Title: Old comrades

Author: Agnes Giberne

Release date: October 29, 2023 [eBook #71978]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: John F. Shaw and Co, 1896

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

BY

AGNES GIBERNE

AUTHOR OF

"LIFE-TANGLES," "IDA'S SECRET," "WON AT LAST,"

"THE EARLS OF THE VILLAGE," ETC.

LONDON

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO.

48 PATERNOSTER ROW

CONTENTS

CHAP.

II. THINGS NOT IN THE COLONEL'S LINE

XV. THE SOMETHING THAT WAS WRONG

OLD COMRADES

A CHRISTMAS CARD

"DOROTHEA!"

The voice was deep-toned, verging on gruffness, and it lingered over the name, not affectionately, but as if the speaker's mind were absent.

No answer came in words from the girl seated beyond the round table. She lowered the book in her hands, and waited.

"Dorothea!"

"Yes," she said.

"Fetch me the first volume of the Encyclopædia."

"The Encyclopædia?"

"Britannica, of course."

"Downstairs?" Dorothea asked hesitatingly.

"Of course!"—again. "Lowest shelf of the bookcase."

"That long row of big volumes! I think I saw the first volume upstairs."

"Then, my dear, it ought not to be. Everything should always be in its right place."

Colonel Tracy spoke with the air of one enunciating a profound truth, disembosomed by himself for the first time in the history of the world. He was a grey-haired veteran, with large features, a complexion of deep-red rust, and solid though not tall figure. Fifteen years of "retired" life had not undone his Indian military training. When giving an order to daughter or domestic, he was apt still to give it as to a Sepoy. "Ready! Present! Fire!" was the Colonel's style. Domestics were disposed to rebel, where the daughter had to endure.

Dorothea laid down her book, and stood up slowly. There was a controlled stillness about her movements, unusual in girls of eighteen, and not too common in women of middle age. She did not remind her father that he, not she, had conveyed the volume to its present resting-place. One week at home—if this could fairly be called "home"—had shown Dorothea that whatever went wrong would be the fault of anybody rather than of the Colonel. So she left that question alone, and vanished.

The Colonel lifted his head, and looked after her. "Quiet!" he muttered in a gratified tone. "Good thing, too! I hate your bouncing women, slamming the doors, and shaking the house at every step." He had himself a heavy footfall, and he was given to loud shutting of doors, but these were exclusive privileges, not to be accorded to anybody else.

The room which Dorothea left was not attractive. Carpet and curtains were faded; wall-paper and furniture were ugly; ornaments were cheap and in bad taste. There were no dainty knick-knacks on brackets or side-tables. An old-fashioned round table stood in the centre, and was strewn with books—dull books in dull bindings.

London lodgings are not wont to be attractive, especially the second-rate sort. This was the "upstairs parlour" of a very second-rate sort, situated in a side-street of exceptional dreariness.

All the houses on either side of the street were exactly like all the rest. Each had a porch with steps; each had an area with more steps; each had one window of a small dining-room beside the porch, and two windows of a little drawing-room above; each had two bedroom windows yet higher, and most had two garret holes at the top. Each was discoloured with smoke, dingy and dismal. Each had white blinds to the bedroom windows, which seemed to keep up a futile struggle after cleanliness.

These particulars would have been patent in daylight; but daylight vanishes early on a December afternoon in town. Night had drawn its pall over the big city an hour before. A tall candle burnt upon the table, close to the Colonel. He was so used to read and write alone by the light of a single candle, that the need of a second for his daughter had not occurred to him.

She came in, carrying the big volume, laid it down, and stood for a moment beside him, as if to await further orders.

There was nothing "school-girlish" about Dorothea, in the ordinary sense of the word, though she had left school but one week earlier. Of good height, she had a pretty figure, the effect of which was somewhat spoilt by the forward carriage of her head, almost amounting to a poke, and due to short sight. Her face was rounded and pale, and in repose was serious. The wistful eyes looked through a pair of "pincer" glasses, balanced on a neat little nose.

Colonel Tracy was making voluminous notes from a decrepit brown volume, which had lost half its binding. He wrote an atrocious hand, which fact had mattered little hitherto, since nobody needed to read it except himself. Now that he was beginning to wake up to the possession of a daughter who might be useful, a new element came into the question.

"Is that all?" asked Dorothea.

"Humph!" was doubtless meant for thanks, and the girl went towards her seat. But before she could reach it, a supplementary order was issued: "Ha! No! It's not here! Second volume."

"Shall I get the second volume?"

Colonel Tracy glanced up, and really did say "Thanks!" with even a suspicion of apology in the tone.

Dorothea ran down the narrow staircase this time, instead of up. She had to light a candle, and take it into the dining-room. Having found the required volume, some impulse led her to the window, where she peeped through the lowered venetians.

A hansom was dashing past; and two ladies on the pavement seemed to be carrying home an armful of packages. Dorothea could detect a merry ring in their voices as they went. Then came a boy, bearing a big bunch of holly. For this was Christmas Eve.

The Colonel had bought no holly. "Nonsense," he had said that morning, when Dorothea petitioned for some. "You are not a child now, my dear; and I have no money to throw away on rubbish."

Was it rubbish? Dorothea considered the question, as she leant against the window, forgetting for the moment the volume which had to be taken to her father.

"He does not, seem to care much about Christmas," she thought. "I used to feel it dull to stay at school; but this seems more dull. Did Mrs. Kirkpatrick guess how it would be, when she told me I should have worries? She said I must try to draw out my father's sympathies, because he has been so long alone. But how? What can I do? He does not care to talk. I can see that it only bothers him. And he seems to have no friends. Nobody calls to see him, not even any letters come. Will it always be so?"

As if in response, the postman's rap sounded.

"Mrs. Kirkpatrick, I dare say! She will not forget me," the girl said joyously, hastening out.

But the one letter handed to her was addressed "Colonel Tracy."

"I shall hear to-morrow. I did not really expect it sooner," she thought, and she ran lightly upstairs.

"Something for you, father. A Christmas card!" she suggested.

Colonel Tracy looked up. "Christmas card!" he repeated. "Where is the volume?"

"The Encyclopædia! O how stupid of me! The postman came, and I forgot. I'll get it at once."

"Make haste!" hurried her steps. She would have liked to wait and see the envelope opened. Expeditious as she was, that process was over by the time she returned. The Colonel sat bolt upright, gazing at something in his hand, with a singular expression on his sunburnt face. It was a Christmas card, as Dorothea had guessed, and she came fearlessly near, to gaze also. There was a background of dull pale blue, and across the background flew a white dove, bearing in its beak a bunch of leaves—presumably an olive-branch. "Peace and Good-Will" in golden letters occupied one corner.

"Why, father, it is quite an old card," Dorothea exclaimed merrily, anxious to throw herself into his interests. "Look at the soiled edges; and a crease all down the middle. It might be years old."

The Colonel was not communicative. He glanced at her with the same odd expression, and said, "Yes."

"Who can it be from? Some old friend of yours?"

"We were friends—once!"

"And not now?"

"No!" decisively.

"But you exchange Christmas cards?"

"We send—this," after a pause. Colonel Tracy seemed unwilling to explain.

Dorothea knelt on a stool close to the table, resting her hands upon it, much interested.

"Do tell me more," she said. "It is Christmas Eve, and I have nobody else to talk to."

"There is nothing to tell. We had a—a trifling disagreement," said the Colonel. "What makes you wear spectacles?"

"Short sight. Why, father, you know that!"

"I had forgotten. Well, I shall put this away," said the Colonel.

"And send another to your friend?"

"No. Certainly not. Next Christmas, I shall return this."

A light dawned on Dorothea. "Is that it? I see. How strange!"

"Not strange at all. We have done so for some years—eight or nine, I think—alternately."

"Always the same card?"

"Yes."

"And you have never met! And never written!"

"No. Why should we?"

Dorothea was silent for a moment. Then she said, "If you met, you would be friends again."

The Colonel made a dubious sound.

"Was it you who sent the card first, or was it he?"

"Not I."

"And when you first got it, did you wait a whole year to send it back?"

"Certainly."

The wonder in Dorothea's tone was lost upon the gallant Colonel.

"And you will wait a whole year now! Not write a letter, or—"

"I shall wait till next Christmas," said the Colonel.

Thereupon, he pushed the little messenger of peace into a square envelope, wrote upon it, "Christmas Card—Erskine—" and hid it away in his desk.

"Is Erskine his name?"

"Colonel Erskine. We were in the same regiment. He was my senior, slightly; and I believe, he retired first."

