Title: Two sailor lads

A story of stirring adventures on sea and land

Author: Gordon Stables

Release date: October 31, 2023 [eBook #71992]

Language: English

Original publication: London: John F. Shaw and Co., Ltd, 1892

Credits: Al Haines

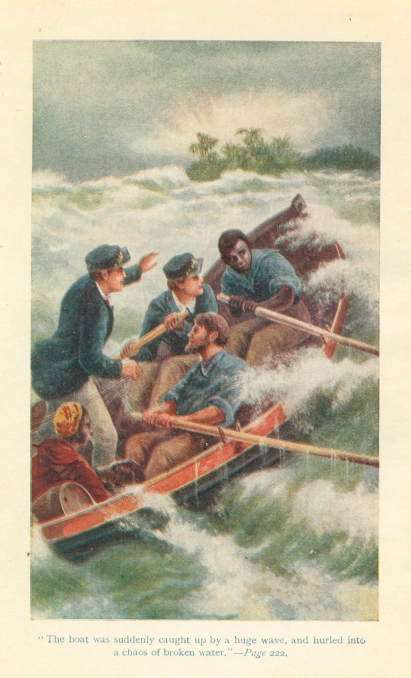

"The boat was suddenly caught up by a huge wave,

and hurled into a chaos of broken water."—Page 222.

A STORY OF

STIRRING ADVENTURES ON SEA AND LAND

BY

GORDON STABLES, M.D., C.M.

(Surgeon, Royal Navy),

AUTHOR OF "FOR ENGLAND, HOME, AND BEAUTY;"

"IN THE DASHING DAYS OF OLD;" "ON TO THE RESCUE;"

ETC. ETC.

"The story of my life,

Even from my boyish days

To the very moment that he bade me tell it."

NEW EDITION.

JOHN F. SHAW AND CO., LTD.,

Publishers,

3, PILGRIM STREET, LONDON, E.C.

CONTENTS.

CHAP.

I. "Hush! Do you Hear that Cry? What can it be?"

II. "But Looking Back, Boys, it is all Like a Dream"

III. An Aimless Life—Peace at Last

IV. Sitting up to Think—The Dignity of Labour

V. At the Fisherman's Cave—Fred's Aquarium

VI. Taking Tea inside a Whale—The strange Story of the Stranded Leviathan

VII. "Five Years Ago this very Night"

VIII. Pleasant Surprises—Frank's Yacht—The Launch of the "Water-Baby"

IX. Playing at Being Pirates—A Storm at Sea—The Wreck

X. On the Desert Island—Toddie's Adventure on the Cliff—the Bonfire

XI. "Friends for Life"—Round the Camp Fire

XII. That Awful Night at Sea—A Ride for Precious Life

XIII. "A Strange, Strange Story," said Frank. "I Wonder how it will all End"

XIV. "Duty, Lad, Duty. Stick to it through Thick and Thin"

XV. The Good Ship "San Salvador."—A Mystery of the Southern Seas

XVI. Deakin and Co. and the Lost Brig "Resolute"

XVII. Southward Ho! to the Sea of Ice

XVIII. Señor Sarpinto

XIX. A Fairy Isle—The Lost Boat

XX. "What their Fate was to be they could not even Guess"

XXI. "A Land flowing with Cocoanut-milk and Honey"

XXII. A Terrible Apparition

XXIII. A Swim for Dear Life—Pursued by Sharks

XXIV. Stingaree

XXV. "Row, Brothers, Row"—Quambo's Shark Story—Fast to a Sword-fish

XXVI. "What was the Mystery surrounding that Strange Vessel?"

XXVII. Frank gazed Aghast

XXVIII. Could he be——Dead?

XXIX. The Arrival of Savages

XXX. "There is no going Back now," Frank said

XXXI. In Cannibal Islands

XXXII. The whole Beach was lined with Yelling Savages

XXXIII. South and South sailed the good Barque

XXXIV. Fighting in Earnest

XXXV. "Would she see their Signals?"

TWO SAILOR LADS.

There is no more beautiful bay than that of Methlin on all the wild west shores of Scotland; there is no quainter or more old-fashioned little town than the fishing village that clusters around its shores, its wee little whitewashed cottages half hidden in the green of waving elders and drooping silver birch trees. Behind the village is a wealth of woodland, stretching for miles away up the valley, between hills so high that at sunrise they cast their darkling shadows far across the sea.

But our story opens at eventide. The sun has already gone down behind the waves, leaving a sky and sea of such gorgeous and startling colours—such a mad mixture of crimson, orange, purple, and grey—as never surely was seen on artist's canvas.

And not only from the water, but even from the wide expanse of wet sand, are these colours reflected.

The sea is very calm, yet the Atlantic Ocean, that swells and heaves and breaks along this coast, never falls quite asleep; and if you glance to-night across the sands at the far-receding tide, you may note long moving lines of orange, and hear the gentle boom of the breaking wavelets.

Right in the centre of this mixed mass of radiant light and colour—darkling against it, and throwing long shadows on the wet flat beach—are two figures. How tall they look! Yes; but they are but boy and girl. Even the sea-gulls that run across the sands appear gigantic birds in that painted haze. Children both they are; he but ten, and she but six.

In looking seaward there is something else one will not fail to note; namely, a long dark wall of rocks, forming the southern horn of the bay, and running straight out into the ocean a mile and more.

There are a few fishing-boats drawn up upon the beach, and this is all the view.

Young though they are, both Fred Arundel and his foster-sister Toddie must be impressed by the solemnity and beauty of the scene, for they are unusually silent, as hand in hand they come homewards across the soloured sands.

But suddenly they start, and stop and listen.

"Hush, Toddie! Did you hear that cry? What can it be?"

"Only a Tatywake, Fled."

"No, Todd, it was no Kittywake. It was no bird at all Hark! There it is again."

Yes; borne towards the beach on the evening breeze, and falling on their listening ears, comes once again a faint but plaintive cry, that anyone less a child of the ocean than Fred, might well have mistaken for the scream of some sea-bird, a gull, or tern, or skua.

Toddie clung fearfully to Fred now.

"O Fleddie," she cried, "I is so flightened. What is it? Some poor man dlowning out there all by his self. Yun home, Fled, and tell daddy. O Fleddie, yun, yun!"

"No," said Fred boldly. "Whoever it is, must be clinging to the rocks. The tide is rising fast, Todd; but the little cobble is handy, and I'll pull out and see."

"And I must come too," insisted Toddie.

"All right," said Fred. "I'll ship the tiller, and you can steer."

"Yes, I'll teer, Fled. Oh, be twick!"

Fred was quick; no boy could have been quicker; and in less than five minutes, impelled by his strong young arms, the cobble was bounding over the rising tide.

Fred had got wet to the waist in launching the boat, but he did not mind that. Something told him there was a precious life to be saved, and he could think of nothing else.

For fully half a mile straight out to the sea ran the rocks and cliffs, ending in a bold and rocky promontory nearly seven hundred feet in height.

Bight along by the rocks rowed Fred, Toddie grasping the tiller in her tiny hands, her anxious, pretty face strained with listening.

Every now and then Fred rested on his oars for a few moments to listen, and ever as he did so, rising high over the screaming of the gulls, they could hear that piteous cry for help.

Quicker and quicker now rowed Fred. He was a good oar, and was warming to his work. No extra finish was there about Fred's rowing, no feathering of oars or any such folly, but a long pull and a strong pull, dipping his blades into the water deep enough to get good purchase, but not an inch deeper, and bending well to every stroke. Right steadily too the lad rowed, so that verily there was music and rhythm 'twixt rowlock and oar.

The clouds had lost their gorgeous colours, and from a rift of blue on the eastern sky one single star looked down.

Night was coming on apace, and there was not wanting evidence that it would be a stormy one. The swell was rising high out here, the surging seas broke white against the cliff foot, and little angry catspaws were already ruffling the water.

Fred rested on his oars and listened once more.

All was still. The wandering sea-birds wheeled near and shrieked their dismal shriek, but no human sound could the children hear.

Fred himself began to get frightened now. The silence was like the silence of death, and even the voices of the birds had a ghostly ring in them. Was it all over then?

No; for even at that moment Fred's quick ear caught the sound of something moving in the water.

"Look! look!" cried Toddie. "A seal, Fled, coming this way all by his self."

Yes, there was a black head yonder, coming rapidly on towards the boat.

Fred quickly shipped his oars now, and stood by to give assistance; for he soon discovered that the black head was human, the face pale and startled-looking.

Presently the swimmer stopped, and trode water not four yards away from the boat's bow.

