Title: An ivory trader in North Kenia

the record of an expedition through Kikuyu to Galla-land in east equatorial Africa; with an account of the Rendili and Burkeneji tribes

Author: A. Arkell-Hardwick

Release date: October 27, 2023 [eBook #71971]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Longmans, Green, and Co, 1903

Credits: Bob Taylor, deaurider and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

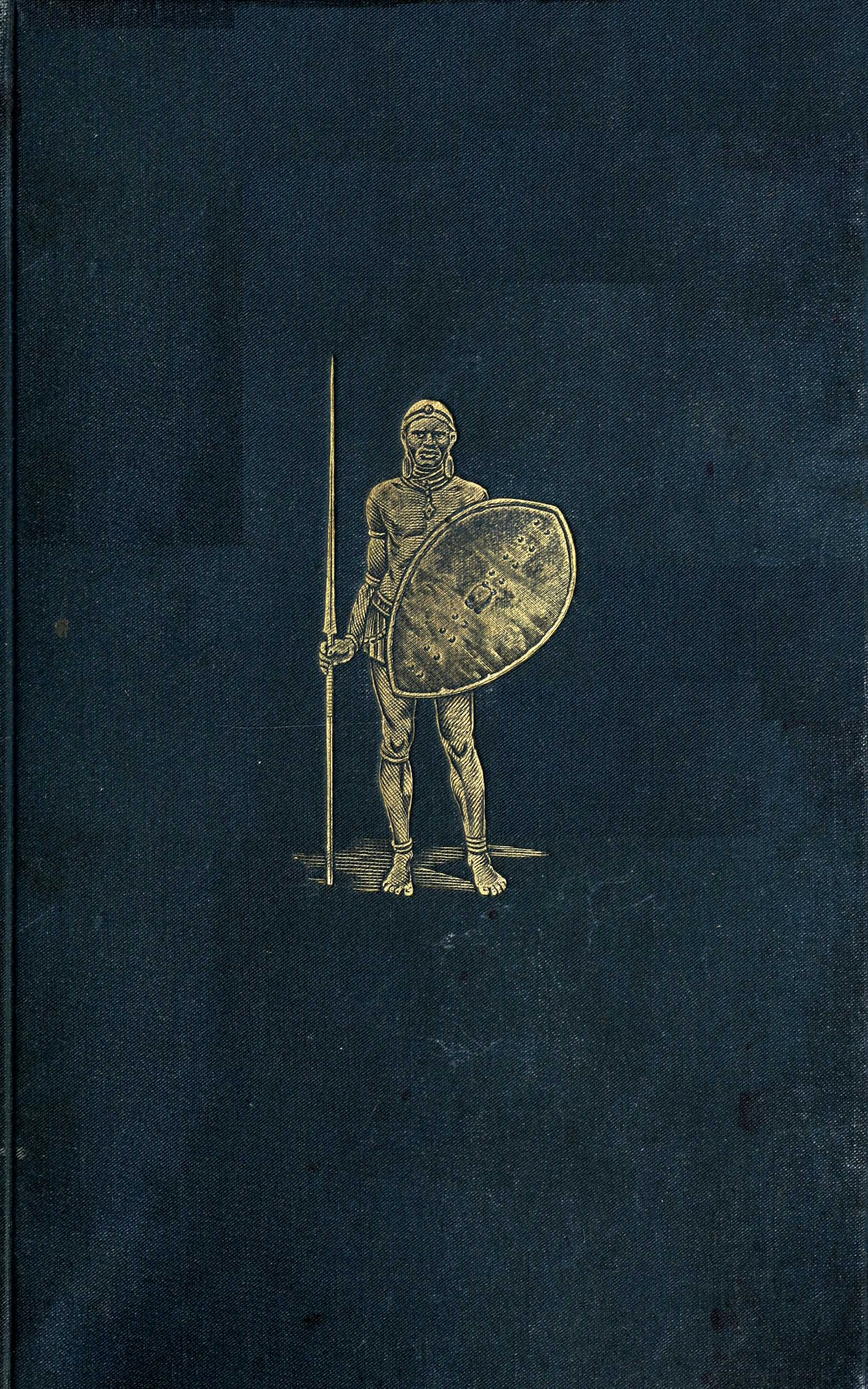

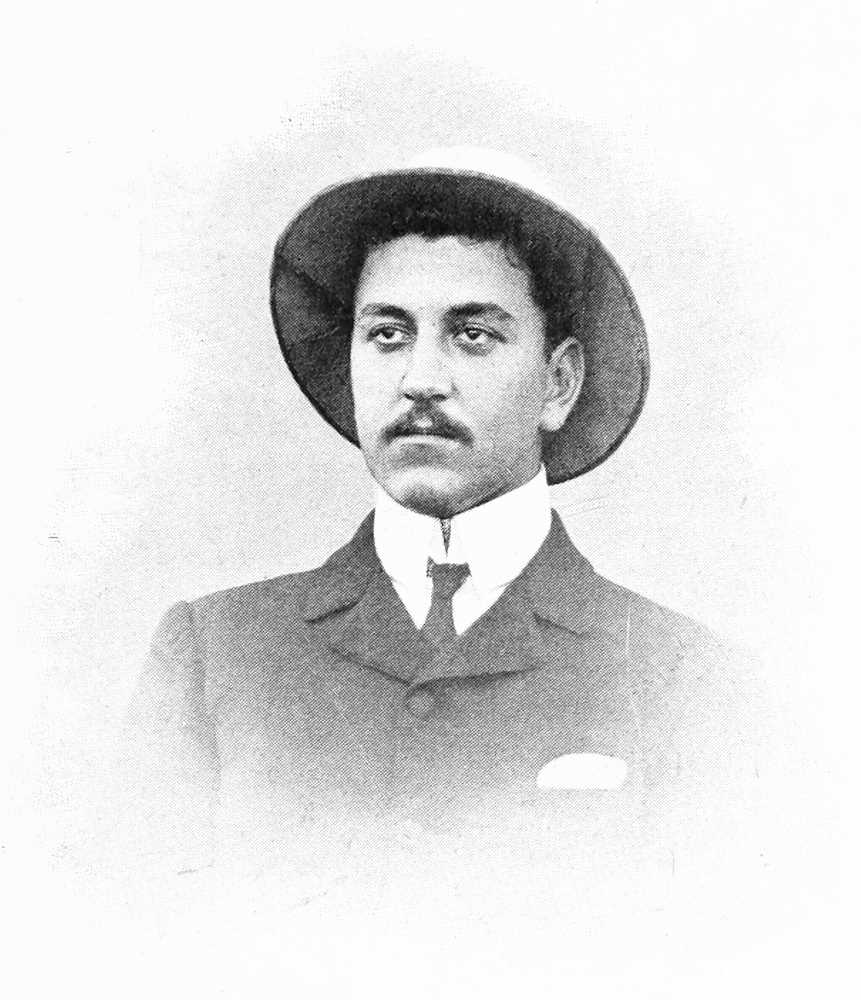

THE AUTHOR.

AN IVORY TRADER IN

NORTH KENIA

THE RECORD OF AN EXPEDITION THROUGH

KIKUYU TO GALLA-LAND IN EAST

EQUATORIAL AFRICA

WITH AN ACCOUNT OF THE RENDILI AND

BURKENEJI TRIBES

BY

A. ARKELL-HARDWICK, F.R.G.S.

WITH TWENTY-THREE ILLUSTRATIONS FROM

PHOTOGRAPHS, AND A MAP

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK AND BOMBAY

1903

All rights reserved

To

COLONEL COLIN HARDING, C.M.G.

OF THE

BRITISH SOUTH AFRICAN POLICE

TO WHOSE KIND ENCOURAGEMENT WHEN IN COMMAND OF

FORT CHICKWAKA, MASHONALAND

THE AUTHOR OWES HIS LATER EFFORTS TO

GAIN COLONIAL EXPERIENCE

THIS WORK IS DEDICATED

[Pg vii]

Although there may be no justification for the production of this work, the reader will perhaps deal leniently with me under the “First Offenders Act.” Among the various reasons which prompted me to commit the crime of adding a contribution to the World’s literature is the fact that little or nothing is known concerning certain peculiar tribes; to wit, the Rendili and Burkeneji. They are a nomadic people whose origin is as yet wrapped in mystery. In addition to this, an account of the trials and difficulties to be encountered in the endeavour to obtain that rapidly vanishing commodity, ivory, will perhaps please those into whose hands this work may fall who delight in “moving accidents by flood and field.”

It has been to me a source of lasting regret that a great many of my photographic negatives were in some way or other unfortunately lost on our homeward journey, and as usually happens on such occasions, they were those I valued most, inasmuch as they included all my photographs of the lower course of the Waso Nyiro River and also those of the Rendili and Burkeneji peoples. I am, however, greatly indebted to Mr. Hazeltine Frost, M.R.P.S.,[Pg viii] of Muswell Hill, N., for the care and skill with which he has rendered some of the remaining badly mutilated negatives suitable for the purposes of illustration.

In the course of this narrative it will be observed that I name the people of the various countries or districts through which we passed by prefixing Wa- to the name of the district they inhabit. This is in accordance with Swahili practice, as they generally designate a native by the name of his country prefixed by an M’, which in this case denotes a man, the plural of M’ being Wa-. The plural of M’Kamba, or inhabitant of Ukamba, is therefore Wa’Kamba, and an M’Unyamwezi, or inhabitant of Unyamwezi, is Wa’Nyamwezi in the plural. Doubtless a hypercritic would argue that this rule only applies to the Swahili language, and consequently the names of those tribes who are in no way connected with the Swahilis would be outside the rule. He would be right; but I am going to call them all Wa- for the sake of convenience and to avoid confusion.

I have endeavoured to place before the reader an account of the incidents, amusing and tragic, as they appeared to me at the time. Should the narrative prove uninteresting, it will, I think, be due to faulty description. The incidents related were sufficiently exciting to stimulate the most jaded imagination, and they have the rarest of all merits—the merit of being true.

A. A.-H.

[Pg ix]

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PREPARATIONS AND START. | |

| PAGE | |

| Engaging porters—Characteristics of Swahili, Wa’Nyamwezi, and Wa’Kamba porters—Selecting trade goods—Provisions—Arms and ammunition—The Munipara—Sketch of some principal porters—Personal servants—List of trade goods taken—Distributing the loads—Refusal of the Government to register our porters—Reported hostility of the natives—Finlay and Gibbons’ disaster—Start of the Somali safaris—We move to Kriger’s Farm—I fall into a game-pit—Camp near Kriger’s Farm—Visitors—The start | 6 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| FROM KRIGER’S TO MARANGA. | |

| Off to Doenyo Sabuk—Troubles of a safari—George takes a bath—The Nairobi Falls—Eaten by ticks—My argument with a rhinoceros—The Athi river—Good fishing—Lions—Camp near Doenyo Sabuk—We find the Athi in flood—We build a raft—Kriger and Knapp bid us adieu—Failure of our raft—We cross the Athi—I open a box of cigars—Crossing the Thika-Thika—Bad country—We unexpectedly reach the Tana—The détour to the Maragua—Crossing the Maragua—In Kikuyuland | 25 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| FROM THE TANA TO M’BU. | |

| We reach and cross the Tana—Maranga—The abundance of food thereof—We open a market—We treat the Maranga elders to[Pg x] cigars with disastrous results—Bad character of the Wa’M’bu—We resume our journey—A misunderstanding with the A’kikuyu—We reach M’bu | 49 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| FROM M’BU, ACROSS EAST KENIA, TO ZURA. | |

| First sight of Kenia—Hostile demonstrations by the M’bu people—We impress two guides—Passage through M’bu—Demonstrations in force by the inhabitants—Farewell to M’bu—The guides desert—Arrival in Zuka—Friendly reception by the Wa’zuka—Passage through Zuka—Muimbe—Igani—Moravi—Arrival at Zura—Welcome by Dirito, the chief of Zura | 65 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| ZURA TO M’THARA, AND A VISIT TO EMBE. | |

| The Somalis suffer a reverse in Embe—We reach Munithu—Karanjui—El Hakim’s disagreement with the Tomori people—Arrival at M’thara—N’Dominuki—Arrival of the Somalis—A war “shauri”—We combine to punish the Wa’embe, but are defeated—Death of Jamah Mahomet—Murder of N’Dominuki’s nephew by Ismail—Return to camp | 83 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| OUR MOVEMENTS IN M’THARA AND MUNITHU. | |

| Attempt of the Wa’M’thara to loot our camp—“Shauri” with Ismail—The Somalis accuse N’Dominuki of treachery—He vindicates himself—That wicked little boy!—Explanation of the Embe reverse—Somalis lose heart—Attacked by ants—El Hakim’s visit to Munithu—Robbery of his goods by the Wa’Gnainu—I join him—We endeavour to recover the stolen property from the Wa’Gnainu—The result | 105 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| RETURN TO M’THARA. | |

| An ivory “shauri”—Death of Sadi ben Heri and his companions—Purchasing ivory—El Hakim and I return to M’thara—A night[Pg xi] in the open—George ill—The Wa’M’thara at their old tricks—Return of the Somalis from Chanjai—They refuse to return to Embe—I interview an elephant | 123 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| THE START FOR THE WASO NYIRO. | |

| Some of El Hakim’s experiences with elephants—I am made a blood-brother of Koromo’s—Departure from M’thara—A toilsome march—A buffalo-hunt—The buffalo camp—Account of Dr. Kolb’s death—An unsuccessful lion-hunt—Apprehension and punishment of a deserter | 141 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| JOURNEY DOWN THE WASO NYIRO. | |

| Arrival at the Waso Nyiro—The “Green Camp”—The “cinder heap”—The camp on fire—Scarcity of game—Hunting a rhino on mule-back | 159 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| RETURN TO THE “GREEN CAMP.” | |

| The “Swamp Camp”—Beautiful climate of the Waso Nyiro—Failure to obtain salt at N’gomba—Beset by midges—No signs of the Rendili—Nor of the Wandorobbo—We decide to retrace our steps—An object-lesson in rhinoceros-shooting—The “Green Camp” once more | 174 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| DOWN THE WASO NYIRO ONCE MORE. | |

| We send to M’thara for guides—Sport at the “Green Camp”—Non-return of the men sent to M’thara—Our anxiety—Their safe return with guides—We continue our march down the river—Desertion of the guides—We push on—Bad country—No[Pg xii] game—We meet some of the Somali’s men—News of the Rendili—Loss of our camels—In sight of the “promised land” | 190 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| IN THE RENDILI ENCAMPMENT. | |

| Narrow escape from a python—Arrival among the Burkeneji and Rendili—No ivory—Buying fat-tailed sheep instead—Massacre of the Somalis porters by the Wa’embe—Consternation of Ismail Robli—His letter to Nairobi | 206 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| THE RENDILI AND BURKENEJI. | |