"And now he lives at—"

"Craye. My dear, we have talked long enough. I have no more time to spare," said the Colonel, turning with assiduity to vol. ii. of the Encyclopædia.

Dorothea subsided into her chair and into silence. She was not timid, but she did not wish to worry him. Besides, she had something fresh to think about, in the slow progress of reconciliation between the two veterans. "But to have gone on all these years!" she said to herself. "And I wish my father had been the first to send the card."

THINGS NOT IN THE COLONEL'S LINE

LONDON is commonly counted a lively place, with plenty to do, and abundance to see; even though it has its little drawbacks in the shape of noise, soot, and fog. But the compensating liveliness seemed unlikely to enter into Dorothea Tracy's town existence.

If a man wishes for freedom from society, he is as likely to get what he wants in London as in the tiniest village—perhaps more so. Colonel Tracy had never been a man of society. He detested the generality of human beings, hated company, abhorred teas, dinners, and conversation.

In earlier life, he had had one friend—the quondam comrade of the olive-leaf card!—and had lost that friend. He had also had a wife, and had lost that wife.

Thenceforward, habits of seclusion had grown upon him apace. As years went on, he troubled himself to see less and less of his child; though always looking forward, curiously, to the time when he would have her to live with him. Now that time was come, and it found him a confirmed hermit. He had no friends. He associated with no one, called upon no one. As a natural corollary, no one called upon, or associated with him. He did not even belong to a club, for a club means acquaintances, and the Colonel wanted no acquaintances. He lived in a huge overgrown parish, the work of which could never be overtaken by the toiling clergy. A call from one of the curates, some months earlier, had met with no gracious reception, and had not yet been repeated.

The manner of life which might suit the tastes of a retired veteran was not precisely fitted for a young girl. This as yet did not cause the Colonel concern; if indeed it occurred to him. He expected to go on as he had done hitherto, with merely the little addition of a silent and useful daughter. He expected Dorothea to conform unquestionably to his will.

She had come "home," as she called it—or rather, as she had called it beforehand—full of young hopes and dreams. At eighteen, one is apt to see future life through rosy spectacles. In one short week, the glasses had gained a leaden hue, borrowed from the leaden atmosphere around. The hopes were dying; the dreams were fading. Dorothea had had, and would have, some rebellious struggles before settling down to the dead level of existence which seemed inevitable. Thus far, the effect of her surroundings was rather to stupefy than to excite. Everything was so different from the previous expectations of the school-girl, that she did not know what to make of her own position.

A girl naturally wishes for companions. Beyond her father, Dorothea had none; and Colonel Tracy was far too self-absorbed a man to render satisfying companionship. Below the rugged surface, he was in the main kind-hearted; but he lacked the mighty gift of sympathy. He neither understood his daughter, nor troubled himself to be understood by her. Each was more or less of an enigma to the other.

He had his own notions of propriety, and after his own fashion, he was careful. "You are too young to walk out alone at present in London," he had said to Dorothea, the day following her arrival. "I always take my constitutional after breakfast, and you may accompany me. I hope you are a good walker. If it should be necessary for you to leave the house at any time when I am otherwise engaged, you must have Mrs. Stirring for a companion. She has promised me to attend to your wants."

Mrs. Stirring was the lodging-house keeper: a highly respectable little woman, "genteel" to a degree in her own estimation, but apt to be plaintive in tone and behindhand in work. So she was not always an available "companion," and when available she was not too cheerful.

The morning "constitutional" became a daily event, regular as breakfast itself when weather permitted. Happily, Dorothea was a very good walker. The Colonel went fast and far; and he never thought of asking whether pace or distance suited his daughter's capabilities. Dorothea enjoyed the rapid motion and the comparative freshness of the morning air. She would have enjoyed some conversation likewise; but the Colonel was seldom in a talkative mood. If she spoke, he grunted; if she asked a question, he answered it, and that was all.

How to fill the remaining hours of the day became, even in one week, something of a problem to Dorothea. She had work in hand, but it is dull, at the age of eighteen, to sit and work with no one to take any interest in the progress of the needle. She dearly loved reading, but the Colonel's books were such as to put that love to a pretty severe test. She could have spent hours happily any day in writing to Mrs. Kirkpatrick and her favourite schoolfellows; but her father's pet economy was in the matter of paper and stamps. So time threatened to hang upon Dorothea's hands.

Nine years had elapsed since the death of Dorothea's mother; and the greater part of those nine years had been spent by her in a small Yorkshire school, kept by Mrs. Kirkpatrick. That had grown to be Dorothea's real "home." She hardly realised the fact while there, loyally reserving the term for future life with her father, and sometimes counting it a little hard to spend so many of her holidays at school. But now that the long-expected life with her father had begun, she knew well enough which was the real home.

Through the nine years Colonel Tracy had lived more or less in London, often going abroad for a while. It had happened curiously often—almost regularly—that he had to go abroad just before Dorothea's holidays, so that he was "quite unable to receive her." Whether the more correct word would not have been "unwilling" may be doubted. He was a man who disliked trouble; and he had no notion of doing on principle that which he disliked, for the sake of others.

About once a year, he had commonly arranged to spend a fortnight at some northern watering-place with Dorothea: this being the least troublesome mode he could devise for amusing a school-girl. From the age of twelve to the age of eighteen, she had never been to London. "Too expensive a journey," the Colonel said, though he made nothing of going himself north or south, travelling first-class. He liked to have Dorothea always within easy reach of Mrs. Kirkpatrick, that he might get her off his hands without difficulty when he found the girlish spirits too much.

Dorothea's recollections of his manner of life in town, seen before her thirteenth birthday, had grown somewhat dim, and perhaps were embellished by distance. Moreover, he had often changed his headquarters since those days, so her recollections were the less important. Certainly she did not expect what she found. The first glimpse of the dingy apartments, which for more than a year, he had made his home, gave a shock. Had the Colonel been aware of her sensations, he would have counted them unreasonable. He had "done his duty by her" in the matter of education. He expected now that she should "do her duty by him" in the matter of submission and usefulness.

Dorothea was a girl of too much character not to be useful, of too much principle to indulge in discontent. Still, this week had been a week of "deadly dulness"; and what there was for her to do, she had, as yet, failed to discover.

The Colonel arranged everything, ordered dinner, interviewed the landlady, and undertook to procure fish and vegetables. He piqued himself upon his intimate acquaintance with household details. He needed neither advice nor help. Dorothea was a mere adjunct in his existence thus far, less important than the said fish, less necessary than the said vegetables. She felt like a stranded boat, cast upon a mudbank, out of reach of the tide of life which surged and roared around. This, in a London street, where cabs and hansoms dashed past, where the sound of the great human Babel never ceased.

* * * * * *

Christmas morning dawned.

"I shall hear from Mrs. Kirkpatrick to-day," thought Dorothea cheerily. "Will my father go to Church with me?"

He had excused himself the Sunday before on the plea of bad weather and "indigestion." "Bad weather" did not keep the Colonel in when he wanted to secure fresh fish for dinner; but Church was another matter. Dorothea had had to content herself with Mrs. Stirring's companionship. The Church was very near, so near that she meant soon to plead for leave to go alone.

"Good morning, father," she said, in her brightest tone, when he came into the dining-room. He was punctual to the moment, yet Dorothea was before him.

An indistinct grunt served for "good morning." The Colonel was exercised in mind, to think that Dorothea should have already made the tea. It was no small trial to give up his tea-making to her, which he had done as in duty bound, he being man and she woman; and he liked to stand close by, watching with critical eyes, as she measured out each spoonful. On the Colonel's plate lay a neat white package, tied round with blue ribbon. He was far too much absorbed in the tea-question to notice it.

"How many spoonfuls did you put in, my dear?"

"Three, father. One for you, one for me, and one for the teapot. Mrs. Kirkpatrick always said—"

"Full spoons, but not piled up?" demanded the Colonel, wrinkling anxiously the skin of his face.

"Yes; just as you showed me."

"And the teapot,—you made the teapot hot first?"

Dorothea nodded. She had to bite her lips to keep from laughing, as the Colonel lifted the lid and peered in.

"Too much water! A great deal too much water!" he said solemnly.

"No, I don't think so indeed. It will all come right," Dorothea assured him with audacious confidence. "O father, never mind the tea. See what Mrs. Kirkpatrick has sent me."

The Colonel did not wish to receive the article in question, but Dorothea put it resolutely in his hands. He found himself dangling helplessly a small blue satin pincushion, with "Happy Christmas" worked in white beads.