"Please were you co-co-coming for m-m-m-me?"

"Of course," cried Fred. "What else? Swim nearer and I'll help you up. Mind, Toddie, we don't capsize."

Toddie held the helm grimly amidships, and sat on the gunwale, and in a moment more Fred had pulled a lad apparently a year or so older than himself in over the bows.

A tallish, gentlemanly-looking boy, dressed in a dripping kilt, and with a strongly English accent.

"It's awfully go-go-good of you," he began. "Oh," he added, "you have a li-li-little la-la-lady on board. Good evening, m-m-miss. The tide was r-r-rising over the rocks, and soon would have drowned me."

Then he raised his hand as if to pull his cap off, but there was no cap there.

"I do-do-don't s-s-stutter, mind," he said, "it is only the co-co-cold."

And Toddie felt she could have cried for this handsome boy, whose teeth were chattering in his head.

"Mammy Mop will soon wa'm oo," said Toddie consolingly.

"Oh, thanks! And may I take an oar? Thanks awfully."

Before the boys had beached the boat and hauled her up the stranger had quite recovered his speech.

"I can never thank you enough," he said, "for rescuing me from what would have been a watery grave."

"Give me oo hand now," said Toddie. "We will all yun home, and oo can tell the stoly to Mammy Mop."

"But really I mustn't——," began the boy.

There was nothing else for it, however; for Fred had seized his other hand, and between Toddie and him they ran him right up the beach, along the road a little way, and through a bonnie garden, towards the door of a cottage, the light from which was streaming out into the gloom of the falling night.

Half an hour afterwards, had you peeped in through the four-paned window of the fisherman's cottage, this is what you would have seen: A bright and cheerful fire of peat and wood burning on a low hearth, a pot with a steaming and savoury stew in it hanging from a soot-blackened chain above it; in one corner, sitting in an old-fashioned high-backed chair, a tall and elderly man, with finely-chiselled features, long hair floating over his jersey, an almost wild look in his eyes, but kindness in every lineament nevertheless. This is Papa Pop, and on his knee sits Toddie, one arm round his neck, but her great wondering blue eyes fixed on the face of that handsome English-looking boy, who, to her way of thinking, seems like the prince of some fairy tale, suddenly dropped out of the clouds. In the other corner sits Fred himself, and at his feet a sonsy cat and a dachshund dog.

Standing on the floor behind this group is the fisherman's wife, tall and bony, rough, but kindly-looking withal, and in front of her, with the firelight streaming on his strangely uncouth face, is Bunko, the fool of the village.

But "fool" is too harsh a word to use; for although but half-witted, there is a deal of sense and shrewdness under that towsy mop of his. Bunko holds in one hand a rough stick or pole higher than himself. This is his rod of office; for Bunko takes all the village cows away to the hills every morning, and besides this he does all kinds of odd jobs that few save he could accomplish.

"Weel, Bunko," the fisherman's wife is saying as she crams his pocket with buttered scones, "you'll tak' the road right over the hills."

"Umphm!" says Bunko.

"And ten miles and a bittock will bring ye to the hoose o' Benshee. Knock at the door—d'ye understan'?"

"Fine that."

"And tell the laird's folk that Master Fielding is safe for the nicht at——"

Bunko strode across the floor and laid a huge red hand on the young stranger.

"Master Fielding—that's this wee blinker, isn't it noo?"

The lad laughed, and put something in Bunko's hand. Bunko looked at the coin.

"A bonnie white shillin'!" he cried. "Hurrah! Noo I tell ye, sirs, the grass winna grow aneath poor Bunko's feet till he's at Benshee-house and back again. Keelie, laddie, whaur are you?"

A wall-eyed collie dog sprang up at the summons. Bunko struck his pole once on the floor, then he and Keelie went out into the darkness, and were seen no more that night.

"I really ought to have gone with Bunko," said Frank Fielding, for that was the stranger's name. "But it doesn't matter much," he added, "only mamma will be quite pleased to hear of our adventure. Fred, you will be a hero, and Miss Toddie a heroine. For mamma is very romantic. And I'm sure, Fred, I'll never forget it. I had been fishing, sir"—he was addressing the old fisherman now—"and was overtaken by the tide. It was very dreadful with the night coming on, and the sea birds moaning and screaming around that cold grey rock, and the water rising, rising, rising. Heigho! it would soon have covered me; so you see, Miss Toddie, you saved my life."

"Well," replied little Miss Consequential, "when oo says oo players to-night, of tourse oo'll thank the dood Lord?"

"Yes, Toddie, I must," said Frank with a little sigh. Well might he sigh! Prayers in the family circle were unknown at Benshee Hall.

Frank was already strangely interested in the inmates of this little cot, and when Mammy Mop, as the children called her, handed down the great old Bible, and when this brown-faced fisherman read a portion, and afterwards prayed more earnestly and in loftier language than ever the parish minister used, Frank looked at him in reverent wonder not unmixed with awe.

Then they all sat round the fire again.

The wind had now risen and was moaning round the cot, and the rain rattled dismally against it.

Fred shuddered a little as he listened to the wind.

"I'm so glad," he said, "that we went down to-night to our aquarium, to feed the blennies, and a new pet of Toddie's that she called Tom."

"Tom has been naughty," said Toddie, "so Tom has been sent home."

"Yes, that is true," said Fred, "very naughty, and we had gone down to the rocks to put Tom away, else we never should have heard your cry."

The children's aquarium, I may tell you, was a marine one in a cave down by the sea. The cave was a shallow one in the south side of the ridge of high cliffs that ran out to sea, but far removed beyond the avaricious clutch of a rising tide unless something out of the common should occur. Bodily the sea had never risen so high as Fred's cave in his time, although in days of storm and tempest, when great green waves broke and thundered on the beach, the spray was often carried far along the face of the cliffs with force enough to drench anyone to the skin who ventured as far as the cave; once inside, however, one was safe enough. Not more than ten feet in depth or width was the cave, though more than nearly twenty feet high, and a very pleasant place to spend an hour or two in by day during the summer months. At noon the sun shone right into it, and penetrated the water of Fred's aquarium at the end. This latter was a natural basin in the rock, a kind of hollow shelf about three feet above the floor, which these children kept filled with water, and stocked with many curious creatures, that they found upon the beach, such as shell fish, tiny medusæ, sea anemones, and little fishes of many kinds. Toddie delighted in droll, weird-looking water things, and used to shout aloud for joy when she found any new form of youthful marine monster left in a pool of the rocks when the tide went back. She never went seawards without Fred, and he carried a little hand landing-net, and whenever a fresh specimen was discovered ugly enough to commend itself to Toddie, she peremptorily ordered her chaperon to fish it out and convey it to the cave aquarium.

Things throve here very well indeed, owing perhapa to the fact that they kept the water constantly changed and carefully removed any wee creature that died. Singularly enough, however, soon after the arrival of Tom, specimens began to disappear in the most mysterious manner.

But it is time to explain who Tom was. Watching the fishermen drawing in their nets one day, in which was a goodly quantity of bonnie silver herrings, Toddie noticed one of the men pull a strange-looking fish out of the net and throw it inland to die. Toddie went straight away after it. The creature had fallen among a lot of dry seaweed, so it was none the worse, though it wriggled alarmingly when the girl lifted it up and put it in her apron. In ten minutes' time she had placed it in Fred's cave aquarium, where it rested on its side a short time, then began a tour of inspection much to Toddie's delight. A long stone-grey, light-spotted thing, with a semicircular mouth away under its chin, and a tail with one half of it much longer than the other. In fact it was that species of small shark that abounds round British coasts, called the dog-fish.

Toddie and Fred had determined to make a great pet of it, so they fed it on sand-hoppers and earthworms, and bait generally. Tom ate everything they gave him greedily enough, and seemed to look for more.

But since his arrival the other specimens began to disappear, and the pretty little sea-minnows, as Fred called them, that had been placed beside Tom to keep him company, had gone also.

On this evening when Fred and Toddie had gone to the cave they found Tom waiting expectantly.

I'm afraid Tom was a very sly fish.

"Just look at me now," he seemed to say, as he gazed at them with that slit of an eye of his, "you see before you one of the most innocent and kind-hearted trouts in all creation. To be sure my shape is rather against me, and so is my colour; but for all that I'm the most gentle and——"

It is a pity that at this very instant the last newcomer, a sea-minnow, should have darted out from under a bit of sea-weed, and sailed to the front.

All Tom's virtue and goodness were forgotten in a moment. He quivered all over from stem to stern, his very eyes appeared to flash fire. Next moment he had thrown himself on his side, the water rippled, the sea-minnow was gone at a snap.