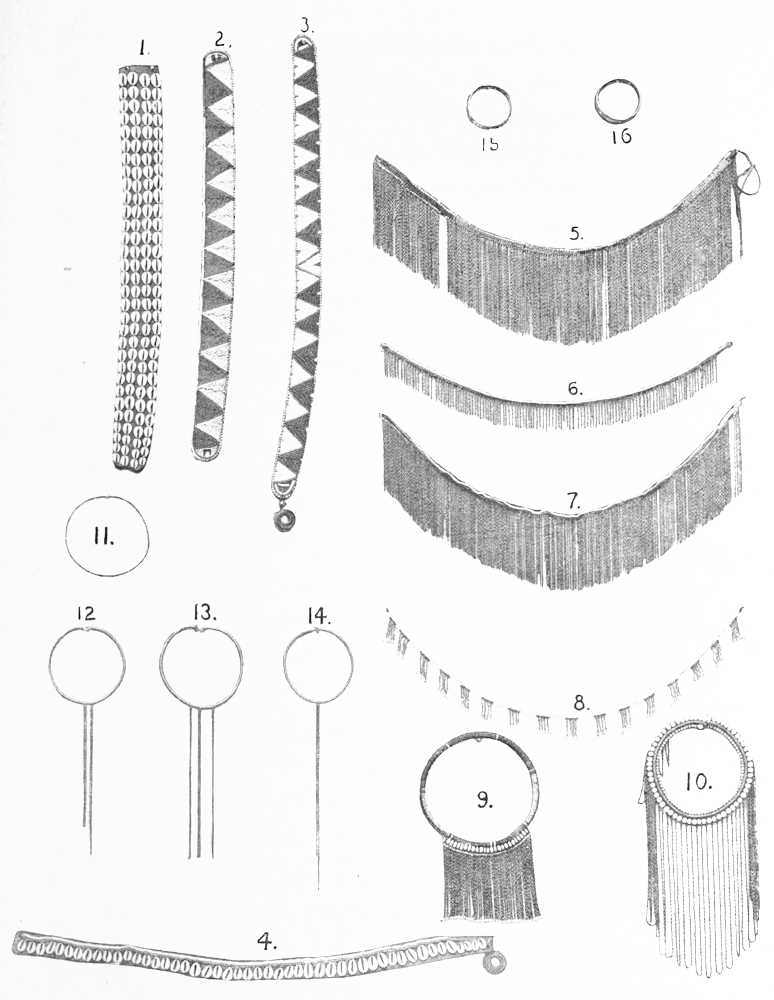

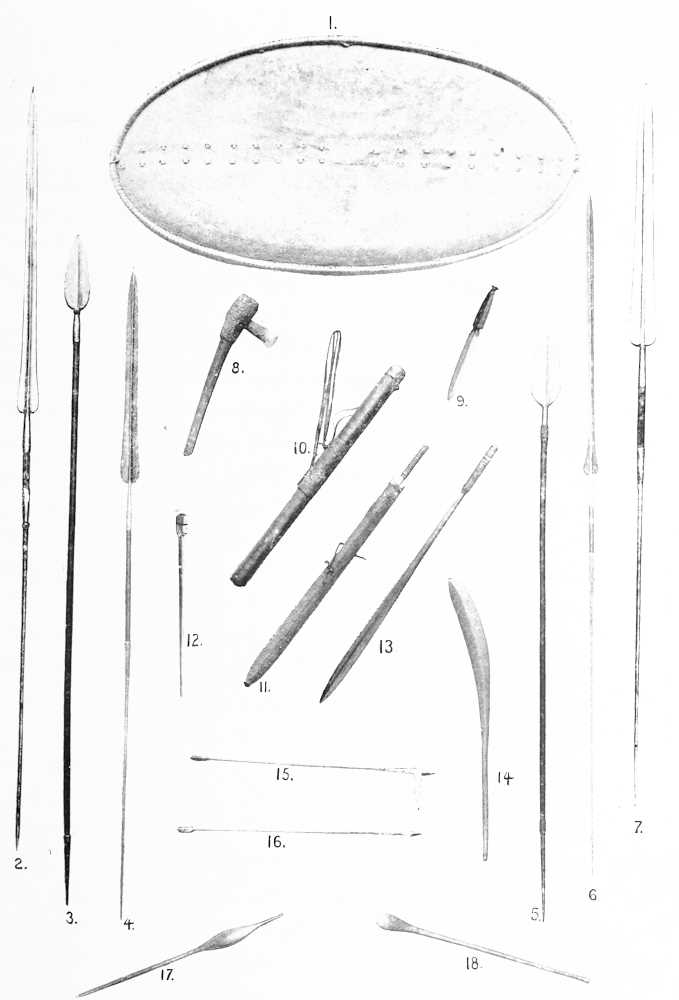

| The Burkeneji—Their quarrelsome disposition—The incident of the spear—The Rendili—Their appearance—Clothing—Ornaments—Weapons—Household utensils—Morals and manners | 221 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE SEARCH FOR LORIAN. | |

| Exchanging presents with the Rendili—El Hakim bitten by a scorpion—We start for Lorian without guides—Zebra—Desolate character of the country—Difficulties with rhinoceros—Unwillingness of our men to proceed—We reach the limit of Mr. Chanler’s journey—No signs of Lorian | 244 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| RETURN FROM THE LORIAN JOURNEY. | |

| An interrupted night’s rest—Photography under difficulties—We go further down stream—Still no signs of Lorian—Sad end of “Spot” the puppy—Our men refuse to go further—Preparations for the return journey—Reasons for our failure to reach Lorian—Return to our Rendili camp—Somalis think of going north to Marsabit—Ismail asks me to accompany him—I decline—The scare in Ismail’s camp—Departure for M’thara | 259[Pg xiii] |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| RETURN TO M’THARA. | |

| Departure from the Rendili settlement—Ismail’s porters desert—The affray between Barri and the Somalis—Ismail wounded—A giraffe hunt—Ismail’s vacillation—Another giraffe hunt—Journey up the Waso Nyiro—Hippopotamus-shooting | 275 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| ARRIVAL AT M’THARA. | |

| In sight of Kenia once more—El Hakim and the lion—The “Green Camp” again—The baby water-buck—El Hakim shoots an elephant—The buried buffalo horns destroyed by hyænas—Bad news from M’thara—Plot to attack and massacre us hatched by Bei-Munithu—N’Dominuki’s fidelity—Baked elephant’s foot—Rain—Arrival at our old camp at M’thara | 290 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| AN ELEPHANT HUNT AND AN ATTACK ON MUNITHU. | |

| We shoot an elephant—Gordon Cumming on elephants—We send to Munithu to buy food—Song of Kinyala—Baked elephant’s foot again a failure—The true recipe—Rain—More rain—The man with the mutilated nose—The sheep die from exposure—Chiggers—The El’Konono—Bei-Munithu’s insolent message—A message from the Wa’Chanjei—George and I march to attack Munithu | 303 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| FIGHT AT MUNITHU AND DEPARTURE FROM M’THARA. | |

| Attack on Bei-Munithu’s village—Poisoned arrows—The burning of the village—The return march—Determined pursuit of the A’kikuyu—Karanjui—George’s fall—Return to the M’thara camp—Interview with Bei-Munithu—His remorse—Departure from M’thara—Rain—Hyænas—A lioness—Bad country—Whistling trees—A lion—Increasing altitude—Zebra | 319[Pg xiv] |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| ROUND NORTH AND WEST KENIA TO THE TANA. | |

| The primeval forests of North Kenia—Difficult country—Ravines—Ngare Moosoor—Rain—Ngare Nanuki—Cedar forests—Open country—No game—Upper waters of the Waso Nyiro—Death of “Sherlock Holmes”—Witchcraft—Zebra—Rhinoceros—Sheep dying off—More rain—The A’kikuyu once more—Attempt of the A’kikuyu to steal sheep—Difficult marches—Rain again—Maranga at last—The Tana impassable | 335 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| CONCLUSION. FROM THE RIVER TANA TO NAIROBI. | |

| Arrival at the Tana river—A visit to M’biri—Crossing the Tana—Smallpox—Kati drowned—I give Ramathani a fright—Peculiar method of transporting goods across the river practised by the Maranga—The safari across—M’biri—Disposal of the sheep—We resume the march—The Maragua once more—The Thika-Thika—The swamps—Kriger’s Farm—Nairobi | 351 |

| INDEX | 365 |

[Pg xv]