"Eh, what? yes. Very pretty," said the Colonel. "Yes, quite smart."

"And three Christmas cards, from my schoolfellows."

"Eh? Yes,—uncommonly pretty. What's the use of them all?" demanded the Colonel, merely because he was at a loss what else to say.

"The use, father! The use of Christmas cards?"

"Well,—yes. What's the use?" persisted the Colonel.

Dorothea stood opposite him, smiling; the light falling full upon her glasses, with the gentle light eyes behind.

"Don't they all do what yours did last night? Don't they all speak of 'peace and good-will'?"

This was a shade too personal, and the Colonel dropped Dorothea's pincushion in a hurry.

"Yes, yes, of course,—all right, no doubt. But such things are not in my line, I'm afraid. Too much trouble for a busy man to bother about a lot of cards."

Did Dorothea hear him? She was looking towards the window wistfully, dreamily; a moist glitter showing through her glasses.

"I'm not sure," she said as if to herself, "but I almost think Christmas cards are a sort of carrying on of the angels' song. A sort of echo of it. Don't you think so, father?"

"My dear, I'll trouble you to ring the bell. Mrs. Stirring will over-do the cutlets, and it's time the tea was poured out. Brewed long enough. You'd better take all that rubbish off the table. What's this?"

Any amount of notes of admiration might have been written after the question. Dorothea watched him, smiling, though she rebelled internally against the word "rubbish."

"Some mistake," said the Colonel gruffly.

"No, father; it is for you. It is from me."

Colonel Tracy looked extremely uncomfortable. He had had presents from Dorothea from time to time; but always as it happened by post; little bits of pretty handiwork, which he could smile over grimly, and consign to a lumber-drawer, only wishing that they would not come because he had to compose a sentence of thanks in his next letter. But for years he had received no present in public, so to speak,—with a witness to his manner of reception. That the giver should be seated opposite was embarrassing, and that he should be expected to show pleasure was more embarrassing still. His red rust complexion grew redder than usual, and an awkward laugh broke from him, as he took refuge in blowing his nose. Still Dorothea looked expectant, and the parcel had to be opened.

"I'm much obliged, I'm sure. But you see this sort of thing isn't in my line," said the Colonel.

"Don't you use shaving-tidies, father? Mrs. Kirkpatrick thought—"

"Well, well, of course I use—something," said the Colonel, shoving his new possession aside, to make room for cutlets and hot plates. "Yes, of course; but you had better not waste pretty things upon me in future, my dear. You see, they're not in my line. Other people appreciate them better."

"But I have nobody else," the girl said.

She was a little hurt and disappointed; no doubt more so than she would admit even to herself. It was evident that her well-meant effort merely bored the Colonel. "I hope you don't expect Christmas presents from me," the Colonel went on, helping himself vigorously. He noted her words, and was alarmed lest something sentimental should follow. "You see, I was not brought up to the sort of thing; and really I could not be troubled to choose. But if you would care to get something for yourself, I have no objection to give you five shillings."

Dorothea did not speak at once.

"That reminds me," pursued the Colonel, anxious to get away from a ticklish subject; "that reminds me! I intend to make you an allowance of twenty pounds for your clothes, beginning with five pounds on the first of January. I hope you will keep strictly to the amount, and on no account allow yourself to run into debt. Nothing worse than debt!"

"Thank you, father," Dorothea said slowly.

"Anything you'd care to do to-day? Take a 'bus and go into the country, if you like?" said the Colonel, meaning that they would do it together.

Dorothea looked surprised. "I am going to Church, of course," she said.

"Oh, ah,—yes, I forgot! No doubt,—quite correct. By-the-bye, I'm not sure about Mrs. Stirring, whether she can escort you, I mean. Turkey and plum-pudding, you know. Couldn't leave them, could she?" The Colonel was old-fashioned, and stuck to early dinner through all vicissitudes of fashion. "So I think you'll have to come out with me this morning, and be content to go to Church in the evening,—eh, my dear?"

"Father, I always go, morning and evening. I could not stay away. Won't you come too?"

"I—really, I should be happy to oblige you, but something at a distance requires my attention. Besides, week-days are not Sundays. Perhaps I'm not quite so much of a Church-goer as you. Now and then we will do it together,—on Sunday,—but I'm not so young as I was, and, in fact,—however, about this morning?"

"If Mrs. Stirring cannot go, I must go alone." She spoke in a resolute low voice. "It is so near; there cannot be any harm. I could not stay away on Christmas Day,—for no real reason."

"H—m!" her father said, in a dubious tone.

"I shall want to go often, when Mrs. Stirring is not free. Please don't make any difficulty. Let me have that one happiness," she pleaded. "Only two streets, and such quiet streets. And I look older than I am."

"Well, well!" the Colonel foresaw agitation, and feminine agitation was his abhorrence. "Well, well,—I suppose I must say yes. But mind, nowhere else, and never after dark. Not after dusk. The distance isn't much, as you say. Take another cutlet?"

The Colonel impaled one on a fork, and held it out.

"No? Why, you don't half eat." He landed the rejected article on his own plate, and disposed of the eatable portions in four mouthfuls. "Coming for a walk this morning?"

"No, I think not. I might be late for Church."

"You're like your mother. She was just such another Church-goer," said the Colonel, as if remarking on an idiosyncrasy of character.

Dorothea could be interested now. She felt relieved and free. "Was my mother like me in other ways?"

"Pretty well. Pretty well," said the Colonel, wiping his moustache.

"Did she know the Erskines?" This question came suddenly, almost surprising Dorothea herself.

"Well—yes. She and Mrs. Erskine were great friends—at one time."

"But not after you and Colonel Erskine quarrelled?"

"Well, not after our—little difference. No, we didn't keep up intercourse. What makes you bother about the Erskines?"

"I don't know. I like to think about them? Do tell me one thing, father,—are there any Erskine girls?"

"I'm sure I don't know. There was one, of course," said Colonel Tracy, getting up. "Done, my dear? For I have to be off. Why, of course! Same name, both of you."

"Dorothea?"

"Yes, Dorothea. Just ring the bell; I want to speak to Mrs. Stirring. She roasted the turkey to a rag last Christmas, and I can't have it happen again. Yes, you were both called Dorothea,—a fancy of the two mothers. Great nonsense, of course; but when women take a notion into their heads, there's an end of it. What a time that girl is! Ring again. The morning will be gone, before I am able to start."

"O! I should like to know if Dorothea Erskine is alive still," cried Dorothea.

USING OPPORTUNITIES

"AND you going out alone, Miss Tracy! And the Colonel that particular! As he wouldn't hear of you crossing the road by yourself."

Mrs. Stirring was manifestly uneasy, counting herself in some sort responsible. She looked upon this motherless young lady as a charge upon her conscience,—otherwise, as one of the many burdens in her life. Mrs. Stirring was a person who professed to carry a great many burdens. She always had been, and always would be, laden with cares; not so much because she had really more cares than other people, as because she had less pluck and endurance for the bearing of them. Where Dorothea would have looked up and smiled, Mrs. Stirring looked down and sighed. The difference was in the individuals themselves; not in the weight of the burdens laid upon them.

To be sure, Mrs. Stirring was a widow, which sounds sad. There are women, however, to whom widowhood comes as a merciful release from unhappy wifehood, and Mrs. Stirring was one of these. She had married in haste, and had repented at leisure. When her husband was taken from her, she had been conscious in her heart of relief from a bitter thraldom, though much too correct a little person to let any such feeling appear through her showers of weeping,—for Mrs. Stirring was a person who had always tears at command. Still—there the consciousness was.

Now for years, she had been a successful lodging-house keeper, and was not only paying her way, but was laying by a nice little sum for the future. She had one child, a pretty winning little girl, and one faithful though uncouth domestic. This was not altogether a bad state of things. Nevertheless, Mrs. Stirring talked on plaintively of her trials and burdens, making capital of the widowhood which had been a release.

"And you going out alone, Miss!" she reiterated, coming upon Dorothea dressed for walking. Mrs. Stirring was apt to be untidy at this hour, and her cap had dropped awry; while Dorothea was the very pink of dainty neatness, in a costume of dark brown, with brown hat to match, relieved by a suggestion of red, the glasses over her happy eyes balanced as usual over the little nose.

"To Church," Dorothea said, smiling. "I wish you could go too."

Mrs. Stirring shook her head dolorously.