Toddie threw up her hands and screamed. Fred stood firm.

"What do you think of that, Todd?" he said.

"Oh, Tom, Tom," cried Toddie, "you naughty dolly fish!"

"It was all a mistake I assure you," Tom seemed to say. "I opened my mouth to yawn, you know, and——"

"Fred! Fred!" said Toddie, "tatch that naughty Tom and put him in the sea."

So Tom's doom was sealed at once.

He was caught, therefore, in the landing-net, carried away to the deeper water close by the rocks, and dropped into the sea.

And that was the last Toddie saw of her "dolly-fish."

"And now," said Frank, addressing Eean, "I know you have a story to tell. Do tell it, sir, and make it as dreadful as possible."

The fisherman laughed as he looked at Frank.

"I don't think," he said, "I must tell you anything very terrible; but if I tell you a story, I promise you it shall be a true one. And a true story is better than a terrible one. Ahem!"

Was it a gleam of pleasure, or the flush from the firelight, that spread over old Eean's face as Frank Fielding made his quiet but ingenuous request, to be favoured with a story?

The fisherman smiled, and now the rugged lineaments of his face softened wonderfully. He did not answer directly, however.

Eppie, his wife, had drawn near to the circle round the fire with her great black spinning-wheel, and it was towards her that Eean turned. Surely too it was for her that smile was intended.

He stretched out his left arm, the one that was nearest to his wife, and laid his hand on her lap. There was something very touching in this simple act, and in the tender look that accompanied it. For a moment or two the birring of the spinning-wheel ceased as Eppie took her husband's hand in both of hers.

He had really asked a question, though not in words; but it was in words that Eppie replied.

"Yes, Eean, yes," she said. "What for no tell the story?"

"Our story, Eppie."

"Ay, ay, our story, Eean."

Birr—rr—rr went the spinning-wheel again; and I'm not sure there was not some moisture in Eppie's eyes as she bent once more over her work.

It was a very old-fashioned pipe of clay that Eean now lit with a morsel of burning peat, and when he got it to go he placed over the bowl the white iron lid which was attached by a tiny chain to the stalk. Then he leaned back in his chair, and for a time seemed intent only on watching the blue rings of smoke, that went curling up towards the blackened rafters of the humble cottage.

"Boys, boys," he said slowly at last, "it is a long, long time ago since my real life-story began. Thirty years and over, lads. Is that not so, Eppie?"

Birr—rr—rr! went the spinning-wheel.

"Imphm," assented Eppie.

"But go on, Eean," she continued; "and if ye ravel in the thread o' your discoorse, I'll try to pit ye straight again."

Thus encouraged, Eean took a few more pulls at his pipe and went on.

"Thirty years seem a long time to look forward to; but looking back, boys, why it's all like a dream. Yet, my lads, life has no business to be a dream. 'Life is real, life is earnest,' as the hymn says; and if your eyes don't open before you are out of your teens, I tell you this, it is a poor look out for you in after-life.

"I notice a weary kind of a light in your eyes, young Master Frank. I know what you're thinking: 'The old man is not telling a story, he's only preaching.' But the ways of old men must be borne with. So patience for a moment, boy; patience!

"I was born with a silver spoon in my mouth. Oh, not a big one, I assure you! But I knew right well that when twenty-one I should have a few thousands to begin life with; and it was this very knowledge, I believe, that made me careless and a dreamer.

"My father was a Highlander, like myself. He had been rich, but he had also been a soldier, and squandered all his own money, though he retired on half-pay with fame and glory; for on many a blood-red field in India his sword had rang and clashed, and his slogan been heard wherever the battle raged the fiercest.

"That was my father, and I was his only son. I had a dear mother that doted on me, and could scarcely bear to have me out of her sight. She would have me to be a child even when I was seventeen years of age. I tell you that up till that age I did nothing on earth but dream my life away. I was to be something great in futuro. There was a castle building for me somewhere, in which I should live when a man. The good fairies were building it, I suppose; but woe is me, boys, fairy promises are but like soap-bubbles that rise and float on the soft summer air, all glitter and beauty, then—burst.

"I was a poet in those days—they tell me I am a bard still—but I fear my verses have lost the fire and frenzy of youth. Never mind, in those dear foolish days I learned nothing that was not pleasant, I did nothing I could not find pleasure in. With gun on shoulder I used to start for the hill. Too often my gun was thrown on the heather, and I lay down beside it in the sun to versify and dream. Or I might take my fishing-rod, and with my dog Kooran at my heels, set off for the lonesome tarn or mountain burn; but, ah, me! the fish seldom rose to my flies, and the streamlet sang to me, and I to the streamlet—there was music in everything around me, in the sailing clouds, in the waving broom, the drooping birch-trees and dark solemn pines themselves.

"Did my conscience never tell me I was doing wrong? It did at times. There were moments when the stern realities of life used to force themselves upon my thoughts. Surely man was made and meant for something better than to be an idle dreamer. Then I would start and awake as if from a lethargy. I would look around me, and even blush to see all men busy but myself, all creatures toiling, yet all, all happier even than I.

"What should I be? What should I be? How often the question would keep recurring to my mind. Be a soldier like my father? No, I cared not for camps and fighting. Be a sailor, and go sailing over the world. Yes, that was better; but the work, it was the work I feared. To sail on, on, on, for ever over sunlit summer seas would have suited me. But seas are not always sunlit, and storms arise, and—no, I would not be a sailor.

"Why not live to sing as Byron, Ossian, and Burns had done? But I must have some one else save the birds and streams and trees to sing to. Then a gloomy spell came over the spirit of my dream, and I thought myself the most miserable of all created beings. The linnet that sang among the golden furze, his nest not far away, seemed to laugh at me. The linnet had love. The wild deer in the forest shook their antlered heads, and appeared to despise me in my forlornness, they were as happy as the summer's day was glad and long. The eagle that floated high above the clouds mocked me. He could soar. Oh, how I wished and wanted to soar! Everything too about me was so lovely, I had a poet's eye for beauty. Even the metallic lustre on the beetles that crept through the grass shot rays of pleasure to my heart. 'Was it possible,' I said to myself one day, as I lounged by a river side. 'Was it possible for me to transfer some of the beauty I saw around me to canvas? Why not? Others have done so. I had been to the great city of London, I had revelled in picture-galleries, all the memory of pictures I had seen came back to me now with a force I had never felt before. Hurrah!' I shouted, starting up, 'I will be an artist. I will build my own castles. Away, fairies, away I'll dream no more. I'll be a man. I am a man.'

"My poor dog must have thought I'd gone mad. I broke my fishing-rod across my knee and flung it far into the dark brown stream, and once more shouted till the wild coneys fled into their holes on the cairney hill sides.

"No, my mother did not object; I should have the best of teachers; the best of teaching; I should go to London; go to Rome. My pictures should be hung, I'd make wealth and fame, her darling boy should be——"

Here old Eean paused for a moment. He shook the ashes from his pipe with a gesture almost of anger.

"Dreams! Dreams! Dreams!" he muttered.

"Boys, I had not learned the art of application early enough in youth, I was thoughtless, my dear mother said in excuse for me, and thoughtlessness was natural to youth.

"But, oh, lads, listen! Thoughtlessness is not, should not be, natural to youths. Life's stern battle is all before them; should they be thoughtless or careless as they gird up their loins to meet the foe? Life's stormy ocean is rolling resistlessly on towards their frail barques; how shall they mount those heaving seas, how fight against wind and tempest, if they trust all to blind chance? I tell you what—and he who tells you knows—that thoughtfulness must be your guide to every good in life; ay, and to the world beyond as well, Oh, my dear lads, grasp these truths, and never, never forget them! Act on them too, and they will make you men, yes, heroes.

"But I am preaching now. Forgive me, and my tale—alas! it is an all too common one as far as it regards myself—shall soon be told.

"I was not by any means what is called a wild youth, while pursuing my studies under masters in London, and elsewhere: the ordinary and sinful frivolities of youths about town had no charm for me. I loathed them, and despised the empty-headed fools who gave way to them. I did not quarrel with these men, I simply avoided them. I preferred my own company to theirs, and my own thoughts. I was often to be seen alone at the play, or opera, or alone in the picture galleries. It was a pity for me I did not visit the latter in company with art critics, but I had found out that some of these were lacking not only in knowledge but in honesty, so I avoided them all, as a child who has been burned fears flame in any and every form.