| PAGE | ||

The Author Frontispiece |

||

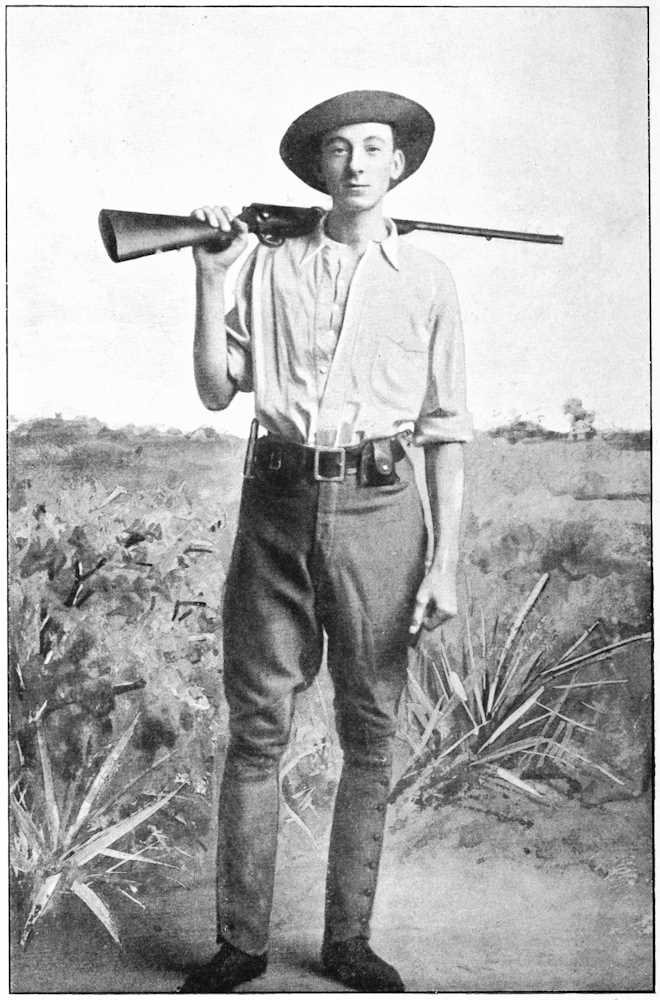

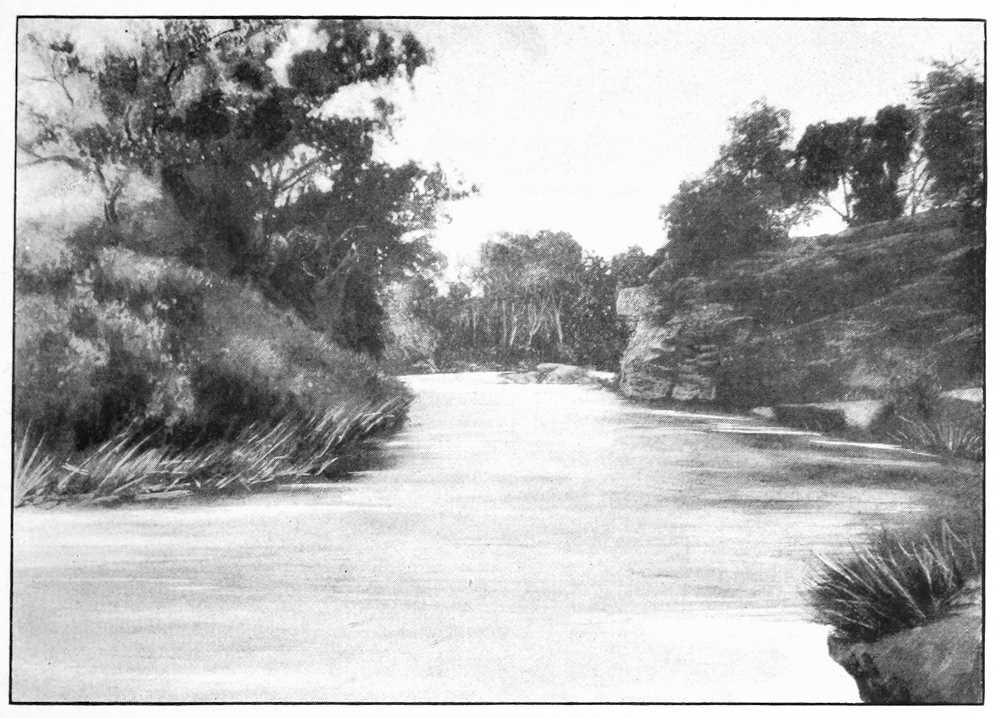

| The Athi River near Doenyo Sabuk | 36 | |

| Crossing an Affluent of the Sagana | ||

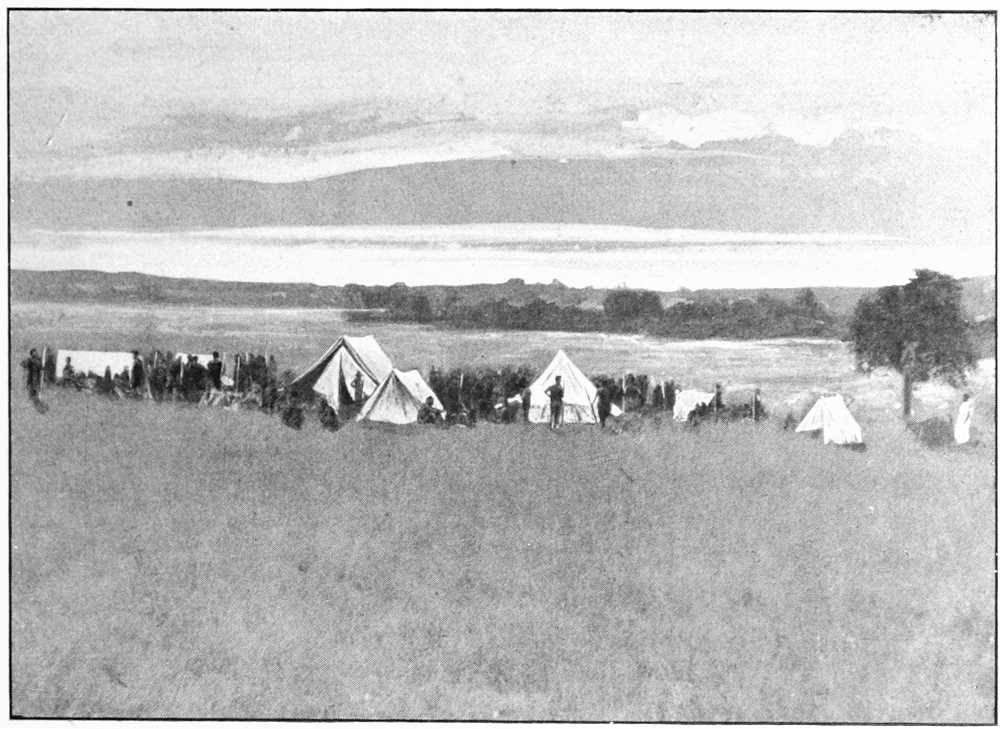

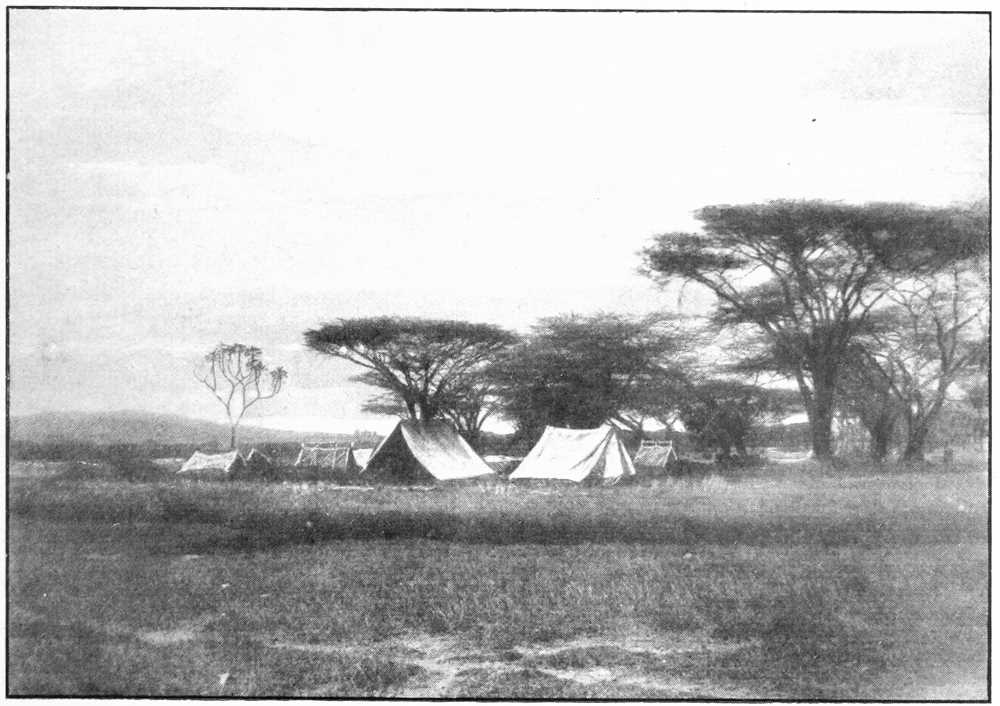

| The Camp at Maranga | 52 | |

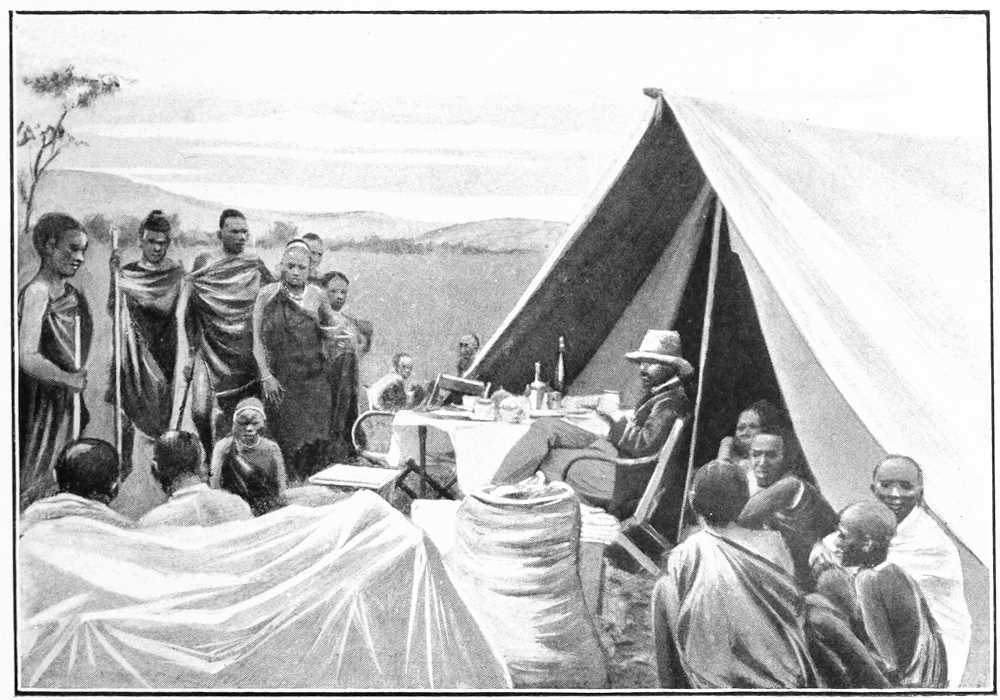

| Buying Food at Maranga | ||

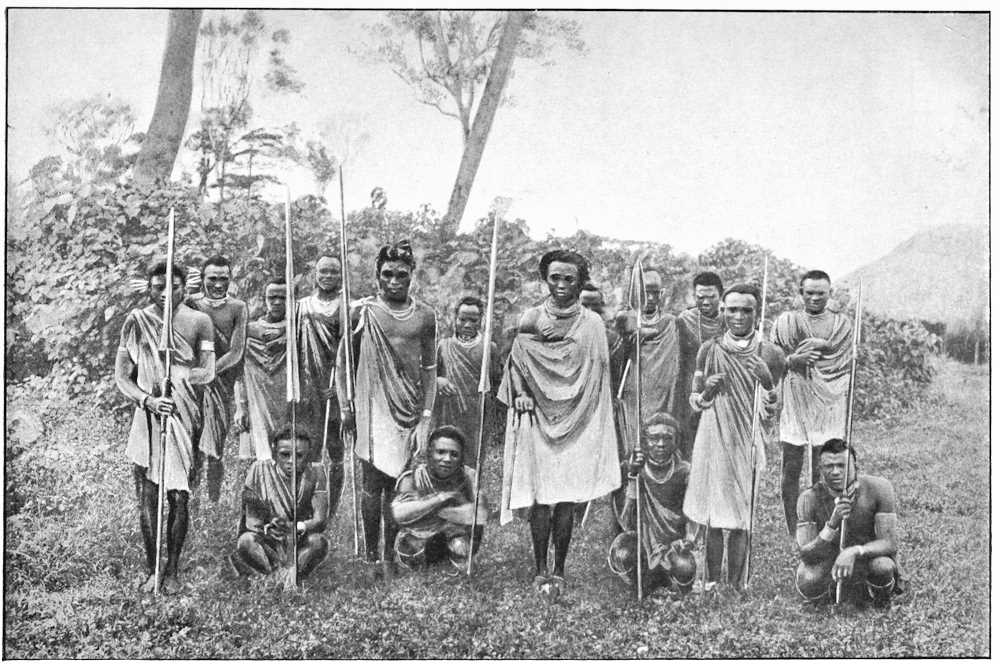

| Group of A’kikuyu | 60 | |

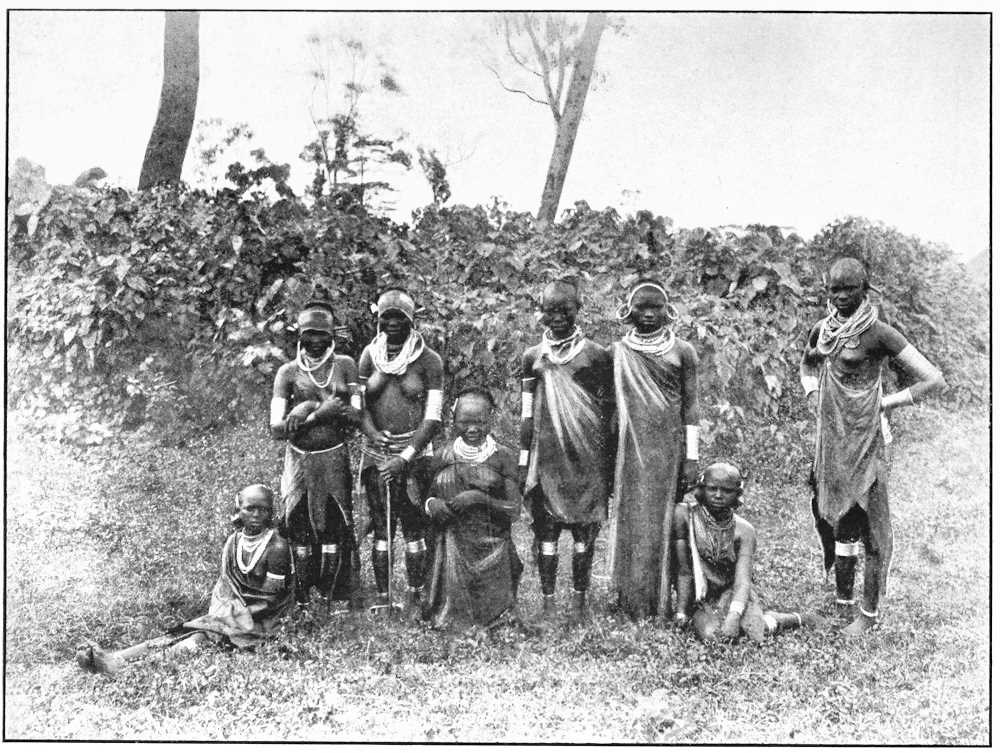

| Group of A’kikuyu Women | 76 | |

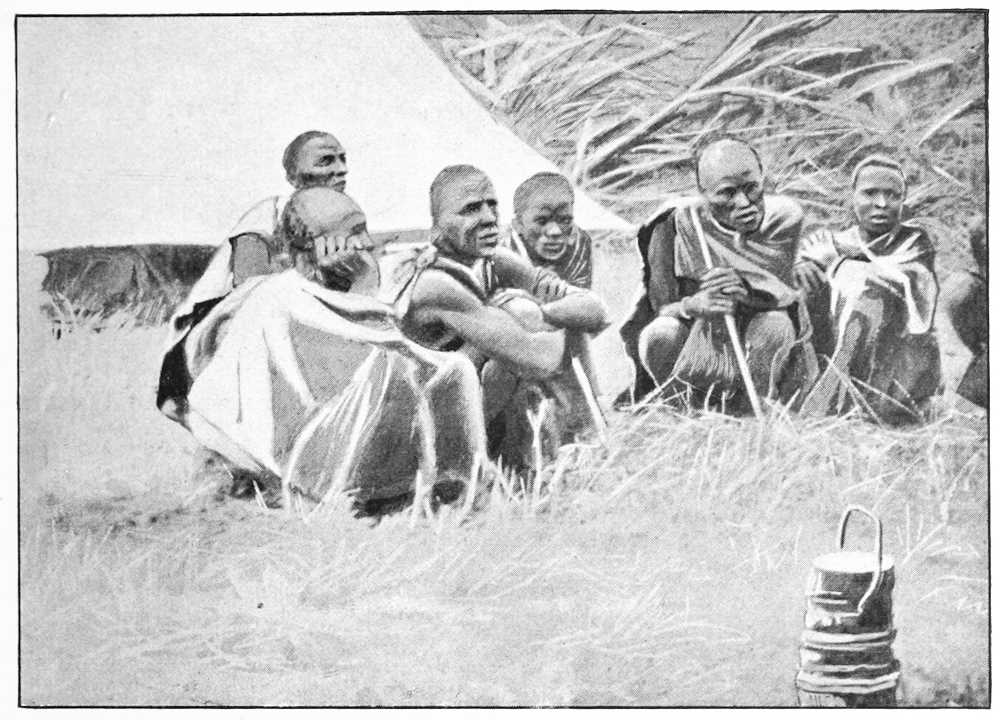

| Elders of M’thara | 114 | |

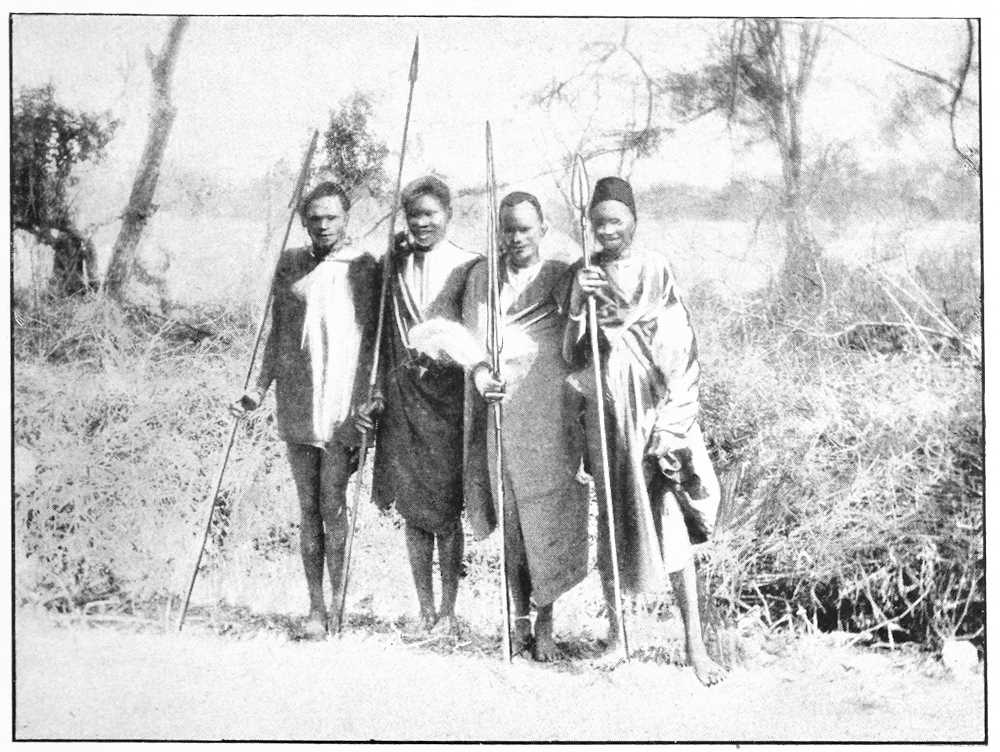

| Dirito and Viseli and Two Followers | ||

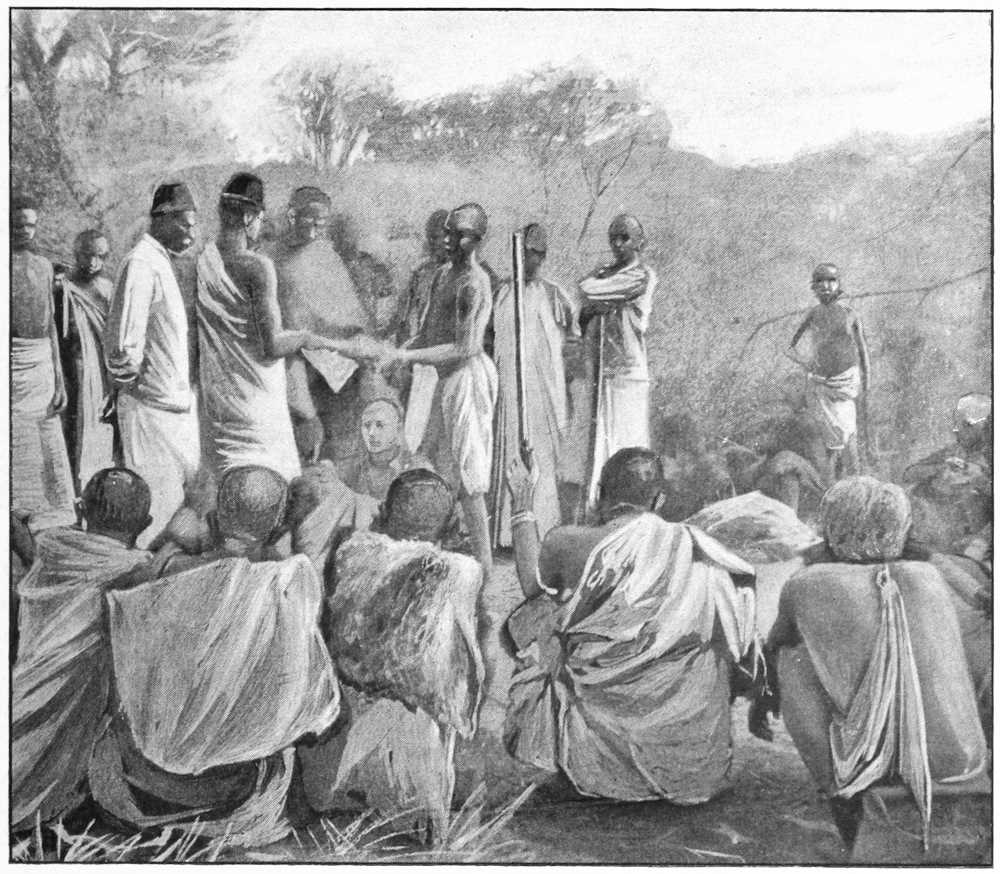

| The Author making Blood-brotherhood with Karama | 148 | |

| The “Green Camp” | ||

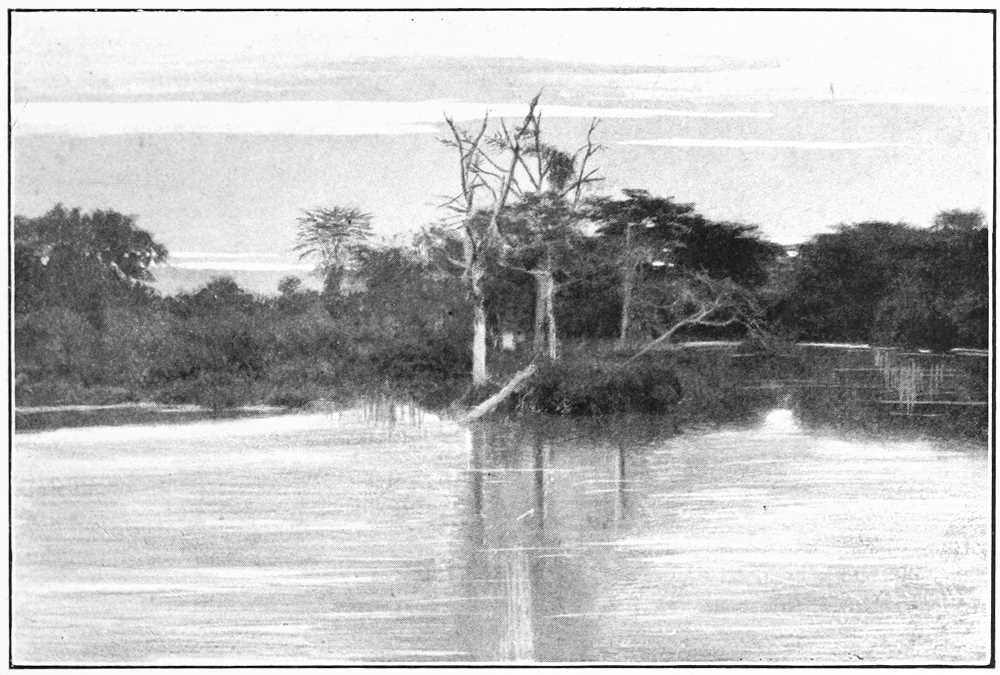

| View on the Waso Nyiro near “Swamp Camp” | 178 | |

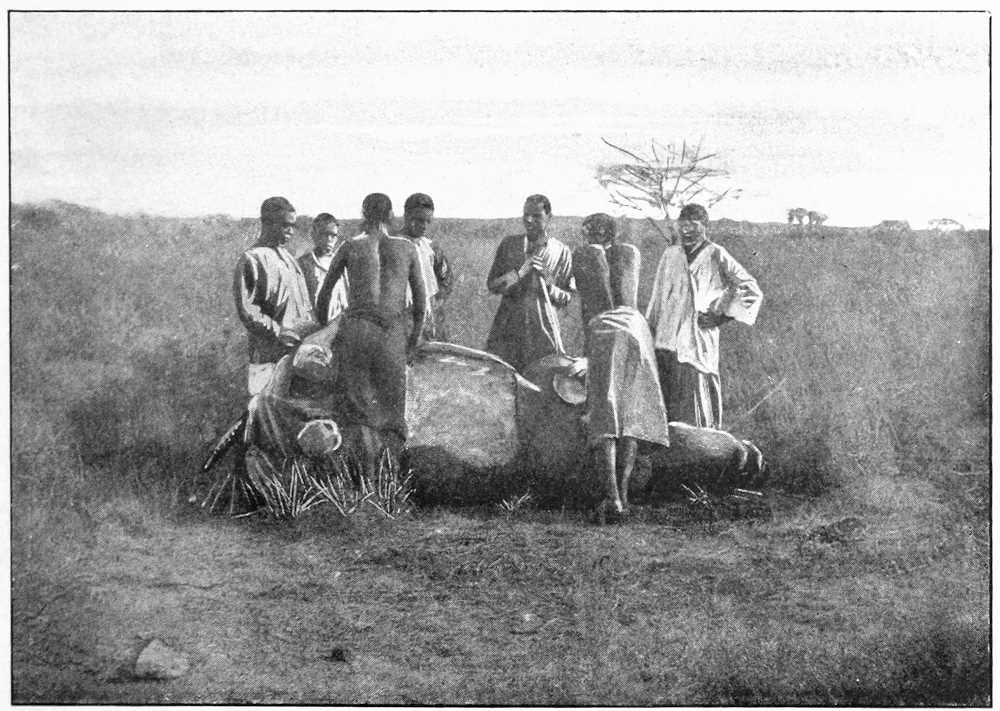

| Cutting up a Rhinoceros for Food | ||

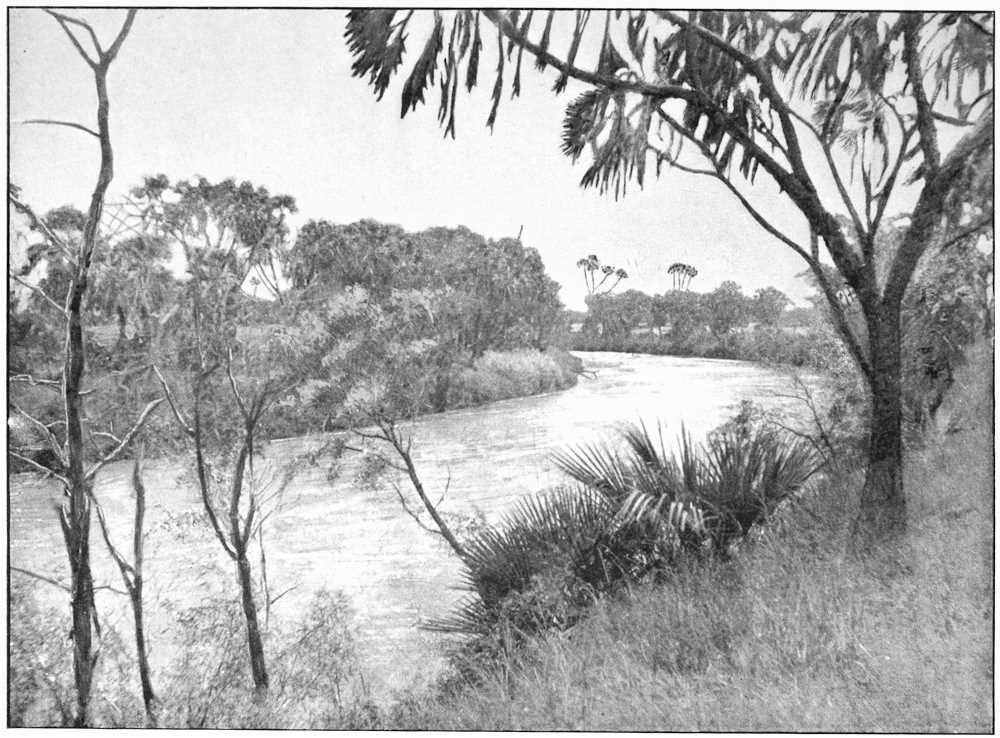

| Palms on the Waso Nyiro | 204 | |

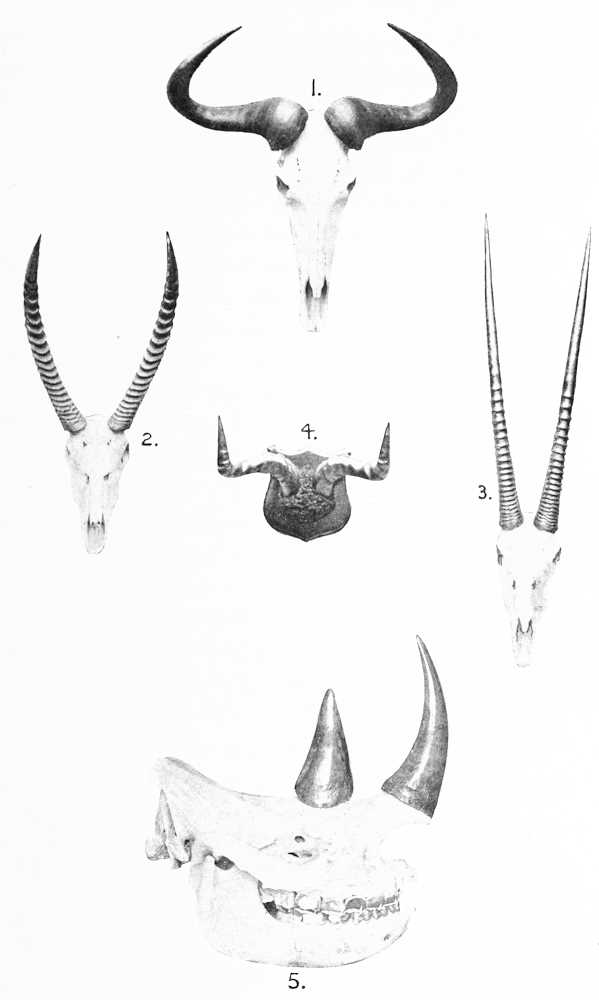

| Horns of Brindled Gnu, etc. | 220 | |

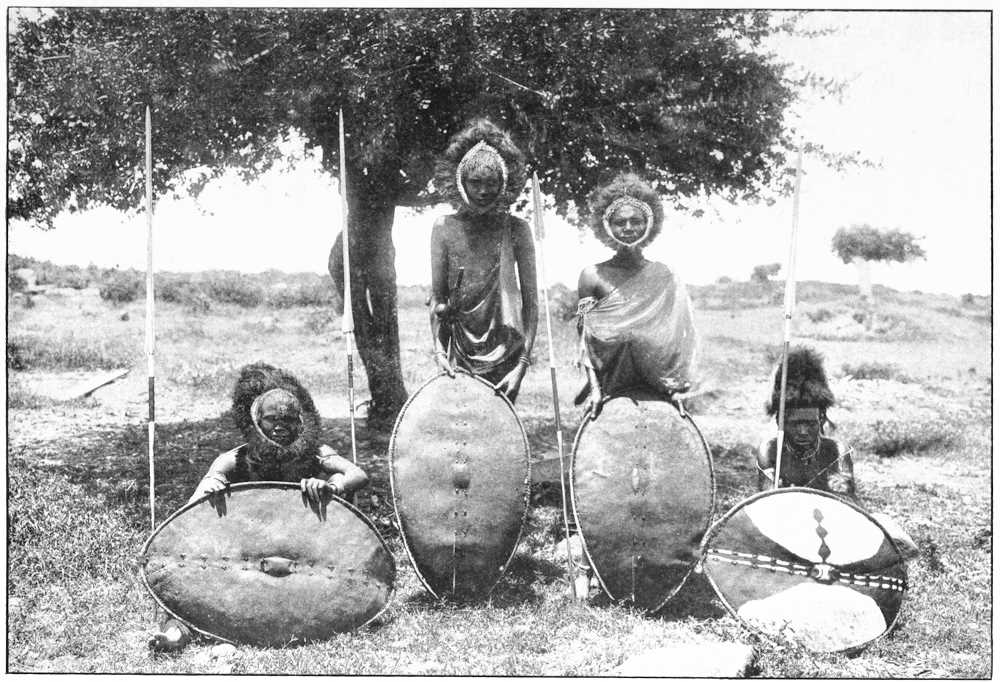

| Masai Elmoran in War Array | 242 | |

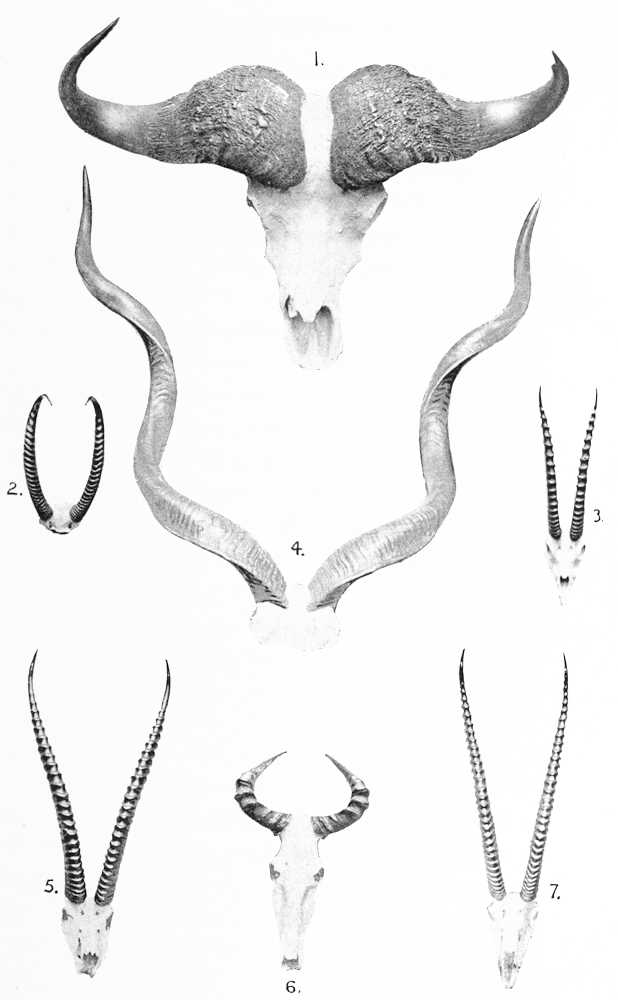

| Horns of Buffalo, etc. | 258 | |

| Portrait of Mr. G. H. West | 294 | |

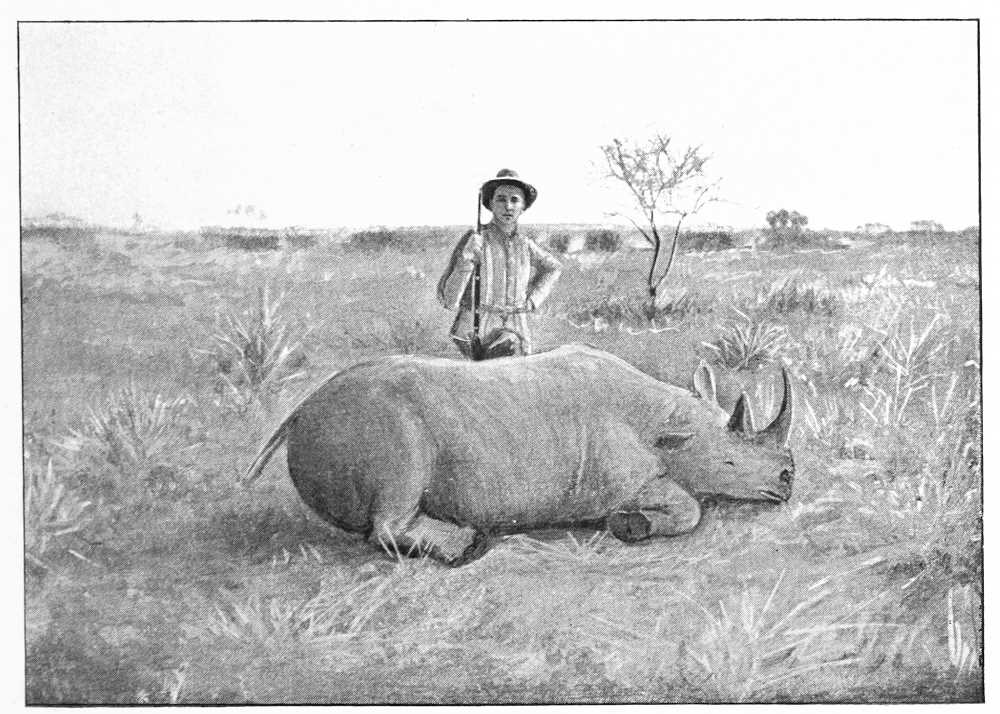

| Rhinoceros Shot by George | ||

| Ornaments worn by A’kikuyu Women | 316[Pg xvi] | |

| A’kikuyu Weapons | 328 | |

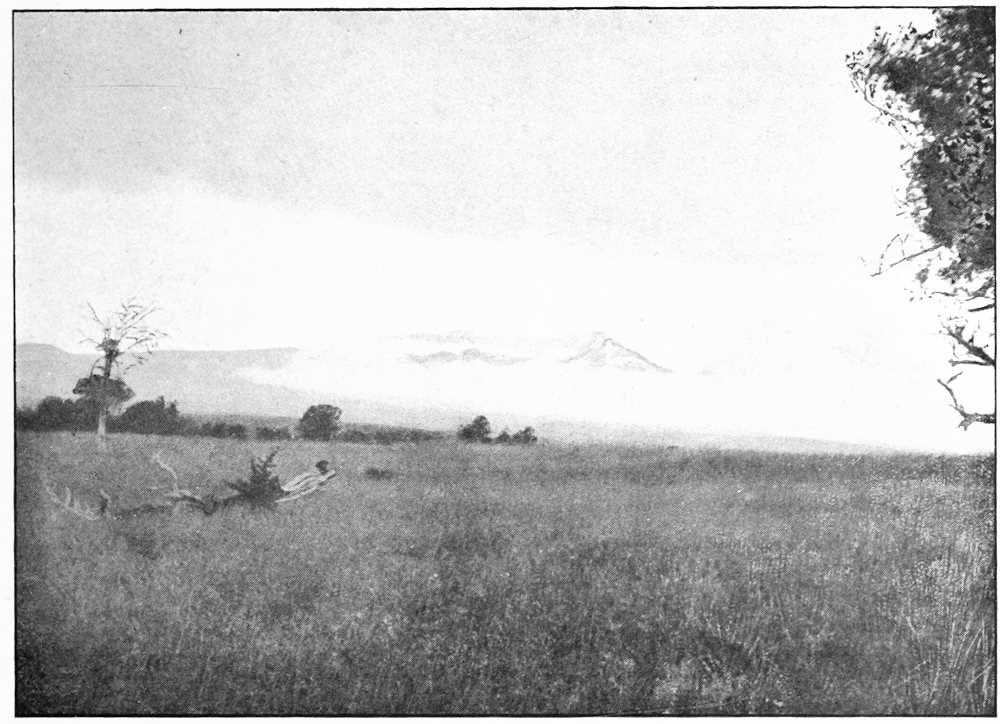

| Mount Kenia from the North | 336 | |

| Mount Kenia from the South-west | ||

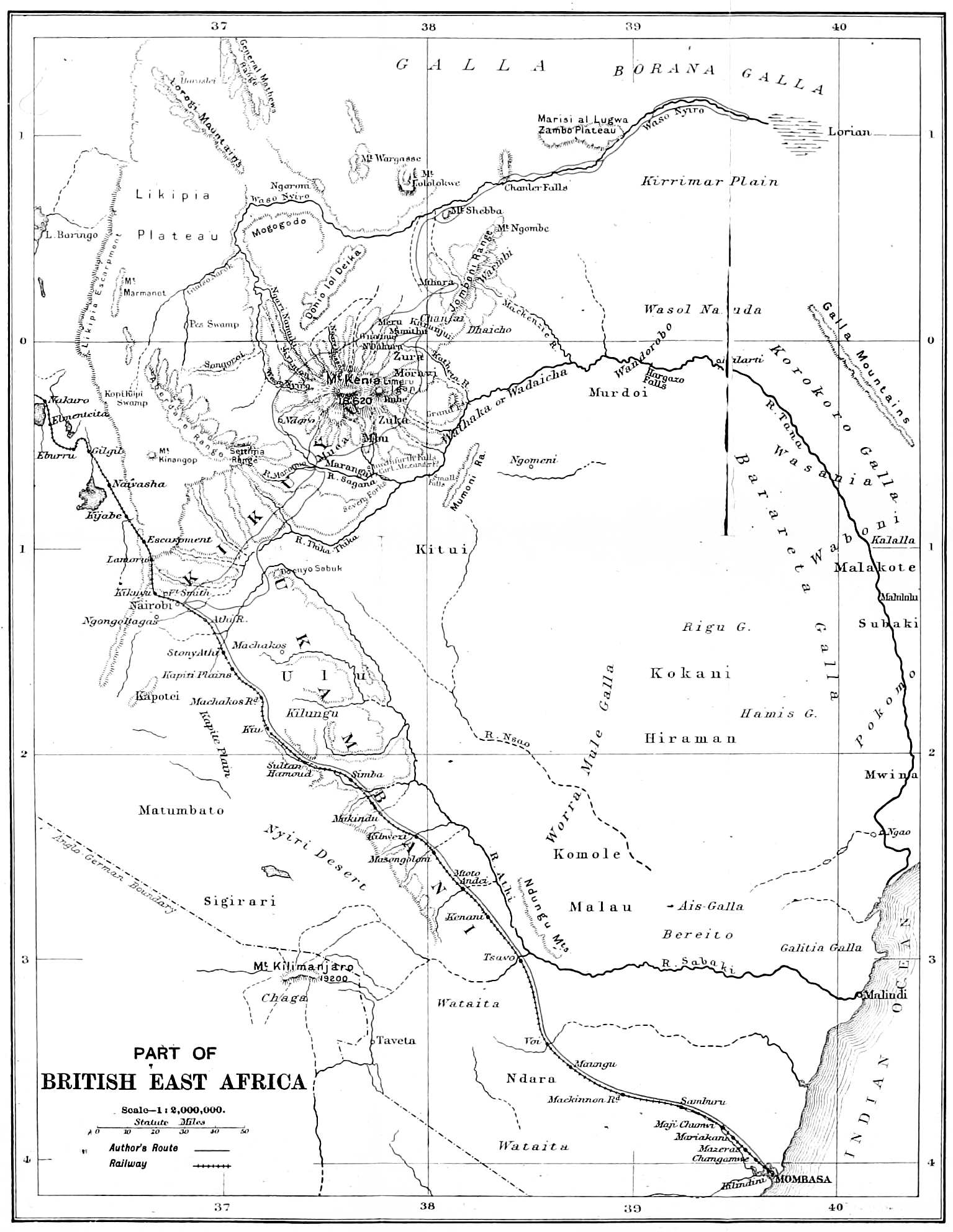

MAP

Part of British East Africa

ERRATA IN MAP

For Ngari Namuki read Ngare Nanuki.

” Guaso Narok ” Waso Narok.

ERRATA

| Page | 135, line 16, for “M’gomba” read “N’gombe.” |

| ” | 135, lines 17, 18, for “due north of Mathara” read “north of the Jombeni Mountains.” |

| ” | 136, line 19, for “Guaso” read “Waso.” |

| ” | 136, line 23, for “Gwarguess” read “Wargasse.” |

| ” | 147, 148, for “Koromo” read “Karama.” |

| ” | 178, lines 9, 10, 13, for “N’gomba” read “N’gombe.” |

| ” | 183, line 2, for “sassi” read “sassa.” |

| ” | 213, lines 30, 32, for “Van Hohnel” read “von Hohnel.” |

| ” | 264, line 30, for “M’Nyanwezi” read “M’Nyamwezi.” |

[Pg 1]

My friend, George Henry West, and myself left Cairo in the latter part of the year 1899, with the intention of proceeding to Uganda viâ Zanzibar and Mombasa. George was an engineer in the service of the Irrigation Department of the Egyptian Government, and had gained a large and varied experience on the new works on the Barrage below Cairo, then being concluded, and in building, running, and repairing both locomotives and launches. As a profession I had followed the sea for three years, leaving it in 1896 in order to join the British South African Police, then engaged in subduing the native rebellion in Mashonaland. At the conclusion of hostilities I wandered over South Africa, and finally found my way to Egypt, where I met George West. A year later, accompanied by George, I was on my way southwards again, en route for British East Africa.

When George and I left Cairo, our idea was to go up-country as far as the Lake Victoria Nyanza, as we considered it extremely probable that there would be something for us to do in the engineering line, either in building launches or in the construction of small harbour works.

We reached Mombasa in due course, and from there[Pg 2] proceeded to Nairobi by the railway then in course of construction to Uganda. Nairobi is 327 miles from the coast, and is an important centre, being the headquarters of both the Civil Administration of the Protectorate and the Uganda railway. On our arrival, George received an offer, which he accepted, to go up to the lake with a steamer, which was then on the way out from England in sections, and on his arrival at the lake with it to rebuild it. I remained in Nairobi.