"There's the turkey and plum-pudden, Miss," she said, in unconscious echo of the Colonel. "Dear me! Why if I was to leave them to Susanna, I don't think your Pa 'd stay a day longer under my roof; I don't, really. He's that particular about the roasting. I'm all of a quake now with the thought of it—if I shouldn't do it right. And there's the stuffing, and the gravy, and the sauce! And the pudden, as I've boiled six hours yesterday, and it's been on again these two hours. Dear me! No; I couldn't go to church! A poor widow like me 's got to stay at home and mind the dinner."

"I wish my father could dine late," said Dorothea.

A scared look came into Mrs. Stirring's face.

"Now don't you put him up to that—don't you, Miss Tracy. Late dinner means a deal of work. If your papa dined late, he'd dine early too—that's what gentlemen come to. No, I wouldn't wish that. But if I was a lady—like yourself, Miss—and hadn't to be at work all the morning, why I'd be glad enough to put on my best, and go off to Church with the rest of the folks. And take Minnie too."

"Minnie! O I never thought of that! Why should not Minnie go with me?"

"It's like you to think of it, Miss." Mrs. Stirring was evidently gratified. "And I'm sure she'd have been glad enough, for she does fret, being kept in. But the bells 'll stop this minute, and she's in her curl-papers."

"Curl-papers. Can't you pull them out, and smooth her hair, and put on her hat and jacket?"

Mrs. Stirring was injured.

"Dear me! No! My Minnie don't go to Church without she's dressed suitable. I couldn't get her ready under twenty minutes. She's in her oldest frock, and not a tucker to it; and I wouldn't have her go without—not for nothing. And them curls do take a lot of time. Not as I grudge it, if it's a duty."

"A duty! But what do curls and tuckers matter?" cried Dorothea. "What does it matter how she is dressed, if only she is there? We don't go to Church to show off our best dresses. At least, I hope not. Let me have Minnie as she is, only with her hair smooth. If I don't care, who else will mind? Curls don't signify. Do let her come! It seems so sad to stay away for nothing on Christmas Day."

No; Mrs. Stirring scouted the proposal. Minnie to go to Church in an old frock and uncurled hair! She was scandalised. What would the neighbours think? Dorothea had to give in, and turn away.

"As if it mattered how one is dressed—there!" she thought.

Shutting the hall door, she went briskly down the street, with a delicious feeling of freedom. She would not have felt so free, perhaps, if even Minnie had been her companion.

It was a sharp day, and for London tolerably clear. Something of wintry haze hung overhead, of course; but a red sun made efforts to pierce it. Puddles in the road were frozen, and here and there a slippery slide might be seen upon the pavement, perilous for elderly people.

The parting interview with Mrs. Stirring had almost made Dorothea late. As she drew near the bells stopped, and her pace became something like a run. She gained the nearest side-door and went softly in.

The Church, a large red brick building, was already crowded, and Dorothea, glancing round, saw no vacant seat; but somebody beckoned to her, and room was made. Almost immediately the choir burst into the old Christmas hymn, "Hark! the herald angels sing," and the congregation joined with heartiness.

Among all that mass of people, Dorothea knew not a single person, and not a single person knew her. She was a stray unit from a distance dropped into their midst.

Yet the lonely and forlorn sensations which had so often assailed her during the past week did not assail her here. Strangers though these people were to her, and she to them, they were one in a Divine fellowship, they served the same Master, they prayed the same prayers, they sang the same hymns; nay, with many of the throng, she would soon be united yet more closely, for they would "partake" of the same "holy food."

How could she be lonely? A realisation of this union, and a glow of happy love, crept into Dorothea's heart, as she lifted her eyes from the hymn-book and looked around. The angelic message of "Peace and good-will" had been to all of them alike.

"If only I could do something for somebody—not live for myself alone," was the next thought.

Then just across the aisle she saw a little old lady in mourning, distressfully fumbling for something which she could not find. Dorothea's quick glance detected a pair of glasses lying on the floor. In a moment she had stepped out of her place, picked up the glasses, and given them to their owner.

"Thanks," came in a whisper of relief, with a very sweet smile. Dorothea stepped back, blushing slightly to feel that she had done a rather prominent thing; yet she would have done it over again, if required.

The sermon was short, earnest, spirited, mainly about the duty of rejoicing. Not rejoicing only on Christmas Day, only when things seem cheery and to one's mind, but always,—on dark days as well as bright ones, amid anxieties as well as pleasures.

"That is for me, I am sure," Dorothea told herself, looking back to some troubled hours in the past week.

MRS. EFFINGHAM

COMING out of Church, Dorothea found the hour later than she had expected. A very large number had stayed, and it was already past the Colonel's dinner-hour.

"I must make haste," Dorothea thought. As she said the words to herself, she dreamily noted the little old lady in mourning a few yards distant, in the act of crossing the road. "I wonder what her name is? Oh!"

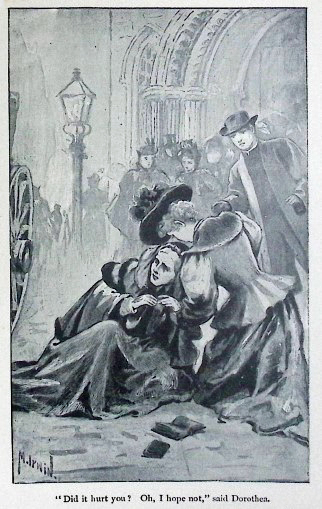

Dorothea's "Oh!" was hardly audible; indeed she felt rather than said it. The old lady had stepped on a slippery spot, or slide, and went down in a helpless heap, just at the instant that a hansom dashed round the nearest corner.

Whether instinct or thought guided Dorothea, she could not afterwards have told. Before she knew what she meant to do, the deed was done.

Two or three ladies near shrieked; and two or three men not so near rushed towards the scene of action. But shrieks were useless, and the men could not be in time.

To everybody's amazement, a young placid-looking girl in spectacles, just leaving the gates, flung herself forward, and by an extraordinary exertion of strength dragged the helpless lady aside from almost under the horse's hoofs. There was not a half-second to spare.

"Did I hurt you? I hope not," said Dorothea, at the sound of a moan. She knelt in the road still, rather paler than usual, but not excited, trying to hold the other up.

"Oh, my dear!" and the old lady burst into tears.

"Hurt! You've saved her life, anyways!" a gruff voice said. "A pluckier thing I never seed!"

Dorothea glanced round, and became aware that her glasses were gone. She had a dim consciousness of a gathering crowd, but to her unaided eyes all beyond a distance of two or three inches was enveloped in mist.

"My spectacles!" she said.

There was a slight laugh, checked instantly, and a gentleman stood by her side, close enough for Dorothea to make out the clerical dress, and a grave rather colourless face.

"I am afraid they have been broken," he said. "Are you sure you are not, hurt yourself?"

"Did it hurt you? Oh, I hope not," said Dorothea.

"Hurt! Oh no!" Dorothea looked up, smiling. "Only I'm so dreadfully blind without glasses. I shouldn't know my own father."

Then a recollection flashed across her of the "turkey and plum-pudden," and of the Colonel's agony of mind if he had to wait.

"But I am afraid I must make haste home," she added. "Could somebody get a cab for—"

"For Mrs. Effingham," as she hesitated. "The hansom will take her home. And you?"

"I live close by—only two streets off. I do hope Mrs. Effingham isn't much hurt," Dorothea went on anxiously.

"My dear, I should have been but for you," said Mrs. Effingham.

The young clergyman had not been idle while speaking to Dorothea, but had gently lifted the little old lady to her feet. Though disorganised as to dress, and agitated still in manner, she was able to stand, with his help.

"No; not much hurt, I think," he said kindly.

"Things might have been very different but for your courage. Now, Mrs. Effingham, I think we had better help you into the hansom. What do you say to dropping this young lady at her door on your way?"

"O no, indeed; it is only three minutes' walk," protested Dorothea. "I wish I had time to see Mrs. Effingham home, but—my father—"

"My dear, I must know where you live. I must come to thank you again," said Mrs. Effingham, her face breaking into its sweet smile, tremulous still.

"I don't want thanks; but I should like to know that you are not the worse for this," said Dorothea. "My father and I live at 77 Willingdon Street."

"And your name, my dear? Miss—"

"Tracy."

"Miss Tracy, 77 Willingdon Street. Will you remember?" Mrs. Effingham asked, looking at the young clergyman, as he led her towards the hansom.

"Certainly," he answered. "I am going to see you home now, if Miss Tracy really prefers to walk."

"Oh, much!" Dorothea answered. She gave her hand girlishly to both of them, then set off at full speed homeward, not in the least upset by her adventure, only smiling to herself.

