perspective, an elephant, a hippopotamus, a rhinoceros, a lion, a leopard, a gorilla, a chimpanzee, several other monkeys, and a python hanging from a tree.

“They are all here,” said some one, in explanation; “but they are not so thick on the ground as you may have supposed.”

REV. A. C. GOOD, Ph.D.

Dr. Good died at Efulen at the age of thirty-seven. He was a man of the Livingstone type.

Upon our arrival at Batanga we at once commenced the preparations for a journey into the bush, than which nothing could have been a greater contrast to the long, idle voyage on the sea; for our physical strength and powers of endurance were to be taxed more than ever before.

There were two others besides myself, Mr. Kerr, a new arrival, and the Rev. A. C. Good, an intrepid and consecrated missionary whose name was already known throughout the United States. Dr. Good had been twelve years in Africa, working most of the time among the Fang of the Ogowé River, but had lately come to Batanga for the purpose of opening the Bulu interior. The language of the Fang was so much like the Bulu that Dr. Good could converse with the latter from the first. Before the arrival of Mr. Kerr and myself Dr. Good had already made one journey into the Bulu country to a distance of seventy-five miles, where he chose the site of the first station, afterwards named Efulen.

In those days nearly all the distance between Efulen and the beach was covered with dense unbroken forest. None of the Bulu as far as we knew had ever been to the coast; and no white man had ever entered that part of the interior. The Mabeya tribe, living immediately behind the coast tribe, were already in trade relations with the Bulu; so that there were roads, that is, foot-paths, through the forest. But they were seldom used, and were only a little better than none at all. The present good bush-road[56] from Batanga to Efulen did not exist in those days. We made it ourselves after we had been there nearly a year, and it has been greatly improved from time to time. The first road which we followed made a great detour to the south, and we walked, according to Dr. Good’s calculation, seventy-five miles from Batanga to Efulen, although the distance by the present straight road is less than sixty miles.

And, by the way, before we enter the forest, bidding a temporary farewell to civilization, we do well to take leave of this highly civilized term, “mile.” It is more than superfluous in such a forest: it is positively misleading. Such roads are not measured in terms of linear distance, but only in measures of time. To say that a place is distant half a day’s journey, or five hours, is to speak intelligibly; but to say that a place is five miles distant is to give not the slightest information as to the time it will take to reach it. On the few good roads which in recent years have been improved by the government one might perhaps walk thirty miles a day: on the worst roads that I have attempted I could not walk five miles a day with equal labour.