In course of time I met the personage referred to in these pages as “El Hakim,”[1] whom I had known previously by repute. He was said to be one of the most daring and resolute, and at the same time one of the most unassuming Englishmen in the Protectorate; a dead shot, and a charming companion. He had been shooting in Somaliland and the neighbourhood of Lake Rudolph for the previous four years, and many were the stories told of his prowess among elephant and other big game.

It was with sincere pleasure, therefore, that I found I was able to do him sundry small services, and we soon became fast friends. In appearance he was nothing out of the common. He was by no means a big man—rather the reverse, in fact—and it was only on closer acquaintance that his striking personality impressed one.

He had dark hair and eyes, and an aquiline nose. He was a man of many and varied attainments. Primarily a member of the medical profession, his opinions on most other subjects were listened to with respect. A very precise speaker, he had a clear and impartial manner of reviewing anything under discussion which never failed to impress his hearers.

[Pg 3]

He was a leader one would have willingly followed to the end of the earth. When, therefore, he proposed that I should accompany him on an ivory trading expedition to Galla-land, that vast stretch of country lying between Mount Kenia on the south and Southern Somaliland on the north, which is nominally under the sphere of influence of the British East African Protectorate, I jumped at the chance; and it was so arranged. He had been over much of the ground we intended covering, and knew the country, so that it promised to be a most interesting trip.

About this time I heard from George that he was coming down country, as the steamer parts had not all arrived from England, and consequently it would probably be months before it would be ready for building. He had also had a bad attack of malarial fever in the unhealthy district immediately surrounding the lake at Ugowe Bay, and altogether he was not very fit. I suggested to El Hakim that George should join us in our proposed expedition, to which he readily agreed; so I wrote to George to that effect.

To render the prospect still more inviting, there existed a certain element of mystery with regard to the river Waso Nyiro (pronounced Wasso Nēro). It has always been supposed to rise in the Aberdare Range, but, as I shall show, I have very good reason to believe that it rises in the western slopes of Kenia Mountain itself. The Waso Nyiro does not empty itself into the sea, but ends in a swamp called Lorian, the position of which was supposed to have been fixed by an exploring party in 1893. But, as I shall also show in the course of this narrative, the position of Lorian varies.

The upper reaches of the Waso Nyiro were visited by the explorer Joseph Thompson, F.R.G.S., on his way to[Pg 4] Lake Baringo during his memorable journey through Masai Land in 1885.

In 1887-1888 a Hungarian nobleman, Count Samuel Teleki von Czeck, accompanied by Lieutenant Ludwig von Hohnel, of the Imperial Austrian Navy, undertook the stupendous journey which resulted in the discovery of Lakes Rudolph and Stephanie. Count Teleki, on his journey north, crossed the Waso Nyiro at a point in North-West Kenia near its source, while Lieutenant von Hohnel went two or three days’ march still further down-stream.

A few years later, in 1892-1893, Professor J. W. Gregory, D.Sc., of the Natural History Museum, South Kensington, made, single-handed, a remarkable journey to Lake Baringo and Mount Kenia, and in the teeth of almost insuperable difficulties, ascended the western face of that mountain and climbed the peak.

At the same time, in the latter part of 1892, an American, Mr. William Astor Chanler, accompanied by Count Teleki’s companion and chronicler, Lieutenant von Hohnel, started from a point in Formosa Bay on the East Coast, and made his way along the course of Tana River to North-East Kenia, intending later to go on to Lake Rudolph, and thence northward. He and his companion, deceived by the reports of the natives, which led them to believe that the Waso Nyiro emptied itself into an extensive lake, and fired by the idea of the possible discovery of another great African lake, made their way down to the Waso Nyiro, and after a fearful march, enduring the greatest hardships, eventually reached Lorian. To their great disappointment, it proved to be nothing more than a swamp, and they turned back without examining it. A few weeks later, Lieutenant von Hohnel, having been seriously injured by a rhinoceros, was sent down[Pg 5] to the coast, his life being despaired of. Shortly afterwards Mr. Chanler’s men deserted him in a body, and returned to the coast also, thus bringing his journey to a premature conclusion; a much-to-be-regretted ending to a well-planned and well-equipped expedition.