"Wasn't it curious—happening just after I had so wished to be of use to somebody? Such a dear old lady! I do hope I shall know her. There's an interest in life already. What will my father say? I'm afraid it's awfully late."

The Colonel stood at the dining-room window, looking out, and he reached the front door before Dorothea.

"Twelve minutes past our dinner-hour! Everything will be in rags," he said sepulchrally.

"Father, I couldn't help—"

"Hush: not a word—get ready at, once. Don't lose a moment," entreated the agonised Colonel.

Dorothea fled upstairs, two stops at a time, tore off jacket, hat, and gloves, brushed her hair, washed her hands, and was downstairs with amazing promptitude. But the Colonel's gloom did not lessen.

"Fifteen minutes late! Everything will be spoilt," was his greeting.

"Father, I'm so sorry; but, indeed I couldn't help it," cried Dorothea. She took her seat, for the turkey had appeared, and smiled across the table at him. "I should have been quite in time, but an old lady fell down in the road, and was nearly run over. I just pulled her on one side, and then I couldn't get away till she was safely off."

"Rags! Rags! Rags!" sighed the Colonel dolorously, shaking his head. "Have a slice of breast?"—in a mournful tone, as much as to say, "Nothing worth eating now!"

"Please, father. I'm ravenously hungry. It cuts as if it were tender, doesn't it?" hazarded Dorothea. "Your knife seems to go so easily."

"Tender! It's cooked to rags. All the goodness gone out of it," groaned the unhappy Colonel.

Dorothea judiciously kept silence for a minute or two. The Colonel passed her some delicate slices, helped himself abundantly, and began to eat.

"Father, do you know a Mrs. Effingham?"

"No—" in a preoccupied tone.

"She says she is coming to see me."

At any other time the Colonel would have taken fright. He really was too much absorbed just now with his dinner miseries to understand aught else.

"She is the dearest little old lady, with such a kind smile." A pause. "Father, this is a delicious turkey; and such nice stuffing."

"The turkey would be well enough—properly cooked. No goodness left in it now," said the Colonel. "What made you so late? The service ought to have been over an hour before."

"I stayed to Holy Communion," said Dorothea gently.

The Colonel grunted.

"If it had not been for the accident, I should have been back almost in time."

"Well, another day, pray remember," said the Colonel shortly. "I expect punctuality at meals, whatever else you choose to do. Have some more turkey?"

"No, thank you."

The Colonel gave himself a second bountiful supply, not without sundry muttered strictures, of which "rags" was the only word which reached Dorothea.

Even the "plum-pudden" failed to console him. It had fallen into three parts—the result, he contended, of the fifteen minutes' delay. Everything was spoilt, as he had predicted! The worst Christmas dinner he had had for years!

Dorothea could only listen patiently till dinner was over, and the Colonel took himself off.

DOLLY'S JOURNAL

"I'M awfully excited to-day, because—NO, that is not the way to begin a journal. Margot advises me to start one, now I am eighteen. She has been advising it ever since my birthday, and this morning she gave me a charming little red book, with lock and key. So I suppose I really must do as she wishes."

"She says it will be a make-weight to my spirits when I am disposed to bubble over. Is there any harm in bubbling over? The world would be very dull if everybody's feelings were always to be kept hermetically sealed."

"No fear of mine being so, at all events. I'm not reserved, and I hate reserve, and I can't get on with reserved people. I like to say out just what I think. Of course there must always be some little inner reserves in everybody; at least I suppose so; but that is different from taking a pride in hiding what one feels, and in trying to seem unlike what one is."

"There's one good thing about a private journal! One can say exactly what one likes, and nobody's feelings are hurt. That is the only difficulty about always saying out what one thinks. Some people are so awfully thin-skinned, always taking offence. Of course the polite way of describing them is to say that they are 'sensitive'; but when I speak out what I think, I call them ill-tempered."

"I suppose the correct opening for a journal is a general statement about everything and everybody; a description of one's home and people and ways of life. But that would take a lot of time and patience. If I have the time, I haven't the patience."

"Still, something has to be written by way of introduction, though really I don't know why. If anybody ever reads what I write, it can only be one who knows all about everything already. And most likely my first entry will be my last."

"However—we live at Woodlands; not a big grand place, but the quaintest of old-fashioned houses in the quaintest of old-fashioned gardens. The house has wings and high gables and queer little windows. And the garden in summer has no horrid carpet-patterns or red triangles and blue squares, but is just one mass of trained sweetness—just Nature under restraint. That was what Edred said one day last spring."

"Craye is ten minutes off, down the hill, a funny old town in a hollow. Craye went to sleep a few hundred years ago, like the Kaiser Barbarossa; and unlike the Kaiser, it has never woke up since, not even once in a century. Yet Craye has a railway station, and actually it is not more by rail than an hour and a half from London. Only, as one always has to wait at least an hour at the Junction, the journey can't be done under two hours and a half."

"Now for the preliminary statement about our important selves."

"There is my father first; the dearest and kindest and best old father that ever lived. Not really old either, and so handsome and soldierly still. He can be sharp sometimes, but not to me. He spends lots of time in the clouds, and when he comes out of them, he does dearly love to spoil his Dolly. I am sure she loves to be spoilt."

"Then there is my mother. She is two years older than my father, which didn't perhaps show when they were young, but it does now. A woman of sixty-three is so much more elderly than a man of sixty-one. At least it is so in this house. Mother has silver-white hair, and she stoops, and is getting infirm—more than many of her age; while my father is still slim and upright and active. He has iron-grey hair and never an ache or a pain, and he makes nothing of a fifteen-miles' walk."

"I sometimes think my mother is almost more like a grandmother in the house; so gentle and invalidish, and able to do so little. Yet nothing would go straight without her; and she and he are like lovers still; except that he has a sort of reverent way of looking up to her. He always calls her 'Mother,' and she calls him 'My dear!' Never anything else."

"Next comes Isabel, our eldest. She is thirty, and looks like forty. She has managed everything for the last ten years, and she is a dear good creature,—only rather fussy about little things. She counts herself tremendously severe with me, though she never can say 'No' when I coax; but then she always gives in 'only this once.' She is full of sense, and can't understand a joke by any possibility.

"Then follows Margot, poor dear! Four years younger than Isabel, and eight years older than me. Margot has a weak spine, and lies down a good deal; still she hates to be called an invalid, and never will talk about herself and her symptoms. So people don't get tired of Margot's invalidism. I don't think I should describe her as the model invalid of story books; and yet she is not what Miss Baynes calls 'the fractious sufferer of real life.' Sometimes she has depressed moods, but when she is happy, she has the sweetest face in the world. And even when she is depressed, she never gets into a temper."

"Last of all there is me—Dolly—the household pet and plague. I am not like Issy or Margot. Issy is substantial and slow; and Margot is tall and slim; while I am small and bony, but not a scrap delicate, and everything that I do is always done in a hurry. I have a great lot of fair hair—golden hair some call it—but the trouble of my life is a snub nose,—a real undeniable little snub. Nothing can hide or cure that. Issy's is too long, with a droop at the end, worse even than mine; but Margot has the sweetest little love of a straight nose, neither long nor short. If only I had a nose like hers, I should be perfectly happy."

"Well, no—not perfectly, perhaps; because I should want to be tall and graceful also. It would be so nice to carry one's head higher than other people, and always to be gentle, and calm, and dignified. I should wish to be like Lady Geraldine—"

"'While as one who quells the lions, with a steady eye serenely

She, with level fronting eyelids, passed out stately from the room.'"

"That would be delicious! I suppose most people's eyelids are level, and face the front; but it sounds distinguished. Mine, of course, are level, only they are always on the move, and I am afraid I haven't 'steady eyes serenely' quelling other people."

"O me, what nonsense I am writing! Is that the good of a journal—to show one more of one's real self?"

"I have done at last with regular lessons, and a daily governess. After the holidays, I shall be supposed to read history and French, and to practise regularly. But my plans always come to grief."

"They say I ought to take Emmeline for my model—good dear Emmeline Claughton, who gets up at six and lives by clockwork, and does everything, and has time for everybody. Whereas I lie in bed till nearly eight, and have to scramble to be in time, and spend every day unlike the rest, and hate rules, and never have time for anything except fun and story books, skating in winter, and tennis in summer. So I don't seem likely to grow into a second Emmeline."

"Would Edred be pleased, if I did?"

"How stupid of me to write that! What did make me? I have a great mind to scratch out the sentence. Now I can never show my journal to anybody."

"After all, why should I show it? And what is the harm of speaking about Edred?"