"Did I work well? I worked fairly well. My fault, and it is a radical one, was, that I was in too great a hurry to be a painter—the rudiments of drawing were to me a weary task. Like a boy I gloated over colour and effect. But I had one picture hung. Oh, bless that day for just one reason—it made my poor dear mother happy! When she received the letter in which I announced my success, she shed more tears over it than if the missive had been one announcing the death of a dear friend. Yes, they were tears of joy.

"Did my single success have a good effect on me? Alas! no, the very reverse. I fancied myself—fool that I was—upon a mountain top of fame and glory. High up among the rosy clouds of sunrise, with all the world at my feet. I determined to do no more work for a time, not genuine study at least—I should set out on a grand walking tour! What a happy idea I thought this was! Mind you, I still was the poet at heart, and Nature in every form still appealed to me. I had come to hate my sky-high studio in London, the dusty winding stairs that led to it, its furniture and furnishings, and even the outlook from its windows.

"I was like a boy while preparing for this grand tour. For more than a week my time by day was occupied in shopping. All my purchases might soon have been made had I been content with the ordinary outfit of a walking artist. But this would not suit my vanity. I believe I was a rather handsome young man then. Was I not, Eppie?"

Birr-rr-rr went the wheel. No word came from Eppie, only a smile lit up her face for a moment.

"So," continued Eean, "I determined to take heavy baggage as well as a knapsack and cudgel. This I would arrange to be sent on by train or coach. Guns, fishing-rod and tackle, books, the best of novels, the best of poets, I even took dress suits. Yes, boys, I feel ashamed now when I think of it, but my vanity led me to believe that I should be fêted and feasted at the houses of the wealthy.

"Away I went, and for many weeks of wandering I was truly happy. I worked too by fits and starts, and my portfolios were getting filled with pretty bits that I culled upon my rambles. I had not yet found out, nor could I have believed, that rural England was so charmingly sweet and pretty. No great wonder that I lingered therein for months and months. True, my dress suits were never once taken out from the trunk that contained them, nor was any squire or nobleman ever likely, I began to think, to invite the wandering artist to dinner or give him even a day's fishing or shooting. Was this fame then? Surely everyone had heard of the rising artist who had had a picture hung. And prettily criticised too. Well, I did not break my heart. I ate my humble meals and slept at village inns, and if I was taken for anything at all by the villagers, it was either for 'a kind of surveyor,' a 'strolling sign painter,' or 'something in tea.'

"But during these long rambles there had been the glamour of spring, and the glory of summer, over all the land, and I was contented and happy.

"I hardly ever thought of writing even, wicked that I was, to my mother. But when at last the summer commenced, and I saw one day a pale yellow splash of foliage on a green ash tree, as if some tint of last night's sunset had fallen on it and lingered there, I bethought me of the purple and crimson heather on the bonnie Highland hills of my wild native land. And in a week's time I was home at my father's house.

"Oh, I had been working hard, I told my mother.

"'I know,' she said, 'and I expected to see you wan and pale, dear boy, instead of rosy red.'

"Then I told her all—where I had been, and spread out before her my portfolios of crude unfinished bits.

"'They will work up, and work into noble pictures when I return to town,' I said.

"It was thus I deceived myself and her.

"I next set out to study the beauties of hill scenery of straths and glens, of loch and stream and torrent, of weird pine forests, far in the depths of rugged mountain passes, of sheep and shepherds' shielings, and of everything that makes up the stern silent grandeur of the Scottish Highlands.

"One day I found myself seated high up the glen here with the reek of this same wee village rising blue above the birchen trees, with the great Atlantic Ocean sobbing on the sandy beach, or breaking into whitest foam against that long ridge of darkest rock that runs westward yonder to meet and welcome the rolling seas. There were white clouds afloat in the sky's blue, there were white sails dotting the blue of the sea, there was the buzz of insect life in the heather all around me, and the afternoon was warm and soft. Had I fallen asleep I wonder? I know not. But I started up at last inspired with a new idea.

"It was an idea that made my cheeks tingle with pleasurable emotion.

"I should write a book, a book that would make me famous. I should in this book wed together the harp and the easel, the thistle and the rose.

"Let me explain to you, boys, for I can see you hardly catch my meaning. The book, then, was to embrace both poetry and painting, the wild songs I should sing of my own mountain land; the illustrations all from my own pencil and brush, hence The Harp and the Easel. But the scenery should be touches from Nature in both Scotland and England, hence the title of The Thistle and the Rose.

"I went down the mountain side at the rush, vaulting as vaults the deer, so strong, so well, so happy was I that my very feet seemed to spurn the turf on which I trode.

"But was it turf? No, surely it was air. So filled with the inspiration of my grand idea was I, that I appeared no longer on earth or even belonging to it.

"Boys, these last words of mine contain a grim kind of a joke which you will at once see. I made just one vault too many, then I was indeed walking on air, and no longer on earth. I was falling, falling, falling! Oh, it did seem such a long, long time ere I reached the foot of that rocky cliff! Then all was a blank.

"I had fallen as it were into sudden darkness, and but for a pine-tree on which I bad luckily alighted, and which lowered me earthward all torn and bleeding, it might have been the darkness of death.

"Eppie, wife, heap more peats upon the fire and stir the blazing drift-wood. Listen, lads, to the moaning wind; surely that is hail that rattles so against the panes. Frank, it is well you haven't to make your way through moor and forest to-night with Bunko."

"I shouldn't have minded being with poor Bunko, sir, I assure you, because I like to be out in storms; but then I could not have heard the conclusion of your story."

"And must I conclude to-night?"

"Oh, sir, yes! You're just coming to the best of it."

"Well, boys, well," said the old bard, "you must be humoured."

"The darkness seemed to lift at last, and I gradually became sensible. Everything around me was hazy for a time—a kind of a gauze curtain seemed to hang 'twixt me and as pretty a rustic picture as I ever yet had seen.

"I was not lying at the cliff foot, I was in a soft, warm bed, all hung round with snow-white curtains. It was so near the gloaming hour that I could see the firelight dancing on the plain deal furniture, and on the pictures of ships and boats that hung on the whitewashed wall. There was a stuffed sea-gull in a case, and the model of a fishing-boat also under glass, and on a little table a big ha' Bible and other devotional books, surmounted by a vase of freshly-culled wild flowers. Then I turned my aching eyes towards the little window, prettily festooned with curtains of dimity, and on the sill of which pot-flowers were growing, the red radiance of sunset lighting up and strangely altering the green of their leaves. But my eyes fell on a picture of a different sort at the same time: a young girl seated by the window sewing, her head bent towards the white seam, her dark hair half hiding a face that to me was as lovely as an angel's.

"Some movement on my part caused her to glance towards the bed, and seeing me awake she put down her work and came towards me.

"'Where am I?' I asked faintly.

"She put her fingers on my lips.

"'You are where ye maun lie,' she said, smiling, though I'm sure there were tears in her eyes; 'where ye maun lie till well, but ye must not speak.'

"Poor, simple lassie! I knew then as I knew after that she was doing her best to talk in English, though far dearer to me was the expressive language of Burns the poet.

"She now put something to my lips in a spoon. I drank, and slumbered again.

"When once more conscious, there stood the village doctor, and an old, white-haired, pleasant-faced dame in a fisher's cap.

"'Will he live, doctor?'

"'Live! yes, if he has plenty of good nursing.'

"'He'll want for naething here, puir laddie, that we can gie him. Ech, sir, but I'm thankful.'

"My young nurse was not there, so I slept for a time, and when I awoke she sat there again.

"'May I talk just a little?'

"'Yes, just a little,' she said. 'Tell me,' she added, 'who your people are, because ye ken they must be told?'

"'Plenty of time. Plenty of time,' I murmured.

"Then bit by bit I told her all my story.

"'I would rather,' I said, 'my mother knew nothing till I am up and about.'

"'But will she not be——'

"'No, no, child,' I said. 'She is used to my wandering ways, and oftentimes I do not write for months.'

"'Isn't that unkind?'

"'I fear so,' I said.

"'Are you good?' she asked pointedly.

"'Not too good I fear.'

"'D' ye say your prayers nicht and mornin'? Had ye said your prayers on that day ye fell o'er that fearfu' cliff?'

"I was silent.

"Only a simple Scotch lassie would have preached to me thus. But she looked so saint-like as she sat there, gazing almost mournfully at me with her calm, tender grey eyes, that really I was thinking then more of painting her in a subject than anything else.

"'No,' I said at last, 'I am not good as you understand it, but you shall teach me.'

"'The way of transgressors is hard,' said the little Puritan; 'but oh, sir, the plan o' salvation is sae simple a bairnie can understan' it. What's your name, sir?'

"'Eean.'