As Mr. Chanler was returning to the coast he met Mr. A. H. Neumann coming up. Mr. Neumann spent the greater part of 1893 in shooting elephants in the Loroghi Mountains, after going north to Lake Rudolph. He also crossed the Waso Nyiro at a point north-east of Mount Kenia.

During the time Mr. Neumann was shooting in the Loroghi Mountains he was obliged to make periodical visits to M’thara, in North-East Kenia, in order to buy food from the natives, and on one such excursion he met Dr. Kolb, a German scientist, who was exploring North Kenia.

Dr. Kolb ascended Mount Kenia from the north, and then returned to Europe. An interesting account of his ascent of the mountain is published in Dr. Petermann’s “Mitteilungen” (42 Band, 1896). Dr. Kolb then returned to Kenia in order to continue his observations, but he was unfortunately killed by a rhinoceros a couple of marches north of M’thara.

Lorian, therefore, with the exception of Mr. Chanler’s hurried visit, was practically unexplored. At the commencement of our trip, El Hakim proposed that, if an opportunity occurred of visiting Lorian, we should take advantage of it, and endeavour to supplement Mr. Chanler’s information. As will be seen, an opportunity did present itself, with what result a perusal of this account of our expedition will disclose.

[1] Anglice, “The Doctor.”

[Pg 6]

Engaging porters—Characteristics of Swahili, Wa’Nyamwezi, and Wa’Kamba porters—Selecting trade goods—Provisions—Arms and ammunition—The Munipara—Sketch of some principal porters—Personal servants—List of trade goods taken—Distributing the loads—Refusal of the Government to register our porters—Reported hostility of the natives—Finley and Gibbons’ disaster—Start of the Somali safaris—We move to Kriger’s Farm—I fall into a game-pit—Camp near Kriger’s Farm—Visitors—The start.

One of the most important items in the organization of a “safari” (caravan) is the judicious selection of the men. Choosing ours was a task that gave us much trouble and vexation of spirit. El Hakim said that for all-round usefulness the Wa’kamba were hard to beat, and thought that we had better form the bulk of the safari from them, and stiffen it with a backbone of Swahilis and Wa’Nyamwezi, as, though the Wa’kamba were very good men when well handled, in the unlikely event of hostilities with the natives it would be advisable to strengthen them with an addition from the lustier tribes. To that end we proposed to engage a dozen Swahili and half that number of Wa’Nyamwezi. Porters at that time were very scarce; but having secured one or two good men as a nucleus, we sent them into the bazaar at Nairobi to bring us any other men they could find who wanted employment.

[Pg 7]

The Swahilis are natives of Zanzibar and the adjacent coasts. They are of mixed—very mixed—descent, being mainly the offspring of various native slaves and their Arab masters. They were originally a race of slaves, but since the abolition of slavery they have become more and more independent, and they now consider themselves a very superior race indeed. They call themselves “Wangwana” (freemen), and allude to all other natives as “Washenzi” (savages). They are incorrigibly conceited, and at times very vicious, lazy, disobedient, and insolent. But once you have, by a judicious display of firmness, gained their respect, they, with of course some exceptions, prove to be a hardy, cheerful, and intelligent people, capable of enduring great hardships without a too ostentatious display of ill-feeling, and will even go so far as to make bad puns in the vernacular upon their empty stomachs, the latter an occurrence not at all infrequent in safari work away from the main roads.