"Perhaps the proper thing here is to make a statement about the Claughtons. They live at the Park and are very rich. There is only one daughter, Emmeline, and Emmeline has two brothers, Mervyn and Edred. Mervyn is the heir, and he does nothing particular, but comes and goes, and bothers people. Edred is a curate in London. I like him—oh, much the best of the two, and so I know does Emmie."

"Mr. Claughton is kind, only too pompous, and I am not very fond of Mrs. Claughton. She has such a way of setting everybody to rights. But very likely, she doesn't mean to be disagreeable."

"I'm most awfully excited about—"

* * * * * *

"I had to leave off in a hurry, because the lunch-bell rang. And now it doesn't seem worth while to go back to that half-written sentence, about being awfully excited! For it is all over, and I am so dreadfully disappointed."

"Edred was expected down yesterday for just two nights—all the time he could spare from his work this Christmas. And Emmeline had asked me to go to the skating on their pond this afternoon. I think it was to pass the time before three o'clock that I took to my journal."

"But at lunch my father said a change had come, and a thaw was setting in. And before we had done, a note arrived from Emmie, telling me that the ice was unsafe, and that Edred had to hurry back to town to-day. So this time I shall not even see him."

"It does seem sometimes as if life were all made up of disappointments."

A POSSIBLE ACQUAINTANCE

DOROTHEA built a good deal upon the promised call from Mrs. Effingham. As one day after another passed, and nobody came, she began to feel flat. Not knowing the old lady's address, she could not ask after her, so nothing remained but to wait.

Three days after Christmas, the frost broke up and a spell of mild weather set in. Dorothea had her morning rambles pretty regularly, but she found the long afternoons and evenings hard to get through, whether alone, or in wordless attendance on her occupied father. What he was always so busy about, Dorothea could not make out. He sent her upstairs or downstairs for books, and sometimes he set her to work copying dry extracts, but he gave no reasons or explanations.

She could not flatter herself that he grew less silent. All her efforts to call out his interest and sympathy were at present a failure.

The oppression of this continual silence was creeping over Dorothea herself. She could not persist in talk which had no response. Silent walks, silent meals, silent tête-à-têtes with the Colonel,—these were steadily subduing her young spirits. At thirty or forty, she could have struck out her own way of life, could have made her own work and interests. At eighteen, she was not free.

A Christmas card had come from Mrs. Kirkpatrick, but no letter. Dorothea, had begun to long with actual heart-sick craving for a letter, a word, a smile, from somebody. Anything to break the dead monotony of her present existence. Yet when New Year's Day brought from happy schoolfellows eager scrawls about their home delights, she had a little shower of tears over them. Her own lot was so different.

"Have you seen St. Paul's?" demanded Colonel Tracy next day at lunch.

"Seen St. Paul!" The girl had not fallen yet into London colloquialisms, and a sudden question from her father always had a bewildering effect.

"Cathedral."

"No, never."

"I'll take you this afternoon—by omnibus. Get ready sharp, you know."

"O father, can we stay to the Service?"

"What for?"

"I should so like it."

"Don't know. I must be back by half-past four."

No hope then. But any innovation in the daily round was delightful, and Dorothea had never been satiated with sight-seeing. She made short work of her dressing, and Colonel Tracy looked in surprise at her bright face.

"You like going about!" he said.

"O yes, indeed."

"Well—we'll do Westminster Abbey some day. Monuments worth looking at there."

Dorothea thought they were worth looking at in St. Paul's. She would have liked to dream over each in succession, and to spend a quiet hour studying the outlines of the great expanse:—not a solitary hour, for she had too much of solitude, but a quiet reverent hour, with her father by her side, feeling—if that had been possible—that he felt with her.

Colonel Tracy's notions of "doing a cathedral" admitted of no dreams. He whisked his daughter through the aisles and past the monuments in the most approved British style. "That's so-and-so, my dear; and that's so-and-so," came in quick succession. The whispering gallery was remarkable in his estimation—"best thing in the Cathedral," he asserted.

Reaching home before five o'clock, they were met in the hall by Mrs. Stirring. "There's been callers, Miss," the little woman said, swelling with gratification. "Callers, Miss—a lady and a gentleman. And they come together, and the lady she was that disappointed to find you out. I did say it was a thousand pities, for you wasn't scarcely never out, and such a dull life too! And she hopes you'll be sure and go to see her, Miss Tracy."

Dorothea took up the cards from the hall slab, following her father into the dining-room. "Mrs. Effingham," she said. "I wish I had been at home. To think that she should have come this day of all days! Father, Mrs. Effingham has called—the lady who slipped down on Christmas Day. Don't you remember—I told you?"

The Colonel's recollections of his over-boiled turkey were vivid: not so his recollections of the cause.

"Eh, what? Somebody slipped down?"

"On Christmas Day, just before dinner; don't you remember?"

"My dear I know you were late, and everything was spoilt," said Colonel Tracy, waking up into a lively air of attention. "Turkey a mere rag—pudding broken to pieces! Never dined worse on Christmas Day. Next year, I'm sure I hope—"

Then he stopped, reading discomfort in his daughter's face, and asked, "Who did you say had slipped down?"

"It was on Christmas Day—a dear old lady, coming out of church. I helped her and that hindered me. I am afraid she would have been run over, if I had not been so near," added Dorothea, feeling it needful to explain.

"A policeman ought to have been at hand. Great shame!" said the Colonel, who, like most people, expected each policeman to parade ubiquitously the whole of his beat. "But it's done—can't be helped now. Old ladies have no business to cross streets alone. Where's the book I left here—what's its name?"

"Father, Mrs. Effingham has been to call on us."

"Eh! Then she wasn't seriously injured! Where is that book?" soliloquised the Colonel, peering about.

"No, and she said she would call. I should so like to know her. Somebody else has been too—'The Rev. E. Claughton!' See, father—he has left two cards. I don't know who Mr. Claughton is, but—"

"One o' the Curates, Miss," came in subdued tones from Mrs. Stirring in the doorway.

"What's the woman dawdling there for?" muttered Colonel Tracy, and at the sound of his growl Mrs. Stirring vanished. Colonel Tracy received the cards from Dorothea, and frowned over them.

"Claughton! Claughton! I don't know anybody of the name of Claughton. Must be a mistake, my dear. Just chuck it into the waste-paper basket."

"O no; I am sure it is meant kindly. Father, he is one of the Curates of our Church. Don't the Clergy always call?" asked Dorothea. "And I think it must be the same who helped to lift up Mrs. Effingham. I should not know his face again, because I am so blind without my glasses; but he had a nice voice, and I really think you would like him."

The Colonel grunted. He had a particular aversion to Curates.

"Mrs. Effingham lives in Willingdon Square, I see. Then, she can't be very far off, can she? Father, shall I call on Mrs. Effingham alone, or will you come with me?"

"I!" uttered the Colonel, as if she had suggested a leap from the iron gallery of St. Paul's.

"Don't you ever pay calls? I thought gentlemen did sometimes. Then may I go alone? It can't be far off."

"Alone! No, certainly not!" Colonel Tracy spoke with sharpness. "Church was to be the outside limit, remember! I can't have you wandering about London."

"Only if it is near—"

"My dear, I won't have it," declared the Colonel irately.

"I ought to return her call."

"There is no 'ought' in the matter. No necessity whatever. You did her a service, and she has called to express her gratitude. That is all. The matter need go no farther. I shall leave my card—perhaps—some day at Mr. Claughton's; not at present. His coming at all was unnecessary."

The Colonel's decision meant no small disappointment to Dorothea, and it took her by surprise. She had kept up so bravely hitherto, that the Colonel had no idea what this new life really was to her. But the fresh blow, however small, proved to be the final straw; and before Dorothea knew what to expect, three or four bright drops fell quickly from behind her glasses.

"Eh hallo! What! Crying!"

Dorothea said, "O no!" involuntarily, and looked up with a resolute smile; yet the wet glimmer was unmistakable.

Colonel Tracy's astonishment was unbounded. He had counted Dorothea a girl of sense, quite superior to feminine weaknesses, and the very model of an obedient cheerful daughter.

"What's the matter?" he asked curtly. "You don't know Mrs. What's-her-name! Why on earth should you care to see her?"

"I don't know—anybody. I have no friends."

"Humph!" growled the Colonel.

"I don't want to grumble indeed," Dorothea went on eagerly. "Only, if I could just have somebody—somebody I could go and talk to."