"'I'll pray for ye, Eean, and so will mother.'

"It was a month after this conversation ere I could stroll about the beach, and paint rock and cloud effects. The girl was seldom with me. She would be away out at sea casting nets with her father, and in her simplest attire, to my eyes, she always made the prettiest picture.

"Boys, this story of mine is in some measure a confession. I have at all events confessed to you already how idle and how vain I was, and now I am going to give you another illustration of my vanity I made up my mind then to make this girl my wife. I positively thought I had only to go in and win.

"I was well now, and it was only for her sake I still lingered in the village. I had taken up my abode at the village inn because, though they had nursed me back to life, those kindly fisher people positively refused to accept of anything in the shape of pecuniary reward. All that I was permitted to do was to paint the old couple sitting together Bible in hand on the stone dais in front of their little cottage door.

"So one day I called on the mother, but was not displeased to find the girl there too.

"I soon stated the object of this particular visit.

"'I intended,' I said, 'to make her daughter my wife.'

"A quick flush came over the girl's face. She glanced just once in my direction, then bent again over her white seam.

"'You intend,' said the old lady, 'to make my daughter your wife. O, sir, do you think sae little of us, that ye imagine ye hae only to command? We are only poor fisher-folks, sir, but we have the pride of honesty in our hearts. Na, na, na, sir, there is a great gulf fixed 'twixt you and us. Gang awa', sir, gang awa', and marry some gentle dame, that ye can introduce to your dear lady mother. May every blessin' on earth he yours, sir. We're nae insensible to the honour ye would do us. Dinna think us ungrateful—' here the good old soul broke down and cried—'but gang and leave us to our poverty and our honest toil.'

"'So be it, madam, so be it,' I said. 'I have yourself and daughter to thank for my life, but it was not to show my gratitude I made the proposal, but because I am wise enough to discover sterling worth and goodness even beneath a humble garb. Good-bye. I'll never think of marriage more.'

"I shook the mother's hand warmly. I but touched the girl's. To have looked even once in her sweet tearful face would have unmanned me, so I all but fled.

"I left the village long before daylight. I went home. Then I told my mother all.

"My muse was now my only comfort, for months went by before I thought again of painting.

"Then the same old idea recurred to me that had so nearly cost me my life on the mountain side.

"The book, The Easel and the Harp. The Thistle and the Rose!

"I commenced work in earnest now. But, alas! misfortune befell me. My soldier father died. He died in debt, and one short year afterwards I laid my darling mother in the church-yard beside him.

"I was alone in the world now—alone and with only a few thousands of pounds betwixt me and want, should I fail with my brush.

"I was awakened at last to the reality of life, and tried hard to do my best to face its storms.

"My great book! I laid my plans before publisher after publisher. Some of these received me kindly, praised the idea, but did not see their way.

"One told me that the people were not educated yet up to such a work, and it was to the people he had to look for success.

"I laid my plans before great artists. Each and all of these dissuaded me from any such undertaking. I called this envy. O the vanity of young manhood!

"I visited printers and lithographers next, as well as engravers. Each and all of these assured me the world was ripe for such a work, and by publishing it myself I should not only secure fame, but all the profits.

"I went home rejoicing, and at once commenced to work out my scheme. I soon after retired to a quiet rural village, and here I lived like a recluse for a whole year, working but dreaming as well.

"My work was finished.

"My book was published. The Easel and the Harp. The Thistle and the Rose!

"It did not go like wild-fire. The critics hardly noticed it, not even to revile. I wished they had. Hardly a copy was sold, and I was all but ruined.

"I saw my vanity when it was too late. How bitterly now I felt the truth of the scriptural text, 'Pride goes before a fall, and haughtiness before destruction.'

"I had not been like the moth that seeks glory by courting a too close acquaintanceship with the candle, and falls groundwards with singed wings; but like the moth that set out to fly to the evening star, when, lo! clouds arose and rain fell, then down came the all too ambitious flutterer, every gossamer featherlet in its downy body draggled and wet, to lie in the grass and suffer sorrow.

"In pride, in reasoning pride, our error lies;

All quit their sphere, and rush into the skies.

Pride still is aiming at the blest abodes,

Men would be angels, angels would be gods.

"I hardly cared now to meet my old associates, much less my old masters. They had warned me in my overweening pride, I spurned their warning, and now I was crushed and hopeless.

"I believe to this day that I took my punishment like a man, I did not even pretend to laugh and treat my discomfiture lightly; so many of my friends would have stuck to me, and assisted me up again once more. But I shook the dust of London from my feet, and went away once more into the country to meditate and think. There still was hope for me. I was young, why should I mourn?

"The moth that tried to reach the star was able to fly again next evening, though it never could be the same moth as before. I had aimed at a too high ideal. I thought I had almost reached it. I fell. But I should rise again. Yes; but never the same man.

"I should leave this country, however and begin life anew in some far distant clime, and—so I vowed—endeavour to climb the ladder of fame one step at a time, instead of foolishly trying to rush it as I had done.

"And now I did the only wise thing I had yet done in my life. I took the little remains of my fortune—it consisted only of hundreds now—and placed it in a bank, keeping but enough to last me with economy a year. Then I left my native land, taking ship for the Antipodes as a steerage passenger. I even changed my name, so determined was I to forget all my past life.

"There was one portion of it, however, I never could forget, and that was the short but happy time I had spent during my convalescence in the little village, and the humble fisher lassie's last tearful looks of adieu. That would be the loadstone that should draw me back to Britain if anything ever could.

"But I became strangely enamoured of a sea life and of ships and sailor men. We had a long, dreary passage out around the Cape in a sailing vessel, and before I had been out a fortnight I asked permission of the captain, and obtained it too, to go before the mast.

"Perhaps I had found my vocation at last. I almost believed I had, for in a month's time there was scarcely any part of a seaman's duty I could not perform, and before we reached Australia I was dubbed a sailor.

"I had been a favourite with my messmates, and even with the few passengers aft, and I believe all were sorry to part with me.

"But the gold fever was then at its height, and what more natural than I should catch it? Not all at once, however. I stayed around Sydney for a time. I managed to beat up several newspaper men and artists like myself. But this work was all too slow, the remuneration too small, for me.

"One day I found myself standing alone in the street in the drizzling rain, without hope, without a home, and nothing belonging to me except the somewhat tattered clothes I wore. I was near a newspaper office, and was about to enter to beg—not for money, boys, I'd have died sooner—but for work, when I found myself face to face with a man who was, like myself, an artist.

"'Off to the diggings!' he cried merrily. 'Join me, old fellow, join me. We will return as rich as Croesus.'

"'I'd go,' I said, 'but I'm——'

"I turned out my empty pockets.

"'I'll wait for you a week,' he said, 'and you shall work. Come in here.'

"He pulled me inside the very office I had been about to enter; and in a fortnight's time we were both marching away to the diggings, with hopes as high as the fleecy clouds and hearts as—well, as light as our purses.

"Did we succeed? At last we did, after ten years of a life of back-breaking slavery. We stuck together all this time, and our adventures would have filled a lordly volume. We found time, too, to write to the papers, and send many a sketch of life at the diggings.

"We made a pile at last, and gladly agreed to leave this rough-and-tumble life and settle in some town, or come back—this was my idea—to Scotland.

"Fools that we were, we gave what was called a 'glorification' to our friends the night before we were to start on horseback with our pile away through the bush.

"I hate to dwell on this part of my story. But there came that evening to our camp two Irish strangers. They seemed green-hands, and I and my friend took them in and treated them well We talked too freely about our wealth of gold, and we lived to repent it.

"We bade all the camp good-bye next day, and with our convoy started for Melbourne.

"Day after day, day after day, through forest and bush, living on damper and wretched tea, and sleeping by night under the stars, but light-hearted and happy.

"'Hold! Put up your hands!'

"It was a shout of command, given by two men on horseback as we rode through a beautiful gully one day.

"We had no time to draw and defend ourselves, and our servants were paralysed with fear.

"The robbers were the self-same Irish green-hands we had entertained in camp.

"Of all our pile they left us barely fifty pounds a piece, and this, they told us, they gave us out of charity.

* * * * *

"Two months after this I was serving as a common sailor on a merchant ship bound for San Francisco.

"During the long, hard years in the Australian bush I had not quite forgotten my art, and I hoped to make it pay in a new land.

"Once more I was partially successful. Once again, boys, I began to dream dreams of greatness, and once again my dreams worked my ruin.

"My art was praised by some, my verses were said by others to have about them the ring and rhythm of the born bard. I forgot or neglected art for poesy, and soon found myself penniless and without work itself.