The Wa’kamba, on the whole, are a very cheerful tribe, and though of small physique, possess wonderful powers of endurance, the women equally with the men. We calculated that some of our men, in addition to their 60-lb. load, carried another 30 lbs. weight in personal effects, rifle, and ammunition; so that altogether they carried 90 lbs. dead weight during one or sometimes two marches a day for weeks at a stretch, often on insufficient food, and sometimes on no food at all.

The Wa’Nyamwezi are, in my opinion, really more reliable than either the Swahili or Wa’kamba. They come from U’Nyamwezi, the country south and east of Lake Victoria Nyanza. We had six of them with us, and we always found them steady and willing, good porters, and less trouble than any other men in the safari. They were very[Pg 8] clannish, keeping very much to themselves, but were quiet and orderly, and seldom complained; and if at any time they imagined they had some cause for complaint, they formed a deputation and quietly stated their case, and on receiving a reply as quietly returned to their fire—very different from the noisy, argumentative Swahili. They appear to me to possess the virtues of both the Swahilis and Wa’kamba without their vices. The Wa’kamba’s great weakness when on the march was a penchant for stealing from the native villages whatever they could lay their hands on, being encouraged thereto by the brave and noble Swahilis, who, while not wishing to risk our displeasure by openly doing likewise, urged on the simple Wa’kamba, afterwards appropriating the lion’s share of the spoil: that is, if we did not hear of the occurrence and confiscate the spoil ourselves.

We had pitched our tent just outside the town of Nairobi, and proceeded to get together our loads of camp equipment, trade goods, and provisions: no easy task on an expedition such as ours, where the number of carriers was to be strictly limited.

In the first place, we required cloth, brass wire, iron wire, and various beads, in sufficient quantities to buy food for the safari for at least six months. Provisions were also a troublesome item, as, although we expected to live a great deal upon native food, we required such things as tea, coffee, sugar, jam, condiments, and also medicines. The question was not what to take, but what not to take. However, after a great amount of discussion, lasting over several days, we settled the food question more or less satisfactorily.

During this time our recruiting officers were bringing into camp numbers of men who, they said, wanted to take service with us as porters. Judging from the specimens[Pg 9] submitted for our approval, they seemed to have raked out the halt, the lame, and the blind. After much trouble we selected those whom we thought likely to be suitable, and gave them an advance of a few rupees as a retaining fee, with which, after the manner of their kind, they immediately repaired to the bazaar for a last long orgie.

There was also the important question of arms and ammunition to be considered, as, although we did not expect any fighting, it would have been foolish in the extreme to have entered such districts as we intended visiting without adequate means of self-defence. We concluded the twenty-five Snider rifles used by El Hakim on a previous trip would suffice. Unfortunately, we could get very little ammunition for them, as at that time Snider ammunition was very scarce in Nairobi, one reason being that it had been bought very largely by a big Somali caravan under Jamah Mahomet and Ismail Robli, which set out just before us, bound for the same districts.

We, however, eventually procured five or six hundred rounds: a ridiculously inadequate amount considering the distance we were to travel and the time we expected to be away.

With regard to our armament, El Hakim possessed by far the best battery. His weapons consisted of an 8-bore Paradox, a ·577 Express, and a single-barrelled ·450 Express, all by Holland and Holland. The 8-bore we never used, as the ·577 Express did all that was required perfectly satisfactorily. The 8-bore would have been a magnificent weapon for camp defence when loaded with slugs, but fortunately our camp was never directly attacked, and consequently the necessity for using it never arose. The ·557 was the best all-round weapon for big game such as[Pg 10] elephant, rhinoceros, and buffalo, and never failed to do its work cleanly and perfectly. Its only disadvantage was that it burnt black powder, and consequently I should be inclined, if I ever made another expedition, to give the preference to one of the new ·450 or ·500 Expresses burning smokeless powder, though, as I have not handled one of the latter, I cannot speak with certainty. El Hakim’s ·450 Express was really a wonderful weapon, though open to the same objection as the ·557—that of burning black powder. It was certainly one of the best all-round weapons I ever saw for bringing down soft-skinned game. It was a single-barrelled, top-lever, hammer-gun, with flat top rib. The sights were set very low down on the rib, to my mind a great advantage, as it seems to me to minimize the chances of accidental canting. Its penetrative power, with hardened lead bullets, was surprising. I have seen it drop a rhinoceros with a bullet through the brain, and yet the same projectile would kill small antelope like Grant’s or Waller’s gazelles without mangling them or going right through and tearing a great hole in its egress, thereby spoiling the skin, which is the great cause of complaint against the ·303 when expanding bullets are used.

I myself carried a ·303 built by Rigby, a really magnificent weapon. I took with me a quantity of every make of ·303 expanding bullets, from copper-tubed to Jeffry’s splits. After repeated trials I found that the Dum-Dum gave the most satisfactory results, “since when I have used no other.”

I also carried a supply of ·303 solid bullets, both for elephants and for possible defensive operations. For rhinoceros, buffalo, or giraffe, I carried an ordinary Martini-Henry military rifle, which answered the purpose admirably.[Pg 11] A 20-bore shot-gun, which proved useful in securing guinea-fowl, etc., for the pot, completed my battery. George carried a ·303 military rifle and a Martini-Henry carbine.

It was essential that we should have a good “Munipara” (head-man), and the individual we engaged to fill that important position was highly recommended to us as a man of energy and resource. His name was Jumbi ben Aloukeri. Jumbi was of medium height, with an honest, good-natured face. He possessed an unlimited capacity for work, but we discovered, too late, that he possessed no real control over the men, which fact afterwards caused us endless trouble and annoyance. He was too easy with them, and made the great mistake—for a head-man—of himself doing anything we wanted, instead of compelling his subordinates to do it, with the result that he was often openly defied, necessitating vigorous intervention on our part to uphold his authority. We usually alluded to him as “the Nobleman,” that being the literal translation of his name.

Next on the list of our Swahili porters was Sadi ben Heri, who had been up to North Kenia before with the late Dr. Kolb, who was killed by a rhinoceros a couple of marches north of M’thara, Sadi was a short, stoutly built, pugnacious little man, with a great deal to say upon most things, especially those which did not concern him. He was a good worker, but never seemed happy unless he was grumbling; and as he had a certain amount of influence among the men, they would grumble with him, to their great mutual satisfaction but ultimate disadvantage. His pugnacious disposition and lax morals soon got him into trouble, and he, together with some of his especial cronies, was killed by natives, as will be related in its proper sequence.

Hamisi ben Abdullah was a man of no marked[Pg 12] peculiarities, except a disposition to back up Sadi in any mischief. The same description applies to Abdullah ben Asmani and Asmani ben Selim.

Coja ben Sowah was a short, thick-set man, so short as to be almost a dwarf. He was one of the most cheery and willing of our men, so much so that it was quite a pleasure to order him to do anything—a pleasure, I fear, we appreciated more than he did. On receiving an order he would run to execute it with a cheery “Ay wallah, bwana” (“Please God, master”), that did one good to hear.

Resarse ben Shokar was our “Kiongozi,” i.e. the leading porter, who sets the step on the march and carries the flag of the safari. He, also, always ran on receiving an order—ran out of sight, in fact; then, when beyond our ken, compelled a weaker man than himself to do what was wanted. I could never cure him of the habit of sleeping on sentry duty, though many a time I have chased him with a stirrup-strap, or a camp-stool, or anything handy when, while making surprise inspections of the sentries, I had found him fast asleep. He was valuable, however, in that he was the wit of the safari. He was a perfect gas-bag, and often during and after a long and probably waterless march we blessed him for causing the men to laugh by some harmless waggish remark at our expense.

Sulieman was a big, hulking, sulky brute, who gave us a great deal of trouble, and finally deserted near Lorian, forgetting to return his rifle, and also absent-mindedly cutting open my bag and abstracting a few small but necessary articles. Docere ben Ali, his chum, was also of a slow and sullen disposition, though he was careful not to exhibit it to us. When anything disturbed him he went forthwith and took it out of the unfortunate Wa’kamba.

[Pg 13]

Of the Wa’kamba I do not remember the names except of two or three who particularly impressed themselves on my memory. The head M’kamba was known as Malwa. He was a cheerful, stupid idiot who worked like a horse, though he never seemed to get any “for’arder.” Another M’kamba, named Macow, afterwards succeeded him in the headmanship of the Wa’kamba when Malwa was deposed for some offence. We nicknamed Macow “Sherlock Holmes,” as he seemed to spend most of his leisure hours prowling round the camp, peering round corners with the true melodrama-detective-Hawkshaw expression in his deep-set, thickly browed eyes. He would often creep silently and mysteriously to our tent, and in a subdued whisper communicate some trifling incident which had occurred on the march; then, without waiting for a reply, steal as silently and mysteriously away.

I must not conclude this chapter without some mention of our personal servants. First and foremost was Ramathani, our head cook and factotum. Ramathani had already been some three months in my service as cook and personal servant, and a most capable man I had found him. My acquaintance with him began one morning when I had sent my cook, before breakfast, to the sokoni (native bazaar) to buy bread, vegetables, etc. As he did not return I went outside to the cook-house in some anxiety as to whether I should get any breakfast. Several native servants were there, and they informed me my cook was still in the bazaar, very drunk, and most likely would not be back till noon. Of course, I was angry, and proceeded to show it, when a soothing voice, speaking in very fair English, fell upon my ear. Turning sharply, I was confronted by a stranger, a good-looking native, neatly dressed in khaki.

[Pg 14]

“Shall I cook breakfast for master?” he inquired softly.

“Are you able?” said I.

“Yes, master.”

“Then do so,” I said; and went back to my quarters and waited with as much patience as I could command under the circumstances.

In a quarter of an hour or so Ramathani—for it was indeed he—brought in a temptingly well-cooked breakfast, such as I was almost a stranger to, and at the same time hinted that he had permanently attached me as his employer. My own cook turned up an hour or so later, very drunk and very abusive, and he was incontinently fired out, Ramathani being established in his stead.

Ramathani had two boys as assistants, Juma and Bilali. Juma was an M’kamba. His upper teeth were filed to sharp points, forming most useful weapons of offence, as we afterwards had occasion to notice.

Bilali was an M’Kikuyu, and a very willing boy. He was always very nervous when in our presence, and used to tremble excessively when laying the table for meals. When gently reproved for putting dirty knives or cups on the table, he would grow quite ludicrous in his hurried efforts to clean the articles mentioned, and would spit on them and rub them with the hem of his dirty robe with a pathetic eagerness to please that disarmed indignation and turned away wrath.

Having finally secured our men, it only remained to pack up and distribute the loads of equipment, provisions, trade goods, etc. We did not take such a large quantity of trade goods as we should have done in the ordinary course, as El Hakim already had a large quantity in charge of a chief in[Pg 15] North Kenia. The following is a list, compiled from memory, of what we took with us:—

Unguo (Cloth).

| 2 | loads | Merikani (American sheeting). |

| 2 | ” | kisuto (red and blue check cloths). |

| 2 | ” | blanketi (blankets, coloured). |

| 1 | load | various, including— |

| gumti (a coarse white cloth). | ||

| laissoes (coloured cloths worn by women). | ||

| kekois (coloured cloth worn by men). | ||

Uzi Wa Madini (Wire).

| seninge (iron wire, No. 6). | ||

| 2 or 3 loads of | masango (copper wire, No. 6). | |

| masango n’eupe (brass wire, No. 6). |

Ushanga (Beads).

| sem Sem (small red Masai beads). | ||

| 2 or 3 loads of | sembaj (white Masai beads). | |

| ukuta (large white opaque beads). | ||

| 2 loads of mixed Venetian beads. | ||

When all the loads were packed, they were placed in a line on the ground; and falling the men in, we told off each to the load we thought best suited to him. To the Swahilis, being good marching men and not apt to straggle on the road, we apportioned our personal equipment, tents, blankets, and table utensils. To the Wa’Nyamwezi we entrusted the ammunition and provisions, and to the Wa’kamba we gave the loads of wire, beads, cloth, etc. Having settled this to our own satisfaction, we considered the matter settled, and ordered each man to take up his load.

Then the trouble began. First one man would come to us and ask if his load might be changed for “that other one,” while the man to whom “that other one” had been given would object with much excited gesticulation and forcible language to any alteration being made, and would come to[Pg 16] us to decide the case. We would then arbitrate, though nine times out of ten they did not abide by our decision. Other men’s loads were bulky, or awkward, or heavy, or had something or other the matter with them which they wanted rectified, so that in a short time we had forty men with forty grievances clamouring for adjustment. We simplified matters by referring every one to Jumbi, and having beaten an inglorious retreat to our tents, solaced ourselves with something eatable till everything was more or less amicably settled.

Nothing is more characteristic of the difference in the races than the way in which they carry their loads. The Swahilis and Wa’Nyamwezi, being used to the open main roads, carry their loads boldly on their heads, or, in some cases, on their shoulders. The Wa’kamba, on the other hand, in the narrow jungle paths of their own district find it impossible, by reason of the overhanging vegetation, to carry a load that way. They tie it up instead with a long broad strip of hide, leaving a large loop, which is passed round the forehead from behind, thus supporting the load, which rests in the small of the back. When the strain on the neck becomes tiring they lean forward, which affords considerable relief, by allowing the load to rest still more upon the back. There were also six donkeys, the property of El Hakim, and these were loaded up as well. A donkey will carry 120 lbs., a weight equal to two men’s loads.

Finally, we had to register our porters at the Sub-Commissioner’s office, as no safaris are allowed to proceed until that important ceremony has been concluded, and the Government has pouched the attendant fees. In our case, however, there appeared to be a certain amount of difficulty. On delivering my application I was told to wait for an[Pg 17] answer, which I should receive in the course of the day. I waited. In the afternoon a most important-looking official document was brought to me by a Nubian orderly. In fear and trembling I opened the envelope, and breathed a heartfelt sigh of relief when I found that the Government had refused to register our porters, giving as their reason that the districts we intended visiting were unsettled and, in their opinion, unsafe, and therefore we should proceed only at our own risk. We did not mind that, and we saved the registration fee anyhow. The Government had already refused to register the Somali’s porters, and they intimated, very rightly, that they could not make any difference in our case.

Jamah Mahomet, who was in command of the Somali safari, started off that day. He had with him Ismail Robli as second in command. A smaller safari, under Noor Adam, had started a week previously. Both these safaris intended visiting the same districts as ourselves. We were fated to hear a great deal more of them before the end of our trip.

In the evening I received a private note from one of the Government officers, informing me that we were likely to have a certain amount of trouble in getting across the river Thika-Thika without fighting, as the natives of that district were very turbulent, and advising us to go another way. My informant cited the case of Messrs. Finlay and Gibbons by way of a cheerful moral.

Finlay and Gibbons were two Englishmen who had been trading somewhere to the north of the Tana River. They had forty men or so, and were trading for ivory with the A’kikuyu, when they were suddenly and treacherously attacked and driven into their “boma” (thorn stockade), and[Pg 18] there besieged by quite six thousand natives. From what I saw later, I can quite believe that their numbers were by no means exaggerated. During a night attack, Finlay was speared through the hand and again in the back, the wound in the back, however, not proving dangerous. They managed to get a message through to Nairobi, and some Nubian troops were sent to their relief, which task they successfully accomplished, though only with the greatest difficulty. It was not till six weeks after he received the wound that Finlay was able to obtain medical assistance, and by that time the tendons of his hand had united wrongly, so that it was rendered permanently useless. This was a nice enlivening story, calculated to encourage men who were setting out for the same districts.