"Talk!" Colonel Tracy uttered the word with disdain. It sounded so feminine. Gentlemen never "talk," they always "converse." If Dorothea had expressed a wish to "hold conversations" with Mrs. Effingham, he would have had more respect for her requirements. But to care for mere "talk!" He shrugged his shoulders, and was mute.

"Of course I must do as you wish," she added sorrowfully.

"What on earth should you want to talk about?"

Dorothea laughed. She could not help it. "Why, father,—everything," she said. "The books I read, and the work I do, and the people I see. Is there any harm in talking?"

"Waste of time, my dear."

"But kind and pleasant words are not waste of time, are they? Words that make other people happy."

The Colonel had a marked objection to any remark which savoured ever so slightly of moralising. It was almost as bad as a Curate, in his estimation.

"Where can that book be?" he muttered.

Dorothea could only look upon the matter as settled. She gave one sigh, wondered what Mrs. Effingham would think, hoped they might some day meet again coming out of church, so that she could explain, and then cheerily set herself to find the missing volume.

"What is the name, father? Who is it by?" she asked, smiling.

The Colonel gave her a look. He had not expected this.

"Can't remember the name," he said. "It is by—by—bother my memory! Half-bound, with red edges."

A long search ended in success; and Dorothea then set herself to the copying out of a dry statement about tropical climates, which had seemingly engaged her father's affection. What could be the use of the extract she was unable to imagine. That fact did not lessen her diligence in making a fair copy.

"Thanks," the Colonel said, when she handed it to him. Not a little to her surprise, the monosyllable was followed by a remark "You write a good sensible hand. Like your mother's."

"I am glad. Then handwriting may be inherited," said Dorothea.

The Colonel scratched away with his squeaking quill for another ten minutes, after which he came to a pause, laid down the quill, gazed hard at Dorothea, and said, "I suppose it will have to be."

"It?" repeated Dorothea.

"Your call on Mrs. What's-her-name. I'll leave you at the door some day or other, when I happen to be going in that direction—and come for you later."

"O thank you!" Dorothea was not demonstrative commonly; but she started up in her sudden pleasure, and gave him a kiss. "Thank you very much. How kind you are!"

The rust-red of Colonel Tracy's complexion deepened into a tint not far removed from mahogany. He had not had such a sudden promiscuous kiss in the course of the day for years past; not even from Dorothea. She was rather surprised at her own unwonted impulse, and the Colonel was very much surprised indeed. At the first moment, his impulse was to mutter "Pshaw!" and to turn brusquely away, yet the next instant he would not have been without the kiss. It had an odd softening effect on his feelings. He felt the better for it, and he liked Dorothea the better. But Dorothea only heard that impatient "Pshaw!" and saw his movement of seeming disgust.

"I forgot,—you don't like being kissed," she said apologetically. "I won't do it again."

The Colonel hoped she would, but he made no sign.

"Only I am so grateful!"

"What makes you want to know people?" demanded Colonel Tracy, all the more gruffly because of the softening within.

"Why, father,—it is so sad to have no friends. So dismal and lonely. And how can one do kindnesses to others if one knows nobody?"

The Colonel scented a moral, and shrank into himself forthwith.

"Some afternoon" proved hard to find for the promised pleasure. One day, the Colonel would not go out. Another day, he had an engagement another direction. Another day it rained. So more than a week passed, and then a note came from Mrs. Effingham.

"DEAR MISS TRACY,—Will you not take tea with me this afternoon?

I want to make better acquaintance with my preserver; and I am

leaving town directly. Forgive informality.—Yours truly,"

"E. EFFINGHAM"

"P.S. No reply will mean that I may expect you at about four."

"May I go?" asked Dorothea, showing the note to her father.

Colonel Tracy noted with satisfaction that Mrs. Effingham would be going away.

"Well, if it has to be," he said. "But Mrs. Stirring must fetch you back. I don't mind if I drop you there."

INTRODUCTIONS

MRS. EFFINGHAM had set her heart on a comfortable tête-à-tête with her "young preserver," as she called Dorothea. But things do not always turn out according to our previous planning; and a little before four o'clock, the front door bell sounded vigorously.

"Dear me! How tiresome! Now I know who that is," murmured the old lady,—not so very old either, for she was only sixty-five; and as everybody knows, sixty-five in the present age of hygiene is not at all advanced. She was very well kept too; little and slender, with a soft pale skin which had not forgotten how to blush, and brown hair only streaked with silver, and brown eyes capable of sparkling still, though not so large as they once had been. She wore a dainty cap of real lace, and a black lace shawl over a dress of black satin. The elderly style of attire gave her a look of greater youth.

"I know who that is," repeated Mrs. Effingham, sighing. Like many people who live alone, she had a habit of talking to herself half-aloud. "Nobody rings like Miss Henniker, and she said she would come before I left. But I wish she had waited till to-morrow."

"Miss Henniker," announced the trim parlour-maid. Mrs. Effingham kept no men-servants, though well able to do so in point of worldly goods. She did not like the responsibility, she said, and "men wanted men to manage them."

Despite her little soliloquy, Mrs. Effingham came forward in a cordial manner to welcome the caller,—a spare middle-aged single lady, of the "usual age," sharp-featured, and conspicuously fashionable in dress.

"My dear Miss Henniker! How do you do? How good of you to come! So busy as you always are," the elder lady's soft voice said, not untruthfully, for she really did count it "good"; only she suppressed the fact that some other afternoon would have been preferable. If Miss Henniker's visits were, like those of angels, few and far between, they were unlike angels' visits in duration. Miss Henniker was a careful economiser of time; and when she did get to a friend's house, she commonly paid six calls in one, thereby saving herself ten walks to and from that house. The reasoning will be found, on examination, unimpeachable.

"How do you do? Quite well, thanks. I have been planning for weeks to see you, but—thanks, this will do nicely," said Miss Henniker, planting herself in the chair which Mrs. Effingham had destined for Dorothea. She did it with the air of one not lightly to be dislodged. "Extremely busy lately, but I have contrived for once an hour's leisure. Really, it is quite dreadful, the way one's time gets filled up. I am told that you are leaving town directly. And you have had an accident! Nothing serious, I hope."

"O no; but it might have been," said Mrs. Effingham. She was aware that, if she did not wish to lengthen Miss Henniker's visit, it would be wiser not to speak of Dorothea; only the temptation was irresistible. "I slipped down coming out of Church on Christmas Day. Oh, I really was not hurt—" in answer to a commiserating sound,—"but I might have been. A hansom drove round the corner, and was almost upon me. I could not possibly move in time, and I must have been run over—killed, most likely—if a young lady had not darted forward and pulled me out of the way. Yes, quite a stranger, and such a nice-looking lady-like girl. I have not seen her since, but she is coming to tea this afternoon,—at least, I hope so. You will stay and see her too, of course," pursued the gentle old lady, vanquished by Miss Henniker's energetic signs of sympathy. "My young preserver, I call her: and really, you know, it was a most courageous thing to do. She might have been killed in saving me. We might both have been killed."

"It was most frightful," said Miss Henniker earnestly, while her busy eyes could not resist a little voyage of discovery round the room. Mrs. Effingham was always buying new pictures, new ornaments, new antimacassars and vases, for her pretty drawing-room; and Miss Henniker was always on the lookout for new ideas. "Yes, really quite terrible," she repeated, after noting with interest a dainty arrangement of grasses and scarves upon a side-table, Mrs. Effingham being addicted to combinations of Liberty's silks with Nature. "You might, as you say, so easily have been killed. It was most distressing. Christmas Day, too."

"Yes, indeed. I felt that I could not be sufficiently thankful. I meant to see Miss Tracy and to tell her how grateful I was, long before this; but I had a cold and could not go out. And she has been long returning my call. However, I hope we shall have her here presently."

"Miss Tracy! Is that her name? Where does she live?"

"O only in Willingdon Street,—in lodgings. It is not a very delightful part," Mrs. Effingham said apologetically for her heroine, as Miss Henniker's look of interest faded. "But that will not affect Miss Tracy herself—and, after all, there is nothing in the street—it is respectable enough, only, of course—well, I fancied that the family might be in town only for a short time; but when I went to call, I found that they actually lived there,—in lodgings. Just Colonel Tracy and his daughter; nobody else. It must be very dull for the poor girl."

"But you know nothing about them. I would not be drawn into an intimacy," said Miss Henniker.

"I assure you, they do not show any inclination to push; the difficulty is to get hold of Miss Tracy. Ah, here I hope she—no,—it is not."

"Mr. and Miss Claughton," announced the maid.