"Ambition, lads, is a grand thing; but it must be guided by a steady hand at the tiller, or it is a ship that will never sail into the haven of success.

"I need not tell you all, nor any of my wild adventures for the next eight years of my life by sea or land. You have heard the mythological tale of the man who prayed that everything he touched might turn into gold, and how the gods granted his prayer, and how his very food became gold as he tried to lift it to his lips, so that he died of starvation. Nothing I touched turned to gold, but, like Dead-sea fruit, every scheme of mine turned to dust in my attempt to grasp it.

"At last, in a fight with lions in the forests of Africa, I was seized and carried away by a man-eater. The monster was wounded, and, though he lacerated me fearfully, he laid down and died at my side. My companions soon followed and found me, and after a weary time I recovered a tithe, but not more, of my former life and spirit.

"The adventure had made almost an old man of me, and in my weakness and debility I had but one wish, one desire—to return to my native land and die!

"I did return. Providence was good to me, and the sea had in some measure restored me a portion of my pristine strength.

"I visited my Highland home and my mother's grave. Then an irresistible longing stole over me to visit this little wild glen.

"I stood one day on the very hill-top where well-nigh twenty years ago I had dreamt of nought save glory.

"All seemed the same on this sweet summer's day, the sea, the hills, the rocks, the wee whitewashed houses standing among the greenery of the waving birches, and the blue smoke trailing over the trees.

"Then I went quietly down the hill. Alas! where now was the bounding fire and fury of my youth? I almost shuddered when I saw the precipice over which I had fallen, and the pine tree still denuded of branches that had saved my life.

"In a few minutes more I stood at the door of the village inn. There were new people here now, but the old folks could scarce have known me, so changed had I become.

"While I munched my morsel of bread and cheese, washed down with milk, a tall figure passed the window leading a child. I knew her step at once, though she too was sadly changed. But I wondered to notice that her hair was sprinkled with gray.

"All my heart seemed to go forth to her.

"'That,' said the landlady, 'is the kindliest creature in all the parish.'

"'Her name?' I almost gasped.

"'Miss Elspet Deane.'

"'Miss? Ah, then she is not married?'

"'No; there is some sad story about her—about an artist she ought to have married, but who went away and was drowned at sea.'

"'And you say she is good and kind?'

"'Good and kind, sir! What would the clachan do without her? We all call her auntie. I don't know why. Some bairnies began it, I suppose. Ah! don't the bairnies love her, sir! And she lives all by herself, and that wee laddie in the house where her parents died. Never a child is ill in the village, sir, that she doesn't attend. She gathers the herbs and simples on the moors, and mixes them with her own honest hands, and little toddlers will take physic from her who would spurn it from the doctor.'

"'Dear sir,' continued this somewhat garrulous landlady, 'death itself doesn't seem so dreadful when she is in the room. And she has aye a word of comfort for poor wives, when their boats are detained at sea or blown far, far away by the raging storm. On that terrible Tuesday, sir, and all the dark drear night that followed, when the wind blew louder and the sea was wilder than anybody ever remembered it before—when out of eleven boats and their brave crews but only five regained the shore, Miss Elspet was everywhere, directing, sir, and comforting, praying with the widows and the fatherless bairns, and sometimes even scolding the women for their want of trust in the Maker—like a very angel in the midst of the great grief that wailed around her.'

"'The boy, sir? He had no mother, and his father was drowned on that stormy night——"

"I stopped to hear no more,

"In ten minutes' time I was in the well-remembered wee room in Elspet's house, and she stood before me.

"I thought that, hardy and strong as she was, she would have faulted.

"'Eppie,' I said, 'it is me!' Yes, boys, I forgot my grammar just then. 'You could not marry me when I was rich and young, now I am old—though not in years—and I am poor and ill. You nursed me once, Eppie. Will you nurse me again?' Ah! lads, it has been a new life to me since the village bells rang on our wedding morn. I have found peace and contentment at last, and after the fever of life I can rest me here. Are we not happy, Eppie?"

He did not give Eppie time to reply.

"Yonder sits the drowned fisherman's son, Fred, who saved your life to-day, Frank Fielding."

"And the wee thing who has gone to sleep on my lap," said Frank Fielding, "she is?"

"A shipwrecked waif; a stray from the sea. But now, lads, to bed."

Then the birr-rr-rr of the wheel ceased, and Eppie, rising, took wee Toddie from Frank to carry her off to bed.

But Toddie was wide awake now, and all dimples, smiles, and yellow hair.

She pointed a fat little forefinger at Frank as she was being borne away on Eppie's shoulder.

"Be a dood boy, Flank," she cried, "and mind oo say oo players."

Frank Fielding wondered where he was when he awoke next morning, and found the sun shining in through the window of the little cosy room in which he had slept so soundly after his adventure, the night before.

Fred's room was in a back wing of the cottage that looked right away out to sea. But Fred had not slept so well, and the reason was not far to seek. He had often before heard his Daddy Pop, as he called the old fisherman, tell snatches of his life story, but never had listened to its complete recital. And when he retired that night to his little chamber he was as full of thought as any boy of his age can be. The feeling uppermost in the lad's innocent mind was one of sorrow for Daddy Pop's sadly wasted life. The old man had made it so plain to his listeners what the cause of his failure had been. He had been a dreamer instead of a student and a worker. Would there, he thought, be any chance for a humble lad like himself doing well in the world if he worked and studied? The question kept him awake half the night, and even then he hadn't half answered it. But long before this he had made up his mind that he would work and study, and he really felt thankful he had the chance, for the parish church school he attended was excellent—in other words, it was thoroughly Scottish—it sent at least half a dozen lads every year straight from it away to the University, and more than one of these had become senior wranglers at Cambridge or double first classes at Oxford.

But what, thought Fred to himself that night, was the good of being a wrangler? whatever the somewhat pugilistic word might mean. He supposed, however, it meant that the wranglership opened the way to one through the thorny jungle of life, and softened many a difficulty.

He thought, nevertheless, he shouldn't care much to be a wrangler. One wrangler, he remembered, had come back to his own Highland parish to die. That was what wrangling had done for him.

Fred did not care a very great deal for either Latin or Greek, both of which languages he was already well versed in. But then Daddy Pop had told him—and didn't Daddy Pop know everything?—that learning and study made one active-minded, clever, and bright; that, in fact, it wasn't so much what anyone actually did learn as the actual learning of it, that did the good, and increased the size and fertility of the brain just as—and these were Daddy's own words—the ploughing and harrowing of a field fitted it to receive any sort of seed that might be sown therein. "But," Daddy Pop had added, "it is as well to learn what will be useful in after life, and the so-called dead languages would be so."

Fred perhaps ought to have gone to sleep as soon as he went to bed; but having once commenced to think he could not. He thought out all Daddy Pop's story, first lying on one side, then he rolled over on the other, and thought it all over again. Then, as it was getting late, he rolled over on his back and determined to sleep. Pah! he might as well have tried to fly.

"Well," he said to himself, "I don't see any good in lying here tumbling all the bed. It is hard work, and nothing good to show for."

So up he jumped, and drew aside his little window-blind. The window was in shadow; but he could sea that the moon was shining brightly over the sea, so he quietly dressed himself, opened wide the window, and sat down beside it.

Toddie's dachshund was out there under a bush, and coughed a low enquiring sort of a bark at him.

"Down, Tippetty, down!" said Fred.

Tippetty did lie down, but not without a little growl of displeasure.

"You ought to be in bed, you know," the little wise fellow appeared to say; "and I'm responsible for the safety of this establishment after nightfall."

Fred gave himself up to thought now, just as heartily as in bed he had tried to avoid it. Of course there was a little castle-building mixed up with these cogitations of his. And I would not care much for a boy who did not build a few castles in the air at times, and inhabit them too; for what, after all, is castle-building but a kind of budding ambition?

Now Fred Arundel's father had been drowned when the boy was far too young to know the meaning of the sacred word "parent," while his mother had been taken away quite in his babyhood. But he had come to love and respect his foster-parents very much indeed. They were all in all to him. Fred was a good-natured lad, and there was nothing he would not have done to give the kindly old couple an hour's happiness.

Well, but for them he might have been running about in rags and wretchedness a "mitherless bairn,"

"When a' other bairnies are hushed to their hame,

By auntie, or cousin, or freckled grand-dame,

Who stands lost and lonely, wi' nobody carin'?

'Tis the poor doited laddie—the mitherless bairn,

"The mitherless bairn gangs to his lone bed,

Nane covers his cauld back, or haps his bare head;

His wee hackit heelies are hard as the iron,

And litheless the lair o' the mitherless bairn."