The following day I received a telegram from George to say that he had arrived from Uganda at the Kedong Camp, at the foot of the Kikuyu Escarpment, so I went up by rail to meet him. He looked very thin and worn after his severe attack of fever. We returned to Nairobi the same evening, and proceeded to our camp. El Hakim, who was away when we arrived, turned up an hour later, and completed our party. He had been to Kriger’s Farm about seven miles out. Messrs. Kriger and Knapp were two American missionaries who had established a mission station that distance out of Nairobi, towards Doenyo Sabuk, or Chianjaw, as it is called by the Wa’kamba.

El Hakim, being anxious to get our men away from the pernicious influence of the native bazaar, arranged that he would go on to Kriger’s early on the following morning, and that George and I should follow later in the day with the safari, and camp for the night near Kriger’s place. Accordingly he started early in the forenoon on the following day.

[Pg 19]

George and I proceeded to finish the packing and make final arrangements—a much longer task than we anticipated. There were so many things that must be done, which we found only at the last minute, that at 3 p.m., as there was no prospect of getting away until an hour or so later, I sent George on with the six loaded donkeys, about thirty of El Hakim’s cattle, and a dozen men, telling him that I would follow. George rode a mule (of which we had two), which El Hakim had bought in Abyssinia two years before. They were splendid animals, and, beyond an inconvenient habit, of which we never cured them, of shying occasionally and then bolting, they had no bad points. They generally managed to pick up a living and get fat in a country where a horse would starve, and, taking them altogether, they answered admirably in every way. I would not have exchanged them for half a dozen of the best horses in the Protectorate. One mule was larger than the other, and lighter in colour, and was consequently known as n’yumbu m’kubwa, i.e. “the big mule.” It was used by George and myself as occasion required. The other, a smaller, darker animal, was known as n’yumbu m’dogo, i.e. “the little mule.” It was ridden exclusively by El Hakim.

After George’s departure I hurried the remaining men as much as possible, but it was already dusk when I finally started on my seven-mile tramp. Some of the men had to be hunted out of the bazaar, where they had lingered, with their loved ones, in a last long farewell.

There is no twilight in those latitudes (within two degrees of the equator), so that very soon after our start we were tramping along in the black darkness. I had no knowledge of the road; only a rough idea of the general direction. I steered by the aid of a pocket-compass and a[Pg 20] box of matches. After the first hour I noticed that the men commenced to stagger and lag behind with their lately unaccustomed burdens, and I had to be continually on the alert to prevent desertions. I numbered them at intervals, to make sure that none of them had given me the slip, but an hour and a half after starting I missed three men with their loads, in spite of all my precautions. I shouted back into the darkness, and the men accompanying me did the same, and, after a slight interval we were relieved to hear an answering shout from the missing men. After waiting a few moments, we shouted again, and were amazed to find that the answering shout was much fainter than before. We continued shouting, but the answers grew gradually fainter and more faint till they died away altogether. I could not understand it at first, but the solution gradually dawned upon me. We were on a large plain, and a few hundred yards to the left of us was a huge belt of forest, which echoed our shouts to such an extent that the men who were looking for us were deceived as to our real position, and in their search were following a path at right angles to our own. I could not light a fire to guide them, as the grass was very long and dry, and I should probably have started a bush fire, the consequences of which would have been terrible. I therefore fired a gun, and was answered by another shot, seemingly far away over the plain to the right. Telling the men to sit down and rest themselves on the path, I ordered Jumbi to follow me, and, after carefully taking my bearings by compass, started to walk quickly across the plain to intercept them.

It was by no means a pleasant experience, trotting across those plains in the pitchy blackness, with the grass up to my waist, and huge boulders scattered about ready and[Pg 21] willing to trip me up. I got very heated and quite unreasonably angry, and expressed my feelings to Jumbi very freely. I was in the midst of a violent diatribe against all natives generally, and Swahili porters in particular, which I must admit he bore with commendable patience, when the earth gave way beneath me, and I was precipitated down some apparently frightful abyss, landing in a heap at the bottom, with all the breath knocked out of my body. I laid there for a little while, and endeavoured to collect my scattered faculties. Soon I stood up, and struck a match, and discovered that I had fallen into an old game-pit, about 8 feet deep. It was shaped like a cone, with a small opening at the top, similar to the old-fashioned oubliette. I looked at the floor, and shuddered when I realized what a narrow squeak I might have had; for on the centre of the floor were the mouldering remains of a pointed stake, which had been originally fixed upright in the earth floor on the place where I had fallen.

“Is Bwana (master) hurt?” said the voice of Jumbi from somewhere in the black darkness above.

I replied that I was not hurt, but that I could not get out without assistance; whereupon Jumbi lowered his rifle, and, to the accompaniment of a vast amount of scrambling and kicking, hauled me bodily out.

We were by this time very near to the men for whom we were searching, as we could hear their voices raised in argument about the path. We stopped and called to them, and presently they joined us, and we all set off together to join my main party. We reached it without further mishap, and resumed our interrupted march.

It was very dark indeed. I could not see my hand when I held it a couple of feet from my face. One of the[Pg 22] men happening to remark that he had been over the path some years before, I immediately placed him in the van as guide, threatening him with all sorts of pains and penalties if he did not land us at our destination some time before midnight.

I was particularly anxious to rejoin George, as I had the tents, blankets, and food, and he would have a very uninteresting time without me. We marched, therefore, with renewed vigour, as our impromptu guide stated that he thought one more hour’s march would do the business. It didn’t, though. For two solid hours we groped blindly through belts of forest, across open spaces, and up and down wooded ravines, until somewhere about eleven p.m., when we reached a very large and terribly steep ravine, thickly clothed with trees, creepers, and dense undergrowth. We could hear the rushing noise of a considerable volume of water at the bottom, and in the darkness it sounded very, very far down.

I halted at the top to consider whether to go on or not, but the thought of George waiting patiently for my appearance with supper and blankets made me so uncomfortable that I decided to push on if it took me all night. We thereupon commenced the difficult descent, but halfway down my doubts as to the advisability of the proceeding were completely set at rest by one of the men falling down in some kind of a fit from over-fatigue. The others were little better, so I reluctantly decided to wait for daylight before proceeding further. I tried to find something to eat among the multifarious loads, and fortunately discovered a piece of dry bread that had been thrown in with the cooking utensils at the last moment. I greedily devoured it, and, wrapping myself in my blankets, endeavoured to sleep as well as I[Pg 23] was able on a slope of forty-five degrees. A thought concerning George struck me just before I dropped off to sleep, which comforted me greatly. “George knows enough to go in when it rains,” I thought. “He will leave the men with the cattle, and go over to Kriger’s place and have a hot supper and a soft bed, and all kinds of good things like that,” and I drew my blankets more closely round me and shivered, and felt quite annoyed with him when I thought of it.

At daylight we were up and off again, and, descending the ravine, crossed the river at the bottom, and continued the march. On the way I shot a guinea-fowl, called by the Swahilis “kanga,” and after an hour and a half of quick walking I came up with George.

He had passed a miserable night, without food, blankets, or fire, and, to make matters worse, it had drizzled all night, while he sat on a stone and kept watch and ward over the cattle. The men who had accompanied him were so tired that they had refused to build a boma to keep the cattle in. He seemed very glad to see me. We at once got the tent put up, a fire made, and the boma built, and soon made things much more comfortable. In fact, we got quite gay and festive on the bread and marmalade, washed down with tea, which formed our breakfast.

El Hakim was at Kriger’s place, about a mile distant. We had to wait two or three days till he was ready to start, as he had a lot of private business to transact. We left all the cattle except nine behind, under Kriger’s charge; we sent the nine back subsequently, as we found they were more trouble than they were worth.

In the evening I went out to shoot guinea-fowl; at least, I intended to shoot guinea-fowl, but unfortunately I saw[Pg 24] none. I lost myself in the darkness, and could not find my way back to camp. After wandering about for some time, I at last spied the flare of the camp fires, halfway up a slope a mile away, opposite to that on which I stood. I made towards them, entirely forgetting the small river that flowed at the foot of the slope. It was most unpleasantly recalled to my memory as I suddenly stepped off the bank and plunged, with a splash, waist deep into the icy water. Ugh!

I scrambled up the opposite bank, and reached the camp safely, though feeling very sorry for myself. El Hakim and George thought it a good joke. I thought they had a very low sense of humour.

On the following morning George and I sallied forth on sport intent. George carried the shot-gun, and I the ·303. We saw no birds; but after an arduous stalk, creeping on all fours through long, wet grass, I secured a congoni. Congoni is the local name for the hartebeeste (Bubalis Cokei). The meat was excellent, and much appreciated. El Hakim joined us in the afternoon, accompanied by Mr. Kriger and Mr. and Mrs. Knapp, who wished to inspect our camp. We did the honours with the greatest zest, knowing it would be the last time for many months that we should see any of our own race.

The day afterwards El Hakim and I rode into Nairobi, accompanied by some of the men, and brought back twelve days’ rations of m’chele (rice) for our safari, as we intended starting the following day. Kriger and Knapp decided to come with us on a little pleasure trip as far as Doenyo Sabuk, a bold, rounded prominence, rising some 800 feet above the level of the plain, the summit being over 6000 feet above sea-level, lying about four days’ journey to the north.

[Pg 25]

Oil to Doenyo Sabuk—Troubles of a safari—George takes a bath—The Nairobi Falls—Eaten by ticks—My argument with a rhinoceros—The Athi River—Good fishing—Lions—Camp near Doenyo Sabuk—We find the Athi in flood—We build a raft—Kriger and Knapp bid us adieu—Failure of our raft—We cross the Athi—I open a box of cigars—Crossing the Thika-Thika—Bad country—We unexpectedly reach the Tana—The détour to the Maragua—Crossing the Maragua—In Kikuyuland.

Kriger and Knapp joined us on the morning of June 7th, and at 2 p.m. we set out on our eventful journey. It was rather a rush at the last moment, as so many things required adjustment. It was impossible to foresee everything. I stopped behind as whipper-in for the first few days, as the porters required something of the sort at the commencement of a safari, in order to prevent desertions, and also to assist those who fell out from fatigue.

On the first day I had a lot of trouble. The donkeys annoyed me considerably; they were not used to their loads, and consequently they kept slipping (the loads, not the donkeys), requiring constant attention.

The porters also were very soft after their long carouse in the bazaar, and every few yards one or another sat down beside his load, and swore, by all the saints in his own[Pg 26] particular calendar, that he could not, and would not, go a step farther. It was my unpleasant duty to persuade them otherwise. The consequence was, that on the evening of the first day I got into a camp an hour after the others, quite tired out. It was delightful to find dinner all ready and waiting. To misquote Kipling, I “didn’t keep it waiting very long.”

The next morning we crossed one of the tributaries of the Athi River. It was thickly overgrown from bank to bank with papyrus reeds, and we were consequently obliged to cut a passage. The donkeys had also to be unloaded, and their loads carried across. We got wet up to the knees in the cold, slimy water, which did not add to our comfort. We passed a rhinoceros on the road, but did not stop to shoot him as we were not in want of meat.

Crossing another river an hour or so later, we made the passage easily by the simple expedient of wading across up to our middles, without troubling to undress or take our boots off; all except George, who was riding the mule. He declared that he “wasn’t going to get wet!” we could be “silly cuckoos” if we liked! he was “going to ride across.” He attempted it; halfway across the mule slipped into deep water, plunged furiously to recover itself, broke the girth, and George and the mule made a glorious dive together into ten feet of water. Jumping in, I succeeded in getting hold of the mule’s head while George scrambled ashore, gasping with cold. In the mean time Kriger and Knapp with El Hakim had got some distance ahead, leaving George and myself to see the safari safely across. When we reached the other side we found ourselves in a swamp, through which we had to wade for over a mile before reaching firm ground. Then the porters struck in a body, saying[Pg 27] they were done up and utterly exhausted, and could go no further. I eventually convinced them, not without a certain amount of difficulty, however, that it would be to their interest to go on.

Soon afterwards I got a touch of sun, and my head ached horribly. I then fastened the saddle on the mule with one of the stirrup straps, and rode some of the way. We reached the Nairobi River towards the close of the afternoon, and crossed by clambering over the boulders plentifully strewn about the river bed. Just below were the Nairobi Falls, which are about 100 feet deep, and extremely beautiful.

At the foot of the Falls the river flows through a deep, rocky glen, which in point of beauty would take a first prize almost anywhere. Great water-worn boulders, clothed with grey-green and purple mosses, among which the water trickled and sparkled in tiny musical cascades; ferns of rare beauty, and flowers of rich and varied hues, gave an artistic finish to the whole; an effect still further accentuated by the feathery tops of the graceful palms and tree ferns that grew boldly out from the steep and rocky sides of that miniature paradise.

We found the others had camped a few yards away from the Falls. Kriger and Knapp had been fishing, and had caught a lot of fine fish; Kriger had also shot a congoni. I had my tent pitched, and immediately turned in, as I felt very tired and feverish. Walking in a broiling sun, and shouting at recalcitrant porters for eight and a half hours, on an empty stomach, is not calculated to improve one physically or morally.

After a good night’s sleep I felt much better, and decided to walk when we made a start next morning, handing the mule over to George, who had been very seedy ever since[Pg 28] we left Nairobi, the result of his recent severe illness in Uganda. When the tents were struck, we headed due northwards to Doenyo Sabuk, which was now beginning to show up more clearly on the horizon. It was about twenty miles distant, and we calculated that two days’ further marching would take us round it.

Soon after we started Knapp shot a guinea-fowl. He used a Winchester repeating shot-gun, a perfectly horrible contrivance, of which he was very proud. When the cartridges were ejected it clanked and rattled like a collection of scrap iron being shaken in a sack.

During that march we had a maddening time with the ticks, with which the Athi plains are infested. They were large, flat, red ticks, similar to those I have seen in Rhodesia (Ixodes plumbeus?). They clung to our clothing and persons like limpets to a rock. We should not have minded a dozen or two, at least not so much, but they swarmed on us literally in thousands. We halted every few moments while Ramathani brushed us down, but, so soon as we were comparatively cleared of them, we picked up a fresh batch from the long grass. They bite very badly, and taking them by and large, as a sailor would say, they were very powerful and vigorous vermin; almost as vigorous as the language we wasted upon them.

About an hour after we started we sighted a rhinoceros fast asleep in the grass, about three hundred yards down wind. George and I examined him with the binoculars—the others were a mile ahead—and as we were not out looking for rhinoceros just then, we passed on. We had proceeded barely a quarter of a mile when a confused shouting from the rear caused us to look round. The sleeping rhinoceros had wakened, and proceeded to impress[Pg 29] the fact upon the safari. Having winded the men he incontinently charged them, and when George and I glanced back we saw the ungainly brute trotting backwards and forwards among our loads, which the men had hurriedly dropped while they scattered for dear life over the landscape. It was certainly very awkward, as it looked very much as if I should have to go back and slay it, which, I will confess, I was very loth to do, as Ramathani was some distance ahead with all my spare ammunition. The magazine of my ·303 contained only half a dozen cartridges, with soft-nosed bullets. I diplomatically waited a while to see if the brute felt disposed to move; but it was apparently perfectly satisfied with its immediate surroundings, and stood over the deserted loads snorting and stamping and looking exceedingly ugly.

The cattle and donkeys, which were under Jumbi’s charge, were also coming up. Jumbi came as near as he dared, and then halted, and waited in the rear till it should please the Bwana (meaning me) to drive the “kifaru” away. The rest of the porters having scuttled to what they considered a safe distance, sat down to await events with a stolid composure born of utter irresponsibility.