"Emmeline Claughton!" exclaimed Mrs. Effingham. "The sweetest girl!" she paused to whisper hurriedly to Miss Henniker. "Sister to the curate, you know. She stayed with him nearly a month last year, and I quite fell in love with her."

"Ah!" Miss Henniker murmured, privately thinking that Mrs. Effingham was apt to fall in love rather easily.

A tall, pale, dark-haired young lady entered, followed by a tall, pale, fair-haired young man. Neither could be called exactly handsome, but both were more than good-looking, and both had a certain distinguished air. Mrs. Effingham hurried forward with genuine delight, unalloyed this time. She threw her arms affectionately round the girl, holding out both hands the next moment to the brother, and then recoiling with a little start of surprise.

"Why it is not—" she exclaimed.

"Not Edred, but Mervyn. My eldest brother," explained Emmeline, and the delicate elderly hand went out again, though less enthusiastically. "We are spending two nights in town, and I promised Edred to see you."

"My dear, I am so glad. Pray sit down," said Mrs. Effingham. "Yes, indeed—delighted to make your brother's acquaintance. Of course, I was quite well aware that you had another brother. But I must introduce you both to my friend,—Miss Henniker, Mr. and Miss Claughton. Miss Henniker knows your other brother well, my dear."

Emmeline's bow was rather distant.

"You will have a cup of tea with me, of course," Mrs. Effingham said, as the tray appeared. Emmeline looked dubiously at her brother, but Mervyn offered no objection. "Somebody else will come directly, I hope," pursued the hostess, turning from one to another, in the anxious endeavour to blend her little circle into one harmonious whole. "Such a very charming girl—a Miss Tracy. She saved me from being run over on Christmas Day. I dare say your brother told you. He was on the spot and saw it all, only not near enough to be in time himself. Did he really not mention it?"

Mrs. Effingham looked disappointed.

"I should have thought,—he seemed so surprised at her action—her promptitude, you know. And I assure you, it was dangerous for herself. She might have been killed. Your brother seemed so much impressed at the moment, that I should have expected—"

"He has been extremely busy," said Emmeline, aware that silence on Edred's part might mean more than speech. "There is always so much going on at Christmas in a London Parish. And one of the curates has fallen ill, so they are short of hands."

"Ah, that explains," Mrs. Effingham said, her glances fluttering round to the silent brother and the attentive Miss Henniker; "that explains why he has not been to see me. He promised to call on Miss Tracy's father—an old Colonel, I believe, living in lodgings. Odd that he should not make a nice home somewhere for his daughter. However, we shall know more about them soon. I am so glad you have both come, my dear Emmeline. So glad you should be here to make acquaintance with—"

"Miss Tracy!" was announced.

The Colonel had brought his daughter to the front door, and there had left her. She was feeling a little shy by this time; but shyness did not mean awkwardness in her case. Dorothea's entrance was all that it should have been; quiet, unobtrusive and self-possessed—not self-conscious. Even when wearing her glasses, she could not see far across the large drawing-room; and her first impression was of an indefinite crowd of people. For a moment she hesitated, not knowing whom to accost; and impulsive Mrs. Effingham hurried towards her.

"My dear, you have come at last. My dear, how do you do? I am so glad. I have been longing to meet you,—to thank you. Yes, indeed, you know well that you saved my life that day at the risk of your own. It was a perfect marvel that we were not both killed," Mrs. Effingham went on, with eager gratification in the idea. To have passed through a peril and come out unhurt is particularly gratifying to some minds, and the greater the peril, the more eminent becomes the position of the individual who has escaped.

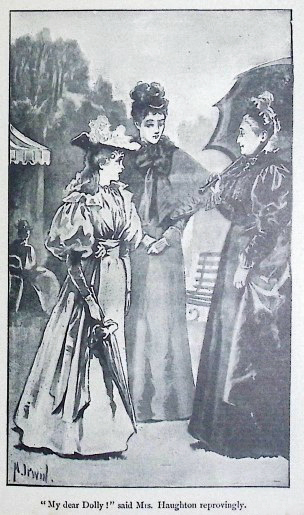

"It was very kind of you to call. I would have come sooner if I had been able," Dorothea said in her soft, quiet voice.

"The kindness was all the other way, my dear Miss Tracy. I assure you, I have been telling my friends about it,—telling them they must welcome you as a heroine. I can never thank you enough, but I shall never forget! We must always be friends. Now you will let me introduce you. Of course introductions are not the fashion; but sometimes, you know—" apologised Mrs. Effingham, who never could resist naming everybody to everybody. "And we are all friends here, or, at least, I am sure we shall be. This is Miss Henniker, a very old friend of mine. Miss Claughton and Mr. Claughton You saw the other Mr. Claughton on Christmas Day,—the clergyman who helped me up, after you had rescued me so bravely, my dear. This is his brother—and sister. I think you and Emmeline Claughton will exactly suit one another. I should like you to be friends."

Dorothea found all this rather embarrassing, while Emmeline looked unapproachably calm and dignified. Mr. Claughton, under his polite demeanour, highly enjoyed the scene. Mrs. Effingham's beaming face clouded over faintly, as she glanced from one to another.

AFTERNOON TEA

"NOW you will sit down, and have some tea," Mrs. Effingham said to Dorothea. "Yes, here—by Emmeline—Miss Claughton, I mean. My dear, pray be kind," she whispered distressfully to the latter, bending close to pick up a fallen antimacassar. Mervyn, starting forward to forestall her, heard the small petition, and noted Emmeline's irresponsive gravity. "Too bad of Em!" he told himself, with a little twirl of his fair moustache, to hide the smile behind it.

Dorothea took the seat indicated, and Emmeline, turning towards her, made a distantly courteous remark upon the weather.

"Yes, very fine," Dorothea answered. She wore her neat dark brown costume, the brown hat, with its suggestion of red, suiting well her rather short and rounded face, and delicate features. The wistful eyes shone as usual through glasses, the set of which on her little nose, combined with the forward carriage of her head, gave a peculiar air of keen attention. There was something about Dorothea altogether out of the common—singularly free from self-consciousness, markedly quiet, the gloved hands lying still, with a lady-like absence of fidgets. She seemed to be neither anxious to push her way, nor susceptible to Emmeline's chilling manner.

Mervyn found her interesting; partly perhaps out of compassion for the charming old lady, Mrs. Effingham; partly perhaps from a perverse love of opposition, inclining him to go the contrary way to his sister; but partly also from a certain quickness of appreciation. He stood up politely to hand cake and tea, and when everybody's wants were supplied, he carelessly took possession of a chair on the other side of Dorothea.

"I suppose you are an experienced Londoner," came in subdued tones.

"I! O no," Dorothea answered. "I came home a week before Christmas."

"From—?" questioningly.

"School."

"Ah!" He had wondered what her age might be. "Not in town?"

"In Scotland. I have not been in London for years."

"And you like it?"

"I like St. Paul's—if one need not go through it merely as a sight."

Mrs. Effingham, listening to Miss Henniker, cast a grateful glance at Mervyn; and Emmeline, hearing the murmur of voices, cast a glance also, not grateful in kind.

The conversation was not at present brilliant.

"Scotland?" Mervyn said musingly. "Edinburgh, perhaps."

"Yes; the outskirts. There is nothing in London like Arthur's Seat."

"Not even the top gallery of St. Paul's?"

"Oh!" Dorothea uttered an indignant monosyllable, then paused.

"Well?" he said, smiling.

"One can't compare the two. And everything is so shut in here. There is no getting away from the people. Yet—" as if to herself, "I wanted to come!"

"I suppose the acmé of a school-girl's desires is to have done with school."

The wistful eyes went straight to his face, dubiously—not occupied with him, but with her own thoughts. They were pretty eyes, he could see.

"I wonder if one goes through life like that,—always wishing for something different?"

Mervyn laughed slightly. "Is that your present state of mind?"

"I don't care for London. And I should like—very much—"

A pause.

"You would like—?" he said.

"One or two friends."

"A modest wish, at all events. Most people 'would like' one or two hundred."

"Would they?"

"Certainly. You are not in the swing of London society yet."

"My father does not care for society. But—one or two hundred friends!" incredulously.

"A lady commonly values herself by the length of her visiting-list. One or two hundred are respectable. Four or five hundred are desirable. Seven or eight hundred are honourable. Don't you see?"

"But how could one ever have time for so many?"

"One has not time. That's the charm of it,—always to be too busy to do anything or see anybody."

As if in echo, Miss Henniker's tones came across the tea-table,—"I assure you, if it had been possible—but I have been so desperately busy,—not a single moment disengaged. Absolutely not one free moment."