But Fred could not have been called "a mitherless bairn." And indeed if you were to have asked the lad confidentially he would have told you he was not a "bairn" in any sense of the word, but almost a man.

"Daddy Pop is old," thought Fred, "but he may live for twenty years and more yet, and so may Mammy too. Twenty years, what a long time! Why I shall be getting old myself in that time. Now although Daddy had some money in the bank before he went away on his long wanderings, and found when he came back that it had grown into a heap more; and although he had enough to build this cottage, and a fine fishing-boat also, still I know he isn't rich. His bed is not a very soft one, he doesn't live so well as I would like him to; he says he can't afford an easy chair, and that his Sunday coat is good enough. Well, if I had money, Daddy would have such a lot of comforts, and so would Mammy Mop. Why shouldn't Mammy have a silk dress as well as farmer Grigg's wife? She shall have it.

"Why shouldn't Daddy have an easy chair and a better pair of specs, and an easier seat in the cave among the rocks in which he writes his beautiful poetry? My Daddy shall be comfortable when I am older. But what shall I be? I can't be a fisher lad. Oh, no! I must travel and see the world, and—but, dear me! common sailors don't get rich, and Sandie Davis told me, after he came back from being all round and round the world, that often and often he was not allowed to put a foot on shore even in some of the prettiest places on the face of the earth. Sandie told me this because he likes me. Sandie wouldn't tell everybody, I'm sure of that. It wasn't for the half crown I lent Sandie that he likes me. Oh, no!

"But what does Sandie do? He comes home wearing his best blue clothes, and a dandy tie, and silver rings and things, and to hear him talk anybody would think he had been first officer of a ship. He smokes and takes beer—not that he pays for it, except by the stories—yarns he calls them—that he tells those who treat him. No, poor Sandie never has a penny to bless himself with after he has been two weeks at home. That isn't the kind of sailor I'm going to be, if ever I'm a sailor at all. Sandie's mother has a lot of 'curios,' as he calls them—some wonderful Japanese boxes, bottles of eau de Cologne, a funny-looking tea-caddy made out of a nut, an ostrich's egg, a savage's spear, and an old bow and arrow; but nothing she can eat or wear. She can't even eat the ostrich's egg, and funny she'd look going about with that dirty old bow and arrow.

"He's not a bad fellow, though he boasts and brags, and talks through his nose, and says words I never heard before, and don't wish to hear again, for sailors like Sandie would make me sick of the sea.

"No, I'll be something—something. I'm going to study and work to begin with, and then——"

Only the moonlight lying clear on the sea, only the lisp of the waves on the shore, only the whisper of wind in the trees, only—why, it can't surely be daylight already!

But it is though, and has been for hours, though Fred still sits there, his face and his arms, and his bare head exposed to the morning breeze.

"Oh, you naughty Fred!" cried Toddie, discovering her foster-brother, and pulling his hair to wake him. "Oo has never been to bed. I declare oo'll bleak my heart; and Flank and I has been all wound the beach and at the atwalium (aquarium) too. Flank's a dear, dood boy. Tome to bleakfast at once, I tell oo."

Fred looked up, smiling sleepily, then he gave himself a shake, as a dog would, jumped right through the window, and patted Toddie's head.

"I'll be back in ten minutes, Toddie, old woman," he said.

Then straight for the rocks he ran, and divesting himself of his clothes in a little recess, sprang in, had a good swim, and returned home singing, and quite as happy as the skylark that was lilting high above the woods.

Frank came out of the cottage to meet him, and the two lads shook hands heartily.

"You're none the worse for your ducking," said Fred.

"No, all the better. Ha! ha! I wonder what mother will say? But tell me, are you always so late of coming down to breakfast?"

Fred laughed.

"It isn't coming down," he said, "because, you know, we haven't any up. Yours is a big fine house, I suppose?"

"It's a fair size. Two story, you know, and all among woods and gardens. Oh, I'm sure you'll like it!"

It was time for Fred to laugh again.

"Very likely I shall see it," he said somewhat ironically; "but come in till I sup my porridge."

"I've had mine long ago, and so has Toddie, and we've had such a game of romps. But of course you'll come often to Benshee House. I have a Shetland pony and a little trap, and can come over to you."

"Oh! but, Frank Fielding," Fred said solemnly, as he dipped his spoon in a basin of creamy milk, "don't forget I'm only a poor working lad, and you are a young gentleman."

The tears sprang to poor Frank's eyes in a moment but he manfully kept even a single one from falling. He stretched out his hand and grasped that of Fred, even though he had the spoon in it.

"There," said Frank, "I've made you spill the milk. But never mind. Now, Fred, just listen. Don't be a fool. I'm not a cad, mind. My father is a Scotchman, though my mother is English. My father made his money in stocks, and might lose it to-morrow."

"Avertit omen," murmured Fred.

"I don't know Chinese, Fred; but I do know this, you and I are going to be fast friends, and bother the rank and riches. My father makes me learn Burns's poems. My mother thinks they are not bon ton."

"Bong tong," said Fred. "Well, I don't know Japanese."

"Never mind. Just listen to this. I'm going to recite. Father makes me do it. Now here is the scene. You are a baronet and I am Bobbie Burns. I have been visiting you, you know, staying a few days at your mansion, when a nobleman—a downright cad—comes also to visit you, and you ask him if he would object to the ploughman poet dining with him.

"'What!' cries this ignoble nobleman, 'a ploughman singing fellow dining with you and me! How very absurd to be sure!'

"Then you, Sir Fred, are awfully put about, and you come to me sheepishly, and explain matters, and I bite my tongue and don't say anything.

"Well, after dinner his lordship says, 'Now, pon honour, I'd like to hear your singing fellow just for five minutes, don't-cher-know?'

"And so I—Robert Burns—am asked in.

"Of course I'm in a boiling rage at being treated thus. So I strut in and bow to you and his lordship, that is Toddie yonder.

"'Singing fellow,' says the lord, 'give us a specimen of your poetic powahs.'

"And this is the specimen I give:

"'Is there, for honest poverty,

That hangs his head, and a' that?

The coward-slave, we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a' that!

For a' that, and a' that,

Our toils obscure, and a' that,

The rank is but a guinea's stamp,

The man's the gowd* for a' that.

"'Ye see yon Birkie,† ca'ed a lord,

(Frank points at Toddie.)

Wha struts, and stares, and a' that;

Tho' hundreds worship at his word,

He's but a coof‡ for a' that:

For a' that, and a' that,

His riband, star, and a' that,

The man of independent mind,

He looks and laughs at a' that.

"'A prince can mak a belted knight,

A marquis, duke, and a' that;

But an honest man's aboon his might,

Guid faith he canna fa'§ that!

For a' that, and a' that,

It's coming yet, for a' that,

That man to man, the warld o'er,

Shall brothers be for a' that.

* Gold.

† Proud, silly fellow.

‡ Blockhead.

§ Manage.

"Oh!" cried little Toddie, clapping her pink hands, "oo is a pletty boy when oo speaks like that."

"Now," said Frank, laughing, "I think like Burns, Fred, and if you don't come and see me and be friendly it will be all your own fault."

"I'll come," said Fred, laughing, "and if I happen to be carrying a creel of lobsters, I suppose you won't set your dogs at me?"

"Oh, no, because father talks about the dignity of labour, and that would be the dignity of labour. And you know—'a man's a man for a' that.'"

"Bravo! Frank Fielding," cried the old fisherman, entering the room, "How I love your sentiments, my boy. Why they are noble—noble. Shake the old bard's hand."

"Now," said Toddie, "evelybody must hold his tongue, I'se goin' to 'cite a piece."

And this little waif and stray that the Atlantic waves had tossed up on the beach as if she had been seaweed, stepped boldly into the arena, that is, into the middle of the sanded floor.

She was a beautiful child, this Toddie, with large eyes, delicate features, and such a wealth of glossy hair that one could not but wonder how it could have grown on a head so young.

She held one wee arm aloft, and in slow and measured tones, with many a brief but impressive pause, spoke as follows:

"There once was a leetle, leetle dirl,

Who—lived—in a shoe,

And she had so many tsilden,

She—didn't—know—what to do.

But the Dood Lord sent a wild, wild stolm,

An' the waves wose—mountains high.

An lightenin's dleamed acloss the hills,

An' sunders shook the sky.

An' a dleat big whale dot vely sick,

Wi' the wobblin' o' the sea,

An' so he tumbled on the beach,

As dead as dead tould be.

But Bunko took the dleat whale's bones,

As none but Bunko tould,

And set them up adainst the rocks,

And lined them all with wood.