I felt, under the circumstances, that it was incumbent upon me to do something, it being so evidently expected; so I advanced towards the rhinoceros, not without some inward trepidation, as I greatly distrusted the ·303. Walking to within fifty yards of the spot where it was stamping defiance, I shouted at it, and said shoo! as sometimes that will drive them away. It did not move this beast, however, so, mentally donning the black cap, I took careful aim, and planked a bullet in his shoulder! If it was undecided before the beast soon made up its mind then, and, jumping round[Pg 30] like a cat, came straight for me at a gallop, head down, ears and tail erect, and a nasty vicious business-like look about the tip of his horn that gave me cold chills down the spine. I don’t wish to deny that I involuntarily turned and ran—almost anybody would, if they obeyed first impulses. I ran a few yards, but reason returned, and I remembered El Hakim’s warning that to run under such circumstances was almost invariably fatal. I turned off sharply to the right, like the hunters in the story books, hoping that my pursuer would pass me, and try one of the porters; but he wouldn’t; he had only one desire in the wide, wide world, and that was to interview me. I, on the other hand, was equally anxious not to be interviewed, but I must admit that at the moment I did not quite see how I was to avoid it. He was getting closer and closer at each stride, so there being logically no other way, I stopped and faced him.

I therefore knelt down and worked my magazine for all I was worth, fervently hoping that it would not jam. In less than ten seconds I put four bullets into the enraged animal at short range. All four took effect, as I distinctly saw the dust spurt from his hide in little puffs where they struck. At the fourth shot he swerved aside, when within fifteen yards of me, and as he turned I gave him my sixth and last cartridge in the flank to hasten his departure; and very glad indeed I was to see him go. He had six bullets in various parts of his anatomy; but I expect they did little more than break the skin, though the shock probably surprised him. He disappeared over a rise in the ground a mile away, still going strong; while I assumed a nonchalant and slightly bored air, and languidly ordered the men to take up their scattered loads and resume the march.

An hour or so after we reached and crossed the Athi[Pg 31] River. It was a hot and dusty tramp. Kriger being some miles ahead, had, with a laudable desire to guide us, fired the grass on his way. The result was hardly what he anticipated. The immense clouds of smoke gave us our direction perfectly well, but the fire barred our progress. Quite half a dozen times we had to rush through a gap in the flames, half choked and slightly singed. Once or twice I thought we should never get the mules or donkeys through at all, but we chivied them past the fire somehow. The burnt ground on the other side was simply horrible to walk on. I fully realized what the sensations of the “cat on hot bricks” of the proverb were. Kriger meant well, but, strange to say, neither George nor I felt at all thankful. As a matter of fact, our language was at times as hot as the ground underfoot, not so much on our own account as on that of our poor barefooted men.

The Athi was not very wide at the point where we crossed, but a little distance lower down it becomes a broad and noble stream flowing round the north side of Doenyo Sabuk till it joins the T’savo River about 120 miles south-east of that mountain, the two combining to form the Sabaki, which flows into the sea at Milindi. The Athi is full of fish, and we saw fresh hippopotamus’ tracks near the spot where we camped at midday.

After lunch George and I went fishing with Kriger and Knapp: net result about 40 lbs. of fine fish, a large eel, and a mud turtle. Afterwards Kriger and I went out shooting. We were very unlucky. Out on the plains towards Doenyo Sabuk we saw vast herds of game, including congoni, thompsonei, zebra, impala, and water-buck, but the country was perfectly flat and open and the wind most vexatiously variable, so that, do what we would, we could[Pg 32] not get within range. I managed to bag a hare with the before-mentioned piece of mechanism which Knapp miscalled a shot-gun. Soon afterwards we were traversing some broken rocky ground when Kriger suddenly exclaimed, “Look, there are some wild pig!” We started after them, and got within a hundred yards before we discovered that the supposed wild pig were a magnificent black-maned lion and four lionesses. They spotted us almost as soon as we had seen them, and when we tried to get near enough for a shot they walked into a patch of tall reeds and remained there growling, nor would they show themselves again. We did not think it good enough to tackle five lions in thick reeds, so we reluctantly withdrew.

Kriger had shot a lion some months previously, and was attacked and badly mauled by the lioness while examining the prostrate body of his quarry, his left arm being bitten through in several places. He struggled with her for some minutes, forcing his arm between her open jaws, and thereby preventing her from seizing his shoulder or throat. His life was only saved by a sudden fall backwards over a bank which was concealed by the undergrowth. The lioness was so surprised by his complete and utterly unexpected disappearance that, casting a bewildered look around, she turned and fled.

We continued our hunt for game, and presently Kriger wounded a congoni. It appeared very badly hit, and we followed it for several miles in the hope that it would drop; but it seemed to get stronger with every step, and finally, to our great disgust and disappointment, joined a herd and galloped away, while we sat down on the hard cold ground and bemoaned our luck. On the way back to camp—and a weary walk it was—we shot another solitary congoni at three[Pg 33] hundred yards’ range, and fortunately hit him; but we put three bullets each into the beast before it dropped, so remarkably tenacious of life are these animals. We returned to camp at dusk, thoroughly tired out. I retired to rest immediately after dinner, thus concluding a not entirely uneventful day.

We did not march the next day, as El Hakim wished to examine the surrounding country from a farming and stock-raising point of view. He and Kriger rode off on the mules after breakfast with that intention. Knapp and I went fishing, while George—sensible chap—laid himself on the grass in the shade and watched us. Knapp caught one very fine fish weighing over 9 lbs., while I caught only two small fish and a sharp attack of fever. I returned to camp and climbed into my blankets. In an hour and a half my temperature rose to 105°, and I felt very queer indeed; but towards evening I recovered sufficiently to eat a little. El Hakim and Kriger returned at 6 p.m., having explored the adjacent country to their satisfaction, and on their return journey they shot a zebra and a congoni. Zebra meat is excellent eating, especially if it has been hung for three or four days. When cooked it is firm and white, in appearance somewhat resembling veal. We always secured the strip of flesh on each side of the backbone, called by the Swahilis “salala” (saddle), and also the under-cut, or “salala n’dani” (inside saddle), for our private consumption. The kidneys are very large, as big as one’s fist; and they, as are also the brains, are excellent eating when fried in hippo fat.

We started at 7 a.m. on the following morning, El Hakim, Kriger, and Knapp going a long way ahead, leaving George and myself with the big mule, to look after the safari. George was still so queer that he could hardly sit on the[Pg 34] mule. He was constantly vomiting, and at every fresh paroxysm the mule shied, so that poor George had anything but a cheerful time. I did not know the way, and depended wholly for guidance on the spoor of the others who had started early.

Soon after starting, a pair of rhinoceros charged us, scattering the safari far and wide over the plain in a medley of men, loads, donkeys, and cattle. I went back with the 8-bore, which I had kept close to me since my experience two days before, but before I could get near them they made off again, nearly getting foul of Jumbi in their retreat. He had hidden himself in the grass, and they passed within a dozen yards of him without becoming aware of his presence.

I have mentioned that I was depending for guidance on the spoor of that portion of the caravan which had preceded me, so it can be imagined that I was exceedingly surprised to come upon a party of the men who had left camp before me, sitting down waiting for me to come up. On being questioned they stated that the “m’sungu” (white men) were “huko m’beli” (somewhere ahead), but as they had lagged behind, and so lost them, they had waited for me to come up and show them the way. I was in something of a quandary, as, the ground being very rough and stony, no tracks were visible. After a moment’s consideration I decided to make for the north end of Doenyo Sabuk, which was quite near, as I knew the others intended going somewhere in that direction. On the road I stalked and shot a congoni, but my Swahili aristocrats refused to touch the meat, as I, and not they, had cut its throat, consequently it was “haran” (i.e. sinful, forbidden). They were much less fastidious later on, and ate with avidity far less palatable food than freshly killed congoni.

[Pg 35]

After a solid eight hours’ march I came up with the others. They had camped on the right bank of the Athi, which at this place is very broad and deep. It makes a vast curve here from due north to south-east, so that we were still on the wrong side of it, and would have to recross it in order to reach the Tana River. Kriger and Knapp were, as usual, fishing, and had caught some magnificent fish, averaging 9 lbs. to 10 lbs. each. On our arrival in camp, George and I had a refreshing wash and a cup of tea, which revived us considerably. In the evening I shot a crested crane (Belearica Pavonina) with the ·303. George went to bed early, as he was very weak and exhausted; I did not feel very bright either, after the smart attack of fever I had had the day before, coupled with that day’s eight-hour tramp in a blazing sun.

We did not move on the following day, as El Hakim wished to examine the surrounding country. He and Kriger accordingly saddled up the mules and made another excursion. They saw a leopard on the road about a mile out of camp, but the man who was carrying their guns was, unfortunately, some distance in the rear at the time. I believe El Hakim used bad language, but I could not say for certain, though I do know the gun-bearer looked very sorry for himself when they returned to camp in the evening. They saw some very pretty falls on the river lower down, situated in the midst of a very lovely stretch of park-like scenery. El Hakim was quite enthusiastic about them.

We spent the next day looking for a place to cross the river. It was from this camp that Kriger and Knapp were to return to their station, and our journey was really to begin. We examined a ford that Kriger knew of, two hours’ journey up the river, but found the river in flood and the[Pg 36] ford deep water. On the way back El Hakim shot a congoni, which gave us a much-needed supply of fresh meat. As there seemed no other way out of the difficulty, we decided to build a raft. We found it a very tough task, there being no material at hand, as the wood growing near was all mimosa thorn, so hard and heavy when green that it will hardly float in water. We spent all the afternoon, waist-deep in the river, lashing logs together with strips of raw hide cut from the congoni skins. When the raft was finished, just before sundown, it looked very clumsy and unserviceable, and we had very grave doubts of its utility, as the volume of water in the river was very great, and the pressure on such an unwieldy structure was bound to be enormous—much more than any rope of ours would stand. However, that was a question that the morrow would decide; so we moored the raft to an island a few yards from the bank, and went back to camp for dinner.

We dined on the crane I had shot two days before. It was as large as a small turkey, and splendid eating, though my ·303 had rather damaged it. El Hakim and I sat up late into the night, making final arrangements and writing letters, which Kriger was to take back with him next morning, when we intended to make a determined effort to cross the river en route for Mount Kenia and the “beyond.”

Kriger and Knapp returned to Nairobi early on the morning of June 14th. They took our remaining cattle back, as we found them too much trouble, and El Hakim had others at Munithu, in North Kenia, which we could use if we required them for trade purposes. We bade them adieu, and they returned the compliment, wishing us all kinds of luck. They then departed on their homeward journey.

THE ATHI RIVER NEAR DOENYO SABUK.

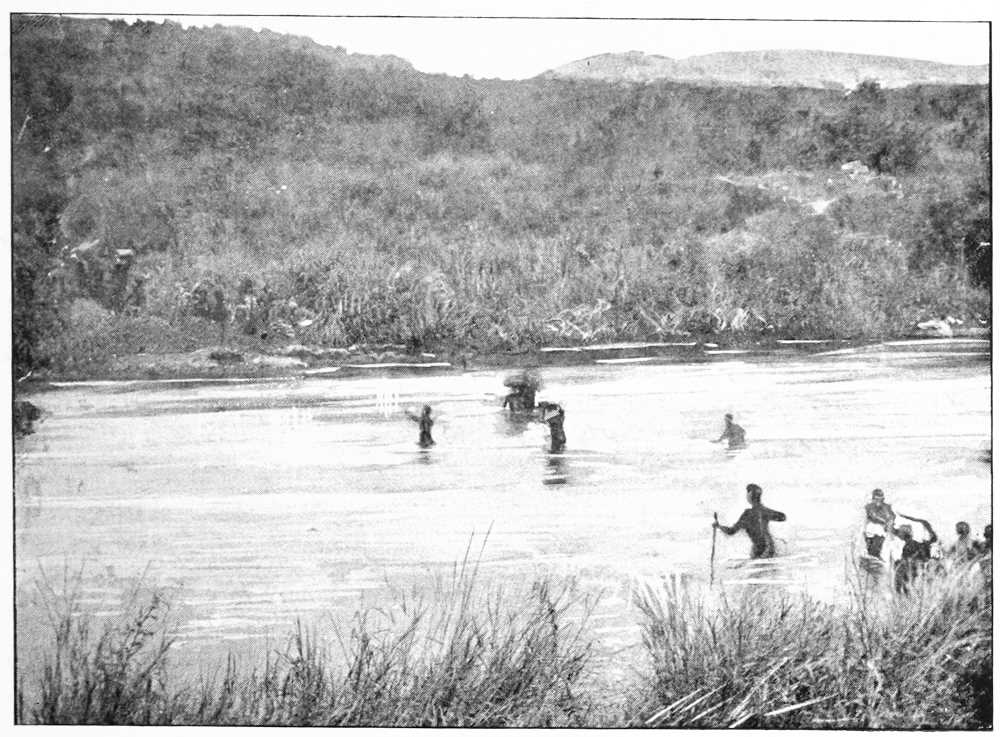

CROSSING AN AFFLUENT OF THE SAGANA. (See page 50.)

[Pg 37]

We found our raft waterlogged and almost entirely useless, but we determined to try what we could do with it. We had great difficulty in persuading the men to go into the water, but managed it at last, and got a rope across the river with which to haul the raft over. We put two loads on it, and though they were got safely across they were soaked through, and once or twice very nearly lost. When we tried to haul our raft back the rope parted, and the unholy contrivance we had spent so much time and labour upon drifted rapidly down-stream, and was lost to sight.

We abandoned the idea of crossing by raft—especially as there was then no raft to play with—and so we prospected up the river-bank for some little distance, and eventually discovered a place that promised a better crossing than any we had previously seen. There were two or three small islands near the hither bank of the river, which narrowed it to more manageable proportions, and by lunch-time we had rigged the rope across the main channel. After lunch we all stripped, and prepared for an afternoon’s hard work; nor were we disappointed. The stream, breast-deep, was running like a mill-race. Its bed was composed of flat slabs of granite polished to the smoothness of glass by the constant water-friction. Strewn here and there were smooth water-worn boulders with deep holes between, which made the crossing both difficult and dangerous. By dint of half wading and half swimming, holding on to the rope for safety, we managed with incredible labour to get all the loads across without accident.

Getting the mules and donkeys across was a still more difficult task. They absolutely refused to face the water, and had to be forced in. Once in, though, they did their best to get across. The mules and four of the donkeys[Pg 38] succeeded after a severe struggle, but the other two donkeys were swept away down-stream. We were unwilling to lose them, so I swam down the river with them, trying to head them towards the opposite bank. I succeeded at last in forcing them under the bank a quarter of a mile or so lower down stream; but at that place it was perfectly perpendicular, and there we stood, the two donkeys and myself, up to our necks in water on a submerged ledge about two feet wide, on one side of us the swiftly rushing river, which none of us wished to face again, and on the other side a perfectly unclimbable bank, topped with dense jungle. I thought of crocodiles, as there were, and are, a great many in the Athi River, and I went cold all over, and wished most heartily that I was somewhere else. I shouted for the men, and presently heard their voices from the top of the bank overhead; they could not reach me, however, as the jungle was so thickly interlaced as to be impenetrable. They tried to cut a way down to me, but gave it up as impossible; besides, they could not have got the donkeys out that way, anyhow.

I grew more than a little anxious about the donkeys, as I was afraid they would lose heart and let themselves drown. Donkeys are like that sometimes when they are in difficulties. I clung to the ears of my two, and held their heads above water by main force. I got cold and chilled, while thoughts of crocodiles would come into my head. Once a submerged log drifted past beneath the surface, and in passing grazed my thigh. I turned actually sick with apprehension, but it went on with the current, and left me shivering as with ague. I ordered some of the men to get into the river and swim down to me, and presently they arrived. I immediately felt much better, as I reflected that my chances of being seized were now considerably lessened.

[Pg 39]