And when the whale was all tomplete,

We named it the Ig-loo,*

And there the little dirl lives,

And all her tsilden too."

* The hut in which Eskimos live.

Frank looked much amused, but quite puzzled; the old bard patted his foster-daughter, and smiled not a little proudly; while Fred roared with laughter because Frank looked so enquiringly droll.

"Is there any meaning in all that?"

"Yes," cried Fred, "and it's all true; at least the last of it. Toddie and I, and Toddie's children, that is her pets and things, do really live in a whale."

"Oh, shouldn't I like to see it!" said Frank. "Hullo!" he added, as the rattling of wheels ceased at the cottage door, "here is mother in the pony chaise, and—why look, there is Bunko himself driving my pony carriage with the Shetland in it! I wonder how the pony allowed him."

"Why not?"

"Oh, because if anybody but myself drives him he nearly always lies down to roll."

Frank ran to meet his mother, who lovingly embraced him. She was a very handsome lady and Toddie really stood in awe of her at first.

"Oh," Toddie said to Fred in a kind of stage whisper, "Oh, Fred, I don't like her much, I weally must suck my fumb."

And so she did.

"And where," said Mrs. Fielding, "are the dear brave children who saved my darling's life?"

"Here is Fred, mamma, and yonder is Toddie, hiding behind her daddy's legs."

"Toddie," said Fred, "take your thumb out of your mouth."

"Come to me both of you. Dear, dear, it was quite an adventure I'm sure. What dear children! I'm sure they ought both to have the Society's medal. Very poor, aren't they? I must do something for them."

These last words, though addressed quietly to Frank, were loud enough for all to hear.

"Oh, ma!" he said.

But the lady heeded not.

"And you are the fisherman poet, are you not, sir?" she said, turning to the bard.

The old man was standing as erect as a statue, his bonnet in his hand, his hair streaming over his neck, and his face somewhat set and stern. He really looked noble. Mrs. Fielding must have felt he did, or she would never have added that little word "sir" in addressing him.

"I've heard of you so often, in really good society too. You write those beautiful verses in a cave, do you not? Why they are in every good magazine. Do you know I should like to see your cave. So romantic! Might I, Mr.——A——."

"Arundel. My cave is a very humble place, Mrs. Fielding; but if you will come with me you shall see it. The road is rough though."

"Oh, I'm very strong!"

Away along by the top of the cliffs he led her for quite a quarter of a mile. Here some bushes grew, and among them was a half-hidden staircase leading downwards into the very bosom of the rocks. The steps had been cut a hundred years ago perhaps by smugglers. No one ever yet found out the mystery of Talbot's cave.

The lady condescended to take the bard's hand, and he led her down. It was almost dark at the bottom, but once in the strange cave it was light enough. Here were two windows, or rather ports, and one of these the bard threw open. Right down beneath was the deep sea, with clear water over shining yellow sand, so clear you could see the beautiful medusæ or jelly fish floating about like splendidly-jewelled parasols. Between the ports was the poet's rough deal table. Here was a bench of deal, and a tall-backed deal chair. The floor was laid with wood, and a great ship-lamp swung from the roof.

The irregular walls were the rough rocks, but much to Mrs. Fielding's amazement, these walls were adorned with water-colour and oil-colour paintings, that to her seemed priceless.

I had almost forgotten to say that there was a fireplace in this cave, and evidence enough too that Eean often had tea here.

But it was the pictures that most attracted the lady's notice.

"These," she said, "are not mere copies?"

"Yes, madam," said the bard, smiling somewhat sadly, "every one of them, but copies from Nature. Mostly things I daubed when travelling abroad, they serve just to remind me of scenes I have passed through during a somewhat chequered career.

"I don't know," said Mrs. Fielding with innocent candour, "which to admire the most, yourself or your surroundings."

"Round every one of these picture things, madam, I have to weave a tale for my foster-children, who come here in the summer and even winter evenings.

"How enchanting. Might my dear boy come sometimes too?"

Eean stretched out his hand as if by sudden impulse, and Mrs. Fielding clasped it cordially.

"Now you do delight me, madam. I love children and your boy is a gentleman."

"I'm so pleased."

Then turning to the windows.

"You will observe," he said, "that the glass in these ports is of very great thickness. Green seas have often dashed over them, yet we have never been flooded. Only on stormy nights I lower great wooden ports."

He untied a chain as he spoke, and down with a thud came a shutter of wood and iron.

"Safe you see against the mightiest gale that ever blew."

"How interesting. The sea too looks charming to-day from your windows. Was it out yonder my poor darling was nearly drowned?"

"Yes, madam."

There was a moment's surcease of talking, during which nothing could be heard but the gentle lap-lapping of the waves on the black rocks beneath.

"Are you fond of animal life, madam?

"Will you be startled if I introduce to you one or two of my pets?"

"But they won't hurt?"

"No, they are good-mannered crabs."

As he spoke the bard took from his pocket a piece of string to which was attached a morsel of fish. This he lowered into the sea through the open port, then slowly drew it up again.

A moment afterwards there came crawling up two immense crabs, and they positively appeared to enter arm in arm, side by side certainly. They paused for a moment on the outside rocky ledge, and gazed at the lady with their stalky eyes.

Seeming perfectly satisfied, they then advanced, and Mrs. Fielding noticed that each had a red cross painted across his dark shell.

The bard quietly spread before them their dinner, and they ate it greedily, rolling their eyes about as they did so with an appearance of great satisfaction.

"Shall I make them dance?" said the poet.

"Oh, do, sir!"

The poet held a morsel of white meat of some kind above them, and in a moment they were standing on one end, hand in hand, or rather claw in claw, dancing round and round and all about in the most comical manner.

The lady laughed till the cave roof rang again.

"Of all things I have ever seen," she said, "that is the most ridiculous."

Then one more morsel was given to each, a red handkerchief was waved, and away the strange performers shuffled, and slowly disappeared over the ledge.

"Now, Mrs. Fielding, what do you think of my red cross knights?"

"Delightful! oh, delightful! But pray, Mr. Arundel, what are the red crosses for?"

"Oh! so that they shall be known by fishermen. They have often been captured in the lobster creels, but no one would think of killing them."

"I have to thank you for such a pleasant hour," said Mrs. Fielding, as they once more emerged upon the cliff top. "Oh, look! Yonder comes my boy with your dear mite on the Shetland pony."

Toddie waved her hand to Daddy Pop.

"Daddy! Daddy!" she shouted as soon as near enough to be heard, "I'se a weal lady now. All I wants is a widing-habit."

"My dear," said Mrs. Fielding, "a riding-habit would hide the beauty of those shapely legs and feet."

Toddie looked at her, and at once commenced to suck her thumb.

"Why do you suck your thumb, dear?"

"Oh, I always suck my fumb when I'se finking!"

"And what are you thinking about, child? What makes you look at me so?"

"Is oo Flank's mammy?"

"Yes, pet."

"Oh-h! Well, I likes Flank mostest. Flank," she added, with the air of a young princess, "we will wide back adain, please."

And away they went at a mad trot, Frank shouting and Toddie screaming.

"Mamma," said Frank when they met at the cottage, "this is a school holiday with Fred. Please may I stay till evening?"

"Did ever I deny you anything, child? But be sure you're home in time. Good-bye, Mr. Arundel. Good-bye, dear children. Drive on, John."

"Dood-bye," shouted Toddie, so gleefully that it must have been evident even to Mrs. Fielding herself that Toddie was glad to be rid of her.

"Now," cried the little madcap, "I feels full of joy up to my mouf. Tippetty and I is off for a wun on the beach. When Tippetty and I has our wun we'll come back for you boys, and to-night we'll have tea in the whale. Tippetty! Tippetty! oh, here tomes Tip!"

And off bounded Toddy and Tip, and no one seeing the two scampering across the level sands would have cared to say which was the wilder or which the defter.

Toddie's little arms and legs were bare, she had pulled off her red fisherman's cap to wave it above her head, and as she dashed on to meet the roaring sea her hair floated straight behind her in the breeze. And Tippetty, the dachshund, barking with all his might, came just a little in advance.

This spoke volumes for the strength of Tip's lungs. Though lovely and hound-like in head, like all dachshunds, he was bandy in legs, very low to the ground, and of tremendous length. So long and low indeed was he, that when at the gallop his black body wriggled like an eel. So long was he that he could not jump on a chair. He could put his two paws and head up, but if asked to spring, he looked about him wisely at his tail end, as much as to say,

"I would jump up willingly with my front part, don't you know? but then the other end of the procession wouldn't come along."